Introduction

Due to the high incidence rates and mortality

burden, cancer is a notable societal, public health and economic

problem. Although a variety of treatments have been proposed, the

therapeutic efficiency and safety remain to be improved. There is

an urgent need to develop more effective treatment strategies

(1). Consequently, understanding

the functional mechanisms of key genes during tumorigenesis holds

notable clinical implications.

The replication factor C (RFC) family consists of

five paralogous members (RFC1-5) characterized by distinct

structural domains and conserved functional motifs. The sequence

homology arises from the strong similarity in the sequences of

these family members. RFC1 exhibits unique structural features

including the exclusive RFC box I domain, while boxes II–VIII are

structurally conserved across all RFC paralogs (2).

Accumulating evidence highlights the critical role

of RFC family members in tumorigenesis and cancer progression.

Functional experimental studies have reported the antitumor or

pro-tumor effects of RFC family members, such as promoting cell

apoptosis (3), inducing cell cycle

arrest (4) and inhibiting

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (5). Numerous studies have also demonstrated

the regulatory function of RFC family members, including microRNA

(miR)-mediated translational suppression (6), post-translational modification via

cascade effects (7) and epigenetic

modification (8). In addition,

substantial evidence suggests some RFC family members also

participate in several key signaling pathways, including the

Wnt/β-catenin (9), Notch pathway

(10) and p53 pathways (11).

Moreover, RFC-like complexes (RLCs) also are

involved in tumorigenic processes, particularly in DNA-related

damage and repair. Notably, RLCs have emerged as integral

components of tumorigenic processes, particularly in maintaining

genomic stability through coordinated participation in DNA damage

response pathways and repair mechanisms (12). Due to the multifaceted roles of RFC

family in the context of cancer, its members have the potential to

be biomarkers for precision oncology. However, comprehensive

analyses of their contributions to tumor development and

progression remain limited.

In the present review, the differential expression

of RFC family members in pan-cancer was systematically evaluated

using Tumor IMmune Estimation Resource (TIMER2.0) (13). As potential biomarkers for patients,

the relationship between expression levels and clinical importance

were investigated. Furthermore, the present review summarized

current research on RFC family members in various malignancies with

particular emphasis on their specific contributions to signaling

pathway regulation. The present article aimed to systematically

summarize the expression characteristics, functional heterogeneity

and molecular mechanisms of the members of the RFC family in

various cancers, and to explore their potential as diagnostic

markers and therapeutic targets.

Overview of RFC

The replication factor C (RFC) protein, first

purified from 293T cells, has been shown to interact with SV40

large T antigen during the initial phases of viral DNA replication

in vitro (14–16). Subsequently, RFC was also purified

from HeLa cells. RFC exhibits multiple activities, including its

ability to participate in DNA replication in an ATP- and

proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-dependent reaction

(17). Moreover, it is also

involved in pleiotropic biological activities, including DNA

repair, transcriptional regulation, cell cycle, apoptosis, cellular

differentiation and telomere-length regulation (14).

Structure and expression of RFC family

members in pan-cancer

The RFC family comprises of five distinct members

(RFC1, RFC2, RFC3, RFC4 and RFC5) with molecular weights of 140,

40, 38, 37 and 36 kDa respectively. These proteins have been

discovered in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Mus musculus, Homo

sapiens, Calf thymus and Escherichia coli (18–22).

It has been reported that p140 (RFC1), p40 (RFC2),

p38 (RFC3), p37 (RFC4) and p36 (RFC5) are

located on human chromosomes at 4p13-p14, 7q11.23, 13q12.3-q13,

3q27 and 12q24.2-q24.3, respectively (23,24).

In humans, the five subunits of RFC complex exhibit

sequence conservation across conserved regions known as RFC boxes

II–VIII, which are critical for their functional interactions

(2,20). The RFC box I, which is located on

the large subunit p140 and consists of 89 amino acids, demonstrates

sequence homology with prokaryotic DNA ligases (2). Additionally, it has been demonstrated

that deletion of RFC box II domain markedly impairs DNA synthesis,

which requires the RFC complex for its function (25). The highly conserved RFC box III

GXXXXGK(S/T) motif contains the phosphate-binding loop (P-loop),

the most evolutionarily conserved structural element within this

motif. By contrast, RFC box IV exhibits limited conservation in

prokaryotic proteins. RFC box V DE(V/A)D and DEAD-box proteins have

similar features. Within the large subunit p140, RFC box VI is

designated VIa, whereas it is referred to as VIb in the other four

small subunits (14,26). RFC box VII (SRC) is conserved within

the small subunits and the prokaryotic accessory proteins, but only

the cysteine is present in the large RFC subunits. Notably, the HYC

motif in RFC1 corresponds to box VII (27). In the human RFC family, RFC box VIII

displays subunit-specific amino acid sequence variations. The

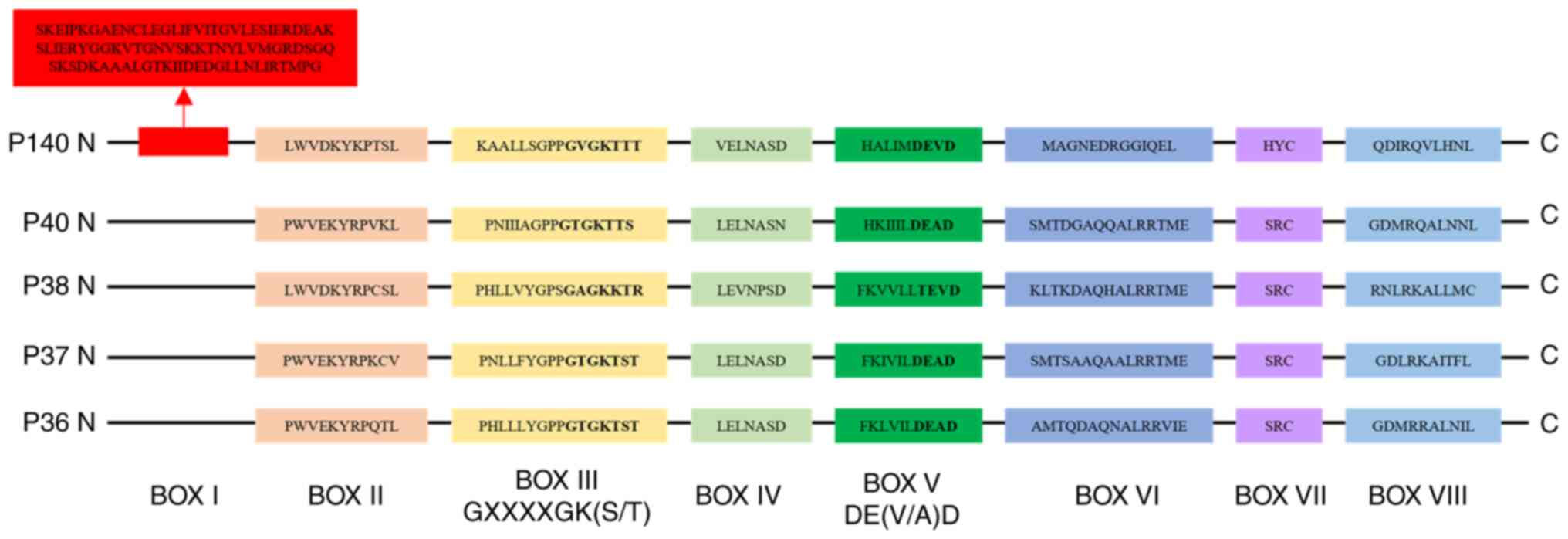

characteristic sequences of RFC boxes are shown in Fig. 1.

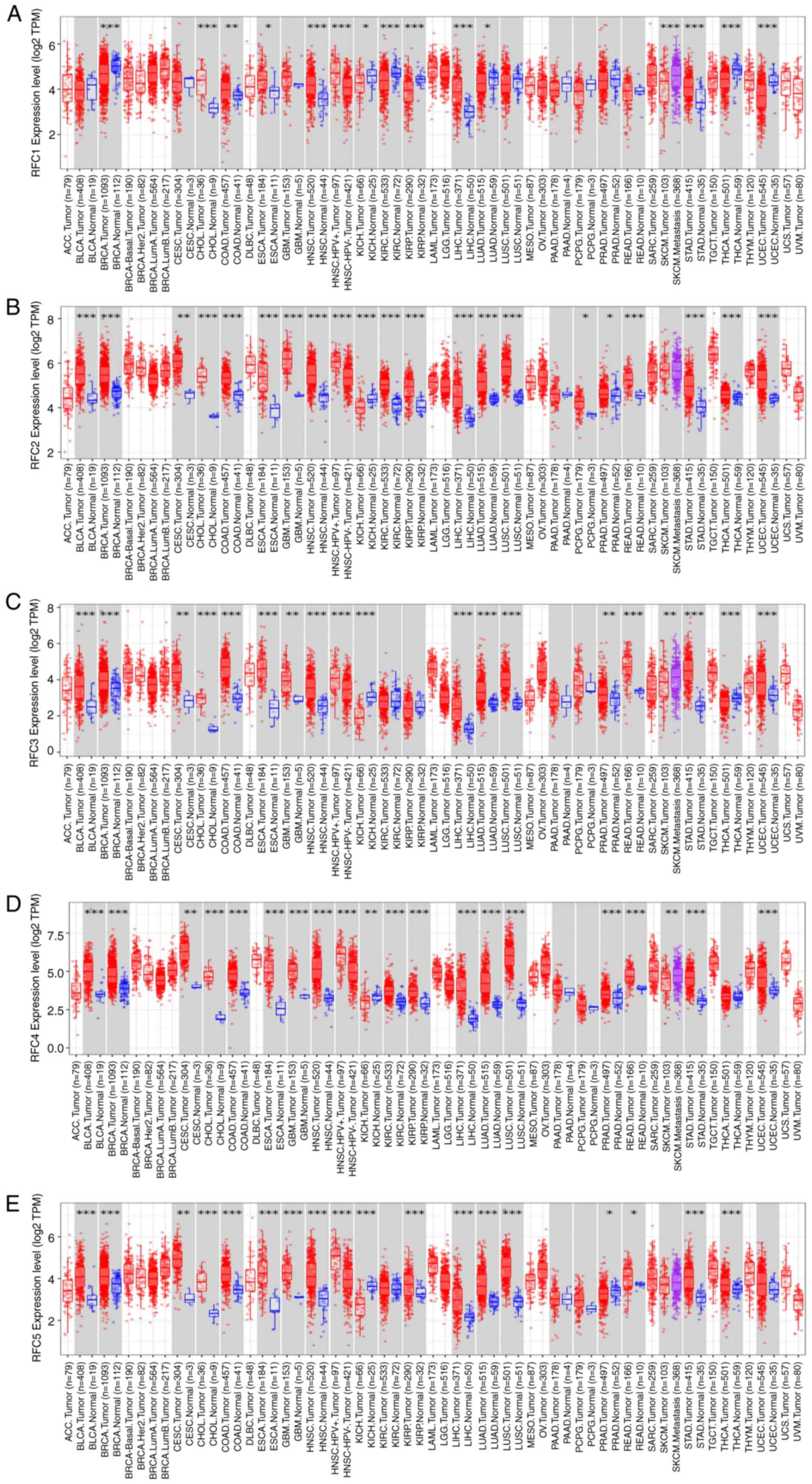

The mRNA expression of RFC family members was

evaluated in pan-cancer using TIMER 2.0 (Fig. 2) (13). According to the results, in the most

types of tumors, the RFC family members are expressed at higher

levels in tumor tissues compared with in normal tissues. Notably,

in kidney chromophobe, the expression levels of all RFC family

members are markedly lower in tumor tissues compared with in normal

tissues. The underlying mechanisms warrant further

investigation.

