Bone sarcomas, osteosarcoma (OS), Ewing sarcoma (ES)

and chondrosarcoma (CS), collectively account for 2–3% of all

childhood and adolescent types of cancer, yet they remain the third

leading cause of cancer-related mortality in patients aged 10–25

years (1). Globocan 2024 reports an

annual incidence of 0.3 for OS, 0.2 for ES and 0.4 for CS per

100,000, with no plateau in incidence over the past decade

(2). Distal extremity primaries

dominate OS and ES, whereas CS arises predominantly in axial

locations and is prone to local relapse (2). Genomic heterogeneity is extreme: OS is

characterized by TP53/RB1 disruption and chromothripsis, ES by

EWSR1-FLI1 translocations and CS by IDH1/2 or COL2A1 mutations,

which shape distinct immune landscapes (3,4). This

biological diversity translates into variable outcomes, 5-year

overall survival is 65–70% for localized OS but decreases to

<30% when metastatic (5); ES

achieves 75% survival with multimodal therapy but remains <25%

after recurrence (6) and high-grade

CS shows only 10–15% survival once unresectable (7). Despite their rarity, these tumors

impose a disproportionate clinical burden that calls for

mechanism-based therapeutic innovation.

Curative intent still hinges on surgery plus

multi-agent cytotoxic chemotherapy, with radiation reserved for

margin-positive or unresectable disease (8). Neoadjuvant response, defined by ≥90%

necrosis, associates with survival, yet 35–45% of patients with OS

achieve poor histologic response and carry a 3-fold higher risk of

metastatic relapse (8). High-grade

CS is intrinsically chemo- and radio-resistant, leaving wide

excision as the only curative option, which is often impossible in

pelvic or skull-base locations. Dose intensification has reached

ceiling toxicity without further survival benefit; therefore,

high-risk groups (metastatic presentation, axial primaries or

<90% necrosis) urgently require alternative strategies (9). Importantly, traditional regimens

neglect the tumor microenvironment (TME), which orchestrates

chemoresistance through hypoxia-induced quiescence, extracellular

matrix (ECM)-mediated drug trapping and immunosuppressive cytokines

such as TGF-β and IL-10. Recognizing these TME-centric escape

mechanisms is essential to explain why even aggressive multimodal

therapy fails in a substantial subset of patients (10,11).

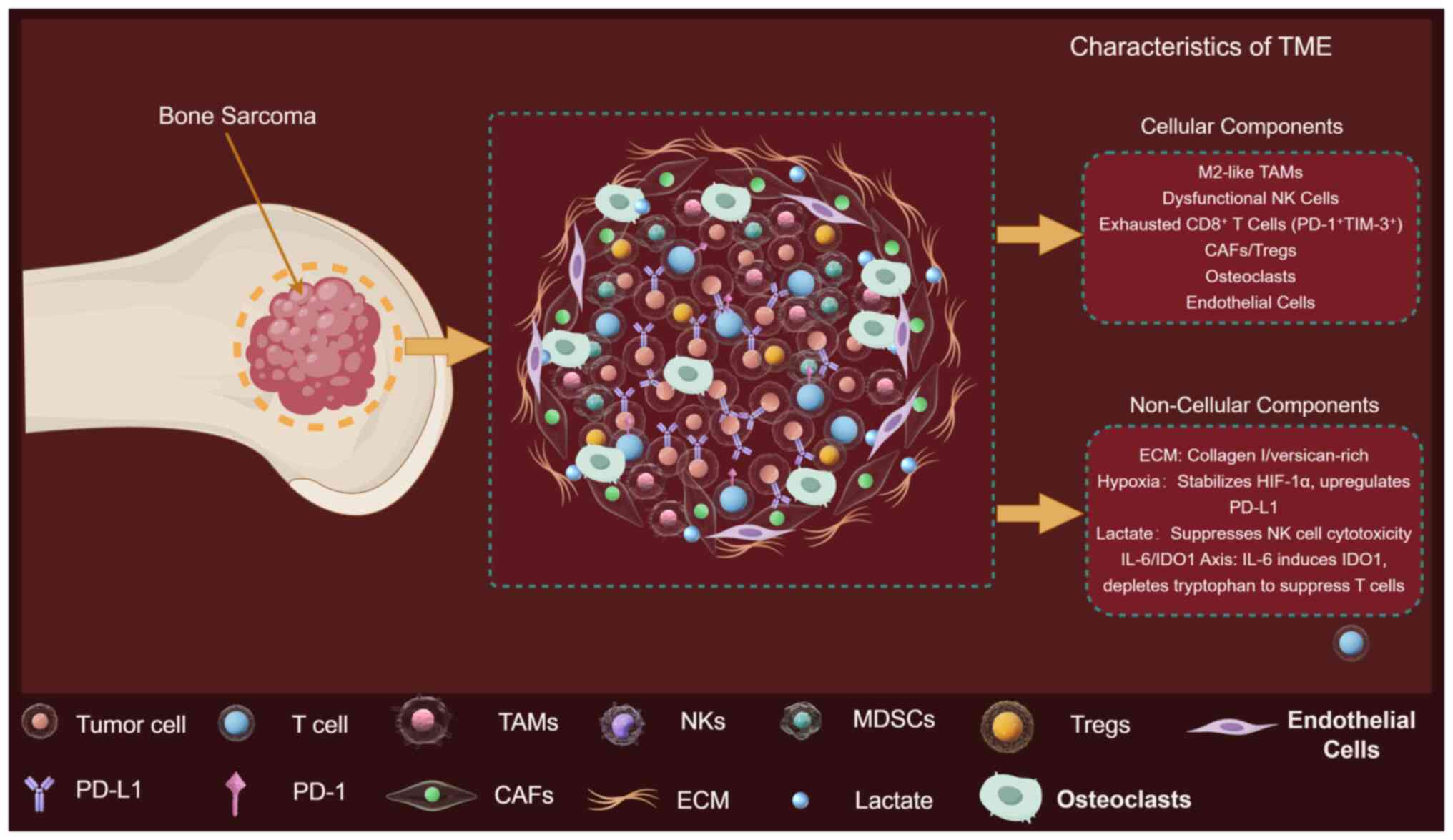

The bone sarcoma TME is an intricate ecosystem

composed of malignant cells interwoven with cancer-associated

fibroblasts (CAFs), bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells,

osteoclasts, endothelial cells and a spectrum of innate and

adaptive immune cells (12).

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) of untreated OS resolved

nine major non-malignant populations, including C1Q+

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), exhausted CD8+ T cells,

regulatory T cells (Tregs) and dysfunctional dendritic cells (DCs)

(13). Non-cellular components are

equally important: A collagen- and versican-rich ECM increases

tissue stiffness, promotes integrin-mediated survival signaling and

impedes cytotoxic T-cell infiltration (14). Hypoxia and acidic pH gradients

generated by aerobic glycolysis stabilize hypoxia inducible factor

(HIF)-1α, upregulate programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and skew

macrophages toward an M2 immunosuppressive phenotype (15). Dynamic crosstalk between these

elements, for example, TAM-derived TGF-β induces OS stemness while

tumor-secreted CSF-1 reciprocally sustains TAMs survival, creates a

self-reinforcing niche that fosters progression and therapy

resistance (16,17).

Pre-clinical lineage-tracing studies demonstrate

that disseminated OS cells seed the lung as early as diagnosis, but

only those that have educated a pre-metastatic niche rich in

S100A8/A9+ myeloid cells and ECM crosslinking enzymes successfully

colonize (18,19). In ES, CD99-mediated reprogramming of

macrophages suppresses antigen presentation, facilitating immune

evasion during transit (20).

Locally, hypoxia-induced exosomes transfer micro (miR)-135b from

tumor cells to endothelial cells, promoting angiogenesis and

subsequent osteolysis (21).

Chemotherapy itself reshapes the TME: Cisplatin increases M2-TAMs

infiltration and PD-L1 expression, whereas doxorubicin enriches ECM

cross-linking enzymes, both contributing to acquired resistance

(22). Radiation upregulates

antigen presentation machinery yet simultaneously expands CD47+

macrophages that blunt T-cell cytotoxicity (23). Thus, the TME not only fuels primary

tumor growth but also orchestrates metastatic spread and shields

residual cells from cytotoxic, targeted and immune attack,

positioning it as the central bottleneck for durable cures.

OS is the most frequent primary malignant bone

neoplasm, with a bimodal age distribution encompassing adolescents

and the elderly (1,2). Despite aggressive multi-modal therapy,

~40% of patients with OS develop pulmonary metastases within 5

years, and the 5-year survival for metastatic disease remains

<30% (5). Single-cell RNA

sequencing coupled to intravital imaging has recently shown that

invasive osteosarcoma cells heighten focal adhesion kinase/SRC

signaling when confronted with extracellular-matrix stiffening

(Young's modulus >30 kPa), facilitating amoeboid migration and

trans-endothelial extravasation (24). Hypoxia-induced exosomal miR-135b

transferred from tumor to endothelial cells enhances vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-independent angiogenesis and

osteolysis, facilitating pre-metastatic niche formation in the lung

(21). Additionally, M2-polarized

TAMs secrete CCL18, which activates the PI3K/AKT pathway in OS

cells and increases MMP9 expression, further augmenting local

invasion and intravasation (25).

