Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is the most

aggressive subtype of breast cancer, defined by the lack of

estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression in tumor

cells. It is characterized by a more aggressive growth pattern and

more enhanced metastatic potential than other subtypes. Despite

advancements in breast cancer therapeutics that have contributed to

improved mortality rates, patients with TNBC continue to face

substantial clinical challenges as they are generally ineligible

for existing targeted therapies (1).

HSP90 is frequently upregulated in cancer, with

expression levels reported to be 2- to 10-fold higher than those in

normal tissues (2). In breast

cancer, its overexpression correlates with adverse

clinicopathological features, including larger tumor size, higher

nuclear grade, and poor prognosis, particularly in early stage

disease (3). Functionally, HSP90

acts as a molecular chaperone that supports the folding and

stability of more than 200 target proteins involved in oncogenic

processes such as cellular proliferation, resistance to apoptosis,

angiogenesis and metastatic progression (4). HSP90 drives tumor progression and

therapy resistance by sustaining pro-survival signaling pathways,

such as JAK/STAT3, AKT and MEK (5,6). Given

its central role in sustaining oncogenic signaling, HSP90 has

emerged as a compelling therapeutic target for TNBC. Therefore,

pharmacological inhibition of HSP90 offers a promising strategy for

simultaneously disrupting multiple oncogenic pathways in this

aggressive breast cancer subtype (7).

Emerging evidence has emphasized the key role of

cancer stem cells (CSCs) in tumor initiation, invasion and

metastasis, particularly in TNBC, where they drive chemoresistance

and metastasis, leading to treatment failure (8). Previous studies have reported that

HSP90 and its co-chaperones are highly implicated in the

maintenance of the CSC phenotype, expression of EMT-related genes,

and stability of pluripotent transcription factors such as Nanog

and Oct4 (9–12). Targeting HSP90 not only disrupts

pro-survival signaling pathways but also impairs the maintenance of

the CSC phenotype, thereby reducing chemoresistance and metastatic

potential, and highlighting its dual role as a promising

therapeutic target in TNBC management.

HSP90 comprises three domains: A N-terminal domain

(NTD) containing an ATP-binding pocket, a middle domain (MD), and a

C-terminal domain (CTD) required for dimerization (13). Most HSP90 inhibitors in clinical

trials target the N-terminus, but none have received FDA approval

owing to serious issues arising from the induction of the heat

shock response (HSR), off-target effects, and organ toxicity

(14,15). NCT-58, a C-terminal HSP90 inhibitor

that interferes with the binding of ATP to its CTD, was developed.

NCT-58 is one of 90 synthesized O-substituted analogs of the B- and

C-ring-truncated scaffolds of deguelin, a naturally occurring

rotenoid. It was observed that NCT-58 exerted antitumor activity in

HER2-positive breast cancer cells by downregulating HER2 and

inducing apoptosis (16). In the

present study, the mechanism underlying the novel effects of NCT-58

on apoptosis, breast cancer stem cells (BCSC)-like properties, and

cell migration in TNBC cells, was explored. Furthermore, the

potential of NCT-58 combined with paclitaxel or doxorubicin was

evaluated, and its potential as a multifaceted therapeutic strategy

for TNBC was highlighted.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

NCT-58 was synthesized according to a previously

established protocol (17). For all

experiments, NCT-58 was prepared as a stock solution (10 mM) in

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and vehicle controls contained the

corresponding final concentration of DMSO (0.1% v/v). Chemicals,

including propidium iodide (PI), DMSO and Triton X-100, were

purchased from MilliporeSigma. Protease and phosphatase inhibitor

tablets were obtained from Roche Applied Science. The primary

antibodies used for western blotting and immunocytochemistry were

specific to vimentin, STAT3, phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705), AKT,

phospho-AKT (Ser473), MEK, phospho-MEK (Ser218/222), PARP, cleaved

PARP, cleaved caspase-3, and −7, heat shock transcription factor-1

(HSF)-1, HSP70, cyclin D1, survivin, F-actin (Texas

Red™-X Phalloidin) and GAPDH. Secondary antibodies

included horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse and

anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 488/594-labeled anti-mouse and

anti-rabbit IgG.

Cell culture

The TNBC cell lines MDA-MB-231 (PerkinElmer, Inc.),

Hs578T (American Type Culture Collection; ATCC), BT549 and 4T1

(Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank), and the

cell line 293 (Korean Cell line Bank) were maintained in MEM or

RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The normal human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A (ATCC) was

cultured in Mammary Epithelial Cell Growth Basal Medium, including

hEGF (20 ng/ml), insulin (10 µg/ml), hydrocortisone (0.5 µg/ml) and

bovine pituitary extract (50 µg/ml) (SingleQuotsTM Kit;

Lonza Group, Ltd.) containing streptomycin-penicillin (100 U/ml).

The cells were then incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing

5% CO2.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter

96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay [MTS,

3-(4,

5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium]

(Promega Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The MTS reagent, which is soluble in cell culture medium, was added

directly to the cells. The quantity of purple formazan product was

determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm using a microplate

reader (Agilent BioTek 800 TS; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Percentage cell viability was calculated relative to that of the

untreated control (set at 100%). IC50 values were

determined by fitting sigmoidal dose-response curves using

nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism 9.0

(Dotmatics).

Cell cycle and Sub-G1 analysis

Cell cycle distribution and sub-G1 populations were

analyzed using flow cytometry. Cells were harvested at 70–80%

confluence, washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS),

and fixed by dropwise addition of pre-chilled 95% ethanol

containing 0.5% Tween-20. The samples were then incubated at −20°C

overnight to ensure complete fixation. Following fixation, cells

were centrifuged (7,160 × g), resuspended in staining buffer

containing propidium iodide (50 µg/ml) and RNase A (50 µg/ml), and

incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. DNA content

was assessed using a Beckman Coulter Expo flow cytometer (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software v10.10

(BD Biosciences).

Aldefluor-positive assay,

CD44high/CD24low staining

To evaluate ALDH1 enzymatic activity, cells were

treated using the Aldefluor™ assay kit (Stemcell

Technologies, Inc.) in accordance with the supplier's protocol.

Briefly, cells (0.5×106) were suspended in assay buffer

containing 1 µM BODIPY-amino-acet-aldehyde and incubated at 37°C

for 45 min. Diethyl-amino-benzaldehyde (50 mM) was added to the

control sample to inhibit ALDH1 activity and establish gating

parameters for the Aldefluor-positive population during flow

cytometric analysis. To identify stem-like cell populations

exhibiting the CD44high/CD24low phenotype,

cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with FITC-labeled anti-CD24

and PE-labeled anti-CD44 antibodies (1:50; BD Biosciences). FITC-

and PE-conjugated isotype-matched mouse IgG antibodies were used as

controls for non-specific staining. The labeled cells were

subsequently subjected to flow cytometry.

Mammosphere formation assay

To assess sphere-forming capacity, 4T1 cells were

seeded at a density of 3×105 cells/ml in ultralow

attachment plates (Corning, Inc.) and cultured in HuMEC basal

serum-free medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

supplemented with B27 (1:50; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF;

MilliporeSigma), 20 ng/ml mouse epidermal growth factor (EGF,

MilliporeSigma), 4 µg/ml heparin, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic

solution, and 15 µg/ml gentamycin. The number and volume of

mammospheres were determined using an Olympus CKX53 inverted

microscope, and the sphere size was quantified using ImageJ

software (v1.54; National Institutes of Health). Mammosphere

volumes were calculated using the formula:

Volume=4/3×3.14×r3.

C-terminal HSP90 inhibition assay

A C-terminal HSP90α Inhibitor Screening Kit (BPS

Bioscience) was used to evaluate inhibition of the interaction

between the C-terminal region of HSP90α and its co-chaperone

peptidylprolyl isomerase D (PPID) by HSP90 inhibitors, as

previously described (11,18). The assay was conducted in 384-well

Optiplates (PerkinElmer, Inc.) and luminescence signals were

detected using the AlphaScreen® technology on a

Varioskan LUX™ microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

N-terminal HSP90 binding activity

assay

To assess compound binding affinity to the NTD of

HSP90α, a fluorescence-based competitive binding assay (HSP90α

N-terminal Assay Kit; BPS Bioscience) was conducted in accordance

with the manufacturer's guidelines. Test compounds (ranging from

0–1,000 nM in DMSO) were mixed with a reaction solution comprising

FITC-tagged geldanamycin (100 nM) and recombinant HSP90α protein

(17 ng/µl), followed by incubation at room temperature for 3 h.

Fluorescence intensity was then measured at an excitation

wavelength of 485 nm and emission at 530 nm using a SpectraMax

Gemini EM microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC) to assess the

binding activity to the NTD of HSP90.

Wound healing assay

Cells were plated in 96-well ImageLock plates (Essen

Bioscience) and grown until they reached ~90% confluency. A uniform

wound was created using a 96-pin WoundMaker, followed by washing

with PBS to eliminate detached cells. Immediately after scratch

formation, cells were exposed to varying concentrations of NCT-58.

Cell migration was monitored in real time by capturing images

hourly for 25 to 50 h using an IncuCyte ZOOM Live-Cell Imaging

System (Essen Bioscience). The progression of wound closure was

quantified using the IncuCyte™ Scratch Wound Cell Migration

analysis software (Essen BioScience).

