Radiotherapy remains a major treatment option for

numerous patients, serving both as a radical therapy and as

palliative care (1,2). Since the discovery of X-rays by

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in 1895, the field of radiotherapy has

undergone marked evolution (3).

This advancement has been driven by the pioneering contributions of

renowned scientists such as Nikola Tesla, Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin

and Maria Sklodowska-Curie (4).

Their innovative efforts have established a solid foundation for

modern clinical applications of radiotherapy, which can be employed

individually or in combination with other therapies for both

curative and palliative purposes at all stages of cancer (5,6). More

than half of all patients with cancer undergo radiotherapy;

however, its effectiveness is often diminished by the emergence of

radioresistance, which can profoundly impact the quality of life of

patients (7,8). Radiation therapy exerts its effects by

destroying cancer cells either directly or indirectly through the

induction of DNA damage. Ionizing radiation (IR) can also activate

several prosurvival signaling pathways, including the p53, ataxia

telangiectasia mutated and NF-κB pathways, which enhance DNA damage

checkpoint activation, promote DNA repair and stimulate autophagy

(9–11). Together, these signaling pathways

provide protection to cancer cells against radiation-induced

damage, thereby contributing to their resistance to treatment

(12).

Autophagy is a vital protein degradation pathway in

cells, and is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and

overall health (13). Autophagy,

which was first identified in human liver cells, is categorized

into three forms in mammalian cells: Macroautophagy, microautophagy

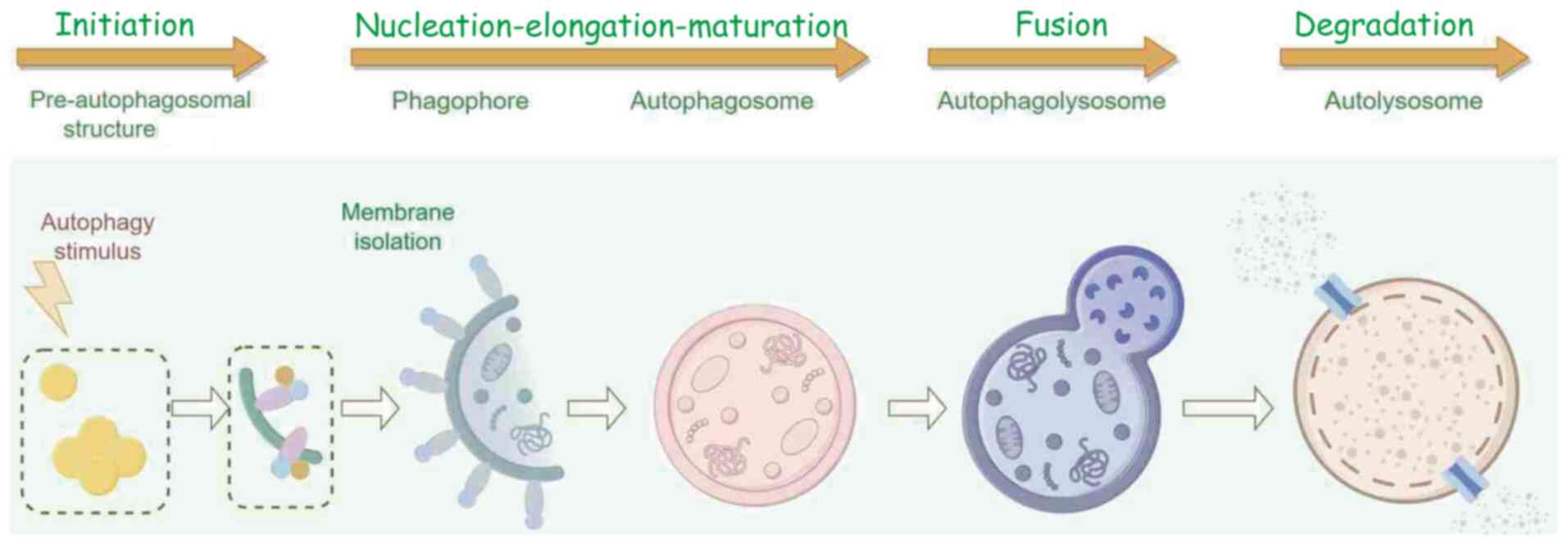

and chaperone-mediated autophagy (14). The autophagy process typically

includes four main stages: Initiation, formation and maturation of

the autophagosome, precise fusion of the autophagosome with the

lysosome, and finally content degradation (15) (Fig.

1). During the autophagy process activated by radiotherapy, a

cellular mechanism directs old, damaged or malfunctioning

biomolecules and organelles to lysosomes for degradation (16,17).

This process is preserved through evolution and is triggered by

different internal and external stressors, including nutrient

shortage, absence of growth factors, IR or low oxygen levels

(18). Under such circumstances,

autophagy functions primarily as a survival tactic by clearing out

dysfunctional organelles or toxic aggregates that could otherwise

lead to apoptosis (19).

Furthermore, the lysosomal decomposition of excess cellular parts

supplies crucial raw materials and nutrients that can be reused to

create important biomolecules (20). Therefore, regulating tumor autophagy

levels to reduce radiotherapy resistance represents a novel

approach.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as

transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that do not encode proteins

(21). Despite their low

conservation across species, lncRNAs function as molecular switches

that influence cell survival, inflammation and lipid metabolism in

the vasculature by regulating autophagy (22). Research has established a

relationship between lncRNAs and resistance to tumor radiotherapy

(23,24). Additionally, lncRNAs serve various

roles, including acting as molecular signals, decoys, guides and

scaffolds (25). Therefore,

reviewing the role of autophagy-modulating lncRNAs in tumor

radioresistance can enhance the understanding of these regulatory

mechanisms and may lead to the identification of novel therapeutic

strategies aimed at increasing tumor radiosensitivity through the

modulation of autophagy.

The present review aims to present the current

understanding of the role of autophagy in cancer and its impact on

tumor radioresistance through interactions with lncRNAs. By

elucidating the function of autophagy-modulating lncRNAs in tumor

radioresistance, the present review aims to provide valuable

insights into the context-dependent applications of therapeutic

strategies.

The role of autophagy in cancer is complex and can

be viewed as a double-edged sword; it has the potential to inhibit

tumor development, while also being implicated in tumor initiation

(26). Autophagy operates at a

basal level in all cell types and actively contributes to tumor

prevention (27). As a critical

intracellular mechanism, autophagy effectively responds to

genotoxic stress through pathways involving reactive oxygen species

(ROS), helping to prevent the accumulation of mutations and

maintain genetic stability (28).

Furthermore, autophagy is responsible for the removal of damaged

organelles, ensuring that cellular damage does not accumulate,

thereby preserving homeostasis and normal cellular function

(29). This underscores its

precise, standardized and essential role in maintaining cellular

health and stability (30).

Among the numerous regulators of autophagy that have

been identified, beclin 1 (BECN1) is recognized as one of the most

crucial (31). As a vital

regulatory protein, BECN1 is essential for initiating autophagy and

serves a role in maintaining the delicate balance between cell

survival and death (32). Research

has indicated that heterozygous loss of the BECN1 gene enhances

tumor development in mice, highlighting its importance in

understanding the mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis (33). Notably, the deletion of the BECN1

gene is frequently observed in various malignant tumors, including

breast, ovarian and prostate cancer, underscoring its critical role

in cancer pathology (34–36). Furthermore, a study has demonstrated

that overexpression of BECN1 in breast cancer cells effectively

inhibited cell proliferation and colony formation, and reduced

tumor growth in nude mice (37). In

addition to BECN1, research has shown that the knockout of the

autophagy-related gene (ATG)5 and ATG7 genes in mice disrupts the

autophagy process, leading to exacerbated oxidative stress

responses and an increased risk of developing liver cancer

(38). These findings emphasize the

crucial role of autophagy in tumor prevention.