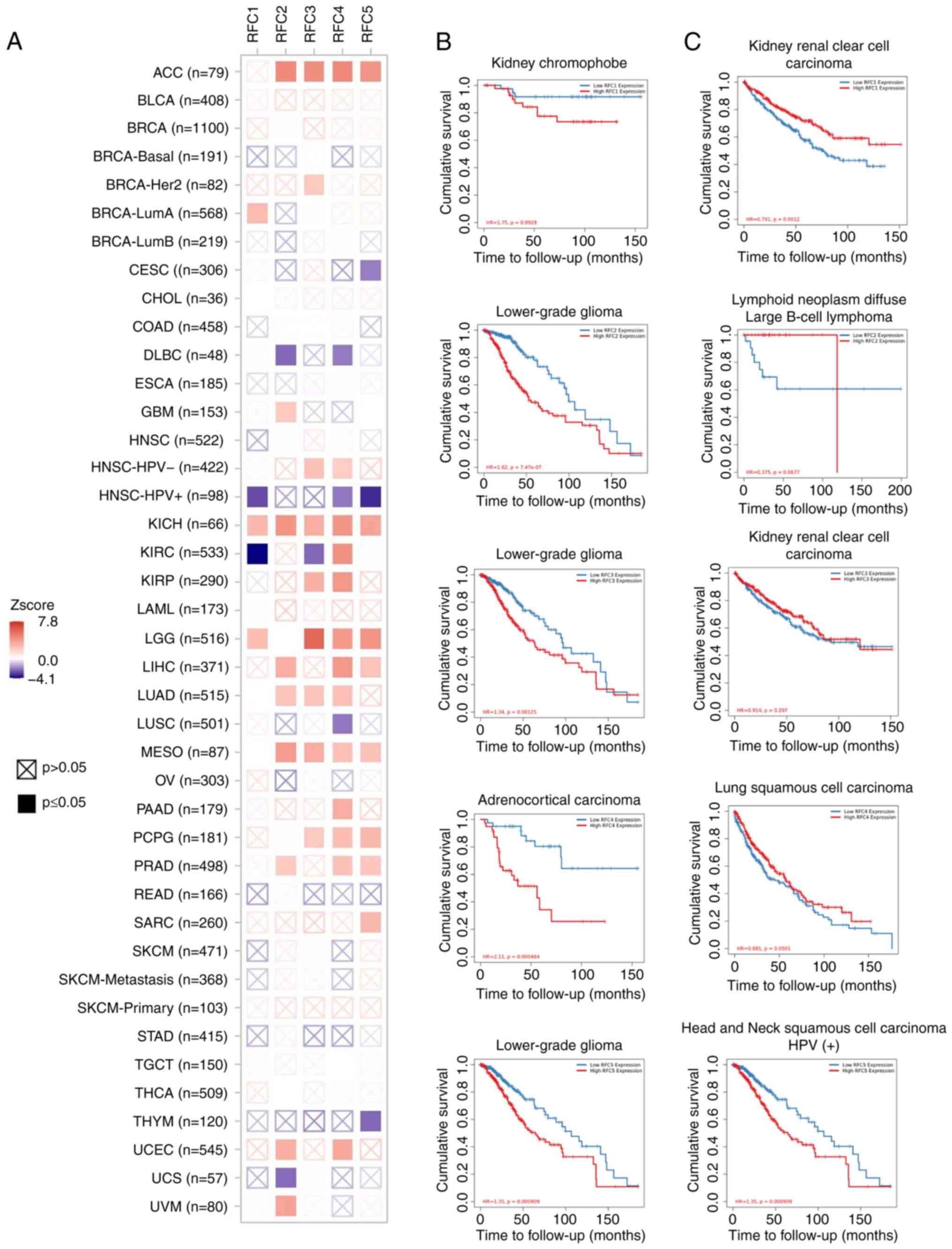

The clinical relevance of RFC gene expression across

various cancer types was assessed using TIMER 2.0 (Fig. 3). For each RFC subunit, the cancer

type with the highest and lowest Z score were summarized. The

results are presented in Table I.

Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to evaluate the overall survival

(OS). The potential relationship between the mRNA expression of RFC

subunits and overall survival (OS) in patients with various cancers

was analyzed (Fig. 3) (28). Elevated expression levels of RFC2,

RFC3 and RFC5 were associated with worse outcomes in brain

lower-grade glioma (LGG). Similarly, high RFC4 expression was

associated with poor survival in adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). By

contrast, reduced RFC1 expression was associated with worse

outcomes in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, while decreased RFC5

expression was associated with poor prognosis in human

papillomavirus (HPV)-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(HNSCC). These results indicate that RFC family members have the

potential to be biomarkers for precision oncology.

| Table I.Association between cancer type and

the mRNA expression of RFC subunits. |

Table I.

Association between cancer type and

the mRNA expression of RFC subunits.

| Gene | Cancer | Z score | adj.p |

|---|

| RFC1 | KICH (n=66) | 2.711109947 | 0.047403342 |

|

| KIRC (n=533) | −4.07798685 | 0.000924303 |

| RFC2 | LGG (n=516) | 7.83870425 |

0.000000000000933 |

|

| DLBC (n=48) | −2.37849173 | 0.091375475 |

| RFC3 | LGG (n=516) | 5.892615212 | 0.00000039 |

|

| KIRC (n=533) | −2.39697366 | 0.091375475 |

| RFC4 | ACC (n=79) | 4.644463897 | 0.00023299 |

|

| LUSC (n=501) | −2.14599312 | 0.142045069 |

| RFC5 | LGG (n=516) | 4.114157942 | 0.000924303 |

|

| HNSC-HPV+

(n=98) | −3.47315808 | 0.005858129 |

Function of RFC subunits in human

cancers

RFC1

The RFC1 gene, localized on chromosome 4, encodes

the ubiquitously expressed RFC1 protein which serves as the largest

subunit of the RFC family. This protein serves a critical role in

DNA replication and repair processes (29). In humans, three functional homologs

of RFC1 have been identified including RAD17 checkpoint clamp

loader component (RAD17), chromosome transmission fidelity factor

18 (CTF18) and ATPase family AAA domain containing 5 (ATAD5). These

homologs can associate with other subunits through protein-protein

interactions, which facilitates the assembly of RLCs (30).

The expression of RFC1 is overexpressed in malignant

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cells (31). In breast cancer (BC), the

curcumin-analog PAC markedly upregulates the expression of RFC1

which is involved in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway

(32). A study on estrogen receptor

(ER)-negative MDA-MB-231 BC cells revealed that 17β-estradiol

exposure downregulated RFC1 expression, leading to re-expression of

ERα (33). Emerging evidence in

colorectal cancer (CRC) research suggests that reduced RFC1

expression may function as a tumor suppressor mechanism.

Mechanistic investigation identified post-transcriptional

regulation of RFC1 via microRNA-26a-5p targeting of its

3′-untranslated region, which modulates critical DNA maintenance

processes, including mismatch repair, DNA replication fidelity and

NER pathway functionality (6). RFC1

demonstrates more distinctive features than the other four RFC

family members, making it a promising candidate for further cancer

research. Now that the notable effects of RFC1 have drawn attention

in cancer research, similar focus has been directed to other

members of the RFC family. Evidently, a deeper understanding of the

roles of RFC family members in cancer biology is crucial, as it may

facilitate the discovery of novel signaling pathways and potential

therapeutic targets.

RFC2

The RFC2 gene, located on chromosome 7, encodes the

unique RFC subunit that can independently unload PCNA and suppress

DNA polymerase activity.

In diffuse LGG, bioinformation analysis has shown

that overexpressed RFC2 is strongly associated with pivotal immune

checkpoint genes [including programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1),

programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), PD-L2, B7-H2 and cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4)] and serves as an

independent predictor of adverse prognosis. In cell models,

functional experiments demonstrate that RFC2 serves an anticancer

role by promoting cell apoptosis, inhibiting proliferation and

inducing cell G2 phase arrest (3). In gastric cancer (GC), circular

RNA-collagen type Iα2 chain functions as a competing endogenous RNA

by sponging miR-1286, upregulating ubiquitin specific peptidase 10

expression and attenuating RFC2 ubiquitination, ultimately

enhancing cell invasion and migration (8). In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as a

novel biomarker for the prognosis, high expression of RFC2 was

associated with worse OS and disease-free survival. Functional

experiments demonstrate that RFC2 knockdown inhibits malignant

behaviors including proliferation and migration of HCC cell lines

(34). In CRC, upregulated RFC2

expression is associated with poor clinical outcomes.

Functional studies have demonstrated that RFC2

silencing notably attenuates malignant phenotypes, including tumor

cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Notably, knockdown of

CAMP responsive element binding protein 5 which is the

transcription factor of RFC2 markedly suppresses RFC2 expression.

Moreover, RFC2 promotes aerobic glycolysis and MET/PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway, thereby driving tumorigenesis (7). In castration-resistant prostate cancer

(CRPC) cell lines, RFC2 downregulation markedly inhibits cell

proliferation, induces apoptosis and aggravates DNA damage

(35). Furthermore, clinical

evidence demonstrates that elevated RFC2 protein expression is

associated with unfavorable prognosis in patients with prostate

cancer (PCa). Notably, RFC2 expression levels are markedly higher

in CRPC tissues compared with localized PCa, suggesting a potential

role in disease progression (35).

In metastatic Ewing's sarcoma (ES), RFC2 mRNA expression is

markedly upregulated. Elevated RFC2 levels are inversely associated

with poor OS and event-free survival in patients with ES (36). In cervical cancer (CC), RFC2 serves

a pivotal role in promoting cervical cancer progression by

enhancing cell growth, regulating the cell cycle and promoting

metastatic behavior (37).

Therefore, RFC2 exerts pro-tumorigenic effects. Designing a

targeted drug tailored to RFC2 may be a promising precision

medicine approach.

RFC3

The RFC3 gene, located on chromosome 13 in humans,

is involved in cell proliferation and DNA damage repair, and its

abnormal activation is associated with various malignant

tumors.

