Platelets are universally recognized for pivotal

role in hemostasis. However, emerging evidence has revealed their

substantial involvement in cancer progression (1). This seminal study revealed how

platelets become indispensable accomplices of circulating tumor

cells (CTCs). The molecular crosstalk between platelets and CTCs

plays a vital role in tumor metastasis, the primary cause of

cancer-related mortality. CTCs, identified as malignant cells

shedding from primary tumors into the vasculature, serve as the

precursors to metastasis by disseminating via the bloodstream to

distant organs (2). Understanding

CTCs helps further explore platelet roles in CTC generation and

metastasis. Platelets confer multifaceted protection to CTCs

through direct or indirect interactions: i) shielding from immune

surveillance and hemodynamic shear forces, and ii) facilitating

endothelial adhesion and extravasation (3,4).

Mechanistically, platelet-derived bioactive molecules (for example,

TGF-β) induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), enabling

tumor cell detachment and intravasation (3). Furthermore, platelet-tumor aggregates

formed via surface receptor interactions enhance CTC survival and

hematogenous spread (5,6).

As time goes by, our comprehension of the

platelet-CTC crosstalk has been continuously deepened, gradually

revealing its significant relationships in multiple aspects such as

promoting the survival of tumor cells, immune escape and metastatic

dissemination (7). Extending the

study of Wang et al (7),

these mechanisms underlying platelet-CTC crosstalk were further

elucidated and their diagnostic and therapeutic potential were

explored. The present review synthesizes contemporary insights into

the following aspects: i) the historical context and progression of

platelet-CTC crosstalk; ii) the molecular mechanisms underlying

platelet-CTC interactions; iii) the bidirectional interactions

between platelets and CTCs; iv) the diagnostic utility of

platelet-CTC-derived biomarkers in liquid biopsies; and v) emerging

therapeutic strategies targeting the platelet-CTC interface.

Platelets are primarily recognized for their

critical function in hemostasis; however, their multifaceted roles

in oncogenesis have garnered increasing scientific interest.

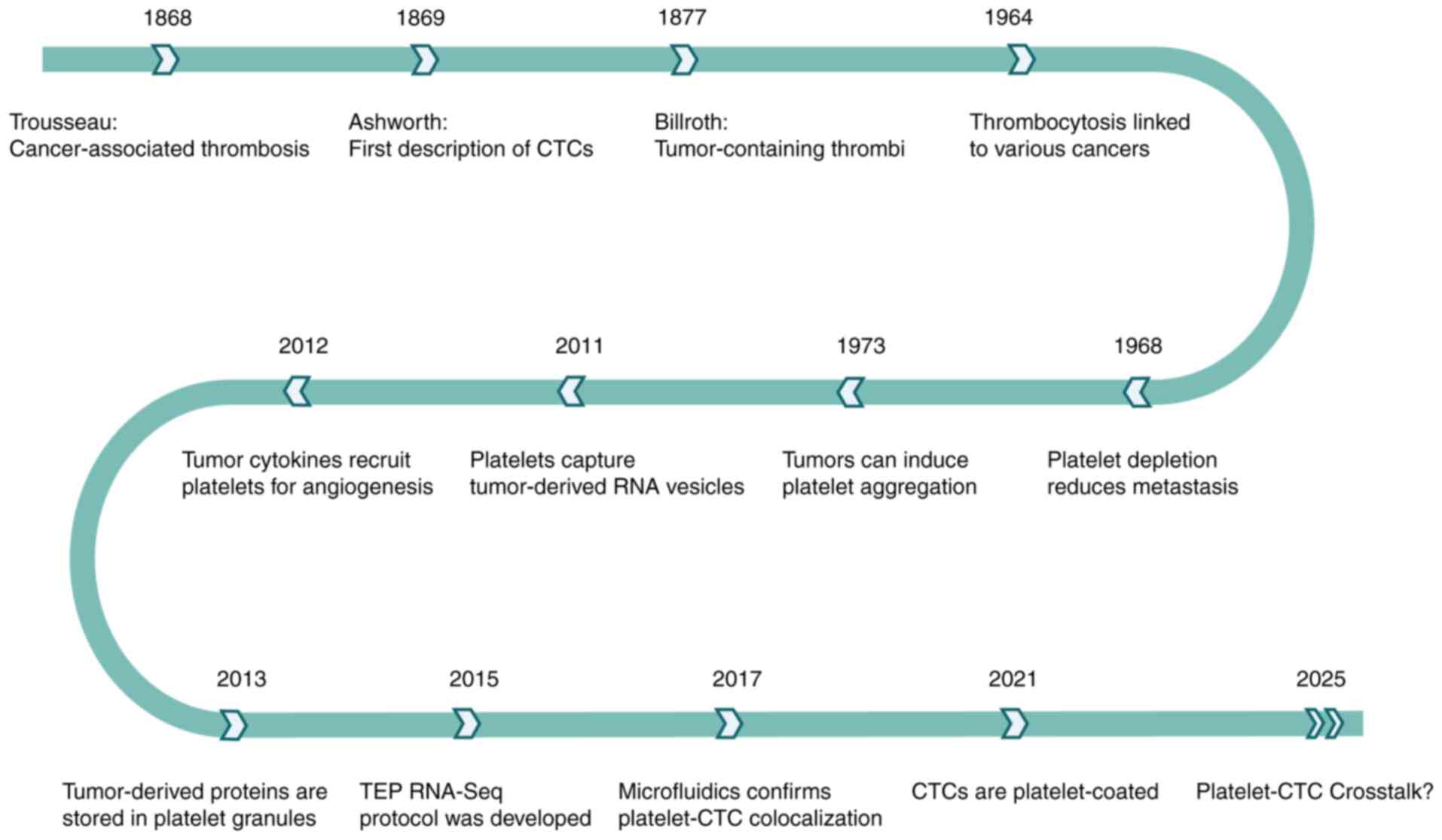

Seminal insights into this relationship emerged in the late 19th

century. In 1868, Trousseau (8)

reported an association between malignancy and spontaneous

coagulation, implicating platelet involvement. Subsequently in

1869, Ashworth documented the presence of aberrant neoplastic cells

within the circulatory system, now acknowledged as the inaugural

identification of CTCs (9). In

1877, Billroth (10) observed

‘thrombi with tumor components’ within the tumor metastasis,

further establishing a direct connection between cancer cells and

blood platelets. Advancing to the mid-20th century, a comprehensive

analysis of blood smears from 14,000 patients revealed a

significant correlation between increased platelet levels and

cancer incidence (11). The

findings indicated that thrombocythemia was notably more prevalent

in malignancies of the lung, stomach, colorectal tract, breast and

ovary. In 1968, Gasic et al (12) observed that thrombocytopenia was

associated with cancer metastasis in murine models. Injecting mice

with antiplatelet serum significantly reduced the number of

metastatic foci; this effect was reversible through platelet-rich

plasma infusion. These findings underscore platelets' facilitatory

role in metastatic dissemination.

In the late 20th century, research elucidated

complex bidirectional interactions between tumors and platelets.

Numerous malignancies induce platelet aggregation both in

vitro and in vivo, resulting in thrombocytopenia,

frequently associated with pulmonary platelet sequestration

(13). By 2011, mechanistic studies

revealed that platelets contribute to cancer progression via

internalization of RNA from tumor-derived extracellular vesicles

(EVs), establishing an RNA transfer network within the bloodstream

by releasing pro-tumorigenic vesicles (14). Concomitantly, tumor-secreted

cytokines are internalized by platelets, recruiting them to the

neoplastic site to support angiogenesis (15). Platelets sequester these proteins

via α-granules, thereby modulating specific cellular pathways

through regulated exocytosis (16).

Clinical investigations concurrently identified thrombocytosis as

an independent prognostic factor in primary lung carcinoma,

suggesting platelet count as a straightforward biomarker for risk

stratification (17,18). Collectively, these advances

highlight platelets' integral roles beyond hemostasis, encompassing

tumor proliferation, metastasis and vascular remodeling.

The advent of microfluidic technology in the 21st

century has revolutionized the research of platelet-CTC crosstalk.

In 2017, microfluidic-based isolation leveraged platelet-derived

surface markers on CTCs, confirming platelet-CTC co-localization

(19). In 2021, Lim et al

(20) discovered using centrifugal

microfluidic technology that 90.7% of CTCs were platelet-coated,

and platelet-encased CTC clusters correlated with rapid disease

progression. Recent investigations (21) have elucidated the molecular

mechanisms underlying the crosstalk between platelets and CTCs. The

interplay provides a critical scientific foundation for advancing

metastasis research and harbors significant potential for clinical

applications. Since the initial recognition of platelet-tumor

interactions in the 19th century, the field has undergone

substantial evolution, with contemporary studies comprehensively

exploring the platelet-CTC crosstalk to uncover pro-tumorigenic

effects (Fig. 1).

