Introduction

Despite the improvements in early detection due to

better imaging, more advanced surgical techniques and

individualized systemic therapies, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

(PDAC) remains a highly fatal type of cancer. In the last 40 years,

several systemic adjuvant chemotherapy protocols have been

evaluated, which have improved disease-free survival and overall

survival (1,2). For example, adding oxaliplatin to

standard gemcitabine therapy has been shown to be more efficacious

than treatment with gemcitabine alone (3,4). At

present, oxaliplatin remains one of the mainstay drugs for PDAC

treatment, including in combination with folinic acid and

5-fluorouracil, or with additional irinotecan (5). The pharmacological mechanism of

oxaliplatin includes cellular uptake, release of the oxalate group,

and the subsequent binding of the positively charged platinum

moiety to the N7 atom of the purine bases adenine and guanine,

leading to cytotoxic adducts at DNA or DNA cross-links.

Accordingly, oxaliplatin resistance is mechanistically related to

these molecular steps (6).

In general, two basic modes can lead to oxaliplatin

resistance: i) Poor oxaliplatin accumulation due to low expression

of important influx transporters, such as organic cation

transporters 1–3 (encoded by SLC22A1-3) or human copper

transporter 1 (encoded by SLC31A1), or high expression of

oxaliplatin efflux transporters, including multidrug

resistance-related protein 2 (MRP2, encoded by ABCC2),

Menkes' protein (encoded by ATP7A) or Wilson disease protein

(encoded by ATP7B) (7,8). ii)

An altered molecular response to the drug (6). Among the numerous molecular factors

involved in unresponsiveness to oxaliplatin, alterations in the DNA

damage response or cell cycle regulation seem to be of particular

relevance (9). For example,

expression and activity of MAPK-activated protein kinase 2

(10), TGF-β-activated kinase-1

(11), RAS oncogene family-like

protein 6 isoform A (12), DNA

methyltransferase 3a (13), BRCA2

(14), the HuR/Wee1 axis (15) or the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1

homeobox A/p53-binding protein 1 axis (16) have been implicated in oxaliplatin

resistance in PDAC. Taken together, oxaliplatin resistance in PDAC

is considered to be caused by the combined effect of poor drug

uptake and an altered molecular response to the cytotoxic threat.

However, there is little knowledge on which mechanism dominates.

Accordingly, the present study evaluated the anti-proliferative

pharmacodynamics of oxaliplatin [half maximal inhibitory

concentration (IC50) values] in PDAC models assessing

both nominal extracellular drug concentrations and also the

resulting intracellular concentrations, allowing for the

quantification of the relative contribution of drug uptake to the

overall resistance phenotype. At identical intracellular platinum

concentrations, the kinetics of caspase 3/7 activity, and

transcriptomic changes associated with DNA damage response, cell

cycle regulation, inflammation and fibrosis signaling, and redox

regulation were recorded. Eventually, baseline expression levels of

associated genes and oxaliplatin drug transporters were

evaluated.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

AsPC-1 (classical-like) and BxPC-3 (basal-like) PDAC

cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The

cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (PAN-Biotech GmbH),

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and

100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate (all from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA), in 75 cm2 flasks at 37°C and 5% CO2.

The medium was changed twice a week and cells were passaged at ~80%

confluence.

Human patient-derived organoids

(hPDOs)

hPDOs were obtained from patients undergoing

surgical PDAC resection (with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy)

and were characterized with much detail (17). h08 is a basal-like organoid, whereas

h19 is a classical-like organoid, with missense mutations in

TP53, BRCA1, SETD2, SPTB, BCORL1, ITPR3 and TLE4.

Moreover, h19 harbors a frameshift deletion in CDKN2A, and

multi-hit mutations in SMAD4 and BRCA2;

phenotypically, it has shown high resistance against several

cytotoxic drugs (17).

Proliferation assay for PDAC cell

lines

To assess the anti-proliferative pharmacodynamics of

oxaliplatin, 2×104 AsPC-1 cells/well or 1×104

BxPC-3 cells/well were seeded into clear 96-well plates. One

cell-free column served as a blank for later staining. After 24 h

of cell attachment, the medium was discarded and replaced with

medium containing different concentrations of cisplatin (control

drug, obtained from the Heidelberg University Hospital Pharmacy as

a 1 mg/ml stock) and oxaliplatin (obtained from the Heidelberg

University Hospital Pharmacy as a 1 mg/ml stock) (AsPC-1, 1–1,000

µM; BxPC-3, 5–500 µM). After 4 h of exposure at 37°C, the

drug-containing medium was replaced with drug-free medium and the

cells were cultured for an additional 48 h at 37°C. Subsequently,

the medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS, after

which 50 µl crystal violet was added to all wells and incubated on

a shaker for 10 min at room temperature. After removal of the

crystal violet solution, all wells were washed with tap water and

dried at 37°C. By adding 99.9% methanol, the cell-bound dye was

dissolved, and the SpectraMax iD3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader

(Molecular Devices, LLC) was used to measure the absorbance at 555

nm.

To obtain values corresponding to the proliferation

at each concentration, the mean of the blank absorption values was

subtracted from all other absorption values, and values from the

drug-treated cells were normalized to untreated cells (18). IC50 values were

calculated based on a sigmoidal dose-response curve with variable

slope of the log-transformed data.

Proliferation assay for hPDOs

The organoids were dissociated into single cells

using TrypLE (cat. no. 12604013; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions and were dispensed

through a 40-µm cell sieve (cat. no. 542040; Greiner Bio-One),

before seeding 1,000 cells in 10 µl Matrigel/well into white

96-well plates. Oxaliplatin was added 72 h after plating, covering

a concentration range of 50–5,000 µM. After 4 h of treatment at

37°C, the medium was replaced with drug-free complete medium and 48

h after this, cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo

3D cell viability assay (Promega Corporation). Briefly, 50 µl

CellTiter Glo 3D was added to the medium of each well, after which,

the plate was placed on an orbital shaker (600 rpm) for 5 min at

room temperature and incubated for a further 25 min at room

temperature. Luminescence was measured using the FLUOstar OPTIMA

(BMG Labtech GmbH). Luminescence values were blank-corrected and

values from the drug-treated cells were normalized to untreated

cells. A four-parameter log-logistic function was fitted to the

drug response curve and IC50 values were calculated.

Evaluating total intracellular

platinum concentrations

Sample preparation

To evaluate the resulting intracellular platinum

concentrations after drug exposure, 1×106 cells (AsPC-1

and BxPC-3) were seeded into each well of 6-well plates and

cultured for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, the

cells were exposed to various concentrations of oxaliplatin or

cisplatin (5, 10, 50, 100 and 1,000 µM) for 4 h at 37°C; after

which, the drug-containing medium was removed and the cells were

washed thoroughly with PBS. HNO3 (0.4%; 150 µl) in

distilled water was then added for cell lysis and the cells were

scraped from the bottom of the well. The lysate was transferred

into a tube and sonicated (35 kHz) for 30 min at room temperature,

followed by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 3 min at room

temperature. The supernatant above the debris pellet was

transferred into a new tube and stored at −20°C until further

analysis.

Drug uptake into hPDOs was evaluated similarly.

After seeding 2×105 cells into the wells of 24-well

plates, drug treatment, lysis, sonication and centrifugation were

performed as aforementioned, and the supernatants were stored at

−20°C until platinum concentrations were analyzed.

Graphite furnace atomic absorption

spectrometry

The platinum concentration of the lysates (obtained

from cell lines and hPDOs) was analyzed with a PinAAcle 900Z

graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometer (PerkinElmer,

Inc.). The samples were loaded into the sample cups of the

autosampler, which injected 20 µl each sample into the graphite

furnace. The furnace protocol consisted of 30 sec at 110°C, 30 sec

at 130°C, 20 sec at 1,300°C, 5 sec at 2,200°C and 3 sec at 2,450°C.

The platinum absorbance was measured at 265.94 nm. For the

calibration curve, six concentrations (25, 50, 100, 500, 1,000 and

5,000 µg/l) were aliquoted by the autosampler from respective stock

solutions. To demonstrate the accuracy of the method, three samples

for quality control (QC) were prepared by spiking 0.4%

HNO3 with the respective volume of platinum stock

solution, leading to QC samples within the low, mid and high range

of the calibration curve.

BCA assay

The protein concentration of all samples was

evaluated using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). For the calibration curve, standard samples of

bovine serum albumin (provided in the kit) in 0.1% HNO3

at concentrations of 0, 25, 125, 250, 500, 750, 1,000, 1,500 and

2,000 µg/ml were prepared and the absorption was measured at 562

nm. The cell lysate samples were analyzed accordingly and the

protein concentration was determined from the absorption via the

linear equation of the calibration curve. The measured platinum

concentrations of the lysates were normalized to the protein

concentration of the lysates, eventually representing the total

intracellular platinum concentration.