In HNSCC, bioinformation analysis has demonstrated

that the high expression of RFC3 is notably associated with

clinicopathological features, including tumor stage, grade,

metastasis and patient survival (38). Additionally, it is also associated

with immune cell infiltration and well-known oncogenic signaling

pathways, such as MYC/MYCN, Hippo and mTOR (38). In the ER-positive BC cell line

MCF-7, upregulated RFC3 is notably associated with poor prognosis,

and downregulated RFC3 induces S phase arrest and attenuated cell

proliferation, migration and invasion (39). The downregulation of

hsa_circ_0011946 inhibits the migration and invasion of MCF-7 cells

by targeting RFC3 (40).

Upregulation of RFC3 is associated with poor prognostic phenotype

in BC (41). In lung adenocarcinoma

(LUAD), RFC3 overexpression is not only associated with poor

prognosis but also facilitates cell cycle progression from

G1 to S phase, potentially contributing to tumor growth.

Mechanistically, RFC3 promotes EMT through the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway (42). Similarly,

RFC3 silencing induces cell cycle arrest at S phase, leading to

proliferation inhibition in HCC (4)

and CC (43). In GC, the

yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1)/TEA domain family member 1 (TEAD)

pathway transcriptionally activates RFC3, driving tumor

progression; conversely, RFC3 depletion abolishes malignant

behaviors in vitro and in vivo (5). In CRC, kinesin family member 14

upregulation counteracts the suppressive effects of RFC3 depletion

on aggressive phenotypes, highlighting its functional role

(44).

RFC4

The RFC4 gene, localized to chromosome 3q27 in

humans, serves a critical role in DNA replication and repair. RFC4

is indispensable for the initiation of DNA template expansion by

DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ) and Pol ε, essential components of the DNA

replication machinery (45).

In NPC, RFC4 expression is markedly upregulated in

tumor tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues. Functional

studies have revealed that RFC4 knockdown induces G2/M

cell cycle arrest and inhibits cellular proliferation both in

vitro and in vivo. Notably, HOXA10 has been identified

as a downstream effector of RFC4, and overexpression of HOXA10

partially rescues the suppressive effects of RFC4 silencing,

including impaired cell proliferation, inhibited colony formation

and cell cycle arrest (46). In

oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), bioinformatics analysis

identified high RFC4 expression is an independent prognostic factor

for poor survival and associated with increased levels of MET,

along with reduced levels of CD274 and CD160 (47). Knockdown of RFC4 led to

G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and inhibited the

proliferation of OSCC cells both in vitro and in vivo

(47).

In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), RFC4

overexpression may be driven by copy number alterations, which

contribute to genomic instability and oncogenic activation.

Notably, RFC4 is upregulated not only in early-stage tumors but

also during early nodal metastasis, implying that it has a role in

early dissemination. Clinically, high RFC4 expression predicts poor

prognosis, independent of the presence of abundant

tumor-infiltrating immune cells (such as CD4+ T cells,

CD8+ T cells, B cells, dendritic cells and monocytes),

suggesting that RFC4-mediated immune evasion or resistance may

bypass immune surveillance (48).

In addition, Zeng et al (49). collected a small sample database

which comprised seven patients and the data showed that patients

with low expression of RFC4 exhibited a higher tumor shrinkage rate

compared with patients with high expression of RFC4. Further

validation in larger cohorts is required to confirm whether RFC4

expression is indeed associated with radiotherapy response in

esophageal cancer.

In CRC, RFC4 functions as a radiation resistance

factor, protecting CRC cells from radiation-induced DNA

double-strand breaks (DSBs) and apoptosis in vitro as well

as in nude mouse xenograft models (50). RFC4 promotes non-homologous end

joining-mediated DNA DSB repair by interacting with the Ku70/Ku80

complex. Moreover, RFC4 upregulation in tumor cells predicts

reduced tumor regression and poor prognosis in patients with

locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) treated with neoadjuvant

radiotherapy. Therefore, RFC4 levels might serve as an effective

predictive biomarker of radiation sensitivity and a target for

radio-sensitization in patients with LARC (50). Additionally, RFC4 is frequently

overexpressed in CRC, driving tumor progression and poor survival

outcomes. Downregulated RFC4 inhibits cell proliferation and

induces S phase arrest (51). In

the HCC cell line HepG2, RFC4 downregulation enhances the cytotoxic

effects of doxorubicin and camptothecin, suggesting a role in

chemoresistance (52). In the lung

cancer cell line A549, RFC4 exhibits notable co-expression with

protein kinase C-like (PKCι) and PKCι knockdown markedly suppresses

RFC4 expression, suggesting a potential regulatory axis between

PKCι and RFC4 (53).

Moreover, Zheng et al (54) reported that high expression of RFC4

was not only associated with poor prognosis but also indicated a

stronger therapeutic response to immunotherapy in patients with

LUAD using bioinformatics methods. Possibly because RFC4

participated in reshaping the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME),

CD8+ T cells and macrophages M1 were positively

associated with RFC4 gene expression. In BC cell lines, silencing

RFC4 inhibited cell proliferation, induced G1 cell cycle

arrest and reduced cell migratory and invasive ability (55). Moreover, knockdown of RFC4

attenuated stemness and downregulated the expression of CD44 and

SOX2. RFC4 silencing inhibited migration and invasion, promoted

apoptosis and improved sensitivity to radiotherapy. Regarding the

mechanism, insulin like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2

(IGF2BP2) can bind to the RFC4 mRNA coding sequence, and knockdown

of RFC4 eliminates the effects of overexpressed IGF2BP2 on

increasing cell viability, invasion, expression of stemness markers

and radio resistance (56).

Therefore, it also has potential to be a therapeutic target for

BC.

In patients with CC, a higher expression of RFC4 is

associated with an improved prognosis, possibly because RFC4 is

positively associated with the expression of three

immunostimulatory factors (UL16 binding protein 1, TNF receptor

superfamily member 13C/18/25 and inducible T cell costimulator

ligand) and three immunosuppressive factors (IL10 receptor subunit

b, V-set domain-containing T-cell activation inhibitor 1 and

galectin 9) (57).

RFC5

The RFC5 gene, located on chromosome 12 in humans,

serves vital roles in DSB repair, DNA excision and cell cycle

regulation, thereby maintaining genomic stability and influencing

tumorigenesis.

Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that astrocyte

elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) knockdown markedly downregulates RFC5

expression, impairing homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA

repair following radiation exposure. This effect is associated with

enhanced radiosensitivity in glioma cells, highlighting RFC5 as a

critical mediator of DNA damage response (58). Clinically, high levels of AEG-1 and

RFC5 are associated with poor prognosis specifically in patients

with glioma undergoing radiotherapy, further supporting their roles

as therapeutic targets (58). RFC5

is upregulated in HPV-negative HNSCC, where it serves a critical

role in DNA damage repair pathways. This upregulation enhances the

tumor cell capacity to withstand genotoxic stress, contributing to

therapy resistance and poor clinical outcomes (59). RFC5 functions as an oncogene in lung

cancer, where its overexpression is notably associated with poor

patient prognosis. Elevated RFC5 levels are associated with

aggressive clinicopathological features, including advanced tumor

stage, lymph node metastasis and enhanced tumor cell proliferation,

thereby promoting tumorigenesis and disease progression (60).

Bioinformatics analyses reveal that RFC5 harbors

putative binding sites for serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 10

(SRSF10). Functional studies have demonstrated that RFC5

overexpression promotes CRC cell proliferation and metastasis, even

when SRSF10 is silenced, suggesting an oncogenic dependency

(61). Mechanistically, SRSF10

regulates alternative splicing of RFC5, preferentially excluding

exon 2-AS1 (alternative splicing isoform 1 of exon 2) (61). Notably, Yao et al (62) confirmed that RFC5 promotes a

malignant phenotype in vitro, and downregulation of RFC5

markedly suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Collectively, the

researchers demonstrate that the circ_0038985/miR-3614-5p/RFC5 axis

serves a critical role in the progression of CRC, and RFC5 may

promote CRC progression via modulation of the VEGFA/VEGFR2/ERK

signaling pathway.

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), bioinformatics

analysis showed that high RFC5 expression served as an independent

prognostic factor for the poor OS of patients with AML.

Additionally, elevated RFC5 mRNA levels were positively associated

with plasma cell and M2 macrophage infiltration, implicating TIME

remodeling in RFC5-driven leukemic progression (63). Zhang et al (64) demonstrated that basic transcription

factor 3 directly binds to the RFC5 promoter and upregulates RFC5

expression in PCa cells.

