Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) represents a major worldwide

health challenge, ranking seventh in incidence and sixth in terms

of cancer-related mortality (1).

There are two main histological variants of EC: Esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma. ESCC is the

predominant variant, accounting for 85% of cases worldwide, with

Chinese patients representing up to 57% of all instances (2,3). Due

to non-specific symptoms in the early stages, a large proportion of

ESCC cases are identified at progressive stages (4). Among patients with locally advanced

ESCC, ~50% are eligible for R0 resection, while the remaining

patients may experience early recurrence post-surgery (5). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant

chemoradiotherapy in conjunction with transthoracic esophagectomy

has become the standard of care, enhancing the R0 resection rate

and survival outcomes (6). However,

the necessity of radiation therapy in neoadjuvant treatment

protocols in China remains a subject of debate (7,8).

Paclitaxel is recognized as an active chemotherapy

agent for ESCC, with paclitaxel-based regimens extensively utilized

in clinical settings. Nevertheless, response rates for both

paclitaxel and cisplatin have been reported to be as low as 33–40%

(9). The efficacy of paclitaxel is

notably compromised by resistance, which is associated with an

increase in postoperative complications and mortality, consequently

contributing to chemotherapy failure and unfavorable prognoses

(10,11). Therefore, further elucidation of the

molecular mechanisms underlying paclitaxel resistance in ESCC is

imperative. In this context, intrinsic resistance to paclitaxel in

ESCC is attributed to particular genetic, epigenetic and metabolic

characteristics (12).

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) represents the most

abundant post-transcriptional alteration in eukaryotic messenger

RNA (mRNA), serving a crucial function in determining RNA fate,

which encompasses mRNA splicing, export, stability, localization

and translation (13). The

biological functions of m6A modification undergo dynamic and

reversible control by three distinct groups of proteins: RNA m6A

methyltransferases (writers), RNA demethylases (erasers) and

m6A-binding proteins (readers). The ‘readers’ specifically identify

and engage with the m6A modification, influencing the destiny of

target transcripts that exhibit m6A methylation. Among this

significant group of readers, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA

binding proteins (IGF2BPs) function to suppress mRNA degradation

and enhance mRNA translation (14).

Notably, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2

(IGF2BP2) emerges as a prominent member. Studies indicated that

IGF2BP2 participates in the metabolism of target mRNAs,

encompassing Sirtuin 1 and 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor 3A in ESCC

(15,16). Nevertheless, the role and mechanisms

through which IGF2BP2 contributes to paclitaxel resistance in ESCC

remain unclear.

The investigation into the relationship between

tumor metabolic characteristics and cancer progression has been

gaining increasing attention within the realm of cancer research.

Cancer cells exhibit a preference for elevated rates of aerobic

glycolysis as their primary source of energy, even when sufficient

oxygen is present, and mitochondrial function remains normal

(referred to as the Warburg effect). This phenomenon enhances the

resistance of cancer cells to apoptotic cell death (17). The aberrantly increased glycolytic

rate in tumors is linked to both intrinsic and acquired resistance

to standard anticancer therapies (17–19).

Therefore, the modulation of tumor metabolism is anticipated to

function as a viable therapeutic strategy for multiple cancer

types, including ESCC.

In the current study, it was revealed that IGF2BP2

mediated paclitaxel resistance in ESCC and explored the mechanism

and identified the IGF2BP2-FOXM1 signaling as a potential biomarker

for predicting paclitaxel resistance in ESCC.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The ESCC cell lines (KYSE30, KYSE150 and KYSE510)

utilized in the present study were procured from the Cell Resource

Center at the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese

Academy of Sciences. All cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum and maintained in an incubator at 37°C with 5%

CO2. The cells were passaged a maximum of 15 times.

Gene expression in ESCC datasets

The gene expression profiles were obtained from The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/). RNA sequencing

(RNA-seq) data from 82 ESCC tumor samples and 11 adjacent normal

tissues were retrieved from the TCGA database. Concurrently, gene

expression profiles GSE23400 and GSE75241 were downloaded from the

GEO database. Differential gene analysis was conducted on the

GSE20347 dataset from the GEO database. To ascertain differentially

expressed genes, the criteria |logFC|>1 and adjusted P<0.05

were employed and the differences were visualized using volcano

plots.

Plasmids

To generate KYSE30 and KYSE150 cells characterized

by FOXM1 overexpression, ESCC cells were transfected with the

FOXM1-overexpression plasmid (GV-FOXM1) or negative-control plasmid

(GV–Vector) using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) at 37°C for 6 h, with 2 µg DNA and 5 µg HG-TransGene per well

in a 6-well plate, according to the supplier's protocols. The

overexpression plasmids utilized in the current study were

engineered and constructed by Genomeditech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

After the culture medium was replaced with fresh complete medium,

the efficiency of the FOXM1 overexpression was confirmed. ESCC

cells exhibiting FOXM1 overexpression were employed for subsequent

experiments 24 h post-medium change.

Cell transfection and lentiviral

infection

The IGF2BP2 RNA interference lentiviral vector and

the corresponding negative control lentiviral vectors were obtained

from Genomeditech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The shRNA was synthesized,

cloned and inserted into pLKO.1-puro vector. The generation system

is the third system. Subsequently, pLKO.1-puro-shRNA plasmid (20

µg), virus packaging plasmids (psPAX2, 15 µg) and envelope plasmids

(pMD2.G, 5 µg) were cotransfected into 293T cells (China Center for

Type Culture Collection) using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 6 h. Then medium was replaced with

fresh DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% FBS and

incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Supernatants were

collected at 48 and 72 h post-transfection, filtered through 0.45

µm PVDF membrane and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (100,000 ×

g). MOI for lentivirus transfection was 10. KYSE30 and KYSE150

cells in the exponential growth phase were seeded in 6-well plates

for 24 h. The IGF2BP2 RNA interference and negative control

lentivirus were infected into KYSE30 and KYSE150 cells,

respectively. Infection was enhanced with 6 µg/ml Polybrene.

Following a 24-h infection, the medium was replaced with complete

medium, and the cells were cultured. Puromycin (cat. no. P8230;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 5 µg/ml was

utilized to select stably transduced cell populations at 72 h

post-infection. The subsequent experiment was performed 10 days

post-medium change. The sequences of all shRNAs were as follows:

shRNA-IGF2BP2-1: 5′-GCCAGAACACUUCCAAGAUAU-3′; shRNA-IGF2BP2-2:

5′-CAGUUACUGGAGAUGAUUAAU-3′; shRNA-IGF2BP2-3:

5′-GCUAUCCACAAGGUCAGUAUU-3′; and non-targeting control shRNA:

5′-CCUAAGGUUAAGUCGCCCUCG-3′.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) of FOXM1 and negative

control were obtained from Genomeditech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. 5 µl

siRNA (20 µM) was diluted in 50 µl Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 5 µl of Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was diluted in 250 µl Opti-MEM. After incubating

separately for 5 min, the mixtures were combined and further

incubated for 20 min. The transfection complex was then added to

ESCC cells seeded in 6-well plates for transfection at 37°C for 6

h. Knockdown efficiency was assessed 24 h after transfection,

followed by subsequent experiments. The sequences of all siRNAs

were as follows: siRNA-FOXM1-1 sense, 5′-GAAGCGGACCUCAAUGUGAATT-3′

and antisense, 5′-UUCACAUUGAGGUCCGCUUCTT-3′; siRNA-FOXM1-2 sense,

5′-GGAGCUCAAGAAUCUGACUAUTT-3′ and antisense,

5′-UAGUCAGAUUCUUGAGCUCCTT-3′; and siRNA-Ctrl sense,

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and antisense,

5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′.

Actinomycin D treatment assays

ESCC cells were placed in a 6-well plate at

1×105 cells per well and exposed to Actinomycin D (2

µg/ml; Abcam) for 12 h. Subsequently, the measurement of the FOXM1

mRNA level was conducted using a reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay.

