Introduction

Gliomas are the most prevalent primary malignant

tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) in adults (1), with diffuse midline glioma (DMG)

standing out for its high invasiveness and abysmal prognosis.

Driven by the histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27)M mutation, DMG exhibits

aggressive behavior and marked resistance to treatment, making it a

formidable challenge in neuro-oncology.

DMG predominantly affects children and adolescents,

whereas adult cases are uncommon. Clinically, numerous pediatric

DMGs present as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a

radiographic entity centered in the pons. Epidemiologic estimates

suggest 20–30 new DIPG cases annually in the UK (2) and 100–400 annually in the US (2,3) and a

Canadian population-based cohort identified 143 pediatric DIPG

cases over a 10-year period (~14 cases per year) (2). DMG remains highly lethal, with a

median overall survival (OS) of ~11 months (4) and 1-, 2- and 5-year survival rates of

42.3, 9.6 and 2.2% in a 1,008-case registry cohort (5).

DMGs are invasive tumors affecting midline

structures such as the thalamus, pons, brainstem and spinal cord.

Clinical manifestations vary by location, including cranial nerve

dysfunction, ataxia and raised intracranial pressure. MRI is key

for diagnosis, showing heterogeneous features such as diffuse or

distinct boundaries, variable contrast enhancement and similarities

to low-grade astrocytomas (6).

Pons-involved DMGs often infiltrate >50% of the pons and may

encase the basilar artery, with minimal T1 contrast enhancement and

uneven T1/T2 signal intensities, often with necrosis or hemorrhage

(7,8), reflecting their histopathological

heterogeneity.

Molecular pathological studies of DMG have revealed

its unique epigenetic characteristics, focusing on the pivotal role

of the H3K27M mutation in its pathogenesis (9). This mutation replaces lysine 27 of

histone H3 with methionine, substantially reducing H3K27

trimethylation (H3K27me3) and causing widespread gene expression

reprogramming. It disrupts epigenetic regulation, promoting tumor

proliferation, invasion and treatment resistance (10). Additionally, the H3K27M mutation

dysregulates multiple key signaling pathways, including MAPK and

PI3K/AKT, driving rapid growth and creating a tumor-supportive

micro-environment (11). These

findings establish H3K27M mutation as a central driver of DMG and

underscore the urgent need for targeted therapeutic strategies.

Despite notable advances in understanding the

molecular basis of DMG, the therapeutic landscape for this disease

remains beset with formidable challenges. Surgery, radiotherapy and

chemotherapy provide minimal improvement in overall survival

currently, as epigenetic alterations driven by the H3K27M mutation

render these tumors highly resistant to conventional treatments.

However, emerging targeted therapies and immunotherapies, including

CAR-T cell therapy, have garnered considerable research interest

(12) though they require further

clinical validation.

Against this backdrop, the present review

systematically summarized the molecular characteristics, genetic

signatures and latest progress in DMG treatment, emphasizing the

effect of histone alterations and innovative therapeutic strategies

to deepen the understanding of DMG and provide theoretical support

and guidance for future research.

Modifications to the definition of DMG

The definition of DMG has evolved markedly with the

2016 and 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) CNS tumor

classifications, shifting towards molecular pathology-based

diagnosis.

Classification and definition in WHO

before 2016

DMG, termed diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG)

before 2016, was first defined by Wilfred Harris in 1926 for its

pontine location and histological features (13,14),

predominantly affecting children aged 5–10 with a dismal prognosis

(median OS less than a year and five-year survival rate <1%)

(15). Traditional classification

could not distinguish subtypes or elucidate molecular mechanisms

(16).

The 2016 WHO classification introduced molecular

diagnostics, defining DMG by the H3K27M histone mutation,

specifically the K27M mutation in the H3F3A, HIST1H3B and HIST1H3C

genes (17,18). This mutation disrupts lysine 27

methylation of histone H3, altering gene regulation and driving

tumorigenesis (19), thereby

enhancing diagnostic precision and differentiation.

Updates in the 2021 WHO

classification

The 2021 WHO classification renamed ‘Diffuse Midline

Glioma, H3K27M-mutant’ to ‘Diffuse Midline Glioma, H3 K27-altered’

to encompass broader molecular changes (20), including EZHIP overexpression

(21,22), which reduces H3K27me3 levels,

promoting invasiveness and therapy resistance (23). These updates improved diagnostic

accuracy, highlighted tumor heterogeneity and facilitated tailored,

patient-specific treatment strategies to enhance outcomes (24).

Significance of histones in cancer

Definition and functions of histone

and oncohistones

Histones are the primary structural proteins of

chromatin, packaging DNA into nucleosomes comprising two copies

each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. Beyond DNA condensation, histones

regulate gene expression through post-translational modifications

such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation and

ubiquitination.

Occurring on lysine residues such as H3K4, H3K27 and

H4K20, methylation can activate or repress transcription based on

its site and extent (mono-, di-, or trimethylation) (25). This process is dynamically regulated

by histone methyltransferases (such as SETD1A, which activates

transcription via H3K4 methylation) and histone demethylases (such

as KDM1A, which represses transcription by demethylating H3K4me2/1)

(26). Catalyzed by histone

acetyltransferases (HATs) such as p300/CBP, acetylation neutralizes

the positive charge of lysine, reducing the electrostatic

interaction of histones with the negatively charged DNA (27), loosening chromatin and facilitating

transcription. Phosphorylation is closely associated with cell

cycle regulation, DNA damage response and transcriptional

activation (28,29). Modifications, such as H2AX serine

139 phosphorylation, signal DNA damage, recruit repair proteins and

coordinate cell cycle responses (30). Ubiquitination, primarily on H2A and

H2B, affects chromatin structure and gene regulation, depending on

the site and mono- or poly-ubiquitination status (31).

Oncohistones, a subset of histones predominantly

observed in H3 (32,33), drive tumorigenesis and cancer

progression by disrupting chromatin structure (34). Mutations alter key modifications

such as H3K27 acetylation, which activates oncogenes such as MYC

and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (35) and H3K27me, which silences tumor

suppressors by compacting chromatin and blocking transcription

factor access. Elevated H3K27me levels are linked to silenced tumor

suppressors in breast, liver and lung cancers (36–38).

These changes promote tumor proliferation, invasiveness and

resistance, making oncohistones pivotal therapeutic targets.

Systemic effects of histone

modifications

Histone modifications orchestrate key pathways such

as PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and MAPK/ERK

(39,40), influencing tumor proliferation,

apoptosis and drug resistance (41). Aberrant modifications disrupt gene

networks, suppress immune responses and drive metastasis, as seen

with elevated HIST1H2BJ activating MMP9 and VEGF in breast cancer

brain metastases (42,43). These changes highlight the critical

role of histone modifications in cancer progression and

metastasis.

