Introduction

Cancer is a disease that poses threats to human

health and life, and is characterized by aberrant cellular

proliferation and the development of malignant tumors. According to

data provided by the World Health Organization, millions of

individuals worldwide are diagnosed with cancer annually (1,2). The

incidence and mortality rates have exhibited an upward trend, and

are subject to temporal and regional variations (3). Although advancements in oncology

research have been made by scientists and clinicians in areas such

as drug discovery, immunotherapy and radiotherapy, effective

treatment of cancer is still facing great challenges, such as drug

resistance, immune tolerance and severe side-effects (4–6). It is

imperative to unravel the mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis and

to develop novel intervention strategies.

Osteopontin (OPN) is a multifunctional

glycophosphoprotein encoded by the secretory phosphoprotein 1

(SPP1) gene, which is expressed in various types of cells and

tissues, including in the bone, dentin, cementum, hypertrophic

cartilage, kidney, brain, bone-marrow-derived metrial gland cells,

vascular tissues, cytotrophoblasts of the chorionic villus in the

uterus and decidua, ganglia of the inner ear, brain cells,

specialized epithelia found in mammary, salivary and sweat glands,

bile and pancreatic ducts, distal renal tubules and the gut, as

well as in activated macrophages and lymphocytes (7,8). OPN

was first reported as a marker of transformation of epithelial

cells in 1979 (9). Subsequently,

more variants of OPN and their corresponding functions have been

identified. For example, OPN splicing isoforms in solid tumors have

been investigated in breast cancer, mesothelioma and lung cancer

(10,11). As a secreted protein, OPN binds with

its receptors, such as integrin or CD44, to exert functions,

including modulating cell proliferation, adhesion, inflammatory

responses, osteogenesis and wound healing (8). The role of OPN in tumorigenesis and

development has attracted increasing attention (12,13).

Abnormal OPN expression has been observed in different types of

cancer such as brain, lung, kidney, liver, bladder and breast

cancer (13,14). Diverse hypotheses have been proposed

regarding the association between OPN and tumorigenesis; however,

to the best of our knowledge, its precise molecular mechanisms

remain to be illustrated. Given the pivotal role of OPN in

tumorigenesis and progression, OPN-based interventions have been

developed and applied in both basic research and clinical settings

(15–17).

The present review, after briefly introducing the

molecular structure, receptors and physiological functions of OPN,

describes how OPN participates in cancer initiation, progression,

metastasis and drug resistance. Furthermore, the present review

summarizes current OPN-based tumor intervention strategies. The

present review also provides perspectives on how to deepen the

insights regarding the exact role of OPN in tumorigenesis in order

to help develop novel strategies for tumor therapeutics. The

present review broadens the knowledge regarding the

pathophysiological role of OPN, so that novel OPN-based cancer

treatment strategies may be proposed.

Profile of OPN

OPN was first reported as a transformation marker of

malignant cells by Senger et al (9) in 1979. With the deepening of research,

more definitions of OPN have been determined, including bone

sialoprotein, SPP1 and early T-lymphocyte activation 1 (Eta-1)

(8). Based on mRNA transcript

variants, OPN can be translated into five subtypes, including

OPN-a, OPN-b, OPN-c, OPN4 and OPN5, which can exist in secretory or

intracellular forms (10).

Therefore, OPN has multiple functions in pathophysiological

conditions such as inflammation, cell survival, adhesion,

migration, differentiation, apoptosis and bone matrix

mineralization (18,19). Comprehensive understanding of the

protein structure, receptors and functions of OPN is necessary and

crucial in order to further reveal its mechanism involved in tumor

genesis and development, and to develop therapeutic strategies.

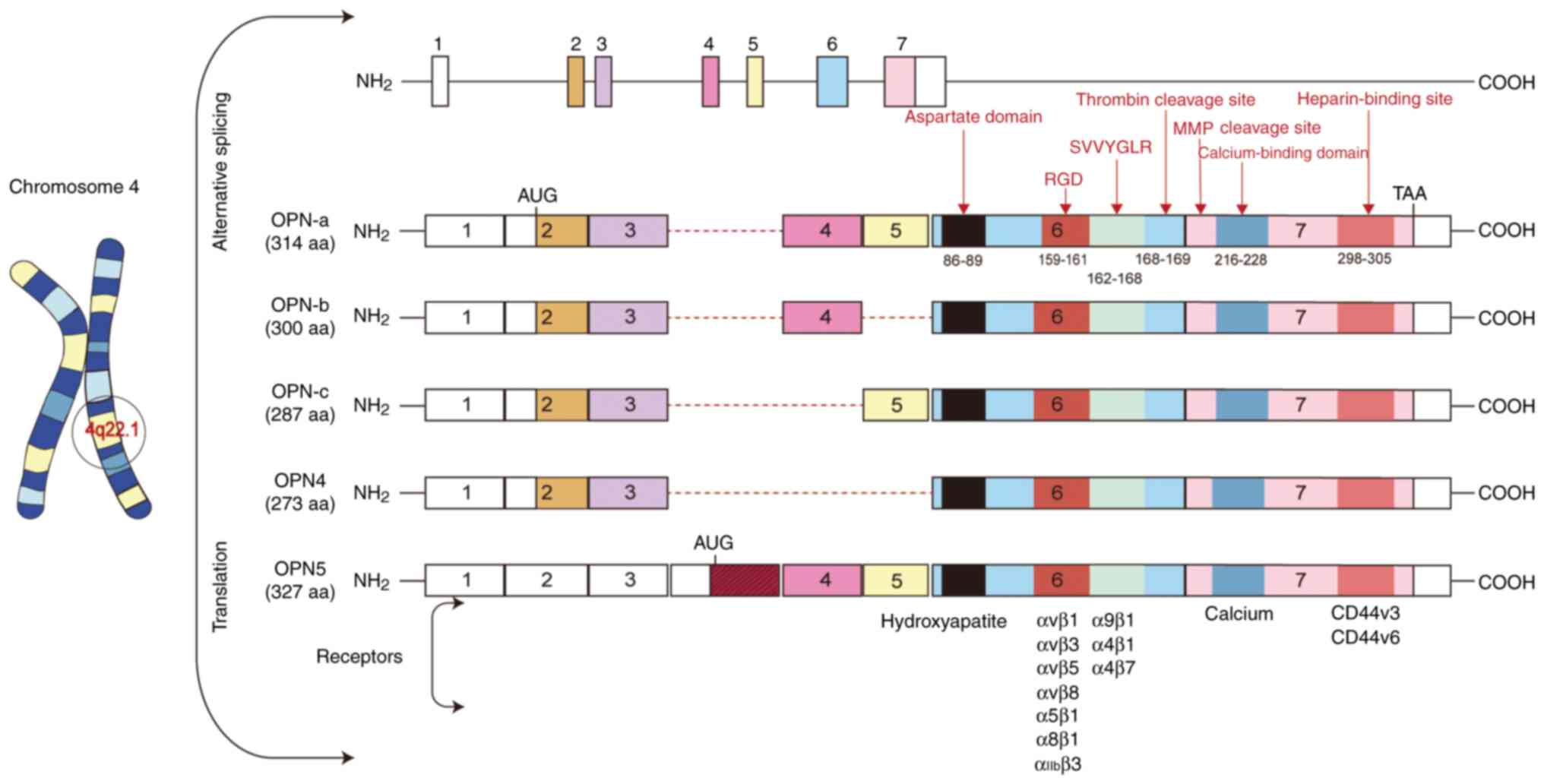

Genomic location and structure of

OPN

OPN is encoded by the SPP1 gene located on

chromosome 4q22.1 (19). The SPP1

gene contains seven exons, which undergo selective splicing to

generate distinct variants. At present, seven exons of SPP1 have

been reported. Exon 1 remains untranslated, whereas exons 2–7

contain coding sequences. Exon 2 encodes a signal peptide along

with two amino acids constituting the mature protein; exon 3

encodes a serine phosphorylation motif; exon 4 encodes a

proline-rich region and transglutaminase site; and exon 5 encodes

an additional protein phosphorylation site. Notably, exons 6 and 7

account for >80% of the expressed OPN protein (19). Five isoforms of OPN have been

reported, including OPN-a (comprising all exons and consisting of

314 amino acids), OPN-b (lacking exon 5 and comprising 300 amino

acids), OPN-c (lacking exon 4 and comprising 287 amino acids), OPN4

(lacking exons 4 and 5, and consisting of 273 amino acids) and OPN5

(containing an additional exon, with a length of 327 amino acids)

(10,20). Distinct splicing of the SPP1 gene

has been implicated in cancer occurrence, progression and prognosis

(19).

Protein structure of OPN

Human OPN contains ~314 amino acid residues, with a

molecular weight ranging between 41 and 75 kDa, depending on

different post-translational modifications (8,21). OPN

contains several highly conserved domains, including the aspartate

domain, arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) domain,

serine-valine-valine-tyrosine-glutamate-leucine-arginine (SVVYGLR)

domain, thrombin cleavage domain, calcium-binding domain and

C-terminal heparin-binding domain (22). Given that OPN is a secreted protein,

it is present not only in various tissues but also in biological

fluids. The secreted OPN is subjected to various post-translational

modifications, including glycosylation, phosphorylation and

sulfuration, which endows OPN with diversified biological functions

(8). Fig. 1 schematically illustrates the

structure and domains of OPN.

