Leukemia is a clonal malignant disorder of

hematopoietic precursor cells that present as an excess of one or

more hematologic cell types in the bone marrow and bloodstream. It

is caused by a disruption of the normal processes of cell

proliferation and cell death. There are four major types of

leukemias: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myelogenous

leukemia (AML), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and chronic

myelogenous leukemia (CML). The classification depends on the

lineage and stage of the presenting leukemia cells and the rate of

leukemia cell proliferation (1). In

2022, there were an estimated 48.7 hundred thousand new cases

(ranked 13th of 33) and 30.5 hundred thousand deaths (ranked 10th

of 33) from leukemia worldwide (2).

Leukemia incidence varies among populations in different age groups

and countries. ALL is most common in children and young adults,

whereas AML, CLL and CML commonly occur in older adults. In adults

aged ≥20 years, AML had the highest incidence and mortality rate

among all leukemia types. A high incidence of leukemia has been

reported in developed regions of the world such as Western Europe,

North America and Australia (3,4).

According to statistics acquired over the last three decades, in

most regions, the cumulative risk of leukemia incidence has

increased faster than the lifetime risk of leukemia mortality

(5,6). The decreasing trends in mortality

rates are potentially a result of significant advancements in

leukemia diagnosis and therapies.

Conventionally, leukemia treatment relies on

chemotherapy, which uses cytotoxic agents to destroy rapidly

dividing leukemia cells. Principal chemotherapy drugs, including

vincristine and an anthracycline, have been used in combination

with other drugs, such as all-trans retinoic acid,

cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and cytarabine, to achieve a

satisfactory complete remission rate (7,8).

However, since these drugs are not selective for cancer cells, they

often cause undesirable side effects, some of which are more severe

than others, such as neurotoxicity (9) and cardiomyopathy (10,11).

These adverse effects not only worsen patient quality of life but

also limit the dose and efficacy of chemotherapy drugs. Moreover,

drug resistance and ineffectiveness in patients with some subtypes

of leukemia have been reported (12,13).

Bone marrow or allogenic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC)

transplantation can be options for the treatment of relapsed or

refractory leukemia. Alternatively, novel therapeutic substances

are needed to simultaneously overcome resistance and alleviate the

adverse effects of chemotherapy. Over the past two decades, an

improved understanding of the pathophysiology of leukemias has

given rise to a rapid progress in leukemia therapeutic research.

Targeted therapy began to play important roles in leukemia

treatment. Cancer cell-selective drugs, including small molecule

inhibitors targeting tyrosine kinases or

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases and antibodies against specific CD

molecules, have emerged as attractive therapeutic options. To lower

the dose of traditional cytotoxic drugs, such targeted drugs have

often been applied in combination regimens. Cytogenetic and

molecular aberrations are key factors that guide the development of

targeted therapies. Consequently, they increase the complete

cytogenetic response rate and improve patient quality of life in

almost every type of leukemia (14). Excellent reviews discussing the

advancement of leukemia therapy have been published recently

(15,16). However, some leukemia subtypes are

refractory or already resistant to newly developed drugs, making

drug discovery research challenging.

Although genetic alterations of oncogenes play a

significant role in leukemia progression, epigenetic aberrations

have been shown to affect transcriptional regulation and the

development of leukemia cells. In the past few years, several new

therapeutic strategies have been proposed for the treatment of

leukemia on the basis of epigenetic aberrations (17,18).

Among numerous epigenetic modulators, histone deacetylase (HDAC), a

deacetylase that acts on histone and non-histone proteins to alter

chromatin structure and regulate gene expression, is the most

intensively studied therapeutic target in leukemia (19). Overexpression of HDAC has been

demonstrated to stimulate the progression of leukemogenesis and

tumorigenesis by inhibiting tumor suppressor gene expression

(20,21). Blocking HDAC activity reactivates

tumor suppressor genes and directly suppresses tumor cell

proliferation and induces apoptosis. This renders HDAC inhibitors

(HDACis) potential targeted therapeutic agents for the management

of leukemia and other cancers. Over the past decade, novel HDACis

have been discovered and developed from both natural and synthetic

sources (22,23). Among the various compounds that

possess HDAC inhibition activity, peptides derived from diverse

sources, including food, environment and laboratory production, are

potential candidate HDACis that can influence epigenetic modulation

(24). Compared with chemical

drugs, peptide drugs provide advantages such as high specificity,

low toxicity and biological diversity. Additionally, peptides can

be rationally designed, which will be beneficial in targeted

therapy development. The present review provides an overview of

HDAC and HDACis types and functions with an emphasis on the role of

HDACs in leukemogenesis. The development of HDACis and the HDAC

inhibitory effects of potential therapeutic peptides on leukemia in

preclinical and clinical trials are discussed.

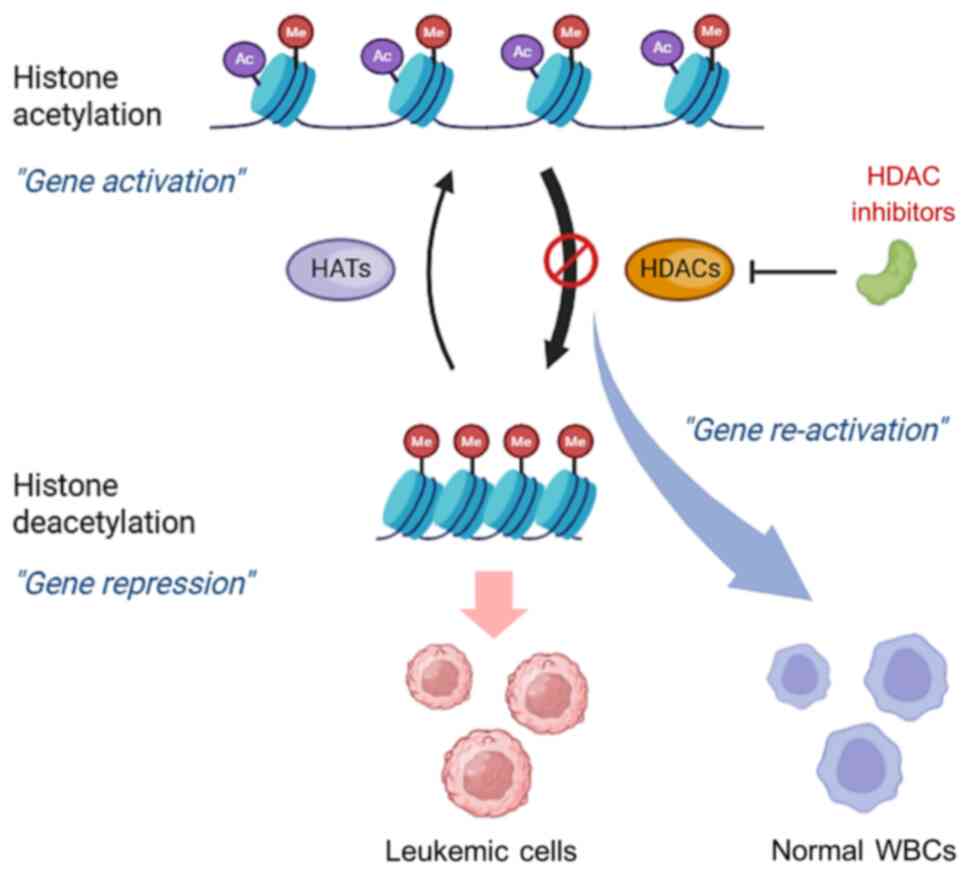

Histone acetylation represents one of the main

mechanisms of epigenetic modifications and is associated with two

different enzymes, namely, histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and

HDACs. HATs mediate the relaxation of nucleosomes to allow opening

of chromatin by adding acetyl groups at the ε-amino group of

N-terminal lysine residues in the histone tail, resulting in the

upregulation of gene expression, whereas deacetylation mediated by

HDACs removes acetyl groups and induces condensation of chromatin,

resulting in the repression of the gene (25). An imbalance in the amount of HAT and

HDAC enzymes interferes with the regulation of gene expression and

induces the progression of several cancers (26).

In humans, HDACs include 18 enzymes categorized into

two families: The classical HDAC family, which is composed of

HDAC1-11, and the silent information regulator (SIR)-2 family,

which is composed of SIRT1-7. These two families can be subdivided

into four classes based on catalytic mechanisms and sequence

homology to yeast deacetylases. HDACs in the same class possess

similar structures and functions (27,28).

HDAC class members and their characteristics are described in

Table I.

Detailed information on the structure and catalytic

mechanisms of each HDAC can be found in the extensive review by

Asmamaw et al (29).

All classes of HDACs participate in hematopoiesis by

regulating multilineage blood cell development. Their functions

involve stemness maintenance of HSCs and the lineage commitment of

progenitor cells. HDACs interact with transcription factors and/or

other cofactor proteins to modulate histone acetylation levels,

which subsequently regulate the expression of several hematopoietic

lineage-related genes (30–32). It has been shown that HDACs play

crucial roles in the cell fate decisions of hematopoietic

progenitors (33,34).

