Introduction

Gliomas are among the most common primary malignant

tumors of the central nervous system (CNS), arise from glial or

neural precursor cells and encompass histological subtypes such as

astrocytoma [including glioblastoma (GBM)], oligodendroglioma,

ependymoma and oligoastrocytoma [now classified as glioma,

isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-mutant] (1). GBM, the most aggressive glioma

subtype, poses major therapeutic challenges due to its highly

malignant phenotype and poor prognosis. Despite significant

advances in anticancer therapies, including immunotherapy, GBM

remains largely unresponsive to conventional and novel

interventions. The limited efficacy of immunotherapy in GBM

primarily stems from its notably immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment and intrinsic resistance mechanisms (2,3). The

2016 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of

the CNS marked a paradigm shift by integrating molecular biomarkers

into diagnostic criteria (4). The

2021 fifth edition of the WHO CNS classification further refined

this framework, establishing histomolecular classification as a

cornerstone of modern neuro-oncology (5). Key molecular biomarkers include IDH

mutations, 1p/19q codeletion, H3F3A alterations, α

thalassemia/mental retardia syndrome X-linked mutations,

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter

methylation, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A)

homozygous deletion, epidermal growth factor receptor

amplification, combined chromosome 7 gain/chromosome 10 loss

(7+/10-) and telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutations

(5,6). In adults, IDH mutation status and MGMT

promoter methylation serve as strong prognostic indicators for

glioma, while CDKN2A homozygous deletion is a critical marker of

histological progression in IDH-mutant astrocytomas (7). Recent discoveries have expanded the

molecular landscape of glioma. For instance, olfactomedin like 3

has emerged as a biomarker associated with poor prognosis; its

knockdown enhances temozolomide sensitivity and may reflect immune

dysregulation within the tumor microenvironment (8). Such findings underscore the pivotal

role of comprehensive molecular profiling in enabling precise

glioma classification and personalized therapy development. Beyond

molecular characterization, integrating multimodal data, including

radiological, histopathological and genomic modalities, has shown

promise for improving prognostic accuracy and deep learning

frameworks capable of jointly analyzing these data types

consistently outperform single-modality approaches (9). Notably, Yuan et al (10) developed a squeeze-and-excitation

deep learning model that integrated preoperative

T1-contrast-enhanced MRI, digitized whole-slide histopathological

images and circulating 5-hydroxymethylcytosine profiles, achieving

a marked prognostic performance (concordance index=0.897) in a

glioma cohort. By effectively capturing glioma heterogeneity across

spatial and temporal dimensions, such multimodal strategies

represent a significant advance toward precision medicine in

neuro-oncology. Current standard management involves maximal safe

surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy with

concurrent temozolomide chemotherapy, typically initiated within 30

days postoperatively (11).

Although emerging molecular-targeted therapies and immunotherapies

have shown promise in select molecular subtypes, most patients with

glioma experience limited clinical benefit due to inadequate target

specificity, restricted blood-brain barrier permeability, acquired

resistance and dose-limiting toxicities (12,13).

Consequently, continued discovery of novel molecular markers

remains essential to elucidate gliomagenesis mechanisms, identify

actionable targets and accelerate the translation of precision

medicine in glioma therapy.

The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) family plays a

pivotal role in regulating signaling pathways that govern

transcriptional control and cell cycle progression. Within the cell

cycle, CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6 coordinate interphase progression,

whereas CDK1 orchestrates mitotic entry (14). As a key G2/M checkpoint kinase

(15), CDK1 drives tumor

proliferation and survival across multiple malignancies, including

breast, colorectal and lung cancer (16–19).

Clinically, elevated CDK1 expression serves as a prognostic

biomarker strongly associated with poor oncological outcomes,

including in colorectal, ovarian, breast and pancreatic cancer

(20–24). The key regulators of the cell cycle,

including proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), minichromosome

maintenance complex component 2–4 (MCM2-4), MCM6, polo-like kinase

1 (PLK1), TTK protein kinase (TTK) and mitotic arrest deficient 2

like 1 (MAD2L1), collectively ensure DNA replication and mitotic

fidelity (25,26). However, the functional relationship

between CDK1 and these regulators remains to be fully elucidated.

Therefore, systematically investigating the molecular mechanisms of

CDK1 in glioma is of significant importance (27–29).

Materials and methods

Microarray data download

Gene expression datasets and associated clinical

data (accession nos. GSE29796, GSE4290, GSE50161 and GSE7696) were

retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The GSE29796

dataset comprises 52 glioma specimens and 20 non-tumoral controls

(30); GSE4290 includes 153 glioma

and 23 non-tumoral samples (31);

GSE50161 contains 117 glioma and 13 non-tumoral samples (32); and GSE7696 includes 80 glioma and 4

non-tumoral specimens (33).

Additional datasets [mRNAseq_693 and mRNAseq_325 (34) were obtained from the Chinese Glioma

Genome Atlas (CGGA; http://www.cgga.org.cn/), encompassing RNA sequencing

profiles and clinical annotations for 1,018 glioma cases, along

with RNA sequencing data from 20 non-tumoral brain tissues. For

independent validation, RNA sequencing data and clinical

information from 592 glioma specimens [449 low-grade glioma (LGG)

and 143 GBM] were acquired from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA;

https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/; TCGA-LGG

and TCGA-GBM datasets; dbGaP accession phs000178) (35,36).

Samples lacking complete clinical annotations were excluded. To

minimize batch effects and technical variability, RNA sequencing

data were normalized using the ‘limma’ package of Sangerbox 3.0

(http://sangerbox.com/) and log2 (x + 1)

transformed before analysis.

Acquisition of tissue samples from 37

patients

Paired tumor specimens and histologically normal

adjacent tissues (collected >2 cm from the tumor margin) were

obtained from 37 patients with histologically confirmed glioma

treated at the Department of Neurosurgery, The Second Hospital of

Hebei Medical University (Shijiazhuang, China). Patient recruitment

and sample collection spanned the period from August 2019 to

December 2024. The enrolled cohort consisted of patients aged

between 30 and 78 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Age ≥18 years; ii) patients

who underwent surgical resection for primary brain tumors at the

Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University; iii) initial diagnosis

of glioma based on preoperative MRI findings and subsequent

histopathological confirmation following surgical resection; iv) no

prior history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy; and v) provision of

written informed consent by the patient or their legal guardian.

Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the

following criteria: i) Diagnosis of other intracranial tumors (such

as meningioma and metastasis); ii) history of any other malignant

tumors; iii) presence of severe cardiac, hepatic or renal

dysfunction; iv) receipt of any preoperative anticancer therapy;

and v) inadequate tissue sample quality for subsequent analysis.

All collected specimens were immediately snap-frozen in liquid

nitrogen post-resection and stored at −80°C until analysis for CDK1

protein expression. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by

the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical

University (Shijiazhuang, China; approval no.2019-R191) and all

procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the

Declaration of Helsinki.

Protein sample extraction

Frozen glioma and matched non-tumoral tissues were

retrieved from −80°C storage, thawed on ice and homogenized in

radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. R0010)

supplemented with phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. P1260) using a tissue

grinder. Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at

4°C, then the supernatants were collected into fresh

microcentrifuge tubes. Protein preparation from U251MG and LN229

cell lines was conducted by placing the processed cells on ice,

adding the aforementioned RIPA buffer containing protein and

phosphatase inhibitors. Lysis was performed on a rocking platform

for 15 min. Protein concentrations were quantified using a BCA

assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. PC0020) and lysates were denatured at 100°C for 15 min in

loading buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. P1019).

Cell culture

The U251MG and LN229 human glioma cell lines were

obtained from the China Infrastructure of Cell Line Resources,

Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical

Sciences (Beijing, China). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.;

cat. no. 11995065) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. A5670801) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin solution (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. P1400) and incubated at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Searching for genes involved in glioma

initiation and progression

For differential expression analysis, the GSE29796,

GSE4290, GSE50161 and GSE7696 datasets were divided into tumor and

non-tumor groups. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were

identified based on adjusted P<0.05 and |log2 fold

change (FC)|>1 criteria. Volcano plots for each dataset were

generated using the ‘limma’ package in R v4.0.5 (37). The jvenn online tool (http://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/usermanual.html)

identified 360 consensus DEGs co-expressed across all four

datasets. These DEGs were imported into the Search Tool for the

Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING; http://string-db.org/) to construct a protein-protein

interaction (PPI) network, excluding nodes with an interaction

confidence score of <0.7 and isolated proteins. The resulting

PPI network, containing 180 proteins, was visualized using

Cytoscape (v3.7.2; http://cytoscape.org/). The cytoHubba plugin

identified CDK1 as the hub gene based on maximal degree

centrality.

CDK1 gene expression analysis

CDK1 expression in glioma and non-tumoral samples

from the four GEO datasets (GSE29796, GSE4290, GSE50161 and

GSE7696) was analyzed using the unpaired t-test for parametric data

or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data in GraphPad

Prism 8 (Dotmatics). Expression validation in GBM and LGG was

further conducted using the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis (GEPIA; http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) and Human Protein Atlas

(HPA; http://www.proteinatlas.org/)

databases. Experimental validation of CDK1 expression was performed

via western blotting under standardized conditions.

Correlation analysis of CDK1

expression level with clinical information and pathological

features

The CGGA dataset comprising mRNA transcriptome data

and clinical information from 1,018 glioma samples was used to

assess associations between CDK1 expression and clinical prognosis,

with findings validated using TCGA data. Samples were stratified

into high- and low-expression groups based on median CDK1

expression levels. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed

using R v4.0.5 with the ‘survival’ and ‘survminer’ packages, while

time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves at

1-, 3- and 5-year intervals were generated using the ‘survivalROC’

package. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were

used to identify independent prognostic factors (significance

threshold: P<0.001). Based on CGGA data, nomograms predicting

1-, 2- and 3-year survival probabilities were constructed using the

‘survival’ and ‘rms’ packages (R; v4.0.5), and calibration curves

were used to assess the predictive accuracy. Finally, based on the

CGGA data, associations between CDK1 expression and

clinicopathological characteristics were analyzed using the

‘beeswarm’ package in R (v3.6.3). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference for all

analyses.

Western blotting

Denatured proteins (described above) from 37 paired

glioma and adjacent normal tissues, as well as the U251MG and LN229

cell lines, were separated by electrophoresis on 10%

SDS-polyacrylamide gels (an equal amount of 30 µg was loaded per

lane) at a constant voltage of 120 V for 90 min and transferred to

0.45 µm PVDF membranes (Merck KGaA; cat. no. IPVH00010). Membranes

were blocked with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline

containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) at 25°C for 1 h. The membranes were

incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies

diluted in blocking buffer: Anti-CDK1 (34 kDa; 1:500; Proteintech

Group, Inc.; cat. no. 19532-1-AP) and β-actin (42 kDa; 1:10,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig). Following three

10-min washes with TBST at 25°C, the membranes were incubated for 1

h at 25°C with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG (H+L)

secondary antibodies (1:10,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. nos.

SA00001-2 and SA00001-1). Protein bands were visualized using an

ECL Western blotting kit (Biosharp Life Sciences; cat. no. BL520B)

and detected via chemiluminescent imaging. Band intensities were

semi-quantified using Image Lab software (v5.2.1; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

CDK1 knockdown

CDK1-targeting small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and

the scrambled negative control (NC) were synthesized by Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. The concentration of nucleic acid used was 20

pmol/µl. Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine

3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. L3000150) in U251MG

and LN229 cells at 70–80% confluency, following the manufacturer's

protocol. Transfection efficiency was verified by western blotting

48 h post-transfection. The effective siRNA duplex sequences were:

CDK1, 5′-CCUAUGGAGUUGUGUAUAAGGTT-3′ (sense) and

5′-CCUUAUACACAACUCCAUAGGTT-3′ (anti-sense); and NC,

5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′

(anti-sense).

Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 assay

Cell viability in the U251MG and LN229 cell lines

was assessed using CCK-8 (MedChemExpress; cat. no. HY-K0301)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were seeded in

96-well plates at 3×103 cells/well in 100 µl of complete

medium and allowed to adhere for 24 h. The medium was replaced with

110 µl of serum-free medium containing 10% (v/v) CCK-8 reagent, and

plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Absorbance at 450 nm was

recorded daily for 7 consecutive days using a NanoQuant

spectrophotometer (Tecan Group, Ltd.). Data were collected from

triplicate wells in three independent experiments.

EdU cell proliferation assay

U251MG and LN229 cells were seeded in 96-well plates

at 1×104 cells/well in 200 µl complete medium and

cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Following the

manufacturer's instructions (EdU Kit; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 40276ES60), cells were incubated with 25 µM EdU

in serum-free medium for 2 h at 37°C. After fixation with 4%

paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min at 25°C and permeabilization with

0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min, cells were washed three times with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). EdU was detected using Apollo 594

fluorescent dye (1:100 dilution) for 30 min in the dark, followed

by nuclear counterstaining with Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/ml) for 10 min.

Proliferating cells were visualized using an inverted fluorescence

microscope (Leica DMi8) at ×200 magnification. The proliferation

index was calculated as the ratio of EdU-positive cells to total

Hoechst 33342-stained nuclei.

Wound healing assay

U251MG cells were seeded in 6-well plates at

5×105 cells/well and cultured to 70–80% confluency in a

humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Linear scratches

were created using a sterile 200 µl pipette tip and initial wound

widths were recorded under a phase-contrast microscope. After three

PBS washes (pH 7.4), cells were maintained in serum-free DMEM

supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Wound closure was

monitored and imaged at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h post-scratch to evaluate

the cell migration rates. The cell migration rate (%) was then

calculated for each time point using the following formula based on

the wound width: Migration rate=[(width at 0 h-width at T h)/width

at 0 h] ×100%, where T represents the specific time point after

scratching.

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide

(AO/EB) assay

U251MG and LN229 cells were seeded in 24-well plates

at 5×104 cells/well in 500 µl complete medium and

incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After aspirating

the medium and washing twice with PBS (pH 7.4), cells were stained

following the manufacturer's protocol (AO/EB Staining Kit; Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.; cat. no. E607308). Briefly, 200 µl AO/EB working

solution was added per well, and cells were incubated in the dark

at room temperature for 5 min. Fluorescence images were captured

using an inverted fluorescence microscope (TRITC filter; ×200

magnification). The apoptotic index was calculated as

(EB+ cells/total cells) ×100%, based on three random

fields per well. Data are from three biological replicates.

Transwell assay

U251MG and LN229 cells were serum-starved in DMEM

for 24–48 h to promote migratory activation. Subsequently,

3×104 treated cells were resuspended in serum-free DMEM

and seeded into the upper chamber of 8 µm pore Transwell inserts

(Corning, Inc.), either uncoated (migration assay) or coated with

Matrigel (invasion assay). The Matrigel coating was performed by

incubating a 1:8 dilution of Matrigel at 37°C for 4 h to form a

thin layer simulating the extracellular matrix. The lower chamber

contained 500 µl of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as a

chemoattractant. After 24–48 h incubation, cells were fixed with 4%

PFA for 15 min at 25°C and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 20

min at 25°C. Non-migrated cells on the upper surface were removed

with a cotton swab, and the migrated/invaded cells on the lower

surface were imaged under a light microscope.