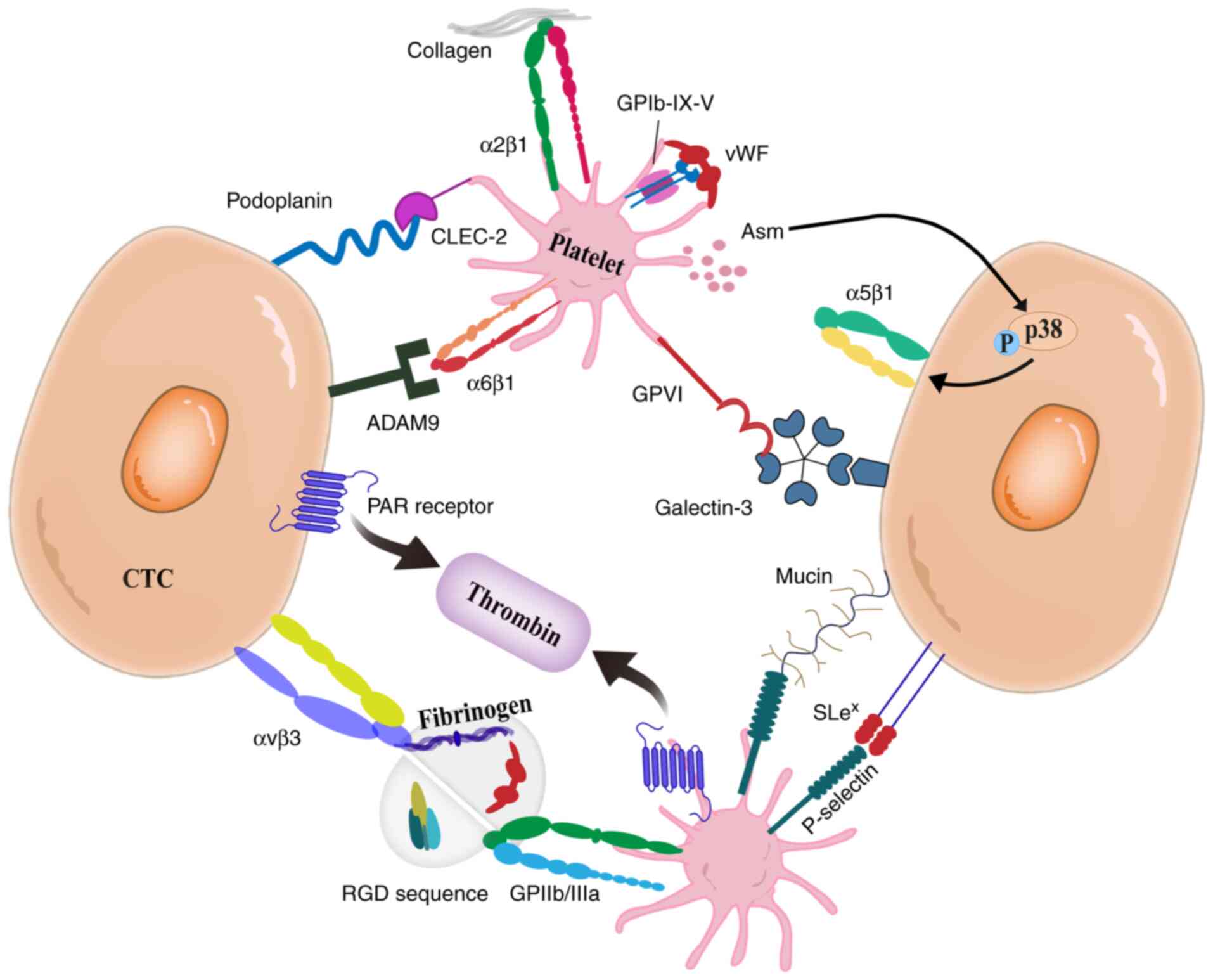

The interplay between platelets and CTCs is

primarily mediated by direct surface receptor binding and by

extracellular proteins that facilitate receptor bridging (Fig. 2). Building on the previous study of

Erpenbeck and Schön (22), the

adhesive mechanisms underlying platelet-CTC crosstalk were refined,

clearly revealing the physical basis of their interaction. Key

mechanisms include: i) the engagement of platelet C-type

lectin-like receptor 2 (CLEC-2) with Podoplanin expressed on tumor

cells, which induces platelet activation and facilitates tumor cell

metastasis (6); ii) the interaction

of the platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX–V complex with tumor cells

via von Willebrand factor (vWF), mediating adhesion (22); iii) platelet GPIIb/IIIa (αIIbβ3

integrin) binding to ligands such as fibrinogen and vWF, enhancing

platelet-tumor cell aggregation (23–25);

iv) metastatic potential is augmented by platelet GPVI receptor

interactions with galectin-3, collagen, or fibrin on tumor cells

(26,27); v) integrin αvβ3 on tumor cells

binding to the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence, promoting adhesion

(28); vi) the activation of

protease-activated receptors (PAR) on tumor cells by thrombin,

enhancing their interaction with platelets (22); vii) integrin α6β1 binding to ADAM9

on tumor cells, promoting metastasis (29); viii) platelet-derived acidic

sphingomyelinase (Asm) inducing p38K phosphorylation in tumor

cells, thereby activating integrin α5β1 and facilitating adhesion

and metastasis (30,31); and ix) P-selectin on the surface of

platelets binds to sialyl Lewisx (SLex) on

the surface of CTCs (22,32). This complex subsequently interacts

with endothelial P-selectin, resulting in CTCs rolling and vascular

retention (22,32). Collectively, these molecular

interactions represent potential therapeutic targets for cancer

treatment.

Secondly, platelet adhesion to CTCs is facilitated

through surface adhesion molecules, including P-selectin, CLEC-2

and GPIIb/IIIa. This interaction promotes CTC-endothelial adhesion

and vascular retention, establishing critical prerequisites for

metastatic colonization in distant organs (38–41). A

previous study by Schlesinger (41)

summarized the role of platelet receptors in tumor metastasis,

which advanced our comprehension of platelet-CTC adhesion. Notably,

surgical stress induces TLR4-dependent ERK5 phosphorylation,

resulting in GPIIb/IIIa integrin activation and subsequent

platelet-CTC aggregation (42).

These aggregates exhibit enhanced entrapment by neutrophil

extracellular traps, thereby promoting their retention within the

pulmonary microvasculature (42).

Heparanase released from α-granules cooperates with P-selectin to

enhance platelet adhesion and promote thrombogenicity, facilitating

metastasis (43). Furthermore,

tissue factor (TF)-induced coagulation facilitates the coating of

CTCs by platelets, leading to the formation of circulating tumor

microemboli (CTM) (44).

Additionally, platelets secrete multiple bioactive

mediators that collectively facilitate metastatic progression. The

platelet release contains TGFβ, ATP, and serotonin, which, in

combination with matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and histamine,

synergistically enhance tumor cell invasiveness, increase vascular

permeability, and promote extravasation and metastatic niche

formation (45–49). For example, TGFβ released via

platelet-CTC crosstalk can activate the metastatic capacity of CTCs

by triggering metabolic reprogramming and bioenergetic adjustment

(50). On the other hand, TGFβ

activates the TGFβ/Smad pathway, inducing SERPINE1/PAI-1 expression

to activate PI3K/AKT signaling, thereby enhancing CTC metastatic

competence (51). Molecular

analyses reveal that platelet-CTC crosstalk upregulates key

oncogenic pathways in CTCs, including MYC, IL33, VEGFB, PTGER2,

PTGS2 and TGFβ2 expression profiles (52). Regulation of angiogenesis is a key

mechanism in tumor progression, with extensive evidence indicating

that platelets directly contribute to this process, likely through

factors released upon their activation (53). Ghosh et al (54) developed an angiogenesis-enabled

tumor microenvironment (TME) chip that recapitulates multicellular

interactions among tumor cells, endothelial cells and platelets in

ovarian cancer, providing direct evidence of platelet-mediated

angiogenesis enhancement. Furthermore, platelets orchestrate

immune-modulatory functions through chemokine release (particularly

CXCL7 and CXCL5 from α-granules), facilitating immune cells'

recruitment and pre-metastatic niche establishment (55,56).

Platelets significantly facilitate EMT during the

dissemination of CTCs via diverse molecular mechanisms (57). TGFβ secreted by platelets triggers

EMT by activating both TGFβ/Smad and NF-κB signaling pathways

(46). Furthermore,

platelet-derived growth factor-D (PDGF-D) promotes EMT by

upregulating transcriptional regulators such as Twist1 and Notch1

in colorectal cancer cells, as well as interacting with PDGFRβ in

tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells, thereby inducing

phosphorylation of key kinases including p38, AKT and ERK (58,59).

Platelets also secrete lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which binds to

LPA receptors on tumor cells to enhance their invasive and

migratory capacities (57,60). Additionally, platelet-derived

microvesicles modulate EMT-associated gene expression in tumor

cells through the transfer of regulatory RNAs, including mRNA and

microRNA (miRNA) (61). Building on

Wang et al's (57) detailed

delineation of platelet-induced EMT signaling pathways, the present

review integrates recent advances to provide a more comprehensive

mechanistic overview. For instance, platelets contribute to CTC

plasticity by maintaining a mesenchymal phenotype during

circulation, enabling more efficient transition to an epithelial

state upon reaching distant metastatic sites. This

epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity augments tumor cell invasiveness

and metastatic potential (52).

These multifaceted roles establish platelets as critical mediators

of cancer metastasis and provide a mechanistic basis for

therapeutic strategies targeting platelet-CTC crosstalk. However,

while current research predominantly focuses on platelet-mediated

EMT in CTC generation, few investigations address how platelets

support CTC colonization via mesenchymal-epithelial transition

(MET) in distant organs.

