Introduction

Skin cancer remains a major global health burden,

with melanoma representing the most aggressive subtype of cutaneous

malignancy (1), which is

responsible for approximately 80% of skin cancer-associated

fatalities (2–5). Recent advances in post-translational

modification research have identified that acetylation fulfills an

indispensable role in regulating gene expression via dynamic

modulation of chromatin structure (6,7).

Emerging evidence indicates that aberrant acetylation homeostasis

is pathologically associated with various dermatological disorders,

particularly with the initiation, progression and therapeutic

resistance of melanoma (8).

Understanding both the underlying mechanisms and consequences of

acetylation in melanoma is essential for guiding the development of

novel therapeutic strategies targeting these epigenetic

modifications. Notably, acetylation-associated biomarkers have been

shown to have significant clinical relevance in melanoma diagnosis

and prognosis, underscoring the translational importance of this

field.

Melanoma and acetylation

Melanoma

Malignant melanoma originates from melanin-producing

cells derived from the neural crest, and it can be induced by a

range of factors, including physical factors, chemical and

biological mediators, and genetic/molecular determinants (9,10).

According to the World Health Organization classification,

melanomas can be categorized into two major groups, namely those

associated with sun exposure and those that are not, and these

groups are reflected in distinct molecular pathways and different

pathological histories (11). The

sun-associated group is further subclassified based on the extent

of chronic sun damage (CSD) into high-CSD and low-CSD melanomas

(12). The latter group is further

subdivided based on the site of origin into mucosal, acral, uveal

and spitzoid melanomas, melanomas arising in blue or congenital

nevi, as well as rare variants originating in the central nervous

system (13). Ultraviolet radiation

(UVR) has a well-established etiological role in melanoma

pathogenesis; however, its effects on skin physiology are complex,

encompassing both detrimental impacts (for example, DNA damage and

mutagenesis) and beneficial aspects, including vitamin D synthesis

and immunomodulatory functions (14–16).

The process of melanogenesis, regulated by neuroendocrine factors

(for example, α-MSH and ACTH) and enzymatic pathways, not only

determines skin pigmentation, but also modulates melanoma behavior

and therapeutic responses (17).

For example, eumelanin may confer photoprotective effects, whereas

pheomelanin has been shown to promote oxidative stress and

contribute to tumor progression (18,19).

The skin operates as a neuro-immunoendocrine organ, producing a

range of mediators (for example, CRH, β-endorphin and cannabinoids)

that are able to locally modulate melanocyte function and

contribute to melanoma pathogenesis. In advanced stages of the

disease, melanoma-derived factors can disrupt systemic homeostasis,

thereby altering energy balance and immune function beyond the

local microenvironment, which has the effects of facilitating

disease progression and metastatic spread (17).

Acetylation

Acetylation, a dynamic post-translational

modification, serves as an epigenetic rheostat regulating chromatin

accessibility, transcriptional activation and protein functional

states. In cancers, dysregulation of this equilibrium, primarily

mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone

deacetylases (HDACs), drives oncogenic transcription programs and

post-translational rewiring of tumor suppressors (20). HATs, including the p300/CBP

(CREB-binding protein) family and the GNAT/MYST subfamilies,

catalyze the transfer of acetyl groups from acetyl-CoA to histone

tails, thereby neutralizing their positive charges to relax

chromatin structure and facilitate transcriptional activation

(21,22). Beyond histone modification, key

HATs, such as p300, function as transcriptional co-activators that

are able to integrate signaling pathways through acetylating both

histones and non-histone targets, including p53 and STAT3, thereby

modulating apoptosis, cellular differentiation and immune

responses. HDACs have the role of counterbalancing HAT activity,

and they function through the removal of acetyl groups. These

enzymes are divided into four classes of enzymes: Class I HDACs

(HDAC1/2/3/8), which are ubiquitously expressed and predominantly

localized to the nuclear compartment, where they exert their most

prominent HDAC activity (23);

Class II HDACs (HDAC4/5/6/7/9/10), which reside in the cytoplasm

and translocate to the nucleus in response to specific cellular

signaling cues; Class III HDACs, also termed sirtuins (SIRT1-7),

which are NAD+-dependent enzymes that remove acetyl

groups to restore chromatin compaction and silence gene expression

(24); and HDAC11, the sole member

of Class IV HDACs, which exhibits higher defatty-acylase activity

compared with its intrinsic deacetylase activity. Numerous studies

have provided evidence in support of the crucial involvement of

HDAC11 in different types of cancer, immune responses and metabolic

processes (25,26).

The dynamics of acetylation critically influence

melanoma pathogenesis through modulating chromatin accessibility,

transcriptional programs and protein functional states (27). Aberrant histone and non-histone

acetylation, driven by dysregulated HAT/HDAC activity, has been

shown to contribute to melanoma initiation through the silencing of

tumor-suppressive genes and hyperactivation of oncogenic pathways.

During metastatic progression, imbalances in acetylation have the

effect of promoting invasive phenotypes through ‘rewiring’ enhancer

landscapes to favor pro-migratory gene networks, and suppressing

differentiation signals. Clinical studies have shown that

therapeutic strategies targeting acetylation, such as the use of

HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) and sirtuin modulators, demonstrate dual

efficacy in terms of restoring tumor-suppressive transcription and

circumventing immune evasion, thereby underscoring the central role

of this type of epigenetic modification across the melanoma

continuum.

Notably, the acetylation landscape and its

functional consequences may vary significantly across melanoma

subtypes, including cutaneous, acral lentiginous and mucosal

melanoma. Acral melanoma exhibits a distinct molecular profile

compared with other cutaneous melanoma subtypes, characterized by a

lower frequency of canonical driver mutations in the B-Raf

proto-oncogene (BRAF) and NRAS proto-oncogene (NRAS) genes, but a

higher prevalence of alterations, such as KIT mutations and copy

number gains involving cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and cyclin

D1 (CCND1) (28–31). This genomic instability, often

manifested through structural variations and amplifications, is a

hallmark of acral lentiginous melanoma, and may be influenced by

mechanical stress rather than UVR, suggesting that the acetylome

regulating these genomic regions is likely to differ substantially

across the subtypes. Consequently, the differential acetylation

landscape gives rise to varied therapeutic responses; for example,

the reduced frequency of BRAF mutations in acral lentiginous

melanoma has been shown to reduce the efficacy of BRAF/MEK

inhibitors, whereas the activation of alternative pathways (for

example, via KIT or CDK4) suggests a potential role for HDACi in

targeting these non-canonical vulnerabilities either by modulating

oncogene expression or reactivating silenced tumor suppressors.

However, although acetylation dynamics are being increasingly

mapped in cutaneous melanoma, subtype-specific patterns in acral

lentiginous melanoma and mucosal melanoma remain incompletely

defined. Preliminary acetylome profiling, however, has suggested

unique enhancer acetylation landscapes in acral lentiginous

melanoma/mucosal melanoma, potentially reflecting their distinct

mutational spectra and microenvironmental contexts, which may

influence tumor biology and responses to epigenetic therapies,

including HDACi or CBP/p300 inhibitors. Dedicated studies using

patient-derived models and subtype-stratified cohorts are warranted

to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the acetylation landscape

and to optimize targeted strategies.

Acetylation modifications in melanoma

pathogenesis and progression

Although the key roles of HATs and HDACs in melanoma

are well-established, the specific functions of individual family

members (such as different sirtuins or specific Class I HDACs) and

their heterogeneity across melanoma subtypes require more detailed

characterization. For example, the ‘paradoxical’ role of SIRT6 in

promoting melanoma proliferation, and yet mediating drug

resistance, highlights the complexity of acetylation network

regulation and its potential context-dependence (32,33).

Understanding the effects of nuanced alterations in the acetylation

network is critical in terms of developing effective precision

targeting strategies.

