In 2020, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most

prevalent malignancy globally and the second leading cause of

cancer-associated deaths (1)

Distant metastasis is a key driver of mortality in CRC, with the

liver being the most common site of metastasis (2). A total of 15–25% of patients with CRC

present with synchronous liver metastases at initial diagnosis,

while a further 15–25% develop metachronous liver metastases

following primary CRC resection (2). Currently, a limited number of these

liver metastases are amenable to surgical resection, and the 5-year

survival rate for these patients is 25–44%. Moreover, up to 60% of

patients experience rapid recurrence following resection (3).

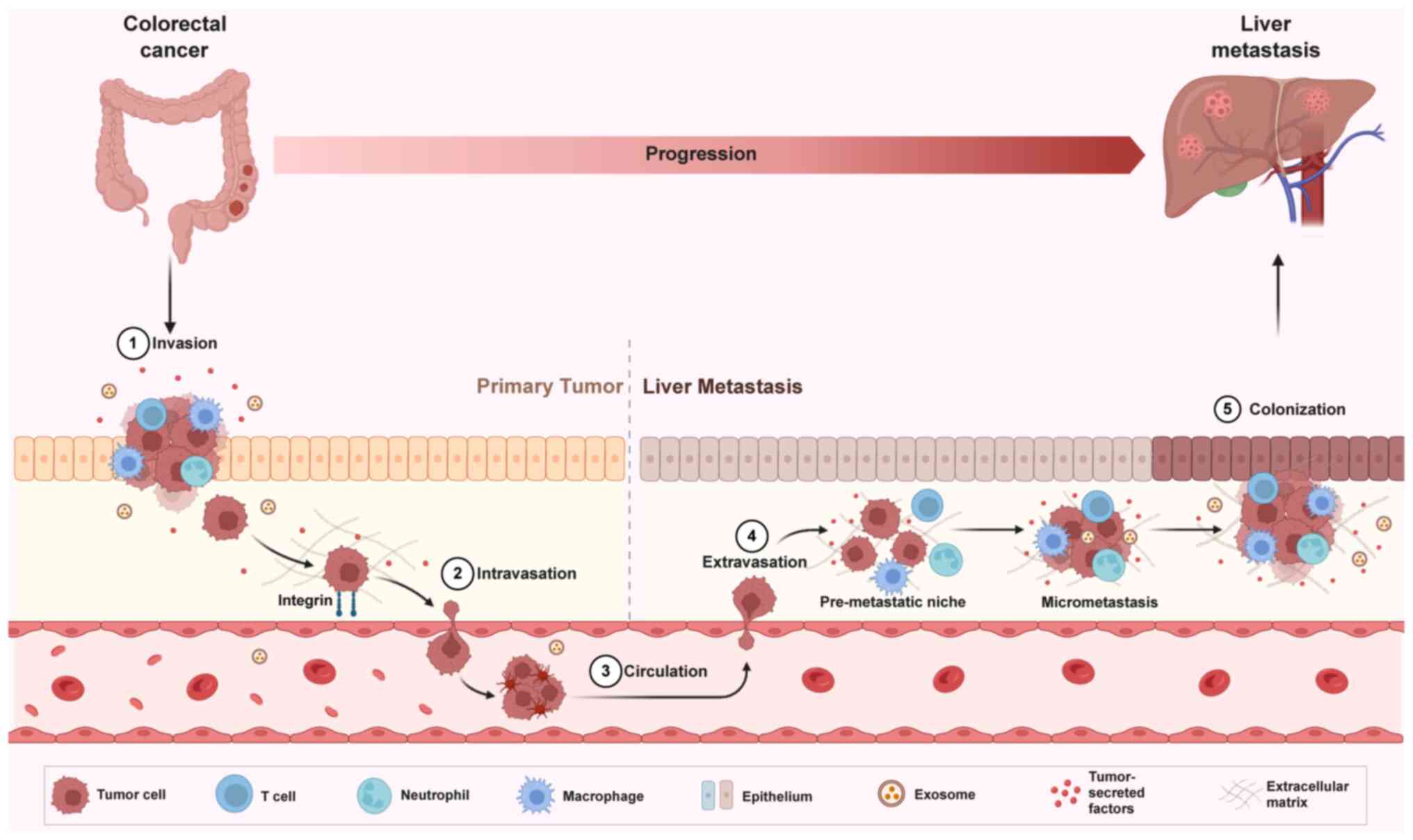

The exact mechanisms underlying colorectal liver

metastasis (CRLM) remain poorly understood. Tumor cell

dissemination from the primary site to distant organs and the

subsequent formation of metastatic tumors involve a dynamic process

regulated by numerous genes and signaling pathways. This process

includes tumor cell detachment from the primary site, entry into

the circulatory or lymphatic system, extravasation and colonization

at secondary sites. Tumor cell invasion, migration, adhesion,

extracellular matrix remodeling, neovascularization and immune

regulation are key in facilitating this metastatic cascade. The

rise of immunotherapy, with its notable clinical success, has

highlighted the critical role of the tumor immune microenvironment

(TIME) in CRLM. CRLM represents a complex interaction between tumor

and microenvironmental cells. Tumor cells, while acquiring invasive

phenotypes, maintain intercellular communication with

microenvironmental cells, regulating their functions through both

direct and indirect mechanisms. This regulation involves the

expression of immune checkpoint molecules and the secretion of

cytokines, establishing a microenvironment conducive to tumor cell

colonization and proliferation (4).

Moreover, suppressive immune cells enhance the invasiveness of

tumor cells by activating pro-metastatic signaling pathways. This

interaction between tumor cells and the microenvironment drives the

development of CRLM (Fig. 1).

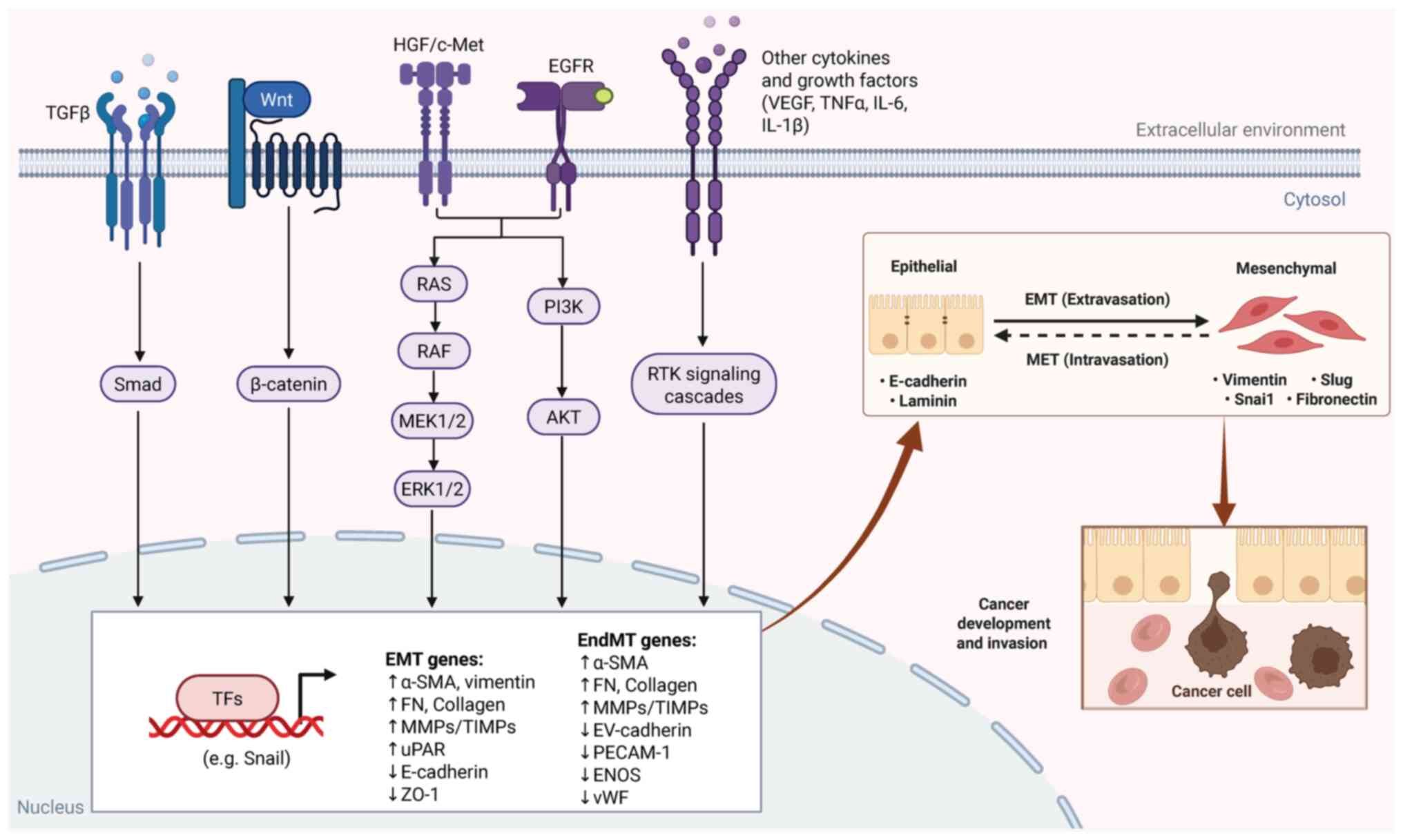

The development, invasion and metastasis of CRC are

complex biological processes involving multiple genetic

alterations. Successive mutations and abnormal expression of genes

such as APC, KRAS, BRAF and PTEN activate signaling pathways

promoting CRC invasion and metastasis (5).

