Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), an aggressive cancer

originating from the biliary epithelium, is the 2nd most common

primary liver cancer after hepatocellular carcinoma (1–4).

Histologically, CCA is typically an adenocarcinoma characterized by

dense desmoplastic stroma and a complex tumor microenvironment

(TME) enriched with cancer-associated fibroblasts and

immunosuppressive cells, which collectively foster tumor

progression and resistance to therapy (5,6). Due

to the absence of early symptoms and lack of effective screening

tools, only 15–30% of patients with CCA are eligible for curative

resection at diagnosis (with >65% presenting with unresectable

or metastatic disease), and recurrence rates after curative-intent

surgery remain high (50–83%) (7–9). The

standard first-line chemotherapy regimen, gemcitabine combined with

cisplatin, confers limited benefit. Although targeted therapies

against FGFR2 and IDH1 mutations have shown promise

in subsets of patients, resistance frequently emerges (10). The combination of molecular

heterogeneity, immunosuppressive TME and intrinsic chemoresistance

results in poor outcomes, with a median survival of only 4–8 months

and a 5-year survival rate of <20% (11). Thus, there is an urgent need to

identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets tailored to the

molecular and anatomical diversity of CCA.

Targeting specific molecular pathways and harnessing

the mechanisms of regulated cell death (RCD) have emerged as

promising strategies for cancer suppression (12–15).

Recently, a distinct RCD form termed disulfidptosis has been

identified, characterized by cytoskeletal collapse caused by

excessive disulfide bonding in actin filaments under

glucose-deprived conditions (16,17).

In cells overexpressing SLC7A11, continuous cystine uptake depletes

NADPH, hindering disulfide bond reduction and promoting toxic

protein crosslinking. Notably, disulfidptosis is unresponsive to

classical RCD inhibitors and can occur independently of ATP levels.

Therapeutic strategies that enhance thiol oxidation or inhibit

glucose uptake exacerbate disulfide stress and trigger this cell

death pathway (16,17). Emerging studies implicate

disulfidptosis in digestive tract malignancies such as gastric and

hepatocellular carcinoma, where disulfidptosis-related gene (DRG)

expression is associated with immune activity and clinical

prognosis (18–26). However, its role in CCA remains

unexplored.

Notably, research has highlighted key features of

CCA biology that suggest a unique vulnerability to disulfidptosis.

First, CCA is dependent on glucose metabolism and undergoes

extensive metabolic reprogramming to survive in a nutrient-poor

TME, creating a state of chronic metabolic stress (5,27).

Second, the aggressive, invasive nature of CCA is dependent on the

dynamic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, and an abnormal

actin network is itself a driver of the malignant phenotype and

metastasis (28). Furthermore, the

emerging susceptibility of CCA to other forms of redox-dependent

cell death such as ferroptosis points towards a reliance on solute

carriers such as the cystine-glutamate transporter xCT, which

includes SLC7A11, to manage oxidative stress (29). These characteristics, glucose

dependency, cytoskeletal vulnerability and active SLC7A11-related

pathways, establish a rationale for investigating disulfidptosis, a

novel cell death pathway that is directly associated with all three

of these biological pillars.

To investigate this unexplored area, DRGs in CCA

were systematically evaluated using RNA sequencing data from The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and European Molecular Biology

Laboratory-European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI).

Differential expression analysis was performed to identify

candidate DRGs, then unsupervised clustering was used to define

patient subgroups with distinct clinical and molecular

characteristics. Building on these findings, a prognostic signature

was developed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

(LASSO) regression and validated through functional assays to

elucidate the ways key DRGs regulate disulfidptosis. To the best of

our knowledge, the present study revealed the first comprehensive

landscape of disulfidptosis in CCA, associating DRG activity to

patient survival, immune microenvironment remodeling and

therapeutic responsiveness. These findings not only offer a

prognostic tool, but also highlight actionable targets, opening new

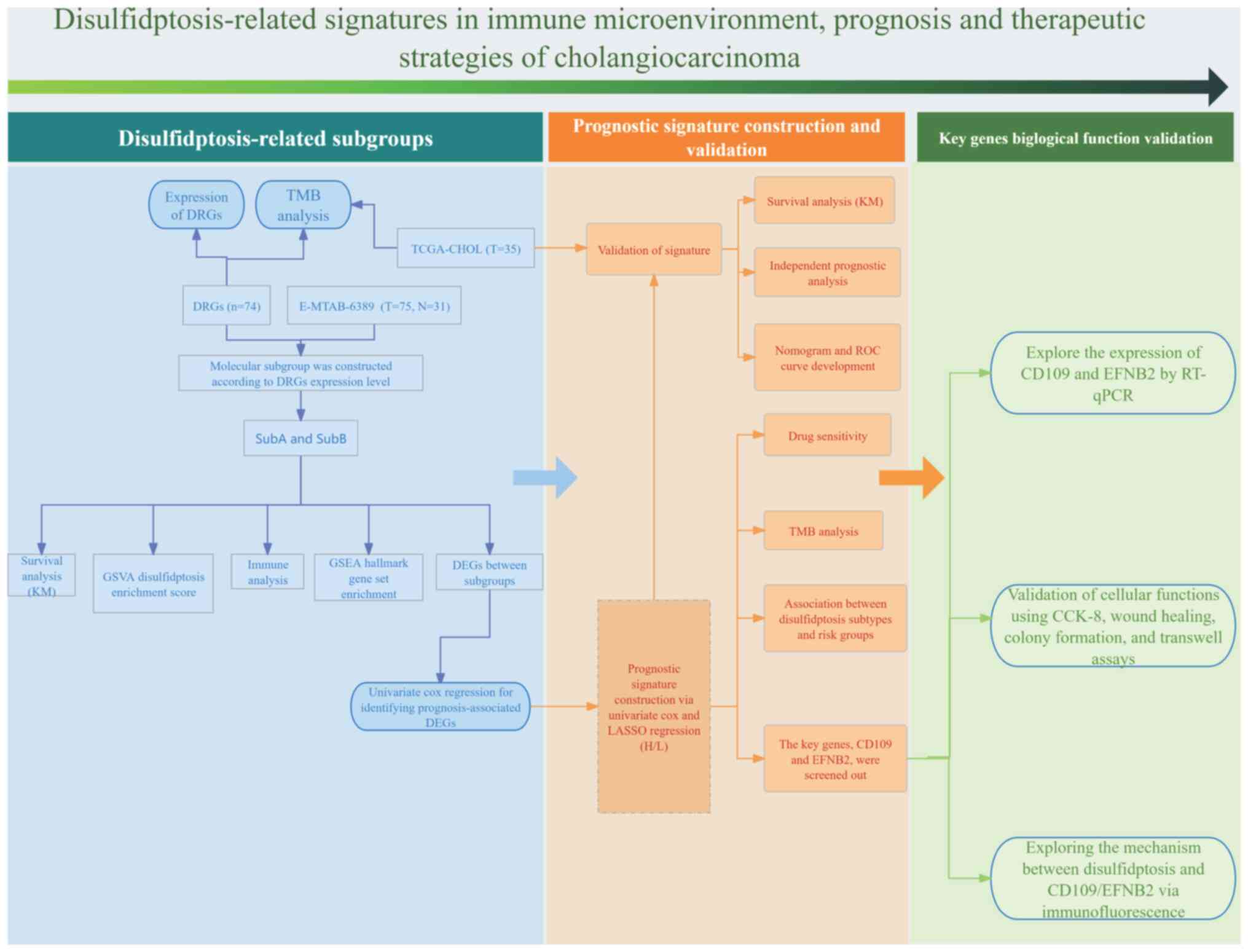

avenues for treating this intractable malignancy. The workflow of

the present study is shown in Fig.

1.

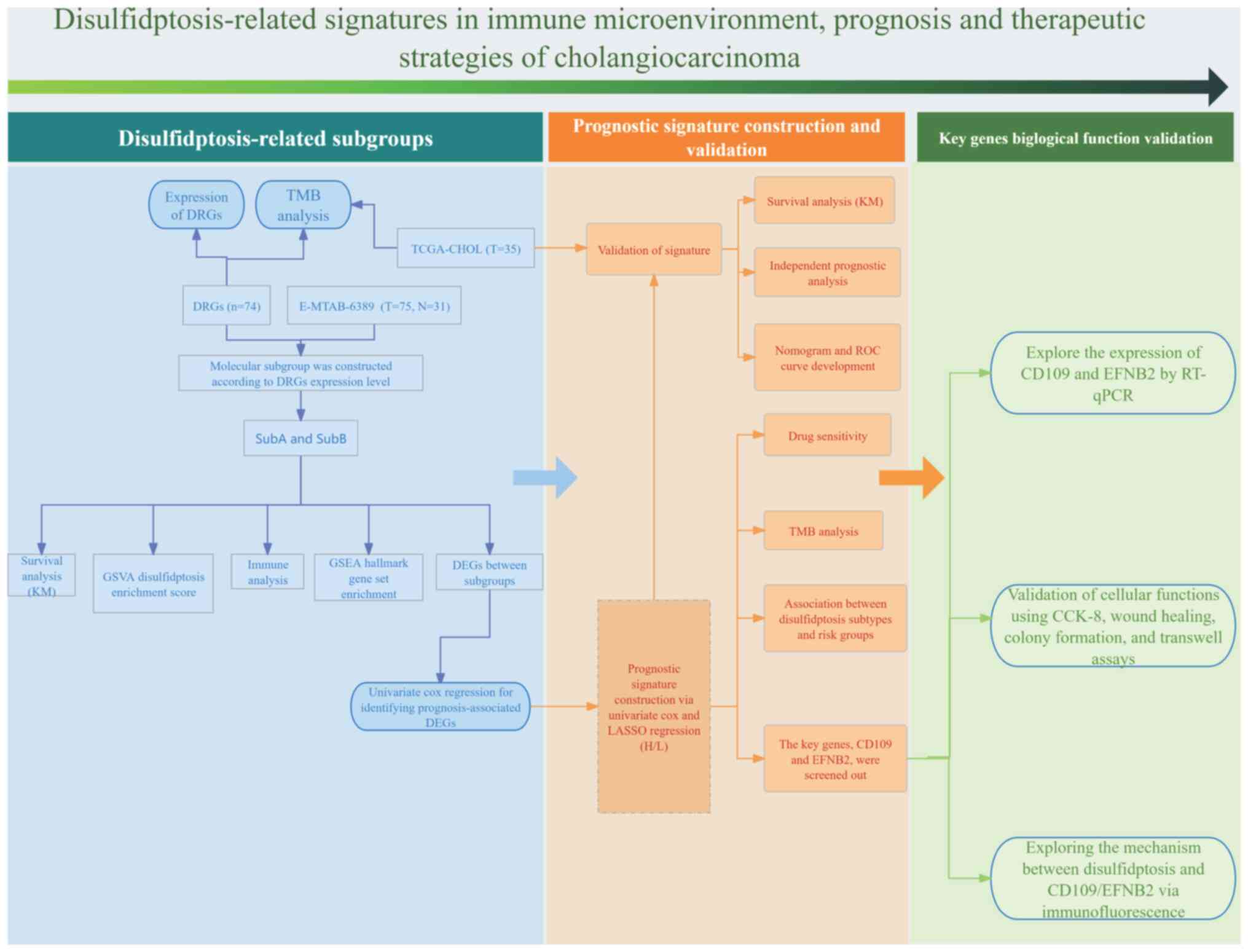

| Figure 1.Flow chart for the present study

analysis. DRGs (n=74) expression was assessed in the E-MTAB-6389

cohort (T=75, N=31), dividing patients into SubA and SubB based on

DRG levels. Molecular subtyping was followed by survival analysis

(KM), GSVA enrichment score, immune analysis and GSEA hallmark

enrichment. Prognosis-related DEGs were identified and used to

build a signature via univariate Cox and LASSO regression,

validated in the TCGA-CHOL cohort (T=35) with KM survival,

independent prognostic, nomogram, ROC, drug sensitivity and TMB

analyses. Disulfidptosis subtypes and risk groups were explored,

highlighting CD109 and EFNB2, validated by RT-qPCR and functional

assays. The disulfidptosis-CD109/EFNB2 mechanism was investigated

via immunofluorescence. DRGs, disulfidptosis-related genes; TCGA,

The Cancer Genome Atlas; GSVA, gene set variation analysis; GSEA,

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and

selection operator; KM, Kaplan-Meier; ROC, receiver operating

characteristic; TMB, tumor mutational burden; RT-qPCR, real-time

quantitative polymerase chain reaction; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8;

TCGA-CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas

database; T, tumor; N, normal. |

Materials and methods

Data collection and processing

To construct and validate the prognostic signature,

independent training and validation cohorts were used. The present

study conducted a systematic search of public repositories,

including the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), The Cancer Genome

Atlas (TCGA) and ArrayExpress. For the training cohort, the

E-MTAB-6389 dataset (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/studies/E-MTAB-6389)

was selected from the ArrayExpress database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) after a

systematic search of public repositories. The dataset was chosen

due to its larger sample size (n=75) which provided greater

statistical power for the initial model construction. This dataset

contains gene expression data from 75 CCA tissues and 31 adjacent

normal tissues, generated on the Affymetrix Human Transcriptome

Array 2.0 microarray platform (GEO platform accession, GPL17585).

