Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common

primary lung cancer, accounting for ~40% of cases (1). Patients with early-stage LUAD mainly

receive surgical therapy, while advanced and metastatic LUAD often

require systemic therapy. These treatments improve symptoms and

prolong their overall survival to a certain extent (2). However, the anti-tumor effect in

patients with LUAD is often limited by chemotherapy or radiotherapy

resistance and immune escape, leading to tumor recurrence and poor

prognosis (3). For patients with

LUAD, individualized and comprehensive treatments should be

developed based on tumor progression. Molecular targeted therapy

targeting oncogenic driver genes, such as Kirsten rat sarcoma viral

oncogene homologue (KRAS), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR),

v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF) and anaplastic

lymphoma kinase (ALK) has greatly advanced the field of treatment

for non-small cell lung cancer, especially LUAD (4). Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been

approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for monotherapy or

combination with other agents in LUAD, which provide hope for

patients with negative expression of driver oncogenes or resistance

to molecular-targeted therapy (5,6).

However, clinical trials have shown that only a small number of

patients benefit from immunotherapy (7,8).

Therefore, it is necessary to identify more biomarkers to ensure

that more patients can benefit from them.

The tumor immune microenvironment is widely

recognized as the key regulator of tumor progression and clinical

response to therapy (9,10). Components of the tumor

microenvironment include cancer and inflammatory cells, and

suppressive cytokines that contribute to the transition of T cells

into ‘exhausted’ T cells by regulating T cell phenotypes and

functions (11,12). T cell exhaustion (TEX) is defined as

a decline in proliferation capacity, weakened effector function,

loss of cytokine production and sustained high expression of

inhibitory receptors (13,14). Exhausted T cells demonstrate

upregulation of immune checkpoint proteins such as cytotoxic T

lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein-1

(PD-1). Transcription and epigenetic reprogramming lead to

mitochondrial dysfunction and decreased metabolic activity, thereby

triggering immune evasion (15).

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy can inhibit negative

regulatory signals and release T cells from exhaustion (16), however not all TEX cells respond to

ICB therapy. Recent studies have revealed heterogeneous

subpopulations within the exhausted T cell lineage including

ICB-sensitive and -resistant subpopulations, which lead to

differences in treatment responses (17,18).

TEX is closely related to tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)

polarization. Metabolites secreted by cancer cells promote cell

escape from M1 TAM polarization towards M2 TAM, contributing

further towards TEX development (19). M2 TAMs promote TEX, resulting in

anti-PD-1 blockade resistance (20). Therefore, inducing the switching of

TAM from M2 to M1 may reverse TEX and restore T cells from an

exhausted state, providing potential targets in tumor

immunotherapy.

The present study performed clustering analysis of

TEX-related genes in patients with LUAD patients by analyzing a

public database; subsequently the present study aimed to construct

a prognostic signature and nomogram to predict prognosis for LUAD.

Then, the study aimed to explored the potential of B cell antigen

receptor complex-associated protein β chain (CD79B) as a prognostic

marker and the role of immune function in LUAD, which may play a

key role in tumor immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Data collection

RNA-sequencing expression profiles and corresponding

clinical information of 516 LUAD samples and 59 para-tumor tissue

samples were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

database (portal.gdc.cancer.gov/; age range: 33–88 year; female:

278, male: 238). STAR-counts data, mutation annotation format (MAF)

data, and corresponding clinical information were downloaded from

the TCGA database (portal.gdc.cancer.gov) (TCGA-LUAD dataset). Data

was then extracted in TPM format and performed normalization using

the log2 (TPM+1) transformation. After retaining samples that

included both RNAseq data and clinical information, 516 LUAD

samples and 59 para-tumor tissue samples were selected for further

analysis (21). Based on previous

research, 12 TEX-related genes that may have prognostic value were

obtained (22). The protein-protein

interaction network was obtained from the Search Tool for the

Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database

(cn.string-db.org/) (23).

Consensus clustering analysis

To evaluate consistency in TCGA-LUAD database, R

package ConsensusClusterPlus (v1.72.0;

bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ConsensusClusterPlus.html)

was used (24), with a maximum of 6

clusters and 80% of the samples were extracted 100 times with

clusterAlg=‘hc’, innerLinkage=‘ward. D2’. Patients were clustered

according to the optimal k-value based on the cumulative

distribution function (CDF) curve and consensus matrix. Principal

component analysis (PCA) was used to analyze the distribution

differences between clusters.

Survival analysis and construction of

prognostic signature

Survival analysis was conducted between clusters in

TCGA-LUAD database using the ‘survival’ and the ‘survminer’ R

packages (v0.4.9;

rdocumentation.org/packages/survminer/versions/0.4.9). The

appropriate conditions for the construction of the nomogram

prediction model were determined using univariate and multivariate

Cox regression analysis. Using the ‘forestplot’ R package (v3.1.7)

(https://github.com/cran/forestplot),

the P-value and hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI)

of each variable were calculated. To predict the overall recurrence

rate over the next × years, a nomogram was created based on the

results of multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis using the

‘rms’ R package (v8.0.0;

cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html); the nomogram

represented factors which can be used to determine the likelihood

of recurrence for an individual patient (25).

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

(LASSO) regression used a feature selection algorithm,

incorporating 10-fold cross-validation, and was examined using the

‘glmnet’ R package (v4.1-10;

cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/index.html) (26). Using the ‘survival’ R package, a

novel prognostic model of TEX-related genes was constructed based

on multivariate Cox regression analysis. The time-receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) (v0.4) (huppertlab.net/home/training/knowledge-base/nirs_toolbox/fulldemos/receiver-operating-characteristic-roc/)

analysis was performed on TEX-related genes to determine the

accuracy and risk score (27).

Functional enrichment analysis

The ‘limma’ R package (v3.40.2)

(bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) was used

to analyze the differential expression of mRNA between clusters

(28). The criteria for statistical

significance were adjusted P<0.05 and log2 (fold-change) >1

or <-1. Using the ClusterProfiler package in R software

(v3.18.0;

bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.htm)

(29), gene functions of enrichment

analysis were investigated in Gene Ontology (GO)

(geneontology.org/) (30) and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) (31). The enrichment scores were calculated

using the Gene Set Variation Analysis package of R software

(v.1.3.0) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) based on

the absolute enrichment scores of gene sets in multiple

publications and gene signatures validated by previous experiments

(32–36), with the parameter chosen as

method=‘ssGESA’ (37). Spearman's

correlation was calculated to determine the relationship between

genes and pathway scores.

Tumor immune microenvironment

analysis

The ‘immuneeconv’ R package (v2.0.3;

rdocumentation.org/packages/immunedeconv/versions/2.0.3) was used

to predict 22 types of immune infiltrating cell based on the

CIBERSORT algorithm (a gene expression-based deconvolution

algorithm) (http://cibersort.stanford.edu/) (38). The mRNA levels of immune

checkpoint-related genes were compared between clusters, including

Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1 (PD-L1/CD274), Cytotoxic

T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4 (CTLA4), Hepatitis A Virus

Cellular Receptor 2 (HAVCR2), Lymphocyte Activating 3 (LAG3),

Programmed Cell Death 1 (PDCD1), Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2

(PDCD1LG2), T Cell Immunoreceptor With Ig And ITIM Domains (TIGIT),

and Sialic Acid Binding Ig Like Lectin 15 (SIGLEC15). To predict

the ICB response, the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE)

algorithm (v6.5.1) (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) was used to simulate

computational approaches to tumor immune evasion, based on two

molecular mechanisms, including dysfunction of tumor infiltrating

cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and rejection of CTLs by

immunosuppressive factors (7). The

correlation between gene expression and immune score was analyzed

by ‘ggstatsplot’ (v0.13.1;

cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggstatsplot/index.html) and

‘pheatmap’ R package (v1.0.13) (https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/pheatmap/versions/1.0.13/topics/pheatmap)

(39).

Prediction of therapeutic drug

sensitivity

The prediction of sensitivity to various therapeutic

agents were performed by the ‘pRRophetic’ R package (v4.0.3)

(github.com/paulgeeleher/pRRophetic), based on the Genomics of Drug

Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) dataset (cancerrxgene.org/) (40). The ridge regression method was used

to evaluate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the

samples, and 10-fold cross-validation was performed based on the

GDSC training set to evaluate the prediction accuracy (41). The IC50 for each sample in TCGA-LUAD

database was estimated from the predictive model evaluated on GDSC

cell line data.

Cell culture and plasmid

transfection

Human normal lung epithelial HBE, macrophage THP-1

and LUAD A549, H358, PC-9, 95C, 95D cell lines were obtained from

the Cell Center of Central South University (Changsha, China). All

cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibo; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone;

Cytiva). The pDONR223-CD79B overexpression plasmid (cat. no.

G104684) and empty vector control pDONR223 were purchased from

Youbio. Lipofectamine™ 3000 Transfection Reagent (cat. no.

L3000150, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to transfect

cells with 6 µg plasmid transfection for 24 h at 37°C, followed by

48 h culture before downstream experiments.

Coculture assay

THP-1 monocytes (2×107 cells) were

differentiated into M0 macrophages by treatment with 100 ng/ml

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; cat. no. P8139,

Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) for 48 h in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10%

FBS (37°C). M0 macrophages (5×104 cells/insert) were

seeded in the upper chamber (0.4 µm pore size; Corning, Inc.) while

A549 cells (2×105 cells/well) were plated in the lower

chamber. Cells were co-cultured for 48 h under standard conditions

(37°C, 5% CO2). Following coculture, upper-chamber cells

were collected for downstream analysis by qPCR.

Quantitative (q)PCR

After 48 h co-culture with CD79B-overexpressing A549

cells in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2), total

RNA was extracted from M0 macrophage THP-1 cells using the RNA

extraction kit (cat. no. 15596026). Reverse transcription kit (cat.

no. K1621; both Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to obtain

cDNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions. SYBR Green kit

(cat. no. 4309155; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for

qPCR analysis by ABI 7500. Thermocycling conditions were as

follows: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec

and 60°C for 60 sec, with a melting-curve stage to confirm amplicon

specificity. β-actin was used as the reference gene for

normalization, and relative gene expression was calculated using

the 2−ΔΔCq method (42).

The primers are list in Table

SI.

Western blotting

The cells (HBE, A549, H358, PC9, 95C, 95D, A549-Vec,

A549-OE-CD79B cells) were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (cat.

no. 87787, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing inhibitors

cocktail (cat. no. 4693116001) and phosphatase inhibitor (cat. no.

4906845001, both Roche Diagnostics). The protein concentration was

measured with BCA reagent (cat. no. AR0197, Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology Ltd.). The samples (50 µg/lane) were separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Merck KGaA). The

membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST (0.1%

Tween-20) at room temperature for 1 h, and then incubated at 4°C

overnight with rabbit anti-CD79B (1:400, cat. no. ab134147, Abcam)

or mouse anti-actin (1:20,000; cat. no. AC026, ABclonal, Biotech

Co., Ltd.), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:6,000; cat. no. AS014, ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the bands

were imaged on a ChemiDoc™ imaging system (Bio-Rad) after detection

with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (cat. no. 36208-A,

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Densitometric analysis

was performed using Image Lab™ 6.1 software (Bio-Rad).

Cell Counting Kit (CCK)8 assay

Cell viability was determined by CCK8 assay (cat.

no. C0005, TargetMol Chemicals, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. A549-Vec and A549-OE-CD79B cells were

inoculated in 96-well plates, and incubated with CCK8 for 2 h. The

optical density at 450 nm was then determined by microplate reader

(BioTek ELx800; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Apoptosis assay

A549-Vec and A549-OE-CD79B cells were collected and

stained with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide using an apoptosis

kit (cat. no. KGA103, Nanjing Keygen Biotech Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were analyzed on a BD

LSRFortessa™ X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were

processed using FlowJo software (version 10.8.1; BD Biosciences),

with apoptotic cells defined as annexin

V+/PI− (early apoptotic) + annexin

V+/PI+ (late apoptotic) populations.

Scratch assay

A549-Vec and A549-OE-CD79B cells were seeded in

6-well culture plates (2×105 cells per well) and

incubated overnight to a density of 70–80% confluence (37°C, 5%

CO2). The medium was replaced with serum-free RPMI-1640,

a straight scratch was made with a sterile 100-µl pipette tip and

floating cells were rinsed away. Plates were incubated at 37°C for

12 h. Phase-contrast images were acquired at 0 and 12 h using an

inverted light microscope (AMEX1200, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.; magnification, ×100), and wound areas were quantified with

ImageJ (v1.53t, NIH, USA) (43).

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell invasion assays were performed using 24-well

plates and Transwell invasion chamber (8 µm pore size, BD

Biosciences). For invasion assays, Matrigel (cat. no. 356234,

Corning, Inc.) was added at 37°C for 1 h before cell seeding.

Migration assays were performed without matrix gel. A549-Vec and

A549-OE-CD79B cells cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 were

trypsinized, resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640, and

5×104 cells in 200 µl were seeded into the upper

chamber. The lower chamber received 800 µl RPMI-1640 containing 10%

FBS as chemoattractant. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C with 5%

CO2, non-invading/migrating cells on the upper surface

were removed with a cotton swab. Cells on the lower surface were

fixed at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min,

stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 10 min,

washed three times with PBS), and air-dried. Invaded/migrated cells

in five randomly selected fields per insert were counted manually

under a light microscope.

