Introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that

comprises multiple intrinsic subtypes, each associated with

distinct clinical and molecular characteristics (1). Based on gene expression profiling,

four major intrinsic subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched

and basal-like) have traditionally been identified (2,3). These

classifications guide treatment and provide insights into prognosis

(4). However, a novel intrinsic

subtype, termed claudin-low, was identified in 2007 (5). Claudin-low breast cancers are unique

due to their low expression of claudins, which are tight junction

adhesion molecules integral to epithelial cell cohesion and

polarity. As a result, claudin-low tumors exhibit characteristics

more typical of mesenchymal cells, including increased motility and

invasiveness. These properties are associated with high expression

levels of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers,

reflecting an inherently aggressive phenotype (6–8).

Over 70% of claudin-low breast cancers are also

classified as triple-negative, which means that they lack estrogen

receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 expression. This renders

claudin-low tumors resistant to conventional endocrine or

HER2-targeted therapies, limiting the treatment options for this

subtype. Beyond the distinctive expression of claudins and EMT

markers, claudin-low tumors share features with cancer stem cells,

such as a CD44+/CD24− surface marker profile

(9). This

CD44+/CD24− phenotype is linked to cancer

stem cell-like traits such as self-renewal and chemoresistance,

contributing to poor clinical outcomes (6,7).

The CD44 protein, a cell surface glycoprotein

involved in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, has been

implicated in various aspects of cancer biology, including cell

proliferation, invasion and metastasis (10). In CD44-positive breast cancer cells,

studies have reported that CD44 inhibition can suppress cell

proliferation and, in some cases, diminish invasive capabilities

(11–14). However, the results regarding

invasion are varied; while some studies have suggested that CD44

inhibition can limit invasiveness (15,16),

others have reported negligible effects on invasion (17,18).

This variation may stem from the complex involvement of CD44 in

multiple signaling pathways that collectively influence cell

behavior in diverse mechanisms. Despite these inconsistencies, the

evidence highlights the substantial role of CD44 in promoting the

aggressive characteristics of claudin-low breast cancers,

particularly through its regulatory impact on EMT processes

(19,20).

EMT is a cellular program that drives epithelial

cells to acquire mesenchymal properties, enhancing their migratory

and invasive capabilities. EMT inhibition in claudin-low breast

cancer may offer dual benefits: Cell motility reduction and tumor

growth suppression (21,22). By targeting the EMT pathway, certain

inhibitors, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors and DNA

methyltransferase inhibitors, could theoretically control the

proliferation and metastatic potential of claudin-low breast

cancers (23). However, studies

suggest that EMT inhibition alone provides only limited therapeutic

benefits, indicating a need for combination therapies that target

multiple pathways (24,25). This observation has driven further

research into the identification of co-targets that may enhance the

efficacy of EMT inhibitors.

Previous findings have indicated that the TGF-β

receptor (TGFBR), an upstream EMT regulator, can directly interact

with CD44, providing a novel therapeutic axis for claudin-low

breast cancers (26). Given the

interplay between CD44 and TGF-β signaling, the dual inhibition of

CD44 and TGFBRs may amplify the antiproliferative and anti-invasive

effects of single-agent treatments (23). Pharmacological agents that

downregulate CD44 expression and inhibit TGF-β signaling could,

therefore, provide a combined approach, targeting the EMT pathway

while impacting the CD44-mediated stem cell-like properties of

claudin-low breast cancers (27,28).

This combined approach may provide a mechanistic rationale for

co-targeting CD44 and TGF-β signaling, as CD44 interacts with the

TGF-β receptor complex, modulating downstream Smad2 activation.

Dual inhibition could simultaneously suppress CD44-mediated stem

cell-like survival and TGF-β-driven EMT and invasion, thereby

enhancing antiproliferative efficacy in claudin-low breast

cancer.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The antibodies used in the present study were

anti-CD44 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-7297; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.), anti-Smad2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 3102; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), anti-phosphorylated (p-)Smad2 (Ser465/467)

(1:1,000; cat. no. 3108; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

anti-TGFBR1 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-101574; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.), anti-TGFBR2 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-17799; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-7382; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-Snai1 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-271977;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-IgG (1:10,000; cat. no. 5415;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-GAPDH (1:1,000; cat. no.

sc-32233; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Cell culture and lentiviral

transduction

The MDA-MB-231, SUM159 and MDA-MB-468 human breast

cancer cell lines were obtained from stocks maintained at Shizuoka

General Hospital (Shizuoka, Japan). MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells

were maintained in DMEM (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) supplemented with

10% FBS (Biowest) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin). SUM159 cells were

maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 5% FBS (Biowest), 5 µg/ml insulin

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 1 µg/ml hydrocortisone

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). All cells were cultured at 37°C in a

humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. These cell lines

were confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination and exhibited

morphological features consistent with previously reported

characteristics [MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells: American Type

Culture Collection; SUM159 cells: (29)]. SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 have

previously been classified as claudin-low breast cancer cell lines,

while MDA-MB-468 has been classified as a basal-like breast cancer

cell line (6,25).

CD44 knockdown was performed using short hairpin RNA

(shRNA/sh; TRCN0000296191; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), which

targeted the sequence 5′-GGACCAATTACCATAACTATT-3′ (sense strand).

The corresponding antisense strand was 5′-AATAGTTATGGTAATTGGTCC-3′.

The shRNA was cloned into the pLKO.1-puro lentiviral vector

(MISSION pLKO.1-puro; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), which expressed

the shRNA under the control of the U6 promoter and included a

puromycin resistance gene for stable selection. MISSION pLKO.1-puro

non-target shRNA control plasmid DNA (SHC016; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) was used as an appropriate control. The sense strand of the

control shRNA was 5′-GCGCGATAGCGCTAATAATTT-3′, and the

corresponding antisense strand was 5′-AAATTATTAGCGCTATCGCGC-3′.

Lentiviral particles were produced in 293 cells (institutional

stock; Shizuoka General Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan) using a

second-generation packaging system (MISSION Lentiviral Packaging

Mix; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and FuGENE HD transfection reagent

(Promega Corporation). For each 10-cm dish, 2.6 µg pLKO.1-puro

transfer plasmid, 26 µl MISSION Lentiviral Packaging Mix and 16 µl

FuGENE HD were combined according to the manufacturers'

instructions and added to cells at 37°C. After 24 h, the medium was

replaced with fresh growth medium. Viral supernatants were

harvested at 48 and 72 h post-transfection and passed through a

0.45-µm filter. MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells were transduced at an

MOI of 5 in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene for 24 h. Stable

transductants were selected with puromycin (1.0 µg/ml) for 5 days,

followed by culture in puromycin-free medium for 72 h to allow

recovery and to minimize cytotoxic stress associated with prolonged

antibiotic exposure, after which downstream assays were

performed.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from each cell line using

the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen KK) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the iScript

cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) in a 20-µl reaction

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Equal cDNA amounts were

used as templates for RT-qPCR to detect mRNA expression relative to

that of GAPDH (endogenous control). mRNA expression was quantitated

using a Thermal Cycler Dice® Real Time System III

(Takara Bio, Inc.) and SYBR-Green qPCR SuperMix (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Melting curve

analysis was performed to verify product specificity. The primers

used were: Smad2 forward, 5′-AGTGTGTAAAATTCCACCAG-3′ and

reverse, 5′-ATTCTAGTTAGCTGATAGACGG-3′; GAPDH forward,

5′-TCGGAGTCAACGGATTTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCAACAATATCCACTTTACCAGAG-3′; snail family transcriptional

repressor 1 (Snai1) forward, 5′-CTCTAATCCAGAGTTTACCTTC-3′

and reverse, 5′-GACAGAGTCCCAGATGAG-3′; and Twist forward,

5′-CTAGATGTCATTGTTTCCAGAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCCTGTTTCTTTGAATTTGG-3′. RT-qPCR reactions were performed in

triplicate, and each experiment was repeated three times. The fold

induction of gene expression was calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (30).

Immunoprecipitation and western

blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH

7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% NP-40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS)

supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche

Diagnostics GmbH). For each immunoprecipitation, 50 µl Dynabeads

Protein G magnetic beads (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) were pre-incubated with 3 µg of the indicated primary

antibody (anti-CD44; cat. no. sc-7297; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.) or normal mouse IgG (cat. no. 5415; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature with gentle

rotation to allow formation of bead-antibody complexes.

Subsequently, 500 µg lysate was added to the bead-antibody

complexes and samples were incubated for 1 h at room temperature

with rotation. The immune complexes were isolated magnetically

using a DynaMag™-2 magnet (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

washed three times with PBS at room temperature. Bound proteins

were eluted by boiling the beads in 2X Laemmli sample buffer

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for 5 min, resolved via SDS-PAGE and

transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Western blotting was

performed using specific antibodies as previously described

(31). These conditions were

applied to all western blot experiments performed in the present

study. For the analysis of TGF-β-induced Smad2 phosphorylation,

cells were treated with recombinant human TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml;

PeproTech, Inc.; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 2 h

prior to protein extraction, unless otherwise specified.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells (2×105 cells/well) were seeded in

6-well plates and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with

5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated

with 10 µM LY2109761 (LY-61; Selleck Chemicals) at 37°C for 48 h.

After trypsinization, the cells were fixed and stained according to

the protocol of the Cell Cycle Phase Determination Kit (item no.

10009349; Cayman Chemical Company). The cell cycle distribution was

analyzed via flow cytometry using a BD FACSMelody™ flow cytometer

(BD Biosciences). Propidium iodide fluorescence was detected in the

BP/700/54 channel with a blue laser, and data were analyzed using

BD FACSChorus software (version 1.3.2; BD Biosciences). Cell cycle

phase distributions (G1, S and G2/M) were

calculated using FlowJo software (version 10.10.0; BD

Biosciences).

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was analyzed according to the protocol

from BioLegend, Inc. After a 48-h incubation at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in either standard

media or media containing 10 µM LY-61, the cells were washed twice

with cold Cell Staining Buffer (cat. no. 420201; BioLegend, Inc.)

and resuspended in Annexin V Binding Buffer (cat. no. 422201;

BioLegend, Inc.) at a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml. A

100-µl aliquot of the cell suspension was transferred into a 5-ml

test tube, and 5 µl FITC-conjugated Annexin V (cat. no. 640906;

BioLegend, Inc.) and 5 µl 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; cat. no.

420403; BioLegend, Inc.) were added simultaneously. Subsequently,

the cells were incubated in the dark for 15 min at room

temperature. After incubation, 400 µl Annexin V Binding Buffer was

added to each sample prior to flow cytometry analysis. Fluorescence

signals were detected using a BD FACSMelody™ flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences) equipped with a 488-nm blue laser, detecting FITC

fluorescence in the BP/530/40 channel and 7-AAD fluorescence in the

BP/700/54 channel. Data were acquired and analyzed using BD

FACSChorus software (version 1.3.2; BD Biosciences), and data were

processed with FlowJo software (version 10.10.0; BD

Biosciences).

