Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent

malignancies worldwide, representing ~1/4 of all cancer diagnoses

and contributing to nearly one-third of cancer-related deaths

(1). New cases of CRC are expected

to increase to 3.2 million and related deaths are expected to reach

1.6 million by 2040. Although most CRC cases occur in developed

countries, the incidence continues to increase in developing

regions (2). Despite advancements

in non-invasive biomarkers for CRC diagnosis and improvements in

surgery, radiotherapy and other treatments, ~50% of CRC cases are

diagnosed at advanced stages, resulting in a 10% 5-year survival

rate (3). Thus, identifying novel

early screening markers and therapeutic targets for CRC is critical

for improving early diagnosis and treatment outcomes.

Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 59 (LRRC59)

is a 244-amino acid endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane protein,

weighing 34 kDa, that was initially identified as a ribosomal

receptor in the ER (4–6). This protein is involved in the

progression of various tumors. Pallai et al (7) observed that LRRC59 translocate from

the ER to the nuclear membrane, facilitating nuclear import of

CIP2A in a PP2A-independent manner, thereby promoting tumorigenesis

in prostate cancer. In lung adenocarcinoma, LRRC59 is significantly

overexpressed and contributes to cancer cell proliferation and

invasion, which is correlated with a poor prognosis (8). Furthermore, LRRC59 is a prognostic

biomarker for risk assessment in patients with urothelial

carcinoma, and its elevated expression is associated with higher

pathological grades. LRRC59 also regulates signaling pathways

during ER stress (ERS). Depletion of LRRC59 potentiates

HYOU1/XBP1-driven ERS signaling, leading to marked inhibition of

malignant cell proliferation and migration (9). These findings suggested that LRRC59 is

broadly involved in tumor development and influences both apoptosis

and ERS. However, the biological functions and molecular mechanisms

of LRRC59 in CRC remain largely uncharacterized, and studies are

needed to determine its role in CRC progression and evaluate its

potential as a therapeutic target.

The ER is a specialized organelle that plays a

critical role in regulating key cellular processes such as protein

synthesis, folding, assembly and transport. ERS arises when

misfolded or unfolded proteins accumulate within the ER, a

condition triggered by factors such as ischemia, oxidative damage,

and disrupted in calcium homeostasis. ERS disrupts ER homeostasis

and affects cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis

(10). A total of 3 critical

sensors of ERS have been identified: protein kinase RNA-like ER

kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and activating

transcription factor 6 (ATF6), which are all embedded in the ER

membrane. Upon activation of ERS, GRP78 dissociates from these

sensors and binds to misfolded or unfolded proteins, initiating the

unfolded protein response (UPR) to restore ER homeostasis (11,12).

However, severe or prolonged ERS can amplify protein misfolding and

initiate both caspase-dependent and independent apoptotic pathways

(13). In various tumor types,

oncogenic factors, and metabolic and transcriptional abnormalities

synergize to maintain a state of chronic ERS in tumor cells

(10,14,15).

Emerging research highlights a pivotal role of ERS in CRC

progression, where ERS-induced activation of PERK or IRE1α through

phosphorylation affects cell fate via the PERK pathway or IRE1α

pathway (16,17). Therefore, the targeted modulation of

ERS is a potential therapeutic approach for CRC. As LRRC59 may

regulate ERS, the starBase database was screened and it was found

that LRRC59 is significantly associated with key genes in the ERS

PERK signaling pathway. Thus, it was hypothesized that LRRC59

affects CRC progression by regulating the PERK signaling

pathway.

The present results demonstrated that LRRC59 was

overexpressed in CRC, leading to the promotion of cell

proliferation, migration and invasion and inhibition of apoptosis.

Additionally, LRRC59 inhibited apoptosis by mitigating PERK

signaling.

Materials and methods

Tissue sample collection

CRC tissues and their corresponding adjacent normal

tissue samples were obtained from six patients who underwent

surgical procedures (July 2024-December 2024) at the Second

Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China).

This was an opportunistic cohort. Detailed clinical and

pathological data for these patients are summarized in Table I [five males and one female, with a

median age of 69.5 years (range 65–80)]. Written informed consent

was obtained for the use of the tissue samples, and the study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital

of Dalian Medical University (approval no. KY2024-136-01; Dalian,

China). The limited specimen availability reflects the stringent

inclusion criteria: i) Signed patient informed consent, ii)

confirmed CRC diagnosis and iii) tissue quality sufficient for

immunohistochemical (IHC) and western blot analysis. While it is

recognized that this precluded formal power calculations, the

present sample size is consistent with exploratory translational

studies (18,19) and yielded statistically significant

results across key endpoints: Animal model outcomes, clinical

specimen IHC analysis and protein expression profiling. It is

acknowledged that larger samples would strengthen these findings

and will address this in future validation studies.

| Table I.Specific details of the patients. |

Table I.

Specific details of the patients.

| Number | Age, years | Sex | Clinical

information | Pathological

information |

|---|

| 1 | 68 | Male | pT2N0M0 | Colonic moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma |

| 2 | 67 | Male | pT3N0M0 | Moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma of the rectum |

| 3 | 75 | Male | pT4N0M0 | Moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma of the rectum |

| 4 | 71 | Male | pT2N0M0 | Colonic moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma |

| 5 | 65 | Female | pT3N0M0 | Colonic moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma |

| 6 | 80 | Male | pT2N0M0 | Colonic moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma |

Cell culture and transfection

The CRC cell lines HCT116 and LoVo, purchased from

Suzhou HyCyte™ Biotechnology Co., Ltd., were cultured in RPMI-1640

medium (cat. no. 11875119; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. A5670701; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(cat. no. SC118; Seven Innovations Biological Technology Co., Ltd).

The cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2

atmosphere. The PERK inhibitor GSK (cat. no. HY-13820;

MedChemExpress) was added to HCT116 and LoVo cells for 12 h (1 µM).

After the cells reached ~50% confluency, LRRC59-small interfering

RNA (siRNA) (20 µM) was transfected (37°C) with Lipofectamine 3000

(cat. no. L3000015; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the cells

were harvested after 24 or 48 h for reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and

western blotting. LRRC59-siRNA constructs were designed by Suzhou

GenePharma Co., Ltd., and siNC was used as a negative control. The

sequences were as follows: si-LRRC59-1:

5′-GACUACUCUACCGUCGGAUTT-3′; si-LRRC59-2:

5′-GUGCAAACAAGGUGUUACATT-3′; and si-NC:

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′. The 293T cell line used in the present

study was purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of

Sciences. The cells were cultured in DMEM medium (cat. no.

PM150210; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. A5670701; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

(cat. no. SC118; Seven Innovations Biological Technology Co., Ltd).

All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2 and were used for subsequent lentiviral

transduction.

Stable transgenic cells via short

hairpin RNA lentiviral transduction

Stable LRRC59-knockdown LoVo cells were constructed

using 3rd-generation lentiviral vectors. The short hairpin

RNA-expressing plasmid pLV3-H1/GFP&Puro-shLRRC59 (target

sequence: 5′-CTGGATCTGTCTTGTAATAAA-3′) and non-targeting control

sh-NC (5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) were obtained from Suzhou

GenePharma Co., Ltd. Viral particles were packaged in 293T cells

(Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences) by co-transfecting

the transfer plasmid with packaging plasmids pGag/Pol, pRev, and

pVSV-G (GenePharma Co., Ltd.) at a mass ratio of 4:2:1:1 using

RNAi-Mate transfection reagent (cat. no. G04001; GenePharma Co.,

Ltd.). Transfection complexes were incubated with the cells in

15-cm dishes for 6h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere,

followed by replacement of the medium with complete medium. Viral

supernatants were harvested 72 h post-transfection, filtered

through 0.45-µm membranes, and concentrated via ultracentrifugation

(32,000 × g, 2 h, 4°C). LoVo cells were transduced with viral

stocks at a multiplicity of infection of 10 in the presence of 5

µg/ml Polybrene (cat. no. H9268; MilliporeSigma) for 24 h at 37°C,

after which the medium was refreshed. Stable populations were

selected with 2 µg/ml puromycin (cat. no. HY-B1743; MedChemExpress)

for 7 days, followed by maintenance in 1 µg/ml puromycin. Knockdown

efficiency was validated by western blotting.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using RNAkey™ Total RNA

Extraction Reagent (cat. no. SM139-02; Seven Innovations Biological

Technology Co., Ltd.). cDNA was synthesized using a two-step

RT-qPCR kit (cat. no. SRQ-01; Seven Innovations Biological

Technology Co., Ltd.) as follows: 50°C for 8 min and 85°C for 5

sec. Real-time PCR amplification of the cDNA templates was

performed using a Two-Step RT and qPCR Kit (cat. no. SRQ-01; Seven

Innovations Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) on a

QuantStudio™ 5 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 sec; 40

cycles at 95°C for 20 sec, and 60°C for 20 sec. The

2−ΔΔCq method was used to calculate the relative mRNA

expression (20). GAPDH was used as

an internal control. The primer sequences were as follows: LRRC59

forward, 5′-CCTTGCCTGTCAGCTTTGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCATGTGCTGTAACACCTTGTTTG-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-CATGTTCGTCATGGGTGTGAA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

CRC cells were transfected with either si-LRRC59 or

si-NC. After 24 h incubation cell counts were determined, and the

cells were seeded into 96-well plates (5×103

cells/well). Following incubation for 24, 48 and 72 h, fresh medium

containing 10% CCK-8 reagent (cat. no. SC119; Seven Innovations

Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) was added. After 2 h, optical

density was measured at 450 nm.