These observations position the TME not only as a barrier to

therapy but also as an active driver of metastatic cascade,

underscoring the urgency of targeting both tumor-intrinsic and

microenvironmental determinants of invasion.

Current regimens yield suboptimal survival in

patients with metastatic or relapsed bone sarcomas, partly because

cytotoxic protocols overlook the immunosuppressive, mechanically

rigid and metabolically hostile TME. Previous publications have

summarized individual TME components in OS pathogenesis and

discussed therapeutic targets (13–15).

This present review extends beyond these earlier reports by

integrating scRNA-seq, spatial proteomics and functional imaging

across OS, ES and CS to define subtype-specific TME archetypes. In

addition, a mechanistic framework that associates

mineralized-matrix mechanics, metabolic acidosis and myeloid

reprogramming to primary and acquired immunotherapy resistance is

presented and biomarker-guided combination strategies are proposed

for addressing these challenges.

Single-cell atlases and spatial proteomics now

resolve OS, Ewing and CS microenvironments into archetypes

dominated by M2 macrophages, exhausted CD8+ T cells and

stiff collagen-versican ECM. Fig. 1

provides the reference framework for dissecting subtype-specific

cellular and non-cellular determinants of immune privilege and drug

resistance.

scRNA-seq has revealed striking inter-tumoral

heterogeneity that directly conditions immunotherapy outcomes

(26). In OS, CD3+ T cells

constitute 8–15% of all viable cells; however, 60–80% of these

cells display an exhausted PD-1+ T-cell Immunoglobulin and

Mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3)+ Lymphocyte Activation

Gene 3 (LAG-3)+ phenotype and are spatially confined to

the tumor periphery by CXCL12-rich reticular networks (27). By contrast, ES lesions harbor an

even lower overall T-cell fraction (2–5%) but a higher

CD8+/ Tregs ratio, possibly explaining the 20% objective

response rate to pembrolizumab monotherapy observed in the

EURO-EWING-2012-NIS trial (NCT 02707557), whereas OS trials have

yet to >5% objective response rate (28). These divergent landscapes argue

against a ‘one-size-fits-all’ checkpoint blockade strategy and

suggest that CXCR4 or CXCL12 inhibition might preferentially

benefit OS by enhancing T-cell trafficking.

Myeloid populations dominate the sarcoma TME across

subtypes, yet their functional states are context-dependent

(29). In OS, two independent

scRNA-seq cohorts (n=11 and n=19) both identified a continuum of

TAMs skewed toward M2-like signatures

(CD163+CCL18+MMP12+), associating

with shorter metastasis-free survival (HR=2.3, P=0.007) (13). Conversely, CS TAMs express higher

inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and tumor necrosis factor- α

(TNF-α), resembling an M1 phenotype, but paradoxically co-express

PD-L1 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase1 (IDO1), indicating a hybrid

state that may blunt anti-PD-1 efficacy despite apparent

‘inflammatory’ polarity (30).

These conflicting data underscore the need for multi-omic spatial

mapping to resolve whether M1/M2 classifications are sufficient

biomarkers in bone sarcomas.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and

regulatory DCs further entrench immunosuppression. In canine OS,

PMN-MDSCs rise from <3% in healthy marrow to 18% within tumor

tissue and their depletion with PI3Kδ inhibitor GS-9820 restores

antigen-specific T-cell proliferation ex vivo (31). A separate study reported that

conventional DC1s are virtually absent in 70% of high-grade CS

specimens, and forced re-introduction of FLT3L-matured DC1s in

patient-derived organoids re-sensitized tumors to γδ T-cell killing

(32). Collectively, these findings

position combinatorial regimens that simultaneously deplete MDSCs

and replenish DC1s as a rational next step for clinical

testing.

Natural killer cells (NKs) abundance is high in ES

(<12%), but their cytotoxicity is crippled by transforming

growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) concentrations >800 pg/ml, levels that

exceed those in OS by 3-fold (33).

Blockade of TGF-βRI with galunisertib restored NKs degranulation

against ES cell lines in vitro, providing a mechanistic

rationale for the ongoing phase I/II trial of galunisertib plus

dinutuximab β (NCT05461567) (34).

CAFs originate from resident bone-marrow mesenchymal

stem cells (MSCs) and adopt heterogeneous phenotypes. CAFs

constitute a dominant stromal component in bone sarcomas and are

increasingly recognized as co-architects of the immunosuppressive

niche (35). scRNA-seq of human OS

biopsies resolved two transcriptionally stable CAF

subsets-myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs, ACTA2high) and

inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs,

IL-6highCXCL12high), that together account

for 25–35% of all non-malignant cells (35). Lineage-tracing studies in

genetically engineered mouse models indicate that the majority of

CAFs arise from local bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal/stem

cells (BM-MSCs) through TGF-β- and bone morphogenetic protein-2

(BMP-2)-driven reprogramming, a process that is molecularly

indistinguishable from the osteoblastic differentiation cascade

that gives rise to the malignant clone itself (35). Consequently, OS cells and CAFs share

an overlapping mesenchymal developmental program, including

expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β,

CD90 and the osteoblastic transcription factor RUNX2, suggesting

that the same oncogenic cues that initiate the tumor concurrently

instruct CAF fate. This ontological convergence explains why CAFs

are uniquely equipped to deposit a collagen- and versican-rich ECM

that matches the stiffness (Young's modulus 25–35 kPa) of the

surrounding mineralized bone, thereby shielding tumor cells from

immune attack and impeding chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T)

cell penetration (36). Two

transcriptionally distinct CAF subpopulations have been delineated:

myCAFs (ACTA2high) and iCAFs (IL-6high

CXCL12high) (37). In

OS, myCAFs aligned along collagen bundles associate with increased

tissue stiffness (Young's modulus 25–35 kPa) and impaired CAR-T

penetration, whereas iCAFs secrete CXCL12 that recruits

CXCR4+ Tregs (38).

Targeting CXCL12 with plerixafor sensitized OS xenografts to

disialoganglioside 2 (GD2). CAR-T therapy, increasing intratumoral

CAR-T density 4-fold (39). These

data highlight CAFs subtyping as a prerequisite for effective

stromal reprogramming.

Osteoblast-lineage cells, often dismissed as

bystanders, actively shape immune privilege (40). Single-cell interactome analyses

revealed 21 ligand-receptor pairs between OS cells and osteoblasts,

including RANKL-RANK and Jagged1-Notch2 axes that polarize

macrophages toward an M2 phenotype and upregulate PD-L1 (41). Pharmacologic RANKL inhibition with

denosumab not only reduced osteoclastogenesis but also decreased

M2-TAMs abundance by 40% in a syngeneic OS model, suggesting dual

anti-resorptive and immunomodulatory benefits (42). Conversely, osteoclasts fuel a

vicious cycle of bone destruction and TGF-β release; TGF-β

concentrations >1 ng/ml were sufficient to convert 50% of CD8+ T

cells into FOXP3+ Tregs in Transwell assays (43). These observations position

osteoclast-directed therapy as a combinatorial partner for TGF-β

inhibition.

Bone sarcomas develop a chaotic vasculature

characterized by tortuous, CD31-high and NG2-low vessels with poor

pericyte coverage (44).

Microvessel density is highest in ES (mean 104 vessels

mm−2) and lowest in CS (42 vessels mm−2),

paralleling VEGF-A expression levels (45). Yet, bevacizumab achieved only modest

disease stabilization [6-month progression-free survival (PFS) 18%]

in a phase II OS trial, possibly because VEGF blockade

paradoxically increased hypoxia and HIF-1α-driven PD-L1 expression

on tumor cells (46). Alternative

strategies that normalize rather than prune vessels, such as

low-dose metronomic cyclophosphamide enhanced CART cells

infiltration in murine ES models without exacerbating hypoxia,

underscoring the need to balance anti-angiogenic and

immunotherapeutic dosing schedules (47).

MSCs are recruited to primary tumors via CCL5-CCR5

signaling and differentiate into either CAFs or osteoblast-like

cells depending on TGF-β and BMP-2 gradients (48). In OS, MSCs-secreted PGE2 induces

IDO1 in DCs, leading to a 60% reduction in T-cell proliferation in

mixed lymphocyte reactions (49).

Genetic ablation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in MSCs restored DCs

function and improved anti-PD-1 efficacy in vivo (50). These findings suggest that

MSCs-educated immune suppression is reversible and that COX-2

inhibition could serve as an adjuvant to checkpoint blockade.

In summary, osteoblast-lineage cells, osteoclasts,

MSCs and endothelial cells each contribute distinct

immunosuppressive cues, including cytokine secretion, ECM

remodeling, and metabolic reprogramming. These interactions not

only reinforce tumor survival but also impede effective immune

surveillance. A summary of key bone-related cells, their ontogeny,

immunosuppressive mediators, and therapeutic implications is

presented in Table I (14,34,42,47,50),

highlighting potential targets for microenvironment-directed

interventions.

The bone sarcoma ECM is a composite of type-I

collagen, hydroxyapatite nanocrystals and oncofetal fibronectin

(51). Atomic-force microscopy

shows that OS ECM stiffness (10–40 kPa) is 3-fold higher than

adjacent marrow, a mechanical cue that activates yes-associated

protein (YAP)/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif

(TAZ) and downregulates MHC-I in tumor cells (52). Lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2)-mediated

collagen cross-linking is elevated in metastatic bone sarcomas and

targeting LOXL2 improves both chemotherapeutic drug delivery and

the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapies (14).

