Introduction

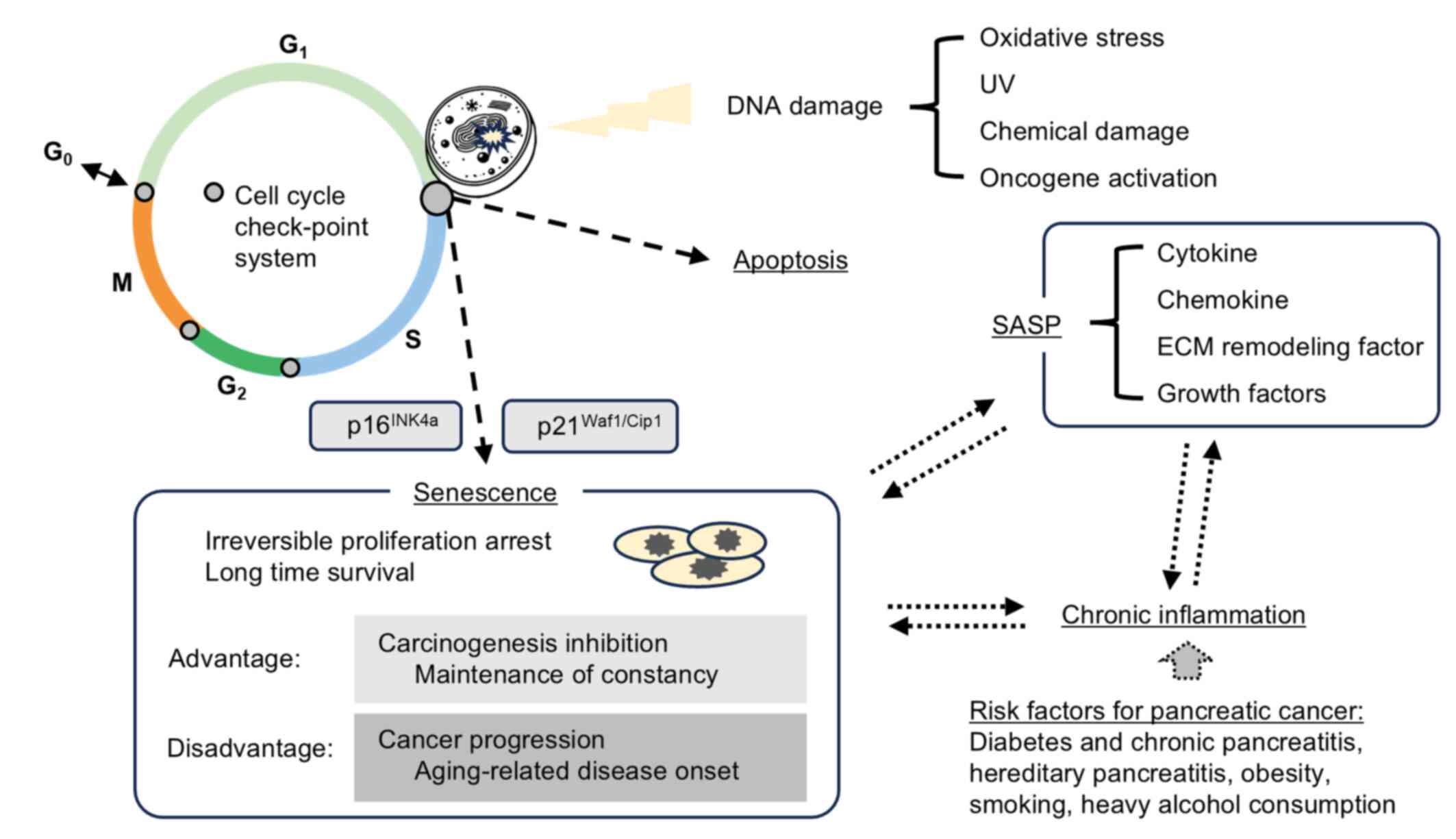

In healthy proliferative cells, irreversible growth

arrest is induced when irreparable DNA damage occurs as a result of

telomere shortening, oncogene activation, excessive oxidative

stress; this state is referred to as cellular senescence (1–3).

Senescent cells have been observed in vivo and are

recognized as a physiological phenomenon (4–7). Key

features of senescent cells include permanent cell cycle arrest,

morphological changes such as cellular enlargement and flattening,

formation of senescence-associated heterochromatic foci, activation

of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) and

upregulation of the cell cycle inhibitors p21 and p16 (3). Similar to apoptosis, cellular

senescence is considered an important tumor-suppressive mechanism

that prevents abnormal proliferation and cancer development

(8,9). However, studies have shown that

senescent cells not only cease proliferating but can also persist

for extended periods, contributing to a phenomenon known as the

senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (5,8,9). The

SASP involves the elevated secretion of various bioactive molecules

with pro-tumorigenic effects, including inflammatory cytokines,

chemokines, extracellular matrix-remodeling enzymes and growth

factors (8). Although SASP factors

serve physiological roles in processes such as tissue development

and wound healing, excessive accumulation of senescent cells and

SASP factors may have detrimental effects. These include the

development of age-related diseases such as atherosclerosis,

induction of chronic inflammation and promotion and progression of

cancer (10,11). Thus, although cellular senescence

serves as a short-term cancer-suppressive mechanism, its long-term

presence and associated SASP may contribute to carcinogenesis and

tumor progression. These findings suggest that cellular senescence

has a dual nature: Protective in the short term, yet potentially

harmful over time (Fig. 1)

(8,9,11).

Senescent cells exhibit morphological changes,

appearing larger and more flattened than proliferating cells. They

accumulate dysfunctional mitochondria and display elevated levels

of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Lysosomal content is increased,

reflected by enhanced β-galactosidase activity in acidic

environments (pH 6.0). Cells exhibiting the SASP secrete a wide

array of factors that promote angiogenesis, extracellular matrix

remodeling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor-promoting

activities (12). Chronic

inflammation induced by senescent cells may also lead to

immunosuppression, contributing to cancer development and

age-related diseases (10,11).

The tissue microenvironment is shaped by the

physical and chemical influences of resident and surrounding cells,

along with local factors such as growth factors, cytokines,

temperature and oxygen levels (8).

In cancerous tissues, the tumor microenvironment is composed of

various cells and signaling molecules that surround cancer cells

and promote tumor progression and invasion. Among these, certain

fibroblasts function as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

(13–16). Studies suggest that a CAF-rich tumor

microenvironment contributes to cancer invasion, metastasis, immune

evasion and drug resistance (17,18).

Stromal depletion through chemotherapy has been shown to improve

drug resistance in cancer (19,20).

Furthermore, senescence and SASP expression have been observed in

fibroblasts within the stroma of several solid tumors (such as

hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer) and

are thought to influence tumor progression, suggesting these are

common features across tumor types (21–23).

Notably, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and diffuse type

gastric cancer are characterized by abundant fibrous stroma and

particularly poor prognoses (24,25).

However, the current understanding of stromal senescence and SASP

expression in PDAC or their prognostic relevance is limited.

The present study focused on PDAC, which is

particularly characterized by a dense fibrotic stroma among types

of digestive system cancer. Using resected specimens from patients

with PDAC, the present study aimed to investigate the presence of

senescent fibroblasts and SASP factor expression in the tumor

stroma, and their association with cancer progression and patient

prognosis. Furthermore, senescent human pancreatic fibroblasts were

established and co-cultured with pancreatic cancer cells with the

aim of evaluating the effects of SASP on tumor cell behavior.

Elucidating the impact of stromal senescence and SASP expression on

patient prognosis in PDAC may help identify novel prognostic

biomarkers and therapeutic targets, potentially leading to the

development of stroma-targeted treatments for this aggressive

cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients and pancreatic tissue

The present study utilized 90 resected specimens

from patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for PDAC

involving the pancreatic head at Kanazawa University Hospital

between 2006 and 2017; retrospective study was conducted on

patients treated between 2006 and 2015. The study protocol was

approved by the Ethics Committee of Kanazawa University Hospital

(approval no. 2016-318; Kanazawa, Japan), and complied with the

Declaration of Helsinki (1975) and the Ethical Guidelines for

Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects by the

Japanese Government (26). Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants for the

anonymous use of resected specimens and clinical data. The clinical

characteristics of the patients were as follows: Median age, 66

years (age range, 35–81); sex distribution, male (62%) and female

(38%); pathological stage of PDAC based on the Union for

International Cancer Control (8th edition) TNM classification

(27): Stage I, n=34; stage II,

n=31; and stage III, n=25; and preoperative chemotherapy in 59

cases (66%). Of the total cohort, 1 patient received preoperative

radiation therapy. All patients were followed up after surgery for

up to 8 years, and survival was defined as the time from

pancreaticoduodenectomy to death or the last visit to the

hospital.

Immunohistochemistry and

immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded sections of 4-µm thickness (10%

neutral buffered formalin-fixed for 24 h at room temperature) were

prepared for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence. The Dako

Envision system (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), which uses

dextran polymers conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, was employed

for immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent staining to avoid any

endogenous biotin contamination. Sections were deparaffinized in

xylene and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Endogenous

peroxidase was blocked by immersing sections in 3%

H2O2 in 100% methanol for 20 min at room

temperature (~26°C). Antigen retrieval was achieved by microwaving

sections at 95°C for 10 min in 0.001 M citrate buffer (pH 6.7).

After blocking endogenous peroxidase, sections were incubated with

Protein Block Serum-Free (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at room

temperature (~26°C) for 10 min to block non-specific staining.

Fibroblasts in the pancreatic cancer stroma were

identified via immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining

with a mouse monoclonal anti-a smooth muscle actin (αSMA; cat. no.

ab7817; Abcam) antibody. A rabbit polyclonal anti-CDKN2A/p16INK4a

(cat. no. ab189034; Abcam) antibody and a mouse monoclonal

anti-interleukin-6 (IL-6; cat. no. ab9324; Abcam) antibody were

used to identify p16- and IL-6-positive fibroblasts within the PDAC

stroma. Primary antibodies were applied for 2 h at room temperature

(~26°C). The fluorescent dyes used were goat anti-mouse IgG H&L

(Alexa Fluor 488; cat. no. ab150113; Abcam), donkey anti-rabbit IgG

H&L (Alexa Fluor 647; cat. no. ab150075; Abcam) and DAPI (cat.

no. ab104139; Abcam). Secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at

room temperature (~26°C).

When staining culture plates, cells were fixed with

4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton

X-100 in 1X PBS for 15 min and blocked with 1% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; Nichirei Biosciences, Inc.) in 1X PBS for 30 min at room

temperature (~26°C). A mouse monoclonal anti-AE1/AE3 (cat. no.

sc-81714; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody and a mouse monoclonal

anti-Vimentin (cat. no. sc-6260; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody

were used to identify established human pancreatic fibroblasts.