MTT assay

MTT assays were performed using the MTT Cell

Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (AR1156; Boster Bio). A

total of 1,000 cells per well were seeded in 96-well cell culture

plates, and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer's

protocol. After incubation with 10 µl MTT labeling reagent for 4 h,

100 µl Formazan Solubilization Solution (included in the kit;

Boster Bio) was added to each well, and the plate was further

incubated at 37°C for 4–18 h to ensure complete dissolution of the

purple formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm

using a microplate reader. Cell viability was quantified on day 5

post-plating, and the relative viability was calculated as the

ratio of absorbance values on day 5.

Clonogenic assay

A total of 500 cells per well were seeded in 6-well

plates and allowed to attach overnight. MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells

were cultured in standard media or media containing 10 µM LY-61 at

37°C with 5% CO2 for 7 days. The colonies were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation)

at room temperature for 15 min, stained with 0.5% crystal violet at

room temperature for 20 min and washed with distilled water.

Colonies (diameter >0.5 mm) were counted manually under a light

microscope.

Invasion assay

The invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells was

evaluated using the CytoSelect™ 24-well Cell Invasion Assay Kit

(cat. no. CBA-110; Cell Biolabs, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocols. Transwell inserts with polycarbonate

membranes (8-µm pore size) were precoated with Matrigel at 37°C for

2 h, and the Matrigel layer was rehydrated at room temperature for

1 h before cell seeding. For the invasion assay, MDA-MB-231 cells

were maintained in DMEM (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and SUM159 cells

were maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) as

aforementioned. A total of 2×105 cells in 300 µl of the

corresponding serum-free medium were added to the upper chamber,

while 500 µl of the same medium containing 10% FBS (Biowest,

distributed by Funakoshi Co., Ltd.) with or without 10 µM LY-61 was

placed in the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After incubation

at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h, non-invading cells were

removed, and invaded cells were stained with the dye solution

provided in the kit at room temperature for 10 min. Stained samples

(100 µl) from each well were transferred to a 96-well plate, and

absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a microplate reader.

Representative images of invaded cells were captured using a Nikon

ECLIPSE TS2 light microscope (Nikon Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad

Prism® version 10.3.1 (Dotmatics) and

Microsoft® Excel Version 2019 (Microsoft Corporation).

All data are presented as the mean ± SD from at least three

independent experiments. Data normality was assessed using the

Shapiro-Wilk test. For normally distributed data, statistical

comparisons among multiple groups were conducted using one-way or

two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's or Dunnett's multiple comparisons

test, as appropriate. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-tests were

used for pairwise comparisons. For non-normally distributed data

(such as mutation burden data), statistical comparisons between two

groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Public dataset analysis

Genomic and clinical data, including copy number

alterations (CNAs) and mRNA expression levels, were obtained from

the METABRIC dataset via cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/). Frequencies of CNAs for

selected genes were summarized according to breast cancer subtype

using the cBioPortal interface. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were

performed in GraphPad Prism using mRNA expression z-scores and

associated clinical outcome data from the METABRIC cohort. Patients

were divided into high and low expression groups based on the

median value, and P-values were calculated using the log-rank test.

No additional statistical software or custom computational

pipelines were used. Data from the METABRIC study were originally

published by Curtis et al (32).

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network analysis

PPI networks were analyzed using the STRING database

(version 11.0; http://string-db.org) (33). Interactions with a medium confidence

score (>0.4) were included.

Results

Genomic alterations in claudin-low

breast cancer: CNA-driven therapeutic implications of CD44, TGFBR1

and TGFBR2

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that

comprises molecular subtypes with distinct genetic and phenotypic

profiles (2,3). CNAs and somatic mutations are crucial

in promoting oncogenesis, as well as influencing tumor progression

and therapeutic response (9,34).

Among the key genes, CD44, a cancer stem cell marker, and TGFBR1/2,

which mediate TGF-β signaling (24,35),

are implicated in tumor invasion and metastasis (36). The presence of CNAs in these genes

suggests that their dysregulation may create potential therapeutic

vulnerabilities, genetic dependencies that could be exploited for

targeted intervention in claudin-low breast cancer.

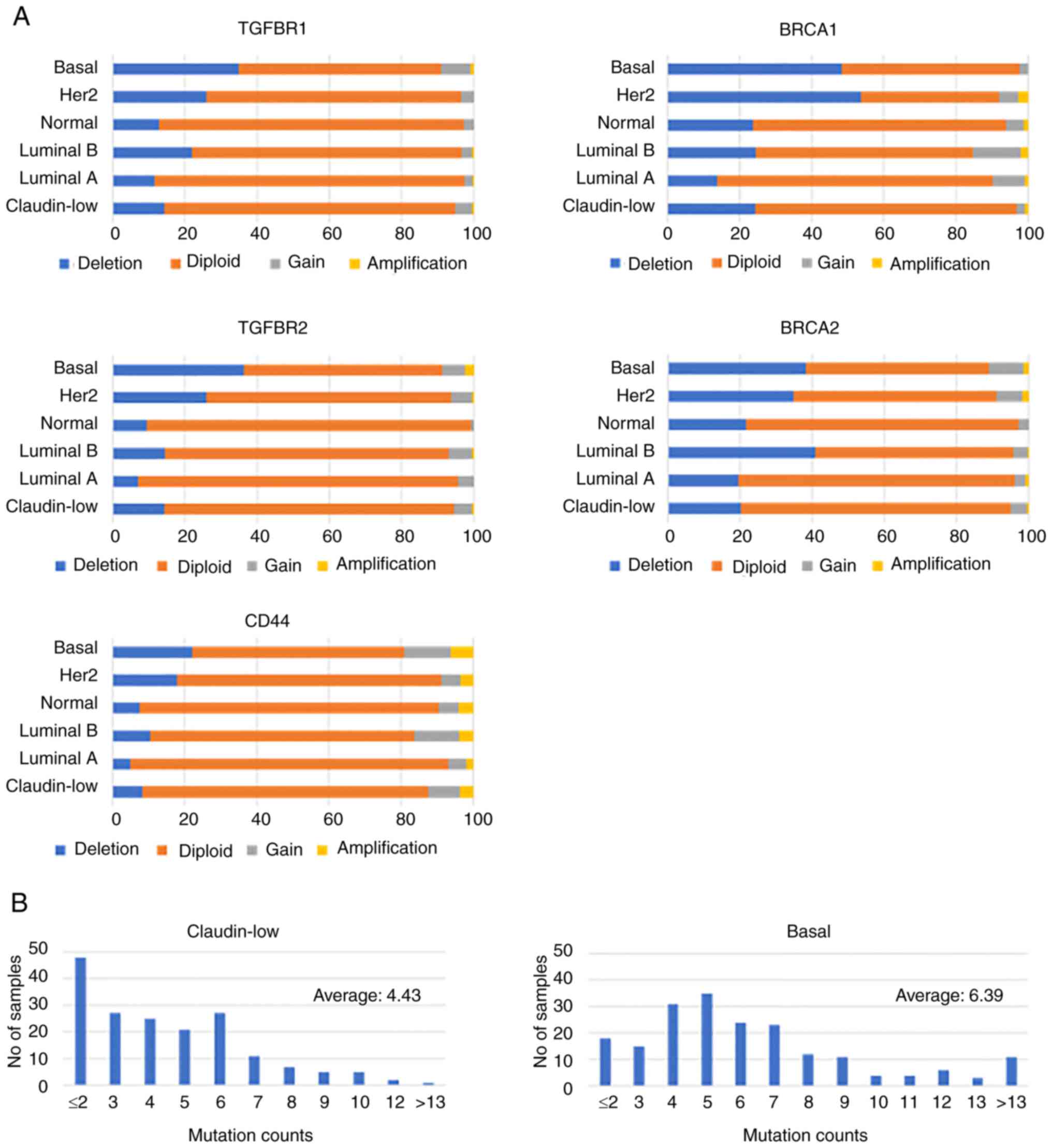

CD44, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 exhibited similar CNA

patterns, characterized by moderate deletion frequencies and rare

amplifications across all subtypes. In the claudin-low subtype,

their deletion frequencies were intermediate, ranking third or

fourth highest among all breast cancer subtypes (generally <10%

for CD44 and 10–15% for TGFBR1/2). By contrast, BRCA1 and BRCA2

displayed higher alteration rates, with basal-like tumors showing

prominent deletion frequencies (~40%) (Fig. 1A). This highlights the unique

genomic roles of CD44, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 in tumor biology, which

are distinct from BRCA1/2.

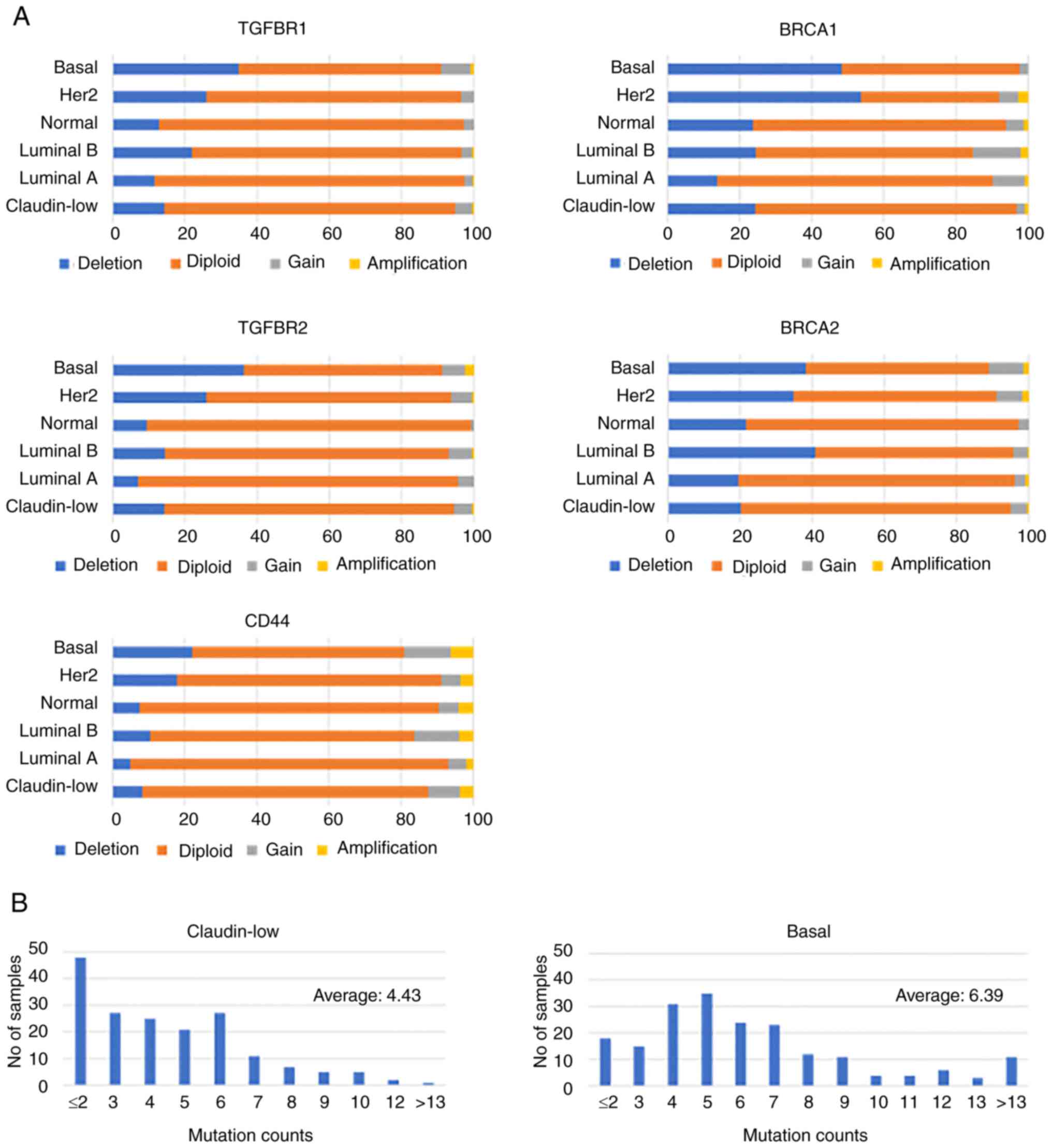

| Figure 1.CNAs and mutation burden across

breast cancer subtypes (METABRIC dataset). (A) Bar plots showing

the distribution of CNAs for TGFBR1, TGFBR2, CD44, BRCA1 and BRCA2

across breast cancer subtypes (claudin-low, luminal A, luminal B,

Her2-enriched, basal and normal-like) based on the METABRIC

dataset. CNAs were categorized as deletions (blue), diploid

(orange), gains (gray) and amplifications (yellow). (B) Histogram

representing the distribution of mutation counts in claudin-low

(n=179) and basal (n=197) breast cancer samples based on the

METABRIC dataset. Claudin-low tumors exhibited a significantly

lower mutational burden (mean ± SD, 4.43±2.70) compared with basal

tumors (mean ± SD, 6.39±3.84) (Mann-Whitney U test; P<0.0001).

