Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant tumor

originating from the mucosal epithelium of the nasopharynx,

exhibiting distinct geographical distribution patterns. It is

highly prevalent in regions such as South China (for example,

Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian and Hunan), Southeast Asia and North

Africa (1). The pathogenesis of NPC

involves genetic susceptibility, environmental factors and

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, with EBV being a

well-established oncogenic driver (1). Currently, the standard treatment for

NPC primarily consists of radiotherapy combined with

cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy. However, chemotherapy

resistance and severe side effects notably limit clinical efficacy

(2). Consequently, there is a need

to develop novel therapeutic strategies that are more effective,

less toxic and capable of overcoming drug resistance.

Ferroptosis is a novel form of iron-dependent

programmed cell death that is distinct from apoptosis and autophagy

(15,16). Its core mechanism involves the

catalysis of lipid peroxidation (LPO) in membrane polyunsaturated

fatty acids (PUFAs) by ferrous iron (Fe2+) or

lipoxygenases (LOXs), leading to membrane damage and subsequent

cell death. Characteristic morphological features include

mitochondrial shrinkage and increased membrane density, while

nuclear structure typically remains intact (17–19).

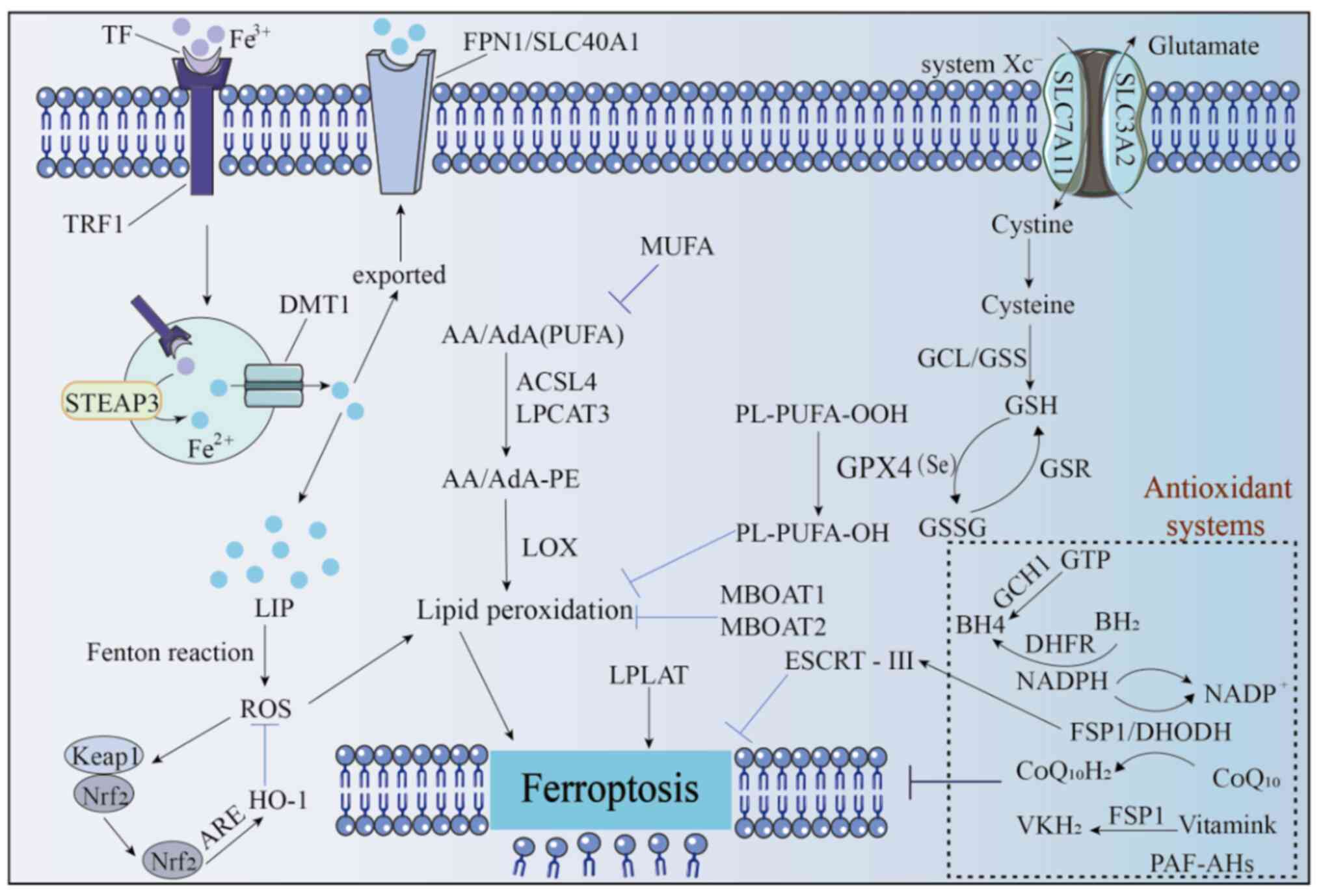

Currently identified regulatory pathways of ferroptosis include:

The system cystine/glutamate transporter (Xc)-/glutathione

(GSH)/GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis; guanosine triphosphate (GTP)

cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1)/tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) pathway;

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH)-mediated pathway;

membrane-bound O-acyltransferase 1/2 (MBOAT1/2)-monounsaturated

fatty acid (MUFA) regulation; Nrf2 signaling; LPO mechanisms and

apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 2 (FSP1 otherwise

known as AIFM2) pathway. The present review systematically examines

the molecular mechanisms and key signaling pathways of ferroptosis.

By integrating the epidemiological characteristics and risk factors

of NPC, the present review elucidates the relationship between

ferroptosis and NPC pathogenesis. Furthermore, the present review

discusses the potential therapeutic value of targeting ferroptosis

in NPC treatment, providing a theoretical foundation for developing

novel anti-tumor strategies.

Ferroptosis has emerged as a prominent research

focus in cell biology as a distinct form of programmed cell death.

A precise understanding of its definition and characteristics forms

the essential foundation for in-depth investigation of this cell

death mechanism. Defined as an iron-overload and reactive oxygen

species (ROS)-dependent cell death process driven by lipid peroxide

accumulation, ferroptosis reveals two key pathogenic factors: Iron

ions and ROS (20–24). Morphologically, ferroptosis exhibits

unique ultrastructural features: Markedly shrunken mitochondria

with increased membrane density, reduced or vanished mitochondrial

cristae, outer mitochondrial membrane rupture and loss of plasma

membrane integrity (25–27). These characteristics distinctly

differentiate ferroptosis from other cell death modalities such as

apoptosis and necroptosis. Notably, nuclear morphology typically

remains intact during ferroptosis, contrasting with classical

apoptotic nuclear fragmentation.

These distinctive features suggest that ferroptosis

is regulated through specific molecular mechanisms. In the

following sections, the present study systematically elaborates on

the key metabolic pathways and molecular mechanisms governing

ferroptosis regulation.

Iron is important for human survival, participating

in physiological activities in the forms of Fe3+ and

Fe2+: It is not only a key participant in the electron

transport chain during oxidative phosphorylation but also the core

of heme in hemoglobin, responsible for oxygen transport in the

blood. The majority of iron in the body is bound to proteins or

stored by ferritin, with only a small amount of free iron forming

the labile iron pool (LIP) (28).

The transport, metabolism and storage of iron are tightly regulated

because free Fe2+, with its redox activity, can promote

the generation of ROS through the Fenton reaction, exacerbating LPO

(29–32). Extracellular Fe3+ first

binds to transferrin and enters cells via endocytosis mediated by

transferrin receptor 1. Within the endosome-lysosome system, as the

pH decreases, Fe3+ dissociates and is reduced to

Fe2+ by the metal reductase STEAP3, then transported to

the cytoplasm by the divalent metal transporter 1 (33,34).

In the cytoplasm, Fe2+ can be reduced and stored as

Fe3+ by ferritin, exported out of the cell via

ferroportin (FPN1/SLC40A1), involved in the synthesis of

iron-containing proteins or exist as part of the transient LIP

(35). Iron homeostasis is vital

for cell survival and iron overload disrupts this balance, thereby

inducing ferroptosis (Fig. 1).

Lipids are the core structural components of cell

membranes and organelle membranes. Under normal physiological

conditions, lipid oxidation and reduction maintain a dynamic

balance, but cellular carcinogenesis or external stimuli can

disrupt this equilibrium (36).

Ferroptosis, a novel form of cell death, is characterized by

oxidative damage to PUFA-containing phospholipids in cell membranes

(37,38). PUFAs are the primary substrates of

LPO and their oxidation severely disrupts membrane structure and

function. By contrast, MUFAs can antagonize ferroptosis by

inhibiting LPO (39–41). Thus, PUFA levels regulate both LPO

and susceptibility to ferroptosis.