Immunoblot analysis

Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), targeting the following proteins: AKT

(1:2,000), phospho-AKT (1:2,000), MEK (1:2,000), phospho-MEK

(1:2,000), STAT3 (1:2,000), phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705, 1:2,000),

survivin (1:2,000), cyclin D1 (1:2,000), PARP (1:2,000), cleaved

PARP (1:2,000), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000), cleaved caspase-7

(1:1,000), and GAPDH (1:3,000). After washing, the membranes were

incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit or

anti-mouse IgG, 1:3,000-1:5,000). Protein bands were visualized

using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay

buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium

deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease and

phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche Diagnostics). The lysates

were incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 25,200 × g

for 15 min at 4°C to remove insoluble debris. The supernatant was

collected, and protein concentrations were determined using a BCA

assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of protein

(20 µg per lane) were mixed with the sample buffer, boiled for 10

min, separated using 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto

PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). Membranes were blocked with 5%

skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently incubated

overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in 5% BSA [AKT

(1:2,000), phospho-AKT (1:2,000), MEK (1:2,000), phospho-MEK

(1:2,000), STAT3 (1:2,000), phospho-STAT3 (Y705; 1:2,000), survivin

(1:2,000), cyclin D1 (1:2,000), PARP (1:2,000), cleaved-PARP

(1:2,000), cleaved-caspase-3 (1:1,000), cleaved-caspase-7

(1:1,000), and GAPDH (1:3,000)]. The catalog numbers and suppliers

of antibodies are included in Table

SI. After washing, the membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3,000-1:5,000) for 1 h at

room temperature. Protein bands were detected using an Enhanced

Chemiluminescence Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), quantified

using AlphaEaseFC software (Alpha Innotech Corporation), and

normalized to GAPDH as the internal loading control.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells cultured on 8-well chamber slides (BD

Biosciences) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 2 h,

rinsed with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10

min. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies against HSP70 (1:100), HSF-1 (1:100), vimentin (1:200),

or F-actin (1:200) diluted in an antibody diluent (Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). After washing, the cells were treated with

fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa

Fluor® 488 or 594). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI

(0.4 µg/ml) and mounted using ProLong™ Gold Antifade

Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Fluorescence images were

captured using a Carl Zeiss confocal microscope, and the signal

intensity was quantified using the intensity profile tool.

Immunofluorescence images were acquired under identical sensitivity

settings, including exposure time, laser power, and gain, across

the control and treated groups. For the nuclear protein HSF1,

nuclei were segmented using DAPI staining in ImageJ. The integrated

density of HSF1 within each nucleus was normalized to the

integrated density of the corresponding DAPI signal (HSF1/DAPI

ratio) to correct for nuclear size and DNA content. For cytoplasmic

proteins HSP70, corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) was

calculated as: CTCF=Integrated density-(Area × Background mean

intensity) with background values obtained from four cell-free

regions per image. Quantification was performed using at least 10

cells from a minimum of three independent fields per condition.

Synergy assessment

To evaluate whether two compounds interact

synergistically, additively, or antagonistically, the combination

index (CI) was determined using CompuSyn® software

(ComboSyn, Inc.; http://www.combosyn.com). A CI value of less than,

equal to, or greater than 1 denotes synergism, additive effects, or

antagonism, respectively. The fraction affected (Fa) represents the

proportion of phenotypic inhibition resulting from treatment with a

compound. Fa=percent inhibition of cell viability/100. The Fa-CI

plot was generated for each group treated with more than one

compound, and the corresponding heat map illustrated the percentage

inhibition of cell viability under the combination conditions. The

CI values at specific effect levels were then used to construct

isobolograms, where data points below, on, or above the line of

additivity indicated synergistic, additive, or antagonistic

effects, respectively.

Molecular docking analysis

In silico molecular docking was conducted

using open-access AutoDock Vina-based platforms including DockThor

(https://www.dockthor.lncc.br) and

CB-Dock2 (https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2). Upon completion of

the docking simulations, both 2D and 3D structures of the

protein-ligand complexes were visualized and analyzed using UCSF

Chimera 1.16 and BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2021. The predicted

binding affinity for the interaction between NCT-58 and the CTD of

hHSP90α (PDB ID: 7RY1) was estimated to be-9.5 kcal/mol. The

binding site and key interactions were analyzed to identify

hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and the overall binding

pocket conformation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the

GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software; Dotmatics). Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM from at least three independent

experiments. Comparisons between groups were conducted using

unpaired Student's t-test or one-/two-way ANOVA, as appropriate.

For two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's post-hoc test was used to evaluate

multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

NCT-58 exerts an anti-proliferative

effect without triggering the HSR

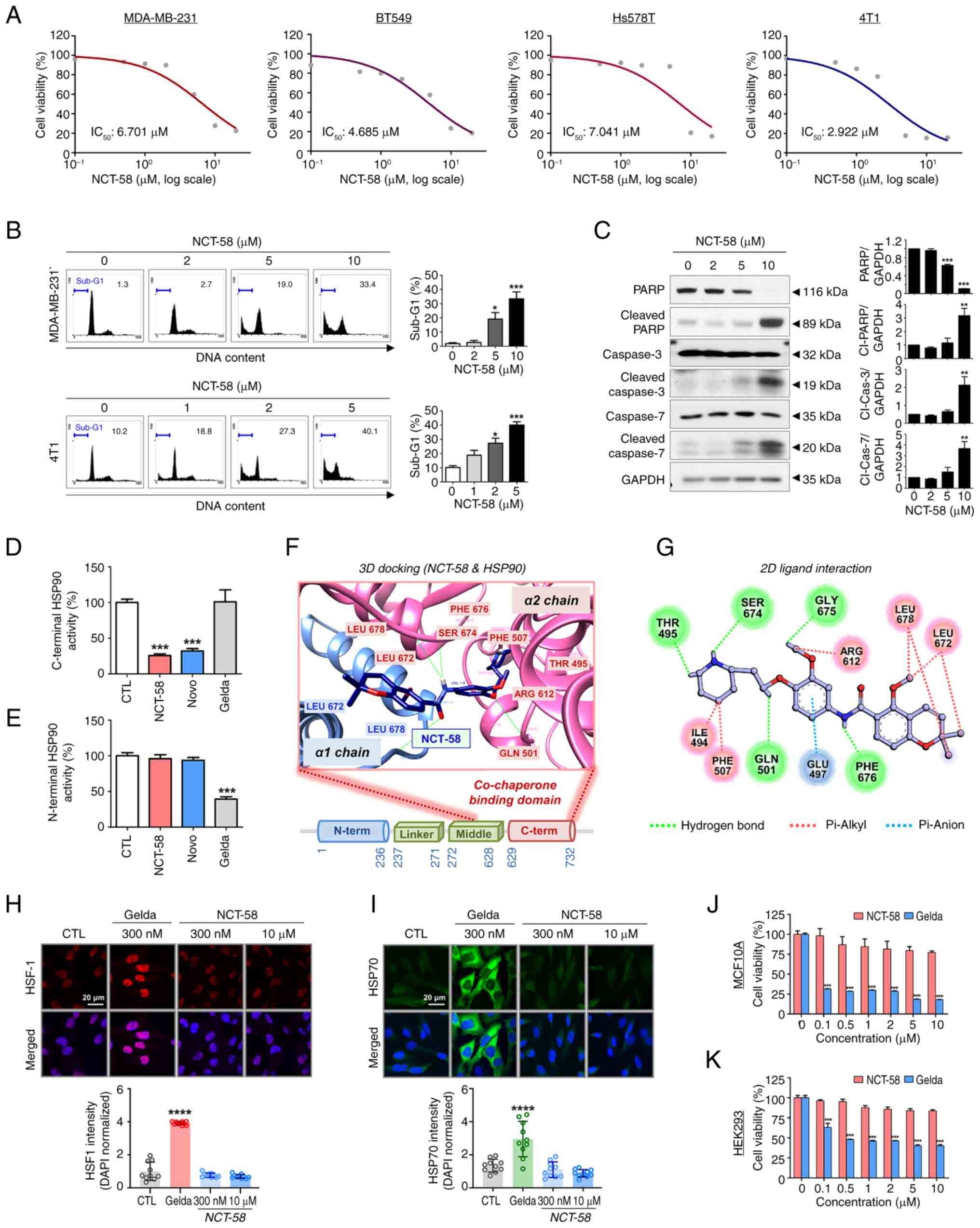

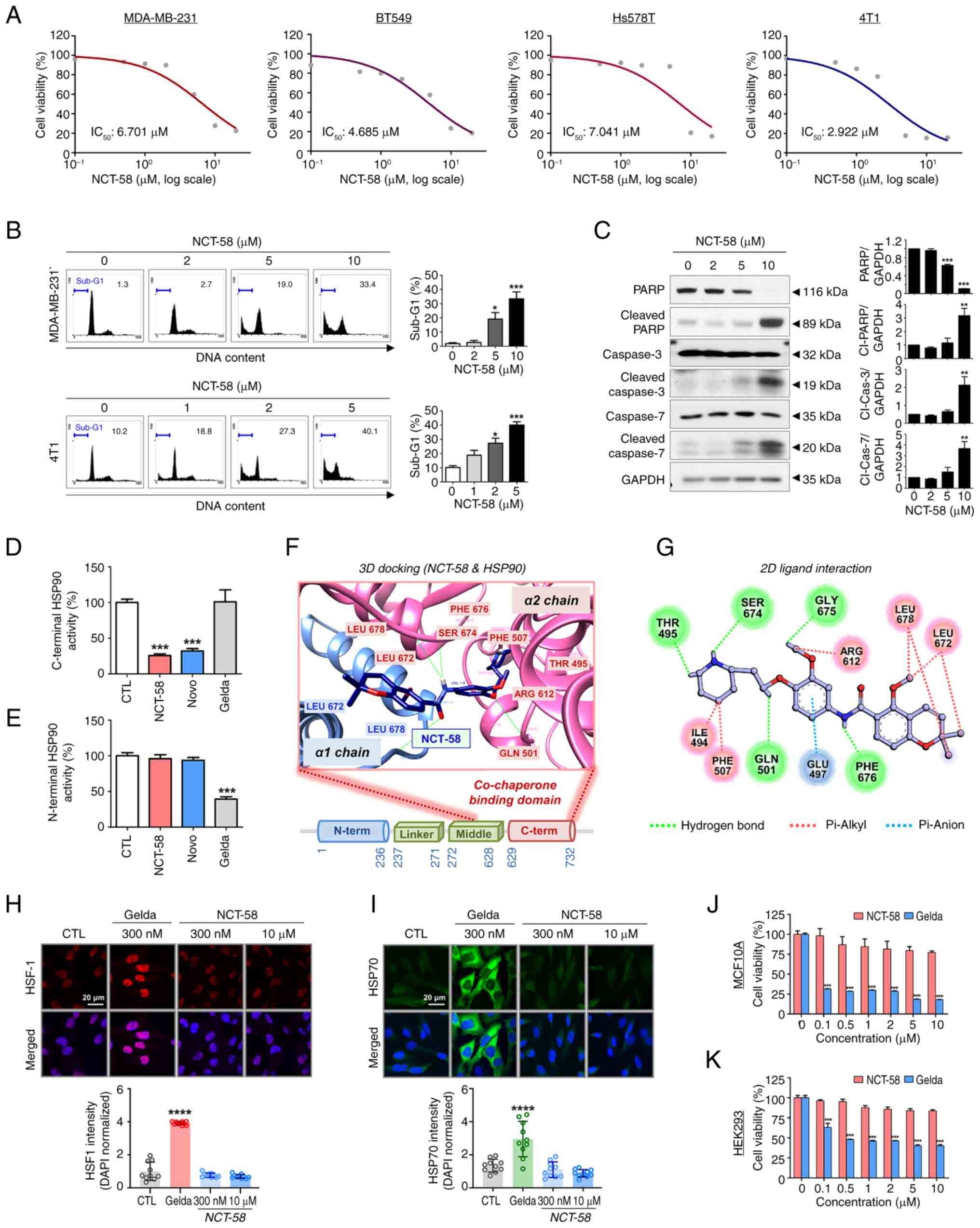

The anti-proliferative effect of NCT-58 in the human

TNBC cell lines MDA-MB-231, BT549 and Hs578T, and the murine

mammary carcinoma line 4T1, were first evaluated. TNBC cell

viability was dose-dependently reduced in the presence of NCT-58

(0–20 µM, 72 h) in vitro (P<0.05; Figs. 1A and S1; Table

SII). The estimated IC50 values for NCT-58 were

6.701, 4.685, 7.041 and 2.922 µM in MDA-MB-231, BT549, Hs578T and

4T1, respectively. Based on IC50 values, a concentration

range of 2–10 µM in MDA-MB-231 and 1–5 µM in 4T1 cells was selected

for further experiments including apoptosis, western blot analysis,

and cancer stem cell-like characterization. Apoptosis was

significantly increased in the presence of NCT-58 at 5 µM in

MDA-MB-231 cells and at 2 µM in 4T1 cells (P<0.05; Fig. 1B) for 72 h, as evidenced by

increased sub-G1 accumulation. Apoptosis induction was confirmed

using caspase-3 and caspase-7 activation, concomitant with

increased cleavage of PARP, a downstream substrate of caspase-3

(P<0.01; Fig. 1C). Further

quantitative analysis confirmed an increased ratio of cleaved to

total forms of caspase-3, caspase-7 and PARP following NCT-58

treatment (P<0.05; Fig.

S2A-C).

| Figure 1.NCT-58 exerts anti-proliferative

effect in TNBC cells by targeting the C-terminal domain of HSP90.

(A) Four TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-231, BT549, Hs578T and 4T1 cells

were treated with various concentrations of NCT-58 (0–20 µM) for 72

h. Cell viability was assessed using MTS assay, and IC50

values were calculated using non-linear regression with a sigmoidal

dose-response curve. (B) MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells were treated at

the indicated concentrations of NCT-58 (0–10 µM) for 72 h.

Apoptosis was determined through sub-G1-DNA analysis using flow

cytometry. (C) Immunoblot analyses of PARP, cleaved-PARP,

caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-7 and cleaved caspase-7

protein expression in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with NCT-58

(0–10 µM, 72 h). GAPDH was used as an internal loading control.

Quantitative graphs of these protein levels. The results are

presented as the mean ± SEM of at least three independent

experiments and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's post hoc test. (D) Effect of NCT-58 on C-terminal

HSP90 binding activity. The inhibitory effect of HSP90 inhibitors

(NCT-58, novobiocin or geldanamycin, 500 µM) on the interaction

between HSP90α (C-terminal) and its co-chaperone peptidylprolyl

isomerase was determined using an HSP90α (C-terminal) inhibitor

screening assay. (E) Influence of NCT-58 on N-terminal HSP90

binding activity. The competitive HSP90α binding activity of HSP90

inhibitors (NCT-58, novobiocin or geldanamycin, 1 µM) with

FITC-labeled geldanamycin was determined using an HSP90α N-terminal

domain assay. (F and G) Molecular docking analysis of NCT-58

binding to the CTD of HSP90 (PDB ID: 7RY1). (F) The binding pose of

NCT-58 at the dimerization interface is displayed as a

space-filling model. The α1 chain of HSP90 is rendered in a blue

ribbon, and the α2 chain in a pink ribbon. Connolly surface

representation of the HSP90 CTD, with NCT-58 modeled within the

binding interface (docking score=−9.5). (G) A 2D interaction

diagram of NCT-58 with key residues in the HSP90 CTD. Hydrogen

bonds and π-anion interactions are indicated by dashed green and

blue lines, respectively. (H and I) Comparison of the effects of

NCT-58 and the N-terminal HSP90 inhibitor geldanamycin on HSF-1 and

HSP70 expression. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with NCT-58 (300 nM

and 10 µM) or geldanamycin (300 nM) for 24 h. Cells were

immuno-stained for HSF-1 (red, H) or HSP70 (green, I) using DAPI

(nuclei, blue). Images were acquired using a confocal microscope,

and quantification of immunofluorescence intensity was performed

using ImageJ software. Nuclear HSF1 intensity was expressed as the

HSF1/DAPI ratio, and cytoplasmic HSP70 intensity was expressed as

corrected total cell fluorescence normalized to DAPI. (J and K)

Effect of NCT-58 and geldanamycin on cytotoxicity in non-malignant

cells. Normal human mammary epithelial MCF10A (J) and 293 (K) cells

were treated with various concentrations (0.1–10 µM) of NCT-58 or

geldanamycin for 72 h. Cell viability was determined using MTS

assay (***P<0.001). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. TNBC, triple-negative breast

cancer; Gelda, geldanamycin; Novo, novobiocin; CTD, C-terminal

domain. |

The C-terminal HSP90 binding activity of NCT-58 was

analyzed using the co-chaperone peptidylprolyl isomerase D (PPID),

which exhibits high-affinity ligand binding activity to the

C-terminus of HSP90. NCT-58 significantly inhibited C-terminal

HSP90 activity, as evidenced by the marked inhibition of the

specific interaction between PPID and the C-terminus of HSP90

(P<0.001; Fig. 1D).

Similar results were observed for novobiocin, a potent C-terminal

HSP90 inhibitor (19), whereas

geldanamycin did not affect this interaction. Furthermore, the

competitive HSP90 binding assay with fluorescence-labeled

geldanamycin did not show N-terminal HSP90 binding activity of

NCT-58 (Fig. 1E). Docking studies

using the crystal structure of HSP90 (PDB ID: 7RY1), which includes

the middle and CTD, revealed that NCT-58 precisely fits into the

dimerization interface of the CTD, which is a critical region

required for chaperone function (Fig.

1F). The interaction between NCT-58 and the HSP90 CTD was

extensively stabilized by five hydrogen bonds with the key residues

Thr495, Gln501, Ser674, Gly675 and Phe676. In addition, a π-anion

interaction was observed between NCT-58 and Glu497 of HSP90,

further enhancing binding stability (Fig. 1G). These findings highlight how

NCT-58 specifically occupies the CTD binding pocket to disrupt

dimerization and impair HSP90 function.

