Introduction

Alternative splicing (AS) enables individual genes

to produce multiple mRNA isoforms, substantially expanding

eukaryotic proteomic diversity and functional complexity (1,2).

Occurring in ~95% of multi-exon genes, AS generates tissue- and

context-specific variants that regulate key processes such as

proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation (1,3,4). AS is

a critical mechanism for regulating gene expression (5). Its biological importance is also

highlighted by genomic studies and ~18% of cancer-associated

single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the COSMIC database are located

within splice-regulatory motifs (6). These mutations compromise exon-intron

recognition, often causing the production of aberrant transcripts

that support oncogenesis and resistance to therapy. In cancer,

aberrant AS causes transcriptomic rewiring that supports tumor

heterogeneity and adaptive evolution; for example, splice variants

such as BRCA1-Δ11q (1) and

BCL2L12 (3) have been

identified that interfere with apoptotic signalling, and variants

of CD44v, which facilitate epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

and metastasis. Pan-cancer analyses have allowed for the

identification of more than 15,000 cancer-specific splice variants,

numerous of which are associated with chemoresistance and stemness

(7,8). Such alterations are often the result

of mutations affecting spliceosomal components (for example,

SF3B1) or dysregulated splicing factors (for example,

QKI and PTBP1), which can rewire tumor phenotypes

allowing them to be more resilient to cell stresses and to survive

(8,9).

Despite significant progress in chemotherapy and

targeted therapies, drug resistance continues to pose a major

challenge in oncology and is responsible for more than 50% of

cancer-related deaths, with relapse rates exceeding 70% in

aggressive cancers such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

and glioblastoma (3,8). Although numerous established

resistance mechanisms involve secondary genetic mutations,

including reversion mutations that restore homologous recombination

in BRCA1/2-mutant cancers, increasing evidence underscores

the clinical relevance of dysregulated RNA splicing. For instance,

in BRCA1-mutant ovarian cancers, secondary splice-site

mutations (SSMs) that cause exon skipping (AS) and produce

resistant BRCA1 isoforms are detected in roughly 10% of patients

following PARP inhibitor therapy, a considerable increase from the

pretreatment frequency of ~1% (10). Pan-cancer analyses further reveal

that AS produces diverse tumor-specific neoantigens and

drug-resistant isoforms that promote immune evasion and treatment

failure across cancer types. Although the exact proportion of

splicing-mediated resistance has yet to be fully quantified and

likely varies by cancer type and regimen, splicing dysregulation

constitutes a major non-mutational pathway contributing

significantly to the overall resistance burden, second only to

genetic alterations (11,12).

AS-mediated mechanisms span diverse therapies:

BRCA1-Δ11q confers resistance to PARP inhibitors and

cisplatin in breast cancer (1),

while c-Mpl-del splice variants promote chemoresistance in acute

megakaryocytic leukemia (13).

Under hypoxic conditions, LUCAT1 recruits PTBP1 to alter

PARP3 splicing and foster oxaliplatin resistance in

colorectal cancer (CRC) (9),

paralleled by FBXO7 stabilization of RBFOX2 to drive

pro-survival FoxM1 and POSTN splicing in

temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma (3).

Key splicing factors act as molecular hubs:

QKI establishes basal-like splicing programs supporting PDAC

chemoresistance (8), while SNHG

family lncRNAs employ intron retention (IR) to suppress snoRNAs and

enhance hepatoblastoma drug tolerance (14). Although hypoxia-induced LUCAT1 binds

PTBP1 to modulate DNA damage response genes (9), the hierarchical organization of these

regulatory networks remains undefined. Elucidating these mechanisms

will require integrated approaches to identify master regulators

and advance isoform-directed therapeutic strategies.

Molecular architecture of AS in cancer

Classification of AS events

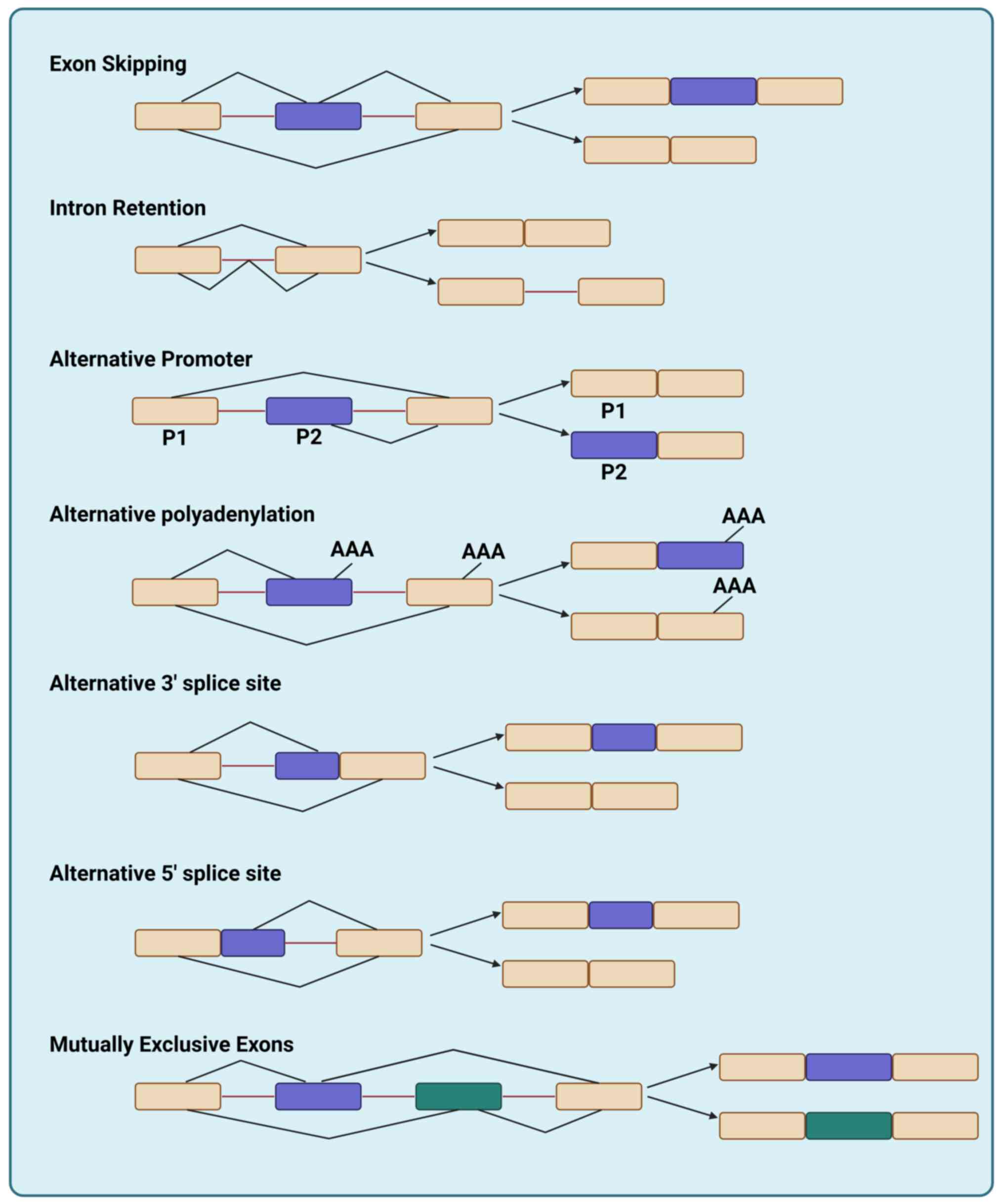

Canonical AS classification and the splicing

resistance map framework

Transcripts from nearly all human protein-coding

genes undergo one or more modes of AS, such as inclusion or

skipping of individual ‘cassette’ exons, selection between

alternative 5′ and 3′ splice sites, differential retention of

introns, mutually exclusive splicing of adjacent exons, and other,

more complex patterns of splicing (15). These diverse outcomes are broadly

classified into classical patterns of AS, such as ES, IR,

alternative promoter (AP) usage, alternative polyadenylation (APA),

alternative 3′ splice site, alternative 5′ splice site and mutually

exclusive exons (MXE) (Fig. 1).

These canonical splicing patterns constitute the foundational

elements of the ‘splicing resistance map’, a unified landscape of

AS events that collectively underlie therapeutic resistance across

diverse cancers. In The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) pan-cancer

analysis, AP and ES were the most prevalent splicing patterns;

importantly, these frequencies were derived from bulk tumor

transcriptomes and therefore reflect composite signals from

malignant and stromal/immune cells (16) (Fig.

S1).

ES is reported to be one of the most common AS

event, characterized by loss of functional domains/sites or a shift

in the open reading frame, leading to a variety of human diseases

(17), which involves the exclusion

of specific exons during mRNA maturation, often modifying protein

domains critical for tumor progression (18–20).

ES events constitute a prominent component of the splicing

resistance map, yielding isoforms that circumvent targeted

therapies. For example, in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC),

PRMT5 inhibition induces ES in AURKB transcripts, resulting

in mitotic catastrophe and chemoresistance by disrupting chromatin

stability (21). In the mesenchymal

subtype of CRC (CMS4), retention of exon 17 in the MYOF gene

and skipping of exon 11 in the ENAH gene underlie poor

prognosis and enhanced chemoresistance by promoting EMT and

augmenting tumor invasiveness (22). IR, once considered rare, is now

recognized as a hallmark of aggressive malignancies (23–26).

IR events represent a major axis of the splicing resistance map,

particularly in advanced and therapy-refractory malignancies. In

prostate cancer, IR induces the accumulation of aberrant

transcripts (for example, SNHG19), which fosters castration

resistance and stemness by impairing DNA repair pathways, enhancing

chemoresistance, and activating oncogenic cascades, thereby

nominating the spliceosome as a promising therapeutic target whose

inhibitors reverse IR-mediated aggressive phenotypes (27,28).

APs, involve the use of different transcription

start sites within a gene, thereby altering the 5′-untranslated

regions (UTRs) sequences to generate distinct variants. Promoters

not only determine when a gene is active and to what extent, but

also regulate which gene isoforms are expressed (29). AP-mediated isoform switching

constitutes a central mechanism within the splicing resistance map,

facilitating adaptive transcriptional reprogramming under

therapeutic pressure. APs enable tissue-specific isoform

expression, as observed in MET exon 14 skipping in non-small cell

lung cancer (NSCLC), where splice site mutations produce oncogenic

isoforms that evade kinase inhibitor targeting (30). In prostate cancer, distal APs

(P2/P3) supersede the proximal promoter (P1) to drive

UGT2B17 transcription, generating n2/n3 isoforms, which

contain additional 5′ exons (for example, 1b/1c) through AS and

encode full-length proteins, that dominate the androgen

inactivation pathway in localized and metastatic tumors (31). In liver cancer, selective DNA

methylation loss in CpG-poor regions increases chromatin

accessibility, thereby enabling the binding of tissue-specific

transcription factors and activation of APs, which drive

tumor-specific transcription (32).