At the molecular level, acyl-CoA synthetase

long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine

acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) are key enzymes regulating PUFA

incorporation into phospholipids. Inhibition or loss of their

activity confers resistance to ferroptosis (42–44).

Specifically, ACSL4 and LPCAT3 work synergistically to esterify

arachidonic acid (AA) or adrenic acid (AdA) into

phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Subsequently, LOXs catalyze the

formation of lipid hydroperoxides. The breakdown products of these

peroxides attack proteins, induce plasma membrane rupture and

ultimately drive ferroptosis (45–47)

(Fig. 1).

As a key precursor, cysteine, together with

glutamate and glycine, is catalyzed by glutamate-cysteine ligase

and GSH synthetase in sequence to synthesize GSH. GSH is an

essential cofactor for GPX4, a selenium-dependent enzyme that can

reduce toxic lipid peroxides (PL-PUFA-OOH) to harmless lipid

alcohols (PL-PUFA-OH), maintaining redox homeostasis (49,50,55).

In addition, GSH reductase can regenerate oxidized

GSH into reduced GSH, thereby maintaining the activity of GPX4 and

blocking ferroptosis triggered by LPO (50,51,56).

Therefore, the targeted regulation of the three-level defense

network of cystine uptake, GSH synthesis and GPX4 function is an

effective strategy for intervening in ferroptosis (Fig. 1).

BH4 and BH2 form a redox cycle that synergistically

scavenges oxygen-free radicals to inhibit ferroptosis (61). This cycle is regulated by

dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), which uses NAD(P)H as a cofactor to

reduce BH2 to BH4. Elevated BH4 levels can induce cellular lipid

remodeling, reducing the proportion of phospholipids containing

di-polyunsaturated fatty acyl groups (diPUFA) and thereby blocking

ferroptosis (62).

Furthermore, BH4 enhances the biosynthesis of

coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) by promoting the synthesis of 4-hydroxybenzoic

acid, associating the GCH1-BH4-DHFR pathway to the FSP1-CoQ10 axis

and forming a synergistic anti-ferroptosis network (Fig. 1).

In the biosynthetic pathway of pyrimidine

nucleotides, DHODH occupies a key position and carries out an

indispensable role in the synthesis of DNA and RNA. Once DHODH is

inhibited, this biosynthetic pathway will be disrupted, resulting

in abnormal or even terminated synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides

(66). This further leads to a

decrease in the availability of pyrimidine nucleotides, making the

purine-pyrimidine base pairing process unable to proceed normally

and ultimately severely hindering the synthesis of RNA (67). Since RNA is a cofactor of GSH, a

decrease in the amount of RNA will lead to an increase in the

amount of GSH. At this time, GPX4 can reduce the peroxidized lipids

back to their original state. As the level of LPO decreases, the

process of ferroptosis is inhibited and the incidence of

ferroptosis also decreases accordingly (68,69)

(Fig. 1).

PE-PUFAs are the preferred substrates for LPO, and

their content directly affects the degree of LPO and cellular

sensitivity to ferroptosis. Thus, MBOAT1 and MBOAT2 regulate the

composition of unsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids,

reducing oxidizable PE-PUFAs and increasing stable PE-MUFAs, to

form a defense against ferroptosis, effectively inhibiting its

occurrence (71). Further studies

showed that their expression and function are specifically

regulated by sex hormone receptors: MBOAT1 is regulated by estrogen

receptors, with activity related to estrogen signaling; MBOAT2 is

regulated by androgen receptors, with function dependent on

androgen signal activation. This makes their ferroptosis-inhibiting

effect sex hormone-dependent, providing a new perspective for

analyzing the differential regulation of ferroptosis under

different sex or hormonal microenvironments (70,72,73).

This mechanism does not rely on classical pathways (70) such as GPX4 or AIFM2, but acts by

directly remodeling the fatty acid composition of membrane

phospholipids, adding new insights into the complexity and

diversity of the ferroptosis regulatory network (Fig. 1).

FSP1, a type II nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-H

(NADH): quinone oxidoreductase (NDH-2) with N-terminal

hydrophobic/membrane (aa 1–27), NADH oxidoreductase (aa 81–285) and

FAD (aa 286–308) domains (74), is

a key anti-ferroptosis factor. Its GSH-independent antioxidant

pathway, parallel to GPX4, regulates iron metabolism and protects

against iron-dependent death (75).

Vitamin K, a lipophilic molecule with

2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone and polyisoprene side chains

(plant-derived phylloquinone K1; animal/bacterial menaquinone K2),

converts to hydroquinone (VKH2) for the vitamin K cycle (79,80–82).

FSP1 acts as a vitamin K reductase, consuming NAD(P)H to produce

VKH2, which inhibits ferroptosis by blocking LPO (83,84)

(Fig. 1).

Additionally, FSP1 enhances membrane repair via the

ESCRT-III-dependent pathway (CoQ-independent) to inhibit

ferroptosis (85). Ferroptosis

inducers trigger FSP1 to suppress tumor cell ferroptosis; FSP1

knockout blocks RSL3-induced plasma membrane expression of CHMP5/6,

while CHMP5 overexpression reverses inducer- and FSP1

knockout-induced cell death (86–89)

(Fig. 1).

Nrf2, the core of cellular antioxidant responses,

binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs) to promote downstream

gene transcription (90). It

carries out a key role in regulating ferroptosis as an important

transcription factor against it, involved in iron, lipid and amino

acid metabolism (91). Its

regulated antioxidant effectors [such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)

and GSH] which contain AREs (92).

Elevated ROS activate the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: Nrf2 dissociates

from Keap1, translocates to the nucleus, binds to AREs, initiates

transcriptional cascades and upregulates downstream antioxidant

genes, which is important for maintaining redox balance and

inhibiting ferroptosis (77)

(Fig. 1).

Additionally, cytoplasmic platelet-activating factor

(PAF) acetylhydrolase (II) specifically inhibits short-chain fatty

acid oxidation, blocks oxidized phospholipid (such as PAF)

accumulation by interfering with cellular redox capacity, thus

inhibiting ferroptosis (78).

whereas LPLAT disrupts lipid bilayers, increases membrane

permeability and triggers ferroptosis (93) (Fig.

1).

NPC is a malignant tumor originating from the

mucosal epithelium of the nasopharynx. Its incidence shows obvious

regional characteristics and is particularly high in Southeast Asia

and North Africa (79). The

pathogenesis of this disease is multifactorial, involving the

complex interaction of various risk factors such as genetic

susceptibility, environmental exposure, EBV infection and lifestyle

(79).

Genetic factors carry out an important role in the

pathogenesis of NPC. Epidemiological studies have shown that NPC

exhibits notable familial aggregation. The risk of disease in

first-degree relatives is markedly compared with that in the

general population, indicating the key role of genetic

susceptibility in the occurrence of this disease (80–82).

Currently, it is considered that specific gene polymorphisms (such

as the HLA gene cluster), mutations in tumor susceptibility genes

(such as TP53) and epigenetic changes may jointly affect the

susceptibility of an individual to NPC. In addition, genetic

factors may interact with environmental factors (such as EBV

infection), further increasing the risk of developing the disease

(Table I).

Environmental exposure is one of the important risk

factors for NPC. Long-term exposure to air pollutants (such as

PM2.5, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides) can lead to chronic

inflammation of the nasopharyngeal mucosa and DNA damage, thus

promoting malignant transformation (94). In addition, occupational exposure to

certain chemical carcinogens (such as formaldehyde or

benzo(a)pyrene) may also increase the risk of NPC. Viral infection

carries out a central role in the development of NPC, especially

EBV infection. EBV can infect nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. By

expressing latent membrane proteins (LMP) 1 and 2 and oncogenic

proteins such as EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1), it can interfere

with the regulation of the cell cycle and induce genomic

instability (86,95) (Table

I).

Unhealthy lifestyles are modifiable risk factors for

NPC. Smoking can notably increase the risk of developing the

disease. Carcinogens in tobacco, such as nitrosamines and

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can directly damage the

nasopharyngeal mucosa and promote the oncogenic effect of EBV

(87,88). Excessive alcohol consumption may

induce the formation of DNA adducts through metabolites (such as

acetaldehyde), exacerbating mucosal damage (89). Dietary factors also play a key role.

Long-term consumption of pickled foods (such as salted fish and

cured meat) may increase the risk of NPC because they are rich in

nitrites, which can be converted into the potent carcinogen

N-nitroso compounds in the body (85). In addition, heterocyclic amines and

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons produced by high-temperature

cooking (such as grilling and smoking) may also promote

tumorigenesis (Table I).

