Introduction

On a global scale, breast cancer ranks as the second

most commonly occurring malignant neoplasm, and the leading cause

of cancer-associated mortality among women (1). Despite substantial advancements in

molecularly targeted interventions and immunotherapeutic

approaches, therapeutic outcomes and prognostic indicators for

patients with breast cancer continue to demonstrate suboptimal

efficacy (2,3). Within the multimodal therapeutic

framework for breast carcinoma, radiation therapy serves as a

crucial component, demonstrating efficacy in managing localized

tumor advancement, reducing the probability of recurrence and

enhancing patient survival outcomes (4–6).

However, the clinical efficacy of radiotherapy is frequently

compromised by inherent or progressively acquired radioresistance

mechanisms (7). Among the various

factors influencing radiosensitivity, dysregulation of DNA repair

mechanisms and cell cycle progression have been identified as

pivotal elements underlying therapeutic resistance in neoplastic

cells (8). Therefore, revealing the

radiation therapy resistance mechanisms in breast cancer may

provide improved opportunities to overcome tumor resistance.

DNA is vulnerable to multiple types of damage; such

damage encompasses harm to the nucleotides (comprising bases and

sugars) that constitute the DNA framework, the formation of

crosslinks, and the occurrence of single-stranded breaks and

double-stranded breaks (DSBs) within the DNA molecule (9). Among them, DSBs represent the most

cytotoxic form of radiation-induced damage, initiating a cascade of

molecular events within the cellular DNA damage response (DDR)

network. This intricate process involves DNA damage perception,

signal transduction pathway activation, DNA repair machinery

engagement and cell cycle regulation (7,10,11).

The defense mechanism of the cell utilizes a variety of strategies

to handle DSBs, with the two primary repair routes being homologous

recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) (12,13).

The NHEJ mechanism, predominantly active during the G1

phase, exhibits rapid repair kinetics but is associated with

reduced fidelity. By contrast, HR-mediated repair, which utilizes

undamaged sister chromatids as templates, demonstrates superior

accuracy in damage correction (14,15).

While DNA damage repair occurs, cell cycle checkpoints are

activated to trigger cell cycle arrest, which provides a critical

repair time for cancer cells and prevents them from entering

mitosis without completing repair (8,16). In

normal cells, these mechanisms act synergistically to maintain

genome stability; however, in tumor cells, aberrant activation of

the DDR often leads to radioresistance. Consequently, one of the

most crucial methods for overcoming tumor radioresistance is to

target the DDR signaling pathway (7,17).

An important part of the spindle assembly checkpoint

system is BUB1 mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine kinase B (BUB1B)

(18), which serves a key role in

maintaining chromosome stability by interacting with Bub3, Mad2 and

Cdc20 to form a mitotic checkpoint complex. Emerging evidence from

numerous previous studies has established a strong association

between dysregulated BUB1B expression and the development of

malignancies, including extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, lung

adenocarcinoma and thyroid carcinoma, with its upregulation

consistently linked to unfavorable clinical outcomes (19–21).

Furthermore, BUB1B is associated with chemoradiotherapy resistance

in cancer, such as bladder cancer, glioblastoma and multiple

myeloma (22–24).

In the present study, the extent of BUB1B expression

in breast cancer and its association with patient prognosis was

assessed. Subsequently, the MDA-MB-231 cell line, which shows a

high level of BUB1B expression, was selected to conduct a more

in-depth exploration of its biological functions during tumor

development and its response to radiation. The present study

underscores the crucial role that BUB1B assumes in breast cancer

and identifies a potential therapeutic target for enhancing the

sensitivity of breast cancer to radiotherapy.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

The UALCAN (The Cancer Genome Atlas module,

http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) and Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) databases were

employed to investigate the expression state of BUB1B in breast

cancer samples. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the GEO

datasets GSE38959 (25) and

GSE65194 (26). Subsequently,

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was

conducted to assess the clinical diagnostic capability of BUB1B.

Survival analysis related to BUB1B expression was analyzed using

the bc-GenExMiner website (http://bcgenex.ico.unicancer.fr). Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis (GSEA) was performed on data from the GEO database using R

language (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Breast cancer samples were categorized into two groups based on the

median expression level of BUB1B mRNA: High-expression and

low-expression cohorts. Subsequently, GSEA was performed to

identify distinct molecular pathways between these two groups.

Cell lines

The normal mammary epithelial cell line MCF-10A, and

breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, BT-549, MCF-7 and BT-474 cell

lines were procured from Procell Life Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd. Different culture media were used for each cell line. MCF-10A

cells were cultured in MCF 10A Cell Complete Medium (cat. no.

CM-0525; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). To

culture MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, high-glucose DMEM (cat. no.

C11995500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no. C04001; Shanghai

VivaCell Biosciences, Ltd.) was employed, whereas BT-549 and BT-474

cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (cat. no. C11875500BT;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS.

All cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator.

Lentivirus infection

The expression of BUB1B was first examined in normal

mammary epithelial cells and different breast cancer cell lines,

and, based on the experimental results, the MDA-MB-231 cell line

was selected for lentiviral infection in subsequent experiments, as

it had the highest expression of BUB1B. The lentiviral short

hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs, comprising non-targeting nonsense

negative control (NC) sequences and specific shBUB1B1/2/3 targeting

human genes, were acquired from Shanghai Hanhang Technology Co.,

Ltd. The shRNA sequences were as follows: NC: Top strand

5′-GATCCGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAATTCAAGAGATTACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAATTTTTTC,

bottom strand

5′-AATTGAAAAAATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAATCTCTTGAATTACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACG;

shBUB1B-1, top strand

5′-GATCCGAGACAACTAAACTGCAAATTCTCGAGAATTTGCAGTTTAGTTGTCTCTTTTTTG,

bottom

5′-AATTCAAAAAAGAGACAACTAAACTGCAAATTCTCGAGAATTTGCAGTTTAGTTGTCTCG-3′;

shBUB1B-2, top strand

5′-GATCCGCCAGTTCTGTTTGTCAAGTAACTCGAGTTACTTGACAAACAGAACTGGTTTTTTG-3′,

bottom strand

5′-AATTCAAAAAACCAGTTCTGTTTGTCAAGTAACTCGAGTTACTTGACAAACAGAACTGGCG-3′;

shBUB1B-3, top strand

5′-GATCCGCTGTATTGTTTGGCACCAATACTCGAGTATTGGTGCCAAACAATACAGTTTTTTG-3′,

bottom strand

5′-AATTCAAAAAACTGTATTGTTTGGCACCAATACTCGAGTATTGGTGCCAAACAATACAGCG-3′.

The second-generation lentiviral packaging system was used. All

vectors, reagents, and cell lines utilized for lentiviral packaging

were provided by Shanghai Hanhang Technology Co., Ltd. The plasmids

used for transfection included: pSPAX2: 10 µg, pMD2G: 5 µg,

pHBLV-U6-MCS-CMV-ZsGreen-PGK-PUROplasmid (carrying shRNA): 10 µg.

These plasmids were co-transfected into the 293T packaging cells

using a transfection reagent (Lipofiter™, 75 µl), and

the cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 h, after which, the viral

supernatant was collected by ultracentrifugation. The lentivirus

was then infected into MDA-MB-231 cells using the half-volume

infection method at a multiplicity of infection of 30, followed by

incubation in a 37°C incubator for 24 h. After replacing the

medium, the cells were cultured for a further 48 h and fluorescence

was observed under a fluorescence microscope. Stable infected cell

lines were selected by culturing the cells in medium containing 4

µg/ml puromycin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 7

days.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the MCF-10A,

MDA-MB-231, BT-549, MCF-7 and BT-474 cell using the Total RNA

Isolation Kit (cat. no. M5105; New Cell & Molecular Biotech).

Subsequently, the concentration and purity of the extracted RNA

were assessed with a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop

Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The extracted RNA

was stored at −80°C. cDNA was obtained from the extracted RNA using

the Script Reverse Transcription Supermix Kit (cat. no. RR047A;

Takara Bio, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Subsequently, qPCR was performed using the TB Green®

Fast qPCR Mix (cat. no. RR430A; Takara Bio, Inc.). The gene

expression levels were measured using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(27), with GAPDH serving as the

internal reference gene. The primer sequences utilized for

amplification were as follows: BUB1B, forward

5′-AAATGACCCTCTGGATGTTTGG-3′ and reverse

5′-GCATAAACGCCCTAATTTAAGCC-3′; and GAPDH, forward

5′-CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT-3′ and reverse

5′-GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT-3′.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis solution (cat. no.

P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and protein

supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was determined

using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The proteins (20 µg) were denatured by boiling and were

separated by SDS-PAGE on a 4.5% stacking gel and 7.5% resolving

gel. The proteins were subsequently transferred to a PVDF membrane,

which was blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature.

The membrane was then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C

overnight. On the next day, secondary antibody incubation was

performed, using HRP-labeled secondary antibodies (cat. nos. 511203

and 511103; 1:5,000; Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at

room temperature. After immersing the membrane in BeyoECL Plus

(cat. no. P0018S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) working

solution for 1 min, the bands were detected using a

chemiluminescence imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software

(version 1.54g; National Institutes of Health). The primary

antibodies used were against BUB1B (cat no. ab183496; 1:20,000;

Abcam), β-actin (cat. no. AB0035; 1:10,000; Shanghai Abways

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), E-cadherin (cat. no. 60335-1-Ig; 1:2,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), N-cadherin (cat. no. R380671; 1:500;

Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.), vimentin (cat. no. R22775;

1:500; Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.), RAD51 (cat. no. R27223;

1:500; Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.), PI3K (cat. no.

60225-1-Ig; 1:2,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.), AKT (cat. no.

60203-1-Ig; 1:2,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.), phosphorylated

(p)-PI3K (cat. no. 341468; 1:500; Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.)

and p-AKT (cat. no. R381555; 1:500; Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co.,

Ltd.).

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

A total of 5,000 cells was added to each well of a

96-well plate, and incubated in a 37°C incubator for 24, 48, 72 or

96 h. Subsequently, CCK-8 reagent (cat. no. A311-01; Vazyme Biotech

Co., Ltd.) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h.

Next, a microplate spectrophotometer was employed to measure the

absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Colony formation assay

To explore the development of cell colonies, cells

were distributed evenly across 6-well culture plates at a density

of 400 cell/.well and were incubated for 10–14 days under standard

culture conditions. The medium was changed and the cell status was

observed every 3 days. Colonies were defined as aggregates of ≥50

cells originating from a single progenitor cell and were manually

counted under a light microscope. The cell colonies were fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 15 min and

stained with 5% crystal violet solution at room temperature for 15

min. After washing with PBS three times, colony quantification and

photographic documentation were performed. Each experimental

condition was independently replicated three times, with

quantitative data normalized to the corresponding control

groups.

EdU staining

Cell proliferation capacity was measured with the

BeyoClick™ EdU-594 Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (cat.

no. C0078S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Cells were

inoculated into 6-well plates at a density of 2×105

cells/well and were incubated for 24 h in a 37°C incubator.