Receptors of OPN

OPN needs to bind with its receptors to exert its

function. The well-characterized receptors of OPN include integrins

and CD44 (23,24). Notably, under some conditions, OPN

is subjected to protease cleavage to expose its specific domains,

which exhibit binding affinity for potential receptors (25).

Integrins are transmembrane heterodimers that

recognize various ligands, including OPN and other extracellular

matrix proteins and cell surface proteins (26). The RGD sequence of OPN exhibits a

strong binding affinity for integrins, including αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5,

αvβ6, αvβ8, α8β1, α5β1 and αIIbβ3 (27,28).

Another integrin-binding domain (SVVYGLR) can only be exposed after

thrombin cleavage at Arg168-Ser169 (29). The exposed SVVYGLR interacts with

integrin subtypes such as α9β1, α4β1 and α4β7 (25,28,30).

Similarly, plasma proteases cleave OPN at

Lys154-Ser155, producing an N-terminal OPN

fragment that binds more strongly to α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins than

the full-length OPN (25). MMP

could cleave OPN at various sites such as

Gly166-Leu167,

Ala201-Tyr202 and

Asp210-Leu211, producing a fragment that

preferably binds with the α4β1 isoform of integrin (29).

CD44, also known as hyaluronic acid receptor, is

expressed in various cell types such as osteocytes, endothelial

cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells

(31). The C-terminal fragment

heparin-binding site of OPN can directly interact with CD44

variants CD44v3 and CD44v6 (30).

Therefore, OPN, with or without cleavage, interacts

with integrins or CD44 to regulate multiple cellular processes,

including cell attachment, migration, chemotaxis and immune

modulation in diverse types of cells (24).

Pathophysiological role of OPN

OPN is expressed in various types of cells and

tissues. With the deepening of research, diverse functions of OPN

in both physiological and pathological conditions have been

revealed (32,33).

Orchestrating the immune response

OPN is also known as Eta-1 and can trigger the

immune response of macrophages, T cells and B cells (34). For example, OPN binds with integrin

(αvβ3) of macrophages and reduces the production of

anti-inflammatory IL-10, while its binding with CD44 promotes the

secretion of proinflammatory IL-12 (23). OPN also influences the migration of

immune cells (27,35). Wang and Denhardt (27) reported that OPN served as a type 1 T

helper cell cytokine, contributing to mucosal defense against viral

pathogens. OPN may regulate inflammatory reactions by stimulating

the natural immune response of macrophages and neutrophils

(27). OPN could also be secreted

by activated T cells to aid in the recruitment and migration of

immune cells, particularly macrophages, toward the site of

inflammation, resulting in persistence and exacerbation of the

inflammatory response (36).

OPN exerts pro-inflammatory effects by activating

inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB and STAT3

pathways, which leads to the secretion of cytokines, including

TNF-α and CD16 (37). Additionally,

OPN modulates immune cell functions by enhancing macrophage

chemotaxis and phagocytic activity, promoting their polarization

toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, and activating the immune

responses of T cells, natural killer cells and dendritic cells

(38,39). Furthermore, OPN stimulates tumor

cells to secrete IL-17, thereby activating the JNK/c-Jun signaling

pathway and contributing to immunosuppressive effects (40). OPN also serves a critical role in

mediating immune escape mechanisms, such as enabling tumor cells to

evade immune surveillance through the suppression of T cell

activity (41). Development of

single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has provided a better way to

define the context-dependent functions of OPN. Ding et al

(42) utilized scRNA-seq and

revealed that CD163+ macrophages were enriched in lung

tissues of patients with coronavirus disease 2019, and these cells

highly expressed OPN. Wang et al (43) used scRNA-seq analysis and revealed

that OPN expression was upregulated in menstrual blood cells from

patients with endometriosis, which in synergy with inflammatory

factors, such as IL-10 and IL-6, promoted local fibrotic

processes.

Aberrant OPN expression may induce dysregulation of

the immune response, thereby impairing the normal recognition and

response to self-antigens and foreign antigens, which contributes

to the initiation and progression of autoimmune disorders (44). Improper expression of OPN is

associated with the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases

(such as multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus,

rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis) and other inflammatory

diseases (including cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease, inflammatory bowel disease, liver diseases and

asthma) (27).

Regulating osteogenesis

OPN also participates in osteogenesis, regulating

bone cell adhesion and osteoclast function, and promoting matrix

mineralization. The strong affinity of OPN for hydroxyapatite leads

to its accumulation in the bone (45–47).

OPN exerts an effect on skeletal cell proliferation,

differentiation and migration, while facilitating calcium phosphate

mineralization (48). Given its

crucial role in bone metabolism, aberrant OPN expression is

associated with various types of bone diseases. In patient with

osteolysis, OPN expression is downregulated, whereas in patients

with fractures, OPN expression is increased (49).

Tissue repair

OPN exhibits an important role in tissue repair and

regeneration by facilitating cell migration, proliferation,

neoangiogenesis and the formation of fibrous connective tissue

(50). For example, OPN has been

found to promote fibroblast proliferation during wound healing

(50). Furthermore, Wen et

al (51) found that, in a model

of regenerating liver after partial hepatectomy, OPN promoted the

inflammatory response and activated the IL-6/STAT3 pathway to

facilitate the proliferation of hepatocytes and the repair of the

liver. A previous study has demonstrated that OPN expression could

induce vascular intimal thickening and promote neointimal formation

following injury, suggesting a role in vascular remodeling

(52). Upregulation of OPN leads to

tissue fibrosis, including liver and kidney fibrosis, by

facilitating the synthesis and deposition of extracellular matrix

proteins (53).

Cardiovascular diseases

OPN also participates in the regulation of

cardiovascular function. OPN is upregulated in atherosclerosis and

present in atherosclerotic plaques, suggesting its potential

relevance (54). Furthermore, it

has been demonstrated that OPN induces vascular calcification by

facilitating mineral uptake and formation of apatite crystals

(55). Speer et al (56) further revealed that phosphorylation

of OPN could induce vascular calcification.

In summary, OPN serves diverse and important

pathophysiological roles in a context-dependent manner. Elucidating

the intricate structure and multifaceted functionality of OPN will

consequently facilitate the development of OPN-based diagnostic and

therapeutic strategies.

Molecular mechanisms of OPN involved in

tumor genesis and development

The role and mechanisms of OPN in tumor genesis and

development have attracted increased attention (57–60).

Increased OPN expression is observed in various malignancies,

including breast cancer, leukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma, lung cancer, squamous

cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and glioblastoma multiforme

(13,61). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that the upregulation of OPN is involved in tumorigenesis,

chemotherapy resistance, angiogenesis and immunosuppression, and

revealing how OPN participates in these processes is essential

(62–67).

OPN is involved in cancer pathogenesis. One study

has revealed high OPN expression in various types of cancer such as

brain tumors, lung cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, bladder

cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, pancreatic cancer,

gastric cancer, colorectal cancer and prostate cancer (13). The precise role and mechanism of OPN

in cancer pathogenesis are not fully understood; however, the

following aspects have been widely implicated in these.

Promoting cell survival and inhibiting

apoptosis

Tumor cells exhibit anti-apoptosis capacities

(68). Sun et al (69) demonstrated that OPN regulated Bcl-2

and Bax expression, thus enhancing the viability of tumor cells.

Another group found that OPN could induce Bcl-2 expression and

attenuate apoptosis (70). In

addition, OPN facilitates tumor progression by regulating tumor

surveillance mechanisms and inhibiting tumor cell apoptosis

(71). Upregulated OPN interacts

with integrin αvβ3 or CD44, facilitating complement factor H cell

surface translocalization, and thus, complement-mediated cell death

is suppressed (72). Zhou et

al (73) found that OPN

knockdown enhanced apoptosis and caused cell cycle arrest in

leukemia stem cells.

Promoting cell migration and

invasion

Tumor metastasis is closely associated with the

capacity of cell migration and invasion (72,74).

Irby et al (75) reported

that overexpressed OPN in SW480, HT29 and HCT116 cells bound with

its receptors, including integrins (αvβ1, αvβ3 and αvβ5) and CD44,

and enhanced colon cancer invasion. OPN has the ability to mediate

the adhesion and interaction between tumor cells and the

surrounding matrix, thereby augmenting the metastatic potential of

tumor cells (76). Kale et

al (77) found that OPN, after

binding with integrin (α9β1), triggered cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)

and prostaglandin E2 expression, and thus, promoted tumor growth

and metastasis. OPN induces the expression and activation of MMP-2,

MMP-3 and urokinase-type plasminogen activator in an

integrin-dependent manner, which promotes extracellular matrix

degradation and consequent metastasis (78). The capacity of OPN to induce

cellular migration and extracellular matrix degradation contributes

to the invasive and metastatic potential of cancer (78).

Promoting angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is a feature of tumors, particularly

solid tumors. Neovascularization enhances the supply of nutrients

and oxygen, thus promoting tumor growth and metastasis (71,79).