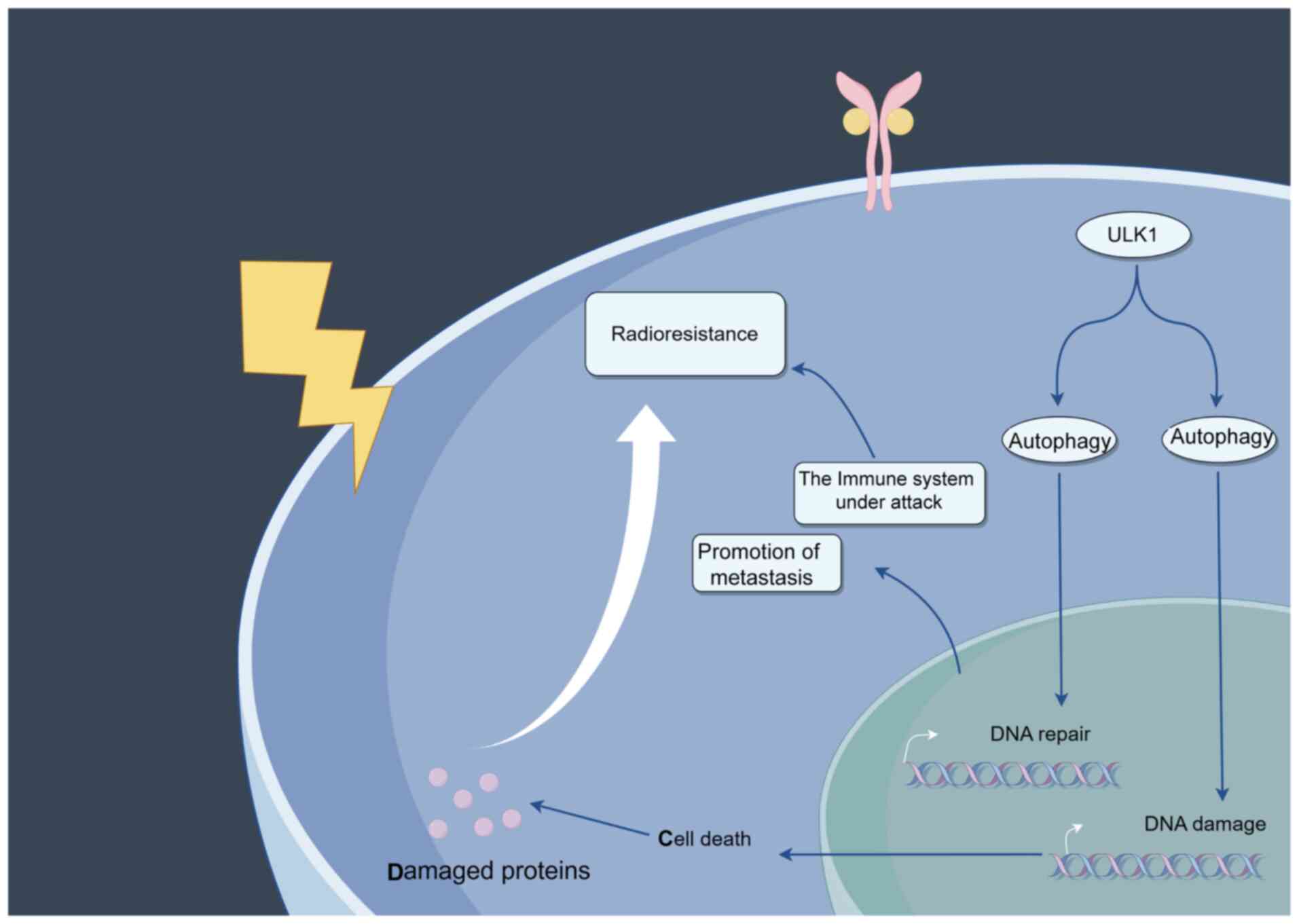

Although radiotherapy is a main approach for the

treatment of cancer, resistance frequently arises, resulting in

unsuccessful treatments (44). This

radioresistance arises from the capacity of tumors to disrupt

stress responses, such as DNA damage and repair processes, which

either promote or inhibit autophagy and aid in nutrient recycling

(45) (Fig. 2). For example, by modulating Unc-51

like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1)-mediated autophagy,

butyrophilin subfamily 3 member A1 contributes to tumor progression

and radiation resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

(46). Xu et al (47) reported that blocking autophagic flux

and DNA repair in tumor cells could enhance the effectiveness of

radiotherapy for orthotopic glioblastoma. In addition to damaged

proteins, various intermediate molecules, their complexes, and

organelles such as mitochondria and micronuclei can serve as cargo

for the autophagy process (48).

Previous studies have revealed both pro-survival and anti-survival

characteristics of autophagic pathways (49,50).

Cancer cells frequently take advantage of the dual role of

autophagy to survive in metabolically difficult conditions, escape

immune system attacks, prevent cell death and induce metastasis

(51,52). Research has revealed that using both

radiation and berberine together suppresses autophagy and

alternative end-joining DNA repair, which are linked to

radioresistance, thereby enhancing sensitivity to radiation

(53).

The sensitivity of tumor cells to radiation is

frequently affected by autophagic processes (54). BECN1 moves to the nucleus after IR

exposure, resulting in G2/M cell cycle arrest (55). Furthermore, autophagy driven by ATG5

has been demonstrated to increase the radiosensitivity of prostate

cancer cells, especially when nutrients are scarce or glutamine is

depleted, and also when MYC is silenced (56). Chen et al (57) proposed that inhibiting the nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) antioxidative pathway

could make U-2 osteosarcoma cells more sensitive to radiation, with

the NRF2 antioxidative response being controlled by

autophagy-driven activation of ERK 1/2 kinases. Consequently,

reducing the expression levels of BECN1, ATG5 or NRF2 has been

shown to decrease the IR sensitivity of cancer cells. Furthermore,

the inhibition of ATG7 by lncRNA HOTAIR, which is notably

upregulated in prostate cancer cell lines exposed to radiation, has

been associated with radioresistance in these cells (58). These results emphasize the essential

function of autophagy in influencing radiosensitivity and suggest

the possibility of targeting autophagic pathways to enhance

radiotherapy effectiveness (58).

Research on breast cancer cells, which naturally

resist apoptosis, further underscores the link between IR and

autophagic pathways (59). After IR

exposure, these cells show increased autophagic characteristics,

resulting in more iron accumulation. This accumulation, in

conjunction with subsequent ROS generation, oxidative stress and

DNA damage, may trigger cell death through a mechanism known as

ferroptosis (60,61). These insights have sparked a rising

interest in pairing autophagic inducers with IR to improve the

radiosensitivity of cancer cells. For instance, in a similar

approach, the treatment of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)

cells with rapamycin alongside a histone deacetylase inhibitor has

been found to promote radiosensitization (62). This combined treatment has two

effects: It boosts autophagy and at the same time hinders DNA

damage repair processes. Observations in cultured cells and tumor

xenograft mouse models have demonstrated the effectiveness of the

strategy, pointing to a potential improvement in radiotherapy

outcomes (63).

Autophagy affects cancer cell survival in complex

ways, acting both as a supporter and an opponent of

radiosensitization (62,64). Various cancer cell types have been

shown to exploit enhanced autophagy as a survival strategy. For

instance, the application of autophagy inhibitors renders otherwise

radio-resistant bladder cancer (BLCA) cells more sensitive to

chemotherapy (65). Similarly,

silencing of ATG5, a key component of the autophagy process, has

been found to increase IR-induced cell death in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma (66). Furthermore, the

use of autophagy inhibitors in combination with IR has emerged as a

factor influencing the bystander and abscopal effects associated

with chemotherapy and radiotherapy (67). These findings underscore the

importance of context in the role of autophagy in cancer treatment

and highlight the potential of targeting autophagy pathways to

enhance treatment efficacy.

Radiotherapy is a common cancer treatment that

induces different forms of cell death, including autophagy

(74). Besides directly causing DNA

strand breaks, IR can lead to the production of significant amounts

of ROS in cells, resulting in oxidative stress damage (75). According to Yang et al

(76), mitophagy triggered by IR

boosts ferroptosis by raising the levels of free fatty acids inside

cells. Lysosomes serve a crucial role in autophagy, a cellular

degradation process (77). A

conserved protein associated with autophagy, Atgs/P62/LC3II,

controls the process (78). In

cancer cells, autophagy is a double-edged sword. In the initial

phases, it might restrict the development of tumors. Nevertheless,

it might also offer a survival advantage for adaptation and

detoxification in challenging conditions such as starvation, low

oxygen levels, and chemotherapy or radiotherapy (79). Investigators have reported that

autophagy activity rises following IR. This acts as a mechanism for

cells to survive when faced with cytotoxic agents, including IR and

temozolomide, in the treatment of glioblastoma (80,81).

Furthermore, researchers have revealed that IR promotes autophagy

via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway (82). In conclusion, IR has an important

effect on tumor autophagy.

Numerous cancer types have been found to exhibit

abnormal expression of lncRNAs, and the relationship between

lncRNAs and autophagy has garnered interest across various cancer

types (Table I), including lung,

gastric, breast and prostate cancer (83). The majority of research suggests

that lncRNAs regulate autophagy mainly through mechanisms such as

microRNA (miRNA/miR) sponging (functioning as competing endogenous

RNAs), interactions between RNAs, RNA-protein regulation and

various other pathways (84,85).