Colony formation assay

CRC cells were transfected with either si-LRRC59 or

si-NC for 24 h. After counting, the cells were seeded into 6-well

plates (1×103 cells/well). The plates were maintained in

culture for one week. Colonies (contains at least 50 cells) were

fixed with 10% methanol (15 min at room temperature) and stained

with 0.1% crystal violet (30 min at room temperature) to enhance

visualization.

Scratch wound healing assay

CRC cells were transfected with si-LRRC59 or si-NC,

seeded into 6-well plates, and cultured to 90% confluence. Scratch

wounds were created using a sterile 10-µl pipette tip, and cellular

debris was removed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Basal medium (without serum) was added, and images of the scratch

areas were captured and measured at both 0 h and 48 h using a Leica

microscope (inverted light microscope). Wound closure percentages

were analyzed using ImageJ 1.54d software (National Institutes of

Health).

Migration and invasion assays

Cells (1×105 cells/well) were plated into

24-well 8-µm pore size Transwell chambers (cat. no. 3422; Corning,

Inc.), with or without Matrigel (cat. no. 354230; Corning, Inc.)

coating (37°C, 6 h). The lower chambers contained basal medium with

10% fetal bovine serum as a chemoattractant. After 48 h, migratory

cells were fixed in methanol (1 h at room temperature) and stained

with 0.1% crystal violet (20 min at room temperature). A total of 5

random fields were selected for analyses.

IHC analysis

CRC tissues, adjacent normal tissues, and xenograft

tumor sections (4-µm thickness) underwent sequential

deparaffinization in xylene and rehydration in a graded ethanol

series at room temperature. Following antigen retrieval in

Tris/EDTA buffer (pH 9.0), endogenous peroxidase activity was

quenched by adding 3% H2O2 incubation (10 min

incubation, room temperature). The sections were rinsed three times

with distilled water (5 min/wash) and equilibrated in PBS for 5

min. After blocking with 5–10% normal goat serum (cat. no.

G1208-5ML; Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min at room

temperature, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the

following primary antibodies: anti-LRRC59 (1:200; cat. no.

27208-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-GRP78 (1:200; cat. no.

11587-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-p-PERK (1:300; cat. no.

PA5-40294; Invitrogen), anti-ATF4 (1:200; cat. no. 28657-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), and anti-CHOP (1:200; cat. no.

15204-1-AP; Proteintech). Next, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. G1213; Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.) was incubated with the sections at 37°C for 1 h. A DAB

Chromogenic Kit cat. no. G1212; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) was used to treat the sections for 15 min, followed by

hematoxylin counterstaining (cat. no. G1004; Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 3 min at room temperature and bright-field

microscopy using a Leica DMI1 system. The staining intensity and

percentage were quantified using the H-score formula: H-score=∑(pi

× i), where pi is the percentage of positive pixels and i is the

intensity grade.

Western blotting and antibodies

Proteins were extracted from tissues and cells using

cell lysis buffer for western blotting and immunoprecipitation (IP;

cat. no. P0013; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) containing

phenyl-methyl-sulphonyl-fluoride (cat. no. SW107; Seven Innovations

Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) and phosphatase inhibitors (cat.

no. SW106; Seven Innovations Biological Technology Co., Ltd.). The

protein concentration was quantified using the BCA assay (cat. no.

KGB2101; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Precast polyacrylamide

gels (7.5–12.5%; cat. no. SW145; Seven Innovations Biological

Technology Co., Ltd) were loaded with 20 µg protein per lane along

with pre-stained protein molecular weight markers (cat. no. SW176;

Seven Innovations Biological Technology Co., Ltd.). Electrophoresis

was performed at 80 V for 30 min followed by 120 V for 60–90 min,

followed by wet transfer (300 mA, 30 min) onto polyvinylidene

fluoride membranes (cat. no. ISEQ00005; MilliporeSigma). The

membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline

containing 0.1% Tween-20 at room temperature for 1 h, followed by

incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The following

primary antibodies were used: β-tubulin (1:10,000; cat. no. AP0064;

Bioworld Technology, Inc.), LRRC59 (1:10,000; cat. no. 27208-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), GRP78 (1:10,000; cat. no. 11587-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), PERK (1:1,000; cat. no. 24390-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), phosphorylated PERK (p-PERK) (1:1,000;

cat. no. AP1501; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), ATF4 (1:10,000; cat.

no. 81798-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), p-EIF2α (1:1,000; cat.

no. AP0692; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), EIF2α (1:10,000; cat. no.

82936-1-PBS; Proteintech Group, Inc.), CHOP (1:1,000; cat. no.

15204-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), Caspase 3 (1:1,0000; cat. no.

82202-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), active-caspase-3 (1:1,000;

cat. no. A11021; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), Bax (1:1,000; cat.

no. A19684; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no.

A19693; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.). Horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated rabbit secondary antibodies (1:2,000; cat.

no. AS014; Abcam) and mouse secondary antibodies (1:2,000; cat. no.

AS003; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) were applied for 1 h at room

temperature. Protein signals were detected using Super ECL Reagent

(cat. no. 36208ES60; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and

visualized using a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.54d

software. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Flow cytometry

HCT116 and LoVo cells (5×104) were

stained using an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (cat.

no. 40302ES50; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The cells

were trypsinized using 0.25% ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic acid-free

trypsin (cat. no. SC108, Seven Innovations Biological Technology

Co., Ltd.) and pelleted by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at

4°C. After two washes with ice-cold PBS (centrifugation: 300 × g,

4°C, 5 min), 5×105 cells were resuspended in 100 µl 1X

Annexin V Binding Buffer. Subsequently, 5 µl FITC-conjugated

Annexin V and 10 µl propidium iodide working solution (20 µg/ml)

were added, followed by gentle vortexing and 15 min incubation in

light-protected conditions at room temperature. The reaction was

terminated by adding 400 µl ice-cold binding buffer. The samples

were maintained on ice and analyzed within 60 min using a NovoCyte

Advanteon flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Apoptosis

levels were assessed using NovoExpress software (version 1.6.2;

Agilent). All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Xenograft tumor formation

Female BALB/c female mice (aged 5 weeks; n=10;

weight, 18.23±0.74 g) were acquired from Beijing Vital River

Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The mice were housed in a

specific pathogen-free grade animal room in individually ventilated

cages within the barrier at a rate of five mice per cage. The mice

were housed under controlled environmental conditions (26–28°C,

40–60% humidity) with a standardized 10 h light/14 h dark

photoperiod. All mice had unrestricted access to standard

laboratory chow and water throughout the study period, along with

environmental enrichment (for example, nesting materials and

shelters). The specific humane endpoint criteria implemented in the

experiment were as follows: i) The tumor volume of any single tumor

did not exceed 2,000 mm3; ii) Tumor ulceration or

necrosis: Progressive ulceration, severe necrosis, or infection of

the tumor surface was expected to be irreversible or cause

significant pain; iii) weight loss: Mice lost more than 20% of

their initial weight within three consecutive days; iv) activity

status and behavioral changes: Mice exhibited severely reduced

activity, hunchbacks, coarse and messy fur, difficulty breathing,

inability to access food or water normally, and other significant

signs of pain or impending death; v) Functional impairment caused

by tumors: Tumor growth significantly impaired the mobility (such

as walking) and normal physiological functions of mice; and vi)

monitoring and execution: Trained researchers observed the

experimental animals at least once daily. Mice were monitored for

any potential signs of humane endpoints twice a day.

When a mouse met any of the humane endpoint criteria

aforementioned, it was euthanized immediately. The maximum tumor

volume was 1372.24 mm3 and the maximum tumor diameter

was 16.14 mm.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd. (approval no. 2024167). The experiments strictly adhered to

the institution's guidelines for animal welfare and use. The mice

were randomly assigned to two groups with five animals per group.

Each mouse received a subcutaneous injection of LoVo cells

(1×107 cells) that had been transfected with either

sh-NC or shLRRC59, resuspended in 100 µl of PBS. Tumor volumes were

measured at 3-day intervals, and the tumors were excised and

weighed after 34 days. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal

injection of 2% tribromoethanol (20 ml/kg), and deep anesthesia was

confirmed by the absence of a pedal reflex. Euthanasia was induced

via cervical dislocation. No experimental procedures were performed

on the mice after tribromoethanol anesthesia.

Our sample size decisions were guided by both

field-specific standards and ethical considerations. Animal studies

(n=5/group): this sample size aligns with established norms for

xenograft tumor models in published literature (21,22).

Consistent with the 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction,

Refinement) under international animal research guidelines, group

sizes were optimized to minimize animal use while maintaining

experimental validity.

The choice of the LoVo cell line for in vivo

studies was based on: Literature-established protocols:

Subcutaneous xenograft models using LoVo are well-documented for

CRC studies (23,24). Ethical optimization: This approach

minimized animal usage while maintaining experimental validity,

consistent with 3R principles. Biological rationale: Complementary

in vitro experiments demonstrated consistent LRRC59 effects

across both HCT116 and LoVo cell lines. Critically, our

dual-cell-line validation confirmed that LRRC59′s modulation of the

PERK pathway occurs independently of cellular context. LoVo cells

were therefore selected for in vivo validation as they

represent a mechanistically conserved model of LRRC59 function in

CRC progression.

Mice were euthanized on Day 34 for two reasons: i)

Tumor size limits: IACUC protocol requires euthanasia before tumor

volume exceeds 2,000 mm3. Projected growth curves

indicated most mice would reach this threshold by Day 34. ii)

Humane endpoints: Mice were monitored daily for distress signs (for

example, >20% weight loss, lethargy, ulceration). Any mouse

meeting these criteria was euthanized immediately; none required

early euthanasia before Day 34. This schedule preempted welfare

violations while allowing meaningful cross-group comparison at a

standardized endpoint.

Blinding method

Blinding was applied to evaluate the results during

the measurement phase of all experiments involving subjective

evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean values accompanied by

standard deviations calculated from three independent experiments.

