Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a highly aggressive

hematologic malignancy in adults, characterized by a high relapse

rate and persistent treatment resistance, which translates to a

5-year overall survival of <10% (1,2).

Although advances in molecular typing and targeted therapies have

improved the prognosis of patients with specific subtypes, the

heterogeneity of AML, its driving mechanisms, and complex

interactions between leukemia stem cells (LSCs) and the bone marrow

microenvironment remain unclear (3). High-intensity chemotherapy and

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are the current

standard of care; however, due to their severe toxic side effects,

harm to normal hematopoiesis, and limitations in eliminating LSCs

and overcoming drug resistance, novel therapeutic approaches that

are more effective and selective are urgently required (4,5).

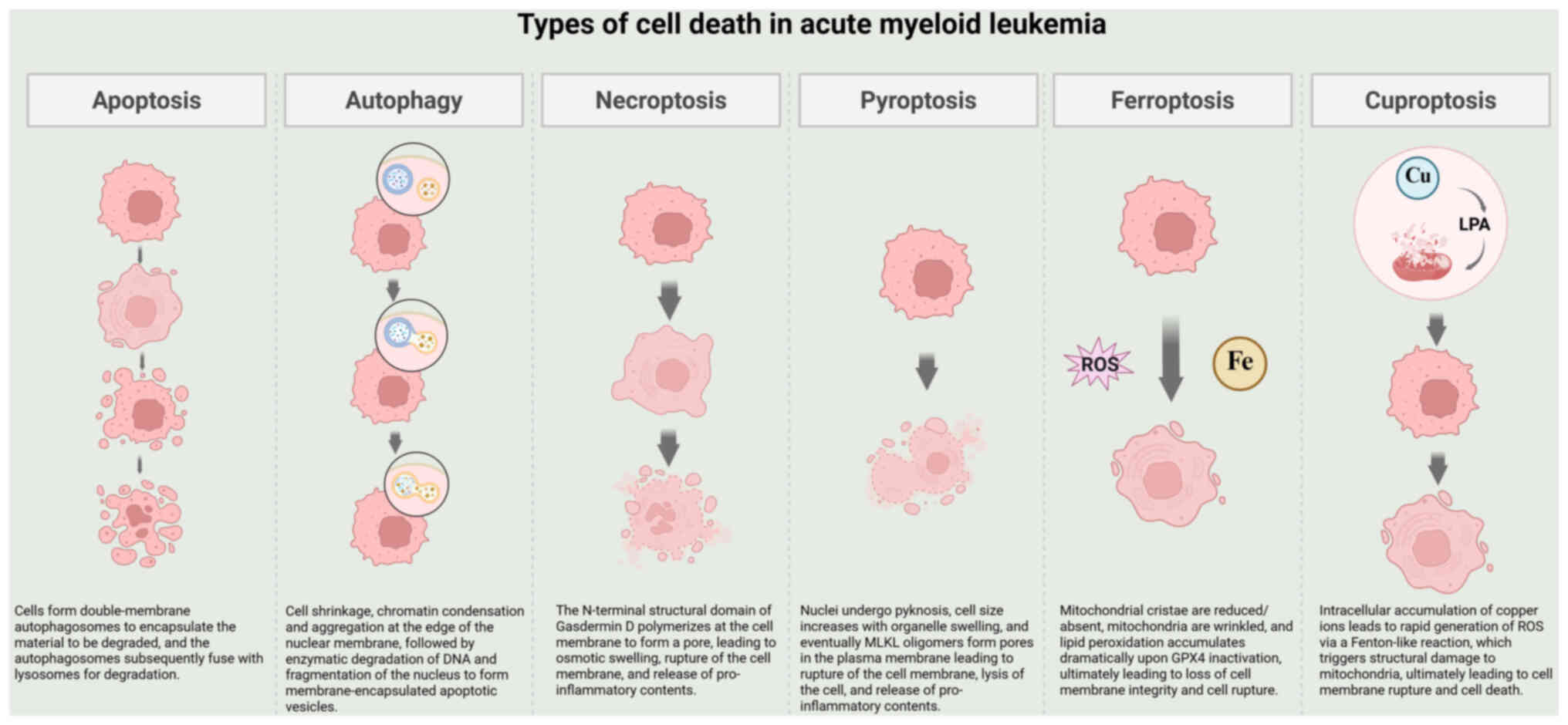

Targeting of regulated cell death (RCD) has

attracted increasing attention from researchers in recent years

(6–9). The primary benefit of this method is

its ability to specifically target LSCs while reshaping the

immunosuppressive bone marrow microenvironment to enhance

anti-leukemic efficacy and minimize damage to normal tissues

(10). Studies have shown that

selective modulation of RCD pathways, such as autophagy, apoptosis,

pyroptosis, necroptosis, ferroptosis and cuproptosis, can

effectively target and eliminate leukemic clones resistant to

traditional therapies (11–16). Furthermore, these RCD pathways form

a highly interconnected regulatory network that operates through

dynamic interactions rather than functioning in isolation (17). This complexity suggests that

combinatorial interventions targeting multiple death pathway nodes

synergistically may more effectively disrupt the death-resistant

barriers of leukemia cells, thereby opening multidimensional attack

pathways to overcome therapeutic bottlenecks caused by AML clonal

evolution and microenvironmental sheltering (18).

The present review aims to achieve three objectives:

i) To assess the latest developments and challenges in targeting

RCD in AML treatment by systematically integrating the

understanding of six major RCD pathways; ii) to explore the

crosstalk and synergistic potential between these pathways, a

critical yet underexplored area; and iii) to apply these insights

in developing a framework for future combinatorial therapies. To

provide novel concepts and strategies for overcoming AML treatment

resistance and improving patient outcomes, the present review

examines the RCD modes of action, their key functions, and

potential synergistic effects in maintaining LSCs, chemoresistance

and bone marrow microenvironment remodeling. The present review

also explores the potential for developing a customized therapeutic

system through precise targeting of the death pathway network. The

profiles of each type of cell death are illustrated in Fig. 1 (8,19).

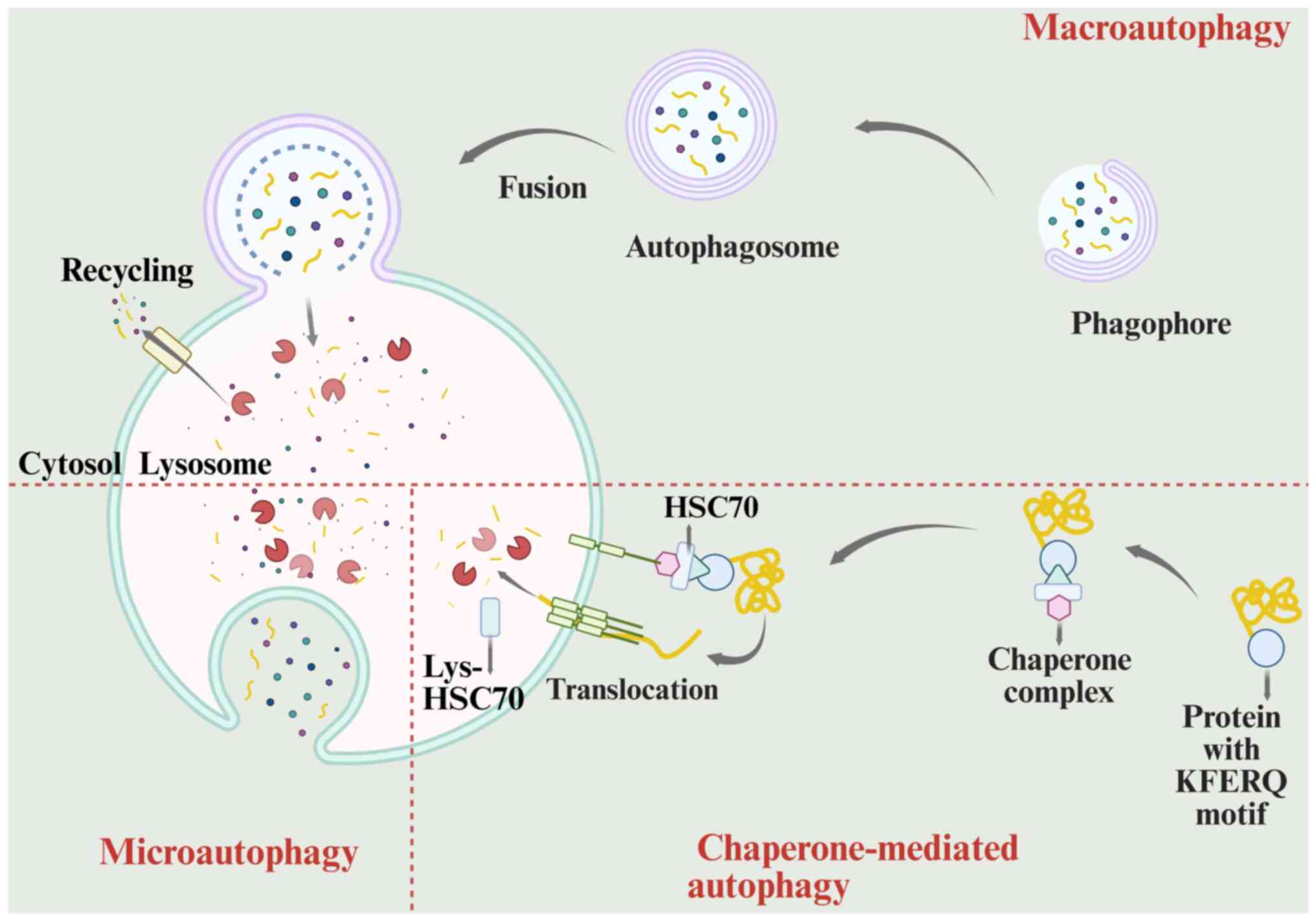

Overview of autophagy. Autophagy is a highly

conserved cellular process that involves the formation of

autophagosomal vesicles. These vesicles encapsulate damaged

organelles, misfolded proteins and other cytoplasmic components

within double-membrane structures. Cellular component recycling

occurs when autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, where the enclosed

contents are enzymatically degraded into smaller molecules

(20).

Autophagy can be classified into three types based

on its mechanism: Microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy and

macroautophagy. Macroautophagy is the most widely studied type of

autophagy and involves the encapsulation of damaged organelles or

denatured proteins by double-membrane autophagic vesicles. These

vesicles then transport the contents to fuse with lysosomes, where

enzymatic degradation occurs (21).

Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 mediates the highly

specific pathway of chaperone-mediated autophagy, in which heat

shock protein 70 recognizes KFERQ motifs in target proteins and

unidirectionally translocates them into the lysosomal lumen for

selective degradation (21). Unlike

the first two autophagic pathways, microautophagy does not involve

the formation of distinct autophagosomal structures. Instead, it

involves creation of phagocytic vesicles through lysosomal membrane

invagination, directly engulfing cytoplasmic components or

organelles and delivering them to the lysosomal lumen for enzymatic

degradation via membrane fusion (22).