Acetylation-mediated control of cell

fate in melanoma: Regulation of proliferation, autophagy and

apoptosis

Acetylation has been shown to critically regulate

key processes associated with melanoma, including proliferation,

autophagy and apoptosis, through modulating both transcriptional

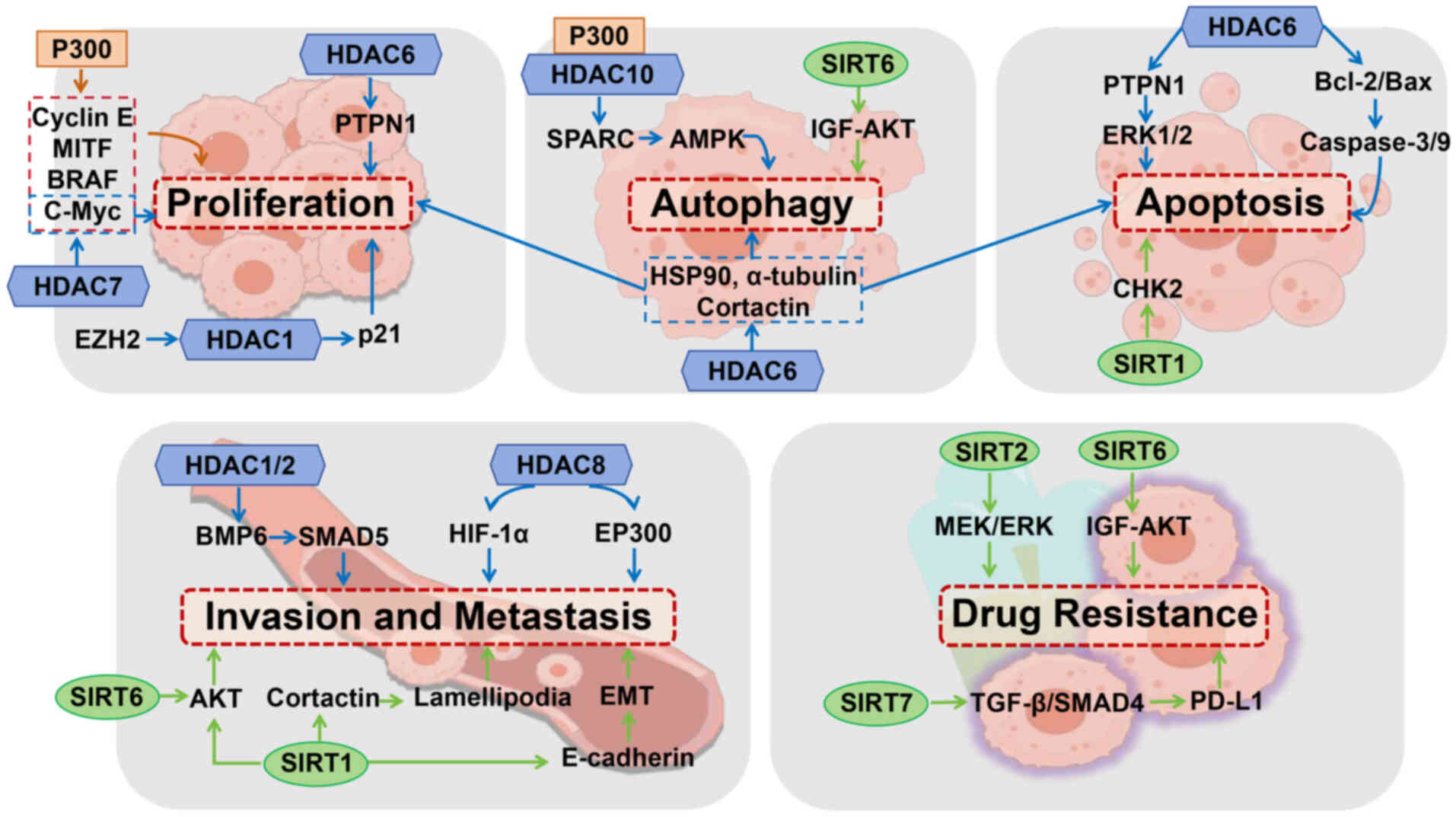

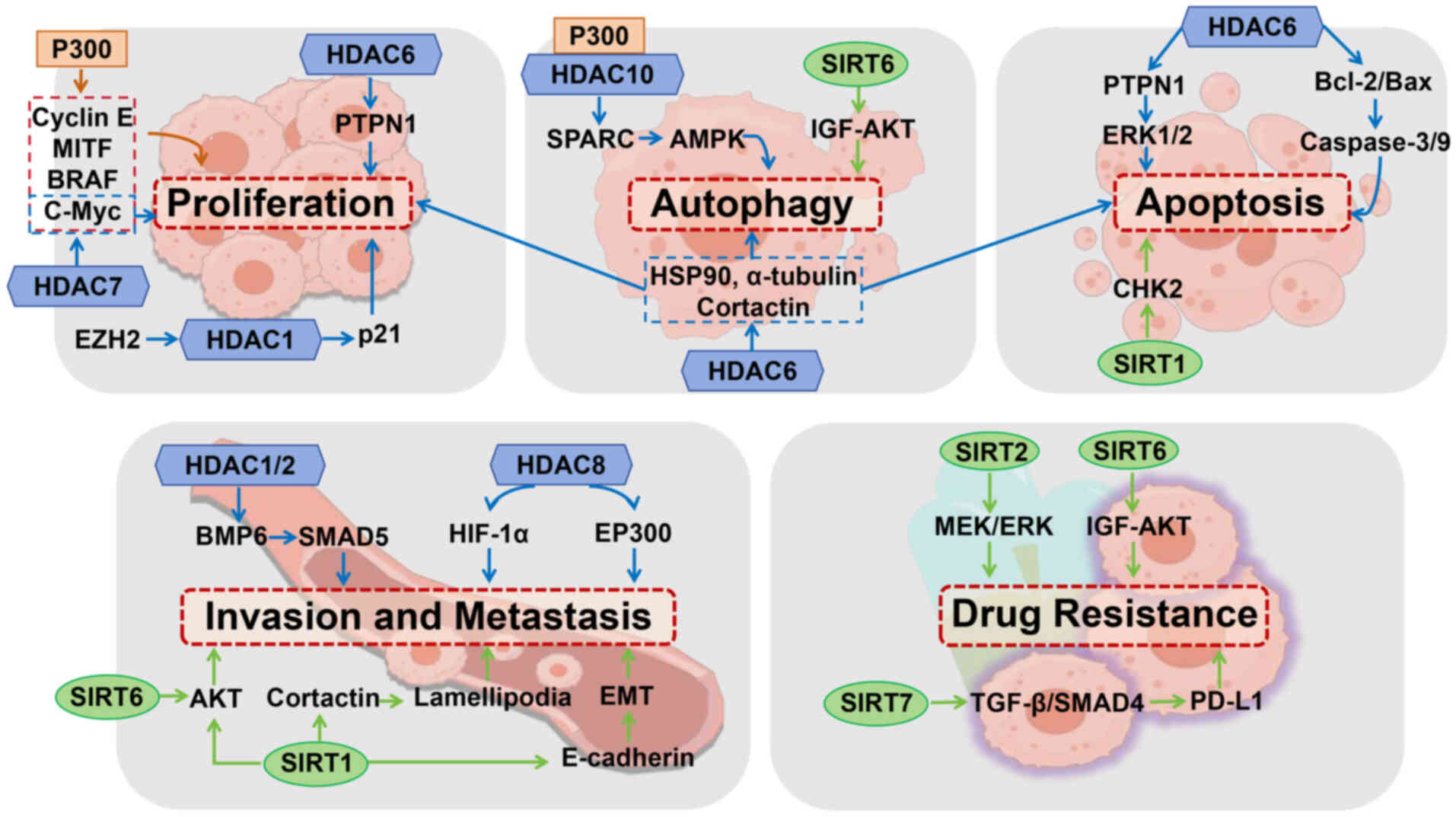

activators and epigenetic repressors (Fig. 1). Subsequently, the following

section will discuss various factors associated with acetylation

and their underlying mechanisms of action (Table I).

| Figure 1.Acetylation-mediated regulation of

melanoma progression. P300 enhances melanoma cell proliferation via

acetylation of cyclin E, MITF, BRAF and c-Myc. EZH2 represses p21

through HDAC1, disrupting the cell cycle. HDAC6 modulates

proliferation, autophagy, and apoptosis via α-tubulin, HSP90,

cortactin, and the PTPN1-ERK1/2 pathway; its inhibition induces

apoptosis via Bcl-2/Bax regulation. HDAC7 promotes growth via

c-Myc, while P300 and HDAC10 coordinate SPARC-mediated autophagy.

SIRT1 and SIRT6 regulate apoptosis and autophagy through CHK2 and

IGF-AKT signaling, respectively. HDAC1/2 activate BMP6-SMAD5 to

inhibit metastasis, while HDAC8 enhances invasion via deacetylation

of HIF-1α and EP300. SIRT1 promotes migration through EMT,

lamellipodia formation, and AKT deacetylation; SIRT6 antagonizes

this effect. SIRT2 and SIRT6 drive resistance via MEK-ERK and

IGF-AKT signaling. SIRT7 promotes PD-L1-mediated immune evasion by

suppressing TGF-β-SMAD4 signaling. HDAC, histone deacetylase; EMT,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. |

| Table I.Summary of HDAC-related function. |

Table I.

Summary of HDAC-related function.

| First author/s,

year | Role of

acetylation | Factor | Target | Mechanism | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Weinert et