Statistical analysis

The bioinformatics data were analyzed using R

software v4.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022), and

the sample test data were processed using SPSS24.0 (IBM Corp.) and

GraphPad Prism8.0.1 (Dotmatics) software. Paired Student t-test and

Wilcoxon test were applied to normally and non-normally distributed

data, respectively. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test was used

to determine the differences among multiple comparative groups. The

sample size for each group was ≥3. All data are presented as the

mean ± SD of three individual experiments. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Cluster and survival analysis of

TEX-related genes in patients with LUAD

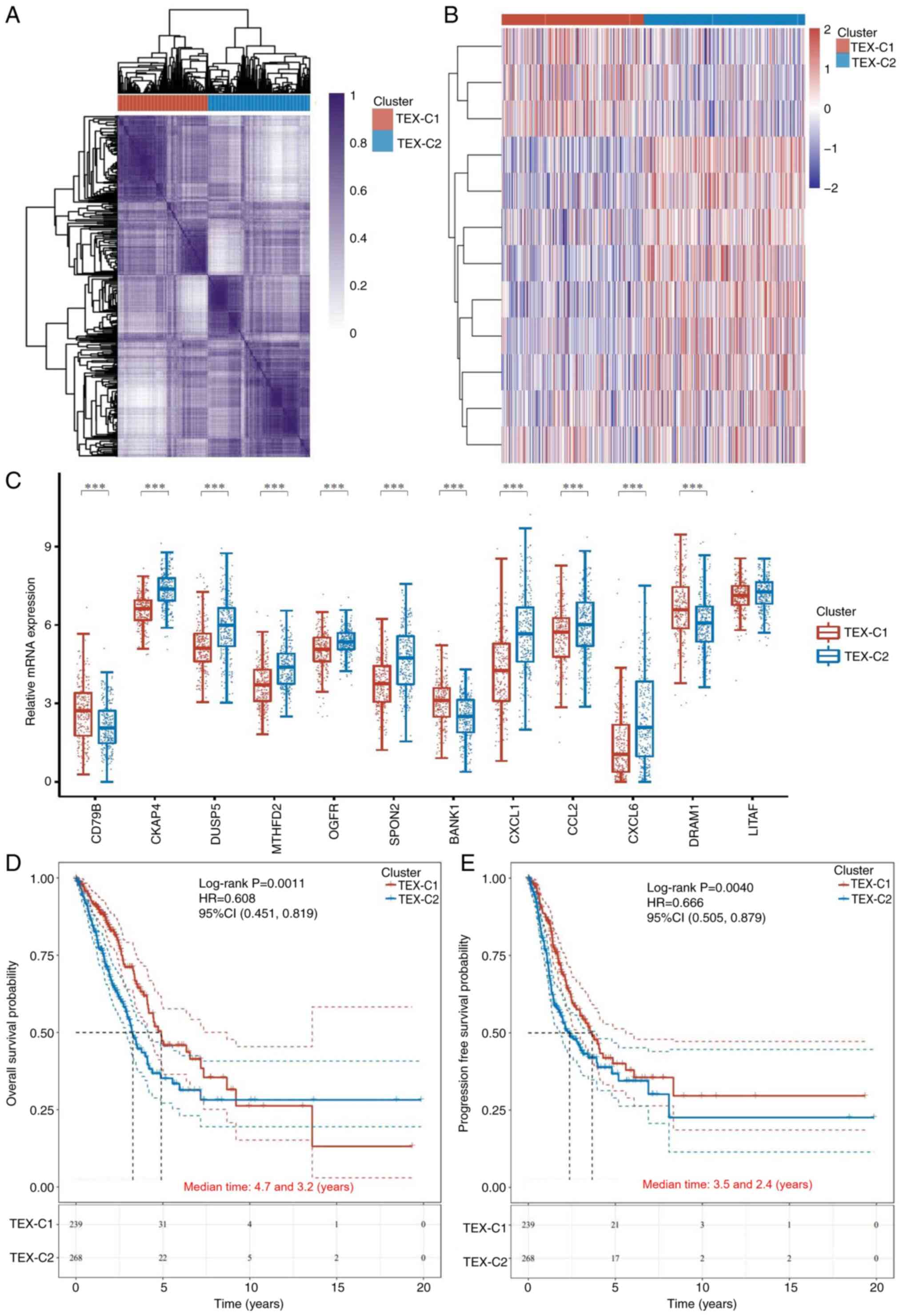

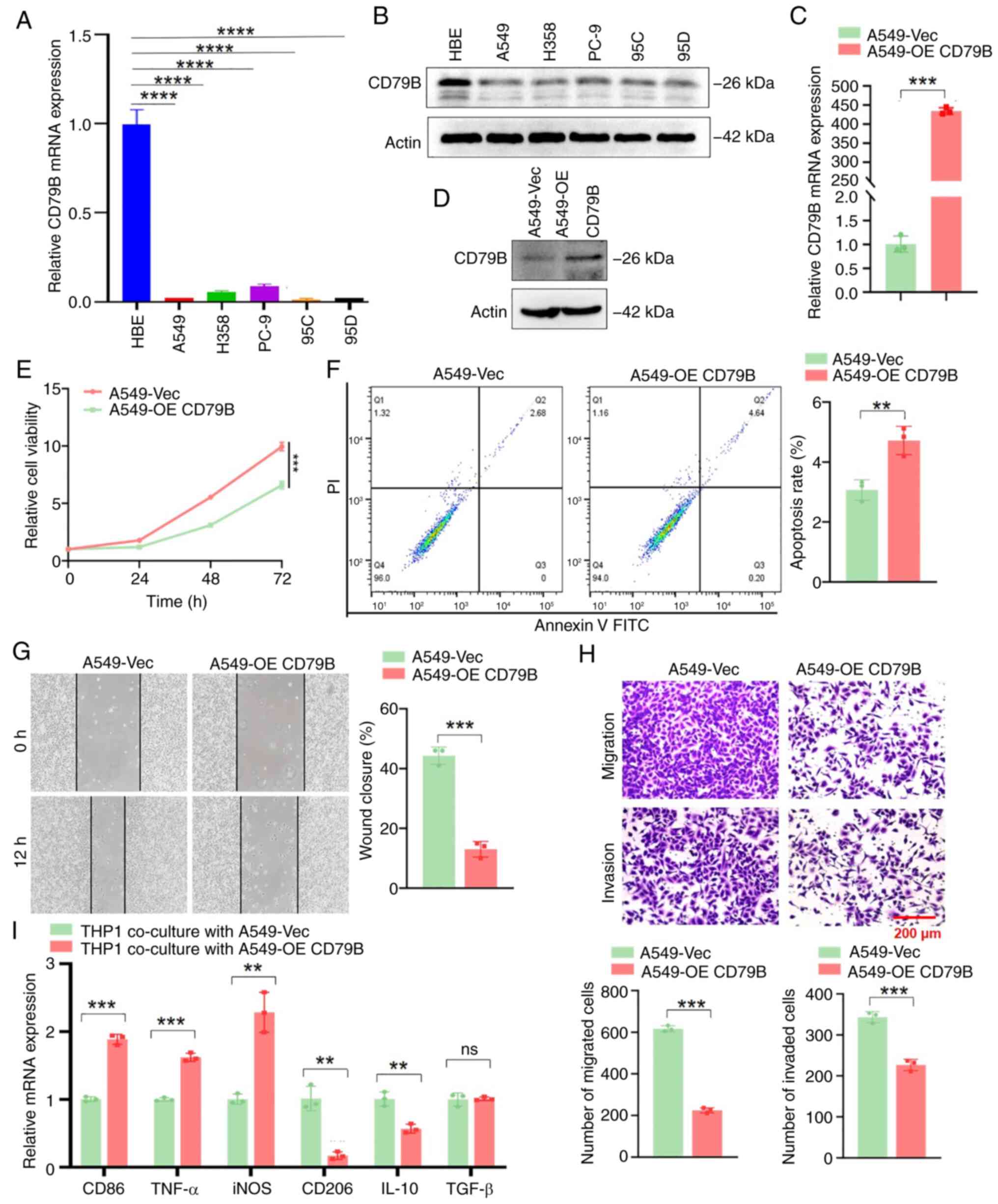

A total of 12 TEX-related genes were collected from

a previous study (22). To explore

the TEX heterogeneity in LUAD, consensus clustering was performed

based on the expression of these 12 TEX-related genes in TCGA-LUAD.

Based on the consensus CDF curve (Fig.

S1A) and relative change in area under the CDF curve (Fig. S1B), k=2 was selected as the best

cluster and two clusters (TEX-C1 and -C2) were identified (Fig. 1A and B). There were 242 patients in

the TEX-C1 and 274 patients in the TEX-C2 cluster. The PCA results

confirmed significant differences between the two clusters

(Fig. S1C). The differences in

clinical characteristics between the two clusters are shown in

Table I. mRNA expression of eight

TEX-related genes was higher in the TEX-C2 than that in the TEX-C1

cluster, including cytoskeleton Associated Protein 4 (CKAP4), Dual

Specificity Phosphatase 5 (DUSP5), methylenetetrahydrofolate

dehydrogenase (NADP+ Dependent) 2 (MTHFD2), Opioid

Growth Factor Receptor (OGFR), Spondin 2 (SPON2), C-X-C Motif

Chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), C-C Motif Chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and

CXCL6. The expression of three TEX-related genes [CD79B, B Cell

Scaffold Protein With Ankyrin Repeats 1 (BANK1) and DNA Damage

Regulated Autophagy Modulator 1 (DRAM1)] was lower in the TEX-C2

cluster, however, the expression of Lipopolysaccharide Induced TNF

Factor (LITAF) was not significantly different between clusters

(Fig. 1C). Patients in the TEX-C2

cluster had worse prognosis with shorter overall survival (OS) and

progression-free survival (PFS), compared with those in the TEX-C1

cluster (Fig. 1D and E).

| Figure 1.Cluster and survival analysis of

TEX-related genes in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. (A)

Unsupervised consensus cluster analysis identifying two clusters

(k=2). (B) Heatmap of TEX-related genes in the two clusters. (C)

mRNA expression of TEX-related genes between clusters. Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis of (D) overall and (E) progression-free survival

between TEX clusters. ***P<0.001. TEX-C, T cell exhaustion

cluster; CD79B, B cell Antigen Receptor Complex-Associated Protein

Beta Chain; DUSP, dual Specificity Phosphatase; MTHFD,

Methylenetetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase; OGFR, Opioid Growth Factor

Receptor; SPON, Spondin; BANK, B Cell Scaffold Protein With Ankyrin

Repeats; CXCL, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand; CCL, C-C Motif

Chemokine Ligand; DRAM, DNA Damage Regulated Autophagy Modulator;

LITAF, Lipopolysaccharide Induced TNF Factor;, HR, Hazard Ratio;

CI, Confidence Interval. |

| Table I.Clinical characteristics between

TEX-C1 and TEX-C2 in lung adenocarcinoma. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics between

TEX-C1 and TEX-C2 in lung adenocarcinoma.

| Characteristic | TEX-C1 | TEX-C2 | P-value |

|---|

| Status |

|

|

|

|

Alive | 170 | 159 |

|

|

Dead | 72 | 115 | 0.005 |

| Mean age,

years | 66.4 (9.8) | 64.3 (10.1) |

|

| Median age, years

(range) | 67 (33–88) | 65 (39–87) | 0.021 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

Female | 128 | 150 |

|

|

Male | 114 | 124 | 0.739 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

Asian | 3 | 5 |

|

|

Black | 24 | 28 |

|

|

White | 189 | 200 |

|

| Native

American | 0 | 1 | 0.788 |

| pT stage |

|

|

|

| T1 | 41 | 26 |

|

|

T1a | 27 | 20 |

|

|

T1b | 34 | 21 |

|

| T2 | 74 | 95 |

|

|

T2a | 32 | 50 |

|

|

T2b | 10 | 17 |

|

| T3 | 15 | 32 |

|

| T4 | 8 | 11 |

|

| TX | 1 | 2 | 0.007 |

| pN stage |

|

|

|

| N0 | 173 | 159 |

|

| N1 | 35 | 61 |

|

| N2 | 25 | 49 |

|

| NX | 8 | 3 |

|

| N3 | 0 | 2 | 0.001 |

| pM stage |

|

|

|

| M0 | 159 | 188 |

|

| M1 | 6 | 12 |

|

|

M1a | 1 | 1 |

|

|

M1b | 1 | 4 |

|

| MX | 73 | 67 | 0.343 |

| pTNM stage |

|

|

|

| I | 1 | 4 |

|

| IA | 86 | 45 |

|

| IB | 68 | 72 |

|

| II | 1 | 0 |

|

|

IIA | 20 | 30 |

|

|

IIB | 24 | 47 |

|

|

IIIA | 25 | 48 |

|

|

IIIB | 4 | 7 |

|

| IV | 8 | 18 | <0.001 |

| New tumor

event |

|

|

|

|

Metastasis (NOS) | 24 | 37 |

|

|

Metastasis (recurrence) | 3 | 5 |

|

|

Primary | 7 | 4 |

|

|

Recurrence | 22 | 26 |

|

|

Metastasis (primary) | 0 | 1 | 0.482 |

| Smoking status |

|

|

|

|

Non-smoking | 40 | 35 |

|

|

Smoking | 194 | 233 | 0.255 |

| Therapy |

|

|

|

|

Ancillary chemotherapy | 2 | 1 |

|

|

Chemotherapy | 70 | 85 |

|

|

Chemotherapy; targeted

molecular therapy | 1 | 5 |

|

|

Targeted molecular

therapy | 2 | 0 |

|

|

Chemotherapy;