CNA, copy number alteration; TGFBR, TGF-β receptor. |

Genome-wide mutation analysis (Fig. 1B) revealed a statistically

significant difference in the mutational burden between claudin-low

and basal subtypes, which are both representatives of

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Claudin-low tumors exhibited

a lower mutational burden (mean, 4.43±2.70; n=179) compared with

basal tumors (mean, 6.39±3.84; n=197), and this difference was

confirmed by a Mann-Whitney U test (P<0.0001). These findings

suggested that claudin-low tumors rely more on CNAs or epigenetic

changes than on mutations.

By contrast, basal tumors exhibited a broader

distribution of mutation counts and higher average burden,

consistent with known genomic instability in this subtype. Such

instability is frequently associated with defects in DNA damage

response pathways, including BRCA1/2 mutations, and may contribute

to the aggressive phenotype characteristic of basal-like TNBC

(9,34).

CD44, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 displayed negligible

mutation frequencies across all subtypes in the METABRIC dataset

(data not shown), suggesting they are more commonly affected by

CNAs rather than point mutations in claudin-low tumors.

The similar CNA patterns observed in CD44, TGFBR1

and TGFBR2 suggest a potentially coordinated regulatory mechanism,

possibly linked to pathways that drive tumor progression. In

claudin-low tumors, which exhibit a lower overall mutational

burden, such CNAs may serve a more prominent role in shaping tumor

biology. This reliance on CNAs, rather than mutations, highlights a

potential therapeutic vulnerability unique to this subtype

(34,37), and underscores the need for further

investigation into the functional significance and targetability of

these genes.

Prognostic role of CD44 expression in

the claudin-low breast cancer subtype

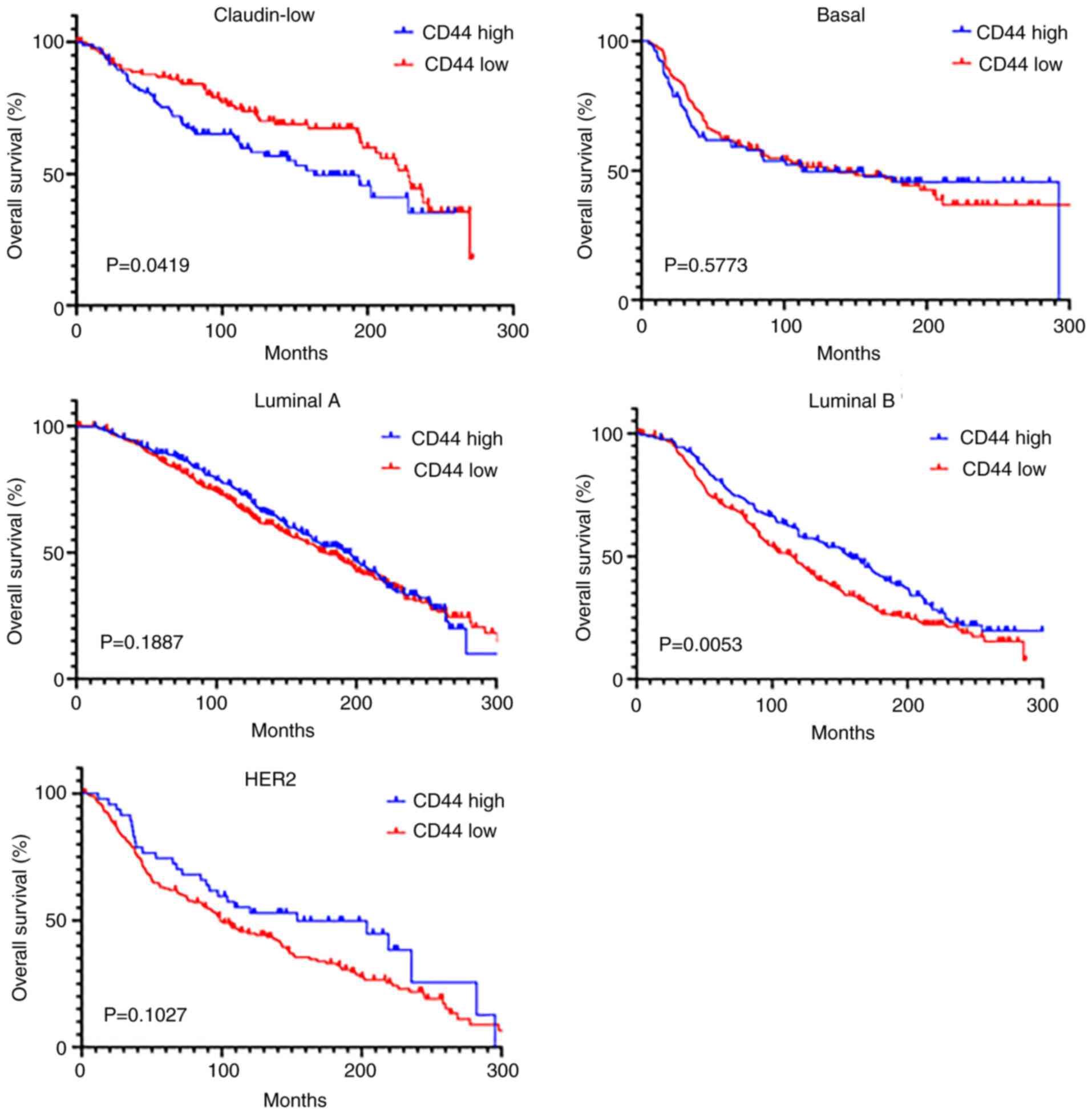

Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on the METABRIC

dataset showed the subtype-specific associations of CD44 expression

with overall survival. In the claudin-low subtype, low CD44

expression was associated with improved survival (P=0.0419),

whereas in the luminal B subtype, low CD44 expression was

associated with poor outcomes (P=0.0053). By contrast, no

significant survival differences were observed between the high and

low CD44 expression groups in patients with the basal, luminal A

and HER2 subtypes (Fig. 2). These

findings suggested that the prognostic value of CD44 was

subtype-specific, highlighting the importance of considering the

breast cancer subtype when evaluating CD44 as a prognostic

biomarker or therapeutic target. This indicated that CD44-targeted

strategies should be tailored to the molecular subtype of the

tumor.