Multiplex cytokine profiling of OS biopsies

identified a high-TGF-β/low-interferon-γ (IFN-γ) signature that

independently predicted poor histologic response to neoadjuvant MAP

chemotherapy (53). Tumor-derived

IL-6 and CXCL12 establish an autocrine/paracrine loop that recruits

CXCR4+ MDSCs and polarizes macrophages to an M2

phenotype (54). These soluble

factors collectively sculpt an immunosuppressive milieu and

establish the rationale for co-targeting IL-6, CXCL12 and TGF-β in

combination regimens.

Lactate concentrations >15 mM in OS interstitial

fluid, suppressing NKs cytotoxicity by 50% via GPR81-dependent

mechanisms (57). Pharmacologic

buffering with oral sodium bicarbonate restored NK function and

improved anti-GD2 antibody efficacy in vivo, supporting a

readily translatable adjunct (58).

Pharmacologic buffering with oral sodium bicarbonate restored NK

cytotoxicity and enhanced anti-GD2 antibody efficacy in orthotopic

OS models, confirming rapid translatability of this metabolic

adjunct (58).

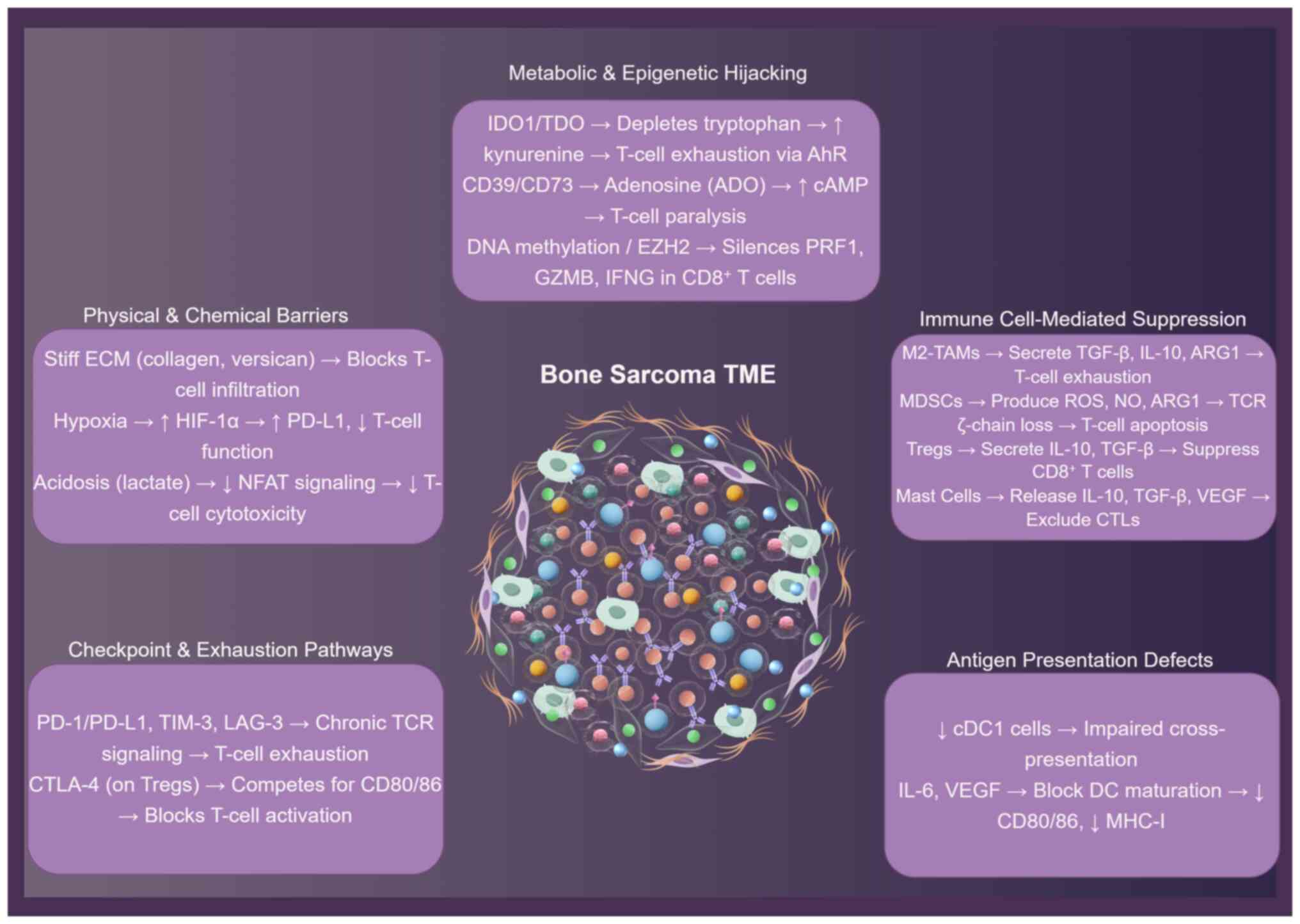

Dense collagen matrices and aberrant chemokines

exclude cytotoxic T cells, while M2 macrophages, MDSCs and Tregs

secrete arginase-1, TGF-β and adenosine to paralyze effector

function (Fig. 2) (13,14).

Exhaustion checkpoints, metabolic acidosis and IDO1-driven

tryptophan depletion reinforce this immunosuppressive circuit, and

immature dendritic cells fail to present antigen, forging an

immune-privileged sanctuary that defies therapy (53–56).

Physical barriers and aberrant chemokine gradients

cooperatively limit intratumoral T-cell accumulation (59). The ECM of OS is enriched in collagen

I/III, fibronectin and hyaluronan; high tissue stiffness reduces

T-cell motility and cytotoxicity in vitro and associates

with low CD8+ infiltration in vivo (60). Chemokine profiling of 22

treatment-naïve OSs revealed a marked paucity of CXCL9/10 and CCL5

concomitant with overexpression of CXCL12 and CCL18, a pattern that

preferentially recruits CXCR4+ Tregs and CCR8+ M2 macrophages while

excluding CXCR3+ CD8+ T cells (61). Consistently, spatial transcriptomics

showed an inverse association between CXCL9/10 levels and distance

of CD8+ T cells from tumor nests (Spearman ρ=−0.63, P<0.01)

(62). The clinical implication is

that forced intratumoral release of CXCL9 or CXCL10 via oncolytic

viruses or STING agonists could enhance ICI efficacy, an approach

currently being tested in early-phase trials (NCT05115319).

Tregs constitute 10–25% of CD4+ tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes (TILs) in OS and exhibit an activated phenotype

(FOXP3high, CD25high and

CTLA-4high) (67).

Functionally, Tregs suppress CD8+ proliferation in vitro via

IL-10, TGF-β and IL-35 and physically deplete IL-2 through

high-affinity IL-2Rα (68,69). Notably, the Treg/CD8 ratio increases

from 0.2 in primary tumors to 0.7 in metastases (P<0.001),

paralleling reduced objective response rates to anti-PD-1 therapy

in metastatic cohorts (8 vs. 26% in localized disease) (70). Depletion models in murine OS (K7M2)

show that transient Treg reduction (anti-CD25) doubles CD8+

granzyme-B production and restores sensitivity to PD-1 blockade

(71).

Chronic antigen exposure in bone sarcomas drives a

progressive exhaustion program (78). sc TCR sequencing revealed

oligoclonal expansion (median 47 unique clonotypes per patient)

with over-representation of exhausted

TCF-1−TOX+ PD-1high

CD8+ subsets (79).

Continuous PD-1 signaling, reinforced by TIM-3 and LAG-3,

upregulates diacylglycerol kinase-α, dampening TCR signaling

(80). Metabolic stress further

exacerbates dysfunction: Lactate (15–20 mM) suppresses nuclear

factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) nuclear translocation, while

adenosine (via CD73/CD39 axis) elevates intracellular cyclic

adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), both impairing cytokine production

(81). Pre-clinical blockade of the

adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) pathway restores T-cell effector

function in hypoxic OS models, providing a rationale for combining

adenosine-targeted agents with immune-checkpoint inhibitors in

future trials (82).

Metabolic reprogramming within the bone sarcoma TME

actively suppresses antitumor immunity (86). Tumor cells exhibit high glycolytic

flux, generating an acidic, lactate-rich milieu that impairs

CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity and cytokine production,

notably via inhibition of NFAT signaling and histone acetylation

(87). Concurrently, tumor and

stromal cell upregulation of IDO1 depletes tryptophan and produces

immunosuppressive kynurenine metabolites, activating the aryl

hydrocarbon receptor in T cells and driving exhaustion (88). Furthermore, the CD39/CD73-A2AR

adenosine axis is a dominant immunosuppressive pathway; adenosine

generated extracellularly suppresses T-cell effector functions via

elevated intracellular cAMP. Elevated CD73 expression associates

with poor response to PD-1 blockade (88,89).

These pathways collectively establish a metabolically hostile

environment for effector immune cells.

