Introduction

Glucosamine is a natural amino sugar that is used as

one of the building blocks of the body, such as in cartilage and

tendon. Therefore, it has been used to treat patients with painful

knee osteoarthritis and in complementary and alternative medicine

as an osteoarthritis cure (1,2). In

addition, a number of studies have reported that glucosamine

inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis in various types of cancer (3,4). Other

studies have described target proteins of glucosamine, such as

transglutaminase 2, p70S6K, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α),

cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and the insulin-like growth factor 1

receptor (IGF-1R)/Akt pathway (5–9). These

studies propose that glucosamine has potential value as an

antiproliferative drug.

Facilitative glucose transporters (GLUTs) are

integral membrane proteins that have 12 transmembrane domains and a

binding site for hexose substrates such as glucose, fructose and

glucosamine (10). A total of 13

GLUT isoforms with highly conserved amino acid sequences and 12

hydrophobic α-helical domains have been identified and

characterized in mammalian cells. Each GLUT isoform has a different

expression level in various tissues and organs and plays a specific

role in the energy-independent uptake of hexoses. For instance,

GLUT1, which is highly expressed in all tissues, is in charge of

basal glucose transport; GLUT2, which is abundant in liver,

pancreatic islet and retinal cells, has a higher affinity for

glucosamine than glucose (11).

Cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to

support their rapid growth and proliferation. One hallmark of this

reprogramming is the Warburg effect, which describes the preference

of cancer cells for aerobic glycolysis, even in the presence of

sufficient oxygen (12). This

phenomenon allows cancer cells to generate ATP quickly while

producing metabolic intermediates essential for biosynthesis. A

number of previous studies have also demonstrated that GLUTs are

overexpressed in various types of cancer, facilitating increased

glucose uptake to sustain the heightened glycolytic flux. This

overexpression of GLUT proteins has been closely associated with

aggressive tumor behavior, including metastasis and poor prognosis

(13,14).

Once hexoses are transported into the cytoplasm,

they are catalyzed by hexokinases (HKs), which carry out the first

and rate-limiting step of the hexose metabolic pathway. In addition

to glycolysis, HK also performs the irreversible step in the

hexosamine pathway that converts hexose to hexose-6-phosphate,

using an ATP molecule to start the process (15). In humans and other mammals, four HK

isoforms have identified; HKI, II, III and IV (glucokinase). HKI,

II and III have a high affinity for glucose and a molecular mass of

~100 kDa, whereas HKIV has a molecular mass of ~50 kDa and can only

phosphorylate glucose, giving it a higher Km than the

other HKs (16). During cancer

progression, among those HKs, HKII, which has low affinity for

glucose and is only slightly expressed in normal tissues, is

markedly upregulated (17),

suggesting that HKII plays an important role in malignancy.

HIF-1, a heterodimer consisting of α and β subunits,

is stabilized under hypoxic conditions and plays a pivotal role in

the glycolytic phenotype in human cancers (18). It has been reported that HIF-1α acts

as a transcription factor and increases expressions of GLUTs and

HKs and thus, tumor cells which are in hypoxic conditions activate

HIF-1α to facilitate glucose uptake and glycolysis to satisfy their

energy demands (19). Furthermore,

since the metabolic reprogramming induced by HIF-1α helps cancer

cells to grow, cancer cells turn on HIF-1α even with enough

oxygens, a phenomenon called pseudohypoxia (20). These features make cancer cells more

resistant to glycolysis inhibitors, such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose

(2-DG), by increasing the number of glycolytic enzymes (21).

Malignant cancer cells have an elevated and

accelerated glucose metabolism due to increased requirements for

glucose, which is essential as an energy source (17). In addition, dysfunction of the Krebs

cycle caused by mitochondrial mutations leads to increased

dependence on glycolysis by cancer cells for ATP production

(22). Therefore, it is not

surprising that the increased aerobic glycolysis in cancer is

closely related to overexpression of GLUTs and HKII in various

types of cancer. A number of researchers have used glucose analogs

such as fluorodeoxyglucose and 2-DG and HKII inhibitors such as

3-bromopyruvate (3-BrPA) to study interference of glucose uptake

and glycolysis (15,23). As stated for the aforementioned

molecules, these results indicate that glucosamine also may be a

glycolysis inhibitor.

Based on these preliminary studies, the present

study sought to determine whether the antiproliferative activity of

glucosamine occurs because it is a glycolysis inhibitor in various

cancer cells and whether GLUTs, HK isoforms and HIF-1α affect the

sensitivity to glucosamine of cancer cells. It showed a new

mechanism of glucosamine to specifically inhibit the glycolytic

pathway to suppress cancer progression.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and agents

Human liver cancer cell lines (HepG2 and Hep3B),

non-small cell lung cancer cell lines (A549, H1299 and H460) and

breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and T47D) were

purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in

RPMI 1640 (PAA Laboratories GmbH) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; PAA Laboratories GmbH) and 100 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The

authenticity of all eight cell lines used in the present study was

validated by short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling, which was

performed using PowerPlex 18D system by commercial service (Cosmo

Genetech).

D-(+)-glucose, D-(+)-glucosamine hydrochloride,

cytochalasin B and phloretin were purchased from MilliporeSigma,

while 2-DG and 3-BrPA were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry.

In the competition experiment between glucose and glucosamine,

glucose-free RPMI 1640 medium (MilliporeSigma) was used and cells

were pre-incubated for 24 h with the indicated doses of glucose

prior to being treated with glucosamine.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using

TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

chloroform extraction. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 5 µg

of total RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Semiquantitative PCR was performed in

a thermal cycler (MyCycler; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) using

gene-specific primer sets and sequences of primers are listed in

the supplementary Table SI. The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 5 min, followed by 25–45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C,

annealing at 42–60°C for 30 sec (depending on the target gene), and

elongation at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 5

min. The reactions were stopped during the exponential phase to

ensure accurate comparisons. ACTB was used as a reference

gene. PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.2–1.5% agarose gel and

visualized using ethidium bromide.

siRNA transfection

A549 and HepG2 cells (2.5×105 cells/well)

were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with double-stranded

small interfering RNA (siRNA). Target-specific siRNAs were designed

for knockdown of GLUT1, GLUT2 and HIF1A were from

Bioneer Corporation and MBiotech, respectively. A scrambled siRNA

(siSCR) was synthesized and validated by Bioneer Corporation. The

sense and anti-sense sequences of siRNAs are listed in the Table SII. Following 25 pmole of siRNA

transfection for 24 h at 37°C using Lipofectamine®

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions, subsequent experiments were

conducted. Knockdown of GLUT1, GLUT2 and HIF1A expression

were validated by semiquantitative RT-PCR. The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 25–45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C, annealing at

42–60°C for 30 sec (depending on the target gene), and elongation

at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The

reactions were stopped during the exponential phase to ensure

accurate comparisons. ACTB was used as a reference gene. PCR

products were electrophoresed on 1.2–1.5% agarose gel and

visualized using ethidium bromide.

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were prepared using RIPA-B lysis

buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 20 mM Tris-Cl

(pH 7.4), 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM

Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 10% glycerol and protease

inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). Protein concentration

was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Equivalent amounts of proteins (10–20 µg per

lane, depending on the target protein) were separated by

electrophoresis on 6, 8, 10 or 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to

a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Pall Corporation). Membranes

were blocked with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1 h. The

membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies against phosphorylated (p-)Akt (1:1,000, cat. no. 9271,

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), Akt (1:1,000, cat. no. 4691, Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), a/β-tubulin (1:1,000, cat. no. 2148,

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), IGF-1R (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-713,

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and COX-2 (1:1,000; cat. no.

sc-1745, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). After washing with

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, the membranes were

incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary

antibodies (1:10,000; cat. no. AbC-5001 for anti-mouse antibody and

cat. no. AbC-5003 for anti-rabbit antibody, Abclon) for 1 h at room

temperature. Immunoreactive bands were detected using enhanced

chemiluminescence (AbSignal; Abclon).

MTT assay

Cells (3.0×103 cells/well) were seeded

into 96-well plates, incubated overnight at 37°C and treated with

glucosamine or other agents. Control groups were given dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO; 0.1% final concentration) or phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS) vehicle. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. An

insoluble purple formazan precipitate was solubilized in DMSO and

the absorbance was determined by microplate spectrometer at 562

nm.

Cell cycle analysis

A549 and HepG2 cells (1.5×105) were

plated onto 60×15 mm dishes for 1 day and then cells were treated

with glucose (1, 10, 20, or 50 mM) and glucosamine (1, 2, or 5 mM)

at 37°C. Glucose was administered for 48 h and glucosamine was

co-administered with glucose during the last 24 h of that period.

After treatment, cells were washed once with PBS, trypsinized and

harvested. All the harvested cells were fixed in 70% ethanol for 1

h at 4°C. After centrifugation for 5 min. at 1,000 × g and 4°C,

cell pellets were washed twice with PBS and then stained with PI

containing RNase A (40 µg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Total

DNA contents were detected by BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences), and analyzed using FlowJo 10.10.0 (FlowJo LLC).

Apoptosis analysis

A549 and HepG2 cells (1.5×105) were

plated onto 60×15 mm dishes for 1 day and after treated with

glucosamine for 48 h, cells were harvested and washed twice with

PBS on ice. Then, cells were stained using the FITC Annexin V

Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences). Cells

were resuspended in 1× binding buffer containing 5 µl of

fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-Annexin V and 5 µl of PI. After

staining, cells were detected by BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences) at 488 and 633 nm, and analyzed using FlowJo 10.10.0

(FlowJo LLC). The apoptotic rate was calculated as the percentage

of early apoptotic cells and the percentage of late apoptotic

cells. All procedures were carried out according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of glucosamine consumption

rate

Cells (2.5×105 cells/well) were seeded in

6-well plates and incubated under RPMI 1640 medium containing the

indicated concentrations of glucosamine. Glucosamine in harvested

culture medium was reacted using D-Glucosamine Assay Kits

(K-GAMINE; Megazyme) and optical density was measured with a

spectrophotometer at 340 nm. All procedures were carried out

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of lactate production

The cellular glycolytic efficiency could be

estimated by measuring the cellular lactate generation rate. Cells

(2.5×105 cells/well) in the exponential growth phase

were plated in 6-well plates for 1 day and cells were washed and

treated with indicated concentrations of glucosamine for an

additional 24 h. Aliquots of the culture medium were withdrawn and

used for analysis of secreted lactic acid using the YSI 2300D STAT

Plus Glucose and Lactate Analyzer (YSI Inc.).

Whole genome gene expression

analysis

A549 cells were treated with DMSO or 5 mM of

glucosamine for 24 h at 37°C and RNA was isolated. From each

sample, 500 ng of total RNA was biotinylated and amplified using

the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

cRNA yield was measured using RiboGreen RNA quantitation kit

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. and 750 ng of the cRNA

sample was hybridized on a human HT-12 expression bead chip

(Illumina, Inc.) profiling 48,804 transcripts per sample. The chips

were stained with streptavidin and scanned using an Illumina

BeadArray Reader (Illumina, Inc.). BeadStudio v3 (Illumina, Inc.)

was used to quantile-normalize the data.