H3K27M mutation in the development of

DMG

Diffuse midline glioma is defined by the H3K27M

oncohistone, which disrupts methylation at histone H3 lysine 27

(H3K27). This missense substitution (lysine-to-methionine) occurs

in H3.1 or H3.3 variants and is associated with a profound

reduction of H3K27me3, a key epigenetic mark of transcriptional

repression. The resulting epigenetic reprogramming reshapes

chromatin accessibility and transcriptional programs, thereby

promoting aggressive phenotypes, including uncontrolled

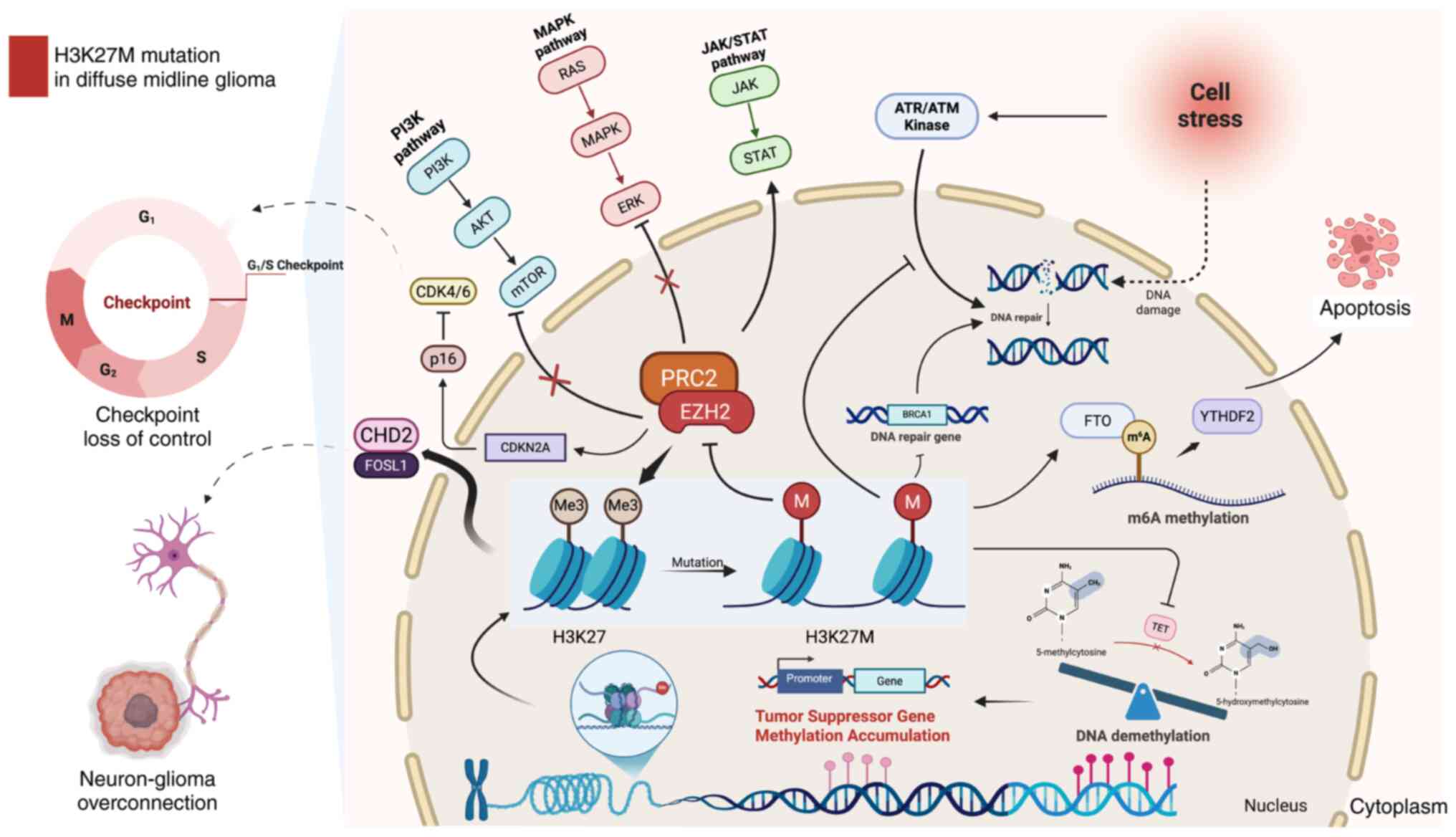

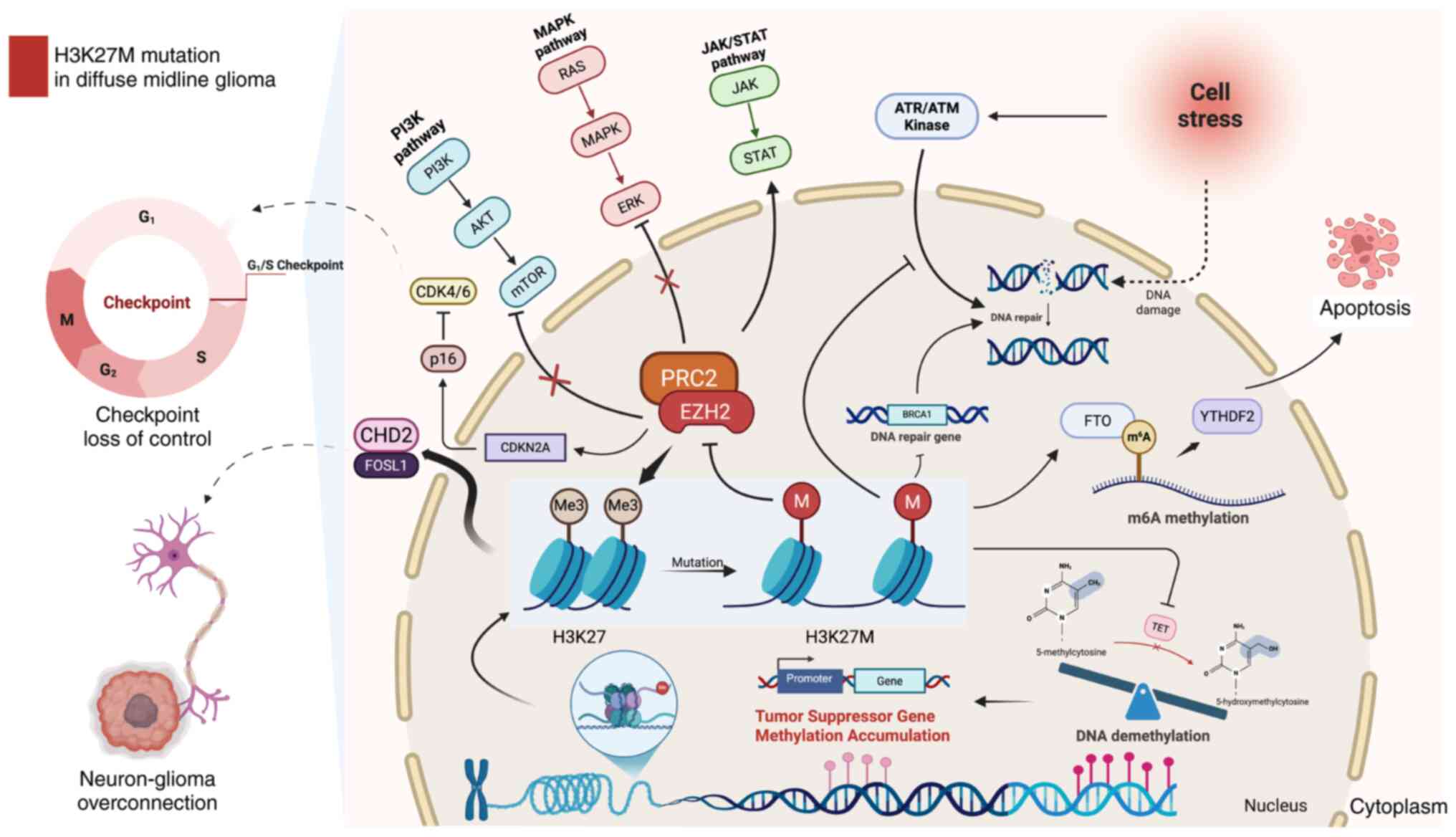

proliferation, invasion and treatment resistance (44) (Fig.

1).

| Figure 1.H3K27M mutation in diffuse midline

glioma. The H3K27M mutation markedly reduces H3K27me3 levels by

inhibiting the EZH2 methyltransferase activity of the PRC2 complex,

leading to disrupted methylation regulation of tumor suppressor

genes and inducing widespread transcriptional abnormalities. This

mutation promotes uncontrolled cell cycle progression, exemplified

by dysregulation of the CDK4/6-p16 pathway and enhances tumor cell

proliferation and invasion through the activation of key signaling

pathways, including MAPK/ERK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and JAK/STAT. The

H3K27M mutation also induces DNA repair deficiencies by impairing

the homologous recombination repair and base excision repair

pathways. It also affects the cellular stress response by altering

the ATR/ATM kinase pathway, compromising the cell's ability to

manage DNA damage. These defects exacerbate genomic instability and

transcriptional dysregulation, further contributing to tumor

progression. The H3K27M mutation alters m6A methylation and FTO

activity, making DMG cells sensitive to FTO inhibition, which

disrupts cell cycle gene expression and induces apoptosis.

Furthermore, the CHD2/FOSL1 axis plays a crucial role in abnormal

synaptic interactions between neurons and tumor cells, enhancing

tumor growth and invasion by promoting excessive neuronal-tumor

connectivity. Figure created using BioRender.com. H3K27, histone H3

lysine 27, H3K27me3, H3K27 trimethylation; PRC2, polycomb

repressive complex 2; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; FTO,

fat-mass- and obesity-associated protein; DMG, diffuse midline

gliomas. |

Inhibition of H3K27me3 by H3K27M

H3K27 trimethylation is primarily catalyzed by the

EZH2 SET domain within the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2),

which maintains Polycomb-mediated transcriptional repression

programs involved in lineage control and proliferation. Structural

and biochemical studies (45) show

that the H3K27M oncohistone engages the PRC2 catalytic groove: the

substituted methionine inserts into the lysine-access channel of

the EZH2 SET domain, thereby competitively inhibiting PRC2

methyltransferase activity and exhibiting markedly higher affinity

than the corresponding wild-type H3K27 peptide [equilibrium

dissociation constant (Kd) ~3.3±0.4 µM for H3K27M

compared with ~52±12 µM for H3K27]. This inhibitory mode provides a

mechanistic basis for the global reduction and redistribution of

H3K27me3/PRC2 and the ensuing transcriptional reprogramming

observed in pediatric H3K27-altered high-grade gliomas (44).

The suppression of H3K27me3 by H3K27M alters gene

expression and activates multiple signaling pathways essential for

cell proliferation, survival and invasion. In the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

axis, growth-factor/RTK inputs activate PI3K and generate PIP3,

recruiting and activating AKT, which phosphorylates downstream

effectors to promote cell-cycle progression and survival while

suppressing apoptosis (39); mTOR

further sustains biosynthetic and metabolic programs that

facilitate rapid tumor expansion (46).

In parallel, aberrant activation of the JAK/STAT

pathway can reinforce proliferative transcriptional programs and

contribute to immune-evasive phenotypes within the tumor

microenvironment, as JAK-dependent STAT phosphorylation promotes

nuclear transcription of genes linked to growth and

immunoregulation (44,47).

Moreover, MAPK/ERK signaling, often downstream of

RTKs, can be potentiated, enabling RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK propagation and

ERK-driven nuclear transcriptional outputs that promote

proliferation and therapy resistance (48).

Extensive changes in DNA

methylation

The H3K27M mutation disrupts histone methylation and

induces widespread changes in DNA methylation. Research by Vanan

et al (49) and Graham et

al (50) revealed that reduced

H3K27me3 in H3K27M mutant cells extends across the genome, altering

DNA methylation beyond the sites of mutant histone localization.

This indicates that the mutation indirectly affects the regulation

of numerous genes.

Further studies by Paine et al (51) demonstrated significant DNA

methylation changes, particularly in the promoter regions of tumor

suppressor genes such as TP53 and RB1, leading to their silencing

and facilitating the malignant progression of tumors.