DNA hypermethylation silences perforin 1 (PRF1),

granzyme B (GZMB) and IFNγ promoters in CD8+ TILs,

whereas H3K27me3 deposition represses T-box transcription factor 21

and eomesodermin loci, locking cells in an exhausted state

(90). OS-derived exosomal

miR-221-3p downregulates suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in

macrophages, enhancing JAK2-STAT3 signaling and sustaining M2

polarization (91). Conversely,

pharmacologic inhibition of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2;

tazemetostat) reactivates PRF1 and GZMB transcription in murine

models, improving response to PD-1 blockade (92). These data raise the prospect of

combining epigenetic modifiers with immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs) to overcome adaptive resistance.

Building upon the aforementioned mechanistic

studies, the clinical record of immune checkpoint and adoptive cell

therapies in bone sarcomas is now systematically reviewed. Table II (93–100)

summarizes objective response rates from landmark ICI trials, while

Table III (35,36,101–124) collates pre-clinical and

early-phase adoptive cell therapies (ACT) data, together revealing

how the immunosuppressive TME continues to dictate therapeutic

outcome.

The advent of ICIs, particularly targeting the

PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 axes, revolutionized oncology. However, their

application in bone sarcomas, primarily OS, has yielded

predominantly modest clinical benefits, underscoring the profound

influence of the TME in shaping resistance (93,94).

Across the published pembrolizumab, nivolumab and

nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab series, objective responses in bone

sarcoma rarely exceed single digits. SARC028, the sentinel

multicenter phase II trial, enrolled 22 patients with OS or CS and

documented only one partial response lasting 32 weeks, yielding an

objective response rate of 5% (93). Two confirmatory studies have since

reproduced this figure: The PEMBROSARC cohort of 30 heavily

pre-treated (≥2 prior lines of systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy or

targeted therapy) patients with OS had no objective responses at

all (94), while the pediatric

ADVL1412 expansion treated 14 patients with OS with nivolumab plus

ipilimumab and observed just one durable partial response

(objective response rate, 7%) (95,96).

Single-arm studies using pembrolizumab monotherapy (Boye et

al (97), 28 patients) or the

nivolumab-sunitinib combination [Palmerini et al (98); 15 patients] produced identical null

response rates.

The mechanistic explanation for this uniformly low

activity lies in three interconnected features of the bone-sarcoma

TME detailed in ‘Mechanisms of immunosuppression within the bone

sarcoma TME’, immunologically ‘cold’ tumors: Spatial mapping shows

PD-L1-expressing cells physically separated from CD8+ CTLs,

creating an excluded infiltrate refractory to checkpoint

reactivation (99). Genomic

quietness: Low mutational burden and minimal neoantigen

presentation deprive T cells of the antigenic signal needed for

ICI-driven expansion (93).

Pronounced myeloid dominance: The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis recruits

monocytic MDSCs that outcompete CTLs for glucose and secrete

arginase-1, directly neutralizing anti-PD-1 efficacy in

pre-clinical models (100).

Notably, the lone responder in SARC028 had chondroblastic OS with

high PD-L1 expression (≥50% tumor cells) and brisk peritumoural CD8

infiltration, illustrating that exceptional responders may arise

when the tumor deviates from the archetypal ‘cold’ bone-sarcoma

microenvironment (93).

PD-L1 expression remains the most interrogated

biomarker, yet results are inconsistent. Discordant PD-L1 status

between primary and metastatic lesions occurs in 35% of patients

with OS, undermining archival tissue reliability (101). In PEMBROSARC, PD-L1 positivity

(≥1%) was present in 30% of cases but was unassociated with benefit

(94). Conversely, Le Cesne et

al (94) reported that high

PD-L1 combined with IDO1 expression enriched for a 10% long-term

disease-control subgroup, hinting at combinatorial biomarker

utility. Spatial transcriptomics now suggests that the spatial

proximity of PD-L1+ macrophages to CTLs, rather than

absolute PD-L1 levels, predicts non-progression (99). Beyond PD-L1, an ‘immune-hot’

signature (CD8+ CTL/Treg ratio >2 and low M-MDSC

density) emerged as an independent predictor of PFS in the

nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab ADVL1412 cohort (HR, 0.31; 95% CI,

0.12–0.78) (96). However, this

signature was present in only 6/38 (16%) sarcoma biopsies,

underscoring the rarity of immunologically favorable bone

sarcomas.

Emerging evidence suggests mast-cell stabilization

as a novel resistance mechanism. Mast cells are tissue-resident,

c-Kit+FcεRI+ innate immune cells that

differentiate in the bone marrow, circulate as progenitors and

mature locally under the influence of stem-cell factor, IL-3, IL-33

and CXCL12. In bone sarcomas, mast cells preferentially localize to

the hypoxic tumor margin and along neo-vessels, where they act as

central hubs integrating stromal and immune signals (102). Upon activation, mast cells rapidly

degranulate histamine, tryptase and chymase, and additionally

secrete IL-4, IL-10, VEGF-A, PDGF-B and TGF-β1. These mediators

collectively enhance vascular permeability, stimulate CAF

proliferation and promote M2-like macrophage polarization, thereby

reinforcing an immunosuppressive niche that blunts cytotoxic T-cell

influx. Pharmacological stabilization of mast cells with cromolyn

or targeted depletion via c-Kit inhibition restores CD8+

T-cell infiltration and sensitizes OS xenografts to anti-PD-1

therapy, underscoring their therapeutic relevance (44). Mast-cell-derived IL-10 and TGF-β

convert macrophages toward M2 and exclude CTLs; pharmacologic

stabilization restored PD-L1 blockade sensitivity pre-clinically

(44), validation in human studies

is required. Finally, host-related factors (human leukocyte antigen

loss of heterozygosity, low peripheral blood T-cell clonality)

associated with primary resistance in soft-tissue sarcomas warrant

investigation in bone sarcomas via ongoing multi-omics studies

(such as NCT 04339738) (34,35,103).

In summary, current ICI trials confirm modest

single-agent activity in bone sarcomas, driven by an

immunologically ‘cold’ and myeloid-dominated TME. Objective

responses cluster in rare cases with inflamed, PD-L1-high, CTL-rich

tumors, but robust predictive biomarkers are still lacking. Future

efforts must integrate spatially resolved TME profiling, systemic

immune monitoring and rational combination strategies to overcome

primary resistance.

CAR T cells therapy has shown notable preclinical

potential in bone sarcomas, targeting various tumor-associated

antigens. Early work demonstrated the efficacy of IGF1R- and

ROR1-specific CAR T cells against sarcoma cell lines and

xenografts, highlighting IGF1R as a particularly potent target

(104). Subsequent research

identified B7-H3 (CD276) as a highly expressed pan-cancer antigen

in pediatric solid tumors, including OS and ES. B7-H3-CAR T cells

exhibited robust antitumor activity in multiple preclinical OS

models, markedly reducing tumor burden and improving survival

(36,105,106). This efficacy was further enhanced

by strategies to overcome TME-driven homing limitations.

Engineering B7-H3-CAR T cells to express chemokine receptors such

as CXCR2 or CXCR1/CXCR2 ligands (for example, IL-8) or redirecting

them towards chemokines (CXCL9 and CXCL10) abundant in OS models,

considerably improved tumor infiltration and antitumor potency

compared with standard CAR T cells (35,107,108). Similarly, CAR T cells targeting

CD166/4-1BB showed efficacy against OS in vitro and in

vivo, inducing cytotoxicity and inhibiting tumor growth

(109). Other promising

preclinical targets include GD2 in ES [where combining GD2-CAR T

cells with hepatocyte growth factor-neutralizing antibody prevented

metastasis (110)], VEGFR2 in ES

vasculature (111), EphA2 [though

efficacy was variable (112)],

folate receptor α (FRα) via a bispecific adaptor approach (113), cancer stem cell antigens DnaJ Heat

Shock Protein Family Member B8 (DNAJB8) (114) and alkaline phosphatase,

biomineralization associated-1 (115) and oncofetal tenascin C using

IL-18R-supported CARs (116).

Membrane-anchored, tumor-targeted IL-12 expressed on CAR T cells or

PBMCs also demonstrated potent antitumor activity against

heterogeneous OS models by remodeling the TME (117,118). Recent strategies involve enhancing

homing via CXCR5/IL-7 co-expression (119), targeting immunosuppressive

pathways such as Regnase-1 to create a proinflammatory TME

(120) or utilizing switchable CAR

systems for improved safety (121).

