Breast cancer (BC) is among the most common cancers

in female patients globally. It has seen rising prevalence and

mortality rates, representing a challenge to both the medical

ERcommunity and society (1). The

etiology of BC involves a complex interplay of modifiable and

non-modifiable factors, which include genetic susceptibility,

environmental exposure, hormone levels, nutritional status and

lifestyle choices (2). Notable risk

factors for BC include personal or positive family history of BC,

obesity, tall height, smoking, alcohol consumption, early menarche,

late menopause, sedentary lifestyle, nulliparity and hormone

replacement therapy (3). Factors

associated with a decreased risk of BC include high parity,

breastfeeding, regular physical activity and weight management.

Increases in BC incidence are attributed to rising obesity rates

and declining fertility (4,5). BC in female patients is the second

most common cancer globally according to the Global Cancer

Observatory Database 2022 (6), with

an estimated 2.3 million new cases accounting for 11.6% of all

cancer cases. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer-associated

death worldwide, resulting in ~666,000 deaths, which constitute

6.9% of all cancer deaths in 2022 (6). This presents significant challenges to

public health and healthcare systems.

The development and homeostasis of multicellular

organisms rely on regulated cell proliferation and proper disposal

of unnecessary or potentially harmful cells. Inflammation is a

biological response of the immune system triggered by viruses,

toxic compounds and other factors (12). Cell damage and infection activate

the immune system, resulting in inflammation, regulated cell death

(RCD) and regeneration of inflammatory cells (13).

Programmed cell death (PCD) was first used to

describe a form of cell death actively driven by endogenous genetic

programs during individual development and tissue homeostasis

maintenance, such as classical apoptosis (14). PCD typically does not trigger an

inflammatory response and is morphologically characterized by cell

shrinkage, chromatin condensation and preservation of membrane

integrity (15). Subsequent studies

have found that, in addition to PCD, numerous cell death events do

not result from external mechanical damage, but occur depending on

the activation or inhibition of specific signaling pathways

(16,17). Therefore, the broader concept of RCD

was proposed. RCD not only includes apoptosis, but also involves

necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis. These death modes differ

in terms of morphology, immunological effects and inflammatory

responses, but collectively reflect the regulation of cell death.

PCD can be regarded as a physiological and evolutionarily conserved

type of RCD, while RCD reveals the dynamic characteristics of cells

regulated through molecular mechanisms to affect immune responses,

inflammation and disease progression under pathological stress and

microenvironmental changes (18).

Membrane-bound and cytoplasmic proteins participate

in RCD, forming a complex cascade through transcriptional changes

and post-translational protein modifications that induce cell death

(19).

Necrotic material activates the immune system and is

promptly phagocytosed and degraded by both macrophages and

neutrophils, efficiently eliminating necrotic cell debris (20,21).

The dissolution of infected or damaged cells constitutes the

primary strategy for eliminating pathogens and preserving health.

This process ensures the replenishment of normal cells in the body

and sustains tissue homeostasis (22). Inflammation becomes problematic when

harmful stimuli cannot be eliminated through RCD (23). Certain scholars believe that RCD

compromises host defense mechanisms against intracellular

pathogens, while others propose that cell bodies resulting from RCD

modulate the innate immune response to facilitate infection

clearance under appropriate immunological and microenvironmental

conditions (24,25).

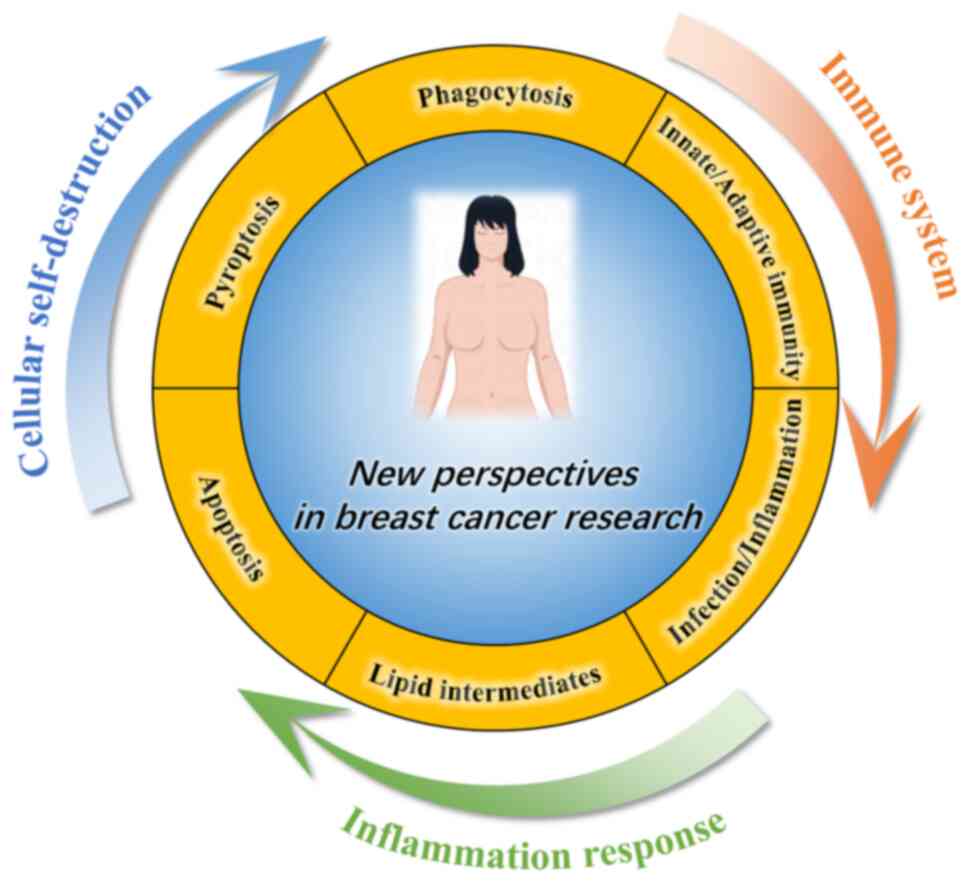

The present review aimed to explore the interplay

among the immune system, inflammatory response and RCD in BC,

seeking novel therapeutic targets and approaches at the molecular

level (Fig. 1).

Microbial and viral infections represent threats to

human health. The immune system has evolved complex mechanisms to

recognize and eliminate pathogens, thereby safeguarding the host

from disease. Human immune response comprises innate and adaptive

immunity (26).

The innate immune system serves as the primary

defense mechanism and initiates the rapid response (27). This system includes physical

barriers such as the skin and mucous membranes, as well as cellular

components, such as phagocytes and natural killer (NK) and

dendritic cells (DCs) (28). Innate

immune cells undergo phenotypical and functional maturation upon

encountering pathogens, leading to the production of highly

efficient antigen-presenting cells that bridge innate and adaptive

immunity (29).

The innate immune system serves a key role in

eradicating nascent tumor cells during the clearance phase of

cancer immunoediting. NK cells recognize stress ligands, such as

major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I polypeptide-related

sequence A/B and poliovirus receptor, on the surface of tumor cells

through their activating receptors natural killer group 2 member D

(NKG2D) and DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1), and induce tumor

cell apoptosis by releasing perforin and granzyme B (30–33).

IFN-γ secreted by NK cells inhibits angiogenesis and activates

macrophages (34). However, the TME

reprograms myeloid cells during the equilibrium and escape stages,

leading to notable immunosuppressive cell infiltration.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are one of the most abundant

types of immune cell with high plasticity in the TME. They exhibit

an M1-like phenotype, secreting pro-inflammatory factors and

exerting antitumor effects. However, they are more commonly

polarized into an M2-like phenotype in most solid tumors, releasing

factors such as IL-10, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and VEGF,

that promote angiogenesis, tissue remodeling and tumor metastasis,

while suppressing T cell-mediated immune responses. Therefore, TAMs

serve a key role in tumor progression and immune escape and are

important targets for current immunotherapy interventions (35).

The innate immune system responds promptly via

macrophages and neutrophils phagocytosing pathogens and sending

inflammatory signals that initiate DC recruitment (36,37).

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) enable innate immune cells to

detect two types of danger signals: Pathogen-associated molecular

patterns from microbial infection and danger-associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs) from dying or damaged cells. PRRs include

toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin receptors, retinoic

acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-1)-like receptors and nucleotide-binding

oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs), which recognize these

signals and activate immune responses (38).

