Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) remains the leading cancer type in

morbidity and mortality worldwide (1), with non-small cell LC (NSCLC)

representing the most prevalent subtype, accounting for ~85% of all

LC cases (2). The aberrant

activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling

pathway is a key driver of NSCLC (2). EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

targeted therapy has demonstrated significant benefits in patients

with NSCLC harboring activating EGFR mutation (3). Moreover, although the response rate to

EGFR-TKIs is substantially lower in patients with NSCLC with

wild-type EGFR compared with those with mutated EGFR (4), clinical trials indicate that

EGFR-TKIs, when used as consolidation and maintenance treatment

following first-line chemotherapy, can improve outcomes in patients

with NSCLC with wild-type EGFR (5).

Nevertheless, the efficacy of EGFR-TKIs is considerably constrained

by intrinsic and acquired resistance, and the underlying mechanisms

of EGFR-TKIs resistance are complicated and heterogeneous,

encompassing secondary mutation in the target kinase domain,

activation of alternative signal pathways, concurrent alteration in

other oncogenes, histological transformation, and tumor

microenvironment (6), which remains

incompletely understood.

Primary cilia are ubiquitous, hair-like organelles

that projected from cell surface, originating from the basal body

and composed of an axoneme with a 9+0 microtubule doublet

configuration (7). The organelle

functions as distinctive sensory structure and signaling hub,

sensing and transducing extracellular chemical and physical stimuli

into intracellular responses by coordinating multiple signaling

pathways, including Hedgehog (HH), G protein-coupled receptor,

receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), and WNT pathways (8). Alterations in ciliation and ciliary

signaling pathway status are significantly associated with various

cancer types, but the role of cilia varies depending on the cancer

type, stage and microenvironment (9). Notably, primary cilia have been

implicated in resistance to chemotherapeutic agents (10–12),

ionizing radiation (12,13), and protein kinase targeted

inhibitors (14,15), suggesting a regulatory role in

cellular response and resistance to cancer therapies.

It has been previously reported that the EGFR-TKI

gefitinib (Gef) remarkably restores ciliogenesis in NSCLC A549

cells, as well as in kidney cancer UMRC2, breast cancer SUM159, and

pancreatic cancer L3.6 cells (16).

Furthermore, a notable increase in cilia frequency, length and

fragmentation has been observed in NSCLC HCC4006, H2228, A549 and

H23 cells that have developed resistance to kinase inhibitors, and

ablation of cilia or inhibition of the cilia-dependent HH signaling

pathway is sufficient to overcome both acquired and de novo

kinase inhibitor resistance in NSCLC cells (14). These findings highlight the

involvement of primary cilia in promoting EGFR-TKIs resistance in

NSCLC, but the precise role and underlying mechanism are still

largely unexplored.

The adenylate cyclase (AC) superfamily, which

comprises nine membrane-bound subtypes (AC1-AC9) and one soluble

subtype, plays critical roles in development, progression and

therapy resistance across various cancer types by modulating the

cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling pathway (17). This pathway's activation and

transduction are often orchestrated by primary cilia (18). AC3 is commonly localized to primary

cilia in mammals and is involved in the regulation of cilia

elongation and HH signaling (19,20).

While emerging evidence has linked AC3 to cell proliferation,

migration and invasion in gastric and pancreatic cancers (21,22),

its role in EGFR-TKIs' resistance mechanisms in NSCLC remains to be

fully elucidated.

In the present study, the prevalence of primary

cilia in EGFR-TKIs' insensitive and sensitive NSCLC cells, as well

as the dynamic alterations in ciliogenesis following EGFR-TKIs

treatment were investigated. The functional roles of primary cilia

and AC3 in modulating cellular responses to EGFR-TKIs were further

studied, which may help to provide a novel strategy for overcoming

drug resistance in NSCLC cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The first and second generation of EGFR-TKIs

gefitinib (Gef; cat. no. HY-50895) and dacomitinib (Dac; cat. no.

HY-13272) were purchased from MedChemExpress. Dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO; cat. no. 472301) and propidium iodide (PI; 1.0 µg/ml; cat.

no. P4864) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. For

immunoblotting experiment, the primary antibodies of ERK (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab184699) and phosphorylated-ERK (p-ERK; 1:1,000; cat. no.

ab201015) were purchased from Abcam; primary antibodies of BCL2

(1:2,000; cat. no. 12789-1-AP), α-tubulin (α-tub; 1:40,000; cat.

no. 11224-1-AP), IFT88 (1:1,000; cat. no. 60227-1-Ig), AC3

(1:1,000; cat. no. 19492-1-AP), Cyclin A2 (CCNA; 1:1,000; cat. no.

18202-1-AP), Cyclin B1 (CCNB; 1:1,000; cat. no. 55004-1-AP), Cyclin

D1 (CCND; 1:3,000; cat. no. 60186-1-Ig), Cyclin E1 (CCNE; 1:1,000;

cat. no. 11554-1-AP), CDK1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 19532-1-AP), CDK2

(1:1,000; cat. no. 10122-1-AP), p21 (1:1,000; cat. no. 10355-1-AP),

p16 (1:1,000; cat. no. 10883-1-AP), GAPDH (1:50,000; cat. no.

60004-1-Ig), and the secondary antibodies including HRP-conjugated

goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-1), HRP-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2) were supplied by

Proteintech Group, Inc. For immunofluorescence staining, the

primary antibodies of ADP ribosylation factor such as GTPase 13B

(ARL13B; 1:500; cat. no. 17711-1-AP/66739-1-Ig), AC3 (1:500; cat.

no. 19492-1-AP) and γ-tubulin (γ-tub; 1:500; cat. no. T6557) were

purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. and Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA respectively. The secondary antibodies including Alexa Fluor

594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG (1:500; cat. no. A-11005), Alexa Fluor

488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500; cat. no. A-11001), Alexa

Fluor Plus 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; cat. no.

A32732), and Alexa Fluor Plus 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG

(1:500; cat. no. A32731) were purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was obtained

from Molecular Probes; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

Cell culture

The human NSCLC cell lines A549 (CSTR:

19375.09.3101HUMSCSP503), NCI-H23 (H23; CSTR:

19375.09.3101HUMSCSP581), PC9 (CSTR: 19375.09.3101HUMSCSP5085) and

HCC827 (CSTR: 19375.09.3101HUMSCSP538) were purchased from the Cell

Bank/Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences. A549 cells were

cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/F-12 (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). H23, PC9 and HCC827 cells were maintained

in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Shanghai

ExCell Biology, Inc.), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.).

Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C under 5%

CO2, and tested negative for mycoplasma.

Cell viability assay

NSCLC cells (1×105) were planted in

6-well plates and incubated for 24 h, followed by treated with

indicated concentrations of Gef or Dac for 48 h. In addition, NSCLC

cells (1×105) were seeded in 6 well-plates for 24 h

before transfected with siIFT88, siARL13B, siAC3, or NC. After

transfection, Gef, Dac, or DMSO was immediately added into the

medium and the cells were continuously cultured for 48 h. The cell

number was counted using a Coulter counter (Z2; Beckman Coulter

Inc.), the cell viability related to control group was determined

and the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of

Gef or Dac was calculated.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min at room

temperature following the pre-chilling methanol at −20°C for 20

min. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for

10 min, then blocked with 5% immunostaining blocking buffer

(Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room

temperature. The primary antibodies of ARL13B and γ-tub were used

to visualize primary cilia and basal bodies, respectively. The

primary antibody of AC3 was used to visualize its localization. The

primary antibodies were incubated for 2 h at room temperature and

then cells were incubated with the secondary antibodies for 1 h.

The cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The images were

captured under an RVL-100-G fluorescence microscope (ECHO). For

cilia frequency analysis, confidence level (α): 95%, Z-score: 1.96,

margin of error (e): 5%, population proportion (p): 1–60%, when

p=60% the population size (n)=369, and more than 500 cells for each

experiment were calculated. For AC3 positive cilia analysis,

confidence level (α): 95%, Z-score: 1.96, margin of error (e): 5%,

population proportion (p): 0–20%, when p=20% the population size

(n)=246, and more than 200 cilia were calculated for each group.

The length of the primary cilium (n>50) was measured using

ImageJ software (Version 1.52; National Institutes of Health).

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The total cellular proteins (20 µg)

were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a

methanol-activated PVDF membrane (Merck KGaA). The membrane was

blocked with 5% protein-free rapid blocking buffer (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) for 2 h at room temperature and

probed with the primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature.

After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, the

protein bands were detected with chemiluminescence reagents (Merck

KGaA), and the images were captured by using Alliance LD4 gel

imaging system (UVITEC) and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Cell cycle distribution analysis

For the cell cycle assay, cells treated with Gef or

Dac for 1–3 days were harvested and fixed in −20°C pre-chilled 70%

alcohol overnight, then stained with 20 µg/ml PI for 15 min at room

temperature. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using Amnis

imaging flow cytometer (Merck KGaA), and at least 10,000 gated

events were acquired from each sample. The data were analyzed with

Amnis IDEAS Application v6.0 (Merck KGaA).

PI staining

The control cells or cells transfected with small

interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were treated with Gef or Dac for

indicated time, then incubated with 20 µg/ml PI for 15 min to stain

the dead cells. The images of bright field (BF) and fluorescence

field were captured by using a DMI6000 fluorescence microscope

(Leica Microsystems GmbH), and at least 500 cells were counted for

each group.

RNA interference

Two individual stealth siRNAs targeting IFT88

(siIFT88-1/2, 25 nM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) or ARL13B

(siARL13B-1/2; 50 nM; Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) were introduced

into the cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) to ablate primary cilia. Three individual siRNAs

against AC3 (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) were employed to

knockdown the target gene expression at a final concentration of 50

nM. A negative control siRNA (NC; siN0000001-1-5; Guangzhou RiboBio

Co., Ltd.) was used as the control group. Cells were transfected

with siRNAs for 5 h at 37°C and then the medium was replaced with

fresh culture medium. The interference efficiency of siRNAs was

evaluated by immunoblotting analysis. The sequences of siRNAs are

as follows: siIFT88-1: 5′-CCAAAGCCAUUAAAUUCUACCGAAU-3′; siIFT88-2:

5′-GAAGAAAGCUGUAUUGCCAAUAGUU-3′; siARL13B-1:

5′-GTGTCAGATAGAACCATGT-3′; siARL13B-2: 5′-GAACCATGTTCAGCAATCT-3′;

siAC3-1: 5′-GCACCAGCTTCCTCAAAGT-3′; siAC3-2:

5′-GGACTGGTGTTGGACATCA-3′; siAC3-3: 5′-GACGTATGATGAGATTGGA-3′. The

sequences of NC were not provided for the commercial patent

security protection.

Cell senescence assay

The cellular senescence was measured by

Senescence-Tracker (Sen-Tra) assay as previously reported (23). Briefly, cells were exposed to DMSO

or Gef (25 µM) for 1–3 days, followed by incubation with Sen-Tra

fluorescence probe (10 µM; cat. no. C0603; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) overnight at 37°C; then, the cells were washed with

PBS for three times before imaging. The fluorescence images of

senescent cells were captured on a DMI6000 fluorescence microscope.