These canonical AS patterns are systematically cataloged in

large-scale projects such as TCGA, which demonstrated that >90%

of cancer-related genes exhibit at least one AS event (33). Computational analysis of these

splicing events employs specialized tools including the SpliceSeq

package, which aligns RNA-Seq reads to a gene-specific exon

junction graph and computes Percent Spliced In values to

systematically quantify exon or splice junction inclusion across

numerous tumor and normal samples (34). Long-read sequencing has recently

revealed that 30% of isoforms in breast cancer contain unannotated

ES or IR events, numerous of which are associated with

HER2+ or TNBC subtypes (21,33).

Other common splicing classes include MXE, exemplified by CD44

variants that promote ovarian cancer metastasis, and alternative

3′/5′ splice site selection that alters EGFR kinase domains to

confer tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance (35).

Functionally classified isoforms in

therapy resistance

New classification systems focus on AS events that

directly influence therapeutic response, particularly those

enabling drug resistance. Understanding these mechanisms requires

precise definition of ‘therapy-resistance-associated isoforms’,

alternatively spliced mRNAs experimentally demonstrated to confer

resistance by modifying drug targets, activating compensatory

pathways, or enhancing survival (10–12).

To qualify, isoforms must satisfy three criteria: i) functional

validation through drug sensitivity assays; ii) association with a

specific treatment; and iii) identification in human tumors or

clinically relevant models.

Numerous examples demonstrate this concept. In PARP

inhibitor-resistant ovarian cancer, BRCA1 exon 11 skipping

generates Δ11q isoforms that restore homologous recombination

repair (HRR) capacity, circumventing nonsense-mediated decay

(10). Similarly, NT5C2 exon

6a inclusion yields a hyperactive nucleotidase conferring

6-mercaptopurine resistance in leukemia (36). NSCLC with KRAS G12 mutations

exhibits MET exon 14 skipping that activates RAS/ERK

signaling to evade MET inhibitor effects (30). Splicing alterations also perturb

epigenetic regulation: PRMT5 inhibition in CDK4/6

inhibitor-resistant breast cancer induces FUS-dependent IR,

impairing DNA synthesis proteins such as PCNA and MCM2 (37). Given their clinical relevance, these

mechanisms are emerging as therapeutic targets themselves, for

instance, CRISPR/dCasRx-mediated exclusion of TIMP1 exons

counteracts SRSF1-driven splicing and attenuates metastasis in CRC

(38). Such subclassifications are

transforming precision oncology, with clinical trials currently

evaluating splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs)

targeting PTBP1 in glioblastoma (39). Additionally, APA events in

BCL2L1 produce anti-apoptotic isoforms in hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC), while poison exon inclusion in MAP3K7

disrupts TGF-β signaling to foster chemoresistance (27,35).

Isoforms are excluded from this category if evidence is purely

computational or derived from correlative expression without direct

functional proof, or if the resistance mechanism is indirect (for

example, via general proliferation effects) (10–12).

Representative isoforms that satisfy these criteria,

highlighting their drug contexts, functional validation methods,

and clinical evidence levels are presented in Table I.

| Table I.Exemplary

therapy-resistance-associated isoforms. |

Table I.

Exemplary

therapy-resistance-associated isoforms.

| First author/s,

year | Isoform | Gene | Drug context | Functional

assay | Clinical evidence

level | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Nesic et al,

2024 | Δ11q | BRCA1 | PARP inhibitors

(olaparib, rucaparib) | RNA-seq, minigene

assays, CRISPR/Cas9 | Patient biopsies,

PDX models | (10) |

| Bradley and

Anczuków, 2023 | BQ323636.1 | NCOR2 | Tamoxifen,

aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole) | RNA-seq,

immunohistochemistry, siRNA knockdown | Patient tissue

microarrays, cell lines | (11) |

| Sciarrillo et

al, 2020 | AR-V7 | AR | Androgen receptor

inhibitors (enzalutamide, abiraterone) | RT-qPCR,

RNA-sequencing, circulating tumor cell analysis | Patient circulating

tumor cells | (40) |

| Kahles et

al, 2018 | PKM2 | PKM | Metabolic

inhibitors (for example, glycolysis inhibitors) | siRNA knockdown,

CRISPR screening | Pan-cancer TCGA

data, cell lines | (12) |

| Sciarrillo et

al, 2020 | HER2Δ16 | ERBB2 | Trastuzumab | Immunoblotting,

colony formation assays | Breast cancer

patient biopsies | (40) |

|

| BRAF p61 | BRAF | Vemurafenib | RNA-seq, protein

immunoprecipitation | Melanoma

biopsies |

|

|

| CD44v6 | CD44 | 5-FU, radiation

therapy | Antibody blockade,

RNA interference | Patient tumor

samples, cell lines |

|

|

| MENAINV | ENAH | Paclitaxel | Invasion assays,

isoform-specific antibodies | Breast cancer

metastases |

|

|

| BARD1β | BARD1 | PARP

inhibitors | Immunoblotting,

homologous | Colon cancer cell

lines |

|

|

|

|

|

| recombination

assays |

|

|

|

| KLF6-SV1 | KLF6 | Sorafenib,

cisplatin | Apoptosis assays,

xenograft models | Hepatocellular

carcinoma samples |

|

|

| CHK1-S | CHEK1 | DNA-damaging

agents | Kinase activity

assays, survival analysis | Patient tumor

tissues |

|

|

|

|

| (for example,

topotecan) |

|

|

|

|

| RonΔ165 | MST1R | MET inhibitors

(crizotinib) | Migration assays,

immunoblotting | PDX models, NSCLC

cell lines |

|

|

| FGFR1β | FGFR1 | FGFR inhibitors

(erdafitinib) | Proliferation

assays, reverse transcription | Bladder cancer

models |

|

|

|

|

|

| PCR |

|

|

|

| IL-6R soluble | IL6R | Tocilizumab | ELISA, signaling

pathway analysis | Patient serum

samples |

|

|

| CD19e2Δ | CD19 | CAR-T therapy | Flow cytometry,

sequencing | B-ALL patient

samples at relapse |

|

|

| CD22e2Δ | CD22 | CAR-T therapy | Isoform-specific

PCR, cytotoxicity assays | B-cell malignancy

models |

|

|

| USP5s | USP5 | Gemcitabine | Splicing

modulation, drug sensitivity tests | Glioma cell

lines |

|

|

| MDM4-S | MDM4 | MDM2 inhibitors

(nutlin-3) | Apoptosis assays,

xenograft studies | Patient tumor

tissues |

|

|

| SRSF3-S | SRSF3 | Paclitaxel | Colony formation,

ASO treatment | Oral squamous cell

carcinoma |

|

|

| circCDYL2 | CDYL2 | Cisplatin,

radiation | RNAi, miRNA

sponging assays | Patient plasma,

xenograft models |

|

|

| VEGFxxxb | VEGFA | Anti-angiogenic

therapies | Splicing reporter

assays, tube formation | Patient serum and

tumor tissues |

|

|

|

|

| (bevacizumab) | assays |

|

|

This systematic compilation underscores the

diversity of splicing-mediated resistance mechanisms, which often

coexist with genetic mutations and contribute substantially to

treatment failure. Functional validation through targeted assays

(for example, CRISPR and ASOs) is essential to establish causality,

while clinical evidence ranges from preclinical models to direct

patient data, highlighting the translational relevance of these

isoforms (10,12,40).

