Introduction

IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) are a group of genes

upregulated in response to IFN stimulation (1). IFNs are cytokines classified into

three main types: Type I, II and III (2). Type I IFNs have a broad range of

biological functions including modulation of innate and adaptive

immune responses, anti-proliferative function and antiviral

activity (3). Type II IFN is IFN-γ,

which is primarily produced by immune cells (activated T cells,

natural killer cells and macrophages) and has been described as an

immunomodulatory cytokine, but it also shows responses to viruses,

bacteria, and parasites (4,5). Type III IFNs are uniquely chemotactic,

with signaling and function largely restricted to epithelial cells,

and these interferons are as key players in mucosal immunity

(6,7). Following viral infection, pathogenic

invasion or other stimuli, pattern recognition receptors(PRR) in

host cells detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns,

triggering an immune response. This induces IFN production, which

then binds to specific cell surface receptors and activates

intracellular signaling cascades, leading to the transcriptional

induction of ISGs (8).

ISG20 is an RNA exonuclease belonging to the Rex4

subfamily, a homolog of yeast RNA exonuclease 4 and a member of the

DEDDh exonuclease family, comprising four conserved acidic

residues, three aspartates (D), and one glutamate(E), distributed

among three separate sequence motifs (Exo I–III) (9,10) and

with a fifth conserved residue of histidine (H). It has the ability

to degrade single-stranded (ss)RNA and DNA, and encodes a 20 kDa

protein (11). Under physiological

conditions, ISG20 primarily contributes to the antiviral defense of

the host. It directly degrades viral RNA and modulates

intracellular antiviral signaling pathways, such as inducing type I

IFN responses, thereby inhibiting viral replication and spread

(12). In addition, ISG20 may

regulate immune cell functions and cytokine signaling (13). Previous advances have further

revealed the complex role of ISG20 in tumorigenesis, attracting

increasing interest (14–18).

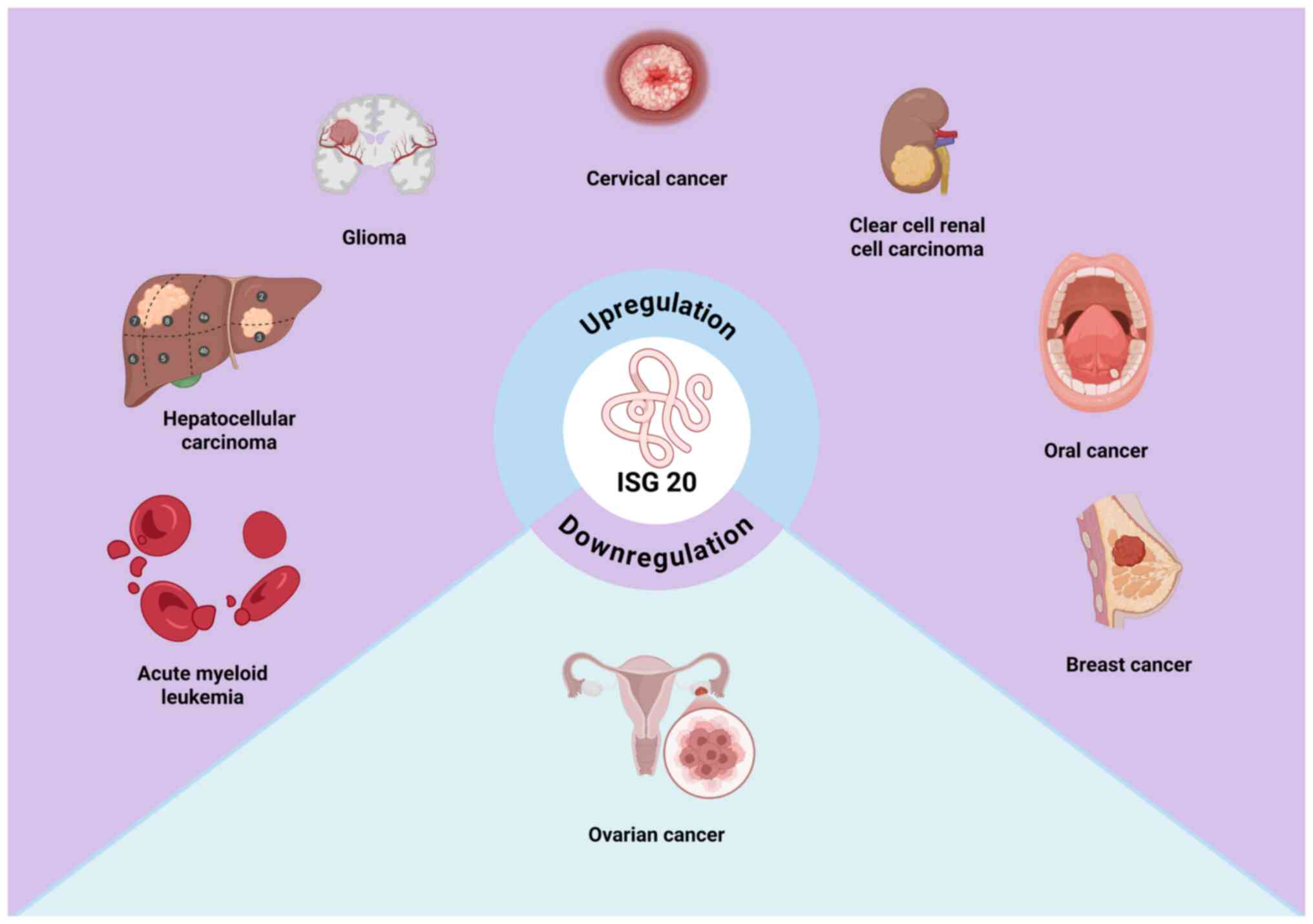

A growing body of research has demonstrated that

ISG20 expression is significantly dysregulated in various types of

cancer (19–22). In clear cell renal cell carcinoma

(ccRCC), ISG20 is markedly upregulated at both the mRNA and protein

levels, and is positively associated with advanced clinical stage.

Elevated ISG20 levels are associated with worse overall survival

(OS) and disease-free survival (DFS), suggesting its potential as a

diagnostic and prognostic biomarker (23). In glioma, ISG20 mRNA expression is

also significantly upregulated compared with that in normal brain

tissue, with differential expression observed across clinical

subgroups. High ISG20 expression is associated with poor prognosis,

and immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analyses have

revealed stronger expression in high-grade glioma, predominantly

localized to M2 macrophages (24).

Furthermore, aberrant ISG20 expression has been reported in other

malignancies, including cervical and oral cancer, hepatocellular

carcinoma, breast cancer and acute myeloid leukemia, where it may

be upregulated, associated with specific tumor-promoting factors or

predictive of unfavorable outcomes (19,25,26).

Although considerable progress has been made in

elucidating the role of ISG20 in cancer, the number of publications

remains limited compared with other ISGs (13,27,28).

Therefore, a comprehensive summary of the functions of ISG20 in

tumorigenesis is key. The present review outlines the historical

discovery of ISG20, and elaborates on its molecular structure and

physiological functions, as well as the role of ISG20 in cancer and

its therapeutic potential.

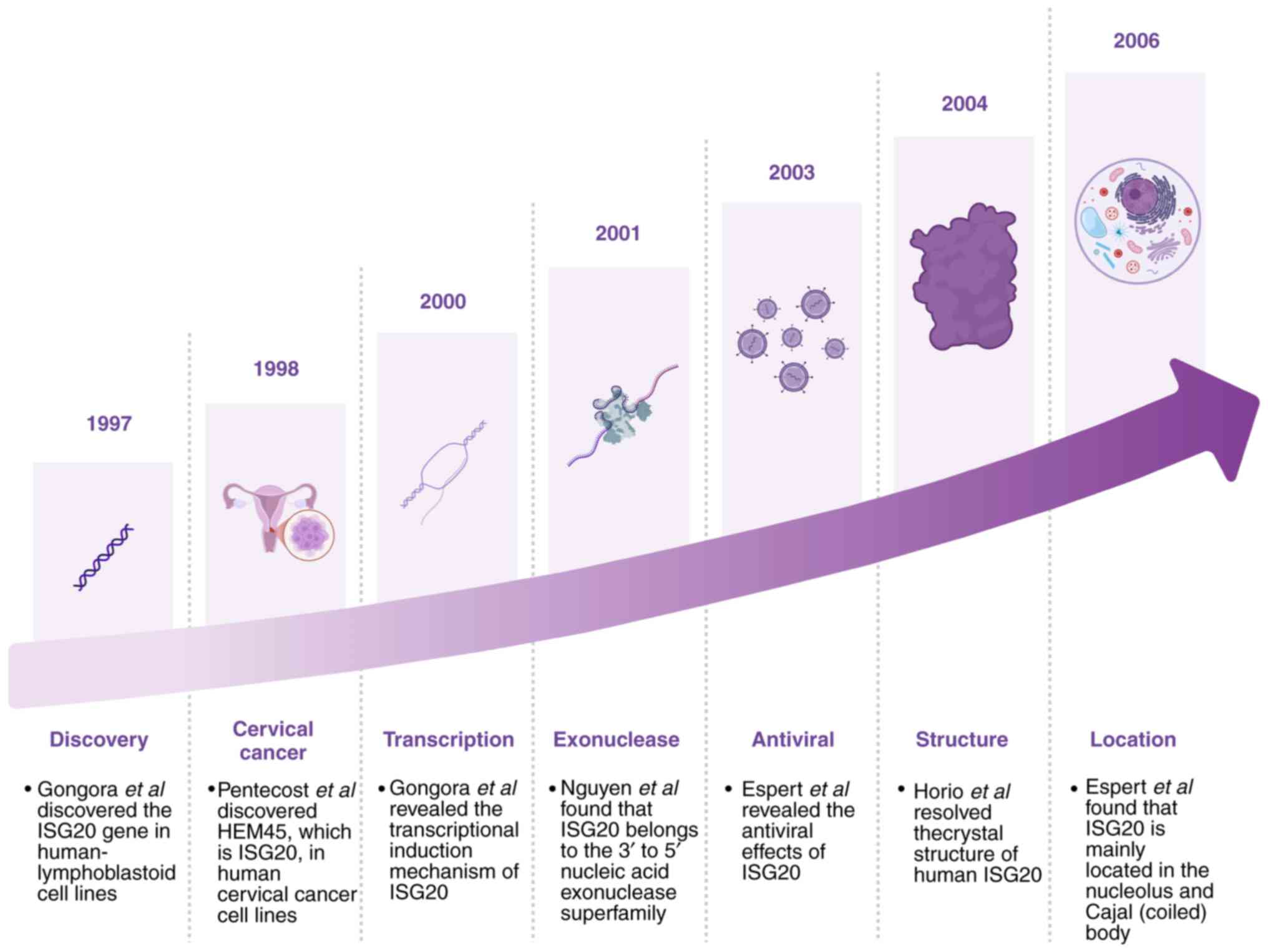

Discovery and molecular characterization of

ISG20

ISG20 was first identified in 1997 by Gongora et

al (29); this study employed

differential display techniques to screen IFN-regulated genes in

human Daudi lymphoblastoid cells treated with IFN-α/β (29). Among these genes, one was notably

inducible by both type I and II IFNs, and was designated as ISG20,

encoding a 20 kDa protein. In 1998, Pentecost (30) identified a transcript with low

baseline expression in multiple cell lines that was significantly

upregulated by estradiol in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast

cancer cells. This transcript, discovered via differential display

PCR in ER-transfected human cervical carcinoma cells (UP1), was

named HeLa estrogen-modulated 45 kDa band (HEM45). Subsequent

studies have confirmed that HEM45 and ISG20 are the same gene

product; as a result, ISG20 is also referred to as HEM45 (29,30).