Subsequently, it was assessed whether NCT-58 induces

the HSR, a limitation of classical N-terminal HSP90 inhibitors.

Geldanamycin, the first and most extensively studied N-terminal

HSP90 inhibitor, was selected as the reference compound and was

used in all experiments requiring an N-terminal HSP90 inhibitor

(20,21). The N-terminal HSP90 inhibitor

induces the phosphorylation and trimerization of heat shock

factor-1 (HSF-1), promoting its nuclear translocation and

subsequent upregulation of heat shock proteins (HSPs), such as

HSP70 and HSP90, which support pro-survival signaling (15,22).

MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with geldanamycin (300 nM), a potent

N-terminal HSP90 ATP binding inhibitor, and NCT-58 (300 nM and 10

µM), followed by the assessment of HSF-1 and HSP70 expression.

Confocal imaging and intensity analysis revealed no increase in

HSF-1 levels upon exposure to NCT-58, whereas geldanamycin

considerably increased the accumulation of HSF-1 in the nuclei of

MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 1H). This

finding was further supported by the fact that geldanamycin induced

the subsequent upregulation of cytoplasmic HSP70, whereas NCT-58

did not elicit this phenomenon (Fig.

1I).

Accumulating preclinical and clinical evidence has

highlighted the significant off-target toxicity of geldanamycin

derivatives, which causes undesirable effects in normal tissues

(23). Notably, NCT-58 exhibited

minimal cytotoxicity at 10 µM in normal mammary gland epithelial

MCF10A cells and 293 cells, while geldanamycin caused significant

cytotoxicity in both normal cell lines at 100 nM, a 1,000-fold

lower concentration (P<0.001; Fig. 1J and K).

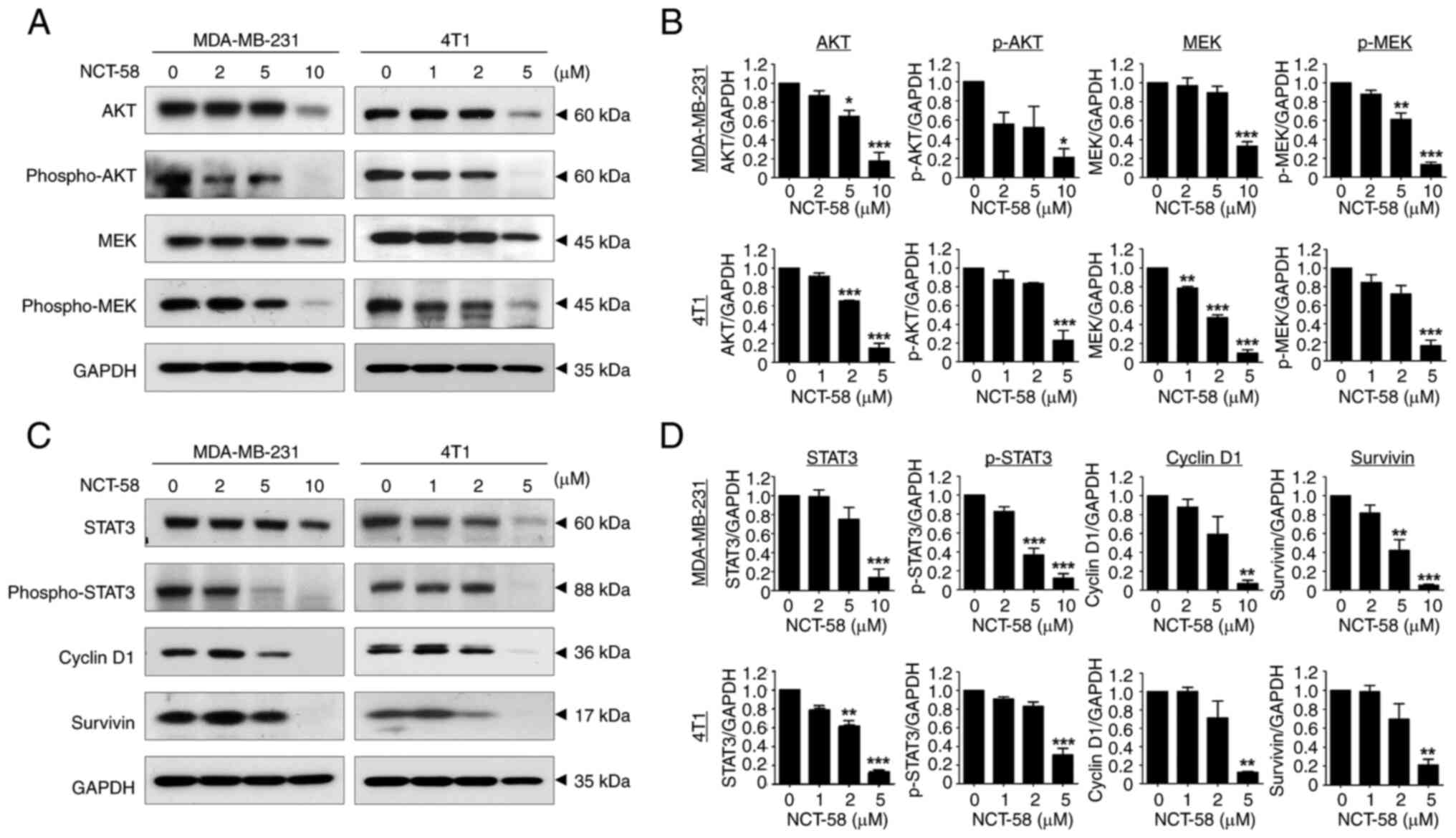

NCT-58 simultaneously targets

pro-survival HSP90 client proteins in TNBC cells

It was observed that NCT-58 significantly

downregulated the expression of AKT and MEK and reduced their

phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells (P<0.05; Fig. 2A and B; Fig. S3A-F), suggesting that the

simultaneous inhibition of these two major survival pathways could

enhance the antiproliferative effect against TNBC cells.

STAT3 is activated by phosphorylation of its

tyrosine residue (Tyr705) in response to stimulation by cytokines

and growth factor receptors, and then translocates to the nucleus

to promote the expression of survival factors such as cyclin D1,

survivin, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (24).

Therefore, inhibition of HSP90 may suppress the expression of

several oncoproteins promoted by STAT3. It was observed that NCT-58

significantly impaired the expression and phosphorylation at Tyr705

of STAT3 in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells, accompanied by the

downregulation of survivin and cyclin D1 (P<0.01; Fig. 2C and D).