Quantification of images obtained from cells was performed using

ImageJ software, and >500 cells were counted for each group.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were repeated at least three

times, and the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

(SD). Statistical analysis was performed with Origin 2019

(OriginLab Corporation) using paired Student's t-test for two

groups and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test for

multiple comparisons. *P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

EGFR-TKIs' insensitive and sensitive

NSCLC cells present different ciliation status

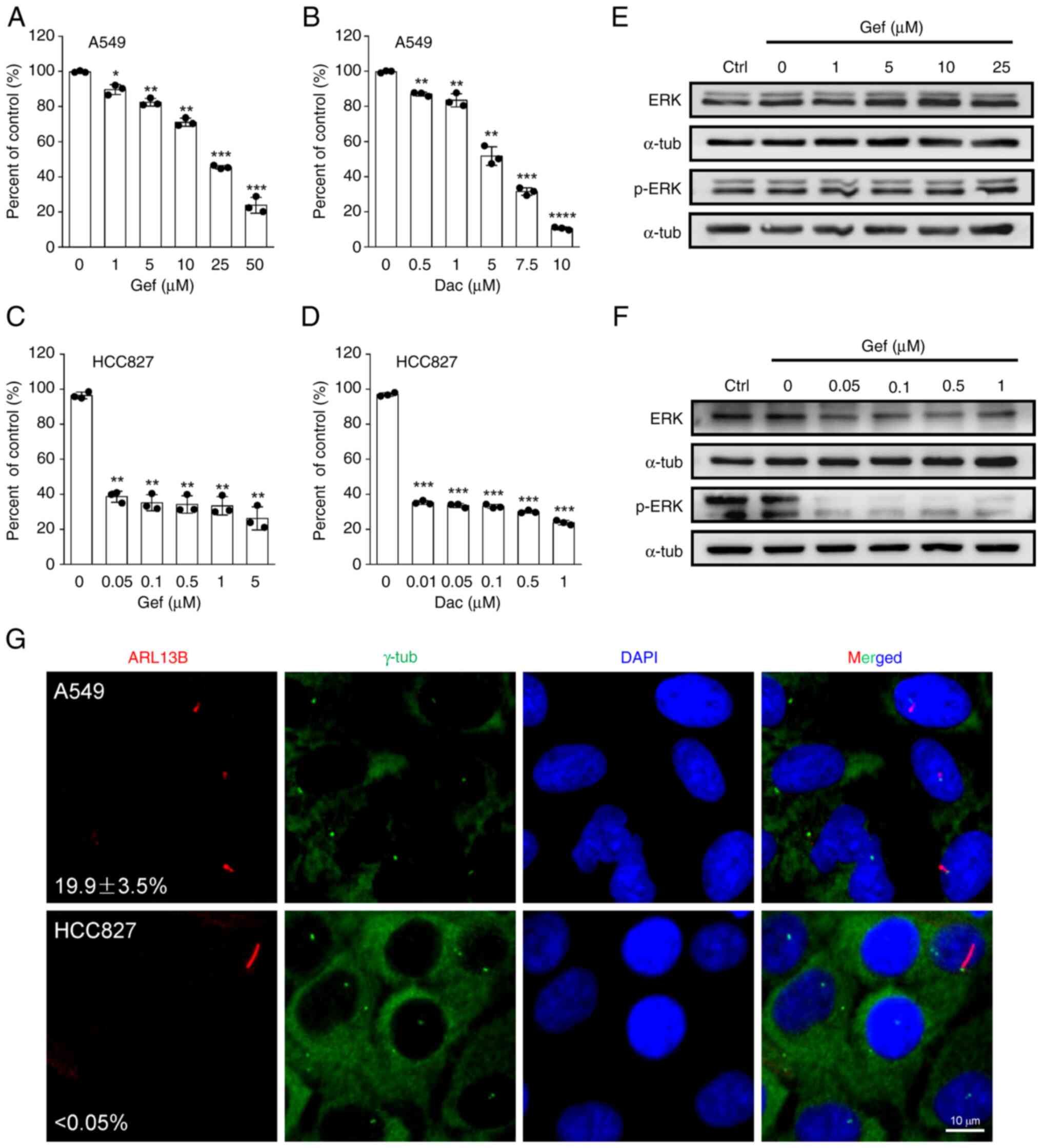

To determine whether primary cilia are associated

with cellular resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC, the

drug-insensitive A549 and H23 cells (EGFR wild-type) and the

drug-sensitive HCC827 and PC9 cells (EGFR mutant) were treated with

increasing concentrations of Gef and Dac for 48 h to measure the

IC50. The results showed that the IC50 values

for A549 and H23 to Gef/Dac are ~20.3/3.9 and 15.5/1.9 µM

respectively (Fig. 1A and B;

Fig. S1A and B), and that for

HCC827/PC9 are significantly lower than 0.05/0.01 and 0.05/0.01 µM

respectively (Fig. 1C and D;

Fig. S1C and D). To further

corroborate the distinct inhibitory effectiveness of EGFR-TKI on

the drug-insensitive and drug-sensitive cells, the activation of

ERK, a key EGFR downstream signaling factor (24), was detected in A549 and HCC827 cells

challenged with different doses of Gef. As demonstrated, the

expression level of activated ERK (p-ERK) exhibited a significant

decrease in HCC827 but not in A549 cells (Fig. 1E and F), indicating that HCC827 is

distinctly more sensitive to Gef and Dac than A549. Next, the

immunofluorescence staining assay with the cilia and basal body

markers ARL13B and γ-tub was performed, and typical primary cilia

structure was observed in A549, H23 and HCC827 cells cultured in

full serum-containing medium (Figs.

1G and S2A), but that was

completely lacking in PC9 cells (Fig.

S2C). The cilia frequency is significantly higher in A549

(19.9±3.5%) and H23 (~1.5%) cells compared with that in HCC827

(<0.05%) and PC9 (none) cells (Figs.

1G and S2), suggesting a

negative association between cilia incidence and cellular

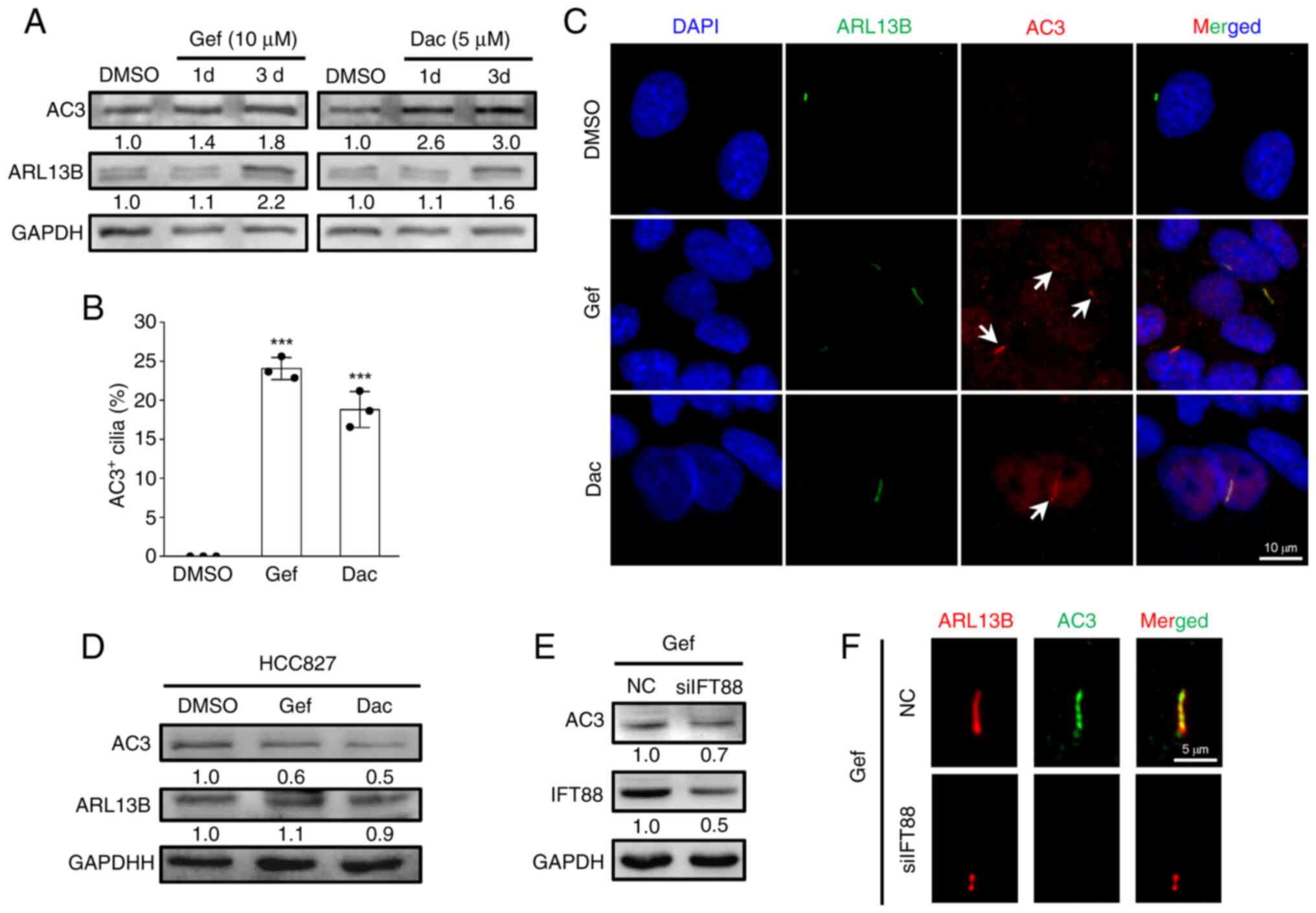

sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs.

| Figure 1.Epidermal growth factor

receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor-insensitive A549 cells harbor

high cilia incidence. (A and B) A549 cells were treated with

increasing concentrations of (A) Gef or (B) Dac, and the cell

viability related to untreated control (Ctrl) was measured at 48 h

post-treatment. (C and D) HCC827 cells were treated with increasing

concentrations of (C) Gef or (D) Dac, and the cell viability

related to untreated control was measured at 48 h post-treatment.

(E and F) A549 and HCC827 cells were exposed to increasing

concentrations of Gef for 48 h, and the immunoblotting analysis was

performed to measure the protein expression levels of ERK and p-ERK

at Thr202/Tyr204. α-tubulin (α-tub) was used as a loading control.

(G) Representative images of primary cilia labeled with ARL13B

(red) and basal bodies labeled with γ-tub (green) in A549 and

HCC827 cells, and the cilia incidence was calculated. The nuclei

were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. All

quantitative data were obtained from three replicates and shown as

the mean ± SD. Error bars, ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 compared with 0 µM (0.1% DMSO).