In 2000, Gongora et al (31) demonstrated that ISG20 transcription

is induced by both type I (α/β) and II (γ) IFNs through a unique

IFN-stimulated response element located in its promoter, regulated

by IFN regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) (31). In 2001, Nguyen et al

(32) revealed that the ISG20

protein shares homology with members of the 3′-5; exonuclease

superfamily, including RNase T and D and the proofreading domain of

Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. The catalytic site

consists of four conserved acidic residues arranged within three

characteristic exonuclease motifs, classifying it under the DEDDh

subfamily of 3′-5′exonucleases (32). In 2003, Espert et al

(33) revealed the antiviral

activity of ISG20; HeLa cells overexpressing ISG20 were resistant

to RNA viruses such as vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), influenza

and encephalomyocarditis virus, even in the absence of IFN

treatment. This antiviral effect was attributed to the exonuclease

activity of ISG20, which also partially contributed to IFN-mediated

anti-VSV effects, demonstrating IFN-driven antiviral mechanisms

(33). ISG20 expression is directly

induced by synthetic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) via activation of

NF-κB and IRF1; this induction is more rapid and robust than that

triggered by IFN (34). Moreover,

ISG20 translocates to the nuclear matrix upon induction. Its site

of action is different from the cytoplasmic functional region of

PKR (dsRNA-activated serine-threonine protein kinase, a member of

the IFN-induced antiviral signaling pathway, which together with

the 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase/RNase L pathway constitutes the

core antiviral mechanism of the IFN system), suggesting its

involvement in the cell antiviral response, potentially through

aPKR-independent innate antiviral and anti-apoptotic pathway

(34). Horio et al (35) resolved the crystal structure of

human ISG20 in complex with two Mn2+ ions and uridine

5′-monophosphate (UMP) at a resolution of 1.9 Å. The structure

revealed marked similarity to DEDDh family DNases, suggesting a

shared catalytic mechanism. Unique residues within ISG20 may confer

its substrate preference for RNA, providing structural insights

into its antiviral function (35).

Espert et al (36) further

demonstrated, using immunofluorescence, that ISG20 primarily

localizes to the nucleolus and Cajal bodies, and associates with

complexes containing nuclear survival of motor neuron protein. As

its structure and regulatory mechanisms have become clearer,

investigations into the physiological roles of ISG20 under various

conditions have expanded (Fig. 1)

(37–39).

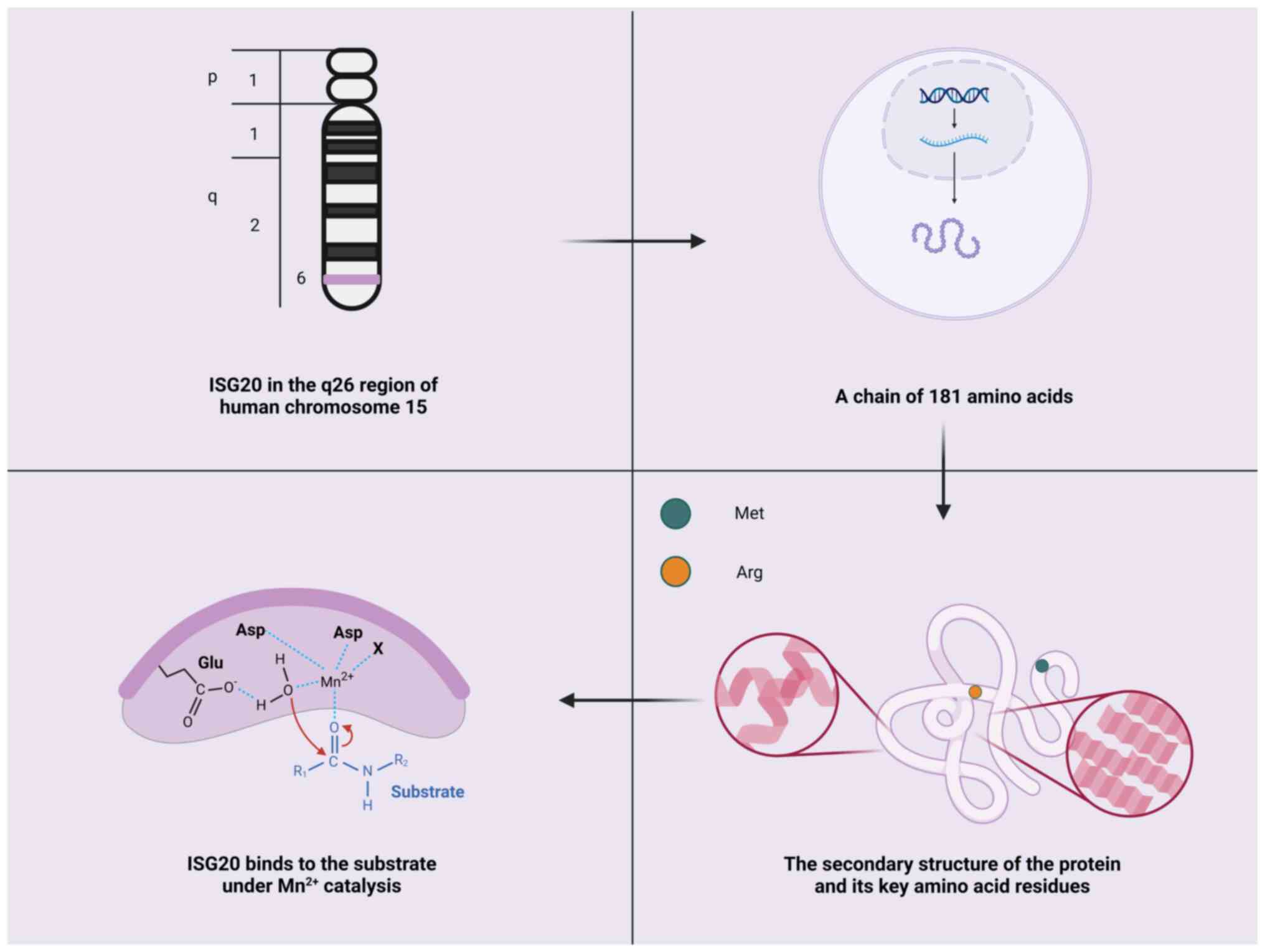

Structural features and physiological

functions of ISG20

ISG20 is located on chromosome 15q26 in humans and

encodes a protein consisting of 181 amino acids with a molecular

weight of ~20.4 kDa (29). ISG20

belongs to the 3′-5′exonuclease superfamily (32). The catalytic site of this

superfamily consists of four conserved acidic residues

(Asp-Glu-Asp-Asp) distributed across three exonuclease motifs

(ExoI, ExoII and ExoIII) (10,40).

These residues coordinate two metal ions necessary for hydrolyzing

the terminal phosphodiester bond of RNA or DNA, thereby

facilitating an enzymatic reaction. Crystal structure analysis has

revealed that ISG20 contains a five-stranded β-sheet core flanked

by two clusters of α-helices (a3, a4 and a1, a2, a5, a7) (35). At the active site, specific amino

acid residues, such as Asp11, Glu13 and Asp154, participate in

coordinating metal ions (such as Mn2+), enabling

catalytic activity (35). In

vitro, ISG20 exhibits exonucleolytic activity against ssRNA and

ssDNA, with a marked preference for RNA substrates. This substrate

preference may be due to residues such as Met14 and Arg53, which

directly interact with the ribose 2′-OH group of UMP (35). However, the precise molecular

mechanism underlying this specificity remains to be elucidated

(Fig. 2).

Although purified ISG20 primarily cleaves ssRNA

in vitro, it may exhibit resistance to substrates with

3′structures. For example, Liu et al (41) found that the encapsidation signal

εRNA of hepatitis B virus (HBV) exhibits resistance to ISG20

(41). The εRNA is located near the

5′ end of the HBV pre-genomic RNA and features a unique secondary

structure, including a long 13-bp basal stem, a 6-nt bulge region

(initiator loop), an 11-bp upper stem and a terminal hexaloop

(42). It has been shown that ISG20

specifically binds the lower stem of εRNA, with binding stability

requiring a lower stem of >9 RNA bps (41). However, despite tight binding, ISG20

is unable to effectively cleave the εRNA substrate. Notably,

deletion of the C-terminal ExoIII motif of ISG20 results in

complete loss of RNA binding, suggesting that the ExoIII motif may

harbor an RNA-binding domain, or that the coordination of MnA by

Asp154 is key for RNA binding (41). In addition to its role in nucleic

acid degradation, ISG20 is involved in other key cellular

processes. ISG20 has been reported to mediate estrogen signaling,

serving a role in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation

(41). Its expression is

significantly upregulated in response to IFN or estrogen, further

highlighting its key role in hormone-regulated cell networks

(43–45).

