Introduction

Mebendazole (Mbz), a broad-spectrum anthelmintic

drug, is widely used to treat various helminthic infections but has

also shown anticancer activity (1).

In preclinical models, Mbz induces dose-dependent direct cytotoxic

effects in adrenocortical carcinoma, lung cancer, melanoma, ovarian

cancer and glioblastoma (2–7). Furthermore, arrest of tumor growth has

been observed in cancer xenograft mouse models (2–5,8).

Clinically meaningful activity of Mbz has also been reported in two

case reports of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and

adrenocortical carcinoma (9,10). The

anticancer properties of Mbz have been proposed to be due to direct

cytotoxic actions such as tubulin polymerization inhibition

(6), protein kinase inhibition

(11), anti-angiogenesis (12) and inhibition of the Hedgehog pathway

(13). More recently, we observed

that Mbz also induces an antitumoral immune response ex vivo

by activation of M1 macrophages through the ERK I/II and Toll-like

receptor-8 dependent pathway (14,15)

along with induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (16).

The concept of administering a combination of two or

more anticancer drugs has been a cornerstone in cancer therapy.

This approach generally enhances the treatment efficacy and reduces

drug resistance (17,18). Traditionally, anticancer drug

combinations have been identified through empirical screening for

non-overlapping toxicities, whereas contemporary strategies

increasingly employ mechanistic rationales for which drugs to

combine (19,20). Preclinical studies frequently report

synergistic interactions when combining drugs, whereas such

interactions hardly apply in the clinic (21). Additive or sub-additive interactions

are more realistic effects to expect and would still provide

clinical benefits (22).

Combinations of Mbz with established anticancer

drugs have been explored in cell line models. For example, in a

melanoma cell line, Mbz increases apoptosis when combined with

trametinib (23). Similarly,

synergetic effects have been observed when Mbz is combined with

temozolomide and vincristine or with gemcitabine in brain and

breast cancer cell lines, respectively (24,25).

We previously found single drug Mbz administration to be

ineffective in patients with advanced previously treated

gastrointestinal cancer (26).

However, in early clinical studies of glioblastoma and CRC,

combining Mbz with chemotherapy was found to be safe and appeared

to provide patient benefit (27–30).

With this background, we considered it relevant to

further characterize the anticancer properties of single agent Mbz

and Mbz in combination with irinotecan, gemcitabine and cisplatin

in a clinically relevant ex vivo model of primary cultures

of patient tumor cells as well as in vivo with a murine

colon cancer model. These cytotoxic drugs were selected based on

their well-characterized mechanisms of action (31), allowing for the assessment of

whether Mbz exhibits broad-spectrum synergy or if its interactions

are specific to certain drug classes. Moreover, all three agents

are standard-of-care therapies for several solid tumors (31). The study was designed to address

certain critical gaps in the research on Mbz as a potential

anticancer drug, mainly its cytotoxic activity as a single drug,

its interaction with standard cytotoxic anticancer drugs and its

modes of action. This motivated the use of a somewhat mixed study

design using clinically relevant ex vivo human tumor models

as well as an immune-competent in vivo colon cancer

model.

Materials and methods

Preparation of patient tumor cells for

ex vivo assessment of direct cytotoxicity

Tumor samples were obtained from adult patients aged

≥18 years with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or colorectal, ovarian

or renal cancer at Akademiska Hospital (Uppsala University

Hospital) (Uppsala, Sweden) by bone marrow or peripheral blood

sampling, intraoperatively or by diagnostic biopsy in accordance

with the approval from the Regional Ethical Committee in Uppsala

(approval no. 2007/237). The samples were collected January

2008-December 2014, prepared as detailed below and then

cryopreserved until use in 2022 for experiments in the present

study. Written informed consent for sample collection and further

analysis was provided by patients before sampling. Inclusion

criteria for sampling were: i) Patients aged ≥18 years; ii)

localized or advanced untreated or previously treated disease; and

iii) the sampling procedure was considered to be safe and with a

prospect that drug sensitivity testing could be of potential

patient benefit. Sex distribution among the included patients was

70% (n=155) women and 30% (n=67) men.

The cell preparation protocol for solid and leukemic

tumors has been described in detail elsewhere (32). Briefly, for the solid tumors, the

samples were manually minced using sterile scissors and dispersed

in collagenase [collagenase type I, 1.5 mg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) and DNase type I, 100 µg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in

CO2 Independent Medium, pH 7.35–7.45 (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.)] for 4 h at 37°C. The samples were then

purified by density gradient centrifugation [200 × g, 5 min, at

room temperature (RT)] (Histopaque®−1077; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) followed by the determination of cell viability and

count using a Bürker chamber. The cells were diluted in complete

culture medium [RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

containing 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 2%

glutamine/penicillin-streptomycin] in a 37°C humidified atmosphere

containing 5% CO2 before seeding in plates for further

analysis.

The leukemic cells were isolated by Ficoll-Paque

density gradient centrifugation (400 × g, 30 min, RT) and then

counted using a Bürker chamber after staining for viability in

Türks solution (33). The cells

were then diluted in complete culture medium until experimental

seeding.

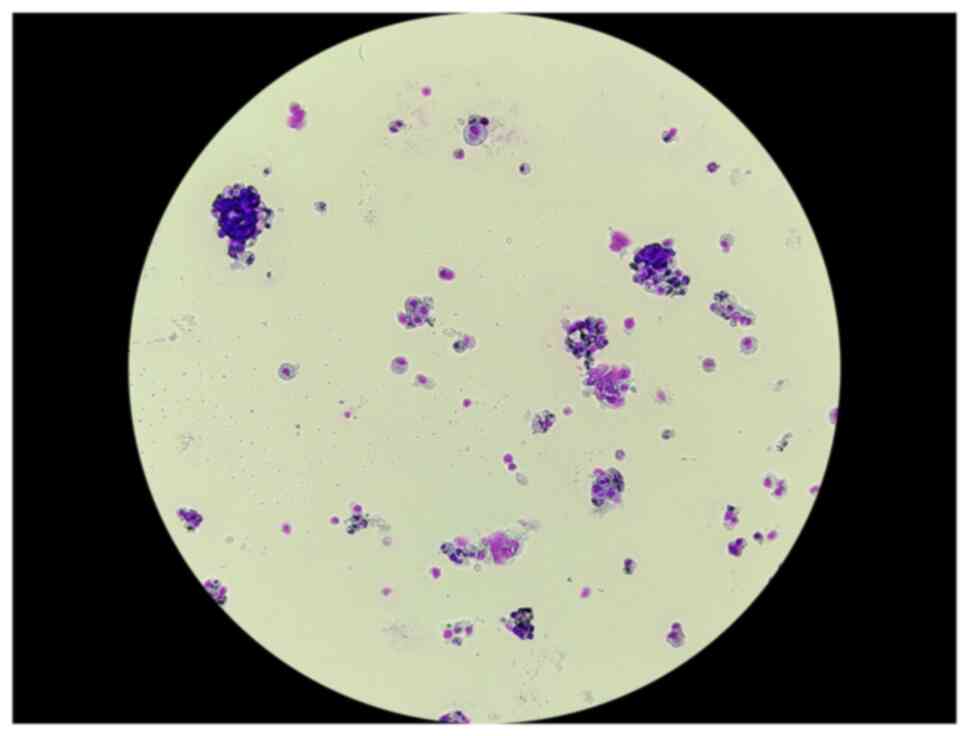

Isolated cells were stained using the May-Grünwald

Giemsa staining method. Cells were placed on slides then first

stained with May-Grünwald solution for 5 min at RT, washed

thoroughly in deionized water and then stained in Giemsa solution

for 10 min at RT, followed by another wash. Slides were air-dried

and evaluated for tumor representativity, based on cell size,

nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, chromatin staining pattern, presence of

nucleoli and mitoses and cellular adhesion tendency, by a trained

cytopathologist. A representative image of May-grünwald Giemsa

stained isolated cells from a colorectal tumor is shown in Fig. 1. Only samples with ≥70% tumor cells

were included in the study.