Dual targeting of CD44 and TGF-β

signaling suppresses viability and invasion in claudin-low breast

cancer cells

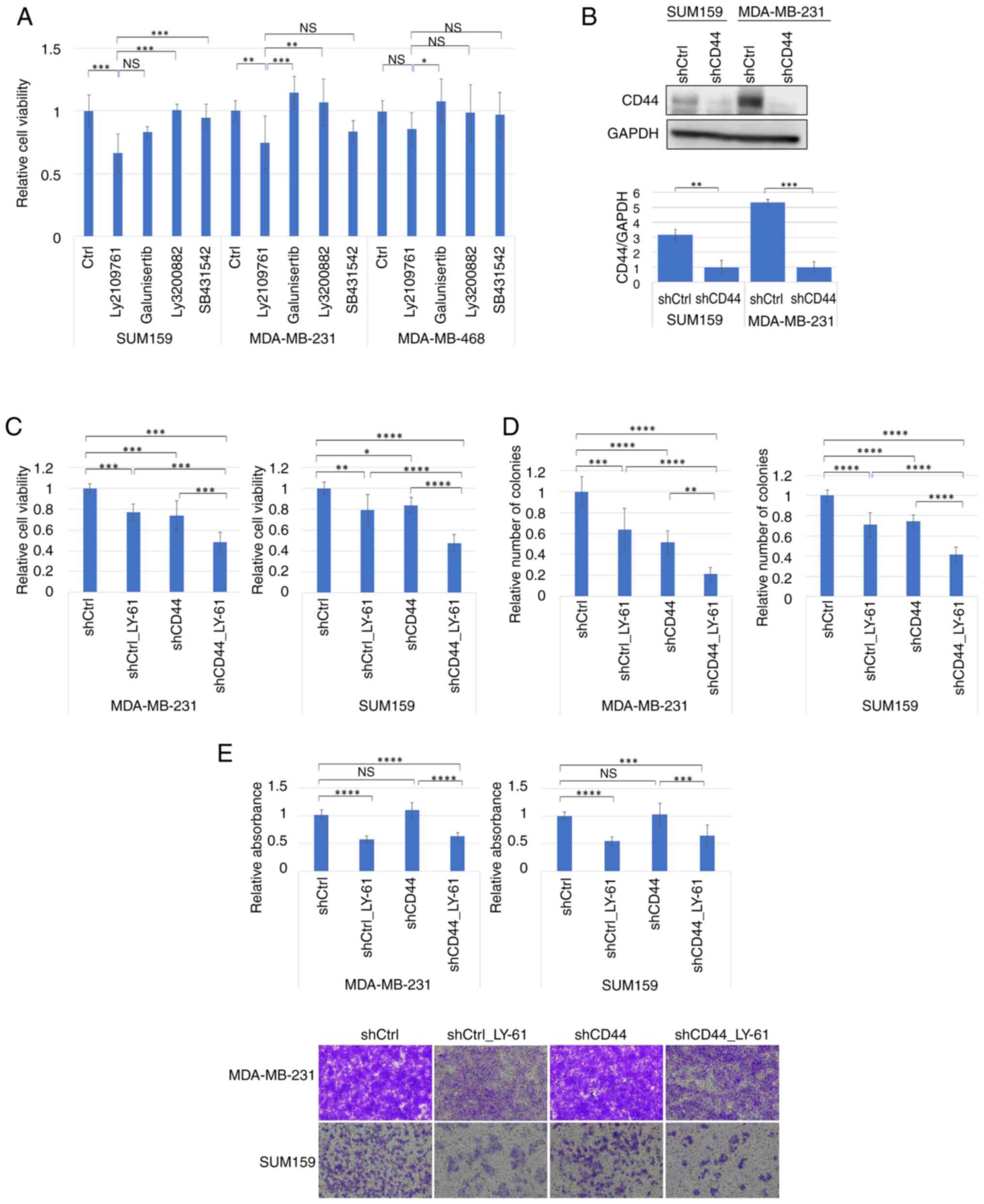

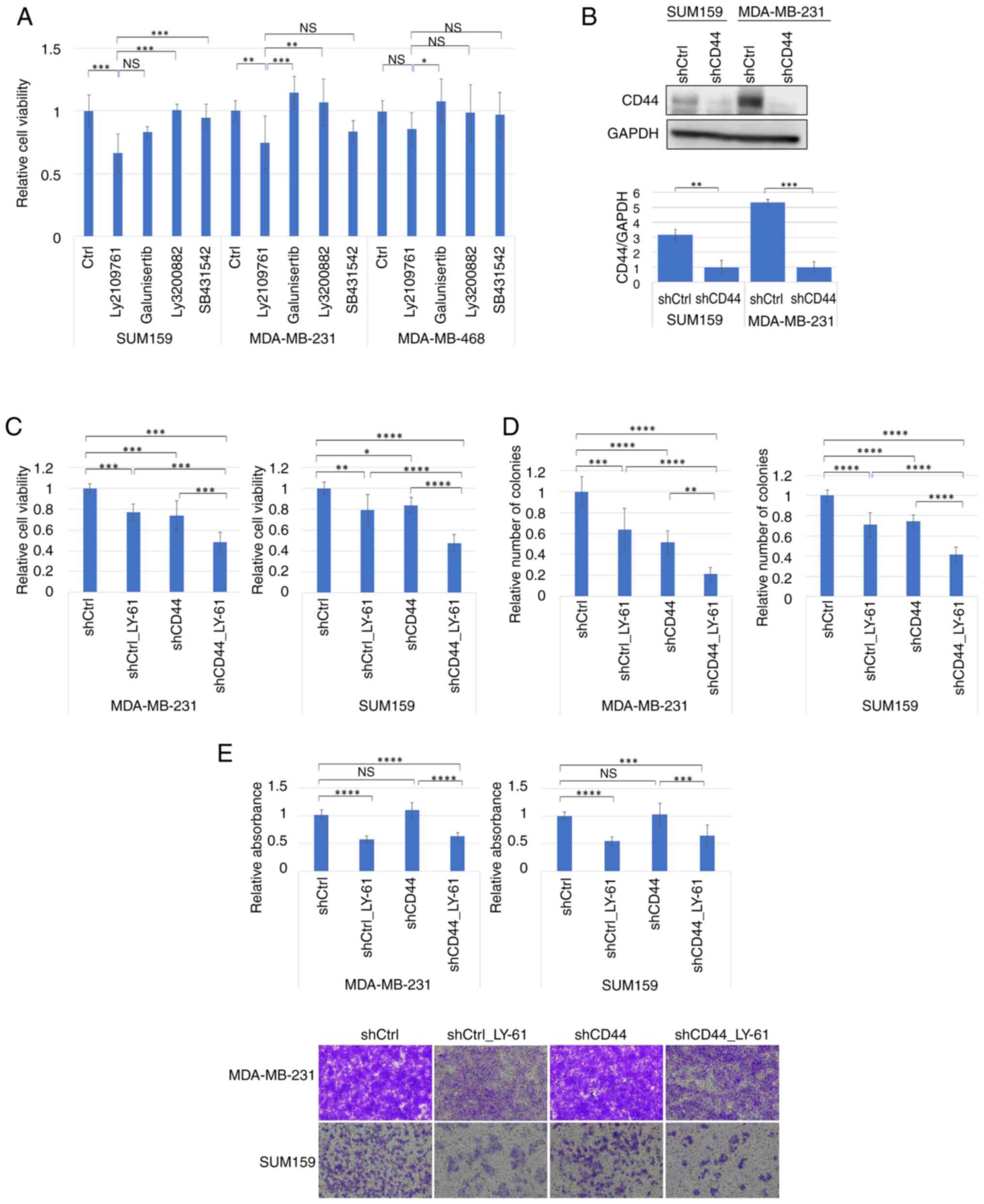

The effects of multiple TGFBR inhibitors, including

LY-61, SB431542 and Galunisertib, on the viability of various

breast cancer cell lines (SUM159, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468) were

evaluated. Among these, LY-61 showed the most pronounced inhibitory

effect on viability, particularly in claudin-low subtype cell lines

such as SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 cells, in which its effects were

statistically significant compared with the control. By contrast,

the basal-like cell line MDA-MB-468 exhibited minimal sensitivity

to these inhibitors (Fig. 3A).

These findings demonstrated that LY-61 potently inhibited cell

viability in claudin-low breast cancer cell lines.

| Figure 3.Additive antitumor effects of LY-61

and CD44 knockdown in claudin-low breast cancer cell lines. (A)

Relative viability of breast cancer cell lines (SUM159, MDA-MB-231

and MDA-MB-468) following treatment with TGF-β receptor inhibitors

(LY-61, Ly3200882, SB431542 and Galunisertib; all at 10 µM). Cells

(1,000 per well) were plated in 96-well plates, and drugs were

added 24 h after plating. Cell viability was measured using the MTT

assay on day 5 after plating. Statistical comparisons were made

using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test

for each cell line. (B) Western blot analysis of CD44 expression in

SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 cells following shRNA transduction.

Densitometric semi-quantification of CD44 protein levels relative

to GAPDH is shown below the blots (n=3). Data are presented as the

mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired

two-tailed t-tests. (C) Relative viability of MDA-MB-231 and SUM159

cells following CD44 knockdown (shCD44) and/or treatment with LY-61

(10 µM). Cells (1,000 per well) were plated in 96-well plates, and

LY-61 was added 24 h after plating. Cell viability was determined

using an MTT assay on day 5 after plating. Statistical significance

was assessed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple

comparisons test. (D) Colony formation assays showing relative

colony numbers in MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells following CD44

knockdown and/or LY-61 treatment. Statistical comparisons were

performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple

comparisons test. (E) Invasion assays in SUM159 and MDA-MB-231

cells showing the relative absorbance and representative microscopy

images of invaded cells stained on the underside of basement

membrane matrix-coated inserts. Cells were treated with LY-61

and/or subjected to CD44 knockdown. Statistical analysis was

performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple

comparisons test. Representative images are shown at a

magnification of ×100. (A and C-E) Data are presented as the mean ±

SD of three independent experiments (n=3). *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. Ctrl, control; LY-61, LY2109761;

NS, not significant; sh/shRNA, short hairpin RNA. |

To validate CD44 knockdown, reduced CD44 expression

was confirmed using western blot analysis in SUM159 and MDA-MB-231

cells (Fig. 3B). Further

experiments combining LY-61 treatment with CD44 knockdown

demonstrated an enhanced inhibitory effect on both cell viability

(Fig. 3C) and colony formation

(Fig. 3D) compared with either

treatment alone. Representative images of colony formation in

SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 cells are shown in Fig. S1A. CD44 knockdown and LY-61

treatment individually suppressed viability and colony formation to

a similar extent; however, their combination resulted in a more

pronounced reduction in both parameters. Although individual

comparisons showed significant differences between treatment

groups, no statistically significant interaction was detected in

the two-way ANOVA, suggesting an additive rather than synergistic

effect.

In the invasion assays (Fig. 3E), both SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 cells

were examined. LY-61 treatment markedly reduced invasion in both

cell lines, whereas CD44 knockdown alone had a minimal impact. This

suggested that LY-61 was particularly effective in impairing the

invasive behavior of cancer cells, likely through mechanisms

independent of CD44.

Collectively, these findings indicated that although

CD44 knockdown effectively suppressed cell viability and colony

formation in SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 cells, it had a limited effect

on cell invasion. By contrast, LY-61 treatment consistently

inhibited proliferative and invasive behaviors in both cell lines.

Notably, the combination of CD44 knockdown and LY-61 treatment led

to greater suppression of cell viability and colony formation, and

also reduced the invasive capacity compared with that in the shCtrl

group without LY-61 treatment, the latter effect being primarily

attributable to LY-61. These results highlight the complementary

effects of targeting CD44 and TGF-β signaling in claudin-low breast

cancer cells.

