Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and deadly

type of brain cancer (1). On the

basis of the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for central

nervous system tumor classification, GBM is a grade IV diffuse

glioma (2). The GBM cell

characteristic of diffuse infiltration has the ability to invade

the surrounding normal brain tissue, resulting in recurrence even

after complete resection (3). The

current standard of care for GBM involves a combination of surgical

resection with radiation and chemotherapy (4–6). In

recent years, despite advancements in therapeutic efficacy against

GBM, its prognosis remains poor. Therefore, it is necessary to

elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing the pathogenesis and

progression of GBM, while exploring potential therapeutic targets

to increase treatment efficacy and prolong patient survival.

S100B, which is located on chromosome 21, is a

Ca2+-binding protein of the S100 family, and numerous

studies have demonstrated its neurotrophic effects. In the central

nervous system, S100B primarily influences the proliferation and

differentiation of glial cells, as well as the maintenance of

calcium homeostasis (7). Its

carboxyl terminus has a strong affinity for Ca2+; when

it binds to Ca2+, S100B undergoes conformational changes

that expose its target protein-binding site and exerts biological

effects through interactions with these target proteins (8,9).

Melanoma, ovarian and breast cancer, and other malignant tumors

have been observed to express S100B at substantially elevated

levels. Furthermore, it is closely associated with tumor

development, malignancy and prognosis (10–12).

In previous studies, S100B silencing in melanoma cells has been

shown to restore p53-mediated apoptosis, which may restrict

malignant cell proliferation (13,14).

Moreover, intervention with S100B expression in ovarian cancer

stem-like cells has been shown to increase p53 activity and reduce

subcutaneous tumor volume, leading to markedly prolonged survival

time in nude mice (12). In

addition, S100B may drive bevacizumab resistance in ovarian cancer

by promoting angiogenesis. Both in vivo resistant tumors and

in vitro S100B-overexpressing cells were found to enhance

human umbilical vein endothelial cell migration and tube formation,

which can be replicated by exogenous S100B treatment.

Mechanistically, endothelial cells uptake tumor-derived S100B,

which suppresses FOXO1 and releases β-catenin for nuclear

pro-angiogenic signaling (15).

Emerging evidence has implicated S100B in GBM pathogenesis,

although mechanistic insights remain limited. Serum S100B levels

are elevated in patients with glioma compared with those obtained

from control individuals with craniocerebral trauma (16). In addition, S100B concentrations are

positively associated with tumor grade; they are notably higher in

high-grade vs. low-grade glioma, according to the WHO

classification system. However, the tissue-specific expression

patterns of S100B in GBM, its clinical relevance and its functional

roles in tumor progression require further investigation.

The present study identified the upregulated

expression of S100B in GBM and its close association with an

unfavorable prognosis. By contrast, the inhibition of S100B

resulted in suppressed proliferative capacity, and a reduction in

invasion, migration and EMT. The results also revealed that

downregulation of TGF-β2 was observed upon inhibition of S100B.

Consistently, cell invasion, migration and the EMT process were

rescued by exogenous recombinant protein TGF-β2 treatment. These

findings indicate the role of S100B in promoting GBM progression.

The current study elucidates the mechanism by which S100B

facilitates GBM cell invasion and migration via the TGF-β2-induced

EMT process that exhibits an infiltrative growth pattern, thus

providing novel insights for GBM treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

The human GBM cell line LN229 (cat. no. CRL-2611)

was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The cell

line was verified through short tandem repeat testing (Guangzhou

Cellcook Biotech Co., Ltd.). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; cat. no. 11995065; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(cat. no. PWL001; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd.) and

1% penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. ST488S; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and were incubated at 37°C with 5%

CO2.

Flow cytometric analysis

A total of 2×106 cells were collected and

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, then washed with PBS.

After incubation with S100B antibody (1:200; cat. no. ab52642;

Abcam) overnight, the cells were washed with PBS and stained with

FITC-Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no.

A22120; Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.) for 1.5 h. The final wash was

completed and used for flow cytometry. Flow cytometric analysis was

conducted on a BD FACSCanto™ Flow Cytometer system (10-colour

configuration; BD Biosciences), followed by processing of the data

using BD FACSDiva Software (BD Biosciences).

Lentiviral transduction to knockdown

S100B

LN229 cells were stably transduced with short

hairpin (sh)RNA vectors to knockdown S100B. The shRNA vectors were

purchased from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. The S100B shRNA vector

(shS100B) sequence was 5′-CTGCCACGAGTTCTTTGAA-3′, and the negative

control (NC) sequence was 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′. For

transduction of the human GBM cell line LN229, 5×104

cells/well in a 12-well plate were transduced with lentiviral

particles (multiplicity of infection, 10) for 12 h. The serum-free

medium was then replaced with medium containing 10% FBS. A total of

48 h after lentivirus transduction, the cells were treated with

puromycin (cat. no. P8230; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) working concentration 2.0 µg/ml for 48 h to

screen successfully transduced positive cells. At 72 h

post-infection, GFP expression was examined using a fluorescence

microscope (Nikon Corporation). The validation of shRNA knockdown

efficiency of S100B was verified by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), western blot analysis and

immunofluorescence (IF) staining. The experimental results were

obtained from three replicate experiments using NC LN229 GBM cells

as a control for relative quantitative analysis. The IF results

were calculated by randomly selecting six fields each time to

analyze their mean fluorescence intensity. The ratio of

S100B-positive cells to all cells in each field was first

calculated separately for the NC and shS100B groups, and then the

relative percentage rate of positive cells was calculated using NC

as the control group. In addition, the shS100B cells were cultured

with recombinant TGF-β2 protein (cat. no. HY-P7119; MedChemExpress)

for 48 h to obtain shS100B + TGF-β2 cells, which were used for

subsequent experimental analyses.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from NC and shS100B LN229 GBM

cells using AG RNAex Pro Reagent (cat. no. AG21101; Accurate

Biology). RT-qPCR was performed using the ABScript III RT Master

Mix for qPCR with gDNA Remover (cat. no. RK20429; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd.) and 2X Universal SYBR Green Fast qPCR Mix (cat. no.

RK21203; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Thermocycling conditions are included in

Tables I and II. GAPDH was used as an internal control

and fold change was determined using the relative quantification

(2−∆∆Cq) method (16).

The sequences of the primers used were as follows: GAPDH forward,

5′-AATGGACAACTGGTCGTGGAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCCTCCAGGGGATCTGTTTG-3′; S100B forward,

5′-AGCTGGAGAAGGCCATGGTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAACTCGTGGCAGGCAGTAG-3′;

and TGF-β2 forward, 5′-CAGCACACTCGATATGGACCA-3′ and reverse,

5′-CCTCGGGCTCAGGATAGTCT-3′.

| Table I.Thermocycling conditions of reverse

transcription reaction. |

Table I.

Thermocycling conditions of reverse

transcription reaction.

| Temperature,°C | Time, min |

|---|

| 37 | 2 |

| 55 | 15 |

| 85 | 5 |

| 4 | Hold |

| Table II.Quantitative PCR reaction

conditions. |

Table II.

Quantitative PCR reaction

conditions.

| Step | Temperature,°C | Time | Number of

cycles |

|---|

|

Pre-denaturation | 95 | 3 min | 1 |

| Cyclic

reaction | 95 | 5 sec | 40-45 |

|

| 60 | 30 sec |

|

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from LN229 cells using a

Whole Cell Lysis Assay Kit (cat. no. KGB5303-100; Nanjing KeyGen

Biotech Co., Ltd.) and a BCA assay (cat. no. KGB2101-500; Nanjing

KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) was used to determine the protein

concentration. In total, 30 µg equivalent amounts of protein were

separated by SDS-PAGE on 15% gels and were transferred to PVDF

membranes (cat. no. ISEQ00010; MilliporeSigma). The primary

antibodies used were anti-S100B (1:200; cat. no. ab52642; Abcam),

anti-GAPDH (1:5,000; cat. no. 10494-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-TGF-β2 (1:200; cat. no. 19999-1-AP;

Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology, Inc.). The corresponding secondary

antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology, Inc.) or HRP-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse

secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-1; Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology, Inc.). After incubation with secondary antibodies, a

chemiluminescence system (G:box; Syngene Europe) was used to detect

immunoreactive proteins, and the band intensity relative to that of

GAPDH was semi-quantified with Quantity One software (version

4.6.2; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

In vivo subcutaneous xenograft

model

Immunodeficient 4-week-old male nude mice weighing

~15 grams from Chongqing Tengxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd., were used

for tumor formation and analysis. Animals were housed in an

specific pathogen free (SPF) environment at 23°C with 30–70%

humidity and 12/12-h light/dark cycle. A total of 1×106

NC cells and shS100B cells in 100 µl DMEM were transplanted

subcutaneously into the nude mice. Tumor size was measured every 3

days during this period. The tumor size was calculated using the

following formula: Volume=width2 × length/2. A total of

six mice were used in the present study. The maximum recorded tumor

volume was 122.301 mm3. At this endpoint, the tumor

length and width measured 6.84 and 5.98 mm, respectively. On day 26

post-injection, the nude mice were placed in a designated

asphyxiator and CO2 is passed through it, with the

CO2 displacing about 70% of the gas in the asphyxiator

per minute, and the animal is removed after it is completely dead.