Assessment of direct cellular toxicity

in patient tumor cells

The fluorometric microculture cytotoxicity assay

(FMCA) described in detail previously (34), was used for the measurement of cell

survival. In the FMCA, living cells with an intact membrane

hydrolyze fluorescein diacetate to fluorescein. By measuring

fluorescence, cell survival is expressed as the survival index %

(SI), calculated as:

SI=(Fsample-Fblank)/(Fcontrol-Fblank)

×100, where Fsample represents the fluorescence in wells

with the drug, Fcontrol the fluorescence in wells with

cells and medium and Fblank the fluorescence in wells

with medium alone. The FMCA is a total cell death assay, the

results of which correspond well with the much more laborious

clonogenic assay (35).

Briefly, 5,000 cells/well (solid tumor samples), or

20,000 cells/well (hematological tumor samples) were seeded in

384-well Nunc culture plates (cat. no. 164688; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) using the pipetting robot, Biomek 4000 (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.). Drugs were added immediately after cell seeding

using an ECHO 550 system (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The plates were

incubated for 72 h in a 37°C humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2 and then transferred to an integrated system for

automated fluorescence scanning and data calculation. A successful

assay was defined by a fluorescence signal in control wells of ≥5

times the mean blank and a coefficient of variation of cell

survival in control cultures of ≤30 and ≥70% tumor cells before

incubation and/or on the assay day.

Mbz was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA)

whereas cisplatin, irinotecan and gemcitabine were either from

commercial clinical preparations or obtained from Selleck Chemicals

or LC Laboratories. Mbz was tested at concentrations of 45, 15, 5,

1.67 and 0.56 µM, cisplatin at 30, 10, 3.3, 1.12 and 0.37 µM,

irinotecan at 180, 60, 20, 6.6 and 2.2 µM, and gemcitabine at 90,

30, 10, 3.34 and 1.12 µM. The procedure of drug dissolution and

storage has been described in detail by Blom et al (32).

Assessment of direct cellular toxicity

in the CT26 cell line

CT26 murine colon carcinoma cells (ATCC) were

diluted in complete culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10%

fetal calf serum and 2% glutamine/penicillin-streptomycin) and

seeded at 500 cells per well into 384-well Corning plates (cat. no.

3764; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Plates were incubated for 24

h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Mbz, cisplatin and gemcitabine were tested at the concentrations

detailed above and were dispensed using an Echo 650 (Backman

Coulter, Inc), followed by a 72 h incubation period in a 37°C

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After

incubation, the plates were centrifuged (200 × g, 5 min, RT) and

the supernatant was removed using an ELx405 plate washer.

CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 reagent (25 µl/well; cat. no. G9243;

Promega Corporation) was added using the Biomek 4000 liquid

handling system. Plates were sealed, wrapped in foil, shaken (600

rpm for 2 min) and incubated in the dark for 10 min. Luminescence

was then measured using a FLUOstar Omega microplate reader (BMG

Labtech GmbH). The ATP-based viability method was chosen over the

FMCA, as CT26 cells exhibit a pronounced fibroblast-like phenotype

that may interfere with fluorescence-based viability measurements

(36).

Drug interaction analysis ex vivo

The interaction between Mbz and cisplatin (0.37–30

µM), irinotecan (2.2–180 µM) or gemcitabine (1.1–90 µM) in solid

tumor samples was assessed by comparing the SI for each drug

separately and when combined with Mbz at 5 µM, a concentration that

induced modest cytotoxicity alone. The drug concentration ranges

used were previously shown to induce a suitable range of cytotoxic

effects in solid tumor samples.

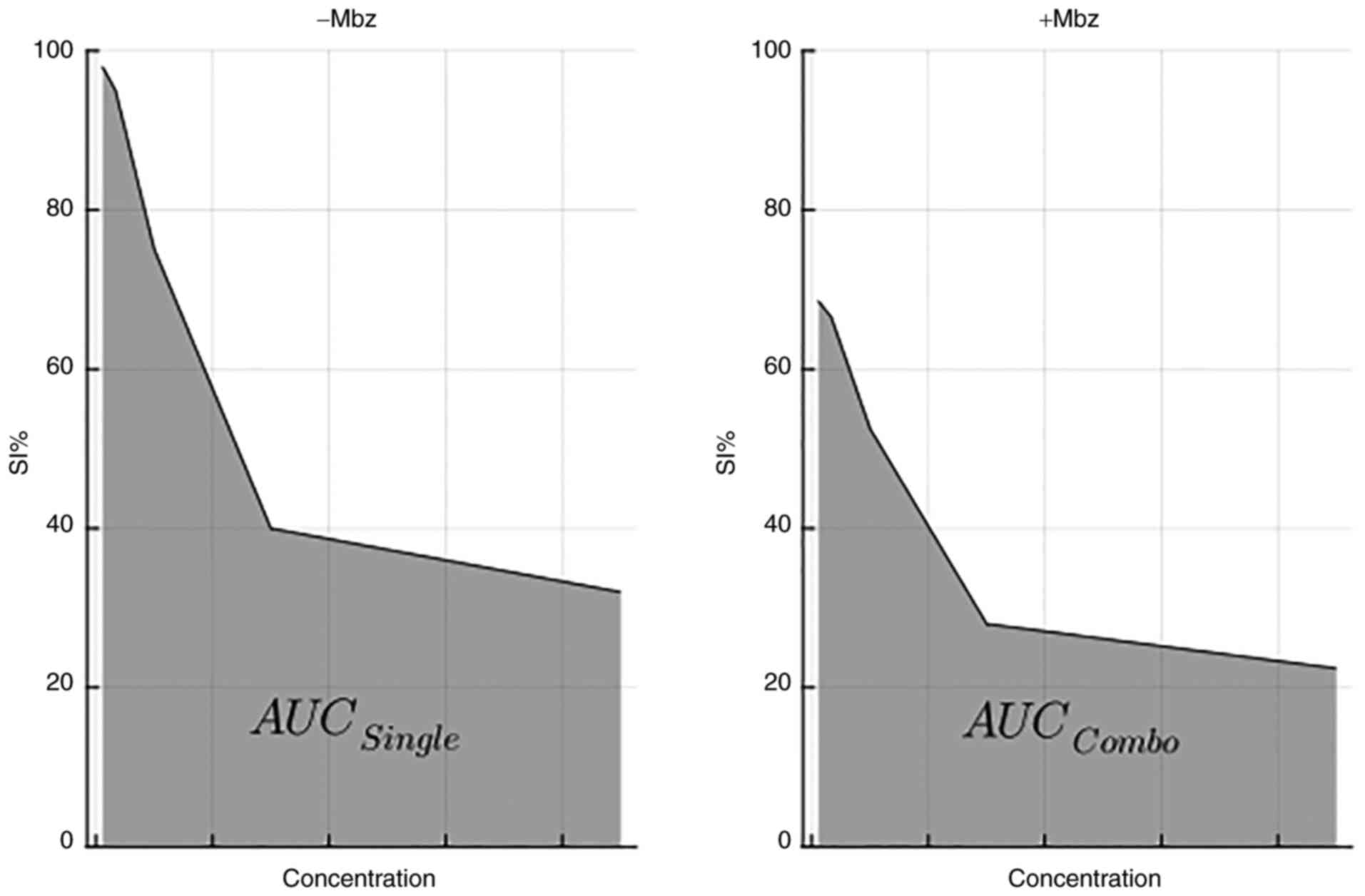

For the assessment of drug interaction for each drug

and sample SI, area under the curve (AUC) was calculated.

AUCi was defined as the

AUCCombo/AUCSingle ratio, where

AUCCombo denotes the area under the concentration-SI

curve for the drug combined with Mbz and AUCSingle

denotes the AUC for the cytotoxic drug alone, as illustrated in

Fig. 2. Thus, AUCi

ratios ≤1 indicate positive interactions (such as sub-additive or

synergistic), whereas ratios >1 indicate negative interactions

(such as antagonistic). The results are illustrated by heatmaps

plotted using the ‘pheatmap’ (version 1.0.12) package in R

(https://www.r-project.org; version

4.1.2), with rows and columns ordered by hierarchical clustering

(average linkage and Euclidean distance).

To further detail the interactions between Mbz and

irinotecan or cisplatin, FMCA experiments were performed using 4

CRC samples and analyzed in SynergyFinder 3.0 (https://synergyfinder.fimm.fi), an online

web-application that enables analysis and visualization of

multi-drug combination screening data (37,38).

