Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal malignant

tumor. Due to the lack of specific symptoms in its early stage and

its highly aggressive nature, patients are usually diagnosed at

later stages of the disease (1,2).

Therefore, the prognosis for pancreatic cancer is poor, with 5-year

survival rates of ≤10% (3). Despite

major advances in oncology in recent years, the treatment of

pancreatic cancer remains a challenge. Currently, the main clinical

treatment methods include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy,

with surgery remaining the most effective option. However, only

15–20% of patients qualify for surgical treatment, and even after

surgery, recurrence and metastasis remain highly prevalent

(4). Gemcitabine (GEM) is a

deoxycytidine analog that inhibits DNA replication and is widely

used for the treatment of various cancer types, including

pancreatic, non-small cell lung, bladder, ovarian and breast cancer

(5,6). For patients with inoperable locally

advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer, GEM monotherapy or

GEM-based combination chemotherapy remain first-line choices

(7). However, enzymatic

deamination, rapid systemic clearance and the emergence of

chemoresistance all limit GEM efficacy, favoring recurrence and

metastasis (6). Therefore,

exploring the mechanisms underlying GEM resistance, improving the

sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to GEM and identifying novel

targeted therapeutic drugs is paramount.

The AKT/mTOR signaling pathway crucially influences

basic cellular processes such as protein synthesis, and cell

growth, proliferation and metabolism, and also participates in the

regulation of autophagy, apoptosis and angiogenesis (8,9).

Over-activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway has been reported

in various tumors, such as skin cancer (10), breast cancer (11), thyroid cancer (12), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

(13) and prostate cancer (14). Abnormal activation of this pathway

is also closely related to the occurrence and development of

pancreatic cancer (15).

Furthermore, sustained activation of AKT/mTOR signaling enhances

drug resistance in pancreatic cancer cells, and creates favorable

conditions for their survival and proliferation by enhancing

metabolic activity and inhibiting apoptosis (16). Therefore, therapeutic inhibition of

the AKT/mTOR pathway has become an important goal in the treatment

of pancreatic cancer.

At present, strategies for reversing drug resistance

in tumor cells mainly include the following approaches: Targeted

inhibition of drug resistance pathways, combination treatments with

conventional agents, administration of traditional Chinese medicine

(TCM) prescriptions, nano-drug delivery systems and gene editing

(17,18). Among these, TCM compounds are

particularly notable for their ability to regulate multiple

targets. This multi-target action can not only enhance the efficacy

of anticancer drugs but also reduce their associated cytotoxicity

and other side effects (19).

Bupleurum, also known as Radix Bupleuri or ‘Chai Hu’, is a

classical herb within TCM (20).

Saikosaponin D (SSD), one of the major bioactive ingredients of

Bupleurum, possesses anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and

immunoregulatory properties (20).

Our previous study demonstrated that SSD exerted cytotoxic effects

on glioma cells and enhanced their sensitivity to temozolomide

chemotherapy (21). Previous

research has further demonstrated that SSD has growth inhibitory

and pro-apoptotic effects in a variety of solid tumors. For

example, Tang et al (22)

found that SSD enhanced the sensitivity of human NSCLC cells to

gefitinib by inhibiting STAT3/Bcl-2 signaling, thereby inducing

tumor cell apoptosis. Hu et al (23) demonstrated that SSD enhanced the

sensitivity of human gastric cancer cells to cisplatin by

inhibiting the IKKβ/NF-κB pathway. In addition, Zhang et al

(24) found that SSD suppressed the

malignant phenotype of Hep3B hepatoma cells and increased the

sensitivity of these cells to chemotherapy in vitro and

in vivo. However, studies on the combination of SSD and GEM

in pancreatic cancer remain scarce. Thus, it remains unclear

whether SSD can enhance the sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells

to GEM and effectively overcome GEM resistance. Furthermore,

although the antitumor activity of SSD has been extensively studied

in multiple solid tumors, where they demonstrated strong potential

for apoptosis induction through multiple pathways (25,26),

it is not clear whether combined administration of SSD and

chemotherapy agents induces apoptosis via regulation of the

AKT/mTOR pathway. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, it

remains unknown whether SSD can improve the chemosensitivity of

pancreatic cancer cells to GEM by downregulating AKT/mTOR

signaling. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate

whether SSD could enhance the sensitivity to GEM chemotherapy,

regulate AKT/mTOR activation, and promote apoptosis and autophagy

in pancreatic cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

SSD (purity ≥98% as determined by high-performance

liquid chromatography) was obtained from Shanghai Yuanye

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. GEM was purchased from GLPBIO Technology

LLC. Stock solutions of each drug (1 mmol/l) were prepared by

dissolution in DMSO and stored protected from light at −20°C. The

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8), Hoechst 33258 staining kit and

immunocytochemistry (ICC) staining kit were acquired from Wuhan

Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd. The Autophagy Dual Stain kit

[using monodansylcadaverine (MDC)] and 0.1% crystal violet ammonium

oxalate solution were procured from Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd. The BCA protein assay kit was obtained from

the Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. The TUNEL Apoptosis Assay

kit was purchased from TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd. The following

antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc.: Mouse

monoclonal antibodies against mTOR (1:500; cat. no. 66888-1-Ig),

phosphorylated (p-)mTOR (Ser2448) (1:2,000; cat. no. 67778-1-Ig),

p-AKT (Ser473) (1:500; cat. no. 66444-1-Ig), caspase-3 (1:2,000;

cat. no. 66470-2-Ig), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no.

66470-2-Ig), Bax (1:500; cat. no. 60267-1-Ig), AKT (1:500; cat. no.

60203-2-Ig) and β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig); as well as

rabbit antibodies, including polyclonal antibodies against Bcl-2

(1:1,000; cat. no. 12789-1-AP), Beclin 1 (1:1,000; cat. no.

11306-1-AP) and LC3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 14600-1-AP). The same

monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 66470-2-Ig) was used for the

detection of both total caspase-3 (at 1:2,000 dilution) and cleaved

caspase-3 (at 1:1,000 dilution), as it recognizes an epitope shared

by both forms of the protein. The higher antibody concentration

(1:1,000) for cleaved caspase-3 was used due to its lower abundance

post-cleavage, ensuring optimal detection sensitivity.

Additionally, a separate rabbit monoclonal anti-Bax antibody

(1:1,000; cat. no. 5023T) was obtained from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc., for western blotting. Peroxidase-conjugated

anti-mouse (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-1) and anti-rabbit (1:5,000;

cat. no. SA00001-2) secondary antibodies were also obtained from

Proteintech Group, Inc.

Chemical structure illustration

The chemical structures of SSD and GEM were

generated based on their canonical representations from the PubChem

database (National Center for Biotechnology Information; http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), using their

unique Compound Identifiers (119361 for SSD and 60750 for GEM), and

were subsequently exported in high-resolution TIFF format for

publication.

Cell lines and culture

The MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 human pancreatic

adenocarcinoma cell lines were obtained from the cell bank of the

Yan'an University Medical Research and Experimental Center (Yan'an,

China). The MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cell lines were originally

acquired from American Type Culture Collection. MIA PaCa-2 and

AsPC-1 cells were cultured in DMEM (cat. no. 11965092; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no.

11875093; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), respectively,

supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no. 10270106; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no.

15140122; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Both cell lines

were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified

incubator. Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were plated for

downstream experiments.

Cell viability assay

MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cell suspensions were

prepared, and cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates

(100 µl; 2.5×103 cells/well), and treated with SSD (0,

2, 4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 µmol/l) or GEM (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 or 8

µmol/l) for 24, 48 or 72 h at 37°C. CCK-8 reagent was added

to each well and cells were incubated in the dark for 1 h at 37°C.

Absorbance values were subsequently measured at 450 nm using a

microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated using GraphPad

Prism 9 software (Dotmatics). According to the effects of SSD and

GEM and their respective IC50, a GEM dose of 0.25 µmol/l

(referred to as G0.25) and SSD doses of 4 or 6 µmol/l (referred to

as S4 and S6, respectively) were selected for downstream assays to

treat MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells. Control groups were treated with

an equal volume of the drug solvent (DMSO) alone, with the final

DMSO concentration not exceeding 0.1% in all groups.

Synergy analysis

Drug interaction effects were quantitatively

analyzed using the Chou-Talalay method (27). Combination Index (CI) values were

calculated from dose-effect curves generated based on CCK-8 and

TUNEL assays, where a CI of <1, =1 and >1 indicates synergy,

additive effects and antagonism, respectively. CalcuSyn software

(version 2.0; Biosoft) was employed for CI calculation with the

following parameters: Fraction affected range, 0.05–0.95; and

median-effect principle for dose-effect relationship modeling.

Cell morphology evaluation

Cell morphology and structure were evaluated by

H&E staining, whereby MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells were seeded

onto sterile glass coverslips in 6-well plates at a density of

5×104 cells/well, allowed to adhere overnight, and

treated with a range of concentrations of SSD (0–12 µmol/l), GEM

(0–8 µmol/l) or the combination of G0.25 + S4 for 48 h at 37°C.

After treatment, all subsequent steps were performed at room

temperature. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 95%

ethanol for 20 min, and stained with Harris's hematoxylin (cat. no.

HHS32; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 8 min. This was followed by

differentiation in 1% acid alcohol for 30 sec, bluing in 0.2%

ammonia water and counterstaining with eosin Y (cat. no. HT110232;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 3 min. The samples were then

dehydrated through an ascending graded ethanol series, cleared in

xylene and mounted with neutral balsam. Morphology was evaluated

under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti2; Nikon Corporation) by

two independent observers. The vehicle control group (0.1% DMSO)

was processed in parallel under identical conditions.

Cell clone formation assay

The cell clone formation assay was performed by

seeding MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells into 6-well plates at a density

of 2×103 cells/well, allowing them to adhere for 24 h at

37°C in complete growth medium without treatment, after which the

medium was replaced with fresh medium containing specified

treatments [GEM (0.25 µmol/l), SSD (4 µmol/l), the combination

G0.25 + S4, or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO)] and cells were cultured

for 7–10 days at 37°C with the medium being refreshed every 3 days.

After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature and stained

with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. The plates

were then gently rinsed with distilled water to remove excess dye,

air-dried and imaged using a light microscope. Colonies, defined as

groups of ≥50 cells, were quantified using ImageJ software (version

1.53t; National Institutes of Health) by measuring the crystal

violet-stained area after applying a consistent threshold. Results

were expressed as a percentage of the control group.

Hoechst 33258 staining

Hoechst 33258 staining was performed by seeding MIA

PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells on sterile glass coverslips in 6-well

plates at a density of 5×104 cells/well, allowing

adhesion for 24 h at 37°C in untreated complete medium, and then

treating cells with GEM (0.25 µmol/l), SSD (4 µmol/l), G0.25 + S4

or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 48 h at 37°C. After treatment, cells

were fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature, washed with

PBS and then stained with Hoechst 33258 (5 µg/ml) for 5 min in the

dark at room temperature. Following another wash with PBS, cells

were mounted with anti-fade medium and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse

Ti2 fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation) equipped with a

DS-Qi2 camera (Nikon Corporation). Image analysis was conducted

using NIS-Elements software (v5.30; Nikon Corporation).

Autophagy assay

The autophagy assay was performed by seeding MIA

PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells into 12-well plates at a density of

5×104 cells/well, followed by treatment the next day

with GEM (0.25 µmol/l), SSD (4 µmol/l), their combination (G0.25 +

S4) or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) for 48 h at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 humidified incubator. Subsequently, cells were

processed using the Autophagy Dual Stain kit (MDC) (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were washed with 1X PBS

and fixed with the kit-provided fixative (4% paraformaldehyde; 20

min at 25°C). After three washes with the kit-supplied 1X wash

buffer, cells were incubated with the MDC working solution (200

µl/well; 60 min at 37°C in the dark). Following three additional

washes with 1X wash buffer, fresh 1X PBS was added to prevent

drying. Image acquisition was performed immediately using a Nikon

Eclipse Ti2 fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation) equipped

with a DS-Qi2 camera. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence

intensity was conducted using NIS-Elements software (v5.30; Nikon

Corporation). Untreated control cells (0.1% DMSO) were processed in

parallel under identical conditions.

TUNEL

The TUNEL assay was conducted by seeding MIA PaCa-2

and AsPC-1 cells onto coverslips in 24-well plates and allowing

them to reach 70% confluence. Cells were then treated with 0.25

µmol/l GEM, 4 µmol/l SSD, their combination G0.25 + S4 or vehicle

control (0.1% DMSO) for 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After

treatment, cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4%

PFA for 20 min at room temperature. Permeabilization was performed

using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. The TUNEL

reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

was applied to each sample, followed by incubation in a humidified

dark chamber at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, cells were washed with

PBS and counterstained with DAPI at a concentration of 1 µg/ml for

10 min at room temperature. After a final rinse with PBS,

coverslips were mounted using antifade mounting medium. Images from

at least five random fields per coverslip were captured using a

fluorescence microscope. Each assay included both a negative

control without terminal transferase enzyme and a vehicle-treated

DMSO control.

Western blotting

MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were treated with 0.25 µmol/l GEM, 4 µmol/l SSD, their

combination G0.25 + S4 or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) for 48 h at

37°C. Immediately following treatment, cells were harvested using

EDTA-free trypsin, washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered

saline, resuspended in precooled PBS and centrifuged at 1,000 × g

for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were lysed on ice for 40 min

using RIPA lysis buffer (P0013B; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail

(P1005; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The lysates were

centrifuged at 16,020 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant

protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay (P0010;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology,). Equal amounts of protein (30

µg per lane) were separated on 10–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and

transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk

for 2 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight

at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Mouse monoclonal

anti-mTOR (1:500; cat. no. 66888-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

anti-p-mTOR (Ser2448) (1:2,000; cat. no. 67778-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), anti-p-AKT (Ser473) (1:500; cat. no. 66444-1-Ig;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-caspase-3 (1:2,000; cat. no.

66470-2-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-cleaved caspase-3

(1:1,000; cat. no. 66470-2-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-AKT

(1:500; cat. no. 60203-2-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

anti-β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; Proteintech Group,

Inc.); and rabbit polyclonal anti-Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no.

12789-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-Beclin 1 (1:1,000; cat.

no. 11306-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and anti-LC3 (1:1,000;

cat. no. 14600-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) antibodies, as well

as an anti-Bax monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; cat. no. 5023T; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.). The same monoclonal antibody (cat. no.

