Introduction

Metastasis accounts for up to 90% of cancer-related

deaths, driven by complex interplay between malignant cells and the

tumor microenvironment (1–4). It is a progressive, multistep process

in which cancer cells disseminate from the primary tumor, invade

surrounding tissue, survive in circulation and colonize distant

organs (5,6). A deeper understanding of how cancer

cells deviate from normal programs of growth, motility and

stromal-immune crosstalk is essential for identifying potential

targets and optimal time windows for detection, prevention and

treatment of the metastatic diseases.

Lung cancer is the most common and most fatal cancer

worldwide, with 2.5 million new cases (12.4% of all global cancers)

and 1.8 million deaths (18.7% of global cancer deaths) in 2022

(7); it remains the leading cause

of cancer mortality largely due to the high incidence of metastasis

(8,9). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

constitutes 80–85% of all lung cancer cases (10). While surgical resection benefits

early-stage NSCLC, a large proportion of patients present with

advanced disease, rendering surgery unfeasible. These patients

often experience poor survival and diminished quality of life, with

limited survival gains from conventional treatments such as

chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Prolonged exposure to radiotherapy or

chemotherapy frequently induces resistance (11). In clinical practice, multiple

therapeutic strategies have been developed to overcome drug

resistance and for patients with lung cancer with targetable driver

gene mutations, such as EGFR or ALK, the treatment paradigm has

evolved. While starting with first-generation inhibitors (such as

gefitinib and crizotinib) was practiced previously, current

first-line standards often involve newer agents (such as

osimertinib and alectinib). Switching to next-generation inhibitors

upon resistance remains the standard strategy (12). For instance, osimertinib effectively

treats EGFR T790M-mediated resistance after first-generation

EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (13,14).

Combination approaches that leverage non-overlapping mechanisms,

such as pairing targeted therapy with chemotherapy or

anti-angiogenic agents, or using dual-target inhibitors, which aim

to suppress parallel pathways, thereby delaying the emergence of

resistant clones (15). For

patients progressing after targeted therapy or chemotherapy, immune

checkpoint inhibitors [such as programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1)/programmed death-ligand (PD-L1) antibodies] offer an

orthogonal strategy independent of traditional cytotoxic pathways

(16,17). These agents act by reinvigorating

anti-tumor T cells, with enhanced efficacy in subsets characterized

by high tumor mutation burden (TMB) or PD-L1 expression (18). These precision treatments have

improved outcomes, yet benefit remains heterogeneous and often

transient.

Given these advances, a focus of current clinical

research is identifying patients most likely to benefit from these

therapies early in the treatment course. However, relying solely on

biomarkers such as PD-L1 and TMB has notable limitations (19). Among advanced NSCLC with PD-L1

expression ≥50%, response rates to single-agent immunotherapy are

~44% (20). Similarly, for TMB ≥10

mutations per megabase, response rates remain <30% (21). While combining immunotherapy with

chemotherapy increases objective response rates to 50–70%,

high-dose chemotherapy can significantly damage key effector

subsets, including CD8+ T cells, potentially shortening

the durability of response relative to immunotherapy alone

(22,23). These gaps underscore the need for

functional, patient-specific models that more faithfully

recapitulate tumor-immune-stromal interactions for drug testing and

response prediction.

Accurate modeling of the tumor microenvironment is

crucial for effective drug screening, particularly for

immunotherapies. Traditional models, such as cell lines and

xenografts, have considerable constraints. Extended passaging of

cell lines (>10–15 passages) leads to loss of the original

intratumoral heterogeneity, and xenografts may not faithfully

recapitulate human stromal and immune contexts due to interspecies

differences (24,25). Most patient-derived organoid (PDO)

models similarly lack critical microenvironment elements, such as

vasculature and immune components (26). Even in vascularized organoids, the

absence of perfusion often results in vascular regression. To

address this, researchers have developed approaches combining

vascularized organoids with immune co-cultures (27). Reconstructing the tumor immune

microenvironment by co-culturing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

(TILs) with tumor cells shows promise for more accurately

predicting responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Lung cancer organoid-based metastasis models utilize

three-dimensional (3D) culture systems that preserve genomic

diversity and phenotypic heterogeneity of patient tumors. These

models can incorporate key microenvironmental components, including

stromal and immune cells, which enables simulation of critical

steps of the metastatic cascade and provides a powerful platform

for investigating metastasis-driving mechanisms.

A key aspect of developing physiologically relevant

lung cancer organoids is the choice of supporting scaffold. Early

models predominantly relied on commercially available basement

membrane extracts (such as Matrigel) (28). While instrumental for initial

success, these matrices suffered from ill-defined composition,

batch-to-batch variability and non-physiological mechanical

properties. Consequently, there is a growing emphasis on defined

and tunable scaffolds, such as synthetic polyethylene glycol (PEG)

hydrogels (29) and decellularized

extracellular matrix (dECM) hydrogels (30), to provide more precise control over

biochemical cues and biophysical properties, improving

reproducibility and enabling hypothesis-driven testing of

matrix-regulated metastatic behaviors.

The present review summarized recent advances in

lung cancer organoid metastasis models, with emphasis on their use

in elucidating metastatic mechanisms, optimizing drug screening and

resolving tumor heterogeneity. Methodological considerations,

persistent technical challenges, barriers to clinical translation

and ethical considerations were discussed. The future directions

described includes interdisciplinary collaborations involving

multi-omics and spatial profiling, artificial intelligence

(AI)-assisted analytics, immune-competent and vascularized

platforms, and standardization effort. The present review aimed to

provide methodological guidance for basic research and a conceptual

foundation for developing precision treatment strategies.

Literature search methodology

To comprehensively review advances in this field, a

systematic literature search of the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was conducted

for publications from 2009 to 2025, prioritizing studies from the

past 5 years, using the terms ‘lung cancer organoids’, ‘metastasis

model’, ‘patient-derived organoids’, ‘tumor microenvironment’ and

‘drug screening’, alone and in combination, to identify original

research articles, high-quality reviews and key methodological

papers. Emerging lung cancer organoid-based metastasis models

recapitulate critical steps of the metastatic cascade, yielding

mechanistic insights and informing therapeutic discovery.

Definitions and stem cell origin of

organoids

Stem cells are central to life sciences research and

are defined by two core properties: Self-renewal and multipotent

differentiation. Self-renewal is the capacity to maintain a stable

stem cell pool through mitotic division, generating daughter cells

with the same genetic characteristics (31). Multipotent differentiation is the

ability to give rise to diverse cell types under specific

environmental conditions and signaling cues, thereby contributing

to tissue formation (32).

Organoids are 3D in vitro constructs derived from stem cells

that recapitulate the cellular composition, spatial organization

and selected functions of their native organs. Organoids provide

essential platforms for studying developmental biology and disease

pathogenesis (33).

Organoids derived from stem cells

Since the pioneering development of intestinal

organoids by Sato et al (34) in 2009, stem cell-derived organoid

technology has rapidly expanded across multiple tissues, including

the brain, liver and diverse tumor types, offering new

opportunities for drug screening and disease modeling. Brain

organoids serve as a prominent example, as they are constructed

through the systematic differentiation of neural stem cells and

precise cellular interactions, ultimately forming highly complex

neural networks. These networks not only exhibit functions similar

to those of the natural brain but also provide essential biological

markers for investigating brain development and neurodegenerative

diseases (35). Leveraging this

advantage, researchers have systematically studied the

pathogenesis, pathological evolution and potential therapeutic

targets of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease

and Parkinson's disease using in vitro models that closely

mimic in vivo physiological conditions (36,37).

