Introduction

It is estimated that one in four people will develop

cancer at some point in their lives. Cancer is the first or second

leading cause of premature death in many countries, with deaths

occurring before the age of 70 years. In the female population, the

incidence and mortality from breast cancer are increasing rapidly

worldwide, with one in five women being diagnosed with breast

cancer during their lifetime (1).

An estimated 43,170 deaths from breast cancer are expected

worldwide in 2023 (2).

Understanding tumor biology is essential to

elucidate the reasons behind the high incidence of cancer

worldwide, especially breast cancer. Detailed analysis of tumor

pathophysiology allows us to identify the cellular and molecular

processes that contribute to the development and progression of

cancer (3–5). Furthermore, this knowledge is crucial

for identifying biological markers that may influence cancer

progression, enabling the formulation of more effective diagnostic

and therapeutic strategies (6–9).

microRNA (miRNA or miR), a post-transcriptional gene modulating

non-coding small molecule, can target multiple genes, and is key to

tumorigenic progression and immune response (10–12).

In patients with breast cancer, altered miRNAs are

linked to different tumor hallmark pathways including the presence

of Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (13,14).

Among the different types of biomarkers the microRNAs are a strong

candidate to be incorporated into the clinical workflow, due to

their stability in the body fluids used for diagnostic analysis,

making them attractive biological entities (15,16).

Moreover, by investigating the miRNAs that trigger and sustain

tumor growth, may facilitate development of targeted interventions

that aim to improve clinical outcomes and increase patient survival

(17). miR-155 has been linked to

tumor biology in breast cancer and immune response such as the

presence or absence of TILs, demonstrating the strong interplay in

tumour biology (18–20).

In the present review, we appraised the current

understanding of the miRNAs 155 and TILs in the breast cancer

context, more specifically the Triple-Negative subtype. TNBC,

presents, gene expression profiling with intrinsic subtypes of

female breast cancer, which may correspond to distinct etiological

pathways and hold significant therapeutic implications, and impact

mortality risk (21).

BC biology and classification

Tumor biology and pathological

characteristics

The mammary parenchyma comprises ductal epithelium

organized in a bilayer arrangement: The luminal epithelial layer

comprises cuboidal or columnar cells and the basal layer contains

contractile myoepithelial cells. The stromal component is composed

of connective tissue, blood vessels and neural elements (22). While tumors of non-epithelial

origin, such as sarcomas or skin tumors, can arise in the breast,

these cases are rare and not classified as BC despite their

anatomical location (23).

On macroscopic pathological examination, lesions

manifest as firm, grayish white, gritty masses that randomly invade

the surrounding tissue, resulting in an irregular formation, termed

stellate configuration. Microscopically, the lesions demonstrate

cords and nests of tumor cells with cytological features ranging

from indolent to highly malignant. As the malignant cells

infiltrate the mammary stroma and adipose tissue, they induce a

fibrotic response, frequently producing a clinically palpable mass

with radiological density and solid ultrasonographic

characteristics typical of invasive carcinoma (24,25).

Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common

type of BC, accounting for 40–70% of cases. Other histological

subtypes include invasive lobular carcinoma (5–15%), apocrine

carcinoma (4%), mucinous carcinoma (2%), tubular carcinoma (1.6%),

micropapillary carcinoma (0.9–2.0%), metaplastic carcinoma

(0.2–1.0%) and cribriform carcinoma (0.4%). Invasive ductal

carcinoma is also referred to as invasive carcinoma of no special

type or invasive carcinoma not otherwise specified (4).

Certain invasive lobular carcinomas exhibit

macroscopic features similar to those of invasive ductal carcinoma.

Consequently, immunohistochemical analysis is necessary to evaluate

the expression of E-cadherin protein, which mediates epithelial

cell adhesion. This protein demonstrates positive expression in

ductal tumors while being characteristically absent in lobular

neoplasms (26).

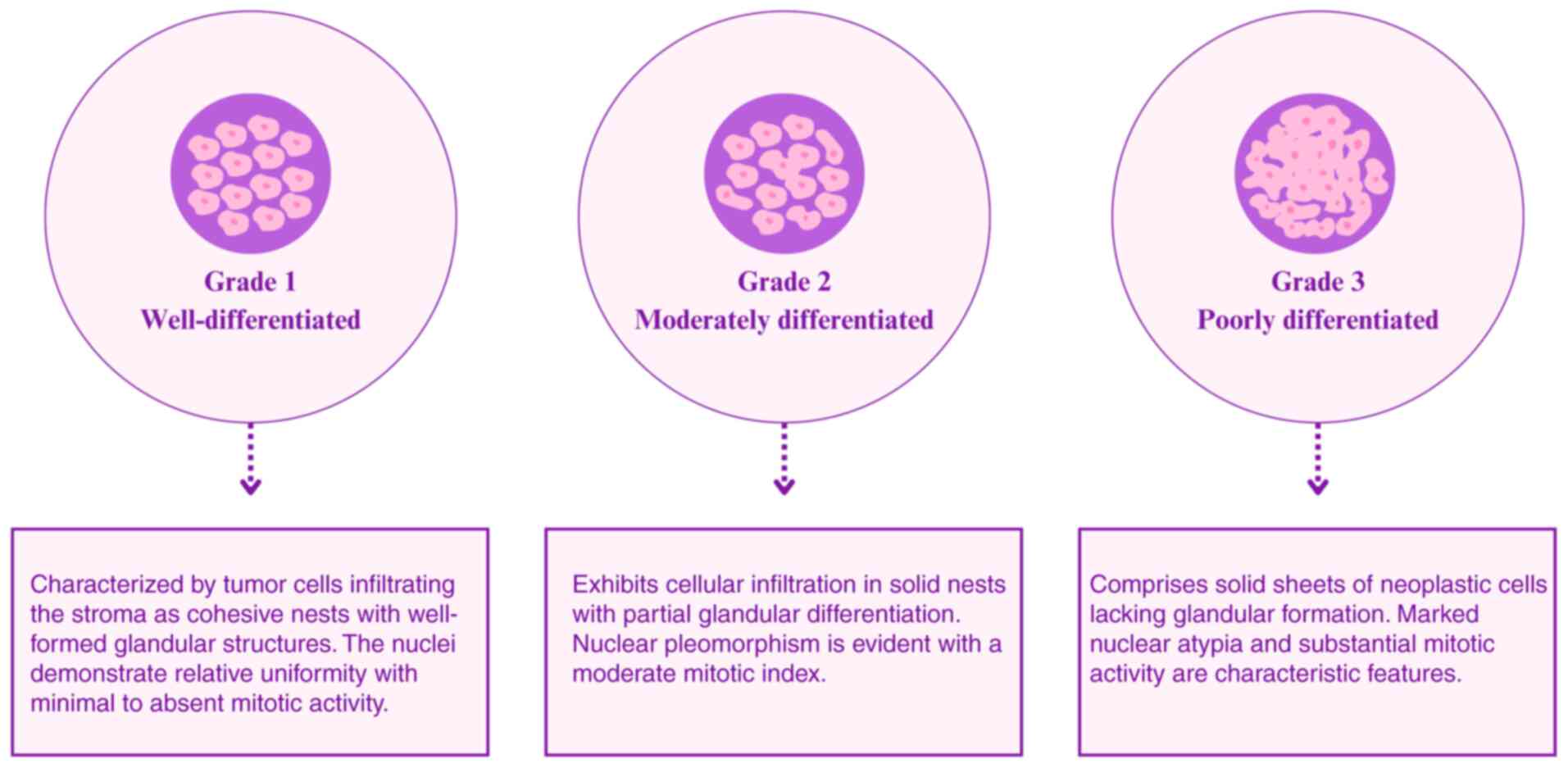

Invasive carcinomas are classified into three

distinct grades based on a comprehensive evaluation of

architectural and cytological features. This classification is

performed using a standardized scoring system that reflects the

degree of cell differentiation (Fig.

1) (27). Histological analysis

at the molecular level is key to grading invasive carcinoma.

Histopathological classification

The histological classification of BC is key for

tumor characterization (Table I).

Moreover, molecular markers serve a pivotal role in guiding

appropriate therapeutic strategies. The molecular classification

system developed by Perou et al (28) remains widely implemented in

contemporary clinical practice.

| Table I.Histological subtypes of breast

cancer. |

Table I.

Histological subtypes of breast

cancer.

| Characteristic | Invasive breast

carcinoma of no special type | Invasive lobular

carcinoma | Invasive mucinous

carcinoma | Rare entities |

|---|

|

Characterization | Heterogeneous group

that cannot be categorized into any other group | Tumor cells that

are discohesive and typically arranged in a single file or

Indian-file pattern, often distributed across a desmoplastic

stroma. | Cluster of low- to

moderate-grade tumor cells floating in a pool of extracellular

mucin. | Tubular carcinoma

Cribriform carcinoma Mucinous carcinoma Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma

Carcinoma with apocrine differentiation Metaplastic carcinoma |

| Frequency of

cases | 80% | 5–15% | 2% | 1% |

| Biomarkers | ER and HER2 | ER+,

HER2− and aberrant E-cadherin | ER+,

PR+ and HER2− | Varies according to

cancer subtype |

The diverse spectrum of BC encompasses distinct

molecular subtypes, exhibiting specific characteristics that guide

therapeutic strategies. Consequently, all newly diagnosed BC must

undergo immunohistochemistry (IHC) to identify the expression of

estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). This molecular

characterization provides essential information for both prognostic

assessment and therapeutic decision-making (Table II) (29).

| Table II.Molecular subtypes of breast cancer

based on receptor status (ER, PR, HER2), proliferation index

(Ki-67), histological grade and clinical parameters. |

Table II.

Molecular subtypes of breast cancer

based on receptor status (ER, PR, HER2), proliferation index

(Ki-67), histological grade and clinical parameters.

|

|

| Luminal B |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | Luminal A | HER2- | HER2+ | HER2+ | TN |

|---|

| Biomarkers | ER+ | ER+ | ER+ | ER- | ER- |

|

| PR+ | PR- | PR-/+ | PR- | PR- |

|

| HER2- | HER2- | HER2+ | HER2+ | HER2- |

|

| Ki-67 low | Ki-67 high | Ki-67 low/high | Ki-67 high | Ki-67 high |

| Frequency of

cases | 40–50% | 20–30% |

| 10–20% | 15–20% |

| Target Therapy | Tamoxifen | Tamoxifen |

| Herceptin | - |

| Response to

Therapies | Endocrine | Endocrine

Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

| PARP

Inhibitors |

| Prognosis | Good | Intermediate |

| Poor | Poor |

| Observations | Controlled cell

growth | Fast cancer cell

growth | Overexpression of

HER2; Faster growth than luminals subtypes | Aggressive subtype;

occurs more often in younger women; highest association with BRCA1

mutations |

A tumor is considered positive for ER and PR when

these receptors are present in >1% of tumor cells, representing

~80% of BC cases (30). HER2

upregulation occurs in 15–20% of patients and is characterized by

intense membrane staining in >10% of invasive tumor cells (IHC

3+) or by HER2 gene amplification, determined through fluorescence

in situ hybridization (FISH), with a HER2/chromosome 17 centromeric

probe ratio ≥2.0 and ≥4 HER2 copy signals/cell. Tumors that do not

express any of these factors are classified as triple-negative

(TN)BC, corresponding to 10–15% of cases (31).

