Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is a highly

malignant cancer with a 5-year survival rate of 30–50% and is the

sixth most common cancer worldwide (1). Surgical excision of this tumor type is

difficult as it occurs in the complex site of the head and neck.

Moreover, even if the tumor is excised, the quality of life of the

patient is significantly reduced. Even after reduction or resection

of head and neck cancer by chemotherapy or surgery, recurrence or

metastasis occurs in 30% of cases (2,3). The

average survival time of metastatic/recurrent cases of head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemotherapy alone is 6–9

months, and the 1-year survival rate is as low as 20–40%. Compared

with no treatment, chemotherapy achieves only a slight survival

benefit (4).

Drug resistance is a critical obstacle to the

effective treatment of patients with cancer. Several multidrug

resistance mechanisms have been identified, such as the expression

of drug efflux ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters (such as

ABCB1 and ABCG2) that discharge anticancer drugs outside of cancer

cells, apoptosis resistance, decreased drug binding as a result of

gene mutations and the activation of survival signals (5). To the best of our knowledge, a

compound that effectively induces cell death in multidrug-resistant

head and neck cancer cells has not been identified.

We previously established a multi-drug resistant

cell line, which we named R HSC-3 (6). R HSC-3 cells were generated by

long-term repeated treatment of the HCS-3 human metastatic oral

squamous cell carcinoma cell line with cisplatin, the first-line

treatment drug for oral squamous cell carcinoma. The cells showed a

maximum 155-fold higher resistance against anticancer drugs such as

SN-38 and docetaxel, which have different mechanisms of action from

cisplatin (7). This cell line

expresses refractory cancer-specific proteins such as the drug

excretion transporter, ABCG2, the cancer stem cell markers, CD44,

SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9) and Notch, and the poor

prognosis factor, fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) (6). This cell line is a useful in

vitro model for multidrug resistance.

The present study investigated compounds that

effectively induce cell death in multidrug-resistant head and neck

cancer cells and explored the mechanism of cell death induction.

These findings may lead to the establishment of a new treatment

strategy for intractable head and neck cancer with acquired drug

resistance.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) and

glucose-free DMEM was obtained from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Fetal bovine serum (FBS; 10%), 1%

antibiotics/antimycotic solution 100X (10,000 U/ml penicillin G,

10,000 µg/ml streptomycin, 25 µg/ml amphotericin B) were purchased

from HyClone (Cytiva). The anti-receptor interacting

serine/threonine kinase 1 (RIP1/RIPK1) mouse monoclonal antibody

was purchased from BD Biosciences (cat. no. 610458).

Anti-calreticulin rabbit monoclonal antibody (cat. no. C4606) and

anti-β-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (cat. no. A5441) were

obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA). Anti-gasdermin D rabbit

monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 97558) and horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. 7074) was from Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc. Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody was

from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (cat. no. sc-2005) and rabbit

anti-mouse IgG H&L (HRP) was purchased from Abcam (cat. no.

ab6728). The RIP1 inhibitor,

5-((7-chloro-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)-3-methylimidazolidine-2,4-dione

(7-Cl-O-Nec1) was obtained from Merck KGaA and the mixed lineage

kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) inhibitor, necrosulfonamide (NSA)

was from R&D Systems, Inc. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and

2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure

Chemical. Shikonin, acetyl shikonin and β-hydroxyisovaleryl

shikonin were purchased from Nagara Science Co., Ltd. The Pierce

BCA Protein Assay Kit was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc. and the Cell Proliferation Kit I (MTT) was obtained from Roche

Diagnostics. The JC-1 MitoMP Detection Kit was purchased from

Dojindo Laboratories, Inc. The CellTiter-Glo®

Luminescent Cell Viability Assay and ROS-Glo™ Assay Kit were

obtained from Promega Corporation.

Cell culture

We established the R HSC-3 multi-drug resistant oral

squamous cell carcinoma cell line in a previous study (6). R HSC-3 cells were generated by

long-term repeated treatment of the HSC-3 human metastatic oral

squamous cell carcinoma cell line (Riken Cell Bank; cat. no.

RBC1975) with cisplatin. The R HSC-3 line was cultured in DMEM with

inactivated 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution 100X at

37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell viability assays

Two types of cell viability assays were used: The

MTT assay and the ATP-based CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent

Cell Viability Assay, which assess mitochondrial activity and

cellular energy status, respectively. Using both assays provided

complementary and comprehensive assessment of cytotoxicity. R HSC-3

cells were plated in a 96-well plate (TPP Techno Plastic Products

AG) at 1×105 cells/ml and incubated for 24 h.

Naphthoquinones were then added at various concentrations (shikonin

1–20 µM, acetyl shikonin 1–30 µM and β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin

1–50 µM) for an additional 48 h. For the MTT assay, MTT

[3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; Cell

Proliferation Kit I] was added, and the insoluble formazan product

was dissolved with 10% SDS in 0.01 M HCl. Absorbance was measured

at a wavelength of 595 nm using TECAN Infinite M Plex (Tecan Group,

Ltd.). For the ATP assay, the ATP extraction reagent

(CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay) was

added according to the manufacturers' instructions. The plates were

incubated for 1 h, then shaken at room temperature for 1 h and

luminescence was measured in relative light units at wavelengths of

485/520 nm using TECAN Infinite M Plex, multimode microplate reader

(Tecan Group, Ltd.). In some experiments, cells were pre-treated

with 5 mM NAC for 24 h, and in some experiments, 2.5 mM NAC was

co-administered with the naphthoquinones.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species

(ROS)

R HSC-3 cells were plated in a 96-well plate at

1×105 cells/ml and incubated for 24 h. The medium was

changed from DMEM with 10% FBS to glucose-free DMEM with 10% FBS

and 10 nM 2DG (2DG-DMEM). After 24 h of incubation, 20 µM shikonin

or 30 µM acetyl shikonin was added to the media. After 6 h of

treatment, ROS was measured using the ROS-Glo™ Assay following the

manufacturer's protocol. In some experiments, 50 µM 7-Cl-O-Nec1, a

RIP1 inhibitor, and 10 µM NSA, a MLKL inhibitor, were first

incubated with the cells for 24 h. Naphthoquinones were then

administered to the pretreated cells and the ROS levels were

measured using the ROS-Glo™ Assay.

Measurement of mitochondrial

toxicity

The Mitochondrial ToxGlo™ Assay (Promega

Corporation) was used to measure mitochondrial toxicity. Cell

membrane integrity was first assessed by measuring the presence or

absence of a distinct protease activity associated with necrosis

using a fluorogenic peptide substrate

(bis-alanyl-alanyl-phenylalanyl-rhodamine 110; bis-AAF-R110) to

measure the dead cell marker protease activity. Next ATP was

measured by adding the ATP extraction reagent, resulting in cell

lysis and the generation of a luminescent signal proportional to

the level of ATP present. R HSC-3 cells were plated in a 96-well

plate at 1×105 cells/ml and cultured in glucose-free

DMEM supplemented with 1 µM galactose and 10% FBS at 37°C for 24 h.

Various concentrations of naphthoquinones were added and the cells

were cultured for 24 h. Next, 5X Cytotoxicity Reagent

(Mitochondrial ToxGlo™ Assay) was added and the cells were shaken

at room temperature for 1 min, then incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

Fluorescence was then measured at wavelengths of 485/520 nm using a

multimode microplate reader. In some experiments, the cells were

pretreated with 2.5 mM NAC for 24 h or 1.25 mM NAC was

co-administered with the naphthoquinones. Oligomycine (FUJIFILM

Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) was used as a positive control

inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).

Lentiviral transduction and

fluorescent live cell imaging

Calreticulin-red fluorescent protein (RFP) cell

lines were generated as follows. R HSC-3 cells were plated in a

6-well plate at 1×105 cells/ml in DMEM with 10% FBS and

incubated at 37°C for 24 h. R HSC-3 cells were transduced with the

pre-packaged LentiBrite™ Calreticulin-RFP-KDEL Lentiviral Biosensor

(Merck KGaA; cat. no. 17-10146) at a multiplicity of infection of

20 and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Lentivirus-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh

growth medium. Cells were cultured for another 24–48 h, with medium

changes every 24 h. RFP expression was observed with a fluorescence

microscope (Olympus IX70; Olympus Corporation).

Lentivirus-infected R HSC-3 cells were seeded at

1×105 cells/ml in a 96-well microplate and cultured in

DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C for 24 h. Hoechst 33342 was added and the

cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Naphthoquinones were then

added, and images were obtained and evaluated using an HS

all-in-one fluorescence microscope (BIOREVO BZ-9000; Keyence

Corporation) and data processing software (BZ-II observation

application, BZ-II image analysis application; version 1.42;

Keyence Corporation).