Flow cytometry

U251MG cells were harvested by trypsinization,

centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and resuspended in 1X

binding buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions

(Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Kit; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.; cat. no. 40302ES08). The cells were subsequently stained with

Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide staining solution and incubated

in the dark at room temperature for 10–15 min. Following staining,

apoptotic rates were quantified using a flow cytometer (Canto II;

BD Biosciences) in strict accordance with the kit protocol to

ensure reproducibility. For statistical analysis, the proportion of

cells within the Q2 quadrant was selected to represent apoptotic

populations using FlowJo software (v10.8.1, FlowJo LLC; BD

Biosciences).

γ-H2AX immunofluorescence assay

U251MG and LN229 cells were seeded in 8-well chamber

slides at a density of 5×104 cells per well in 300 µl of

complete medium and cultured for 24 h at 37°C under 5%

CO2. After exposure to 5 Gy X-irradiation, cells were

fixed with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at the specified

time points (0.5, 2, 6 and 24 h post-irradiation). Permeabilization

was performed using 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at room

temperature, followed by blocking with 2% BSA (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat no. A8010) for 1 h at 25°C.

For γ-H2AX foci detection, cells were incubated overnight at 4°C

with rabbit anti-γ-H2AX monoclonal antibody (1:200; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.; cat. no. 9718S). After three 5-min PBS washes,

Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Proteintech

Group, Inc.; cat. no. SA00013-2) was applied for 1 h at room

temperature in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI

(Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.; cat. no. BMU107) for 30 min at 25°C.

Fluorescent images were acquired using a confocal microscope, and

γ-H2AX foci were quantified using ImageJ software (v2.3.0; National

Institutes of Health).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from glioma cells using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). cDNA

synthesis was performed using Hifair® III 1st Strand

cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. 11141ES60) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Briefly, the reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C for 5 min,

followed by reverse transcription at 55°C for 15 min and final

enzyme inactivation at 85°C for 5 min. qPCR was carried out using

Hieff UNICON® Universal Blue qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix

(Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 11201ES08) on a

Bio-Rad qPCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Thermal cycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec (denaturation), 60°C for

10 sec (annealing) and 72°C for 20 sec (extension), ending with a

final hold at 4°C. Primer sequences were as follows: CDK1:

5′-CAGACTAGAAAGTGAAGAGGAAGG-3′ (forward) and

5′-ACTGACCAGGAGGGATAGAATC-3′ (reverse); MCM6:

5′-GAGGAACTGATTCGTCCTGAGA-3′ (forward) and

5′-CAAGGCCCGACACAGGTAAG-3′ (reverse); MCM3:

5′-CTGAAGGCGAGGAATGTTGGTG-3′ (forward) and

5′-GATGGGAAGTAGGGCGGATGAG-3′ (reverse); PLK1:

5′-CCTGCACCGAAACCGAGTTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TAGGAGTCCCACACAGGGTC-3′

(reverse); MCM2: 5′-GTTCAGCGTCATGCGGAGTAT-3′ (forward) and

5′-TCTCGCCGGAAGGAGAGATA-3′ (reverse); MCM4:

5′-CAACGGCATCTGCTGTATCG-3′ (forward) and

5′-CTGACAGATGATCCCAGCCTTT-3′ (reverse); MAD2L1:

5′-ACGGTGACATTTCTGCCACT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGTCCCGACTCTTCCCATT-3′

(reverse); PCNA: 5′-TCGTCTCACGTCTCCTTGGT-3′ (forward) and

5′-TTTTGGACATGCTGGTGAGGT-3′ (reverse); GAPDH:

5′-TCATTTCCTGGTATGACAACGA-3′ (forward) and

5′-GTCTTACTCCTTGGAGGCC-3′ (reverse). GAPDH served as the internal

control for normalization and relative mRNA expression levels were

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (38).

DEG analysis and pathway enrichment

analysis of the CDK1 gene

To investigate the specific biological functions of

the hub gene CDK1 in glioma, a subsequent and distinct DEG analysis

was performed. Unlike the initial analysis aimed at discovering

pan-glioma associated genes across multiple datasets (GSE29796,

GSE4290, GSE50161 and GSE7696), this analysis focused on comparing

transcriptional profiles between CDK1-high and CDK1-low expression

groups within the CGGA glioma cohort. mRNA sequencing data from the

CGGA glioma dataset were retrieved and normalized as

aforementioned. Samples were divided into CDK1-high and CDK1-low

groups based on the median CDK1 expression. DEGs were identified

using thresholds of P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1,

resulting in 638 significant DEGs [false discovery rate

(FDR)<0.05]. Volcano plots were generated using the limma

package in R (v4.3.1) (37). To

elucidate the functional implications of these DEGs, enrichment

analyses were conducted. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment was

performed using Metascape (39)

(https://metascape.org/), while Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment was assessed via

Sangerbox 3.0 (http://sangerbox.com/) using Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). Gene sets were considered significantly

enriched when normalized enrichment score (NES)>1, P<0.05 and

FDR <0.05.

Association analysis between CDK1 and

hub genes

GO and GSEA revealed a prominent association of CDK1

with mitotic cell cycle regulation in glioma. Genes involved in the

cell cycle were intersected between the Metascape and GSEA datasets

using a Venn diagram (http://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/usermanual.html).

The 29 overlapping genes were imported into the STRING database

(https://string-db.org/) to construct a

high-confidence protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

(interaction score >0.9; FDR <0.01). The resulting network

was visualized in Cytoscape, and the top 8 hub proteins showing

co-expression coefficients of >0.9 relative to CDK1 were

identified. Spearman correlation analysis using the Sangerbox

platform (http://sangerbox.com/) confirmed strong

correlations (ρ>0.65) between CDK1 and these hub genes.

Expression and survival analyses were subsequently performed for

each hub gene using TCGA dataset, assessing their clinical

relevance in glioma prognosis.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were analyzed and visualized

using R software (v4.2.2) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics),

respectively. Overall survival (OS) differences were assessed using

the log-rank test and illustrated via Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the

Shapiro-Wilk test prior to statistical comparisons. The statistical

analysis of western blot data (from 37 paired glioma and adjacent

normal tissues) was performed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon

matched-pairs signed-rank test. Statistical comparisons between two

independent groups (such as data derived from CDK1 mRNA expression

in GEO datasets and the EdU, AO/EB, Transwell and apoptotic assays)

were performed using the unpaired t-test for parametric data and

the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data. For comparisons

among more than two groups under one independent variable (such as

transfection efficiency validation across the Blank, NC and siRNA

groups), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc

test was used for parametric data, while the Kruskal-Wallis test

followed by Dunn's post hoc test was applied to non-parametric

data. In cases involving two independent variables (such as CCK-8

assay across days 1 to 7, wound healing assay at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h

and the γ-H2AX assay at 0.5, 2, 6 and 24 h), a two-way ANOVA was

used to assess main effects and interactions, with Sidak's test

employed for multiple comparisons. Correlations were determined

using Pearson's correlation coefficient. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

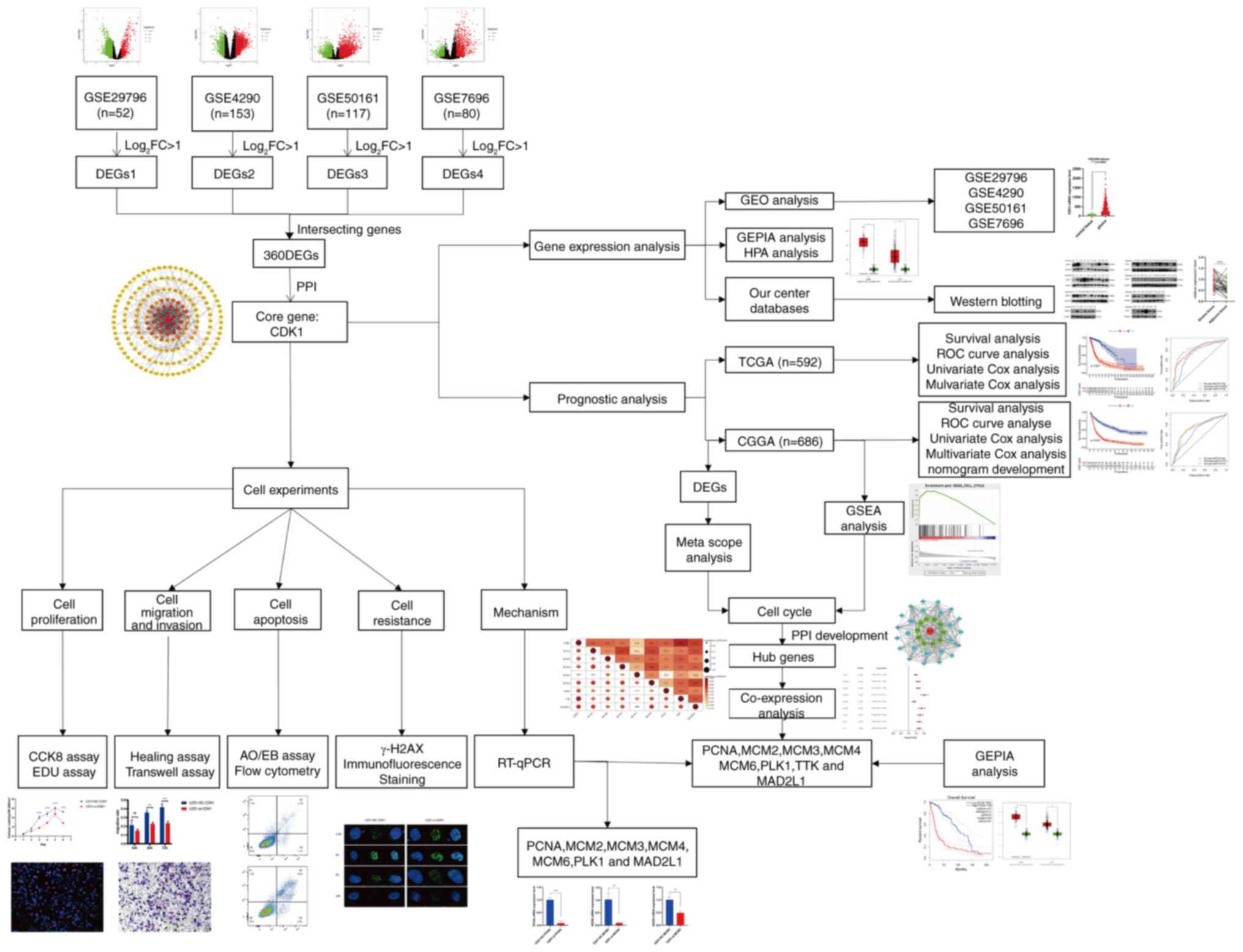

Research workflow and sample

characteristics

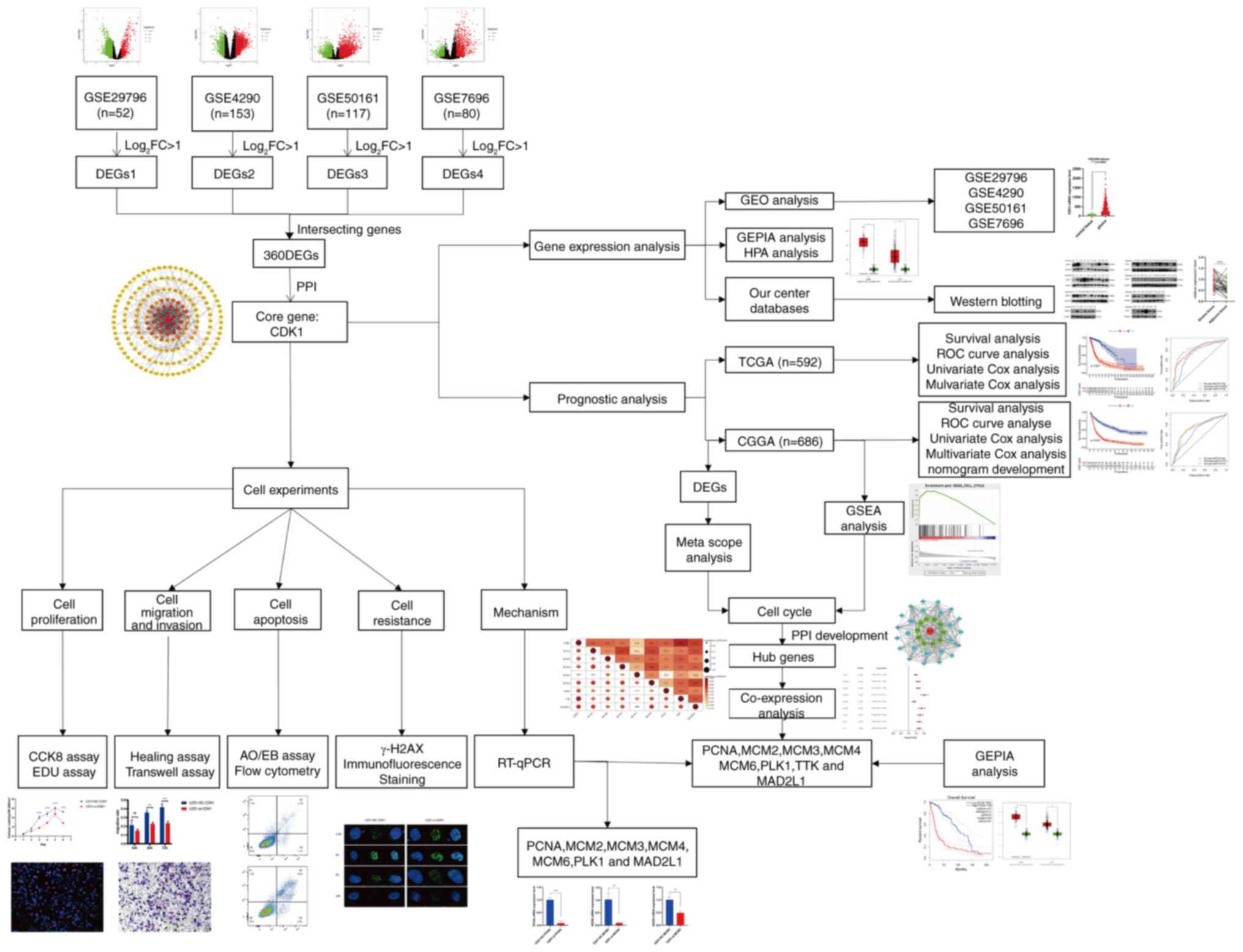

The overall research workflow is summarized in

Fig. 1. Based on predefined

screening criteria, gene expression profiles (GSE29796, GSE4290,

GSE50161 and GSE7696) and corresponding clinical data were

retrieved from the GEO database. These datasets included 52, 153,

117 and 80 glioma specimens, respectively, alongside 20, 23, 13 and

4 non-tumorous controls. Clinicopathological information, such as

age, tumor grade, histological classification, 1p/19q codeletion

and IDH mutation status, was obtained from the CGGA and TCGA

databases. Additional data on chemoradiotherapy history and MGMT

promoter methylation were available exclusively from the CGGA

dataset. Detailed clinical characteristics are provided in Table SI.

| Figure 1.Workflow of the whole study. FC, fold

change; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; CDK1,

cyclin-dependent kinase 1; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis; N, normal tissue; T, tumor; CGGA, Chinese

Glioma Genome Atlas; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; ROC, receiver

operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve; PRS,

prognostic risk score; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; MGMT,

O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase; OS, overall survival; WHO,