RT-qPCR

According to the manufacturer's instructions, total

RNA was extracted from tissues using TRIzol (cat. no. 15596026;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The extracted RNA was subsequently

converted to cDNA employing the Evo M-MLV RT Premix (cat. no.

AG11706; Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the

supplier's instructions. The SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq

HS qPCR kit (cat. no. AG11701; Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

was used for qPCR, according to the manufacturer's instructions,

and the target sequence was amplified using a LightCycler 480II

device (Roche Diagnostics). The thermocycling parameters were set

as follows: Preincubation for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles

of 10 sec at 95°C, 10 sec at 60°C, and 10 sec at 72°C. β-actin was

utilized as an internal control, and relative RNA expression was

analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (20). The primer sequences were as follows:

FOXM1 forward, 5′-GCAGCGACAGGTTAAGGTTGAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGTGCTGTTGATGGCGAATTGTAT-3′; IGF2BP2 forward,

5′-TCGTCAGAATTATCGGGCACTTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCTGCTGCTTCACCTGTTGTA-3′; and β-actin forward

5′-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3′ and reverse,

5′-CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3′.

Western blot (WB) analysis

To extract proteins, ESCC cells were lysed in

PMSF-containing RIPA buffer solution (cat. no. R0010; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and centrifuged at

12,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. The protein concentration was

determined using the Bicinchoninic acid reagent test kit (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Protein samples (30 µg) were separated

by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels (cat. no. PG112; Shanghai EpiZyme Co.,

Ltd.) and then transferred onto PVDF membranes (cat. no. WGPVDF22;

Servicebio Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, the membranes were blocked

with high-efficiency western blocking reagent (cat. no. GF1815;

Shanghai Genefist Co., Ltd.) for 15 min at room temperature and

maintained overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies, including

anti-IGF2BP2 (1:2,000; cat. no. 11601-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), anti-FOXM1 (1:2,000; cat. no. 13147-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) and anti-GAPDH (1:5,000; cat. no. 10494-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.). After rinsing the membrane three times with TBST

(cat. no. G2150-1L; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), the

PVDF membranes were exposed to secondary rabbit antibodies

(1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 1 h at

ambient temperature. An enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (cat.

no. SQ201; Shanghai EpiZyme Co., Ltd.) was employed to detect

protein signals. Band intensities were analyzed utilizing ImageJ

software (V1.54p; National Institutes of Health), with GAPDH

serving as the internal control for normalizing target protein

expression.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

ESCC cells in the exponential growth phase from both

the control and treated groups were inoculated into a 96-well plate

at 3,000 cells per well and maintained for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h.

After removing the culture medium, each well was washed with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the CCK-8 reagent

(MedChemExpress) was combined with serum-free medium to achieve a

concentration of 10%. Subsequently, a volume of 100 µl of the

prepared solution was dispensed into each well. Following

incubation of the 96-well plate at 37°C for 1 h, the absorbance of

each well was measured at 450 nm.

Colony formation assays

Following the counting of ESCC cells in both the

control and treated groups, the cells were placed into 6-well

plates at 1,000 cells per well and subsequently cultured in an

environment maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. When the

count of cells within a single clone colony exceeded 50 or the

culture duration surpassed 14 days, the culture medium was

aspirated, and the plate underwent PBS washing. Following fixation

in 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30

min, staining was performed using 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) at ambient temperature for 15 min.

Colonies were counted utilizing ImageJ software.

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) cell

proliferation assays

Exponential growth ESCC cells from both the control

and treated groups were inoculated into 96-well plates at 5,000

cells per well and maintained for 24 h. The prepared EdU solution

(cat. no. C10310-1; Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) was incorporated

into the culture medium and incubated for 2 h for EdU labeling.

Following the removal of the medium and washing with PBS, 4%

paraformaldehyde (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was

introduced, and the plates were incubated for 30 min at ambient

conditions. Subsequently, glycine solution (MedChemExpress), PBS,

and an osmotic agent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were

sequentially added to immobilize the cells. The wells were then

subjected to Apollo and DNA staining for 30 min at ambient

temperature respectively, with images acquired and analyzed using a

fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×200).

Flow cytometry

The Annexin V-FITC Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit

(cat. no. E-CK-A211; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was

employed to evaluate the level of cell apoptosis. ESCC cells

underwent trypsin digestion to obtain a single-cell suspension (the

density of cells was 5×105/ml). Following a 15-min dual

staining procedure with V-FITC and PI in the 200-µl single-cell

suspension, the cell specimens were examined via flow cytometry

using BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences), BD FACSDivaTM

software (V7.0; BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (V10.8.1;

FlowJo LLC).

Glycolysis assays

A glycolysis assay was performed utilizing a lactate

assay kit (cat. no. 600450; Cayman Chemical Company). Exponentially

growing ESCC cells from both the control and treated groups were

inoculated into 96-well plates at 5,000 cells per well. After 24 h,

the culture medium was harvested for lactate content assessment.

The specimens were examined following the instructions outlined in

the reagent kit, the values were noted, and calculations were

performed.

RNA-seq

Following transfection of IGF2BP2-knockdown KYSE30

and control cells, the cell samples were collected by scraping and

subsequently lysed in TRIzol (cat. no. 15596026; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for total RNA extraction. DNase (cat. no.

AG12001; Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used to remove

genomic DNA contamination. The purity of the sample was determined

by NanoPhotometer® (IMPLEN, USA). The concentration and

integrity of RNA samples were detected by Agilent 2100 RNA nano

6000 assay kit (cat. no. 5067-1511; Agilent Technology Co., Ltd.).

Sequencing libraries were generated using VAHTS Universal V6

RNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (cat. no.

NR604-01/02; Vazyme Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's

recommendations. Poly-T magnetic beads were used to isolate mRNA,

which was then fragmented. First- and second-strand cDNA were

synthesized, purified, and subjected to end repair, adenylation,

and adapter ligation. The library was size-selected and enriched by

PCR prior to sequencing. The library was quantified using the

Bio-RAD CFX 96 fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument with the

iQ™ SYBR® Green kit (cat. no. 1708880; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) to the effective concentration of >10 nM.

Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform

(Illumina, Inc.) with the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit V1.5 (cat.

no. 20028312; Illumina, Inc.), generating 150 bp paired-end reads.

DESeq2 (V1.44.0) and EdgeR (V3.44.0) were used for Difference

analysis (21,22), and the Gene Ontology (GO; http://geneontology.org/) was used for function

enrichment analysis.

m6A-qPCR and m6A sequencing

(m6A-seq)

Total RNA was obtained and purified from ESCC

samples with TRIzol (cat. no. 15596026; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following

extraction, RNA was incubated with m6A antibodies utilizing the

Magna Methylated RNA Immunoprecipitation m6A Kit (MilliporeSigma)

for immunoprecipitation. The concentration of m6A-modified mRNA

underwent examination through m6A-qPCR or m6A-seq methodologies

(Haplox Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Primers targeting the negative

region of FOXM1 m6A served as negative controls, whereas primers

targeting the positive region of FOXM1 m6A were employed as

positive controls. For m6A-seq, the enriched m6A RNA underwent

reverse transcription to generate cDNA, and the library was

prepared per the instructions provided by Illumina's NEBNext Ultra

RNA Library Preparation Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc.).