Role of the RFC family in different

signaling pathways

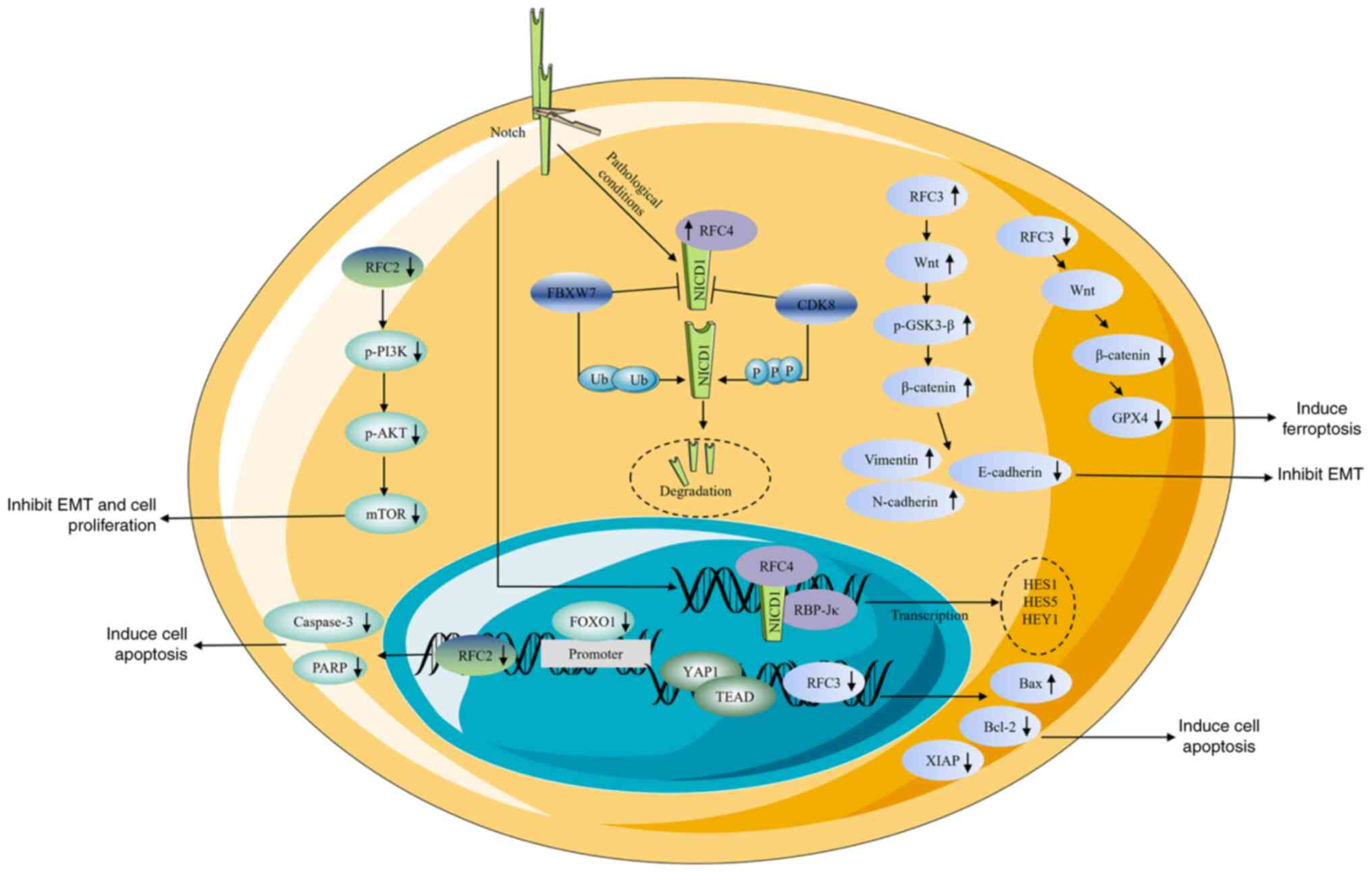

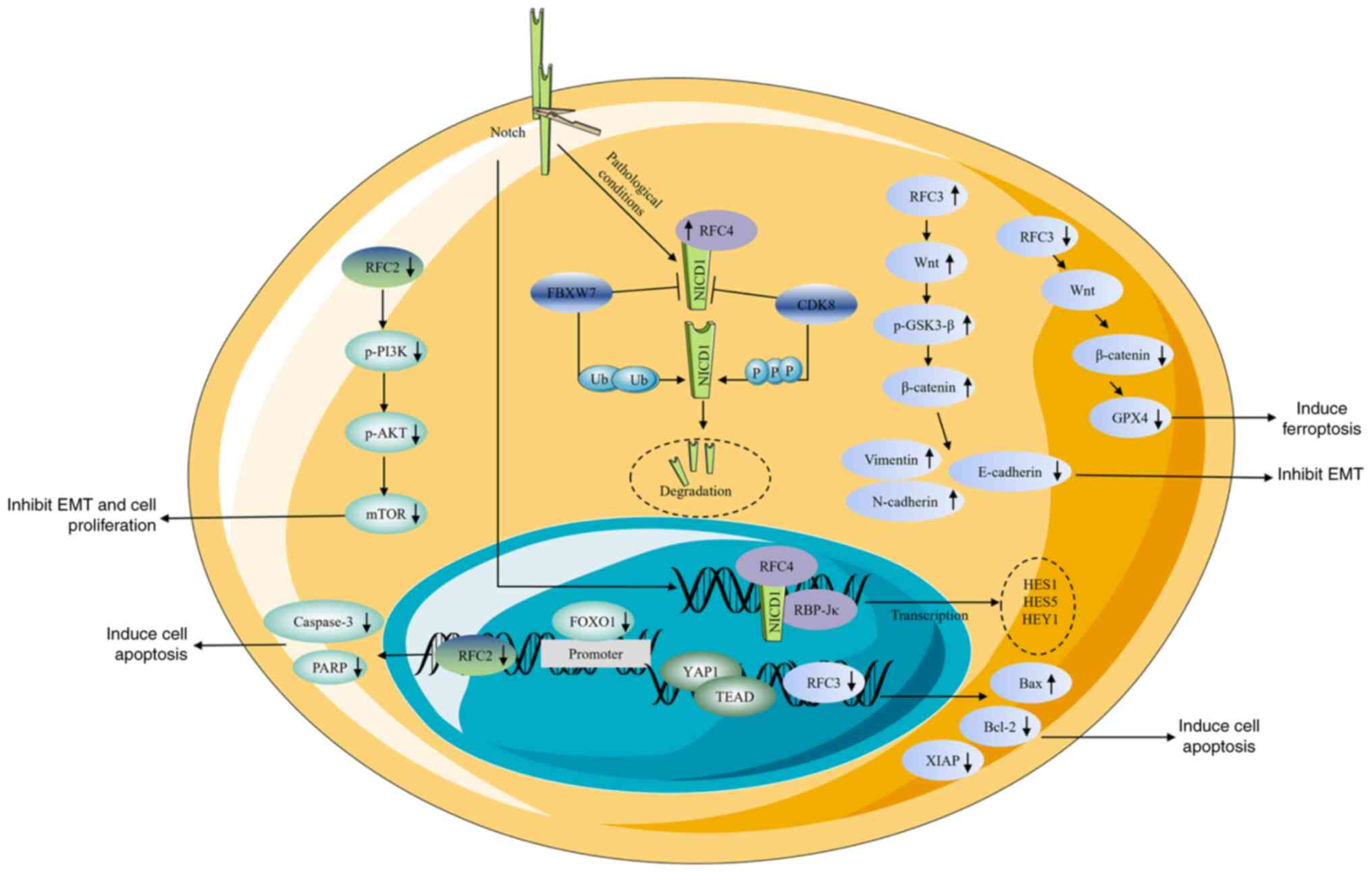

The RFC family members mainly participate in DNA

associated regulation. Here, the molecular mechanism associated

with the RFC family in cancers are discussed (Fig. 4).

| Figure 4.Roles of RFC subunits in different

signaling pathways. RFC2 participates in the FOXO1 and PI3K/AKT

signal pathways. RFC3 participates in the YAP1/TEAD1 and

Wnt/β-catenin signal pathways. RFC4 participates in Notch1

signaling pathway. ↑, increase; ↓, decrease; RFC, replication

factor C; FOXO1, Forkhead box protein O1; YAP1, yes-associated

protein 1; TEAD, TEA domain family member 1; p-, phosphorylated;

PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal

transition GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3 β; GPX4, glutathione

peroxidase 4. |

It has been demonstrated that Forkhead box O1

(FOXO1), a nuclear transcription factor, is able to directly

activate RFC2 expression in a transcriptional process by binding to

the promoter of RFC2. Knockdown of the FOXO1/RFC2 gene regulatory

network increases caspase-3 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)

in temozolomide resistance a glioma cell line (65). In CRC cells, RFC2 activates the

MET/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and RFC2 knockdown decreases the levels

of phosphorylated (p-)PI3K, p-AKT, p-mTOR and p-70S6K in both

HCT116 and SW480 cell lines (7). In

CRC chemo-resistant cells, knockdown of RFC3 inhibited the

expression of β-catenin and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4).

Immunostaining assays further demonstrated that the loss of RFC3

diminished the nuclear localization of β-catenin in these cells and

rescue experiments also supported these results. These findings

indicate that RFC3 knockdown disrupts the Wnt/β-catenin/GPX4 axis

(9).

In GC, transcriptional coactivator YAP1 binds to the

transcriptional factor TEAD and induces the expression of RFC3.

RFC3 silencing increased the expression of Bax and decreased the

expression of Bcl-2 (5). In

addition, RFC3 knockdown also reduces X-linked inhibitor of

apoptosis protein expression (5).

Overexpression of RFC3 increased Wnt expression, the

p-GSK3β(Ser9)/GSK3β ratio, and β-catenin protein levels. Since

β-catenin has a critical function in EMT, this results in

downregulated E-cadherin and upregulated N-cadherin. These results

suggest that RFC3 may trigger the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

and promote LUAD migration and invasion through EMT (42).

Upon canonical Notch signaling activation, the

Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD1) undergoes nuclear translocation

and binds to the transcription factor recombination signal binding

protein for immunoglobulin kJ, initiating transcription of

downstream targets such as hairy and enhancer of split (HES) 1,

HES5 and hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW

motif 1. These transcriptional repressors suppress

differentiation-promoting genes, maintaining progenitor cell

states. Under pathological conditions, RFC4 directly interacts with

NICD1 via high-affinity binding. This interaction competitively

abrogates CDK8-induced phosphorylation and F-box and WD repeat

domain containing 7-induced ubiquitination-dependent degradation of

NICD1. A feedforward loop between elevated RFC4 and NICD1 levels

drives sustained overactivation of Notch signaling, promoting NSCLC

tumorigenesis and metastasis (10).

In ESCC cells, overexpression of RFC4 increases cyclin D1 and Rad51

levels, whereas p53 and p21 levels are notably decreased.

Conversely, RFC4 knockdown has the opposite effect (11). However, the precise nature of the

regulation of the p53 signaling pathway by RFC4 remains somewhat

unclear.

Function and regulation of RLCs in

humans

Rad17-RFC complex

RAD17 interacts with the small subunits RFC2-5 and

forms a sophisticated complex, which is composed of two effective

layers: i) The lower part is an open and slightly twisted C-shaped

ring formed by the N-terminal Rossmann fold domains and central

helical bundle domains of RAD17, RFC2, RFC3, RFC4 and RFC5; and ii)

the upper ring, which forms a collar over the central cavity, is

offset from the central of the lower C-shaped ring, lying

predominantly over RFC3, RFC4 and RFC5 (66).

The Rad17-RFC complex functions as DNA damage sensor

(67). When DNA damage occurs, it

recruits the 9-1-1 (RAD9-RAD1-HUS1 checkpoint clamp component)

complex in an ATP-dependent manner to the damage site and initiates

the phosphorylation of ATM serine/threonine kinase and ataxia

telangiectasia and Rad3 related (ATR) (68). Additionally, it loads the 9-1-1

complex at the double stranded DNA/single stranded DNA junctions of

DNA damage sites in an replication protein-dependent manner and

promotes the activation of ATR and checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1)

(12). Wang et al (69) demonstrated that RAD17 knockout

HCT116 cells are unable to form colonies, and the protein level of

Chk1phospho-Ser 345 is also downregulated. These results

indicate that the RAD17 complex is required for ATR-mediated

phosphorylation of Chk1 (69). The

Rad17-RFC complex and 9-1-1 complex also bind with DNA

topoisomerase II binding protein 1 which participates in the

activation of ATR (12). Moreover,

the Rad17-RFC complex is involved in ATP hydrolysis, but the

precise role of this process remains unclear.

CTF18-RFC

The multifunctional factor CTF18 exhibits two

distinct binding modalities within the cellular context: i) CTF18

stably associates with DNA replication and sister chromatid

cohesion 1 (DCC1) and CTF8, and the three proteins form a

heptameric complex with RFC2-5; and ii) CTF18 can also combine with

RFC2-5 to form a pentamer. The heptameric CTF18-DCC1-CTF8-RLC

complex (CTF18-RLC) has emerged as a central regulator of DNA

metabolism, orchestrating pivotal processes such as PCNA loading at

replication forks, establishment of sister chromatid cohesion and

activation of the DNA replication checkpoint (12).

