As one of the most prevalent and deadly malignancies

worldwide, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for >85%

of LC cases (1–3). NSCLC exhibits notable molecular

heterogeneity, with key driver gene mutations including epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR), kirsten ratsarcoma viral oncogene

homolog (KRAS) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. These mutations play

a crucial role in determining treatment strategies and prognosis

for patients (4,5). Although targeted therapies and

immunotherapies have notably improved survival in some patients,

the 5-year survival rate for NSCLC remains <20%, particularly in

advanced-stage cases, where tumor heterogeneity, metastatic

potential and drug resistance pose notable therapeutic challenges

(6,7). Therefore, investigating the mechanisms

underlying NSCLC development and progression, as well as

identifying novel therapeutic targets, remains a key focus.

Members of the SOX family are evolutionarily

conserved transcription factors that regulate gene expression by

binding DNA, playing a central role in embryonic development, cell

fate determination and the maintenance of stem cell pluripotency

(8,9). Studies have revealed the abnormal

expression of SOX family members such as SOX2, SOX4 and SOX9 in

various solid tumors, including colorectal, breast and liver

cancers (10–12). These factors contribute to tumor

malignancy by regulating cancer stemness, epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT), metabolic reprogramming and microenvironment

remodeling (13,14). Particularly in NSCLC, SOX proteins

exhibit dual regulatory functions: Certain members (SOX2) may

promote chemotherapy resistance by maintaining cancer stem cell

properties, whereas others (SOX17) serve as tumor suppressors by

inhibiting oncogenic signaling pathways (15). This functional diversity suggests

the SOX family forms a complex regulatory network in NSCLC, the

precise mechanisms of which require systematic elucidation.

However, expression patterns of different SOX members across NSCLC

subtypes and molecular classifications, as well as their clinical

significance, remain incompletely understood. Moreover, the

interplay between their downstream regulatory networks and

epigenetic modifications requires further investigation.

Furthermore, translating the molecular functions of SOX proteins

into clinical applications, such as their development as biomarkers

or therapeutic targets, remains a notable challenge.

With advancements in high-throughput sequencing

technologies, researchers can gain a more detailed understanding of

genomic alterations in SOX family members, offering insight into

the complexity of NSCLC. Single-cell RNA sequencing provides an

opportunity to analyze intratumoral heterogeneity more precisely,

which is key for identifying the specific functions and roles of

SOX family members (16). Notably,

intervention strategies targeting SOX family members are also

evolving. Techniques based on small interfering (si)RNA or

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic

repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) have been

explored to suppress the expression or function of SOX proteins

with the aim of achieving therapeutic effects (17). These emerging therapeutic approaches

not only expand understanding of potential NSCLC treatments but

also offer new perspectives for future personalized medicine.

The present study aimed to summarize the expression

patterns, molecular mechanism and clinical relevance of SOX protein

in NSCLC, with emphasis on SOX2, SOX4 and SOX9 (implicated in

critical oncogenic processes, including cell proliferation,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, stemness maintenance, and

chemoresistance (18–21), their role in tumor progression, stem

cells and drug resistance, as well as their potential as diagnostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Comprehensive understanding of

the SOX family in NSCLC may drive the development of more

personalized and effective treatments, ultimately improving patient

outcomes and quality of life.

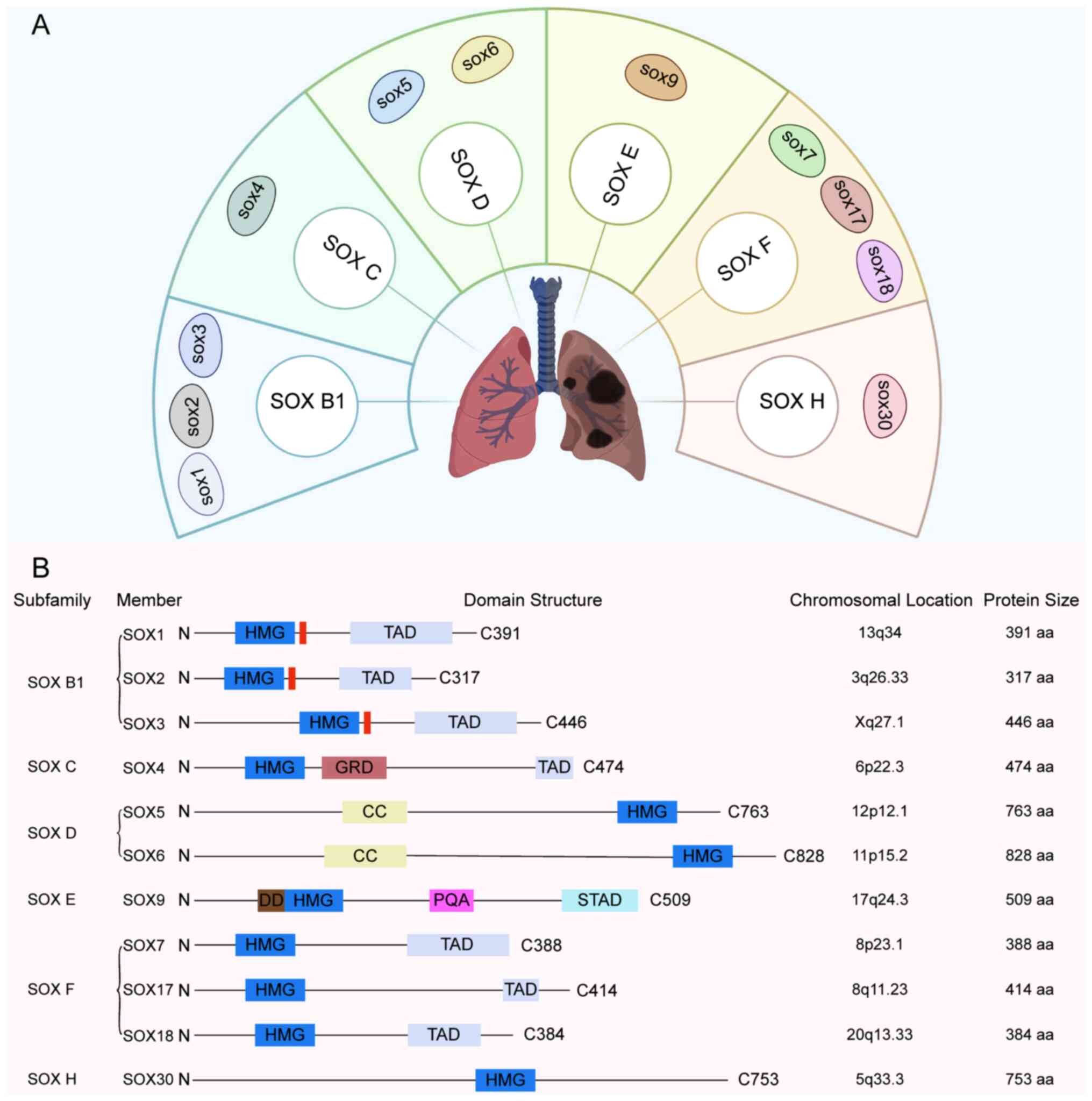

The SOX gene family encodes a series of

transcription factors characterized by a highly conserved domain

and is classified into ten subgroups (A-J) based on protein

homology (22). In LC research, the

subgroups most frequently involved include B1, C, D, E, F and H

(Fig. 1). These transcription

factors bind DNA through their high mobility group box domains and

regulate gene expression, thereby serving pivotal roles in

physiological processes such as embryonic development, cell fate

determination and differentiation. For example, SOX4, a member of

the C subgroup, serves as a key mediator of TNF-α-induced

transformation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in the pathological

progression of arthritis. It exerts its regulatory effects by

interacting with the transcription factor v-rel

reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A/p65) in the NF-κB

signaling pathway, thereby cooperatively modulating the expression

of downstream genes under TNF signaling (23). Similarly, SOX3, a member of the

SOXB1 subfamily, is broadly expressed during embryogenesis,

neurogenesis and gonadal development in Misgurnus (loach),

and this expression pattern is conserved throughout vertebrate

evolution (24). In addition, the

expression of multiple SOX genes is observed in stem,

undifferentiated progenitor and differentiated cells with

neuro-sensory characteristics in cnidarians, further supporting the

ancient evolutionary conservation of the SOX gene family in

developmental biology (22).

Different SOX subgroups demonstrate functional specificity. For

example, SOX5 and SOX6 from the SOXD subgroup are involved in

transcriptional regulation during embryonic development, neural

growth and chondrogenesis (25). A

member of the SOXE subgroup, SOX9, serves a key role in sex

determination and gonadal development in various species (26). Notably, the majority of SOX family

members exhibit aberrant expression in NSCLC, influenced by

mechanisms including gene mutations, DNA methylation and regulation

by microRNAs (miRs; Table I)

(27). These dysregulated SOX genes

have notable effects on the initiation and progression of NSCLC.

Elucidating the functions and regulatory mechanisms of these SOX

genes will not only deepen understanding of NSCLC pathogenesis but

may provide potential targets for the development of novel targeted

therapeutic strategies.

SOX4 plays a pivotal role in the initiation and

progression of NSCLC. Studies have demonstrated that SOX4 is

significantly upregulated in NSCLC tissue and serves as an

independent prognostic marker, underlining its key role in

malignant tumor progression (33,34).