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a

critical precursor to CRLM. EMT refers to the phenotypical

transformation of tumor epithelial cells into a mesenchymal

phenotype, which enhances their migratory capacity (6). This involves the loss of intercellular

junctions, increased secretion of intercellular plasma hydrolases

and disruption of apical polarity, resulting in a breakdown of

cell-cell adhesion. Concurrently, these changes induce the

expression of N-cadherin, vimentin and α-smooth muscle actin,

facilitating the transition from polarized epithelial cells to

multipolar mesenchymal cells. This transformation increases cell

motility, enabling tumor cells to detach from epithelial clusters

and migrate individually in a mesenchymal manner, further enhancing

the metastatic potential (7). The

E-cadherin-β-catenin complex serves a pivotal role in maintaining

epithelial integrity. Disruption of this complex leads to the

detachment of cells from the primary tumor, enabling invasion and

migration through the extracellular matrix and entry into the

circulatory or lymphatic system. This is an important initiating

step in the development of CRLM (8).

The acquisition of an invasive phenotype in CRC is

governed by signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin (9,10),

TGF-β (11,12), PI3K/AKT (13–15),

MEK/ERK (16,17) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/MET

(18). These pathways are regulated

by intracellular oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, as well as

tumor microenvironmental signaling factors that influence tumor

cell invasion and metastasis (Fig.

2).

Hepatic susceptibility to colonization by

circulating tumor cells compared with other metastasis sites such

as the lungs and peritoneum is primarily attributed to its highly

permeable blood vessels, unique hemodynamic properties and distinct

immune microenvironment. Notably, the ability to tolerate immune

responses contributes to the creation of an immunosuppressive

microenvironment, which protects the organ from excessive immune

reactions to antigens. Additionally, liver homeostasis is

maintained by specialized resident cells and diverse immune cell

populations, which collectively regulate immune responses and

oncogenesis (19–21).

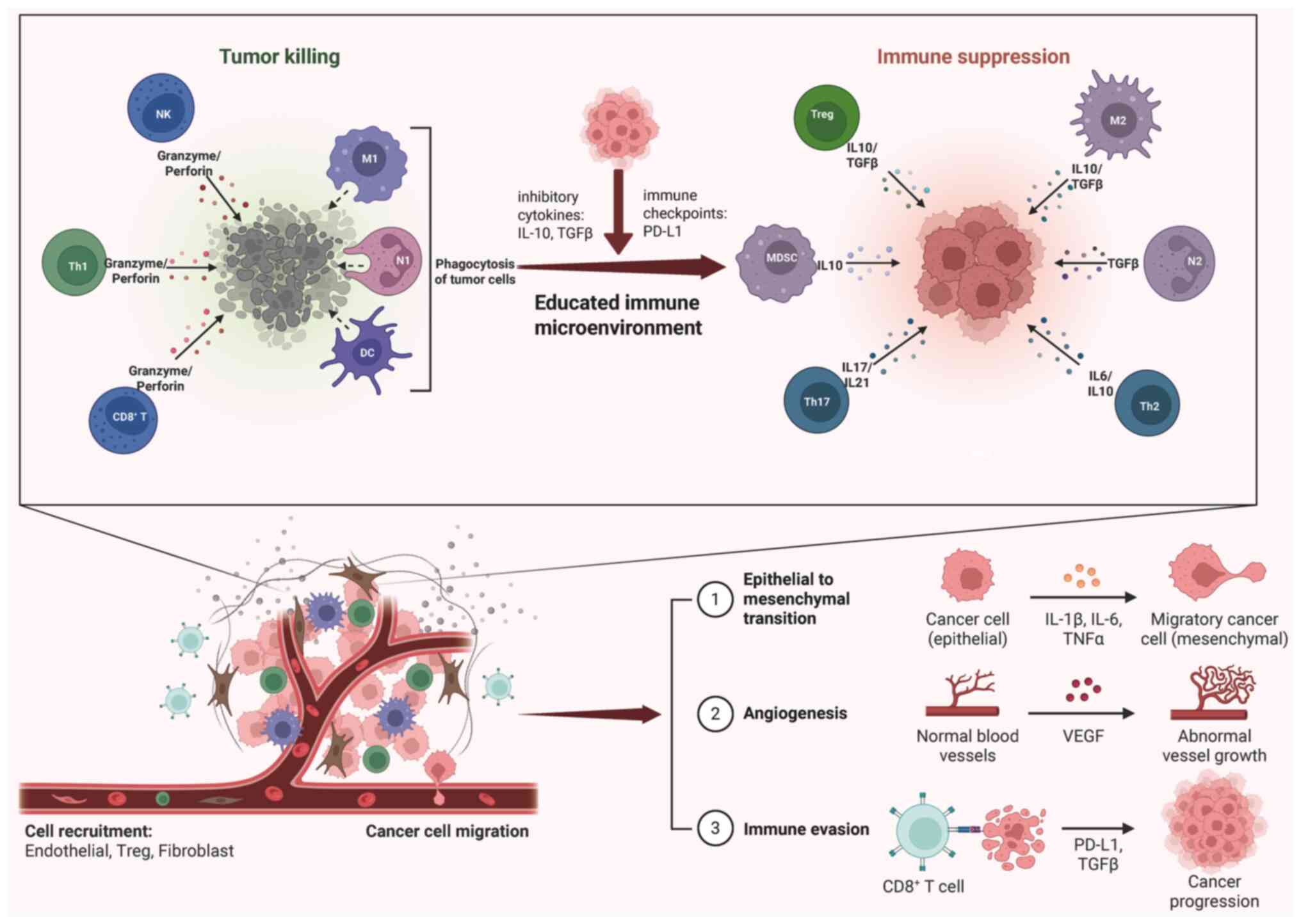

During liver metastasis, immune cells undergo

functional changes as a result of communication with tumor cells.

Typically, under the influence of tumor cells, immune cells shift

toward an immunosuppressive phenotype. Simultaneously, these immune

cells reverse their roles to promote the invasive behavior of tumor

cells by releasing pro-metastatic cytokines. This facilitates the

establishment of a pre-metastatic niche, supporting the

colonization of metastatic tumor cells and leading to the formation

of metastatic foci (Fig. 3)

(22).

Regulatory T cells (Tregs), identified by the

expression of CD25 and FoxP3, are classical immune suppressors

(38). In CRLM, Tregs are the

primary source of IL-10, which increases PD-L1 expression on

monocytes. This interaction diminishes CD8+ T cell

infiltration and impairs antitumor immunity in CRLM (39). Previous studies have shown a

significant increase in the proportion of Tregs in both mouse

models (39,40) and resected CRLM specimens from

patients (41). Furthermore,

Treg-mediated suppression of the antitumor immune response is

linked to clinical prognosis of patients with CRLM (42). Studies have revealed a paradox where

elevated infiltration of FOXP3+ T cells in CRC is

associated with improved relapse-free and disease-specific

survival, while low FOXP3+ T cell infiltration is

associated with poor prognosis (31,43).

This discrepancy may be due to the heterogeneity of Tregs within

the tumor microenvironment (TME). Saito et al (44) identified two distinct subpopulations

of Tregs in CRC terminally differentiated immunosuppressive

FoxP3high and pro-inflammatory FoxP3low

subtypes. Inflammatory Treg-infiltrating CRC showed significant

upregulation of genes associated with inflammation and immune

responses. Functionally distinct subpopulations of Tregs influence

CRC prognosis in opposing directions, with high FOXP3 expression in

immunosuppressive Treg-infiltrating tumors associated with poorer

outcomes. Pedroza-Gonzalez et al (45) demonstrated that, compared with Tregs

from primary hepatocellular carcinoma, Tregs in CRLM exhibit higher

expression of glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor

and stronger immunosuppressive activity. These findings suggest

that a more precise characterization of Treg subpopulations in CRC

and its liver metastases may deepen the understanding of Treg

function in CRLM and help refine therapeutic strategies.

Macrophages within the TME exhibit notable

plasticity and heterogeneity, classified into M1-type macrophages

with pro-inflammatory, immune activating and antitumor properties,

and M2-type macrophages, which possess immunosuppressive and

pro-tumor functions. M2 macrophages are the dominant subtype in

liver metastases (46,47) and associated with poor prognosis

(48).

M2 macrophages facilitate tumor invasion and

metastasis through several mechanisms, such as remodeling the

extracellular matrix (49) and

inducing EMT (50,51). Additionally, M2 macrophages

contribute to tumor angiogenesis through the secretion of VEGF

(52) and support immune evasion by

releasing immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β

(53). Aberrant expression and

activation of signaling molecules such as X-box binding protein 1

(XBP1) in M2 macrophages are further amplified by elevated cytokine

secretion of cytokines, including IL-6 and VEGFA, which accelerate

CRLM progression (54).