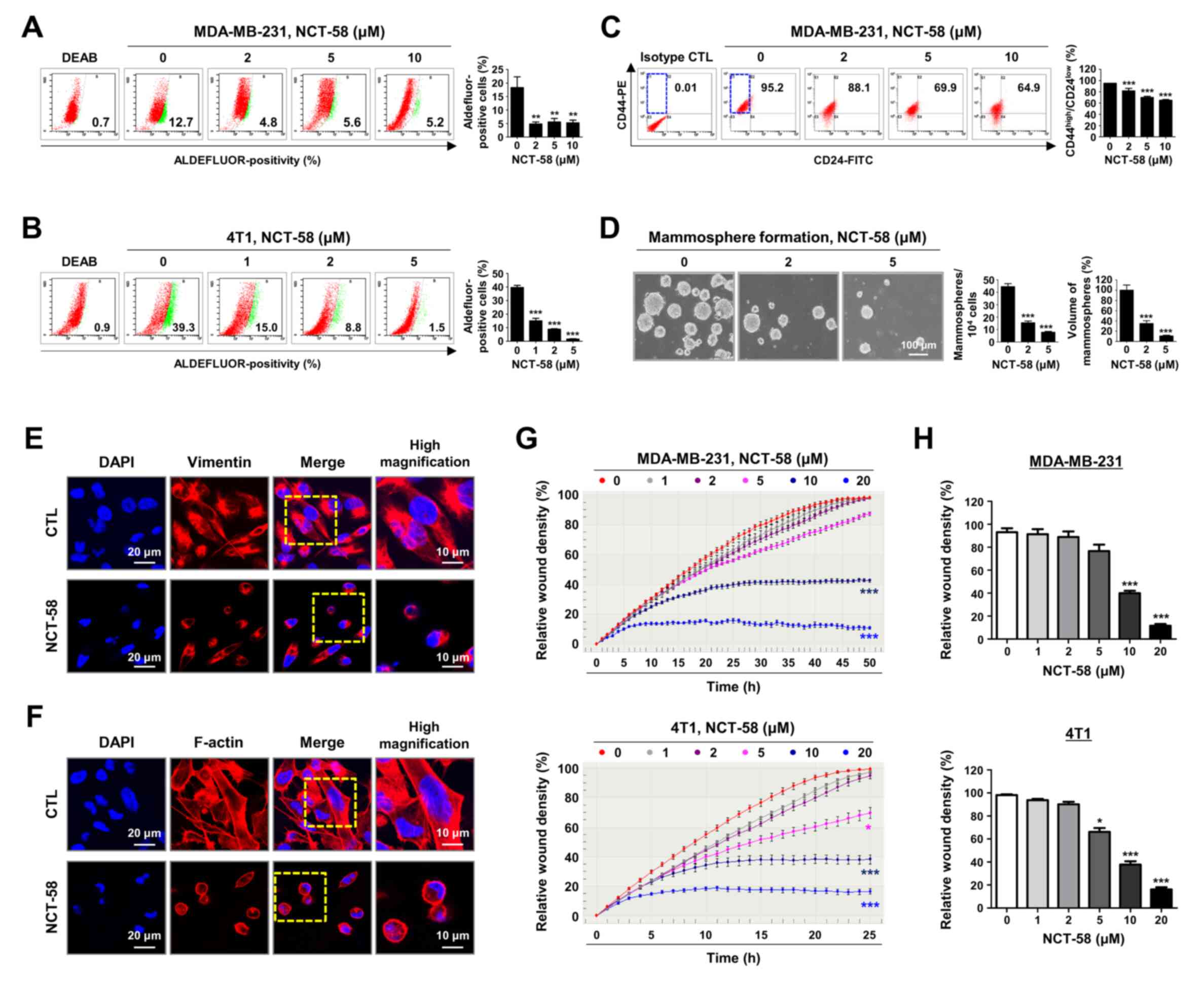

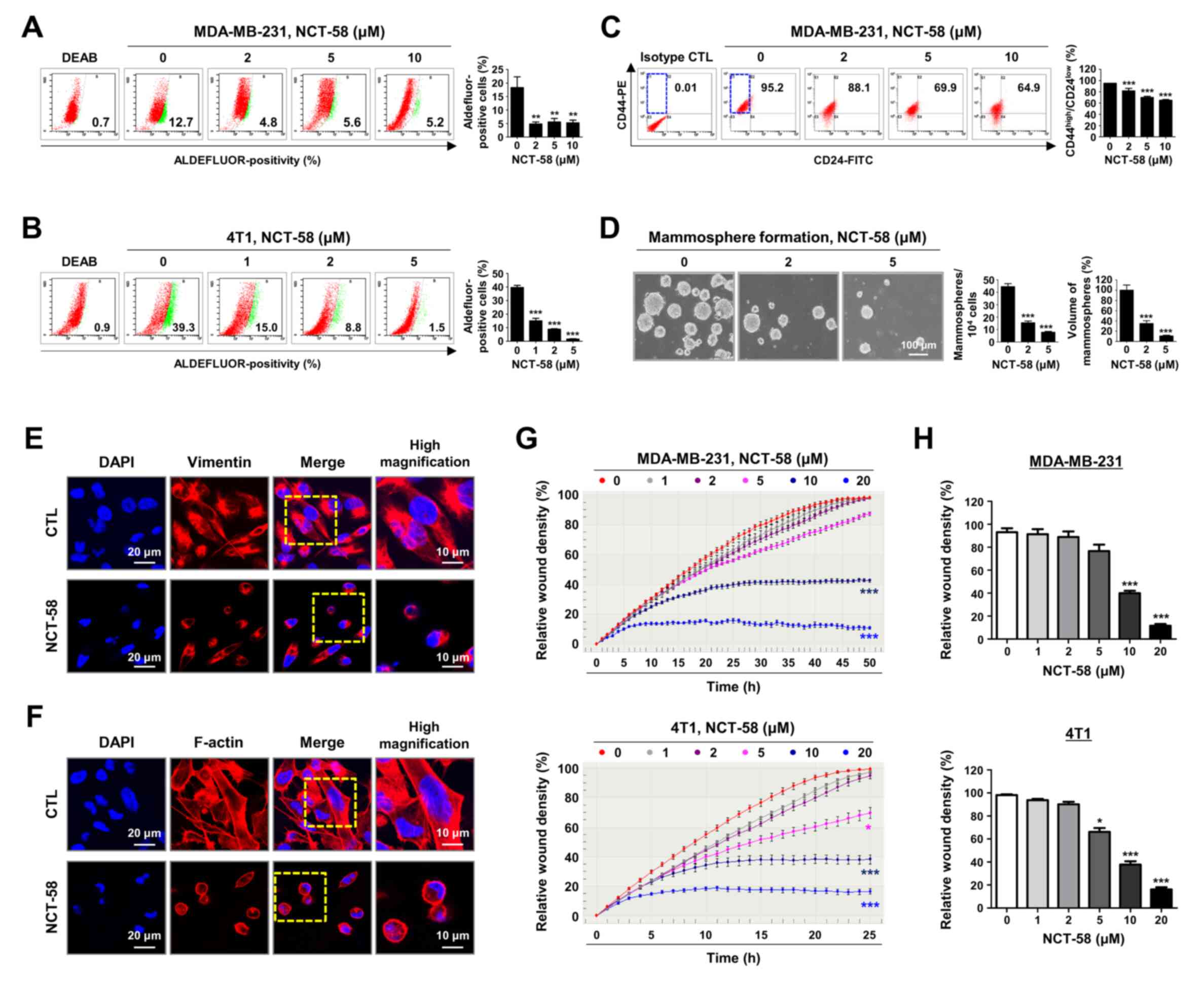

NCT-58 hampers cancer stem-like

characteristics and migratory ability in TNBC cells

BCSCs confer resistance to chemotherapy during TNBC

treatment and are thought to be a prerequisite for invasion and

metastasis (8). It was examined

whether NCT-58 affects BCSC-like properties, ALDH1 activity,

CD44high/CD24low stem-like populations, and

mammosphere formation. Treatment with NCT-58 significantly

suppressed ALDH1 activity in MDA-MB-231 (P<0.01; Fig. 3A) and 4T1 cells (P<0.01; Fig. 3B). The

CD44high/CD24low phenotype is associated with

a higher incidence of relapse or distant metastasis (25). A significant reduction in the

CD44high/CD24low-population was observed in

MDA-MB-231 cells after NCT-58 challenge (P<0.001; Fig. 3C). Mammosphere 3D culture is a

useful tool for assessing the tumor-like properties of BCSCs

capable of propagating mammary and progenitor cells in vitro

(26,27). The assay revealed that NCT-58

attenuated the mammosphere-forming ability, as evidenced by

significant reductions in the number and volume of mammospheres

derived from 4T1 cells (P<0.001; Fig. 3D).

| Figure 3.NCT-58 suppresses cancer stem-like

properties and migratory activity in TNBC cells. (A and B) Effect

of NCT-58 (0–10 µM, 72 h) on ALDH1 activity in (A) MDA-MB-231 and

(B) 4T1 cells. The specific inhibitor diethyl-amino-benzaldehyde

was used to define the Aldefluor-positive population.

Aldefluor-positive cells were quantified using flow cytometry

(right panel). (C) Effect of NCT-58 (0–10 µM, 72 h) on the

CD44high/CD24low stem-like population in

MDA-MB-231 cells. The CD44high/CD24low

population was quantified through flow cytometry. (D) Effect of

NCT-58 on mammosphere formation in vitro. 4T1 cells

(5×104 cells/ml) were cultured in ultralow attachment

plates in the presence or absence of NCT-58 (2–5 µM, 5 days). The

number and volume of mammospheres were quantified using optical

microscopy. (E and F) After exposure to NCT-58 (10 µM) for 48 h,

MDA-MB-231 cells were immuno-stained for vimentin (1:100, E) and

F-actin (1:100, Texas Red-X phalloidin, F) with DAPI nuclear stain

(blue). (G and H) Effect of NCT-58 on TNBC cell migration. (G)

After exposure to NCT-58 (0–20 µM) in MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells,

kinetic analysis of cell migration was determined using the

IncuCyte™ Live-Cell Imaging System and quantified for

the indicated time duration. The kinetic graphs of cell migration

represent the relative wound density. (H) Relative wound density

(%) in MDA-MB-231 cells at 50 h and in 4T1 cells at 25 h,

respectively. The results are presented as the mean ± SEM of at

least three independent experiments and analyzed using one- or

two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. TNBC,

triple-negative breast cancer. |

Actin and vimentin are major HSP90 target proteins

and cytoskeletal components that play important roles in cell

interaction, motility, invasiveness and adhesion (13,28).

Vimentin intermediate filament is a hallmark of EMT, and appears to

be involved in TNBC metastasis (29). To explore whether NCT-58 affected

the expression of HSP90 target cytoskeletons, the spatial

distribution of vimentin and filamentous-actin was observed using

immunofluorescence analysis. NCT-58 treatment resulted in vimentin

and F-actin reorganization and the disruption of filament networks,

resulting in concomitant cytoplasmic contraction and cellular

rounding (Fig. 3E and F). Kinetic

analysis of cell migration revealed that NCT-58 significantly and

dose-dependently reduced the migration of both MDA-MB-231 and 4T1

cells in vitro (P<0.05; Fig.

3G and H), indicating that the collapse of filament dynamics

may contribute to the suppression of migratory ability.