Subsequently, the cells were treated with pre-warmed (37°C) 2X EdU

working solution (20 µM) at equal volumes, achieving a final 1X EdU

concentration. After 2 h of incubation under standard culture

conditions, cellular samples were subjected to washing with PBS,

followed by 4% paraformaldehyde fixation for 30 min at room

temperature and 0.5% Triton X-100 permeabilization for 10 min at

room temperature. Next, a Click reaction solution was performed by

incubating the cells with 500 µl reaction mixture for 30 min in the

dark at room temperature. Nuclear counterstaining was accomplished

using 1,000 µl 1X Hoechst 33342 solution for 10 min in the dark at

room temperature. Fluorescence imaging was conducted using an

inverted fluorescence microscope, with quantification based on

positive cell counts from five randomly selected fields per

sample.

Xenograft tumor assay

A total of 10 BALB/c-nu female mice (age, 4 weeks;

weight, 16–20 g) from Guangxi Medical University Laboratory Animal

Center (Nanning, China) were selected for the experiment. The mice

were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment with a

temperature of 26–28°C, humidity of 40–60% and under a 12-h

light/dark cycle. The mice were fed an irradiated sterilized high

protein feed ad libitum, and the drinking water was

ultrapure water, with the water bottle changed daily. The Guangxi

Medical University Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee approved the

present animal studies (approval no. 202410013).

BALB/c nude mice were randomly allocated into two

groups (n=5/group): i) Control group receiving MDA-MB-231-NC cells

and ii) experimental group, inoculated with MDA-MB-231-shBUB1B

cells. A suspension containing 1×10⁶ cells in 100 µl PBS was

subcutaneously injected into the right axilla of each mouse. Tumor

growth was monitored every 3 days by measuring orthogonal diameters

with digital calipers, and tumor volume (TV) was calculated using

the ellipsoid formula: TV=1/2 × length × width2. Humane

endpoints were strictly enforced, and experiments were terminated

when mice had a tumor volume ≥1,500 mm3 or lost >20%

of their body weight. The experiment was terminated after 5 weeks

and no mice were sacrificed due to reaching the aforementioned

humane endpoints. Mice were anesthetized via an intraperitoneal

injection of 1.25% tribromoethanol (250 mg/kg body weight) and

euthanized by cervical dislocation. All animals died from

euthanasia. Death was confirmed by continuous observation of

respiratory movements for ≥5 min, including cessation of breathing

and absence of chest rise and fall, and loss of corneal and pain

reflexes.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, nude mouse tissue

specimens of xenograft tumor origin were incubated in 4%

paraformaldehyde solution for at room temperature 72 h, embedded in

paraffin and sectioned into 4-µm slices. Tissue sections then

underwent sequential processing (deparaffinization in xylene and

rehydration through an alcohol gradient series), and were soaked in

citrate buffer for 3 min for antigen retrieval. Bovine serum

albumin (BSA; cat no. G5001; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

was used to block the sections at room temperature for 30 min.

Subsequently, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies

against Ki67 (cat. no. AF20068; 1:200; Hunan Aifang Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) overnight at 4°C, and then with a Polymer-HRP anti-mouse

secondary antibody kit (cat. no. AFIHC002; Hunan Aifang

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at 37°C. DAB (cat. no.

AFIHC004; Hunan Aifang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) reagent was used

for staining, whereas for counterstaining, the sections were

incubated with hematoxylin at room temperature for 3 min, followed

by sequential dehydration through an ethanol gradient and xylene.

The staining was observed under a light microscope (E100; Nikon

Corporation). Panoramic scanning was performed under a 20X

objective lens using a DS-U3 imaging system (Nikon

Corporation).

TUNEL staining was performed using a TUNEL kit (cat.

no. AFIHC030-C; Hunan Aifang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) to evaluate

tissue apoptosis. The procedures for tissue fixation, paraffin

embedding, sectioning and antigen retrieval were the same as

aforementioned. Subsequently, a mixture of TDT enzyme and dUTP

(mixed at a ratio of 1:50) was used to cover the tissues, followed

by incubation at 37°C for 1–2 h. Nuclear staining was conducted at

room temperature using 20X DAB staining solution (cat no. AFIHC004;

Hunan Aifang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The staining was monitored

under a light microscope (cat no. E100; Nikon Corporation) and the

staining was terminated when brownish-yellow signals appeared. The

stained sections were subjected to panoramic scanning under a 20X

objective using the DS-U3 imaging system (Nikon Corporation).

Gap closure assay

Cell migration was evaluated using the ibidi

Culture-Insert 2 Well (cat no. 81176; ibidi GmbH). The inserts were

placed in 6-well plates, and each well was seeded with 70 µl cell

suspension containing 6×104 cells. After the cell

confluence reached 95%, the inserts were carefully removed. The

cell monolayer was then washed once with PBS and cultured in

serum-free medium. The gap area was captured using a light

microscope immediately after washing in PBS (designated as 0 h) and

was established as the baseline. Images of the same positions were

acquired at 12 and 24 h. The migratory capacity of the cells was

assessed by measuring the changes in the gap area using ImageJ

software (version 1.54g; National Institutes of Health, USA).

Transwell assay

Both Transwell invasion and migration assays were

performed. For the invasion assay, the bottom of the 24-well

Transwell inserts (pore size, 9 µm) were coated with Matrigel

(Corning, Inc.), whereas the migration assay inserts remained

uncoated. The Matrigel was thawed overnight in a refrigerator at

4°C, and the next day it was spread evenly on the bottom of the

chamber and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h to solidify. A total of

200 µl cells resuspended in serum-free DMEM (containing 2×10⁵

cells/well) were seeded into the upper chamber, and 600 µl complete

medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber.

After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the Transwell inserts were washed

twice with PBS. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 15 min at room temperature, followed by staining with crystal

violet for 15 min at room temperature. After rinsing the inserts

twice with PBS, the stained cells were visualized and images were

captured using a light microscope.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells (5×104) were inoculated in 6-well

plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The cells were then treated

with 8 Gy irradiation using a linear accelerator (Elekta Instrument

AB) at a dose rate of 1 Gy/min before the detection of γ-H2AX by

immunofluorescence assay. No irradiation was required for detection

of the other indicators. Upon rinsing with PBS, cells were fixed

using a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min at room

temperature. After fixation, cell permeability was induced by

treating the cells with a PBS solution containing 0.1% Triton

X-100. Next, to prevent non-specific binding, a blocking procedure

was carried out by incubating the cells with a 5% BSA solution for

30 min at room temperature. Once the blocking step was completed,

the cells were incubated with the following primary antibodies

overnight at 4°C: E-cadherin (cat. no. 60335-1-Ig; 1:200;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), N-cadherin (cat. no. 22018-1-AP; 1:200;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), vimentin (cat. no. R22775; 1:100; Chengdu

Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.) and γ-H2AX (cat. no. ab81299; 1:250;

Abcam). After rinsing with PBS, Alexa Fluor (AF)-conjugated Goat

Anti-Mouse lgG H&L (AF594) (cat. no. 550042; Positive Bio) and

Goat Anti-Rabbit lgG H&L (AF594) (cat. no. 550043; Positive

Bio) secondary antibodies were added (dilution, 1:500) and

incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Next, nuclear

counterstaining was carried out using DAPI (cat. no. G1012; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min at room temperature.

Finally, fluorescence imaging of the samples was performed using a

Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope (Zeiss AG).

Neutral comet assay

DNA damage analysis was conducted 2 h after 8 Gy

irradiation using a Comet Assay Kit (cat. no. KGA1302-20; Nanjing

KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). A total of 100 µl 1% normal melting

point agarose was added to the slide, followed by its

solidification at 4°C for 10 min. Next, a cellular suspension

containing 10⁵ cells and 75 µl 0.75% low melting point agarose were

combined, followed by solidification under identical temperature

conditions for 30 min. The slides were then immersed in lysis

buffer for 2 h at 4°C, and the samples were then electrophoresed

for 20 min at 22 V after being equilibrated for 30 min in a neutral

electrophoresis solution. Post-electrophoresis processing included

PBS immersion (pH 7.2–7.4) for 30 min at 4°C and propidium iodide

staining for 10 min at room temperature. Fluorescent images were

obtained with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss AG).

Quantitative analysis was performed using Comet Assay Software

Project (28) (version 1.2.3

beta1), counting 20 cells per group, and the olive tail moments

were shown.

Cell cycle analysis

A commercially available Cell Cycle Staining Kit

[cat. no. CCS012; Multisciences (Lianke) Biotech, Co., Ltd.] was

employed to assess the distribution of the cell cycle. Briefly,

2×10⁵ cells were inoculated in a 6-well dish, placed in an

incubator overnight. On the second day, the cells were treated with

8 Gy irradiation. Trypsin was used to collect cells at

predetermined times post-treatment (0, 12 and 24 h), followed by

washing in PBS and resuspension. Subsequently, 10 µl

permeabilization solution and 1 ml propidium iodide staining

solution (containing RNase A) were incorporated into the mixture

according to the Cell Cycle Staining Kit instructions. The

resulting combination was then incubated at room temperature for 10

min in the dark. Data were acquired using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer

(Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Upon data collection, assessment of the

cell cycle phases was carried out with the aid of FlowJo analysis

software (version 10.8.1; BD Biosciences).

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from NC and shBUB1B cells

using the MJZol Total RNA Extraction Kit (cat no. T01-200; Shanghai

Majorbio) at 8 h after 8 Gy irradiation. Subsequently, RNA quality

was determined using a 5300 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies,

Inc.) and RNA was quantified using the ND-2000 (NanoDrop; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The molar concentrations of libraries was

determined by fluorescence quantification (Qubit™ 4.0;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The final loading concentration

was adjusted to 2 nM, and 150 bp paired-end sequencing was

performed on the NovaSeq X Plus platform (PE150; Illumina, Inc.)

using the NovaSeq 6000 SP reagent kit (100 cycles; cat. no.

2002746; Illumina Inc.). Bioinformatics processing and initial data

analysis were performed by Shanghai Meiji Biological Co., Ltd.

DESeq2 software (http://bioconductor.org/packages/stats/bioc/DESeq2/)

was used to assess differential gene expression and significant

changes were found using two criteria: P<0.05 and |log2

fold-change|≥1. The Goatools program (https://github.com/tanghaibao/GOatools) was used for

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, and the Python SciPy

package (https://scipy.org/install/) was used

for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analysis.

Statistical analysis

All experimental procedures were independently

performed in triplicate, with representative results shown.

