Introduction

Senescent cells are characterized by a permanent

cell cycle arrest, resistance to apoptosis and the bioactive

secretion phenotype known as the senescence-associated secretory

phenotype (SASP) (1–4). While cellular senescence has

beneficial effects in early carcinogenesis and tumor therapy,

studies have shown that the accumulation of senescent cells in

age-related diseases, including cancer, has detrimental

consequences. The persistence of these cells promotes cancer cell

growth, aggressiveness and metastasis while contributing to an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) (5,6).

Previous research has highlighted the potential prognostic

importance of senescent cells in HNSCC patients (7). The expression of SASP components has

been linked to certain clinicopathological features, suggesting

that senescence-related mechanisms may impact tumor progression and

patient outcomes (8). Specific

senescence-related genes hold prognostic value in HNSCC. For

instance, a prognostic risk model incorporating these genes has

been developed, offering potential as a biomarker for patient

stratification and personalized treatment approaches (9). Cellular senescence can be effected by

DNA damage caused by radiation therapy, which is one of the main

treatment pillars in HNSCC. This therapy-induced senescence (TIS)

contributes to tumor control by arresting the growth of cancer

cells. However, the accumulation of senescent cells

post-irradiation can also promote radioresistance. Early onset of

senescence and the subsequent production of SASP factors have been

identified as key determinants of this resistance in HNSCC

(9).

The expression of radiation-induced

senescence-associated genes has been suggested to have prognostic

implications in HNSCC (10).

Exposure to IR causes compensatory activation of intracellular

signaling cascades securing tumor cell survival (11–13)

such as signaling pathways MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT in HNSCC (14,15).

Our own previous studies verify the IR-dependent induction of these

cascades in vitro as well as in a 3D HNSCC ex vivo

model most likely as a mechanism of resistance against radiotherapy

(16–19). The response to therapeutic

strategies in HNSCC is generally determined by a pronounced

intratumorigenic heterogeneity (20) followed by a high variety in

treatment response.

Immunotherapy has revolutionized treatment for a

number of cancers including HNSCC over the past decade. In

recurrent or metastatic HNSCC PD-1 inhibitors play an essential

role (21,22). However, the majority of patients do

not exhibit stable responses, suggesting the presence of mechanisms

underlying de novo or acquired resistance to checkpoint

inhibitors (CPI). Despite advances in the field, there remains a

lack of robust biomarkers to predict clinical response and/or

resistance to CPI (23).

Senescent cells have been shown to heterogeneously

express the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1 and that PD-L1+

senescent cells accumulate with age in vivo. In the context

of potential anti-ageing therapy, the elimination of PD-L1+

senescent cells by immune checkpoint blockade has been described as

a promising approach (24).

Senescent cells upregulate PD-L1, the ligand for PD-1 on immune

cells, leading to immune cell inactivation. Consequently, targeting

PD-L1 has been proposed as a novel strategy for addressing

senescence (25). Additionally,

PD-L1 plays a role in the senescence of malignant cells via

interferon-dependent cell cycle regulatory cascades or through its

destabilization by cyclin D-CDK4 kinase (26–28).

Notably, silencing PD-L1 in cancer cells has been shown to induce

senescence (29). A potential link

between checkpoint regulation and senescence is further supported

by an investigation by Moreira et al (30), which investigated whether senescence

markers could predict response to CPI in melanoma patients.

Additionally, aging-related genes have been associated with

chemotherapy resistance and linked to CPI response in HNSCC

(7). Early senescence and the

production of senescence-associated cytokines have also been

identified as major determinants of radioresistance in HNSCC

(9). Moreover, there is a notable

connection between mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway

activation and senescence. This relationship is exemplified by the

association between MAPK ERK1/2 and p21, a key marker of senescence

activation (31). Recently, we

demonstrated a potential co-regulation of pERK1/2 and PD-L1

expression as a response to standard HNSCC treatment revealing a

direct link between oncogenic drivers and PD-L1 expression

(32).

Building on these findings, the present study used a

2D in vitro and a 3D ex vivo HNSCC model to map the

effect of fractionated IR on the induction of senescence as well as

its influence on checkpoint expression and survival signaling as

part of a potential tumoral bailout mechanism.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The cell lines UM-SCC-11B, UM-SCC-14C and UM-SCC-22B

were obtained from Dr TE Carey (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor,

MI, USA). Origins of the cell lines were larynx, oral cavity and

hypopharynx, respectively (Table I)

(33). Original tumors were not

human papilloma virus-driven. The cells were cultivated in

Dulbecco´s modified Eagle´s medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific

Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The

authentication of all cell lines was confirmed by a recent Short

Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling which is a DNA-based method used for

authenticating and identifying cell lines (CLS Cell Lines Service

GmbH; latest update Nov 2022).

| Table I.Characteristics of the head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (33). |

Table I.

Characteristics of the head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (33).

| Characteristic | UM-SCC-11B | UM-SCC-14C | UM-SCC-22B |

|---|

| Specimen | Primary | Local

recurrence | Lymph node

metastasis |

| Tumor site | Larynx | Floor of mouth | Hypopharynx |

| TNM status | T2N2a | T2N0 | T2N1 |

| Previous

therapy | CT | SU + CRT | None |

Irradiation experiments

For each cell line, 200,000 cells/well were seeded

in six-well plates and irradiated day 4 post-seeding on four

consecutive days with a daily dose of 2 Gy using a linear

accelerator (a device used in radiation therapy to deliver

high-energy X-rays or electrons to tumors) with 6 megavolts (MV)

photon energy (Elekta Synergy AB) and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)

plates as water and tissue equivalents, respectively. Cells were

left to recover again on days 8 and 9 and were harvested on day 10.

Controls were mock-treated. Each experiment was performed three

times (n=3).

Senescence-associated ß-galactosidase

(SA-ß-Gal) staining

The cells were cultured in 9-well plates. After 48 h

in culture, cells were irradiated with 2 Gy on four consecutive as

aforementioned. Mock-treated samples served as controls. At 4 h

after the last irradiation session, SA-ß-Gal staining was performed

according to the manufacturer's instructions (Senescence

β-galactosidase Staining Kit; cat. no. 9860; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.). First, the growth medium was removed and the

cells were washed once with 1X PBS. Then, 1 ml of 1X fixative

solution was added to each 35 mm well and the cells were fixed for

10–15 min at room temperature (RT). After rinsing off the fixative

solution with 1X PBS, 1 ml of the prepared β-galactosidase staining

solution (comprising 930 µl of 1X Staining Solution, 10 µl of 100X

Solution A, 10 µl of 100X Solution B and 50 µl of 20 mg/ml X-Gal)

was added to each 35 mm well. The plate was sealed to prevent

evaporation and incubated overnight at 37°C in a dry incubator. The

cells were then examined under the microscope (magnification, ×200)

for the development of blue staining. For long-term storage, the

β-galactosidase staining solution was removed and the cells were

overlaid with 70% glycerol. The plates were stored at 4°C. The

experiment was repeated three times.

Senescence induction was quantified by ImageJ

software (National Institutes of Health, version 1.54p) and is

given as relative amount of positive cells. Due to the small sample

size normal distribution could not be assumed hence statistical

assessment was performed using Mann Whitney U Test.

Immunohistochemical (IHC)

staining

Cells were treated as described for SA

ß-galactosidase staining and fixed by ice-cold ethanol/acetone

(2:1) for 15 min on ice followed by treatment with antigen

retrieval with Tris-EDTA buffer or Citrate buffer for antigen

retrieval and subsequently endogenous peroxidase blockage with DAKO

Peroxidase blocking solution (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). After

preincubation with sheep normal serum 1:10 (BIOZOL Diagnostica

Vertrieb GmbH) for 30 min at RT to avoid unspecific binding,

primary antibodies [phosphorylated-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2;

Thr202/Tyr204); cat. no. 9101 Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.;

1:400; PD-L1; cat. no. 13684, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.;

1:400; p21 Waf1/Cip1 (12D1) Rabbit mAb cat. no. 2947, Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:500, Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139;

20E3) Rabbit mAb cat. no. 9718, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.;

1:1,000)] were incubated overnight. A biotinylated secondary

antibody, diluted 1:200 in streptavidin biotinylated horseradish

peroxidase for 45 min at RT (Cytiva), was added. Afterwards,

3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC; ScyTek Laboratories, Inc.) was used

as a substrate. All washing procedures were performed in PBS.

Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin for 5 min at RT.

Sections incubated without the primary antibody served as negative

controls and additional controls were performed with the secondary

antibody only (data not shown). Samples were imaged using Zeiss

Axio Observer Z1 with AxioCam 505 color and analysed with

Zen-software version 2.3 (Carl Zeiss AG).

Ex vivo treatment of HNSCC vital

tissue cultures

Fresh tissue HNSCC samples (n=4; 1 from the

oropharynx, 1 from the oral cavity, 1 from the hypopharynx and 1

from the larynx; Table II) were

procured immediately after surgical resection at the Department of

Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Mannheim University

Hospital, Germany. All four donors were male. The mean age was 56.5

years (±1.73 years). Recruitment took place between February 2025

and June 2025. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects

involved in the study after the review of the local ethics board

(ethic vote 2020-558N). The consent forms provided clear

information on the study's purpose, procedures, risks, benefits and

the right to withdraw at any time and were presented tailored to

the participants' comprehension level. Patients were informed by

the principal investigator of the study and consented orally and in

written after having the opportunity to ask questions and address

concerns. Patients were to be included in the study if they had

been diagnosed with HNSCC and have undergone treatment at the

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery,

University Hospital Mannheim. Sufficient formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor material had to be available for the

planned analyses. Patients were to be excluded from the study if

they have a pre-existing mental illness that might interfere with

study participation, a history of a previous HNSCC diagnosis, or

another active malignant disease at the time of inclusion. Patients

with medical conditions associated with an increased risk of

bleeding or impaired wound healing were also excluded. Further

exclusion criteria include being under the age of 18, not being

fully capable of giving informed consent, or testing positive for

HIV, HBV, or HCV. Table II gives

characteristics of ex vivo specimens.

| Table II.Characteristics of ex vivo

specimens. |

Table II.

Characteristics of ex vivo

specimens.

| Fresh tissue

sample | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 |

|---|

| Patient age,

sex | 59, male | 56, male | 56, male | 55, male |

| Tumor site | Oropharynx (Left

Tonsil) | Oral cavity (Lower

lip) | Larynx | Hypopharynx |

| TNM status | pT1 N0 M0 | pT3 pN0 M0 | rcT4a cN0 M0 | pT4a pN2b M0 |

| Histological risk

factors | V0 L0 Pn0 R0

G2 | V0 L0 Pn1 R0

G2 | L0 V0 Pn0 G2 | L1 V0 Pn1 R0

G3 |

| Date (month/year)

of sample collection | 02/2024 | 05/2024 | 05/2024 | 06/2024 |

Specimens were transported to the laboratory in

transport media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented

with Primocin) within 30 min after resection. Fresh tissue was

sectioned with a scalpel to fragments of 2–3 mm2 under

sterile conditions. For ex vivo analysis of tumor response

to fractionated IR, tumor sections were maintained in twelve-well

plates with inserts (ThinCert; Greiner Bio One Ltd.) in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

and antibiotics (penicillin 100 U/ml and streptomycin 100 µg/ml).

After five days in culture, samples were irradiated on three

consecutive days with a daily dose of 2 Gy. Mock-treated samples

served as controls. According to the cell line experiments, a

linear accelerator with 6 megavolts (MV) photon energy (Elekta

Synergy AB) and PMMA plates as water and tissue equivalents,

respectively, were employed.

Previously, the total dose and time scheme of 3×2 Gy

applied on days 6–8 had been evaluated by dose and time row

experiments to achieve an optimal IR effect without overdosing the

tissue samples. Fractionated IR instead of a single dose was chosen

to adapt the experimental setting to the norm fractionation scheme

applied in HNSCC patients as closely as possible (32,34).

The medium was changed every second day. The samples were harvested

on day 10 to be evaluated for histopathological and

immunohistochemical features (34,35).

Morphological and immunohistochemical

evaluation of ex vivo HNSCC cultures

Ex vivo cultivated tissue was FFPE. From

these FFPE tissue blocks, 0.5 µM sections were cut and

deparaffinized. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, a routine

histological technique to visualize tissue morphology was performed

(Eosin 10 min, hematoxylin 5 min, at RT). According to the

immunohistochemistry protocol used in cell lines, staining was

performed analogously with adaptation of the concentrations of

antibodies as follows: [Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2;

Thr202/Tyr204); cat. no. 9101; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.;

1:100; t(total) ERK1/2 p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2); cat. no. 9102; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:100; PD-L1; cat. no. 13684; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:200, p21 Waf1/Cip1 (12D1) Rabbit mAb

cat. no. 2947 Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:100,

phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139; 20E3) Rabbit mAb cat. no. 9718, Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:200]. Incubation with the primary

antibodies was at 4°C overnight.

Quantification of IHC results in cell

and tissue cultures

The intensity of IHC staining was determined using

the immunoreactive score (IRS) proposed by Remmele and Stegner

(36) with slight modifications as

follows.

Staining intensity × percentage of positive

cells=IRS.

The percentage of immunoreactive tumor cells was

rated as follows: No staining=0; less than 10% positive cells=1;

10–50% positive cells=2; 51–80% positive cells=3; greater than 80%

positive cells=4. The intensity of staining was evaluated as

follows: no color reaction=0; weak/mild color reaction=1; moderate

=2; strong/intense color reaction=3. The expression score was

obtained by multiplying the percentage of immunoreactive tumor

cells by the staining intensity. The score was determined by three

independent observers and the mean value was calculated.

Shapiro-Wilk-Test was performed with the null hypothesis of normal

distribution of the data. Since most p-values were significant a

Gaussian distribution was not presumed and statistical significance

was calculated using Mann Whitney U test.

Statistical analysis

Results were graphed and analyzed using GraphPad

Prism software (version 9.4.1; Dotmatics). Data are presented as

means (bars) with standard error of the mean (whiskers) from three

independent experiments.

A Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to assess the

normality of the data. Since most P-values were significant, the

present study did not assume a Gaussian distribution.

For SA-ß-Gal staining, a Mann-Whitney U test was

performed. The null hypothesis stated that there was no difference

in positive SA-ß-Gal staining between IR cells and controls.

The results of both ex vivo and in

vitro experiments were also analyzed statistically.

Immunoreactivity scores assigned by three independent observers

were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. The null hypothesis

stated that there was no difference in scoring between treated

cells and mock-treated controls. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Morphologic alterations of the

nuclei

Multiple publications describe morphologic

alterations, such as enlarged cell volume and nuclei, irregularly

shaped nuclei and cytoplasmic vacuoles as characteristic features

of senescent cells (37–39). After fractionated IR, the present

study found a subpopulation of tumor cells with enlarged nuclei in

all three HNSCC cell lines (Fig.

1A). Other morphologic alterations, such as enlarged cell

volume, irregularly shaped nuclei and cytoplasmic vacuoles as

characteristic features of senescence, were also visible. The

altered morphology was clearly recognizable across all cell lines.

There was a small number of cells with this phenotype in untreated

cells, which distinctly increased in response to fractionated

IR.

Evidence for senescence induction by

SA-ß-Gal staining

To confirm a potential induction of senescence by

fractionated IR, SA-ß-Gal staining was performed.

SA-ß-Gal staining is a widely used histochemical

assay to detect cellular senescence. It identifies senescent cells

by measuring ß-galactosidase enzyme activity at pH 6.0, a

characteristic feature of senescent cells. The assay involves

staining cells or tissue samples with X-gal, a substrate that

produces a blue color when cleaved by SA-ß-Gal.