The application offers interaction analysis with different models:

Loewe additivity (39), Bliss

excess (40), Zero Interaction

Potency (ZIP) (41) and Highest

Single Agent (HSA) (42). The

interactions are visualized as two-dimensional heatmaps and then

summarized over a dose-response matrix as an interaction score

calculated for each interaction model. The synergy experiments were

performed in triplicate.

Antitumor activity of Mbz and

irinotecan in vivo

The animal care and in vivo experimental

procedures were performed by Adlego Biomedical AB (Solna, Sweden)

according to Good Laboratory Practice standards and per ethical

approval by the regional animal ethics committee in Stockholm,

Sweden (approval no. 12201-2019). The study started late 2021 and

was finalized, including subsequent analyses in our laboratory,

late 2022.

In total, 54 female BALB/c mice aged 6–7 weeks at

arrival were obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. The

animals were kept 4–5 animals/cage in individually ventilated cages

(type IVC 4). Bedding was provided by BeeKay Scanbur AB and all of

the cages were enriched with happy homes, play tunnels, sizzle nest

and soft paper wool (Scanbur AB). The mice were kept at 22±3°C with

50±20% humidity. Lighting was regulated to 12-h light and dark

cycles and the animals had free access to food and water (RM 3;

Special Diet Services). Animals weighed 17.0–18.4 g at arrival and

19.3–21.2 g on day 20 with no obvious differences between

groups.

CT26, a murine colorectal carcinoma cell line

derived from the BALB/c strain, was purchased from ATCC. Irinotecan

was purchased from Fresenius Kabi AG and Mbz was purchased from

Recipharm AB. On Day-11, animals were inoculated with

3×105 CT26 cells (diluted in complete RPMI 1640 medium

to a total volume of 100 µl), subcutaneously in the right rear

flank. Tumor volumes, body weights and the animal general health

status were measured 3 times weekly by designated animal house

technicians. In addition, the team conducting the experiments

monitored the animals on each day of treatment and during the

endpoint procedures. Tumor volumes (in mm3) were

measured using a caliper and calculated by the following formula:

Length × width × width ×0.44.

On Day-1, when the tumors had reached a mean volume

of 46.5±1.97 mm3, the animals were stratified into 6

experimental groups, with 9 animals per group. Treatment was then

started at day 0, as detailed in Table

I. The dosing schedule was aimed to be as clinically relevant

as possible with Mbz considered to be a drug continuously

administered orally and irinotecan intermittently intravenously,

each at doses giving effects allowing for analysis of interactions

(5,43). Treatment was to be continued for a

maximum of 41 days after which the animals were euthanized by

cervical dislocation. Animals with tumors >2,000 mm3

and/or tumor-related wounds, were to be euthanized pre-term in

accordance with the ethical permit governing these experiments. For

this reason, most animals were euthanized around day 20, thus tumor

growth data are presented up until that day. Survival was defined

as time from stratification to pre-term termination or day 41.

Following euthanasia, tumors were extracted and placed in medium

(CO2 Independent Medium) with 5% heat-inactivated fetal

calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 1.1%

glutamine/penicillin-streptomycin consisting of equal parts 200 mM

L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and penicillin-streptomycin

(10,000 U/ml penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin in 0.9% NaCl;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and shipped directly to our laboratory

for preparation of the cells for flow cytometric evaluation.

| Table I.Treatment schedules for the

experimental groups. |

Table I.

Treatment schedules for the

experimental groups.

| Compound | Administration

route | Dose (mg/kg) | Schedule |

|---|

| Saline | i.v. | - | Twice weekly |

| LD Mbz | p.o. | 20 | Five

times/week |

| HD Mbz | p.o. | 50 | Five

times/week |

| Irinotecan | i.p. | 15 | Once weekly |

| Irinotecan + LD

Mbz | i.p./p.o. | 15+20 | Once weekly + five

times/week |

| Irinotecan + HD

Mbz | i.p./p.o. | 15+50 | Once weekly + five

times/week |

Flow cytometry

Immune cell infiltration in the mouse tumors was

assessed by flow cytometry. Mouse tumor tissues were prepared by

mechanical disintegration and collagenase digestion as

aforementioned. Cells were then enriched for CD45+

expression using an AutoMACS Pro (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH).

Prior to flow cytometry analysis, the cells were

washed and diluted with PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

human serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) (PBS-HSA) 0.1% for

5 min at 4°C. Gating antibodies were added to the cells according

to the following: i) Macrophage panel: Lymphocyte antigen 6

complex, locus G FITC (cat. no. 127605; Biolegend, Inc.), CD45

Pacific Orange (cat. no. MCD4530; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

CD163 PE (cat. no. 156704; Biolegend, Inc.), CD38 Pacific blue

(cat. no. 102720; Biolegend, Inc.), F4/80 PE/Cy7 (cat. no. 123114;

Biolegend, Inc.) and CD11b Violet 711 (cat. no. 101241; Biolegend,

Inc.); and ii) T cell panel: CD8 FITC/CD4 PE/CD3 PC7 (cat. no.

558391; BD Biosciences) and CD45 Pacific Orange. All antibodies

were diluted in PBS-HSA 0.1%. The cell and antibody mixture was

incubated for 20 min in the dark, washed with cold 1% PBS-HSA and

centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Finally, flow cytometry

was performed using a Navios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.)

and data were analyzed using Navios software v1.2 (Beckman Coulter,

Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism™ 6 (Dotmatics). Between group differences were first analyzed

by one-way ANOVA and if statistically significant, comparisons

between groups were made using Dunnett's post hoc test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

The data are presented as mean ± SD throughout.

Results

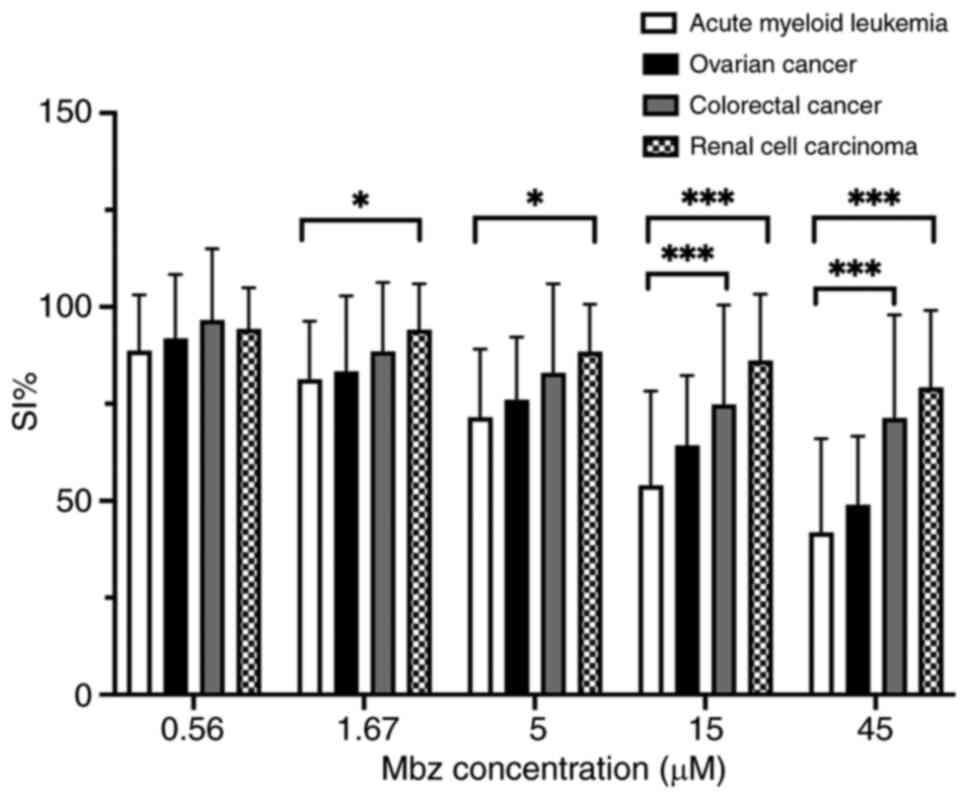

Mbz shows modest cytotoxicity in

patient tumor cells ex vivo

In total, 222 patient samples fulfilled the FMCA

quality criteria including AML (n=24) and ovarian (n=78),

colorectal (n=71) and renal (n=49) cancer samples. The single-drug

effect of Mbz was modest across all tumor types, with AML showing

the highest sensitivity, followed by ovarian, colorectal and renal

cancer (Fig. 3). Statistical

analysis confirmed a significant difference between AML and CRC at

the two highest concentrations (P<0.001). Moreover, a

significant difference was observed between AML and renal cell

carcinoma at all tested concentrations except the lowest

(P<0.001 for the two highest concentrations and P<0.05 for

the remaining concentrations). Mbz had a modest effect at 5 µM

(mean SI% 72, 76, 83 and 88 in AML, ovarian, colorectal and renal

cancer, respectively) and this concentration was selected for the

combination experiments.