Studies have indicated that lncRNAs are involved in various phases

of the autophagy process from the beginning to the maturation stage

(86,87). They assist in starting autophagic

phagocytosis by controlling essential proteins such as ULK1, mTOR

and BECN1, and they also affect the extension of autophagic

vesicles by regulating ATG3, ATG5, ATG4, ATG12 and ATG7 (88). The present review highlights the

complex and diverse functions of lncRNAs in regulating autophagy,

and their possible impact on cancer biology and treatment.

Proliferation is one of the most critical malignant

phenotypes observed in cancer, while apoptosis is equally

significant in the context of neoplastic development (89). Although their functions are

fundamentally opposite (proliferation promotes cell growth and

survival, while apoptosis leads to programmed cell death), their

interactions work synergistically to regulate cancer development.

This delicate balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis

serves a crucial role in tumor progression and resistance to

therapy (90). In digestive system

cancers, various lncRNAs have been identified to serve roles in

tumor progression and autophagy regulation (91). For instance, lncRNA SNHG11 is

upregulated in gastric cancer and is associated with poor patient

prognosis. lncRNA SNHG11 post-transcriptionally enhances ATG12

expression through miR-1276, thereby promoting autophagy, cell

proliferation and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

(92). Similarly, in HCC, lncRNA

MALAT1 exhibits elevated expression levels compared with those in

normal tissues. Silencing MALAT1 has been shown to increase HCC

autophagy by promoting the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II and

simultaneously suppressing HCC cell proliferation (93). Conversely, lncRNA NBR2 acts as a

tumor suppressor in HCC by inhibiting BECN1 and autophagy through

the ERK/JNK pathways, thereby restraining HCC cell proliferation

(94). In colorectal cancer (CRC),

lncRNA SLCO4A1-AS1 acts as an oncogenic element, exhibiting a

positive association with par-3 family cell polarity regulator

(PARD3) and sponging miR-508-3p. This lncRNA enhances the

proliferation of CRC cells and initiates autophagy through the

miR-508-3p/PARD3 pathway. Nonetheless, the regulatory effect is

interrupted by the application of the autophagy inhibitor

3-methyladenine (95). Another

lncRNA in CRC, FIRRE, directly interacts with polypyrimidine tract

binding protein 1 to enhance BECN1 mRNA stability, thus reducing

autophagy and promoting CRC cell proliferation (96). In the context of oral squamous cell

carcinoma (OSCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), several upregulated

lncRNAs have been shown to suppress autophagy. For instance,

LINC01207 is highly expressed in OSCC, where its upregulation

promotes cell proliferation but inhibits both apoptosis and

autophagy via the miR-1301-3p/lactate dehydrogenase A axis

(97). By contrast, overexpression

of LINC00958 reduces apoptosis while promoting autophagy by

upregulating autophagy-related proteins such as BECN1 and ATG5, and

increasing the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, driven by p53 mediated by

sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) (98). In CCA,

lncRNA HOTAIR inhibits both apoptotic and autophagic processes,

thereby promoting the proliferation of CCA cells by targeting the

miR-204-5p/high mobility group box 1 axis (99). Pancreatic cancer (PANC), known for

its poor prognosis, remains a complex malignancy with unclear

progression mechanisms (100). A

study by Wu et al (101)

revealed that LZTS1-AS1, a highly expressed lncRNA in PANC cells

and tissues, promoted PANC cell proliferation while inhibiting

apoptosis and autophagy via the miR-532/twist family bHLH

transcription factor 1 axis. Overall, these findings highlight the

diverse and critical roles of lncRNAs in modulating autophagy and

influencing the malignant phenotypes of various cancer types.

The downregulation of lncRNA CASC2 enhances

apoptosis in NSCLC and diminishes ATG5-mediated autophagy by

regulating the miR-214/tripartite motif containing 16 axis in A549

and H1299 NSCLC cell lines (105).

Conversely, a reversed autophagic state has been noted in papillary

thyroid carcinoma (PTC), where overexpression of lncRNA SLC26A4-AS1

inhibited the proliferation of PTC cells and stimulated autophagy

by recruiting the transcription factor ETS1 and elevating inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 expression (106). Additionally, Qin et al

(107) revealed that lncRNA SNHG5

was stabilized by RNA binding motif protein 47 (RBM47) and directed

to FOXO3, resulting in decreased proliferation and the activation

of autophagy in PTC cells through the RBM47/small nucleolar RNA

host gene 5/FOXO3 pathway.

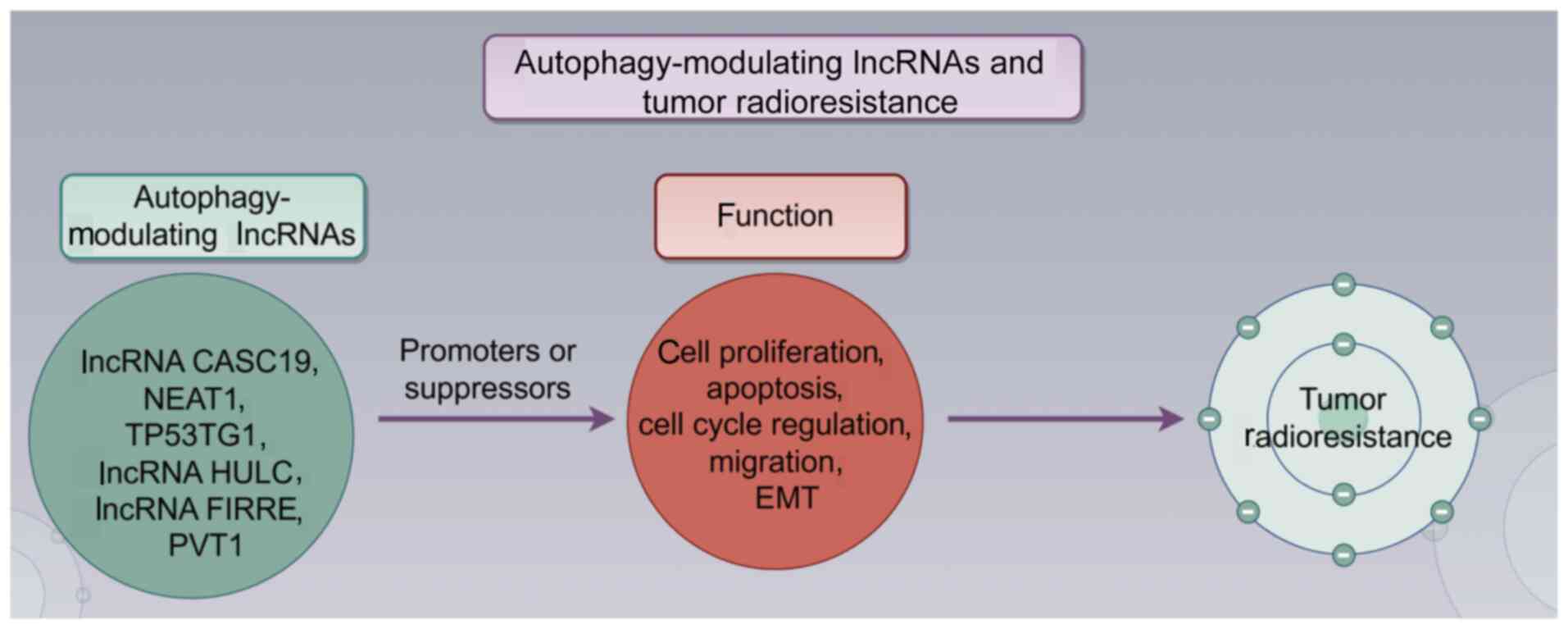

CASC19, a newly identified lncRNA located on

chromosome 8q24.21, consists of 324 nucleotides (110). A study has demonstrated that

CASC19 expression is upregulated in a variety of human cancer

types, including NSCLC, gastric cancer, CRC, PANC, ccRCC, glioma,

cervical cancer and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (111). Notably, some research has

indicated that CASC19 can enhance radioresistance in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma by modulating autophagy signaling pathways (112,113). Furthermore, the dysregulation of

CASC19 has been closely linked to numerous clinicopathological

characteristics (prognosis and pathological staging) and cancer

progression, particularly in HCC and gastric cancer (114,115). In summary, CASC19 influences

various cellular phenotypes, including cell proliferation,

apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, migration, invasion, EMT,

autophagy and therapeutic resistance (116).