High-throughput library sequencing was conducted to acquire

sequence information about m6A-modified RNA using the Illumina

HiSeq X™ Ten platform (Illumina, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed utilizing

GraphPad Prism 9 (Dotmatics). Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD). Comparisons among several groups were

performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Least Significance

Difference test was used for the post hoc test, whereas evaluations

between paired groups employed paired Student's t-test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

IGF2BP2 is highly expressed in

ESCC

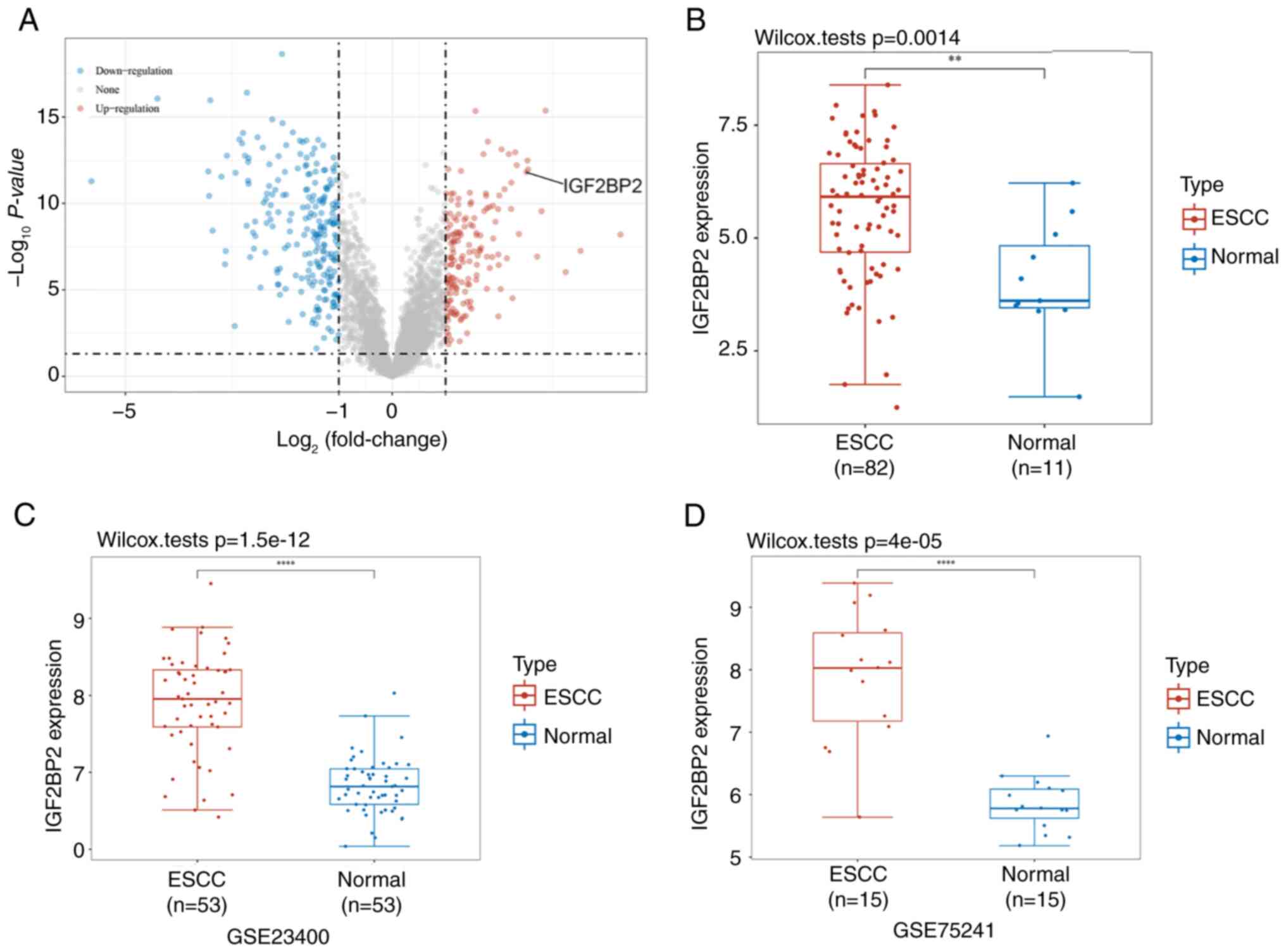

Differential gene analysis was performed utilizing

the GSE20347 dataset, which revealed a total of 389 differentially

expressed genes, encompassing 226 downregulated and 163 upregulated

genes (Fig. 1A). Among these, the

10 most markedly upregulated genes were identified as COL11A1,

ZIC1, COL1A2, ECT2, ACKR3, LUM, MFHAS1, FNDC3B, IGF2BP2 and KIF23.

Furthermore, a comparison of IGF2BP2 expression levels between ESCC

tumor tissues and normal tissue samples from the TCGA database

indicated a significant increase in IGF2BP2 expression (P=0.0014;

Fig. 1B). Data obtained from

GSE23400 and GSE75241 confirmed the upregulation of IGF2BP2 in ESCC

(P<0.0001; Fig. 1C and D).

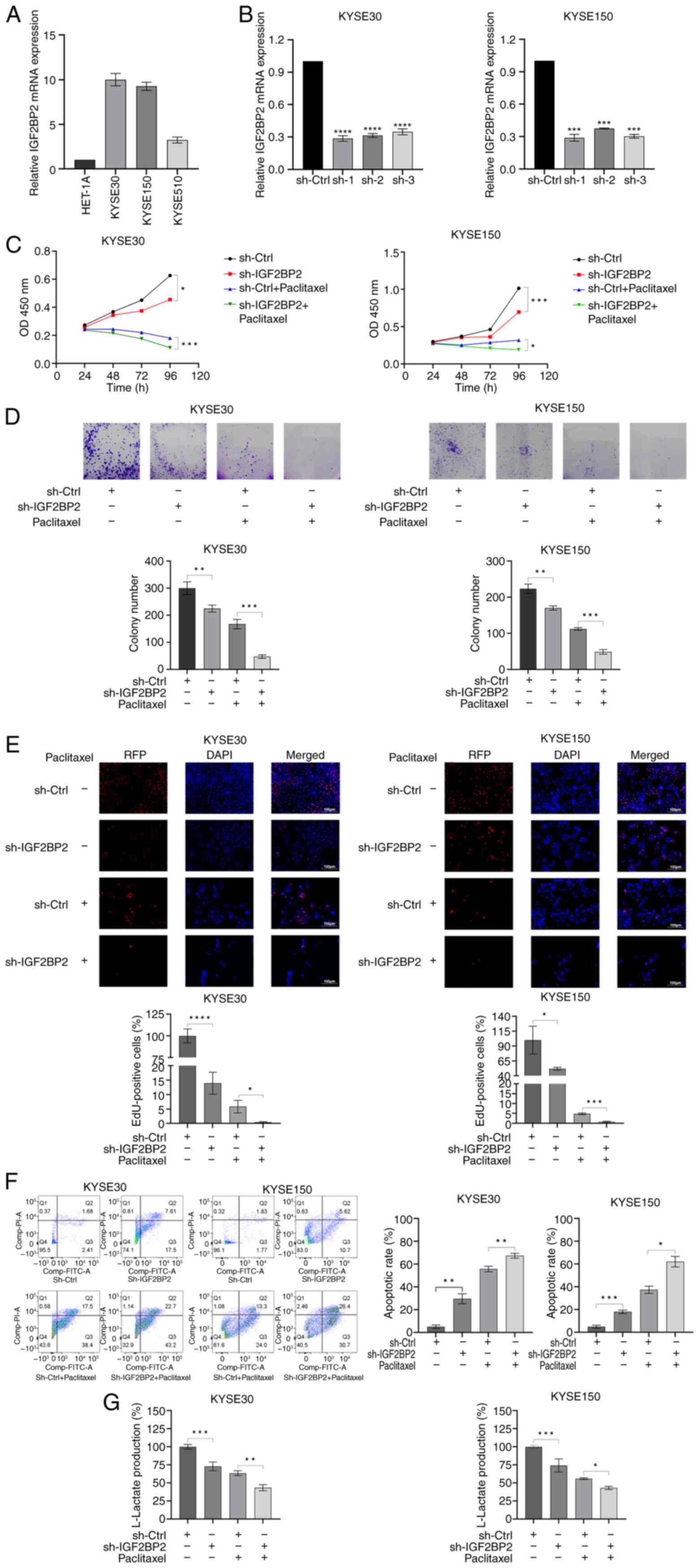

Regarding the ESCC cell lines, RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A) demonstrated a significant

upregulation of IGF2BP2 in KYSE30 and KYSE150 relative to HET-1A

(the normal esophageal cell line). Consequently, both cell lines

were chosen for the following investigations.