Hormone receptor-positive

(HR+) tumors

Tumors that test positive for the hormone receptors

estrogen (ER) or progesterone (PR) are classified as hormone

receptor-positive (HR+) and are typically categorized as luminal

subtypes, according to Perou et al (28). The receptors are located in target

cells and serve as ligand-dependent transcription factors. When

estrogen or an estrogen analog bind ER in the cell nucleus, a

conformational change occurs in the binding domain, enabling

interactions with coactivators if the ligand is an agonist and

blocking these interactions if it is an antagonist, thereby

affecting the transcription rates of estrogen-responsive genes

(32).

The updated American Society of Clinical

Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines established

that cancers with ER-positive staining in 1–10% of cells should be

classified as ER low positive (33). Limited data currently supports

endocrine therapy in this context, as these tumors typically

exhibit behavioral patterns more closely resembling TN rather than

luminal BC (34).

Superexpressing HER2 tumors

The HER2 oncogene belongs to the epidermal growth

factor receptor family. These receptors play a fundamental role in

activating signal transduction pathways responsible for epithelial

cell proliferation and differentiation, as well as angiogenesis

(35). High levels of HER2

expression indicate that patients may benefit from

receptor-targeted therapies.

HER2 is primarily identified through western

blotting, ELISA or IHC. In cases of indeterminate results,

alternative techniques may be employed, including ISH, FISH,

chromogenic or silver-enhanced ISH or PCR (36). HER2 expression is classified as

negative (IHC 0/1+), indeterminate (IHC 2+), or positive (IHC 3+)

based on staining intensity and tumor cell percentage, with

indeterminate and positive results requiring confirmatory testing

(30).

TNBC

TNBC refers to BC that does not express ER and PR,

or with IHC staining levels <1%. Additionally, the HER2 status

is 0 or 1+, with negative hybridization (FISH) for HER2+

expression (37).

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is considered

more aggressive than other breast cancer subtypes. It lacks

specific targeted therapies, such as hormone therapy used for

luminal tumors or anti-HER2 agents indicated for HER2 IHC 3+ cases.

TNBC accounts for approximately 15% of breast cancer diagnoses

worldwide and is more frequently observed in female patients under

the age of 40 years (21).

TNBC is characterized by distinct risk factors

supported by epidemiological evidence (38). BRCA mutations, particularly in

BRCA1, are found in up to 20% of patients with TNBC, indicating a

notable genetic predisposition. Also, African-American patients

demonstrate higher susceptibility compared with Caucasian patients,

as documented in population-based studies (39,40).

Premenopausal status is also a relevant risk factor (21). The absence of targeted therapies for

TNBC has driven extensive research to identify predictive

biomarkers for treatment response (41–43).

Investigations into immune system interactions with TNBC have

yielded notable insights into treatment responsiveness (44–46).

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in

BC

Role of TILs in tumor progression and

clinical value

Tumor biological behavior is influenced by its

intrinsic characteristics and the tumor microenvironment, which

interacts with the cancerous cells. This environment is formed by

various structures and substances, such as vessels, fibroblasts,

myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells (47).

Genetic alterations leading to malignancy are common

in somatic cells, and the immune system serves a crucial role in

the elimination or inactivation of abnormal cells. Studies in mice

have demonstrated an increased incidence of malignant neoplasms in

immunodeficient individuals, highlighting the importance of

immunity in cancer prevention (48–50).

TIL-mediated immunoediting:

Elimination and escape mechanism

TILs are used for tumor classification in the

clinical setting. These lymphocytes dynamically engage with other

immune system and cancer cells, termed cancer immunoediting cell

neoplasia, serving roles that can be either favorable or

detrimental to the tumor (51).

This process comprises three phases: Elimination, equilibrium and

escape (52). The elimination phase

occurs when tumor antigens are presented to CD8+

cytotoxic lymphocytes by cells, in combination with human leukocyte

antigen molecules for recognition by the T cell receptor (53). Most TILs in cancer are of T cell

phenotype, including CD4+ lymphocytes (helper cells) and

CD8+ (cytotoxic cells). CD4+ T lymphocytes

are essential for priming tumor-specific CD8+ TILs, in

addition to supporting their expansion and memory (54). Tumor elimination also involves the

action of natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages in antigen

identification. NK cells target tumor cells that have managed to

escape from cytotoxic lymphocyte control (55).

During the equilibrium phase, the FOXP3 protein

plays a critical role in the generation of CD4+

regulatory T cells (Tregs), which promote immunosuppression,

resulting in immunological tolerance for CD8+ cells.

Excessive FOXP3 expression is associated with Treg proliferation

and severe immunodeficiency, while its absence leads to immune

system activation. FOXP3 is also involved in immune escape

mechanisms, with impacts on low survival in breast cancer, as it

acts by decreasing the immune response in the tumor (56). In the equilibrium phase, the tumor

microenvironment presents a high proportion of cytotoxic cells and

a low proportion of Tregs due to decreased FOXP3 protein, allowing

progression to the next phase (57).

The third stage of the process is immune system

evasion, which can occur through decreased immunological

recognition due to antigen loss in neoplastic cells, increased cell

resistance or survival, reducing apoptosis through STAT3 or BCL-2

activation and development of an immunosuppressive

microenvironment. The latter involves the expression of cytokines

(VEGF, IL-10, TGF-β) and immunoregulatory molecules, including the

B7 family and CD3 expression (52).

The B7 family comprise the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1),

also known as CD279, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), cytotoxic

T-Lymphocyte associated protein 4 CTLA-4, V-domain Ig suppressor of

T cell Activation (VISTA), B7 homolog 4 and B and T Lymphocyte

Attenuator (BTLA).

Prospective use of TILs in precision

oncology

Characterization of immune evasion mechanisms

expands prognostic and therapeutic frameworks in oncology.

PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition has demonstrated substantial

efficacy across multiple malignancies, like cutaneous squamous cell

carcinoma, with notable response rates in TNBC (58). This approach exemplifies successful

translation of immunobiological mechanisms into effective clinical

intervention (59). Similarly,

CTLA-4 blockade improves survival outcomes in patients with

melanoma (60). Recent

investigations have identified microRNA (miRNA or miR)-155 as a key

immunomodulatory factor influencing effector T cell function and

potentially predicting therapeutic response (18,61–63).

Integration of multidimensional biomarkers, including PD-L1

expression, tumor mutational burden, microsatellite instability,

miR-155 profile and TIL quantification, provides essential

stratification parameters, enabling precision in patient selection

and treatment optimization protocols (18).

T cell activation requires interaction between

complementary costimulatory molecules (B7 on antigen-presenting

cells and CD28 on T cells), providing essential secondary

signaling. Optimal T cell activation depends on the synchronous

delivery of both antigenic peptide recognition and costimulatory

signaling (64). In the absence of

co-stimulation, antigenic peptide presentation fails to induce

complete T cell activation, instead promoting immunological

tolerance (65). The degree of T

cell activation is determined by the balance between co-stimulation

and co-suppression. Clinical trials have demonstrated that PD-1

pathway blockade with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy enhances T

cell-mediated anticancer responses without causing serious adverse

events (66,67).

Beyond intrinsic T cell regulation, their activation

is influenced by extrinsic factors. Cytokines such as IL-2,

released by CD4+ T helper (Th) cells (Th1 and Th17),

serve a direct role in promoting the expansion of cancer-specific T

cells (68). However, these

regulatory cells inhibit specific T cell function, inducing

immunosuppression and decreasing immunotherapy efficacy (69).

TILs Working Group consider breast carcinomas rich

in inflammatory infiltrates when they exhibit >50% lymphocytic

presence in the tumor stroma (70).

A previous study showed that, in this context, TNBC is associated

with improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival

(OS) (42). A meta-analysis

including >22,000 patients demonstrated the presence of

CD8+ lymphocytes is associated with favorable prognosis,

while FOXP3 expression is associated with lower OS and PFS rates

(71).

In tumors treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy,

high TIL levels favor the achievement of pathological complete

response (pCR) (72,73). A study involving 3,771 patients with

different molecular subtypes of BC undergoing neoadjuvant

chemotherapy classified TIL expression into three categories

(74): Low (0–10%), intermediate

(11–59%) and high (60–100%). In patients with luminal cancer, pCR

occurred in 45 (6%) of 759 patients with low TILs, 48 (11%) of 435

with intermediate TILs and 49 (28%) of 172 with high TILs. In

HER2-positive subtype, pCR was observed in 194 (32%) of 605

patients with low TILs, 198 (39%) of 512 with intermediate TILs and

127 (48%) of 262 with high TIL levels. In patients with TNBC, pCR

was achieved in 80 (31%) of 260 patients with low, 117 (31%) of 373

with intermediate and 136 (50%) of 273 with high TIL levels. In

univariate analysis, a 10% increase in TILs demonstrated a hazard

ratio of 0.93 for disease-free survival (DFS) and 0.92 for OS in

TNBC, showing negative results in other tumor subtypes (74).

A study of 1,966 patients with TNBC revealed a 94%

recurrence-free survival (RFS) and 95% OS rate in stage I patients

with TIL levels ≥50% with TNBC (75). In patients with TIL levels <30%,

RFS and OS rates were 78 and 82%, respectively, in patients who did

not undergo neoadjuvant therapy. These results confirm TIL

abundance in tissue as a notable prognostic factor for patients

with TNBC (75).

The clinical evidence regarding the prognostic and

predictive value of TILs in BC, particularly in TNBC, affirms their

potential use as a clinically actionable biomarker (76). However, the implementation of TILs

assessment in routine clinical practice necessitates standardized

methodological approaches and clearly defined threshold values for

optimal patient stratification. Given the continuous nature of TIL

measurements and their varying importance across molecular

subtypes, establishing clinically relevant cut-off values is a key

step toward integrating this immunological parameter into treatment

decision protocols.