Immune cells eliminate pathogens upon activation via

cytokine and chemokine secretion, as well as phagocytosis.

Cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and

IFN, initiate signaling pathways. For example, IL-1 and TNF-α are

involved in the activation of the NF-κB pathway, while IFN

stimulates the JAK/STAT pathway to induce an antiviral state

mediated by IFN-stimulated genes (39,40).

Cytokines in the TME construct a complex signaling network with a

context-dependent function. Type I IFN is a core coordinating

factor in antitumor immunity. It directly inhibits tumor cell

proliferation via the JAK1/tyrosine kinase 2-mediated

STAT1/STAT2/interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) signaling complex

(41), while upregulating MHC-I

molecule expression, promoting DC maturation (42) and enhancing the survival and

effector functions of CD8+ T cells (43).

The inflammasome is a molecular platform of innate

immunity that responds to cell stress and infection. The NLRP3

inflammasome senses multiple upstream signals [ion flux, reactive

oxygen species (ROS) and lysosomal damage] and forms a complex that

activates caspase-1 (44).

Activated caspase-1 serves two key functions: Processing pro-IL-1β

and pro-IL-18 into their mature cytokine forms (45) and cleaving gasdermin D (GSDMD) to

release its N-terminal fragment, which oligomerizes in the plasma

membrane to form pores and induce pyroptosis (46).

Inflammasome signaling in BC has context-dependent

effects. NLRP3 activation within tumor cells in estrogen

receptor-negative tumors, such as triple-negative BC (TNBC),

promotes pre-metastatic niche formation and distant metastasis

through IL-1β autocrine/paracrine loops (47). By contrast, inflammasome activation

in hematopoietic cells enhances antitumor immunity, where

pyroptosis releases tumor antigens, which facilitate DC priming and

T cell activation (48). Histone

deacetylase inhibitors in TNBC can switch caspase-3 activity from

apoptosis toward pyroptosis by cleaving GSDME (49). This causes tumor cell lysis and DAMP

release, which recruit CD11b+ myeloid cells, enhance

antigen presentation and increase CD8+ T cell

infiltration and granzyme B secretion, restoring antitumor immunity

(50). Conversely, silencing or

loss of pyroptotic effectors, such as GSDME, during tumor

progression allows BC cells to maintain a ‘cold tumor’ state,

characterized by low immune cell infiltration and weak immune

activation, and escape immune surveillance (51).

The adaptive immune system mediates antigen-specific

responses through specific T and B cell receptors, forming

long-lasting immune memory. It serves as the core force for

eliminating tumor cells (52–54).

The efficacy of the adaptive immune response in BC directly

determines patient prognosis and immunotherapy response (55,56).

Numerous types of conventional anticancer therapy, such as

anthracyclines, oxaliplatin and radiotherapy, can induce

immunogenic cell death, exposing tumor cells to calreticulin and

releasing DAMPs such as ATP and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1).

These signals enhance the phagocytic, maturation and

cross-presentation capabilities of DCs (57).

The core of the adaptive immune system antitumor

effect lies in cellular immunity, particularly the recognition and

killing of tumor neoantigens presented by tumor cells via MHC-I

molecules by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)

(58). CD4+ T helper

(Th) cells regulate the function of CTLs and NK and

antigen-presenting cells by secreting cytokines, such as IFN-γ and

IL-2. They also provide assistance to B cells, coordinating the

humoral immune response (59).

However, the TME of BC typically secretes factors,

such as VEGF, IL-10 and TGF-β, to suppress DC maturation, thereby

impeding T cell priming (60).

Simultaneously, activated T cells are prone to exhaustion under

sustained antigenic stimulation, manifesting as high expression of

inhibitory receptors, such as PD-1, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin

domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3) and lymphocyte activation gene

3 (LAG-3), and gradually losing their effector function (61). BC cells actively induce T cell

exhaustion by binding PD-1 through high programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) expression, representing one of the primary adaptive immune

escape mechanisms. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) restore T

cell function and enhance antitumor immune responses by blocking

the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway (62).

Beyond antibody production, B cells participate in

antigen presentation and cytokine secretion, forming tertiary

lymphoid structures (TLSs) within tumor tissue. TLSs comprise T and

B cells and DCs and sustain local antitumor immune responses. Their

presence is typically associated with higher T cell infiltration,

more active immune response and improved patient prognosis

(63).

Adaptive immune pathways serve tumor-suppressing

roles and drive immune escape in BC development and progression.

The efficacy of cancer vaccines, adoptive cell therapy and ICIs

depends on the integrity of antigen presentation, T cell activation

and effector function (64–66). CTLs become exhausted due to

persistent antigen stimulation when DCs are blocked. Alternatively,

tumor cells evade immune recognition by downregulating MHC-I and

upregulating PD-L1. The adaptive immune response becomes difficult

to sustain, allowing tumors to progress (67). The presence of B cells and TLSs

enhances local immune responses, but their antitumor functions are

typically weakened under the regulation of immunosuppressive

cytokines, such as TGF-β and IL-10, and may shift toward pro-tumor

effects (68). Therefore, immune

escape in BC is the outcome of a prolonged ‘arms race’ between the

adaptive immune system and the tumor. On one hand, the immune

system shapes tumor evolution by recognizing and eliminating it

(69). On the other hand, the tumor

reciprocally reprograms the immune response through multiple

mechanisms, such as secreting immunosuppressive cytokines (TGF-β

and IL-10), inducing regulatory T cells, and upregulating immune

checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1 (70,71).

Future therapeutic strategies may simultaneously enhance adaptive

immune effects and prevent TME suppression to disrupt this

malignant equilibrium and achieve durable antitumor control.

Continuous signal release during apoptosis attracts

phagocytes and facilitates cell clearance (72). Granzyme family molecules released

from activated T and NK cells induce apoptosis. These protein

hydrolases target cysteine aspartyl proteases or BH3-interacting

domain death agonist, activating them and bypassing upstream

signaling, thus initiating target cell apoptosis (73). Tanzer et al (74) identified a specific secretome

signature distinguishing apoptosis from other forms of cell death,

where apoptotic cells predominantly release nucleosomal components.

Saxena et al (64)

discovered that apoptotic lymphocytes and macrophages release

anti-inflammatory metabolites, maintaining plasma membrane

integrity and inducing genetic programs promoting inflammation

suppression, cell proliferation and wound healing.

Apoptosis is key for tissue development and renewal

as it regulates cell population balance. Additionally, CTLs

maintain tissue health by inducing apoptosis in target or

virus-infected cells (75). Reports

indicate that apoptosis is key in the adaptive immune system,

contributing to the loss of auto- or non-reactive T cell receptor

expression by thymocytes and the absence of auto-reactive immature

B cells (76,77). Inflammation resolution involves the

emergence of apoptotic neutrophils (78).

Apoptosis defects result in autoimmune

abnormalities. Lymphoproliferation (LPR) and generalized

lymphoproliferative disease (GLD) are natural mouse mutants

associated with lymph node and spleen enlargement and the

development of systemic lupus erythematosus-like autoimmune

disorder (79). Functional defects

in Fas and FasL genes result in LPR and GLD phenotypes (80). Patients with autoimmune

lymphoproliferative syndrome carry mutations in somatic or germ

cells encoding Fas or FasL genes. The Fas-mediated extrinsic

apoptotic pathway clears peripheral T cells and eliminates

self-reactive B cells. Studies have shown that Bcl-2-interacting

mediator of cell death (Bim)-mediated apoptosis regulates

short-lived myeloid cells, including eosinophils, neutrophils and

monocytes (81,82). These findings highlight the key role

of the Fas-FasL system and Bim-mediated endogenous and exogenous

apoptotic pathways in autoimmune disease development (83).

In addition to exogenous stimuli, apoptosis is

regulated or activated by internal stimuli, such as DNA damage and

oxidative stress (84). The

intrinsic pathway for this process is characterized by

mitochondrial regulation and non-receptor-mediated initiation.

Stimuli such as oxidative stress cause mitochondrial membrane

disruption, leading to the formation of mitochondrial permeability

transition pores, thereby allowing pro-apoptotic factors to enter

the cytosol. This intrinsic apoptosis pathway involves key

mediators, such as Bcl-2 family proteins, including pro-apoptotic

Bax and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 (85).