Validation of platinum drug

uptake

The intracellular platinum concentration was plotted

over the extracellular concentration for the two PDAC cell lines. A

simple linear regression was used to determine an equation

describing the uptake of each cell line treated with either

cisplatin or oxaliplatin. The regression line was used to determine

the necessary extracellular concentration that leads to the same

intracellular platinum concentration in all cells. The uptake was

validated by exposing the cells to these concentrations and

analyzing the intracellular concentration again.

Caspase 3/7 assay

The enzyme activity of caspase 3/7 was analyzed at

0, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24 and 48 h after the 4-h treatment of PDAC cell

lines at 37°C with drug concentrations (AsPC-1: 150 µM cisplatin or

176 µM oxaliplatin; BxPC-3: 65 µM cisplatin or 150 µM oxaliplatin)

known to result in identical total intracellular platinum

concentrations using the Caspase-Glo® 3/7 kit (cat. no.

G8091; Promega Corporation). Caspase 3/7 activity was additionally

recorded in AsPC-1 cells 36 h after treatment. Briefly,

1.5×103 cells/well were seeded into white 96-well plates

with a clear bottom and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2

overnight for adherence. After the 4-h drug treatment, the

drug-containing medium was discarded and replaced with 50 µl fresh

medium. At each time point, 50 µl of the Caspase-Glo reaction

reagent was added to the wells, the plate was shaken for 30 sec and

was subsequently incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The

luminescence of each well was analyzed using the SpectraMax iD3

Multi-Mode Microplate Reader. The luminescence values were

normalized to the untreated control at each time point.

Treatment-related transcriptomic

changes in PDAC cell lines

To record the transcriptional changes in PDAC cell

lines upon identical total intracellular platinum challenge, a

high-throughput reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

analysis was performed according to our previously published

protocol using a Standard BioTools Inc. dynamic array on a BioMark™

system (19,20). After RNA isolation using the

NucleoSpin® RNA Plus Kit (Machery-Nagel GmbH), 1 µg

total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the qScript™ cDNA

Synthesis Kit (Quantabio) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Specific target gene amplification was performed to

obtain sufficient amounts of templates of the target genes for the

subsequent high-throughput qPCR, followed by enzymatic digestion

with Escherichia coli exonuclease I (New England BioLabs,

Inc.) to remove unincorporated primers and dNTPs. For

high-throughput qPCR, samples and primers [sequences of which are

provided in a previous study (19)]

were loaded onto a 96.96 Dynamic Array Integrated Fluidic Circuit

(Standard BioTools Inc.), which was transferred into the BioMark HD

System (Standard BioTools Inc.). qPCR (initial denaturation step at

95°C for 10 min, followed by 12 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C for

denaturation, 4 min at 60°C for annealing and elongation, and a

final holding temperature of 4°C) and melting curve analyses were

performed as described previously (19). Evaluation and data analysis were

performed with GenEx software (version 5.3.6.170; MultiD Analyses

AB). For normalization, five reference genes were used [β-actin,

β2-microglobulin (β2MG), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase, glucuronidase-β (GUSB) and hypoxanthine

phosphoribosyltransferase 1]. Changes in the transcript levels of

the target genes were displayed as fold change compared with the

untreated control group by calculating relative quantities

corresponding to the ΔΔCq method (21). The alterations in gene expression

are shown as log2-fold changes with a value of 0 for the untreated

control. This depiction was chosen as it enables a clear

presentation of both induction (with the value 1 for two-fold

enhancement) and repression (with the value-1 for reduction to 50%)

of transcription.

Evaluating drug transporter expression

levels in PDAC cell lines using RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from untreated As-PC1 and

Bx-PC3 cells using the GeneElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the

RevertAid™ H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A

random hexamer primer was used according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The mRNA expression levels of ABCC2, ATP7A, ATP7B,

SLC22A1, SLC22A2, SLC22A3 and SCL31A1 were quantified by

qPCR [initial denaturation step at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40

cycles of 15 sec at 95°C for strand melting, 30 sec at variable

temperatures (see Table I) for

primer annealing and 30 sec at 72°C for elongation, followed by a

melting curve analysis of 5 sec at 95°C, 60 sec at 70°C and 5 sec

at 95°C using a LightCycler® 480 (Roche Applied Science)

and the Quantifast SYBR Green Master mix (Qiagen GmbH) as described

previously (22,23). The quantification of SLC22A1

was performed using the Quantitect Hs_SLC22A1 kit (Qiagen GmbH).

All other primer sequences were used as published previously

(23,24) (Table

I). Among a set of six housekeeping genes tested,

glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase, GUSB and β2MG were

used for normalization. This approach minimizes the potential bias

from correcting target gene expression levels to only one

housekeeping gene (25).

Accordingly, the Roche LightCycler 480 software determined the

geometric mean Cq value of the three housekeeping genes by

calculating the third root of [1st housekeeping gene × 2nd

housekeeping gene × 3rd housekeeping gene], and the normalized

expression level of the target gene was subsequently computed in

line with the ΔCq method including an efficiency correction. Taken

together, the data were analyzed as described previously (22). Three independent biological

replicates with technical duplicates were performed for

RT-qPCR.

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward primer

sequence, 5′-3′ | Reverse primer

sequence, 5′-3′ | Primer annealing

temperature, °C |

|---|

| ABCC2 |

ACAGAGGCTGGTGGCAACC |

ACCATTACCTTGTCACTGTCCATGA | 57 |

| ATP7A |

ATGATGAGCTGTGTGGCTTG |

TGCCAACCTGAGAAGCAATAG | 60 |

| ATP7B |

TACCCATTGCAGCAGGTGTC |

ACTTGAGCTGCAGGGATGAG | 57 |

| SLC31A1 |

AGCTGGAGAAATGGCTGGAG |

AGGTGAGGAAAGCTCAGCATC | 63 |

| SLC22A2 |

TCTACTCTGCCCTGGTTGAATTC |

ATGCAGCCCAAGGGTAACG | 57 |

| SLC22A3 |

GGAGTTTCGCTCTGTTCAGG |

GGAATGTGGACTGCCAAGTT | 55 |

| β2mg |

CCAGCAGAGAATGGAAAGTC |

CATGTCTCGATCCCACTTAAC | 61 |

| G6PDH |

ATCGACCACTACCTGGGCAA |

TCTGCATCACGTCCCGGA | 61 |

| GUSB |

TTCACCAGGATCCACCTCTG |

AGCACTCTCGTCGGTGACTG | 61 |

RNA sequencing (RNAseq) data

evaluation of hPDOs

RNA isolation, RT to cDNA, preparation of sequencing

libraries and sequencing were performed as described previously

(17). Briefly, total RNA was

extracted from snap-frozen hPDO pellets using the AllPrep

DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit (Qiagen GmbH) and mRNA was purified

using oligo(dT) beads. Poly(A)+ RNA was fragmented to 150 bp and

converted to cDNA, which was end-repaired, adenylated on the 3-end,

adapter-ligated and amplified with 15 cycles of PCR. Sequencing

libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq mRNA stranded kit

(Illumina, Inc.) according the manufacturer's instructions. The

final libraries were validated using Qubit (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Tapetstation (Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). Finally, 2×100 bp paired-end sequencing was performed on the

Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. At least 54 Mio reads per sample were

generated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and generation of all figures

were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software (Version 9.0.0;

Dotmatics). Differences between IC50 values [presented

as the mean ± SD of four (cell lines) or three (hPDOs) independent

experiments] were evaluated by unpaired Student's t-test. The

statistical significance between the mean total intracellular

platinum levels of the cell lines (treated with oxaliplatin or

cisplatin) and the respective single experiments (AsPC-1 treated

with 150 µM cisplatin; AsPC-1 treated with 176 µM oxaliplatin;

BxPC-3 treated with 65 µM cisplatin; BxPC-3 treated with 150 µM

oxaliplatin; presented as the mean ± SD of four to five independent

experiments) was evaluated by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test

and Dunn's post-hoc test, controlling for multiple testing.