Gef, gefitinib; Dac, dacomitinib; p-, phosphorylated; SD, standard

deviation. |

EGFR-TKIs facilitate primary cilia

formation and elongation in A549 and H23 but not HCC827 and PC9

cells

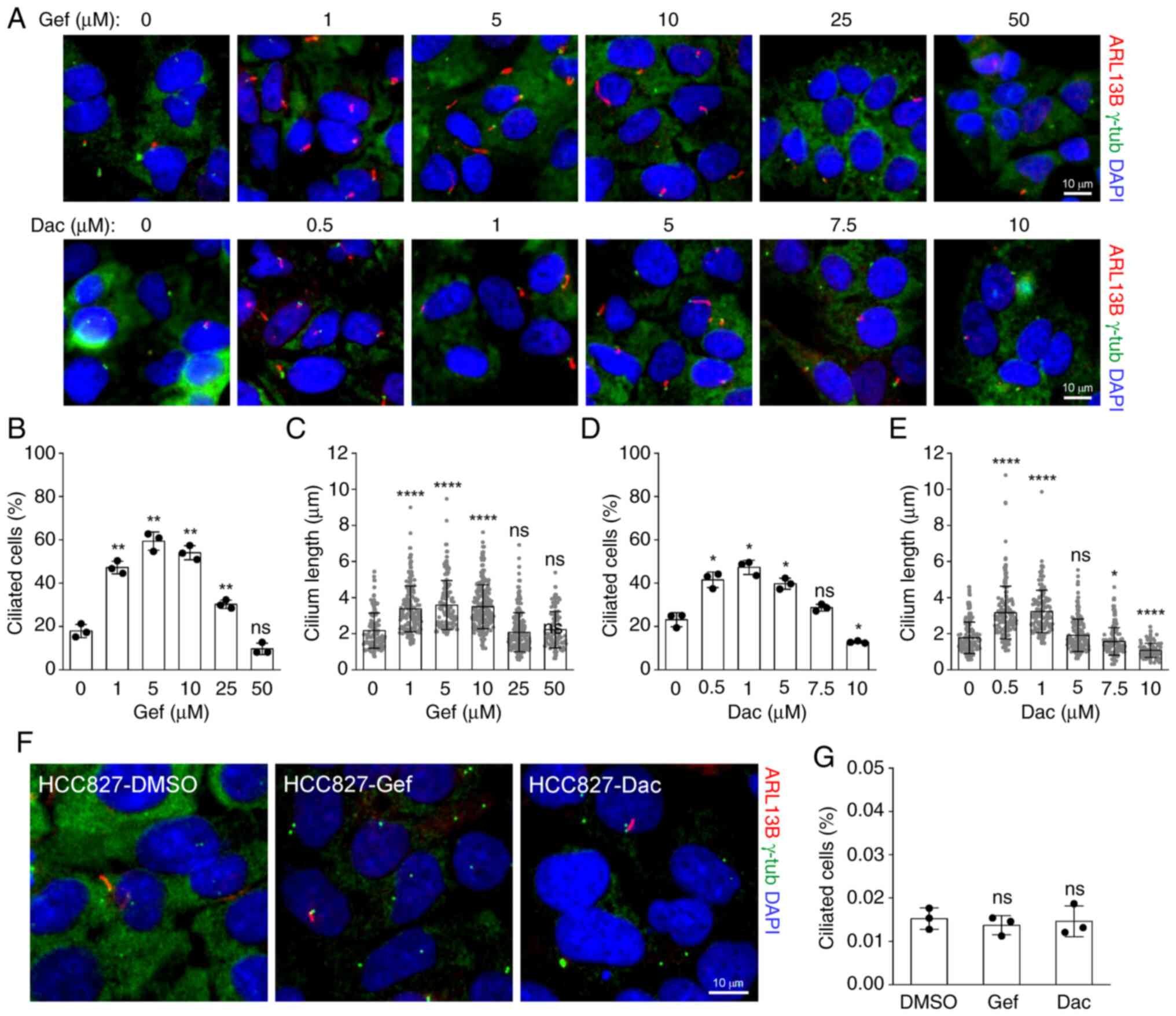

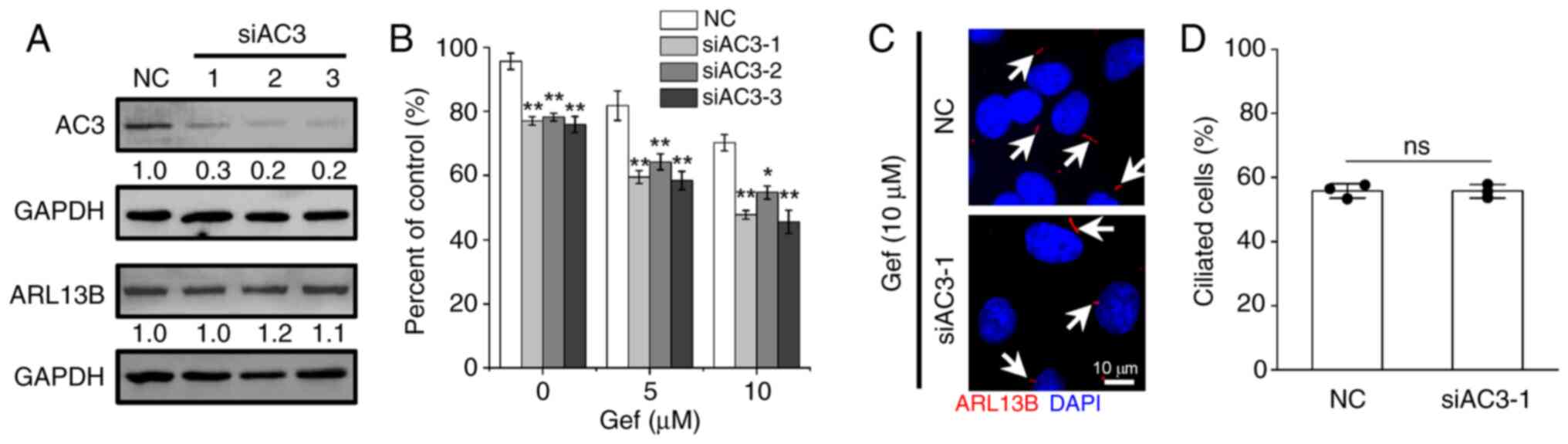

Increased cilia frequency and length have been

reported in TKI-resistant NSCLC cells, such as erlotinib-resistant

HCC4006 (14) and

dasatinib-resistant A549 cells (25), but no significant alterations in

afatinib- and erlotinib-resistant PC9 cells compared with the

parental cells (14). To

investigate the effects of EGFR-TKIs on primary ciliogenesis in

NSCLC cells, the A549, H23, HCC827 and PC9 cells were treated with

multiple doses of Gef and Dac. As revealed in Fig. 2A-E, administration of Gef and Dac

resulted in remarkable cilia formation and elongation in A549 cells

in a dose-dependent manner. The proportion of ciliated cells was

raised from ~20% in DMSO (0 µM Gef)-treated cells to nearly 60% in

5 µM Gef-treated cells, and to nearly 50% in 1 µM Dac-treated

cells. Similar alterations were observed in H23 cells treated with

5 µM Gef or 1 µM Dac (Fig. S2A and

B). As the drug concentration increased, the cilia incidence

and length were gradually decreased, and exposure to 50 µM Gef or

10 µM Dac even lead to deciliation in A549 cells. However, Gef and

Dac were not able to induce cilia formation in HCC827 and PC9 cells

(Fig. 2F and G; Fig. S2C). Together, these data suggested

that the ciliogenesis responding to EGF-TKIs maybe contribute to

drug resistance in NSCLC cells.

| Figure 2.Epidermal growth factor

receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors promote ciliogenesis in

dose-dependent manner in A549 but not HCC827 cells. (A)

Representative images of primary cilia labeled with ARL13B (red)

and basal bodies labeled with γ-tub (green) in A549 cells treated

with increasing doses of Gef or Dac for 48 h. (B and C)

Quantification of (B) ciliated cells and the (C) cilium length of

A549 cells treated with 0 (n=117), 1 (n=176), 5 (n=133), 10

(n=216), 25 (n=210), 50 (n=95) µM Gef for 48 h. **P<0.01 and

****P<0.0001 compared with 0 µM; ns, not significant. (D and E)

Quantification of (D) ciliated cells and the (E) cilium length of

A549 cells treated with 0 (n=133), 0.5 (n=153), 1 (n=138), 5

(n=163), 7.5 (n=130), 10 (n=80) µM Dac for 48 h. *P<0.05 and

****P<0.0001 compared with 0 µM; ns, not significant. (F)

Representative images of primary cilia labeled with ARL13B (red)