These proteins regulate the release of cytochrome c from the

mitochondria into the cytosol, where it forms a complex with

apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 and procaspase-9, known as

the apoptosome (86). This complex

activates mTOR, which triggers executioner caspases such as

caspase-3, −6 and −7, leading to apoptosis (87). Additionally, proteins, such as

second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase/direct IAP-binding

protein with low pI (SMAC/DIABLO) and apoptosis-inducing factor,

participate in caspase-dependent and -independent pathways,

respectively. SMAC/DIABLO inactivates apoptosis protein inhibitors,

thus facilitating apoptosis, while apoptosis-inducing factor

translocates to the nucleus once released from the mitochondria to

induce DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation (88).

Research indicates that the endoplasmic reticulum

(ER) is also involved in apoptosis (89). Excess accumulation of proteins

within the ER and disruption of calcium homeostasis trigger ER

stress, leading to apoptosis (90).

Caspase-12 is located on the ER membrane and is key for ER-mediated

apoptosis (91). The ER response

triggers caspase-12 expression while translocating cytosolic

caspase-7 to the ER membrane, where caspase-12 is activated,

leading to apoptosis (87).

Autophagy and apoptosis exhibit a complex and

dynamic interplay in BC, jointly determining cell fate. Autophagy

is a survival mechanism that can suppress apoptosis by clearing

damaged organelles, such as dysfunctional mitochondria, and

decreasing ROS accumulation, promoting cancer cell survival under

chemotherapy stress and leading to therapeutic resistance (92,93).

On the other hand, excessive or sustained autophagic activity can

result in type II PCD, also known as autophagic cell death,

characterized by massive autophagosome formation and degradation of

cellular components. Key proteins, such as glucose-regulated

protein 78 (GRP78), serve an important role during ER stress. GRP78

activates protective autophagy by inhibiting the mTOR pathway while

suppressing apoptosis, thus supporting cell survival under estrogen

deprivation or tamoxifen treatment and contributing to endocrine

therapy resistance (94,95).

Autophagy serves as a key adaptive mechanism for BC

cell survival in the nutrient-deficient TME, such as that of

hypoxia or glucose deprivation (96,97).

Autophagy is activated under stress conditions to degrade redundant

or damaged intracellular proteins and organelles, recycling key

metabolites, such as amino and fatty acids, for energy production

and biosynthesis, maintaining cellular energy homeostasis (98). Moreover, the hypoxia signaling

pathway mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α)

upregulates autophagy (99),

facilitating the clearance of toxic substances generated under

hypoxic conditions and sustaining the stemness and self-renewal

capacity of BC stem cell populations (100,101). This enables residual cancer cells

to enter a dormant state and contribute to disease recurrence

(102).

Disruptions in lipid metabolism promote autophagy.

Lipophagy is a key autophagy function, in which lipid droplets are

selectively degraded to release free fatty acids for β-oxidation

and energy production, which is key under glucose-deprived

conditions. BC cells typically undergo metabolic reprogramming,

while autophagy influences intracellular metabolite levels by

regulating amino acid transporters, such as solute carrier family 6

member 14 (SLC6A14). Decreased activity of these transporters

disrupts amino acid availability and stimulates autophagy,

contributing to endocrine therapy resistance (95). Thus, metabolic dysregulation may

modulate autophagic activity by affecting key energy-sensing

pathways, such as mTOR and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK),

forming a metabolic adaptive feedback loop that influences cancer

cell survival, proliferation and therapeutic response (103,104).

Cell pyroptosis is a type of RCD with lytic and

inflammatory characteristics. It is mediated by the cleavage of

GSDM family proteins. GSDMD is cleaved by inflammatory caspases

(caspase-1, −4, −5, and −11) at a specific site to release its

N-terminal domain, which forms pores in the plasma membrane,

whereas GSDME is cleaved by caspase-3 at a distinct site, linking

apoptosis and pyroptosis (105).

This results in cell swelling, lysis and release of

pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-1β, IL-18, ATP and HMGB1.

Acute pyroptosis activation may induce immune cell infiltration,

potentially inhibiting tumor growth (106). GSDM proteins are activated by

distinct signaling pathways to execute pyroptotic functions in

specific contexts. GSDMD serves as the primary executor of

classical inflammatory pyroptosis. It is primarily cleaved by

caspase-1 or −4/5/11 activated by inflammasomes, commonly observed

during immune cell defense against pathogenic infection (46,107).

However, GSDME is typically cleaved by apoptosis-associated

caspase-3. When caspase-3 is activated, the cell fate shifts from

non-inflammatory apoptosis to inflammatory pyroptosis (108). In addition, granzyme B secreted by

CTLs directly cleaves GSDME (109). Overall, inducing cellular

pyroptosis within tumors may represent a potential strategy for

treating numerous types of cancers. Tumor cells undergoing

pyroptosis recruit tumor-suppressing immune cells. Wang et

al (110) employed a

bioorthogonal system to demonstrate that pyroptosis in <15% of

tumor cells eliminates entire tumor grafts in live mice. This

orthogonal system is capable of controlled drug release by

combining nanoparticle-mediated delivery with Phe-boron

trifluoride-catalyzed desilylation to selectively release client

proteins, including active GSDM, into tumor cells in mice. Zhang

et al (109) demonstrated

that CD8+ T and NK cells induce pyroptosis in tumor

cells through granzyme B in a pyroptosis-activated immune ME,

establishing a positive feedback loop. However, tumor suppression

is abolished in perforin-deficient mice and mice lacking killer

lymphocytes. A total of 20/22 tested cancer-associated GSDME

mutations decrease its function, indicating that GSDME inactivation

may be employed by cancer cells to evade immune attacks. This is

particularly relevant in BC. On one hand, genetic mutations

directly impair the pore-forming ability of GSDME and decrease the

occurrence of pyroptosis. On the other hand, promoter

hypermethylation of GSDME is frequently reported in BC, and

demethylating treatment can restore its expression and enhance

chemotherapy- or immune-induced pyroptosis (108,111). The loss or dysfunction of GSDME in

BC allows tumor cells to evade immune surveillance by decreasing

pyroptosis and DAMP release, which decreases the infiltration and

activation of CD8+ T and NK cells. This loss can result

from gene mutations or promoter methylation, suggesting that

restoring GSDME expression or function may be a potential strategy

to enhance antitumor immune responses.

Phagocytosis removes cell debris generated during

RCD and breaks it into macronutrients for use by other cells

(112). This maintains

intracellular environment stability and recycles cell components,

providing the necessary material for normal cell function.

Specialized cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes, DCs

and osteoclasts are capable of phagocytosis. Phagocytosis is not an

isolated cell reaction. It typically occurs concurrently with other

cellular processes, such as ROS production, proinflammatory

mediator secretion, antimicrobial molecule degranulation and

cytokine production (113).

Phagocytosis eliminates pathogens and host cells undergoing

apoptosis during infection (114).

Phagocytosis is key for antitumor immunity. Specific

macrophages enhance the antitumor response through distinct

phenotypes and functions. For example, TAMs hinder the efficacy of

glioblastoma immunotherapy (115).

CD169 macrophages enhance tumor-specific T cell responses by

promoting apoptotic glioma cell phagocytosis (116). Inflammatory macrophages regulate

macrophage phagocytosis and enhance tumor cell phagocytosis via

non-traditional pro-phagocytic integrins such as the CD47/signal

regulatory protein α) signaling pathway (117). Additionally, CTL-associated

protein 4 (CTLA-4) blockade stimulates microglial cells and

enhances tumor cell phagocytosis, promoting antitumor effects

(118). Immunotherapeutic

strategies may offer novel approaches for glioblastoma treatment by

activating synergistic interactions between macrophages and Th1 and

microglial cells and by boosting immune cell activation and

infiltration.

Tumor cells employ diverse mechanisms within the TME

to escape or inhibit phagocytosis, promoting tumor progression and

immune evasion. Tumor cells hinder phagocytosis and evade immune

clearance by expressing innate immune checkpoints, such as the

CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway. Blocking phagocytosis checkpoints

enhances phagocytic activity against tumor cells and encourages

their clearance (119). PD-L1

expression may hinder T cell cytotoxicity and macrophage-mediated

phagocytosis. Disrupting this pathway may trigger antitumor

immunity (120). Overall,

phagocytosis serves a pivotal role in pathogen clearance, cellular

waste disposal and antitumor defense mechanisms.

Optimal nutritional status is key for regulating

inflammatory and oxidative stress processes, which are connected

with the immune system (121).