World Health Organization; NC, negative control; si, small

interfering RNA; OD, optical density; AO/EB, acridine

orange/ethidium bromide; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; PPI,

protein-protein interaction; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear

antigen; MCM2/3/4/6, minichromosome maintenance complex component

2/3/4/6; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; MAD2L1, mitotic arrest deficient

2 like 1; GBM, glioblastoma; LGG, low-grade glioma. |

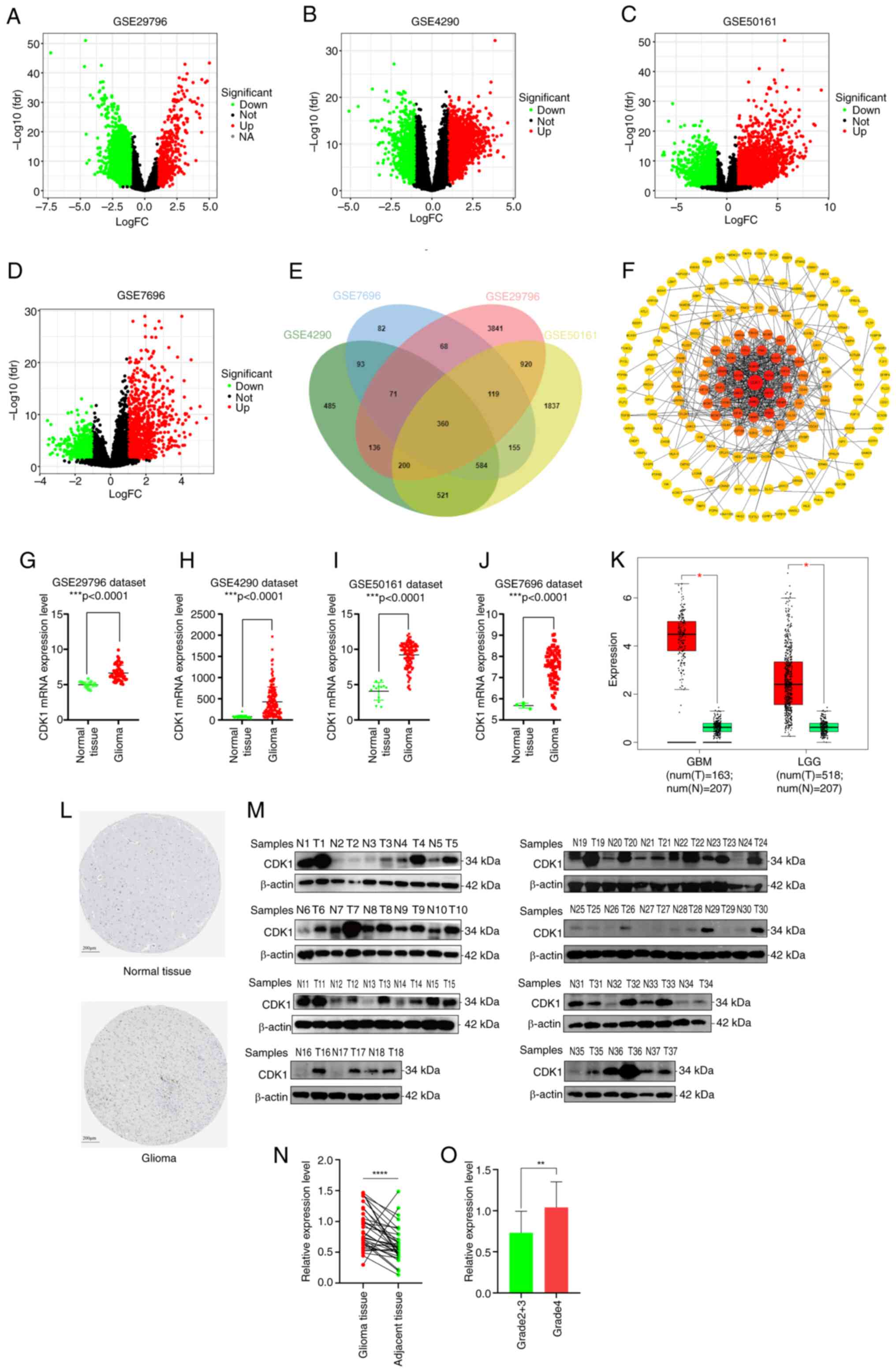

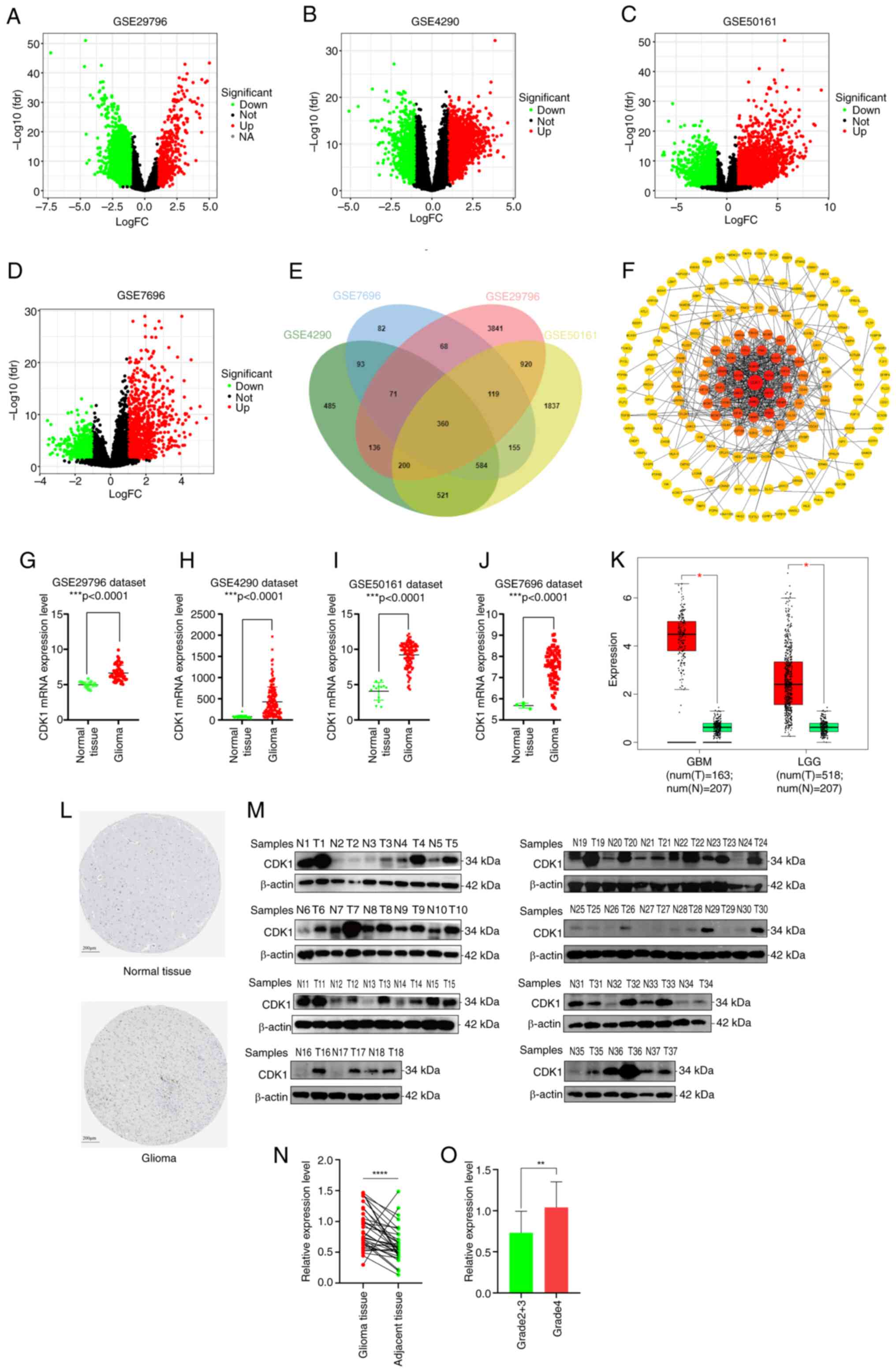

Identification of important genes

involved in glioma initiation and progression

Gene expression profiles from the GSE29796, GSE4290,

GSE50161 and GSE7696 datasets were stratified into tumor and

non-tumor groups for differential expression analysis. DEGs were

identified using a significance threshold of P<0.05 and

|log2FC|>1. The GSE29796 dataset included 5,715 DEGs

(599 upregulated and 5,116 downregulated; Fig. 2A), GSE4290 included 2,450 DEGs

(1,425 upregulated and 1,025 downregulated; Fig. 2B), GSE50161 included 4,696 DEGs

(2,320 upregulated and 2,376 downregulated; Fig. 2C) and GSE7696 included 1,532 DEGs

(915 upregulated and 617 downregulated; Fig. 2D). Intersecting DEGs across all four

datasets via a Venn diagram (Fig.

2E) yielded 360 commonly dysregulated genes. A PPI network was

generated using STRING and 180 proteins were imported into

Cytoscape for visualization. Subsequent topological analysis using

the cytoHubba plugin identified CDK1 as the core hub gene with the

highest degree value (Fig. 2F).

| Figure 2.Core gene and its expression levels

in normal tissue and glioma were retrieved. (A) Volcano plots of

the 5,715 DEGs in the GSE29796 dataset (599 upregulated and 5,116

downregulated). (B) Volcano plots of the 2,450 DEGs in the GSE4290

dataset (1,425 upregulated and 1,025 downregulated). (C) Volcano

plots of the 4,696 DEG in the GSE50161 dataset (2,320 upregulated

and 2,376 downregulated). (D) Volcano plots of the 1,532 DEGs in

the GSE7696 dataset (915 upregulated and 617 downregulated). The

red nodes represent the significantly upregulated genes with

log2FC>1 and P<0.05. The green nodes represent the

significantly downregulated genes with log2FC<-1 and P<0.05.

(E) Intersecting genes of the four groups of DEGs are displayed by

Venn diagram. (F) Protein-protein interaction network was

constructed and the core protein with the highest degree of

topology value was screened out, based on the STRING website and

Cytoscape visualization software. Comparison of CDK1 mRNA

expression levels in normal tissue and glioma using the (G)

GSE29796, (H) GSE4290, (I) GSE50161 and (J) GSE7696 datasets. (K)

CDK1 expression levels in normal tissue and glioma via GEPIA

analysis. (L) The protein levels of CDK1 in normal (intensity:

negative; quantity: none) and glioma (intensity: strong; quantity:

<25%) tissue from the Human Protein Atlas. (M) Western blot

assay and (N) Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (P<0.0001)

of 37 pairs of glioma and adjacent tissues. (O) Data from the

internal cohort showed that CDK1 expression was a statistically

significant difference between Grade 2+3 gliomas (n=20) and Grade 4

gliomas (n=17) (P=0.0018). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired t-test, Mann

Whitney test or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. FC, fold

change; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; CDK1,

cyclin-dependent kinase 1; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis; N, normal tissue; T, tumor. |

CDK1 expression level in glioma

CDK1 expression across GEO datasets revealed

significantly elevated levels in glioma tissues relative to the

normal controls (Fig. 2G-J).

Consistent findings from GEPIA analyses further confirmed

upregulated CDK1 expression in both GBM and LGG cohorts (Fig. 2K). Additionally, immunohistochemical

data from the HPA database demonstrated significantly higher CDK1

protein abundance in glioma tissues compared with normal brain

tissue (Fig. 2L). To experimentally

validate these bioinformatic observations, CDK1 protein expression

in an internal cohort of 37 paired glioma and adjacent normal

tissues was assessed via western blotting. Despite the limited

cohort size, the results consistently showed elevated CDK1 protein

levels in glioma samples (P<0.0001, paired t-test; Fig. 2M and N). Furthermore, data from the

internal cohort showed CDK1 expression was significantly higher in

WHO grade 4 gliomas (n=17) than in WHO grade 2+3 gliomas (n=20)

(P=0.0018; Fig. 2O).