NEAT1 is predominantly located in the nucleus,

although a smaller fraction is present in the cytoplasm (117). NEAT1 functions as a structural

component of nuclear paraspeckles and is involved in regulating

gene expression at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional

levels (118). Research has

demonstrated that NEAT1 contributes to radioresistance in HCC cells

by inducing autophagy through GABA type A receptor-associated

protein (119). The role of NEAT1

in carcinogenesis is multifaceted, encompassing interactions with

miRNAs, modulation of gene expression, regulation of epigenetic

factors and participation in various signaling pathways, such as

the PI3K-AKT and TGF-β1 pathways (120). Additionally, the involvement of

NEAT1 in cancer is complicated by its impact on CSCs and the tumor

microenvironment (121). The

interaction of NEAT1 with autophagy further adds to the complexity

of its functions in cancer biology (122). Understanding the interactions

between NEAT1, autophagy and radioresistance is crucial for

researchers as it may lead to the identification of novel

therapeutic targets and strategies aimed at disrupting oncogenic

processes, reducing treatment resistance and improving patient

survival (123). Consequently,

this understanding could facilitate the development of specialized

treatment approaches and regimens.

lncRNA TP53TG1 (National Center for Biotechnology

Information reference sequence, NR_015381.1), located on chromosome

12, is transcribed as an ~0.7-kilobase lncRNA molecule (124). Its expression can be induced under

conditions of cellular stress in a wild-type TP53-dependent manner

(125). As a relatively recent

discovery in the field of lncRNAs, TP53TG1 has been implicated to

serve oncogenic and anti-oncogenic roles across various cancer

types, such as gastric and breast cancer (126). For example, overexpression of

TP53TG1 promotes proliferation of colon cancer cells (127). In addition, Cheng et al

(128) found that lncRNA TP53TG1

exerted anticancer effects in cervical cancer by comprehensively

regulating the transcriptome profile of HeLa cells. Research has

indicated a close association between TP53TG1 and autophagy

(129). Furthermore, it has been

demonstrated that lncRNA TP53TG1 contributes to the radioresistance

of glioma cells through the miR-524-5p/RAB5A axis (130). Given these findings, TP53TG1

represents a promising target to enhance the sensitivity of tumors

to radiotherapy.

HULC, found on chromosome 6p24.3, has been

identified to be upregulated in HCC and is linked to cancer

advancement (131). The expression

of this transcript is regulated by miRNAs and transcriptionally

modulated by Sp1 family factors (132). HULC has been identified as a novel

biomarker in different types of cancer, such as prostate cancer and

CRC, serving a role as an oncogenic factor (133). Research conducted previously

indicated that inhibiting HULC could reduce angiogenesis in human

gliomas (134). Another study

demonstrated that HULC facilitated the advancement of CRC (135). A study has shown that lncRNA HULC

serves a role in radioresistance by reducing autophagy in prostate

cancer cells (136). Thus, lncRNA

HULC could serve as a therapeutic target to combat tumor resistance

to radiotherapy.

PVT1, a lncRNA, was initially identified as a driver

of variant translocations in mouse plasmacytomas (142). The human lncPVT1 gene is situated

on chromosome 8q24.21, sharing the same location as the MYC

oncogene (143). lncPVT1 has been

identified as a factor that accelerates the development of several

cancer types, such as nasopharyngeal cancer and lung cancer

(144,145). Radioresistance poses a major

challenge to tumor treatment success, and is connected to the

abnormal regulation of physiological functions in cancer cells,

including apoptosis, autophagy, stemness (for CSCs), hypoxia, EMT

and DNA damage repair (146,147). Recently, lncPVT1 has been linked

to the modulation of radioresistance in certain cancer types,

including nasopharyngeal cancer and lung cancer (148).

Research interest in lncRNA therapeutics has only

emerged in the past decade, and so far, no treatments targeting

lncRNAs have reached clinical development (149). SP100-AS1, a lncRNA that targets

the antisense sequence of the SP100 gene, is upregulated in the

tissues of patients with CRC who are resistant to radiation,

according to RNA-sequencing analysis (150). Notably, reducing SP100-AS1

expression lowered radioresistance and decreased cell proliferation

and tumor growth in both laboratory and live models. To identify

the proteins and miRNAs interacting with SP100-AS1, mass

spectrometry and bioinformatics analyses were utilized. SP100-AS1

was shown to interact with and stabilize the ATG3 protein via the

ubiquitination-dependent proteasome mechanism (150). This interaction highlights the

possible involvement of SP100-AS1 in regulating autophagy-related

mechanisms and enhancing radioresistance in CRC. SP100-AS1 holds

potential as a therapeutic target to enhance the response of CRC to

radiation therapy (150). As

aforementioned, autophagy affects tumor cell proliferation,

survival and the response to treatment in intricate ways across

different types of cancer, such as nasopharyngeal cancer and CRC.

Methods to target autophagy might involve aiming at specific

proteins or pathways associated with autophagy, as well as using

agents that promote or block autophagy.

Scientists seek to improve treatment effectiveness

by utilizing the interaction between autophagy and processes

regulated by lncRNAs. They aim to develop more effective treatments

by integrating autophagy modulation with lncRNA-targeted methods

(151). Furthermore, these

combination therapies provide a comprehensive strategy to boost

patient outcomes (152).

There are both obstacles and prospects in the future

research of radiation oncology and lncRNAomics (153). For precise tumor targeting,

technological advancements such as hybrid MRI and positron emission

tomography scans are vital, although they entail significant costs

and demand specialized expertise (154). One major obstacle in lncRNA

research is the restricted knowledge gained from examining just a

small portion of lncRNAs, which limits the understanding of their

mechanisms, roles and structures (155). Despite significant progress in the

field, delivering oligonucleotides to solid tumors continues to be

a major challenge. Advancements in artificial intelligence and

sophisticated statistical modeling have enabled molecular-guided

treatment plans customized for each patient, representing a

significant achievement in precision medicine. Autophagy-modulating

lncRNAs represent a vast yet largely unexplored reservoir of

oncogenes, tumor suppressors and radioresponse modifiers.

Integrating this knowledge into treatment strategies, from

diagnosis and response prediction to the design of targeted

therapies, could greatly enhance management and outcomes for

patients with cancer (156). In

conclusion, the present review summarizes the effects of

autophagy-modulating lncRNAs on tumor radioresistance, providing

novel ideas for tumor radiosensitization.

lncRNAs that modulate autophagy are crucial elements

in the radioresistance of tumors. These lncRNAs are crucial in

different stages of cancer development and advancement, such as

tumor expansion, spread and resistance to treatment. Studies are

concentrating on using autophagy-based treatment methods to tackle

radioresistance in patients with cancer (157,158). Modifying autophagy can influence

the survival of tumor cells, their response to therapy and the

overall success of treatment. Creating targeted cancer treatments

requires a deep comprehension of the interaction between lncRNAs

and autophagy. Targeting specific lncRNAs could potentially adjust

autophagy and increase tumor radiosensitivity. Current clinical

trials and preclinical research are investigating the potential of

targeting autophagy and lncRNAs to enhance treatment outcomes for

patients with cancers resistant to radiation (159,160).

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by The Wings Scientific and

Technological Foundation of The First People's Hospital of Changde

City (grant no. Z2025ZC04) and Interdisciplinary Research Program

in Medicine and Engineering, The First Affiliated Hospital of

University of South China (grant no. IRP-M&E-2025-05)

Not applicable.

HL wrote and reviewed the drafts of the paper, while

ZH created the figures and tables, and revised the paper. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Schaue D and McBride WH: Opportunities and

challenges of radiotherapy for treating cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

12:527–540. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yerolatsite M, Torounidou N, Amylidi AL,

Rapti IC, Zarkavelis G, Kampletsas E and Voulgari PV: A Systematic

review of pneumonitis following treatment with immune checkpoint

inhibitors and radiotherapy. Biomedicines. 13:9462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Tubiana M: Wilhelm conrad röntgen and the

discovery of X-rays. Bull Acad Natl Med. 180:97–108. 1996.(In

French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Babic RR, Stankovic Babic G, Babic SR and

Babic NR: 120 years since the discovery of X-Rays. Med Pregl.

69:323–330. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Klucznik KA, Ravkilde T, Skouboe S, Møller

DS, Hokland S, Keall P, Buus S, Bentzen L and Poulsen PR: Cone-beam

CT-based estimations of prostate motion and dose distortion during

radiotherapy. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 35:1007982025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lam MB, Landrum MB, McWilliams JM, Buzzee

B, Wright AA, Keating NL and Landon BE: Practice-level spending

variation for radiation treatment episodes among older adults with

cancer. JAMA Health Forum. 6:e2519522025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hill RM, Fok M, Grundy G, Parsons JL and

Rocha S: The role of autophagy in hypoxia-induced radioresistance.

Radiother Oncol. 189:1099512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang C, Song R, Yuan J, Hou G, Chu AL,

Huang Y, Xiao C, Chai T, Sun C and Liu Z: Exosome-Shuttled METTL14

From AML-Derived mesenchymal stem cells promotes the proliferation

and radioresistance in AML cells by stabilizing ROCK1 expression

via an m6A-IGF2BP3-dependent mechanism. Drug Dev Res.