LY-61 attenuates CD44

knockdown-mediated activation of the TGF-β/Smad2 pathway

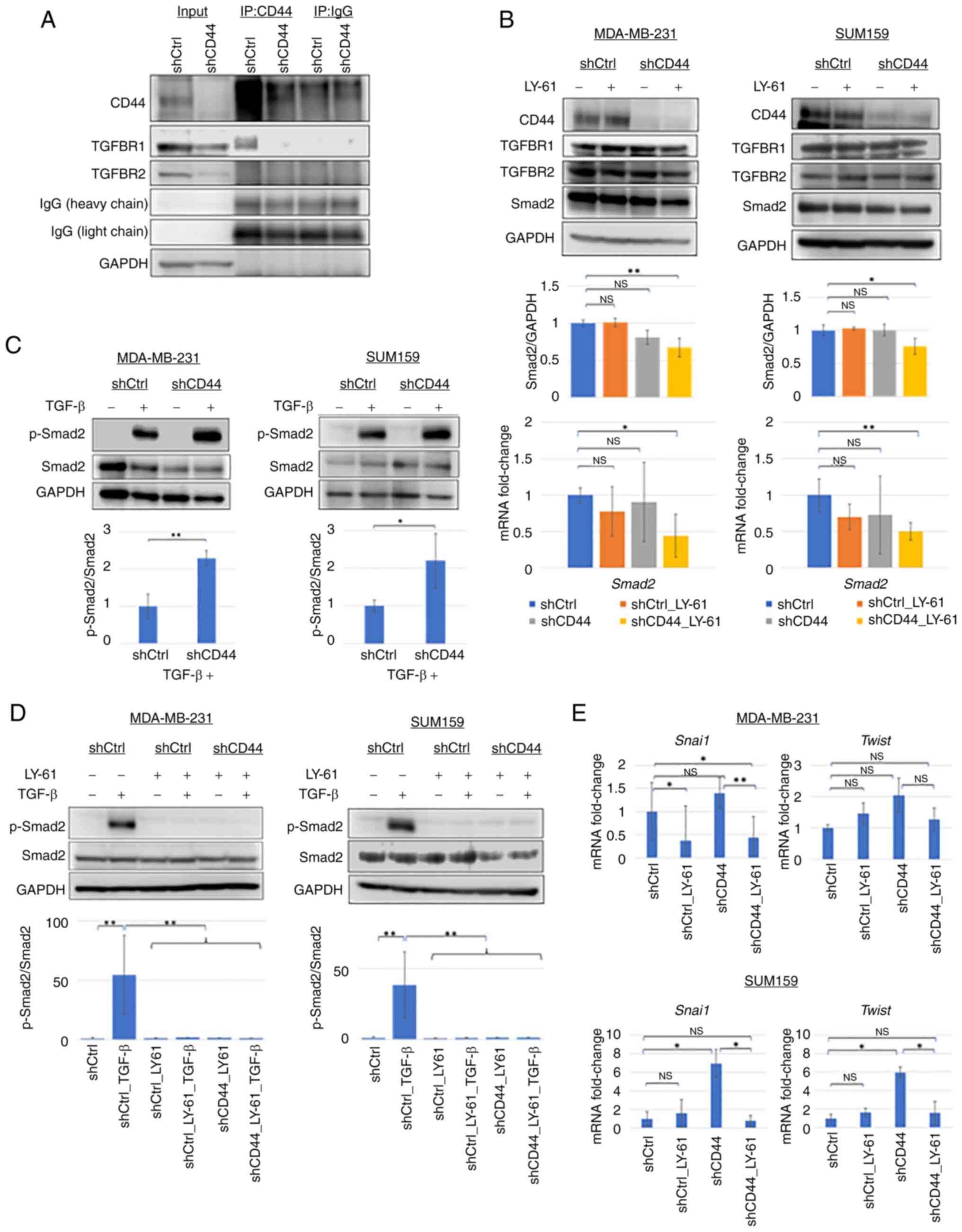

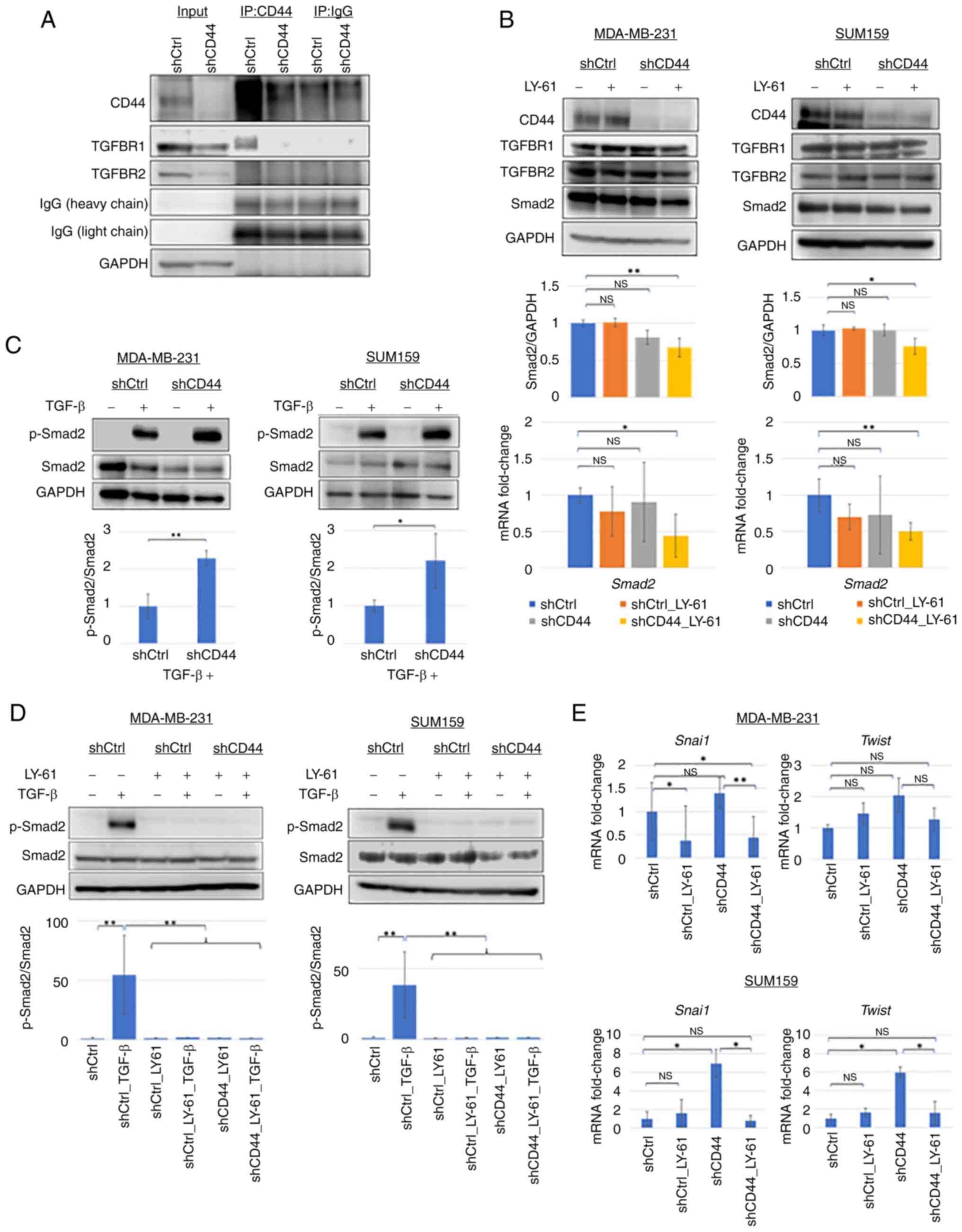

The STRING network analysis (Fig. S1B) revealed a strong interaction

between CD44 and TGFBR1, suggesting that CD44 serves a potential

regulatory role in TGF-β signaling. This association was confirmed

by co-immunoprecipitation assays (Fig.

4A), as CD44 and TGFBR1 co-precipitated in control cells

transduced with non-targeting shRNA (shCtrl); however, this

interaction was lost following CD44 knockdown. These findings

indicated that CD44 may modulate TGF-β signaling through TGFBR1 by

influencing receptor stability or complex formation.

| Figure 4.Effects of LY-61 and CD44 knockdown

on the TGF-β/Smad2 pathway in claudin-low breast cancer cell lines.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation assays showing that CD44 co-precipitated

with TGFBR1 in MDA-MB-231 cells. The CD44-TGFBR1 interaction signal

was reduced in shCD44 cells. No detectable co-precipitation was

observed between CD44 and TGFBR2. (B) Western blotting and RT-qPCR

showing Smad2 protein and mRNA levels in MDA-MB-231 and SUM159

cells following CD44 knockdown and/or LY-61 treatment.

Representative western blots (top), densitometric

semi-quantification of Smad2 protein levels (middle) and mRNA

expression levels determined by RT-qPCR (bottom) are shown. Data

are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments

(n=3). (C) Western blot analysis of p-Smad2 and total Smad2 protein

levels after TGF-β stimulation in MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells with

or without CD44 knockdown. The semi-quantification of Smad2

phosphorylation was performed by calculating the p-Smad2/Smad2

ratio. CD44 knockdown increased TGF-β-induced p-Smad2 levels in

both cell lines. (D) Western blotting showing the effect of LY-61

treatment on p-Smad2 levels in MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells.

Densitometric semi-quantification of the p-Smad2/Smad2 ratio from

three independent experiments (n=3) is shown below the blots. (E)

Relative mRNA expression levels of Snai1 and Twist in

SUM159 and MDA-MB-231 cells following CD44 knockdown and/or LY-61

treatment, as determined using RT-qPCR. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n=3). Statistical

significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by (B)

Dunnett's or (D and E) Tukey's multiple comparisons test, or (C)

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Ctrl, control; LY-61, LY2109761; NS, not significant; p-,

phosphorylated; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

sh, short hairpin RNA; Snai1, snail family transcriptional

repressor 1; TGFBR, TGF-β receptor; IP, immunoprecipitation. |

Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B) showed that Smad2 protein levels

were not notably altered by LY-61 treatment or CD44 knockdown alone

in both MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells. However, a modest decrease in

Smad2 protein levels was observed following combined treatment.

Consistently, the results shown in Fig. S1C confirmed efficient CD44

knockdown and showed no marked changes in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2

expression. This pattern was also reflected in the RT-qPCR results,

where Smad2 mRNA levels showed a similar downward trend following

combined treatment. These findings suggested that dual inhibition

exerted a cumulative suppressive effect on Smad2 expression,

although the magnitude of the change remained limited.

A crucial observation was the impact of CD44

knockdown on Smad2 phosphorylation (p-Smad2) in response to TGF-β

stimulation (Fig. 4C). In the

MDA-MB-231 and SUM159 cells, TGF-β treatment markedly increased the

p-Smad2 levels. CD44 knockdown alone did not induce Smad2

phosphorylation; however, it enhanced TGF-β-induced Smad2

phosphorylation compared with that in shCtrl cells, indicating

increased sensitivity to TGF-β signaling. Notably, LY-61 treatment

markedly inhibited TGF-β-induced Smad2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4D), demonstrating its potent

inhibitory effect on Smad2 activation, regardless of CD44

expression.

To assess whether CD44 knockdown affects

TGF-β-induced EMT, the expression levels of the EMT-related

transcription factors Snai1 and Twist were

subsequently examined. As shown in Fig.

4E, CD44 knockdown significantly increased Snai1 and

Twist mRNA expression in SUM159 cells (P<0.05), whereas

only a non-significant upward trend was observed in MDA-MB-231

cells. In MDA-MB-231 cells, LY-61 monotherapy (shCtrl_LY-61)

significantly downregulated Snai1 expression (P<0.05),

while Twist expression remained unchanged. Notably,

treatment with LY-61 significantly reduced Snai1 expression

in CD44-knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells (P<0.01), whereas

Twist showed a non-significant downward trend. In SUM159

cells, LY-61 significantly suppressed both Snai1 and

Twist expression in the context of CD44 knockdown

(P<0.05). These findings suggested that LY-61 counteracted

TGF-β/Smad2-mediated EMT transcriptional activity, even under

conditions of CD44 knockdown, as shown by its suppression of

TGF-β-induced Smad2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4D) and the concomitant reduction of

Snai1 and Twist expression in LY-61-treated

CD44-knockdown cells compared with untreated CD44-knockdown cells

(Fig. 4E). Consistently, LY-61 also

reduced Snai1 protein levels in CD44-knockdown SUM159 cells, with

the combination group (shCD44_LY-61) showing the lowest Snai1/GAPDH

ratio. By contrast, CD44 knockdown alone did not significantly

increase Snai1 expression (Fig.

S1D).

These findings suggested that CD44 knockdown did not

directly enhance Smad2 phosphorylation but increased EMT-related

gene expression, indicating that CD44 may influence TGFBR1-mediated

signaling rather than Smad2 activation itself. LY-61 effectively

inhibited Smad2 phosphorylation and suppressed EMT marker

expression, highlighting its potential to counteract TGF-β-driven

invasive behavior in claudin-low breast cancer.