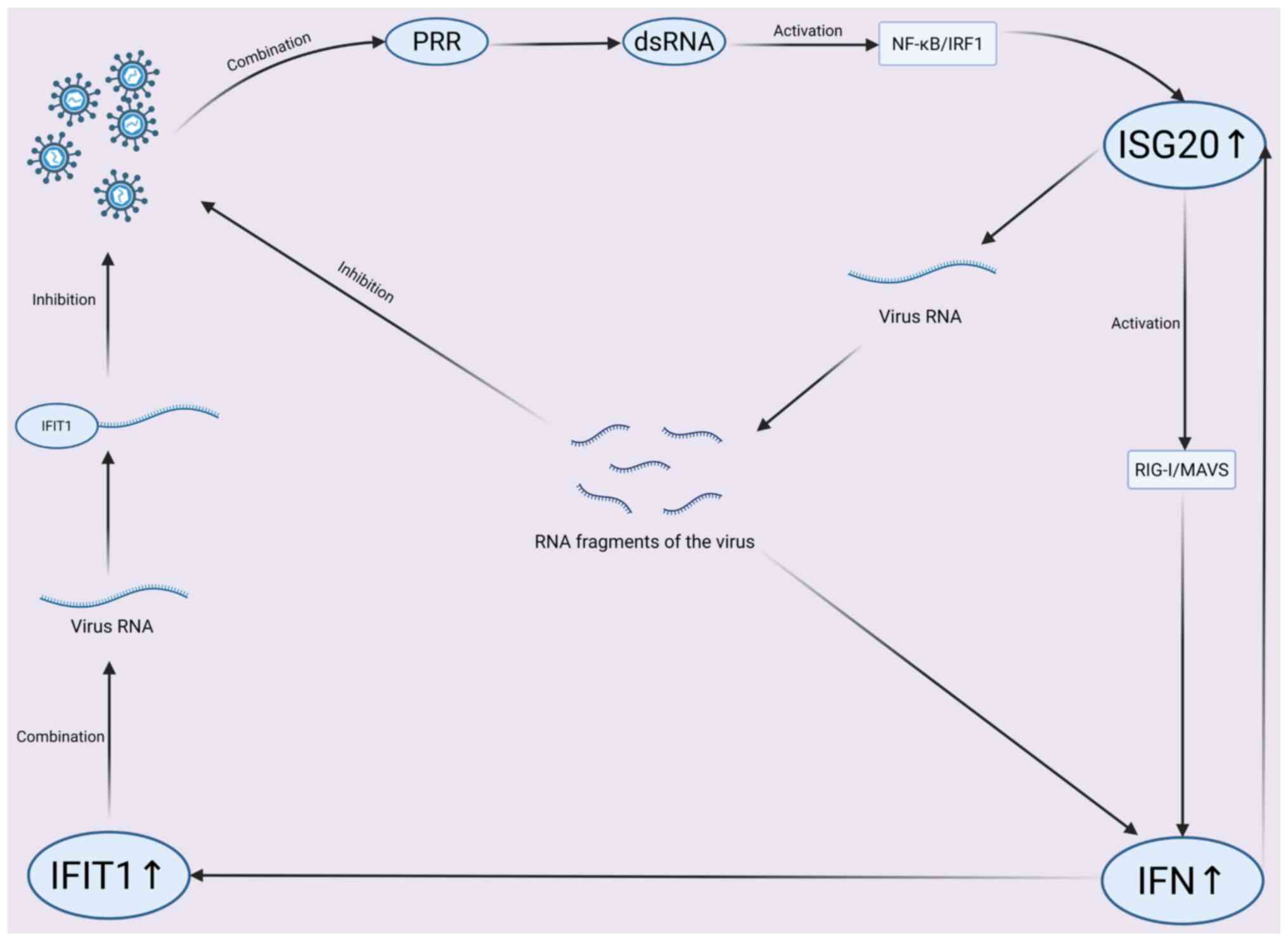

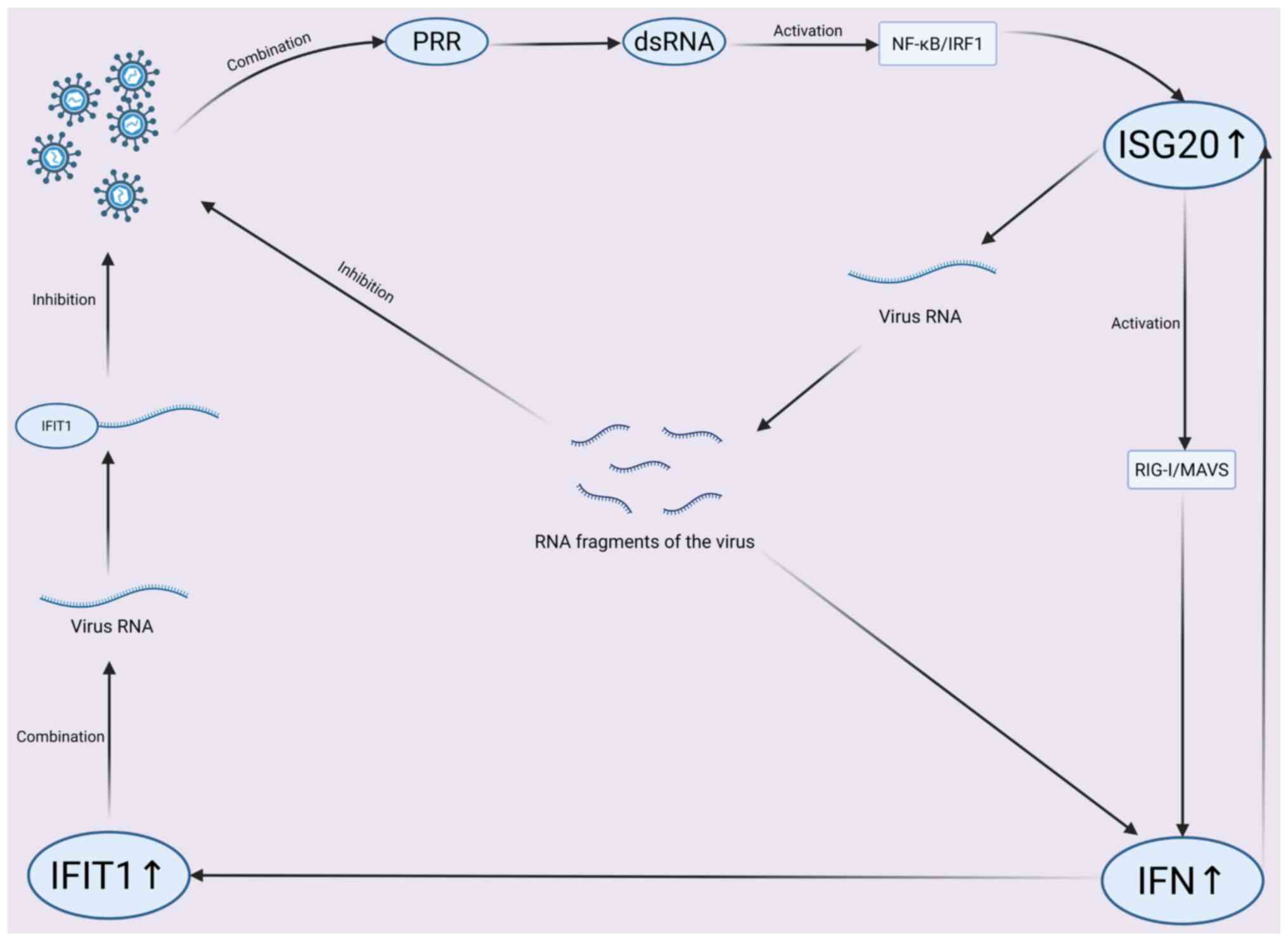

The antiviral effects of ISG20 have been extensively

studied (12,45,47).

These include direct degradation of viral RNA, deamination of viral

DNA, IFN-induced and IFIT1 (IFN-induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats1)-mediated suppression of viral RNA

translation and non-IFN-induced inhibition of non-self RNA

translation (Fig. 3) (48). ISG20 exhibits RNase activity,

capable of degrading viral ssRNA and ssDNA. As aforementioned,

ISG20 can degrade HBV RNA by directly binding the ε-stem-loop

structure of viral RNA, thereby inhibiting HBV replication.

Additionally, Kang et al (49) studied the inhibitory mechanism of

ISG20 on bluetongue virus (BTV), and found that mutating Asp94 to

Gly in ISG20 to create a nuclease-deficient mutant significantly

decreased its inhibitory effect on BTV replication, suggesting that

ISG20 may directly degrade viral RNA through its exonuclease

activity during BTV infection (49). However, there remains controversy

regarding whether ISG20 directly degrades viral RNA and its

antiviral mechanism and specificity are not fully understood

(11,41,50).

| Figure 3.Mechanistic pathway of ISG20

antiviral activity. Viral dsRNA is recognized by PRR, activating

NF-κB/IRF1 to upregulate ISG20. ISG20 degrades viral RNA and

activates RIG-I/MAVS for IFN production. IFN-induced IFIT1 binds

viral RNA, inhibiting replication and viral-PRR interaction. Viral

RNA fragments modulate the response, forming a coordinated innate

immune network. ISG, IFN-stimulated gene; IFIT, Interferon-induced

protein with tetratricopeptide repeats; IRF, IFN regulatory factor;

PRR, Pattern recognition receptor; ds, double-stranded; RIG-I,

Retinoic Acid-Inducible Gene I; MAVS, Mitochondrial Antiviral

Signaling Protein. |

Some studies have suggested that ISG20 may exert its

effects more through translational inhibition than RNA degradation

(12,46). For example, in mouse embryonic

fibroblasts, overexpression of mouse ISG20 indirectly suppresses

viral translation by inducing an IFN response and IFIT1, without

involving viral RNA degradation (12). However, ISG20 is an IFN regulatory

protein, and the mechanism by which it induces IFN, as well as how

it mediates suppression of a range of viruses, remains unclear.

Additionally, the source of the RNA (cellular or viral) targeted by

ISG20 during IFN induction has yet to be determined. Furthermore,

it has been demonstrated that the subcellular localization and

dynamic changes of ISG20 may influence its antiviral function

(36,46,51).

For example, under uninfected conditions, ISG20 is predominantly

localized in the nucleus, associated with nuclear structures such

as promyelocytic leukemia bodies, nucleoli and Cajal bodies, and

potentially involved in RNA processing and transcriptional

regulation (48). After viral

infection, a fraction of ISG20 translocates to processing bodies (P

bodies) in the cytoplasm, which serve a crucial role in RNA

degradation and translational regulation. The localization of ISG20

in P bodies may aid degradation of viral RNA or the suppression of

viral RNA translation, thereby contributing to its antiviral

activity (11).

ISG20 not only serves a key role in antiviral

responses but also participates in the immune regulation processes,

affecting numerous aspects of the immune system (52,53).

In innate immunity, ISG20 may serve as an important effector

molecule, participating in the responses of immune cells such as

macrophages and dendritic cells to pathogens (54). ISG20 serves a key role in

macrophages resisting Listeria infection, and in dendritic

cells responding to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and

Toxoplasma gondii infection, suggesting it may enhance

innate immune defense by regulating immune cell function (54,55).