Autophagy is a five-stage molecular process

involving initiation, nucleation, membrane extension, fusion and

degradation (23). When cells

experience nutrient deprivation, the activity of mTOR, a key

energy-sensing kinase, is suppressed, triggering the autophagy

signaling cascade (24). The UNC-51

like kinase 1 (ULK1) complex, which consists of essential

components including ULK1, ATG13 and FIP200, is phosphorylated by

AMP-activated protein kinase. This phosphorylation reverses the

inhibitory effect of mTOR on the complex (25). Upon activation, the complex migrates

towards the autophagy initiation site, where ULK1 catalyzes the

phosphorylation of FIP200 and ATG13 (25). This phosphorylation event recruits

downstream ATG proteins to initiate the formation of the

pre-autophagosome complex (26).

The nucleation phase of autophagy begins with the activation of the

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase class III complex, which catalyzes

the formation of a lipid-signaling platform at the membrane surface

through phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (27). This platform recruits effector

proteins containing the FYVE/PX domain, which promote the assembly

of pre-autophagosomal structures (28). Membrane expansion during autophagy

is driven by two ubiquitin-like modification processes: Atg7

functions as an E1-like enzyme in the Atg5-Atg12 coupling system,

facilitating the covalent binding of Atg12 to Atg5 (29). This complex then associates with

autophagy related 16-like 1 to regulate membrane curvature and

promote the growth of autophagic vesicles (29). In the LC3 lipidation pathway, Atg4

cleaves the LC3 precursor to generate LC3-I, which is then

covalently linked by Atg7 to Atg3, forming membrane-anchored LC3-II

that integrates into the autophagosome membrane, promoting membrane

extension and serving as a marker for substrate recognition,

thereby facilitating targeted transport (30). The two pathways collaborate to

complete autophagosome maturation (31). Ultimately, the autophagic vesicle

membrane closes, enabling fusion with the lysosome to form an

autophagic lysosome. During this process, the autophagosomes are

degraded, and the resulting molecules are recycled for use by the

cell (32,33). Fig.

2 illustrates the three types of autophagy and their respective

processes (24).

Autophagy in AML. AML development is marked by the

dynamic bidirectional regulation of autophagy (34). By eliminating oxidatively damaged

DNA, autophagy maintains the metabolic balance and protects the

genomic integrity of hematopoietic stem cells, preventing their

malignant transformation under normal conditions (35,36).

Autophagy undergoes a dynamic shift during leukemia progression: In

the early stages, it promotes oncogenesis by limiting genomic

instability, while in the later stages, it becomes an adaptive

mechanism that supports tumor cell survival and helps leukemia

cells endure stressful environments through metabolic remodeling

(37,38). This dichotomy suggests that

autophagy dysfunction may contribute to leukemia development, with

an imbalance in its regulatory network accelerating the emergence

of malignant phenotypes (39).

Research has elucidated the mechanisms by which

autophagy contributes to AML development. Targeting the

ATF4-dependent autophagy pathway could offer a therapeutic approach

for patients with Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) mutations, as

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD)

expression increases basal autophagy, which is essential for AML

cell survival (40). KIT mutations

increase the likelihood of AML relapse, which is directly linked to

STAT3-mediated autophagy (41,42).

Nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) mutations are common in AML, where NPM1

induces autophagy through the oncogene PML, thereby promoting AML

cell proliferation (43). By

inhibiting autophagy, the TP53 mutation, which is less common in

hematological cancers than in solid tumors, increases p53

expression and triggers apoptotic responses dependent on

p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis and BAX, leading to AML cell

destruction (44). Glycolysis, a

key metabolic pathway in AML, influences the disease process by

promoting abnormal invasion, proliferation and drug resistance

(45). Research has demonstrated

that combination of autophagy inducers with glycolysis inhibitors

enhanced leukemia cell sensitivity to chemotherapy (46,47).

In relapsed cases, LSCs promote mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation by stimulating fatty acid β-oxidation, creating a

distinct metabolism-dependent drug resistance mechanism (48). Fatty acid metabolism is also

directly linked to AML progression (49–51).

The interconnections among these metabolic pathways create a

complex regulatory network that supports AML cell survival and

treatment resistance. Some of the aforementioned research has

translated into clinical practice, with studies showing that

combination of autophagy inducers with chemotherapeutic drugs

enhanced their effectiveness (52–54).

For instance, the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, when combined with

chemotherapy drugs, can increase AML cell sensitivity to treatment

and promote apoptosis, providing a novel approach to enhance

chemotherapy efficacy (55).

Combining autophagy inhibitors with targeted therapies has also

improved efficacy. Inhibition of autophagy enhances the

anti-leukemic effect of FLT3 inhibitors in FLT3-ITD-positive AML,

offering a novel strategy to overcome resistance to targeted

therapies (56). Furthermore,

combination of multiple autophagy regulators can more effectively

control the autophagy process in AML cells. For example,

co-treatment with an mTOR inhibitor and a Beclin-1 activator

increases autophagy levels, promoting cell differentiation and

apoptosis, suggesting the potential therapeutic benefits of using

multiple regulators simultaneously (57). Further research on the mechanisms of

AML autophagy, as well as on the clinical efficacy and specific

applicability of related therapies, is required.

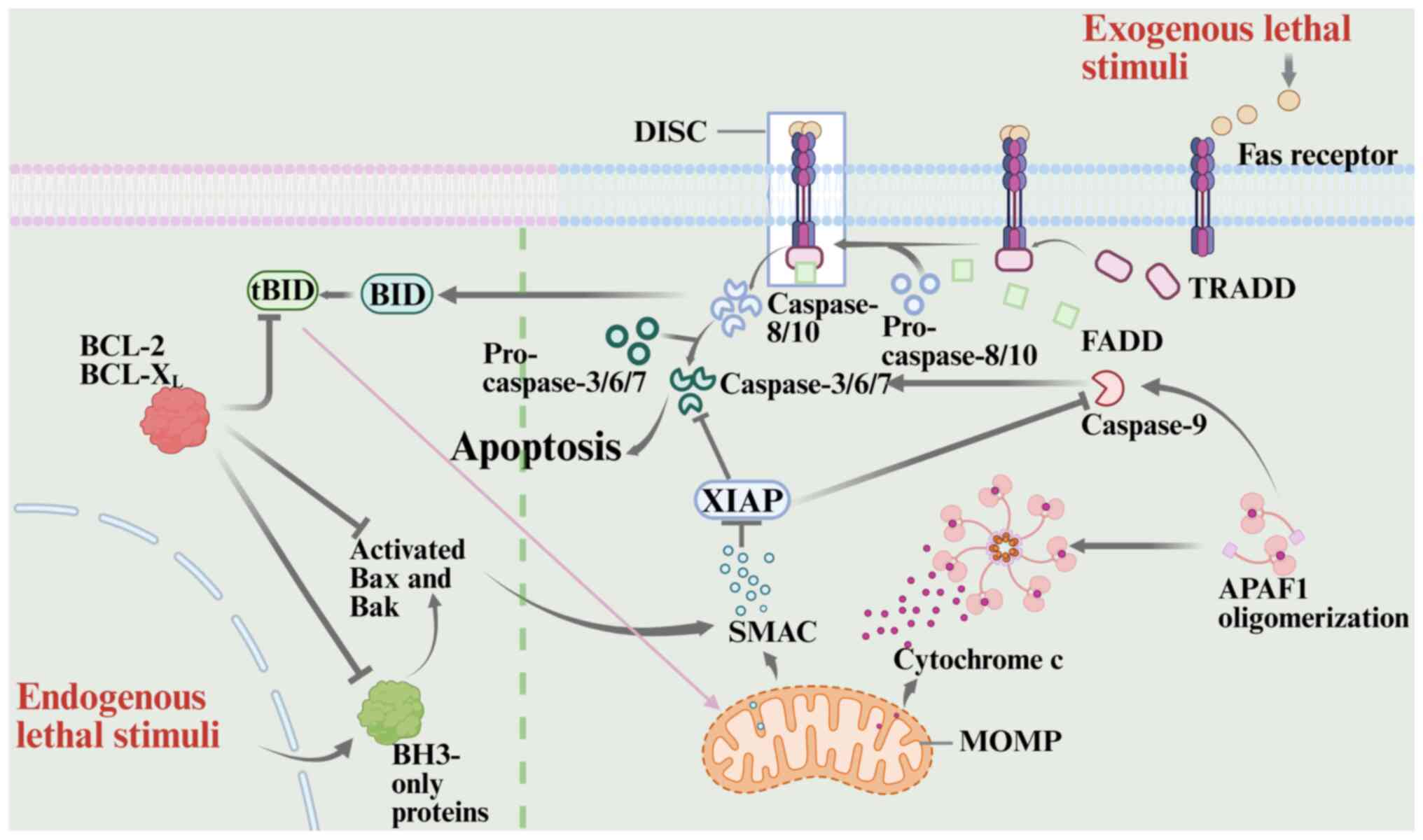

Overview of apoptosis. Apoptosis is a genetically

regulated process of programmed cell death that requires ATP to

execute a series of typical events (58). Endogenous and exogenous apoptosis

are two distinct pathways, and both are regulated by caspases

(59).

Proteins from the Bcl-2 and caspase-9 families are

crucial to the endogenous, or mitochondrial, apoptotic pathway. The

members are classified into pro-apoptotic proteins, which contain

only the BH3 domain, and anti-apoptotic proteins, based on their

function (60). Anti-apoptotic

proteins form heterodimers with pro-apoptotic proteins through the

BH1-3 domains, thereby inhibiting their pro-apoptotic activity

(61). Bax, a pro-apoptotic

protein, is upregulated and undergoes a conformational change upon

DNA damage or oxidative stress, triggering apoptotic signaling

(62). Bax then translocates from

the cytoplasm to the outer mitochondrial membrane, where it

oligomerizes to form channels (63). Meanwhile, BCL2 antagonist/killer,

originally located in the outer mitochondrial membrane, is

activated by BH3-only proteins, triggering a cascade that leads to

oligomerization and the formation of a transmembrane pore (58,64).

The two interact to increase mitochondrial outer membrane

permeability, resulting in the release of cytochrome c (CytC) from

the intermembrane space into the cytoplasm (65). Upon binding to apoptotic protease

activating factor-1, free CytC oligomerizes into heptameric

apoptotic vesicles, driven by deoxyadenosine triphosphate. The

exposed caspase recruitment domain (CARD) then recruits and

activates the initiator caspase-9, which subsequently cleaves the

effector caspase-3, triggering apoptosis (66).

Apoptosis in AML. In AML, the anti-apoptotic protein

BCL-2 is upregulated, enabling leukemia cells to evade apoptosis

and continue their growth (75,76).

Based on the understanding that BCL-2 interacts with pro-apoptotic

proteins, scientists have developed several BCL-2 inhibitors,

including oblimersen, obatoclax mesylate (GX15-070), ABT-737,

ABT-263 (navitoclax), ABT-199 (venetoclax) and S6384559 (77). Venetoclax, one of the most

extensively studied medications, has demonstrated strong clinical

efficacy both as a monotherapy and in combination with other drugs,

particularly low-dose cytarabine or demethylating agents, improving

patient survival and remission rates (78–80).