immunotherapy | 4 | 0 |

|

|

Immunotherapy | 1 | 0 |

|

|

Vaccine | 0 | 1 | 0.378 |

Differential gene expression and gene

enrichment analysis of TEX-based clusters in patients with

LUAD

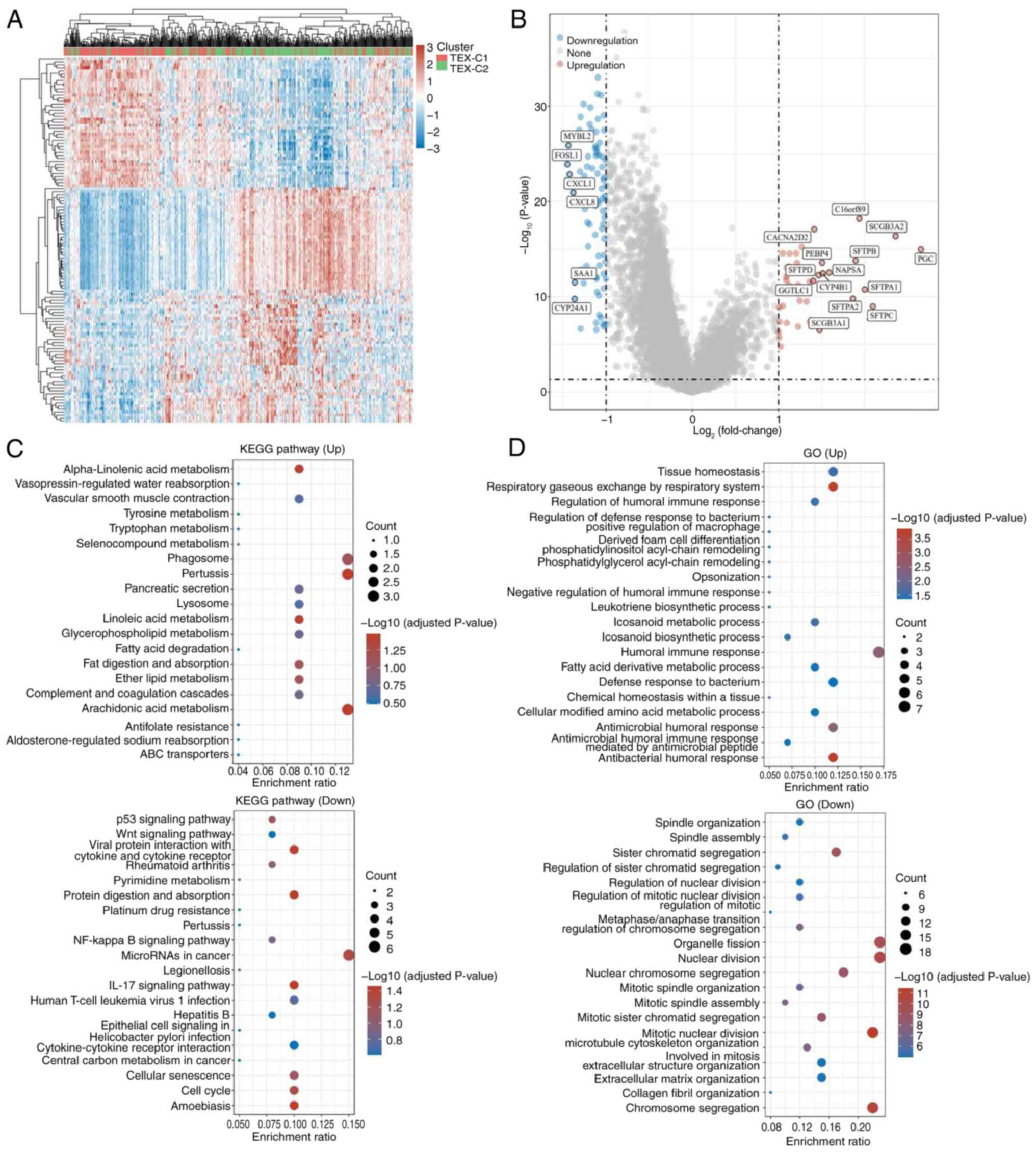

TEX-C1 and TEX-C2 clusters demonstrated 121

differentially expressed genes. Compared with the TEX-C1 cluster,

43 genes were upregulated in the TEX-C2 cluster, such as the

pepsinogen C and Surfactant Protein B (SFTP) families. SFTP is a

pulmonary surface-active substance synthesized by alveolar

epithelial type II cells, which is involved in the development and

progression of LUAD by regulating multiple immune-associated

pathways (44). In the TEX-C2

cluster, 78 genes were downregulated, including CXCL1 and CXCL8,

which are ligands for the chemokine receptor CXCR2 and involved in

the recruitment of tumor immune cells such as TAMs and regulatory T

cells (Tregs; Fig. 2A and B)

(45). Compared with the TEX-C1

cluster, the differentially expressed genes in the TEX-C2 cluster

were mainly involved in immune-related pathways. The KEGG analysis

of upregulated genes in the TEX-C2 cluster demonstrated enrichment

of metabolism-related pathways, while downregulated genes were

associated with ‘p53 signaling pathway’, ‘Wnt signaling pathways’,

‘NF-κB signaling pathways’, ‘IL-17 signaling pathways’ and other

signaling pathways (Fig. 2C). In

addition, upregulated genes in the TEX-C2 cluster were enriched in

metabolism-related pathways according to GO enrichment analysis;

downregulated genes were enriched in mitosis (Fig. 2D). Therefore, worse prognosis for

patients in the TEX-C2 cluster may be related to tumor immune- and

metabolism-associated pathways.

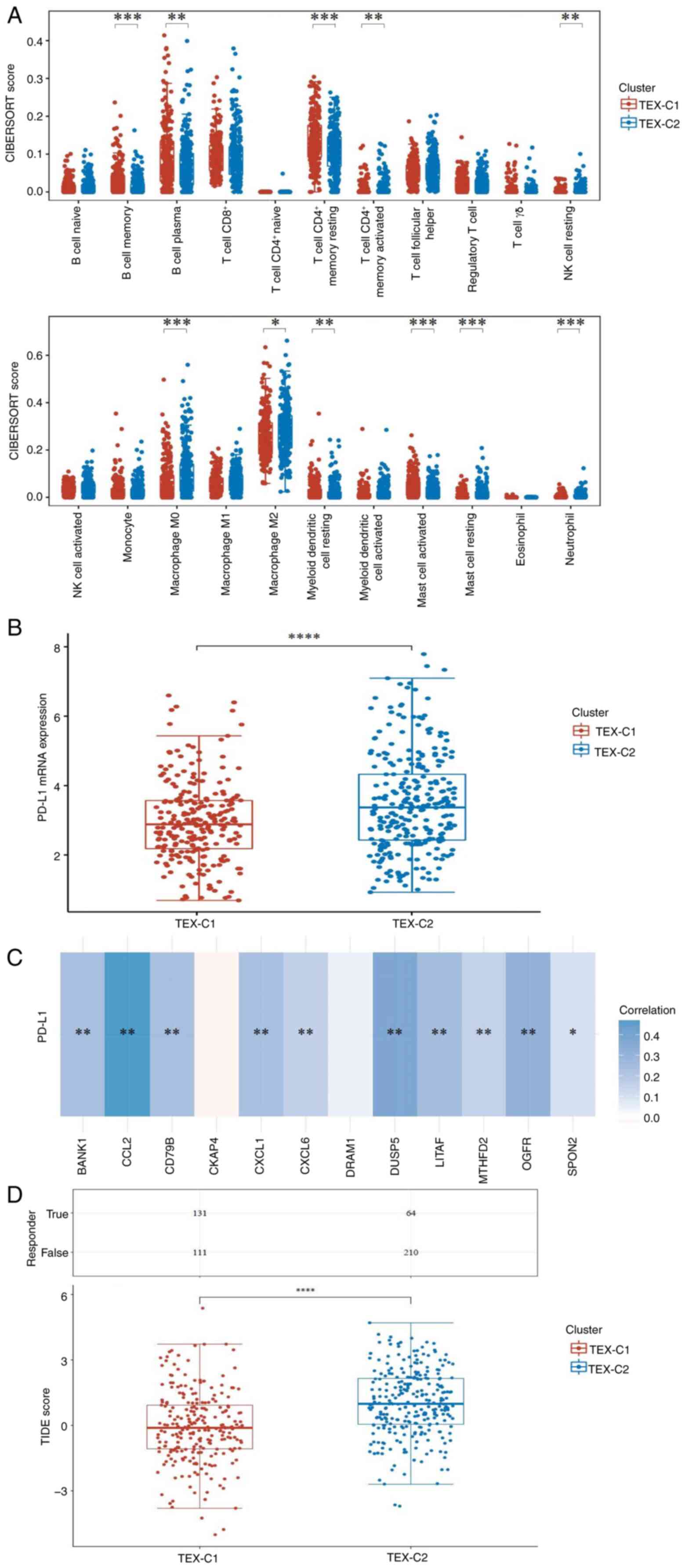

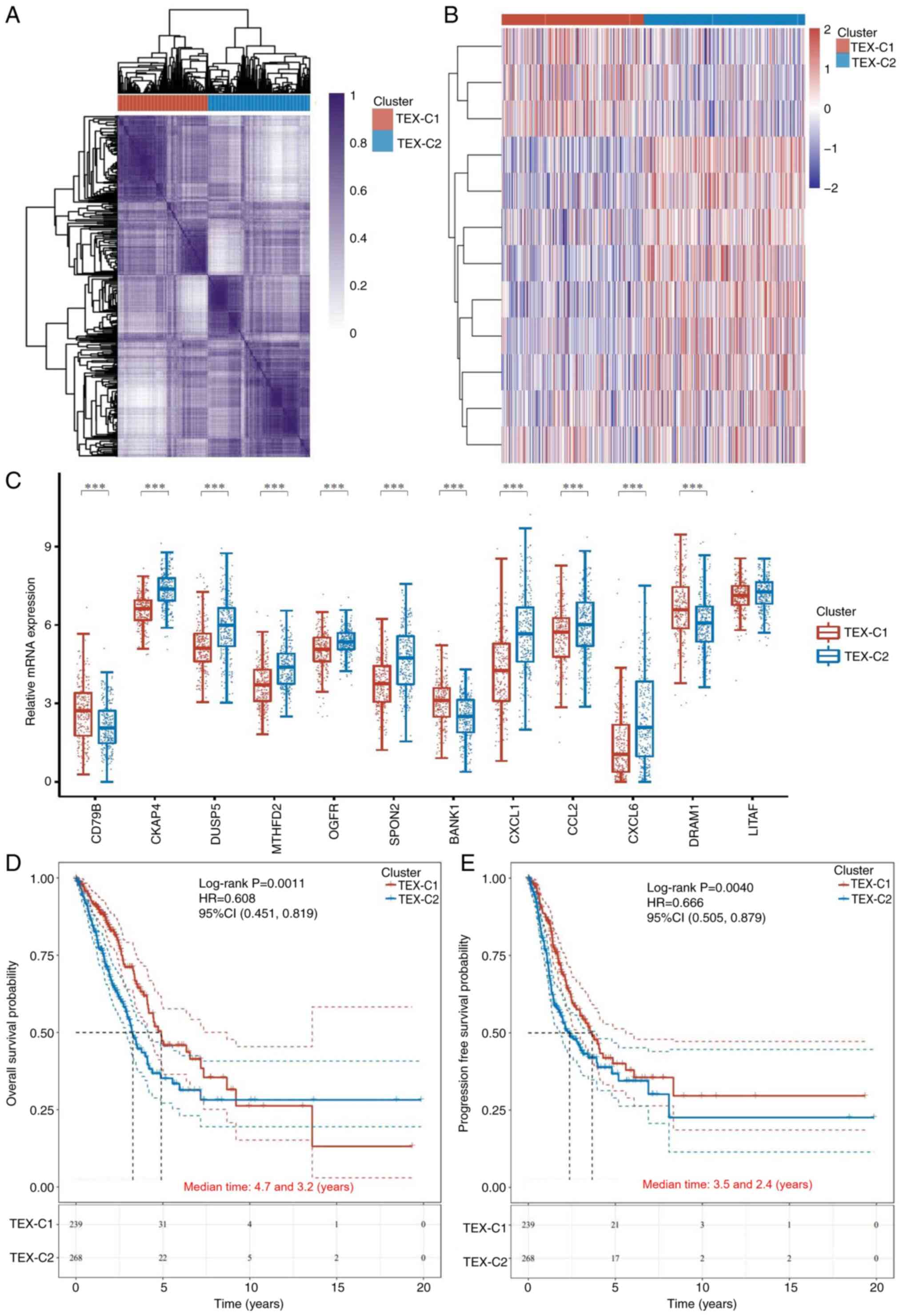

Tumor immune microenvironment analysis

of TEX-based clusters in patients with LUAD

To investigate the heterogeneity of the tumor immune

microenvironment between clusters, tumor immune cell infiltration

was calculated using the CIBERSORT algorithm (Fig. 3A). Compared with the TEX-C1 cluster,

the TEX-C2 cluster had a significantly higher abundance of M0 and

M2 macrophage cells, while the abundance of CD4 memory T and B

cells was lower. PD-L1 is used as an indicator to predict responses

to immunotherapy (46). The present

study investigated the association between PD-L1 and TEX in LUAD;

expression of PD-L1 in the TEX-C2 cluster was significantly higher

than that in the TEX-C1 cluster (Fig.

3B). Moreover, PD-L1 expression was positively correlated with

the expression of TEX-related genes such as BANK1, CCL2, CD79B,

CXCL1 and CXCL6 (Fig. 3C). TIDE

method was used to predict response to ICB. The TIDE score of the

TEX-C2 cluster was significantly higher than that of the TEX-C1

cluster, suggesting this cluster had a poor ICB response and

shorter survival time following ICB treatment (Fig. 3D).

| Figure 3.Tumor immune microenvironment

analysis of TEX-based clusters in patients with lung

adenocarcinoma. (A) Infiltration of immune cells between TEX

clusters was analyzed using the CIBERSORT algorithm. (B) mRNA

expression of PD-L1 between TEX clusters. (C) Heatmap of

correlation between PD-L1 and TEX-related genes. Blue, positive;

red, negative; the darker the color, the stronger the association.