ISG20 may also play a role in adaptive immunity. For example,

Rodríguez-Galán et al (56)

reported that the ISG20 family member ISG20L2 specifically binds

uridylated microRNAs (miRs), is upregulated in T lymphocytes under

T cell receptor and type I IFN stimulation, and participates in

regulating T cell function. Knockout of this gene may lead to

delayed T cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, abnormal

expression of activation-associated molecules, increased IL-2

secretion and impaired immunological synapse formation and

dynamics, indicating that ISG20 may influence T cell activation and

function, thereby indirectly affecting the adaptive immune response

(56).

The role of ISG20 in immune regulation may also be

associated with its impact on the interaction between immune and

tumor cells. In the tumor microenvironment (TME), the functional

state of immune cells markedly influences tumor initiation,

progression and the effectiveness of immunotherapy. Studies have

indicated that ISG20 may affect the immune balance in the TME by

regulating immune cell infiltration, modulating immune signaling

pathways and adjusting chemokines, thereby influencing tumor cell

proliferation and metastasis (14,43).

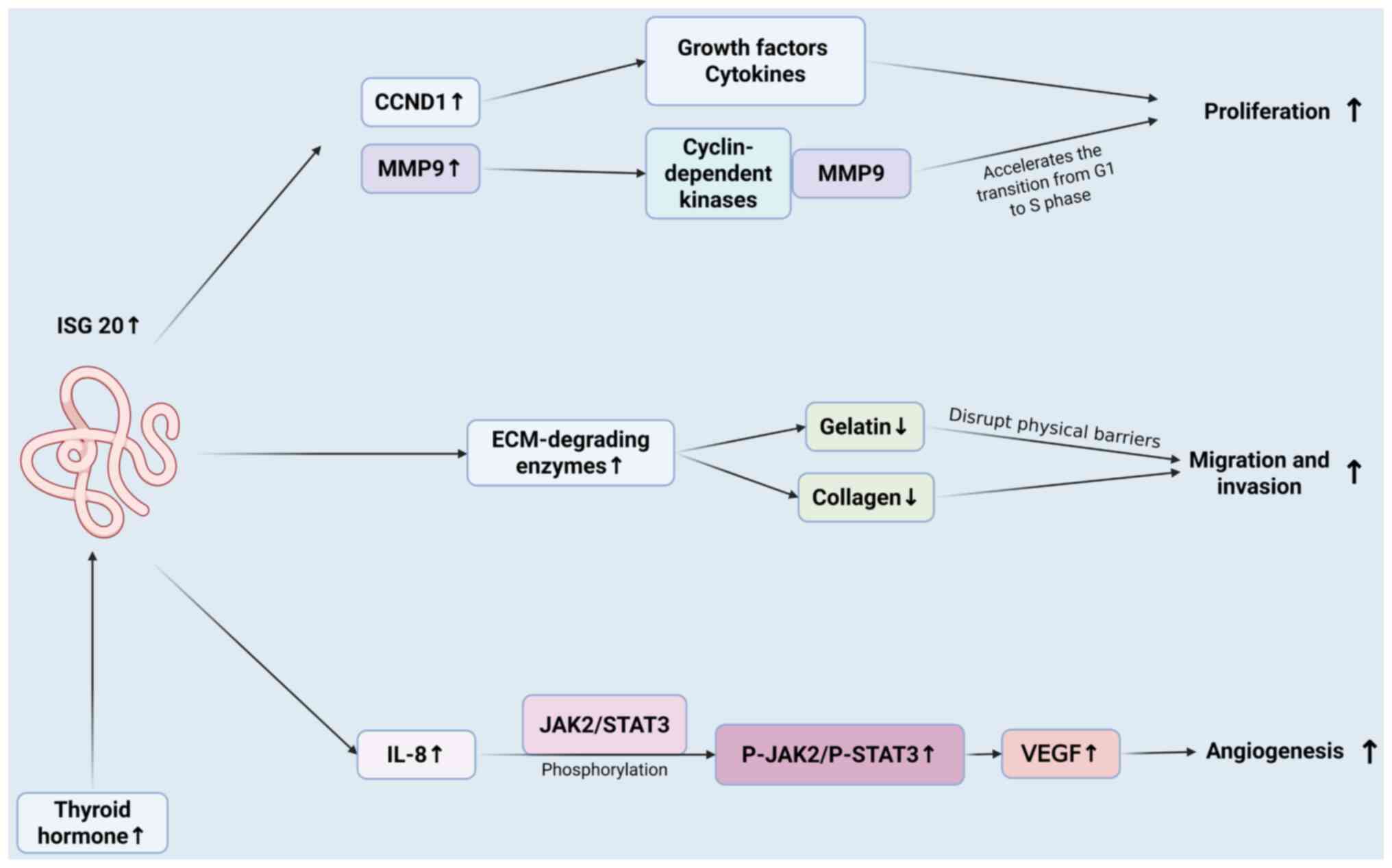

Role of ISG20 in cancer

ISG20 exhibits opposing mechanisms of action in

tumors, necessitating further research. From an immunological

perspective, when tumor cells successfully evade immune responses,

cancer progression occurs (57).

IFNs are a family of secreted proteins, also known as key drivers

of inflammation in the TME, that have a crucial role in triggering

immune responses in immune cells (57–59).

As the second protein induced by IFNs or dsRNA, ISG20 exhibits

differential expression in healthy individuals and certain types of

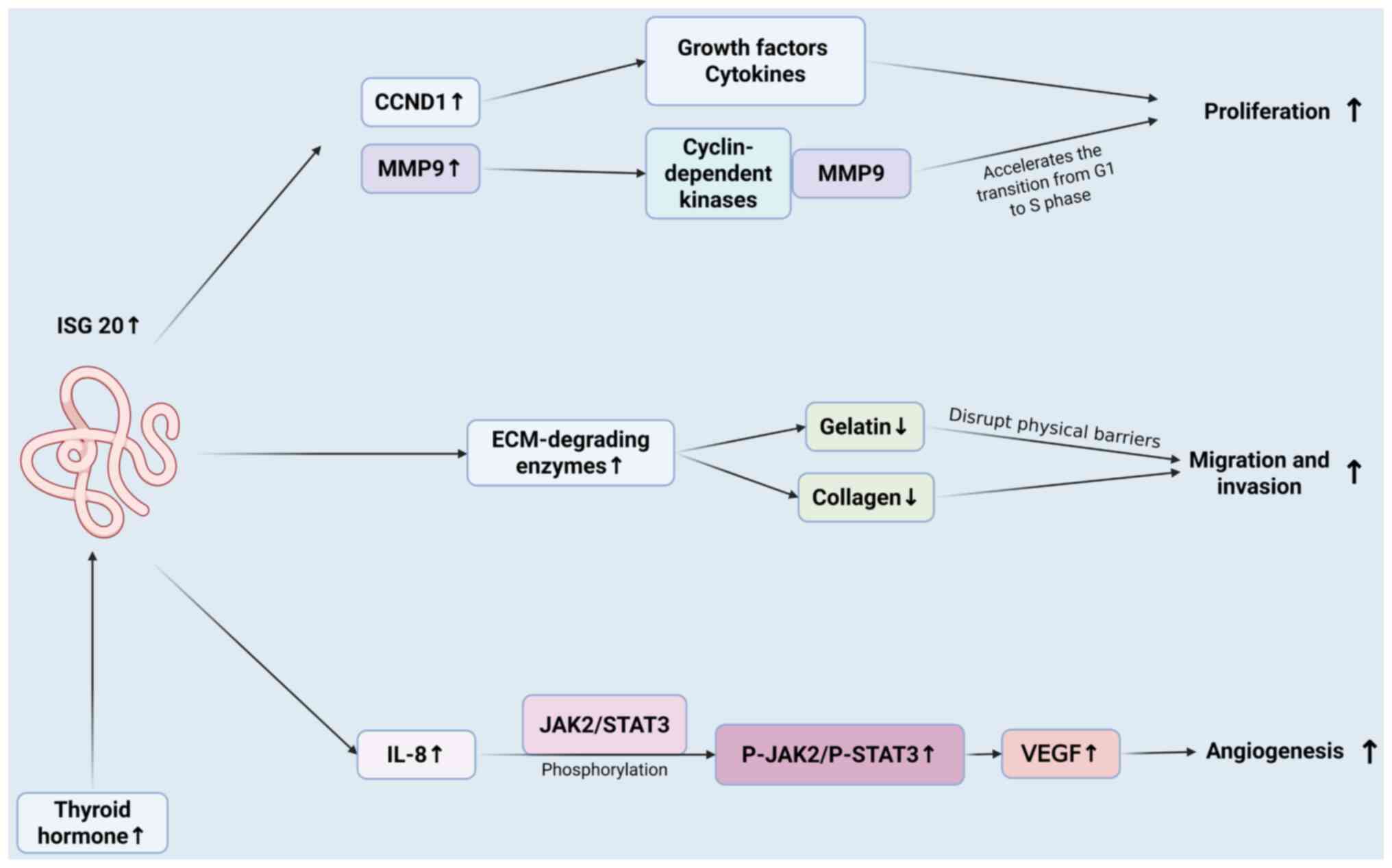

tumors, but its precise mechanism remains to be explored (Fig. 4).

| Figure 4.Mechanism of ISG20 in promoting tumor

cell proliferation, migration, invasion and angiogenesis. ISG20,

induced by thyroid hormone, promotes cancer cell proliferation,

migration, invasion and angiogenesis. It acts via pathways like

CCND1/MMP9 for proliferation, ECM-degrading enzymes for

migration/invasion, and IL-8-JAK2/STAT3-VEGF for angiogenesis. ISG,

IFN-stimulated gene; CCND, cyclin D1; P, phosphorylation. |

Impact on tumor cell

proliferation

In certain types of cancer, such as RCC, breast and

cervical cancer, glioblastoma (GBM) and hepatocellular carcinoma,

ISG20 promotes tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 5). In ccRCC, Xu et al

(23) conducted Gene Set Enrichment

Analysis and revealed that high ISG20 expression notably

contributes to the ‘cell cycle pathway’, promoting tumor cell

proliferation. The aforementioned study also revealed that

silencing ISG20 leads to significant downregulation of MMP9 and

CCND1 expression in ccRCC, both of which are typically upregulated

in ccRCC (23). Therefore, ISG20

may accelerate the cell cycle progression and promote rapid tumor

cell proliferation by positively regulating the expression of the

cell cycle-associated proteins MMP9 and CCND1. Furthermore, ISG20

has been identified as a potential prognostic target in ccRCC.

Rajkumar et al (18) used

microarray technology to analyze samples from various stages of

cervical cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and normal

cervical tissue; the findings initially indicated a potential

expression difference for ISG20, which was validated by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and calibrated to normal samples,

confirming high ISG20 expression in cervical cancer tissue. These

results suggested that ISG20 may serve an important role in the

progression of cervical cancer (18).