Typically, the TET family of enzymes (TET1, TET2 and

TET3) oxidizes 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine

(5-hmC) in a process known as DNA demethylation (52). However, the H3K27M mutation inhibits

TET enzyme activity by disrupting chromatin-associated factors,

reducing TET recruitment and markedly decreasing 5-hmC levels. This

results in the accumulation of DNA methylation, particularly in the

promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes (53,54),

creating an epigenetic landscape that promotes DMG invasiveness and

proliferation.

Regulation of m6A RNA methylation

Recent research (55) reveals that H3K27M-mutant DMG

exhibits unique m6A RNA methylation patterns, with m6A marks

enriched on key cell cycle genes. The m6A demethylase fat-mass- and

obesity-associated protein (FTO) is critical for DMG cell

proliferation; inhibition of FTO (such as by FB23-2) increases m6A

levels, disrupts cell cycle progression, reduces tumor cell

survival and induces apoptosis. These effects are partly mediated

by the m6A reader YTHDF2, which is highly expressed in DMG and

promotes degradation of cell cycle transcripts. Targeting

FTO-driven m6A dynamics thus represents a promising therapeutic

strategy for DMG.

Cell cycle regulation by H3K27M

mutation

The H3K27M mutation disrupts cell cycle regulation

by inhibiting the activity of the PRC2 complex and silencing tumor

suppressor genes such as RB1 and CDKN2A. This leads to the loss of

G1/S checkpoint control, allowing cells to bypass

critical regulatory mechanisms and proliferate uncontrollably

(56) (Fig. 1).

Williams et al (57) highlighted the pivotal role of the

p16 protein, encoded by CDKN2A, in maintaining cell cycle control

by inhibiting CDK4/6 activity and preventing the transition from

the G1 to S phase. In H3K27M mutant tumor cells, the

loss of p16 function results in cell cycle imbalance and

accelerated tumor growth.

H3K27M mutation inhibits DNA

repair

The H3K27M mutation additionally impairs DNA repair

processes, exacerbating genomic instability. In normal cells, DNA

damage is repaired to preserve genomic integrity. However, in

H3K27M mutant cells, the capacity for DNA repair, particularly in

the homologous recombination repair and base excision repair

pathways, is markedly compromised (Fig.

1). The expression of essential DNA repair genes, including

BRCA1, is notably diminished, rendering them prone to accumulating

genetic mutations and facilitating tumor progression (58). Furthermore, H3K27M rewires the DNA

damage response (DDR) and checkpoint circuitry (including

ATM/ATR-linked pathways), which can contribute to treatment

resistance but also creates actionable vulnerabilities for

DDR-targeted radio sensitization strategies (59).

Neuron-tumor cell interactions

Beyond epigenetic changes, the H3K27M mutation

promotes tumor expansion by regulating neuron-tumor interactions

(Fig. 1).

Chromodomain-Helicase-DNA-binding protein 2 (CHD2) plays a crucial

role in chromatin remodeling within the neuronal-tumor

microenvironment, regulating genes essential for synaptic

formation, neuronal excitability and nerve transmission, such as

SYP and PSD95, which maintain synaptic integrity (60).

In H3K27M mutant cells, CHD2 remodels chromatin

accessibility and drives an axon-guidance/synaptic transcriptional

program; mechanistically, a FOSL1-CHD2 regulatory axis promotes

neuron-glioma interactions and neuron-induced tumor proliferation

(60). Upregulation of

axon-guidance and synaptic gene programs strengthens neuron-glioma

interactions and neuron-induced proliferation in H3K27-altered

DMG.

Other histone modifications in DMG

Beyond the dysregulation of H3K27 trimethylation by

the H3K27M mutation, other histone modifications markedly

contribute to DMG progression. These modifications regulate

chromatin structure and gene expression, driving tumor cell

proliferation, differentiation and invasion (61). Critical histone modifications and

their roles in DMG are outlined below.

H3K27ac

H3K27ac, the acetylation of lysine 27 on histone H3,

is associated with active chromatin states, promoting gene

transcription by maintaining chromatin openness, predominantly at

promoters and enhancers.

In DMG, the H3K27M mutation indirectly increases

H3K27ac by inhibiting H3K27me3, activating oncogenes such as MYC

and PDGFRA, which drive tumor growth. Additionally, this

upregulation keeps chromatin at promoter and enhancer regions open,

facilitating transcription factors such as SP1 and AP-1 binding

(62). Menez et al (56) demonstrated that HATs such as p300

and CBP reinforce this open state, creating a positive feedback

loop that amplifies the expression of genes promoting

proliferation, survival and invasion.

Mota et al (63) found that the SWI/SNF chromatin

remodeling complex, particularly the BAF subtype, contributed to

H3K27ac accumulation. The antagonistic interaction between BAF and

PRC2 enhances the effects of H3K27ac. Targeting this pathway with

AU-15330, which is a PROTAC compound that degrades SMARCA4, SMARCA2

and PBRM1, effectively reduces H3K27ac levels, impairing chromatin

openness and inhibiting tumor proliferation.

H3K9me3

H3K9me3 is a repressive histone mark enriched in

heterochromatin regions, suppressing gene transcription through

chromatin compaction. In DMG, altered H3K9me3 levels are associated

with silencing tumor suppressor genes.

Xin et al (64) revealed that the histone

methyltransferase SUV39H1 generates H3K9me3 marks, recruiting

protein complexes to compact chromatin and repress tumor suppressor

genes such as CDKN1A, CDKN2B and CDKN2D, thereby promoting tumor

cell proliferation. The fungal metabolite Chaetocin, a SUV39H1

inhibitor, reduces H3K9me3 levels, which restores tumor suppressor

gene expression and induces apoptosis in DMG cells.

Notably, when H3K9me3 levels are inhibited, DMG

cells activate compensatory pathways such as the dopamine receptor

D2 (DRD2) pathway to sustain tumor growth. A combination therapy of

Chaetocin and DRD2 antagonists (such as ONC201) has been shown to

enhance anti-tumor effects and reduce treatment resistance

(64).

H3K36me3

H3K36me3 is an activating histone mark involved in

transcriptional elongation and DNA repair. The H3.3G34R/V mutation

reduces H3K36me3 levels (51),

disrupting transcriptional elongation and mismatch repair,

contributing to a mild ‘hyper-mutator’ phenotype by impairing DNA

repair mechanisms (65).

The loss of H3K36me3 compromises genomic stability,

allowing the accumulation of mutations that drive tumorigenesis.

These findings highlight the essential role of H3K36me3 in

maintaining cellular function and its dysregulation as a key factor

in cancer progression.

Given the pivotal role of these epigenetic

modifications in DMG pathogenesis, targeting these epigenetic

alterations presents a promising avenue for developing novel

therapeutic strategies to combat DMG.

Current treatment regimens

Local treatments, primarily encompassing surgery and

radiotherapy, are central to managing DMG. However, the invasive

nature of DMG and its midline location limit their effectiveness,

underscoring the need for more effective therapeutic options.

Surgical treatments

Surgery for DMG aims to obtain tissue for diagnosis

and molecular analysis, as its midline location makes complete

resection highly risky. Biopsies, particularly stereotactic ones,

highlighted in CPN Paris 2011, are vital for identifying mutations

such as H3K27M, enabling targeted therapies (66). Advances in minimally invasive

techniques and molecular profiling have made biopsy a key clinical

tool, offering critical insights with minimized risks (67).

A multicenter study revealed no survival benefit

from resection over biopsy in H3K27M-mutant DMG patients, with OS

at 12 months for resection and 11 months for biopsy (68). However, resection was associated

with longer ICU stays and higher neurological deficits. Moreover,

the surgical intervention did not improve the Karnofsky Performance

Status (68,69). Similarly, a systematic review

reported a 13.02% complication rate for stereotactic biopsy, with

no biopsy-related deaths and a diagnostic success rate of 97.4%

(69). While biopsies do not

markedly extend survival, they provide invaluable molecular data

for personalized therapies.

Radiotherapies

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT)

EBRT remains the standard treatment for DMG,

delivering 54–59.4 Gy over 30–33 sessions (70). While it temporarily alleviates

symptoms and delays progression for 6–12 months, recurrence is

almost inevitable within a year, with a median OS of 8–12 months

(71).

Hyper-fractionated radiotherapy and

hypo-fractionated radiotherapy

Alternative approaches have been tested, such as

hyper-fractionated (e.g., 70.2 Gy in smaller fractions) and

hypo-fractionated (e.g., 39 Gy in larger fractions) radiotherapy,

but have shown no significant survival benefits. Median survival

remains 7.8–8.5 months (71,72),

with logistical benefits being the primary advantage.

Proton radiotherapy

Proton therapy minimizes damage to the healthy

brain, particularly in pediatric patients, but does not markedly

improve long-term survival. Re-radiation after recurrence offers

limited benefits and poses a higher risk of radiation-induced

damage (73), such as neurological

and cognitive impairments (74,75).

Limitations of radiotherapy

Despite temporary relief, tumor progression is

inevitable, with progression-free survival (PFS) of only 6–8 months

and a 5-year survival rate <1% (76,77).

Combining radiotherapy with agents such as Bromodomain and

Extra-Terminal motif (BET) inhibitors or epigenetic drugs (such as

chitosan) shows potential in augmenting its tumor-killing effects

by disrupting DNA repair (66,78).

Chemotherapies

Chemotherapy serves as a complementary treatment for

DMG, largely as an adjunct to radiotherapy when resection is not

feasible. However, across prospective and registry-era experiences,

conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy has not produced a consistent

survival benefit beyond radiotherapy alone and its use is

increasingly framed within clinical trials or rational combinations

rather than as stand-alone escalation (Table I).

| Table I.Summary of clinical trials on

chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy in the treatment

of DMG. |

Table I.