IGF2BP2 inhibition decreases anaerobic

glycolysis and increases the sensitivity to paclitaxel in ESCC

cells

To explore the role of IGF2BP2 in ESCC, alterations

in cellular phenotypes were assessed following the inhibition of

IGF2BP2 expression in cell lines. Efficient knockdown of IGF2BP2

was achieved using two short-hairpin (sh)RNAs (sh-IGF2BP2-1 and

sh-IGF2BP2-2) in both KYSE30 and KYSE150 cells (Fig. 2B). Given that sh-IGF2BP2-1 exhibited

the highest efficiency, this sequence was selected for subsequent

depletion experiments.

CCK-8 assays were performed to evaluate the

influence of IGF2BP2 on the proliferation of ESCC cells. The

results demonstrated that IGF2BP2 knockdown resulted in

significantly decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 2C). Images obtained from colony

formation assays illustrated that silencing IGF2BP2 significantly

impaired the formation of colonies of ESCC cells (Fig. 2D). Moreover, EdU assays validated

the substantial suppressive effect of IGF2BP2 knockdown on ESCC

cell proliferation (Fig. 2E).

Additionally, flow cytometry assays indicated that the knockdown of

IGF2BP2 markedly enhanced the apoptosis of ESCC cells (Fig. 2F). Notably, it was observed that

silencing IGF2BP2 resulted in a reduction of anaerobic glycolysis

in KYSE30 and KYSE150 cells (Fig.

2G). Moreover, the depletion of IGF2BP2 significantly enhanced

ESCC cell responsiveness to paclitaxel (Fig. 2C-F). Collectively, these findings

indicated that IGF2BP2 serves a crucial function in anaerobic

glycolysis and resistance to paclitaxel in ESCC cells.

FOXM1 is the m6A modification target

of IGF2BP2

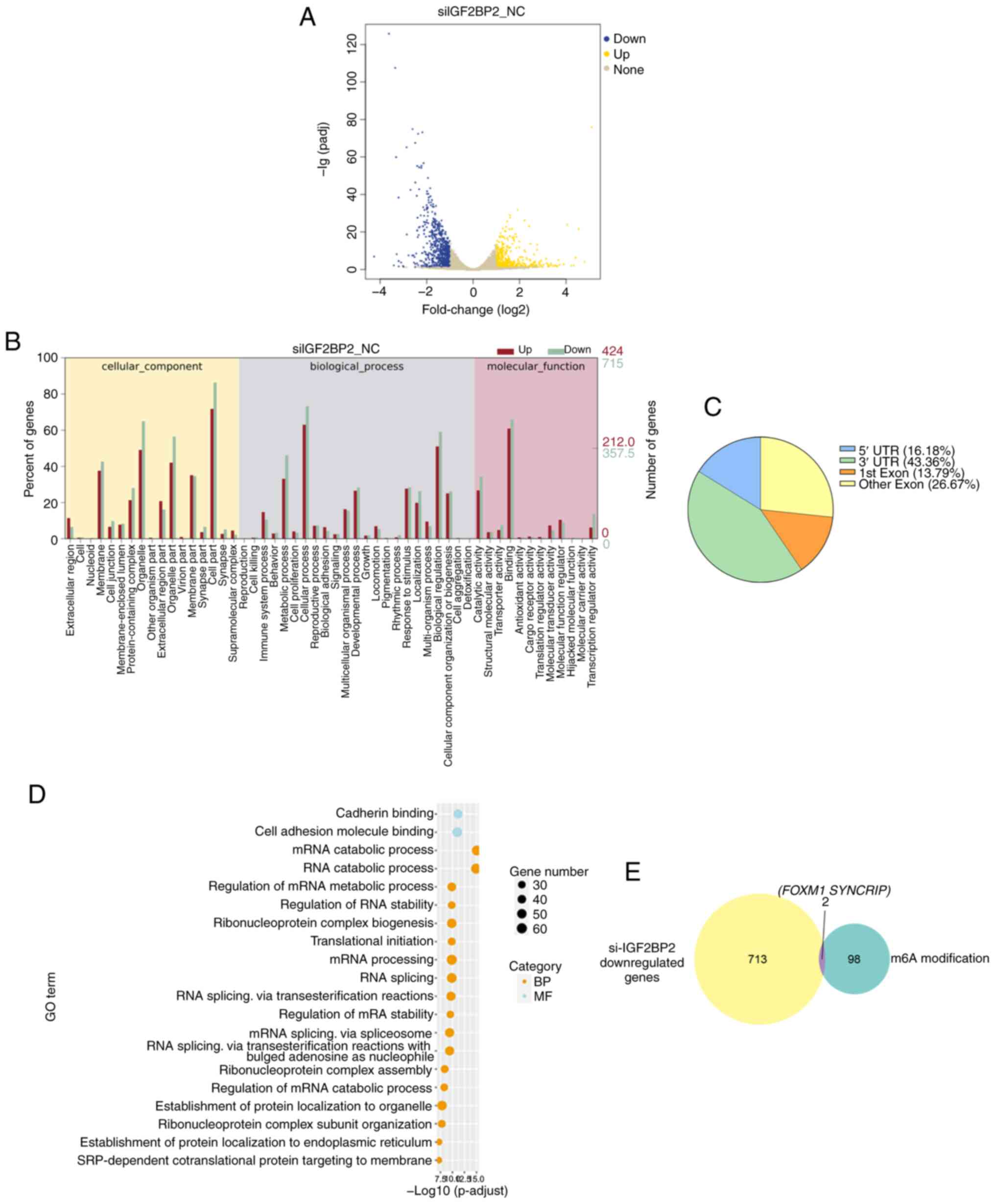

To elucidate the mechanism through which IGF2BP2

contributes to paclitaxel resistance in ESCC, RNA-seq was conducted

using both IGF2BP2-knockdown KYSE30 and control cells. It was

demonstrated that the expression of 1,139 genes was globally

modified following IGF2BP2 knockdown, with 424 genes exhibiting

upregulation and 715 genes displaying downregulation (Fig. 3A). GO analysis suggested that

several pathways, encompassing the MAPK signaling pathway, TGF-β

signaling pathway, and protein processing in the endoplasmic

reticulum, were markedly enriched (Fig.

3B). These findings collectively highlight the oncogenic role

of IGF2BP2 in ESCC.

It is widely acknowledged that IGF2BP2 functions as

an m6A reader, capable of recognizing and binding to m6A-methylated

transcripts to regulate target genes. Consequently, m6A-seq was

conducted in KYSE30 cells, resulting in the identification of 8,104

m6A modification peaks across 3,990 genes. The majority of these

m6A modifications were located within the 3′-untranslated regions

(3′-UTRs; 43.36%; Fig. 3C).

Functional annotation indicated that these mRNAs were associated

with several distinct gene clusters, including the regulation of

RNA stability and RNA splicing (Fig.

3D). Given that IGF2BP2 has been recognized for its role in

maintaining RNA stability (14),

the attention was directed towards transcripts that were

downregulated following IGF2BP2 knockdown and exhibited the top 100

highest peak m6A modifications. By overlapping the results from

RNA-seq and m6A modification analyses, two candidate genes, FOXM1

and SYNCRIP, were identified as meeting the criteria. Among these,

FOXM1 mRNA levels declined more markedly upon IGF2BP2 knockdown in

ESCC cell lines. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggested that

FOXM1 contributes to paclitaxel resistance (23). These findings prompted a shift in

focus towards FOXM1, which is considered a critical factor in the

mediation of paclitaxel resistance through IGF2BP2 in ESCC

(Fig. 3E).

