Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most frequently

diagnosed cancer among women worldwide, accounting for ~266,000

deaths and 528,000 new cases each year (1). CC contributes to 7.5% of all female

cancer-related deaths, establishing itself as a notable cause of

mortality among women (2).

Well-structured screening programs that incorporate affordable

treatment techniques, such as cryotherapy, loop electrosurgical

excision and thermal ablation, can facilitate the early detection

and management of precancerous lesions, thereby reducing the

overall disease burden (3).

Nevertheless, in low- and middle-income countries,

late-stage CC remains prevalent due to limited access to early

diagnostic services and preventive care. Although chemotherapy and

radiotherapy continue to serve as the standard treatments for CC,

their overall effectiveness remains limited, with a number of

patients exhibiting suboptimal responses (4). Notably, targeted therapy and

immunotherapy have gained recognition as promising treatment

strategies. The approval of PD-1 inhibitors for the management of

recurrent or metastatic CC has enhanced host immune responses

against human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive malignancies (5). However, despite their potential,

several challenges persist, including the immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment, tumor immune evasion, low patient response rates

and acquired drug resistance, all of which compromise treatment

(6). In the future, treatment

paradigms are expected to emphasize personalized medicine by

refining targeted therapies to improve cure rates and extend

patient survival.

Eukaryotic chromatin is primarily composed of

histones and nucleosomes, with nucleosomes consisting of DNA

wrapped around histone proteins. The tail regions of histones

frequently undergo a range of post-translational modifications

(7), collectively referred to as

histone modifications. These modifications influence gene

transcription through multiple pathways (8) and are essential for several key

biological processes. Common histone modifications include

acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination, with acetylation and

methylation recognized as the predominant types (9). Recently, additional modifications,

such as glycosylation, lactylation and palmitoylation, have been

identified, further increasing the complexity of histone regulation

(10–13). These modifications are vital for

regulating gene expression, repairing DNA damage, and controlling

the cell cycle, differentiation, apoptosis and tumor progression

(14,15).

Histone modifications may act cooperatively or

antagonistically, contributing to the formation of a ‘histone code’

that fine-tunes cellular functions (16,17).

Disruptions in histone modification patterns are closely associated

with various diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative

disorders and immune dysfunction, in which these alterations in

gene expression contribute to disease progression (18,19).

As a result, epigenetic therapies targeting histone modifications

have emerged as a critical area of research in precision

medicine.

In CC, histone modifications, an essential component

of epigenetic regulation, affect key processes such as persistent

HPV infection, dysregulation of the cell cycle, immune evasion and

treatment resistance. These pathological features arise from

chromatin remodeling and aberrant gene expression (20). Epigenetic therapies aimed at

correcting abnormal histone modifications, including histone

deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, are increasingly being recognized as

potential treatments for CC (20).

Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of the role of histone

modifications in CC and their clinical implications may offer

valuable insights into precision treatment strategies.

CC ranks as the fourth most frequently diagnosed

cancer among women worldwide, with ~660,000 new cases reported in

2022 (21). The World Health

Organization estimates that CC affects 662,000 individuals

globally, including 151,000 women in China (22). Despite a substantial reduction in

incidence over the past three decades, CC remains a major global

public health concern, with considerable regional disparities in

both incidence and mortality rates (23,24).

In high-income countries, incidence and mortality rates are notably

lower than those in developing regions, largely due to widespread

HPV vaccination, comprehensive screening programs and greater

access to healthcare resources (25–27).

Nevertheless, in the later stages of CC, mortality rates in

developed nations can be elevated or comparable to those in

developing countries, primarily due to the limited availability of

effective treatments for advanced disease (28).

CC can be classified into two primary histological

types: Cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC), which arises from

squamous cells; and cervical adenocarcinoma, which originates from

glandular epithelial cells (29).

CSCC accounts for >80% of CC cases worldwide and is associated

with high incidence and mortality rates (25). This cancer progresses through a

series of well-defined precancerous stages, culminating in cellular

dysplasia, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and ultimately,

squamous cell carcinoma (30).

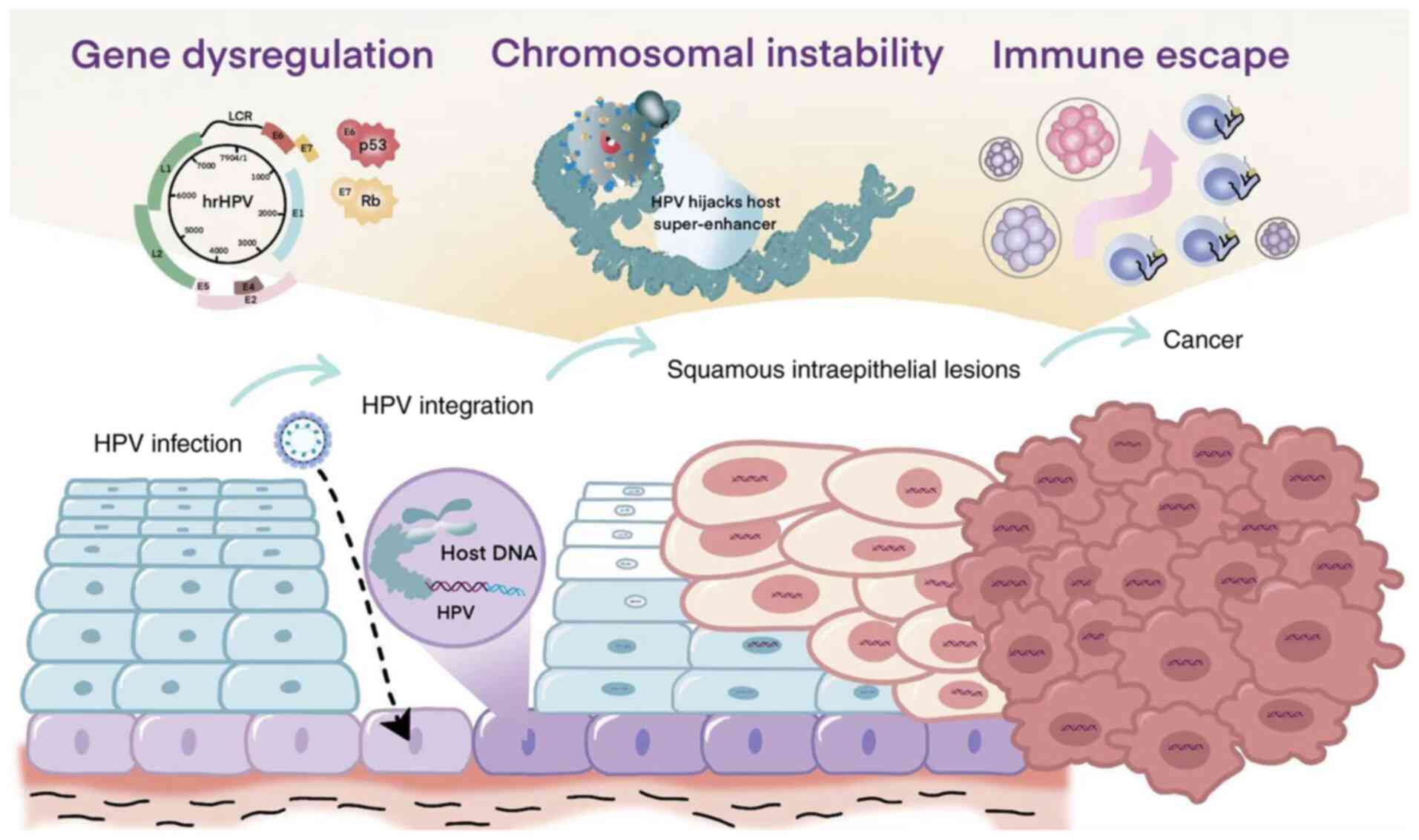

All HPV types, regardless of risk classification,

infect epithelial cells, particularly keratinocytes, leading to

cellular immortalization (30). The

HPV genome consists of three primary functional regions: The early

(E) region, which encodes proteins E1-E7 that are necessary for

viral replication; the late (L) region, which produces structural

proteins L1 and L2 that are essential for virion assembly; and the

long control region, a non-coding segment that contains

cis-regulatory elements critical for DNA replication and

transcription (33). E1 and E2 are

essential for viral DNA replication and act as transcriptional

regulators. The viral genome also encodes early genes, such as E5,

E6 and E7, which contribute to oncogenic transformation. E5

enhances immune evasion, reduces dependence on growth factors and

promotes cellular proliferation (34). E6 interacts with the tumor

suppressor protein p53, leading to its degradation (35). E7 binds to retinoblastoma protein,

mediating its degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system and

promoting cell cycle progression (36).