By contrast, in ovarian cancer, ISG20 inhibits tumor

cell proliferation both in vivo and in vitro

(45). ISG20 overexpression can

significantly inhibit the proliferation of Caov3 cells in

vivo. Additionally, xenograft tumor assays in nude mice

revealed that stable overexpression of ISG20 in Caov3 cells using

pLVX–ISG20-IRES-Neo slows tumor growth. These results suggested

that ISG20 may suppress tumorigenesis in vivo (45).

Effect on tumor cell migration and

invasion

Tumor migration and invasion are regulated by

multiple factors, including genetic mutation, signaling pathway

activation, TME remodeling and phenotypic plasticity. ISG20exhibits

heterogeneity in its effect on tumor migration and invasion.

Alsheikh et al (43)

reported that the NMI (N-Myc and STAT interactor protein)-STAT5A

signaling axis inhibits ISG20 expression via miR-20a, maintaining

normal breast epithelial differentiation and suppressing tumor

metastasis. Clinical samples revealed that in 70% of patients with

metastatic breast cancer, NMI protein levels are lower than those

in primary tumor samples, whereas ISG20 expression is significantly

higher in metastatic than in primary sites. Functional assays,

including Transwell, Matrigel and lung metastasis experiments,

confirmed that ISG20 overexpression enhances migration, invasion

and lung metastasis potential in breast cancer cells (43).

Additionally, ISG20 may promote the expression of

certain extracellular matrix (ECM)-degrading enzymes, leading to

the breakdown of collagen and gelatin components in the ECM,

thereby disrupting physical barriers around tumor cells and

facilitating migration and invasion (23). Notably, in ccRCC, high ISG20

expression may promote MMP9 activity, thereby enhancing tumor

migration and invasion (23). MMP9,

a key ECM-degrading enzyme, disrupts the basement membrane and ECM,

providing a physical passage for tumor cell migration (60). ISG20 knockdown inhibits cell

invasion, confirming its role in ECM remodeling through an

MMP9-dependent mechanism (23).

However, in ovarian cancer, Yu et al

(45) employed Transwell assays to

assess the invasion and migration of Caov3 cells in vitro,

finding that ISG20 overexpression significantly inhibited cell

invasion and migration compared with the control group, however,

the underlying mechanism remains unclear (45).

ISG20 upregulation induces tumor

angiogenesis

Tumor formation is typically driven by the

proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells, which depend on the

ability of tumor cells to recruit their own blood supply.

Angiogenesis is the key pathway by which tumors acquire nutrients

and oxygen and achieve distant dissemination, and is therefore key

for the development of human cancer (61). In the intricate regulatory network

of angiogenesis, the positive regulator vascular endothelial growth

factor and the negative regulator thrombospondin-1 form a dynamic

balance (62,63).

Previous studies have shown that ISG20

overexpression does not inhibit angiogenesis, whereas its dominant

negative mutation ExoII (lacking exonuclease activity) inhibits

angiogenesis by 43% (64,65). In addition, fibrin gel assay

suggested that the exonuclease activity of ISG20 may be essential

for angiogenesis (64). In

hepatocellular carcinoma, Lin et al (65) reported that thyroid hormone

(triiodothyronine) upregulates ISG20, which promotes hepatocellular

carcinoma angiogenesis by regulating IL-8 and activating the

phosphorylated (p-)JAK2/p-STAT3 signaling pathway, providing

therapeutic targets and a theoretical basis for liver cancer

treatment. In vitro, conditioned medium from

ISG20-overexpressing hepatocellular carcinoma cells significantly

promotes the formation of lumen-like structures by human umbilical

vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), whereas ISG20 knockdown may

inhibit thyroid hormone-induced HUVEC tube formation (65). In vivo, experiments using the

Matrigel plug and chicken embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM)

models have confirmed that ISG20-overexpressing cells enhance

angiogenesis, as evidenced by increased hemoglobin content in the

Matrigel plugs, more CAM blood vessel branches and elevated

expression of the endothelial marker CD31 (65). Knockdown of ISG20 decreases these

effects. Clinical analysis has also revealed that ISG20 expression

in liver cancer tissue is positively associated with

angiogenesis-associated clinical parameters, such as vascular

invasion and tumor size (65).

Additionally, patients with high ISG20 expression have shorter

recurrence-free survival, providing evidence that ISG20 promotes

angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma (65,66).

Furthermore, human angiogenesis chip assays have revealed that

ISG20 overexpression significantly upregulate the angiogenic factor

IL-8 and activates the p-JAK2/p-STAT3 signaling pathway in HUVECs

(65). By contrast, knockdown of

IL-8 or the use of IL-8 neutralizing antibodies inhibits

ISG20-induced tube formation in vitro and angiogenesis in

vivo. Treatment with JAK2/STAT3 inhibitors also significantly

blocks ISG20-mediated angiogenesis, confirming the key role of this

pathway (65).

Regulation of TME

The TME refers to the local environment that

supports the survival and development of tumor cells, encompassing

various cells, molecules and the ECM, including tumor and immune

cells (67). These components form

a complex ecosystem that serves a key role in tumor initiation,

growth, metastasis and response to treatment (68). The regulatory mechanisms of ISG20

expression in the TME involve numerous signaling pathways and

molecular mechanisms, with its effect on tumor cells varying

depending on tumor type and microenvironment. In some tumors, it

may suppress tumor progression by enhancing immune responses,

whereas in others, it may promote tumor progression by fostering

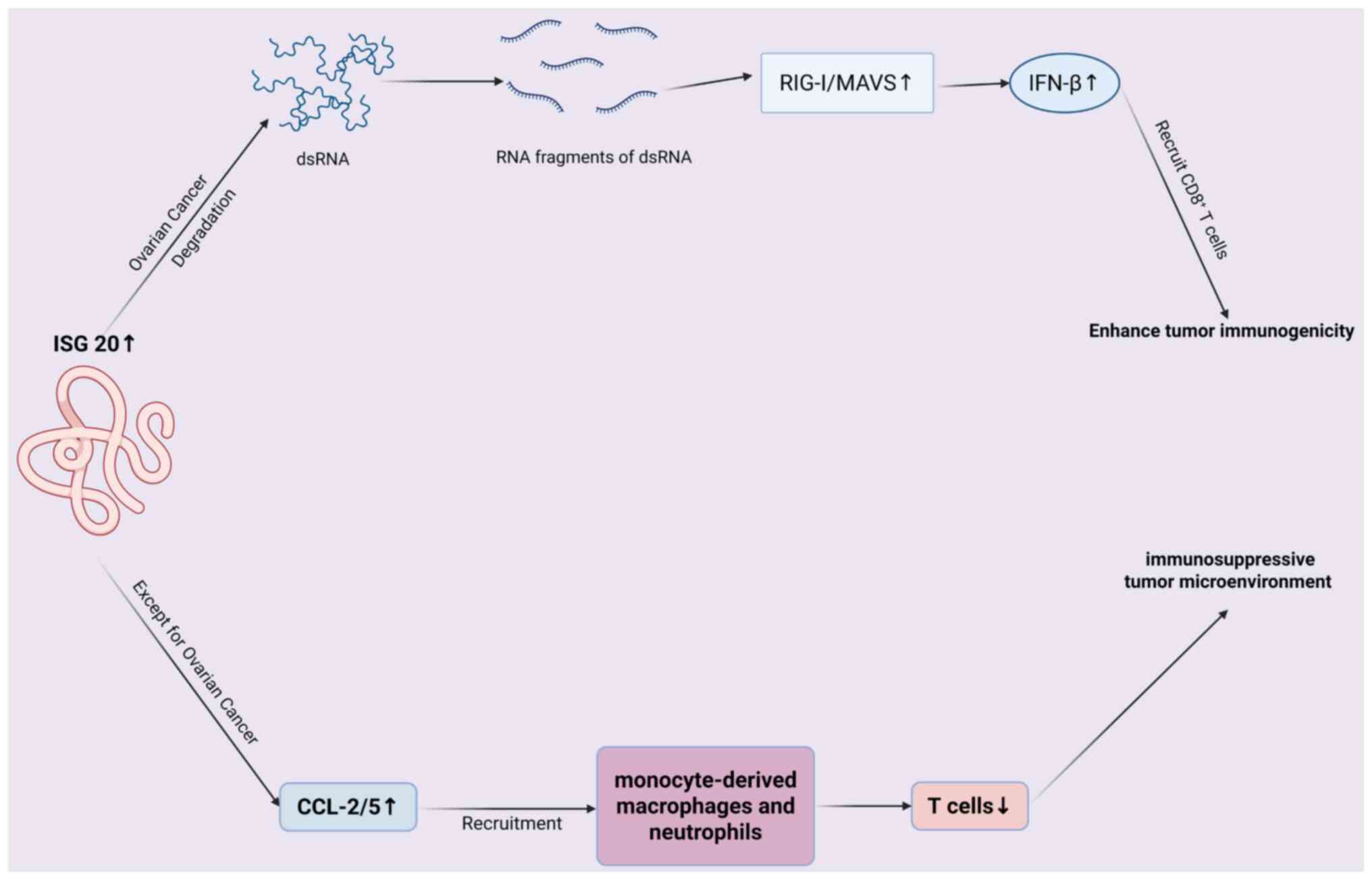

immune suppression or enhancing tumor invasiveness (Fig. 6) (14,22,23).

| Figure 6.Mechanism of ISG20 regulating tumor

immune microenvironment. In ovarian cancer, ISG20 degrades dsRNA

into fragments, activating RIG-I/MAVS to induce IFN-β, which

recruits CD8+ T cells and enhances immunogenicity. In

other cancers, ISG20 upregulates CCL-2/5, recruiting

monocyte-derived macrophages/neutrophils, reducing T cells and

forming an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. ISG,

IFN-stimulated gene; ds, double-stranded; RIG-I, retinoic

Acid-Inducible Gene I; MAVS, Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling

Protein. |

Chen et al (22) revealed that ISG20 stimulates

antitumor immunity in ovarian cancer through a dsRNA-induced IFN

response (22). Specifically,

through protein-protein interactions and survival analysis, ISG20

was identified as the only gene significantly associated with OS in

patients with ovarian cancer. Comparison of the high and low ISG20

subgroups in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) ovarian cancer dataset

revealed that high ISG20 expression is associated with increased

CD8+ T-cell infiltration and enhanced tumor

immunogenicity. Functional experiments demonstrated that ISG20

degrades endogenous long dsRNA into shorter fragments through its

exonuclease activity, activating the RIG-I/MAVS (retinoic

acid-inducible gene I/Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein)

signaling pathway and promoting IFN-β secretion. IFN-β upregulates

ISGs, such as CXCL10 and CXCL11, enhancing tumor cell

immunogenicity and CD8+ T cell infiltration. The

aforementioned study identified the critical role of the RIG-I/MAVS

signaling pathway, dependent on ISG20 exonuclease activity, in

ovarian cancer. Enhancing the ISG20/RIG-I pathway (through dsRNA

agonists) or use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as

anti-PD-1) may offer novel therapeutic strategies for ovarian

cancer immunotherapy.