Summary of clinical trials on

chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy in the treatment

of DMG.

| First author/s,

year | Treatment type | Drug | Targets | Patients (n) | PFS (months) | mOS (months) | Other outcomes | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Bailey et

al, 2013 | Chemotherapy | Temozolomide | / | 43 | / | 9.5 | 1-year OS ~35%;

2-year OS ~17% | (79) |

| Chassot et

al, 2013 |

| Temozolomide |

| 22 | 7.5 | 11.7 |

| (80) |

| Massimino et

al, 2008 |

| Cisplatin +

Etoposide |

| 62 | 7 | / | 1-year OS: 45% | (87) |

| Ono et al,

2021 |

|

Cisplatin/Etoposide |

| 1 | / | / | OS >6 years | (89) |

| Veldhuijzen van

Zanten et al, 2017 |

| Gemcitabine |

| 9 | 4.8 | 8.7 |

| (90) |

| Kilburn et

al, 2018 |

| Capecitabine |

| 44 | / | / | 1-year PFS rate:

7.2% | (91) |

| Krystal et

al, 2024 |

| Irinotecan +

Bevacizumab + Mebendazole |

| 10 | 4.7 | 11.4 |

| (93) |

| Lin et al,

2024 |

| Cyclophosphamide +

GD2.CART |

| 11 | / | / | 7/11 neurological

improvement | (95) |

| Venneti et

al, 2023 | Targeted

Therapies | ONC-201 | ClpP | 30 | 3.4 | 9.3 |

| (100) |

| Arrillaga-Romany

et al, 2024 |

| ONC-201 | ClpP | 477 | / | / |

| (101) |

| Su et al,

2022 |

| Vorinostat | HDAC | 79 | / | / | 1-year PFS rate:

5.85%; 1-year OS rate:39.2% | (105) |

| Mueller et

al, 2023 |

| Panobinostat | HDAC | 7 | 7 | 26.1 |

| (104) |

| Neth et al,

2022 |

| Panobinostat | HDAC | 10 | 19 | 42 |

| (106) |

| DeWire et

al, 2020 |

| Ribociclib | CDK4/6 | 10 | / | 16.1 |

| (111) |

| DeWire et

al, 2022 |

| Ribociclib +

Everolimus | CDK4/6 + mTOR | 19 | / | 13.9 |

| (112) |

| Fleischhack et

al, 2019 |

| Nimotuzumab | EGFR | 42 | 5.8 | 9.4 |

| (114) |

| Liu et al,

2025 |

| Nimotuzumab | EGFR | 48 | 7.8 | 10.5 |

| (118) |

| Majzner et

al, 2022 | Immunotherapy | GD2-CAR T | / | 4 | / | / | 3/4 Tumor volume

reduction or stabilization | (120) |

| Lin et al,

2024 |

| C7R-GD2.CART |

| 11 | / | / | Feasibility;

on-target neuroinflammation/TIAN and CRS | (95) |

| Vitanza et

al, 2025 |

| B7-H3 CAR-T |

| 21 | / | / | Repetitive ICV

dosing feasible; DLT reported (intratumoral hemorrhage) | (122) |

| Pérez-Larraya et

al, 2022 |

| DNX-2401 |

| 12 | / | 17.8 |

| (124) |

| Grassl et

al, 2023 |

| H3K27M-vac |

| 8 | 6.2 | 12.8 |

| (125) |

| Mueller et

al, 2020 |

| H3.3K27M peptide

vaccine |

| 29 (A=19;

B=10) | / | 16.1 vs. 9.8 |

| (128) |

Temozolomide

TMZ is an oral alkylating agent whose key cytotoxic

lesion is O6-methylguanine, which can trigger

replication-associated mismatch repair-dependent DNA damage and

apoptosis. In a UK phase II study evaluating dose-dense TMZ with

standard radiotherapy for classical DIPG/DMG, median OS was 9.5

months, with 1-year OS of 35% and the regimen did not demonstrate a

survival benefit over radiotherapy alone; hematologic toxicity led

to treatment withdrawal and frequent dose reductions (79) (Table

I). Similarly, radiotherapy with concurrent and adjuvant TMZ

yielded median OS of 11.7 months and 1-year OS of 50%, but no

significant improvement in outcome and higher hematologic toxicity

compared with radiotherapy alone (80). A major biological constraint is

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)-mediated repair of

TMZ-induced O6 lesions: H3K27M-altered DMG frequently shows lack of

MGMT promoter methylation and increased MGMT expression, which is

associated with TMZ resistance in DMG models (81). Accordingly, pharmacologic MGMT

inhibition, such as O6-benzylguanine, has been limited by increased

hematologic toxicity and often necessitates substantial TMZ dose

reduction, constraining clinical utility (82,83).

Studies (84–86) demonstrate that BET inhibitors, as

well as other epigenetic modulators, including histone deacetylase

(HDAC) and EZH2 inhibitors, can sensitize DMG cells to TMZ, with

preclinical evidence supporting synergistic antitumor effects when

combined.

Cisplatin and etoposide

Cisplatin primarily induces cytotoxicity by forming

DNA cross-links, whereas etoposide inhibits topoisomerase II and

triggers DNA double-strand breaks; together they provide a

rationale for combination regimens that converge on

DNA-damage-driven apoptosis.

In a mono-institutional 20-year experience of

pediatric diffuse pontine gliomas treated with multi-agent therapy

incorporating cisplatin/etoposide (plus isotretinoin and others),

the reported median survival was 7 months and the 1-year survival

rate was 45% (87). Clinically,

limited benefit is assumed to be related in part to inadequate CNS

drug exposure under an intact/tight blood-brain barrier (BBB) in

DMG (88), although rare long

survivors exist. For example, a pineal-region DMG case with

>6-year survival after multimodal management in which initial

carboplatin-etoposide was ineffective but extensive resection,

high-dose radiotherapy and bevacizumab-based maintenance was

associated with durable control (89).

Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine is a cytidine analog that inhibits DNA

synthesis via DNA polymerase and ribonucleotide reductase and has

been explored as a radiosensitizer in DMG (9,90).

In a phase I/II trial of weekly gemcitabine with

radiotherapy, treatment was safe and well tolerated, with PFS 4.8

months and median OS 8.7 months (90); Quality of life tended to improve,

but survival was not superior to historical controls, supporting

mainly palliative value.

Capecitabine

Capecitabine is an oral prodrug of 5-fluorouracil;

because radiation can induce thymidine phosphorylase, capecitabine

has been tested as a potential RT-sensitizing strategy in DMG

(91). In the PBTC phase Il study

(91), capecitabine + RT was

tolerable, but outcomes were not improved: 1-year PFS 7.21 vs.

15.59% in the historical control (P=0.007) and no OS difference

(P=0.30), leading to the conclusion that capecitabine did not

improve prognosis in newly diagnosed DMG.

Irinotecan

Irinotecan is a topoisomerase I inhibitor that

stabilizes the cleavage complex and induces lethal DNA strand

breaks, thereby suppressing tumor proliferation (92). In a phase I trial, Krystal et

al (93) evaluated irinotecan

plus bevacizumab and mebendazole in 10 pediatric/AYA HGG patients,

including 7 DMG, reporting no dose limiting toxicities and a PFS

and OS of 4.7 and 11.4 months from treatment initiation; the

overall response rate was 33% (two PRs and one CR sustained for 10

months).

Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating pro-drug that

generates phosphoramide mustard, producing DNA cross-links and

triggering apoptosis (94).

In a phase I trial of intravenous GD2. CAR T cells,

cyclophosphamide (with fludarabine) was used for standard

lymphodepletion in 11 patients and therapy was delivered without

dose-limiting toxicity. The C7R-GD2.CAR T cohort developed grade 1

TIAN in 7/8 and achieved transient neurologic improvement (2 to

>12 months), with partial responses in 2/7 DMG patients by iRANO

(95).

Overall, conventional chemotherapies have shown

limited and largely non-practice-changing benefit in DMG. Future

efforts should prioritize rational combinations (such as chemo with

targeted/epigenetic or immunotherapies) and trial designs that

emphasize clinically meaningful endpoints, including neurologic

function and quality of life.