Class I HDACs, especially HDAC1, are major HDACs

expressed in hematopoietic cells. They are found in all

hematopoietic stages, but expression levels differ among the types

of blood cells. HDAC1 is undetectable in early progenitor cells,

moderately expressed in committed progenitor cells, and disappears

in mature granulocytes, reflecting its dose-dependent role in

modulating progenitor cell differentiation (35). A previous study in hematopoietic

cell lines demonstrated that HDAC1 plays essential roles in

maintaining the immature state of committed progenitor cells and

contributes to GATA-1 mediated erythroid differentiation (36). HDAC1 transactivation is driven by

Sp1 and GATA-1, whereas its transcriptional repression is mediated

by C/EBPα and C/EBPβ (34). HDAC1

is accompanied by GATA1-Sp1 complexes during the differentiation of

common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) into megakaryocyte-erythrocyte

progenitor cells. By contrast, HDAC1 is downregulated by

GATA2-C/EBP complexes during CMP differentiation into

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells (37,38).

The upregulation of HDAC1 facilitates the movement of

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells toward granulocytic cells,

whereas its downregulation induces the development of

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells into monocytes, macrophages

and dendritic cells (39). A

previous study in a mouse model indicated that both HDAC1 and HDAC2

in a complex with their corepressor, Sin3A, serve as

cell-autonomous regulators of HSC maintenance (40). They also play a role in the

differentiation of megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitor cells

(41), pre-B cells (42), T lymphocytes (43) and NK cells (44). HDAC1 and HDAC3 are accompanied by

Runx1 as repressor complexes to control the progression and

maturation of granulocytes from progenitor cells, ensuring proper

granulocytic development and function. Class IIa HDAC4 has been

reported to act as a corepressor recruited by BCL6 to repress genes

critical for regulating B-cell development process (45), and class IIa HDAC7 plays a role in

the control of thymic selection during T-cell development (46). In addition, class IIb HDAC6 and

class I HDAC2 stimulate the enucleation process of orthochromatic

normoblasts. Members of class III HDACs have also been implicated

in hematopoiesis. SIRT1 promotes the hematopoietic microenvironment

through CXCL12 upregulation (47),

and influences granulopoiesis through a regulatory loop between

G-CFGR and G-CSF (48). Defects in

hematopoietic progenitor differentiation and the downregulation of

genes associated with hematopoietic development have been

demonstrated in SIRT1-deficient mouse (49). SIRT2, SIRT3 and SIRT7 also play

important roles in HSC maintenance and homeostasis, especially

under stress and in elderly individuals (50–52).

The last HDAC group, class IV HDAC11, is involved in the

development of promyelocytes into neutrophils (53).

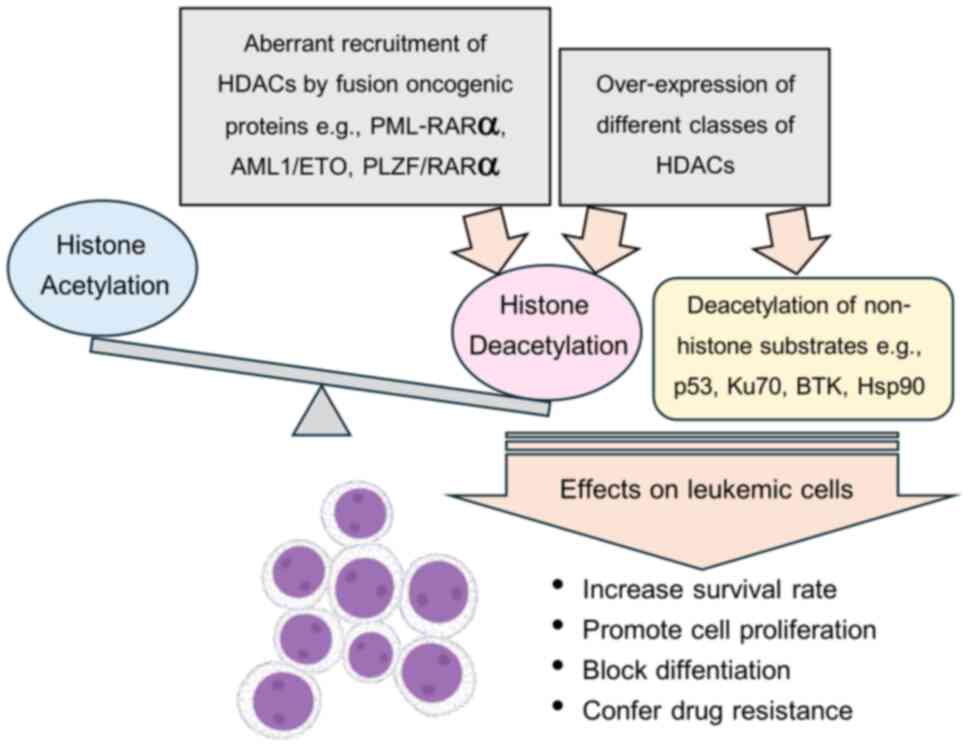

Abnormal histone deacetylation has been implicated

in leukemia initiation and progression via two mechanisms; aberrant

recruitment of an HDAC enzyme by an oncogenic fusion protein and

alteration in the expression of HDACs. Some notable implications of

HDACs in leukemogenesis are described.

It is well-known that one of the most common genetic

rearrangements that causes leukemia is chromosome translocation,

leading to the expression of fusion proteins associated with

oncogenic transformation. In acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL),

the most frequent chromosomal translocation t (15;17) results in

the fusion protein PML-RARα. PML-induced dimerization of RARα

enhances the binding of the corepressor complex NCoR/SMRT and class

I and class II HDACs, thus repressing the expression of retinoic

acid (RA)-target genes which in turn block differentiation of

myeloid precursors (54).

Similarly, other fusion proteins found in AML such as PLZF/RARα and

AML1/EMO have been reported to induce transcriptional repression of

genes critical to the differentiation of granulocytic precursors

through enhanced recruitment of the HDAC-corepressor complex

(55,56). HDAC1 and HDAC3 are recruited by

fusion proteins such as AML1/ETO and subsequently form a complex

that acts as an abnormal TF leading to leukemogenesis. Moreover,

AML1-ETO can recruit HDAC1 and HDAC2 to bind NCoR-mSin3 and

prevents leukemia cells from undergoing TNF-related apoptosis

(57). Overexpression of SETBP1, an

oncogenic protein resulting from t (12;18) in AML, was also

reported to induce leukemia development through transcriptional

repression of the critical hematopoiesis regulator gene Runx1 via

recruitment of HDAC1 (58).

An imbalance in HAT and HDAC enzyme levels also

affects gene transcription and is involved in the development of

hematological malignancies. Cumulative evidence suggests that the

aberrant hypoacetylation of histones associated with the

overexpression of HDACs leads to the repression of tumor suppressor

genes that regulate the cell cycle and DNA repair pathways and

alteration of the cell differentiation program, leading to

leukemogenesis (59,35,60).

The differential overexpression of HDAC isoforms is related to

different subtypes of leukemia. For instance, HDAC1 overexpression

is associated with ALL, CML and AML, whereas the high expression of

HDAC3, 6, and 7 is linked to pathogenesis and prognosis in ALL and

CLL (61). A comprehensive study of

the expression of all 18 HDAC isoforms in 200 CLL patients by Van

Damme et al (62) showed

that there are variations in the expression levels of different

HDACs. HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC11, SIRT3, SIRT6 and SIRT7 were

upregulated, whereas HDAC2 and SIRT4 were significantly

downregulated in patients with CLL compared with normal B cells.

Correlation analysis revealed that high levels of HDAC6 are

significantly associated with longer treatment-free survival, and

high levels of HDAC3, SIRT2, SIRT3 and SIRT6 are associated with a

longer overall survival. Additionally, the results suggested that

HDAC7 and HDAC10 overexpression and HDAC6 and SIRT3

under-expression are associated with poor prognosis (62). Recently, Verbeek et al

(63) demonstrated that relevancy

between Class IIA HDAC isoforms (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7) shows

critical prognostic relevance in KMT2A-rearranged ALL. Knockdown or

selective inhibition of such HDAC isoforms induced apoptosis and

impacted leukemic infiltration in protective niches such as bone

marrow and CNS, which is crucial for prognosis in infant ALL

(63). HDACs not only act on

histone tails but also affect nonhistone substrates, including

transcription factors and other cofactor proteins. The first

described non-histone substrate of HATs and HDACS is the tumor

suppressor p53 protein, which is the key transcription factor in

cellular stress response pathways (64). P53 plays important roles in

regulating several biological mechanisms, including cell

proliferation, cell differentiation, the cell cycle, the apoptotic

pathway and DNA repair (65).