and basal bodies labeled with γ-tub (green) in HCC827 cells treated

with 0.01 µM Gef or 0.001 µM Dac for 48 h. (G) Quantification of

ciliated cells in HCC827 cells in (F). ns, not significant compared

with DMSO. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale

bar, 10 µm. All quantitative data were obtained from three

replicates and shown as the mean ± SD. Error bars, ± SD. Gef,

gefitinib; Dac, dacomitinib; p-, phosphorylated; SD, standard

deviation; ns, not significant. |

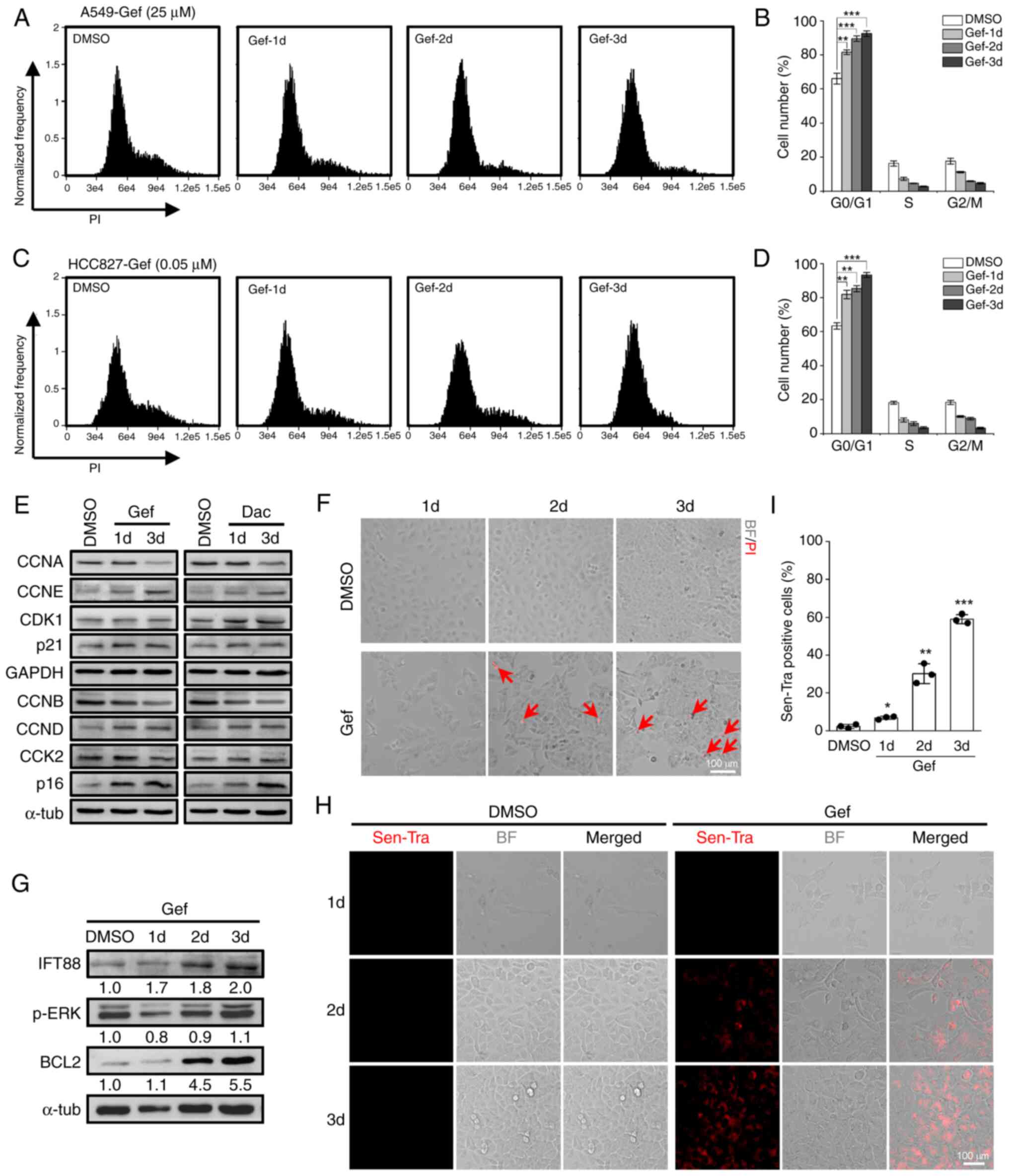

EGFR-TKIs induce cytostatic but not

cytotoxic effects

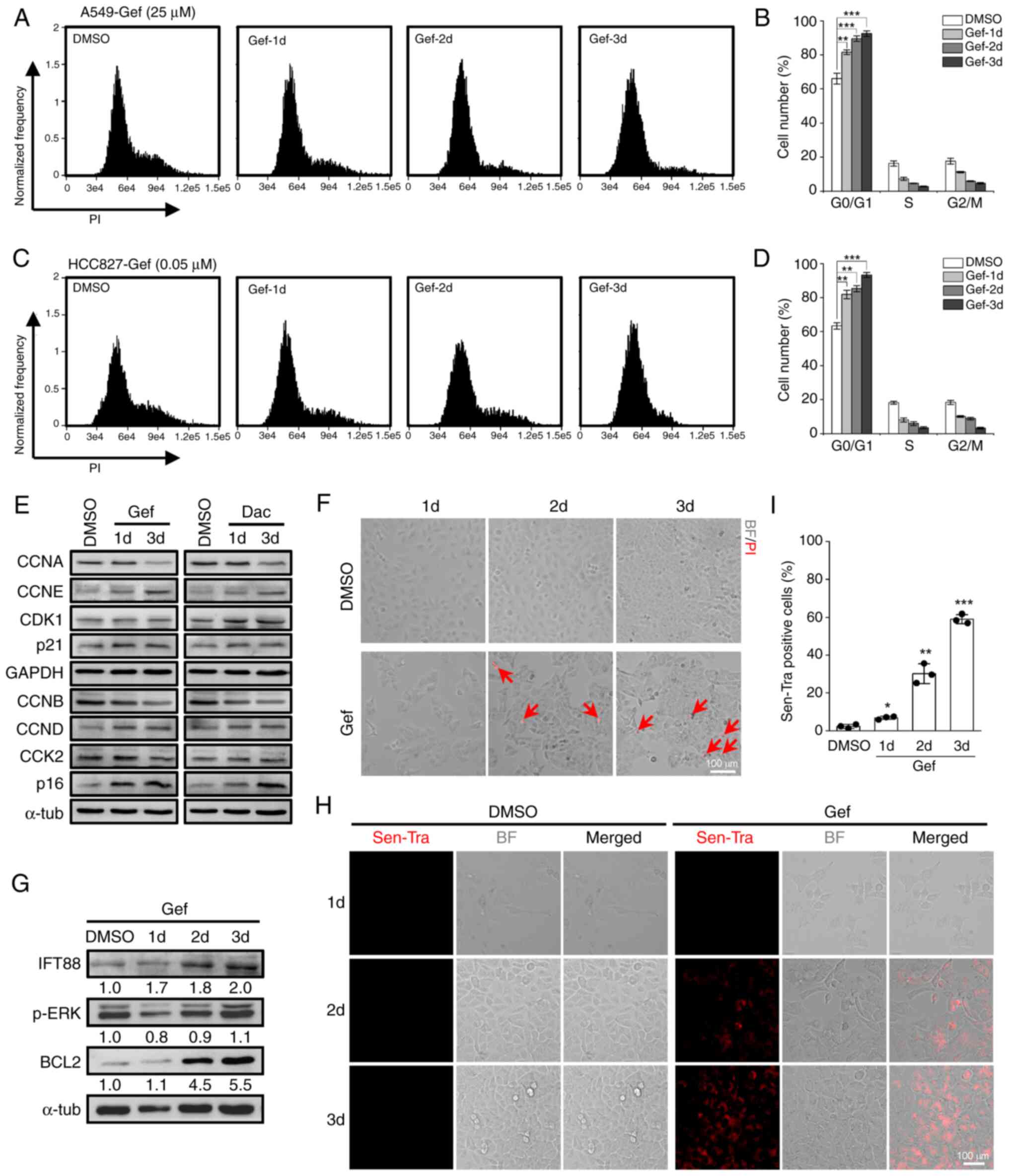

Next, the effects of EGF-TKIs on the cell cycle and

cell fate were investigated. Upon Gef (25 µM) treatment, A549 cells

were predominantly blocked in G0/G1 phase in a time-dependent

manner (Fig. 3A and B). Similar

phenomenon was observed in HCC827 exposed to 0.05 µM Gef (Fig. 3C and D). Moreover, the expression

levels of G1 cyclins (CCND and CCNE) and cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitor (p16 and p21) were consistently upregulated following Gef

and Dac treatment in A549 cells, while the expression levels of S

and G2/M cyclins (CCNA and CCNB) were suppressed, and the

cyclin-dependent kinase CDK1 and CDK2 showed slight changes

(Fig. 3E), supporting a G1 phase

arrest induced by EGFR-TKIs. Notably, Gef treatment resulted in

little cell death in A549 cells; <5% dead cells were detected at

3 days post-treatment (Fig. 3F).

The expression levels of p-ERK in Gef-treated cells showed modest

reduction compared with the DMSO-treated group, but the positive

ciliogenesis modulator IFT88 and the negative apoptosis regulator

BCL2 were gradually elevated (Fig.

3G), indicating enhanced capacities of ciliogenesis and

anti-apoptosis. Strikingly, increased senescent cells were detected

by the Sen-Tra labeling assay in A549 cells exposed to 25 µM Gef

(Fig. 3H), and the proportion of

senescent cells reached ~60% at 3 days after Gef exposure (Fig. 3I). Collectively, these data

demonstrated that EGFR-TKIs induce cytostatic but not cytotoxic

effects in NSCLC cells.

| Figure 3.Gef treatment leads to G1 phase

arrest and senescence. (A and B) Cell cycle distribution assay of

A549 cells treated with DMSO (0.1%) or 25 µM Gef for 1, 2, and 3

days (d) by flow cytometry with (A) PI staining; (B) quantification

data. (C and D) Cell cycle distribution assay of HCC827 cells

treated with DMSO (0.1%) or 0.05 µM Gef for 1, 2, and 3 days by

flow cytometry with (C) PI staining; (D) quantification data. (E)

Immunoblotting analysis of the expression levels of CCNA, CCNB,

CCND, CCNE, CDK1, CDK2, p16 and p21 in A549 cells treated with

DMSO, Gef (25 µM), or Dac (5 µM) for 1 and 3 days. α-tubulin

(α-tub) and GAPDH were used as loading controls. (F) Representative

PI staining images of A549 cells exposed to DMSO (0.1%) or Gef (25

µM) for 1, 2, 3 days, the dead cells (red) were stained with PI and

indicated with red arrows. Scale bar, 100 µm. (G) Immunoblotting

analysis of the expression levels of IFT88, p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204)

and BCL2 in A549 cells treated with DMSO (0.1%) or Gef (25 µM) for

1, 2, 3 days. α-tubulin (α-tub) was used as a loading control. The

values under the immunoblot bands indicate the quantitative

densitometry value measured using ImageJ software. (H and I) The

(H) cellular senescence assay of A549 cells treated with DMSO

(0.1%) or Gef (25 µM) for 1–3 d labeling by senescence-tracker

(Sen-Tra) fluorescence probe, and the (I) quantification data.

Scale bar, 100 µm. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Error bars,

± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with DMSO.