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0

software (GraphPad, Inc.; Dotmatics). For comparisons between two

groups, two-tailed, paired Student's t-test was used, whereas

one-way analysis of variance was used to analyze multiple groups.

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for all

experimental groups, with results indicating P>0.05 for each

dataset, confirming adherence to normality assumptions. Prior to

ANOVA, homogeneity of variance was further verified using Levene's

test (P>0.05), confirming that all ANOVA prerequisites were

satisfied. For comparisons across the three groups (including

controls), Dunnett's post hoc test was applied. All pairwise

comparisons against the control group showed statistically

significant differences (P<0.05). Statistical significance

thresholds were set at *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001.

Results

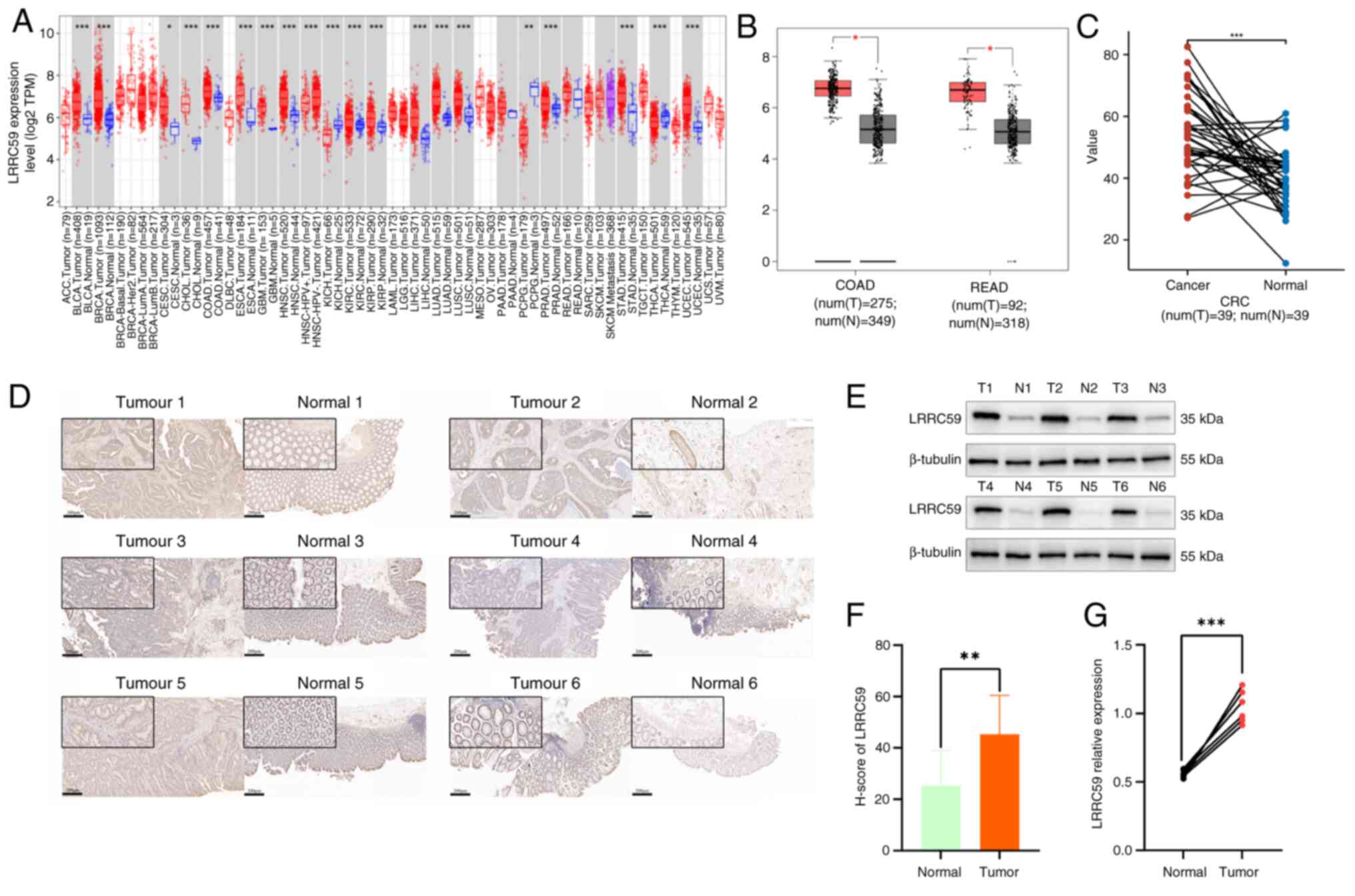

Elevated expression of LRRC59 in CRC

tissues

To evaluate the LRRC59 expression in CRC tissues in

compared with that in normal tissues, mRNA expression levels were

initially analyzed using the TIMER2.0 database (http://timer.comp-genomics.org/) (Fig. 1A). The results revealed

significantly higher LRRC59 mRNA levels in colon adenocarcinoma

tissues than in normal tissues. Further data were acquired from

both paired and unpaired CRC samples using the GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html)

(Fig. 1B) and TCGA databases

(https://www.tcpaportal.org/) (Fig. 1C), respectively. Statistical

analyses showed that LRRC59 mRNA expression was markedly

upregulated in CRC tissues compared with that in corresponding

adjacent normal tissues. To substantiate these results, CRC and

adjacent normal tissues from six patients were analyzed using IHC

(Fig. 1D and F) and western

blotting (Fig. 1E and G). The

results revealed a significant increase in LRRC59 protein

expression in CRC tissues compared with that in their normal tissue

counterparts. Collectively, these findings indicated that LRRC59 is

substantially overexpressed in CRC tissues compared with in normal

paracancerous tissues.

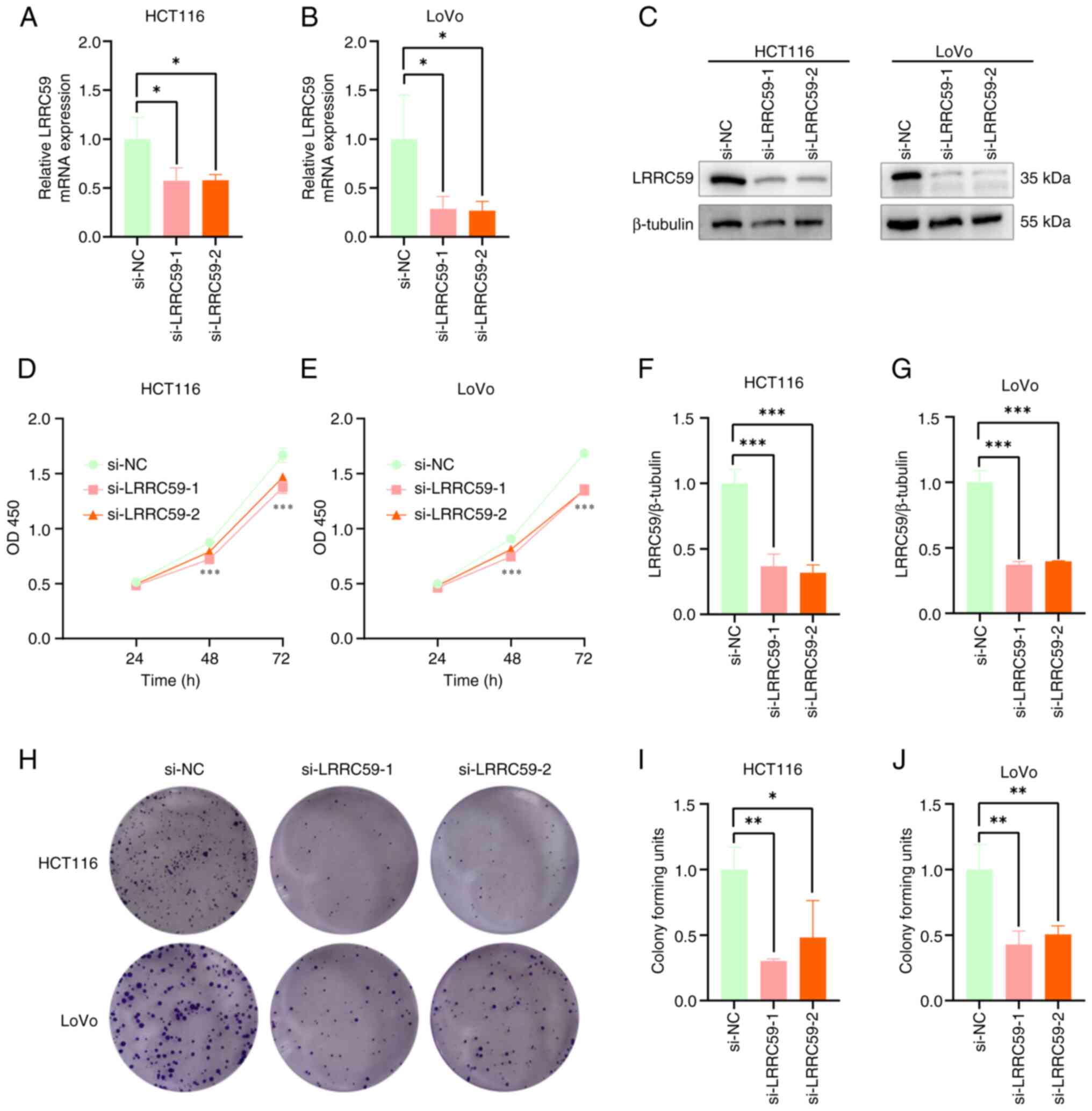

LRRC59 knockdown suppresses CRC cell

proliferation

The function of LRRC59 in promoting CRC cell

proliferation was examined by silencing its expression in HCT116

and LoVo cell lines using siRNA. RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A and B) and western blot analysis

(Fig. 2C-E) confirmed the

successful silencing of LRRC59. Cell viability and proliferation

potential were detected using the CCK-8 (Fig. 2F and G) and colony formation assays

(Fig. 2H-J). These results revealed

reduced colony formation and inhibition of cell proliferation

following LRRC59 knockdown. These findings suggested that LRRC59

promotes CRC cell proliferation.