The raw data were processed using the robust multi-array average

algorithm and subsequently log2-transformed. For external

validation, TCGA-CHOL cohort was used, acquired from the Genomic

Data Commons portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). This cohort consisted

of 35 patients with CCA and corresponding overall survival (OS)

data. Gene expression was quantified as Fragments Per Kilobase of

transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) on the Illumina HiSeq

2000 platform (Illumina, Inc.), and the values were

log2-transformed [log2(FPKM+1)] for subsequent analyses. Due to

incomplete clinical information in the training cohort, survival

modeling and mutation profiling were performed exclusively on TCGA

dataset. A total of 100 DRGs were identified through a systematic

literature review. The selection process began with core

mechanistic genes established in foundational studies, and was

expanded by incorporating DRGs from recent high-quality

bioinformatics and experimental studies that constructed prognostic

models or molecular subtypes (molecular subs; distinct tumor

subgroups characterized by specific disulfidptosis-related gene

expression profiles and clinical outcomes) across malignancies

(Table SI) (16–26).

All datasets are publicly available and adhere to ethical

standards. The harmonized clinicopathological characteristics for

subsequent analyses are elaborated in Table I.

| Table I.Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with cholangiocarcinoma in The Cancer Genome Atlas. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of patients with cholangiocarcinoma in The Cancer Genome Atlas.

| Clinicopathological

characteristics | TCGA cohort

(N=35) |

|---|

| Age (years), no.

(%) |

|

|

≤65 | 17 (48.6%) |

|

>65 | 18 (51.4%) |

| Gender, no.

(%) |

|

|

Female | 19 (54.3%) |

|

Male | 16 (45.7%) |

| Stage, no. (%) |

|

| I | 18 (51.4%) |

| II | 9 (25.7%) |

|

III | 1 (2.9%) |

| IV | 7 (20%) |

| T, no. (%) |

|

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1 | 18 (51.4%) |

| 2 | 6 (17.1%) |

| 2a | 2 (5.7%) |

| 2b | 4 (11.5%) |

| 3 | 5 (14.3%) |

| 4 | 0 (0.0%) |

| N, no. (%) |

|

| N0 | 25 (71.4%) |

| N1 | 5 (14.3%) |

| NX | 5 (14.3%) |

| M, no. (%) |

|

| M0 | 27 (77.1%) |

| M1 | 5 (14.3%) |

| MX | 3 (8.6%) |

| Survival status,

no. (%) |

|

|

Alive | 17 (48.6%) |

|

Dead | 18 (51.4%) |

| Overall survival

time, days |

|

| Mean ±

SD | 742.54±548.58 |

|

Median | 640 |

Expression of DRGs and molecular

subtyping in CCA

An integrated analysis of 100 DRGs in CCA was

conducted. Expression profiles were extracted from the E-MTAB-6389

dataset, and differential expression was assessed using Wilcoxon

rank-sum tests (FDR <0.05). Significant DRGs were visualized

using boxplots. Pairwise co-expression relationships were evaluated

using Pearson's correlation analysis. All statistical and

bioinformatic analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1

(30). Somatic mutation landscapes

were analyzed using TCGA data and the ‘maftools’ package (31) (https://bioconductor.uib.no/packages/release/bioc/html/maftools.html)

version 2.18.0, with alterations depicted in waterfall plots. To

identify disulfidptosis-driven molecular Subs, unsupervised

consensus clustering was performed on tumor samples using the

‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ package (32) (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ConsensusClusterPlus.html)

version 1.54.0.

Prognostic, immune microenvironment

and mechanistic profiling of disulfidptosis-related molecular Subs

in CCA

To investigate the prognostic and biological

significance of disulfidptosis-related molecular Subs in CCA,

survival analysis was performed to compare OS across Subs.

Enrichment scores for disulfidptosis pathways were computed by

integrating gene sets with CCA expression matrices using the ‘GSVA’

R package, with Sub-specific differences assessed via Wilcoxon

tests. For immune microenvironment analysis, three complementary

approaches were used. Stromal and immune cell infiltration scores

were quantified using the Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in

Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression data (ESTIMATE) algorithm

with the ‘estimate’ R package. Proportions of 22 immune cell types

were estimated through Cell-type Identification by Estimating

Relative Subsets of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT) deconvolution using

the ‘CIBERSORT’ R package. Immune cell-specific enrichment scores

were derived via single-sample (ss) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

(GSEA) with the ‘GSVA’ R package. Subtype differences were

evaluated using Wilcoxon tests. Expression profiles of immune

checkpoint and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) family genes were

compared across Subs. Molecular pathway characterization was

performed using GSEA.

Identification of DRGs, and

construction and validation of the prognostic signature in CCA

Utilizing the ‘limma’ package in R, P-values and

log2FC were calculated for each gene, applying multiple testing

correction to obtain adjusted P-values (adj.P.Value). Genes with

adj.P.Value <0.05 and |log2FC|>0.585 were classified as

differentially expressed and disulfidptosis related. To identify

prognostic Sub-specific genes, univariate Cox regression analysis

was conducted using gene expression and survival data from CCA

samples. Genes with P<0.01 were deemed significant. A prognostic

model was then constructed using LASSO regression analysis using

the ‘lars’ package, incorporating 10-fold cross-validation for gene

selection. The risk score formula, RiskScore=β1X1 + β2X2 + ... +

βnXn, was employed, where β signifies LASSO regression coefficients

and X represents gene expression levels. Risk scores were

calculated for each sample in both the EMBL-EBI training set and

TCGA validation cohort, with patients stratified into high (H)-risk

and low (L)-risk groups based on an optimal risk score cut-off.

Kaplan-Meier assessed the association between risk groups and

survival outcomes. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression

analyses determined whether the model functioned as an independent

prognostic factor for CCA. Significant clinical features were

incorporated into a nomogram constructed with the ‘rms’ R package.

Calibration curves assessed model consistency, while receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curves and clinical decision curves

evaluated the nomogram's predictive accuracy and practical

utility.

Drug sensitivity analysis of risk

groups

Drug sensitivity was analyzed between H- and L-risk

groups by employing predicted IC50 values sourced from

the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). Utilizing the

‘pRRophetic’ R package, IC50 values were computed.

Significant disparities in drug sensitivity among the risk

subgroups were uncovered using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests,

highlighting therapeutic diversity.

Mutational landscape stratification by

risk groups

For the analysis of somatic variant profiles from

TCGA cohorts, the ‘maftools’ package was employed to investigate

oncogenic landscapes across risk subgroups. The varying mutation

frequencies among the top 20 driver genes were visualized using

‘oncoplots’. Additionally, the tumor mutational burden (TMB) was

quantified and evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Association between disulfidptosis

Subs and risk groups

To explore the relationship between disulfidptosis

Subs and risk groups, the R ‘ggalluvial’ package was used to

generate Sankey diagrams. These diagrams visually represented the

distribution of samples across disulfidptosis Subs and H-/L-risk

groups, revealing the associations between these

classifications.

Cell culture

HuCCT1 cells (Procell Life Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.), primary human intrahepatic bile duct epithelial cells

(HiBEpiCs; passage 2; cat. no. CP-H042; Pricella Biotechnology),

RBE cells (The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese

Academy of Sciences) and HuH-28 cells (cat. no. ZQ1030; Zhong Qiao

Xin Zhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium

(HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified 5%

CO2 incubator (Heal Force Bio-Meditech Holdings, Ltd.).

All cell handling procedures were performed in a biological safety

cabinet (BHC-1300IIA2; Suzhou Antai Air Technology Co., Ltd.). For

thawing, cells were rapidly thawed in a 37°C water bath (HWS-12;

Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.) and gently

agitated. After centrifugation (200 × gp; 5 min; room temperature),

cells were resuspended in culture medium, seeded into dishes and

incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. When cells achieved

80–90% confluency, they were trypsinized, centrifuged (200 × g; 5

min; room temperature) and re-seeded. For cryopreservation,

5×106 cells/ml were resuspended in Cell Freezing Medium

(cat. no. C0210; Beyotime Biotechnology), aliquoted into cryovials

and frozen at −80°C before storage in liquid nitrogen.

Small interfering (si)RNA

transfection

siRNA transfection was performed to knock down

CD109 and EFNB2 expression in HuCCT1 and RBE cells.

The specific siRNA sequences (listed in Table II) were synthesized by Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd. A total of 5×105 cells/ml were seeded

in 2 ml culture medium in a 6-well plate and incubated for 24 h at

37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. siRNAs [negative control

(NC) siRNA, CD109 siRNA and EFNB2 siRNA] were diluted to 100

pmol/µl. For transfection, 1 µl siRNA was mixed with 150 µl

Opti-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated for

5 min at room temperature. Similarly, 5 µl

Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (cat. no. 13778150; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was mixed with 150 µl Opti-MEM. After 20 min of

incubation at room temperature, the transfection complex was added

dropwise to the cells. After 6 h at 37°C, the medium was replaced

with DMEM (cat. no. 11965-118; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific

Inc.) containing 10% FBS, and cells were cultured for further

analysis. Transfection efficiency and plasmid construction were

validated using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and western blotting (WB)

24 h post-transfection.

| Table II.siRNA sequences about CD109, EFNB2

and si-NC. |

Table II.

siRNA sequences about CD109, EFNB2

and si-NC.

| siRNA | Sense, 5′-3′ | Antisense,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| si-NC | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU

(dT dT) | ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA

(dT dT) |

| CD109-siRNA1 | AUCAAACCUCACUGUCUCU

(dT dT) | AGAGACAGUGAGGUUUGAU

(dT dT) |

| CD109-siRNA2 | ACACUUACUCUUCCAUCAC

(dT dT) | GUGAUGGAAGAGUAAGUGU

(dT dT) |

| CD109-siRNA3 | ACAAGCCAAAGCAAGAAGU

(dT dT) | ACUUCUUGCUUUGGCUUGU

(dT dT) |

| EFNB2-siRNA1 | ACCUGGACAAGGACUGGUA

(dT dT) | UACCAGUCCUUGUCCAGGU

(dT dT) |

| EFNB2-siRNA2 | GUUGGCCAGUAUGAAUAUU

(dT dT) | AAUAUUCAUACUGGCCAAC

(dT dT) |

| EFNB2-siRNA3 | GUGCCAAACCAGACCAAGA

(dT dT) | UCUUGGUCUGGUUUGGCAC

(dT dT) |

Reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from normal intrahepatic

biliary epithelial cells (HIBEpiC) and CCA cell lines (HuCCT1, RBE,

and HuH-28) using 1 ml TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), followed by chloroform separation, isopropanol

precipitation and ethanol washing. RNA concentration and purity

were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg

RNA using Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

with Oligo-dT. The reaction was incubated at 70°C for 5 min, 37°C

for 5 min, 42°C for 60 min and 70°C for 5 min. qPCR was performed

to a 10 µl reaction containing 4 µl diluted cDNA, 5 µl

BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qPCR Mix (2X) (cat. no. D7260;

Beyotime Biotechnology), 0.4 µl forward and reverse primer (10 µM)

and 0.6 µl water on a CFX96 system. The thermocycling conditions

for qPCR were: 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and

60°C for 20 sec, followed by a melting step and cooling at 40°C for

30 sec. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(33) with GAPDH as the

reference gene. Primer sequences are shown in Table III.

| Table III.Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR primer sequences. |

Table III.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR primer sequences.

| Gene | Sense, 5′-3′ | Antisense,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| CD109 |

AAGCCAGTGAAAGGAGACGTA |

CCAGGGGAAGATAGATCCAGG |

| EFNB2 |

TATGCAGAACTGCGATTTCCAA |

TGGGTATAGTACCAGTCCTTGTC |

| GAPDH |

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

WB

Total protein was collected from HuCCT1 and RBE

cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology) supplemented

with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The lysate was collected

by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and protein

concentration was measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no.