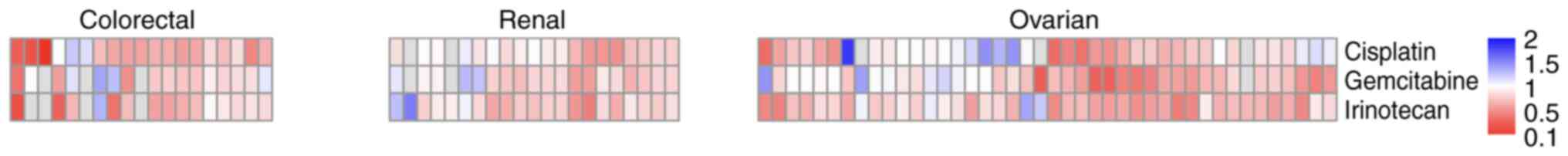

Mbz enhances the effect of cytotoxic

drugs in patient tumor cells

Drug interactions notably differed between samples

and tumor types (Fig. 4). In all of

the samples (n=82), regardless of diagnosis, a positive interaction

following the addition of Mbz was observed in 68% of the samples

(50/74) for cisplatin, 77% (58/75) for gemcitabine and in 88%

(72/82) for irinotecan. The corresponding numbers for renal cancer

were 73% (14/19), 79% (15/19) and 85% (18/21), for ovarian cancer

64% (25/39), 68% (28/41) and 90% (38/42) and for CRC 84% (16/19),

69% (12/16) and 93% (14/15). Notably, some drug-sample combinations

were not tested in all experiments (indicated in grey in Fig. 4), which explains why the sum of

subgroup analyses does not equal the total number of samples.

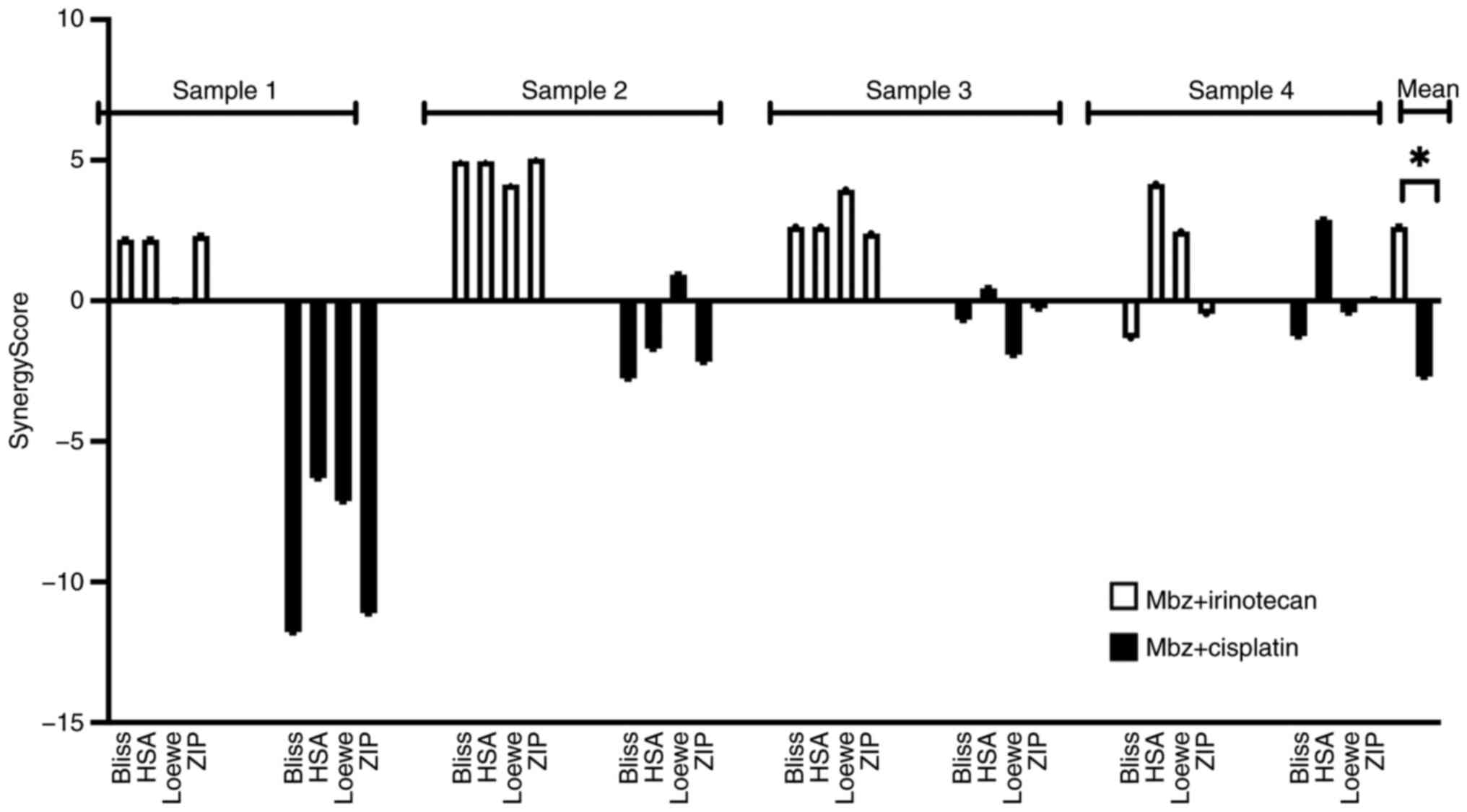

To investigate the observed interactions between Mbz

and irinotecan or cisplatin in more detail, a new set of FMCA

experiments with 4 CRC samples were performed using the

SynergyFinder application with four models for drug interactions.

According to the application, interaction scores in the −10 to +10

range suggests additive interactions, >+10 synergistic and

<-10 antagonistic interactions (36). The interaction scores for each

patient and each interaction model are shown in Fig. 5. Overall, the interaction scores for

the Mbz/irinotecan combination were higher across most interaction

models compared with the Mbz/cisplatin combination, suggesting the

Mbz/irinotecan combination to be the most favorable. Therefore,

this combination was selected for the in vivo study. The

majority of synergy scores for both combinations fell within the

range of −10 to +10, indicating additive effects. However, the

Mbz/irinotecan combinations occasionally exceeded +10 in certain

models and samples, suggesting potential synergistic

interactions.

Using Mann-Whitney test, a statistically

significantly higher overall mean score was observed for the

Mbz/irinotecan combination compared with the Mbz/cisplatin

combination [mean synergy score for Mbz/irinotecan, 2.63 (Bliss

excess, 2.11; HSA, 3.48; Loewe additivity, 2.63; ZIP, 2.32) vs.

mean synergy score for Mbz/cisplatin, −2.69 (Bliss excess, −4.11;

HSA, −1.16; Loewe additivity, −2.12; ZIP, −3.37); P<0.0001;

Fig. 5].

The low synergy scores for the Mbz/cisplatin

combination in sample 1 likely reflect the intrinsic drug

sensitivity and resistance of that particular tumor sample.

Individual tumor samples exhibit substantial heterogeneity in drug

response, which underscores the value of using a patient-derived

cell model to reflect drug activity in the clinic.

Cytotoxic effects in the CT26 murine

colon cancer cell line in vitro

As a basis for the assessment of drug interactions

in vivo, a corresponding set of experiments with in

vitro CT26 cells were conducted using Mbz alone and in

combination with cisplatin or irinotecan. Mbz alone showed a modest

and an almost concentration independent activity (Fig. S1A), whereas both cisplatin and

irinotecan induced a dose-dependent cytotoxicity (Fig. S1A and B). Furthermore, Mbz at 5 µM

enhanced the cytotoxic effect of cisplatin and irinotecan in an

additive/sub-additive pattern without notable differences between

these drugs (Fig. S1A-C).