Cell line-specific effects of LY-61

and CD44 knockdown on the cell cycle and apoptosis in claudin-low

breast cancer cells

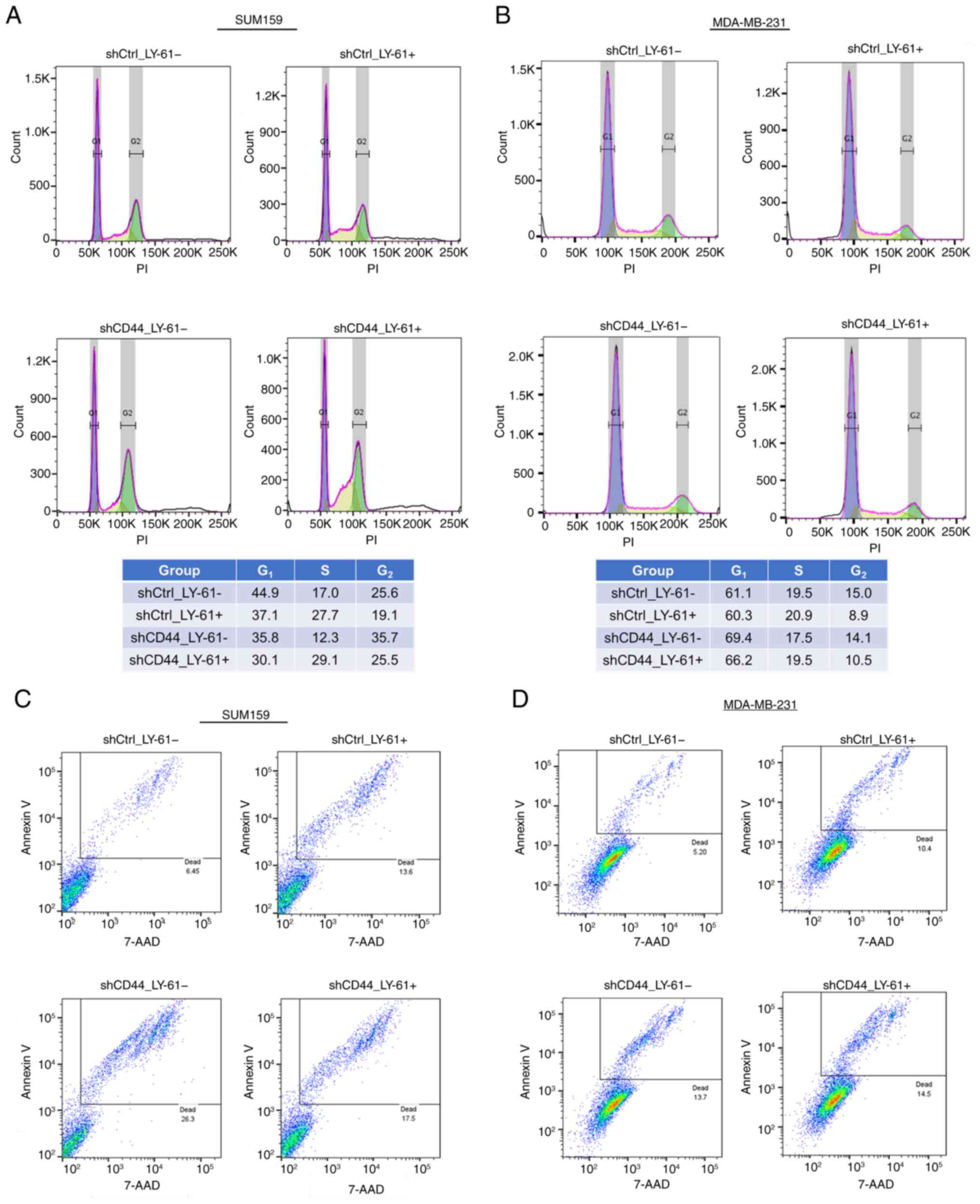

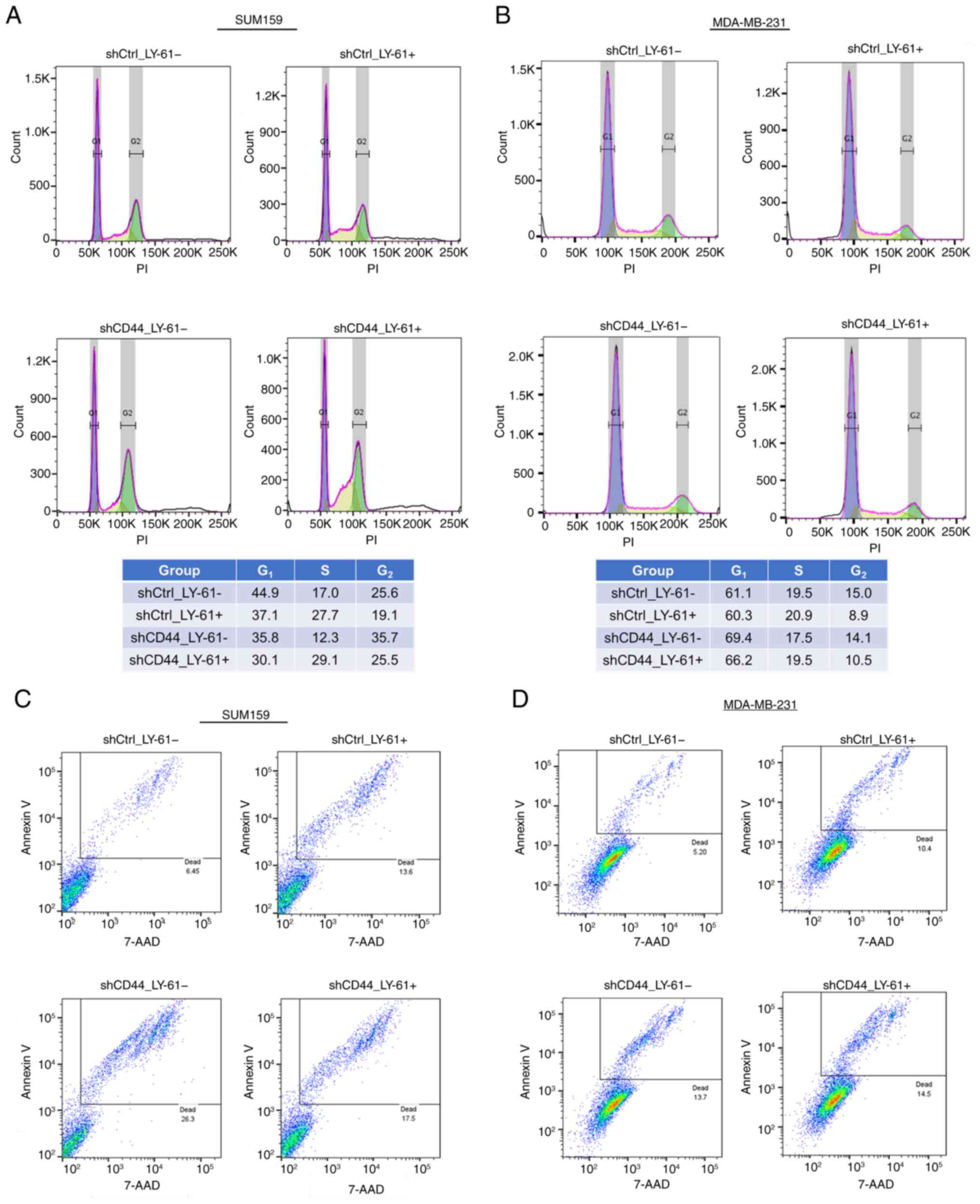

In SUM159 cells, LY-61 treatment increased the

proportion of cells in the S phase under both control

(shCtrl_LY-61) and CD44-knockdown conditions (shCD44_LY-61),

suggesting delayed DNA replication and potential checkpoint

activation rather than full cell cycle arrest (38). Furthermore, G2 phase

accumulation was observed following CD44 knockdown in SUM159 cells,

suggesting that CD44 loss may contribute to delayed cell cycle

progression at G2. By contrast, MDA-MB-231 cells showed

only a slight increase in the S phase fraction after LY-61

treatment, and CD44 knockdown exerted a negligible effect on

G2 phase distribution, indicating that the influence of

CD44 on cell cycle regulation differed between these two cell lines

(Fig. 5A and B).

| Figure 5.Effects of LY-61 and CD44 knockdown

on cell cycle progression and apoptosis in claudin-low breast

cancer cells. (A and B) Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle

distribution in (A) SUM159 and (B) MDA-MB-231 cells treated with

LY-61 and/or CD44 knockdown. LY-61 treatment induced S phase

accumulation, most prominently in SUM159 cells. In SUM159 cells,

CD44 knockdown increased G2 phase accumulation,

suggesting delayed progression through the cell cycle. By contrast,

in MDA-MB-231 cells, the proportion of cells in the G2

phase remained relatively unchanged. The tables summarize the

percentages of cells in each phase. Percentages may not total

exactly 100% due to the exclusion of sub-G1 and debris

populations and rounding errors (values were rounded to one decimal

place after calculation from two decimal places, which may cause

minor deviations such as totals slightly >100%). (C and D)

Apoptosis analysis using annexin V/7-AAD staining in (C) SUM159 and

(D) MDA-MB-231 cells following CD44 knockdown and/or LY-61

treatment. CD44 knockdown increased apoptosis, whereas LY-61

treatment alone had a minimal effect. 7-AAD, 7-aminoactinomycin D;

Ctrl, control; LY-61, LY2109761; sh, short hairpin RNA. |

Apoptosis assays (Fig.

5C and D) revealed that CD44 knockdown increased apoptosis, as

indicated by a higher percentage of annexin V-positive cells

compared with the shCtrl group. This suggested that CD44 knockdown

compromised tumor cell survival by enhancing apoptotic signaling.

Western blotting further showed that CD44 knockdown decreased Bcl-2

protein levels in MDA-MB-231 cells, although the reduction was not

statistically significant (Fig.

S1E), suggesting a role of CD44 in pro-survival signaling via

Bcl-2 regulation.

When LY-61 treatment was combined with CD44

knockdown (shCD44_LY-61), the percentage of apoptotic cells

remained increased compared with that in the shCtrl group but was

slightly reduced compared with that following CD44 knockdown alone

in SUM159 cells, while in MDA-MB-231 cells it was higher than that

in the shCtrl group and similar to that in the CD44 knockdown

group. These findings suggest that LY-61 treatment and CD44

inhibition acted through distinct but complementary mechanisms to

suppress tumor cell survival. LY-61 mainly affected cell cycle

progression by inducing S phase accumulation, particularly in

SUM159 cells, whereas CD44 knockdown increased apoptosis, thereby

reducing the overall proliferative capacity.

These findings highlighted the cell line-specific

effects of LY-61 and CD44 knockdown on cell cycle progression and

apoptosis. LY-61-mediated S phase accumulation was pronounced in

SUM159 cells but only slight in MDA-MB-231 cells, underscoring the

context-dependent nature of cell cycle regulation in claudin-low

breast cancer. Meanwhile, CD44 knockdown consistently increased

apoptosis across both cell lines, demonstrating the role of CD44 in

supporting tumor cell survival. The combined inhibition of CD44 and

TGF-β signaling (via LY-61) is a promising strategy for the

simultaneous disruption of proliferation and survival mechanisms in

claudin-low breast cancer subtypes.

Discussion

The present study provided novel insights into

genomic alterations and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities in

the claudin-low breast cancer subtype, with a particular focus on

CD44, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. The present results suggested that

claudin-low tumors relied more on CNAs and epigenetic changes than

mutations. This pattern was consistent with the lower overall

mutational burden observed in claudin-low tumors compared with

basal-like tumors, indicating that while mutations are involved,

alternative mechanisms, such as CNAs and epigenetic changes, may

serve a more prominent role in promoting tumor progression in this

subtype (9,34,37).

These findings highlight the unique genomic landscape of

claudin-low breast cancer, distinct from basal-like tumors, which

are characterized by high genomic instability and frequent BRCA1/2

mutations (9,34,37,39).

Understanding these subtype-specific differences is crucial for the

identification of effective therapeutic targets.