al, 2018 | Proliferation,

autophagy and apoptosis | p300 | Cell cycle | Directly activates

the cyclin E promoter | (21) |

| Kim et al,

2019 |

|

| MITF | The MITF is

regulated by p300-mediated histone acetylation. | (35) |

| Dai et al,

2022 |

|

| BRAF | p300 promotes B-Raf

proto-oncogene kinase activity. | (36) |

| Vervoorts et

al, 2003 |

|

| c-Myc | Co-expression of

CBP with c-Myc stimulates acetylation. | (37) |

| Kim et al,

2019; |

| HDAC1 | Cell cycle | HDAC1 is a key

component of EZH2 regulatory axis. | (35,38) |

| Fan et al,

2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Kovacs et

al, 2005; |

| HDAC6 | Various | Targeting

substrates such as α-tubulin, HSP90, and cortactin. | (39,40) |

| Pulya et al,

2021 |

|

| cellular

functions |

|

|

| Liu et al,

2018 |

|

| ERK1/2 | Interacting with

the PTPN1; Activating ERK1/2 signaling. | (41) |

| Pulya et al,

2021; |

|

| Bcl-2, Bax, | Inhibiting HDAC6

resulted in a decrease in Bcl-2 and an increase | (40,42) |

| Bai et al,

2015 |

|

| caspase | in

Bax/Caspase-3/9. |

|

| Ling et al,

2023 |

| HDAC10 | SPARC | Depletion of HDAC10

upregulates SPARC and inhibits melanoma growth. | (43) |

| Zhang et al,

2020 |

| SIRT1 | CHK2 | SIRT1 deficiency

induces CHK2 hyperacetylation and results in cell death via mitotic

catastrophe. | (47) |

| Wang et al,

2018 |

| SIRT6 | IGF-AKT | IGF-AKT pathway

mediates the effect of SIRT6 on autophagy in melanoma. | (32) |

| Min et al,

2022 | Invasion and

metastasis | HDAC1/2 | BMP6 | HDAC1/2 inhibits

melanoma metastasis through regulating BMP6/SMAD5 signaling. | (50) |

| Kim et al,

2023 |

| HDAC8 | HIF-1α | HDAC8 deacetylates

HIF-1α, enhancing its protein stability and transcriptional

activity. | (52) |

| Emmons et

al, 2023 |

|

| EP300 | By deacetylating

EP300, HDAC8 inactivates its catalytic function. | (53) |

| Kong et al,

2022 | Drug

resistance | SIRT1 | E-cadherin | SIRT1 suppresses

E-cadherin expression. | (55) |

| Kunimoto et

al, 2014; |

|

| AKT | SIRT1 deacetylates

AKT. | (57–59) |

| Porta et al,

2014; |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yang et al,

2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bajpe et al,

2015; |

| SIRT2 | MEK/ERK | Inhibition of SIRT2

leads to resistance by modulating the MEK/ERK | (60,61) |

| Zhao et al,

2022 |

|

|

| pathway. |

|

| Strub et al,

2018; |

| SIRT6 | IGFBP2 | SIRT6

haploinsufficiency upregulates IGFBP2 expression and confers | (33,62) |

| Wang et al,

2015 |

|

|

| resistance to MAPK

inhibitors. |

|

| Yi et al,

2023 |

| SIRT7 | SMAD4 | SIRT7 deacetylates

SMAD4, thereby antagonizing the TGF-β-SMAD4 pathway. | (63) |

| Yu et al,

2023 |

| HDAC2 | PD-L1 | HDAC2-mediated

deacetylation promotes the nuclear translocation of PD-L1. | (64) |

| Gao et al,

2020 |

| p300 | PD-L1 | p300-mediated

acetylation of PD-L1 prevents its nuclear translocation. | (65) |

Central to the regulatory function mediated via

protein acetylation is the HAT p300, which promotes

melanoma-genesis through multiple interconnected mechanisms. One

key mechanism which involves p300 is the direct activation of the

cyclin E promoter, which thereby facilitates the G1/S

phase transition. Accordingly, inhibition of p300, either by

expressing a dominant negative p300 mutant (DN p300) or using the

pharmacological inhibitor Lys-CoA, was found to markedly reduce

cyclin E transcription, thereby inducing cell cycle arrest

(21). These findings aligned with

its established role in facilitating G1/S progression

through the acetylation of key factors such as E2F1 (34). Furthermore, p300 has been shown to

sustain the pro-proliferative activity of the lineage-survival

oncogene MITF via catalyzing histone acetylation at its proximal

regulatory regions. The inhibitory effect of p300 blockade on the

proliferation of MITFhigh melanoma cells (cells that are

characterized by high levels of the MITF transcription factor)

underscores the significance of this regulatory axis (35). Beyond cell cycle and oncogene

support, p300 also activates the BRAF kinase by promoting BRAF K601

acetylation, thereby enhancing its kinase activity and promoting

melanoma cell proliferation. Significantly, this K601 acetylation

contributes to resistance against BRAFV600E inhibitors

in melanomas harboring the common BRAFV600E mutation, an

effect that is counteracted by the opposing deacetylase activity of

SIRT1 (36). These findings

collectively illustrate the multifaceted roles of p300-mediated

acetylation in melanoma (Table

I).

Building on its multifaceted roles in melanoma,

p300/CBP also acts as a critical positive cofactor for the Myc

family of transcription factors (c-Myc, N-Myc and L-Myc). These

potent regulators drive cell proliferation and suppress

differentiation across diverse cell types. Specifically in the case

of c-Myc, CBP has been shown to acetylate c-Myc in vitro.

Crucially, co-expressing CBP with c-Myc in vivo was shown to

enhance c-Myc acetylation, leading to reduced ubiquitination and

consequently stabilizing the c-Myc protein (37).

Beyond the multifaceted roles of HATs such as p300,

HDACs also have a crucial role in regulating tumor cell

proliferation and apoptosis through epigenetic reprogramming. A key

example is HDAC1, which cooperates with the polycomb group protein,

enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), to drive cell cycle

dysregulation in melanoma. EZH2 is highly expressed in metastatic

melanoma cells, where it suppresses the expression of p21 (encoded

by CDKN1A), a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor regulated by

histone acetylation. Mechanistically, EZH2 facilitates the

recruitment and retention of HDAC1 at the CDKN1A promoter, thereby

repressing p21 transcription through histone deacetylation.

Consequently, HDAC1 downregulation reactivates p21 expression,

triggering G1/S phase arrest and halting tumor

progression (35,38).

Complementing the multifaceted roles of HATs such as

p300, HDAC6 has emerged as a structurally unique epigenetic

regulator. HDAC6, distinguished by its dual deacetylase domains and

a C-terminal ubiquitin-binding zinc finger domain, targets

substrates such as α-tubulin, heat shock protein 90 and cortactin

(39). These substrates are

involved in various cellular functions, including cell

proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy and DNA repair (40). Functionally, HDAC6 has been shown to

orchestrate a pro-survival signaling network in melanoma. It

directly binds and stabilizes protein tyrosine phosphatase

non-receptor type 1, thereby activating ERK1/2 signaling to drive

cell proliferation, colony formation and metastasis, while

suppressing apoptosis (41). This

axis is further amplified by the regulation of mitochondrial

apoptosis pathways mediated by HDAC6: HDAC6 inhibition has been

shown to trigger reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent

mitochondrial depolarization, leading to reduced levels of Bcl-2,

increased levels of Bax, the release of cytochrome c and activation

of caspases-9 and −3, ultimately inducing apoptosis (40,42).

Looking beyond HDAC6′s regulation of pro-survival

signaling networks, the secreted glycoprotein known as secreted

protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) exemplifies how

acetylation-dependent epigenetic mechanisms converge to control the

cell fate of melanoma. Of crucial importance to this axis is

HDAC10, which acts in concert with HAT p300 to dynamically modulate

H3K27ac, a key epigenetic marker on histone H3, at SPARC regulatory

elements. This epigenetic remodeling facilitates the recruitment of

bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), a critical transcriptional

co-activator, to SPARC enhancers, thereby repressing SPARC

transcription. Notably, either HDAC10 depletion or its

pharmacological inhibition was shown to reverse this repression,

leading to the robust upregulation of SPARC. The resultant SPARC

overexpression triggers AMPK-dependent autophagy (43), which, in turn, inhibits the activity

of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), induces

autophagosome formation and activates Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1)

to drive the lysosomal degradation of oncogenic cargo (44). This autophagic flux ultimately

suppresses melanoma proliferation and metastasis. Crucially,

SPARC-mediated autophagy also resensitizes BRAF inhibitor-resistant

melanoma, rendering it susceptible to targeted therapy, thereby

revealing a dual antitumor mechanism (45). Collectively, HDAC10 and SPARC form

an epigenetic-metabolic checkpoint that regulates melanoma

progression, thereby providing a molecular rationale for targeting

this axis in combination therapies.

Beyond the SPARC/HDAC10 axis that couples epigenetic

remodeling with autophagic flux, checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) has

emerged as a critical guardian of genomic integrity, orchestrating

DNA damage responses and cell fate decisions in melanoma. Upon

sensing DNA double-strand breaks, CHK2 undergoes ATM-dependent

phosphorylation at Thr-68, triggering dimerization and activation

to enforce either G1/S or G2/M cell cycle

arrest, thereby either enabling DNA repair, or initiating apoptosis

should the damage be irreparable (46). Intriguingly, the

NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 has been shown to

directly interact with CHK2, deacetylating it at the Lys-520 site

(47). This deacetylation

subsequently antagonizes CHK2 phosphorylation and dimerization,

effectively suppressing its activation. Consequently, SIRT1

deficiency induces CHK2 hyperacetylation, leading to aberrant

kinase activation, mitotic catastrophe and ROS-dependent cell

death, a mechanism exploited by oxidative stress in melanoma

therapy (48). Simultaneously, the

SIRT family member SIRT6 is positively associated with the levels

of autophagy in melanoma. Mechanistically, SIRT6 has been shown to

induce abnormal autophagy in melanoma through inhibiting the

insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)-AKT signaling pathway

(32). Collectively, the SIRT1-CHK2

and SIRT6-autophagy axes form an integrated network that balances

cell survival and death in response to genomic and metabolic

stresses.

This section of the review has systematically

delineated how multiple acetyl-regulatory factors, including p300,

HDAC1/6/7/10 and SIRT1/6, have been demonstrated to influence the

fate of melanoma cells through modulating key molecules (Cyclin E,

MITF, BRAF, c-Myc, p21, SPARC, CHK2 and IGF-AKT). However, existing

studies have predominantly focused on individual factors, and thus

both a holistic understanding of the dynamic equilibrium within the

acetylation network and knowledge regarding its crosstalk with

other signaling pathways (for example, MAPK and PI3K/AKT) are

currently lacking. Notably, the divergent roles of SIRT1 and SIRT6

in regulating cellular apoptosis/autophagy vs. migration, coupled

with HDAC6′s established function as a multi-pathway hub, suggest

that targeting these molecules may yield pleiotropic effects,

although this would potentially be counterbalanced by a concurrent

increase in off-target risks.

Acetylation-mediated control of cell

fate in melanoma: Influence on invasion and metastasis

The invasion of melanoma cells, which represents a

critical step in metastatic dissemination, relies on the epigenetic

reprogramming of chromatin states that determines phenotypic

plasticity. The epigenetic landscape of acetylation serves as a

critical determinant of melanoma cell invasion and phenotypic

plasticity (Fig. 1). Key evidence

has come from a study by Mendelson et al (49), who stratified primary melanomas into

low-risk (Epgn1, proliferative) and high-risk (Epgn3, invasive)

subtypes based on enhancer landscapes driven by H3K27ac. This

contradiction highlights how acetylated-driven enhancer remodeling

dynamically balances pro- and anti-invasive gene networks, thereby

determining their metastatic potential.

Complementing the epigenetic axis, the bone

morphogenetic protein (BMP)/SMAD signaling pathway, representing a

branch of the TGF-β superfamily, has been shown to orchestrate

melanoma metastasis through dual regulatory modes. Min et al

(50) demonstrated that HDAC1/2

deacetylases suppress metastasis through activating BMP6-dependent

SMAD5 signaling, which leads to an upregulation of adhesion

molecules (for example, E-cadherin) and inhibits matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs). On the other hand, HDAC1/2 loss triggers

BMP6-SMAD5 axis suppression, which has the effect of enhancing

invasion via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) transcription

factors (for example, Twist and Slug) and extracellular matrix

(ECM) degradation, a mechanism consistent with earlier findings

reported in a study by Hornig et al (51). Therefore, the HDAC-BMP-SMAD cascade

converges with the dynamics of H3K27ac enhancers to regulate

melanoma invasion.