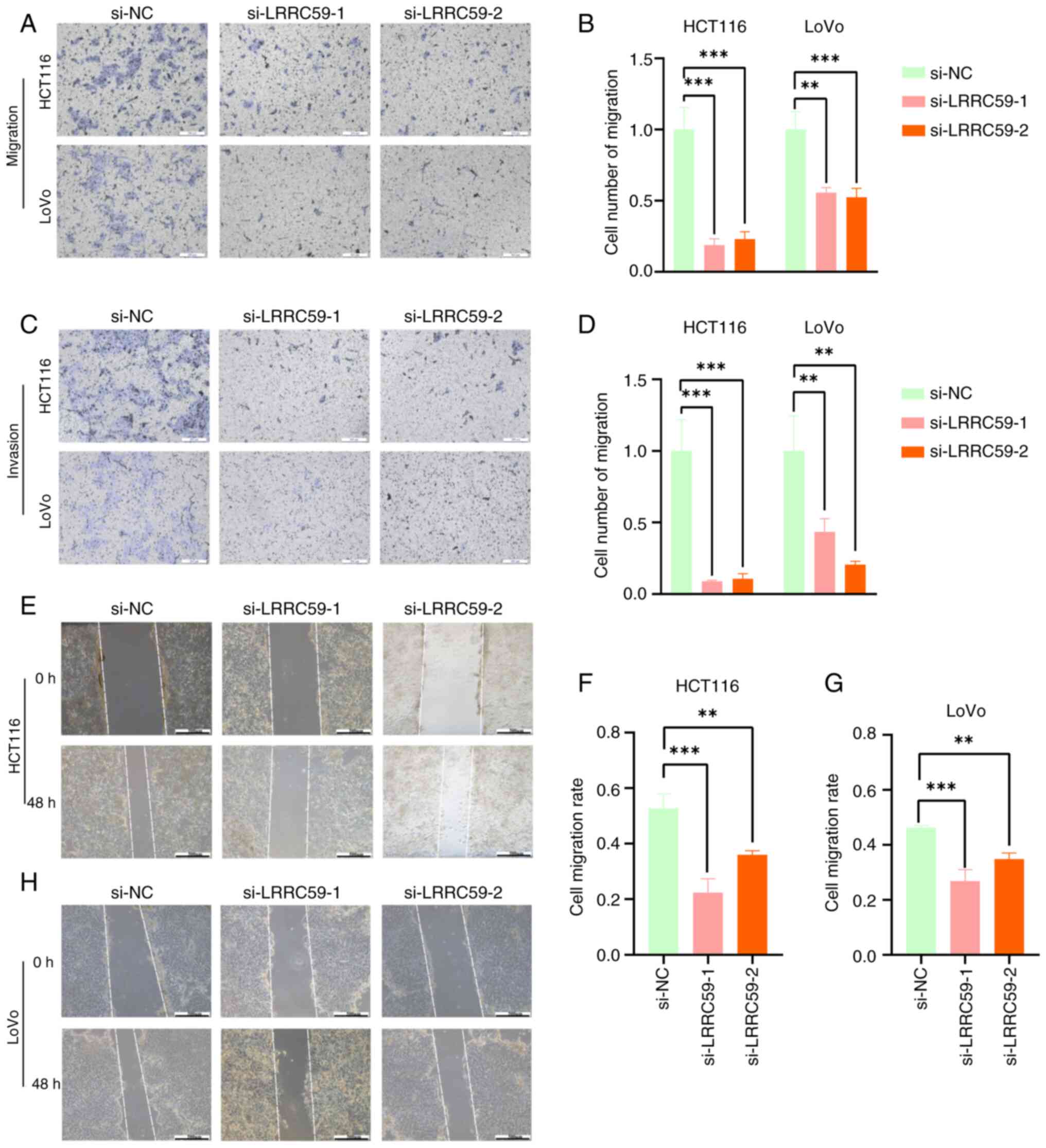

Silencing LRRC59 reduces CRC cell

migration and invasion

The effect of LRRC59 on CRC cell migration and

invasion was evaluated using Transwell and wound healing assays.

LRRC59 silencing significantly reduced the number of cells that

migrated through the porous membrane or Matrigel-coated inserts

(Fig. 3A-D). Similarly, wound

healing assays revealed diminished motility in cells with reduced

LRRC59 expression (Fig. 3E-H).

These results highlighted the role of LRRC59 in promoting CRC cell

migration and invasion.