Targeted therapies

Targeted therapy for diffuse midline glioma aims to

exploit actionable biological dependencies that sustain tumor

growth. Current strategies include mitochondrial stress-based

approaches centered on caseinolytic protease P (ClpP)/imipridones

such as ONC201, epigenetic modulation such as HDAC inhibitors,

panobinostat for epigenetic regulation and combination therapies

targeting CDK4/6 and mTOR and receptor-directed interventions

focusing on EGFR inhibition. These modalities are being evaluated

to counteract core metabolic/epigenetic vulnerabilities and

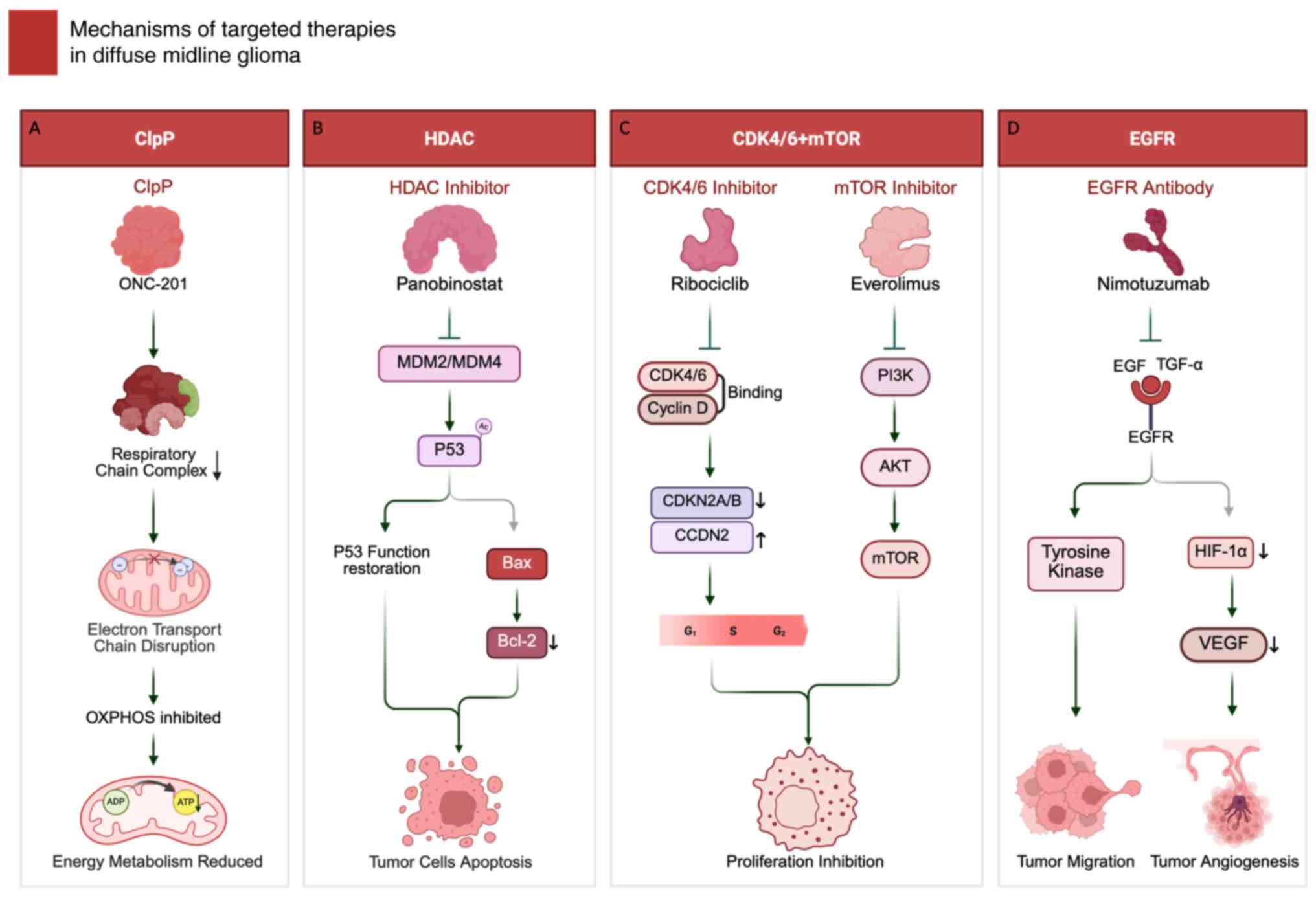

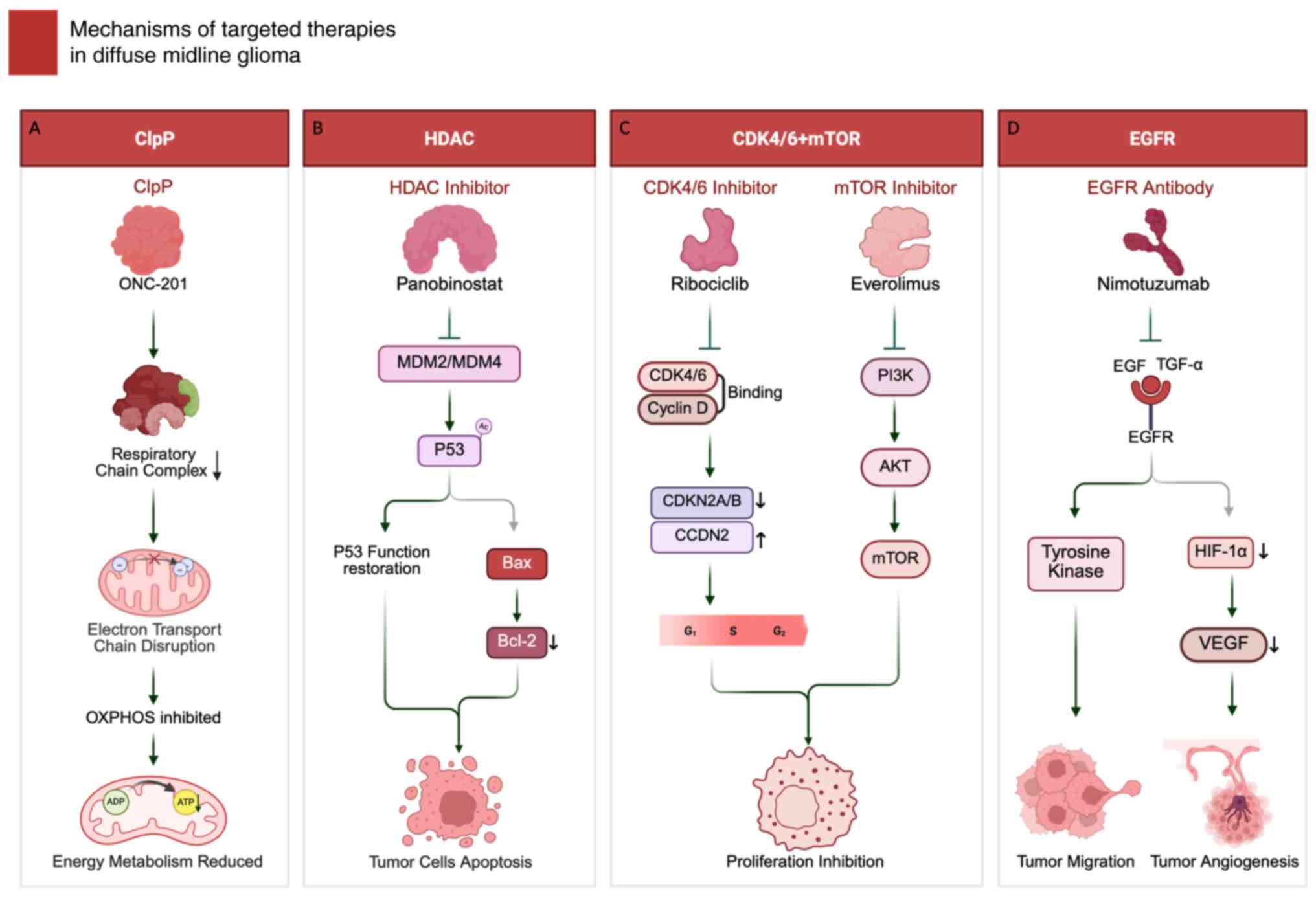

aberrant signaling programs in DMG (Fig. 2; Table

I).

| Figure 2.Mechanisms of targeted therapy in

diffuse midline glioma. (A) ClpP agonist ONC-201 hyperactivates

mitochondrial protease ClpP, leading to respiratory chain protein

degradation, electron transport chain disruption, OXPHOS inhibition

and reduced ATP production. (B) HDAC inhibitor panobinostat

restores p53 function through MDM2/MDM4 modulation and enhanced p53

acetylation, upregulating pro-apoptotic Bax while downregulating

anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 to induce tumor cell apoptosis. (C) CDK4/6

inhibitor ribociclib blocks CDK4/6-cyclin D interaction, inducing

G1 arrest; mTOR inhibitor everolimus suppresses

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling to inhibit proliferation and metabolism.

(D) Anti-EGFR antibody nimotuzumab blocks EGF/TGF-α binding,

inhibiting downstream tyrosine kinase signaling and

HIF-1α/VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Figure created using

BioRender.com. ClpP, caseinolytic protease P; HDAC, histone

deacetylase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; EGFR, epidermal

growth factor receptor; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor

1-alpha. |

ClpP

ClpP, a mitochondrial serine protease, forms the

ClpXP complex to maintain mitochondrial proteostasis. Pharmacologic

hyperactivation of ClpP can drive excessive proteolysis of

respiratory-chain proteins, leading to electron transport chain

disruption, OXPHOS inhibition, ATP depletion and apoptotic cell

death (96).

ONC201, an imipridone, acts as an allosteric ClpP

agonist and antagonizes DRD2. In H3K27M-altered DMG models,

ONC201-ClpP engagement promotes degradation of key respiratory

chain components, collapses mitochondrial bioenergetics

(ETC/OXPHOS) and suppresses tumor energy metabolism-features that

match the present study's mechanistic schematic (96,97)

(Fig. 2A). Downstream, ONC201

induces an ATF4/CHOP-linked integrated stress response and can

promote DR5/TRAIL-mediated apoptosis (98), with reported modulation of Akt/ERK

signaling consistent with a pro-apoptotic shift (99).

Clinically, integrated analysis of ONC201-treated

H3K27M-mutant DMG reported longer survival when initiated after

radiotherapy but before recurrence (median OS 21.7 months; PFS 7.3

months) compared with initiation after recurrence (median OS 9.3

months; PFS 3.4 months), with molecular correlates including

increased 2-hydroxyglutarate and partial restoration of H3K27me3

(100). A randomized, double-blind

phase 3 trial (101) is ongoing to

evaluate ONC201 as post-radiotherapy maintenance therapy in newly

diagnosed H3 K27M-mutant diffuse glioma, with OS and PFS as primary

endpoints.