Inflammation is recognized as a primary driver of malnutrition in

disease (122). It triggers

various physiological responses, such as loss of appetite,

decreased food intake, muscle breakdown, and insulin resistance,

leading to a catabolic state (122). Patients with colorectal cancer are

prone to chronic inflammation, malnutrition and complications

arising from chronic nutritional and energy depletion, insufficient

dietary intake, stress and metabolic disruptions due to surgeries,

chemotherapy or radiation therapy (123). Though most commonly attributed to

systemic inflammatory responses, hypoalbuminemia can result from

various other causes. For example, liver cirrhosis causes

hepatocyte damage and reduced synthetic capacity, while kidney

disease leads to increased albumin excretion in urine.

Additionally, dietary deficiencies in key amino acids cause

decreased albumin levels (124).

Albumin serves a key role in maintaining oncotic pressure,

neutralizing reactive species and preserving microvascular

integrity, thus protecting against inflammatory tissue damage

(125). Albumin is the most

abundant plasma protein and reflects both nutritional status and

inflammatory responses of the host. Recent evidence has

demonstrated its independent prognostic value in BC (126). In a large cohort study of nearly

3,000 patients with BC, a low albumin-to-globulin ratio and

decreased prealbumin levels were significantly associated with

inferior overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival.

Importantly, these markers retained independent prognostic

significance in multivariate models following adjustment for

conventional factors, such as TNM stage and molecular subtype

(127). Similarly, serum albumin

levels <43 g/l are predictive of shorter OS in an independent

cohort of patients with metastatic BC, with low albumin identified

as an independent adverse prognostic factor [hazard ratio

(HR)=0.47, P<0.01] (128).

Low levels of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty

acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid in

Western diets may contribute to chronic inflammation (129), as these fatty acids exert

anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokine

production and modulating eicosanoid synthesis (130). Various dietary and nutrient

components, such as omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin A and C and

phytochemicals such as polyphenols and carotenoids found in plant

foods, possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

Moreover, dietary fiber in plant foods that is fermented by gut

microbiota to produce short-chain fatty acids is associated with

health benefits, including anti-inflammatory properties (131).

Lipids, including fatty acids, cholesterol and

phospholipids, form a diverse group of metabolites crucial for

constructing cell and organelle membranes, generating cell energy

and engaging in intracellular and hormonal signaling (132). In a healthy organism, free fatty

acids undergo β-oxidation to produce ATP and maintain nutrient flux

balance. Excess fatty acids are packaged into inert triglycerides

using a glycerol backbone and stored in intracellular lipid

droplets (133). Excessive

nutrition can lead to the accumulation of lipid intermediates in

new non-adipose tissue, resulting in lipotoxicity and further

tissue damage (134).

Large lipid loads in organ systems impair the

efficient fat catabolism and conversion of fatty acids to

triglycerides in cells, leading to increased lipogenesis or

triglyceride storage in adipose tissue. Glucose oxidation is

enhanced in muscle cells, while lipolysis in adipose tissue and

fatty acid oxidation in muscle cells increase to provide energy

during fasting conditions. These metabolic changes primarily occur

in the brain, heart, liver, pancreas, kidney and adipose tissue

(135).

In human clinical studies, lipid accumulation is

associated with renal dysfunction, while dyslipidemia directly or

indirectly impacts the kidney via systemic inflammation, oxidative

stress, vascular injury and alterations in signaling molecules such

as hormones (136,137). Glomeruli and tubules, especially

proximal tubules, are prone to lipid accumulation, contributing to

renal injury and dysfunction, which are key factors in diabetic

nephropathy (138). Non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease is associated with dysregulated lipid synthesis

and lipolysis pathways, with studies suggesting decreased lysosomal

acid lipase activity in such patients (139,140).

Moreover, endogenous lipid palmitic acid hydroxy

stearic acids positively impact blood glucose levels and insulin

sensitivity by regulating fat deposition and adipose tissue

lipolysis. Long-chain fatty acid oxidation influences postnatal

skeletal development. EPA is a long-chain polyunsaturated n-3 fatty

acid that regulates fatty acid re-esterification, impacting

substrate cycling in human skeletal muscle cells (141). The heart demonstrates the highest

energy demand and the most extensive fatty acid oxidation in the

body that efficiently accesses circulating lipids. However,

increased lipid availability exacerbates ischemia-induced cardiac

dysfunction (142). Lipid droplet

accumulation in glial cells is hypothesized to offer a protective

mechanism against the detrimental effects of neuronal activity by

detoxifying toxic fatty acids (143).

Abnormal lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses

form a cycle in certain pathological conditions, such as obesity,

type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease, exacerbating disease progression. Lipid accumulation

triggers oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, releasing

oxidized lipid intermediates that stimulate cytokine production by

inflammatory cells, leading to abnormal lipid metabolism (134). The lipid intermediates invade

healthy non-adipose tissue, causing lipotoxicity and additional

damage. Damaged cells undergo PCD to release more nutrients. During

this process, the levels of the primary products of the

inflammatory response (lipid intermediates) are amplified,

initiating a cycle of deleterious stimuli to the tissues/cells.

Free fatty acids can act as endogenous danger signals by binding

the TLR4/myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2) complex, activating

the downstream MyD88/interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase

(IRAK)/TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) signaling pathway.

This leads to the activation of the IκB kinase complex and IκB

degradation, releasing NF-κB dimers that translocate into the

nucleus to induce the transcription and secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α. This mechanism

serves a key role in chronic low-grade inflammation associated with

obesity and insulin resistance and contributes to the initiation

and progression of cancer such as BC (144,145).

The cycle between abnormal lipid metabolism and

inflammation impairs normal cellular and tissue metabolic functions

and accelerates the progression of conditions such as

atherosclerosis (146), obesity

and fatty liver disease (147). In

the context of BC, this lipid-inflammation feedback loop

contributes to a tumor-promoting microenvironment by enhancing

cytokine production, sustaining NF-κB activation and supporting

cancer cell survival. It triggers a cytokine storm with the release

of large amounts of cytokines, and the dysregulated inflammatory

response forms a self-reinforcing feedback loop that may endanger

the host (148). The levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF and IFN-γ), especially

TNF and IFN-γ, are elevated during cytokine storms (149). These factors induce cell death in

numerous types of cell, leading to diseases, such as neurological

disorder, liver injury, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

fibrosis and osteoporosis (150).

TNF and IFN-γ activation also induces cell death pathways,

including pyroptosis, apoptosis and necrosis, further stimulating

cytokine release and triggering a cytokine storm (151).

The link between BC and viral infection is debated

in terms of its causes and may interact with other environmental

factors to promote tumorigenesis (152,153). DNA from viruses, including human

papillomavirus (HPV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human

cytomegalovirus (HCMV), herpes simplex virus and Kaposi's

sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human γ herpesvirus 8, have been

detected in BC samples (152).

However, these viral DNA particles are not present in all BC

subtypes and do not control apoptosis, autophagy and pyroptosis in

the same way across all subtypes (152). The impact of viral infections can

vary depending on the specific BC subtype and the viral mechanisms

involved.

High-risk HPV subtypes, particularly HPV16 and

HPV18, are most commonly associated with carcinogenic effects and

employ unique mechanisms to suppress apoptosis (154). HPV inhibits cancer cell apoptosis

by upregulating the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily

death receptor (155).

Furthermore, autophagy inhibition, which is typically mediated by

the E7 oncoprotein, exhibits subtype specificity. A study in

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma indicated that HPV16 uses

E7-mediated degradation of the autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1

protein to suppress autophagy, rendering cells more sensitive to

cisplatin-induced apoptosis (156). By contrast, EBV encodes an

anti-apoptotic product that enhances infected cell viability and

resistance to chemotherapy, promoting the development of

EBV-associated disease (157).

HCMV is a slow-replicating virus that has evolved and acquired

anti-apoptotic genes, including pUL38 and UL138, which encode

apoptosis inhibitors, ensuring HCMV replication by inhibiting

apoptosis (158).

Mounting evidence suggests the BC microenvironment

is diverse and dynamic, with cell pyroptosis playing a crucial role

in its control (159,160). GSDMD and GSDME are key pyroptosis

substrates that play key roles in BC etiology and pathogenesis

(161). GSDM protein family plays

a pivotal role in cellular pyroptosis (162). MicroRNA-200b activates GSDMD by

targeting the NF-κB, maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3), juxtaposed

with another zinc finger 1 and JAK2/STAT3 pathways, whereas

uncoupling protein 1, dopamine receptor D2, the

AMPK/SIRT1/NF-κB/BAK and the STAT3/ROS/JNK pathway activate GSDME

(163). Additionally, some PRRs,

such as absent in melanoma 2, melanoma differentiation-associated

gene 5 and RIG-I, can activate GSDME (164). Furthermore, complexes containing

PD-L1 and STAT3 upregulate GSDMC expression under hypoxic

conditions (165).