86:e700252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Luo H, Huang MF, Xu A, Wang D, Gingold JA,

Tu J, Wang R, Huo Z, Chiang YT, Tsai KL, et al: Mutant p53 confers

chemoresistance by activating KMT5B-mediated DNA repair pathway in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 625:2177362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Feng Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Zhou K,

Yang Z, Zhu W, Zhang Q, Cao J, Wang L and Jiao Y: NEDD4-mediated

endothelial-mesenchymal transition participates in

radiation-induced lung injury through the ATM signaling pathway.

Dose Response. 23:155932582513527262025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Qu Z, Shi L, Wang P, Zhao A, Zheng X and

Yin Q: Dual targeting of inflammatory and immune checkpoint

pathways to overcome radiotherapy resistance in esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma. J Inflamm Res. 18:9091–9106. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Porrazzo A, Cassandri M, D'Alessandro A,

Morciano P, Rota R, Marampon F and Cenci G: DNA repair in tumor

radioresistance: Insights from fruit flies genetics. Cell Oncol.

47:717–732. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cursaro I, Rossi S, Butini S, Gemma S,

Carullo G and Campiani G: A focus on natural autophagy modulators

as potential host-directed weapons against emerging and re-emerging

viruses. Med Res Rev. Jul 16–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Parzych KR and Klionsky DJ: An overview of

autophagy: Morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 20:460–473. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vafadar A, Tajbakhsh A,

Hosseinpour-Soleimani F, Savardshtaki A and Hashempur MH:

Phytochemical-mediated efferocytosis and autophagy in inflammation

control. Cell Death Discov. 10:4932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Feng X, Zhang H, Meng L, Song H, Zhou Q,

Qu C, Zhao P, Li Q, Zou C, Liu X and Zhang Z: Hypoxia-induced

acetylation of PAK1 enhances autophagy and promotes brain

tumorigenesis via phosphorylating ATG5. Autophagy. 17:723–742.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S and Wang Y:

Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 14:6482023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Martini-Stoica H, Xu Y, Ballabio A and

Zheng H: The autophagy-lysosomal pathway in neurodegeneration: A

TFEB perspective. Trends Neurosci. 39:221–234. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lin W, Zhou Q, Wang CQ, Zhu L, Bi C, Zhang

S, Wang X and Jin H: LncRNAs regulate metabolism in cancer. Int J

Biol Sci. 16:1194–1206. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fu Y, Liu L, Wu H, Zheng Y, Zhan H and Li

L: LncRNA GAS5 regulated by FTO-mediated m6A demethylation promotes

autophagic cell death in NSCLC by targeting UPF1/BRD4 axis. Mol

Cell Biochem. 479:553–566. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhou X, Tong Y, Yu C, Pu J, Zhu W, Zhou Y,

Wang Y, Xiong Y and Sun X: FAP positive cancer-associated

fibroblasts promote tumor progression and radioresistance in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by transferring exosomal lncRNA

AFAP1-AS1. Mol Carcinog. 63:1922–1937. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hjazi A, Jasim SA, Altalbawy FMA, Kaur H,

Hamzah HF, Kaur I, Deorari M, Kumar A, Elawady A and Fenjan MN:

Relationship between lncRNA MALAT1 and Chemo-radiotherapy

resistance of cancer cells: Uncovered truths. Cell Biochem Biophys.

82:1613–1627. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Huang H, Jin H, Lei R, He Z, He S, Chen J,

Saw PE, Qiu Z, Ren G and Nie Y: lncRNA-WAL promotes triple-negative

breast cancer aggression by inducing β-catenin nuclear

translocation. Mol Cancer Res. 22:1036–1050. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Russell RC and Guan KL: The multifaceted

role of autophagy in cancer. EMBO J. 41:e1100312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bhol CS, Senapati PK, Kar RK, Chew G,

Mahapatra KK, Lee EHC, Kumar AP, Bhutia SK and Sethi G: Autophagy

paradox: Genetic and epigenetic control of autophagy in cancer

progression. Cancer Lett. 630:2179092025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gao L, Loveless J, Shay C and Teng Y:

Targeting ROS-Mediated crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in

cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1260:1–12. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Carretero-Fernández M, Cabrera-Serrano AJ,

Sánchez-Maldonado JM, Ruiz-Durán L, Jiménez-Romera F,

García-Verdejo FJ, González-Olmedo C, Cardús A, Díaz-Beltrán L,

Gutiérrez-Bautista JF, et al: Autophagy and oxidative stress in

solid tumors: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 212:1048202025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hama Y, Ogasawara Y and Noda NN: Autophagy

and cancer: Basic mechanisms and inhibitor development. Cancer Sci.

114:2699–2708. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li Z, Liu F, Li F, Zeng G, Wen X, Ding J

and Zhou J: DHX9-mediated epigenetic silencing of BECN1 contributes

to impaired autophagy and tumor progression in breast cancer via

recruitment of HDAC5. Cell Death Dis. 16:5242025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cao Z, Tian K, Ran Y, Zhou H, Zhou L, Ding

Y and Tang X: Beclin-1: A therapeutic target at the intersection of

autophagy, immunotherapy, and cancer treatment. Front Immunol.

15:15064262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li X, Yang KB, Chen W, Mai J, Wu XQ, Sun

T, Wu RY, Jiao L, Li DD, Ji J, et al: CUL3 (cullin 3)-mediated

ubiquitination and degradation of BECN1 (beclin 1) inhibit

autophagy and promote tumor progression. Autophagy. 17:4323–4340.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen X, Sun Y, Wang B and Wang H:

Prognostic significance of autophagy-related genes BECN1 and LC3 in

ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. J Int Med Res.

48:3000605209682992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu C, Xu P, Chen D, Fan X, Xu Y, Li M,

Yang X and Wang C: Roles of autophagy-related genes Beclin-1 and

LC3 in the development and progression of prostate cancer and

benign prostatic hyperplasia. Biomed Rep. 1:855–860. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yao Q, Chen J, Lv Y, Wang T, Zhang J, Fan

J and Wang L: The significance of expression of autophagy-related

gene Beclin, Bcl-2, and Bax in breast cancer tissues. Tumour Biol.

32:1163–1171. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu CL, Liu JF, Liu Y, Wang YX, Fu KF, Yu

XJ, Pu Q, Chen XX and Zhou LJ: BECN1 inhibition enhances

paclitaxel-mediated cytotoxicity in breast cancer in vitro and in

vivo. Int J Mol Med. 43:1866–1878. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Tran S, Juliani J, Harris TJ, Evangelista

M, Ratcliffe J, Ellis SL, Baloyan D, Reehorst CM, Nightingale R,

Luk IY, et al: BECN1 is essential for intestinal homeostasis

involving autophagy-independent mechanisms through its function in

endocytic trafficking. Commun Biol. 7:2092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ishaq M, Ojha R, Sharma AP and Singh SK:

Autophagy in cancer: Recent advances and future directions. Semin

Cancer Biol Semin Cancer Biol. 66:171–181. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Senapati PK, Mahapatra KK, Singh A and

Bhutia SK: mTOR inhibitors in targeting autophagy and

autophagy-associated signaling for cancer cell death and therapy.

Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1880:1893422025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ferro F, Servais S, Besson P, Roger S,

Dumas JF and Brisson L: Autophagy and mitophagy in cancer metabolic

remodelling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 98:129–138. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang M, Liu S, Chua MS, Li H, Luo D, Wang

S, Zhang S, Han B and Sun C: SOCS5 inhibition induces autophagy to

impair metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Death Dis. 10:6122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Maycotte P, Jones KL, Goodall ML, Thorburn

J and Thorburn A: Autophagy supports breast cancer stem cell

maintenance by regulating IL6 secretion. Mol Cancer Res.

13:651–658. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Song J, Yang P, Chen C, Ding W, Tillement

O, Bai H and Zhang S: Targeting epigenetic regulators as a

promising avenue to overcome cancer therapy resistance. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 10:2192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

ALKhemeiri N, Eljack S and Saber-Ayad MM:

Perspectives of targeting autophagy as an adjuvant to

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy for colorectal cancer treatment. Cells.

14:7452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yang W, Cheng B, Chen P, Sun X, Wen Z and

Cheng Y: BTN3A1 promotes tumor progression and radiation resistance

in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating ULK1-mediated

autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 13:9842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Xu Q, Zhang H, Liu H, Han Y, Qiu W and Li

Z: Inhibiting autophagy flux and DNA repair of tumor cells to boost

radiotherapy of orthotopic glioblastoma. Biomaterials.

280:1212872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chaurasia M, Bhatt AN, Das A, Dwarakanath

BS and Sharma K: Radiation-induced autophagy: Mechanisms and

consequences. Free Radic Res. 50:273–290. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yue T, Zheng D, Yang J, He J and Hou J:

Potential value and cardiovascular risks of programmed cell death

in cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 16:16159742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu S, Wang L, Zhu L, Zhao T, Han P, Yan

F, Wang X, Li C, Wang Z and Yang BF: Mechanism and regulation of

mitophagy in liver diseases: A review. Front Cell Dev Biol.