Immunoblot analyses

R HSC-3 cells were treated with 1, 3, 5, 6 or 8 µM

shikonin in 2DG-DMEM for 5 h. Whole cell extracts were obtained

using 10X RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) with 1 mM

PMSF plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, EDTA-free; Roche

Diagnostics). Total protein concentration in the lysates was

assayed using the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein extracts (50 µg) were separated

on 8% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride

membrane. Membranes were blocked with 10% non-fat milk for 1 h at

room temperature and then incubated with the following primary

antibodies at 4°C overnight: Anti-calreticulin (1:10,000),

anti-RIP1 (1:1,000), anti-gasdermin D (1:1,000) and anti-β-actin

(1:10,000). Following the primary antibody incubation, the

membranes were incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated goat

anti-mouse (1:10,000) or anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000) antibodies for

1 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized using Clarity

Western ECL Substrate Peroxide solution (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). The blots were developed and images analyzed with

Luminescent Image Analyzer LAS-3000 (FUJIFILM Corporation) and

Science Lab 2001 Image Gauge version 4.0 (FUJIFILM

Corporation).

JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential

assay

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Dj m) was assessed

using the JC-1 MitoMP Detection Kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were seeded and

treated with naphthoquinones as aforementioned. Cells were

incubated with 1 mM JC-1 dye at 37°C for 30 min, followed by

Hoechst 33342 staining (1:2,000 in PBS) for 1 h. Fluorescence

images were acquired using a BZ-X810 all-in-one fluorescence

microscope (Keyence Corporation) and analyzed with BZ-H4CM software

(Keyence Corporation).

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD

from at least three independent experiments. The unpaired Student's

t-test was used to analyze statistical differences between two

groups of data, while two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc

test was applied for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical

analysis was performed using Mac Ver.3.0 (Esumi Co. Ltd.) and EZR

software (Easy R) version 1.68 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi

Medical University) (8).

Results

Naphthoquinones induce cell death of

multidrug-resistant oral squamous cell carcinoma cells

We previously generated a multidrug-resistant head

and neck squamous cell line, named R HSC-3, by culturing the HSC-3

human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line in

cisplatin-containing media (6). R

HSC-3 cells were 29 times more resistant to cisplatin than

wild-type HSC-3 cells. In the present study the half maximal

inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of various

anticancer drugs and naphthoquinones in R HSC-3 cells were examined

using MTT assays. The IC50 values of all examined drugs

were higher in R HSC-3 cells compared with parental cells (Table I). Notably, the IC50

values of shikonin and acetylshikonin, which are naphthoquinones,

were ≤3-fold higher in R HSC-3 cells compared with parental cells

and did not show a significant difference between the parental

strain and resistant strain. These data indicated that

naphthoquinones may exhibit potency against multidrug-resistant

cancer cells.

| Table I.IC50 values in

drug-resistant and parental HSC-3 cells. |

Table I.

IC50 values in

drug-resistant and parental HSC-3 cells.

| Drug | Unit | IC50 in

HSC-3a (µM) | IC50 in

R HSC-3a (µM) | P-value |

|---|

| Cisplatin | µM | 0.68±0.17 | 20.30±6.32 | P<0.001 |

| SN-38 | nM | 7.11±1.68 | 22.18±3.70 | P<0.001 |

| Docetaxel | nM | 0.90±0.20 | 6.57±1.16 | P=0.002 |

| Erlotinib | µM | 0.21±0.04 | 31.90±2.00 | P<0.001 |

| Doxorubicin | nM | 26.57±6.00 | 223.63±15.70 | P=0.028 |

| Shikonin | µM | 4.37±0.53 | 8.10±0.58 | P=0.003 |

| Acetyl

shikonin | µM | 7.83±1.40 | 23.90±6.50 | P<0.001 |

Naphthoquinones induce expression of

the necroptosis-associated protein, RIP1

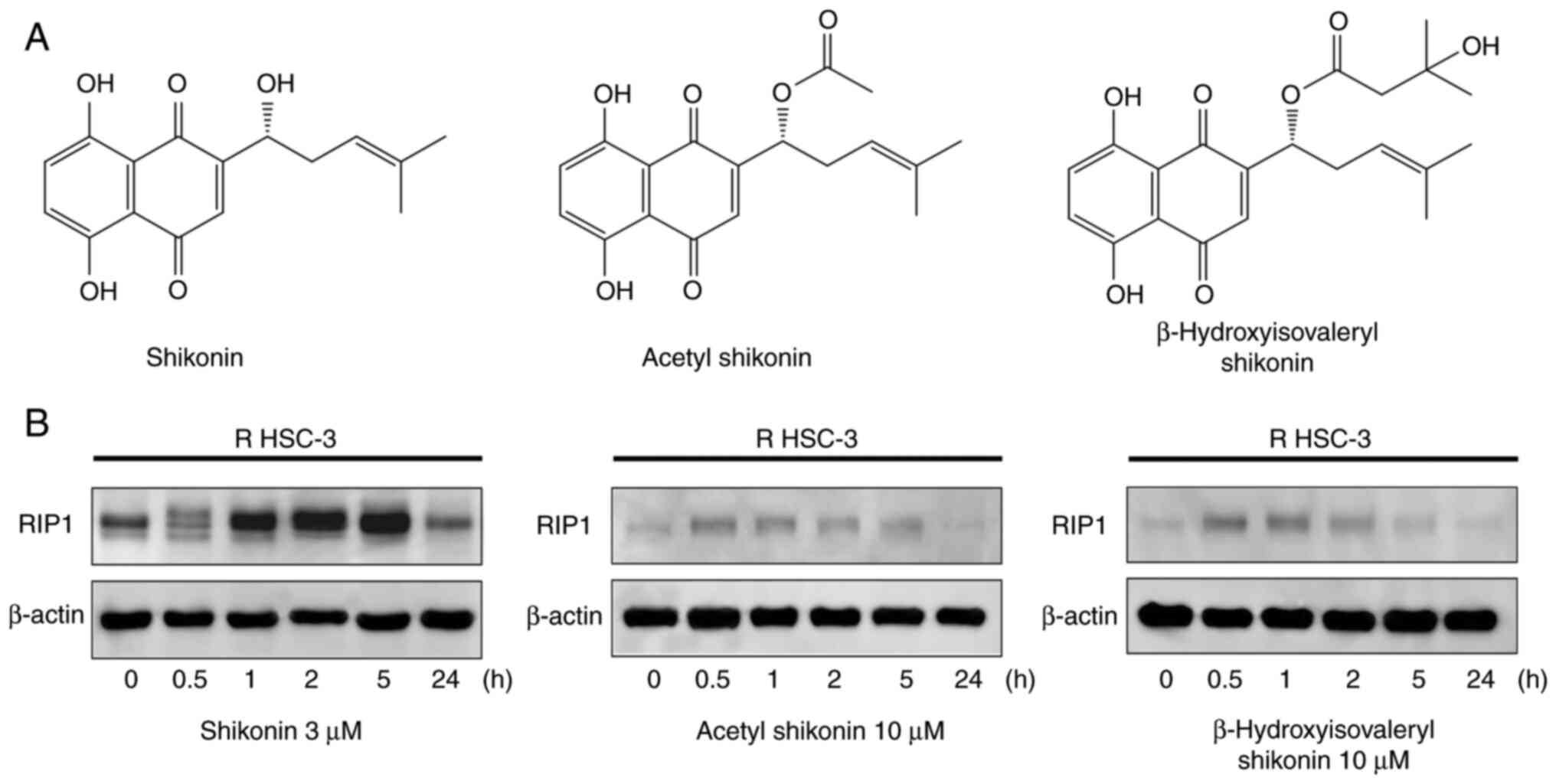

Naphthoquinones are natural red pigment components

isolated from the root of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. The

chemical structures of 1,4-naphthoquinones, including shikonin

(5,8-dihydroxy-2-[(1R)-1-hydroxy-4-methyl-3-penten-1-yl]-1,4-naphthalenedione),

acetylshikonin and β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin, are shown in

Fig. 1A. Shikonin is a compound

with an OH group at the β-position of the isoprene side chain of

the naphthoquinone skeleton. Acetyl shikonin and

β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin have side chains in which an acetyl

group and a β-hydroxyisovaleryl group, respectively, are

ester-bonded as substituents to the OH group. The mechanism of cell

death of R HSC-3 cells caused by naphthoquinones were next

examined. The induction of cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

(PARP), a marker of apoptosis induction, was observed by

immunoblot, but reproducible cleaved PARP expression could not be

obtained (data not shown). Therefore, other forms of cell death

were explored. RIP1 is a kinase involved in necroptosis, one of the

forms of non-apoptotic cell death. Treatment with all

naphthoquinones led to the induction and subsequent decrease of

RIP1 within 0.5 to 5 h (Fig. 1B).

The observed decrease in RIP1 expression after its initial

induction may reflect its degradation through caspase-dependent or

proteasomal pathways, which has been previously reported (9).