P0012; Beyotime Biotechnology). Samples were mixed with 4X Sample

Buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology) containing 100 mM dithiothreitol,

denatured at 95°C for 5 min and separated on 4–20% Bis-Tris gels

(cat. no. M00657; GenScript). Proteins were transferred to PVDF

membranes which were then blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS-Tween

[TBST; Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (V/V) Tween 20] for 2 h

at room temperature. The membranes were subsequently incubated with

primary antibodies diluted in TBST containing 5% bovine serum

albumin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The specific primary

antibodies used were: CD109 (1:1,000; cat. no. A23787; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.) and Ephrin B2 Polyclonal antibody (1:1,500; cat.

no. 26533-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). The incubation was

performed overnight (12–16 h) at 4°C on a shaker. Following primary

antibody incubation, membranes were washed three times with TBST

(10 min each) and incubated with HRP-linked secondary antibody

(1:6,000; cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) for 1 h at

room temperature for detection. For the loading control, membranes

were probed separately using GAPDH (D16H11) Rabbit mAb (HRP

Conjugate) (cat. no. 8884; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), which

was detected directly. Chemiluminescent signals were captured with

a Tanon-4600 imaging system and analyzed using Quantity One

(version 4.6.6; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

A total of 2×104 cells/ml were seeded in

100 µl DMEM with 10% FBS in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h

at 37°C with 5% CO2. At 0, 24, 48 and 72 h, 10 µl CCK-8

solution (Beyotime Biotechnology) was added to each well, avoiding

bubbles. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and absorbance was

measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Cell cloning assay

Cells were serially diluted and seeded at 100 cells

per 60-mm dish. Dishes were gently rotated for even distribution

and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2–3 weeks. When

visible clones appeared, the medium was removed and cells were

washed twice with 1X PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min

at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10–30

min at room temperature. After washing and air drying, clones were

imaged using a light microscope and imaging system (Olympus

Corporation) and quantified with ImageJ software (version 1.54;

National Institutes of Health).

Wound healing assay

A total of 5×105 HuCCT1 and RBE tumor

cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured for 16–24 h at

37°C until 90% confluence. A 10-µl pipette tip was used to create

3–5 linear scratches per well. Cells were washed three times with

PBS to remove debris and cultured in serum-free DMEM for 24 h at

37°C. Wound closure was imaged at 0 and 24 h using a light

microscope (Nikon Corporation) and analyzed using ImageJ software

(version 1.54; National Institutes of Health).

Transwell assay

Tumor cell migration and invasion were assessed

using 24-well Transwell inserts with an 8-µm pore size

polycarbonate membrane. For the migration assay, cells were

trypsinized using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5

min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS and resuspended in

serum-free RPMI-1640 medium with 1% FBS to a concentration of

5×105 cells/ml. Subsequently, 200 µl of the cell

suspension (1×105 cells) was seeded into the upper

chamber. For the invasion assay, Transwell inserts were pre-coated

with Matrigel Matrix and solidified for 1 h at 37°C before seeding

cells. RPMI-1640 medium containing 20% FBS was added to the lower

chamber as a chemoattractant. The plates were incubated for 24 h at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Non-migrated cells on the upper surface were removed using cotton

swabs. Migrated or invaded cells on the lower surface were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and stained

with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 20 min at room temperature.

The inserts were washed with PBS, and the stained cells were imaged

and counted using ImageJ software (version 1.54; National

Institutes of Health) for quantitative analysis.

F-actin immunofluorescence

staining

A total of 2×104 cells/ml were added in

500 µl medium in 6-well plates (Corning, Inc.) and cultured in DMEM

(cat. no. 11965-118; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 24

h at 37°C with 5% CO2 until reaching 50% confluence. To

investigate the role of EFNB2 and CD109 in disulfidptosis, the

medium was replaced with glucose-free DMEM (cat. no. 11966-025;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for glucose deprivation.

Cells were then treated with the GLUT1 inhibitor BAY-876 (10 µM;

cat. no. HY-100017, MedChemExpress) and/or the reducing agent,

Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP; 20 mM; cat.

no. A600974; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 6 h at 37°C. Following

treatment, cells were washed twice with pre-warmed 1X PBS (pH 7.4;

Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.). Cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) in

PBS for 10 min at room temperature, followed by three PBS washes.

Permeabilization was performed with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, followed

by PBS washes. Cells were then incubated with Alexa

Fluor™ 594 Phalloidin (1:400 dilution in 1% BSA/PBS;

cat. no. A12381, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) for 30 min in a,

humidified chamber in the dark. After washing, cells were

counterstained with DAPI (100 nM; cat. no. HY-D0814,

MedChemExpress) for 30 sec at room temperature. Coverslips were

mounted on slides with AntiFade Mounting Medium (cat. no. HY-K1042;

MedChemExpress) and sealed. Fluorescence was observed using a ZEISS

LSM800 confocal microscope (ZEISS).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R (version

4.4.1; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing), SPSS (version

26.0; IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism (version 10.0; Dotmatics).

Intergroup comparisons were carried out using the Wilcoxon rank-sum

test, while chi-square tests assessed association between subgroups

and clinicopathological features. Survival curves were plotted

using the Kaplan-Meier method. Prognostic factors for CCA were

identified via LASSO regression, followed by univariate and

multivariate Cox regression to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and

95% confidence intervals (CIs). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference with FDR <0.05.

Significance levels are denoted as *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Results

Development of

disulfidptosis-regulated clusters and their characteristics in

CCA

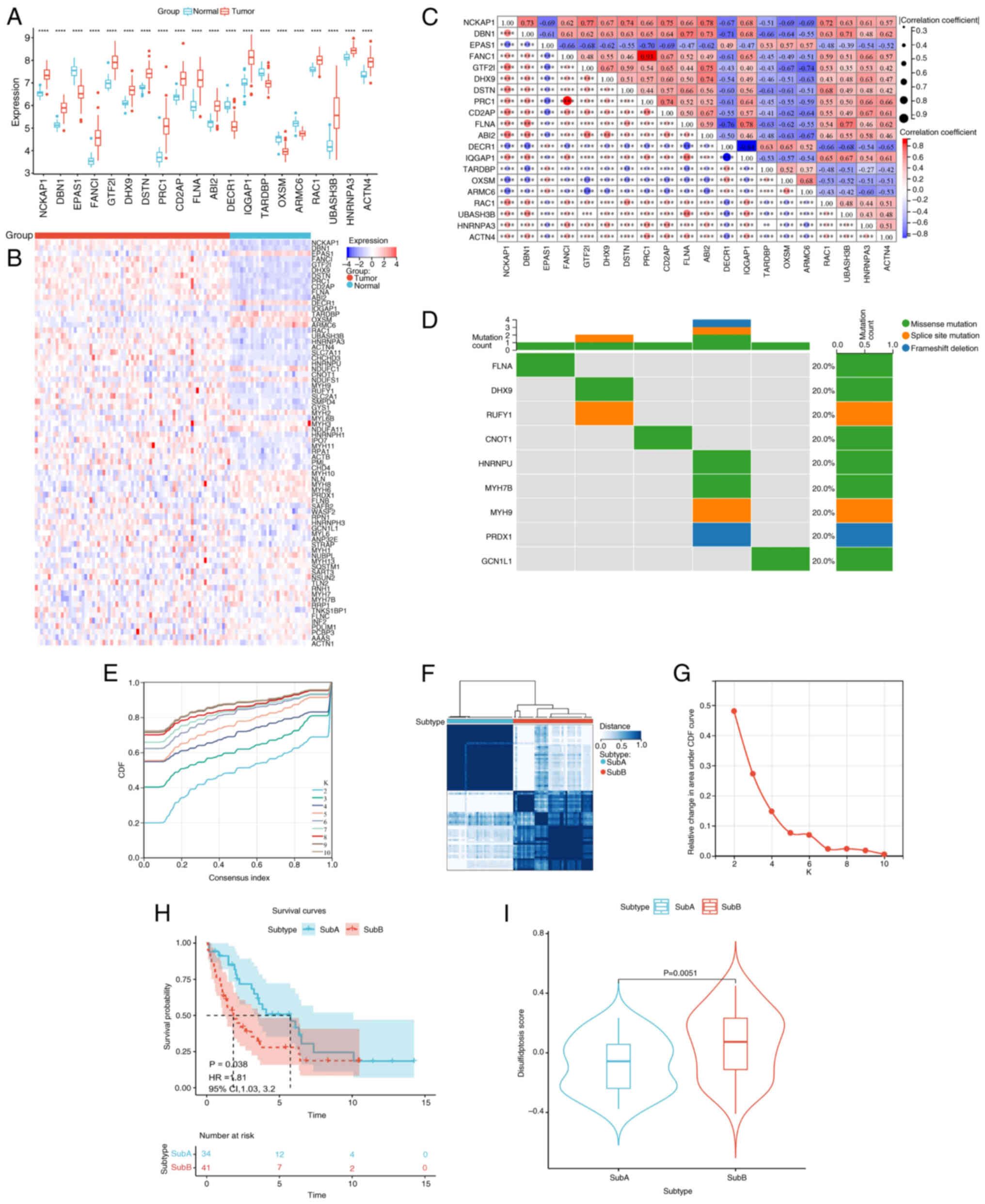

Differential expression analysis of 100 DRGs in CCA

vs. adjacent normal tissues identified 74 DRGs (|log2FC|>1; FDR

<0.05) using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (Table SII). The top 20 DRGs are shown in

Fig. 2A and a correlation heatmap

of all 74 DRGs is shown in Fig. 2B.

Co-expression analysis of the top 20 DRGs revealed significant

intergenic correlations (Fig. 2C).

Somatic mutation analysis via TCGA data detected mutations in nine

DRGs (Fig. 2D). Unsupervised

consensus clustering (K=2; range, 2–10; Fig. 2E) classified 75 samples into SubA

(n=34) and SubB (n=41) Subs (Fig.

2F; Table SIII). Sub stability

was confirmed using cumulative distribution function curve analysis

(Fig. 2G). Kaplan-Meier analysis

indicated shorter OS for SubB (P=0.038; Fig. 2H). GSVA revealed elevated

disulfidptosis pathway activity in SubB (P=0.005; Fig. 2I; Table

SIV).

