Introduction

The major cellular components and mediators of the

tumor microenvironment (TME), including cancer cells, immune cells

[such as T cells, B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), myeloid-derived

suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)],

stromal cells [cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and

tumor-associated endothelial cells], cytokines and chemokines,

tumor vasculature, lymphoid tissue, as well as adipocytes and

exosomes, serve a critical role in cancer initiation, progression,

spread and metastasis (1–3). Interactions between the tumor stroma,

especially those mediated by CAFs and other stromal components,

actively promote immune evasion and malignant growth in a variety

of solid tumors, including lung and breast cancer as well as other

epithelial malignancies (2).

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a crucial part of antitumor

immunity among the immune cells found in tumors and a recent study

has demonstrated that immunotherapies can alter TIL activity as

well as the interactions between immune and stromal cells in the

TME. The TME usually contains signals that inhibit the immune

response, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived

suppressor cells, which prevent the infiltration and killing

function of immune cells (3).

Breaking through this immunosuppression has long been the key to

immunotherapy.

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, the TME manifests as an

immunosuppressive phenotype. Compared with EGFR wild-type (wt)

cancer, these tumors usually have a much lower tumor mutational

burden, which results in a limited development of neoantigens that

can successfully trigger immune recognition. Insufficient

neoantigen presentation weakens T-cell priming and activation,

resulting in a relatively ‘immune-cold’ environment. The blunting

of antitumor immune activation under such conditions is primarily

responsible for the lower therapeutic benefit observed with immune

checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in this population (4,5).

However, the TME in NSCLC can be affected by chemotherapy,

radiotherapy or EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Short-term

TKI treatment excels in tumor clearance and immunological

upregulation, improving the overall survival and quality of life of

patients (6). Nevertheless, the

immunosuppressive TME gradually emerges with time, and EGFR-TKI

resistance is unavoidable (7–9). This

process reveals the dynamic evolution in tumor immune

microenvironment induced by EGFR-TKI treatment (10).

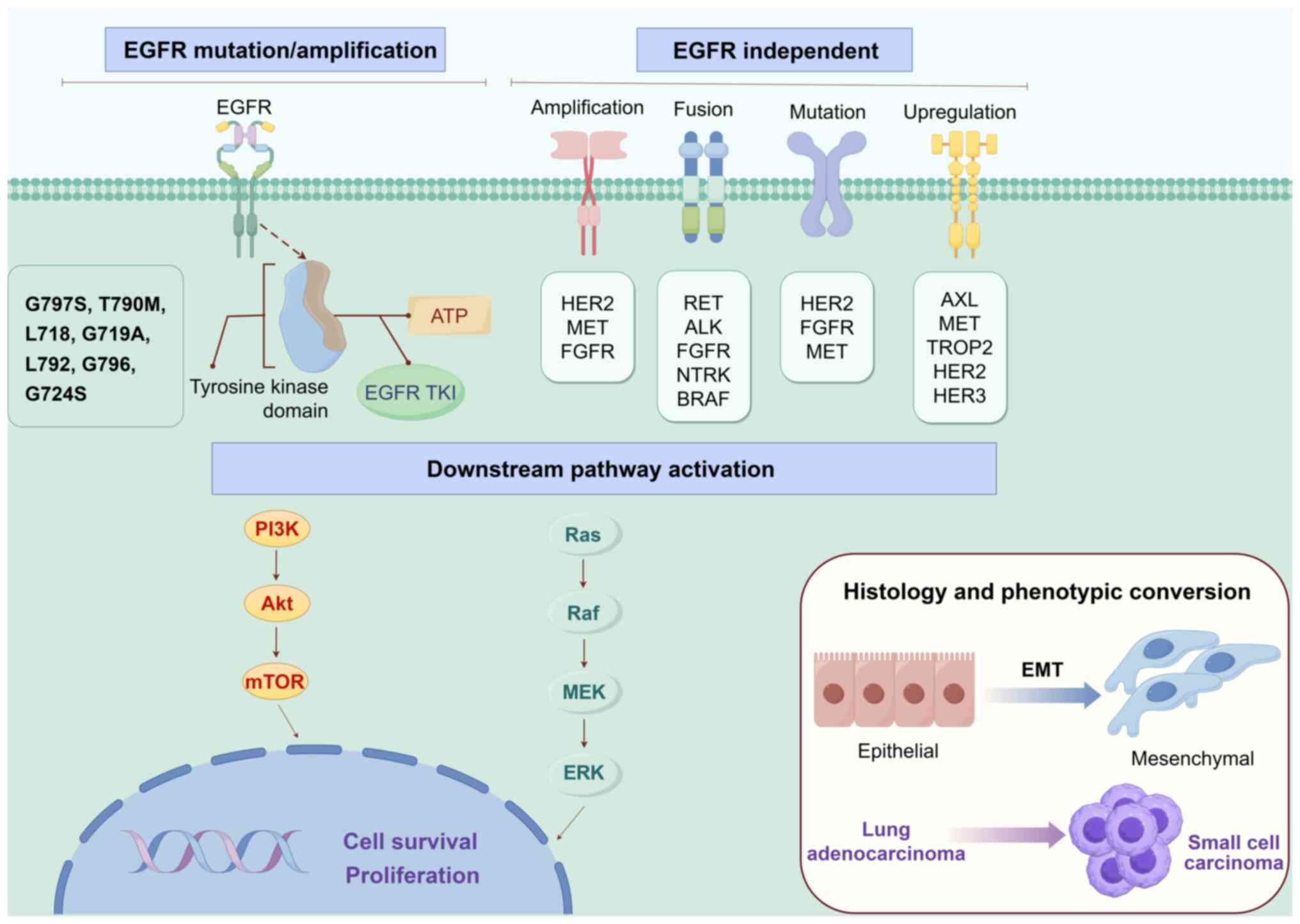

Mechanisms of resistance to EGFR-TKIs

In Asian populations, over half of patients with

NSCLC had EGFR-activating mutations (11). For individuals with locally

progressed or metastatic NSCLC, EGFR-TKIs are now the standard

therapy regimen (12,13). Their principal mechanism is

competitive binding to the ATP-binding site inside the EGFR kinase

domain, which inhibits kinase autophosphorylation and downstream

signaling cascades. This effect inhibits tumor cell development,

proliferation and metastasis (14).

With improvements in medical research, numerous EGFR-TKIs from the

first to third generations are now clinically available, markedly

improving patient survival rates. However, despite initial success,

nearly all patients develop acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI

therapy, with a median progression-free survival (mPFS) of ~1 year

(15,16). Resistance to EGFR-TKIs can be

divided into two categories: Primary and acquired (16). Of patients with EGFR mutations, ~30%

demonstrate primary resistance at the start of initial treatment,

indicating no objective response to TKI therapy; however, the

mechanisms causing this resistance remain unknown. However,

acquired resistance refers to disease progression that occurs

following an initial response to treatment. Its causes are

complicated and diverse, consisting mostly of EGFR-dependent

resistance, non-EGFR-dependent resistance (induced by activation of

EGFR bypass or downstream signaling pathways) and histological or

phenotypic alteration (17).

EGFR-dependent drug resistance

The T790M mutation accounts for 50–60% of acquired

resistance in patients treated with first- and second-generation

EGFR-TKIs (18). This mutation

replaces a bulky methionine (M) with a threonine (T) at position

790 in exon 20 of the EGFR gene. This substitution creates steric

hindrance between the aniline moiety of EGFR-TKIs and the

drug-binding site within the ATP pocket of EGFR, thereby weakening

drug-binding affinity. Additional mechanisms include a marked

increase in ATP binding affinity for EGFR T790M, alterations in the

catalytic domain and changes in overall conformational dynamics,

collectively contributing to acquired resistance to TKIs (18,19).

With the widespread usage of the third-generation

EGFR-TKI osimertinib, the C797S mutation has emerged as the

predominant mode of resistance. The EGFR C797S mutation, located at

position 797 in exon 20 of the EGFR gene, is a missense mutation in

which serine replaces cysteine. It accounts for 10–26% of

second-line osimertinib resistance cases and 7% of first-line

resistance cases (20). This

mutation damages the ATP-binding pocket, preventing

third-generation TKIs from making covalent connections with the

ATP-binding domain and so losing their inhibitory function

(21). The C797S mutation commonly

coexists with EGFR T790M in two structural forms: Cis (EGFR T790M

and C797S occur on the same allele) and trans (EGFR T790M and C797S

occur on different alleles). In ~85% of instances, the EGFR

C797S/T790M mutation is in the cis configuration, with ~10% of

patients having the C797S/T790M trans configuration. Whether the

C797S and T790M mutations form a cis structure has important

biological implications since it influences the therapeutic

efficacy of subsequent TKIs (17,22).

In addition to the most prevalent C797S mutation, C797G is another

missense mutation at the same location that causes drug resistance

by affecting the binding of the drug to the residue.

Aside from the classic T790M and C797S mutations,

uncommon mutations at other places within the EGFR kinase domain

can also cause resistance to osimertinib, mostly through

interference with drug-kinase binding. Mutations at the L718 site

(such as L718Q and L718V) and the adjacent G719A mutation primarily

interfere spatially, preventing the critical alanine ring in the

osimertinib molecule from forming a stable bond with its binding

pocket. L792 mutations (most commonly and notably L792H) directly

disrupt the tight binding of osimertinib to the kinase domain.

Mutations at the G796 site sterically clash with the solvent-front

aromatic ring of osimertinib, preventing kinase domain binding. The

G724S mutation is located in the ATP-binding region and may

interfere with osimertinib binding to its target by a variety of

mechanisms, including generating protein structural changes,

increasing ATP affinity or maintaining the kinase activation state,

resulting in drug resistance. Another form of resistance is target

upregulation caused by EGFR gene amplification (17,20,23).

EGFR-independent drug resistance

Activation of bypasses and downstream pathways, such

as HER2, HER3, MET, KRAS, NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase (NRAS), BRAF,

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α

(PIK3CA), AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL) and insulin-like

growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), were often classified as

‘bypass’ mechanisms of resistance. These pathways enable tumor

cells to activate alternative routes that engage key EGFR effectors

essential for tumor cell growth and survival. The most common

bypass mechanism of resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR

TKIs is HER2 amplification (24,25).

Downstream signaling pathways activated following receptor

phosphorylation included the mitogen-activated protein kinase

pathway, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway,

phospholipase Cγ1, protein kinase C and various transcriptional

regulators that modulate gene expression (26).

The MET gene encoded a receptor tyrosine kinase

known as c-Met, or hepatocyte growth factor receptor, which

supports cancer cell growth and survival by activating the

HER3-PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathways, thereby

bypassing the inhibitory effects of EGFR receptor signaling

(18,27). The Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is

crucial for regulating cell cycle progression and proliferation.