Mbz inhibits tumor growth in the CT26

murine colon cancer model

Animal body weight and health status assessments

showed that drug administration was not associated with a decrease

in overall animal health status. Tumor growth was rapid and some

animals (1–3 animals in each group) developed tumor-related wounds

and were thus euthanized prior to the final study day.

Tumor-related wound development was evenly distributed throughout

groups and likely not correlated to drug administration. The

maximum measured tumor diameter and volume were 17.6 mm and 2,877

mm3, respectively.

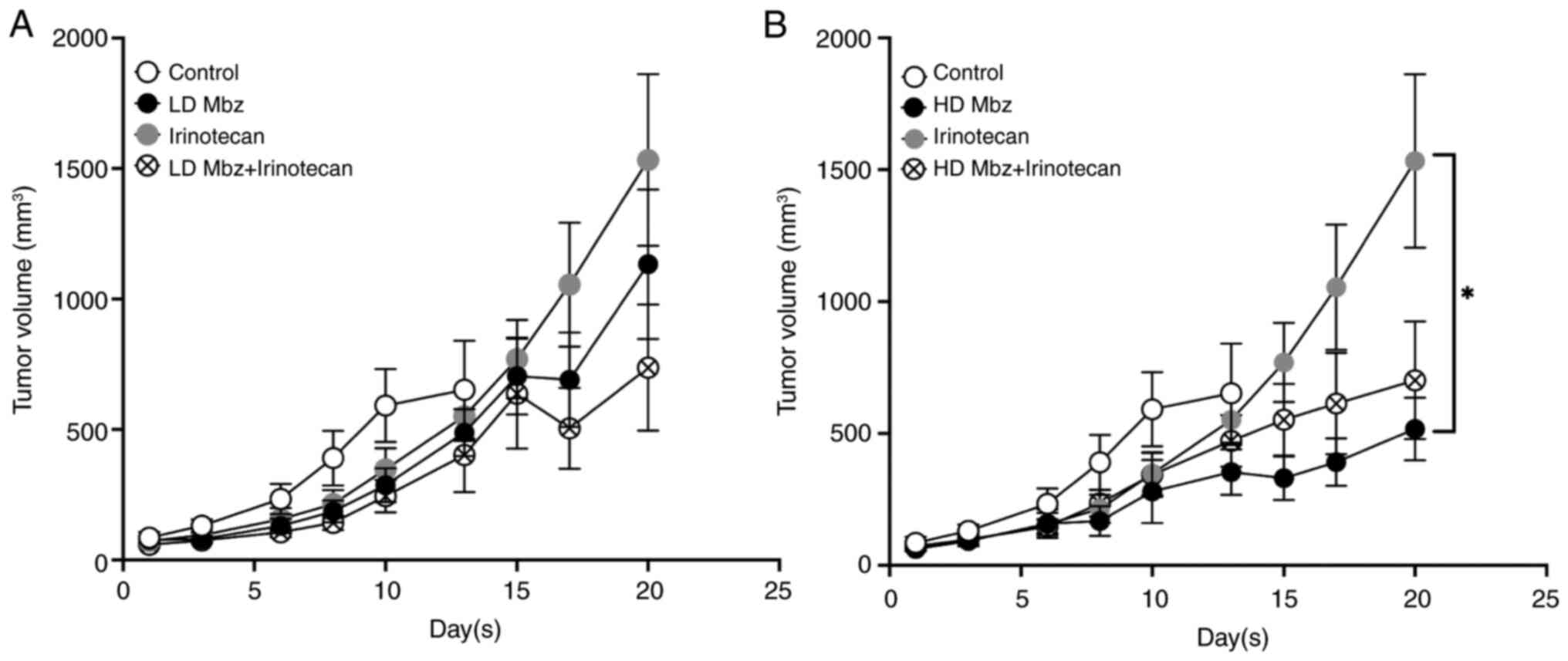

The mean tumor volumes for the control and

experimental groups are shown in Fig.

6, divided into a and b for clarity. The values are presented

up until day 13 for the control group as after this day most

animals in this group had been euthanized pre-term, in accordance

with the study protocol due to tumor growth, whereas most animals

in the experimental groups were continued to day 20. At day 13, the

control group had a mean tumor volume of 651 mm3

compared with 488 mm3 in the low dose Mbz group and 353

mm3 in the high dose Mbz group. The mean tumor volume at

day 13 in animals treated with irinotecan was 523 mm3

and when irinotecan was combined with low or high dose Mbz, the

volumes were 402 mm3 and 472 mm3,

respectively. Differences between the groups were not statically

significant. At day 20, the mean tumor volume in the irinotecan

group was 1,533 mm3, the low dose Mbz group was 1,133

mm3 and the high dose Mbz group was 517 mm3.

The tumor volume for irinotecan combined with low dose Mbz at day

20 was 737 mm3 and 699 mm3 for high dose Mbz.

Compared with irinotecan alone, the differences were not

statistically significant. At day 20, the difference between all

groups was statistically significant according to one-way ANOVA

(P=0.048), but only the difference between the mean tumor volumes

in the irinotecan and high dose Mbz groups was statistically

significant following post hoc test (P=0.04).

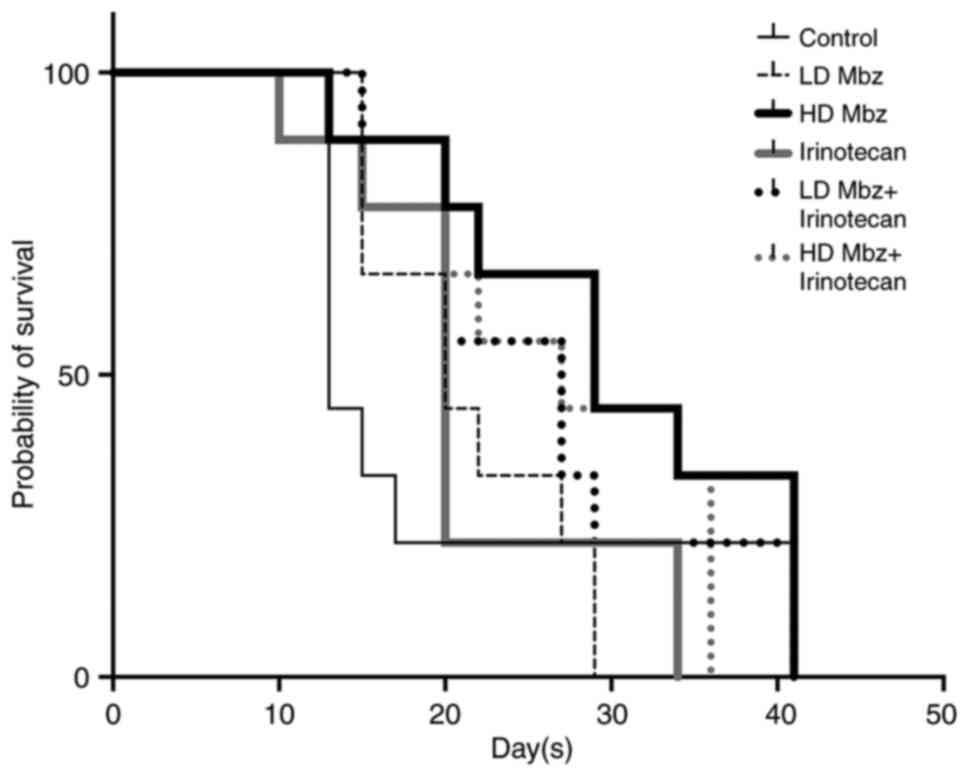

Kaplan Meier survival curves are presented in

Fig. 7. Drug exposed animals showed

a longer survival compared with the control animals. Control

animals had a median survival time of 13 days, compared with 20–29

days for those drugs exposed. In agreement with the effect on tumor

volumes, a dose-dependent effect of Mbz alone was indicated, with a

median survival time of 20 days in animals treated with low dose

Mbz compared with 29 days for high dose Mbz. Animals treated with

irinotecan combined with low or high dose Mbz had median survival

times of 27 days.