EBV belongs to the gammaherpesvirus family and is

widely prevalent in the human population, with >90% of adults

having been infected. It can establish a lifelong latent state in

epithelial cells and B cells. EBV is closely associated with a

variety of lymphoid malignancies, such as Burkitt's lymphoma,

Hodgkin's lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, NK/T-cell lymphoma, as well as

two types of epithelial cancer: NPC and gastric cancer (96). EBV exhibits two distinctly different

life cycle states: lytic (productive) and latent (persistent).

During primary infection, EBV first replicates in nasopharyngeal

epithelial cells, then crosses the epithelial layer of the

nasopharyngeal lining, infects naive B cells and continues to

replicate, and finally establishes a stable latent state in host

cells in the form of histone-associated episomes. To maintain

latent viruses and serve as a stable reservoir for EBV-induced

tumorigenesis, latent viruses need to be periodically reactivated.

In NPC, the prevalence of type 2 and type 3 EBV reaches 100%, and

high-level viral reactivation is a risk factor for EBV-associated

NPC (97). The interaction between

EBV infection, environmental factors, and genetic factors is the

core of the pathogenesis of NPC. Recent studies have shown that

abortive lytic infection promotes the establishment of the latent

state during primary infection and the development of

EBV-associated tumors. In-depth exploration of the mechanisms by

which EBV viral products drive the development of NPC will help

design more effective EBV-targeted therapies (98,99).

During the latent period, the virus only expresses a

small number of genes key for genome maintenance and regulation.

Based on late gene expression profiles, EBV latency can be divided

into four types (100,101). In NPC, EBV infection is largely in

type 2 latency, during which EBNA1, LMP1 and LMP2 protein are

expressed. At the same time, some non-coding RNAs are also

expressed, such as EBV-encoded RNA (EBER), BamHI A rightward

transcript (BART), and BART miRNA. These expressed viral genes

provide signals necessary for the maintenance of replication and

survival of both EBV and host cells. However, EBV lytic phase

proteins, such as BGLF5 (DNase) and BALF3, cause host genome

instability and play an important role in the tumorigenesis of NPC

(100).

Ferroptosis is a novel form of programmed cell

death, characterized by iron-dependent accumulation of lipid

peroxides, which ultimately leads to cell death (102,103). The occurrence of ferroptosis is

associated with the balance of intracellular iron metabolism, lipid

metabolism and antioxidant systems. In the field of tumor research,

abnormal regulation of ferroptosis is associated with the

occurrence, development and therapeutic sensitivity of tumors

(104–106). The regulatory role of EBV

infection on ferroptosis in NPC is an important content that

urgently needs to be supplemented and improved in current research.

In the type 2 latency of EBV infection in NPC, the expressed EBNA1,

LMP1, LMP2 proteins and non-coding RNAs such as EBER, BART and BART

miRNA may carry out key roles in regulating the ferroptosis process

(107–109).

EBNA1, as an important nuclear antigen during EBV

latency, not only participates in the replication and maintenance

of the viral genome but also affects the physiological functions of

host cells by regulating intracellular signaling pathways. Studies

have shown that EBNA1 can affect the expression of intracellular

antioxidant-related genes by activating the NF-κB signaling

pathway. The activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway can promote

the expression of GPX4 (110–113). As a key inhibitor of ferroptosis,

GPX4 can inhibit the occurrence of ferroptosis by reducing LPOs to

non-toxic alcohols. Therefore, EBNA1 may upregulate the expression

of GPX4 by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby

inhibiting ferroptosis in NPC cells and providing favorable

conditions for the survival of cancer cells (114).

As a transmembrane protein, LMP1 can mimic the

signal transduction function of members of the tumor necrosis

factor receptor family and activate a variety of intracellular

signaling pathways, such as MAPK and PI3K/Akt (115,116). Among them, the activation of the

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway can promote the degradation of

intracellular iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP2). IRP2 can bind to

the mRNAs of ferritin heavy chain (FTH1) and ferritin light chain

(FTL), inhibiting their translation and thus reducing the synthesis

of intracellular ferritin (117,118). Ferritin is an important protein

for intracellular iron storage; a decrease in ferritin content

leads to an increase in intracellular free iron levels, which in

turn promotes the occurrence of ferroptosis. However, after LMP1

activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, it can increase the

expression of FTH1 and FTL by promoting the degradation of IRP2,

thereby increasing the intracellular ferritin content and reducing

free iron levels, which inhibits ferroptosis in NPC cells (119,120). In addition, LMP1 can also

upregulate the expression of SLC7A11 by activating the MAPK

signaling pathway. SLC7A11 is an important component of the Xc-,

which can promote the entry of cystine into cells and provide raw

materials for the synthesis of GSH. GSH is an important coenzyme

for GPX4 to exert its antioxidant effect; an increase in GSH

content can enhance the activity of GPX4 and further inhibit the

occurrence of ferroptosis (121–124).

LMP2 protein mainly includes two subtypes: LMP2A and

LMP2B, among which LMP2A carries out an important role in the

occurrence and development of NPC. LMP2A can activate signaling

pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK by mimicking the signal

transduction of the B-cell receptor and its regulation of

ferroptosis may be similar to that of LMP1. In addition, studies

have found that LMP2A can affect the expression of intracellular

iron metabolism-related genes, such as downregulating the

expression of TFR1 (125–128). TFR1 is an important receptor for

iron uptake by cells; a decrease in TFR1 expression reduces iron

uptake by cells, lowers intracellular iron levels and thereby

inhibits the occurrence of ferroptosis.

EBER is a small non-coding RNA encoded by EBV,

mainly including two types: EBER1 and EBER2. Although EBER does not

encode proteins, it can regulate the physiological functions and

signaling pathways of cells by interacting with a variety of host

cell proteins. Studies have shown that EBER can induce the

production of IFNs by activating the toll-like receptor 3 signaling

pathway and IFN can affect the balance of intracellular iron

metabolism and antioxidant systems. In addition, EBER can also

interact with RNA-activated protein (RIG-I) to activate downstream

signaling pathways and regulate the expression of associated genes,

which may further affect ferroptosis. For example, after EBER

activates the RIG-I signaling pathway, it can promote the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and some pro-inflammatory

cytokines can upregulate the expression of SLC7A11 and inhibit the

occurrence of ferroptosis.

EBV lytic phase proteins, such as BGLF5 and BALF3,

not only cause host genome instability but also may regulate

ferroptosis in NPC cells (103).

BGLF5 is a DNase expressed during the EBV lytic phase, which can

degrade the DNA of host cells and viruses, leading to genome

instability. Genome instability causes an increase in intracellular

oxidative stress levels and oxidative stress is one of the

important inducers of ferroptosis (129–131). By degrading DNA, BGLF5 may

increase intracellular ROS levels; ROS can attack intracellular

lipid molecules, trigger LPO reactions and thereby promote the

occurrence of ferroptosis. In addition, BGLF5 may also regulate the

cellular stress response by affecting the expression of

intracellular DNA damage repair-related genes, further influencing

the process of ferroptosis. For example, BGLF5 can inhibit the

expression of DNA damage repair proteins, preventing cells from

effectively repairing DNA damage, leading cells to be in a

continuous stress state and increasing their sensitivity to

ferroptosis (132,133).

BALF3 is a DNA helicase expressed during the EBV

lytic phase and is involved in the replication and packaging of

viral DNA. In the process of exerting its biological functions,

BALF3 may affect the intracellular redox balance and iron

metabolism. Studies have shown that BALF3 can interact with certain

intracellular antioxidant proteins, inhibiting their activity,

reducing the antioxidant capacity of cells and thereby increasing

the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis (134–136). In addition, BALF3 may also

regulate the expression of iron metabolism-related genes, such as

upregulating the expression of TFR1, increasing iron uptake by

cells, raising intracellular iron levels and promoting the

occurrence of ferroptosis (137,138).

In addition to BGLF5 and BALF3, the EBV lytic phase

also expresses a variety of other proteins, such as ZEBRA (BZLF1)

and RTA (BRLF1). These proteins carry out key roles in initiating

EBV lytic infection and may also regulate ferroptosis. For example,

ZEBRA can regulate the expression of intracellular oxidative stress

and iron metabolism-related genes by activating a variety of

signaling pathways, thereby influencing the occurrence of

ferroptosis (139,140). RTA can also interact with host

cell proteins, affecting the physiological functions and signaling

pathways of cells, which may indirectly affect ferroptosis

(141,142).

In summary, EBV can regulate the ferroptosis process

of NPC cells from multiple aspects, including iron metabolism,

lipid metabolism and antioxidant systems, through its

latency-related molecules and lytic phase-related proteins.

In-depth study of the mechanism by which EBV regulates ferroptosis

in NPC can not only improve the research on the pathogenesis of EBV

and NPC but also provide new targets and strategies for the

treatment of NPC (102,143,144). For example, designing

corresponding inhibitors or antagonists targeting key molecules or

signaling pathways involved in EBV-regulated ferroptosis may

enhance the sensitivity of NPC cells to ferroptosis and improve the

therapeutic effect of NPC (145,146) (Table

I).