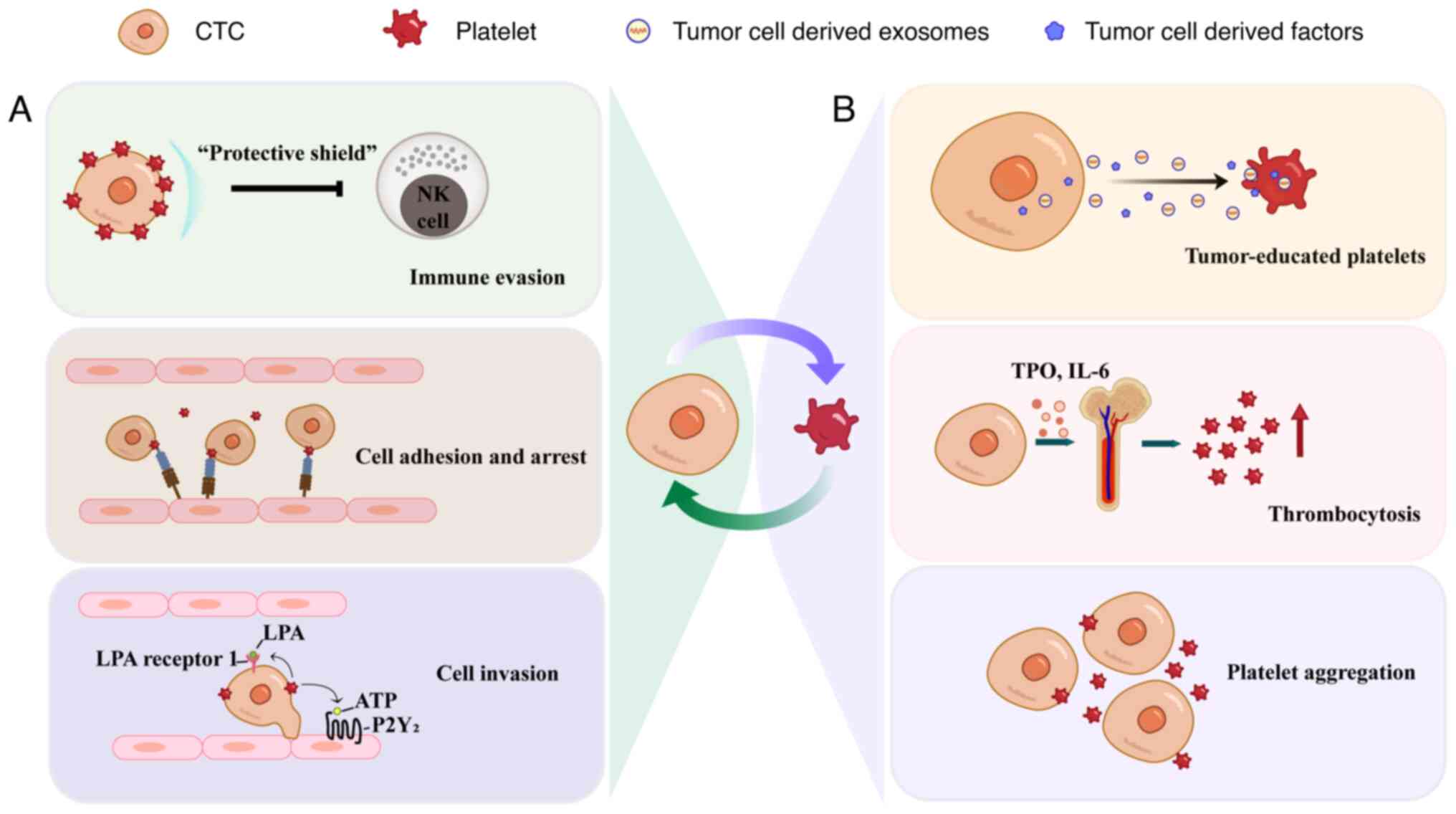

Emerging evidence demonstrates a complex

bidirectional interplay between platelets and tumor cells (7) (Fig.

3B). This interaction induces platelet activation, phenotypic

transformation and transcriptomic reprogramming, culminating in the

formation of tumor-educated platelets (TEPs). TEPs are

characterized by their capacity to sequester and enrich

tumor-specific substances (including proteins, nucleic acids, EVs)

during their interaction with tumors, leading to distinct

alterations in DNA, RNA and protein expression profiles (62). A recent study has demonstrated that

platelets actively internalize DNA-containing EVs and membrane-free

DNA fragments, thereby sequestering tumor-derived DNA (63). These platelets play pivotal roles in

tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis (41). Through interaction with cancer

cells, platelets are ‘educated’ and carry tumor-related biological

information (64). Due to the short

lifespan and enclosed membrane structure, TEPs provide real-time

molecular snapshots of tumor activity; therefore, they are regarded

as promising indicators for cancer detection and disease monitoring

(65).

The tumor-induced platelet education process

operates through several critical aspects. Firstly, tumor cells

initiate platelet aggregation via direct binding to platelet

surface receptors or through extracellular protein-mediated

bridging, which is known as ‘tumor cell-induced platelet

aggregation’ (TCIPA) (33). In

metastatic models, TCIPA formation occurs within 1 min of tumor

cell intravasation, shielding tumor cells from immune attacks and

facilitating tumor growth and metastasis (33,56,66).

Beyond inducing TCIPA, Strasenburg et al (66) elucidated multiple mechanisms of

tumor-mediated platelet activation, substantially expanding our

understanding of this process. Secondly, tumor-derived factors,

including thrombopoietin and interleukin-6, stimulate

megakaryopoiesis and platelet generation in bone marrow, leading to

paraneoplastic thrombocytosis, a well-established poor prognostic

indicator across multiple malignancies (67). Furthermore, tumor cells trigger

platelet degranulation, releasing immunosuppressive (for example,

CD40L) and procoagulant (for example, TF) mediators that reshape

the TME (68,69). Elevated tumor TF expression

initiates the coagulation cascade, inducing platelet activation and

fibrin production. The resulting fibrin mediates TCIPA and enhances

adhesion of CTM to the mesothelium, ultimately promoting polyclonal

metastasis (70). Fibrinogen, upon

conversion to fibrin, may form a matrix scaffold that influences

the recruitment of immune cells, mediates inflammatory responses,

stimulates angiogenesis, and increases vascular permeability,

collectively facilitating the development of a pre-metastatic niche

that supports tumor progression (71). Collectively, tumor cells orchestrate

the function and quantity of platelets through multiple mechanisms,

establishing a microenvironment conducive to tumor development and

metastasis (72).

Cancer diagnosis has historically relied on biopsy,

a method offering high specificity but constrained by invasiveness,

spatial resolution limitations, and incomplete capture of tumor

heterogeneity. To address the increasing need for early cancer

detection and monitoring, non-invasive approaches have been

investigated, including circulating tumor DNA/RNA (ctDNA/RNA) and

CTCs (73–76). ctDNA/RNA analysis enables

plasma-based sequencing. In addition, CTCs can be enriched by size,

density, or surface markers, followed by quantification using

fluorescence immunostaining or morphological examination (77). Moreover, CTCs can be captured intact

or through secreted exosomes for nucleic acid analysis, enhancing

their utility as tumor biomarkers (78).

Platelets, as abundant and readily isolatable blood

components, interact with CTCs to form platelet-CTC complexes,

thereby presenting novel diagnostic opportunities. Platelet-related

indices, including platelet count, mean platelet volume, and

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, are associated with tumor progression

(79,80). However, these parameters may be

confounded by inflammation or chemotherapy-induced bone marrow

suppression (79–81). Technological advancements now

facilitate precise analysis of platelet-CTC complexes, enhancing

diagnostic accuracy and specificity. For instance, a microfluidic

platform was developed to isolate platelet-covered CTCs through a

two-stage strategy: Initial removal of unbound platelets, followed

by antibody-mediated CTC capture targeting platelet-specific

markers (19). The shielding of CTC

surface markers (for example, EpCAM) by platelet encapsulation

impairs antibody-dependent capture and can also alter cellular

morphology and molecular profiles, complicating subsequent

analysis. To address this, bifunctional monomers or zwitterionic 3D

network structures can be employed to suppress platelet adhesion

and preserve CTC integrity (82,83).

This technology represents a promising tool for cancer metastasis

research and non-invasive cancer diagnosis, though further

mechanistic and clinical validation remains essential.

Although anucleate, platelets harbor diverse

biomolecules, including RNA, DNA and proteins derived from

megakaryocytes or the TME. Their 7-to-10-day circulatory lifespan

confers superior stability compared with ctDNA/RNA or exosomes,

making platelets ideal for longitudinal monitoring. During

circulation, platelets continuously assimilate and enrich

tumor-related substances, culminating in the formation of TEPs

(84). TEPs exhibit diagnostic

utility across multiple cancer types, including pan-cancer

detection and companion diagnostics (85). The RNA profiles of TEPs, including

miRNA, lncRNA, mRNA, and small nuclear RNA (snRNA), exhibit

significant potential for tumor diagnosis (Table I) (67,75,86–92).

Specifically, dysregulation of snRNAs (for example, U1, U2 and U5),

which mediate RNA splicing, is mechanistically linked to tumor

progression and displays diagnostic potential in malignancies such

as lung cancer (67,93). Previous studies have detailed the

diagnostic utility of snRNA, mRNA and proteins from TEPs,

highlighting the great potential of TEP RNA profiles in cancer

diagnosis and prognosis monitoring (67,84).

Particularly, platelet RNA-seq emerges as a highly promising

screening methodology (94). This

approach offers several advantages, including minimal invasiveness,

relatively low cost, and absence of radiation exposure. Moreover,

it has the potential to identify primary tumor origins (95). Protocols, such as thromboSeq, were

proposed based on TEP RNA analysis for cancer diagnosis and

therapeutic monitoring. Notably, TEP-derived RNA signatures also

enable dynamic monitoring of tumor progression. Comparative

efficacy of TEP RNA sequencing across tumor types is systematically

summarized in Table I (96).

Platelets accumulate tumor-derived DNA across a wide

spectrum of neoplastic conditions, from advanced malignancies with

high ctDNA load to low-burden diseases such as early-stage cancers

and precancerous colorectal polyps (63). Compared with other blood components,

including red blood cells and mononuclear cells, platelets exhibit

superior efficiency in the uptake of tumor-derived DNA, suggesting

their role as a reservoir for genetic material derived from tumors

(63). An important advantage of

this platelet-based capture is that the DNA is shielded from

nuclease activity, thereby preserving low-frequency mutations that

might otherwise be degraded (63).