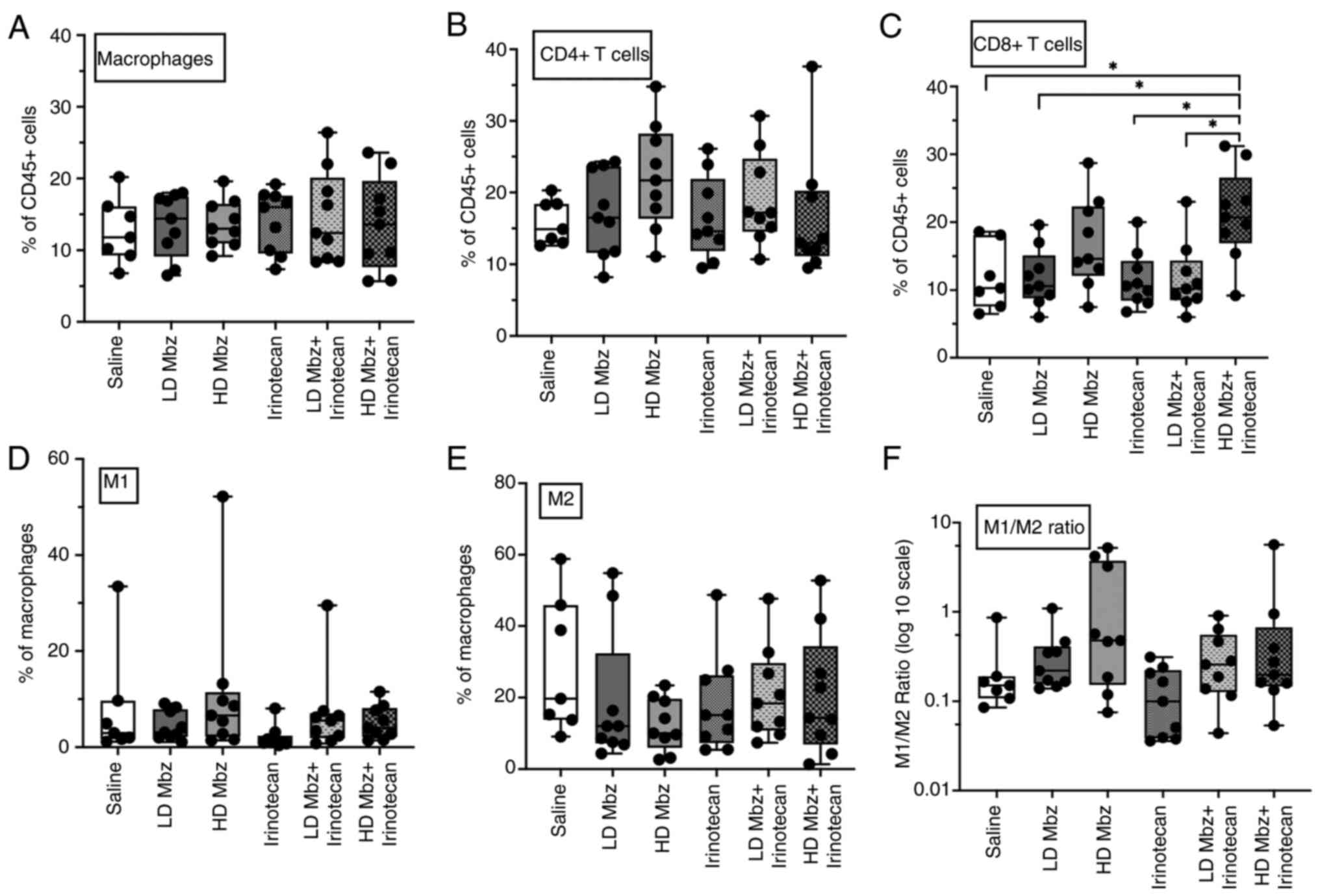

Mbz modulates tumor immune cell

infiltration in vivo

Based on our previous ex vivo findings of an

immunomodulatory effect of Mbz switching macrophages from the M2 to

M1 type (14,16), tumor tissue from the animals was

retrieved and analyzed by flow cytometry to detect the presence of

various subsets of immune cells. CD45+ cells were sorted

for CD4+/CD8+ T cells, and macrophages were

then classified further as type M1

(CD38+/CD80+) or type M2 (CD206+).

Fig. S2, Fig. S3, Fig.

S4, Fig. S5, Fig. S6, Fig.

S7 illustrate the gating strategies used to identify

macrophages and T cells, for each group separately.

Overall, Mbz slightly increased the infiltration of

macrophages and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 8A and B). Mbz tended to

dose-dependently increase the levels of M1 macrophages and decrease

M2 macrophages (Fig. 8D-F). Thus,

the mean M1/M2 ratio for low and high dose Mbz were 0.26 (range,

0.15–1.09) and 1.35 (range, 0.12–5.22), respectively, compared with

0.25 (range, 0.08–0.78) for the control group.

Mbz in combination with irinotecan increased the

M1/M2 ratio, but not beyond the effect of Mbz alone. Irinotecan

alone seemingly increased the macrophage infiltration but otherwise

did not notably alter the immune cell infiltration. The tumor

immune cell data exhibited substantial variability and no

statistically significant differences were observed between groups,

except for CD8+ T cells. A significant increase in

CD8+ T cells was observed in the high dose Mbz +

irinotecan group compared with the control, low dose Mbz +

irinotecan, low dose Mbz and irinotecan alone groups (P=0.01;

Fig. 8C).

Discussion

Ex vivo drug sensitivity testing of primary

cultures of tumor cells from patients using FMCA has previously

shown a good correlation with clinical outcomes in several tumor

types (44–47). Using this model in the present

study, it was demonstrated that Mbz alone had a modest direct

cytotoxic activity, in agreement with the general chemotherapeutic

drug sensitivity known from our previous ex vivo

characterization and from the clinic (2,3,48,49).

This finding is in contrast to that observed in various cell line

models, in which Mbz alone exhibits strong cytotoxic activity

(2–7). However, cell lines have several

limitations as tumor models and generally do not adequately

reproduce drug sensitivity in the clinic (50,51),

in contrast to primary cultures of tumor cells from patients

(50). Nevertheless, it should be

acknowledged that single-cell culture models, including

patient-derived cells, lack the complex interactions with immune

cells and extracellular matrix components that are present in the

in vivo tumor microenvironment.

Several mechanisms for a direct tumor cell Mbz

cytotoxicity have been reported (52) such as tubulin polymerization

inhibition (6), protein kinase

inhibition (11), anti-angiogenesis

(12) and inhibition of the

Hedgehog pathway (13), and are

considered notable for an anticancer drug. Together with the very

advantageous safety profile of Mbz, these observations have fueled

an interest in trying single drug Mbz for cancer treatment in

patients. Mbz has been reported to induce tumor remission in case

reports of patients with neuroendocrine and colon cancer (9,10).

Furthermore, in early clinical trials with patients with brain

tumors, Mbz at higher dose (up to 200 mg/kg/day) seemingly stops

tumor progression (28). Such

observations are in line with the observed Mbz-induced tumor growth

inhibition in different mouse models (2,5) and

are corroborated by the dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth

observed in the in vivo CT26 colon cancer model in the

present study.

However, the aforementioned findings contrast with

our phase II clinical trial of last line, individualized, single

drug Mbz in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer

(26). In the trial, no objective

tumor response to single-agent Mbz was observed, and a subset of

patients showed unusually rapid disease progression, suggestive of

hyperprogression, a phenomenon reported in patients treated with

immune checkpoint inhibitors (53).

Although it cannot be concluded that Mbz directly induced

hyperprogression, one possible explanation is that Mbz modulates

the immune system in a complex, context-dependent manner. While Mbz

can promote pro-inflammatory responses in controlled ex vivo

settings (16), the tumor

microenvironment in patients, particularly in heavily pre-treated

and immunosuppressed individuals, may respond differently.

The concept of combining several drugs remains a

cornerstone of cancer therapy. This approach generally improves the

benefit-risk balance compared with single drug treatment (17,18).