Death was confirmed by the sustained absence of spontaneous

respiration observed for at least two min, followed by the loss of

all critical reflexes, including pupillary, corneal, and toe-pinch

responses, prior to proceeding with subsequent experiments.

Euthanasia of immunodeficient mice was required if tumor growth

exceeded 10% of body weight, if individual tumors exceeded 17 mm in

diameter, if ulceration, necrosis or infection developed on the

surface of the tumor, or if the mouse lost 15% of its body weight.

The tumor tissues were immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h before being stored in 30% sucrose solution. The fixed and

dehydrated tissues were then embedded in O.C.T. compound (cat. no.

4583; Sakura Finetek USA, Inc.), frozen, sectioned, placed on

slides and subjected to IF staining.

IF staining

For IF staining, NC and shS100B LN229 GBM cells were

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and frozen tissues from NC and

shS100B mice were cut into 15-µm sections. Tumor tissues and GBM

cells were stained with an anti-S100B antibody (1:200; cat. no.

ab52642; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After being washed three times

with PBS, the samples were incubated with a DyLight 549 goat

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. A23320;

Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.) for 1.5 h at 4°C. The nuclei were

stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (cat. no. C1002; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 15 min. Images were captured using

a laser confocal microscope (Nikon A1R; Nikon Corporation) and were

prepared via Nikon NIS-Elements AR Analysis 5.20.02.64-bit software

for further analysis.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

proliferation analysis

Cell viability was determined using a CCK-8 assay.

NC and shS100B LN229 GBM cells were cultured in 96-well plates at

1,000 cells/well. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the

cells were incubated with a mixture containing 10 µl CCK solution

(cat. no. M4839; Abmole Bioscience, Inc.) and 90 µl culture medium

for 2 h at 37°C. The OD value was acquired at 450 nm using a

microplate reader (Epoch; BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Notably, OD values were recorded on days 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)

proliferation analysis

Another method was also used to evaluate the effect

of S100B on cell proliferation. Briefly, NC and shS100B LN229 GBM

cells were treated with the BeyoClick™ EdU Cell

Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 555 (cat. no. C0075L; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Subsequently, the cells were stained with

4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (cat. no. C1002; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 15 min. Images were captured using a laser

confocal microscope (Nikon A1R) and were analyzed with NIS-Elements

AR Analysis 5.20.02.64-bit software.

Colony formation assay

NC and shS100B LN229 cells were seeded into 12-well

plates at a density of 2,000 cells/well and were cultured at 37°C

and 5% CO2 for 8 days. On day 4, the medium was replaced

with fresh medium. On day 8, the medium was removed, the cells were

washed with PBS, and the cells were subsequently fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Finally, the cells were stained with

crystal violet staining solution (cat. no. C0121-100 ml; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 15 min, and the wells were imaged

by full scanning using a microplate reader (Epoch) to count the

number of visible colonies (≥30 cells).

Transwell migration and invasion

assays

First, NC and shS100B LN229 cells were cultured in

DMEM without FBS for 12 h. Subsequently, 0.5×105 cells

were seeded in the upper chambers of Transwell plates (24 wells;

8-µm pore size; cat. no. 353097; Falcon; Corning, Inc.), which were

precoated with Matrigel (cat. no. HY-K6002; MedChemExpress) at 37°C

for 30 min for the invasion assay or uncoated for the migration

assay. DMEM without FBS was added to the upper chambers, and DMEM

with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers. After 48 h of

incubation, the migratory/invasive cells in the lower chambers of

the Transwell plate membranes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

and stained with crystal violet solution for 15 min. However, the

non-migratory/invasive cells in the upper chambers were removed.

The number of migratory/invasive cells in the six fields was

randomly determined using a microplate reader at ×100

magnification. The relative proportion of migrating/invasive cells

was calculated using NC as the controls. And the experiment was

repeated three times.

Cross-scratch assay

A scratch assay was used to assess the migratory

properties of the NC and shS100B groups. Briefly, 1×106

cells were seeded in 6-well plates with complete DMEM, and when the

cells formed a confluent monolayer, they were incubated for 24 h at

37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. A cross-scratch was made

using a sterile 10-µl pipette tip, and the cells were then washed

with sterile PBS to remove nonadherent cells in suspension. The

cells were subsequently cultured in DMEM without FBS, and a

microplate reader (Epoch) was used to capture the center of the

cross-scratch at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. The areas of the scratches

were analyzed using NIS-Elements AR Analysis 5.20.02.64-bit

software, and the percentage of migrating cells was calculated. The

cell migration rate was calculated as the cell migration area

divided by the cross-scratch area.

Database analysis

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA; http://www.proteinatlas.org/) contains both mRNA and

protein expression data from different human tissues, and

antibodies with different cat. no. have been used to determine the

protein expression level. Thus, using this online database, the

mRNA and protein expression data of S100B in different types of

cancer were obtained. Moreover, the association between gene

expression level and survival time was explored via these

databases.

The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

(GEPIA) dataset is an online database used to analyze RNA

sequencing data and Genotype-Tissue Expression projects (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/). GEPIA can be used to

perform analyses including tumor and normal differential expression

analysis, patient survival analysis and gene correlation analysis.

For the present study, the mRNA expression of S100B in GBM and

paired normal tissues was evaluated using this database.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga)

is a Cancer Genomics Program, which includes genomic, epigenomic,

transcriptomic and proteomic data. Notably, >20,000 primary

cancer samples and matched normal samples from 33 cancer types have

been molecularly characterized. The database was used to analyze

the expression of S100B in different tumor tissues and normal

tissues, and its expression in association with patient survival

time.

Gene expression profiles of tumor and normal brain

samples generated via chips were obtained from the GSE50161 dataset

from the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The online website

SangerBOX (http://sangerbox.com/) was used for

patient survival analysis.