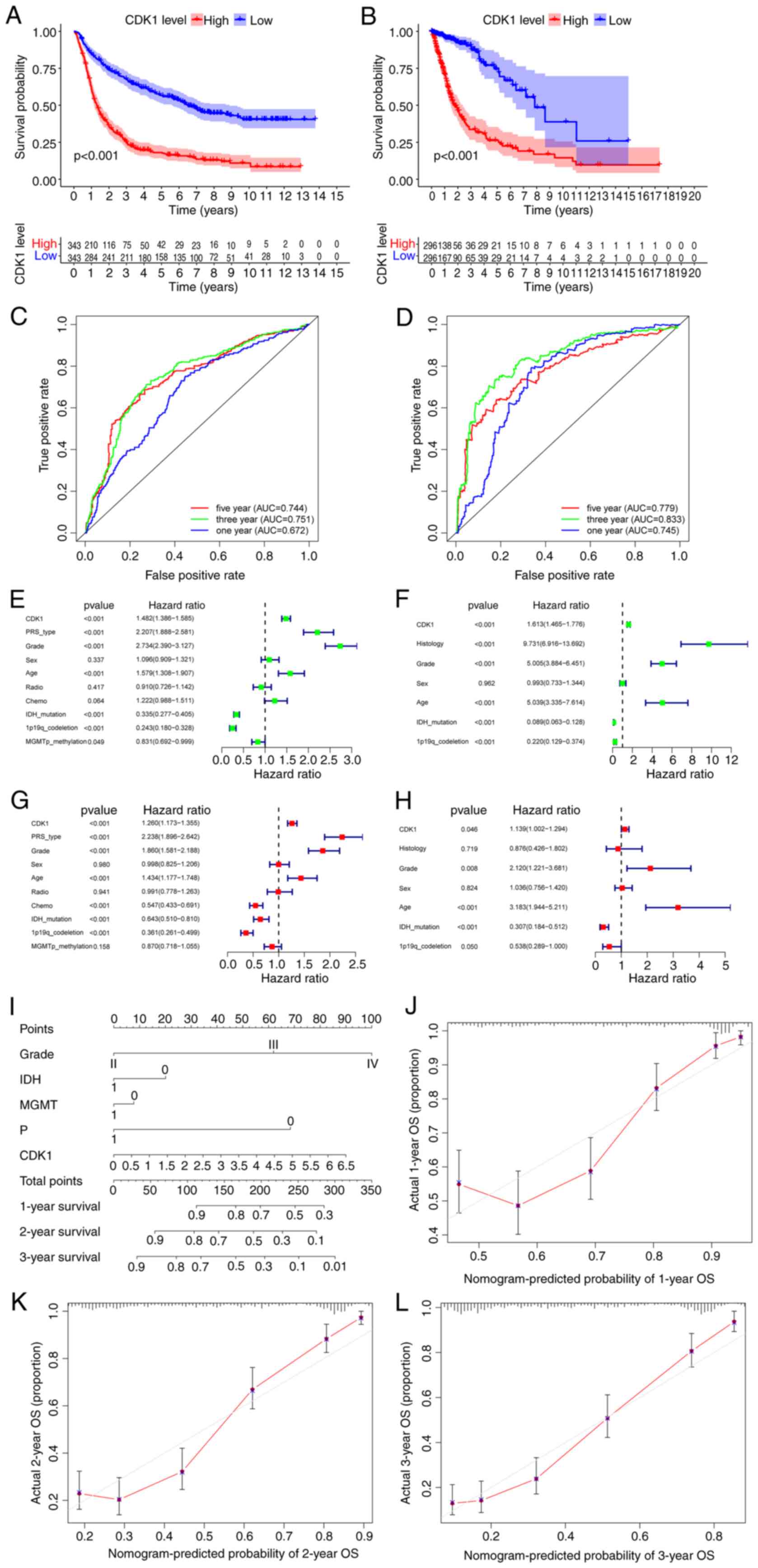

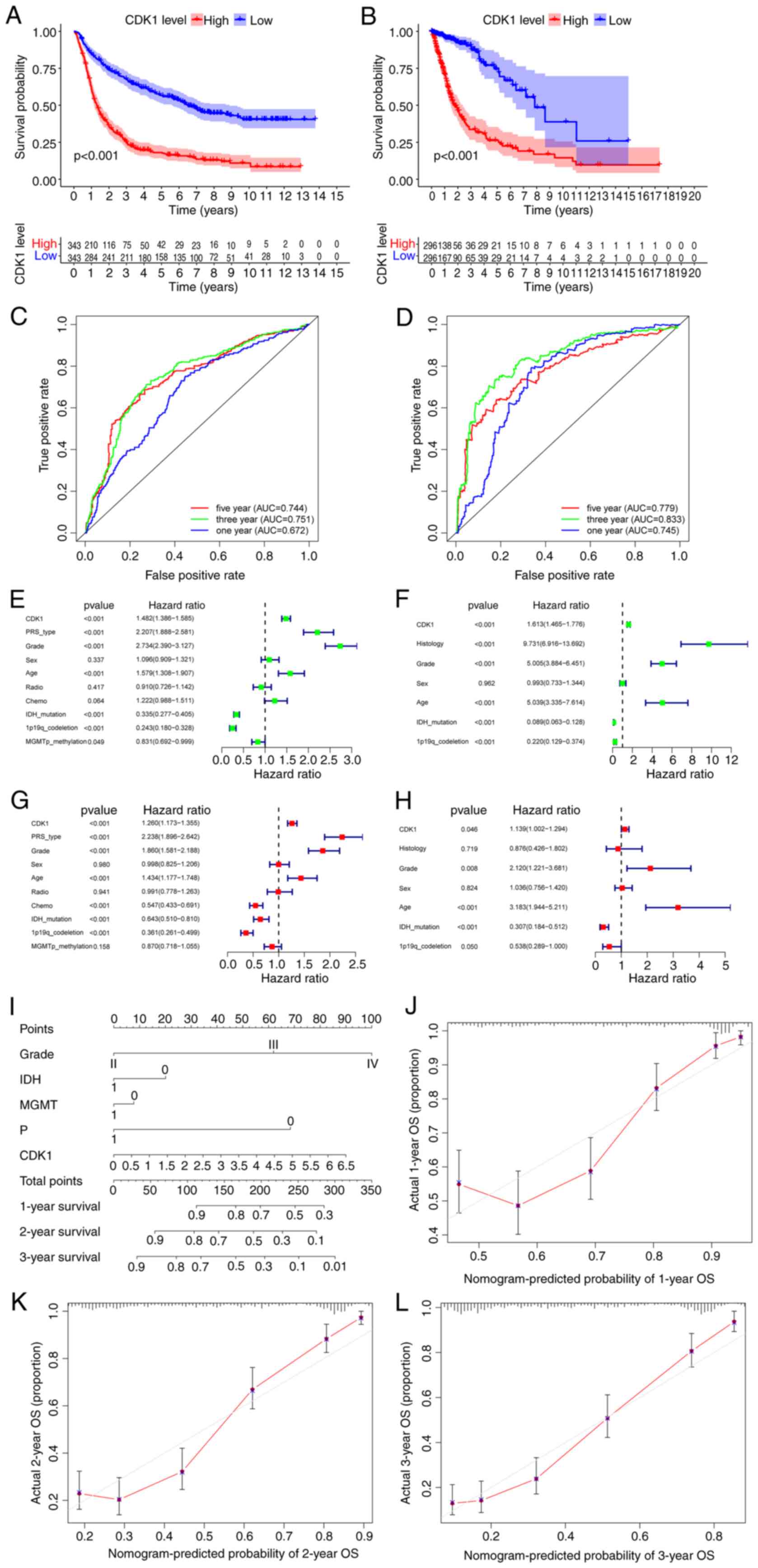

CDK1 upregulation is combined with a

poorer survival and prognosis in patients with glioma

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the CGGA dataset

revealed significantly reduced OS in patients with high CDK1

expression (log-rank P<0.001; Fig.

3A), findings that were independently validated using the TCGA

cohort (P<0.001; Fig. 3B). ROC

analysis demonstrated consistent prognostic performance across both

datasets. In the CGGA cohort, CDK1 showed predictive value for 1-,

3- and 5-year survival with area under the curves (AUCs) of 0.672,

0.751 and 0.744, respectively (Fig.

3C). Correspondingly, the TCGA dataset yielded AUCs of 0.745,

0.833 and 0.779 for the same time intervals (Fig. 3D). To assess CDK1 as an independent

prognostic determinant, univariate and multivariate Cox regression

analyses were performed using the CGGA dataset. Univariate analysis

identified significant associations between OS and CDK1 expression

[hazard ratio (HR), 1.482; 95% confidence interval (CI),

1.386–1.585; P<0.001], as well as progression status, tumor

grade, age, IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion status (Fig. 3E). Multivariate analysis confirmed

CDK1 as an independent prognostic factor (HR, 1.260; 95% CI,

1.173–1.355; P<0.001), alongside progression status, grade, age,

chemotherapy, IDH mutation, and 1p/19q codeletion status (Fig. 3G). The emergence of chemotherapy as

a significant prognostic factor only in the multivariate analysis

indicates that its effect is not independent but becomes evident

after accounting for other covariates. This pattern implies that

the efficacy of chemotherapy may depend on specific contexts, such

as particular molecular subgroups (such as gliomas with MGMT

promoter methylation), where a significant benefit might be diluted

and non-significant in a heterogeneous cohort under univariate

assessment. These associations were validated using the TCGA

dataset (Fig. 3F and H).

Collectively, these results establish CDK1 as an independent

prognostic biomarker for glioma. A prognostic nomogram integrating

tumor grade, IDH mutation status, MGMT promoter methylation, 1p/19q

codeletion status and CDK1 expression was constructed using the

CGGA cohort (Fig. 3I). Among the

variables integrated into the nomogram, CDK1 expression was

established as a key driver of the predictive power of the model

based on variable importance analysis. Calibration plots

demonstrated good concordance between predicted and observed

survival probabilities, particularly for 3-year OS (Fig. 3J-L).

| Figure 3.Survival analysis and independent

prognostic analysis of CDK1 based on bioinformatics analysis.

Survival analysis of the high and low CDK1 groups in patients with

glioma from the (A) CGGA and (B) TCGA datasets. The ROC curves of

CDK1 at 1, 3 and 5 year survival in the (C) CGGA and (D) TCGA

datasets. Univariate analysis of CDK1 in the (E) CGGA and (F) TCGA

datasets. Multivariate analysis of CDK1 in the (G) CGGA and (H)

TCGA datasets. (I) Prognostic nomogram constructed based on the

CGGA dataset including clinical information to predict the survival

of patients with glioma. Calibration curves of the nomogram

constructed based on the CGGA dataset to predict survival at (J) 1

year, (K) 2 years and (L) 3 years. CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1;

CGGA, Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve;

PRS, prognostic risk score; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; MGMT,

O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase; OS, overall survival. |

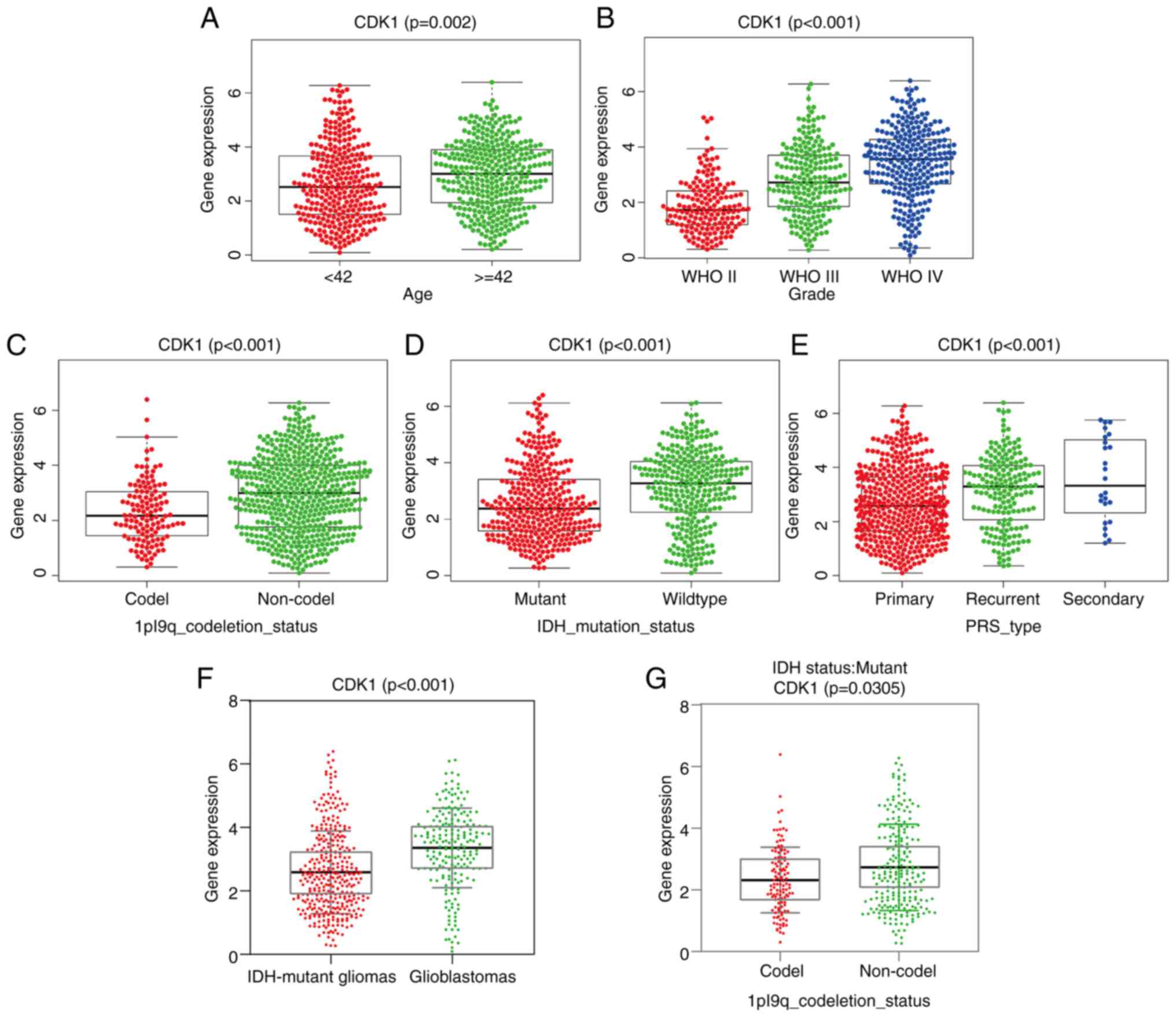

Relative analysis of CDK1 gene

expression and clinicopathological features based on the CGGA

dataset

CDK1 expression was significantly elevated in

patients >42 years (P=0.002; Fig.

4A) and increased progressively with tumor grade (P<0.001;

Fig. 4B). Conversely, significantly

lower CDK1 levels were observed in IDH-mutant and 1p/19q codeleted

gliomas (both P<0.001; Fig. 4C and

D). Recurrent and secondary gliomas exhibited significantly

higher CDK1 expression compared with primary tumors (P<0.001;

Fig. 4E). Stratification by

molecular subtype further revealed CDK1 upregulation in IDH-wild

type glioblastomas relative to IDH-mutant astrocytomas and

oligodendrogliomas (P<0.001; Fig.

4F). Within the IDH-mutant subgroup, astrocytomas (IDH-mutant,

1p/19q non-codel) displayed higher CDK1 expression than

oligodendrogliomas (IDH-mutant, 1p/19q codeleted) (P=0.0305;

Fig. 4G), underscoring its

subtype-specific regulation.