At the molecular level, SOX4 promotes NSCLC cell migration,

invasion and EMT by upregulating B cell-specific MLV integration

site-1 (BMI1) expression (35).

BMI1 induces the ubiquitination of histone H2A, which suppresses

the expression of zinc finger protein 24 and decreases the

secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor A, thereby

promoting tumor angiogenesis and providing support for tumor cell

proliferation and metastasis. Moreover, SOX4 regulates cell

processes, including proliferation, survival and migration of NSCLC

cells, through interactions with signaling pathways such as

PI3K/AKT (36,37). Furthermore, the hypoxia-sensitive

lncRNA CASC15 can promote the occurrence of LC by regulating the

SOX4/β-catenin axis. Under hypoxic conditions, CASC15 transcription

is activated, promoting the expression of SOX4, stabilizing the

β-catenin protein and ultimately enhancing NSCLC cell proliferation

and migration abilities (38).

Meanwhile, circular (circ)RNA circ_0020714 serves as an endogenous

miR-30a-5p sponge, enhancing the expression of SOX4 and promoting

immune escape and anti-PD-1 resistance in patients with NSCLC

(39). These findings highlight the

multifaceted role of SOX4 in NSCLC pathogenesis and progression,

making it a potential target for therapeutic interventions.

EGFR and KRAS mutations are common oncogenic drivers

in lung adenocarcinoma and serve a crucial role in tumorigenesis

(40). SOX9 expression is elevated

in lung adenocarcinoma, particularly those with KRAS mutations, and

mediates Notch1-induced EMT. A previous study demonstrated higher

SOX9 mRNA in KRAS-compared with EGFR-mutant tumors (41). This suggests SOX9 acts downstream of

Notch in KRAS-driven NSCLC, promoting invasion and metastasis, with

potential indirect antagonism to EGFR signaling due to mutual

exclusivity of KRAS/EGFR mutations (41). Furthermore, SOX9 is essential for

KRAS-driven lung adenocarcinoma progression. Loss of SOX9 decreases

tumor burden, extends survival and enhances anti-tumor immunity by

increasing levels of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells and

CD8+ T cells (42).

Although direct evidence regarding the interaction between SOX9 and

the EGFR/KRAS pathways in lung adenocarcinoma remains limited,

studies in other types of cancer suggest that SOX9 may regulate the

biological behavior of lung adenocarcinoma cells through crosstalk

with these signaling pathways (42–44).

For example, aberrant activation of EGFR or KRAS may regulate SOX9

expression or activity via downstream signaling cascades, thereby

affecting cell processes such as proliferation, differentiation,

migration and invasion (42–44).

Additionally, in colorectal cancer, SOX9 activates the canonical

Wnt/β-catenin pathway by promoting β-catenin stability, nuclear

translocation, and transcription of Wnt components like FZD7 and

LRP6, which drives tumor growth, metastasis, and stem cell-like

properties (45,46). In pancreatic cancer, the oncogene

KRAS induces the expression of SOX9 at both the mRNA and protein

levels, including its phosphorylated form, thereby promoting SOX9

nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity (47,48).

The transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1/IκBα/NF-κB

signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of SOX9 by KRAS. In

addition, SOX9 modulates the expression of mediator of DNA damage

checkpoint 1and minichromosome maintenance complex components,

which are associated with tumor cell proliferation, invasion and

metastasis (47). Furthermore, in

the context of KRAS mutations, ectopic expression of SOX9 in acinar

cells synergizes with oncogenic KRAS to markedly accelerate the

formation of precancerous lesions (48). In urothelial carcinoma, the

activation of EGFR can upregulate the expression of SOX9 via the

ERK signaling pathway, thereby promoting tumor occurrence; the

EGFR-ERK-SOX9 signaling cascade mechanism suggests that a similar

regulatory pathway may also exist in EGFR-mutated NSCLC (44). Elucidating the mechanistic interplay

between SOX9 and the EGFR/KRAS pathways in lung adenocarcinoma

holds promise for identifying novel therapeutic targets and

developing precision medicine strategies.

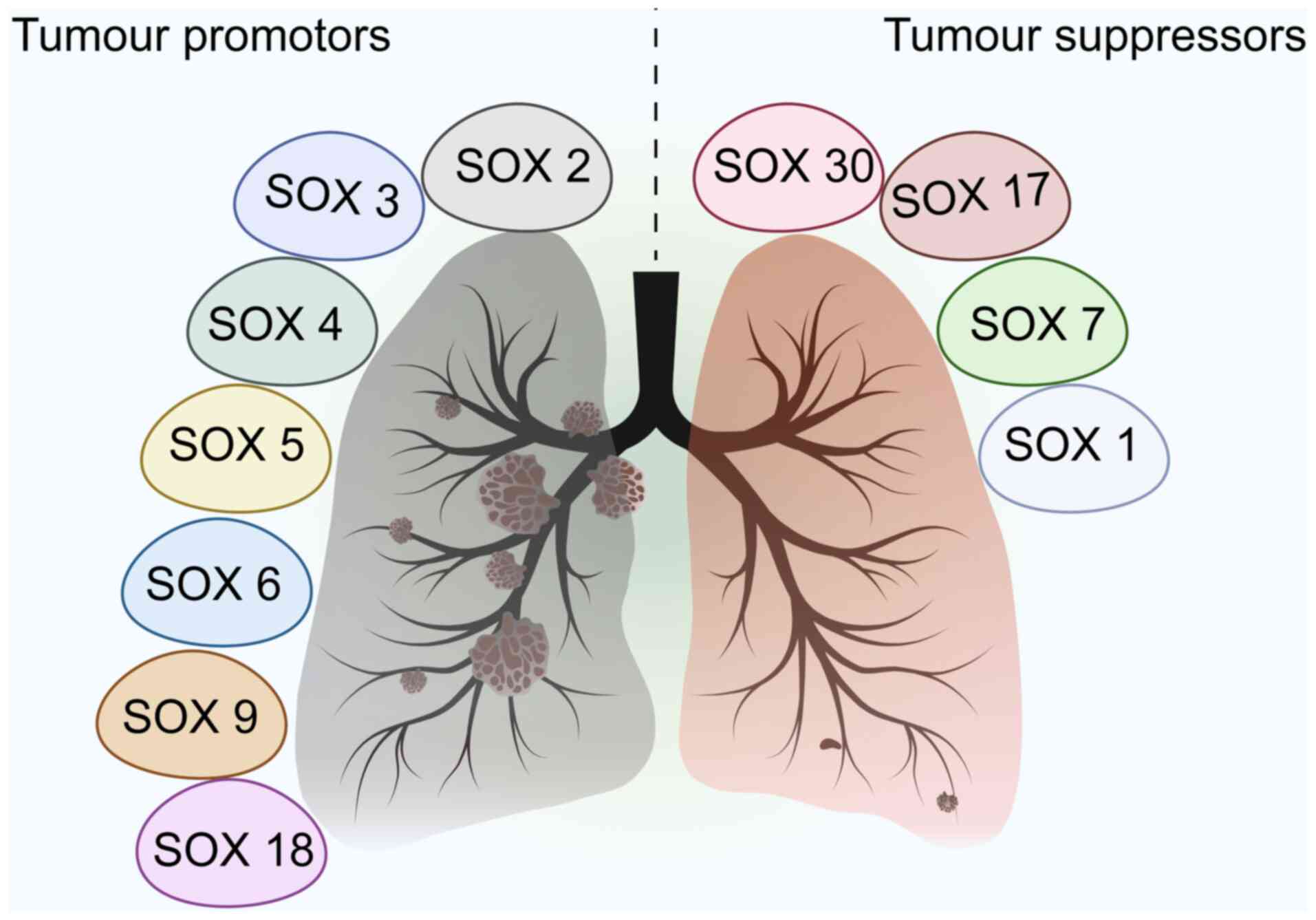

In addition to SOX2, SOX4, and SOX9, other members

of the SOX family regulate the initiation and progression of NSCLC

(Fig. 2). For example, SOX5 is

highly expressed in NSCLC and may serve as a supportive prognostic

marker for the diagnosis of NSCLC (49,50).

In a cohort of 90 patients with lung adenocarcinoma,

immunohistochemical analysis revealed elevated SOX5 expression in

tumor compared with adjacent non-tumor tissues. High SOX5 levels

were significantly associated with advanced clinical stage, lymph

node metastasis and reduced overall survival. Multivariate Cox

regression confirmed SOX5 as an independent prognostic factor for

poor survival (51). Functional

assays show SOX5 promotes EMT, enhancing invasion and migration,

while knockdown inhibits these processes in vitro and in

vivo (52). SOX5 is also

aberrantly upregulated in NSCLC cell lines, where it promotes

proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT via interaction with

YAP1. Knockdown of SOX5 suppresses tumor growth and metastasis, and

ncRNAs such as miR-143-3p that target SOX5 inhibit cancer

progression, underscoring its prognostic significance (51,53).

Additionally, elevated SOX18 expression is associated with poor

prognosis, and knockdown of SOX18 notably impairs cellular

migratory capacity (54,55). In a cohort of 198 NSCLC cases, SOX18

was expressed in the nuclei and cytoplasm of cancer cells in 94.4

and 47% of the NSCLC cases, respectively (54). SOX18 mRNA levels are lower in NSCLC

than in non-malignant lung tissue, but protein levels are higher.