GraphPad Prism software version 10.0 (Dotmatics) was utilized to

conduct statistical comparisons. Comparisons between two groups

were performed using the two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. For

comparisons among multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by

Dunnett's post hoc test or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's

multiple comparisons test were applied. The quantitative outcomes

are presented as the mean ± standard. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

BUB1B is highly expressed in breast

cancer and is associated with poor prognosis

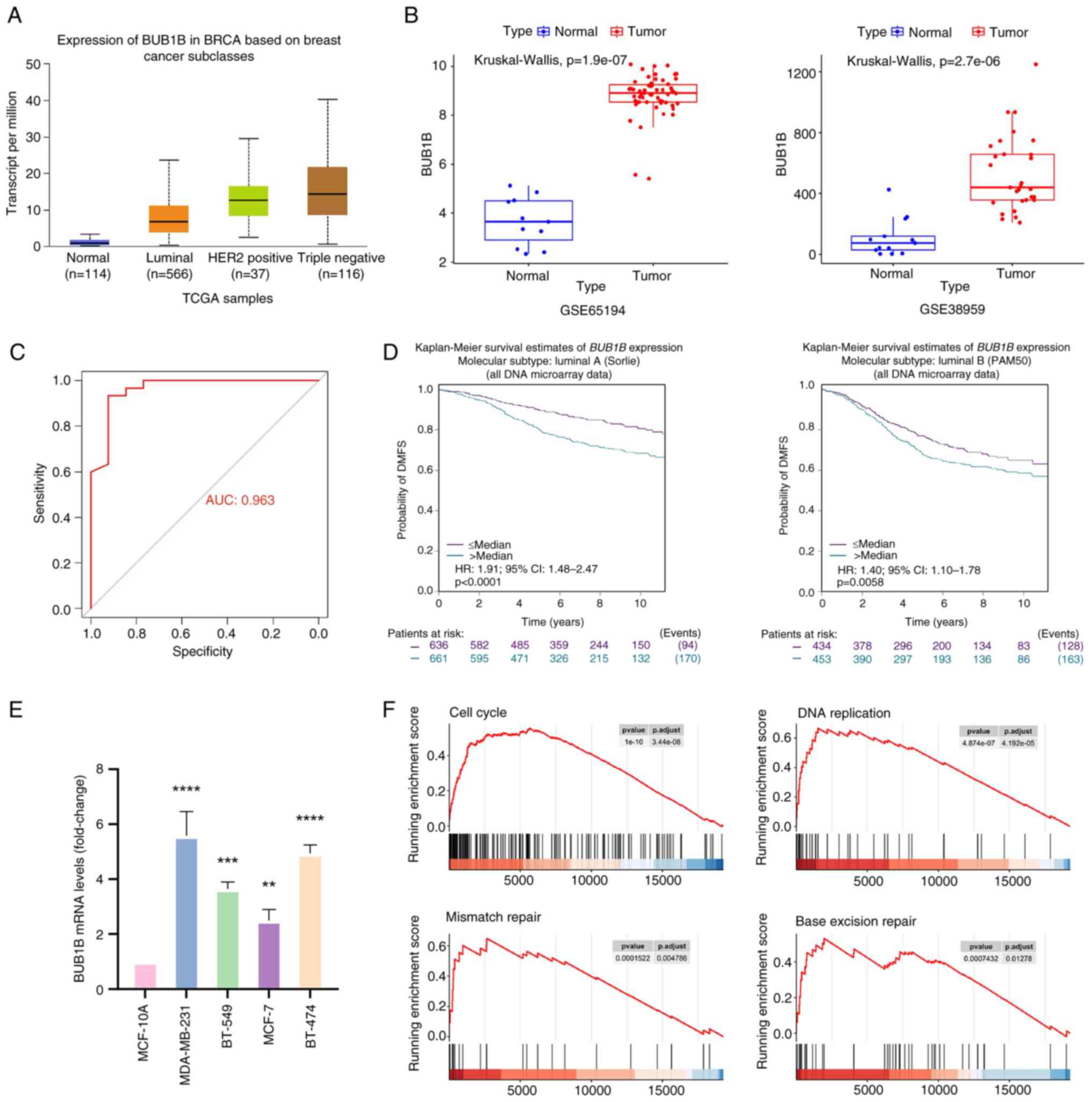

Analysis of the UALCAN database showed that the

expression levels of BUB1B were significantly higher in breast

cancer tissues compared with in the normal tissues of healthy

controls (Fig. 1A). Among them, the

expression levels of BUB1B were highest in triple-negative breast

cancer, followed by HER2-positive breast cancer, and it was lowest

in luminal breast cancer. Analysis of GEO datasets using the

Mann-Whitney U test revealed that BUB1B expression was markedly

higher in breast cancer tissues vs. normal breast tissues from

healthy controls in the GSE65194 dataset (Fig. 1B). Similarly, BUB1B gene expression

was significantly elevated in breast cancer cells compared with in

normal mammary ductal cells from healthy controls in the GSE38959

dataset (Fig. 1C). Based on the

mRNA expression levels, a ROC curve was generated (Fig. 1D). The area under the ROC curve was

calculated to be 0.963, which suggested that the mRNA levels of

BUB1B may effectively distinguish between patients with breast

cancer and healthy individuals.

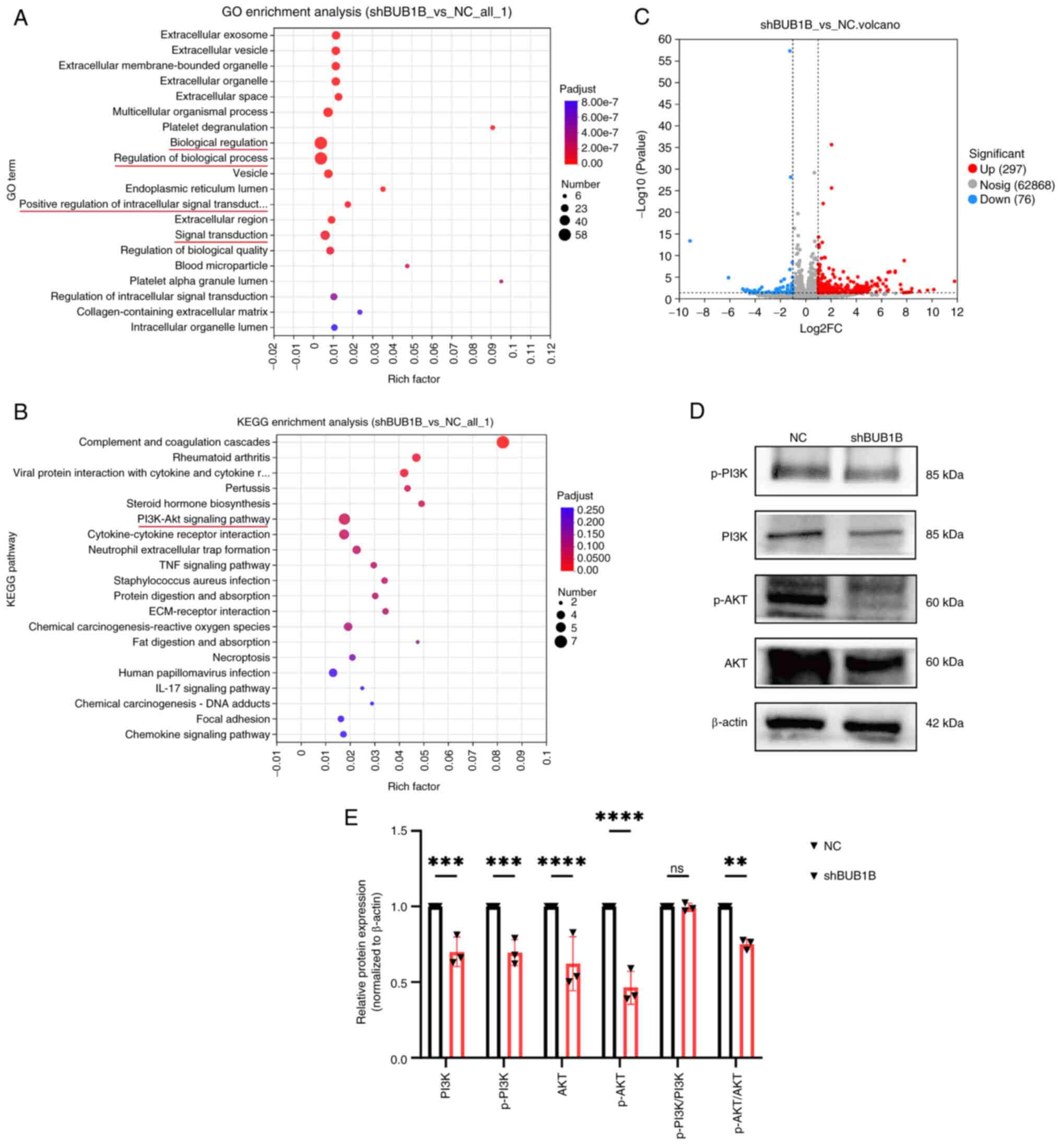

| Figure 1.BUB1B is highly expressed in breast

cancer and is associated with a poor prognosis. (A) BUB1B

expression in healthy and breast cancer tissues in the UALCAN

database. Compared with the Normal group, the P-values for Luminal,

HER2-positive and triple-negative groups were all <0.001. (B)

Expression levels of BUB1B in GSE38959 and GSE65194 datasets. (C)

Receiver operating characteristic curve based on BUB1B mRNA

expression levels. (D) bc-GenExMiner website was used to evaluate

the association between BUB1B and DMFS. (E) mRNA expression levels

of BUB1B in normal mammary epithelial and breast cancer cells. Data

are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001 vs. MCF-10A (one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's

post hoc test). (F) Comparative GSEA was conducted using

transcriptomics data from the GSE38959 dataset. Four representative

plots of GSEA enrichment have been demonstrated. AUC, area under

the curve; BUB1B, BUB1 mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine kinase

B; DMFS, distant metastasis-free survival; GSEA, gene set

enrichment analysis; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas. |

The prognostic value of BUB1B was assessed via

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank testing using

bc-GenExMiner. The present findings showed that higher BUB1B levels

were associated with a lower probability of distant metastasis-free

survival (DMFS) (Fig. 1D).

Additionally, BUB1B mRNA expression was quantified in normal

mammary epithelial cells (MCF-10A) and in multiple breast cancer

cell lines (MDA-MB-231, BT-549, MCF-7 and BT-474) using RT-qPCR.

The results demonstrated significantly elevated BUB1B mRNA levels

in all breast cancer cell lines compared with in normal mammary

epithelial cells (Fig. 1E).

Furthermore, GSEA of GEO datasets revealed that the expression of

BUB1B was associated with cell cycle, DNA replication, mismatch

repair and base excision repair (Fig.

1F). These results suggested that BUB1B may be associated with

biological processes, such as proliferation, cell cycle regulation

and DNA damage repair in breast cancer cells.