Cytokines and exosomes serve pivotal roles in CRC

cells by inducing macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype.

TGF-β, a classical cytokine, regulates macrophage polarization and,

in CRLM, is modulated by pro-oncogenic factors such as collagen

triple helix repeat containing 1, which further promotes CRLM by

remodeling infiltrating macrophages via TGF-β signaling (55). Additionally, CCL2 is a key regulator

of M2-type polarization, which fosters CRLM progression.

Pro-oncogenic factors such as STAT3, transcription factor 4 (TCF4)

and spondin 2 in CRC cells stimulate CCL2 secretion (56–58).

Targeting the CCL2/CCR2 chemokine pathway reduces

M2-typetumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) at metastatic sites,

disrupts the immunosuppressive TME and enhances the susceptibility

of mCRC to antitumor T cell responses (59). Tumor-derived factors such as CCL20,

IL-10, VEGF and IL-1β also serve key roles in promoting macrophage

infiltration and M2 polarization in CRLM (60,61).

Exosome-mediated release of pro-oncogenic factors also contributes

to the M2 polarization. CRC cells induce M2 polarization and

establish an immunosuppressive pre-metastatic niche via the

exosomal release of microRNAs (miRs; such as miR-25-3p, miR-130b-3p

and miR-425-5p, miR-21-5p, miR-203, miR-934, miR-135a-5p and

miR-106a-5p) and signaling molecules such as heat shock protein

90B1, and circ-0034880, which promote CRLM (62–69).

Neutrophils in the TME exhibit dual roles: In

early-stage tumors, they enhance T cell responses, while in

advanced tumors, they adopt an immunosuppressive function (72). Similarly to macrophages, neutrophils

in the TME can differentiate into distinct subsets, categorized as

antitumor N1- and pro-tumor N2-type (73). N1-type neutrophils enhance tumor

cell killing by expressing immune-activating cytokines and

chemokines while inhibiting arginase expression. TGF-β in the TME

induces the polarization of neutrophils from N1 to N2-type. N2-type

neutrophils suppress tumor-killing T cell activity (74) and promote tumor invasion and

metastasis by stimulating angiogenesis (75).

Tumor cells induce neutrophil infiltration via

multiple pathways. CRC cells secrete granulocyte colony stimulating

factor, which recruits neutrophils and upregulates Bv8/Prokineticin

2 expression, promoting immunosuppression and angiogenesis, thereby

contributing to CRC metastasis (75,79).

Seubert et al (80)

demonstrated that tumor-derived tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinases 1(TIMP-1) upregulates stromal derived factor-1,

recruiting neutrophils to the liver, and promoting liver

metastasis. Aberrantly expressed molecules such as cell migration

inducing hyaluronidase 1 (81) and

DNA rrimase subunit 1 (82) in CRLM

ead to the production of CXCL1 and CXCL3, causing accumulation of

immunosuppressive neutrophils, ultimately enhancing CRLM

progression. These findings suggest potential therapeutic targets

for future CRLM research and treatment.

MDSCs, a heterogeneous group of immature myeloid

cells, serve a pivotal role in facilitating CRLM by inducing

immunosuppression, remodeling the extracellular matrix and

promoting angiogenesis (83).

Additionally, MDSCs are involved in the formation of NETs within

the pre-metastatic niche (84).

Abnormal expression and secretion of cytokines trigger MDSC

infiltration, further advancing CRLM. CCL2-CCR2 signaling has been

shown to induce MDSC infiltration in a STAT3-dependent manner,

enhancing their immunosuppressive functions and contributing to CRC

progression (85–87). Furthermore, CRC-derived CCL15

(88) and TME-derived CXCL1

(89,90) recruit MDSCs to establish a

pre-metastatic niche and promote CRLM. Cytokines such as CCL7

(91), IL-6 (92), IL-33 (93) and exosomes containing long

non-coding RNA MIR181A1HG (94)

also serve critical roles in inducing MDSC infiltration, enhancing

tumor invasiveness, supporting neovascularization and facilitating

the creation of a pre-metastatic ecological niche in the liver.

Targeted inhibition of these cytokines may offer an effective

therapeutic approach for CRLM.

DCs, as antigen-presenting cells, initiate immune

responses by capturing exogenous antigens and presenting them to T

cells. To evade immune surveillance, tumor cells suppress antigen

presentation by releasing inhibitory cytokines such as TGF-β

(95). Compared with DCs from

healthy individuals, those from patients with CRC exhibit impaired

antigen presentation, decreased expression of costimulatory

molecules, increased secretion of immunosuppressive IL-10 and

reduced levels of immunostimulatory IL-12 and TNF-α (96). Nagorsen et al (97) found that tumor-infiltrating

S100+ DCs in CRC are negatively associated with systemic

antigen-specific T cell responses and positively associated with

Tregs. Hsu et al (98)

discovered elevated CXCL1 expression in CRC patient-derived DCs,

which enhanced cell migration, increased matrix metalloproteinase 7

expression and promoted EMT, reflecting the altered functionality

of DCs within the CRC TME. Huang et al (99) revealed that tumor-associated

fibroblasts in CRC secrete WNT2, which suppresses DC function

through the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Targeting WNT2 may restore

DC-mediated antitumor immunity. Further exploration of the

mechanisms regulating DC function in CRC may identify new

therapeutic targets for CRC treatment.

As a key component of innate immunity, NK cells

exert antitumor effects by releasing cytotoxic molecules such as

TRAIL and FasL. In a mouse model of CRLM, NK cells were shown to

inhibit liver metastasis of CRC (100). Increased NK cell infiltration is

associated with improved overall survival (OS) in patients with

CRLM (101).

However, NK cell function is impaired in both CRC

and liver metastases compared with NK cells in healthy livers. CRC

cells regulate the TME pH by producing lactic acid, which lowers

the pH within NK cells, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and

apoptosis. This enables tumor cells to evade the cytotoxic effects

of NK cells (105). Metabolic

dysfunction in the metastatic niche notably impacts NK cell

functionality. Increased glutamine uptake by cancer cells depletes

glutamine availability for NK cells, decreasing their activity and

cytotoxicity, thereby promoting CRLM progression (106).

Upon entering the portal circulation, tumor cells

reach the hepatic sinusoidal capillaries through the portal vein.

These tumor cells trigger non-specific liver defense mechanisms,

leading to their phagocytosis by resident immune cells such as

Kupffer cells (KCs) and NK cells (107).

KCs, the resident macrophages of the liver, serve a

pivotal role in maintaining liver homeostasis and are key

contributors to the pathogenesis of liver disease. KCs are

essential in defending against liver metastasis due to their

phagocytic capability, cytokine production and promotion of

tertiary lymphoid structures (108). Dysfunction of phagocytosis in KCs

is a key driving force in CRLM. Some tumor cells can evade

phagocytosis by KCs, highlighting the need for further research

into this evasion mechanism to identify novel therapeutic targets

for liver metastasis (109). The

balance between pro-phagocytic ‘eat me’ signals, such as

tumor-associated antigens, calreticulin, SLAM Family Member 7 and

Erythroblast Membrane Associated Protein (ERMAP), and

anti-phagocytic ‘don't eat me’ signals, including CD47, PD-L1, CD24

and β2-microglobulin, is a key determinant in the phagocytosis

process (110). Additionally, the

functional reprogramming of KCs warrants attention. Following

metastatic colonization of the liver, KCs undergo transcriptional

reprogramming typical of TAMs, which facilitates tumor progression

(111). The phagocytosis of

exosomes released by the primary tumor into the circulation and

into the liver by KCs can initiate the formation of a

pre-metastatic niche in the liver (66).

Liver-resident specialized NK cells also serve a

significant role in the early stages of metastasis by contributing

to the establishment of pre-metastatic niches. Invariant NK T cells

in the liver promote metastasis by producing fibrogenic cytokines

such as IL-4 and IL-13, independent of T cell receptor activation,

thereby inducing a fibrotic niche in the liver. Targeted disruption

of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathways in hepatic stellate cells

inhibits their trans differentiation into extracellular

matrix-producing myofibroblasts, thereby impeding the metastatic

proliferation of disseminated cancer cells (112).

Tumor cells that evade innate immune surveillance

extravasate from blood vessels and form metastatic lesions. Tumor

cell adhesion to the vascular system is not only driven by

mechanical blockage of the vasculature, but also by specific

cellular adhesion processes that facilitate tumor cell attachment

and extravasation (113,114). Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

express the cell adhesion molecule E-selectin, which promotes tumor

cell attachment to hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells. Inhibition

of E-selectin effectively decreases the formation of liver

metastases (115). Moreover, tumor

cells can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such

as TNF-α, from KCs, which upregulates the expression of adhesion

molecules, such as E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

and intercellular adhesion molecule 1(ICAM1) on hepatic sinusoidal

endothelial cells. This increase in adhesion molecule expression

enhances tumor cell colonization in the liver (116).