Cytoplasmic SOX18 expression is associated with poor patient

outcome, and nuclear SOX18 is positively associated with Ki-67

proliferation index, suggesting its role in tumor progression and

potential as a prognostic biomarker (54). Although the specific role of SOX3 in

NSCLC remains largely unexplored, aberrant expression of SOX3 has

been reported in other malignancies such as osteosarcoma and breast

cancer (56,57). In these contexts, SOX3 dysregulation

is implicated in tumor development and progression, potentially via

its influence on apoptosis, migration and proliferation (56,58,59).

To elucidate its potential role in NSCLC, machine learning

approaches may be employed to integrate multi-omics datasets (such

as The Cancer Genome Atlas/Gene Expression Omnibus) for predicting

SOX3 interactions with pathways such as Wnt or EGFR. Furthermore,

artificial intelligence-driven clustering of SOX expression with

tumor mutational burden (TMB) and immune signatures may help

identify resistance patterns or novel biomarkers, while

bioinformatics analysis of SOX3 methylation may demonstrate

diagnostic value (60,61). Furthermore, SOX7 and SOX17 are

notably associated with prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma (60,62,63).

Patients with high expression of SOX7 and SOX17 exhibit better

overall survival, suggesting these genes may serve as potential

prognostic biomarkers (60,62,63).

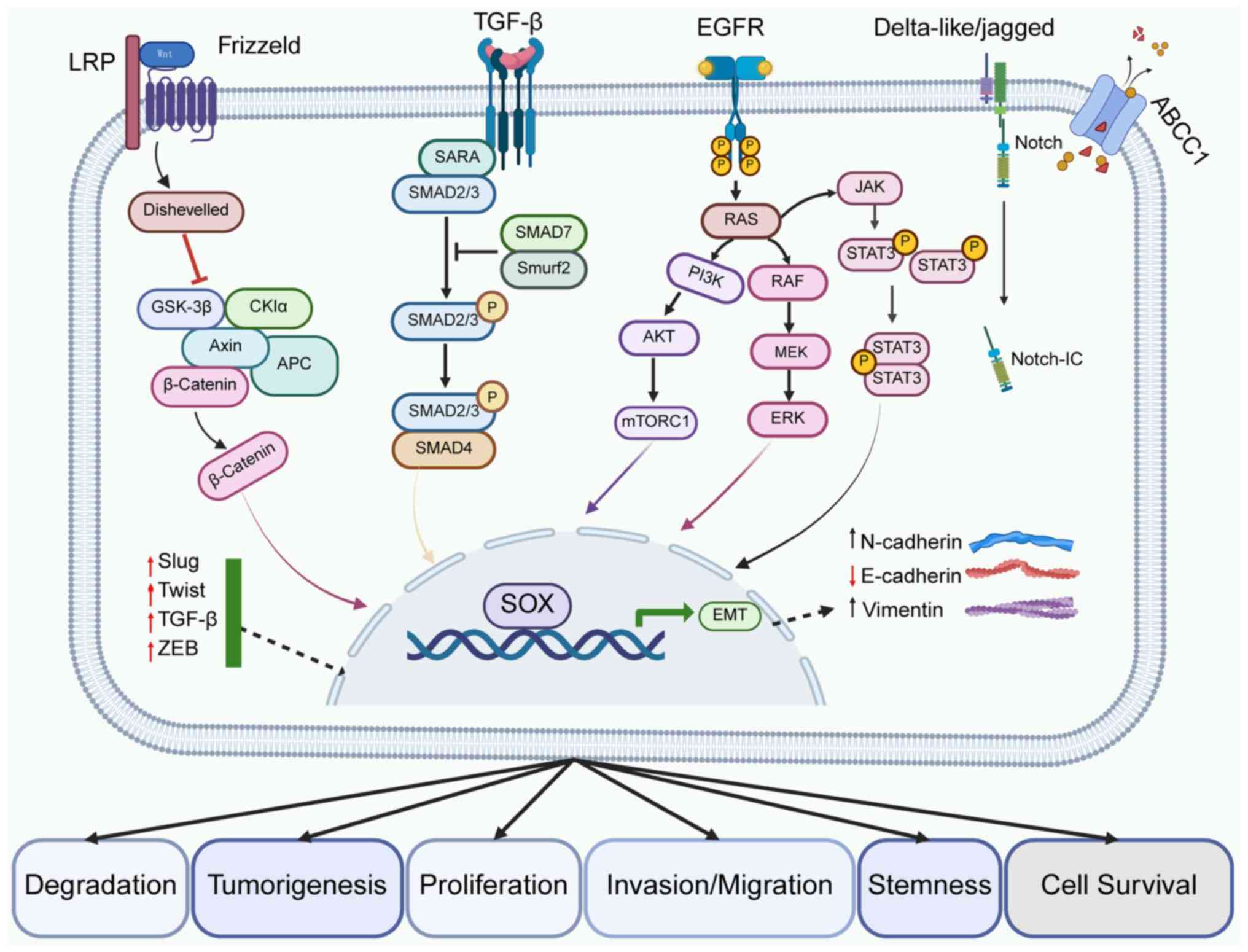

The SOX family is involved and development of NSCLC

by regulating biological behaviors, including cell proliferation,

apoptosis, invasion and metastasis, as well as the maintenance of

tumor stem cells (Fig. 3).

Studies have demonstrated that certain SOX members

actively promote NSCLC cell proliferation (35,63,64).

For example, SOX2 facilitates cell proliferation and survival by

regulating cell cycle progression and DNA damage repair (64). In models of radioresistant NSCLC

cell lines, SOX2 expression is markedly upregulated (65–67).

Overexpression of SOX2 enhances resistance to radiotherapy and

improves DNA repair capacity, thereby promoting proliferation

(68). Conversely, SOX2 knockdown

impairs these functions and suppresses cell proliferation (69). Similarly, SOX4 supports NSCLC cell

proliferation indirectly by promoting migration, invasion and EMT

(21). Analyses of patients with

NSCLC has revealed significantly elevated SOX4 expression in tumor

tissue, identifying it as an independent prognostic marker

(35). However, not all SOX family

members serve as oncogenes. For example, SOX17 is downregulated in

lung adenocarcinoma, and its upregulation suppresses NSCLC cell

proliferation, suggesting a potential tumor-suppressive function

(63).

The SOX family serves a key role in the regulation

of apoptosis in NSCLC cells, constituting an essential component of

its involvement in tumor pathophysiology (70). SOX6 not only inhibits the

proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma cells but also promotes

apoptosis by modulating the expression of key proteins such as p53,

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, cyclin D1 and β-catenin,

thereby impacting cell cycle control and apoptosis-associated

signaling pathways (71). In

studies of erlotinib resistance in NSCLC cells, OTU

domain-containing 1 (OTUD1) enhances cellular sensitivity to

erlotinib by inhibiting YAP1 nuclear translocation, accompanied by

the inactivation of the SOX9/secreted phosphoprotein 1 pathway

(72,73). Notably, overexpression of SOX9

reverses the sensitizing effects of OTUD1, indicating a role for

SOX9 in apoptosis and drug resistance mechanisms in NSCLC (72). In addition, SOX9, together with

STAT3, forms a differential regulatory network that may contribute

to erlotinib resistance by modulating cellular proliferation and

survival signaling pathways (73).

Furthermore, SOX-associated signaling pathways are also involved in

the regulation of apoptosis. For example, in endometrial cancer

cells, propofol inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion, and

promotes apoptosis by downregulating SOX4 expression, which is

associated with inactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway, indicating that the Wnt/β-catenin-SOX4 axis may be involve

in the apoptosis of NSCLC cells (74). Furthermore, SOX4 affects the

proliferation and apoptosis of NSCLC cells by regulating cell

cycle-associated proteins (33).

For example, SOX4 may alter the expression of proteins such as

Cyclin D1, promoting the transition of cells from the G1 to the S

phase, thereby promoting cell proliferation. By regulating the

expression of apoptosis-associated proteins such as Bax and Bcl-2,

SOX4 affects the occurrence of apoptosis (33). circ_0089823 affects cell

proliferation and apoptosis by regulating SOX4. Knockdown of

circ_0089823 inhibits the proliferation of NSCLC cells, induces

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (75). Overexpression of circ_0089823

promotes malignant behavior such as cell proliferation, and SOX4 is

positively regulated by circ_0089823. Silencing SOX4 can counteract

the effect of overexpression of circ_0089823 on NSCLC cells

(75).

In the invasion and metastasis of NSCLC, multiple

signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms are associated with the

SOX family (76). For example, in

LC, SOX1 expression is markedly downregulated, which contributes to

tumor initiation and progression. SOX1 suppresses the malignant

progression of NSCLC by inhibiting the hairy and enhancer of split

1 factor, thereby suppressing anchorage-independent growth,

invasion and metastatic behavior (77). Furthermore, SOX4 promotes tumor

invasion and metastasis by upregulating LEM domain containing 1,

which activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in colorectal

cancer, implying that SOX4 may facilitate NSCLC progression through

a similar mechanism (78). In

addition, miR-363-3p can inhibit the migration, invasion and EMT of

NSCLC cells by targeting SOX4. The overexpression of miR-363-3p

inhibits cell migration and invasion, while knockdown of miR-363-3p

shows the opposite effect (79).