In human cells, CTF18-RLC interacts with Pol ε by

binding to the CTF18-DCC1-CTF8 (CTF18-1-8) module's core component

DCC1 and loads PCNA; this combination is more efficient compared

with the pentamer. Meanwhile, Terret et al (70) further underscore the critical role

of CTF18-RLC in sister chromatid cohesion and maintenance of

processive DNA replication fork. The authors studies using

DCC1-knockout hTERT-RPE1 cells revealed severe defects in these

pathways, highlighting the indispensable nature of the intact

heptameric complex for genomic stability (70). Mounting evidence demonstrates that

patients with CRC and high DCC1 expression have a lower survival

rate compared with the lower-expression group. It has also been

demonstrated that HCT116 cells with DCC1 knockdown grow more slowly

and exhibit lower invasiveness compared with the control group. The

low protein expression levels of cyclin D1 and E-cadherin in the

DCC1 knockdown group also support these phenotypic changes.

Furthermore, DCC1 knockdown induces the proteolysis

of CTF18, whereas CTF18 knockdown does not affect cell invasion.

This differential effect establishes DCC1 as the dominant

functional component within the CTF18-1-8 module for promoting CRC

progression. It may be a promising molecular target for therapeutic

intervention in CRC (71).

ATAD5-RLC

Once DNA synthesis has ceased, PCNA must be

unloaded, a process primarily mediated by the ATAD5-RLC complex

(12). The C-terminal region of

ATAD5 contains both an ATPase domain and an RFC2-5 binding motif,

which are essential for efficient PCNA unloading. Experimental

evidence demonstrates that ATAD5 depletion leads to S phase arrest,

impaired PCNA unloading and markedly reduced DNA replication rates

(72). The N-terminal domain of

ATAD5 facilitates interactions with multiple protein partners

involved in regulating various aspects of DNA metabolism (72). With the depletion of ATAD5,

spontaneous HR increases and the DSB-induced HR decreases (73).

In U2OS cells, the ATAD5 knockdown group showed

higher sensitivity to olaparib compared with the control group.

This result was caused by trapping of PARP1 on chromatin (30). This observation was further

validated in both HeLa and 293T cell lines, where ATAD5 depletion

resulted in the accumulation of replication factors on chromatin in

a PCNA-dependent manner (74).

These findings collectively suggest that ATAD5 serves a crucial

role in regulating interactions between proteins and chromatin

during DNA replication and repair processes.

Exploration of RFC family molecular

functions and regulation pathways using bioinformation tools

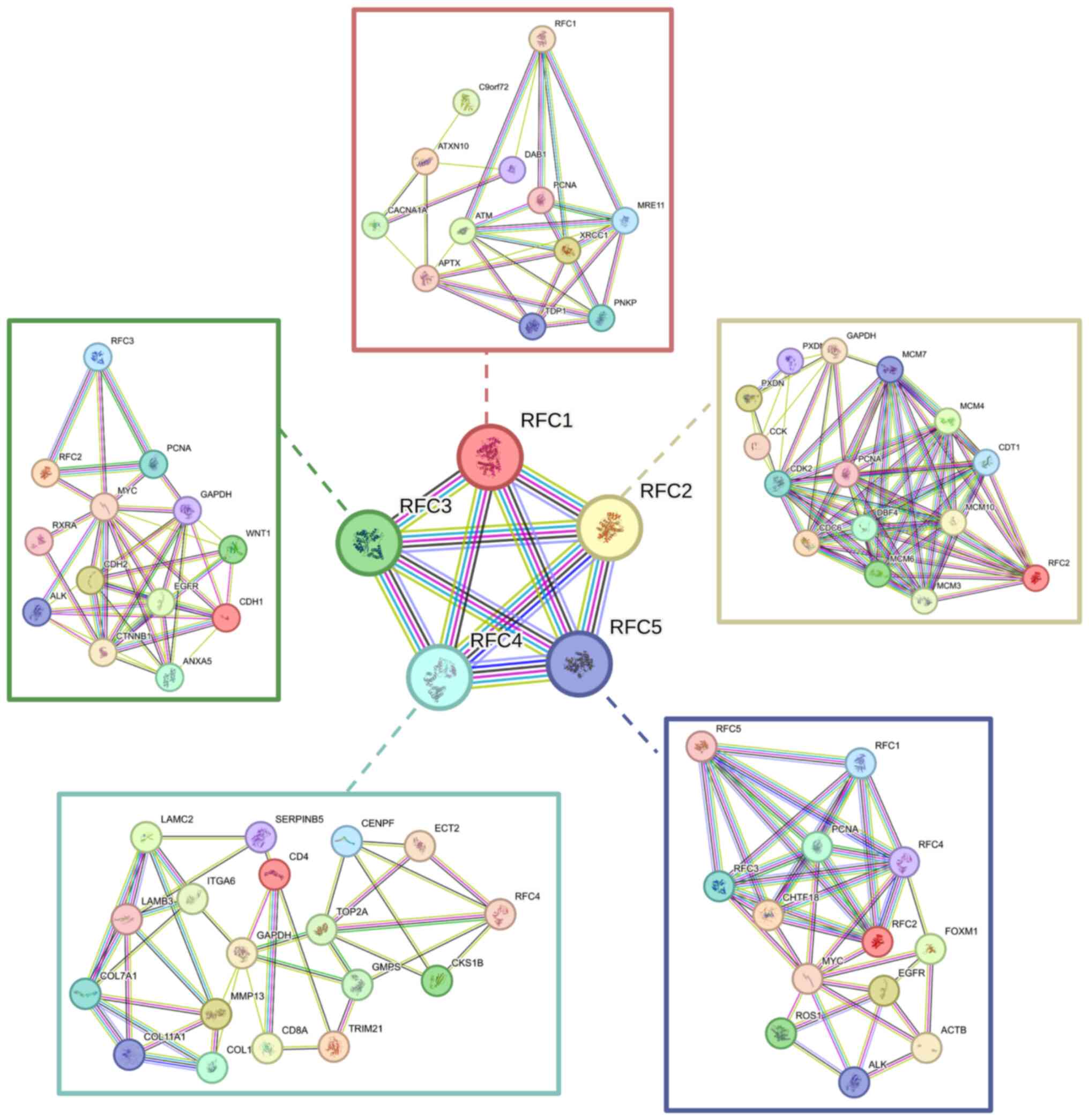

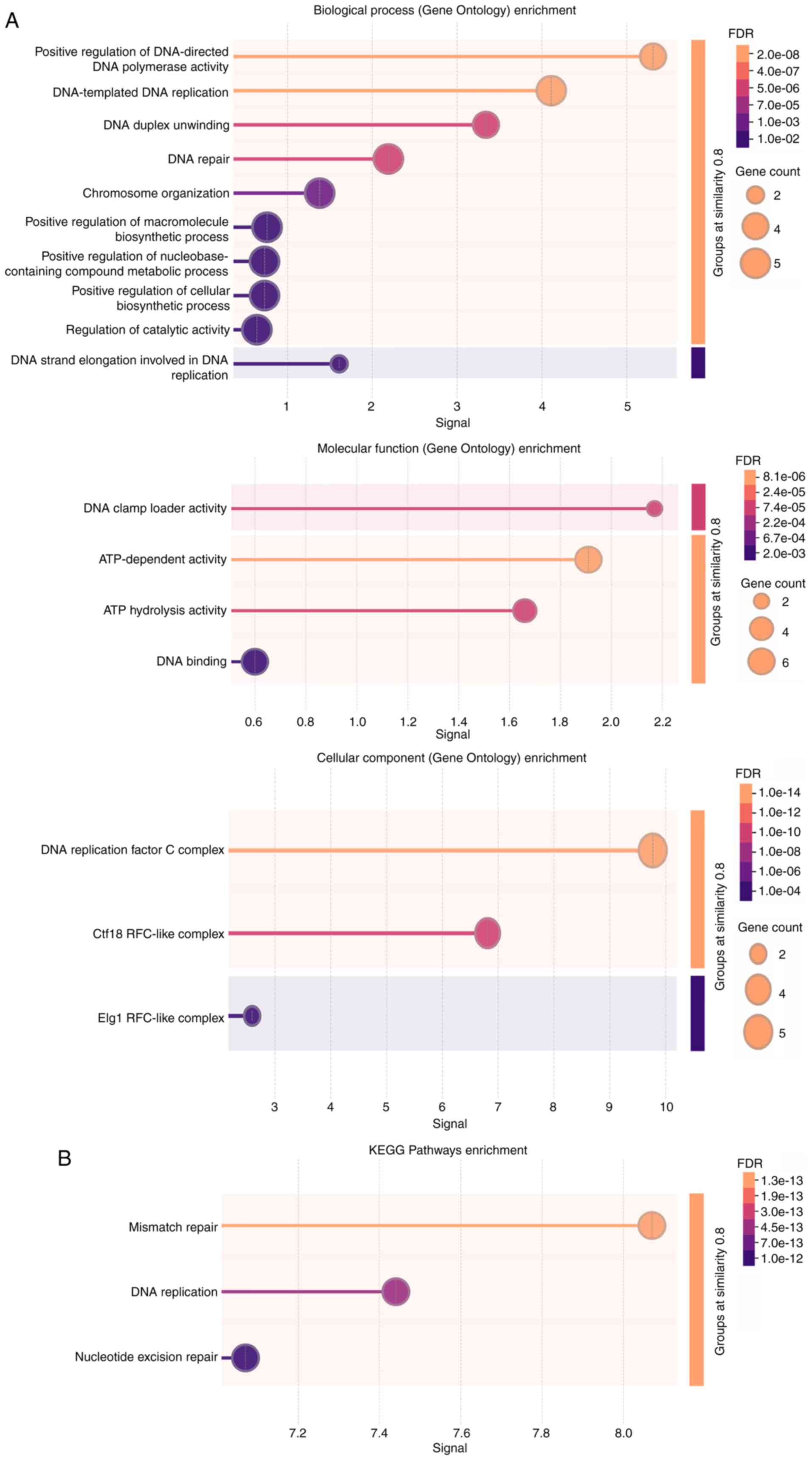

Using bioinformatics tools, the potential molecular

functions involved in interactions and regulatory pathways of the

RFC family have been explored. First, a co-expression network among

RFC family members was constructing using the STRING database

(75) and their potential

connections with other genes were investigated (Fig. 5). Additionally, Gene Ontology

analysis was performed on the RFC family (Fig. 6A) to identify their biological

processes, molecular functions and cellular components. Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis was performed to

identify molecular pathways in which RFC family members were

involved (Fig. 6B). In summary, RFC

family members primarily participate in DNA damage and repair.

Since DNA damage acts as an initiator of innate immunity (76), future investigations should focus on

the connection between RFC family members and immune

regulation.

Clinical relevance of the RFC family

In recent years, research on biomarkers has drawn

increasing attention due to its ability to improve diagnostic

accuracy, guide individualized treatment and evaluate long-term

prognosis. Moreover, biomarkers also assist doctors in assessing

the potential effectiveness of treatments and prognosis (77). The rise of bioinformatics methods

contributes to identification of new biomarkers using tumor data

platforms. In CRC, sarcoma, HCC and LGG, patients with high RFC2

expression had worse OS (3,7,78,79).