Normally, p53 activity is modulated by CBP/p300-mediated

acetylation. It has been found that upregulation of HDAC1

potentially block apoptosis induced by the deacetylation of p53,

which results in an increased survival rate of AML cells (66). In AML with inv(16)+, high expression

of HDAC8 was detected in primitive CD34+ cells and it was recruited

by CBFβ-SMMHC fusion proteins to form complexes with p53. These

complexes mediate the aberrant deacetylation of p53 by HDAC8 and

subsequently promote AML progression (67). Furthermore, high expression of class

I HDACs induces aberrant acetylation of p53 and Ku70, resulting in

resistance to imatinib in patients with CML with positive

Philadelphia chromosome (68). It

has been reported that HDAC7 regulates the phagocytic activity of

monocyte-derived macrophages obtained from patients with CLL

through direct modulation of BTK acetylation and phosphorylation.

It has been suggested that HDAC7 contributes to therapeutic

antibody resistance in patients with CLL and CLL who have high HDAC

expression may result in a poor prognosis (69). The proven mechanisms that lead to

abnormal deacetylation, resulting in leukemogenesis and leukemia

progression, are depicted in Fig.

1.

Unlike genetic alterations, aberrant epigenetic

modifications are reversible; therefore, targeting epigenetic

modulators is a promising approach for the treatment of leukemia.

Understanding of HDAC-related leukemogenesis has encouraged the

development of HDACis that aim to restore normal gene expression by

reactivating silenced tumor suppressor genes, inducing

differentiation, and promoting the cessation of leukemia cell

proliferation. In recent years, numerous HDACis have been

extensively investigated in the search for viable therapeutics for

leukemia. Some HDACis can be combined with conventional therapy to

improve treatment efficacy and overcome resistance. Moreover,

precision therapy can be established by rationally designing

selective HDACi-based treatments via the guidance of HDAC

expression profiling or the development of muti-targeted

dual/hybrid inhibitors.

As aforementioned, several lines of evidence suggest

that the aberrant expression and function of HDAC enzymes play

important roles in several solid cancers and hematological

malignancies. HDACs facilitate tumor suppressor gene silencing in

cancer cells, preventing them from undergoing apoptosis. Thus, the

development of a new therapeutic agent that targets the HDAC enzyme

to restore the acetylation of histones is needed (Fig. 2). It has been clearly described that

HDACis can induce cell cycle arrest and cancer cell death. The main

inhibitory mechanism of HDACis involves blocking the substrate

binding of HDAC by interacting with the enzyme catalytic domain.

HDACis have been discovered and identified from both natural and

synthetic sources. HDACis can be classified into 4 groups based on

their chemical structure. The three groups are small-molecule

inhibitors, which include short-chain fatty acids, hydroxamic acids

and benzamides. The other group is cyclic peptide inhibitors.

Small-molecule HDACis are usually pan-HDACis, whereas peptide-based

HDACis are more class-selective or isoform-selective HDACis due to

their larger molecular dimensions and conformational flexibility.

This feature enables them to mimic natural protein interactions

more precisely. All HDACis share the same core structure consisting

of three domains, which consists of a cap region, a hydrophobic

linker and a zinc binding group (ZBG). The cap region interacts on

the surface at the entrance of the substrate, ZBG is the position

of the functional group that binds and chelates a zinc ion in the

catalytic site, and the hydrophobic linker domain is the region

between the cap region and ZBG (70,71).

Peptide inhibitors typically have a more complex ‘cap group’ that

binds extensively to the enzyme surface (72), triggering disruption of HDAC

interactions with specific corepressor complexes or

chromatin-associated scaffolds in leukemia cells. This allows them

to potentially modulate leukemia-specific epigenetic states more

precisely. On the other hand, small-molecule inhibitors

predominantly rely on zinc-chelation and catalytic site blockade,

thus broadly inhibiting catalytic activity and affecting multiple

HDAC isoforms and complexes (73).

This mechanistic difference highlights the potential of peptides

for refined epigenetic therapy in leukemia. The differences between

small-molecule and peptide-based HDACis are summarized in Table II.

Short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate and

valproic acid (VPA) are inhibitors of class I and IIa HDACs.

Butyrate is produced natively by anaerobic bacterial fermentation

of carbohydrates in the colon and longer-chain fatty acid

metabolism. It has been reported that the possible HDAC inhibition

mechanism of butyrate may be attributed to its hydrophobic

interaction with the HDAC active pocket; hence, it binds

non-specifically (74). Butyrate

induces the hyperacetylation of histones, regulating gene

expression, and has been used for cancer treatment (75,76).

It is characterized by low activity, short half-life and rapid

metabolism, leading to a high effective concentration in

vivo (77,78). VPA, a short chain aliphatic acid,

has been reported to have antileukemic effects, such as

anti-proliferation, induction of differentiation and stimulation of

apoptosis, in AML (79,80). Certain studies have shown that VPA

also has low HDAC inhibition activity; however, the combination of

VPA with another chemotherapy drugs could increase the response in

patients with leukemia (81,82).

Hydroxamic acids are organic compounds that can form

table complexes with a variety of metal ions; therefore, their

mechanism of action involves chelation zinc ions in the HDAC

catalytic site (71). Hydroxamic

acids act as potent pan-HDACis that affect HDAC classes I and II.

Trichostatin A (TSA) is a naturally occurring compound that

consists of an aromatic group as a cap region linked by a diene

region connected to the hydroxamate tail. TSA has been proposed as

an effective drug for the treatment of CLL (83). Since it has been shown that the

mutant HDAC enzyme affects the binding activity between TSA and

HDAC isoforms, TSA is used in clinical treatment with limitations

(84). Suberoylanilide hydroxamic

acid (SAHA; vorinostat) is a synthetic hydroxamic acid-containing

HDACi that is structurally related to TSA. SAHA was approved by the

FDA for the treatment of refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

(85). Other HDACi drugs composed

of hydroxamic acid groups are belinostat and panobinostat (86,87).

These hydroxamate compounds have been recently investigated in

clinical trials for the treatment of other hematological

malignancies.

Benzamides (amino anilides) are synthetic compounds

that display selective inhibitory activity against class I HDACs.

Benzamides can interact with and chelate a zinc ion in the HDAC

pocket site, but their chelating activity is lower than that of

hydroxamate and cyclic peptide compounds (88). Several benzamide derivatives,

including entinostat and mocetinostat, have been reported to

inhibit malignant cell proliferation and are currently undergoing

clinical trials for the treatment of hematologic malignancies

(89,90).