OPN is involved in tumor angiogenesis by facilitating the migration

and proliferation of vascular endothelial cells, which promotes

neovascularization (79). Gupta

et al (80) reported that

OPN activated MMP-9, which resulted in increased VEGF secretion and

promoted the angiogenesis of prostate cancer, while OPN knockdown

or αvβ3 mutation reversed these effects. Fukusada et al

(81) reported that OPN induced

VEGF expression and angiogenesis, which promoted pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma progression.

Modulating the tumor microenvironment

(TME)

Tumor cells are surrounded by the TME, which

consists of extracellular matrix, stromal cells, blood vessels,

immune cells, fibroblasts and secretory factors (82). A recent study has demonstrated that

the interplay between tumor cells and the TME governs

tumorigenesis, invasion, metastasis, chemotherapy resistance and

the immune response, thereby driving tumor progression and invasion

(83). OPN, as a component of the

TME, could derive from tumor cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts

and immune cells. OPN exerts an influence on the formation and

regulation of the TME (9,84,85).

Wei et al (36) found that

OPN promoted tumor progression by attracting macrophages and

activating T cells in the glioblastoma TME. Butti et al

(86) reported that OPN could

remodel the TME immune suppression and promoted tumor progression

by modulating the polarization of T helper cells, T-regulatory

cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Rogers et al

(87) reported that myofibroblastic

cancer-associated fibroblasts in the TME promoted cancer stem cell

proliferation and metastasis, whereas inhibition of OPN in a mouse

breast cancer model resulted in diminished tumor stemness.

Therefore, destruction of the TME by targeting OPN may effectively

inhibit tumor progression.

OPN exhibits distinct effects across various cancer

types. For example, OPN inhibits autophagy in colorectal cancer

cells, induces breast cancer cell migration and increases

angiogenesis in breast cancer, and leads to cell migration and

invasion in lung adenocarcinoma (88,89).

Further studies elucidating the precise involvement of OPN in

cancer pathogenesis are required.

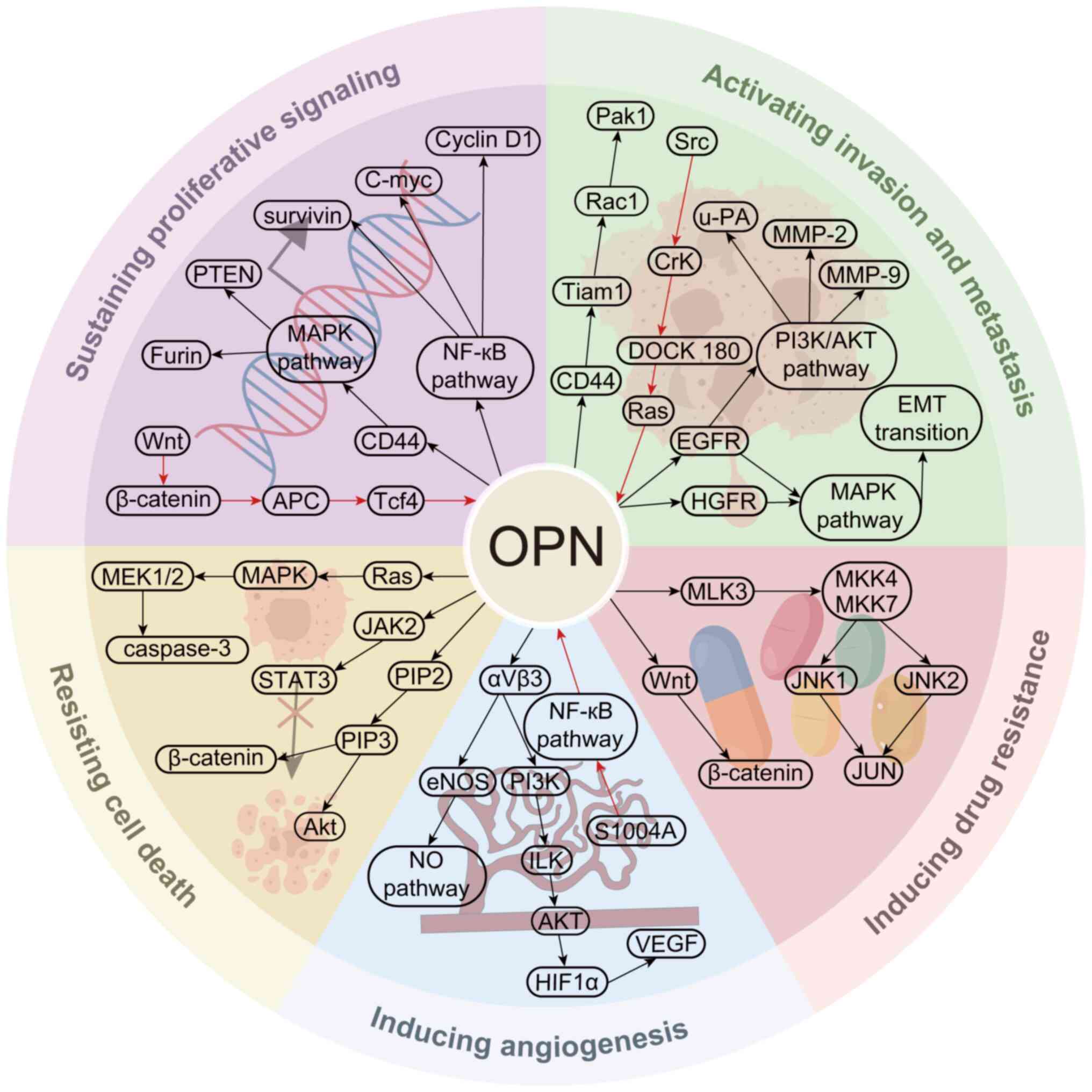

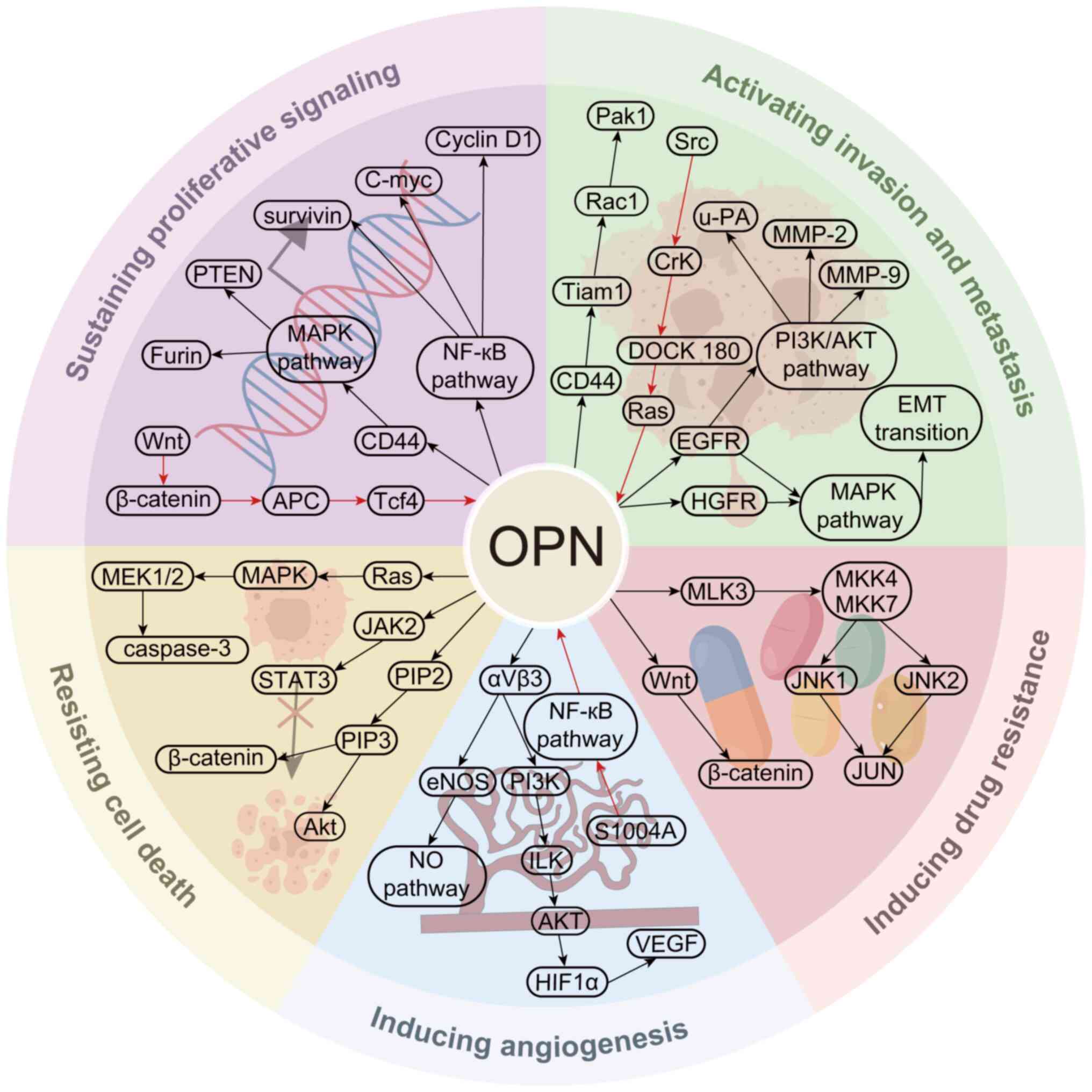

OPN triggers signaling pathways in

tumor pathogenesis

The essential role of OPN in tumorigenesis and

development is well-established, and OPN exerts its effects by

activating multiple intertwined signaling pathways such as the JNK,

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT, NF-κB and TIAM

Rac1 associated GEF 1/Rac1 pathways (14,57).