Beyond the epigenetic reprogramming of

invasion-associated chromatin states, hypoxia-inducible factor 1

(HIF-1) has been found to be pathologically overexpressed, and its

overexpression drives the malignant transformation of melanocytes

through enhancing their proliferation, metastasis and immune

evasion. Critically, acetylation dynamics have the effect of

‘fine-tuning’ the activity of HIF-1α and that of its downstream

regulators. Among these regulators, the Class I HDAC, HDAC8, has

emerged as a pivotal orchestrator. Mechanistically, HDAC8

deacetylates HIF-1α, which has the effect of enhancing its protein

stability and transcriptional activity, thereby promoting the

expression of its target genes and accelerating cellular migration

(52). Moreover, through

deacetylating the HAT EP300, HDAC8 inactivates its catalytic

function, thereby redirecting chromatin accessibility towards

pro-invasive transcription factors such as c-Jun. This modification

has been shown to enhance melanoma cell invasion and resistance to

stress, thereby promoting the development of brain metastasis

(53). Considered altogether, HDAC8

integrates HIF-1α stabilization and EP300 suppression to establish

a feed-forward loop that amplifies melanoma aggressiveness, and

this dual mechanism underscores HDAC8 as a therapeutic node to

disrupt metastatic adaptation in hypoxic and inflammatory

microenvironments.

Building on the HIF-1α-HDAC8 axis that drives

metastatic adaptation, the EMT emerges as a pivotal reprogramming

event, enabling melanoma cells to dissociate from primary tumors

and invade distant tissues. Central to this plasticity is dynamic

lysine acetylation, which fine-tunes the activity of EMT-associated

transcription factors (54,55). Among the multiple acetylation

regulators, the NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 is

pathologically overexpressed in metastatic melanoma, providing a

signature that correlates with poor prognosis (56). Interestingly, SIRT1 has been shown

to promote cell migration and invasion by inducing EMT through the

suppression of E-cadherin expression (55). Moreover, SIRT1 regulates the

extension of lamellipodia, which are crucial structures for cell

migration, by deacetylating cortactin (56,57).

Previous studies have shown that SIRT1 inhibitors, including

nicotinamide, are able to significantly impair melanoma cell

migration through blocking lamellipodial extension, whereas SIRT1

activation enhances the migratory capability of the cells (56,57).

In addition, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) has been shown to

facilitate the formation of membrane protrusions induced by

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), a process that is regulated

by SIRT1 through deacetylation of AKT (57–59).

On the other hand, nuclear-localized SIRT6 was found to exert an

antagonistic effect on cytoplasmic SIRT1-AKT signaling through

suppressing AKT activity at the chromatin level, thereby

contributing to the regulation of melanoma cell migration. This

SIRT1-SIRT6 antagonism creates a therapeutic vulnerability: SIRT1

inhibitors (for example, nicotinamide) lead to impairments of

lamellipodial extension and EMT, whereas SIRT6 activation restricts

metastatic dissemination. Targeting this axis may therefore prove

to be an effective means of disrupting the acetylation-dependent

‘migratory plasticity’ of melanoma cells.

The role of acetylation in driving melanoma invasion

and metastasis is highly context-dependent. For example, the

distinct subgroups defined by H3K27ac patterns, the regulation of

HIF-1α and p300 by HDAC8, and the promotion of EMT and cytoskeletal

dynamics by SIRT1 collectively underscore the central importance of

epigenetic reprogramming in determining metastatic potential.

However, it is critical to understand how these processes

dynamically respond to the tumor microenvironment (TME) in

vivo, including hypoxia and immune cell infiltration. Although

current studies have provided robust evidence for the

pro-metastatic roles of HDAC8 and SIRT1, the validation of

effective selective inhibitors through creating metastatic models

has remained limited. Future studies are required that have the

objective of integrating spatial omics technologies to map the

evolution of acetylation modifications across primary tumors,

circulating tumor cells and metastatic niches, which should lead to

the identification of actionable targets. Notably, targeting

metastasis-associated acetylation regulators (for example, HDAC8

and SIRT1) may face significant challenges due to the essential

functions that they perform in normal physiology (for example,

embryonic development and immune regulation), which will

necessitate a rigorous evaluation of the therapeutic window.

Acetylation-mediated control of cell

fate in melanoma: Influence on drug resistance

DNA-damaging agents, including alkylating drugs such

as temozolomide, dacarbazine and fotemustine, are pivotal in the

treatment of metastatic melanoma. However, melanoma cells often

develop resistance to these agents, and this can be attributed, in

part, to epigenetic alterations mediated by acetylation activity.

Overall, the intricate interplay between acetylation modifications

and the cellular response to various anticancer agents underscores

the complexity of melanoma biology (Fig. 1).

Within the regulatory network of melanoma resistance

and immune evasion, the sirtuin family exerts pivotal control

through dynamic acetylation modifications, with individual members

exhibiting both functional heterogeneity and paradoxical roles

across tumor progression stages. For example, SIRT2, a member of

the sirtuin family, drives resistance to BRAF inhibitors (for

example, vemurafenib) through deacetylating and activating the

MEK/ERK pathway (60,61). Interestingly, SIRT6

haploinsufficiency has been found to cause an upregulation of IGF

binding protein 2 (IGFBP2) expression through mechanisms involving

increased chromatin accessibility and H3K56 acetylation at the

IGFBP2 locus, coupled with enhanced IGF-AKT signaling. This

upregulation subsequently confers resistance to MAPK inhibitors in

BRAF-mutant melanoma cells, thereby highlighting its

context-dependent function (33,62).

Furthermore, SIRT7 critically promotes melanoma

progression by enhancing tumor cell survival and facilitating

immune evasion. Deficiency in SIRT7 leads to an increase in tumor

cell death under stress conditions in vitro and a

suppression of tumor growth in vivo. Mechanistically, SIRT7

directly deacetylates SMAD4 protein, which antagonizes the

TGF-β-SMAD4 signaling pathway, ultimately leading to an

upregulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) protein. This

SIRT7-mediated increase in PD-L1 enables immune evasion and

contributes to resistance against immune checkpoint blockade

therapies (63). The regulation of

PD-L1 itself is also subject to acetylation dynamics, as revealed

by contrasting findings: HDAC2-mediated deacetylation was found to

promote PD-L1 nuclear translocation, enabling it to form a complex

with phosphorylated (p-)STAT3 and to activate early growth response

1-mediated tumor angiogenesis (64), whereas p300-mediated acetylation

prevents PD-L1 nuclear translocation, thereby reprogramming

immune-response-associated gene expression and consequently

enhancing the antitumor response to PD-1 blockade (65). Collectively, these findings

underscore the intricate and often context-specific interplay

between sirtuin-mediated acetylation, immune regulation and

therapeutic resistance pathways in melanoma.

The role of acetylation modifications in mediating

melanoma resistance to targeted therapies (for example, BRAF/MEK

inhibitors) and immunotherapies (for example, anti-PD-1) is

increasingly being recognized, especially concerning the

contributions of sirtuins (SIRT2/6/7) and specific HDACs (for

example, HDAC2). The regulation of PD-L1 acetylation status by

p300, and its impact on immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy,

represent a discovery that has significant clinical translational

potential. Nevertheless, resistance mechanisms are highly complex

and heterogeneous, where alterations in a single acetylation factor

may constitute only one component of an intricate resistance

network. Furthermore, when evaluating strategies targeting

acetylation (for example, combining HDACi or sirtuin inhibitors) to

reverse resistance, it is essential to consider their dual effects

on both tumor cells and immune cells (for example, T-cell

function), as exemplified by SIRT7′s involvement in tumor cell

survival and PD-L1 regulation. Therefore, optimizing the time,

dosage and sequence of combination therapies is critical for

overcoming resistance.

Acetylation modifications in melanoma

diagnosis and prognosis

The prognostic significance of acetylation in

melanoma has become evident, based on the multidimensional

regulatory axis that includes epigenetic reprogramming, metastatic

competence and remodeling of the TME. Numerous studies have shown

that acetylation levels differ across different tumor types, and

that these are correlated with various clinicopathological

parameters and patient survival rates (66–69).

For example, malignant melanoma cells have been shown to exhibit

higher levels of HDAC1/2/3 expression compared with their

non-cancerous counterparts. This positions acetylation status not

only as a potential biomarker for staging, but also as a dynamic

guide for therapeutic intervention.

The HAT Tip60 (Tat interactive protein, 60 kDa)

exemplifies this prognostic value, as its expression is inversely

correlated with primary tumor thickness, serving as an independent

prognostic marker across disease stages; diminished Tip60 levels

were also found to be associated with significantly reduced 5-year

disease-specific survival rates in patients with melanoma (70–72).

Mechanistically, Tip60 promotes apoptosis through p53 acetylation

at K120 (73,74), and its downregulation results in

decreased levels of acetylated DNA methyltransferase 1 (ac-DNMT1).

This Tip60/ac-DNMT1 axis is critically associated with melanoma

progression, and low levels of ac-DNMT1 are correlated with poorer

prognosis in stage IV disease; by contrast, elevated levels of

ac-DNMT1 are a predictor of improved survival (75).

Similarly, the HAT p300 demonstrates significant

stage-dependent prognostic relevance. Clinical analyses have

revealed a redistribution pattern in advanced melanoma,

characterized by nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic accumulation,

and this is strongly correlated with the higher American Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer stages. This redistribution is

mechanistically driven by the BRAF-MAPK/ERK pathway, which targets

nuclear p300 for ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation. Consequently, a

high BRAF/low nuclear p300 profile predicts metastatic transition,

whereas a low BRAF/high nuclear p300 signature aids in

distinguishing nevi from melanoma (36,76).