Effect of naphthoquinones on cell

viability and the involvement of oxidative stress

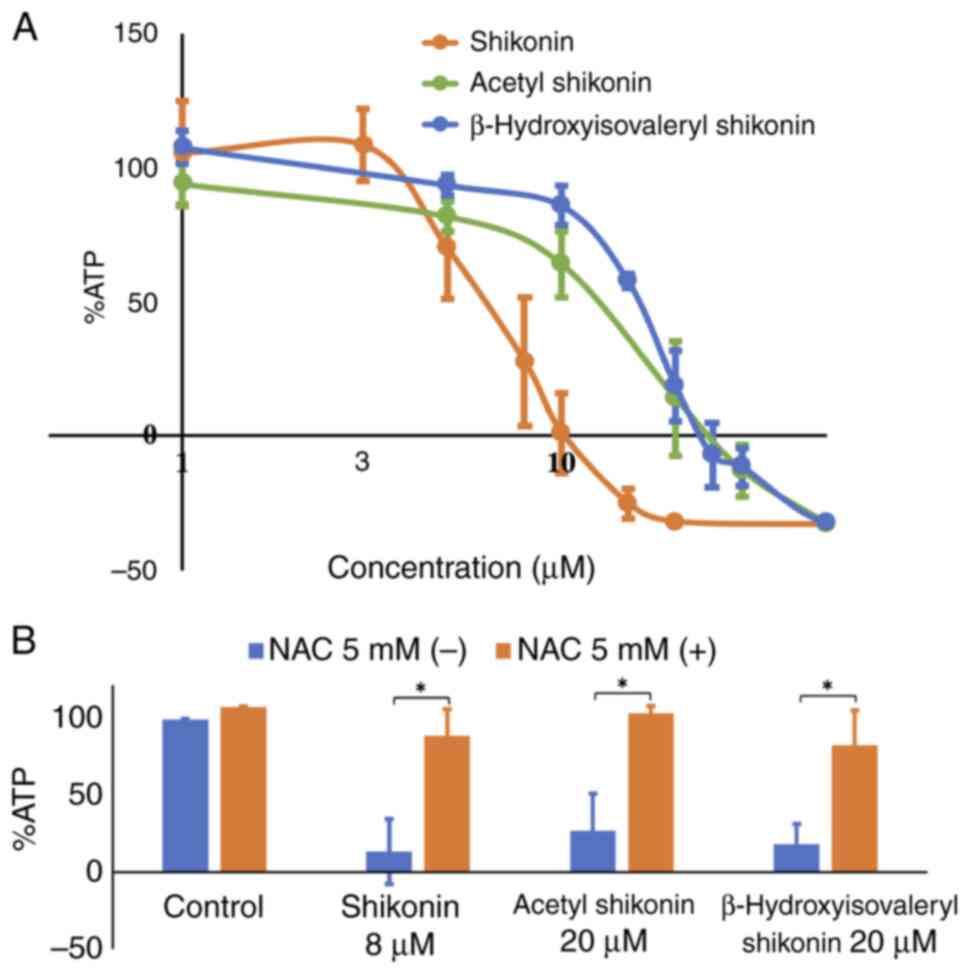

Next, the effects of naphthoquinones on the cell

viability of drug-resistant cells were evaluated using assays that

quantify the ATP levels. The treatment of R HSC-3 cells with all

naphthoquinones reduced the ATP levels in a concentration-dependent

manner, reflecting cell death (Fig.

2A). The IC50 values of shikonin, acetyl shikonin

and β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin were 6.0, 12.7 and 15.7 µM,

respectively. These results indicate that the IC50

values of acetyl shikonin and β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin, whose

OH group is modified, were 2–2.6 times higher than that for

shikonin, which has a free OH group on its side chain.

Oxidative stress is a significant inducer of

necroptosis, primarily through the production of ROS that activate

necroptosis signaling pathways (10). Thus, whether the

naphthoquinone-induced cell death is related to oxidative stress

was next examined using the antioxidant, NAC. Treatment with NAC

prevented the cytotoxicity induced by naphthoquinones and restored

viability to near control levels (Fig.

2B). Simultaneous treatment of 5 mM NAC significantly increased

survival from 27.4 to 103.8% with shikonin at 8 µM (P=0.018), 13.7

to 89.3% with acetyl shikonin at 20 µM (P=0.037) and 18.6 to 83.1%

with β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin at 20 µM (P=0.025). NAC alone did

not cause cytotoxicity. This result indicated that oxidative stress

is involved in the induction of cell death in multidrug-resistant

head and neck cancer cells caused by naphthoquinones.

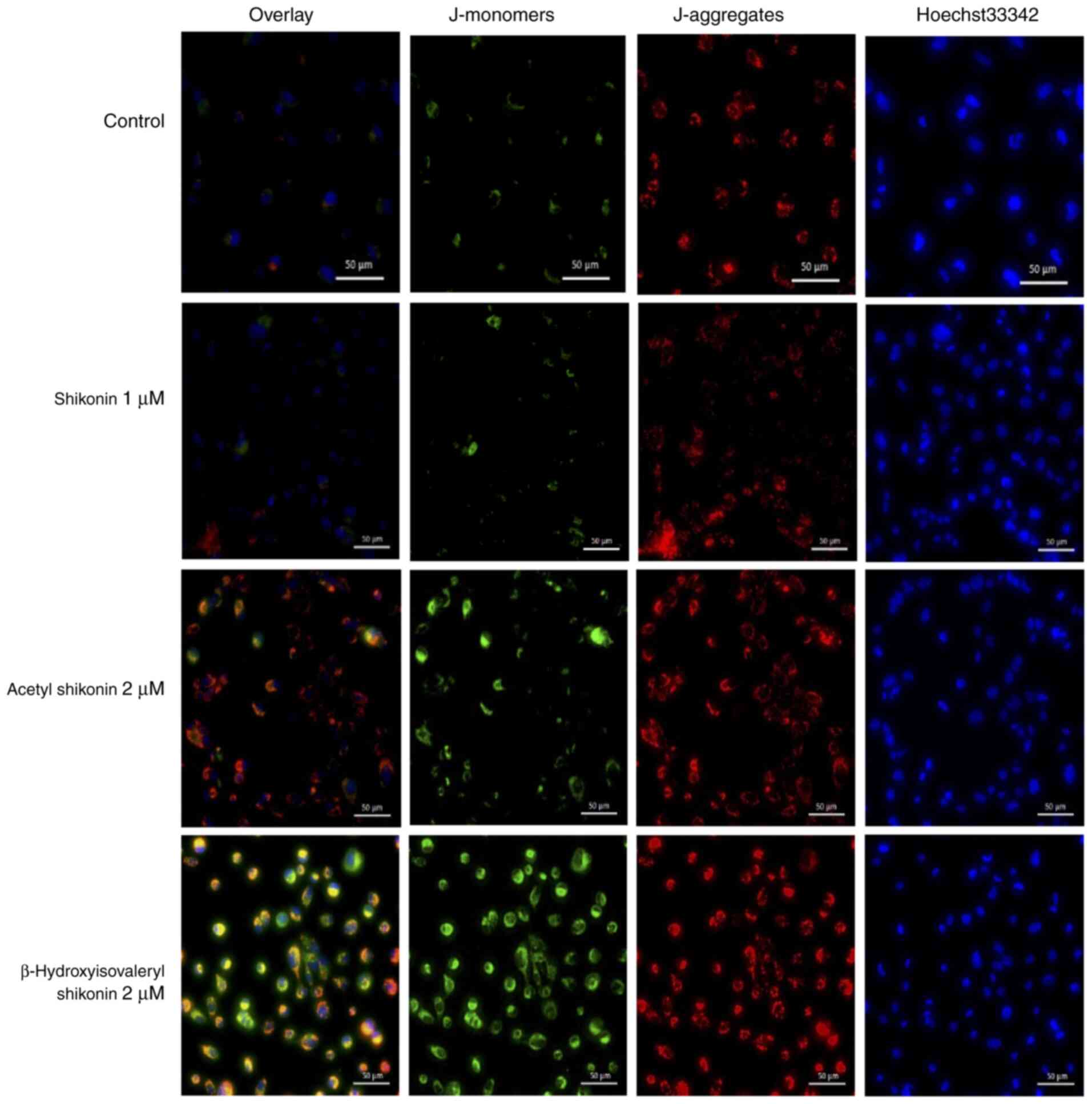

Changes in the mitochondrial membrane

potential by naphthoquinones

In total, >90% of ROS in cells is produced in

mitochondria (11). Excess ROS

causes oxidative stress damage in cells and mitochondrial

dysfunction (12,13). To examine whether mitochondrial ROS

production is involved in oxidative stress-induced cell death

caused by naphthoquinones, changes in the mitochondrial membrane

potential were investigated using the JC-1 reagent. When the

mitochondrial membrane potential is normal, JC-1 emits red

fluorescence, and when the membrane potential decreases from

apoptosis or necroptosis, JC-1 emits green fluorescence.