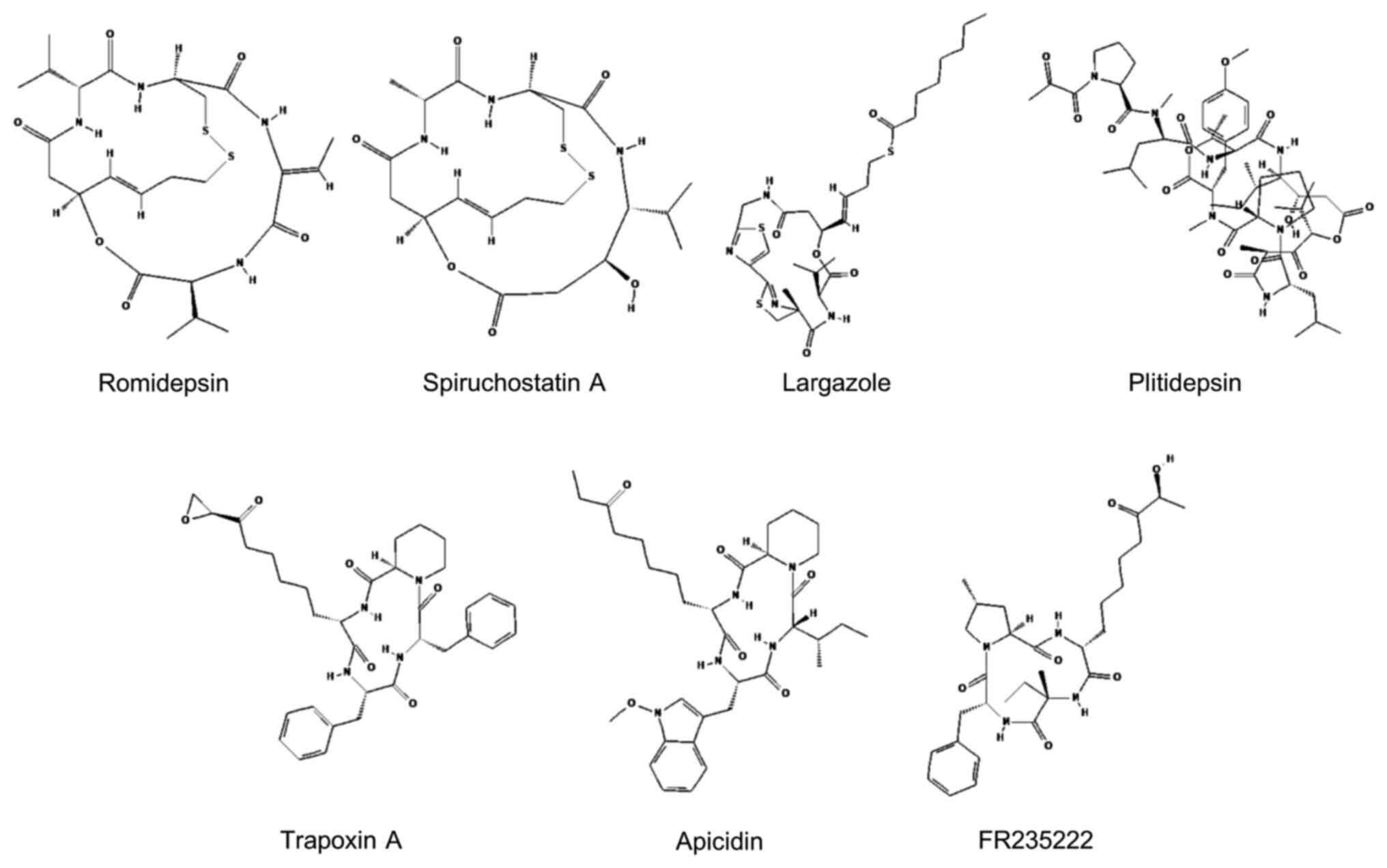

Cyclic peptides are the most structurally diverse

class of HDACis. They can be divided into the following two main

groups: Cyclic tetrapeptides and bicyclic depsipeptides. Cyclic

tetrapeptides contain epoxy ketone groups that interact with amino

acids at the HDAC catalytic site, mainly through covalent bonds.

The bicyclic depsipeptide structure contains disulfide bonds that

attach to a zinc ion in the HDAC active site, leading to inhibition

of HDAC activity. These cyclic peptides play important roles in

targeting different HDAC isoforms depending on variations in cap

regions (72,91). Owing to their strong inhibitory

activity and potential HDAC-isoform selectivity, cyclic peptides

are being intensively studied as prospective candidates for

anticancer therapy development. Insights into cyclic peptide HDACis

that have been investigated for leukemia therapy applications are

elaborated upon in the following section. Their chemical structures

are shown in Fig. 3.

Romidepsin (FK228), a natural bicyclic depsipeptide,

was first isolated from the gram-negative bacterium,

Chromobacterium violaceum, and characterized as an antitumor

substance both in vitro and in vivo (92). Romidepsin possesses HDAC inhibitory

activity by interacting with zinc ions in the active region of HDAC

enzymes. It acts as a prodrug because it is reduced to the active

compound after uptake into cells (93). Romidepsin is mainly responsible for

binding class I HDAC enzymes, including HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 and

HDAC8, but this drug has minimal selectivity for HDAC6 targeting

(94). It is the most extensively

studied among peptide HDACis for its impact and mechanism of action

in a hematological aspect. Since 2009, the FDA has approved

romidepsin for the treatment of numerous hematological

malignancies, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and

peripheral T-cell lymphoma (95,96).

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that romidepsin has antitumor

effects in various subtypes of leukemia. Romidepsin demonstrated

antileukemic activity against APL cell lines by inducing APL cell

apoptosis via a mitochondria-dependent pathway and targeting the

NF-κB and p53 transcription factors (97) and increasing cell differentiation

induced by retinoic acid (98).

With respect to CML, romidepsin has been associated with the

induction of apoptosis by inactivation of the BCR-ABL fusion

protein (99). Another study in

AML1/ETO positive leukemia cell supported that romidepsin can exert

both differentiation and cytotoxic activity in AML cells,

regardless of the underlying genomic aberration (100). The combination of a

DNA-methyltransferase inhibitor and romidepsin has been reported to

enhance several biological activities, including histone

hyperacetylation, cytotoxic activity and IL-3 expression, in

leukemia cells (100,101). Additionally, the use of romidepsin

in combination with chemotherapy drugs has shown the potential to

overcome drug resistance in numerous types of leukemia (102,103). Recently, a phase I trial of

romidepsin in combination with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and

dexamethasone (Romi-GemOxD), has been conducted in patients with

relapsed or refractory aggressive lymphomas (104). The study showed that Romi-GemOxD

is a well-tolerated and effective treatment option. The overall

response rate was 52%, with a notably high complete response rate

of 43%. Most toxicities were hematologic (thrombocytopenia and

lymphopenia) which are manageable without delays in subsequent

cycles.

Largazole is a cyclic depsipeptide that contains a

4-methylthiazoline unit linearly fused with a thiazole ring. It is

derived from marine cyanobacteria of Symploca spp (105). Largazole shares the same

zinc-binding motif with romidepsin and spiruchostasin. It is also a

prodrug that requires conversion to a thiol derivative in order to

function. Largazole thiol has been shown to be a more effective

HDACi than romidepsin and spiruchostasin (106). In vitro, largazole

demonstrated significant suppressive activity in solid cancer cell

lines (107). Several studies have

synthesized analogs of largazole to improve its activity (108,109). To increase the stability of the

peptide conformation and to enhance HDAC inhibitory activity,

largazole was modified by addition of a C7-benzyl and the

bithiazole analog and capping with an octanoyl group to generate

largazole 4a. A study in the NB4 human leukemia cell line

demonstrated that largazole 4a selectively inhibit the activity of

class I and class II HDAC enzymes (HDAC1 and HDAC4, respectively).

Additionally, it has been shown to upregulatep21 and R-tubulin

acetylation at H3 in the NB4 cell line. However, this compound is

less potent than SAHA (a pan HDAC inhibitor drug that the FDA

approved for the treatment of relapsed CTCL). Previously, an in

vitro study using leukemia cells harvested from patients with

CML demonstrated that largazole induce apoptosis and inhibit CML

cell proliferation (110). It was

suggested that largazole exert its antileukemic effect by

downregulating the expression of the RNA-binding protein Musashi-2,

which subsequently suppresses the mammalian target of rapamycin

signaling pathway.

Apicidin is a cyclic tetrapeptide derived from the

fermenting broth of the fungus Fusarium spp. It was

identified as a hemorrhagic factor and was shown to exhibit

cytotoxic effect on human and mouse leukemia cell lines (134). Like that of trapoxin, its function

is based on an epoxide functional group of Aoe, which mimics the

ε-amino of lysine residues on histones. Apicidin acts as an HDAC

inhibitor with cytotoxic effects on several cancer cell lines

(135). It induced apoptosis in a

Bcr-abl positive leukemia cell line (K562) and primary leukemia

cells from patients with CML. Several reactions have been revealed

to be associated with apoptosis induction in K562 cells, including

increased histone H4 acetylation, disruption of mitochondrial

function, downregulation of Bcr-abl expression, and activation of

the caspase-cascade (136). These

findings indicate that apicidin acts via an intrinsic apoptotic

pathway. In addition, combining apicidin with the tyrosine kinase

inhibitor imatinib, leads to significant enhancement of apoptotic

effect in K562 cells. Apicidin can also induce apoptosis in Bcr-abl

negative leukemia cell lines, namely Jurkat, U937 and HL-60 cells.

However, a synergistic effect of the apicidin/imatinib combination

was not observed (137).

Previously, Ferrante et al (138) demonstrated inhibitory activity of

apicidin against HDAC3, which is shown to be a positive regulator

of the Notch signaling pathway. The study showed that HDAC3

deacetylated the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) protein

preventing it from degrading. Apicidin inhibited HDAC3 activity and

destabilized the NICD, which subsequently affected leukemia cell

survival. Correspondently, compared with normal lymphoid cells,

lymphoblastic leukemia cells had higher levels of HDAC3 expression.

Treatment with apicidin resulted in decreased cell viability in

human T-ALL cells and mantle cell lymphoma cells, but the apoptotic

ratio and cell cycle distribution were not altered. These results

suggested that apicidin could be a promising drug for the treatment

of leukemias. However, additional mechanisms underlying

antileukemic activity of apicidin still need to be explored.

Histone modification is an epigenetic regulator that

plays important roles in the development and progression of

leukemia. HDAC overexpression disrupts gene expression homeostasis

associated with cell survival, proliferation and differentiation.

Recent studies have shown that HDACis can be used to counteract

HDAC activity leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (142,143). Therefore, these compounds could be

potential candidates for novel cancer drugs. The present review

describes numerous peptides that act as HDACis as well as their

therapeutic mechanisms and outcomes in cancer studies. Compared

with small molecules, peptide inhibitors exhibit superior

properties, especially high selectivity, offering the potential for

reduced adverse effects and more precise targeting. Personalized

therapy based on HDAC levels can be conducted to avoid pan-HDACis

in favor of isoform-selective inhibitors, thereby improving safety

while retaining antileukemic activity. Combinatorial strategies

employing HDACis with other targeted therapies have also been

explored, aiming to enhance treatment efficacy while overcoming

resistance and minimizing toxicity. Translationally, it can be

suggested that cyclic peptide HDACis can enhance multimodal therapy

efficacy while maintaining acceptable safety profiles.