Critically, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was employed to confirm

that low nuclear p300 expression, but not low p300 cytoplasmic

expression, is a strong predictor of significantly worse overall

and disease-specific 5-year survival rates (77).

Collectively, these findings have underscored the

complex interplay between specific HATs (Tip60, p300), histone

deacetylases (HDACs), and associated modifiers (for example,

ac-DNMT1) within the acetylation landscape, solidifying their

crucial roles as prognostic indicators and potential therapeutic

targets across the spectrum of melanoma progression. However,

translating these findings into clinical practice faces challenges:

Validating the value of independent prognostic indicators requires

large-scale, multicenter prospective cohorts, and standardized

protocols need to be established for detecting and scoring systems.

Overcoming these challenges will enable acetylation-associated

biomarkers to facilitate clinical risk stratification, thereby

guiding therapeutic decision-making.

Acetylation modifications as therapeutic

targets in melanoma

Recent studies have provided valuable insights into

the mechanisms via which HDAC influences melanoma progression,

which have highlighted the potential of HDACi as a therapeutic

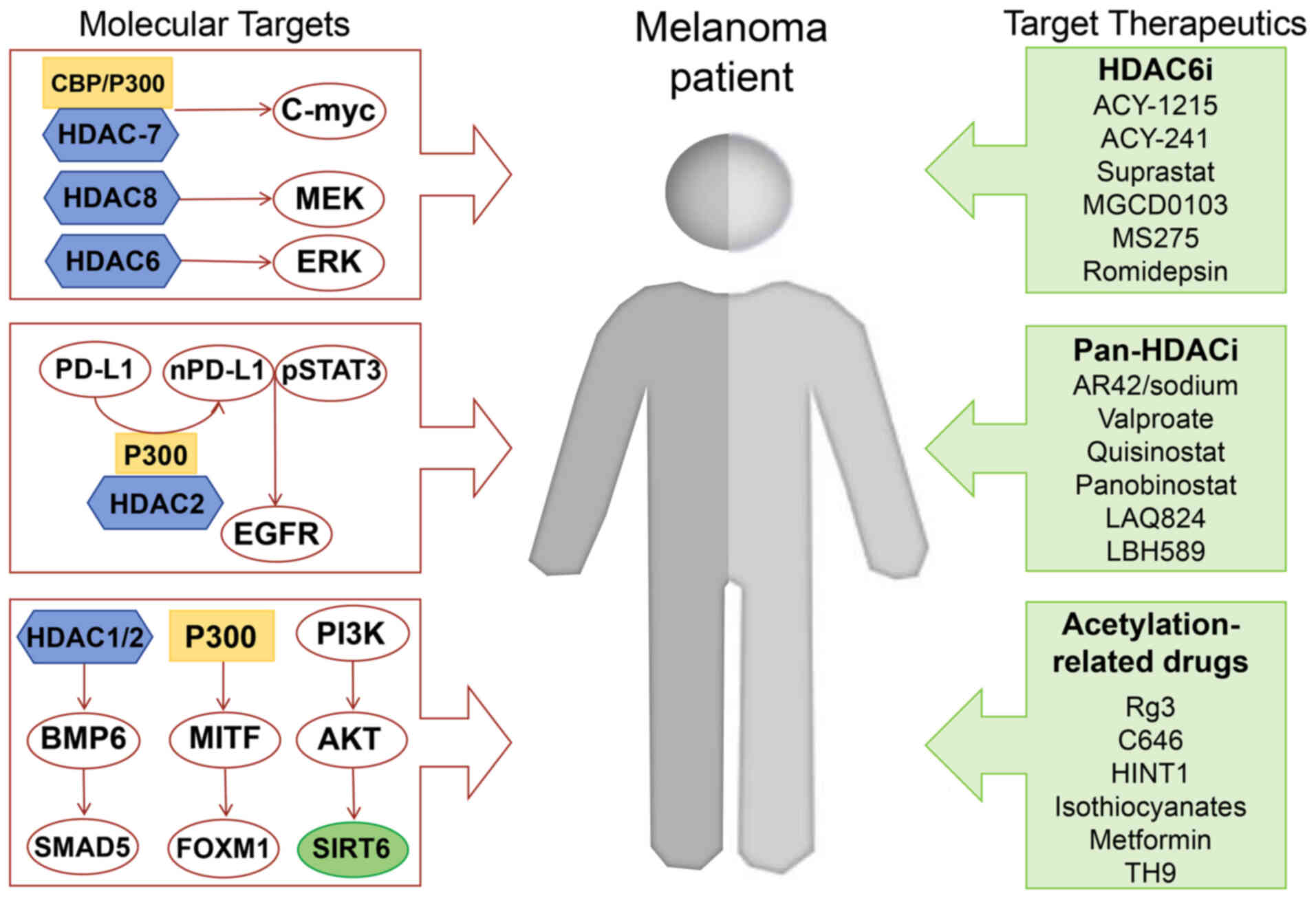

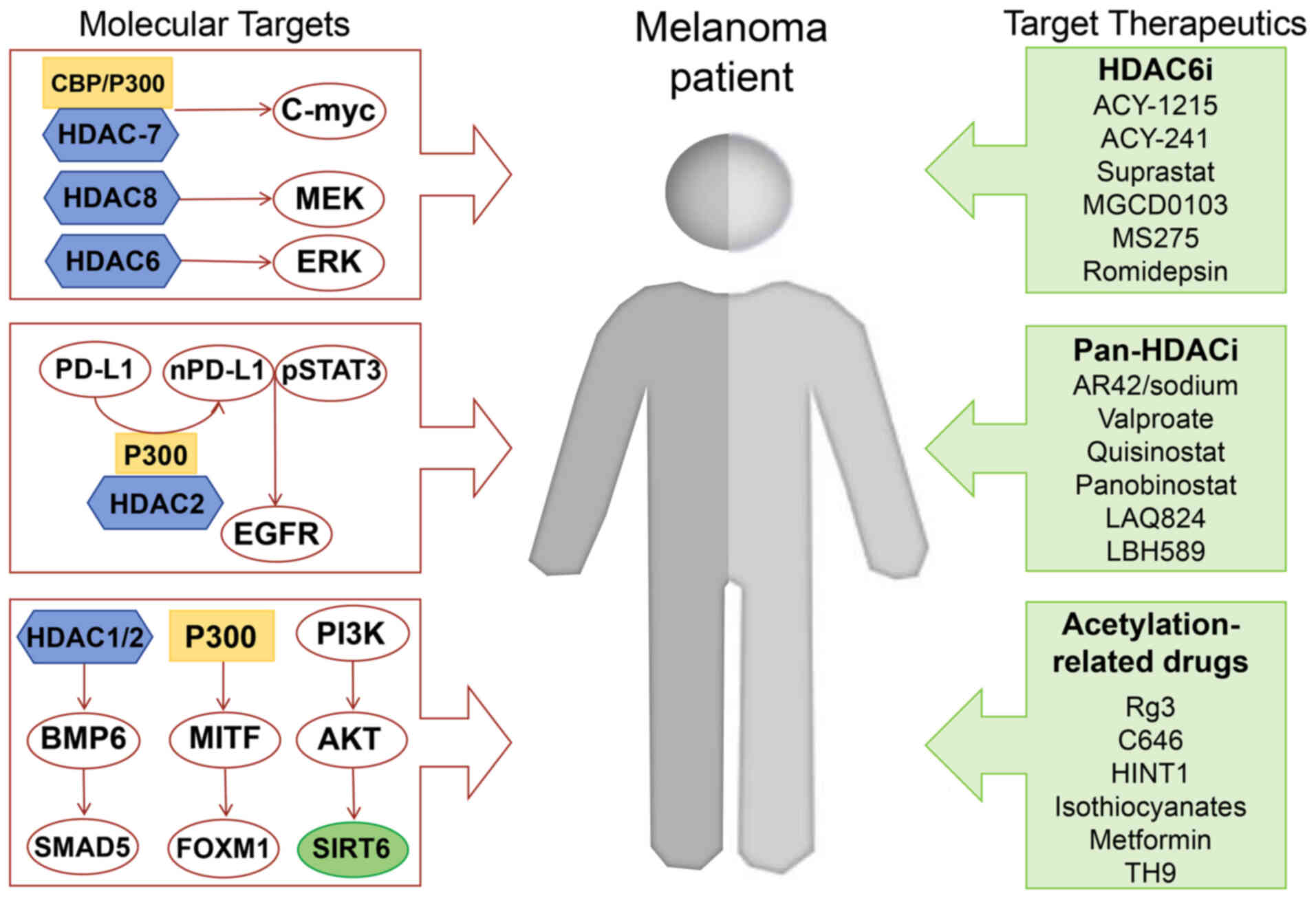

strategy (Fig. 2). The development

of HDACi as therapeutic agents holds promise for the treatment of

melanoma; however, the specific effects of these inhibitors may

differ, according to the HDAC isoform and the cellular context

(Table II).

| Figure 2.Integrated signaling pathways and

targeted therapeutic agents in melanoma. Pathways are outlined in

red boxes with directional arrows. Drug categories are color-coded

in light green. Schematic depicts interconnected pathways driving

melanoma pathogenesis: CBP/P300 and HDAC 7/8/6 regulate the

expression of c-Myc, MEK and ERK. SIRT6 is the downstream product

of the PI3K-AKT pathway and P300-MITF-FOXM1 transcriptional network

controlling melanocyte differentiation and proliferation.

HDAC1/2-BMP6-SMAD5 pathway modulating TGF-β signaling.

HDAC6-selective inhibitors (HDAC6i): ACY-1215, ACY-241, Suprastat,

MGCD0103, MS275, and romidepsin. Pan-HDAC inhibitors (Pan-HDACi):

AR42/sodium valproate, quisinostat, panobinostat, LAQ824, and

LBH589. Acetylation-targeting agents: Rg3, C646, HINT1,

isothiocyanates, metformin, and TH9. HDAC, histone deacetylase;

HDACi, HDAC inhibitor. |

| Table II.Summary of HDAC-related therapeutic

agents. |

Table II.