PDOs

In oncology research, tumor organoids derived from

patient samples often retain the phenotypic characteristics,

genomic heterogeneity and mutational landscape of the original

tumor. Tumor organoids derived from patient samples preserve the

architectural, molecular and genetic features of the primary tumor,

including structure, function, mutation spectrum and gene

expression profile. These organoids are effectively used for

disease characterization, mechanism exploration, high-throughput

drug screening and evaluation, discovery of innovative therapeutic

targets and potential compounds and the development of personalized

treatment strategies based on individual tumor characteristics

(38).

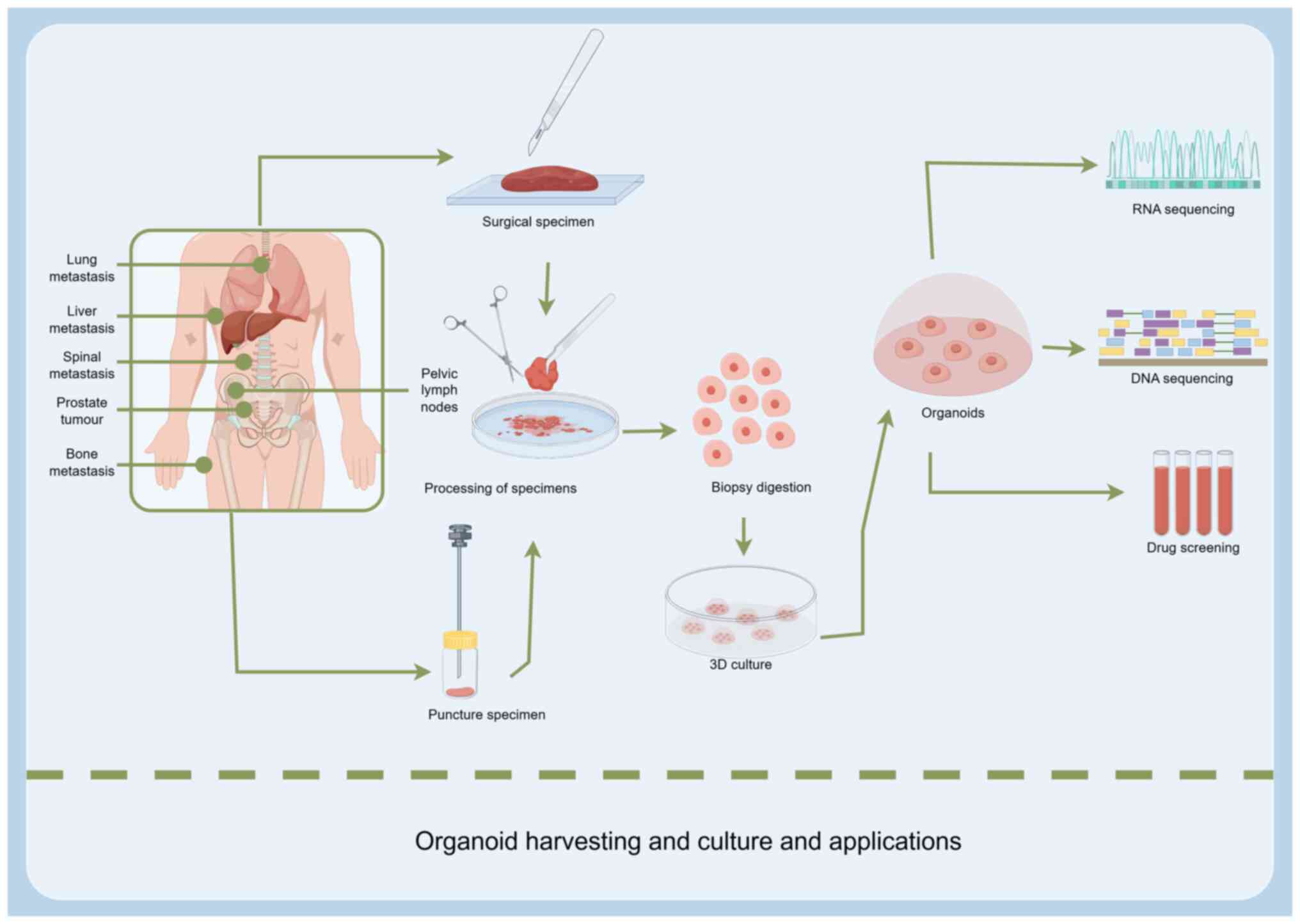

The construction of lung cancer organoid metastasis

models begins with the acquisition of suitable tissue samples.

Primary lung cancer tissues, obtained from surgical resections or

biopsies are commonly used (39,40).

To investigate metastatic mechanisms, tissues from metastatic

lesions are particularly valuable, including samples from brain,

bone or liver metastases, which directly reflect the

characteristics of tumor cells within site-specific metastatic

microenvironments. For example, a previous study successfully

established organoid models from surgical specimens of brain

metastases in patients with lung cancer, providing essential tools

for exploring the mechanisms of brain metastasis (41).

Malignant pleural effusions (MPEs), including

pleural effusion and ascitic fluids, represent an important source

for organoid construction. MPEs are rich in tumor cells, and their

collection is relatively noninvasive (42). Mazzocchi et al (43) successfully developed 3D lung cancer

organoids from pleural effusion. These organoids, composed of tumor

and stromal cells embedded in a hydrogel that mimics the ECM,

exhibited alveolar-like structures and in vivo-like drug

responses. The study confirmed that pleural effusion-derived

organoids are suitable for investigating lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD)

and that 3D cultures outperform two-dimensional (2D) cultures in

disease modeling and drug screening. In another study, Wang et

al (44) established lung

cancer organoids from both tumor tissue and MPE. It was found that

MPE significantly enhanced organoid formation, reduced culture time

by >50% and altered drug sensitivity profiles, resulting in

increased resistance to certain drugs. Mechanistically, although

MPE did not alter the genomic composition of the organoids, it

influenced stem cell distribution and cell architecture, including

expansion of the extracellular space. Gene expression analyses

revealed significant enrichment of pathways related to the ECM and

mitochondrial function.

Distinct challenges in developing lung

cancer organoids

The development of lung cancer organoids presents

unique challenges that are not typically encountered in other

organoid systems. A primary obstacle is the need for multiple,

subtype-specific culture protocols to account for the substantial

histological and genetic diversity between NSCLC and small cell

lung cancer (SCLC). Furthermore, the high clinical mortality

associated with metastasis necessitates modeling organ-specific

metastatic niches, such as those in the brain and bone. In

addition, given the focus on guiding precision therapies,

particularly immunotherapy, there is a pressing need to develop

sophisticated, immune-competent co-culture models. This combination

of factors makes lung cancer organoids a highly specialized and

complex platform.

Advantages of organoids as drug

screening platforms

Organoids provide physiologically relevant platforms

for drug screening and sensitivity testing by closely replicating

the in vivo architecture and functional characteristics of

human tissues. Furthermore, organoids retain tissue-specific

features and preserve critical cellular interactions, and capture

tumor heterogeneity more accurately. This makes them especially

valuable for personalized treatment strategies (45). Drug responses can be evaluated by

treating patient-derived tumor organoids (PDTOs) with a range of

therapeutic agents and measuring efficacy through multiple

analytical readouts. In oncology, organoid-based models are widely

used to assess cancer drug sensitivity and to predict therapeutic

outcomes, covering a variety of agents, including targeted

therapies, immune monotherapies, combination immunotherapies and

anti-angiogenic drugs (46,47). For example, clinical studies have

employed organoid drug sensitivity assays to anticipate

chemotherapy efficacy (48,49).

Modeling key steps of the metastatic cascade

in organoids

Lung cancer organoid models are powerful tools for

deconstructing the complex, multistep process of metastasis into

discrete, investigable mechanisms. By engineering specific culture

conditions, these models can replicate key biological events,

including ECM remodeling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

and tumor-immune interactions, which collectively drive metastatic

progression.