Notably, in clinical applications, numerous HDACis

fail owing to their low therapeutic effectiveness and risk of

adverse effects. Only two depsipeptides have been approved by the

FDA and are commercially available. Major limitations of peptide

drugs are that, compared with small-molecule inhibitors, they tend

to have higher molecular weights and show lower oral

bioavailability as a result of enzymatic degradation in the

gastrointestinal tract. Their pharmacokinetics are often

characterized by limited membrane permeability, relatively short

half-lives, and challenges in achieving adequate systemic exposure.

The enhancement of the pharmacokinetic properties of peptide drugs

by promising strategies, including encapsulation, drug delivery and

structure alteration, will be beneficial to their application in

leukemia. Nano-delivery technology is widely employed to improve

the bioavailability, antileukemic activity and tolerability of

peptide-based HDACis, as exemplified by developments of

nano-romidepsin (144,145). Furthermore, nanoparticles can be

functionalized with targeting ligands, such as antibodies or

aptamers that specifically bind to proteins presented in abundance

on tumor cells (for example, transferrin receptor, CD20, CD33 and

nucleophosmin). This approach may facilitate selective absorption

of HDACis into target cells, resulting in increased local

concentration. Homotypic targeting using nanoparticles coated with

membranes from leukemia cells or stem cells is also an attractive

option. Structural alteration, such as D-amino acid substitution,

PEGylation, cyclization and cationization, can improve the

stability and permeability of peptide drugs (146). Computational modeling technology

has been used as a tool to modify and optimize structure of HDACis

based on molecular docking and binding interaction analysis to

ensure drug selectivity and stability (147). Additionally, peptidomimetics can

be designed and constructed to generate stabilized peptide HDACis

with improved efficiency and selectivity (148). Future research should also focus

on the design of customized peptide inhibitors enabling precise

treatment for individuals.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Ratchadapisek Sompoch

Endowment Fund (2023), Chulalongkorn University (grant no.

Review_66_005_3700_002).

Not applicable.

PP and YS conceptualized and designed the study and

reviewed the manuscript. PP wrote the manuscript. YS acquired

funding, prepared tables and figures, and revised the manuscript.

Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Brown G: Introduction and Classification

of Leukemias. Leukemia Stem Cells: Methods and Protocols. Cobaleda

C and Sánchez-García I: Springer; New York, NY: pp. 3–23. 2021

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Daltveit DS, Morgan E, Colombet M,

Steliarova-Foucher E, Bendahhou K, Marcos-Gragera R, Rongshou Z,

Smith A, Wei H and Soerjomataram I: Global patterns of leukemia by

subtype, age, and sex in 185 countries in 2022. Leukemia.

39:412–419. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Du M, Chen W, Liu K, Wang L, Hu Y, Mao Y,

Sun X, Luo Y, Shi J, Shao K, et al: The global burden of leukemia

and its attributable factors in 204 countries and territories:

Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study and

projections to 2030. J Oncol. 2022:16127022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dong Y, Shi O, Zeng Q, Lu X, Wang W, Li Y

and Wang Q: Leukemia incidence trends at the global, regional, and

national level between 1990 and 2017. Exp Hematol Oncol. 9:142020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sharma R and Jani C: Mapping incidence and

mortality of leukemia and its subtypes in 21 world regions in last

three decades and projections to 2030. Ann Hematol. 101:1523–1534.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Briot T, Roger E, Thépot S and Lagarce F:

Advances in treatment formulations for acute myeloid leukemia. Drug

Discov Today. 23:1936–1949. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Škubník J, Pavlíčková VS, Ruml T and

Rimpelová S: Vincristine in combination therapy of cancer: Emerging

trends in clinics. Biology (Basel). 10:8492021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Park SB, Goldstein D, Krishnan AV, Lin CS,

Friedlander ML, Cassidy J, Koltzenburg M and Kiernan MC:

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: A critical analysis.

CA Cancer J Clin. 63:419–437. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mort MK, Sen JM, Morris AL, DeGregory KA,

McLoughlin EM, Mort JF, Dunn SP, Abuannadi M and Keng MK:

Evaluation of cardiomyopathy in acute myeloid leukemia patients

treated with anthracyclines. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 26:680–687. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wallace KB: Doxorubicin-induced cardiac

mitochondrionopathy. Pharmacol Toxicol. 93:105–115. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pogorzala M, Kubicka M, Rafinska B,

Wysocki M and Styczynski J: Drug-resistance profile in

multiple-relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Anticancer Res. 35:5667–5670. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xia CQ and Smith PG: Drug efflux

transporters and multidrug resistance in acute leukemia:

Therapeutic impact and novel approaches to mediation. Mol

Pharmacol. 82:1008–1021. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kantarjian HM, Keating MJ and Freireich

EJ: Toward the potential cure of leukemias in the next decade.

Cancer. 124:4301–4313. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bhansali RS, Pratz KW and Lai C: Recent

advances in targeted therapies in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Brivio E, Baruchel A, Beishuizen A,

Bourquin JP, Brown PA, Cooper T, Gore L, Kolb EA, Locatelli F,

Maude SL, et al: Targeted inhibitors and antibody immunotherapies:

Novel therapies for paediatric leukaemia and lymphoma. Eur J

Cancer. 164:1–17. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Das AB, Smith-Díaz CC and Vissers MCM:

Emerging epigenetic therapeutics for myeloid leukemia: Modulating

demethylase activity with ascorbate. Haematologica. 106:14–25.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang X, Wang H, Zhang Y and Wang X:

Advances in epigenetic alterations of chronic lymphocytic leukemia:

From pathogenesis to treatment. Clin Exp Med. 24:542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bian J and Zhang L, Han Y, Wang C and

Zhang L: Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Potent anti-leukemic

agents. Curr Med Chem. 22:2065–2074. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gaál Z, Oláh É, Rejtő L, Erdődi F and

Csernoch L: Strong correlation between the expression levels of

HDAC4 and SIRT6 in hematological malignancies of the adults. Pathol

Oncol Res. 23:493–504. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang F, Li Z, Zhou J, Wang G, Zhang W, Xu

J and Liang A: SIRT1 regulates the phosphorylation and degradation

of P27 by deacetylating CDK2 to promote T-cell acute lymphoblastic

leukemia progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:2592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Merarchi M, Sethi G, Shanmugam MK, Fan L,

Arfuso F and Ahn KS: Role of natural products in modulating histone

deacetylases in cancer. Molecules. 24:10472019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Singh AK, Bishayee A and Pandey AK:

Targeting histone deacetylases with natural and synthetic agents:

An emerging anticancer strategy. Nutrients. 10:7312018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Janssens Y, Wynendaele E, Vanden Berghe W

and De Spiegeleer B: Peptides as epigenetic modulators: Therapeutic

implications. Clin Epigenetics. 11:1012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang XJ and Seto E: HATs and HDACs: From

structure, function and regulation to novel strategies for therapy

and prevention. Oncogene. 26:5310–5318. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gray SG and Teh BT: Histone

acetylation/deacetylation and cancer: An ‘open’ and ‘shut’ case?

Curr Mol Med. 1:401–429. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lawson M, Uciechowska U, Schemies J, Rumpf

T, Jung M and Sippl W: Inhibitors to understand molecular

mechanisms of NAD(+)-dependent deacetylases (sirtuins). Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1799:726–739. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Seto E and Yoshida M: Erasers of histone

acetylation: The histone deacetylase enzymes. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 6:a0187132014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Asmamaw MD, He A, Zhang LR, Liu HM and Gao

Y: Histone deacetylase complexes: Structure, regulation and

function. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1879:1891502024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Duan Z, Zarebski A, Montoya-Durango D,

Grimes HL and Horwitz M: Gfi1 coordinates epigenetic repression of

p21 Cip/WAF1 by recruitment of histone lysine methyltransferase G9a

and histone deacetylase 1. Mol Cell biol. 25:10338–10351. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fujiwara T, Lee HY, Sanalkumar R and

Bresnick EH: Building multifunctionality into a complex containing

master regulators of hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:20429–20434. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

van Oorschot R, Hansen M, Koornneef JM,

Marneth AE, Bergevoet SM, van Bergen MGJM, van Alphen FPJ, van der

Zwaan C, Martens JHA, Vermeulen M, et al: Molecular mechanisms of

bleeding disorder associated GFI1BQ287* mutation and its affected

pathways in megakaryocytes and platelets. Haematologica.

104:1460–1472. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Calderon A, Mestvirishvili T, Boccalatte

F, Ruggles KV and David G: Chromatin accessibility and cell cycle

progression are controlled by the HDAC-associated Sin3B protein in

murine hematopoietic stem cells. Epigenetics Chromatin. 17:22024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wada T, Kikuchi J, Nishimura N, Shimizu R,

Kitamura T and Furukawa Y: Expression levels of histone

deacetylases determine the cell fate of hematopoietic progenitors.