HDAC

HDAC inhibitors reprogram chromatin by increasing

histone acetylation and can reactivate the MDM2/MDM4-p53 axis, in

part by reducing MDM2/MDM4 repression and enhancing p53

acetylation/transcriptional activity, thereby promoting apoptosis

(102). Downstream, they

upregulate pro-apoptotic genes such as Bax while downregulate

anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl-2, activating the intrinsic

apoptotic pathway (103) (Fig. 2B).

Panobinostat is a multi-HDAC inhibitor with strong

preclinical rationale in DMG, but systemic delivery is constrained

by exposure/toxicity and uncertain BBB penetration, motivating

local delivery approaches (104).

In a phase I/II trial by Su et al (105), panobinostat combined with

radiotherapy and voriostat, followed by maintenance, was

well-tolerated but showed limited survival benefits, with a 1-year

PFS of 5.85% and OS of 39.2%. By contrast, PNOC015 using repeat CED

of MTX110 reported median OS of 26.1 months and median PFS 7

months, supporting intra-tumoral HDAC inhibition with reduced

systemic exposure (104). In

adults, compassionate-use panobinostat showed good tolerability

with median OS 42 months and median PFS 19 months in a small

series, suggesting potential context-dependence that requires

prospective validation (106).

Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6

(CDK4/6) + mTOR

CDK4/6 regulate the G1-to-S phase

transition by phosphorylating retinoblastoma (RB) protein via

cyclin D, activating E2F transcription factors and driving cell

cycle progression (107,108). The mTOR in the PI3K/Akt pathway

governs metabolism, protein synthesis and proliferation, with

aberrations frequently observed in DMG, contributing to unchecked

tumor proliferation and metabolic dependency (107).

Ribociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, halts cell cycle

progression at the G1 phase by disrupting CDK4/6-cyclin

D interaction (109) (Fig. 2C), targeting CDKN2A/B deletions and

CCND2 amplifications seen in DMG. Meanwhile, everolimus, which is a

mTORC1 inhibitor, suppresses tumor proliferation, glycolysis and

angiogenesis (110), particularly

in tumors with H3.1 mutations linked to PIK3CA or PIK3R1

alterations (40). The combination

of ribociclib and everolimus provides dual inhibition of cell cycle

and metabolic pathways, enhancing antitumor effects with reduced

overlapping toxicity.

A phase I/II study of post-radiotherapy single-agent

ribociclib reported feasibility with myelosuppression as the main

severe toxicity and a median OS of 16.1 months in DIPG/DMG,

reinforcing ongoing interest in rational combinations and

biomarker-guided selection (111).

As additional supportive evidence for CDK4/6 targeting in this

setting, A phase I trial assessed this combination in 19 pediatric

DMG patients following radiotherapy, establishing phase II doses of

170 mg/m2 for ribociclib and 1.5 mg/m2 for

everolimus (112). The median OS

was 13.9 months, with 12-, 24- and 36-month survival rates of 53.3,

38.9 and 38.9%, respectively. These promising results warrant

further investigation of this approach.

EGFR

EGFR is a receptor tyrosine kinase that propagates

mitogenic and pro-survival signals mainly through the

RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT cascades, thereby promoting

proliferation, invasion and treatment resistance (113). Additionally, EGFR pathway activity

intersects with hypoxia/angiogenic programs, in part via

PI3K/AKT-hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α)-VEGF, providing

a rationale for EGFR-directed strategies to suppress both tumor

growth and angiogenesis (114).

Nimotuzumab, an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody,

blocks EGF/TGF-α-EGFR engagement and thereby attenuates downstream

oncogenic signaling; clinically, however, its benefit has been

inconsistent (115). It induces

G1 phase arrest, preventing tumor cell progression into

the S phase (116). Additionally,

it destabilizes HIF-1α, suppresses VEGF transcription and reduces

angiogenesis, collectively curbing tumor growth and metastasis

(117) (Fig. 2D).

A phase III trial in 42 DMG patients evaluated

nimotuzumab with radiotherapy, reporting a median PFS of 5.8 months

and median OS of 9.4 months (114). One- and two-year survival rates

were 33.3 and 4.8%, respectively, with rare serious events

including intratumoral bleeding. More recently, adding nimotuzumab

to chemoradiation was feasible, with median OS 10.5 months and PFS

7.8 months, but did not meet a prespecified ORR-improvement

threshold vs. historical data, supporting continued

biomarker-guided optimization rather than routine adoption

(118).

Immunotherapies

Diffuse midline glioma is characterized as an

immunologically ‘cold tumor’, with low lymphocytic infiltration and

a microenvironment dominated by myeloid-lineage populations, which

collectively constrains adaptive anti-tumor immunity and limits the

efficacy of conventional immunotherapy approaches (119). These features highlight why DMG

immunotherapy remains early-stage and why locoregional,

antigen-directed strategies have become a central development focus

(Table I).

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T

therapy

CAR-T-cell therapy aims to bypass limited endogenous

T-cell priming by engineering T cells to recognize DMG-associated

surface antigens, most prominently GD2 and B7-H3 (120). Upon antigen engagement, CAR

signaling through CD3Z activates canonical T-cell effector

programs, such as cytokine production and cytotoxicity, enabling

direct killing of antigen-expressing tumor cells.

For GD2 targeting, first-in-human clinical

experience demonstrated feasibility and early signals of activity,

while highlighting neuroinflammation as an on-target risk that

requires proactive monitoring and management (120). More recently, a phase I study of

constitutively active IL-7 receptor-engineered GD2 CAR T cells

(C7R-GD2.CART), further supported feasibility in H3K27-altered DMG,

with tumor-inflammation-associated neurotoxicity and

cytokine-release syndrome as key safety considerations and

preliminary objective responses observed in a subset (95).

In parallel, B7-H3-directed CAR T cells have

advanced through BrainChild-03 using repeated

intra-cerebroventricular dosing; early DIPG evaluable cases showed

no dose-limiting toxicities and evidence of local immune activation

with a durable clinical/radiographic improvement in one patient

(121). Updated Arm C results in

DIPG expanded these observations by establishing feasibility of

repetitive ICV dosing at higher planned dose regimens and providing

benchmark survival and neurotoxicity profiles for future multi-site

evaluation (122).

Oncolytic virus DNX-2401

DNX-2401 is a conditionally replicating adenovirus

designed to preferentially replicate in tumors with RB pathway

dysregulation via a Δ24 deletion in E1A and its RGD modification

can facilitate integrin-mediated entry (123).

In a phase I study of 12 newly diagnosed DMG/DIPG

patients, a single stereotactic intra-tumoral infusion of DNX-2401

(1×1010 or 5×1010 viral particles) followed

by radiotherapy achieved 92% disease control and a median OS of

17.8 months; 12- and 18-month OS were 75 and 50%, respectively

(124). Correlative analysis

supported treatment-associated immune activation, including

increased T-cell-related activity, aligning with an oncolytic

‘viro-immunotherapy’ rationale in DMG.

Cancer vaccine

Cancer vaccines aims to induce tumor

antigen-specific adaptive immunity. In DMG, the shared clonal

neo-antigen H3K27M has enabled peptide-vaccine strategies that

predominantly prime mutation-specific CD4+ T-cell responses, with

potential downstream support for cytotoxic effector programs and

can increase immune infiltration in selected patients (125). Mechanistically, deeper immune

profiling in a long-term recovered responder following H3K27M

vaccination, identified broad HLA background coverage with both B-

and T-cell responses, supporting the concept that vaccine-elicited

anti-H3K27M immunity can be durable in selected cases (126,127).

The first-in-human H3K27M peptide vaccine

(H3K27M-vac) study enrolled eight adults with H3K27M-altered DMG

and showed favorable tolerability with mutation-specific immune

responses dominated by CD4+ T cells; reported outcomes included

median PFS 6.2 months and median OS 12.8 months (125). In younger patients, PNOC007

evaluated an HLA-restricted H3.3K27M peptide vaccine with adjuvant

immunostimulation after radiotherapy and demonstrated

immunogenicity with acceptable safety, reporting ~40% (DIPG) and

~39% (non-pontine DMG) 12-month OS benchmarks (128). INTERCEPT H3 is currently

evaluating the use of H3K27M-vac concurrently with standard

radiotherapy and in combination with the PD-L1 antibody

atezolizumab for maintenance after radiotherapy to clarify its

safety and immunogenicity (129).

Conclusion

Diffuse midline glioma, particularly the

H3K27M-mutated subtype, remains a formidable CNS malignancy due to

its unique molecular features and invasiveness. The present review

emphasized the pivotal role of histone alterations, especially

H3K27M, in reshaping chromatin states and gene expression programs

that drive malignant proliferation, invasion and therapeutic

resistance. Although surgery and radiotherapy remain foundational,

their effect is constrained by anatomical inoperability and diffuse

infiltration. Chemotherapy provides only a modest benefit and is

frequently limited by resistance. By contrast, emerging targeted

approaches, including ONC-201, panobinostat-based strategies and

CDK4/6 inhibition combined with mTOR blockade, directly address

molecular vulnerabilities, while early immunotherapy studies,

including locoregional CAR-T platforms, DNX-2401 virotherapy and

H3K27M-directed vaccination, illustrate feasibility and biological

activity in selected settings.

