Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) remains the leading cause of

cancer-related incidence and mortality among women worldwide and is

characterized by substantial biological heterogeneity (1). This heterogeneity significantly

influences therapeutic responses and clinical outcomes, posing a

major challenge to the implementation of personalized medicine

(2,3). The progression of BC, particularly

invasion, metastasis and therapeutic resistance, results not only

from genetic mutations within cancer cells but also from complex

interactions with the tumor microenvironment (TME) (4,5).

In clinical oncology, tumor-associated elevations of

serum Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) levels are commonly observed

(6). KL-6, a high-molecular-weight

mucin glycoprotein linked to mucin 1 (MUC1), is primarily used as a

biomarker for interstitial pneumonia (7). Although KL-6 is considered to be

co-expressed with membrane-bound MUC1 in tumor tissues, a previous

study indicated its potential role in facilitating invasion and

metastasis in pancreatic cancer; however, its functional

significance in other malignancies remains unclear (8).

Tumor hypoxia and the subsequent activation of

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) are key central drivers of cancer

cell invasion, metastasis and TME remodeling (9–11).

Notably, MUC1 expression is upregulated by HIF-1α under hypoxic

conditions in models of lung adenocarcinoma and renal cell

carcinoma (12–14). Although HIF-1α-mediated regulation

of MUC1 has been established, the impact of hypoxia on KL-6

expression has not yet been reported.

The present study aimed to investigate the effects

of hypoxia on KL-6 expression and its association with invasive

behavior in BC cells and spheroid models. Hypoxia-induced changes

in KL-6 expression were examined in triple-negative BC cell lines,

with particular attention to membrane localization and association

with invasion-associated phenotypes, using immunostaining, western

blot analysis and electron microscopy. Additionally, the interplay

between KL-6 expression and HIF-1α activity was investigated to

elucidate the role of KL-6 in the hypoxic response. These findings

provide novel insights into the regulatory mechanisms underlying

KL-6 expression and its contribution to BC invasion and metastasis,

suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker.

Materials and methods

Clinical data of patients with BC

The clinical data of 30 patients with early-stage BC

who underwent treatment at Kochi Medical School Hospital (Nankoku,

Japan) from January 2015 to December 2019 and completed at least 1

year of follow-up were retrospectively reviewed. All 30 patients

were women, with a median age of 64 years (range, 40–91 years). The

study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Board of

Kochi Medical School (approval no. 2023-146; April 19, 2024), which

waived the requirement for obtaining individual written informed

consent and approved the use of an opt-out procedure as an

alternative. All patients underwent surgical treatment, and the

resected tissues were formalin-fixed at room temperature (about

20–25°C) in 20% neutral buffered formalin for 12–24 h and then

embedded in paraffin blocks. Immunohistochemical (IHC) evaluations

of the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and

human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) status were

obtained from clinicopathological reports at the time of initial

diagnosis. ER and PR positivity was defined as positive staining in

≥1% of tumor cells. HER2 expression was evaluated using a

four-tiered scale (0, 1+, 2+, or 3+) in accordance with the 2018

American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American

Pathologists guidelines. Patients with a score of 2+ were

re-evaluated by in situ hybridization, and HER2 positivity

was defined as a score of 3+ or a positive in situ

hybridization result.

KL-6 IHC evaluation

A total of 9 tissue samples obtained from patients

who developed metastases or recurrence within the 1-year follow-up

period were sectioned into 4-µm-thick slices and subjected to

heat-induced antigen retrieval using ULTRA Cell Conditioning 1

Solution (Roche Tissue Diagnostics) at 95°C for 30 min. IHC

staining was performed with an anti-KL-6 mouse monoclonal antibody

(cat. no. LNM-KR-067; Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd.) using the Ventana

automated system at a dilution of 1:2,000, with incubation at 4°C

overnight (18 h). A total of 21 consecutive tissue samples from

patients without metastasis or recurrence were processed

identically and served as controls. KL-6 expression was evaluated

using the Allred scoring system (13,14).

Briefly, the proportion of positively stained cells was scored as

follows: 0 (none), 1 (<1%), 2 (1–10%), 3 (11–33%), 4 (34–66%)

and 5 (≥66%). Staining intensity in the most predominant areas was

rated as 0 (none), 1 (weak), 2 (intermediate), or 3 (strong). The

Allred score (range: 0–8 points) was calculated by summing the

proportion and intensity scores. Immunostaining assessments were

independently performed by two experienced pathologists (Mitsuko

Iguchi and Makoto Toi).

Fluorescent immunocytochemical

staining

For immunocytochemical staining, MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells (Health Science Research Resources Bank), each at

a density of 4×104 cells/ml, were cultured in slide

chambers, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Nacalai Tesque,

Inc.) at 4°C for 30 min, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). The cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C with an

anti-KL-6 mouse monoclonal antibody diluted at 1:2,000, followed by

incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse

immunoglobulin (IgG) antibodies (cat. no. F-2761; 1:200; Molecular

Probes; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room

temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 0.001 mg/ml; MilliporeSigma).

Fluorescence images were acquired using a BX53 fluorescence

microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from cells using a

radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Corporation). Protein concentrations were measured using the Pierce

BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal

amounts of protein (20 µg per lane) were separated by 10% sodium

dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride

membranes using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Membranes were blocked at room temperature for

1 h with Blocking One (cat. no. 03953-93; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and

subsequently incubated overnight incubation at 4°C with an

anti-KL-6 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:2,000) and a glyceraldehyde

3-phosphate dehydrogenase mouse monoclonal antibody (1:2,000; cat.

no. 20035, ProMab Biotechnologies, Inc.). Subsequently, membranes

were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse polyclonal antibody

(1:2,000; cat. no. P0447; Dako, Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Protein bands were visualized using Enhanced Chemiluminescence

Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Amersham; Cytiva) and

detected with an LAS-4000 Lumino-Image Analyzer (FUJIFILM Wako Pure

Chemicals Corporation).

Wound healing assay

Wound healing assays were performed as previously

described (15). Trypsinized MCF-7

cells were counted using a C-Chip™ disposable hemocytometer (SKC,

Inc.; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), seeded at a density of

2×104 cells/ml into 35-mm diameter dishes, and incubated

at 37°C for 48 h. Upon reaching ~90% confluency, three linear

scratches were created in the cell monolayer of each dish using a

20-µl pipette tip. Phase-contrast images were captured at 0, 12, 24

and 36 h post-scratch at 50 randomly marked locations per 35-mm

dish using an Olympus CKX41 microscope (original magnification,

×200; Olympus Corporation). The scratch areas devoid of cell

migration were quantified using the ImageJ software version 1.53

(National Institutes of Health). The average migration across the

50 sites per dish was calculated. The relative cell migration rates

at each time point were normalized to the 0-h measurement, which

was set as 1.0.

Hematoxylin-eosin and IHC staining of

MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in Cell Matrix®

MDA-MB-231 cells (1×104 cells/ml) were

prepared as described in Fluorescent immunocytochemical

staining. Cellmatrix (Nitta Gelatin Inc.) was prepared

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each cell group was

mixed with 500 µl of Cellmatrix® and plated into 35-mm

dishes pre-coated with Cellmatrix, followed by incubation at 37°C

for 30 min. The gels were overlaid with 200 µl of Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; MilliporeSigma) and cultured at 37°C

for 10 days. After incubation, the gels were fixed overnight in 20%

buffered formaldehyde at room temperature and embedded in paraffin.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed using Mayer's hematoxylin

(10 min) and 1% eosin (5 min) at room temperature. IHC staining for

KL-6 and HIF-1α was subsequently performed. Paraffin-embedded

tissue sections (4-µm thick) were subjected to antigen retrieval by

immersion in Immunosaver (Nisshin EM Co., Ltd.) at 98°C for 30 min.

Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 0.3%

hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min at room temperature. Then,

sections were blocked with Blocking One for 1 h at room temperature

and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies:

anti-KL-6 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:2,000) and anti-HIF-1α mouse

monoclonal antibody (1:100; cat. no. AP2054a, Abgent, Inc.). After

washing with PBS, the sections were incubated for 1 h at room

temperature with Universal ImmPRESS HRP Reagent (MP-7500; Vector

Laboratories, Inc.), followed by additional PBS washes. Color

development was achieved using the DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit

(SK-4100; Vector Laboratories, Inc.), and the nuclei were

counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 1 min at room

temperature. Optical microscopic images were captured using an

Olympus BX53 microscope equipped with the cellSens imaging system

(Olympus Corporation).