Multiple mechanisms prevent apoptosis in BC TME.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) secrete factors such as IL-6

and CXCL12 that activate survival pathways in cancer cells,

enhancing their resistance to apoptosis (166). TAMs produce cytokines, such as

IL-10 and TGF-β, which promote tumor cell survival (70). Additionally, the hypoxic conditions

within tumors induce HIF-1α expression, leading to the upregulation

of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and survivin (167). These factors create an environment

that supports cancer cell survival and proliferation by inhibiting

apoptotic pathways (168).

The inflammatory microenvironment in BC continuously

shapes RCD pathways through persistent signaling, consequently

influencing tumor progression (169). Pro-inflammatory cytokines,

including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, activate key signaling cascades,

such as NF-κB, JAK/STAT3, and PI3K/AKT. These drive the

transcription of anti-apoptotic molecules such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein, while simultaneously

suppressing Bax/Bak-mediated mitochondrial outer membrane

permeabilization and blocking cytochrome c release (170). This weakens the mitochondrial

apoptotic response and allows tumor cells to maintain survival

advantages under adverse conditions. At the same time, these

signals alter inflammatory cell death modalities, for example, by

activating the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD or GSDME pathways to promote

pyroptosis, inducing immune activation and T cell infiltration

(171). Pyroptosis may be

attenuated in the absence of effector molecules or when signals are

reprogrammed, enabling tumors to evade immune surveillance

(172). The inflammatory

microenvironment in BC exhibits both pro-tumor and antitumor

potential through this dynamic regulation of both the threshold and

mode of cell death, ultimately determining the course of disease

progression and therapeutic responses.

The innate immune system is key for BC immunity. It

comprises innate lymphocytes (ILCs), whose differentiation and

function are associated with the immune response (173,174). ILCs are a newly discovered class

of innate immune cell derived from pluripotent hematopoietic stem

cells (175). These cells are

predominantly found in tissue and are common on the mucosal

surfaces of the lung and intestines (176). ILCs are divided into three groups.

The first group includes ILC1s and NK cells, the second group

comprises ILC2s and regulatory ILCs (ILCregs) and the third group

consists of ILC3s and lymphoid tissue-inducing cells (177). ILC1s are characterized by their

ability to produce IFN-γ and are key in the early BC stages due to

their role in activating cytotoxic immune responses. In advanced

tumors, ILC1s are typically induced by factors such as TGF-β in the

TME to drive the conversion of NK cells into an ILC1-like phenotype

(178–180). These cells lose their potent

cytotoxic activity and promote angiogenesis and immune tolerance

via secretion of factors such as VEGF. At the same time, ILC1s

within tumor tissue commonly upregulate multiple immune checkpoint

receptors, including NKG2A, killer cell lectin-like receptor

subfamily G member 1, CTLA-4, CD96 and LAG3, leading to marked

functional suppression. Overall, they exhibit immunosuppressive and

tumor-promoting effects (181).

ILC2s produce type 2 cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, and

are involved in tissue repair and immune regulation. However, their

role in cancer is either promotive or inhibitory depending on the

context. ILC3s produce IL-17 and IL-22, contributing to both

pro-inflammatory and tissue-regenerative processes. Their role in

tumor development can also vary (182).

Myeloid cells, notably granulocytes, macrophages and

DCs, are crucial for maintaining immune system homeostasis and

exert key effects within the TME (183). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

(MDSCs) are immune-suppressive cells that serve a key role in BC

development and progression. Their regulatory mechanisms involve

multiple cytokines, such as granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating

factor (G-CSF), VEGF and interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, IL-13, IL-17,

IL-20, IL-33 and IL-34), as well as signaling pathways, including

the STAT family (STAT3, STAT6), NF-κB, Notch, ER stress response

and JAK/STAT and PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascades (184). The complement system activity is

crucial in BC immunity, with components such as C1q, C3a, and C5a

associated with tumor growth, metastasis and immune responses

(185). The complement system also

promotes tumor progression through various mechanisms by enhancing

angiogenesis, suppressing antitumor immune responses and aiding in

the creation of a tumor-friendly microenvironment (186). Additionally, host defense peptides

and antimicrobial agents have antitumor activity against cancer

cells (187).

B and T cells from the adaptive immune system are

key for the antitumor response. B cells secrete antibodies and

regulate immune responses. Activated B cells infiltrating tumors

have antitumor effects in BC (188). Regulatory B cells may influence

the tumor immune microenvironment by secreting inhibitory factors

such as IL-10 and TGF-β (189). T

cells, notably CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, are key

in BC. CD8+ T cells directly eliminate cancer cells via

CTL production, while the differentiation status and secreted

cytokines of CD4+ T cells impact the immune response

direction (190). Th1 cell

activity contributes to tumor growth inhibition and spread

(191). Moreover, T regulatory

cells (Tregs), a subset of CD4+ T cells characterized by

transcription factor FOXP3 expression, play a critical role in

maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing autoimmune responses.

Tregs also contribute to immunosuppression in cancer by inhibiting

the function of effector T cells, including CD8+ CTLs,

which can facilitate tumor progression (192). Additionally, T cell exhaustion,

which is marked by the upregulation of inhibitory receptors, such

as PD-1 and CTLA-4, leads to a dysfunctional state in which T cells

lose their effector functions, contributing to the

immunosuppressive TME (193).

Additionally, specific immunomodulatory proteins such as

prolactin-inducible protein are crucial in BC immunomodulation, and

their absence may result in tumor development (194).

BC cells typically downregulate MHC-I molecules via

epigenetic mechanisms to evade immune surveillance, with DNA

methylation and histone modification serving key roles. DNA

methyltransferase-mediated promoter hypermethylation can silence

genes, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A/B/C and

β2-microglobulin, while also suppressing the expression of

antigen-processing components, including transporter associated

with antigen processing (TAP)1/2, thereby weakening antigen

presentation. At the same time, the EZH2/PRC2 complex suppresses

transcriptional regulators such as CIITA via H3K27me3

modifications, further reducing MHC-I transcription. As a result,

the surface expression of MHC-I on BC cells is markedly diminished,

leading to impaired recognition by CD8+ T cells,

resulting in immune evasion (195,196).

Glycolytic reprogramming (the Warburg effect) in

the TME provides energy and metabolic intermediates for tumor cells

and impairs the antitumor functions of the immune system via

multiple mechanisms (204).

Excessive lactate accumulation leads to local acidification, which

directly suppresses the effector activity of cytotoxic T and NK

cells, while decreasing the production of key cytokines, such as

IFN-γ and TNF-α (205). At the

same time, the high glucose demand of tumors creates energy

competition, placing T cells and DCs in a metabolically restricted

state, thus diminishing their proliferative capacity and antitumor

responses (206). Lactate also

drives TAMs toward an immunosuppressive M2 polarization and hinders

DC maturation, further promoting MDSC accumulation and shaping an

immunosuppressive microenvironment (207). In addition, glycolytic metabolites

activate signaling pathways, such as HIF-1α, and induce PD-L1

upregulation, inhibiting T cell function through immune checkpoint

mechanisms (196,208,209).

In summary, the interplay between the innate and

adaptive immune systems, coupled with the regulatory roles of

diverse cells and molecules, is key in the onset, progression and

treatment of BC. Gaining a deeper understanding of these mechanisms

may aid in devising more effective immunotherapy strategies,

enhancing the survival and quality of life for patients with

BC.

BC development is associated with inflammation,

which is marked by the presence of immune system and other

inflammation-associated cells in its tissues. Infiltration of

inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, macrophages, DCs,

monocytes and neutrophils, is a common characteristic of BC

(210). It can result in the

release of inflammatory factors, such as IL-17A and IL-6, which

activate pathways associated with cancer and facilitate BC

development (211). Studies have

demonstrated an association between the degree of inflammatory cell

infiltration in BC tissue and cancer survival (212,213). Specifically, the presence of

CD8+ T cells within the tumor is linked to patient

survival (214). Notably, IL-6

serves an important role in the inflammatory microenvironment of

BC, particularly in aggressive subtypes, including TNBC and

HER2+ BC. IL-6 promotes tumor progression and metastasis

via the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in TNBC, and high IL-6 serum

levels are associated with poor prognosis (215,216). IL-6 contributes to trastuzumab

resistance in HER2+ BC by expanding cancer stem cell

populations via an autocrine inflammatory loop (217). These findings highlight the

potential of targeting IL-6 signaling as a therapeutic strategy in

specific BC subtypes.