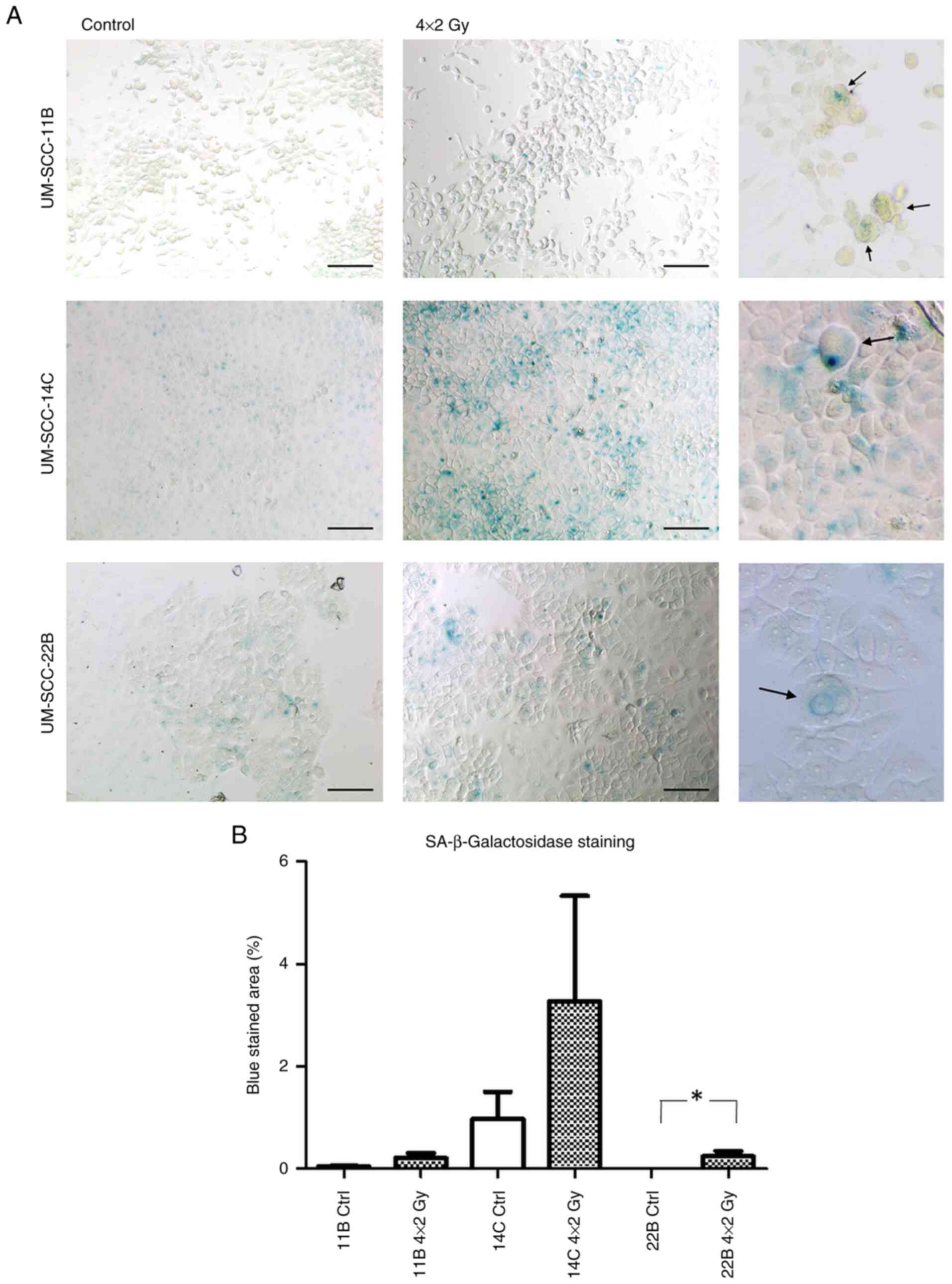

An increase in SA-ß-Gal was observed after

irradiation in all cell lines, which was most distinct in UMSCC-14C

cells. In UM-SCC 22B the changes where statistically significant

(P=0.0286; Fig. 1A; for

quantification see Fig. 1B).