66470-2-Ig) was used for the detection of both total caspase-3 (at

1:2,000 dilution) and cleaved caspase-3 (at 1:1,000 dilution), as

it recognizes an epitope shared by both forms of the protein. The

higher antibody concentration (1:1,000) for cleaved caspase-3 was

used due to its lower abundance post-cleavage, ensuring optimal

detection sensitivity. The membranes were then washed three times

with TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and incubated for 1.5 h at room

temperature with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:5,000;

SA00001-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or goat anti-rabbit (1:5,000;

SA00001-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) secondary antibodies. Following

three additional washes with TBST, the protein bands were

visualized using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence reagent (P0018FS;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and images were captured with

a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software

(National Institutes of Health) with β-actin serving as the loading

control for normalization.

ICC

MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells were seeded onto

coverslips in 24-well plates at a density of 5×104 cells

per well and cultured for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 0.25

µmol/l GEM, 4 µmol/l SSD, their combination G0.25 + S4 or vehicle

control (0.1% DMSO) for 48 h at 37°C. After treatment, cells were

fixed with 4% PFA at 4°C for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton

X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and

incubated with 3% H2O2 in deionized water at

37°C for 10 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Blocking

was performed with 5% BSA (product no. A8020; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) for 20 min at room temperature. The following primary

antibodies from Proteintech Group, Inc., were applied overnight at

4°C: Mouse monoclonal anti-Bax (1:500; 60267-1-Ig), rabbit

polyclonal anti-Bcl-2 (1:1,000; 12789-1-AP), mouse monoclonal

anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 66470-2-Ig), mouse

monoclonal anti-p-AKT (Ser473) (1:500; 66444-1-Ig) and mouse

monoclonal anti-p-mTOR (Ser2448) (1:2,000; 67778-1-Ig). The next

day, samples were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse

(1:5,000; SA00001-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or goat anti-rabbit

(1:5,000; SA00001-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) secondary antibodies

for 1.5 h at room temperature. After three washes with TBST,

signals were developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). DAB

development was monitored in real-time under a Nikon Eclipse Ti2

light microscope (Nikon Corporation), and the reaction was stopped

by rinsing with pure water once moderate brown cytoplasmic staining

became visible. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin for 3

min at room temperature, followed by washing and dehydration.

Coverslips were mounted with neutral resin and observed under a

light microscope. Images were captured and analyzed using

NIS-Elements software (v5.30; Nikon Corporation). Each experiment

included a negative control with non-immune IgG and a

vehicle-treated DMSO control.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (Dotmatics) was used for

all statistical analyses and graphing. Based on an a priori power

analysis using G*Power 3.1 (ANOVA: Effect size f=0.4, α=0.05,

power=0.8), five independent biological replicates (n=5) per group

were performed to ensure adequate statistical power. Prior to

analysis, data normality and variance homogeneity were assessed

using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Brown-Forsythe test, respectively.

To account for multiple comparisons, all P-values were adjusted

using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction (false discovery rate

<0.05). Effect sizes with 95% CIs were calculated through

bootstrap resampling (1,000 iterations). Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation. An adjusted P-value <0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Specific statistical tests were applied based on the experimental

design: Two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test was used to

compare cell viability across time points and treatments; one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test was used for multiple group

comparisons at a single time point. Effect sizes are reported as

partial η2 for ANOVA. Non-parametric alternatives

(Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc test) were used when

parametric assumptions were violated.

Results

SSD inhibits pancreatic cancer cell

proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner

To determine the sensitivity of MIA PaCa-2 and

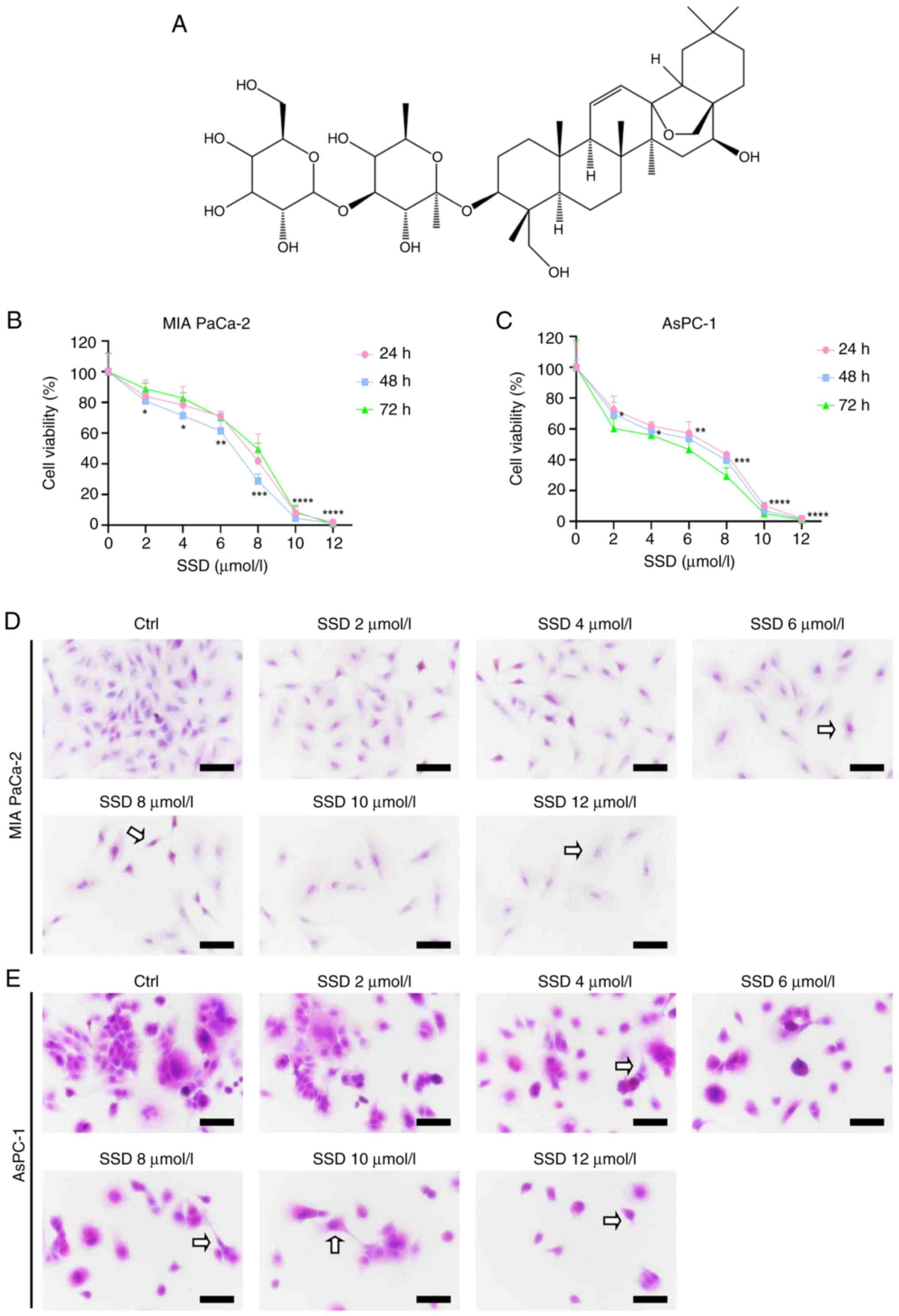

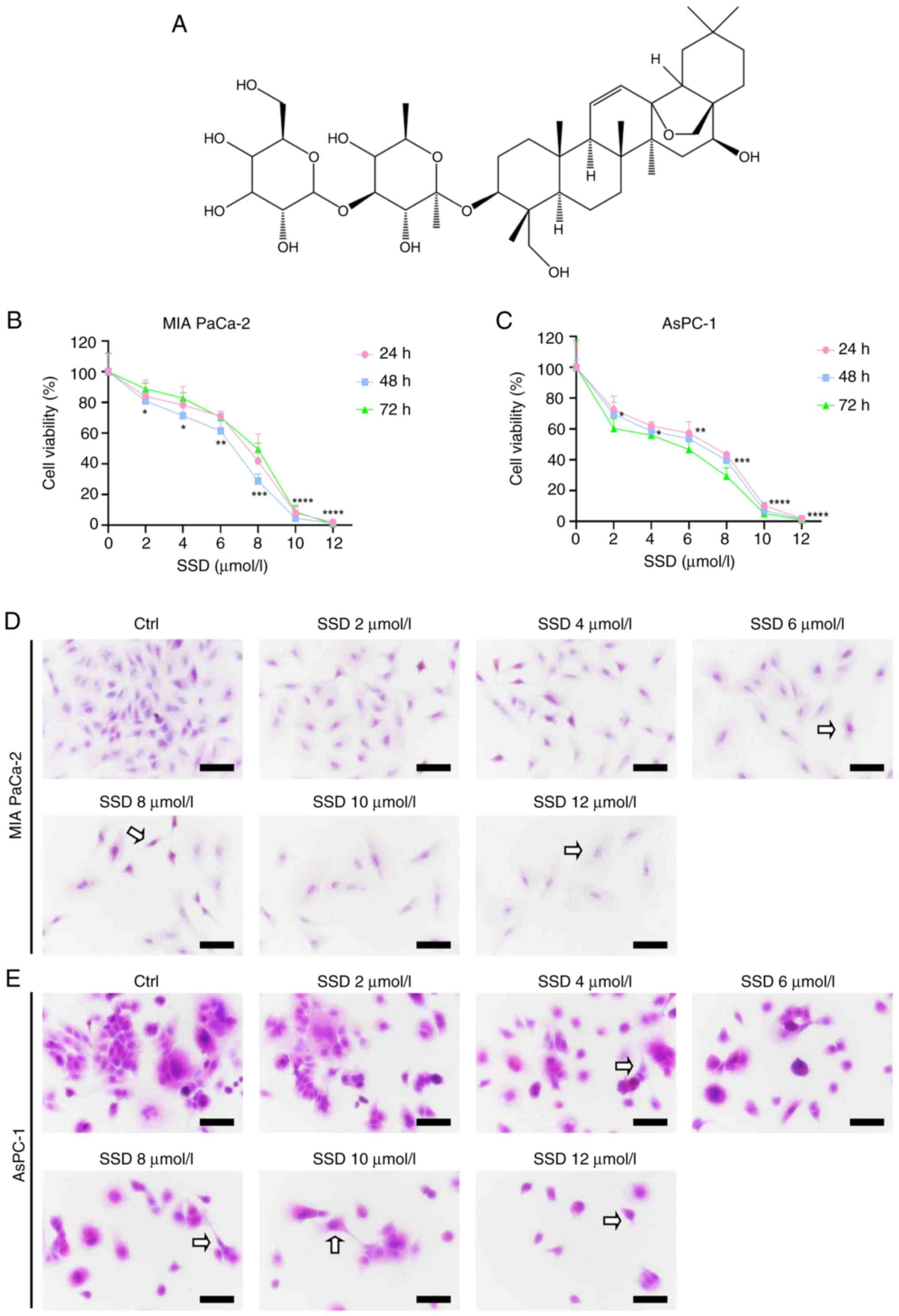

AsPC-1 cells to SSD (Fig. 1A), cell

proliferation was examined using a CCK-8 assay. Treatment with a

concentration range of 0-12 µmol/l SSD (where 0 µmol/l represents

the vehicle control group) for 24–72 h significantly inhibited the

proliferation of both cell lines in a concentration-dependent

manner (Fig. 1B and C).

Specifically, significant decreases were observed starting at 2

µmol/l after 48 h, with viability falling to <20% of the control

at 10 µmol/l. The sensitivity to SSD treatment was greater in

AsPC-1 cells than in MIA PaCa-2 cells, as evidenced by their lower

survival rates of 58.65% at 4 µmol/l and 53.60% at 6 µmol/l after

48 h of treatment, compared with 71.37 and 61.48% for MIA PaCa-2

cells at the respective concentrations (Fig. 1B and C). Concurrently, H&E

staining demonstrated concentration-dependent morphological

alterations, showing mild cytoplasmic shrinkage and reduced cell

density at 2–4 µmol/l, and pronounced nuclear condensation,

apoptotic body formation and widespread cell detachment at higher

concentrations (6–12 µmol/l) in both cell lines (Fig. 1D and E).

| Figure 1.Dose-dependent effects of SSD on

pancreatic cancer cells. (A) Chemical structure of SSD. (B) MIA

PaCa-2 and (C) AsPC-1 cell viability after treatment with various

concentrations of SSD (0–12 µmol/l; 24–72 h; Cell Counting Kit-8

assay). The Ctrl group was treated with 0 µmol/l SSD. Morphological

changes in (D) MIA PaCa-2 and (E) AsPC-1 cells based on H&E

staining (magnification, ×40). Arrows point to SSD-induced

apoptotic alterations, including nuclear condensation, cytoplasmic

shrinkage and apoptotic bodies. Data are presented as the mean ± SD

(n=5). At the 48-h mark, S12 sharply reduced cell viability in MIA

PaCa-2 cells. The same effect was observed in AsPC-1 cells, where

S12 also significantly inhibited cell proliferation. The

statistical details for S12 are as follows: MIA PaCa-2 cells,

Padj<0.0001; η2=0.73; and AsPC-1 cells,

Padj<0.0001; η2=0.81. All P-values were

adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Scale bar, 50 µm. The

significance indicators in (B and C) (*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001) represent the comparison between