Spheroids of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

cells

A total of 1×104 parental, MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells per well were counted as aforementioned and seeded

into PrimeSurface® 96-well ultra-low attachment

round-bottom plates (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd.). The cells were

cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 6 days to

form multicellular spheroids. Following culture, spheroids were

fixed and subjected to IHC staining for KL-6 and HIF-1α, as

aforementioned and observed under an Olympus BX53 microscope.

Hypoxia induction experiment using

MDA-MB-231 cells

Hypoxia-induced changes in KL-6 protein expression

were evaluated in MDA-MB-231 cells using immunocytochemistry. Cells

(1×104) were cultured for 2 days in three 2-well slide

chambers (cat. no. 192-002; Watson Co., Ltd.). In each chamber, one

well was treated with cobalt chloride (CoCl2) to induce

hypoxia, whereas the other well served as an untreated control. The

cells were incubated in DMEM supplemented with CoCl2 (2

µmol/l; cat. no. 15862-1ML-F; MilliporeSigma) at 37°C for 8 h.

Following incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and

fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C for 30 min. Each of the three slides was

then assigned to a specific assay: One for KL-6 immunocytochemical

staining, one for HIF-1α immunocytochemical staining, and one for

hypoxia detection. Hypoxia was visualized using the LOX-1 hypoxia

probe (cat. no. NC-LOX-1S; MBL Co., Ltd.). Briefly, after the 8-h

incubation, LOX-1 was added to the DMEM at a concentration of 10

µl/ml. The cells were subsequently fixed again in 4% PFA (4°C for

30 min), washed twice with PBS, counterstained with DAPI, and

examined under a fluorescence microscope.

Immunoelectron microscopy

Immunoelectron microscopy was performed as

previously described (16).

MDA-MB-231 cells and spheroids were cultured on chamber slides or

PrimeSurface 96-well ultra-low attachment plates and fixed with 4%

PFA containing 0.01% glutaraldehyde (Wako Pure Chemical Industries)

at room temperature for 10 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was

blocked by incubating the samples in methanol containing 0.3%

H2O2 for 10 min. After washing with PBS,

non-specific binding was blocked by incubation in PBS supplemented

with 10% normal goat serum for 10 min. The samples were then

incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse monoclonal antibody against

KL-6. After washing with PBS, the slides were incubated at room

temperature for 60 min with the ImmPRESS detection reagent (Vector

Laboratories, Inc.). The peroxidase reaction was visualized using

DAB substrate solution (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 10 min.

After several rinses with distilled water, the slides were treated

with 0.01% aqueous hydrogen tetrachloroaurate(III) tetrahydrate

(HAuCl4·3H2O; MilliporeSigma) for 10 min,

rinsed again in distilled water, and dried using an air blower. The

slides were then incubated in a humid chamber at 37°C for 15 h,

followed by air-drying. As a control, parallel slides were

incubated under dry air conditions. All samples were examined under

a JSM-6010LV microscope (JEOL, Ltd.).

Statistical analyses

All quantitative data were obtained from at least

three independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation. To compare KL-6-positive cell rates between the

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, Levene's test was initially used

to assess the homogeneity of variances. As unequal variances were

observed, Welch's t-test was applied for statistical comparison.

Western blotting was performed to evaluate the KL-6 expression in

MCF-7 cells treated with or without CoCl2, a chemical

hypoxia-inducing agent. The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed normal

distribution in both groups, whereas Levene's test revealed unequal

variances; therefore, Welch's t-test was used for statistical

comparison.

In the wound healing assay, the relative area

covered by cells was measured at 0 and 36 h post-treatment. As the

data from both treatment groups (KL-6 neutralizing antibody and

non-immune IgG control) were not normally distributed, according to

the Shapiro-Wilk test, comparisons were performed using the

non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. All statistical analyses were

performed using the R software (version 4.4.3, http://www.R-project.org/) with a significance level

set at α=0.05. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Association between KL-6 and HIF-1α

expressions and BC recurrence and metastasis

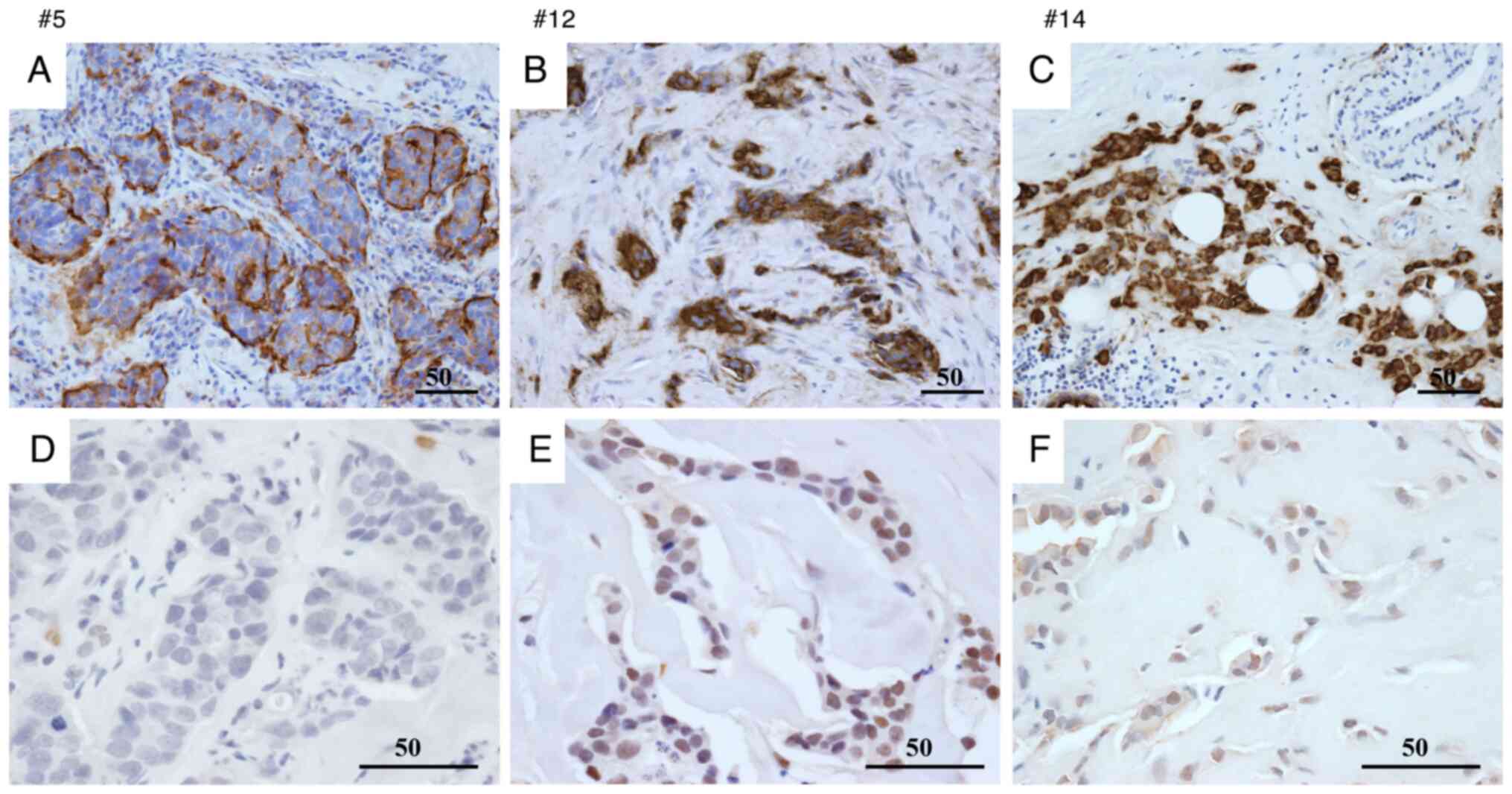

The association between BC recurrence or metastasis

and the IHC expression of KL-6 and HIF-1α in surgical pathology

specimens was investigated. Among the 30 patients, eight

experienced recurrence or metastasis, whereas 20 showed no evidence

of disease progression (Table

SI).

Expression levels were quantified using the Allred

scoring system (range, 0–8). Based on the observed score

distribution, the top three score categories were defined as ‘high’

expression, and the remaining categories were classified as ‘low’

expression.

For KL-6, 7/9 patients in the recurrence/metastasis

group were classified as having high expression, whereas 2/9 were

classified as having low expression. This pattern is suggestive but

should be interpreted with caution given the small sample (Fig. 1A-C).

For HIF-1α, 4/9 patients in the

recurrence/metastasis group were classified as having high

expression, whereas 5/9 were classified as having low expression.