Genomic instability refers to an increased tendency

for errors in DNA replication or repair, leading to changes such as

mutations and deletions in the genome. Causes for genomic

instability include endogenous abnormal cellular processes and

exogenous environmental factors (such as radiation, chemicals and

viruses) (147). There is evidence

indicating that genomic instability is key in the development of

NPC and several factors can promote the genomic instability of NPC.

For example, EBV can cause DNA damage, inhibit the DNA repair

mechanism of infected cells and increase the risk of mutations and

chromosomal abnormalities. Exposure to environmental factors such

as tobacco smoke, alcohol, formaldehyde and nitrosamines is

associated with DNA damage and genomic instability, which can

trigger NPC (148–150). Genetic factors (such as mutations

in tumor suppressor genes or DNA repair genes) can also increase

the susceptibility to NPC by impairing the ability of a cell to

maintain genomic stability.

As a malignant tumor, NPC has complex and diverse

clinical manifestations and early diagnosis is difficult. The

clinical manifestations of NPC vary with the progression of the

disease course. In the early stage, NPC may have no obvious

symptoms. Some patients with NPC may have mild symptoms such as

blood in nasal discharge or nasal bleeding. These symptoms are

often ignored by patients, thus delaying the best treatment

opportunity. As the disease progresses, the symptoms of NPC

gradually become more obvious, including nasal bleeding, ulcers or

cauliflower-like masses, tinnitus, hearing loss, nasal congestion,

persistent unilateral headache or eye symptoms (151,152). Currently, radiotherapy alone or in

combination with chemotherapy is the main treatment method for NPC;

however, a large number of patients succumb to NPC due to

recurrence and tumor metastasis. Distant metastasis is an important

cause of treatment failure and mortality in patients with NPC.

Previous studies have shown the key role of ferroptosis in tumor

metastasis, emphasizing the importance of ferroptosis in tumor

growth and metastasis (13,153–155). Determining new anti-cancer

strategies and discovering new drugs that induce ferroptosis will

be beneficial for improving the cure rate of advanced patients with

NPC (Table I).

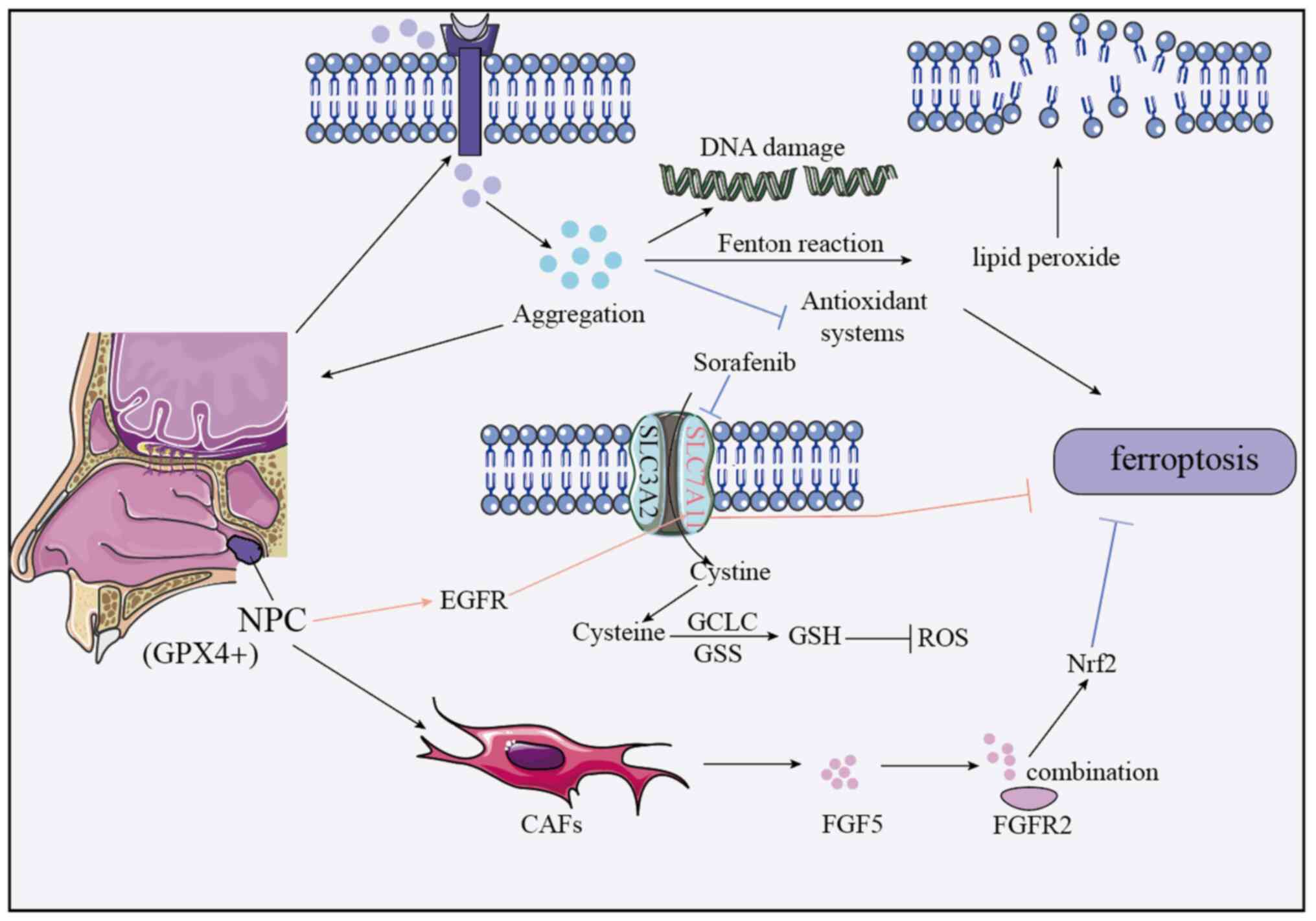

NPC development is associated with abnormal iron

metabolism. Cancer cells, with higher iron demand, accumulate

intracellular iron by increasing Trf for enhanced uptake and

regulating genes to reduce iron transport/storage (156). High iron levels trigger Fenton

reactions, leading to LPO accumulation, membrane damage and

exacerbated ferroptosis (possibly via antioxidant system

inhibition). Iron imbalance also fuels proliferation, oxidative

stress and DNA damage, accelerating progression (Fig. 2).

Ferroptosis interacts with other pathways in

regulating NPC, such as the FGF5/FGFR2/Nrf2 pathway inhibits

ferroptosis and reduces cisplatin sensitivity. Cancer-associated

fibroblasts (CAFs)-secreted FGF5 binds FGFR2, activating Nrf2 to

inhibit ferroptosis (159),

indicating a role for CAFs and potential targets (Fig. 2).

GPX4, a key antioxidant enzyme converting lipid

peroxides to inactive forms, has higher positivity in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) tissues than normal nasopharyngeal

tissues (102). Its expression

associates with clinical features of NPC: Higher in stage III–IV

vs. I–II NPC, poorly vs. well-differentiated tumors, patients with

vs. without lymph node metastasis, and those with poor vs. good

radiotherapy response. Moreover, GPX4-positive NPC cases have lower

5-year survival rates than GPX4-negative cases (160), indicating high GPX4 as a poor

prognosis marker for NPC (Fig.

2).

The protein arginine methyltransferase (Prmt) family

catalyzes the methylation of arginine residues in both histones and

non-histone proteins. As a key post-translational modification,

arginine methylation is widely involved in regulating various

cellular processes. Prmt4, also known as coactivator-associated

arginine methyltransferase 1, is the first identified member of the

PRMT family. It can catalyze the asymmetric dimethylation of

arginine residues in protein substrates, carries out a key role in

the regulation of gene transcription and participates in the

modulation of multiple cellular processes (161).

Studies have shown that Prmt4 is overexpressed in a

variety of tumors, including breast cancer, prostate cancer and

colorectal cancer (162–164). Its overexpression activates key

factors of multiple oncogenic signaling pathways, such as FOS,

E2F1, Wnt/β-catenin and nuclear receptor coactivator 3

(NCOA3/AIB1), thereby creating a favorable microenvironment for

tumor growth, invasion and metastasis. A study by Pu et al

(161) further revealed that the

upregulation of PRMT4 reduces the sensitivity of

cisplatin-resistant NPC cells to erastin-induced ferroptosis

through mitochondrial damage; additionally, the interaction between

PRMT4 and Nrf2 promotes the enzymatic methylation activity of

PRMT4. These findings indicate that m6A methylation enhances the

stability of PRMT4 in cisplatin-resistant NPC cells, thereby

affecting the erastin-induced ferroptosis process.