(D) TIDE scores in TEX clusters. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. TEX-C, T cell exhaustion

cluster; TIDE, Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion; CD79B, B

cell Antigen Receptor Complex-Associated Protein Beta Chain; DUSP,

Dual Specificity Phosphatase; MTHFD, Methylenetetrahydrofolate

Dehydrogenase; OGFR, Opioid Growth Factor Receptor; SPON, Spondin;

BANK, B Cell Scaffold Protein With Ankyrin Repeats; CXCL, C-X-C

Motif Chemokine Ligand; CCL, C-C motif chemokine ligand; DRAM, DNA

Damage Regulated Autophagy Modulator; LITAF, Lipopolysaccharide

Induced TNF Factor; PD-L1, Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1; NK,

natural killer cell. |

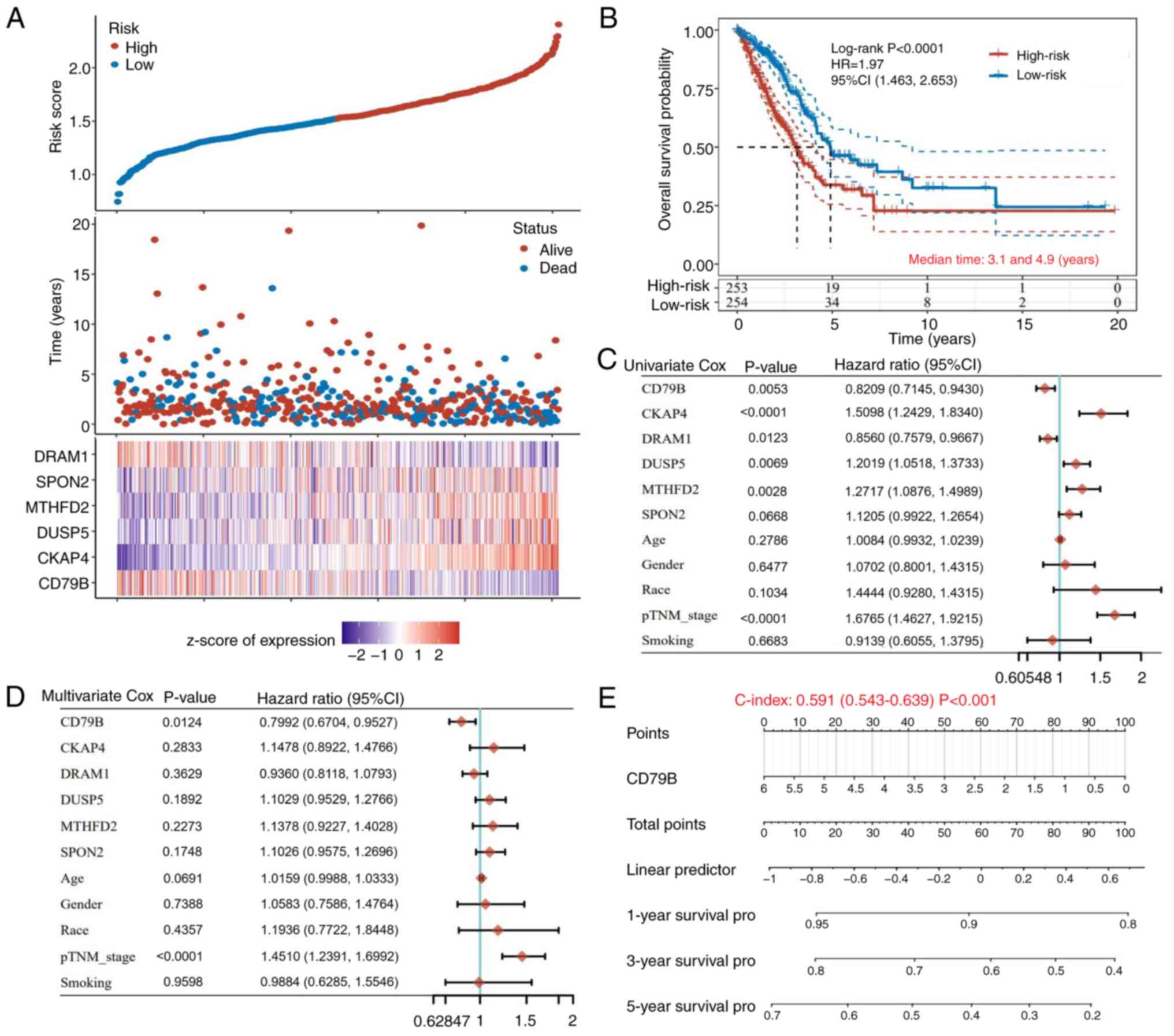

Construction of the prognostic

TEX-related gene signature in patients with LUAD

A risk prediction model for patients with LUAD was

constructed based on TEX-related genes and prognosis-related genes

were selected using the LASSO algorithm combined with 10-fold

cross-validation for further analysis in the best subset

regression. A total of six genes (CD79B, CKAP4, DUSP5, MTHFD2,

SPON2 and DRAM1) were identified as the best candidates, with a λ

value of 0.027. The risk score for prognosis prediction was

calculated as follows: Risk score=(−0.0863) × CD79B + (0.2314) ×

CKAP4 + (0.068) × DUSP5 + (0.0249) × MTHFD2 + (0.0203) × SPON2 +

(−0.0694) × DRAM1. The best subset regression model and coefficient

and deviance profiles are shown in Figs. 4A and S2A and B. Patients were divided into low-

and high-risk groups using median risk score (1.487) as the cutoff

value. Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated that the median OS of

the low-risk group was longer than that of the high-risk group

(Fig. 4B). ROC analysis showed that

the 1-, 3- and 5-year prediction accuracies of the TEX-related gene

prediction model were 0.695, 0.668 and 0.645, respectively

(Fig. S2C). Cox analysis was

performed to analyze the association between CD79B, CKAP4, DUSP5,

MTHFD2, SPON2, DRAM1 and clinicopathological factors such as age,

sex, ethnicity and grade in the OS of patients with LUAD.

Univariate prognostic analysis indicated that CD79B, CKAP4, DUSP5,

DRAM1, MTHFD2 and p-TNM grades were associated with OS in patients

with LUAD (Fig. 4C). Multivariate

prognostic analysis further demonstrated that CD79B and pTNM grade

were reliable independent prognostic factors for predicting the

prognosis of patients with LUAD. In survival analysis, CD79B

indicated a decreased risk while pTNM grade indicated an increased

risk (Fig. 4D). CD79B was marked

with a scale indicating the value range; the length of the line

reflected contribution to the prognostic analysis; consistency

between the prognosis predicted by CD79B and the actual occurrence

was statistically significant. (Fig.

4E). Based on the score of these factors, the nomogram

predicted the 1-, 3- and 5-year OS in patients with LUAD (Fig. S2D).

Prognosis analysis between CD79B

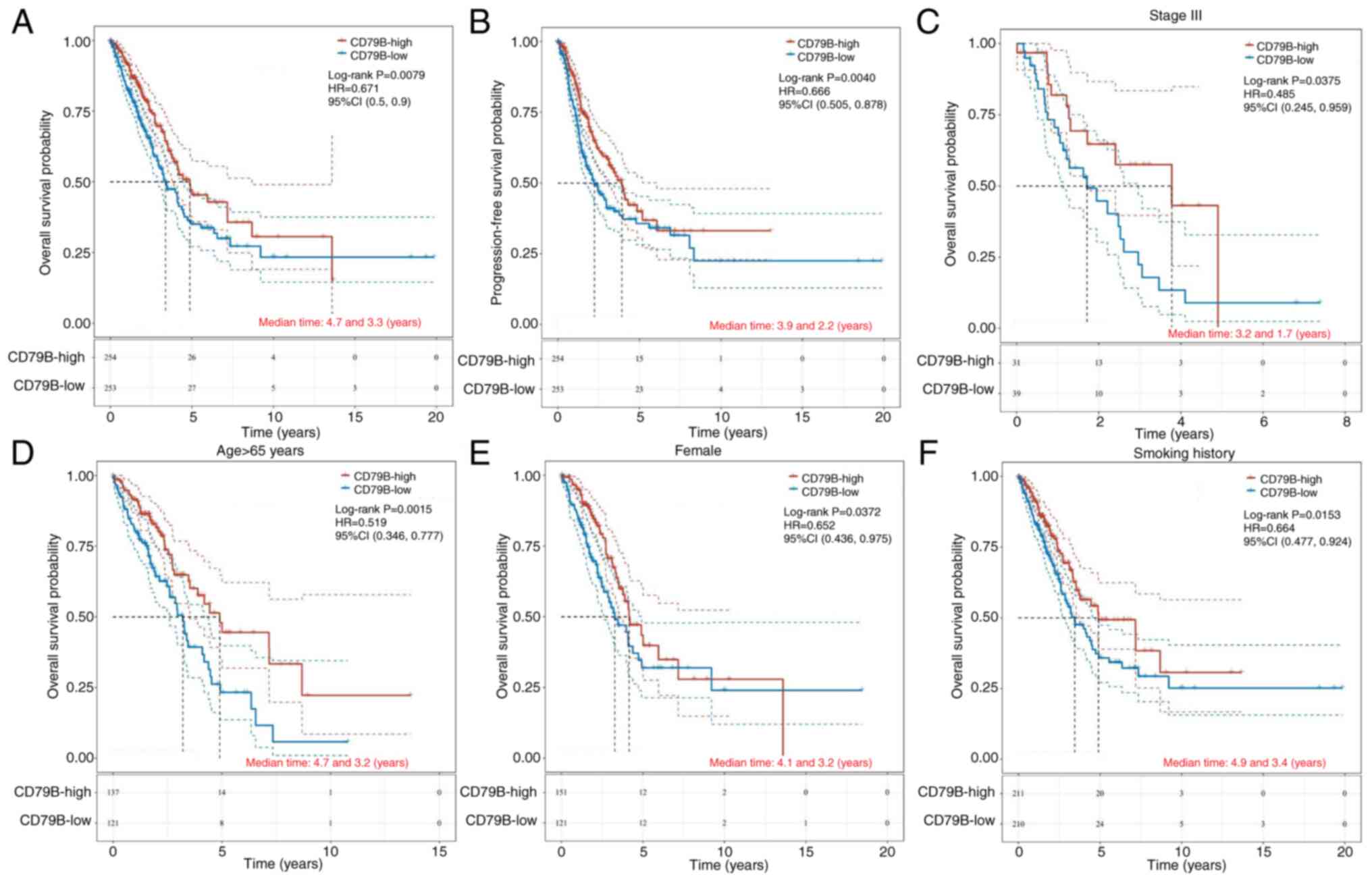

expression and clinical data in patients with LUAD

To confirm the prognostic role of CD79B in LUAD,

TCGA-LUAD patients were divided into a CD79B-low and a -high group

based on the median CD79B mRNA expression (2.391). Low CD79B

expression in patients with LUAD was associated with shorter OS and

PFS, compared with those with high expression of CD79B (Fig. 5A and B). Survival analysis showed

that patients with higher CD79B expression had better prognosis in

advanced LUAD (stage III; Fig. 5C),

while there was no significant difference in the prognostic effect

of CD79B in early-stage lung cancer (stages I and II; Fig. S3A). Similarly, elderly patients

(aged ≥65 years) with high CD79B expression had longer OS, compared

with low CD79B expression (Fig.

5D), while there was no significant difference in the

prognostic role of CD79B for patients <65 years (Fig. S3B). Female patients with high CD79B

expression had better prognosis than male patients, however, there

was no significant difference in prognosis among male patients

based on CD79B levels (P=0.109; Fig.

S3C). High expression of CD79B in smokers indicated better

prognosis (Fig. 5F), however, there

was no significant difference in prognosis for non-smokers based on

CD79B levels (Fig. S3D). These

results suggested that CD79B can be a potential prognostic

biomarker for LUAD, especially in advanced cases, elderly

individuals, female patients and those with a history of

smoking.

Bioinformatics and tumor immune

microenvironment analysis of CD79B expression in patients with

LUAD

Tumor proliferation signature and G2M checkpoint

were negatively associated with CD79B expression by Spearman's

correlation analysis based on the Gene Set Variation Analysis

(Fig. S4A). However, the p53

pathway, apoptosis, inflammatory response and IL-10

anti-inflammatory signaling pathway were positively correlated with

CD79B expression (Fig. S4A). The

IL-10 signaling pathway inhibits activation of pro-inflammatory

macrophages by downregulating mTOR and promoting mitochondrial

autophagy (47). IL-10 is secreted

by Tregs, which synergistically promote TEX in tumors by regulating

the expression of numerous inhibitory receptors (48). In KEGG enrichment analysis, genes

upregulated by CD79B expression were associated with immune-related

pathways such as ‘T cell receptor signaling pathway’, ‘B cell

receptor signaling pathway’, ‘Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation’,

‘Th17 cell differentiation’, ‘PD-L1 expression and PD-1’ and

‘primary immunodeficiency’ (Fig.

S4B). GO analysis of CD79B expression demonstrated enrichment

of innate and adaptive immune-related pathways, including

‘mononuclear cell proliferation’ and ‘leukocyte proliferation’ as

well as ‘T cell activation’, ‘T cell proliferation’ and ‘B cell

activation’ (Fig. S4C). The

protein-protein interaction network of CD79B was obtained from the

STRING database. Most of the proteins interacting with CD79B were B

cell markers (CD19 and CD79A) as well as components of B cell

receptor (BCR)-dependent kinase signaling pathways (Spleen

Associated Tyrosine Kinase and Bruton Tyrosine Kinase, BTK), which

are common in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL; Fig. S4D) (49). These results indicated that CD79B

may affect prognosis in patients with LUAD patients through

immune-related pathways.