Primary antibodies were applied for 2 h at room temperature

(~26°C). Peroxidase activity was detected using the enzyme

substrate DAB. Samples were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1

min or DAPI for 30 min at room temperature (~26°C).

The mean expression intensities of p16- and

IL-6-positive fibroblasts were quantified by counting three fields

per specimen (magnification, ×100). To evaluate expression levels

quantitively, H-score analysis was employed (28,29).

Immunohistochemical images were captured using an optical

microscope (BX-50; Olympus Corporation), and fluorescent images

were captured using a BZ-X710 microscope (Keyence Corporation).

Establishment of human pancreatic

fibroblasts

A human pancreatic fibroblast cell line was

established using a resected pancreatic specimen of the

non-tumorous area from a patient with pancreatic cancer, performed

as previously described (30,31).

To maintain sterility, pancreatic tissue from the non-tumorous area

(~5 µm3) with adequate margin was collected under clean

conditions. The tissue was minced using scissors and cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% FBS in a 10-cm culture dish. After 3–4 days

of incubation at 37°C, proliferation of bipolar or multipolar

spindle-shaped cells was observed, whereas no proliferation was

seen in cell populations with other morphologies. Pancreatic

fibroblasts were successfully established based on cell morphology

and marker expression; spindle-shaped cells tested positive for

αSMA and vimentin by immunostaining. Fibroblasts between passages 4

and 8 were used.

Cell lines and culture conditions

The Panc-1 cell line, derived from human pancreatic

cancer cells (cat. no. CRL-1469; American Type Culture Collection)

was used in the present study. Pancreatic cancer cell lines and

pancreatic fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10%

FBS at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The

culture medium was replaced 2–3 times per week.

Induction of cellular senescence in

human pancreatic fibroblasts

Confluent monolayers of human pancreatic fibroblasts

cultured in 6-well plates were irradiated with X-rays at a dose of

10 Gy. The fibroblasts were maintained using the culture conditions

described above, with medium changes every 3 days. On days 0, 3, 6

and 9 after irradiation, SA-β-gal staining was performed using a

Cellular Senescence Kit (OZ Biosciences) according to the

manufacturer's instructions to evaluate cellular senescence. To

assess the dose-dependent induction of senescence, fibroblasts were

irradiated at 3, 6 and 10 Gy, and SA-β-gal staining was performed

on day 9 after irradiation. Fibroblasts irradiated with 10 Gy in

6-cm culture dishes were collected on day 9 post-irradiation for

further analysis.

Real-time PCR

Total mRNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and reverse transcription was

performed using the AffinityScript QPCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted

using an Mx3000P system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) with a SYBR

Green PCR Kit (Qiagen GmbH) in triplicate, using specific primers.

The primer sequences used to assess target gene expression were as

follows: IL-6, forward (F), 5′-ATGAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGC-3′ and reverse

(R), 5′-GTTTTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTTG-3′; IL-1, F,

5′-ATCAGTACCTCACGGCTGCT-3′ R, 5′-TGGGTATCTCAGGCATCTCC-3′; IL-8 F,

5′-AACATGACTTCCAAGCTGGC-3′ R, 5′-AAACTTCTCCACAACCCTCTGC-3′; MMP-1

F, 5′-AGCTAGCTCAGGATGACATTGATG-3′ R, 5′-GCCGATGGGCTGGACAG-3′; VEGF

F, 5′-ATGAACTTTCTGCTGTCTTGGGT-3′ R, 5′-TGGCCTTGGTGAGGTTTGATCC-3′;

p16 F, 5′-CCCAACGCACCGAATAGTTA-3′ R, 5′-ACCAGCGTGTCCAGGAAG-3′; and

GAPDH F, 5′-GACAGTCAGCCGCATCTTCT-3′ R, 5′-TTAAAAGCAGCCCTGGTGAC-3′

The following thermocycling conditions were used for qPCR: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C

for 30 sec; annealing at 55°C for 1 min; and extension at 72°C for

1 min. Real-time PCR was conducted according to the

2−ΔΔCq method (32),

with GAPDH as the internal control.

Western blotting

After collection, cells were lysed on ice in RIPA

lysis buffer (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.) containing a

protease inhibitor. Protein concentrations were measured using the

Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Total cellular proteins (20 µg) from each sample were separated by

12.5% gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (e-PAGEL; ATTO

Corporation) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane.

Membranes were blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR

Biosciences) for 2 h at 26°C and incubated overnight at 4°C with

the primary antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used:

p16 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab189034; Abcam), IL-6 (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab9324; Abcam) and β-actin (1:10,000; cat. no. A5441; Sigma-Adrich;

Merck KGaA), which served as the internal control. After three

10-min washes with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% of Tween

20, membranes were incubated for 1 h at 26°C with either IRDye

680RD-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; cat. no.

925-68071; LI-COR Biosciences) or IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000; cat. no. 925-32210; LI-COR Biosciences).

Western blot images were analyzed using an Odyssey infrared imaging

system software (version 4.0; LI-COR Biosciences).

Matrigel invasion assay

A Corning Matrigel Invasion Chamber (cat. no.

354480; Corning, Inc.) in a 24-well plate format (cat. no. 353504;

Corning, Inc.) was used and two groups of fibroblasts were

prepared: Pancreatic fibroblasts collected 9 days after irradiation

and non-irradiated pancreatic fibroblasts maintained in culture for

the same duration (9 days). Matrigel precoating was performed at

37°C for 1 h for the invasion assay. First, 1×105

fibroblasts in 1 ml DMEM were seeded into the lower chamber. After

2 h, 5×104 Panc-1 cells in 500 µl DMEM were added to the

upper chamber to initiate co-culture (n=6). The culture medium used

was DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 24 h of incubation at

37°C, the chambers were collected. Following gel removal, membranes

were stained with hematoxylin for 2 min at 26°C. The number of

pancreatic cancer cells that had invaded through the membrane was

counted under an optical microscope (BX-50, Olympus Corporation).

As a control, Panc-1 cells were cultured in the upper chamber

without fibroblasts in the lower chamber.

Scratch assay and application of

culture supernatant

Pancreatic fibroblasts were cultured into confluent

in 10-cm dishes containing (either 9 days post-irradiation or

non-irradiated). After culturing the fibroblasts in DMEM

supplemented with 1% FBS for 48 h at 37°C, the culture supernatant

was collected for use in subsequent experiments. Simultaneously,

6-well plates containing confluent monolayers of Panc-1 cells

cultured in serum-free DMEM for 24 h at 37°C were scratched using a

pipette tip. The collected culture supernatants from irradiated and

non-irradiated fibroblasts were added to the wells (2 ml/well), and

the plates were incubated at 37°C. After 24 h, the area into which

Panc-1 cells had migrated was measured. As a control, scratched

confluent monolayers of Panc-1 cells were cultured in serum-free

DMEM not containing fibroblast culture supernatant. A microscope

(BX-50, Olympus Corporation) was used for cell observation.

Migration was quantified by comparing the final images with

baseline images captured immediately after scratching (n=6), using

the ImageJ software (version 1.51k; National Institutes of Health)

(33). For each group, the cell

migration area was calculated by subtracting the area of the

cell-free region (scratch line) at 24 h from the area at 0 h. The

cell migration area for the control group was set as 1, and the

cell migration area for each group was calculated as a ratio.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured using the MTT assay

(n=8). Confluent monolayers of irradiated pancreatic fibroblasts in

10-cm dishes were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS for 48

h, and the resulting culture supernatant was collected. Panc-1

cells were seeded at a density of 6,000 cells per well in 96-well

plates, and 200 µl of the fibroblast supernatant, adjusted to

contain 10% FBS, was added to each well. Cells were incubated for

24 and 48 h at 37°C. After incubation, the medium was removed, and

the crystallized formazan was solubilized by addition of dimethyl

sulfoxide. Absorbance was measured at 535 nm using a microplate

reader (Bio-Rad 550; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Panc-1 cells

cultured without the fibroblast supernatant were used as

controls.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using EZR

software (version 1.63; Saitama Medical Center; Jichi Medical

University). Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics

were summarized using descriptive statistics. To compare

characteristics between groups, the χ2 test was used for

categorical variables, and Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA

followed by Turkey's post hoc test was used for unpaired continuous

variables. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess

correlations between the expression levels of p16- and

IL-6-positive fibroblasts in the pancreatic cancer stroma, and

between IL-6-positive fibroblast expression and postoperative

survival time. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

analysis was used to determine the IL-6 cut-off value for

prognosis. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier

method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis

was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model on variables

that showed significance in univariate analysis. Results are

presented as mean ± standard deviation. All statistical tests were

two-tailed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Assessment of PDAC stromal senescence