Currently, research on PRMT4 is mainly in the

preclinical stage. Although notable achievements have been made in

cellular and animal experiments, progress in clinical trials is

relatively slow. The application of PRMT4 as a therapeutic target

for tumors faces numerous challenges in clinical practice. Firstly,

due to the complexity of the human physiological environment,

PRMT4-targeted drugs are difficult to act precisely and tend to

interfere with the normal physiological functions of healthy cells,

leading to adverse reactions such as myelosuppression and liver

injury. Secondly, tumor cells exhibit high heterogeneity, and there

are key differences in PRMT4-related characteristics (including

expression level, activity and associated signaling pathways) among

tumor cells from patients with different types of cancer or even

within the same cancer type, making it difficult to develop a

unified and effective treatment regimen. Thirdly, long-term use of

PRMT4 inhibitors may lead to tumor drug resistance; tumor cells can

evade the effects of drugs through alternative pathways or gene

mutations, thereby impairing therapeutic efficacy (161). Therefore, to promote the

translational application of PRMT4-targeted tumor therapy in the

future, it is necessary to optimize the specificity of drugs and

reduce their toxic and side effects by leveraging structural

biology and targeted delivery technologies; establish personalized

diagnosis and treatment regimens through multi-omics stratification

and predictive models; and clarify the mechanisms of drug

resistance while exploring the combined use of PRMT4 inhibitors

with ferroptosis inducers (such as erastin) and chemotherapeutic

drugs (such as cisplatin) to reverse drug resistance (Table II).

GSH S-transferase mu 3 (GSTM3) is a member of the

GSH S-transferase family and has multiple effects on the

progression of various malignant tumors (160). To investigate the effect of GSTM3

on ionizing radiation (IR; induced ferroptosis in vivo,

researchers subcutaneously injected GSTM3-overexpressing stable

5–8F cells into nude mice, leading to the formation of palpable

tumors (174,175). Subsequently, the mice bearing

xenograft tumors received conventional IR treatment. The results

showed that the body weight of the mice remained stable throughout

the treatment period (176,177).

Compared with the control group, in the xenograft model, GSTM3

overexpression alone did not exhibit any effect on tumor growth,

while IR effectively inhibited tumor growth. Notably, compared with

the group treated with IR alone, the combination of GSTM3

overexpression and IR treatment led to a notable reduction in tumor

size and weight. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) serves as a

ferroptosis marker reflecting the level of LPO. Immunohistochemical

staining showed that IR moderately increased the contents of GSTM3

and 4-HNE (178–180). In addition, GSTM3 overexpression

combined with IR treatment resulted in a marked increase in the

signal level of 4-HNE (181,182). Overall, these results indicate

that GSTM3 enhances IR-mediated ferroptosis and improves the

radiosensitivity of NPC.

To the best of our knowledge, currently, clinical

research on GSTM3 is relatively limited. Expression of GSTM3 is

associated with the inhibition of breast cancer stem cell

phenotypes and favorable clinical prognosis (183,184). Additionally, chemotherapeutic

drugs can inhibit GSTM3 expression, which promotes the enrichment

of breast cancer stem cells and ultimately leads to tumor

recurrence and metastasis (182,185). In clinical application, due to the

functional redundancy of the GSTM3 family and high heterogeneity of

tumor cells, single-target intervention on GSTM3 shows poor

efficacy, and it is difficult to develop a unified targeted

treatment plan. In the future, it is necessary to analyze the

functional cooperation mechanism between GSTM3 and its family

members, and construct a patient stratification model using

multi-omics technology to promote the translation of GSTM3-related

targeted strategies from basic research to clinical practice,

thereby providing a new direction for improving tumor treatment

efficacy (186) (Table II).

Ferroptosis is triggered by LPO and is strictly

regulated by SLC7A11 and SLC3A2, which are key components of the

cystine-glutamate antiporter (187). Due to the inhibition of LPO, the

downregulation of GPX4 can directly or indirectly trigger

ferroptosis. To determine the specific molecular mechanism of

BBR-induced ferroptosis, Wu et al (187) treated NPC cells with different

concentrations of BBR and detected the mRNA and protein levels of

GPX4, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2. The results showed that the protein

levels of GPX4, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 in S18 and 5–8F NPC cells

decreased in a dose-dependent manner. Meanwhile, the mRNA levels of

GPX4, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 also decreased (188–190). Moreover, the use of deferoxamine

(DFO) and Fer-1 reversed the expression levels of proteins and

mRNAs associated with BBR-induced ferroptosis. In addition, the

results of the study on the in vivo anti-metastatic effect

of berberine (BBR) on nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cells (using a

nude mouse xenograft model) showed that the number of metastatic

lesions in the BBR treatment group was reduced compared with that

in the control group (191).

Moreover, compared with the control group, the proteins of GPX4,

SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 were elevated, which was consistent with the

in vitro results of the downregulation of the expression of

GPX4, SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 in the BBR treatment group (190,192). These findings indicate that BBR

considerably inhibits NPC metastasis both in vitro and in

vivo. In conclusion, GPX4 is a major molecule and the Xc-/GPX4

axis system carries out an important role in BBR-induced

ferroptosis of NPC cells (189,193).

In terms of clinical trial progress, studies have

shown that BBR can inhibit high glucose-induced ferroptosis in

cells associated with diabetic retinopathy by activating the

Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 pathway (194–196), providing a theoretical basis for

its application in the treatment of associated diseases. Although

in vitro and animal experiments have confirmed that BBR can

inhibit tumor cell growth and induce ferroptosis (197–200), its clinical application in NPC

still faces challenges. Specifically, the complex human

physiological environment leads to differences in the

pharmacokinetics of BBR between in vivo and in vitro

settings, making it difficult to ensure that BBR acts precisely on

NPC cells to induce ferroptosis while avoiding damage to normal

cells. Additionally, NPC cells exhibit high heterogeneity, patients

vary in their sensitivity to BBR and the expression of molecules

related to the Xc−/GPX4 axis, which hinders the

development of a unified and effective clinical treatment regimen

(201–203). In the future, more large-scale,

multi-center clinical trials are needed to investigate the safety

and efficacy of BBR in humans, explore personalized treatment

strategies and promote the translation of BBR from basic research

to clinical application in NPC treatment (Table II).

Numerous studies have shown that the NF-κB pathway

carries out an important role in the regulation of oxidative stress

and ferroptosis (204–208). Based on this, Luo et al

(209) speculated that

isoquercitrin might play a promoting role in the oxidative stress

and ferroptosis processes of NPC cells by regulating the NF-κB

pathway (210,211). By detecting the expression levels

of proteins associated with the NF-κB pathway, it was found that

isoquercitrin markedly reduced the ratios of phosphorylated

(p)-p65/p65 and p-IκB/IκB and simultaneously inhibited the

expression of IL-1β. These results indicate that isoquercitrin can

inhibit the activation of the NF-κB pathway (212,213).

In addition, as a key molecule regulating various

metabolic processes (including oxidative stress), the activity of

AMPK is also affected by isoquercitrin. Zhang et al

(214) showed that isoquercitrin

markedly reduced the ratio of p-AMPK/AMPK, indicating that it has

an inhibitory effect on the activity of AMPK. These results suggest

that isoquercitrin may carry out a role in NPC by inhibiting the

AMPK/NF-κB p65 signaling axis. To further verify this mechanism,

Luo et al (209)

established a xenograft tumor model. Analysis revealed that

isoquercitrin markedly reduced tumor weight, however, had no

obvious effect on the body weight of the mice. At the same time,

the level of LPO in the isoquercitrin treatment group was notably

increased, while the expressions of ferroptosis-related markers

(such as ATF4, xCT, GPX4 and HO-1) were considerably decreased,

indicating that isoquercitrin can induce ferroptosis in vivo

(215,216). In conclusion, isoquercitrin may

inhibit tumorigenesis of NPC in vivo, enhance oxidative

stress and promote ferroptosis by inhibiting the AMPK/NF-κB p65

signaling pathway (209,217).

To the best of our knowledge, to date, there are no

publicly available dedicated clinical studies on isoquercitrin for

NPC. However, research has explored its potential in other diseases

and tumor types: for instance, in early clinical observations of

colorectal cancer, isoquercitrin combined with chemotherapy showed

a synergistic effect in inhibiting tumor growth without notably

increasing adverse reactions, initially demonstrating its safety

and potential for combined therapy (218). In small-sample trials for

ulcerative colitis (a chronic inflammation-related disease),

isoquercitrin alleviated intestinal inflammation by regulating the

NF-κB pathway (219,220), this mechanism shares commonality

with the ‘NF-κB pathway inhibition’ observed in NPC research

(221), providing an indirect

reference value. Nevertheless, to promote the application of

isoquercitrin in NPC treatment, targeted Phase I and II clinical

trials are still needed to verify its pharmacokinetic

characteristics, the efficacy of monotherapy or combined therapy

and long-term safety. Additionally, it is necessary to clarify the

differences in efficacy across patients with NPC with different

molecular subtypes, so as to provide a basis for formulating

subsequent clinical protocols (222–226) (Table

II).