Simulating metastatic microenvironment

conditions

To mimic the in vivo tumor microenvironment,

lung cancer organoids are cultured in 3D matrices such as Matrigel,

which provide both structural support and biochemical cues

(50). Cultures are maintained in a

base medium (such as advanced DMEM/F12) supplemented with growth

factors and nutrients essential for organoid survival and expansion

(51,52). Furthermore, media are tailored to

histological subtypes. NSCLC organoids typically require the

addition of EGF, FGF, R-spondin1 and Noggin, whereas SCLC organoids

often need additional factors to maintain their neuroendocrine

characteristics (53) Further

optimization is necessary to model organ-specific metastasis more

accurately. For brain metastasis models, neural-supportive medium

components such as Neurobasal™ (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) are incorporated into the medium (54). Culture conditions, including oxygen

tension, temperature and humidity, are tightly controlled. Hypoxia,

in particular, can preserve cancer stem-like phenotypes and

upregulate metastasis-associated programs, providing a more

physiologically relevant context for studying tumor invasion,

spread and therapy response (55,56).

Modeling ECM remodeling

The 3D scaffold not only supports organoid growth

but also serves as a modifiable ECM surrogate. Tumor organoids

dynamically remodel their surrounding matrix to facilitate

invasion, which can be captured by live imaging using fluorescent

ECM components (57,58). Parallel biochemical analyses of

conditioned media reveals elevated levels of matrix

metalloproteinases and other ECM-modifying enzymes, providing

quantitative readouts of invasive potential (59).

Inducing EMT

EMT is a key transcriptional reprogramming event

that confers migratory and invasive capacities. In organoid

systems, EMT can be reproducibly elicited by microenvironmental

stimuli. Exposure to hypoxia or exogenous transforming growth

factor-β (TGF-β) drives molecular and morphological shifts,

including downregulation of epithelial markers (such as

E-cadherin), upregulation of mesenchymal markers (such as vimentin)

and morphological transitions from smooth, spherical structures to

irregular, invasive protrusions. This phenotypic change, often

mediated by effectors, directly enhances tumor cell migration and

invasion, thereby modeling early metastatic steps (60).

Reconstituting tumor-immune

interactions

Immune-organoid co-culture systems are crucial for

elucidating the dynamic interactions between tumor cells and the

immune microenvironment, particularly the mechanisms by which

cancer cells evade immune surveillance during metastasis. Lung

cancer organoids can be directly co-cultured with autologous immune

components, such as TILs or peripheral blood mononuclear cells

(Fig. 1) (61), to recapitulate patient-specific

immune responses. This setup enables real-time assessment of immune

cell cytotoxicity and tumor cell lysis, and it captures adaptive

immune evasion mechanisms, including the upregulation of checkpoint

molecules such as PD-L1 on organoid cells. These co-culture models

also provide a physiologically relevant platform for evaluating

immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors such as

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies, by quantifying treatment-induced

organoid death (62).

Construction strategies and key technologies

for lung cancer organoid metastasis models

Leveraging organoids for lung cancer metastasis

research requires a multifaceted approach. Key elements include

developing subtype-tailored culture protocols, creating customized

models through gene editing, recapitulating metastatic steps via

in vivo transplantation, and directly capturing

disseminating cells using circulating tumor cell (CTC)-derived

organoids (Fig. 2; Table I).

| Table I.Comparative analysis of primary

strategies for establishing lung cancer organoid metastasis

modelsa. |

Table I.

Comparative analysis of primary

strategies for establishing lung cancer organoid metastasis

modelsa.

| Strategy | Core

advantages | Limitations | Relative cost | Translational

readiness | Primary application

scenarios |

|---|

| PDOs | Preserves genomic

heterogeneity, phenotype, and drug response of he toriginal tumor.

Short establishment time (weeks), suitable for high-throughput

screening. Provides a platform for personalized medicine. | Suboptimal overall

culture success rate (particularly for SCLC and rare subtypes).

Difficult to fully recapitulate the complete tumor microenvironment

(for example, vasculature and immune components). | Medium-high | Intermediate (used

in retrospective studies guiding clinical therapy, requires

prospective trial validation) | Disease modeling,

drug sensitivity testing, personalized therapy exploration, tumor

heterogeneity research |

|

|

| Lack of

standardized protocols. |

|

|

|

| Gene-edited

organoids | Enables precise

study of causal roles of specific genes in metastasis. Allows

creation of customized models driven by specific driver

mutations. | Ethical and safety

considerations. Technically complex, requires specialized

platform. | High | Low (primarily a

powerful basic research tool; direct clinical translation path is

long) | Mechanism studies,

target validation, gene function research, overcoming drug

resistance |

|

| Useful for gene

knockout, knock in, and correcting resistance mutations | Single-gene editing

may not mimic the complex polygenic background of human

cancer. |

|

|

|

| In vivo

organoid transplantation | Provides the most

physiologically relevant in vivo microenvironment; models

the entire metastatic cascade. The ‘gold standard’ for validating

the tumorigenicity and metastatic potential of organoids. | Time-consuming

(months). Immunodeficient mouse models lack a human immune system,

limiting immunotherapy research. | High | Intermediate (core

component of preclinical research but species differences are a

translational bottleneck) | Validation of in

vitro findings, studying the metastatic cascade, preclinical

drug efficacy evaluation. |

|

| Evaluates drug

efficacy within a whole body physiological context. |

|

|

|

|

| CTC-derived

organoids (liquid biopsy). | Minimally invasive

sample acquisition Directly derived from metastatic cell

populations, representing real time tumor status. Potential to

capture cell subpopulations with high metastatic potential. | Extreme rarity of

CTCs in blood, high technical challenge. Very low culture success

rate (for example, ~58% in prostate cancer) Requires tumor-specific

culture conditions | Very high | Low (the technology

itself is immature, but has great future translational potential as

an extension of liquid biopsy) | Metastasis

mechanism research, dynamic therapy monitoring, personalized

therapy for metastatic disease |

Specific culture requirements for

primary lung cancer subtypes

The successful establishment of lung cancer

organoids critically depends on tailoring culture conditions to

each subtype, reflecting their distinct cellular origins and

oncogenic drivers.

i) LUAD organoids

LUAD often originates from alveolar type II (AT2)

cells and thus requires culture conditions that sustain AT2

stemness and proliferative capacity. The base medium typically

includes essential mediators such as EGF, FGF-7/10, Noggin and

R-spondin 1 to promote proliferation and maintain an AT2-like

state. This protocol was further optimized by inhibiting the BMP

signaling pathway and supplementing with ligands such as

heregulin-β1 to better mimic the alveolar niche, as demonstrated in

feeder-free systems that enable long-term expansion and modeling of

LUAD (63,64).

ii) Lung squamous cell carcinoma

(LUSC) organoids

LUSC, which arises from bronchial basal cells, often

relies more on ECM-derived physical and biochemical cues than

exogenous growth factors. A robust LUSC model was established using

a base medium without the addition of growth factors such as

R-spondin, EGF or BMP-4. The success of this system hinged on a

tailored ECM composed of Matrigel and collagen I, as well as the

strategic initiation of cultures from pre-formed cell spheroids.

This approach reproducibly generated organoids that self-organize

into a characteristic hierarchical structure with a p63-positive

basal cell layer and inward differentiation, providing a

distinctive model for studying LUSC biology (65).

iii) SCLC organoids and metastatic

modeling

The high-grade neuroendocrine phenotype of SCLC

necessitates specialized culture conditions. A base media typically

includes B27 and N2 supplements, key mitogens (bFGF, EGF and

insulin), hydrocortisone and ROCK inhibitors to prevent anoikis and

support suspension growth. To model metastasis, particularly brain

metastasis, advanced platforms co-culture SCLC cells with human

cerebral organoids in a Matrigel-based 3D environment. When

combined with modulation of key pathways such as Notch and

longitudinal monitoring using live-cell imaging, this platform

enables real-time assessment of invasion, colonization and subtype

plasticity within the brain microenvironment (66,67).