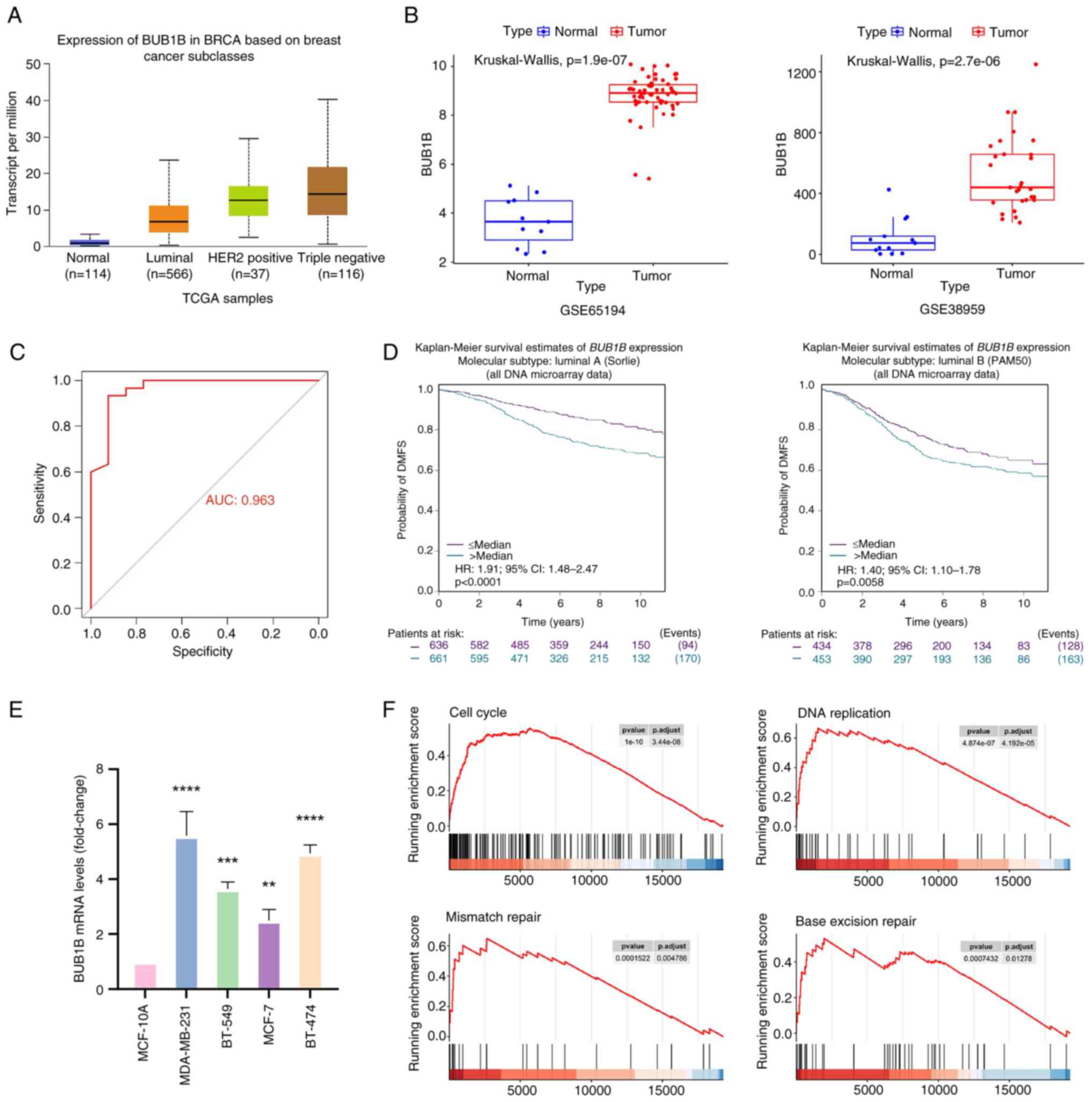

BUB1B induces MDA-MB-231 cell

proliferation in vivo and in vitro

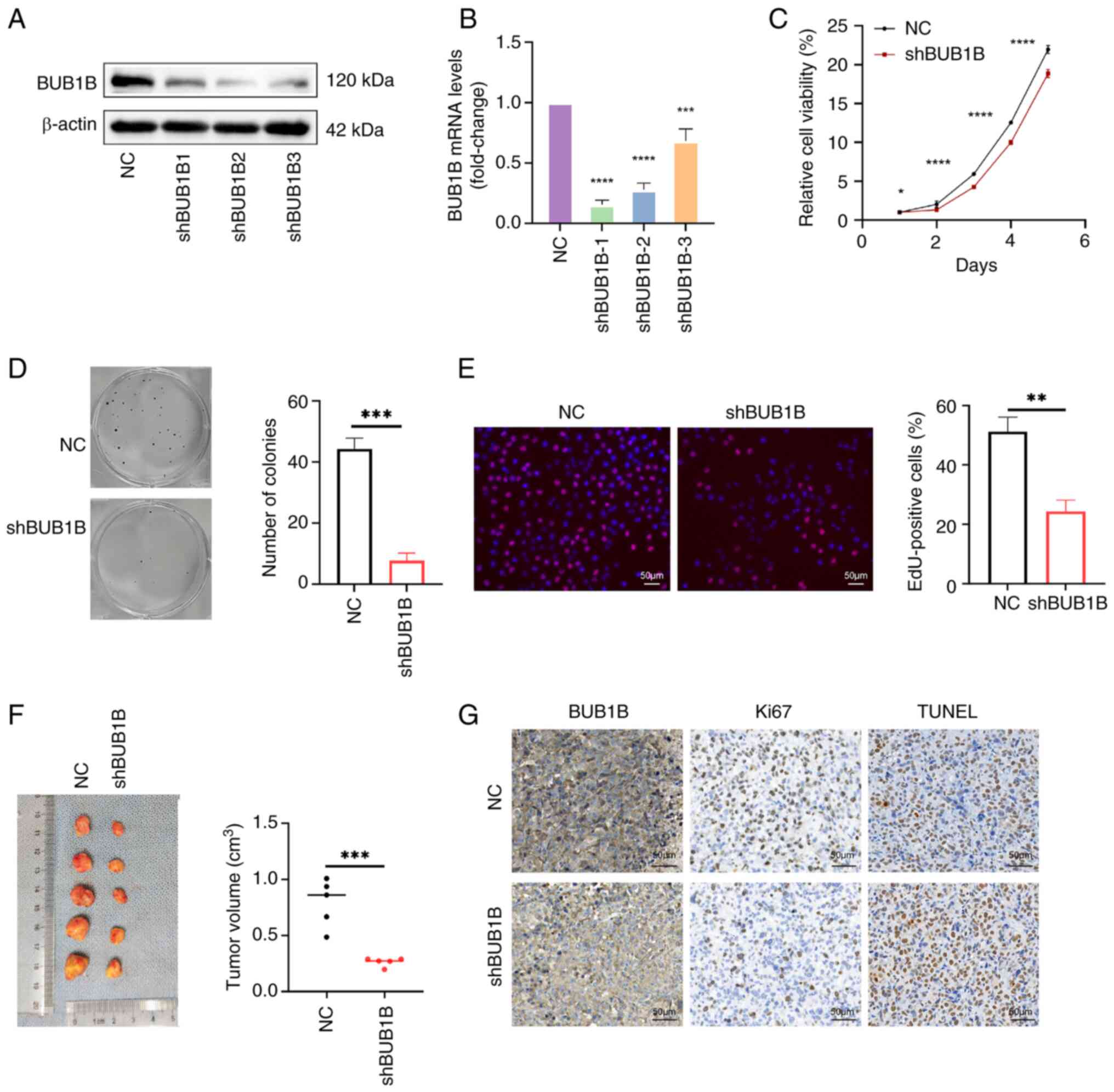

To investigate the role of BUB1B in breast cancer, a

stable knockdown of BUB1B was established in MDA-MB-231 cells

(Fig. 2A and B) and BUB1B knockdown

cell lines constructed using shRNA-2 were selected for cellular

experiments. To assess the impact of BUB1B knockdown on cell

proliferation under in vitro conditions, CCK-8 and colony

formation assays were employed. Knocking down BUB1B significantly

reduced MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation (Fig. 2C and D). EdU staining also

demonstrated that DNA replication was significantly suppressed by

BUB1B knockdown (Fig. 2E). To

evaluate the impact of BUB1B on tumor formation in living

organisms, nude mice were injected with MDA-MB-231 cells that

either exhibited normal BUB1B expression or had BUB1B knockdown.

The findings from the in vivo experiments were consistent

with the aforementioned in vitro findings. Specifically, the

results demonstrated that tumor growth was significantly reduced in

the BUB1B knockdown group compared with that in the control group

(Fig. 2F). Furthermore,

immunohistochemical analysis revealed that BUB1B suppression

resulted in decreased Ki67-positive proliferating cells and

elevated TUNEL-positive apoptotic cell populations (Fig. 2G). These results suggested that

knockdown of BUB1B may affect the growth of transplanted tumors

in vivo by inhibiting cell proliferation and promoting

apoptosis.

| Figure 2.BUB1B promotes the proliferation of

MDA-MB-231 cells in vivo and in vitro. BUB1B

expression in MDA-MB-231 cells stably infected with NC or shBUB1B

was detected by (A) western blotting and (B) reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs.

NC (one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test). (C) Cell

Counting Kit-8 assay was used to detect the proliferation of

MDA-MB-231 cells. *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001 vs. NC (two-way ANOVA

followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test). (D) Colony

formation assay was used to detect the colony-forming ability of

MDA-MB-231 cells. ***P<0.001 vs. NC (unpaired Student's t-test).

(E) EdU assay of DNA replication in MDA-MB-231 cells. Scale bar, 50

µm; magnification, ×200. **P<0.01 vs. NC (unpaired Student's

t-test). (B-E) Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. (F)