During the later phases of infection, viral late

genes become active within the suprabasal layers, initiating

circular genome replication and the synthesis of structural

proteins. As the virus ascends to the outer layers of the skin or

mucosal surfaces, mature viral particles are assembled and

subsequently released. Additionally, HPV alters gene expression and

activates several signaling pathways, such as those mediated by

growth factor receptors, Notch, RAS and PI3K/Akt/mTOR, all of which

promote host cell survival and proliferation. These molecular

alterations collectively contribute to cervical carcinogenesis

(37–39) (Fig.

1).

Given the pivotal role of HPV in the pathogenesis of

CC, prevention strategies targeting the virus have proven highly

effective. Specifically, vaccination against high-risk HPV types

has led to a notable reduction in CC incidence, particularly in

developed countries (40). In

addition, surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are the standard

treatments for locally advanced cervical cancer and have notably

reduced the mortality rate of patients with CC; however, their

effectiveness in treating more advanced or recurrent disease

remains limited (41–43).

Advancements in immunotherapy and targeted therapy

have demonstrated considerable promise in cancer treatment.

Inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab,

function by disrupting immune checkpoint pathways, thereby

enhancing the ability of the immune system to detect and eliminate

cancer cells (44). Additionally,

the use of CTLA-4 inhibitors, such as ipilimumab, has been explored

as an immune checkpoint-based therapy for CC (45). Emerging evidence has indicated that

these therapies exhibit substantial efficacy, particularly when

combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy, in patients with

advanced or recurrent disease (46,47).

Although these therapies hold considerable promise,

several challenges persist. Immunotherapy can induce immune-related

adverse events, such as autoimmune disorders and severe

inflammation, and its efficacy is often reduced in tumors

exhibiting strong immune tolerance (48–50).

Similarly, although targeted therapies are designed to act on

specific molecular targets, their effectiveness is limited by tumor

heterogeneity and the development of drug resistance, thereby

reducing their long-term efficacy (48–50).

Moreover, the success of both therapeutic approaches is influenced

by individual patient factors and the complexity of the tumor

microenvironment (48–50). As a result, future therapeutic

strategies should emphasize personalized medicine and the continued

development of targeted therapies, with the aim of improving cure

rates and extending patient survival.

Histone modifications serve a critical role in

regulating biological processes by altering chromatin structure,

thereby influencing the expression of specific genes. Although most

research has focused on well-characterized modifications, such as

acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation, histones also undergo

a variety of other modifications (51). These include citrullination,

ubiquitination, ADP-ribosylation and O-GlcNAcylation, as well as

less-studied modifications such as propionylation, butyrylation,

crotonylation, lactylation and palmitoylation (51). These diverse modifications affect

chromatin structure and gene expression, contributing to critical

processes such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, differentiation and

immune regulation. They also serve a role in the pathogenesis of

diseases, including cancer (including CC), neurodegenerative

disorders (such as Alzheimer's disease) and metabolic conditions

(including diabetes mellitus) (52–54).

The regulation of histone modifications is mediated

by ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’, enzymes that add or remove

modifications, thereby ensuring appropriate gene expression

(55). For example, histone

acetyltransferases (HATs) introduce acetyl groups, leading to

chromatin relaxation and enhanced transcription, whereas HDACs

remove acetyl groups, resulting in chromatin condensation and

transcriptional repression (56).

Similarly, histone methylation is catalyzed by histone

methyltransferases (HMTs), whereas histone demethylases are

responsible for removing methyl groups. The coordinated activity of

these enzymes modulates chromatin architecture and is essential for

the regulation of gene expression (57). Notably, certain ‘writers’ and

‘erasers’ are capable of regulating multiple types of histone

modifications. For example, G9a, a HMT, primarily catalyzes the

methylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 (H3K9), but also modulates

histone acetylation, thereby influencing gene silencing and

chromatin structure (58).

Likewise, p300/CBP, a HAT, facilitates histone acetylation and

transcriptional activation (59),

and has also been shown to catalyze histone lactylation, a

modification particularly relevant under conditions of altered

cellular metabolism, such as hypoxia or inflammation (60). Similarly, HDACs primarily remove

acetyl groups, leading to chromatin condensation and

transcriptional repression; however, certain HDAC family members,

such as sirtuin (SIRT)1, serve pivotal roles not only in histone

deacetylation but also in regulating non-histone proteins, such as

p53, thereby modulating apoptosis and DNA repair (61,62).

In addition, lysine-specific demethylase (KDM)1, an ‘eraser’, can

remove methyl groups from lysine 4 on histone H3 (H3K4) to suppress

gene expression and from H3K9 to promote gene activation (54,63).

The cross-regulation by these multifunctional enzymes indicates

that histone modification is not a linear process but rather a

highly dynamic and interactive network that enables precise control

of gene expression, allowing cells to adapt to environmental

changes and maintain gene expression homeostasis. A comprehensive

summary of the major histone modifications, including ‘writer’ and

‘eraser’ proteins, their family classifications, target sites and

functional roles, is presented in Table

I.

Histone modifications are fundamental to the

initiation and progression of cancer, primarily through their

effects on chromatin structure and gene expression. Consequently,

these modifications influence the transcription of genes involved

in tumorigenesis. Aberrant histone modifications, including

acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination, can

lead to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes or the activation

of oncogenes, thereby facilitating tumor progression. For example,

trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3), a repressive

histone mark mediated by EZH2, is frequently observed in breast

cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), leading to the silencing

of key tumor suppressor genes (64,65).

For example, EZH2 promotes the stemness of HCC by inducing the

transcriptional repression of the tumor suppressor gene TOP2A

through H3K27me3-mediated silencing (65). Similarly, elevated levels of histone

H3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9ac) and H3 lysine 27 acetylation have

been associated with oncogene activation, contributing to the

progression of colorectal and lung cancer (66). Moreover, histone modifications

influence DNA damage repair pathways; for example, phosphorylation

of H2AX is activated in response to DNA damage, and affect the

tumor microenvironment, such as HDAC-driven immune suppression

(67). They are also associated

with resistance mechanisms; for example, KDM5A-mediated

demethylation enhances chemotherapy resistance (68). As a result, epigenetic therapies

targeting histone modifications, including inhibitors of HDACs and

HMTs/KDMs, hold notable promise for precision cancer treatment,

particularly when used in combination with immunotherapy and

molecular targeted therapies.

Histone modifications serve a critical role in

regulating the initiation, progression and therapeutic response of

CC. Modifications such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation

and ubiquitination are central to modulating gene expression,

altering chromatin architecture and influencing cellular signaling

networks, all of which contribute to cancer development. Aberrant

histone modifications can lead to the suppression of tumor

suppressor genes or the activation of oncogenes, thereby promoting

cellular processes, such as proliferation, invasion and immune

evasion. Furthermore, histone modifications are closely associated

with the development of resistance to therapies, including

chemotherapy, radiotherapy and targeted treatments. This section

examines the role of histone modifications in the pathophysiology

of CC.