Once tumor cells extravasate into the Disse

interstitium, hepatic stellate cells are activated by cytokines

such as TGF-β, which is secreted by KCs. This activation prompts

hepatic stellate cells to produce extracellular matrix proteins

such as collagen, laminin and fibronectin, creating a supportive

environment for tumor cell colonization. Additionally, KCs and

neutrophils secrete matrix metalloproteinases and elastases, which

degrade and remodel the extracellular matrix, facilitating tumor

cell invasion. Concurrently, hepatic stellate cells promote a

suppressive microenvironment by inducing the apoptosis of cytotoxic

T cells and expanding immune-regulatory T cells, creating a

favorable environment for tumor cell colonization in the liver

(117).

Research into liver metastasis in CRC has revealed

numerous potential therapeutic targets, with targeted therapy and

immunotherapy emerging as the leading strategies for managing CRLM

(121). In addition to traditional

neoadjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy and adjuvant therapy

following surgical resection, integrating targeted and

immunotherapies with radiotherapy/chemotherapy and surgery has

established a comprehensive treatment system for CRLM (122). This combination therapy offers

dual benefits: By initiating neoadjuvant treatment, previously

unresectable CRLM can become surgically resectable, increasing the

number of patients eligible for hepatic resection while decreasing

perioperative morbidity and mortality (123). Second, these combination therapies

show promise in enhancing long-term survival rates for patients

(124).

EGFR, a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase (TK)

family, serves a key role in CRC development and invasive

metastasis through downstream signaling pathways, including the

RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways (125). Cetuximab, the first monoclonal

antibody targeting EGFR, significantly improves OS and

progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with CRC who are

resistant to other treatment (126). When combined with chemotherapy,

cetuximab has demonstrated favorable therapeutic outcomes. The

combination of cetuximab with FOLFIRI (irinotecan, fluorouracil and

leucovorin) significantly decreases the risk of disease progression

in patients with mCRC compared with FOLFIRI alone (127). The combination of cetuximab with

FOLFOX4(oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and fluorouracil) as first-line

treatment for mCRC has also shown superior remission rates compared

with the FOLFOX4 regimen alone (128). However, mutations in the RAS gene

in CRC confer resistance to cetuximab, meaning cetuximab is

effective in patients with RAS wild-type mCRC (129) Another EGFR targeting drug,

panitumumab, is a fully humanized antibody that does not induce

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (125). The PRIME trial, which examined the

efficacy of FOLFOX alone and in combination with panitumumab in

patients with mCRC, found that the combination therapy resulted in

higher OS and PFS compared with FOLFOX treatment alone (130,131).

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the

angiogenesis inhibitor VEGF, has received US Food and Drug

Administration approval for the treatment of mCRC and demonstrated

favorable efficacy (132). A

meta-analysis by Cao et al (133), which included 1,838 patients with

mCRC, showed that chemotherapy combined with bevacizumab following

primary tumor resection significantly prolonged OS compared with

chemotherapy alone. The study also revealed improved OS in patients

who were initially unable to undergo resection of their primary

tumor when treated with bevacizumab. Additionally, the combination

of bevacizumab with chemotherapy may enhance the resectability of

CRLM. In a study by Tang et al (134), the combination of bevacizumab with

mFOLFOX6 as first-line treatment for patients with unresectable

CRLM harboring RAS mutations demonstrated significantly superior

efficacy compared with mFOLFOX6 monotherapy. This combination not

only markedly increased the R0 resection rate of liver metastases

but also improved the overall resectability of liver metastases,

leading to improved PFS and OS in patients. Ramucirumab, a VEGFR

antagonist that specifically binds VEGFR2 and blocks

ligand-receptor binding, has also shown promising results in mCRC

treatment (135). In a study by

Tabernero et al (136), the

combination of ramucirumab and FOLFIRI was evaluated against a

placebo in patients with mCRC. Ramucirumab and FOLFIRI combination

significantly improved OS in patients. Ramucirumab is currently

approved for use in the second-line treatment of mCRC.

Receptor TKs, located on the cell surface and

intracellularly, play a key role in intercellular signaling, which

influences cell function. TKIs block the activity of kinase

proteins that contribute to tumor cell proliferation and the

development of tumor vasculature. Regorafenib is an oral,

multi-targeted TKI that inhibits VEGFR1-3, PDGFR, FGFR, KIT, RET1

and BRAF and has been shown to improve survival in patients with

refractory mCRC (137).

Regorafenib is used to treat mCRC that progresses despite previous

chemotherapy, anti-VEGF or anti-EGFR therapy (138). In addition to regorafenib,

fruquintinib is an oral TKI that selectively inhibits different

subtypes of VEGFR, thereby inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and growth

(139). The FRESCO study evaluated

the effectiveness and safety of fruquintinib as a third-line or

subsequent treatment for patients with mCRC. The results

demonstrated that fruquintinib monotherapy significantly prolonged

survival in patients with mCRC who had failed second-line or higher

chemotherapy (140). FRESCO-2, an

international, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3

study, also demonstrated that fruquintinib significantly improved

overall survival in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal

cancer compared to placebo (141).

Fruquintinib is currently approved by FDA for use in patients with

mCRC who have previously undergone fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-,

and irinotecan-based chemotherapy, an anti-VEGF therapy, and if RAS

wild-type and medically appropriate, an anti-EGFR therapy (142).

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors have

garnered attention due to their success in achieving long-lasting

responses in a range of previously difficult-to-treat solid tumors

(143). Overman et al

(144) demonstrated the

significant efficacy of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab alone in

individuals with deficient mismatch repair/microsatellite

instability(dMMR/MSI) CRC in a multicenter phase II clinical trial

(CheckMate142). Similarly, the KEYNOTE-177 (145) study showed a significant

improvement in PFS in patients with dMMR/MSI mCRC treated with the

PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab as first-line therapy, compared with

standard treatment. PD-1 inhibitors are currently approved by FDA

for patients with dMMR/MSI mCRC who experience disease progression

following standard chemotherapy (146). This approval highlights their

importance as a pivotal immunotherapy approach, particularly for

individuals with liver metastases from CRC. However, the efficacy

of PD-1 inhibitors varies among patients, and some do not benefit

from them. Patients with proficient mismatch repair/microsatellite

stability(pMMR/MSS) CRC, which constitutes the majority of the

patient population, derive limited benefits from PD-1 inhibitor

therapy. For individuals with dMMR/MSI CRC, who are currently

considered candidates for PD-1 inhibitor treatment, the observed

efficacy rate is suboptimal. In the KEYNOTE-016 trial,

pembrolizumab was administered to a cohort of 41 patients with CRC,

including both pMMR/MSS and dMMR/MSI subgroups, who experienced

disease progression following chemotherapy. In patients with

dMMR/MSI CRC, the immune-related objective response rate was 40%

and the 20-week PFS rate was 78%. By contrast, patients with

pMMR/MSS CRC exhibited an immune-related objective response rate of

0% and a 20-week PFS rate of 11% (147). Furthermore, liver metastases from

CRC induce systemic immune tolerance through a unique

immunosuppressive mechanism, which may further affect the efficacy

of PD-1 inhibitor therapy (148–150). Exploring effective combination

therapies may enhance the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors. The

CheckMate-142 study demonstrated that combining PD-1 inhibitors

with CTLA4 inhibitors improves antitumor efficacy (151). In addition to immune checkpoint

inhibitors, drugs such as regorafenib have gained widespread

attention as potential combination therapies with PD-1 inhibitors

due to their promising role in modulating immunity and improving

the TME (152,153).

Cancer vaccines, adoptive cell transfer (ACT)

therapy and oncolytic viruses have emerged as prominent areas of

research in CRLM (154–156). As a form of active immunotherapy,

cancer vaccines present the immune system with tumor-specific or

-associated antigens, inducing antitumor cytotoxic responses that

help the immune system recognize and destroy cancer cells (157). ACT therapy enhances the natural

anti-cancer response by activating or genetically modifying

autologous or allogeneic immune cells in vitro to boost

tumor-fighting capabilities, followed by reinfusion into patients.

ACT includes therapies such as cytokine-induced killer cells and

chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapies (158). Oncolytic virus therapy uses

naturally occurring or genetically engineered viruses to

selectively target and lyse tumor cells. This strategy not only

modulates the TIME but also activates specific anti-tumor immune

responses (159). Additionally, it

is crucial to explore the role of cytokines, chemokines and

adjuvants in enhancing the precision and efficacy of

immunotherapies in CRLM.

Liver metastasis is a major factor influencing the

prognosis of patients with CRC. The process of liver metastasis in

CRC is complex and involves interconnected stages. Key pathways

that affect the invasive and metastatic potential of CRC cells have

been identified, along with prognostic and therapeutic molecules.

Additionally, factors within the TME influencing liver metastasis

in CRC have been preliminarily analyzed. Notably, the discovery of

immune-associated targets holds promise for treating liver

metastasis in CRC and improving prognosis. However, the clinical

application of these targets and associated drugs in individuals

with CRLM remains limited, and many patients do not benefit from

current targeted therapies and immunotherapies. Therapeutic

strategies aimed at modulating the immunosuppressive

microenvironment, such as depleting immunosuppressive cells,

inhibiting immune checkpoint pathways and stimulating cytotoxic

cells are critical approaches for enhancing the effectiveness of

immunotherapy.