Application of gene editing

technologies

Patient-derived lung cancer organoids faithfully

replicate the pathological and genomic characteristics of their

source tumors, preserving key driver alterations, while maintaining

malignant cell phenotypes (68).

Using gene editing technologies such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system

(69), lung cancer organoids can be

genetically modified to create metastasis models driven by specific

gene mutations. By knocking out or inserting key genes associated

with lung cancer metastasis, researchers can study gene function

and its impact on the metastatic process.

For example, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has been used to

knock out the SOX9 gene in human embryonic stem cells prior

to directed differentiation into lung organoids. While SOX9

deletion did not affect epithelial cell differentiation, it

impaired proliferation and increased apoptosis. Upon

transplantation under the renal capsule of immunodeficient mice or

orthotopically into bleomycin-injured mouse lungs, SOX9

inactivation was found to affect the expression of specific cell

markers and cell maturation. Techniques such as immunofluorescence

and histological analysis revealed these changes, which provided

direct evidence for the role of SOX9 in human lung

epithelial development (70).

Application of functionalized hydrogel

scaffolds in organoid culture

Gmeiner et al (71) (2020) successfully established small

cell lung cancer PDX-derived organoid models using HyStem-HP

hydrogel scaffolds and demonstrated that the novel drug CF10 could

overcome tumor chemoresistance. Functionalized hydrogels are

defined scaffolds with well-defined compositions and precisely

tunable properties. As a result, they are increasingly supplanting

animal-derived matrices such as Matrigel, whose undefined

composition and batch variability limit reproducibility and

mechanistic control. Current advancements are primarily focused on

two main directions. The first involves synthetic hydrogels, such

as PEG and polyisocyanopeptides, which provide a highly

controllable microenvironment for organoids through the grafting of

cell-adhesive peptides (such as RGD and GFOGER), and through

fine-tuning of mechanical properties (such as stiffness and

viscoelasticity). This approach enables precise investigation of

the role of mechanical signals in organoid growth, EMT and invasion

(72). The other direction focuses

on engineered natural polymers, such as organ-specific dECM,

peptide-functionalized nanocellulose and alginate (73). These materials retain

tissue-specific biological signals and enhance functionality

through chemical modifications, effectively promoting structural

maturity and functional complexity of organoids (such as

vascularization). The establishment of these functionalized

hydrogel scaffold systems has significantly improved the

reliability and utility of organoids in standardized modeling,

disease mechanism research, drug screening and clinical translation

(74–76).

In vivo transplantation and

comparative analysis of preclinical models

The metastatic cascade unfolds within a complex

physiological milieu that is difficult to fully recapitulate in

vitro. Consequently, the in vivo transplantation of

organoids serves as a critical intermediary, validating their

tumorigenic and metastatic capacities in a more physiologically

relevant framework for investigation. For example, orthotopic

transplantation of lung cancer organoids into the lungs of

immunodeficient mice can reproduce the native tumor

microenvironment, enabling comprehensive observation of the

metastatic continuum from local invasion to distant colonization

(77).

Organoid transplantation for

metastasis research

The utility of organoid transplantation has been

extensively demonstrated across multiple cancer types. In

colorectal cancer, organoid libraries retain stable pathological

and genetic characteristics. GFP-labeled organoids derived from

patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), when transplanted into

immunodeficient mice, facilitate visualization and quantification

of micrometastatic lesions (such as hepatic metastases following

splenic injection) (78).

Comparable strategies have been employed in models of lung, breast

(79), pancreatic (80) and brain (81) cancer, effectively recapitulating

tumor dynamics and supporting preclinical evaluation of therapeutic

efficacy.

By constructing humanized lung cancer PDX models

through engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells into

immunodeficient mice to reconstitute a human immune system,

researchers can effectively evaluate the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1

inhibitors such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab (82).

A comparative perspective on

preclinical models

While organoid transplantation is a versatile tool

in metastasis research, it is one of several available preclinical

models. A comparative evaluation of these mainstream platforms

underscores their distinct advantages and optimal applications,

with PDOs occupying a unique and increasingly important niche in

translational studies.

i) PDOs vs. PDXs

Comparative studies have highlighted the distinct

advantages of PDOs over PDXs in several key aspects. PDOs can often

be established within weeks, which is significantly faster than the

months typically required for PDXs. PDOs are more cost-effective

and offer greater scalability, making them suitable for

high-throughput in vitro studies (83). A critical limitation of conventional

PDX models, which are grown in immunodeficient mice, is the absence

of a functional human immune system, restricting their application

in immunotherapy research. Humanized PDX models address this issue

to some extent, but still face challenges such as incomplete immune

reconstitution. Additionally, murine stromal cells gradually

replace the human tumor microenvironment in PDXs, potentially

altering key aspects of tumor biology. Although PDOs also face

challenges in fully replicating the tumor microenvironment, they

offer greater flexibility for incorporating human immune components

through co-culture systems (84).

ii) Characteristics and limitations of

spheroids

Spheroids are simple 3D cell aggregates that are

valuable for high-throughput drug screening and for studying basic

nutrient gradients. However, they generally lack the complex and

architecturally accurate tissue morphology, cellular diversity

(including stromal components) and long-term functional

differentiation that characterize PDOs derived from stem or

progenitor cells. These shortcomings limit their ability to mimic

the complexity of native tissues (85,86).

iii) Comparative analysis of PDOs and

lung-on-a-chip models

Organ-on-a-chip platforms are highly effective at

engineering precise physiological microenvironments, incorporating

fluid flow, mechanical forces and multi-cellular interactions to

model dynamic processes such as vascular perfusion and immune cell

trafficking. Their limitation often stems from the use of

established cell lines, which may not fully represent the

patient-specific genomic heterogeneity. PDOs complement these

systems by offering a genetically accurate, patient-derived tissue

source, which can be integrated into chip-based devices to create

more personalized and representative models (87).

iv) Comparative analysis of PDOs and

genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs)

GEMMs are an optimal model for studying

tumorigenesis and metastasis within an intact, immunocompetent

organism and in the context of developing tissues. However, their

primary limitations include long timelines, high costs and inherent

species differences, which can hinder the direct translation of

findings to human patients. PDOs offer a more rapid, human-based

platform for personalized screening and genetic manipulation,

providing a valuable complement to GEMMs (88).

v) Integrating preclinical models:

Synergistic applications

These models are not mutually exclusive, and they

are highly complementary. Insights gained from high-throughput drug

screening in PDOs can be validated within the more physiologically

intact contexts of PDXs or GEMMs. Conversely, PDOs can be

integrated into organ-on-a-chip devices to create more complex,

human-relevant organoid-on-a-chip systems. The choice of model

depends on the specific research question, with PDOs offering a

balanced platform that preserves human tumor heterogeneity while

enabling scalable in vitro experimentation.

vi) Advances in patient-derived models

for studying metabolism-immunity interplay in lung cancer

PDOs and patient-derived organotypic tissue cultures

(PD-OTCs) have recently demonstrated notable value in

recapitulating the lung cancer tumor microenvironment and

elucidating its functional dynamics, particularly the interactions

between metabolism and immunity. Using stable isotope-resolved

metabolomics, Fan et al (89) found that PD-OTCs more accurately

reproduce complex metabolic reprogramming features observed in

patients, including enhanced glycolysis, nucleotide synthesis and

anaplerotic reactions, compared with PDX models of NSCLC. Building

on this platform, the study directly uncovered key regulatory

mechanisms along the metabolism-immunity axis. It demonstrated that

immunomodulators (such as β-glucan) and checkpoint inhibitors can

reprogram the metabolic state of immune cells, effectively

reversing immunosuppression by shifting TAMs from the M2

anti-inflammatory phenotype to the M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype.