Single-cell data were sourced from Tumor Immune

Single Cell Hub (TISCH; http://tisch.comp-genomics.org/gallery/), which

contains single-cell sequencing data from 17 glioma projects. The

database was used to access the expression profiles of S100B in

different cell types.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed

unpaired Student's t-test, One-way ANOVA with GraphPad Prism 9.0

software (Dotmatics). All data are presented as the mean ± standard

error of the mean. Every experiment was repeated at least three

times, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

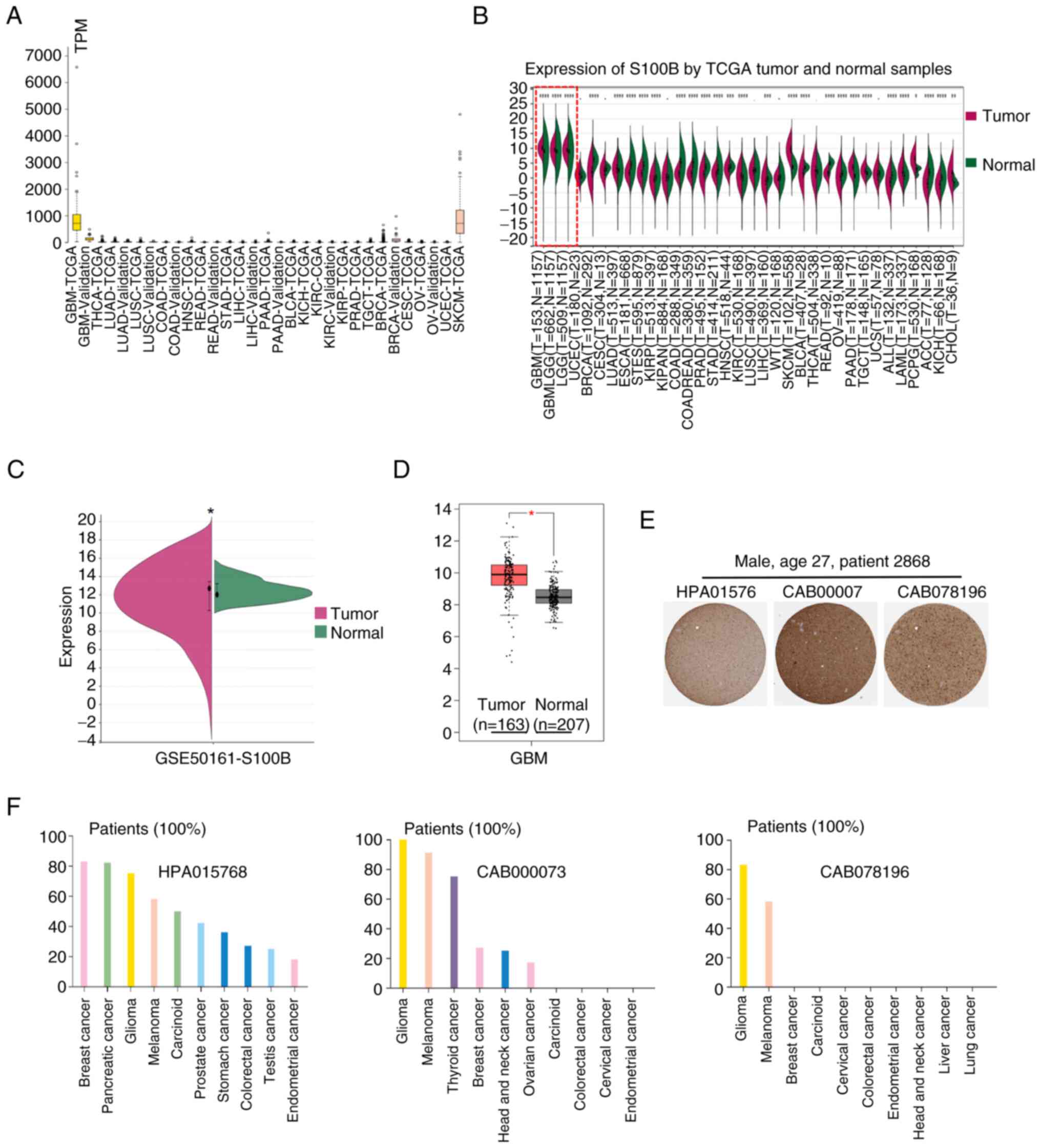

S100B is highly expressed in GBM

tissue

Bioinformatics analyses from two independent

databases consistently revealed elevated S100B expression in GBM.

The HPA demonstrated significantly higher S100B mRNA levels in GBM,

and melanoma compared with other tumor types (Fig. 1A). Notably, this finding was

corroborated by TCGA data, where S100B transcription was markedly

increased in GBM tissues relative to normal controls, a contrast

more pronounced than that detected in other malignancies (Fig. 1B). This phenomenon was subsequently

confirmed in the GSE50161 dataset and the GEPIA database (Fig. 1C and D). Immunohistochemical

examination demonstrated the distribution and expression pattern of

S100B at the protein level in patients with glioma; most samples

displayed moderate to strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity,

which was greater than that of melanoma and other types of cancer

(Fig. 1E and F).

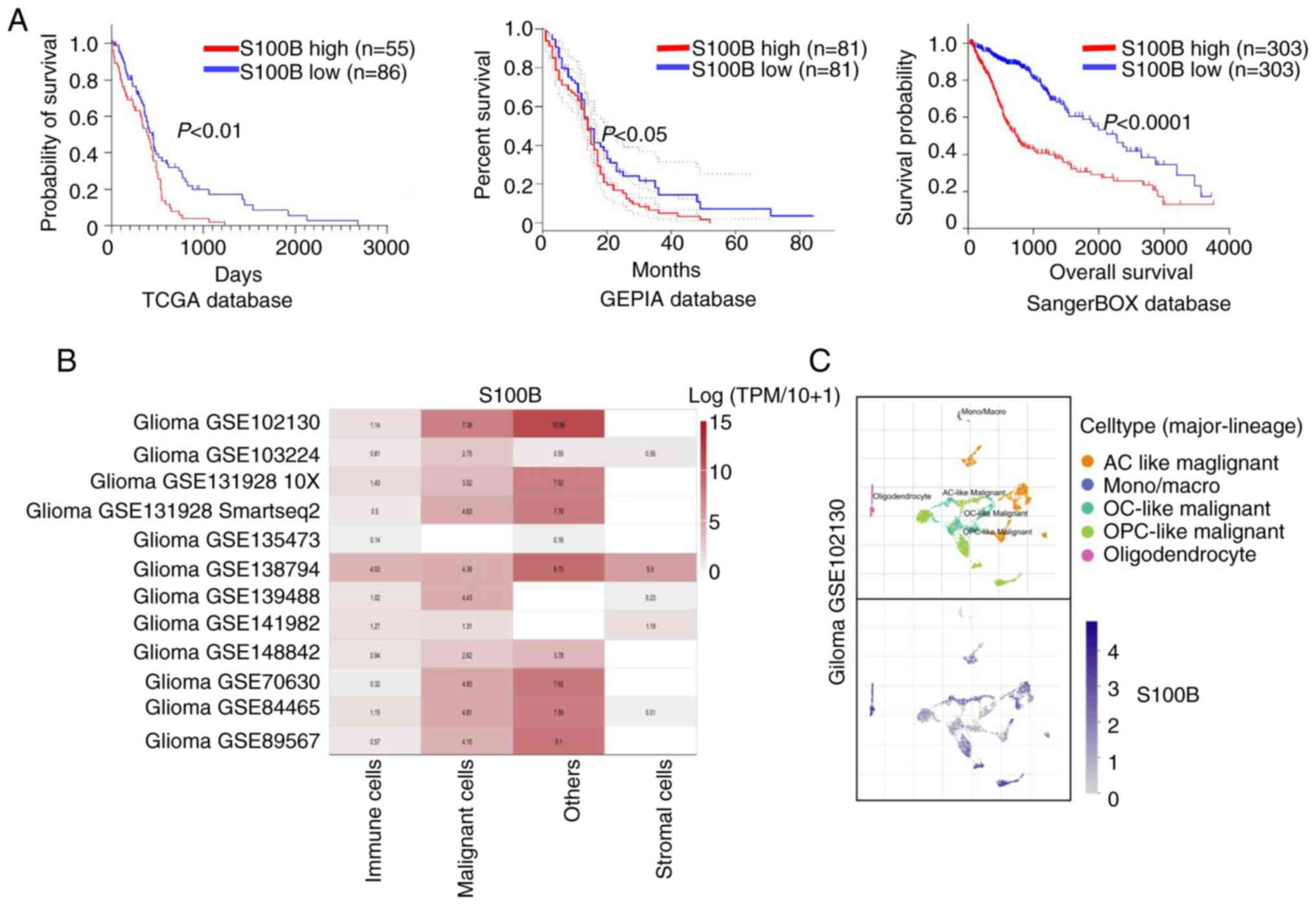

High S100B expression is strongly

associated with adverse outcomes in glioma

To systematically evaluate the prognostic value of

S100B in glioma, multi-omics data from TCGA, GEPIA and SangerBOX

databases were analyzed. Survival analysis revealed that patients

with elevated S100B expression exhibited significantly shorter

overall survival compared with those with lower expression levels

(Fig. 2A), indicating its strong

association with a poor prognosis. The present study also assessed

glioma single-cell transcriptome data from the TISCH database

(17), which confirmed that S100B

was markedly upregulated in malignant cells (Fig. 2B). This result was further supported

by the Synapse (Fig. 2C). These

findings strongly implicate S100B as a potential key regulator and

a promising molecular target worthy of further mechanistic

investigation in glioma therapeutics.