Currently, novel immunotherapies for CRLM remain in

preclinical or clinical trials, and their successful integration

into clinical practice faces challenges. Firstly, CRLM creates a

highly immunosuppressive microenvironment within the liver. This

hostile TME actively inhibits the function of effector immune cells

(such as cytotoxic T cells and NK cells), rendering many

immunotherapies ineffective. Secondly, tumor heterogeneity and

evolution make it difficult to identify universal therapeutic

targets. Thirdly, lack of predictive biomarkers makes it difficult

to select patients most likely to benefit from expensive and

potentially toxic immunotherapies, leading to low response rates

and inefficient resource use. Lastly, overcoming the aforementioned

challenges above often requires combining immunotherapies (e.g.,

dual checkpoint blockade) with other modalities like chemotherapy,

targeted therapy (e.g., anti-VEGF, anti-EGFR), radiotherapy,

liver-directed therapies (ablation, embolization), or other

immunomodulators. Combinations significantly increase the risk of

severe immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including hepatitis,

colitis, pneumonitis, and endocrine toxicities. Managing

overlapping toxicities, especially in patients with liver

involvement, is challenging and can limit dosing or lead to

treatment discontinuation.

Overcoming these multifaceted challenges requires

further intensive studies to understand the CRLM biology and liver

immunology, elucidate the underlying mechanisms, discovering robust

biomarkers and identify novel therapeutic targets. Deeper

understanding of the key molecules and signaling pathways

influencing the invasive and metastatic potential of CRC is key,

achievable through the integration of high-throughput genomic

technology. Considering the complex and heterogeneous influence of

the TME on liver metastasis, it is necessary to investigate the

functional characteristics and dynamic changes of distinct cell

populations throughout the liver metastasis process, at a

single-cell level to identify key cells and molecules driving TME

remodeling. Moreover, as the understanding of the mechanisms

underlying CRLM advances, the diagnosis and treatment of this

condition may shift toward a multidisciplinary approach and enhance

patient care by facilitating a comprehensive and integrated

treatment strategy.

In conclusion, further research is required into the

mechanisms in CRLM, the exploration of novel targets for

personalized treatment and the development of innovative

intervention strategies to improve CRLM therapy efficacy.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82272841).

Not applicable.

CJY conceptualized the study and wrote the

manuscript. LZ performed the literature review. CHW and YJY

contributed to conception and design. ZLS revised and edited the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Horn SR, Stoltzfus KC, Lehrer EJ, Dawson

LA, Tchelebi L, Gusani NJ, Sharma NK, Chen H, Trifiletti DM and

Zaorsky NG: Epidemiology of liver metastases. Cancer Epidemiol.

67:1017602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O'Rourke T

and John TG: Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic

resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: A multifactorial model

of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 247:125–135. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Joyce JA and Pollard JW:

Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:239–252. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Medici B, Benatti S, Dominici M and

Gelsomino F: New frontiers of biomarkers in metastatic colorectal

cancer: Potential and critical issues. Int J Mol Sci. 26:52682025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tsubakihara Y and Moustakas A:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis under the control

of transforming growth factor β. Int J Mol Sci. 19:36722018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

van Zijl F, Krupitza G and Mikulits W:

Initial steps of metastasis: Cell invasion and endothelial

transmigration. Mutat Res. 728:23–34. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Qi J and Zhu YQ: Targeting the most

upstream site of Wnt signaling pathway provides a strategic

advantage for therapy in colorectal cancer. Curr Drug Targets.

9:548–557. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rubinfeld B, Albert I, Porfiri E, Fiol C,

Munemitsu S and Polakis P: Binding of GSK3beta to the

APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly.

Science. 272:1023–1026. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang Z, Gao Y, Qian Y, Wei B, Jiang K,

Sun Z, Zhang F, Yang M, Baldi S, Yu X, et al: The Lyn/RUVBL1

complex promotes colorectal cancer liver metastasis by regulating

arachidonic acid metabolism through chromatin remodeling. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24065622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zubeldia IG, Bleau AM, Redrado M, Serrano

D, Agliano A, Gil-Puig C, Vidal-Vanaclocha F, Lecanda J and Calvo

A: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell

phenotypes leading to liver metastasis are abrogated by the novel

TGFβ1-targeting peptides P17 and P144. Exp Cell Res. 319:12–22.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang Y, Yang Y, Qi X, Cui P, Kang Y, Liu

H, Wei Z and Wang H: SLC14A1 and TGF-β signaling: A feedback loop

driving EMT and colorectal cancer metachronous liver metastasis. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:2082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shin AE, Sugiura K, Kariuki SW, Cohen DA,

Flashner SP, Klein-Szanto AJ, Nishiwaki N, De D, Vasan N, Gabre JT,

et al: LIN28B-mediated PI3K/AKT pathway activation promotes

metastasis in colorectal cancer models. J Clin Invest.

135:e1860352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sun X, Zhang J, Dong B, Xiong Q, Wang X,

Gu Y, Wang Z, Liu H, Zhang J, He X, et al: Targeting SLITRK4

restrains proliferation and liver metastasis in colorectal cancer

via regulating PI3K/AKT/NFκB pathway and tumor-associated

macrophage. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24003672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dong Z, She X, Ma J, Chen Q, Gao Y, Chen

R, Qin H, Shen B and Gao H: The E3 Ligase NEDD4L prevents

colorectal cancer liver metastasis via degradation of PRMT5 to

inhibit the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Adv Sci (Weinh).

2025:e25047042025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Urosevic J, Blasco MT, Llorente A,

Bellmunt A, Berenguer-Llergo A, Guiu M, Cañellas A, Fernandez E,

Burkov I, Clapés M, et al: ERK1/2 signaling induces upregulation of

ANGPT2 and CXCR4 to mediate liver metastasis in colon cancer.

Cancer Res. 80:4668–4680. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chu PC, Lin PC, Wu HY, Lin KT, Wu C,

Bekaii-Saab T, Lin YJ, Lee CT, Lee JC and Chen CS: Mutant KRAS

promotes liver metastasis of colorectal cancer, in part, by

upregulating the MEK-Sp1-DNMT1-miR-137-YB-1-IGF-IR signaling

pathway. Oncogene. 37:3440–3455. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yao JF, Li XJ, Yan LK, He S, Zheng JB,

Wang XR, Zhou PH, Zhang L, Wei GB and Sun XJ: Role of HGF/c-Met in

the treatment of colorectal cancer with liver metastasis. J Biochem

Mol Toxicol. 33:e223162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xu W, Xu J, Liu J, Wang N, Zhou L and Guo

J: Liver metastasis in cancer: Molecular mechanisms and management.

MedComm (2020). 6:e701192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dunbar KJ, Efe G, Cunningham K, Esquea E,

Navaridas R and Rustgi AK: Regulation of metastatic organotropism.

Trends Cancer. 11:216–231. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhu C, Liao JY, Liu YY, Chen ZY, Chang RZ,

Chen XP, Zhang BX and Liang JN: Immune dynamics shaping

pre-metastatic and metastatic niches in liver metastases: From

molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Mol Cancer.

23:2542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li Y, Liu F, Cai Q, Deng L, Ouyang Q,

Zhang XH and Zheng J: Invasion and metastasis in cancer: Molecular

insights and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

10:572025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Glaire MA, Domingo E, Sveen A, Bruun J,

Nesbakken A, Nicholson G, Novelli M, Lawson K, Oukrif D, Kildal W,

et al: Tumour-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes and

colorectal cancer recurrence by tumour and nodal stage. Br J

Cancer. 121:474–482. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Trailin A, Ali E, Ye W, Pavlov S,

Červenková L, Vyčítal O, Ambrozkiewicz F, Hošek P, Daum O, Liška V

and Hemminki K: Prognostic assessment of T-cells in primary

colorectal cancer and paired synchronous or metachronous liver

metastasis. Int J Cancer. 156:1282–1292. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang A, Zhou M, Gao Y and Zhang Y:

Mechanisms of CD8+ T cell exhaustion and its clinical

significance in prognosis of anti-tumor therapies: A review. Int

Immunopharmacol. 159:1148432025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shan T, Chen S, Wu T, Yang Y, Li S and

Chen X: PD-L1 expression in colon cancer and its relationship with

clinical prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 12:1764–1769.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhao T, Li Y, Zhang J and Zhang B: PD-L1

expression increased by IFN-γ via JAK2-STAT1 signaling and predicts

a poor survival in colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 20:1127–1134.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wei XL, Luo X, Sheng H, Wang Y, Chen DL,

Li JN, Wang FH and Xu RH: PD-L1 expression in liver metastasis: Its

clinical significance and discordance with primary tumor in

colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 18:4752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rong D, Sun G, Zheng Z, Liu L, Chen X, Wu

F, Gu Y, Dai Y, Zhong W, Hao X, et al: MGP promotes CD8+

T cell exhaustion by activating the NF-κB pathway leading to liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 18:2345–2361.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun G, Zhao S, Fan Z, Wang Y, Liu H, Cao

H, Sun G, Huang T, Cai H, Pan H, et al: CHSY1 promotes

CD8+ T cell exhaustion through activation of succinate

metabolism pathway leading to colorectal cancer liver metastasis

based on CRISPR/Cas9 screening. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:2482023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kuwahara T, Hazama S, Suzuki N, Yoshida S,