Consequently, platelet DNA analysis emerges as a highly promising

tool for liquid biopsy. However, the extraction of platelet DNA

necessitates an initial platelet isolation step to avoid

contamination from other cellular components, rendering this method

more technically complex than ctDNA analysis. Furthermore, the

field currently lacks standardized protocols, large-scale clinical

validation, and robust evidence supporting its diagnostic utility.

Future research in large-scale clinical cohorts is warranted to

translate this discovery into improved strategies for cancer

diagnosis and monitoring.

In addition to RNA and DNA, platelets contain a

diverse array of biologically active proteins that represent a

promising source for cancer biomarkers. Utilizing advanced

proteomics approaches, researchers have identified protein panels

exhibiting differential expression patterns between ovarian cancer

(FIGO stages III–IV) and benign adnexal lesions, with diagnostic

accuracies showing high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (88%)

(97). Similarly, targeted

methodologies involving nano liquid chromatography-tandem mass

spectrometry have revealed seven potential platelet protein markers

associated with early-stage malignancies (98). Nevertheless, the underlying

molecular mechanisms remain insufficiently characterized.

Therefore, further research is essential to elucidate the

mechanisms of these proteins.

Extensive preclinical and clinical evidence

demonstrates that common antiplatelet agents, including aspirin,

clopidogrel and c7E3/ReoPro, exert significant antitumor effects

(99). The multifaceted mechanisms

of aspirin include: Direct suppression of tumor cell proliferation,

inhibition of platelet-CTC crosstalk, and attenuation of

platelet-derived pro-angiogenic and growth factors, cytokines and

chemokines (100). Notably,

aspirin may exert anticancer properties through non-COX-dependent

pathways, including the inhibition of inflammatory processes and

the induction of apoptosis, as well as the suppression of signal

transduction mediated by IκB kinase β and ERK (99,101).

In 2016, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force endorsed low-dose

aspirin for cancer prevention in selected populations (aged 50–69

years), albeit with the caveat that its benefits may be offset by

the risk of major bleeding (102,103).

In addition to aspirin, other antiplatelet agents

also exhibit significant roles in cancer therapy. Preclinical

studies demonstrated the therapeutic potential of P2Y12

inhibitors (for example, clopidogrel and ticagrelor) in disrupting

platelet-tumor interactions, thereby inhibiting cancer cell

migration and metastasis (104–106). Experimental models demonstrate

that ticagrelor and EP3 antagonist DG-041 inhibit platelet-induced

phenotypic changes in colon cancer cells (106). Such changes include the

downregulation of E-cadherin, upregulation of Twist1, enhanced cell

motility and increased platelet aggregation (106).

Some antiplatelet agents inhibit platelet-CTC

crosstalk by targeting specific platelet surface receptors.

Notably, multiple surface proteins, including GPVI, CLEC-2,

GPIIb/IIIa, etc., represent validated therapeutic targets for

attenuating tumor progression and metastasis (107). For instance, GPIIb/IIIa

antagonists (for example, eptifibatide) have demonstrated efficacy

in inhibiting cancer cell metastasis both in vitro and in

animal models (108,109). Furthermore, activated GPIIb/IIIa

receptors serve as dual-function targets for molecular imaging

probes, enabling tumor visualization, and chemotherapeutic agents,

facilitating precise therapeutic delivery (110,111). GPVI blockers (for example,

revacept) reduce thrombosis by disrupting platelet-collagen

interactions and concurrently block platelet-induced EMT and COX-2

expression in cancer cells (112).

Targeting podoplanin on CTCs selectively inhibits the binding of

CLEC-2 receptors on platelets to podoplanin, thereby preventing

platelet-mediated tumor protection (113). Additionally, inhibitors of GPIbα

and P-selectin exhibit potential in preclinical studies for

inhibiting the interaction between platelets and cancer cells

(39,114). Several published reviews have

summarized various antiplatelet agents for cancer therapy,

synthesizing fragmented findings in the field and further advancing

the understanding of targeting platelets for cancer treatment

(78,107). Based on current advances,

integrating antiplatelet agents into comprehensive therapeutic

strategies, such as in combination with chemotherapy or targeted

therapy, may enhance efficacy through complementary mechanisms.

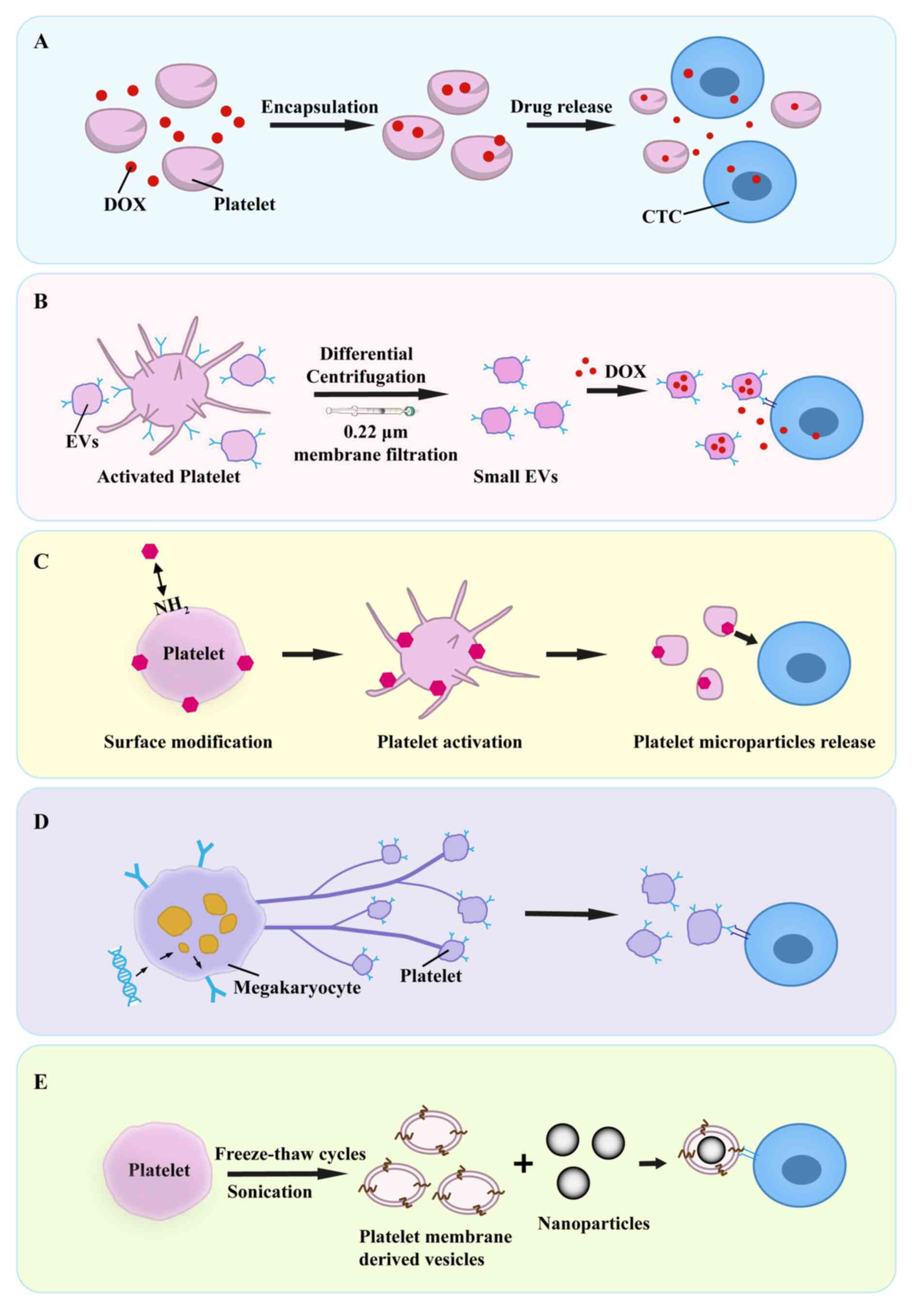

Engineered platelet technologies represent a

promising paradigm for cancer therapy, leveraging fabrication

techniques such as drug loading, genetic engineering and membrane

modification to create intelligent drug delivery systems.

Concerning the combination therapy with chemotherapeutic agents,

two principal strategies have been established. Firstly, the

incorporation of doxorubicin (DOX) into platelets significantly

enhances therapeutic efficacy against lymphoma (Fig. 4A) (115). Secondly, small EVs derived from

platelets can be exploited to encapsulate DOX, subsequently

facilitating targeted delivery to CTCs (Fig. 4B) (116). An innovative approach involves

disrupting CTC clusters through platelet-CTC crosstalk; loading

platelet decoys or lyophilized platelets with tissue-type

plasminogen activator facilitates dissociation of these clusters,

thereby inhibiting metastatic potential (117). Within the domain of genetic

engineering, a study by Li et al (118) utilized lentiviral vector-mediated

transduction of hematopoietic stem cells to generate platelets

expressing tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

(TRAIL) (Fig. 4D). These engineered

platelets substantially reduced hepatic metastasis in a prostate

cancer mouse model while preserving native hemostatic function

(118). Collectively, these

advancements not only enhance treatment specificity but also

minimize off-target effects.

Furthermore, engineered platelets represent a

promising platform for integration with tumor immunotherapy,

enabling novel therapeutic strategies. One approach utilizes

engineered platelets as carriers for immune checkpoint blockade.

Surface conjugation of anti-PD-L1 antibodies onto platelets

leverages their inherent tumor tropism, facilitating targeted

accumulation within post-resection inflammatory niches (119). Upon activation, platelets release

microparticles encapsulating anti-PD-L1 antibodies, which block the

PD-L1/PD-1 interaction between tumor cells and T cells,

consequently reversing immunosuppression and potentiating T

cell-mediated antitumor responses (Fig.