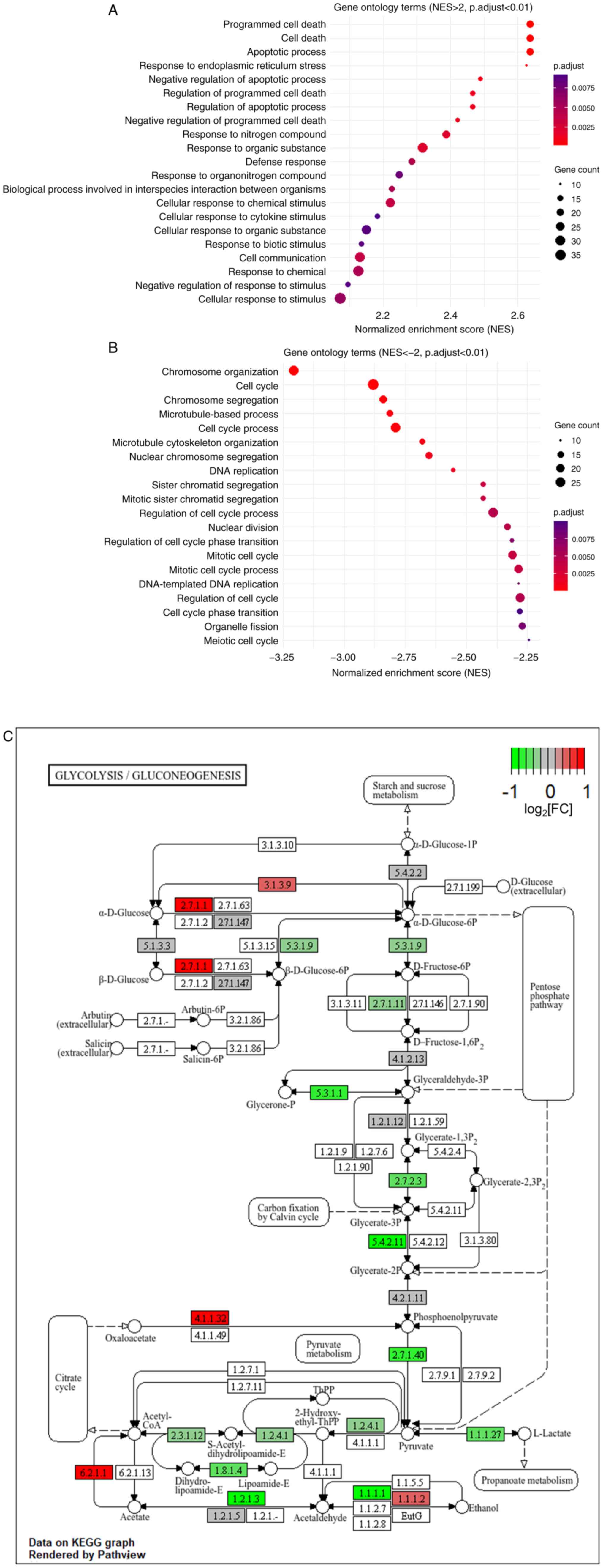

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed on genes

that were increased or decreased by more than 2-fold in the

glucosamine-treated sample compared with the control. The analysis

was conducted using the gseGO function in the clusterProfiler

package (ver. 4.14.3) (24) in R

software (ver. 4.4.1, R Core Team, 2024) (25), based on the Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis approach. GO terms which have adjust P-value <0.01 were

considered markedly regulated GO. Up- or downregulated GO terms

were featured by R software.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway enrichment analysis was performed on differentially

expressed genes using the enrichKEGG function from the

clusterProfiler package in R software. The result of glycolysis

pathway (hsa00010) was visualized using the Pathview package

(Release 3.20) (26).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using

GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft

Corporation). For comparisons involving more than three groups,

one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. For

comparisons between two groups, the Student's t-test was employed.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Glucosamine regulates some gene sets

related to glycolysis

In 1953, J.H. Quastel and A. Cantero demonstrated,

for the first time, that D-glucosamine inhibits the tumor growth in

a xenograft mouse model (27).

After their findings, a number of studies have sought to discover

the mechanism and related molecules in this antiproliferative

effect. A number of studies have demonstrated that glucosamine

decreases the ATP level in cancer cells and inhibits oncogenes,

such as IGF-1R, HIF-1α and COX-2 (8,9,21).

However, the mechanism has not been described in detail. Therefore,

the present study used a microarray to screen genes that are

regulated directly or affected indirectly by glucosamine. Genes

induced by glucosamine more than two folds were categorized mainly

into pro-apoptosis and cell death (Fig.

1A), while genes downregulated by glucosamine more than two

folds mostly belonged to cell cycle and DNA damage responses

(Fig. 1B). Next, the present study

examined whether the genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism,

biomolecules biosynthesis and glycosylation, which pathways are

highly associated with glycolysis (28–30),

are regulated by glucosamine. Notably, as shown in Table SIII, several genes upregulated by

glucosamine more than twofold were involved in these pathways.

Also, pathway enrichment of differential genes was used and then

the KEGG pathway analysis results viewed to see whether the

differential genes are enriched in glycolysis. As a result,

differential genes are represented in the glycolysis pathway and

their expression is primarily downregulated by glucosamine

(Fig. 1C). With all these findings,

glucosamine's similar structure to glucose and its reduction of ATP

levels in cancer cells (4), as

demonstrated by previous studies, it was assumed that glycolysis is

the main target pathway of glucosamine.

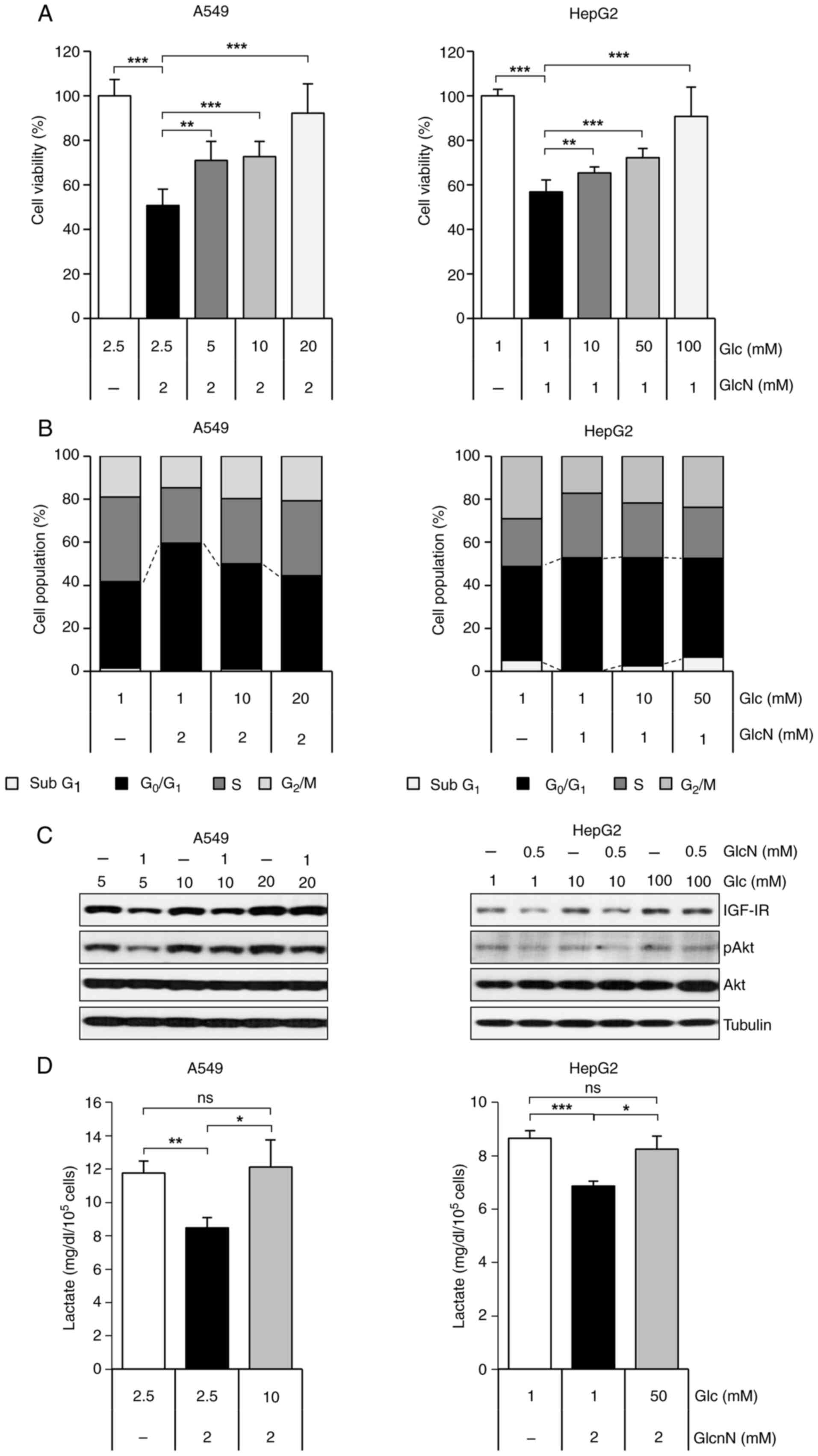

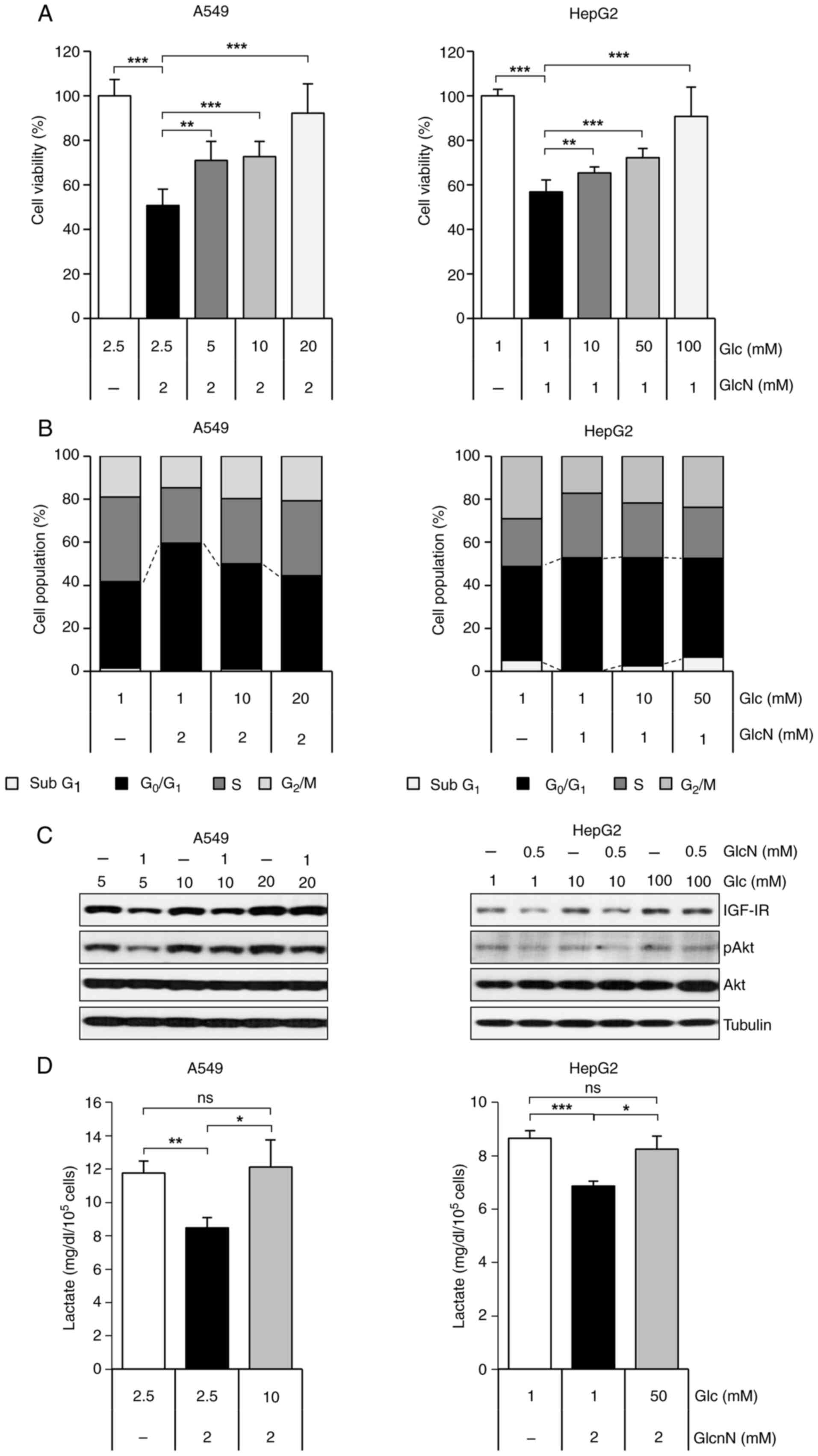

Competitive relationship between

glucose and glucosamine constrains the inhibitory effects of

glucosamine in cancer cells

Other than its NH2 group, glucosamine has

a structure very similar to that of glucose. In fact, several

studies have demonstrated that glucosamine competes with glucose in

carbohydrate metabolism (31–33).