Clinically relevant cut-off values for TILs

in pre-neoadjuvant biopsy samples

Proportion of TILs in BC

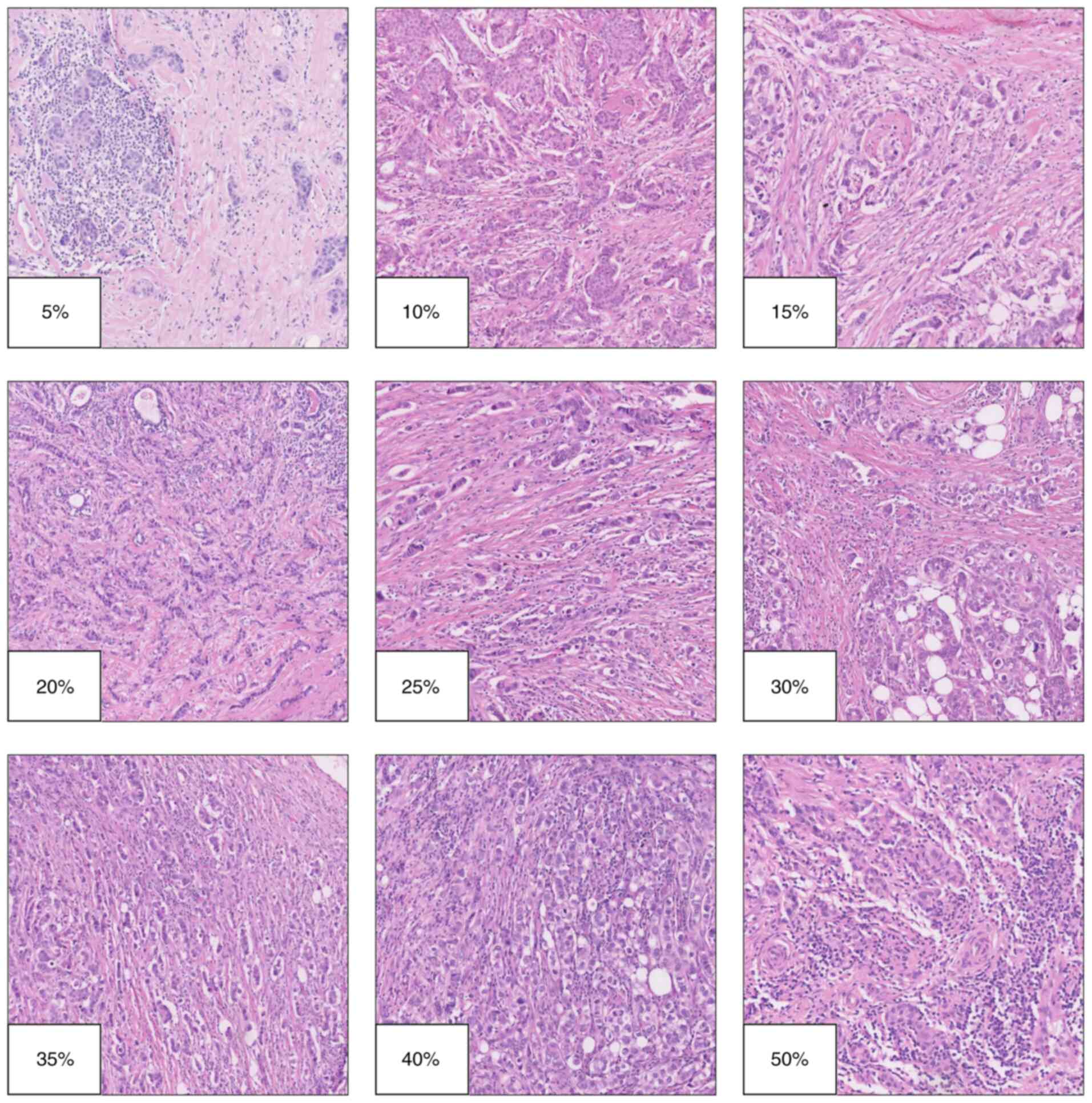

Numerous critical aspects must be considered when

analyzing TILs. First, the pathologist-reported value refers to the

percentage of TILs. The proportion of TILs represents the area of

tumor stroma infiltrated total lymphocytes relative to the total

area of stroma examined by the pathologist and should be measured

using the hematoxylin-eosin method (Fig. 2). Adherence to recommendations by

the TILs Working Group is essential for accuracy and

reproducibility (70,77).

Higher levels of lymphocytic infiltration serve as

predictors of pCR (78). However, a

formal recommendation of a clinically relevant cut-off value

categorizing breast tumors as having high lymphocytic infiltration

is lacking, complicating the establishment of a universal standard

for this variable as a therapeutic response biomarker.

Meta-analyses reveal cut-off values ranging from 10 to 60%

(79,80).

The relevance of high TILs as biomarkers of good

therapeutic response has more clinical value for TN tumors compared

with other BC subtypes (81). Ochi

et al (82) categorized

tumors into three groups: Low TILs (0–9%), intermediate (10–49%)

and high TILs (≥50%), the latter being known as

lymphocyte-predominant (LP)BC. The pCR rates in TN tumors with low

TILs are 4%, compared with 43.6% in those with intermediate or high

TILs. In HER2-positive tumors, pCR rates are 26 vs. 51.9%,

respectively, and significant in both cases (82). Loi et al (83) observed higher TILs in TNBC (n=134)

and HER2+ (n=209) compared with luminal BC subtypes

(n=591) (83). The second quartile

median of TILs expression was 25.0, 15.0 and 7.5% for these tumor

types, respectively. Despite substantial variability in

infiltration percentages for TNBC, HER2+ and luminal

groups, the upper quartile showed 40.0, 30.0 and 12.5%

infiltration, respectively. This aligns with findings of Stanton

et al (78,84), which demonstrated TNBC and

HER2+ as most frequent subtype of LPBC (78,84)

Denkert et al (74)

reinforced these findings, reporting high TIL percentages (>60%)

in 30% of TNBC tumors, 19% in HER2+ and 13% in

luminal-HER2-negative tumors (74).

Loi et al (83) identified

TILs (LPBC with a cut-off ≥50%) as predictors of good prognosis for

distant disease-free survival in TNBC but not in HER2+

or luminal BC (83). Additionally,

Russo et al (85) supported

these findings by using TILs ≥30% for LPBC classification, a

cut-off derived from Liu et al (86). In an analysis of 41 TNBC samples,

Russo et al (85) found that

34% had TILs >30%, with a pCR rate of 78.6% (11/14) compared

with 14.8% (4/27) in those with TILs <30%. Furthermore, a

significant pCR rate of 71.4% was noted in HER2+

individuals with TILs >30%.

Thresholds for LPBCs: Issues and

sensitivity limitations

A fundamental aspect of using TILs for prognosis is

determining the appropriate percentage of lymphocytic infiltration

that characterizes LPBCs. A widely accepted cut-off value is 50%

for high lymphocytic infiltration, as recommended by the TILs

Working Group (70). Establishing

this threshold is key for accurately identifying LPBCs, which can

impact treatment decisions and prognostic evaluation.

Salgado et al (70) proposed LPBC classification for

tumors with ‘more lymphocytes than tumor cells’, meaning they

exhibit 50–60% lymphocytic infiltration (70). Denkert et al (87) reported that 40% of patients with

LPBC (>50% TILs) achieved pCR, compared with 7% of patients

without lymphocytic infiltration (87). Cut-off values of 50 or 60% predict

both short-term pCR responses and long-term OS and DFS (Table III) (82,83,88–91)

.

| Table III.TIL thresholds and study

characteristics. |

Table III.

TIL thresholds and study

characteristics.

| First author(s),

year | Cut-off value,

% | Breast

subtypes | Lymphocyte

type | Number of

patients | Duration of

follow-up, months | Evaluation

indicator | Country | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Dieci et al,

2014 | 60 | TNBC | All | 278 | 76 | OS, DFS | France | High-TIL (n=27):

91% 5-year OS (95% CI, 68–97%). Low-TIL: 55% 5-year OS (95% CI

48–61%) | (88) |

| Loi et al,

2019 | 50 | HER2+,

HR+, TNBC | All | 1,010 | 62 | OS, DFS | Australia | TNBC (n=134): 10%

increase in TILs associated with decreased distant recurrence (HR

0.77, 95% CI 0.61–0.98, P=0.02). | (95) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HER2+ BC

(n=209): 10% increase in lymphocytic infiltration associated with

decreased distant recurrence in trastuzumab-treated patients (P=

0.025). |

|

| Ochi et al,

2019 | 50 | HER2+,

TNBC | All | 209 | 120 | DFS, pCR | Japan | Low pre-NAT TILs

associated with lower pCR rate: TNBC (4.0 vs. 43.6%);

HER2+ BC (26.0 vs. 51.9%). | (82) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In TNBC with RD:

Low pre-NAT TILs associated with shorter RFS (HR 3.844, P=0.024).

Low post-NAT TILs demonstrate a non-significant association with

shorter RFS (HR 2.836, P=0.061). No association between TIL change

and RFS in TNBC or HER2+ BC |

|

| Cerbelli et

al, 2017 | 50 | TNBC | All | 54 | - | pCR | Italy | pCR achieved in 35%

of cases. Univariate analysis: PD-L1 expression in ≥25% of

neoplastic cells associated with pCR (P=0.024). ≥50% sTILs

associated with higher pCR frequency (P<0.001). Multivariate

analysis: PD-L1 expression on tumor cells significantly associated

with pCR (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01–1.27). | (91) |

| Van Bockstal et

al, 2020 | 40 | HER2+,

TNBC | All | 35 | 8 | pCR | Belgium | High sTILs (≥40%)

significantly associated with increased pCR rate | (92) |

| Loi et al,

2014 | 30 | TNBC | All |

2,148a | >78 | DFS, OS | Australia, France,

Italy, Finland, Belgium, Germany and USA | 736 iDFS and 548

D-DFS events; 533 deaths. sTILs are a significant prognostic

biomarker for: iDFS (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.83–0.91, P<0.001), D-DFS

(HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.79–0.88, P<0.001), OS (HR 0.84, 95% CI

0.79–0.89, P<0.001) Node-negative patients with sTILs ≥30%,

showed the following outcomes at 3 years outcomes: iDFS, 92% (95%

CI 89–98%), D-DFS, 97% (95% CI 95–99%), OS, 99% (95% CI

97–100%) | (83) |

| Park et al,

2019 | 30 | TNBC | All |

476b | 96 | DFS, OS | France, Italy, | A total of 107

deaths, 173 iDFS and 118 D-DFS events. sTILs have independent

prognostic value for iDFS | (96) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| South Korea | (HR 0.90, 95% CI

0.82–0.97, P<0.01), D-DFS (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77–0.95,

P<0.01), OS (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79–0.98, P=0.015). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Patients with stage

I tumors and sTILs ≥30% (n=74) had the following 5-year outcomes:

iDFS, 91% (95% CI 84–96%), D-DFS, 97% (95% CI 93–100%), OS, 98%

(95% CI 95–100%). |

|

| Russo et al,

2019 | 30 | HER2+,

TNBC | All | 187 | 62.5 | OS, pCR | Venezuela | pCR rate: TILs ≥30%

= 58.5% (odds ratio, 8.85); TILs <30% = 11% (P<0.001) | (85) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Association in

HER2+ and TN subtypes. No association between TILs and

OS (P=0.834) or DFS (P=0.937) |

|

| Floris et

al, 2021 | 30 | TNBC | All | 445 | 91.56 | pCR | Belgium | High sTIL

associated with pCR in lean (OR 4.24; 95% CI 2.10–8.56, P<0.001)

but not heavier patients (OR 1.48, 95% CI 0.75–2.91, P=0.26) | (93) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| High sTIL

associated with increased event-free survival in lean patients (HR

0.22, 95% CI 0.08–0.62, P=0.004) but not heavier patients (HR 0.53,

95% CI 0.26–1.08, P=0.08) Similar results for OS |

|

| Dieci et al,

2020 | 30 | TNBC | All | 244 | 81.6 | pCR | Italy | TILs confirmed as

independent prognostic factor. PD-L1 is a prognostic biomarker: LR

χ2 4.60, P=0.032 (model with classical factors,

including age, stage, histological grade and TIL 10% increments).