Further studies have found that miR-363-3p directly binds the

3′-untranslated region of SOX4 and negatively regulates its

expression, and neural precursor cell expressed developmentally

downregulated 9 or SOX4 knockdown can salvage the

translocation-promoting effect of antagomiR-363-3p (80–82).

In lung adenocarcinoma, SOX30 inhibits Wnt signaling by directly

suppressing the transcription of β-catenin, thereby blocking cell

migration and invasion. High SOX30 expression is associated with

better patient prognosis (76,83).

Additionally, interactions between SOX genes and other molecular

regulators influence NSCLC metastasis (76). For example, elevated expression of

lncRNA KCNQ1OT1 is notably associated with tumor size, TNM stage

and lymph node metastasis in NSCLC. This lncRNA promotes

proliferation, migration and invasion via the miR-129-5p/Jagged1

pathway. While SOX genes are not directly involved in this pathway,

the associated signaling networks suggest potential regulatory

interplay (84). Moreover, miR-548l

suppresses NSCLC cell migration and invasion by targeting the AKT1

signaling pathway, indicating SOX genes may participate in

coordinated regulation of invasion and metastasis through crosstalk

with such pathways (85).

The SOX family serves a notable role in the

development of drug resistance in NSCLC (18,90).

For example, SOX2 is associated with resistance to paclitaxel and

platinum-based chemotherapeutics. In studies using A549 NSCLC cell

lines (68,91), SOX2 enhances resistance to

paclitaxel by promoting the transcription of chloride voltage-gated

channel 3 (ClC-3). Knockdown of either SOX2 or ClC-3 significantly

decreases drug resistance (68).

SOX2 overexpression attenuates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity

in both lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells and cisplatin-resistant

counterpart A549/DDP cells through upregulation of GSK3β, a key

negative regulator of this pathway (91). Additionally, SOX2 modulates

resistance to cisplatin through the AP endonuclease 1 (APE1)

signaling pathway, and silencing SOX2 restores cisplatin

sensitivity (69). Other SOX family

members are also implicated in resistance mechanisms. For example,

upregulation of SOX4 is associated with chemoresistance in NSCLC

(92,93). miR-129-2 enhances chemosensitivity

by targeting SOX4 and inducing apoptosis, indicating modulation of

SOX4 levels influences drug response (92). In-depth exploration of the molecular

mechanisms underlying SOX-mediated resistance in NSCLC may provide

valuable insights for the development of novel therapeutic

strategies.

Given the critical role of the SOX family in NSCLC

development, individualized therapies targeting these genes hold

promise. Analyzing the expression profiles, mutation status and

associated signaling pathways of SOX genes in tumors enables

precise patient stratification, providing a basis for tailoring

individualized treatment strategies. For example, in patients with

high SOX gene expression associated with poor prognosis, targeted

interventions [such as small-molecule inhibitors, RNA interference

(RNAi) or immunotherapy-based combination strategies] can be

developed or selected to suppress SOX gene function. Integrating

these findings with clinical features and molecular markers may

further refine treatment regimens and enhance therapeutic efficacy

(17). Moreover, advancements in

drug development technologies have facilitated the creation of

SOX-specific targeted therapies. These drugs precisely target SOX

genes or their related signaling pathways, minimizing toxicity to

normal cells while improving treatment safety and effectiveness

(94,95). Additionally, integrating genetic

backgrounds and lifestyle factors contributes to more precise

individualized therapies, improving NSCLC prognosis.

Targeting SOX genes represents a promising

therapeutic strategy for NSCLC, aiming to suppress tumor growth by

modulating SOX gene expression or activity. RNAi has been employed

to silence SOX gene expression, altering the biological behavior of

NSCLC cells. For example, in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cell lines,

SOX2 upregulation promotes resistance via APE1 signaling. Small

interfering (si)RNA-mediated SOX2 knockdown (siSOX2) inhibits

colony formation, decreases cell viability, enhances apoptosis and

restores cisplatin sensitivity. Combined siSOX2 and cisplatin

treatment inhibits tumor progression in vitro, with low SOX2

expression linked to better patient survival (69). Silencing SOX4 has been shown to

inhibit proliferation, migration and invasion of osteosarcoma

cells, while also inducing apoptosis (96). These findings suggest that targeting

SOX4 may similarly regulate progression of NSCLC (96). Additionally, several novel

small-molecule compounds have been developed to target SOX

proteins: Nobiletin, a small molecule, binds to the transcription

factor SOX5, exhibiting synergistic cytotoxic effects when combined

with doxorubicin in SOX5-overexpressing cells (97). This highlights a potential

combination therapy approach for NSCLC. Furthermore, the

development of targeted drugs based on signaling pathways involving

SOX genes has become a focal point of research (98–100).

In NSCLC, histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7) promotes tumor

proliferation and metastasis by activating the β-catenin/FGF18

pathway, suggesting that targeting HDAC7 or its associated

signaling cascades may serve as a novel therapeutic strategy

(98). Moreover, CRISPR/Cas9

gene-editing technology offers a tool to modify SOX genes (101). Although this approach currently

faces technical challenges (off-target effects, delivery

challenges, editing efficiency) (102,103) for clinical translation, it holds

promise for personalized cancer therapies. To the best of our

knowledge, no clinical trials involving siRNA therapy targeting SOX

genes have been reported to date. The majority of research remains

at the preclinical stage (69,96,97),

encompassing in vitro studies, animal models and the

optimization of small molecule delivery systems. This delay in

clinical translation may be attributed to challenges associated

with siRNA delivery, including issues of stability, targeting

efficiency and off-target effects (104,105). Although clinical research on siRNA

therapies targeting SOX genes in LC remains in its early stages,

siRNA technology has demonstrated notable clinical progress across

various oncological indications, providing robust support for its

potential application in malignancy. For example, NBF-006, a lipid

nanoparticle-formulated siRNA targeting the KRAS G12D mutation

(present in ~25% of patients with NSCLC), has been evaluated in a

Phase I clinical trial (106) for

KRAS-mutant NSCLC and pancreatic and colorectal cancer. This trial

has demonstrated sustained KRAS silencing within tumors and

improved safety and tolerability compared with small-molecule

inhibitors (106). In glioblastoma

multiforme (GBM), NU-0129, a gold nanoparticle-conjugated siRNA

targeting bcl-2-like protein 12, an anti-apoptotic factor

upregulated in GBM, achieves localized tumor delivery via

convection-enhanced delivery. In patients with recurrent GBM, it

induces tumor cell apoptosis without evidence of neurotoxicity,

progressing to a Phase Ib expansion study (107). Additionally, CALAA-01, a

cyclodextrin-based nanoparticle delivery system to target the M2

subunit of ribonucleotide reductase, was investigated in a Phase I

trial (108) across various solid

tumors, including ovarian and peritoneal cancer. Tumor biopsy

confirmed activation of the RNAi mechanism, with clinical outcomes

indicating partial responses in 11% of patients and disease

stabilization in 48% (108,109).

Collectively, these early-phase clinical studies validate the

feasibility and therapeutic potential of siRNA-based approaches in

multiple types of cancer. They also provide a key foundation for

the development of novel RNAi strategies targeting the SOX pathway,

offering promise for advancing precision therapeutics in NSCLC and

optimization and innovation in its treatment paradigm.

Immunotherapy harnesses the host immune system to

target tumor cells, and SOX genes may play a pivotal regulatory

role within the tumor immune microenvironment. The integration of

SOX family-targeted therapies with immunotherapy offers new

possibilities for the treatment of NSCLC. Expression of certain SOX

genes is notably associated with the quantity and type of

tumor-infiltrating immune cells, suggesting their potential

influence on immunotherapy efficacy (39,110).

For example, expression of SOXF family genes is positively

associated with CD4+ T cell infiltration, a

characteristic that may modulate tumor response to immunotherapy

(60). In NSCLC, SOX2 upregulates

IL6 via FOS-like antigen 2, promoting inflammation and metastasis

while suppressing CD8+ T cell infiltration via cyclic

GMP-AMP synthase/STING degradation (111). SOX2/SOX9 enable natural killer

cell evasion by downregulating major histocompatibility complex

class I markers in cancer cells. SOX expression is associated with

checkpoints and TMB, predicting immunotherapy response. Targeting

SOX may enhance PD-1 blockade and radioimmunotherapy (112). Furthermore, targeting SOX genes

can enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy in NSCLC. For

example, the use of proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) to

degrade EGFR L858R has been shown to downregulate PD-L1 and

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 protein levels, thereby amplifying

anti-tumor immune responses and providing an approach to NSCLC

immunotherapy (113).

Additionally, combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with

modulators targeting SOX gene-associated signaling pathways in

NSCLC immunotherapy has also shown enhanced efficacy (114). For instance, tumor-intrinsic SOX2

signaling in NSCLC promotes the recruitment of regulatory T cells

(Tregs) by upregulating CCL2, thereby mediating resistance to ICIs.

Depletion of Tregs or inhibition of the SOX2 pathway restores T

cell infiltration and markedly suppresses tumor growth, suggesting

that targeting the SOX2 pathway may synergistically enhance the

therapeutic efficacy of ICIs (110). This strategy may optimize the

tumor immune microenvironment and improve therapeutic outcomes,

warranting further exploration and validation.