Xenograft tumor assay validated the effect of BUB1B on cell

proliferation in vivo. Data are presented as the mean ± SD,

n=5. ***P<0.001 vs. NC (unpaired Student's t-test). (G) TUNEL

and Ki67 were detected by immunohistochemical staining in tumor

tissues. Scale bar, 50 µm; magnification, ×200. BUB1B, BUB1 mitotic

checkpoint serine/threonine kinase B; NC, negative control; sh,

short hairpin. |

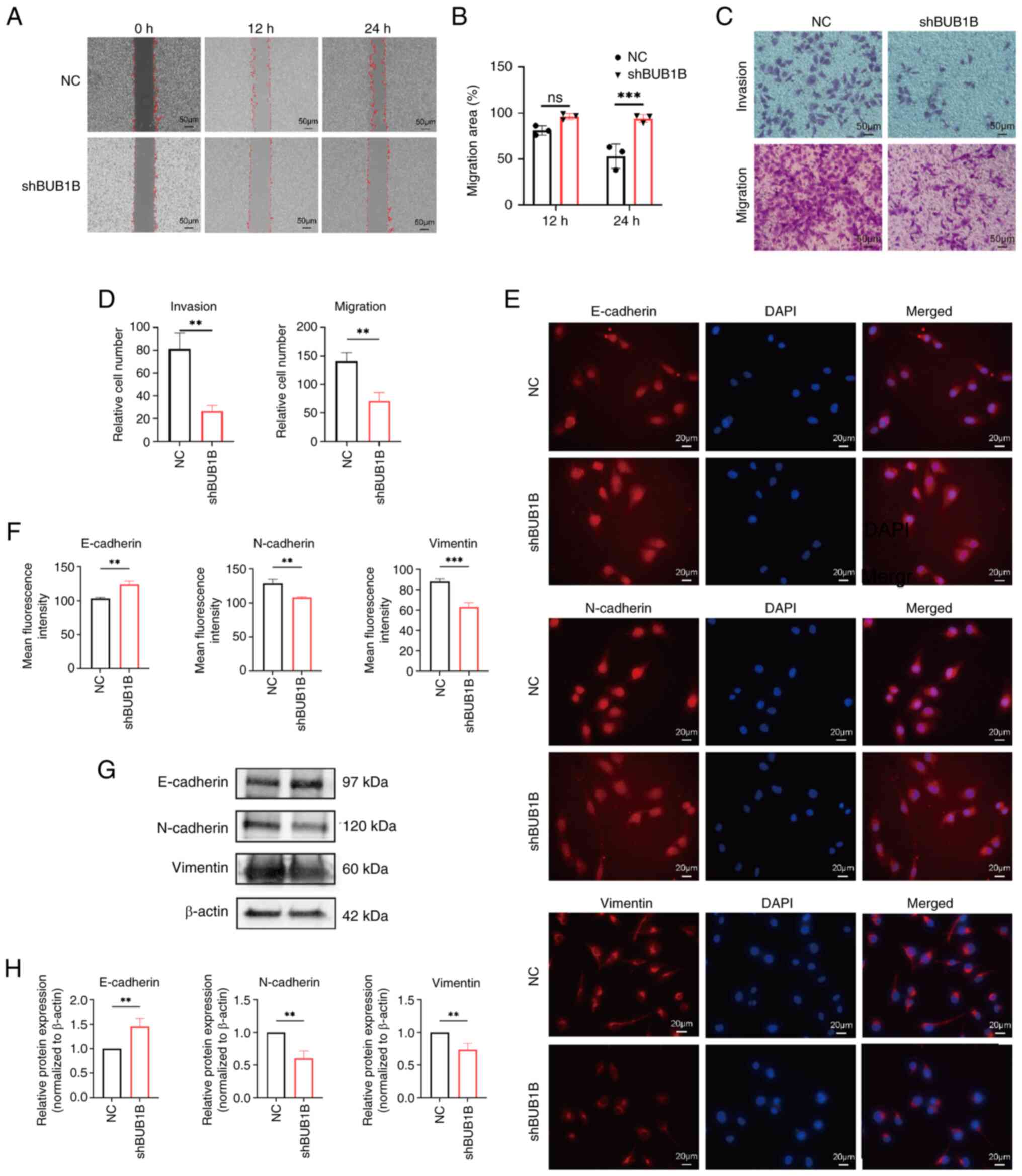

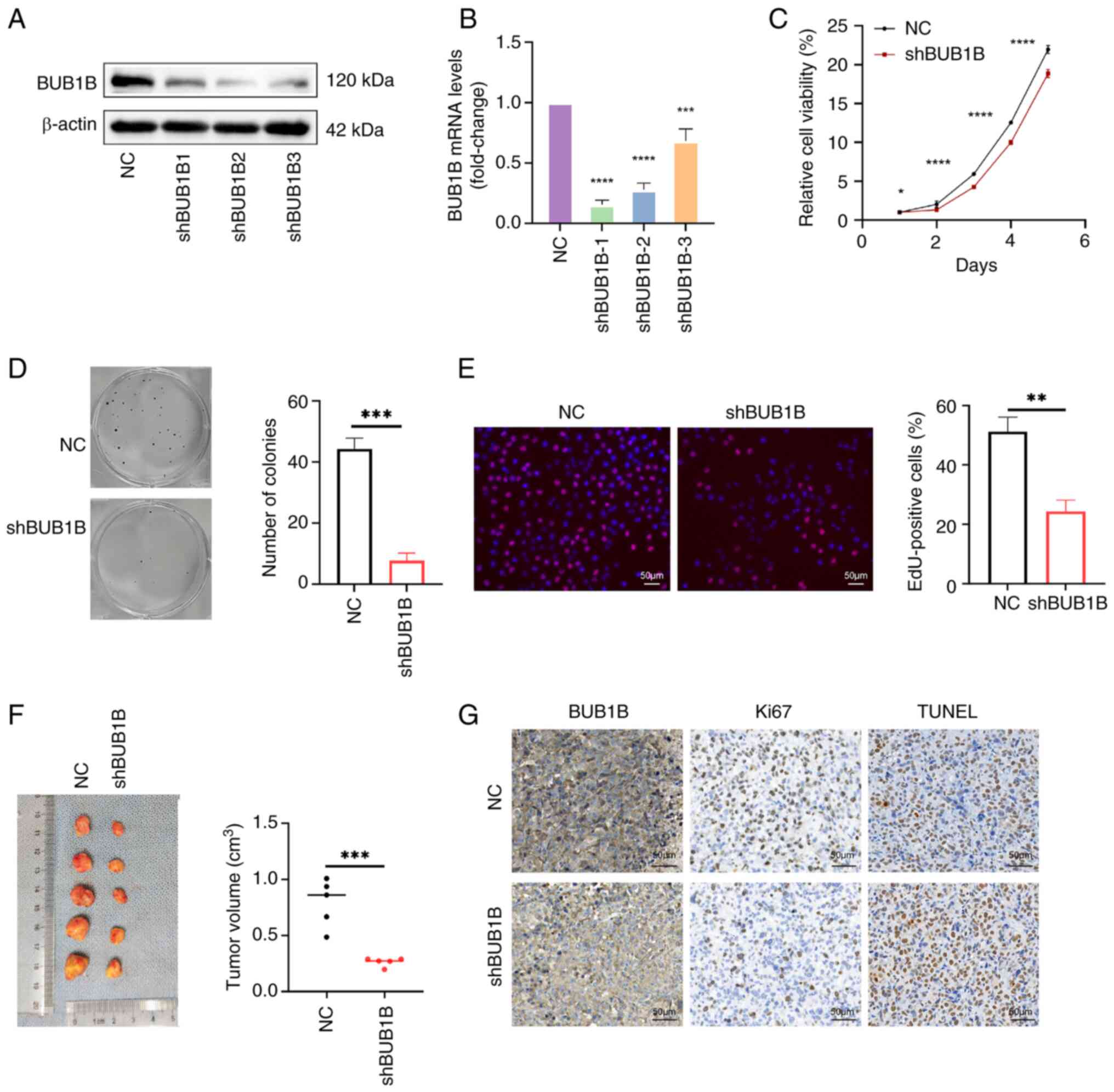

BUB1B promotes the migration and

invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells

Gap closure and Transwell migration assays were used

to assess the influence of BUB1B on the migratory and invasive

capabilities of breast cancer cells. The findings indicated that

downregulation of BUB1B expression suppressed the migration and

invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig.

3A-D). Immunofluorescence assay was utilized to verify the

influence of BUB1B on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

of breast cancer cells. The findings showed that, when BUB1B was

knocked down in MDA-MB-231 cells, the expression levels of the

epithelial marker E-cadherin were significantly increased, whereas

the levels of mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin and vimentin) were

decreased, compared with those in the NC group (Fig. 3E and F). This result was further

verified by western blot analysis (Fig.

3G and H). These findings suggested that knocking down BUB1B

may inhibit the invasion and metastatic potential of breast cancer

cells through modulating the EMT process.

| Figure 3.BUB1B promotes the migration and

invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Representative images and (B)

quantitative analysis of cell migration assessed using the gap

closure assay. Scale bar, 50 µm; magnification, ×200. ***P<0.001

vs. NC (two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons

test). (C) Representative images and (D) quantitative analysis of

migratory and invasive capacity of cells detected by Transwell

assay. Scale bar, 50 µm; magnification, ×200. **P<0.01 vs. NC

(unpaired Student's t-test). (E) Representative immunofluorescence

staining images of the EMT markers E-cadherin, N-cadherin and

vimentin. (F) Semi-quantitative analysis of NC and shBUB1B cells

after irradiation. Scale bar, 20 µm; magnification, ×400.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC (unpaired Student's t-test). (G)

Representative images and (H) semi-quantitative analysis of the EMT

markers E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin detected by western

blot analysis. **P<0.01 vs. NC (unpaired Students' t-test). All

data are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. BUB1B, BUB1 mitotic