As a key element in the mitochondrial respiratory

chain, iron carries out an important role in the process of

ferroptosis. Lipid hydroperoxides are considered to be the main

driving force and marker of ferroptosis. To explore the mechanism

of action of CuB, Huang et al (227) detected the concentrations of

intracellular iron and lipid peroxides. The results showed that

after treatment with CuB, the contents of intracellular iron and

lipid peroxides increased considerably in a dose-dependent manner,

and this effect could be effectively reversed by inhibitors such as

DFO, CPX and Fer-1. In addition, GPX4, as a key regulatory factor

of ferroptosis, its expression level decreased markedly after CuB

treatment, further supporting the role of CuB in inducing

ferroptosis.

To the best of our knowledge, there are currently

no publicly available clinical trial data on CuB for NPC, and it

has not yet entered the formal clinical trial phase, with only some

preliminary explorations conducted. To promote the clinical

translation of CuB in the future, targeted Phase II and III

clinical trials are still needed to evaluate the objective response

rate, progression-free survival, and long-term safety (especially

the effects on the hematopoietic system and liver/kidney function)

of its monotherapy or combined therapy regimens, thereby providing

sufficient clinical evidence (Table

II).

DSF is a drug clinically used for the treatment of

alcoholism, which exerts its effect by inhibiting the activity of

aldehyde dehydrogenase (228).

Studies have shown that DSF has potential application value in

cancer treatment. The combined action of DSF and Cu can induce the

aggregation of NPL4, leading to complex cellular phenotypes and

ultimately triggering cell death (229–231). Experiments have shown that DSF/Cu

treatment upregulates the expression of p53 protein and its

downstream targets p21 and BAX, and this effect can be reversed by

the p53 inhibitor Pifithrin-α (232). In addition, DSF/Cu markedly

increases the level of lipid ROS in 5–8F cells, and the ROS

scavenger N-acetylcysteine can partially reverse this phenomenon.

In the 5–8F xenograft model, DSF/Cu markedly inhibits tumor growth

without causing changes in the body weight of the mice (233–235). These results indicate that DSF/Cu

carries out an important role in the treatment of NPC by inducing

ROS-mediated ferroptosis and has the potential to be used as an

adjuvant therapeutic drug in clinical practice (236,237).

Although DSF/Cu shows promising prospects in NPC

treatment research, its clinical application faces challenges: DSF

has a short half-life and is easily metabolized into inactive

substances after oral administration, making it difficult to

maintain effective concentrations (238,239); the complex human physiological

environment and pronounced individual differences in

pharmacokinetics complicate the determination of precise dosages;

additionally, tumor cell heterogeneity increases the difficulty of

personalized treatment (240,241). In the future, it is necessary to

deepen basic research to clarify the molecular mechanism of

DSF/Cu-induced ferroptosis and differences across NPC subtypes,

conduct Phase I–III clinical trials to verify its pharmacokinetics,

efficacy and safety, screen patients sensitive to DSF/Cu with

precision medicine technologies (such as genetic testing and liquid

biopsy), and explore innovative drug delivery systems to improve

pharmacokinetic properties of DSF, all to promote its development

as a clinical adjuvant treatment for NPC (242,243) (Table

II).

P4H is a heterotetramer composed of P4HA subtypes

(P4HA1, P4HA2 and P4HA3) and P4HB, forming P4H1, P4H2 and P4H3

holoenzymes respectively. It carries out a key role in the proline

hydroxylation of procollagen, catalyzing the formation of

hydroxyproline from the proline residues in the Xaa-Pro-Gly

triplet, which is essential for the folding of procollagen into a

stable triple-helix structure and its secretion out of the cell

(244,245). In addition, P4H also regulates the

hydroxylation modification of proteins containing collagen-like

sequences (246,247) (such as AGO2).

Previous studies have found that P4HA1 is a novel

regulator of ferroptosis. Its overexpression enhances the

ferroptosis resistance of NPC cells by activating HMGCS1 (248,249). Meanwhile, the P4HA1/HMGCS1

regulatory axis also promotes the proliferation of NPC cells, as

well as the survival and ferroptosis resistance of NPC cells that

are separated from the extracellular matrix (248,250,251).

Currently, relevant research on P4HA1 is mostly in

the stages of basic research and model validation, but preliminary

attempts have been made in other cancer fields: A retrospective

study on non-small cell lung cancer revealed that high expression

of P4HA1 is associated with poor prognosis in patients, providing

indirect evidence for its potential as a prognostic marker and

therapeutic target (252,253); In early preclinical trials for

pancreatic cancer, small-molecule inhibitors of P4HA1 were able to

inhibit tumor growth without obvious toxicity, laying a foundation

for research on P4HA1 in NPC (254). In the future, it is first

necessary to conduct large-scale retrospective studies to clarify

the association between P4HA1 expression and the prognosis, staging

and treatment response of patients with NPC. On this basis, Phase

I/II clinical trials of P4HA1 inhibitors should be advanced to

evaluate their safety, pharmacokinetic characteristics and

efficacy, thereby providing evidence for clinical translation

(Table II).

Icaritin has a variety of pharmacological effects,

including antioxidant effects, prevention and treatment of

osteoporosis, improvement of cardiovascular function and protection

against neurodegenerative damage (255,256). In terms of anti-tumor effects,

icaritin has been proven to inhibit the proliferation and induce

apoptosis of a variety of tumor cells. These effects make icaritin

a potential anti-tumor drug.

Studies have shown that icaritin can regulate the

expression of proteins associated with ferroptosis. For example, In

NPC cells, the expression of ACSL4, a marker protein of

ferroptosis, is upregulated, while the expression of GPX4 is

downregulated. Similarly, when icaritin is combined with

radiotherapy, it can markedly promote the accumulation of ROS in

NPC cells (255,257,258). The accumulation of ROS will

further lead to DNA damage, such as the upregulation of the

expression of γ-H2AX (259,260).

These damages will exacerbate the death of NPC cells, thereby

improving the effect of radiotherapy. In addition, icaritin can

also cause NPC cells to arrest in the G2 phase. This arrest will

further affect the proliferation and division ability of cells,

thus enhancing the killing effect of radiotherapy on NPC cells. The

aforementioned studies indicate that icaritin may enhance the

radiosensitivity of NPC cells by promoting the occurrence of

ferroptosis (261,262).

However, there are still challenges in applying

icariin to the clinical treatment of NPC: It remains unclear

whether the mechanism by which icariin regulates ferroptosis and

enhances radiosensitivity in experiments is fully applicable in the

complex human environment (263,264). Additionally, there is a lack of

clinical data to support balancing efficacy and adverse reactions

(such as mucosal damage and myelosuppression) when combined with

radiotherapy (256,266). To address these issues in the

future, breakthroughs can be made in three aspects: Conducting

clinical sample studies on NPC to verify the effect of icariin on

ferroptosis-related pathways and the impact of molecular subtypes;

developing local formulations for the nasopharynx (such as

nano-sprays) to increase drug concentration in tumor tissues; and

advancing small-sample Phase I/II clinical trials to explore the

safe dosage and administration timing of icariin combined with

radiotherapy (267) (Table II).

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a head and neck

malignant tumor, with >70% of new cases occurring in East Asia

and Southeast Asia (268–270), and its treatment has been a major

focus of clinical and research attention (271). Traditional treatment methods, such

as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, have achieved curative effects,

but present side effects and drugs that need to be addressed. In

recent years, with the in-depth study of the mechanism of cell

death, ferroptosis, as a new type of programmed cell death, has

provided a new perspective and strategy for the treatment of NPC

(13,272–274).

Ferroptosis, also referred to as iron-dependent

LPO-mediated cell death, is a unique form of cell death driven by

iron ions and LPO. Its core characteristic is the intracellular

accumulation of iron ions coupled with an uncontrolled LPO

reaction, which ultimately results in cell membrane rupture and

subsequent cell death. Compared with traditional cell death methods

such as apoptosis and necrosis, ferroptosis has its own uniqueness

in morphological, biochemical and genetic characteristics.

Numerous studies have shown that ferroptosis

carries out an important role in the occurrence, development and

treatment of NPC (10,275–278). Conversely, the abnormal iron

metabolism and increased LPO levels in NPC cells make them more

sensitive to ferroptosis. On the other hand, some chemotherapeutic

drugs, such as cisplatin, have been shown to be able to induce

ferroptosis in NPCnuo cells (279–281), thereby exerting an anti-tumor

effect. Based on the important role of ferroptosis in NPC,

researchers have begun to explore the application of ferroptosis

inducers in the treatment of NPC. For example, Erastin, as a small

molecule compound that can induce ferroptosis in a variety of

cancer cells, has been proven to enhance the sensitivity of

traditional anti-cancer drugs to NPC cells (161,282). In addition, some new

chemotherapeutic drugs and targeted therapeutic drugs are also

being developed. They induce ferroptosis in NPC cells by regulating

ferroptosis-related signaling pathways, such as GPX4 and SLC7A11.