KRAS and NRAS, both members of the Ras family, could activate MEK

and ERK through this signaling pathway, contributing to drug

resistance (28,29). BRAF mutations, although rare in

EGFR-mutant (mt) NSCLC, involve kinases located downstream of RAS

in the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway and may contribute to the activation

of the GFR/RAS/RAF signaling pathway (30). PIK3CA, a catalytic subunit of the

PI3K family of lipid kinases, serves an oncogenic role in lung

adenocarcinoma by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. This

signaling pathway regulates key cellular functions, including

growth, proliferation, metabolism, angiogenesis and metastasis, and

is frequently mutated or hyperactivated in various cancers.

Patients with PIK3CA mutations generally exhibit a worse prognosis

and shorter median survival compared with those without these

mutations (31,32). IGF-1R and AXL serve key roles in

regulating cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, transformation

and other critical physiological processes through the downstream

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby contributing to the development

of secondary drug resistance (33,34).

Histology and phenotypic

conversion

Another mechanism of drug resistance involves

histological transformation within the tumor itself. Specifically,

some EGFR-mt lung adenocarcinomas develop into small cell lung

cancer (SCLC), accounting for 3–14% of acquired resistance cases.

This transformation is confirmed by histopathological biopsy, and

transformed tumors typically respond to standard SCLC treatment

regimens (35–38). Research indicates that the

co-deletion of Rb1 and TP53 genes constitutes the key molecular

basis driving such transformation (16,39).

Tumor cells can also undergo epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) and develop treatment resistance. During this

process, epithelial markers are downregulated and mesenchymal

markers are upregulated, resulting in increased proliferation,

invasion, migration and metastatic potential. However, the exact

processes underpinning EMT are unknown; this process may be driven

by AXL through activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

(40,41) (Fig.

1).

| Figure 1.The illustration outlines the key

mechanisms of resistance to EGFR-TKIs in EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

EGFR-dependent resistance arises from evolution of the target

itself (e.g., T790M/C797S mutations or gene amplification), which

restores EGFR kinase activity and re-activates the downstream

PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathways. EGFR independent

resistance occurs via bypass activation or downstream nodal

mutations, circumventing EGFR inhibition and ultimately converging

on the same core pathways. In addition, tumors may evade therapy

through histology or phenotypic transformation, such as

transformation to SCLC or EMT. EGFR, epidermal growth factor

receptor; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; NSCLC, non-small cell

lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; EMT,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. |

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells

CD4+/CD8+ T

cells/Treg cells

Infiltration of CD8+ T cells is lower in

EGFR-mt lung adenocarcinoma (LA) compared with in EGFR-wt LA, and T

cell proliferation is inhibited (42,43).

It has been shown that after TKI treatment, immune cell

infiltration is increased and the antitumor response is enhanced in

EGFR-mt patient samples (44).

However, changes in the TME by TKI treatment appear

to be dynamic. TKI treatment induces the recruitment of

CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (45). With short-term TKI treatment, the

expression levels of CD8 and granzyme B (GB) in EGFR-TKI-treated T

cells co-cultured with tumor cells initially increases and then

decreases with the duration of treatment, and T cells infiltration

shifts from enhanced to suppressed (10). Evidence has shown that following TKI

resistance, the tumor can transform into a ‘hot’ tumor with

increased immune cell infiltration, with notable effector and T

cell infiltration (46).

In the early stages of treatment, sensitive

EGFR-TKIs can increase the number of cytotoxic CD8+ T

cells, while short-term EGFR inhibition reduces the proportion of

Foxp3+ Tregs. However, these changes in the TME, which

favor immune-mediated combination therapies for cancer, may

gradually diminish with continued treatment (47).

TAMs

TAMs serve an important role in tumor progression in

EGFR-mt NSCLC, and their enrichment in human NSCLC is associated

with poor clinical outcomes (48).

How M1 and M2 type macrophages are distinguished may be influenced

by the TME and macrophages may exhibit a mixed phenotype of both

types of markers.

EGFR mutations promote the expansion of alveolar

macrophages (AM), but TKI treatment markedly reduces AM numbers in

tumor-bearing mice (48). In

EGFR-mt cells, M2 macrophages increase, and while short-term TKI

treatment reduces M2 infiltration, the number of M2 macrophages

rise again with the onset of TKI resistance (10,45).

DCs

EGFR-mt lung cancer (LC) drives the immune phenotype

of tumor-infiltrating DCs (TIDC) toward an immunosuppressive

direction and is closely associated with exosomes. Tumor-derived

exosomes (TEXs) bridge the interaction between tumor cells and

immune cells, thereby altering antitumor immune responses. Research

has shown that TEXs can inhibit myeloid differentiation, promoting

the transformation of monocytes from immune-stimulating to

immune-suppressive cells, thereby supporting immune evasion

(49). There is also evidence that

EGFR activation by TEXs weakens the innate immunity of the host

(50) and promotes tumor metastasis

(51).

Compared with EGFR-wt tumor-bearing mice, TIDCs and

lymph node (LN) DCs isolated from EGFR-19del tumor-bearing mice

produced markedly less IL-12p40. This finding suggests that

EGFR-19del Lewis LC tumors drive the process of immunosuppression

by affecting DCs in both the tumor and LN. Furthermore, EGFR-mt LC

cells may influence DC function by secreting exosomes in

vitro. These exosomes not only accelerate tumor growth but also

induce immune suppression (43).

However, short-term TKI treatment markedly increases DC

infiltration within the TME (47).

Natural killer (NK) cells

In EGFR-mt tumors, both the innate and adaptive

lymphocyte compartments exhibit signs of functional exhaustion. The

proportion of cytotoxic NK cells is reduced, whereas NK T cell

(NKT) subsets with low cytotoxic potential are markedly increased

(52,53). These NKT subsets display diminished

expression of activation and cytotoxicity-related genes, indicating

weakened innate immune cytotoxicity within the EGFR-mt TME.

In EGFR-mt LC, TKI therapy increases NK cell

infiltration and cytotoxicity (44,54).

Elevated IL-6 levels are linked to decreased immune cell

infiltration during short-term TKI treatment. On the other hand, NK

cell activity is decreased in EGFR-mt NSCLC with acquired TKI

resistance due to increased upregulation of IL-6 (55).

B cells

Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) are primarily

composed of B lymphocytes, which are essential to their development

(53). TLS are associated with a

higher response to immunotherapies and increased survival. In the

TME of EGFR-negative LUAD, B cells build the TLS (56). Tumor-infiltrating B cells and

antigen presentation-related markers were notably lower in EGFR-mt

tumors compared with in EGFR-wt tumors, according to single-cell

transcriptome analysis, which resulted in decreased T-cell

activation (52). Immune

infiltration, including B cells and CD8+ T cells, is

increased in TKI-responsive samples but not in resistant ones after

EGFR-TKI treatment, indicating that combining ICIs may be more

advantageous prior to the development of TKI resistance (44).

Immunomodulatory molecules

Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1)

PD-L1 is a critical immune checkpoint protein that

is broadly expressed on the surface of tumor cells and

tumor-infiltrating immune cells. It inhibits anticancer immune

responses by binding to programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) on T

cells, B cells, DCs and NK T cells, and is an indicator of poor

survival in most advanced cancers (57–59).

It is regulated in NSCLC by two distinct mechanisms: Driver genetic

alterations and inflammation. Previous research has reported the

dynamic relationship between EGFR mutation status and PD-L1

expression before and after EGFR-TKI, but the exact relationship

remains controversial. Meanwhile, it is worth noting that there may

be an association between the levels of PD-L1 expression and the

efficacy of EGFR-TKI therapy (60).

Compared with EGFR-wt, EGFR-mt typically results in

upregulation of PD-L1 (59,61–65), a

process that is closely associated with activation of the

IL-6/JAK/STAT3 and p-ERK1/2/p-c-Jun signaling pathways (66,67).

However, one clinical study found that EGFR-mt patients exhibit

relatively low PD-L1 expression (16%; PD-L1 ≥5%) before TKI

treatment (68). An analysis

involving 18 studies and 3,969 patients revealed that, compared

with EGFR-wt tumors, EGFR-mt NSCLC is less likely to display PD-L1

positivity (65).

EGFR-TKI not only directly inhibits the activity of

tumor cells, but also indirectly enhances the antitumor immune

response by downregulating PD-L1 (61,66).

After short-term TKI treatment, PD-L1 expression is markedly

reduced (10), which can be

monitored by immuno-positron emission tomography imaging (69–71).

This downregulation of PD-L1 may be partly dependent on the

activation of the NF-kB pathway or AKT-STAT3 pathway (62,63).

However, a previous study suggested the opposite conclusion,

proposing that TKI treatment increases PD-L1 expression in patients

with EGFR-mt NSCLC (72). As

reported in one study (73), PD-L1

expression showed marked changes following EGFR-TKI treatment, with

the proportion of patients with PD-L1 strong positive tumors [tumor

proportion score (TPS) ≥50%] increasing from 14% at baseline to 28%

after TKI treatment. With subsequent ICI treatment, patients with

high PD-L1 expression (TPS ≥50%) achieved a longer mPFS compared

with those with low PD-L1 expression [TPS <50%; 7.1 vs. 1.7

months; HR=0.18 (0.04–0.56); P=0.0033]. The PD-1 signaling pathway

is activated in EGFR-TKI resistant tumors (74). After long-term TKI treatment, the

expression levels of PD-1 typically increase (10,72).

As EGFR-TKI resistance develops, the proportion of patients with

PD-L1 strong positive tumors increases from baseline (73). A retrospective analysis showed that

PD-L1 expression levels changed during the development of

resistance in 16 patients (28%), of which 12 patients had higher

PD-L1 expression levels after resistance (68). In addition, changes in PD-L1

expression levels in tumor-infiltrating immune cells between

baseline and the development of EGFR-TKI resistance were also of

interest, with the proportion of patients with ≥10% PD-L1

expression in tumor-infiltrating immune cells increasing from 11%

at baseline to 25% after TKI treatment.

Evidence suggests that patients with EGFR-TKI

resistance, particularly those who are T790M negative, may derive

greater benefit from PD-1 inhibitors, in part due to their higher

PD-L1 expression levels (75). This

suggests that further research is needed to determine whether

patients with EGFR-TKI resistance can benefit from PD-1 inhibitor

therapy. Due to the potential efficacy of immunotherapy in patients

with active PD-1 pathways, investigating the combined effects of

immunotherapy and its interactions with TKIs after TKI resistance

may help to optimize treatment strategies for these patients.

MHC-II, CD40, CD80 and CD86

LN DC and AM in EGFR-mt tumor-bearing mice exhibit

an immunosuppressive phenotype compared with EGFR-wt tumor-bearing

mice, characterized by downregulation of MHC-II and the

costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 (43,48).

CD47

Integrin-associated protein (CD47) is a cell surface

immunoglobulin-like molecule that inhibits phagocytosis by

interacting with signal regulatory protein α on phagocytes. CD47 is

selectively upregulated in patients with EGFR mutations. After

treatment with TKI, CD47 expression is downregulated, which

promotes DC phagocytosis of NSCLC cells. However, after the

development of resistance in vitro, CD47 expression is

upregulated (76).