Venetoclax resistance has become increasingly evident as research

progresses, primarily due to dysfunction in pro-apoptotic

mechanisms and the upregulation of compensatory anti-apoptotic

proteins, such as myeloid cell leukemia-1 (MCL-1). To overcome

venetoclax resistance, appropriate inhibitors are being developed

in parallel (10,81). Despite the use of venetoclax,

additional apoptosis inducers are emerging. For instance, second

mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (SMAC) analogs

targeting inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) can antagonize IAPs

and promote apoptosis by mimicking endogenous SMAC proteins

(82). A pivotal clinical study has

demonstrated that SMAC analogs, when combined with conventional

chemotherapies or targeted therapies, can enhance the cytotoxic

effects on AML cells (83).

P53, a key pro-apoptotic transcription factor, is

closely associated with complex karyotypes, treatment resistance

and poor survival outcomes in patients with AML. This unique

clinical-molecular feature suggests that dysregulation of the TP53

signaling pathway is not only a key pathogenic mechanism of AML,

but also a potential marker for molecular stratification and a

target for targeted therapies, supporting the optimization of

precision treatment strategies (12). Thus, drugs such as MDM2 inhibitors

and P53 reactivators are being investigated for patients with TP53

mutations who have poor prognoses (84–86).

Numerous studies have demonstrated that leukemia

cells can also undergo apoptosis via activation of the death

receptor pathway, offering a potential basis for immunotherapy in

AML (87,88). AML cell apoptosis is strongly

influenced by the bone marrow microenvironment (89). Components of this microenvironment,

such as the extracellular matrix, regulate the expression of

apoptosis-related proteins in AML cells, affecting their

sensitivity to chemotherapy (90).

Future studies on apoptosis and AML should focus on

enhancing the efficacy and availability of current treatments while

minimizing their side effects to provide more effective AML

therapies.

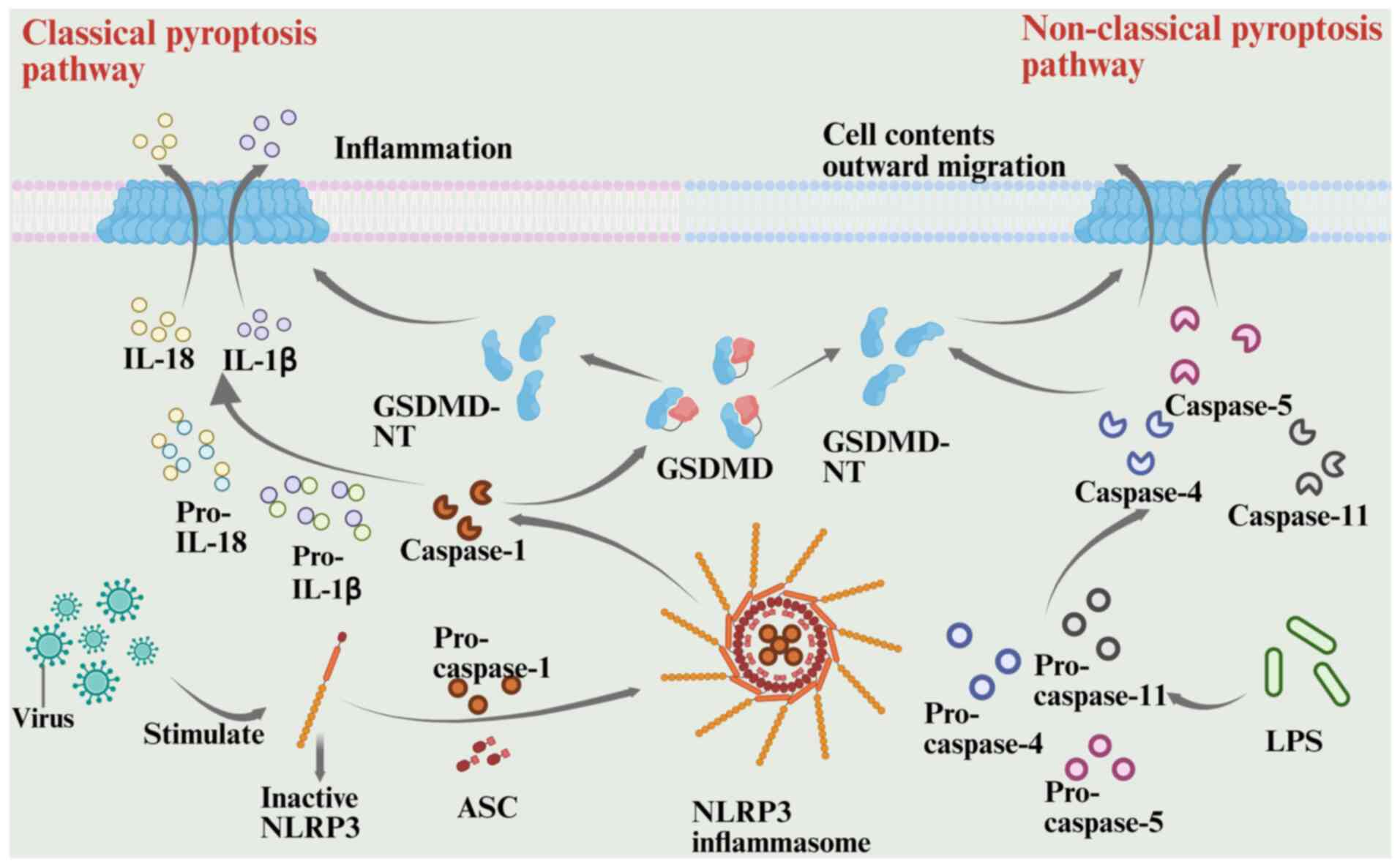

Overview of pyroptosis. The gasdermin (GSDM) family

includes six members (GSDMA, GSDMB, GSDMC, GSDMD, GSDME and

pejvakin), which are primarily expressed in tissues such as the

gastrointestinal tract and skin, and serve a key role in regulating

pyroptosis (91–93). GSDMD-induced pyroptosis can be

categorized into classical and non-classical pathways.

The classical pyroptosis pathway begins with pattern

recognition triggered by pathogen infection and proceeds through

the inflammatory vesicle-GSDMD axis. When intracellular NOD-like

receptors detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns, the pyrin

domain (PYD) recruits the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated

speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC). This forms a platform

for multimerization and recruits pro-caspase-1, which assembles

into a functional inflammatory vesicle complex (94,95).

When the complex activates caspase-1, it cleaves GSDMD. This

cleavage releases the C-terminal domain of GSDMD, thereby relieving

its inhibition of the N-terminal pore-forming domain. The released

GSDMD N-terminal oligomerizes and embeds in the cell membrane,

forming a nanoscale pore that disrupts cellular osmolality, causes

content leakage and triggers pyroptosis, characterized by cell

swelling (96–98). The primary mechanism of the

anti-infective immunity of the host involves processing the

precursors of IL-1β and IL-18, which are released extracellularly

through the GSDMD pore in their mature forms. This recruits

neutrophils and other inflammatory cells, triggering a cascade

amplification effect (94,99). This is achieved through membrane

pore-mediated ‘inflammatory death’, which eliminates infected cells

while tightly regulating the local inflammatory response (100).

The nonclassical pyroptosis pathway is triggered by

the direct sensing of lipid components, with caspase-4/5/11

detecting intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (101–103). Unlike the traditional system, this

mechanism does not involve ASC bridging proteins. Caspase-4/5/11

directly binds LPS through its CARD and undergoes oligomerization

for self-activation (102–104). Activated caspase-4/5/11

specifically cleaves GSDMD to release the N-terminal pore domain

(NT), leading to cell membrane perforation and pyroptosis (105). However, since NT does not directly

process IL-1β/IL-18 precursors, the inflammatory response is only

mildly activated (102,106). In non-immune cells, caspase-4

indirectly cleaves pro-IL-18 through conformational changes,

amplifying local inflammatory signals (107) Similarly, by promoting the

activation of inflammatory vesicles containing NACHT, LRR and PYD

domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), caspase-11 enhances

caspase-1-mediated IL-1β maturation and secretion, forming a

synergistic network of classical and non-classical regulatory

mechanisms (104).

The pathophysiological relevance of pyroptosis in

infections, tumors and inflammatory diseases is underscored by the

ability of certain GSDM family members (specifically GSDMD, GSDMB

and GSDMC) to induce focal cell death via specific protease

cleavage and link programmed death with the immune response through

a multidimensional regulatory network (108–110). Both the classical and

non-classical pathways of pyroptosis are illustrated in Fig. 4 (100).

Pyroptosis in AML. Research has shown that

inflammasomes, key molecular complexes involved in pyroptosis,

serve a dual role in the occurrence, progression and treatment of

leukemia, with potential clinical applications (111). Evidence suggests that pyroptosis

serves a critical, bidirectional role in both the progression of

AML and its treatment response (111). Mechanistic research has

demonstrated that chemotherapy or targeted therapies enhance

anti-AML efficacy by activating the focal cell death pathway

(18). A study by Ren et al

(12) showed that estrogen receptor

activation enhanced the anti-AML effect of the BCL-2 inhibitor

vincristine, via the pyroptosis pathway. Demethylating agents can

promote venetoclax-induced AML pyroptosis by restoring GSDME

expression, offering a potential strategy to overcome resistance to

BCL-2 inhibitors (14). In addition

to enhancing existing targeted therapies and chemotherapy,

pyroptosis could provide a novel target for AML treatment. Small

molecule inhibitors targeting serine dipeptidyl peptidase

(DPP)8/DPP9 have been shown to induce cellular pyroptosis in a

majority of a panel of human AML cell lines and primary samples,

suggesting that this target may offer a novel approach for AML

treatment (112). Suppression of

reticulocalbin 1 gene expression reduces bone marrow mononuclear

cell activity in patients with AML, further confirming the crucial

role of cellular pyroptosis in AML pathogenesis (113).

The ‘immunogenic death’ feature of pyroptosis, which

releases cytokines that reshape the tumor immune environment and

reduce immunosuppressive cells, underlies its significance in AML

therapy by helping overcome immune escape (12). For example, receptor-interacting

serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 effectively inhibits aberrant

bone marrow proliferation in the FLT3-ITD mutant AML model by

regulating IL-1β production via inflammatory vesicles. However, it

can also modify the bone marrow microenvironment, impairing normal

hematopoietic stem progenitor cell function while promoting LSC

development (114–116). Cytarabine promotes IL-1β secretion

through NLRP3 inflammasomes, offering a novel approach to improve

treatment strategies (117). Ren

et al (12) also

demonstrated that targeted activation of G protein-coupled estrogen

receptor improved vincristine efficacy by enhancing leukemic cell

pyroptosis and CD8+ T-cell immunity in patients with

AML, a process mediated by IL-1β/18.