13:16149402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yun CW and Lee SH: The roles of autophagy

in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 19:34662018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Singh SS, Vats S, Chia AY, Tan TZ, Deng S,

Ong MS, Arfuso F, Yap CT, Goh BC, Sethi G, et al: Dual role of

autophagy in hallmarks of cancer. Oncogene. 37:1142–1158. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Clark A, Villarreal MR, Huang SB,

Jayamohan S, Rivas P, Hussain SS, Ybarra M, Osmulski P, Gaczynska

ME, Shim EY, et al: Targeting S6K/NFκB/SQSTM1/Polθ signaling to

suppress radiation resistance in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett.

597:2170632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Sezen Us A, Dagsuyu E, Us H, Cöremen M,

Karabulut Bulan O and Yanardag R: Apocynin may alleviate side

effects of autophagy-blocked radiotherapy through antioxidant

effects. Biotech Histochem. Jun 30–2025.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ma S, Fu X, Liu L, Liu Y, Feng H, Jiang H,

Liu X, Liu R, Liang Z, Li M, et al: Iron-dependent autophagic cell

death induced by radiation in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9:7238012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Mukha A, Kahya U, Linge A, Chen O, Löck S,

Lukiyanchuk V, Richter S, Alves TC, Peitzsch M, Telychko V, et al:

GLS-driven glutamine catabolism contributes to prostate cancer

radiosensitivity by regulating the redox state, stemness and

ATG5-mediated autophagy. Theranostics. 11:7844–7868. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Chen N, Zhang R, Konishi T and Wang J:

Upregulation of NRF2 through autophagy/ERK 1/2 ameliorates ionizing

radiation induced cell death of human osteosarcoma U-2 OS. Mutat

Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 813:10–17. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wu C, Yang L, Qi X, Wang T, Li M and Xu K:

Inhibition of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR enhances radiosensitivity

via regulating autophagy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Manag Res.

10:5261–5271. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Cui L, Song Z, Liang B, Jia L, Ma S and

Liu X: Radiation induces autophagic cell death via the p53/DRAM

signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 35:3639–3647.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Lei G, Zhang Y, Koppula P, Liu X, Zhang J,

Lin SH, Ajani JA, Xiao Q, Liao Z, Wang H and Gan B: The role of

ferroptosis in ionizing radiation-induced cell death and tumor

suppression. Cell Res. 30:146–162. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G and Tang D:

Broadening horizons: The role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 18:280–296. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang Y, Liu F, Fang C, Xu L, Chen L, Xu Z,

Chen J, Peng W, Fu B and Li Y: Combination of rapamycin and SAHA

enhanced radiosensitization by inducing autophagy and acetylation

in NSCLC. Aging (Albany NY). 13:18223–18237. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chen J, Luo H, Wu X, Dong M, Wang D, Ou Y,

Wang Y, Sun S, Liu Z, Yang Z, et al: Inhibition of Phosphoglycerate

Kinase 1 Enhances Radiosensitivity of Esophageal Squamous Cell

Carcinoma to X-rays and Carbon Ion Irradiation. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 30:364302025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Mukha A, Kahya U and Dubrovska A:

Targeting glutamine metabolism and autophagy: The combination for

prostate cancer radiosensitization. Autophagy. 17:3879–3881. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Ma X, Mao G, Chang R, Wang F, Zhang X and

Kong Z: Down-regulation of autophagy-associated protein increased

acquired radio-resistance bladder cancer cells sensitivity to

taxol. Int J Radiat Biol. 97:507–516. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Mo N, Lu YK, Xie WM, Liu Y, Zhou WX, Wang

HX, Nong L, Jia YX, Tan AH, Chen Y, et al: Inhibition of autophagy

enhances the radiosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by

reducing Rad51 expression. Oncol Rep. 32:1905–1912. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Prise KM and O'Sullivan JM:

Radiation-induced bystander signalling in cancer therapy. Nat Rev

Cancer. 9:351–360. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Jia H, Wei J, Zheng W and Li Z: The dual

role of autophagy in cancer stem cells: Implications for tumor

progression and therapy resistance. J Transl Med. 23:5832025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan

A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al: The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties

of stem cells. Cell. 133:704–715. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zhou S, Wang X, Ding J, Yang H and Xie Y:

Increased ATG5 expression predicts poor prognosis and promotes EMT

in cervical carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7571842021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Pustovalova M, Alhaddad L, Blokhina T,

Smetanina N, Chigasova A, Chuprov-Netochin R, Eremin P,

Gilmutdinova I, Osipov AN and Leonov S: The CD44high subpopulation

of multifraction irradiation-surviving NSCLC cells exhibits partial

EMT-program activation and DNA damage response depending on their

p53 Status. Int J Mol Sci. 22:23692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Yazal T, Bailleul J, Ruan Y, Sung D, Chu

FI, Palomera D, Dao A, Sehgal A, Gurunathan V, Aryan L, et al:

Radiosensitizing pancreatic cancer via effective autophagy

inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 21:79–88. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Gajate C, Gayet O, Fraunhoffer NA, Iovanna

J, Dusetti N and Mollinedo F: Induction of apoptosis in human

pancreatic cancer stem cells by the endoplasmic reticulum-targeted

alkylphospholipid analog edelfosine and potentiation by autophagy

inhibition. Cancers (Basel). 13:61242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Fischer P, Schmid M, Ohradanova-Repic A,

Schneeweiss R, Hadatsch J, Grünert O, Benedum J, Röhrer A,

Staudinger F, Schatzlmaier P, et al: Molecular features of TNBC

govern heterogeneity in the response to radiation and autophagy

inhibition. Cell Death Dis. 16:5402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Xiao S, Wang Y, Pan S, Mu M, Chen B, Li H,

Feng C, Fan R, Yu W, Han B, et al: Bismuth-functionalized

probiotics for enhanced antitumor radiotherapy and immune

activation. J Mater Chem B. Jul 14–2025.(Epub ahead of print).

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Yang P, Li J, Zhang T, Ren Y, Zhang Q, Liu

R, Li H, Hua J, Wang WA, Wang J and Zhou H: Ionizing

radiation-induced mitophagy promotes ferroptosis by increasing

intracellular free fatty acids. Cell Death Differ. 30:2432–2445.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Liu C, Liu X, Li Z, Wei Y, Liu B, Zhu P,

Liu Y and Zhao R: VPS37A activates the autophagy-lysosomal pathway

for TNFR1 degradation and induces NF-κB-Regulated cell death under

metabolic stress in colorectal cancer. Oncol Res. 33:2085–2105.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Azmat MA, Zaheer M, Shaban M, Arshad S,

Hasan M, Ashraf A, Naeem M, Ahmad A and Munawar N: Autophagy: A new

avenue and biochemical mechanisms to mitigate the climate change.

Scientifica (Cairo). 2024:99083232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Choi Y, Bowman JW and Jung JU: Autophagy

during viral infection-a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Microbiol.

16:341–354. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Daniel P, Sabri S, Chaddad A, Meehan B,

Jean-Claude B, Rak J and Abdulkarim BS: Temozolomide induced

hypermutation in glioma: Evolutionary mechanisms and therapeutic

opportunities. Front Oncol. 9:412019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Liu EK, Sulman EP, Wen PY and Kurz SC:

Novel therapies for glioblastoma. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.

20:192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Tsai CY, Ko HJ, Huang CF, Lin CY, Chiou

SJ, Su YF, Lieu AS, Loh JK, Kwan AL, Chuang TH and Hong YR:

Ionizing radiation induces resistant glioblastoma stem-like cells

by promoting autophagy via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Life (Basel).

11:4512021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Wang Y, Fu Y, Lu Y, Chen S, Zhang J, Liu B

and Yuan Y: Unravelling the complexity of lncRNAs in autophagy to

improve potential cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1878:1889322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zheng J, Mat Ludin AF, Rajab NF, Shaolong

L and Jufri NF: The roles of lncMALAT1 in coronary artery disease

regulation and therapeutic perspective: A systematic review.

iScience. 28:1129452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Zhang X, Shi Y, Wang C and Zhang K: LncRNA

MALAT1 knockdown inhibits apoptosis of mouse hippocampus neuron

cells with high glucose by Silencing autophagy. BMC Endocr Disord.