These pathways regulate cell proliferation, adhesion, diffusion,

migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of

tumor cells, as well as immunosuppression and drug resistance

(1). The main pathways regulated by

OPN that are involved in tumorigenesis and development are

summarized and illustrated in Fig.

2 (90–99).

| Figure 2.Representative signaling pathways

involved in OPN participating in cancer genesis and development.

Black arrows indicates that OPN initiates the signaling pathway,

while red arrows indicate that the signaling pathway ends with OPN

modulation. APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; EMT,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide

synthase; HGFR, hepatocyte growth factor receptor; HIF1α,

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; ILK, integrin linked kinase; JAK2,

Janus kinase 2; MKK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; MLK3,

mixed lineage kinase 3; NO, nitric oxide; OPN, osteopontin; Pak1,

p21 (RAC1) activated kinase 1; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol

(3,4,5)-trisphosphate; S1004A, S100 calcium

binding protein A4; Tcf4, transcription factor 4; Tiam1, TIAM Rac1

associated GEF 1; u-PA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator. |

JNK signaling pathway

The JNK signaling pathway has been demonstrated to

be activated in various types of cancer such as lymphoma,

pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and childhood sarcoma

(91). Messex et al

(100) found that extraneously

added OPN activated the JNK pathway, which accelerated cell

proliferation and prostate cancer development. Insua-Rodríguez

et al (101) demonstrated

that JNK was activated in breast cancer xenograft tumor mouse

models, which enhanced OPN expression, resulting in chemotherapy

resistance and metastasis. Li et al (102) demonstrated that OPN bound to MB231

breast cancer cells and activated the JNK signaling pathway, which

resulted in EMT initiation and cellular migration.

Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway

The Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway serves a vital

role in promoting cell proliferation, survival and metastasis in

various cancer types (103). Yang

et al (104) reported that

knockdown of OPN in squalene synthase-overexpressing lung cancer

cells inhibited their migration and invasion. Chernaya et al

(105) found that, in thyroid

cancer, activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK pathway led to upregulation

of OPN and its receptors (integrin), which in turn increased the

metastatic potential of tumor cells. Sun et al (106) adopted RNA interference (RNAi) to

reduce OPN expression, which resulted in a decrease in the

expression levels of MMP-2 and inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway,

eventually retarding hepatic carcinoma growth and metastasis.

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is aberrantly

activated in various types of cancer (91). OPN has been found to activate the

PI3K/AKT pathway by binding with CD44, consequently promoting cell

proliferation and suppressing apoptosis (107). Zhang et al (108) reported that OPN bound with

integrin αvβ3 and activated the PI3K/AKT pathway in breast cancer,

while knockdown of OPN suppressed breast cancer metastasis.

Furthermore, Fu et al (109) revealed that upregulation of OPN

facilitated chemoresistance of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),

while silencing of OPN inhibited the phosphorylation of AKT and

ERK, weakening gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cells.

JAK/STAT signaling pathway

The JAK/STAT signaling pathway is overactivated in

cancer (110). OPN interacts with

CD44 and triggers the activation of JAK protein kinase, which

induces STAT phosphorylation and consequent enhanced hepatic

carcinoma cell proliferation (111). Behera et al (112) demonstrated that OPN activated

JAK2/STAT3 signaling and stimulated breast tumor growth in mice.

JAK2 inhibitor (AG 490) administration could suppress OPN-induced

STAT3 phosphorylation and promote tumor cell apoptosis (112).

NF-κB signaling pathway

The NF-κB signaling pathway has been found to be

activated in cancer (104). OPN

binding to integrin αvβ3 results in the translocation of NF-κB from

the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and promotes tumorigenesis,

proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis of HCC (113). Chen et al (114) demonstrated that specific small

interfering RNA (siRNA) inhibition of OPN could effectively

attenuate NF-κB levels, thereby inhibiting proliferation of

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells and suppressing tumor

formation and metastasis. Saurav et al (115) reported that inhibition of OPN

and/or NF-κB signaling could enhance the efficacy of irinotecan,

and the combination of OPN and/or an NF-κB inhibitor with

irinotecan may enhance the therapeutic efficacy while reducing the

development of drug resistance.

p38 MAPK signaling pathway

The p38 MAPK signaling pathway is a key signal

transduction cascade that cells possess in response to

environmental stimuli, and has attracted much attention as a

promising target for cancer therapy (116,117). Yu et al (118) reported that OPN was highly

expressed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), and OPN

promoted the proliferation and invasion of HNSCC cells by

activating the p38-MAPK signaling pathway. Huang et al

(66) stated that OPN participated

in the activation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, thereby

promoting cell migration and invasion of colorectal cancer.

OPN-conferred chemoresistance is also associated with the p38 MAPK

signaling pathway. Pang et al (119) demonstrated that OPN mediated

cyclophosphamide resistance in MDA-MB-231 tumor cells by activating

p38 MAPK.

OPN-based cancer treatment

Cancer is threatening the life of millions of

individuals worldwide, and its therapeutics still face great

challenges (120). OPN possesses

various functions in the context of cancer, including the

enhancement of tumor progression and metastasis, inhibition of

tumor cell apoptosis, regulation of the TME, and induction of

chemotherapeutic drug resistance. OPN represents a promising

therapeutic target for the improved treatment of cancer. RNAi,

small-molecule inhibitors, aptamers targeting OPN, and blockade

binding of OPN and its receptor are expected to be alternative

methods for cancer therapy (14,89).

Table I outlines available

OPN-based therapeutic strategies.

| Table I.OPN-based cancer interventions. |

Table I.

OPN-based cancer interventions.

| First author/s,

year | Targeting

strategy | Inhibitor | Target molecule(s)

and/or related signaling pathways | Application

model | Effect/outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kumar et al,

2010 | RNAi | siRNA | OPN, CD44, MKK3/6,

p38-dependent NF-κB activation | Human cervical

cancer cells (HeLa and SiHa), female NOD/SCID mice | OPN silencing

causes reduced growth, migration and invasion | (16) |

| Saleh et al,

2016 |

| siRNA | OPN | Murine mammary

tumor cells (RM11A, RJ348 and RJ345) | Inhibits cancer

cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion | (141) |

| Zhang et al,

2014 |

| siRNA | OPN, LC3, Beclin1,

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway | Human breast cancer

cells (MDA-MB-231) | Knockdown decreases

the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, inhibits migration and

invasion, and induces autophagy in cancer cells | (108) |

| Cho et al,

2015 |

| siRNA | OPN, PSOT | Human lung

adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line (A549), large cell lung

carcinoma cancer cell line (H460), male nude mice (BALB/c-nu) | siOPN treatment

reduces tumor size and weight | (142) |

| Bhattacharya et

al, 2010 |

| miRNA | OPN, miRNA

181a | HCC cell lines (Hep

G2 and Hep 3B) | OPN expression is

regulated by miRNA 181a, and the presence of siOPN attenuates the

adhesion, migration and invasion of tumor cells | (143) |

| Zagani et

al, 2009 | Small-molecule

inhibitors | Parecoxib (COX-2

inhibitor) | OPN, Wnt/β-catenin

pathway | Mouse colon

adenocarcinoma (CT26) Apcmin/+ mice | Downregulation of

OPN expression by COX-2 inhibitors inhibits tumor growth | (17) |

| Matsuura et

al, 2010 |

| Simvastatin

(HMG-CoA inhibitors) | OPN,

3-hydroxy-3-methylgluaryl coenzyme A reductase | Human ovarian

carcinoma cell lines (RMG-1 and TOV-21G), human adenocarcinoma cell

lines (HTOA, MH and KFr), human mucinous adenocarcinoma cell line

(MCAS) | Apoptosis, growth

arrest and enhanced invasion were induced by reducing OPN

expression | (127) |

| Kumar et al,

2012 |

|

Andrographolide | OPN, PI3 kinase/Akt

signaling | Human breast

adenocarcinoma cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7), mouse fibroblast