The challenge lies in the bidirectional regulation

of pyroptosis, where its intensity must be carefully controlled to

prevent inflammatory storms. Despite clinical studies demonstrating

the therapeutic benefit and safety of pyroptosis-inducing therapies

in AML, further research is needed to optimize these treatments and

understand their long-term effects on patients (12,117).

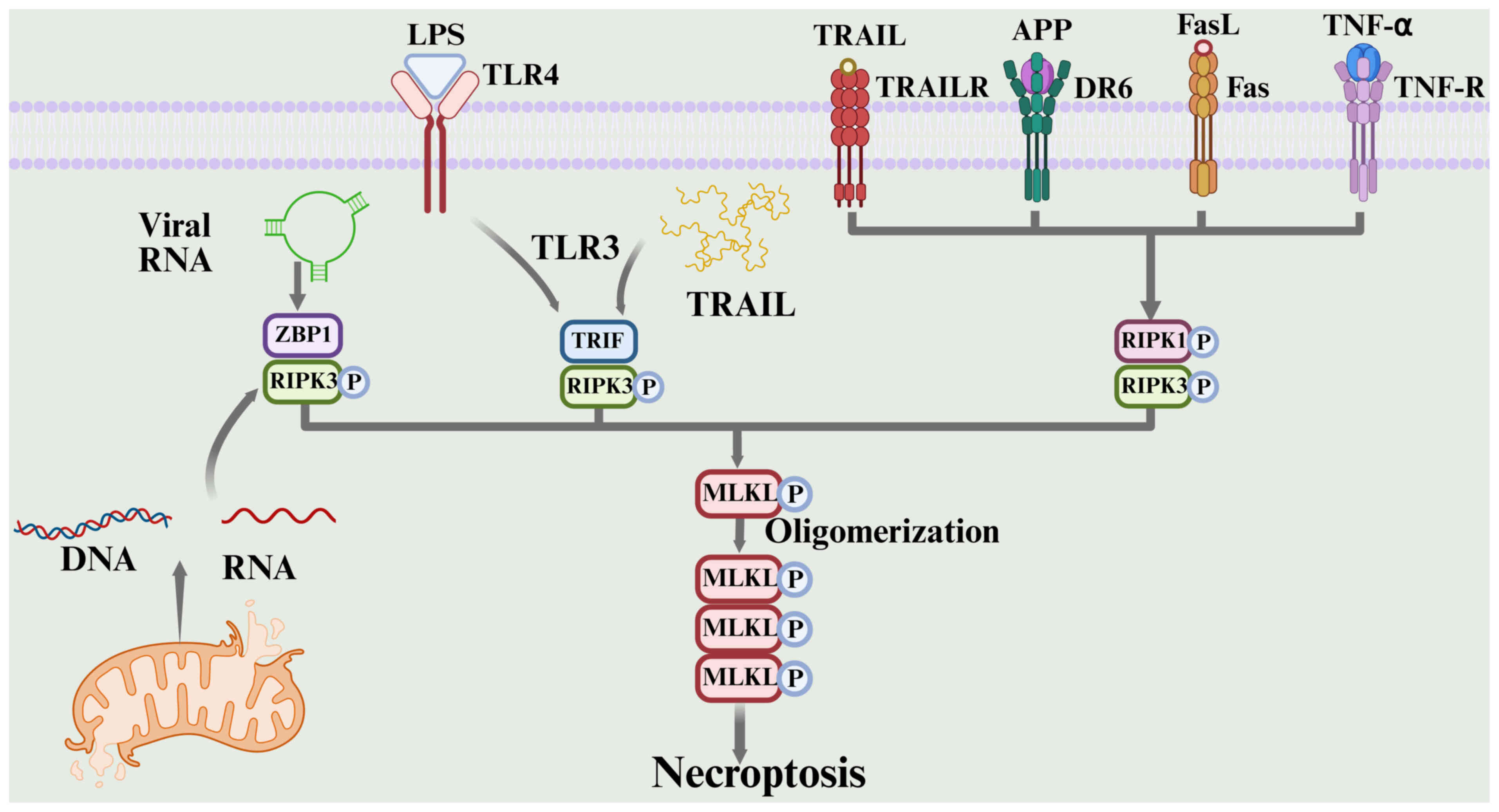

Overview of necroptosis. Necroptosis is a programmed

cell death mechanism independent of cysteine proteases, typically

induced when the apoptotic pathway is blocked by viruses or

medications (118). Its molecular

core involves the receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 1

(RIPK1)-receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 3

(RIPK3)-mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase (MLKL)

signaling axis (119). The

activation pathway is complex and diverse. In the classical

pathway, the TNF receptor superfamily recruits RIPK1 through its

death domain when caspase-8, the main executor of apoptosis, is

inhibited genetically or pharmacologically. This results in the

formation of an amyloid-fibril-like signaling complex (necrosome)

with RIPK3, triggering an autophosphorylation cascade of RIPK3

(118,120–122). By contrast, in pattern recognition

receptor-mediated bypass, toll-like receptor 3 directly recruits

RIPK3 via the TIR domain-containing adapter molecule 1 (TRIF),

forming a nonclassical necrosome complex that bypasses RIPK1. This

facilitates signal transduction upon recognition of viral

double-stranded RNA or toll-like receptor 4 in response to

endotoxin LPS (118,123). Additionally, Z-DNA binding protein

1 (ZBP1) acts as a nucleic acid sensor, detecting endogenous

DNA/RNA released from viral replication intermediates or

mitochondrial stress. ZBP1 specifically binds to RIPK3 through its

receptor-interacting protein kinase homotypic interaction motif,

initiating a necroptosis program independent of RIPK1 and TRIF

(118,124). The multi-pathway signals converge,

indicating that RIPK3 phosphorylates the MLKL pseudokinase domain,

triggering a conformational change in MLKL and the formation of

transmembrane pores. This leads to intracellular calcium overload,

osmotic imbalance and loss of membrane integrity, resulting in the

release of cellular contents and a potent pro-inflammatory response

(118,125–129). Notably, the small molecule

necrostatin-1 serves as a molecular tool for precisely modulating

necrotic apoptosis subtypes by blocking RIPK1-dependent necroptosis

through the ATP-binding pocket of the RIPK1 kinase domain. However,

it is ineffective against ZBP1- or TRIF-mediated nonclassical

pathways (130). The flexibility

of this signaling pathway and multiple regulatory mechanisms make

necroptosis potentially bidirectional in tumor microenvironment

remodeling, chemotherapeutic resistance and immune escape, namely,

it can exert both antitumor and pro-tumor effects depending on the

context (131). The process of

necroptosis is shown in Fig. 5

(132).

Necroptosis in AML. The RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL axis serves

a crucial role in necroptosis, with its dysregulation in AML cells

closely linked to disease progression (13). The role of RIPK3 in AML is complex

and context-dependent. In early leukemogenesis, RIPK3 may act as a

tumor suppressor by inducing necroptosis and promoting the

differentiation of leukemia-initiating cells, thereby preventing

myeloid leukemia progression (13,133).

However, in established AML, the role of RIPK3 is often reversed.

Clinical evidence shows that high RIPK3 expression is associated

with poor prognosis in specific AML subtypes, such as NPM1-mutant

AML (134). Wang et al

(134) specifically reported that

elevated RIPK3 expression was an independent predictor of poor

overall survival in specific AML subtypes, such as FAB-M4/M5,

normal karyotype and NPM1 mutation subtypes, a finding strongly

supported by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank P=0.021;

hazard ratio, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2–2.5). This paradox

(tumor-suppressive role in initiation but oncogenic role in

progression) highlights the dual role of RIPK3 and emphasizes the

need for expression-based patient stratification in future

therapeutic strategies (135). A

study by Zhu et al (136)

identified restoring RIPK3 expression to reverse

R-2-hydroxyglutarate-induced necroptosis in isocitrate

dehydrogenase-mutant AML cells as a potential therapeutic strategy

for patients with AML. However, Hillert et al (137) suggested that targeting the RIPK1

pathway offered a more promising therapeutic approach for patients

with FLT3-ITD-mutant AML. Targeting necroptosis pathways in

combination with traditional chemotherapy or targeted therapies

holds potential for effective treatment (138,139). Li et al (138) found that combination of the RIPK1

inhibitor 22b with cidabenamide enhanced its antileukemic effect in

FLT3-ITD-positive AML cell lines and primary samples. Combining the

RIPK1 inhibitor with the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax promotes

apoptosis in AML cells and overcomes resistance to single-drug

treatment (139). A study has

shown that A20 deletion in AML restored sensitivity to

anthracycline by inducing necroptosis (140). Although the aforementioned studies

have demonstrated that targeting the necroptosis pathway is a

viable strategy in AML, the clinical relevance of the

RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL axis remains unclear (135–137). Future research should focus on

developing biomarkers to predict patient response to therapies

targeting the necroptosis pathway, aiding in precision

medicine.