Differences in gene expression levels between drug-treated cell

lines (presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments)

were evaluated by a two-way ANOVA with Sidak's post-hoc test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Anti-proliferative pharmacodynamics of

oxaliplatin

First, the anti-proliferative pharmacodynamics of

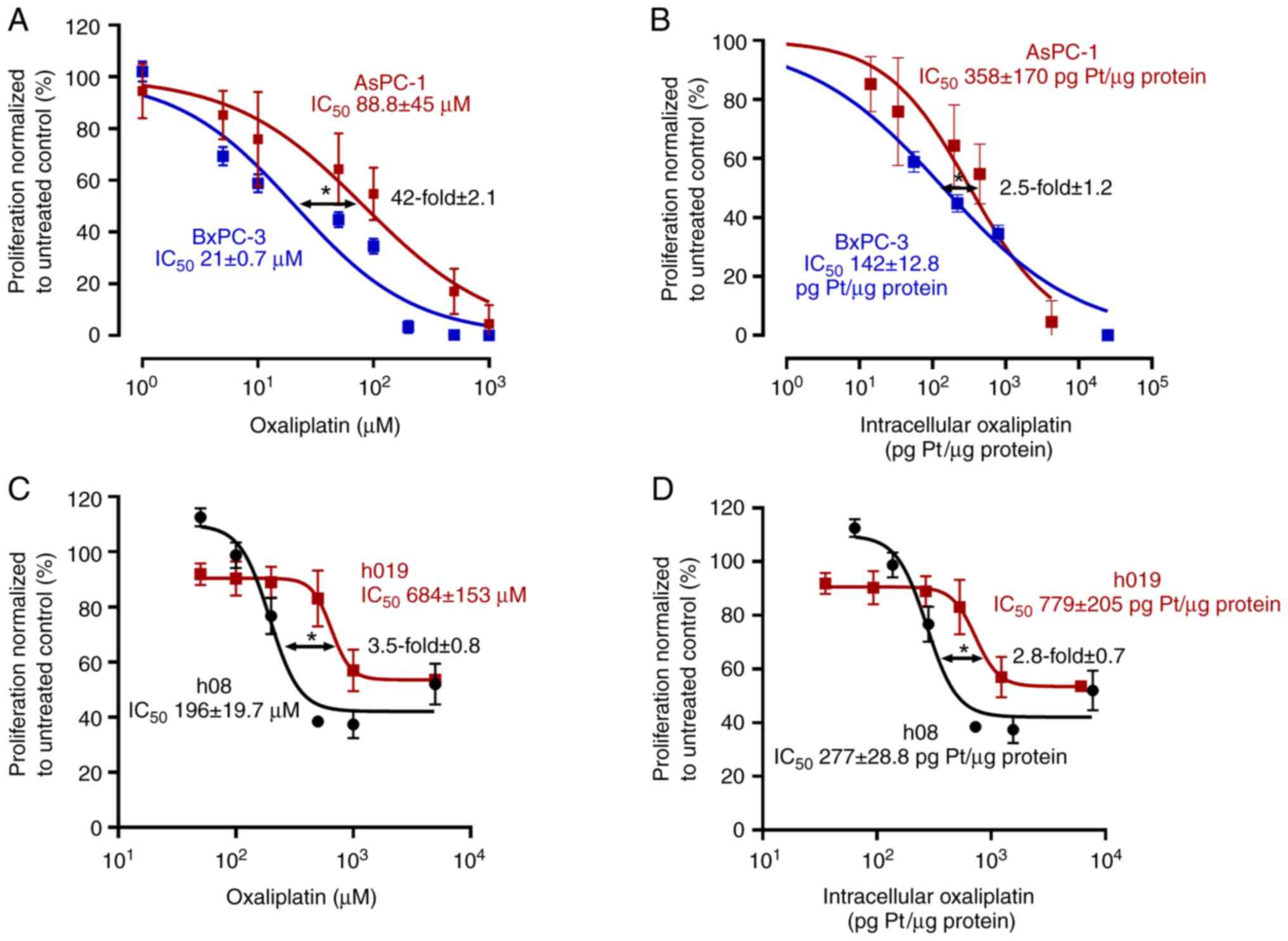

oxaliplatin were evaluated in the cell lines (Fig. 1A and B). The IC50 of

oxaliplatin in AsPC-1 cells was 88.8±45 µM, whereas it was 21±0.7

µM in BxPC-3 cells (P=0.02). Accordingly, AsPC-1 cells were

4.2-fold (±2.1) more oxaliplatin resistant than BxPC-3 cells.

However, when anti-proliferative effects were normalized to total

intracellular platinum levels, AsPC-1 cells (IC50,

358±170 pg Pt/µg protein) remained 2.5-fold (±1.2) more resistant

to oxaliplatin than BxPC-3 cells (IC50, 142±12.8 pg

Pt/µg protein; P=0.04), a non-significant decrease of resistance by

40% (P=0.21).

Second, the effects of oxaliplatin were tested on

hPDOs (Fig. 1C and D). The

IC50 of oxaliplatin in h19 cells was 684±153 µM, where

it was 196±19.7 µM for h08 (P<0.029). Therefore, h19 was

3.5-fold (±0.8) more resistant to oxaliplatin than h08. After

normalizing the anti-proliferative effects to total intracellular

platinum levels, h19 (IC50 779±205 pg Pt/µg protein)

remained 2.8-fold (±0.7) more resistant than h08 (IC50,

277±28.8 pg Pt/µg protein; P=0.04), a non-significant decrease of

resistance by 20% (P=0.34).

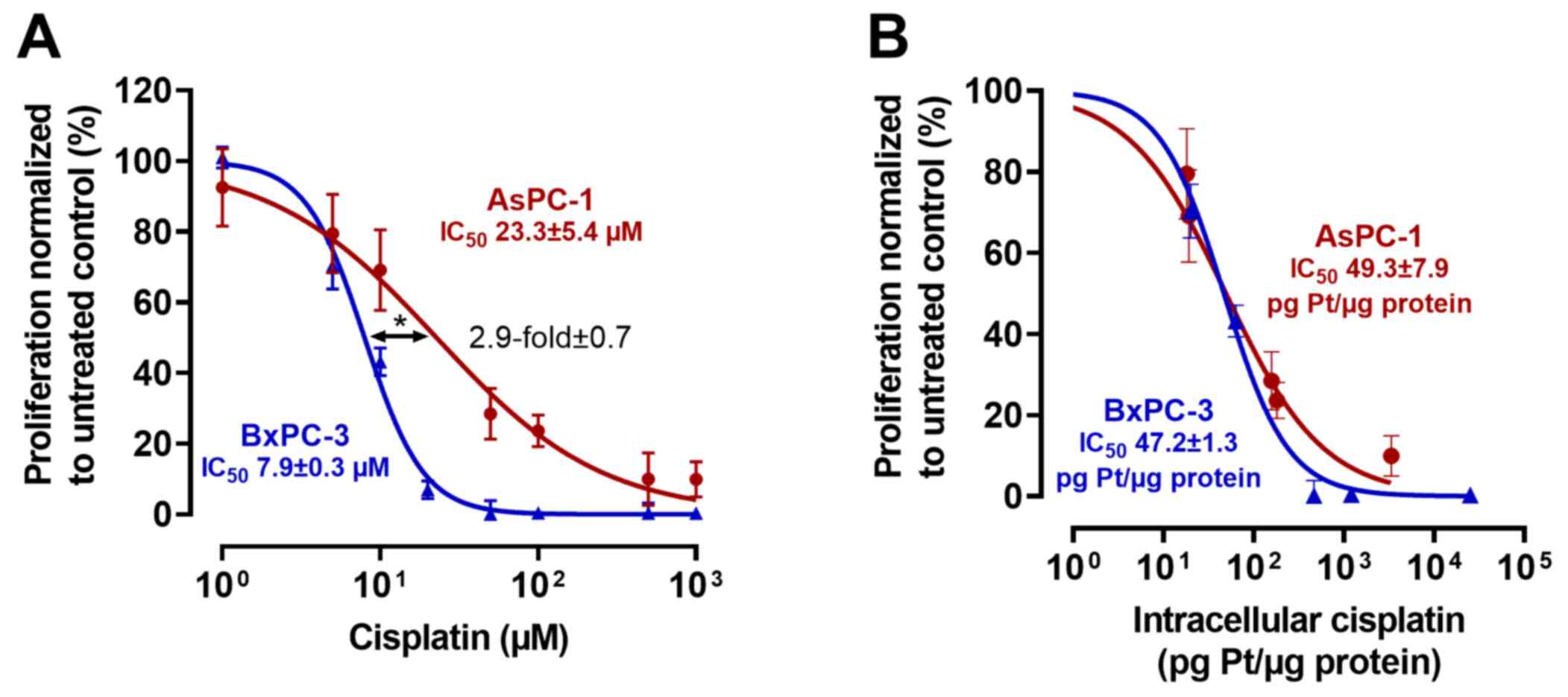

To test for plausibility, the cell line experiments

were repeated with cisplatin as a control drug (Fig. 2). The IC50 of cisplatin

in AsPC-1 cells was 23.3±5.4 µM, whereas it was 7.9±0.3 µM in

BxPC-3 cells (P<0.0013), a nominal resistance difference of

2.9-fold (±0.7). After normalization to total intracellular

platinum levels, IC50 values were very similar (AsPC-1

IC50, 49.3±7.9 pg Pt/µg protein; BxPC-3 IC50,

47.2±1.3 pg Pt/µg protein), indicating a major role of drug uptake

for cisplatin resistance.