In the non-recurrence/metastasis group, 1/21 patients were

classified as having high expression, whereas 20/21 were classified

as having low expression. These counts indicate a numerical

enrichment of higher HIF-1α expression in patients with recurrence

or metastasis (Fig. 1D-F).

A single-center analysis was conducted with a

limited number of events (n=9), yielding an events-per-variable

(EPV) below commonly accepted thresholds for stable multivariable

modeling. To prevent overfitting and unstable estimates,

statistical analyses, including multivariable modeling and

hypothesis testing, were not performed; accordingly, inferential

statistics (for example, P-values or confidence intervals) were not

reported in this subsection. The findings are therefore descriptive

and hypothesis-generating and require validation in larger,

multicenter cohorts with adequate EPV.

KL-6 expression in BC cell lines

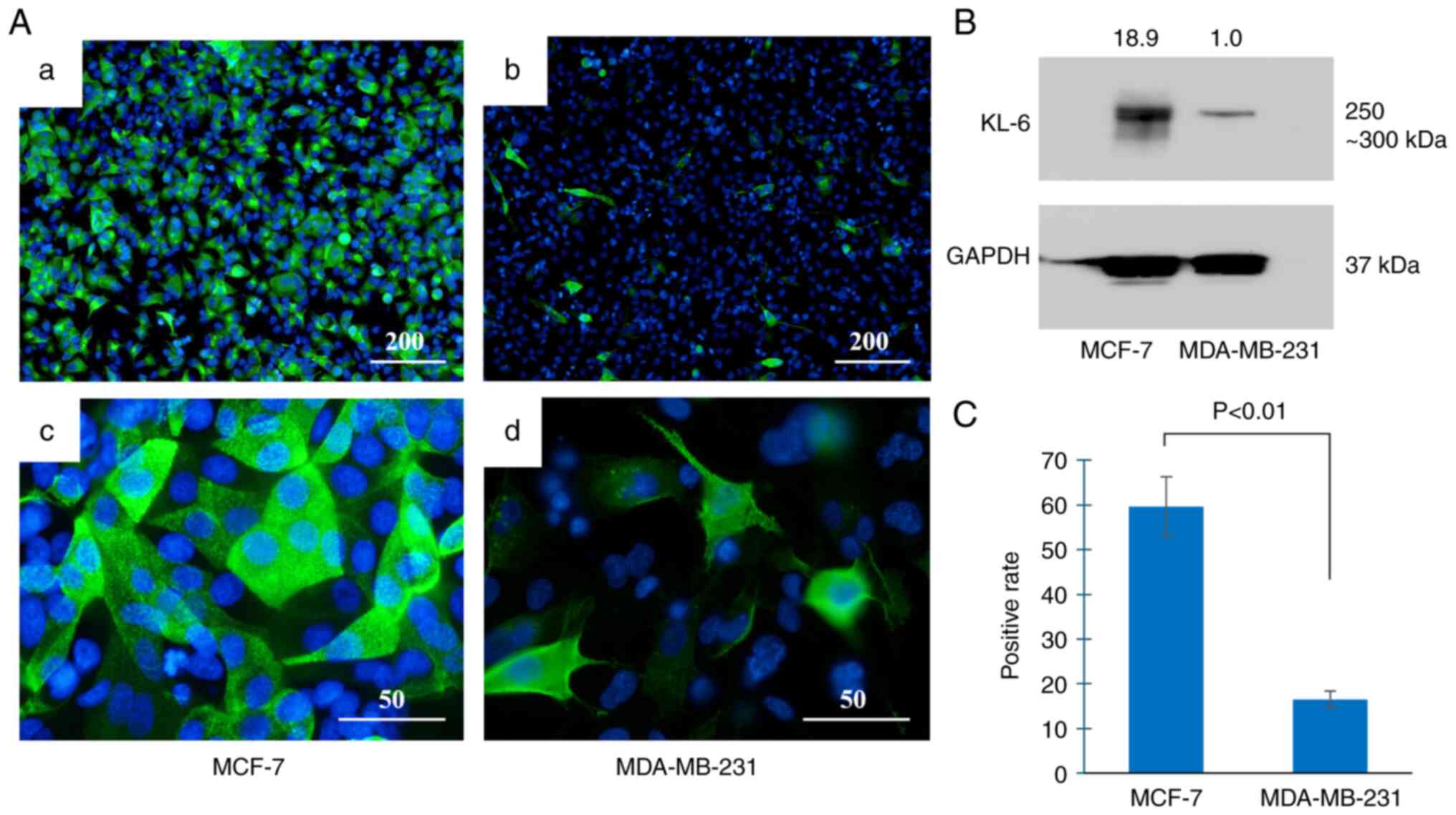

KL-6 protein expression in the BC cell lines was

evaluated using immunofluorescence staining and western blot

analysis (Fig. 2).

Immunofluorescence staining (Fig.

2A) demonstrated that the majority of MCF-7 cells exhibited

KL-6-positive signals (Fig. 2Aa),

whereas only a small proportion of MDA-MB-231 cells were positive

for KL-6 expression (Fig. 2Ab).

Subcellular localization analysis revealed that KL-6 in MCF-7 cells

was present as punctate staining along the cell membrane (Fig. 2Ac). By contrast, KL-6 localization

in MDA-MB-231 cells was primarily observed at the membrane edges

and cellular protrusions (Fig.

2Ad).

Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B) demonstrated markedly lower KL-6

expression in MDA-MB-231 cells compared with MCF-7 cells.

Quantitative analysis (Fig. 2C)

confirmed a higher proportion of KL-6-positive cells in MCF-7 than

in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Prior to group comparison, data distribution was

assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which confirmed normality in

both cell lines. Levene's test indicated unequal variances;

therefore, Welch's t-test was applied. A significantly higher

percentage of KL-6-positive cells was observed in MCF-7 cells

compared with MDA-MB-231 cells (P<0.01).