Immune landscape and checkpoint gene

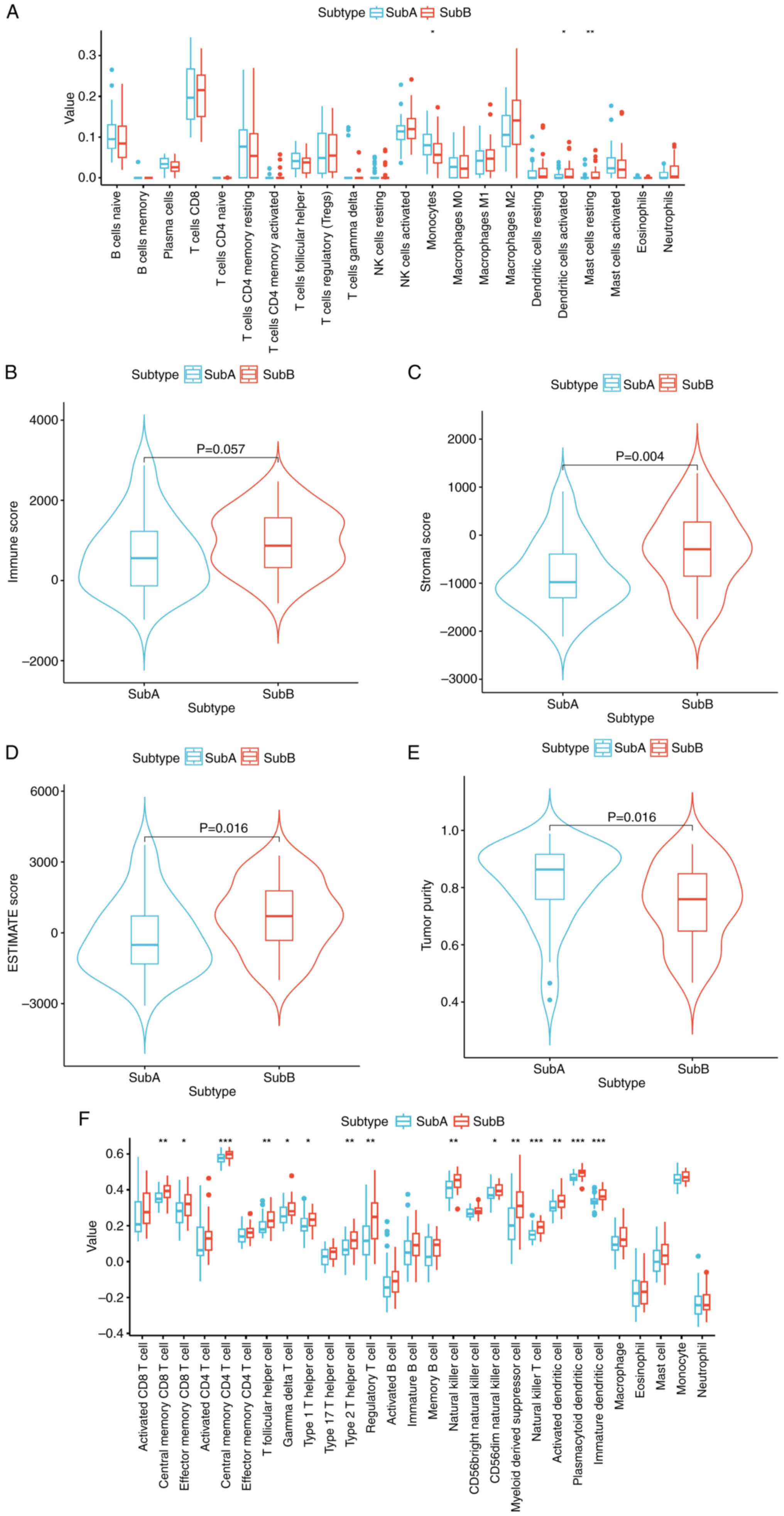

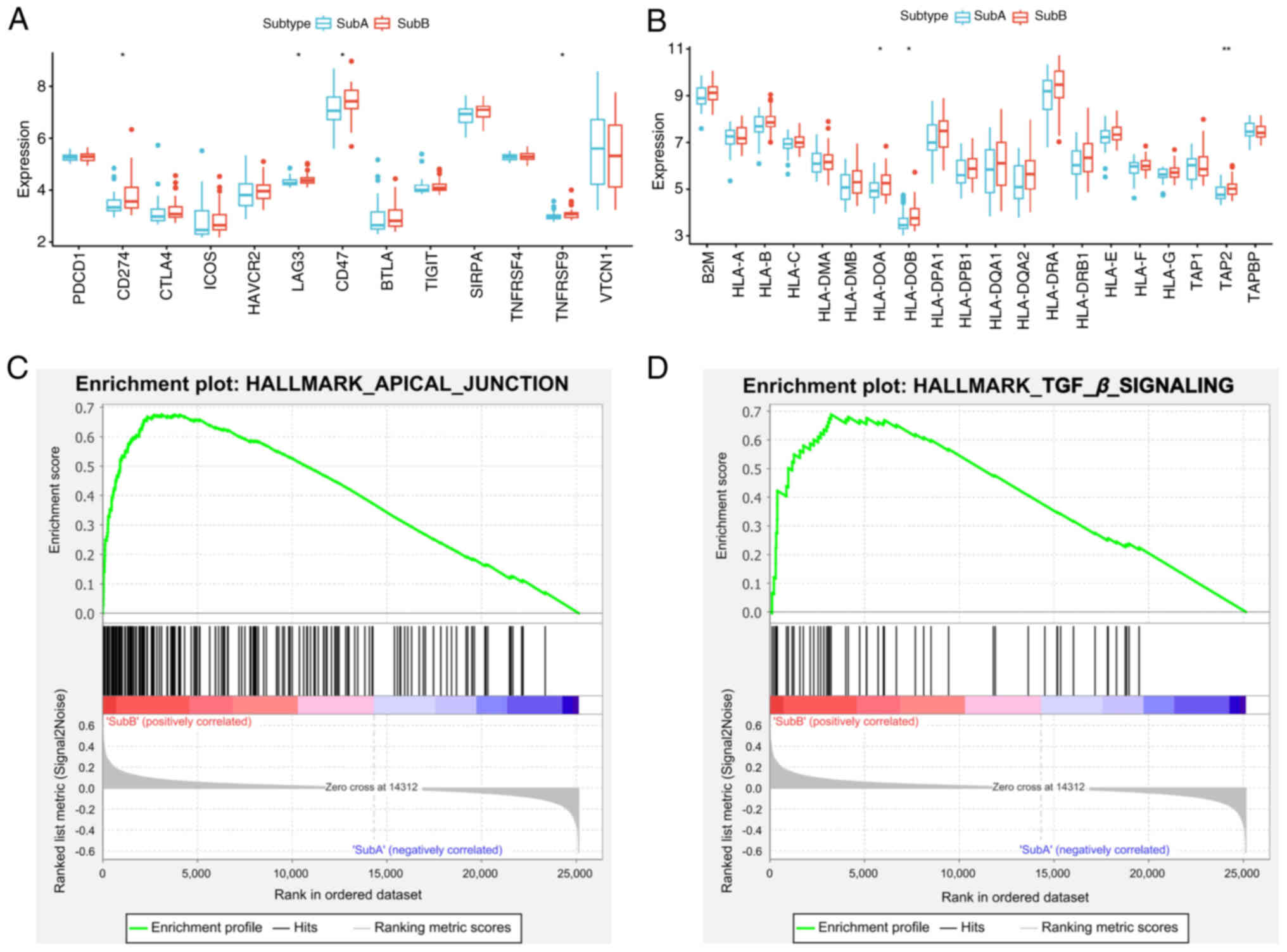

expression profiles in disulfidptosis Subs of CCA

To investigate the relationship between

disulfidptosis Subs and the immune microenvironment in CCA, the

CIBERSORT algorithm was applied to evaluate infiltration of 22

immune cell types. Comparative analysis (P<0.05) revealed

significantly lower monocyte levels in SubB compared with SubA,

with an increased number of activated dendritic and resting mast

cells in SubB (Fig. 3A). ESTIMATE

analysis indicated higher stromal and ESTIMATE scores in SubB

(P<0.05), while SubA exhibited greater tumor purity (Fig. 3B-E). Immune scores trended higher in

SubB. ssGSEA analysis revealed significantly enhanced effector

immune cell activity in SubB, including CD8+ T cells,

CD4+ T cells and natural killer cells (P<0.05),

indicating robust antitumor immunity (Fig. 3F). By contrast, SubA exhibited

elevated levels of γδ T cells and dendritic cells, associated with

adaptive immunity and antigen presentation. Immune checkpoint genes

(PD-L1, LAG3, CD47 and TNFRSF9) and HLA antigen

presentation genes (HLA-DOA, HLA-DOB and TAP2) were

significantly upregulated in SubB (P<0.05; Fig. 4A and B). GSEA analysis of the

E-MTAB-6389 dataset revealed SubB enrichment in APICAL_JUNCTION and

TGF_β_SIGNALING pathways (Fig. 4C and

D; FDR <0.05), suggesting roles in immune evasion and

structural remodeling.