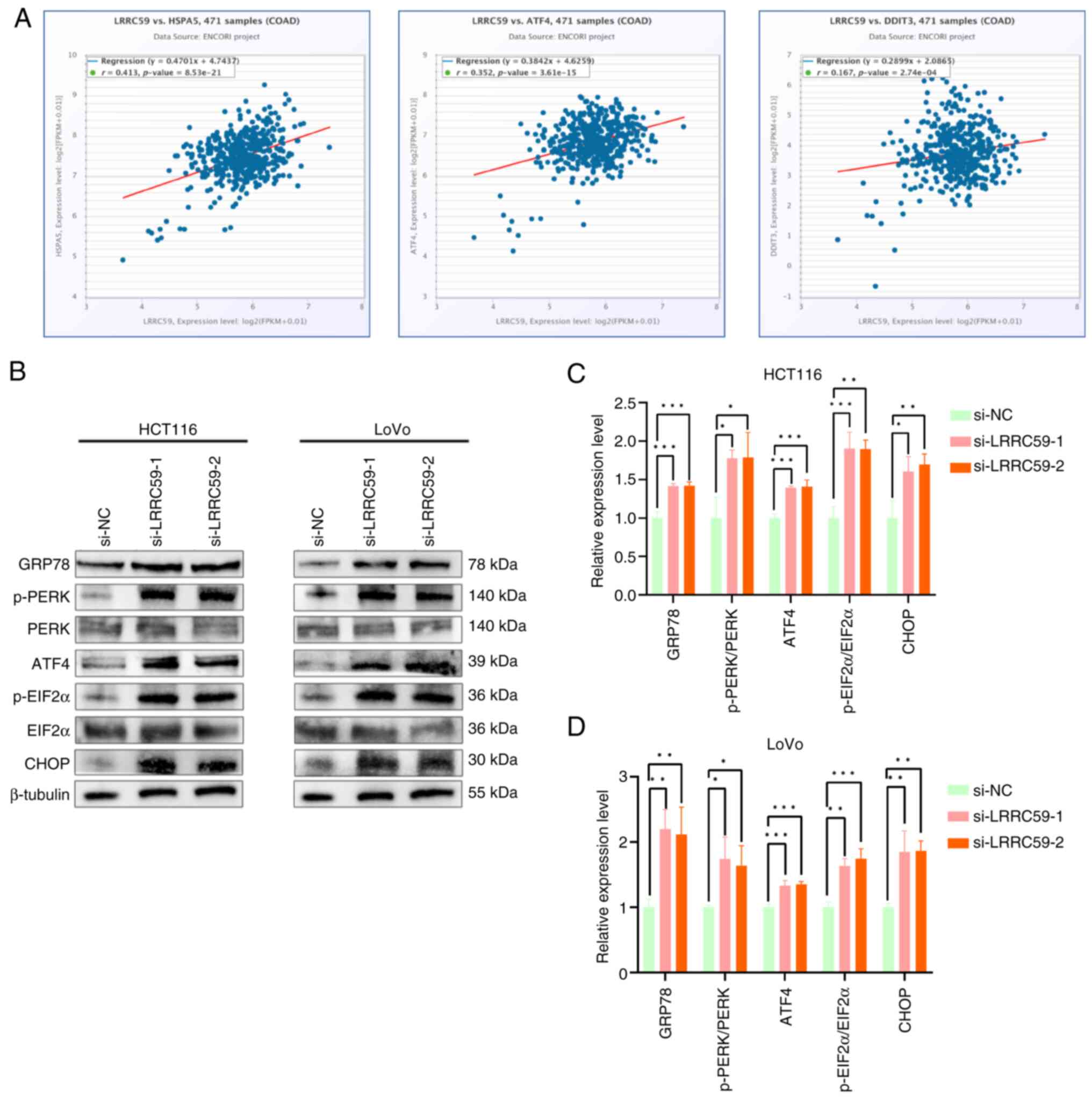

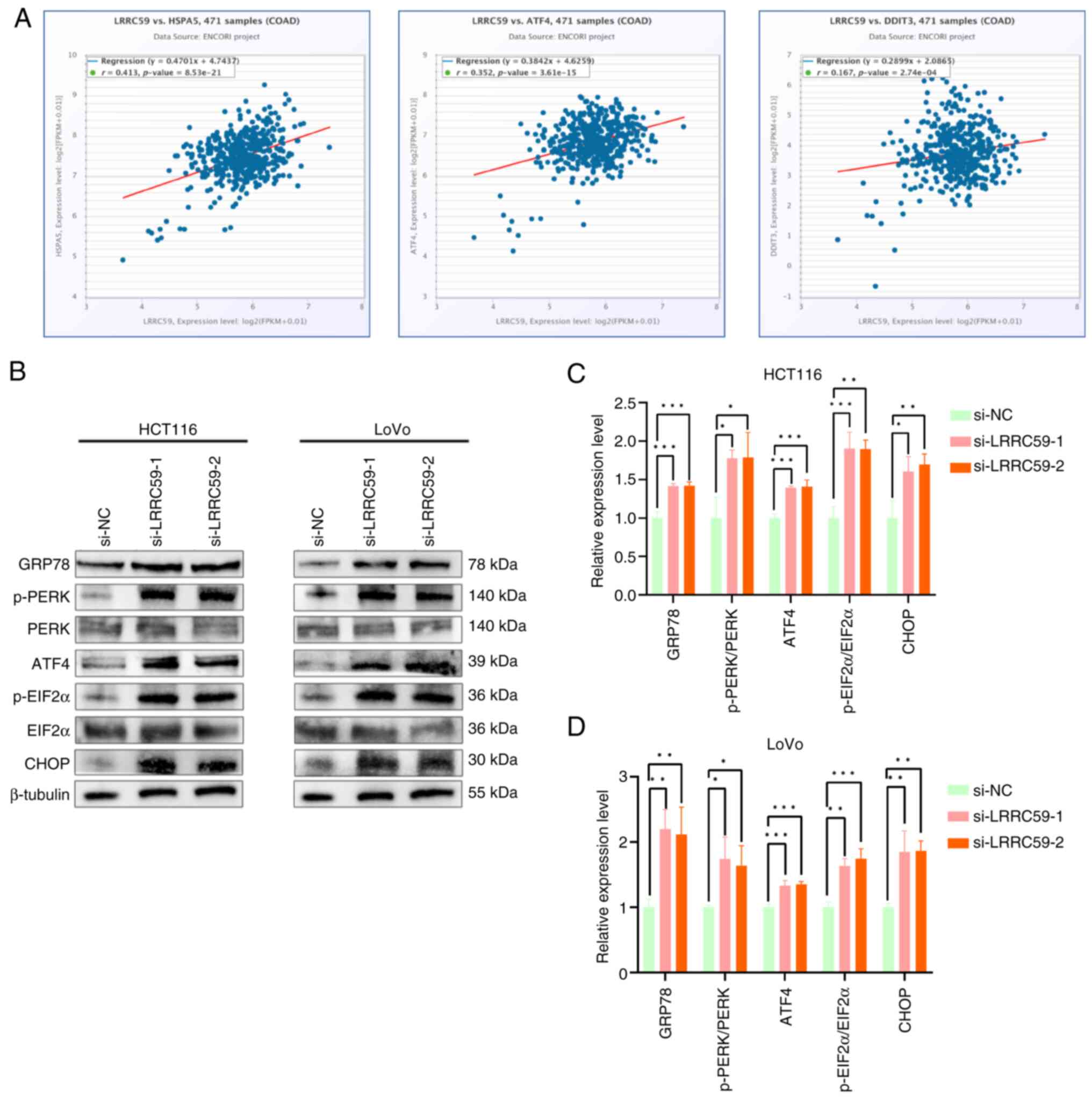

Knockdown of LRRC59 induces activation

of the PERK pathway in CRC cells

Emerging evidence suggests that LRRC59 is involved

in ERS regulation (9).

Bioinformatics analysis using the starBase database (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) revealed a significant

positive correlation between LRRC59 and GRP78 (HSPA5), a master

chaperone of ERS. These results suggested that LRRC59 modulates ERS

signaling, implicating a regulatory role in CRC pathogenesis. The

potential associations between LRRC59 and key regulatory components

of the three UPR branches were subsequently examined: IRE1α, PERK

and ATF6 pathways. The results revealed a significant association

between LRRC59 and PERK signaling pathways (ATF4 and CHOP)

(Fig. 4A). To validate these

findings, LRRC59 in HCT116 and LoVo cells was knocked down,

followed by western blot analysis of PERK pathway components.

Altered expression of PERK pathway-related proteins was observed,

including increased levels of GRP78, p-PERK, p-EIF2α, ATF4 and

CHOP, in LRRC59-silenced cells (Fig.

4B-D). These data demonstrated that LRRC59 is a negative

regulator of PERK-mediated ERS signaling in CRC cells.

| Figure 4.LRRC59 regulates the PERK-mediated

ERS signaling pathway. (A) According to the starBase database,

LRRC59 is associated with ERS pathway key genes GRP78, ATF4, and

CHOP in colorectal cancer. (B-D) Western blot analysis of PERK

pathway-related proteins (GRP78, p-PERK, PERK, ATF4, p-EIF2α, EIF2α

and CHOP). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ER,

endoplasmic reticulum; PERK, protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase;

ERS, ER stress; p-, phosphorylated; si-, small interfering; NC,

negative control; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma. |

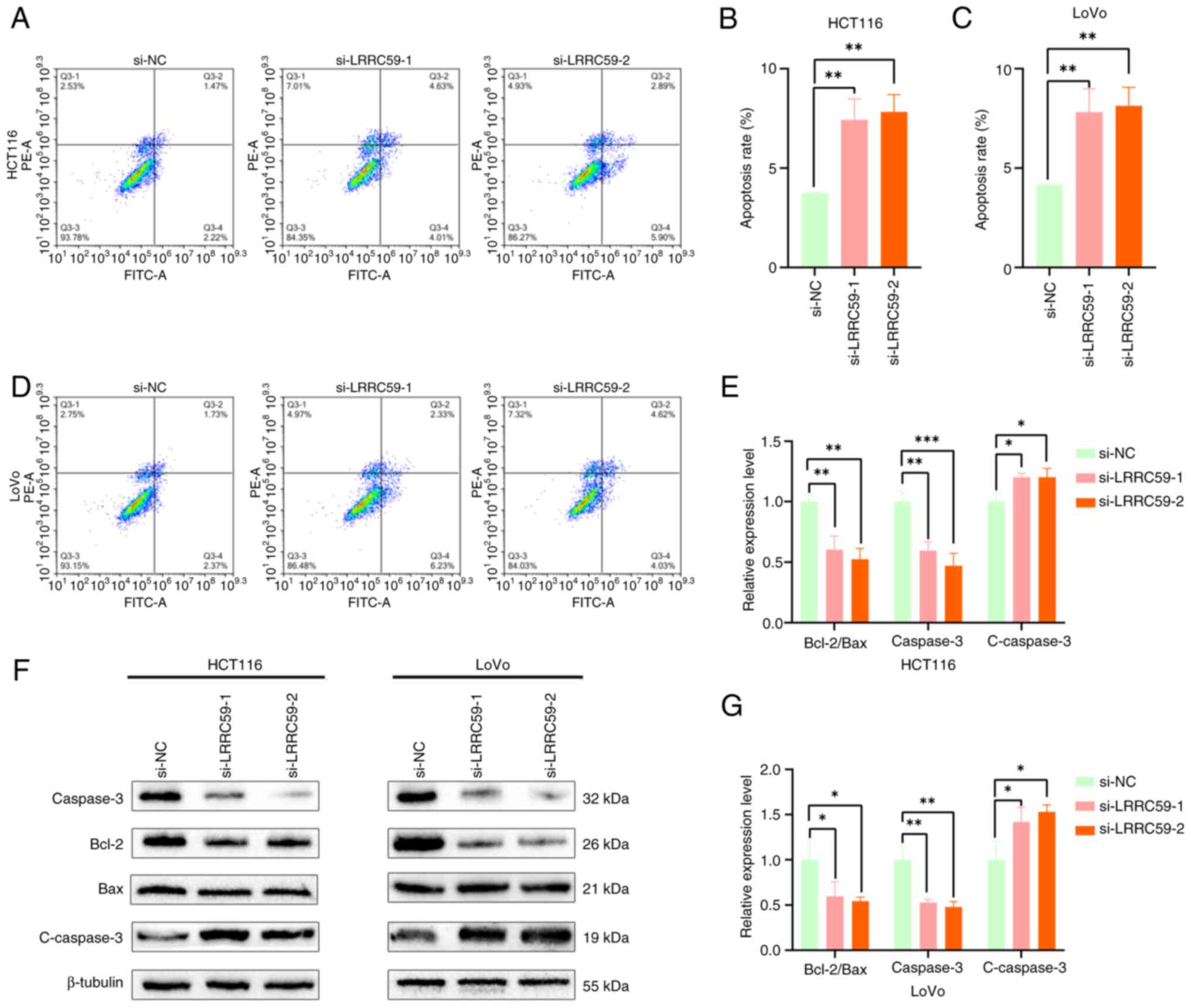

LRRC59 suppresses apoptosis in CRC

cells

ERS plays a critical role in modulating apoptosis

(25–27). To investigate whether LRRC59

regulates apoptosis through ERS pathways, apoptotic responses were

first examined following LRRC59 knockdown. Flow cytometric analysis

demonstrated that LRRC59 deficiency in HCT116 and LoVo cells

resulted in a substantial increase in apoptotic cells compared with

that in control cells (Fig. 5A-D).

Western blot analysis of apoptosis-related proteins (Fig. 5E-G) demonstrated upregulation of

active caspase-3 and decreased Bcl-2 and Caspase3 expression. These

findings provided further evidence that LRRC59 functions as an

anti-apoptotic factor in CRC cells.