each SSD-treated group and the Ctrl group (0 µmol/l). Statistical

analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post

hoc test. Ctrl, control; SSD, Saikosaponin D. |

GEM exhibits time- and

concentration-dependent growth inhibitory effects on pancreatic

cancer cells

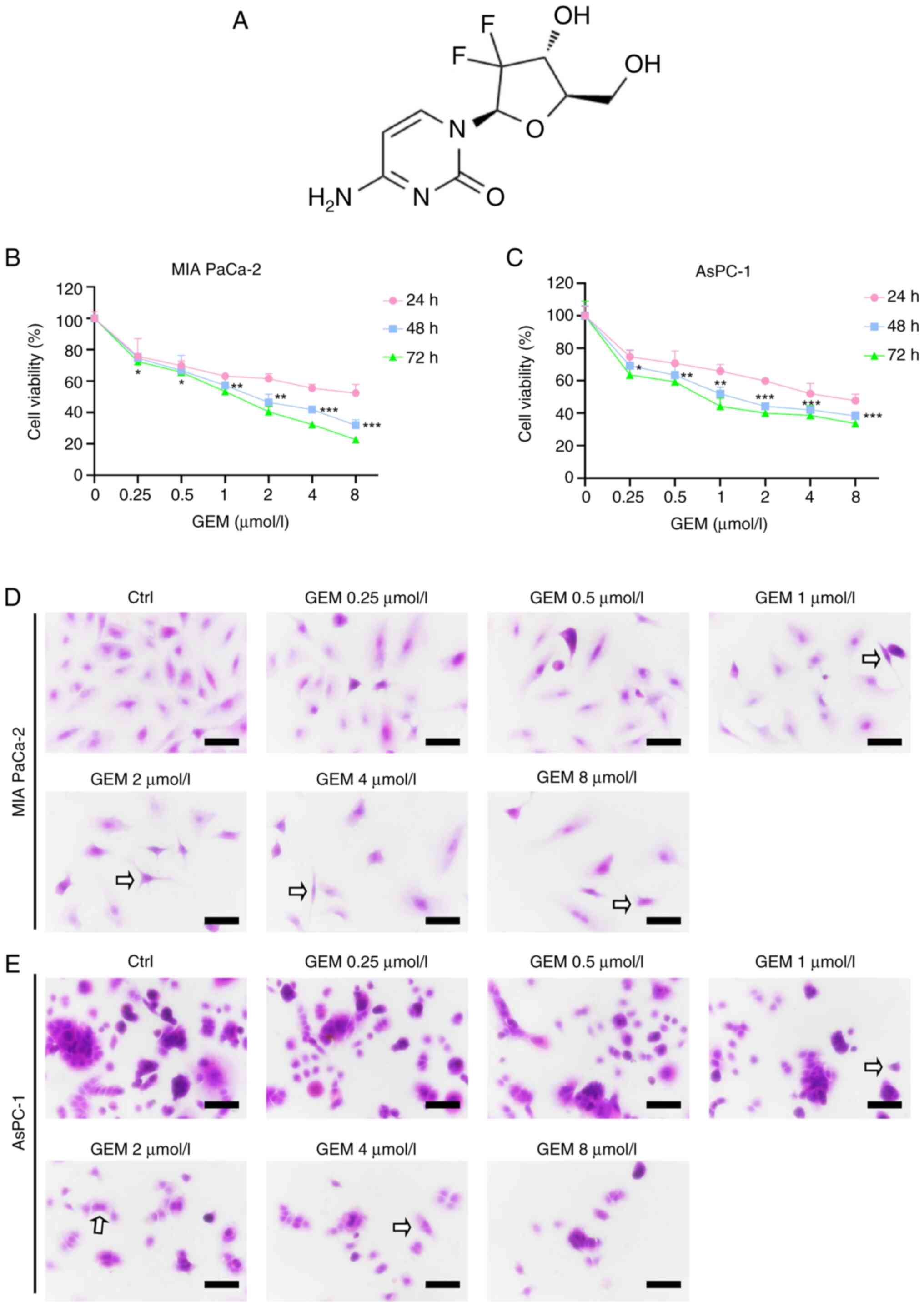

To evaluate the sensitivity of MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1

cells to GEM (Fig. 2A), cells were

treated with various concentrations of GEM (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4

and 8 µmol/l) for 24, 48 or 72 h. CCK-8 assay results demonstrated

that GEM significantly suppressed the proliferation of both cell

lines in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2B and C), as determined by one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test comparing each concentration group

to the vehicle control (0 µmol/l) at each time point. Both cell

lines exhibited reduced proliferation capacity after treatment with

0.25 µmol/l GEM; specifically, after 24, 48 and 72 h of exposure,

the viability of MIA PaCa-2 cells decreased to 75.75, 74.68 and

72.44%, respectively, while that of AsPC-1 cells decreased to

74.80, 69.22 and 63.59%, respectively. Based on this significant

growth inhibition observed at 0.25 µmol/l and to model a sub-lethal

chemotherapeutic pressure, this concentration of GEM (denoted as

G0.25) was selected for subsequent combination experiments.

Similarly, SSD concentrations of 4 and 6 µmol/l (denoted as S4 and

S6, respectively) were chosen for combination treatments as they

induced moderate yet significant growth inhibition (Fig. 1B and C) while maintaining low

cytotoxicity, making them suitable for evaluating synergistic

effects with GEM. H&E staining further confirmed dose-dependent

morphological alterations induced by GEM (0.25–8 µmol/l), including

mild cytoplasmic shrinkage and reduced cell density at lower

concentrations (0.25–1 µmol/l), and marked nuclear condensation,

apoptotic body formation and cell detachment at higher doses (2–8

µmol/l) in both cell lines (Fig. 2D and

E).

SSD significantly enhances the

anti-proliferative effects of GEM in pancreatic cancer cells

through synergistic growth inhibition

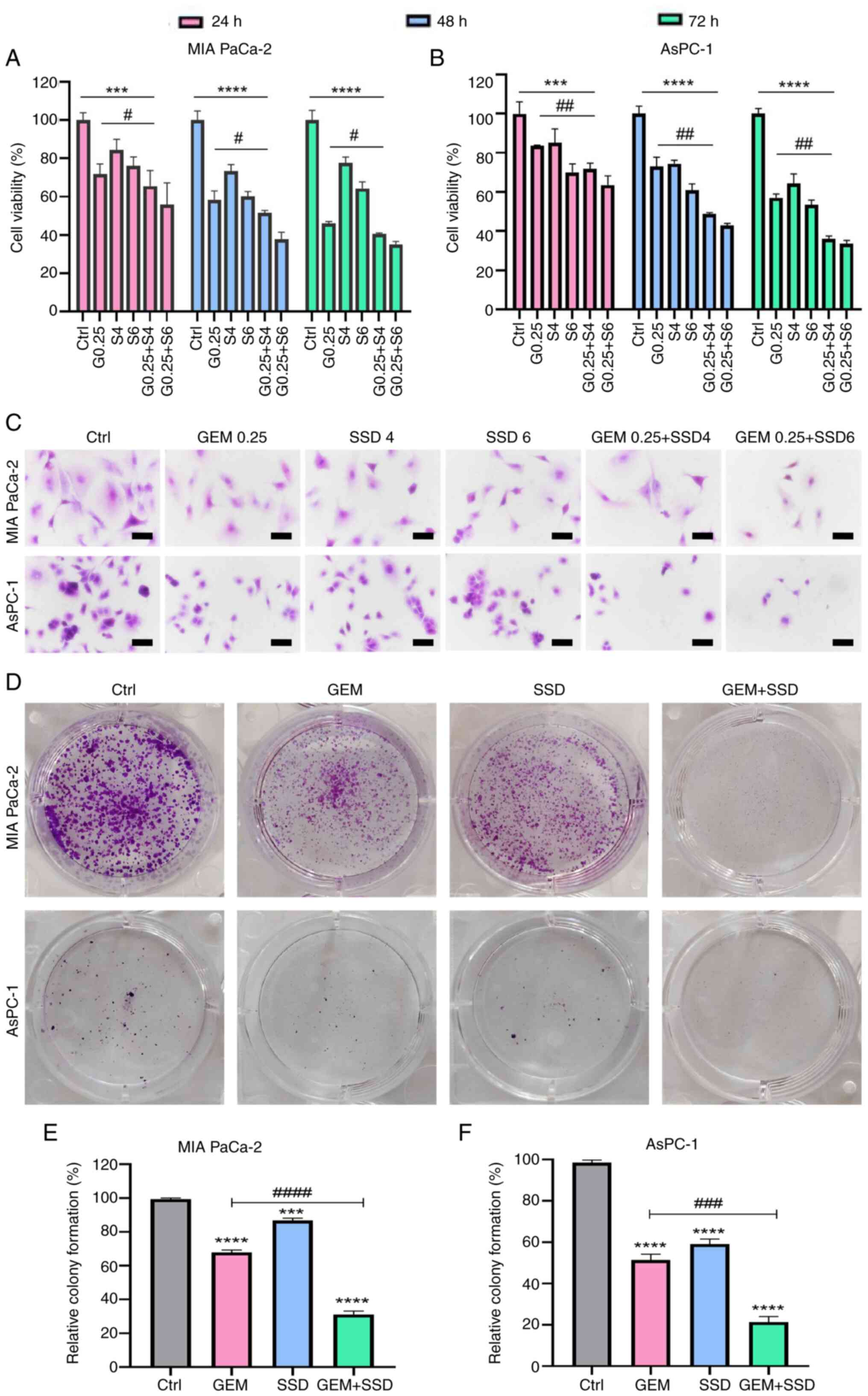

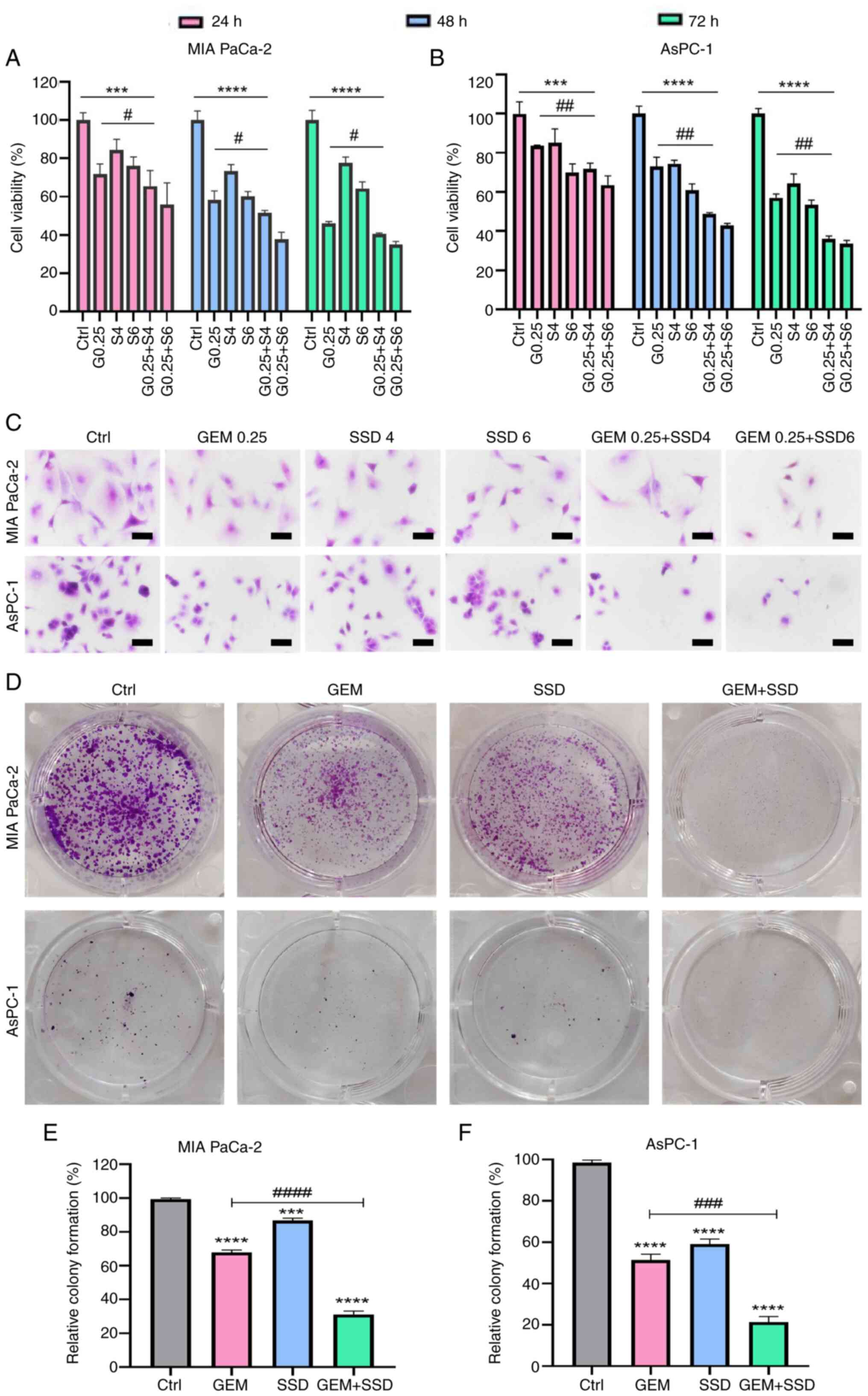

The inhibitory effects of 24-, 48- and 72-h

treatments with low-dose SSD and GEM (G0.25 and S4) on the

proliferation of MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells were examined. CCK-8

assay results revealed that after 48 h of combined treatment (G0.25

+ S4), the viability of MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells was

significantly inhibited compared with the Ctrl group (Fig. 3A and B). The combination therapy

exhibited a stronger inhibitory effect than either monotherapy, as

evidenced by the lower cell viability values. The synergistic

enhancement of the anti-proliferative effect of GEM by SSD is

further quantified in Table I. For

both MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells, the addition of SSD (S4 or S6) to

a sub-lethal dose of GEM (G0.25) markedly reduced cell survival

rates beyond the level achieved by GEM alone.

| Figure 3.Combinatorial effects of GEM and SSD

on pancreatic cancer cells. Viability of (A) MIA PaCa-2 and (B)

AsPC-1 cells treated with G0.25, S4, S6 or combinations (G0.25 +

S4/S6) for 24–72 h. (C) H&E staining showing morphological

changes (magnification, ×40). Scale bar, 50 µm. (D-F) Colony

formation assays. (D) Representative images, and quantification in

(E) MIA PaCa-2 and (F) AsPC-1 cells. (D-F) GEM, 0.25 µmol/l and

SSD, 4 µmol/l. The colony formation rate for each group is

expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control (Ctrl)

group, which was set to 100%. Note that the absolute colony-forming

capacity of the Ctrl group under baseline culture conditions was

defined as the reference point. Data are presented as the mean ± SD

(n=5). The data demonstrate that the combination treatment (G0.25 +

S4) resulted in significantly enhanced antitumor effects compared

with GEM monotherapy (G0.25). With regard to cell viability, the

combination was significantly more effective

(Padj=0.003; effect size: η2=0.62; 95% CI,

0.41–0.79). A strong synergistic effect was also observed in the

colony formation assay, where the combination treatment led to a

marked reduction in clonogenic survival (Padj=0.001;

effect size, η2=0.68; 95% CI, 0.46–0.83). All P-values

are Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 for

comparisons vs. Ctrl; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001,

####P<0.0001 for G0.25 + S4 vs. G0.25. Statistical

analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc

test (A and B) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (E and

F). Ctrl, control; GEM, gemcitabine; SSD, Saikosaponin D; G0.25,

0.25 µmol/l GEM; SX, X µmol/l SSD. |

| Table I.Growth inhibitory effects of combined

GEM + SSD exposure on pancreatic cancer cell lines. |

Table I.