Similarly, increased expression of RFC3 predicts worsened OS in

HNSCC, BC and LC (38,41,42).

Higher RFC4 expression is associated with worse prognosis in ESCC

and HCC (3,48), whereas it is associated with

improved OS in patients with CC (57,80).

For patients with CRC and CC, higher RFC5 expression is associated

with a worse OS (62,81). These results provide new insights

for cancer research; however, to a certain extent, they reflect the

association between clinical prognosis and potential biomarker

expression level. Further experimental validation and larger

databases are needed to draw more definitive conclusions in the

future.

Numerous patients have benefited from multiple

treatments, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy;

however, the benefits remain limited. Chemoresistance and

radioresistance are the main causes of treatment failure; thus,

combination therapies may overcome the limitations of therapeutic

outcomes. Oshima et al (35)

proposed that RFC2 inhibition could be a potential therapeutic

strategy for CRPC resistant to PARP inhibitor (PARPi) by inhibiting

the NER pathway. In glioma, knockdown of RFC2 suppressed

temozolomide resistance (65,82).

Wu et al (9) demonstrated

that depletion of RFC3 enhances the sensitivity of CRC cells to

oxaliplatin by inducing ferroptosis. In BC, RFC3 knockdown enhances

tamoxifen sensitivity by inducing S-phase arrest (39). RFC4 deficiency enhances

radiosensitivity by promoting DNA damage in ESCC, BC and LARC

(11,50,56).

Nelarabine, in combination with other chemotherapies, is able to

reduce RFC4 gene expression (83).

In addition, RFC5 knockdown enhances radiation sensitivity by

impaired homologous recombination repair activity (58). The high RFC4 expression indicates a

stronger therapeutic response to immunotherapy in LUAD (54). Notably, most of these studies are

based on model organisms; therefore, more clinical trials are

needed in the future.

Due to the poor selectivity and off-target effects,

traditional treatments have notable clinical limitations. Thus, the

specific target therapy focusing on the molecular targets has

become a potential alternative. Previously, research by Alaa et

al (83) and colleagues

demonstrated that vorinostat and trichostatin A act as RFC4

inhibitors using molecular docking and molecular dynamics

simulation.

Moreover, the potential application of RLCs in

clinical treatment has also drawn more attention. ATAD5-depleted

cells show high sensitivity to antitumor drugs including methyl

methanesulphonate, camptothecin, mitomycin C and PARPi (30). Rohde et al (84) discovered a new compound ML367 which

inhibits ATAD5 stabilization. ML367 could block DNA repair pathways

including RPA32-phosphorylation and CHK1-phosphorylation in

response to UV irradiation. It serves as a sensitizer of PARPi to

enhance the antitumor effects synergistically. For inhibitors

intended for clinical use, further experimental validation is

essential. In ESCC, negative elongation factor complex member A

(NELFA) mRNA promotes cell apoptosis, partially by inhibiting the

interaction between Rad17 and the Rad17-RFC2-5 complex.

Furthermore, higher NELFA expression is associated with worse OS.

As a key regulator of the Rad17-RFC2-5 complex, NELFA holds promise

as a novel therapeutic target in cancer (85).

Conclusions and future perspectives

The RFC family members serve critical roles in

tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Specifically, individual RFC

subunits serve as crucial regulators of malignant phenotypes

including aberrant cell proliferation, EMT and tumor metastasis.

Clinically, elevated expression levels of RFC members are

associated with poor OS across multiple malignancies, establishing

them as potent diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Although

current research emphasizes the effects of RFC family member on

particular signaling pathways, there are relatively few studies

regarding RFC1 and RFC5. In 2019, the (AAAGGG)n motif expansions of

RFC1 were first shown to be a main cause late-onset ataxia

(86). To date, the majority of

research into RFC1 are concentrated on genopathy (29). Moreover, research on the regulatory

mechanisms of RFC5 in cancers has not been sufficiently in-depth.

This may be a new direction in cancer biology.

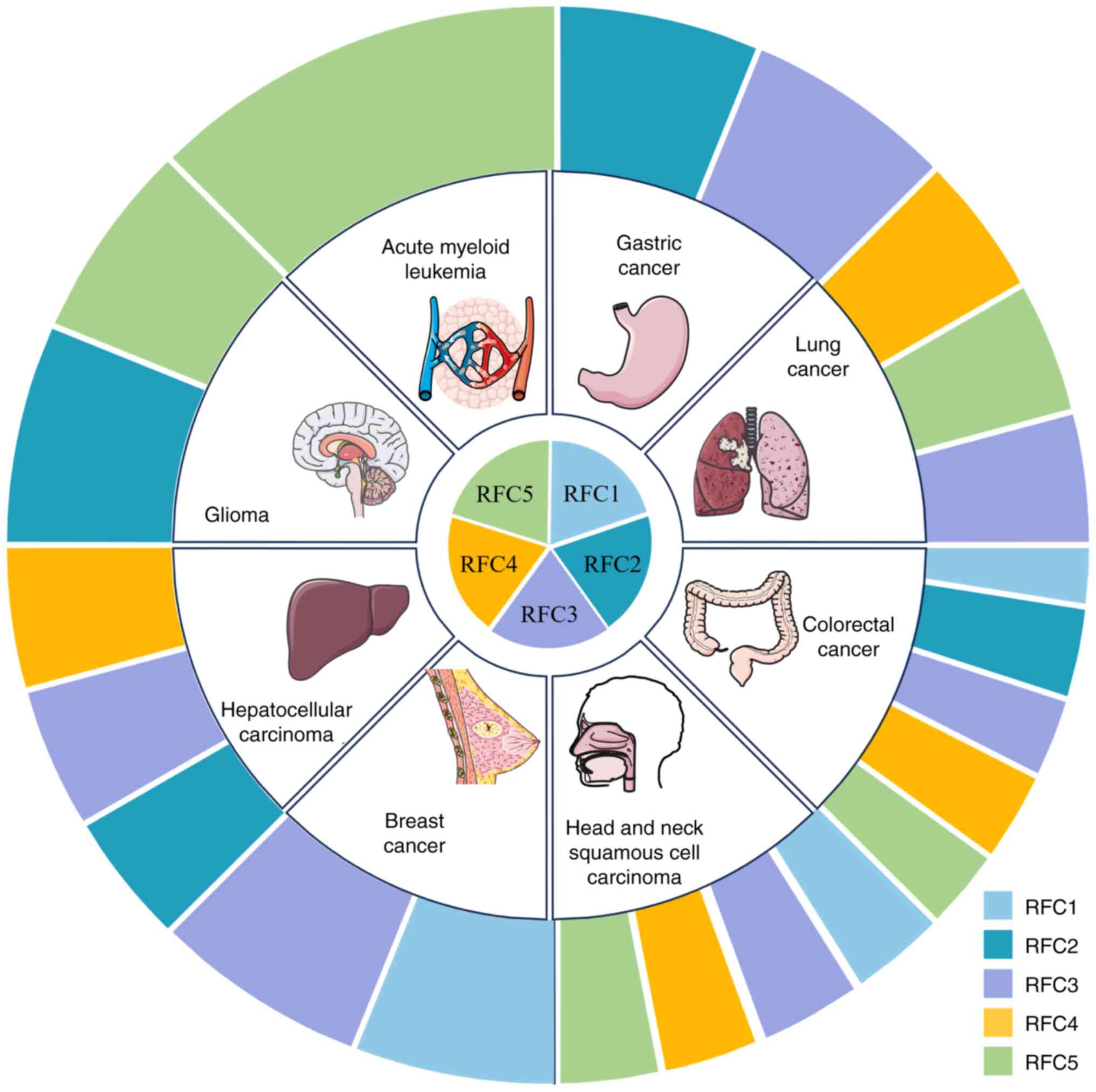

In the present review, the map of RFC family members

which are associated with cancers is shown in Fig. 7 and the regulation mechanisms are

shown in Table II. The present

review had some limitations. Much of the analysis remains at basic

experimental level, lacking forward-looking perspective.

Additionally, there is insufficient discussion on the connection

between RFC family members. With the rapid progression of

understanding of RFC family members in human cancers, their dual

potential as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors have been

demonstrated. It was hypothesized that the contradictory effects

observed in previous studies arise from variations in sample

sources and tumor heterogeneity. Cancer cells and the TIME can

exhibit molecular characteristic variations; these changes may

further contribute to the distinct roles of specific factors across

different tumors (87). Functional

experiments often rely on immortalized cell lines and standardized

animal models, which may overlook other potential influencing

factors. Furthermore, some results derived from publicly available

datasets could be affected by multiple confounding variables,

including variations in sample composition, batch effects,

differences in sequencing technologies, data processing pipelines

and normalization methods (88).

| Table II.Expression and function of

replication factor C family members in human cancers. |

Table II.

Expression and function of

replication factor C family members in human cancers.

| RFC family

members | Cancer type | Roles in human

cancers |

|---|

| RFC1 | Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma | Overexpressed |

|

| Breast cancer | Repressed by E2 in

ERα-negative breast cancer cells in which ERα has been

re-expressed. |

|

| Colorectal

cancer | Targeted by

microRNA-26a-5p. |

| RFC2 | Lower-grade

glioma | RFC2 overexpression

correlates with immune checkpoint genes. An independent predictor

of adverse prognosis. An anti-tumor factor. |

|

| Gastric cancer | RFC2 ubiquitination

enhances cell invasion and migration. |

|

| Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Severed as a novel

biomarker for the prognosis. RFC2 silencing inhibits proliferation

and migration. |

|

| Colorectal

cancer | Upregulated RFC2

expression correlates with poor clinical outcomes. RFC2 promotes

aerobic glycolysis and MET/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. |

|

|

Castration-resistant prostate cancer | Overexpressed. RFC2

downregulation inhibits cell proliferation, induces apoptosis and

aggravates DNA damage. Elevated RFC2 protein expression is

associated with unfavorable prognosis |

|

| Ewing's

sarcoma | Overexpressed. High

expression predicted poor OS and EFS. |

| RFC3 | Head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma | High expression

predicts poor clinicopathological features and associates with

oncogenic signaling pathways, such as MYC/MYCN, HIPPO, and

mTOR. |

|

| ER positive breast

cancer | High expression

predicts poor prognosis, downregulated RFC3 induces S phase arrest

and attenuated cell. |

|

| Lung

adenocarcinoma | High expression

predicts poor prognosis, overexpressed RFC3 facilitates cell cycle

progression from G1 to S phase, RFC3 promoted EMT

through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. |

|

| Hepatocellular

carcinoma | RFC3 silencing

induces cell cycle arrest at S phase. |

|

| Gastric cancer | The YAP1/TEAD

pathway transcriptionally activated RFC3, driving tumor

progression. |

|

| Colorectal

cancer | KIF14 upregulation

counteracts the suppressive effects of RFC3 depletion on aggressive

phenotypes. |

| RFC4 | Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma | Overexpressed. RFC4

knockdown induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and inhibits

cellular proliferation. Overexpression of HOXA10 partially rescues

the suppressive effects of RFC4 silencing. |

|

| Esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma | Overexpressed. high