Tomochika S, Nakagami Y, Matsui H, Shindo Y, Kanekiyo S, Tokumitsu

Y, et al: Intratumoural-infiltrating CD4+ and FOXP3 + T cells as

strong positive predictive markers for the prognosis of resectable

colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 121:659–665. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Katz SC, Pillarisetty V, Bamboat ZM, Shia

J, Hedvat C, Gonen M, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, Blumgart L, D'Angelica M

and DeMatteo RP: T cell infiltrate predicts long-term survival

following resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Ann Surg

Oncol. 16:2524–2530. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Katz SC, Pillarisetty VG, Bleier JI,

Kingham TP, Chaudhry UI, Shah AB and DeMatteo RP: Conventional

liver CD4 T cells are functionally distinct and suppressed by

environmental factors. Hepatology. 42:293–300. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B,

Fredriksen T, Mauger S, Bindea G, Berger A, Bruneval P, Fridman WH,

Pagès F and Galon J: Clinical impact of different classes of

infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, th2, treg, th17) in

patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 71:1263–1271. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu X, Wang X, Yang Q, Luo L, Liu Z, Ren

X, Lei K, Li S, Xie Z, Zheng G, et al: Th17 cells Secrete TWEAK to

trigger epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promote colorectal

cancer liver metastasis. Cancer Res. 84:1352–1371. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

De Simone V, Pallone F, Monteleone G and

Stolfi C: Role of T(H)17 cytokines in the control of colorectal

cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2:e266172013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kroemer M, Turco C, Spehner L, Viot J,

Idirène I, Bouard A, Renaude E, Deschamps M, Godet Y, Adotévi O, et

al: Investigation of the prognostic value of CD4 T cell subsets

expanded from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes of colorectal cancer

liver metastases. J Immunother Cancer. 8:e0014782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Olguín JE, Medina-Andrade I, Rodríguez T,

Rodríguez-Sosa M and Terrazas LI: Relevance of regulatory T cells

during colorectal cancer development. Cancers (Basel). 12:18882020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shiri AM, Zhang T, Bedke T, Zazara DE,

Zhao L, Lücke J, Sabihi M, Fazio A, Zhang S, Tauriello DVF, et al:

IL-10 dampens antitumor immunity and promotes liver metastasis via

PD-L1 induction. J Hepatol. 80:634–644. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Huang X, Chen Z, Zhang N, Zhu C, Lin X, Yu

J, Chen Z, Lan P and Wan Y: Increase in

CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cell number and

upregulation of the HGF/c-Met signaling pathway during the liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 20:2113–2118. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Katz SC, Bamboat ZM, Maker AV, Shia J,

Pillarisetty VG, Yopp AC, Hedvat CV, Gonen M, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y,

et al: Regulatory T cell infiltration predicts outcome following

resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol.

20:946–955. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Brudvik KW, Henjum K, Aandahl EM,

Bjørnbeth BA and Taskén K: Regulatory T-cell-mediated inhibition of

antitumor immune responses is associated with clinical outcome in

patients with liver metastasis from colorectal cancer. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 61:1045–1053. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Salama P, Phillips M, Grieu F, Morris M,

Zeps N, Joseph D, Platell C and Iacopetta B: Tumor-infiltrating

FOXP3+ T regulatory cells show strong prognostic significance in

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:186–192. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Saito T, Nishikawa H, Wada H, Nagano Y,

Sugiyama D, Atarashi K, Maeda Y, Hamaguchi M, Ohkura N, Sato E, et

al: Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T cell subpopulations distinctly control the

prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat Med. 22:679–684. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pedroza-Gonzalez A, Verhoef C, Ijzermans

JN, Peppelenbosch MP, Kwekkeboom J, Verheij J, Janssen HL and

Sprengers D: Activated tumor-infiltrating CD4+ regulatory T cells

restrain antitumor immunity in patients with primary or metastatic

liver cancer. Hepatology. 57:183–194. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

He Y, Han Y, Fan AH, Li D, Wang B, Ji K,

Wang X, Zhao X and Lu Y: Multi-perspective comparison of the immune

microenvironment of primary colorectal cancer and liver metastases.

J Transl Med. 20:4542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang D, Wang X, Si M, Yang J, Sun S, Wu H,

Cui S, Qu X and Yu X: Exosome-encapsulated miRNAs contribute to

CXCL12/CXCR4-induced liver metastasis of colorectal cancer by

enhancing M2 polarization of macrophages. Cancer Lett. 474:36–52.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lee YS, Song SJ, Hong HK, Oh BY, Lee WY

and Cho YB: The FBW7-MCL-1 axis is key in M1 and M2

macrophage-related colon cancer cell progression: Validating the

immunotherapeutic value of targeting PI3Kγ. Exp Mol Med.

52:815–831. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Afik R, Zigmond E, Vugman M, Klepfish M,

Shimshoni E, Pasmanik-Chor M, Shenoy A, Bassat E, Halpern Z, Geiger

T, et al: Tumor macrophages are pivotal constructors of tumor

collagenous matrix. J Exp Med. 213:2315–2331. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Cai J, Xia L, Li J, Ni S, Song H and Wu X:

Tumor-associated macrophages derived TGF-β-induced epithelial to

mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer cells through

Smad2,3-4/Snail signaling pathway. Cancer Res Treat. 51:252–266.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wei C, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Zhang C, Lin

X, Liu Q, Dou R and Xiong B: Crosstalk between cancer cells and

tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal

circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol

Cancer. 18:642019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Suarez-Lopez L, Sriram G, Kong YW,

Morandell S, Merrick KA, Hernandez Y, Haigis KM and Yaffe MB: MK2

contributes to tumor progression by promoting M2 macrophage

polarization and tumor angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

115:E4236–E4244. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhong X, Chen B and Yang Z: The role of

Tumor-associated macrophages in colorectal carcinoma progression.

Cell Physiol Biochem. 45:356–365. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhao Y, Zhang W, Huo M, Wang P, Liu X,

Wang Y, Li Y, Zhou Z, Xu N and Zhu H: XBP1 regulates the protumoral

function of tumor-associated macrophages in human colorectal

cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:3572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang XL, Hu LP, Yang Q, Qin WT, Wang X,

Xu CJ, Tian GA, Yang XM, Yao LL, Zhu L, et al: CTHRC1 promotes

liver metastasis by reshaping infiltrated macrophages through

physical interactions with TGF-β receptors in colorectal cancer.

Oncogene. 40:3959–3973. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Huang C, Ou R, Chen X, Zhang Y, Li J,

Liang Y, Zhu X, Liu L, Li M, Lin D, et al: Tumor cell-derived SPON2

promotes M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and

cancer progression by activating PYK2 in CRC. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 40:3042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wang X, Wang J, Zhao J, Wang H, Chen J and

Wu J: HMGA2 facilitates colorectal cancer progression via

STAT3-mediated tumor-associated macrophage recruitment.

Theranostics. 12:963–975. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Tu W, Gong J, Zhou Z, Tian D and Wang Z:

TCF4 enhances hepatic metastasis of colorectal cancer by regulating

tumor-associated macrophage via CCL2/CCR2 signaling. Cell Death

Dis. 12:8822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Grossman JG, Nywening TM, Belt BA, Panni

RZ, Krasnick BA, DeNardo DG, Hawkins WG, Goedegebuure SP, Linehan

DC and Fields RC: Recruitment of CCR2+ tumor associated

macrophage to sites of liver metastasis confers a poor prognosis in

human colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 7:e14707292018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Xu C, Fan L, Lin Y, Shen W, Qi Y, Zhang Y,

Chen Z, Wang L, Long Y, Hou T, et al: Fusobacterium

nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through

miR-1322/CCL20 axis and M2 polarization. Gut Microbes.

13:19803472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Ohashi K, Wang Z, Yang YM, Billet S, Tu W,

Pimienta M, Cassel SL, Pandol SJ, Lu SC, Sutterwala FS, et al:

NOD-like receptor C4 inflammasome regulates the growth of colon

cancer liver metastasis in NAFLD. Hepatology. 70:1582–1599. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhou J, Song Q, Li H, Han Y, Pu Y, Li L,

Rong W, Liu X, Wang Z, Sun J, et al: Targeting

circ-0034880-enriched tumor extracellular vesicles to impede

SPP1highCD206+ pro-tumor macrophages mediated

pre-metastatic niche formation in colorectal cancer liver

metastasis. Mol Cancer. 23:1682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Shao Y, Chen T, Zheng X, Yang S, Xu K,

Chen X, Xu F, Wang L, Shen Y, Wang T, et al: Colorectal

cancer-derived small extracellular vesicles establish an

inflammatory premetastatic niche in liver metastasis.