25:1732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Yang L, Wang H, Shen Q, Feng L and Jin H:

Long non-coding RNAs involved in autophagy regulation. Cell Death

Dis. 8:e30732017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Xia N, Zhang P, Yang L, Yin X, Wu SQ, Yao

Y, Shang MY and Weng L: The lncRNA MIR503HG/miR-16-5p/FOSL1 pathway

mediates autophagy to promote esophageal epithelial cells

proliferation and EMT in esophageal restenosis. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 772:1105362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Zhu X, Sun Y, Yu Q, Wang X, Wang Y and

Zhao Y: Exosomal lncRNA GAS5 promotes M1 macrophage polarization in

allergic rhinitis via restraining mTORC1/ULK1/ATG13-mediated

autophagy and subsequently activating NF-кB signaling. Int

Immunopharmacol. 121:1104502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G

and Thompson CB: The biology of cancer: Metabolic reprogramming

fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 7:11–20. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhou X, Song Y, Wang Z, Fu L, Xu L, Feng

X, Zhang Z and Yuan K: Dietary sugar intervention: A promising

approach for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1880:1894022025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Li C, Wang K, Zhao L, Liu J, Jin Y, Zhang

C, Xu M, Wang M, Kuang Y, Liu J, et al: LINC00622 transcriptionally

promotes RRAGD to repress mTORC1-modulated autophagic cell death by

associating with BTF3 in cutaneous melanoma. Cell Death Dis.

16:5152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Wu Q, Ma J, Wei J, Meng W, Wang Y and Shi

M: lncRNA SNHG11 promotes gastric cancer progression by activating

the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway and oncogenic autophagy. Mol Ther.

29:1258–1278. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chen F, Zhong Z, Tan HY, Guo W, Zhang C,

Cheng CS, Wang N, Ren J and Feng Y: Suppression of lncRNA MALAT1 by

betulinic acid inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression by

targeting IAPs via miR-22-3p. Clin Transl Med. 10:e1902020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Sheng JQ, Wang MR, Fang D, Liu L, Huang

WJ, Tian DA, He XX and Li PY: LncRNA NBR2 inhibits tumorigenesis by

regulating autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed

Pharmacother. 133:1110232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wang Z and Jin J: LncRNA SLCO4A1-AS1

promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation by enhancing

autophagy via miR-508-3p/PARD3 axis. Aging (Albany NY).

11:4876–4889. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Wang Y, Li Z, Xu S, Li W, Chen M, Jiang M

and Fan X: LncRNA FIRRE functions as a tumor promoter by

interaction with PTBP1 to stabilize BECN1 mRNA and facilitate

autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 13:982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Lu X, Chen L, Li Y, Huang R, Meng X and

Sun F: Long non-coding RNA LINC01207 promotes cell proliferation

and migration but suppresses apoptosis and autophagy in oral

squamous cell carcinoma by the microRNA-1301-3p/lactate

dehydrogenase isoform A axis. Bioengineered. 12:7780–7793. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Jiang N, Zhang X, Gu X, Li X and Shang L:

Progress in understanding the role of lncRNA in programmed cell

death. Cell Death Discov. 7:302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Lu M, Qin X, Zhou Y, Li G, Liu Z, Yue H

and Geng X: LncRNA HOTAIR suppresses cell apoptosis, autophagy and

induces cell proliferation in cholangiocarcinoma by modulating the

miR-204-5p/HMGB1 axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 130:1105662020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Murakami K, Yokoi Y, Hirane N, Otaki M and

Nishimura SI: Nanosomal irinotecan targeting pancreatic cancer cell

surface neuraminidase-1 sialidase. Adv Healthc Mater. Jul

22–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Wu H, Li A, Zheng Q, Gu J and Zhou W:

LncRNA LZTS1-AS1 induces proliferation, metastasis and inhibits

autophagy of pancreatic cancer cells through the miR-532/TWIST1

signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 23:1302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Lv D, Xiang Y, Yang Q, Yao J and Dong Q:

Long Non-Coding RNA TUG1 promotes cell proliferation and inhibits

cell apoptosis, autophagy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma via

MiR-31-5p/FLOT1 axis. Onco Targets Ther. 13:5857–5868. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Shao Q, Wang Q and Wang J: LncRNA SCAMP1

regulates ZEB1/JUN and autophagy to promote pediatric renal cell

carcinoma under oxidative stress via miR-429. Biomed Pharmacother.

120:1094602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhang Z, Jia JP, Zhang YJ, Liu G, Zhou F

and Zhang BC: Long Noncoding RNA ADAMTS9-AS2 inhibits the

proliferation, migration, and invasion in bladder tumor cells. Onco

Targets Ther. 13:7089–7100. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Li Q, Chen K, Dong R and Lu H: LncRNA

CASC2 inhibits autophagy and promotes apoptosis in non-small cell

lung cancer cells via regulating the miR-214/TRIM16 axis. RSC Adv.

8:40846–40855. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Peng D, Li W, Zhang B and Liu X:

Overexpression of lncRNA SLC26A4-AS1 inhibits papillary thyroid

carcinoma progression through recruiting ETS1 to promote

ITPR1-mediated autophagy. J Cell Mol Med. 25:8148–8158. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Qin Y, Sun W, Wang Z, Dong W, He L, Zhang

T, Lv C and Zhang H: RBM47/SNHG5/FOXO3 axis activates autophagy and

inhibits cell proliferation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell

Death Dis. 13:2702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Wang Y, Liu Z, Xu Z, Shao W, Hu D, Zhong H

and Zhang J: Introduction of long non-coding RNAs to regulate

autophagy-associated therapy resistance in cancer. Mol Biol Rep.

49:10761–10773. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Shaw A and Gullerova M: Home and away: The

role of non-coding RNA in intracellular and intercellular DNA

damage response. Genes (Basel). 12:14752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Wang S, Qiao C, Fang R, Yang S, Zhao G,

Liu S and Li P: LncRNA CASC19: A novel oncogene involved in human

cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 25:2841–2851. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Wu Y, Mou J, Zhou G and Yuan C: CASC19: An

oncogenic long non-coding RNA in different cancers. Curr Pharm Des.

30:1157–1166. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Liu H, Zheng W, Chen Q, Zhou Y, Pan Y,

Zhang J, Bai Y and Shao C: lncRNA CASC19 contributes to

radioresistance of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by promoting autophagy

via AMPK-mTOR pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 22:14072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Liu H, Chen Q, Zheng W, Zhou Y, Bai Y, Pan

Y, Zhang J and Shao C: LncRNA CASC19 enhances the radioresistance

of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by regulating the miR-340-3p/FKBP5

axis. Int J Mol Sci. 24:30472023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Wang WJ, Guo CA, Li R, Xu ZP, Yu JP, Ye Y,

Zhao J, Wang J, Wang WA, Zhang A, et al: Long non-coding RNA CASC19

is associated with the progression and prognosis of advanced

gastric cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 11:5829–5847. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Hou Y, Tang Y, Ma C, Yu J and Jia Y:

Overexpression of CASC19 contributes to tumor progression and

predicts poor prognosis after radical resection in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 55:799–806. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Teng S, Ge J, Yang Y, Cui Z, Min L, Li W,

Yang G, Liu K and Wu J: M1 macrophages deliver CASC19 via exosomes

to inhibit the proliferation and migration of colon cancer cells.

Med Oncol. 41:2862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Chiu HS, Somvanshi S, Patel E, Chen TW,

Singh VP, Zorman B, Patil SL, Pan Y, Chatterjee SS; Cancer Genome

Atlas Research Network;, ; et al: Pan-cancer analysis of lncRNA

regulation supports their targeting of cancer genes in each tumor

context. Cell Rep. 23:297–312.e12. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Huang Z, Li X, Wang X, Wu J, Gong Z, Kõks

S and Wang M: Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 promotes

photophobia behavior in mice via miR-196a-5p/Trpm3 coupling. J

Headache Pain. 26:1182025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Sakaguchi H, Tsuchiya H, Kitagawa Y,

Tanino T, Yoshida K, Uchida N and Shiota G: NEAT1 Confers

radioresistance to hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inducing

autophagy through GABARAP. Int J Mol Sci. 23:7112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Mahmoud HS, Eldesoky NA, Shaker OG and

El-Husseiny AA: The diagnostic value of LncRNA NEAT1 targeting

miR-129-5p in pancreatic cancer patients. Sci Rep. 15:276382025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Dong P, Xiong Y, Yue J, Xu D, Ihira K,

Konno Y, Kobayashi N, Todo Y and Watari H: Long noncoding RNA NEAT1

drives aggressive endometrial cancer progression via

miR-361-regulated networks involving STAT3 and tumor

microenvironment-related genes. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:2952019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Almujri SS and Almalki WH: The paradox of

autophagy in cancer: NEAT1′s role in tumorigenesis and therapeutic

resistance. Pathol Res Pract. 262:1555232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Wen J, Zheng W, Zeng L, Wang B, Chen D,

Chen Y, Lu X, Shao C, Chen J and Fan M: LTF Induces Radioresistance

by Promoting Autophagy and Forms an AMPK/SP2/NEAT1/miR-214-5p

feedback loop in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci.