Gef, gefitinib; PI, propidium iodide; CCNA, Cyclin A2; CCNB, Cyclin

B1; CCND, Cyclin D1; CCNE, Cyclin E1; Dac, dacomitinib; BF, bright

field; p-, phosphorylated; SD, standard deviation. |

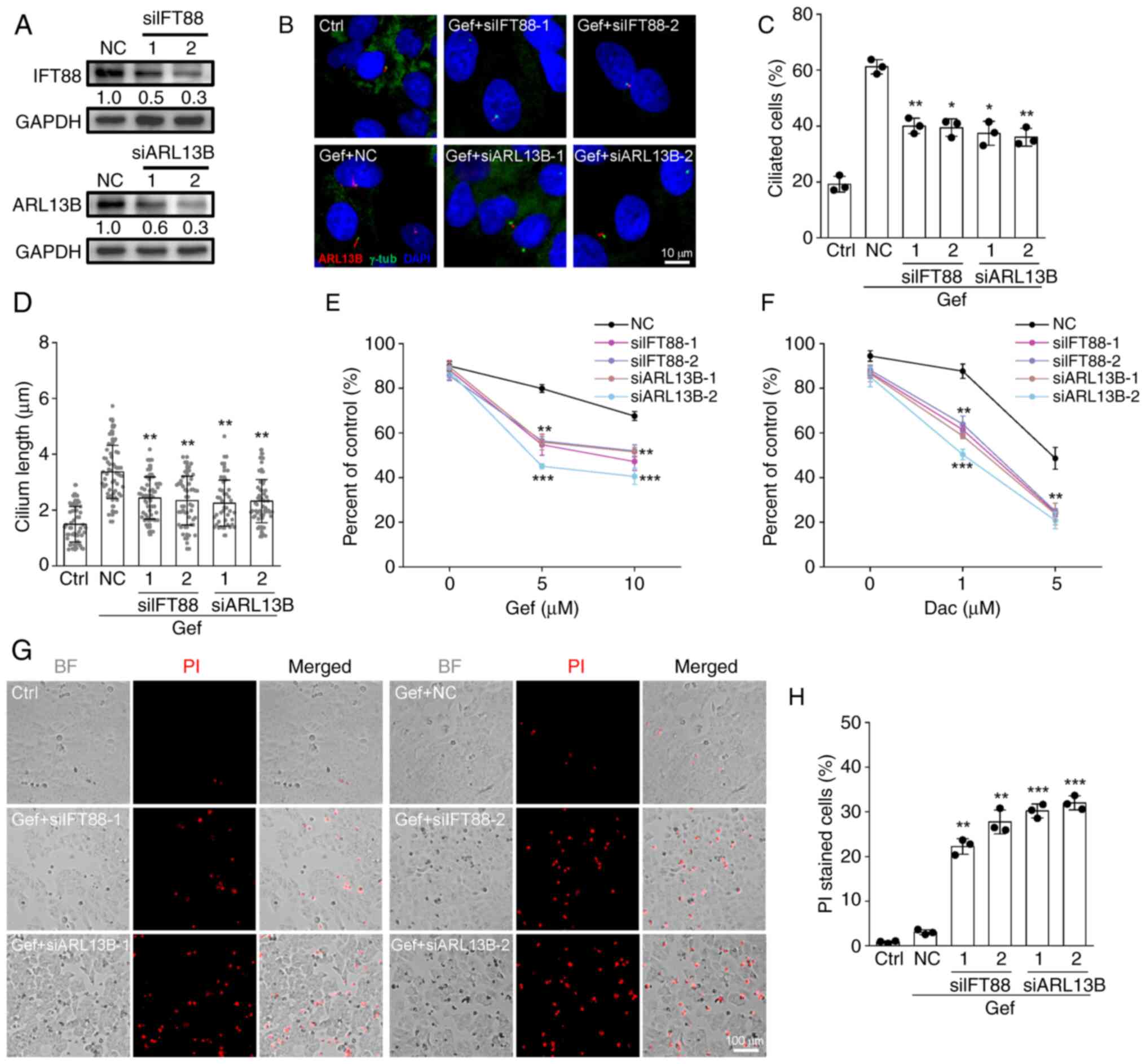

Disruption of ciliogenesis attenuates

cellular resistance to EGFR-TKIs

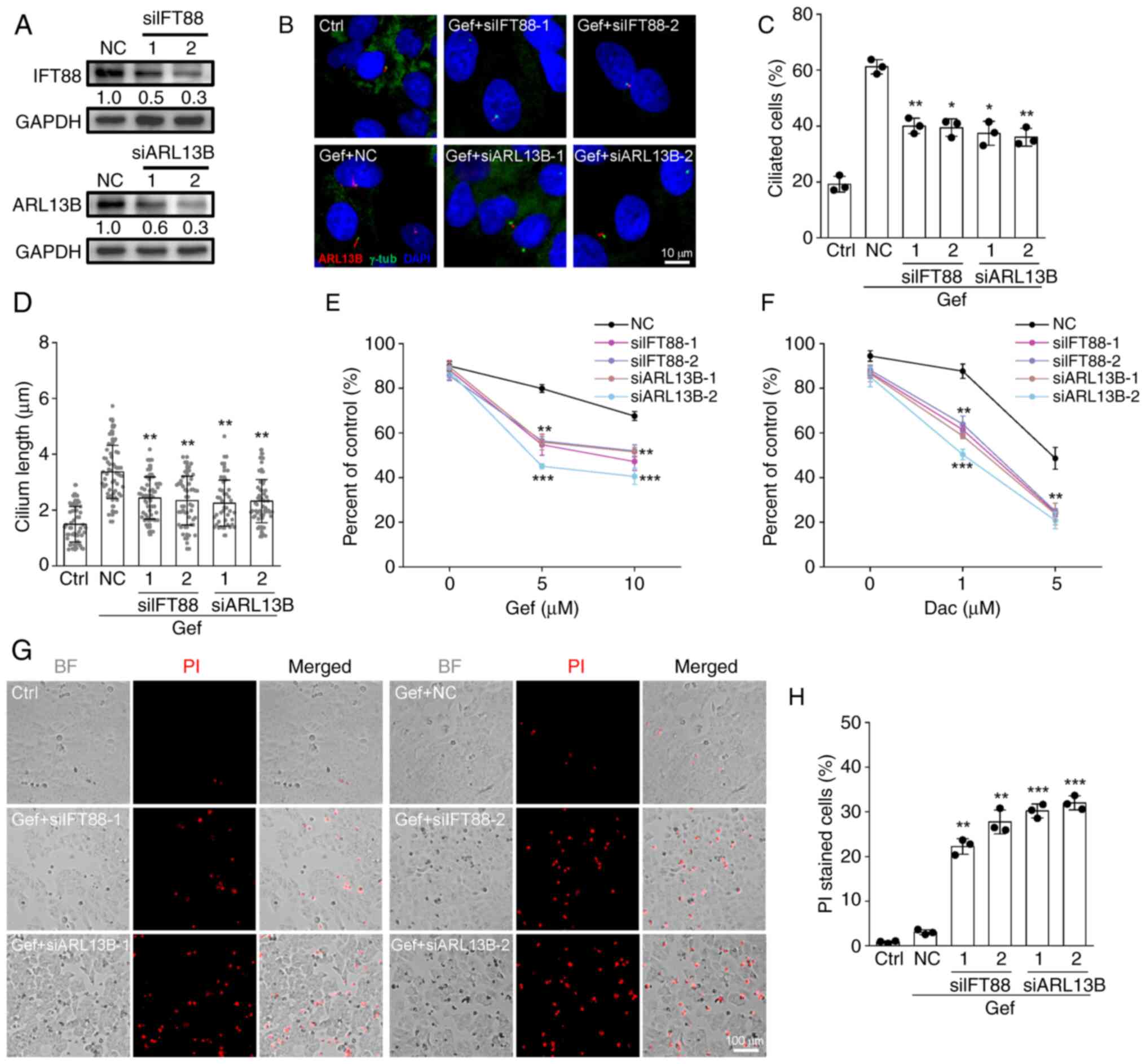

Given that Gef and Dac can promote primary cilia

formation in A549 and H23 cells (Figs.

2A and S2A), it is likely that

the primary cilia may play important roles in responding to

EGFR-TKIs in the insensitive NSCLC cells. To determine this

conjecture, the siRNAs targeting IFT88 (siIFT88-1/2) or ARL13B

(siARL13B-1/2) were introduced into A549 cells. The results showed

that transfection of siIFT88 or siARL13B prominently suppressed the

protein expression levels of IFT88 or ARL13B in A549 cells

(Fig. 4A). Moreover, knockdown of

IFT88 or ARL13B by siRNAs resulted in significant decreases in the

cilia frequency and length in A549 cells exposed to Gef as expected

(Fig. 4B-D). Importantly, the

ablation of primary cilia by siIFT88 and siARL13B profoundly

improved the inhibitory efficacy of Gef and Dac against A549 cells

(Fig. 4E and F). In addition, the

PI staining assay revealed that the abrogation of ciliogenesis by

IFT88 or ARL13b silencing strongly provoked the cell death in A549

cells exposed to 25 µM Gef (Fig.

4G), and the proportion of dead cells rose to ~30% at 3 days

after treatment (Fig. 4H). These

results indicated that the inhibition of ciliogenesis sensitizes

A549 cells to EGFR-TKIs by switching senescence to cell death.

| Figure 4.Inhibition of ciliogenesis sensitizes

A549 cells to epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase

inhibitors. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of the protein expression

levels of IFT88 and ARL13B in A549 cells transfected with siRNAs

against IFT88 (siIFT88-1/2), ARL13B (siARL13B-1/2), or NC. GAPDH

was employed as a loading control. The values under the immunoblot

bands indicate the quantitative densitometry value measured using

ImageJ software. (B-D) Immunofluorescence labeling of primary cilia

(ARL13B, red) and basal bodies (γ-tub, green) in A549 control cells

(Ctrl) and cells transfected with siIFT88-1/2, siARL13B-1/2, or NC

following treated with 10 µM Gef for 48 h, (C) the proportion of

ciliated cells and (D) cilium length in each group. Ctrl, n=52;

Gef-NC, n=59; Gef-siIFT88-1, n=57; Gef-siIFT88-2, n=64;

Gef-siARL13B-1, n=56; Gef-siARL13B-2, n=69. The nuclei were stained

with DAPI (blue). (E and F) A549 cells transfected with NC,

siIFT88-1/2, or ARL13B-1/2 siRNAs were exposed to (E) Gef (0, 5, 10

µM) or (F) Dac (0, 1, 5 µM) for 48 h, the cell viability related to

untreated control was measured. (G and H) A549 cells transfected

with indicated siRNAs were exposed 10 µM Gef for 48 h and stained

with PI to detect the dead cells and quantification data for each

group. Scale bar, 100 µm. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Error bars, ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001