IGF2BP2 sustains the stability of

FOXM1 mRNA

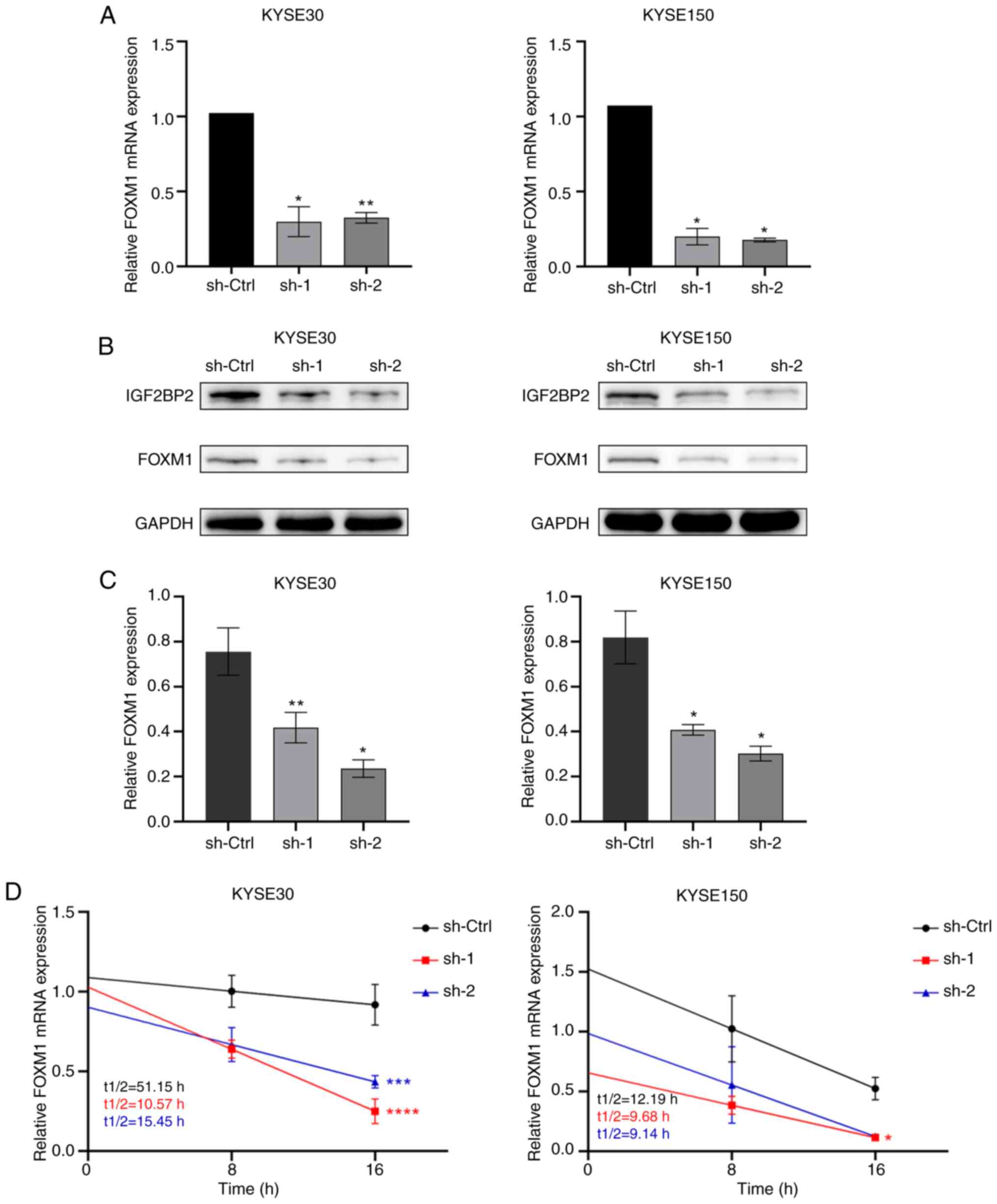

To ascertain whether IGF2BP2 modulates FOXM1

expression in ESCC cells, FOXM1 expression was assessed at both

transcriptional and translational levels following IGF2BP2

knockdown, utilizing RT-qPCR and WB analysis, respectively. As

anticipated, both the RNA expression levels (Fig. 4A) and protein levels (Fig. 4B and C) of FOXM1 exhibited a

significant decrease correlating with IGF2BP2 depletion. Given that

IGF2BP2 deficiency impaired the levels of FOXM1 mRNA, it was

hypothesized that IGF2BP2 may regulate FOXM1 by maintaining the

stability of FOXM1 mRNA. Subsequently, 2 g/ml Actinomycin D was

administered to treat KYSE30 cells transfected with IGF2BP2-shRNA

or control shRNA at various time points. As illustrated in Fig. 4D, a significantly accelerated decay

of FOXM1 mRNA was observed in the absence of IGF2BP2 (Fig. 4D), indicating that IGF2BP2 can

sustain the stability of FOXM1 mRNA.

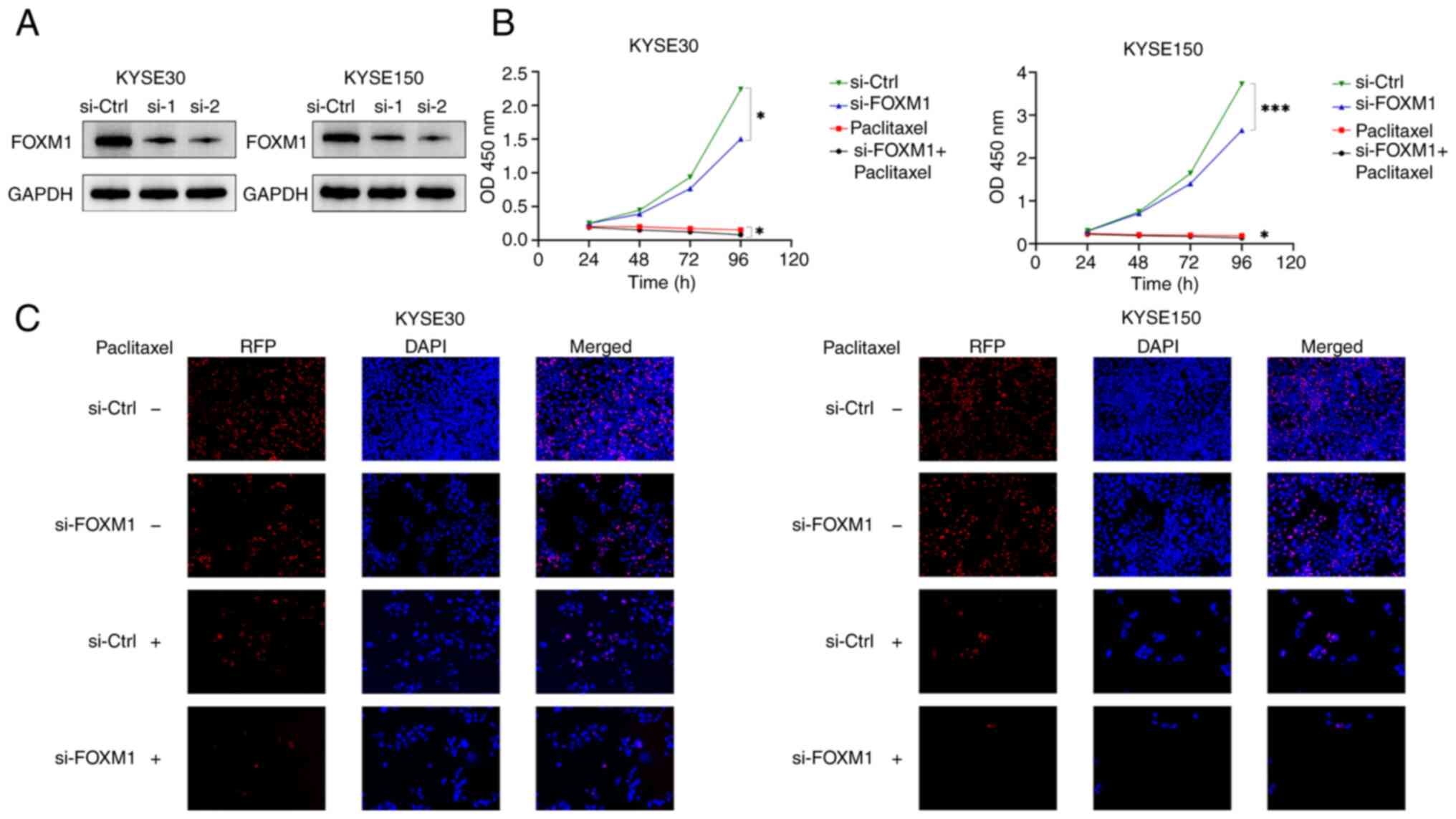

FOXM1 serves an oncogenic function in

ESCC cells

The oncogenic function of FOXM1 has been documented

in ESCC (21–23). To further validate the function of

FOXM1 in ESCC, the phenotypes of ESCC cells, encompassing cell

growth and proliferation, were examined through gene-loss

experiments following FOXM1 depletion (Fig. 5A). Notably, a significant reduction

in cell growth (Fig. 5B) was

observed through the CCK-8 assays, alongside a diminished formation

of colonies (Fig. 5C) of the KYSE30

and KYSE150 cells observed in the EdU assays. Consequently, it was

hypothesized that FOXM1 facilitates oncogenesis in ESCC cells.