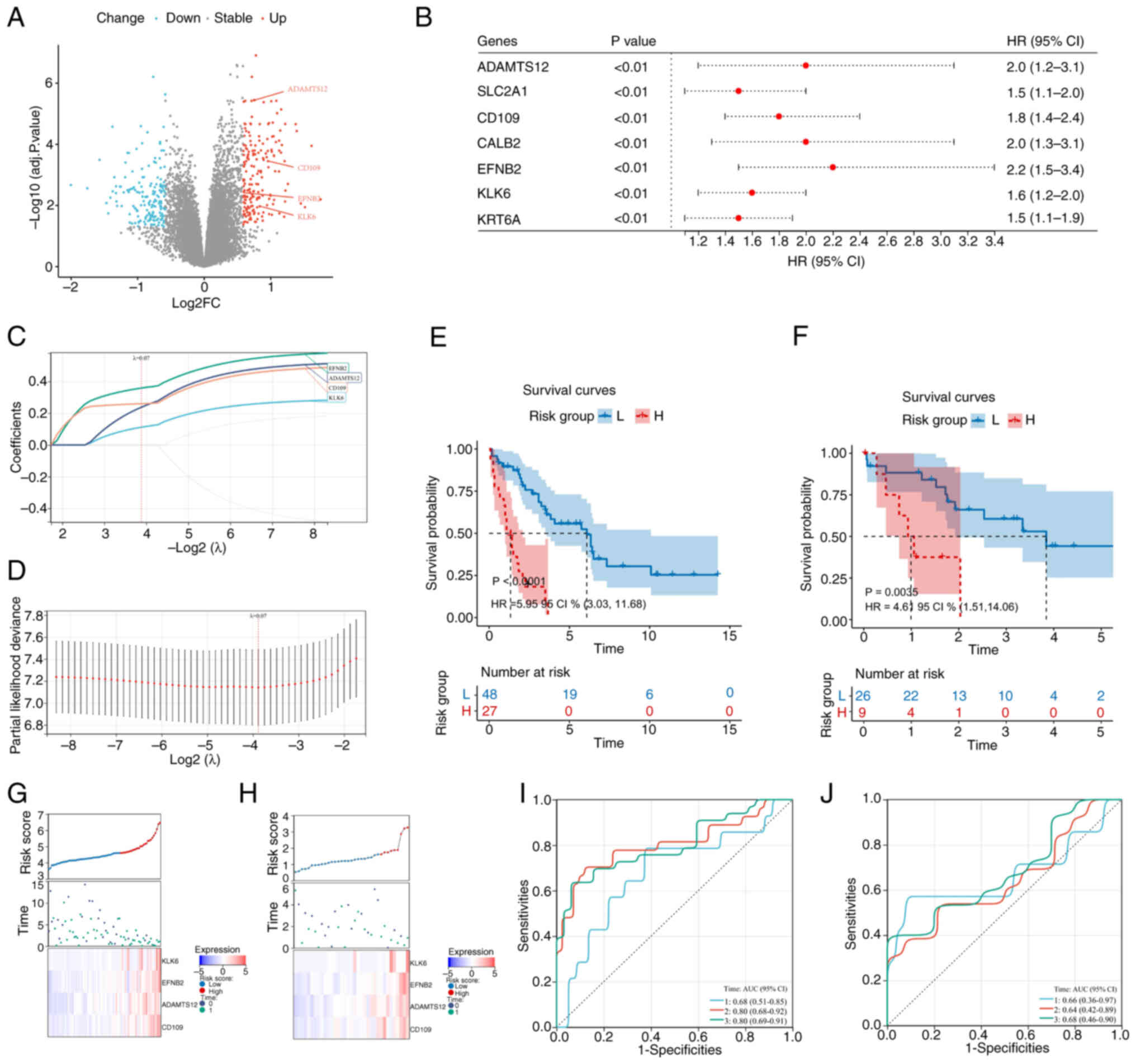

Identifying DRGs, construction and

validation of the disulfidptosis-related predictive signature in

CCA

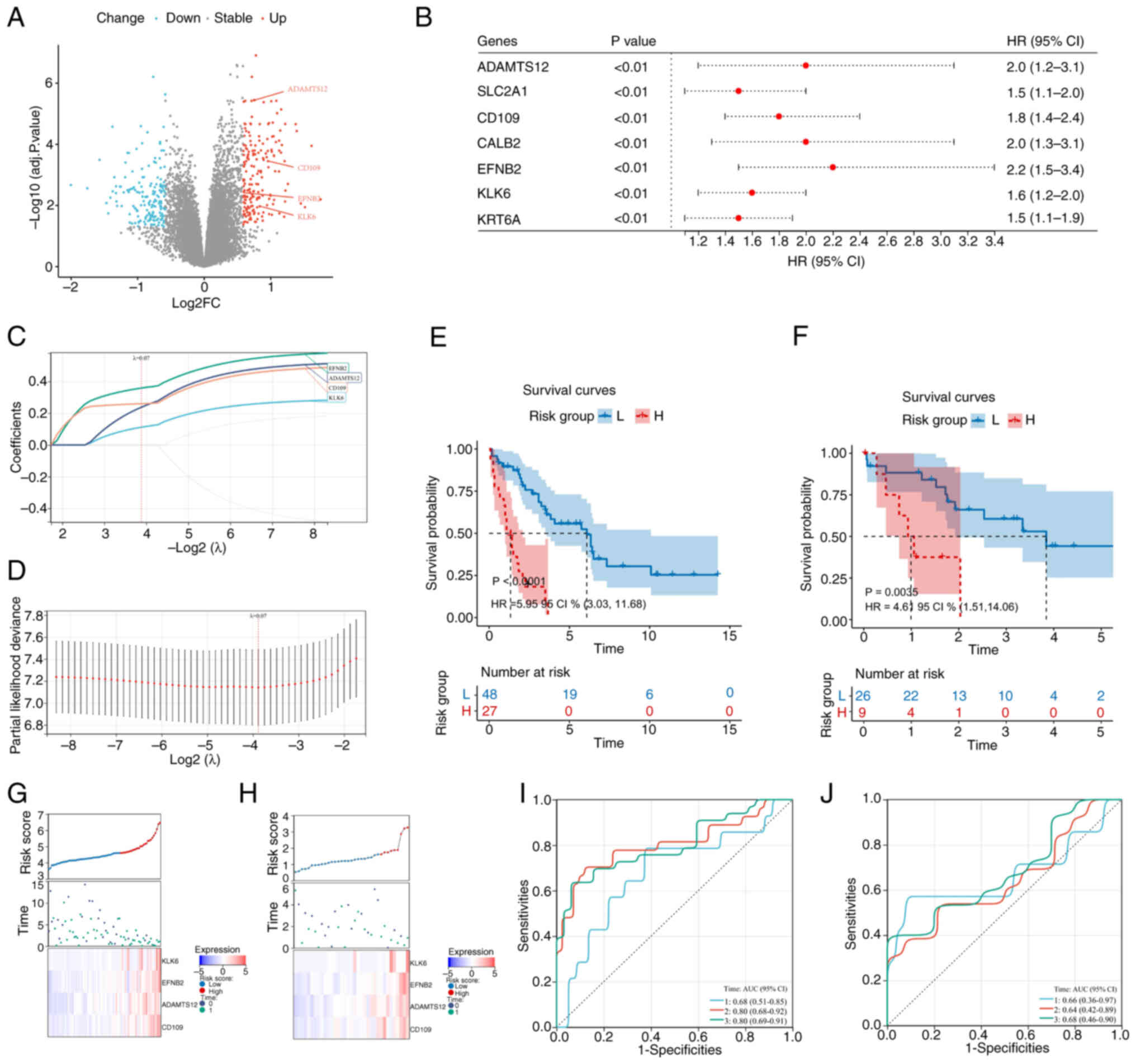

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis between

the DRG subgroups identified 190 upregulated genes and 173

downregulated genes (Fig. 5A;

Table SV). Univariate Cox

regression analysis of the 363 DEGs revealed seven

prognosis-related genes (ADAMTS12, SLC2A1, CD109, CALB2, EFNB2,

KLK6 and KRT6A) with P<0.01 and HRs ranging from 1.5

(95% CI, 1.1–1.9) to 2.2 (95% CI, 1.5–3.4; Fig. 5B). LASSO regression selected a

four-gene prognostic signature (EFNB2, CD109, KLK6 and

ADAMTS12) with positive coefficients (Fig. 5C and D; Table SVI). The risk score was calculated

as follows: RiskScore=0.3589 × Exp (EFNB2) + 0.2604 × Exp

(CD109) +0.2382 × Exp (ADAMTS12) + 0.1120 × Exp

(KLK6).

| Figure 5.Prognostic gene signature and risk

score analysis in cholangiocarcinoma. (A) Volcano plot of

differentially expressed genes (blue, downregulated; red,

upregulated); (B) Univariate Cox regression forest plot of seven

prognostic genes; (C) LASSO coefficient distribution profile; (D)

likelihood deviance for LASSO coefficients, with vertical dashed

lines indicating λ. min (left) and λ.1se (right); (E) Kaplan-Meier

survival curves for patients stratified by the 4-gene signature in

the training cohort (Risk group; P<0.0001; HR=5.95; 95% CI

3.03–11.68); (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients

stratified by the 4-gene signature in the validation cohort; (G)

training cohort: Risk score distribution (top), survival status

(middle) and gene expression heatmap (bottom); (H) validation

cohort: Risk score distribution (top), survival status (middle) and

gene expression heatmap (bottom); (I) time-dependent ROC curves

(1-, 2-, 3-year) in the training cohort; (J) time-dependent ROC

curves (1-, 2-, 3-year) in the validation cohort. LASSO, least

absolute shrinkage and selection operator; HR, hazard ratio; AUC,

area under the curve. |

Using optimal cut-offs (EMBL-EBI; 4.595; TCGA,

1.608), patients with CCA were classified into H- and L-risk

groups. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significant survival

differences in both the EMBL-EBI (P=0.0001; HR, 5.95; 95% CI,

3.03–11.68) and TCGA (P=0.0035; HR, 4.61; 95% CI, 1.51–14.06)

datasets (Fig. 5E and F). Heatmaps

showed increased expression of the signature genes in H-risk

patients, consistent with positive coefficients (Fig. 5G and H). Time-dependent ROC analysis

demonstrated area under the curves (AUCs) of 0.680, 0.800 and 0.800

(EMBL-EBI) and 0.660, 0.640 and 0.680 (TCGA; Fig. 5I and J) at 1, 2 and 3 years,

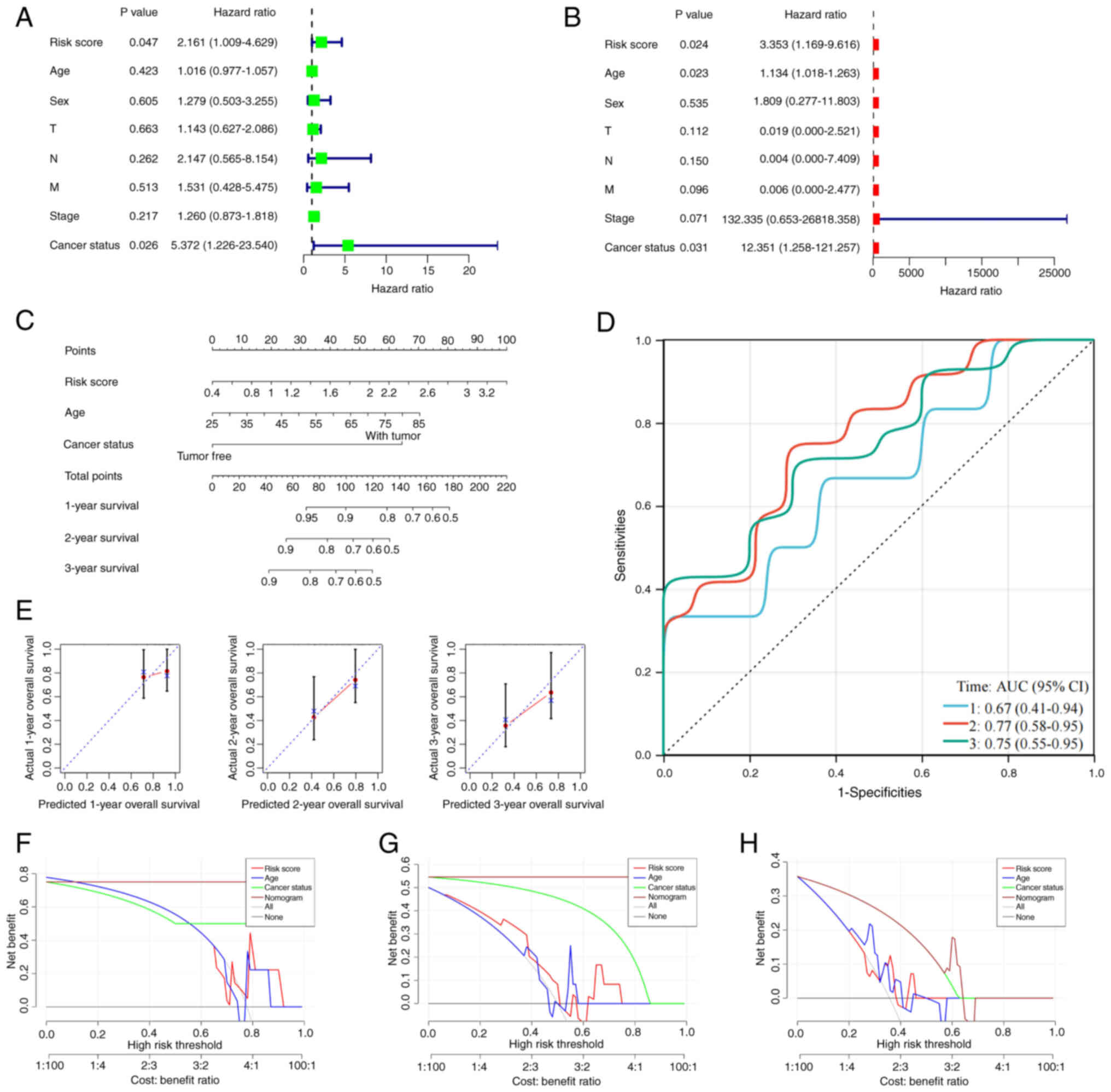

respectively. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression confirmed

that the risk score was an independent prognostic factor (P=0.024;

HR, 3.353; 95% CI, 1.169–9.616) and multivariate analysis,

including age (P=0.023; HR, 1.134; 95% CI, 1.018–1.263) and cancer

status (P=0.031; HR, 12.351; 95% CI, 1.258–121.257), further

validated its independence (Fig. 6A and

B; Table SVII). A nomogram

integrating the risk score, age and cancer status achieved AUCs of

0.670, 0.770 and 0.750 for 1-, 2- and 3-year predictions (Fig. 6C and D; Table SVIII). Calibration curves indicated

strong agreement between predicted and observed outcomes (Fig. 6E). Decision curve analysis for the

1-, 2- and 3-year outcomes showed that the risk score model

provided superior net benefit over age or cancer status alone,

especially at medium-to-high thresholds, confirming its clinical

utility in risk stratification and treatment decision-making for

CCA (Fig. 6F-H).

To elucidate the biological underpinnings of this

signature, the genes with the strongest contribution to the risk

score were prioritized for functional validation. Given that

EFNB2 and CD109 possessed the two highest risk

coefficients in the LASSO model, they were selected for subsequent

in vitro experiments.

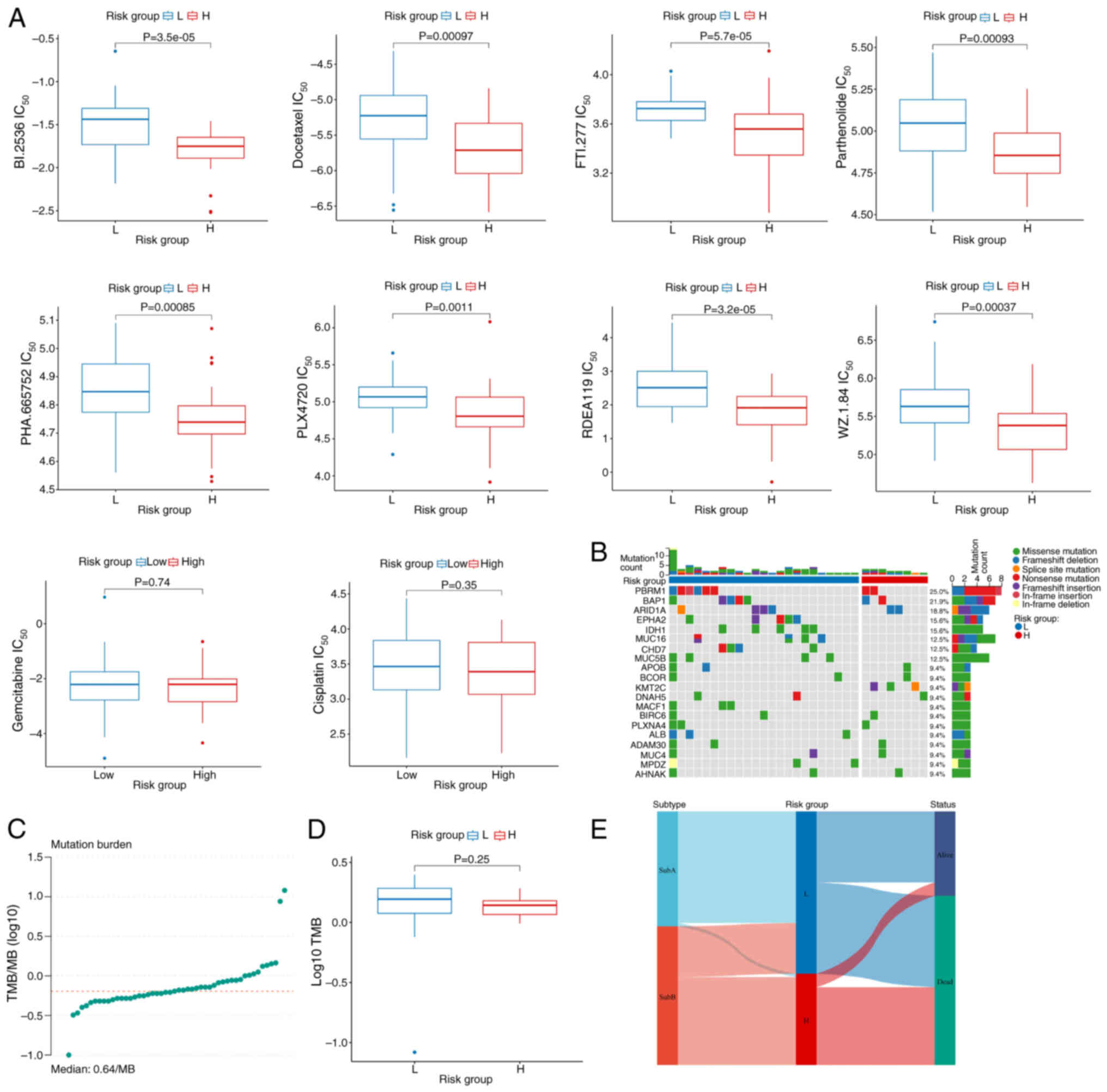

Integrated profiling of drug

sensitivity, TMB and molecular Subs in the prognostic risk

model

Chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity analysis

demonstrated that eight antineoplastic agents, PLX-4720, WZ-1-84,

refametinib, PHA-665752, parthenolide, FTI-277, docetaxel and

BI2536, exhibited significantly lower IC50 values in the

H-risk group compared with those in the L-risk group, suggesting

heightened chemosensitivity in H-risk patients with CCA. However,

no significant difference in efficacy was observed between risk

groups for the standard first-line regimen, gemcitabine plus

cisplatin (P<0.05; Fig. 7A;

Table SIX). Mutation analysis

identified PBRM1 as the most frequently altered gene among

the top 20 mutated genes (Fig. 7B).