Growth inhibitory effects of combined

GEM + SSD exposure on pancreatic cancer cell lines.

|

| Cell survival rate,

% |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Cell line | G0.25 | G0.25 + S4 | G0.25 + S6 |

|---|

| MIA PaCa-2 | 69.22 | 56.97a | 40.65a |

| AsPC-1 | 74.68 | 45.64b | 42.13b |

To further demonstrate the inhibitory effect of SSD

combined with GEM on the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cell

lines, H&E staining and colony formation assays were performed.

H&E staining was performed to observe morphological changes in

MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells treated with SSD, GEM or their

combination. The results showed that the proliferation of both

pancreatic cancer cell lines was inhibited, accompanied by a

reduction in cell number, cell shrinkage, rounding, chromatin

condensation, increased cell debris and formation of apoptotic

bodies (Fig. 3C). Colony formation

assay results showed that the combined treatment group (G0.25 + S4)

exhibited significantly reduced colony formation compared with the

corresponding single-drug GEM group (Fig. 3D). In MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells

treated with SSD + GEM (G0.25 + S4), the colony formation rates

decreased by 32.6 and 23.4%, respectively, compared with the

corresponding single-drug GEM groups (Fig. 3E and F).

Synergistic induction of apoptosis by

SSD and GEM in pancreatic cancer cells through modulation of

apoptotic proteins

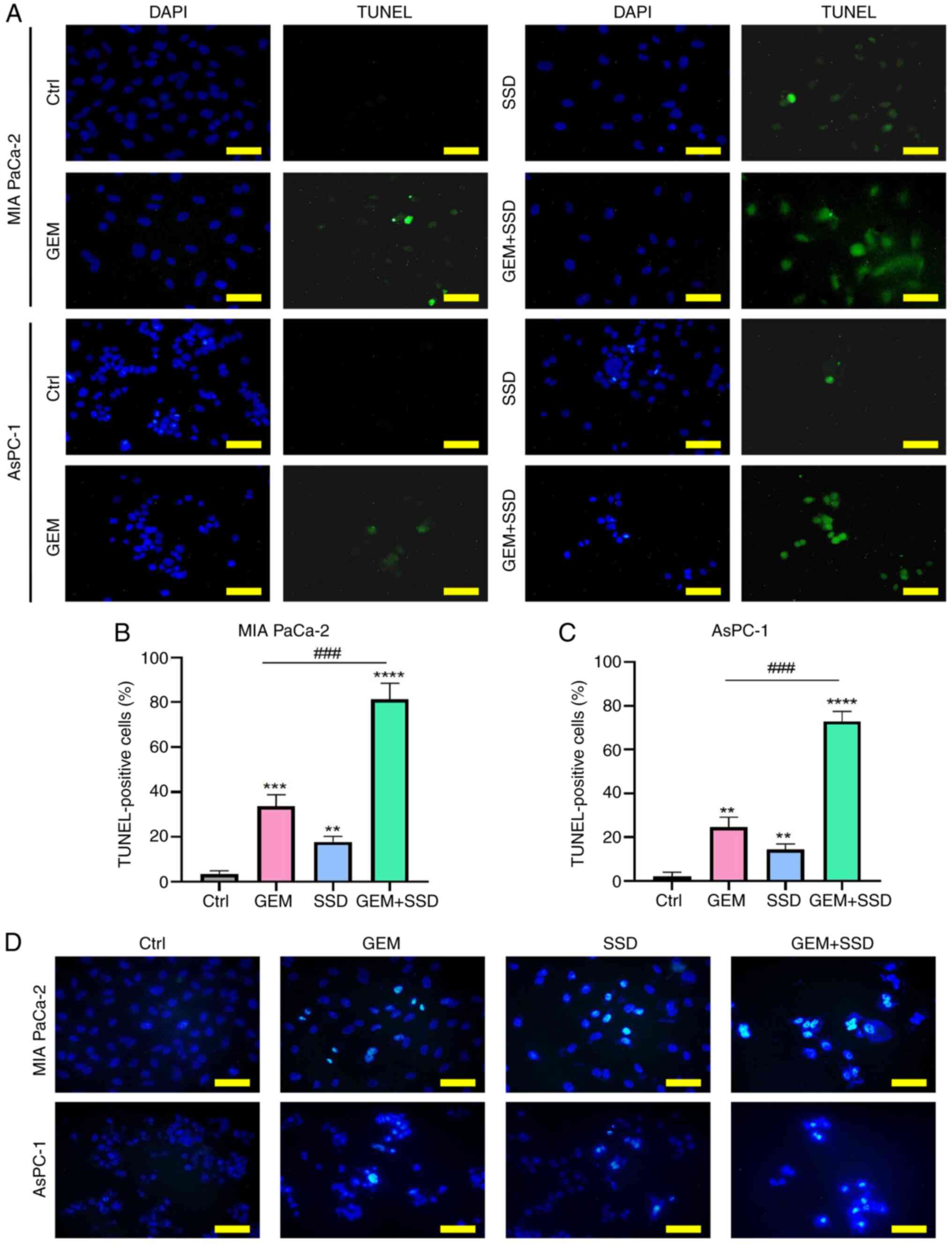

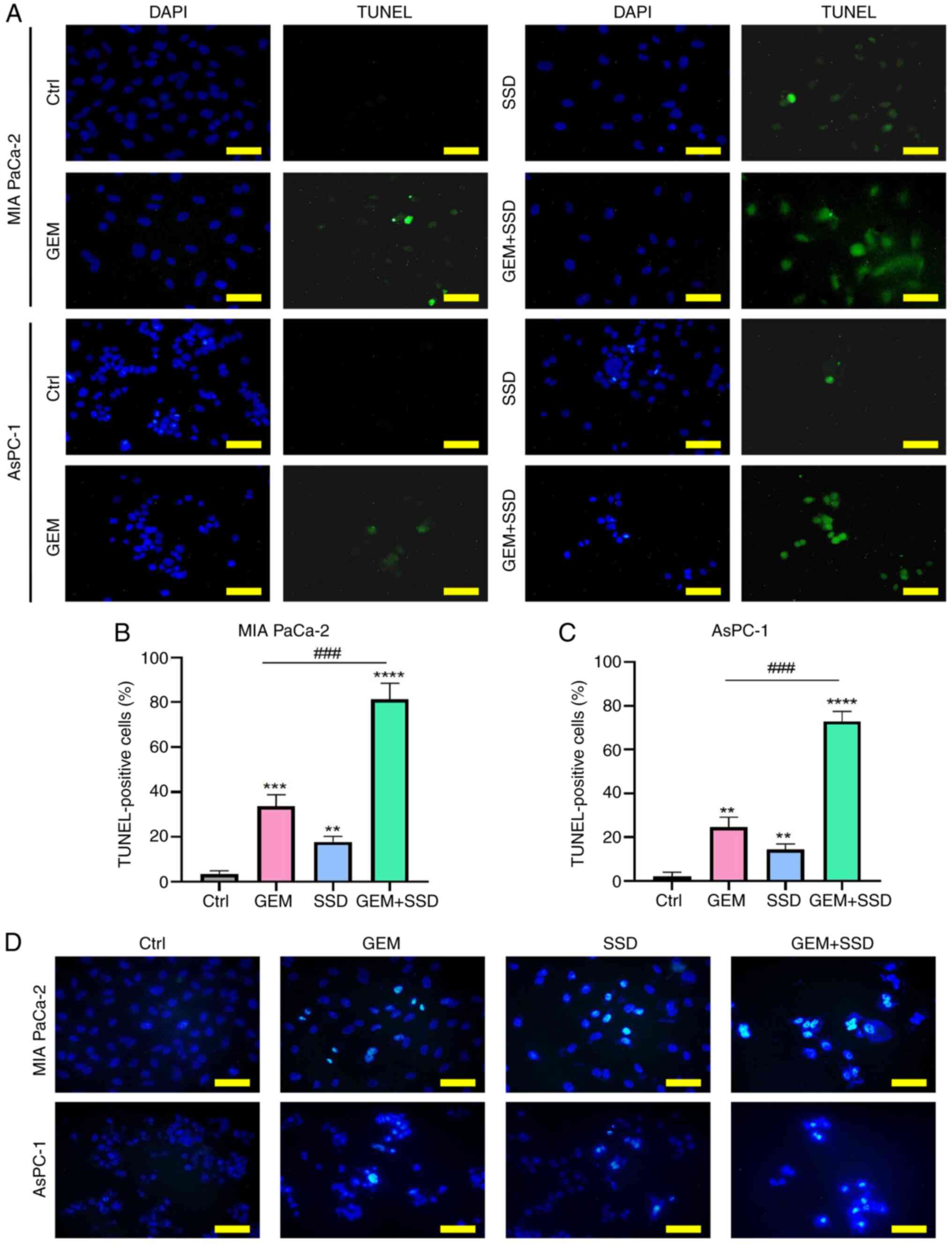

TUNEL assays were subsequently performed to evaluate

the effect of SSD, GEM and combined SSD + GEM treatment on the

apoptosis of MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells. The results showed that

when applied alone, SSD and GEM induced modest, albeit significant,

increases in TUNEL fluorescence intensity in both cell lines

(Fig. 4A). However, the combined

SSD + GEM treatment for 48 h induced a significantly stronger

apoptotic response compared with GEM monotherapy in both MIA PaCa-2

and AsPC-1 cells (Fig. 4B and C;

Padj<0.001), suggesting a synergistic interaction.

This suggested that SSD may act synergistically with GEM to induce

apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Apoptotic features were next

verified by Hoechst 33258 staining, which revealed brightly

stained, irregularly shaped, dense nuclei characteristic of

apoptotic cells (Fig. 4D).

| Figure 4.Apoptosis induction by GEM and SSD

combination therapy. (A) Representative TUNEL/DAPI staining images

(green, apoptotic cells; blue, nuclei) in MIA PaCa-2 (top) and

AsPC-1 (bottom) cells treated with Ctrl, G0.25, S4 or the

combination (G0.25 + S4). Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells in

(B) MIA PaCa-2 and (C) AsPC-1 cells. (D) Hoechst 33258 staining

showing apoptotic nuclei with condensed chromatin. In the figure,

GEM represents 0.25 µmol/l GEM and SSD represents 4 µmol/l SSD.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=5). The data show that the

combination treatment (G0.25 + S4) significantly enhanced the

induction of apoptosis compared with GEM monotherapy (G0.25). The

combination treatment significantly increased apoptosis, evidenced

by a substantial rise in TUNEL-positive cells

(Padj=0.002; η2=0.59; 95% CI, 0.36–0.77) and

a corresponding increase in condensed chromatin, a hallmark of

apoptosis, as shown by Hoechst 33258 staining

(Padj=0.004; η2=0.55; 95% CI, 0.31–0.74). All

P-values are Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted. Scale bar, 50 µm.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 for comparisons vs.

Ctrl; ###P<0.001 for G0.25 + S4 vs. G0.25.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's