Based on this, whether its antiproliferative effect is linked to

this competitive relationship was investigated. A recent study has

shown that glucosamine exhibits antiproliferative effects on a

liver cancer cell line (34), while

our previous research demonstrated similar effects on lung cancer

cell lines (9). Therefore, the

present study initially conducted experiments on HepG2 liver cancer

cell line and A549 lung cancer cell line. Under low level of

glucose, glucosamine inhibited proliferation of A549 and HepG2

cancer cells, which anti-proliferative effects of glucosamine were

reversed by increasing glucose concentration (Fig. 2A). Glucose-treated cells also showed

a dose-dependent recovery of the G0/G1 arrest induced by

glucosamine (Fig. 2B). Since

previous studies showed that glucosamine inhibits the IGF-1R/Akt

pathway (9,35), the present study next investigated

the effect of glucose on these target molecules. As expected,

IGF-1R and p-Akt expression levels that had been reduced by

glucosamine were restored as concentrations of glucose increased

(Fig. 2C). To determine whether the

competitive effect of glucose and glucosamine occurs during

glycolysis in cancer cells, the level of lactate, which is produced

from pyruvate during glycolysis was investigated. Glucosamine

markedly suppressed lactate production, but this suppression was

nearly reversed with a high dose of glucose (Fig. 2D). These findings suggested that the

antiproliferative effect of glucosamine was closely related to

competition between glucose and glucosamine, which occurs during

glycolysis.

| Figure 2.GlcN-induced anticancer effect occurs

through competition with Glc. (A) Cell viability of A549 and HepG2

cells after treatment with Glc and GlcN for 48 h. Cell viability

was measured by MTT assay and results are presented as mean ±

standard deviation. (B) Cell population by cell cycle of A549 and

HepG2 cells after treated with Glc and GlcN. Cells were treated

with Glc for 24 h, followed by additional 24 h treatment with GlcN.

Cell cycle analysis was performed after propidium-iodide staining.

(C) Western blot analysis of IGF-1R, p-Akt and Akt expression

levels in A549 and HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with indicated

concentrations of Glc and GlcN for 24 h. (D) Lactate production in

A549 and HepG2 cell lines after treatment with Glc and GlcN for 24

h. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, no significance; Glc, glucose;

GlcN, glucosamine; p-, phosphorylated; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth

factor 1 receptor. |

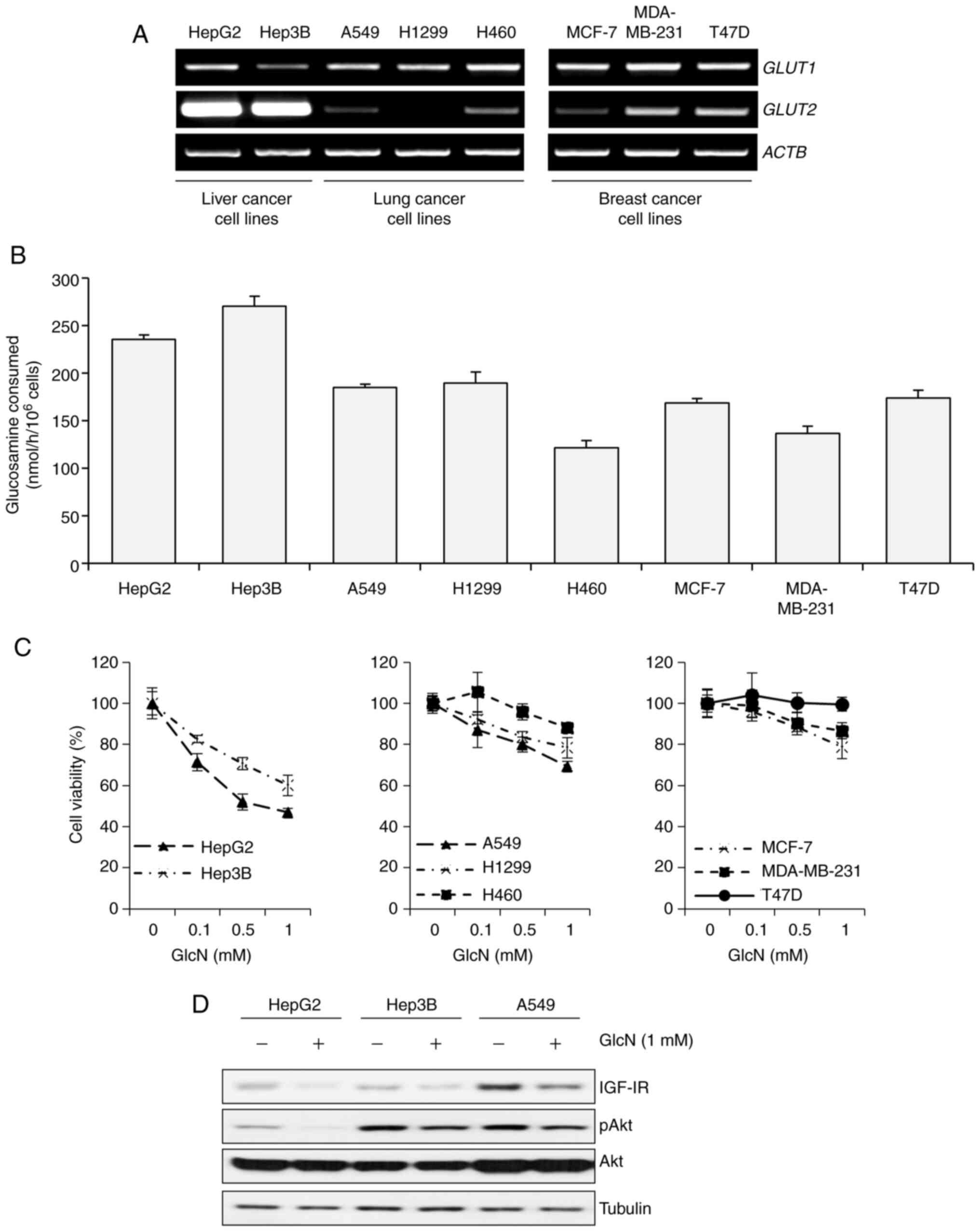

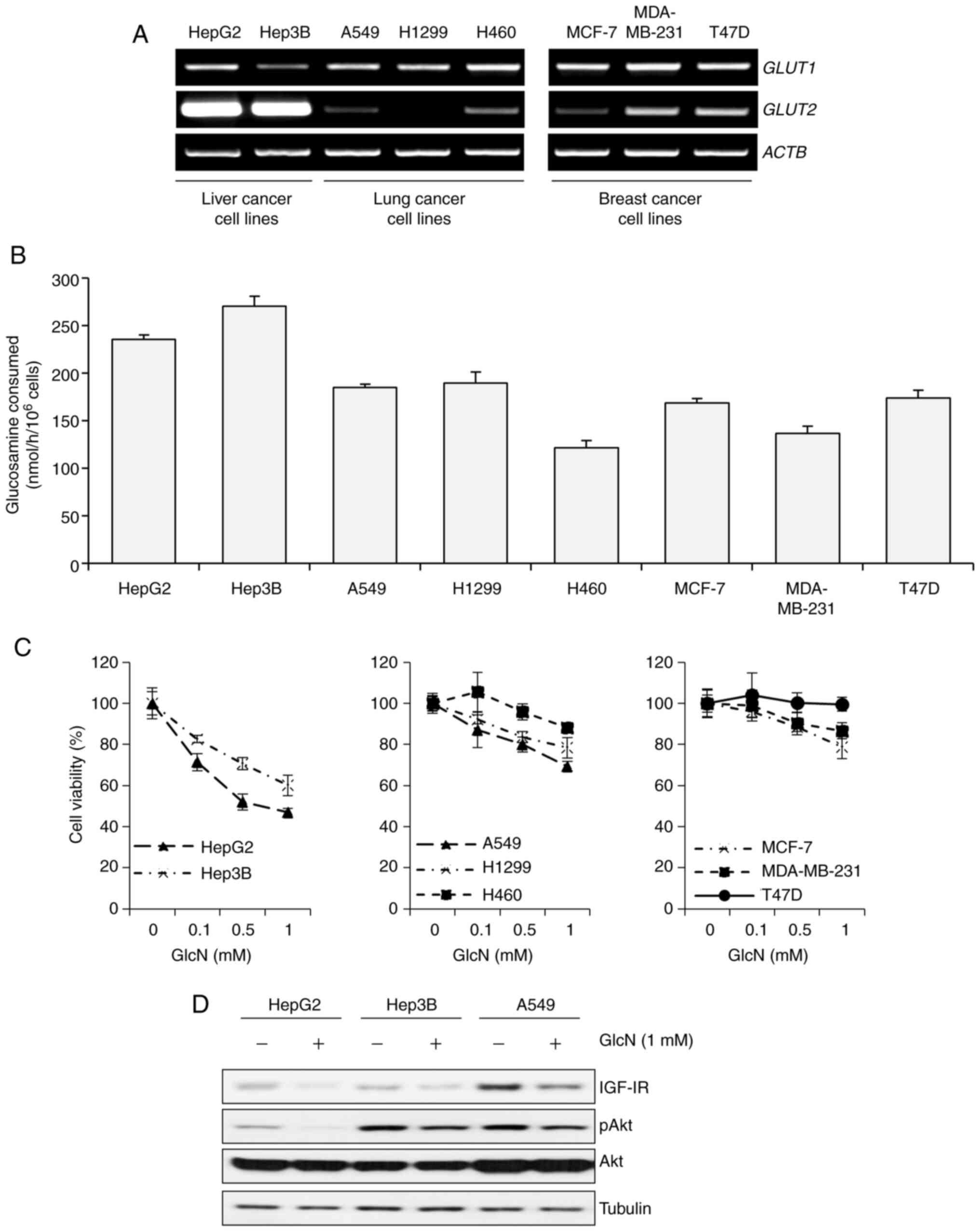

Antiproliferative effect of

glucosamine is related to basal expression level of GLUT2 and basal

activity of glucosamine consumption

Glucosamine enters the cell mostly via GLUT2, along

with other isoforms of GLUT (11).