cell line (NIH-3T3) | Inhibition of

cancer cell proliferation, adhesion, apoptosis, migration and

invasion | (126) |

| Sharma et

al, 2010 |

| Trichostatin A

(histone deacetylase inhibitor) | HDAC1 inhibitor,

OPN, c-Jun, cyclin D1, u-PA | Human cervical

carcinoma cells (HeLa and SiHa), female NOD/SCID mice | Cancer cell cycle

arrest, stimulates differentiation and induces apoptosis | (125) |

| Lv et al,

2013 |

| Curcumin + BPS | OPN, CD44,

MMP-9 | Human ovarian

cancer cells (SKOV3) | Reduces invasion of

ovarian cancer and dendritic cells | (128) |

| Mason et al,

2008 |

| Agelastatin A | β-catenin, Tcf4

signaling | Mammary epithelial

cells (MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-435s) | Inhibits

OPN-mediated invasion, adhesion and colony formation of malignant

cells | (144) |

| Mi et al,

2009 | Aptamers | OPN-R3 | OPN, JNK1/2,

PI3K | Human breast cancer

cells (MDA-MB-231) | OPN-R3 effectively

inhibits adhesion, migration and invasion of cancer cells | (15) |

| Dai et al,

2010 | Blocking

antibodies | Anti-OPN

antibody | OPN, hu1A12 | Human breast cancer

cells (MDA-MB-435S) | Inhibition of

cancer cell proliferation, survival, adhesion, migration and

invasion potential | (145) |

| Ahmed and Kundu,

2010 |

| Anti-αvβ3 integrin

antibody | αvβ3-integrin | Breast cancer cells

(MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468) | Inhibits

OPN-induced tumor growth and angiogenesis | (132) |

| Teramoto et

al, 2005 |

| Anti-CD44

antibody | CD44 receptor | Mouse embryonic

fibroblasts (NIH3T3) | Reduces tumor

progression induced by OPN | (146) |

| Moorman et

al, 2020 |

| AOM1 | Blocking the αvβ3

integrin-binding site on OPN | NSCLC tumor-bearing

mice | Increases the

efficacy of PD-1-based ICB immunotherapy | (61) |

| Chiou et al,

2019 | OPN

inactivation | OPN | FSTL-1 | Lung cancer cell

lines (A549, H1299, PC13 and PC14) | OPN inactivation

prevents tumor progression | (134) |

OPN gene interference

siRNAs and short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) can

efficiently downregulate the expression of specific genes.

Knockdown of OPN with siRNA represents a promising intervention for

various types of cancer such as liver tumors, chronic myeloid

leukemia, familial adenomatous polyposis and metastatic melanoma,

and it is currently undergoing clinical trial (121). Ben-David-Naim et al

(122) demonstrated that

administration of nanoparticle-encapsulated OPN siRNA effectively

reduced OPN expression and suppressed tumor growth in a mouse

breast cancer model. Yang et al (123) reported that knockdown of OPN with

specific siRNA or shRNA could inhibit breast tumor progression.

These findings suggest that downregulation of OPN expression could

inhibit tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, angiogenesis

and other processes. Using siRNA technology to silence OPN offers a

plethora of strategic opportunities to develop effective treatment

modalities against cancer.

Small-molecule inhibitors of OPN

Given their compact size and efficient cell membrane

permeability, small-molecule inhibitors targeting specific

signaling pathways have attracted increasing attention in disease

intervention (23,124). Small-molecule inhibitors toward

OPN have been applied for cancer treatment. Sharma et al

(125) demonstrated that

inhibition of OPN expression with trichostatin A effectively

prevented tumor growth and metastasis in a mouse xenograft model.

Androstenedione (Andro), a diterpenoid compound isolated from

androsacetum, inhibits OPN expression, resulting in cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis of breast cancer cells, as well as

tumor-endothelial cell interactions (126). Kumar et al (126) further demonstrated that Andro

suppressed breast cancer cell proliferation by downregulating c-jun

expression and inhibiting PI3K/Akt signaling activation. Parecoxib,

a traditional COX-2 inhibitor, has been reported to retard the

progression of colorectal cancer by suppressing OPN expression via

blockade of the nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 2 and

Wnt signaling pathways (17).

Matsuura et al (127)

demonstrated that simvastatin, a high mobility group-CoA inhibitor,

downregulated the expression levels of OPN and αvβ1, αvβ3, α5β1 and

α5β3 integrin, accompanied by an enhancement in the invasion of

ovarian cancer. Lv et al (128) found that combined administration

of curcumin and basilic polysaccharides could effectively suppress

cell proliferation and invasion by downregulating OPN and its

receptor in ovarian cancer.

Aptamers of OPN

Aptamers, as short single-stranded deoxyribonucleic

acid or ribonucleic acid molecules, have unique biometric

capabilities. They are able to fold to form a three-dimensional

conformation and precisely bind to a protein target (129). This process enables the aptamers

to bind to specific targets with high selectivity, including

proteins, peptides, small carbohydrate molecules and even living

cells, showing great potential in biomedical research and

diagnostic applications (130).

Aptamers exhibit advantages such as high affinity for the target,

biochemical stability and low immunogenicity, and could potentially

be used as cancer therapeutics (130). Mi et al (15) demonstrated that the treatment of

MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells with OPN aptamers, OPN-R3, resulted

in inhibition of cell adhesion, migration and invasion. The authors

further demonstrated that OPN-R3 inactivated OPN-associated

signaling pathways, including the PI3K, JNK1/2, Src and Akt

pathways (15). Furthermore, in

vivo, OPN-R3 administration prevented tumor growth in breast

cancer xenotransplantation mouse models (131).

Blocking binding of OPN with its

receptors

OPN needs to bind with its receptors to exert its

roles in tumor genesis and progression. Therefore, disrupting the

binding of OPN and its receptors represents an alternative strategy

for tumor treatment. Rangaswami et al (90) reported that blocking antibodies

against αvβ3-integrin effectively suppressed OPN-induced tumor

growth and angiogenesis. Furthermore, αvβ3-blocking antibodies have

been found to effectively inhibit OPN-mediated activator protein 1

activation in breast cancer cells (132). Ahmed et al (133) showed that administration of CD44

antibody disrupted the interaction between OPN and CD44,

consequently restricting OPN-CD44 mediated tumor invasion and

metastasis. Blocking the binding of OPN with its receptors offers a

novel therapeutic strategy.

OPN inactivation

OPN needs to be cleaved by specific proteases to

expose its receptor binding domain in order to exert its function.

Therefore, blocking enzyme cleavage could render OPN inactive.

Chiou et al (134) showed

that follistatin-like protein 1 directly bound to the uncleaved

form of OPN and inhibited the proteolytic activation of OPN, which

blocked OPN-integrin/CD44-related signaling pathways and consequent

lung cancer metastasis. Thrombin has been demonstrated to

participate in OPN hydrolysis, which is essential for effective

binding of OPN with its receptors (135). Peraramelli et al (136) reported that a thrombin inhibitor,

dabigatran etexilate, retarded B16 melanoma growth by blocking OPN

activation. Therefore, inhibiting OPN activation by blocking OPN

signaling and proteolytic processing may be a feasible therapeutic

approach to stop tumor progression. Current OPN-based interventions

are summarized in Table I.

Although OPN is a promising target for cancer

therapy, there are still some limitations in practical

applications. Gene interference technologies such as RNAi have poor

stability and low delivery efficiency, making it difficult to

continuously and specifically inhibit OPN expression in vivo

(137). Small-molecule inhibitors

have several drawbacks, including a short half-life, poor oral

bioavailability, drug resistance, multiple side effects and high

production costs. Off-target effects occur when a molecule in the

body binds non-specifically to molecules other than its intended

target, which may lead to unexpected biological effects or adverse

reactions (138). Blocking the

interaction between OPN and receptors is also challenging because

OPN can bind to multiple receptors, and single blocking has limited

effects, and may also trigger unknown biological effects. Complete

inactivation of OPN may affect its normal physiological functions

and cause side effects. Despite the limitations of current

strategies, each approach has its unique advantages and applicable

scenarios (23). In practical

applications, appropriate strategies should be selected based on

specific diseases and treatment requirements, and their limitations

should be overcome through technological innovation and

optimization. For example, the therapeutic efficacy and safety can

be effectively improved by optimizing aptamer design, improving

delivery systems and enhancing the bioavailability of

small-molecule inhibitors (89).

The combination of multiple therapeutic strategies

could provide more comprehensive and effective treatments, and a

representative combination is OPN inhibitors together with immune

checkpoint intervention. Lu et al (139) found that administration of the WD

repeat domain 5 protein (WDR5), an inhibitor of OPN, suppressed the

growth of orthotopic pancreatic tumors in mice. Furthermore, WDR5

enhanced the efficacy of anti-programmed cell death protein 1

immunotherapy in inhibiting pancreatic tumor growth in mice

(139). Zhu et al (140) reported that OPN expression in HCC

was positively associated with the programmed death-ligand 1

levels, whereas OPN knockout enhanced the antitumor function of

T-helper 1 cells. Future research should focus on mechanism

verification and optimization of multi-target combination

strategies to achieve more precise antitumor treatment.

Summary and perspectives

OPN, as a secretory protein, is aberrantly

expressed in various types of cancer and exhibits a crucial role in

both the pathogenesis and progression of cancer. OPN exerts an

oncogenesis-promoting effect by stimulating cell proliferation,

antagonizing apoptosis, promoting angiogenesis, suppressing

immunity and inducing drug resistance. Given its pivotal role, OPN

has been regarded as one of the targets for cancer treatment.

OPN-based cancer therapeutics based on gene interference,

inhibitors and immunoregulation have displayed great potential in

research and clinical settings. However, a few aspects deserve to

be considered to broaden OPN-based cancer interventions. Firstly,

the molecular pathways through which OPN participates in

tumorigenesis could be revealed by multiple-omics analysis.