These experimental findings provide empirical support for the

theoretical framework proposed in the study by Huang et al

(90), which suggested that

metabolic networks within the tumor microenvironment coordinate

immune responses and drive immune evasion. In summary, PDOs and

PD-OTCs have emerged as key bridges connecting the theory of

metabolic reprogramming with the practice of immunotherapy,

establishing a methodological foundation for developing

individualized combination strategies that target the

metabolism-immunity axis.

CTC-derived organoids

By contrast, CTC-derived organoids are established

from tumor cells shed into the bloodstream from primary or

metastatic sites, thereby capturing dynamic and comprehensive

tumor-related information. Culturing organoids from sources such as

intestinal tissues is relatively straightforward, as these models

can be stably cultured and passaged in defined media and matrix

gels using well-established protocols. However, culturing CTC

organoids poses greater technical challenges. CTCs are extremely

rare in peripheral blood, typically on the order of 1 to 10

cells/ml, making their isolation and enrichment particularly

demanding. CTCs derived from different tumor types require

tumor-specific culture conditions, further contributing to low

success rates (91,92). In prostate cancer, for example, the

reported success rate of culturing CTCs is ~5.8% (93).

Regarding practical applications, general organoids

are widely used to study organ development, disease modeling and

drug testing. CTC organoids are particularly valuable for

investigating tumor metastasis, personalized cancer therapy and

drug resistance mechanisms. In terms of cellular characteristics,

organoids derived from normal tissue stem cells typically exhibit

stable morphology and function, while those derived tumor tissues

retain some malignant features of the original tumor cells. CTC

organoids display a high degree of heterogeneity that reflects the

diversity of tumor cells during the metastatic process, and they

may exhibit stronger metastatic potential (94).

CTC organoids derived from blood samples of patients

with SCLC can simulate the tumor microenvironment and support drug

response testing. By preserving tumor cell heterogeneity, CTC

organoids can improve prediction of drug efficacy relative to

traditional preclinical models. This enables clinicians to identify

effective therapeutic agents tailored to individual patients,

prioritize drugs with higher sensitivity, avoid those with

potential resistance and reduce adverse effects associated with

ineffective treatments. Ultimately, this approach can improve

clinical outcomes and enhance patient life quality. Beyond their

utility in guiding personalized therapy, CTC organoids serve as a

powerful tool for investigating the biological features of SCLC,

including the mechanisms of tumor initiation, progression and

metastasis (94,95). They also offer insights into the

development of drug resistance and inform strategies to overcome

it. From a translational perspective, molecular analysis of CTC

organoids can facilitate the discovery of novel therapeutic

targets, assist in evaluating the efficacy and safety of emerging

drug candidates and support early-stage clinical trials due to

their operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness and relatively

short culture time (96).

Application of lung cancer organoid

metastasis models in research

Mechanistic studies of metastasis

Lung cancer organoid-based metastasis models provide

an effective platform for in-depth exploration of metastatic

mechanisms. Research on metastasis-related genes and signaling

pathways has revealed that numerous genes serve critical roles in

lung cancer metastasis. For example, deletion of the histone

methyltransferase gene KMT2C promotes distant metastasis in

SCLC through DNMT3A-mediated epigenetic reprogramming. In

lung cancer organoid models, KMT2C knockout markedly

increases organoid invasiveness and metastatic potential. Further

analyses have revealed associated alterations in histone

modification and DNA methylation patterns, which regulate

downstream genes involved in metastatic progression (97).

These models are also instrumental for studying the

impact of the tumor microenvironment on metastasis. Cellular

components such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and

fibroblasts interact with tumor cells and modulate their metastatic

behavior. Co-culture experiments involving TAMs and lung cancer

organoids have demonstrated that macrophages secrete cytokines that

enhance organoid invasion and migration. This pro-metastatic effect

has been further validated in vivo, where the presence of

TAMs significantly promoted metastatic spread following

transplantation (98).

Drug screening and efficacy

evaluation

Lung cancer organoid metastasis models are valuable

for drug screening and efficacy evaluation. They support

high-throughput screening of anti-metastatic drugs by evaluating

treatment-induced changes in cancer cell migration, invasion and

expression of metastasis-associated markers. Lung cancer organoid

metastasis models are also well suited for assessing the

synergistic effects of combination therapies, thereby informing

optimization of clinical treatment strategies. In addition,

correlating genetic characteristics and molecular marker expression

in patient-derived lung cancer organoids with clinical metastasis

data may facilitate the development of predictive models for

metastatic risk. For example, elevated expression of specific genes

or proteins could indicate increased metastatic risk and poor

prognosis, aiding early intervention and improved outcomes

(99).

Metastasis is a major determinant of prognosis in

lung cancer. A previous study established lung cancer organoids

from malignant serous effusions that retained key tumor

characteristics and showed high genomic concordance with the

original tumors. The Lung Cancer Organoids-Drug Sensitivity Test

(LCO-DST) demonstrated strong predictive performance, with a

sensitivity of 84.0%, specificity of 82.8% and accuracy of 83.3%

for distinguishing drug-sensitive from drug-resistant patients.

This test effectively predicted responses to targeted therapies and

chemotherapy. Notably, lung cancer organoids exhibit both stability

and inter-patient heterogeneity. Organoids derived at different

time points from the same patient maintained consistent genomic

features, while organoids from different patients showed distinct

morphologies and drug sensitivities. These findings highlight the

potential of LCO-DST for predicting the effectiveness of

combination therapies in advanced lung cancer (100).

Using lung cancer brain metastasis organoid models

as an example, researchers have evaluated the impact of various

therapeutic agents on the growth and invasion of brain metastases.

Treating lung cancer brain metastases (LCBM) remains a significant

clinical challenge, underscoring the importance of drug screening.

Traditional cancer cell lines and PDX models have notable

limitations; cell lines often lack in vivo tumor

heterogeneity and PDX models face interspecies incompatibilities

and low establishment efficiency (101). By contrast, LCBM organoids

recapitulate the molecular and phenotypic features of metastatic

tumors. They can be used to screen targeted therapies based on

specific genetic alterations such as EGFR or ALK

mutations, to identify potential radiosensitizers and evaluate the

combined radio-chemotherapy efficacy. With access to large-scale

drug libraries, organoid models enable high-throughput drug

screening, providing strong support for LCBM drug development and

clinical treatment selection (101).

Research on tumor heterogeneity

Tumor heterogeneity is a critical factor in the

development, therapeutic resistance and metastasis of lung cancer.

The dynamic evolution of tumor heterogeneity in space (between

primary and metastatic sites and within different tumor regions)

and in time (before and after treatment or at different disease

stages), poses significant challenges for constructing effective

metastasis models (102–104). Compared with traditional cell

lines and GEMMs, lung cancer organoids more accurately preserve

genomic diversity, phenotypic variations and key components of the

tumor microenvironment, including co-culture systems that

incorporate stromal and immune cells from the original tumors

(105).

Single-cell sequencing studies (106–109) have demonstrated that lung cancer

organoids retain subclonal structures and transcriptomic

heterogeneity comparable to those of the primary tumors. These

organoids are also enriched for invasive front cell populations,

particularly cells undergoing EMT, which serve crucial roles in

metastasis (110). However,

replicating the dynamic evolution of heterogeneity within

organoid-based metastasis models remains technically challenging.

As the metastatic cascade involves selection of heterogeneous CTCs,

current organoid systems are limited in their ability to mimic

circulatory dynamics, including fluid shear stress and

trans-endothelial migration. To address these limitations,

integration with organ-on-a-chip technologies will be necessary to

achieve more physiologically relevant spatiotemporal reconstruction

(111–113).