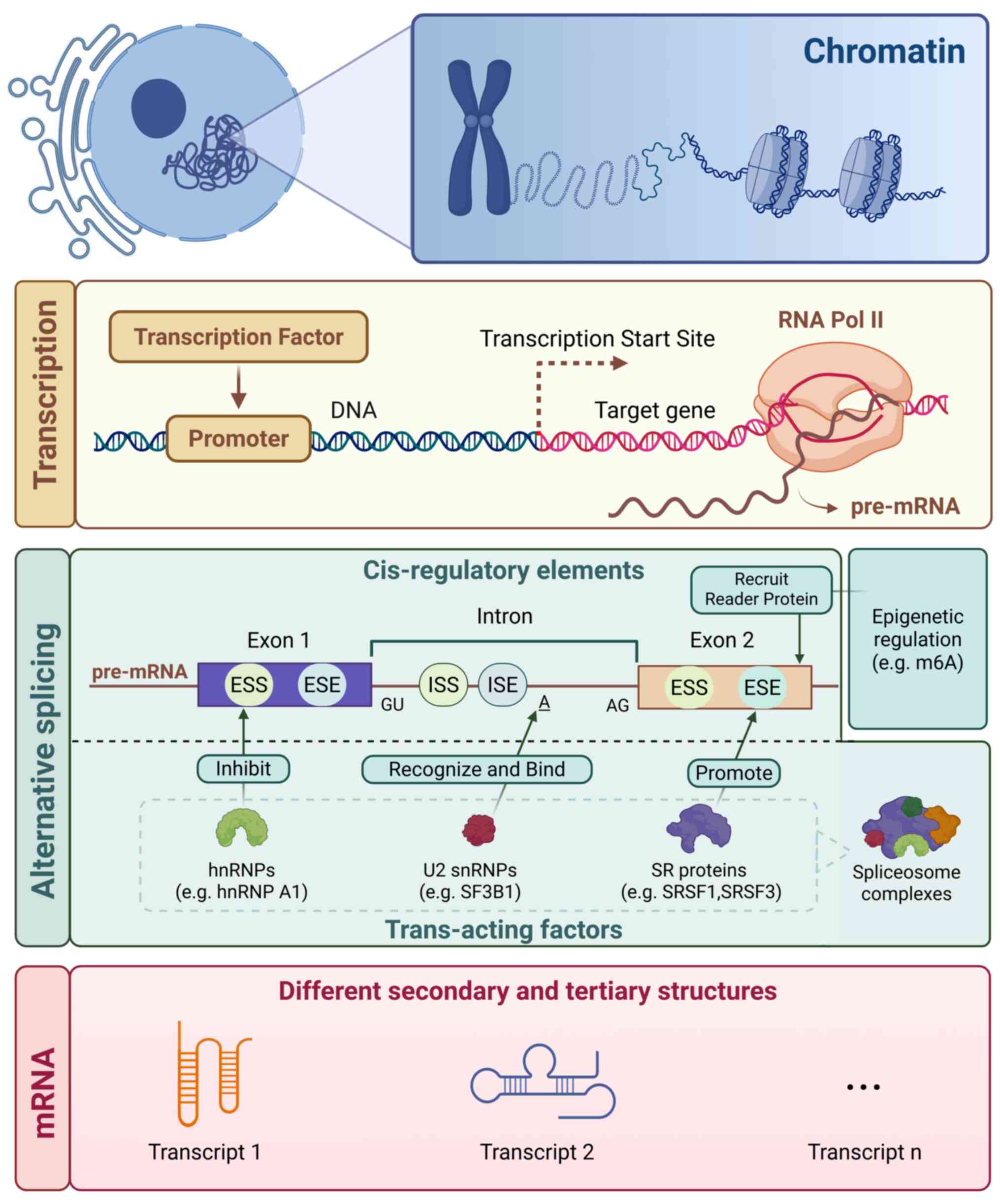

Cis-regulatory elements and trans-acting

factors

Cis-regulatory elements and

trans-acting factors form the molecular scaffold of AS regulation

in cancer

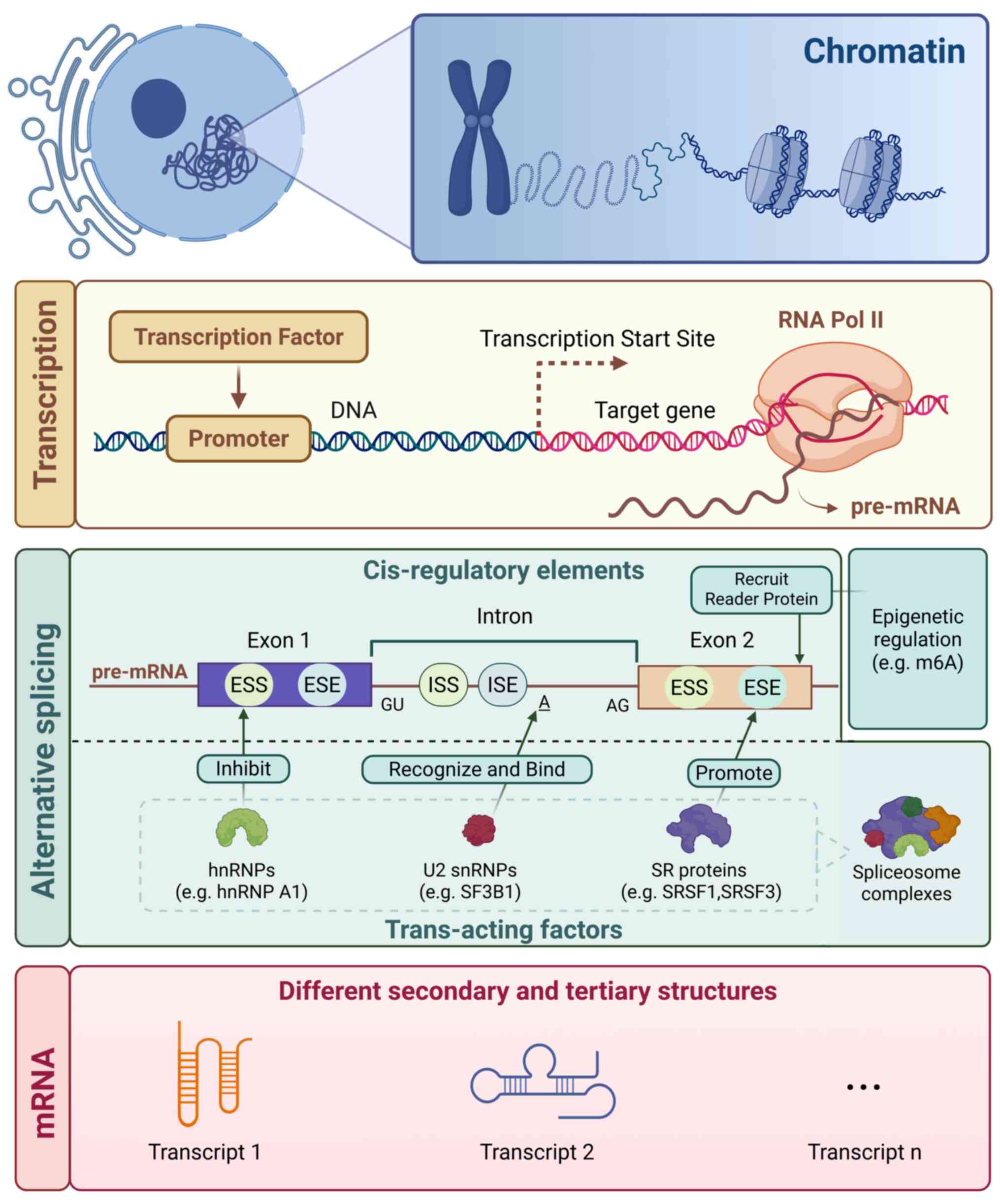

Cis-acting elements, including exonic/intronic

splicing enhancers (ESE/ISE) and silencers (ESS/ISS), are

nucleotide sequences within pre-mRNA that recruit trans-acting

regulators (for example, SR proteins, hnRNPs) to govern splice site

selection (41,42), Cell-type specific gene expression

patterns are regulated by cis-regulatory elements such as promoters

and enhancers (43) (Fig. 2). Moreover, the regulation of AS

entails recognition of cis-acting RNA elements in the pre-mRNA by

trans-acting protein splicing factors (44). These elements operate

combinatorially to enhance or repress spliceosome assembly, with

mutations or dysregulated expression commonly observed in cancer

(12). For example, BCL2L1

ESE mutations drive pro-survival BCL2L1-L isoform

expression, conferring apoptosis resistance (40). Genome-wide analyses indicate that

~15% of cancer-associated mutations map to splicing regulatory

elements, with ESE/ESS regions in oncogenes for example,

MET) exhibiting recurrent alterations (12,45).

| Figure 2.Alternative splicing mechanism and

spliceosome complex proteins with their functions. Pre-mRNA

splicing is the process of removal of intronic regions and joining

the exons to form mature mRNA. Trans-acting factors consist of

splicing factors which recognize conserved premRNA sequences

(cis-regulatory elements) and recruit the core spliceosome

machinery which coordinates and executes the excision of introns.

U2 snRNP (for example, SF3B1) recognizes and binds to branch point

A, initiating spliceosome assembly and splicing reactions; SR

proteins (for example, SRSF1) primarily bind to ESE elements (with

partial assistance from ISE elements) to promote splicing; hnRNPs

(for example, hnRNP A1) inhibit splicing by binding to ESS/ISS

elements; epigenetic regulation (for example, m6A modification)

acts on exons through recruiting reader proteins (for example,

YTHDC1). These factors collectively act on pre-mRNA, regulating

alternative splicing and ultimately generating distinct mRNA

transcripts. ESE, exonic splicing enhancer; ISE, intronic splicing

enhancer; ESS, exonic splicing silencer; ISS, intronic splicing

silencer. |

Integrated cis-trans-epigenetic

mechanisms enable adaptive therapy resistance

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells exhibit ESS

defects in SRSF1-targeted transcripts (for example, PRKCH),

sustaining oncogenic signaling despite BCR-ABL1 inhibition

(46). Glioblastoma-associated

SF3B1 inhibition alters BCL2L1 splicing, favoring

anti-apoptotic isoform expression (47). High-throughput studies identify

recurrent ESE/ESS mutations in drug resistance genes (for example,

ABCB1), which disrupt repressive elements to circumvent

therapy (44). For example,

aberrant ESS motifs in TP53 exon 6 promote ES, generating

dominant-negative isoforms that compromise chemotherapy-induced

apoptosis (40). SR proteins (for

example, SRSF1) and hnRNPs (for example, hnRNP A1) are frequently

overexpressed in therapy-resistant cancers. In CML, SRSF1

upregulation enhances BCL2L1 exon 2 inclusion, elevating

pro-survival BCL2L1-S isoforms and undermining imatinib-induced

apoptosis (46). SF3B1 dysfunction

in glioblastoma drives BCL2L1-L overexpression via preferential 3′

splice site selection, facilitating temozolomide evasion (47). Post-transcriptional modifications

further modulate splicing factor activity: METTL3-mediated m6A

methylation stabilizes SRSF1 mRNA in pancreatic cancer,

potentiating cisplatin resistance (48). Epigenetic regulation, encompassing

DNA methylation and RNA epitranscriptomics (for example, m6A),

modulates splicing by altering RNA-protein interactions (49–51).

In gastric cancer, SNORA37 promotes CMTR1-ELAVL1

interaction to drive CD44 AS and tumor progression (52). Dysregulation of the epigenome drives

aberrant transcriptional programs that promote cancer onset and

progression (53,54). METTL3 deposits m6A on

QSOX1 exon 14, recruiting YTHDC1 to enhance exon inclusion

and β-catenin activation, thereby conferring gefitinib resistance

in NSCLC (55). Conversely, ALKBH5

erases m6A from FOXO1 mRNA, enabling SRSF3 binding and

anti-apoptotic isoform generation (55). Chromatin remodelers (for example,

SWI/SNF) also influence splicing: ARID1A loss induces

BRD9 ES, activating Wnt signaling in ovarian cancer

(44). These findings collectively

define a dynamic ‘splicing code’ that integrates cis-regulatory

mutations, trans-factor dysregulation and epigenetic modifications,

a multilayered system that enables tumor cells to rapidly adapt and

develop resistance to targeted therapies, chemotherapy, and

epigenetic drugs (Fig. 2).

Splicing dysregulation: Protein

alterations and cis-element mutations

Altered spliceosome proteins due to somatic

mutations, overexpression or post-translational modifications are

key drivers of aberrant splicing that promotes tumour survival and

therapy resistance. Mutations in SF3B1 in glioblastoma lead

to ES such as BRCA1-Δ11q that results in a hypomorphic

isoform that provides resistance to PARP inhibition (12). In CML, SRSF1 is overexpressed in

leukemic blasts and IL-3 maintains SRSF1 expression following

BCR-ABL1 inhibition, leading to imatinib resistance via PKC-

and PLC-dependent mechanisms (46).

These events promote proliferation and inhibit apoptosis providing

a selective advantage in cancer.

DNA cis-element mutations (for example, in exonic

splicing silencers) disrupt trans-factor binding, leading to

aberrant splicing and drug resistance. In acute lymphoblastic

leukemia (ALL), NT5C2 exon 6a inclusion creates a

gain-of-function isoform with elevated nucleotidase activity,

driving resistance to 6-mercaptopurine (36). These mutations are enriched in

relapse samples and represent promising targets for ASOs due to

their sequence-specific nature; ASOs can be designed to bind mutant

cis-elements or aberrant splice sites, blocking incorrect splicing

and restoring normal isoform expression. This re-sensitizes cells

to therapy, as demonstrated in leukemia models where ASOs reversed

chemoresistance by correcting NT5C2 splicing (Figs. 3B and 4) (36).