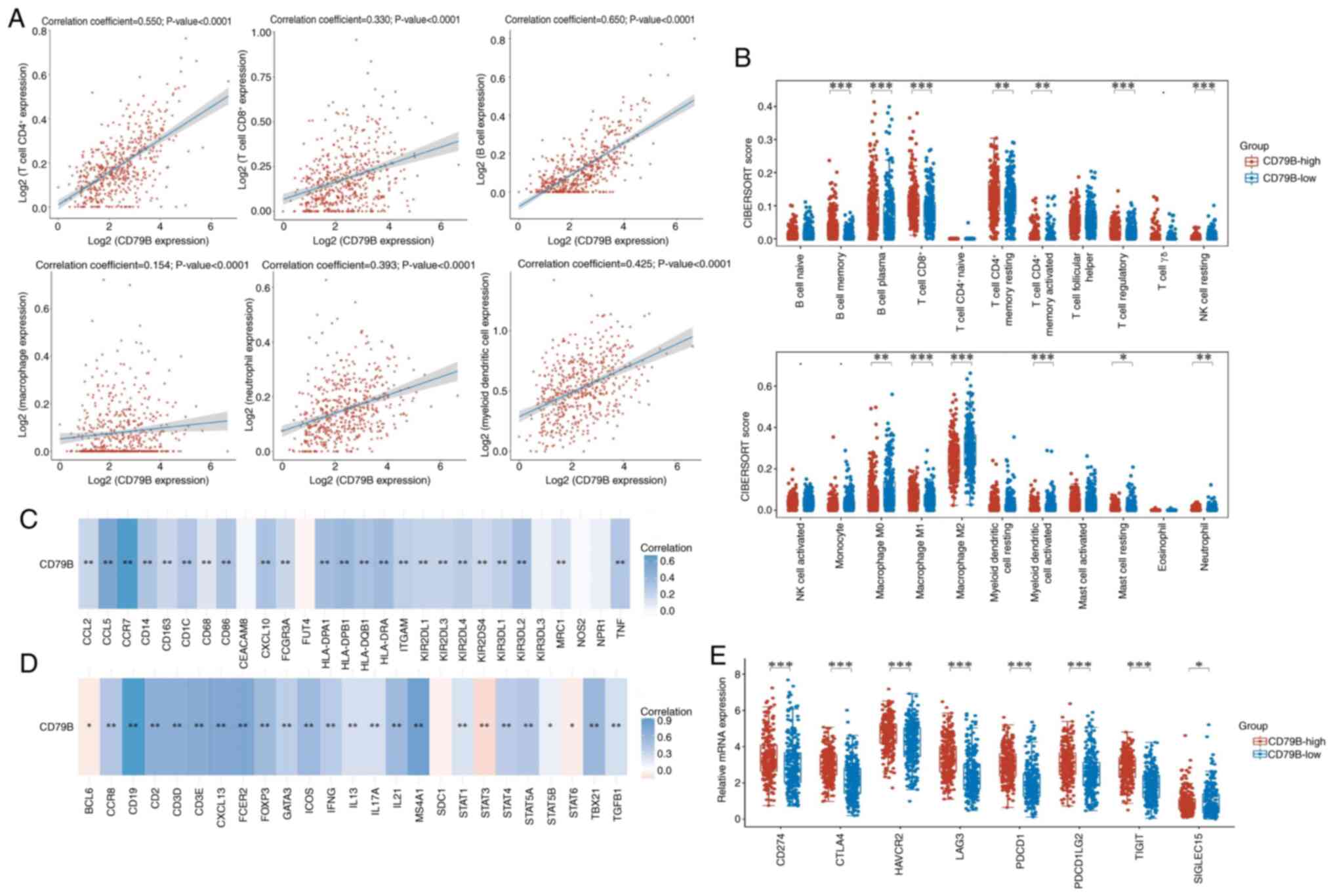

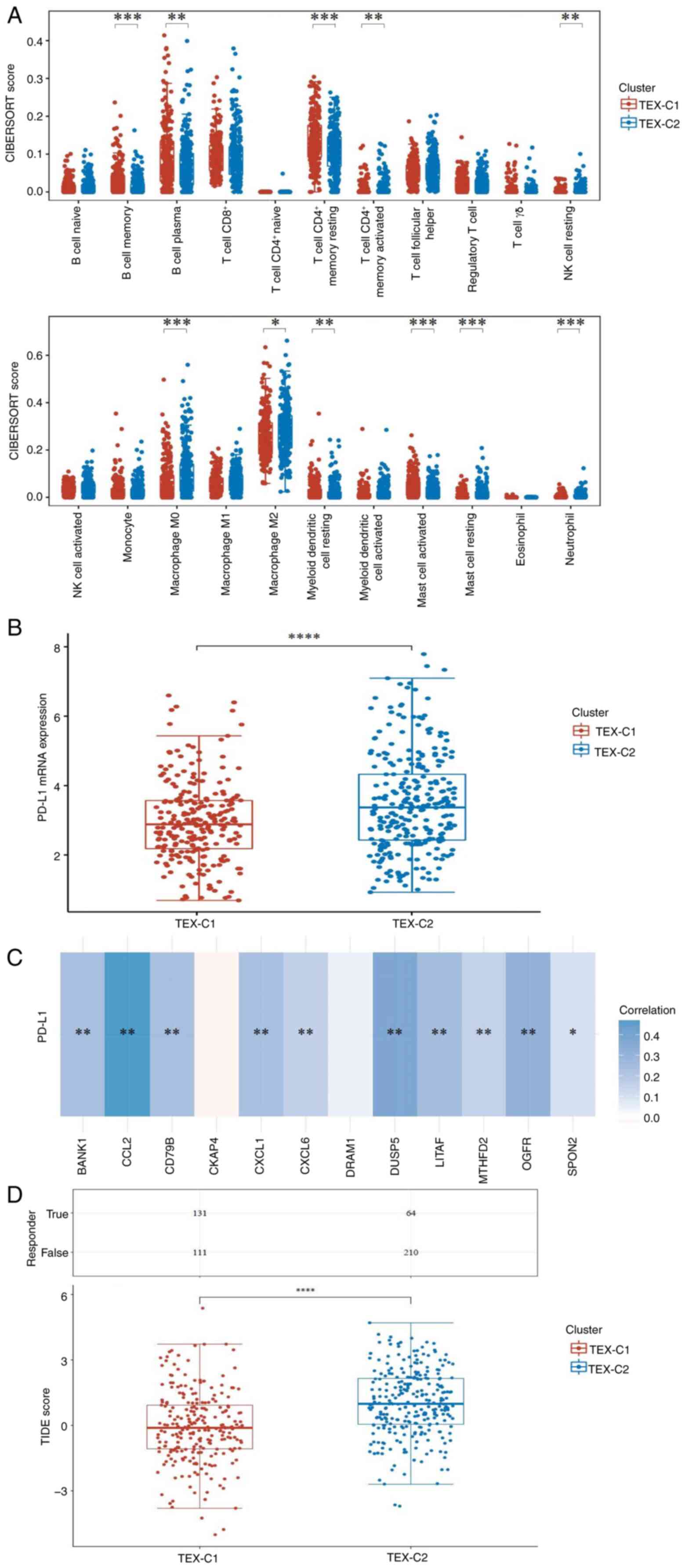

The correlation between CD79B expression and immune

cell levels in patients with LUAD was analyzed; six types of immune

cells (B and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells,

neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells) were all positively

correlated with CD79B expression (Fig.

6A). CIBERSORT algorithm was used to investigate the

association between CD79B expression and selected immune cells to

determine their effect on the tumor microenvironment. Compared with

the CD79B-low group, there was more infiltration of CD8+

T cells and M1 macrophages (classically activated type 1,

pro-inflammatory type), but less infiltration of M0 (the

undifferentiated) and M2 macrophages (the alternatively activated

type 2, anti-inflammatory type), which may be relevant to the

inhibition of TEX (Fig. 6B). In

addition, the association between CD79B and immune markers of

infiltrating immune cells in LUAD was investigated. The expression

of CD79B in LUAD was strongly correlated with innate immune cell

markers, including monocyte [CD14, CD86 and Fc γ receptor IIIa

(FCGR3A)], TAM (CD68, CCL2 and CCL5), M1 [CXCL10 and Tumor Necrosis

Factor (TNF)] and M2 macrophage [Mannose Receptor C-Type 1 (MRC1)

and CD163], neutrophil [Integrin Subunit Alpha M (ITGAM) and C-C

Motif Chemokine Receptor 7 (CCR7)] and natural killer [Killer Cell

Immunoglobulin Like Receptor, Two Ig Domains And long cytoplasmic

tail 1 (KIR2DL1), KIR2DL3, KIR2DL4, KIR3DL1, KIR3DL2 and KIR2DS4]

and dendritic cell markers [Major Histocompatibility Complex, Class

II, DP Beta 1 (HLA-DPB1), HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRA, HLA-DPA1 and CD1C;

Table II]. The CD79B expression

was significantly correlated with adaptive immunity cell markers,

including CD3D, CD3E and CD2 of T cells, CD19, Membrane Spanning

4-Domains A1 (MS4A1) and Fc Epsilon Receptor II (FCER2) of B cells,

T-Box Transcription Factor 21 (TBX21), Signal Transducer And

Activator Of Transcription 4 (STAT4), STAT1 and Interferon Gamma

(IFNG) of T helper 1 (Th1) cells, Trans-Acting T-Cell-Specific

Transcription Factor GATA-3 (GATA3), STAT6, STAT5A and Interleukin

13 (IL13) of Th2 cells, B Cell CLL/Lymphoma 6 (BCL6), IL21,

Inducible T Cell Costimulator (ICOS) and CXCL13 of T follicular

helper (Tfh) cells, STAT3 and IL17A of Th17 cells, as well as

Forkhead Box P3 (FOXP3), CCR8, STAT5B, Transforming Growth Factor

Beta 1 (TGFB1) and Interleukin 2 Receptor Subunit Alpha (IL2RA) of

Tregs (Table III). The expression

of CD79B was significantly correlated with gene markers for both

innate and adaptive immune cells; most correlations were positive,

CD79B negatively correlated with BCL6, STAT6 and STAT3 (Fig. 6C and D). mRNA expression of eight

immune checkpoint genes was significantly increased in the

CD79B-high group (Fig. 6E). Based

on these results, the high expression of CD79B was closely

associated with immune cell infiltration in LUAD, which may serve a

key role in reprogramming T cells from TEX states.

| Figure 6.Tumor immune microenvironment

analysis of CD79B expression in patients with lung adenocarcinoma.

(A) Correlation between CD79B expression and immune cell levels was

analyzed using Spearman's correlation. (B) Infiltration of immune

cells between CD79B-low and -high groups was analyzed using the

CIBERSORT algorithm. Correlation between CD79B and markers of (C)

innate and (D) adaptive immune cells. (E) mRNA expression levels of

immune checkpoint genes between CD79B-low and -high groups.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CD79B, B cell Antigen

Receptor Complex-Associated Protein Beta Chain; NK, natural killer

cell; CTLA, Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4; HAVCR,

Hepatitis A Virus cellular receptor 1; LAG, Lymphocyte Activating

3; PDCD1LG2, Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2; TIGIT, T Cell

Immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM Domains; SIGLEC, Sialic Acid

Binding Ig Like Lectin. |

| Table II.Correlation analysis between B cell

Antigen Receptor Complex-Associated Protein Beta Chain and markers

of innate immunity cells. |

Table II.

Correlation analysis between B cell

Antigen Receptor Complex-Associated Protein Beta Chain and markers

of innate immunity cells.

| Cell | Gene markers | Cor | P-value |

|---|

| Monocyte | CD14 | 0.306 | <0.001 |

|

| CD86 | 0.313 | <0.001 |

|

| FCGR3A | 0.192 | <0.001 |

| TAM | CD68 | 0.124 | 0.005 |

|

| CCL2 | 0.200 | <0.001 |

|

| CCL5 | 0.544 | <0.001 |

| M1 macrophage | NOS2 | 0.029 | 0.515 |

|

| CXCL10 | 0.319 | <0.001 |

|

| TNF | 0.300 | <0.001 |

| M2 macrophage | MRC1 | 0.145 | <0.001 |

|

| CD163 | 0.192 | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils | CEACAM8 | 0.042 | 0.338 |

|

| ITGAM | 0.240 | <0.001 |

|

| CCR7 | 0.666 | <0.001 |

|

| FUT4 | −0.342 | 0.438 |

| Natural killer | KIR2DL1 | 0.214 | <0.001 |

|

| KIR2DL3 | 0.209 | <0.001 |

|

| KIR2DL4 | 0.250 | <0.001 |

|

| KIR3DL1 | 0.232 | <0.001 |

|

| KIR3DL2 | 0.353 | <0.001 |

|

| KIR3DL3 | 0.063 | 0.154 |

|

| KIR2DS4 | 0.185 | <0.001 |

| Dendritic | HLA-DPB1 | 0.394 | <0.001 |

|

| HLA-DQB1 | 0.324 | <0.001 |

|

| HLA-DRA | 0.367 | <0.001 |

|

| HLA-DPA1 | 0.349 | <0.001 |

|

| CD1C | 0.298 | <0.001 |

|

| NPR1 | 0.068 | 0.123 |

| Table III.Correlation analysis between CD79B

and markers of adaptive immunity cells. |

Table III.