Drug uptake

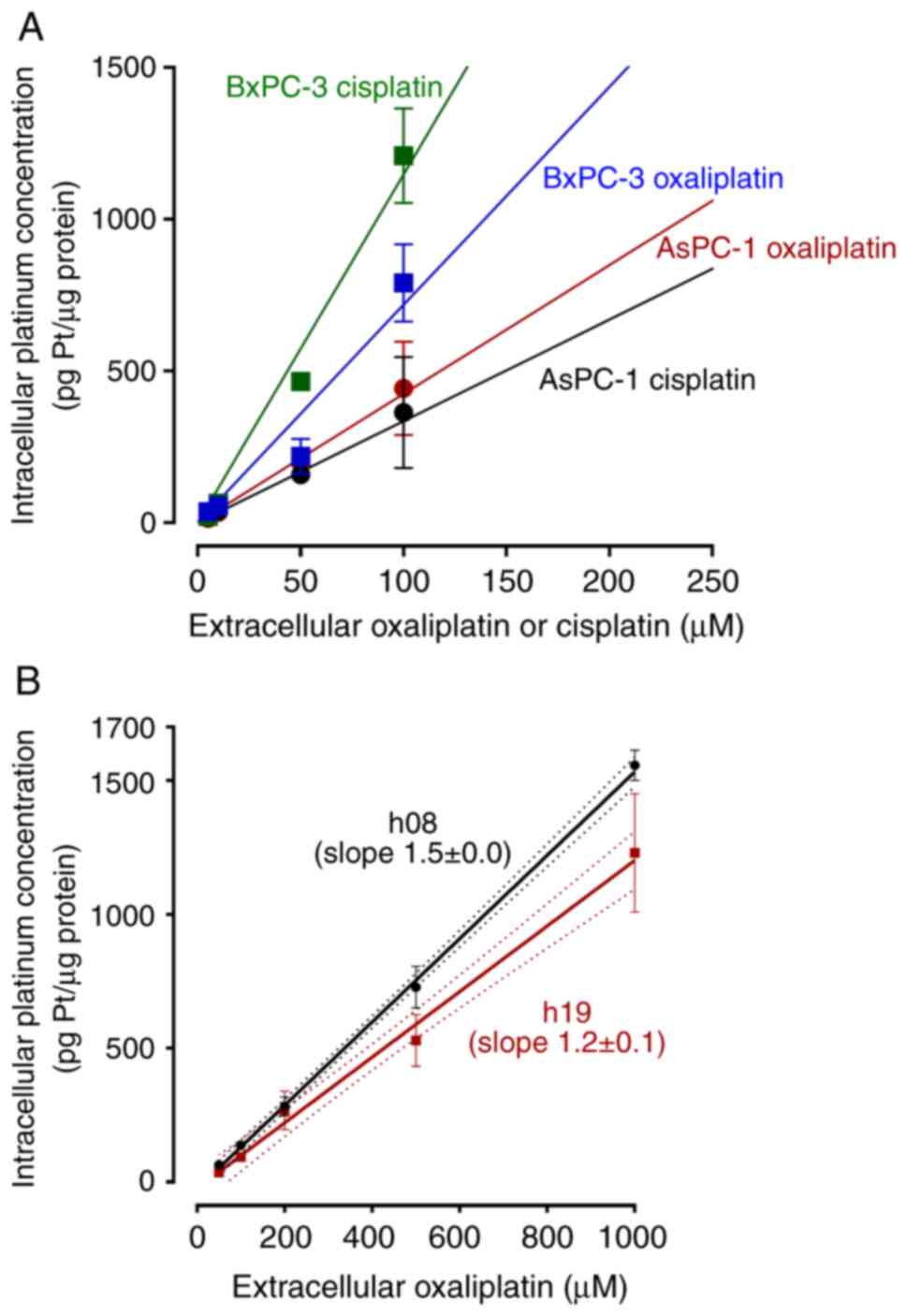

Drug uptake was calculated for two reasons. First,

to again evaluate uptake characteristics. Second, to deduce

extracellular concentrations that are needed to achieve the same

intracellular drug concentrations during subsequent experiments. In

the PDAC cell lines, uptake of oxaliplatin or cisplatin varied

between the drugs and cell lines, as reflected by different slopes

of the linear regression curves (Fig.

3A). In the hPDOs (Fig. 3B),

the slopes for oxaliplatin uptake were significantly different

(h08, slope 1.5±0.0; h19, slope 1.2±0.1; P=0.0003). By calculating

the area-under-the-line, oxaliplatin uptake into h19 was 22% less

than that into h08.

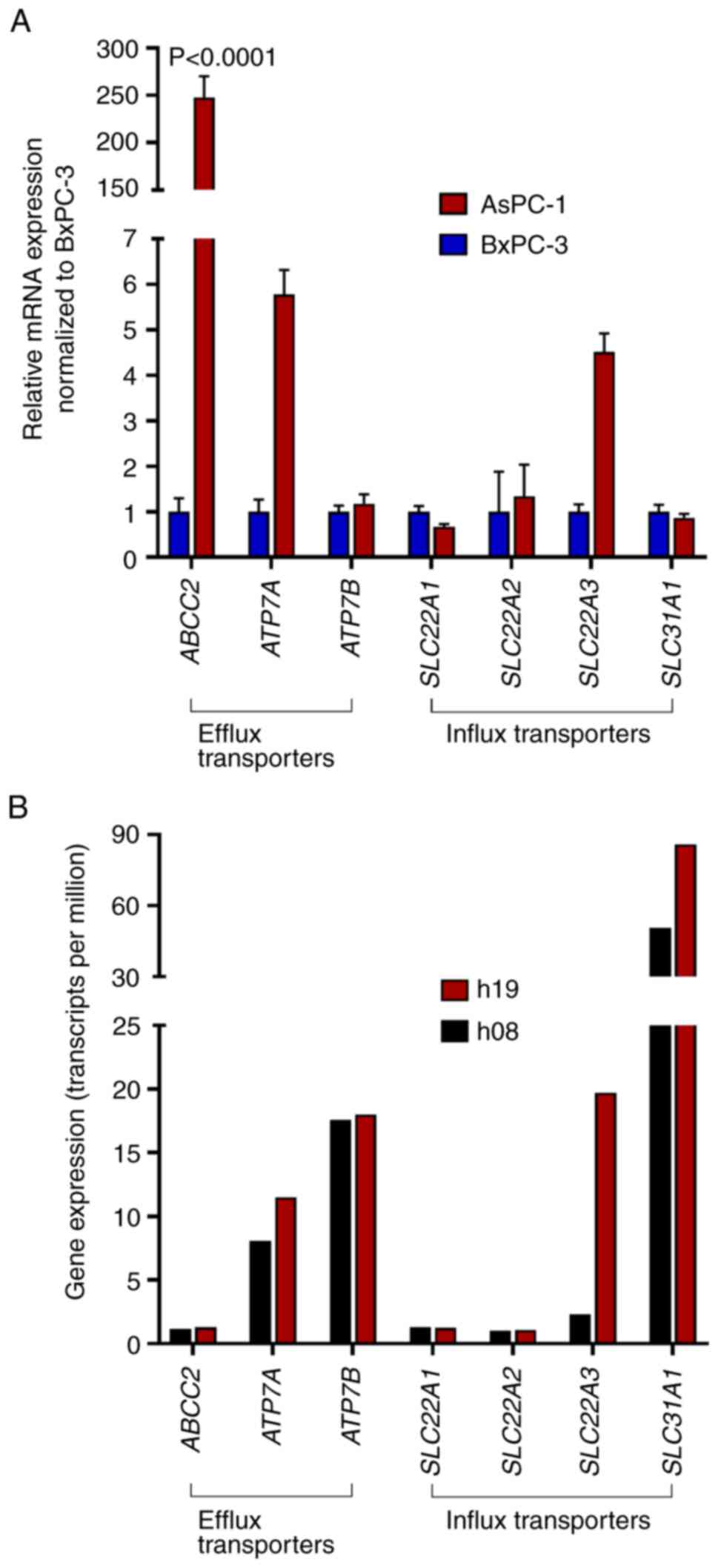

The mRNA expression levels of major platinum drug

transporters were evaluated by PCR (cell lines) or were extracted

from RNAseq data (hPDOs) (Fig. 4).