Although ferroptosis inducers have shown great potential in the

treatment of NPC, ferroptosis inhibitors also carry out a role that

cannot be ignored. A number of studies have shown that ferroptosis

inhibitors can protect normal cells from ferroptosis, thereby

reducing the side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs (283–285). In addition, ferroptosis inhibitors

can also be used in combination with ferroptosis inducers. By

regulating the degree and speed of ferroptosis, a more precise

therapeutic effect can be achieved.

Although the application of ferroptosis in the

treatment of NPC has made progress, there are still several issues

that remain to be solved. For example, how to precisely regulate

the degree and speed of ferroptosis to achieve the best therapeutic

effect; how to overcome the problem of drug resistance and improve

the sensitivity of ferroptosis inducers; how to develop safer and

more effective ferroptosis inducers and inhibitors and new

treatment methods all need to go through clinical trials and

evaluations to ensure their safety and effectiveness. In the

future, with the in-depth study of the mechanism of ferroptosis and

the development of new drugs, it is considered that ferroptosis

will carry out a greater role in the treatment of NPC, and it is

expected to achieve more precise and effective therapeutic

effects.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by the grants from Yan'an

science and technology bureau (grant no. 2024SF-YBXM-037

Y.Y.L).

Not applicable.

SB was responsible for writing and revising the

manuscript. YG was responsible for the preparation of figures and

revisions of the present review. QQ was responsible for the

revisions of the present review. JQ was responsible for the

revisions of the present review. YY was responsible for revising

the article. All authors contributed to the article and all authors

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Lim CY, Ng GWY, Goh CK, Lee MKC, Cheong I,

Ooi EE, Liu J, West RB, Loh KS and Tay JK: Impact of high-risk EBV

strains on nasopharyngeal carcinoma gene expression. Oral Oncol.

157:1069412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yip PL, Lee AWM and Chua MLK: Adjuvant

chemotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 24:713–715.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lee S, Hwang N, Seok BG, Lee S, Lee SJ and

Chung SW: Autophagy mediates an amplification loop during

ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 14:4642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kinowaki Y, Taguchi T, Onishi I, Kirimura

S, Kitagawa M and Yamamoto K: Overview of ferroptosis and synthetic

lethality strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 22:92712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Alborzinia H, Chen Z, Yildiz U, Freitas

FP, Vogel FCE, Varga JP, Batani J, Bartenhagen C, Schmitz W, Büchel

G, et al: LRP8-mediated selenocysteine uptake is a targetable

vulnerability in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. EMBO Mol Med.

15:e180142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Floros KV, Cai J, Jacob S, Kurupi R,

Fairchild CK, Shende M, Coon CM, Powell KM, Belvin BR, Hu B, et al:

MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma is addicted to iron and vulnerable to

inhibition of the system Xc-/glutathione axis. Cancer Res.

81:1896–1908. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lu Y, Yang Q, Su Y, Ji Y, Li G, Yang X, Xu

L, Lu Z, Dong J, Wu Y, et al: MYCN mediates TFRC-dependent

ferroptosis and reveals vulnerabilities in neuroblastoma. Cell

Death Dis. 12:5112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lei G, Zhuang L and Gan B: Targeting

ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

22:381–396. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhou J, Guo T, Zhou L, Bao M, Wang L, Zhou

W, Tan S, Li G, He B and Guo Z: The ferroptosis signature predicts

the prognosis and immune microenvironment of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. Sci Rep. 13:18612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Teng Y, Gao L, Mäkitie AA, Florek E,

Czarnywojtek A, Saba NF and Ferlito A: Iron, ferroptosis, and head

and neck cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:151272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mao C, Wang M, Zhuang L and Gan B:

Metabolic cell death in cancer: Ferroptosis, cuproptosis,

disulfidptosis, and beyond. Protein Cell. 15:642–660. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Luo T, Wang Y and Wang J: Ferroptosis

assassinates tumor. J Nanobiotechnology. 20:4672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xu Y, Wang Q, Li X, Chen Y and Xu G:

Itraconazole attenuates the stemness of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

cells via triggering ferroptosis. Environ Toxicol. 36:257–266.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li Y, Du Y, Zhou Y, Chen Q, Luo Z, Ren Y,

Chen X and Chen G: Iron and copper: critical executioners of

ferroptosis, cuproptosis and other forms of cell death. Cell Commun

Signal. 21:3272023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hadian K and Stockwell BR: SnapShot:

Ferroptosis. Cell. 181:1188–1188.e1. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ma TL, Chen JX, Zhu P, Zhang CB, Zhou Y

and Duan JX: Focus on ferroptosis regulation: Exploring novel

mechanisms and applications of ferroptosis regulator. Life Sci.

307:1208682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gan B: Mitochondrial regulation of

ferroptosis. J Cell Biol. 220:e2021050432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen Y, Guo X, Zeng Y, Mo X, Hong S, He H,

Li J, Fatima S and Liu Q: Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial

iron overload and ferroptotic cell death. Sci Rep. 13:155152023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wahida A and Conrad M: Ferroptosis: Under

pressure! Curr Biol. 33:R269–R272. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lai L, Tan M, Hu M, Yue X, Tao L, Zhai Y

and Li Y: Important molecular mechanisms in ferroptosis. Mol Cell

Biochem. 480:639–658. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang XD, Liu ZY, Wang MS, Guo YX, Wang

XK, Luo K, Huang S and Li RF: Mechanisms and regulations of

ferroptosis. Front Immunol. 14:12694512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zheng J and Conrad M: The metabolic

underpinnings of ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 32:920–937. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang Z, Lu M, Chen C, Tong X, Li Y, Yang

K, Lv H, Xu J and Qin L: Holo-lactoferrin: the link between

ferroptosis and radiotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer.

Theranostics. 11:3167–3182. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu J, Kang R and Tang D: Signaling

pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J.

289:7038–7050. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen X, Li J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang

D: Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy. 17:2054–2081.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Seibt T, Wahida A, Hoeft K, Kemmner S,

Linkermann A, Mishima E and Conrad M: The biology of ferroptosis in

kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 39:1754–1761. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Dutt S, Hamza I and Bartnikas TB:

Molecular mechanisms of iron and heme metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr.

42:311–335. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhao Y, Yang M and Liang X: The role of

mitochondria in iron overload-induced damage. J Transl Med.

22:10572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang H, Zhang Z, Ruan S, Yan Q, Chen Y,

Cui J, Wang X, Huang S and Hou B: Regulation of iron metabolism and

ferroptosis in cancer stem cells. Front Oncol. 13:12515612023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li S, Zhang G, Hu J, Tian Y and Fu X:

Ferroptosis at the nexus of metabolism and metabolic diseases.

Theranostics. 14:5826–5852. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Venkataramani V: Iron homeostasis and

metabolism: Two sides of a coin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1301:25–40.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Huang L, Bian M, Zhang J and Jiang L: Iron

metabolism and ferroptosis in peripheral nerve injury. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2022:59182182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Capelletti MM, Manceau H, Puy H and Peoc'h

K: Ferroptosis in liver diseases: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci.

21:49082020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu L, Xian X, Tan Z, Dong F, Xu G, Zhang M

and Zhang F: The role of iron metabolism, lipid metabolism, and

redox homeostasis in Alzheimer's disease: From the perspective of

ferroptosis. Mol Neurobiol. 60:2832–2850. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lyamzaev KG, Panteleeva AA, Simonyan RA,

Avetisyan AV and Chernyak BV: Mitochondrial lipid peroxidation is

responsible for ferroptosis. Cells. 12:6112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Do Q and Xu L: How do different lipid

peroxidation mechanisms contribute to ferroptosis? Cell Rep Phys

Sci. 4:1016832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Naowarojna N, Wu TW, Pan Z, Li M, Han JR

and Zou Y: Dynamic regulation of ferroptosis by lipid metabolism.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 39:59–78. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xin S and Schick JA: PUFAs dictate the

balance of power in ferroptosis. Cell Calcium. 110:1027032023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Cui S, Simmons G Jr, Vale G, Deng Y, Kim

J, Kim H, Zhang R, McDonald JG and Ye J: FAF1 blocks ferroptosis by

inhibiting peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 119:e21071891192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Qiu B, Zandkarimi F, Bezjian CT, Reznik E,

Soni RK, Gu W, Jiang X and Stockwell BR: Phospholipids with two

polyunsaturated fatty acyl tails promote ferroptosis. Cell.