In glioma, ISG20 has been shown to promote local

tumor immunity (14). Gao et

al (14) used functional

enrichment and correlation analysis to reveal that ISG20 recruits

monocyte-derived macrophages and neutrophils by upregulating

chemokines such as CCL2/5, while inhibiting the infiltration of

antitumor T cell subsets, including central memory and follicular

helper T cells. This expression pattern is positively associated

with immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA4 and

JAK/STAT pathway activation, thus shaping an immune-suppressive

microenvironment (14). Although

the aforementioned study revealed the key role of ISG20 in the

glioma immune microenvironment, its specific molecular mechanisms,

such as direct target interactions and signaling pathway

regulation, require further investigation. Another study using

large TCGA cohorts and meta-analysis demonstrated that higher ISG20

expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with

glioma (24). The aforementioned

study further revealed that ISG20 is expressed in tumor-associated

macrophages, influencing immune cell infiltration and immune

checkpoint regulation, thereby participating in the regulation of

the glioma immune microenvironment (24). ISG20 is primarily expressed in

M2-type tumor-associated macrophages, with high expression

positively associated with M2 macrophage and regulatory T cell

(Treg) infiltration, and negatively associated with plasma and

naïve T cells (24). It was also

positively associated with immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1

and CTLA4, suggesting that it promotes tumor immune escape by

shaping an immune-suppressive microenvironment (24). Immunofluorescence confirmed the

co-localization of ISG20 with CD163, indicating its predominant

expression in M2-type tumor-associated macrophages. Furthermore,

enrichment analysis showed that ISG20-associated genes are directly

involved in pathways such as IL6/JAK/STAT3 (cell proliferation),

PI3K/AKT/mTOR (survival signaling) and ECM remodeling (invasion and

metastasis) (24). This suggested

that ISG20 may serve as a novel biomarker for malignant phenotype

and prognosis in glioma. It influences tumor progression by

regulating the immune microenvironment and pro-cancer pathways,

offering a target for immunotherapy aimed at M2 macrophages.

A previous study investigated the precise effect of

ISG20 on macrophage polarization in GBM (69). The results demonstrated that

FOSL2(Fos-like 2), a potential transcription factor, may activate

ISG20 transcription through DNA hypomethylation, inducing

macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype. This can lead to

the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and

TGF-β, which suppress T cell function and establish an

immune-suppressive microenvironment, thus promoting tumor

progression. The aforementioned study reveals the critical role of

the FOSL2/ISG20 pathway in GBM progression, providing new targets

for therapies aimed at M2 macrophage polarization and

FOSL2/ISG20-associated treatment strategies. However, the

aforementioned study did not elucidate the mechanism by which ISG20

induces M2 macrophage polarization in the GBM TME.

In ccRCC, ISG20 promote the infiltration of

suppressive immune cells, enhances immune checkpoint signaling and

regulates disulfide metabolism, thereby constructing an

immune-suppressive TME that enables tumor cells to evade host

immune surveillance and attack (70). Specifically, in the C2 subtype

(high-risk group) with high ISG20 expression, tumor-infiltrating

immune cells, including Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells,

are significantly enriched (70).

Single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses

(70) have revealed that ISG20 is

highly expressed in Tregs and exhausted CD8+ T cells,

co-localizing with T cell exhaustion markers such as lymphocyte

activation Gene 3). This suggests that ISG20 may maintain the

immunosuppressive phenotype of Tregs and the functional decline of

exhausted T cells, thus inhibiting effector T cell activity

(70). Furthermore, high ISG20

expression is significantly associated with the upregulation of

immune checkpoint proteins, such as PD-1, CTLA-4 and T cell

Immunoglobulin and ITIM Domain), which transmit inhibitory signals

leading to T cell inactivation (70). The high-risk group exhibits

significantly higher T cell exhaustion and dysfunction scores,

further confirming that ISG20 contributes to the inhibitory TME,

hindering T cell attacks on tumors (70). ISG20 is also positively associated

with the disulfide death core gene SLC7A11 at the protein level,

and their co-expression may regulate intracellular disulfide bond

metabolism and redox homeostasis, influencing ferroptosis and

shaping a microenvironment that supports tumor survival (70).

In summary, ISG20 exhibits a dual role in the TME,

driving anti-tumor immunity while promoting immunosuppression and

tumor progression. This functional heterogeneity is shaped by a

series of key determinants of tumor type specificity. In-depth

investigation of these factors is essential for understanding the

biological role of ISG20 and developing precision targeting

strategies. Cellular localization of ISG20 action is a key factor.

In ovarian cancer, Chen et al (22) clarified that its function mainly

originates from the expression of tumor cells, which activates the

RIG-I/MAVS/IFN-β pathway through degradation of endogenous dsRNA in

tumor cells, which in turn recruits CD8+ T cells. By

contrast, in glioma and ccRCC, key evidence (co-localization with

CD163, expression in Tregs/depleted CD8+ T cells)

suggests that the pro-tumorigenic effect of ISG20 stems primarily

from its expression in specific immune cell subsets (especially

M2-type tumor-associated macrophages and Tregs), which are the key

components of the immune-suppressive TME. Downstream pathways and

effector molecules activated by ISG20 show functional shifts due to

differences in the molecular composition of the TME. The abundant

endogenous dsRNA in ovarian cancer provides ISG20 with a substrate

to activate the RIG-I pathway, which produces chemokines such as

CXCL10/11 that recruit effector T cells. In glioma, high expression

of ISG20 (potentially activated by FOSL2 transcription) is

associated with the sustained activation of the JAK/STAT pathway,

leading to the upregulation of chemokines such as CCL2/5 that

recruit suppressor myeloid cells and promoting the expression of

immune checkpoints such as PD-1/PD-L1. Renal cancer studies

(22,23). have further revealed ISG20 synergy

with disulfide death-related genes (such as SLC7A11) and its

spatial co-localization with T cell depletion markers, suggesting

that it may shape the suppressive TME by regulating cell metabolism

and directly participating in the maintenance of the depletion

phenotype. Finally, the ‘functional output’ of ISG20 is dependent

on the composition and activation status of the immune cell network

in which it operates. CCL2/5 may recruit different cell types in

different TMEs; ISG20-induced production of IFN-β may enhance

immunogenicity in ovarian cancer, whereas it may promote immune

tolerance or depletion in the context of chronic inflammation or in

the presence of other suppressive signals. The association of high

ISG20 expression with decreased infiltration of specific T cell

subsets (central memory and follicular helper T) observed in glioma

studies (14,24) and with Tregs/myeloid-Derived

Suppressor Cells) enrichment and elevated T cell dysfunction score

in renal carcinoma (70) is a

manifestation of this network dependence. Thus, ISG20 functions are

affected by the cellular ecological niche, molecular signaling

network and immune context of specific tumor types. Understanding

the determinants of tumor specificity, such as cellular

localization, microenvironmental molecular context (substrate,

pathway coupling) and immune cell network composition and status,

is a fundamental prerequisite for resolving its dual roles,

evaluating its value as a biomarker and designing effective

targeted intervention strategies. Furthermore, in terms of

potential molecular mechanisms between ISG20 and immune checkpoint

regulation, existing studies (14,24)

have primarily provided correlation evidence (co-expression,

co-localization) and pathway associations (JAK/STAT), but lack

conclusive molecular mechanistic models (key transcription factor

complexes, direct substrate-product association, specific protein

interactions) and in-depth experimental validation such as

chromatin and RNA immunoprecipitation followed by Sequencing,

reporter gene analysis, effects of conditional

knockout/overexpression in specific cell types. In glioblastoma

(69), the transcription factor

FOSL2 activates ISG20 transcription through DNA hypomethylation,

induces macrophage polarization towards M2 type and secretes

inhibitory factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β. M2 type macrophages may

further upregulate PD-L1 expression through the JAK/STAT pathway,

creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment. In ccRCC (70), high ISG20 expression was positively

associated with the phosphorylation of STAT3, a key transcriptional

activator of PD-L1, which is enhanced by direct binding to the

PD-L1 promoter. In addition, ISG20 is positively correlated with

the disulfide death core gene SLC7A11 in renal cancer, which

regulates intracellular redox homeostasis. SLC7A11 enhances PD-L1

transcription by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, and ISG20

may indirectly support this process through metabolic reprogramming

(70). Future studies are needed to

characterize these factors in more tumor types and explore the

precise molecular mechanisms of their interaction.

Potential application of ISG20 in cancer

therapy

As a tumor-associated antigen

Due to marked dysregulation of the IFN signaling

pathway in various tumors, ISG20 is upregulated in tumors of the

brain, uterus, breast, cervix, esophagus, kidney, liver, pancreas,

skin and testes (24). In ovarian

cancer, ISG20 enhances type I IFN signaling, increasing the

immunogenicity of tumor cells and promoting immune cell

infiltration and antitumor immune responses (22). This suggests that ISG20 gene

delivery via viral vectors (including lentiviruses) may directly

increase ISG20 expression in tumor cells, promoting dsRNA

fragmentation and IFN-β secretion, thereby activating both innate

and adaptive immune responses. Alternatively, drugs specifically

activating ISG20 RNase activity, or alleviating ISG20 inhibitors

(protein modification regulation), may be developed to induce

endogenous dsRNA accumulation and IFN pathway activation for

ovarian cancer treatment. However, ISG20 has a tumor-promoting role

in most types of cancer, including glioma and ccRCC (23,24).

In the future, ISG20 could be used as a tumor-associated antigen to

design vaccines (such as peptide, DNA/RNA or dendritic cell

vaccines) to activate specific immune responses targeting tumor

cells for antitumor effects. However, due to the complex and

potentially risky mechanisms of ISG20 in different tumors, the

development of ISG20-based vaccines requires further research and

validation. Future research should focus on clarifying the specific

mechanisms of ISG20 in different types of disease, optimizing

vaccine design and evaluating their safety and efficacy.

As a potential biomarker

Biomarkers are typically defined as objective

indicators that can be measured to reflect physiological or

pathological processes, as well as biological effects following

exposure to treatment or intervention. As aforementioned, ISG20 is

upregulated in various tumors, and is significantly associated with

disease progression and prognosis. Therefore, ISG20 is increasingly

recognized as a potential biomarker for certain types of tumor

(14,23,71).