Secondly, the dynamic changes of OPNs during cancer development and

treatment should be precisely monitored. Thirdly, OPN-based

therapeutics should be combined with other treatment strategies. In

summary, by elucidating the various roles of OPN in cancer genesis

and development, the present review could deepen the understanding

of cancer biology and help develop a more effective cancer

treatment strategy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Peng Ye (Shanxi

Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi 030000, China) and Ms. Shangyu

Xie (Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi 030000, China) for

their drafting guidance in preparing the manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Doctoral Fund of Shanxi

Medical University (grant no. XD1805), the Doctoral Provincial

Research Fund of Shanxi Medical University (grant no. SD1806), the

Research Fund of Shanxi Province Health Commission (grant no.

2021060), the Shanxi Basic Research Program for Young Scientists

(grant no. 202203021212366) and the Basic Research Plan Project of

Shanxi Province (grant no. 20210302123265).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

CZ proposed the concept and edited the draft. WX

and ZB wrote original draft. FF, LL and LC reviewed and finalized

the draft. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kariya Y and Kariya Y: Osteopontin in

cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Int J Transl Med.

2:419–447. 2022.

|

|

2

|

Liu X, Fang J, Huang S, Wu X, Xie X, Wang

J, Liu F, Zhang M, Peng Z and Hu N: Tumor-on-a-chip: From

bioinspired design to biomedical application. Microsyst Nanoeng.

7:502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang M, Cui M, Sun Y, Liu S and Jiang W:

Mechanisms, combination therapy, and biomarkers in cancer

immunotherapy resistance. Cell Commun Signa. 22:3382024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Toledo B, Deiana C, Scianò F, Brandi G,

Marchal JA, Perán M and Giovannetti E: Treatment resistance in

pancreatic and biliary tract cancer: Molecular and clinical

pharmacology perspectives. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 17:323–347.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang Z, Bao C, Jiang L, Wang S, Wang K,

Lu C and Fang H: When cancer drug resistance meets metabolomics

(bulk, single-cell and/or spatial): Progress, potential, and

perspective. Front Oncol. 12:10542332022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yim A, Smith C and Brown AM:

Osteopontin/secreted phosphoprotein-1 harnesses glial-, immune-,

and neuronal cell ligand-receptor interactions to sense and

regulate acute and chronic neuroinflammation. Immunol Rev.

311:224–233. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sodek J, Ganss B and McKee MD:

Osteopontin. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 11:279–303. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Senger DR, Wirth DF and Hynes RO:

Transformed mammalian cells secrete specific proteins and

phosphoproteins. Cell. 16:885–893. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bastos ACSF, Blunck CB, Emerenciano M and

Gimba ERP: Osteopontin and their roles in hematological

malignancies: Splice variants on the new avenues. Cancer Lett.

408:138–143. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gimba ER and Tilli TM: Human osteopontin

splicing isoforms: Known roles, potential clinical applications and

activated signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 331:11–17. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Jia Q, Ouyang Y, Yang Y, Yao S, Chen X and

Hu Z: Osteopontin: A novel therapeutic target for respiratory

diseases. Lung. 202:25–39. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhao H, Chen Q, Alam A, Cui J, Suen KC,

Soo AP, Eguchi S, Gu J and Ma D: The role of osteopontin in the

progression of solid organ tumour. Cell Death Dis. 9:3562018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Panda VK, Mishra B, Nath AN, Butti R,

Yadav AS, Malhotra D, Khanra S, Mahapatra S, Mishra P, Swain B, et

al: Osteopontin: A key multifaceted regulator in tumor progression

and immunomodulation. Biomedicines. 12:15272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mi Z, Guo H, Russell MB, Liu Y, Sullenger

BA and Kuo PC: RNA aptamer blockade of osteopontin inhibits growth

and metastasis of MDA-MB231 breast cancer cells. Mol Ther.

17:153–161. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kumar V, Behera R, Lohite K, Karnik S and

Kundu GC: p38 kinase is crucial for osteopontin-induced furin

expression that supports cervical cancer progression. Cancer Res.

70:10381–10391. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zagani R, Hamzaoui N, Cacheux W, de

Reyniès A, Terris B, Chaussade S, Romagnolo B, Perret C and

Lamarque D: Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors down-regulate osteopontin

and Nr4A2-new therapeutic targets for colorectal cancers.

Gastroenterology. 137:1358–1366.e1-e3. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Standal T, Borset M and Sundan A: Role of

osteopontin in adhesion, migration, cell survival and bone

remodeling. Exp Oncol. 26:179–184. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Briones-Orta MA, Avendaño-Vázquez SE,

Aparicio-Bautista DI, Coombes JD, Weber GF and Syn WK: Osteopontin

splice variants and polymorphisms in cancer progression and

prognosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1868:93–108.A. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hao C, Cui Y, Owen S, Li W, Cheng S and

Jiang WG: Human osteopontin: Potential clinical applications in

cancer (review). Int J Mol Med. 39:1327–1337. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

O'Regan A and Berman JS: Osteopontin: A

key cytokine in cell-mediated and granulomatous inflammation. Int J

Exp Pathol. 81:373–390. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Mirzaei A, Mohammadi S, Ghaffari SH,

Yaghmaie M, Vaezi M, Alimoghaddam K and Ghavamzadeh A: Osteopontin

b and c splice isoforms in leukemias and solid tumors: Angiogenesis

alongside chemoresistance. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 19:615–623.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Castello LM, Raineri D, Salmi L, Clemente

N, Vaschetto R, Quaglia M, Garzaro M, Gentilli S, Navalesi P,

Cantaluppi V, et al: Osteopontin at the crossroads of inflammation

and tumor progression. Mediators Inflamm. 2017:40490982017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lamort AS, Giopanou I, Psallidas I and

Stathopoulos GT: Osteopontin as a link between inflammation and

cancer: The thorax in the spotlight. Cells. 8:8152019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Schytte GN, Christensen B, Bregenov I,

Kjøge K, Scavenius C, Petersen SV, Enghild JJ and Sørensen ES:

FAM20C phosphorylation of the RGDSVVYGLR motif in osteopontin

inhibits interaction with the αvβ3 integrin. J Cell Biochem.

121:4809–4818. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Clark EA and Brugge JS: Integrins and

signal transduction pathways: The road taken. Science. 268:233–239.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang KX and Denhardt DT: Osteopontin: Role

in immune regulation and stress responses. Cytokine Growth Factor

Rev. 19:333–345. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yokosaki Y, Matsuura N, Sasaki T, Murakami

I, Schneider H, Higashiyama S, Saitoh Y, Yamakido M, Taooka Y and

Sheppard D: The integrin alpha(9)beta(1) binds to a novel

recognition sequence (SVVYGLR) in the thrombin-cleaved

amino-terminal fragment of osteopontin. J Biol Chem.

274:36328–36334. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ito K, Kon S, Nakayama Y, Kurotaki D,

Saito Y, Kanayama M, Kimura C, Diao H, Morimoto J, Matsui Y and

Uede T: The differential amino acid requirement within osteopontin

in alpha4 and alpha9 integrin-mediated cell binding and migration.

Matrix Biol. 28:11–19. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Maeda N and Maenaka K: The roles of

matricellular proteins in oncogenic virus-induced cancers and their

potential utilities as therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci.

17:21982017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Denhardt DT and Guo X: Osteopontin: A

protein with diverse functions. FASEB J. 7:1475–1482. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kazanecki CC, Uzwiak DJ and Denhardt DT:

Control of osteopontin signaling and function by post-translational

phosphorylation and protein folding. J Cell Biochem. 102:912–924.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bellahcène A, Castronovo V, Ogbureke KUE,

Fisher LW and Fedarko NS: Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked

glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): Multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat

Rev Cancer. 8:212–226. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dalal S, Zha Q, Daniels CR, Steagall RJ,

Joyner WL, Gadeau AP, Singh M and Singh K: Osteopontin stimulates

apoptosis in adult cardiac myocytes via the involvement of CD44

receptors, mitochondrial death pathway, and endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 306:H1182–H1191. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Miyazaki K, Okada Y, Yamanaka O, Kitano A,

Ikeda K, Kon S, Uede T, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Kao WW and Saika

S: Corneal wound healing in an osteopontin-deficient mouse. Invest

Ophth Vis Sci. 49:1367–1375. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wei J, Marisetty A, Schrand B,

Gabrusiewicz K, Hashimoto Y, Ott M, Grami Z, Kong LY, Ling X,

Caruso H, et al: Osteopontin mediates glioblastoma-associated

macrophage infiltration and is a potential therapeutic target. J

Clin Invest. 129:137–149. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sun C, Rahman MSU, Enkhjargal B, Peng J,

Zhou K, Xie Z, Wu L, Zhang T, Zhu Q, Tang J, et al: Osteopontin

modulates microglial activation states and attenuates inflammatory

responses after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Exp Neurol.