CDK1 facilitates the malignant

biological phenotypes of glioma cells

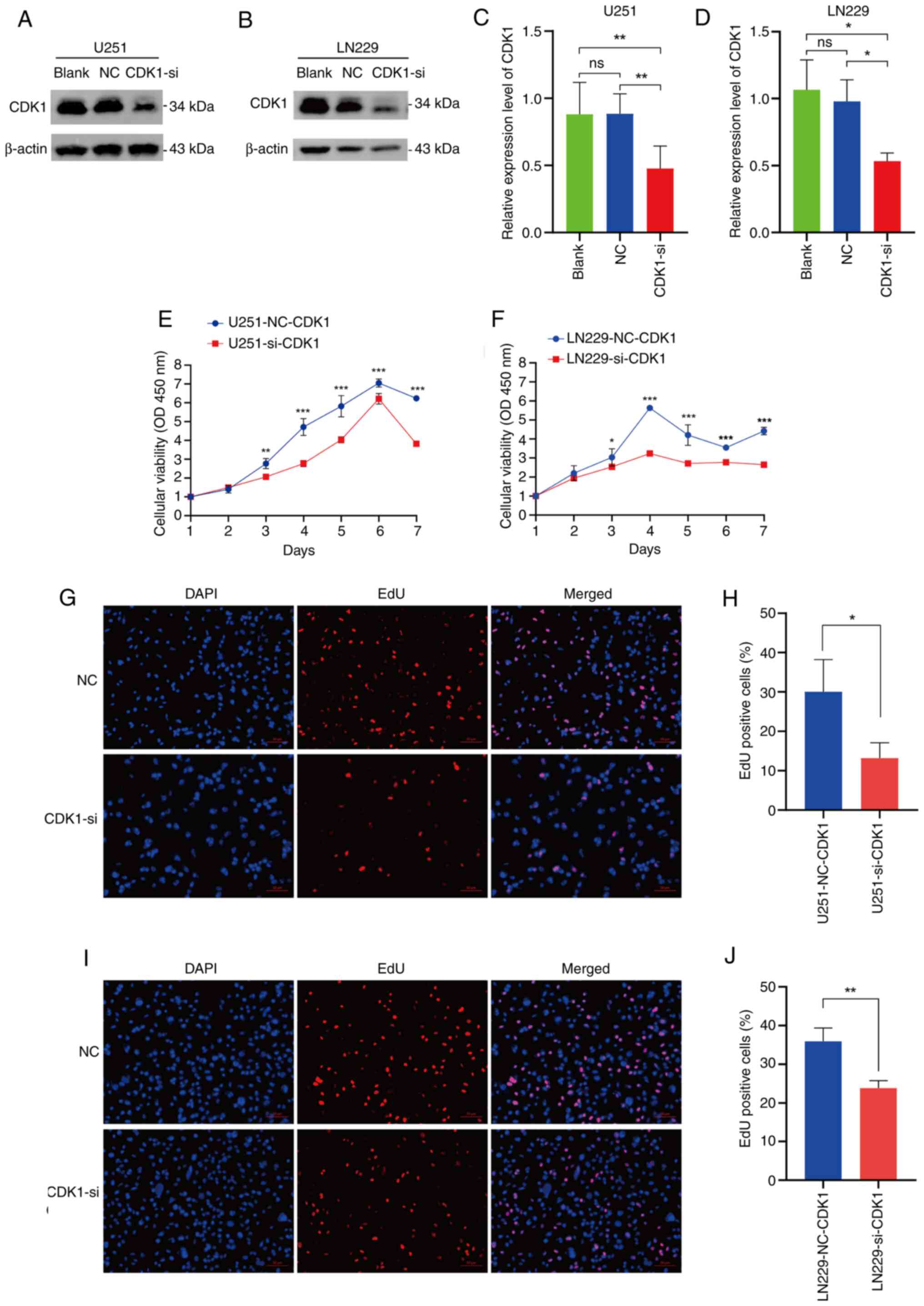

Construction of glioma cells line with CDK1

knockdown

To investigate CDK1 function, U251MG and LN229

glioma cell lines were transiently transfected with

sequence-specific CDK1 siRNA. Western blot analysis confirmed the

efficient knockdown of CDK1 protein expression in both the U251MG

and LN229 cell lines transfected with CDK1-siRNA, compared with the

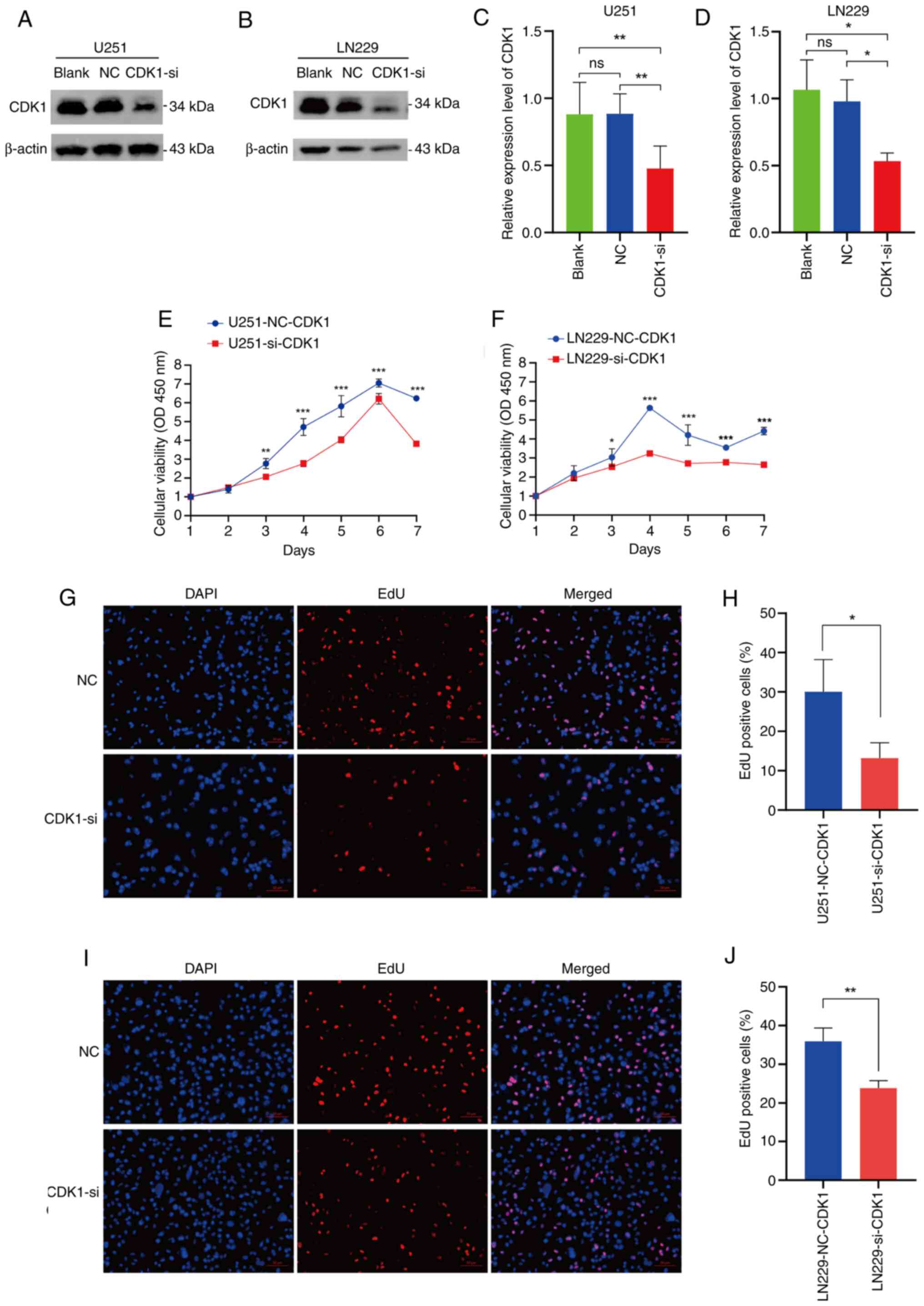

Blank and negative control (NC) groups (P<0.05; Fig. 5A-D).

| Figure 5.Verification of CDK1 knockdown and

its role in the proliferative ability of glioma cells. Validation

of CDK1 knockdown was achieved through western blot analysis in the

(A) U251MG and (B) LN229 glioma cell lines. (C and D) Statistical

comparisons of the western blot data for the (C) U251MG (Blank vs.

NC, P=0.9992; Blank vs. CDK1-si, P=0.0057; NC vs. CDK1-si,

P=0.0053) and LN229 (Blank vs. NC, P=0.7960; Blank vs. CDK1-si,

P=0.0161; NC vs. CDK1-si, P=0.0343) cell lines (n=3, each group).

(E and F) Cell Counting Kit-8 cell viability assays demonstrated a

decrease in proliferation potential upon CDK1 knockdown in (E)

U251MG and (F) LN229 cells (n=4, each group). (G) Representative

images (magnification, ×10) and (H) quantitative analysis of the

EdU assay performed in the U251MG cell line (NC vs. CDK1-si,

P=0.0325; n=3, each group). (I) Representative images

(magnification, ×10) and (J) quantitative analysis of the EdU assay

performed in the LN229 cell line (NC vs. CDK1-si, P=0.0057; n=3,

each group). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical

significance was calculated using one-way analysis of variance

followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test, unpaired t-test or

one-way analysis of variance followed by Sidak's multiple

comparisons test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CDK1,

cyclin-dependent kinase 1; NC, negative control; si, small

interfering (RNA); OD, optical density. |

CDK1 positively regulates the cell

proliferative ability of glioma cells

CCK-8 assays demonstrated that CDK1 knockdown

significantly suppressed proliferation in both U251MG and LN229

cells (P<0.001; Fig. 5E and F).

EdU fluorescence staining confirmed that proliferation was

significantly reduced in the CDK1-siRNA group compared with the NC

(U251: P=0.0325; Fig. 5G and H)

(LN229: P=0.0057; Fig. 5I and J).

These results establish CDK1 as a potential promoter of glioma cell

proliferation.

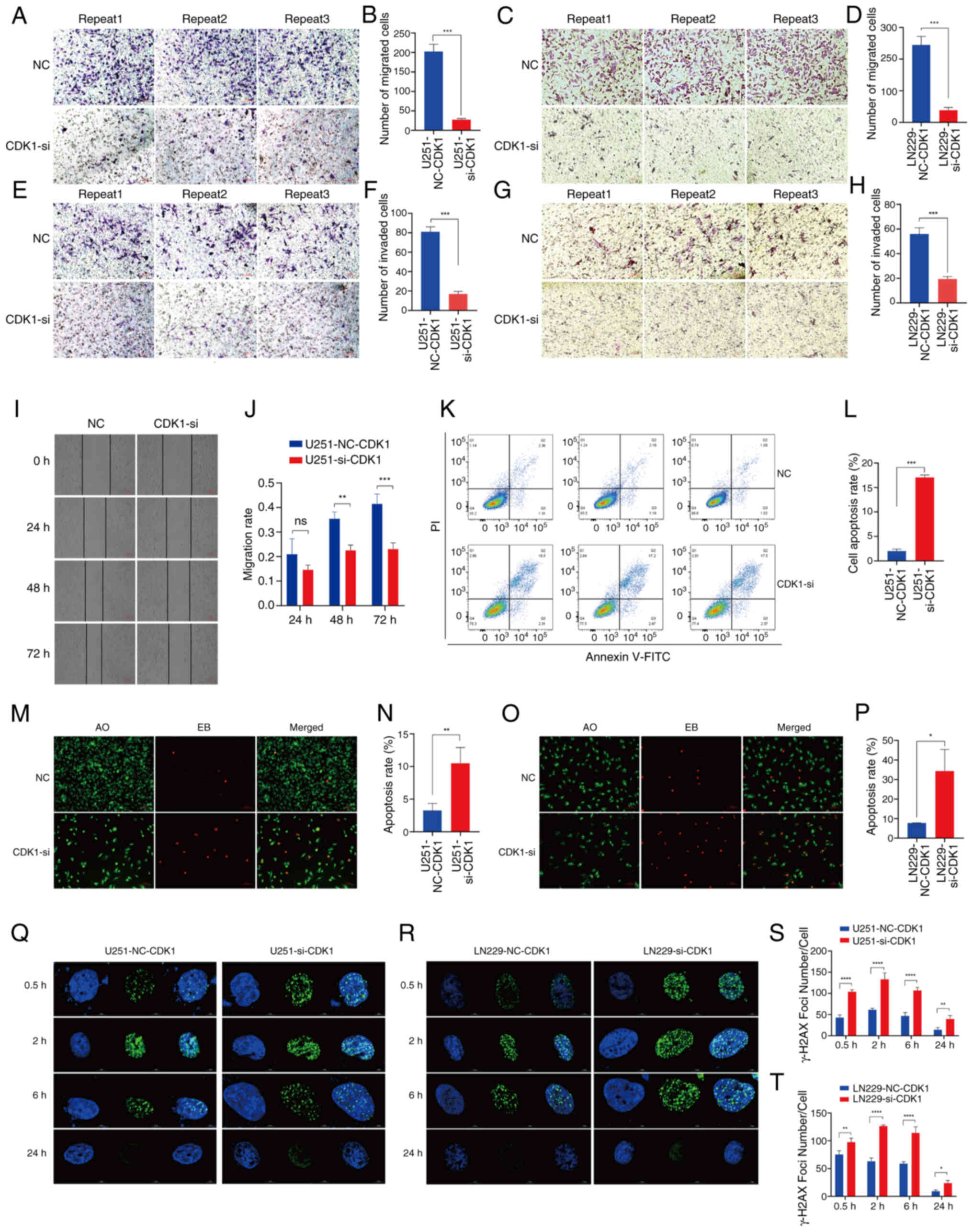

CDK1 enhances the migration and

invasive abilities of glioma cells

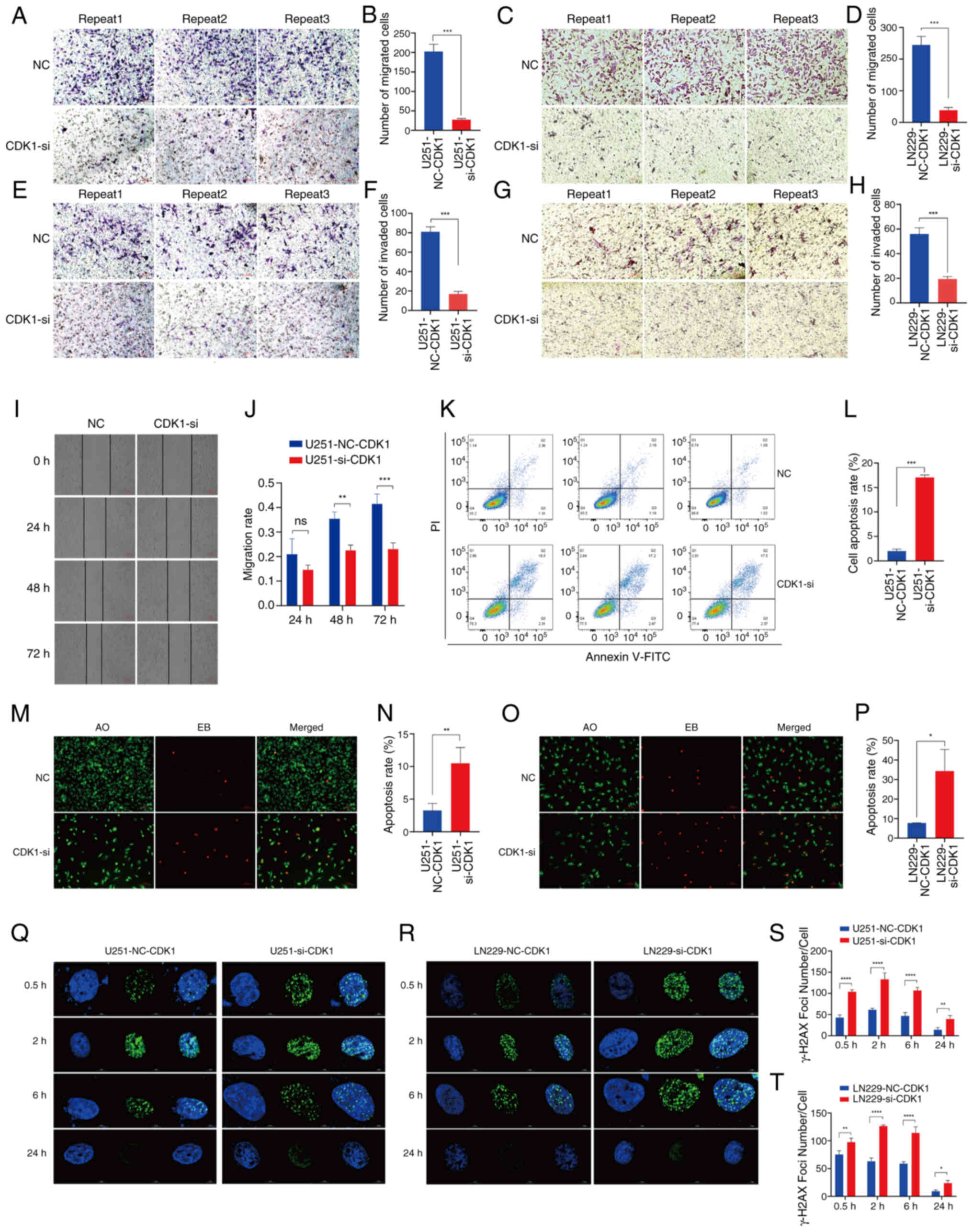

Transwell migration assays revealed a significant

reduction in migrated cell counts following CDK1 knockdown (U251:

P<0.001; Fig. 6A and B) (LN229:

P=0.0002; Fig. 6C and D).

Similarly, Matrigel invasion assays demonstrated significant

suppression of invasive potential in CDK1-siRNA cells (U251:

P<0.001; Fig. 6E and F) (LN229:

P=0.0003; Fig. 6G and H). Scratch

wound healing assays in U251MG cells confirmed progressive

inhibition of migration at 48 and 72 h post-transfection (P=0.0027

and P<0.0001, respectively; Fig. 6I

and J). Collectively, these findings underscore the role of

CDK1 in driving glioma cell motility and invasiveness.

| Figure 6.Impact of CDK1 on the

migration/invasion capability and DNA damage repair ability of

glioma cells. (A) Representative images of the U251MG cell

Transwell migration assay (magnification, ×10) and the (B)

quantitative analysis of the number of migrated cells (NC vs.