TMB analysis using TCGA-CHOL data showed similar distributions

across risk groups, with no significant differences in TMB values

(Fig. 7C and D). Sankey diagram

analysis revealed a predominant clustering of H-risk cases within

the SubB disulfidptosis Sub (Fig.

7E), consistent with the association of the Sub with worse

clinical outcomes.

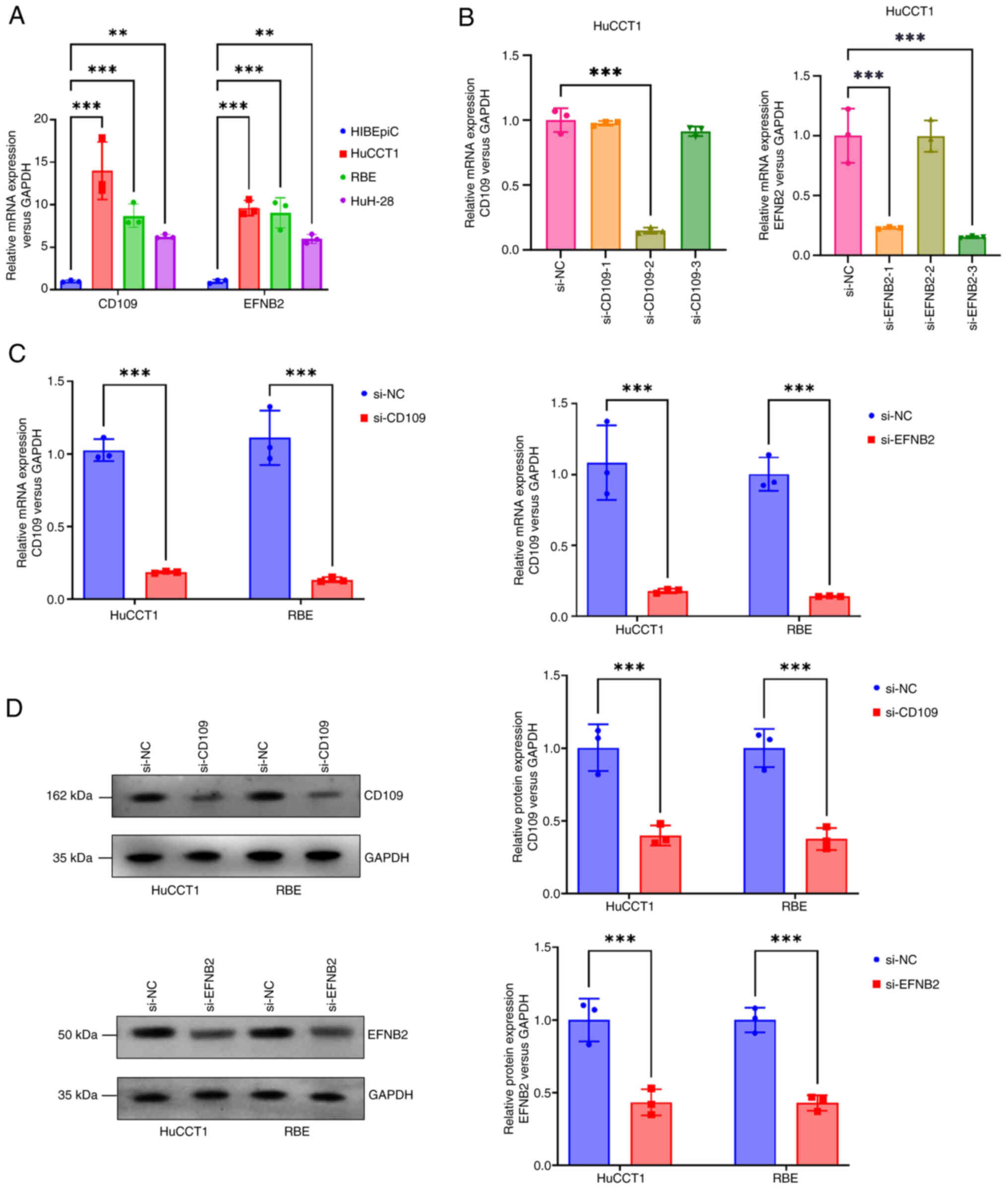

Establishment of CD109 and EFNB2

knockdown CCA cell model

RT-qPCR was performed to assess mRNA expression of

CD109 and EFNB2 in three CCA cell lines (HuCCT1, RBE

and HuH-28) and in normal human intrahepatic biliary epithelial

cells (HiBEpiCs). Compared with HiBEpiCs, CD109 and

EFNB2 expression was significantly upregulated in HuCCT1 and

RBE cells (P<0.001), and moderately upregulated in HuH-28 cells

(P<0.01; Fig. 8A). Based on

these results, HuCCT1 and RBE cells were selected for

siRNA-mediated knockdown of CD109 and EFNB2. Three

siRNAs were designed for each gene, and their mRNA suppression

efficiency was evaluated by RT-qPCR. In HuCCT1 cells, si-CD109-2

and si-EFNB2-3 showed the most significant downregulation

(P<0.001; Fig. 8B), and were

selected for subsequent experiments. After transfecting si-CD109

and si-EFNB2 into HuCCT1 and RBE cells, RT-qPCR confirmed

significant reductions in CD109 and EFNB2 mRNA levels

(P<0.001; Fig. 8C), indicating

efficient transfection. WB further revealed significantly reduced

CD109 and EFNB2 protein levels in both cell lines (P<0.001;

Fig. 8D), consistent with mRNA

changes.

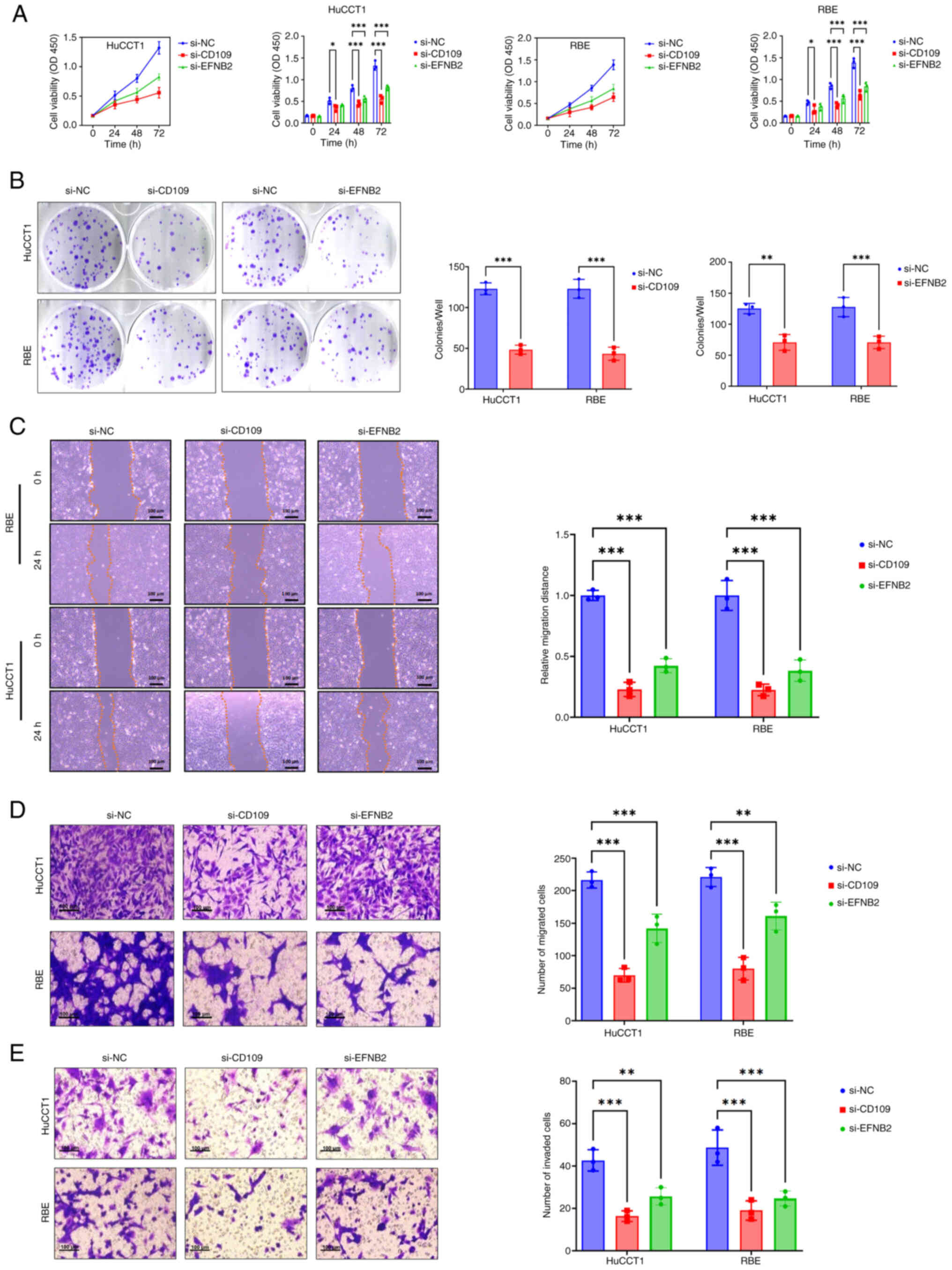

Functional assays for CD109 and EFNB2

knockdown in CCA cells

To evaluate the effects of CD109 and

EFNB2 knockdown on CCA cell behavior, cell proliferation was

assessed using the CCK-8 assay at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h in HuCCT1 and

RBE cells transfected with si-CD109, si-EFNB2 or si-NC (control).

Compared with the si-NC group, knockdown of CD109 or

EFNB2 significantly reduced cell proliferation, with

pronounced effects at 48 and 72 h (P<0.001); notably, si-CD109

exhibited stronger inhibition compared with si-EFNB2 (Fig. 9A). Clonogenic assays were performed

to assess colony formation. HuCCT1 and RBE cells transfected with

si-CD109 or si-EFNB2 formed significantly fewer colonies compared

with the si-NC group (P<0.001; Fig.

9B). Wound healing assays evaluated cell migration. Compared

with the si-NC group, the si-CD109 and si-EFNB2 groups exhibited

significantly reduced wound closure in HuCCT1 and RBE cells, with

si-CD109 showing greater inhibition (P<0.001; Fig. 9C). Transwell assays assessed

migration and invasion. Migration assays showed significantly fewer

migrating cells in si-CD109 and si-EFNB2 groups compared with si-NC

(P<0.001; Fig. 9D). Invasion

assays revealed similarly reduced invasive cell numbers in both

knockdown groups (P<0.001; Fig.

9E). These findings indicate that CD109 and EFNB2

knockdown significantly inhibits proliferation, colony formation,

migration and invasion in HuCCT1 and RBE cells, suggesting their

key roles in CCA progression.