Cytokines and chemokines

Cytokines and chemokines in the TME are also

regulated by EGFR-TKIs. According to molecular research, cytokines

can modulate immunological signaling by causing target-cell

receptors to undergo structural or functional changes, such as

receptor breakage or shedding (77–79).

In patients with EGFR-mt NSCLC, the pro-inflammatory cytokine

IL-17A was highly expressed, along with markedly increased

expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which are

closely associated with cell proliferation and induction of TKI

resistance (80,81). Compared with AM in control mice, AM

in hormone mice produced more cytokines (such as IL-1α and TNF-α)

and chemokines [such as CXC motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 1 and

CXCL2] (48). In addition, the

chemokine CXCL2 secreted by CAFs is considered to induce the

expression of PD-L1 in LA cells, thereby indirectly modulating

tumor immunity (82).

TKI treatment promotes the transformation of EGFR-mt

NSCLC from a ‘cold’ to a ‘hot’ tumor. After EGFR-TKI treatment, the

level of type I interferon (IFN) is notably increased in EGFR-mt

human LC cell lines, and the expression of the chemokines CXCL9,

CXCL10 and CXCL11 is also markedly upregulated. Meanwhile, the

CXCL10/CXCR3 pathway is activated in the EGFR-mt LC transgenic

mouse model (10,42,55).

Furthermore, an analysis of serum IFN-γ levels in 20 patients with

NSCLC treated with EGFR-TKI revealed that serum IFN-γ levels were

markedly higher compared with baseline levels in treated patients

(66).

In EGFR-TKI-resistant patients, the TME remodels

from a non-inflammatory to an inflammatory state. Studies have

shown that acquired resistance to TKI therapy can promote an

inflammatory response, with the IFN-γ pathway becoming markedly

enriched after TKI resistance, along with higher levels of granzyme

A expression (46). Type I IFN

levels are decreased in resistant cell lines, whereas expression of

the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TGF-β1 is notably increased

(10,81,83,84).

CD24 and lymphocyte-activation gene 3

(LAG-3)

In a related study (85), the expression of the innate immune

checkpoint CD24 was found to be upregulated in EGFR-mt cells in

vitro following EGFR-TKI treatment, which is consistent with

the observation after TKI resistance. These findings suggest that

EGFR inhibition in EGFR-mt NSCLC cells promotes the development of

a TME conducive to immune escape. Furthermore, the expression of

the checkpoint protein LAG-3 is markedly elevated after EGFR-TKI

treatment (86).

Immunotherapy clinical trials in EGFR-mt

advanced NSCLC

Immunological monotherapy or dual

therapy

A pair of meta-analyses (87,88),

which included studies such as CheckMate057, KEYNOTE-010, OAK and

POPLAR, demonstrated that the efficacy of immunotherapy monotherapy

was inferior compared with that of docetaxel monotherapy in

patients with EGFR-mt LC. As a result, patients with EGFR-mt NSCLC

are less likely to derive notable benefits from immunotherapy

monotherapy. The BIRCH study (89),

a phase II, single-arm, multicenter clinical trial evaluating the

efficacy and safety of atezolizumab monotherapy in advanced

PD-L1-expressing NSCLC, included 45 patients with EGFR mutations.

The results showed that atezolizumab exhibited antitumor activity

regardless of EGFR status and was particularly effective in the

high PD-L1-expressing subgroup (TC3 or IC3). However, even among

EGFR-mt patients with high PD-L1 expression, the objective response

rate (ORR) and median overall survival (mOS) remained notably lower

compared with those in EGFR-wt patients. The ATLANTIC (90) study was a single-arm, open-label,

phase II trial evaluating durvalumab (an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal

antibody) as a third-line or later treatment for advanced NSCLC,

enrolling a total of 77 patients with EGFR mutations. Subgroup

analysis revealed that while the ORR in patients with EGFR-mt NSCLC

with PD-L1 expression ≥25% was higher compared with those with low

PD-L1 expression [12.2% (9/74) vs. 3.6% (1/28)], it was still lower

compared with EGFR-wt patients [16.4% (24/146) vs. 7.5%

(7/93)].

In one cohort of the KEYNOTE-021 study (91), a total of 11 patients were enrolled.

The combination of ipilimumab [anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antibody] and pembrolizumab showed

limited efficacy in patients with EGFR-mt NSCLC, with an ORR of

only 10%, substantially lower than the 30% observed in EGFR-wt

patients. Overall, the data suggest that while the combination

therapy exhibits some antitumor activity in patients with advanced

NSCLC who had received multiple lines of therapy, it was less

effective and more toxic in EGFR-mt patients, with a 64% incidence

of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), including 29% of grade

3–5 severe AEs. The study suggests that dual immunotherapy has

limited effectiveness in EGFR-mt patients and must be chosen with

caution, especially when PD-L1 expression levels are low. In

conclusion, these clinical trial data indicate that the overall

response rate to immunotherapy is lower in patients with EGFR-mt

NSCLC compared with those with EGFR-wt. Nevertheless, antitumor

activity was observed in EGFR-mt patients with high PD-L1

expression, suggesting that high PD-L1 expression may serve as an

important predictor of potential benefit from immunotherapy in this

subgroup.

Immunotherapy combined with targeted

therapy

CAURAL (92) is a

phase II clinical trial investigating the combination of

osimertinib (a third-generation EGFR-TKI) and durvalumab in

patients with advanced NSCLC with EGFR T790M mutations who had

progressed after prior EGFR-TKI treatment. The primary objective of

the trial was to evaluate safety, with efficacy assessed as an

exploratory endpoint. The results demonstrated an ORR of 64% in the

combination therapy arm, lower than the 80% observed in the

osimertinib monotherapy arm, failing to show an advantage over

single-agent therapy. Nonetheless, the trial was terminated early

due to the elevated risk of interstitial lung disease observed in

related studies. This highlights that safety issues need to be

considered when combining an EGFR-TKI with an ICI.

Immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy

CT18 (93) is a

multicenter, single-arm, phase II clinical trial evaluating the

efficacy and safety of toripalimab (anti-PD-1 antibody) in

combination with carboplatin and pemetrexed in patients (n=40) with

advanced EGFR-mt NSCLC who had failed EGFR-TKI therapy and lacked

T790M mutations. The results showed an ORR of 50.0% (95% CI,

33.8–66.2), and a disease control rate (DCR) of 87.5% (95% CI,

73.2–95.8). The mPFS was 7.0 months (95% CI, 4.8–8.4), while the

mOS reached 23.5 months (95% CI, 18.0 to NR months). The overall

safety profile of the treatment was manageable, with 97.5% of

patients experiencing treatment-related AEs (TRAEs), of which 65.0%

were grade 3 or higher, most commonly bone marrow suppression,

elevated transaminases and nausea. Immune-related AEs occurred in

40% of patients, with only 5.0% being grade 3 or higher.

CheckMate722 (94)

is a phase III clinical trial designed for patients with advanced

NSCLC characterized by EGFR mutations and resistance to TKI therapy

(n=294). This investigation sought to compare the efficacy of

nivolumab combined with chemotherapy against chemotherapy alone.

While the combination therapy group showed a modest improvement in

mPFS (5.6 vs. 5.4 months; HR=0.75), the difference fell short of

statistical significance. Likewise, the combination treatment did

not notably extend mOS (19.4 vs. 15.9 months; HR=0.82). The ORR was

31.3 and 26.7% in the combination and chemotherapy groups,

respectively. Post-hoc subgroup analyses revealed a potential trend

of enhanced PFS in specific subpopulations, including those with

sensitizing EGFR mutations or patients treated exclusively with

first-line TKI therapy, with HRs of 0.72 and 0.64,

respectively.

The KEYNOTE-789 study (95), a randomized, double-blind phase III

trial in 492 patients with TKI-resistant, EGFR-mt advanced NSCLC,

demonstrated that pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy

only slightly improved mPFS (5.6 vs. 5.5 months; HR=0.80; P=0.0122)

or mOS (15.9 vs. 14.7 months; HR=0.84; P=0.0362) compared with

chemotherapy alone. Neither the CheckMate722 nor the KEYNOTE-789

trial met their primary endpoints, suggesting that merely combining

anti-PD-1 ICIs with chemotherapy may not provide meaningful

clinical benefits for this patient population. Consequently, it is

essential to further investigate potential biomarkers and refine

combination treatment strategies to enhance therapeutic

outcomes.

Immunotherapy combined with

chemotherapy + anti-angiogenic drugs

IMpower150 (96,97) is

a phase III clinical trial that enrolled 123 patients with EGFR-mt

NSCLC to assess the efficacy of three regimens of atezolizumab in

combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel (ACP), bevacizumab plus

carboplatin and paclitaxel (BCP) and atezolizumab plus bevacizumab

plus carboplatin and paclitaxel (ABCP). The results showed that

patients with EGFR mutations or ALK translocations in the ABCP

group demonstrated a longer mPFS compared with those in the BCP

group, at 9.7 vs. 6.1 months, respectively (HR=0.59; 95% CI,

0.37–0.94; P=0.025). The mOS for the ABCP group was 29.4 months,

which was notably superior to the 18.1 months observed in the BCP

group (HR=0.60; 95% CI, 0.31–1.14), while the ACP group (19.0

months) was similar to the BCP group (HR=1.00; 95% CI, 0.57–1.74).

In terms of safety, 100% of patients in the ABCP group experienced

TRAEs, of which 66.7% were grade 3/4, although no grade 5 events

were reported. The incidence of TRAE in the ACP and BCP groups was

88.6% (with 56.8% grade 3/4) and 95.3% (55.8% grade 3/4),

respectively. In summary, the IMpower150 study demonstrated that

the ABCP regimen substantially prolonged OS in patients with

EGFR-mt NSCLC with controllable AEs and had a favorable safety and

tolerability profile.

ORIENT-31 (98) is a

phase III clinical trial designed to assess the efficacy of

sintilimab ± IBI305 combined with chemotherapy (pemetrexed +

cisplatin) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mt

non-squamous NSCLC who have progressed after EGFR-TKI treatment.