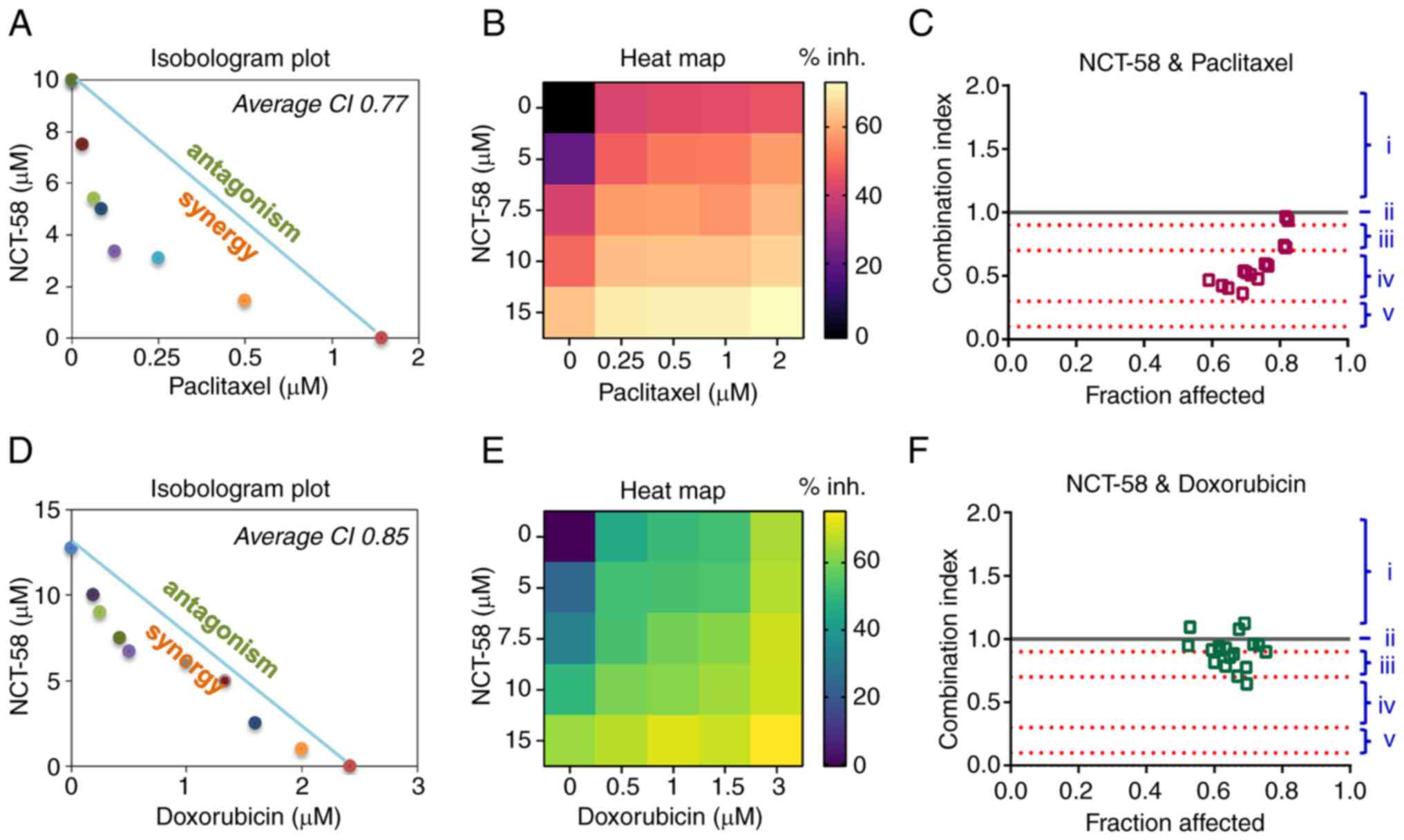

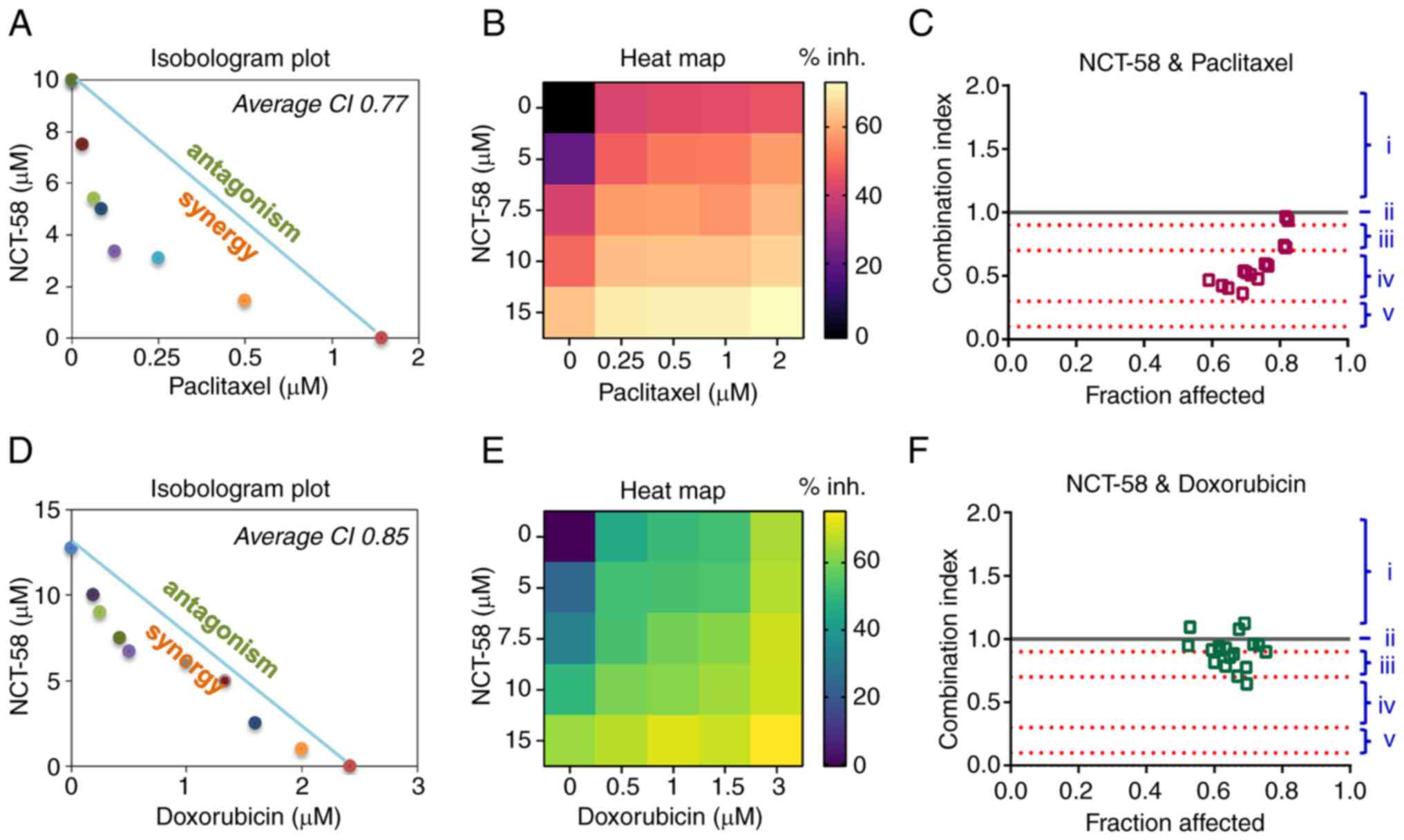

NCT-58 significantly enhances the

anti-proliferative effects of paclitaxel and doxorubicin in a

synergistic manner

It was investigated whether NCT-58 could enhance the

sensitivity of cells to the conventional chemotherapeutic agents

paclitaxel and doxorubicin. To assess the synergistic effects of

NCT-58 on paclitaxel- or doxorubicin-induced suppression of cell

viability, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with NCT-58 (0–20 µM)

combined with paclitaxel (0–2 µM) or doxorubicin (0–3 µM) for 72 h.

The interaction between NCT-58 and paclitaxel or doxorubicin was

evaluated by isobologram analysis, which uses a graphical

representation (isobole) to assess drug effects. Additive

interactions are represented as points along the line connecting

the effective concentration 50 (EC50) values of each

drug, whereas the co-treatment of NCT-58 with paclitaxel or

doxorubicin demonstrated synergistic effects, as indicated by

points positioned below the isobole (Fig. 4A and D). The heat map intensity

represents the relative cell viability of drug combination effects

compared with the control treatment with DMSO alone (Fig. 4B and E). The CI further confirmed

these synergistic interactions, highlighting the potential of

NCT-58 to enhance the efficacy of conventional cytotoxic agents

(Fig. 4C and F).

| Figure 4.Synergistic effects of combining

NCT-58 with paclitaxel or doxorubicin in triple-negative breast

cancer cells. (A-F) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the

indicated concentrations of NCT-58 (0–15 µM) and paclitaxel (0–2

µM, A-C) or doxorubicin (0–3 µM, D-F) for 72 h and cell viability

was assessed using MTS assay. The isobologram plot, heat map (%

inh., Inhibition rate), and CI were analyzed to assess the

drug-drug synergy of various dose combinations of NCT-58 with

paclitaxel or doxorubicin. Isobologram plot and average CI values

were generated using the CompuSyn software to quantify drug

interactions, where CI<1 indicates synergism, CI=1 indicates an

additive effect, and CI>1 indicates antagonism. (i, antagonism;

ii, addictive effect; iii, moderate synergism; iv, synergism; and

v, strong synergism). The heat map depicts relative cell viability

compared with the DMSO control. CI, combination index. |

Discussion

In the present study, it was demonstrated that

NCT-58, a C-terminal HSP90 inhibitor, exerts multifaceted antitumor

effects in TNBC. Classical HSP90 inhibitors have not been

successful owing to concerns regarding off-target toxicity and the

induction of HSR, which leads to cytoprotective responses (14,15).