187:1177–1190.e18. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ma XH, Liu JH, Liu CY, Sun WY, Duan WJ,

Wang G, Kurihara H, He RR, Li YF, Chen Y and Shang H:

ALOX15-launched PUFA-phospholipids peroxidation increases the

susceptibility of ferroptosis in ischemia-induced myocardial

damage. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:2882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Do Q, Zhang R, Hooper G and Xu L:

Differential contributions of distinct free radical peroxidation

mechanisms to the induction of ferroptosis. JACS Au. 3:1100–1117.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li Y, Li Z, Ran Q and Wang P: Sterols in

ferroptosis: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies.

Trends Mol Med. 31:36–49. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Gan B: ACSL4, PUFA, and ferroptosis: New

arsenal in anti-tumor immunity. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

7:1282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sokol KH, Lee CJ, Rogers TJ, Waldhart A,

Ellis AE, Madireddy S, Daniels SR, House RRJ, Ye X, Olesnavich M,

et al: Lipid availability influences ferroptosis sensitivity in

cancer cells by regulating polyunsaturated fatty acid trafficking.

Cell Chem Biol. 32:408–422.e6. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hirata Y, Ferreri C, Yamada Y, Inoue A,

Sansone A, Vetica F, Suzuki W, Takano S, Noguchi T, Matsuzawa A and

Chatgilialoglu C: Geometrical isomerization of arachidonic acid

during lipid peroxidation interferes with ferroptosis. Free Radic

Biol Med. 204:374–384. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Liu S, Zhang HL, Li J, Ye ZP, Du T, Li LC,

Guo YQ, Yang D, Li ZL, Cao JH, et al: Tubastatin A potently

inhibits GPX4 activity to potentiate cancer radiotherapy through

boosting ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 62:1026772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Nishida Xavier da Silva T, Friedmann

Angeli JP and Ingold I: GPX4: Old lessons, new features. Biochem

Soc Trans. 50:1205–1213. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chen T, Leng J, Tan J, Zhao Y, Xie S, Zhao

S, Yan X, Zhu L, Luo J, Kong L and Yin Y: Discovery of novel potent

covalent glutathione peroxidase 4 inhibitors as highly selective

ferroptosis inducers for the treatment of triple-negative breast

cancer. J Med Chem. 66:10036–10059. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, Zeller M,

Cottin Y and Vergely C: Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: Two

corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:4492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Guo W, Li K, Sun B, Xu D, Tong L, Yin H,

Liao Y, Song H, Wang T, Jing B, et al: Dysregulated glutamate

transporter SLC1A1 propels cystine uptake via Xc− for

glutathione synthesis in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 81:552–566. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Li Z, Li Y, Yang Y, Gong Z, Zhu H and Qian

Y: In vivo tracking cystine/glutamate antiporter-mediated

cysteine/cystine pool under ferroptosis. Anal Chim Acta.

1125:66–75. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Koppula P, Zhuang L and Gan B: Cystine

transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: Ferroptosis, nutrient

dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 12:599–620. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang Y, Zheng L, Shang W, Yang Z, Li T,

Liu F, Shao W, Lv L, Chai L, Qu L, et al: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling confers ferroptosis resistance by targeting GPX4 in

gastric cancer. Cell Death Differ. 29:2190–2202. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Xia C, Xing X, Zhang W, Wang Y, Jin X,

Wang Y, Tian M, Ba X and Hao F: Cysteine and homocysteine can be

exploited by GPX4 in ferroptosis inhibition independent of GSH

synthesis. Redox Biol. 69:1029992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wang F and Min J: DHODH tangoing with GPX4

on the ferroptotic stage. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:2442021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hu Q, Wei W, Wu D, Huang F, Li M, Li W,

Yin J, Peng Y, Lu Y, Zhao Q and Liu L: Blockade of GCH1/BH4 axis

activates ferritinophagy to mitigate the resistance of colorectal

cancer to erastin-induced ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol.

10:8103272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP cyclohydrolase

1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Feng Y, Feng Y, Gu L, Mo W, Wang X, Song

B, Hong M, Geng F, Huang P, Yang H, et al: Tetrahydrobiopterin

metabolism attenuates ROS generation and radiosensitivity through

LDHA S-nitrosylation: Novel insight into radiogenic lung injury.

Exp Mol Med. 56:1107–1122. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Soula M, Weber RA, Zilka O, Alwaseem H, La

K, Yen F, Molina H, Garcia-Bermudez J, Pratt DA and Birsoy K:

Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to canonical

ferroptosis inducers. Nat Chem Biol. 16:1351–1360. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lv Y, Wu M, Wang Z and Wang J:

Ferroptosis: From regulation of lipid peroxidation to the treatment

of diseases. Cell Biol Toxicol. 39:827–851. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang S, Kang L, Dai X, Chen J, Chen Z,

Wang M, Jiang H, Wang X, Bu S, Liu X, et al: Manganese induces

tumor cell ferroptosis through type-I IFN dependent inhibition of

mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Free Radic Biol Med.

193:202–212. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Amos A, Amos A, Wu L and Xia H: The

Warburg effect modulates DHODH role in ferroptosis: A review. Cell

Commun Signal. 21:1002023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee

H, Koppula P, Wu S, Zhuang L, Fang B, et al: DHODH-mediated

ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer.

Nature. 593:586–590. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Desler C, Durhuus JA, Hansen TLL, Anugula

S, Zelander NT, Bøggild S and Rasmussen LJ: Partial inhibition of

mitochondrial-linked pyrimidine synthesis increases tumorigenic

potential and lysosome accumulation. Mitochondrion. 64:73–81. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Tarangelo A, Rodencal J, Kim JT, Magtanong

L, Long JZ and Dixon SJ: Nucleotide biosynthesis links glutathione

metabolism to ferroptosis sensitivity. Life Sci Alliance.

5:e2021011572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Yang C, Zhao Y, Wang L, Guo Z, Ma L, Yang

R, Wu Y, Li X, Niu J, Chu Q, et al: De novo pyrimidine biosynthetic

complexes support cancer cell proliferation and ferroptosis

defence. Nat Cell Biol. 25:836–847. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Liu Y, Lu S, Wu LL, Yang L, Yang L and

Wang J: The diversified role of mitochondria in ferroptosis in

cancer. Cell Death Dis. 14:5192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liang D, Feng Y, Zandkarimi F, Wang H,

Zhang Z, Kim J, Cai Y, Gu W, Stockwell BR and Jiang X: Ferroptosis

surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by

sex hormones. Cell. 186:2748–64.e22. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Sun S, Shen J, Jiang J, Wang F and Min J:

Targeting ferroptosis opens new avenues for the development of

novel therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3722023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Li P, Xu J, Xu B, Hu X, Xiong Y, Wang Y

and Liu P: NR5A2 (located on chromosome 1q32) inhibits ferroptosis

and promotes drug resistance by regulating phospholipid remodeling

in multiple myeloma. Int J Biol Sci. 21:5789–5801. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Phat NK, Tien NTN, Anh NK, Yen NTH, Lee

YA, Trinh HKT, Le KM, Ahn S, Cho YS, Park S, et al: Alterations of

lipid-related genes during anti-tuberculosis treatment: insights

into host immune responses and potential transcriptional

biomarkers. Front Immunol. 14:12103722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Nguyen HP, Yi D, Lin F, Viscarra JA,

Tabuchi C, Ngo K, Shin G, Lee AY, Wang Y and Sul HS: Aifm2, a NADH

oxidase, supports robust glycolysis and is required for cold- and

diet-induced thermogenesis. Mol Cell. 77:600–617.e4. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Lv Y, Liang C, Sun Q, Zhu J, Xu H, Li X,

Li YY, Wang Q, Yuan H, Chu B and Zhu D: Structural insights into

FSP1 catalysis and ferroptosis inhibition. Nat Commun. 14:59332023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Guo J, Chen L and Ma M: Ginsenoside Rg1

suppresses ferroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells in

sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via the FSP1-CoQ10-

NAD(P)H pathway. Curr Med Chem. 31:2119–2132. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Mikac S, Dziadosz A, Padariya M, Kalathiya

U, Fahraeus R, Marek-Trzonkowska N, Chruściel E, Urban-Wójciuk Z,

Papak I, Arcimowicz Ł, et al: Keap1-resistant ΔN-Nrf2 isoform does

not translocate to the nucleus upon electrophilic stress. bioRxiv.

2022.06. 10.495609. 2022.

|

|

78

|

Zhang Q, Sun T, Yu F, Liu W, Gao J, Chen

J, Zheng H, Liu J, Miao C, Guo H, et al: PAFAH2 suppresses

synchronized ferroptosis to ameliorate acute kidney injury. Nat

Chem Biol. 20:835–846. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Su ZY, Siak PY, Lwin YY and Cheah SC:

Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Current insights and

future outlook. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43:919–939. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Siak PY, Khoo AS, Leong CO, Hoh BP and

Cheah SC: Current status and future perspectives about molecular