Traditionally, anticancer drug combinations were established

empirically, focusing on identifying regimens with non-overlapping

toxicities. More recently, however, combination strategies are

increasingly guided by mechanistic rationale based on tumor biology

(19,20). Preclinical studies frequently report

synergistic interactions when combining drugs whereas such

interactions hardly apply in the clinic (21). Instead, additive or sub-additive

interactions are more common and can still yield clinically

meaningful benefits (22). Given

the benefits of drug combinations and the negative results from our

aforementioned single-drug Mbz clinical trial, it is notable that a

recent randomized study reported improved outcomes in advanced CRC

when Mbz was combined with standard chemotherapy (FOLFOX) compared

with chemotherapy alone (27). This

finding prompted the investigation of the effect of Mbz combined

with mechanistically different standard cytotoxic drugs in the

present study. In patient tumor and CT26 cells, positive

interactions in the sub-additive to additive range were observed,

with the strongest effect noted for Mbz combined with irinotecan in

patient cells. This finding suggests that the Mbz/irinotecan

combination may be suitable for clinical testing, particularly in

tumor types where irinotecan is part of the standard treatment,

such as CRC.

In the present study, the observed positive

interaction between Mbz and irinotecan was partly corroborated in

the CT26 colon cancer mouse model. Low dose Mbz combined with

irinotecan was more active than each drug individually, although

this result was not statistically significant. By contrast, high

dose Mbz combined with irinotecan tended to be less active than Mbz

alone. The reason for this seemingly dose-dependent interaction

difference is unclear. However, it could be speculated that the

stronger tumor growth inhibition from high dose Mbz compared with

low dose Mbz was reduced by irinotecan-induced counteracting

changes in the tumor macrophage infiltration.

From a clinical point of view, the observations of

the present study make the selection of candidate Mbz combinations

for clinical testing complicated. If the anticancer effect of Mbz

in vivo is mainly due to changes in tumor immune cell

infiltration, screening of drugs suitable for combination with Mbz

using cell lines or patient-derived primary culture models will not

produce data applicable in vivo. Other models that also

reflect drug effects on immune cells would be necessary to select

drugs appropriate for combination with Mbz. Notably, Mbz has been

successfully combined with FOLFOX in treating CRC (27), but has also been combined with

bevazicumab, irinotecan, temozolomide or lomustine in early

clinical trials of patients with brain tumors (28–30).

The antitumor activity in these trials was seemingly very modest

and the trial design did not allow for any conclusions on whether

these combinations were justified from a mechanistic point of view.

In this context, combination of Mbz with other immunomodulatory

drugs is conceptually interesting. Indeed, preliminary results in

our laboratory from in vivo experiments of the CT26 model

treated with an immune checkpoint inhibiting antibody indicate a

positive interaction with Mbz. Another important avenue in

repurposing Mbz for use in cancer therapy is the development of

drug carriers or prodrugs to overcome the pharmacokinetic issues

associated with Mbz (54).

One strength of the present study is the use of

primary cultures of patient tumor cells, a model known to better

reflect clinical outcomes than tumor cell lines (55). While the findings of the present

study provide valuable insights into the anticancer properties of

Mbz, the limitations of the study should be acknowledged. The ex

vivo, in vivo and in vitro models utilized do not

recapitulate the complexity of cancer, necessitating further

validation in preclinical and clinical models.

In conclusion, the present study highlights the

multifaceted anticancer properties of Mbz. Thus, findings from this

and other published studies suggest that a key mechanism of the

anticancer effect of Mbz may be immune modulation in addition to

direct cytotoxicity. It would be of interest to explore whether

pharmacological agents known to promote M1 to M2 macrophage

polarization might antagonize the effects of Mbz. Such studies

could provide valuable insights into the immunomodulatory role of

Mbz and inform on combination strategies. However, selection of the

best drugs to combine with Mbz for efficacy optimization requires

careful consideration based on further research.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from The Swedish Cancer

Society (grant nos. 14 445, 17 0661 and 20 844) and The Cancer

Research Fund at the Uppsala University hospital (grant no.

2022-PN).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

The study was designed and performed with

significant contributions from all authors. SM, CA, PN, MF and RL

conceptualized and designed the study. SM and KB performed the

experiments and collected the data. SM, KB, CA and PN analyzed the

data. SM and PN wrote the manuscript. KB, CA, MF and RL revised the

manuscript. SM and PN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The collection of patient tumor samples was approved

from the Swedish Ethics Review Board (approval no. 2007/237).

Written informed consent for sample collection and further analysis

was provided by all patients before sample collection. The in

vivo experiments were approval by the regional animal ethics

committee in Stockholm (approval no. 12201-2019).

Patient consent for publication

Written patient consent for tumor sampling also

included the publication of results.

Competing interests

RL, PN and MF are co-founders and shareholders of

Repos Pharma AB, a Swedish research and development company

dedicated to investigations of drug repositioning. Repos Pharma AB

was not involved in the study design, execution, data analysis or

writing of the manuscript. The remaining authors declare that they

have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, Sukhatme

V and Sukhatme VP: Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)-mebendazole

as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 8:4432014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mukhopadhyay T, Sasaki J, Ramesh R and

Roth JA: Mebendazole elicits a potent antitumor effect on human

cancer cell lines both in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res.

8:2963–2969. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Martarelli D, Pompei P, Baldi C and

Mazzoni G: Mebendazole inhibits growth of human adrenocortical

carcinoma cell lines implanted in nude mice. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 61:809–817. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Doudican NA, Byron SA, Pollock PM and

Orlow SJ: XIAP downregulation accompanies mebendazole growth

inhibition in melanoma xenografts. Anticancer Drugs. 24:181–188.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bai RY, Staedtke V, Aprhys CM, Gallia GL

and Riggins GJ: Antiparasitic mebendazole shows survival benefit in

2 preclinical models of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol.

13:974–982. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sasaki J, Ramesh R, Chada S, Gomyo Y, Roth

JA and Mukhopadhyay T: The anthelmintic drug mebendazole induces

mitotic arrest and apoptosis by depolymerizing tubulin in non-small

cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 1:1201–1209.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pourgholami MH, Cai ZY, Chu SW, Galettis P

and Morris DL: The influence of ovarian cancer induced peritoneal

carcinomatosis on the pharmacokinetics of albendazole in nude mice.

Anticancer Res. 30:423–428. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Aliabadi A, Haghshenas MR, Kiani R,

Koohi-Hosseinabadi O, Purkhosrow A, Pirsalami F, Panjehshahin MR

and Erfani N: In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of

mebendazole in colon cancer: A promising drug repositioning. Naunyn

Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 397:2379–2388. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nygren P and Larsson R: Drug repositioning

from bench to bedside: Tumour remission by the antihelmintic drug

mebendazole in refractory metastatic colon cancer. Acta Oncol.

53:427–428. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dobrosotskaya IY, Hammer GD, Schteingart

DE, Maturen KE and Worden FP: Mebendazole monotherapy and long-term

disease control in metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma. Endocr

Pract. 17:e59–e62. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nygren P, Fryknäs M, Agerup B and Larsson

R: Repositioning of the anthelmintic drug mebendazole for the

treatment for colon cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 139:2133–2140.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Bai RY, Staedtke V, Rudin CM, Bunz F and

Riggins GJ: Effective treatment of diverse medulloblastoma models

with mebendazole and its impact on tumor angiogenesis. Neuro Oncol.

17:545–554. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Larsen AR, Bai RY, Chung JH, Borodovsky A,

Rudin CM, Riggins GJ and Bunz F: Repurposing the antihelmintic

mebendazole as a hedgehog inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 14:3–13.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Blom K, Rubin J, Berglund M, Jarvius M,

Lenhammar L, Parrow V, Andersson C, Loskog A, Fryknäs M, Nygren P

and Larsson R: Mebendazole-induced M1 polarisation of THP-1

macrophages may involve DYRK1B inhibition. BMC Res Notes.

12:2342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Blom K, Senkowski W, Jarvius M, Berglund

M, Rubin J, Lenhammar L, Parrow V, Andersson C, Loskog A, Fryknäs

M, et al: The anticancer effect of mebendazole may be due to M1

monocyte/macrophage activation via ERK1/2 and TLR8-dependent

inflammasome activation. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 39:199–210.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rubin J, Mansoori S, Blom K, Berglund M,

Lenhammar L, Andersson C, Loskog A, Fryknäs M, Nygren P and Larsson

R: Mebendazole stimulates CD14+ myeloid cells to enhance T-cell

activation and tumour cell killing. Oncotarget. 9:30805–30813.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bayat Mokhtari R, Homayouni TS, Baluch N,

Morgatskaya E, Kumar S, Das B and Yeger H: Combination therapy in

combating cancer. Oncotarget. 8:38022–38043. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK and Jordan RE:

Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure

lowering drugs: Analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ.