Hoechst33342 was used to stain nuclei and facilitate visualization

of all cells. Treatment of cells with acetyl shikonin and

β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin for 2 h resulted in mitochondrial

membrane potential changes and accumulation of JC-1 monomers, and

an increase in red fluorescence and green fluorescence was observed

(Fig. 3). This suggests that the

oxidative stress that induces cell death in multidrug-resistant

head and neck cancer cells by acetyl shikonin and

β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin is related to the mitochondrial

electron transport system. Shikonin did not appear to elicit

changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential.

Effects of changes in intracellular

energy metabolism on naphthoquinone-induced cell death

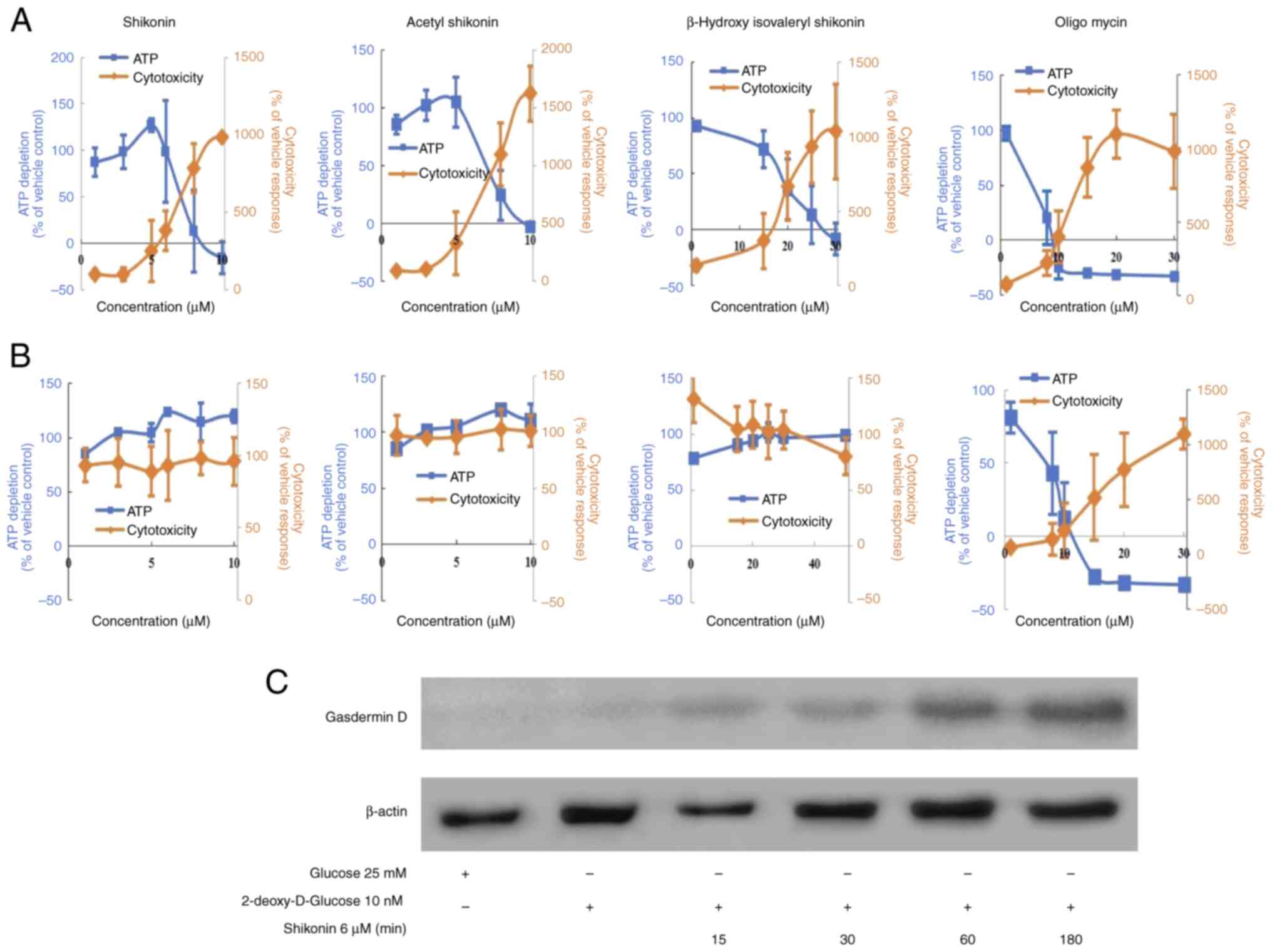

The cell death induced by acetyl shikonin and

β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin involves the production of ROS but

shikonin had no effects on the mitochondrial membrane potential

(Fig. 3). One possibility for the

difference in effects is that cancer cells, even under aerobic

conditions, exhibit enhanced ATP production by the glycolytic

pathway rather than mitochondrial OXPHOS (also known as the Warburg

effect) (14). ATP production in

glycolysis is reported to be ~100 times faster than that in

mitochondria (15). Thus, we

speculated that it may be difficult to observe mitochondrial

membrane changes induced by shikonin in drug-resistant head and

neck squamous cells. Therefore, the effect of naphthoquinones on

the mitochondrial respiratory chain of R HSC-3 cells were next

examined. By switching the carbon source of the medium to

galactose, the mitochondrial OXPHOS-dominant state is moderated,

and the effects of mitochondrial toxicity and ATP production can be

examined (16). To confirm that

mitochondrial toxicity is derived from ROS, the antioxidant, NAC,

was used. Mitochondrial toxicity was evaluated by simultaneously

measuring cytotoxicity (mitochondrial-derived dead cell protease)

and ATP production. Cell membrane integrity was first assessed by

measuring the presence or absence of a distinct protease activity

associated with necrosis using a fluorogenic peptide substrate

(bis-AAF-R110) to measure the dead cell marker protease activity.

Fluorescence associated with cytotoxicity was measured, ATP

extraction reagent was added and luminescence associated with the

amount of ATP as a marker of viable cell number was measured

(17). As a positive control,

oligomycin, which is an OXPHOS inhibitor (complex V inhibitor), was

used. Under conditions in which the carbon source in the medium was

galactose, the ATP half maximal effective concentration

(EC50) values for shikonin, acetylshikonin and

β-hydroxyisovaleryl shikonin were 7.2, 7.3 and 18.4 µM,

respectively (Fig. 4A and Table II). The cytotoxicity

EC50 values, representing mitochondrial toxicity, were

3.5, 3.4 and 11.8 µM, respectively (Table II).

| Table II.Effects of naphthoquinones under

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation conditions was evaluated by

Mitochondrial ToxGlo™ assay. |

Table II.

Effects of naphthoquinones under

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation conditions was evaluated by

Mitochondrial ToxGlo™ assay.

| Drug | Cytotoxicity

EC50 (µM) | ATP EC50

(µM) |

|---|

| Shikonin | 3.47 | 7.18 |

| Acetyl

shikonin | 3.43 | 7.27 |

| β-Hydroxy

isovaleryl shikonin | 11.77 | 18.43 |

|

Oligomycina | 6.45 | 3.44 |

The cell viability (%ATP amount) decreased in

response to naphthoquinones and oligomycin in a

concentration-dependent manner; this was accompanied by an increase

in cytotoxicity (mitochondrial-derived dead cell protease)

(Fig. 4A). However, these effects

were almost abolished when cells were co-treated with the

antioxidant NAC (Fig. 4B and

Tables II and III, where Table II shows the results without NAC and

Table III shows the results with

NAC). These results revealed that naphthoquinone-induced cell death

of drug-resistant cancer cells involved mitochondrial toxicity

caused by ROS production. Mitochondrial toxicities that induce

mitochondrial ROS and/or loss of transmembrane potential could

cause pyroptosis (18), which is a

process mediated by the pore-forming cleavage of gasdermin D. To

further verify the properties of shikonin-induced cell death under

OXPHOS, the presence of gasdermin D was analyzed. As a result,

Shikonin induced the expression of gasdermin D under OXPHOS in R

HSC-3 cells (Fig. 4C).

| Table III.Effects of naphthoquinones under

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation conditions and in the

presence of the antioxidant, N-acetyl cysteine, was

evaluated by Mitochondrial ToxGlo™ assay. |

Table III.