CDK1-si, P<0.001; n=3). (C) Representative images of the LN229

cell Transwell migration assay (magnification, ×10) and the (D)

quantitative analysis of the number of migrated cells (NC vs.

CDK1-si, P=0.0002; n=3). (E) Representative images of the U251MG

cell Transwell invasion assay (magnification, ×10) and the (F)

quantitative analysis (NC vs. CDK1-si, P<0.001; n=3). (G)

Representative images of the LN229 cell Transwell invasion assay

(magnification, ×10) and the (H) quantitative analysis (NC vs.

CDK1-si, P=0.0003; n=3). (I) The assessment of cell migration via

scratch experiments demonstrated a significant effect of CDK1

knockdown on reducing glioma cell motility. (J) Statistical results

of the U251MG cell line migration assay (NC vs. CDK1-si, 24 h

P=0.1445; 48 h P=0.0027; 72 h P=0.0001; n=3). (K and L) Analysis of

apoptosis by flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC and PI staining in

U251MG cells. (K) Representative dot plots and (L) quantitative

analysis (NC vs. CDK1-si, P<0.001; n=3). (M and N) Detection of

apoptosis by AO/EB fluorescence staining in U251MG cells. (M)

Representative fluorescence images (magnification, ×10) and the (N)

quantitative analysis (NC vs. CDK1-si, P=0.0089; n=3). (O and P)

Detection of apoptosis by AO/EB fluorescence staining in LN229

cells. (O) Representative fluorescence images (magnification, ×10)

and the (P) quantitative analysis (NC vs. CDK1-si, P=0.0143; n=3).

Images of γ-H2AX foci formed in (Q) U251MG and (R) LN229 cell lines

at 0.5, 2, 6 and 24 h after 5 Gy radiation. The statistical

analysis of γ-H2AX foci formed in (S) U251MG and (T) LN229 cell

lines (NC vs. CDK1-si; n=3). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired t-test or

one-way analysis of variance followed by Sidak's multiple

comparisons test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. ns, not significant. CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase

1; NC, negative control; si, small interfering (RNA); AO/EB,

acridine orange/ethidium bromide. |

CDK1 inhibits glioma cell

apoptosis

Flow cytometry analysis revealed that RNA

interference-mediated CDK1 knockdown resulted in a 7-fold increase

in apoptosis relative to the NC group (P<0.001; Fig. 6K and L). AO/EB staining, a

dual-fluorescence apoptosis assay, exploits the ability of AO to

permeate intact membranes, intercalate with nuclear DNA and emit

bright green fluorescence. By contrast, EB penetrates only cells

with compromised membranes, binds nuclear DNA and produces

orange-red fluorescence. Accordingly, apoptotic cells exhibit

uniform, condensed or fragmented red-orange fluorescent nuclei,

whereas viable cells display diffuse green fluorescence. AO/EB

staining of U251MG and LN229 glioma cells demonstrated

significantly increased red fluorescence in siRNA-treated groups,

corresponding to 3.2-fold and 4.4-fold elevations in apoptotic

rates, respectively (U251MG: P=0.0089; LN229: P=0.0143; Fig. 6M-P). These findings collectively

confirm that CDK1 suppression significantly enhanced apoptosis in

glioma cells.

CDK1 boosts DNA damage repair ability

in glioma cells

X-ray-induced DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair

following 5 Gy irradiation was evaluated using γ-H2AX

immunofluorescence (Fig. 6Q and R).

Quantitative analysis in U251MG cells (Fig. 6S) revealed that the siRNA group

displayed significantly slower kinetics of γ-H2AX foci

disappearance, indicative of impaired DSB repair, compared with the

NC group at all time points: 0.5 h (P<0.0001), 2 h

(P<0.0001), 6 h (P<0.0001) and 24 h (P=0.0065). The

resolution of the γ-H2AX signal primarily involves the

dephosphorylation of γ-H2AX and the disassembly of repair protein

complexes at the damage site, which occurs upon successful DSB

repair. Therefore, the prolonged presence of γ-H2AX foci in the

siRNA group suggests a deficiency in completing the repair process.

Consistent results were obtained in LN229 cells under identical

conditions (Fig. 6T): 0.5 h

(P=0.0017), 2 h (P<0.0001), 6 h (P<0.0001) and 24 h

(P=0.0470). CDK1 knockdown by siRNA significantly impaired DSB

repair fidelity, linking its role in cell cycle regulation to

enhanced DNA damage response and radiation resistance.

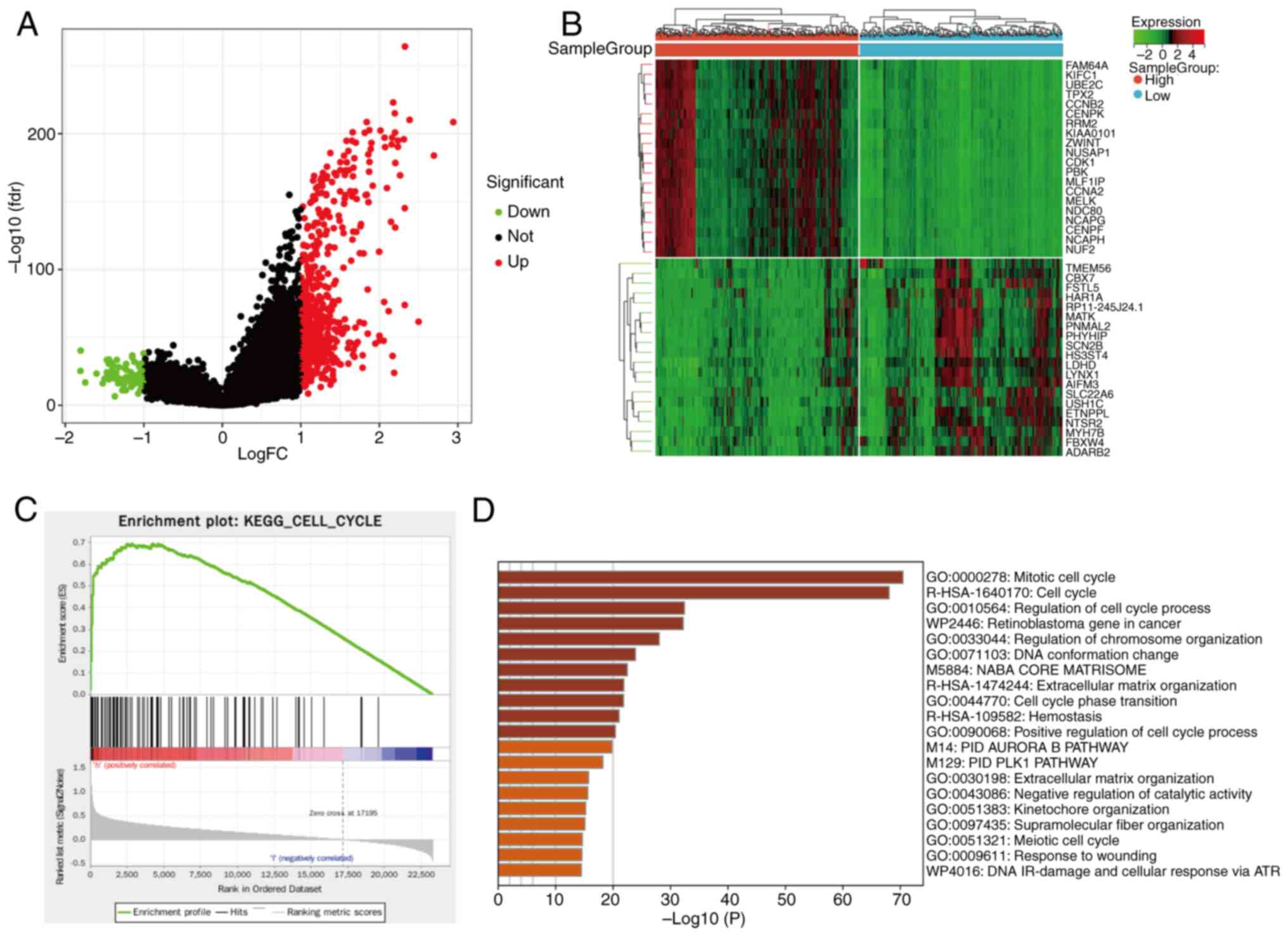

DEG analysis and signal pathway

enrichment analysis of the CDK1 gene

Using the median CDK1 expression value to stratify

samples into high- and low-expression groups, subsequent

differential expression analysis comparing these two groups yielded

638 DEGs, including 93 upregulated and 546 downregulated genes. A

volcano plot of DEGs was generated using R software (Fig. 7A), and a heatmap illustrated the

most significantly altered genes (Fig.

7B). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed significant

enrichment of cell cycle-related pathways in the high-CDK1

expression group (NES=2.0351, normalized P<0.05, FDR=0.0101;

Fig. 7C). Consistently, Metascape

analysis indicated strong enrichment of DEGs in the ‘mitotic cell

cycle’ pathway (Fig. 7D).

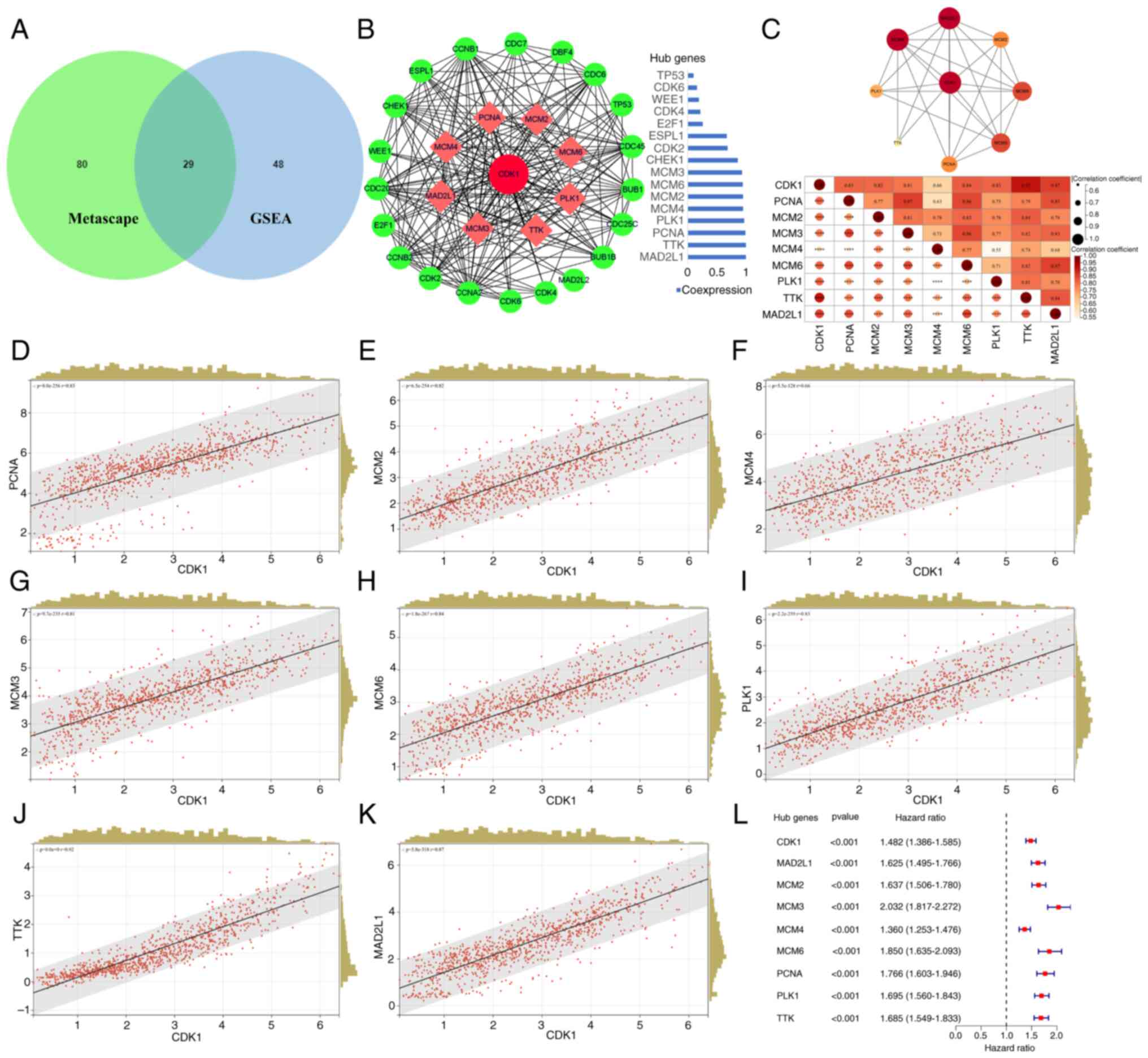

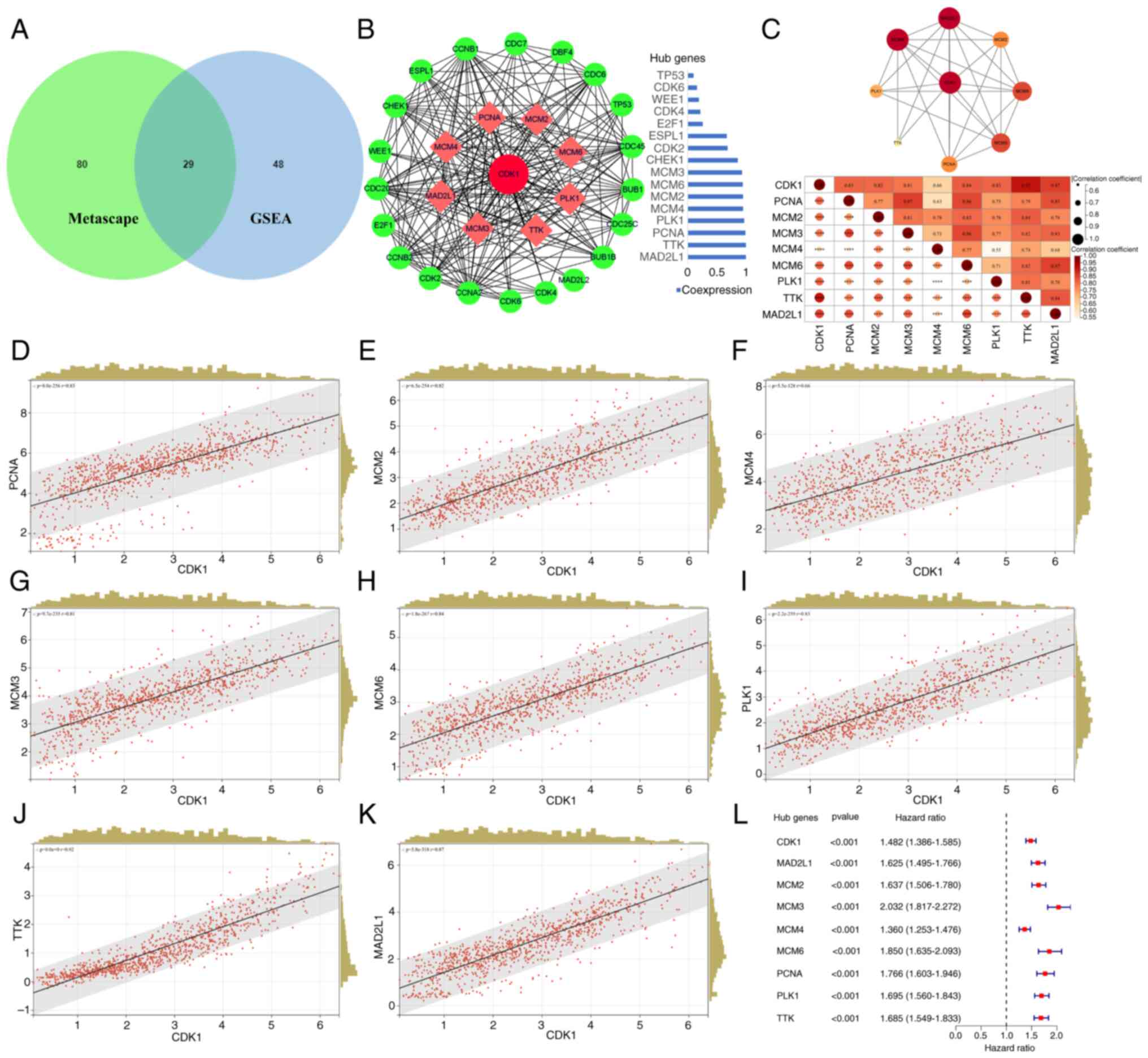

Core genes highly associated with CDK1

and PPI network in the cell cycle pathway

Both GSEA and Metascape enrichment analyses

highlighted convergence on cell cycle-associated pathways. Venn

diagram intersection identified 29 overlapping genes from the two

analyses (Fig. 8A). To identify

core regulators associated with CDK1, these genes were uploaded to

STRING for PPI network analysis, which was visualized in Cytoscape.