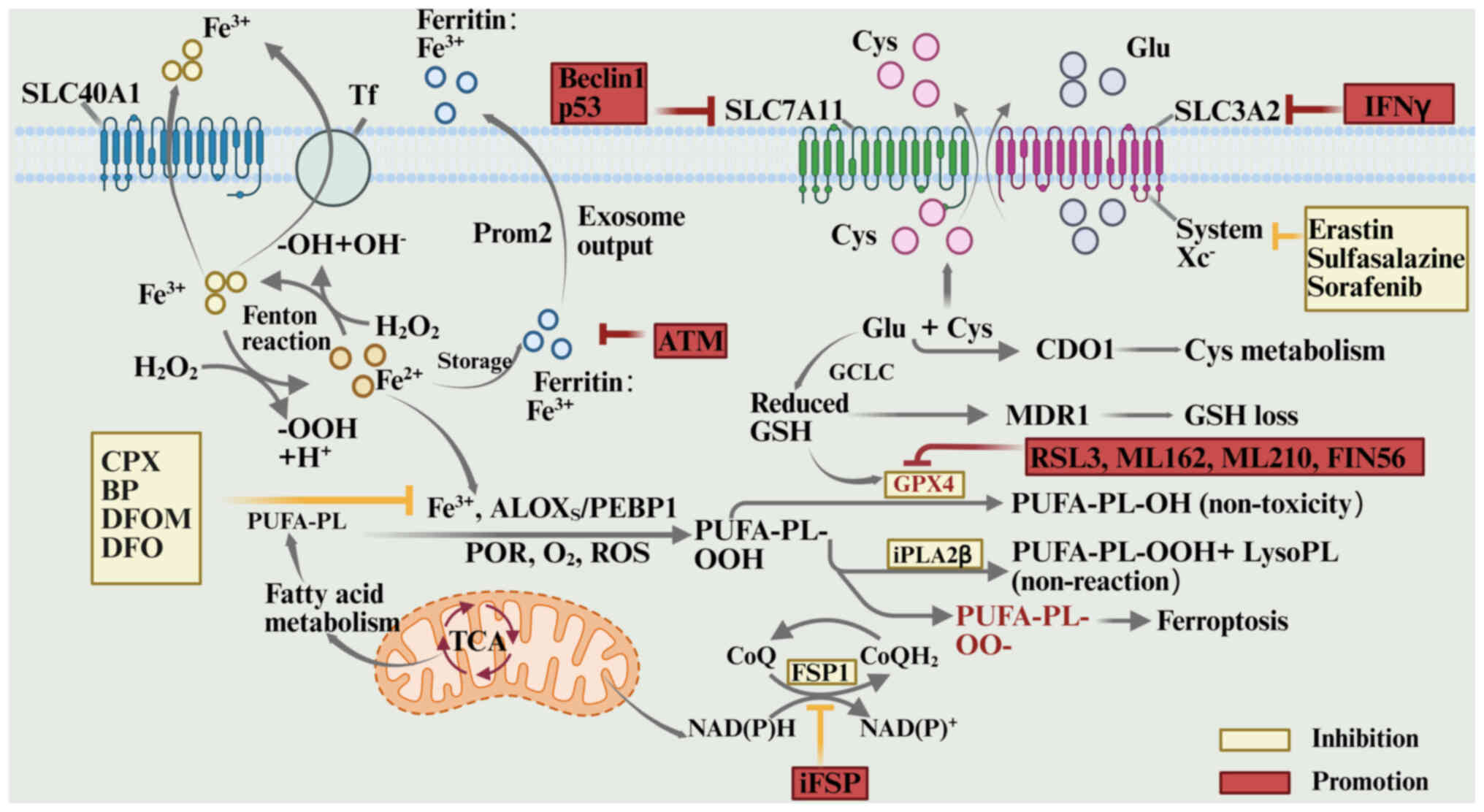

Overview of ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is a form of

programmed cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation

(141). Ferroptosis results from

metabolic disruption caused by the imbalance of intracellular redox

homeostasis (142). At

physiological levels, iron serves as a key cofactor for redox

enzymes, contributing to electron transport and energy metabolism

(143). Excess free iron

(Fe2+) generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) through

the Fenton reaction, causing lipid peroxidation of the membrane

(144). This disturbs cellular

membrane integrity and organelle function (145).

The primary mechanism of ferroptosis is a dynamic

imbalance of lipid peroxides, regulated by the glutathione (GSH)

metabolic pathway and antioxidant defenses (146–149). Polyunsaturated fatty acid

phospholipid hydroperoxide (PUFA-PL-OOH) is the key effector in

this process, produced through the combined action of

Fe2+, lipoxygenases (arachidonate lipoxygenases),

phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 complexes, cytochrome

P450 reductase and ROS. These molecules collaborate to convert

PUFA-PL into the harmful PUFA-PL-OOH (147). Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1

(FSP1) and GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) are the main mechanisms

maintaining PUFA-PL-OOH at steady state. GPX4 reduces PUFA-PL-OOH

via a GSH-dependent process, converting it to its non-toxic form

(147). By contrast, FSP1

scavenges lipophilic free radicals and inhibits the lipid

peroxidation chain reaction by producing the reduced form of

coenzyme Q10 (CoQH2) (148,149). In the absence of GPX4 inhibition

or FSP1-CoQH2 system dysfunction, lipid peroxides

accumulate due to impaired scavenging. Furthermore, Fe2+

catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide into hydroxyl

radicals via the Fenton reaction, intensifying lipid peroxidation

and ROS bursts, and ultimately causing enzyme system collapse and

cellular structural damage (146,147–152).

The ferroptosis regulatory network is multilayered.

At the metabolic input level, the System Xc−

transporter, composed of solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11) and solute carrier family 3 member 2, mediates cystine

uptake, providing essential precursors for GSH synthesis (147,153–155). Inhibitors of this system reduce

intracellular GSH levels by blocking cystine uptake, impairing GPX4

function and triggering ferroptosis (156). At the enzymatic regulatory level,

GPX4 activity can be directly inhibited by small molecules such as

RAS-selective lethal 3 and ML162, while GSH production is blocked

by buthionine sulfoximine (157).

Iron homeostasis is crucial, with divalent iron either removed by

chelating agents such as desferrioxamine and bipyridine or expelled

via the exosomal pathway after being stored as Fe3+ in

ferritin (158,159). In addition, external ROS

stimulation or disruption of lipid peroxidation detoxification can

disrupt the redox balance, leading to the accumulation of toxic

lipid products and triggering ferroptosis (160). These multidimensional regulatory

mechanisms collectively shape the complex biological effects of

iron death in cell fate decisions (145). The process of ferroptosis, with

its inhibitory factors and promoting factors, is illustrated in

Fig. 6 (145).

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic

cell death, offers unique potential for pathological modulation and

therapeutic intervention in AML (15). AML cells are more susceptible to

ferroptosis due to metabolic reprogramming and disrupted redox

homeostasis (161). This

susceptibility is further supported by significantly lower GPX4

expression in primary AML samples compared with normal bone marrow

(P=1.3×10−6), along with reduced GSH levels and

increased mitochondrial lipid peroxidation (162).

Ferroptosis holds significant potential in targeted

therapy for AML. Research suggests that several natural products

possess the potential to induce ferroptosis in cancer treatment

(163). Crotonoside, a key

constituent of Crotonus sativus listed in the Chinese

Pharmacopoeia, induces ferroptosis in AML cells by stimulating

lipid peroxidation and increasing autophagy, offering a novel

approach for AML treatment (164).

Birsen et al (165)

demonstrated that APR-246-induced AML cell death was inhibited by

iron chelators, lipophilic antioxidants and lipid peroxidation

inhibitors, suggesting that APR-246 induced ferroptosis in AML

cells. Lin et al (166)

demonstrated that biomimetic high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles

could disrupt intracellular cholesterol homeostasis by targeting

the scavenger receptor class B type 1 receptor, which was

upregulated in AML cells. This inhibited the GPX4-mediated

antioxidant pathway and induced ferroptosis in AML cells at

nanomolar concentrations, representing a major innovation in AML

treatment.

Research indicates that M2 macrophage-derived growth

differentiation factor 15 confers ferroptosis resistance in the

tumor microenvironment, identifying a key drug resistance mechanism

(167). AML cells are more

resistant to mitoxantrone when co-cultured with M2 macrophages,

providing a novel approach for overcoming AML

microenvironment-mediated drug resistance (168). As a potent ferroptosis inducer and

chemotherapeutic drug carrier for AML treatment, Yu et al

(169) showed that the

ferroptosis-inducing nanomedicine glutathione-capped ferrite

nanoparticles successfully overcame AML resistance. Inhibition of

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) expression

enhanced the anti-AML effect of vinpocetine by inducing AML cell

death via the ferroptosis pathway (170). Pardieu et al (171) determined that SLC7A11 promoted AML

cell survival by encoding the xCT cystine importer. The authors

also demonstrated that combining daunorubicin with xCT inhibition

achieved optimal anti-AML efficacy, suggesting that xCT inhibition

combined with chemotherapy could be a promising strategy for AML

treatment.

While ferroptosis has shown considerable promise in

AML treatment, several challenges remain (172). These include the lack of

techniques for monitoring ferroptosis dynamics, tumor

heterogeneity-related differences in response and unclear

mechanisms of microenvironment regulation. Addressing these issues

is crucial for improving the long-term survival of patients with

AML.

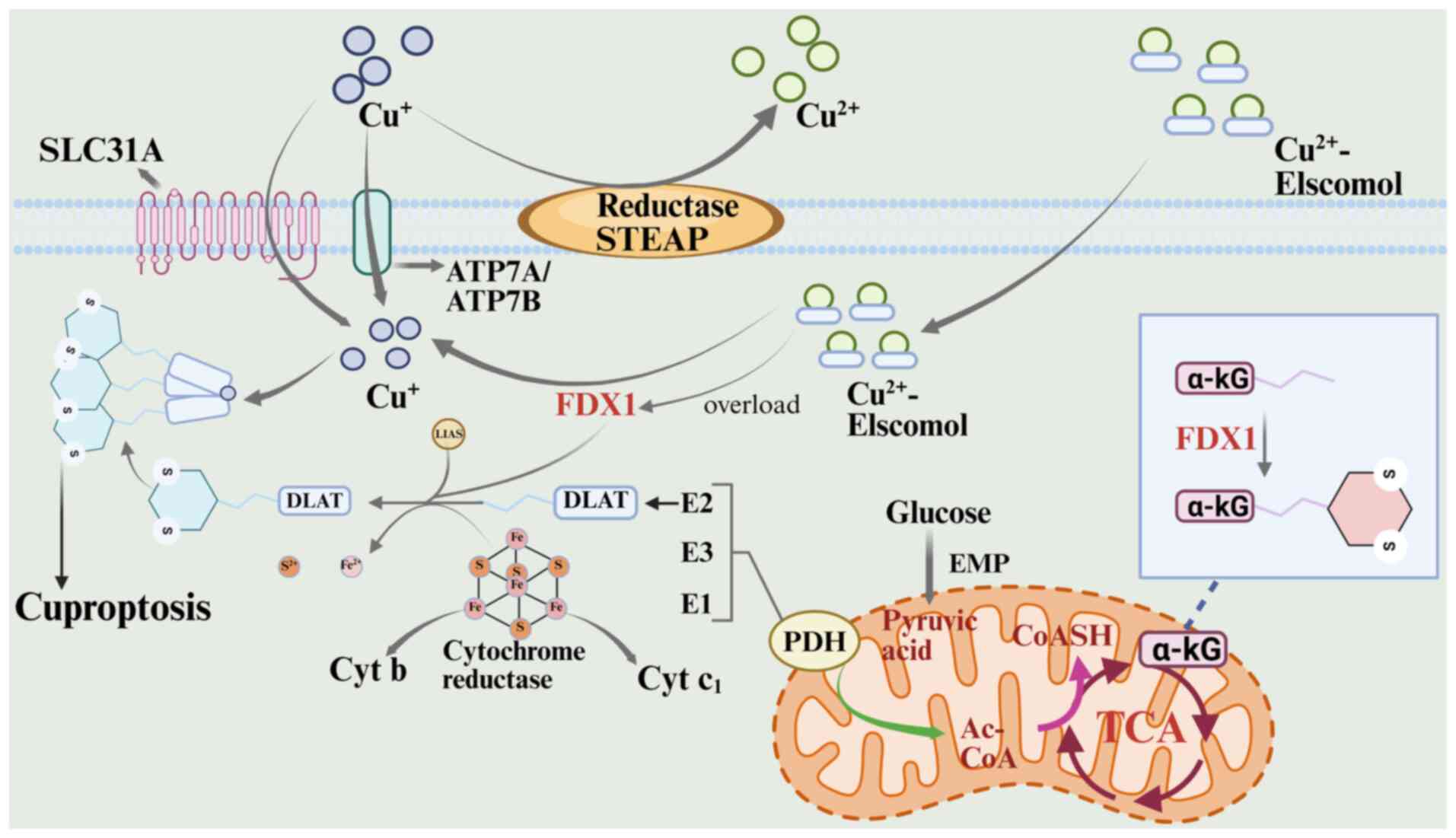

Overview of cuproptosis. Cuproptosis, a

copper-dependent form of RCD, was first proposed by Tsvetkov et

al (173) in 2022. The unique

mechanism distinguishes cuproptosis from other death pathways, such

as apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis and ferroptosis. Cuproptosis

is based on the direct binding of copper ions to lipoylase proteins

in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, leading to abnormal aggregation

(174). This copper-mediated

interaction destabilizes iron-sulfur cluster proteins, disrupting

key components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and inducing

protein homeostatic imbalance and oxidative stress, ultimately

driving cell death via the proteotoxic stress pathway (175).