Compared with in BxPC-3 cells, AsPC-1 cells expressed significantly

higher levels of ABCC2 (248±22-fold; P<0.0001).

ATP7A (5.77±0.5-fold) and SLC22A3 (4.5±0.4-fold) were

also enhanced but the differences did not reach statistical

significance (P>0.94). In the two hPDOs, there were also only

minor differences in expression levels of platinum drug

transporters, with one exception; SLC22A3 was more highly

expressed in h19 (19.7 transcripts per million) than in h08 (2.3

transcripts per million).

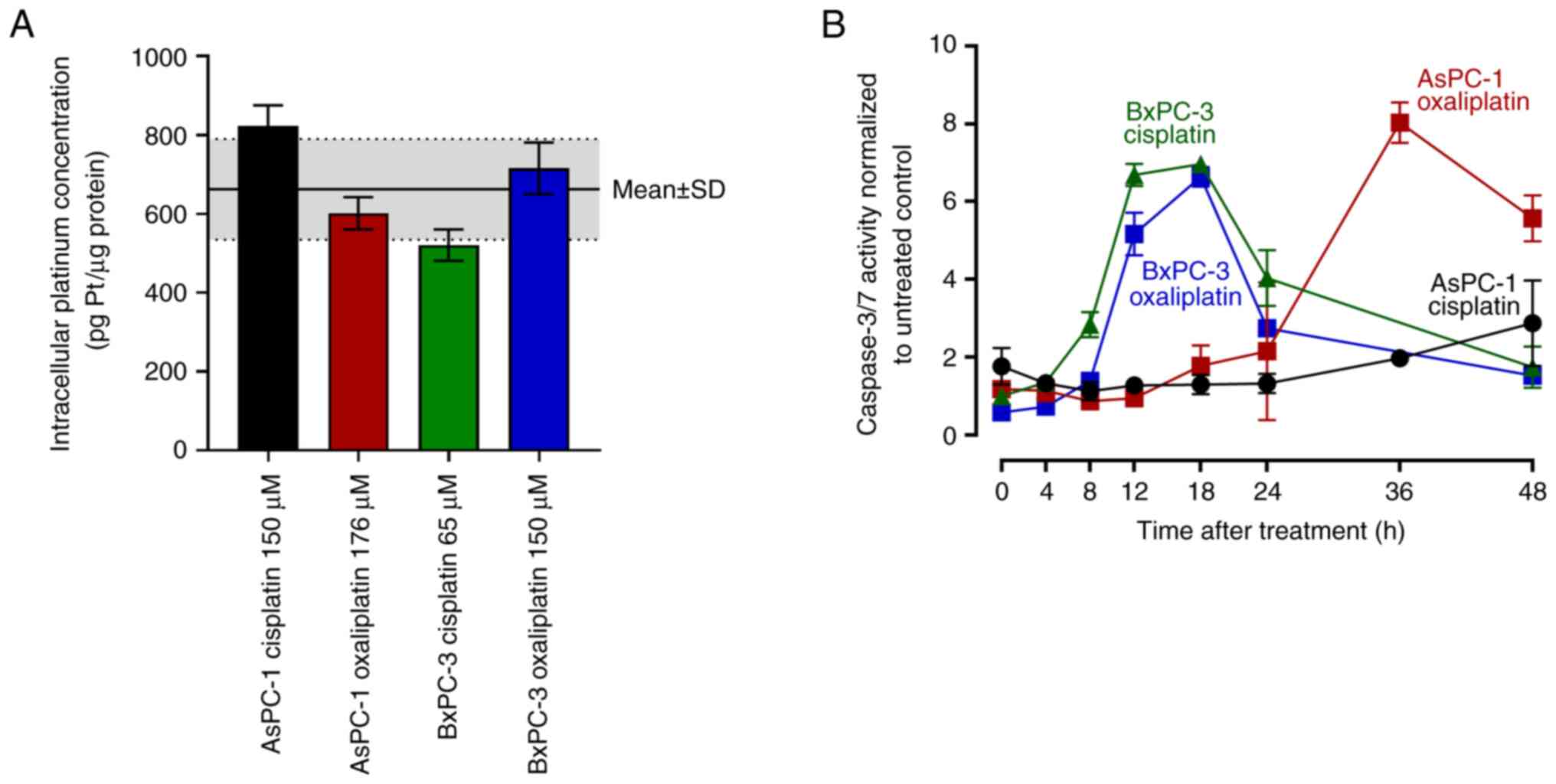

Caspase 3/7 assay

To assess caspase 3/7 activity in response to

similar intracellular drug exposure, AsPC-1 cells were treated for

4 h with 150 µM cisplatin or 176 µM oxaliplatin, whereas BxPC-3

cells were treated with 65 µM cisplatin or 150 µM oxaliplatin.

These treatments led to a mean total intracellular platinum

concentration of 662±128 pg Pt/µg protein, with no statistical

difference between any of the single experiments (Fig. 5A). Caspase 3/7 activity in BxPC-3

cells set in as early as 12 h post-treatment and peaked at 18 h

(7-fold higher compared with the untreated control) without

relevant differences between cells treated with oxaliplatin and

cisplatin. By contrast, caspase 3/7 activity in AsPC-1 cells peaked

36 h after the end of oxaliplatin treatment (8-fold higher compared

with the untreated control), whereas cisplatin treatment only

weakly increased caspase 3/7 activity in AsPC-1 cells (3-fold 48 h

post-treatment) (Fig. 5B).