The randomized trial with 476 patients indicated that sintilimab

combined with chemotherapy significantly improved mPFS, with 5.5

vs. 4.3 months for chemotherapy alone (HR=0.72; 95% CI, 0.55–0.94;

P=0.016). Sintilimab plus IBI305 and chemotherapy extended mPFS to

7.2 months, compared with 4.3 months for chemotherapy alone

(HR=0.51; 95% CI, 0.39–0.67; P<0.0001), demonstrating

significant benefit. Regarding mOS, the sintilimab plus IBI305

combination chemotherapy group had a mOS of 21.1 months (95% CI,

17.5–23.9), which was similar to the 19.2 months observed in the

chemotherapy alone group (HR=0.98; 95% CI, 0.72–1.34; P=0.8883),

with no statistically significant difference. The mOS for the

sintilimab plus chemotherapy group was 20.5 months (95% CI,

15.8–25.3), which was comparable to the chemotherapy alone group at

19.2 months (HR=0.97; 95% CI, 0.71–1.32; P=0.8202). In terms of

safety, 56% of patients (88/158) in the sintilimab plus IBI305 plus

chemotherapy group developed a grade 3 or higher TRAE, which was

notably higher compared with in the sintilimab plus chemotherapy

(41%) and chemotherapy alone (49%) groups. Despite immunotherapy

side effects (such as immune pneumonitis and rash) were more

common, overall safety and tolerability were satisfactory and most

AEs could be mitigated with appropriate management.

IMpower151 (99) is

a phase III study that included 305 patients with advanced

non-squamous NSCLC. The trial assessed the efficacy of atezolizumab

in combination with bevacizumab (an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody)

and chemotherapy (carboplatin + pemetrexed) as a first-line

treatment. Preliminary findings indicated that the combination

therapy (ABCP) showed limited benefits in mPFS and mOS compared

with the control group (BCP), without reaching statistical

significance. The mPFS was 9.5 and 7.1 months (HR=0.84; 95% CI,

0.65–1.09; P=0.18) and the mOS was 20.7 and 18.7 months (HR=0.93;

95% CI, 0.67–1.28) for the two groups, respectively. These results

suggest that although the combination of immunotherapy and

chemotherapy provided a slight survival benefit for patients with

EGFR-mt NSCLC, the effect was modest compared with other NSCLC

subtypes and did not substantially alter the prognosis. Safety

analyses revealed a high incidence of AEs in both groups and no new

safety signals. The rates of all-cause AEs were 99.3% in the ABCP

group (with 66.4% being grade 3/4) and 100% in the BCP group (61.4%

grade 3/4).

ATTLAS (100) is a

phase III study performed in Korea that enrolled 225 patients with

stage IV NSCLC diagnosed with EGFR sensitizing mutations or ALK

translocations, including the ABCP group (n=151) and the PC group

(n=74). All patients had disease progression or intolerance to one

or more EGFR or ALK TKIs. A total of 168 patients with EGFR-mt

NSCLC who were resistant to EGFR-TKI were enrolled in the study,

109 in the ABCP arm and 59 in the PC arm. The results demonstrated

that the ABPC arm significantly improved PFS compared with the PC

arm, with mPFS of 8.48 vs. 5.62 months, respectively [HR=0.62 (95%

CI, 0.45–0.86); P=0.004]. Subgroup analysis of patients with

EGFR-TKI-resistant EGFR-mt NSCLC revealed similar findings, with

mPFS of 8.7 months in the ABCP arm and 5.6 months in the PC arm

(HR=0.60; 95% CI, 0.43–0.84; P=0.002). However, no notable OS

benefit was observed in either group. In terms of safety, the

incidence of grade 3 or higher TRAEs was higher in the ABCP arm

compared with in the PC arm, primarily related to cytotoxic

chemotherapy. Nevertheless, bevacizumab-related TRAEs were

generally manageable with appropriate supportive care.

HARMONi-A (101,102) is a phase III clinical trial

performed in China, enrolling 322 patients with advanced or

metastatic EGFR-mt NSCLC who experienced disease progression during

EGFR-TKI treatment. This study evaluated the efficacy of

ivonescimab in combination with chemotherapy compared with

chemotherapy alone. In the trial, eligible patients were randomized

1:1 to receive ivonescimab plus chemotherapy (pemetrexed and

carboplatin) or placebo plus chemotherapy. Results showed that

ivonescimab plus chemotherapy resulted in a significant improvement

in mPFS compared with the chemotherapy group at 7.1 and 4.8 months,

respectively [HR=0.46 (95% CI; 0.34–0.62); P<0.001]. The ORRs of

the two groups were 50.6 and 35.4%, respectively, and the DCRs were

93.1 and 83.2%, respectively. In terms of safety, the incidence of

AEs was 99.4 and 97.5% in the two groups, and the incidence of

grade 3 or higher treatment-emergent AEs was 61.5 and 49.1%,

respectively.

In addition, two ongoing phases II clinical trials

(103,104) have shown preliminary efficacy. A

single-arm phase II study enrolled 64 patients with EGFR-mt NSCLC

who had progressed following EGFR-TKI treatment and received

combination chemotherapy with PM8002/BNT327, a bispecific antibody

targeting PD-L1 and VEGF-A. The results revealed an overall ORR of

54.7% (95% CI, 41.8–67.2). In patients with a TPS ≥50%, the ORR

reached 92.3% (95% CI, 64.0–99.8), indicating that the antitumor

activity of PM8002/BNT327 treatment was positively associated with

tumor PD-L1 expression levels. Additionally, cohort 5

(EGFR-TKI-resistant cohort) of the DUBHE-L-201 study (104) included 31 patients. The cohort

received QL1706 + carboplatin + pemetrexed + bevacizumab

administered intravenously on day 1 of a 21-day cycle for four

cycles. Maintenance therapy was QL1706 + pemetrexed + bevacizumab.

QL1706 is a bifunctional MabPair product containing anti-PD-1 and

anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. The primary endpoint of the study was

safety and secondary endpoints include confirmed ORR,

investigator-assessed duration of remission (DoR), PFS and OS.

Preliminary results showed a median DoR of 11.3 months (95% CI,

4.2–19.9), PFS of 8.5 months (95% CI, 5.7–13.3) and OS of 26.5

months (95% CI, 12.8-not evaluable) (Table I).

| Table I.ICI-based immunotherapy combinations

for EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC. |

Table I.

ICI-based immunotherapy combinations

for EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC.

| A, Immunotherapy

combined with targeted therapy |

|---|

|

|---|

| NCT | Clinical trial | Phase | Intervention | Result | (Refs.) |

|---|

| NCT02454933 | CAURAL | III | Osi + Durva

(n=14) | ORR:64% vs.

80% | (92) |

|

|

|

| Osi (n=15) |

|

|

|

| B, Immunotherapy

combined with chemotherapy |

|

| NCT03513666 | CT18 | II | Tori + Carbo +

Pem | ORR=50.0% (95% CI,

33.8–66.2) | (93) |

|

|

|

| (n=40) | DCR=87.5% (95%CI,

73.2–95.8) |

|

|

|

|

|

| mPFS=7.0 m (95% CI,

4.8–8.4) |

|

|

|

|

|

| mOS=23.5 m (95% CI,

18.0-NR) |

|

| NCT02864251 | CheckMate722 | III | Nivo + Chemo | mPFS:5.6 m vs. 5.4

m (HR=0.75; |

|

|

|

|

| (n=144) | 95% CI, 0.56–1.00)

mOS:19.4 m | (94) |

|

|

|

| Chemo (n=150) | vs. 15.9 m

(HR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.61–1.10) |

|

| NCT03515837 | KEYNOTE-789 | III | Pembro + Chemo | mPFS:5.6 mvs5.5 m

(HR=0.80; | (95) |

|

|

|

| (n=245) | 95% CI,

0.65–0.97) |

|

|

|

|

| Placebo +

Chemo | mOS:15.9 vs. 14.7

(HR=0.84; |

|

|

|

|

| (n=247) | 95% CI,

0.69–1.02) |

|

|

| C, Immunotherapy

combined with chemotherapy + anti-angiogenic drugs |

|

| NCT02366143 | IMpower150 | III | ABCP: Atezo + | mPFS: ABCP vs.

BCP:9.70 m | (96,97) |

|

|

|

| Bev + Carbo+ | vs. 6.1 m (HR=0.59;

95% CI, |

|

|

|

|

| Pac (n=34) | 0.37–0.94) |

|

|

|

|

| BCP: (n=44) | mOS: ABCP vs.

BCP:26.1 m |

|

|

|

|

| ACP: (n=45) | vs. 20.3 m

(HR=0.91; 95% CI, |

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.53–1.59) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ACP vs. BCP: 21.4 m

vs. 20.3 m |

|

|

|

|

|

| (HR=1.16; 95% CI,

0.71–1.89) |

|

| NCT03802240 | ORIENT-31 | III | SIC: Sinti + | mPFS: SIC vs. C:7.2

m vs. 4.3 m | (98) |

|

|

|

| IBI305 + Chemo | (HR=0.51; 95% CI,

0.39–0.67) |

|

|

|

|

| (n=158) | SC vs. C: 5.5 m vs.

4.3 m |

|

|

|

|

| SC: Sinti +

Chemo | (HR=0.72; 95% CI,

0.55–0.94) |

|

|

|

|

| (n=158) | mOS: SIC: 21.1 m

(95% CI) |

|

|

|

|

| C: Chemov

(n=160) | 17.5–23.9) SC:20.5

m (95% CI) |

|

|

|

|

|

| 15.8–25.3) C:19.2 m

(95% CI |

|

|

|

|

|

| (15.8–22.4) |

|

| NCT04194203 | IMpower151 | III | ABCP: (n=152) | mPFS: 9.5 m vs. 7.1

m (HR=0.84; | (99) |

|

|

|

| BCP: (n=153) | 95% CI, 0.65–1.09;

P=0.18) |

|

|

|

|

|

| mOS: 20.7 m vs.

18.7 m |

|

|

|

|

|

| (HR=0.93; 95% CI,

0.67–1.28) |

|

| NCT03991403 | ATTLAS | III | ABPC: Atezo + | mPFS: ABCP vs.