LR χ2 6.50, P=0.011 (model with classical factors and

TIL >30 vs. <30%). | (94) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In patients treated

with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, FOXP3 is a prognostic biomarker in

addition to classical factors, including age, stage, histologic

grade -, TILs, and pCR (LR χ2 5.01, P=0.025). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In patients without

pCR, CD8 and PD-L1 expression significantly increase from baseline

to residual disease |

|

| Jimenez et

al, 2022 | 20 | TNBC | All | 80 | - | pCR | USA | 38/145 extracted

MRIRF significantly associated with pCR; 5 non-redundant imaging

features. | (215) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MRIRF model

accuracy (P=0.001, 72.7% PPV, 72.0% NPV). TIL model accuracy

(P=0.038; 65.5% PPV, 72.6% NPV). Combined MRIRF and TIL model has

improved prognostic accuracy (P<0.001, 90.9% PPV; 81.4%

NPV)-AUC: 0.632 (TIL); 0.712 (MRIRF); 0.752 (TIL + MRIRF). |

|

| Asano et al,

2018 | 10 | HER2+,

TNBC | All | 177 | 40 | OS, DFS, pCR,

HR | Japan | High-(n=96) vs.

low-TIL (n=81): TNBC and HER2+ BC more frequent (P<0.001 and

P=0.040, respectively); higher pCR rate (P=0.003). | (216) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In TNBC and HER2+

BC, pCR rate is higher in high-TIL group (P=0.013 and P=0.014,

respectively). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Multivariable

analysis: High-TIL status independently predicts favorable

prognosis (HR=0.24, P=0.023 and HR=0.13, P=0.036). Biopsy specimens

from local recurrence following NAT show decreased TIL. |

|

| Song et al,

2017 | 10 | TNBC | All, T, B | 180 | 34.9 | DFS, pCR | Korea | Mean number of HEVs

in pre-NAT biopsy, 12 (range, 0–72). TILs, TLSs, HEV density and

CXCL13 expression are associated with each other | (217) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Higher

CD8+ cell density and CXCL13 expression are

significantly associated with better DFS rate |

|

| Khoury et

al, 2018 | 46 | HER2+,

TNBC luminal | All | 331 | - | pCR | Canadian | pCR rate: TBNC

30.9% (29/95); HER2+ 32.5% (25/77); Luminal 5.6%

(9/159) | (218) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Independent

predictors of pCR: Luminal subtype iTIL (OR=1.44, 95% CI 1.08–1.9,

P=0.013), TNBC subtype sTIL (OR=1.68, 95% CI 1.29–2.18, P=0.001)

and iTIL (OR=1.31, 95% CI 1.05–1.63, P=0.017). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HER2+

subtype: sTIL and iTIL do not predict pCR. |

|

| Ruan et al,

2018 | 20 or 10 | TNBC | All | 166 | - | pCR | China | Univariate logistic

regression analysis: sTILs (P=0.0001) and iTILs (P=0.001) are

associated with pCR. Multivariate logistic regression analysis:

sTILs (P=0.006) and iTILs (P=0.04) independent predictors of pCR

ROC curve analysis of TNBCs with >20% sTILs (P=0.001) or >10%

iTILs (P=0.003) associated with higher pCR rate. Multivariate

analysis: 20% sTILs (P=0.005) independently predicts pCR | (219) |

Using a >50% TIL cut-off as a significant

infiltration marker has limitations regarding sensitivity, as

relatively few breast tumors reach this cut-off. Stanton et

al (78,84) found that ~20% of TN and

HER2+ tumors exhibit LPBC with >50% TILs (78,84).

Denkert et al (47) assessed

3,771 samples, reporting pCR in 50% of high-TIL TNBC tumors and 48%

of high-TIL HER2+ tumors (>60% TILs) (74). pCR rates for TNBC and

HER2+ with intermediate infiltration (11–59%) were 31

and 39%, respectively. Hence, a cut-off between 11 (low

infiltration) and 50% (high infiltration) could enhance sensitivity

for identifying individuals with favorable prognosis without

compromising the discriminative accuracy.

Comparison of accuracy and sensitivity

in LPBCs using lymphocyte infiltration thresholds between 30 and

50%

Studies have used cut-offs between 30 and 50% for

defining LPBC (Table III). An

analysis from Belgium employed a 40% cut-off (92), while other studies in Venezuela,

Belgium and Italy used a 30% cut-off (85,93,94).

The prognostic significance of TILs in early-stage TNBC was

demonstrated by two pivotal multicenter studies (95) (96).

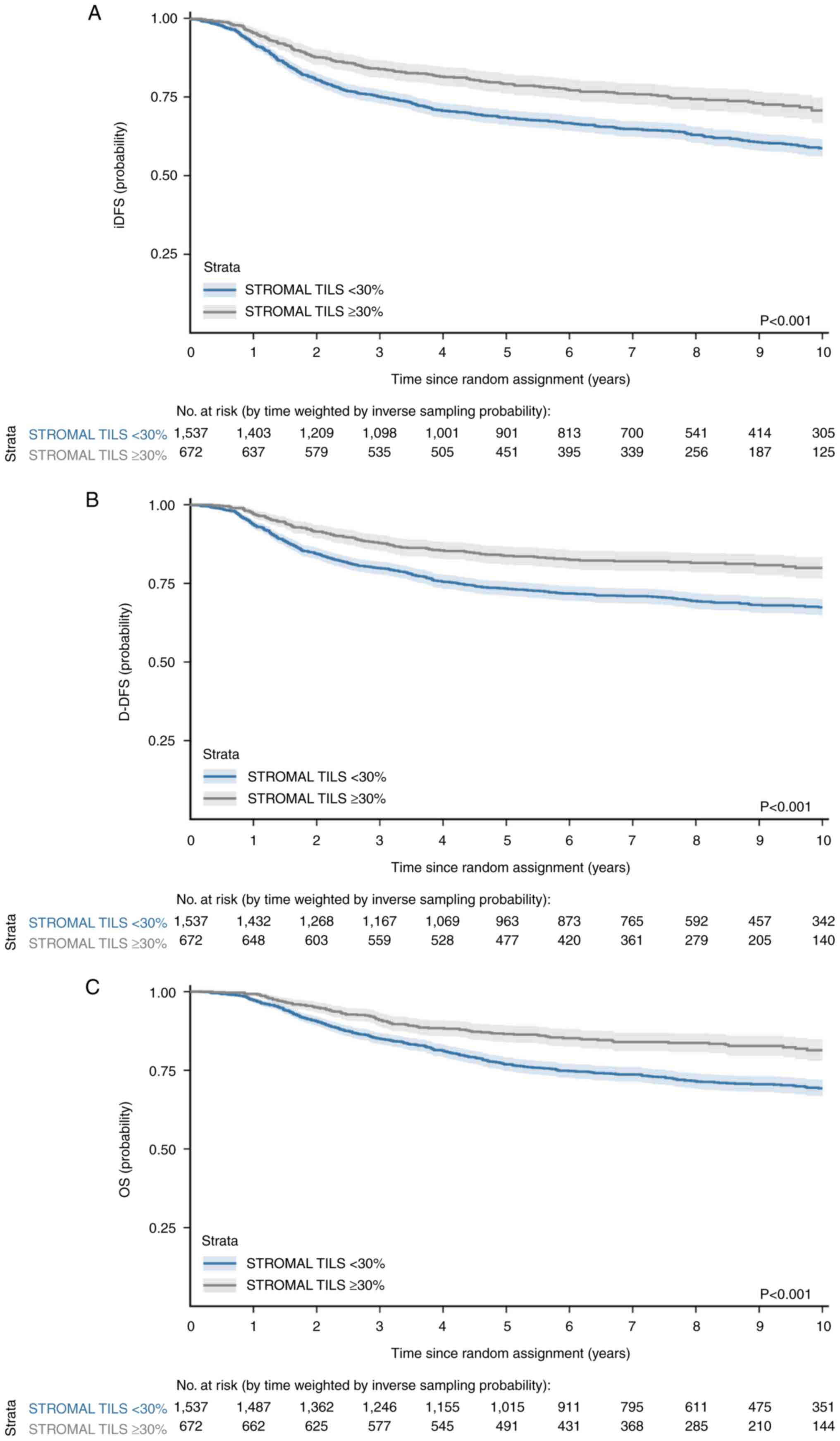

Firstly, a retrospective individual patient data (IPD)

meta-analysis was conducted using data from 2,148 early-stage TNBC

patients across 9 international studies from Australia, Europe

(France, Italy, Finland, Belgium, Germany), and the United States.

The analysis demonstrated that a stromal TIL cut-off of ≥30% was

associated with significantly better prognosis in early-stage TNBC

patients (95). The second study

was a retrospective pooled analysis of 476 early-stage TNBC

patients from 4 centers who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy,

showing that Stage I patients with sTILs ≥30% had excellent 5-year

survival (91–98%) without any systemic treatment (96). The former study evaluated invasive

(i)DFS (primary endpoint), distant (D-)DFS and OS, treating TILs as

a continuous variable. Treatments included either an anthracycline

or a combination of anthracycline and taxane. Patients with

node-negative TILs ≥30% showed three-year iDFS of 92% (95% CI,

89–98%), D-DFS of 97% (95% CI, 95–99%) and OS of 99% (95% CI,

97–100%; Fig. 3). The

aforementioned study recommend integrating TILs into

clinical-pathological diagnostic models (97). In 2,148 individuals, TIL exhibited

an interquartile range from 10 to 30%, with a median of 15%.

Notably, about one-third of patients showed ≥30% TILs, broadening

the pool of individuals benefiting from the biomarker compared with

studies using 50% TILs, which was present in one-fifth of patients

(78,84). The 30% cut-off aligns with Q3

indicating 30% lymphocytic infiltration as the threshold parameter

(95).