J Biol Chem. 284:30673–30683. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang P, Wang Z and Liu J: Role of HDACs in

normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Mol Cancer. 19:52020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yan B, Yang J, Kim MY, Luo H, Cesari N,

Yang T, Strouboulis J, Zhang J, Hardison R, Huang S and Qiu Y:

HDAC1 is required for GATA-1 transcription activity, global

chromatin occupancy and hematopoiesis. Nucleic Acids Res.

49:9783–9798. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Iwasaki H, Mizuno S, Arinobu Y, Ozawa H,

Mori Y, Shigematsu H, Takatsu K, Tenen DG and Akashi K: The order

of expression of transcription factors directs hierarchical

specification of hematopoietic lineages. Genes Dev. 20:3010–3021.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yamamura K, Ohishi K, Katayama N, Yu Z,

Kato K, Masuya M, Fujieda A, Sugimoto Y, Miyata E, Shibasaki T, et

al: Pleiotropic role of histone deacetylases in the regulation of

human adult erythropoiesis. Br J Haematol. 135:242–253. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Das Gupta K, Shakespear MR, Iyer A,

Fairlie DP and Sweet MJ: Histone deacetylases in

monocyte/macrophage development, activation and metabolism:

refining HDAC targets for inflammatory and infectious diseases.

Clin Transl Immunol. 5:e622016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Heideman MR, Lancini C, Proost N, Yanover

E, Jacobs H and Dannenberg JH: Sin3a-associated Hdac1 and Hdac2 are

essential for hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis and contribute

differentially to hematopoiesis. Haematologica. 99:1292–1303. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu B, Ohishi K, Yamamura K, Suzuki K,

Monma F, Ino K, Nishii K, Masuya M, Sekine T, Heike Y, et al: A

potential activity of valproic acid in the stimulation of

interleukin-3−mediated megakaryopoiesis and erythropoiesis. Exp

Hematol. 38:685–695. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yamaguchi T, Cubizolles F, Zhang Y,

Reichert N, Kohler H, Seiser C and Matthias P: Histone deacetylases

1 and 2 act in concert to promote the G1-to-S progression. Genes

Dev. 24:455–469. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Boucheron N, Tschismarov R, Göschl L,

Moser MA, Lagger S, Sakaguchi S, Winter M, Lenz F, Vitko D,

Breitwieser FP, et al: CD4+ T cell lineage integrity is controlled

by the histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2. Nat Immunol.

15:439–448. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ni L, Wang L, Yao C, Ni Z, Liu F, Gong C,

Zhu X, Yan X, Watowich SS, Lee DA and Zhu S: The histone

deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid inhibits NKG2D expression in

natural killer cells through suppression of STAT3 and HDAC3. Sci

Rep. 7:452662017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lemercier C, Brocard MP, Puvion-Dutilleul

F, Kao HY, Albagli O and Khochbin S: Class II histone deacetylases

are directly recruited by BCL6 transcriptional repressor. J Biol

Chem. 277:22045–22052. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kasler HG and Verdin E: Histone

deacetylase 7 functions as a key regulator of genes involved in

both positive and negative selection of thymocytes. Mol Cell Biol.

27:5184–5200. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li J, Li X, Sun W, Zhang J, Yan Q, Wu J,

Jin J, Lu R and Miao D: Specific overexpression of SIRT1 in

mesenchymal stem cells rescues hematopoiesis niche in BMI1 knockout

mice through promoting CXCL12 expression. Int J Biol Sci.

18:2091–2103. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Skokowa J, Lan D, Thakur BK, Wang F, Gupta

K, Cario G, Brechlin AM, Schambach A, Hinrichsen L, Meyer G, et al:

NAMPT is essential for the G-CSF-induced myeloid differentiation

via a NAD(+)-sirtuin-1-dependent pathway. Nat Med. 15:151–158.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ou X, Chae HD, Wang RH, Shelley WC, Cooper

S, Taylor T, Kim YJ, Deng CX, Yoder MC and Broxmeyer HE: SIRT1

deficiency compromises mouse embryonic stem cell hematopoietic

differentiation, and embryonic and adult hematopoiesis in the

mouse. Blood. 117:440–450. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Brown K, Xie S, Qiu X, Mohrin M, Shin J,

Liu Y, Zhang D, Scadden DT and Chen D: SIRT3 reverses

aging-associated degeneration. Cell Rep. 3:319–327. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Kaiser A, Schmidt M, Huber O, Frietsch JJ,

Scholl S, Heidel FH, Hochhaus A, Müller JP and Ernst T: SIRT7: An

influence factor in healthy aging and the development of

age-dependent myeloid stem-cell disorders. Leukemia. 34:2206–2216.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Luo H, Mu WC, Karki R, Chiang HH, Mohrin

M, Shin JJ, Ohkubo R, Ito K, Kanneganti TD and Chen D:

Mitochondrial stress-Initiated aberrant activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome regulates the functional deterioration of

hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Rep. 26:945–954.e4. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sahakian E, Chen J, Powers JJ, Chen X,

Maharaj K, Deng SL, Achille AN, Lienlaf M, Wang HW, Cheng F, et al:

Essential role for histone deacetylase 11 (HDAC11) in neutrophil

biology. J Leukoc Biol. 102:475–486. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Grignani F, De Matteis S, Nervi C,

Tomassoni L, Gelmetti V, Cioce M, Fanelli M, Ruthardt M, Ferrara

FF, Zamir I, et al: Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid

receptor-alpha recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic

leukaemia. Nature. 391:815–818. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Gelmetti V, Zhang J, Fanelli M, Minucci S,

Pelicci PG and Lazar MA: Aberrant recruitment of the nuclear

receptor corepressor-histone deacetylase complex by the acute

myeloid leukemia fusion partner ETO. Mol Cell Biol. 18:7185–7191.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Girard N, Tremblay M, Humbert M, Grondin

B, Haman A, Labrecque J, Chen B, Chen Z, Chen SJ and Hoang T:

RARα-PLZF oncogene inhibits C/EBPα function in myeloid cells. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:13522–13527. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang J, Hug BA, Huang EY, Chen CW,

Gelmetti V, Maccarana M, Minucci S, Pelicci PG and Lazar MA:

Oligomerization of ETO is obligatory for corepressor interaction.

Mol Cell Biol. 21:156–163. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Vishwakarma BA, Nguyen N, Makishima H,

Hosono N, Gudmundsson KO, Negi V, Oakley K, Han Y, Przychodzen B,

Maciejewski JP and Du Y: Runx1 repression by histone deacetylation

is critical for Setbp1-induced mouse myeloid leukemia development.

Leukemia. 30:200–208. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Nakata S, Yoshida T, Horinaka M, Shiraishi

T, Wakada M and Sakai T: Histone deacetylase inhibitors upregulate

death receptor 5/TRAIL-R2 and sensitize apoptosis induced by

TRAIL/APO2-L in human malignant tumor cells. Oncogene.

23:6261–6271. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Yoo CB and Jones PA: Epigenetic therapy of

cancer: past, present and future. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 5:37–50.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Mehrpouri M, Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi A and

Bashash D: The contributory roles of histone deacetylases (HDACs)

in hematopoiesis regulation and possibilities for pharmacologic

interventions in hematologic malignancies. Int Immunopharmacol.

100:1081142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Van Damme M, Crompot E, Meuleman N, Mineur

P, Bron D, Lagneaux L and Stamatopoulos B: HDAC isoenzyme

expression is deregulated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells

and has a complex prognostic significance. Epigenetics.

7:1403–1412. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Verbeek TCAI, Vrenken KS, Arentsen-Peters

STCJM, Castro PG, van de Ven M, van Tellingen O, Pieters R and Stam

RW: Selective inhibition of HDAC class IIA as therapeutic

intervention for KMT2A-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Commun Biol. 7:12572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Gu W and Roeder RG: Activation of p53

sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal

domain. Cell. 90:595–606. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Molica M, Mazzone C, Niscola P and de

Fabritiis P: TP53 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: Still a

daunting challenge? Front Oncol. 10:6108202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Kuo YH, Qi J and Cook GJ: Regain control

of p53: Targeting leukemia stem cells by isoform-specific HDAC

inhibition. Exp Hematol. 44:315–321. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Qi J, Singh S, Hua WK, Cai Q, Chao SW, Li

L, Liu H, Ho Y, McDonald T, Lin A, et al: HDAC8 inhibition

specifically targets inv(16) acute myeloid leukemic stem cells by

restoring p53 acetylation. Cell Stem Cell. 17:597–610. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Lee SM, Bae JH, Kim MJ, Lee HS, Lee MK,

Chung BS, Kim DW, Kang CD and Kim SH: Bcr-Abl-independent

imatinib-resistant K562 cells show aberrant protein acetylation and

increased sensitivity to histone deacetylase inhibitors. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 322:1084–1092. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Burgess M, Chen YCE, Mapp S, Blumenthal A,

Mollee P, Gill D and Saunders NA: HDAC7 is an actionable driver of

therapeutic antibody resistance by macrophages from CLL patients.