Effect of fractioned IR on

proliferation of senescence marker p21

To further confirm senescence induction, IHC

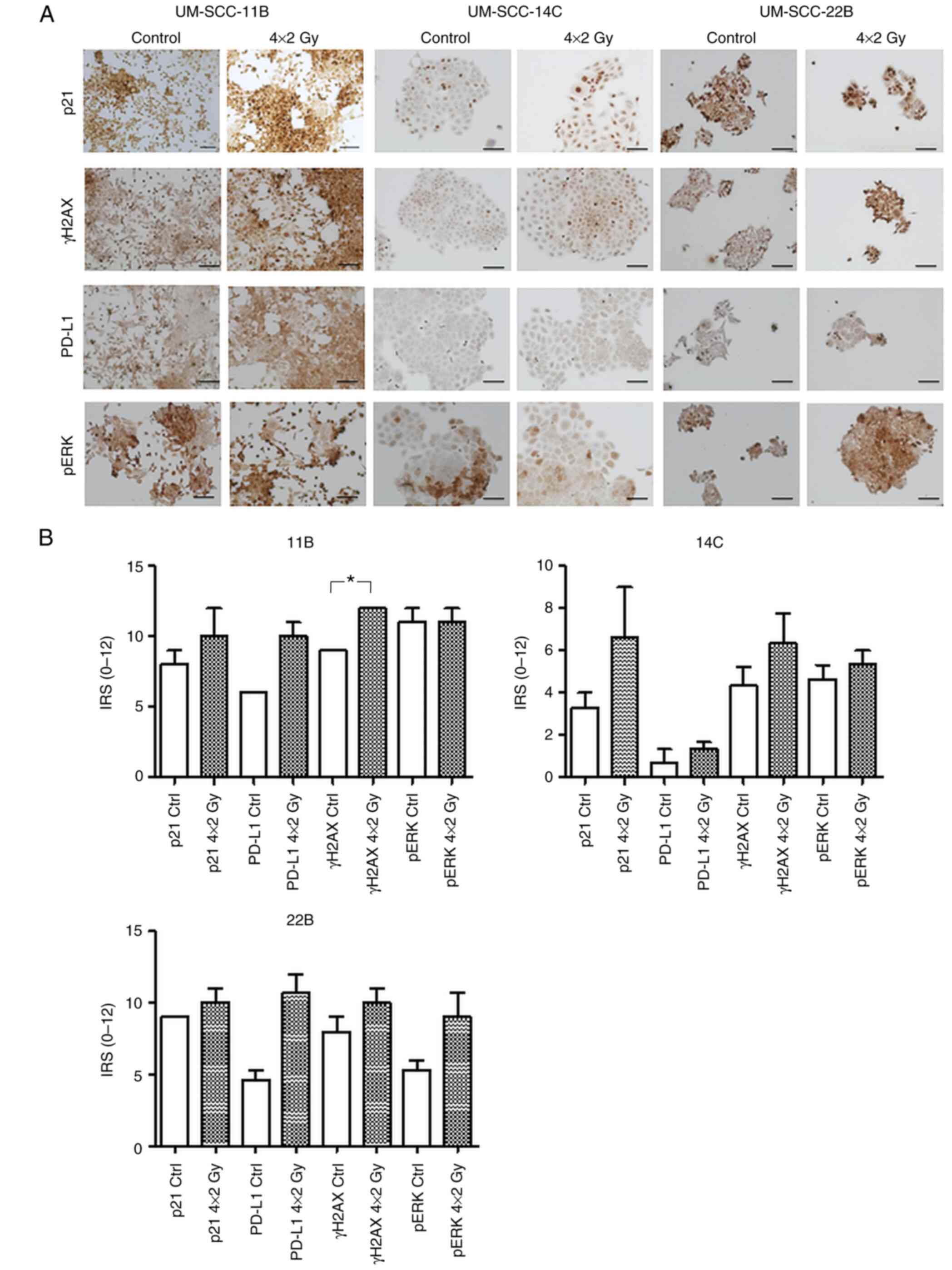

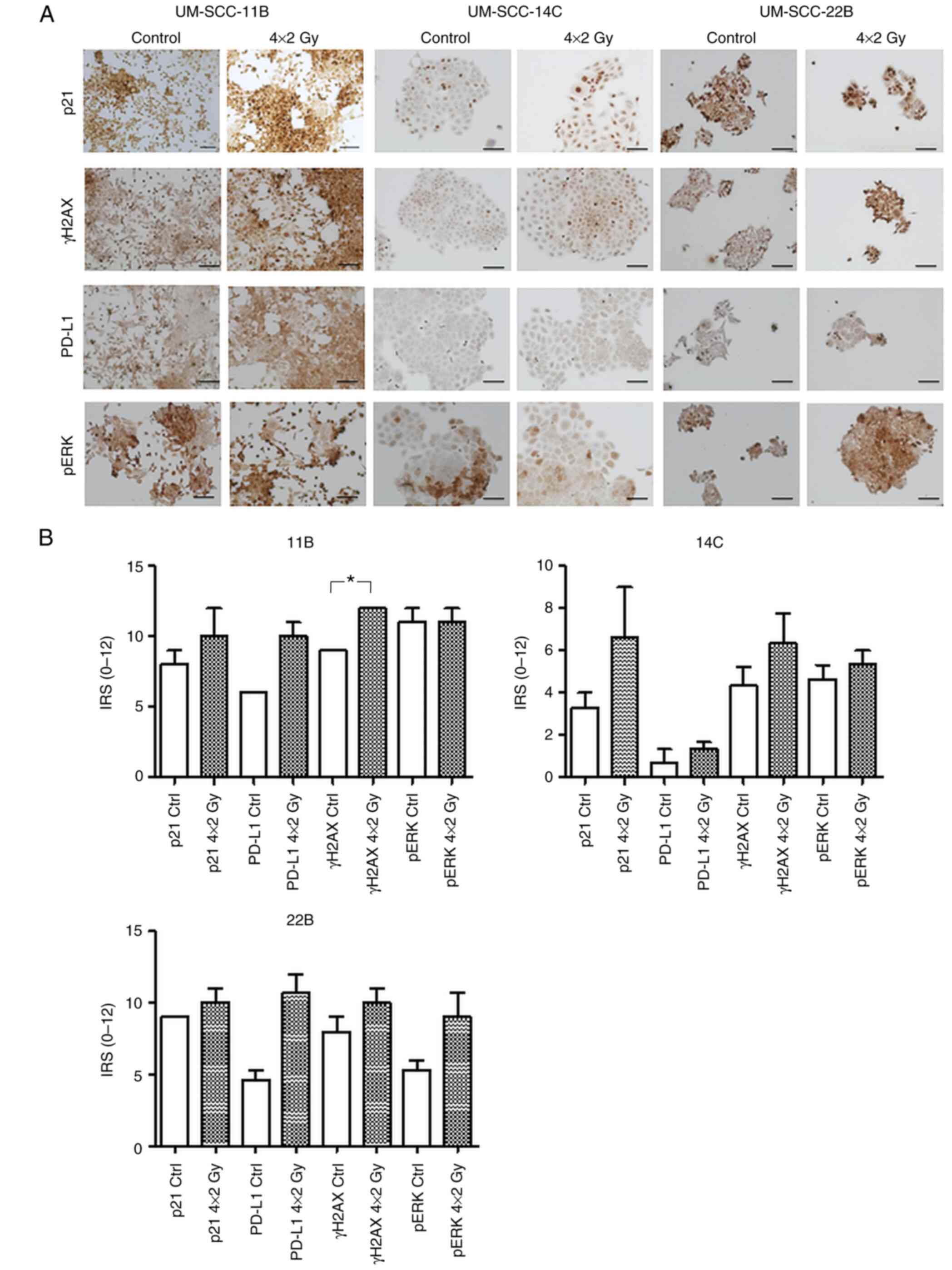

staining of the senescence marker p21 was performed. As seen in

Fig. 2, there was a slight increase

in p21 protein expression in UM-SCC-11B and UM-SCC-22B as well as a

marked increase in UM-SCC-14C compared with mock-treated controls

(Fig. 2A and B).

| Figure 2.Differential expression and

quantification of p21, pERK1/2, PD-L1 and γH2AX in HNSCC cell lines

following fractionated IR. (A) Expression of p21, pERK1/2, PD-L1

and γH2AX in HNSCC cell lines UM-SCC-11B, UM-SCC-14C and UM-SCC-22B

post IR. IHC staining of p21, γH2AX, PD-L1 and pERK1/2 after

fractionated IR (4×2 Gy) compared with mock-treated controls

displayed differential modulations of target proteins

(representative images shown). (B) Quantification of IHC results.

The IRS was obtained by visual examination. Results were quantified

using the IRS modified according to Remmele and Stegner (36). The mean ± SD value was calculated.

Statistical significance (*P<0.05) was assessed using Mann

Whitney U test. p, phosphorylated; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand

1; γH2AX, histone H2AX; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma; IR, ionizing radiation; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IRS,

immunoreactive score. Scale bar=100 µm. |

Effect of fractioned IR on

proliferation of γH2AX

There was a visible increase in positive staining of

γH2AX indicating postradiogenic DNA double strand breaks in all

three cell lines, but due to the small sample size the results of

the statistical evaluation were non-significant (11B P=0.059; 14C

P=0.48; 22B P=0.3; Fig. 2A and

B).

Fractionated IR modulates PD-L1

surface expression

Unlike in previous studies where cells and tissue

samples were treated with a single irradiation dose and immediately

analyzed post IR, the present study was interested in examining

also mid- and long-term adjustment mechanisms to a fractionated

protocol (4×2 Gy) according to the norm fractionation scheme

applied to HNSCC patients. All three cell lines displayed a strong

induction of PD-L1 which was most distinct in cells from the

UM-SCC-22B cell line (Fig. 2A and

B).

Effect of fractionated IR on MAPK ERK

signaling

UM-SCC-22B cells showed a strong induction of

activated ERK1/2, similar to the PD-L1 expression pattern. There

was a minor induction in pERK1/2 in UM-SCC-14C, while no

modifications in pERK1/2 protein expression were detected in

UM-SCC-11B compared with mock-treated controls (Fig. 2A and B).