RFC4 expression predicts poor prognosis. |

|

| Locally advanced

rectal cancer | A radiation

resistance factor. Served as an effective predictive biomarker of

radiation sensitivity and a target for radio-sensitization. |

|

| Colorectal

cancer | Overexpressed,

Downregulated RFC4 inhibits cell proliferation and induces S phase

arrest. |

|

| Hepatocellular

carcinoma | RFC4 downregulation

enhances the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin and

camptothecin. |

|

| Lung

adenocarcinoma | RFC4 exhibits

significant co-expression with PKCι, and PKCι knockdown markedly

suppresses RFC4 expression. |

| RFC5 | Glioma | AEG-1 knockdown

downregulates RFC5 expression. RFC5 serves as a critical mediator

of DNA damage response. High levels of RFC5 is associated with poor

prognosis. |

|

| HPV negative

squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | Overexpressed RFC5

enhances the tumor cells' capacity to withstand genotoxic

stress. |

|

| Lung cancer | RFC5 functions as

an oncogene in lung cancer. Elevated RFC5 levels correlate with

aggressive clinicopathological features. |

|

| Colorectal

cancer | RFC5 overexpression

promotes CRC cell proliferation and metastasis. RFC5 may promote

CRC progression via modulation of the VEGFA/VEGFR2/ERK signaling

pathway. |

|

| Acute myeloid

leukemia | High RFC5

expression served as an independent prognostic factor for the poor

OS. Elevated RFC5 mRNA levels correlated positively with plasma

cell and M2 macrophage infiltration. |

While individual members of the RFC have been

characterized across various cancer types, their underlying

mechanisms require further investigation. Several critical

questions emerge from the current research: First, do the family

members have more notable oncogenic effects collectively compared

with individually, potentially through synergistic interactions?

Second, are there novel mechanisms being explored to elucidate

tumorigenesis? Finally, from a clinical perspective, could the RFC

family members serve as valuable diagnostic and prognostic

biomarkers? Addressing these questions will require comprehensive

studies to elucidate the complex roles of RFC proteins in cancer

biology and their potential translational applications. Future

research should focus on characterizing these molecular

relationships and evaluating their clinical utility for improved

cancer management.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of Hubei Province (grant no. 2022CFB808) and the Open

Project of Minda Hospital Affiliated to Hubei University for

Nationalities (grant no. OIR202302Q).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

DL wrote the original draft. DL and BL prepared the

figures. XJ reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors

reviewed the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.

|

|

2

|

Uhlmann F, Gibbs E, Cai J, O'Donnell M and

Hurwitz J: Identification of regions within the four small subunits

of human replication factor C required for complex formation and

DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 272:10065–10071. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhao X, Wang Y, Li J, Qu F, Fu X, Liu S,

Wang X, Xie Y and Zhang X: RFC2: A prognosis biomarker correlated

with the immune signature in diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Sci Rep.

12:31222022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yao Z, Hu K, Huang HE, Xu S, Wang Q, Zhang

P, Yang P and Liu B: shRNA-mediated silencing of the RFC3 gene

suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation. Int J Mol

Med. 36:1393–1399. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Guo Z and Guo L: Abnormal activation of

RFC3, A YAP1/TEAD downstream target, promotes gastric cancer

progression. Int J Clin Oncol. 29:442–455. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Misbah M, Kumar M, Najmi AK and Akhtar M:

Identification of expression profiles and prognostic value of RFCs

in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 14:66072024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lou F and Zhang M: RFC2 promotes aerobic

glycolysis and progression of colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol.

23:3532023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Li H, Chai L, Ding Z and He H: CircCOL1A2

sponges MiR-1286 to promote cell invasion and migration of gastric

cancer by elevating expression of USP10 to downregulate RFC2

ubiquitination level. J Microbiol Biotechn. 32:938–948. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wu Y, Chen T, Wu S, Huang Y and Li F:

Knockdown of RFC3 enhances the sensitivity of colon cancer cells to

oxaliplatin by inducing ferroptosis. Fund Clin Pharmacol.

39:e130442025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu L, Tao T, Liu S, Yang X, Chen X, Liang

J, Hong R, Wang W, Yang Y, Li X, et al: An RFC4/Notch1 signaling

feedback loop promotes NSCLC metastasis and stemness. Nat Commun.

12:26932021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yang T, Fan Y, Bai G and Huang Y: RFC4

confers radioresistance of esophagus squamous cell carcinoma

through regulating DNA damage response. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol.

328:C367–C380. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee K and Park SH: Eukaryotic clamp

loaders and unloaders in the maintenance of genome stability. Exp

Mol Med. 52:1948–1958. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q,

Li B and Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:W509–W514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mossi R and Hubscher U: Clamping down on

clamps and clamp Loaders-the eukaryotic replication factor C. Eur J

Biochem. 254:209–216. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Virshup DM, Kauffman MG and Kelly TJ:

Activation of SV40 DNA replication in vitro by cellular protein

phosphatase 2A. EMBO J. 8:3891–3898. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Virshup DM and Kelly TJ: Purification of

replication protein C, a cellular protein involved in the initial

stages of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 86:3584–3588. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yoder BL and Burgers PM: Saccharomyces

cerevisiae replication factor C. I. Purification and

characterization of its ATPase activity. J Biol Chem.

266:22689–22697. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Burbelo PD, Utani A, Pan ZQ and Yamada Y:

Cloning of the large subunit of activator 1 (replication factor C)

reveals homology with bacterial DNA ligases. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 90:11543–11547. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li X and Burgers PM: Cloning and

characterization of the essential Saccharomyces cerevisiae RFC4

gene encoding the 37-kDa subunit of replication factor C. J Biol

Chem. 269:21880–21884. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Li X and Burgers PM: Molecular cloning and

expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RFC3 gene, an essential

component of replication factor C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

91:868–872. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Noskov V, Maki S, Kawasaki Y, Leem SH, Ono

B, Araki H, Pavlov Y and Sugino A: The RFC2 gene encoding a subunit

of replication factor C of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids

Res. 22:1527–1535. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Podust VN, Georgaki A, Strack B and

Hubscher U: Calf thymus RF-C as an essential component for DNA

polymerase delta and epsilon holoenzymes function. Nucleic Acids

Res. 20:4159–4165. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Li Y, Gan S, Ren L, Yuan L, Liu J, Wang W,

Wang X, Zhang Y, Jiang J, Zhang F and Qi X: Multifaceted regulation

and functions of replication factor C family in human cancers. Am J

Cancer Res. 8:1343–1355. 2018.

|

|

24

|

Okumura K, Nogami M, Taguchi H, Dean FB,

Chen M, Pan ZQ, Hurwitz J, Shiratori A, Murakami Y and Ozawa K:

Assignment of the 36.5-kDa (RFC5), 37-kDa (RFC4), 38-kDa (RFC3),

and 40-kDa (RFC2) subunit genes of human replication factor C to

chromosome bands 12q24.2-q24.3, 3q27, 13q12.3-q13, and 7q11.23.

Genomics. 25:274–278. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Uhlmann F, Cai J, Gibbs E, O'Donnell M and

Hurwitz J: Deletion analysis of the large subunit p140 in human

replication factor C reveals regions required for complex formation

and replication activities. J Biol Chem. 272:10058–10064. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cai J, Gibbs E, Uhlmann F, Phillips B, Yao

N, O'Donnell M and Hurwitz J: A complex consisting of human

replication Factor C p40, p37, and p36 subunits is a DNA-dependent

ATPase and an intermediate in the assembly of the holoenzyme. J

Biol Chem. 272:18974–18981. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cullmann G, Fien K, Kobayashi R and

Stillman B: Characterization of the five replication factor C genes

of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 15:4661–4671. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T and Zhang Z:

GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for Large-scale expression profiling

and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:W556–W560. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Delforge V, Tard C, Davion JB, Dujardin K,

Wissocq A, Dhaenens CM, Mutez E and Huin V: RFC1: Motifs and

phenotypes. Rev Neurol (Paris). 180:393–409. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Giovannini S, Weller M, Hanzlíková H,

Shiota T, Takeda S and Jiricny J: ATAD5 deficiency alters DNA

damage metabolism and sensitizes cells to PARP inhibition. Nucleic

Acids Res. 48:4928–4939. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Fung LF, Lo AK, Yuen PW, Liu Y, Wang XH

and Tsao SW: Differential gene expression in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cells. Life Sci. 67:923–936. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Almalki E, Al-Amri A, Alrashed R,

AL-Zharani M and Semlali A: The curcumin analog PAC is a potential

solution for the treatment of Triple-negative breast cancer by

modulating the gene expression of DNA repair pathways. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:96492023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Moggs JG, Murphy TC, Lim FL, Moore DJ,

Stuckey R, Antrobus K, Kimber I and Orphanides G:

Anti-proliferative effect of estrogen in breast cancer cells that

re-express ERalpha is mediated by aberrant regulation of cell cycle

genes. J Mol Endocrinol. 34:535–551. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ji Z, Li J and Wang J: Up-regulated RFC2

predicts unfavorable progression in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hereditas. 158:172021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Oshima M, Takayama K, Yamada Y, Kimura N,

Kume H, Fujimura T and Inoue S: Identification of DNA damage

response-related genes as biomarkers for castration-resistant

prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 13:196022023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Li G, Zhang P, Zhang W, Lei Z, He J, Meng

J, Di T and Yan W: Identification of key genes and pathways in

Ewing's sarcoma patients associated with metastasis and poor

prognosis. Onco Targets Ther. 12:4153–4165. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Koh JW and Park S: Knockdown of RFC2

prevents the proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical

cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 45:989–1000. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Avs KR, Pandi C, Kannan B, Pandi A,

Jayaseelan VP and Arumugam P: RFC3 serves as a novel prognostic

biomarker and target for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Clin Oral Invest. 27:6961–6969. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhu J, Ye L, Sun S, Yuan J, Huang J and

Zeng Z: Involvement of RFC3 in tamoxifen resistance in ER-positive

breast cancer through the cell cycle. Aging. 15:13738–13752. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Zhou J, Zhang W, Peng F, Sun J, He Z and

Wu S: Downregulation of hsa_circ_0011946 suppresses the migration

and invasion of the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 by targeting

RFC3. Cancer Manag Res. 10:535–544. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

He Z, Wu S, Peng F, Zhang Q, Luo Y, Chen M

and Bao Y: Up-Regulation of RFC3 promotes triple negative breast

cancer metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis via EMT.

Transl Oncol. 10:1–9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Gong S, Qu X, Yang S, Zhou S, Li P and

Zhang Q: RFC3 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung

adenocarcinoma cells through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and

possesses prognostic value in lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Med.