Oncogene. 39:5756–5767. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Micelli C and Rastelli G: Histone

deacetylases: Structural determinants of inhibitor selectivity.

Drug Discov Today. 20:718–735. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhang L, Zhang J, Jiang Q, Zhang L and

Song W: Zinc binding groups for histone deacetylase inhibitors. J

Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 33:714–721. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Rajak H, Singh A, Dewangan PK, Patel V,

Jain DK, Tiwari SK, Veerasamy R and Sharma PC: Peptide based

aacrocycles: Selective histone deacetylase inhibitors with

antiproliferative activity. Curr Med Chem. 20:1887–1903. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Curcio A, Rocca R, Alcaro S and Artese A:

The histone deacetylase family: Structural features and application

of combined computational methods. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

17:6202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Davie JR: Inhibition of histone

deacetylase activity by butyrate. J Nutr. 133 (7

Suppl):2485S–2493S. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Luu M, Riester Z, Baldrich A, Reichardt N,

Yuille S, Busetti A, Klein M, Wempe A, Leister H, Raifer H, et al:

Microbial short-chain fatty acids modulate CD8(+) T cell responses

and improve adoptive immunotherapy for cancer. Nat Commun.

12:40772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Ozkan AD, Eskiler GG, Kazan N and Turna O:

Histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate regulates the

activation of toll-like receptor 4/interferon regulatory factor-3

signaling pathways in prostate cancer cells. J Cancer Res Ther.

19:1812–1817. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Sampathkumar SG, Jones MB, Meledeo MA,

Campbell CT, Choi SS, Hida K, Gomutputra P, Sheh A, Gilmartin T,

Head SR and Yarema KJ: Targeting glycosylation pathways and the

cell cycle: Sugar-dependent activity of butyrate-carbohydrate

cancer prodrugs. Chem Biol. 13:1265–1275. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Steliou K, Boosalis MS, Perrine SP,

Sangerman J and Faller DV: Butyrate histone deacetylase inhibitors.

Biores Open Access. 1:192–198. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Tang R, Faussat AM, Majdak P, Perrot JY,

Chaoui D, Legrand O and Marie JP: Valproic acid inhibits

proliferation and induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells

expressing P-gp and MRP1. Leukemia. 18:1246–1251. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Zapotocky M, Mejstrikova E, Smetana K,

Stary J, Trka J and Starkova J: Valproic acid triggers

differentiation and apoptosis in AML1/ETO-positive leukemic cells

specifically. Cancer Lett. 319:144–153. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Fredly H, Gjertsen BT and Bruserud Ø:

Histone deacetylase inhibition in the treatment of acute myeloid

leukemia: The effects of valproic acid on leukemic cells, and the

clinical and experimental evidence for combining valproic acid with

other antileukemic agents. Clin Epigenetics. 5:122013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian HM,

Sanchez-Gonzalez B, Yang H, Rosner G, Verstovsek S, Rytting M,

Wierda WG, Ravandi F, Koller C, et al: Phase 1/2 study of the

combination of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine with valproic acid in

patients with leukemia. Blood. 108:3271–3279. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Peiffer L, Poll-Wolbeck SJ, Flamme H,

Gehrke I, Hallek M and Kreuzer KA: Trichostatin A effectively

induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells via

inhibition of Wnt signaling and histone deacetylation. J Cancer Res

Clin Oncol. 140:1283–1293. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Khan N, Jeffers M, Kumar S, Hackett C,

Boldog F, Khramtsov N, Qian X, Mills E, Berghs SC, Carey N, et al:

Determination of the class and isoform selectivity of

small-molecule histone deacetylase inhibitors. Biochem J.

409:581–589. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Duvic M, Talpur R, Ni X, Zhang C, Hazarika

P, Kelly C, Chiao JH, Reilly JF, Ricker JL, Richon VM and Frankel

SR: Phase 2 trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic

acid, SAHA) for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood.

109:31–39. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Campbell P and Thomas CM: Belinostat for

the treatment of relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

J Oncol Pharm Pract. 23:143–147. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Laubach JP, Moreau P, San-Miguel JF and

Richardson PG: Panobinostat for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

Clin Cancer Res. 21:4767–4773. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Wagner JM, Hackanson B, Lübbert M and Jung

M: Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in recent clinical trials

for cancer therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 1:117–136. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Batlevi CL, Crump M, Andreadis C, Rizzieri

D, Assouline SE, Fox S, van der Jagt RHC, Copeland A, Potvin D,

Chao R and Younes A: A phase 2 study of mocetinostat, a histone

deacetylase inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory lymphoma. Br J

Haematol. 178:434–441. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Carraway HE, Sawalha Y, Gojo I, Lee MJ,

Lee S, Tomita Y, Yuno A, Greer J, Smith BD, Pratz KW, et al: Phase

1 study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat plus

clofarabine for poor-risk Philadelphia chromosome-negative (newly

diagnosed older adults or adults with relapsed refractory disease)

acute lymphoblastic leukemia or biphenotypic leukemia. Leuk Res.

110:1067072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Maolanon AR, Kristensen HM, Leman LJ,

Ghadiri MR and Olsen CA: Natural and synthetic macrocyclic

inhibitors of the histone deacetylase enzymes. Chembiochem.

18:5–49. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Ueda H, Manda T, Matsumoto S, Mukumoto S,

Nishigaki F, Kawamura I and Shimomura K: FR901228, a novel

antitumor bicyclic depsipeptide produced by Chromobacterium

violaceum No. 968. III. Antitumor activities on experimental tumors

in mice. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 47:315–323. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Furumai R, Matsuyama A, Kobashi N, Lee KH,

Nishiyama M, Nakajima H, Tanaka A, Komatsu Y, Nishino N, Yoshida M

and Horinouchi S: FK228 (depsipeptide) as a natural prodrug that

inhibits class I histone deacetylases. Cancer Res. 62:4916–4921.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Murata M, Towatari M, Kosugi H, Tanimoto

M, Ueda R, Saito H and Naoe T: Apoptotic cytotoxic effects of a

histone deacetylase inhibitor, FK228, on malignant lymphoid cells.

Jpn J Cancer Res. 91:1154–1160. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Campas-Moya C: Romidepsin for the

treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Drugs Today (Barc).

45:787–795. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Coiffier B, Pro B, Prince HM, Foss F,

Sokol L, Greenwood M, Caballero D, Morschhauser F, Wilhelm M,

Pinter-Brown L, et al: Romidepsin for the treatment of

relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: Pivotal study

update demonstrates durable responses. J Hematol Oncol. 7:112014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Savickiene J, Treigyte G, Borutinskaite V,

Navakauskiene R and Magnusson KE: The histone deacetylase inhibitor

FK228 distinctly sensitizes the human leukemia cells to retinoic

acid-induced differentiation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1091:368–384. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Kosugi H, Ito M, Yamamoto Y, Towatari M,

Ito M, Ueda R, Saito H and Naoe T: In vivo effects of a histone

deacetylase inhibitor, FK228, on human acute promyelocytic leukemia

in NOD/Shi-scid/scid mice. Jpn J Cancer Res. 92:529–536. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Okabe S, Tauchi T, Nakajima A, Sashida G,

Gotoh A, Broxmeyer HE, Ohyashiki JH and Ohyashiki K: Depsipeptide

(FK228) preferentially induces apoptosis in BCR/ABL-expressing cell

lines and cells from patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in

blast crisis. Stem Cells Dev. 16:503–514. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Klisovic MI, Maghraby EA, Parthun MR,

Guimond M, Sklenar AR, Whitman SP, Chan KK, Murphy T, Anon J,

Archer KJ, et al: Depsipeptide (FR 901228) promotes histone

acetylation, gene transcription, apoptosis and its activity is

enhanced by DNA methyltransferase inhibitors in AML1/ETO-positive

leukemic cells. Leukemia. 17:350–358. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Shaker S, Bernstein M, Momparler LF and

Momparler RL: Preclinical evaluation of antineoplastic activity of

inhibitors of DNA methylation (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) and histone

deacetylation (trichostatin A, depsipeptide) in combination against

myeloid leukemic cells. Leuk Res. 27:437–444. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Brunvand MW and Carson J: Complete

remission with romidepsin in a patient with T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia refractory to induction hyper-CVAD. Hematol

Oncol. 36:340–343. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Cox WPJ, Evander N, Van Ingen Schenau DS,

Stoll GR, Anderson N, De Groot L, Grünewald KJT, Hagelaar R, Butler

M, Kuiper RP, et al: Histone deacetylase inhibition sensitizes

p53-deficient B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia to

chemotherapy. Haematologica. 109:1755–1765. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Foley N, Riedell PA, Bartlett NL, Cashen

AF, Kahl BS, Fehniger TA, Fischer A, Moreno C, Liu J, Carson KR and

Mehta-Shah N: A phase I study of romidepsin in combination with

gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and dexamethasone in patients with

relapsed or refractory aggressive lymphomas enriched for T-Cell

lymphomas. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 25:328–336. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Seiser T, Kamena F and Cramer N: Synthesis

and biological activity of largazole and derivatives. Angew Chem

Int Ed Engl. 47:6483–6485. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Bowers A, West N, Taunton J, Schreiber SL,

Bradner JE and Williams RM: Total synthesis and biological mode of

action of largazole: A potent class I histone deacetylase

inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 130:11219–11222. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Taori K, Paul VJ and Luesch H: Structure

and activity of largazole, a potent antiproliferative agent from

the floridian marine cyanobacterium symploca sp. J Am Chem Soc.