Summary of HDAC-related therapeutic

agents.

| First author/s,

year | Category | Medicine | Target | Mechanism | Model | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Booth et al,

2017 | HDACi | AR42/sodium

valproate | Pan-HDACi | Enhancing of

anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA4 antibodies | TPF-12-293

cells | (79) |

| Heijkants et

al, 2018 |

| quisinostat | Pan-HDACi | Combining the

treatment with CDK inhibition using flavopiridol | Uveal melanoma cell

lines | (93) |

| Gallagher et

al, 2018 |

| panobinostat | Pan-HDACi | Inducing

caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death | Patient derived

melanoma | (94) |

| Booth et al,

2017 |

| Suprastat | HDAC6i | Increasing the

infiltration of CD8+ effector and memory T-cells | SM1 murine melanoma

model | (80) |

| Vo et al,

2009; |

| LAQ824; | Pan-HDACi | Enhancing the

efficacy of ACT | B16 murine

model | (90,92) |

| Lisiero et

al, 2014 |

| LBH589 |

|

|

|

|

| Noonepalle et

al, 2020 |

| MGCD0103; | Class I-HDACi | Upregulating PD-L1

expression | B16 murine

melanoma | (83) |

|

|

| MS275 |

|

|

|

|

| Badamchi-Zadeh

et al, 2018 |

| Romidepsin |

HDAC1/2-inhibitor | Increasing the

frequency of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells | C57BL/6 mice | (95) |

| Shan et al,

2014 | Other

acetylation-related treatments | Rg3 | - | Inducing cell cycle

arrest; decreasing HDAC3 and increasing p53 acetylation | A375; SK-MEL-28;

Xenograft tumor | (96) |

| Yan et al,

2013 |

| C646 | - | Inducing cell cycle

arrest | WM35 cells | (97) |

| Mitsiogianni et

al, 2021 |

|

Isothiocyanates | - | Inducing cell cycle

arrest and cellular senescence in melanoma cells by inhibiting

p300/ CBP | A375, Hs294T, VMM1

and B16F-10 melanoma | (103) |

| Li et al,

2018 |

| Metformin | - | Inhibiting

KAT5-mediated SMAD3 acetylation, transcriptional activity and TRIB3

expression | C57BL/6 mice and

KK-Ay mice | (104) |

HDACi

HDACi hinder the effective repair of DNA damage.

This persistent damage either disrupts or inhibits essential

cellular processes, including transcription and DNA replication,

which ultimately triggers a cell death mechanism in cancer cells

(78).

HDACi and immune checkpoint

therapy

The integration of HDACi with immune checkpoint

therapy represents a paradigm-shifting approach in melanoma

treatment, leveraging epigenetic priming to overcome tumor immune

evasion. Notably, pan-HDACi agents such as AR42 or valproic acid,

when combined with kinase inhibitors such as pazopanib, have

demonstrated significant antitumor activity that extends beyond

growth suppression to the downregulation of the immune checkpoint

molecules, PD-L1/PD-L2. This epigenetic reprogramming leads to a

critical enhancement of tumor responsiveness to subsequent immune

checkpoint blockade, thereby amplifying antitumor immunity

(51,79). The synergy arises through

multifaceted mechanisms; For example, HDACi remodel the TME by

promoting the infiltration of macrophages, natural killer (NK)

cells, neutrophils and activated T cells (80), whereas Class I HDACi also modulate

checkpoint ligand expression, causing an upregulation of PD-L1 and

PD-L2 in melanoma (81,82). For example, the pan-HDACi LBH589

(targeting Class I/II/IV) in combination with PD-1 blockade was

shown to reduce tumor burden and to extend survival in melanoma

models. Similarly, selective HDAC6 inhibitors, such as Suprastat,

exhibit combinatorial efficacy with PD-L1 blockade by reshaping

immune populations, having the effect of reducing the numbers of

pro-tumoral M2 macrophages while enhancing infiltration of

antitumor CD8+ T-cells and memory T-cells (83,84).

This rational combinatorial approach, which is grounded in

overcoming epigenetic-mediated immune resistance, underpins the

clinical success that has already been observed in metastatic

melanoma and other malignancies that target co-inhibitory pathways.

However, the process of clinical translation warrants caution: Even

though preclinical studies (for example, utilizing LBH589,

Suprastat) have demonstrated efficacy, early clinical trial results

have been mixed. Therefore, developing more selective HDACi (for

example, HDAC6 inhibitors) or tumor-targeted HDACi, or optimizing

currently existing dosing regimens (for example, intermittent

administration), may help to improve the therapeutic window and

efficacy of this combination therapy.

Though the combination therapy involving HDACi and

the immune checkpoint cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

(CTLA-4) targeting agent nivolumab has demonstrated improved

efficacy in patients with melanoma (80), there remains a notable scarcity of

studies that have directly investigated the mechanistic links

between acetylation and immune checkpoints such as CTLA-4,

lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) and T cell immunoreceptor with

immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT). Limited evidence has

suggested that HDACi is able to modulate the tumor immune

microenvironment, potentially enhancing T cell function and antigen

presentation. For example, Li et al (85) demonstrated that co-inhibitory

receptors such as CTLA-4, LAG-3 and PD-1 provide essential

balancing signals for T cell activation. Their study also revealed

that the intrinsic HDAC activity within the Tcf1 transcription

factor is crucial for preventing the excessive induction of CTLA-4

in T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, thereby protecting their B-cell

helper function. Specifically, mutations in key amino acids within

the HDAC domain of Tcf1 led to the de-repression of CTLA-4 in Tfh

cells. In spite of these insights, however, the direct mechanistic

interplay between HDACi and the regulation of CTLA-4, LAG-3 or

TIGIT expression and function specifically within the context of

melanoma remains poorly understood. The majority of published

studies to date have focused on the phenotypic outcomes of

combination therapies, rather than on the underlying epigenetic

modifications. Therefore, elucidating how HDACi modulate the

acetylation status of histones or non-histone proteins associated

with genes encoding these immune checkpoints in melanoma represents

a critical and promising direction for future research.

HDACi and adoptive cell therapy

(ACT)

ACT represents a transformative approach for

metastatic melanoma, and its efficacy may be significantly enhanced

through strategic epigenetic modulation with HDACi (86,87).

HDACi reprogram the tumor-immune interface via dual mechanisms: i)

through inducing chromatin relaxation to enhance tumor antigen

presentation; and ii) through reversing T-cell exhaustion by

restoring acetylation-dependent transcriptional programs in

CD8+ T cells (88,89).

Crucially, preclinical studies have demonstrated how this

mechanistic synergy is translated into therapeutic enhancement. For

example, the pan-HDACi LAQ824, when combined with ACT using

gp100-specific pmel-1 T cells, was shown to cause a significant

amplification of the cytotoxic function of the transferred cells,

which led to a heightened level of tumor eradication in a B16

melanoma model (90,91). In addition to enhanced tumor cell

eradication, this combination also led to superior antitumor

efficacy. Similarly, combining the pan-HDACi LBH589 with

gp100-specific T-cell therapy led to substantially prolonged T-cell

survival and reduced tumor burden in melanoma models (92). Furthermore, the activity of HDACi

extend beyond modulating immediate effector functions. For example,

previous studies have shown that exposure to HDACi and

interleukin-21 (IL-21) caused a reprogramming of differentiated

human CD8+ T cells into central memory-like T cells.

This dedifferentiation process is initiated through histone H3

acetylation at the CD28 promoter region, which facilitates

IL-21-mediated p-STAT3 binding to the CD28 locus, thereby

generating a highly persistent T cell population (91). These findings collectively served to

position HDACi as essential adjuvants for overcoming the epigenetic

barriers that limit ACT efficacy in immune-cold melanomas.

Utilizing HDACi to enhance ACT, especially through

modifying memory T cell phenotypes and augmenting their

persistence, represents an innovative therapeutic strategy.

However, this approach is currently being validated primarily in

murine models. When translating HDACi such as LAQ824 or LBH589 to

human ACT, critical evaluations must focus on their potential

toxicity towards both the infused T cells and the host immune

system, as well as the impact they may have on T cell receptor

diversity. Furthermore, substantial optimization work needs to be

undertaken to precisely control the HDACi treatment conditions

(concentration, duration) during ex vivo T cell expansion,

which is required in order to maximize the therapeutic benefits

while minimizing functional impairment.

HDACi and other treatments

The combination of HDACi with CDK blockade offers a

paradigm-shifting strategy for overcoming therapeutic resistance in

refractory melanomas. The potential of this as combination therapy

has been robustly demonstrated preclinically: Utilizing BRAF

wild-type cutaneous melanoma tumors as a model, Heijkants et

al (93) reported that the

combination of pan-HDACi quisinostat and pan-CDK inhibitor

flavopiridol significantly reduced tumor volume to a greater extent

than was accomplished via flavopiridol monotherapy. Promising

therapeutic effects were also observed in patient-derived xenograft

models of cutaneous melanoma (93).

Looking beyond CDK inhibition, HDACi further enhance

targeted therapy through distinct molecular mechanisms. Another

study, conducted by Gallagher et al demonstrated the

synergistic effects of combining the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib

with the HDACi panobinostat in melanoma cells (94). This combination induced

caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death, primarily via the

downregulation of c-Myc expression and by decreasing PI3K pathway

activity, suggesting that the combination of HDACi and MAPK

inhibitors may have therapeutic potential in melanoma

treatment.