PC:8.71 m | (100) |

|

|

|

| Bev + Pac + | vs. 5.62 m

(HR=0.60; 95% CI, |

|

|

|

|

| Carbo (n=109) | 0.43–0.84) |

|

|

|

|

| PC: (n=59) |

|

|

| NCT05184712 | HARMONi-A | III | ivonescimab + Chemo

(n=161) | mPFS: 7.1 m vs. 4.8

m (HR=0.46; 95% CI, 0.34–0.62) | (101,102) |

|

|

|

| Chemo (n=161) |

|

|

| NCT05756972 | - | II | PM8002/BNT327

+ | ORR:54.7% | (103) |

|

|

|

| Carbo + Pem

(n=64) |

|

|

| NCT05329025 | DUBHE-L-201 | II | QL1706+ Carbo + Pem

+ Bev (n=31) | mDoR, PFS, and OS

were 11.3 (95% CI, 4.2–19.9), 8.5 (5.7–13.3), and 26.5 months

(12.8-not evaluable), respectively | (104) |

Discussion and future perspectives

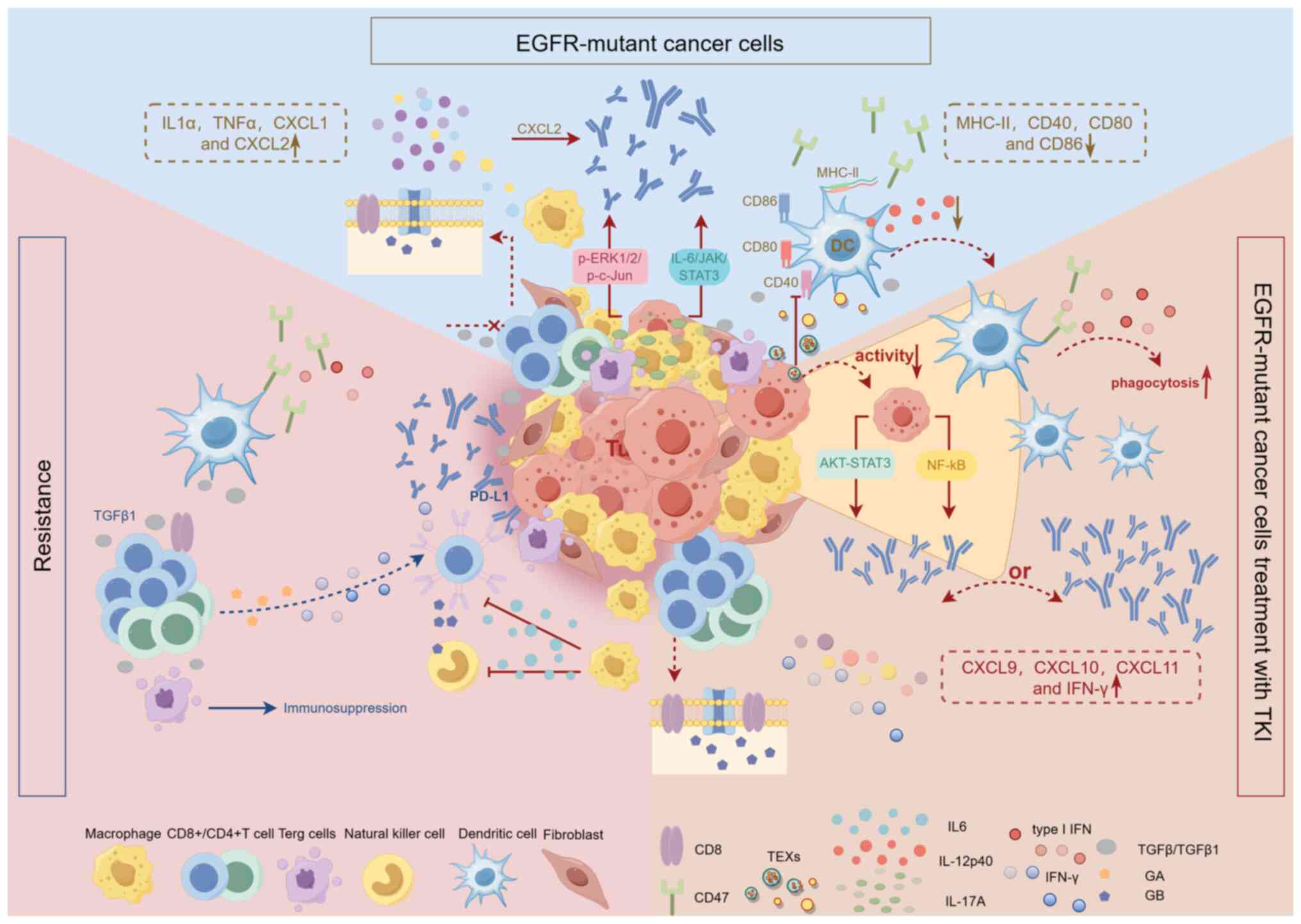

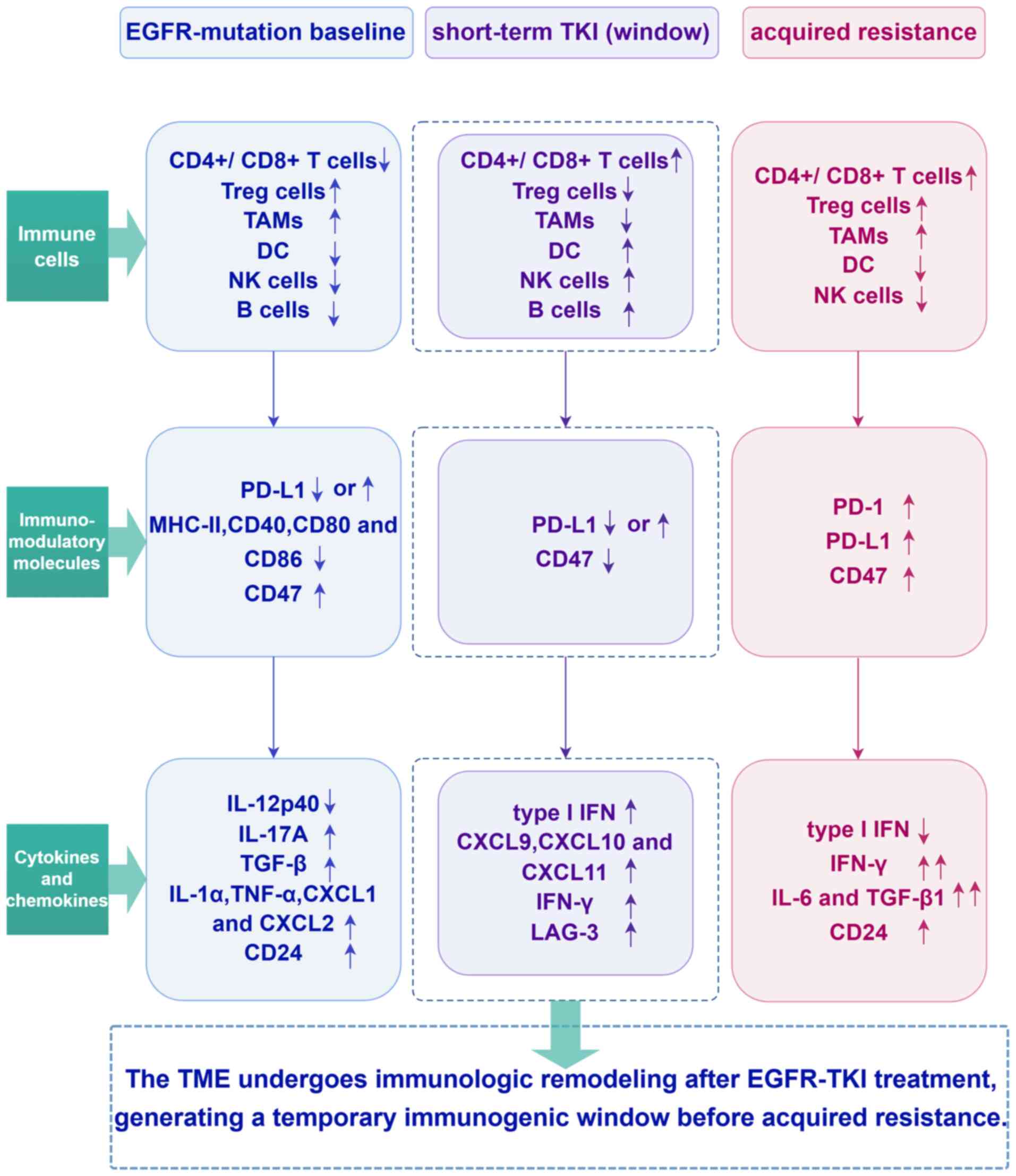

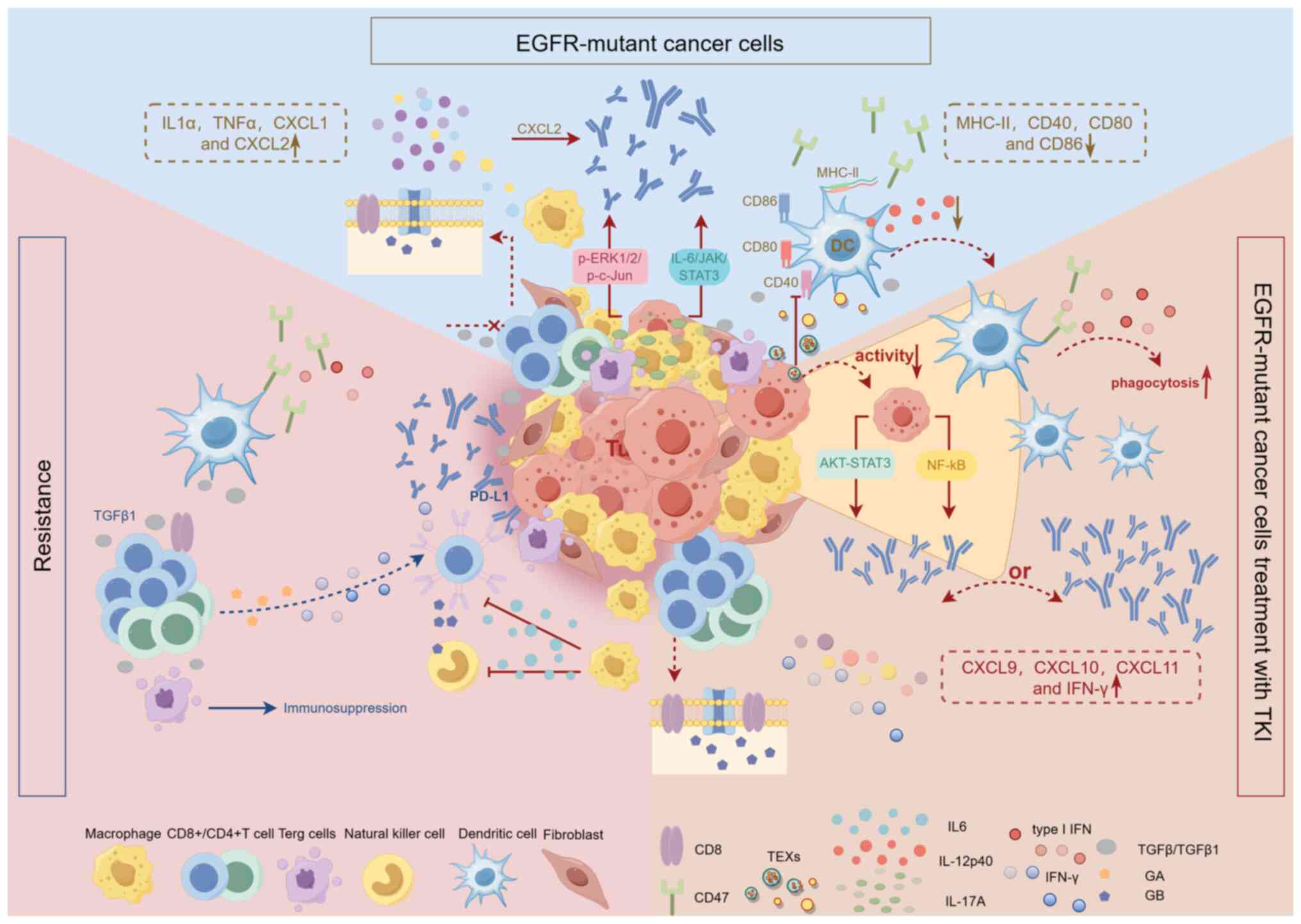

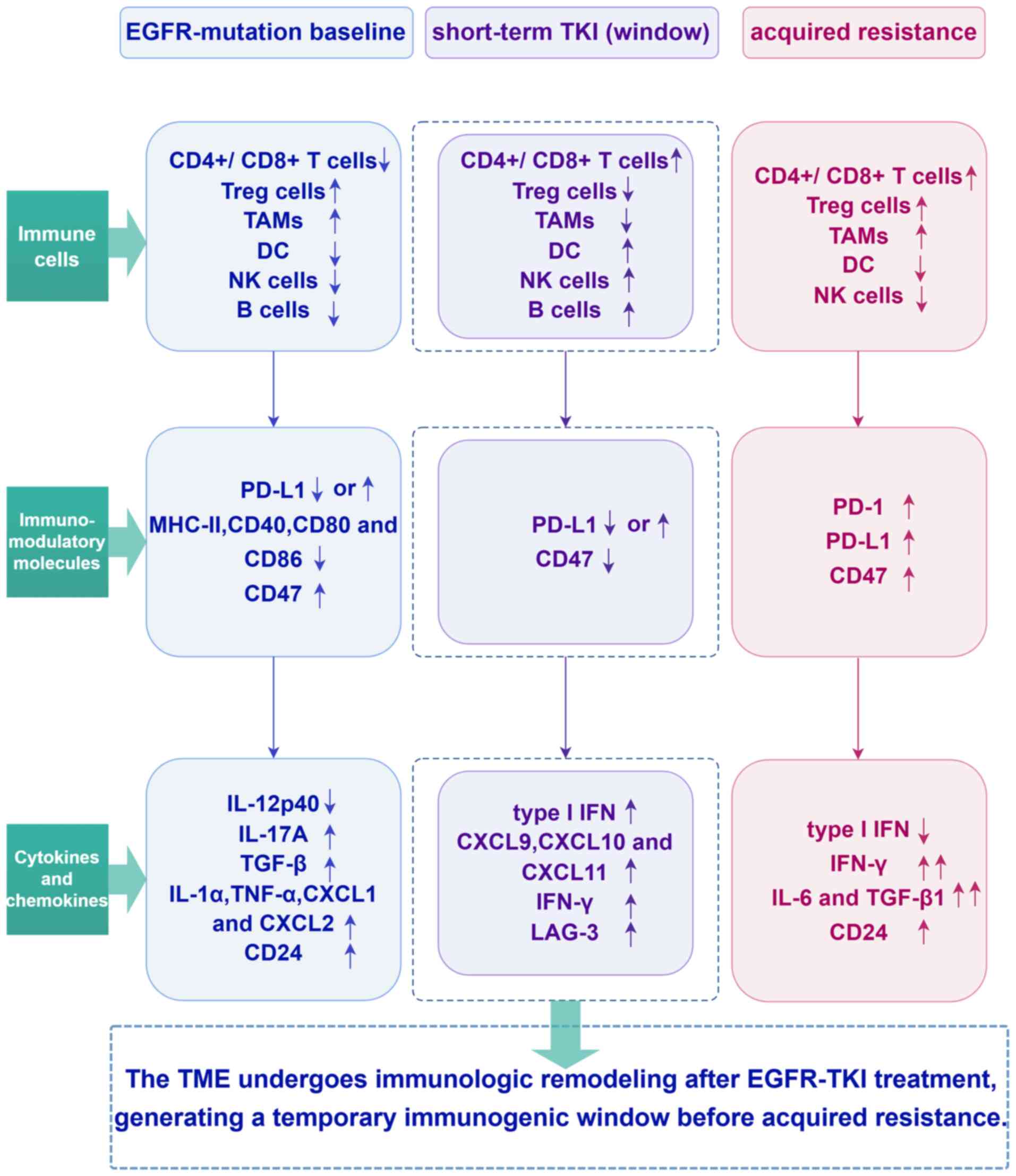

In summary, TKI-treated and TKI-resistant TMEs show

a shift towards a ‘hot’ tumor with increased immune cell

infiltration (Fig. 2), with an

increase in the immune-activating components of the TME, including

increased numbers or upregulation of tumor-infiltrating immune

cells, immunomodulatory molecules, cytokines or chemokines and a

reduction or impairment of immunosuppressive components. Notably,

acquired EGFR-TKI resistance promotes immune escape in lung cancer

by upregulating PD-L1 expression. Detailed studies have shown that

changes in the TME following TKI treatment are dynamic, with

short-term effects suggesting a potential therapeutic window during

which TKI treatment could more effectively leverage the immune

system to target tumors (Fig. 3).

However, the long-term effects of TKI therapy are more complex and

may be influenced by various factors, such as treatment cycles,

drug sensitivity and the specific treatment regimen employed.

| Figure 2.TME in EGFR-mutant NSCLC and its

dynamics during short-term TKI treatment and resistance. The TME of

EGFR-mutant NSCLC is immunosuppressive. Low CD8+ T-cell

infiltration and inhibition of their proliferation and activation

by the cytokine TGF-β; EGFR mutation promotes AM proliferation;

TEXs inhibit DC function and reduce IL-12p40 production; MHC-II and

co-stimulatory molecules of DCs and AMs (CD40, CD80, CD86)

expression were downregulated; CD47 was selectively overexpressed;

EGFR mutations upregulated PD-L1 via IL-6/JAK/STAT3 and

p-ERK1/2/p-c-Jun pathways; high expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokine IL-17A; increased expression of cytokines TGF-β, IL1α and

TNFα and chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2; and CAFs release of CXCL2

induced PD-L1 expression. EGFR-TKI can directly inhibit the

activity of tumor cells. Short-term TKI treatment transformed ‘cold

tumors’ into ‘hot tumors’, with an increase in T-cell and DC

infiltration, an increase in CD8 and GB expression levels Compared

with pre-treatment and a marked decrease in TAM infiltration and

Foxp3+ Tregs; CD47 is downregulated, enhancing

DC-mediated phagocytosis; PD-L1 expression could be reduced or

upregulated, and the reduced PL-L1 was considered to be associated

with the NF-κB and AKT-STAT3 pathways; the level of type I IFNs

(IFN-α, IFN-β) was increased and the expression of IFN-γ and the

chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 was upregulated. Upon TKI

resistance, the TME was remodeled towards inflammation, with

enrichment of inflammatory and IFN-γ pathway; CD8 and GB expression

decreased and granzyme A expression increased; TAM numbers rise;

CD47 was re-upregulated; the PD-1 pathway was activated and the

expression level of PD-L1 was increased; type I IFN decreased and

the expression of IL-6 and TGF-β1 was increased; the increased

expression of IL-6 suppressed T cell and NK cell cytotoxicity and

GB marker expression. TME, tumor microenvironment; EGFR, epidermal

growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TGF-β,

transforming growth factor-β; AM, alveolar macrophages; CXCL, CXC

motif chemokine ligand; TEXs, tumor-derived exosomes; p-,

phosphorylated; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CAFs,

cancer-associated fibroblasts; GB, granzyme B; IFN, interferon;

Tregs, regulatory T cells; DC, dendritic cell; TAMs,

tumor-associated macrophages; NK, natural killer; PD-L1, programmed

death ligand 1; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor. |

| Figure 3.A timeline schematic illustrating

dynamic changes in the TME from the EGFR-mutant baseline state

through short-term TKI exposure to the development of acquired

resistance. TME, tumor microenvironment; EGFR, epidermal growth

factor receptor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; Treg cells,

regulatory T cells; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; DC,

dendritic cell; NK, natural killer; PD-L1, programmed death ligand

1; IL, interleukin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TNF, tumor

necrosis factor; CXCL, CXC motif chemokine ligand; IFN, interferon;

LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; PD-1, programmed cell death

protein-1. |

Previous reports have shown that patients with high

PD-L1 expression have a greater survival benefit following

treatment with first-generation EGFR-TKI. However, the subsequent

FLAURA trial (105) reported

conflicting results, suggesting a shorter PFS in patients with high

PD-L1 expression. With second and third-generation TKI therapies,

high PD-L1 expression has been associated with worse survival and

higher rates of drug resistance. These findings suggest a strong

relationship between PD-L1 expression levels and TKI efficacy.

Previous cases are described in Table

II (106–117). However, discrepancies between

studies may be due to differences in drug generations, PD-L1

detection methods and thresholds for defining PD-L1 expression

levels. Most existing studies are retrospective, with limited

prospective studies and notable regional variability. There is an

urgent need for larger, multicenter, prospective clinical trials to

validate the relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinical

outcomes. Standardization of PD-L1 detection methods is also

critical to identifying the optimal population for ICI treatments,

ultimately providing greater clinical benefit to patients.

| Table II.Association between PD-L1 expression

and treatment efficacy of EGFR-TKI in EGFR-mutant NSCLC

patients. |

Table II.

Association between PD-L1 expression

and treatment efficacy of EGFR-TKI in EGFR-mutant NSCLC

patients.

| First

author/s,year | Gen. | EGFR-TKI | Country | EGFR-mutant (PD-L1

Testing) Patients (n) | PD-L1 expression in

EGFR-mutant/after TKIs | Associated clinical

outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| D'Incecco et

al, 2015 | I | Gefitinib or

erlotinib | Italian | 95/123 | PD-L1 positivity

(2+ or 3+) in >5% of TCs: 55.3%/- | PD-L1+: higher RR

(61.2% vs. 34.8%, P=0.001), longer TTP (11.7 m vs. 5.7 m,

P<0.0001), and longer OS (21.9m vs. 12.5 m, P=0.09) | (64) |

| Lin et al,

2015 |

| Gefitinib or

erlotinib | China | 56 | Positive in 53.6%

of tumor specimens/- | PD-L1+: higher DCR

(93.3% vs. 61.5%, P=0.004), longer mPFS (16.5 vs. 8.6 m, P=0.001)

and mOS (35.3 vs. 19.8 m, P=0.004) | (106) |

| Soo et al,

2017 | I/II | Erlotinib,

gefitinib, or dacomitinib | South Korea | 90 | ≥1% positive: ICs

44%, TCs 59%/no association | PD-L1+: shorter PFS

[HR=1.008 (1.001–1.015), P=0.017] | (107) |

| Yoneshima et

al, 2018 |

| - | Japan | 71 | TPS of ≥1%:

42.3%/- | TPS ≥1% vs. <1%:

shorter mPFS (9 vs. 14 m, P=0.016) | (108) |

| Su et al,

2018 |

| - | China | 101 | Positive (TC3/IC3,

TC1-2/IC1-2): 35.6%/- | TC3/IC3 vs.