Effects of naphthoquinones under

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation conditions and in the

presence of the antioxidant, N-acetyl cysteine, was

evaluated by Mitochondrial ToxGlo™ assay.

| Drug | Cytotoxicity

EC50 (µM) | ATP EC50

(µM) |

|---|

| Shikonin | >10.00 | >10.00 |

| Acetyl

shikonin | >20.00 | >10.00 |

| β-Hydroxy

isovaleryl shikonin | >50.00 | >50.00 |

|

Oligomycina | 5.57 | 2.42 |

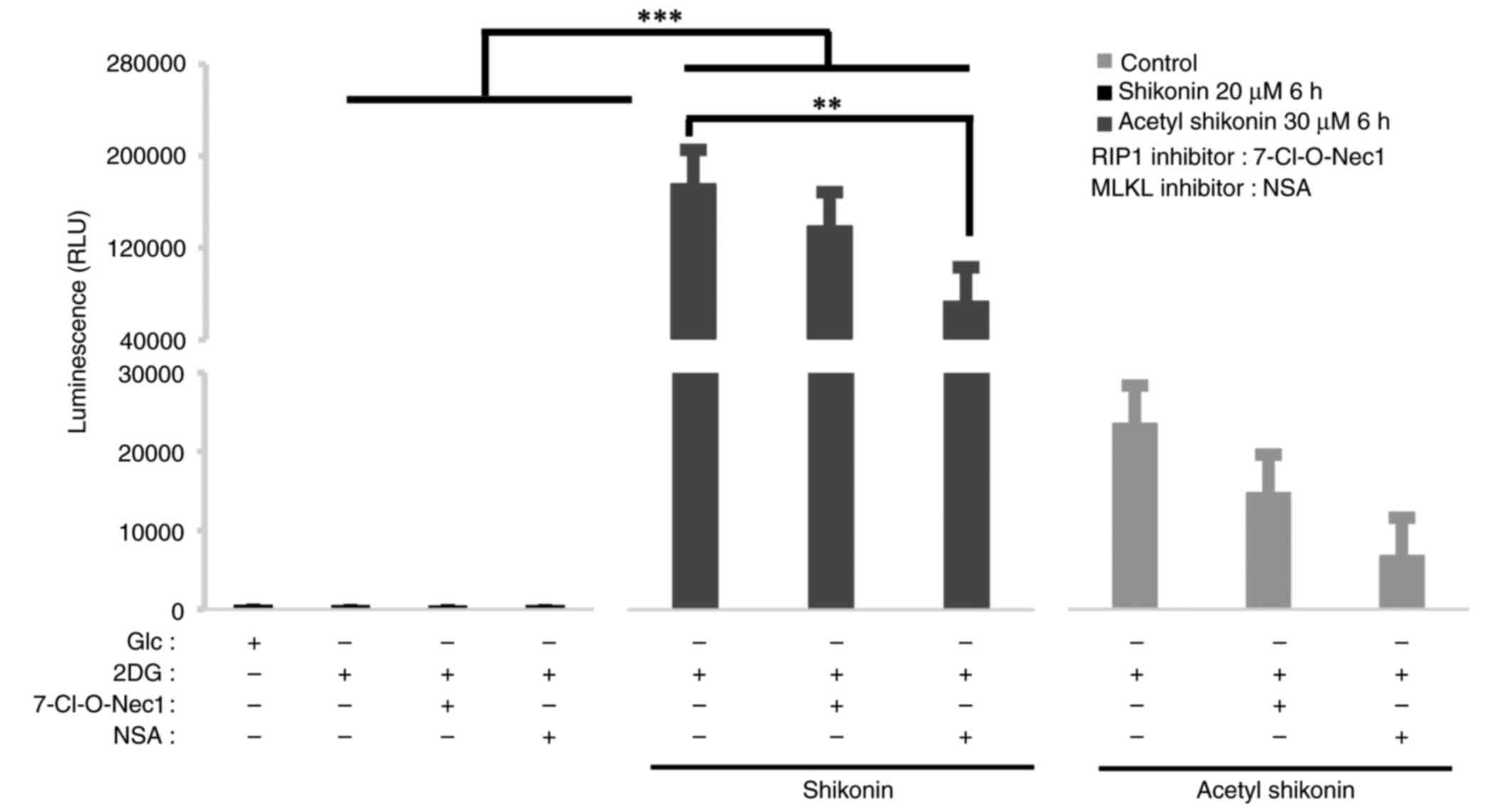

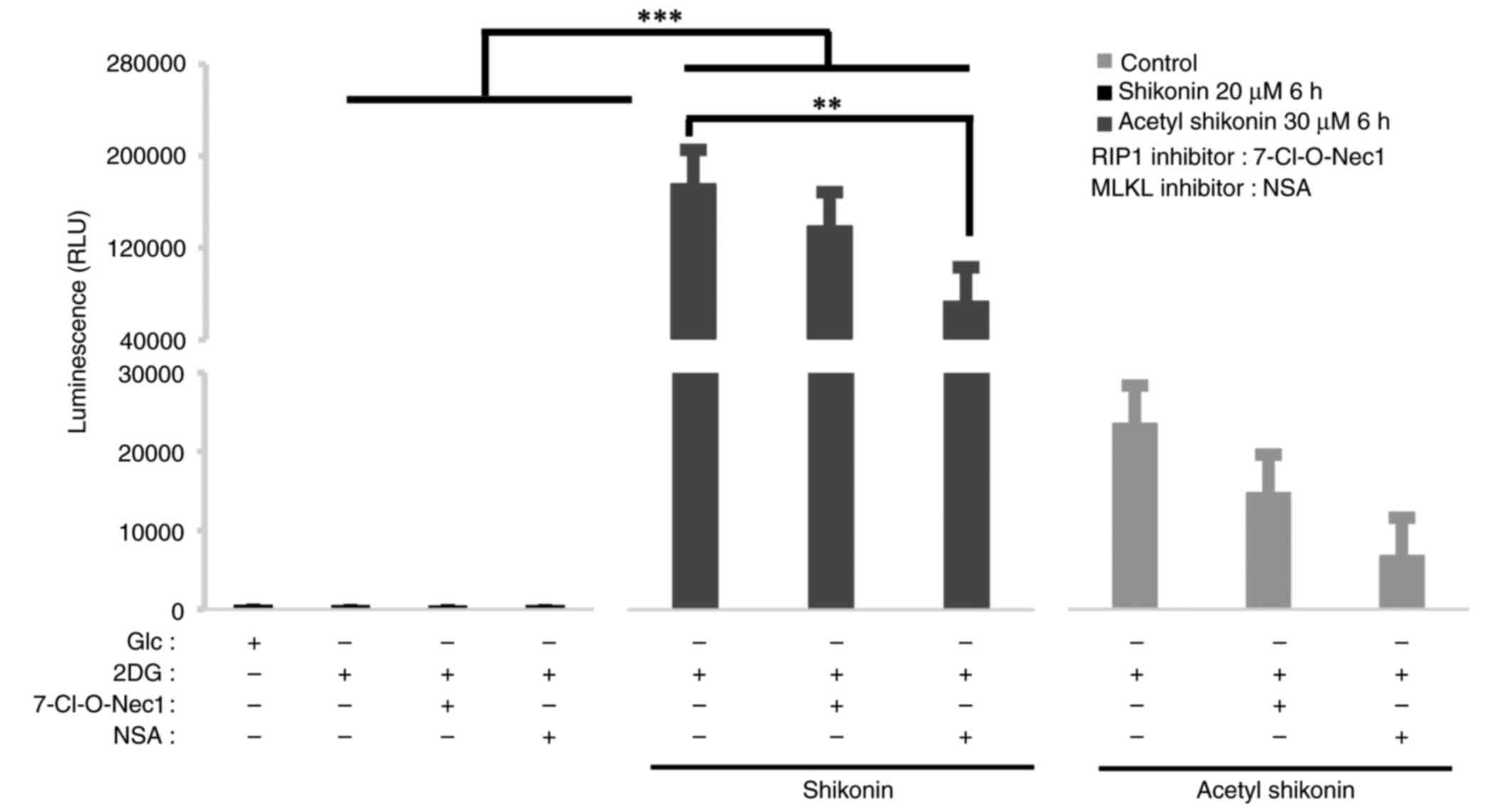

Effects of necroptosis inhibitors on

oxidative stress induced by naphthoquinones

To explore the relationship between

mitochondrial-derived ROS and necroptosis signals, 7-Cl-O-Nec1, a

RIP1 inhibitor, and NSA, an MLKL inhibitor, were used as

necroptosis inhibitors. RIP1 is a signaling molecule for early

necroptosis, and MLKL is a kinase-like molecule that induces pore

formation and destruction of the cell membrane (19–22).