post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Ctrl, control; GEM,

gemcitabine; SSD, Saikosaponin D. |

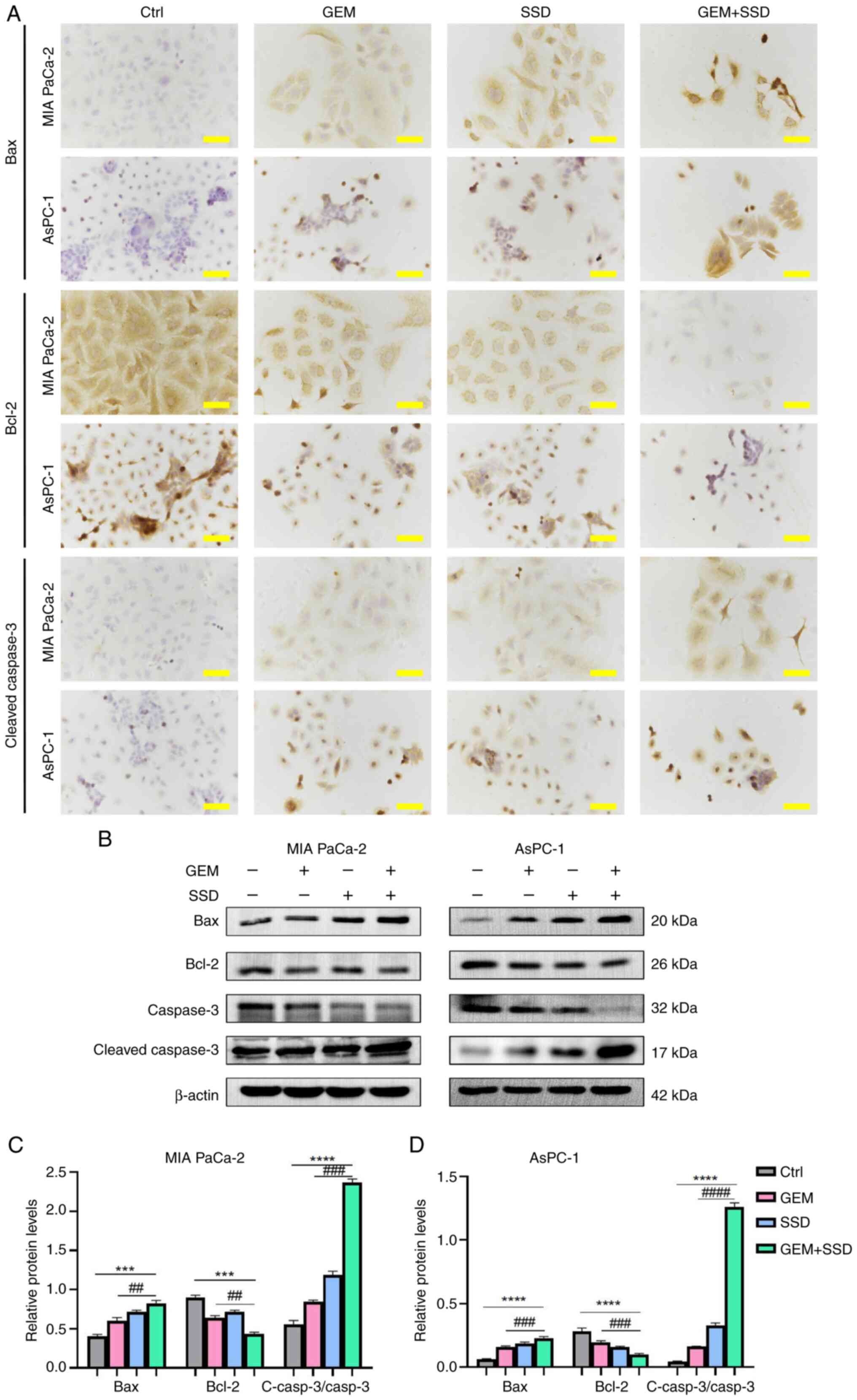

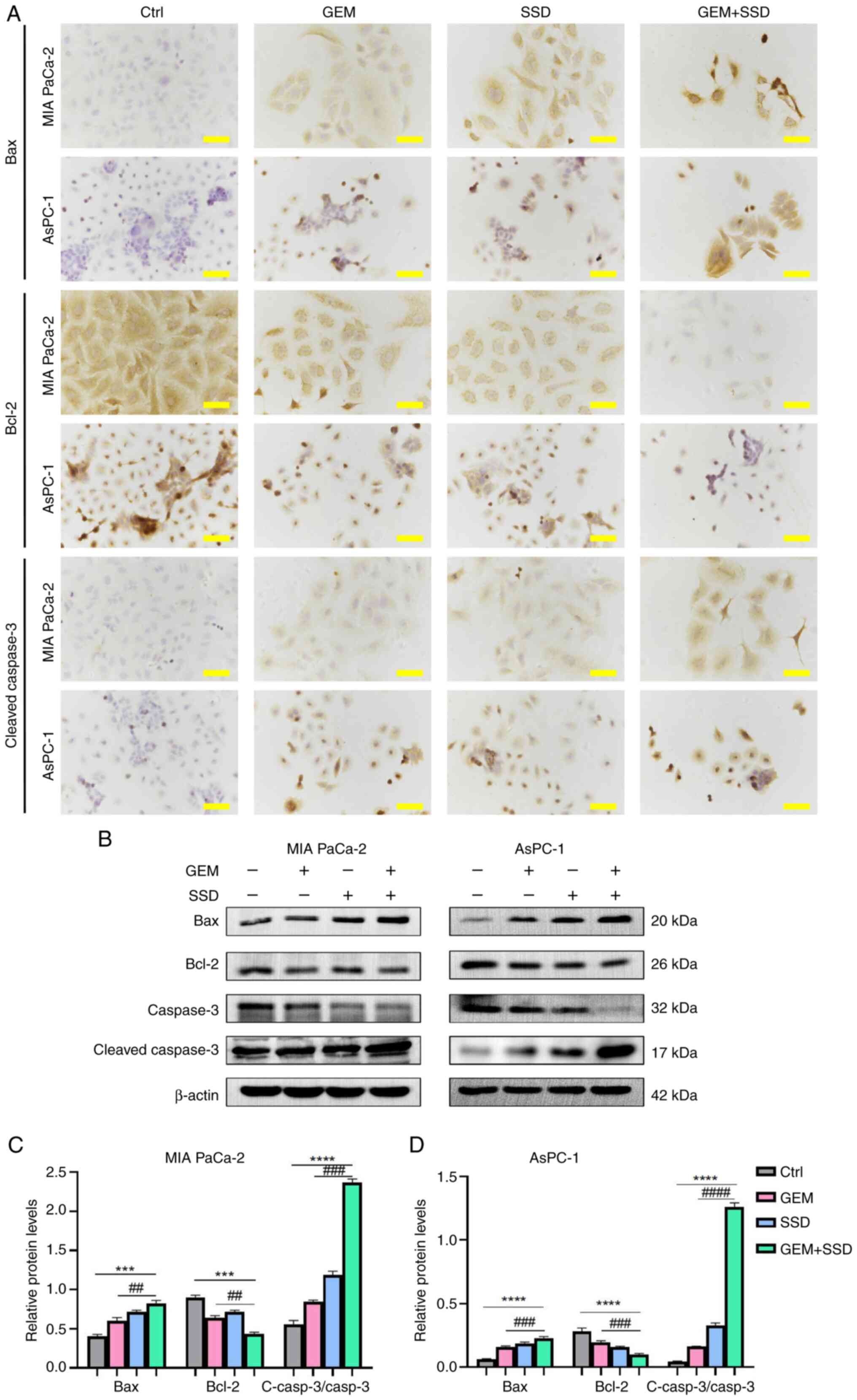

In addition, ICC analysis revealed distinct protein

expression patterns of key apoptotic regulators; specifically,

increased expression of pro-apoptotic Bax and cleaved caspase-3,

alongside decreased expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2-in SSD +

GEM-treated pancreatic cancer cells compared with GEM-only treated

controls (Fig. 5A). These ICC

findings were further corroborated by western blot analysis

(Fig. 5B). The combination

treatment potently altered the levels of apoptosis-related proteins

relative to the control. Specifically, it increased the levels of

Bax and cleaved caspase-3, while decreasing the levels of Bcl-2 and

total caspase-3 in both cell lines (Fig. 5C and D). These consistent results

from both ICC and western blot analyses demonstrated that SSD not

only induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells but also enhanced

the pro-apoptotic effect of GEM by modulating key apoptotic

regulators. The observed changes in protein expression levels shown

in Fig. 5C and D are consistent

with a synergistic enhancement of apoptosis by the combination

treatment.

| Figure 5.Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis

induction by GEM and SSD combination treatment. (A)

Immunocytochemistry of MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells treated with

Ctrl, G0.25, S4 or the combination (G0.25 + S4; magnification,

×40). Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Western blot analysis of apoptosis

markers Bax (20 kDa), Bcl-2 (26 kDa), caspase-3 (32 kDa) and

cleaved caspase-3 (17 kDa), and β-actin (42 kDa).

Semi-quantification of immunoblots for (C) MIA PaCa-2 and (D)

AsPC-1 cells. In the figure, GEM represents 0.25 µmol/l GEM and SSD

represents 4 µmol/l SSD. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=5).

The combination treatment (G0.25 + S4) increased the expression of

pro-apoptotic Bax and cleaved caspase-3, and elevated the

c-Casp3/Casp3 ratio, while decreasing the expression of

anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 compared with GEM monotherapy (G0.25).

Specifically, Bax expression increased by 2.3-fold in MIA PaCa-2

cells and 3.1-fold in AsPC-1 cells. Conversely, Bcl-2 expression

was reduced to 45 and 38% of GEM monotherapy levels in MIA PaCa-2

and AsPC-1 cells, respectively. The c-Casp3/Casp3 ratio was

significantly enhanced by the combination treatment, indicating

robust activation of the apoptotic executioner pathway. All

P-values are Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted. ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001 for G0.25 + S4 vs. Ctrl; ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001, ####P<0.0001 for G0.25 + S4

vs. G0.25. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA

with Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Ctrl, control;

GEM, gemcitabine; SSD, Saikosaponin D; Casp3, caspase-3; c-Casp3,

cleaved caspase-3. |

To quantitatively validate the mechanistic synergy

between GEM and SSD, drug interaction was analyzed using the

Chou-Talalay method. This analysis confirmed robust synergistic

effects across multiple cellular endpoints (data not shown).

Specifically, the calculated CI values were consistently below the

synergy threshold (CI<1) in both pancreatic cancer cell lines,

indicating pharmacological synergy. These results further support

the conclusion that SSD enhances the efficacy of GEM through

synergistic inhibition of cell viability and induction of

apoptosis.

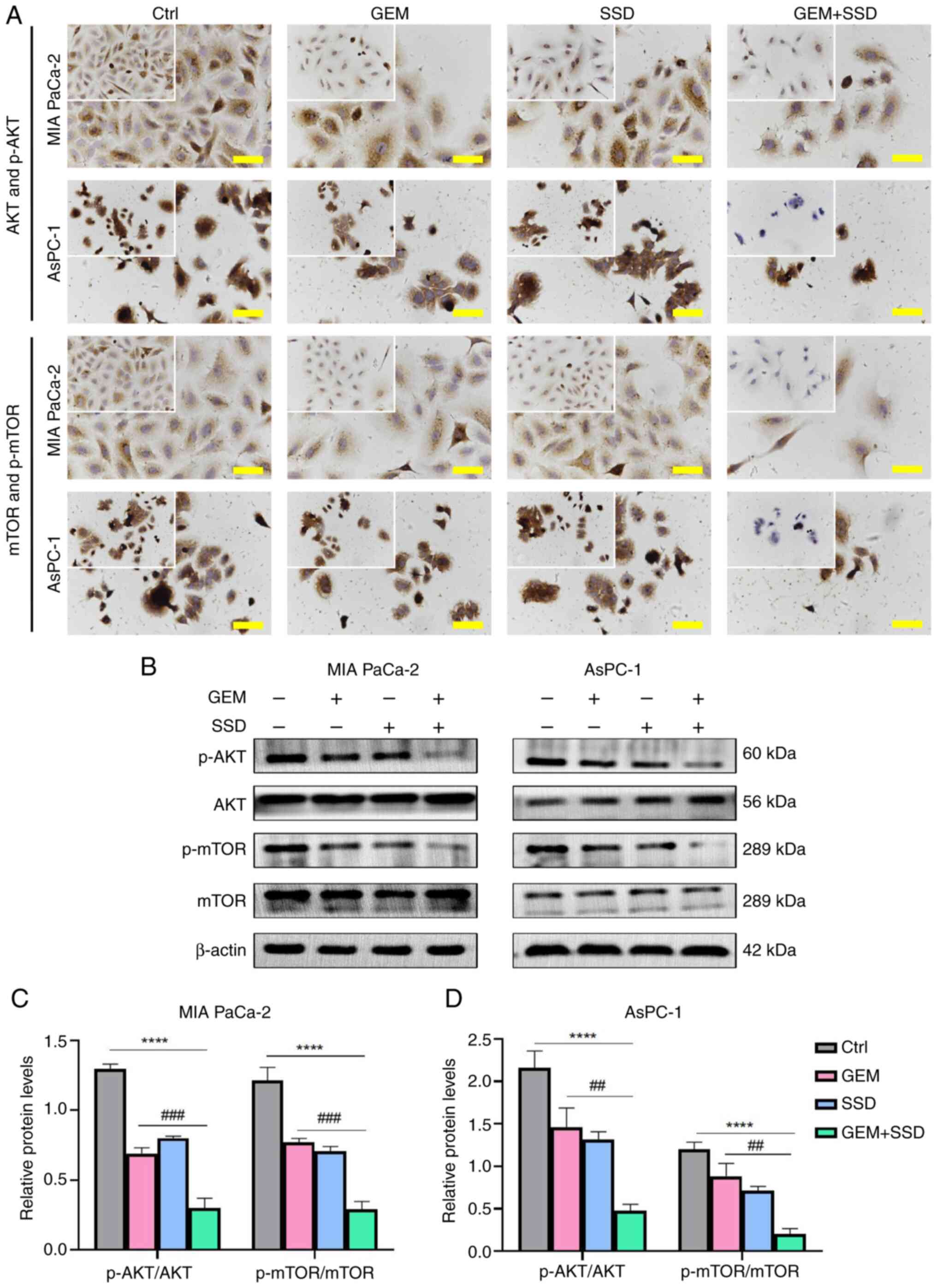

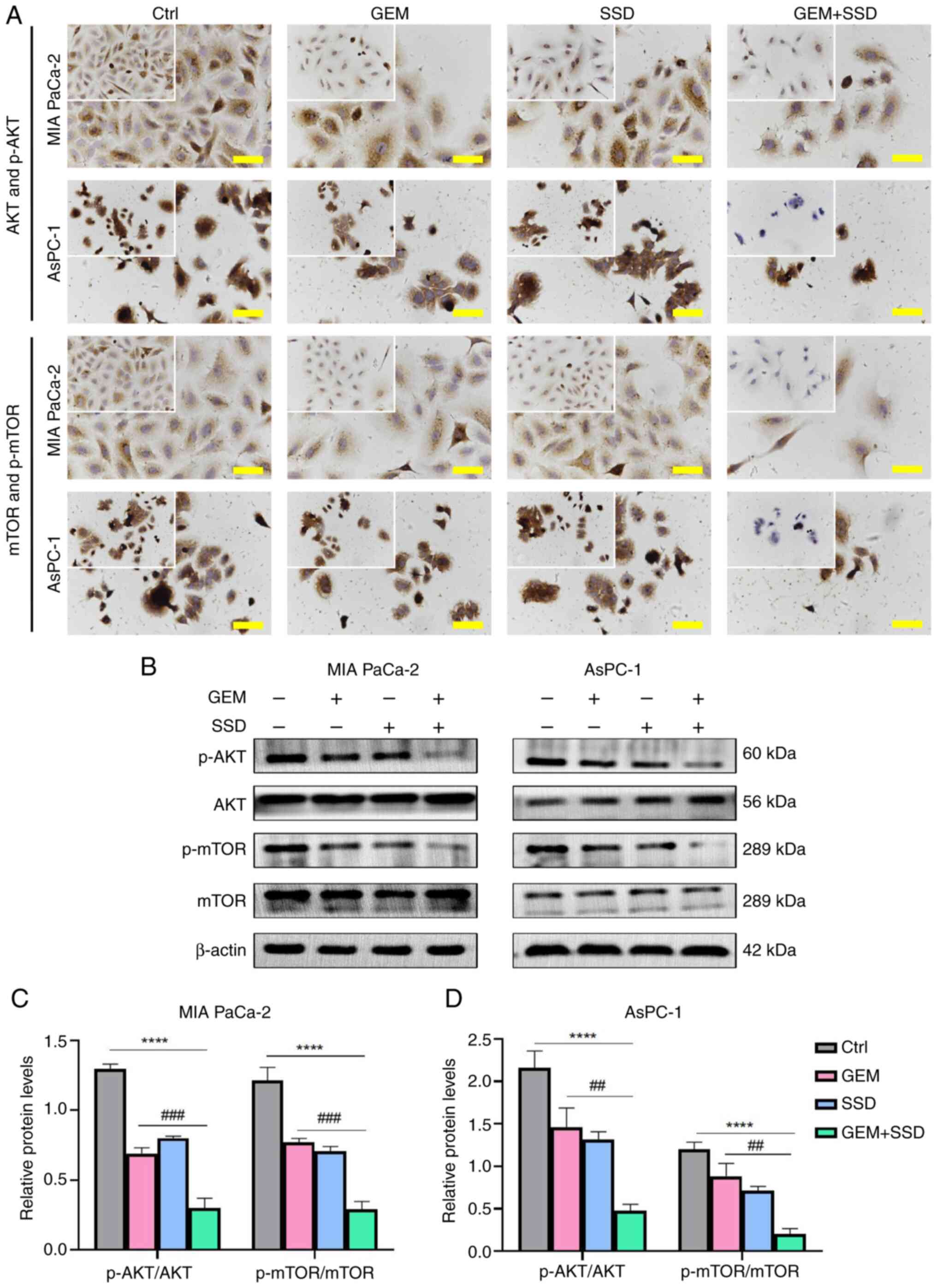

SSD potentiates the antitumor effects

of GEM through enhanced AKT/mTOR suppression

The involvement of AKT/mTOR signaling in pancreatic

cancer progression is well established (14,21).