130:1806–1807. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Souto JA, Vaz E, Lepore I, Pöppler AC,

Franci G, Alvarez R, Altucci L and de Lera AR: Synthesis and

biological characterization of the histone deacetylase inhibitor

largazole and C7-modified analogues. J Med Chem. 53:4654–4667.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Zhang B, Ruan ZW, Luo D, Zhu Y, Ding T,

Sui Q and Lei X: Unexpected enhancement of HDACs inhibition by MeS

substitution at C-2 position of fluoro largazole. Mar Drugs.

18:3442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Wang M, Sun XY, Zhou YC, Zhang KJ, Lu YZ,

Liu J, Huang YC, Wang GZ, Jiang S and Zhou GB: Suppression of

Musashi-2 by the small compound largazole exerts inhibitory effects

on malignant cells. Int J Oncol. 56:1274–1283. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Yurek-George A, Habens F, Brimmell M,

Packham G and Ganesan A: Total synthesis of spiruchostatin A, a

potent histone deacetylase inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 126:1030–1031.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Narita K, Fukui Y, Sano Y, Yamori T, Ito

A, Yoshida M and Katoh T: Total synthesis of bicyclic depsipeptides

spiruchostatins C and D and investigation of their histone

deacetylase inhibitory and antiproliferative activities. Eur J Med

Chem. 60:295–304. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Kanno S, Maeda N, Tomizawa A, Yomogida S,

Katoh T and Ishikawa M: Involvement of p21waf1/cip1 expression in

the cytotoxicity of the potent histone deacetylase inhibitor

spiruchostatin B towards susceptible NALM-6 human B cell leukemia

cells. Int J Oncol. 40:1391–1396. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Rehman MU, Jawaid P, Yoshihisa Y, Li P,

Zhao QL, Narita K, Katoh T, Kondo T and Shimizu T: Spiruchostatin A

and B, novel histone deacetylase inhibitors, induce apoptosis

through reactive oxygen species-mitochondria pathway in human

lymphoma U937 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 221:24–34. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Yao L: Aplidin PharmaMar. IDrugs.

6:246–250. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Erba E, Bassano L, Di Liberti G, Muradore

I, Chiorino G, Ubezio P, Vignati S, Codegoni A, Desiderio MA,

Faircloth G, et al: Cell cycle phase perturbations and apoptosis in

tumour cells induced by aplidine. Br J Cancer. 86:1510–1517. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Erba E, Serafini M, Gaipa G, Tognon G,

Marchini S, Celli N, Rotilio D, Broggini M, Jimeno J, Faircloth GT,

et al: Effect of aplidin in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cells. Br

J Cancer. 89:763–773. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Bresters D, Broekhuizen AJ, Kaaijk P,

Faircloth GT, Jimeno J and Kaspers GJ: In vitro cytotoxicity of

aplidin and crossresistance with other cytotoxic drugs in childhood

leukemic and normal bone marrow and blood samples: A rational basis

for clinical development. Leukemia. 17:1338–1343. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Gómez SG, Bueren JA, Faircloth GT, Jimeno

J and Albella B: In vitro toxicity of three new antitumoral drugs

(trabectedin, aplidin, and kahalalide F) on hematopoietic

progenitors and stem cells. Exp Hematol. 31:1104–1111. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Gajate C, An F and Mollinedo F: Rapid and

selective apoptosis in human leukemic cells induced by Aplidine

through a Fas/CD95- and mitochondrial-mediated mechanism. Clin

Cancer Res. 9:1535–1545. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Mitsiades CS, Ocio EM, Pandiella A, Maiso

P, Gajate C, Garayoa M, Vilanova D, Montero JC, Mitsiades N,

McMullan CJ, et al: Aplidin, a marine organism-derived compound

with potent antimyeloma activity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res.

68:5216–5225. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Muñoz-Alonso MJ, Álvarez E,

Guillén-Navarro MJ, Pollán M, Avilés P, Galmarini CM and Muñoz A:

c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation is a biomarker of

plitidepsin activity. Mar Drugs. 11:1677–1692. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Broggini M, Marchini SV, Galliera E,

Borsotti P, Taraboletti G, Erba E, Sironi M, Jimeno J, Faircloth

GT, Giavazzi R and D'Incalci M: Aplidine, a new anticancer agent of

marine origin, inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

secretion and blocks VEGF-VEGFR-1 (flt-1) autocrine loop in human

leukemia cells MOLT-4. Leukemia. 17:52–59. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Morande PE, Zanetti SR, Borge M, Nannini

P, Jancic C, Bezares RF, Bitsmans A, González M, Rodríguez AL,

Galmarini CM, et al: The cytotoxic activity of Aplidin in chronic

lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is mediated by a direct effect on

leukemic cells and an indirect effect on monocyte-derived cells.

Invest New Drugs. 30:1830–1840. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Barboza NM, Medina DJ, Budak-Alpdogan T,

Aracil M, Jimeno JM, Bertino JR and Banerjee D: Plitidepsin

(Aplidin) is a potent inhibitor of diffuse large cell and Burkitt

lymphoma and is synergistic with rituximab. Cancer Biol Ther.

13:114–122. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Humeniuk R, Menon LG, Mishra PJ, Saydam G,

Longo-Sorbello GS, Elisseyeff Y, Lewis LD, Aracil M, Jimeno J,

Bertino JR and Banerjee D: Aplidin synergizes with cytosine

arabinoside: Functional relevance of mitochondria in

Aplidin-induced cytotoxicity. Leukemia. 21:2399–2405. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Spicka I, Ocio EM, Oakervee HE, Greil R,

Banh RH, Huang SY, D'Rozario JM, Dimopoulos MA, Martínez S,

Extremera S, et al: Randomized phase III study (ADMYRE) of

plitidepsin in combination with dexamethasone vs. dexamethasone

alone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Ann

Hematol. 98:2139–2150. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Mateos MV, Prosper F, Martin Sánchez J,

Ocio EM, Oriol A, Motlló C, Michot JM, Jarque I, Iglesias R, Solé

M, et al: Phase I study of plitidepsin in combination with

bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory

multiple myeloma. Cancer Med. 12:3999–4009. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Itazaki H, Nagashima K, Sugita K, Yoshida

H, Kawamura Y, Yasuda Y, Matsumoto K, Ishii K, Uotani N, Nakai H,

et al: Isolation and structural elucidation of new

cyclotetrapeptides, trapoxins A and B, having detransformation

activities as antitumor agents. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 43:1524–1532.

1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Furumai R, Komatsu Y, Nishino N, Khochbin

S, Yoshida M and Horinouchi S: Potent histone deacetylase

inhibitors built from trichostatin A and cyclic tetrapeptide

antibiotics including trapoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:87–92.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Kijima M, Yoshida M, Sugita K, Horinouchi

S and Beppu T: Trapoxin, an antitumor cyclic tetrapeptide, is an

irreversible inhibitor of mammalian histone deacetylase. J Biol

Chem. 268:22429–22435. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Kosugi H, Towatari M, Hatano S, Kitamura

K, Kiyoi H, Kinoshita T, Tanimoto M, Murate T, Kawashima K, Saito H

and Naoe T: Histone deacetylase inhibitors are the potent

inducer/enhancer of differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia: A

new approach to anti-leukemia therapy. Leukemia. 13:1316–1324.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Maeda T, Towatari M, Kosugi H and Saito H:

Up-regulation of costimulatory/adhesion molecules by histone

deacetylase inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood.

96:3847–3856. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Park JS, Lee KR, Kim JC, Lim SH, Seo JA

and Lee YW: A hemorrhagic factor (Apicidin) produced by toxic

Fusarium isolates from soybean seeds. Appl Environ Microbiol.

65:126–130. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Han JW, Ahn SH, Park SH, Wang SY, Bae GU,

Seo DW, Kwon HK, Hong S, Lee HY, Lee YW and Lee HW: Apicidin, a

histone deacetylase inhibitor, inhibits proliferation of tumor

cells via induction of p21WAF1/Cip1 and gelsolin. Cancer Res.

60:6068–6074. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Cheong JW, Chong SY, Kim JY, Eom JI, Jeung

HK, Maeng HY, Lee ST and Min YH: Induction of apoptosis by