Although several studies have examined the kinetics of glucosamine

transport, there is no direct evidence on how glucosamine,

particularly its antiproliferative effects, influences these

kinetics. Thus, it was hypothesized that cancer cells with higher

expression levels of GLUT2 were more sensitive to the

antiproliferative effect of glucosamine. First, the expression

level of GLUT1 and GLUT2 in cancer cell lines

originating from various types of cancer including liver cancer,

lung cancer and breast cancer was screened. For this purpose, two

liver cancer cell lines (HepG2 and Hep3B), three lung cancer cell

lines (A549, H1299 and H460) and three breast cancer cell lines

(MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and T47D) were used. Among them, liver cancer

cell lines showed higher levels of GLUT2 compared with the

others, while most of the cell lines showed similar levels of

GLUT1 (Fig. 3A). Then, to

assess the correlation between glucosamine uptake and GLUT2

expression levels, a glucosamine consumption assay was performed

and the results showed that liver cancer cell lines, which showed

highly expressed GLUT2, consumed glucosamine more actively

than others (Fig. 3B). Next,

whether the expression level of GLUT2 and the rate of

glucosamine uptake are related to the antiproliferative effect of

glucosamine was investigated. As a result, liver cancer cell lines,

which showed higher expressions of GLUT2 and actively

consumed glucosamine, were more sensitive to glucosamine than

others (Fig. 3C). Along with these

results, HepG2 and Hep3B cells showed greater decreases in IGF-1R

and p-Akt expression levels in the presence of glucosamine than

A549 cells, which were the most sensitive among the remaining cell

lines (Fig. 3D). Taken together,

these results implied that the antiproliferative effect of

glucosamine has a strong relationship with the expression level of

GLUT2 and the uptake rate of glucosamine.

| Figure 3.GLUT2 basal level is associated with

GlcN sensitivity in liver, lung and breast cancer cell lines. (A)

Semiquantitative PCR of GLUT1 and GLUT2 in various

cancer cell lines. Total mRNA from the following cancer cell lines

was isolated and used for analysis: HepG2, Hep3B, A549, H1299,

H460, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and T47D. ACTB was included as a

loading control. (B) GlcN consumption rates in the eight cell

lines. Each cell line was incubated in Glc-free RPMI 1640

containing both 1 mM Glc and 5 mM GlcN for 6 h. Results are

presented as mean ± standard deviation. (C) Cell viability of the

eight cell lines after treated with GlcN for 48 h. Cell viability

was measured by MTT assay and results are presented as mean ±

standard deviation. (D) Western blot analysis of IGF-1R, p-Akt and

Akt expression levels in HepG2, Hep3B and A549 cells after 1mM of

glucosamine treatment for 12 h. GLUT, glucose transporter; GlcN,

glucosamine; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. |

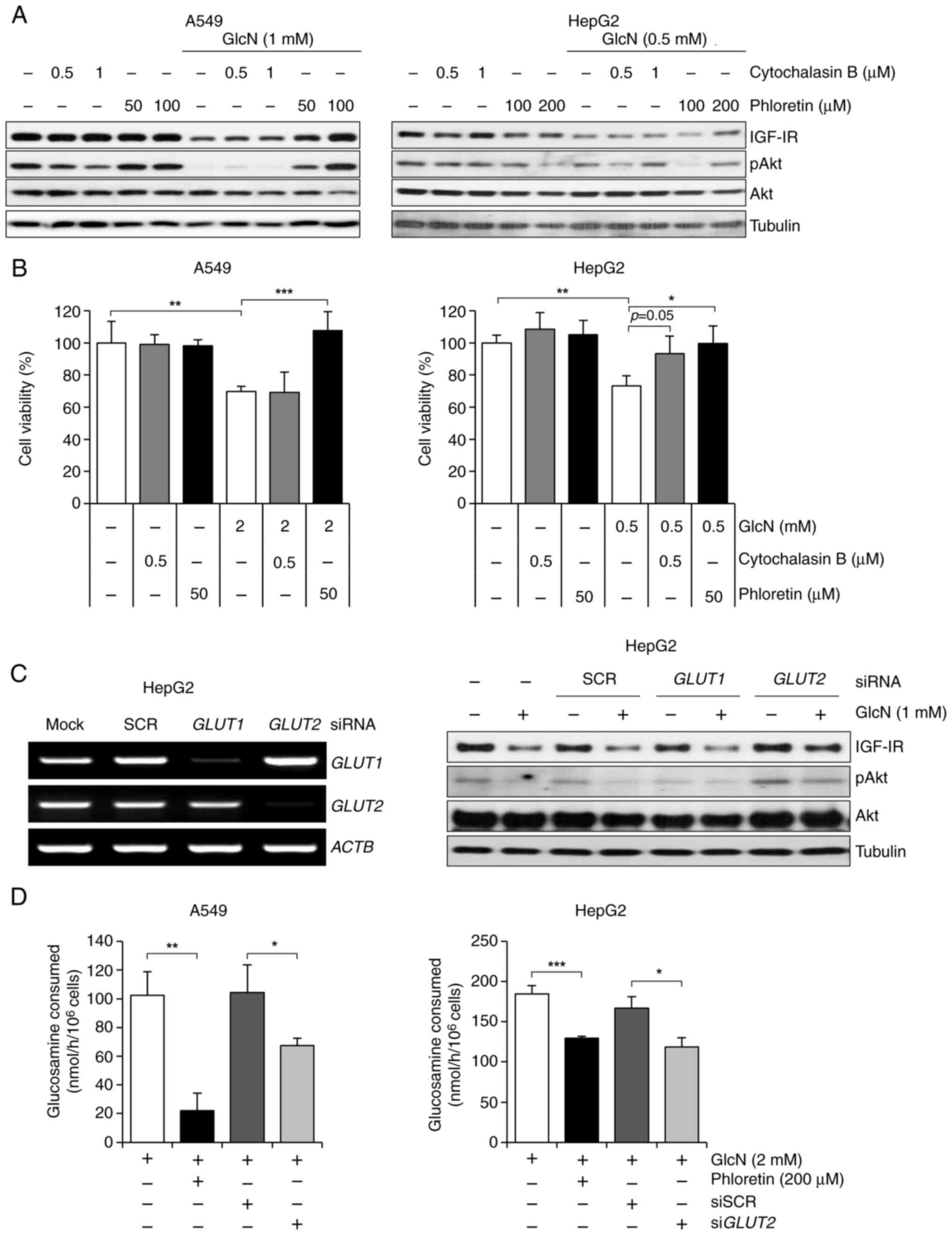

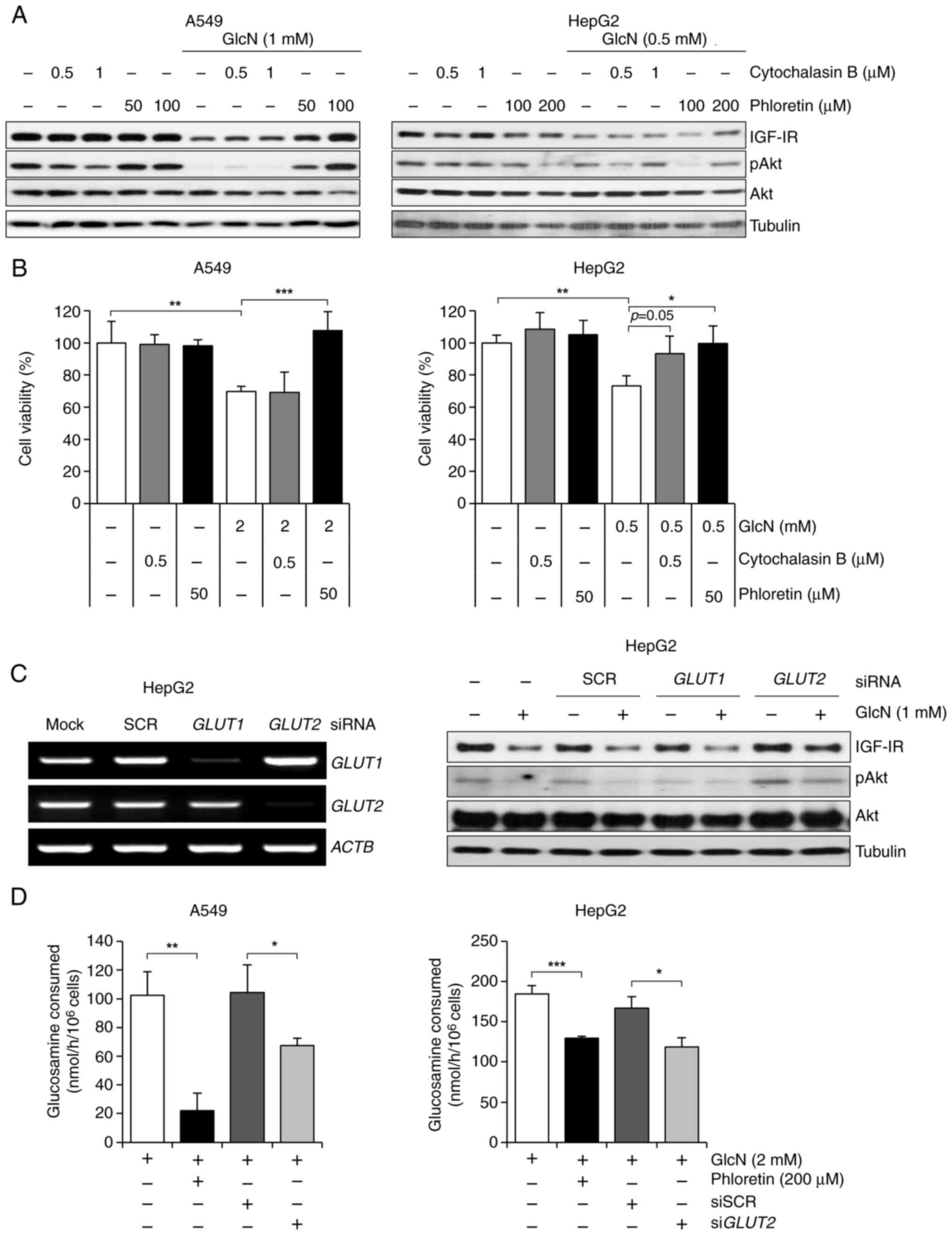

Antiproliferative effect of

glucosamine is dependent on the absorption process of glucosamine

into cancer cell lines through GLUT2, not GLUT1

Then it was explored whether cancer cells uptake

glucosamine through GLUT2, not GLUT1, and whether the uptake of

glucosamine is an essential step for its antiproliferative effects.

A549 and HepG2 cells were treated with cytochalasin B, a

GLUT1-specific inhibitor, or phloretin, a GLUT2-specific inhibitor,

in combination with glucosamine, respectively. Cytochalasin B and

phloretin concentrations were taken from previously reported

studies (36,37). As a result, phloretin recovered

glucosamine-induced downregulation of IGF-1R and p-Akt expressions

in both cancer cell lines, while cytochalasin B showed no recovery

effects in A549 cells and partial recovery effects in HepG2 cells

(Fig. 4A). In addition, glucosamine

shifted the molecular mass of COX-2 as previously reported

(38), which were markedly reversed

by phloretin, but not by cytochalasin B in A549 cells (Fig. S1). Following these changes in

molecular features, phloretin-mediated GLUT2 inhibition

sufficiently rescued A549 and HepG2 cells from glucosamine-induced

cell death, while the effects of cytochalasin B were not

significant (Fig. 4B). Along with

the results using inhibitors, GLUT2-knockdowned HepG2 cells by

transfection of siGLUT2 showed recovery of IGF-1R and p-Akt

expression levels decreased by glucosamine, while there were no

changes in those expressions in GLUT1-knockdowned HepG2 cells

(Fig. 4C). The present study also

investigated whether treatment with phloretin or siGLUT2,

which have an inhibitory effect on glucosamine transportation,

could decrease consumption of glucosamine in both cancer cell lines

and it was found that glucosamine consumption rate was reduced when

GLUT2 was inhibited by phloretin and siGLUT2 (Fig. 4D). These findings demonstrate that

the absorption of glucosamine via GLUT2 is the basic and necessary

process for the antiproliferative effect of glucosamine.

| Figure 4.GlcN entrance into cancer cells

through GLUT2 leads to its anticancer activities. (A) Western blot

analysis of IGF-1R, p-Akt and Akt expression levels in A549 and

HepG2 cells treated with cytochalasin B or phloretin for 24 h.