checkpoint serine/threonine kinase B; NC, negative control; sh,

short hairpin. |

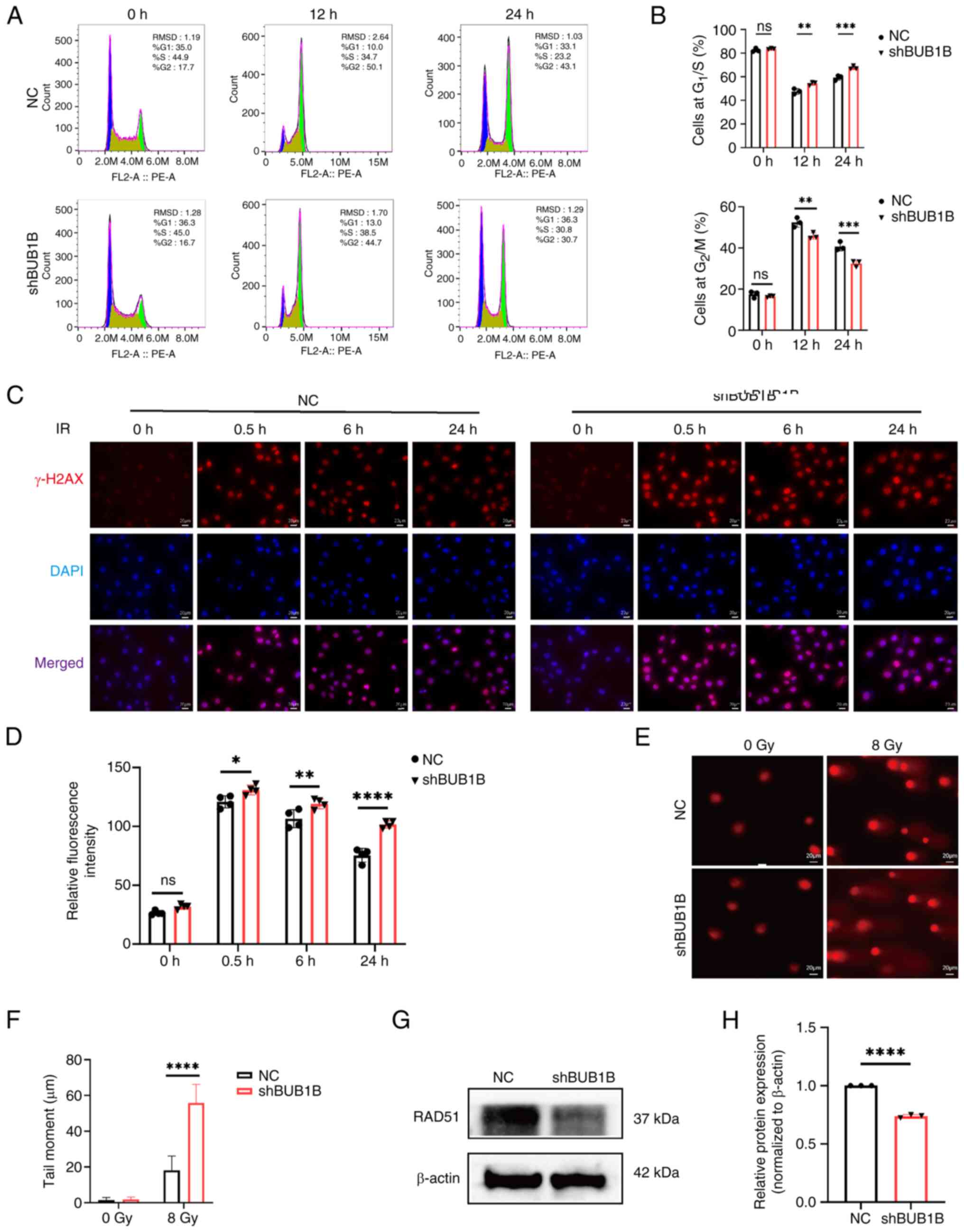

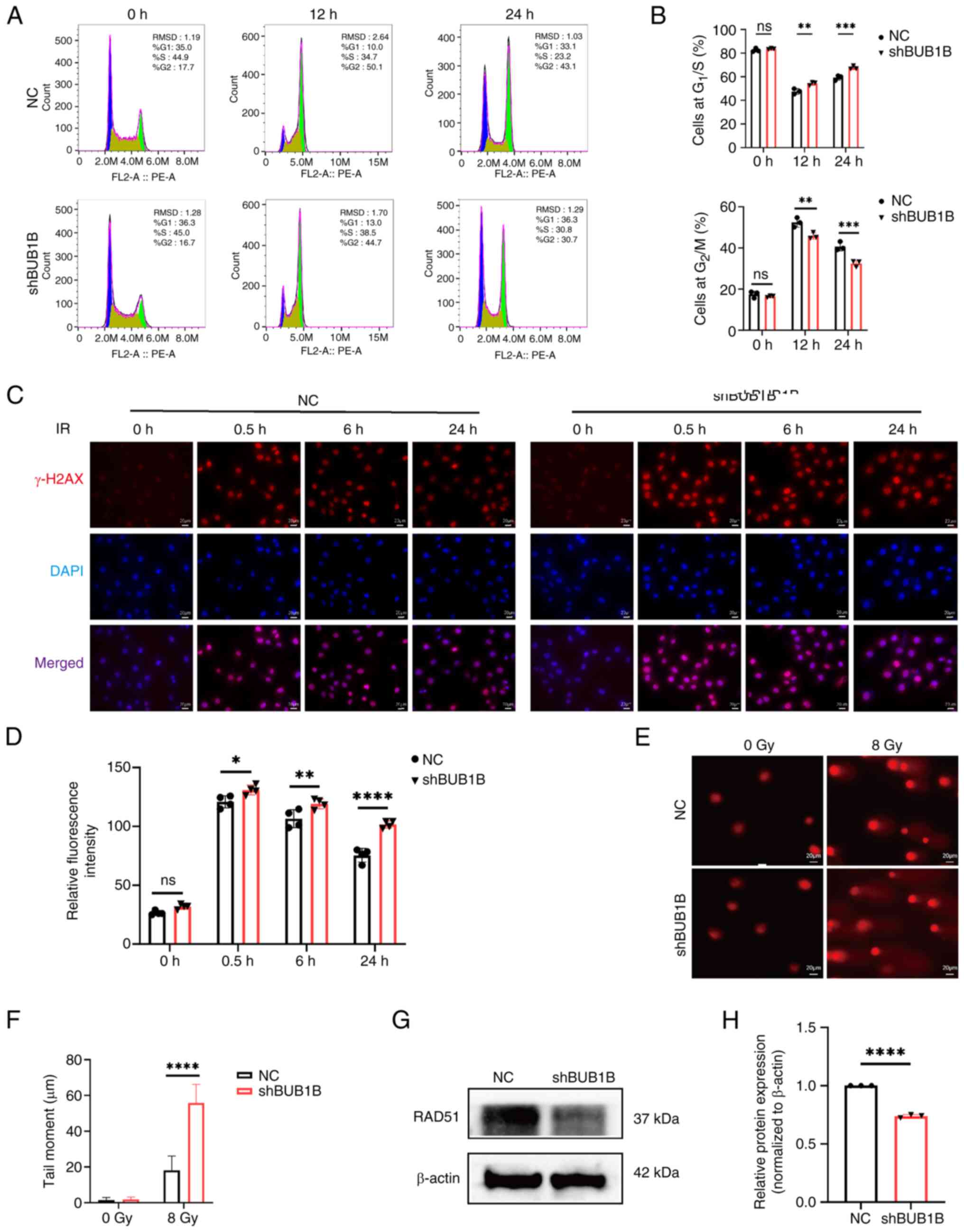

BUB1B promotes cell cycle arrest in

breast cancer cells after irradiation

There is a close association between

radiosensitivity and regulation of the cell cycle (29). Flow cytometry was employed to assess

the impact of BUB1B on the cell cycle after exposure to ionizing

radiation. The results indicated that, upon treatment with ionizing

radiation, in contrast to NC cells, shBUB1B cells exhibited an

increased proportion in the G1/S phase and a concomitant

decrease in the G2/M phase (Fig. 4A and B). These results indicated

that breast cancer cells mainly underwent G2/M phase

cycle arrest when exposed to radiation. Notably, compared with that

in the NC group, the percentage of BUB1B-silenced cells in

G2/M phase was considerably lower. These findings

indicated that silencing BUB1B could impede the G2/M

phase arrest triggered by ionizing radiation.

| Figure 4.BUB1B serves an importatn role in the

cell cycle arrest and DNA damage repair after irradiation. (A)

Representative flow cytometry plots of cell cycle analysis and (B)

quantitative analysis of NC and shBUB1B cells after irradiation.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC (two-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test). (C) Representative γ-H2AX

immunofluorescence images and (D) semi-quantitative analysis of NC

and shBUB1B cells after irradiation. Scale bar, 20 µm;

magnification, ×400. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs.

NC (two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons

test). (A-D) Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. (E)

Representative images of the comet assay and (F) tail moment

quantification analysis in MDA-MB-231 cells in the NC and shBUB1B

groups after irradiation. Data are presented as the mean ± SD,

n=20. Scale bar, 20 µm; magnification, ×400. ****P<0.0001 vs. NC

(unpaired Student's t-test). (G) Representative images and (H)

semi-quantitative analysis of RAD51 protein levels detected by

western blot analysis. ****P<0.0001 vs. NC (unpaired Student's

t-test). All data are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. BUB1B, BUB1

mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine kinase B; IR, ionizing

radiation; NC, negative control; sh, short hairpin. |

BUB1B promotes DNA damage repair in a

HR-biased manner

The primary mechanism of action of radiation therapy

is to cause notable DNA damage (30); therefore, the present study examined

how BUB1B contributes to DNA repair. Immunofluorescence was used to

assess the expression levels of γ-H2AX, a conventional DNA

double-strand break marker, in MDA-MB-231 cells. The results

revealed that cells with BUB1B knockdown had higher levels of

γ-H2AX than NC cells (Fig. 4C and

D). After irradiation with 8 Gy, the comet assay was employed

to detect DSBs. Compared with in the NC cell group, BUB1B-knockdown

cells had a longer olive tail moment (Fig. 4E and F), which indicated that BUB1B

knockdown cells may have more pronounced DNA double-strand breaks.

Together, these results suggested that BUB1B knockdown cells were

more severely DNA damaged than NC cells after irradiation.

HR and NHEJ have been reported to be the two main

pathways of cellular DSB repair. The present study confirmed that

BUB1B knockdown can inhibit irradiation-induced G2/M

phase arrest, which primarily affects cellular HR repair.

Therefore, the study further examined the effect of BUB1B knockdown

on RAD51, a key protein in the HR repair pathway, through western

blot analysis. The results revealed that BUB1B knockdown

significantly suppressed the expression levels of RAD51 (Fig. 4G and H). These results indicated

that BUB1B may promote the repair of DNA damage via HR, which could

offer a novel mechanism for DNA damage repair.