To investigate whether SSD mediates its effects through this

pathway, ICC analysis was first performed. As shown in Fig. 6A, ICC staining demonstrated markedly

reduced cytoplasmic levels of p-AKT and p-mTOR in SSD + GEM-treated

cells compared with either single-agent treatment or control

groups, with more pronounced inhibition observed in AsPC-1 cells

than in MIA PaCa-2 cells. These ICC findings were

semi-quantitatively confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 6B). SSD treatment alone exhibited

comparable inhibition of p-AKT and p-mTOR levels to GEM

monotherapy. However, the combination treatment exerted

significantly greater suppressive effects compared with GEM alone,

as quantified by western blot analysis (Fig. 6C and D). Densitometric evaluation

revealed a reduction in the p-AKT/AKT ratio by 42.3% in MIA PaCa-2

cells and 72.1% in AsPC-1 cells. Similarly, the p-mTOR/mTOR ratio

was reduced by 51.4 and 80.3% in MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells,

respectively. Notably, AsPC-1 cells exhibited more substantial

pathway inhibition than MIA PaCa-2 cells across both detection

methods. These consistent results from complementary techniques

demonstrated that SSD effectively suppressed AKT/mTOR signaling in

pancreatic cancer cells, with enhanced inhibition when combined

with GEM. The combination treatment (G0.25 + S4) resulted in

significantly greater inhibition of both the p-AKT/AKT and

p-mTOR/mTOR ratios compared with GEM alone (G0.25), with these

effects being consistently more pronounced in AsPC-1 cells

(Fig. 6C and D). The inhibition was

statistically significant for both the p-AKT/AKT ratio

(Padj<0.0001; η2=0.73; 95% CI, 0.55–0.86)

and the p-mTOR/mTOR ratio (Padj<0.0001;

η2=0.81; 95% CI, 0.67–0.91).

| Figure 6.AKT/mTOR pathway inhibition by GEM

and SSD combination therapy. (A) Immunocytochemistry staining of

AKT/mTOR signaling proteins in MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells treated

with Ctrl, G0.25, S4 or the combination (G0.25 + S4; magnification,

×40; insets show phosphoprotein details). Scale bar, 50 µm. (B)

Western blot analysis of p-AKT (60 kDa), AKT (56 kDa), p-mTOR (289

kDa), mTOR (289 kDa) and β-actin (42 kDa). Semi-quantification of

phosphorylation ratios in (C) MIA PaCa-2 and (D) AsPC-1 cells. In

the figure, GEM represents 0.25 µmol/l GEM and SSD represents 4

µmol/l SSD. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=5). Compared

with GEM monotherapy, the G0.25 + S4 combination led to a greater

reduction in both p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR ratios (both

Padj<0.0001), with large effect sizes

(η2=0.73 and 0.81, respectively). All P-values are

Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted. ****P<0.0001 for G0.25 + S4 vs.

Ctrl; ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 for G0.25 +

S4 vs. G0.25. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way

ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. Ctrl, control; GEM, gemcitabine;

SSD, Saikosaponin D; p-, phosphorylated. |

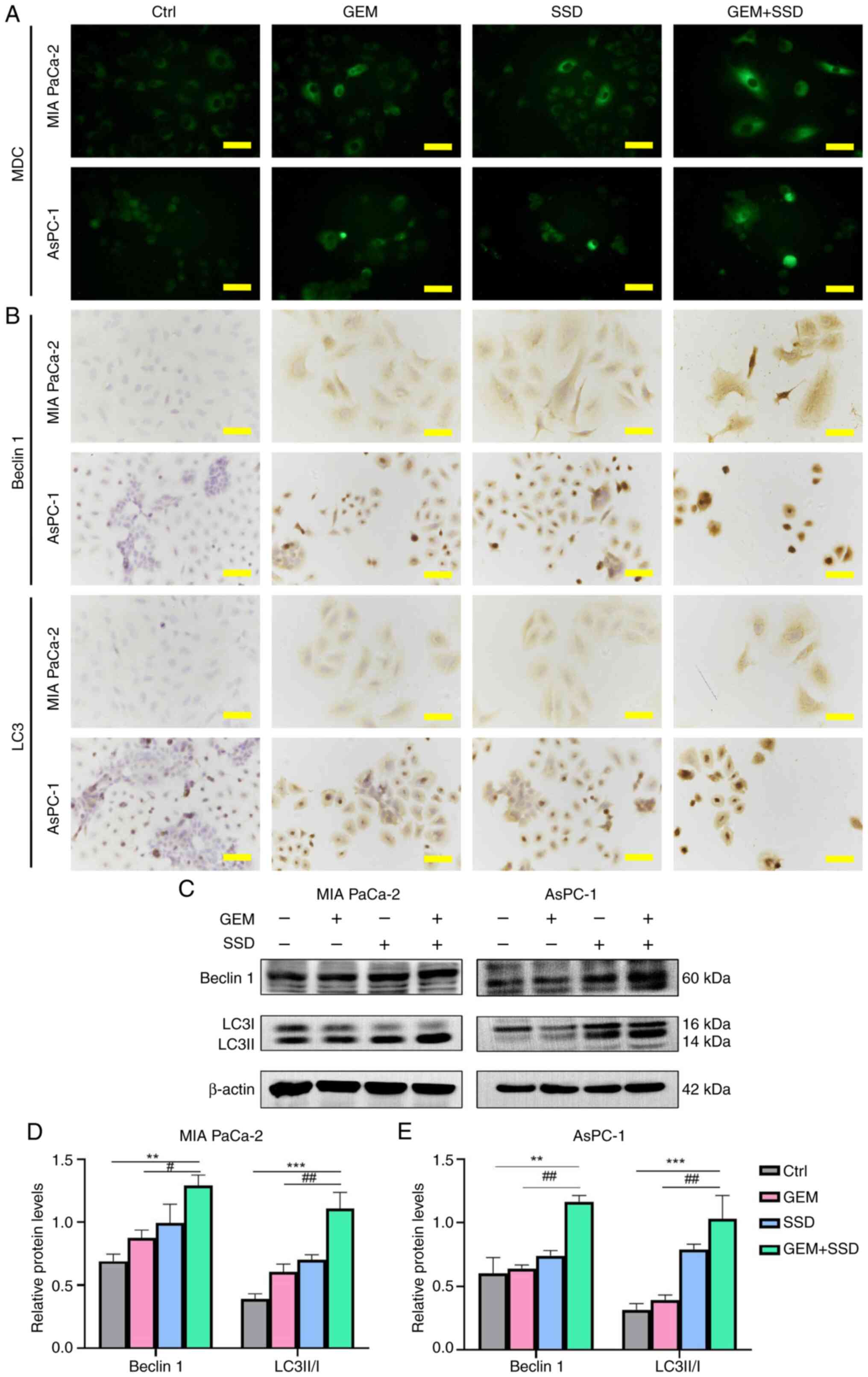

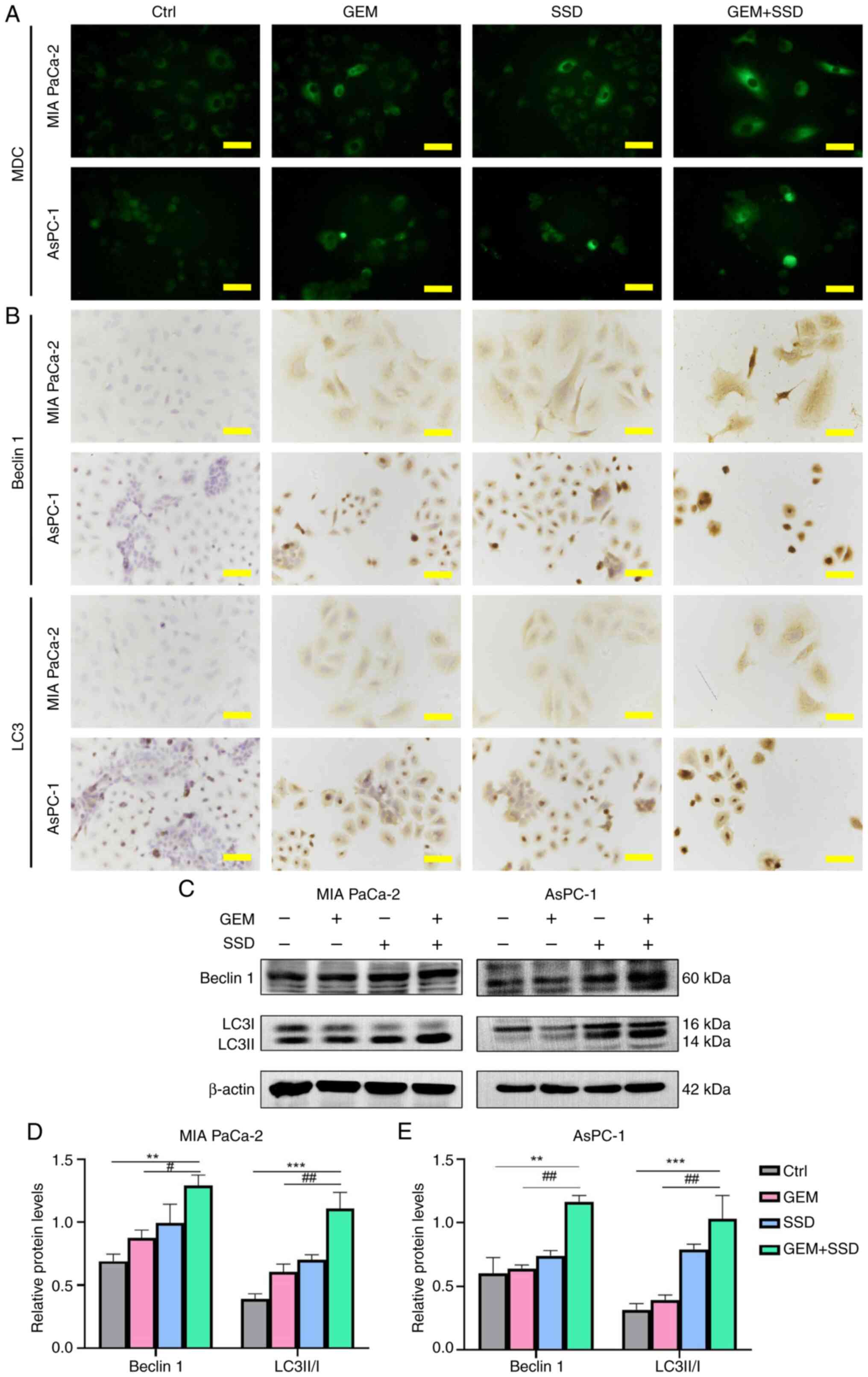

SSD promotes autophagy in pancreatic

cancer cells

The interconnected roles of autophagy and apoptosis

in cancer regulation are well documented (28–32).

Having observed SSD-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells,

the present study next investigated its potential to induce

autophagy. Initial assessment by MDC staining revealed substantial

accumulation of autophagic vesicles in both MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1

cells following treatment. While single-agent SSD or GEM treatment

increased autophagic activity, the combination therapy exerted

markedly greater effects, substantially elevating MDC fluorescence

intensity in both MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells compared with GEM

alone (Fig. 7A). ICC analysis

corroborated these findings, demonstrating increased cytoplasmic

expression of autophagy markers Beclin 1 and LC3 in cells treated

with the SSD and GEM combination (G0.25 + S4) (Fig. 7B). The intensity and distribution of

staining were most pronounced in the SSD + GEM combination groups,

consistent with the MDC results. Western blotting

semi-quantification provided precise molecular characterization of

these effects (Fig. 7C). Treatment

with the SSD and GEM combination (G0.25 + S4) elevated both Beclin

1 expression and the LC3II/LC3I ratio compared with GEM alone, with

Beclin 1 expression increasing by 33.5% in MIA PaCa-2 cells and

42.3% in AsPC-1 cells, and the LC3II/LC3I ratio increasing by 48.1%

in MIA PaCa-2 cells and 56.7% in AsPC-1 cells (Fig. 7D and E). The combination treatment

showed additive effects across all autophagy markers, with AsPC-1

cells again exhibiting greater sensitivity than MIA PaCa-2 cells.

These complementary analyses demonstrated that SSD not only induced

autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells but synergistically enhanced

GEM-mediated autophagy activation through inhibition of the

AKT/mTOR pathway (Fig. 8),

potentially contributing to the observed antitumor efficacy of the

combination therapy. The combination treatment (G0.25 + S4)

significantly enhanced autophagic activity compared with GEM

(G0.25) alone. Specifically, it increased the LC3II/LC3I ratio

(Padj=0.001; η2=0.65; 95% CI, 0.43–0.81) and

elevated Beclin 1 expression (Padj=0.002;

η2=0.59; 95% CI, 0.36–0.77).

| Figure 7.Autophagy induction by GEM and SSD

combination treatment. (A) MDC staining (green) showing

autophagosome accumulation in MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells treated

with Ctrl, G0.25, S4 or the combination (G0.25 + S4; magnification,

×40). (B) Immunocytochemistry of autophagy markers. (C) Western

blot analysis of Beclin 1 (60 kDa), LC3I (16 kDa), LC3II (14 kDa)

and β-actin (42 kDa). Semi-quantification of autophagy markers in

(D) MIA PaCa-2 and (E) AsPC-1 cells. In the figure, GEM represents

0.25 µmol/l GEM and SSD represents 4 µmol/l SSD. Data are presented

as the mean ± SD (n=5). Compared with GEM monotherapy, the G0.25 +

S4 combination significantly increased the LC3-II/I ratio

(Padj=0.001; η2=0.65; 95% CI, 0.43–0.81) and

Beclin 1 levels (Padj=0.002; η2=0.61; 95% CI,

0.38–0.78), indicating strong induction of autophagy. All P-values

are Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted. Scale bar, 50 µm. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 for G0.25 + S4 vs. Ctrl; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01 for G0.25 + S4 vs. G0.25. Statistical

analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc

test. Ctrl, control; GEM, gemcitabine; SSD, Saikosaponin D; MDC,

monodasylcadaverine. |

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal

malignant tumors, and is often described as the most aggressive of

all cancers due to its highly metastatic nature, coupled with high

mortality, low early detection and poor survival rates (1,33). In

recent years, the incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer have

continued to rise worldwide (34).