Despite promising preclinical results, translating

CAR T-cells efficacy to the clinic for solid tumors such as bone

sarcomas faces major hurdles imposed by the TME. Trafficking to

tumor sites remains a key barrier. Poor homing has been observed,

partly due to inadequate chemokine receptor expression on CAR T

cells mismatched with the chemokine profile of the TME (108,111). Persistence of functional CAR T

cells in vivo is often limited. Wang et al (122) demonstrated the utility of PET

reporter gene imaging to monitor CAR T cells location and

persistence, revealing challenges in maintaining therapeutic cell

numbers within solid tumors. Factors contributing to poor

persistence include T-cell exhaustion within the immunosuppressive

TME and potential fratricide when targeting widely expressed

antigens. Suppression by the TME is a dominant challenge. The TME

fosters immunosuppressive cell populations (TAMs, MDSCs and Tregs)

and expresses immune checkpoint molecules. While Altvater et

al (123) found that HLA-G and

HLA-E, though expressed in ES, had limited functional impact on

GD2-CAR T cells in vitro, other immunosuppressive mechanisms

are potent. Tumor-derived soluble factors, particularly granulocyte

colony-stimulating factor, have been shown to create an

immunosuppressive myeloid-rich TME that markedly impairs the

efficacy of GD2-CAR T cells in OS models (124). The physical barriers of the tumor

stroma and hypoxia further impede CAR T cell function. Clinical

experience with CAR T cells in bone sarcomas remains limited

primarily to early-phase trials, often showing modest activity

compared with hematologic malignancies. Recent analyses, such as

the identification of immune determinants of CAR T cell expansion

in GD2-CAR T treated patients with solid tumor (including OS/ES),

underscore the complex interplay between patient factors, product

attributes and the TME that dictates clinical outcomes (125). Kaczanowska et al (125) found that early expansion kinetics

and T cell phenotypes notably influenced outcomes in GD2-CAR trials

for sarcomas and neuroblastoma, while Arnett and Heczey (126) emphasized that beyond T cell

fitness, the immunosuppressive TME is a major limiting factor

requiring combination approaches.

T cell receptor-engineered T (TCR-T) cell therapy

and TIL therapy represent alternative ACT strategies, but their

application in bone sarcomas is less advanced than CAR T therapy

and faces distinct challenges. TCR-T cells can target intracellular

antigens presented by MHC molecules, potentially broadening the

targetable antigen repertoire. Lu et al reported a clinical

trial using an MHC class II-restricted TCR targeting the cancer

germline antigen MAGE-A3. While the trial included patients with

various types of metastatic cancer, one patient with metastatic

sarcoma (unspecified subtype) achieved a complete response lasting

>24 months, demonstrating the potential therapeutic activity of

TCR-T cells in sarcoma (127).

Recently, Hamada et al (128) developed TCR-T cells targeting the

sarcoma-associated antigen papillomavirus binding factor (PBF).

These TCR-T cells demonstrated specific cytotoxicity against

PBF-positive sarcoma cell lines in vitro and inhibited tumor

growth in xenograft models. Watanabe et al (114) targeted the cancer stem cell

antigen DNAJB8 with TCR-T cells, showing efficacy against various

solid tumors in vitro and in vivo, though specific

bone sarcoma data were limited.

TCR-T therapy faces considerable hurdles in bone

sarcomas. Key challenges include identifying truly tumor-specific

intracellular antigens shared across subtypes, dependence on tumor

MHC expression, intratumoral heterogeneity enabling escape and the

critical risk of off-target toxicity due to TCR cross-reactivity

(114,128). Furthermore, as with CAR T cells,

TCR-T cells must overcome the profoundly immunosuppressive TME to

traffic, persist and function effectively, with specific bone

sarcoma TME interaction data currently limited.

Pre-clinical studies show that oncolytic viruses

can control OS growth, yet the immunocompetent microenvironment

rapidly blunts efficacy (129–131). Intratumoral Semliki Forest virus

encoding HSV-TK shrank orthotopic 143B-luc tumors by 74% in nude

mice, but complete regressions were absent and viral genomes

disappeared within 7 days, leaving the contribution of antitumor

immunity unaddressed (129).

Similarly, intravenous reovirus cleared Ras-activated xenografts

yet failed against A673 or SJSA-1 lesions, and its benefit was lost

in syngeneic K7M2 mice owing to neutralizing antibodies and

T-cell-mediated viral clearance (130).

Live-attenuated Listeria monocytogenes vaccines

offer a complementary strategy. Musser et al (133) administered Lm-LLO-E7 to 15

OS-bearing dogs; although only mild pyrexia and lymphopenia

occurred, median survival appeared prolonged vs. historical

controls (234 vs. 180 days). However, lack of randomization and

heterogeneous adjuvant chemotherapy preclude definitive efficacy

claims and anti-Listeria immunity may limit booster efficacy.

Pre-clinical reprogramming strategies, CSF-1R

inhibition, LOXL2 knockdown, hypoxia-activated prodrugs and EZH2

blockade, restore CTL infiltration and sensitize tumors to

checkpoint blockade (Table IV)

(55,61,135–144). Composite biomarker panels

integrating stiffness, hypoxia scores and immune infiltrate predict

2-3-fold increases in durable regressions across OS models.

Translation strategies: Systemic CSF-1R inhibition

(pexidartinib) eradicated >70% M2-TAMs in mice, tripled

CD8+ TILs, but caused grade-3 hepatotoxicity in 25% of

pediatric patients with only transient responses (145). While promising, repeated

intralesional injection is impractical for multifocal disease, and

long-term immunogenicity is unknown.

Collagen cross-linking enzyme LOXL2 is a central

regulator of ECM stiffness in OS. LOXL2 knockdown reduced stiffness

(35 to 15 kPa), doubled doxorubicin penetration and improved CAR-T

infiltration (145).

Paradoxically, partial ECM degradation increased metastasis by

releasing VEGF-sequestered matrices (138), suggesting indiscriminate

collagenolysis is counterproductive. This underscores the need for

spatiotemporally controlled strategies, such as photo-activatable

MMP-9 inhibitors.

CAFs fortify barriers via paracrine TGF-β and

CXCL12. CLTC-TFG signaling in CAFs upregulates TGF-β, excluding

CD8+ T cells (139).

The bifunctional anti-PD-L1/TGF-β antibody TQB2858 achieved a 33%

objective response rate in relapsed OS (140), yet CAFs heterogeneity predicted

variable CXCL12 levels and inconsistent T-cell recruitment. To

address plasticity, membrane-anchored IL-12 T cells converted

FAP+ CAFs to an inflammatory phenotype, reduced collagen

by 60% and improved CAR-T persistence (141). Unfortunately, sustained IL-12

induced cachexia in 20% of mice, necessitating inducible expression

systems.

Hypoxia-activated prodrugs such as TH-302 kill

hypoxic cells. Combined with anti-PD-1, it improved survival in

metastatic OS mice (55). However,

variable hypoxic thresholds and a lack of consensus imaging

biomarkers hinder application. Integrating 18F-MISO PET

with circulating hypoxia gene signatures may stratify responders,

but needs validation.

IDO1 is upregulated in 60% of OS and associated

with kynurenine-mediated T-cell suppression (143). Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab

produced a 33% ORR, yet IDO1 expression did not predict benefit,

possibly due to compensatory tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase activation

(145). Dual IDO/TDO inhibitors

are under investigation, with off-target hepatic toxicity a

concern.

Translating the aforementioned mechanistic insights

and combination strategies into reliable clinical benefit demands

experimental platforms that faithfully replicate the mineralized,

immune-privileged bone sarcoma niche. Integrating stiffness-tunable

3D hydrogels with humanized mouse models now enables longitudinal

tracking of CAR T cells trafficking, myeloid reprogramming and ECM

modulation, thereby accelerating the validation of biomarker-driven

regimens before paediatric trial entry.

Conventional preclinical models, including cell

monolayers and immunodeficient xenografts, inadequately

recapitulate the spatial, mechanical and immunosuppressive features

of bone sarcoma TME. In vitro 2D cultures fail to model

mineralized bone matrices, which physically impede CAR-T cell

trafficking and alter metabolic crosstalk between tumor cells and

stromal components such as osteoblasts or marrow adipocytes

(149,150). Murine xenograft models (such as

NOD-SCID) lack functional human immune systems, rendering them

incapable of evaluating immunotherapies dependent on human-specific

antigen presentation or checkpoint interactions. For instance, such

models could not predict the clinical failure of HER2-targeted CAR

T cells in OS, which later was attributed to TME-driven exhaustion

markers (PD-1, TIM-3) and TGF-β-mediated suppression (149,151). Even syngeneic mouse models exhibit

interspecies discrepancies in cytokine networks; the

TGF-β/osteopontin (OPN) axis is key for osteoclast-mediated

immunosuppression in human bone metastases, poorly mirrored in

murine systems, leading to overstated efficacy of immune checkpoint

blockade in bone tumors (152).

These limitations underscore a key gap: Conventional models cannot

simulate the dynamic immunosuppressive reprogramming induced by

bone-specific niches, resulting in unreliable therapeutic

predictions.

To address these shortcomings, genetically

engineered and humanized murine platforms incorporating functional

human immunity have emerged (153,154). huHSC-NOG mice reconstituted with

human hematopoietic stem cells enable long-term (≥6 months) study

of human T-cell differentiation and memory responses, making them

ideal for evaluating sustained immunotherapy efficacy (153). For example, F. Hoffmann-La Roche

Ltd's CEA-TCB bispecific antibody combined with atezolizumab

(anti-PD-L1) showed synergistic tumor reduction in huHSC-NOG models

of colorectal cancer, a finding later validated clinically

(155,156). Conversely, huPBMC-NOG models,

which rapidly reconstitute mature T cells within 2–4 weeks, are

suited for short-term assessments of T-cell-engaging therapies such

as blinatumomab (157). However,

their utility is constrained by graft-vs.-host disease) and

deficient B-cell reconstitution, limiting studies on

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (158).

Advanced 3D engineered systems now integrate

biomechanical cues to mimic bone TME pathophysiology.