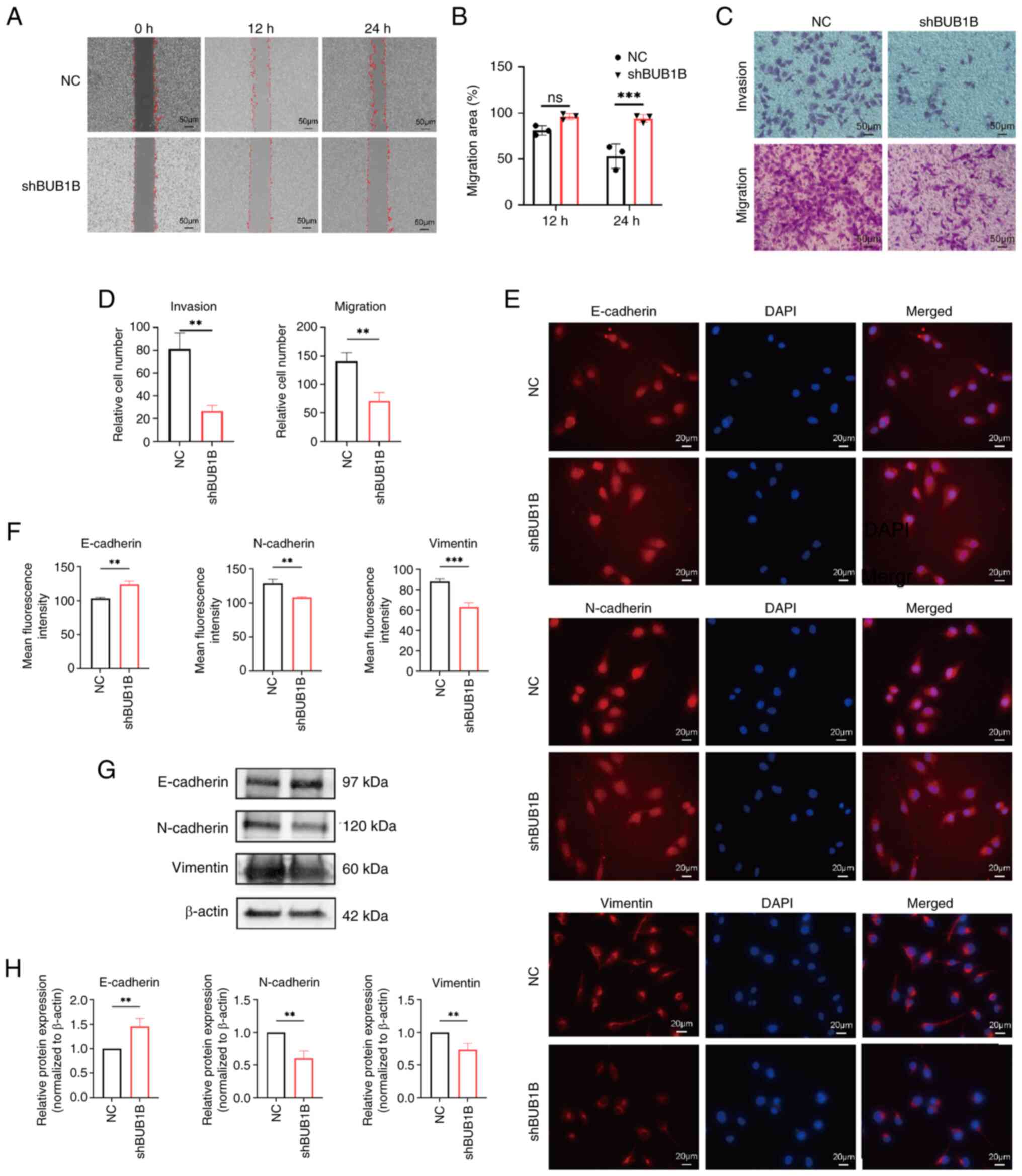

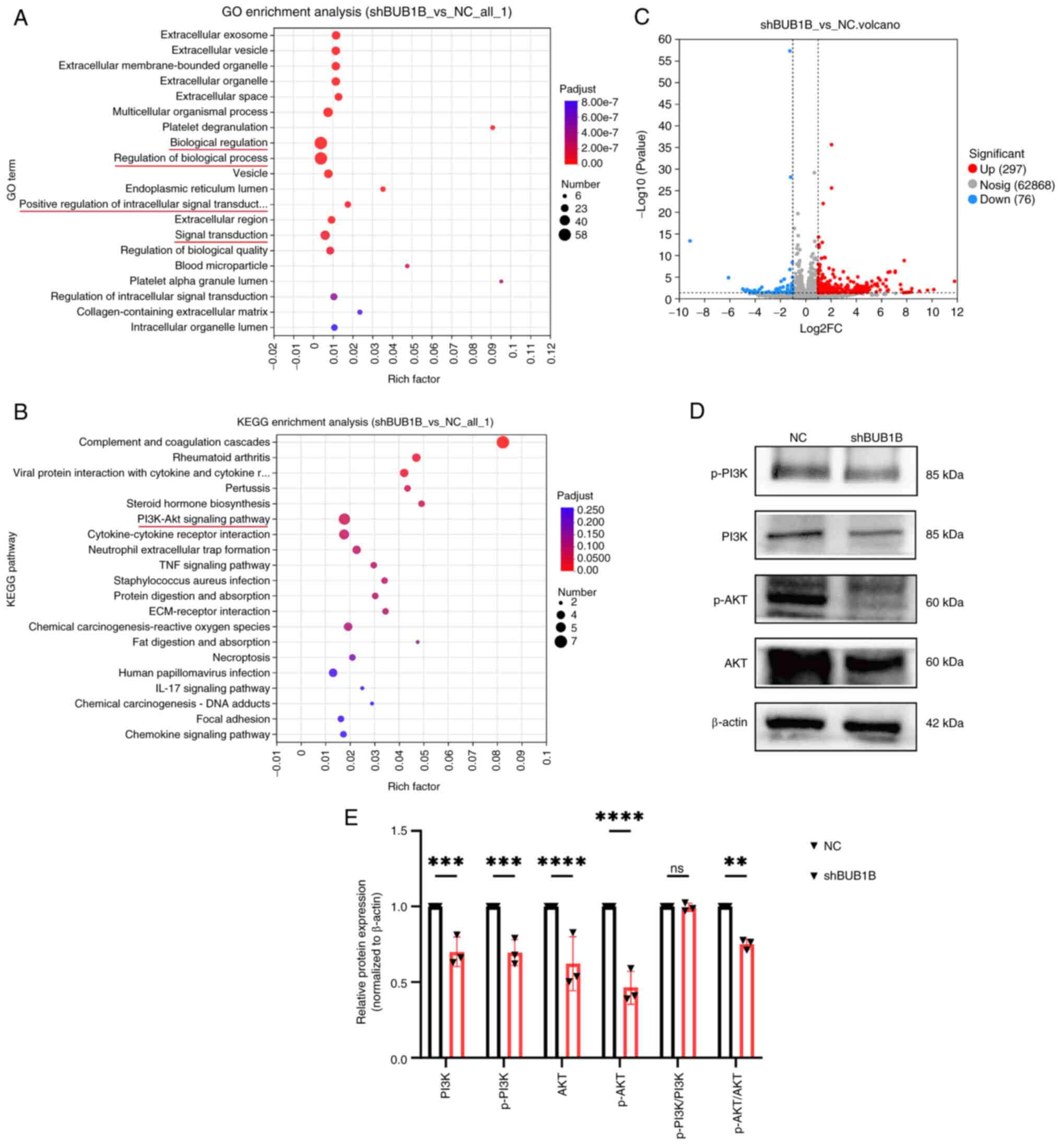

BUB1B regulates the expression of the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

To further identify the potential signaling pathways

regulated by BUB1B, differentially expressed genes were screened in

irradiated NC and BUB1B-knockdown cells by RNA sequencing, and GO

and KEGG analyses were performed. The results showed that 297 genes

were upregulated and 76 were downregulated in the BUB1B-knockdown

group compared with in the NC group (Fig. 5C). Further GO functional analysis

revealed that the differentially expressed genes were mainly

involved in functions such as ‘regulation of cellular biological

processes’ and ‘signal transduction’ (Fig. 5A). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

revealed that the activity of the ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’ was

associated with the BUB1B expression level (Fig. 5B). Several core proteins involved in

the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway were detected by western blotting.

The results showed that the protein levels of PI3K, AKT, p-PI3K and

p-AKT were significantly reduced in MDA-MB-231 cells after

downregulation of BUB1B expression (Fig. 5D and E). These data suggested that

BUB1B regulates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

| Figure 5.BUB1B regulates the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway. (A) GO and (B) KEGG enrichment analyses of

differentially expressed genes in irradiated shBUB1B MDA-MB-231

cells vs. irradiated NC MDA-MB-231 cells. (C) After irradiation, a

volcano plot of the genes that were differentially expressed in

irradiated shBUB1B MDA-MB-231 cells vs. irradiated NC MDA-MB-231

cells was generated (P<0.05, |log2FC|≥1). (D) Representative

images and (E) semi-quantitative analysis of the protein levels in

the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway determined by western blotting. Data

are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001 vs. NC (two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's

multiple comparisons test. BUB1B, BUB1 mitotic checkpoint

serine/threonine kinase B; GO, Gene Ontology; IR, ionizing

radiation; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NC,

negative control; ns, not significant; p-, phosphorylated; sh,

short hairpin. |

Discussion

The present results suggested that BUB1B is

upregulated in breast cancer, with higher expression levels

significantly associated with poorer patient survival. Functional

knockdown of BUB1B suppressed breast cancer cell proliferation,

invasion, migration and tumorigenic potential. In addition, BUB1B

was suggested to be a key regulator of radioresistance in breast

cancer: BUB1B knockdown attenuated radiation-induced

G2/M cell cycle arrest and impaired HR-mediated DNA

damage repair following irradiation. Collectively, these findings

indicated that BUB1B may modulate breast cancer radiosensitivity by

orchestrating cell cycle progression and DNA repair capacity,

establishing it as a promising therapeutic target for improving

radiation efficacy in breast cancer treatment.

Increasing evidence has indicated that BUB1B drives

malignant progression in hepatocellular carcinoma, extrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma and renal cell carcinoma by

promoting cell proliferation and oncogenic signaling pathways,

which is associated with poor patient prognosis (19,20,31,32).

For example, in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, aberrant BUB1B

upregulation is significantly associated with a shorter overall

survival and disease-free survival. Mechanistically, BUB1B promotes

tumor cell proliferation, migration and invasion via activation of

the JNK/c-Jun signaling axis (19).

Additionally, knockdown of BUB1B in human breast cancer cells has

been shown to inhibit carcinomatous growth and induce chromosomal

abnormalities (33). These findings

align with the current study, which confirmed that BUB1B was

upregulated in breast cancer and demonstrated a significant

association between high BUB1B expression and shorter DMFS.

Functional analyses further revealed that BUB1B may enhance breast

cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness. Collectively, these

results established BUB1B as a tumor promoter with critical

prognostic significance in breast cancer. The long-term effects of

BUB1B on breast cancer cells, including tumor recurrence and

metastasis, require further validation in the future by

constructing nude mouse metastatic tumor models.

Certain studies have proposed that BUB1B is involved

in radioresistance in malignant tumors, but its biological

mechanism remains controversial. For example, Komura et al

(23) showed that, in bladder

cancer, BUB1B interacts with ATM proteins to enhance cellular DNA

damage repair via mutagenic NHEJ, leading to radioresistance in

bladder cancer. Ma et al (22) demonstrated that, in glioblastoma,

FOXM1 transcriptionally regulates BUB1B expression, thereby

inducing tumor cell radioresistance. By contrast, treatment with a

FOXM1 inhibitor could attenuate tumor radioresistance in

vitro and in vivo (22).

The present findings support the hypothesis that increased BUB1B

expression is associated with the development of radioresistance.

In the current study, GSEA indicated that BUB1B may modulate cell

cycle progression and DNA damage repair. Molecular biology

experiments validated that BUB1B knockdown reduced

irradiation-induced G2/M phase arrest and exacerbated

DNA damage in cells. DNA damage repair is dependent on HR and NHEJ

(34,35). G2/M phase arrest provides

a temporal window for HR repair, such that inhibiting

G2/M arrest predominantly impairs HR repair efficiency.

As RAD51 is a major component of HR-mediated DNA repair, the

present study demonstrated that BUB1B knockdown downregulated

IR-induced RAD51 protein expression, thus suggesting that BUB1B

knockdown may modulate breast cancer radiosensitivity by

suppressing HR-mediated DNA damage repair. However, the impact of

BUB1B knockdown on DNA damage repair efficiency currently lacks

more direct experimental validation, such as verification using the

direct repeat-green fluorescent protein reporter assay system.

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway serves an important

role in regulating tumor proliferation, invasion and apoptosis

(36–38). Previous research has shown that

activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is also associated with tumor

radiotherapy resistance (39).

Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway has been reported to increase

the radiosensitivity of cancer cells in different types of tumor,

including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (40), non-small cell lung cancer (41), oral squamous cell carcinoma

(42) and glioblastoma (43,44).

In breast cancer, No et al (45) showed that inhibition of the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway can enhance the radiosensitivity of

SKBR3 cells by inhibiting DNA damage repair, suggesting that the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway may be a key pathway influencing

radioresistance in breast cancer. The present results of

transcriptome sequencing analysis suggested that the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway may be a downstream signaling pathway regulated

by BUB1B. Further studies demonstrated that the expression levels

of PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT and p-AKT were downregulated in

BUB1B-knockdown breast cancer cell lines. The concurrent reduction

in both total and phosphorylated levels of PI3K/AKT upon BUB1B

knockdown may be attributed to the synergistic interplay of

multiple mechanisms. BUB1B may enhance the expression of total

PI3K/AKT proteins through interactions with transcription

regulatory factors, or alternatively, it could modulate their total

protein levels by suppressing ubiquitin-mediated degradation. The

decreased phosphorylated forms (p-PI3K, p-AKT) might either

represent a secondary effect of reduced total protein abundance or

result from the direct regulation of phosphorylation-related

machinery by BUB1B. These results demonstrated that BUB1B may serve

as an upstream regulator of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

Collectively, the findings of the current study lead to a

reasonable speculation that BUB1B may promote cell cycle arrest and

DNA damage repair in breast cancer cells by activating the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway, thereby contributing to radioresistance.

Therefore, the combined inhibition of BUB1B and targeted

suppression of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway could represent an

effective strategy for radiosensitization in breast cancer.

PARP inhibitors exert therapeutic effects in tumors

with HR repair deficiencies through synthetic lethality, such as in

BRCA1/2-mutated breast and ovarian cancer (46). However, they exhibit limited

efficacy in tumors with intact HR repair function. The present

study demonstrated that BUB1B knockdown inhibited the HR repair

pathway by downregulating RAD51, a key protein in HR repair. The

current findings highlight the potential of combining BUB1B

inhibition with PARP inhibitors for treating cancer insensitive to

PARP inhibitors alone.

The present study has the following limitations:

Firstly, in terms of clinical validation, the current study lacks

validation of the expression level of BUB1B in clinical samples and

its association with clinical parameters, such as patient prognosis

and treatment response. Secondly, at the experimental model level,

the functional validation in the present study was only performed

in the MDA-MB-231 cell line, and further validation in other breast

cancer cell models is needed. Furthermore, when validating the

effect of BUB1B on DNA damage repair efficiency, a control group

using DNA damage repair inhibitors was lacking. Additionally, since

both immunofluorescence and western blotting are protein-level

verification experiments, only immunofluorescence verification of

γ-H2AX was performed, not western blotting. In addition, at the

level of molecular mechanism, the detailed mechanism underlying the

regulatory effects of BUB1B on the PI3K/AKT pathway remains to be

identified and verified by further experiments. Despite the

aforementioned limitations, the present study contributed to an

increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms of breast

cancer radiosensitivity, and provides novel molecular targets and

experimental bases for the in-depth exploration of the regulatory

network of tumor radiosensitivity.

In conclusion, the present study identified BUB1B as

a gene associated with breast cancer radiotherapy resistance, which

is involved in cellular DNA damage repair, especially HR repair, by

regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. The current findings

provide a novel mechanism for breast cancer radiotherapy resistance

and suggest that BUB1B may be a potential target for improving the

efficacy of breast cancer radiotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Lin Yuan

(Guangxi Medical University) for providing the laboratory.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research and

Technology Development Program (grant no. Guike AB24010055) of the

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. This research was also supported

by the following grants: Guangxi Project for the Development and

Promotion of Appropriate Traditional Chinese Medicine Technologies

(grant no. GZSY22-70); Guangxi Project for the Development and

Application of Appropriate Medical and Health Technologies (grant

no. S2018008); and the Wuming District, Nanning City Scientific

Research and Technology Development Program (grant no.