Cytochalasin B was used as a GLUT1-specific inhibitor, while

phloretin was used as a GLUT2-specific inhibitor. (B) Cell

viability of A549 and HepG2 cells after treatment with glucosamine,

cytochalasin B and phloretin for 48 h. Cell viability was measured

by MTT assay and results are presented as mean ± standard

deviation. (C) Left: Semiquantitative PCR of GLUT1 and

GLUT2 in HepG2 cells after transfection with siSCR,

siGLUT1, or siGLUT2. ACTB served as a loading

control. Right: Western blot analysis of IGF-1R, p-Akt and Akt

expression levels in GLUT1 or GLUT2 knockdown HepG2 cells after 1

mM of GlcN treatment for 24 h. (D) GlcN consumption rates in A549

and HepG2 cells. GLUT2 was inhibited by phloretin or siGLUT2

and then GlcN treatment for 6 h. Results are presented as mean ±

standard deviation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. GlcN,

glucosamine; GLUT, glucose transporter; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth

factor 1 receptor; si, small interfering. |

Inhibition of glycolysis by

glucosamine is greater in cancer cells with lower HKII levels

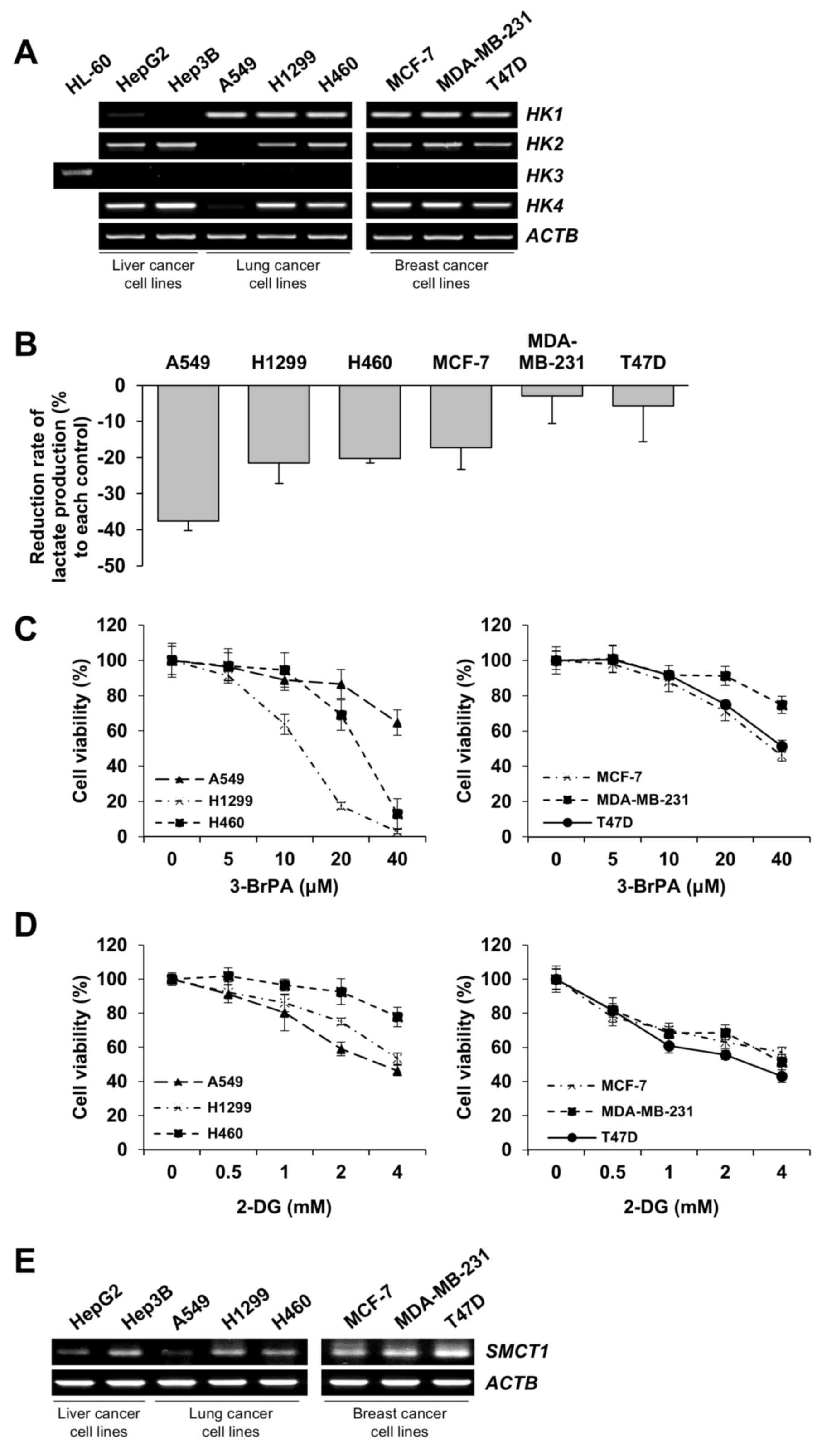

Although the other six cell lines expressed lower

levels of GLUT2 compared with HepG2 and Hep3B cells, there were

differences in the antiproliferative effect of glucosamine among

those six cell lines (Fig. 3B and

C), suggesting that cellular sensitivity to glucosamine is

influenced by not only uptake through GLUT2 but also by post-uptake

processes. Glucosamine can be phosphorylated by yeast hexokinase

(39,40). In addition, yeast hexokinase is

similar to rat hexokinase, human hexokinase N-terminal and

C-terminal in respect of its sequence and structure amino acids,

especially in the active site (41). Thus, it could be hypothesized that

glucosamine serves as a substrate for hexokinase in mammalian cells

including those of human origin (42–44).

Thus, the present study examined the basic expression levels of HK

isoforms (HK1-4) in the studied eight cell lines. Most cell

lines showed similar levels of HK1 expression and rarely

expressed HK3. Notably, the six cell lines showed lower

GLUT2 expression and reduced glucosamine consumption rates

compared with HepG2 and Hep3B cells, A549 cells exhibited the

lowest HK2 expression level compared with the other five

cell lines (Fig. 5A). Next, since

HK is the first enzyme to be activated during glycolysis and this

activation is a rate-limiting step that regulates the speed of

glycolysis (45), the differences

in glycolytic rates and the extent of glycolysis inhibition by

glucosamine was assessed. Notably, the rate of lactate production

was most markedly reduced by glucosamine in A549 cells which were

the most sensitive to glucosamine after liver cancer cell lines. It

was observed that 3-BrPA or 2-DG, which are used as HKII inhibitors

(46,47), sufficiently inhibited the

proliferation of those six cell lines (Fig. 5C and D). In case of A549 cells, the

anti-proliferative effect of 3-BrPA was relatively weak compared

with other lung cancer cell lines, H1299 and H460, and this was

probably due to the lower level of sodium-coupled monocarboxylate

transporter 1 (SMCT1), which is responsible for the

transportation of 3-BrPA into cells (48), than other cancer cell lines tested

(Fig. 5E). Taken together, these

results showed that glycolysis inhibition by glucosamine is

negatively related to the level of HKs, especially HKII.

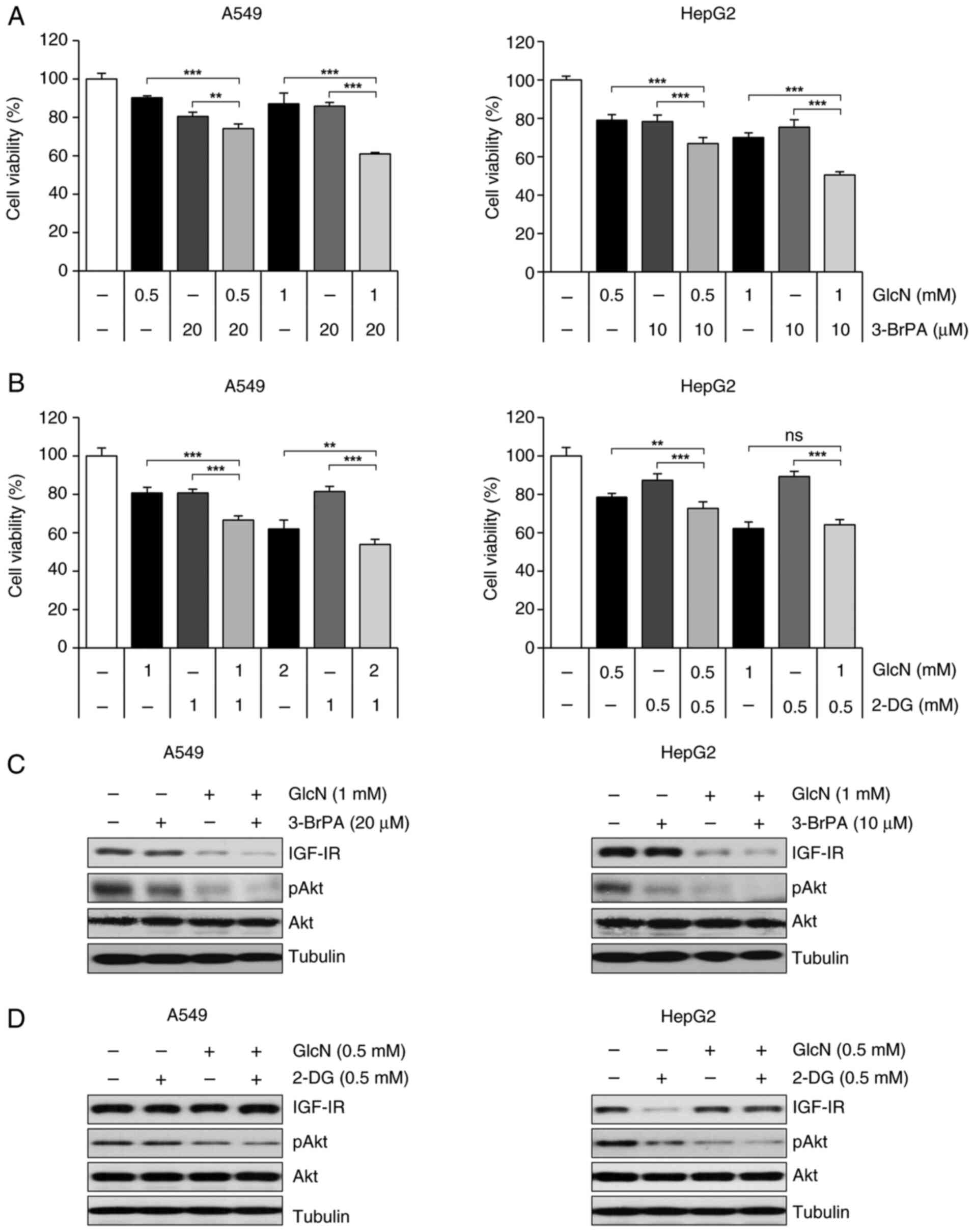

Glucosamine and 3-BrPA enhance the

antiproliferative activity of one another

3-BrPA, 2-DG and glucosamine, which are all

glycolysis inhibitors, take different pathways to enter cells and

work along different mechanisms. For example, 2-DG enters cells via

GLUT1 and GLUT4 like glucose and works as a competitor of glucose,

which eventually lowers the efficiency of glycolysis (23), whereas glucosamine is transported

into cells efficiently via GLUT2 rather than GLUT1 and competes

with glucose for HK. By contrast, 3-BrPA is taken up into cells by

SMCT1 and directly suppresses the activity of HKII (47,48).

Therefore, it was examined whether the antiproliferative effect of

glucosamine is elevated when co-treated with 2-DG or 3-BrPA.

Co-treatment of 3-BrPA with glucosamine increased the

anti-proliferative effects of glucosamine in both A549 and HepG2

cells (Fig. 6A), whereas 2-DG

showed a slight combinational effect and no combinational effect in

A549 cells and HepG2 cells, respectively (Fig. 6B). Along with these results,

glucosamine-induced decreased in IGF-1R and p-Akt expression level

were tended to be enhanced by co-treatment of 3-BrPA (Fig. 6C), but not by co-treatment of 2-DG

(Fig. 6D). These results suggested

that the mechanism of glucosamine inhibiting HK is similar to that

of 2-DG and different from that of 3-BrPA and that 3-BrPA may be a

suitable HK inhibitor for co-administration with glucosamine.