The ROS production induced by naphthoquinones was suppressed by

pretreatment with the RIP1 and MLKL inhibitors (Fig. 5). Under 2DG culture conditions,

shikonin treatment markedly increased ROS production. When compared

with the 2DG + shikonin group, co-treatment with the RIP1 inhibitor

slightly reduced ROS by 21% but this reduction was not

statistically significant (P=0.661). By contrast, co-treatment with

the MLKL inhibitor significantly reduced ROS levels by 59% compared

with the 2DG + shikonin group (P=0.0019). For acetyl shikonin, ROS

levels were reduced by 37% with RIP1 inhibitor (P=0.999) and 71%

with MLKL inhibition (P=0.994) compared with the corresponding 2DG

+ acetyl shikonin group, but neither reduction reached statistical

significance. These results suggest that ROS induction by

naphtoquinones depends more strongly on MLKL than on RIP1, although

the effect of acetyl shikonin was less pronounced.

| Figure 5.Effect of naphthoquinone-induced ROS

production in combination with necroptosis inhibitors on R HSC-3

cells. ROS assay of R HSC-3 cells pretreated with RIP1 inhibitor

(50 µM, 7-O-Cl-Nec1) and MLKL inhibitor (10 µM, necrosulfonamide)

before naphthoquinone treatment (20 µM shikonin or 30 µM acetyl

shikonin, 6 h) and cultured in OXPHOS conditions (culture medium

containing 10 nM 2DG) for 24 h. Naphthoquinones (20 µM shikonin or

30 µM acetyl shikonin) were applied to necroptosis inhibitor

pretreated R HSC-3 cells for 6 h, and ROS production was measured.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). **P<0.01,

***P<0.0005. ROS, reactive oxygen species; RIP1, receptor

interacting protein 1 kinase; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase-domain

like; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; 2DG, deoxy-D-glucose; Glc,

glucose; NSA, necrosulfonamide; RLU, relative fluorescence

units. |

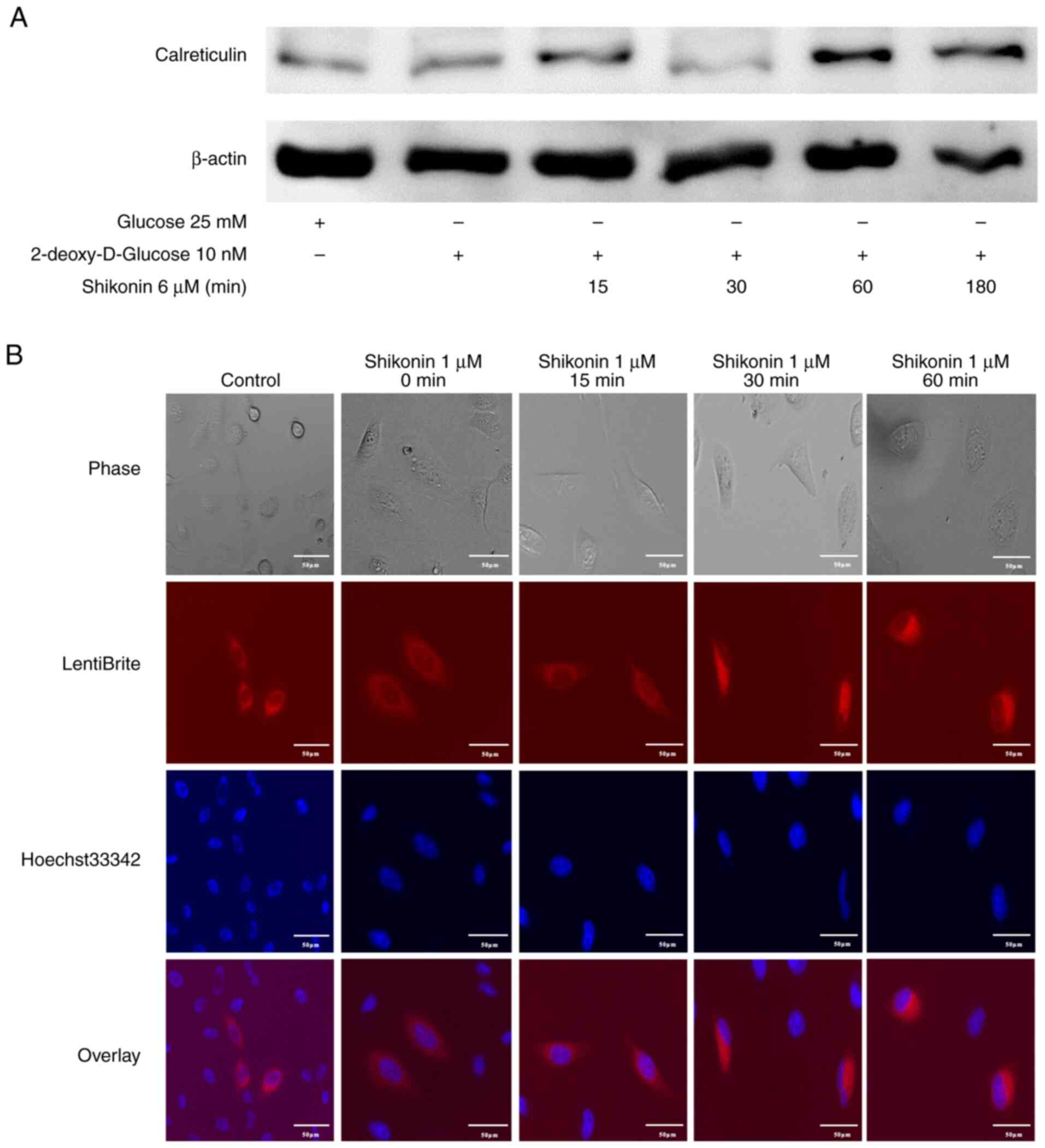

Induction of the damage-associated

molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule calreticulin in R HSC-3 cells by

shikonin

Cancer cells undergoing necroptotic cell death

release DAMPs, which are immunogenic and potentiate cancer

progression (23). DAMPs, such as

extracellular release of ATP and exposure of calreticulin to the

cell membrane surface, are important indicators of immunogenic cell

death (ICD), a form of cell death that induces host immune

responses. Calreticulin has been reported to act as an ‘eat me’

signal for dendritic cells (24,25).

Therefore, it was examined whether necroptosis induced by

naphthoquinones induces the expression of calreticulin, one of the

ICD-related DAMP molecules. R HSC-3 cells cultured for 2 h in

2DG-DMEM, which induces OXPHOS, were treated with shikonin for 5 h

and the expression of calreticulin was examined. The induction of

calreticulin in R HSC-3 cells treated with shikonin was observed

(Fig. 6A). Next, live cell imaging

of intracellular calreticulin in R HSC-3 cells infected with

lentivirus expressing calreticulin-RFP was performed. The

fluorescence intensity in the cytoplasm increased after 30 min of

shikonin treatment (Fig. 6B). This

result indicated that drug-resistant cancer cell death caused by

naphthoquinones may result in ICD, which induces tumor

immunity.

Discussion

In the present study, compounds that induce cell

death in multidrug-resistant head and neck cancer cells were

searched for. The investigation identified naphthoquinones and the

mechanism of their cell death induction activity were further

explored. These results may aid in the development of new

therapeutic agents for multidrug-resistant head and neck cancer

cells. In a cytostatic test using the R HSC-3 multidrug-resistant

head and neck cancer cell line, naphthoquinones, including

shikonin, were effective at reducing cell viability at a low

concentration, with the IC50 values ≤3 times those of

chemotherapeutic drugs. This suggests that naphthoquinones may be

useful for head and neck cancer cells with acquired multidrug

resistance. Shikonin, acetyl shikonin and β-hydroxyisovaleryl

shikonin were analyzed; the latter two are naphthoquinones with

different side chains. All tested naphthoquinones exhibited

cytotoxic effects in cell viability assays. The IC50

results indicated that the side-chain OH group was related to the

strength of cytotoxicity. All three naphthoquinones induced RIP1

expression in the R HSC-3 multidrug-resistant cancer cell line,

suggesting that the common naphthoquinone skeleton was involved in

the necroptosis-inducing activity.

The mechanism by which naphthoquinones induce

necroptosis in multidrug-resistant head and neck cancer cells were

further explored in the present study. Addition of the antioxidant,

NAC, inhibited the cytotoxicity induced by naphthoquinones,

suggesting that ROS, which cause oxidative stress, are involved in

the cell death caused by naphthoquinones. In total, >90% of

intracellular ROS are derived from mitochondria (11). Next, the mitochondrial membrane

potential was measured using the membrane-permeable JC-1 dye.

Treatment with naphthoquinones, except for shikonin, resulted in an

accumulation of JC-1 monomers. These results suggest that

naphthoquinones induce ROS production by altering the mitochondrial

membrane potential. By contrast, another study reported that

shikonin induces ROS production through mitochondrial

depolarization (26). This suggests

that the fluorescence of the mitochondrial membrane potential may

be shorter than the measurement time, which may be why the changes

in the mitochondrial membrane potential induced by shikonin were

not detected in the present study. The absence of detectable

mitochondrial membrane depolarization by shikonin may be due to

transient changes that were not captured at the time of measurement

or to the generation of ROS from non-mitochondrial sources such as

NADPH oxidases (27,28).

Cancer cells predominantly generate ATP produced

through glycolysis rather than mitochondrial OXPHOS, a phenomenon

known as the Warburg effect (14).

In the present study, to investigate the involvement of

mitochondria in ROS induced by naphthoquinones, ROS were measured

under conditions in which energy metabolism was tilted toward

OXPHOS dominance. Naphthoquinones induced the generation of ROS in

R HSC-3 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. ROS production

was stronger with shikonin, showing a difference of >7-fold

compared with acetyl shikonin. When the carbon source was changed

from glycolysis-dependent glucose to mitochondrial-dominant

galactose, treatment with naphthoquinones resulted in

concentration-dependent decreases in ATP levels and increase in

dead cell proteases. This suggests that cell death induced by

naphthoquinones caused mitochondrial dysfunction manifested as a

decrease in ATP levels. The increased mitochondrial toxicity and

decreased ATP levels caused by naphthoquinones were recovered by

the addition of NAC. This indicated that mitochondrial dysfunction

caused by naphthoquinones was due to the production of ROS. The

positive control oligomycin, an OXPHOS inhibitor (complex V

inhibitor) was not affected by NAC. This suggests that

naphthoquinones likely have an effect upstream of mitochondrial

complex V to induce cell death.