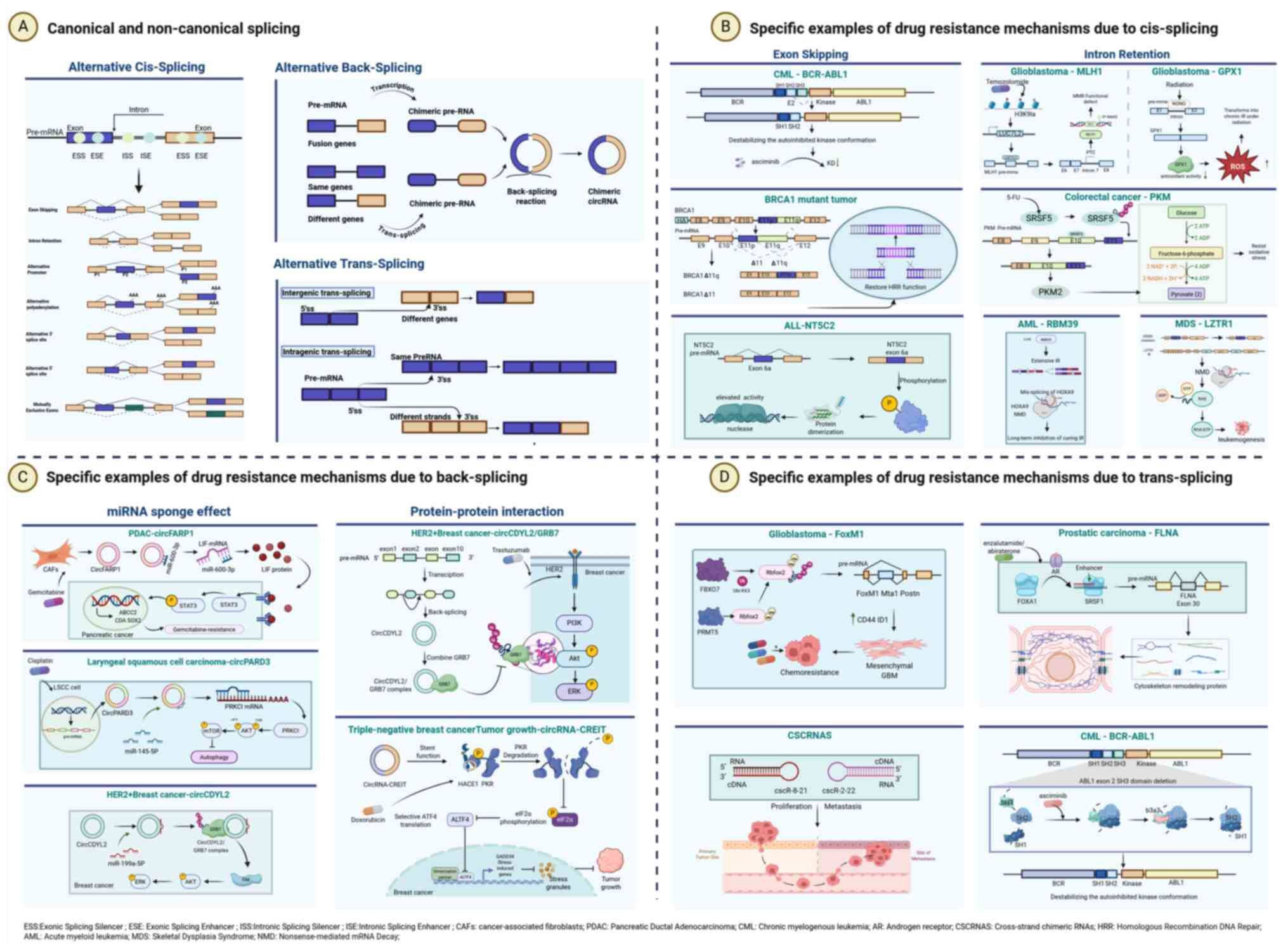

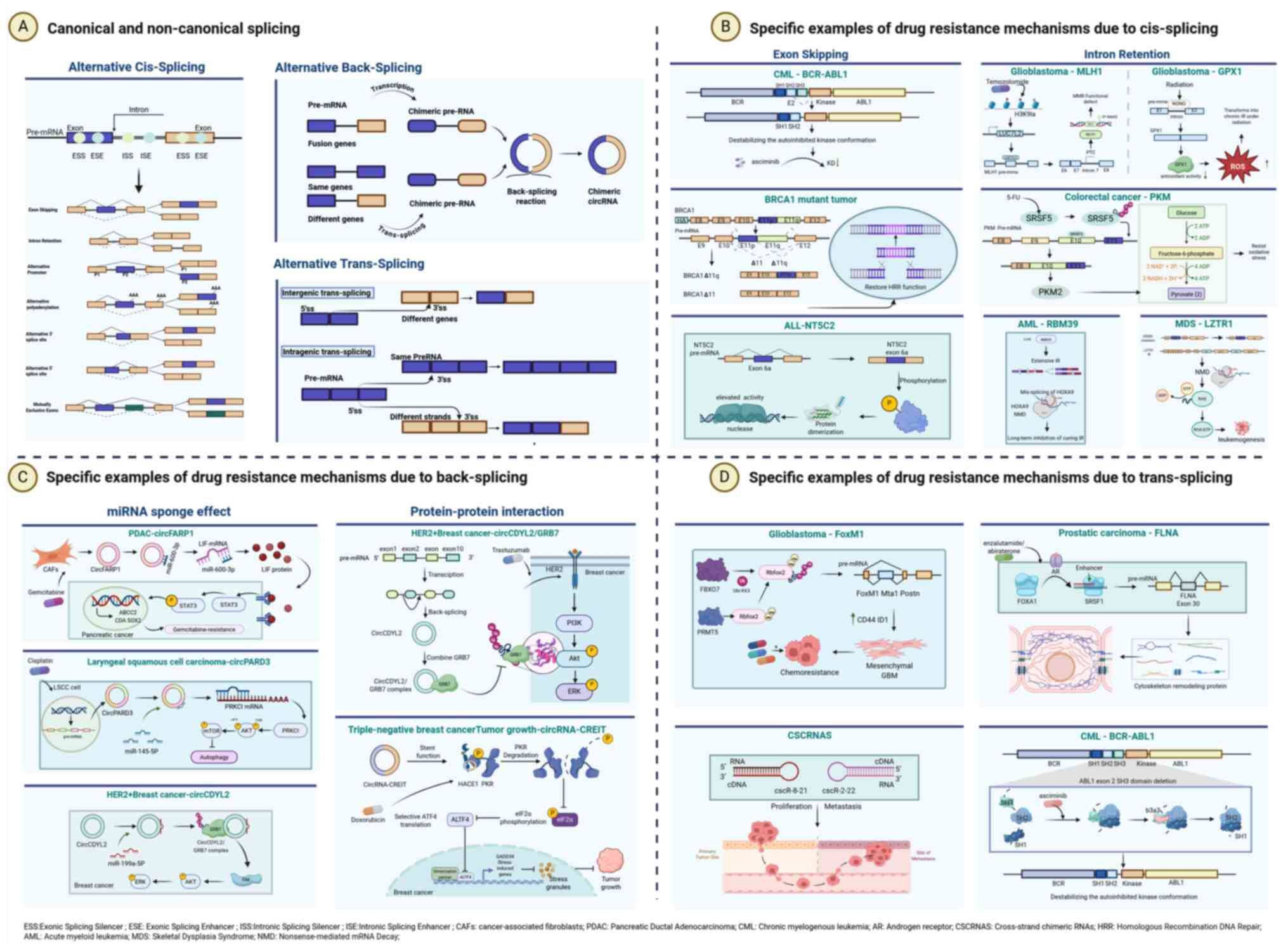

| Figure 3.Canonical vs. non-canonical splicing

events and their associated resistance mechanisms. (A) The AS can

be classified into two categories, canonical splicing events: ACS

and non-canonical splicing events: ATS and ABS. There are seven

subtypes of ACS, consistent with the content in Fig. 1. ABS is a non-canonical RNA

processing mechanism distinct from linear splicing, wherein a

downstream splice donor site covalently joins an upstream splice

acceptor site, forming a closed-loop RNA structure called circular

RNA (circRNA). ATS connects fragments from two distinct primary RNA

transcripts generating chimeric RNAs. ATS can be classified into

two types based on the origin of the primary RNA transcripts,

involving intragenic and intergenic trans-splicing. (B) Specific

examples of drug resistance mechanisms due to cis-splicing. Exon

skipping (left panel) confers resistance through alterations in

protein structure and function. Examples include: deletion of the

SH3 domain in BCR-ABL1, which reduces asciminib binding in chronic

myeloid leukemia (CML); skipping of exon 11 in BRCA1, which

restores homologous recombination repair (HRR) and leads to PARP

inhibitor (PARPi) resistance; and inclusion of exon 6a in NT5C2,

which promotes dimerization and enhances enzymatic activity in

acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Intron retention (right panel)

facilitates resistance via rapid stress response and regulation of

gene expression. Key instances are: temozolomide-induced detained

introns in MLH1, resulting in mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency in

glioblastoma; radiation-induced intron retention in GPX1, mediated

by NONO, that impairs its antioxidant function, elevates reactive

oxygen species (ROS), and promotes radiation resistance in

glioblastoma; SRSF5-mediated retention of intron 9 in PKM,

upregulating PKM2 to enhance glycolysis and confer oxidative stress

resistance in colorectal cancer; widespread intron retention

following RBM39 loss, which triggers nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)

of oncogenic transcripts in acute myeloid leukemia (AML); and

finally, intron retention in LZTR1 in myelodysplastic syndromes

(MDS) that evades NMD, thereby activating the RAS pathway and

driving leukemogenesis. (C) Specific examples of drug resistance

mechanisms due to back-splicing. The miRNA sponge mechanism (left

panel) is illustrated by the following: exosomal circFARP1 derived

from cancer-associated fibroblasts sequesters miR-660-3p, leading

to upregulation of LIF and activation of STAT3 signaling, thereby

promoting stemness and gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma; circPARD3 acts as a sponge for miR-145-5p,

activating the PRKCI/AKT/mTOR pathway to suppress autophagy and

induce cisplatin resistance in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma;

and circCDYL2 sequesters miR-199a-5p, resulting in elevated GRB7

expression and subsequent FAK signaling activation, which

contributes to trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast

cancer. Protein-protein interactions (right panels) are

demonstrated through two examples: circCDYL2 directly binds to and

stabilizes GRB7, sustaining HER2/AKT/ERK signaling; and

circRNA-CREIT scaffolds the HACE1-mediated degradation of PKR,

which disrupts stress granule formation and promotes doxorubicin

resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. (D) Specific examples

of drug resistance mechanisms due to trans-splicing. In

glioblastoma, Rbfox2 stabilized by FBXO7 promotes trans-splicing,

generating FoxM1 variants that upregulate stemness markers (for

example, CD44, ID1) and confer chemoresistance. In prostate cancer,

FOXA1 facilitates the inclusion of FLNA exon 30 via trans-splicing,

resulting in cytoskeletal remodeling and resistance to androgen

receptor inhibitors. Trans-splicing between sense and antisense

transcripts also produces cross-strand chimeric RNAs (such as

cscR-8-21 and cscR-2-22), which contribute to cancer cell survival

and have been implicated in therapy resistance. Furthermore, in

chronic myeloid leukemia, trans-splicing gives rise to truncated

BCR-ABL1 isoforms (for example, b3a3) that lack the SH3 domain,

leading to constitutive kinase activity and resistance to

allosteric inhibitors such as asciminib. ACS, alternative

cis-Splicing; ATS, alternative trans-splicing; ABS, alternative

back-splicing |

AS-driven drug resistance mechanisms

Cis splicing in drug resistance

Overview of cis splicing

In cancer, dysregulated cis splicing promotes tumor

progression and therapy resistance by altering protein function,

stability, or subcellular localization (56). For instance, aberrant splicing of

apoptosis regulators, oncogenic kinases and drug transporters

directly affects treatment efficacy and disease relapse (10). The clinical relevance of

cis-splicing is underscored by its association with poor prognosis

and resistance to targeted therapies, immunotherapies and

chemotherapy (57).

ES

AS-mediated exclusion of ABL1 exon 2 results

in an in-frame deletion of SH3 domain residues. This 31-amino-acid

deletion in BCR-ABL1 weakens asciminib binding by 18-fold and

impairs the autoinhibitory conformation required for drug efficacy,

conferring resistance in CML (58).