44:2276–2288. 2019.

|

|

43

|

Koh JW and Park S: RFC3 Knockdown

decreases cervical cancer cell proliferation, migration and

invasion. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 22:127–135. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Yu R, Wu X, Qian F and Yang Q: RFC3 drives

the proliferation, migration, invasion and angiogenesis of

colorectal cancer cells by binding KIF14. Exp Ther Med. 27:2222024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Yu L, Li J, Zhang M, Li Y, Bai J, Liu P,

Yan J and Wang C: Identification of RFC4 as a potential biomarker

for pan-cancer involving prognosis, tumour immune microenvironment

and drugs. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e184782024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Guan S, Feng L, Wei J, Wang G and Wu L:

Knockdown of RFC4 inhibits the cell proliferation of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Front Med. 17:132–142. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

You P, Wang D, Liu Z, Guan S, Xiao N, Chen

H, Zhang X, Wu L, Wang G and Dong H: Knockdown of RFC 4 inhibits

cell proliferation of oral squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in

vivo. FEBS Open Bio. 15:346–358. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wang J, Luo F, Huang T, Mei Y, Peng L,

Qian C and Huang B: The upregulated expression of RFC4 and GMPS

mediated by DNA copy number alteration is associated with the early

diagnosis and immune escape of ESCC based on a bioinformatic

analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 13:21758–21777. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Zeng B, Liu X, Liu J, Qiu H, Zhang T, Chen

X and Wang L: Roles of MARCKSL1, MCM6, RFC4, and PLAU genes in

esophageal cancer and their association with radiotherapy response.

Sci Rep. 15:235592025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Wang X, Yue X, Zhang R, Liu T, Pan Z, Yang

M, Lu Z, Wang Z, Peng J, Le L, et al: Genome-wide RNAi screening

identifies RFC4 as a factor that mediates radioresistance in

colorectal cancer by facilitating nonhomologous end joining repair.

Clin Cancer Res. 25:4567–4579. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Xiang J, Fang L, Luo Y, Yang Z, Liao Y,

Cui J, Huang M, Yang Z, Huang Y, Fan X, et al: Levels of human

replication factor C4, a clamp loader, correlate with tumor

progression and predict the prognosis for colorectal cancer. J

Transl Med. 12:3202014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Arai M, Kondoh N, Imazeki N, Hada A,

Hatsuse K, Matsubara O and Yamamoto M: The knockdown of endogenous

replication factor C4 decreases the growth and enhances the

chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Liver Int.

29:55–62. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Erdogan E, Klee EW, Thompson EA and Fields

AP: Meta-analysis of oncogenic protein kinase Ciota signaling in

lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 15:1527–1533. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zheng J, Lin N, Huang B, Wu M, Xiao L and

Zeng B: Comprehensive analysis of RFC4 as a potential biomarker for

regulating the immune microenvironment and predicting immune

therapy response in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol.

16:15782432025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Koh JW and Park S: Replication Factor C

Subunit 4 plays a role in human breast cancer cell progression.

Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 22:478–490. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Zhu XY, Li PS, Qu H, Ai X, Zhao ZT and He

JB: Replication factor C4, which is regulated by insulin-like

growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2, enhances the

radioresistance of breast cancer by promoting the stemness of tumor

cells. Hum Cell. 38:652025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Huang B, Zheng J, Chen B, Wu M and Xiao L:

Analysis of the correlation between RFC4 expression and tumor

immune microenvironment and prognosis in patients with cervical

cancer. Front Genet. 16:15143832025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Zhao X, Sun Y, Sun X, Li J, Shi X, Liang

Z, Ma Y and Zhang X: AEG-1 Knockdown sensitizes glioma cells to

radiation through impairing homologous recombination via targeting

RFC5. DNA Cell Biol. 40:895–905. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Martinez I, Wang J, Hobson KF, Ferris RL

and Khan SA: Identification of differentially expressed genes in

HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell

carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 43:415–432. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Wang M, Xie T, Wu Y, Yin Q, Xie S, Yao Q,

Xiong J and Zhang Q: Identification of RFC5 as a novel potential

prognostic biomarker in lung cancer through bioinformatics

analysis. Oncol Lett. 16:4201–4210. 2018.

|

|

61

|

Xu S, Zhong F, Jiang J, Yao F, Li M, Tang

M, Cheng Y, Yang Y, Wen W, Zhang X, et al: High Expression of

SRSF10 promotes colorectal cancer progression by aberrant

alternative splicing of RFC5. Technol Cancer Res.

23:153303382412719062024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Yao H, Zhou X, Zhou A, Chen J, Chen G, Shi

X, Shi B, Tai Q, Mi X, Zhou G, et al: RFC5, regulated by

circ_0038985/miR-3614-5p, functions as an oncogene in the

progression of colorectal cancer. Mol Carcinog. 62:771–785. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Li W, Wu D, Zhou Y, Zhang C and Liao X:

Prognostic biomarker replication factor C subunit 5 and its

correlation with immune infiltrates in acute myeloid leukemia.

Hematology. 27:555–564. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Zhang Y, Gao X, Yi J, Sang X, Dai Z, Tao

Z, Wang M, Shen L, Jia Y, Xie D, et al: BTF3 confers oncogenic

activity in prostate cancer through transcriptional upregulation of

Replication Factor C. Cell Death Dis. 12:122021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Qiu X, Tan G, Wen H, Lian L and Xiao S:

Forkhead box O1 targeting replication factor C subunit 2 expression

promotes glioma temozolomide resistance and survival. Ann Transl

Med. 9:6922021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Day M, Oliver AW and Pearl LH: Structure

of the human RAD17-RFC clamp loader and 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp

bound to a dsDNA-ssDNA junction. Nucleic Acids Res. 50:8279–8289.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Niida H and Nakanishi M: DNA damage

checkpoints in mammals. Mutagenesis. 21:3–9. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Bermudez VP, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Cesare AJ,

Maniwa Y, Griffith JD, Hurwitz J and Sancar A: Loading of the human

9-1-1 checkpoint complex onto DNA by the checkpoint clamp loader

hRad17-replication factor C complex in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 100:1633–1638. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Wang X, Zou L, Zheng H, Wei Q, Elledge SJ

and Li L: Genomic instability and endoreduplication triggered by

RAD17 deletion. Gene Dev. 17:965–970. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Terret ME, Sherwood R, Rahman S, Qin J and

Jallepalli PV: Cohesin acetylation speeds the replication fork.

Nature. 462:231–234. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Kim JT, Cho HJ, Park SY, Oh BM, Hwang YS,

Baek KE, Lee YH, Kim HC and Lee HG: DNA replication and sister

chromatid cohesion 1 (DSCC1) of the replication factor complex

CTF18-RFC is critical for colon cancer cell growth. J Cancer.

10:6142–6153. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Kang M, Ryu E, Lee S, Park J, Ha NY, Ra

JS, Kim YJ, Kim J, Abdel-Rahman M, Park SH, et al: Regulation of

PCNA cycling on replicating DNA by RFC and RFC-like complexes. Nat

Commun. 10:24202019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Sikdar N, Banerjee S, Lee KY, Wincovitch

S, Pak E, Nakanishi K, Jasin M, Dutra A and Myung K: DNA damage

responses by human ELG1 in S phase are important to maintain

genomic integrity. Cell Cycle. 8:3199–3207. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Lee KY, Fu H, Aladjem MI and Myung K:

ATAD5 regulates the lifespan of DNA replication factories by

modulating PCNA level on the chromatin. J Cell Biol. 200:31–44.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Szklarczyk D, Nastou K, Koutrouli M,

Kirsch R, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Hu D, Peluso ME, Huang Q, Fang T,

et al: The STRING database in 2025: Protein networks with

directionality of regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 53:D730–D737.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Hopfner KP and Hornung V: Molecular

mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS-STING signalling. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Bio. 21:501–521. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Yuan Q, Cai S, Chang Y, Zhang J, Wang M,

Yang K and Jiang D: The multifaceted roles of mucins family in lung

cancer: From prognostic biomarkers to promising targets. Front

Immunol. 16:16081402025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Wu G, Zhou J, Zhu X, Tang X, Liu J, Zhou

Q, Chen Z, Liu T, Wang W, Xiao X and Wu T: Integrative analysis of

expression, prognostic significance and immune infiltration of RFC

family genes in human sarcoma. Aging (Albany NY). 14:3705–3719.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Deng J, Zhong F, Gu W and Qiu F:

Exploration of prognostic biomarkers among replication factor C

family in the hepatocellular carcinoma. Evol Bioinform.

17:11769343219941092021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Zhang J, Meng S, Wang X, Wang J, Fan X,

Sun H, Ning R, Xiao B, Li X, Jia Y, et al: Sequential gene

expression analysis of cervical malignant transformation identifies

RFC4 as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. BMC Med.

20:4372022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Tu S, Zhang H, Yang X, Wen W, Song K, Yu X

and Qu X: Screening of cervical cancer-related hub genes based on

comprehensive bioinformatics analysis. Cancer Biomark. 32:303–315.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Ho KH, Kuo TC, Lee YT, Chen PH, Shih CM,

Cheng CH, Liu AJ, Lee CC and Chen KC: Xanthohumol regulates

miR-4749-5p-inhibited RFC2 signaling in enhancing temozolomide

cytotoxicity to glioblastoma. Life Sci. 254:1178072020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Alaa Eldeen M, Mamdouh F, Abdulsahib WK,

Eid RA, Alhanshani AA, Shati AA, Alqahtani YA, Alshehri MA, Samir

A, Zaki M, et al: Oncogenic potential of replication factor C

subunit 4: Correlations with tumor progression and assessment of

potential inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17:1522024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Rohde JM, Rai G, Choi YJ, Sakamuru S, Fox

JT, Huang R, Xia M, Myung K, Boxer MB and Maloney DJ: Discovery of

ML367, inhibitor of ATAD5 stabilization. Probe Reports from the NIH

Molecular Libraries Program [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National

Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2010

|

|

85

|

Xu J, Wang G, Gong W, Guo S, Li D and Zhan

Q: The noncoding function of NELFA mRNA promotes the development of

oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating the Rad17-RFC2-5

complex. Mol Oncol. 14:611–624. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Cortese A, Simone R, Sullivan R,

Vandrovcova J, Tariq H, Yau WY, Humphrey J, Jaunmuktane Z,

Sivakumar P, Polke J, et al: Biallelic expansion of an intronic

repeat in RFC1 is a common cause of late-onsetataxia. Nat Genet.

51:649–658. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Haffner MC, Zwart W, Roudier MP, True LD,

Nelson WG, Epstein JI, De Marzo AM, Nelson PS and Yegnasubramanian

S: Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev

Urol. 18:79–92. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Huang S, Chen Y, Hu M, Fu S, Yao Z, He H,

Wang L, Chen Z and Liu X: The role of the SIX family in cancer

development and therapy: Insights from foundational and

cutting-edge research. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat. 214:1048602025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|