N-terminal HSP90 inhibitors trigger HSF-1 activation and

translocation into the nucleus, resulting in elevated transcription

of HSPs such as HSP70 and HSP90, which promote pro-survival

signaling (15,22). NCT-58 effectively suppressed cell

viability and induced apoptosis without triggering the HSR, which

is a major limitation of current HSP90 inhibitors. Although

geldanamycin, a N-terminal HSP90 inhibitor, markedly induced HSF-1

nuclear translocation and the subsequent upregulation of HSP70,

NCT-58 did not produce these effects. This finding suggests that

inhibiting the CTD prevents a key pitfall of numerous existing

HSP90 inhibitors, namely the cytoprotective feedback loop, which

diminishes therapeutic efficacy and enhances cytotoxicity in normal

cells. The present data revealed the minimal cytotoxic effects of

NCT-58 in normal mammary epithelial (MCF10A) and 293 cells, whereas

geldanamycin significantly suppressed cell viability at

considerably lower concentrations.

Mechanistically, NCT-58 simultaneously disrupted the

functions of multiple HSP90 client proteins. By blocking HSP90

C-terminal dimerization, NCT-58 caused pronounced downregulation of

AKT, MEK and STAT3, which are the major pro-survival pathways in

TNBC. Previous genomic profiling revealed STAT3 overexpression and

aberrant activation in TNBC, highlighting its potential as both a

molecular target and biomarker (24,30).

STAT3 inhibition is associated with reduced transcription of

critical survival genes such as survivin and cyclin D1. Consistent

with this observation, NCT-58 treatment decreased STAT3 activation

and its downstream targets, thereby enhancing apoptosis and

diminishing proliferative capacity. A particularly notable finding

was the ability of NCT-58 to target the CSC-like properties of TNBC

cells. The CSC subpopulation, typically characterized by elevated

ALDH1 activity and a CD44high/CD24low

phenotype, plays a pivotal role in tumor initiation and recurrence

(27,31). These cells exhibit robust

self-renewal abilities and multipotency, which contribute to their

resistance to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy (32). ALDH is a detoxifying enzyme and its

ability to convert retinol to retinoic acid is implicated in cancer

cell proliferation and CSC differentiation (33). Cyclophosphamide, a commonly used

chemotherapy agent for TNBC, undergoes inactivation through

ALDH-mediated oxidation during its metabolic process (34,35).

Consequently, patients with elevated ALDH expression often

experience relatively poor clinical outcomes and exhibit resistance

to alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide

(31,35,36).

Therefore, strategies targeting ALDH activity show significant

promise for the effective eradication of CSCs and the prevention of

chemoresistance and recurrence. Treatment with NCT-58 significantly

reduced ALDH1 activity and decreased the percentage of

CD44high/CD24low cells, ultimately impairing

mammosphere formation in 3D culture. These data align with those of

previous reports implicating HSP90 in the maintenance of CSC

phenotypes and highlight the importance of targeting CSCs to

minimize relapse and metastasis. Accordingly, the 4T1 cell line was

employed, which exhibits highly aggressive and stem cell-like

characteristics, and is widely recognized as a preclinical model

for evaluating cancer stemness and metastatic potential (37–39).

In the in vitro experiments of the present study, 4T1 cells

clearly demonstrated that NCT-58 reduces CSC-related traits such as

ALDH1 activity, thereby supporting the results observed in human

MDA-MB-231 cells. By simultaneously affecting both bulk tumor cells

and CSC-like populations, NCT-58 can potentially overcome the major

mechanisms of resistance in TNBC.

NCT-58 also inhibited cell migration, likely by

modulating the HSP90 client proteins, vimentin and F-actin. During

EMT, vimentin orchestrates cytoskeletal organization and

cell-matrix interactions, enabling cancer cells to remodel the

extracellular matrix and adopt a more flexible and invasive

phenotype (40). Consequently,

vimentin-enriched cells are more elastic and motile, facilitating

tissue invasion, vascular or lymphatic entry, and survival under

mechanical stress (41,42). By disrupting vimentin and F-actin

filament dynamics, NCT-58 induced cytoskeletal reorganization and

collapse, thereby reducing the migratory capacity of TNBC

cells.

In a previous investigation by the authors, it was

demonstrated that NCT-58 overcomes trastuzumab resistance in

HER2-positive breast cancer by destabilizing HER2 family proteins,

including HER2, HER3, Akt and truncated p95HER2. Moreover, NCT-58

downregulated the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, thereby impairing

downstream oncogenic signaling (16). These findings established NCT-58 as

a promising therapeutic option for trastuzumab-resistant

HER2-positive disease. In the present study, these observations

were extended to TNBC, and it was shown that NCT-58 suppresses

multiple HSP90 client proteins such as AKT, MEK and STAT3, leading

to impaired pro-survival signaling, reduced cancer stem-like

traits, and diminished migratory potential. Notably, distinct HSP90

client proteins are expressed depending on the breast cancer

subtype (43,44). By targeting HSP90, NCT-58 can

modulate these subtype-specific proteins and thereby block the

oncogenic pathways that drive tumor growth in a subtype-specific

manner. Collectively, the results of the present study highlight

NCT-58 as a versatile therapeutic strategy with efficacy across

different breast cancer subtypes.

Conventional treatments for TNBC are typically

dependent on anthracyclines and taxanes. In recent years,

immunotherapies and antibody-drug conjugates have broadened

therapeutic options, prompting the latest National Comprehensive

Cancer Network guidelines to recommend combining pembrolizumab with

chemotherapy in PD-L1-positive cases (combined positive score ≥10).

Sacituzumab-govitecan (SC) is an additional treatment option for

advanced TNBC following first-line treatment failure (45). However, these approaches are limited

by stringent biomarker requirements, suboptimal patient eligibility

rates (~40% only qualify for immunotherapy) (46), and the potential for acquired

resistance or cost-ineffectiveness (47). For instance, TNBC cells exposed to

SC can eventually develop resistance by altering both the antibody

target and toxic payload (48).

Consequently, achieving sustained therapeutic efficacy in TNBC

remains a significant clinical challenge.

Combination regimens are often required to address

the heterogeneity of TNBC and forestall the emergence of drug

resistance. NCT-58 exhibited synergistic anti-proliferative effects

when co-administered with paclitaxel or doxorubicin, two

foundational chemotherapeutic agents frequently used in TNBC. CI

analysis confirmed this synergy, suggesting that the simultaneous

disruption of HSP90 client protein function by NCT-58 may sensitize

TNBC cells to cytotoxic agents.

Overall, the findings of the present study suggested

that NCT-58 is a promising therapeutic candidate for TNBC,

targeting both proliferative tumor cells and cancer stem-like

populations, while avoiding the limitations of classical HSP90

inhibitors. By targeting key oncogenic pathways, including AKT, MEK

and STAT3, NCT-58 significantly compromises cancer cell survival

and induces apoptosis. Notably, NCT-58 exhibited minimal

cytotoxicity in non-malignant cells, highlighting its favorable

therapeutic profile. The present study has certain limitations, as

additional in vivo validation is warranted. In particular,

investigations using a 4T1-derived syngeneic model will be

necessary to further elucidate the effects of NCT-58 on tumor

growth, angiogenesis, metastasis, and the tumor microenvironment.

Furthermore, comprehensive preclinical studies evaluating long-term

toxicity and safety will be essential prior to clinical application

in TNBC patients. Finally, NCT-58 enhances the anticancer efficacy

of standard chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel and

doxorubicin in a synergistic manner, highlighting its potential as

a potent and well-tolerated treatment option for TNBC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Korea Health Technology

R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development

Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic

of Korea (grant nos. HA17C0053 and HR20C0021); the National

Research Foundation funded by the Korean government (grant nos.

2021R1A2C2009723, 2023R1A2C3004010, RS-2024-00342677,

RS-2025-02634306 and RS-2025-00558356); the Korea University Guro

Hospital (grant no. O2411391) and the Brain Korea 21 Plus

Program.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

EJ, KL, JL, YJK, JYK and JHS conceived and designed

the experiments. SJ, EJ, SP, KL, EO, DK, YJK and JYK performed the

experiments. EJ, SJ, KL, SP, MP, DK, SK, YKK, KDN, YJK, LF and JYK

analyzed the data. CTN, MTL, and JA synthesized NCT-58. EJ, KL, LF,

YJK and JYK wrote the manuscript. EJ, JYK and YJK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zagami P and Carey LA: Triple negative

breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. NPJ Breast Cancer. 8:952022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferrarini M, Heltai S, Zocchi MR and

Rugarli C: Unusual expression and localization of heat-shock

proteins in human tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 51:613–619. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Pick E, Kluger Y, Giltnane JM, Moeder C,

Camp RL, Rimm DL and Kluger HM: High HSP90 expression is associated

with decreased survival in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 67:2932–2937.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Isaacs JS, Xu W and Neckers L: Heat shock

protein 90 as a molecular target for cancer therapeutics. Cancer

Cell. 3:213–217. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bocchini CE, Kasembeli MM, Roh SH and

Tweardy DJ: Contribution of chaperones to STAT pathway signaling.