Validation of senescence-associated

markers in a 3D ex vivo HNSCC tissue culture model

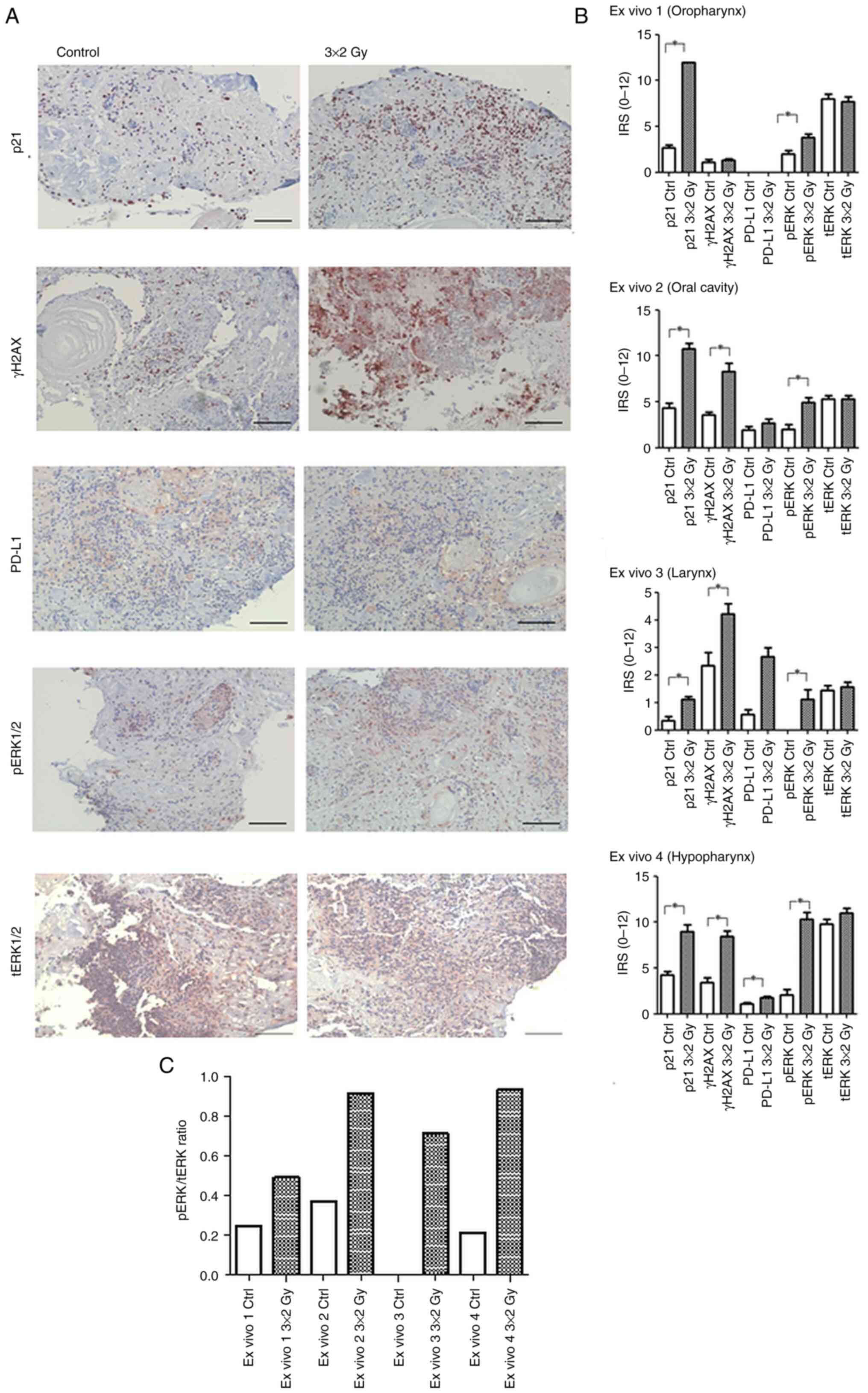

In order to verify the findings of cellular response

to fractionated IR observed in the cell lines, the expression of

senescence-associated markers was validated in human HNSCC tumor

tissue. This explant model offers the advantage of taking the

composition of the individual patient's tumor and a potential

impact of the TME into account, which is not depicted in 2D cell

culture model.

One specimen each from the typical anatomical HNSCC

sites (oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx) was

included.

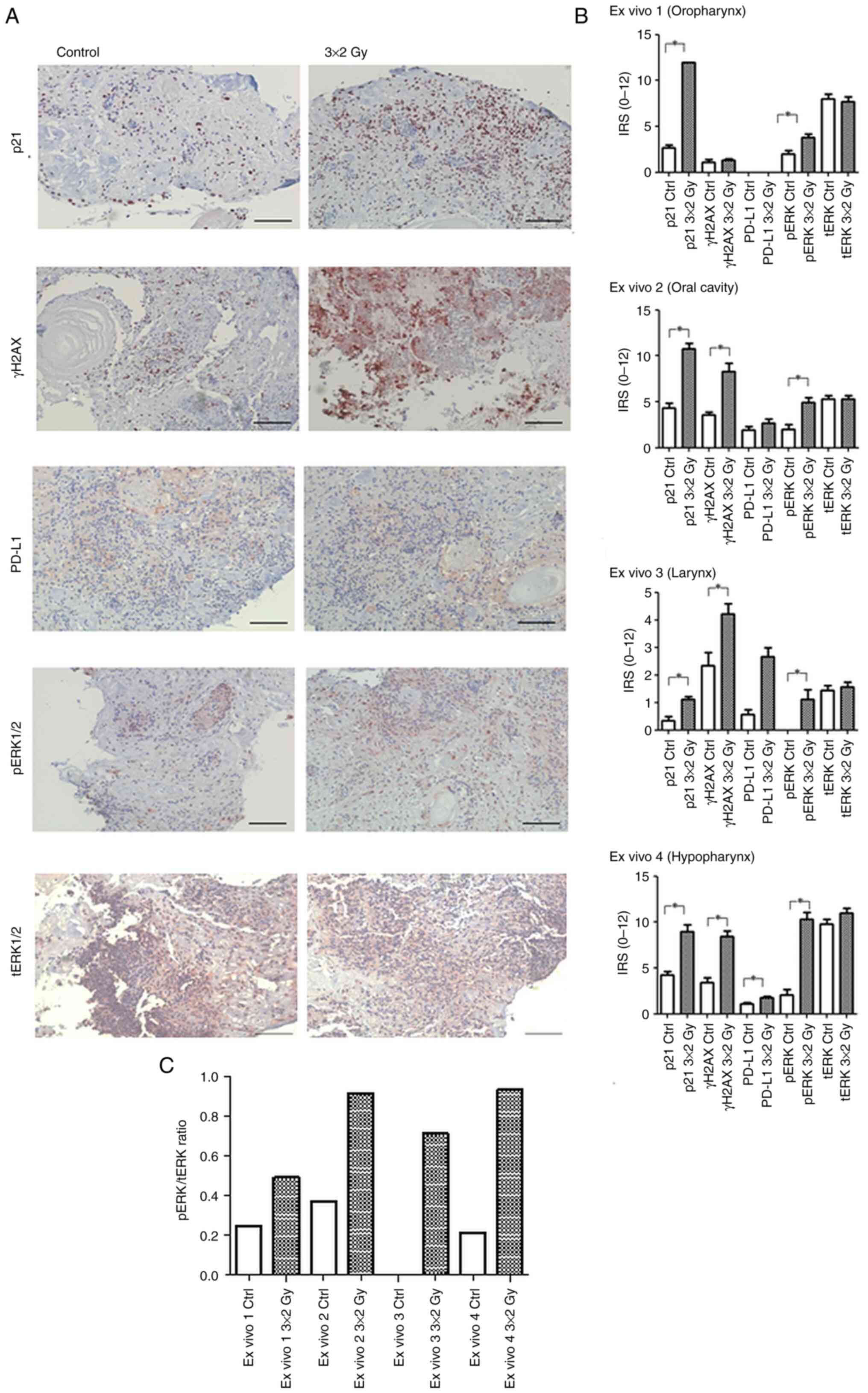

A statistically significant increase in p21

expression post IR was observed in all four specimens indicating

that radiotherapy affects senescence regulation (EV1 P=0.0001, EV2

P=0.003, EV 3 P=0.004, EV 4 P=0.0005). Accordingly, there was a

parallel raise in γH2AX as additional senescence marker in all

samples. The difference reached significance in oral cavity, larynx

and hypopharynx samples (EV2 P=0.0002, EV3 P=0.0137, EV 4

P=0.0004).

As expected, the 3D model enabled confirmation of

the 2D results regarding a postradiogenic upregulation of PD-L1 and

pERK1/2. Except the oropharyngeal specimen, which did not express

any PD-L1 at baseline and after treatment, PD-L1 levels were

significantly enhanced after IR in the hypopharyngeal tissue

(P=0.0066) while there was a minor increase in ex vivo

specimens derived from the larynx and the oral cavity. pERK1/2 was

activated in all four ex vivo samples reaching significance

in all cases (EV1: P=0.011; EV2: 0.0039; EV3: 0.0052; EV4: 0,0004).

tERK1/2 expression appeared stable after fractionated IR in all

specimens (Fig. 3A and B).

| Figure 3.Expression and quantification of p21,

γH2AX, PD-L1, and ERK1/2 in irradiated 3D ex vivo HNSCC

tissue. (A) IHC staining of p21, γH2AX, PD-L1, pERK1/2 and tERK1/2

in irradiated 3D ex vivo HNSCC tissue cultures. Expression

patterns in an ex vivo human HNSCC tissue culture model.

Simultaneous increase of PD-L1 and p21 after fractionated IR in the

IHC, compared with mock-treated controls (representative images

shown; scale bar, 100 µm). (B) Quantification of IHC results. The

IRS was obtained by visual examination. Results were quantified

using the IRS modified according to Remmele and Stegner (36) as performed for the in vitro

data. The mean ± SD was calculated. Statistical significance

(*P<0.05) was assessed using Mann Whitney U tests. (C) pERK1/2

to tERK1/2 ratio in ex vivo samples following radiation

treatment. Bar graph showing the pERK1/2/ERK1/2 ratio in ex

vivo 1–4. IHC, immunohistochemistry; γH2AX, histone H2AX;

PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; p, phosphorylated; HNSCC, head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma; IR, ionizing radiation; IHC,

immunohistochemistry; IRS, immunoreactive score. Scale bar=100

µm. |

Discussion

The present study described the expression of

senescence-associated molecules γH2AX, SA-β-Gal and p21, alongside

morphological criteria for detecting senescence in HNSCC cell lines

and viable HNSCC human tissue samples. The findings demonstrated

that these features are associated with irradiation-induced

induction of PD-L1 along with activation of the MAPK ERK survival

pathway.

In HNSCC patients, norm-fractionated radiotherapy

alone is most commonly administered at a dose of 1.6–2.0 Gy per

fraction per day, five days a week, over a period of 6–7 weeks

(40). Therefore, the present study

established an experimental regimen using single daily fractions of

2 Gy, based on our previous demonstration that these doses are

sufficient to produce an effect (32,34).