Limitations of the current evidence base include

small patient numbers, heterogeneous cohorts (age, tumor location,

co-alterations and prior therapy) and variable drug-delivery

strategies, which collectively limit cross-trial comparability and

may inflate apparent signals in single-arm studies. Future progress

will require biomarker-guided stratification, rational combination

regimens aligned to DMG biology (including radiotherapy-integrated

approaches) and delivery-optimized platforms that improve

intra-tumoral exposure while maintaining neurological safety.

Equally important, standardized response assessment and integrated

correlative monitoring (molecular and immune profiling,

longitudinal sampling, where feasible) should be embedded into

multicenter trials to distinguish durable benefit from transient

inflammatory effects and to enable definitive efficacy testing.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support provided

by the National High-Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding

(grant no. 2022-PUMCH-B-113), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical

Sciences (grant no. 2021-12M-1-014) and the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82151302), which markedly

contributed to the advance of this research.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

WBW and WLC performed the literature search,

extracted and synthesized data on the epigenetic mechanisms and

therapeutic strategies of diffuse midline glioma and drafted the

original manuscript. WBW prepared and revised the figures and

schematic illustrations and WLC organized the tables. WBM and YW

conceived and supervised the overall topic and structure of the

present review, provided critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content and oversaw the final interpretation

of the literature. YW and WBM are the corresponding authors and

take primary responsibility for the integrity of the work as a

whole. WBW and WLC contributed equally to this work. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, Cioffi G,

Waite KA, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical

report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors

diagnosed in the United States in 2016–2020. Neuro Oncol. 25 (12

Suppl 2):iv1–iv99. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fonseca A, Afzal S, Bowes L, Crooks B,

Larouche V, Jabado N, Perreault S, Johnston DL, Zelcer S, Fleming

A, et al: Pontine gliomas a 10-year population-based study: A

report from The Canadian Paediatric Brain Tumour Consortium

(CPBTC). J Neurooncol. 149:45–54. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Patil N, Kelly ME, Yeboa DN, Buerki RA,

Cioffi G, Balaji S, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS:

Epidemiology of brainstem high-grade gliomas in children and

adolescents in the United States, 2000–2017. Neuro Oncol.

23:990–998. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Erker C, Lane A, Chaney B, Leary S,

Minturn JE, Bartels U, Packer RJ, Dorris K, Gottardo NG, Warren KE,

et al: Characteristics of patients ≥10 years of age with diffuse

intrinsic pontine glioma: A report from the International DIPG/DMG

registry. Neuro Oncol. 24:141–152. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hoffman LM, Veldhuijzen van Zanten SEM,

Colditz N, Baugh J, Chaney B, Hoffmann M, Lane A, Fuller C, Miles

L, Hawkins C, et al: Clinical, radiologic, pathologic, and

molecular characteristics of long-term survivors of diffuse

intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG): A collaborative report from the

international and European society for pediatric oncology DIPG

registries. J Clin Oncol. 36:1963–1972. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ying Y, Liu X, Li X, Mei N, Ruan Z, Lu Y

and Yin B: Distinct MRI characteristics of spinal cord diffuse

midline glioma, H3 K27-altered in comparison to spinal cord glioma

without H3 K27-alteration and demyelination disorder. Acta Radiol.

65:284–293. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Nafe R, Porto L, Samp PF, You SJ and

Hattingen E: Adult-type and Pediatric-type diffuse gliomas what the

neuroradiologist should know. Clin Neuroradiol. 33:611–624. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Coleman C, Chen K, Lu A, Seashore E,

Stoller S, Davis T, Braunstein S, Gupta N and Mueller S:

Interdisciplinary care of children with diffuse midline glioma.

Neoplasia. 35:1008512023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Saratsis AM, Knowles T, Petrovic A and

Nazarian J: H3K27M mutant glioma: Disease definition and biological

underpinnings. Neuro Oncol. 26 (Suppl 2):S92–S100. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tarapore RS, Arain S, Blaine E, Hsiung A,

Melemed AS and Allen JE: Immunohistochemistry detection of Histone

H3 K27M mutation in human glioma tissue. Appl Immunohistochem Mol

Morphol. 32:96–101. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Duchatel RJ, Jackson ER, Alvaro F, Nixon

B, Hondermarck H and Dun MD: Signal transduction in diffuse

intrinsic pontine glioma. Proteomics. 19:e18004792019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Testa U, Castelli G and Pelosi E: CAR-T

cells in the treatment of nervous system tumors. Cancers (Basel).

16:29132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Harris W: A case of pontine glioma, with

special reference to the paths of gustatory sensation. Proc R Soc

Med. 19:1–5. 1926.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Janssens GO, Kramm CM and von Bueren AO:

Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPG) at recurrence: Is there a

window to test new therapies in some patients? J Neurooncol.

139:5012018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B

and Jemal A: Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA

Cancer J Clin. 64:83–103. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gwak HS and Park HJ: Developing

chemotherapy for diffuse pontine intrinsic gliomas (DIPG). Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 120:111–119. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von

Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD,

Kleihues P and Ellison DW: The 2016 World Health Organization

classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary.

Acta Neuropathol. 131:803–820. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Huang TY, Piunti A, Lulla RR, Qi J,

Horbinski CM, Tomita T, James CD, Shilatifard A and Saratsis AM:

Detection of Histone H3 mutations in cerebrospinal fluid-derived

tumor DNA from children with diffuse midline glioma. Acta

Neuropathol Commun. 5:282017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang Q, Niu W and Pan H: Targeted therapy

with anlotinib for a H3K27M mutation diffuse midline glioma patient

with PDGFR-alpha mutation: A case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien).

164:2063–2066. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

McNamara C, Mankad K, Thust S, Dixon L,

Limback-Stanic C, D'Arco F, Jacques TS and Löbel U: 2021 WHO

classification of tumours of the central nervous system: A review

for the neuroradiologist. Neuroradiology. 64:1919–1950. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cooney TM, Lubanszky E, Prasad R, Hawkins

C and Mueller S: Diffuse midline glioma: review of epigenetics. J

Neurooncol. 150:27–34. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Park YW, Vollmuth P, Foltyn-Dumitru M,

Sahm F, Ahn SS, Chang JH and Kim SH: The 2021 WHO Classification

for Gliomas and implications on imaging diagnosis: Part 2-summary

of imaging findings on pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas,

pediatric-type diffuse low-grade gliomas, and circumscribed

astrocytic gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 58:690–708. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cassim A, Dun MD, Gallego-Ortega D and

Valdes-Mora F: EZHIP's role in diffuse midline glioma: echoes of

oncohistones? Trends Cancer. 10:1095–1105. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hoffman LM, DeWire M, Ryall S, Buczkowicz

P, Leach J, Miles L, Ramani A, Brudno M, Kumar SS, Drissi R, et al:

Spatial genomic heterogeneity in diffuse intrinsic pontine and

midline high-grade glioma: Implications for diagnostic biopsy and

targeted therapeutics. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 4:12016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Greer EL and Shi Y: Histone methylation: A

dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet.

13:343–357. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hyun K, Jeon J, Park K and Kim J: Writing,

erasing and reading histone lysine methylations. Exp Mol Med.

49:e3242017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Shvedunova M and Akhtar A: Modulation of

cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 23:329–349. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

An T, Liu Y, Gourguechon S, Wang CC and Li

Z: CDK phosphorylation of translation initiation factors couples

protein translation with cell-cycle transition. Cell Rep.

25:3204–3214.e5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Justice JL, Reed TJ, Phelan B, Greco TM,

Hutton JE and Cristea IM: DNA-PK and ATM drive phosphorylation

signatures that antagonistically regulate cytokine responses to

herpesvirus infection or DNA damage. Cell Syst. 15:339–361.e8.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen Q, Bian C, Wang X, Liu X, Ahmad

Kassab M, Yu Y and Yu X: ADP-ribosylation of histone variant H2AX

promotes base excision repair. EMBO J. 40:e1045422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mattiroli F and Penengo L: Histone

Ubiquitination: An integrative signaling platform in genome

stability. Trends Genet. 37:566–581. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang X and Zhang Z: Oncohistone mutations

in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Trends Cancer. 5:799–808.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY,

Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K, Sturm D, Fontebasso AM, Quang DA,

Tönjes M, et al: Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin

remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 482:226–231.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Qin J, Wen B, Liang Y, Yu W and Li H:

Histone modifications and their role in colorectal cancer (review).

Pathol Oncol Res. 26:2023–2033. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Caslini C, Hong S, Ban YJ, Chen XS and

Ince TA: HDAC7 regulates histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation and

transcriptional activity at super-enhancer-associated genes in

breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 38:6599–6614. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Deng L, Meng T, Chen L, Wei W and Wang P:

The role of ubiquitination in tumorigenesis and targeted drug

discovery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5:112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cole AJ, Clifton-Bligh R and Marsh DJ:

Histone H2B monoubiquitination: Roles to play in human malignancy.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 22:T19–T33. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen X, Song N, Matsumoto K, Nanashima A,

Nagayasu T, Hayashi T, Ying M, Endo D, Wu Z and Koji T: High

expression of trimethylated histone H3 at lysine 27 predicts better

prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Oncol. 43:1467–1480.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Stitzlein LM, Adams JT, Stitzlein EN,

Dudley RW and Chandra J: Current and future therapeutic strategies

for high-grade gliomas leveraging the interplay between epigenetic

regulators and kinase signaling networks. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

43:122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pearson AD, DuBois SG, Macy ME, de Rojas

T, Donoghue M, Weiner S, Knoderer H, Bernardi R, Buenger V, Canaud

G, et al: Paediatric strategy forum for medicinal product

development of PI3-K, mTOR, AKT and GSK3beta inhibitors in children

and adolescents with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 207:1141452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yan Y and Zhang J: Mechanisms of tamoxifen

resistance: Insight from long non-coding RNAs. Front Oncol.