Correlation analysis between CD79B

and markers of adaptive immunity cells.

| Cell | Gene markers | Cor | P-value |

|---|

| T | CD3D | 0.641 | <0.001 |

|

| CD3E | 0.672 | <0.001 |

|

| CD2 | 0.631 | <0.001 |

| B | CD19 | 0.902 | <0.001 |

|

| MS4A1 | 0.816 | <0.001 |

|

| SDC1 | −0.075 | 0.088 |

|

| FCER2 | 0.722 | <0.001 |

| Th1 | TBX21 | 0.541 | <0.001 |

|

| STAT4 | 0.346 | <0.001 |

|

| STAT1 | 0.187 | <0.001 |

|

| IFNG | 0.357 | <0.001 |

| Th2 | GATA3 | 0.334 | <0.001 |

|

| STAT6 | −0.090 | 0.041 |

|

| STAT5A | 0.378 | <0.001 |

|

| IL13 | 0.197 | <0.001 |

| Tfh | BCL6 | −0.098 | 0.026 |

|

| IL21 | 0.516 | <0.001 |

|

| ICOS | 0.521 | <0.001 |

|

| CXCL13 | 0.701 | <0.001 |

| Th17 | STAT3 | −0.179 | <0.001 |

|

| IL17A | 0.208 | <0.001 |

| Regulatory T | FOXP3 | 0.515 | <0.001 |

|

| CCR8 | 0.397 | <0.001 |

|

| STAT5B | 0.095 | 0.031 |

|

| TGFB1 | 0.212 |

|

|

| IL2RA | 0.369 | <0.001 |

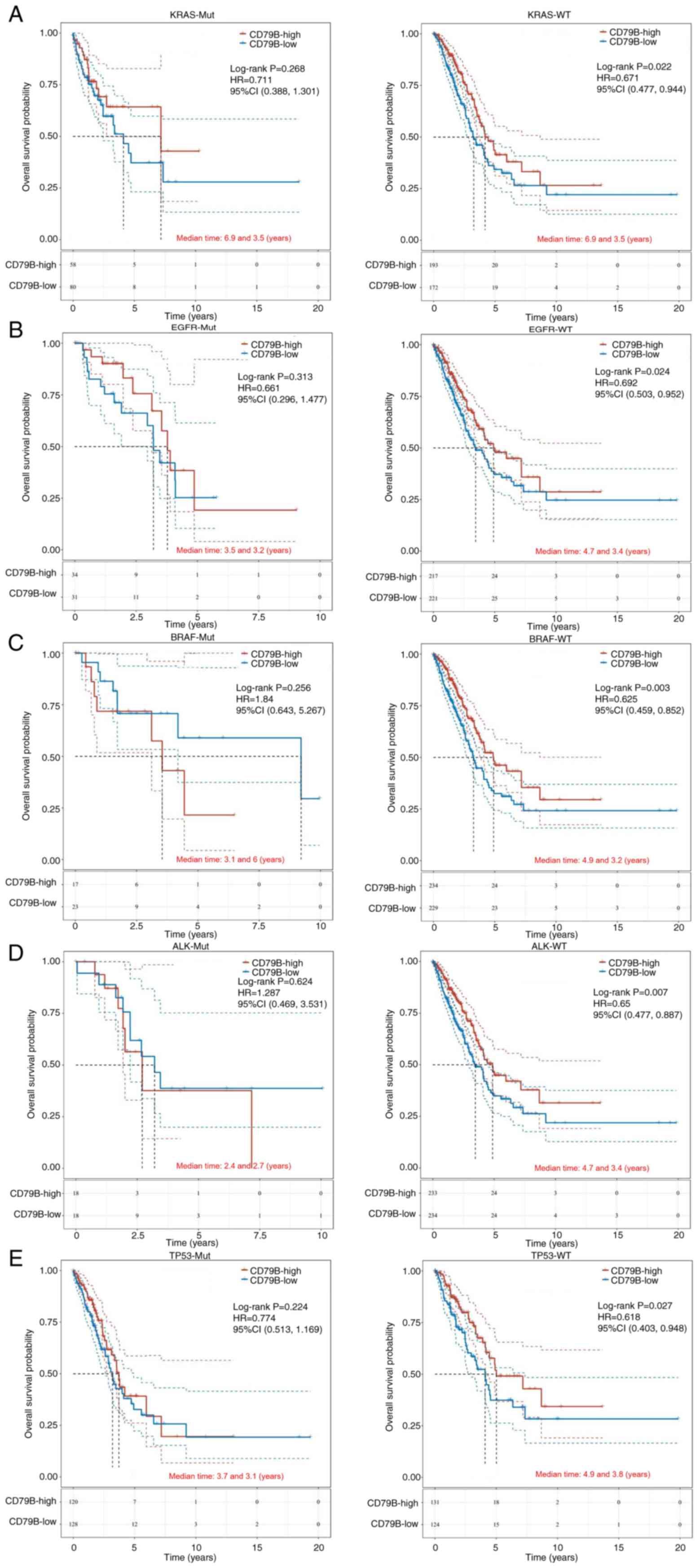

Survival analysis between CD79B

expression and driver gene mutations in patients with LUAD

MAF files from TCGA database were used to show the

mutation rate in LUAD patients, and the top 20 gene landscape of

driver genes with mutation frequency is illustrated in Fig. S5. Patients with LUAD with high

CD79B expression and wild-type KRAS, EGFR, BRAF, ALK or TP53 had

better OS compared with the CD79B-low group (Fig. 7). However, there was no significant

difference in OS between patients with KRAS, EGFR, BRAF, ALK or

TP53 mutations.

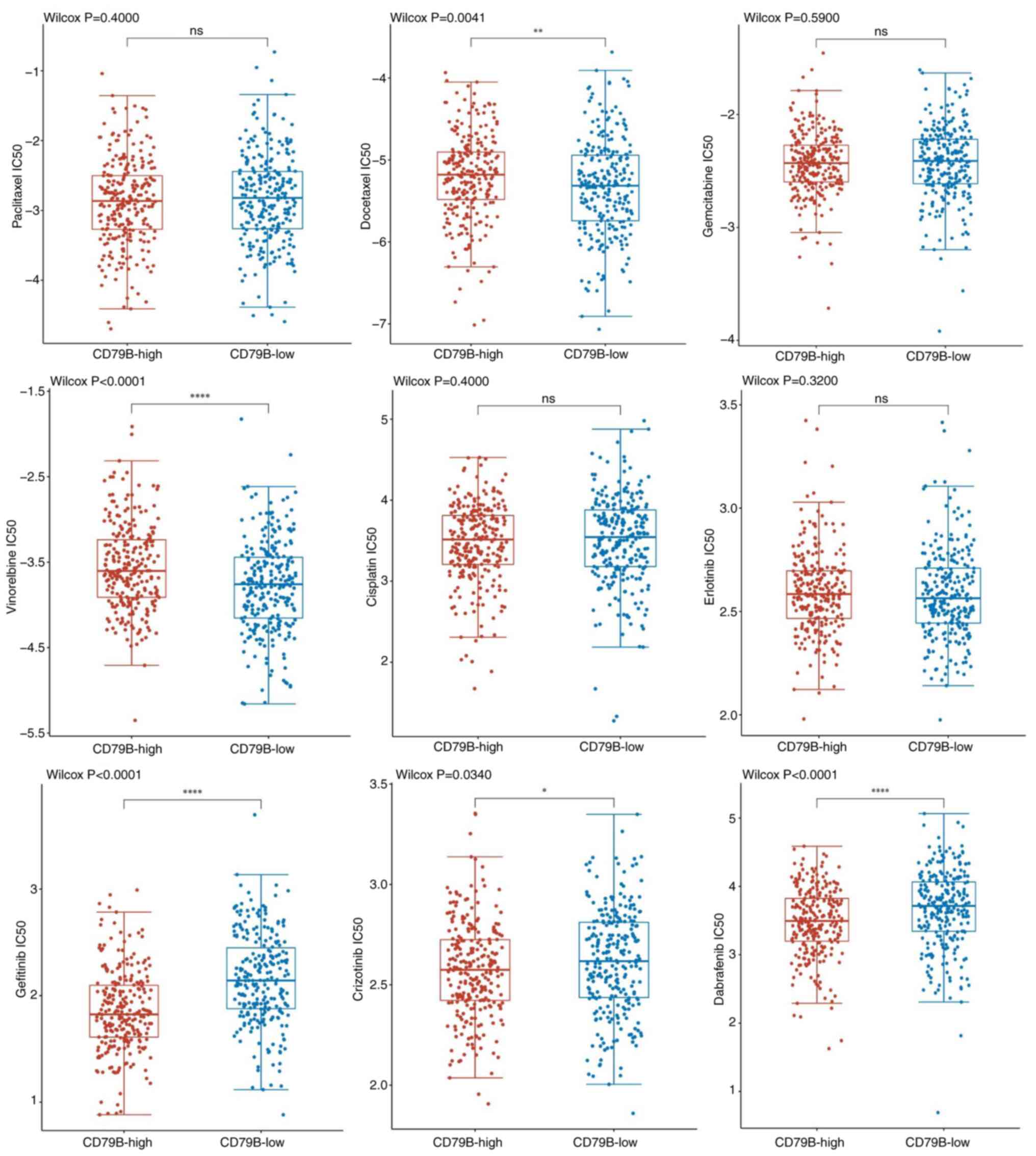

Prediction of therapeutic drug

sensitivity based on CD79B expression in patients with LUAD

To explore the drug sensitivity between CD79B

expression subgroups, IC50 values of common chemotherapy and

molecular targeted therapeutic drugs for LUAD were calculated. The

CD79B-low group had higher sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs

such as docetaxel and vinorelbine, compared with CD79B-high group.

However, patients in the CD79B-high group had higher sensitivity to

targeted agents such as gefitinib, crizotinib and dabrafenib.

Additionally, there was no significant difference in the

sensitivity to paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cisplatin and erlotinib

(Fig. 8). Given the extensive

crosstalk between tumor and immune cells within the tumor

microenvironment (50), TEX-related

gene CD79B may be a potential target for combination therapy to

improve tumor immunotherapy.