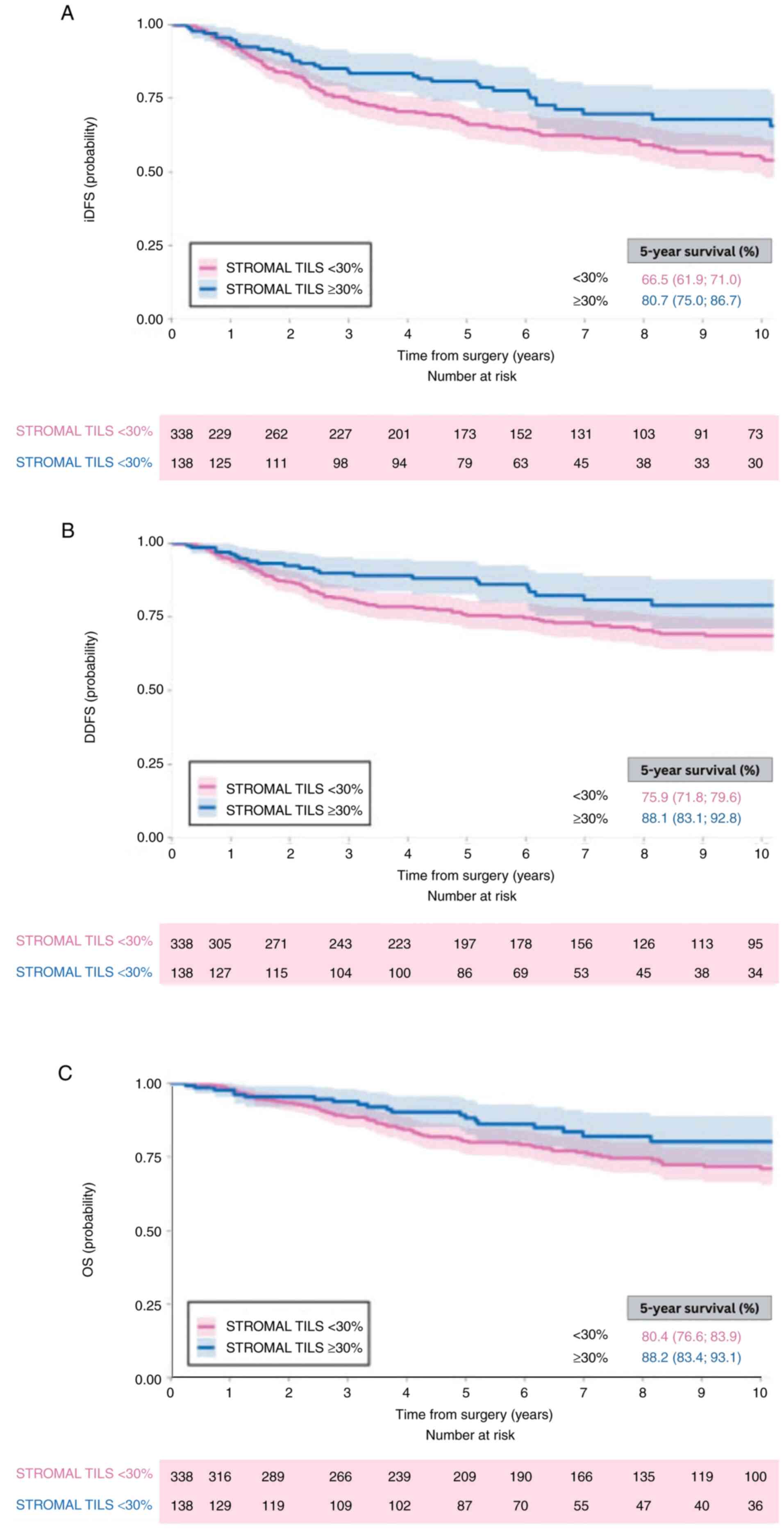

Park et al (96) investigated whether TILs ≥30%

identify those who might not require adjuvant chemotherapy

(96). Patients with stage I TNBC

(n=74) presented a 5-year iDFS of 91% (95% CI 84–96%), D-DFS of 97%

(95% CI 93–100%) and OS of 98% (95% CI 95–100%; Fig. 4). The aforementioned study used the

Q3-based cut-off of 30%, consistent with Loi et al (95). Compared with the aforementioned

study, the median was lower (10 vs. 15%), while the third quartile

remained at 30%, confirming its consistency. Stromal TILs ≥30%

could signify a subgroup of patients with stage I TNBC with

excellent prognosis without adjuvant therapy. This suggests

vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or those with comorbidities,

may be spared from the toxicity and costs of adjuvant chemotherapy

without jeopardizing survival rates. Moreover, TIL evaluation at

30% may yield good reproducibility among pathologists, as at this

level, visual differences are easier to be detected. Nonetheless,

the use of biomarkers necessitates caution concerning established

clinical diagnostic criteria, such as tumor size and lymph node

status, to refine pathological analysis and therapeutic insights

for each clinical case (98).

Russo et al (85), Floris et al (93) and Dieci et al (94) demonstrated good discriminative

capacity with a TIL cut-off of 30% (85,93,94).

Russo et al (85) reported a

five-fold greater incidence of pCR for patients with TILs ≥30%

compared with those with TILs <30% (58.5 vs. 11.0%) (85).

TIL thresholds of 30 or 50% not only serve as

promising biomarkers for guiding chemotherapy de-escalation in

early-stage TNBC, but also inform therapeutic decisions regarding

immune checkpoint inhibitors. Measuring TIL and PD-L1 expression

aids in identifying immune-enriched tumors, thereby enhancing

selection of patients with advanced TNBC or HER2+ BC who

are likely to respond to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (99).

Comparative analyses between 30 and

50% thresholds for LPBCs

The recommendation to adopt 30 or 50% as clinical

cut-off values for LPBCs is based on their predictive value for pCR

and favorable prognostic outcomes in BC. TILs ≥50% are associated

with both short-term pCR responses and long-term OS as well as DFS

(82,83,88–91).

This threshold was initially proposed by the TILs Working Group

(70).

Further studies have indicated that cut-off values

<50% can also predict favorable prognosis, with the majority

using 30% as the cut-off value (85,93,94).

Specifically, two studies employed TILs ≥30%: The first identified

patients who would benefit from adjuvant therapy, while the second

identified individuals with a favorable prognosis who may not

require adjuvant chemotherapy (95,96).

In conclusion, both cut-off values for LPBCs are

effective in identifying patients who are likely to benefit from

therapeutic intervention. The 30% threshold is particularly

inclusive, enabling the identification of a broader patient

population compared with the stricter 50%, which is less frequently

achieved in clinical practice (78,84).

miR-155 and TIL activity

The prognostic value of TILs in TNBC is mediated

through complex molecular regulatory networks. Post-transcriptional

gene regulation via miRNAs is a critical mechanism in the

modulation of the tumor inflammatory landscape, with miR-155

emerging as a key mediator. miRNAs are a class of small,

non-coding, single-stranded RNAs, typically 18–25 nucleotides in

length, that play a crucial role in the post-transcriptional

regulation of gene expression. By directly binding to the 3′

untranslated regions (UTRs) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs),

miRNAs promote mRNA degradation or inhibit translation (100,101). This control of protein synthesis

allows miRNAs to function as modulators of gene expression rather

than as complete silencers (100,101).