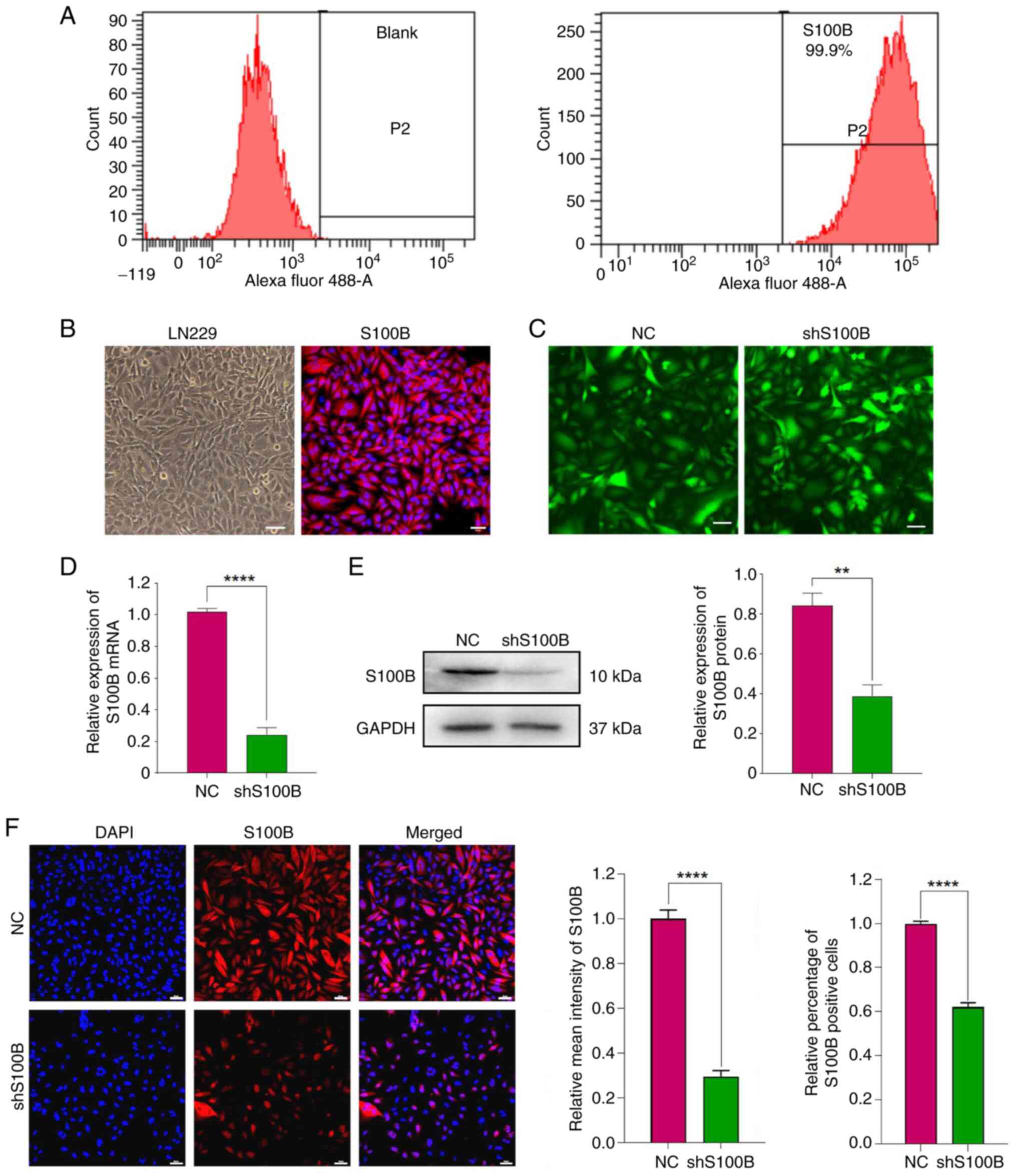

Knockdown of S100B in LN229 cells

Flow cytometric and IF analyses of LN229 GBM cells

stained with S100B revealed that the percentage of positive cells

was as high as 99.9% (Fig. 3A and

B). These results confirmed that S100B is highly expressed in

the GBM cell line LN229. Lentiviral transduction with shS100B

induced intracellular S100B suppression at both transcriptional and

translational levels, as indicated by significantly reduced mRNA

expression and diminished protein abundance compared with that in

the NC group (Fig. 3C-E).

Concurrent IF analysis confirmed this knockdown efficiency at the

cellular level, with both mean intensity and S100B-positive cells

decreased in the shS100B-treated group (Fig. 3F). According to the aforementioned

findings, a stable cell line with low S100B expression was

successfully constructed.

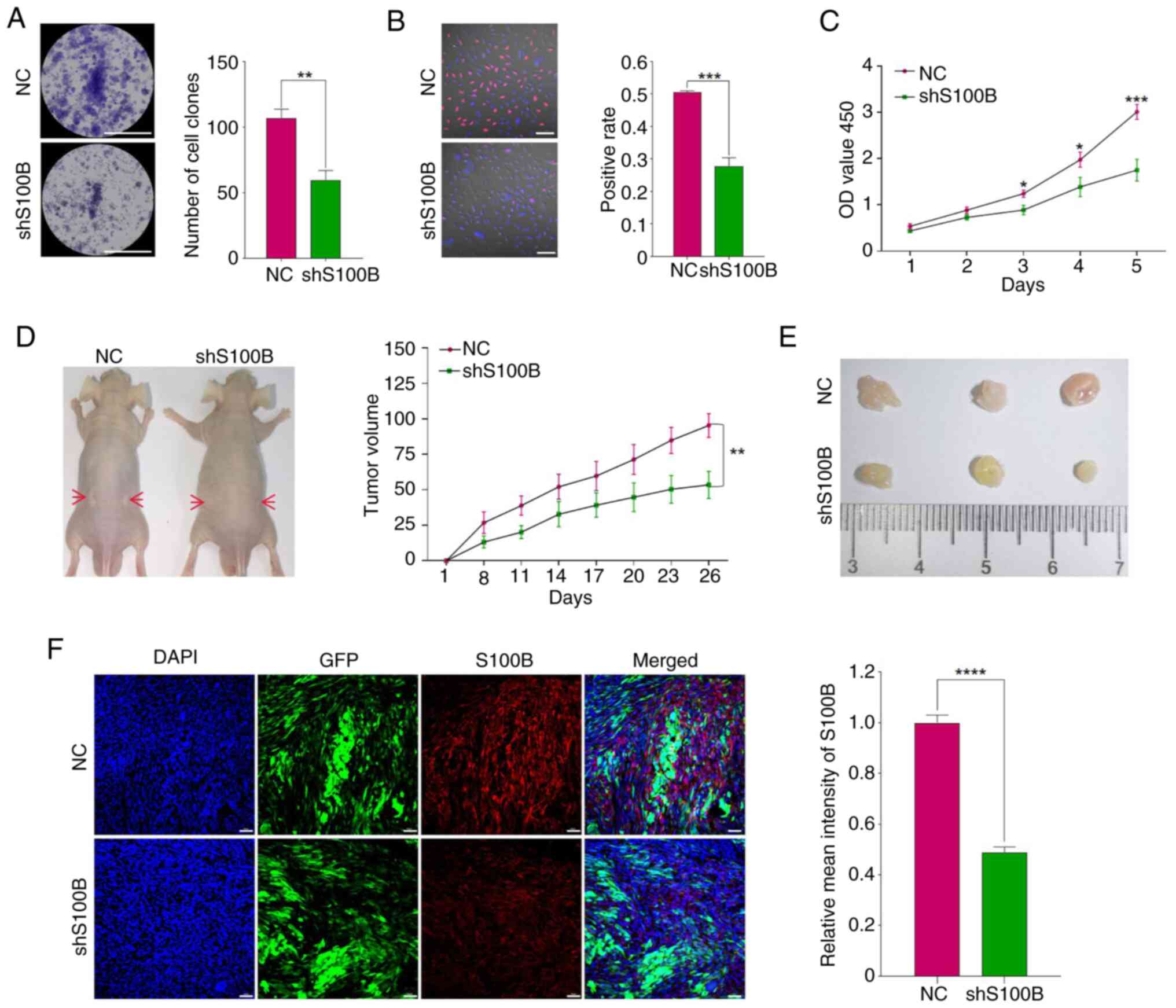

Target-oriented S100B suppresses LN229

proliferative capacity in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo

Colony formation assays demonstrated that S100B

knockdown significantly impaired clonogenic potential (Fig. 4A), a finding corroborated by EdU

incorporation assays showing significantly decreased DNA synthesis

in shS100B LN229 cells (Fig. 4B).

Furthermore, the results of the CCK-8 assay confirmed that the

inhibition of S100B strongly suppressed the proliferation of LN229

cells (Fig. 4C). To evaluate the

effects of S100B on tumorigenicity, NC and shS100B cells were

transplanted into nude mice. Quantitative analysis revealed that

xenograft tumors in the shS100B group exhibited significantly

slower growth kinetics compared with those in the NC group

(Fig. 4D). Consistently, endpoint

measurements demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in

tumor volume within the shS100B cohort relative to the NC group

(Fig. 4E). Upon termination of the

experiment at day 26 post-implantation, histopathological

examination of resected tumors showed well-circumscribed masses

without evidence of local tissue invasion or metastatic

dissemination. This observation indicated that the subcutaneous

xenograft model, while suitable for evaluating primary tumor growth

parameters, has limitations in assessing invasive and migratory

phenotypes. Subsequently, IF staining of frozen sections

demonstrated that S100B expression in shS100B LN229 tumor tissue

was significantly lower than that in the NC group (Fig. 4F). These collective findings

strongly suggest that S100B depletion attenuates tumorigenic

capacity in this preclinical model.