In total, 8 hub proteins exhibiting strong co-expression with CDK1

(correlation >0.9) were identified: PCNA, MCM2, MCM3, MCM4,

MCM6, PLK1, TTK and MAD2L1 (Fig.

8B). STRING-based PPI analysis confirmed robust

interconnectivity among these proteins (Fig. 8C, top), and correlation analysis

further demonstrated strong positive associations between CDK1 and

the 8 hub genes (Fig. 8C, bottom),

corroborated by scatter plots (Fig.

8D-K). Univariate regression analysis revealed that all 8 genes

functioned as oncogenic drivers in glioma (P<0.001; Fig. 8L).

| Figure 8.Association analysis between CDK1 and

cell cycle hub genes. (A) Intersecting genes of the cell cycle

signaling pathway-related genes from Metascape analysis and GSEA

are displayed by the Venn diagram. (B) CDK1 PPI network was

constructed and the top 8 hub proteins with a co-expression value

of >0.9 were screened out based on the STRING website and

Cytoscape visualization software. (C) STRING-based PPI analysis

among the top 8 hub proteins (top). Matrix correlation analysis and

visualization of CDK1 and hub genes (bottom). Scatter plot analysis

of the correlation between CDK1 and hub genes expression: (D) PCNA,

(E) MCM2, (F) MCM4, (G) MCM3, (H) MCM6, (I) PLK1, (J) TTK and (K)

MAD2L1. (L) Univariate regression analysis of the top 8 Hub genes.

Statistical significance was calculated using Pearson's correlation

coefficient. CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1; GSEA, Gene Set

Enrichment Analysis; PPI, protein-protein interaction; PCNA,

proliferating cell nuclear antigen; MCM2/3/4/6, minichromosome

maintenance complex component 2/3/4/6; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1;

MAD2L1, mitotic arrest deficient 2 like 1. |

Malignant phenotypes are promoted

through modulation of the cell cycle pathway via influencing CDK1

expression

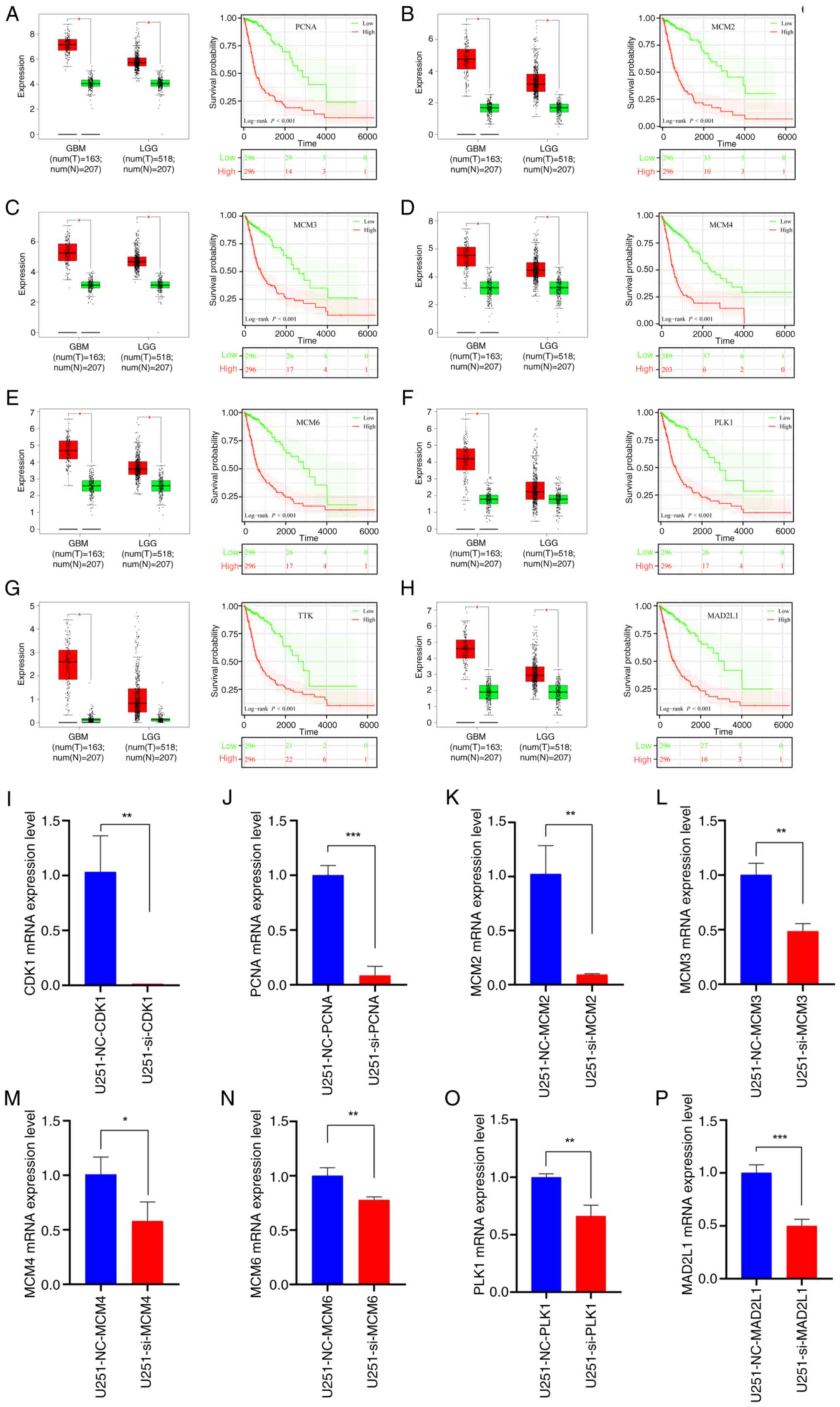

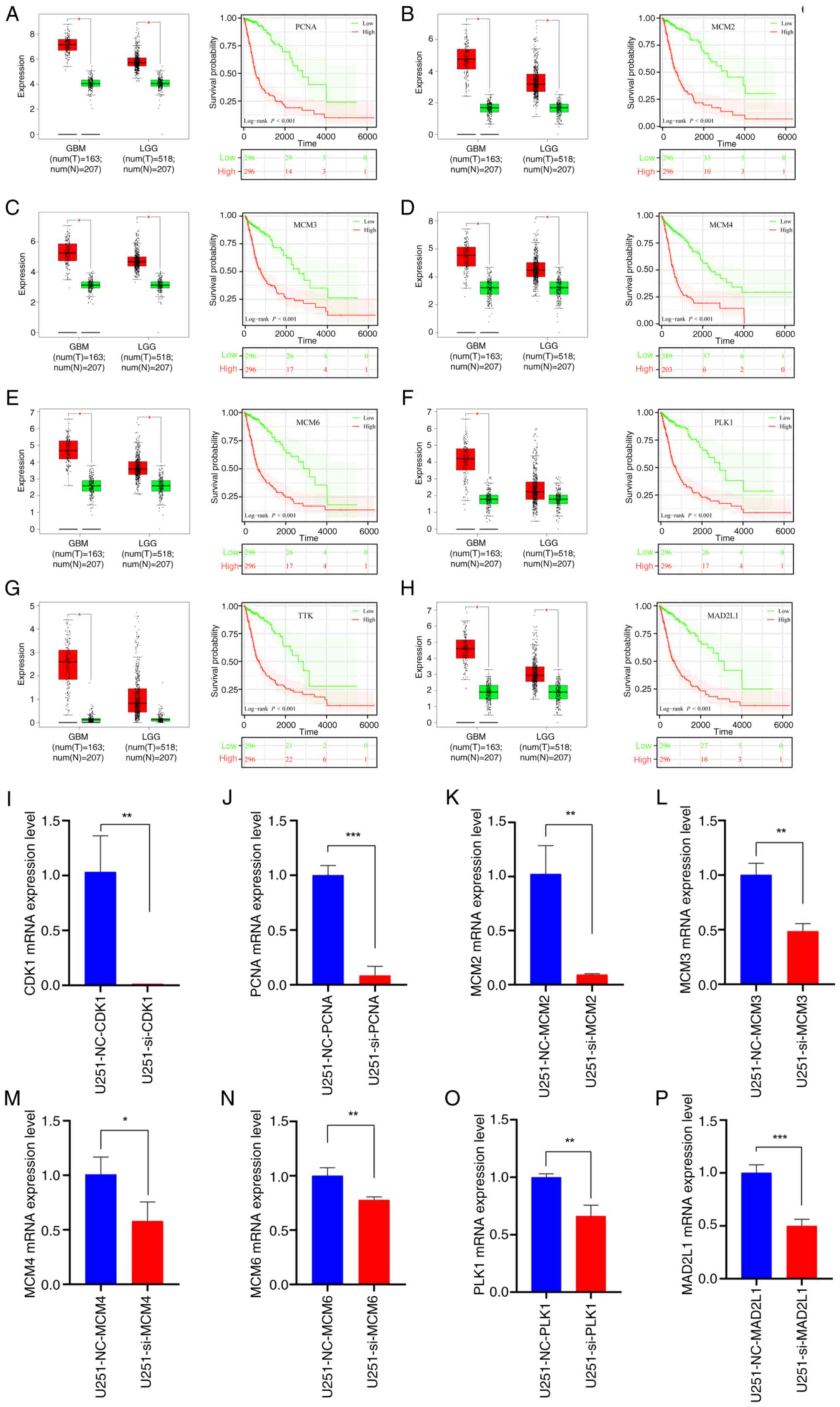

Hub gene survival and prognosis analysis based on

TCGA dataset

In glioma tissues, expression levels of the

identified hub genes were significantly elevated relative to normal

tissues, and their upregulation was associated with a poor OS

(Fig. 9A-H).

| Figure 9.Expression of the top 8 hub genes and

prognostic analysis. Expression level of the hub genes in glioma

and normal tissues based on the TCGA dataset alongside survival

analysis curves for (A) PCNA, (B) MCM2, (C) MCM3, (D) MCM4, (E)

MCM6, (F) PLK1, (G) TTK and (H) MAD2L1. (I-P) Quantitative PCR

results following CDK1 knock down (n=3) of (I) CDK1, (J) PCNA, (K)

MCM2, (L) MCM3, (M) MCM4, (N) MCM6, (O) PLK1 and (P) MAD2L1. Data

are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated

using log-rank test or Student's t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen;

MCM2/3/4/6, minichromosome maintenance complex component 2/3/4/6;

PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; MAD2L1, mitotic arrest deficient 2 like

1; GBM, glioblastoma; LGG, low-grade glioma; NC, negative control;

si, small interfering (RNA); CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1. |

Suppression of CDK1 expression can

inhibit the cell cycle pathway, thereby downregulating the

malignant phenotypes of tumors

qPCR confirmed that CDK1 knockdown suppressed the

expression of PCNA, MCM2, MCM3, MCM4, MCM6, PLK1 and MAD2L1,

providing mechanistic evidence that CDK1 inhibition disrupts cell

cycle progression (Fig. 9I-O).

Discussion

Glioma constitutes the most common primary malignant

tumor of the brain and is classified into localized and diffuse

subtypes (40). In contrast to

localized gliomas, which are often completely resectable and

potentially curable, diffuse gliomas are frequently incompletely

resectable due to their infiltrative growth and high malignancy,

properties that confer extreme aggressiveness, particularly in

high-grade forms (12). Among them,

GBM represents the most prevalent and lethal high-grade glioma,

accounting for 57% of all gliomas and 48% of primary CNS

malignancies (41). The standard

therapeutic regimen combines postoperative radiotherapy with

temozolomide-based chemotherapy. In recent years, alternating

current field therapy (TTF) has been incorporated into National

Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines; however, patient

outcomes remain poor (42). The

evolving WHO classification of CNS tumors, from 2016 to 2021, has

integrated molecular biomarkers, revolutionizing glioma diagnostics

and therapeutic stratification (5,43).

This paradigm shift underscores the need for diagnostic strategies

that accurately capture tumor biology. In this context, serum

metabolic profiling has emerged as a promising liquid biopsy

approach for brain tumors. This method exploits the partial

permeability of the blood-brain barrier to small-molecule

metabolites, enabling non-invasive detection of tumor-derived

metabolic signatures. Among recent innovations,

nanoparticle-enhanced laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry

(NPELDI-MS) represents a major advance. A study has demonstrated

its ability to characterize metabolic signatures in brainstem

gliomas with high diagnostic accuracy (AUC=0.933) and significant

prognostic value. Moreover, NPELDI-MS facilitates longitudinal

monitoring of treatment response through serial blood sampling,

offering a powerful adjunct to conventional imaging and

histopathology (44). Despite rapid

progress in immunotherapy and targeted therapy, most patients with

glioma remain unresponsive due to the complex biology of the tumor

and the unique microenvironment of the brain (11,45).

Consequently, the systematic identification of novel molecular

targets remains an urgent priority in glioma research.

The findings of the present study provide compelling

evidence that CDK1 acts as a critical driver of glioma progression.

Its upregulation is significantly associated with higher tumor

grades, poorer survival and unfavorable prognosis, aligning with

reports implicating CDK1 in oncogenic regulation of the cell cycle

(46,47). Notably, the present study

demonstrated that CDK1 expression was markedly elevated in

high-grade gliomas and in patients >42 years of age, suggesting

its potential as a biomarker for disease severity and progression.

This age-dependent upregulation may reflect the accumulation of

genetic and epigenetic alterations promoting CDK1 dysregulation,

consistent with emerging insights into age-related oncogenesis

(48). These findings emphasize the

importance of exploring age-specific molecular mechanisms in

glioma, which could reveal novel therapeutic opportunities for

older patients who typically experience poorer outcomes (49). In the present study, at the

molecular level, the reduced CDK1 expression observed in IDH-mutant

and 1p/19q codeleted gliomas highlights the heterogeneity of glioma

subtypes and their distinct molecular profiles. This pattern is

consistent with evidence that IDH mutations and 1p/19q codeletion

confer more favorable prognosis and altered cell cycle regulation

(5,50,51).