4C) (119). Engineered

platelets can also augment chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell

therapy. Surface-anchored anti-PD-L1 antibodies obstruct the

PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, preventing CAR-T cell exhaustion, while

activated platelets secrete cytokines such as IL-15 to enhance

CAR-T cell proliferation and activity (120). Additionally, platelet-derived

microparticles and chemokines enhance CAR-T cell infiltration into

tumors (120). Beyond immune

modulation, a distinct strategy involves loading engineered

platelets with cytotoxic complexes, such as granzyme B and

perforin, enabling immune-independent cytotoxicity against CTCs

through mechanisms mimicking T cell effector functions, thereby

inhibiting metastasis (121).

These strategies enhance therapeutic efficacy synergistically when

combined with chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

However, research on engineered platelets as

carriers for radiosensitizers remains limited but promising;

targeted tumor delivery improves radiotherapy efficacy while

sparing normal tissues (122,123). In vitro megakaryocyte

cultures provide platelets for engineering, yet scaling

clinical-grade, donation-independent production requires overcoming

yield and quality barriers (124).

Nanotechnology demonstrates significant potential in

modulating platelet-CTC crosstalk. For instance, perfluorocarbon

nanoparticles inhibit platelet activation, thereby enhancing T cell

infiltration into tumors and improving immunotherapy efficacy

(125). Similarly, chlorogenic

acid nanoparticles also suppress platelet activation, disrupting

the tumor vascular barrier to augment chemotherapeutic drug

permeability (126). Additionally,

nanoparticles functionalized with activated platelet membranes

target CTC-associated microthrombi, significantly reducing lung

metastasis in a breast cancer model (Fig. 4E) (127). Photodynamic nanostrategies enable

the release of nitric oxide, which suppresses platelet activation

by downregulating the expression of P-selectin and blocking the

activated configuration of GPIIb/IIIa (128). This intervention not only reduces

tumor-derived procoagulant factors secretion but also avoids

hemorrhagic risks associated with systemic anticoagulation.

Collectively, these approaches provide a novel therapeutic paradigm

for inhibiting tumor metastasis through precise platelet function

modulation.

Several nanostrategies disrupt platelet-CTC

crosstalk without direct targeting. For example, MMP2-responsive

polymer-lipid-peptide nanoparticles encapsulate DOX and an

anti-platelet antibody R300 (129). Upon MMP2 activation in the TME,

the release of R300 induces platelet micro-aggregation and

depletion, which facilitates vascular permeabilization and DOX

delivery for enhanced anticancer efficacy (129). Furthermore, strategies focusing on

adhesion disruption include CD44-targeted DOX-loaded liposomes that

incorporate the Lys-Leu-Val-Phe-Phe (KLVFF) peptide motifs that

self-assemble into nanofiber networks on CTC surfaces, physically

impeding platelet aggregation (130). By blocking platelet-CTC crosstalk,

such approaches effectively suppress tumor invasion and metastasis.

These nanotechnological innovations illustrate promising avenues

for cancer therapy, offering novel insights for developing precise

and efficient treatment strategies.

Beyond the aforementioned strategies, substantial

advancements have been achieved in direct approaches specifically

targeting CTCs. An intelligent nano-diagnostic system was developed

for targeting CTCs of metastatic breast cancer (131). This nano-diagnostic system is

composed of targeted multi-responsive nanomicelles encapsulating

near-infrared fluorescent superparamagnetic iron oxide

nanoparticles, featuring dual-mode imaging and dual toxicity. It

tracks and eliminates CTCs before colonization at distant sites,

thereby impeding metastatic progression (131). Furthermore, CTCs exhibit unique

functional properties that render them ideal targets for

personalized drug sensitivity testing. In vitro isolation

and culture of CTCs, followed by pharmacological screening, can

predict patient-specific therapeutic responses, mitigating the risk

of ineffective or adverse treatments (132).

The present review systematically examines the

mechanisms, diagnostic applications and therapeutic implications of

platelet-CTC crosstalk. Beginning with historical observations such

as cancer-related thrombocytosis, the evolution of research toward

molecular-level insights is traced. A systematic overview of

adhesion molecules between CTCs and platelets is provided,

clarifying the physical basis of their interactions, a perspective

that distinguishes the present study from Yang et al

(21), who focused primarily on

platelets as CTC ‘shelters’. The review further offers a broader

examination of CTC effects on platelets, covering platelet

education (leading to TEP formation), TCIPA, enhanced

thrombocytosis and platelet activation. Beyond existing concepts,

particular emphasis is placed on the novel capacity of platelets to

capture tumor-derived DNA, adding a molecular dimension to TEP

research.

A key focus lies in the clinical translational

potential of TEPs. In addition to systematically summarizing the

diagnostic performance of TEP RNA-seq across multiple cancer types

in tabular form, the review highlights the promising applications

of RNA, DNA and protein profiles in TEPs as emerging biomarkers, an

aspect not sufficiently explored in the study by Yang et al

(21). Moreover, given the

extensive reviews on CTC detection technologies elsewhere, only a

brief overview was provided. Therapeutically, antiplatelet agents

and strategies targeting platelet-CTC crosstalk were reviewed to

highlight promising avenues for future therapeutic development.

Furthermore, advances in smart delivery systems enable exploration

of engineered platelets, leveraging their natural homing properties

for drug loading, and their combination with chemotherapy or

immunotherapy, thereby revealing potential therapeutic avenues.

Progress in nanotechnology targeting this interaction was also

discussed, broadening research perspectives in the field.

The present review advances the field by

synthesizing fundamental research on platelet-CTC crosstalk,

organized around several integrative themes. Its uniqueness lies in

several key integrative aspects: i) a dedicated focus on the

bidirectional crosstalk in the vascular niche; ii) an expansion of

the TEP concept to include the novel dimension of tumor-DNA capture

for diagnostics, complemented by a systematic consolidation of the

current landscape of TEP RNA-seq for cancer diagnosis and its

clinical translational potential; and iii) a comprehensive,

cross-disciplinary synthesis of next-generation therapeutic

platforms (for example, engineered platelets and nanotherapeutics),

moving beyond traditional antiplatelet agents. By bridging

molecular mechanisms with translational applications, the present

review offers a forward-looking perspective and a strategic

resource for ongoing research and therapeutic development.

Looking forward, critical research directions

warrant further investigation: Elucidating the precise mechanisms

through which platelets facilitate CTC extravasation across vessel

walls and influence MET during metastatic colonization;

investigating variations in platelet-CTC crosstalk across diverse

cancer types to enable precise therapeutic targeting; advancing the

clinical translation of TEP-based diagnostics, particularly

validating the efficacy of integrated platelet DNA analysis in

large-scale clinical cohorts; and overcoming challenges in the

large-scale ex vivo culture of functional platelets to

realize the potential of engineered platelet therapies. Future

efforts include preclinical evaluation of translationally promising

engineered platelet strategies, leveraging their inherent

tumor-homing properties for drug delivery, and exploring

synergistic combinations with multimodal treatments. Progress in

these areas may inform novel therapeutic strategies to inhibit

metastatic progression and enhance patient survival outcomes.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Opening Project of Hubei

Key Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine and Multi-disciplinary

Translational Research (grant no. 2023zsyx007).

Not applicable.

LZ wrote the original draft and created the

visualizations. YY acquired funding, conceived the study, performed

critical revision, and provided substantial improvement of the

manuscript. YD reviewed the manuscript, contributed to

visualizations, provided constructive feedback, and polished the

language. FC and LW jointly supervised the study. FC oversaw the

research design and project administration. LW led the

investigation, provided resources, and performed technical

validation. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript and take full responsibility for the integrity and

accuracy of all aspects of the work. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Lou XL, Sun J, Gong SQ, Yu XF, Gong R and

Deng H: Interaction between circulating cancer cells and platelets:

Clinical implication. Chin J Cancer Res. 27:450–460.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lawrence R, Watters M, Davies CR, Pantel K

and Lu YJ: Circulating tumour cells for early detection of

clinically relevant cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:487–500. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Morris K, Schnoor B and Papa AL: Platelet

cancer cell interplay as a new therapeutic target. Biochim Biophys

Acta Rev Cancer. 1877:1887702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sun Y, Li T, Ding L, Wang J, Chen C, Liu

T, Liu Y, Li Q, Wang C, Huo R, et al: Platelet-mediated circulating

tumor cell evasion from natural killer cell killing through immune

checkpoint CD155-TIGIT. Hepatology. 81:791–807. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Qi Y, Chen W, Liang X, Xu K, Gu X, Wu F,

Fan X, Ren S, Liu J, Zhang J, et al: Novel antibodies against GPIbα

inhibit pulmonary metastasis by affecting vWF-GPIbα interaction. J

Hematol Oncol. 11:1172018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Suzuki-Inoue K: Platelets and

cancer-associated thrombosis: Focusing on the platelet activation

receptor CLEC-2 and podoplanin. Blood. 134:1912–1918. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang S, Li Z and Xu R: Human cancer and

platelet interaction, a potential therapeutic target. Int J Mol

Sci. 19:12462018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Trousseau A: Lectures on clinical

medicine, delivered at the Hotel-Dieu, Paris, New Sydenham Society.

London: 1868

|

|

9

|

Ashworth TR: A case of cancer in which

cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after

death. Australas Med J. 14:146–147. 1869.

|

|

10

|

Billroth T: Metastatic tumours. Lectures

on surgical pathology and therapeutics. A handbook for students and

practitioners. The New Sydenham society; London: pp. 352–368.

1877

|

|

11

|

Levin J and Conley CL: Thrombocytosis

associated with malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 114:497–500.

1964. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gasic GJ, Gasic TB and Stewart CC:

Antimetastatic effects associated with platelet reduction. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 61:46–52. 1968. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gasic GJ, Gasic TB, Galanti N, Johnson T

and Murphy S: Platelet-tumor-cell interactions in mice. The role of

platelets in the spread of malignant disease. Int J Cancer.