371:1145852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhao Y, Huang Z, Gao L, Ma H and Chang R:

Osteopontin/SPP1: A potential mediator between immune cells and

vascular calcification. Front Immunol. 15:13955962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tang S, Hu H, Li M, Zhang K, Wu Q, Liu X,

Wu L, Yu B and Chen X: OPN promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine

expression via ERK/JNK pathway and M1 macrophage polarization in

rosacea. Front Immunol. 14:12859512024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhao L, Wang Z, Tan Y, Ma J, Huang W,

Zhang X, Jin C, Zhang T, Liu W and Yang YG: IL-17A/CEBPβ/OPN/LYVE-1

axis inhibits anti-tumor immunity by promoting tumor-associated

tissue-resident macrophages. Cell Rep. 43:1150392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

He Z, Shen S, Yi Y, Ren L, Tao H, Wang F

and Jia Y: CD31 promotes diffuse large B-cell lymphoma metastasis

by upregulating OPN through the AKT pathway and inhibiting CD8+ T

cells through the mTOR pathway. Am J Transl Res. 15:2656–2675.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ding W, Deng S, Wang Z, Chen X, Xu Z,

Zhong J, Wu X, Lin R, Ye S, Li C and Li H: CD163+ macrophages drive

rapid pulmonary fibrosis via osteopontin secretion. Int

Immunopharmacol. 161:1149762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang H, Gan Z, Wang Y, Hu D, Zhang L, Ye F

and Duan P: A noninvasive menstrual Blood-based diagnostic platform

for endometriosis using digital droplet Enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assay and Single-cell RNA sequencing. Research (Wash DC).

8:06522025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Crawford HC, Matrisian LM and Liaw L:

Distinct roles of osteopontin in host defense activity and tumor

survival during squamous cell carcinoma progression in vivo. Cancer

Res. 58:5206–5215. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Icer MA and Gezmen-Karadag M: The multiple

functions and mechanisms of osteopontin. Clin Biochem. 59:17–24.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Steitz SA, Speer MY, McKee MD, Liaw L,

Almeida M, Yang H and Giachelli CM: Osteopontin inhibits mineral

deposition and promotes regression of ectopic calcification. Am J

Pathol. 161:2035–2046. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Giachelli CM and Steitz S: Osteopontin: A

versatile regulator of inflammation and biomineralization. Matrix

Biol. 19:615–622. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

McKee MD, Pedraza CE and Kaartinen MT:

Osteopontin and wound healing in bone. Cells Tissues Organs.

194:313–319. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ishijima M, Rittling SR, Yamashita T,

Tsuji K, Kurosawa H, Nifuji A, Denhardt DT and Noda M: Enhancement

of osteoclastic bone resorption and suppression of osteoblastic

bone formation in response to reduced mechanical stress do not

occur in the absence of osteopontin. J Exp Med. 193:399–404. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Miragliotta V, Pirone A, Donadio E, Abramo

F, Ricciardi MP and Theoret CL: Osteopontin expression in healing

wounds of horses and in human keloids. Equine Vet J. 48:72–77.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wen Y, Feng D, Wu H, Liu W, Li H, Wang F,

Xia Q, Gao WQ and Kong X: Defective initiation of liver

regeneration in osteopontin-deficient mice after partial

hepatectomy due to insufficient activation of IL-6/Stat3 pathway.

Int J Biol Sci. 11:1236–1247. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ström A, Franzén A, Wängnerud C, Knutsson

AK, Heinegård D and Hultgårdh-Nilsson A: Altered vascular

remodeling in osteopontin-deficient atherosclerotic mice. J Vasc

Res. 41:314–322. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Khuri FR, Shin DM, Glisson BS, Lippman SM

and Hong WK: Treatment of patients with recurrent or metastatic

squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Current status and

future directions. Semin Oncol. 27:25–33. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Peng Y, Feng W, Huang H, Chen Y and Yang

SY: Macrophage-targeting antisenescence nanomedicine enables

in-situ NO induction for gaseous and antioxidative atherosclerosis

intervention. Bioact Mater. 48:294–312. 2025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lomashvili KA, Cobbs S, Hennigar RA,

Hardcastle KI and O'Neill WC: Phosphate-induced vascular

calcification: Role of pyrophosphate and osteopontin. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 15:1392–1401. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Speer MY, McKee MD, Guldberg RE, Liaw L,

Yang HY, Tung E, Karsenty G and Giachelli CM: Inactivation of the

osteopontin gene enhances vascular calcification of matrix Gla

Protein-deficient mice: Evidence for osteopontin as an inducible

inhibitor of vascular calcification in vivo. J Exp Med.

196:1047–1055. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Bandopadhyay M, Bulbule A, Butti R,

Chakraborty G, Ghorpade P, Ghosh P, Gorain M, Kale S, Kumar D,

Kumar S, et al: Osteopontin as a therapeutic target for cancer.

Expert Opin Ther Targets. 18:883–895. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chambers AF, Wilson SM, Kerkvliet N,

O'Malley FP, Harris JF and Casson AG: Osteopontin expression in

lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 15:311–323. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Gotoh M, Sakamoto M, Kanetaka K, Chuuma M

and Hirohashi S: Overexpression of osteopontin in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Pathol Int. 52:19–24. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cook AC, Tuck AB, McCarthy S, Turner JG,

Irby RB, Bloom GC, Yeatman TJ and Chambers AF: Osteopontin induces

multiple changes in gene expression that reflect the six ‘hallmarks

of cancer’ in a model of breast cancer progression. Mol Carcinog.

43:225–236. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Moorman HR, Poschel D, Klement JD, Lu C,

Redd PS and Liu K: Osteopontin: A key regulator of tumor

progression and immunomodulation. Cancers (Basel). 12:33792020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Kariya Y, Oyama M, Kariya Y and Hashimoto

Y: Phosphorylated osteopontin secreted from cancer cells induces

cancer cell motility. Biomolecules. 11:13232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Klement JD, Paschall AV, Redd PS, Ibrahim

ML, Lu C, Yang D, Celis E, Abrams SI, Ozato K and Liu K: An

osteopontin/CD44 immune checkpoint controls CD8+ T cell activation

and tumor immune evasion. J Clin Invest. 128:5549–5560. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Cao J, Li J, Sun L, Qin T, Xiao Y, Chen K,

Qian W, Duan W, Lei J, Ma J, et al: Hypoxia-driven paracrine

osteopontin/integrin αvβ3 signaling promotes pancreatic cancer cell

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like

properties by modulating forkhead box protein M1. Mol Oncol.

13:228–245. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Qian J, LeSavage BL, Hubka KM, Ma C,

Natarajan S, Eggold JT, Xiao Y, Fuh KC, Krishnan V, Enejder A, et

al: Cancer-associated mesothelial cells promote ovarian cancer

chemoresistance through paracrine osteopontin signaling. J Clin

Invest. 131:e1461862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Huang R, Quan Y, Chen JH, Wang TF, Xu M,

Ye M, Yuan H, Zhang CJ, Liu XJ and Min ZJ: Osteopontin promotes

cell migration and invasion, and inhibits apoptosis and autophagy

in colorectal cancer by activating the p38 MAPK signaling pathway.

Cell Physiol Biochem. 41:1851–1864. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ahmed M, Sottnik JL, Dancik GM, Sahu D,

Hansel DE, Theodorescu D and Schwartz MA: An osteopontin/CD44 Axis

in RhoGDI2-Mediated metastasis suppression. Cancer Cell.

30:432–443. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Fresno Vara JA, Casado E, de Castro J,

Cejas P, Belda-Iniesta C and González-Barón M: PI3K/akt signalling

pathway and cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 30:193–204. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Sun C, Enkhjargal B, Reis C, Zhou KR, Xie

ZY, Wu LY, Zhang TY, Zhu QQ, Tang JP, Jiang XD and Zhang JH:

Osteopontin attenuates early brain injury through regulating

autophagy-apoptosis interaction after subarachnoid hemorrhage in

rats. Cns Neurosci Ther. 25:1162–1172. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wei R, Wong JPC and Kwok HF: Osteopontin-a

promising biomarker for cancer therapy. J Cancer. 8:2173–2183.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhao J, Dong L, Lu B, Wu G, Xu D, Chen J,

Li K, Tong X, Dai J, Yao S, et al: Down-regulation of osteopontin

suppresses growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via

induction of apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 135:956–968. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Fedarko NS, Fohr B, Robey PG, Young MF and

Fisher LW: Factor H binding to bone sialoprotein and osteopontin

enables tumor cell evasion of complement-mediated attack. J Biol

Chem. 275:16666–16672. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhou J, Chen X, Zhou P, Sun X, Chen Y, Li

M, Chu Y, Zhou J, Hu X, Luo Y, et al: Osteopontin is required for

the maintenance of leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 600:29–34. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Chen Q, Shou P, Zhang L, Xu C, Zheng C,

Han Y, Li W, Huang Y, Zhang X, Shao C, et al: An

osteopontin-integrin interaction plays a critical role in directing

adipogenesis and osteogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Stem

Cells. 32:327–337. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Irby RB, Mccarthy SM and Yeatman TJ:

Osteopontin regulates multiple functions contributing to human

colon cancer development and progression. Clin Exp Metastas.

21:515–523. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Denhardt DT, Mistretta D, Chambers AF,

Krishna S, Porter JF, Raghuram S and Rittling SR: Transcriptional

regulation of osteopontin and the metastatic phenotype: Evidence

for a Ras-activated enhancer in the human OPN promoter. Clin Exp

Metastas. 20:77–84. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Kale S, Raja R, Thorat D, Soundararajan G,

Patil TV and Kundu GC: Osteopontin signaling upregulates

cyclooxygenase-2 expression in tumor-associated macrophages leading

to enhanced angiogenesis and melanoma growth via α9β1 integrin.