TC1-2/IC1-2 vs. TC0/IC0: lower ORR (35.7% vs. 63.2% vs. 67.3%,

P=0.002), shorter mPFS (3.8 vs. 6.0 vs. 9.5m, P<0.001), and

higher primary resistance rates (66.7% vs. 30.2%) P=0.009) | (109) |

| Hsu et al,

2019 |

| Gefitinib,

erlotinib, or afatinib | China | 123 | TPS of ≥1%:

30.1%/- | TPS ≥1% vs. <1%:

shorter mPFS (2.1 vs. 7.3 m, P<0.001) and mOS (11.2 vs. 38.2,

P=0.002), higher primary resistance rates (OR=5.95, 95% CI

2.35–15.05, P<0.001) | (110) |

| Yang et al,

2020 |

| Gefitinib,

erlotinib, or afatinib | China | 153 | TPS 1–49%: 25.5%,

TPS ≥50%: 11.8%/Stable in 60% (9/15), increased in 40% upon

progression | TPS 0% vs. 1–49%

vs. ≥50%: ORR (65.6% vs. 56.4% vs. 38.9%, P<0.001), DCR (93.8%

vs. 97.4% vs. 55.6%, P<0.001), mPFS (2.5 vs. 12.8 vs. 5.9 m,

P=0.027), primary resistance rates (6.3% vs. 2.6% vs. 44.4%,

P<0.001) | (60) |

| Isomoto et

al, 2020 | I/II/III | Gefitinib,

erlotinib, afatinib, dacomitinib or osimertinib | Japan | 134 | TPS of ≥50%:

14%/TPS of ≥50%: 28% | - | (73) |

| Brown et al,

2018 | I/III | Osimertinib vs.

gefitinib/erlotinib | Global | 128 | TC ≥1%: 51%/- | TC ≥1% vs. <1%:

Osimertinib group (n=54): similar mPFS (18.4 vs. 18.9 m);

gefitinib/erlotinib group (n=52): shorter mPFS (6.9 vs. 10.9

m) | (105) |

| Sakata et

al, 2021 | III | Osimertinib | Japan | 538 | TPS ≥50%: 11.9%,

1–49%: 31.6%, <1%: 30%, Unknown: 26.6%/- | mPFS: TPS ≥50%:

11.1 m (95% CI 8.3-NR) [HR=2.24 (1.17–4.30), P=0.015], TPS

1–49%:14.7 m (95% CI 13.6–20.5) [HR=1.66 (1.05–2.63), P=0.029], TPS

<1%: NR (95% CI 20.7-NR) | (111) |

| Alves et al,

2022 | I/III | Gefitinib,

erlotinib or osimertinib | Brazil | 278/188 | TC ≥1%:

36.7%/- | Higher PD-L1 (TPS

≥50% vs. 1–49% vs. <1%): not associated with mOS (37.5 vs. 46.5

vs. 50.4 m, P=0.48), and decreased event-free survival (median:9

vs. 34 vs. 26 m, P=0.014) | (112) |

| Papazyan et

al, 2024 | III | Osimertinib | France | 96 | TPS ≥50%:

20.8%/decreased in 4/15 patients at relapse | TPS ≥50% vs.

<50%: shorter mPFS (9.3 vs. 17.5 m, P=0.044), and mOS (14.3 vs.

26.0 m, P=0.025), ORR (53.3% vs. 46.5%, P>0.9) | (113) |

| Lakkunarajah et

al, 2023 |

| Osimertinib | Canada | 231 | TPS ≥50%:

29.4%/- | TPS ≥50% vs.

<1%: shorter PFS (HR=1.59, 95% CI 1.07–2.36, P=0.023), and OS

(HR=1.82, 95% CI 1.10–2.99, P=0.019) | (114) |

| Yoshimura et

al, 2021 |

| Osimertinib | Japan | 71 | TPS ≥50%:

21.1%/- | TPS ≥50% vs.

<50%: lower ORR (53.3% vs. 81.1%, P=0.043) and DCR (73.3% vs.

98.1%, P=0.007), shorter mPFS (5.0 vs. 17.4 m, P<0.001); TPS

≥50% vs. 1–49% vs. <1%: higher primary resistance rates (33.33%

vs. 3.85% vs3.45%, P=0.006) | (115) |

| Hsu et al,

2022 |

| Osimertinib | China | 85/71 | TPS ≥50%:

9.4%/- | TPS ≥50% vs.

<50%: shorter mPFS [9.7 vs. 26.5 m, aHR=0.19 (0.06–0.67),

P=0.009], shorter mOS [25.4 vs. NR, aHR=0.09 (0.01–0.70),

P=0.021] | (116) |

| Hamakawa et

al, 2023 |

| Osimertinib | Japan | 64 | TPS ≥20%:

34.4%/- | TPS ≥20% vs.

<20%: shorter mPFS (9.1 vs. 28.1 m, log-rank P=0.013), with

PD-L1 TPS ≥20% associated with early resistance to osimertinib | (117) |

Recent research has focused on patients with high

PD-L1 expression. Available evidence suggests that immunotherapy

can offer notable benefits to patients, both during short-term TKI

therapy and after the development of resistance. However, the

effect of short-course TKI therapy on PD-L1 expression levels has

long been a topic of debate. The timing of immunotherapy

interventions and the monitoring of their efficacy need to be

further confirmed. On the one hand, the immunological

characteristics of the TME, such as inflammatory or

immunosuppressive status, as well as the level of PD-L1 expression

should guide the choice of treatment. On the other hand,

identifying reliable biomarkers, such as PD-L1 and cytokine levels,

is crucial for accurately predicting treatment response. It is

particularly critical and urgent to conduct large-scale,

multicenter clinical trials to validate the role of these

biomarkers and to promote their standardized application in

clinical practice.

The growing importance of immunotherapy is further

underscored by the emergence of resistance to TKI therapy. In

patients with high PD-L1 expression and EGFR-TKI resistance,

immunotherapy may provide a notable survival benefit (73,103).

Conversely, in patients with low PD-L1 expression and EGFR-TKI

resistance, immunotherapy interventions do not yield the desired

therapeutic outcomes. Fourth-generation EGFR-TKI and antibody-drug

conjugates (ADCs) offer novel therapeutic strategies for patients

who have failed conventional TKI therapy and exhibit low PD-L1

expression. Fourth-generation TKIs are designed to overcome the

limitations of third-generation TKIs in the face of drug

resistance. ADCs targeting trophoblast surface antigen 2 have shown

notable therapeutic efficacy in immunotherapy non-responders.

Future studies should focus on elucidating the underlying

mechanisms of dynamic immune changes in the TME, as well as

performing comprehensive and systematic evaluations of combination

therapies that include TKIs, ICIs, ADCs and anti-angiogenic drugs.

Moreover, actively exploring the optimal therapeutic window and

addressing the safety issues associated with combination therapies

will greatly advance the field of oncology and bring new hope to

more patients.

Acknowledgements

No applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Renxin Medical Research

Program of the Beijing Weiai Public Welfare Foundation (grant no.

RXYS2025-0200630118), the Scientific Research Program of the

Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (grant no. 2025ZD061), and

the Scientific Research Program of the Hebei Administration of

Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no. T2026091).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and

design. HM and LL conceived the study and wrote and revised the

manuscript. CJ, YC and JH wrote the manuscript. HM, LL, QT and CJ

wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. DY contributed to the

manuscript preparation. YZ supervised the study. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Osipov A, Saung MT, Zheng L and Murphy AG:

Small molecule immunomodulation: The tumor microenvironment and

overcoming immune escape. J Immunother Cancer. 7:2242019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Vuletic A, Mirjacic Martinovic K and

Jurisic V: The role of tumor microenvironment in triple-negative

breast cancer and its therapeutic targeting. Cells. 14:13532025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kraja FP, Jurisic VB, Hromić-Jahjefendić

A, Rossopoulou N, Katsila T, Mirjacic Martinovic K, De Las Rivas J,

Diaconu CC and Szöőr Á: Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer

immunotherapy: From chemotactic recruitment to translational

modeling. Front Immunol. 16:16017732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Vryza P, Fischer T, Mistakidi E and

Zaravinos A: Tumor mutation burden in the prognosis and response of

lung cancer patients to immune-checkpoint inhibition therapies.

Transl Oncol. 38:1017882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

To KKW, Fong W and Cho WCS: Immunotherapy

in treating EGFR-mutant lung cancer: Current challenges and new

strategies. Front Oncol. 11:6350072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jurisic V, Vukovic V, Obradovic J,

Gulyaeva LF, Kushlinskii NE and Djordjević N: EGFR polymorphism and

survival of NSCLC patients treated with TKIs: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Oncol. 2020:19732412020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li K, Quan L, Huang F, Li Y and Shen Z:

ADAM12 promotes the resistance of lung adenocarcinoma cells to

EGFR-TKI and regulates the immune microenvironment by activating

PI3K/Akt/mTOR and RAS signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol.

122:1105802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jeong HO, Lee H, Kim H, Jang J, Kim S,

Hwang T, Choi DW, Kim HS, Lee N, Lee YM, et al: Cellular plasticity

and immune microenvironment of malignant pleural effusion are

associated with EGFR-TKI resistance in non-small-cell lung

carcinoma. iScience. 25:1053582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu L, Wang C, Li S, Bai H and Wang J:

Tumor immune microenvironment in epidermal growth factor

receptor-mutated non-small cell lung cancer before and after

epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

treatment: A narrative review. Transl Lung Cancer Res.

10:3823–3839. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lu C, Gao Z, Wu D, Zheng J, Hu C, Huang D,

He C, Liu Y, Lin C, Peng T, et al: Understanding the dynamics of

TKI-induced changes in the tumor immune microenvironment for

improved therapeutic effect. J Immunother Cancer. 12:e0091652024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Corvaja C, Passaro A, Attili I, Aliaga PT,

Spitaleri G, Signore ED and De Marinis F: Advancements in

fourth-generation EGFR TKIs in EGFR-mutant NSCLC: Bridging

biological insights and therapeutic development. Cancer Treat Rev.

130:1028242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Owen DH, Ismaila N, Ahluwalia A, Feldman

J, Gadgeel S, Mullane M, Naidoo J, Presley CJ, Reuss JE, Singhi EK

and Patel JD: Therapy for stage IV non-small cell lung cancer with

driver alterations: ASCO living guideline, version 2024.3. J Clin

Oncol. 43:e2–e16. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Obradović J, Niševic-Lazović J, Sekeruš V,

Milašin J, Perin B and Jurisic V: Investigating the frequencies of

EGFR mutations and EGFR single nucleotide polymorphisms genotypes

and their predictive role in NSCLC patients in Republic of Serbia.