11:704–718. 1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nilsson RJA, Balaj L, Hulleman E, van Rijn

S, Pegtel DM, Walraven M, Widmark A, Gerritsen WR, Verheul HM,

Vandertop WP, et al: Blood platelets contain tumor-derived RNA

biomarkers. Blood. 118:3680–3683. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kuznetsov HS, Marsh T, Markens BA, Castaño

Z, Greene-Colozzi A, Hay SA, Brown VE, Richardson AL, Signoretti S,

Battinelli EM and McAllister SS: Identification of luminal breast

cancers that establish a tumor-supportive macroenvironment defined

by proangiogenic platelets and bone marrow-derived cells. Cancer

Discov. 2:1150–1165. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kerr BA, McCabe NP, Feng W and Byzova TV:

Platelets govern pre-metastatic tumor communication to bone.

Oncogene. 32:4319–4324. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Costantini V, Zacharski LR, Moritz TE and

Edwards RL: The platelet count in carcinoma of the lung and colon.

Thromb Haemost. 64:501–505. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Pedersen LM and Milman N: Prognostic

significance of thrombocytosis in patients with primary lung

cancer. Eur Respir J. 9:1826–1830. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jiang X, Wong KHK, Khankhel AH, Zeinali M,

Reategui E, Phillips MJ, Luo X, Aceto N, Fachin F, Hoang AN, et al:

Microfluidic isolation of platelet-covered circulating tumor cells.

Lab Chip. 17:3498–3503. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lim M, Park S, Jeong H, Park SH, Kumar S,

Jang A, Lee S, Kim DU and Cho Y: Circulating tumor cell clusters

are cloaked with platelets and correlate with poor prognosis in

unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13:52722021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang J, Xu P, Zhang G, Wang D, Ye B and Wu

L: Advances and potentials in platelet-circulating tumor cell

crosstalk. Am J Cancer Res. 15:407–425. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Erpenbeck L and Schön MP: Deadly allies:

The fatal interplay between platelets and metastasizing cancer

cells. Blood. 115:3427–3436. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Goh CY, Patmore S, Smolenski A, Howard J,

Evans S, O'Sullivan J and McCann A: The role of von Willebrand

factor in breast cancer metastasis. Transl Oncol. 14:1010332021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kitagawa H, Yamamoto N, Yamamoto K, Tanoue

K, Kosaki G and Yamazaki H: Involvement of platelet membrane

glycoprotein Ib and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex in

thrombin-dependent and -independent platelet aggregations induced

by tumor cells. Cancer Res. 49:537–541. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lonsdorf AS, Krämer BF, Fahrleitner M,

Schönberger T, Gnerlich S, Ring S, Gehring S, Schneider SW, Kruhlak

MJ, Meuth SG, et al: Engagement of αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) with ανβ3

integrin mediates interaction of melanoma cells with platelets: A

connection to hematogenous metastasis. J Biol Chem. 287:2168–2178.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mammadova-Bach E, Gil-Pulido J,

Sarukhanyan E, Burkard P, Shityakov S, Schonhart C, Stegner D,

Remer K, Nurden P, Nurden AT, et al: Platelet glycoprotein VI

promotes metastasis through interaction with cancer cell-derived

galectin-3. Blood. 135:1146–1160. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Saha B, Mathur T, Tronolone JJ, Chokshi M,

Lokhande GK, Selahi A, Gaharwar AK, Afshar-Kharghan V, Sood AK, Bao

G and Jain A: Human tumor microenvironment chip evaluates the

consequences of platelet extravasation and combinatorial

antitumor-antiplatelet therapy in ovarian cancer. Sci Adv.

7:eabg52832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Eliceiri BP and Cheresh DA: The role of

alphav integrins during angiogenesis: Insights into potential

mechanisms of action and clinical development. J Clin Invest.

103:1227–1230. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mammadova-Bach E, Zigrino P, Brucker C,

Bourdon C, Freund M, De Arcangelis A, Abrams SI, Orend G, Gachet C

and Mangin PH: Platelet integrin α 6 β 1 controls lung metastasis

through direct binding to cancer cell-derived ADAM9. JCI Insight.

1:e882452016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Carpinteiro A, Becker KA, Japtok L,

Hessler G, Keitsch S, Požgajovà M, Schmid KW, Adams C, Müller S,

Kleuser B, et al: Regulation of hematogenous tumor metastasis by

acid sphingomyelinase. EMBO Mol Med. 7:714–734. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Carpinteiro A, Beckmann N, Seitz A,

Hessler G, Wilker B, Soddemann M, Helfrich I, Edelmann B, Gulbins E

and Becker KA: Role of acid sphingomyelinase-induced signaling in

melanoma cells for hematogenous tumor metastasis. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 38:1–14. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

McCarty OJ, Mousa SA, Bray PF and

Konstantopoulos K: Immobilized platelets support human colon

carcinoma cell tethering, rolling, and firm adhesion under dynamic

flow conditions. Blood. 96:1789–1797. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shu L, Lin S, Zhou S and Yuan T:

Glycan-Lectin interactions between platelets and tumor cells drive

hematogenous metastasis. Platelets. 35:23150372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Egan K, Cooke N and Kenny D: Living in

shear: Platelets protect cancer cells from shear induced damage.

Clin Exp Metastasis. 31:697–704. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nieswandt B, Hafner M, Echtenacher B and

Männel DN: Lysis of tumor cells by natural killer cells in mice is

impeded by platelets. Cancer Res. 59:1295–1300. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Placke T, Kopp H and Salih HR: Modulation

of natural killer cell anti-tumor reactivity by platelets. J Innate

Immun. 3:374–382. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Anvari S, Osei E and Maftoon N:

Interactions of platelets with circulating tumor cells contribute

to cancer metastasis. Sci Rep. 11:154772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fabricius HÅ, Starzonek S and Lange T: The

role of platelet cell surface P-selectin for the direct

platelet-tumor cell contact during metastasis formation in human

tumors. Front Oncol. 11:6427612021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ling T and Liu J, Dong L and Liu J: The

roles of P-selectin in cancer cachexia. Med Oncol. 40:3382023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Liu Y, Zhao F, Gu W, Yang H, Meng Q, Zhang

Y, Yang H and Duan Q: The roles of platelet GPIIb/IIIa and

alphavbeta3 integrins during HeLa cells adhesion, migration, and

invasion to monolayer endothelium under static and dynamic shear

flow. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009:8292432009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Schlesinger M: Role of platelets and

platelet receptors in cancer metastasis. J Hematol Oncol.

11:1252018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ren J, He J, Zhang H, Xia Y, Hu Z,

Loughran P, Billiar T, Huang H and Tsung A: Platelet TLR4-ERK5 axis

facilitates NET-mediated capturing of circulating tumor cells and

distant metastasis after surgical stress. Cancer Res. 81:2373–2385.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cui H, Tan YX, Österholm C, Zhang X, Hedin

U, Vlodavsky I and Li JP: Heparanase expression upregulates

platelet adhesion activity and thrombogenicity. Oncotarget.

7:39486–39496. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Li H, Yu Y, Gao L, Zheng P, Liu X and Chen

H: Tissue factor: A neglected role in cancer biology. J Thromb

Thrombolysis. 54:97–108. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Deryugina EI and Quigley JP: Matrix

metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

25:9–34. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Labelle M, Begum S and Hynes RO: Direct

signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an

epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis.

Cancer Cell. 20:576–590. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Medina VA and Rivera ES: Histamine

receptors and cancer pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 161:755–767.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Schumacher D, Strilic B, Sivaraj KK,

Wettschureck N and Offermanns S: Platelet-derived nucleotides

promote tumor-cell transendothelial migration and metastasis via

P2Y2 receptor. Cancer Cell. 24:130–137. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Skolnik G, Bagge U, Blomqvist G, Djärv L

and Ahlman H: The role of calcium channels and serotonin (5-HT2)

receptors for tumour cell lodgement in the liver. Clin Exp

Metastasis. 7:169–174. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhong C, Wang W, Yao Y, Lian S, Xie X, Xu

J, He S, Luo L, Ye Z, Zhang J, et al: TGF-β secreted by cancer

cells-platelets interaction activates cancer metastasis potential

by inducing metabolic reprogramming and bioenergetic adaptation. J

Cancer. 16:1310–1323. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tong H, Li K, Zhou M, Wu R, Yang H, Peng

Z, Zhao Q and Luo KQ: Coculture of cancer cells with platelets

increases their survival and metastasis by activating the

TGFβ/Smad/PAI-1 and PI3K/AKT pathways. Int J Biol Sci.

19:4259–4277. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Eslami-S Z, Cortés-Hernández LE,

Glogovitis I, Antunes-Ferreira M, D Ambrosi S, Kurma K, Garima F,

Cayrefourcq L, Best MG, Koppers-Lalic D, et al: In vitro cross-talk

between metastasis-competent circulating tumor cells and platelets

in colon cancer: A malicious association during the harsh journey

in the blood. Front Cell Dev Biol. 11:12098462023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Filippelli A, Del Gaudio C, Simonis V,

Ciccone V, Spini A and Donnini S: Scoping review on platelets and

tumor angiogenesis: Do we need more evidence or better analysis?

Int J Mol Sci. 23:134012022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Ghosh LD, Mathur T, Tronolone JJ, Chuong

A, Rangel K, Corvigno S, Sood AK and Jain A: Angiogenesis-enabled

human ovarian tumor microenvironment-chip evaluates pathophysiology

of platelets in microcirculation. Adv Healthc Mater.