Inflammatory cytokines in BC regulate the balance

between apoptosis and autophagy through multiple signaling

pathways, influencing cell fate. Studies have shown that TNF-α and

IL-1β can upregulate the expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 via

the NF-κB pathway, inhibiting mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis

(218,219). However, TNF-α also activates the

JNK pathway under strong inflammatory stimulation to promote

Bax/Bak-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization,

ultimately inducing caspase cascades and triggering apoptosis

(220). At the same time, IFN-γ

enhances the expression of effector molecules, such as caspase-3,

through the JAK/STAT1 pathway, amplifying apoptotic effects.

Furthermore, IL-6 suppresses autophagic activity via the

JAK/STAT3/mTOR signaling pathway, helping BC cells to maintain

survival and acquire drug resistance under adverse conditions

(221). The IL-6/STAT3 pathway,

persistently activated in TNBC and some HER2+ BC, not

only suppresses autophagy but also induces PD-L1 expression,

driving immune evasion and serving as a key target for combined

immunotherapy (222). The NLRP3

inflammasome and its downstream caspase-1/GSDMD pyroptotic pathway

can both promote metastasis via IL-1β secretion and trigger

immunogenic cell death, thus offering bidirectional therapeutic

value. Hypermethylation-mediated silencing of GSDME dampens

pyroptosis-associated immunogenic signals, whereas demethylating

agents restore GSDME expression and enhance the efficacy of

immunotherapy (223). In addition,

the IL-17A/STAT3/VEGF axis promotes angiogenesis and

immunosuppression, making it a promising target to block metastasis

(11). Thus, inflammatory cytokines

are not only inducers of cell death but also remodel the dynamic

balance between autophagy and apoptosis through key pathways, such

as NF-κB, JAK/STAT and mTOR, impacting BC progression and

therapeutic responses.

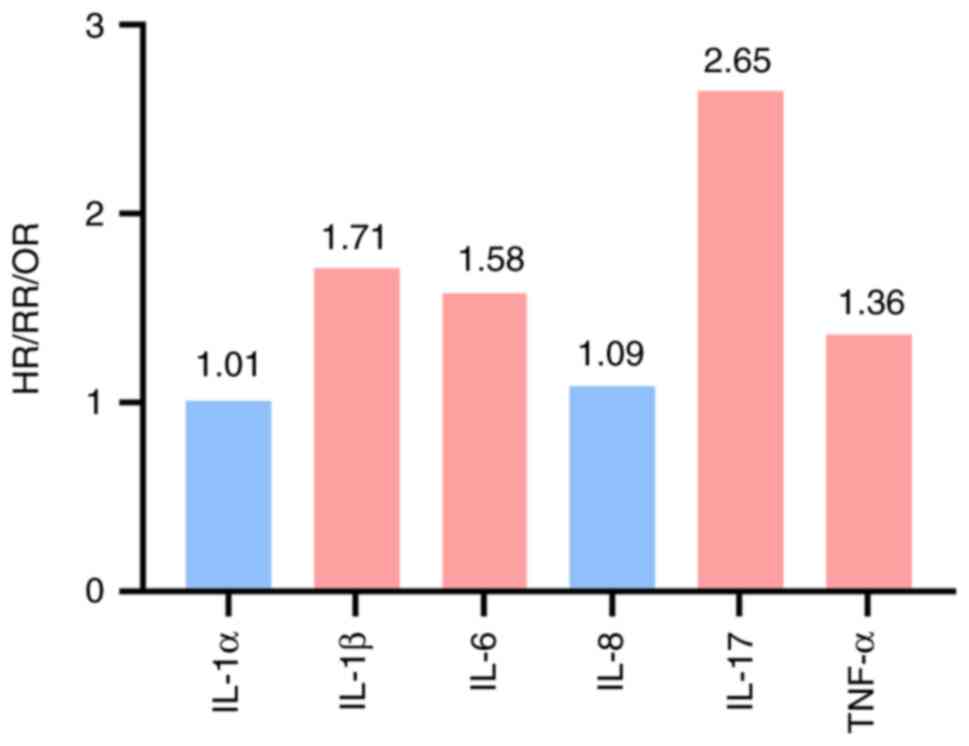

The association between inflammatory factors and BC

risk has been reported in multiple studies (224,225). The strength of the role served by

different inflammatory factors in BC pathogenesis varies. IL-17

confers the hazard risk (HR=2.65), with IL-1β [odds ratio

(OR)=1.71] and IL-6 [relative risk (RR)=1.58] also associated with

increased risk (226,227). The risks associated with TNF-α

(RR=1.36) and IL-8 (OR=1.09) are slightly increased, while IL-1α

(OR=1.01) is not associated with increased risk (Fig. 2) (226–228).

Numerous types of inflammatory cell play distinct

roles in BC. For example, macrophages serve key roles in chronic

inflammation associated with BC and can adopt M1 or M2 phenotype

(229). M1 macrophages release

pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6, as well

as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which influence tumor

proliferation, invasion and metastasis. By contrast, M2 macrophages

release anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, CCL5 and TGF-β,

which contribute to tissue repair and tumor progression. IL-6

exerts both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects (230). However, the concept that

pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages play

opposing roles in inflammation is oversimplified due to the high

plasticity of these cells in response to microenvironmental stimuli

(231). Moreover, the abundance of

macrophages is associated with clinical characteristics and

prognosis of BC (232).

Conversely, the presence of cancer-associated

adipocytes and corpuscular structures within BC tissue also

significantly influences tumor development (233). Cancer-associated adipocytes

secrete diverse inflammatory factors that alter BC cell behavior,

thereby promoting tumor invasion and metastasis (233). On the other hand, corpuscular

structures comprise macrophages, which serve as histological

indicators of pro-inflammatory processes and are present in adipose

tissue adjacent to BC (234).

These cells release pro-inflammatory factors that may induce a

chronic inflammatory state, influencing tumor progression and

prognosis.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and CAFs serve key

roles in inflammatory processes associated with BC. MSCs secrete

chemokines and cytokines that influence tumor growth and

metastasis. MSCs have been shown to promote tumorigenesis by

differentiating into CAFs and enhancing the immunosuppressive

environment, leading to increased tumor cell proliferation and

invasion (235). CAFs represent

one of the predominant stromal cell populations in BC and

participate in inflammation-mediated TME regulation. CAFs

contribute to tumorigenesis by remodeling the extracellular matrix,

promoting angiogenesis and secreting factors, such as TGF-β, VEGF

and IL-6, which enhance the metastatic potential of tumor cells

(236). CAFs are involved in

resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies by creating a

protective niche for cancer cells and modulating immune cell

infiltration (237). This dual

role of MSCs and CAFs underscores their importance in BC

progression and treatment resistance.

Chronic inflammation is associated with BC

development and may also accelerate metastatic progression. Immune

cells and inflammatory mediators in the inflammatory

microenvironment enhance tumor cell migration and invasion, thus

elevating metastatic risk. Similarly, inflammation exerts

beneficial antitumor effects in the early stages of tumor

development. IFN-γ is a key factor in this process, as it

upregulates MHC-I expression in tumor cells, enhances antigen

presentation and promotes DC-mediated CD8+ T cell

activation, enabling them to directly kill tumor cells (238,239). Inflammation strengthens the

functions of NK cells and macrophages, further eliminating abnormal

cells and providing long-term surveillance via the formation of

immune memory, protecting the host during the initial tumorigenesis

stages (240). Thus, deeper

comprehension of chronic inflammation in BC is key for devising

more efficacious therapeutic approaches, potentially improving

patient prognosis and guiding future research.

Overnutrition is a notable risk factor for various

human diseases, especially those associated with obesity, such as

neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorder and cancer (241). Therefore, adopting a reasonable

fasting regimen is key. Fasting has notable lasting positive

effects on multiple health indicators by improving insulin

sensitivity, lowering blood pressure, decreasing body fat content

and stabilizing blood glucose levels and lipid metabolism (242). The relationship between obesity

and BC has garnered notable attention (243,244). The biological effects of obesity

extend beyond weight gain to include inflammatory responses,

endocrine alterations and metabolic dysregulation, which are

factors that collectively promote BC initiation and progression

(245,246).