compared with NC. siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative

control; Gef, gefitinib; Dac, dacomitinib; BF, bright field; SD,

standard deviation. |

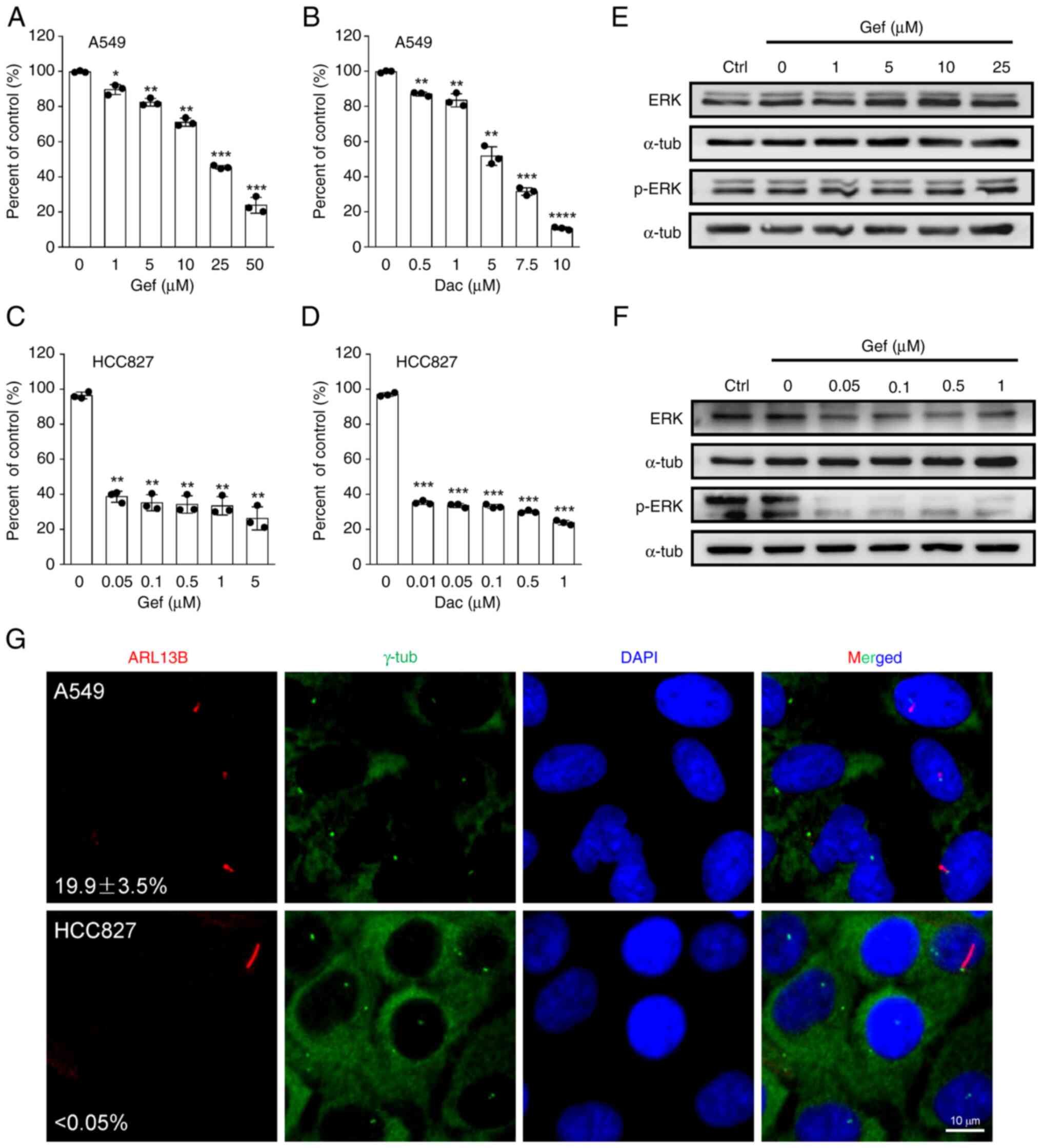

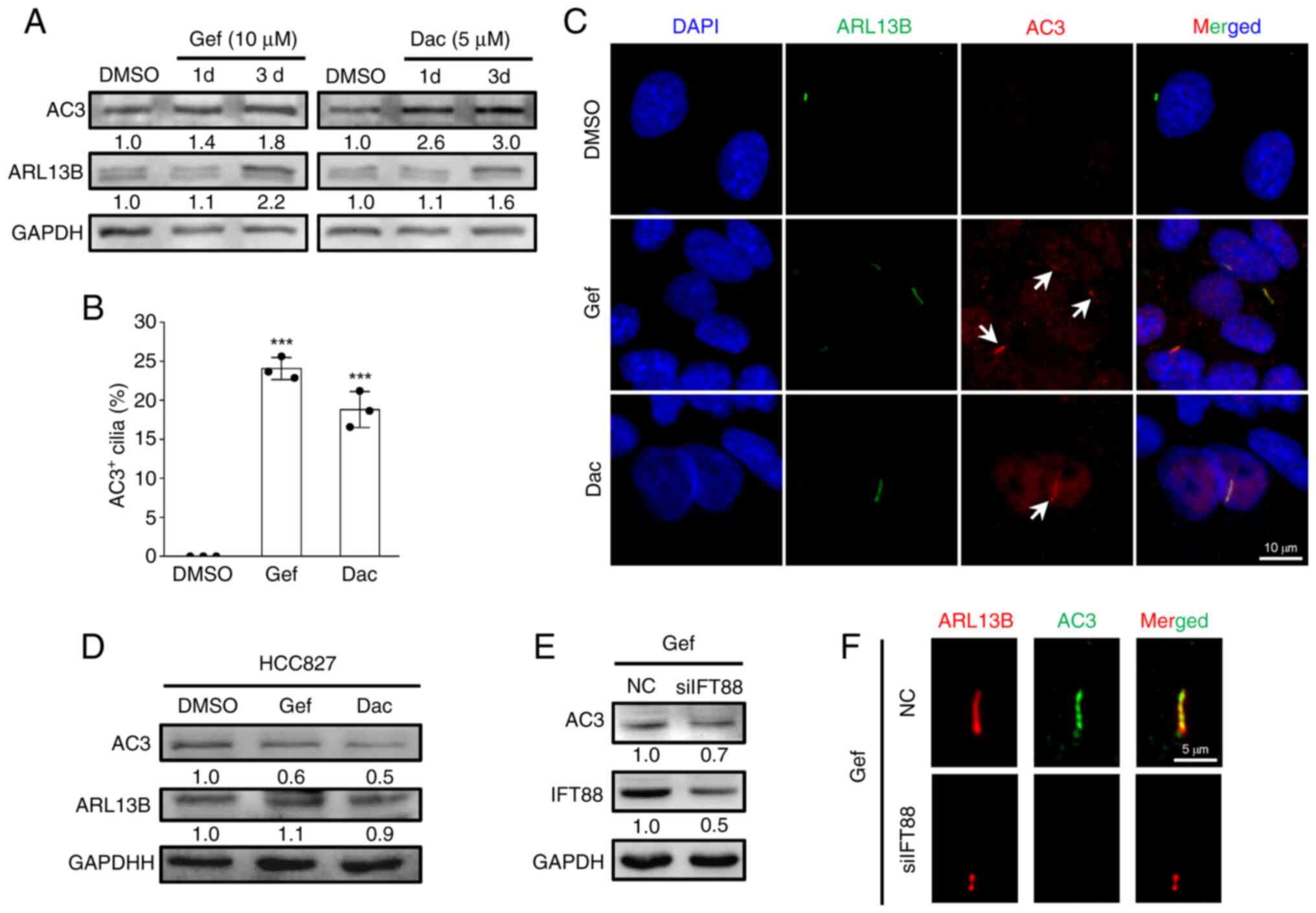

EGFR-TKIs promote AC3 expression and

ciliary localization

To gain insight into the role for AC3 in primary

cilia-mediated cellular resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC cells, the

expression of AC3 in responding to Gef and Dac stresses in A549

cells were detected. As demonstrated in Fig. 5A, both Gef and Dac treatment leads

to persistent upregulation of AC3 protein expression, which is in

accordance with ciliary gene ARL13B protein expression. Previously,

it has been reported that AC3 presents on primary cilia in multiple

cell types such as synoviocyte (20) osteocyte (26) and astrocyte (27). To determine AC3 subcellular

localization in NSCLC cells exposed to EGFR-TKIs, A549 cells were

treated with DMSO (0.1%), Gef (10 µM) and Dac (5 µM) for 3 days

followed by visualization of the primary cilia with

immunofluorescence staining of antibodies against ARL13B, and the

results identified that the proportion of AC3 positive cilia

increased to >20% in Gef- and Dar-treated cells while that was

merely found in DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 5B and C). However, EGFR-TKIs

treatment slightly altered ARL13B expression levels and even

decreased AC3 expression levels in HCC827 cells (Fig. 5D), indicating different responses of

ciliogenesis and AC3 expression to EGFR-TKI stress between A549 and

HCC827 cells. Furthermore, it was found that Gef-induced AC3

expression and ciliary localization were mitigated by disruption of

primary cilia (Fig. 5E and F).

Collectively, these results indicated that EGFR-TKI-induced AC3

expression and localization to primary cilia may contribute to

cellular drug resistance.

| Figure 5.Epidermal growth factor

receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors induce AC3 expression and

ciliary localization. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of the expression

levels of AC3 and ARL13B in A549 cells exposed to DMSO (0.1%), Gef

(10 µM) and Dac (5 µM) for 1 and 3 days. (B and C)

Immunofluorescence labeling of primary cilia (Arl13b, green) and

AC3 (red, indicated by white arrows) in A549 cells administrated

with DMSO (0.1%), Gef (10 µM), and Dac (5 µM) for 3 days, and

quantification of AC3 positive (AC3+) cilia in each

group. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm.

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Error bars, ± SD.

***P<0.001 compared with DMSO. (D) Immunoblotting analysis of

the expression levels of AC3 and ARL13B in HCC827 cells exposed to

DMSO (0.1%), Gef (0.05 µM) and Dac (0.01 µM) for 3 days. (E)

Immunoblotting analysis of the protein expression levels of AC3 and

IFT88 in Gef-treated A549 cells transfected with siIFT88-1

(siIFT88) or NC siRNA for 3 days. (F) Immunofluorescence labeling

of primary cilia (Arl13b, red) and AC3 (green) in cells in (E).