In BRCA1, secondary SSMs induce exon 11

skipping, producing truncated Δ11 and Δ11q isoforms that restore

HRR capacity. These isoforms allow tumor cells to bypass

PARPi-induced synthetic lethality (10).

In relapsed ALL, the inclusion of exon 6a introduces

a novel phosphorylation site that promotes NT5C2

dimerization, leading to a 15-fold increase in enzymatic activity

of the protein compared with the wild-type protein (36).

IR

IR and the more recent concept of ‘detained introns’

(DIs), a type of IR, are critical splicing events that drive

resistance to cancer therapies (59,60).

DIs are introns that are retained in polyadenylated transcripts

owing to a stalled co-transcriptional splicing process. These

splicing events act as rapid and reversible regulators of gene

expression, whereas classical IR, is defined by persistent IR in

mature mRNAs.

In glioblastoma, multiple of splicing mechanisms

cooperate to mediate both acute and chronic therapy resistance.

Chemoradiation with agents such as temozolomide stalls RNA

polymerase II elongation and induces DIs in MLH1 through

H3K9 lactylation-dependent upregulation of LUC7L2 (62), which introduces a frameshift

mutation truncating the protein and leading to mismatch repair

(MMR) dysfunction. The functional loss of MMR leads to acute

chemoresistance. These DIs are capable of acting as rapid stress

sensors, such that inhibition of lactylation rescues MLH1

splicing and re-sensitizes the tumors to treatment (63). In addition, NONO-induced IR in

GPX1 results in the loss of antioxidant activity and an

increase in reactive oxygen species which leads to apoptosis

(63). Radiation further stalls

splicing progression, converting the acute DI response into chronic

IR in an epigenetically dependent manner, highlighting how stress

duration mediates resistance plasticity (61).

In CRC, SRSF5-induced IR in PKM intron 9

leads to the upregulation of PKM2, which increases glycolysis and

enables survival under 5-fluorouracil-induced oxidative stress

(56).

In AML, loss of RBM39 leads to widespread IR

promoting the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of pro-leukemic

transcripts including HOXA9 targets (64). IR in spliceosome mutant cells

mediates their acute vulnerability to this mechanism, providing a

measurable biomarker of therapeutic response. Chronic RBM39

inhibition leads to the consolidation of the IR state promoting

continual NMD.

In myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), loss of

ZRSR2 causes IR in a subset of minor introns in LZTR1

inducing NMD and subsequent RAS pathway activation, which drives

leukemogenesis in these patients (65). Taken together, chemoradiation stalls

co-transcriptional splicing, inducing DIs as an acute, reversible

response to therapy (61). Chronic

stress promotes the conversion of DIs into stable IR states,

allowing chronic resistance to be established. This dichotomy

explains how tumors adapt rapidly (via DIs) and persist (via IR)

under therapeutic pressure (Fig. 3A and

B).

Back-splicing and circRNA-driven drug

resistance.

Back-splicing: Mechanisms,

classification and functional roles in drug resistance

Back-splicing is a non-canonical RNA processing

mechanism distinct from linear splicing, wherein a downstream

splice donor site covalently joins an upstream splice acceptor

site, forming a closed-loop RNA structure called circular RNA

(circRNA) (66). Numerous

protein-coding genes in higher eukaryotes are capable of producing

circRNAs through back-splicing of exons (67–69).

This process competes with canonical splicing for splice sites

(70–72), resulting in exonuclease-resistant

circRNAs that lack 5′ caps and 3′ poly(A) tails, thereby enhancing

their stability and allowing secretion via extracellular vesicles

(73,74). Experimental evidence underscores the

remarkable stability of circRNAs; for instance, Enuka et al

(75) demonstrated, using metabolic

labeling that the median half-life of circRNAs in mammary cells

ranges from 18.8–23.7 h, significantly longer than the 4.0–7.4 h

observed for linear RNAs. Their exceptional longevity makes

circRNAs well-suited as biomarkers, a feature demonstrated across

multiple studies to stem from their covalently closed circular

architecture which confers intrinsic resistance to exonuclease

degradation (76–78). CircRNAs are broadly classified into

three subtypes: Exonic circRNAs (ecircRNAs), intronic circRNAs and

exon-intron circRNAs (EIciRNAs), with ecircRNAs being the most

prevalent and functionally characterized in cancer (79) (Fig.

3A). Their aberrant expression in cancers provides insights

into roles in tumorigenesis (80),

and they can act as miRNA sponges, protein scaffolds or peptide

templates (74,81). For example, circCDYL2 in

HER2+ breast cancer stabilizes GRB7 to sustain

HER2/AKT/ERK signaling and confers trastuzumab resistance (73), while circPARD3 in laryngeal squamous

cell carcinoma sponges miR-145-5p to activate PRKCI/AKT/mTOR

signaling and suppress autophagy, promoting chemoresistance

(79). The conservation of

back-splicing and its dysregulation in tumors highlight its role in

therapy evasion, with circRNAs like circRNA-CREIT in TNBC serving

as biomarkers for poor prognosis under doxorubicin treatment

(74).

Role of the circFARP1 miRNA sponge

effect in gemcitabine resistance through the miR-660-3p/ leukemia

inhibitory factor (LIF) axis

CircRNAs may act as competing endogenous RNAs to

sponge miRNAs and relieve repression of oncogenic targets. In PDAC,

cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete exosomal circFARP1, which

sponges miR-660-3p to upregulate LIF, activating STAT3 signaling to

induce stemness and gemcitabine resistance (81). In this way, circFARP1 may bind

miR-660-3p to derepress the cytokine LIF, which in turn promotes

IL-6/STAT3 survival signaling pathways (81). Likewise, circPARD3 acts as a sponge

for miR-145-5p, leading to upregulation of PRKCI to activate

AKT/mTOR signaling and inhibit autophagy to enhance cisplatin

resistance in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (79). Such circRNA/miRNA/protein signaling

axes are often amplified in tumor cells that are resistant to

therapy, for example, circCDYL2 sponges miR-199a-5p to upregulate

growth factor adaptor protein GRB7 and focal adhesion kinase

signaling in HER2+ breast cancer (73). CircRNA sponging can also be blocked

in tumor cells to sensitize them to chemotherapy such as with

anti-circFARP1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) to to restore miRNA

activity (Fig. 3C) (81).

CircRNA-protein interactions in therapy

resistance: CircCDYL2/growth factor receptor-bound protein 7

(GRB7) complex formation and circRNA-CREIT-mediated protein

kinase R (PKR) degradation. CircRNAs also participate in direct

protein interactions that modulate cellular function. In

HER2+ breast cancer, circCDYL2 binds GRB7,

protecting it from ubiquitination, and thereby maintaining

HER2/AKT/ERK signaling in the presence of trastuzumab (73). This leads to HER2+

tumors exhibiting resistance to HER2− targeted

therapies (73). In TNBC,

circRNA-CREIT acts as a molecular scaffold to bring HACE1 (HACE1

ubiquitin protein ligase) and PKR together, leading to degradation

of PKR and disruption of stress granules, and thereby allowing the

tumor to exhibit resistance to doxorubicin (74). These protein-interaction mechanisms

establish circRNAs as versatile regulators of therapeutic

resistance, suggesting that targeting such interfaces, for instance

through GRB7 inhibition, may represent a promising approach to

reestablish treatment sensitivity (Fig.

3C).

Trans-splicing. Definition, mechanisms

and classification of alternative trans-splicing (ATS)

ATS generates chimeric mRNAs by joining exons from

two distinct pre-mRNA transcripts through spliceosome-mediated

ligation (82,83). Unlike conventional cis-splicing, ATS

connects splice sites located on different RNA molecules, often

mediated by complementary base pairing or trans-acting factors

(4,84). The process involves coordinated

recruitment of spliceosomal components, including U1 and U2 snRNPs,

to donor and acceptor sites on distinct pre-mRNAs, enabling exon

joining via transesterification reactions (11). ATS events are classified as

intergenic when combining exons from different chromosomal loci or

intragenic when linking exons from alternative transcripts of the

same gene (4,12) (Fig.

3A). This mechanism is thus expected to substantially increase

transcript diversity in cancers and likely underlies oncogenic

adaptation in treatment-resistant tumors (84). Although fusion genes such as

ABL/BCR are widely considered to arise from translocations

such as the Philadelphia chromosome, ATS alone can generate similar

chimeric transcripts at the RNA level.

In CML, ATS gives rise to fusion transcripts such

as CLEC12A-MIR223HG, which has been found in both malignant and

normal cells, demonstrating its capacity to diversify the

transcriptome in the absence of DNA rearrangement (85). ATS variants of the BCR-ABL

oncogene may escape detection or cause resistance to imatinib due

to an altered configuration of the kinase domain (58). By augmenting the functional

transcriptome beyond what the genome can encode, ATS can increase

the adaptability of tumor cells for oncogenic adaptation under

therapeutic pressure (86,87).

Mechanisms of ATS in drug

resistance

ATS confers drug resistance through the production

of oncogenic chimeric transcripts or via the disruption of

drug-target interactions. In glioblastoma, FBXO7 stabilizes

RBFOX2 to induce trans-splicing events that produce FOXM1

variants, which further promote the expression of stemness-related

markers such as CD44 and ID1, thereby conferring chemotherapy

resistance (3) (Fig. 3D). Apart from resistance to

chemotherapy, ATS may also play a role in immune escape mechanisms.

Pan-cancer analyses have identified tumor-specific splicing

junctions, or ‘neojunctions’, that produce peptides not found in

normal tissues, and computational predictions suggest these

peptides may serve as ligands for MHC-I proteins and thereby

influence the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (12). Trans-splicing between BCL2L1

and adjacent genes generates truncated BCL2 variants that impair

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis (11). These mechanisms highlight how ATS

diversifies the transcriptome to promote survival under therapeutic

pressure.

Case studies of ATS in drug-resistant

cancers

Specific ATS events are linked to therapy

resistance. In prostate cancer, FOXA1 orchestrates ATS by binding

enhancer regions of splicing factors such as SRSF1, leading to exon

30 inclusion in FLNA, which stabilizes isoforms promoting

cytoskeletal remodeling and resistance to androgen receptor (AR)

inhibitors (88). Additionally,

FBXO7-driven trans-splicing in glioblastoma stabilizes RBFOX2,

which coordinates splicing of mesenchymal genes such as

POSTN to augment temozolomide resistance through

integrin-mediated survival signaling (3). Furthermore, cross-strand chimeric RNAs

(cscRNAs) produced by ATS between sense and antisense transcripts

have been identified in multiple cancer cells. For instance, in

prostate cancer PC3 cells and HCC Huh7 cells, specific cscRNAs such

as cscR-8-21 and cscR-2-22 are generated through the fusion of

transcripts from opposite DNA strands. Knockdown of these cscRNAs

using siRNA significantly diminishes cell proliferation, colony

formation and migration, as validated by reverse transcription PCR,

Sanger sequencing, RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization,

and functional assays, supporting their role in promoting cancer

cell survival and potentially contributing to therapy resistance

(89). In CML, canonical splicing

of BCR-ABL produces p210 or p190 transcripts, but ATS can

generate truncated isoforms for example, BCR-ABL1/b3a3) that

lack ABL1 exon 2-encoded SH3 domain residues, leading to

constitutive kinase activity and resistance to allosteric

inhibitors such as asciminib by destabilizing the autoinhibited

kinase conformation (58).