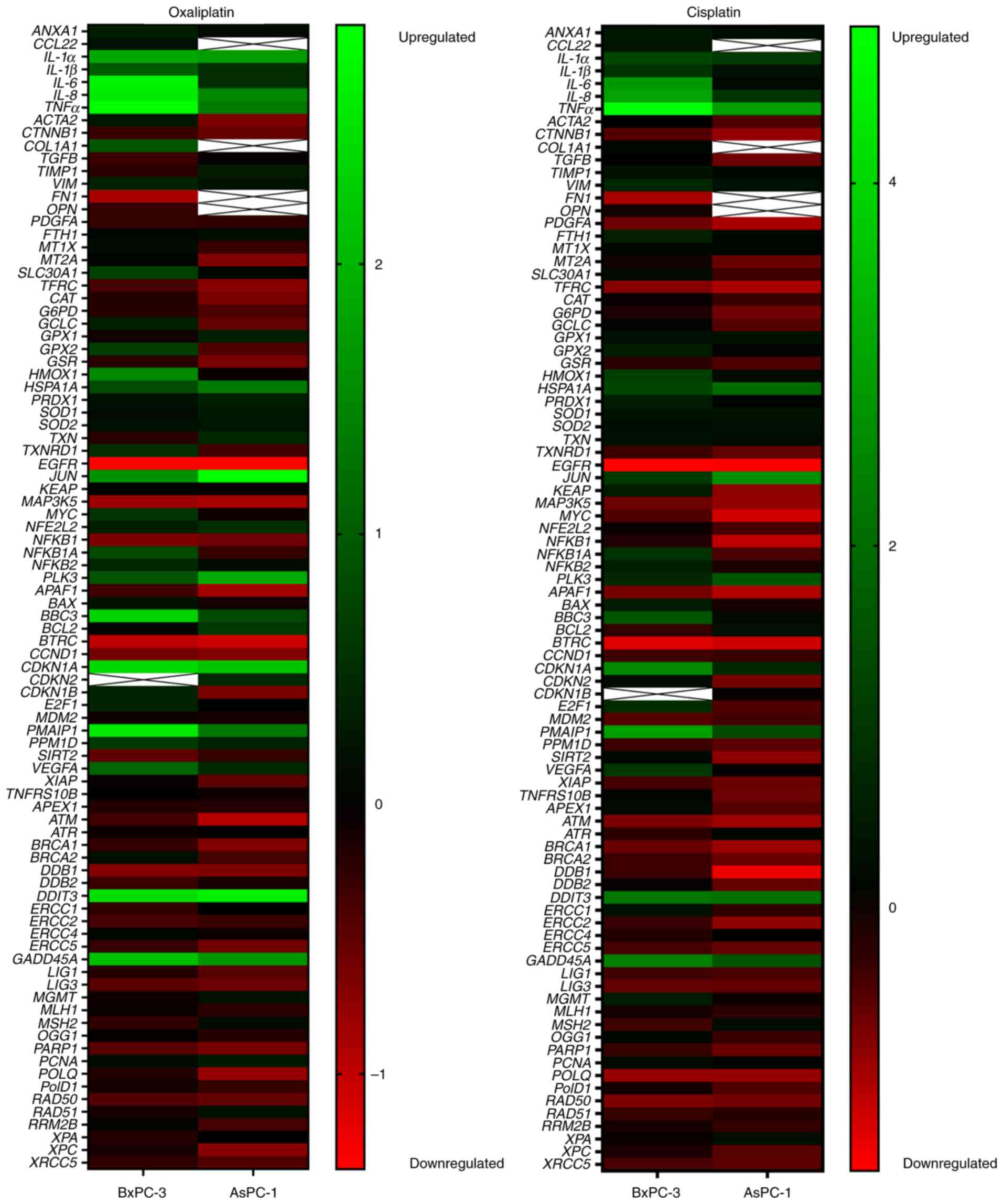

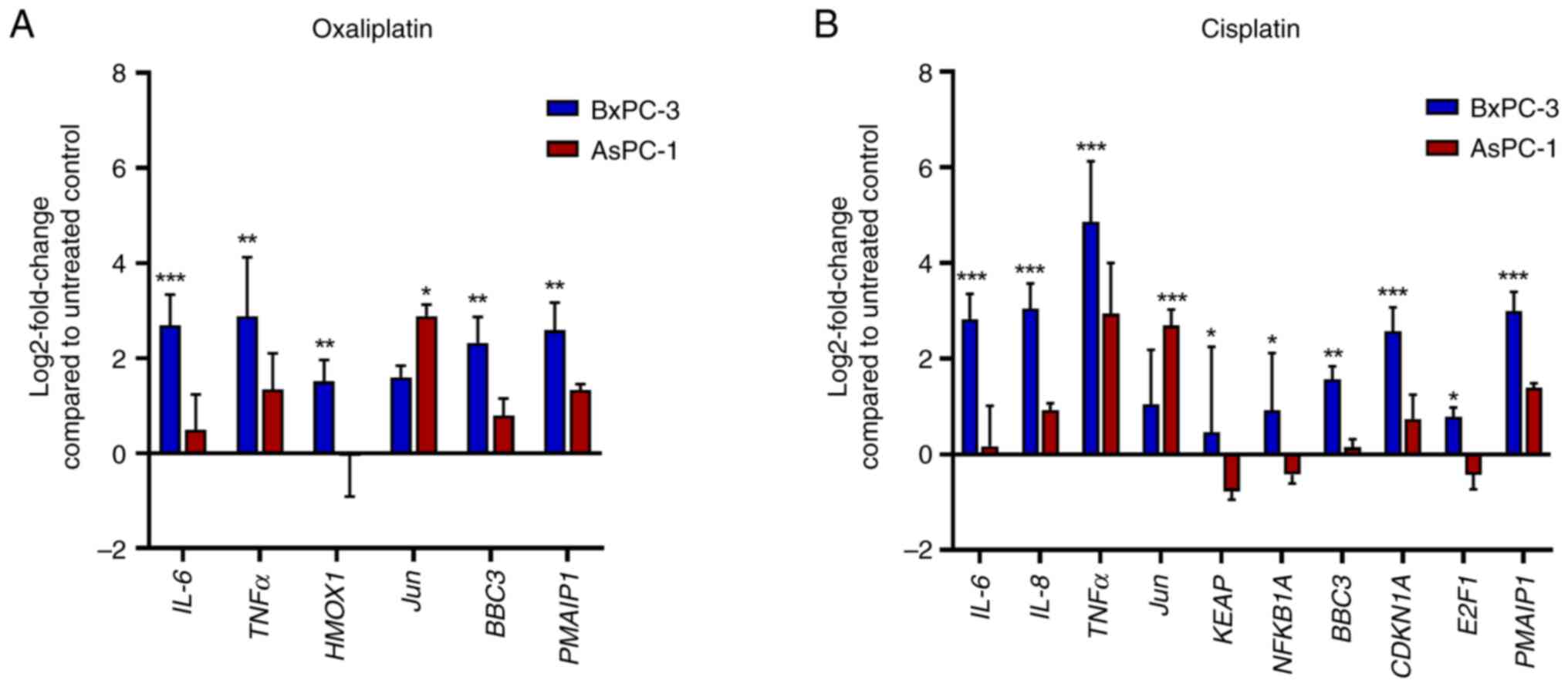

Transcriptomics analysis of the

response of PDAC cell lines to a cytotoxic threat

Cell lines were also screened for transcriptomic

responses after exposure to the same intracellular drug levels as

aforementioned. Treatment with oxaliplatin significantly enhanced

the expression levels of genes implicated in inflammation.

IL-6 and TNFα were enhanced up to 2.5-fold in AsPC-1

cells and up to 7-fold in BxPC-3 cells (Figs. 6 and 7). Compared with in BxPC-3 cells,

oxaliplatin treatment of AsPC-1 cells had a significantly weaker

inducing effect on the pro-apoptotic BBC3 (1.7-fold vs.

5-fold) and PMAIP1 (2.5-fold vs. 6-fold), but a

significantly stronger enhancing effect on the anti-apoptotic

Jun (7-fold vs. 3-fold). Cisplatin (control drug) again

enhanced IL-6 (7-fold) and TNFα (29-fold) in BxPC-3

cells, whereas IL-6 (1.12-fold) and TNFα (7.6-fold)

inductions were rather weak in AsPC-1 cells. BBC3 (1.1-fold

vs. 3-fold) and PMAIP1 (2.6-fold vs. 8-fold) were also more

weakly induced in AsPC-1 cells than in BxPC-3 cells, and Jun

was more strongly enhanced in AsPC-1 cells (6.5-fold) than in

BxPC-3 cells (2-fold).

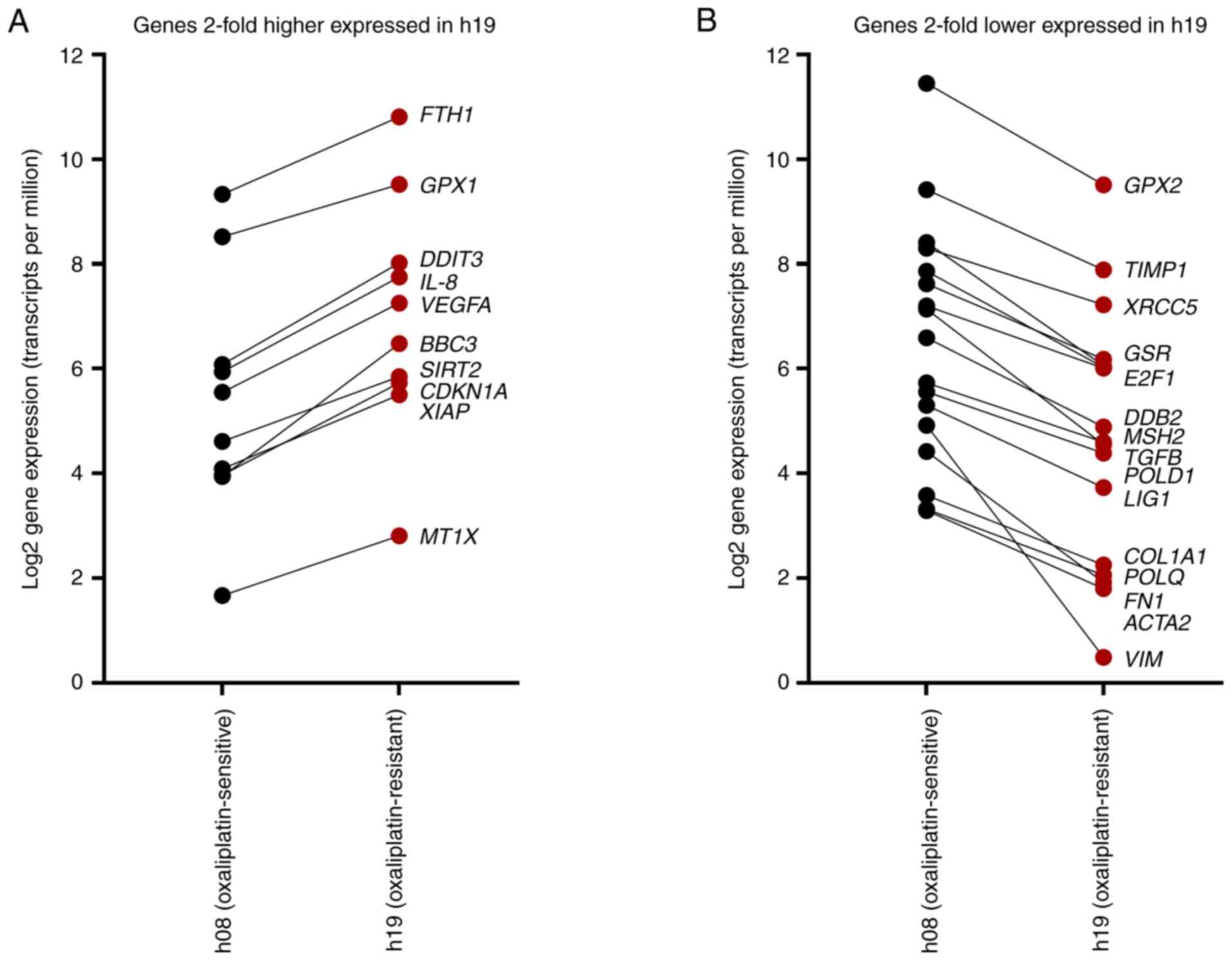

Gene expression levels in hPDOs

The genes evaluated in PDAC cell lines after drug

treatment were also quantified in untreated hPDOs by extracting the

expression levels from RNAseq data. Genes that were >2-fold

higher expressed in h19 compared with h08 included FTH1, GPX1,

DDIT3, IL-8, VEGFA, BBC3, SIRT2, CDKN1A, XIAP and MT1X

(Fig. 8A). By contrast, 17 genes

were >2-fold lower expressed (equals <50% relative

expression) in h19, namely GPX2, TIMP1, XRCC5, GSR, E2F1, DDB2,

MSH2, TGFB, POLD1, LIG1, COL1A1, POLQ, FN1, ACTA2 and

VIM (Fig. 8B).