Conversely, the elevated CDK1 levels in recurrent and secondary

gliomas underscore its role in tumor relapse and progression,

possibly by enhancing proliferation, survival and therapy

resistance (52). This is

particularly significant given the paucity of effective treatments

for recurrent gliomas (53). In the

present study, functional assays, including CCK8, EdU, wound

healing, Transwell, AO/EB and flow cytometry, demonstrated that

CDK1 knockdown markedly inhibited glioma cell proliferation and

migration/invasion while promoting apoptosis. The suppression of

migration and invasion following CDK1 depletion may involve

modulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process

governed by transcription factors such as TWIST1 and SNAI2

(54). Although direct evidence

linking CDK1 to EMT regulation in glioma remains limited, a study

on head and neck squamous cell carcinomas indicates that CDK1 can

enhance EMT by modulating these key regulators (55). Therefore, we hypothesize that CDK1

knockdown may attenuate glioma cell invasiveness at least partly

through EMT inhibition, a hypothesis warranting further mechanistic

investigation (56). Collectively,

these results reinforce the established role of CDK1 in cell cycle

control and underscore its oncogenic potential (15).

In the present study, the dynamic attenuation of

γ-H2AX foci observed in U251MG and LN229 cell lines following 5 Gy

X-irradiation underscores the pivotal role of CDK1 in maintaining

DNA DSB repair fidelity. siRNA-mediated depletion of CDK1 markedly

delayed γ-H2AX signal resolution across sequential post-irradiation

intervals (0.5–24 h), indicating impaired DSB repair kinetics.

Conversely, the NC control group preserved rapid and precise

repair, demonstrating the contribution of basal CDK1 activity to

radiation resistance. These findings reinforce the established

paradigm that CDK1 orchestrates G2/M checkpoint activation and DNA

damage response signaling, primarily through phosphorylation of

homologous recombination mediators such as BRCA1 and

CtBP-interacting protein (CtIP) (57).

The molecular function of CDK1 extends beyond cell

cycle regulation to encompass a direct role in DSB repair. A study

has demonstrated preferential localization of CDK1-cyclin complexes

at DSB sites, where phosphorylation of resection mediators

(particularly CtIP and replication protein A 32 kDa subunit)

facilitates efficient homologous recombination-mediated repair

(57). This kinase activity is

essential for resolving replication-associated damage, as CDK1

inhibition disrupts replication fork progression and exacerbates

genomic instability (58). The

delayed γ-H2AX attenuation observed in CDK1-depleted cells likely

reflects defective homologous recombination-repair, consistent with

the requirement of CDK1-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1 at

Ser1497 for effective RAD51 recruitment and strand invasion

(59).

In the present study, KEGG and GSEA pathway analyses

further revealed that CDK1 exerts its principal regulatory effects

through the cell cycle pathway, consistent with its established

role as a master regulator of mitosis and cell division (60). Notably, a CDK1-centered regulatory

network encompassing PCNA, minichromosome maintenance complex

components (MCM2/3/4/6), PLK1, TTK and MAD2L1 was delineated, which

are key effectors that collectively maintain DNA replication

fidelity, checkpoint integrity and chromosomal stability (61–63).

Concomitant upregulation of these effectors in gliomas is

significantly correlated with reduced OS, highlighting the

potential central pathogenetic role of CDK1 (64,65).

In the present study, qPCR validation confirmed marked

downregulation of these network components following CDK1

depletion, mechanistically linking CDK1 inhibition to cell cycle

disruption and revealing its therapeutic potential in glioma

management. This mechanistic insight is particularly noteworthy as

it not only substantiates the canonical function of CDK1 in cell

cycle control but also identifies downstream effectors that may

represent additional therapeutic targets. For example, the MCM

family, critical for DNA replication initiation and elongation, has

recently emerged as a promising target in cancer therapy (66). Likewise, PLK1, a key mitotic kinase

implicated in glioma progression, is currently undergoing

evaluation in clinical trials (67). Collectively, these findings

establish an integrated model of CDK1-centric regulatory topology

in gliomagenesis, advocating combinatorial therapeutic strategies

targeting multiple interconnected network nodes.

Previous research has consistently demonstrated that

activation of CDK family members critically drives tumor cell cycle

progression during oncogenesis. Several CDK inhibitors have already

received FDA approval (13). For

instance, CDK4/6 inhibitors selectively target CDK4 and CDK6 to

prevent retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation, thereby halting

G1-S transition through inhibition of E2F-dependent gene

transcription (68). These

inhibitors are now widely used to treat patients with metastatic,

hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer (69,70).

Similarly, CDK1 upregulation is correlated with a poor prognosis

across multiple malignancies (20,21).

Knockdown of CDK1 via short hairpin RNA has been shown to increase

apoptosis and enhance chemosensitivity in epithelial ovarian cancer

cells (21). Therefore, targeted

inhibition of CDK1 expression holds notable therapeutic promise for

tumor growth suppression, although the precise regulatory

mechanisms warrant further elucidation.

Several limitations of the present study merit

consideration. First, the analyses primarily relied on public

datasets (TCGA and CGGA) and in vitro models, necessitating

validation in vivo. Second, critical clinicopathological

covariates, such as MGMT promoter methylation status, were

unavailable in the referenced datasets, limiting comprehensive

prognostic interpretation. Finally, although several downstream

CDK1 effectors were identified, upstream regulatory mechanisms,

including the roles of specific cyclins and modulatory kinases such

as Wee1, and potential feedback loops governing CDK1 activity in

glioma remain undefined. Future studies aimed at elucidating these

upstream regulators are essential to construct a fully integrated

model of the CDK1 signaling network and to identify synergistic

intervention points for therapeutic development.

In conclusion, glioma remains a life-threatening

malignancy with a rising global incidence, particularly for diffuse

subtypes that pose formidable therapeutic challenges. Despite

advances in treatment modalities, OS has shown minimal improvement

(12,40). Therefore, identifying novel

molecular markers is essential to elucidate oncogenic mechanisms

and facilitate the development of targeted therapies. The present

study establishes CDK1 as a critical driver of glioma progression,

with its upregulation associated with higher tumor grades,

increased recurrence risk and poorer patient outcomes. The

age-dependent and subtype-specific expression patterns of CDK1

underscore its potential as both a prognostic biomarker and a

therapeutic target. Functional analyses confirmed that CDK1

promotes cell cycle dysregulation through predicted direct

interactions with core effectors such as PLK1 and the MCM complex,

providing a mechanistic rationale for CDK1-targeted glioma therapy.

Notably, the findings of the present study emphasize the importance

of dissecting age-specific molecular mechanisms in glioma and

delineate a CDK1-centric interactome (PCNAMCM/PLK1/TTK/MAD2L1) with

high co-targeting potential. Future investigations should focus on

the development of selective CDK1 inhibitors and their evaluation

in preclinical and clinical settings, particularly in combination

with other therapeutic modalities to overcome resistance and

improve clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The project was supported by Hebei Natural Science Foundation

(grant nos. H2023206913 and J230003), Medical Science Research

Project of Hebei (grant no. 20230646) and Hebei Provincial

Government funded Clinical Medicine Excellent Talents Project

(grant no. ZF2025093).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YW and HZ conceived and designed the experiments,

conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures

and/or table and authored and/or verified drafts of manuscripts.

XH, DZ, LH, HL, TF and SL contributed to data analysis and revised

the manuscript. XX conceived and designed the experiments and

authored or reviewed drafts of the paper. YW and HZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures performed in the present study

involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical

standards of the institutional and/or national research committee

and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or

comparable ethical standards. The present study was approved by the

Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University

(approval no. 2019-R191). Informed consent to participate was

obtained from all participants included in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

PPI

|

protein-protein interaction

|

|

HPA

|

Human Protein Atlas

|

|

GEPIA

|

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

Analysis

|

|

CGGA

|

Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas

|

|

TCGA

|

The Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

GSEA

|

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

|

|

CDK1

|

cyclin-dependent kinase 1

|

|

PCNA

|

proliferating cell nuclear

antigen

|

|

PLK1

|

polo-like kinase 1

|

|

MCM2/3/4/6

|

minichromosome maintenance complex

component 2/3/4/6

|

|

TTK

|

TTK protein kinase

|

|

MAD2L1

|

mitotic arrest deficient 2 like 1

|

|

IDH

|

isocitrate dehydrogenase

|

|

MGMT

|

O-6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase

|

|

CDKN2A

|

cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor

2A

|

|

FDR

|

false discovery rate

|

|

NES

|

normalized enrichment score

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

|

|

DSB

|

double-strand break

|

|

CtIP

|

CtBP-interacting protein

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

|

|

AUC

|

area under the curve

|

|

WHO

|

World Health Organization

|

|

OD

|

optical density

|

|

NC

|

negative control

|

|

si

|

small interfering (RNA)

|

|

AO/EB

|

acridine orange/ethidium bromide

|

|

GBM

|

glioblastoma

|

|

LGG

|

low-grade glioma

|

References

|

1

|

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia

A, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical report:

Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in

the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol. 20:iv1–iv86. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rong L, Li N and Zhang Z: Emerging

therapies for glioblastoma: Current state and future directions. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 41:1422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yu MW and Quail DF: Immunotherapy for

glioblastoma: Current progress and challenges. Front Immunol.

12:6763012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von

Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD,

Kleihues P and Ellison DW: The 2016 world health organization

classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary.

Acta Neuropathol. 131:803–820. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bruford EA, Braschi B, Denny P, Jones TEM,

Seal RL and Tweedie S: Guidelines for human gene nomenclature. Nat

Genet. 52:754–758. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Śledzińska P, Bebyn MG, Furtak J,

Kowalewski J and Lewandowska MA: Prognostic and predictive

biomarkers in gliomas. Int J Mol Sci. 22:103732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Qu S, Huang C, Zhu T, Wang K, Zhang H,

Wang L, Xu R, Zheng H, Yuan X, Liu G, et al: OLFML3, as a potential

predictor of prognosis and therapeutic target for glioma, is

closely related to immune cell infiltration. VIEW. 4:202200522023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alleman K, Knecht E, Huang J, Zhang L, Lam

S and DeCuypere M: Multimodal deep learning-based prognostication

in glioma patients: A systematic review. Cancers (Basel).

15:5452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yuan Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Li H, Qi Z, Du Z,

Chu YH, Feng D, Hu J, Xie Q, et al: Multimodal data integration

using deep learning predicts overall survival of patients with

glioma. VIEW. 5:202400012024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xu S, Tang L, Li X, Fan F and Liu Z:

Immunotherapy for glioma: Current management and future

application. Cancer Lett. 476:1–12. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang K, Wu Z, Zhang H, Zhang N, Wu W, Wang

Z, Dai Z, Zhang X, Zhang L, Peng Y, et al: Glioma targeted therapy:

Insight into future of molecular approaches. Mol Cancer. 21:392022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Le Rhun E, Preusser M, Roth P, Reardon DA,

van den Bent M, Wen P, Reifenberger G and Weller M: Molecular

targeted therapy of glioblastoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 80:1018962019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Malumbres M: Cyclin-dependent kinases.

Genome Biol. 15:1222014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Malumbres M and Barbacid M: Cell cycle,

CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:153–166.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Han Z, Jia Q, Zhang J, Chen M, Wang L,

Tong K, He W, Zhang Y, Zhu W, Qin J, et al: Deubiquitylase YOD1

regulates CDK1 stability and drives triple-negative breast cancer

tumorigenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:2282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zeng K, Li W, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang L,

Zhang W, Xing Y and Zhou C: Inhibition of CDK1 overcomes

oxaliplatin resistance by regulating ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis in

colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23010882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shen J, Gong X, Tan S, Zhang Y, Xia R, Xu

S, Wang S, Zhou H, Jiang Y, Zhao T, et al: CDK1 acts as a

prognostic biomarker associated with immune infiltration in

pan-cancer, especially in gastrointestinal tumors. Curr Med Chem.

32:4836–4857. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xue J, Song Y, Xu W and Zhu Y: The

CDK1-related lncRNA and CXCL8 mediated immune resistance in lung

adenocarcinoma. Cells. 11:26882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sung WW, Lin YM, Wu PR, Yen HH, Lai HW, Su

TC, Huang RH, Wen CK, Chen CY, Chen CJ and Yeh KT: High

nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of Cdk1 expression predicts poor

prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 14:9512014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xi Q, Huang M, Wang Y, Zhong J, Liu R, Xu

G, Jiang L, Wang J, Fang Z and Yang S: The expression of CDK1 is

associated with proliferation and can be a prognostic factor in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Tumour Biol. 36:4939–4948. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang C, Elkahloun AG, Robertson M, Gills

JJ, Tsurutani J, Shih JH, Fukuoka J, Hollander MC, Harris CC,

Travis WD, et al: Loss of cytoplasmic CDK1 predicts poor survival

in human lung cancer and confers chemotherapeutic resistance. PLoS

One. 6:e238492011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

van Nes JG, Smit VT, Putter H, Kuppen PJ,

Kim SJ, Daito M, Ding J, Shibayama M, Numada S, Gohda K, et al:

Validation study of the prognostic value of cyclin-dependent kinase

(CDK)-based risk in Caucasian breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer.

100:494–500. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Piao J, Zhu L, Sun J, Li N, Dong B, Yang Y

and Chen L: High expression of CDK1 and BUB1 predicts poor

prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gene. 701:15–22.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jones MJ and Jones MC: Cell cycle control

by cell-matrix interactions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 86:1022882024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lemmens B, Hegarat N, Akopyan K,

Sala-Gaston J, Bartek J, Hochegger H and Lindqvist A: DNA

replication determines timing of mitosis by restricting CDK1 and

PLK1 activation. Mol Cell. 71:117–128.e113. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ci M, Zhao G, Li C, Liu R, Hu X, Pan J,

Shen Y, Zhang G, Li Y, Zhang L, et al: OTUD4 promotes the

progression of glioblastoma by deubiquitinating CDK1 and activating

MAPK signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 15:1792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Shi YX, Zhu T, Zou T, Zhuo W, Chen YX,

Huang MS, Zheng W, Wang CJ, Li X, Mao XY, et al: Prognostic and

predictive values of CDK1 and MAD2L1 in lung adenocarcinoma.

Oncotarget. 7:85235–85243. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Faienza F, Polverino F, Rajendraprasad G,

Milletti G, Hu Z, Colella B, Gargano D, Strappazzon F, Rizza S,

Vistesen MV, et al: AMBRA1 phosphorylation by CDK1 and PLK1

regulates mitotic spindle orientation. Cell Mol Life Sci.

80:2512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Auvergne RM, Sim FJ, Wang S,

Chandler-Militello D, Burch J, Al Fanek Y, Davis D, Benraiss A,

Walter K, Achanta P, et al: Transcriptional differences between

normal and glioma-derived glial progenitor cells identify a core

set of dysregulated genes. Cell Rep. 3:2127–2141. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sun L, Hui AM, Su Q, Vortmeyer A,

Kotliarov Y, Pastorino S, Passaniti A, Menon J, Walling J, Bailey

R, et al: Neuronal and glioma-derived stem cell factor induces