One of the key findings of the present study was the

complex role of CD44 in claudin-low breast cancer. While low CD44

expression was associated with improved survival in claudin-low

tumors, CD44 knockdown led to significant upregulation of

Snai1 and Twist expression in SUM159 cells, whereas

only a modest, non-significant increase was observed in MDA-MB-231

cells. This suggests a potential enhancement of EMT-related

transcriptional responsiveness. Although previous studies have

predominantly reported that CD44 promotes EMT and stemness in

various cancer types, including breast cancer (10,28,40–42),

some reports suggest that CD44 may also restrain EMT under specific

conditions (for example, when differences in the cellular context,

microenvironment or signaling network alter its downstream

interactions) (10,12–14).

The present findings differ from numerous previous reports

describing CD44 knockdown as suppressing EMT markers and invasive

potential (10,42,28),

but may reflect a context-specific response in claudin-low cells.

This contradiction indicates that CD44 serves dual roles:

Supporting tumor cell survival while modulating TGF-β signaling in

a way that restrains EMT. The present results demonstrated that

CD44 knockdown increased apoptosis, which may explain the improved

prognosis associated with low CD44 expression regardless of its

pro-EMT effects. These findings underscore the context-dependent

functions of CD44 in claudin-low breast cancer and the importance

of considering subtype-specific differences when evaluating CD44 as

a biomarker or therapeutic target.

From a therapeutic perspective, the present study

demonstrated that LY-61, a TGFBR inhibitor, exerted potent

antitumor effects on claudin-low breast cancer cell lines. However,

its effects on cell cycle regulation differed between SUM159 and

MDA-MB-231 cells. In SUM159 cells, LY-61 induced S phase

accumulation and G2 phase delay, indicating impaired

cell cycle progression. By contrast, MDA-MB-231 cells exhibited a

slight increase in the S-phase fraction accompanied by a modest

reduction in the G2-phase fraction compared with the

control, suggesting that LY-61 did not induce full cell cycle

arrest but rather delayed S phase progression in a cell

line-dependent manner. These differences may reflect variations in

DNA damage response or checkpoint activation (38).

These findings align with the known complexity of

TGF-β signaling in breast cancer. Although TGF-β typically induces

G1 arrest via CDK inhibitors, this mechanism is often

dysregulated in cancer (35,43).

Inhibition of TGF-β signaling may promote S phase entry by

bypassing residual G1 control (24). In the present study, S phase

accumulation was observed in both cell lines following LY-61

treatment, but the effect was more pronounced in SUM159 cells,

whereas only a slight increase was detected in MDA-MB-231 cells. In

both cell lines, LY-61 treatment was accompanied by a comparable

reduction in the G2-phase fraction (from 25.6 to 19.1%

in SUM159 cells and from 15.0 to 8.9% in MDA-MB-231 cells),

consistent with delayed progression from S to G2. These

results underscore the cell line-specific nature of TGF-β pathway

responses and suggest that therapeutic strategies targeting this

pathway may need to account for differences in cell cycle

regulation.

Aside from affecting cell cycle progression, LY-61

also effectively counteracted the modest EMT-related gene

expression changes observed following CD44 knockdown. CD44

knockdown increased Snai1 and Twist expression in

SUM159 cells, while the changes were modest in MDA-MB-231 cells.

However, LY-61 treatment markedly inhibited TGF-β-induced Smad2

phosphorylation, and also suppressed the expression of Snai1

and Twist compared with that in CD44-knockdown cells without

LY-61 treatment, effectively counteracting the pro-invasive signals

induced by TGF-β. These findings suggested that while CD44

knockdown may enhance tumor cell plasticity, LY-61 mitigated this

effect by inhibiting the key drivers of EMT.

These findings are consistent with previous studies

showing that pharmacological inhibition of TGF-β signaling (for

example, using SB431542) suppressed Smad2 phosphorylation and

downregulated EMT-related transcription factors such as

Snai1 and Twist, thereby inhibiting TGF-β-induced

invasion in breast cancer cells (36,44,45).

Although CD44 has been reported to promote EMT and its knockdown

has been reported to suppress EMT markers (28,41,42),

the present data revealed a modest increase in Snai1 and

Twist expression following CD44 knockdown. This discrepancy

may reflect differences in cellular context, such as variations in

TGF-β signaling activity or other regulatory pathways. It is

possible that, under certain conditions, CD44 knockdown sensitizes

cells to TGF-β-induced EMT. This complexity may also help explain

why low CD44 expression was not consistently associated with

improved prognosis across subtypes, showing a favorable association

in claudin-low tumors, but not in basal, luminal A, luminal B or

HER2-enriched subtypes. Even in tumors with low CD44 expression,

EMT-inducing pathways such as TGF-β signaling may remain active,

thereby limiting the survival benefit associated with low CD44

expression (40,46–48).

The present data revealed a functional interplay

between CD44 and TGF-β signaling in claudin-low breast cancer.

Co-immunoprecipitation assays in MDA-MB-231 cells demonstrated a

physical interaction between CD44 and TGFBR1, and this interaction

was lost following CD44 knockdown. These findings suggest that CD44

may exert its role in TGF-β signaling not through the direct

modulation of Smad2 phosphorylation, but rather through its

interaction with TGFBR1, possibly affecting receptor stability or

accessibility to downstream effectors, consistent with a previous

study describing the functional relevance of CD44 in TGF-β receptor

regulation (26). Although SUM159

cells also exhibit claudin-low characteristics, CD44 knockdown and

LY-61 treatment did not induce an apparent reduction in TGFBR1 and

TGFBR2 protein levels, whereas MDA-MB-231 cells showed a tendency

toward decreased TGFBR2 expression, while TGFBR1 levels remained

largely unchanged. This difference may reflect subtle, cell

line-specific variations in the regulation of TGFBR stability or

turnover. It should be noted that the CD44-TGFBR1 interaction was

assessed only in MDA-MB-231 cells; thus, further studies are

required to determine whether similar mechanisms operate in SUM159

cells.

While CD44 knockdown alone markedly increased

apoptosis, the combination of LY-61 and CD44 knockdown resulted in

comparable or slightly lower apoptosis levels than CD44 knockdown

alone; however, apoptosis remained elevated compared with shCtrl

cells. This suggested that LY-61 and CD44 inhibition acted through

distinct but complementary mechanisms. CD44 depletion increased

apoptosis by disrupting survival signaling, whereas LY-61 delayed

cell cycle progression, which may reduce apoptotic stress in a

compensatory manner. Although LY-61 reduced the level of apoptosis

observed compared with CD44 knockdown alone in SUM159 cells, no

such decrease was observed in MDA-MB-231 cells. Nevertheless,

combined treatment with LY-61 and CD44 knockdown effectively

suppressed both proliferation and invasion compared with those in

the shCtrl group without LY-61 treatment, suggesting a

complementary therapeutic mechanism.

These results highlighted the complex and

potentially dual role of CD44 in claudin-low breast cancer. While

CD44 supports tumor survival, it may also restrain EMT by

modulating TGF-β signaling, as suggested by the present findings

and supported by a previous report demonstrating the regulatory

interaction between CD44 and TGFBR1 (26). In the present study, CD44 knockdown

increased apoptosis and was associated with a modest upregulation

of EMT-related transcription factors such as Snai1 and

Twist, possibly reflecting a compensatory response to the

loss of survival signaling. These findings are consistent with

previous reports showing that CD44 promoted cancer stemness and may

suppress EMT under certain conditions (10,11),

whereas other studies have linked CD44 upregulation to enhanced EMT

and metastasis (10,40). It remains to be clarified whether

this EMT-related gene expression change is a direct effect of CD44

loss or a secondary adaptation due to disrupted cell survival

mechanisms.

The effects of TGFBR inhibition observed in the

present study underscore the therapeutic significance of this

pathway in claudin-low breast cancer. Prior studies have

demonstrated that TGF-β serves a role in mediating EMT, immune

evasion and resistance to therapy (36,49).

The present results reinforced the notion that selective inhibition

of TGF-β signaling, particularly when combined with disruption of

CD44-mediated pathways, may represent a promising strategy for

managing claudin-low tumors, which currently lack effective

treatment options.

The findings of the present study suggest a

potential therapeutic strategy for claudin-low breast cancer by

targeting the TGF-β/Smad2 pathway (via LY-61) and CD44-mediated

survival mechanisms. However, the differential effects of LY-61 on

cell cycle progression across claudin-low cell lines underscore the

need for further investigation into the molecular determinants of

its efficacy.

A key limitation of the present study was the lack

of in vivo validation. Although the present in vitro

findings provided strong mechanistic insights into the cooperative

effects of CD44 knockdown and TGFBR inhibition, the therapeutic

implications of this dual-targeting strategy remain hypothetical.

Future studies using xenograft models or patient-derived organoids

will be essential to validate these in vitro observations in

physiologically relevant systems, and to evaluate treatment

efficacy, systemic toxicity and interactions within the tumor

microenvironment.

Although in vivo analyses were beyond the

scope of the present study, the present findings offer a valuable

preclinical framework. The present study demonstrated how CD44 and

TGF-β signaling interacted to regulate proliferation, invasion, EMT

and cell survival in claudin-low breast cancer. These insights

establish a basis for future translational research aimed at

developing combinatorial therapeutic strategies for this aggressive

and poorly understood subtype. Additional investigations should

also explore potential compensatory signaling pathways that might

limit the effectiveness of TGF-β blockade and evaluate the

long-term outcomes of Smad2 inhibition in vivo.

Aside from the CD44-TGF-β axis investigated in the

present study, other EMT-related transcription factors (such as

zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1, forkhead box C2 and Slug) and

cancer stemness-associated pathways (such as the Wnt/β-catenin and

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 pathways) may also trigger the malignant

phenotype of claudin-low breast cancer (50–53).

The present findings demonstrated that dual targeting of CD44 and

TGF-β signaling suppressed cell proliferation and invasion, CD44

knockdown increased apoptosis, and LY-61 counteracted EMT-related

transcriptional activation. These results support the therapeutic

potential of this combinatorial approach and provide a mechanistic

basis for further development of more comprehensive treatment

approaches.

Although most comparisons using standard statistical

methods (such as t-tests and ANOVA) yielded significant results,

more advanced multivariate approaches, such as interaction models

or multiple regression, could have yielded deeper insights into the

interplay among CD44 knockdown, TGF-β inhibition and downstream

signaling networks. As such, future studies should incorporate such

analyses to better capture the complex relationships among these

pathways under varying experimental conditions.

The differential responses observed in SUM159 and

MDA-MB-231 cells highlight the need for further mechanistic studies

to understand the cell line-specific effects. These differences

likely reflect underlying biological heterogeneity within

claudin-low breast cancer, including variations in TGFBR

expression, downstream signaling responsiveness or EMT status.

Additional preclinical studies using a broader panel of claudin-low

cell lines and patient-derived xenografts will be required to

validate the generalizability of the present findings and assess

their translational relevance.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Yoshihiro Sowa

(Department of Molecular-Targeting Cancer Prevention, Kyoto

Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan) and Dr Masahiro

Shibata (Department of Breast Surgery, Nagoya Eiseikai Hospital,

Nagoya, Japan) for their valuable advice. This abstract was

presented at the 2024 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, held on

December 10–14, 2024, in San Antonio, TX, USA, and was published as

Abstract no. P2-04-06.

Funding

The present study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant no.