Cell invasion and migration are

decreased in the S100B-knockdown group via the inhibition of

EMT

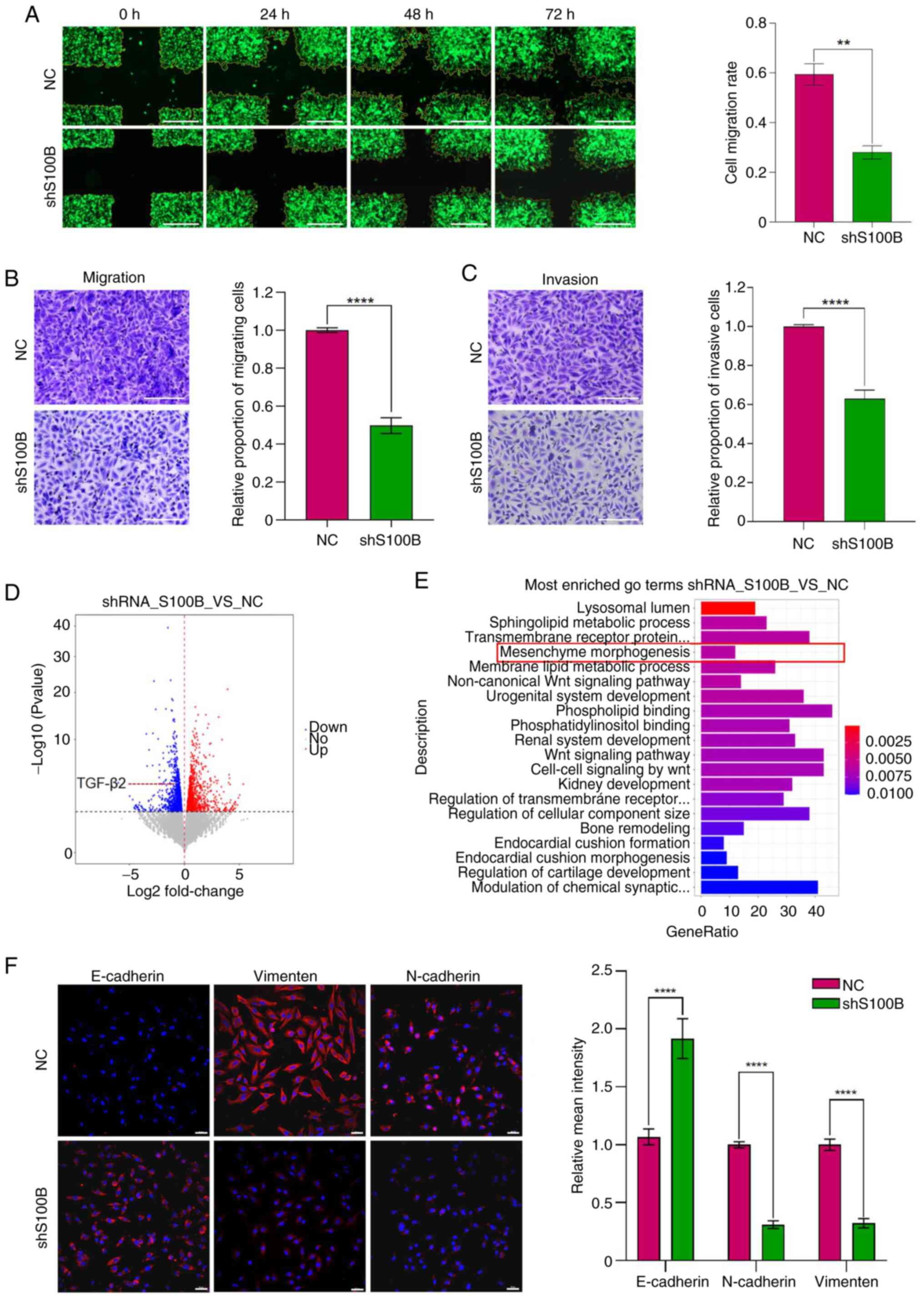

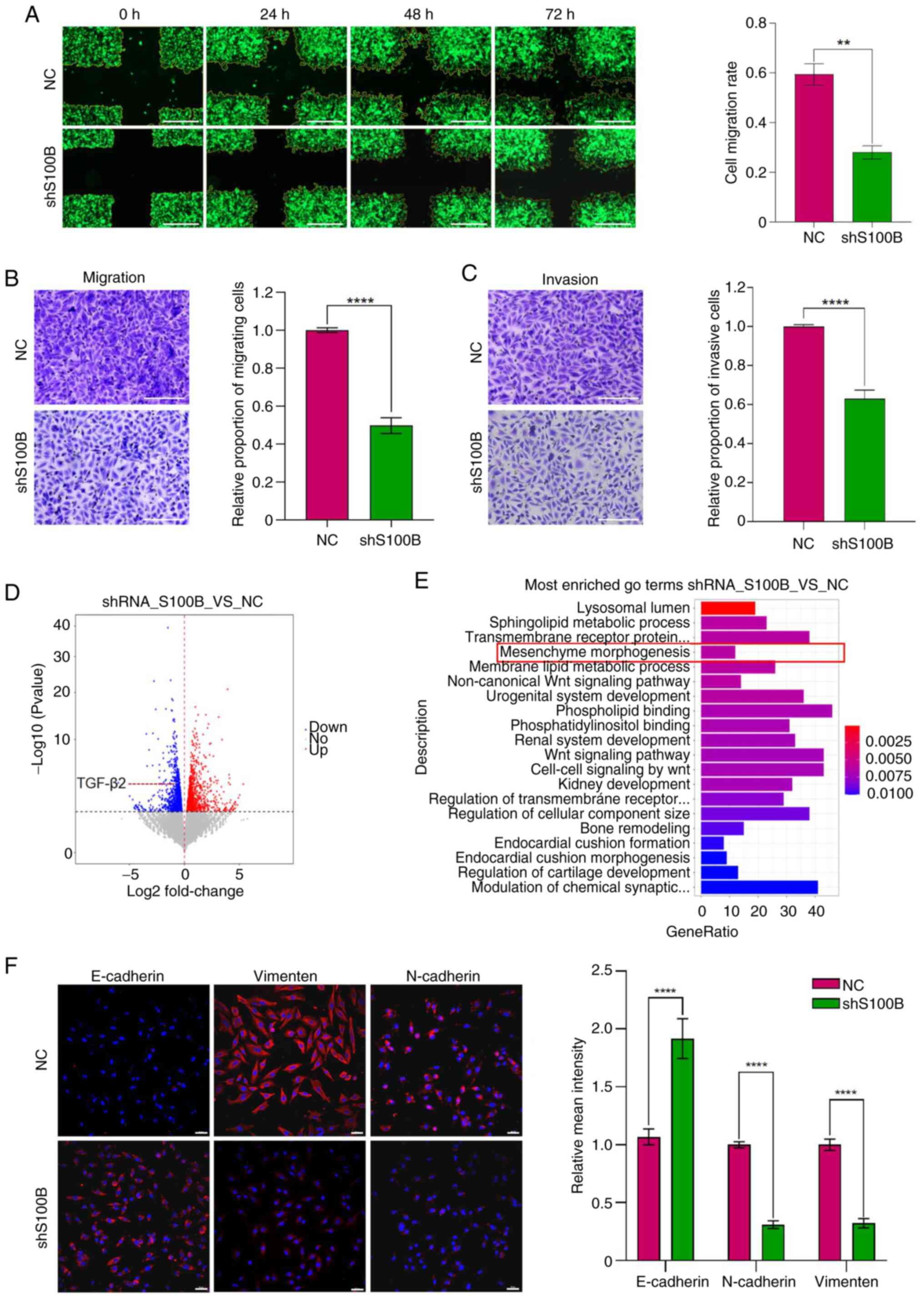

The current study further examined the effects of

S100B on GBM cell invasion and migration. Wound healing assays

revealed a significantly reduced migratory capability in the

shS100B group compared with that in the NC group (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, Transwell assays

with or without Matrigel coating demonstrated significantly fewer

invasive/migratory cells in the shS100B group vs. the NC group

(Fig. 5B and C). Collectively,

these results demonstrated that S100B knockdown could attenuate the

invasive and migratory capacities of GBM cells. To elucidate the

molecular mechanism by which S100B affects the invasion and

migration of GBM cells, transcriptome sequencing of NC and shS100B

LN229 cells was performed. RNA sequencing identified 2,294

differentially expressed genes (fold change >2, P<0.05),

comprising 1,130 upregulated and 1,164 downregulated genes between

the two groups (Fig. 5D). Gene

Ontology (GO) analyses revealed that the induction of mesenchyme

morphogenesis, a biological process related to EMT, was among the

20 pathways with the greatest differences in downregulated genes

(Fig. 5E). The expression levels of

the EMT markers E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin were

subsequently analyzed in both the NC and shS100B groups. S100B

downregulation upregulated E-cadherin, whereas it downregulated

N-cadherin and vimentin, suggesting suppression of EMT, which could

consequently impair the invasive and migratory capacities of GBM

cells (Fig. 5F).

| Figure 5.S100B affects the invasion and

migration of GBM cells via epithelial-mesenchymal transition. (A)

Detection of cell migration ability by cross-scratch assay; Scale

bar, 500 µm. Cell migration rate = Cell migration area/cross

scratch area. (B and C) Transwell assays analyzed the migratory and

invasive capacity of NC and shS100B GBM cells, Scale bar, 200 µm.