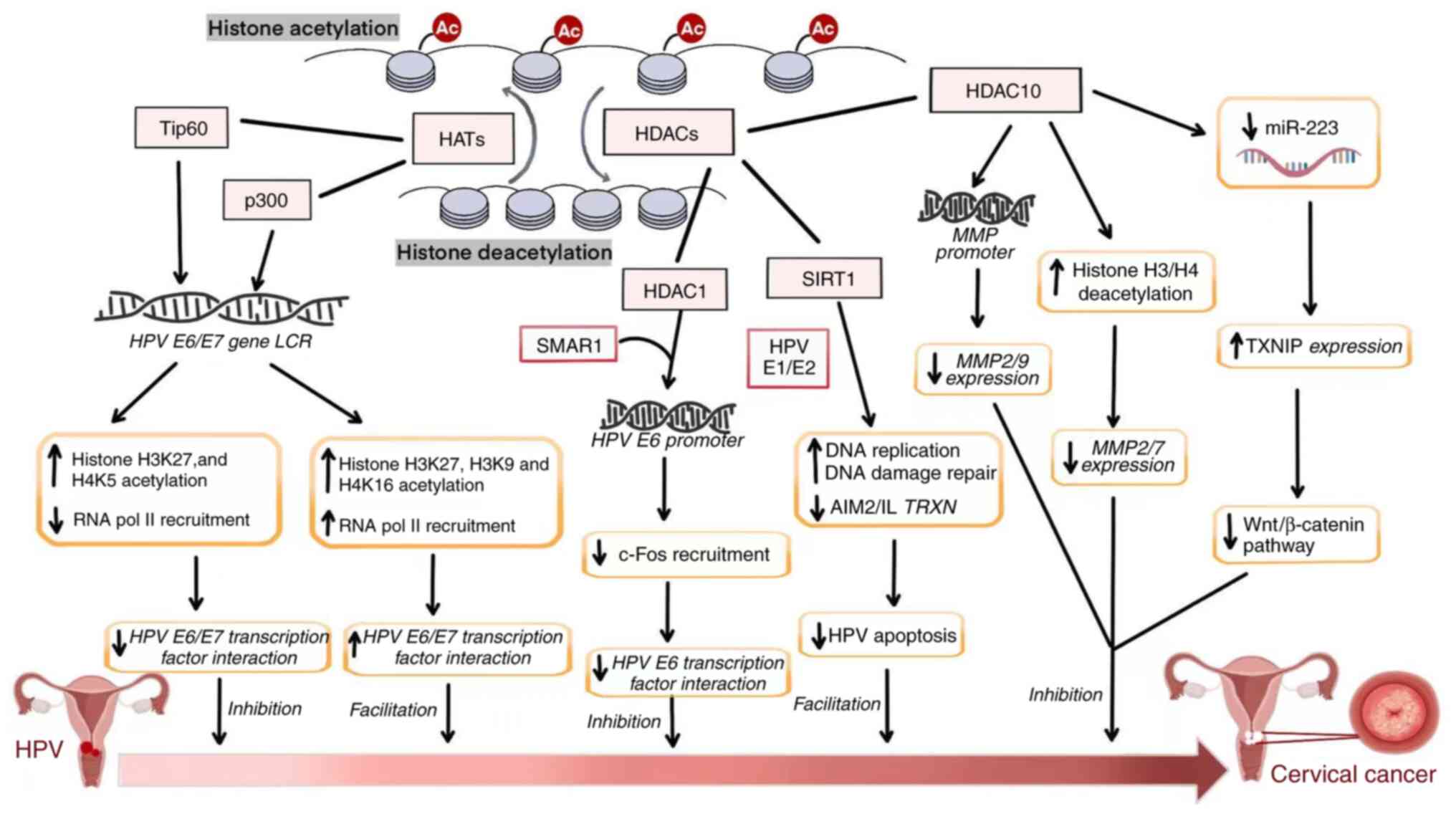

Histone acetylation, regulated by HATs and HDACs, is

a reversible and dynamic process. HATs modify nucleosome structure

by promoting chromatin relaxation, thereby facilitating gene

transcription (Fig. 2). More than

20 HAT proteins have been identified, with key members belonging to

the GNAT, MYST and p300/CBP families (69). Yang et al (70) demonstrated that the HAT CSRP2BP

markedly promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and

metastasis in CC cells by activating N-cadherin. Notably, in CC

tissues, elevated CSRP2BP expression was observed and revealed to

be associated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, overexpression of

CSRP2BP enhanced the proliferation and metastasis of CC cells in

both in vitro and in vivo models, whereas its

silencing had the opposite effect. CSRP2BP was also identified as a

key contributor to cisplatin resistance. At the molecular level,

CSRP2BP was revealed to catalyze acetylation of histone H4 at

lysine residues 5 and 12, to form a complex with the transcription

factor SMAD4 and to bind to the SEB2 sequence in the promoter

region of N-cadherin, thereby upregulating its transcription. This

mechanism may promote EMT and enhance metastasis in CC cells

(70). These findings underscore

the essential role of histone acetylation in the initiation,

progression and development of drug resistance in CC. Similarly,

the acetyltransferase p300 catalyzes acetylation of histone H3 at

lysine 27 (H3K27), which enhances the activity of the NDUFA8

promoter, thereby stimulating CC cell proliferation (71).

Histone methylation is a dynamic and reversible

process regulated by HMTs and KDMs. Methylation occurs through the

activity of HMTs, which add methyl groups to specific histone

residues, thereby modifying chromatin structure and function. These

modifications are typically associated with either gene activation

or repression, depending on the specific site and context (88–90).

Numerous HMTs, including members of the SET, DOT1L and SUV39H

families, are involved in regulating gene expression, DNA repair

mechanisms and cell cycle progression (88–90).

Zhang et al (91)

demonstrated that HPV18 E6/E7 increases the transcriptional

activity of EZH2, resulting in elevated H3K27me3 levels in CC.

Furthermore, Beyer et al showed that histone modifications,

such as H3K9ac and trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone H3 are

closely associated with clinicopathological parameters and 10-year

survival outcomes, underscoring their prognostic value in CC

(92). Chen et al (93) reported that NSD2, a HMT, promotes

proliferation, migration and invasion of CC cells by activating the

endothelial nitric oxide synthase and AKT/MMP-2 signaling pathways.

Additionally, Ansari et al (94) identified the H3K4-specific

methyltransferase MLL as a critical factor in cervical tumor

growth. Knockdown of MLL reduced the expression of several key

growth and angiogenesis-related factors, including HIF1α, VEGF and

CD31, thereby inhibiting CC progression. Notably, studies have

shown interest in histone methylation enzymes as potential

therapeutic targets. Zhang et al (95) reported that SUV39H1 upregulates

DNMT3A expression in CC cells via trimethylation of lysine 9 on

histone H3, while simultaneously downregulating immunosuppressive

factors. such as Tim-3 and galectin-9. This activity may improve

the tumor immune microenvironment and enhance therapeutic efficacy.

Moreover, Osawa et al (96)

showed that the histone demethylase JHDM1D suppresses

angiogenesis-related factors, including VEGF-B and angiopoietin,

under conditions of nutrient deprivation, thereby limiting

angiogenesis and exerting tumor-suppressive effects.

In summary, studies have identified the critical

roles of histone methylation and demethylation in tumor

progression, immune regulation, cell invasion and angiogenesis, all

of which markedly contribute to CC development.

The regulation of histone phosphorylation involves

histone kinases (HKs) and phosphatases (PPs), with both enzymatic

processes being dynamic and reversible. Histone phosphorylation,

catalyzed by HKs, modifies chromatin structure and function,

typically influencing gene transcription by either activating or

repressing it (97,98). Several HKs, including members of the

Aurora, CDK and MSK families, serve essential roles in gene

expression, DNA repair, cell cycle progression and signal

transduction (97,98). In CC cells, phosphorylation of

histone H2AX serves as a key indicator of DNA damage, reflecting

cellular sensitivity to radiation and the efficiency of DNA repair

mechanisms; this makes H2AX phosphorylation a promising biomarker

for evaluating the therapeutic response to radiotherapy in CC

(99). Zhao et al (100) also reported that alterations in

H2AX phosphorylation levels before and after neoadjuvant

chemotherapy provide valuable insights for assessing treatment

response in patients with CC. Several additional studies have

investigated histone phosphorylation as a potential biomarker for

prognosis and treatment efficacy in CC (101–103).

Preclinical studies have further suggested that

targeting PPs or their upstream kinases can effectively inhibit

tumor growth. For example, Zhang and Zhang (104) demonstrated that ZM447439, a potent

Aurora kinase B inhibitor, suppresses the proliferation of SiHa CC

cells while enhancing cisplatin sensitivity. Similarly, Cheung

et al (105) reported that

BPR1K653, a novel Aurora kinase inhibitor, exhibits strong

antiproliferative effects in multidrug-resistant cancer cells

mediated by MDR1 (P-gp170).

In conclusion, although histone phosphorylation has

been extensively studied in various tumors, research specifically

focusing on CC remains limited. Most studies have investigated

phosphorylated histones as potential biomarkers or examined HKs

that suppress CC progression. However, these investigations are

still relatively preliminary and lack comprehensive mechanistic

insights.