Oncogene. 33:2295–2306. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Mi Z, Guo H, Wai PY, Gao C and Kuo PC:

Integrin-linked kinase regulates osteopontin-dependent MMP-2 and

uPA expression to convey metastatic function in murine mammary

epithelial cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 27:1134–1145. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wai PY and Kuo PC: The role of osteopontin

in tumor metastasis. J Surg Res. 121:228–241. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Gupta A, Zhou C and Chellaiah M:

Osteopontin and MMP9: Associations with VEGF expression/secretion

and angiogenesis in PC3 prostate cancer cells. Cancers (Basel).

5:617–638. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Fukusada S, Shimura T, Natsume M,

Nishigaki R, Okuda Y, Iwasaki H, Sugimura N, Kitagawa M, Katano T,

Tanaka M, et al: Osteopontin secreted from obese adipocytes

enhances angiogenesis and promotes progression of pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma in obesity. Cell Oncol. 45:229–244. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wei R, Liu S, Zhang S, Min L and Zhu S:

Cellular and extracellular components in tumor microenvironment and

their application in early diagnosis of cancers. Anal Cell Pathol

(Amst). 2020:62837962020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Tan Y, Zhao L, Yang YG and Liu W: The role

of osteopontin in tumor progression through tumor-associated

macrophages. Front Oncol. 12:9532832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Shao L, Zhang B, Wang L, Wu L, Kan Q and

Fan K: MMP-9-cleaved osteopontin isoform mediates tumor immune

escape by inducing expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 493:1478–1484. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kariya Y, Oyama M, Hashimoto Y, Gu J and

Kariya Y: β4-integrin/PI3K signaling promotes tumor progression

through the galectin-3-N-glycan complex. Mol Cancer Res.

16:1024–1034. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Butti R, Kumar TVS, Nimma R, Banerjee P,

Kundu IG and Kundu GC: Osteopontin signaling in shaping tumor

microenvironment conducive to malignant progression. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1329:419–441. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Rogers MP, Kothari A, Read M, Kuo PC and

Mi Z: Maintaining myofibroblastic-like cancer-associated

fibroblasts by cancer stemness signal transduction feedback loop.

Cureus. 14:e293542022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Leung LL, Myles T and Morser J: Thrombin

cleavage of osteopontin and the host anti-tumor immune response.

Cancers. 15:34802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Yan Z, Hu X, Tang B and Deng F: Role of

osteopontin in cancer development and treatment. Heliyon.

9:e210552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Rangaswami H, Bulbule A and Kundu GC:

Osteopontin: Role in cell signaling and cancer progression. Trends

Cell Biol. 16:79–87. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Abdelrahman KS, Hassan HA, Abdel-Aziz SA,

Marzouk AA, Narumi A, Konno H and Abdel-Aziz M: JNK signaling as a

target for anticancer therapy. Pharmacol Rep. 73:405–434. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Shi L and Wang X: Role of osteopontin in

lung cancer evolution and heterogeneity. Semin Cell Dev Biol.

64:40–47. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Iida T, Wagatsuma K, Hirayama D and Nakase

H: Is osteopontin a friend or foe of cell apoptosis in inflammatory

gastrointestinal and liver diseases? Int J Mol Sci. 19:72017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Katoh M: Multi-layered prevention and

treatment of chronic inflammation, organ fibrosis and cancer

associated with canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling activation

(review). Int J Mol Med. 42:713–725. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Bastos ACSDF, Gomes AVP, Silva GR,

Emerenciano M, Ferreira LB and Gimba ERP: The intracellular and

secreted sides of osteopontin and their putative physiopathological

roles. Int J Mol Sci. 24:29422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Berge G, Pettersen S, Grotterød I, Bettum

IJ, Boye K and Mælandsmo GM: Osteopontin-an important downstream

effector of S100A4-mediated invasion and metastasis. Int J Cancer.

129:780–790. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Amilca-Seba K, Sabbah M, Larsen AK and

Denis JA: Osteopontin as a regulator of colorectal cancer

progression and its clinical applications. Cancers. 13:37932021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Hao C, Lane J and Jiang WG: Osteopontin

and cancer: Insights into its role in drug resistance.

Biomedicines. 11:1972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Moldogazieva NT, Mokhosoev IM, Zavadskiy

SP and Terentiev AA: Proteomic profiling and artificial

intelligence for hepatocellular carcinoma translational medicine.

Biomedicines. 9:1592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Messex JK, Byrd CJ, Thomas MU and Liou GY:

Macrophages cytokine Spp1 increases growth of prostate

intraepithelial neoplasia to promote prostate tumor progression.

Int J Mol Sci. 23:42472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Insua-Rodríguez J, Pein M, Hongu T, Meier

J, Descot A, Lowy CM, De Braekeleer E, Sinn HP, Spaich S, Sütterlin

M, et al: Stress signaling in breast cancer cells induces matrix

components that promote chemoresistant metastasis. EMBO Mol Med.

10:e90032018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Li NY, Weber CE, Wai PY, Cuevas BD, Zhang

J, Kuo PC and Mi Z: An MAPK-dependent pathway induces

epithelial-mesenchymal transition via twist activation in human

breast cancer cell lines. Surgery. 154:404–410. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH,

Abrams SL, Montalto G, Cervello M, Nicoletti F, Fagone P, Malaponte

G, Mazzarino MC, et al: Mutations and deregulation of

ras/raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/akt/mTOR cascades which alter therapy

response. Oncotarget. 3:954–987. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Yang YF, Chang YC, Jan YH, Yang CJ, Huang

MS and Hsiao M: Squalene synthase promotes the invasion of lung

cancer cells via the osteopontin/ERK pathway. Oncogenesis.

9:782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Chernaya G, Mikhno N, Khabalova T,

Svyatchenko S, Mostovich L, Shevchenko S and Gulyaeva L: The

expression profile of integrin receptors and osteopontin in thyroid

malignancies varies depending on the tumor progression rate and

presence of BRAF V600E mutation. Surg Oncol. 27:702–708. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Sun BS, Dong QZ, Ye QH, Sun HJ, Jia HL,

Zhu XQ, Liu DY, Chen J, Xue Q, Zhou HJ, et al: Lentiviral-mediated

miRNA against osteopontin suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of

human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 48:1834–1842. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Lin YH and Yang-Yen HF: The

osteopontin-CD44 survival signal involves activation of the

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem.

276:46024–46030. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Zhang H, Guo M, Chen JH, Wang Z, Du XF,

Liu PX and Li WH: Osteopontin knockdown inhibits αv,β3

integrin-induced cell migration and invasion and promotes apoptosis

of breast cancer cells by inducing autophagy and inactivating the

PI3K/akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 33:991–1002. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Fu Y, Zhang Y, Lei Z, Liu T, Cai T, Wang

A, Du W, Zeng Y, Zhu J, Liu Z and Huang JA: Abnormally activated

OPN/integrin αVβ3/FAK signalling is responsible for EGFR-TKI

resistance in EGFR mutant Non-small-cell lung cancer. J Hematol

Oncol. 13:1692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Hui T, Sørensen ES and Rittling SR:

Osteopontin binding to the alpha 4 integrin requires highest

affinity integrin conformation, but is independent of

Post-translational modifications of osteopontin. Matrix Biol.

41:19–25. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Wu Q, Li L, Miao C, Hasnat M, Sun L, Jiang

Z and Zhang L: Osteopontin promotes hepatocellular carcinoma

progression through inducing JAK2/STAT3/NOX1-mediated ROS

production. Cell Death Dis. 13:3412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Behera R, Kumar V, Lohite K, Karnik S and

Kundu GC: Activation of JAK2/STAT3 signaling by osteopontin

promotes tumor growth in human breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis.

31:192–200. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Cao L, Fan X, Jing W, Liang Y, Chen R, Liu

Y, Zhu M, Jia R, Wang H, Zhang X, et al: Osteopontin promotes a

cancer stem cell-like phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma cells

via an integrin-NF-κB-HIF-1α pathway. Oncotarget. 6:6627–6640.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Chen B, Liang S, Guo H, Xu L, Li J and

Peng J: OPN promotes cell proliferation and invasion through NF-κB

in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Genet Res (Camb).

2022:31548272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Saurav S, Karfa S, Vu T, Liu Z, Datta A,

Manne U, Samuel T and Datta PK: Overcoming irinotecan resistance by

targeting its downstream signaling pathways in colon cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 16:34912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Graessmann M, Berg B, Fuchs B, Klein A and

Graessmann A: Chemotherapy resistance of mouse WAP-SVT/t breast

cancer cells is mediated by osteopontin, inhibiting apoptosis

downstream of caspase-3. Oncogene. 26:2840–2850. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Yong HY, Koh MS and Moon A: The p38 MAPK

inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and cancer.

Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 18:1893–1905. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Yu X, Du Y, Liang S, Zhang N, Jing S, Sui

L, Kong Y, Dong M and Kong H: OPN up-regulated proliferation and

invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma through the

p38MAPK signaling pathway. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol. 136:70–79. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Pang H, Cai L, Yang Y, Chen X, Sui G and

Zhao C: Knockdown of osteopontin chemosensitizes MDA-MB-231 cells

to cyclophosphamide by enhancing apoptosis through activating p38

MAPK pathway. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 26:165–173.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|