Relative proportion of migratory or invasive cells: Number of

migratory or invasive cells in shS100B group/number of migratory or

invasive cells in NC group. (D) Volcano plot showing the DEGs in

the NC and shS100B groups. (E) GO enrichment analysis of the

functions of downregulated DEG. (F) E-cadherin, N-cadherin and

vimentin expression in NC and shS100B LN229 cells were measured by

immunofluorescence staining. Blue represents cell nuclei, red

represents E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin. Statistical

analysis of relative mean fluorescence intensity was performed.

Scale bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. **P<0.01

and ****P<0.0001. GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; shS100B, shRNA

S100B; NC, negative control; DEGs, differentially expressed genes;

GO, Gene Ontology. |

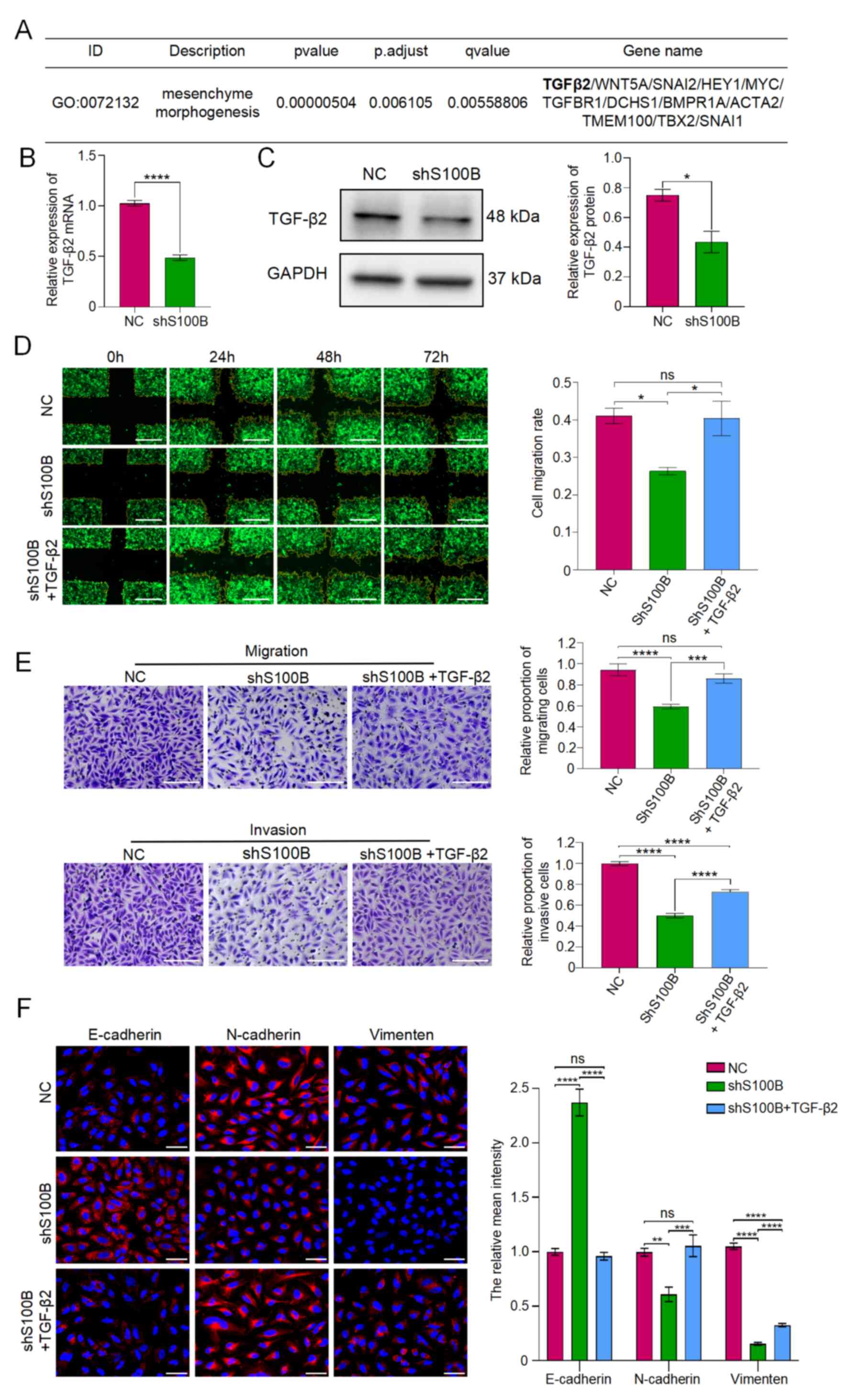

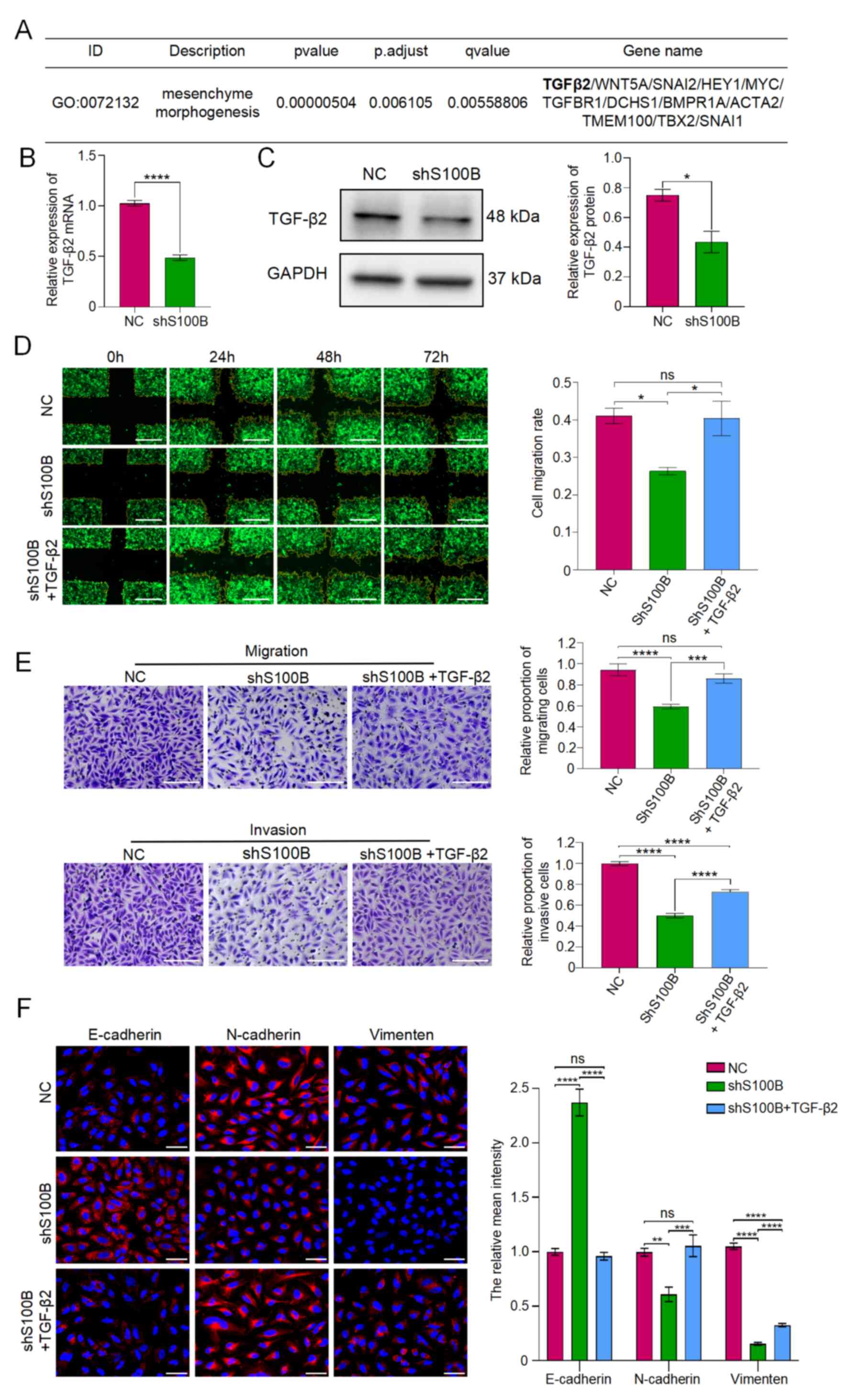

S100B affects the EMT process through

TGF-β2

During mesenchyme morphogenesis pathway activation,

the EMT-associated gene TGF-β2 exhibited significant downregulation

(Fig. 6A). This suppression was

further validated by RT-qPCR and western blotting in

S100B-knockdown cells (Fig. 6B and

C). Accordingly, it was hypothesized that S100B may influence

GBM cell motility through TGF-β2-mediated EMT. To confirm this

hypothesis, GBM cells with downregulated S100B expression were

treated with human recombinant TGF-β2 protein. The experimental

results revealed that compared with those in the shS100B group, the

shS100B + TGF-β2 group had stronger migratory and invasive

properties (Fig. 6D and E).