Scale bar, 5 µm. GAPDH was used as a loading control; the values

under the immunoblot bands indicate the quantitative densitometry

value measured using ImageJ software. Gef, gefitinib; Dac,

dacomitinib; SD, standard deviation; si-, small interfering; NC,

negative control; AC3, adenylate cyclase 3. |

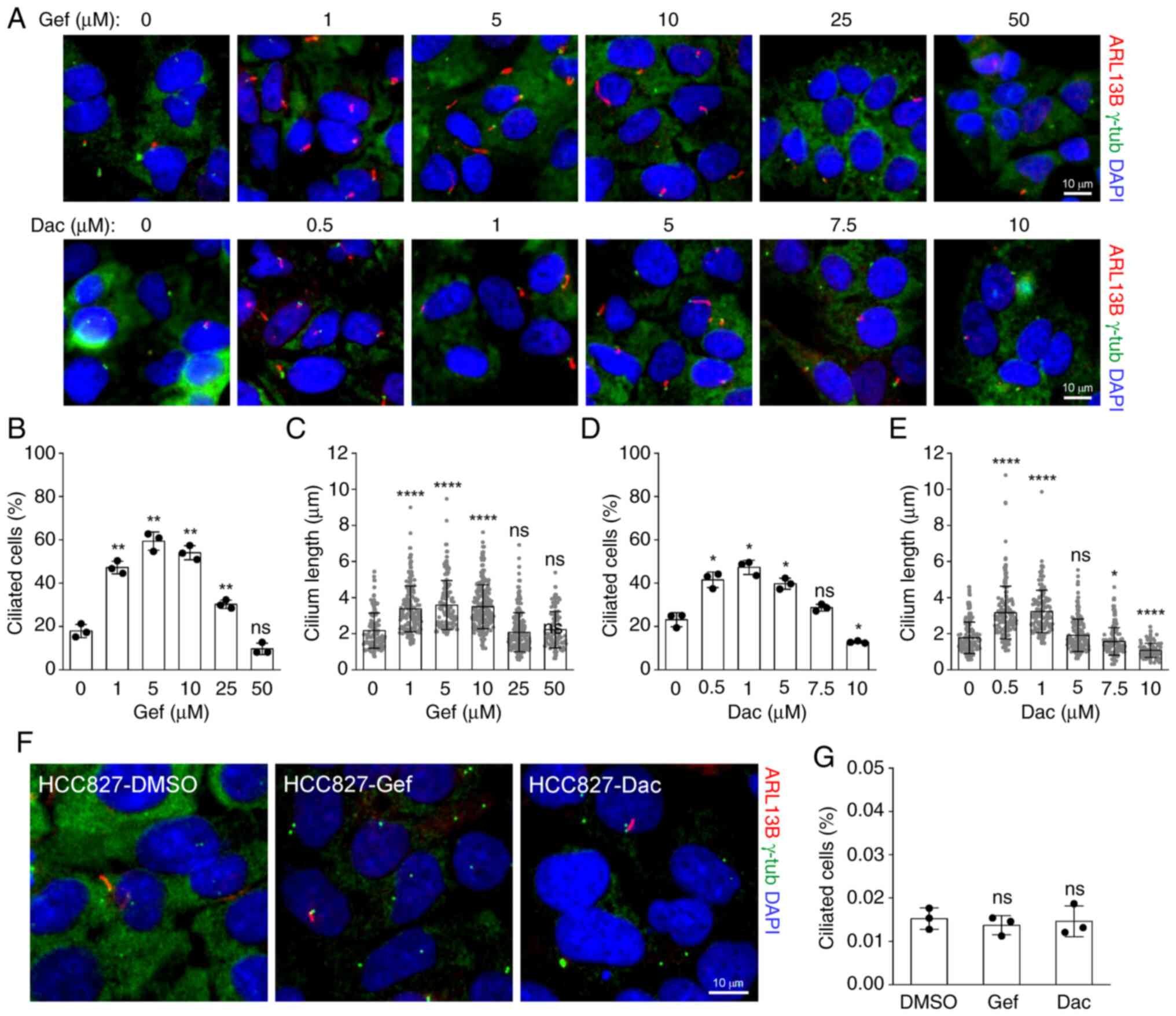

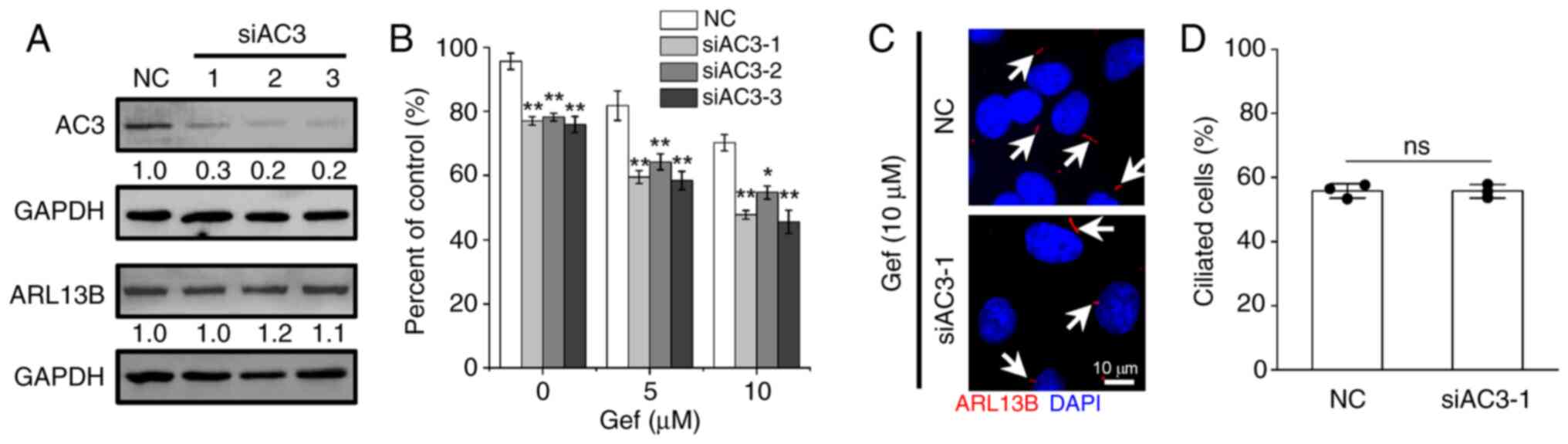

Suppression of AC3 expression is

sufficient to sensitize A549 cells to Gef

Given that EGFR-TKIs promote AC3 expression and

presence on primary cilia, the role of AC3 in cellular EGFR-TKI

sensitivity was investigated. Three individual siRNAs specifically

against AC3 (siAC3-1/2/3) were introduced to suppress its protein

expression (Fig. 6A), whereas the

expression of ARL13b was merely affected upon siAC3 treatment.

Subsequently, the cell viability was measured and the results

showed that the cellular sensitivity was significantly enhanced in

A549 cells transfected with siAC3 compared with that transfected

with NC siRNA following Gef combination treatment at 0, 5 and 10 µM

for 48 h (Fig. 6B), indicating a

positive association between AC3, cell proliferation and drug

resistance ability. Additionally, inhibition of AC3 could induce or

reduce cilia elongation in different cell types (20,26),

suggesting a feedback regulation of AC3 for ciliogenesis. To

address this issue, the cilia frequency of A549 cells transfected

with siAC3-1 or NC was detected following 10 µM Gef administrations

for 48 h. However, it was found that the proportion of ciliated

cells was barely altered upon AC3 suppression (Fig. 6C and D), indicating that

EGFR-TKIs-induced cilia formation is not associated with AC3

expression and cilia localization.

| Figure 6.Silencing AC3 expression enhances

cellular sensitivity to Gef. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of the

expression levels of AC3 and ARL13B in A549 cells transfected with

siRNAs targeting AC3 (siAC3-1/2/3) or NC for 48 h. GAPDH was used

as a loading control. The values under the immunoblot bands

indicate the quantitative densitometry value measured using ImageJ

software. (B) A549 cells transfected NC or siAC3-1/2/3 were exposed

to Gef (0, 5, 10 µM) for 48 h, the cell viability related to

untreated control was measured. (C and D) Immunofluorescence

labeling of primary cilia (Arl13b, red, indicated by white arrows)

in A549 cells transfected with NC and siAC3-1 following

administrated with Gef (10 µM) for 3 days, and quantification of

ciliated cells in each group. The nuclei were stained with DAPI

(blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Error bars, ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 compared with NC. AC3,

adenylate cyclase 3; Gef, gefitinib; si-, small interfering; NC,

negative control; SD, standard deviation; ns, not significant. |

Discussion

In the present study, it was demonstrated that

EGFR-TKIs facilitate primary ciliogenesis in the drug-insensitive

A549 and H23 cells but not in the drug-sensitive HCC827 and PC9

cells. Specifically, it was revealed that the disruption of primary

cilia reduces cellular resistance to EGFR-TKIs, potentially linked

to AC3 expression and its ciliary localization. Together, these

results suggested a connection between the primary cilia-AC3 axis

and cellular sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC.

Primary cilia, functioning as antennae on cell

surface, play a crucial role in responding to extracellular signals

by coordinate various signaling pathways that regulate cell

proliferation, division, migration, metabolism and physiology

(28). Despite the frequent loss or

repression of primary cilia in numerous solid tumor types (9), an increasing number of small molecular

anticancer drugs, including diverse protein kinase inhibitors, have

been identified that can restore ciliogenesis in cancer cells

(14,16,29,30).

This restoration suppresses cancer progression and alters drug

sensitivity simultaneously (31).

In the EGFR-mutant NSCLS cell line HCC4006, which completely lacks

primary cilia, sustained administration of the EGFR-TKI erlotinib

results in acquired drug resistance and increased ciliogenesis

(14). In the present study, the

results revealed that EGFR-TKI de novo-resistant NSCLC A549

cells maintain a significantly larger population of ciliated cells

than drug-sensitive HCC827 cells (Fig.

1), and short-term exposure to Gef and Dac further enhances

primary cilia formation in A549 and H23 cells but not in HCC827 and

PC9 cells (Figs. 2 and S2), suggesting that primary cilia may be

one of the EGFR-TKI resistance mechanisms in EGFR wild-type NSCLC

compared with EGFR mutant type. Thus, these results robustly

confirm the involvement of primary cilia in both the innate and

adaptive resistance of NSCLC to EGFR-TKIs.

The molecular mechanisms underlying acquired

resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC predominantly involve

reactivation, bypass and indifference of the EGFR pathway (6). However, it remains limited in cancer

types lacking mutations of the drug target, hindering the

development and application of novel therapeutic strategies. As a

distinctive sensory organelle, primary cilia play crucial role in

cell fate determination in responding to anticancer drugs by

regulating receptors located on cilia (32). Notably, EGFR has been shown to

localize to primary cilia (33),

where its signaling activity is restrict appropriately (33). Additionally, the aberrant activation

of EGFR signaling leads to the loss of primary cilia via Aurora A

in oral mucosa carcinoma and human retinal epithelia RPE1 cells

(34,35), suggesting a negative feedback loop

between primary cilia and EGFR.

Activation of the EGFR pathway drives cell

proliferation, migration and metabolism through downstream

effectors including the PI3K-AKT, JAK-STAT and RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK

pathways (6). A recent study has

uncovered the role of primary cilia in facilitating AKT and ERK

activation induced by type A platelet-derived growth factor during

Leydig cell development (36).

Additionally, treatment with EGFR-TKIs significantly reduces

proliferation without causing cell death in various cancer cells,

with a process linked to YAP-mediated ciliogenesis (37,38).

The present findings also demonstrated that A549 cells experienced

strong G1 cell cycle arrest (Fig.

3A), formed cilia (Fig. 2A),

and subsequently entered senescence (Fig. 3H) rather than undergoing cell death

(Fig. 3F) after Gef and Dac

treatment, implicating a positive relationship between primary

cilia and senescence induced by EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC.

Accumulating evidence has highlighted the functional

role of primary cilia in cell fate determination. Loss of primary

cilia in thyroid cancer cells leads to apoptogenic stimuli and

subsequent apoptotic cell death both in vitro and in

vivo (39). Genotoxic

stress-induced ciliogenesis drives cell senescence initiation and

maintenance (13,40,41),

the removal of cilia increases cellular sensitivity to ionizing

radiation by inducing apoptosis in senescent cells (13). In the present study, results also

revealed that the suppression of primary cilia by knockdown of

ciliary gene IFT88 or ARL13B significantly enhanced the efficacy of

EGFR-TKIs against NSCLC (Fig. 4E and

F), potentially due to increased cell death (Fig. 4G and H). However, the specific type

of cell death remains unconfirmed in the present study. Further

investigation into the role of primary cilia in cell fate

determination and the underlying mechanisms may facilitate the

identification of novel therapeutic avenue to sensitize NSCLC to

EGFR-TKIs.

Accumulating evidence indicates a reciprocal

relationship between primary cilia and cellular senescence.

Increased ciliogenesis have been observed in senescent cells

triggered by various stimuli (13,42,43).

Conversely, it has been demonstrated that primary ciliogenesis is

an essential cellular process in senescence induction induced by

etoposide (43) or ionizing

radiation (13), mediated through

autophagy or HH signaling activation in tumor cells. Furthermore,

Ma et al (41) demonstrated

that stress-induced transient primary ciliogenesis is required for

senescence initiation in human fetal lung fibroblast IMR-90 cells

exposed to ionizing radiation, oxidative stress, or inflammatory

stimuli, and that these cilia disassemble after senescence entry

(41). However, a recent study by

the authors revealed persistent primary ciliogenesis in senescent

tumor cells following ionizing radiation, which critically

contributes to both the initiation and maintenance of senescence,

and targeting either primary cilia or the senescence-associated

BCL2 pathway with ABT-263 significantly enhanced the lethal effects

of radiation (44). Therefore,

targeting the crosstalk between primary cilia and senescence may

represent an effective strategy for improving treatment

efficacy.

The AC family numbers play a pivotal role in

physiological and biological processes by modulating cAMP-related

signaling pathways, primarily involving protein kinase A (PKA) and

cAMP-activated guanine exchange factor (EPAC) (17,45).

The upregulation of cAMP by AC1 has been shown to reduce apoptosis

induced by DNA damage by promoting DNA damage repair mechanisms,

thereby increasing cellular resistance to chemotherapy and

radiotherapy (46,47). AC3, recognized as a marker for

cilia, is localized within primary cilia in a cell type-dependent

manner (19). In the present study,

it was reported for the first time to the best of our knowledge,

that EGFR-TKIs provoke the expression and ciliary localization of

AC3 in NSCLC cells with wild-type EGFR that are insensitive to the

drugs (Fig. 5A-C). Furthermore, the

inhibition of AC3 expression was found to enhance the cytotoxic

effects of EGFR-TKIs (Fig. 6).

Although the downstream signaling pathways of AC3 were not

investigated, it is imperative to focus on cAMP-PKA/EPAC pathways,

as they are closely associated with senescence and survival

(45). Understanding these factors

is crucial for elucidating the mechanism of EGFR-TKI resistance

mediated by the cilia-AC3 axis.