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess which cellular

factor contributes most to the oxaliplatin resistance phenotype in

PDAC models. The investigation used two well-established PDAC cell

lines, including AsPC-1 cells that have previously been shown to be

oxaliplatin-resistant (26,27); the present study confirmed this by

showing that the oxaliplatin IC50 in AsPC-1 cells was

4-fold higher than that in in BxPC-3 cells. From these data,

however, it cannot be deduced as to whether this resistance

originates from a lower drug uptake or if AsPC-1 cells possess

molecular mechanisms that withstand the cytotoxic threat.

Accordingly, drug uptake was evaluated and the recorded

anti-proliferative effects were subsequently normalized to

intracellular oxaliplatin concentrations. Notably, the resistance

difference non-significantly decreased and remained at 2.5-fold. To

substantiate this finding, two control experiments were performed.

First, in contrast to oxaliplatin resistance, cisplatin resistance

in AsPC-1 cells appeared to be more profoundly mediated by

diminished drug uptake, given the near-perfect overlap of the

concentration-response curves after normalization for intracellular

cisplatin concentrations. Second, the oxaliplatin experiments were

performed using two well-characterized hPDOs (17). In agreement with the cell lines, the

oxaliplatin sensitivity of the hPDOs remained different despite

identical intracellular oxaliplatin concentrations. Taken together,

these findings suggested that poor oxaliplatin uptake may be of

minor relevance for the resistance phenotype. This agrees with

previous evaluations. A previous investigation on

oxaliplatin-resistant colorectal cancer cell lines (generated by

long-term oxaliplatin exposure) showed 5-fold (LoVo-Li cells) to

10-fold (LoVo-92 cells) higher oxaliplatin resistance than their

parental counterparts, but with either only a 50% reduction of

oxaliplatin accumulation (LoVo-92) or no alterations at all

(LoVo-Li) compared with the parental counterparts prior to

resistance induction (28). These

findings indicate that high degrees of oxaliplatin resistance are

not necessarily in line with drug accumulation. In the PDAC cell

lines used in the present study, differences in the expression

pattern of oxaliplatin transporters were also rather minor, with

one exception. ABCC2 (encoding the oxaliplatin efflux

transporter MRP2) was 248-fold more highly expressed in AsPC-1

cells than in BxPC-3 cells. MRP2 has previously been implicated in

oxaliplatin resistance. For example, a knockdown of ABCC2 by

50% also decreased oxaliplatin IC50 by 50–60% (29). Alternatively, transfection-mediated

MRP2 overexpression has been shown to decrease platinum

accumulation by 50% and to make cells 2-fold more oxaliplatin

resistant (30). These findings

however indicate that even a genetically engineered cell model with

artificially high transporter expression eventually only exhibits a

2-fold change in oxaliplatin potency, again questioning the

relevance of drug uptake or transporter expression. Furthermore,

both AsPC-1 cells and the h19 hPDO exhibited SLC22A3

upregulation; this solute carrier is considered a biomarker for

PDAC prognosis (31,32).

To scrutinize the molecular level of oxaliplatin

resistance, the cell lines were treated with oxaliplatin (and

cisplatin as a control) to obtain similar intracellular platinum

levels (~662 pg Pt/µg protein) and subsequently underwent several

experiments. Overall, the data indicated that AsPC-1 cells may

handle the cytotoxic challenge differently than BxPC-3 cells. For

example, caspase 3/7 activity was initiated later in AsPC-1 cells

than that in BxPC-3 cells. Notably, the pro-apoptotic genes

BBC3 and PMAIP1 were weakly enhanced in the

oxaliplatin-resistant AsPC-1 cells, whereas the expression of the

anti-apoptotic Jun was considerably boosted in AsPC-1 cells.

Taken together, these findings suggest that PDAC may exhibit

molecular switches that render cells resistant to pro-apoptotic

signals or trigger sustained proliferation signals. This in turn

also suggests these molecular switches being attractive

pharmacological targets. However, most of the targeted therapeutics

(including kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies) have thus

far disappointed in clinical assessments (1). Therefore, new targets are required.

Among the known driver oncogenes in PDAC (including CDKN2A,

TP53 and SMAD4) that mediate sustained proliferation,

mutated KRAS has been targeted in experimental and clinical

investigations with somewhat promising results (2). Recently, a combined histone

deacetylase/glycogen synthase kinase 3-β inhibitor (Metavert) has

been shown to be efficacious against PDAC hPDOs, both alone, and

particularly in combination with standard anti-PDAC drugs such as

irinotecan (17). This shows that

new agents may be developed, which can selectively address distinct

pathogenic or resistance-mediating mechanisms.

The present study has weaknesses and strengths.

Firstly, a broad set of resistance genes were evaluated at the mRNA

level (such as Jun) and functional apoptosis initiation was

assessed using a caspase 3/7 assay; however, these findings were

not confirmed on the protein level (for example, by western

blotting of select proteins) or by knockdown experiments.

Accordingly, mass spectrometry-based profiling of the relevant

proteins and their manipulation (such as knockdown) should be the

next step in follow-up projects. Notably, the main limitation of

the current study is that most of the data were obtained from

established PDAC cell lines; therefore, general conclusions cannot

be made for clinical PDAC. However, AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 cells are

well-characterized PDAC models with precise information regarding

their origin, differentiation, invasive capacity, angiogenic

potential, tumorigenicity and genotype (33). Thus, these cell lines are considered

meaningful models, which resemble important PDAC features. The

present study provides important information on oxaliplatin uptake

and the expression of drug transporters, and indicates that it is

unlikely that the already observed oxaliplatin resistance in AsPC-1

cells (27) results from poor

oxaliplatin accumulation, which was confirmed in hPDOs. Finally,

the observations regarding delayed caspase 3/7 initiation and

strong induction of Jun in AsPC-1 cells are in agreement

with the p53-deficiency and apoptosis resistance already observed

during the treatment of AsPC-1 cells with gemcitabine or

interferon-γ (34,35).

In conclusion, oxaliplatin resistance in PDAC models

may be highly linked to a poor apoptotic response (weak apoptosis

initiation and poor induction of pro-apoptotic genes), while drug

uptake seems to be of minor relevance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Corina Mueller

(Internal Medicine IX-Department of Clinical Pharmacology and

Pharmacoepidemiology, Heidelberg University, Medical Faculty

Heidelberg, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany),

Ms. Jana Kuhn, Ms. Marlene Parsdorfer, Ms. Tatjana Lumpp and Ms.

Sandra Stößer (all affiliated with Department of Food Chemistry and

Toxicology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany)

for their valuable technical assistance.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The RNAseq raw data generated in the present study

may be found in the European Genome-Phenome Archive under accession

number EGAS00001007143 or at the following URL: https://ega–archive.org/studies/EGAS00001007143. The

gene expression data (RT-qPCR) of the cell lines generated in the

present study may be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus

repository under accession number GSE308898 or at the following

URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE308898.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HR, LT, BK, TP, KS, BK and DT designed the study,

performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the

manuscript draft. JW, JB and JPN analyzed and interpreted the data

and made manuscript revisions. DT and BK confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Organoids were obtained during a previous study,

which has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Heidelberg

University (Heidelberg, Germany) for use in pancreatic cancer

tissue and organoid generation (project nos. S-018/2020, S-708/2019

and S-083/2021). All patients provided written informed consent for

use of their tissue and clinical data in accordance with The

Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

PDAC

|

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

|

|

hPDOs

|

human patient-derived organoids

|

|

IC50

|

half maximal inhibitory

concentration

|

References

|

1

|

Neoptolemos JP, Kleeff J, Michl P,

Costello E, Greenhalf W and Palmer DH: Therapeutic developments in

pancreatic cancer: Current and future perspectives. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:333–348. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hu ZI and O'Reilly EM: Therapeutic

developments in pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

21:7–24. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gresham GK, Wells GA, Gill S, Cameron C

and Jonker DJ: Chemotherapy regimens for advanced pancreatic

cancer: A systematic review and network Meta-analysis. BMC Cancer.