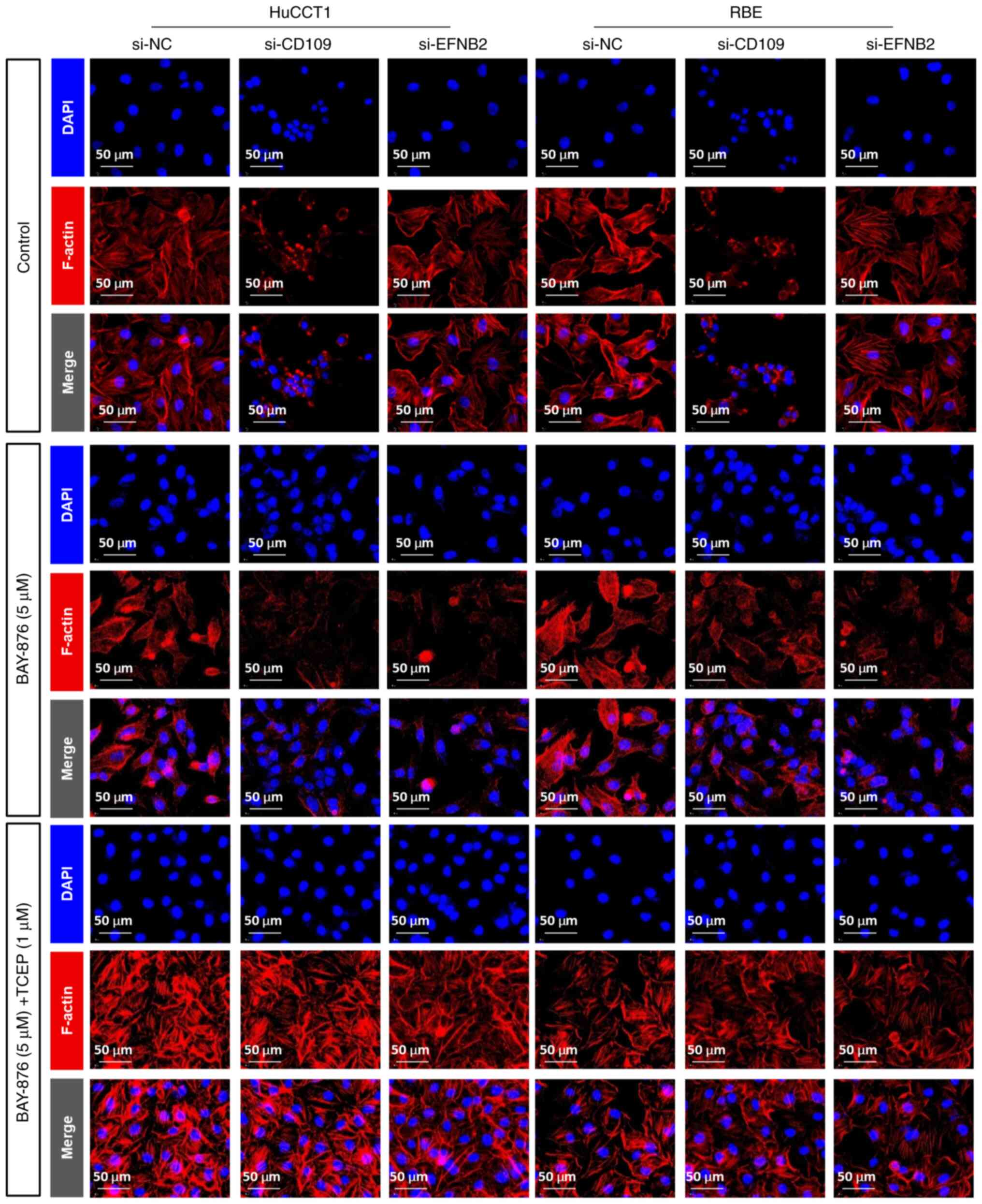

Role of EFNB2 and CD109 in

disulfidptosis

To investigate the role of EFNB2 and CD109 in

disulfidptosis, immunofluorescence staining was carried out. The

results (Fig. 10) showed that

under glucose deprivation conditions, knocking down EFNB2 or

CD109 in HuCCT1 and RBE cells induced cell shrinkage and

abnormal F-actin aggregation. Treatment with the GLUT1 inhibitor

BAY-876 exacerbated these morphological changes, with more

pronounced actin depolymerization observed in the si-CD109 group,

suggesting that CD109 may regulate cytoskeletal dynamics during

disulfide bond accumulation. Intervention with the reducing agent

TCEP largely alleviated F-actin aggregation in the si-CD109 group,

but only partially in the si-EFNB2 group, indicating that EFNB2 may

carry out a more key role in maintaining cytoskeletal stability.

These findings suggest that the knockout of EFNB2 and

CD109 enhances BAY-876-induced disulfidptosis, with TCEP

preventing these effects.

Discussion

In the present study, the first comprehensive

analysis of disulfidptosis in CCA, a malignancy characterized by

metabolic dysregulation and oxidative stress, was presented

(1). By integrating transcriptomic

profiling, molecular subtyping and prognostic modeling, its

potential as a novel therapeutic target was unveiled. Through

unsupervised clustering of 74 DRGs, two distinct molecular Subs

(SubA and SubB) with significant differences in prognosis and the

TME were identified. The more clinically aggressive SubB exhibited

heightened disulfidptosis pathway activity. This finding mirrors

observations in ferroptosis, where sublethal stress can foster

tumor adaptation. It is hypothesized that under metabolic stress

such as glucose deprivation CCA cells in the SubB adaptively

leverage components of the disulfidptosis machinery, potentially

through stress-activated pathways such as PI3K/AKT or MAPK/ERK

(34–39), could enhance invasive potential.

Leveraging these Sub distinctions, a robust

four-gene prognostic signature (CD109, EFNB2, KLK6 and

ADAMTS12) was developed and validated using LASSO Cox

regression. This model effectively stratified patients into H- and

L-risk groups, with the H-risk group showing significantly lower OS

in both the training and validation cohorts. The strong predictive

accuracy of the model for 1-, 2- and 3-year survival and its status

as an independent prognostic factor highlight its clinical

potential. The interplay between disulfidptosis and the TME is a

key, yet underexplored, determinant of CCA progression. The

findings of the present study reveal distinct immune profiles

between the molecular Subs, with the aggressive SubB harboring an

immunogenic yet profoundly immunosuppressive TME. CIBERSORT and

ssGSEA analyses demonstrated that SubB, despite enhanced

infiltration of effector immune cells such as CD8+ T

cells, also exhibited significant upregulation of immune checkpoint

genes (PD-L1, LAG3, CD47 and TNFRSF9) and HLA-related

genes. This ‘activated-exhausted’ phenotype where cytotoxic

lymphocytes co-express inhibitory checkpoint molecules, points

toward a compromised antitumor response and aligns with the worse

survival outcomes of the Sub (40–43).

GSEA provided a compelling mechanistic association

for this phenotype, revealing a significant enrichment of the TGF-β

signaling pathway in SubB. Mechanistically, it is hypothesized that

sustained TGF-β signaling orchestrates this immunosuppressive

landscape. While TGF-β can initially act as a chemoattractant for

effector immune cells such as CD8+ T cells, its chronic

presence drives extensive extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and

induces the expression of multiple immune checkpoints on both tumor

and stromal cells (44,45). Within this remodeled TME,

infiltrating CD8+ T cells rapidly transition from an

activated to an exhausted state, characterized by functional

impairment and high inhibitory receptor expression. This

‘activation-to-exhaustion’ shift effectively aborts antitumor

immunity and promotes malignant progression, suggesting that

targeting the TGF-β axis could be key to reversing

immunosuppression in these patients.

The prognostic signature of the present study is

anchored by four genes: CD109, EFNB2, KLK6 and

ADAMTS12. Among these, CD109 and EFNB2 possess

the highest risk coefficients and are intrinsically associated with

this TGF-β driven malignancy. CD109 functions as a negative

co-receptor for TGF-β, acting as a rheostat that suppresses

canonical tumor-suppressive signals while enhancing pro-tumorigenic

outputs such as EMT (46–48). EFNB2, through Ephrin receptor

signaling, activates downstream pathways to promote the dynamic

cytoskeletal remodeling essential for invasion and metastasis

(49–51). In vitro validation confirmed

their roles as key drivers of CCA malignancy. Silencing either

CD109 or EFNB2 markedly suppressed proliferation,

migration and invasion. Mechanistically, it was demonstrated that

these genes protect CCA cells from glucose starvation-induced

disulfidptosis, an effect that was reversed by the reducing agent

TCEP. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that silencing these

genes led to F-actin cytoskeletal collapse under metabolic stress.

It is therefore hypothesized that CD109 and EFNB2 confer resistance

to disulfidptosis by preserving cytoskeletal integrity through

redox modulation, possibly by enhancing NADPH regeneration or

regulating SLC7A11-dependent cystine metabolism to maintain the

glutathione pool (52).

Concurrently, they might restrain the excessive actin network

polymerization seen in disulfidptosis by influencing key regulatory

nodes, such as the Rac1-WAVE pathway that governs actin dynamics.

Future investigations employing metabolomics, live-cell redox

imaging and non-reducing protein electrophoresis will be essential

to systematically assess the way CD109 or EFNB2 depletion alters

intracellular NADPH pools, thioredoxin system activity and actin

disulfide cross-linking.

Beyond the experimentally validated markers, the

prognostic signature of the present study incorporates KLK6

and ADAMTS12. The inclusion of these genes is justified by

robust bioinformatic and literature-based evidence. Both genes are

significantly upregulated in CCA tumors and are associated with

worse survival, aligning with their positive risk coefficients from

LASSO regression. KLK6, a serine protease, exerts dual roles in

inflammation and tumor progression (53,54).

In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), KLK6 promotes

invasiveness, indicating potential therapeutic relevance for CCA

(54). ADAMTS12, a

metalloproteinase, modulates ECM remodeling in inflammation,

fibrosis and cancer. In PDAC, ADAMTS12 enhances cell migration,

while in hepatocellular carcinoma, it is associated with poor

differentiation and recurrence (55,56).

By collectively shaping a microenvironment conducive to tumor

invasion and metastasis, these two genes serve as rational and key

components of the H-risk prognostic model of the present study.

Elucidating their direct functional roles in the disulfidptosis

pathway remains an important direction for future

investigation.

Despite the novel insights provided by the present

study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the

reliance on public databases, particularly TCGA-CHOL cohort with

its limited sample size (n=35), may constrain the statistical power

and generalizability of the prognostic model and limits its utility

for more detailed investigations, such as Sub analyses. A key

limitation is that the TMB analysis was confined to TCGA cohort, as

comprehensive mutation data were unavailable in other datasets,

thereby precluding independent validation of these findings.

Furthermore, the prognostic model is derived from bioinformatic

approaches and awaits validation with prospective clinical data.

Therefore, large-scale, multi-center prospective studies are

essential to confirm its clinical robustness. Second, while the

functional roles of CD109 and EFNB2 were established,

the contributions of the other two signature genes KLK6 and

ADAMTS12 to disulfidptosis and CCA progression remain to be

experimentally elucidated, which is a direction for future

research. Third, the drug sensitivity analysis was based solely on

computational predictions, which may not fully capture the

complexity of the TME. Experimental validation in clinically

relevant models such as patient-derived organoids or xenografts is

necessary to assess the therapeutic potential of the predicted

agents. Finally, regarding clinical translation, although measuring

the expression of signature genes such as CD109 and

EFNB2 in patient samples for example via

immunohistochemistry on FFPE tissues is technically feasible,

establishing standardized and reproducible protocols is a key

prerequisite for future clinical application.

In conclusion, the DRG risk model developed in the

present study provides a valuable tool for survival prediction in

patients with CCA, reinforcing the central role of disulfidptosis

in CCA pathogenesis. Specifically, CD109 and EFNB2,

by collaboratively regulating cytoskeletal stability, metabolic

reprogramming and immune suppression, hold promise as potential

therapeutic targets for reversing tumor progression and overcoming

treatment resistance. This not only offers important insights for

personalized treatment strategies, but also lays the theoretical

foundation for the development of disulfidptosis-based precision

therapies in CCA.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Changzhou Sci

& Tech Program (grant no. CJ20220064, CJ20243007), the 2023

Changzhou Health Commission Science and Technology Project (grant

no. QY202301), Youth Talent Science and Technology Project of

Changzhou Health Commission (grant no. QN202434), Science and

Technology Project of Changzhou Health Commission (grant no.