Biogenesis and function

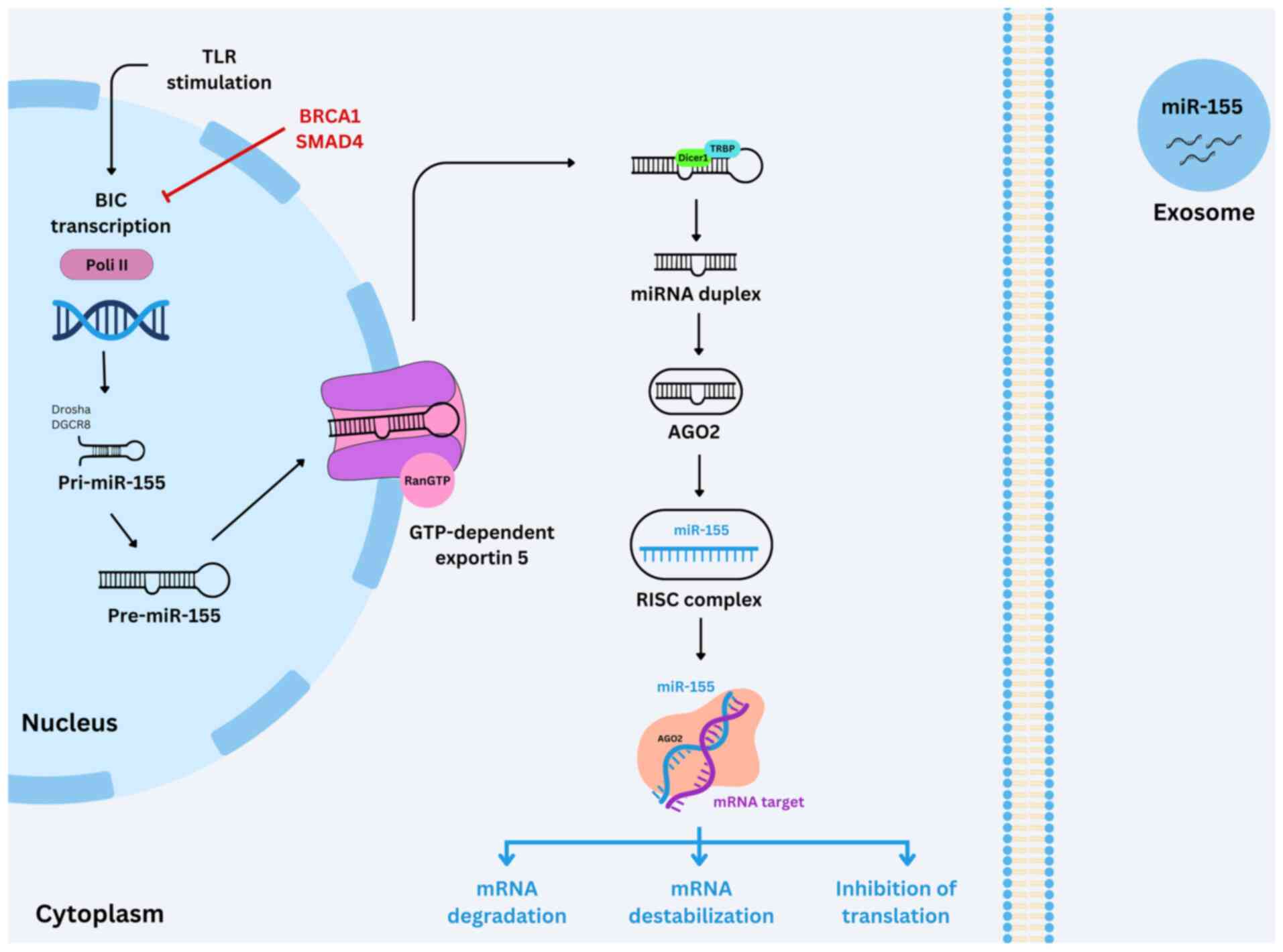

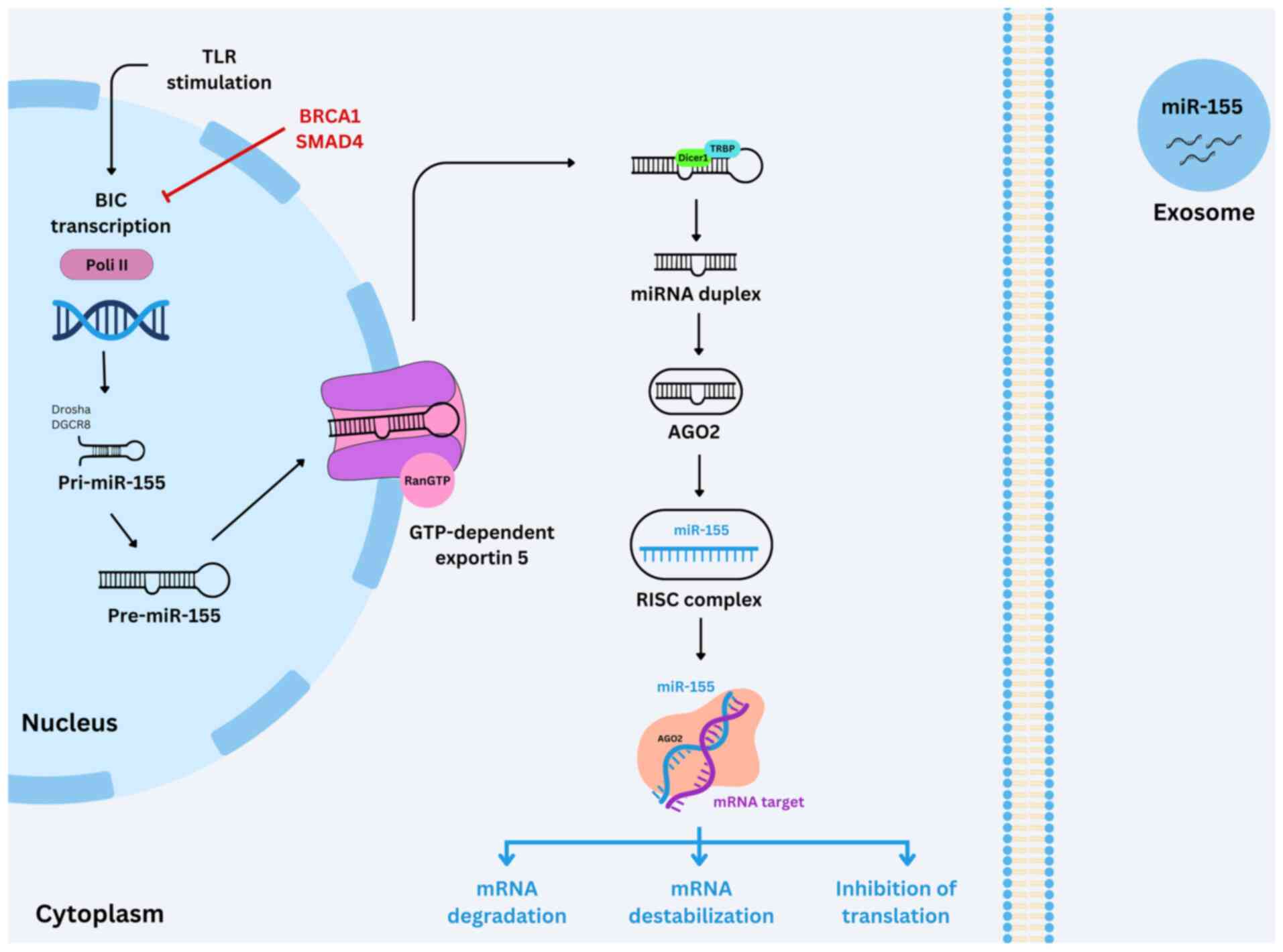

In animals, miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase

II (Pol II) as primary transcripts known as primary miRNAs

(pri-miRNAs), which adopt a characteristic hairpin structure

(Fig. 5). These pri-miRNAs are

processed in the nucleus by the enzymes Drosha and DiGeorge

syndrome critical region 8 DGCR8 (DGCR8) is a protein that serves a

crucial role in the maturation of microRNAs to generate precursor

miRNAs (pre-miRNAs), which are transported to the cytoplasm by the

protein exportin-5. In the cytoplasm, a second processing step is

performed by the enzyme Dicer, in association with the

double-stranded RNA-binding proteins trans-activation response

RNA-binding protein. It's a cellular protein that primarily binds

to the trans-activation response RNA-binding protein (TRBP) or

protein activator of PKR (Protein Kinase R), that are

double-stranded RNA-binding proteins resulting in a miRNA duplex

18–25 nucleotides in length. Subsequently, the passenger (sense)

strand is degraded, while the guide (antisense) strand,

representing the mature miRNA, is incorporated into the RNA-induced

silencing complex (RISC). Within RISC, argonaute proteins serve a

central role in directing the complex to target mRNAs containing

partially complementary sequences within their 3′ UTRs. This

interaction leads to gene silencing through either translational

suppression or mRNA destabilization (102–105).

| Figure 5.Biogenesis and function of miR-155.

TLR stimulation initiates BIC transcription by Pol II in the

nucleus, producing pri-miR-155 (negatively regulated by

BRCA1/SMAD4). Drosha/DGCR8 processing generates pre-miR-155, which

is exported to the cytoplasm via exportin 5. Cytoplasmic

Dicer1/TRBP cleaves pre-miR-155 into a duplex that incorporates

into AGO2, forming the RISC complex. Mature miR-155 mediates mRNA

degradation, destabilization or translational inhibition. miR-155

can be packaged into exosomes for intercellular signaling. miR,

microRNA; TLR, toll-like receptor; pri-miR, primary microRNA;

DGCR8, DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 protein; TRBP,

transactivation response RNA binding protein; AGO, argonaut

proteins; RISC, RNA-induced silencing; BIC, B cell integration

cluster; Pol, polymerase. |

Evolutionarily conserved across a range of

organisms, miRNAs comprise ~1% of the human genome. Despite their

small size, these regulatory RNAs exert post-transcriptional

control over more than one-third of all protein-coding genes,

underscoring their key role in numerous cellular processes and

disease pathogenesis (106,107)

. miRNA dysregulation is implicated in various pathological

conditions, most notably cancer, where altered expression patterns

contribute to tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis

(20,105,108). Therefore, understanding the role

of miRNAs in oncogenesis is key for the development of novel

diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (20,105,108)

The first miRNA sequence database, established in

2002, contained 506 entries across six organisms (109,110). By 2010, the number of annotated

human miRNAs had grown to 1,424 (111). However, miRNAs may be reclassified

over time due to initial misannotations, often stemming from high

sequence similarity between precursor miRNAs and minor sequence

variants (112).

miRNAs in BC

The search for predictive biomarkers to improve

early cancer diagnosis and therapeutic outcomes increasingly

emphasizes the analysis of molecular signatures in normal tissue

prior to the clinical manifestation of disease (112–114). In BC, miRNAs have been

consistently identified as dysregulated in both tissue and

serum/plasma samples (115–117).

These alterations contribute to early disease development and

progression by modulating the post-transcriptional expression of

proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Such findings

underscore the potential of miRNAs as valuable biomarkers for early

detection and targeted intervention in BC (118,119).

The prognostic value of miRNAs in BC connects

directly to critical genomic alterations. Genomic instability, a

key hallmark of malignancy, affects and is influenced by miRNA

expression patterns. This enables tumor cells to acquire multiple

growth advantages such as autonomous growth signaling, resistance

to inhibitory stimuli, apoptosis evasion, sustained angiogenesis

and enhanced metastatic capacity (120). This instability also affects miRNA

expression, disrupting key regulatory pathways involved in tumor

initiation and progression. miRNAs have emerged as key regulators

in the interplay between cancer cells and the immune

microenvironment (121). Moreover,

miRNAs promote genomic instability by influencing DNA double-strand

break repair, mismatch repair mechanisms and DNA methylation

patterns (100)

miRNAs are key regulators of the interplay between

cancer cells and the immune system, functioning as either oncogenes

or tumor suppressors depending on the cellular context. They

influence key biological processes including tumorigenesis, cell

proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis. Notably, miR-21 and

miR-155 are frequently upregulated across numerous types of cancer,

like lung cancer or prostate and hematologic tumor, highlighting

their prominent roles in tumor initiation and progression (122).

miRNAs exhibit context-dependent functions. For

example, miR-10b, miR-103/107 and miR-30d have been characterized

as oncogenic, whereas miR-31, miR-29 and members of the miR-200

family act as tumor suppressors (123). Additionally, miR-7 is a negative

regulator of epidermal growth factor receptor expression in BC

cells, further illustrating the diverse mechanisms by which miRNAs

modulate oncogenic signaling pathways (124).

In BC, miRNAs serve influential roles across all

molecular subtypes, with specific subsets contributing to key

regulatory pathways. For example, miR-21, miR-18a/b, miR-193,

miR-302, miR-92, let-7, miR-22, miR-221/222, miR-449a/b and the

miR-17-92 cluster modulate ER signaling, a pathway central to

HR-positive BC. Furthermore, HER2 protein, a major oncogenic driver

in HER2+ BC, is regulated by miR-125a/b, highlighting

the diverse roles of miRNAs in shaping the molecular landscape of

BC (125).

Beyond their regulatory functions, miRNAs serve as

promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in BC research

(116). Their dysregulation in

tumor development and progression supports their potential use in

detection, diagnosis, subtype classification and targeted therapy

(117). Distinct miRNA expression

profiles reliably differentiate BC tissue from normal counterparts

(121). For example, upregulation

of miR-21, miR-106a and miR-155, along with reduced expression of

miR-126, miR-199a and miR-335, is observed in BC compared with

normal tissues (126).

The first comprehensive study evaluating miRNA

expression in BC tissue analyzed 76 tumor samples and identified 29

miRNAs with differential expression compared with normal breast

tissue; among these, miR-10b, miR-125b, miR-145, miR-21 and miR-155

were key candidates, with miR-155 demonstrating the most pronounced

dysregulation (127).

miR-21 is one of the most extensively studied

miRNAs in BC and is associated with aggressive tumor

characteristics, including advanced clinical stage, high

histological grade and HR-negative status (128–130). Its expression is positively

regulated by TGF-β, and its upregulation is observed in BC tissue

(131).

Further research has revealed subtype-specific

miRNA expression patterns (132,133). For example, miR-342 expression is

elevated in ER+ and HER2+ tumors but

decreased in TNBC (134).

Conversely, miR-520 is upregulated in HR− tumors,

suggesting distinct functional roles across BC subtypes (135). Analysis examining 309 miRNAs in 93

breast tumor samples identified 31 miRNAs associated with favorable

prognostic features, including low histological grade and

ER+ status (136).

Notably, miR-155 is upregulated in BC tissues compared with normal

controls and elevated in ER− compared with

ER+ tumors (136).