Stiffness-tunable hydrogels (such as poly-aspartate scaffolds)

revealed that matrix rigidity >40 kPa, mimicking mineralized

bone, induces YAP overexpression in OS cells, synergizing with

TNF-α from TAMs to drive STAT3-mediated chemoresistance (159). These platforms also demonstrate

context-dependent therapeutic vulnerabilities; STAT3 inhibition

reversed doxorubicin resistance in stiff 3D models but showed

minimal efficacy in 2D cultures (151). For giant cell tumor of bone

(GCTB), mass cytometry of patient-derived samples identified

denosumab-induced depletion of γδTCR+ osteoclast-like giant cells

and expansion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, a shift not reproducible

in non-humanized models (160).

Despite progress, discrepancies persist: while 3D models predict

enhanced CAR-T cytotoxicity under dynamic flow, clinical

translation remains hampered by poor infiltration into osteoid-rich

niches 5.

sc and spatial omics technologies are dissecting

the cellular heterogeneity and topographical drivers of

immunotherapy resistance in bone sarcomas. Mass cytometry (CyTOF)

of GCTB identified a spatially restricted PD-1hiTIM-3+CD69+ CD8+

T-cell population juxtaposed with SIRPα+ TAMs, suggesting localized

exhaustion within the TME (161).

In OS, multi-omics integration of transcriptomic and sc data

defined a palmitoylation-driven metabolic-immune subtype

characterized by ZDHHC3/21/23 upregulation, which induces ‘cold

tumor’ phenotypes via dual suppression of MAPK signaling and CD8+

T-cell infiltration. High-risk patients, as defined by a

palmitoylation-driven prognostic score (PPS) above the 75th

percentile, showed resistance to PD-L1 inhibitors in the IMvigor210

cohort, highlighting this subtype's clinical relevance (162).

Spatial transcriptomics further maps cytokine

gradients underpinning immunosuppressive niches. In bone

metastases, osteoclast-derived OPN creates CXCL12-rich ecological

niches that sequester Tregs and exclude cytotoxic T cells, a

mechanism validated through in situ hybridization in clinical

biopsies (152). Radiation

modeling in microphysiological systems revealed that proton therapy

amplifies localized TGF-β secretion from damaged osteoblasts,

spatially associating with PD-L1 upregulation in surviving tumor

cells (159). However,

technological constraints remain: Current spatial methods lack

resolution for bone's mineralized matrix and sc datasets are biased

toward non-mineralized zones due to tissue dissociation artifacts

(163). Discrepancies also arise

in immune subset classification; CyTOF-defined TAM subsets in GCTB

contradict scRNA-seq annotations due to antibody specificity issues

vs. dropout effects in sequencing (164,165).

The next translational leap hinges on replacing

PD-L1-centric paradigms with multidimensional TME biomarkers,

refining patient stratification through dynamic profiling and

engineering bone-selective delivery systems that respect skeletal

physiology. Integrating TME modulators demands rigorous

longitudinal toxicity surveillance, especially in pediatric

populations. Collaborative, biomarker-driven trials embedding

real-time immune-monitoring and skeletal health endpoints are

indispensable to convert mechanistic insights into durable clinical

benefit. Multiplex IHC and spatial transcriptomics of OS biopsies

reveal CD8+ T cells proximal to antigen-presenting

fibroblasts predict prolonged metastasis-free survival, while high

neutrophil-to-CD8+ distance associates with

pembrolizumab resistance (166).

scRNA-seq resolved a metabolically distinct arginine-depleting TAM

cluster inversely associating with post-chemotherapy T-cell

expansion (167). However, CyTOF

antibody cross-reactivity in mineralized tissue overestimates TAM

frequency by ~30% vs. transcriptomics, highlighting the need for

orthogonal validation (20).

Composite signatures integrating spatial proximity, metabolic flux

and cross-platform profiling likely outperform PD-L1 alone, but

standardization remains a challenge.

Unsupervised clustering of 84 OS transcriptomes

identified three TME subtypes: ‘immune-hot’

(CXCL9/PD-L1high), ‘myeloid-rich/cold’

(CSF1R/STAT3high) and ‘fibrotic-desert’

(COL1A1high/CD45low) (168). In SARC028, pembrolizumab response

was confined to immune-hot tumors (objective response rate, 38%),

while myeloid-rich tumors progressed rapidly despite PD-L1

(169). Conversely, neoadjuvant

axitinib plus pembrolizumab converted 5/9 myeloid-rich tumors to

immune-active and tripled CD8+ density, achieving 66%

3-month PFS (170). These findings

illustrate dynamic conversion is achievable, but baseline

stratification is insufficient; longitudinal TME monitoring is

required to guide adaptive combinations.

The mineralized matrix and high interstitial

pressure limit penetration of antibodies and cellular therapeutics

(171). Osteotropic peptide

(Asp-Ser-Ser)-modified liposomal alendronate achieved 7-fold higher

OS accumulation and reduced tumor burden when loaded with

doxorubicin (172).

Anti-CD117-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles co-delivering

imatinib and STAT3 siRNA deplete MDSCs and sensitize to PD-1

blockade (173). Heterogeneity in

pediatric vs. adult bone density may impede nanoparticle

extravasation (174),

necessitating patient-specific models calibrated with PET perfusion

data.

Chronic CSF1R inhibition in adolescent mice

transiently decreased trabecular bone volume (BV/TV-22%) due to

impaired osteoclastogenesis (175). Combined with PD-1 blockade,

sustained Treg reduction led to persistent IFN-γ elevation and

prolonged suppression of bone formation markers (osteocalcin −35%

at 12 weeks), raising fracture risk concerns in growing patients

(176). Conversely, local low-dose

irradiation (8Gy) followed by GD2-CAR-T infusion increased bone

mineral density at metastatic sites via T-cell-mediated osteoblast

activation (177). These divergent

outcomes underscore the necessity of integrating serial skeletal

imaging and biomechanical testing into TME-targeting trials.

Pre-operative DNMT inhibitor (5-azacytidine) plus

HDAC inhibitor (entinostat) upregulated neoantigens and synergized

with doxorubicin, reducing lung micrometastases by 90% in mice

(178). Followed by GD2-CAR-T, the

triple combination extended median survival to 85 vs. 42 days for

chemo alone (179). However, a

phase I study combining pembrolizumab with standard MAP reported

unexpected early cardiotoxicity, possibly due to PD-1 blockade

enhancing doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress (180). Rational sequencing and dose

de-escalation informed by real-time TME profiling are key to

maximize synergy while limiting toxicities.

Despite compelling pre-clinical data, only two

registered trials (NCT04443235 and NCT05121269) prospectively

stratify patients with bone sarcoma by integrated TME signatures.

Early results from NCT04443235, a phase II study allocating

immune-hot OS to pembrolizumab plus stereotactic radiotherapy and

myeloid-rich tumors to CSF1R inhibitor pexidartinib plus

pembrolizumab, show an interim overall response rate of 45 vs. 11%

in historical controls. Cross-trial comparison reveals that trials

lacking biomarker selection consistently report objective response

rate below 15%, reinforcing the key impact of patient enrichment.

Standardized tissue acquisition protocols, centralized multiplex

imaging pipelines and open-access data repositories are proposed to

accelerate validation of next-generation biomarkers and ensure

reproducibility across centers.

Current regimens leave metastatic bone sarcomas

largely incurable because the immunosuppressive, mineralized and

metabolically hostile TME repels effector immunity. Integrating sc,

spatial and functional data across OS, ES and CS reveals

subtype-specific immune archetypes, tractable stromal targets and

delivery barriers. Translation now demands biomarker-driven,

bone-selective combinations with real-time monitoring to convert

mechanistic insight into durable cures.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

WL contributed to conceptualization, literature

review, writing (original draft) and visualization. LL contributed

to literature review, writing (original draft) and retrieve

literature. YJ contributed to writing (review and editing) and

resources. XY contributed to supervision, project administration,

writing (review and editing, and funding acquisition). All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication

not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Strauss SJ, Frezza AM, Abecassis N, Bajpai

J, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Blay JY, Bolle S, Bonvalot I, et

al: Bone sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS-ERN PaedCan clinical

practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann

Oncol. 32:1520–1536. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Perry JA, Kiezun A, Tonzi P, Van Allen EM,

Carter SL, Baca SC, Cowley GS, Bhatt AS, Rheinbay E, Pedamallu CS,

et al: Complementary genomic approaches highlight the PI3K/mTOR

pathway as a common vulnerability in osteosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 111:E5564–E5573. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Behjati S, Tarpey PS, Sheldon H,

Martincorena I, Van Loo P, Gundem G, Wedge DC, Ramakrishna M, Cooke

SL, Pillay N, et al: Recurrent PTPRB and PLCG1 mutations in

angiosarcoma. Nat Genet. 46:376–379. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Marina NM, Smeland S, Bielack SS,

Bernstein M, Jovic G, Krailo MD, Hook JM, Arndt C, van den Berg H,

Brennan B, et al: Comparison of MAPIE versus MAP in patients with a

poor response to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed

high-grade osteosarcoma (EURAMOS-1): An open-label, international,

randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 17:1396–1408. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, Lewis IJ,

Ferrari S, Le Deley MC, Kovar H, Grimer R, Whelan J, Claude L, et

al: Ewing sarcoma: Current management and future approaches through

collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 33:3036–3046. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

van Maldegem AM, Gelderblom H, Palmerini

E, Dijkstra SD, Gambarotti M, Ruggieri P, Nout RA, van de Sande MA,

Ferrari C, Ferrari S, et al: Outcome of advanced, unresectable

conventional central chondrosarcoma. Cancer. 120:3159–3164. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Nakano K: Challenges of systemic therapy

investigations for bone sarcomas. Int J Mol Sci. 23:35402022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tlemsani C, Larousserie F, De Percin S,

Audard V, Hadjadj D, Chen J, Biau D, Anract P, Terris B, Goldwasser

F, et al: Biology and management of high-grade chondrosarcoma: An

Update on targets and treatment options. Int J Mol Sci.