LCBMs are a common and severe complication in

advanced diseases. Brain metastases exhibit higher median absolute

deviation and higher mutation allele tumor heterogeneity scores

than primary tumors, indicating greater genomic diversity (114). In addition, single-cell RNA

sequencing has revealed marked differences in gene expression

between tumor cells from brain metastases and those from primary

sites, highlighting cell-level heterogeneity that may influence

disease progression and therapeutic response (115). In the future, the integration of

spatial transcriptomics, live-cell imaging and AI-driven algorithms

for quantifying heterogeneity will enable lung cancer organoid

models to capture dynamic tumor evolution at single-cell

resolution. These advances will support early prediction and

precise intervention for metastatic risk.

Challenges and future directions in lung

cancer organoid metastasis models

Clinical translation of lung cancer organoid

metastasis models faces several intertwined technical,

translational and ethical challenges. Overcoming these obstacles is

essential for advancing the field, and future development will

depend on integrating innovative technologies and establishing

standardized practices. Addressing these challenges will enable

more effective and personalized approaches to lung cancer research

and treatment.

Current challenges. i) Technical

hurdles in model construction

The success rate of organoid culture remains

suboptimal for certain lung cancer subtypes, such SCLC and

sarcomatoid carcinoma, due to their limited stemness and strong

dependence on the ECM (116). A

major bottleneck is the widespread use of ill-defined matrices such

as Matrigel, which are affected by batch-to-batch variability,

undefined composition and non-physiological mechanical properties.

Although dECM provides a more native biochemical environment,

donor-dependent variability complicates standardization (117–119).

Reconstructing the tumor microenvironment also

presents significant challenges. Co-culture systems that integrate

immune cells are hindered by poor immune cell infiltration into

dense hydrogel domes and by the difficulty of sourcing authentic

TILs. These limitations impede accurate modeling of complex tumor

microenvironment interactions that are crucial for studying

tumor-immune dynamics and metastasis (120). In addition, current models are

limited in ability to replicate full cellular diversity and complex

stromal interactions, including functional vasculature, which

limits the ability to model tumor growth, metastatic dissemination

and dynamic interactions between tumor cells and their

microenvironment.

ii) Barriers to clinical translation

and ethical considerations

From a clinical perspective, the absence of

standardized protocols for model construction, culture and

assessment severely limits reproducibility and hinders large-scale

application. High costs associated with tissue acquisition,

organoid culture and molecular analyses present significant

economic barriers. Additionally, there is a lack of large-scale,

multi-center clinical validation to confirm the predictive accuracy

of these models for drug response and personalized therapy, which

impedes the broader clinical adoption (121).

Ethically, the collection and use of patient-derived

tissues requires rigorous informed consent processes. The

application of advanced techniques such as gene editing introduces

additional ethical complexities, requiring clear regulatory

frameworks for safety assessment and intellectual property

management.

Integrated future directions

To address these challenges, the field is moving

towards a multi-faceted strategy that leverages cutting-edge

technologies and promotes standardization.

i) Advancing model fidelity through

technology integration

Integrating multi-omics technologies, including

genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, with

organoid models will provide a comprehensive molecular view of

metastasis. This approach may reveal novel drivers, elucidate

dysregulated metabolic pathways and uncover complex molecular

interactions within the tumor microenvironment. Combining these

high-throughput techniques with organoid models will deepen

mechanistic insights and accelerate the development of more

targeted and effective therapies (122).

A key goal in cancer research is the development of

sophisticated immune-organoid models. By co-culturing lung cancer

organoids with autologous immune cells, including T cells and

natural killer cells, or by utilizing humanized mouse models,

researchers can better replicate crucial tumor-immune interactions.

These models provide a powerful platform for evaluating

immunotherapy efficacy and for studying mechanisms of immune

evasion. Understanding how tumors interact with immune cells in a

more physiologically relevant context can accelerate the discovery

of novel therapeutic strategies and improve the precision of cancer

immunotherapy (123–128).

The synergy between organoid models and liquid

biopsy is also highly promising. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA

(ctDNA) from patient plasma or from organoid culture supernatants,

provides a non-invasive method to track tumor evolution in

real-time. This approach can guide drug selection in organoid

models, enabling personalized and adaptive treatment strategies. By

incorporating ctDNA analysis, researchers can continuously monitor

treatment response and identify emerging resistance mechanisms,

creating a closed-loop feedback system that enhances the precision

and flexibility of oncology therapies. This combination has the

potential to transform personalized cancer care by aligning

treatments with the evolving molecular landscape of each tumor

(91,129–131). Single-cell RNA sequencing is

another pivotal tool; it can resolve cellular heterogeneity within

organoids and their tumor microenvironment, validate model fidelity

and identify rare cell populations critical to metastasis research

(106).

ii) Leveraging AI and

standardization

The application of AI and machine learning is poised

to transform the field. AI algorithms can analyze high-content

imaging data from organoids to automate quantification of

metastatic phenotypes, including invasion and migration, which

streamlines the screening process (132–134). Furthermore, AI can integrate

multi-omics and drug response data to build predictive models for

metastatic risk and therapy optimization, thereby guiding

personalized treatment decisions. These advances must be supported

by rigorous standardization. Harmonized protocols for tissue

processing, culture conditions and quality control are essential to

ensure reproducibility, enable multi-center collaborations and

facilitate clinical adoption. In parallel, optimizing workflows and

reducing costs are important for improving accessibility.

Conclusion

Lung cancer organoid metastasis models have emerged

as pivotal platforms for deciphering metastatic mechanisms and

advancing precision therapy. Despite persistent challenges in

standardization and tumor microenvironment recapitulation, future

investigations should prioritize the following directions:

Integrating multi-omics with spatial transcriptomics to

systematically resolve spatiotemporal dynamics of metastasis;

developing immunocompetent organoid co-culture systems to deepen

understanding of tumor-immune interactions; employing chemically

defined functionalized hydrogels for precise modulation of the

tumor microenvironment; and combining artificial intelligence with

liquid biopsy to establish dynamic drug response prediction models.

Through interdisciplinary integration and standardized framework

development, these organoid models will accelerate anti-metastatic

drug discovery and ultimately facilitate the clinical translation

of precision medicine for lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Xi'an Science and

Technology Program (grant no. 2024JH-ZCLGG-0040), the Wu Jieping

Medical Foundation Clinical Research Special Grant Fund (grant no.

320.6750.2023-17-23), the Technology Program (grant no.

2024YXYJ0133), The Xi'an Science and Technology Program (grant no.

24YXYJ0179), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central

Universities (‘Free Exploration’ Teacher Project) of Xi'an Jiaotong

University (grant no. xzy012025151), the Beijing KC Medical

Development Foundation Research Project (grant no.

KC2023-JX-0288-PM92) and the China Health and Medical Development

Foundation (grant no. chmdf2024-xrzx09-20).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JJ conceived the study. JJ, GMD, QG, ZYZ, XYL, FSH,

SNL, JQM, JB, HW and ZZ wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

El-Kenawi A, Hänggi K and Ruffell B: The

immune microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Med. 10:a0374242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Seyfried TN and Huysentruyt LC: On the

origin of cancer metastasis. Crit Rev Oncog. 18:43–73. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Peitzsch C, Tyutyunnykova A, Pantel K and

Dubrovska A: Cancer stem cells: The root of tumor recurrence and

metastases. Semin Cancer Biol. 44:10–24. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sulekha Suresh D and Guruvayoorappan C:

Molecular principles of tissue invasion and metastasis. Am J

Physiol Cell Physiol. 324:C971–C991. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jin K, Li T, van Dam H, Zhou F and Zhang

L: Molecular insights into tumour metastasis: Tracing the dominant

events. J Pathol. 241:567–577. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kalita B and Coumar MS: Deciphering

molecular mechanisms of metastasis: Novel insights into targets and

therapeutics. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 44:751–775. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Smolarz B, Łukasiewicz H, Samulak D,

Piekarska E, Kołaciński R and Romanowicz H: Lung

cancer-epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment and molecular aspect

(review of literature). Int J Mol Sci. 26:20492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Orooji N, Babaei S, Fadaee M,

Abbasi-Kenarsari H, Eslami M, Kazemi T and Yousefi B: Novel

therapeutic approaches for non-small cell lung cancer: An updated

view. J Drug Target. 33:1306–1321. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang Q, Abdo R, Iosef C, Kaneko T,

Cecchini M, Han VK and Li SS: The spatial transcriptomic landscape

of non-small cell lung cancer brain metastasis. Nat Commun.