It is well established that standard oncological treatments, such

as radiochemotherapy (RCT), induce senescence in solid tumors

(40–42). Additionally, senescent cells are

known to contribute to certain chemotherapy-related side effects

(43,44). The senescent phenotype is

characterized by irreversible growth arrest while maintaining

viability and metabolic activity. Key features of this phenotype

include distinct cellular morphology (enlarged and flattened

cells), increased expression of p53 and p21, markers of DNA

double-strand breaks (DSBs) and the presence of SA-ß-Gal, along

with an elevated number of γH2AX foci, one of the most sensitive

markers of DSBs (45–48).

Standard oncological treatment such as RCT induces

senescence in solid tumors (41–43)

Additionally, senescent cells are known to cause certain

chemotherapy-related side effects (38,44).

The senescent phenotype is featured by irreversible growth arrest

while maintaining viability and metabolic activity. This phenotype

includes a distinct cellular morphology (enlarged and flattened

cells), increased expression of p53, p21, markers of DNA DSBs and

the presence of SA-ß-Gal as well as an increased number of γH2AX

foci, the most sensitive marker of DSBs (39,45–47).

Senescence has been described as a double-edged sword exhibiting

both tumor suppressive and promoting properties (48–51).

While therapy-induced senescence can contribute to metastasis,

recurrence and adverse reactions to cancer treatment (52), current anti-cancer strategies

provide an ideal foundation for TME-associated damage responses,

which result in the promotion of senescence as a resistance

mechanism (53): It is well

documented that senescent cells within the TME contribute to tumor

progression, metastasis and therapy resistance (54). Cellular senescence is increasingly

recognized as a patients' response to various anticancer therapies

(55) and is probably associated

with poor treatment response in different cancer entities (56–59).

As one of the most prominent markers of senescence,

p21 has been described to harbor either tumor suppressor activity

or tumor-promoting properties (60). In the p21 analyses, the present

study detected an increased postradiogenic nuclear p21 expression

in HNSCC tumor cell lines and ex vivo cultures, accompanied

by an increase in ß Gal positive cells and γH2AX protein levels,

compared with control, indicating that IR might trigger senescence

in HNSCC cells which could induce resistance to this fundamental

treatment pillar.

In parallel, the MAPK signaling pathway plays an

important role in oncogene-induced senescence (61,62).

MEK and subsequently ERK1/2, so-called gerogens, are capable of

arresting the cell cycle via p53, p21 and p16 (63). Patel et al (64) recently showed that continued

MAPK/ERK activation in oncogene-induced senescent cells offers a

potential escape route after ~1 month leading to c-MYC dependent

reactivation of telomerase. This reinforces the role of MAPK/ERK in

the formation of resistance based on senescent cells. While there

are various 3D models of ERK-induced senescence, so far none have

been detected specifically for head and neck cancer (65).

Woo et al (66) describe that that inhibition of MEK

and PI3K signaling pathways increases the sensitivity of HNSCC

cells to radiotherapy by enhancing therapy-induced senescence.

However, this study was only conducted in a 2D cell culture

approach, which does not reflect tumor-TME interactions. Indeed, a

rationale for including the tumor-TME-interrelations when

investigating senescence is provided by studies showing that the

epithelial to mesenchymal transition phenotype is resistant to

radiochemotherapy (67) and that

interactions with the TME can influence the tumor's sensitivity

against treatment (68). A improved

understanding of this mechanism is of great interest as there is

evidence for radioresistance already in quiescent cells in HNSCC

cell lines (69). This aggressive

phenotype could be further promoted by coexisting senescent cells

(70,71) leading to an undesirable outcome that

must not be underestimated.

Similarly, the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1, the

ligand for PD-1 on immune cells, which drives immune cell

inactivation, is associated with cellular senescence. In line with

the present data, Onorati et al (25) report that senescent cells upregulate

PD-L1. This induction of PD-L1 in senescence is shown to depend on

the proinflammatory program. The clinical benefit of PD-1

inhibitors is restricted by immunosuppressive properties of the TME

(72–74) and the insufficient reactivation of

antitumor immunity by the drug alone (75). There have been considerations as to

whether responses to CPI are linked to cellular senescence as CPI

treatment has been observed to increase the presence of senescent T

cells (76). These findings on a

potential link between senescence and CPI response justify the

employment of 2D and 3D HNSCC models as performed in the present

study as only <20% of HNSCC patients respond to CPI monotherapy

(77). So more elucidation of

factors contributing to CPI sensitivity are clearly needed. For

other tumor entities such as breast cancer this issue has already

been addressed. Si et al (4)

observed that blockade of PD-L1 and STAT3 could prevent

tumor-associated regulatory T cell-induced senescence in dendritic

cells. Although that study focuses on breast cancer, the results

may also be relevant for head and neck cancer, as similar

mechanisms of immunomodulation may be involved.

The present study included cell lines and tissue

samples from different localities in the head and neck region to

illustrate diversity in tumoral behavior, which is known to be

associated with varying response to cancer treatment and found

comparable results. This observation is particularly notable

because it has variously been shown that differences in survival

and molecular biology exist between HNSCC anatomical sites and TME

of these sites may guide immune and radiation therapies (78). However, this observation is

provisional, as the present sample size was small, which must be

considered as a limitation of the study. The results can be

considered more of a pilot project but are worth testing in a

larger cohort. In terms of clinical applicability, it could be of

relevance that recent data show senolytic agents such as B-cell

lymphoma-x large inhibitor ABT-263 (Navitoclax) in combination with

cisplatin probably being useful for eliminating residual senescent

tumor cells after chemotherapy and thereby potentially delay

disease recurrence in head and neck cancer patients (79).

Hence, it is expected, based on these and previous

data, that the ex vivo model is a useful tool to provide a

platform for sensitivity testing of novel combination therapies,

such as cisplatin and senolytics, as part of a personalized

treatment approach.

The prognostic effect of therapy-induced senescence

remains incomplete. Previously we demonstrated tumor cell-mediated

regulation of PD-L1 upon platinum-based CRT in HNSCC and their

exosomes (32). The present study

aimed to define whether there is a correlation between

postradiogenic induction of senescence, ERK1/2 signaling and PD-L1

expression. The data provided evidence that fractionated IR

generated a subpopulation of HNSCC tumor cells exhibiting

senescence-associated cellular changes and increased expression of

pERK1/2 and PD-L1. The results suggested a link between survival

signaling, radiation-induced checkpoint activation and the

emergence of senescence in HNSCC. Additionally, the ex vivo

3D tissue model has proved to be a valuable tool for validation and

complementing in vitro data, offering insights into

tumor-TME correlations. In the future, further analyses,

particularly in larger cohorts, are required to better elucidate

the clinical relevance and significance of therapy-induced

senescence in the treatment of cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the excellent

technical support of Ms. Petra Prohaska, Scientific Laboratory at

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery,

University Hospital Mannheim, Medical Faculty Mannheim of

Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany.

Funding

The present study was substantially supported by the Program for

the Promotion of Equality and Careers of Female Physicians and

Scientists at the University Medical Center Mannheim (to AA).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

LB and AA were responsible for data curation and

formal analysis. Funding acquisition was by AA and ES. FJ, JF and

AL made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and

interpretation of data for the work. Supervision was by JK, NR and

CS. Visualization was by AA, LB and ES. Writing the original draft

was by LB and AA. Writing, reviewing and editing was by LB, AA, CS,

JK and NR. LB, AA, and JK confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines

of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional

Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Heidelberg University,

Medical Faculty Mannheim (protocol code 2020-558N, date of approval

4 Jun 2020). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects

involved in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Herranz N and Gil J: Mechanisms and

functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest. 128:1238–1246.

2018. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kim HS, Song MC, Kwak IH, Park TJ and Lim

IK: Constitutive induction of p-Erk1/2 accompanied by reduced

activities of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A and MKP3 due to

reactive oxygen species during cellular senescence. J Biol Chem.

278:37497–37510. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

White RR and Vijg J: Do DNA double-strand

breaks drive aging? Mol Cell. 63:729–738. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Si F, Liu X, Tao Y, Zhang Y, Ma F, Hsueh

EC, Puram SV and Peng G: Blocking senescence and tolerogenic

function of dendritic cells induced by γδ Treg cells enhances

tumor-specific immunity for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother

Cancer. 12:e0082192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ruhland MK and Alspach E: Senescence and

immunoregulation in the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:7540692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Toso A, Revandkar A, Di Mitri D, Guccini

I, Proietti M, Sarti M, Pinton S, Zhang J, Kalathur M, Civenni G,

et al: Enhancing chemotherapy efficacy in Pten-deficient prostate

tumors by activating the senescence-associated antitumor immunity.