and expression of SASP factors in PDAC specimens

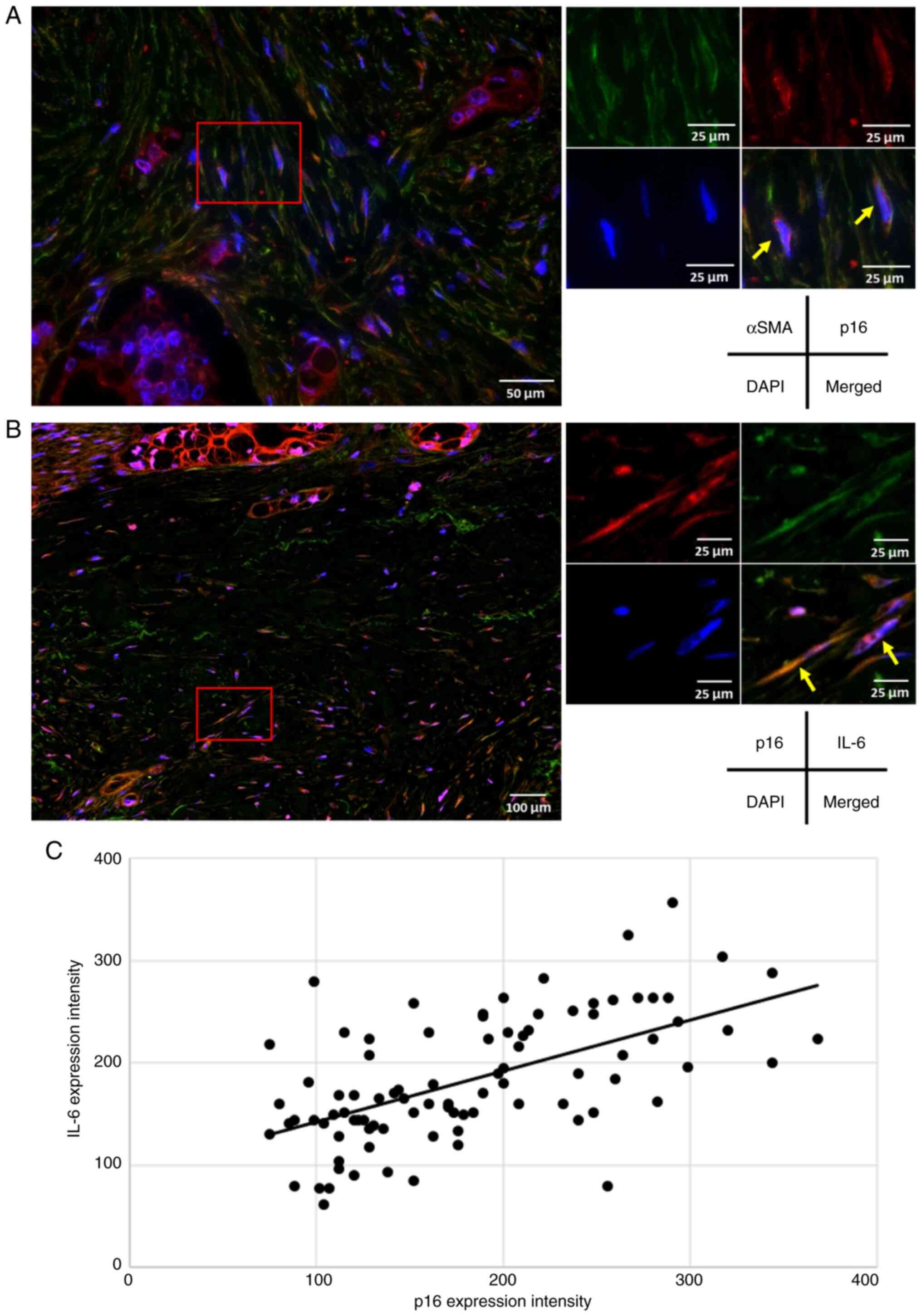

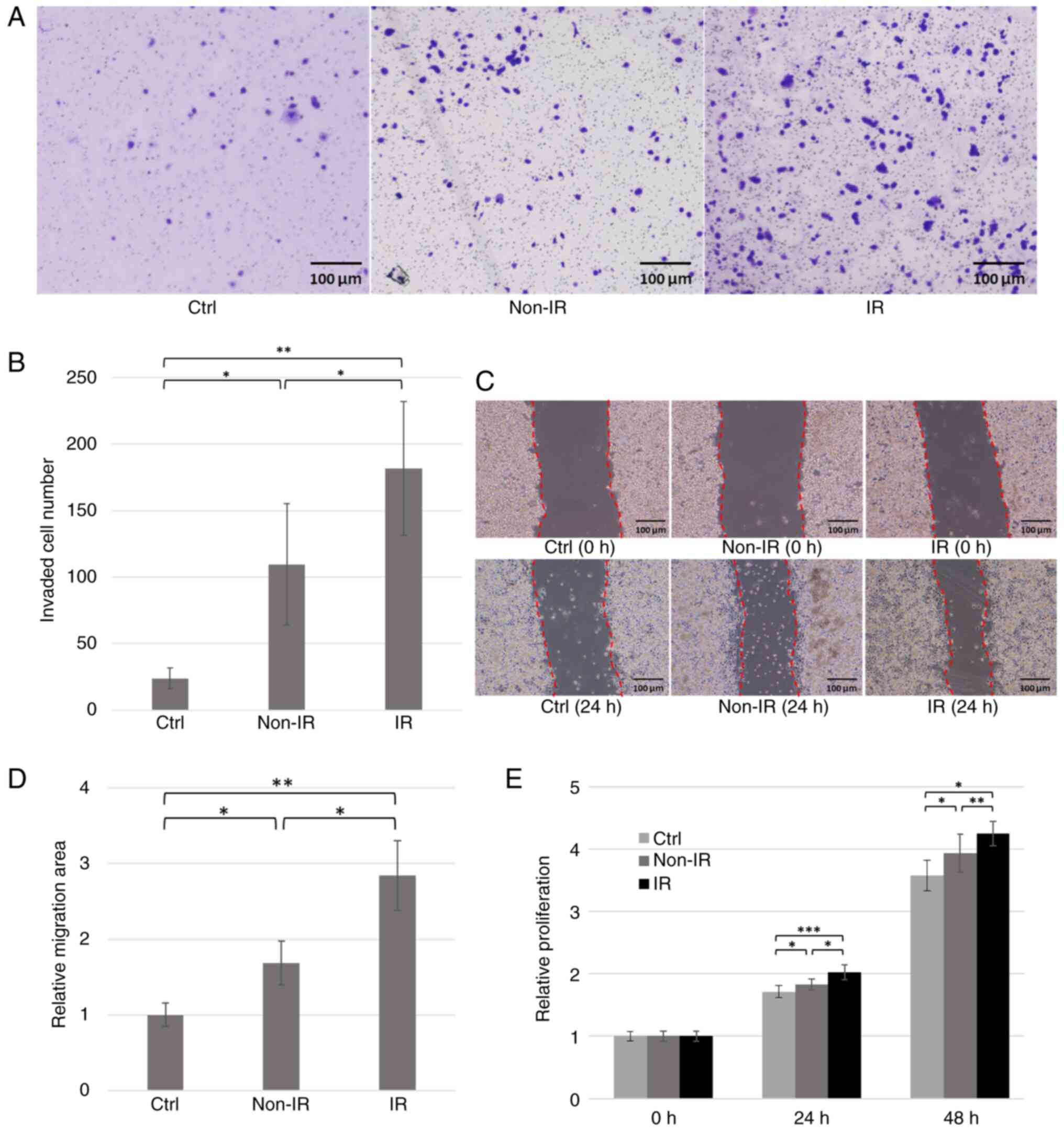

Using resected pancreatic cancer specimens, the

presence of senescent fibroblasts in the pancreatic cancer stroma

and the expression of SASP factors were evaluated. αSMA was used as

a marker for pancreatic fibroblasts (13,19).

Although multiple proteins are known markers of cellular senescence

(8,13,16),

p16 expression levels were evaluated as its expression is extremely

low in proliferating cells but increases markedly when cells reach

their mitotic limit or are exposed to carcinogenic stress, inducing

cellular senescence (34,35). Simultaneous immunofluorescence

staining for αSMA and p16 revealed double-positive cells within the

pancreatic cancer stroma, which confirmed the presence of

fibroblasts exhibiting features of cellular senescence (Fig. 2A). Although various cytokines,

chemokines, growth factors and extracellular matrix-degrading

factors are recognized as SASP components, IL-6 was assessed as a

representative and pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine (8,9,13). The

fibroblasts were positive for both p16 and IL-6 in the tumor stroma

(Fig. 2B), indicating that

senescent fibroblasts in the PDAC stroma express the SASP factor

IL-6. Using resected pancreatic cancer specimens,

immunohistochemistry with p16 and IL-6 targeting the pancreatic

cancer stroma was then performed. A significant positive

correlation was found between p16 and IL-6 expression (r=0.585,

P<0.0001; Fig. 2C), which

suggested that IL-6 expression increased proportionally with the

number of senescent fibroblasts in the tumor stroma. Based on these

findings, subsequent analyses on IL-6 expression in the PDAC stroma

was conducted.

| Figure 2.Evaluation of p16- and IL-6-positive

cells in the stroma of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. (A)

Representative immunofluorescence staining of a pancreatic cancer

resection specimen (αSMA, green; p16, red; DAPI, blue; scale bar,

50 and 25 µm). In the pancreatic cancer stroma, pancreatic

fibroblasts (αSMA-positive) expressing the senescence marker p16

were identified (yellow arrows). (B) Representative

immunofluorescence staining of a pancreatic cancer resection

specimen (p16, red; IL-6, green; DAPI, blue; scale bar, 100 and 25

µm). Fibroblasts positive for p16 and the senescence-associated

secretory phenotype factor IL-6 were observed in the pancreatic

cancer stroma (yellow arrows). (C) A significant positive

correlation between the expression intensity of p16- and

IL-6-positive fibroblasts in the pancreatic cancer stroma

(Pearson's correlation coefficient, r=0.585; P<0.0001). |

Postoperative prognosis according to

IL-6 expression in the PDAC stroma

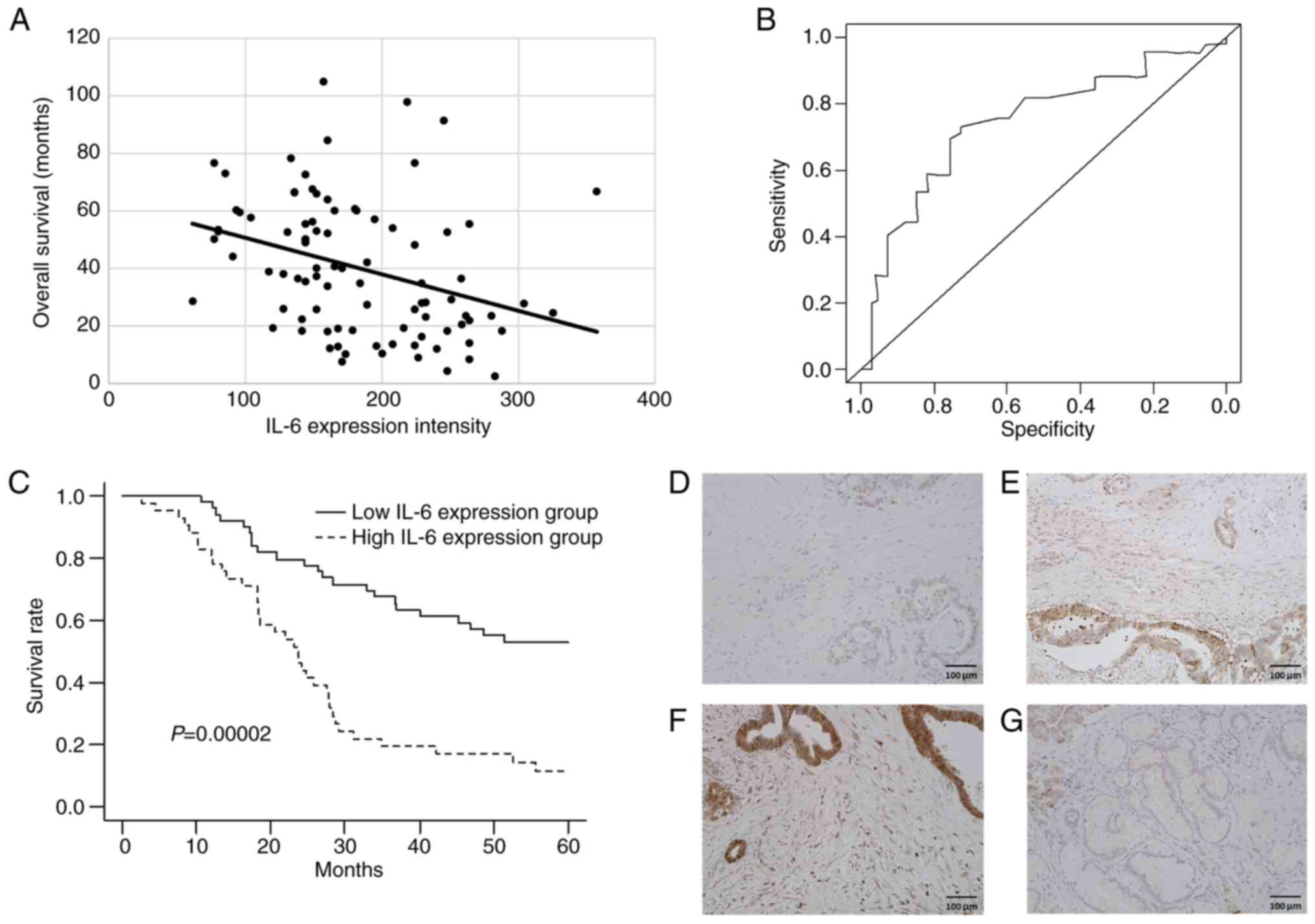

The association between IL-6 expression in stromal

fibroblasts and overall survival (OS) following

pancreaticoduodenectomy was investigated. A significant negative

correlation was found between IL-6-positive fibroblast expression

and postoperative survival (r=−0.336, P=0.0012; Fig. 3A). Therefore, it was considered that