Obesity increases systemic inflammatory responses

and drives metabolic disorder, including insulin resistance,

hyperinsulinemia and dysregulated lipid metabolism. These metabolic

abnormalities impair immune surveillance through multiple

mechanisms. For example, hyperinsulinemia and elevated insulin-like

growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling enhances tumor cell proliferation

and survival by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (247,248). Obesity-associated lipid

accumulation skews macrophages toward an M2-like immunosuppressive

phenotype and impairs DC maturation, weakening antigen presentation

(249). In addition, chronic

low-grade inflammation leads to persistent IL-6, TNF-α and leptin

secretion, which promotes Treg expansion and MDSC recruitment and

decreases CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity (250,251). Collectively, these

metabolic-immune alterations create a permissive TME that

facilitates BC cell proliferation, immune evasion and therapeutic

resistance.

The association between obesity and BC is a complex

and multifactorial research area that has attracted attention

(252,253). Epidemiological evidence indicates

that each 1 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) is

associated with a ~3.4% increase in BC risk in postmenopausal

patients [RR=1.034; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.020–1.048].

Higher BMI shows a neutral or inverse association with BC risk in

premenopausal patients (RR=0.79; 95% CI: 0.70–0.88) (254). Severe obesity (BMI ≥35

kg/m2) further increases the risk, with HR of ~1.58 (95%

CI: 1.40–1.79) for invasive BC and ~1.86 (95% CI: 1.60–2.17) for

the ER+/PR+ subtype (255). Overweight and obese patients are

at a higher risk for lymph node-positive disease (HR=1.64; 95% CI:

1.09–2.48) and ER+ tumors (HR: 1.20–1.40) (256). Weight gain after adulthood is also

a key factor, with each 5 kg increase in body weight associated

with ~12% higher risk of postmenopausal BC (257).

Adipokines are bioactive hormones originating from

adipose tissue that regulate metabolism, caloric intake,

angiogenesis and cell proliferation. Adipokine levels typically

become dysregulated in obesity and are associated with cancer

development and metastasis (258).

Lipid metabolism influences BC proliferation, migration and

apoptosis (259). Lipids are key

to cellular structure and play pivotal roles in intercellular

signaling and metabolism (260).

Research indicates that cancer cells require substantial lipid

amounts for synthesizing biofilms, organelles and signaling

molecules that drive tumor progression (261). Chronic inflammation of white

adipose tissue is a crucial mechanistic link between obesity and

elevated BC risk (262). Activated

macrophages and elevated inflammatory mediators (IL-6, TNF-α and

IL-1β) amplify both local and systemic inflammation in obesity,

reshaping the TME and promoting angiogenesis, proliferation and

metastasis (263).

Cholesterol is a notable lipid component that plays

a vital role in BC pathogenesis. High cholesterol levels are

associated with increased BC risk and progression (264). Studies have shown that BC cells

exhibit altered cholesterol metabolism, which promotes tumor growth

and metastasis (265,266). Cholesterol influences BC cell

signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT and ERK pathways,

contributing to cancer cell survival and proliferation. Moreover,

cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in the cell membrane serve as

platforms for oncogenic signaling. For instance, cholesterol

involvement in the PI3K/AKT pathway leads to the activation of a

key regulator of cell proliferation and survival, mTOR, thereby

promoting tumor development (267). The ERK pathway is modulated by

cholesterol and serves a crucial role in cell division and

differentiation, further aiding cancer progression (268).

Cholesterol also affects the composition and

fluidity of cell membranes, influencing the function of

membrane-bound proteins involved in signal transduction (269). This modulation enhances the

ability of cancer cells to invade surrounding tissue and

metastasize. Furthermore, the interaction between cholesterol and

caveolin-1, a structural protein in caveolae (specialized lipid

rafts), is implicated in tumorigenesis regulation (270).

Elevated circulating estrogen levels are associated

with a higher risk of hormone-sensitive BC (271). Peripheral adipose tissue becomes

the primary site of estrogen production during the postmenopausal

period, where aromatase converts androgens into estrogens.

Excessive adipose tissue leads to higher circulating estrogen

levels with an increasing BMI, contributing to an increase in BC

incidence (272). However, this

appears to contradict the decrease in circulating estrogen levels

following menopause, which may demonstrate the complex association

between obesity and BC (273).

Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance are

associated with BC development and prognosis. Hyperinsulinemia is

associated with heightened synthesis of IGF-1, activating signaling

pathways that enhance cancer cell proliferation, migration and

survival (274). Insulin also

serves a key role in lipid metabolism (275). Elevated insulin levels,

characteristic of insulin resistance, trigger lipolysis and the

release of substantial amounts of free fatty acids, impacting

metabolic health status and establishing a detrimental cycle

(276,277).

In summary, the association between obesity and BC

involves a complex, multifactorial process that involves the

interaction of various biological mechanisms. A thorough

understanding of these mechanisms may aid in more effective

prevention and treatment of BC, especially in obese patients.

Traditional treatments for BC, such as surgical

excision, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, are not

universally applicable and have a range of side effects. Thus,

identifying novel treatment strategies is key for enhancing the

prognosis of patients with BC. Immunotherapy, which comprises both

passive and active approaches, has potential in treating various

cancers (278,279). Passive immunotherapy involves the

administration of immune components, such as monoclonal antibodies

(trastuzumab), to directly target tumor cells. Active immunotherapy

aims to stimulate the host immune system to attack tumors. These

strategies include ICIs, cancer vaccines and cellular therapy

(280).

Subtype-specific immunotherapeutic strategies are

key given the heterogeneity of BC. For example, combining

trastuzumab with IL-6R inhibitors (tocilizumab) in HER2+

BC has shown promise in overcoming resistance mediated by

IL-6-driven cancer stem cell expansion (217). Dual blockade of IL-6 and CCL5

signaling has been demonstrated to synergistically inhibit tumor

growth and metastasis in TNBC (216). Ongoing clinical trials are

evaluating the efficacy of IL-6 pathway inhibitors in combination

with standard therapies for patients with metastatic

HER2+ BC and TNBC, underscoring the translational

potential of targeting inflammatory pathways in BC immunotherapy

(281–283).

Immunotherapeutic approaches for BC involve

therapies using humanized monoclonal antibodies that target altered

molecules expressed by cancer cells (284). Trastuzumab is a humanized

monoclonal antibody approved in 1998 for HER2+ BC that

represents a key therapeutic advancement (285). Trastuzumab is traditionally

classified as a molecularly targeted drug because it inhibits

HER2-mediated signaling and blocks downstream proliferation

pathways (286). However, growing

evidence indicates that its therapeutic effects also depend on

immune-mediated mechanisms, particularly antibody-dependent

cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (287,288). In this process, the Fc fragment of

trastuzumab binds FcγRIIIa (CD16) on the surface of NK cells,

prompting them to release perforin, granzyme and pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α (287). This leads to tumor cell lysis and

recruitment of other immune cells to participate in the response.

The dual action links HER2 signaling inhibition with immune

activation, enabling trastuzumab and other HER2-targeted antibodies

to be incorporated into cancer immunotherapy (289). HER2-targeted drugs suppress

oncogene signaling and mobilize the immune response, highlighting

their dual attributes as both targeted therapy and immunotherapy

(288,290). Other anti-HER2 agents, including

the monoclonal antibody pertuzumab and small molecule tyrosine

kinase inhibitors (lapatinib, neratinib, gefitinib and afatinib),

have subsequently been used (291). Monoclonal antibodies primarily

exert immune-mediated effects such as ADCC, while tyrosine kinase

inhibitors function via intracellular signal blockade (292). Nevertheless, monoclonal antibody

therapy encounters challenges, including moderate remission rates

and drug resistance development (293). Another strategy involves the use

of antibody-drug conjugates and T cell bispecific antibodies

(294). The IMpassion130 trial

demonstrated that atezolizumab combined with nab-paclitaxel

improves progression-free survival in patients with TNBC, but the

clinical benefit is confined to the PD-L1-positive subgroup

(295). The aforementioned trial

did not show a significant OS advantage in the intention-to-treat

population and was discontinued due to the lack of efficacy in the

overall cohort (295).