Furthermore, E-cadherin was reduced, whereas N-cadherin and

vimentin were notably restored in the shS100B + TGF-β2 group

(Fig. 6F). These results indicated

that downregulation of S100B may attenuate TGF-β2-induced EMT, as

well as cell invasion and migration.

| Figure 6.TGF-β2 induces epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and enhances the invasion and migration of glioblastoma

multiforme cells. (A) Relevant downregulated genes of the

mesenchyme morphogenesis pathway. (B and C) Expression of TGF-β2 in

NC and shS100B LN229 cells was analyzed by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and western blotting. (D)

Cross-scratch assay evaluated the migratory capacity of NC, shS100B

and shS100B + TGF-β2 groups, Scale bar, 500 µm. (E) Transwell assay

analyzed the migratory or invasive capacity of NC, shS100B and

shS100B + TGF-β2 groups; Scale bar, 200 µm. Relative proportion of

migratory or invasive cells: Number of migratory or invasive cells

in shS100B group or shS100B + TGF-β2 group/number of migrated or

invaded cells in NC group. (F) E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin

were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining. Blue represents cell

nuclei, and red represents E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin.

Scale bar, 50 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. NC, negative

control; shS100B, shRNA S100B. |

Discussion

GBM is the most aggressive and common type of

malignant brain tumor in the central nervous system. Patients with

GBM have an overall median survival time of 12–16 months (18,19),

and a 5-year survival rate of <5% (20,21).

GBM possesses highly aggressive tumor cells that proliferate in an

infiltrative manner, which results in the absence of a clear

boundary between tumor and healthy areas of brain tissue, making it

difficult to completely remove the tumor during surgery. Although

treatment efficacy has improved with the use of temozolomide and

other combination therapies, the prognosis for patients with GBM

has remained unfavorable for the past 20 years (22). Therefore, identifying the cellular

mechanisms of GBM invasion and preventing its infiltrative growth

by means of molecularly specific therapeutic approaches may be

valuable in enhancing treatment effectiveness and extending patient

survival.

Currently, there are limited findings on the

molecular signaling pathway that underlies the effects of S100B on

the migration and invasion of GBM, and there is little research on

the association between S100B and glioma, especially GBM. S100B is

a member of the multigene family of Ca2+-binding

proteins with EF-hand motifs, which regulate cellular activities

such as metabolism, motility and proliferation. Notably, there is

clear evidence that S100B is elevated in primary malignant melanoma

(13,14). The results of the present study

reported a significantly elevated expression of S100B in both GBM

and melanoma samples, as revealed using the HPA database analysis.

Our previous studies have indicated that S100B is highly expressed

in mouse C6 (23), and in human

U251 and LN229 cell lines. In other databases, S100B was shown to

be negatively associated with patient survival time, and higher

S100B expression was indicated to result in higher mortality in

patients with GBM. In a previous in vitro study, S100B was

shown to promote the proliferation of U251 and T98G GBM cells

(24). Furthermore, overexpression

of S100B has been reported to upregulate CCL2 secretion in G261

glioma cells, leading to increased infiltration of tumor-associated

macrophages into the tumor, increased secretion of inflammatory

factors and tumor angiogenesis, which is favorable to enhance the

growth of malignant tumors (25).

By contrast, decreasing S100B expression in a murine glioma model

has been reported to alter the tumor microenvironment (TME),

inhibit tumor-associated macrophage migration and suppress tumor

progression (26).

The current study demonstrated that targeted

knockdown of S100B using shRNA significantly inhibited GBM

progression both in vitro and in vivo, establishing

S100B as a critical regulator of GBM pathogenesis and a potential

prognostic biomarker. Notably, S100B silencing in LN229 cells

significantly reduced cellular invasion and migration in

vitro, suggesting its pivotal role in tumor metastasis.

However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these effects

remain to be elucidated through further investigation. GO pathway

analysis revealed that multiple pathways, including mesenchyme

morphogenesis, were enriched. Despite the fact that neural tissue

does not originate from a traditional epithelial setting, there is

now substantial evidence that the process known as EMT drives

glioma invasion and migration in the brain (27,28).

Cancer cells undergo EMT, allowing them to acquire mesenchymal

characteristics that facilitate invasion and migration. Throughout

this process, cancer cells lose intercellular adhesion and

epithelial cell polarity, which is accompanied by a downregulation

of E-cadherin, ultimately resulting in decreased cell-to-cell or

cell-to-extracellular matrix adhesion. Moreover, N-cadherin and

vimentin expression is upregulated (29). The current investigation revealed

that the process of EMT was reversed following the knockdown of

S100B and resulted in inhibition of tumor cell invasion and

migration, thus indicating that S100B serves an important role in

regulating EMT. The results of the present study highlighted that

TGF-β2 may be a vital signaling molecule that is associated with

mesenchyme morphogenesis and management of the EMT process in GBM.

TGF-β2 is a member of the TGF-β family, which also includes TGF-β1

and TGF-β3. These three subtypes of TGF-β (TGF-β1-3) have the

ability to induce EMT in epithelial cells (30–33).

By contrast, inhibition or deletion of TGF-β expression can trigger

dysregulation of EMT function (34–36).

According to the RNA sequencing results of the present study,

suppression of S100B resulted in significant downregulation of

TGF-β2, but not of TGF-β1 or TGF-β3.

In the present study, the addition of exogenous

recombinant TGF-β2 protein restored the EMT phenotype, which was

inhibited by S100B knockdown, and restored the invasiveness and

migratory ability of the LN229 cell line. It has been demonstrated

that TGF-β mediates the EMT of various tumors, including GBM. For

example, it has been documented that TGF-β causes GBM cells to pass

through a mesenchymal phenotypic transition via enhancing the

expression of ZEB and pSmad2 (37).

Enhydrin hinders EMT, thereby minimizing both migration and

invasion of GBM cells, by mediating the Jun/Smad7/TGF-β1 signaling

process (38). Acidosis adaptation

in cervical and colorectal cancer cells has been shown to lead to

autocrine secretion of TGF-β2, which stimulates the formation of

lipid droplets and facilitates the EMT of tumor cells to support

malignant progression, such as invasion (39). In gastric cancer, HOXA10 mediates

EMT to promote metastasis by regulating the TGF-β2/Smad/METTL3

signaling axis (40). The present

findings suggest a close association between TGF-β2, and tumor

migration and invasion in GBM. However, to the best of the authors'

knowledge, there are no studies at present on the potential role of

the S100B-TGFβ2 axis in promoting GBM cell invasiveness and

migratory ability through the EMT.

The present study revealed that S100B was

predominantly upregulated in GBM tissue, and its elevated

expression levels were associated with shorter patient survival

time, indicating an adverse prognostic impact. Inhibition of S100B

resulted in attenuated cell proliferation, invasion, migration and

EMT. Moreover, S100B knockdown induced downregulation of TGF-β2

expression, and decreased cell invasion and migration, whereas the

EMT process was restored by the addition of recombinant TGF-β2

protein. From the perspective of EMT, the current study elucidated

the mechanism by which S100B promotes the motility of glioma cells

and also revealed that S100B modulates the expression of TGF-β2 to

mediate the occurrence of EMT. These valuable findings indicate

that S100B may be an important marker and potential target site for

GBM therapies. Despite elucidating the pivotal role of S100B in

promoting GBM cell migration and invasion through modulation of the

TGF-β2/EMT axis in vitro, the current study is inherently

limited by the absence of in situ validation, a critical gap

given the profound influence of the complex EMT on metastatic

behavior. To further investigate the role of S100B in GBM

progression, the intracranial GBM xenograft model in

immunocompromised mice is recommended to enable rigorous assessment

of the impact of S100B on invasion via bioluminescence and

histopathological analyses. Furthermore, the transparent zebrafish

system with GFP-labeled tumor cells may offer real-time

visualization of micro-metastasis formation (41,42).

This dual-model approach would not only complement the present

in vitro findings but also provide mechanistic insights into

the role of S100B across different biological contexts. Future

investigations will leverage these platforms to evaluate the

therapeutic potential of S100B through targeted genetic

interventions, potentially paving the way for novel anti-metastatic

strategies in GBM.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Youth Basic Research

Project from the Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Child

Development and Disorders (grant no. YBRP-202113) and the Science

and Technology Research Program of the Chongqing Municipal

Education Commission (grant no. KJQN202400427).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XL obtained most of the study's outcome data

independently, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the

manuscript, and obtained funding. YX made significant contributions

to the acquisition and analysis of part of the data, and provided

valuable assistance in conducting a portion of the experiments. HZ,

QY and SD were involved in obtaining some of the research results.