IL-6 expression in the tumor stroma may potentially serve as a

prognostic factor after surgery. Using an ROC curve, the H-score

cut-off value of 179 of IL-6 expression was determined to

distinguish prognostic groups [area under the curve (AUC)=0.754,

sensitivity=0.736 and specificity=0.734; Fig. 3B]. The H-score cut-off was used to

patients divide into high- (≥179) and low-IL-6 (<179) expression

groups and Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS of the two groups was

performed. The high-IL-6 expression group demonstrated a

significantly poorer OS compared with that of the low-IL-6 group

(log-rank test, P=0.00002; Fig.

3C). IHC was performed on representative PDAC specimens with

weak (Fig. 3D), moderate (Fig. 3E) and strong (Fig. 3F) IL-6 positivity, and a

non-tumorous pancreatic specimen (Fig.

3G). Univariate analysis identified curability, T factor (T3 or

T4), lymph node metastasis, neuroplexus invasion and high-IL-6

expression as significant prognostic factors. Multivariate analysis

further confirmed lymph node metastasis and high IL-6 expression as

independent prognostic indicators (Table I). Patient demographics and

clinicopathological characteristics of high- and low-IL-6

expression groups are summarized in Table II. There were no significant

differences between groups in terms of baseline characteristics,

including preoperative chemotherapy, combined portal vein or

arterial resection and curative resection. The high IL-6 expression

group demonstrated a notably higher proportion of patients with

advanced T and N classifications compared with that of the

low-expression group, although this not statistically significant.

To evaluate whether patient characteristics or tumoral factors

influenced IL-6 expression in stromal fibroblasts of PDAC, a

subgroup analysis was conducted. Stromal IL-6 expression was not

associated with any patient characteristics or tumoral factors

(Table III). In this cohort,

neither patient age nor preoperative chemotherapy were associated

with IL-6 expression in senescent stromal fibroblasts.

| Table I.Factors associated with overall

survival in operated patients with pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma. |

Table I.

Factors associated with overall

survival in operated patients with pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, ≥65 years |

|

| 0.401 |

|

|

|

| Sex, male |

|

| 0.748 |

|

|

|

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy |

|

| 0.838 |

|

|

|

| Curability (R1 or

2) | 2.173 | 1.372–3.441 | 0.001 | 1.214 | 0.670–2.107 | 0.490 |

| Histological

differentiationa |

|

| 0.119 |

|

|

|

| Tumor

factora |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T3 or

4 | 2.671 | 1.445–4.938 | 0.002 | 2.101 | 0.860–5.135 | 0.104 |

| N1 or

2 | 4.607 | 2.411–8.806 | 0.00001 | 3.594 | 1.636–7.893 | 0.001 |

| Histopathological

factor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lymphatic invasion |

|

| 0.516 |

|

|

|

|

Vascular invasion |

|

| 0.102 |

|

|

|

|

Neuroplexus invasion | 2.025 | 1.181–3.473 | 0.010 | 1.576 | 0.835–2.972 | 0.160 |

| High IL-6

expression | 4.486 | 2.564–7.846 | 0.00001 | 3.483 | 1.519–6.852 | 0.001 |

| Table II.Relationship between stromal IL-6

expression and clinicopathological factors. |

Table II.

Relationship between stromal IL-6

expression and clinicopathological factors.

| Characteristic | Low IL-6

expression, n | High IL-6

expression, n | P-value |

|---|

| Total patients | 49 | 41 |

|

| Age, years |

|

| 0.623 |

|

<65 | 30 | 23 |

|

|

≥65 | 19 | 18 |

|

| Sex |

|

| 0.823 |

|

Male | 31 | 25 |

|

|

Female | 18 | 16 |

|

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy |

|

| 0.957 |

|

Present | 32 | 27 |

|

|

Absent | 17 | 14 |

|

| Portal vein

resection |

|

| 0.317 |

|

Present | 31 | 30 |

|

|

Absent | 18 | 11 |

|

| Artery

resection |

|

| 0.525 |

|

Present | 4 | 5 |

|

|

Absent | 45 | 36 |

|

| Curability |

|

| 0.828 |

| R0 | 38 | 31 |

|

|

R1/2 | 11 | 10 |

|

| T

categorya |

|

| 0.189 |

|

T1/2 | 41 | 33 |

|

|

T3/4 | 8 | 8 |

|

| N

categorya |

|

| 0.156 |

| N0 | 24 | 12 |

|

| N1 | 14 | 15 |

|

| N2 | 11 | 14 |

|

| UICC

stagea |

|

| 0.267 |

| I | 22 | 12 |

|

| II | 16 | 15 |

|

|

III | 11 | 14 |

|

| Histological

differentiationa |

|

| 0.449 |

|

Well | 10 | 6 |

|

|

Moderate | 34 | 32 |

|

|

Poor | 7 | 3 |

|

| Lymphatic

invasion |

|

| 0.881 |

|

Present | 45 | 38 |

|

|

Absent | 4 | 3 |

|

| Vascular

invasion |

|

| 0.361 |

|

Present | 41 | 37 |

|

|

Absent | 8 | 4 |

|

| Neuroplexus

invasion |

|

| 0.365 |

|

Present | 24 | 24 |

|

|

Absent | 25 | 17 |

|

| Table III.Subgroup analysis of the association

with IL-6 expression in stromal fibroblasts was performed. |

Table III.

Subgroup analysis of the association

with IL-6 expression in stromal fibroblasts was performed.

| Factor | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age (≥65

years) | 0.749 | 0.293–1.910 | 0.546 |

| Sex (male) | 0.800 | 0.312–2.050 | 0.643 |

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy | 0.963 | 0.364–2.540 | 0.939 |