Changes in cell migration capacity

following KL-6 functional inhibition: a wound healing assay

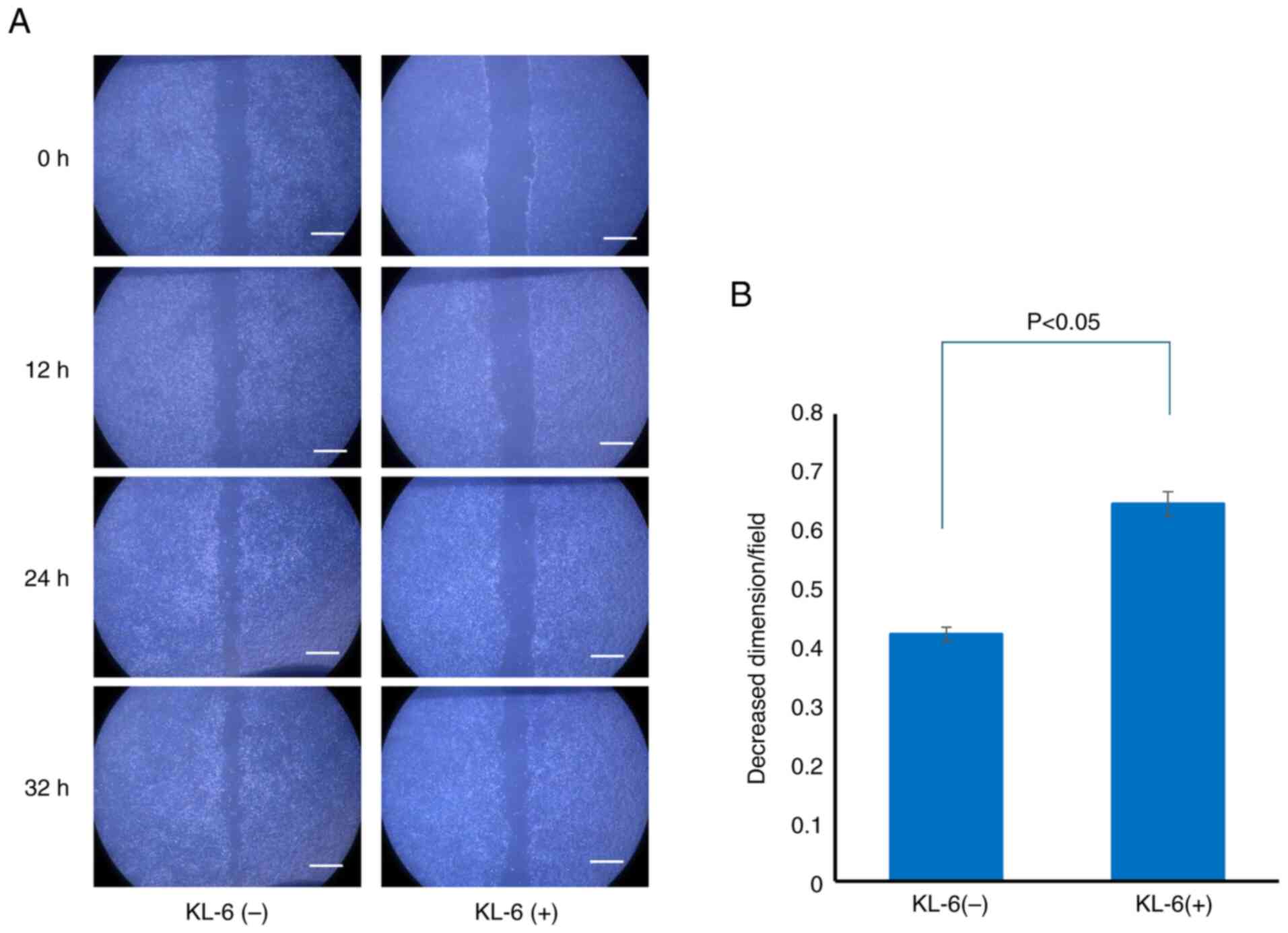

To elucidate the role of KL-6 in cell migration, a

wound healing assay was conducted. MCF-7 cells were selected for

this analysis due to their markedly higher KL-6 expression compared

with MDA-MB-231 cells, as demonstrated using western blot

analysis.

Following the creation of a linear wound in the cell

monolayer, two treatment groups were established: cells treated

with a KL-6 neutralizing antibody and control cells treated with

non-immune IgG. Wound closure was assessed 36 h after treatment.

Substantial wound closure was observed in the control group,

whereas closure was notably inhibited in the KL-6 antibody-treated

group (Fig. 3A).

For quantitative analysis, the relative wound area

covered at 0 and 36 h post-treatment was calculated and compared

between the groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that data from

both groups were not normally distributed; therefore, the

non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was employed. The analysis

demonstrated that the KL-6 neutralizing antibody-treated group

exhibited a significantly smaller relative covered area compared

with the control group, indicating reduced migratory capacity

(P<0.05; Fig. 3B).

These findings suggested that KL-6 positively

regulates MCF-7 cell migration, supporting its role as a functional

contributor to BC cell invasiveness.

Expression of KL-6 and HIF-1α in the

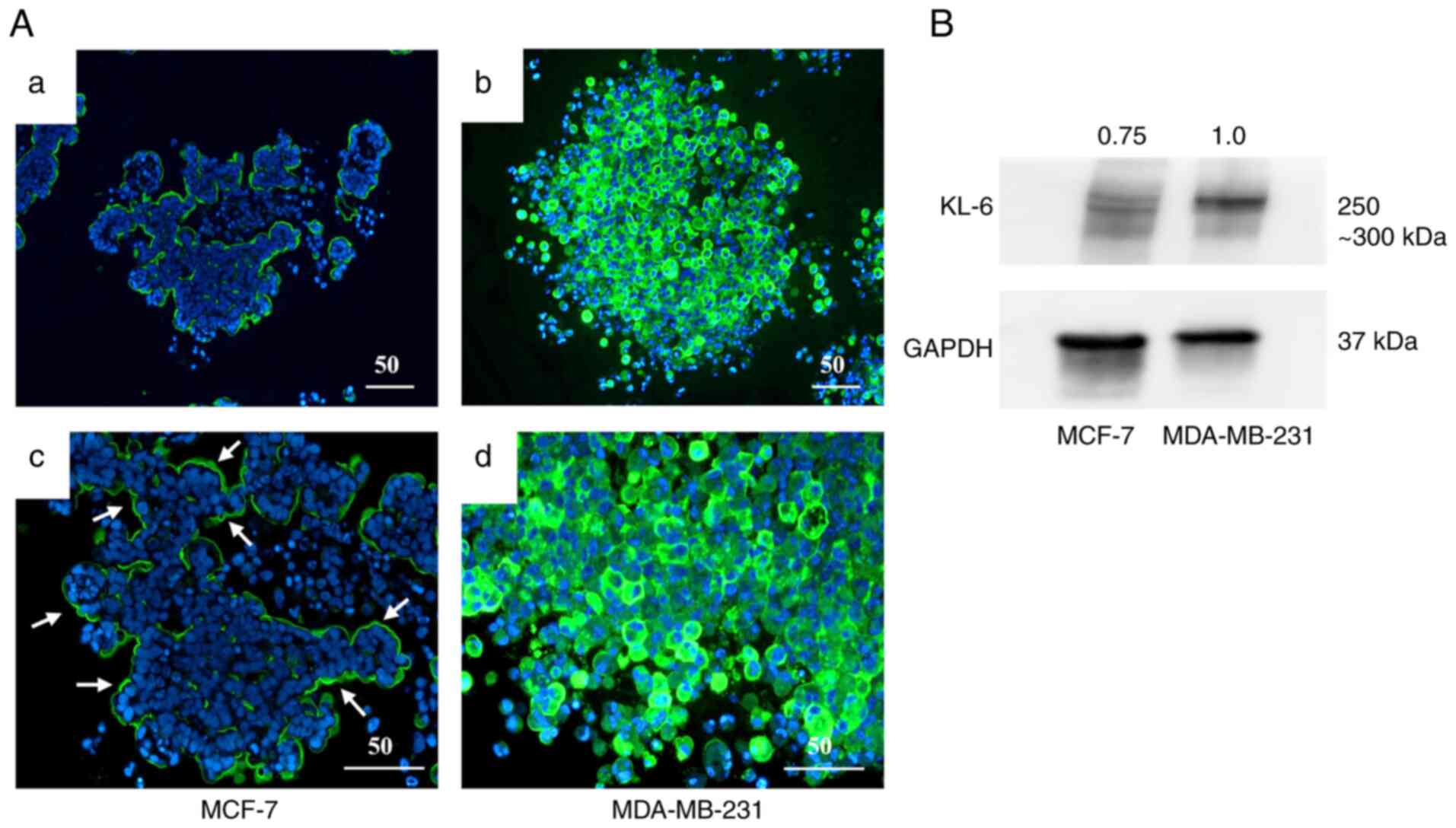

spheroid model

A three-dimensional spheroid culture model was used

to evaluate KL-6 expression in the BC cell lines MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 through IHC and western blot analysis (Fig. 4).

IHC analysis (Fig.

4A) demonstrated that KL-6 positivity in MCF-7 spheroids was

predominantly localized to the peripheral regions of the spheroid

structure (Fig. 4Aa and c). By

contrast, strong KL-6 positivity in MDA-MB-231 spheroids was

observed throughout the entire spheroid, including the central

regions (Fig. 4Ab and d).

Quantitative assessment by western blotting

(Fig. 4B) demonstrated higher KL-6

protein levels (Fig. 4B) in

MDA-MB-231 spheroids compared with MCF-7 spheroids. These findings

indicated that KL-6 expression was markedly upregulated in

MDA-MB-231 cells under three-dimensional culture conditions.