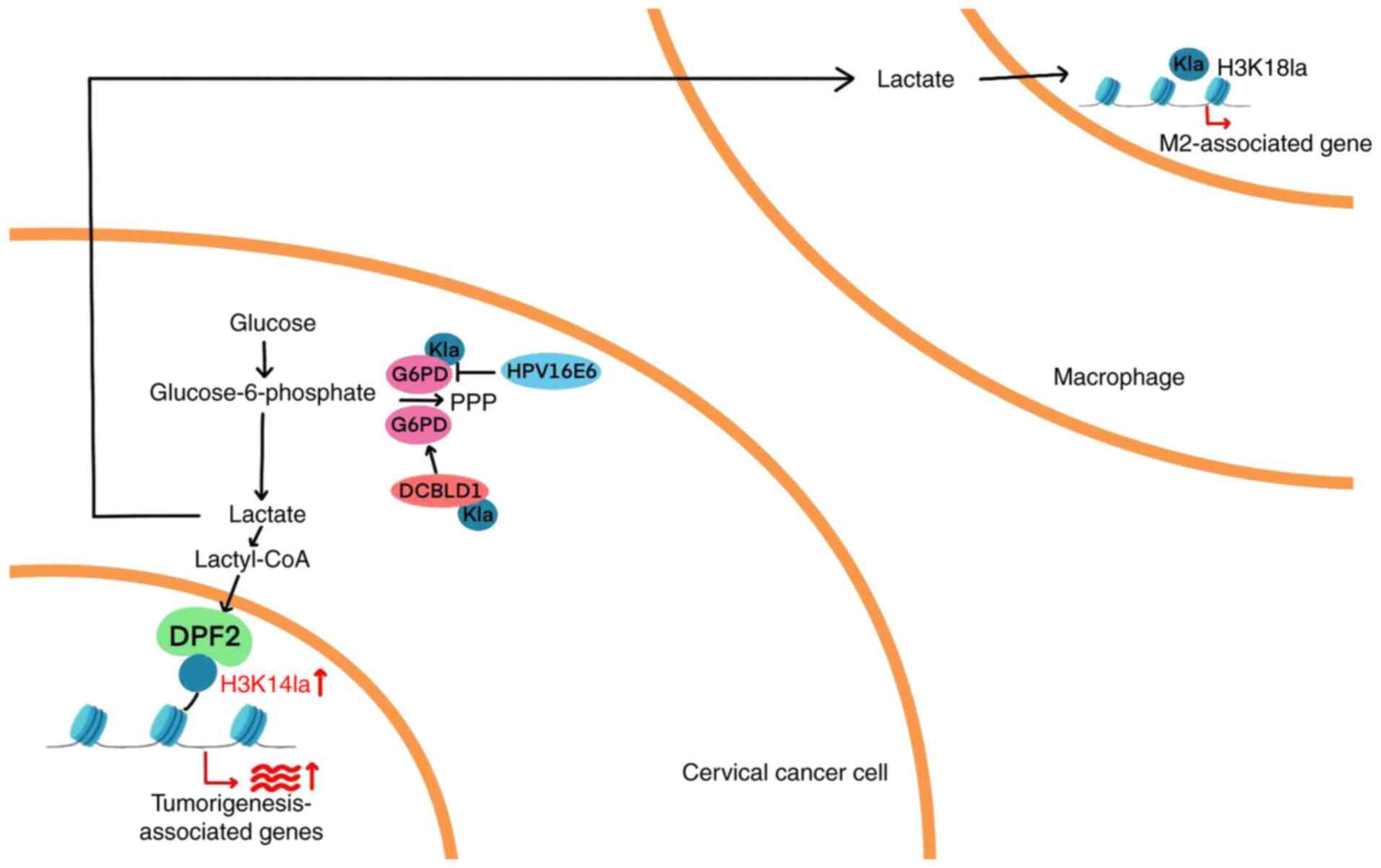

Histone lactylation is a newly identified epigenetic

modification in which lactate molecules are covalently attached to

lysine residues on histones, resulting in altered chromatin

structure and changes in gene transcription. This modification has

attracted increasing scientific attention over the past 3 years

(106). In CC, a previous study

has shown that DPF2, a member of the DPF protein family, recognizes

lactylated histones and facilitates gene activation. Specifically,

DPF2 binds to lactylated histones and promotes the transcription of

target genes (SEMA5A, FUT8, ROCK1 and SOAT1), thereby contributing

to the initiation and progression of CC. Histone lactylation is

closely associated with cellular metabolism and transcriptional

regulation, and serves a substantial role in CC development. These

findings suggest that DPF2 may serve as a promising therapeutic

target for CC (106). In addition,

histone lactylation presents potential therapeutic targets for

metabolic and immune-based interventions. Huang et al

(107) investigated how CC cells

modulate histone lactylation in macrophages through lactate

secretion. Their findings revealed that lactate released by CC

cells upregulates lactylation of lysine 18 on histone and M2

macrophage markers (arginase-1), while downregulating M1 markers

(inducible nitric oxide synthase). Overall, lactate was shown to

enhance GPD2 expression via histone lactylation, promoting M2

macrophage polarization and facilitating tumor progression. In

summary, although histone lactylation is a relatively recent

discovery with limited research in CC, its critical role in other

malignancies underscores the importance of further investigation

(Fig. 3).

Crotonylation is a histone modification in which a

crotonyl group, an unsaturated short-chain fatty acid, is added to

lysine residues on histones. This modification is associated with

gene activation and the regulation of cellular metabolism. Over the

past 3 years, crotonylation has garnered increasing attention in

epigenetics research (108). In

CC, a previous study has shown that p300-mediated crotonylation

enhances the proliferation, invasion and migration of HeLa cells by

promoting the activity of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

A1 (hnRNP A1). Specifically, p300 modulates hnRNP A1 function by

catalyzing histone crotonylation, which subsequently influences

transcriptional and epigenetic regulation. This pathway serves a

critical role in tumor growth and metastasis (108).

Several other histone modifications, such as

ubiquitination, ADP-ribosylation, palmitoylation, propionylation

and butyrylation, remain either rare or relatively newly

characterized, thereby limiting their current investigation in CC.

However, these modifications are expected to become important areas

of future research, offering considerable potential for

understanding the epigenetic regulation of CC.

Numerous preclinical studies have explored the

potential of targeting histone-modifying enzymes as a therapeutic

approach for CC. Histone modifications, such as acetylation and

methylation, serve essential roles in regulating cancer cell

proliferation, metastasis and resistance to therapy. For example,

small-molecule inhibitors (such as p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid,

sinapinic acid and resveratrol) that target HDACs or HMTs have

demonstrated efficacy in reducing the proliferation and migration

of CC cells, thereby inhibiting tumor progression (109–112).

In addition, some clinical studies have begun

investigating the utility of histone modifications as prognostic

biomarkers (97,103). By examining specific histone

modification patterns in CC tissues, clinicians can obtain early

insights into disease progression, recurrence risk and treatment

response. Changes in histone modifications may be associated with

tumor invasiveness, metastatic potential and resistance to standard

therapies, offering valuable guidance for personalized treatment

planning.

Although the clinical application of histone

modification-targeted therapies in CC is still in its infancy, such

agents, especially in the context of hematologic malignancies, have

already advanced to large-scale clinical trials and have

demonstrated encouraging results (Table II). Ongoing research suggests that

these strategies may evolve into effective therapeutic options for

CC. In the future, precise modulation of histone modification

pathways could lead to advancements in early detection, prognostic

evaluation and the development of individualized treatment

strategies.

Histone modifications serve a crucial role in

regulating the proliferation, migration, invasion and drug

resistance of CC cells by altering chromatin structure and

modulating gene expression. Although research into therapies

targeting histone modifications in CC is still in its early stages,

preclinical studies have suggested that enzymes such as HDACs and

HMTs may effectively inhibit tumor growth and metastasis.

Moreover, histone modifications hold promise as

biomarkers for early diagnosis, prognostic assessment and

monitoring therapeutic responses. Distinct histone modification

patterns may help predict tumor invasiveness and response to

treatment. While drugs targeting histone modifications have not yet

undergone widespread clinical testing in CC, emerging research

indicates that these therapies may represent a novel option for

personalized treatment strategies.

However, in low- and middle-income countries, the

high cost and limited accessibility of histone

modification-targeting therapies present substantial barriers to

their use. Challenges such as inadequate healthcare infrastructure,

unstable drug supply chains and restricted insurance coverage

prevent a number of patients from receiving timely and effective

treatments (113–115). Therefore, reducing drug costs,

enhancing access to therapies and strengthening public health

policy support are critical steps toward expanding the availability

of these promising treatments, particularly for CC, which has a

disproportionately high incidence in resource-limited settings.

In conclusion, histone modifications are integral to

the pathogenesis of CC and offer substantial clinical potential.

Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular

mechanisms underlying these modifications and advancing clinically

applicable therapies for early detection, individualized treatment

and prognostic prediction.

Not applicable.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

All authors contributed to the conception and design

of the study. XL, MZ and ZR drafted the initial manuscript and

prepared the figures. JY and SY provided constructive feedback.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Vu M, Yu J, Awolude OA and Chuang L:

Cervical cancer worldwide. Curr Probl Cancer. 42:457–465. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cao W, Qin K, Li F and Chen W:

Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality: An

analysis of GLOBOCAN 2022. Chin Med J (Engl). 137:1407–1413. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sharma S, Deep A and Sharma AK: Current

treatment for cervical cancer: An update. Anticancer Agents Med

Chem. 20:1768–1779. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Caird H, Simkin J, Smith L, Van Niekerk D

and Ogilvie G: The path to eliminating cervical cancer in canada:

Past, present and future directions. Curr Oncol. 29:1117–1122.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ferrall L, Lin KY, Roden RBS, Hung CF and

Wu TC: Cervical cancer immunotherapy: Facts and hopes. Clin Cancer

Res. 27:4953–4973. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yu L, Lanqing G, Huang Z, Xin X, Minglin

L, Fa-Hui L, Zou H and Min J: T cell immunotherapy for cervical

cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Front Immunol.