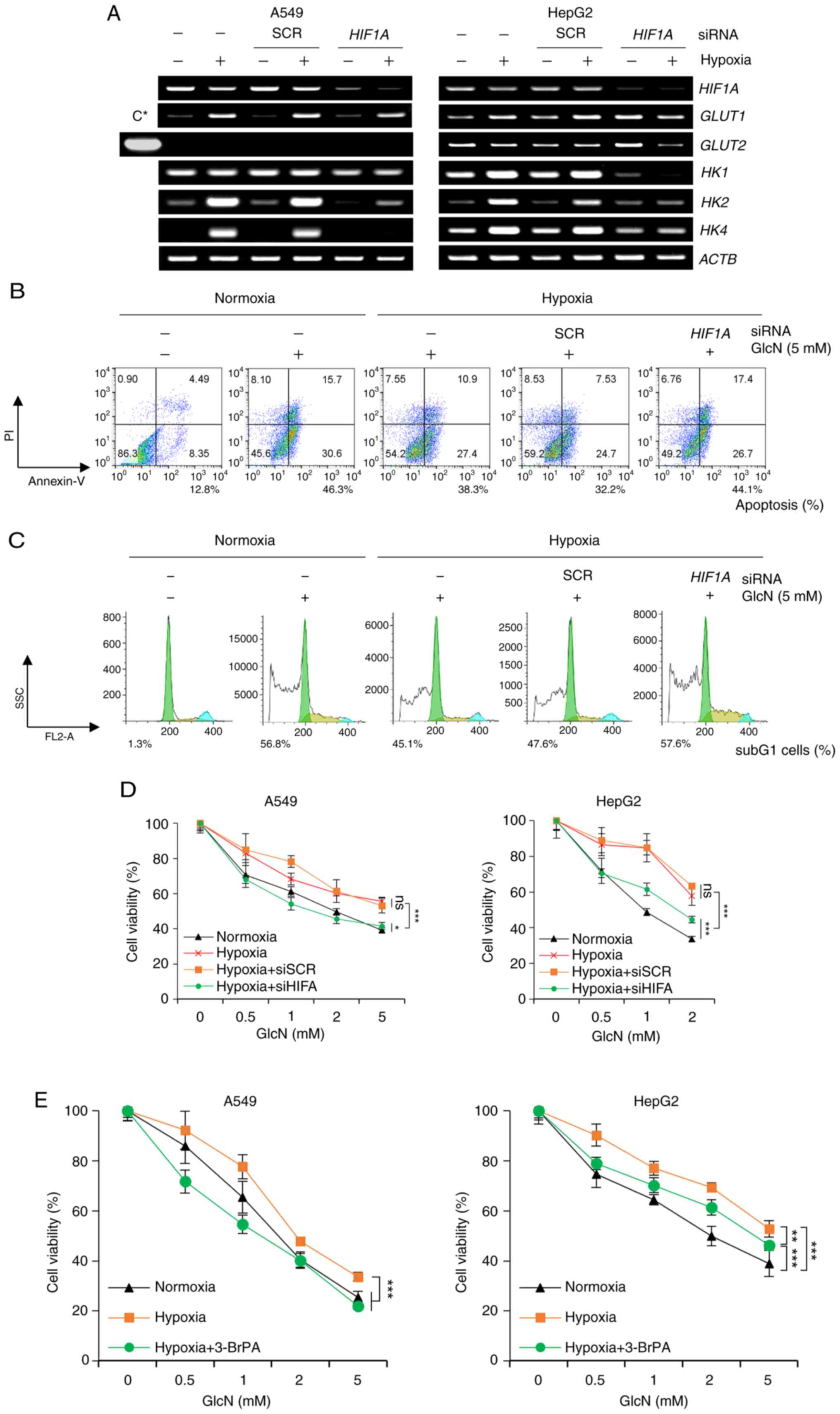

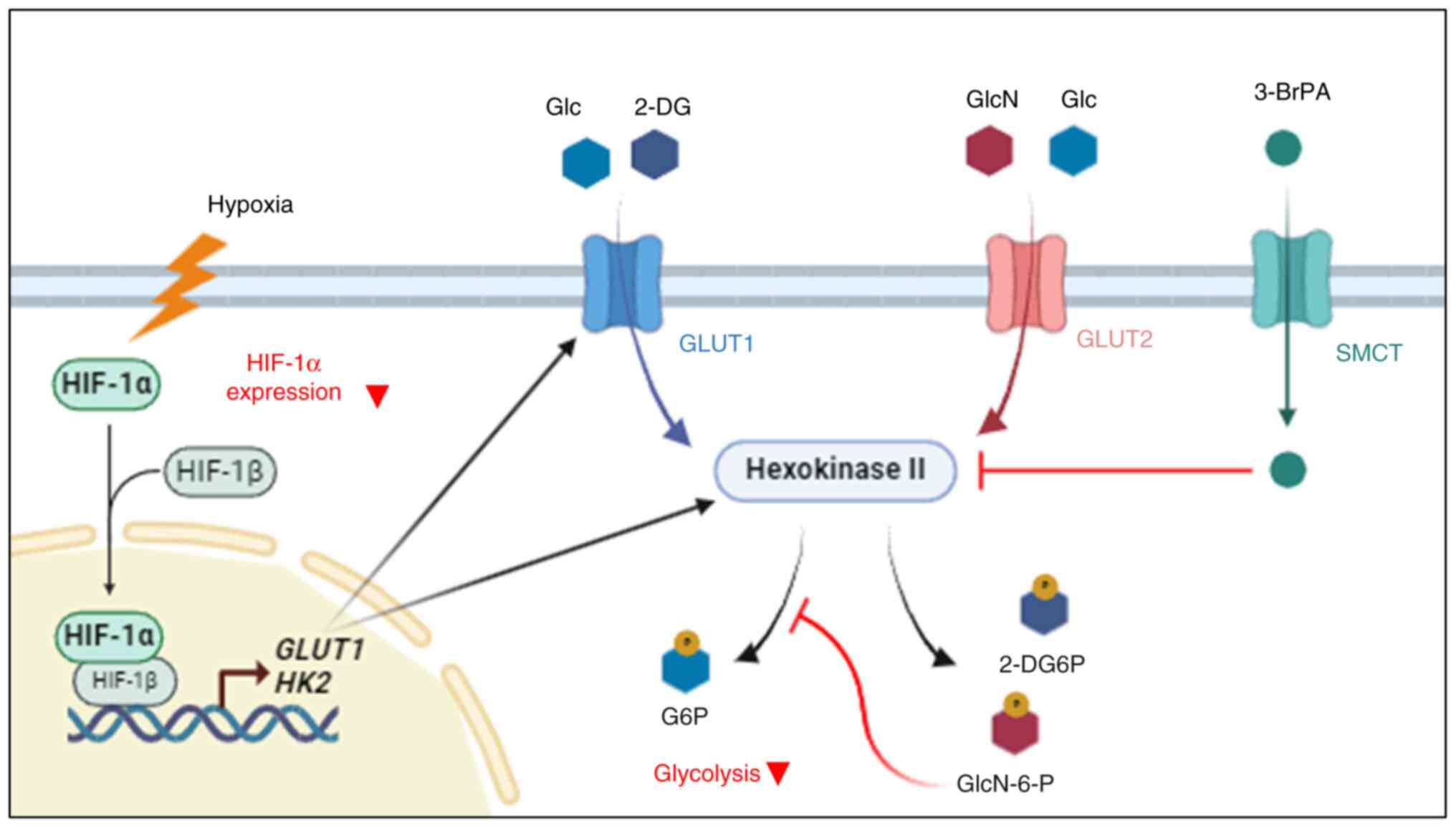

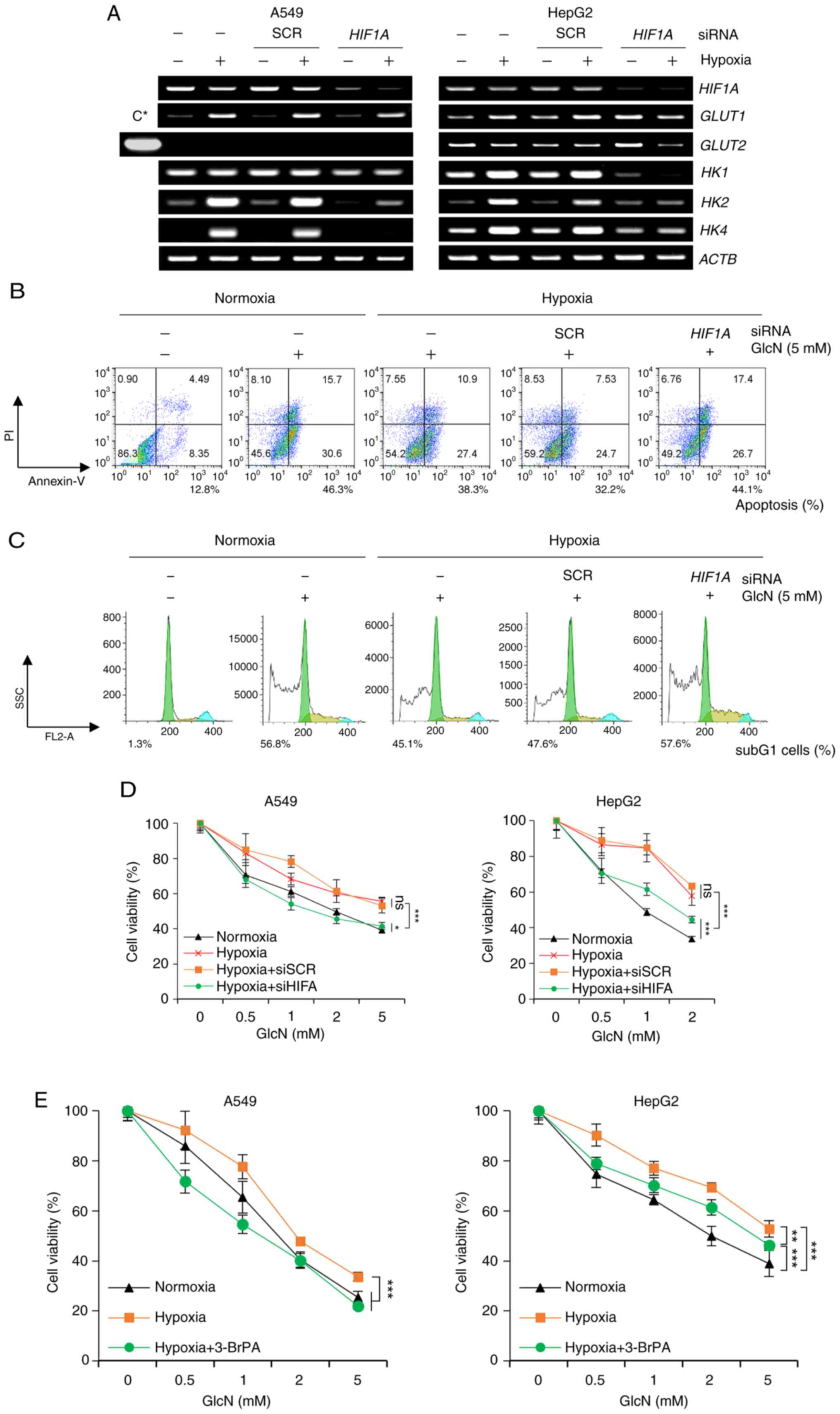

HIF-1α/HKII signaling is responsible

for hypoxia-induced glucosamine resistance

Glycolysis is mainly regulated by the quantity of

glucose taken up into cells and the activity of HK, a rate-limiting

step of the glycolysis pathway. Therefore, the expression level of

GLUTs and HKs is an important factor in the glycolysis process.