NSCLC, the predominant subtype of LC, poses notable

clinical challenges due to its molecular heterogeneity, drug

resistance and low survival rate (115,116). The present review summarized the

key role of the SOX family of transcription factors in the

initiation, progression and treatment of NSCLC. Key members such as

SOX2, SOX4 and SOX9 notably influence the malignant progression of

NSCLC by regulating processes including tumor stemness, EMT, cell

proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis and drug resistance

(35,89,117).

For example, SOX2 sustains tumor stemness to promote chemotherapy

resistance, SOX4 modulates EMT and angiogenesis and SOX9

collaborates with EGFR/KRAS signaling pathways to drive tumor

invasion. Conversely, other SOX family members, such as SOX17,

exhibit tumor-suppressive potential, underscoring the dual

functionality within the SOX family (63).

Molecular mechanistic studies have revealed that SOX

genes participate in NSCLC pathogenesis through intricate signaling

networks (such as Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/AKT) and epigenetic

regulation (118,119). Clinically, dysregulated SOX

expression is associated with patient outcomes, highlighting the

potential of SOX family members as diagnostic biomarkers and

therapeutic targets (76,120). In parallel, certain emerging

technologies (such as single-cell sequencing and CRISPR/Cas9)

provide novel tools to determine the roles of the SOX family, while

the development of SOX-targeted therapy (including RNAi and

PROTACs) and their integration with immunotherapy offer new avenues

for precision NSCLC therapy. However, clinical translatability

remains a challenge. siRNA-based RNAi, for example, excels in

sequence-specific SOX silencing, with preclinical NSCLC models

showing decreased tumor growth and stemness following SOX2 or SOX9

knockdown (69,121,122). However, its limitations include

poor in vivo stability (rapid nuclease degradation and renal

clearance, often limiting half-life to <24 h), inefficient cell

uptake due to negative charge, endosomal entrapment and potential

off-target effects or immune activation in the fibrotic NSCLC tumor

microenvironment (123–125). PROTACs induce sustained

ubiquitin-mediated degradation of SOX proteins, targeting

undruggable surfaces without relying on enzymatic pockets,

potentially overcoming compensatory upregulation seen in SOX family

members. In NSCLC, PROTACs have shown promise against transcription

factors such as STAT3 analogs, but face hurdles in E3 ligase

selectivity (risking off-target toxicity) and dependency on

endogenous ubiquitin machinery (126,127). CRISPR/Cas9 offers permanent

genomic editing of SOX loci, bypassing delivery instability by

enabling knockout or base editing in preclinical patient-derived

tumor xenograft models (128–130), where SOX9 ablation halts

metastasis more durably than siRNA. However, its application is

constrained by vector-associated immunogenicity, potential

off-target genomic alterations and ethical and regulatory barriers

(17,131,132).

Taken together, the present findings highlight the

promise and the limitations of SOX-targeted strategies in NSCLC.

Future studies should focus on optimizing delivery platforms,

enhancing therapeutic specificity and integrating SOX-based

interventions with existing targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

Addressing these translational barriers may unlock the clinical

potential of SOX-targeted approaches to develop more personalized

and effective treatment strategies for NSCLC.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. U24A20765 and T2321005), China

Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2024M762310), Jiangsu

Provincial Science and Technology Plan Special Fund (grant no.

BM2023003), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Key Discipline (grant no.

ZDXK202247) and the Priority Academic Program Development of the

Jiangsu Higher Education Institutes.

Not applicable.

LYM conceived the study and edited the manuscript.

KWW, YQL, ZNG, LS, XLD, LSL, TH, YCB, and CRH performed the

literature review and prepared the figures.. KWW, YQL and ZNG wrote

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Tung CH, Huang MF, Liang CH, Wu YY, Wu JE,

Hsu CL, Chen YL and Hong TM: α-Catulin promotes cancer stemness by

antagonizing WWP1-mediated KLF5 degradation in lung cancer.

Theranostics. 12:1173–1186. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

He Q, Yang L, Gao K, Ding P, Chen Q, Xiong

J, Yang W, Song Y, Wang L, Wang Y, et al: FTSJ1 regulates tRNA

2′-O-methyladenosine modification and suppresses the malignancy of

NSCLC via inhibiting DRAM1 expression. Cell Death Dis. 11:3482020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jia Z, Wang K, Duan Y, Hu K, Zhang Y, Wang

M, Xiao K, Liu S, Pan Z and Ding X: Claudin1 decrease induced by

1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 potentiates gefitinib resistance therapy

through inhibiting AKT activation-mediated cancer stem-like

properties in NSCLC cells. Cell Death Discov. 8:1222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhou Y, Dang J, Chang KY, Yau E, Aza-Blanc

P, Moscat J and Rana TM: miR-1298 inhibits Mutant KRAS-driven tumor

growth by repressing FAK and LAMB3. Cancer Res. 76:5777–5787. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Skoulidis F and Heymach JV: Co-occurring

genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer biology and

therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 19:495–509. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhang P, Yorke E, Mageras G, Rimner A,

Sonke JJ and Deasy JO: Validating a predictive atlas of tumor

shrinkage for adaptive radiotherapy of locally advanced lung

cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 102:978–986. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lahiri A, Maji A, Potdar PD, Singh N,

Parikh P, Bisht B, Mukherjee A and Paul MK: Lung cancer

immunotherapy: Progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol Cancer.

22:402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sarkar A and Hochedlinger K: The sox

family of transcription factors: Versatile regulators of stem and

progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 12:15–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Saloni, Sachan M, Rahul Verma RS and Patel

GK: SOXs: Master architects of development and versatile emulators

of oncogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1880:1892952025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tang Q, Chen J, Di Z, Yuan W, Zhou Z, Liu

Z, Han S, Liu Y, Ying G, Shu X and Di M: TM4SF1 promotes EMT and

cancer stemness via the Wnt/β-catenin/SOX2 pathway in colorectal

cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:2322020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bagati A, Kumar S, Jiang P, Pyrdol J, Zou

AE, Godicelj A, Mathewson ND, Cartwright ANR, Cejas P, Brown M, et

al: Integrin αvβ6-TGFβ-SOX4 pathway drives immune evasion in

triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 39:54–67.e9. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ma XL, Hu B, Tang WG, Xie SH, Ren N, Guo L

and Lu RQ: CD73 sustained cancer-stem-cell traits by promoting SOX9

expression and stability in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol

Oncol. 13:112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shang J, Zheng Y, Mo J, Wang W, Luo Z, Li

Y, Chen X, Zhang Q, Wu K, Liu W and Wu J: Sox4 represses host

innate immunity to facilitate pathogen infection by hijacking the

TLR signaling networks. Virulence. 12:704–722. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zu F, Chen C, Geng Q, Li H, Chan B, Luo G,

Wu M, Ilmer M, Renz BW, Bentum-Ennin L, et al: Smad2 cooperating

with TGIF2 contributes to EMT and cancer stem cells properties in

pancreatic cancer via co-targeting SOX2. Int J Biol Sci.

21:524–543. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Balgkouranidou I, Chimonidou M, Milaki G,

Tsaroucha E, Kakolyris S, Georgoulias V and Lianidou E: SOX17

promoter methylation in plasma circulating tumor DNA of patients

with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med. 54:1385–1393.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cao YH, Ding J, Tang QH, Zhang J, Huang

ZY, Tang XM, Liu JB, Ma YS and Fu D: Deciphering cell-cell

interactions and communication in the tumor microenvironment and

unraveling intratumoral genetic heterogeneity via single-cell

genomic sequencing. Bioengineered. 13:14974–14986. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dehshahri A, Biagioni A, Bayat H, Lee EHC,

Hashemabadi M, Fekri HS, Zarrabi A, Mohammadinejad R and Kumar AP:

Editing SOX genes by CRISPR-Cas: Current insights and future

perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 22:113212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tripathi SK and Biswal BK: SOX9 promotes

epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor

resistance via targeting β-catenin and epithelial to mesenchymal

transition in lung cancer. Life Sci. 277:1196082021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hushmandi K, Saadat SH, Mirilavasani S,

Daneshi S, Aref AR, Nabavi N, Raesi R, Taheriazam A and Hashemi M:

The multifaceted role of SOX2 in breast and lung cancer dynamics.

Pathol Res Pract. 260:1553862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen S, Xu Y, Chen Y, Li X, Mou W, Wang L,

Liu Y, Reisfeld RA, Xiang R, Lv D and Li N: SOX2 gene regulates the

transcriptional network of oncogenes and affects tumorigenesis of

human lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 7:e363262012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li Y, Chen P, Zu L, Liu B, Wang M and Zhou

Q: MicroRNA-338-3p suppresses metastasis of lung cancer cells by

targeting the EMT regulator Sox4. Am J Cancer Res. 6:127–140.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liang Z, Xu J and Gu C: Novel role of the

SRY-related high-mobility-group box D gene in cancer. Semin Cancer

Biol. 67:83–90. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jones K, Ramirez-Perez S, Niu S,

Gangishetti U, Drissi H and Bhattaram P: SOX4 and RELA function as

transcriptional partners to regulate the expression of

TNF-responsive genes in fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Front

Immunol. 13:7893492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xia X, Huo W, Wan R, Zhang L, Xia X and

Chang Z: Molecular cloning and expression analysis of Sox3 during

gonad and embryonic development in Misgurnus

anguillicaudatus. Int J Dev Biol. 61:565–570. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Baroti T, Schillinger A, Wegner M and

Stolt CC: Sox13 functionally complements the related Sox5 and Sox6

as important developmental modulators in mouse spinal cord

oligodendrocytes. J Neurochem. 136:316–328. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wan H, Liao J, Zhang Z, Zeng X, Liang K

and Wang Y: Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression

analysis of a sex-biased transcriptional factor sox9 gene of mud

crab Scylla paramamosain. Gene. 774:1454232021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Olbromski M, Podhorska-Okołów M and

Dzięgiel P: Role of SOX protein groups F and H in lung cancer

progression. Cancers (Basel). 12:32352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Toschi L, Finocchiaro G, Nguyen TT, Skokan

MC, Giordano L, Gianoncelli L, Perrino M, Siracusano L, Di Tommaso

L, Infante M, et al: Increased SOX2 gene copy number is associated

with FGFR1 and PIK3CA gene gain in non-small cell lung cancer and

predicts improved survival in early stage disease. PLoS One.