Although the present results suggest a potential

functional interplay between primary cilia and cellular resistance

to EGFR-TKIs in wild-type EGFR NSCLC, several limitations and open

questions remain: i) While the present study discloses a novel

association between primary cilia and intrinsic resistance to

EGFR-TKIs, the absence of drug-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell

models precludes conclusions about their role in acquired

resistance; ii) neither alternative RTK pathway activation nor

aberrant EGFR downstream pathway activation, two crucial resistance

mechanisms (24), were examined, as

well as their relationship to primary cilia; iii) increased cell

death was observed in cilia-disrupted A549 cells treated with Gef

using PI staining, a method that cannot distinguish type of cell

death; iv) the study lacks in vivo validation using

tumor-bearing animal models or patient-derived organoids to

substantiate the functional role of primary cilia; and v) it was

found that EGFR-TKI treatment promotes cilia formation (Fig. 2A-E) and AC3 ciliary localization

(Fig. 5B and C), and the disruption

of ciliogenesis and interference of AC3 expression increases cell

sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs in A549 cells, whereas the involvement of

AC3 downstream signaling, particularly the cAMP-PKA/EPAC pathway

(45), in response to EGFR-TKI and

its contribution to drug resistance remain unexplored. Further

research is therefore required to elucidate the mechanisms by which

the primary cilia-AC3 axis modulates EGFR-TKI resistance in

NSCLC.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that the

primary cilia-AC3 axis contributes to cellular resistance to

EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC and underscores its potential as a sensitizing

strategy for combination therapy in NSCLC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Dan Xu and Dr

Qingfeng Wu (Biomedical Platform of the Public Technology Center,

Institute of Modern Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for

providing technical assistance in flow cytometric analysis.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Non-profit Central

Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

(grant no. 2019PT320005), the Science and Technology Research

Project of Gansu (grant nos. 23JRRA533, 24JRRA952 and 25JRRA1204),

the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

12375355) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (grant

no. 2021415).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LJ, LW and JHu conducted investigation, curated

data, developed methodology, acquired funding and wrote the

original draft. RZ and JC conducted investigation and developed

methodology. JHe and YY conceptualized and supervised the study,

wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and acquired funding.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

JHe and YY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hendriks LEL, Remon J, Faivre-Finn C,

Garassino MC, Heymach JV, Kerr KM, Tan DSW, Veronesi G and Reck M:

Non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 10:712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Pao W and Chmielecki J: Rational,

biologically based treatment of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 10:760–774. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, Maemondo M,

Kimura Y, Morikawa N, Watanabe H, Saijo Y and Nukiwa T: Prospective

phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naive patients with

advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor

receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol. 24:3340–3346. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L,

Cicenas S, Szczésna A, Juhász E, Esteban E, Molinier O, Brugger W,

Melezínek I, et al: Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicentre, randomised,

placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 11:521–529. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Du Z, Kan H, Sun J, Liu Y, Gu J,

Akemujiang S, Zou Y, Jiang L, Wang Q, Li C, et al: Molecular

mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase

inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Resist Updat.

82:1012662025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Satir P, Pedersen LB and Christensen ST:

The primary cilium at a glance. J Cell Sci. 123:499–503. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Anvarian Z, Mykytyn K, Mukhopadhyay S,

Pedersen LB and Christensen ST: Cellular signalling by primary

cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol.

15:199–219. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kiseleva AA, Nikonova AS and Golemis EA:

Patterns of ciliation and ciliary signaling in cancer. Rev Physiol

Biochem Pharmacol. 185:87–105. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shireman JM, Atashi F, Lee G, Ali ES,

Saathoff MR, Park CH, Savchuk S, Baisiwala S, Miska J, Lesniak MS,

et al: De novo purine biosynthesis is a major driver of

chemoresistance in glioblastoma. Brain. 144:1230–1246. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chao YY, Huang BM, Peng IC, Lee PR, Lai

YS, Chiu WT, Lin YS, Lin SC, Chang JH, Chen PS, et al: ATM- and

ATR-induced primary ciliogenesis promotes cisplatin resistance in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 237:4487–4503.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wei L, Ma W, Cai H, Peng SP, Tian HB, Wang

JF, Gao L and He JP: Inhibition of ciliogenesis enhances the

cellular sensitivity to temozolomide and ionizing radiation in

human glioblastoma cells. Biomed Environ Sci. 35:419–436.

2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ma W, Wei L, Jin L, Ma Q, Zhang T, Zhao Y,

Hua J, Zhang Y, Wei W, Ding N, et al: YAP/Aurora A-mediated

ciliogenesis regulates ionizing radiation-induced senescence via

Hedgehog pathway in tumor cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis

Dis. 1870:1670622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jenks AD, Vyse S, Wong JP, Kostaras E,

Keller D, Burgoyne T, Shoemark A, Tsalikis A, de la Roche M,

Michaelis M, et al: Primary cilia mediate diverse kinase inhibitor

resistance mechanisms in cancer. Cell Rep. 23:3042–3055. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee C, Yi J, Park J, Ahn B, Won YW, Jeon

J, Lee BJ, Cho WJ and Park JW: Hedgehog signalling is involved in

acquired resistance to KRASG12C inhibitors in lung

cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 15:562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Khan NA, Willemarck N, Talebi A, Marchand

A, Binda MM, Dehairs J, Rueda-Rincon N, Daniels VW, Bagadi M,

Thimiri Govinda Raj DB, et al: Identification of drugs that restore

primary cilium expression in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 7:9975–9992.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guo R, Liu T, Shasaltaneh MD, Wang X,

Imani S and Wen Q: Targeting adenylate cyclase family: New concept

of targeted cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 12:8292122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Johnson JLF and Leroux MR: cAMP and cGMP

signaling: Sensory systems with prokaryotic roots adopted by

eukaryotic cilia. Trends Cell Biol. 20:435–444. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Brewer KK, Brewer KM, Terry TT, Caspary T,

Vaisse C and Berbari NF: Postnatal dynamic ciliary ARL13B and ADCY3

localization in the mouse brain. Cells. 13:2592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ou Y, Ruan Y, Cheng M, Moser JJ, Rattner

JB and van der Hoorn FA: Adenylate cyclase regulates elongation of

mammalian primary cilia. Exp Cell Res. 315:2802–2817. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hong SH, Goh SH, Lee SJ, Hwang JA, Lee J,

Choi IJ, Seo H, Park JH, Suzuki H, Yamamoto E, et al: Upregulation

of adenylate cyclase 3 (ADCY3) increases the tumorigenic potential

of cells by activating the CREB pathway. Oncotarget. 4:1791–1803.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Quinn SN, Graves SH, Dains-McGahee C,

Friedman EM, Hassan H, Witkowski P and Sabbatini ME: Adenylyl

cyclase 3/adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 (CAP1) complex

mediates the anti-migratory effect of forskolin in pancreatic

cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 56:1344–1360. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hu L, Dong C, Wang Z, He S, Yang Y, Zi M,

Li H, Zhang Y, Chen C, Zheng R, et al: A rationally designed

fluorescence probe achieves highly specific and long-term detection

of senescence in vitro and in vivo. Aging Cell. 22:e138962023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yang Y, Li S, Wang Y, Zhao Y and Li Q:

Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in malignant tumors:

Molecular mechanisms and future perspective. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:3292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kim SO, Kim BY and Lee KH: Synergistic

effect of anticancer drug resistance and Wnt3a on primary

ciliogenesis in A549 cell-derived anticancer drug-resistant subcell

lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 635:1–11. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Duffy MP, Sup ME and Guo XE: Adenylyl

cyclase 3 regulates osteocyte mechanotransduction and primary

cilium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 573:145–150. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sterpka A and Chen X: Neuronal and

astrocytic primary cilia in the mature brain. Pharmacol Res.

137:114–121. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hilgendorf KI, Myers BR and Reiter JF:

Emerging mechanistic understanding of cilia function in cellular

signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25:555–573. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kiseleva AA, Korobeynikov VA, Nikonova AS,

Zhang P, Makhov P, Deneka AY, Einarson MB, Serebriiskii IG, Liu H,

Peterson JR and Golemis EA: Unexpected activities in regulating

ciliation contribute to off-target effects of targeted drugs. Clin

Cancer Res. 25:4179–4193. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Guen VJ and Prigent C: Targeting Primary

ciliogenesis with small-molecule inhibitors. Cell Chem Biol.

27:1224–1228. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Collinson R and Tanos B: Primary cilia and

cancer: A tale of many faces. Oncogene. 44:1551–1566. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Saito M, Otsu W, Miyadera K and Nishimura

Y: Recent advances in the understanding of cilia mechanisms and

their applications as therapeutic targets. Front Mol Biosci.

10:12321882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pant K, Richard S, Peixoto E, Baral S,

Yang R, Ren Y, Masyuk TV, LaRusso NF and Gradilone SA:

Cholangiocyte ciliary defects induce sustained epidermal growth

factor receptor signaling. Hepatology. 81:1132–1145. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yin F, Chen Q, Shi Y, Xu H, Huang J, Qing

M, Zhong L, Li J, Xie L and Zeng X: Activation of EGFR-Aurora A

induces loss of primary cilia in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral

Dis. 28:621–630. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kasahara K, Aoki H, Kiyono T, Wang S,

Kagiwada H, Yuge M, Tanaka T, Nishimura Y, Mizoguchi A, Goshima N

and Inagaki M: EGF receptor kinase suppresses ciliogenesis through

activation of USP8 deubiquitinase. Nat Commun. 9:7582018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tsai YC, Kuo TN, Chao YY, Lee PR, Lin RC,

Xiao XY, Huang BM and Wang CY: PDGF-AA activates AKT and ERK

signaling for testicular interstitial Leydig cell growth via

primary cilia. J Cell Biochem. 124:89–102. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee JE, Park HS, Lee D, Yoo G, Kim T, Jeon

H, Yeo MK, Lee CS, Moon JY, Jung SS, et al: Hippo pathway effector

YAP inhibition restores the sensitivity of EGFR-TKI in lung

adenocarcinoma having primary or acquired EGFR-TKI resistance.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 474:154–160. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Guo Y, Dupart M, Irondelle M, Peraldi P,

Bost F and Mazure NM: YAP1 modulation of primary cilia-mediated

ciliogenesis in 2D and 3D prostate cancer models. FEBS Lett.

598:3071–3086. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lee J, Park KC, Sul HJ, Hong HJ, Kim KH,

Kero J and Shong M: Loss of primary cilia promotes

mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in thyroid cancer. Sci Rep.

11:41812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jeffries EP, Di Filippo M and Galbiati F:

Failure to reabsorb the primary cilium induces cellular senescence.

FASEB J. 33:4866–4882. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ma X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Huang Y,

He K, Chen C, Hao J, Zhao D, LeBrasseur NK, et al: A stress-induced

cilium-to-PML-NB route drives senescence initiation. Nat Commun.

14:18402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Breslin L, Prosser SL, Cuffe S and

Morrison CG: Ciliary abnormalities in senescent human fibroblasts

impair proliferative capacity. Cell Cycle. 13:2773–2779. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Teng YN, Chang HC, Chao YY, Cheng HL, Lien

WC and Wang CY: Etoposide triggers cellular senescence by inducing

multiple centrosomes and primary cilia in adrenocortical tumor

cells. Cells. 10:14662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liu X, Wei L, Zhang R, Chen J, Zhang T,

Hua J, Wang J, He J and Xie X: The DNA-PKcs-primary cilia axis

maintains ionizing radiation-induced senescence in tumor cells.

Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2025.Doi: 10.3724/abbs.2025168.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhang H, Liu Y, Liu J, Chen J, Wang J, Hua

H and Jiang Y: cAMP-PKA/EPAC signaling and cancer: The interplay in

tumor microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol. 17:52024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ginsberg G, Angle K, Guyton K and Sonawane

B: Polymorphism in the DNA repair enzyme XRCC1: Utility of current

database and implications for human health risk assessment. Mutat

Res. 727:1–15. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zou T, Liu J, She L, Chen J, Zhu T, Yin J,

Li X, Li X, Zhou H and Liu Z: A perspective profile of ADCY1 in

cAMP signaling with drug-resistance in lung cancer. J Cancer.

10:6848–6857. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|