HIF-1α, one of the upstream transcriptional factors of GLUTs and

HKs, plays an important role in controlling glycolysis (19). Based on this knowledge, it was first

investigated whether the expression of GLUTs and HKs changes under

hypoxic conditions in A549 and HepG2 cells and whether this is

regulated by HIF-1α. As expected, the expression of GLUT1, HK1,

HK2 and HK4 markedly increased under hypoxic conditions

and it was confirmed that knocking down HIF-1 α markedly reduced

their expression again (Fig. 7A).

The expression of GLUT2 was constant in the examined

conditions and the expression of HK1 was induced by hypoxic

stress in HepG2 cells, but not in A549 cells. Next, the effects of

hypoxia on the antiproliferative effects of glucosamine was

examined. Notably, glucosamine reduced HIF-1α expression under

hypoxic conditions in cancer cells (Fig. S2) and it was found that

glucosamine-induced apoptosis was diminished under hypoxic

conditions and this hypoxia-induced glucosamine resistance were

restored by HIF-1α knockdown (Fig.

7B). Furthermore, cell cycle analysis found that the subG1

hypodiploid population, which was increased by glucosamine, was

reduced by hypoxic stress and this hypoxic stress-induced change

was not observed in HIF-1α depleted cells (Fig. 7C). Along with these results obtained

from flow cytometry analysis, MTT assays showed that the

anti-proliferation effects of glucosamine were reduced by hypoxic

stress and this hypoxia-induced resistance was markedly ablated by

HIF-1α downregulation in both A549 and HepG2 cells (Fig. 7D). Lastly, it was found that 3-BrPA,

HKII inhibitor, also effectively reversed hypoxia-induced

glucosamine resistance in both A549 and HepG2 cells (Fig. 7E). Collectively, these results

suggested that glucosamine exerts its antiproliferative activity by

inhibiting HKII within the cell and that the induction of HIF-1α

and transactivation of its target genes, particularly HKII, are

responsible for hypoxia-induced glucosamine resistance (Fig. 8).

| Figure 7.Anticancer effects of GlcN are

regulated through changing of HK levels during hypoxia. (A)

Semiquantitative PCR of HIF1A, GLUT1, GLUT2 and HK isoforms

of A549 and HepG2 cells. Cells were transfected with siSCR or

siHIF1A and then cultured under normoxic (20% O2)

or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions for 24 h. HepG2 sample

(C*) in Fig. 3A was used as a

positive control for GLUT2 expression in the left panel.

ACTB served as a loading control. Flow cytometric analysis

of (B) apoptosis and (C) cell cycle in A549 cells. Cells were

transfected with siSCR or siHIF1A for 24 h and further

incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24h followed by

glucosamine treatment for additional 48 h. Subsequently, cells were

stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI. Apoptosis (%) indicates sum of

Annexin V single positive proportion and Annexin V-PI double

positive proportion. Cell cycle analysis was performed with

linearized value of PI intensity and population of subG1 cells is

presented. (D) Cell viability of A549 and HepG2 cells. Cells were

transfected with siSCR or siHIF1A for 24 h and further

incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 h followed by

GlcN treatment for additional 48 h. Cell viability was measured by

MTT assay and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

(E) Cell viability of A549 and HepG2 cells. Cells were incubated

under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 h followed by GlcN and

3-BrPA (10 or 20 µM for A549 or HepG2 cells, respectively)

treatment for additional 48 h. Cell viability was measured by MTT

assay and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, no significance; GlcN,

glucosamine; HK, hexokinase; si, small interfering. |

Discussion

A number of cancer cells exhibit elevated glycolysis

even in the presence of oxygen, relying more heavily on this

process to produce ATP compared with normal cells. This phenomenon,

known as the Warburg effect, has become a key focus in cancer

treatment strategies, particularly through the development of

glycolytic inhibitors (15,23). Meanwhile, glycolysis is more than

just an energy-generating pathway; it plays a crucial role in

regulating various cellular processes necessary for cancer cell

growth and physiology (49,50). Hence, glycolysis inhibition has been

studied as an antiproliferative strategy. Although the inhibitory

effects of glucosamine on glycolysis and tumor growth were reported

in the late 1900s (27,32), the precise mechanisms of action of

glucosamine driving antiproliferative effects have not been fully

understood and thus, the present study investigated the

antiproliferative mechanism of glucosamine.

At first, to gain a broader understanding of the

mechanism behind glucosamine's antiproliferative effects,

microarray technology, a powerful tool for high-throughput

screening was employed. By using a whole-genome chip, the present

study aimed to identify changes in the gene expression profile of

A549 cells following the introduction of glucosamine. Genes

upregulated by glucosamine by more than two-fold were primarily

associated with pro-apoptosis and cell death, while those

downregulated by more than two-fold were mostly linked to cell

cycle regulation and DNA damage response. Additionally, glucosamine

was found to influence genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism,

biomolecule biosynthesis and glycosylation; processes related to

glycolysis. In particular, the result showing that genes related to

glycosylation were regulated by glucosamine is supported by

previous reports demonstrating that glucosamine induces abnormal

glycosylation of the IGF-1R prototype and COX-2 and eventually

decreases their molecular mass (9,35).

KEGG pathway analysis revealed that glucosamine downregulated the

overall glycolysis pathway, while some enzymes regulating the entry

into glycolysis were upregulated, possibly as a compensatory

response to glycolysis inhibition. This compensatory mechanism is

consistent with findings from previous studies using other

glycolysis inhibitors (51,52). Given these findings, along with

glucosamine's structural similarity to glucose and its previously

reported effect of reducing ATP levels in cancer cells, it is

suggested that glycolysis is the main target pathway of

glucosamine.

Glucosamine, structurally similar to glucose except

for its NH2 group, has been shown to compete with

glucose in carbohydrate metabolism (23). According to this, glucose

competitively inhibited glucosamine-induced antiproliferative

effects and restored glycolysis as indicated by the recovery of

lactate production that had been suppressed by glucosamine. Since

glucosamine is known to inhibit the IGF-1R/Akt pathway (9), it was found that increasing glucose

restored IGF-1R and p-Akt expression levels reduced by glucosamine.

The results supported that glucosamine inhibited the rate of

proliferation of cancer cell lines mainly by competing with glucose

during glycolysis.

Based on the structural similarity of glucosamine

and glucose, it was predicted that plasma membranes, especially

where glucose transports exist, would be the battlefield of

glucosamine and glucose. Among GLUT isoforms, expression levels in

liver cancer cell lines of GLUT2, which is responsible for

transportation of glucosamine as well (11), were much higher compared with other

cell lines, while GLUT1 expression levels were similar between

types of cancer. These GLUT2-rich liver cancer cell lines (HepG2

and Hep3B) consumed more glucosamine and were more sensitive to

glucosamine than other GLUT2-poor cell lines. In addition,

glucosamine consumption and the antiproliferative effects of

glucosamine were abrogated by inhibiting GLUT2 with its specific

inhibitor (Phloretin) or siGLUT2 transfection. Thus, so far,

it can be said that GLUT2 is the main gate for glucosamine to get

into cells and high dose of glucose can keep glucosamine from

entering into cells at GLUT2. Previous studies report that cancer

cells have higher GLUT2 expression levels compared with normal

cells (37,53). These facts suggested that the amount

of GLUT2 expression in each cancer cell can be a crucial biomarker

in determining the sensitivity against glucosamine and also proves

that glucosamine is more effective against cancer cells than normal

cells.

Glucosamine and glucose not only have a similar

structure but are also catalyzed by the same enzyme, HKs and are

converted to GlcN-6-phosphate and Glc-6-phosphate, respectively,

after transport into the cell (33). The lower the expression of HKII, the

greater the inhibitory effect of glucosamine on glycolysis.

Compared with the known glycolysis inhibitors, 3-BrPA and 2-DG, the

effective dose range of glucosamine was similar to 2-DG, not to

3-BrPA which is entered into cells by SMCT rather than GLUTs,

demonstrating that glucosamine inhibits glycolysis by competing

with glucose as does 2-DG, rather than by directly inhibiting HKs.

The synergistic effect observed when two drugs with different

mechanisms of action are combined suggests distinct pathways

(54). While the combination of

glucosamine and 3-BrPA showed enhanced antiproliferative effects,

the same was not observed with 2-DG. Considering these results and

the structure of glucosamine, it can be inferred that the mechanism

of action of glucosamine is probably different from that of 3-BrPA

and similar to that of 2-DG.

Various former studies reveal that HIF-1α regulates

the expression level of HKs and GLUT1 efficiently by working as a

transcription factor (17,19,55).

Furthermore, the increased stability of HIF-1α under hypoxic

conditions has been reported to influence sensitivity of types of

cancer to a number of anticancer agents (56,57).

In particular, studies have demonstrated that the antiproliferative

effect of 2-DG is decreased when there are high levels of HIF-1α

and that this phenomenon is related to increased levels of HKs,

which are induced by HIF-1α (21).

The present study showed that A549 cells, which have low basal

levels of HKII and lactate, inhibited glycolysis and decreased cell

proliferation when treated with glucosamine. Under hypoxic

conditions, GLUT2 expression levels were relatively constant

in HepG2 cells, suggesting that the uptake amount of glucosamine

would not be changed by HIF-1α activation. However, activated

HIF-1α induced HKII expressions in lung and liver cancer cell lines

and this activated HIF-1α/HKII pathway made cancer cell lines more

resistant to glucosamine. In addition, genetically depleting

HIF1A and pharmacologically inhibiting HKII markedly

restored glucosamine-induced antiproliferative effects.

In humans, cohort studies found that regularly

taking glucosamine as a supplement reduced the incidence and

mortality of colorectal cancer, lung cancer and kidney cancer and

the overall cancer mortality could be 6% lower compared with

non-users (58,59). We previously reported in vivo

anti-tumor effects of glucosamine using a xenograft mouse model

(9). Furthermore, the present

results supported the relationship between glucosamine intake and

lower cancer mortality with the molecular mechanism of

glucosamine-induced antiproliferative effects. Collectively,

glucosamine can act like a roadblock on the path of glycolysis,

competing with glucose for HK, slowing down the process like a

rival runner in a race for the same baton. Nevertheless, the

present study was limited by its exclusive use of cell line models,

which may not fully reflect in vivo conditions. Further

studies should focus on validating these findings in more

physiologically relevant models and exploring the broader

therapeutic potential of glucosamine under diverse biological

conditions. Such efforts could clarify its efficacy across

different tumor types and microenvironments, ultimately

strengthening its clinical applicability.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that

glucosamine reduced growth, decreased cell viability and impaired

glucose metabolism in the studied cancer cell lines. Moreover,

GLUT2 and HKII were identified as biomarkers determining

sensitivity to glucosamine. While the precise molecular mechanisms

underlying the antiproliferative effects of glucosamine remain to

be fully elucidated, the present study provided significant

insights by demonstrating its mode of action as a glucose

metabolism inhibitor in cancer cells. Furthermore, the findings

suggested potential therapeutic markers for identifying types of

cancer or characteristics that are most responsive to glucosamine,

thereby offering a rationale for its use in combination therapy.

These findings contributed to expanding the potential of

glucosamine as an effective anticancer agent.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the New Faculty Startup Fund

(grant no. 550-20240054) from Seoul National University (Seoul,

Korea).

Availability of data and materials

Microarray datasets generated in the present study

has been submitted to ArrayExpress (accession number:

E-MTAB-14871), and publicly accessible under this URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress/studies/E-MTAB-14871.

Other data generated in the present study may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SP, KS and JK participated in the study design,

conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, and

drafted the initial manuscript. JK and SO supervised the study,

contributed to the study design and data interpretation, and

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content. All authors confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests. ViroCure Inc. had no commercial interest in this

study.