A key breakthrough in cuproptosis research was the

2019 discovery by Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard

teams of the copper ion carriers disulfiram and ilithromycin (ES),

two small molecules that can specifically mediate copper ion

transport across membranes, providing a central tool for studying

copper-dependent cell death (176). As an anticancer treatment

targeting mitochondrial metabolism, ES not only increases oxidative

stress and ROS formation, but also triggers a novel cell death

pathway through the accumulation of copper ions, according to

recent findings (173). Tsvetkov

et al (173) demonstrated

that ES-induced cell death occurred without caspase-3 activation

and was resistant to both classical apoptosis inhibitors and other

death pathway blockers, confirming its independence from known

death mechanisms. In-depth mechanistic studies revealed that ES

penetrates the cell membrane by forming a complex with

extracellular Cu2+, reducing Cu2+ to

Cu+, and releasing highly reactive ROS in the

mitochondria. Free ES then re-enters the circulatory system to

transport Cu2+, ultimately leading to copper overloading

in mitochondria through the ‘ion shuttle’ mechanism (177–179). The lethal effects of ES were

reduced by electron transport chain complexes and the mitochondrial

pyruvate carrier, but not by mitochondrial uncouplers. Metabolomics

analyses revealed a time-dependent increase in tricarboxylic acid

cycle intermediates during ES treatment, suggesting that copper

toxicity primarily disrupts the tricarboxylic acid cycle rather

than oxidative phosphorylation (180,181).

Genetic evidence has indicated that ferredoxin 1

(FDX1)-knockout cells were resistant to cuproptosis, confirming

that loss of FDX1, a key regulator of copper toxicity signaling,

prevents the lipoylated protein aggregation cascade triggered by

copper accumulation. This established that FDX1-mediated metabolic

disruption is a core molecular pathway for cuproptosis execution

(182). FDX1-mediated toxicity in

cuproptosis occurs through the specific interaction of

Cu+ with the mitochondrial lipoylase system, which

triggers deleterious protein aggregation (173). Cu+ binds to the fatty

acylated pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, inducing abnormal

oligomerization and inactivation of the enzyme, which prevents

pyruvate conversion to acetyl-CoA and disrupts metabolic flow via

the tricarboxylic acid cycle (173,183). FDX1 serves multiple roles in this

process: It catalyzes the lipid acylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase

and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and enhances copper ion toxicity

by converting Cu2+ to the more toxic Cu+

(184). Lipoic acid synthase,

meanwhile, facilitates lipid acylation by synthesizing lipoic acid

and aids the assembly of Fe-S cluster proteins in collaboration

with FDX1, together forming the molecular network underlying copper

ion toxicity (184). In this

process, depletion of large Fe-S clusters disrupts the electron

transport chain, while the blockage of the tricarboxylic acid cycle

further impairs mitochondrial energy metabolism, ultimately leading

to cell death through proteotoxic stress and metabolic disruption

(173). This pathway aligns

closely with the previously identified ES-induced cuproptosis

pathway (173). Loss of FDX1

function inhibits both copper ion-mediated lipoylated protein

aggregation and metabolic reprogramming, highlighting its critical

role in cuproptosis signaling (185). The entire process of the

cuproptosis pathway is illustrated in Fig. 7 (174).

The copper-disulfide complex (Cu-DSF) binding

system selectively targets cancer cells and cancer stem cells

(186). The Cu-DSF exhibits

dose-dependent cytotoxicity in LSCs, with minimal effects on normal

hematopoietic progenitor cells. This selective toxicity is likely

due to the enhanced copper ion enrichment in cancer cells (16). A study has demonstrated that

patients with AML had reduced serum levels of zinc and selenium,

accompanied by elevated copper levels, suggesting that disruptions

in copper metabolism contribute to disease progression (187). Since LSCs contain higher copper

levels than normal tissues, researchers have suggested using copper

ion carriers to selectively transport copper ions into tumor cell

mitochondria. This induces intracellular copper overload,

triggering lethal effects such as oxidative stress, proteotoxicity

and mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately achieving the specific

killing of tumor cells (188).

Current copper-targeted therapies for AML focus on

the antitumor effects of copper chelators in hematologic

malignancies (189–191). Disulfiram-copper complexes

demonstrate anti-AML activity in both in vitro and in

vivo assays, and partially overcome drug resistance in AML

cells (192,193). Xu et al (16) demonstrated that disulfiram, either

alone or in combination with copper, inhibited AML cell

proliferation and induced apoptosis through mechanisms involving

inactivation of the NRF2-NF-κB signaling pathway and activation of

the ROS-JNK stress pathway due to copper accumulation. Furthermore,

in the non-obese diabetic/severe combined immune deficiency mouse

model, disulfiram also suppressed the growth of human

CD34+/CD38+ AML cell xenograft tumors,

further confirming its therapeutic potential in vivo. The

clinical translation of copper-targeted therapies faces challenges,

including off-target effects, systemic toxicity and drug resistance

(194). For instance, copper

chelators damage normal cells due to nonspecific binding, while

long-term use of copper transporter inhibitors may lead to

compensatory metabolic adaptation (195). A growing body of evidence

underscores a strong association between cuproptosis and the

pathogenesis of AML (196–198). This includes the dynamic

expression of copper transporter proteins, the regulation of copper

storage proteins, and the interplay between copper metabolism and

the tumor microenvironment (188,194). Further research is needed to

optimize copper carrier targeting with nanodelivery technologies

and explore the synergistic effects of copper overload on cell

death pathways, aiming to enhance therapeutic specificity and

minimize the toxicity risk (194).

Cell death pathways are intricately interlinked,

forming a complex signaling network that collectively governs cell

fate (199). Autophagy also

mitigates pyroptosis and its associated inflammation by removing

inflammatory vesicle components, inflammatory factor precursors and

damaged mitochondria (200).

Autophagy serves a critical and bidirectional role in ferroptosis:

Lipophagy scavenges lipid peroxides, while ferritin phagocytosis, a

selective form of autophagy, releases ferric ions and drives

ferroptosis (201). In the context

of cuproptosis, autophagy may regulate the process by removing

copper-induced aggregation of proteins or damaged mitochondria

(173). Apoptosis, a conventional

form of programmed cell death, is reciprocally suppressed by

necroptosis: The apoptotic executor caspase-8 cleaves and

inactivates RIPK1/RIPK3, key kinases involved in necroptosis

(202). Necroptosis often serves

as an alternative pathway when apoptosis is inhibited (203). By contrast, apoptosis and

pyroptosis are linked by GSDM proteins; caspase-8 cleavage of GSDME

converts apoptosis into an inflammatory form of cell death

characterized by pyroptosis (203). Apoptosis and ferroptosis share

common regulators, such as p53, which initiate both processes.

Additionally, anti-apoptotic proteins can suppress ferroptosis,

while mitochondrial damage induced by ferroptosis may also trigger

apoptosis (204,205). Oxidative or endoplasmic reticulum

stress caused by copper ion accumulation may indirectly activate

apoptotic pathways (178).

Necroptosis and pyroptosis are forms of inflammatory programmed

necrosis that share the upstream signal RIPK1 (206). At the execution level, their

terminal effectors, MLKL and GSDMD, can further interact through

synergistic or competitive mechanisms during pore formation

(207). Both necroptosis and

pyroptosis share ROS triggers with ferroptosis. TNF produced by

necroptosis or inflammatory factors released during pyroptosis can

create a pro-oxidative environment that indirectly promotes

ferroptosis (208). Additionally,

damage-associated molecular patterns released by ferroptosis can

activate inflammatory vesicles, triggering pyroptosis through a

feedback mechanism (209).

Although ferroptosis and cuproptosis have distinct core mechanisms,

both involve metal ions and oxidative stress. Iron and copper

metabolism are interconnected, with key regulatory nodes, such as

mitochondrial function, ROS levels, inflammatory signaling and the

balance of iron/copper/cystine, serving as pivotal points in the

crosstalk between these death pathways (210). Understanding this complex network

is crucial for explaining cell fate regulation during cancer

pathogenesis and for developing precision treatments that target

specific death pathways, as inhibition of one may trigger

compensatory activation of another.

Although preclinical evidence strongly supports

targeting multiple RCD pathways in AML, clinical translation faces

challenges due to variable patient responses (18). The most successful approach to date

focuses on apoptosis, where the combination of the BCL-2 inhibitor

venetoclax and hypomethylating agents has improved outcomes for

elderly patients with AML or those ineligible for intensive

chemotherapy. This strategy has been validated in phase III trials

and has received regulatory approval, providing an effective means

to overcome apoptosis escape (204). Current research is focused on

overcoming venetoclax resistance, particularly by targeting

complementary anti-apoptotic proteins such as MCL-1 or by combining

it with other targeted therapies, such as FLT3 inhibitors. Several

clinical trials are actively exploring these approaches (204,211,212).

By contrast, direct modulation of other RCD

pathways, such as autophagy, necroptosis, pyroptosis and

ferroptosis, is still in its early stages. Current clinical

evidence primarily comes from observations where these death

pathways are incidentally induced by conventional chemotherapies or

targeted therapies. Targeting autophagy has been particularly

challenging due to its context-dependent dual role, with

non-specific inhibitors such as chloroquine showing limited

efficacy, highlighting the need for more precise agents (213). For example, hypomethylating agents

promote GSDME-mediated pyroptosis, while the p53 reactivator

APR-246 induces ferroptosis, suggesting that the partial

therapeutic efficacy of these agents may stem from non-apoptotic

death mechanisms (14,158). However, first-in-class drugs

designed to activate these pathways, such as DPP8/9 inhibitors for

pyroptosis, RIPK1 activators for necroptosis and GPX4 inhibitors

for ferroptosis, have yet to enter clinical trials for AML,

highlighting a translational gap and the need for further research

(13,103,159).

The copper ionophore disulfiram has been used for

decades with sporadic anticancer activity, while its systematic

evaluation in AML is still confined to an early-stage trial,

highlighting a significant translational challenge for the

cuproptosis pathway (214). The

novel copper ionophore electrochlorol is currently under

early-stage investigation for solid tumors, and its potential to

target mitochondria-rich LSCs in AML remains a hypothesis awaiting

clinical validation (188).