Temporal changes in hypoxia induction

and KL-6 expression in spheroid cultures and their involvement in

cell invasion

To further examine the relationship between KL-6

expression and hypoxia, the MDA-MB-231 spheroids were analyzed at

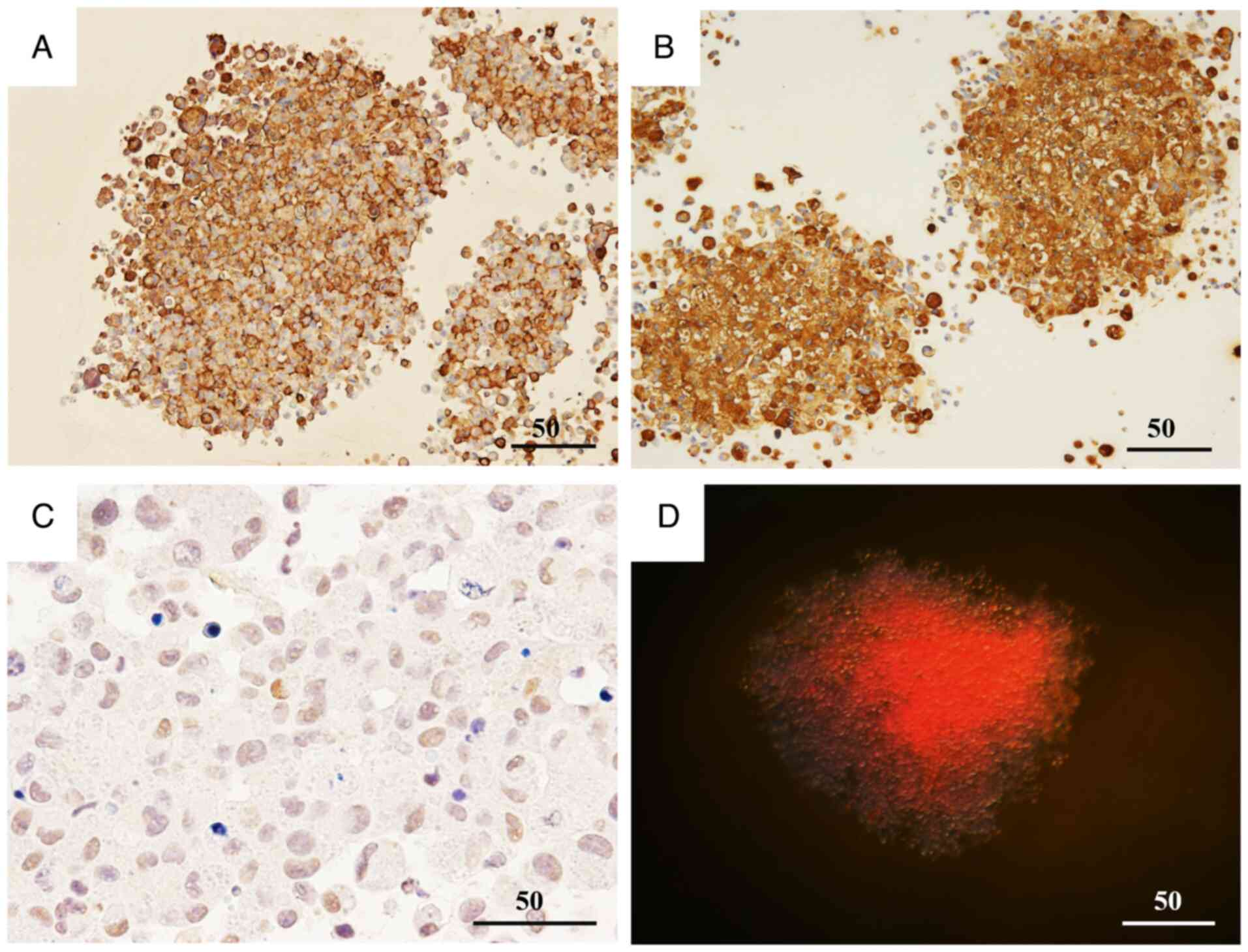

various time points (Fig. 5). IHC

analysis demonstrated a mosaic-like pattern of KL-6 expression 2

days after seeding (Fig. 5A); by

day 6, the majority of cells exhibited KL-6 positivity (Fig. 5B). Nuclear expression of HIF-1α, a

marker of hypoxia, was detected on day 6 (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, hypoxia probe-based

detection demonstrated strong fluorescence signals within the

spheroid core at this time point (Fig.

5D). These findings suggested that hypoxia develops

progressively during spheroid culture and is associated with

increased KL-6 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells.

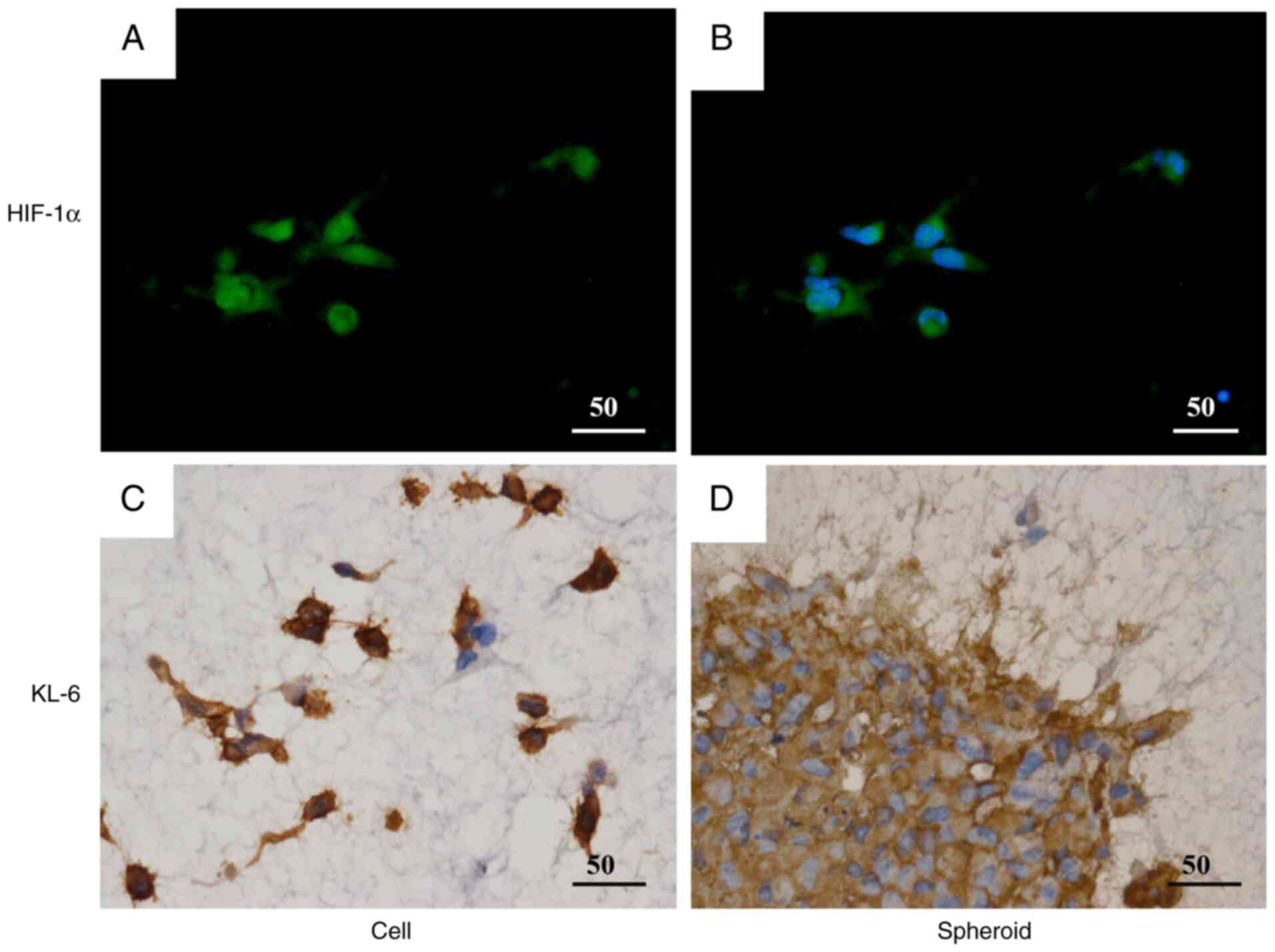

KL-6 expression was subsequently assessed in

MDA-MB-231 cells and spheroids embedded within a three-dimensional

extracellular matrix (Fig. 6).

Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that most embedded cells

exhibited nuclear localization of HIF-1α, as evidenced by

co-localization with DAPI staining (Fig. 6A and B). IHC analysis further

revealed prominent KL-6 expression in cellular protrusions

extending from the spheroids into the surrounding matrix (Fig. 6C and D). These results suggested

that KL-6 contributes to the invasive behavior of MDA-MB-231 cells

under hypoxic conditions within a three-dimensional matrix

environment.