14:11052652023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hake SB, Xiao A and Allis CD: Linking the

epigenetic ‘language’ of covalent histone modifications to cancer.

Br J Cancer. 90:761–769. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Vinci MC, Polvani G and Pesce M:

Epigenetic programming and risk: The birthplace of cardiovascular

disease? Stem Cell Rev Rep. 9:241–253. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wu D, Shi Y, Zhang H and Miao C:

Epigenetic mechanisms of Immune remodeling in sepsis: Targeting

histone modification. Cell Death Dis. 14:1122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fan X, Sun S, Yang H, Ma H, Zhao C, Niu W,

Fan J, Fang Z and Chen X: SETD2 palmitoylation mediated by ZDHHC16

in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated glioblastoma promotes

ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys. 113:648–660. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gao X, Kuo CW, Main A, Brown E, Rios FJ,

Camargo LL, Mary S, Wypijewski K, Gök C, Touyz RM and Fuller W:

Palmitoylation regulates cellular distribution of and transmembrane

Ca flux through TrpM7. Cell Calcium. 106:1026392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li X, Yu T, Li X, He X, Zhang B and Yang

Y: Role of novel protein acylation modifications in immunity and

its related diseases. Immunology. 173:53–75. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xu Y, Shi Z and Bao L: An expanding

repertoire of protein acylations. Mol Cell Proteomics.

21:1001932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zaib S, Rana N and Khan I: Histone

modifications and their role in epigenetics of cancer. Curr Med

Chem. 29:2399–2411. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Park J, Lee K, Kim K and Yi SJ: The role

of histone modifications: From neurodevelopment to neurodiseases.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:2172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Maksimovic I and David Y: Non-enzymatic

covalent modifications as a new chapter in the histone code. Trends

Biochem Sci. 46:718–730. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Srivastava R and Ahn SH: Modifications of

RNA polymerase II CTD: Connections to the histone code and cellular

function. Biotechnol Adv. 33:856–872. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jin ML and Jeong KW: Histone modifications

in drug-resistant cancers: From a cancer stem cell and immune

evasion perspective. Exp Mol Med. 55:1333–1347. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yang J, Ren B, Ren J, Yang G, Fang Y, Wang

X, Zhou F, You L and Zhao Y: Epigenetic reprogramming-induced

guanidinoacetic acid synthesis promotes pancreatic cancer

metastasis and transcription-activating histone modifications. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:1552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dueñas-González A, Lizano M, Candelaria M,

Cetina L, Arce C and Cervera E: Epigenetics of cervical cancer. An

overview and therapeutic perspectives. Mol Cancer. 4:382005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu M, Cao C, Wu P, Huang X and Ma D:

Advances in cervical cancer: Current insights and future

directions. Cancer Commun (Lond). 45:77–109. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gavinski K and DiNardo D: Cervical cancer

screening. Med Clin North Am. 107:259–269. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rahangdale L, Mungo C, O'Connor S,

Chibwesha CJ and Brewer NT: Human papillomavirus vaccination and

cervical cancer risk. BMJ. 379:e0701152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sahasrabuddhe VV: Cervical cancer:

Precursors and prevention. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 38:771–781.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Viveros-Carreño D, Fernandes A and Pareja

R: Updates on cervical cancer prevention. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

33:394–402. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ang DJM and Chan JJ: Evolving standards

and future directions for systemic therapies in cervical cancer. J

Gynecol Oncol. 35:e652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mayadev JS, Ke G, Mahantshetty U, Pereira

MD, Tarnawski R and Toita T: Global challenges of radiotherapy for

the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 32:436–445. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Revathidevi S, Murugan AK, Nakaoka H,

Inoue I and Munirajan AK: APOBEC: A molecular driver in cervical

cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Lett. 496:104–116. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Willemsen A and Bravo IG: Origin and

evolution of papillomavirus (onco)genes and genomes. Philos Trans R

Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 374:201803032019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Burd EM: Human papillomavirus and cervical

cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 16:1–17. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Olusola P, Banerjee HN, Philley JV and

Dasgupta S: Human papilloma virus-associated cervical cancer and

health disparities. Cells. 8:6222019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C

and Murakami I: Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease

association. Rev Med Virol. 25 (Suppl 1):S2–S23. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Venuti A, Paolini F, Nasir L, Corteggio A,

Roperto S, Campo MS and Borzacchiello G: Papillomavirus E5: The

smallest oncoprotein with many functions. Mol Cancer. 10:1402011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Idres YM, McMillan NAJ and Idris A:

Hyperactivating p53 in human papillomavirus-driven cancers: A

potential therapeutic intervention. Mol Diagn Ther. 26:301–308.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hoppe-Seyler K, Bossler F, Braun JA,

Herrmann AL and Hoppe-Seyler F: The HPV E6/E7 oncogenes: Key

factors for viral carcinogenesis and therapeutic targets. Trends

Microbiol. 26:158–168. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bhattacharjee R, Das SS, Biswal SS, Nath

A, Das D, Basu A, Malik S, Kumar L, Kar S, Singh SK, et al:

Mechanistic role of HPV-associated early proteins in cervical

cancer: Molecular pathways and targeted therapeutic strategies.

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 174:1036752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gao F, Yin J, Wang Y, Li H and Wang D:

miR-182 promotes cervical cancer progression via activating the

Wnt/β-catenin axis. Am J Cancer Res. 13:3591–3598. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Maliekal TT, Bajaj J, Giri V, Subramanyam

D and Krishna S: The role of Notch signaling in human cervical

cancer: Implications for solid tumors. Oncogene. 27:5110–5114.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Amboree TL, Paguio J and Sonawane K: HPV

vaccine: the key to eliminating cervical cancer inequities. BMJ.

385:q9962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Arend R, Barber

E, Bradley K, Brooks R, Campos SM, Chino J, Chon HS, Crispens MA,

et al: NCCN Guidelines® insights: Cervical cancer,

version 1.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:1224–1233. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kasius JC, van der Velden J, Denswil NP,

Tromp JM and Mom CH: Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in fertility-sparing

cervical cancer treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

75:82–100. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li H, Wu X and Cheng X: Advances in

diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer. J Gynecol

Oncol. 27:e432016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Turinetto M, Valsecchi AA, Tuninetti V,

Scotto G, Borella F and Valabrega G: Immunotherapy for cervical

cancer: Are we ready for prime time? Int J Mol Sci. 23:35592022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Grau JF, Farinas-Madrid L, Garcia-Duran C,

Garcia-Illescas D and Oaknin A: Advances in immunotherapy in

cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 33:403–413. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Huang H, Nie CP, Liu XF, Song B, Yue JH,

Xu JX, He J, Li K, Feng YL, Wan T, et al: Phase I study of adjuvant

immunotherapy with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in

locally advanced cervical cancer. J Clin Invest. 132:e1577262022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li J, Cao Y, Liu Y, Yu L, Zhang Z, Wang X,

Bai H, Zhang Y, Liu S, Gao M, et al: Multiomics profiling reveals

the benefits of gamma-delta (γδ) T lymphocytes for improving the

tumor microenvironment, immunotherapy efficacy and prognosis in

cervical cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 12:e0083552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ma Z, Zou X, Yan Z, Chen C, Chen Y and Fu

A: Preliminary analysis of cervical cancer immunotherapy. Am J Clin

Oncol. 45:486–490. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ogasawara A and Hasegawa K: Recent

advances in immunotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Clin Oncol.

30:434–448. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ramanathan P, Dhandapani H, Jayakumar H,

Seetharaman A and Thangarajan R: Immunotherapy for cervical cancer:

Can it do another lung cancer? Curr Probl Cancer. 42:148–160. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Garzón-Porras AM, Chory E and Gryder BE:

Dynamic opposition of histone modifications. ACS Chem Biol.

18:1027–1036. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Santana DA, Smith MAC and Chen ES: Histone

modifications in Alzheimer's disease. Genes (Basel). 14:3472023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yao W, Hu X and Wang X: Crossing

epigenetic frontiers: The intersection of novel histone

modifications and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

9:2322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhao A, Xu W, Han R, Wei J, Yu Q, Wang M,

Li H, Li M and Chi G: Role of histone modifications in neurogenesis

and neurodegenerative disease development. Ageing Res Rev.