9:e953032014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pradhan S, Guddattu V and Solomon MC:

Association of the co-expression of SOX2 and Podoplanin in the

progression of oral squamous cell carcinomas-an immunohistochemical

study. J Appl Oral Sci. 27:e201803482019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Choi CM, Jang SJ, Park SY, Choi YB, Jeong

JH, Kim DS, Kim HK, Park KS, Nam BH, Kim HR, et al:

Transglutaminase 2 as an independent prognostic marker for survival

of patients with non-adenocarcinoma subtype of non-small cell lung

cancer. Mol Cancer. 10:1192011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li C, He B, Huang C, Yang H, Cao L, Huang

J and Hu C: Sex-determining region Y-box 2 promotes growth of lung

squamous cell carcinoma and directly targets cyclin D1. DNA Cell

Biol. 36:264–272. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu B, Liu Y, Zou J, Zou M and Cheng Z:

Smoking is associated with lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous

cell carcinoma progression through inducing distinguishing lncRNA

alterations in different genders. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.

22:1541–1550. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhou Y, Wang X, Huang Y, Chen Y, Zhao G,

Yao Q, Jin C, Huang Y, Liu X and Li G: Down-regulated SOX4

expression suppresses cell proliferation, metastasis and induces

apoptosis in Xuanwei female lung cancer patients. J Cell Biochem.

116:1007–1018. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang D, Hao T, Pan Y, Qian X and Zhou D:

Increased expression of SOX4 is a biomarker for malignant status

and poor prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Mol

Cell Biochem. 402:75–82. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wen T, Zhang X, Gao Y, Tian H, Fan L and

Yang P: SOX4-BMI1 axis promotes non-small cell lung cancer

progression and facilitates angiogenesis by suppressing ZNF24. Cell

Death Dis. 15:6982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu X, Wang Y, Zhou G, Zhou J, Tian Z and

Xu J: circGRAMD1B contributes to migration, invasion and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lung adenocarcinoma cells via

modulating the expression of SOX4. Funct Integr Genomics.

23:752023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sasaki A, Abe H, Mochizuki S, Shimoda M

and Okada Y: SOX4, an epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer,

transactivates ADAM28 gene expression and co-localizes with ADAM28

at the invasive front of human breast and lung carcinomas. Pathol

Int. June 7–2018.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sun J, Xiong Y, Jiang K, Xin B, Jiang T,

Wei R, Zou Y, Tan H, Jiang T, Yang A, et al: Hypoxia-sensitive long

noncoding RNA CASC15 promotes lung tumorigenesis by regulating the

SOX4/β-catenin axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wu J, Zhu MX, Li KS, Peng L and Zhang PF:

Circular RNA drives resistance to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by

regulating the miR-30a-5p/SOX4 axis in non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancer Drug Resist. 5:261–270. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fois SS, Paliogiannis P, Zinellu A, Fois

AG, Cossu A and Palmieri G: Molecular epidemiology of the main

druggable genetic alterations in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J

Mol Sci. 22:6122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Capaccione KM, Hong X, Morgan KM, Liu W,

Bishop JM, Liu L, Markert E, Deen M, Minerowicz C, Bertino JR, et

al: Sox9 mediates Notch1-induced mesenchymal features in lung

adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 5:3636–3650. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhong H, Lu W, Tang Y, Wiel C, Wei Y, Cao

J, Riedlinger G, Papagiannakopoulos T, Guo JY, Bergo MO, et al:

SOX9 drives KRAS-induced lung adenocarcinoma progression and

suppresses anti-tumor immunity. Oncogene. 42:2183–2194. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen NM, Singh G, Koenig A, Liou GY, Storz

P, Zhang JS, Regul L, Nagarajan S, Kühnemuth B, Johnsen SA, et al:

NFATc1 links EGFR signaling to induction of Sox9 transcription and

acinar-ductal transdifferentiation in the pancreas.

Gastroenterology. 148:1024–1034.e9. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ling S, Chang X, Schultz L, Lee TK, Chaux

A, Marchionni L, Netto GJ, Sidransky D and Berman DM: An

EGFR-ERK-SOX9 signaling cascade links urothelial development and

regeneration to cancer. Cancer Res. 71:3812–3821. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Xue VW, Ng SSM, Tsang HF, Wong HT, Leung

WW, Wong YN, Wong YKE, Yu ACS, Yim AKY, Cho WCS, et al: The

non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer via a SOX9-based gene

panel. Clin Exp Med. 23:2421–2432. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ramakrishnan AB, Burby PE, Adiga K and

Cadigan KM: SOX9 and TCF transcription factors associate to mediate

Wnt/β-catenin target gene activation in colorectal cancer. J Biol

Chem. 299:1027352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhou H, Qin Y, Ji S, Ling J, Fu J, Zhuang

Z, Fan X, Song L, Yu X and Chiao PJ: SOX9 activity is induced by

oncogenic Kras to affect MDC1 and MCMs expression in pancreatic

cancer. Oncogene. 37:912–923. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kopp JL, von Figura G, Mayes E, Liu FF,

Dubois CL, Morris JP IV, Pan FC, Akiyama H, Wright CV, Jensen K, et

al: Identification of Sox9-dependent acinar-to-ductal reprogramming

as the principal mechanism for initiation of pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 22:737–750. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zou H, Wang S, Wang S, Wu H, Yu J, Chen Q,

Cui W, Yuan Y, Wen X, He J, et al: SOX5 interacts with YAP1 to

drive malignant potential of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Am J

Cancer Res. 8:866–878. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen D, Wang R, Yu C, Cao F, Zhang X, Yan

F, Chen L, Zhu H, Yu Z and Feng J: FOX-A1 contributes to

acquisition of chemoresistance in human lung adenocarcinoma via

transactivation of SOX5. EBioMedicine. 44:150–161. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen R, Zhang C, Cheng Y, Wang S, Lin H

and Zhang H: LncRNA UCC promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition

via the miR-143-3p/SOX5 axis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lab

Invest. 101:1153–1165. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chen X, Fu Y, Xu H, Teng P, Xie Q, Zhang

Y, Yan C, Xu Y, Li C, Zhou J, et al: SOX5 predicts poor prognosis

in lung adenocarcinoma and promotes tumor metastasis through

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 9:10891–10904. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Xue JD, Xiang WF, Cai MQ and Lv XY:

Biological functions and therapeutic potential of SRY related high

mobility group box 5 in human cancer. Front Oncol. 14:13321482024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Jethon A, Pula B, Olbromski M, Werynska B,

Muszczynska-Bernhard B, Witkiewicz W, Dziegiel P and

Podhorska-Okolow M: Prognostic significance of SOX18 expression in

non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Oncol. 46:123–132. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Olbromski M, Grzegrzolka J,

Jankowska-Konsur A, Witkiewicz W, Podhorska-Okolow M and Dziegiel

P: MicroRNAs modulate the expression of the SOX18 transcript in

lung squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 36:2884–2892. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

de Souza Silva FH, Underwood A, Almeida

CP, Ribeiro TS, Souza-Fagundes EM, Martins AS, Eliezeck M,

Guatimosim S, Andrade LO, Rezende L, et al: Transcription factor

SOX3 upregulated pro-apoptotic genes expression in human breast

cancer. Med Oncol. 39:2122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Guo Y, Yin J, Tang M and Yu X:

Downregulation of SOX3 leads to the inhibition of the

proliferation, migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells. Int J

Oncol. 52:1277–1284. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Del Puerto HL, Miranda APGS, Qutob D,

Ferreira E, Silva FHS, Lima BM, Carvalho BA, Roque-Souza B, Gutseit

E, Castro DC, et al: Clinical correlation of transcription factor

SOX3 in cancer: Unveiling its role in tumorigenesis. Genes (Basel).