Carcinogenesis. 39:1368–1379. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Takano Y, Masuda T, Iinuma H, Yamaguchi R,

Sato K, Tobo T, Hirata H, Kuroda Y, Nambara S, Hayashi N, et al:

Circulating exosomal microRNA-203 is associated with metastasis

possibly via inducing tumor-associated macrophages in colorectal

cancer. Oncotarget. 8:78598–78613. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhao S, Mi Y, Guan B, Zheng B, Wei P, Gu

Y, Zhang Z, Cai S, Xu Y, Li X, et al: Tumor-derived exosomal

miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1562020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sun H, Meng Q, Shi C, Yang H, Li X, Wu S,

Familiari G, Relucenti M, Aschner M, Wang X and Chen R:

Hypoxia-inducible exosomes facilitate liver-tropic premetastatic

niche in colorectal cancer. Hepatology. 74:2633–2651. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Li S, Fu X, Ning D, Liu Q, Zhao J, Cheng

Q, Chen X and Jiang L: Colon cancer exosome-associated HSP90B1

initiates pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver by polarizing

M1 macrophage into M2 phenotype. Biol Direct. 20:522025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Liang Y, Li J, Yuan Y, Ju H, Liao H, Li M,

Liu Y, Yao Y, Yang L, Li T and Lei X: Exosomal miR-106a-5p from

highly metastatic colorectal cancer cells drives liver metastasis

by inducing macrophage M2 polarization in the tumor

microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:2812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Wei X, Ye J, Pei Y, Wang C, Yang H, Tian

J, Si G, Ma Y, Wang K and Liu G: Extracellular vesicles from

colorectal cancer cells promote metastasis via the NOD1 signalling

pathway. J Extracell Vesicles. 11:e122642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liu Y, Zhang Q, Xing B, Luo N, Gao R, Yu

K, Hu X, Bu Z, Peng J, Ren X and Zhang Z: Immune phenotypic linkage

between colorectal cancer and liver metastasis. Cancer Cell.

40:424–437.e5. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wu Y, Yang S, Ma J, Chen Z, Song G, Rao D,

Cheng Y, Huang S, Liu Y, Jiang S, et al: Spatiotemporal immune

landscape of colorectal cancer liver metastasis at Single-cell

level. Cancer Discov. 12:134–153. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Eruslanov EB, Bhojnagarwala PS, Quatromoni

JG, Stephen TL, Ranganathan A, Deshpande C, Akimova T, Vachani A,

Litzky L, Hancock WW, et al: Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate

T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J Clin Invest.

124:5466–5480. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V,

Cheng G, Ling L, Worthen GS and Albelda SM: Polarization of

tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: ‘N1’ versus ‘N2’

TAN. Cancer Cell. 16:183–194. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Germann M, Zangger N, Sauvain MO, Sempoux

C, Bowler AD, Wirapati P, Kandalaft LE, Delorenzi M, Tejpar S,

Coukos G and Radtke F: Neutrophils suppress tumor-infiltrating T

cells in colon cancer via matrix metalloproteinase-mediated

activation of TGFβ. EMBO Mol Med. 12:e106812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Itatani Y, Yamamoto T, Zhong C, Molinolo

AA, Ruppel J, Hegde P, Taketo MM and Ferrara N: Suppressing

neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis abrogates resistance to anti-VEGF

antibody in a genetic model of colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 117:21598–21608. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Gordon-Weeks AN, Lim SY, Yuzhalin AE,

Jones K, Markelc B, Kim KJ, Buzzelli JN, Fokas E, Cao Y, Smart S

and Muschel R: Neutrophils promote hepatic metastasis growth

through fibroblast growth factor 2-dependent angiogenesis in mice.

Hepatology. 65:1920–1935. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Yang L, Liu L, Zhang R, Hong J, Wang Y,

Wang J, Zuo J, Zhang J, Chen J and Hao H: IL-8 mediates a positive

loop connecting increased neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and

colorectal cancer liver metastasis. J Cancer. 11:4384–4396. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Tan H, Jiang Y, Shen L, Nuerhashi G, Wen

C, Gu L, Wang Y, Qi H, Cao F, Huang T, et al: Cryoablation-induced

neutrophil Ca2+ elevation and NET formation exacerbate

immune escape in colorectal cancer liver metastasis. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 43:3192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jiang Y, Long G, Huang X, Wang W, Cheng B

and Pan W: Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals dynamic

changes in the liver microenvironment during colorectal cancer

metastatic progression. J Transl Med. 23:3362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Seubert B, Grünwald B, Kobuch J, Cui H,

Schelter F, Schaten S, Siveke JT, Lim NH, Nagase H, Simonavicius N,

et al: Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 creates a

premetastatic niche in the liver through SDF-1/CXCR4-dependent

neutrophil recruitment in mice. Hepatology. 61:238–248. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wang H, Zhang B, Li R, Chen J, Xu G, Zhu

Y, Li J, Liang Q, Hua Q, Wang L, et al: KIAA1199 drives immune

suppression to promote colorectal cancer liver metastasis by

modulating neutrophil infiltration. Hepatology. 76:967–981. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wu J, Song J, Ge Y, Hou S, Chang Y, Chen

X, Nie Z, Guo L and Yin J: PRIM1 enhances colorectal cancer liver

metastasis via promoting neutrophil recruitment and formation of

neutrophil extracellular trap. Cell Signal. 132:1118222025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zhang QQ, Hu XW, Liu YL, Ye ZJ, Gui YH,

Zhou DL, Qi CL, He XD, Wang H and Wang LJ: CD11b deficiency

suppresses intestinal tumor growth by reducing myeloid cell

recruitment. Sci Rep. 5:159482015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Cao X, Lan Q, Xu H, Liu W, Cheng H, Hu X,

He J, Yang Q, Lai W and Chu Z: Granulocyte-like myeloid-derived

suppressor cells: The culprits of neutrophil extracellular traps

formation in the pre-metastatic niche. Int Immunopharmacol.

143:1135002024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lim SY, Gordon-Weeks AN, Zhao L, Tapmeier

TT, Im JH, Cao Y, Beech J, Allen D, Smart S and Muschel RJ:

Recruitment of myeloid cells to the tumor microenvironment supports

liver metastasis. Oncoimmunology. 2:e231872013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Zhao L, Lim SY, Gordon-Weeks AN, Tapmeier

TT, Im JH, Cao Y, Beech J, Allen D, Smart S and Muschel RJ:

Recruitment of a myeloid cell subset (CD11b/Gr1 mid) via CCL2/CCR2

promotes the development of colorectal cancer liver metastasis.

Hepatology. 57:829–839. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Chun E, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Gallini CA,

Kim J, Soucy G, Odze R, Glickman JN and Garrett WS: CCL2 promotes

colorectal carcinogenesis by enhancing polymorphonuclear

myeloid-derived suppressor cell population and function. Cell Rep.

12:244–257. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Inamoto S, Itatani Y, Yamamoto T,

Minamiguchi S, Hirai H, Iwamoto M, Hasegawa S, Taketo MM, Sakai Y

and Kawada K: Loss of SMAD4 promotes colorectal cancer progression

by accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells through the

CCL15-CCR1 chemokine axis. Clin Cancer Res. 22:492–501. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wang D, Sun H, Wei J, Cen B and DuBois RN:

CXCL1 is critical for premetastatic niche formation and metastasis

in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 77:3655–3665. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Dang Y, Yu J, Zhao S, Cao X and Wang Q:

HOXA7 promotes the metastasis of KRAS mutant colorectal cancer by

regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Cell Int.

22:882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Ren X, Xiao J, Zhang W, Wang F, Yan Y, Wu

X, Zeng Z, He Y, Yang W, Liao W, et al: Inhibition of CCL7 derived

from Mo-MDSCs prevents metastatic progression from latency in

colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 12:4842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Lin Q, Ren L, Jian M, Xu P, Li J, Zheng P,

Feng Q, Yang L, Ji M, Wei Y and Xu J: The mechanism of the

premetastatic niche facilitating colorectal cancer liver metastasis

generated from myeloid-derived suppressor cells induced by the

S1PR1-STAT3 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 10:6932019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zhang Y, Davis C, Shah S, Hughes D, Ryan

JC, Altomare D and Peña MM: IL-33 promotes growth and liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer in mice by remodeling the tumor

microenvironment and inducing angiogenesis. Mol Carcinog.

56:272–287. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Gu Y, Mi Y, Cao Y, Yu K, Zhang Z, Lian P,

Li D, Qin J and Zhao S: The lncRNA MIR181A1HG in extracellular

vesicles derived from highly metastatic colorectal cancer cells

promotes liver metastasis by remodeling the extracellular matrix

and recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cell Biosci.