98:1023242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li Y: Modern epigenetics methods in

biological research. Methods. 187:104–113. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Sahu RK, Dhakshnamoorthy J, Jain S, Folco

HD, Wheeler D and Grewal SIS: Nucleosome remodeler exclusion by

histone deacetylation enforces heterochromatic silencing and

epigenetic inheritance. Mol Cell. 84:3175–3191.e8. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Perez MF and Sarkies P: Histone

methyltransferase activity affects metabolism in human cells

independently of transcriptional regulation. PLoS Biol.

21:e30023542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Casciello F, Windloch K, Gannon F and Lee

JS: Functional role of G9a histone methyltransferase in cancer.

Front Immunol. 6:4872015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Li S: Implication of posttranslational

histone modifications in nucleotide excision repair. Int J Mol Sci.

13:12461–12486. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Gao J, Liu R, Huang K, Li Z, Sheng X,

Chakraborty K, Han C, Zhang D, Becker L and Zhao Y: Dynamic

investigation of hypoxia-induced L-lactylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 122:e24048991222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Dong W, Lu J, Li Y, Zeng J, Du X, Yu A,

Zhao X, Chi F, Xi Z and Cao S: SIRT1: A novel regulator in

colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 178:1171762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yang Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Chao Y, Zhang J,

Jia Y, Tie J and Hu D: Regulation of SIRT1 and its roles in

inflammation. Front Immunol. 13:8311682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Fang Y, Yang C, Yu Z, Li X, Mu Q, Liao G

and Yu B: Natural products as LSD1 inhibitors for cancer therapy.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:621–631. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Marsolier J, Prompsy P, Durand A, Lyne AM,

Landragin C, Trouchet A, Bento ST, Eisele A, Foulon S, Baudre L, et

al: H3K27me3 conditions chemotolerance in triple-negative breast

cancer. Nat Genet. 54:459–468. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang K, Jiang X, Jiang Y, Liu J, Du Y,

Zhang Z, Li Y, Zhao X, Li J and Zhang R: EZH2-H3K27me3-mediated

silencing of mir-139-5p inhibits cellular senescence in

hepatocellular carcinoma by activating TOP2A. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 42:3202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Benard A, van de Velde CJ, Lessard L,

Putter H, Takeshima L, Kuppen PJ and Hoon DS: Epigenetic status of

LINE-1 predicts clinical outcome in early-stage rectal cancer. Br J

Cancer. 109:3073–3083. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Gerić M, Gajski G and Garaj-Vrhovac V:

γ-H2AX as a biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks in

ecotoxicology. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 105:13–21. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Hinohara K, Wu HJ, Vigneau S, McDonald TO,

Igarashi KJ, Yamamoto KN, Madsen T, Fassl A, Egri SB, Papanastasiou

M, et al: KDM5 histone demethylase activity links cellular

transcriptomic heterogeneity to therapeutic resistance. Cancer

Cell. 34:939–953.e9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Liu H, Ma H, Li Y and Zhao H: Advances in

epigenetic modifications and cervical cancer research. Biochim

Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1888942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Yang X, Sun F, Gao Y, Li M, Liu M, Wei Y,

Jie Q, Wang Y, Mei J, Mei J, et al: Histone acetyltransferase

CSRP2BP promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

metastasis of cervical cancer cells by activating N-cadherin. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 42:2682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Xiang H, Tang H, He Q, Sun J, Yang Y, Kong

L and Wang Y: NDUFA8 is transcriptionally regulated by P300/H3K27ac

and promotes mitochondrial respiration to support proliferation and

inhibit apoptosis in cervical cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

693:1493742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Pan B, Liu C, Su J and Xia C: Activation

of AMPK inhibits cervical cancer growth by hyperacetylation of H3K9

through PCAF. Cell Commun Signal. 22:3062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Qiao L, Zhang Q, Zhang W and Chen JJ: The

lysine acetyltransferase GCN5 contributes to human papillomavirus

oncoprotein E7-induced cell proliferation via up-regulating E2F1. J

Cell Mol Med. 22:5333–5345. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Avvakumov N, Torchia J and Mymryk JS:

Interaction of the HPV E7 proteins with the pCAF acetyltransferase.

Oncogene. 22:3833–3841. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Bernat A, Avvakumov N, Mymryk JS and Banks

L: Interaction between the HPV E7 oncoprotein and the

transcriptional coactivator p300. Oncogene. 22:7871–7881. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Groves IJ, Knight EL, Ang QY, Scarpini CG

and Coleman N: HPV16 oncogene expression levels during early

cervical carcinogenesis are determined by the balance of epigenetic

chromatin modifications at the integrated virus genome. Oncogene.

35:4773–4786. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zimmermann H, Degenkolbe R, Bernard HU and

O'Connor MJ: The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 oncoprotein can

down-regulate p53 activity by targeting the transcriptional

coactivator CBP/p300. J Virol. 73:6209–6219. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Zhu J and Han S: Histone deacetylase 10

exerts anti-tumor effects on cervical cancer via a novel

microRNA-223/TXNIP/Wnt/β-catenin pathway. IUBMB Life. Jan

22–2021.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Lu X, Jin P, Tang Q, Zhou M, Xu H, Su C,

Wang L, Xu F, Zhao M, Yin Y, et al: NAD(+) metabolism reprogramming

drives SIRT1-dependent deacetylation inducing PD-L1 nuclear

localization in cervical cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e24121092025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Sun X, Shu Y, Ye G, Wu C, Xu M, Gao R,

Huang D and Zhang J: Histone deacetylase inhibitors inhibit

cervical cancer growth through Parkin acetylation-mediated

mitophagy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 12:838–852. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

He H, Lai Y, Hao Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Liu X,

Guo C, Zhang M, Zhou H, Wang N, et al: Selective p300 inhibitor

C646 inhibited HPV E6-E7 genes, altered glucose metabolism and

induced apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol.

812:206–215. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Lourenço de Freitas N, Deberaldini MG,

Gomes D, Pavan AR, Sousa Â, Dos Santos JL and Soares CP: Histone

deacetylase inhibitors as therapeutic interventions on cervical

cancer induced by human papillomavirus. Front Cell Dev Biol.

8:5928682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zhang T, Zhou C, Lv M, Yu J, Cheng S, Cui

X, Wan X, Ahmad M, X B, Qin J, et al: Trifluoromethyl quinoline

derivative targets inhibiting HDAC1 for promoting the acetylation

of histone in cervical cancer cells. Eur J Pharm Sci.

194:1067062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liu N, Zhao LJ, Li XP, Wang JL, Chai GL

and Wei LH: Histone deacetylase inhibitors inducing human cervical

cancer cell apoptosis by decreasing DNA-methyltransferase 3B. Chin

Med J (Engl). 125:3273–3278. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Li H and Wu X: Histone deacetylase

inhibitor, Trichostatin A, activates p21WAF1/CIP1 expression

through downregulation of c-myc and release of the repression of

c-myc from the promoter in human cervical cancer cells. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 324:860–867. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wagner W, Ciszewski WM and Kania KD: L-

and D-lactate enhance DNA repair and modulate the resistance of

cervical carcinoma cells to anticancer drugs via histone

deacetylase inhibition and hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1

activation. Cell Commun Signal. 13:362015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Wasim L and Chopra M: Panobinostat induces

apoptosis via production of reactive oxygen species and synergizes

with topoisomerase inhibitors in cervical cancer cells. Biomed

Pharmacother. 84:1393–1405. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Khanduja JS, Joh RI, Perez MM, Paulo JA,

Palmieri CM, Zhang J, Gulka AOD, Haas W, Gygi SP and Motamedi M:

RNA quality control factors nucleate Clr4/SUV39H and trigger

constitutive heterochromatin assembly. Cell. 187:3262–3283.e23.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Marmorstein R: Structure of SET domain

proteins: A new twist on histone methylation. Trends Biochem Sci.

28:59–62. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Yi Y and Ge S: Targeting the histone H3

lysine 79 methyltransferase DOT1L in MLL-rearranged leukemias. J

Hematol Oncol. 15:352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Zhang L, Tian S, Pei M, Zhao M, Wang L,

Jiang Y, Yang T, Zhao J, Song L and Yang X: Crosstalk between

histone modification and DNA methylation orchestrates the

epigenetic regulation of the costimulatory factors, Tim-3 and

galectin-9, in cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 42:2655–2669.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Beyer S, Zhu J, Mayr D, Kuhn C, Schulze S,

Hofmann S, Dannecker C, Jeschke U and Kost BP: Histone H3 acetyl K9

and histone H3 tri methyl K4 as prognostic markers for patients

with cervical cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 18:4772017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chen R, Chen Y, Zhao W, Fang C, Zhou W,

Yang X and Ji M: The role of methyltransferase NSD2 as a potential

oncogene in human solid tumors. Onco Targets Ther. 13:6837–6846.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Ansari KI, Kasiri S and Mandal SS: Histone

methylase MLL1 has critical roles in tumor growth and angiogenesis

and its knockdown suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Oncogene.