15:7772024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Qiu M, Chen D, Shen C, Shen J, Zhao H and

He Y: Sex-determining region Y-box protein 3 induces

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in osteosarcoma cells via

transcriptional activation of Snail1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

36:462017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wu D, Jiang C, Zheng JJ, Luo DS, Ma J, Que

HF, Li C, Ma C, Wang HY, Wang W and Xu HT: Bioinformatics analysis

of SOXF family genes reveals potential regulatory mechanism and

diagnostic value in cancers. Ann Transl Med. 10:7012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Cook M, Qorri B, Baskar A, Ziauddin J,

Pani L, Yenkanchi S and Geraci J: Small patient datasets reveal

genetic drivers of non-small cell lung cancer subtypes using

machine learning for hypothesis generation. Exp Med. 4:428–440.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Hayano T, Garg M, Yin D, Sudo M, Kawamata

N, Shi S, Chien W, Ding LW, Leong G, Mori S, et al: SOX7 is

down-regulated in lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 32:172013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wu X, Liu H, Zhang M, Ma J, Qi S, Tan Q,

Jiang Y, Hong Y and Yan L: miR-200a-3p promoted cell proliferation

and metastasis by downregulating SOX17 in non-small cell lung

cancer cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 36:e230372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Zang K, Yu ZH, Wang M, Huang Y, Zhu XX and

Yao B: SOX2 como posible biomarcador pronóstico y diana molecular

en el cáncer de pulmón: Metaanálisis. Rev Clin Esp (Barc).

222:584–592. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang S, Li Z, Li P, Li L, Liu Y, Feng Y,

Li R and Xia S: SOX2 promotes radioresistance in non-small cell

lung cancer by regulating tumor cells dedifferentiation. Int J Med

Sci. 20:781–796. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Yun HS, Baek JH, Yim JH, Um HD, Park JK,

Song JY, Park IC, Kim JS, Lee SJ, Lee CW and Hwang SG: Radiotherapy

diagnostic biomarkers in radioresistant human H460 lung cancer

stem-like cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 17:208–218. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Gomez-Casal R, Bhattacharya C, Ganesh N,

Bailey L, Basse P, Gibson M, Epperly M and Levina V: Non-small cell

lung cancer cells survived ionizing radiation treatment display

cancer stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotypes.

Mol Cancer. 12:942013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Huang Y, Wang X, Hu R, Pan G and Lin X:

SOX2 regulates paclitaxel resistance of A549 non-small cell lung

cancer cells via promoting transcription of ClC-3. Oncol Rep.

48:1812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Chen TY, Zhou J, Li PC, Tang CH, Xu K, Li

T and Ren T: SOX2 knockdown with siRNA reverses cisplatin

resistance in NSCLC by regulating APE1 signaling. Med Oncol.

39:362022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Han F, Liu W, Jiang X, Shi X, Yin L, Ao L,

Cui Z, Li Y, Huang C, Cao J and Liu J: SOX30, a novel epigenetic

silenced tumor suppressor, promotes tumor cell apoptosis by

transcriptional activating p53 in lung cancer. Oncogene.

34:4391–4402. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Lv L, Zhou M, Zhang J, Liu F, Qi L, Zhang

S, Bi Y and Yu Y: SOX6 suppresses the development of lung

adenocarcinoma by regulating expression of p53, p21CIPI,

cyclin D1 and β-catenin. FEBS Open Bio. 10:135–146. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Liu H, Zhong L, Lu Y, Liu X, Wei J, Ding

Y, Huang H, Nie Q and Liao X: Deubiquitylase OTUD1 confers

Erlotinib sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer through

inhibition of nuclear translocation of YAP1. Cell Death Discov.

8:4032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yu Y, Luo Y, Zheng Y, Zheng X, Li W, Yang

L and Jiang J: Exploring the mechanism of non-small-cell lung

cancer cell lines resistant to epidermal growth factor receptor

tyrosine kinase inhibitor. J Cancer Res Ther. 12:121–125. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Du Q, Liu J, Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhu H, Wei

M and Wang S: Propofol inhibits proliferation, migration, and

invasion but promotes apoptosis by regulation of Sox4 in

endometrial cancer cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 51:e68032018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Li J, Zhu Z, Li S, Han Z, Meng F and Wei

L: Circ_0089823 reinforces malignant behaviors of non-small cell

lung cancer by acting as a sponge for microRNAs targeting SOX4.

Neoplasia. 23:887–897. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Han F, Zhang MQ, Liu WB, Sun L, Hao XL,

Yin L, Jiang X, Cao J and Liu JY: SOX30 specially prevents

Wnt-signaling to suppress metastasis and improve prognosis of lung

adenocarcinoma patients. Respir Res. 19:2412018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Chang SY, Wu TH, Shih YL, Chen YC, Su HY,

Chian CF and Lin YW: SOX1 functions as a tumor suppressor by

repressing HES1 in lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 15:22072023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Li D, Wang D, Liu H and Jiang X: LEM

domain containing 1 (LEMD1) transcriptionally activated by

SRY-related high-mobility-group box 4 (SOX4) accelerates the

progression of colon cancer by upregulating phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway.

Bioengineered. 13:8087–8100. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jin L, Chen C, Huang L, Sun Q and Bu L:

Long noncoding RNA NR2F1-AS1 stimulates the tumorigenic behavior of

non-small cell lung cancer cells by sponging miR-363-3p to increase

SOX4. Open Med (Wars). 17:87–95. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Chang J, Gao F, Chu H, Lou L, Wang H and

Chen Y: miR-363-3p inhibits migration, invasion, and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting NEDD9 and SOX4 in

non-small-cell lung cancer. J Cell Physiol. 235:1808–1820. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Ye Q, Raese R, Luo D, Cao S, Wan YW, Qian

Y and Guo NL: MicroRNA, mRNA, and proteomics biomarkers and

therapeutic targets for improving lung cancer treatment outcomes.

Cancers (Basel). 15:22942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Martínez-Espinosa I, Serrato JA,

Cabello-Gutiérrez C, Carlos-Reyes Á and Ortiz-Quintero B:

Mechanisms of microRNA regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) in lung cancer. Life (Basel).

14:14312024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Han F, Liu WB, Shi XY, Yang JT, Zhang X,

Li ZM, Jiang X, Yin L, Li JJ, Huang CS, et al: SOX30 inhibits tumor

metastasis through attenuating Wnt-signaling via transcriptional

and posttranslational regulation of β-catenin in lung cancer.

EBioMedicine. 31:253–266. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Wang Y, Zhang L, Yang J and Sun R: LncRNA

KCNQ1OT1 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion via

regulating miR-129-5p/JAG1 axis in non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancer Cell Int. 20:1442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Liu C, Yang H, Xu Z, Li D, Zhou M, Xiao K,

Shi Z, Zhu L, Yang L and Zhou R: microRNA-548l is involved in the

migration and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting

the AKT1 signaling pathway. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 141:431–441.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wang X, Chen Y, Wang X, Tian H, Wang Y,

Jin J, Shan Z, Liu Y, Cai Z, Tong X, et al: Stem cell factor SOX2

confers ferroptosis resistance in lung cancer via upregulation of

SLC7A11. Cancer Res. 81:5217–5229. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Loh JJ and Ma S: Hallmarks of cancer

stemness. Cell Stem Cell. 31:617–639. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Wan X, Ma D, Song G, Tang L, Jiang X, Tian

Y, Yi Z, Jiang C, Jin Y, Hu A and Bai Y: The SOX2/PDIA6 axis

mediates aerobic glycolysis to promote stemness in non-small cell

lung cancer cells. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 56:323–332. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Yan F, Teng Y, Li X, Zhong Y, Li C, Yan F

and He X: Hypoxia promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell

stemness, migration, and invasion via promoting glycolysis by

lactylation of SOX9. Cancer Biol Ther. 25:23041612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Jia Z, Zhang Y, Yan A, Wang M, Han Q, Wang

K, Wang J, Qiao C, Pan Z, Chen C, et al: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3

signaling-induced decreases in IRX4 inhibits NANOG-mediated cancer

stem-like properties and gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cells. Cell

Death Dis. 11:6702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

He J, Shi J, Zhang K, Xue J, Li J, Yang J,

Chen J, Wei J, Ren H and Liu X: Sox2 inhibits Wnt-β-catenin

signaling and metastatic potency of cisplatin-resistant lung

adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 15:1693–1701. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zhou W, Cai C, Lu J and Fan Q: miR-129-2

upregulation induces apoptosis and promotes NSCLC chemosensitivity

by targeting SOX4. Thorac Cancer. 13:956–964. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Huang Q, Xing S, Peng A and Yu Z: NORAD

accelerates chemo-resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer via

targeting at miR-129-1-3p/SOX4 axis. Biosci Rep.