Induction of KL-6, HIF-1α and LOX-1 by

CoCl2 treatment

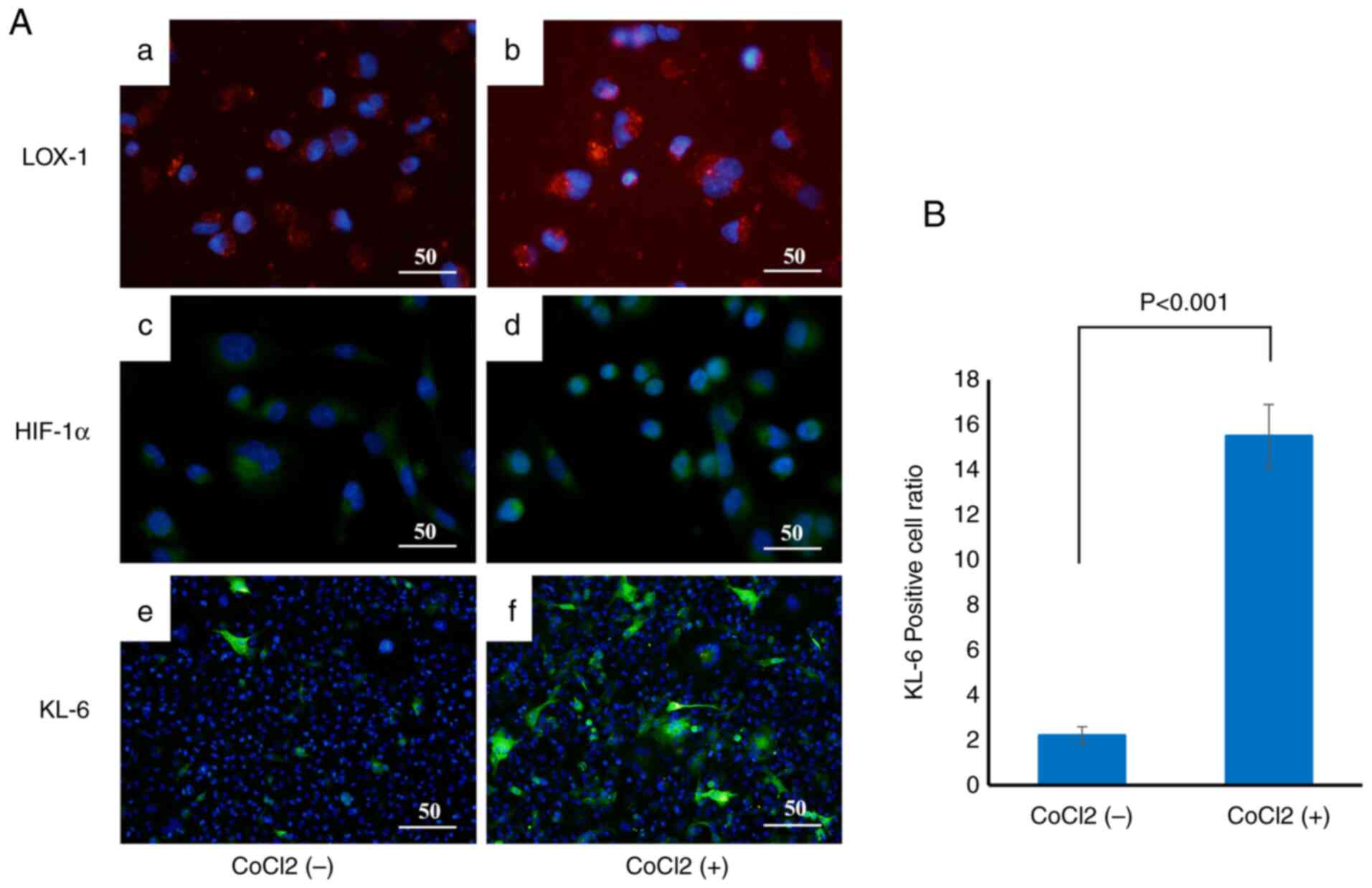

To examine the effect of hypoxic conditions on KL-6

expression in BC cells, CoCl2, a chemical hypoxia

inducer, was used to treat the cells, and changes in the expression

of the hypoxia markers LOX-1 and HIF-1α, as well as KL-6, were

evaluated by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 7A).

MCF-7 cells were incubated with CoCl2 at

concentrations of 2 and 4 µmol/l for 6 h at 37°C.

Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that the fluorescence

intensities of LOX-1 (Fig. 7Aa and

b) and HIF-1α (Fig. 7Ac and d)

were markedly increased in the CoCl2-treated groups,

indicating effective induction of hypoxic conditions. KL-6

fluorescence was also significantly enhanced in

CoCl2-treated cells (Fig.

7Af) compared with the untreated controls (Fig. 7Ae).

Quantitative analysis of the proportion of

KL-6-positive cells relative to the total cell population revealed

a significant increase in the CoCl2-treated group

compared with the untreated group (P<0.001), as determined by

Welch's t-test (Fig. 7B).

Morphological observation of KL-6

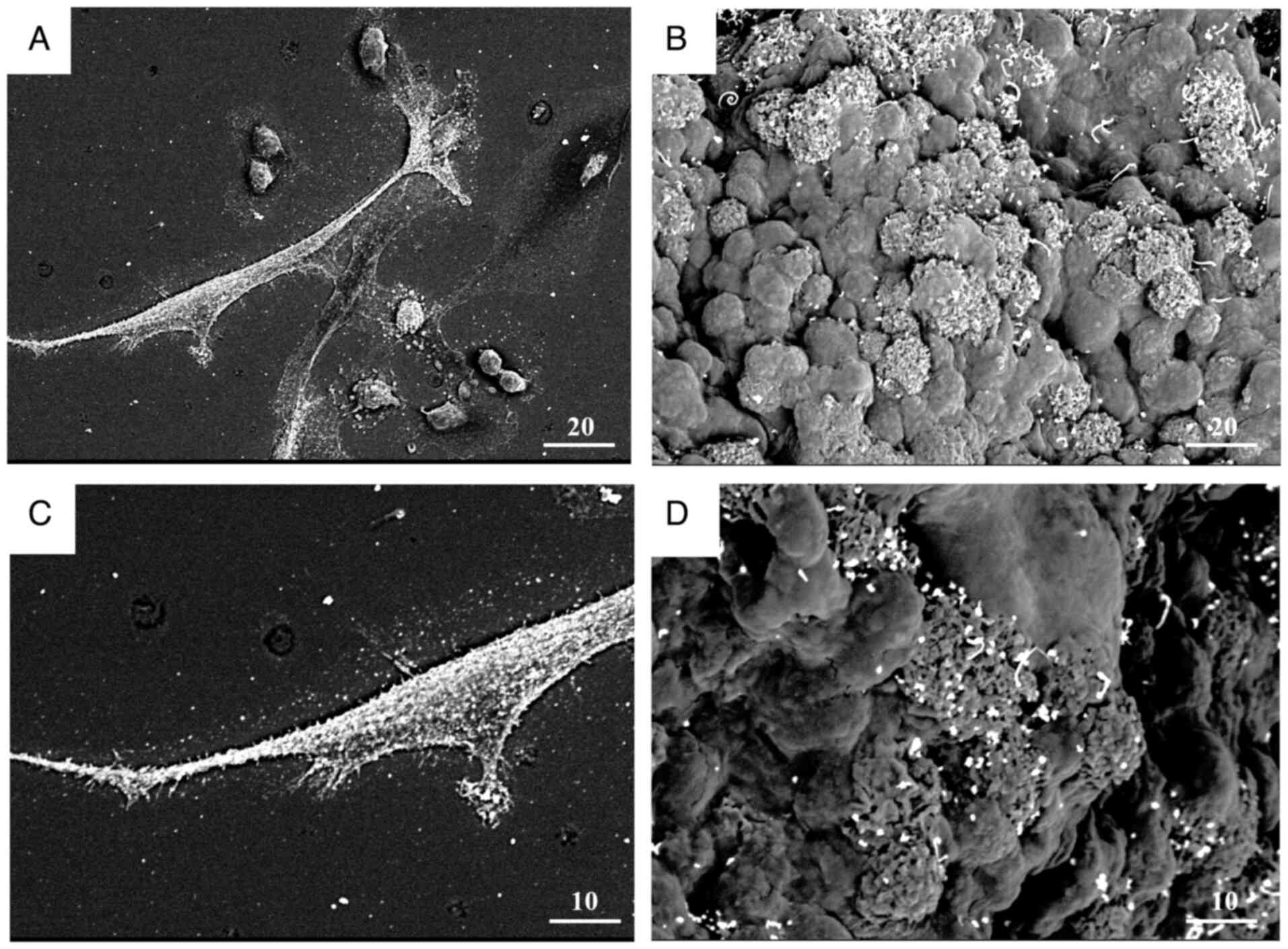

localization via immunoelectron microscopy

To elucidate the ultrastructural localization of

KL-6, immunogold labeling combined with low-vacuum scanning

electron microscopy was performed on MDA-MB-231 cells and spheroids

(Fig. 8).

Immunoelectron micrographs of MDA-MB-231 monolayer

cells and spheroids (Fig. 8A and C)

demonstrated KL-6-positive gold particles prominently localized on

the cell membrane, within cellular protrusions, and at sites of

cell-cell contact. Surface imaging of spheroids (Fig. 8B and D) further demonstrated the

accumulation of KL-6-associated gold particles in regions enriched

with protrusive structures.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that hypoxia

increases KL-6/MUC1 expression in BC, at least in part via HIF-1α,

and that KL-6 contributes to invasive behavior. Supporting evidence

includes KL-6 enrichment on invasive protrusions, its upregulation

in hypoxic spheroids and CoCl2-treated models, and the

reduction of cell migration following KL-6 blockade.