Cell Rep. 9:75–89. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang J, Zhou CC, Sun HC, Li Q, Hu JD,

Jiang T and Zhou S: Identification of several senescence-associated

genes signature in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin

Lab Anal. 36:e245552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ostrowska K, Niewinski P, Piotrowski I,

Ostapowicz J, Koczot S, Suchorska WM, Golusiński P, Masternak MM

and Golusiński W: Senescence in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma: relationship between senescence-associated secretory

phenotype (SASP) mRNA expression level and clinicopathological

features. Clin Transl Oncol. 26:1022–1032. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Schoetz U, Klein D, Hess J, Shnayien S,

Spoerl S, Orth M, Mutlu S, Hennel R, Sieber A, Ganswindt U, et al:

Early senescence and production of senescence-associated cytokines

are major determinants of radioresistance in head-and-neck squamous

cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 12:11622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lee YC, Nam Y, Kim M, Kim SI, Lee JW, Eun

YG and Kim D: Prognostic significance of senescence-related tumor

microenvironment genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Aging (Albany NY). 16:985–1001. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH,

Abrams SL, Wong EW, Chang F, Lehmann B, Terrian DM, Milella M,

Tafuri A, et al: Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth,

malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1773:1263–1284. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Golding SE, Morgan RN, Adams BR, Hawkins

AJ, Povirk LF and Valerie K: Pro-survival AKT and ERK signaling

from EGFR and mutant EGFRvIII enhances DNA double-strand break

repair in human glioma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 8:730–738. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hein AL, Ouellette MM and Yan Y:

Radiation-induced signaling pathways that promote cancer cell

survival (review). Int J Oncol. 45:1813–1819. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chung EJ, Brown AP, Asano H, Mandler M,

Burgan WE, Carter D, Camphausen K and Citrin D: In vitro and in

vivo radiosensitization with AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), an inhibitor of

mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated

kinase 1/2 kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 15:3050–3057. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Leiker AJ, DeGraff W, Choudhuri R, Sowers

AL, Thetford A, Cook JA, Van Waes C and Mitchell JB: Radiation

enhancement of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by the Dual

PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor PF-05212384. Clin Cancer Res. 21:2792–2801.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Affolter A, Drigotas M, Fruth K,

Schmidtmann I, Brochhausen C, Mann WJ and Brieger J: Increased

radioresistance via G12S K-Ras by compensatory upregulation of MAPK

and PI3K pathways in epithelial cancer. Head Neck. 35:220–228.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Affolter A, Fruth K, Brochhausen C,

Schmidtmann I, Mann WJ and Brieger J: Activation of

mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-related

kinase in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas after irradiation

as part of a rescue mechanism. Head Neck. 33:1448–1457. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Affolter A and Hess J: Preclinical models

in head and neck tumors: Evaluation of cellular and molecular

resistance mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. HNO.

64:860–869. 2016.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Affolter A, Samosny G, Heimes AS,

Schneider J, Weichert W, Stenzinger A, Sommer K, Jensen A, Mayer A,

Brenner W, et al: Multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib as

radiosensitizers in head and neck cancer cell lines. Head Neck.

39:623–632. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Perri F, Pacelli R, Della Vittoria

Scarpati G, Cella L, Giuliano M, Caponigro F and Pepe S:

Radioresistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:

Biological bases and therapeutic implications. Head Neck.

37:763–770. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sharon S and Bell RB: Immunotherapy in

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A narrative review. Front

Oral Maxillofac Med. 4:282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen Z, Wong PY, Ng CWK, Lan L, Fung S, Li

JW, Cai L, Lei P, Mou Q, Wong SH, et al: The intersection between

oral microbiota, host gene methylation and patient outcomes in head

and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 12:34252020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Affolter A, Kern J, Bieback K, Scherl C,

Rotter N and Lammert A: Biomarkers and 3D models predicting

response to immune checkpoint blockade in head and neck cancer

(Review). Int J Oncol. 61:882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang TW, Johmura Y, Suzuki N, Omori S,

Migita T, Yamaguchi K, Hatakeyama S, Yamazaki S, Shimizu E, Imoto

S, et al: Blocking PD-L1-PD-1 improves senescence surveillance and

ageing phenotypes. Nature. 611:358–364. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Onorati A, Havas AP, Lin B, Rajagopal J,

Sen P, Adams PD and Dou Z: Upregulation of PD-L1 in Senescence and

Aging. Mol Cell Biol. 42:e00171222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Brenner E, Schörg BF, Ahmetlić F, Wieder

T, Hilke FJ, Simon N, Schroeder C, Demidov G, Riedel T,

Fehrenbacher B, et al: Cancer immune control needs senescence

induction by interferon-dependent cell cycle regulator pathways in

tumours. Nat Commun. 11:13352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chen Z, Hu K, Feng L, Su R, Lai N, Yang Z

and Kang S: Senescent cells re-engineered to express soluble

programmed death receptor-1 for inhibiting programmed death

receptor-1/programmed death ligand-1 as a vaccination approach

against breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 109:1753–1763. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang J, Bu X, Wang H, Zhu Y, Geng Y,

Nihira NT, Tan Y, Ci Y, Wu F, Dai X, et al: Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase

destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune

surveillance. Nature. 553:91–95. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lee JJ, Kim SY, Kim SH, Choi S, Lee B and

Shin JS: STING mediates nuclear PD-L1 targeting-induced senescence

in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 13:7912022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Moreira A, Gross S, Kirchberger MC,

Erdmann M, Schuler G and Heinzerling L: Senescence markers:

Predictive for response to checkpoint inhibitors. Int J Cancer.

144:1147–1150. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Abdel-Naby R, Wang K, Song D, Bozentka J,

LaFonte M, Ou P, Stanek A, Mueller C, Alfonso A and Huan C:

Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK)-dependent p21

(WAF1/Cip1) Expression Is Associated with Gemcitabine Resistance in

Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J Am Coll Surg. 219:S272014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Affolter A, Liebel K, Tengler L, Seiz E,

Tiedtke M, Azhakesan A, Schütz J, Theodoraki MN, Kern J, Ruder AM,

et al: Modulation of PD-L1 expression by standard therapy in head

and neck cancer cell lines and exosomes. Int J Oncol. 63:1022023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Welters MJ, Fichtinger-Schepman AM, Baan

RA, Hermsen MA, van der Vijgh WJ, Cloos J and Braakhuis BJ:

Relationship between the parameters cellular differentiation,

doubling time and platinum accumulation and cisplatin sensitivity

in a panel of head and neck cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer.

71:410–415. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Engelmann L, Thierauf J, Koerich Laureano

N, Stark HJ, Prigge ES, Horn D, Freier K, Grabe N, Rong C,

Federspil P, et al: Organotypic co-cultures as a novel 3D model for

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel).

12:23302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Affolter A, Muller MF, Sommer K,

Stenzinger A, Zaoui K, Lorenz K, Wolf T, Sharma S, Wolf J, Perner

S, et al: Targeting irradiation-induced mitogen-activated protein

kinase activation in vitro and in an ex vivo model for human head

and neck cancer. Head Neck. 38 (Suppl 1):E2049–E2061. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Remmele W and Stegner HE: Recommendation

for uniform definition of an immunoreactive score (IRS) for

immunohistochemical estrogen receptor detection (ER-ICA) in breast

cancer tissue. Pathologe. 8:138–140. 1987.(In German). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Muñoz-Espín D and Serrano M: Cellular

senescence: From physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

15:482–496. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Demaria M: Senescent cells: New target for

an old treatment? Mol Cell Oncol. 4:e12996662017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bernadotte A, Mikhelson VM and Spivak IM:

Markers of cellular senescence. Telomere shortening as a marker of

cellular senescence. Aging (Albany NY). 8:3–11. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Matuschek C, Haussmann J, Bölke E, Gripp

S, Schuler PJ, Tamaskovics B, Gerber PA, Djiepmo-Njanang FJ,

Kammers K, Plettenberg C, et al: Accelerated vs. conventionally

fractionated adjuvant radiotherapy in high-risk head and neck

cancer: A meta-analysis. Radiat Oncol. 13:1952018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Qin S, Schulte BA and Wang GY: Role of

senescence induction in cancer treatment. World J Clin Oncol.