32:3359–3370. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Zhang L, Tian S, Zhao M, Yang T, Quan S,

Yang Q, Song L and Yang X: SUV39H1-DNMT3A-mediated epigenetic

regulation of Tim-3 and galectin-9 in the cervical cancer. Cancer

Cell Int. 20:3252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Osawa T, Muramatsu M, Wang F, Tsuchida R,

Kodama T, Minami T and Shibuya M: Increased expression of histone

demethylase JHDM1D under nutrient starvation suppresses tumor

growth via down-regulating angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:20725–20729. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Gascoigne KE and Cheeseman IM:

CDK-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion coordinately

control kinetochore assembly state. J Cell Biol. 201:23–32. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Yang D, He Y, Li R, Huang Z, Zhou Y, Shi

Y, Deng Z, Wu J and Gao Y: Histone H3K79 methylation by DOT1L

promotes Aurora B localization at centromeres in mitosis. Cell Rep.

42:1128852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Banáth JP, Macphail SH and Olive PL:

Radiation sensitivity, H2AX phosphorylation, and kinetics of repair

of DNA strand breaks in irradiated cervical cancer cell lines.

Cancer Res. 64:7144–7149. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zhao J, Wang Q, Li J, Si TB, Pei SY, Guo Z

and Jiang C: Comparative study of phosphorylated histone H2AX

expressions in the cervical cancer patients of pre- and

post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 36:318–322.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Bañuelos CA, Banáth JP, Kim JY,

Aquino-Parsons C and Olive PL: GammaH2AX expression in tumors

exposed to cisplatin and fractionated irradiation. Clin Cancer Res.

15:3344–3353. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Brustmann H, Hinterholzer S and Brunner A:

Expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX (γ-H2AX) in normal and

neoplastic squamous epithelia of the uterine cervix: An

immunohistochemical study with epidermal growth factor receptor.

Int J Gynecol Pathol. 30:76–83. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Fuhrman CB, Kilgore J, LaCoursiere YD, Lee

CM, Milash BA, Soisson AP and Zempolich KA: Radiosensitization of

cervical cancer cells via double-strand DNA break repair

inhibition. Gynecol Oncol. 110:93–98. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhang L and Zhang S: ZM447439, the Aurora

kinase B inhibitor, suppresses the growth of cervical cancer SiHa

cells and enhances the chemosensitivity to cisplatin. J Obstet

Gynaecol Res. 37:591–600. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Cheung CH, Lin WH, Hsu JT, Hour TC, Yeh

TK, Ko S, Lien TW, Coumar MS, Liu JF, Lai WY, et al: BPR1K653, a

novel Aurora kinase inhibitor, exhibits potent anti-proliferative

activity in MDR1 (P-gp170)-mediated multidrug-resistant cancer

cells. PLoS One. 6:e234852011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Zhai G, Niu Z, Jiang Z, Zhao F, Wang S,

Chen C, Zheng W, Wang A, Zang Y, Han Y and Zhang K: DPF2 reads

histone lactylation to drive transcription and tumorigenesis. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 121:e24214961212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Huang C, Xue L, Lin X, Shen Y and Wang X:

Histone lactylation-driven GPD2 mediates M2 macrophage polarization

to promote malignant transformation of cervical cancer progression.

DNA Cell Biol. 43:605–618. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Han X, Xiang X, Yang H, Zhang H, Liang S,

Wei J and Yu J: p300-catalyzed lysine crotonylation promotes the

proliferation, invasion, and migration of HeLa cells via

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. Anal Cell Pathol

(Amst). 2020:56323422020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Chen D, Cai B, Zhu Y, Ma Y, Yu X, Xiong J,

Shen J, Tie W, Zhang Y and Guo F: Targeting histone demethylases

JMJD3 and UTX: Selenium as a potential therapeutic agent for

cervical cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 16:512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Kedhari Sundaram M, Hussain A, Haque S,

Raina R and Afroze N: Quercetin modifies 5′CpG promoter methylation

and reactivates various tumor suppressor genes by modulating

epigenetic marks in human cervical cancer cells. J Cell Biochem.

120:18357–18369. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Mani E, Medina LA, Isaac-Olivé K and

Dueñas-González A: Radiosensitization of cervical cancer cells with

epigenetic drugs hydralazine and valproate. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol.

35:140–142. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Saenglee S, Jogloy S, Patanothai A, Leid M

and Senawong T: Cytotoxic effects of peanut phenolics possessing

histone deacetylase inhibitory activity in breast and cervical

cancer cell lines. Pharmacol Rep. 68:1102–1110. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Bishop TR, Subramanian C, Bilotta EM,

Garnar-Wortzel L, Ramos AR, Zhang Y, Asiaban JN, Ott CJ, Rock CO

and Erb MA: Acetyl-CoA biosynthesis drives resistance to histone

acetyltransferase inhibition. Nat Chem Biol. 19:1215–1222. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Chan HM and La Thangue NB: p300/CBP

proteins: HATs for transcriptional bridges and scaffolds. J Cell

Sci. 114:2363–2373. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Lasko LM, Jakob CG, Edalji RP, Qiu W,

Montgomery D, Digiammarino EL, Hansen TM, Risi RM, Frey R, Manaves

V, et al: Discovery of a selective catalytic p300/CBP inhibitor

that targets lineage-specific tumours. Nature. 550:128–132. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Zhou Y and Shao C: Histone methylation can

either promote or reduce cellular radiosensitivity by regulating

DNA repair pathways. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 787:1083622021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Mentch SJ and Locasale JW: One-carbon

metabolism and epigenetics: Understanding the specificity. Ann N Y

Acad Sci. 1363:91–98. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Zhao Y, Jiang B, Gu Z, Chen T, Yu W, Liu

S, Liu X, Chen D, Li F and Chen W: Discovery of cysteine-targeting

covalent histone methyltransferase inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem.

246:1150282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Lim Y, De Bellis D, Sandow JJ, Capalbo L,

D'Avino PP, Murphy JM, Webb AI, Dorstyn L and Kumar S:

Phosphorylation by Aurora B kinase regulates caspase-2 activity and

function. Cell Death Differ. 28:349–366. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Zhang W, Zhang Z, Xiang Y, Gu DD, Chen J,

Chen Y, Zhai S, Liu Y, Jiang T, Liu C, et al: Aurora kinase

A-mediated phosphorylation triggers structural alteration of Rab1A

to enhance ER complexity during mitosis. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

31:219–231. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Mattiroli F and Penengo L: Histone

ubiquitination: An integrative signaling platform in genome

stability. Trends Genet. 37:566–581. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Oss-Ronen L, Sarusi T and Cohen I: Histone

mono-ubiquitination in transcriptional regulation and its mark on

life: Emerging roles in tissue development and disease. Cells.

11:24042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Yadav P, Subbarayalu P, Medina D, Nirzhor

S, Timilsina S, Rajamanickam S, Eedunuri VK, Gupta Y, Zheng S,

Abdelfattah N, et al: M6A RNA methylation regulates histone

ubiquitination to support cancer growth and progression. Cancer

Res. 82:1872–1889. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Bonfiglio JJ, Leidecker O, Dauben H,

Longarini EJ, Colby T, San Segundo-Acosta P, Perez KA and Matic I:

An HPF1/PARP1-Based chemical biology strategy for exploring

ADP-Ribosylation. Cell. 183:1086–1102.e23. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Messner S and Hottiger MO: Histone

ADP-ribosylation in DNA repair, replication and transcription.

Trends Cell Biol. 21:534–542. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Lv X, Lv Y and Dai X: Lactate, histone

lactylation and cancer hallmarks. Expert Rev Mol Med. 25:e72023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Wu X, Li X, Wang L, Bi X, Zhong W, Yue J

and Chin YE: Lysine deacetylation is a key function of the lysyl

oxidase family of proteins in cancer. Cancer Res. 84:652–658. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Jambhekar A, Dhall A and Shi Y: Roles and

regulation of histone methylation in animal development. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 20:625–641. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Perillo B, Tramontano A, Pezone A and

Migliaccio A: LSD1: More than demethylation of histone lysine

residues. Exp Mol Med. 52:1936–1947. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Liu R, Wu J, Guo H, Yao W, Li S, Lu Y, Jia

Y, Liang X, Tang J and Zhang H: Post-translational modifications of

histones: Mechanisms, biological functions, and therapeutic

targets. MedComm (2020). 4:e2922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Roth SY and Allis CD: Chromatin

condensation: Does histone H1 dephosphorylation play a role? Trends

Biochem Sci. 17:93–98. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Clague MJ, Coulson JM and Urbé S:

Deciphering histone 2A deubiquitination. Genome Biol. 9:2022008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

He X, Li Y, Li J, Li Y, Chen S, Yan X, Xie

Z, Du J, Chen G, Song J and Mei Q: HDAC2-Mediated METTL3

delactylation promotes DNA damage repair and chemotherapy

resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24131212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Wu N, Sun Q, Yang L, Sun H, Zhou Z, Hu Q,

Li C, Wang D, Zhang L, Hu Y and Cong X: HDAC3 and Snail2 complex

promotes melanoma metastasis by epigenetic repression of IGFBP3.