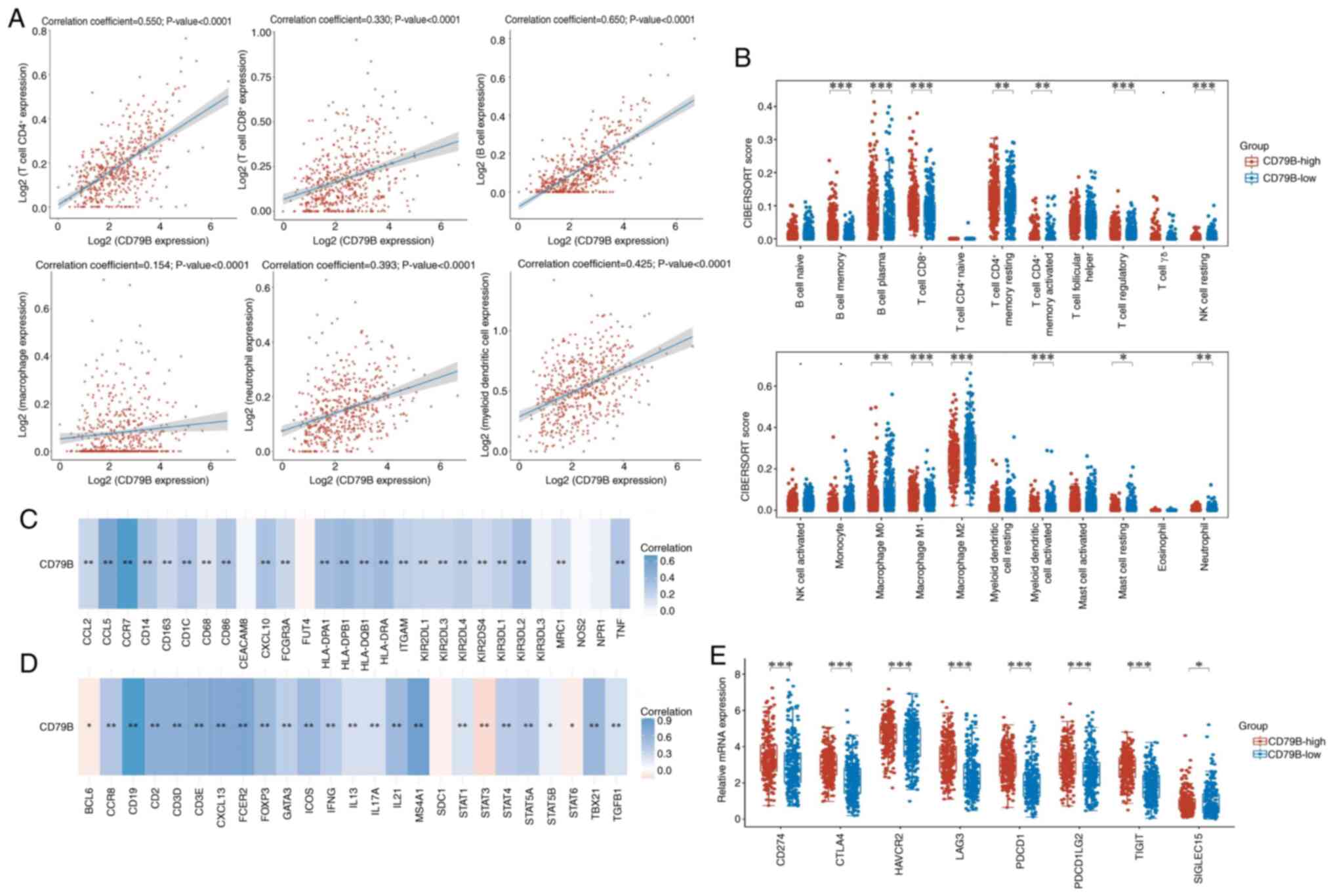

CD79B inhibits proliferation,

migration and invasion and promotes apoptosis of LUAD cells, and

induces M1-like TAM polarization in vitro

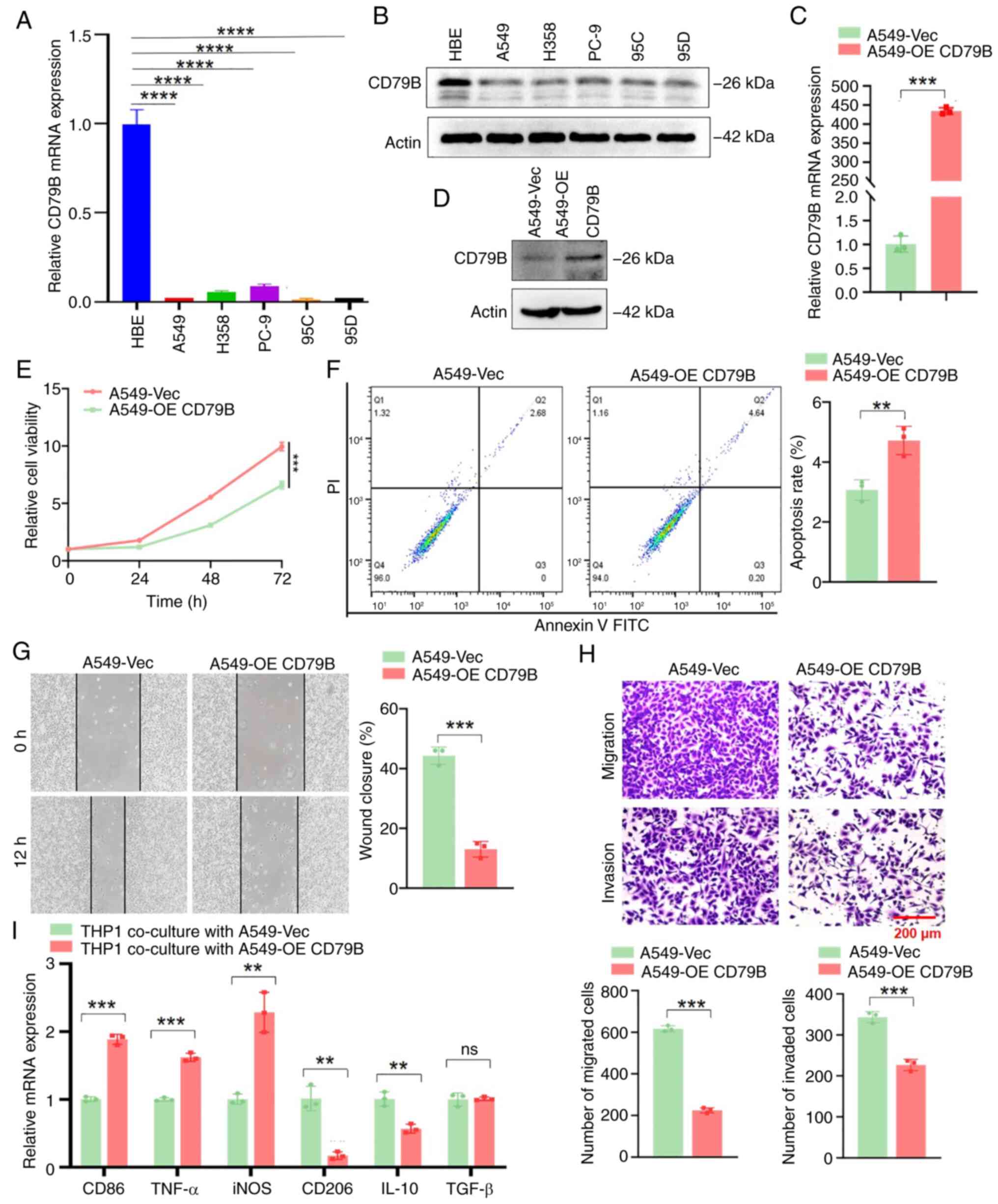

qPCR and western blotting showed that the expression

of CD79B in LUAD cells was lower than that in normal lung

epithelial cells (Fig. 9A and B).

To investigate the role of CD79B in LUAD cells, A549 cells were

transfected with the CD79B-overexpression plasmid and verified by

qPCR and western blotting (Fig. 9C and

D). Compared with the control group, the viability of A549

cells overexpressing CD79B was significantly inhibited (Fig. 9E). Flow cytometry revealed that

overexpression of CD79B could induce apoptosis in A549 cells

(Fig. 9F). Scratch and Transwell

assay results indicated that the migration and invasion ability of

A549 cells overexpressing CD79B significantly weakened (Fig. 9G and H). M0 macrophage THP-1 cells

were co-culture with A549 cells overexpressing CD79B. Compared with

the vector group, macrophages co-cultured with A549 cells

overexpressing CD79B demonstrated upregulation of M1 marker genes

such as CD86, TNF-α and iNOS, while expression of M2 macrophage

marker genes such as CD206 and IL-10 was significantly decreased

(Fig. 9I). Thus, the TEX-related

gene CD79B is not only involved in proliferation, invasion,

migration and apoptosis of cancer cells but also contributed to

M1-like TAM polarization in LUAD.

| Figure 9.CD79B inhibits proliferation,

migration and invasion and promotes apoptosis of LUAD cells, and

induces M1-like tumor-associated macrophage polarization in

vitro. mRNA and protein expression of CD79B were detected by

(A) qPCR and (B) western blotting in normal lung epithelial HBE and

LUAD cells. A549 cells were transfected with the CD79B-OE plasmid

and mRNA and protein expression of CD79B were detected by (C) qPCR

and (D) western blotting. (E) Cell viability was detected by Cell

Counting Kit 8 assay. (F) Flow cytometry was used to analyze cell

apoptosis. (G) Scratch assay was used to detect cell migration. (H)

Transwell assay was used to analyze cell migration and invasion

ability. (I) M0 macrophage THP-1 cells were co-culture with A549

cells, and the mRNA levels of M1/M2 marker genes were detected by

qPCR after 48 h. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001.

CD79B, B-Cell Antigen Receptor Complex-Associated Protein Beta

Chain; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; q, quantitative; OE,

Over-Expression; ns, not significant; Vec, Vector; iNOS. Nitric

Oxide Synthase, Inducible. |

Discussion

TEX, a state of effector T cell dysfunction, is a

notable obstacle to developing effective cancer immunotherapy

(51). Therefore, exploring the

mechanism of TEX and the effect of immunotherapy has become a

target in anti-tumor research (17,52).

The present study performed consensus clustering analysis of

TCGA-LUAD patients based on the expression of 12 TEX-related genes,

and the patients were divided into two clusters. Patients in the

TEX-C2 cluster had worse OS and PFS compared with those in the

TEX-C1 cluster. Upregulated genes in the TEX-C2 cluster were

enriched in metabolism-related pathways, while downregulated genes

were enriched in p53, NF-κB and IL-17 signaling pathways. TEX-C2

cluster had a poor ICB response and shorter survival following ICB

treatment. T cells are prone to exhaustion in an environment

characterized by mitochondrial capacity loss, glucose metabolism

defects and exposure to hypoxia, particularly intolerable levels of

reactive oxygen species (53). TEX

may further reduce metabolic fitness, resulting in anti-tumor

immune dysfunction and suppression (54). In acute myeloid leukemia with TP53

mutation, Tregs show gene expression signatures suggestive of

metabolic adaptation to their environment, whereas CTLs exhibit

features of exhaustion/dysfunction with stronger expression of T

cell Immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (55). Inhibition of NF-κB activity due to

loss of Interleukin 1 Receptor Associated Kinase 4 leads to T cell

dysfunction through production of immunosuppressive factors and

checkpoint ligands in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (56). CD4+ T cells trigger the

recruitment of CD11b+Gr-1+ Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

to promote terminal exhaustion of CD8+ T cells and tumor

progression in vivo by secreting IL-17 (57). ICB therapy is used to inhibit TEX by

blocking antibodies against immune checkpoints, including CTLA4,

PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1. However, the efficacy of ICB therapy

depends on the stage of T cell differentiation and is most

successful when antigen-specific T cells are functional,

proliferate and produce effective responses to maintain antitumor

function (58). Additionally, ICB

therapy alone does not reprogram T cells out of their exhausted

state (59). Current studies aim to

develop new strategies to target terminally exhausted T cells to

reactivate and restore their immune function for immunotherapy

(60,61). The present results indicate that the

poor prognosis of TEX-C2 cluster patients may be associated with

higher susceptibility to TEX due to tumor immune metabolism-related

pathways, which makes it more difficult to benefit from ICB

therapy.

A prognostic TEX-related gene signature model was

constructed to predict the prognosis of patients with LUAD. Among

the prognosis-related genes, CD79B was considered an independent

prognostic biomarker. Survival analysis showed that the high

expression of CD79B in patients with LUAD was associated with a

good prognosis, especially in advanced lung cancer, the elderly,

female patients and patients with a history of smoking. The results

of qPCR and western blot showed that CD79B was expressed at low

levels in LUAD cells. Previous studies have shown that CD79B

expression is also downregulated in cervical cancer tissues and

hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (62,63).

CD79B, as a component of the B cell antigen receptor, has a notable

impact on immune synapse formation, antigen affinity and cell

migration and serves a crucial role in the maturation and

maintenance of B cells (64). CD79B

is highly expressed on the surface of cells in almost all patients

with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

(65). There generally exists a

positive correlation between the intensity of BCR signaling and the

expression of CD79B (66). Another

mechanism through which mutated CD79B increases BCR signaling is

its inability to properly activate the Src-family kinase Lyn, which

triggers a negative feedback loop-based inhibition of BCR signaling

(67). However, in tumor cells from

classical Hodgkin lymphoma, many B cell lineage-specific genes are

downregulated, including CD79B. Silencing of CD79B is associated

with its promoter methylation (68). In CD30-positive diffuse large B cell

lymphoma, low CD79B expression is related to paired box 5

interacting with complexes of histones that modify enhancers and

promoters for target genes, thereby influencing transcriptional

activation (69). In Epstein-Barr

Virus-negative Burkitt lymphoma cells, Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen

2 inhibits the expression of CD79B by binding its promoter and

interfering with the binding and transcriptional activation of

Early B cell factor 1 (70).

However, the molecular mechanisms underlying downregulation of

CD79B expression remain to be elucidated in LUAD. These may involve

complex alterations in gene regulatory networks, abnormal signaling

pathways and other factors such as promoter methylation.

In the present study, high CD79B expression was

associated with immune-related pathways. Moreover, CD79B was

strongly associated with a large number of immune cell populations

and most immune genetic markers, including immune

checkpoint-related genes, which also supported the poor OS of the

CD79B-low group. In addition, CD79B was positively correlated with

infiltrating CD8+ T cells and M1 macrophages and

negatively correlated with M0 and M2 macrophages. Regardless of the

expression of CD79B, targeted therapy could affect the prognosis of

LUAD patients with driver gene mutations. EGFR, ALK, BRAF, KRAS and

TP53 can provide targeted therapy for eligible patients with LUAD

(71). In vitro,

upregulation of CD79B could inhibit proliferation, migration and

invasion while promoting apoptosis of LUAD cells and inducing

M1-like TAM polarization. Expansion of IFN gene numbers can be

found at the CD79B locus (72). IFN

is associated with numerous B cell receptor pathway genes and genes

involved in adaptive immune responses. Among them, CD79B has also

been validated as an IFN-γ response gene in multiple sclerosis

(73). CD79B lymphocyte cells

produce notable amounts of IL-2, granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (CSF), IFN-γ, and IL-17A in response to

tumor cells in B cell lymphomas (74). M1 macrophages are generated

following stimulation by lipopolysaccharide and IFN-γ while M2

macrophages are generated by IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 stimulation

(75). Therefore, it was

hypothesized that the upregulation of CD79B in tumor cells may

promote the production of cytokines such as IFN-γ, thereby

facilitating the polarization of M0 to M1 macrophages and

reprogramming TEX to inhibit malignant progression of LUAD cells.

Exhausted T cells could contribute to the recruitment and

polarization of macrophages by secreting CSF1 (76). TAMs present cancer cell antigens to

CD8+ T cells via interferon regulatory factor 8, leading

to the induction of PD-1 expression, a decrease in effector

cytokines and TEX (77). M0 TAMs

significantly increase the expression of PD-L2 via the PD-1

signaling pathway, which promotes the polarization of

immunosuppressive M2 type macrophages and decreases anti-tumor

effector T cells, leading to immune evasion and tumor promotion

(78). Xanthine oxidoreductase loss

in TAMs promotes M2-like polarization by increasing Isocitrate

Dehydrogenase [NADP(+)] 3 activity and α-ketoglutarate production.

It can also promote CD8+ TEX by upregulating

immunosuppressive metabolites, thereby exacerbating hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) progression (79).

Inhibition of 3-Oxoacid CoA-Transferase 1 (OXCT1) expression in

TAMs promotes reprogramming to an M1 phenotype via the

succinyl-H3K4me3-Arg1 axis, which may also decrease CD8+

TEX and enhance the anti-tumor effect of T cells (80). In breast cancer model mice,

Interleukin 1 Receptor Type 2 (IL1R2) blockade could decrease tumor

burden and prolong survival by decreasing PD-L1 transcriptional

activators and macrophage recruitment while inhibiting TAM

polarization and CD8+ TEX (81). Hence, TAM M2 polarization results in

CD8+ TEX, whereas TAM M1 polarization restores migration

and infiltration of CD8+ T cells. This suggests that TAM

M1 polarization may be an immunotherapeutic target for

reprogramming TEX.

TAM serves key functions in promoting a suppressive

tumor immune microenvironment and immune evasion, which limits the

treatment effects of ICB therapy in different types of cancer. By

using TAM modulators, the suppressive tumor immune microenvironment

may be reversed, thereby polarizing M2 into M1 TAMs releasing

IL-12, IL-6 and TNF-α, enhancing the activation of CD8+

T and natural killer cells, and possibly synergizing with

PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition to enhance anti-cancer immune

responses (82). In glioblastoma

multiforme, combination therapy with rapamycin and

hydroxychloroquine downregulates the CD47-signal regulatory protein

α) axis in tumor cells, promoting the polarization of TAMs to a

pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype and enhancing the therapeutic

response to anti-PD-1 antibody (83). Humanized modified macrophage-derived

microparticles loaded with methionine induce M2-like TAMs to

repolarize into the M1 phenotype, promote the infiltration of

CD8+ T cells into tumor tissue, and thereby enhance the

anti-cancer activity of anti-PD-1 antibody (84). In the treatment of oral cancer, the

combination of selective receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor and ICB

immunotherapy increases the ratio of M1 to M2 macrophages in the

tumor microenvironment while promoting polarization of TAMs towards

an immunostimulatory state, thereby prolonging survival time

(85). The aforementioned studies

indicate that TAMs may serve as a potential target for combination

therapy to enhance the efficacy of tumor immunotherapy. Patients in

CD79B-high group had higher sensitivity to targeted agents such as

gefitinib, crizotinib and dabrafenib. The upregulation of CD79B

induced M1-like TAM polarization to inhibit malignant progression

of LUAD cells in vitro. It was hypothesized that patients

with high levels of CD79B may exhibit a better response to combined

use of immune checkpoint inhibitors and TAM polarizing agents.

However, there are certain limitations in the

present study. Firstly, the present retrospective study was based

on TCGA database, which may have potential selection bias.