20220117).

Availability of data and materials

The RNA-sequencing data generated in the present

study may be found in the NCBI BioProject database under accession

number PRJNA1277467 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1277467.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XL and WZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. XL conceptualized the study, developed the methodology,

conducted the investigations and drafted the original manuscript.

YW performed the investigations, and contributed to visualization

and data curation. HL carried out validation and formal analysis.

NX conducted the investigations and contributed to visualization.

WZ conceptualized the study, provided supervision, secured funding,

and revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The experimental protocols involving animal subjects

were carried out in compliance with ethical guidelines and received

formal approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee at Guangxi Medical University (Ethical Approval Number

202410013).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Filho AM, Laversanne M, Ferlay J, Colombet

M, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Parkin DM, Soerjomataram I and Bray F: The

GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer estimates: Data sources, methods, and a

snapshot of the cancer burden worldwide. Int J Cancer.

156:1336–1346. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Peng L, Jiang J, Tang B, Nice EC, Zhang YY

and Xie N: Managing therapeutic resistance in breast cancer: From

the lncRNAs perspective. Theranostics. 10:10360–10377. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen S, Paul MR, Sterner CJ, Belka GK,

Wang D, Xu P, Sreekumar A, Pan T, Pant DK, Makhlin I, et al: PAQR8

promotes breast cancer recurrence and confers resistance to

multiple therapies. Breast Cancer Res. 25:12023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Azria D, Brengues M, Gourgou S and

Bourgier C: Personalizing breast cancer irradiation using biology:

From bench to the accelerator. Front Oncol. 8:832018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Vaidya JS, Bulsara M, Baum M, Wenz F,

Massarut S, Pigorsch S, Alvarado M, Douek M, Saunders C, Flyger HL,

et al: Long term survival and local control outcomes from single

dose targeted intraoperative radiotherapy during lumpectomy

(TARGIT-IORT) for early breast cancer: TARGIT-A randomised clinical

trial. BMJ. 370:m28362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sousa C, Cruz M, Neto A, Pereira K,

Peixoto M, Bastos J, Henriques M, Roda D, Marques R, Miranda C, et

al: Neoadjuvant radiotherapy in the approach of locally advanced

breast cancer. ESMO Open. 4 (Suppl 2):e0006402020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Huang RX and Zhou PK: DNA damage response

signaling pathways and targets for radiotherapy sensitization in

cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wu Y, Song Y, Wang R and Wang T: Molecular

mechanisms of tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Mol Cancer.

22:962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu J, Bi K, Yang R, Li H, Nikitaki Z and

Chang L: Role of DNA damage and repair in radiation cancer therapy:

A current update and a look to the future. Int J Radiat Biol.

96:1329–1338. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Piotto C, Biscontin A, Millino C and

Mognato M: Functional validation of miRNAs targeting genes of DNA

double-strand break repair to radiosensitize non-small lung cancer

cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 1861:1102–1118. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Santivasi WL and Xia F: Ionizing

radiation-induced DNA damage, response, and repair. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 21:251–259. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

van Oorschot B, Granata G, Di Franco S,

Ten Cate R, Rodermond HM, Todaro M, Medema JP and Franken NAP:

Targeting DNA double strand break repair with hyperthermia and

DNA-PKcs inhibition to enhance the effect of radiation treatment.

Oncotarget. 7:65504–65513. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Dietlein F, Thelen L and Reinhardt HC:

Cancer-specific defects in DNA repair pathways as targets for

personalized therapeutic approaches. Trends Genet. 30:326–339.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mekonnen N, Yang H and Shin YK: Homologous

recombination deficiency in ovarian, breast, colorectal,

pancreatic, non-small cell lung and prostate cancers, and the

mechanisms of resistance to PARP inhibitors. Front Oncol.

12:8806432022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Panier S and Boulton SJ: Double-strand

break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

15:7–18. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tian J, Wen M, Gao P, Feng M and Wei G:

RUVBL1 ubiquitination by DTL promotes RUVBL1/2-β-catenin-mediated

transcriptional regulation of NHEJ pathway and enhances radiation

resistance in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 15:2592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chan Wah Hak CML, Rullan A, Patin EC,

Pedersen M, Melcher AA and Harrington KJ: Enhancing anti-tumour

innate immunity by targeting the DNA damage response and pattern

recognition receptors in combination with radiotherapy. Front

Oncol. 12:9719592022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Karess RE, Wassmann K and Rahmani Z: New

insights into the role of BubR1 in mitosis and beyond. Int Rev Cell

Mol Biol. 306:223–273. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jiao CY, Feng QC, Li CX, Wang D, Han S,

Zhang YD, Jiang WJ, Chang J, Wang X and Li XC: BUB1B promotes

extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma progression via JNK/c-Jun pathways.

Cell Death Dis. 12:632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhou X, Yuan Y, Kuang H, Tang B, Zhang H

and Zhang M: BUB1B (BUB1 mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine kinase

B) promotes lung adenocarcinoma by interacting with zinc finger

protein ZNF143 and regulating glycolysis. Bioengineered.

13:2471–2485. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yan HC and Xiang C: Aberrant expression of

BUB1B contributes to the progression of thyroid carcinoma and

predicts poor outcomes for patients. J Cancer. 13:2336–2351. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ma Q, Liu Y, Shang L, Yu J and Qu Q: The

FOXM1/BUB1B signaling pathway is essential for the tumorigenicity

and radioresistance of glioblastoma. Oncol Rep. 38:3367–3375.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Komura K, Inamoto T, Tsujino T, Matsui Y,

Konuma T, Nishimura K, Uchimoto T, Tsutsumi T, Matsunaga T,

Maenosono R, et al: Increased BUB1B/BUBR1 expression contributes to

aberrant DNA repair activity leading to resistance to DNA-damaging

agents. Oncogene. 40:6210–6222. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tang X, Guo M, Ding P, Deng Z, Ke M, Yuan

Y, Zhou Y, Lin Z, Li M, Gu C, et al: BUB1B and circBUB1B_544aa

aggravate multiple myeloma malignancy through evoking chromosomal

instability. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:3612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Komatsu M, Yoshimaru T, Matsuo T, Kiyotani

K, Miyoshi Y, Tanahashi T, Rokutan K, Yamaguchi R, Saito A, Imoto

S, et al: Molecular features of triple negative breast cancer cells

by genome-wide gene expression profiling analysis. Int J Oncol.

42:478–506. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Maubant S, Tesson B, Maire V, Ye M,

Rigaill G, Gentien D, Cruzalegui F, Tucker GC, Roman-Roman S and

Dubois T: Transcriptome analysis of Wnt3a-treated triple-negative

breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 10:e01223332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Końca K, Lankoff A, Banasik A, Lisowska H,

Kuszewski T, Góźdź S, Koza Z and Wojcik A: A cross-platform public

domain PC image-analysis program for the comet assay. Mutat Res.

534:15–20. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ho SY, Wu WS, Lin LC, Wu YH, Chiu HW, Yeh

YL, Huang BM and Wang YJ: Cordycepin enhances radiosensitivity in

oral squamous carcinoma cells by inducing autophagy and apoptosis

through cell cycle arrest. Int J Mol Sci. 20:53662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu T, Wang H, Chen Y, Wan Z, Du Z, Shen

H, Yu Y, Ma S, Xu Y, Li Z, et al: SENP5 promotes homologous

recombination-mediated DNA damage repair in colorectal cancer cells

through H2AZ deSUMOylation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:2342023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Qiu J, Zhang S, Wang P, Wang H, Sha B,

Peng H, Ju Z, Rao J and Lu L: BUB1B promotes hepatocellular

carcinoma progression via activation of the mTORC1 signaling

pathway. Cancer Med. 9:8159–8172. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sekino Y, Han X, Kobayashi G, Babasaki T,

Miyamoto S, Kobatake K, Kitano H, Ikeda K, Goto K, Inoue S, et al:

BUB1B overexpression is an independent prognostic marker and

associated with CD44, p53, and PD-L1 in renal cell carcinoma.

Oncology. 99:240–250. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Koyuncu D, Sharma U, Goka ET and Lippman

ME: Spindle assembly checkpoint gene BUB1B is essential in breast

cancer cell survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 185:331–341. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mladenov E, Mladenova V, Stuschke M and

Iliakis G: New facets of DNA double strand break repair: Radiation

dose as key determinant of HR versus c-NHEJ engagement. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:149562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hu C, Bugbee T, Dacus D, Palinski R and

Wallace N: Beta human papillomavirus 8 E6 allows colocalization of

non-homologous end joining and homologous recombination repair

factors. PLoS Pathog. 18:e10102752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhou K, Wu C, Cheng W, Zhang B, Wei R,

Cheng D, Li Y, Cao Y, Zhang W, Yao Z and Zhang X: Transglutaminase

3 regulates cutaneous squamous carcinoma differentiation and

inhibits progression via PI3K-AKT signaling pathway-mediated

Keratin 14 degradation. Cell Death Dis. 15:2522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zheng D, Zhu G, Liao S, Yi W, Luo G, He J,

Pei Z, Li G and Zhou Y: Dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway affects cell cycle and apoptosis of side population cells

in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 10:182–188. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dong J, Ru Y, Zhai L, Gao Y, Guo X, Chen B

and Lv X: LMNB1 deletion in ovarian cancer inhibits the

proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells through PI3K/Akt

pathway. Exp Cell Res. 426:1135732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dong C, Wu J, Chen Y, Nie J and Chen C:

Activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway causes drug resistance in

breast cancer. Front Pharmacol. 12:6286902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen Q, Zheng W, Zhu L, Yao D, Wang C,

Song Y, Hu S, Liu H, Bai Y, Pan Y, et al: ANXA6 contributes to

radioresistance by promoting autophagy via inhibiting the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 8:2322020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen K, Shang Z, Dai AL and Dai PL: Novel

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors plus radiotherapy: Strategy for

non-small cell lung cancer with mutant RAS gene. Life Sci.

255:1178162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yu CC, Hung SK, Lin HY, Chiou WY, Lee MS,

Liao HF, Huang HB, Ho HC and Su YC: Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway as an effectively radiosensitizing strategy for

treating human oral squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo.

Oncotarget. 8:68641–68653. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gil del Alcazar CR, Hardebeck MC,

Mukherjee B, Tomimatsu N, Gao X, Yan J, Xie XJ, Bachoo R, Li L,

Habib AA and Burma S: Inhibition of DNA double-strand break repair

by the dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 as a strategy for

radiosensitization of glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 20:1235–1248.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Kao GD, Jiang Z, Fernandes AM, Gupta AK

and Maity A: Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase/Akt

signaling impairs DNA repair in glioblastoma cells following

ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem. 282:21206–21212. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

No M, Choi EJ and Kim IA: Targeting HER2

signaling pathway for radiosensitization: Alternative strategy for

therapeutic resistance. Cancer Biol Ther. 8:2351–2361. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sun Y, Dong D, Xia Y, Hao L, Wang W and

Zhao C: YTHDF1 promotes breast cancer cell growth, DNA damage

repair and chemoresistance. Cell Death Dis. 13:2302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|