24:13612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhang S, Wang X, Dou H, Yu

X, Zhang Z, Yang S and Xiao M: Extracellular matrix remodeling in

tumor progression and immune escape: From mechanisms to treatments.

Mol Cancer. 22:482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Naser R, Fakhoury I, El-Fouani A,

Abi-Habib R and El-Sibai M: Role of the tumor microenvironment in

cancer hallmarks and targeted therapy (Review). Int J Oncol.

62:232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Alfranca A, Martinez-Cruzado L, Tornin J,

Abarrategi A, Amaral T, de Alava E, Menendez P, Garcia-Castro J and

Rodriguez R: Bone microenvironment signals in osteosarcoma

development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 72:3097–3113. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou Y, Yang D, Yang Q, Lv X, Huang W,

Zhou Z, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Yuan T, Ding X, et al: Single-cell RNA

landscape of intratumoral heterogeneity and immunosuppressive

microenvironment in advanced osteosarcoma. Nat Commun. 11:63222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nicolas-Boluda A, Vaquero J, Vimeux L,

Guilbert T, Barrin S, Kantari-Mimoun C, Ponzo M, Renault G, Deptula

P, Pogoda K, et al: Tumor stiffening reversion through collagen

crosslinking inhibition improves T cell migration and anti-PD-1

treatment. Elife. 10:e586882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shurin MR and Umansky V: Cross-talk

between HIF and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways in carcinogenesis and therapy.

J Clin Invest. 132:e1594732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jinushi M, Chiba S, Yoshiyama H, Masutomi

K, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H, Yagita H, Takaoka A and Tahara H:

Tumor-associated macrophages regulate tumorigenicity and anticancer

drug responses of cancer stem/initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 108:12425–12430. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Saito M, Ichikawa J, Ando T, Schoenecker

JG, Ohba T, Koyama K, Suzuki-Inoue K and Haro H: Platelet-derived

TGF-β induces tissue factor expression via the smad3 pathway in

osteosarcoma cells. J Bone Miner Res. 33:2048–2058. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Sakurai Y,

Akashi-Takamura S, Ishibashi S, Miyake K, Shibuya M, Akira S,

Aburatani H and Maru Y: The S100A8-serum amyloid A3-TLR4 paracrine

cascade establishes a pre-metastatic phase. Nat Cell Biol.

10:1349–1355. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu X, Li J, Yang X, Li X, Kong J, Qi D,

Zhang F, Sun B, Liu Y and Liu T: Carcinoma-associated

fibroblast-derived lysyl oxidase-rich extracellular vesicles

mediate collagen crosslinking and promote epithelial-mesenchymal

transition via p-FAK/p-paxillin/YAP signaling. Int J Oral Sci.

15:322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chevrier S, Crowell HL, Zanotelli VRT,

Engler S, Robinson MD and Bodenmiller B: Compensation of signal

spillover in suspension and imaging mass cytometry. Cell Syst.

6:612–620.e5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Umezu T, Tadokoro H, Azuma K, Yoshizawa S,

Ohyashiki K and Ohyashiki JH: Exosomal miR-135b shed from hypoxic

multiple myeloma cells enhances angiogenesis by targeting

factor-inhibiting HIF-1. Blood. 124:3748–3757. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Principe DR, Kamath SD, Korc M and Munshi

HG: The immune modifying effects of chemotherapy and advances in

chemo-immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 236:1081112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Han C, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Shen A, Dong C,

Zhang A, Moore C, Ren Z, Lu C, Cao X, et al: Tumor cells suppress

radiation-induced immunity by hijacking caspase 9 signaling. Nat

Immunol. 21:546–554. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yu Y, Li K, Peng Y, Zhang Z, Pu F, Shao Z

and Wu W: Tumor microenvironment in osteosarcoma: From cellular

mechanism to clinical therapy. Genes Dis. 12:1015692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dutour A, Pasello M, Farrow L, Amer MH,

Entz-Werlé N, Nathrath M, Scotlandi K, Mittnacht S and

Gomez-Mascard A: Microenvironment matters: Insights from the FOSTER

consortium on microenvironment-driven approaches to osteosarcoma

therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 44:442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, Cornish AE,

Konopacki C, Prabhakaran S, Nainys J, Wu K, Kiseliovas V and Setty

M: Single-Cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor

microenvironment. Cell. 174:1293–1308.e36. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sun CY, Zhang Z, Tao L, Xu FF, Li HY,

Zhang HY and Liu W: T cell exhaustion drives osteosarcoma

pathogenesis. Ann Transl Med. 9:14472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Visser LL, Bleijs M, Margaritis T, van de

Wetering M, Holstege FCP and Clevers H: Ewing sarcoma single-cell

transcriptome analysis reveals functionally impaired

antigen-presenting cells. Cancer Res Commun. 3:2158–2169. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guimarães GR, Maklouf GR, Teixeira CE, de

Oliveira Santos L, Tessarollo NG, de Toledo NE, Serain AF, de Lanna

CA, Pretti MA, da Cruz JGV, et al: Single-cell resolution

characterization of myeloid-derived cell states with implication in

cancer outcome. Nat Commun. 15:56942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kashfi K, Kannikal J and Nath N:

Macrophage reprogramming and cancer therapeutics: Role of

iNOS-Derived NO. Cells. 10:31942021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ka HI, Mun SH, Han S and Yang Y: Targeting

myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment:

Potential therapeutic approaches for osteosarcoma. Oncol Res.

33:519–531. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhao L, Liu P, Mao M, Zhang S, Bigenwald

C, Dutertre CA, Lehmann CHK, Pan H, Paulhan N, Amon L, et al: BCL2

inhibition reveals a dendritic cell-specific immune checkpoint that

controls tumor immunosurveillance. Cancer Discov. 13:2448–2469.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shaim H, Shanley M, Basar R, Daher M,

Gumin J, Zamler DB, Uprety N, Wang F, Huang Y, Gabrusiewicz K, et

al: Targeting the αv integrin/TGF-β axis improves natural killer

cell function against glioblastoma stem cells. J Clin Invest.

131:e421162021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Tran HC, Wan Z, Sheard MA, Sun J, Jackson

JR, Malvar J, Xu Y, Wang L, Sposto R, Kim ES, et al: TGFβR1

blockade with galunisertib (LY2157299) enhances anti-neuroblastoma

activity of the anti-GD2 antibody dinutuximab (ch14.18) with

natural killer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 23:804–813. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Cao JW, Lake J, Impastato R, Chow L, Perez

L, Chubb L, Kurihara J, Verneris MR and Dow S: Targeting

osteosarcoma with canine B7-H3 CAR T cells and impact of CXCR2

Co-expression on functional activity. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

73:772024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Liu G, Li D, Gu Z, Zhang

L, Pan Y, Cui X, Wang L, Liu G, et al: B7-H3 targeted CAR-T cells

show highly efficient anti-tumor function against osteosarcoma both

in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer. 22:11242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fotsitzoudis C, Koulouridi A, Messaritakis

I, Konstantinidis T, Gouvas N, Tsiaoussis J and Souglakos J:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts: The origin, biological

characteristics and role in cancer-a glance on colorectal cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 14:43942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cao Z, Quazi S, Arora S, Osellame LD,

Burvenich IJ, Janes PW and Scott AM: Cancer-associated fibroblasts

as therapeutic targets for cancer: Advances, challenges, and future

prospects. J Biomed Sci. 32:72025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Long AH, Highfill SL, Cui Y, Smith JP,

Walker AJ, Ramakrishna S, El-Etriby R, Galli S, Tsokos MG, Orentas

RJ and Mackall CL: Reduction of MDSCs with all-trans retinoic acid

improves CAR therapy efficacy for sarcomas. Cancer Immunol Res.