Moreover, EZH2-mediated repression of splicing factors such as

CELF2 in CML results in aberrant splicing patterns that promote

stem cell-like properties and diminish sensitivity to tyrosine

kinase inhibitors (Fig. 3D)

(87). These ATS-derived variants

activate alternative signaling pathways, such as dynamic

phosphorylation events, thereby contributing to treatment failure

and relapse (86). These findings

demonstrate that ATS actively contributes to the development of

aggressive, therapy-resistant cancers.

ATS and its prominence compared with

chromosomal abnormalities

AS events including trans-splicing, are prevalent

somatic perturbations in cancer that promote tumor heterogeneity

and therapy resistance (90). By

contrast, hereditary cancer syndromes are frequently driven by

germline chromosomal abnormalities, including RB1 deletions

in retinoblastoma, TP53 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome,

NF1 deletions in neurofibromatosis type 1, APC

mutations in familial adenomatous polyposis, and BRCA1/BRCA2

germline mutations in hereditary breast cancer (91–93).

AS predominantly occurs as a somatic event that broadly reprograms

gene networks, while chromosomal abnormalities generally underlie

inherited cancer syndromes with high penetrance. In

neurofibromatosis type 1, mis-splicing of NF1 exon 23a

disrupts neurofibromin function in high-grade gliomas, thereby

activating the Ras/MAPK pathway to drive tumor formation (94).

Similarly, retinoblastoma exhibits upregulated

spliceosome activity regulated by pRB/E2F3a under oncogenic stress

(90). Genomic studies establish AS

dysregulation as a nearly universal feature of tumorigenesis,

whereas chromosomal abnormalities primarily drive ~10–20% of

hereditary cancer syndromes (91–93).

This predominance establishes AS as a central mechanism in sporadic

cancers and a promising therapeutic target, as exemplified by

metabolic vulnerabilities conferred by TP53 splicing

variants in Li-Fraumeni syndrome (95).

Splicing regulation in cancer immunity,

computational discovery, and systems crosstalk

Splicing-derived neoantigens and

resistance to immunotherapy

Somatic mutations in core spliceosomal components

including SRSF2 and SF3B1 produce recurrent

mis-splicing events that create novel immunogenic peptides, these

splicing-derived neoantigens are presented by MHC class I molecules

and trigger CD8+ T-cell responses in myeloid

malignancies (96,97). While these neoantigens provide

effective targets for immunotherapy, tumors can develop resistance

through selection of low-immunogenicity splice variants or impaired

antigen presentation through mechanisms such as aberrant HLA-I

splicing (98). Pharmacological

spliceosome modulation with agents such as indisulam or MS-023

counteracts this resistance by restoring neoantigen presentation,

and exhibits synergistic effects with anti-PD-1 therapy to enhance

T-cell-mediated tumor clearance in preclinical models (97).

Mis-splicing of microexons, short exons typically

regulated in tissue-specific patterns, represents an important

disease mechanism that disrupts essential protein interaction

networks, in autism spectrum disorder, CPEB4 microexon mis-splicing

drives protein aggregation and functional impairment (99). While this mechanism has been

primarily characterized in neurological disorders, similar

processes likely operate in cancer biology, where microexon

alterations may influence oncogenic signaling pathways and immune

evasion capabilities, thereby creating opportunities for novel

biomarkers and therapeutic strategies (98,99).

These observations underscore splicing-derived neoantigens as

promising biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade

response and as a basis for emerging approaches such as

personalized cancer vaccines and combination therapies that target

spliceosome activity is targeted (97,98).

Computational deconvolution and

single-cell dissection of splicing networks

Computational methods have been developed to enable

systematic study of splicing heterogeneity with both bulk and

single-cell RNA sequencing data (scRNA-seq). Deep learning models

such as APARENT-Perturb can predict splicing from sequence and

uncover key regulatory mechanisms including the CFIm complex, as

well as clinically relevant splicing signatures associated with

drug resistance (100).

Integrating these models with large-scale genomic repositories such

as TCGA enables systematic pan-cancer studies that associate

specific splicing patterns with clinical outcomes.

Single-cell technologies provide an unprecedented

resolution of splicing dynamics among cell populations in the tumor

microenvironment (TME). Reference atlases such as Tabula Sapiens

show cell-type-specific splicing of MYL6 and other genes,

and highlight the required resolution to resolve complex cellular

heterogeneity (101). In aplastic

anemia, scRNA-seq enables detection of aberrant splicing in the

rare population of hematopoietic stem cells, and can provide

mechanistic hypotheses for clonal evolution and treatment

resistance (102).

Recent work in computational biology has led to the

development of advanced frameworks for integration of multi-omics

data and the mapping of splicing regulatory networks. The model

APARENT-Perturb relies on deep neural networks to predict the

effect of genetic perturbations on splicing outcomes, and has

uncovered functional interactions between regulatory elements, as

well as sequence features influencing polyadenylation site

selection (100). Integration of

splicing data with other molecular measurements using tools such as

CellPhoneDB enables systematic investigation of networks of

cell-cell communication that underlie splicing heterogeneity in

tissue microenvironments (101).

Systemic crosstalk of pre-mRNA

splicing with metabolism, cellular stress and epitranscriptome

Splicing regulation can dynamically respond to

metabolic and stress signals through adaptive systems such as the

minor spliceosome (MiS), which is activated during cancer

progression. In prostate cancer, a progressively dysregulated MiS,

as evidenced by elevated U6atac snRNA levels, has been associated

with disease progression and splicing reprogramming under metabolic

stress (103). Cellular stressors,

including androgen deprivation therapy and AR pathway inhibition,

have been shown to further enhance the efficiency of minor intron

splicing, a clear indication of how treatment-related stress can

remodel the spliceosome to facilitate the development of

therapeutic resistance (103).

This dynamic regulation of splicing in turn selectively reprograms

the splicing network to express additional antiapoptotic isoforms,

firmly positioning MiS at the center of the adaptive response in

cancer.

The U12-type spliceosome functions as a specialized

regulatory system for processing stress and oncogenic signals via

minor intron splicing. The structural analyses of the MiS point to

MiS-specific components, such as SCNM110 and PPIL2, as key factors

that ensure a stable catalytic core required for the accurate

processing of genes involved in cell-cycle checkpoint and DNA

repair pathways (104,105). The evolutionary conservation of

this system and the mutational vulnerability of its key components

underscore the importance of MiS in preserving cellular homeostasis

under metabolic and therapeutic stress (103,104).

In conclusion, splicing serves as an integrator of

metabolic and stress signals, and the U12-type spliceosome offers a

compelling model of how an ancient system of gene regulation can

influence the tumor adaptive response. Further work is needed to

elucidate the direct links between metabolism and splicing as well

as the epitranscriptomic layer of regulation, both of which still

remain to be fully characterized in the current literature.

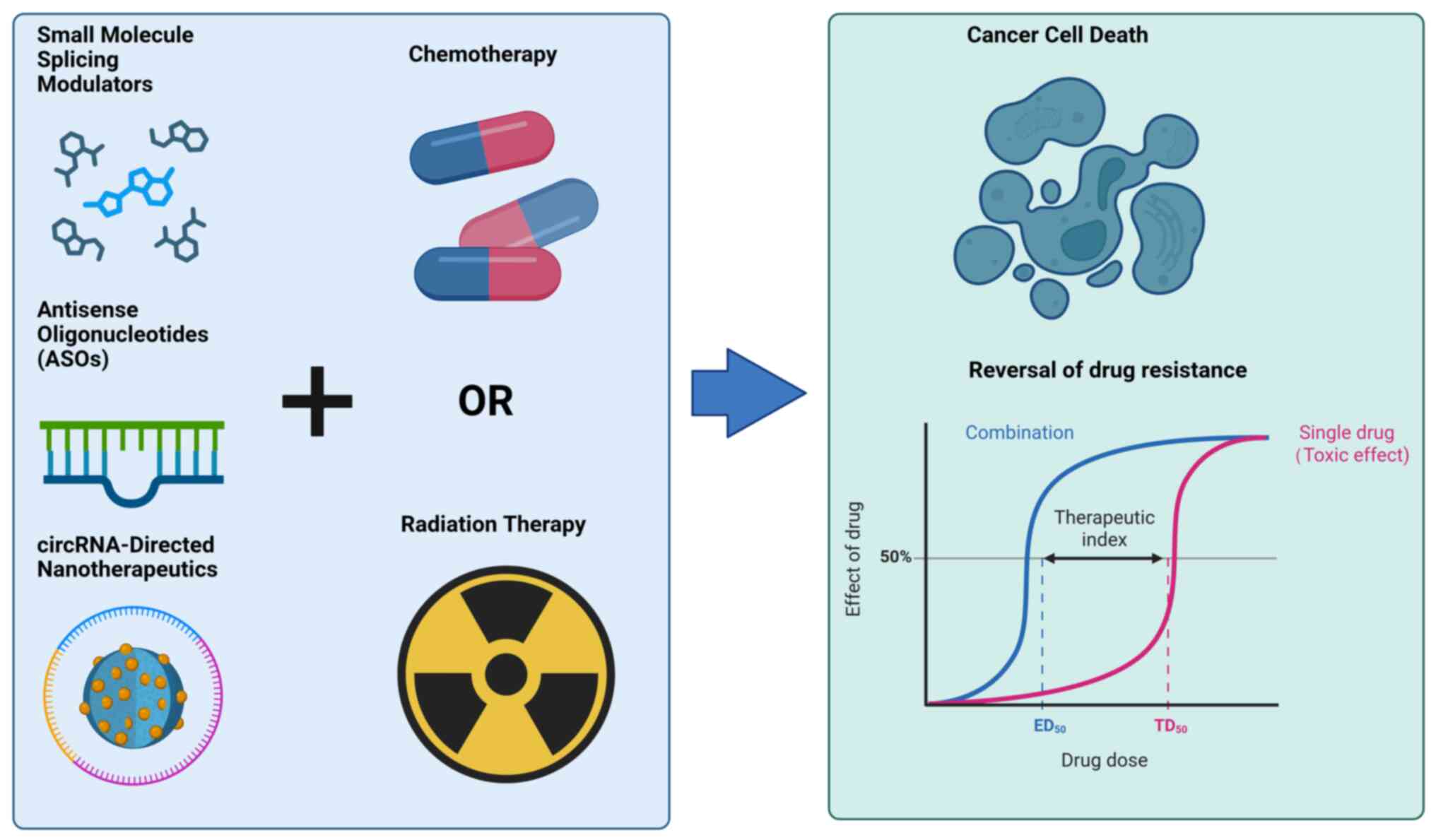

Therapeutic targeting of aberrant

splicing

Perturbations in splicing patterns are well

documented in cancer, and mutations in spliceosomal proteins and

cancer driver genes are enriched across malignancies (106). Aberrant AS contributes to tumor

progression and therapeutic resistance by generating tumor-specific

splice variants that evade conventional therapies. New therapeutic

modalities are under development to directly target dysregulated

splicing machinery or its downstream effects. These include small

molecules that inhibit the activity of specific splicing factors or

the assembly of the spliceosome, ASOs that block the selection of

pathogenic splice sites, and nanoparticle-delivered circRNAs that

leverage the endogenous splicing machinery.