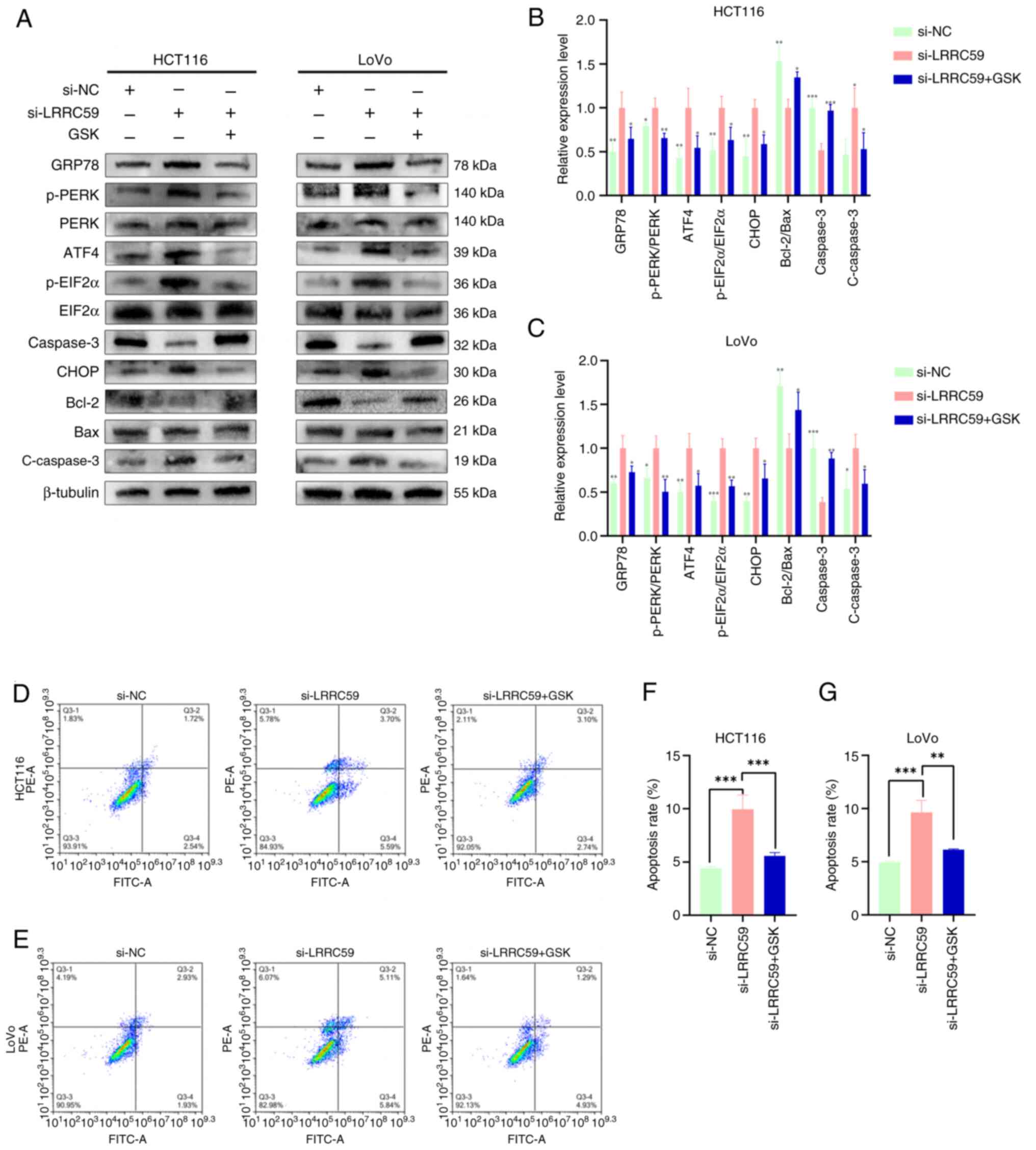

LRRC59 modulates apoptosis via PERK

signaling in CRC

Increased PERK phosphorylation is a hallmark of PERK

pathway activation. To assess whether LRRC59 influenced apoptosis

by regulating the PERK pathway, LRRC59 knockdown CRC cells were

treated with GSK, a PERK pathway inhibitor. The results showed that

GSK treatment significantly inhibited PERK phosphorylation. Western

blot analysis (Fig. 6A-C) revealed

decreased expression of ERS pathway proteins and a reduction in

apoptosis-related proteins, including active-caspase-3, whereas the

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was upregulated. Flow cytometry

(Fig. 6D-G) confirmed a significant

reduction in apoptosis following GSK treatment. These findings

suggested that LRRC59 regulates apoptosis by modulating the PERK

signaling pathway in CRC cells.

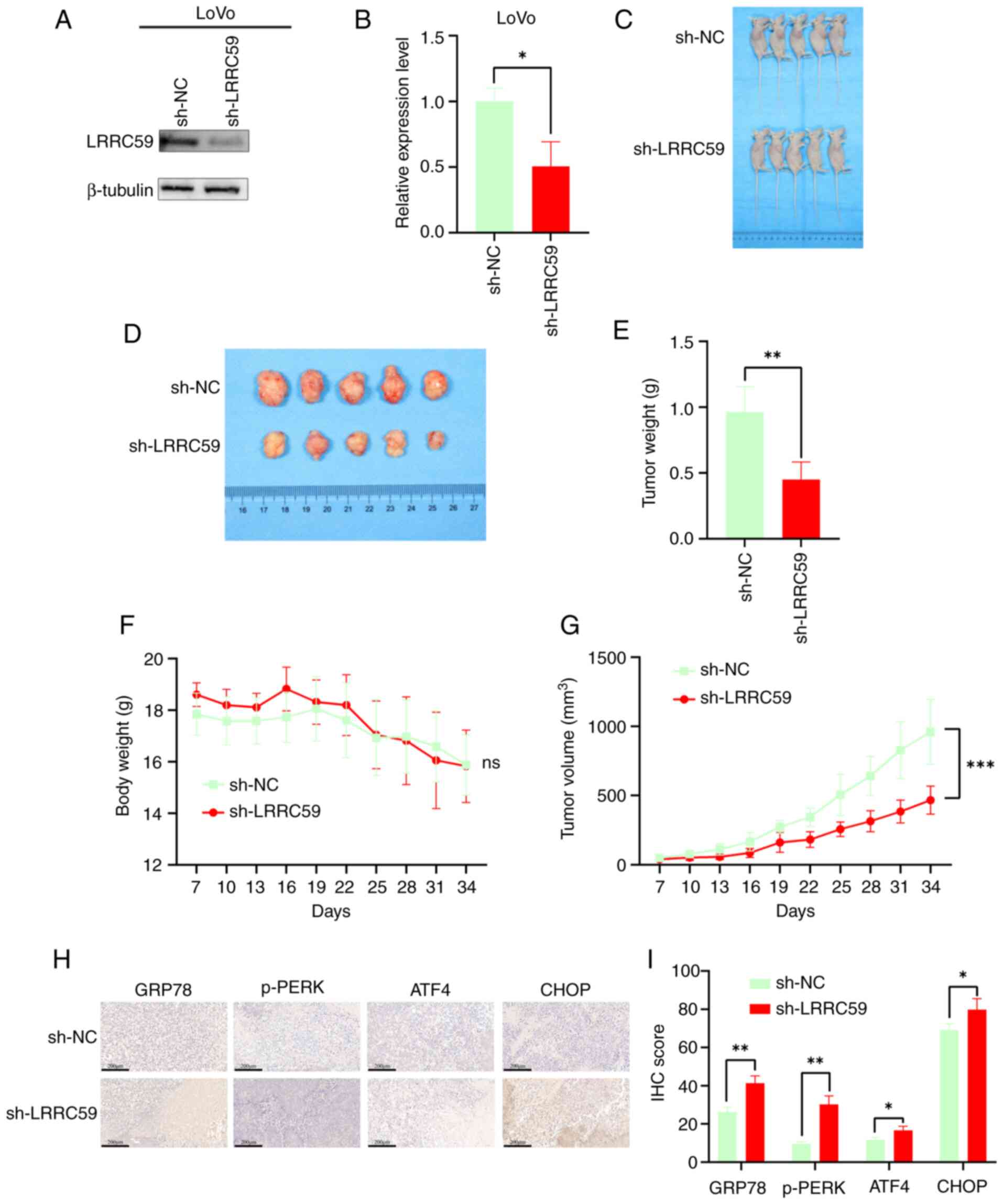

LRRC59 knockdown reduces tumor growth

in mice

The effect of LRRC59 on CRC tumorigenesis was

assessed in vivo in a mouse xenograft model. Western blot

analysis confirmed the successful establishment of stable

LRRC59-knockdown LoVo cells prior to implantation (Fig. 7A and B). Mice injected with

sh-LRRC59 transfected LoVo cells exhibited significantly smaller

tumor volumes and weights than the controls (Fig. 7C-E and G). Body weight remained

consistent across groups (Fig. 7F).

IHC analysis demonstrated increased activation of the PERK pathway

in sh-LRRC59 tumors (Fig. 7H and

I). These results indicated that LRRC59 knockdown hinders CRC

progression by activating the PERK pathway.

Discussion

The role of LRRC59 in CRC progression was

investigated. The present findings revealed notable upregulation of

LRRC59 expression in CRC tissues, leading to the promotion of cell

proliferation, migration and invasion. Additionally, LRRC59

inhibited apoptosis by modulating the PERK signaling. These results

suggested that LRRC59 can be used as target for the treatment of

CRC.

LRRC59 is a 244-amino acid protein localized to the

ER membrane that was initially identified as a ribosome-binding

protein (4–6). It is involved in various cellular

functions, including immune responses, anti-inflammatory

activities, and the translation and translocation of proteins

within the ER (28). Previous

studies highlighted the involvement of LRRC59 in multiple cancer

types (7–9,29,30).

However, its role in CRC remains unclear. A recent study suggested

that LRRC59 suppresses CRC progression (31), which contrast the current findings.

It was found that LRRC59 mRNA expression was significantly higher

in CRC tissues than in adjacent normal tissues. Subsequent analyses

confirmed its overexpression at the protein level in CRC tissues.

Furthermore, silencing of LRRC59 reduced CRC cell proliferation and

impaired cell migration and invasion. Additionally, LRRC59

knockdown significantly attenuated tumor growth in a mouse

xenograft model. These findings suggest that LRRC59 is

significantly overexpressed in CRC and plays a key role in

promoting CRC progression by inhibiting apoptosis.