Mol Biol Rep. 52:3502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yamaoka T, Ohba M and Ohmori T:

Molecular-targeted therapies for epidermal growth factor receptor

and its resistance mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 18:24202017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS,

Zakowski MF, Pao W, Kris MG, Miller VA, Ladanyi M and Riely GJ:

Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to

EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

Clin Cancer Res. 19:2240–2247. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu SG and Shih JY: Management of acquired

resistance to EGFR TKI-targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell

lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 17:382018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zalaquett Z, Catherine Rita Hachem M,

Kassis Y, Hachem S, Eid R, Raphael Kourie H and Planchard D:

Acquired resistance mechanisms to osimertinib: The constant battle.

Cancer Treat Rev. 116:1025572023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Westover D, Zugazagoitia J, Cho BC, Lovly

CM and Paz-Ares L: Mechanisms of acquired resistance to first- and

second-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 29

(Suppl 1):i10–i19. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ko B, Paucar D and Halmos B: EGFR T790M:

Revealing the secrets of a gatekeeper. Lung Cancer (Auckl).

8:147–159. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Leonetti A, Sharma S, Minari R, Perego P,

Giovannetti E and Tiseo M: Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in

EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 121:725–737.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Thress KS, Paweletz CP, Felip E, Cho BC,

Stetson D, Dougherty B, Lai Z, Markovets A, Vivancos A, Kuang Y, et

al: Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in

non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat Med.

21:560–562. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Niederst MJ, Hu H, Mulvey HE, Lockerman

EL, Garcia AR, Piotrowska Z, Sequist LV and Engelman JA: The

allelic context of the C797S mutation acquired upon treatment with

third-generation EGFR inhibitors impacts sensitivity to subsequent

treatment strategies. Clin Cancer Res. 21:3924–3933. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Passaro A, Jänne PA, Mok T and Peters S:

Overcoming therapy resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Nat

Cancer. 2:377–391. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Proto C, Lo Russo G, Corrao G, Ganzinelli

M, Facchinetti F, Minari R, Tiseo M and Garassino MC: Treatment in

EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer: How to block the receptor

and overcome resistance mechanisms. Tumori. 103:325–337. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Du X, Yang B, An Q, Assaraf YG, Cao X and

Xia J: Acquired resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs and

emerging next-generation EGFR inhibitors. Innovation (Camb).

2:1001032021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Roy V and Perez EA: Beyond trastuzumab:

Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors in HER-2-positive breast

cancer. Oncologist. 14:1061–1069. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T,

Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, Lindeman N, Gale CM, Zhao X, Christensen

J, et al: MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung

cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 316:1039–1043. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Punekar SR, Velcheti V, Neel BG and Wong

KK: The current state of the art and future trends in RAS-targeted

cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:637–655. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ohashi K, Sequist LV, Arcila ME, Lovly CM,

Chen X, Rudin CM, Moran T, Camidge DR, Vnencak-Jones CL, Berry L,

et al: Characteristics of lung cancers harboring NRAS mutations.

Clin Cancer Res. 19:2584–2591. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Simanshu DK, Nissley DV and McCormick F:

RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell.

170:17–33. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Polivka J and Janku F: Molecular targets

for cancer therapy in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Pharmacol Ther.

142:164–175. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Eng J, Woo KM, Sima CS, Plodkowski A,

Hellmann MD, Chaft JE, Kris MG, Arcila ME, Ladanyi M and Drilon A:

Impact of concurrent PIK3CA mutations on response to EGFR tyrosine

kinase inhibition in EGFR-mutant lung cancers and on prognosis in

oncogene-driven lung adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 10:1713–1719.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pollak M: Insulin and insulin-like growth

factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 8:915–928. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Namba K, Shien K, Takahashi Y, Torigoe H,

Sato H, Yoshioka T, Takeda T, Kurihara E, Ogoshi Y, Yamamoto H, et

al: Activation of AXL as a preclinical acquired resistance

mechanism against osimertinib treatment in EGFR-mutant non-small

Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Mol Cancer Res. 17:499–507. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D,

Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Gettinger

S, Cosper AK, et al: Genotypic and histological evolution of lung

cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med.

3:75ra262011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Oser MG, Niederst MJ, Sequist LV and

Engelman JA: Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to

small-cell lung cancer: Molecular drivers and cells of origin.

Lancet Oncol. 16:e165–e172. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yin X, Li Y, Wang H, Jia T, Wang E, Luo Y,

Wei Y, Qin Z and Ma X: Small cell lung cancer transformation: From

pathogenesis to treatment. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:595–606. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li Y, Xie T, Wang S, Yang L, Hao X, Wang

Y, Hu X, Wang L, Li J, Ying J and Xing P: Mechanism exploration and

model construction for small cell transformation in EGFR-mutant

lung adenocarcinomas. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:2612024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lee JK, Lee J, Kim S, Kim S, Youk J, Park

S, An Y, Keam B, Kim DW, Heo DS, et al: Clonal history and genetic

predictors of transformation into small-cell carcinomas from lung

adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 35:3065–3074. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Huang L and Fu L: Mechanisms of resistance

to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 5:390–401.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Neel DS and Bivona TG: Secrets of drug

resistance in NSCLC exposed by new molecular definition of EMT.

Clin Cancer Res. 19:3–5. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Sumimoto H, Takano A, Igarashi T, Hanaoka

J, Teramoto K and Daigo Y: Oncogenic epidermal growth factor

receptor signal-induced histone deacetylation suppresses chemokine

gene expression in human lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 13:50872023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yu S, Sha H, Qin X, Chen Y, Li X, Shi M

and Feng J: EGFR E746-A750 deletion in lung cancer represses

antitumor immunity through the exosome-mediated inhibition of

dendritic cells. Oncogene. 39:2643–2657. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Fang Y, Wang Y, Zeng D, Zhi S, Shu T,

Huang N, Zheng S, Wu J, Liu Y, Huang G, et al: Comprehensive

analyses reveal TKI-induced remodeling of the tumor immune

microenvironment in EGFR/ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer.

Oncoimmunology. 10:19510192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lin Z, Wang Q, Jiang T, Wang W and Zhao

JJ: Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with STING agonism

improves the antitumor efficacy of osimertinib in a mouse model of

EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Front Immunol. 14:10772032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen Q, Xia L, Wang J, Zhu S, Wang J, Li

X, Yu Y, Li Z, Wang Y, Zhu G and Lu S: EGFR-mutant NSCLC may

remodel TME from non-inflamed to inflamed through acquiring

resistance to EGFR-TKI treatment. Lung Cancer. 192:1078152024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Jia Y, Li X, Jiang T, Zhao S, Zhao C,

Zhang L, Liu X, Shi J, Qiao M, Luo J, et al: EGFR-targeted therapy

alters the tumor microenvironment in EGFR-driven lung tumors:

Implications for combination therapies. Int J Cancer.

145:1432–1444. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wang DH, Lee HS, Yoon D, Berry G, Wheeler

TM, Sugarbaker DJ, Kheradmand F, Engleman E and Burt BM:

Progression of EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma is driven by

alveolar macrophages. Clin Cancer Res. 23:778–788. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Valenti R, Huber V, Iero M, Filipazzi P,

Parmiani G and Rivoltini L: Tumor-released microvesicles as

vehicles of immunosuppression. Cancer Res. 67:2912–2915. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gao L, Wang L, Dai T, Jin K, Zhang Z, Wang

S, Xie F, Fang P, Yang B, Huang H, et al: Tumor-derived exosomes

antagonize innate antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol. 19:233–245.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang H, Deng T, Liu R, Bai M, Zhou L,

Wang X, Li S, Wang X, Yang H, Li J, et al: Exosome-delivered EGFR

regulates liver microenvironment to promote gastric cancer liver

metastasis. Nat Commun. 8:150162017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Cho JW, Park S, Kim G, Han H, Shim HS,

Shin S, Bae YS, Park SY, Ha SJ, Lee I and Kim HR: Dysregulation of

TFH-B-TRM lymphocyte cooperation is

associated with unfavorable anti-PD-1 responses in EGFR-mutant lung

cancer. Nat Commun. 12:60682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhao J, Lu Y, Wang Z, Wang H, Zhang D, Cai

J, Zhang B, Zhang J, Huang M, Pircher A, et al: Tumor immune

microenvironment analysis of non-small cell lung cancer development

through multiplex immunofluorescence. Transl Lung Cancer Res.

13:2395–2410. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

He S, Yin T, Li D, Gao X, Wan Y, Ma X, Ye

T, Guo F, Sun J, Lin Z and Wang Y: Enhanced interaction between

natural killer cells and lung cancer cells: Involvement in

gefitinib-mediated immunoregulation. J Transl Med. 11:1862013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Patel SA, Nilsson MB, Yang Y, Le X, Tran

HT, Elamin YY, Yu X, Zhang F, Poteete A, Ren X, et al: IL6 Mediates

suppression of T- and NK-cell function in EMT-associated

TKI-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res. 29:1292–1304.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yang L, He YT, Dong S, Wei XW, Chen ZH,

Zhang B, Chen WD, Yang XR, Wang F, Shang XM, et al: Single-cell

transcriptome analysis revealed a suppressive tumor immune

microenvironment in EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother

Cancer. 10:e0035342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Chen J, Jiang CC, Jin L and Zhang XD:

Regulation of PD-L1: A novel role of pro-survival signalling in

cancer. Ann Oncol. 27:409–416. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang Y, Wang L, Li Y, Pan Y, Wang R, Hu

H, Li H, Luo X, Ye T, Sun Y and Chen H: Protein expression of

programmed death 1 ligand 1 and ligand 2 independently predict poor

prognosis in surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets

Ther. 7:567–573. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Azuma K, Ota K, Kawahara A, Hattori S,

Iwama E, Harada T, Matsumoto K, Takayama K, Takamori S, Kage M, et

al: Association of PD-L1 overexpression with activating EGFR

mutations in surgically resected nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann

Oncol. 25:1935–1940. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Yang CY, Liao WY, Ho CC, Chen KY, Tsai TH,

Hsu CL, Su KY, Chang YL, Wu CT, Hsu CC, et al: Association between

programmed death-ligand 1 expression, immune microenvironments, and

clinical outcomes in epidermal growth factor receptor mutant lung

adenocarcinoma patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Eur J Cancer. 124:110–122. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, Altabef

A, Tchaicha JH, Christensen CL, Mikse OR, Cherniack AD, Beauchamp

EM, Pugh TJ, et al: Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to

immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov.

3:1355–1363. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lin K, Cheng J, Yang T, Li Y and Zhu B:

EGFR-TKI down-regulates PD-L1 in EGFR mutant NSCLC through

inhibiting NF-κB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 463:95–101. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Abdelhamed S, Ogura K, Yokoyama S, Saiki I

and Hayakawa Y: AKT-STAT3 pathway as a downstream target of EGFR

signaling to regulate PD-L1 expression on NSCLC cells. J Cancer.

7:1579–1586. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

D'Incecco A, Andreozzi M, Ludovini V,

Rossi E, Capodanno A, Landi L, Tibaldi C, Minuti G, Salvini J,

Coppi E, et al: PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in molecularly selected