19:1509–1527. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

He H: Targeting TP53TG1: A promising

prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for personalized cancer

therapy. Discov Oncol. 16:12712025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Li J, Liu R, Hu H, Huang Y, Shi Y, Li H,

Chen H, Cai M, Wang N, Yan T, et al: Methionine deprivation

inhibits glioma proliferation and EMT via the

TP53TG1/miR-96-5p/STK17B ceRNA pathway. NPJ Precis Oncol.

8:2702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Liao D, Liu X, Yuan X, Feng P, Ouyang Z,

Liu Y and Li C: Long non-coding RNA tumor protein 53 target gene 1

promotes cervical cancer development via regulating microRNA-33a-5p

to target forkhead box K2. Cell Cycle. 21:572–584. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Ji W, Wang W and Wei Y: TP53TG1/STAT axis

is involved in the development of colon cancer through affecting

PD-L1 expression and immune escape mechanism of tumor cells. Am J

Cancer Res. 13:5218–5235. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Cheng Y, Huang N, Yin Q, Cheng C, Chen D,

Gong C, Xiong H, Zhao J, Wang J, Li X, et al: LncRNA TP53TG1 plays

an anti-oncogenic role in cervical cancer by synthetically

regulating transcriptome profile in HeLa cells. Front Genet.

13:9810302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Luan F, Chen W, Chen M, Yan J, Chen H, Yu

H, Liu T and Mo L: An autophagy-related long non-coding RNA

signature for glioma. FEBS Open Bio. 9:653–667. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Gao W, Qiao M and Luo K: Long noncoding

RNA TP53TG1 contributes to radioresistance of glioma cells Via

miR-524-5p/RAB5A Axis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 36:600–612.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Wang C, Li Y, Yan S, Wang H, Shao X, Xiao

M, Yang B, Qin G, Kong R, Chen R and Zhang N: Interactome analysis

reveals that lncRNA HULC promotes aerobic glycolysis through LDHA

and PKM2. Nat Commun. 11:31622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Gandhy SU, Imanirad P, Jin UH, Nair V,

Hedrick E, Cheng Y, Corton JC, Kim K and Safe S: Specificity

protein (Sp) transcription factors and metformin regulate

expression of the long non-coding RNA HULC. Oncotarget.

6:26359–26372. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Chen X, Lin J, Liu Y, Peng J, Cao Y, Su Z,

Wang T, Cheng J and Hu D: AlncRNA HULC as an effective biomarker

for surveillance of the outcome of cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS

One. 12:e01712102017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Li YP, Liu Y, Xiao LM, Chen LK, Tao EX,

Zeng EM and Xu CH: Induction of cancer cell stemness in glioma

through glycolysis and the long noncoding RNA HULC-activated

FOXM1/AGR2/HIF-1α axis. Lab Invest. 102:691–701. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Li S, Chang M, Tong L, Wang Y, Wang M and

Wang F: Screening potential lncRNA biomarkers for breast cancer and

colorectal cancer combining random walk and logistic matrix

factorization. Front Genet. 13:10236152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Chen C, Wang K, Wang Q and Wang X: LncRNA

HULC mediates radioresistance via autophagy in prostate cancer

cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 51:e70802018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Hacisuleyman E, Goff LA, Trapnell C,

Williams A, Henao-Mejia J, Sun L, McClanahan P, Hendrickson DG,

Sauvageau M, Kelley DR, et al: Topological organization of

multichromosomal regions by the long intergenic noncoding RNA

Firre. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 21:198–206. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Meng X, Fang E, Zhao X and Feng J:

Identification of prognostic long noncoding RNAs associated with

spontaneous regression of neuroblastoma. Cancer Med. 9:3800–3815.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Shi X, Cui Z, Liu X, Wu S, Wu Y, Fang F

and Zhao H: LncRNA FIRRE is activated by MYC and promotes the

development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma via Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 510:594–600. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Wang Z, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhao R, Zhou X and

Wang H: An integrated autophagy-related long noncoding RNA

signature as a prognostic biomarker for human endometrial cancer: A

bioinformatics-based approach. Biomed Res Int. 2020:57174982020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Cai J, Wang R, Chen Y, Zhang C, Fu L and

Fan C: LncRNA FIRRE regulated endometrial cancer radiotherapy

sensitivity via the miR-199b-5p/SIRT1/BECN1 axis-mediated

autophagy. Genomics. 116:1107502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Cory S, Graham M, Webb E, Corcoran L and

Adams JM: Variant (6;15) translocations in murine plasmacytomas

involve a chromosome 15 locus at least 72 kb from the c-myc

oncogene. EMBO J. 4:675–681. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Tseng YY, Moriarity BS, Gong W, Akiyama R,

Tiwari A, Kawakami H, Ronning P, Reuland B, Guenther K, Beadnell

TC, et al: PVT1 dependence in cancer with MYC copy-number increase.

Nature. 512:82–86. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Boloix A, Masanas M, Jiménez C, Antonelli

R, Soriano A, Roma J, Sánchez de Toledo J, Gallego S and Segura MF:

Long Non-coding RNA PVT1 as a prognostic and therapeutic target in

pediatric cancer. Front Oncol. 9:11732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Ogunwobi OO and Segura MF: Editorial: PVT1

in cancer. Front Oncol. 10:5887862020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Lai SW, Chen MY, Bamodu OA, Hsieh MS,

Huang TY, Yeh CT, Lee WH and Cherng YG: Exosomal lncRNA PVT1/VEGFA

axis promotes colon cancer metastasis and stemness by

downregulation of tumor suppressor miR-152-3p. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2021:99598072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Zhu Y, Wu F, Gui W, Zhang N, Matro E, Zhu

L, Eserberg DT and Lin X: A positive feedback regulatory loop

involving the lncRNA PVT1 and HIF-1α in pancreatic cancer. J Mol

Cell Biol. 13:676–689. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Yao W, Li S, Liu R, Jiang M, Gao L, Lu Y,

Liang X and Zhang H: Long non-coding RNA PVT1: A promising

chemotherapy and radiotherapy sensitizer. Front Oncol.

12:9592082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Tan YT, Lin JF, Li T, Li JJ, Xu RH and Ju

HQ: LncRNA-mediated posttranslational modifications and

reprogramming of energy metabolism in cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond).

41:109–120. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Zhou Y, Shao Y, Hu W, Zhang J, Shi Y, Kong

X and Jiang J: A novel long noncoding RNA SP100-AS1 induces

radioresistance of colorectal cancer via sponging miR-622 and

stabilizing ATG3. Cell Death Differ. 30:111–124. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

151

|

Guo Z, Zhang X, Zhu H, Zhong N, Luo X,

Zhang Y, Tu F, Zhong J, Wang X, He J and Huang L: TELO2 induced

progression of colorectal cancer by binding with RICTOR through

mTORC2. Oncol Rep. 45:523–534. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Chang S, Zhang M, Liu C, Li M, Lou Y and

Tan H: Redox mechanism of glycerophospholipids and relevant

targeted therapy in ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 11:3582025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Zhang L, Yu S, Wang C, Jia C, Lu Z and

Chen J: Establishment of a non-coding RNAomics screening platform

for the regulation of KRAS in pancreatic cancer by RNA sequencing.

Int J Oncol. 53:2659–2670. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Muthoni A, Anyango A and V Wanjala H:

Mucilage-based nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy-design,

functionalization, and therapeutic potential. Drug Dev Ind Pharm.

Aug 4–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Wu T and Du Y: LncRNAs: From basic

research to medical application. Int J Biol Sci. 13:295–307. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

156

|

Zhang L, Chen H, Yang Y, Zhao L, Xie H, Li

P, Lv X, He L, Liu N and Liu B: Targeting LINC02320 prevents

colorectal cancer growth via GRB7-dependent inhibition of MAPK

signaling pathway. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 30:862025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

157

|

Taylor MA, Das BC and Ray SK: Targeting

autophagy for combating chemoresistance and radioresistance in

glioblastoma. Apoptosis. 23:563–575. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

158

|

Han F, Chen S, Zhang K, Zhang K, Wang M

and Wang P: Targeting the HNRNPA2B1/HDGF/PTN axis to overcome

radioresistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 43:189–214. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

159

|

Liu Y, Chen X, Chen X, Liu J, Gu H, Fan R

and Ge H: Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR knockdown enhances

radiosensitivity through regulating microRNA-93/ATG12 axis in

colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 11:1752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Yan Y, Chen X, Wang X, Zhao Z, Hu W, Zeng

S, Wei J, Yang X, Qian L, Zhou S, et al: The effects and the

mechanisms of autophagy on the cancer-associated fibroblasts in

cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:1712019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|