4:869–880. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber

JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P,

Bringhurst FR, et al: Osteoblastic cells regulate the

haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 425:841–846. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang S, Greenbaum J, Qiu C, Gong Y, Wang

Z, Lin X, Liu Y, He P, Meng X, Zhang Q, et al: Single-cell RNA

sequencing reveals in vivo osteoimmunology interactions between the

immune and skeletal systems. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:11075112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Canon JR, Roudier M, Bryant R, Morony S,

Stolina M, Kostenuik PJ and Dougall WC: Inhibition of RANKL blocks

skeletal tumor progression and improves survival in a mouse model

of breast cancer bone metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 25:119–129.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kiesel JR, Buchwald ZS and Aurora R:

Cross-presentation by osteoclasts induces FoxP3 in CD8+ T cells. J

Immunol. 182:5477–5487. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Panagi M, Mpekris F, Voutouri C,

Hadjigeorgiou AG, Symeonidou C, Porfyriou E, Michael C, Stylianou

A, Martin JD, Cabral H, et al: Stabilizing tumor-resident mast

cells restores T-cell infiltration and sensitizes sarcomas to PD-L1

inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 30:2582–2597. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Białas M, Dyduch G, Dudała J,

Bereza-Buziak M, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Budzyński A and Okoń K:

Study of microvessel density and the expression of vascular

endothelial growth factors in adrenal gland pheochromocytomas. Int

J Endocrinol. 2014:1041292014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce

C, Stroud I, Garren N, Mackey M, Butman JA and Camphausen K: Phase

II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus

irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin

Oncol. 27:740–745. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Dong X, Ren J, Amoozgar Z, Lee S, Datta M,

Roberge S, Duquette M, Fukumura D and Jain RK: Anti-VEGF therapy

improves EGFR-vIII-CAR-T cell delivery and efficacy in syngeneic

glioblastoma models in mice. J Immunother Cancer. 11:e0055832023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A,

Brooks MW, Bell GW, Richardson AL, Polyak K, Tubo R and Weinberg

RA: Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast

cancer metastasis. Nature. 449:557–563. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Trabanelli S, Lecciso M, Salvestrini V,

Cavo M, Očadlíková D, Lemoli RM and Curti A: PGE2-induced IDO1

inhibits the capacity of fully mature DCs to elicit an in vitro

antileukemic immune response. J Immunol Res. 2015:2531912015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zelenay S, van der Veen AG, Böttcher JP,

Snelgrove KJ, Rogers N, Acton SE, Chakravarty P, Girotti MR, Marais

R, Quezada SA, et al: Cyclooxygenase-dependent tumor growth through

evasion of immunity. Cell. 162:1257–1270. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Kolb AD and Bussard KM: The bone

extracellular matrix as an ideal milieu for cancer cell metastases.

Cancers (Basel). 11:10202019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Molina ER, Chim LK, Salazar MC, Mehta SM,

Menegaz BA, Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, Satish T, Mohiuddin S, McCall D,

Zaske AM, et al: Mechanically tunable coaxial electrospun models of

YAP/TAZ mechanoresponse and IGF-1R activation in osteosarcoma. Acta

Biomater. 100:38–51. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liu D, Peng Y, Li X, Zhu Z, Mi Z, Zhang Z

and Fan H: Comprehensive landscape of TGFβ-related signature in

osteosarcoma for predicting prognosis, immune characteristics, and

therapeutic response. J Bone Oncol. 40:1004842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Highfill SL, Cui Y, Giles AJ, Smith JP,

Zhang H, Morse E, Kaplan RN and Mackall CL: Disruption of

CXCR2-mediated MDSC tumor trafficking enhances anti-PD1 efficacy.

Sci Transl Med. 6:237ra672014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhao TT, Zhou TJ, Zhang C, Liu YX, Wang

WJ, Li C, Xing L and Jiang HL: Hypoxia inhibitor combined with

chemotherapeutic agents for antitumor and antimetastatic efficacy

against osteosarcoma. Mol Pharm. 20:2612–2623. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Khojastehnezhad MA, Seyedi SMR, Raoufi F

and Asoodeh A: Association of hypoxia-inducible factor 1

expressions with prognosis role as a survival prognostic biomarker

in the patients with osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis. Expert Rev Mol

Diagn. 22:1099–1106. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Shi W, Cassmann TJ, Bhagwate AV, Hitosugi

T and Ip WKE: Lactic acid induces transcriptional repression of

macrophage inflammatory response via histone acetylation. Cell Rep.

43:1137462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hashim AI, Cornnell HH, Mde LC, Abrahams

D, Cunningham J, Lloyd M, Martinez GV, Gatenby RA and Gillies RJ:

Reduction of metastasis using a non-volatile buffer. Clin Exp

Metastasis. 28:841–849. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Aquino A and Franzese O: Reciprocal

modulation of tumour and immune cell motility: Uncovering dynamic

interplays and therapeutic approaches. Cancers (Basel).

17:15472025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cui J, Dean D, Hornicek FJ, Chen Z and

Duan Z: The role of extracelluar matrix in osteosarcoma progression

and metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:1782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Liu W, Hu H, Shao Z, Lv X, Zhang Z, Deng

X, Song Q, Han Y, Guo T, Xiong L, et al: Characterizing the tumor

microenvironment at the single-cell level reveals a novel immune

evasion mechanism in osteosarcoma. Bone Res. 11:42023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Gorchs L, Oosthoek M, Yucel-Lindberg T,

Moro CF and Kaipe H: Chemokine receptor expression on T cells is

modulated by CAFs and chemokines affect the spatial distribution of

T cells in pancreatic tumors. Cancers (Basel). 14:38262022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Park HK, Kim M, Sung M, Lee SE, Kim YJ and

Choi YL: Status of programmed death-ligand 1 expression in

sarcomas. J Transl Med. 16:3032018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yang R, Sun L, Li CF, Wang YH, Yao J, Li

H, Yan M, Chang WC, Hsu JM, Cha JH, et al: Galectin-9 interacts

with PD-1 and TIM-3 to regulate T cell death and is a target for

cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 12:8322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Selby MJ, Engelhardt JJ, Quigley M,

Henning KA, Chen T, Srinivasan M and Korman AJ: Anti-CTLA-4

antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through

reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Res.

1:32–42. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Jiang X, Li L, Li Y and Li Q: Molecular

mechanisms and countermeasures of immunotherapy resistance in

malignant tumor. J Cancer. 10:1764–1771. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Tian H, Cao J, Li B, Nice EC, Mao H, Zhang

Y and Huang C: Managing the immune microenvironment of

osteosarcoma: The outlook for osteosarcoma treatment. Bone Res.

11:112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Starska-Kowarska K: The role of different

immunocompetent cell populations in the pathogenesis of head and

neck cancer-regulatory mechanisms of pro- and anti-cancer activity

and their impact on immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 15:16422023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Li C, Jiang P, Wei S, Xu X and Wang J:

Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: New mechanisms,

potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol Cancer.

19:1162020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Denize T, Jegede OA, Matar S, El Ahmar N,

West DJ, Walton E, Bagheri AS, Savla V, Laimon YN, Gupta S, et al:

PD-1 expression on intratumoral regulatory T cells is associated

with lack of benefit from Anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic

clear-cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res.

30:803–813. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Merchant MS, Melchionda F, Sinha M, Khanna

C, Helman L and Mackall CL: Immune reconstitution prevents

metastatic recurrence of murine osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 56:1037–1046. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Han Q, Shi H and Liu F: CD163(+) M2-type

tumor-associated macrophage support the suppression of

tumor-infiltrating T cells in osteosarcoma. Int Immunopharmacol.

34:101–106. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Gallina G, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, De

Santo C, Marigo I, Colombo MP, Basso G, Brombacher F, Borrello I,

Zanovello P, et al: Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory

monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8+ T cells. J Clin

Invest. 116:2777–2790. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Munder M: Arginase: An emerging key player

in the mammalian immune system. Br J Pharmacol. 158:638–651. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Yang Y, Li C, Liu T, Dai X and Bazhin AV:

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors: from mechanisms to

antigen specificity and microenvironmental regulation. Front

Immunol. 11:13712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zhu Y, Knolhoff BL, Meyer MA, Nywening TM,

West BL, Luo J, Wang-Gillam A, Goedegebuure SP, Linehan DC and

DeNardo DG: CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating

macrophages and improves response to T-cell checkpoint

immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res.

74:5057–5069. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

DeNardo DG, Brennan DJ, Rexhepaj E,

Ruffell B, Shiao SL, Madden SF, Gallagher WM, Wadhwani N, Keil SD,

Junaid SA, et al: Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer

survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy.

Cancer Discov. 1:54–67. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hashimoto M, Kamphorst AO, Im SJ, Kissick

HT, Pillai RN, Ramalingam SS, Araki K and Ahmed R: CD8 T cell

exhaustion in chronic infection and cancer: Opportunities for

interventions. Annu Rev Med. 69:301–318. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Depuydt MAC, Schaftenaar FH, Prange KHM,

Boltjes A, Hemme E, Delfos L, de Mol J, de Jong MJM, Kleijn MNA,

Peeters JAHM, et al: Single-cell T cell receptor sequencing of

paired human atherosclerotic plaques and blood reveals

autoimmune-like features of expanded effector T cells. Nat

Cardiovasc Res. 2:112–125. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Shin J, O'Brien TF, Grayson JM and Zhong

XP: Differential regulation of primary and memory CD8 T cell immune

responses by diacylglycerol kinases. J Immunol. 188:2111–2117.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Gu XY, Yang JL, Lai R, Zhou ZJ, Tang D, Hu

L and Zhao LJ: Impact of lactate on immune cell function in the

tumor microenvironment: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives.

Front Immunol. 16:15633032025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Leone RD, Sun IM, Oh MH, Sun IH, Wen J,

Englert J and Powell JD: Inhibition of the adenosine A2a receptor

modulates expression of T cell coinhibitory receptors and improves

effector function for enhanced checkpoint blockade and ACT in

murine cancer models. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 67:1271–1284.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|