The leucine-rich repeat domain of LRRC59 mediates

protein-protein interactions, which influence processes such as

apoptosis, autophagy and nuclear mRNA transport (32). Previous studies demonstrated that

LRRC59 interacts with FGF1 to promote its nuclear import; inhibit

apoptosis; and regulate tumor cell survival, proliferation and

migration (33,34). Additionally, LRRC59 knockdown

induced G1 cell cycle arrest, thereby inhibiting tumor progression.

In the present study, silencing of LRRC59 elevated apoptotic

markers such as active-caspase-3 in CRC cells and decreased

expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. These results

suggested that LRRC59 suppresses apoptosis in CRC cells.

Malignant tumor progression is characterized by

uncontrolled cell proliferation, which creates a highly metabolic,

hypoxic, nutrient-deficient and acidic microenvironment. This

environment activates the UPR, which amplifies the ERS (35,36).

ERS is a dynamic process that responds to protein imbalances in the

ER by activating the IRE1-, PERK- and ATF6-mediated ERS pathways

during CRC development, thus helping to restore ER homeostasis and

support cell survival (37). These

pathways initially reduce protein overload in the ER through

mechanisms such as PERK-mediated EIF2α phosphorylation,

IRE1-dependent mRNA decay, and autophagy activation via the

IRE1α-JNK axis. UPR transcription factors activate ATF6 and splice

XBP1 to promote adaptive responses, restore ER function, and

support cell survival (38–43). However, if ERS persists, the cells

shift from an adaptive response to a death-inducing response

(44,45). Numerous studies indicated that the

overactivation of the ERS signaling promotes apoptosis, autophagy

and ferroptosis in tumor cells (46–50).

When ERS conditions are prolonged, IRE1α recruits TRAF2, activating

ASK1 and JNK to promote apoptosis (51). Sustained PERK signaling induces

apoptosis by upregulating CHOP, a pro-apoptotic transcription

factor that downregulates BCL-2 and induces BH3-only protein

expression, leading to cell death (52). LRRC59 affects HYOU1- and

XBP1-mediated ERS signaling and promotes cancer cell proliferation

and migration. However, whether LRRC59 plays a role in CRC via the

ERS pathway remains unclear. An association between LRRC59 and the

expression of key proteins involved in the PERK-mediated ERS

pathway was identified. In CRC cell lines with LRRC59 knockdown,

expression of GRP78, p-PERK, p-EIF2α, ATF4 and CHOP was increased.

To confirm whether LRRC59 affects apoptosis through the

PERK-mediated ERS pathway, the PERK pathway-specific inhibitor GSK

was used, which resulted in reduced apoptosis of CRC cells,

increased expression of Bcl-2, and decreased expression of

active-caspase-3. These findings suggested that LRRC59 inhibits

apoptosis and promotes CRC cell survival by suppressing excessive

activation of the PERK-mediated ERS signaling pathway.

Given that the PERK pathway plays a central role in

the ERS response in CRC cells, targeting the PERK pathway for the

treatment of CRC may have broad application prospects (36). Numerous drugs or compounds capable

of directly acting on ER-associated proteins have been discovered

(53). For instance, V8, a novel

derivative of the natural flavonoid wogonin and a potential

anticancer agent, has demonstrated significant antitumor activity

both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro studies using

acute myeloid leukemia cell lines showed that V8 selectively

activates the PERK pathway, ultimately triggering CHOP-mediated

apoptosis via an ERS-specific pathway (54). Terpenoids, one of the largest and

most structurally diverse classes of natural compounds, have been

shown in some studies to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer

and promote cancer cell apoptosis through the PERK pathway

(55). 2-Deoxyglucose, a glucose

analog, has been found to exert antitumor effects by promoting the

PERK pathway; when combined with HCQ, it can further inhibit the

viability and migration of breast tumor cells and induce apoptosis

(56). However, the vast majority

of currently identified compounds or drugs that may act against

tumors via the PERK pathway are still confined to preclinical

studies, and their translation into clinical therapies requires

further validation through clinical trials. Recent research

suggests that cancer treatment strategies employing nanoparticles

to target the ER and regulate programmed cell death may represent a

promising new direction for clinical translation (57). In the field of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma, relevant in vitro studies have been conducted: A

photothermal nano-vaccine based on phenylboronic acid-modified poly

dendrimers of generation 5 attached with indocyanine green can

serve as a carrier for the ERS-inducing drug toyocamycin,

demonstrating satisfactory antitumor efficacy in vitro

(58). However, direct targeting of

the PERK pathway in vivo may not be effective and could

result in systemic effects (59).

PERK inhibition destroys pancreatic cells and osteoblasts, leading

to diabetes and severe bone defects (60,61).

Therefore, indirectly affecting the PERK pathway through LRRC59 may

be a safe approach for treating CRC. Although LRRC59 shows

potential as a therapeutic target, the development of inhibitors

and related drugs targeting LRRC59 requires further analysis.

Although it was found that LRRC59 can affect CRC

cells through the PERK pathway, there were limitations to the

present study. The numbers of clinical specimens and animal model

samples used were relatively small, and only two CRC cell lines

were evaluated, limiting the generalizability of the results.

Further studies are needed to expand the number of clinical

samples, increase the number of CRC cell lines and animal models,

and explore the molecular mechanism of LRRC59 in greater depth to

obtain more universally applicable results. The main objective of

the present study was to preliminarily validate the effect of

LRRC59 knockdown on CRC cells in vivo using a mouse

xenograft model. Additional studies are necessary to establish

in situ transplantation and metastasis models to

comprehensively examine the effects of LRRC59 on CRC metastasis and

the tumor microenvironment. In the present study, focus was

addressed on the PERK pathway branch in ERS, and the literature

suggests that LRRC59 is related to other branches of ERS (62). Given the complexity of the UPR

pathway, future multi-omics analysis is needed to determine whether

LRRC59 can affect CRC through the other two main branches, the

IRE1α and ATF6 pathways. Although the PERK pathway was established

as the main target of LRRC59, the involvement of non-PERK pathways

in tumor progression cannot be ruled out. This is an important

topic for future research.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

LRRC59 is significantly upregulated in CRC tissues, where it

enhances cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Moreover,

LRRC59 suppresses apoptosis by attenuating PERK-mediated activation

of the ERS pathway. Although research on LRRC59 remains in the

early stages, further mechanistic explorations and large-scale

clinical trials are required. The current findings indicate the

potential of LRRC59 as a therapeutic target for CRC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Liaoning (grant no. 2024-MS-152).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

XH and YW contributed to the methodology,

validation, and writing of the original draft. YC participated in

data validation. PZ was involved in conceptualization of the study.

GW contributed to study conceptualization, writing, review and

editing of the manuscript. BLi conducted formal analyses. BLu

performed the experiments. HJ provided resources and performed the

experiments. SN was responsible for conceptualization, funding

acquisition, supervision, and writing, reviewing and editing the

manuscript. XH and SN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved (approval no.

kY2024-136-01) by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated

Hospital of Dalian Medical University (Dalian, China). Animal

experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines

and were approved (approval no. 2024167) by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA

and Jemal A: Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin.

73:233–254. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V,

Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N and Bray F:

Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and

mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 72:338–344. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Leowattana W, Leowattana P and Leowattana

T: Systemic treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J

Gastroenterol. 29:1569–1588. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ichimura T, Shindo Y, Uda Y, Ohsumi T,

Omata S and Sugano H: Anti-(p34 protein) antibodies inhibit

ribosome binding to and protein translocation across the rough

microsomal membrane. FEBS Lett. 326:241–245. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ohsumi T, Ichimura T, Sugano H, Omata S,

Isobe T and Kuwano R: Ribosome-binding protein p34 is a member of

the leucine-rich-repeat-protein superfamily. Biochem J.

294:465–472. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ichimura T, Ohsumi T, Shindo Y, Ohwada T,

Yagame H, Momose Y, Omata S and Sugano H: Isolation and some

properties of a 34-kDa-membrane protein that may be responsible for

ribosome binding in rat liver rough microsomes. FEBS Lett.

296:7–10. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pallai R, Bhaskar A, Barnett-Bernodat N,

Gallo-Ebert C, Pusey M, Nickels JT Jr and Rice LM: Leucine-rich

repeat-containing protein 59 mediates nuclear import of cancerous

inhibitor of PP2A in prostate cancer cells. Tumour Biol.

36:6383–6390. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li D, Xing Y, Tian T, Guo Y and Qian J:

Overexpression of LRRC59 is associated with poor prognosis and

promotes cell proliferation and invasion in lung adenocarcinoma.

Onco Targets Ther. 13:6453–6463. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pei L, Zhu Q, Zhuang X, Ruan H, Zhao Z,

Qin H and Lin Q: Identification of leucine-rich repeat-containing

protein 59 (LRRC59) located in the endoplasmic reticulum as a novel

prognostic factor for urothelial carcinoma. Transl Oncol.

23:1014742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chen X and Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment.

Nat Rev Cancer. 21:71–88. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Walter P and Ron D: The unfolded protein

response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science.