To clarify the relationship between

mitochondrial-derived ROS and necroptosis signals, two necroptosis

inhibitors of RIP1 and MLKL were used. RIP1 is an early necroptosis

signaling molecule, and MLKL is a kinase-like molecule that induces

the formation and destruction of membrane pores (29). ROS production induced by

naphthoquinones was suppressed by pretreatment with the necroptosis

inhibitors. MLKL inhibition led to a higher inhibitory effect on

ROS production than RIP1 inhibition. This suggests that

naphthoquinone-induced ROS-induced cell death depends more on the

MLKL execution factor than on RIP1. These results indicate that

naphthoquinones induce necroptotic cell death in

multidrug-resistant cancer cells by oxidative stress damage

mediated by mitochondria-derived ROS.

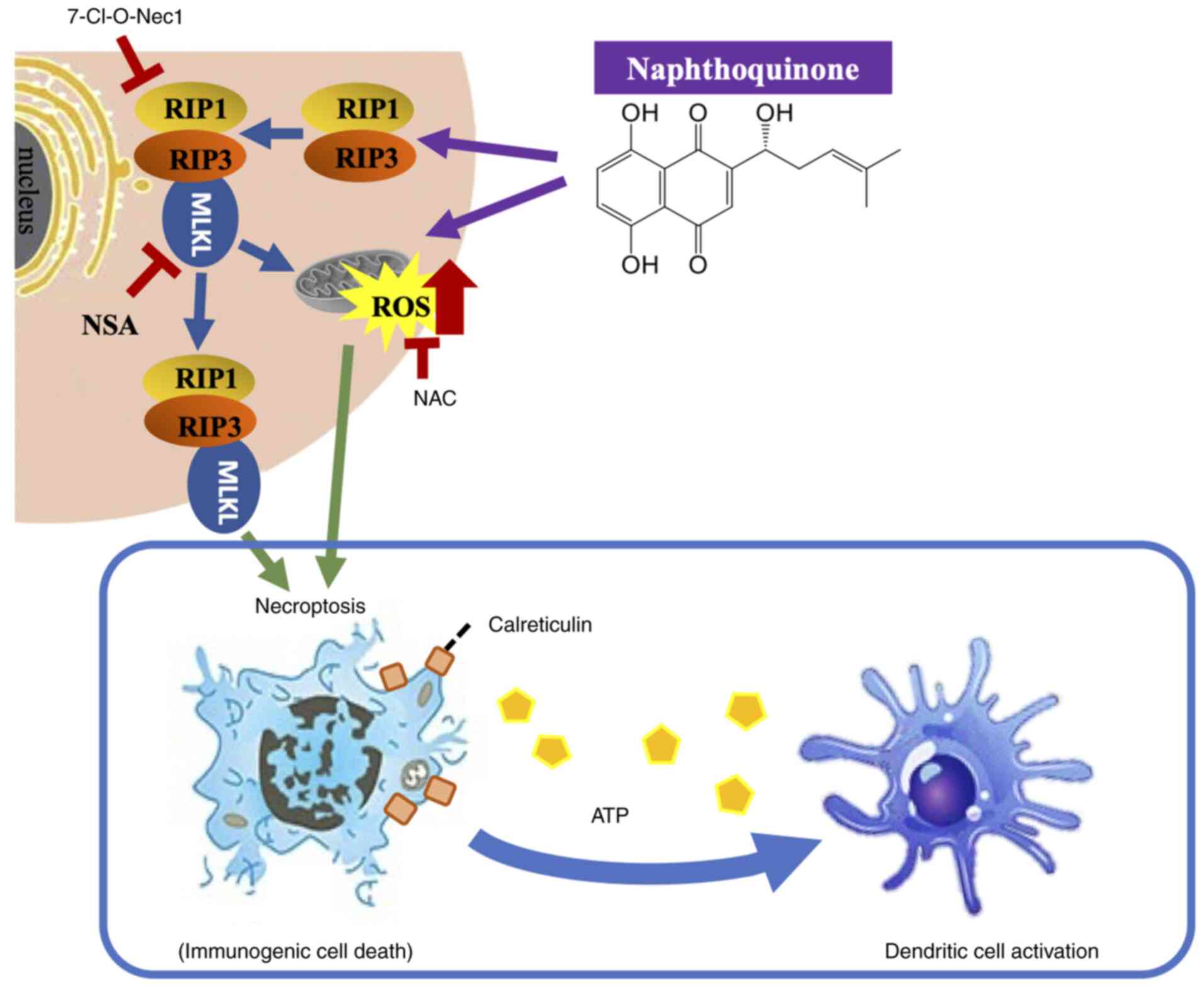

The present study showed that naphthoquinones induce

necroptosis in multidrug-resistant head and neck cancer cells.

Furthermore, naphthoquinones induced necroptosis signals, including

activation of the RIP1 and MLKL pathways, mediated by

mitochondria-derived oxidative stress. The possibility of

immunogenicity as a result of necroptosis was also suggested. In

recent years, the induction of non-apoptotic cell death has

attracted significant interest in the study of therapy-resistant

and refractory cancer types. Among the cell death mechanisms,

necroptosis has been increasingly recognized as a distinct form of

programmed cell death (30,31). RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL have been

identified as regulators of necroptosis (32–35). A

signal transduction pathway through the RIP1-RIP3-MLKL complex

plays a key role in necroptosis (36–41).

Necroptosis causes cell rupture as a result of morphological

changes such as cell swelling, mitochondrial swelling or rupture

and organelle membrane disruption, and subsequently cell death with

the release of DAMPs (35,42–45).

In cancer cells, DAMPs act on immune cells and are thought to

strengthen their ability to attack cancer (23). ICD is a type of programmed cell

death that stimulates an antitumor immune response. Necroptosis has

emerged as a key contributor to ICD due to its ability to induce

the release of immunostimulatory signals. DAMPs, such as the

exposure of calreticulin to the cell membrane surface and the

extracellular release of ATP, are important indicators of ICD

(46). Calreticulin acts primarily

as an ‘eat me’ signal to dendritic cells (24,25),

and cancer-specific antigens are presented to cytotoxic T cells via

dendritic cells, contributing to the activation of immune cells

with high attack power against cancer (25,47). A

previous transcriptomic analysis showed that patients with head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma with high ICD-related gene signatures

have an improved prognosis and responsiveness to immune checkpoint

inhibitors compared with those with low ICD-related gene signatures

(48) This supports the potential

clinical value of ICD-inducing agents such as shikonin in

combination with immunotherapy. In the present study, it was found

that shikonin induced necroptosis in multidrug-resistant head and

neck cancer cells and induced the expression of calreticulin in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

7).

The present study has several limitations. First,

whether NAC affects the uptake or metabolism of napthoquinones was

not assessed, which could potentially influence the interpretation

of its ROS-scavenging effects. Additionally, NAC is primarily

recognized as a ROS scavenger, and its influence on shikonin

pharmacokinetics is considered minimal but cannot be completely

ruled out (49,50). In the present study, it was also

observed that shikonin induced ROS production but did not alter the

mitochondrial membrane potential at 2 h post-treatment, suggesting

that any membrane depolarization might have been transient or

undetectable at this time point. Moreover, only in vitro

experiments were conducted in the present study. Future studies

using animal models, such as immunodeficient mice bearing

xenografts of drug-resistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

cells, are required to validate the antitumor activity of

naphthoquinones in this disease. Further research should also

examine whether naphthoquinones influence tumor immunity.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

mitochondrial-derived ROS-mediated oxidative stress damage by

naphthoquinones caused necroptotic cell death in

multidrug-resistant head and neck cancer cells. Given the high

levels of ROS induced by naphthoquinones, the potential for

systemic toxicity in vivo must be carefully evaluated.

Dose-escalation studies and histopathological analysis of major

organs (such as liver, kidney and heart) should be performed to

assess safety. Co-administration of antioxidants such as NAC may

help mitigate off-target oxidative damage without compromising

antitumor efficacy (49,50). Necroptotic cell death by shikonin

releases DAMPs from multidrug-resistant cancer cells, and these may

contribute to immunogenicity (Fig.