| Curability (R1 or

2) | 0.731 | 0.301–1.780 | 0.491 |

| Histological

differentiationa

(moderate or poor) | 0.947 | 0.232–3.860 | 0.939 |

| Tumor factor

a |

|

|

|

| T3 or

4 | 0.904 | 0.278–2.930 | 0.867 |

| N1 or

2 | 2.680 | 0.901–7.960 | 0.076 |

| Histopathological

factor |

|

|

|

|

Lymphatic invasion | 0.440 | 0.047–4.110 | 0.471 |

|

Vascular invasion | 2.370 | 0.387–14.600 | 0.350 |

|

Neuroplexus invasion | 1.190 | 0.433–3.300 | 0.731 |

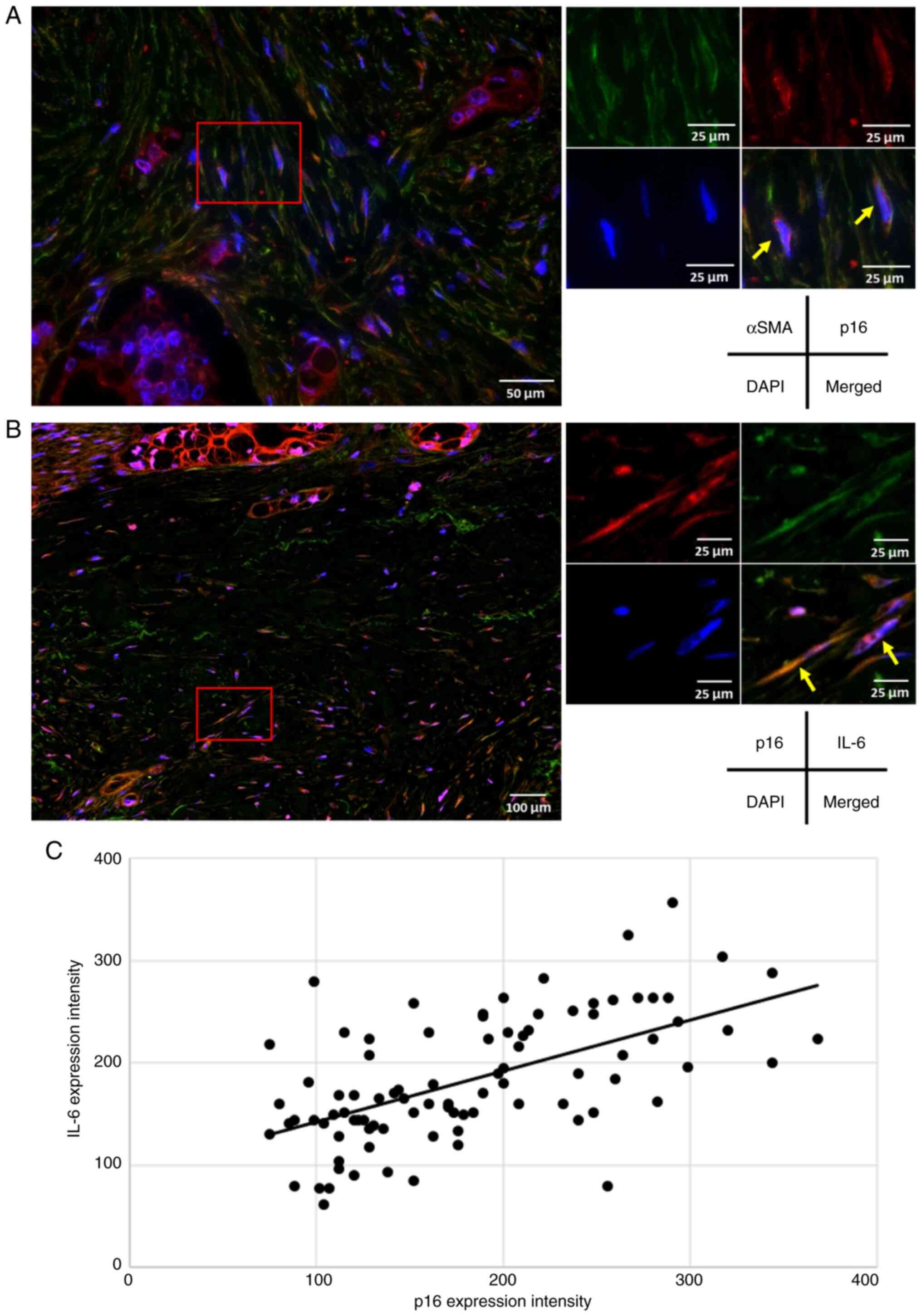

Induction of cellular senescence in

established human pancreatic fibroblasts and co-cultures with PDAC

cell lines

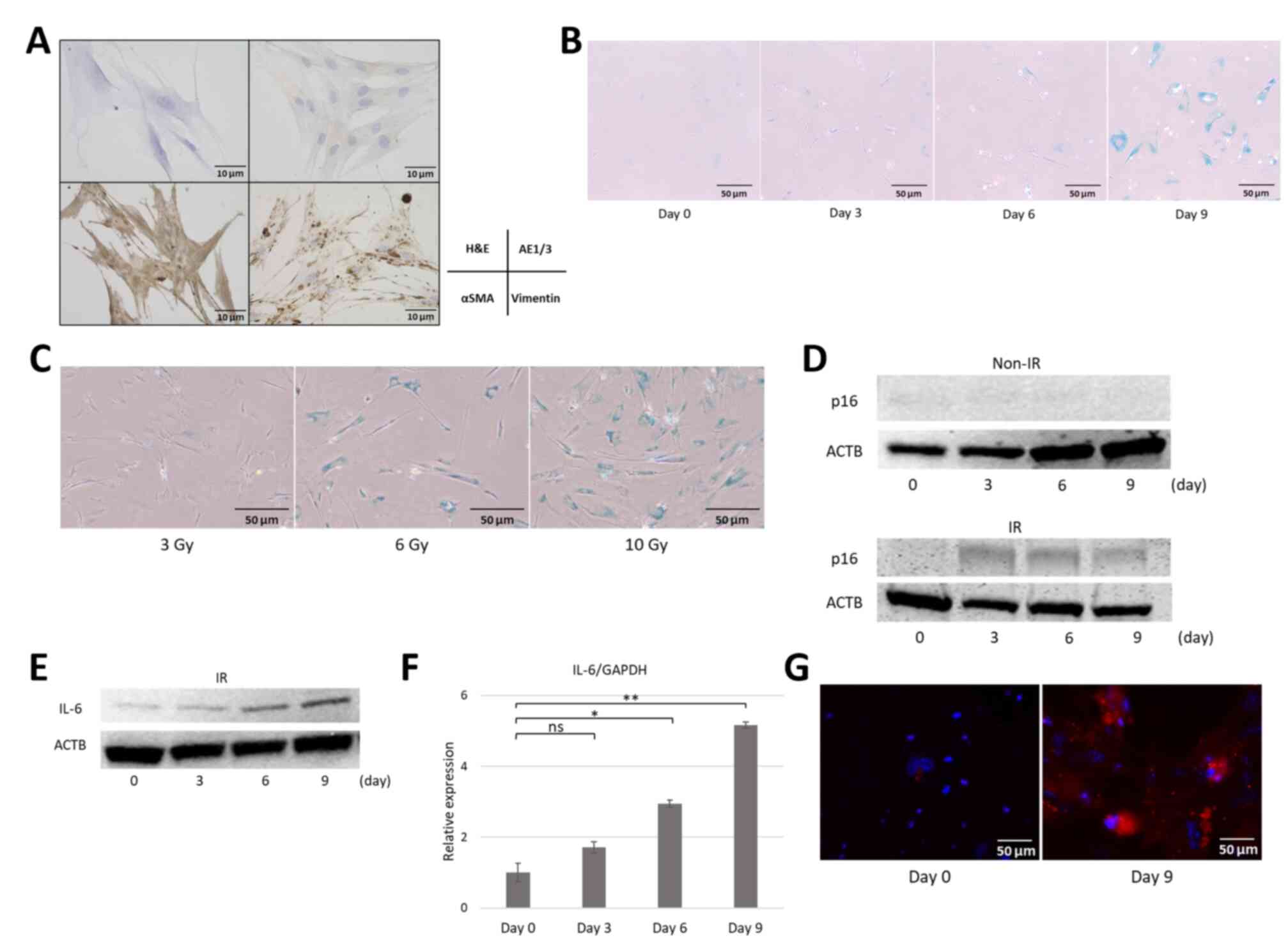

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of cells established

from resected pancreatic specimens was used to confirm the

proliferation of bipolar or multipolar spindle-shaped cells with

basophilic nuclei and cytoplasm. AE1/3 staining was negative,

whereas αSMA and vimentin were diffusely positive (Fig. 4A), which demonstrated the successful

isolation of pancreatic fibroblasts from pancreatic specimens.

Next, cellular senescence in the established pancreatic fibroblasts

was induced. Cells were exposed to 10 Gy X-ray irradiation to

induce DNA damage, and changes were observed over time by every 3

days (up to 9 days) post irradiation. The irradiated fibroblasts

gradually ceased proliferation and exhibited cell and nuclear

enlargement, which are hallmarks of senescent cells, and exhibited

positive SA-β-gal staining (Fig.

4B), which indicated that radiation-induced DNA damage

successfully induced cellular senescence in pancreatic fibroblasts.

To assess the degree of senescence, a dose-gradient approach (3, 6

and 10 Gy irradiation) was applied. SA-β-gal staining was performed

9 days after irradiation. With increasing radiation doses,

fibroblasts appeared flattened and exhibited enhanced SA-β-gal

staining (Fig. 4C). Based on these

temporal and dose-dependent findings, fibroblasts that were

irradiated with 10 Gy and cultured for 9 days were used in

subsequent experiments. The expression levels of p16INK4a, as a

marker of senescence in the fibroblasts, were then evaluated.

Western blotting demonstrated no p16 expression in non-irradiated

cells; however, irradiated fibroblasts showed consistently

increased p16 expression from day 3 onward (Fig. 4D). Regarding the SASP factor IL-6,

western blotting demonstrated a gradual increase in IL-6 protein

expression beginning on day 3 (Fig.

4E), paralleled by a similar significant increase in IL-6 mRNA

levels as confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig.

4F). Immunofluorescence analysis on day 9 post-irradiation

demonstrated cytoplasmic IL-6 staining in pancreatic fibroblasts

(Fig. 4G). Additionally, the mRNA

expression of other SASP components, including cytokines (IL-1),

chemokines (IL-8), extracellular matrix remodeling factors (MMP-1

and PAI-1) and a growth factor (VEGF) were assessed; these SASP

components were significantly upregulated in irradiated fibroblasts

(Fig. S1). These results suggested

that radiation-induced DNA damage triggered cellular senescence and

promoted SASP factor expression in pancreatic fibroblasts.

| Figure 4.Establishment of human pancreatic

fibroblast cell lines and induction of cellular senescence and the

senescence-associated secretory phenotype. (A) Pancreatic

fibroblasts established from resected pancreatic specimens. Cells

showed a spindle-shaped morphology with cytoplasmic protrusions

(AE1/3-negative, αSMA- and vimentin-positive; scale bar, 10 µm).

(B) SA-β-gal staining of IR pancreatic fibroblasts (10 Gy)

increased over time (scale bar, 50 µm). (C) SA-β-gal staining of

pancreatic fibroblasts 9 days increased with gradient irradiation

(3, 6 and 10 Gy; scale bar, 50 µm). (D) Western blot analysis of

p16 protein expression in IR pancreatic fibroblasts (10 Gy X-rays

on days 0, 3, 6 and 9) showed increased p16 protein expression from

day 3 onward compared with the non-IR group. (E) Western blot

analysis showed a gradual increase of IL-6 protein expression from

day 3 onwards to day 9 post-irradiation. (F) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR confirmed increased IL-6 mRNA

expression after irradiation over 9 days of culture. Data are

presented as mean ± SD (n=6). (G) Immunofluorescence of pancreatic

fibroblasts. IL-6 expression was increased on day 9 (IL-6, red;

DAPI, blue; scale bar, 50 µm). *P<0.01 and **P<0.001. ns, not

significant; H&E, hemoxylin and eosin; SA-β-gal,

senescence-associated β-galactosidase; aSMA, a smooth muscle actin;