13:59832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xie S, Wu Z, Qi Y, Wu B and Zhu X: The

metastasizing mechanisms of lung cancer: Recent advances and

therapeutic challenges. Biomed Pharmacother. 138:1114502021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim SY, Park HS and Chiang AC: Small cell

lung cancer: A review. JAMA. 333:1906–1917. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Malapelle U, Ricciuti B, Baglivo S, Pepe

F, Pisapia P, Anastasi P, Tazza M, Sidoni A, Liberati AM, Bellezza

G, et al: Osimertinib. Recent Results Cancer Res. 211:257–276.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang JC, Ahn MJ, Kim DW, Ramalingam SS,

Sequist LV, Su WC, Kim SW, Kim JH, Planchard D, Felip E, et al:

Osimertinib in pretreated T790M-positive advanced non-small-cell

lung cancer: AURA study phase II extension component. J Clin Oncol.

35:1288–1296. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Patil BR, Bhadane KV, Ahmad I, Agrawal YJ,

Shimpi AA, Dhangar MS and Patel HM: Exploring the structural

activity relationship of the Osimertinib: A covalent inhibitor of

double mutant EGFRL858R/T790M tyrosine kinase for the

treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Bioorg Med Chem.

109:1177962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhan Z, Chen B, Xu S, Lin R, Chen H, Ma X,

Lin X, Huang W, Zhuo C, Chen Y and Guo Z: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

combined with antiangiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint

inhibitors for the treatment of locally advanced gastric cancer: A

real-world retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol.

16:15182172025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen Y, Chen Z, Chen R, Fang C, Zhang C,

Ji M and Yang X: Immunotherapy-based combination strategies for

treatment of EGFR-TKI-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. Future

Oncol. 18:1757–1775. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li J, Yao X, Qiu L, Zhang R and Wang G:

Research progress in immune checkpoint inhibitors combination

therapy applied to non-small cell lung cancer after EGFR

mutation-targeted therapy resistance. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi.

26:392–399. 2023.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gotwals P, Cameron S, Cipolletta D,

Cremasco V, Crystal A, Hewes B, Mueller B, Quaratino S,

Sabatos-Peyton C, Petruzzelli L, et al: Prospects for combining

targeted and conventional cancer therapy with immunotherapy. Nat

Rev Cancer. 17:286–301. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rizzo A, Ricci AD and Brandi G: PD-L1,

TMB, MSI, and other predictors of response to immune checkpoint

inhibitors in biliary tract cancer. Cancers (Basel). 13:5582021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hektoen HH, Tsuruda KM, Fjellbirkeland L,

Nilssen Y, Brustugun OT and Andreassen BK: Real-world evidence for

pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: A nationwide cohort

study. Br J Cancer. 132:93–102. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Griffiths AD, Young RO, Yuan Y, Chaudhary

MA, Lee A, Gordon J and McEwan P: Cost-effectiveness of nivolumab

plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated

metastatic NSCLC using mixture-cure survival analysis based on

CheckMate 227 5-year data. Pharmacoecon Open. 9:247–257. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Du Z, Ge X, Li Y, Qin Y, Fan H, Lv Y, Du X

and Liu Z: Clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of

long-term responders for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer

patients with first-line PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors: A multicenter

retrospective study. Postgrad Med J. 101:1072–1080. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ul Bassar W, Ogedegbe OJ, Qammar A, Sumia

F, Ul Islam M, Chaudhari SS, Ntukidem OL and Khan A: Efficacy of

tislelizumab in lung cancer treatment: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cureus.

17:e806092025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Prasad CP, Tripathi SC, Kumar M and

Mohapatra P: Passage number of cancer cell lines: Importance,

intricacies, and way-forward. Biotechnol Bioeng. 120:2049–2055.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mestas J and Hughes CCW: Of mice and not

men: Differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol.

172:2731–2738. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guan X, Wu D, Zhu H, Zhu B, Wang Z, Xing

H, Zhang X, Yan J, Guo Y and Lu Y: 3D pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma desmoplastic model: Glycolysis facilitating stemness

via ITGAV-PI3K-AKT-YAP1. Biomater Adv. 170:2142152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Smabers LP, Wensink E, Verissimo CS,

Koedoot E, Pitsa KC, Huismans MA, Higuera Barón C, Doorn M,

Valkenburg-van Iersel LB, Cirkel GA, et al: Organoids as a

biomarker for personalized treatment in metastatic colorectal

cancer: Drug screen optimization and correlation with patient

response. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhao KY, Du YX, Cao HM, Su LY, Su XL and

Li X: The biological macromolecules constructed Matrigel for

cultured organoids in biomedical and tissue engineering. Colloids

Surf B Biointerfaces. 247:1144352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fu S, Zhu X, Huang F and Chen X: Anti-PEG

antibodies and their biological impact on PEGylated drugs:

Challenges and strategies for optimization. Pharmaceutics.

17:10742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhu L, Yuhan J, Yu H, Zhang B, Huang K and

Zhu L: Decellularized extracellular matrix for remodeling

bioengineering organoid's microenvironment. Small. 19:e22077522023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

He S, Nakada D and Morrison SJ: Mechanisms

of stem cell self-renewal. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 25:377–406.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Dalton S: Linking the cell cycle to cell

fate decisions. Trends Cell Biol. 25:592–600. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Corrò C, Novellasdemunt L and Li VSW: A

brief history of organoids. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol.

319:C151–C165. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de

Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters

PJ and Clevers H: Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus

structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature.

459:262–265. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhou Y, Song H and Ming GL: Genetics of

human brain development. Nat Rev Genet. 25:26–45. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li Y, Zeng PM, Wu J and Luo ZG: Advances

and applications of brain organoids. Neurosci Bull. 39:1703–1716.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kanupriya K, Pal Verma S, Sharma V, Mishra

I and Mishra R: Advances in human brain organoids: Methodological

innovations and future directions for drug discovery. Curr Drug Res

Rev. 17:360–374. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xu H, Jiao D, Liu A and Wu K: Tumor

organoids: Applications in cancer modeling and potentials in

precision medicine. J Hematol Oncol. 15:582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li Z, Yu L, Chen D, Meng Z, Chen W and

Huang W: Protocol for generation of lung adenocarcinoma organoids

from clinical samples. STAR Protoc. 2:1002392020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Phifer CJ, Bergdorf KN, Bechard ME,

Vilgelm A, Baregamian N, McDonald OG, Lee E and Weiss VL: Obtaining

patient-derived cancer organoid cultures via fine-needle

aspiration. STAR Protoc. 2:1002202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kim SY, Kim SM, Lim S, Lee JY, Choi SJ,

Yang SD, Yun MR, Kim CG, Gu SR, Park C, et al: Modeling clinical

responses to targeted therapies by patient-derived organoids of

advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 27:4397–4409. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Mazzocchi A, Devarasetty M, Herberg S,

Petty WJ, Marini F, Miller L, Kucera G, Dukes DK, Ruiz J, Skardal A

and Soker S: Pleural effusion aspirate for use in 3D lung cancer

modeling and chemotherapy screening. ACS Biomater Sci Eng.