Advancing this field requires overcoming several

key challenges: The lack of reliable biomarkers for predicting

treatment response and enabling precise patient stratification;

managing the complex and often severe immune-related toxicities

triggered by inflammatory cell death; the biological complexity and

potential for overlapping toxicities when designing combination

therapies to exploit synergistic effects across pathways; and the

difficulty in creating targeted delivery systems that enhance

efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. In summary,

translation of mechanistic insights into clinical applications

remains a dynamic frontier. The success of venetoclax demonstrates

the potential of targeting cell death pathways. Future efforts

should focus on translating insights from other RCD pathways into

safe and effective clinical strategies, overcoming resistance and

improving AML outcomes by expanding the therapeutic arsenal. The

clinical development targeting the RCD pathway in AML is summarized

in Table I (13,14,103,158,159,188,204,211–214).

AML is a highly aggressive hematologic malignancy

in adults, characterized by a high recurrence rate and treatment

resistance, both of which threaten patient survival (215). Despite advancements in molecular

typing and targeted therapies that have improved the prognosis of

some subtypes, the mechanisms driving AML heterogeneity and its

microenvironmental interactions remain poorly understood (215). The limitations of chemotherapy and

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation have prompted researchers

to explore novel strategies targeting programmed cell death. These

approaches aim to enhance treatment efficacy while reducing damage

to the normal hematopoietic system, either by selectively inducing

LSC clearance or remodeling the bone marrow immune

microenvironment. Studies have shown that regulation of cell death

processes, including autophagy, apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis and cuproptosis, can successfully target drug-resistant

clones (17,216,217). Notably, autophagy can exhibit a

context-dependent dual role in this process. In LSCs, autophagy

helps maintain chemoresistance through homeostatic functions;

however, its overactivation may trigger type II programmed death,

eliminating metabolically compromised cells (53). The BCL-2/MCL-1 balance in the

apoptotic pathway is disrupted in drug-resistant clones, and BH3

mimics can alter mitochondrial apoptotic thresholds, thereby

overcoming anti-apoptotic defenses. In the AML microenvironment,

the RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL necroptosis cascade is suppressed; however,

its activation can bypass apoptosis resistance and induce

inflammatory cell death. Pyroptosis-induced pore formation by GSDM

family proteins and activation of inflammatory vesicles result in a

dual mechanism that eliminates leukemia cells and reshapes the

immunosuppressive microenvironment. Ferroptosis regulates lipid

peroxidation via the GPX4/acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family

member 4 axis, and targeting of GSH metabolism selectively

eliminates resistant subpopulations that are dependent on

antioxidant defenses. The emerging cuproptosis mechanism induces

proteotoxic stress via FDX1-mediated copper ion overload, providing

a novel strategy to target recalcitrant LSCs with abnormal

mitochondrial metabolism. These RCD processes form a networked

system of spatiotemporal regulation. A combinatorial intervention

targeting multiple nodes can synergistically overcome the

death-resistance barrier of leukemia cells, offering a

multidimensional approach to address therapeutic challenges posed

by AML clonal evolution and microenvironmental sheltering.

Combination therapies targeting RCD are being clinically validated,

but their long-term effects on clonal evolution, immune homeostasis

and metabolic reprogramming remain to be fully explored. Future

research should investigate the synergistic impact of different RCD

modalities on AML stem cell maintenance, chemoresistance and

microenvironmental remodeling in order to enable the development of

personalized therapies that precisely target death pathways.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Tianjin Health

Commission, Research Project of TCM and Western Integrative

Medicine (grant no. 2023130), the Tianjin Education Commission,

Tianjin Education Commission Research Project (General Project)

(grant no. 2021KJ145), and the Shi Zhexin Tianjin Famous

Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance Studio (grant no.

tjmzy2406).

Not applicable.

RJ, HC and XY contributed to the conception of the

review, conducted the literature search and screening, and wrote

the original manuscript. LY, YG, CF, XH and GZ assisted with

literature search, analysis of the published data and proofreading

of the drafts. ZS, as the corresponding author, contributed to the

design of the review framework, provided critical revisions for

important intellectual content, and supervised the entire project.

RJ and ZS confirm the accuracy and comprehensive nature of the

literature review presented in this manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Pollyea DA, Altman JK, Assi R, Bixby D,

Fathi AT, Foran JM, Gojo I, Hall AC, Jonas BA, Kishtagari A, et al:

Acute myeloid leukemia, version 3.2023, NCCN clinical practice

guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:503–513. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Moore CG, Stein A, Fathi AT and Pullarkat

V: Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory AML-Novel treatment options

including immunotherapy. Am J Hematol. 100:23–37. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sasaki K, Ravandi F, Kadia TM, DiNardo CD,

Short NJ, Borthakur G, Jabbour E and Kantarjian HM: De novo acute

myeloid leukemia: A population-based study of outcome in the United

States based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

(SEER) database, 1980 to 2017. Cancer. 127:2049–2061. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Halik A, Tilgner M, Silva P, Estrada N,

Altwasser R, Jahn E, Heuser M, Hou HA, Pratcorona M, Hills RK, et

al: Genomic characterization of AML with aberrations of chromosome

7: A multinational cohort of 519 patients. J Hematol Oncol.

17:702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kantarjian H, Borthakur G, Daver N,

DiNardo CD, Issa G, Jabbour E, Kadia T, Sasaki K, Short NJ, Yilmaz

M and Ravandi F: Current status and research directions in acute

myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 14:1632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lee E, Song CH, Bae SJ, Ha KT and Karki R:

Regulated cell death pathways and their roles in homeostasis,

infection, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Exp Mol Med.

55:1632–1643. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Peng J, Zou M, Zhang Q, Liu D, Chen S,

Fang R, Gao Y, Yan X and Hao L: Symphony of regulated cell death:

Unveiling therapeutic horizons in sarcopenia. Metabolism.

172:1563592025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen C, Wang J, Zhang S, Zhu X, Hu J, Liu

C and Liu L: Epigenetic regulation of diverse regulated cell death

modalities in cardiovascular disease: Insights into necroptosis,

pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and cuproptosis. Redox Biol.

76:1033212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sorokin O, Hause F, Wedler A, Alakhras T,

Bauchspiess T, Dietrich A, Günther WF, Guha C, Obika KB, Kraft J,

et al: Comprehensive analysis of regulated cell death pathways:

Intrinsic disorder, protein-protein interactions, and cross-pathway

communication. Apoptosis. 30:2110–2162. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Peng F, Liao M, Qin R, Zhu S, Peng C, Fu

L, Chen Y and Han B: Regulated cell death (RCD) in cancer: Key

pathways and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

7:2862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Seo W, Silwal P, Song IC and Jo EK: The

dual role of autophagy in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol.

15:512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ren J, Tao Y, Peng M, Xiao Q, Jing Y,

Huang J, Yang J, Lin C, Sun M, Lei L, et al: Targeted activation of

GPER enhances the efficacy of venetoclax by boosting leukemic

pyroptosis and CD8+ T cell immune function in acute myeloid

leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 13:9152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chan FK: RIPK3 Slams the Brake on

Leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell. 30:7–9. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ye F, Zhang W, Fan C, Dong J, Peng M, Deng

W, Zhang H and Yang L: Antileukemic effect of venetoclax and

hypomethylating agents via caspase-3/GSDME-mediated pyroptosis. J

Transl Med. 21:6062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An Iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xu B, Wang S, Li R, Chen K, He L, Deng M,

Kannappan V, Zha J, Dong H and Wang W: Disulfiram/copper

selectively eradicates AML leukemia stem cells in vitro and in vivo

by simultaneous induction of ROS-JNK and inhibition of NF-κB and

Nrf2. Cell Death Dis. 8:e27972017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guo Z, Liu Y, Chen D, Sun Y, Li D, Meng Y,

Zhou Q, Zeng F, Deng G and Chen X: Targeting regulated cell death:

Apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and cuproptosis in

anticancer immunity. J Transl Int Med. 13:10–32. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Garciaz S, Miller T, Collette Y and Vey N:

Targeting regulated cell death pathways in acute myeloid leukemia.

Cancer Drug Resist. 6:151–168. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

He R, Liu Y, Fu W, He X, Liu S, Xiao D and

Tao Y: Mechanisms and Cross-talk of regulated cell death and their

epigenetic modifications in tumor progression. Mol Cancer.

23:2672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dikic I and Elazar Z: Mechanism and

medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

19:349–364. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kaushik S and Cuervo AM: The coming of age

of Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19:365–381.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yamamoto H and Matsui T: Molecular

mechanisms of macroautophagy, microautophagy, and

Chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Nippon Med Sch. 91:2–9. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Niu X, You Q, Hou K, Tian Y, Wei P, Zhu Y,

Gao B, Ashrafizadeh M, Aref AR, Kalbasi A, et al: Autophagy in

cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug

Resist Updat. 78:1011702025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sankar DS, Kaeser-Pebernard S, Vionnet C,

Favre S, de Oliveira Marchioro L, Pillet B, Zhou J, Stumpe M,

Kovacs WJ, Kressler D, et al: The ULK1 effector BAG2 regulates

autophagy initiation by modulating AMBRA1 localization. Cell Rep.

43:1146892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Xi H, Wang S, Wang B, Hong X, Liu X, Li M,

Shen R and Dong Q: The role of interaction between autophagy and

apoptosis in tumorigenesis (Review). Oncol Reps. 48:2082022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cook ASI, Chen M, Nguyen TN, Cabezudo AC,

Khuu G, Rao S, Garcia SN, Yang M, Iavarone AT, Ren X, et al:

Structural pathway for PI3-kinase regulation by VPS15 in autophagy.

Science. 388:eadl37872025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nascimbeni AC, Codogno P and Morel E:

Local detection of PtdIns3P at autophagosome biogenesis membrane

platforms. Autophagy. 13:1602–1612. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wani WY, Boyer-Guittaut M, Dodson M,

Chatham J, Darley-Usmar V and Zhang J: Regulation of autophagy by

protein post-translational modification. Lab Invest. 95:14–25.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Huang R, Xu Y, Wan W, Shou X, Qian J, You

Z, Liu B, Chang C, Zhou T, Lippincott-Schwartz J and Liu W:

Deacetylation of nuclear LC3 drives autophagy initiation under

starvation. Mol Cell. 57:456–466. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y,

Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, Mizushima N, Tanida I, Kominami E, Ohsumi

M, et al: A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation.