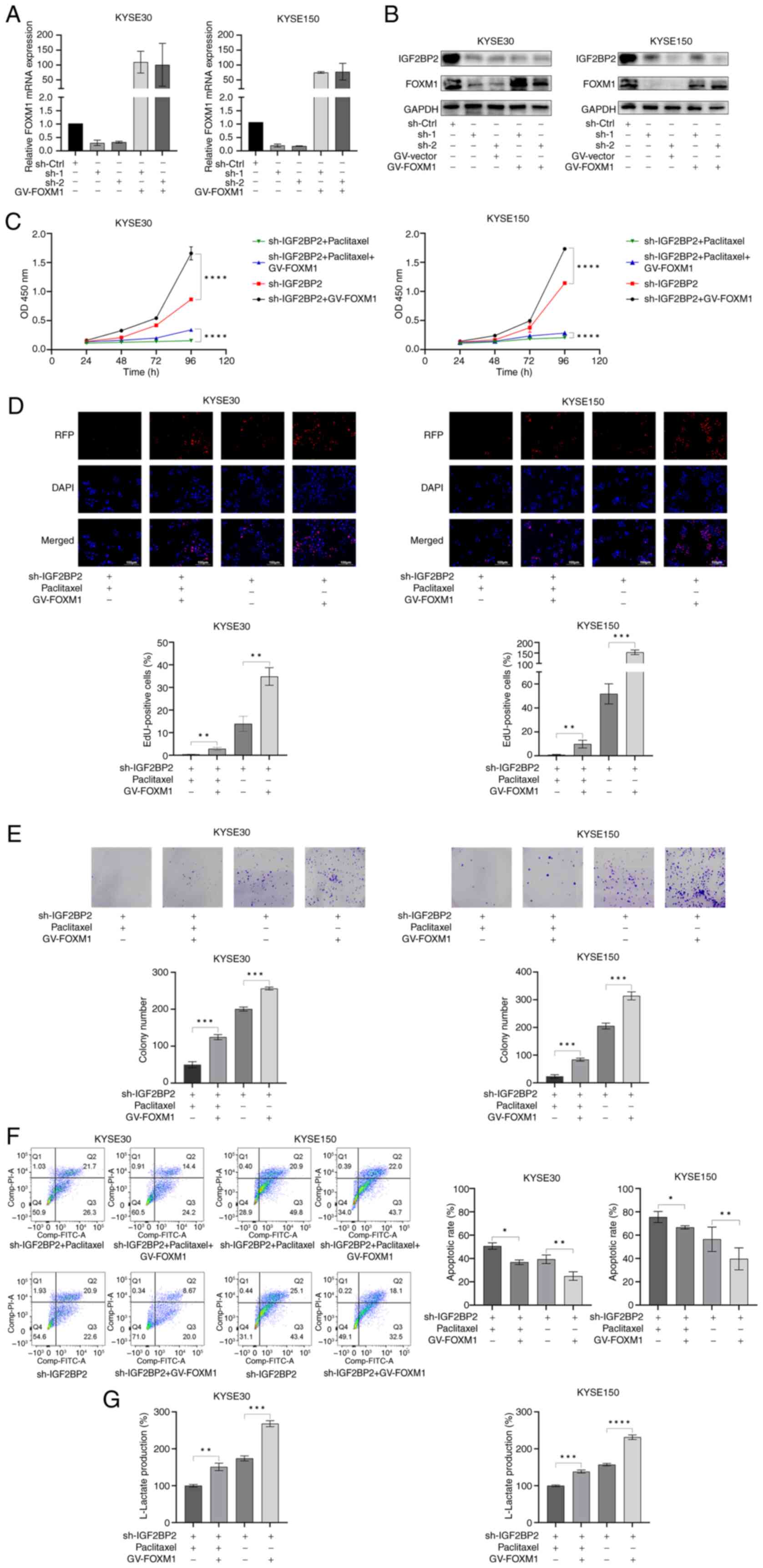

Ectopic expression of FOXM1

ameliorates the impact of IGF2BP2 deficiency in ESCC cells

To further investigate whether FOXM1 mediates the

oncogenic effects of IGF2BP2, FOXM1 expression was upregulated in

ESCC cells that were silenced for IGF2BP2. The efficacy of FOXM1

overexpression was validated through WB analysis (Fig. S1A and B). Furthermore, the efficacy

of ectopic FOXM1 expression in conjunction with silenced IGF2BP2

was assessed at both transcriptional and translational levels

through RT-qPCR and WB analysis, respectively. The results

indicated that both RNA expression (Fig. 6A) and protein abundance (Fig. 6B) of ectopically expressed FOXM1

were markedly increased in IGF2BP2-silenced ESCC cells.

Subsequently, a series of functional assays were conducted to

evaluate ESCC cell activity. CCK-8 assays suggested that the

proliferation rate of ESCC cells exhibiting ectopic FOXM1

expression was significantly higher than that of cells lacking

ectopic FOXM1, irrespective of the presence of paclitaxel (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, EdU assays

illustrated that the reduced cell proliferation activity due to

IGF2BP2 depletion was significantly enhanced through ectopic FOXM1

expression (Fig. 6D). The results

of colony formation assays corroborated the findings observed in

the EdU assays (Fig. 6E). Moreover,

flow cytometric analysis revealed that ectopic FOXM1 expression

mitigated the apoptosis induced through IGF2BP2 silencing (Fig. 6F). These findings demonstrated that