13:e23042632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Gleissner CA: Platelet-derived chemokines

in atherogenesis: What's new? Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 10:563–569.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Labelle M, Begum S and Hynes RO: Platelets

guide the formation of early metastatic niches. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 111:E3053–E3061. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wang X, Zhao S, Wang Z and Gao T:

Platelets involved tumor cell EMT during circulation:

Communications and interventions. Cell Commun Signal. 20:822022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Chen J, Yuan W, Wu L, Tang Q, Xia Q, Ji J,

Liu Z, Ma Z, Zhou Z, Cheng Y and Shu X: PDGF-D promotes cell

growth, aggressiveness, angiogenesis and EMT transformation of

colorectal cancer by activation of Notch1/Twist1 pathway.

Oncotarget. 8:9961–9973. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Zhang H, Sun JD, Yan LJ and Zhao XP:

PDGF-D/PDGFRβ promotes tongue squamous carcinoma cell (TSCC)

progression via activating p38/AKT/ERK/EMT signal pathway. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 478:845–851. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Takagi S, Sasaki Y, Koike S, Takemoto A,

Seto Y, Haraguchi M, Ukaji T, Kawaguchi T, Sugawara M, Saito M, et

al: Platelet-derived lysophosphatidic acid mediated LPAR1

activation as a therapeutic target for osteosarcoma metastasis.

Oncogene. 40:5548–5558. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Plantureux L, Mège D, Crescence L,

Carminita E, Robert S, Cointe S, Brouilly N, Ezzedine W,

Dignat-George F, Dubois C and Panicot-Dubois L: The interaction of

platelets with colorectal cancer cells inhibits tumor growth but

promotes metastasis. Cancer Res. 80:291–303. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Li W, Liu JB, Hou LK, Yu F, Zhang J, Wu W,

Tang XM, Sun F, Lu HM, Deng J, et al: Liquid biopsy in lung cancer:

Significance in diagnostics, prediction, and treatment monitoring.

Mol Cancer. 21:252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Murphy L, Inchauspé J, Valenzano G,

Holland P, Sousos N, Belnoue-Davis HL, Li R, Jooss NJ, Benlabiod C,

Murphy E, et al: Platelets sequester extracellular DNA, capturing

tumor-derived and free fetal DNA. Science. 389:eadp39712025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Roweth HG and Battinelli EM: Lessons to

learn from tumor-educated platelets. Blood. 137:3174–3180. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Best MG, Wesseling P and Wurdinger T:

Tumor-educated platelets as a noninvasive biomarker source for

cancer detection and progression monitoring. Cancer Res.

78:3407–3412. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Strasenburg W, Jóźwicki J, Durślewicz J,

Kuffel B, Kulczyk MP, Kowalewski A, Grzanka D, Drewa T and

Adamowicz J: Tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation as an emerging

therapeutic target for cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 12:9097672022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Ding S, Dong X and Song X: Tumor educated

platelet: The novel biosource for cancer detection. Cancer Cell

Int. 23:912023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Amirkhosravi A, Amaya M, Desai H and

Francis JL: Platelet-CD40 ligand interaction with melanoma cell and

monocyte CD40 enhances cellular procoagulant activity. Blood Coagul

Fibrinolysis. 13:505–512. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Mezouar S, Darbousset R, Dignat-George F,

Panicot-Dubois L and Dubois C: Inhibition of platelet activation

prevents the P-selectin and integrin-dependent accumulation of

cancer cell microparticles and reduces tumor growth and metastasis

in vivo. Int J Cancer. 136:462–475. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Miyazaki M, Nakabo A, Nagano Y, Nagamura

Y, Yanagihara K, Ohki R, Nakamura Y, Fukami K, Kawamoto J,

Umayahara K, et al: Tissue factor-induced fibrinogenesis mediates

cancer cell clustering and multiclonal peritoneal metastasis.

Cancer Lett. 553:2159832023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhang J, Mafa T, Zhang J,

Zhu H, Chen L, Zong Z and Yang L: Fibrinogen: A new player and

target on the formation of pre-metastatic niche in tumor

metastasis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 207:1046252025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Catani MV, Savini I, Tullio V and Gasperi

V: The ‘janus face’ of platelets in cancer. Int J Mol Sci.

21:7882020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Allegra A, Cancemi G, Mirabile G, Tonacci

A, Musolino C and Gangemi S: Circulating tumour cells, cell free

DNA and tumour-educated platelets as reliable prognostic and

management biomarkers for the liquid biopsy in multiple myeloma.

Cancers (Basel). 14:41362022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Feng W, Jia N, Jiao H, Chen J, Chen Y,

Zhang Y, Zhu M, Zhu C, Shen L and Long W: Circulating tumor DNA as

a prognostic marker in high-risk endometrial cancer. J Transl Med.

19:512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hu H, Song H, Han B, Zhao H and He J:

Tumor-educated platelet RNA and circulating free RNA: Emerging

liquid biopsy markers for different tumor types. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 29:802024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Pereira-Veiga T, Martínez-Fernández M,

Abuin C, Piñeiro R, Cebey V, Cueva J, Palacios P, Blanco C,

Muinelo-Romay L, Abalo A, et al: CTCs expression profiling for

advanced breast cancer monitoring. Cancers (Basel). 11:19412019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Li TT, Liu H, Yu J, Shi GY, Zhao LY and Li

GX: Prognostic and predictive blood biomarkers in gastric cancer

and the potential application of circulating tumor cells. World J

Gastroenterol. 24:2236–2246. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Haemmerle M, Stone RL, Menter DG,

Afshar-Kharghan V and Sood AK: The platelet lifeline to cancer:

Challenges and opportunities. Cancer Cell. 33:965–983. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Gao L, Zhang H, Zhang B, Zhang L and Wang

C: Prognostic value of combination of preoperative platelet count

and mean platelet volume in patients with resectable non-small cell

lung cancer. Oncotarget. 8:15632–15641. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Mandaliya H, Jones M, Oldmeadow C and

Nordman IIC: Prognostic biomarkers in stage IV non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC): Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte to

monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and

advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI). Transl Lung Cancer

Res. 8:886–894. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Palacios-Acedo AL, Mège D, Crescence L,

Dignat-George F, Dubois C and Panicot-Dubois L: Platelets,

thrombo-inflammation, and cancer: Collaborating with the enemy.

Front Immunol. 10:18052019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Kobayashi S, Sugasaki A, Yamamoto Y,

Shigenoi Y, Udaka A, Yamamoto A and Tanaka M: Enrichment of cancer

cells based on antibody-free selective cell adhesion. ACS Biomater

Sci Eng. 8:4547–4556. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ma Y, Zhang J, Tian Y, Fu Y, Tian S, Li Q,

Yang J and Zhang L: Zwitterionic microgel preservation platform for

circulating tumor cells in whole blood specimen. Nat Commun.

14:49582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Plantureux L, Mège D, Crescence L,

Dignat-George F, Dubois C and Panicot-Dubois L: Impacts of cancer

on platelet production, activation and education and mechanisms of

cancer-associated thrombosis. Cancers (Basel). 10:4412018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Best MG, Sol N, Kooi I, Tannous J,

Westerman BA, Rustenburg F, Schellen P, Verschueren H, Post E,

Koster J, et al: RNA-seq of tumor-educated platelets enables

blood-based pan-cancer, multiclass, and molecular pathway cancer

diagnostics. Cancer Cell. 28:666–676. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

D'Ambrosi S, Nilsson RJ and Wurdinger T:

Platelets and tumor-associated RNA transfer. Blood. 137:3181–3191.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Heinhuis KM, In't Veld SGJG, Dwarshuis G,

van den Broek D, Sol N, Best MG, Coevorden FV, Haas RL, Beijnen JH,

van Houdt WJ, et al: RNA-sequencing of tumor-educated platelets, a

novel biomarker for blood-based sarcoma diagnostics. Cancers

(Basel). 12:13722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Antunes-Ferreira M, D Ambrosi S, Arkani M,

Post E, In't Veld SGJG, Ramaker J, Zwaan K, Kucukguzel ED, Wedekind

LE, Griffioen AW, et al: Tumor-educated platelet blood tests for

non-small cell lung cancer detection and management. Sci Rep.

13:93592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Gao Y, Liu CJ, Li HY, Xiong XM, Li GL,

In't Veld SGJG, Cai GY, Xie GY, Zeng SQ, Wu Y, et al: Platelet RNA

enables accurate detection of ovarian cancer: An intercontinental,

biomarker identification study. Protein Cell. 14:579–590. 2023.

|

|

90

|

Sol N, In't Veld SGJG, Vancura A,

Tjerkstra M, Leurs C, Rustenburg F, Schellen P, Verschueren H, Post

E, Zwaan K, et al: Tumor-educated platelet RNA for the detection

and (pseudo)progression monitoring of glioblastoma. Cell Rep Med.

1:1001012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Mantini G, Meijer LL, Glogovitis I, In't

Veld SGJG, Paleckyte R, Capula M, Le Large TYS, Morelli L, Pham TV,

Piersma SR, et al: Omics analysis of educated platelets in cancer

and benign disease of the pancreas. Cancers (Basel). 13:662020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Łukasiewicz M, Pastuszak K,

Łapińska-Szumczyk S, Różański R, Veld SGJG, Bieńkowski M, Stokowy

T, Ratajska M, Best MG, Würdinger T, et al: Diagnostic accuracy of

liquid biopsy in endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel).

13:57312021.

|

|

93

|

Dong X, Ding S, Yu M, Niu L, Xue L, Zhao

Y, Xie L and Song X and Song X: Small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U5) in

tumor-educated platelets are downregulated and act as promising

biomarkers in lung cancer. Front Oncol. 10:16272020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Xu L, Li X, Li X, Wang X, Ma Q, She D, Lu

X, Zhang J, Yang Q, Lei S, et al: RNA profiling of blood platelets

noninvasively differentiates colorectal cancer from healthy donors

and noncancerous intestinal diseases: A retrospective cohort study.