Disruption of miRNA expression patterns can lead to

widespread cell dysfunction, including aberrant cell cycle

regulation and uncontrolled tumor proliferation (16).

miR-155

miR-155 is an evolutionarily conserved molecule

encoded by the host gene MIR155HG, located on chromosome 21 at the

21q21.3 locus (137). This gene

spans ~13 kilobases and comprises three exons, with the third exon

containing a 1,500-base-pair primary transcript, pri-miR-155, which

undergoes sequential processing to produce the mature miR-155

(138). Initially identified as

the B cell integration cluster, MIR155HG was first recognized for

its role as a retroviral integration site in B cell lymphoma in

both human and animal models, marking its role in oncogenesis

(139). Mature miR-155 exists in

two isoforms: miR-155-5p and miR-155-3p, each exerting distinct

regulatory effects. miR-155-3p enhances the production of IFN-α/β

by promoting degradation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated

kinase 3, whereas miR-155-5p suppresses IFN-α/β production by

targeting Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-activated kinase 1,

also known as MAP3K7 binding protein 2 (138,140,141). miR-155-5p also modulates immune

responses and contributes to drug resistance, while miR-155-3p is

implicated in multiple types of cancer, like lung cancer and

glioblastoma (141). These diverse

functions underscore the multifaceted role of miR-155 in cancer

progression and immune regulation (20,138,140–143).

miR-155 has emerged as a promising therapeutic

target due to its involvement in immunosuppressive mechanisms and

its potential to enhance antitumor immune responses. This miRNA

serves a key role in augmenting T cell-mediated immunity by

improving T cell functionality, memory formation, cytotoxic

activity and IFN-γ production (12). However, while enhancing miRNA

expression can potentiate T cell responses against tumors, IFN-γ

signaling induces the expression of PD-L1, which may paradoxically

promote a pro-tumorigenic environment (12).

miR-155 is one of the most extensively

characterized miRNAs in BC (19,20,142,144–148). Initially classified as an oncomiR,

it has been implicated in promoting tumorigenesis and disease

progression. Elevated expression of miR-155 is associated with

tumor development, poor prognosis and resistance to therapy in both

solid tumors and hematological malignancies (138,141). Functioning as an oncogene, miR-155

targets genes involved in immune regulation, DNA repair, hypoxia

responses and inflammation, thereby influencing both tumor cell

behavior and the tumor microenvironment (149). Studies have reported that high

miR-155 expression is associated with improved OS in various

cancers, including BC (19). This

may be attributed to its dual role in both the innate and adaptive

immune systems, as it is expressed in immune as well as in tumor

cells (150). Consequently, the

functional impact of miR-155 in BC remains context-dependent, and

whether its expression is pro- or antitumorigenic is under

investigation (12,18).

In patients with BC, circulating levels of miR-155

are significantly elevated compared with healthy individuals.

Moreover, miR-155 levels tend to decrease following adjuvant cancer

treatment, such as surgery and chemotherapy and are highest in

tumor with diameter >5 cm, suggesting its potential utility as a

biomarker for therapeutic monitoring. Elevated circulating miR-155

is also linked to early-stage tumor recurrence, further supporting

its relevance in disease surveillance (151,152).

Upregulation of miR-155 is associated with

treatment resistance, notably in trastuzumab-resistant BC. In

early-stage patients receiving trastuzumab-based therapy, elevated

levels of circulating exosomal miR-155 are an independent predictor

of poor event-free survival. Similarly, in metastatic patients

undergoing trastuzumab-containing regimens, high circulating

miR-155 levels are associated with decreased PFS. These findings

underscore the prognostic value of miR-155 in predicting adverse

clinical outcomes in both early-stage and metastatic BC (153).

In another study (154), patients with early-stage and

metastatic BC were stratified into high and low miR-155 expression

groups. Among early-stage patients, decreased miR-155 expression

was associated with shorter DFS compared with those with higher

expression. Furthermore, miR-155 expression was significantly lower

in patients who experienced relapse than in those who remained

relapse-free, further supporting its potential prognostic value in

BC (154).

A systematic review (147) of 28 studies found that miR-155

overexpression is associated with higher tumor grade and advanced

staging. However, inconsistencies were noted across studies

regarding the association between miR-155 levels and HR status, and

no definitive association was observed between miR-155 expression

and other key patient prognostic factors (147).

The diagnostic utility of circulating miR-155 also

varies across studies (148,151). Notably, serum-derived miR-155 has

greater diagnostic accuracy compared with plasma-derived miR-155

(155). This discrepancy may stem

from the coagulation process, which influences the extracellular

miRNA profile in blood. Despite these findings, the limited number

of studies examining plasma miR-155 underscores the need for

further investigation to establish its diagnostic potential in BC

(148).

In metastasis, exosomes (nanometer-sized vesicles

capable of transporting various biomolecules, including miRNAs) are

hypothesized to mediate the transfer of malignant traits to distant

cells. miR-155 is enriched in exosomes derived from metastatic BC,

suggesting a role in promoting metastatic behavior (156). This is consistent with studies

linking miR-155 to chemoresistance, as it has also been detected in

exosomes isolated from cancer stem and drug-resistant tumor cells

(157,158). Furthermore, a panel of circulating

miRNAs, including miR-155, is elevated in the plasma of patients

with non-metastatic BC prior to treatment, with levels declining

following therapy, supporting its potential use as a biomarker for

therapeutic monitoring (159).

miR-155 is a promising therapeutic target due to

its involvement in immunoregulatory pathways and its capacity to

enhance antitumor immune responses. It serves a critical role in

augmenting T cell-mediated immunity by enhancing T cell

functionality, memory formation, cytotoxic activity and IFN-γ

production. However, while modulation of miR-155 expression

strengthens antitumor T cell responses, the resulting increase in

IFN-γ signaling may induce upregulation of PD-L1, thereby

contributing to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment

(160).

The search for biomarkers in TNBC has prompted

extensive investigation into miRNAs as potential therapeutic

targets, providing deeper insight into tumor biology (161,162). miR-155 has emerged as a key

regulator of cell proliferation, in part due to its role in

maintaining thiamine metabolism in TNBC, as well as its involvement

in promoting TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(12). Although miR-155 is

typically characterized as an oncogenic miRNA that promotes tumor

growth, angiogenesis and aggressiveness, emerging evidence suggests

a context-dependent, protective role in TNBC (163). In this subtype, miR-155

upregulation is associated with improved survival outcomes. A

systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that low miR-155

expression is predictive of poor OS in patients with TNBC,

potentially due to its influence on molecular pathways involved in

DNA damage response and repair (163).

miR-155 modulates cell pathways

involved in TIL activity

Although BC has not traditionally been considered

an immunogenic tumor, the presence of TILs has been consistently

documented and is associated with favorable clinical outcomes,

particularly in patients with TNBC subtype (75,83,164).

In TNBC, an evaluation of plasma miR-155 expression revealed that

lower levels are significantly associated with shorter median DFS

and OS. Notably, in multivariate analysis, miR-155 emerged as the

only independent predictor of decreased DFS (154). Given the key immunoregulatory

functions of miR-155, including its roles in B lymphocyte and

CD4+ T cell differentiation, as well as Treg activation,

these findings suggest that elevated plasma miR-155 levels may

reflect a more robust antitumor immune response (154).

miR-155 upregulation enhances TIL

activity in tumor immunoediting

Studies using T cell-specific Dicer knockout mice

have demonstrated impaired T cell development, aberrant Th cell

differentiation and altered cytokine production, underscoring the

key role of miRNAs in T cell maturation and function (165,

166).

miR-155 has been identified as a key regulator of

Treg and Th17 cell differentiation through its direct targeting of

suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), a negative regulator of

the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. By suppressing SOCS1, miR-155

enhances phosphorylation of STAT5 and STAT3, potentially by

alleviating SOCS1-mediated inhibition. Furthermore, miR-155

promotes Th17 cell differentiation and effector function via

distinct mechanisms. It facilitates activation of the IL-6/STAT3

signaling pathway, which is key for Th17 lineage commitment and

IL-17A production (167).

Additionally, miR-155 counteracts the inhibitory effects of IL-10

and TGF-β1 on IL-17A expression, thereby augmenting the

pro-inflammatory potential of Th17 cells (167).

Wang et al (18) identified a positive association

between the expression levels of miR-155 in breast tumors and the

presence of antitumoral immune cells, such as CD8+ T

cells and M1 macrophages. Conversely, they noted a negative

association with protumoral cell types, including Tregs and M2

macrophages. The forced overexpression of miR-155 enhances the

production of chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11, which is driven

by SOCS1 inhibition and an increased ratio of phosphorylated

STAT1/STAT3. Furthermore, a convolutional neural network analysis

confirmed that elevated levels of miR-155 are associated with an

increased proportion of TILs, emphasizing its role in enhancing

both innate and adaptive immunity (18).

In a mouse model with miR-155-overexpressing

tumors, there was an increase in immune checkpoint molecules such

as PD-L1 and CTLA4, which are known to inhibit antitumor activity

(18). This upregulation was also

observed in human BC tissue miR-155 overexpression results in

increased PD-L1 expression in both human and murine BC cell lines,

suggesting a potential sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade

therapy (18,168).

miR-155 inhibits SOCS1, which affects

the activity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)

The downregulation of SOCS1 by direct miR-155

targeting serving a pivotal role in enhancing TILs activity in

TNBC. SOCS1, a member of the STAT-induced STAT inhibitor family,

negatively modulates pro-inflammatory cytokines via two mechanisms.

Firstly, SOCS1 catalyzes the ubiquitination of signaling

intermediates recruited by SOCS1. Secondly, it directly inhibits

the JAK/STAT pathway (169),

thereby preventing excessive levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines,

such as IFN (170) and ILs

(171).

Increased IFN-γ is associated with more effective

anti-tumor response and with an enhancement of T cell response

(138,141). Therefore, by targeting SOCS1,

miR-155 indirectly promotes IFN-γ production, resulting in more

active TILs, which, in TNBC, is associated with a positive

prognosis. However, in other types of cancer, such as colorectal

cancer (172) and pancreatic

cancer (173), SOCS1 is considered

a tumor suppressor, and downregulation of SOCS1 can be associated

with tumor progression (174).

PI3K/AKT is modulated by

miR-155/SOCS1, leading to enhanced TIL activity in the tumor

microenvironment

SOCS1 suppresses the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is

involved in cell proliferation, meaning miR-155 also promotes cell

proliferation. SH-2 containing inositol 5′ polyphosphatase 1

(SHIP1), an inositol phosphatase, together with PTEN is a key

negative regulator of PI3K/AKT and miR-155 directly targets its

expression; when miR-155 is upregulated, SHIP1 expression is

reduced, and cell proliferation is promoted together with increased

pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. AKT promotes the production of

ILs such as IL-6 and IL-12. High TIL levels influence the migration

and infiltration of TILs into the tumor site. By increasing

chemokine production and cell motility, this pathway may promote

the recruitment of TILs into the tumor microenvironment, improving

the immune response (175).

miR-155 can also enhance the cytotoxic activity of CD8+

T cells, promoting tumor cell death (175).

miR-155 triggers a suppressive cascade

that reduces Treg function

SOCS1 maintains FOXP3 expression and Treg cell

stability under inflammatory conditions. Treg cells serve an

immunosuppressive role in the tumor microenvironment. The

transcription factor FOXP3 is key for the normal development of

Tregs; decreased FOXP3 is associated with higher proportions of

cytotoxic cells, which can lead to a better prognosis. High

expression of FOXP3 is associated with immune tolerance of cancer

cells. During the equilibrium phase of the immune response in the

tumor microenvironment, there is a low proportion of Tregs due to

decreased FOXP3 expression, and a high proportion of cytotoxic

cells (56,57,176,177).

miR-155 suppresses expression of

PD-L1, enhancing TIL activity in TNBC

PD-L1 is a cell surface protein that serves a

critical role in suppressing the immune response; its expression on

tumor cells is a mechanism for evading immunosurveillance. The

interplay between miR-155 and PD-L1 has notable implications for

TIL activity in TNBC. When miR-155 downregulates PD-L1, T cell

inhibition is reduced, thus enhancing the anti-tumor immune

response mediated by TILs (178).

Studies have confirmed that miR-155 regulates TILs by targeting

specific regions of PD-L1 mRNA (179,180).