For example, Xu et al (23)

reported that ISG20 is highly upregulated in ccRCC tumors, where it

enhances tumor cell proliferation and metastasis by modulating the

MMP9/CCND1 signaling pathway. ISG20 has been identified as a

potential predictive target for ccRCC, with high ISG20 expression

associated with poorer OS and DFS (23). In cervical cancer tissue, Rajkumar

et al (29) observed high

expression of ISG20, which may be associated with the onset and

progression of cervical cancer (18). In ovarian cancer (72), a significant decrease in ISG20

levels has been observed, which may be associated with ethnicity,

advanced clinical stage, higher pathological grade and poor

prognosis. Lower ISG20 mRNA expression is detected in

cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer compared with in a

cisplatin-sensitive group (25).

Furthermore, Lin et al (65)

reported that ISG20 upregulation in patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma is positively associated with clinical factors such as

vascular invasion and tumor size, and poorer relapse-free survival

(65). Additionally, in

radioresistant oral cancer cells, the mRNA and protein expression

levels of ISG20 are higher than those in corresponding parental

cells, suggesting that ISG20 upregulation may be essential for the

radioresistant phenotype in oral cancer (26). In summary, ISG20 may serve as a

potential biomarker for early tumor diagnosis, prognostic

assessment and treatment response prediction.

As an immunological adjuvant

An immunoadjuvant is a non-specific immune

enhancer, typically administered with an antigen to enhance the

immune response to a specific antigen or alter the type of immune

response. Its primary function is to improve vaccine efficacy and

immune response strength by altering the physical properties of the

antigen, promoting antigen processing and presentation and

stimulating immune cell activation (73). Tumor neoantigen vaccines and PD-L1

inhibitors are promising immunotherapeutic approaches to the

clinical treatment of various types of tumor, but show limited

efficacy in patients with tumors lacking functional T cell

infiltration (74,75). As aforementioned, ISG20 has been

shown to enhance tumor immunogenicity in ovarian cancer, recruiting

various immune cells, including CD8+ T cells, to

infiltrate tumor tissue and enhance antitumor immune responses

(22). This suggests that ISG20 may

serve as an immunoadjuvant when combined with tumor antigens to

achieve antitumor immune effects. However, studies have shown that

ISG20 promotes tumor immune evasion in glioma, indicating that its

use as an immunoadjuvant should be selected based on the specific

tumor type and microenvironment (14,24).

Conclusion

ISG20 is an insufficiently explored molecular

target in cancer. It is upregulated in various types of tumor

tissue, and influences processes such as tumor cell proliferation,

migration, invasion, angiogenesis and immune modulation in the TME

through complex mechanisms. ISG20 may serve as a tumor antigen,

biomarker and immunoadjuvant. However, prior to clinical

application, further research is needed to clarify its structure

and functional sites as a tumor antigen, evaluate its role as a

biomarker and explore its precise application as an immunoadjuvant

across different tumor types and microenvironments.

Future research should focus on elucidating the

molecular mechanisms underlying the roles of ISG20 in various

tumors and further investigating its regulatory network in the TME,

particularly its impact on immune cells. Leveraging advanced

technology to analyze its three-dimensional structure and

protein-protein interaction sites may accelerate the development of

small-molecule drugs or biologics targeting ISG20. Additionally,

large-scale, multicenter clinical studies should be conducted to

validate its value in tumor precision diagnosis and personalized

treatment, facilitating its efficient translation from basic

research to clinical application, and providing novel strategies

and approaches for cancer treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82260596), the Natural Science

Foundation of Jiangxi Province (grant nos. 20242BAB25506 and

20242BAB20406), the Science and Technology Program of Jiangxi

Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission (grant no.

202410246), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no.

2023M741523), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Jiangxi Province

(grant no. 20252BAC220050), the Graduate Student Innovation Special

Foundation of Jiangxi Province (grant no. YC2025-S245) and the

Science and Technology Program of Jiangxi Provincial Administration

of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no. 2024A0028).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XZ and SJ designed the study. LZ and SZ wrote the

manuscript. HZ, JZ and LC constructed the figures. HL and ZZ

performed the literature review. All authors have read and approved

the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang X, Yang W, Wang X, Zhang X, Tian H,

Deng H, Zhang L and Gao G: Identification of new type I

interferon-stimulated genes and investigation of their involvement

in IFN-β activation. Protein Cell. 9:799–807. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Negishi H, Taniguchi T and Yanai H: The

interferon (IFN) class of cytokines and the IFN regulatory factor

(IRF) transcription factor family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

10:a0284232017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

LaFleur DW, Nardelli B, Tsareva T, Mather

D, Feng P, Semenuk M, Taylor K, Buergin M, Chinchilla D, Roshke V,

et al: Interferon-kappa, a novel type I interferon expressed in

human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 276:39765–39771. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bach EA, Aguet M and Schreiber RD: The IFN

gamma receptor: A paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu

Rev Immunol. 15:563–591. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T and Hume

DA: Interferon-gamma: An overview of signals, mechanisms and

functions. J Leukoc Biol. 75:163–189. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kotenko SV, Gallagher G, Baurin VV,

Lewis-Antes A, Shen M, Shah NK, Langer JA, Sheikh F, Dickensheets H

and Donnelly RP: IFN-lambdas mediate antiviral protection through a

distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nat Immunol. 4:69–77.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ank N, Iversen MB, Bartholdy C, Staeheli

P, Hartmann R, Jensen UB, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Thomsen AR, Chen Z,

Haugen H, et al: An important role for type III interferon

(IFN-lambda/IL-28) in TLR-induced antiviral activity. J Immunol.

180:2474–2485. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Schoggins JW: Interferon-stimulated genes:

What do they all do? Annu Rev Virol. 6:567–584. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Moser MJ, Holley WR, Chatterjee A and Mian

IS: The proofreading domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I

and other DNA and/or RNA exonuclease domains. Nucleic Acids Res.

25:5110–5118. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zuo Y and Deutscher MP: Exoribonuclease

superfamilies: Structural analysis and phylogenetic distribution.

Nucleic Acids Res. 29:1017–1026. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zheng Z, Wang L and Pan J:

Interferon-stimulated gene 20-kDa protein (ISG20) in infection and

disease: Review and outlook. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 6:35–40.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Weiss CM, Trobaugh DW, Sun C, Lucas TM,

Diamond MS, Ryman KD and Klimstra WB: The Interferon-Induced

exonuclease ISG20 exerts antiviral activity through upregulation of

type I interferon response proteins. mSphere. 3:e00209–18. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang Y, Suo J, Wang Z, Ran K, Tian Y, Han

W, Liu Y and Peng X: The PTPRZ1-MET/STAT3/ISG20 axis in glioma

stem-like cells modulates Tumor-associated macrophage polarization.

Cell Signal. 120:1111912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gao M, Lin Y, Liu X, Li Y, Zhang C, Wang

Z, Wang Z, Wang Y and Guo Z: ISG20 promotes local tumor immunity

and contributes to poor survival in human glioma. Oncoimmunology.

8:e15340382018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhong R, Li JQ, Wu SW, He XM, Xuan JC,

Long H and Liu HQ: Transcriptome analysis reveals possible

antitumor mechanism of Chlorella exopolysaccharide. Gene.

779:1454942021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shou Y, Yang L, Yang Y, Zhu X, Li F and Xu

J: Determination of hypoxia signature to predict prognosis and the

tumor immune microenvironment in melanoma. Mol Omics. 17:307–316.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wei C, Liu X, Wang Q, Li Q and Xie M:

Identification of hypoxia signature to assess the tumor immune

microenvironment and predict prognosis in patients with ovarian

cancer. Int J Endocrinol. 2021:41561872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Rajkumar T, Sabitha K, Vijayalakshmi N,

Shirley S, Bose MV, Gopal G and Selvaluxmy G: Identification and

validation of genes involved in cervical tumourigenesis. BMC

Cancer. 11:802011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xiong H, Zhang X, Chen X, Liu Y, Duan J

and Huang C: High expression of ISG20 predicts a poor prognosis in

acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Biomark. 31:255–261. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jiang Z, Xu J, Zhang S, Lan H and Bao Y: A

pairwise immune gene model for predicting overall survival and

stratifying subtypes of colon adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin

Oncol. 149:10813–10829. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bishara I, Liu X, Griffiths Jl, Cosgrove

PA, McQuerry JR, Liu J, Ihle KK, Bacon ER, Chi F, Wallet P, et al:

Abstract 5133: End-stage breast cancer metastases manifest as two

subtypes with distinct dissemination patterns, proliferation/EMT

signatures, and immune microenvironments. Cancer Res. 85 (Suppl

1):S51332025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chen Z, Yin M, Jia H, Chen Q and Zhang H:

ISG20 stimulates anti-tumor immunity via a double-stranded

RNA-induced interferon response in ovarian cancer. Front Immunol.

14:11761032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xu T, Ruan H, Gao S, Liu J, Liu Y, Song Z,

Cao Q, Wang K, Bao L, Liu D, et al: ISG20 serves as a potential

biomarker and drives tumor progression in clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 12:1808–1827. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Peng Y, Liu H, Wu Q, Wang L, Yu Y, Yin F,

Feng C, Ren X, Liu T, Chen L and Zhu H: Integrated bioinformatics

analysis and experimental validation reveal ISG20 as a novel

prognostic indicator expressed on M2 macrophage in glioma. BMC

Cancer. 23:5962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu J, Jiang L, Wang S, Peng L, Zhang R and

Liu Z: TGF β1 promotes the polarization of M2-type macrophages and

activates PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway by inhibiting ISG20 to

sensitize ovarian cancer to cisplatin. Int Immunopharmacol.

134:1122352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Miyashita H and Fukumoto M, Kuwahara Y,

Takahashi T and Fukumoto M: ISG20 is overexpressed in clinically

relevant radioresistant oral cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol.

13:1633–1639. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lin H, Zhou Z, Sun H, Li C, Lu Y, Wu Z,

Zhou L, Wang Y, Pu Z, Mou L and Yang MM: Mapping the role of

cytokine signaling at single-cell and structural resolution in

uveal melanoma. Genes Immun. Jun 9–2025.doi:

10.1038/s41435-025-00337-3 (Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Wang T, Liu Y, Wu X, Wang X, Shi S, Song

X, Ma Y, Zhang Z, Gao J, Sun R and Song G: Multi-omics reveals

miR-181a-5p regulates PPAR-driven lipid metabolism in Oral squamous

cell carcinoma: Insights from CRISPR/Cas9 knockout models. J

Proteomics. 319:1054802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gongora C, David G, Pintard L, Tissot C,

Hua TD, Dejean A and Mechti N: Molecular cloning of a new

Interferon-induced PML nuclear Body-associated Protein. J Biol

Chem. 272:19457–19463. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pentecost BT: Expression and estrogen

regulation of the HEM45 MRNA in human tumor lines and in the rat

uterus. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 64:25–33. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Gongora C, Degols G, Espert L, Hua TD and

Mechti N: A unique ISRE, in the TATA-less human Isg20 promoter,

confers IRF-1-mediated responsiveness to both interferon type I and

type II. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2333–2341. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Nguyen LH, Espert L, Mechti N and Wilson

DM III: The human interferon- and estrogen-regulated ISG20/HEM45

gene product degrades single-stranded RNA and DNA in vitro.