5:1937–1943. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mazzocchi A, Dominijanni A and Soker S:

Pleural effusion aspirate for use in 3D lung cancer modeling and

chemotherapy screening. Methods Mol Biol. 2394:471–483. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang L, Yu Y, Fang Y, Li Y, Yu W, Wang Z,

Lv J, Wang R and Liang S: Malignant pleural effusion facilitates

the establishment and maintenance of tumor organoid biobank with

multiple patient-derived lung tumor cell sources. Exp Hematol

Oncol. 13:1152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Driehuis E, Kretzschmar K and Clevers H:

Establishment of patient-derived cancer organoids for

drug-screening applications. Nat Protoc. 15:3380–3409. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Taverna JA, Hung CN, Williams M, Williams

R, Chen M, Kamali S, Sambandam V, Hsiang-Ling Chiu C, Osmulski PA,

Gaczynska ME, et al: Ex vivo drug testing of patient-derived lung

organoids to predict treatment responses for personalized medicine.

Lung Cancer. 190:1075332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Xie C, Gu A, Khan M, Yao X, Chen L, He J,

Yuan F, Wang P, Yang Y, Wei Y, et al: Opportunities and challenges

of hepatocellular carcinoma organoids for targeted drugs

sensitivity screening. Front Oncol. 12:11054542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Demyan L, Habowski AN, Plenker D, King DA,

Standring OJ, Tsang C, St Surin L, Rishi A, Crawford JM, Boyd J, et

al: Pancreatic cancer patient-derived organoids can predict

response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 276:450–462. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Merrill NM, Kaffenberger SD, Bao L,

Vandecan N, Goo L, Apfel A, Cheng X, Qin Z, Liu CJ, Bankhead A, et

al: Integrative drug screening and multiomic characterization of

patient-derived bladder cancer organoids reveal novel molecular

correlates of gemcitabine response. Eur Urol. 86:434–444. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Hughes CS, Postovit LM and Lajoie GA:

Matrigel: A complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of

cell culture. Proteomics. 10:1886–1890. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Seiji Y, Ito T, Nakamura Y,

Nakaishi-Fukuchi Y, Matsuo A, Sato N and Nogawa H: Alveolus-like

organoid from isolated tip epithelium of embryonic mouse lung. Hum

Cell. 32:103–113. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Bhattacharya S, Calar K and de la Puente

P: Mimicking tumor hypoxia and tumor-immune interactions employing

three-dimensional in vitro models. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

39:752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Poggio F, Brofiga M, Callegari F, Tedesco

M and Massobrio P: Developmental conditions and culture medium

influence the neuromodulated response of in vitro cortical

networks. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2023:1–4.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Valian N, Heravi M, Ahmadiani A and

Dargahi L: Comparison of rat primary midbrain neurons cultured in

DMEM/F12 and neurobasal mediums. Basic Clin Neurosci. 12:205–212.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ziółkowska-Suchanek I: Mimicking tumor

hypoxia in non-small cell lung cancer employing three-dimensional

in vitro models. Cells. 10:1412021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Li Y, Zou J, Fang Y, Zuo J, Wang R and

Liang S: Lung tumor organoids migrate as cell clusters containing

cancer stem cells under hypoxic condition. Biol Cell.

117:e24000812025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu C, Pei M, Li Q and Zhang Y:

Decellularized extracellular matrix mediates tissue construction

and regeneration. Front Med. 16:56–82. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Pasupuleti V, Vora L, Prasad R, Nandakumar

DN and Khatri DK: Glioblastoma preclinical models: Strengths and

weaknesses. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1879:1890592024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Cui X, Liu H, Liu Y, Yu Z, Wang D, Wei W

and Wang S: Tissue-specific decellularized extracellular matrix

rich in collagen, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans and its

applications in advanced organoid engineering: A review. Int J Biol

Macromol. 315:1444692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Low RRJ, Fung KY, Gao H, Preaudet A,

Dagley LF, Yousef J, Lee B, Emery-Corbin SJ, Nguyen PM, Larsen RH,

et al: S100 family proteins are linked to organoid morphology and

EMT in pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Differ. 30:1155–1165. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Jeong SR and Kang M: Exploring

tumor-immune interactions in co-culture models of T cells and tumor

organoids derived from patients. Int J Mol Sci. 24:146092023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yuan J, Li X and Yu S: Cancer organoid

co-culture model system: Novel approach to guide precision

medicine. Front Immunol. 13:10613882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Liu Y, Chudgar N, Mastrogiacomo B, He D,

Lankadasari MB, Bapat S, Jones GD, Sanchez-Vega F, Tan KS, Schultz

N, et al: A germline SNP in BRMS1 predisposes patients with lung

adenocarcinoma to metastasis and can be ameliorated by targeting

c-fos. Sci Transl Med. 14:eabo10502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Naranjo S, Cabana CM, LaFave LM, Romero R,

Shanahan SL, Bhutkar A, Westcott PMK, Schenkel JM, Ghosh A, Liao

LZ, et al: Modeling diverse genetic subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma

with a next-generation alveolar type 2 organoid platform. Genes

Dev. 36:936–949. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kawai S, Nakano K, Tamai K, Fujii E,

Yamada M, Komoda H, Sakumoto H, Natori O and Suzuki M: Generation

of a lung squamous cell carcinoma three-dimensional culture model

with keratinizing structures. Sci Rep. 11:243052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Qu F, Brough SC, Michno W, Madubata CJ,

Hartmann GG, Puno A, Drainas AP, Bhattacharya D, Tomasich E, Lee

MC, et al: Crosstalk between small-cell lung cancer cells and

astrocytes mimics brain development to promote brain metastasis.

Nat Cell Biol. 25:1506–1519. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Quaranta V and Linkous A: Organoids as a

systems platform for SCLC brain metastasis. Front Oncol.

12:8819892022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Meng Y, Shu X, Yang J, Liang Y, Zhu M,

Wang X, Li Y and Kong F: Lung cancer organoids: A new strategy for

precision medicine research. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 14:575–590.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Butterfield GL, Reisman SJ, Iglesias N and

Gersbach CA: Gene regulation technologies for gene and cell

therapy. Mol Ther. 33:2104–2122. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Li L, Feng J, Zhao S, Rong Z and Lin Y:

SOX9 inactivation affects the proliferation and differentiation of

human lung organoids. Stem Cell Res Ther. 12:3432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Gmeiner WH, Miller LD, Chou JW,

Dominijanni A, Mutkus L, Marini F, Ruiz J, Dotson T, Thomas KW,

Parks G and Bellinger CR: Dysregulated pyrimidine biosynthesis

contributes to 5-FU resistance in SCLC patient-derived organoids

but response to a novel polymeric fluoropyrimidine, CF10. Cancers

(Basel). 12:7882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zhang Q and Zhang M: Recent advances in

lung cancer organoid (tumoroid) research (review). Exp Ther Med.

28:3832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Curvello R and Garnier G: Cationic

cross-linked nanocellulose-based matrices for the growth and

recovery of intestinal organoids. Biomacromolecules. 22:701–709.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Feng Y, He D and An X: Hydrogel

innovations for 3D organoid culture. Biomed Mater. 20:2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Luo L, Liu L, Ding Y, Dong Y and Ma M:

Advances in biomimetic hydrogels for organoid culture. Chem Commun

(Camb). 59:9675–9686. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Li C, An N, Song Q, Hu Y, Yin W, Wang Q,

Le Y, Pan W, Yan X, Wang Y and Liu J: Enhancing organoid culture:

Harnessing the potential of decellularized extracellular matrix

hydrogels for mimicking microenvironments. J Biomed Sci. 31:962024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ishigamori R, Naruse M, Hirata A, Maru Y,

Hippo Y and Imai T: The potential of organoids in toxicologic

pathology: Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of

a mouse normal tissue-derived organoid-based carcinogenesis model.

J Toxicol Pathol. 35:211–223. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Yoshida GJ: Applications of

patient-derived tumor xenograft models and tumor organoids. J

Hematol Oncol. 13:42020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Kabraji S, Ni J, Sammons S, Li T, Van

Swearingen AED, Wang Y, Pereslete A, Hsu L, DiPiro PJ, Lascola C,