ACTB, β-actin; IR, irradiated. |

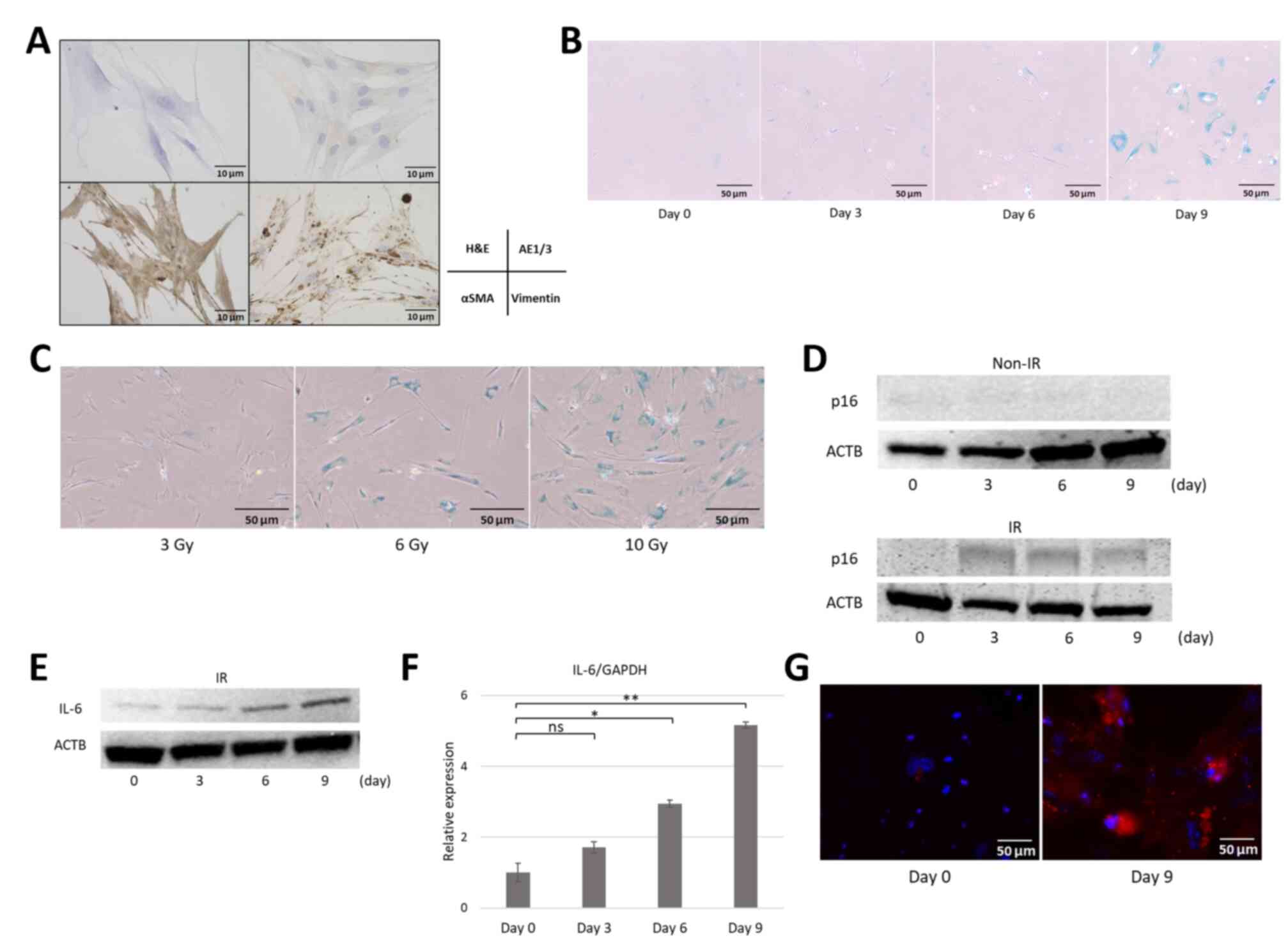

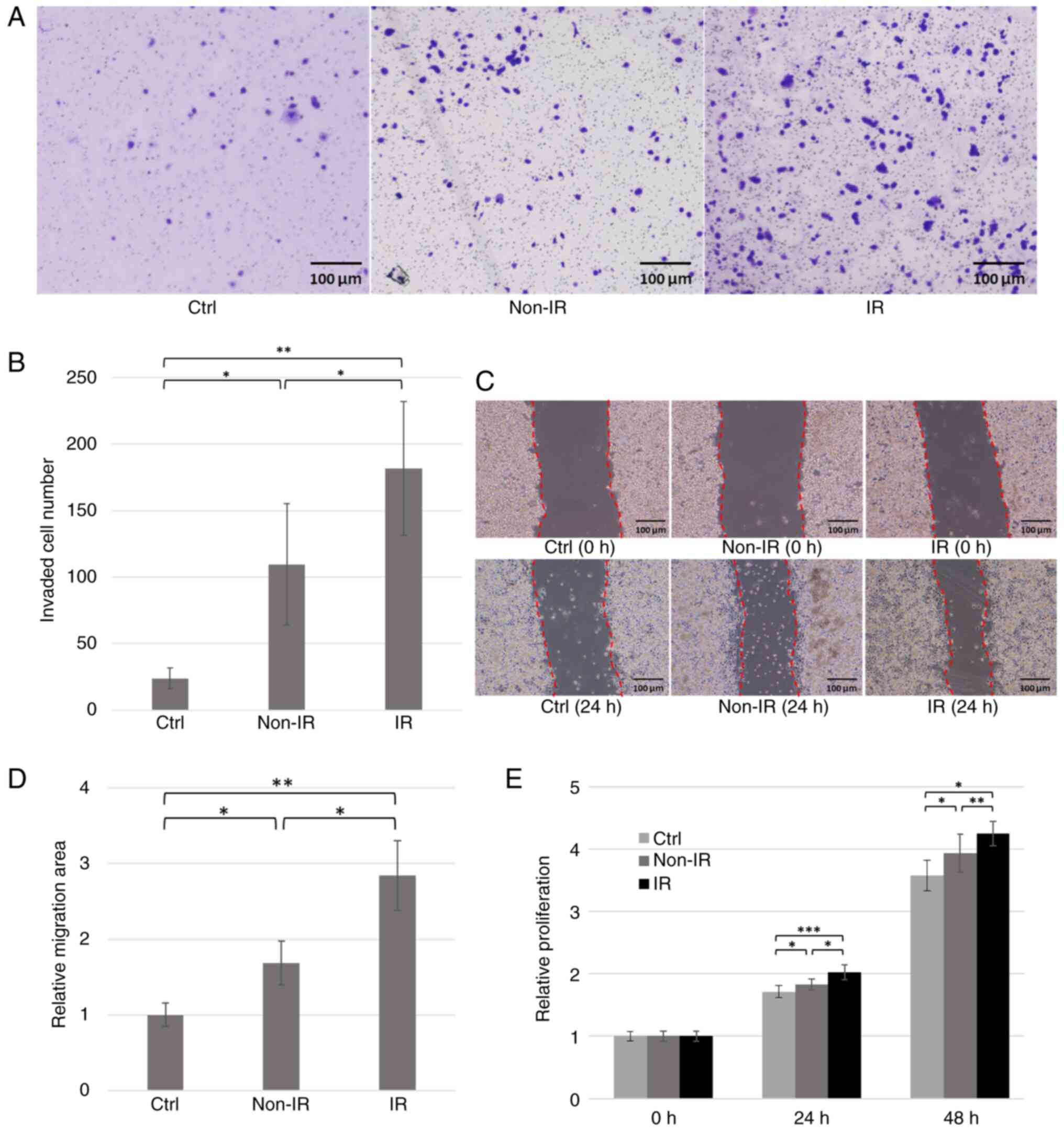

Invasive, migratory and proliferative

capacities of Panc-1 cells with irradiated human pancreatic

fibroblasts or culture supernatant

The invasive potential of Panc-1 cells co-cultured

with fibroblasts 9 days post-irradiation was evaluated. Panc-1

cells were co-cultured with fibroblasts, and the number of cancer

cells that migrated through the Matrigel and membrane was

quantified. Co-culture with pancreatic fibroblasts significantly

enhanced Panc-1 invasion compared with that of control cells, and

this effect was further amplified by co-culture with irradiated,

SASP-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 5A

and B).

| Figure 5.Co-culture experiments of Panc-1

cells with IR human pancreatic fibroblasts or their culture

supernatants. (A) Representative images of pancreatic fibroblasts

(10 Gy IR or non-IR) that were co-cultured with Panc-1 cells (scale

bar, 100 µm), and (B) the number of cells that invaded through the

gel and membrane was counted (n=6). (C) A confluent monolayer of

Panc-1 cells was scratched with a pipette, and the culture

supernatant of IR or non-IR pancreatic fibroblasts was added (scale

bar, 100 µm). (D) After 12 h, the area of cell migration was

measured (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. (E) Panc-1 cells were

cultured with culture supernatants of IR or non-IR pancreatic

fibroblasts, and proliferation was assessed after 24 and 48 h using

the MTT assay (n=8). Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. aSMA, a smooth muscle actin; Ctrl,

control; IR, irradiated. |

Panc-1 cells were cultured in the conditioned medium

from irradiated or non-irradiated fibroblasts, and their migration

capacity was evaluated. The groups treated with conditioned medium

showed significantly larger migration areas compared with control.

Furthermore, the group treated with conditioned medium from

irradiated, SASP-expressing fibroblasts showed a significantly

larger migration area compared with that of cells treated with

medium from non-irradiated fibroblasts (Fig. 5C and D).

Cell proliferation of Panc-1 cells was assessed

using the MTT assay (n=8). Panc-1 cells cultured in

fibroblast-conditioned medium exhibited significantly higher

proliferation compared with those cultured in standard

serum-containing medium. Furthermore, conditioned medium from

irradiated fibroblasts demonstrated significantly increased Panc-1

proliferation compared with cells treated with either

serum-containing medium or medium from non-irradiated fibroblasts

(Fig. 5E). These findings indicated

that pancreatic fibroblasts expressing the SASP significantly

enhanced the proliferative capacity of pancreatic cancer cells.

Discussion

Research has shown that cells and molecules within

or around the cancer stroma form the cancer microenvironment in

various carcinomas. Furthermore, the fibrous stroma serves an

important role in shaping the cancer microenvironment (13–16).

In particular, cellular senescence of the fibrotic stroma and the

expression of SASP factors associated with cellular senescence have

been reported to significantly impact cancer progression in several

carcinomas (such as hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian and prostate

cancer) (21–23). In gastrointestinal carcinomas,

pancreatic ductal and diffuse-type gastric cancer have a more

abundant fibrotic stroma than other malignant tumors of the

digestive tract and are known to have poor prognoses (24,25).

Certain underlying health conditions and lifestyle

factors are risk factors for pancreatic cancer, including diabetes,

chronic pancreatitis, hereditary pancreatitis, obesity, smoking and

heavy drinking (36–39). These are also risk factors for

chronic inflammation, whereas obesity, smoking and alcohol

consumption are known risk factors for other types of malignancies

(40–43). This suggests that systemic and/or

local chronic inflammation in the pancreas caused by underlying

diseases and/or lifestyle factors induces cellular senescence and

SASP in the pancreatic stroma, and that oxidative stress, DNA

damage and oncogene activation occur in the pancreatic stroma

before pancreatic cancer develops. After carcinogenesis, various

cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxygen species produced by

cancer cells interact with the surrounding stroma, inducing further

fibroblast production and forming a desmoplastic microenvironment

(13,17).

The status of lymph node metastasis is widely

recognized as an important prognostic factor for pancreatic cancer

and is reflected in the TNM classification of cancer staging

(27,44). In the present study, multivariate

analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model indicated that

lymph node metastasis and high IL-6 expression were significant

prognostic factors. The presence of fibroblasts positive for p16

and IL-6, representative SASP factors, was confirmed in the stroma

of resected PDAC specimens. These results suggested that senescent

fibroblasts exist in the pancreatic cancer stroma and express SASP

factors. The expression intensity of IL-6-positive cells in the

pancreatic cancer stroma was calculated using H-score analysis, and

a cut-off value of 179 was defined using an ROC curve. Based on

this cut-off value, it was demonstrated that the OS of patients in

the high IL-6 expression group was significantly shorter compared

with that in the low IL-6 expression group. In the present study,

consecutive patients with PDAC who underwent surgery were included.

As multidisciplinary treatment is the standard for pancreatic

cancer, it could be considered that the inclusion of numerous

patients who received preoperative chemotherapy (66%) may reflect

the current status of pancreatic cancer treatment. Although it was

considered that advanced age and preoperative chemotherapy may

directly contribute to pancreatic stromal senescence, subgroup

analysis demonstrated that IL-6 expression in PDAC stromal

fibroblasts was not associated with any patient demographics and

clinicopathological characteristics. Since pancreatic

carcinogenesis is suggested to occur against a background of

chronic inflammation (36–39), it was considered that cellular

senescence of the pancreatic stroma begins at the

pre-carcinogenesis stage. Although stromal depletion after

preoperative chemotherapy has been reported (19), the present study found no evidence

that preoperative chemotherapy directly induces further senescence

in the cancer stroma. In summary, high expression intensity of IL-6

in the pancreatic cancer stromal fibroblasts was significantly

associated with shorter survival after pancreatic cancer surgery.