Notable progress has been made in immunotherapy

based on BC subtypes. Clinical trial, such as KEYNOTE-355, have

confirmed that PD-1 inhibitors (pembrolizumab) combined with

chemotherapy significantly improve progression-free survival and OS

in TNBC, and this regimen has been approved by the US Food and Drug

Administration as a first-line standard treatment (296). Antibody-drug conjugates, such as

trastuzumab deruxtecan, have demonstrated efficacy in later-line

treatments for HER2+ BC and are being investigated in

combination with ICIs (297). In

addition, cancer vaccines, bispecific antibodies and cell therapies

are also increasingly explored in subtype-stratified BC treatments

(298,299). There are notable differences in

the immune response rate to PD-L1 inhibitors between patients,

which may be associated with biomarkers, such as tumor-infiltrating

lymphocyte (TIL) density, PD-L1 expression heterogeneity and tumor

mutational burden (TMB) (300).

Integrating molecular biomarkers, including PD-L1 expression, TIL

density and TMB, with the immune microenvironment status to guide

personalized treatment represents a key direction for improving

therapeutic efficacy (178,301).

Immune evasion mechanisms in BC involve alterations

in both the TME and tumor cells. Tumor immunogenicity depends on BC

subtype. For example, HER2-positive BC and TNBC exhibit distinct

immunogenic characteristics (297). Tumor cell recognition is key for

the success of immunotherapy, and elevated estrogen levels may

interfere with immune system activity (302). Therefore, combining anti-estrogen

therapy with immunotherapy may represent a reasonable strategy.

Furthermore, the anti-apoptotic tumor cell mechanisms and HLA-I

expression also impact the efficacy of immunotherapy (303). Targeting alterations in tumor

cells, such as via combination therapy with inhibitors, may enhance

clinical benefits for patients and alleviate treatment resistance.

Overall, the success of BC immunotherapy depends on overcoming the

tumor immune evasion mechanisms, optimizing the TME and enhancing

tumor cell recognition, which require consideration of both tumor

characteristics and individual patient differences.

The primary mechanism of BC vaccines is to activate

antigen-specific T cells, which target and eliminate cancer cells

(304). BC vaccines are classified

into those targeting HER2 or associated antigens and those

targeting non-HER2-associated antigens. The E75 vaccine is a safe

and effective immunotherapeutic agent that induces a peptide-based

immune response. A clinical trial demonstrated that the E75 vaccine

significantly decreases cancer recurrence in 95.2% of patients with

high-risk BC expressing HER2 when combined with booster

immunization (305). GP2 exhibits

lower HLA-A2 affinity compared with E75, but it may have higher

immunogenicity levels. GP2 induces T cell responses and

delayed-type hypersensitivity when administered concurrently with

GM-CSF in patients with high-risk BC (306). The AE37 vaccine is typically used

as adjuvant immunotherapy for BC (307).

As an emerging field in BC treatment, immunotherapy

faces challenges, such as low complete remission rates and

increased adverse events. Successful treatment involves overcoming

tumor immune evasion mechanisms and optimizing the TME to enhance

tumor cell recognition. Integrating individual patient differences

may help develop more effective treatment regimens.

The immune system, inflammatory response and RCD

are interconnected in BC, collectively influencing tumor

progression and treatment outcomes. The immune system is typically

suppressed in patients with BC, leading to immune evasion by the

tumor. Prolonged chronic inflammation promotes tumor development

and is associated with the malignant features of BC. Cytokines and

inflammatory mediators produced during inflammation affect the

proliferation, invasion and metastatic potential of tumor cells.

Abnormal regulation of apoptosis and autophagy in BC cells leads to

tumor proliferation and survival. Aberrant regulatory mechanisms of

RCD include apoptosis evasion and autophagy inhibition. These

abnormalities are associated with drug resistance and malignant

tumor characteristics. Studying the mechanisms and regulation of

these interactions may deepen understanding of BC development and

progression, offering novel strategies for its prevention and

treatment. In recent years, immunotherapy has achieved progress in

BC treatment, particularly that of TNBC (328). Pembrolizumab

combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improves

pathological complete response rates in high-risk patients with

early TNBC and demonstrates favorable efficacy and safety in

clinical practice (KEYNOTE-522 and KEYNOTE-756 Phase III trials and

real-world studies) (309–311). These data support immunotherapy as

a standard treatment approach in high-risk early TNBC and highlight

the importance of individualized treatment strategies. Future

research directions should focus on BC subtypes and the role of

cytokines in the TME, while also adopting advanced technical

strategies. Single-cell RNA sequencing is used to map the

transcriptional profiles of immune cells across BC subtypes in

order to delineate subtype-specific immune regulatory networks.

Gene-editing approaches, such as clustered regularly interspaced

short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9

(CRISPR/Cas9), may be employed to investigate the functional roles

of key cytokines in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance to

establish causal mechanisms. Moreover, integrating these approaches

with spatial transcriptomics or proteomics may further uncover

cell-cell interactions and microenvironmental heterogeneity.

Together, these strategies may provide more precise insight and

promote the development of personalized immunotherapeutic

approaches.

Future research should focus on the roles of

inflammatory factors and cell death-associated pathways in

different molecular subtypes of BC, with particular attention to

the key functions of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and their associated

signaling pathways in driving immune evasion and therapy resistance

(312). It is also important to

address the loss of immunogenicity caused by the silencing of GSDME

through promoter methylation, which impairs pyroptosis, as well as

the decrease in antigen presentation resulting from the

downregulation of PD-L1 and HLA-I (313,314). In addition, attention should be

given to obesity-associated inflammatory factors and abnormal lipid

metabolism, which contribute to an immunosuppressive TME.

Approaches such as single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial

transcriptomics can be employed to map the distribution and

interactions of immune cells and these key factors across BC

subtypes (315). Functional

validation of molecules such as IL-6, GSDME and TAP1/2 can be

performed using CRISPR/Cas9 technology in patient-derived organoids

and humanized mouse models. Furthermore, the effects of modulating

epigenetic states and metabolic pathways on immune cell

infiltration and treatment responses can be explored. Integrating

these findings with large-scale clinical data to analyze the

associations between these key molecules and patient prognosis and

treatment outcomes may provide novel targets and evidence-based

support for the development of more precise, subtype-specific

immunotherapy combinations for BC, such as ICIs combined with IL-6

inhibitors or epigenetic drugs.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Science and Technology

Innovation Fund Project of Dalian (grant no. 2023JJ13SN050) and

Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (grant no.

2024-MS-281), Liaoning Province ‘Xingliao Talent Program’ Medical

Experts Project, Young Medical Experts Special Project

(XLYC2412097).

Not applicable.

GL, BJ and JZ wrote the manuscript. ZF and SF

revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Britt KL, Cuzick J and Phillips KA: Key

steps for effective breast cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer.

20:417–436. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Admoun C and Mayrovitz HN: The etiology of

breast cancer. Mayrovitz HN: Breast Cancer [Internet] Brisbane

(AU): Exon Publications; 2022, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Youn HJ and Han W: A review of the

epidemiology of breast cancer in Asia: Focus on risk factors. Asian

Pac J Cancer Prev. 21:867–880. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ligibel JA, Ballman KV, McCall L, Goodwin

PJ, Alfano CM, Bernstein V, Crane TE, Delahanty LM, Frank E, Hahn

O, et al: Impact of a weight loss intervention on 1-year weight

change in women with stage II/III breast cancer: Secondary analysis

of the breast cancer weight loss (BWEL) trial. JAMA Oncol.

11:1194–1203. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bellanger M, Lima SM, Cowppli-Bony A,

Molinié F and Terry MB: Effects of fertility on breast cancer

incidence trends: Comparing France and US. Cancer Causes Control.

32:903–910. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Herdiana Y, Sriwidodo S, Sofian FF, Wilar

G and Diantini A: Nanoparticle-based antioxidants in stress

signaling and programmed cell death in breast cancer treatment.

Molecules. 28:53052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Propper DJ and Balkwill FR: Harnessing

cytokines and chemokines for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

19:237–253. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ruggieri L, Moretti A, Berardi R, Cona MS,

Dalu D, Villa C, Chizzoniti D, Piva S, Gambaro A and La Verde N:

Host-related factors in the interplay among inflammation, immunity

and dormancy in breast cancer recurrence and prognosis: An overview

for clinicians. Int J Mol Sci. 24:49742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li L, Yu R, Cai T, Chen Z, Lan M, Zou T,

Wang B, Wang Q, Zhao Y and Cai Y: Effects of immune cells and

cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor

microenvironment. Int Immunopharmacol. 88:1069392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|