40:BSR201934892020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Xia Y, Tang G, Chen Y, Wang C, Guo M, Xu

T, Zhao M and Zhou Y: Tumor-targeted delivery of siRNA to silence

Sox2 gene expression enhances therapeutic response in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioact Mater. 6:1330–1340.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Masarwy R, Breier D, Stotsky-Oterin L,

Ad-El N, Qassem S, Naidu GS, Aitha A, Ezra A, Goldsmith M,

Hazan-Halevy I and Peer D: Targeted CRISPR/Cas9 lipid nanoparticles

elicits therapeutic genome editing in head and neck cancer. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24110322025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Chen D, Hu C, Wen G, Yang Q, Zhang C and

Yang H: DownRegulated SOX4 expression suppresses cell

proliferation, migration, and induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma in

vitro and in vivo. Calcif Tissue Int. 102:117–127. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Adham AN, Abdelfatah S, Naqishbandi A,

Sugimoto Y, Fleischer E and Efferth T: Transcriptomics, molecular

docking, and cross-resistance profiling of nobiletin in cancer

cells and synergistic interaction with doxorubicin upon SOX5

transfection. Phytomedicine. 100:1540642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Guo K, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Han L, Shao C, Feng

Y, Gao F, Di S, Zhang Z, Zhang J, et al: HDAC7 promotes NSCLC

proliferation and metastasis via stabilization by deubiquitinase

USP10 and activation of β-catenin-FGF18 pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 41:912022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Taniguchi J, Pandian GN, Hidaka T, Hashiya

K, Bando T, Kim KK and Sugiyama H: A synthetic DNA-binding

inhibitor of SOX2 guides human induced pluripotent stem cells to

differentiate into mesoderm. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:9219–9228. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Panda M, Tripathi SK and Biswal BK: SOX9:

An emerging driving factor from cancer progression to drug

resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1875:1885172021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Liu Z, Liao Z, Chen Y, Zhou L, Huangting W

and Xiao H: Research on CRISPR/system in major cancers and its

potential in cancer treatments. Clin Transl Oncol. 23:425–433.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML,

Reyon D, Joung JK and Sander JD: High-frequency off-target

mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat

Biotechnol. 31:822–826. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA and

Liu DR: Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA

without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 533:420–424. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Hu B, Zhong L, Weng Y, Peng L, Huang Y,

Zhao Y and Liang XJ: Therapeutic siRNA: State of the art. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 5:1012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Bobbin ML and Rossi JJ: RNA interference

(RNAi)-based therapeutics: Delivering on the promise? Annu Rev

Pharmacol Toxicol. 56:103–122. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Cina C, Majeti B, O'Brien Z, Wang L,

Clamme JP, Adami R, Tsang KY, Harborth J, Ying W and Zabludoff S: A

novel lipid nanoparticle NBF-006 encapsulating glutathione

S-transferase P siRNA for the treatment of KRAS-driven non-small

cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 24:7–17. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Kumthekar P, Ko CH, Paunesku T, Dixit K,

Sonabend AM, Bloch O, Tate M, Schwartz M, Zuckerman L, Lezon R, et

al: A first-in-human phase 0 clinical study of RNA

interference-based spherical nucleic acids in patients with

recurrent glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 13:eabb39452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Zuckerman JE, Gritli I, Tolcher A, Heidel

JD, Lim D, Morgan R, Chmielowski B, Ribas A, Davis ME and Yen Y:

Correlating animal and human phase Ia/Ib clinical data with

CALAA-01, a targeted, polymer-based nanoparticle containing siRNA.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:11449–11454. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Molinar C, Tannous M, Meloni D, Cavalli R

and Scomparin A: Current status and trends in nucleic acids for

cancer therapy: A focus on polysaccharide-based nanomedicines.

Macromol Biosci. 23:e23001022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Torres-Mejia E, Weng S, Whittaker CA,

Nguyen KB, Duong E, Yim L and Spranger S: Lung cancer-intrinsic

SOX2 expression mediates resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy

by inducing treg-dependent CD8+ T-cell exclusion. Cancer Immunol

Res. 13:496–516. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Njouendou AJ, Szarvas T, Tiofack AAZ,

Kenfack RN, Tonouo PD, Ananga SN, Bell EHMD, Simo G, Hoheisel JD,

Siveke JT and Lueong SS: SOX2 dosage sustains tumor-promoting

inflammation to drive disease aggressiveness by modulating the

FOSL2/IL6 axis. Mol Cancer. 22:522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Jiang J, Wang Y, Sun M, Luo X, Zhang Z,

Wang Y, Li S, Hu D, Zhang J, Wu Z, et al: SOX on tumors, a comfort

or a constraint? Cell Death Discov. 10:672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Wang K and Zhou H: Proteolysis targeting

chimera (PROTAC) for epidermal growth factor receptor enhances

anti-tumor immunity in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Dev Res.

82:422–429. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Jie C, Li R, Cheng Y, Wang Z, Wu Q and Xie

C: Prospects and feasibility of synergistic therapy with

radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors

in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 14:11223522023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Memon D, Schoenfeld AJ, Ye D, Fromm G,

Rizvi H, Zhang X, Keddar MR, Mathew D, Yoo KJ, Qiu J, et al:

Clinical and molecular features of acquired resistance to

immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell.

42:209–224.e9. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Rotow J and Bivona TG: Understanding and

targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat Rev Cancer.

17:637–658. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Justilien V, Walsh MP, Ali SA, Thompson

EA, Murray NR and Fields AP: The PRKCI and SOX2 oncogenes are

coamplified and cooperate to activate Hedgehog signaling in lung

squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 25:139–151. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Wu JL, Xu CF, Yang XH and Wang MS:

Fibronectin promotes tumor progression through integrin

αvβ3/PI3K/AKT/SOX2 signaling in non-small cell lung cancer.

Heliyon. 9:e201852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Huang JQ, Wei FK, Xu XL, Ye SX, Song JW,

Ding PK, Zhu J, Li HF, Luo XP, Gong H, et al: SOX9 drives the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small-cell lung cancer

through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. J Transl Med. 17:1432019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Singh S, Trevino J, Bora-Singhal N,

Coppola D, Haura E, Altiok S and Chellappan SP: EGFR/Src/Akt

signaling modulates Sox2 expression and self-renewal of stem-like

side-population cells in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer.

11:732012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Voronkova MA, Rojanasakul LW,

Kiratipaiboon C and Rojanasakul Y: The SOX9-aldehyde dehydrogenase

axis determines resistance to chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung

cancer. Mol Cell Biol. 40:e00307–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Weina K and Utikal J: SOX2 and cancer:

Current research and its implications in the clinic. Clin Transl

Med. 3:192014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Ciccone G, Ibba ML, Coppola G, Catuogno S

and Esposito CL: The small RNA landscape in NSCLC: Current

therapeutic applications and progresses. Int J Mol Sci.

24:61212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Paul A, Muralidharan A, Biswas A, Kamath

BV, Joseph A and Alex AT: siRNA therapeutics and its challenges:

Recent advances in effective delivery for cancer therapy. OpenNano.

7:1000632022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Khan P, Siddiqui JA, Lakshmanan I, Ganti

AK, Salgia R, Jain M, Batra SK and Nasser MW: RNA-based therapies:

A cog in the wheel of lung cancer defense. Mol Cancer. 20:542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Li JW, Zheng G, Kaye FJ and Wu L: PROTAC

therapy as a new targeted therapy for lung cancer. Mol Ther.

31:647–656. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Li S, Wang X, Huang J, Cao X, Liu Y, Bai

S, Zeng T, Chen Q, Li C, Lu C and Yang H: Decoy-PROTAC for specific

degradation of ‘undruggable’ STAT3 transcription factor. Cell Death

Dis. 16:1972025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Ravindran Menon D, Luo Y, Arcaroli JJ, Liu

S, KrishnanKutty LN, Osborne DG, Li Y, Samson JM, Bagby S, Tan AC,

et al: CDK1 interacts with SOX2 and promotes tumor initiation in

human melanoma. Cancer Res. 78:6561–6574. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Maurizi G, Verma N, Gadi A, Mansukhani A

and Basilico C: SOX2 is required for tumor development and cancer

cell proliferation in osteosarcoma. Oncogene. 37:4626–4632. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Domenici G, Aurrekoetxea-Rodríguez I,

Simões BM, Rábano M, Lee SY, Millán JS, Comaills V, Oliemuller E,

López-Ruiz JA, Zabalza I, et al: A Sox2-Sox9 signalling axis

maintains human breast luminal progenitor and breast cancer stem

cells. Oncogene. 38:3151–3169. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Wang Q, Li J, Zhu J, Mao J, Duan C, Liang

X, Zhu L, Zhu M, Zhang Z, Lin F and Guo R: Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9

screening for therapeutic targets in NSCLC carrying wild-type TP53

and receptor tyrosine kinase genes. Clin Transl Med. 12:e8822022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Liu B, Wang Z, Gu M, Wang J and Tan J:

Research into overcoming drug resistance in lung cancer treatment

using CRISPR-Cas9 technology: A narrative review. Transl Lung

Cancer Res. 13:2067–2081. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Li N and Li S: Epigenetic inactivation of

SOX1 promotes cell migration in lung cancer. Tumour Biol.

36:4603–4610. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Ai C, Huang Z, Rong T, Shen W, Yang F, Li

Q, Bi L and Li W: The impact of SOX4-activated CTHRC1

transcriptional activity regulating DNA damage repair on cisplatin

resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Electrophoresis. 45:1408–1417.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Chen X, Zheng Q, Li W, Lu Y, Ni Y, Ma L

and Fu Y: SOX5 induces lung adenocarcinoma angiogenesis by inducing

the expression of VEGF through STAT3 signaling. Onco Targets Ther.

11:5733–5741. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Zhou Y, Zheng X, Chen LJ, Xu B and Jiang

JT: microRNA-181b suppresses the metastasis of lung cancer cells by

targeting sex determining region Y-related high mobility group-box

6 (Sox6). Pathol Res Pract. 215:335–342. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Sun QY, Ding LW, Johnson K, Zhou S, Tyner

JW, Yang H, Doan NB, Said JW, Xiao JF, Loh XY, et al: SOX7

regulates MAPK/ERK-BIM mediated apoptosis in cancer cells.

Oncogene. 38:6196–6210. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Hao X, Han F, Ma B, Zhang N, Chen H, Jiang

X, Yin L, Liu W, Ao L, Cao J and Liu J: SOX30 is a key regulator of

desmosomal gene suppressing tumor growth and metastasis in lung