ectopic FOXM1 expression improved cell proliferation, enhanced the

formation of colonies and alleviated apoptosis associated with

IGF2BP2 deficiency in ESCC cells. Notably, it was observed that the

decrease in anaerobic glycolysis resulting from IGF2BP2 silencing

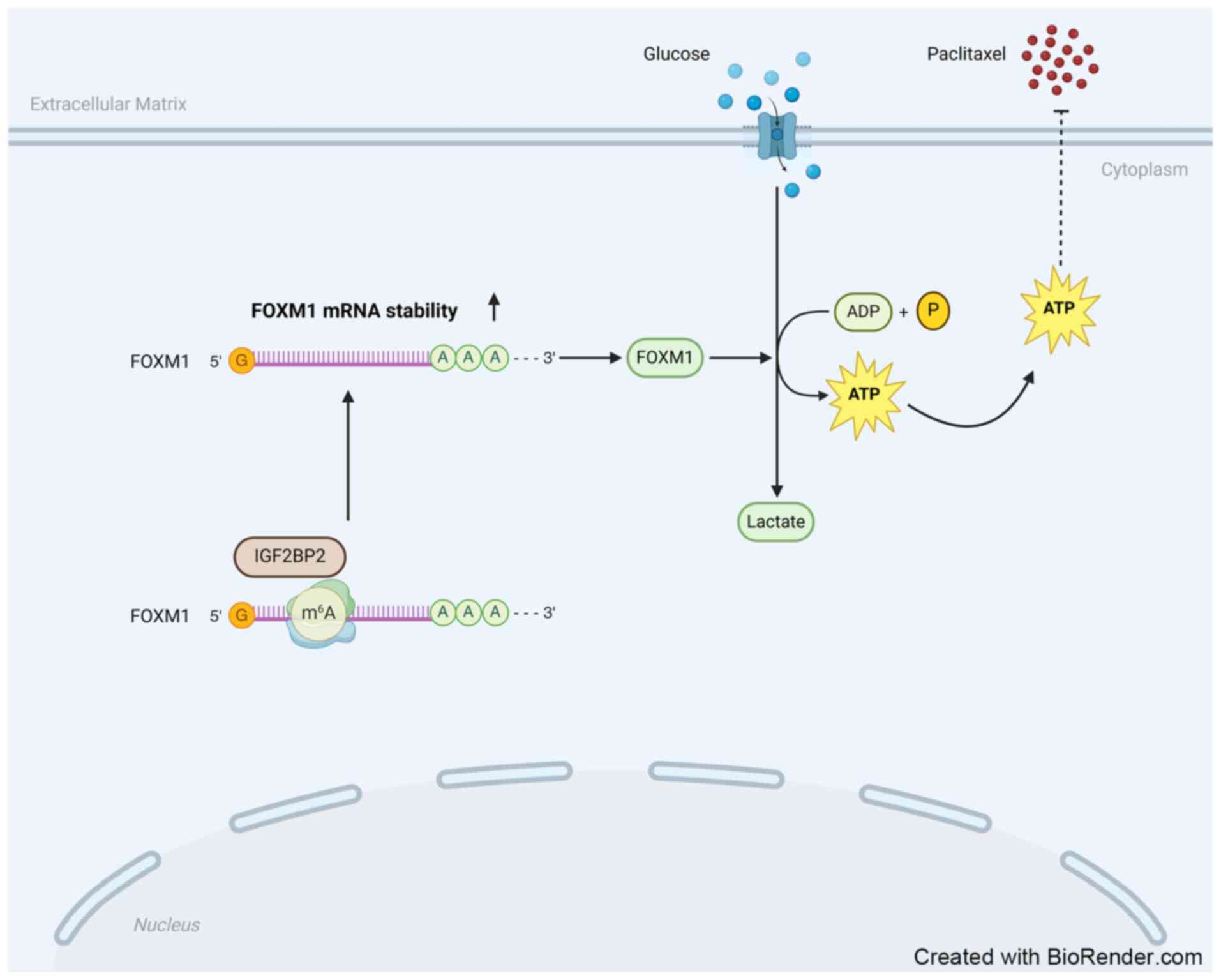

in ESCC cells was reversed upon FOXM1 upregulation (Fig. 6G). Therefore, it is proposed that

IGF2BP2 promotes anaerobic glycolysis and diminishes sensitivity to

paclitaxel in ESCC cells by regulating FOXM1 (Fig. 7).

Discussion

In the current investigation, the overexpression of

IGF2BP2 was confirmed, along with its association with paclitaxel

resistance and anaerobic glycolysis in ESCC in vitro.

Mechanistically, it was demonstrated that IGF2BP2 stabilizes FOXM1

mRNA.

Paclitaxel is extensively utilized in combination

chemotherapy for ESCC. However, tumor resistance to paclitaxel

frequently results in treatment failure, prompting considerable

attention towards underlying the mechanisms. Wu et al

(12) conducted single-cell RNA-seq

experiments to elucidate the heterogeneity of gene expression in

paclitaxel-resistant ESCC cells, which may contribute to the

observed resistance. The findings were validated through drug

toxicity assays, colony formation assays and rodent xenograft model

experiments. It was concluded that intrinsic paclitaxel resistance

exists in KYSE30 ESCC cells, with potential association with KRT19

expression. In the current study, KYSE30 ESCC cells were similarly

selected to focus on the role of the m6A reader IGF2BP2 in

paclitaxel resistance within ESCC. RNA m6A modification has been

reported to mediate paclitaxel resistance in various malignancies.

Liu et al (27) demonstrated

that lncRNA RFPL1S-202 was capable of boosting paclitaxel

cytotoxicity in ovarian cancer by physically interacting with

DEAD-Box Helicase 3 X-linked (DDX3X) protein, thereby increasing

the m6A modification of IFNB1 to reduce the expression of

IFN-inducible genes. Additionally, Xie et al (28) reported that LINC02489 with m6A

modification linked to PKNOX2 via the PTEN/mTOR axis, thereby

enhancing the sensitivity of ovarian cancer to paclitaxel and

reducing the migration and invasion of chemotherapy-resistant

ovarian cancer cells.

A recent study reported that m6A reader IGF2BP2 is

upregulated in ESCC tissues in comparison with normal esophageal

mucosa. Li et al (29)

demonstrated a significant upregulation of IGF2BP2 in ESCC tissues

through epi-transcriptomics. Additionally, Wang et al

(30) suggested that IGF2BP2

exhibits elevated expression in ESCC than those in normal

esophageal tissues, with its overexpression being closely linked to

lymph node metastasis. In the present study, the upregulation of

IGF2BP2 in ESCC was confirmed, consistent with previous findings

(26–28).

Furthermore, it was demonstrated for the first time

that IGF2BP2 expression is positively linked to paclitaxel

resistance in ESCC. The current study serves as a valuable

supplement to the understanding of m6A modification in the

regulation of paclitaxel resistance across various malignancies.

One of the hallmarks of cancer is the observation that, even in the

presence of normal oxygen concentrations, cancer cells

predominantly generate energy through glycolysis at elevated rates,

a phenomenon referred to as the Warburg effect. In addition to its

tumor-promoting properties, aerobic glycolysis is capable of

enhancing drug resistance in cancer cells by creating a supportive

microenvironment (32).

Consequently, this may present a novel clinical approach,

suggesting that the inhibition of glycolysis could partially

reverse chemotherapy resistance.

Enhanced sensitivity of KYSE150 ESCC cells to

cisplatin, both in vitro and in vivo, was reported to

be associated with inhibited glycolysis, as evidenced by reduced

glucose consumption and diminished lactate production. This

observation suggests that enhancing the sensitivity of ESCC to

cisplatin could be achieved through the reduction of glycolysis

(33). Wu et al (34) demonstrated that disrupted glycolysis

was positively correlated with paclitaxel resistance in epithelial

ovarian cancer. In the present study, it was revealed for the first

time, to the best of our knowledge, that the inhibition of IGF2BP2

markedly reversed paclitaxel resistance while concurrently

decreasing anaerobic glycolysis in ESCC. Further study will be

implemented to investigate whether IGF2BP2 mediates paclitaxel

resistance in ESCC by modulating glycolytic pathways.

As an m6A reader, the biological function of IGF2BP2

is contingent upon its interaction with m6A-modified RNA. In the

present study, m6A modifications in ESCC were systematically

screened, revealing a prevalence of such modifications in the UTRs

of mRNAs, aligning with previous findings (35). Concurrently, transcriptional

analysis following IGF2BP2 knockdown in ESCC cells indicated that

the majority of transcripts exhibiting m6A modification were

downregulated, suggesting that IGF2BP2 maintains mRNA stability in

an m6A-dependent manner within ESCC. Among these genes, it was

confirmed that FOXM1 serves as a direct target of IGF2BP2 in ESCC.

A previous study indicated that the Akt/FOXM1 signaling cascade

inhibits paclitaxel-induced cell death in ESCC (23). In the present investigation, it was

established that FOXM1 is modulated by IGF2BP2 at both

transcriptional and translational levels in ESCC. Further

experiments demonstrated that FOXM1 represents a pivotal factor

through which IGF2BP2 mediates paclitaxel resistance and aberrant

anaerobic glycolysis in ESCC. The results showed that the FOXM1

transcript is m6A-modified and its expression decreases upon

IGF2BP2 knockdown, indicating that IGF2BP2 regulates FOXM1

expression in an m6A-dependent manner.