9:180–187. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Milanovic M, Fan DNY, Belenki D, Däbritz

JHM, Zhao Z, Yu Y, Dörr JR, Dimitrova L, Lenze D, Monteiro Barbosa

IA, et al: Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer

stemness. Nature. 553:96–100. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Nicolas AM, Pesic M, Engel E, Ziegler PK,

Diefenhardt M, Kennel KB, Buettner F, Conche C, Petrocelli V,

Elwakeel E, et al: Inflammatory fibroblasts mediate resistance to

neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 40:168–184.e13.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Demaria M, O'Leary MN, Chang J, Shao L,

Liu S, Alimirah F, Koenig K, Le C, Mitin N, Deal AM, et al:

Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and

cancer relapse. Cancer Discov. 7:165–176. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gu L and Kitamura M: Sensitive detection

and monitoring of senescence-associated secretory phenotype by

SASP-RAP assay. PLoS One. 7:e523052012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Sordet O, Dickey

JS, Gouliaeva K, Tabb B, Lawrence S, Kinders RJ, Bonner WM and

Sedelnikova OA: γ-H2AX detection in peripheral blood lymphocytes,

splenocytes, bone marrow, xenografts, and skin. Methods Mol Biol.

682:249–270. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Sedelnikova OA, Horikawa I, Zimonjic DB,

Popescu NC, Bonner WM and Barrett JC: Senescing human cells and

ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand

breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 6:168–170. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Golomb L, Sagiv A, Pateras IS, Maly A,

Krizhanovsky V, Gorgoulis VG, Oren M and Ben-Yehuda A:

Age-associated inflammation connects RAS-induced senescence to stem

cell dysfunction and epidermal malignancy. Cell Death Differ.

22:1764–1774. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S,

Desprez PY and Campisi J: Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial

cell growth and tumorigenesis: A link between cancer and aging.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:12072–12077. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Halazonetis TD, Gorgoulis VG and Bartek J:

An oncogene-induced DNA damage model for cancer development.

Science. 319:1352–1355. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D

and Lowe SW: Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence

associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 88:593–602.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang B, Kohli J and Demaria M: Senescent

cells in cancer therapy: Friends or Foes? Trends Cancer. 6:838–857.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Gordon RR and Nelson PS: Cellular

senescence and cancer chemotherapy resistance. Drug Resist Updat.

15:123–131. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

D'Ambrosio M and Gil J: Reshaping of the

tumor microenvironment by cellular senescence: An opportunity for

senotherapies. Dev Cell. 58:1007–1021. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Domen A, Deben C, Verswyvel J, Flieswasser

T, Prenen H, Peeters M, Lardon F and Wouters A: Cellular senescence

in cancer: Clinical detection and prognostic implications. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 41:3602022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

George B, Horn D, Bayo P, Zaoui K,

Flechtenmacher C, Grabe N, Plinkert P, Krizhanovsky V and Hess J:

Regulation and function of Myb-binding protein 1A (MYBBP1A) in

cellular senescence and pathogenesis of head and neck cancer.

Cancer Lett. 358:191–199. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mosieniak G, Sliwinska M, Alster O,

Strzeszewska A, Sunderland P, Piechota M, Was H and Sikora E:

Polyploidy formation in doxorubicin-treated cancer cells can favor

escape from senescence. Neoplasia. 17:882–893. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wang Q, Wu PC, Dong DZ, Ivanova I, Chu E,

Zeliadt S, Vesselle H and Wu DY: Polyploidy road to therapy-induced

cellular senescence and escape. Int J Cancer. 132:1505–1515. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhai J, Han J, Li C, Lv D, Ma F and Xu B:

Tumor senescence leads to poor survival and therapeutic resistance

in human breast cancer. Front Oncol. 13:10975132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Stivala LA, Cazzalini O and Prosperi E:

The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CDKN1A as a target of

anti-cancer drugs. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 12:85–96. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Xu Y, Li N, Xiang R and Sun P: Emerging

roles of the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in

oncogene-induced senescence. Trends Biochem Sci. 39:268–276. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Anerillas C, Abdelmohsen K and Gorospe M:

Regulation of senescence traits by MAPKs. Geroscience. 42:397–408.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chambard JC, Lefloch R, Pouysségur J and

Lenormand P: ERK implication in cell cycle regulation. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1773:1299–1310. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Patel PL, Suram A, Mirani N, Bischof O and

Herbig U: Derepression of hTERT gene expression promotes escape

from oncogene-induced cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

113:E5024–E5033. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Schmitt CA, Wang B and Demaria M:

Senescence and cancer-role and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 19:619–636. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Woo SH, Yang LP, Chuang HC, Fitzgerald A,

Lee HY, Pickering C, Myers JN and Skinner HD: Down-regulation of

malic enzyme 1 and 2: Sensitizing head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma cells to therapy-induced senescence. Head Neck. 38 (Suppl

1):E934–E940. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

McConkey DJ, Choi W, Marquis L, Martin F,

Williams MB, Shah J, Svatek R, Das A, Adam L, Kamat A, et al: Role

of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in drug sensitivity

and metastasis in bladder cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

28:335–344. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Khalaf K, Hana D, Chou JT, Singh C,

Mackiewicz A and Kaczmarek M: Aspects of the tumor microenvironment

involved in immune resistance and drug resistance. Front Immunol.

12:6563642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Eckers JC, Kalen AL, Sarsour EH, Tompkins

VS, Janz S, Son JM, Doskey CM, Buettner GR and Goswami PC: Forkhead

box M1 regulates quiescence-associated radioresistance of human

head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Radiat Res. 182:420–429.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Cahu J, Bustany S and Sola B:

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype favors the emergence of

cancer stem-like cells. Cell Death Dis. 3:e4462012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Özcan S, Alessio N, Acar MB, Mert E,

Omerli F, Peluso G and Galderisi U: Unbiased analysis of senescence

associated secretory phenotype (SASP) to identify common components

following different genotoxic stresses. Aging (Albany NY).

8:1316–1329. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Fares CM, Van Allen EM, Drake CG, Allison

JP and Hu-Lieskovan S: Mechanisms of resistance to immune

checkpoint blockade: Why does checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy

not work for all patients? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 39:147–164.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Nowicki TS, Hu-Lieskovan S and Ribas A:

Mechanisms of resistance to PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade. Cancer J.

24:47–53. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Saleh R and Elkord E: Acquired resistance

to cancer immunotherapy: Role of tumor-mediated immunosuppression.

Semin Cancer Biol. 65:13–27. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Haratani K, Yonesaka K, Takamura S,

Maenishi O, Kato R, Takegawa N, Kawakami H, Tanaka K, Hayashi H,

Takeda M, et al: U3-1402 sensitizes HER3-expressing tumors to PD-1

blockade by immune activation. J Clin Invest. 130:374–388. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Arasanz H, Zuazo M, Bocanegra A, Gato M,

Martínez-Aguillo M, Morilla I, Fernández G, Hernández B, López P,

Alberdi N, et al: Early detection of hyperprogressive disease in

non-small cell lung cancer by monitoring of systemic T cell

dynamics. Cancers (Basel). 12:3442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Hirsch L, Zitvogel L, Eggermont A and

Marabelle A: PD-Loma: A cancer entity with a shared sensitivity to

the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway blockade. Br J Cancer. 120:3–5. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Kim HAJ, Zeng PYF, Shaikh MH, Mundi N,

Ghasemi F, Di Gravio E, Khan H, MacNeil D, Khan MI, Patel K, et al:

All HPV-negative head and neck cancers are not the same: Analysis

of the TCGA dataset reveals that anatomical sites have distinct

mutation, transcriptome, hypoxia, and tumor microenvironment

profiles. Oral Oncol. 116:1052602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Ahmadinejad F, Bos T, Hu B, Britt E,

Koblinski J, Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Faber AC, Gewirtz DA and

Harada H: Senolytic-mediated elimination of head and neck tumor

cells induced into senescence by cisplatin. Mol Pharmacol.

101:168–180. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|