The presence of senescent fibroblasts and expression of SASP

factors in the pancreatic cancer stroma may potentially serve as

prognostic factors for pancreatic cancer.

The present in vitro studies demonstrated the

successful establishment of pancreatic fibroblasts and confirmed

the induction of cellular senescence and the expression of SASP

factors in these fibroblasts following DNA damage by irradiation.

Co-culture of pancreatic fibroblasts expressing SASP factors with

pancreatic cancer cells revealed that the invasive, migratory and

proliferative capacities of the cancer cells were significantly

enhanced. The results of the in vitro analyses suggest that

a microenvironment promoting cancer growth and spread is formed in

pancreatic tissues subjected to X-ray irradiation, mimicking stress

or DNA damage caused by chronic inflammation. Most forms of

cellular senescence, such as replicative exhaustion,

therapy-induced senescence or expression of oncogenic RAS, are

associated with unrepaired DNA damage, similar to that caused by

X-rays, and the choice of senescence inducer has been shown to have

little effect on the senescent phenotype (8). Based on this finding, X ray

irradiation was employed in the present study. To the best of our

knowledge, no basic research on pancreatic cancer, a typical

refractory solid tumor, has focused on cellular senescence and SASP

in cancer stromal fibroblasts to clarify their effects on the tumor

microenvironment and the promotion of cancer progression.

Numerous reports have demonstrated the role of CAFs

in the tumor microenvironment. Several CAF markers have been

documented, with the most commonly used including fibroblast

activation protein α (FAP), αSMA and podoplanin (13–16).

In the present study, increased FAP expression levels were observed

in irradiated pancreatic fibroblasts (data not shown), which

exhibited cellular senescence and the SASP. However, the expression

of CAF markers is highly heterogeneous and varies significantly

among CAF subpopulations (45).

Furthermore, identifying CAFs remains challenging, and further

investigation is needed to standardize CAF identification across

studies. A limitation of the present study is that the overlap

between senescent fibroblasts and CAFs was not assessed; therefore,

it could not be determined whether they represent the same or

distinct cell populations. Nevertheless, it remains possible that

some senescent fibroblasts exhibiting SASP may function as CAFs

within the tumor microenvironment to promote invasion and

metastasis.

Cellular senescence is characterized by irreversible

cell cycle arrest. Representative protein markers include p16INK4a,

p21 (Waf1/Clip1/Sdi1), p53 and Rb (3). Activation of p53 directly induces

apoptosis and enhances the expression of p21, a cyclin-dependent

kinase (CDK) inhibitor; by inhibiting CDKs, p21 activates Rb and

suppresses the function of E2F, which regulates the transcription

of genes that promote cell proliferation (3). E2F is responsible for the

G1-to-S phase transition of the cell cycle; its

inhibition arrests cells in the G1 phase (3). In parallel, p16INK4a inhibits CDK4/6,

which also serves a role in G1 progression. During

cellular senescence, Rb remains constantly activated through these

two CDK-inhibitory pathways. Although p21 and p16INK4a alone weakly

activate Rb, their combined action robustly maintains Rb activation

and arrests cell cycle progression (46). p16INK4a expression is extremely low

in cells with normal proliferative potential and is nearly

undetectable. However, its expression markedly increases when

normal cells reach their mitotic limit or experience oncogenic

stress, thereby inducing senescence (34,35).

Therefore, p16INK4a is a key marker of cellular senescence.

The SASP comprises multiple factors, including IL-6,

which may act synergistically within the cancer microenvironment.

IL-6, a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine, has been shown to

promote senescence and influence tumor formation (47,48).

IL-6 is associated with DNA damage (and tumorigenic stress) induced

senescence in keratinocytes, melanocytes, monocytes, fibroblasts

and epithelial cells (47,49–51).

According to previous reports, IL-6 affects tumor cells and the

surrounding microenvironment by upregulating various genes (such as

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, ILs, matrix

metalloproteinase-2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2,

receptor for advanced glycation end-products and VEGF) and

activating multiple tumor-promoting processes, such as angiogenesis

and metastasis (52). The IL-6

signaling pathway is considered a key contributor to pancreatic

cancer development. Through IL-6 expression, senescent fibroblasts

can influence nearby cells expressing the IL-6 receptor (gp80) and

gp130 signaling complex, such as epithelial and endothelial cells

(8). IL-6 binding to its receptor

activates Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), which transmits signals to the

downstream STAT3 protein. STAT3 promotes pancreatic cancer

progression by inducing genes such as cyclin D1 and Bcl-2,

upregulating VEGF, promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

inhibiting dendritic cell-mediated immune responses (53). STAT3 is considered an oncogene owing

to its widespread activation in cancer. In addition to JAK-STAT3,

IL-6 also activates the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)

and phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathways, which contribute

to anti-apoptotic and tumorigenic effects (54). In various malignancies, including

colorectal, renal, prostate, breast and ovarian cancer, as well as

multiple myeloma and non-small cell lung cancer, increased serum

IL-6 concentrations have been associated with advanced tumor stage

and poor survival (52). In the

present study, it was found that senescent pancreatic fibroblasts

induced by X-ray irradiation exhibited simultaneous upregulation of

multiple mRNA transcripts, including IL-6. A key limitation of the

present study is the lack of a systematic evaluation of IL-6 in

relation to other critical factors. This limitation arises from the

inherent constraints of in vitro systems in recapitulating

the complex tumor microenvironment, which is shaped by the dynamic

interplay of various cell types and molecular signals. Furthermore,

the SASP encompasses a broad array of factors, making it difficult

to comprehensively assess SASP function. However, given that IL-6

signaling is widely recognized as a major contributor to pancreatic

cancer progression, the present study focused on IL-6 as the most

representative SASP factor. Future research on cellular senescence

within the tumor microenvironment will enable a more complete

evaluation of SASP function. Specifically, these include spatial

gene expression analysis to visualize gene expression in specific

regions of biological tissue and investigate the localization of

SASP factors and the microenvironment in which SASP factors are

released, as well as biological approaches such as creating animal

models with specific SASP factors deleted to identify their

functions and examine their effects on senescence and disease

within the organism.

A previous report established a mouse model

(p16-CreERT2-DTR-tdTomato) that enables the removal of p16-positive

cells, showing positive results (55). In that study, non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis (NASH) was induced by feeding mice a

choline-deficient L-amino acid high-fat diet for 6 weeks. Removal

of p16-positive cells during the final 3 weeks improved hepatic

steatosis and inflammation. These findings indicate that NASH

progression may be suppressed by eliminating p16-positive cells.

Senescent cells have an apoptosis resistance mechanism similar to

that of cancer cells, including high expression of the

anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Based on the concept that

senescent cells can be selectively eliminated by chemotherapy,

various drugs have been screened, and the development of senolytic

agents that specifically target senescent cells is advancing.

Dasatinib plus quercetin, the first senolytic drug, has progressed

to clinical trials for multiple diseases and has shown efficacy

(56,57). In addition, studies have reported

that the removal of senescent cells from atherosclerotic plaques

(58) and the central nervous

system (59) in mice suppresses the

progression of age-related diseases. Other reports demonstrate the

effectiveness of senolytic drugs via p53 activation, which promotes

apoptosis in senescent cells (60,61).

Most of these studies have targeted age-related diseases and

excluded malignant tumors. Presently, no senolytic drugs have shown

statistically significant effects in clinical trials involving

living organisms. However, in the future, new therapies targeting

malignant tumors by removing senescent cells may be developed.

Senescent fibroblasts in the cancer stroma produce

various substances, such as SASP factors, that influence cancer

progression. The present study demonstrated the presence of

senescent fibroblasts in the pancreatic cancer stroma, with a

positive correlation between p16 and IL-6 expression in

fibroblasts. Furthermore, IL-6 expression in pancreatic cancer

stromal fibroblasts was identified as a significant prognostic

factor, along with lymph node metastasis, following pancreatic

cancer surgery. Therefore, evaluating the presence of senescent

cells and the expression of SASP factors in the pancreatic cancer

stroma may be useful for predicting postoperative prognosis in

patients with pancreatic cancer in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Yasuyo Futakuchi

and Ms. Kyoko Yoshida, the Medical Technologist of Gastrointestinal

Surgery, Kanazawa University, who provided technical support for

the experiments and made significant contribution.

Funding

The present study was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant no.

JP23K08163).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YK, TM, YY, NI and SY designed and conceived the

study. YK, TM and TS analyzed and interpreted the results and

drafted the manuscript. TM and YY supervised this study. YK and IM

collected the data. YE contributed to the establishment of

pancreatic fibroblasts. TS, YY, NI and SY edited and revised the

manuscript critically for intellectual content. All the authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. YK and

TM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study followed the provisions of the

Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Review

Committee of Kanazawa University Hospital (approval no. 2016-318).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for the

anonymous use of resected specimens and clinical data.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

YK, 0000-0003-1941-9074; TM, 0000-0002-3771-0773;

TS, 0009-0001-5490-8271; IM, 0000-0001-6023-7163; YE,

0000-0003-0785-2006; YY, 0000-0003-1326-4649; NI,

0000-0002-4241-5015; SY, 0000-0001-7465-5761.

References

|

1

|

Hayflick L and Moorhead PS: The serial

cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res.

25:585–621. 1961. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Campisi J and d'Adda di Fagagna F:

Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 8:729–740. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ohtani N, Mann DJ and Hara E: Cellular

senescence: Its role in tumor suppression and aging. Cancer Sci.

100:792–797. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott

G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O,

et al: A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture

and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 92:9363–9367.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ and

Peeper DS: The essence of senescence. Genes Dev. 24:2463–2479.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Harper JW and Elledge SJ: The DNA damage

response: Ten years after. Mol Cell. 28:739–745. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mallette FA and Ferbeyre G: The DNA damage

signaling pathway connects oncogenic stress to cellular senescence.

Cell Cycle. 6:1831–1836. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Coppé JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A and

Campisi J: The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: The dark

side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol. 5:99–118. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, Campisi

J and Kirkland JL: Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory

phenotype: Therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 123:966–972.

2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Muñoz-Espín D, Cañamero M, Maraver A,

Gómez-López G, Contreras J, Murillo-Cuesta S, Rodríguez-Baeza A,

Varela-Nieto I, Ruberte J, Collado M and Serrano M: Programmed cell

senescence during mammalian embryonic development. Cell.