Together these modalities aim to reestablish

physiologic splice patterns and counteract tumor-promoting isoforms

to overcome therapeutic resistance (Fig. 4). The development of these agents

reflects an increasing focus on splicing-targeted therapeutics that

integrate mechanistic insights into splicing dysregulation with

recent advances in drug design and delivery (Table II).

| Table II.Clinical trials of splicing-targeted

therapies in cancer. |

Table II.

Clinical trials of splicing-targeted

therapies in cancer.

| First author/s,

year | Therapeutic

agent | Target | Cancer type | Clinical trial

identifier and phase | Key Findings /

Status | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Steensma et

al, 2021; | H3B-8800 | SF3B1 |

Myelodysplastic | NCT02841540 | Established maximum

tolerated dose (MTD); reversible | (107,108) |

| Seiler et

al, 2018 |

| (Spliceosome) | syndromes,

leukemia | (Phase I) | QTcF prolongation

and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity as common adverse events. Showed

antitumor activity in SF3B1-mutant patients. |

|

| Chi et al,

2017 | Custirsen | Clusterin (via

ASO) | Metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer | SYNERGY (Phase

III) | Failed to improve

overall survival when combined with docetaxel, highlighting

delivery challenges for antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) in solid

tumors. | (109) |

Small molecule splicing

modulators

Small molecule splicing modulators are an emerging

class of therapeutics designed to correct or exploit dysregulated

pre-mRNA splicing in cancer. These molecules bind to core

components of the spliceosome, the macromolecular machinery that

mediates intron removal and exon ligation, thereby either directly

altering splice site selection or modulating the kinetics of

spliceosome assembly. One prominent target is the SF3b complex, a

subcomplex of the U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (U2snRNP) that

is responsible for recognizing the branchpoint sequences during the

early stages of spliceosome assembly. Inhibitors of SF3b, such as

pladienolide derivatives including H3B-8800 and E7107, stabilize a

conformation that prevents its interaction with pre-mRNA, leading

to widespread IR or ES (108,110). The effect of these inhibitors is

amplified in cancer cells harboring mutations in spliceosomal genes

(for example, SF3B1, U2AF1, or SRSF2) since these cells

exhibit heightened dependence on already compromised spliceosome

function. Recent studies also highlight the role of nuclear

condensates, which are phase-separated compartment enriched in

splicing factors, in potentially concentrating splicing modulators

selectively in cancer cells (111). In addition to SF3b-targeting

molecules, several small molecules have been identified that

modulate other components of the splicing machinery, such as SR

proteins, or even target upstream RNA modification pathways, such

as METTL3, which mediates N6-methyladenosine (m6A)

methylation, a post-transcriptional modification known to regulate

splicing efficiency and pre-mRNA transcript stability (112,113). Consequently, the diversity of

mechanisms underlying the action of splicing modulators suggests

their potential efficacy across a wide range of splicing-driven

malignancies.

The therapeutic efficacy of SF3b inhibitors is

exemplified in MDS and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), where

recurrent SF3B1 mutations drive aberrant splicing and

oncogenesis. H3B-8800, an orally bioavailable pladienolide

derivative, selectively eliminates spliceosome-mutant cells by

causing retention of short GC-rich introns in genes that encode

spliceosome proteins and increase splicing stress (108). Preclinical studies in

SF3B1-mutated pancreatic cancer and leukemia models have

shown that H3B-8800 reduced viability by greater than 50% at

nanomolar concentrations, with only mild effects in wild-type

cells. Resistance to H3B-8800 was caused by mutations in other

components of SF3b, such as PHF5A-Y36C, indicating on-target

activity (108). In MDS, the

SF3B1 mutations lead to a hypersensitivity to splicing

perturbation, as these cells depend on residual activity of the

spliceosome to produce transcripts critical for the survival of

mutant cells (110). In early

clinical trials in MDS, H3B-8800 treatment led to a reduction in

blasts and an improvement in other hematologic parameters in

patients with SF3B1-mutated MDS (108).

However, the Phase I first-in-human dose-escalation

study of H3B-8800 (NCT02841540) completed dose escalation with

defined dose-limiting toxicities, including ocular toxicity

observed with prior pladienolide derivatives (for example, E7107).

The trial identified reversible QTcF prolongation and

gastrointestinal disturbances (diarrhea, nausea and vomiting) as

common treatment-emergent adverse events, with the maximum

tolerated dose established at 30 mg for a 5-days-on/9-days-off

schedule and 14 mg for a 21-days-on/7-days-off schedule (107). Despite safety considerations,

these findings validate SF3b as a therapeutically tractable node in

spliceosome-mutant cancers and provide a roadmap for targeting

splicing vulnerabilities in other malignancies.

Aberrant splicing also underlies resistance to

targeted therapies, as observed in BRAF-mutant melanomas

treated with vemurafenib. ~30% of resistant tumors express

BRAF splice variants (for example, BRAF3-9), which

lack the RAS-binding domain and dimerize independently of upstream

signals (113). A C-to-G mutation

in intron 8 of BRAF creates a cryptic branchpoint, promoting

BRAF3-9 expression through enhanced recognition by mutant

SF3B1 (113). The splicing

modulators, including spliceostatin A (SSA), reverse the shift in

isoform expression by inhibiting SF3b and thus re-establishing

sensitivity to BRAF inhibitors. In vemurafenib-resistant melanoma

xenografts, SSA treatment decreased BRAF3-9 levels by 60% and

slowed tumor growth by 40%, showing that splicing modulation can

overcome drug resistance (113).

The splicing modulators and BRAF inhibitors are enriched in nuclear

condensates containing MED1 and BRD4, which enhance the efficacy of

the combination therapy (111).

Parallel studies implicate RNA m6A methylation in regulating

BRAF splicing, as METTL3 knockdown reduces

BRAF3-9 expression and synergizes with vemurafenib (112). These insights highlight the dual

utility of splicing modulators: As monotherapies in

spliceosome-mutant cancers and as adjuvants to reverse adaptive

splicing in drug-resistant tumors.

ASOs

ASOs are short synthetic nucleic acids.

Specifically, ASOs are single-stranded, chemically modifiable short

nucleic acid sequences usually in the range of 18–25 nucleotides in

length (114). They are designed

to bind pre-mRNA and modulate splicing events by blocking

splice-site recognition or altering exon inclusion. These molecules

are chemically modified (for example, phosphorothioate backbones,

2′-MOE/cEt modifications) to enhance stability and binding

affinity. For example, in HCC, ASO1-cEt/DNA targeting PKM

pre-mRNA induced a splice switch from the oncogenic PKM2 isoform to

tumor-suppressive PKM1, suppressing glycolysis and tumor growth in

xenografts (115). Similarly, in

KRAS Q61K-mutant cancers, ASOs disrupting exonic splicing

enhancer motifs near cryptic splice sites induced ES, generating

non-functional KRAS transcripts and sensitizing tumors to

osimertinib (116). These studies

underscore ASOs' ability to target splicing-dependent oncogenic

drivers with high specificity.

A key design strategy is to target variants that

mediate resistance to therapy. In gallbladder cancer, PTBP3

mediates the skipping of IL-18 exon 3, leading to the

expression of a tumor-specific ΔIL-18 isoform that in turn

is responsible for the suppression of the tumour-fighting activity

of CD8+ T-cells. ASO4, designed to block the splice site

of the ΔIL-18 isoform, was shown to restore expression of

full-length IL-18 and also to induce improved tumor

clearance by T-cells in vivo (117). Likewise, in B-cell tumors, two

CD20 mRNA isoforms with different 5′-UTRs (V1/V3) have been shown

to control protein translation. In these isoforms, splice-switching

morpholinos selecting for the translation-competent V3 isoform

raised CD20 levels, the increased CD20 expression resensitized

rituximab-resistant cell lines (118). These examples demonstrate how ASOs

can reverse resistance by reprogramming splicing toward

nonpathogenic isoforms.

Clinical progress in solid tumors mirrors advances

observed with nusinersen (a spinal muscular atrophy therapy). In

ovarian cancer, BUD31 sustains antiapoptotic BCL2L12

expression by promoting exon 3 inclusion. BUD31-targeting ASOs

induced ES, triggering nonsense-mediated decay of BCL2L12

mRNA and apoptosis in xenograft models (119). Meanwhile, in HCC, systemic

delivery of a mouse-specific ASO (mASO3-cEt/DNA) redirected

PKM splicing, inhibiting tumorigenesis without toxicity

(115). Similarly, in lung cancer

models, the addition of the MERTK ASO to

XRT+anti-PD1 and XRT+ anti-CTLA4 profoundly

slowed the growth of both primary and secondary tumors and

significantly extended survival (120). Challenges remain in tumor-specific

delivery, but chemical conjugates (for example, GalNAc for hepatic

targeting) and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) show promise.

Previous advances in delivery platforms have

significantly enhanced the in vivo efficacy of ASOs by

improving targeted delivery and splice-switching efficiency. GalNAc

conjugates, which facilitate hepatocyte-specific uptake through

asialoglycoprotein receptor-mediated endocytosis, have demonstrated

a 10-fold improvement in gene silencing potency in murine liver

models, highlighting their specificity for hepatic applications

(121). LNPs, engineered to

encapsulate splice-switching oligonucleotides, have achieved over

60% splice correction in tumor xenografts, as measured by

functional recovery of target genes, underscoring their utility in

oncology settings (122). Exosomes

allow delivery of nucleic acids to neurons by exosomes, which can

be functionalized with RVG peptides to target delivery to the

brain. It has led to ~50% reduction in models of neurodegenerative

disorders (123). These approaches

allow for delivery to be more precise, and for the systemic levels

of agents to be lower, reducing off-target effects and improving

therapeutic indices.

However, the translation of ASO medicines into the

clinic for the treatment of solid tumors is significantly hampered

by challenges that arise during systemic delivery. This includes

poor tissue penetration, limited uptake and poor transport of ASOs

into and within cells. A key clinical failure for systemic delivery

of ASOs was the SYNERGY Phase 3 trial of custirsen, a

clusterin-targeting ASO, in combination with docetaxel and

prednisone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant

prostate cancer. It was observed that custirsen had no impact on

overall survival in these patients, a finding that underscores the

need to overcome delivery barriers through means such as ligand

conjugates and nanocarriers (109).

circRNA-directed nanotherapeutics

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are covalently closed RNA

molecules formed by back-splicing of precursor mRNAs. CircRNAs are

highly stable molecules that are resistant to exonucleases.

CircRNAs are involved in the development of cancers by regulating

the expression of target genes through microRNA sponging, protein

interactions and transcriptional regulation (124,125). CircRNA-directed nanotherapeutics

is a preclinical proof-of-concept approach that employs RNA

interference technology in combination with a delivery system that

integrates nanoparticles to target oncogenic circRNAs.

CircRNA-directed nanotherapeutics utilizes siRNAs or ASOs

encapsulated in biocompatible nanoparticles to enhance stability,

targeted delivery and mitigate off-target effects relative to free

RNA agents. This strategy holds promise to overcome issues such as

rapid renal clearance and enzymatic degradation of free RNA, and

has been shown to enable specific targeting of dysregulated

circRNAs in tumors (126,127).