The therapeutic scope of HDACi combinations extends

significantly into the immunomodulatory landscape. The

combinatorial targeting of epigenetic regulators, especially

through HDACi and the bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET)

family, has emerged as a transformative strategy to overcome

therapeutic resistance in melanoma. The HDACi romidepsin (RMD) and

the BET inhibitor IBET151, both individually and in combination,

have been shown to enhance the frequency of vaccine-elicited

CD8+ T cells and to improve therapeutic and prophylactic

protection against B16-OVA melanoma. Additionally, the increased

IL-6 production and pro-apoptotic gene expression following

RMD+ IBET151 treatment are likely to be contributors

towards the enhanced cancer vaccine responses (95). These findings have identified HDACi

as versatile adjuvants whose synergistic interactions with CDK

inhibitors, BRAF inhibitors and BET inhibitors extend beyond simple

growth suppression to encompass targeted elimination and enhanced

immune surveillance. Optimizing these potent combinations

represents a critical frontier for advancing melanoma treatment,

necessitating a focus on clinical translation studies to fully

realize their potential.

Other acetylation-associated

treatments

Emerging pharmacological strategies targeting

acetylation dynamics extend beyond traditional HDACi, demonstrating

multifaceted antitumor potential through epigenetic-metabolic

crosstalk and combinatorial synergy. For example, Rg3, a bioactive

compound extracted from ginseng roots, has demonstrated efficacy in

inhibiting melanoma cell proliferation via downregulating HDAC3

expression and enhancing the level of p53 acetylation on lysine

residues. This dual action not only serves to arrest cell cycle

progression but also potentiates p53-dependent transcriptional

activation; in vivo studies that were performed using A375

×enografts confirmed these significant antiproliferative effects

(96). Complementing these natural

agents, synthetic inhibitors such as C646 have been shown to target

p300/CBP acetyltransferase activity to induce cell cycle arrest and

to synergize with DNA-damaging agents. Notably, C646 enhances

cisplatin-induced apoptosis in melanoma cells via sensitizing cells

to genomic instability (97–100).

Further broadening the therapeutic landscape,

isothiocyanates (ITCs), which are phytochemicals abundant in

cruciferous vegetables, function as pan-HDACi to suppress p300/CBP

activity, thereby triggering G0/G1 arrest and

senescence in melanoma (101).

Mechanistically, ITCs orchestrate a pleiotropic epigenetic

reprogramming landscape through reducing the total HDAC activity,

modulating the expression of histone-modifying enzymes (HDACs, HATs

and methyltransferases), and altering acetylation-methylation

crosstalk on histones H3/H4 (102,103). This multifaceted activity

positions ITCs as ideal partners for kinase inhibitor combinations

in refractory melanoma. Looking beyond their role as direct

acetylation modifiers, targeting stress-responsive nodes, such as

pseudokinase TRIB3, reveals novel metabolic-epigenetic

interdependencies. Li et al (104) found that treatment with metformin

led to melanoma growth and metastasis via reducing TRIB3

expression. Mechanistically, metformin was shown both to suppress

SMAD3 phosphorylation and to weaken the interaction between the

histone acetylase KAT5 and SMAD3, which, in turn, reduces

KAT5-mediated acetylation of SMAD3, leading to a decrease in SMAD3

transcriptional activity and subsequent TRIB3 expression, and

thereby antagonizing melanoma progression.

Beyond HDACi, targeting HATs, utilizing natural

compounds, or employing repurposed drugs are diverse strategies for

modulating acetylation against melanoma. These substances often

exhibit poly-pharmacology (namely, the design and use of a single

drug that simultaneously acts on multiple biological targets to

achieve a therapeutic effect), which may lead to complex biological

effects and potential off-target risks; however, their in

vivo antitumor activity, pharmacokinetic properties,

bioavailability and synergistic potential with standard therapies

require systematic evaluation in models that closely resemble the

clinical setting. Examples such as Rg3 and metformin suggest that

modulating acetylation might represent an essential component of

their known antitumor mechanisms, providing novel insights into

their modes of action, especially in the case of some established

agents (or ‘old drugs’). However, translating these findings into

effective clinical treatment regimens necessitates addressing

challenges that are associated with optimal dosing, routes of

administration, and how best to integrate these non-canonical

epigenetic agents within standard therapeutic frameworks.

Prospects and perspectives

Acetylation, a critical post-translational

modification, has been increasingly recognized for its profound

impact on the progression and metastasis of melanoma. Given the

critical role of acetylation in melanoma pathogenesis, targeting

this modification has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy.

Various HDACi have been developed, ranging from pan-HDACi that

target multiple HDAC isoforms, to more selective inhibitors

targeting specific HDACs. Despite the promise that they hold, the

clinical application of HDACi in melanoma treatment continues to

face several challenges. The efficacy and safety profiles of these

compounds require further validation through extensive clinical

trials.

First, one of the primary challenges in the clinical

application of HDACi is the heterogeneity of melanoma tumors, and

the variability in acetylation patterns among patients. This

heterogeneity may lead to variable responses to HDACi treatment,

which would necessitate personalized approaches to therapy.

Secondly, the redundancy and context-dependence of acetylation

networks (such as the dual pro-oncogenic/tumor-suppressive roles of

different sirtuins or HDACs) necessitate the development of more

precise targeting strategies. The toxicity and side effects of

pan-inhibitors limit their application, highlighting the urgent

need to develop highly selective inhibitors (targeting specific

HDAC/HAT isoforms or even specific acetylation sites). Thirdly,

numerous preclinical findings to date that hold promise for

clinical applications in the future have yet to achieve widespread

success in clinical trials. Key reasons for this include: i) model

limitations; specifically, that cell lines and genetically

engineered mouse models are generally not suitable for fully

recapitulating human tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment

complexity; ii) toxicity management, due to the fact that the

toxicity of HDACi limit their sufficient dosing within combination

regimens; and iii) lack of patient selection, given that there is

an absence of reliable predictive biomarkers for response to

acetylation-targeted therapies. Finally, emerging evidence

highlights the significance of other lysine acylations,

particularly lactylation, in cancer biology (105). Lactylation involves the transfer

of a lactate-derived lactyl group to lysine residues on histones

and non-histone proteins, which is analogous to the transfer of an

acetyl group in acetylation (106). Histone lactylation has been shown

to regulate gene expression programs that are distinct from

acetylation, influencing multiple physiological and pathological

processes (107). Mechanistically,

the enzymes involved in adding or removing lactyl marks are still

being identified, although evidence already exists to suggest

potential interplay or competition with acetylation pathways, given

that both modifications target lysine residues (108,109). This presents a compelling future

direction-namely, to explore the potential crosstalk and hierarchy

between different types of acylation reactions (for example,

acetylation and lactylation) that shape melanoma pathogenesis.

Therefore, future studies should not only continue to delineate the

acetylation-specific networks but also map the landscape of

lactylation and other novel modifications in melanoma, which will

serve to identify their convergent and unique roles in

oncogenesis.

In conclusion, acetylation modifications fulfill a

crucial role in the pathogenesis and progression of melanoma.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these

modifications may provide insights into novel therapeutic

strategies. Future studies should focus on a number of different

aspects, including developing isoform-selective HDACi to minimize

toxicity, validating acetylation-based biomarkers in large clinical

cohorts for patient stratification, and elucidating

subtype-specific acetylation patterns in acral and mucosal

melanoma. Through harnessing the power of epigenetics, we will be

able to pave the way for more effective and personalized treatments

for this devastating disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82103726), the Guangdong Basic and

Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant nos. 2023A1515010575 and

2025A1515010947), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program

(grant nos. JCYJ20210324110008023 and JCYJ20230807095809019), the

Shenzhen Sanming Project (grant no. SZSM202311029), the Shenzhen

Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (grant no. SZXK040) and

the Shenzhen High-level Hospital Construction Fund and Peking

University Shenzhen Hospital Scientific Research Fund (grant no.

KYQD2024378).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JW and XC wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

JW, XC and CH created the images. ZZ, XL, KZ and CW performed

literature review. CH and BY provided advice in revising the

manuscript and supervised the study. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Fateeva A, Eddy K and Chen S: Current

state of melanoma therapy and next steps: Battling therapeutic

resistance. Cancers (Basel). 16:15712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Urban K, Mehrmal S, Uppal P, Giesey RL and

Delost GR: The global burden of skin cancer: A longitudinal

analysis from the global burden of disease study, 1990–2017. JAAD

Int. 2:98–108. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J,

Vaccarella S, Meheus F, Cust AE, de Vries E, Whiteman DC and Bray

F: Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to

2040. JAMA Dermatol. 158:495–503. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Beasley GM and Terando AM: Articles from

2022 to 2023 to inform your cancer practice: Melanoma. Ann Surg

Oncol. 31:1851–1856. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yuan J, Li X and Yu S: Global, regional,

and national incidence trend analysis of malignant skin melanoma

between 1990 and 2019, and projections until 2034. Cancer Control.

31:107327482412273402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gracia-Hernandez M, Munoz Z and Villagra

A: Enhancing therapeutic approaches for melanoma patients targeting

epigenetic modifiers. Cancers (Basel). 13:61802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yang L and Yan Y: Emerging roles of

post-translational modifications in skin diseases: Current

knowledge, challenges and future perspectives. J Inflamm Res.

15:965–975. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Reolid A, Muñoz-Aceituno E, Abad-Santos F,

Ovejero-Benito MC and Daudén E: Epigenetics in non-tumor

immune-mediated skin diseases. Mol Diagn Ther. 25:137–161. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Centeno PP, Pavet V and Marais R: The

journey from melanocytes to melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 23:372–390.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shain AH and Bastian BC: From melanocytes

to melanomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 16:345–358. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Elder DE, Bastian BC, Cree IA, Massi D and

Scolyer RA: The 2018 World Health Organization classification of

cutaneous, mucosal, and uveal melanoma: Detailed analysis of 9

distinct subtypes defined by their evolutionary pathway. Arch

Pathol Lab Med. 144:500–522. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM,

Gershenwald JE and Scolyer RA: Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet.