Nature. 408:488–492. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Rogov V, Dötsch V, Johansen T and Kirkin

V: Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like

proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol

Cell. 53:167–178. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kimmelman AC and White E: Autophagy and

tumor metabolism. Cell Metab. 25:1037–1043. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Santos de Macedo BG, Albuquerque de Melo

M, Pereira-Martins DA, Machado-Neto JA and Traina F: An updated

outlook on autophagy mechanism and how it supports acute myeloid

leukemia maintenance. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1879:1892142024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nomura N, Ito C, Ooshio T, Tadokoro Y,

Kohno S, Ueno M, Kobayashi M, Kasahara A, Takase Y, Kurayoshi K, et

al: Essential role of autophagy in protecting neonatal

haematopoietic stem cells from oxidative stress in a

p62-independent manner. Sci Rep. 11:16662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen Y, Luo X, Zou Z and Liang Y: The role

of reactive oxygen species in tumor treatment and its impact on

bone marrow hematopoiesis. Curr Drug Targets. 21:477–498. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sharma P, Piya S, Ma H, Baran N, Anna Zal

M, Hindley CJ, Dao K, Sims M, Zal T, Ruvolo V, et al: ERK1/2

inhibition overcomes resistance in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and

alters mitochondrial dynamics. Blood. 138:33382021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Folkerts H, Wierenga AT, van den Heuvel

FA, Woldhuis RR, Kluit DS, Jaques J, Schuringa JJ and Vellenga E:

Elevated VMP1 expression in acute myeloid leukemia amplifies

autophagy and is protective against venetoclax-induced apoptosis.

Cell Death Dis. 10:4212019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Khan A, Singh VK, Thakral D and Gupta R:

Autophagy in acute myeloid leukemia: A paradoxical role in

chemoresistance. Clin Transl Oncol. 24:1459–1469. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Heydt Q, Larrue C, Saland E, Bertoli S,

Sarry JE, Besson A, Manenti S, Joffre C and Mansat-De Mas V:

Oncogenic FLT3-ITD supports autophagy via ATF4 in acute myeloid

leukemia. Oncogene. 37:787–797. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Omori I, Yamaguchi H, Miyake K, Miyake N,

Kitano T and Inokuchi K: D816V mutation in the KIT gene activation

loop has greater cell-proliferative and anti-apoptotic ability than

N822K mutation in core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Exp

Hematol. 52:56–64.e54. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Larrue C, Heydt Q, Saland E, Boutzen H,

Kaoma T, Sarry JE, Joffre C and Récher C: Oncogenic KIT mutations

induce STAT3-dependent autophagy to support cell proliferation in

acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogenesis. 8:392019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zou Q, Tan S, Yang Z, Zhan Q, Jin H, Xian

J, Zhang S, Yang L, Wang L and Zhang L: NPM1 mutant mediated PML

delocalization and stabilization enhances autophagy and cell

survival in leukemic cells. Theranostics. 7:2289–2304. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Folkerts H, Hilgendorf S, Wierenga ATJ,

Jaques J, Mulder AB, Coffer PJ, Schuringa JJ and Vellenga E:

Inhibition of autophagy as a treatment strategy for p53 wild-type

acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 8:e29272017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang Y, Pu J and Yang Y: Glycolysis and

chemoresistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Heliyon. 10:e357212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang YH, Israelsen WJ, Lee D, Yu VWC,

Jeanson NT, Clish CB, Cantley LC, Vander Heiden MG and Scadden DT:

Cell-state-specific metabolic dependency in hematopoiesis and

leukemogenesis. Cell. 158:1309–1323. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen S, Tao Y, Wang Q, Ren J, Jing Y,

Huang J, Zhang L and Li R: Glucose Induced-AKT/mTOR activation

accelerates glycolysis and promotes cell survival in acute myeloid

leukemia. Leuk Res. 128:1070592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Stevens BM, Jones CL, Pollyea DA,

Culp-Hill R, D'Alessandro A, Winters A, Krug A, Abbott D, Goosman

M, Pei S, et al: Fatty acid metabolism underlies venetoclax

resistance in acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Nat Cancer.

1:1176–1187. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Carter JL, Su Y, Qiao X, Zhao J, Wang G,

Howard M, Edwards H, Bao X, Li J, Hüttemann M, et al: Acquired

resistance to venetoclax plus azacitidine in acute myeloid

leukemia: In vitro models and mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol.

216:1157592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang HB, Sun ZK, Zhong FM, Yao FY, Liu J,

Zhang J, Zhang N, Lin J, Li SQ, Li MY, et al: A novel fatty acid

metabolism-related signature identifies features of the tumor

microenvironment and predicts clinical outcome in acute myeloid

leukemia. Lipids Health Dis. 21:792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tcheng M, Roma A, Ahmed N, Smith RW,

Jayanth P, Minden MD, Schimmer AD, Hess DA, Hope K, Rea KA, et al:

Very long chain fatty acid metabolism is required in acute myeloid

leukemia. Blood. 137:3518–3532. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhao Y, Guo H, Niu L and Zhao J: Metabolic

pathways and chemotherapy resistance in acute myeloid leukemia

(AML): Insights into Enoyl-CoA hydratase domain-containing protein

3 (ECHDC3) as a potential therapeutic target. Cancer Pathogenesis

and Therapy; 2025, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Du W, Xu A, Huang Y, Cao J, Zhu H, Yang B,

Shao X, He Q and Ying M: The role of autophagy in targeted therapy

for acute myeloid leukemia. Autophagy. 17:2665–2679. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Li X, Qian Q, Li J, Zhang L, Wang L, Huang

D, Xu Q and Chen W: The RNA-binding protein CELF1 targets ATG5 to

regulate autophagy and promote drug resistance in acute myeloid

leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 16:5992025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Herschbein L and Liesveld JL: Dueling for

dual inhibition: Means to enhance effectiveness of PI3K/Akt/mTOR

inhibitors in AML. Blood Rev. 32:235–248. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Koschade SE, Klann K, Shaid S, Vick B,

Stratmann JA, Thölken M, Meyer LM, Nguyen TD, Campe J, Moser LM, et

al: Translatome proteomics identifies autophagy as a resistance

mechanism to on-target FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia.

Leukemia. 36:2396–2407. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Cao Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhang X, Zuo Y, Ge

X, Sun C, Ren B, Liu Y, Wang M and Lu J: Voacamine initiates the

PI3K/mTOR/Beclin1 pathway to induce autophagy and potentiate

apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Phytomedicine. 143:1568592025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Nössing C and Ryan KM: 50 years on and

still very much alive: ‘Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon

with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics’. Br J Cancer.

128:426–431. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yoon JH and Gores GJ: Death

receptor-mediated apoptosis and the liver. J Hepatol. 37:400–410.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

O'Neill KL, Huang K, Zhang J, Chen Y and

Luo X: Inactivation of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins activates Bax/Bak

through the outer mitochondrial membrane. Genes Dev. 30:973–988.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Xiong S, Mu T, Wang G and Jiang X:

Mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in mammals. Protein Cell.

5:737–749. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Croce CM, Vaux D, Strasser A, Opferman JT,

Czabotar PE and Fesik SW: The BCL-2 protein family: from discovery

to drug development. Cell Death Differ. 32:1369–1381. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Reyna DE, Garner TP, Lopez A, Kopp F,

Choudhary GS, Sridharan A, Narayanagari SR, Mitchell K, Dong B,

Bartholdy BA, et al: Direct activation of BAX by BTSA1 overcomes

apoptosis resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell.

32:490–505.e10. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Singh G, Guibao CD, Seetharaman J,

Aggarwal A, Grace CR, McNamara DE, Vaithiyalingam S, Waddell MB and

Moldoveanu T: Structural basis of BAK activation in mitochondrial

apoptosis initiation. Nat Commun. 13:2502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Tait SW and Green DR: Mitochondria and

cell death: Outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 11:621–632. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Cain K, Bratton SB and Cohen GM: The

Apaf-1 apoptosome: A large caspase-activating complex. Biochimie.

84:203–214. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Kashyap D, Garg VK and Goel N: Intrinsic

and extrinsic pathways of apoptosis: Role in cancer development and

prognosis. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 125:73–120. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zheng L, Yao Y and Lenardo MJ: Death

receptor 5 rises to the occasion. Cell Res. 33:199–200. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Helmke C, Raab M, Rödel F, Matthess Y,

Oellerich T, Mandal R, Sanhaji M, Urlaub H, Rödel C, Becker S and

Strebhardt K: Ligand stimulation of CD95 induces activation of Plk3

followed by phosphorylation of caspase-8. Cell Res. 26:914–934.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Huang K, Zhang J, O'Neill KL, Gurumurthy

CB, Quadros RM, Tu Y and Luo X: Cleavage by Caspase 8 and

mitochondrial membrane association activate the BH3-only protein

bid during TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 291:11843–11851.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

D'Arcy MS: Cell death: A review of the

major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell Biol Int.

43:582–592. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Kantari C and Walczak H: Caspase-8 and

bid: Caught in the act between death receptors and mitochondria.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813:558–563. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Kim WS, Lee KS, Kim JH, Kim CK, Lee G,

Choe J, Won MH, Kim TH, Jeoung D, Lee H, et al: The

caspase-8/Bid/cytochrome c axis links signals from death receptors

to mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Free Radic

Biol Med. 112:567–577. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Moyer A, Tanaka K and Cheng EH: Apoptosis

in cancer biology and therapy. Annu Rev Pathol. 20:303–328. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Pfeffer CM and Singh ATK: Apoptosis: A

target for anticancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 19:4482018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Campbell KJ and Tait SWG: Targeting BCL-2

regulated apoptosis in cancer. Open Biol. 8:1800022018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ashkenazi A, Fairbrother WJ, Leverson JD

and Souers AJ: From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced

selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 16:273–284.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Konopleva M, Pollyea DA, Potluri J, Chyla

B, Hogdal L, Busman T, McKeegan E, Salem AH, Zhu M, Ricker JL, et

al: Efficacy and biological correlates of response in a phase II

study of venetoclax monotherapy in patients with acute myelogenous

leukemia. Cancer Discov. 6:1106–1117. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Wei AH, Strickland SA Jr, Hou JZ, Fiedler

W, Lin TL, Walter RB, Enjeti A, Tiong IS, Savona M, Lee S, et al:

Venetoclax combined with Low-dose cytarabine for previously

untreated patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Results from a

Phase Ib/II study. J Clin Oncol. 37:1277–1284. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman

MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, Konopleva M, Döhner H, Letai A, Fenaux P, et

al: Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute

myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 383:617–629. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Jiao CQ, Hu C, Sun MH, Li Y, Wu C, Xu F,

Zhang L, Huang FR, Zhou JJ, Dai JF, et al: Targeting METTL3

mitigates venetoclax resistance via proteasome-mediated modulation

of MCL1 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 16:2332025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Chai J, Du C, Wu JW, Kyin S, Wang X and

Shi Y: Structural and biochemical basis of apoptotic activation by

Smac/DIABLO. Nature. 406:855–862. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Carter BZ, Mak PY, Mak DH, Shi Y, Qiu Y,

Bogenberger JM, Mu H, Tibes R, Yao H, Coombes KR, et al:

Synergistic targeting of AML stem/progenitor cells with IAP

antagonist birinapant and demethylating agents. J Natl Cancer Inst.

106:djt4402014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Gencel-Augusto J and Lozano G: Targeted

degradation of mutant p53 reverses the Pro-oncogenic

Dominant-negative effect. Cancer Res. 85:1955–1956. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Tuval A, Strandgren C, Heldin A,

Palomar-Siles M and Wiman KG: Pharmacological reactivation of p53