155:1104–1118. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Demaria M, Ohtani N, Youssef SA, Rodier F,

Toussaint W, Mitchell JR, Laberge RM, Vijg J, Van Steeg H, Dollé

ME, et al: An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound

healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell. 31:722–733. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Laberge RM, Awad P, Campisi J and Desprez

PY: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by senescent

fibroblasts. Cancer Microenviron. 5:39–44. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Von Ahrens D, Bhagat TD, Nagrath D, Maitra

A and Verma A: The role of stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts in

pancreatic cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 10:762017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kawase T, Yasui Y, Nishina S, Hara Y,

Yanatori I, Tomiyama Y, Nakashima Y, Yoshida K, Kishi F, Nakamura M

and Hino K: Fibroblast activation protein-α-expressing fibroblasts

promote the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC

Gastroenterol. 15:1092015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tabola R, Zaremba-Czogalla M, Baczynska D,

Cirocchi R, Stach K, Grabowski K and Augoff K: Fibroblast

activating protein-α expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the

esophagus in primary and irradiated tumors: The use of archival

FFPE material for molecular techniques. Eur J Histochem.

61:27932017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shindo K, Aishima S, Ohuchida K, Fujiwara

K, Fujino M, Mizuuchi Y, Hattori M, Mizumoto K, Tanaka M and Oda Y:

Podoplanin expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts enhances

tumor progression of invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Mol

Cancer. 12:1682013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Su S, Chen J, Yao H, Liu J, Yu S, Lao L,

Wang M, Luo M, Xing Y, Chen F, et al: CD10+GPR77+ Cancer-associated

fibroblasts promote cancer formation and chemoresistance by

sustaining cancer stemness. Cell. 172:841–856.e16. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Paulsson J, Rydén L, Strell C, Frings O,

Tobin NP, Fornander T, Bergh J, Landberg G, Stål O and Östman A:

High expression of stromal PDGFRβ is associated with reduced

benefit of tamoxifen in breast cancer. J Pathol Clin Res. 3:38–43.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Miyashita T, Tajima H, Makino I, Okazaki

M, Yamaguchi T, Ohbatake Y, Nakanuma S, Hayashi H, Takamura H,

Ninomiya I, et al: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus

nab-paclitaxel reduces the number of cancer-associated fibroblasts

through depletion of pancreatic stroma. Anticancer Res. 38:337–343.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Miyashita T, Tajima H, Gabata R, Okazaki

M, Shimbashi H, Ohbatake Y, Okamoto K, Nakanuma S, Sakai S, Makino

I, et al: Impact of extravasated platelet activation and

podoplanin-positive cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic

cancer stroma. Anticancer Res. 39:5565–5572. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lee JS, Yoo JE, Kim H, Rhee H, Koh MJ,

Nahm JH, Choi JS, Lee KH and Park YN: Tumor stroma with

senescence-associated secretory phenotype in steatohepatitic

hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 12:e01719222017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Harper EI, Sheedy EF and Stack MS: With

great age comes great metastatic ability: Ovarian cancer and the

appeal of the aging peritoneal microenvironment. Cancers (Basel).

10:2302018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mori JO, Elhussin I, Brennen WN, Graham

MK, Lotan TL, Yates CC, De Marzo AM, Denmeade SR, Yegnasubramanian

S, Nelson WG, et al: Prognostic and therapeutic potential of

senescent stromal fibroblasts in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol.

21:258–273. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Nakayama I: Therapeutic strategy for

scirrhous type gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 55:860–870. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yamamoto Y, Kasashima H, Fukui Y, Tsujio

G, Yashiro M and Maeda K: The heterogeneity of cancer-associated

fibroblast subpopulations: Their origins, biomarkers, and roles in

the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Sci. 114:16–24. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ministry of Education Culture Sports

Science Technology Ministry of Health Labour Welfare, Ministry of

Economy, TradeIndustry, . Ethical guidelines for medical and

biological research involving human subjects (In Japanese).

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000757566.pdf2021.

|

|

27

|

Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK and

Wittekind C: Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). TNM

Classification of Malignant Tumors. 8th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell;

2017

|

|

28

|

Tsuta K, Wistuba II and Moran CA:

Differential expression of somatostatin receptors 1–5 in

neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung. Pathol Res Pract.

208:470–474. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Schmid HA, Lambertini C, van Vugt HH,

Barzaghi-Rinaudo P, Schäfer J, Hillenbrand R, Sailer AW, Kaufmann M

and Nuciforo P: Monoclonal antibodies against the human

somatostatin receptor subtypes 1–5: Development and

immunohistochemical application in neuroendocrine tumors.

Neuroendocrinology. 95:232–247. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Roncoroni L, Elli L, Doneda L, Piodi L,

Ciulla MM, Paliotti R and Bardella MT: Isolation and culture of

fibroblasts from endoscopic duodenal biopsies of celiac patients. J

Transl Med. 7:402009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Seluanov A, Vaidya A and Gorbunova V:

Establishing primary adult fibroblast cultures from rodents. J Vis

Exp. 5:20332010.

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Rasband WS: ImageJ. U.S. National

Institutes of Health. (Bethesda, MD). 2011.http://imagej.nih.gov/ij

|

|

34

|

Hara E, Smith R, Parry D, Tahara H, Stone

S and Peters G: Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its

implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol Cell

Biol. 16:859–867. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D

and Lowe SW: Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence

associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 88:593–602.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Morselli-Labate

AM, Maisonneuve P and Pezzilli R: Pancreatic cancer in chronic

pancreatitis; aetiology, incidence, and early detection. Best Pract

Res Clin Gastroenterol. 24:349–358. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Qiu D, Kurosawa M, Lin Y, Inaba Y, Matsuba

T, Kikuchi S, Yagyu K, Motohashi Y and Tamakoshi A; JACC Study

Group, : Overview of the epidemiology of pancreatic cancer focusing

on the JACC study. J Epidemiol. 15 (Suppl II):S157–S167. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Iodice S, Gandini S, Maisonneuve P and

Lowenfels AB: Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: A review

and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 393:535–545. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tramacere I, Scotti L, Jenab M, Bagnardi

V, Bellocco R, Rota M, Corrao G, Bravi F, Boffetta P and La Vecchia

C: Alcohol drinking and pancreatic cancer risk: A meta-analysis of

the dose-risk relation. Int J Cancer. 126:1474–1486. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gosavi R, Jaya J, Yap R, Narasimhan V and

Ooi G: Obesity and gastrointestinal cancer: A converging epidemic

with surgical consequence. Eur J Surg Oncol. 51:1103582025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cuomo RE: Distinct somatic mutation

profiles in colon cancer by behavioral comorbidity. Future Sci OA.

11:25615012025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang J, Qiu K, Zhou S, Gan Y, Jiang K,

Wang D and Wang H: Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: An

umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med.

57:24555392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ni L, Liu Z, Xiang L, Li Y and Zhang Y:

Comprehensive evaluation of risk factors for LNM and distant

metastasis in patients with NSCLC. Sci Rep. 15:308092025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Min SK, You Y, Choi DW, Han IW, Shin SH,

Yoon S, Jung JH, Yoon SJ and Heo JS: Prognosis of pancreatic head

cancer with different patterns of lymph node metastasis. J

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 29:1004–1013. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Nurmik M, Ullmann P, Rodriguez F, Haan S

and Letellier E: In search of definitions: Cancer-associated

fibroblasts and their markers. Int J Cancer. 146:895–905. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ohtani N, Imamura Y, Yamakoshi K, Hirota

F, Nakayama R, Kubo Y, Ishimaru N, Takahashi A, Hirao A, Shimizu T,

et al: Visualizing the dynamics of p21(Waf1/Cip1) cyclin-dependent

kinase inhibitor expression in living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 104:15034–15039. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC,

Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ and Peeper DS:

Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent

inflammatory network. Cell. 133:1019–1031. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ancrile B, Lim KH and Counter CM:

Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for

tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 21:1714–1719. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Munoz

DP, Goldstein J, Nelson PS, Desprez PY and Campisi J:

Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal

cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor

suppressor. PLoS Biol. 6:2853–2868. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Lu SY, Chang KW, Liu CJ, Tseng YH, Lu HH,

Lee SY and Lin SC: Ripe areca nut extract induces G1 phase arrests

and senescence-associated phenotypes in normal human oral

keratinocyte. Carcinogenesis. 27:1273–1284. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Sarkar D, Lebedeva IV, Emdad L, Kang DC,

Baldwin AS Jr and Fisher PB: Human polynucleotide phosphorylase

(hPNPaseold-35): A potential link between aging and inflammation.

Cancer Res. 64:7473–7478. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Holmer R, Goumas FA, Waetzig GH, Rose-John

S and Kalthoff H: Interleukin-6: A villain in the drama of

pancreatic cancer development and progression. Hepatobiliary

Pancreat Dis Int. 13:371–380. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Song M, Tang Y, Cao K, Qi L and Xie K:

Unveiling the role of interleukin-6 in pancreatic cancer occurrence

and progression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15:14083122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ara T and Declerck YA: Interleukin-6 in

bone metastasis and cancer progression. Eur J Cancer. 46:1223–1231.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Omori S, Wang TW, Johmura Y, Kanai T,

Nakano Y, Kido T, Susaki EA, Nakajima T, Shichino S, Ueha S, et al:

Generation of a p16 reporter mouse and its use to characterize and

target p16high cells in vivo. Cell Metab. 32:814–828.e6.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA,

Evans TK, Giorgadze N, Hashmi SK, Herrmann SM, Jensen MD, Jia Q,

Jordan KL, et al: Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans:

Preliminary report from a clinical trial of dasatinib plus

quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease.

EBiomedicine. 47:446–456. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Farr JN, Atkinson EJ, Achenbach SJ,

Volkman TL, Tweed AJ, Vos SJ, Ruan M, Sfeir J, Drake MT, Saul D, et

al: Effects of intermittent senolytic therapy on bone metabolism in

postmenopausal women: A phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Nat

Med. 30:2605–2612. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Bussian TJ, Aziz A, Meyer CF, Swenson BL,

van Deursen JM and Baker DJ: Clearance of senescent glial cells

prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature.

562:578–582. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Childs BG, Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Conover

CA, Campisi J and van Deursen JM: Senescent intimal foam cells are

deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science. 354:472–477.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Paez-Ribes M, González-Gualda E, Doherty

GJ and Muñoz-Espín D: Targeting senescent cells in translational

medicine. EMBO Mol Med. 11:e102342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Baar MP, Brandt RMC, Putavet DA, Klein

JDD, Derks KWJ, Bourgeois BRM, Stryeck S, Rijksen Y, van

Willigenburg H, Feijtel DA, et al: Targeted apoptosis of senescent

cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and

aging. Cell. 169:132–147.e16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|