BT presented the original research concept and design, analyzed and

interpreted the data, revised the contents of the manuscript,

obtained funding and supervised the research. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. XL and BT confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal use protocol was reviewed and approved by

the Ethics Committee of Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical

University (IACUC approval no: CHCMU-IACUC20210114024; Chongqing,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma multiforme

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

WHO

|

World Health Organization

|

|

DMEM

|

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

|

|

shS100B

|

shRNA S100B LN229 GBM cells

|

|

NC

|

negative control LN229 GBM cells

|

|

GEPIA

|

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

TISCH

|

Tumor Immune Single Cell Hub

|

|

EdU

|

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

|

References

|

1

|

Tan AC, Ashley DM, López GY, Malinzak M,

Friedman HS and Khasraw M: Management of glioblastoma: State of the

art and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 70:299–312.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sahm F, Capper D, Jeibmann A, Habel A,

Paulus W, Troost D and von Deimling A: Addressing diffuse glioma as

a systemic brain disease with single-cell analysis. Arch Neurol.

69:523–526. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Omuro A and DeAngelis LM: Glioblastoma and

other malignant gliomas: A clinical review. JAMA. 310:1842–1850.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Alexander BM and Cloughesy TF: Adult

glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 35:2402–2409. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

McKinnon C, Nandhabalan M, Murray SA and

Plaha P: Glioblastoma: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and

management. BMJ. 374:n15602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Donato R, Cannon BR, Sorci G, Riuzzi F,

Hsu K, Weber DJ and Geczy CL: Functions of S100 proteins. Curr Mol

Med. 13:24–57. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Schafer BW and Heizmann CW: The S100

family of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins: Functions and

pathology. Trends Biochem Sci. 21:134–140. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Donato R, Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Arcuri C,

Bianchi R, Brozzi F, Tubaro C and Giambanco I: S100B's double life:

intracellular regulator and extracellular signal. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1793:1008–1022. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xiong TF, Pan FQ and Li D: Expression and

clinical significance of S100 family genes in patients with

melanoma. Melanoma Res. 29:23–29. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yen MC, Huang YC, Kan JY, Kuo PL, Hou MF

and Hsu YL: S100B expression in breast cancer as a predictive

marker for cancer metastasis. Int J Oncol. 52:433–440.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang T, Cheng J, Yang Y, Qi W, Zhao Y,

Long H, Xie R and Zhu B: S100B mediates stemness of ovarian cancer

stem-like cells through inhibiting p53. Stem Cells. 35:325–336.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lin J, Yang Q, Yan Z, Markowitz J, Wilder

PT, Carrier F and Weber DJ: Inhibiting S100B restores p53 levels in

primary malignant melanoma cancer cells. J Biol Chem.

279:34071–34077. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Roy Choudhury S, Heflin B, Taylor E, Koss

B, Avaritt NL and Tackett AJ: CRISPR/dCas9-KRAB-mediated

suppression of S100b restores p53-mediated apoptosis in melanoma

cells. Cells. 12:7302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Xu H, Li W, Yue H, Bai Y, Li J, Lu X and

Wang J: S100B induces angiogenesis via the clathrin/FOXO1/β-catenin

signaling pathway and contributes to bevacizumab resistance in

epithelial ovarian cancer. J Adv Res. May 31–2025.(Epub ahead of

print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sun D, Wang J, Han Y, Dong X, Ge J, Zheng

R, Shi X, Wang B, Li Z, Ren P, et al: TISCH: A comprehensive web

resource enabling interactive single-cell transcriptome

visualization of tumor microenvironment. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(D1):

D1420–D1430. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller

M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn

U, et al: Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide

for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 352:987–996. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wen PY and Kesari S: Malignant gliomas in

adults. N Engl J Med. 359:492–507. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent

MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B,

Belanger K, et al: Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and

adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in

glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of

the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 10:459–466. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, de Blank PM,

Finlay JL, Gurney JG, McKean-Cowdin R, Stearns DS, Wolff JE, Liu M,

Wolinsky Y, et al: American brain tumor association adolescent and

young adult primary brain and central nervous system tumors

diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol. 18 (Suppl

1):i1–i50. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Witthayanuwat S, Pesee M, Supaadirek C,

Supakalin N, Thamronganantasakul K and Krusun S: Survival analysis

of glioblastoma multiforme. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 19:2613–2617.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tan B, Shen L, Yang K, Huang D, Li X, Li

Y, Zhao L, Chen J, Yi Q, Xu H, et al: C6 glioma-conditioned medium

induces malignant transformation of mesenchymal stem cells:

Possible role of S100B/RAGE pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

495:78–85. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hu Y, Song J, Wang Z, Kan J, Ge Y, Wang D,

Zhang R, Zhang W and Liu Y: A novel S100 family-based signature

associated with prognosis and immune microenvironment in glioma. J

Oncol. 2021:35865892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang H, Zhang L, Zhang IY, Chen X, Da

Fonseca A, Wu S, Ren H, Badie S, Sadeghi S, Ouyang M, et al: S100B

promotes glioma growth through chemoattraction of myeloid-derived

macrophages. Clin Cancer Res. 19:3764–3775. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gao H, Zhang IY, Zhang L, Song Y, Liu S,

Ren H, Liu H, Zhou H, Su Y, Yang Y and Badie B: S100B suppression

alters polarization of infiltrating myeloid-derived cells in

gliomas and inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 439:91–100. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kahlert UD, Joseph JV and Kruyt FAE: EMT-

and MET-related processes in nonepithelial tumors: Importance for

disease progression, prognosis, and therapeutic opportunities. Mol

Oncol. 11:860–877. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xie C, Zhou M, Lin J, Wu Z, Ding S, Luo J,

Zhan Z, Cai Y, Xue S and Song Y: EEF1D promotes glioma

proliferation, migration, and invasion through EMT and PI3K/Akt

pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2020:78047062020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Dongre A and Weinberg RA: New insights

into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:69–84. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR and

Derynck R: TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary

epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: Involvement of type I

receptors. J Cell Biol. 127:2021–2036. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Piek E, Moustakas A, Kurisaki A, Heldin CH

and ten Dijke P: TGF-(beta) type I receptor/ALK-5 and Smad proteins

mediate epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation in NMuMG

breast epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 112:4557–4568. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Valcourt U, Kowanetz M, Niimi H, Heldin CH

and Moustakas A: TGF-beta and the Smad signaling pathway support

transcriptomic reprogramming during epithelial-mesenchymal cell

transition. Mol Biol Cell. 16:1987–2002. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gao J, Zhu Y, Nilsson M and Sundfeldt K:

TGF-β isoforms induce EMT independent migration of ovarian cancer

cells. Cancer Cell Int. 14:722014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Su J, Morgani SM, David CJ, Wang Q, Er EE,

Huang YH, Basnet H, Zou Y, Shu W, Soni RK, et al: TGF-beta

orchestrates fibrogenic and developmental EMTs via the RAS effector

RREB1. Nature. 577:566–571. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xu J, Lamouille S and Derynck R:

TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res.

19:156–172. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Leung DHL, Phon BWS, Sivalingam M,

Radhakrishnan AK and Kamarudin MNA: Regulation of EMT markers,

extracellular matrix, and associated signalling pathways by long

non-coding RNAs in glioblastoma mesenchymal transition: A scoping

review. Biology (Basel). 12:8182023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Joseph JV, Conroy S, Tomar T,

Eggens-Meijer E, Bhat K, Copray S, Walenkamp AM, Boddeke E,

Balasubramanyian V, Wagemakers M, et al: TGF-β is an inducer of

ZEB1-dependent mesenchymal transdifferentiation in glioblastoma

that is associated with tumor invasion. Cell Death Dis.

5:e14432014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen J, Hu J, Li X, Zong S, Zhang G, Guo Z

and Jing Z: Enhydrin suppresses the malignant phenotype of GBM via

Jun/Smad7/TGF-β1 signaling pathway. Biochem Pharmacol.

226:1163802024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Corbet C, Bastien E, Santiago de Jesus JP,

Dierge E, Martherus R, Vander Linden C, Doix B, Degavre C, Guilbaud

C, Petit L, et al: TGFβ2-induced formation of lipid droplets

supports acidosis-driven EMT and the metastatic spreading of cancer

cells. Nat Commun. 11:4542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Song C and Zhou C: HOXA10 mediates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote gastric cancer

metastasis partly via modulation of TGFB2/Smad/METTL3 signaling

axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:622021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Almstedt E, Rosén E, Gloger M, Stockgard

R, Hekmati N, Koltowska K, Krona C and Nelander S: Real-time

evaluation of glioblastoma growth in patient-specific zebrafish

xenografts. Neuro Oncol. 24:726–738. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Larsson S, Kettunen P and Carén H:

Orthotopic transplantation of human paediatric high-grade glioma in

zebrafish larvae. Brain Sci. 12:6252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|