In the clinical cohort, the KL-6 and HIF-1α

expression levels were numerically higher in patients who

experienced recurrence or metastasis, suggesting a potential

association. However, this analysis was conducted in a

single-center cohort with a limited number of events (n=9),

resulting in an EPV below commonly accepted thresholds for stable

multivariable modeling. To avoid overfitting and unstable

estimates, multivariable modeling and formal hypothesis testing

were not performed, and only descriptive associations were

reported. Consequently, these findings are hypothesis-generating

and should be interpreted with caution, as potential confounding

factors such as tumor stage, treatment, and subtype could not be

adjusted for in this analysis.

In the experiments of the present study (Fig. 2), the proportion of KL-6-positive

cells was significantly higher in MCF-7 than in MDA-MB-231 cells

(P<0.01), indicating that basal KL-6 expression is enriched in

MCF-7 under the assay conditions employed. Consistent with

established biology, MCF-7 cells display a luminal A epithelial

phenotype characterized by strong E-cadherin and low vimentin

expression. Conversely, MDA-MB-231 cells exhibit a mesenchymal

program, including loss of E-cadherin, vimentin and N-cadherin

expression; activation of the Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin

substrate-extracellular signal-regulated kinase-nuclear factor

kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells signaling pathway;

and elevated matrix metalloproteinase activity. These traits

support extracellular matrix degradation, stromal adhesion and

motility, thereby conferring greater invasive potential (17–21).

Collectively, these observations indicate that higher KL-6

expression in MCF-7 cells does not, by itself, determine invasive

capacity; rather, invasion likely reflects the integrated effects

of KL-6-dependent and KL-6-independent mechanisms, including

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) status, NF-κB/Rac

signaling, protease activity, and tumor-stroma interactions.

The structural characteristics of KL-6, particularly

its sialic acid modifications, have been implicated in promoting

cancer cell invasiveness and metastatic potential (22). Sialylation represents a key

molecular alteration that facilitates tumor cell migration,

adhesion and immune evasion (22).

Consistent with other sialylated glycans, KL-6 was observed at the

cell membrane in the current electron microscopy analyses (23). This localization suggests a role in

mediating cell-cell adhesion and interactions with the

extracellular matrix. Given the established involvement of

sialylated glycans in promoting cancer cell invasiveness and

dissemination, KL-6 may similarly enhance invasion and metastasis

by modulating cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions within the TME

(22). These findings suggest that

KL-6 may function beyond its utility as a biomarker and actively

contribute to malignant BC phenotypes through mechanisms

characteristic of sialylated glycoconjugates (24).

IHC and western blot analyses demonstrated elevated

KL-6 expression in MDA-MB-231 cell spheroids compared with

conventional monolayer cultures. This observation led to the

hypothesis that the increased KL-6 expression observed in the

spheroid models may be attributable to the hypoxic conditions

characteristic of three-dimensional cultures (25). To test this hypothesis, a chemical

hypoxia model was established using CoCl2. Following

CoCl2 treatment, the upregulation of HIF-1α expression

was observed, confirming the successful induction of a hypoxic

environment. Concurrently, a significant increase in the proportion

of KL-6-positive cells was detected, indicating that KL-6

expression is inducible under hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia modulates

the expression of adhesion molecules and glycosylation-related

proteins, enhancing the invasive and metastatic potential of cancer

cells (26,27). HIF-1α, a central regulator of the

cellular hypoxic response, governs the expression of numerous

tumor-associated genes (10). The

present findings suggest that KL-6 may act downstream of the HIF-1α

signaling, contributing to the malignant phenotype of BC cells.

Additionally, sialic acid modifications, which are promoted under

hypoxic conditions, have been shown to facilitate tumor invasion

and metastasis; KL-6 may similarly participate in these

sialylation-mediated mechanisms (22).

KL-6 is a glycan-dependent epitope on MUC1 (cluster

9). The minimal epitope recognized by the KL-6 antibody is located

within the MUC1 tandem repeat bearing an α2,3-sialyl-T structure

(7). Consequently, increased MUC1

expression and sialylation are expected to enhance KL-6 detection

in tumor cells. Under chronic hypoxia, HIF-1α and NF-κB p65

cooperatively induce MUC1/MUC1-C, and direct genetic perturbation

abolishes this response. Using a hypoxia fate-mapping/CRISPR

system, knockout of HIF-1α or NF-κB p65 prevented hypoxia-induced

MUC1-C accumulation (14).

Functionally, either deletion of MUC1 under hypoxic conditions or

pharmacologic inhibition of MUC1-C with the cell-penetrant

inhibitor GO-203 increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in

circulating tumor cells and reduced the contribution of

hypoxia-experienced cells to lung metastasis in vivo

(14).

Multiple independent lines of evidence indicate that

MUC1 is a direct HIF-1 target gene (12,13,28).

In clear-cell renal cell carcinoma models, stabilization of HIF-1α

by CoCl2 led to increased MUC1 mRNA levels, whereas

HIF-1α knockdown via small interfering RNA and the HIF-1 inhibitor

YC-1 reduced hypoxia-induced MUC1 expression. Chromatin

immunoprecipitation and electrophoretic mobility shift assay

identified HIF-1α binding at two hypoxia-responsive elements within

the MUC1 promoter, establishing direct transcriptional control

(13). In conjunction with studies

that MUC1 stabilizes HIF-1α and co-activates hypoxia-metabolic

targets, these findings support the existence of a feed-forward

HIF-MUC1 axis that reinforces hypoxic adaptation. Functionally,

hypoxia increased invasion and migration by ~4.7-fold and 3.9-fold,

respectively, whereas MUC1 knockdown significantly reversed these

hypoxia-enhanced phenotypes (13).

Building on these findings, a coherent model is proposed in which

KL-6/MUC1 promotes invasion and metastasis through HIF-1α-dependent

transcriptional control.

Sialic acid-modified mucin family molecules have

been reported to alter the physical and biological properties of

cell surfaces, thereby facilitating the acquisition of invasive and

metastatic capabilities (29).

α2,3-linked sialylation has been consistently associated with

metastatic behavior across multiple tumor types. In gastric cancer,

elevated α2,3-linked sialic acids correlate with increased

metastasis and poorer prognosis, consistent with the present

observation that the α2,3-sialylated KL-6 epitope is elevated in

motile states (30). These findings

support a model in which α2,3 sialylation marks an invasive

phenotype. ST3GAL1 catalyzes the installation of terminal

α2,3-sialic acid on O-glycans, the same linkage that defines the

KL-6 (sialyl-T) motif on MUC1. Functionally, ST3GAL1 promotes

migration, invasion, and TGF-β1-induced EMT in ovarian cancer

(31). In melanoma, ST3GAL1

enhances dimerization and activation of the receptor tyrosine

kinase AXL, increasing invasion and metastatic seeding (32). Collectively, these findings support

a coherent mechanism in which a KL-6-high state reflects

ST3GAL1-driven α2,3 sialylation on MUC1 and other surface proteins,

thereby potentiating receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-centered

signaling (for example, AXL) that promotes invasion (31,32).

This delineates a plausible downstream pathway by which KL-6 may

facilitate invasion through ST3GAL1-dependent α2,3 sialylation and

subsequent activation of RTK signaling.

The present study has certain limitations. First,

the relatively small sample size necessitates cautious

interpretation when generalizing the observed association between

KL-6 expression and recurrence or metastasis risk (29). Future studies with larger sample

sizes and multi-institutional collaborations are required to

validate these findings. Second, although a chemical hypoxia model

(CoCl2 treatment) was employed, it may not fully

replicate the sustained and multifactorial hypoxic conditions

present within TMEs. Future studies should evaluate KL-6 expression

dynamics using physical hypoxia culture systems and in vivo

models.

Furthermore, the downstream signaling pathways and

functional roles of KL-6 in cell adhesion and invasion require

further elucidation. In particular, the identification of specific

receptor molecules and extracellular matrix components that

interact with KL-6 remains a critical challenge and is directly

relevant to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for

BC.