Therefore, it is necessary to conduct prospective studies to verify

the conclusions. Secondly, there was a lack of molecular mechanism

studies to investigate the functional role of CD79B in TAM

polarization toward the M1 phenotype. Further in vitro and

in vivo experiments are required to elucidate the potential

regulatory mechanisms. Thirdly, given the absence of relevant data

from patients with LUAD, the results require further validation

through clinical studies involving larger sample sizes.

In summary, the present study performed clustering

analysis using TEX-related genes and developed a prognostic

TEX-related gene signature model to predict the prognosis of

patients with LUAD. Among the prognosis-related genes, CD79B was

considered an independent prognostic marker. Upregulation of CD79B

inhibited proliferation, migration and invasion while promoting

apoptosis in LUAD cells and inducing M1-like TAM polarization.

These results demonstrated the clinical value of TEX-related genes,

suggesting CD79B may be a potential prognostic indicator and

therapeutic target for improving tumor immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Hunan Province, China (grant no. 2025JJ50551) and the

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central

South University (grant no. 2024ZZTS0912).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XW constructed figures, analyzed data, performed

experiments and wrote the manuscript. CQ performed experiments. YO

designed and performed the experiments. LY analyzed data, designed

and performed the experiments and edited the manuscript. WJ

conceived the study, designed and performed the experiments,

analyzed data and edited the manuscript. XW and CQ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D and Boshoff C:

The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature.

553:446–454. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL,

Kwon R, Curran WJ, Wu YL and Paz-Ares L: Lung cancer: Current

therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 389:299–311. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Succony L, Rassl DM, Barker AP, McCaughan

FM and Rintoul RC: Adenocarcinoma spectrum lesions of the lung:

Detection, pathology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev.

99:1022372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hughes PE, Caenepeel S and Wu LC: Targeted

therapy and checkpoint immunotherapy combinations for the treatment

of cancer. Trends Immunol. 37:462–476. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Smit EF and Baas P: Lung cancer in 2015:

Bypassing checkpoints, overcoming resistance, and honing in on new

targets. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 13:75–76. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N,

Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L,

et al: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 372:2018–2028. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X,

Li Z, Traugh N, Bu X, Li B, et al: Signatures of T cell dysfunction

and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med.

24:1550–1558. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Parra ER, Zhang J, Duose DY,

Gonzalez-Kozlova E, Redman MW, Chen H, Manyam GC, Kumar G, Zhang J,

Song X, et al: Multi-omics analysis reveals immune features

associated with immunotherapy benefit in patients with squamous

cell lung cancer from phase III Lung-MAP S1400I trial. Clin Cancer

Res. 30:1655–1668. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mao X, Xu J, Wang W, Liang C, Hua J, Liu

J, Zhang B, Meng Q, Yu X and Shi S: Crosstalk between

cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor

microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol Cancer.

20:1312021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhang S, Wang X, Dou H, Yu

X, Zhang Z, Yang S and Xiao M: Extracellular matrix remodeling in

tumor progression and immune escape: From mechanisms to treatments.

Mol Cancer. 22:482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS and Wherry EJ:

CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and cancer.

Annu Rev Immunol. 37:457–495. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cai MC, Zhao X, Cao M, Ma P, Chen M, Wu J,

Jia C, He C, Fu Y, Tan L, et al: T-cell exhaustion interrelates

with immune cytolytic activity to shape the inflamed tumor

microenvironment. J Pathol. 251:147–159. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wherry EJ: T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol.

12:492–499. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang Z, Chen L, Chen H, Zhao J, Li K, Sun

J and Zhou M: Pan-cancer landscape of T-cell exhaustion

heterogeneity within the tumor microenvironment revealed a

progressive roadmap of hierarchical dysfunction associated with

prognosis and therapeutic efficacy. EBioMedicine. 83:104–207. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Liu J, Li M, Wu J, Qi Q, Li Y, Wang S,

Liang S, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Huang R, et al: Identification of ST3GAL5

as a prognostic biomarker correlating with CD8+ T cell exhaustion

in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 13:9796052022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xu-Monette ZY, Zhang M, Li J and Young KH:

PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade: Have we found the key to unleash the antitumor

immune response? Front Immunol. 8:15972017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu Z, Zhang Y, Ma N, Yang Y, Ma Y, Wang

F, Wang Y, Wei J, Chen H, Tartarone A, et al: Progenitor-like

exhausted SPRY1+CD8+ T cells potentiate responsiveness to

neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Cell. 41:1852–1870.e9. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tanoue K, Ohmura H, Uehara K, Ito M,

Yamaguchi K, Tsuchihashi K, Shinohara Y, Lu P, Tamura S, Shimokawa

H, et al: Spatial dynamics of CD39+CD8+ exhausted T cell reveal

tertiary lymphoid structures-mediated response to PD-1 blockade in

esophageal cancer. Nat Commun. 15:90332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang H, Wu C, Tong X and Chen S: A

Biomimetic Metal-organic framework nanosystem modulates

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment metabolism to amplify

immunotherapy. J Control Release. 353:727–737. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li W, Wu F, Zhao S, Shi P, Wang S and Cui

D: Correlation between PD-1/PD-L1 expression and polarization in

tumor-associated macrophages: A key player in tumor immunotherapy.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 67:49–57. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang T, Hao L, Cui R, Liu H, Chen J, An J,

Qi S and Li Z: Identification of an immune prognostic 11-gene

signature for lung adenocarcinoma. PeerJ. 9:e107492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu YH, Jin HQ and Liu HP: Identification

of T-cell exhaustion-related gene signature for predicting

prognosis in glioblastoma multiforme. J Cell Mol Med. 27:3503–3513.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M,

Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Gable AL, Fang T, Doncheva NT,

Pyysalo S, et al: The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein

association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any

sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D638–D646.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wilkerson MD and Hayes DN:

ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence

assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 26:1572–1573. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ and

DeMatteo RP: Nomograms in oncology: More than meets the eye. Lancet

Oncol. 16:e173–e180. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Xi LJ, Guo ZY, Yang XK and Ping ZG:

Application of LASSO and its extended method in variable selection

of regression analysis. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 57:107–111.

2023.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li Y, Lu F and Yin Y: Applying logistic

LASSO regression for the diagnosis of atypical Crohn's disease. Sci

Rep. 12:113402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA. Botstein

D. Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT,

et al: Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat

Genet. 25:25–29. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M

and Hirakawa M: KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular

networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res.

38:D355–D360. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK,

Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub

TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP: Gene set enrichment analysis: A

knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression

profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:15545–15550. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hung JH, Yang TH, Hu Z, Weng Z and DeLisi

C: Gene set enrichment analysis: Performance evaluation and usage

guidelines. Brief Bioinform. 13:281–291. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Edelman E, Porrello A, Guinney J,

Balakumaran B, Bild A, Febbo PG and Mukherjee S: Analysis of sample

set enrichment scores: Assaying the enrichment of sets of genes for

individual samples in genome-wide expression profiles.

Bioinformatics. 22:e108–e116. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lee E, Chuang HY, Kim JW, Ideker T and Lee

D: Inferring pathway activity toward precise disease

classification. PLoS Comput Biol. 4:e10002172008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tomfohr J, Lu J and Kepler TB: Pathway

level analysis of gene expression using singular value

decomposition. BMC Bioinformatics. 6:2252005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hänzelmann S, Castelo R and Guinney J:

GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data.

BMC Bioinformatics. 14:72013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV,

Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, et al: The

prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across

human cancers. Nat Med. 21:938–945. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hu W, Wang G, Chen Y, Yarmus LB, Liu B and

Wan Y: Coupled immune stratification and identification of

therapeutic candidates in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Aging

(Albany NY). 12:16514–16538. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Geeleher P, Cox NJ and Huang RS: Clinical

drug response can be predicted using baseline gene expression

levels and in vitro drug sensitivity in cell lines. Genome Biol.

15:R472014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Geeleher P, Cox N and Huang RS:

pRRophetic: An R package for prediction of clinical

chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PLoS

One. 9:e1074682014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Suarez-Arnedo A, Torres Figueroa F,

Clavijo C, Arbeláez P, Cruz JC and Muñoz-Camargo C: An image J

plugin for the high throughput image analysis of in vitro scratch

wound healing assays. PLoS One. 15:e02325652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yuan L, Wu X, Zhang L, Yang M, Wang X,

Huang W, Pan H, Wu Y, Huang J, Liang W, et al: SFTPA1 is a

potential prognostic biomarker correlated with immune cell

infltration and response to immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma.

Cancer Immunol Immunother. 71:399–415. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Korbecki J, Kupnicka P, Chlubek M, Gorący

J, Gutowska I and Baranowska-Bosiacka I: CXCR2 receptor: Regulation

of expression, signal transduction, and involvement in cancer. Int

J Mol Sci. 23:21682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lee D, Cho M, Kim E, Seo Y and Cha JH:

PD-L1: From cancer immunotherapy to therapeutic implications in

multiple disorders. Mol Ther. 32:4235–4255. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ip EWK, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S and

Medzhitov R: Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by

metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science. 356:513–519. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sawant DV, Yano H, Chikina M, Zhang Q,

Liao M, Liu C, Callahan DJ, Sun Z, Sun T, Tabib T, et al: Adaptive

plasticity of IL-10+ and IL-35+ Treg cells cooperatively promotes

tumor T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 20:724–735. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Phelan JD, Young RM, Webster DE, Roulland

S, Wright GW, Kasbekar M, Shaffer AL, Ceribelli M, Wang JQ, Schmitz

R, et al: A multiprotein supercomplex controlling oncogenic

signalling in lymphoma. Nature. 560:387–391. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Shukla M and Sarkar RR: Differential

cellular communication in tumor immune microenvironment during

early and advanced stages of lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Genet

Genomics. 299:1002024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chi X, Luo S, Ye P, Hwang WL, Cha JH, Yan

X and Yang WH: T-cell exhaustion and stemness in antitumor

immunity: Characteristics, mechanisms, and implications. Front

Immunol. 14:11047712023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Pichler AC, Carrié N, Cuisinier M, Ghazali

S, Voisin A, Axisa PP, Tosolini M, Mazzotti C, Golec DP, Maheo S,

et al: TCR-independent CD137 (4-1BB) signaling promotes

CD8+-exhausted T cell proliferation and terminal differentiation.

Immunity. 56:1631–1648.e10. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Scharping NE, Rivadeneira DB, Menk AV,

Vignali PDA, Ford BR, Rittenhouse NL, Peralta R, Wang Y, Wang Y,

DePeaux K, et al: Mitochondrial stress induced by continuous

stimulation under hypoxia rapidly drives T cell exhaustion. Nat

Immunol. 22:205–215. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Watowich MB, Gilbert MR and Larion M: T

cell exhaustion in malignant gliomas. Trends Cancer. 9:270–292.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Abolhalaj M, Sincic V, Lilljebjörn H,

Sandén C, Aab A, Hägerbrand K, Ellmark P, Borrebaeck CAK, Fioretos

T and Lundberg K: Transcriptional profiling demonstrates altered

characteristics of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells and regulatory T-cells in

TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Med. 11:3023–3032.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Somani VK, Zhang D, Dodhiawala PB, Lander

VE, Liu X, Kang LI, Chen HP, Knolhoff BL, Li L, Grierson PM, et al:

IRAK4 signaling drives resistance to checkpoint immunotherapy in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 162:2047–2062.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kim BS, Kuen DS, Koh CH, Kim HD, Chang SH,

Kim S, Jeon YK, Park YJ, Choi G, Kim J, et al: Type 17 immunity

promotes the exhaustion of CD8+ T cells in cancer. J Immunother

Cancer. 9:e0026032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Huang Y, Jia A, Wang Y and Liu G: CD8+ T

cell exhaustion in anti-tumour immunity: The new insights for

cancer immunotherapy. Immunology. 168:30–48. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zebley CC and Youngblood B: Mechanisms of

T cell exhaustion guiding next generation immunotherapy. Trends

Cancer. 8:726–734. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ford BR, Vignali PDA, Rittenhouse NL,

Scharping NE, Peralta R, Lontos K, Frisch AT, Delgoffe GM and

Poholek AC: Tumor microenvironmental signals reshape chromatin

landscapes to limit the functional potential of exhausted T cells.

Sci Immunol. 7:eabj91232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang L, Zhang B, Li L, Ye Y, Wu Y, Yuan

Q, Xu W, Wen X, Guo X and Nian S: Novel targets for immunotherapy

associated with exhausted CD8 + T cells in cancer. J Cancer Res

Clin Oncol. 149:2243–2258. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Pu D, Liu D, Li C, Chen C, Che Y, Lv J,

Yang Y and Wang X: A novel ten-gene prognostic signature for

cervical cancer based on CD79B-related immunomodulators. Front

Genet. 13:9337982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wang Y, Yang Y, Zhao Z, Sun H, Luo D,

Huttad L, Zhang B and Han B: A new nomogram model for prognosis of

hepatocellular carcinoma based on novel gene signature that

regulates cross-talk between immune and tumor cells. BMC Cancer.

22:3792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Huse K, Bai B, Hilden VI, Bollum LK,

Våtsveen TK, Munthe LA, Smeland EB, Irish JM, Wälchli S and

Myklebust JH: Mechanism of CD79A and CD79B support for IgM+ B cell

fitness through BCR surface expression. J Immunol. 209:2042–2053.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Tkachenko A, Kupcova K and Havranek O:

B-cell receptor signaling and beyond: The role of Igα (CD79a)/Igβ

(CD79b) in normal and malignant B cells. Int J Mol Sci. 25:102023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ramesh S, Go M, Call ME and Call MJ: Deep

mutational scanning reveals transmembrane features governing

surface expression of the B cell antigen receptor. Front Immunol.

15:14267952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Xie Z, Qin Y, Chen X, Yang S, Yang J, Gui

L, Liu P, He X, Zhou S, Zhang C, et al: Deciphering the prognostic

significance of MYD88 and CD79B mutations in diffuse large B-Cell

lymphoma: Insights into treatment outcomes. Target Oncol.

19:383–400. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|