Recent studies have provided proof-of-concept

evidence that circRNA-targeted nanomedicines can be effective in

different cancer types in mouse models. In gastric cancer,

lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles carrying siRNAs to knockdown

circ_0008315 resensitized tumors to cisplatin by disrupting

miR-3666/CPEB4 signaling. This nano-formulation exhibited

2.3-fold higher tumoral accumulation than free siRNA and

significantly decreased tumor volumes in a patient-derived

xenograft model (65.8 mm3 vs. 132.4 mm3 in

free siRNA-treated mice; with no effects on organ function)

(124). In HCC, poly(β-amino

ester)-based nanoparticles carrying circMDK siRNA achieved (78%

target gene knockdown) inhibited tumor growth by upregulating

ATG16L1 via an m6A-associated mechanism. The nanoparticles

were designed with pH-sensitive components, so that 92% of the

siRNA payload could be released specifically in the TME, suggesting

potential superiority over conventional chemotherapy treatment in

an orthotopic tumor model (126).

These examples underscore the potential, at a proof-of-concept

stage, for nanocarriers to improve the pharmacokinetic properties

of circRNA-targeting agents in a preclinical model.

There are other examples of preclinical validation

of circRNA nanotherapeutics, whereby multifunctional nanoparticle

designs provide supporting evidence (Table III). For instance, delivery of

circRHBDD1 siRNA in PLGA-PEG nanoparticles effectively

blocked the the IGF2BP2/PD-L1 axis and increased

infiltration of CD8+ T cells by 4.1-fold in murine

gastric cancer, achieving complete tumor regression in 40% of

treated animals when combined with anti-PD-1 antibody (125). PLGA nanoparticles were also used

to deliver si-cSERPINE2 to breast cancer cells in orthotopic

mouse models. This treatment attenuated IL-6-mediated

crosstalk between breast cancer cells and tumor-associated

macrophages, and inhibited lung metastasis by 72% (127). Current early-phase clinical trials

are beginning to validate such alternative strategies. For

instance, a Phase I clinical trial of LNP-formulated circRNA

inhibitors was conducted in solid tumors, and indicated a favorable

safety profile, but was undertaken as an exploratory study and was

not further validated in large animal studies.

| Table III.Summary of therapeutic strategies

targeting alternative splicing in cancer. |

Table III.

Summary of therapeutic strategies

targeting alternative splicing in cancer.

| First author/s,

year | Therapeutic

modality | Specific

agent/approach | Molecular

target/action | Resistance

mechanism addressed |

Proof-of-concept/model | Clinical

status | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Steensma et

al, 2021; Seiler et al, 2018 | Small molecule

inhibitors | H3B-8800 | SF3b complex

modulator | Induces lethal

splicing errors in spliceosomemutant cells | SF3B1-mutant

leukemia and pancreatic cancer models | Clinical Phase

I | (107,108) |

| Salton et

al, 2015 |

| Spliceostatin

A | SF3b complex

inhibitor | Reverses BRAF3-9

isoform expression |

Vemurafenib-resistant melanoma

xenografts | Preclinical | (113) |

| Xu et al,

2023 |

| NVP2 (SRPK1

inhibitor) | Inhibits SR protein

kinase | Normalizes VEGF

splicing | Pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma models | Preclinical | (128) |

| Ma et al,

2022 | ASOs | PKM-targeting

ASO | Switches PKM2 to

PKM1 isoform | Suppresses

oncogenic glycolysis | HCC xenografts | Preclinical | (115) |

| Zhao et al,

2024 |

| IL-18-targeting

ASO | Corrects pathogenic

IL-18 splicing | Restores

CD8+ T-cell function | Gallbladder cancer

models | Preclinical | (117) |

| Chi et al,

2017 |

| Custirsen | Clusterin mRNA

(ASO) | Aimed to inhibit

anti-apoptotic protein | Patients with

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Clinical Phase III

(Failed) | (109) |

| Sun et al,

2023 |

CRISPR/Splice-Switching | CRISPR/dCasRx | Targets TIMP1

pre-mRNA | Reverses

SRSF1-driven pro-metastatic splicing | Colorectal cancer

models | Preclinical | (38) |

| Fei et al,

2024; Li et al, 2024; Du et al, 2022 |

Nanotherapeutics | siRNA-loaded

nanoparticles | Targets oncogenic

circRNAs (for example, circ_0008315, circRHBDD1) | Reverses

chemoresistance or immune evasion | Gastric cancer, HCC

xenograft models | Preclinical | (124–126) |

Conclusions and future perspectives

The detailed association between dysregulation of

AS and cancer drug resistance is increasingly appreciated, wherein

numerous splicing events, including ES, IR, and selection of

alternative splice sites, can directly influence therapeutic

response. Recent advances in long-read sequencing methods,

particularly Oxford Nanopore Technologies and PacBio sequencing,

have enabled the resolution of full-length transcript isoforms,

allowing cancer-specific AS events to be precisely identified. For

instance, in spatial isoform transcriptomics of esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma (ESCC), the isoform switching of CD74 was found to

contribute to chemoresistance by promoting the interaction of

C1QC+ tumor associated macrophages and exhausted

CD8+ T-cells, which in turn fosters an immunosuppressive

TME (129). In PDAC, the circRNA

hsa_circ_0007919 was found to be involved in gemcitabine resistance

by recruiting the transcription factors FOXA1 and

TET1 to demethylate the LIG1 promoter, thereby

boosting DNA repair by regulating AS (128). These observations align with

splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTL) studies in CRC, in which a

genetic variant was found to impact the splicing of PRMT7,

which in turn was implicated in the MAPK signalling pathway and

chemotherapy resistance (27).

Importantly, recent structural analyses of the minor spliceosome

have identified several components specific to U11 or U12 snRNPs

(for example, 35K and 48K) and lactylated nucleolin (NCL) that are

required for stabilizing the recognition of U12-type introns, which

in turn drive the oncogenic splicing programs (104,130). Together, these findings highlight

the dual role of AS in both driving molecular diversity and

representing a potential vulnerability for therapeutic intervention

in cancer.

In the future, it will be essential to optimise

long-read sequencing protocols to improve their accuracy and

scalability in studying spatially resolved isoform diversity in the

metastatic niche. A key priority would be to study how the minor

spliceosome, responsible for excising a minority of spliceosomal

introns (U12, accounting for ~0.5% of all human genes) that often

include oncogenes and tumor suppressors, is regulated.

Cryo-electron microscopy studies have elucidated the structure of

the spliceosome responsible for processing U12-dependent introns,

which revealed that some of the components appear to be

functionally orthologous to the SF3a complex that stabilizes

branchpoint recognition in the major spliceosome, notably

SCNM1, and demonstrated that a U-box protein PPIL2 is

essential for the assembly of the catalytic core (104). On a more clinical note, it might

also be valuable to examine spatially resolved splicing that is sex

or tissue specific, as such splicing patterns could provide useful

biomarkers for precision medicine. Multi-ancestry sQTL studies have

shown that the spliceosome component PRPF8 is regulated in

an ancestry-specific manner in TNBC where DHX9 suppresses

circRNA-CREIT and induces chemoresistance (27,74).

Furthermore, combining single-cell isoform sequencing with spatial

transcriptomics in tumor microenvironments could be explored to

identify how subclonal splicing variants drive adaptive resistance.

Yang et al (130) showed

that in cholangiocarcinoma, lactate-driven NCL lactylation

reprograms the RNA splicing machinery via MADD isoform

switching, which could be a potential therapeutic target. Such

studies will require collaboration between basic scientists and

clinicians to standardize isoform annotation pipelines and

cross-validate key splicing nodes in multiple models.

Therapeutic strategies specifically targeting

AS-mediated drug resistance are rapidly evolving with promising

approaches being investigated in preclinical models that target the

cis-regulatory elements, trans-acting factors and various

spliceosome inhibitors. Small molecules such as the SRPK1

kinase inhibitor NVP2 act by normalizing VEGF splicing in

PDAC to resensitize tumour cells to cisplatin (128). ASOs targeting the pathogenic

isoform in ESCC, such as CD74v6, which is known to promote immune

evasion via macrophage apoptosis, demonstrated efficacy in

suppressing metastasis in preclinical trials (129). Inhibition of lactylation-dependent

activation of NCL by SGC3027 also abrogated oncogenic MADD

splicing in cholangiocarcinoma and synergized with chemotherapy to

reduce tumor burden (130).

Combinatorial approaches are also gaining traction; for instance,

pairing spliceosome modulators for example, pladienolide B) with

immune checkpoint blockers enhances T-cell infiltration in tumors

with high SF3B1 mutation burden (27). Structural information about the

minor spliceosome will also provide a framework for rational drug

design as has been recently demonstrated for the interaction of

PPIL2-U5 snRNA to inhibit tri-snRNP assembly (104). However, the main concern regarding

these drugs is mitigating off-target effects due to the ubiquitous

nature of the splicing machinery in normal cells. Clinical trials

should aim to develop isoform-specific therapies, and leveraging

CRISPR-based screens that identify synthetic lethal interactions

between splicing factors and chemotherapeutic drugs could be

employed. As the field progresses, integrating splicing-centric

therapies with conventional regimens will be pivotal for overcoming

the adaptive plasticity of cancer cells and improving patient

outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Key Science and Technology

Tackling Program of Henan (grant no. 232102311077), the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82503868), the

medical science and technology Project of Henan (grant nos.

LHGJ20220198, LHGJ20240104 and LHGJ20240108), the Natural Science

Foundation of Henan (grant no. 242300420578), the Henan Provincial

Medical Education Research Project (grant no. Wjlx2020107), the

Graduate Education Reform Research and Curriculum Development

Program of the Academy of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University

(grant no. 040012023B062) and the National Key Clinical Discipline

Construction Project.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

WZhu, ZW and CL conceptualized the study. WZhu

wrote the original draft. BB, WZha and GC wrote, reviewed and

edited the manuscript. HY and HA supervised the research work, and

contributed to the study methodology, investigation and data

curation. FL and ZL solicited for funding, contributed to project

administration, validation and provision of resources. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

ALL

|

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

|

|

AP

|

alternative promoter

|

|

APA

|

alternative polyadenylation

|

|

AR

|

androgen receptor

|

|

AS

|

alternative splicing

|

|

ASO

|

antisense oligonucleotide

|

|

ATS

|

alternative trans-splicing

|

|

CML

|

chronic myeloid leukemia

|

|

circRNA

|

circular RNA

|

|

DIs

|

detained introns

|

|

ecircRNA

|

exonic circRNA

|

|

EIciRNA

|

exon-intron circRNA

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

ER

|

estrogen receptor

|

|

ESE

|

exonic splicing enhancer

|

|

ESS

|

exonic splicing silencer

|

|

ES

|

exon skipping

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

HRR

|

homologous recombination repair

|

|

IR

|

intron retention

|

|

ISE

|

intronic splicing enhancer

|

|

ISS

|

intronic splicing silencer

|

|

LNP

|

lipid nanoparticle

|

|

MDS

|

myelodysplastic syndromes

|

|

MiS

|

minor spliceosome