15:232025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Kobie JJ, Wu RS, Kurt RA, Lou S, Adelman

MK, Whitesell LJ, Ramanathapuram LV, Arteaga CL and Akporiaye ET:

Transforming growth factor beta inhibits the antigen-presenting

functions and antitumor activity of dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer

Res. 63:1860–1864. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Orsini G, Legitimo A, Failli A, Ferrari P,

Nicolini A, Spisni R, Miccoli P and Consolini R: Defective

generation and maturation of dendritic cells from monocytes in

colorectal cancer patients during the course of disease. Int J Mol

Sci. 14:22022–22041. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Nagorsen D, Voigt S, Berg E, Stein H,

Thiel E and Loddenkemper C: Tumor-infiltrating macrophages and

dendritic cells in human colorectal cancer: Relation to local

regulatory T cells, systemic T-cell response against

tumor-associated antigens and survival. J Transl Med. 5:622007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Hsu YL, Chen YJ, Chang WA, Jian SF, Fan

HL, Wang JY and Kuo PL: Interaction between tumor-associated

dendritic cells and colon cancer cells contributes to tumor

progression via CXCL1. Int J Mol Sci. 19:24272018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Huang TX, Tan XY, Huang HS, Li YT, Liu BL,

Liu KS, Chen X, Chen Z, Guan XY, Zou C and Fu L: Targeting

cancer-associated fibroblast-secreted WNT2 restores dendritic

cell-mediated antitumour immunity. Gut. 71:333–344. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Sun Y, Hu H, Liu Z, Xu J, Gao Y, Zhan X,

Zhou S, Zhong W, Wu D, Wang P, et al: Macrophage STING signaling

promotes NK cell to suppress colorectal cancer liver metastasis via

4-1BBL/4-1BB co-stimulation. J Immunother Cancer. 11:e0064812023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Donadon M, Hudspeth K, Cimino M, Di

Tommaso L, Preti M, Tentorio P, Roncalli M, Mavilio D and Torzilli

G: Increased infiltration of natural killer and T cells in

colorectal liver metastases improves patient overall survival. J

Gastrointest Surg. 21:1226–1236. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Dupaul-Chicoine J, Arabzadeh A, Dagenais

M, Douglas T, Champagne C, Morizot A, Rodrigue-Gervais IG, Breton

V, Colpitts SL, Beauchemin N and Saleh M: The Nlrp3 inflammasome

suppresses colorectal cancer metastatic growth in the liver by

promoting natural killer cell tumoricidal activity. Immunity.

43:751–763. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ, Kayagaki

N, Yamaguchi N, Kakuta S, Iwakura Y, Yagita H and Okumura K:

Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing

ligand in surveillance of tumor metastasis by liver natural killer

cells. Nat Med. 7:94–100. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Russo E, D'Aquino C, Di Censo C,

Laffranchi M, Tomaipitinca L, Licursi V, Garofalo S, Promeuschel J,

Peruzzi G, Sozio F, et al: Cxcr3 promotes protection from

colorectal cancer liver metastasis by driving NK cell infiltration

and plasticity. J Clin Invest. 135:e1840362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Harmon C, Robinson MW, Hand F, Almuaili D,

Mentor K, Houlihan DD, Hoti E, Lynch L, Geoghegan J and O'Farrelly

C: Lactate-mediated acidification of tumor microenvironment induces

apoptosis of liver-resident NK cells in colorectal liver

metastasis. Cancer Immunol Res. 7:335–346. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Fang H, Dai W, Gu R, Zhang Y, Li J, Luo W,

Tong S, Han L, Wang Y, Jiang C, et al: myCAF-derived exosomal PWAR6

accelerates CRC liver metastasis via altering glutamine

availability and NK cell function in the tumor microenvironment. J

Hematol Oncol. 17:1262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Matsumura H, Kondo T, Ogawa K, Tamura T,

Fukunaga K, Murata S and Ohkohchi N: Kupffer cells decrease

metastasis of colon cancer cells to the liver in the early stage.

Int J Oncol. 45:2303–2310. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Wortzel I, Seo Y, Akano I, Shaashua L,

Tobias GC, Hebert J, Kim KA, Kim D, Dror S, Liu Y, et al: Unique

structural configuration of EV-DNA primes Kupffer cell-mediated

antitumor immunity to prevent metastatic progression. Nat Cancer.

5:1815–1833. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Lu WP, Liu YD, Zhang ZF, Liu J, Ye JW,

Wang SY, Lin XY, Lai YR, Li J, Liu SY, et al:

m6A-modified MIR670HG suppresses tumor liver metastasis

through enhancing Kupffer cell phagocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci.

82:1852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Li J, Liu XG, Ge RL, Yin YP, Liu YD, Lu

WP, Huang M, He XY, Wang J, Cai G, et al: The ligation between

ERMAP, galectin-9 and dectin-2 promotes Kupffer cell phagocytosis

and antitumor immunity. Nat Immunol. 24:1813–1824. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Bresesti C, Carito E, Notaro M, Giacca G,

Breggion S, Kerzel T, Mercado CM, Beretta S, Monti M, Merelli I, et

al: Reprogramming liver metastasis-associated macrophages toward an

anti-tumoral phenotype through enforced miR-342 expression. Cell

Rep. 44:1155922025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Nater M, Brügger M, Cecconi V, Pereira P,

Forni G, Köksal H, Dimakou D, Herbst M, Calvanese AL, Lucchiari G,

et al: Hepatic iNKT cells facilitate colorectal cancer metastasis

by inducing a fibrotic niche in the liver. iScience. 28:1123642025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Gassmann P, Hemping-Bovenkerk A, Mees ST

and Haier J: Metastatic tumor cell arrest in the liver-lumen

occlusion and specific adhesion are not exclusive. Int J Colorectal

Dis. 24:851–858. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Haier J, Korb T, Hotz B, Spiegel HU and

Senninger N: An intravital model to monitor steps of metastatic

tumor cell adhesion within the hepatic microcirculation. J

Gastrointest Surg. 7:507–515. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Khatib AM, Fallavollita L, Wancewicz EV,

Monia BP and Brodt P: Inhibition of hepatic endothelial E-selectin

expression by C-raf antisense oligonucleotides blocks colorectal

carcinoma liver metastasis. Cancer Res. 62:5393–5398.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Khatib AM, Auguste P, Fallavollita L, Wang

N, Samani A, Kontogiannea M, Meterissian S and Brodt P:

Characterization of the host proinflammatory response to tumor

cells during the initial stages of liver metastasis. Am J Pathol.

167:749–759. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Huang WH, Zhou MW, Zhu YF, Xiang JB, Li

ZY, Wang ZH, Zhou YM, Yang Y, Chen ZY and Gu XD: The role of

hepatic stellate cells in promoting liver metastasis of colorectal

carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 12:7573–7580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Zeng X, Zhou J, Xiong Z, Sun H, Yang W,

Mok MTS, Wang J, Li J, Liu M, Tang W, et al: Cell cycle-related

kinase reprograms the liver immune microenvironment to promote

cancer metastasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 18:1005–1015. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Yang Y, Chen Y, Liu Z, Chang Z, Sun Z and

Zhao L: Concomitant NAFLD facilitates liver metastases and

PD-1-refractory by recruiting MDSCs via CXCL5/CXCR2 in Colorectal

Cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:1013512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Wang Z, Kim SY, Tu W, Kim J, Xu A, Yang

YM, Matsuda M, Reolizo L, Tsuchiya T, Billet S, et al:

Extracellular vesicles in fatty liver promote a metastatic tumor

microenvironment. Cell Metab. 35:1209–1226.e13. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Ruff SM, Brown ZJ and Pawlik TM: A review

of targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic

colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 51:1019932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Hernandez Dominguez O, Yilmaz S and Steele

SR: Stage IV colorectal cancer management and treatment. J Clin

Med. 12:20722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Cheng XF, Zhao F, Chen D and Liu FL:

Current landscape of preoperative neoadjuvant therapies for initial

resectable colorectal cancer liver metastasis. World J

Gastroenterol. 30:663–672. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Tatsuta K, Sakata M, Kojima T, Booka E,

Kurachi K and Takeuchi H: Updated insights into the impact of

adjuvant chemotherapy on recurrence and survival after curative

resection of liver or lung metastases in colorectal cancer: A rapid

review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 23:562025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Yarom N and Jonker DJ: The role of the

epidermal growth factor receptor in the mechanism and treatment of

colorectal cancer. Discov Med. 11:95–105. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS,

Zalcberg JR, Tu D, Au HJ, Au HJ, Berry SR, Krahn M, Price T, et al:

Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med.

357:2040–2048. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski

J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D'Haens G, Pintér T, Lim R, Bodoky G,

et al: Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for

metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 360:1408–1417. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A,

Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G,

Stroh C, et al: Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and

without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:663–671. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S, Scala E,

Janakiraman M, Liska D, Valtorta E, Schiavo R, Buscarino M,

Siravegna G, et al: Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired

resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature.

486:532–536. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J,

Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham

D, Jassem J, et al: Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with

infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4)

versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with

previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: The PRIME study.

J Clin Oncol. 28:4697–4705. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J,

Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham

D, Jassem J, et al: Final results from PRIME: Randomized phase III

study of panitumumab with FOLFOX4 for first-line treatment of

metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 25:1346–1355. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Choi HY and Chang JE: Targeted therapy for

cancers: From ongoing clinical trials to FDA-Approved drugs. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:136182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Cao D, Zheng Y, Xu H, Ge W and Xu X:

Bevacizumab improves survival in metastatic colorectal cancer

patients with primary tumor resection: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep.

9:203262019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Tang W, Ren L, Liu T, Ye Q, Wei Y, He G,

Lin Q, Wang X, Wang M, Liang F, et al: Bevacizumab Plus mFOLFOX6

versus mFOLFOX6 Alone as First-line treatment for RAS mutant

unresectable colorectal Liver-limited metastases: The BECOME

randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 38:3175–3184. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Debeuckelaere C, Murgioni S, Lonardi S,