326:14272003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Foucquier J and Guedj M: Analysis of drug

combinations: Current methodological landscape. Pharmacol Res

Perspect. 3:e001492015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Boshuizen J and Peeper DS: Rational cancer

treatment combinations: An urgent clinical need. Mol Cell.

78:1002–1018. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ocana A, Amir E, Yeung C, Seruga B and

Tannock IF: How valid are claims for synergy in published clinical

studies? Ann Oncol. 23:2161–2166. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hwangbo H, Patterson SC, Dai A, Plana D

and Palmer AC: Additivity predicts the efficacy of most approved

combination therapies for advanced cancer. Nat Cancer. 4:1693–1704.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Dakshanamurthy S,

Gaur A, Chen YS, Fang HB, Abdussamad M, Zhou H, Zapas J, Calvert V,

Petricoin EF, et al: The repurposed anthelmintic mebendazole in

combination with trametinib suppresses refractory NRASQ61K

melanoma. Oncotarget. 8:12576–12595. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kipper FC, Silva AO, Marc AL, Confortin G,

Junqueira AV, Neto EP and Lenz G: Vinblastine and antihelmintic

mebendazole potentiate temozolomide in resistant gliomas. Invest

New Drugs. 36:323–331. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Coyne CP, Jones T and Bear R:

Gemcitabine-(C4-amide)-[anti- HER2/neu] Anti-neoplastic

cytotoxicity in dual combination with mebendazole against

chemotherapeutic-resistant mammary adenocarcinoma. J Clin Exp

Oncol. 2:10001092013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mansoori S, Fryknäs M, Alvfors C, Loskog

A, Larsson R and Nygren P: A phase 2a clinical study on the safety

and efficacy of individualized dosed mebendazole in patients with

advanced gastrointestinal cancer. Sci Rep. 11:89812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hegazy SK, El-Azab GA, Zakaria F, Mostafa

MF and El-Ghoneimy RA: Mebendazole; from an anti-parasitic drug to

a promising candidate for drug repurposing in colorectal cancer.

Life Sci. 299:1205362022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Gallia GL, Holdhoff M, Brem H, Joshi AD,

Hann CL, Bai RY, Staedtke V, Blakeley JO, Sengupta S, Jarrell TC,

et al: Mebendazole and temozolomide in patients with newly

diagnosed high-grade gliomas: Results of a phase 1 clinical trial.

Neurooncol Adv. 3:vdaa1542020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Krystal J, Hanson D, Donnelly D and Atlas

M: A phase 1 study of mebendazole with bevacizumab and irinotecan

in high-grade gliomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 71:e308742024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Patil VM, Menon N, Chatterjee A, Tonse R,

Choudhari A, Mahajan A, Puranik AD, Epari S, Jadhav M, Pathak S, et

al: Mebendazole plus lomustine or temozolomide in patients with

recurrent glioblastoma: A randomised open-label phase II trial.

EClinicalMedicine. 49:1014492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Anand U, Dey A, Chandel AKS, Sanyal R,

Mishra A, Pandey DK, Falco VD, Upadhyay A, Kandimalla R, Chaudhary

A, et al: Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug

candidate, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics.

Genes Disease. 10:136–1401. 2022.

|

|

32

|

Blom K, Nygren P, Alvarsson J, Larsson R

and Andersson CR: Ex vivo assessment of drug activity in patient

tumor cells as a basis for tailored cancer therapy. J Lab Autom.

21:178–187. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Larsson R and Nygren P: Laboratory

prediction of clinical chemotherapeutic drug resistance: A working

model exemplified by acute leukaemia. Eur J Cancer. 29A:1208–1212.

1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lindhagen E, Nygren P and Larsson R: The

fluorometric microculture cytotoxicity assay. Nat Protoc.

3:1364–1369. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Karlsson H, Fryknäs M, Senkowski W,

Larsson R and Nygren P: Selective radiosensitization by

nitazoxanice of quiescent clonogenic colon cancer tumour cells.

Oncol Lett. 23:1232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Miles FL, Lynch JE and Sikes RA:

Cell-based assays using calcein acetoxymethyl ester show variation

in fluorescence with treatment conditions. J Biol Method.

2:e292015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ianevski A, Giri AK and Aittokallio T:

SynergyFinder 2.0: Visual analytics of Multi-drug combination

synergies. Nucleic Acids Res. 48:W488–W493. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ianevski A, Giri AK and Aittokallio T:

SynergyFinder 3.0: An interactive analysis and consensus

interpretation of multi-drug synergies across multiple samples.

Nucleic Acids Res. 50:W739–W743. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Loewe S: The problem of synergism and

antagonism of combined drugs. Arzneimittelforschung. 3:285–290.

1953.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bliss CI: The toxicity of poisions applied

jointly. Ann Appl Biol. 26:585–615. 1939. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Yadav B, Wennerberg K, Aittokallio T and

Tang J: Searching for drug synergy in complex dose-Response

landscapes using an interaction potency model. Comput Struct

Biotechnol J. 13:504–513. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Berenbaum MC: What is synergy? Pharmacol

Rev. 41:93–141. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Moon CH, Lee SJ, Lee HY, Lee JC, Cha H,

Cho WJ, Park JW, Park HJ, Seo J, Lee YH, et al: KML001 displays

vascular disrupting properties and irinotecan combined antitumor

activities in a murine tumor model. PLoS One. 8:e539002013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Csóka K, Tholander B, Gerdin E, de la

Torre M, Larsson R and Nygren P: In vitro determination of

cytotoxic drug response in ovarian carcinoma using the fluorometric

microculture cytotoxicity assay (FMCA). Int J Cancer. 72:1008–1012.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

von Heideman A, Tholander B, Grundmark B,

Cajander S, Gerdin E, Holm L, Axelsson A, Rosenberg P, Mahteme H,

Daniel E, et al: Chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity of primary

cultures of epithelial ovarian cancer cells from patients in

relation to tumour characteristics and therapeutic outcome. Acta

Oncol. 53:242–250. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cashin PH, Söderström M, Blom K, Artursson

S, Andersson C, Larsson R and Nygren P: Ex vivo assessment of

chemotherapy sensitivity of colorectal cancer peritoneal

metastases. Br J Surg. 110:1080–1083. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Bjersand K, Blom K, Poromaa IS, Stålberg

K, Lejon AM, Bäckman F, Nyberg Å, Andersson C, Larsson R and Nygren

P: Ex vivo assessment of cancer drug sensitivity in epithelial

ovarian cancer and its association with histopathological type,

treatment history and clinical outcome. Int J Oncol. 61:1282022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang X, Zhao J, Gao X, Pei D and Gao C:

Anthelmintic drug albendazole arrests human gastric cancer cells at

the mitotic phase and induces apoptosis. Exp Ther Med. 13:595–603.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Huang L, Zhao L, Zhang J, He F, Wang H,

Liu Q, Shi D, Ni N, Wagstaff W, Chen C, et al: Antiparasitic

mebendazole (MBZ) effectively overcomes cisplatin resistance in

human ovarian cancer cells by inhibiting multiple cancer-associated

signaling pathways. Aging (Albany NY). 13:17407–17427. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Salvadores M, Fuster-Tormo F and Supek F:

Matching cell lines with cancer type and subtype of origin via

mutational, epigenomic, and transcriptomic patterns. Sci Adv.

6:eaba18622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mirabelli P, Coppola L and Salvatore M:

Cancer cell lines are useful model systems for medical research.

Cancers (Basel). 11:10982019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Guerini AE, Triggiani L, Maddalo M, Bonù

ML, Frassine F, Baiguini A, Alghisi A, Tomasini D, Borghetti P,

Pasinetti N, et al: Mebendazole as a candidate for drug repurposing

in oncology: An extensive review of current literature. Cancers

(Basel). 11:12842019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Champiat S, Ferrara R, Massard C, Besse B,

Marabelle A, Soria JC and Ferté C: Hyperprogressive disease:

Recognizing a novel pattern to improve patient management. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 15:748–762. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Abu-Hdaib B, Nsairat H, El-Tanani M,

Al-Deeb I and Hasasna N: In vivo evaluation of mebendazole and Ran

GTPase inhibition in breast cancer model system. Nanomedicine

(Lond). 19:1087–1101. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Idrisova K, Simon H and Gomzikova M: Role

of patient-derived models of cancer in translational oncology.

Cancers. 15:1392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|