21K08612) and the Medical Research Support Project of Shizuoka

Prefectural Hospital Organization.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RM designed the study. RM and KK performed the

experiments and confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. RM,

KK, SI, SS, RH and MT contributed to data analysis and manuscript

preparation. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dai X, Li T, Bai Z, Yang Y, Liu X, Zhan J

and Shi B: Breast cancer intrinsic subtype classification, clinical

use and future trends. Am J Cancer Res. 5:2929–2943.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn

M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA,

et al: Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature.

406:747–752. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T,

Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey

SS, et al: Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas

distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 98:10869–10874. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Xiong X, Zheng LW, Ding Y, Chen YF, Cai

YW, Wang LP, Huang L, Liu CC, Shao ZM and Yu KD: Breast cancer:

Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

10:492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Herschkowitz JI, Simin K, Weigman VJ,

Mikaelian I, Usary J, Hu Z, Rasmussen KE, Jones LP, Assefnia S,

Chandrasekharan S, et al: Identification of conserved gene

expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and

human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 8:R762007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Prat A, Parker JS, Karginova O, Fan C,

Livasy C, Herschkowitz JI, He X and Perou CM: Phenotypic and

molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of

breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 12:R682010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sabatier R, Finetti P, Guille A, Adelaide

J, Chaffanet M, Viens P, Birnbaum D and Bertucci F: Claudin-low

breast cancers: Clinical, pathological, molecular and prognostic

characterization. Mol Cancer. 13:2282014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fougner C, Bergholtz H, Norum JH and

Sørlie T: Re-definition of claudin-low as a breast cancer

phenotype. Nat Commun. 11:17872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Garrido-Castro AC, Lin NU and Polyak K:

Insights into molecular classifications of triple-negative breast

cancer: Improving patient selection for treatment. Cancer Discov.

9:176–198. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hassn Mesrati M, Syafruddin SE, Mohtar MA

and Syahir A: CD44: A multifunctional mediator of cancer

progression. Biomolecules. 11:18502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim KJ, Godarova A, Seedle K, Kim MH, Ince

TA, Wells SI, Driscoll JJ and Godar S: Rb suppresses collective

invasion, circulation and metastasis of breast cancer cells in

CD44-dependent manner. PLoS One. 8:e805902013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dehbokri SG, Noorolyai S, Baghbani E,

Moghaddamneshat N, Javaheri T and Baradaran B: Effects of CD44

siRNA on inhibition, survival, and apoptosis of breast cancer cell

lines (MDA-MB-231 and 4T1). Mol Biol Rep. 51:6462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nam K, Oh S, Lee KM, Yoo SA and Shin I:

CD44 regulates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via

modulation of c-Src transcription in human breast cancer cells.

Cell Signal. 27:1882–1894. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang Z, Chen D, Nie J, Zhou S, Wang J,

Tang Q and Yang X: MicroRNA-143 targets CD44 to inhibit breast

cancer progression and stem cell-like properties. Mol Med Rep.

13:5193–5199. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Montgomery N, Hill A, McFarlane S, Neisen

J, O'Grady A, Conlon S, Jirstrom K, Kay EW and Waugh DJ: CD44

enhances invasion of basal-like breast cancer cells by upregulating

serine protease and collagen-degrading enzymatic expression and

activity. Breast Cancer Res. 14:R842012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ouhtit A, Madani S, Gupta I,

Shanmuganathan S, Abdraboh ME, Al-Riyami H, Al-Farsi YM and Raj MH:

TGF-β2: A novel target of CD44-promoted breast cancer invasion. J

Cancer. 4:566–572. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xu H, Niu M, Yuan X, Wu K and Liu A: CD44

as a tumor biomarker and therapeutic target. Exp Hematol Oncol.

9:362020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhou L, Sheng D, Deng Q, Wang D and Liu S:

Development of a novel method for rapid cloning of shRNA vectors,

which successfully knocked down CD44 in mesenchymal triple-negative

breast cancer cells. Cancer Commun (Lond). 38:572018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huang P, Chen A, He W, Li Z, Zhang G, Liu

Z, Liu G, Liu X, He S, Xiao G, et al: BMP-2 induces EMT and breast

cancer stemness through Rb and CD44. Cell Death Discov.

3:170392017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gao F, Zhang G, Liu Y, He Y, Sheng Y, Sun

X, Du Y and Yang C: Activation of CD44 signaling in leader cells

induced by tumor-associated macrophages drives collective

detachment in luminal breast carcinomas. Cell Death Dis.

13:5402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pan C, Xu A, Ma X, Yao Y, Zhao Y, Wang C

and Chen C: Research progress of Claudin-low breast cancer. Front

Oncol. 13:12261182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pommier RM, Sanlaville A, Tonon L,

Kielbassa J, Thomas E, Ferrari A, Sertier AS, Hollande F, Martinez

P, Tissier A, et al: Comprehensive characterization of claudin-low

breast tumors reflects the impact of the cell-of-origin on cancer

evolution. Nature Commun. 11:34312020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gooding AJ and Schiemann WP:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition programs and cancer stem cell

phenotypes: Mediators of breast cancer therapy resistance. Mol

Cancer Res. 18:1257–1270. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Akhurst RJ and Hata A: Targeting the TGFβ

signalling pathway in disease. Nat Revi Drug Discov. 11:790–811.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Matsunuma R, Chan DW, Kim BJ, Singh P, Han

A, Saltzman AB, Cheng C, Lei JT, Wang J, Roberto da Silva L, et al:

DPYSL3 modulates mitosis, migration, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition in claudin-low breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

115:E11978–E11987. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Porsch H, Mehić M, Olofsson B, Heldin P

and Heldin CH: Platelet-derived growth factor β-receptor,

transforming growth factor β type I receptor, and CD44 protein

modulate each other's signaling and stability. J Biol Chem.

289:19747–19757. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yang K and Yi T: Tumor cell stemness in

gastrointestinal cancer: Regulation and targeted therapy. Front Mol

Biosci. 10:12976112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A and Freeman JW:

The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: Therapeutic

implications. J Hematol Oncol. 11:642018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Flanagan L, Van Weelden K, Ammerman C,

Ethier SP and Welsh J: SUM-159PT cells: A novel estrogen

independent human breast cancer model system. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 58:193–204. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chan DW, Mody CH, Ting NS and Lees-Miller

SP: Purification and characterization of the double-stranded

DNA-activated protein kinase, DNA-PK, from human placenta. Biochem

Cell Biol. 74:67–73. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G,

Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, Speed D, Lynch AG, Samarajiwa S, Yuan Y, et

al: The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast

tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 486:346–352. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A,

Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork

P, et al: STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with

increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide

experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:D607–D613. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Voutsadakis IA: Molecular characteristics

and therapeutic vulnerabilities of claudin-low breast cancers

derived from cell line models. Cancer Genomics Proteomics.

20:5392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Donovan J and Slingerland J: Transforming

growth factor-beta and breast cancer: Cell cycle arrest by

transforming growth factor-beta and its disruption in cancer.

Breast Cancer Res. 2:116–124. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang X, Eichhorn PJA and Thiery JP: TGF-β,

EMT, and resistance to anti-cancer treatment. Semin Cancer Biol.

97:1–11. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fougner C, Bergholtz H, Kuiper R, Norum JH

and Sørlie T: Claudin-low-like mouse mammary tumors show distinct

transcriptomic patterns uncoupled from genomic drivers. Breast

Cancer Res. 21:852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Barcellos-Hoff MH and Gulley JL: Molecular

pathways and mechanisms of TGFβ in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res.

29:2025–2033. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kwei KA, Kung Y, Salari K, Holcomb IN and

Pollack JR: Genomic instability in breast cancer: Pathogenesis and

clinical implications. Mol Oncol. 4:255–266. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Xu H, Tian Y, Yuan X, Wu H, Liu Q, Pestell

RG and Wu K: The role of CD44 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition

and cancer development. Onco Targets Ther. 8:3783–3792.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li L, Qi L, Liang Z, Song W, Liu Y, Wang

Y, Sun B, Zhang B and Cao W: Transforming growth factor-β1 induces

EMT by the transactivation of epidermal growth factor signaling

through HA/CD44 in lung and breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Med.

36:113–122. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gao Y, Ruan B, Liu W, Wang J, Yang X,

Zhang Z, Li X, Duan J, Zhang F, Ding R, et al: Knockdown of CD44

inhibits the invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma

both in vitro and in vivo by reversing epithelial-mesenchymal

transition. Oncotarget. 6:7828–7837. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Deng Z, Fan T, Xiao C, Tian H, Zheng Y, Li

C and He J: TGF-β signaling in health, disease and therapeutics.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chanmee T, Ontong P, Mochizuki N,

Kongtawelert P, Konno K and Itano N: Excessive hyaluronan

production promotes acquisition of cancer stem cell signatures

through the coordinated regulation of Twist and the transforming

growth factor β (TGF-β)-Snail signaling axis. J Biol Chem.

289:26038–26056. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang K, Liu X, Hao F, Dong A and Chen D:

Targeting TGF-β1 inhibits invasion of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma

cell through SMAD2-dependent S100A4-MMP-2/9 signalling. Am J Transl

Res. 8:2196–2209. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Katsuno Y, Meyer DS, Zhang Z, Shokat KM,

Akhurst RJ, Miyazono K and Derynck R: Chronic TGF-β exposure drives

stabilized EMT, tumor stemness, and cancer drug resistance with

vulnerability to bitopic mTOR inhibition. Sci Signal.

12:eaau85442019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ouhtit A, Madani S, Gupta I,

Shanmuganathan S, Abdraboh ME, Al-Riyami H, Al-Farsi YM and Raj MH:

TGF-β2: A novel target of CD44-promoted breast cancer invasion. J

Cancer. 4:566–572. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Park NR, Cha JH, Jang JW, Bae SH, Jang B,

Kim JH, Hur W, Choi JY and Yoon SK: Synergistic effects of CD44 and

TGF-β1 through AKT/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling during

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in liver cancer cells. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 477:568–574. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hao Y, Baker D and Ten Dijke P:

TGF-β-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer

metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 20:27672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Voutsadakis IA: EMT Features in

Claudin-Low versus Claudin-Non-Suppressed Breast Cancers and the

Role of Epigenetic Modifications. Curr Issues Mol Biol.

45:6040–6054. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Werden SJ, Sphyris N, Sarkar TR, Paranjape

AN, LaBaff AM, Taube JH, Hollier BG, Ramirez-Peña EQ, Soundararajan

R, den Hollander P, et al: Phosphorylation of serine 367 of FOXC2

by p38 regulates ZEB1 and breast cancer metastasis, without

impacting primary tumor growth. Oncogene. 35:5977–5988. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Taube JH, Herschkowitz JI, Komurov K, Zhou

AY, Gupta S, Yang J, Hartwell K, Onder TT, Gupta PB, Evans KW, et

al: Core epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition interactome

gene-expression signature is associated with claudin-low and

metaplastic breast cancer subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:15449–15454. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liang H, Benard O, Kumar V, Griffen A, Ren

Z, Sivalingam K, Wang J, de Simone Benito E, Zhang X, Zhang J, et

al: Wnt/ERK/CDK4/6 activation in the partial EMT state coordinates

mammary cancer stemness with self-renewal and inhibition of

differentiation. Br J Cancer. 133:986–1002. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|