In conclusion, the present study provides novel

insights into the biological significance of KL-6 in BC. Further

investigations are warranted to explore its potential clinical

applications.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Division of Functional Analysis

for Life Science, Science Research Center and Kochi University for

their valuable support in immunohistochemical analysis and for

providing technical expertise and access to electron microscopy,

which greatly contributed to this study.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Kochi Medical School

Hospital President's Discretionary Grant for the procurement of

essential research materials and additional support was provided by

the Department of Pathology, Kochi Medical School.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TI conceived and designed the study, drafted the

manuscript, and performed data analysis and interpretation. YH

performed the experimental procedures. TS contributed to the

study's conceptualization and assisted in data analysis and

interpretation. YH and TS served as primary contributors to the

research. MI and MT performed the immunohistochemical staining of

pathological tissues. HS and IM confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data and contributed to the interpretation of the experimental

findings and to the intellectual development of the manuscript,

including the conception and logical organization of the

background, methods, results, and discussion sections. All authors

critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Ethical Review Board of Kochi Medical School (approval no.

2023-146; April 19, 2024). The study was conducted using an opt-out

approach, whereby information about the research was publicly

disclosed, and participants were provided the opportunity to

decline participation to the fullest extent possible.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

KL-6

|

Krebs von den Lungen-6

|

|

MUC1

|

mucin 1

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

HIF-1α

|

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

|

|

ER

|

estrogen receptor

|

|

PR

|

progesterone receptor

|

|

HER2

|

human epidermal growth factor receptor

type2

|

|

PFA

|

paraformaldehyde

|

|

PBS

|

phosphate-buffered saline

|

|

DAPI

|

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

|

|

HRP

|

horseradish peroxidase

|

|

CoCl2

|

cobalt chloride

|

|

EPV

|

events-per-variable

|

|

Rac-ERK-NF-κB

|

signaling pathway

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

RTK

|

receptor tyrosine kinase

|

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Salemme V, Centonze G, Avalle L, Natalini

D, Piccolantonio A, Arina P, Morellato A, Ala U, Taverna D, Turco E

and Defilippi P: The role of tumor microenvironment in drug

resistance: Emerging technologies to unravel breast cancer

heterogeneity. Front Oncol. 13:11702642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Network, .

Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature.

490:61–70. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mittal S, Brown NJ and Holen I: The breast

tumor microenvironment: role in cancer development, progression and

response to therapy. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 18:227–243. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Quail DF and Joyce JA: Microenvironmental

regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med.

19:1423–1437. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ogawa Y, Ishikawa T, Ikeda K, Nakata B,

Sawada T, Ogisawa K, Kato Y and Hirakawa K: Evaluation of serum

KL-6, a mucin-like glycoprotein, as a tumor marker for breast

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 6:4069–4072. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ohyabu N, Hinou H, Matsushita T, Izumi R,

Shimizu H, Kawamoto K, Numata Y, Togame H, Takemoto H, Kondo H and

Nishimura S: An essential epitope of anti-MUC1 monoclonal antibody

KL-6 revealed by focused glycopeptide library. J Am Chem Soc.

131:17102–17109. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xu HL, Zhao X, Zhang KM, Tang W and Kokudo

N: Inhibition of KL-6/MUC1 glycosylation limits aggressive

progression of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

20:1217–12181. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wong CC, Gilkes DM, Zhang H, Chen J, Wei

H, Chaturvedi P, Fraley SI, Wong CM, Khoo US, Ng IO, et al:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a master regulator of breast cancer

metastatic niche formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:16369–16374. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Basheeruddin M and Qausain S:

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1alpha) and cancer:

Mechanisms of tumor hypoxia and therapeutic targeting. Cureus.

16:e707002024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rankin EB, Nam JM and Giaccia AJ: Hypoxia:

Signaling the metastatic cascade. Trends Cancer. 2:295–304. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mikami Y, Hisatsune A, Tashiro T, Isohama

Y and Katsuki H: Hypoxia enhances MUC1 expression in a lung

adenocarcinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

379:1060–1065. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Aubert S, Fauquette V, Hémon B, Lepoivre

R, Briez N, Bernard D, Van Seuningen I, Leroy X and Perrais M:

MUC1, a new hypoxia inducible factor target gene, is an actor in

clear renal cell carcinoma tumor progression. Cancer Res.

69:5707–5715. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Godet I, Oza HH, Shi Y, Joe NS, Weinstein

AG, Johnson J, Considine M, Talluri S, Zhang J, Xu R, et al:

Hypoxia induces ROS-resistant memory upon reoxygenation in vivo

promoting metastasis in part via MUC1-C. Nat Commun. 15:84162024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yamamoto Y, Hayashi Y, Sakaki H and

Murakami I: Downregulation of fascin induces collective cell

migration in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 50:1502023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hayashi Y, Yamamoto Y and Murakami I:

Micromorphological observation of HLE cells under knockdown of

fascin using LV-SEM. Med Mol Morphol. 56:257–265. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Isert L, Mehta A, Loiudice G, Oliva A,

Roidl A and Merkel OM: An in vitro approach to model emt in breast

cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:77572023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Liu CY, Lin HH, Tang MJ and Wang YK:

Vimentin contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition cancer

cell mechanics by mediating cytoskeletal organization and focal

adhesion maturation. Oncotarget. 6:15966–15983. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gest C, Joimel U, Huang L, Pritchard LL,

Petit A, Dulong C, Buquet C, Hu CQ, Mirshahi P, Laurent M, et al:

Rac3 induces a molecular pathway triggering breast cancer cell

aggressiveness: differences in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer

cell lines. BMC Cancer. 13:632013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nguyen CH, Senfter D, Basilio J, Holzner

S, Stadler S, Krieger S, Huttary N, Milovanovic D, Viola K,

Simonitsch-Klupp I, et al: NF-κB contributes to MMP1 expression in

breast cancer spheroids causing paracrine PAR1 activation and

disintegrations in the lymph endothelial barrier in vitro.

Oncotarget. 6:39262–39275. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li H, Qiu Z, Li F and Wang C: The

relationship between MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression levels with breast

cancer incidence and prognosis. Oncol Lett. 14:5865–5870.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Dobie C and Skropeta D: Insights into the

role of sialylation in cancer progression and metastasis. Br J

Cancer. 124:76–90. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Julien S, Lagadec C, Krzewinski-Recchi MA,

Courtand G, Le Bourhis X and Delannoy P: Stable expression of

sialyl-Tn antigen in T47-D cells induces a decrease of cell

adhesion and an increase of cell migration. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 90:77–84. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhou X, Chi K, Zhang C, Liu Q and Yang G:

Sialylation: A cloak for tumors to trick the immune system in the

microenvironment. Biology (Basel). 12:8322023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tian X, Wang W, Zhang Q, Zhao L, Wei J,

Xing H, Song Y, Wang S, Ma D, Meng L and Chen G: Hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α enhances the malignant phenotype of multicellular

spheroid HeLa cells in vitro. Oncol Lett. 1:893–897. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Koike T, Kimura N, Miyazaki K, Yabuta T,

Kumamoto K, Takenoshita S, Chen J, Kobayashi M, Hosokawa M,

Taniguchi A, et al: Hypoxia induces adhesion molecules on cancer

cells: a missing link between Warburg effect and induction of

selectin-ligand carbohydrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

101:8132–8137. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Arriagada C, Silva P and Torres VA: Role

of glycosylation in hypoxia-driven cell migration and invasion.

Cell Adh Migr. 13:13–22. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Goudarzi H, Iizasa H, Furuhashi M,

Nakazawa S, Nakane R, Liang S, Hida Y, Yanagihara K, Kubo T,

Nakagawa K, et al: Enhancement of in vitro cell motility and

invasiveness of human malignant pleural mesothelioma cells through

the HIF-1α-MUC1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 339:82–92. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Habeeb IF, Alao TE, Delgado D and Buffone

A Jr: When a negative (charge) is not a positive: Sialylation and

its role in cancer mechanics and progression. Front Oncol.

14:14873062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Shen L, Luo Z, Wu J, Qiu L, Luo M, Ke Q

and Dong X: Enhanced expression of α2,3-linked sialic acids

promotes gastric cancer cell metastasis and correlates with poor

prognosis. Int J Oncol. 50:1201–1210. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wu X, Zhao J, Ruan Y, Sun L, Xu C and

Jiang H: Sialyltransferase ST3GAL1 promotes cell migration,

invasion, and TGF-β1-induced EMT and confers paclitaxel resistance

in ovarian cancer. Cell Death Dis. 9:11022018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Pietrobono S, Anichini G, Sala C, Manetti

F, Almada LL, Pepe S, Carr RM, Paradise BD, Sarkaria JN, Davila JI,

et al: ST3GAL1 is a target of the SOX2-GLI1 transcriptional complex

and promotes melanoma metastasis through AXL. Nat Commun.

11:58652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|