7). This suggests that the ICD of metastatic oral cancer with

acquired multidrug resistance, which is an intractable cancer, may

be a target of the immune system and induce cytotoxic T cells with

higher selectivity. The effect of naphthoquinones on improving the

response rate of head and neck cancer to immunotherapy should be

explored in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant

nos. 23K09401 and 20H03785).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SK performed most of the experiments and drafted the

manuscript. NU contributed to the experimental design and drafted

the manuscript. HM performed some experiments and data analysis. MA

performed some experiments and data analysis. HY participated in

the study design, manuscript preparation and critically revised the

manuscript. EO contributed to the experimental conceptualization

and data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. SK

and NU confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Naoki Umemura, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3249-782X; Hiromi Miyazaki,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7719-4913; Makoto Adachi,

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9382-7052;

Emika Ohkoshi, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9700-9973.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D and

Ferris RL: Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 371:1695–1709. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Price KA and Cohen EE: Current treatment

options for metastatic head and neck cancer. Curr Treat Options

Oncol. 13:35–46. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chang JH, Wu CC, Yuan KS, Wu ATH and Wu

SY: Locoregionally recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:

Incidence, survival, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes.

Oncotarget. 8:55600–55612. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sugimoto Y, Tsukahara S, Sato S, Suzuki M,

Nunoi H, Malech HL, Gottesman MM and Tsuruo T: Drug-selected

co-expression of P-glycoprotein and gp91 in vivo from an

MDR1-bicistronic retrovirus vector Ha-MDR-IRES-gp91. J Gene Med.

5:366–376. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Murakami K, Umemura N, Adachi M, Motoki M

and Ohkoshi E: ABCG2, CD44 and SOX9 are increased with the

acquisition of drug resistance and involved in cancer stem cell

activities in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Exp Ther

Med. 24:7222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Smith ER, Wang JQ, Yang DH and Xu XX:

Paclitaxel resistance related to nuclear envelope structural

sturdiness. Drug Resist Updat. 65:1008812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ofengeim D and Yuan J: Regulation of RIP1

kinase signalling at the crossroads of inflammation and cell death.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14:727–736. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xie Y, Zhao G, Lei X, Cui N and Wang H:

Advances in the regulatory mechanisms of mTOR in necroptosis. Front

Immunol. 14:12974082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Murphy MP: How mitochondria produce

reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 417:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Butow RA and Avadhani NG: Mitochondrial

signaling: The retrograde response. Mol Cell. 14:1–15. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sena LA and Chandel NS: Physiological

roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell.

48:158–167. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Warburg O: On the origin of cancer cells.

Science. 123:309–314. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pfeiffer T, Schuster S and Bonhoeffer S:

Cooperation and competition in the evolution of ATP-producing

pathways. Science. 292:504–507. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Marroquin LD, Hynes J, Dykens JA, Jamieson

JD and Will Y: Circumventing the Crabtree effect: Replacing media

glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of HepG2 cells to

mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol Sci. 97:539–547. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Niles AL, Moravec RA, Eric Hesselberth P,

Scurria MA, Daily WJ and Riss TL: A homogeneous assay to measure

live and dead cells in the same sample by detecting different

protease markers. Anal Biochem. 366:197–206. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Miao R, Jiang C, Chang WY, Zhang H, An J,

Ho F, Chen P, Zhang H, Junqueira C, Amgalan D, et al: Gasdermin D

permeabilization of mitochondrial inner and outer membranes

accelerates and enhances pyroptosis. Immunity. 56:2523–2541.e8.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rickard JA, O'Donnell JA, Evans JM,

Lalaoui N, Poh AR, Rogers T, Vince JE, Lawlor KE, Ninnis RL,

Anderton H, et al: RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic

inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell. 157:1175–1188.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Rodriguez DA,

Cripps JG, Quarato G, Gurung P, Verbist KC, Brewer TL, Llambi F,

Gong YN, et al: RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by

caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 157:1189–1202. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Huang Z, Zhou T, Sun X, Zheng Y, Cheng B,

Li M, Liu X and He C: Necroptosis in microglia contributes to

neuroinflammation and retinal degeneration through TLR4 activation.

Cell Death Differ. 25:180–189. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yu Z, Jiang N, Su W and Zhuo Y:

Necroptosis: A novel pathway in neuroinflammation. Front Pharmacol.

12:7015642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wellenstein MD and de Visser KE:

Cancer-cell-intrinsic mechanisms shaping the tumor immune

landscape. Immunity. 48:399–416. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gardai SJ, McPhillips KA, Frasch SC,

Janssen WJ, Starefeldt A, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Bratton DL, Oldenborg

PA, Michalak M and Henson PM: Cell-surface calreticulin initiates

clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of

LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 123:321–334. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tesniere A, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Joza

N, Panaretakis T, Kepp O, Schlemmer F, Zitvogel L and Kroemer G:

Immunogenic cancer cell death: A key-lock paradigm. Curr Opin

Immunol. 20:504–511. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee MJ, Kao SH, Hunag JE, Sheu GT, Yeh CW,

Hseu YC, Wang CJ and Hsu LS: Shikonin time-dependently induced

necrosis or apoptosis in gastric cancer cells via generation of

reactive oxygen species. Chem Biol Interact. 211:44–53. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Forrester SJ, Kikuchi DS, Hernandes MS, Xu

Q and Griendling KK: Reactive oxygen species in metabolic and

inflammatory signaling. Circ Res. 122:877–902. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li J, Pang J, Liu Z, Ge X, Zhen Y, Jiang

CC, Liu Y, Huo Q, Sun Y and Liu H: Shikonin induces programmed

death of fibroblast synovial cells in rheumatoid arthritis by

inhibiting energy pathways. Sci Rep. 11:182632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu XN, Yang ZH, Wang XK, Zhang Y, Wan H,

Song Y, Chen X, Shao J and Han J: Distinct roles of RIP1-RIP3

hetero- and RIP3-RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis.

Cell Death Differ. 21:1709–1720. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Christofferson DE and Yuan J: Necroptosis

as an alternative form of programmed cell death. Curr Opin Cell

Biol. 22:263–268. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Smith CC and Yellon DM: Necroptosis,

necrostatins and tissue injury. J Cell Mol Med. 15:1797–1806. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch'en

IL, Korkina O, Teng X, Abbott D, Cuny GD, Yuan C, Wagner G, et al:

Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of

necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 4:313–321. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray

TD, Guildford M and Chan FK: Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the

RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced

inflammation. Cell. 137:1112–1123. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao

D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X and Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase

domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3

kinase. Cell. 148:213–227. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Linkermann A and Green DR: Necroptosis. N

Engl J Med. 370:455–465. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhao J, Jitkaew S, Cai Z, Choksi S, Li Q,

Luo J and Liu ZG: Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key

receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced

necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:5322–5327. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang

LF, Wang FS and Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein

MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by

RIP3. Mol Cell. 54:133–146. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Moreno-Gonzalez G, Vandenabeele P and

Krysko DV: Necroptosis: A novel cell death modality and its

potential relevance for critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med. 194:415–428. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Quarato G, Guy CS, Grace CR, Llambi F,

Nourse A, Rodriguez DA, Wakefield R, Frase S, Moldoveanu T and

Green DR: Sequential engagement of distinct MLKL

Phosphatidylinositol-binding sites executes necroptosis. Mol Cell.

61:589–601. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dhuriya YK and Sharma D: Necroptosis: A

regulated inflammatory mode of cell death. J Neuroinflammation.

15:1992018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Green DR: The coming decade of cell death

research: Five riddles. Cell. 177:1094–1107. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Aaes TL, Kaczmarek A, Delvaeye T, De

Craene B, De Koker S, Heyndrickx L, Delrue I, Taminau J, Wiernicki

B, De Groote P, et al: Vaccination with necroptotic cancer cells

induces efficient anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. 15:274–287. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gong YN, Guy C, Crawford JC and Green DR:

Biological events and molecular signaling following MLKL activation

during necroptosis. Cell Cycle. 16:1748–1760. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Grootjans S, Vanden Berghe T and

Vandenabeele P: Initiation and execution mechanisms of necroptosis:

An overview. Cell Death Differ. 24:1184–1195. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams

JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, Alnemri ES, Altucci L, Amelio I, Andrews

DW, et al: Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of

the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ.

25:486–541. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang Y, Liu L, Jin L, Yi X, Dang E, Yang

Y, Li C and Gao T: Oxidative stress-induced calreticulin expression

and translocation: New insights into the destruction of

melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 134:183–191. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Fimia

GM, Apetoh L, Perfettini JL, Castedo M, Mignot G, Panaretakis T,

Casares N, et al: Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity

of cancer cell death. Nat Med. 13:54–61. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang X, Wu S, Liu F, Ke D, Wang X, Pan D,

Xu W, Zhou L and He W: An Immunogenic cell death-related

classification predicts prognosis and response to immunotherapy in

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol.

12:7814662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bauza-Thorbrugge M, Peris E, Zamani S,

Micallef P, Paul A, Bartesaghi S, Benrick A and Wernstedt Asterholm

I: NRF2 is essential for adaptative browning of white adipocytes.

Redox Biol. 68:1029512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen S, Ren Q, Zhang J, Ye Y, Zhang Z, Xu

Y, Guo M, Ji H, Xu C, Gu C, et al: N-acetyl-L-cysteine protects

against cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting

ROS-dependent activation of Akt/mTOR pathway in mouse brain.

Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 40:759–777. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|