402:485–502. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gelmi MC, Houtzagers LE, Strub T, Krossa I

and Jager MJ: MITF in normal melanocytes, cutaneous and uveal

melanoma: A delicate balance. Int J Mol Sci. 23:60012022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Slominski RM, Raman C, Chen JY and

Slominski AT: How cancer hijacks the body's homeostasis through the

neuroendocrine system. Trends Neurosci. 46:263–275. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Slominski RM, Kim TK, Janjetovic Z,

Brożyna AA, Podgorska E, Dixon KM, Mason RS, Tuckey RC, Sharma R,

Crossman DK, et al: Malignant melanoma: An overview, new

perspectives, and vitamin D signaling. Cancers (Basel).

16:22622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Slominski RM, Chen JY, Raman C and

Slominski AT: Photo-neuro-immuno-endocrinology: How the ultraviolet

radiation regulates the body, brain, and immune system. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 121:e23083741212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Slominski RM, Raman C, Jetten AM and

Slominski AT: Neuro-immuno-endocrinology of the skin: how

environment regulates body homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

21:495–509. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Slominski RM, Sarna T, Płonka PM, Raman C,

Brożyna AA and Slominski AT: Melanoma, melanin, and melanogenesis:

The Yin and Yang RELATIONSHIP. Front Oncol. 12:8424962022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wacker M and Holick MF: Sunlight and

vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinol.

5:51–108. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Menzies KJ, Zhang H, Katsyuba E and Auwerx

J: Protein acetylation in metabolism-metabolites and cofactors. Nat

Rev Endocrinol. 12:43–60. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Weinert BT, Narita T, Satpathy S,

Srinivasan B, Hansen BK, Schölz C, Hamilton WB, Zucconi BE, Wang

WW, Liu WR, et al: Time-resolved analysis reveals rapid dynamics

and broad scope of the CBP/p300 acetylome. Cell. 174:231–244.e12.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shvedunova M and Akhtar A: Modulation of

cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23:329–349. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Parveen R, Harihar D and Chatterji BP:

Recent histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Cancer.

129:3372–3380. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lee HY, Hsu MJ, Chang HH, Chang WC, Huang

WC and Cho EC: Enhancing anti-cancer capacity: Novel class I/II

HDAC inhibitors modulate EMT, cell cycle, and apoptosis pathways.

Bioorg Med Chem. 109:1177922024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu Y, Tong X, Hu W and Chen D: HDAC11: A

novel target for improved cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother.

166:1154182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jia G, Liu J, Hou X, Jiang Y and Li X:

Biological function and small molecule inhibitors of histone

deacetylase 11. Eur J Med Chem. 276:1166342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Strub T, Ballotti R and Bertolotto C: The

‘ART’ of epigenetics in melanoma: From histone ‘alterations, to

resistance and therapies’. Theranostics. 10:1777–1797. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cintra Lopes Carapeto F, Neves Comodo A,

Germano A, Pereira Guimarães D, Barcelos D, Fernandes M and Landman

G: Marker protein expression combined with expression heterogeneity

is a powerful indicator of malignancy in acral lentiginous

melanomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 39:114–120. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Comodo-Navarro AN, Fernandes M, Barcelos

D, Carapeto FCL, Guimarães DP, de Sousa Moraes L, Cerutti J,

Iwamura ESM and Landman G: Intratumor heterogeneity of KIT gene

mutations in acral lentiginous melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol.

42:265–271. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cheng PF: Medical bioinformatics in

melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 30:113–117. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Castillo JJAQ, Silva W, Barcelos D and

Landman G: Molecular landscape of acral melanoma: an integrative

review. Surg Exp Pathol. 8:172025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wang L, Guo W, Ma J, Dai W, Liu L, Guo S,

Chen J, Wang H, Yang Y, Yi X, et al: Aberrant SIRT6 expression

contributes to melanoma growth: Role of the autophagy paradox and

IGF-AKT signaling. Autophagy. 14:518–533. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Strub T, Ghiraldini FG, Carcamo S, Li M,

Wroblewska A, Singh R, Goldberg MS, Hasson D, Wang Z, Gallagher SJ,

et al: SIRT6 haploinsufficiency induces BRAFV600E

melanoma cell resistance to MAPK inhibitors via IGF signalling. Nat

Commun. 9:34402018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Manickavinayaham S, Vélez-Cruz R, Biswas

AK, Bedford E, Klein BJ, Kutateladze TG, Liu B, Bedford MT and

Johnson DG: E2F1 acetylation directs p300/CBP-mediated histone

acetylation at DNA double-strand breaks to facilitate repair. Nat

Commun. 10:49512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kim E, Zucconi BE, Wu M, Nocco SE, Meyers

DJ, McGee JS, Venkatesh S, Cohen DL, Gonzalez EC, Ryu B, et al:

MITF expression predicts therapeutic vulnerability to p300

inhibition in human melanoma. Cancer Res. 79:2649–2661. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dai X, Zhang X, Yin Q, Hu J, Guo J, Gao Y,

Snell AH, Inuzuka H, Wan L and Wei W: Acetylation-dependent

regulation of BRAF oncogenic function. Cell Rep. 38:1102502022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Vervoorts J, Lüscher-Firzlaff JM, Rottmann

S, Lilischkis R, Walsemann G, Dohmann K, Austen M and Lüscher B:

Stimulation of c-MYC transcriptional activity and acetylation by

recruitment of the cofactor CBP. EMBO Rep. 4:484–490. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fan T, Jiang S, Chung N, Alikhan A, Ni C,

Lee C-CR and Hornyak TJ: EZH2-dependent suppression of a cellular

senescence phenotype in melanoma cells by inhibition of p21/CDKN1A

expression. Mol Cancer Res. 9:418–429. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kovacs JJ, Murphy PJM, Gaillard S, Zhao X,

Wu JT, Nicchitta CV, Yoshida M, Toft DO, Pratt WB and Yao TP: HDAC6

regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of

glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell. 18:601–607. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pulya S, Amin SA, Adhikari N, Biswas S,

Jha T and Ghosh B: HDAC6 as privileged target in drug discovery: A

perspective. Pharmacol Res. 163:1052742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu J, Luan W, Zhang Y, Gu J, Shi Y, Yang

Y, Feng Z and Qi F: HDAC6 interacts with PTPN1 to enhance melanoma

cells progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 495:2630–2636. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bai J, Lei Y, An G and He L:

Down-regulation of deacetylase HDAC6 inhibits the melanoma cell

line A375.S2 growth through ROS-dependent mitochondrial pathway.

PLoS One. 10:e01212472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ling H, Li Y, Peng C, Yang S and Seto E:

HDAC10 blockade upregulates SPARC expression thereby repressing

melanoma cell growth and BRAF inhibitor resistance. bioRxiv

[Preprint]. 2023.12.05.570182. 2023.

|

|

44

|

Yuan W, Fang W, Zhang R, Lyu H, Xiao S,

Guo D, Ali DW, Michalak M, Chen XZ, Zhou C and Tang J: Therapeutic

strategies targeting AMPK-dependent autophagy in cancer cells.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1870:1195372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ling H, Li Y, Peng C, Yang S and Seto E:

HDAC10 inhibition represses melanoma cell growth and BRAF inhibitor

resistance via upregulating SPARC expression. NAR Cancer.

6:zcae0182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Mustofa MK, Tanoue Y, Tateishi C, Vaziri C

and Tateishi S: Roles of Chk2/CHEK2 in guarding against

environmentally induced DNA damage and replication-stress. Environ

Mol Mutagen. 61:730–735. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang W, Feng Y, Guo Q, Guo W, Xu H, Li X,

Yi F, Guan Y, Geng N, Wang P, et al: SIRT1 modulates cell cycle

progression by regulating CHK2 acetylation-phosphorylation. Cell

Death Differ. 27:482–496. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Guo QQ, Wang SS, Zhang SS, Xu HD, Li XM,

Guan Y, Yi F, Zhou TT, Jiang B, Bai N, et al: ATM-CHK2-Beclin 1

axis promotes autophagy to maintain ROS homeostasis under oxidative

stress. EMBO J. 39:e1031112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Mendelson K, Martin TC, Nguyen CB, Hsu M,

Xu J, Lang C, Dummer R, Saenger Y, Messina JL, Sondak VK, et al:

Differential histone acetylation and super-enhancer regulation

underlie melanoma cell dedifferentiation. JCI Insight.

9:e1666112024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Min D, Byun J, Lee EJ, Khan AA, Liu C,

Loudig O, Hu W, Zhao Y, Herlyn M, Tycko B, et al: Epigenetic

silencing of BMP6 by the SIN3A-HDAC1/2 repressor complex drives

melanoma metastasis via FAM83G/PAWS1. Mol Cancer Res. 20:217–230.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hornig E, Heppt MV, Graf SA, Ruzicka T and

Berking C: Inhibition of histone deacetylases in melanoma-a

perspective from bench to bedside. Exp Dermatol. 25:831–838. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kim JY, Cho H, Yoo J, Kim GW, Jeon YH, Lee

SW and Kwon SH: HDAC8 deacetylates HIF-1α and enhances its protein

stability to promote tumor growth and migration in melanoma.

Cancers (Basel). 15:11232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Emmons MF, Bennett RL, Riva A, Gupta K,

Carvalho LADC, Zhang C, Macaulay R, Dupéré-Richér D, Fang B, Seto

E, et al: HDAC8-mediated inhibition of EP300 drives a

transcriptional state that increases melanoma brain metastasis. Nat

Commun. 14:77592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lamouille S, Xu J and Derynck R: Molecular

mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 15:178–196. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kong F, Ma L, Wang X, You H, Zheng K and

Tang R: Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition by protein

lysine acetylation. Cell Commun Signal. 20:572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Sun T, Jiao L, Wang Y, Yu Y and Ming L:

SIRT1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition by promoting

autophagic degradation of E-cadherin in melanoma cells. Cell Death

Dis. 9:1362018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kunimoto R, Jimbow K, Tanimura A, Sato M,

Horimoto K, Hayashi T, Hisahara S, Sugino T, Hirobe T, Yamashita T

and Horio Y: SIRT1 regulates lamellipodium extension and migration

of melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 134:1693–1700. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Porta C, Paglino C and Mosca A: Targeting