Genome Med. 14:262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

In't Veld SGJG, Arkani M, Post E,

Antunes-Ferreira M, D'Ambrosi S, Vessies DCL, Vermunt L, Vancura A,

Muller M, Niemeijer AN, et al: Detection and localization of early-

and late-stage cancers using platelet RNA. Cancer Cell.

40:999–1009.e6. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Xiao R, Liu C, Zhang B and Ma L:

Tumor-educated platelets as a promising biomarker for blood-based

detection of renal cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 12:8445202022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Lomnytska M, Pinto R, Becker S, Engström

U, Gustafsson S, Björklund C, Templin M, Bergstrand J, Xu L,

Widengren J, et al: Platelet protein biomarker panel for ovarian

cancer diagnosis. Biomark Res. 6:22018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Sabrkhany S, Kuijpers MJE, Knol JC, Olde

Damink SWM, Dingemans AC, Verheul HM, Piersma SR, Pham TV,

Griffioen AW, Oude Egbrink MGA and Jimenez CR: Exploration of the

platelet proteome in patients with early-stage cancer. J

Proteomics. 177:65–74. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Tao DL, Tassi Yunga S, Williams CD and

McCarty OJT: Aspirin and antiplatelet treatments in cancer. Blood.

137:3201–3211. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Johnson KE, Ceglowski JR, Roweth HG,

Forward JA, Tippy MD, El-Husayni S, Kulenthirarajan R, Malloy MW,

Machlus KR, Chen WY, et al: Aspirin inhibits platelets from

reprogramming breast tumor cells and promoting metastasis. Blood

Adv. 3:198–211. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

McCarty MF and Block KI: Preadministration

of high-dose salicylates, suppressors of NF-kappaB activation, may

increase the chemosensitivity of many cancers: An example of

proapoptotic signal modulation therapy. Integr Cancer Ther.

5:252–268. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Chan AT and Ladabaum U: Where do we stand

with aspirin for the prevention of colorectal cancer? The USPSTF

recommendations. Gastroenterology. 150:14–18. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Chubak J, Whitlock EP, Williams SB,

Kamineni A, Burda BU, Buist DSM and Anderson ML: Aspirin for the

prevention of cancer incidence and mortality: Systematic evidence

reviews for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Intern

Med. 164:814–825. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Bruno A, Dovizio M, Tacconelli S, Contursi

A, Ballerini P and Patrignani P: Antithrombotic agents and cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 10:2532018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Cho MS, Noh K, Haemmerle M, Li D, Park H,

Hu Q, Hisamatsu T, Mitamura T, Mak SLC, Kunapuli S, et al: Role of

ADP receptors on platelets in the growth of ovarian cancer. Blood.

130:1235–1242. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Guillem-Llobat P, Dovizio M, Bruno A,

Ricciotti E, Cufino V, Sacco A, Grande R, Alberti S, Arena V,

Cirillo M, et al: Aspirin prevents colorectal cancer metastasis in

mice by splitting the crosstalk between platelets and tumor cells.

Oncotarget. 7:32462–32477. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Xu XR, Yousef GM and Ni H: Cancer and

platelet crosstalk: Opportunities and challenges for aspirin and

other antiplatelet agents. Blood. 131:1777–1789. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Zhang C, Liu Y, Gao Y, Shen J, Zheng S,

Wei M and Zeng X: Modified heparins inhibit integrin

alpha(IIb)beta(3) mediated adhesion of melanoma cells to platelets

in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 125:2058–2065. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Kononczuk J, Surazynski A, Czyzewska U,

Prokop I, Tomczyk M, Palka J and Miltyk W: αIIbβ3-integrin ligands:

Abciximab and eptifibatide as proapoptotic factors in MCF-7 human

breast cancer cells. Curr Drug Targets. 16:1429–1437. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Yap ML, McFadyen JD, Wang X, Zia NA,

Hohmann JD, Ziegler M, Yao Y, Pham A, Harris M, Donnelly PS, et al:

Targeting activated platelets: A unique and potentially universal

approach for cancer imaging. Theranostics. 7:2565–2574. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Yap ML, McFadyen JD, Wang X, Ziegler M,

Chen YC, Willcox A, Nowell CJ, Scott AM, Sloan EK, Hogarth PM, et

al: Activated platelets in the tumor microenvironment for targeting

of antibody-drug conjugates to tumors and metastases. Theranostics.

9:1154–1169. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Dovizio M, Maier TJ, Alberti S, Di

Francesco L, Marcantoni E, Münch G, John CM, Suess B, Sgambato A,

Steinhilber D, et al: Pharmacological inhibition of platelet-tumor

cell cross-talk prevents platelet-induced overexpression of

cyclooxygenase-2 in HT29 human colon carcinoma cells. Mol

Pharmacol. 84:25–40. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Tsai HJ, Cheng KW, Li JC, Ruan TX, Chang

TH, Wang JR and Tseng CP: Identification of podoplanin aptamers by

SELEX for protein detection and inhibition of platelet aggregation

stimulated by C-type lectin-like receptor 2. Biosensors (Basel).

14:4642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Erpenbeck L, Nieswandt B, Schön M,

Pozgajova M and Schön MP: Inhibition of platelet GPIb alpha and

promotion of melanoma metastasis. J Invest Dermatol. 130:576–586.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Xu P, Zuo H, Chen B, Wang R, Ahmed A, Hu Y

and Ouyang J: Doxorubicin-loaded platelets as a smart drug delivery

system: An improved therapy for lymphoma. Sci Rep. 7:426322017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Zhao J, Ye H, Lu Q, Wang K, Chen X, Song

J, Wang H, Lu Y, Cheng M, He Z, et al: Inhibition of post-surgery

tumour recurrence via a sprayable chemo-immunotherapy gel releasing

PD-L1 antibody and platelet-derived small EVs. J Nanobiotechnology.

20:622022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Schnoor B, Morris K, Kottana RK, Muldoon

R, Barron J and Papa AL: Fibrinolytic platelet decoys reduce cancer

metastasis by dissociating circulating tumor cell clusters. Adv

Healthc Mater. 13:e23043742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Li J, Sharkey CC, Wun B, Liesveld JL and

King MR: Genetic engineering of platelets to neutralize circulating

tumor cells. J Control Release. 228:38–47. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Wang C, Sun W, Ye Y, Hu Q, Bomba HN and Gu

Z: In situ activation of platelets with checkpoint inhibitors for

post-surgical cancer immunotherapy. Nat Biomed Eng. 1:00112017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Hu Q, Li H, Archibong E, Chen Q, Ruan H,

Ahn S, Dukhovlinova E, Kang Y, Wen D, Dotti G and Gu Z: Inhibition

of post-surgery tumour recurrence via a hydrogel releasing CAR-T

cells and anti-PDL1-conjugated platelets. Nat Biomed Eng.

5:1038–1047. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Yang Y, Wang Y, Yao Y, Wang S, Zhang Y,

Dotti G, Yu J and Gu Z: T cell-mimicking platelet-drug conjugates.

Matter. 6:2340–2355. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Chen M, Wang P, Jiang D, Bao Z and Quan H:

Platelet membranes coated gold nanocages for tumor targeted drug

delivery and amplificated low-dose radiotherapy. Front Oncol.

11:7930062021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Xia D, Hang D, Li Y, Jiang W, Zhu J, Ding

Y, Gu H and Hu Y: Au-hemoglobin loaded platelet alleviating tumor

hypoxia and enhancing the radiotherapy effect with low-dose X-ray.

ACS Nano. 14:15654–15668. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Sim X, Poncz M, Gadue P and French DL:

Understanding platelet generation from megakaryocytes: Implications

for in vitro-derived platelets. Blood. 127:1227–1233. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Zhou Z, Zhang B, Zai W, Kang L, Yuan A, Hu

Y and Wu J: Perfluorocarbon nanoparticle-mediated platelet

inhibition promotes intratumoral infiltration of T cells and boosts

immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:11972–11977. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Ke Y, Ma Z, Ye H, Guan X, Xiang Z, Xia Y

and Shi Q: Chlorogenic acid-conjugated nanoparticles suppression of

platelet activation and disruption to tumor vascular barriers for

enhancing drug penetration in tumor. Adv Healthc Mater.

12:22022052023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

127

|

Li J, Ai Y, Wang L, Bu P, Sharkey CC, Wu

Q, Wun B, Roy S, Shen X and King MR: Targeted drug delivery to

circulating tumor cells via platelet membrane-functionalized

particles. Biomaterials. 76:52–65. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Liu R, Xu B, Ma Z, Ye H, Guan X, Ke Y,

Xiang Z and Shi Q: Controlled release of nitric oxide for enhanced

tumor drug delivery and reduction of thrombosis risk. RSC Adv.

12:32355–32364. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Li S, Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhao Y, Ji T, Zhao

X, Ding Y, Zhao X, Zhao R, Li F, et al: Nanoparticle-mediated local

depletion of tumour-associated platelets disrupts vascular barriers

and augments drug accumulation in tumours. Nat Biomed Eng.

1:667–679. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Luo S, Feng J, Xiao L, Guo L, Deng L, Du

Z, Xue Y, Song X, Sun X, Zhang Z, et al: Targeting self-assembly

peptide for inhibiting breast tumor progression and metastasis.

Biomaterials. 249:1200552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Dhandapani R, Sethuraman S, Krishnan UM

and Subramanian A: Self-assembled multifunctional nanotheranostics

against circulating tumor clusters in metastatic breast cancer.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 13:1711–1725. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Smit DJ, Pantel K and Jücker M:

Circulating tumor cells as a promising target for individualized

drug susceptibility tests in cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol.

188:1145892021. View Article : Google Scholar

|