Biochemistry. 40:7174–7179. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Espert L, Degols G, Gongora C, Blondel D,

Williams BR, Silverman RH and Mechti N: ISG20, a new

interferon-induced RNase specific for single-stranded RNA, defines

an alternative antiviral pathway against RNA genomic viruses. J

Biol Chem. 278:16151–16158. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Espert L, Rey C, Gonzalez L, Degols G,

Chelbi-Alix MK, Mechti N and Gongora C: The exonuclease ISG20 is

directly induced by synthetic dsRNA via NF-kappaB and IRF1

activation. Oncogene. 23:4636–4640. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Horio T, Murai M, Inoue T, Hamasaki T,

Tanaka T and Ohgi T: Crystal structure of human ISG20, an

interferon-induced antiviral ribonuclease. FEBS Lett. 577:111–116.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Espert L, Eldin P, Gongora C, Bayard B,

Harper F, Chelbi-Alix MK, Bertrand E, Degols G and Mechti N: The

exonuclease ISG20 mainly localizes in the nucleolus and the Cajal

(Coiled) bodies and is associated with nuclear SMN

protein-containing complexes. J Cell Biochem. 98:1320–1333. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Karasawa T, Sato R, Imaizumi T, Fujita M,

Aizawa T, Tsugawa K, Mattinzoli D, Kawaguchi S, Seya K, Terui K, et

al: Expression of interferon-stimulated gene 20 (ISG20), an

antiviral effector protein, in glomerular endothelial cells:

Possible involvement of ISG20 in lupus nephritis. Ren Fail.

45:22248902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jia M, Li L, Chen R, Du J, Qiao Z, Zhou D,

Liu M, Wang X, Wu J, Xie Y, et al: Targeting RNA oxidation by

ISG20-mediated degradation is a potential therapeutic strategy for

acute kidney injury. Mol Ther. 31:3034–3051. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Louvat C, Deymier S, Nguyen XN, Labaronne

E, Noy K, Cariou M, Corbin A, Mateo M, Ricci EP, Fiorini F and

Cimarelli A: Stable structures or PABP1 loading protects cellular

and viral RNAs against ISG20-mediated decay. Life Sci Alliance.

7:e2023022332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Viswanathan M and Lovett ST: Exonuclease X

of Escherichia coli. A novel 3′-5′ DNase and Dnaq superfamily

member involved in DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 274:30094–31100. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu Y, Nie H, Mao R, Mitra B, Cai D, Yan

R, Guo JT, Block TM, Mechti N and Guo H: Interferon-inducible

ribonuclease ISG20 inhibits hepatitis B virus replication through

directly binding to the epsilon stem-loop structure of viral RNA.

PLoS Pathog. 13:e10062962017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Pollack JR and Ganem D: An RNA stem-loop

structure directs hepatitis B virus genomic RNA encapsidation. J

Virol. 67:3254–3263. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Alsheikh HAM, Metge BJ, Pruitt HC,

Kammerud SC, Chen D, Wei S, Shevde LA and Samant RS: Disruption of

STAT5A and NMI signaling axis leads to ISG20-driven metastatic

mammary tumors. Oncogenesis. 10:452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Qu X, Shi Z, Guo J, Guo C, Qiu J and Hua

K: Identification of a novel six-gene signature with potential

prognostic and therapeutic value in cervical cancer. Cancer Med.

10:6881–6896. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yu J, Liu TT, Liang LL, Liu J, Cai HQ,

Zeng J, Wang TT, Li J, Xiu L, Li N and Wu LY: Identification and

validation of a novel glycolysis-related gene signature for

predicting the prognosis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell Int.

21:3532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wu N, Nguyen XN, Wang L, Appourchaux R,

Zhang C, Panthu B, Gruffat H, Journo C, Alais S, Qin J, et al: The

interferon stimulated gene 20 protein (ISG20) is an innate defense

antiviral factor that discriminates self versus Non-self

translation. PLoS Pathog. 15:e10080932019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

El Kazzi P, Rabah N, Chamontin C, Poulain

L, Ferron F, Debart F, Rossi S, Bribes I, Rouilly L, Simonin Y, et

al: Internal RNA 2′O-methylation in the HIV-1 genome counteracts

ISG20 nuclease-mediated antiviral effect. Nucleic Acids Res.

51:2501–2515. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Deymier S, Louvat C, Fiorini F and

Cimarelli A: ISG20: An enigmatic antiviral RNase targeting multiple

viruses. FEBS Open Bio. 12:1096–1111. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kang D, Gao S, Tian Z, Zhang G, Guan G,

Liu G, Luo J, Du J and Yin H: ISG20 inhibits bluetongue virus

replication. Virol Sin. 37:521–530. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Espert L, Degols G, Lin YL, Vincent T,

Benkirane M and Mechti N: Interferon-induced exonuclease ISG20

exhibits an antiviral activity against human immunodeficiency virus

type 1. J Gen Virol. 86:2221–2229. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Decker CJ and Parker R: P-bodies and

stress granules: possible roles in the control of translation and

mRNA degradation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 4:a0122862012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hehl M, Scherer M, Raubuch EM, Ploil C,

Rummel T, Kirchner P, Kottmann N, Reichel A, Katharina R, König AC,

et al: Exonuclease ISG20 inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication

by inducing an innate immune defense signature. bioRxiv. Feb

10–2025.doi: 10.1101/2025.02.10.637376.

|

|

53

|

Xing L, Meng G, Chen T, Zhang X, Bai D and

Xu H: Crosstalk between RNA-Binding proteins and immune

microenvironment revealed Two RBP regulatory patterns with distinct

immunophenotypes in periodontitis. J Immunol Res. 2021:55884292021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Staege H, Brauchlin A, Schoedon G and

Schaffner A: Two novel genes FIND and LIND differentially expressed

in deactivated and Listeria-infected human macrophages.

Immunogenetics. 53:105–113. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chaussabel D, Semnani RT, McDowell MA,

Sacks D, Sher A and Nutman TB: Unique gene expression profiles of

human macrophages and dendritic cells to phylogenetically distinct

parasites. Blood. 102:672–681. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Rodríguez-Galán A, Dosil SG, Hrčková A,

Fernández-Messina L, Feketová Z, Pokorná J, Fernández-Delgado I,

Camafeita E, Gómez MJ, Ramírez-Huesca M, et al: ISG20L2: An RNA

nuclease regulating T cell activation. Cell Mol Life Sci.

80:2732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Budhwani M, Mazzieri R and Dolcetti R:

Plasticity of Type I Interferon-mediated responses in cancer

therapy: From Anti-tumor immunity to resistance. Front Oncol.

8:3222018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Dunn GP, Koebel CM and Schreiber RD:

Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol.

6:836–848. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Hervas-Stubbs S, Perez-Gracia JL, Rouzaut

A, Sanmamed MF, Le Bon A and Melero I: Direct effects of type I

interferons on cells of the immune system. Clin Cancer Res.

17:2619–2627. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Brinckerhoff CE and Matrisian LM: Matrix

metalloproteinases: A tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 3:207–214. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Baeriswyl V and Christofori G: The

angiogenic switch in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 19:329–337.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Zhou L, Isenberg JS, Cao Z and Roberts DD:

Type I collagen is a molecular target for inhibition of

angiogenesis by endogenous thrombospondin-1. Oncogene. 25:536–545.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Herbert SP and Stainier DYR: Molecular

control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel

morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 12:551–564. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Taylor KL, Leaman DW, Grane R, Mechti N,

Borden EC and Lindner DJ: Identification of

interferon-beta-stimulated genes that inhibit angiogenesis in

vitro. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 28:733–740. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lin SL, Wu SM, Chung IH, Lin YH, Chen CY,

Chi HC, Lin TK, Yeh CT and Lin KH: Stimulation of

Interferon-stimulated gene 20 by thyroid hormone enhances

angiogenesis in liver cancer. Neoplasia. 20:57–68. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Waugh DJ and Wilson C: The interleukin-8

pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 14:6735–6741. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Mun JY, Leem SH, Lee JH and Kim HS: Dual

relationship between stromal cells and immune cells in the tumor

microenvironment. Front Immunol. 13:8647392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Shah DD, Chorawala MR, Raghani NR, Patel

R, Fareed M, Kashid VA and Prajapati BG: Tumor microenvironment:

Recent advances in understanding and its role in modulating cancer

therapies. Med Oncol. 42:1172025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Du H, Sun J, Wang X, Zhao L, Liu X, Zhang

C, Wang F and Wu J: FOSL2-mediated transcription of ISG20 induces

M2 polarization of macrophages and enhances tumorigenic ability of

glioblastoma cells. J Neurooncol. 169:659–670. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Peng K, Wang N, Liu Q, Wang L, Duan X, Xie

G, Li J and Ding D: Identification of disulfidptosis-related

subtypes and development of a prognosis model based on stacking

framework in renal clear cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

149:13793–13810. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Meng K, Li YY, Liu DY, Hu LL, Pan YL,

Zhang CZ and He QY: A five-protein prognostic signature with GBP2

functioning in immune cell infiltration of clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 21:2621–2630. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Geng H, Zhang H, Cheng L and Dong S:

Corrigendum to ‘Sivelestat ameliorates sepsis-induced myocardial

dysfunction by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway’

[Int. Immunopharmacol. 128 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111466simplehttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111466].

Int Immunopharmacol. 131:1118732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Banstola A, Jeong JH and Yook S:

Immunoadjuvants for cancer immunotherapy: A review of recent

developments. Acta Biomater. 114:16–30. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Moehler M, Delic M, Goepfert K, Aust D,

Grabsch HI, Halama N, Heinrich B, Julie C, Lordick F, Lutz MP, et

al: Immunotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer: Recent results,

current studies and future perspectives. Eur J Cancer. 59:160–170.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Yang M, Cui M, Sun Y, Liu S and Jiang W:

Mechanisms, combination therapy, and biomarkers in cancer

immunotherapy resistance. Cell Commun Signal. 22:3382024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|