Int J Biol Macromol. 300:1403102025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Zhu Y, Chen JC, Zhang JL, Wang FF and Liu

RP: A new mechanism of arterial calcification in diabetes:

interaction between H3K18 lactylation and CHI3L1. Clin Sci (Lond).

139:115–130. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Morschhauser F, Tilly H, Chaidos A, McKay

P, Phillips T, Assouline S, Batlevi CL, Campbell P, Ribrag V, Damaj

GL, et al: Tazemetostat for patients with relapsed or refractory

follicular lymphoma: An open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase

2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21:1433–1442. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Zauderer MG, Szlosarek PW, Le Moulec S,

Popat S, Taylor P, Planchard D, Scherpereel A, Koczywas M, Forster

M, Cameron RB, et al: EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat in patients with

relapsed or refractory, BAP1-inactivated malignant pleural

mesothelioma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet

Oncol. 23:758–767. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Zinzani PL, Izutsu K, Mehta-Shah N, Barta

SK, Ishitsuka K, Córdoba R, Kusumoto S, Bachy E, Cwynarski K,

Gritti G, et al: Valemetostat for patients with relapsed or

refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (VALENTINE-PTCL01): A

multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol.

25:1602–1613. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Maruyama D, Jacobsen E, Porcu P, Allen P,

Ishitsuka K, Kusumoto S, Narita T, Tobinai K, Foss F, Tsukasaki K,

et al: Valemetostat monotherapy in patients with relapsed or

refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A first-in-human, multicentre,

open-label, single-arm, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 25:1589–1601.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Yap TA, Winter JN, Giulino-Roth L, Longley

J, Lopez J, Michot JM, Leonard JP, Ribrag V, McCabe MT, Creasy CL,

et al: Phase I study of the novel enhancer of zeste homolog 2

(EZH2) inhibitor GSK2816126 in patients with advanced hematologic

and solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 25:7331–7339. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Ribrag V, Iglesias L, De Braud F, Ma B,

Yokota T, Zander T, Spreafico A, Subbiah V, Illert AL, Tan D, et

al: A first-in-human phase 1/2 dose-escalation study of MAK683 (EED

inhibitor) in patients with advanced malignancies. Eur J Cancer.

216:1151222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Stein EM, Garcia-Manero G, Rizzieri DA,

Tibes R, Berdeja JG, Savona MR, Jongen-Lavrenic M, Altman JK,

Thomson B, Blakemore SJ, et al: The DOT1L inhibitor pinometostat

reduces H3K79 methylation and has modest clinical activity in adult

acute leukemia. Blood. 131:2661–2669. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Issa GC, Aldoss I, DiPersio J, Cuglievan

B, Stone R, Arellano M, Thirman MJ, Patel MR, Dickens DS, Shenoy S,

et al: The menin inhibitor revumenib in KMT2A-rearranged or

NPM1-mutant leukaemia. Nature. 615:920–924. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Issa GC, Aldoss I, Thirman MJ, DiPersio J,

Arellano M, Blachly JS, Mannis GN, Perl A, Dickens DS, McMahon CM,

et al: Menin inhibition with revumenib for KMT2A-Rearranged

relapsed or refractory acute leukemia (AUGMENT-101). J Clin Oncol.

43:75–84. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Wang ES, Issa GC, Erba HP, Altman JK,

Montesinos P, DeBotton S, Walter RB, Pettit K, Savona MR, Shah MV,

et al: Ziftomenib in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia

(KOMET-001): A multicentre, open-label, multi-cohort, phase 1

trial. Lancet Oncol. 25:1310–1324. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Gold S and Shilatifard A: Epigenetic

therapies targeting histone lysine methylation: Complex mechanisms

and clinical challenges. J Clin Invest. 134:e1833912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Hollebecque A, Salvagni S, Plummer R,

Isambert N, Niccoli P, Capdevila J, Curigliano G, Moreno V,

Martin-Romano P, Baudin E, et al: Phase I study of lysine-specific

demethylase 1 inhibitor, CC-90011, in patients with advanced solid

tumors and relapsed/refractory non-hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer

Res. 27:438–446. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Wass M, Göllner S, Besenbeck B, Schlenk

RF, Mundmann P, Göthert JR, Noppeney R, Schliemann C, Mikesch JH,

Lenz G, et al: A proof of concept phase I/II pilot trial of LSD1

inhibition by tranylcypromine combined with ATRA in

refractory/relapsed AML patients not eligible for intensive

therapy. Leukemia. 35:701–711. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Tayari MM, Santos HGD, Kwon D, Bradley TJ,

Thomassen A, Chen C, Dinh Y, Perez A, Zelent A, Morey L, et al:

Clinical responsiveness to all-trans retinoic acid is potentiated

by LSD1 inhibition and associated with a quiescent transcriptome in

myeloid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 27:1893–1903. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

151

|

Wang F, Jin Y, Wang M, Luo HY, Fang WJ,

Wang YN, Chen YX, Huang RJ, Guan WL, Li JB, et al: Combined

anti-PD-1, HDAC inhibitor and anti-VEGF for MSS/pMMR colorectal

cancer: A randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 30:1035–1043. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Younes A, Oki Y, Bociek RG, Kuruvilla J,

Fanale M, Neelapu S, Copeland A, Buglio D, Galal A, Besterman J, et

al: Mocetinostat for relapsed classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: An

open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 12:1222–1228.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Johnson ML, Strauss J, Patel MR, Garon EB,

Eaton KD, Neskorik T, Morin J, Chao R and Halmos B: Mocetinostat in

combination with durvalumab for patients with advanced NSCLC:

Results from a phase I/II study. Clin Lung Cancer. 24:218–227.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Awad MM, Le Bruchec Y, Lu B, Ye J, Miller

J, Lizotte PH, Cavanaugh ME, Rode AJ, Dumitru CD and Spira A:

Selective histone deacetylase inhibitor ACY-241 (Citarinostat) plus

nivolumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Results from a

phase Ib study. Front Oncol. 11:6965122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Jiang Z, Li W, Hu X, Zhang Q, Sun T, Cui

S, Wang S, Ouyang Q, Yin Y, Geng C, et al: Tucidinostat plus

exemestane for postmenopausal patients with advanced, hormone

receptor-positive breast cancer (ACE): A randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20:806–815. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

156

|

Kim YH, Bagot M, Pinter-Brown L, Rook AH,

Porcu P, Horwitz SM, Whittaker S, Tokura Y, Vermeer M, Zinzani PL,

et al: Mogamulizumab versus vorinostat in previously treated

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (MAVORIC): An international, open-label,

randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19:1192–1204.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

157

|

Garcia-Manero G, Podoltsev NA, Othus M,

Pagel JM, Radich JP, Fang M, Rizzieri DA, Marcucci G, Strickland

SA, Litzow MR, et al: A randomized phase III study of standard

versus high-dose cytarabine with or without vorinostat for AML.

Leukemia. 38:58–66. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

158

|

Monje M, Cooney T, Glod J, Huang J, Peer

CJ, Faury D, Baxter P, Kramer K, Lenzen A, Robison NJ, et al: Phase

I trial of panobinostat in children with diffuse intrinsic pontine

glioma: A report from the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium

(PBTC-047). Neuro Oncol. 25:2262–2272. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

159

|

Horwitz SM, Nirmal AJ, Rahman J, Xu R,

Drill E, Galasso N, Ganesan N, Davey T, Hancock H, Perez L, et al:

Duvelisib plus romidepsin in relapsed/refractory T cell lymphomas:

A phase 1b/2a trial. Nat Med. 30:2517–2527. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Maher KR, Shafer D, Schaar D,

Bandyopadhyay D, Deng X, Wright J, Piekarz R, Rudek MA, Harvey RD

and Grant S: A phase I study of MLN4924 and belinostat in

relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic

syndrome. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 95:242025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|