However, the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines

such as TNF-α and IFN-γ can indirectly increase PD-L1 expression;

the net result of this interaction will dictate the immune evasion

in TNBC (181).miR-155 inhibits

the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. IL-6 and miR-155 form a positive feedback

loop: IL-6 stimulates the expression of miR-155, which inhibits

SOCS. By inhibiting SOCS, miR-155 allows increased signaling of

cytokines, such as IL-6, further promoting the activation of the

IL-6/STAT3 pathway. When SOCS1 is inhibited by miR-155, the

IL-6/STAT3 pathway becomes more active, leading to increased

production of IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines.

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine that serves an

important role in physiological processes, including cell

proliferation, immune surveillance, acute inflammation, metabolism

and bone remodeling. IL-6 binds to the IL-6 receptor, which

subsequently binds to the glycoprotein 130 receptor creating a

signal transducing hexameric receptor complex. JAKs are recruited

and activated; activated JAK phosphorylates STAT3 for activation,

leading to gene regulation. Constitutively active IL-6/JAK/STAT3

signaling promotes cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness while

suppressing apoptosis, and STAT3 enhances IL-6 signaling to promote

an inflammatory feedback loop (182).

The IL-6/STAT3 pathway is a key signaling pathway

in cancer. IL-6 activates STAT3, which regulates the expression of

genes involved in cell proliferation, survival, and inflammation.

Targeting this IL-6 has a dual effect on BC which may either be

tumorigenic or antitumorigenic. The tumorigenic effect is caused by

inhibiting apoptosis, triggering the survival of tumor cells, and

allowing metastasis. IL-6 stimulates miR-155 expression, which

targets SOCS, hence promoting the progression of BC (183). Blocking IL-6 pathway can prevent

this progression via the inhibition of tumor migration and invasion

(184).

Upregulation of miR-155 in dendritic

cells (DCs) induces T cell proliferation and IFN-γ and IL-2

secretion

miR-155 promotes DC maturation and increases the

expression of MHC Class II (MHCII), CD86, CD40 and CD83, which are

key for T cell activation and the generation of effective TILs

(185). This enhances the ability

of DCs to present antigens to CD4+ T cells, a key step

in activating the adaptive immune response and generating effective

TILs (55). By increasing CD86

expression, miR-155 enhances the costimulatory signal needed for T

cell activation, promoting a more robust immune response and

enhancing TIL function. CD40 signaling is vital for effective

antigen-presenting cells (APC) activation, which is a key step in

generating potent TIL responses. As a marker of mature DCs, the

presence of CD83+ DCs in the tumor microenvironment

indicates a more active T cell response, enhancing anti-tumor

immunity through TILs. miR-155 promotes the production of IL12p70,

a cytokine that promotes the differentiation of CD4+ T

into Th1 cells, enhances CD8+ cytotoxic T cell activity

and stimulates IFN-γ production. These factors that contribute to

an enhanced anti-tumor immune response and are necessary for

effective TIL function (53,184,185).

miR-155 exerts an inhibitory effect on

ecto-5′-nucleotidase (NT5E) expression

NT5E is an enzyme that produces immunosuppressive

adenosine in the tumor microenvironment by hydrolyzing AMP. This

adenosine helps cancer cells evade destruction by cytotoxic T

lymphocytes. Inhibition of NT5E could enhance the ability of the

immune system to target and kill tumor cells. NT5E exists in two

isoforms, with the shorter isoform able to bind to the longer one

and cause its degradation. Several studies have shown that

miR-155-5p can directly inhibit NT5E expression by binding its 3′

UTR (186,187).

Dual functionality of miR-155 in

BC

miR-155 exemplifies the complex, context-dependent

functionality characteristic of miRNAs in BC pathophysiology

(138,141). miRNA expression profiles vary

across the five molecular subtypes of BC, creating unique molecular

environments that modulate miRNA function (136). Alteration of the level of

expression and activity of the enzymes involved in the biogenesis

of the miRNA may drive the unique profiles observed in BC subtypes

(138,141). Robust inverse associations have

been established between miR-155 expression and ER positivity,

demonstrating a direct association with TNBC phenotypes (136).

Interaction with other non-coding RNA regulatory

mechanisms and target availability determined by competing

endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) may explain the positive prognostic

association observed with miR-155 expression in TNBC (188). Genomic alterations characteristic

of TNBC, including mutations and copy number variations, may modify

the expression of transcripts and UTRs, thereby altering the

abundance of miRNA response elements. These molecular perturbations

disrupt ceRNA network homeostasis, potentially influencing miRNA

sequestration dynamics, and target transcript regulation, including

the positive prognostic association of miR-155 expression in TNBC

genomic contexts-which is characterized by high mutational burden,

genomic instability and heterogeneity (189).

The unique TNBC microenvironment affects miR-155

functionality through cell-type specific regulatory networks and

signaling cascades (138,190). Furthermore, miR-155 demonstrates

notable stage-specific effects; elevated expression may promote

recurrence in early-stage disease but is associated with improved

outcomes in established TNBC. This temporal heterogeneity is

complemented by spatial expression gradients within the tumor

architecture, emphasizing the contextual nature of miR-155 function

in BC progression (190).

The complex regulatory mechanisms of miR-155 within

the TNBC microenvironment illustrate the key intersection between

basic molecular oncology and translational medicine. The

context-dependent functions of miR-155 presents both challenges and

opportunities for clinical application, and barriers remain in

translating these molecular insights into practical clinical

tools.

Translating scientific findings into

clinical practice and limitations

Strategies for modifying miRNA content

in tumor cells

Wang et al (18) demonstrated that miRNAs notably

enhance the inflammatory state of breast tumors (18) . This finding is important because

tumors characterized by a high percentage of TILs, specifically

those classified as LPBC (TILs ≥30 or 50%), are associated with

improved outcomes for anticancer therapy (70,95,96).

The relationship between TILs and tumor response offers a

compelling rationale for exploring strategies to enhance lymphocyte

infiltration into tumors, thereby generating tumors with an

enhanced immune response dubbed as ‘hot tumors’. This are

characterized by proinflammatory cytokines and T cell

infiltration.

Approaches to modulate the tumor microenvironment

using checkpoint inhibitor have been investigated to convert ‘cold’

into ‘hot’ tumors, which are expected to respond more effectively

to immune-modulatory agents (191,192). Wang et al (18) demonstrated that increased expression

of miR-155 enhances the recruitment of antitumor immune cells to

the tumor microenvironment, effectively transforming ‘cold’ into

‘hot’ tumors (18).

Modifying miRNA levels in cells is accomplished

through two primary methods: Increasing their concentration with

target mimics known as miRNA mimics or decreasing their levels

using antisense sequences that inhibit specific targets, referred

to as antimiRs. Both strategies can be implemented using

oligonucleotides or viral vectors. Advancements in biotechnology

have improved the stability of synthetic RNA nucleotides,

facilitating their use alongside nanoparticles that exhibit high

transfection efficiency (193).

This progress in nanotechnology, in conjunction with enhancements

in oligonucleotide chemistry, has accelerated the development of

RNA interference therapeutics (194,195). Challenges in optimizing the use of

short RNA nucleotides include improving targeted delivery,

enhancing exosomal delivery, using both viral and non-viral vectors

and minimizing toxicity and costs (196,197).

The biotechnological development of a miRNA-based

strategy aimed at producing an approved drug necessitates an

organized workflow. This process begins with a preclinical stage

focused on establishing the proof-of-concept, which involves

demonstrating that the alteration of specific miRNAs yields a

notable anticancer effect. This is followed by preclinical studies

using animal models, ultimately leading to clinical trials designed

to secure approval for the treatment as an anticancer therapy

(198–200).

miRNAs as blood-based biomarkers for

BC

Wang et al (18) demonstrated that miR-155 levels in

blood samples from patients are an indicator of the tumor

inflammatory state (18).

Specifically, higher levels of miR-155 in serum are associated with

increased expression of this miRNA in tumor samples, as well as an

enhanced immune status.

The biotechnological development of blood-based

biomarkers necessitates a carefully designed strategy to ensure

safe translation to clinical practice. Standardized protocols and

testing targets through multicenter studies are crucial for

effectively translating miRNA-based signatures to the clinic. One

of the challenges of standardization is identifying suitable

reference genes to normalize quantitative PCR results.

Additionally, following analytical guidelines for accurate data

quantification is key. Multicenter studies involving large,

independent cohorts of patients from various countries,

representing diverse ethnic groups, are required to validate the

proposed miRNA-based biomarkers (201,202).

A typical study involves at least two phases, each

with distinct patient cohorts, as illustrated by Zou et al

(203), which developed a panel of

serum miRNAs for BC screening. In the initial phase, known as the

discovery cohort, researchers assessed a broad range of targets

(324 miRNAs) to identify the most promising candidates whose

expression levels significantly differ between patients and healthy

controls. The targets selected from this phase, often referred to

as the ‘miRNA signature’, are then evaluated in a validation cohort

(203). This systematic approach

ensures that the identified miRNA signatures possess clinical

relevance across different populations, enhancing their potential

application in clinical settings. The next step involves conducting

clinical trials to evaluate the accuracy of the selected miRNAs in

diagnosing the intended disease. These trials are key for

establishing the clinical use of biomarkers. Previous reviews have

highlighted ongoing trials focused on validating miRNA-based

biomarkers (147,148,151,155). In cancer such lymphoma, leukemia

and most solid cancers it is consider an oncogenic miRNA.

Differently, in TNBC it is linked with a better prognosis due to

the regulation of TILs (204–207).

Limitations

Mounting evidence supports the consensus that the

proportion of TILs is one of the most reliable biomarkers for

prognosticating outcomes in TNBC (78,79).

However, determining this proportion can be subjective, heavily

relying on the pathologist microscopic evaluation. Previous studies

have identified reproducibility issues among different pathologists

(77,208). To address this limitation,

multicenter initiatives have been launched, particularly by the

TILs Working Group, to provide standardized guidelines and training

(70,78). While TILs are valuable biomarkers,

standardization is crucial for developing laboratory assessments

that effectively guide treatment decisions and prognosis in

clinical settings (209,210).

The analysis of miRNAs in tumor biology has been

advanced by large datasets, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas

(211), which provide clinical

information alongside mRNA and miRNA expression patterns. This

highlights the complexity of the BC transcriptome, characterized by

clusters of expressed genes (212). Each miRNA can regulate hundreds of

genes, and the miRNome of tumor cells often exhibits multiple

dysregulated miRNAs. Thus, it is key to investigate the role of

specific miRNAs to ascertain their involvement in cancer biology

and the inflammatory status of tumors (213,214).

Research has elucidated the roles of specific

miRNAs in TNBC and their potential as biomarkers for TIL

infiltration and tumor outcomes, particularly miR-155. Wang et

al (18) revealed a significant

association between miR-155 levels in blood and tumor samples, as

well as with cytokines CCL5 and CXCL9/10/11. The sample size for

biomarker validation is key, highlighting the need for multicenter

studies. Developing multi-target signatures can enhance the

accuracy of miRNA biomarkers, making it essential to evaluate