ZD202428) and Top Talent of Changzhou ‘The 14th Five-Year Plan’

High-level Health Personnel Training Project (grant no.

2022260).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC, JWu, DZha and WH contributed to the conception

and design of the study. YC, WH, DZhu, LJ and JWa were involved in

the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. YC and WH

drafted the manuscript. DZhu, LJ and JWa critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. JWu, DZha and WH

supervised the study. YC and WH confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and

agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CCA

|

cholangiocarcinoma

|

|

EMBL-EBI

|

European Molecular Biology

Laboratory-European Bioinformatics Institute

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

DRGs

|

Disulfidptosis-related genes

|

|

KM

|

Kaplan-Meier

|

|

GSVA

|

gene set enrichment analysis

|

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

ssGSEA

|

single-sample gene set enrichment

analysis

|

|

GSEA

|

gene set enrichment analysis

|

|

LASSO

|

least absolute shrinkage and

selection operator

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

DCA

|

clinical decision curves

|

|

EFNB2

|

ephrin-B2

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

|

TMB

|

tumor mutational burden

|

|

ADAMTS12

|

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase

with thrombospondin motifs 12

|

|

KLK6

|

Kallikrein-related peptidase 6

|

|

RCD

|

regulated cell death

|

|

ESTIMATE

|

Estimation of Stromal and Immune

cells in Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression

|

|

CIBERSORT

|

Cell-type Identification by

Estimating Relative Subsets of RNA Transcripts

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

WB

|

western blot analysis

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

IF

|

immunofluorescence

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

References

|

1

|

Brindley PJ, Bachini M, Ilyas SI, Khan SA,

Loukas A, Sirica AE, Teh BT, Wongkham S and Gores GJ:

Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7:652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cardinale V: Classifications and

misclassification in cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 39:260–212.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Banales JM, Cardinale V, Carpino G,

Marzioni M, Andersen JB, Invernizzi P, Lind GE, Folseraas T, Forbes

SJ, Fouassier L, et al: Expert consensus document:

Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and future perspectives

consensus statement from the European network for the study of

cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

13:261–280. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Clements O, Eliahoo J, Kim JU,

Taylor-Robinson SD and Khan SA: Risk factors for intrahepatic and

extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 72:95–103. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sirica AE, Gores GJ, Groopman JD, Selaru

FM, Strazzabosco M, Wei Wang X and Zhu AX: Intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma: Continuing challenges and translational

advances. Hepatology. 69:1803–1815. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fabris L, Perugorria MJ, Mertens J,

Björkström NK, Cramer T, Lleo A, Solinas A, Sänger H, Lukacs-Kornek

V, Moncsek A, et al: The tumour microenvironment and immune milieu

of cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 39 (Suppl 1):S63–S78. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Arrivé L and Djelouah M: Refining

prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: The expanding role of

imaging. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 7:e2503832025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Bile

duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma) treatment (PDQ®), . Health

Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. National

Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2002

|

|

9

|

Lockie EB, Sylivris A, Pandanaboyana S,

Zalcberg J, Skandarajah A and Loveday BP: Relationship between

pancreatic cancer resection rate and survival at population level:

Systematic review. BJS Open. 9:zraf0072025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Valle JW, Lamarca A, Goyal L, Barriuso J

and Zhu AX: New horizons for precision medicine in biliary tract

cancers. Cancer Discov. 7:943–962. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A,

Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Andersen

JB, Braconi C, et al: Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in

mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

17:557–588. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kerr JF, Wyllie AH and Currie AR:

Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging

implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 26:239–257. 1972.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P

and Kroemer G: The molecular machinery of regulated cell death.

Cell Res. 29:347–364. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shi Y, Wang Y, Niu K, Zhang W, Lv Q and

Zhang Y: How CLSPN could demystify its prognostic value and

potential molecular mechanism for hepatocellular carcinoma: A

crosstalk study. Comput Biol Med. 172:1082602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shi Y, Wang Y, Niu K and Zhang Y: A

commentary on ‘A bibliometric analysis of gastric cancer liver

metastases: Advances in mechanisms of occurrence and treatment

options’. Int J Surg. 110:5897–5898. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu X, Nie L, Zhang Y, Yan Y, Wang C,

Colic M, Olszewski K, Horbath A, Chen X, Lei G, et al: Actin

cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates

disulfidptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 25:404–414. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Liu X, Zhuang L and Gan B: Disulfidptosis:

Disulfide stress-induced cell death. Trends Cell Biol. 34:327–337.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zheng T, Liu Q, Xing F, Zeng C and Wang W:

Disulfidptosis: A new form of programmed cell death. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 42:1372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tang J, Peng X, Xiao D, Liu S, Tao Y and

Shu L: Disulfidptosis-related signature predicts prognosis and

characterizes the immune microenvironment in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 24:192024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang HB, Pan JY and Zhu T: A

disulfidptosis-related lncRNA prognostic model to predict survival

and response to immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Front

Pharmacol. 14:12541192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Huang J, Zhang J, Zhang F, Lu S, Guo S,

Shi R, Zhai Y, Gao Y, Tao X, Jin Z, et al: Identification of a

disulfidptosis-related genes signature for prognostic implication

in lung adenocarcinoma. Comput Biol Med. 165:107402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen Y, Xue W, Zhang Y, Gao Y and Wang Y:

A novel disulfidptosis-related immune checkpoint genes signature:

Forecasting the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res

Clin Oncol. 149:12843–12854. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dong X, Liao P, Liu X, Yang Z, Wang Y,

Zhong W and Wang B: Construction and validation of a reliable

disulfidptosis-related LncRNAs signature of the subtype,

prognostic, and immune landscape in colon cancer. Int J Mol Sci.

24:129152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kang K, Li X, Peng Y and Zhou Y:

Comprehensive analysis of disulfidptosis-related LncRNAs in

molecular classification, immune microenvironment characterization

and prognosis of gastric cancer. Biomedicines. 11:31652023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Feng Z, Zhao Q, Ding Y, Xu Y, Sun X, Chen

Q, Zhang Y, Miao J and Zhu J: Identification a unique

disulfidptosis classification regarding prognosis and immune

landscapes in thyroid carcinoma and providing therapeutic

strategies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 149:11157–11170. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Qi C, Ma J, Sun J, Wu X and Ding J: The

role of molecular subtypes and immune infiltration characteristics

based on disulfidptosis-associated genes in lung adenocarcinoma.

Aging (Albany NY). 15:5075–5095. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Raggi C, Taddei ML, Rae C, Braconi C and

Marra F: Metabolic reprogramming in cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol.

77:849–864. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Duwe L, Fouassier L, Lafuente-Barquero J

and Andersen JB: Unraveling the actin cytoskeleton in the malignant

transformation of cholangiocyte biology. Transl Oncol.

26:1015312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhao X, Zhang M, He J, Li X and Zhuang X:

Emerging insights into ferroptosis in cholangiocarcinoma (review).

Oncol Lett. 28:6062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

R Core Team, . R: A language and

environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical

Computing; Vienna: 2024, URL. https://www.R–project.org/

|

|

31

|

Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C

and Koeffler HP: Maftools: Efficient and comprehensive analysis of

somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28:1747–1756. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wilkerson MD and Hayes DN:

ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence

assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 26:1572–1573. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang ZJ, Huang YP, Li XX, Liu ZT, Liu K,

Deng XF, Xiong L, Zou H and Wen Y: A novel ferroptosis-related

4-gene prognostic signature for cholangiocarcinoma and photodynamic

therapy. Front Oncol. 11:7474452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Amontailak S, Titapun A, Jusakul A, Thanan

R, Kimawaha P, Jamnongkan W, Thanee M, Sirithawat P and Techasen A:

Prognostic values of ferroptosis-related proteins ACSL4, SLC7A11,

and CHAC1 in cholangiocarcinoma. Biomedicines. 12:20912024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wan S, Liang C, Wu C, Wang S, Wang J, Xu

L, Zhang X, Hou Y, Xia Y, Xu L and Huang X: Disulfidptosis in tumor

progression. Cell Death Discov. 11:2052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hu F and Lito P: Insights into how

adeno-squamous transition drives KRAS inhibitor resistance. Cancer

Cell. 42:330–332. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mi T, Kong X, Chen M, Guo P and He D:

Inducing disulfidptosis in tumors: Potential pathways and

significance. MedComm (2020). 5:e7912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Xiao Y, Li ZZ, Zhong NN, Cao LM, Liu B and

Bu LL: Charting new frontiers: Co-inhibitory immune checkpoint

proteins in therapeutics, biomarkers, and drug delivery systems in

cancer care. Transl Oncol. 38:1017942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cruz D, Rodríguez-Romanos R,

González-Bartulos M, García-Cadenas I, de la Cámara R, Heras I,

Buño I, Santos N, Lloveras N, Velarde P, et al: LAG3 genotype of

the donor and clinical outcome after allogeneic transplantation

from HLA-identical sibling donors. Front Immunol. 14:10663932023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Perea F, Sánchez-Palencia A, Gómez-Morales

M, Bernal M, Concha Á, García MM, González-Ramírez AR, Kerick M,

Martin J, Garrido F, et al: HLA class I loss and PD-L1 expression

in lung cancer: Impact on T-cell infiltration and immune escape.

Oncotarget. 9:4120–4133. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Saigí M, Mate JL, Carcereny E,

Martínez-Cardús A, Esteve A, Andreo F, Centeno C, Cucurull M, Mesia

R, Pros E and Sanchez-Cespedes M: HLA-I levels correlate with

survival outcomes in response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in

non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 189:1075022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Itatani Y, Kawada K and Sakai Y:

Transforming growth Factor-β signaling pathway in colorectal cancer

and its tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 20:58222019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hao Y, Baker D and Ten Dijke P:

TGF-β-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer

metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 20:27672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Naoi H, Suzuki Y, Miyagi A, Horiguchi R,

Aono Y, Inoue Y, Yasui H, Hozumi H, Karayama M, Furuhashi K, et al:

CD109 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting

TGF-β signaling. J Immunol. 212:1221–1231. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Taki T, Shiraki Y, Enomoto A, Weng L, Chen

C, Asai N, Murakumo Y, Yokoi K, Takahashi M and Mii S: CD109

regulates in vivo tumor invasion in lung adenocarcinoma through

TGF-β signaling. Cancer Sci. 111:4616–4628. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Litvinov IV, Bizet AA, Binamer Y, Jones

DA, Sasseville D and Philip A: CD109 release from the cell surface

in human keratinocytes regulates TGF-β receptor expression, TGF-β

signalling and STAT3 activation: Relevance to psoriasis. Exp

Dermatol. 20:627–632. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zeng X, Hunt A, Jin SC, Duran D, Gaillard

J and Kahle KT: EphrinB2-EphB4-RASA1 signaling in human

cerebrovascular development and disease. Trends Mol Med.

25:265–286. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhu F, Dai SN, Xu DL, Hou CQ, Liu TT, Chen

QY, Wu JL and Miao Y: EFNB2 facilitates cell proliferation,

migration, and invasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via the

p53/p21 pathway and EMT. Biomed Pharmacother. 125:1099722020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Xu C, Gu L, Kuerbanjiang M, Jiang C, Hu L,

Liu Y, Xue H, Li J, Zhang Z and Xu Q: Adaptive activation of

EFNB2/EPHB4 axis promotes post-metastatic growth of colorectal

cancer liver metastases by LDLR-mediated cholesterol uptake.

Oncogene. 42:99–112. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Koppula P, Zhang Y, Zhuang L and Gan B:

Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating

redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 38:122018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hwang YS, Cho HJ, Park ES, Lim J, Yoon HR,

Kim JT, Yoon SR, Jung H, Choe YK, Kim YH, et al: KLK6/PAR1 axis

promotes tumor growth and metastasis by regulating cross-talk

between tumor cells and macrophages. Cells. 11:41012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang L, Lovell S, De Vita E, Jagtap PKA,

Lucy D, Goya Grocin A, Kjær S, Borg A, Hennig J, Miller AK and Tate

EW: A KLK6 activity-based probe reveals a role for KLK6 activity in

pancreatic cancer cell invasion. J Am Chem Soc. 144:22493–22504.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

He RZ, Zheng JH, Yao HF, Xu DP, Yang MW,

Liu DJ, Sun YW and Huo YM: ADAMTS12 promotes migration and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and predicts poor prognosis for

pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 22:169–178.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Dekky B, Azar F, Bonnier D, Monseur C,

Kalebić C, Arpigny E, Colige A, Legagneux V and Théret N: ADAMTS12

is a stromal modulator in chronic liver disease. FASEB J.

37:e232372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|