While the current findings yielded several

significant conclusions, certain limitations persist. The mechanism

by which IGF2BP2 regulates FOXM1 in an m6A-dependent manner remains

to be experimentally substantiated due to the complexity of the

associated experiments. IGF2BP2 comprises six canonical RNA-binding

domains, encompassing two RNA recognition motifs and four K

homology domains. It has been established that the KH3-4 di-domains

are critical for IGF2BP2 to bind to m6A-modified mRNAs and modulate

the expression of target genes. In forthcoming research, basic

experiments will be undertaken to elucidate the mechanism by which

IGF2BP2 regulates FOXM1 through the creation of an IGF2BP2 mutant

featuring alterations in the KH domains, alongside an assessment of

the interaction between IGF2BP2 and FOXM1 mRNA.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the

significant role of IGF2BP2-FOXM1 signaling in modulating

paclitaxel resistance in ESCC. The insights and conclusions

presented may offer novel directions for the effective treatment of

ESCC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Shandong (grant no. ZR2021MH155).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The data generated in the

present study may be found in the Figshare under accession number

10.6084/m9.figshare.29312819.v2 or at the following URL:

(https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29312819.v2).

Authors' contributions

SR and WJ conceived and designed the study. SR and

JW performed the experiments. JW conducted statistical analysis

using GraphPad Prism. GG performed bioinformatics analysis. LZ

assisted in experiments, contributed to manuscript editing based on

reviewers' comments and revised figures. WJ secured funding,

supervised the project and provided critical revision of the

manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of

the article. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. SR and WJ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Abnet CC, Arnold M and Wei WQ:

Epidemiology of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Gastroenterology. 154:360–373. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Morgan E, Soerjomataram I, Rumgay H,

Coleman HG, Thrift AP, Vignat J, Laversanne M, Ferlay J and Arnold

M: The Global landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and

esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in 2020 and

projections to 2040: New estimates from GLOBOCAN 2020.

Gastroenterology. 163:649–658.e2. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

An L, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, Chen R,

Wang S, Sun K, Li L, Wei W and He J: The survival of esophageal

cancer by subtype in China with comparison to the United States.

Int J Cancer. 152:151–161. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rustgi AK and El-Serag HB: Esophageal

carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 371:2499–2509. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Leng XF, Daiko H, Han YT and Mao YS:

Optimal preoperative neoadjuvant therapy for resectable locally

advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

1482:213–224. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhu H, Ma X, Ye T, Wang H, Wang Z, Liu Q

and Zhao K: Esophageal cancer in China: Practice and research in

the new era. Int J Cancer. 152:1741–1751. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, Zhu C, Fang W, Yu

Z, Mao W, Xiang J, Han Y, Chen Z, et al: Neoadjuvant

Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for

locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

(NEOCRTEC5010): A phase III multicenter, randomized, open-label

clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 36:2796–2803. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kotecki N, Hiret S, Etienne PL, Penel N,

Tresch E, François E, Galais MP, Ben Abdelghani M, Michel P, Dahan

L, et al: First-line chemotherapy for metastatic esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma: Clinico-biological predictors of disease

control. Oncology. 90:88–96. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mariette C, Dahan L, Mornex F, Maillard E,

Thomas PA, Meunier B, Boige V, Pezet D, Robb WB, Le Brun-Ly V, et

al: Surgery alone versus chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for

stage I and II esophageal cancer: Final analysis of randomized

controlled phase III trial FFCD 9901. J Clin Oncol. 32:2416–2422.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chan KKW, Saluja R, Delos Santos K, Lien

K, Shah K, Cramarossa G, Zhu X and Wong RKS: Neoadjuvant treatments

for locally advanced, resectable esophageal cancer: A network

meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 143:430–437. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wu H, Chen S, Yu J, Li Y, Zhang XY, Yang

L, Zhang H, Hou Q, Jiang M, Brunicardi FC, et al: Single-cell

Transcriptome analyses reveal molecular signals to intrinsic and

acquired paclitaxel resistance in esophageal squamous cancer cells.

Cancer Lett. 420:156–167. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Meyer KD and Jaffrey SR: The dynamic

epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15:313–326. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu

H, Zhao BS, Mesquita A, Liu C, Yuan CL, et al: Recognition of RNA

N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA

stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol. 20:285–295. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang Z, Wan J, Ma L, Li Z, Yang R, Yang H,

Li J, Zhou F and Ming L: Long non-coding RNA HOXC-AS1 exerts its

oncogenic effects in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by

interaction with IGF2BP2 to stabilize SIRT1 expression. J Clin Lab

Anal. 37:e248012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang GW, Chen QQ, Ma CC, Xie LH and Gu J:

Linc01305 promotes metastasis and proliferation of esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma through interacting with IGF2BP2 and

IGF2BP3 to stabilize HTR3A mRNA. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

136:1060152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liberti MV and Locasale JW: The warburg

effect: How does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci.

41:211–218. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Haque MM and Desai KV: Pathways to

endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 10:5732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ma L and Zong X: Metabolic symbiosis in

Chemoresistance: Refocusing the role of aerobic glycolysis. Front

Oncol. 10:52020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ and Smyth GK:

edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis

of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26:139–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Meng RY, Jin H, Nguyen TV, Chai OH, Park

BH and Kim SM: Ursolic acid accelerates paclitaxel-induced cell

death in esophageal cancer cells by suppressing Akt/FOXM1 signaling

cascade. Int J Mol Sci. 22:114862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hu C, Liu T, Han C, Xuan Y, Jiang D, Sun

Y, Zhang X, Zhang W, Xu Y, Liu Y, et al: HPV E6/E7 promotes aerobic

glycolysis in cervical cancer by regulating IGF2BP2 to stabilize

m6A-MYC expression. Int J Biol Sci. 18:507–521. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pu J, Wang J, Qin Z, Wang A, Zhang Y, Wu

X, Wu Y, Li W, Xu Z, Lu Y, et al: IGF2BP2 promotes liver cancer

growth through an m6A-FEN1-dependent mechanism. Front Oncol.

10:5788162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang Y, Lu JH, Wu QN, Jin Y, Wang DS, Chen

YX, Liu J, Luo XJ, Meng Q, Pu HY, et al: LncRNA LINRIS stabilizes

IGF2BP2 and promotes the aerobic glycolysis in colorectal cancer.

Mol Cancer. 18:1742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu S, Chen X, Huang K, Xiong X, Shi Y,

Wang X, Pan X, Cong Y, Sun Y, Ge L, et al: Long noncoding RNA

RFPL1S-202 inhibits ovarian cancer progression by downregulating

the IFN-β/STAT1 signaling. Exp Cell Res. 422:1134382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xie Y, Wang L, Luo Y, Chen H, Yang Y, Shen

Q and Cao G: LINC02489 with m6a modification increase paclitaxel

sensitivity by inhibiting migration and invasion of ovarian cancer

cells. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 39:1128–1142. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li Y, Xiao Z, Wang Y, Zhang D and Chen Z:

The m6A reader IGF2BP2 promotes esophageal cell

carcinoma progression by enhancing EIF4A1 translation. Cancer Cell

Int. 24:1622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang C, Zhou M, Zhu P, Ju C, Sheng J, Du

D, Wan J, Yin H, Xing Y, Li H, et al: IGF2BP2-induced circRUNX1

facilitates the growth and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma through miR-449b-5p/FOXP3 axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

41:3472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xiao Y, Tang J, Yang D, Zhang B, Wu J, Wu

Z, Liao Q, Wang H, Wang W and Su M: Long noncoding RNA LIPH-4

promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression by

regulating the miR-216b/IGF2BP2 axis. Biomark Res. 10:602022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bhattacharya B, Mohd Omar MF and Soong R:

The Warburg effect and drug resistance. Br J Pharmacol.

173:970–979. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fang J, Ma Y, Li Y, Li J, Zhang X, Han X,

Ma S and Guan F: CCT4 knockdown enhances the sensitivity of

cisplatin by inhibiting glycolysis in human esophageal squamous

cell carcinomas. Mol Carcinog. 61:1043–1055. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wu X, Qiu L, Feng H, Zhang H, Yu H, Du Y,

Wu H, Zhu S, Ruan Y and Jiang H: KHDRBS3 promotes paclitaxel

resistance and induces glycolysis through modulated MIR17HG/CLDN6

signaling in epithelial ovarian cancer. Life Sci. 293:1203282022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zaccara S, Ries RJ and Jaffrey SR:

Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 20:608–624. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|