Although GEM monotherapy or combination therapy with other agents

is widely used as a first-line treatment for pancreatic cancer, the

prognosis remains poor due to the rapid development of drug

resistance in vivo (35).

Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify or develop

anticancer agents with low toxicity and high efficiency to enhance

the sensitivity to GEM and improve treatment outcomes for

pancreatic cancer. TCM has gained increasing attention in cancer

therapy research due to its multi-target pharmacological properties

and favorable safety profiles (19,36,37).

Additionally, TCM formulations contain a variety of bioactive

components, some of which, such as berberine, curcumin and

artemisinin derivatives, have shown potential against pancreatic

cancer in pre-clinical and clinical research (38,39).

SSD is a triterpenoid saponin monomer extracted from

Bupleurum chinense roots (Radix Bupleuri), a classic TCM

formula (40). SSD has antitumor,

anti-inflammatory and antiviral properties, and is considered to be

one of the most bioactive natural saponins (41). Furthermore, SSD has been reported to

be relatively safe in an appropriate dose range (42). In the experimental treatment of

glioma and certain pancreatic cancers, the typical concentration of

SSD is maintained between 5–20 µmol/l, with the lowest effective

dose observed at ~5 µmol/l in in vitro studies (25). The concentration of SSD (4 µmol/l)

selected in the present study therefore falls within this safe

range. The routine clinical dose of GEM is usually 1,000

mg/m2 administered once a week, with a week off after

several weeks of continuous use (43). In the present study, 0.25 µmol/l was

selected as a sub-lethal and biologically relevant concentration of

GEM for combination treatments, based on dose-response curves

demonstrating significant growth inhibition at this dose; the

lowest concentration tested that produced a statistically

significant anti-proliferative effect in both MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1

cell lines.

The present study demonstrated that low-dose SSD

exposure inhibited the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells

in vitro, and also enhanced the antiproliferative effects of

GEM in these cells. While SSD inhibited the proliferation of MIA

PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner, AsPC-1 cells

were more sensitive to SSD than MIA PaCa-2 cells. These effects

were further demonstrated through colony formation assays, which

additionally indicated increased inhibition of tumor cell

clonogenic capacity following combined treatment with SSD and GEM.

TUNEL and Hoechst 33258 staining assays also demonstrated that SSD

induced apoptosis in both cell lines. Notably, TUNEL fluorescence

estimates suggested potential synergistic effects for SSD when

applied in combination with GEM. Furthermore, the combination of

SSD and GEM exhibited synergistic effects on the induction of

autophagy in both MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells. These findings

suggest robust potential for SSD as an adjuvant therapy for

pancreatic cancer in patients treated with GEM.

The AKT/mTOR signaling pathway serves an important

role in critical cellular processes, and its dysregulation

contributes to tumor development and progression in numerous cancer

types, as demonstrated in NSCLC (13), breast cancer (11), hepatocellular carcinoma (44) and pancreatic cancer (15). PI3K generates phosphatidylinositol

(3,4,5)-trisphosphate, which binds to and

recruits phosphatidylinositol-dependent protein kinase 1 and AKT to

the cell membrane, thereby activating AKT. Activated AKT regulates

multiple downstream targets, including mTOR and Bad, and through

phosphorylation reactions, regulates a variety of cellular

physiological processes such as proliferation, survival, apoptosis

and metabolism (9). The association

of AKT/mTOR activity with apoptosis and autophagy in cancer cells

has been documented. Wang et al (13) demonstrated that PTPRH promoted NSCLC

progression through glycolysis mediated by the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway. Lai et al (42) showed that SSD inhibited

proliferation and promoted apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells via

activation of the MKK4-JNK signaling pathway. In line with this

evidence, the present study suggested that inhibition of the

AKT/mTOR pathway underlies SSD + GEM-induced apoptosis and

autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells, as demonstrated by western

blotting and ICC results showing that SSD and GEM inhibited the

phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR. Upon activation, AKT

phosphorylates the pro-apoptotic Bad protein, preventing its

binding to the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. This

results in inhibition of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, impeding

the occurrence of apoptosis. Accordingly, when AKT is inhibited,

Bax activation leads to the release of cytochrome c from

mitochondria, which activates caspase-3 (45). Caspase-3 in turn cleaves its

substrate poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, an enzyme involved in DNA

repair, which accelerates the apoptotic process (46). In the present study, evidence of

SSD-mediated induction of apoptosis was provided by western

blotting and ICC analyses showing downregulated expression of Bcl-2

and total caspase-3, along with upregulated expression of Bax and

cleaved caspase-3, following treatment with SSD, GEM or their

combination. These findings suggested that SSD, both alone and in

combination with GEM, inhibited pancreatic cancer cell

proliferation and induced apoptosis by inhibiting the AKT/mTOR

pathway.

Studies have further highlighted the pivotal role of

AKT/mTOR dysregulation in pancreatic cancer chemoresistance. For

instance, Mortazavi et al (47) highlighted that hyperactivation of

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling not only promoted tumor survival but also

mediated adaptive resistance to GEM by upregulating efflux pumps

and DNA repair mechanisms. Similarly, Sheng et al (48) demonstrated that mTOR inhibition

sensitized pancreatic cancer cells to GEM through suppression of

musashi RNA binding protein 2-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal

transition. Notably, Shimia et al (17) reported that dual targeting of AKT

and mTOR synergized with conventional chemotherapy by disrupting

feedback loops that sustain tumor survival. These findings align

with the present results, reinforcing that AKT/mTOR inhibition of

SSD could disrupt multiple resistance mechanisms, including

metabolic reprogramming and anti-apoptotic signaling.

In the present study, combinatorial testing of 4 and

6 µmol/l SSD with sub-lethal GEM (0.25 µmol/l) was conducted. The 4

µmol/l SSD dose (G0.25 + S4) was chosen for detailed mechanistic

analysis to investigate the basis of the synergistic effects under

conditions of minimal cytotoxicity. Specifically, the 4 µmol/l SSD

+ GEM combination achieved proliferation inhibition comparable to

that of higher doses, reducing colony formation by 29.3% in MIA

PaCa-2 cells vs. 15.1% in AsPC-1 cells. Furthermore, this

combination induced marked apoptosis and autophagy in MIA PaCa-2

cells, evidenced by a 61.6% increase in cleaved caspase-3 levels

and a 56.7% rise in LC3-II/I ratios. The favorable safety profile

of this concentration, consistent with prior applications of SSD in

pancreatic models (42), further

supports its suitability for prolonged mechanistic investigation.

Although higher SSD doses (6 µmol/l) further reduced viability (for

instance, resulting in a 31.6% decrease in survival in AsPC-1 cells

treated with G0.25 + S6 at 72 h), the 4 µmol/l dose provided the

best efficacy-toxicity balance, reflecting clinical strategies that

prioritize minimizing chemotherapy doses through the use of

sensitizing adjuvants.

While the present study demonstrated that SSD

synergized with GEM primarily through AKT/mTOR inhibition, the

reported effects of SSD on STAT3/Bcl-2 and IKKβ/NF-κB pathways in

other cancer types (22,23), including NSCLC and gastric cancer,

suggest potential parallel mechanisms in pancreatic cancer.

Although these pathways were not explicitly examined in the present

study, the observed upregulation of Bax and downregulation of Bcl-2

align with STAT3/Bcl-2 axis modulation, as STAT3 often

transcriptionally regulates Bcl-2. Similarly, NF-κB suppression

could further amplify apoptosis via caspase-3 activation (49). Future studies should dissect these

interactions to fully unravel the pleiotropic antitumor effects of

SSD.

Untreated MIA PaCa-2 cells exhibited detectable

cleaved caspase-3 levels, consistent with their known genetic

profile. This cell line carries oncogenic KRASG12J and

mutant TP53R248W (50),

driving constitutive endoplasmic reticulum stress and DNA damage

responses that prime apoptotic pathways even in untreated

conditions. Similar basal caspase activation has been reported in

other KRAS-mutant pancreatic models (51). The present data demonstrated that

SSD + GEM combination therapy further amplified cleaved caspase-3

levels by 47.5% over this elevated baseline, confirming robust

induction of apoptosis beyond intrinsic stress signaling. This

highlights the aggressive biology of pancreatic adenocarcinoma,

where pro-survival and pro-death signals coexist, and underscores

the therapeutic potential of overcoming inherent resistance

mechanisms.

Apoptosis and autophagy are two distinct forms of

cell death. Although there are obvious morphological and molecular

differences between these processes, they are not completely

independent (52,53). Studies have shown that apoptosis and

autophagy affect and restrict each other in different cellular

contexts (28–30). Increasing evidence has shown that a

number of chemotherapies and anticancer drugs, such as temozolomide

(in glioma), cisplatin (in gastric and ovarian cancer) and rapalogs

(such aseverolimus in various solid tumors), can induce autophagy

in a variety of cancer cells (54,55).

Therefore, targeting of autophagy is becoming a promising strategy

for cancer treatment. The unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1

(ULK1) complex, which includes ULK1, autophagy-related protein

(ATG)13, focal adhesion kinase family-interacting protein of 200

kDa and ATG101, is a key regulator of autophagy initiation

(56). The AMP-activated protein

kinase (AMPK) and mTOR signaling pathways can initiate autophagy by

regulating the activity of ULK1 (57). In response to nutrient or energy

deprivation, AMPK activates ULK1, while mTOR inhibition promotes

the formation of ULK1 complexes and initiates the autophagic

process. In addition, some upstream signaling molecules such as

Bcl-2 are involved in autophagosome formation by regulating the

activity of Beclin 1 and affecting its binding to vacuolar protein

sorting 34 (58,59). In response to autophagy signals, the

C-terminal amino acid of pro-LC3 is first cleaved by ATG4,

resulting in the formation of LC3I. Subsequently, ATG7 activates

LC3I, which is transferred to ATG3 to be converted into LC3II,

which binds to the autophagosome membrane to promote autophagy

(60). In the present study,

western blotting and ICC assays confirmed that SSD and GEM, both

alone and in combination, increased the expression of Beclin 1 and

the ratio of LC3II/LC3I in pancreatic cancer cells. MDC assays

showed that the accumulation and relative fluorescence intensity of

autophagic vesicles in the cytoplasm of pancreatic cancer cells

were markedly increased upon combined SSD + GEM exposure compared

with either treatment alone, suggesting a potential synergistic

effect.

The Chou-Talalay analysis (27,61)

demonstrated that low-dose SSD (4 µmol/l) synergistically enhanced

GEM efficacy (CI, 0.42–0.72), which mechanistically aligns with the

dual regulation of the AKT/mTOR pathway and autophagic flux. This

synergistic interaction may allow dose reduction of both agents

while maintaining antitumor efficacy, potentially mitigating

GEM-associated toxicity in clinical settings. Particularly

noteworthy is the more pronounced synergy in AsPC-1 cells (CI,

0.42–0.65 vs. 0.58–0.72 in MIA PaCa-2 cells), suggesting cell

line-specific response patterns that warrant further

investigation.

The therapeutic potential of this combination is

further underscored by the favorable safety profile of SSD. The

safety profile of SSD is supported by its selective cytotoxicity,

with reported IC50 values >20 µmol/l in normal

pancreatic cells vs. 4–6 µmol/l in cancer cells (42), suggesting a favorable therapeutic

window. Emerging preclinical evidence from patient-derived

xenograft models has demonstrated the translational potential of

TCM-derived compounds such as SSD in combination with conventional

chemotherapy (19), which aligns

with the present findings. Mechanistically, the observed synergy

may stem from SSD's multifaceted regulation of AKT/mTOR signaling,

a critical node governing both metastatic progression and cellular

metabolism in pancreatic cancer (15), where concurrent pathway inhibition

and autophagy induction create a synthetic lethal effect.

A recognized limitation of the present study is its

focus on two pancreatic cancer cell lines without inclusion of

additional in vitro models [such as normal cell controls or

heterogeneous pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) subtypes] or

in vivo validation. These aspects are crucial to

comprehensively evaluate the translational relevance and safety of

the combination therapy. Therefore, future studies will prioritize

expanding the biological validation to include toxicity assessments

in non-malignant cells, a broader panel of cell lines representing

the genetic diversity of PDAC and robust in vivo models to

firmly establish the efficacy and therapeutic window of SSD +

GEM.

In the present study, ICC staining utilizing DAB was

employed to evaluate protein expression and subcellular

localization. Although DAB-based methods provide advantages such as

brightfield microscopy compatibility and archival stability, they

are limited by poorer spatial resolution and interpretive

subjectivity. To address these concerns, all ICC findings were

rigorously validated through complementary quantitative approaches:

Western blotting provided objective semi-quantitative measurements

of protein expression, such as the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, LC3-II/LC3-I

conversion and the p-AKT/AKT ratio, and fluorescence-based assays

(TUNEL, Hoechst and MDC staining) enabled high-resolution

visualization of apoptosis and autophagy, corroborating ICC trends.

The concordance across these orthogonal methods confirmed the

reliability of the ICC data. Future studies would benefit from

multiplex immunofluorescence to enhance spatial resolution for

complex signaling networks.