334:1081–1086. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hetz C, Zhang K and Kaufman RJ:

Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein

response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:421–438. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shore GC, Papa FR and Oakes SA: Signaling

cell death from the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Curr

Opin Cell Biol. 23:143–149. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Long D, Chen K, Yang Y and Tian X:

Unfolded protein response activated by endoplasmic reticulum stress

in pancreatic cancer: Potential therapeutical target. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 26:1689–1696. 2021. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Song M and Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress responses in intratumoral immune cells:

Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 40:128–141.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Geng J, Guo Y, Xie M, Li Z, Wang P, Zhu D,

Li J and Cui X: Characteristics of endoplasmic reticulum stress in

colorectal cancer for predicting prognosis and developing treatment

options. Cancer Med. 12:12000–12017. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhou F, Gao H, Shang L, Li J, Zhang M,

Wang S, Li R, Ye L and Yang S: Oridonin promotes endoplasmic

reticulum stress via TP53-repressed TCF4 transactivation in

colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:1502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li F, Dong Q, Kai Z, Pan Q and Liu C:

CYP8B1 is a prognostic biomarker with important functional

implications in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 54:1042025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ma H, Suleman M, Zhang F, Cao T, Wen S,

Sun D, Chen L, Jiang B, Wang Y, Lin F, et al: Pirin inhibits

FAS-mediated apoptosis to support colorectal cancer survival. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 11:e23014762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu H, Wang T, Nie H, Sun Q, Jin C, Yang S,

Chen Z, Wang X, Tang J, Feng Y and Sun Y: USP36 promotes colorectal

cancer progression through inhibition of p53 signaling pathway via

stabilizing RBM28. Oncogene. 43:3442–3455. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhao L, Sun X, Hou C, Yang Y, Wang P, Xu

Z, Chen Z, Zhang X, Wu G, Chen H, et al: CPNE7 promotes colorectal

tumorigenesis by interacting with NONO to initiate ZFP42

transcription. Cell Death Dis. 15:8962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim J, Jeong Y, Shin YM, Kim SE and Shin

SJ: FL118 enhances therapeutic efficacy in colorectal cancer by

inhibiting the homologous recombination repair pathway through

survivin-RAD51 downregulation. Cancers (Basel). 16:33852024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang Z, Wang L, Zhao L, Wang Q, Yang C,

Zhang M, Wang B, Jiang K, Ye Y, Wang S and Shen Z:

N6-methyladenosine demethylase ALKBH5 suppresses colorectal cancer

progression potentially by decreasing PHF20 mRNA methylation. Clin

Transl Med. 12:e9402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu H, Zheng S, Zhang J, Xu S and Miao Z:

Cadmium induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in

pig pancreas via the increase of Th1 cells. Toxicology.

457:1527902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee H, Lee YS, Harenda Q, Pietrzak S,

Oktay HZ, Schreiber S, Liao Y, Sonthalia S, Ciecko AE, Chen YG, et

al: Beta cell dedifferentiation induced by IRE1α deletion prevents

type 1 diabetes. Cell Metab. 31:822–836.e825. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kim TW, Lee SY, Kim M, Cheon C and Ko SG:

Kaempferol induces autophagic cell death via IRE1-JNK-CHOP pathway

and inhibition of G9a in gastric cancer cells. Cell Death Dis.

9:8752018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pallai R, Bhaskar A, Barnett-Bernodat N,

Gallo-Ebert C, Nickels JT Jr and Rice LM: Cancerous inhibitor of

protein phosphatase 2A promotes premature chromosome segregation

and aneuploidy in prostate cancer cells through association with

shugoshin. Tumour Biol. 36:6067–6074. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Maurizio E, Wiśniewski JR, Ciani Y, Amato

A, Arnoldo L, Penzo C, Pegoraro S, Giancotti V, Zambelli A, Piazza

S, et al: Translating proteomic into functional data: An high

mobility group A1 (HMGA1) proteomic signature has prognostic value

in breast cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 15:109–123. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pan B, Cheng J, Tan W, Wu X, Fan Q, Fan L,

Jiang M, Yu R, Cheng X and Deng Y: Pan-cancer analysis of LRRC59

with a focus on prognostic and immunological roles in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 16:8171–8197.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen H, Zhao T, Fan J, Yu Z, Ge Y, Zhu H,

Dong P, Zhang F, Zhang L, Xue X and Lin X: Construction of a

prognostic model for colorectal adenocarcinoma based on Zn

transport-related genes identified by single-cell sequencing and

weighted co-expression network analysis. Front Oncol.

13:12074992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xian H, Yang S, Jin S, Zhang Y and Cui J:

LRRC59 modulates type I interferon signaling by restraining the

SQSTM1/p62-mediated autophagic degradation of pattern recognition

receptor DDX58/RIG-I. Autophagy. 16:408–418. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhen Y, Sørensen V, Skjerpen CS, Haugsten

EM, Jin Y, Wälchli S, Olsnes S and Wiedlocha A: Nuclear import of

exogenous FGF1 requires the ER-protein LRRC59 and the importins

Kpnα1 and Kpnβ1. Traffic. 13:650–664. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu N, Zhang J, Sun S, Yang L, Zhou Z, Sun

Q and Niu J: Expression and clinical significance of fibroblast

growth factor 1 in gastric adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther.

8:615–621. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Oakes SA: Endoplasmic reticulum stress

signaling in cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 190:934–946. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Huang J, Pan H, Wang J, Wang T, Huo X, Ma

Y, Lu Z, Sun B and Jiang H: Unfolded protein response in colorectal

cancer. Cell Biosci. 11:262021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Urra H, Dufey E, Avril T, Chevet E and

Hetz C: Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the hallmarks of cancer.

Trends Cancer. 2:252–262. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek

R, Schapira M and Ron D: Regulated translation initiation controls

stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell.

6:1099–1108. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Han D, Lerner AG, Vande Walle L, Upton JP,

Xu W, Hagen A, Backes BJ, Oakes SA and Papa FR: IRE1alpha kinase

activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to

determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 138:562–575. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

4Hollien J, Lin JH, Li H, Stevens N,

Walter P and Weissman JS: Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of

messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 186:323–331. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hollien J and Weissman JS: Decay of

endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein

response. Science. 313:104–107. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN and Glimcher LH: XBP-1

regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone

genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol.

23:7448–7459. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ameri K and Harris AL: Activating

transcription factor 4. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 40:14–21. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Shi Y, Jiang B and Zhao J: Induction

mechanisms of autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress in

intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury, inflammatory bowel disease,

and colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 170:1159842024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sisinni L, Pietrafesa M, Lepore S,

Maddalena F, Condelli V, Esposito F and Landriscina M: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in breast cancer:

The balance between apoptosis and autophagy and its role in drug

resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 20:8572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ji X, Chen Z, Lin W, Wu Q, Wu Y, Hong Y,

Tong H, Wang C and Zhang Y: Esculin induces endoplasmic reticulum

stress and drives apoptosis and ferroptosis in colorectal cancer

via PERK regulating eIF2α/CHOP and Nrf2/HO-1 cascades. J

Ethnopharmacol. 328:1181392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Qu J, Zeng C, Zou T, Chen X, Yang X and

Lin Z: Autophagy induction by trichodermic acid attenuates

endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer

cells. Int J Mol Sci. 22:55662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang G, Han J, Wang G, Wu X, Huang Y, Wu M

and Chen Y: ERO1α mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced

apoptosis via microRNA-101/EZH2 axis in colon cancer RKO and HT-29

cells. Hum Cell. 34:932–944. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Piao MJ, Han X, Kang KA, Fernando PDSM,

Herath HMUL and Hyun JW: The endoplasmic reticulum stress response

mediates shikonin-induced apoptosis of 5-fluorouracil-resistant

colorectal cancer cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 30:265–273. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Quan JH, Gao FF, Chu JQ, Cha GH, Yuk JM,

Wu W and Lee YH: Silver nanoparticles induce apoptosis via

NOX4-derived mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and

endoplasmic reticulum stress in colorectal cancer cells.

Nanomedicine (Lond). 16:1357–1375. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y,

Chung P, Harding HP and Ron D: Coupling of stress in the ER to

activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase

IRE1. Science. 287:664–666. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Tabas I and Ron D: Integrating the

mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Nat Cell Biol. 13:184–190. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhou R, Wang W, Li B, Li Z, Huang J and Li

X: Endo-plasmic reticulum stress in cancer. MedComm (2020).

6:e702632025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Guo YJ, Zhu MY, Wang ZY, Chen HY, Qing YJ,

Wang HZ, Xu JY, Hui H and Li H: Therapeutic effect of V8 affecting

mitophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress in acute myeloid

leukemia mediated by ROS and CHOP signaling. FASEB J.

39:e706222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang P, Liu H, Yu Y, Peng S, Zeng A and

Song L: Terpenoids mediated cell apoptotsis in cervical cancer:

Mechanisms, advances and prospects. Fitoterapia. 180:1063232024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhou N, Liu Q, Wang X, He L, Zhang T, Zhou

H, Zhu X, Zhou T, Deng G and Qiu C: The combination of

hydroxychloroquine and 2-deoxyglucose enhances apoptosis in breast

cancer cells by blocking protective autophagy and sustaining

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Discov. 8:2862022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liang L, Zhu Z, Jiang X, Tang Y, Li J,

Zhang Z, Ding B, Li X, Yu M and Gan Y: Endoplasmic

reticulum-targeted strategies for programmed cell death in cancer

therapy: Approaches and prospects. J Control Release.

385:1140592025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liu Z, Deng X, Wang Z, Guo Y, Hameed MMA,

El-Newehy M, Zhang J, Shi X and Shen M: A biomimetic therapeutic

nanovaccine based on dendrimer-drug conjugates coated with

metal-phenolic networks for combination therapy of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: An in vitro investigation. J Mater Chem B.

13:5440–5452. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yeap JW, Ali IAH, Ibrahim B and Tan ML:

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emerging ER

stress-related therapeutic targets. Pulm Pharmacol Ther.

81:1022182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R,

Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD and Ron D: Diabetes mellitus and

exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk-/- mice reveals a role for

translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell.

7:1153–1163. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang P, McGrath B, Li S, Frank A, Zambito

F, Reinert J, Gannon M, Ma K, McNaughton K and Cavener DR: The PERK

eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase is required for the

development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the

function and viability of the pancreas. Mol Cell Biol.

22:3864–3874. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yuan Z, Wang Y, Xu S, Zhang M and Tang J:

Construction of a prognostic model for colon cancer by combining

endoplasmic reticulum stress responsive genes. J Proteomics.

309:1052842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|