References

|

1

|

Sanders M and Grundmann O: The use of

glucosamine, devil's claw (Harpagophytum procumbens), and

acupuncture as complementary and alternative treatments for

osteoarthritis. Altern Med Rev. 16:228–238. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhu X, Sang L, Wu D, Rong J and Jiang L:

Effectiveness and safety of glucosamine and chondroitin for the

treatment of osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res. 13:1702018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang LS, Chen SJ, Zhang JF, Liu MN, Zheng

JH and Yao XD: Anti-proliferative potential of Glucosamine in renal

cancer cells via inducing cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase. BMC

Urol. 17:382017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zahedipour F, Dalirfardouei R, Karimi G

and Jamialahmadi K: Molecular mechanisms of anticancer effects of

Glucosamine. Biomed Pharmacother. 95:1051–1058. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kim DS, Park KS, Jeong KC, Lee BI, Lee CH

and Kim SY: Glucosamine is an effective chemo-sensitizer via

transglutaminase 2 inhibition. Cancer Lett. 273:243–249. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Oh HJ, Lee JS, Song DK, Shin DH, Jang BC,

Suh SI, Park JW, Suh MH and Baek WK: D-glucosamine inhibits

proliferation of human cancer cells through inhibition of p70S6K.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 360:840–845. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jo JR, Park YK and Jang BC: Short-term

treatment with glucosamine hydrochloride specifically downregulates

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α at the protein level in YD-8 human

tongue cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 44:1699–1706. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chou WY, Chuang KH, Sun D, Lee YH, Kao PH,

Lin YY, Wang HW and Wu YL: Inhibition of PKC-Induced COX-2 and IL-8

expression in human breast cancer cells by glucosamine. J Cell

Physiol. 230:2240–2251. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Song KH, Kang JH, Woo JK, Nam JS, Min HY,

Lee HY, Kim SY and Oh SH: The novel IGF-IR/Akt-dependent anticancer

activities of glucosamine. BMC Cancer. 14:312014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cura AJ and Carruthers A: Role of

monosaccharide transport proteins in carbohydrate assimilation,

distribution, metabolism, and homeostasis. Compr Physiol.

2:863–914. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Uldry M, Ibberson M, Hosokawa M and

Thorens B: GLUT2 is a high affinity glucosamine transporter. FEBS

Lett. 524:199–203. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pouyssegur J, Marchiq I, Parks SK,

Durivault J, Zdralevic M and Vucetic M: ‘Warburg effect’ controls

tumor growth, bacterial, viral infections and immunity-Genetic

deconstruction and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol.

86((Pt 2)): 334–346. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Barron CC, Bilan PJ, Tsakiridis T and

Tsiani E: Facilitative glucose transporters: Implications for

cancer detection, prognosis and treatment. Metabolism. 65:124–139.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ancey PB, Contat C and Meylan E: Glucose

transporters in cancer - from tumor cells to the tumor

microenvironment. FEBS J. 285:2926–2943. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pelicano H, Martin DS, Xu RH and Huang P:

Glycolysis inhibition for anticancer treatment. Oncogene.

25:4633–4646. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wilson JE: Isozymes of mammalian

hexokinase: Structure, subcellular localization and metabolic

function. J Exp Biol. 206((Pt 12)): 2049–2057. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guo D, Meng Y, Jiang X and Lu Z:

Hexokinases in cancer and other pathologies. Cell Insight.

2:1000772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Paredes F, Williams HC and San Martin A:

Metabolic adaptation in hypoxia and cancer. Cancer Lett.

502:133–142. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Denko NC: Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose

metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 8:705–713. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Iommarini L, Porcelli AM, Gasparre G and

Kurelac I: Non-canonical mechanisms regulating hypoxia-inducible

factor 1 alpha in cancer. Front Oncol. 7:2862017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Maher JC, Wangpaichitr M, Savaraj N,

Kurtoglu M and Lampidis TJ: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 confers

resistance to the glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Mol

Cancer Ther. 6:732–741. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hsu CC, Tseng LM and Lee HC: Role of

mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer progression. Exp Biol Med

(Maywood). 241:1281–1295. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang Y, Li Q, Huang Z, Li B, Nice EC,

Huang C, Wei L and Zou B: Targeting glucose metabolism enzymes in

cancer treatment: current and emerging strategies. Cancers (Basel).

14:45682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

R Core Team, . R: A language and

environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical

Computing; Vienna: 2024, http://www.R-project.org/

|

|

26

|

Luo W and Brouwer C: Pathview: An

R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and

visualization. Bioinformatics. 29:1830–1831. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Quastel JH and Cantero A: Inhibition of

tumour growth by D-glucosamine. Nature. 171:252–254. 1953.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tamayo B, Kercher K, Vosburg C, Massimino

C, Jernigan MR, Hasan DL, Harper D, Mathew A, Adkins S, Shippy T,

et al: Annotation of glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and

trehaloneogenesis pathways provide insight into carbohydrate

metabolism in the Asian citrus psyllid. GigaByte.

2022:gigabyte412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Suginohara T, Wakabayashi K, Ato S and

Ogasawara R: Effect of 2-deoxyglucose-mediated inhibition of

glycolysis on the regulation of mTOR signaling and protein

synthesis before and after high-intensity muscle contraction.

Metabolism. 114:1544192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Berthe A, Zaffino M, Muller C, Foulquier

F, Houdou M, Schulz C, Bost F, De Fay E, Mazerbourg S and Flament

S: Protein N-glycosylation alteration and glycolysis inhibition

both contribute to the antiproliferative action of 2-deoxyglucose

in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 171:581–591. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bertoni JM and Weintraub ST: Competitive

inhibition of human brain hexokinase by metrizamide and related

compounds. J Neurochem. 42:513–518. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tesoriere G, Vento R and Calvaruso G:

Inhibitory effect of D-glucosamine on glycolysis in bovine retina.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 385:58–67. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Marshall S, Yamasaki K and Okuyama R:

Glucosamine induces rapid desensitization of glucose transport in

isolated adipocytes by increasing GlcN-6-P levels. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 329:1155–1161. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Samizu M and Iida K: Glucosamine inhibits

the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by eliciting

apoptosis, autophagy, and the anti-warburg effect. Scientifica

(Cairo). 2025:56858842025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jang BC, Sung SH, Park JG, Park JW, Bae

JH, Shin DH, Park GY, Han SB and Suh SI: Glucosamine hydrochloride

specifically inhibits COX-2 by preventing COX-2 N-glycosylation and

by increasing COX-2 protein turnover in a proteasome-dependent

manner. J Biol Chem. 282:27622–27632. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kapoor K, Finer-Moore JS, Pedersen BP,

Caboni L, Waight A, Hillig RC, Bringmann P, Heisler I, Müller T,

Siebeneicher H and Stroud RM: Mechanism of inhibition of human

glucose transporter GLUT1 is conserved between cytochalasin B and

phenylalanine amides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:4711–4716. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu CH, Ho YS, Tsai CY, Wang YJ, Tseng H,

Wei PL, Lee CH, Liu RS and Lin SY: In vitro and in vivo study of

phloretin-induced apoptosis in human liver cancer cells involving

inhibition of type II glucose transporter. Int J Cancer.

124:2210–2219. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kapoor M, Mineau F, Fahmi H, Pelletier JP

and Martel-Pelletier J: Glucosamine sulfate reduces prostaglandin

E(2) production in osteoarthritic chondrocytes through inhibition

of microsomal PGE synthase-1. J Rheumatol. 39:635–644. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sols A, De La Fuente G, Villarpalasi C and

Asensio C: Substrate specificity and some other properties of

baker's yeast hexokinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 30:92–101. 1958.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Brown DH: The phosphorylation of D (+)

glucosamine by crystalline yeast hexokinase. Biochim Biophys Acta.

7:487–493. 1951. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kuser PR, Krauchenco S, Antunes OA and

Polikarpov I: The high resolution crystal structure of yeast

hexokinase PII with the correct primary sequence provides new

insights into its mechanism of action. J Biol Chem.

275:20814–20821. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen YH and Cheng WH: Hexosamine

biosynthesis and related pathways, protein N-glycosylation and

O-GlcNAcylation: Their interconnection and role in plants. Front

Plant Sci. 15:13490642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Paneque A, Fortus H, Zheng J, Werlen G and

Jacinto E: The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway: Regulation and

function. Genes (Basel). 14:9932023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Salazar J, Bello L, Chavez M, Anez R,

Rojas J and Bermudez V: Glucosamine for osteoarthritis: Biological

effects, clinical efficacy, and safety on glucose metabolism.

Arthritis. 2014:4324632014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Robey RB and Hay N: Mitochondrial

hexokinases, novel mediators of the antiapoptotic effects of growth

factors and Akt. Oncogene. 25:4683–4696. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Xian H and Wang Y, Bao X, Zhang H, Wei F,

Song Y and Wang Y, Wei Y and Wang Y: Hexokinase inhibitor

2-deoxyglucose coordinates citrullination of vimentin and apoptosis

of fibroblast-like synoviocytes by inhibiting HK2/mTORC1-induced

autophagy. Int Immunopharmacol. 114:1095562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Rai Y, Yadav P, Kumari N, Kalra N and

Bhatt AN: Hexokinase II inhibition by 3-bromopyruvate sensitizes

myeloid leukemic cells K-562 to anti-leukemic drug, daunorubicin.

Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201908802019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Thangaraju M, Karunakaran SK, Itagaki S,

Gopal E, Elangovan S, Prasad PD and Ganapathy V: Transport by

SLC5A8 with subsequent inhibition of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1)

and HDAC3 underlies the antitumor activity of 3-bromopyruvate.

Cancer. 115:4655–4666. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Paul S, Ghosh S and Kumar S: Tumor

glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer

Biol. 86((Pt 3)): 1216–1230. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Bose S, Zhang C and Le A: Glucose

metabolism in cancer: The warburg effect and beyond. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1311:3–15. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhao J, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Fu B, Wu X, Li Q,

Cai G, Chen X and Bai XY: Low-dose 2-deoxyglucose and metformin

synergically inhibit proliferation of human polycystic kidney cells

by modulating glucose metabolism. Cell Death Discov. 5:762019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang Z, Zhang L, Zhang D, Sun R, Wang Q

and Liu X: Glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose suppresses

carcinogen-induced rat hepatocarcinogenesis by restricting cancer

cell metabolism. Mol Med Rep. 11:1917–1924. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Medina RA and Owen GI: Glucose

transporters: Expression, regulation and cancer. Biol Res. 35:9–26.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lehar J, Krueger AS, Avery W, Heilbut AM,

Johansen LM, Price ER, Rickles RJ, Short GF III, Staunton JE, Jin

X, et al: Synergistic drug combinations tend to improve

therapeutically relevant selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 27:659–666.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sadlecki P, Bodnar M, Grabiec M, Marszalek

A, Walentowicz P, Sokup A, Zegarska J and Walentowicz-Sadlecka M:

The role of Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha, glucose

transporter-1, (GLUT-1) and carbon anhydrase IX in endometrial

cancer patients. Biomed Res Int. 2014:6168502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang P, Wan W, Xiong S, Wang J, Zou D, Lan

C, Yu S, Liao B, Feng H and Wu N: HIF1α regulates glioma

chemosensitivity through the transformation between differentiation

and dedifferentiation in various oxygen levels. Sci Rep.

7:79652017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Sharma A, Sinha S and Shrivastava N:

Therapeutic targeting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) in cancer:

Cutting gordian knot of cancer cell metabolism. Front Genet.

13:8490402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhou J, Wu Z, Lin Z, Wang W, Wan R and Liu

T: Association between glucosamine use and cancer mortality: A

large prospective cohort study. Front Nutr. 9:9478182022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Li ZH, Gao X, Chung VC, Zhong WF, Fu Q, Lv

YB, Wang ZH, Shen D, Zhang XR, Zhang PD, et al: Associations of

regular glucosamine use with all-cause and cause-specific

mortality: A large prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis.

79:829–836. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|