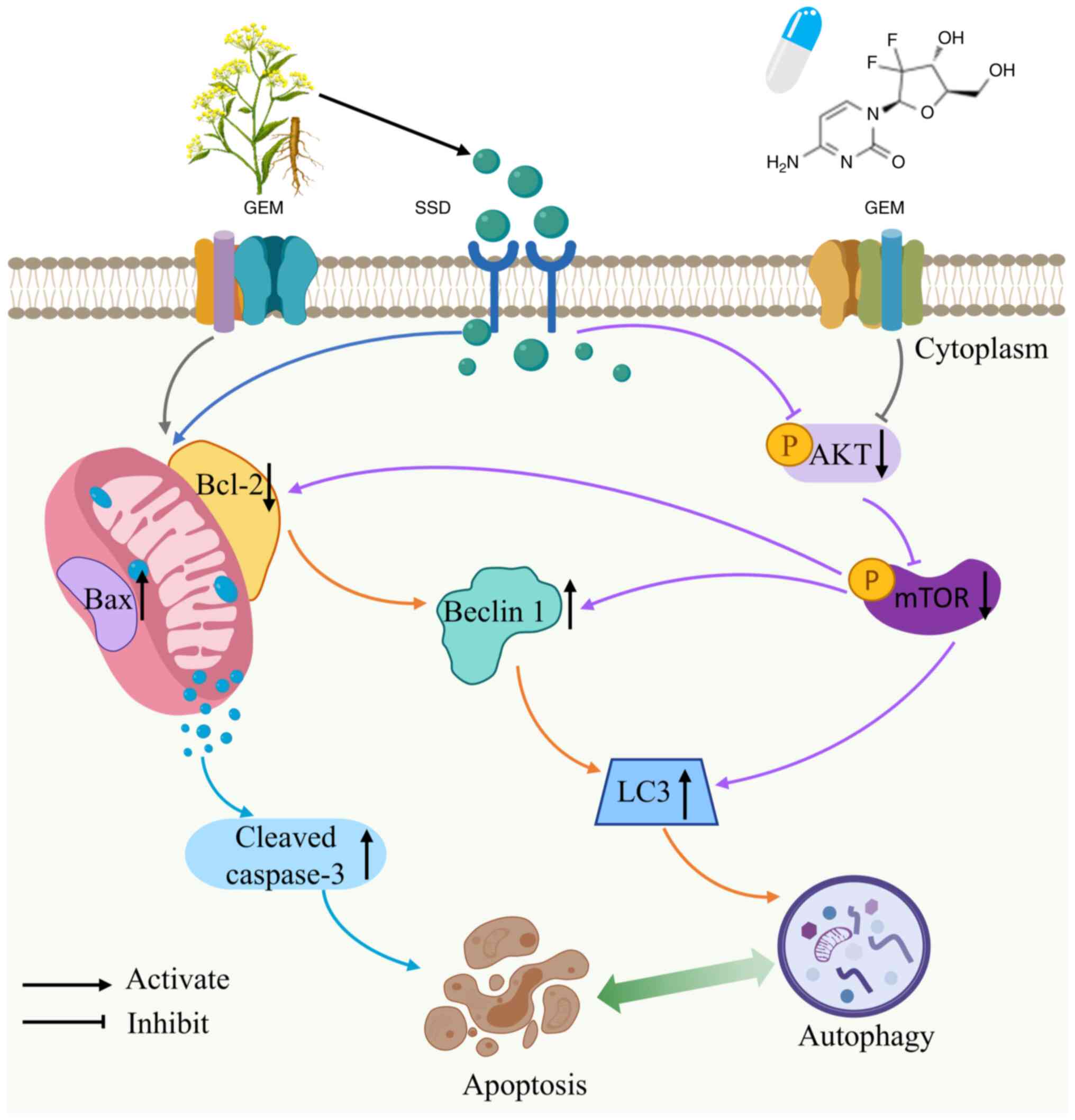

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

SSD inhibited proliferation, and induced autophagy and apoptosis of

pancreatic cancer cells, thereby enhancing the anticancer activity

of GEM. The present data further suggested that negative regulation

of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway may be, at least in part,

responsible for these effects (Fig.

8). These results provide a strong rationale for the

combination of GEM and SSD in the treatment of pancreatic

cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82260489 and 82560545), the Shaanxi

Province Youth Talent Lifting Project (grant no. 20240316), the

Shanxi Science and Technology Department Project (grant no.

2025JC-YBQN-1175), the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training

Program for College Students (grant no. S202210719100), the General

Project of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (grant no.

24JK0727), and Yan'an University Doctoral Research Project (grant

no. YDBK2020-29).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YZ and YL conceived and designed the study, and

drafted the original manuscript. RZ, YY, SZ and GL performed the

experiments and analyzed the data. All authors participated in

scientific discussions and data interpretation. YL contributed to

data acquisition and authenticity verification. XL performed

statistical analysis. YZ and YL confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cai J, Chen H, Lu M, Zhang Y, Lu B, You L,

Zhang T, Dai M and Zhao Y: Advances in the epidemiology of

pancreatic cancer: Trends, risk factors, screening, and prognosis.

Cancer Lett. 520:1–11. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Klatte DCF, Wallace MB, Löhr M, Bruno MJ

and van Leerdam ME: Hereditary pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res

Clin Gastroenterol. 58-59:1017832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Domagała-Haduch M, Gorzelak-Magiera A,

Michalecki Ł and Gisterek-Grocholska I: Radiochemotherapy in

pancreatic cancer. Curr Oncol. 31:3291–3300. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Brozos-Vázquez E, Toledano-Fonseca M,

Costa-Fraga N, García-Ortiz MV, Díaz-Lagares Á, Rodríguez-Ariza A,

Aranda E and López-López R: Pancreatic cancer biomarkers: A pathway

to advance in personalized treatment selection. Cancer Treat Rev.

125:1027192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Miao H, Chen X and Luan Y: Small molecular

gemcitabine prodrugs for cancer therapy. Curr Med Chem.

27:5562–5582. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pandit B and Royzen M: Recent development

of prodrugs of gemcitabine. Genes (Basel). 13:4662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cui J, Guo Y, Yin T, Gou S, Xiong J, Liang

X, Lu C and Peng T: USP8 promotes gemcitabine resistance of

pancreatic cancer via deubiquitinating and stabilizing Nrf2. Biomed

Pharmacother. 166:1153592023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shu X, Zhan PP, Sun LX, Yu L, Liu J, Sun

LC, Yang ZH, Ran YL and Sun YM: BCAT1 activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway and contributes to the angiogenesis and tumorigenicity of

gastric cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6592602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yu L, Wei J and Liu P: Attacking the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment

in human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 85:69–94. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rahaman A, Chaudhuri A, Sarkar A,

Chakraborty S, Bhattacharjee S and Mandal DP: Eucalyptol targets

PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway to inhibit skin cancer metastasis.

Carcinogenesis. 43:571–583. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhou X, Zhao J, Yan T, Ye D, Wang Y, Zhou

B, Liu D, Wang X, Zheng W, Zheng B, et al: ANXA9 facilitates S100A4

and promotes breast cancer progression through modulating STAT3

pathway. Cell Death Dis. 15:2602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Jiang Q, Guan Y, Zheng J and Lu H: TBK1

promotes thyroid cancer progress by activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR

signaling pathway. Immun Inflamm Dis. 11:e7962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang S, Cheng Z, Cui Y, Xu S, Luan Q, Jing

S, Du B, Li X and Li Y: PTPRH promotes the progression of non-small

cell lung cancer via glycolysis mediated by the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway. J Transl Med. 21:8192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang S, Zhang C, Xu Z, Chen MH, Yu H, Wang

L and Liu R: Differential impact of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling on

tumor initiation and progression in animal models of prostate

cancer. Prostate. 83:97–108. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mortazavi M, Moosavi F, Martini M,

Giovannetti E and Firuzi O: Prospects of targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway in pancreatic cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

176:1037492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang L, Sun J, Ma Y, Chen H, Tian C and

Dong M: MSI2 regulates NLK-mediated EMT and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

to promote pancreatic cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int.

24:2732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shimia M, Amini M, Ravari AO, Tabnak P,

Valizadeh A, Ghaheri M and Yousefi B: Thymoquinone reversed

doxorubicin resistance in U87 glioblastoma cells via targeting

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling. Chem Biol Drug Des. 104:e145872024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang M, Xue W, Yuan H, Wang Z and Yu L:

Nano-drug delivery systems targeting CAFs: A promising treatment

for pancreatic cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 19:2823–2849. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang Y, Xu H, Li Y, Sun Y and Peng X:

Advances in the treatment of pancreatic cancer with traditional

Chinese medicine. Front Pharmacol. 14:10892452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Manoharan S, Deivendran B and Perumal E:

Chemotherapeutic potential of saikosaponin D: Experimental

evidence. J Xenobiot. 12:378–405. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu G, Guan Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang J, Liu

Y and Liu X: Saikosaponin D inducing apoptosis and autophagy

through the activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress in

glioblastoma. Biomed Res Int. 2022:54895532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tang JC, Long F, Zhao J, Hang J, Ren YG,

Chen JY and Mu B: The effects and mechanisms by which

saikosaponin-D enhances the sensitivity of human non-small cell

lung cancer cells to gefitinib. J Cancer. 10:6666–6672. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hu J, Li P, Shi B and Tie J: Effects and

mechanisms of saikosaponin d improving the sensitivity of human

gastric cancer cells to cisplatin. ACS Omega. 6:18745–18755. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang CY, Jiang ZM, Ma XF, Li Y, Liu XZ,

Li LL, Wu WH and Wang T: Saikosaponin-d inhibits the hepatoma cells

and enhances chemosensitivity through SENP5-dependent inhibition of

gli1 sumoylation under hypoxia. Front Pharmacol. 10:10392019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liang J, Sun J, Liu A, Chen L, Ma X, Liu X

and Zhang C: Saikosaponin D improves chemosensitivity of

glioblastoma by reducing the its stemness maintenance. Biochem

Biophys Rep. 32:1013422022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tang TT, Jiang L, Zhong Q, Ni ZJ, Thakur

K, Khan MR and Wei ZJ: Saikosaponin D exerts cytotoxicity on human

endometrial cancer ishikawa cells by inducing apoptosis and

inhibiting metastasis through MAPK pathways. Food Chem Toxicol.

177:1138152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chou TC: Drug combination studies and

their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer

Res. 70:440–446. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xi H, Wang S, Wang B, Hong X, Liu X, Li M,

Shen R and Dong Q: The role of interaction between autophagy and

apoptosis in tumorigenesis (Review). Oncol Rep. 48:2082022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sorice M: Crosstalk of autophagy and

apoptosis. Cells. 11:14792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S and Wang Y:

Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 14:6482023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Niu X, You Q, Hou K, Tian Y, Wei P, Zhu Y,

Gao B, Ashrafizadeh M, Aref AR, Kalbasi A, et al: Autophagy in

cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug

Resist Updat. 78:1011702025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu J, Wu Y, Meng S, Xu P, Li S, Li Y, Hu

X, Ouyang L and Wang G: Selective autophagy in cancer: mechanisms,

therapeutic implications, and future perspectives. Mol Cancer.

23:222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhao Y, Tang J, Jiang K, Liu SY, Aicher A

and Heeschen C: Liquid biopsy in pancreatic cancer-current

perspective and future outlook. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1878:1888682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhong BH, Ma YT, Sun J, Tang JT and Dong

M: Transcription factor FOXF2 promotes the development and

progression of pancreatic cancer by targeting MSI2. Oncol Rep.

52:932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen J, Hua Q, Wang H, Zhang D, Zhao L, Yu

D, Pi G, Zhang T and Lin Z: Meta-analysis and indirect treatment

comparison of modified FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus

nab-paclitaxel as first-line chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic

cancer. BMC Cancer. 21:8532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ji J, Wen Q, Yu Y, Xiong F, Zheng X and

Ruan S: Personalized traditional Chinese medicine in oncology:

Bridging the macro state with micro targets. Am J Chin Med.

14:1–34. 2025.

|

|

37

|

Ke Y, Pan Y, Huang X, Bai X, Liu X, Zhang

M, Wei Y, Jiang T and Zhang G: Efficacy and safety of traditional

Chinese medicine (TCM) combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs) for the treatment of cancer: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 31:16615032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Okuno K, Xu C, Pascual-Sabater S, Tokunaga

M, Han H, Fillat C, Kinugas Y and Goel A: Berberine overcomes

gemcitabine-associated chemoresistance through regulation of

Rap1/PI3K-Akt signaling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15:11992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bhattacharyya S, Ghosh H,

Covarrubias-Zambrano O, Jain K, Swamy KV, Kasi A, Hamza A, Anant S,

Van Saun M, Weir SJ, et al: Anticancer activity of novel

difluorinated curcumin analog and its inclusion complex with

2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin against pancreatic cancer. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:63362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ashour ML and Wink M: Genus bupleurum: A

review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology and modes of action. J

Pharm Pharmacol. 63:305–321. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cheng Y, Liu G, Li Z, Zhou Y and Gao N:

Screening saikosaponin d (SSd)-producing endophytic fungi from

Bupleurum scorzonerifolium Willd. World J Microbiol Biotechnol.

38:2422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lai M, Ge Y, Chen M, Sun S, Chen J and

Cheng R: Saikosaponin D inhibits proliferation and promotes

apoptosis through activation of MKK4-JNK signaling pathway in

pancreatic cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 13:9465–9479. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Conroy T, Castan F, Lopez A, Turpin A, Ben

Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Mitry E, Biagi JJ, Evesque L, Artru P, et al:

Five-year outcomes of FOLFIRINOX vs. gemcitabine as adjuvant

therapy for pancreatic cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA

Oncol. 8:1571–1578. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sun EJ, Wankell M, Palamuthusingam P,

McFarlane C and Hebbard L: Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomedicines. 9:16392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kale J, Kutuk O, Brito GC, Andrews TS,

Leber B, Letai A and Andrews DW: Phosphorylation switches Bax from

promoting to inhibiting apoptosis thereby increasing drug

resistance. EMBO Rep. 19:e452352018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li X, He S and Ma B: Autophagy and

autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol Cancer. 19:122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Mehra S, Deshpande N and Nagathihalli N:

Targeting PI3K pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma:

Rationale and progress. Cancers (Basel). 13:44342021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sheng W, Shi X, Lin Y, Tang J, Jia C, Cao

R, Sun J, Wang G, Zhou L and Dong M: Musashi2 promotes EGF-induced

EMT in pancreatic cancer via ZEB1-ERK/MAPK signaling. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 39:162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Johnson DE, O'Keefe RA and Grandis JR:

Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev

Clin Oncol. 15:234–248. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Deer EL, González-Hernández J, Coursen JD,

Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, Firpo MA and Mulvihill SJ: Phenotype

and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas. 39:425–435.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Fianco G, Mongiardi MP, Levi A, De Luca T,

Desideri M, Trisciuoglio D, Del Bufalo D, Cinà I, Di Benedetto A,

Mottolese M, et al: Caspase-8 contributes to angiogenesis and

chemotherapy resistance in glioblastoma. Elife. 6:e225932017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wei S, Han C, Mo S, Huang H and Luo X:

Advancements in programmed cell death research in antitumor

therapy: A comprehensive overview. Apoptosis. 30:401–421. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Das S, Shukla N, Singh SS, Kushwaha S and

Shrivastava R: Mechanism of interaction between autophagy and

apoptosis in cancer. Apoptosis. 26:512–533. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Hajdú B, Holczer M, Horváth G, Szederkényi