27:4712014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chan K, Shah K, Lien K, Coyle D, Lam H and

Ko YJ: A Bayesian meta–analysis of multiple treatment comparisons

of systemic regimens for advanced pancreatic cancer. PLoS One.

9:e1087492014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Springfeld C, Jäger D, Büchler MW, Strobel

O, Hackert T, Palmer DH and Neoptolemos JP: Chemotherapy for

pancreatic cancer. Presse Med. 48:e159–e174. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Martinez-Balibrea E, Martínez-Cardús A,

Ginés A, Ruiz de Porras V, Moutinho C, Layos L, Manzano JL, Bugés

C, Bystrup S, Esteller M and Abad A: Tumor-related molecular

mechanisms of oxaliplatin resistance. Mol Cancer Ther.

14:1767–1776. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Burger H, Loos WJ, Eechoute K, Verweij J,

Mathijssen RH and Wiemer EA: Drug transporters of Platinum-based

anticancer agents and their clinical significance. Drug Resist

Updat. 14:22–34. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Buß I, Hamacher A, Sarin N, Kassack MU and

Kalayda GV: Relevance of copper transporter 1 and organic cation

transporters 1–3 for oxaliplatin uptake and drug resistance in

colorectal cancer cells. Metallomics. 10:414–425. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Martin LP, Hamilton TC and Schilder RJ:

Platinum resistance: The role of DNA repair pathways. Clin Cancer

Res. 14:1291–1295. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Grierson PM, Dodhiawala PB, Cheng Y, Chen

TH, Khawar IA, Wei Q, Zhang D, Li L, Herndon J, Monahan JB, et al:

The MK2/Hsp27 axis is a major survival mechanism for pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma under genotoxic stress. Sci Transl Med.

13:eabb54452021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Melisi D, Xia Q, Paradiso G, Ling J,

Moccia T, Carbone C, Budillon A, Abbruzzese JL and Chiao PJ:

Modulation of pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by inhibition of

TAK1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 103:1190–1204. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Muniz VP, Askeland RW, Zhang X, Reed SM,

Tompkins VS, Hagen J, McDowell BD, Button A, Smith BJ, Weydert JA,

et al: RABL6A promotes oxaliplatin resistance in tumor cells and is

a new marker of survival for resected pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma patients. Genes Cancer. 4:273–284. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jing W, Song N, Liu Y, Qu X, Hou K, Yang X

and Che X: DNA methyltransferase 3a modulates chemosensitivity to

gemcitabine and oxaliplatin via CHK1 and AKT in p53-deficient

pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 17:117–124. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pishvaian MJ, Biankin AV, Bailey P, Chang

DK, Laheru D, Wolfgang CL and Brody JR: BRCA2 secondary

mutation-mediated resistance to platinum and PARP Inhibitor-based

therapy in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 116:1021–1026. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lal S, Burkhart RA, Beeharry N,

Bhattacharjee V, Londin ER, Cozzitorto JA, Romeo C, Jimbo M, Norris

ZA, Yeo CJ, et al: HuR posttranscriptionally regulates WEE1:

Implications for the DNA damage response in pancreatic cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 74:1128–1140. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xia R, Hu C, Ye Y, Zhang X, Li T, He R,

Zheng S, Wen X and Chen R: HNF1A regulates oxaliplatin resistance

in pancreatic cancer by targeting 53BP1. Int J Oncol. 62:452023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

An J, Kurilov R, Peccerella T, Bergmann F,

Edderkaoui M, Lim A, Zhou X, Pfütze K, Schulz A, Wolf S, et al:

Metavert synergises with standard cytotoxics in human PDAC

organoids and is associated with transcriptomic signatures of

therapeutic response. Transl Oncol. 49:1021092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Peters T, Lindenmaier H, Haefeli WE and

Weiss J: Interaction of the mitotic kinesin Eg5 inhibitor monastrol

with P-glycoprotein. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol.

372:291–299. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fischer BM, Neumann D, Piberger AL, Risnes

SF, Köberle B and Hartwig A: Use of high-throughput RT-qPCR to

assess modulations of gene expression profiles related to genomic

stability and interactions by cadmium. Arch Toxicol. 90:2745–2761.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rose F, Köberle B, Honnen S, Bay C,

Burhenne J, Weiss J, Haefeli WE and Theile D: RNA is a

pro-apoptotic target of cisplatin in cancer cell lines and C.

elegans. Biomed Pharmacother. 173:1164502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pfaffl MW: A new mathematical model for

relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res.

29:e452001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Albermann N, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH,

Z'graggen K, Volk C, Hoffmann MM, Haefeli WE and Weiss J:

Expression of the drug transporters MDR1/ABCB1, MRP1/ABCC1,

MRP2/ABCC2, BCRP/ABCG2, and PXR in peripheral blood mononuclear

cells and their relationship with the expression in intestine and

liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 70:949–958. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Weiss J, Herzog M and Haefeli WE:

Differential modulation of the expression of important drug

metabolising enzymes and transporters by endothelin-1 receptor

antagonists ambrisentan and bosentan in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol.

660:298–304. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Theile D, Ketabi-Kiyanvash N, Herold-Mende

C, Dyckhoff G, Efferth T, Bertholet V, Haefeli WE and Weiss J:

Evaluation of drug transporters' significance for multidrug

resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck.

33:959–968. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F,

Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A and Speleman F: Accurate

normalization of Real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric

averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol.

3:RESEARCH00342002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kuo SH, Yang SH, Wei MF, Lee HW, Tien YW,

Cheng AL and Yeh KH: Contribution of nuclear BCL10 expression to

tumor progression and poor prognosis of advanced and/or metastatic

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by activating NF-κB-related

signaling. Cancer Cell Int. 21:4362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lee JH, Lee SH, Lee SK, Choi JH, Lim S,

Kim MS, Lee KM, Lee MW, Ku JL, Kim DH, et al: Antiproliferative

activity of krukovine by regulating transmembrane protein 139

(TMEM139) in Oxaliplatin-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Cancers

(Basel). 15:26422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Noordhuis P, Laan AC, van de Born K,

Honeywell RJ and Peters GJ: Coexisting molecular determinants of

acquired oxaliplatin resistance in human colorectal and ovarian

cancer cell lines. Int J Mol Sci. 20:36192019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Biswas R, Bugde P, He J, Merien F, Lu J,

Liu DX, Myint K, Liu J, McKeage M and Li Y: Transport-mediated

oxaliplatin resistance associated with endogenous overexpression of

MRP2 in Caco-2 and PANC-1 Cells. Cancers (Basel). 11:13302019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Myint K, Biswas R, Li Y, Jong N, Jamieson

S, Liu J, Han C, Squire C, Merien F, Lu J, et al: Identification of

MRP2 as a targetable factor limiting oxaliplatin accumulation and

response in gastrointestinal cancer. Sci Rep. 9:22452019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mohelnikova-Duchonova B, Brynychova V,

Hlavac V, Kocik M, Oliverius M, Hlavsa J, Honsova E, Mazanec J,

Kala Z, Melichar B and Soucek P: The association between the

expression of solute carrier transporters and the prognosis of

pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 72:669–682. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cervenkova L, Vycital O, Bruha J,

Rosendorf J, Palek R, Liska V, Daum O, Mohelnikova-Duchonova B and

Soucek P: Protein expression of ABCC2 and SLC22A3 associates with

prognosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 9:197822019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Deer EL, González-Hernández J, Coursen JD,

Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, Firpo MA and Mulvihill SJ: Phenotype

and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas. 39:425–435.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sugimoto H, Nakamura M, Yoda H, Hiraoka K,

Shinohara K, Sang M, Fujiwara K, Shimozato O, Nagase H and Ozaki T:

Silencing of RUNX2 enhances gemcitabine sensitivity of

p53-deficient human pancreatic cancer AsPC-1 cells through the

stimulation of TAp63-mediated cell death. Cell Death Dis.

6:e19142015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Detjen KM, Farwig K, Welzel M, Wiedenmann

B and Rosewicz S: Interferon gamma inhibits growth of human

pancreatic carcinoma cells via caspase-1 dependent induction of

apoptosis. Gut. 49:251–262. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|