JAKSTAT. 3:e9704592014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Streicher JM: The role of heat shock

proteins in regulating receptor signal transduction. Mol Pharmacol.

95:468–474. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Edkins AL: Hsp90 co-chaperones as drug

targets in cancer: Current perspectives. Heat Shock Protein

Inhibitors. McAlpine S and Edkins A: Topics in Medicinal Chemistry,

19. Springer; Cham: pp. 21–54. 2016, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Collina F, Di Bonito M, Li Bergolis V, De

Laurentiis M, Vitagliano C, Cerrone M, Nuzzo F, Cantile M and Botti

G: Prognostic value of cancer stem cells markers in triple-negative

breast cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2015:1586822015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kabakov A, Yakimova A and Matchuk O:

Molecular chaperones in cancer stem cells: Determinants of stemness

and potential targets for antitumor therapy. Cells. 9:8922020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cho TM, Kim JY, Kim YJ, Sung D, Oh E, Jang

S, Farrand L, Hoang VH, Nguyen CT, Ann J, et al: C-terminal HSP90

inhibitor L80 elicits anti-metastatic effects in triple-negative

breast cancer via STAT3 inhibition. Cancer Lett. 447:141–153. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Park JM, Kim YJ, Park S, Park M, Farrand

L, Nguyen CT, Ann J, Nam G, Park HJ, Lee J, et al: A novel HSP90

inhibitor targeting the C-terminal domain attenuates trastuzumab

resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:1612020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Park M, Jung E, Park JM, Park S, Ko D, Seo

J, Kim S, Nam KD, Kang YK, Farrand L, et al: The HSP90 inhibitor

HVH-2930 exhibits potent efficacy against trastuzumab-resistant

HER2-positive breast cancer. Theranostics. 14:2442–2463. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hoter A, El-Sabban ME and Naim HY: The

HSP90 family: Structure, regulation, function, and implications in

health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 19:25602018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Garcia-Carbonero R, Carnero A and Paz-Ares

L: Inhibition of HSP90 molecular chaperones: Moving into the

clinic. Lancet Oncol. 14:e358–e369. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wang Y and McAlpine SR: N-terminal and

C-terminal modulation of Hsp90 produce dissimilar phenotypes. Chem

Commun (Camb). 51:1410–1413. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Park S, Kim YJ, Park JM, Park M, Nam KD,

Farrand L, Nguyen CT, La MT, Ann J, Lee J, et al: The C-terminal

HSP90 inhibitor NCT-58 kills trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer

stem-like cells. Cell Death Discov. 7:3542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nguyen CT, Ann J, Sahu R, Byun WS, Lee S,

Nam G, Park HJ, Park S, Kim YJ, Kim JY, et al: Discovery of novel

anti-breast cancer agents derived from deguelin as inhibitors of

heat shock protein 90 (HSP90). Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 30:1273742020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim JY, Cho TM, Park JM, Park S, Park M,

Nam KD, Ko D, Seo J, Kim S, Jung E, et al: A novel HSP90 inhibitor

SL-145 suppresses metastatic triple-negative breast cancer without

triggering the heat shock response. Oncogene. 41:3289–3297. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Donnelly A and Blagg BSJ: Novobiocin and

additional inhibitors of the Hsp90 C-terminal nucleotide-binding

pocket. Curr Med Chem. 15:2702–2717. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen

N, Hartl FU and Pavletich NP: Crystal structure of an

Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: Targeting of a protein chaperone by an

antitumor agent. Cell. 89:239–250. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gooljarsingh LT, Fernandes C, Yan K, Zhang

H, Grooms M, Johanson K, Sinnamon RH, Kirkpatrick RB, Kerrigan J,

Lewis T, et al: A biochemical rationale for the anticancer effects

of Hsp90 inhibitors: Slow, tight binding inhibition by geldanamycin

and its analogues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:7625–7630. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wu J, Liu T, Rios Z, Mei Q, Lin X and Cao

S: Heat shock proteins and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci.

38:226–256. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Neckers L, Blagg B, Haystead T, Trepel JB,

Whitesell L and Picard D: Methods to validate Hsp90 inhibitor

specificity, to identify off-target effects, and to rethink

approaches for further clinical development. Cell Stress

Chaperones. 23:467–482. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Qin JJ, Yan L, Zhang J and Zhang WD: STAT3

as a potential therapeutic target in triple negative breast cancer:

A systematic review. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:1952019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang H, Wang L, Song Y, Wang S, Huang X,

Xuan Q, Kang X and Zhang Q: CD44+/CD24−

phenotype predicts a poor prognosis in triple-negative breast

cancer. Oncol Lett. 14:5890–5898. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan

A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al: The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties

of stem cells. Cell. 133:704–715. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Oh E, Kim YJ, An H, Sung D, Cho TM,

Farrand L, Jang S, Seo JH and Kim JY: Flubendazole elicits

anti-metastatic effects in triple-negative breast cancer via STAT3

inhibition. Int J Cancer. 143:1978–1993. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang MH, Lee JS, Kim HJ, Jin DI, Kim JI,

Lee KJ and Seo JS: HSP90 protects apoptotic cleavage of vimentin in

geldanamycin-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 281:111–121.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yamashita N, Tokunaga E, Kitao H,

Hisamatsu Y, Taketani K, Akiyoshi S, Okada S, Aishima S, Morita M

and Maehara Y: Vimentin as a poor prognostic factor for

triple-negative breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

139:739–746. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sirkisoon SR, Carpenter RL, Rimkus T,

Anderson A, Harrison A, Lange AM, Jin G, Watabe K and Lo HW:

Interaction between STAT3 and GLI1/tGLI1 oncogenic transcription

factors promotes the aggressiveness of triple-negative breast

cancers and HER2-enriched breast cancer. Oncogene. 37:2502–2514.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E,

Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG,

Liu S, et al: ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human

mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell

Stem Cell. 1:555–567. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wei Y, Li Y, Chen Y, Liu P, Huang S, Zhang

Y, Sun Y, Wu Z, Hu M, Wu Q, et al: ALDH1: A potential therapeutic

target for cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Front Oncol.

12:10262782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Clark DW and Palle K: Aldehyde

dehydrogenases in cancer stem cells: Potential as therapeutic

targets. Ann Transl Med. 4:5182016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sládek NE: Aldehyde dehydrogenase-mediated

cellular relative insensitivity to the oxazaphosphorines. Curr

Pharm Des. 5:607–625. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sladek NE: Metabolism of

oxazaphosphorines. Pharmacol Ther. 37:301–355. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Moreb JS: Aldehyde dehydrogenase as a

marker for stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 3:237–246. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Schrörs B, Boegel S, Albrecht C, Bukur T,

Bukur V, Holtsträter C, Ritzel C, Manninen K, Tadmor AD, Vormehr M,

et al: Multi-omics characterization of the 4T1 murine mammary gland

tumor model. Front Oncol. 10:11952020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Herndon ME, Ayers M, Gibson-Corley KN,

Wendt MK, Wallrath LL, Henry MD and Stipp CS: The highly metastatic

4T1 breast carcinoma model possesses features of a hybrid

epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype. Dis Model Mech. 17:dmm0507712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tao K, Fang M, Alroy J and Sahagian GG:

Imagable 4T1 model for the study of late stage breast cancer. BMC

Cancer. 8:2282008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Satelli A and Li S: Vimentin in cancer and

its potential as a molecular target for cancer therapy. Cell Mol

Life Sci. 68:3033–3046. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RYJ and Nieto

MA: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease.

Cell. 139:871–890. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lu W and Kang Y: Epithelial-mesenchymal

plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis. Dev Cell.

49:361–374. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zagouri F, Bournakis E, Koutsoukos K and

Papadimitriou CA: Heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) expression and

breast cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 5:1008–1020. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wei H, Zhang Y, Jia Y, Chen X, Niu T,

Chatterjee A, He P and Hou G: Heat shock protein 90: Biological

functions, diseases, and therapeutic targets. MedComm (2020).

5:e4702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J,

Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Burstein HJ,

Chew H, et al: NCCN guidelines® insights: Breast cancer,

version 4.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:594–608. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cortes J, Rugo HS, Cescon DW, Im SA, Yusof

MM, Gallardo C, Lipatov O, Barrios CH, Perez-Garcia J, Iwata H, et

al: Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced triple-negative

breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 387:217–226. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Xie J, Li S, Li Y and Li J:

Cost-effectiveness of sacituzumab govitecan versus chemotherapy in

patients with relapsed or refractory metastatic triple-negative

breast cancer. BMC Health Serv Res. 23:7062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Coates JT, Sun S, Leshchiner I, Thimmiah

N, Martin EE, McLoughlin D, Danysh BP, Slowik K, Jacobs RA,

Rhrissorrakrai K, et al: Parallel genomic alterations of antigen

and payload targets mediate polyclonal acquired clinical resistance

to sacituzumab govitecan in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer

Discov. 11:2436–2445. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|