14:14585882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang Y, Tapinos N, Lulla R and El-Deiry

WS: Dopamine pre-treatment impairs the anti-cancer effect of

integrated stress response- and TRAIL pathway-inducing ONC201,

ONC206 and ONC212 imipridones in pancreatic, colorectal cancer but

not DMG cells. Am J Cancer Res. 14:2453–2464. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Nandy D, Rajam SM and Dutta D: A three

layered histone epigenetics in breast cancer metastasis. Cell

Biosci. 10:522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Blasco-Santana L and Colmenero I:

Molecular and pathological features of paediatric high-grade

gliomas. Int J Mol Sci. 25:84982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Justin N, Zhang Y, Tarricone C, Martin SR,

Chen S, Underwood E, De Marco V, Haire LF, Walker PA, Reinberg D,

et al: Structural basis of oncogenic histone H3K27M inhibition of

human polycomb repressive complex 2. Nat Commun. 7:113162016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Arakaki AKS, Szulzewsky F, Gilbert MR,

Gujral TS and Holland EC: Utilizing preclinical models to develop

targeted therapies for rare central nervous system cancers. Neuro

Oncol. 23 (23 Suppl 5):S4–S15. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Pal S, Kaplan JP, Nguyen H, Stopka SA,

Savani MR, Regan MS, Nguyen QD, Jones KL, Moreau LA, Peng J, et al:

A druggable addiction to de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis in diffuse

midline glioma. Cancer Cell. 40:957–972.e10. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tsai JW, Cejas P, Coppola M, Wang DK,

Patel S, Wu DW, Arounleut P, Wei X, Zhou N, Syamala S, et al:

Abstract 3562: Dissecting mechanisms underlying FOXR2-mediated

gliomagenesis in diffuse midline gliomas. Cancer Res. 83:35622023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Vanan MI, Underhill DA and Eisenstat DD:

Targeting epigenetic pathways in the treatment of pediatric diffuse

(High Grade) gliomas. Neurotherapeutics. 14:274–283. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Graham MS and Mellinghoff IK:

Histone-Mutant glioma: Molecular mechanisms, preclinical models,

and implications for therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 21:71932020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Paine DZ: Molecular Determinants of

Diffuse Midline Glioma of the Pons Vulnerability to the Histone

Deacetylase Inhibitor, Quisinostat. Doctoral dissertation.

University of Arizona; Tucson, USA: 2023

|

|

52

|

Xu Y, Wu F, Tan L, Kong L, Xiong L, Deng

J, Barbera AJ, Zheng L, Zhang H, Huang S, et al: Genome-wide

Regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in

mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 42:451–464. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hashizume R: Epigenetic targeted therapy

for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo).

57:331–342. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Markouli M, Strepkos D, Papavassiliou KA,

Papavassiliou AG and Piperi C: Crosstalk of epigenetic and

metabolic signaling underpinning glioblastoma pathogenesis. Cancers

(Basel). 14:26552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ross SE, Holliday H, Tsoli M, Ziegler DS

and Dinger ME: Abstract B015: RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) as a

therapeutic target in Diffuse Midline Glioma (DMG). Cancer Res.

84:B015. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Menez V, Kergrohen T, Shasha T,

Silva-Evangelista C, Le Dret L, Auffret L, Subecz C, Lancien M,

Ajlil Y, Vilchis IS, et al: VRK3 depletion induces cell cycle

arrest and metabolic reprogramming of pontine diffuse midline

glioma-H3K27 altered cells. Front Oncol. 13:12293122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Williams EA, Brastianos PK, Wakimoto H,

Zolal A, Filbin MG, Cahill DP, Santagata S and Juratli TA: A

comprehensive genomic study of 390 H3F3A-mutant pediatric and adult

diffuse high-grade gliomas, CNS WHO grade 4. Acta Neuropathol.

146:515–525. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yan Y: Abstract 1719: Targeting H3.3

serine 28 phosphorylation as a novel therapeutic strategy for

diffuse midline glioma. Cancer Res. 84:1719. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Mangoli A, Valentine V, Maingi SM, Wu SR,

Liu HQ, Aksu M, Jain V, Foreman BE, Regal JA, Weidenhammer LB, et

al: Disruption of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated kinase enhances

radiation therapy efficacy in spatially directed diffuse midline

glioma models. J Clin Invest. 135:e1793952025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhang X, Duan S, Apostolou PE, Wu X,

Watanabe J, Gallitto M, Barron T, Taylor KR, Woo PJ, Hua X, et al:

CHD2 Regulates Neuron-glioma interactions in pediatric glioma.

Cancer Discov. 14:1732–1754. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Diaz AK and Baker SJ: The genetic

signatures of pediatric high-grade glioma: No longer a one-act

play. Semin Radiat Oncol. 24:240–247. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Sharma M, Barravecchia I, Magnuson B,

Ferris SF, Apfelbaum A, Mbah NE, Cruz J, Krishnamoorthy V, Teis R,

Kauss M, et al: Histone H3 K27M-mediated regulation of cancer cell

stemness and differentiation in diffuse midline glioma. Neoplasia.

44:1009312023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Mota M, Sweha SR, Pun M, Natarajan SK,

Ding Y, Chung C, Hawes D, Yang F, Judkins AR, Samajdar S, et al:

Targeting SWI/SNF ATPases in H3.3K27M diffuse intrinsic pontine

gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 120:e22211751202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Xin DE, Liao Y, Rao R, Ogurek S, Sengupta

S, Xin M, Bayat AE, Seibel WL, Graham RT, Koschmann C and Lu QR:

Chaetocin-mediated SUV39H1 inhibition targets stemness and

oncogenic networks of diffuse midline gliomas and synergizes with

ONC201. Neuro Oncol. 26:735–748. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Fang J, Huang Y, Mao G, Yang S, Rennert G,

Gu L, Li H and Li GM: Cancer-driving H3G34V/R/D mutations block

H3K36 methylation and H3K36me3-MutSα interaction. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 115:9598–9603. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sheikh SR, Patel NJ and Recinos VMR:

Safety and technical efficacy of pediatric brainstem biopsies: An

updated meta-analysis of 1000+ children. World Neurosurg.

189:428–438.e2. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Walker DA, Liu J, Kieran M, Jabado N,

Picton S, Packer R and St Rose C; CPN Paris 2011 Conference

Consensus Group, : A multi-disciplinary consensus statement

concerning surgical approaches to Low-grade, High-grade

astrocytomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas in childhood

(CPN Paris 2011) using the Delphi method. Neuro Oncol. 15:462–468.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Ryba A, Özdemir Z, Nissimov N, Hönikl L,

Neidert N, Jakobs M, Kalasauskas D, Krigers A, Thomé C, Freyschlag

CF, et al: Insights from a multicenter study on adult H3

K27M-mutated glioma: Surgical resection's limited influence on

overall survival, ATRX as molecular prognosticator. Neuro Oncol.

26:1479–1493. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Dalmage M, LoPresti MA, Sarkar P,

Ranganathan S, Abdelmageed S, Pagadala M, Shlobin NA, Lam S and

DeCuypere M: Survival and neurological outcomes after stereotactic

biopsy of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: A systematic review. J

Neurosurg Pediatr. 32:665–672. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Gajjar A, Mahajan A, Abdelbaki M, Anderson

C, Antony R, Bale T, Bindra R, Bowers DC, Cohen K, Cole B, et al:

Pediatric central nervous system cancers, version 2.2023, NCCN

clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

20:1339–1362. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Kim HJ and Suh CO: Radiotherapy for

diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: Insufficient but indispensable.

Brain Tumor Res Treat. 11:79–85. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Cohen KJ, Jabado N and Grill J: Diffuse

intrinsic pontine gliomas-current management and new biologic

insights. Is there a glimmer of hope? Neuro Oncol. 19:1025–1034.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wawrzuta D, Chojnacka M, Drogosiewicz M,

Pedziwiatr K and Dembowska-Baginska B: Reirradiation for diffuse

intrinsic pontine glioma: Prognostic radiomic factors at

progression. Strahlenther Onkol. 200:797–804. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Esparragosa Vazquez I and Ducray F: The

role of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies in adult

intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Cancers (Basel). 16:27812024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Yang Z, Sun L, Chen H, Sun C and Xia L:

New progress in the treatment of diffuse midline glioma with H3K27M

alteration. Heliyon. 10:e248772024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Argersinger DP, Rivas SR, Shah AH, Jackson

S and Heiss JD: New developments in the pathogenesis, therapeutic

targeting, and treatment of H3K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma.

Cancers (Basel). 13:52802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Mandorino M, Maitra A, Armenise D,

Baldelli OM, Miciaccia M, Ferorelli S, Perrone MG and Scilimati A:

Pediatric diffuse midline glioma H3K27-altered: From developmental

origins to therapeutic challenges. Cancers (Basel). 16:18142024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Watanabe J, Clutter MR, Gullette MJ,

Sasaki T, Uchida E, Kaur S, Mo Y, Abe K, Ishi Y, Takata N, et al:

BET bromodomain inhibition potentiates radiosensitivity in models

of H3K27-altered diffuse midline glioma. J Clin Invest.

134:e1747942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Bailey S, Howman A, Wheatley K, Wherton D,

Boota N, Pizer B, Fisher D, Kearns P, Picton S, Saran F, et al:

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma treated with prolonged

temozolomide and radiotherapy-results of a United Kingdom phase II

trial (CNS 2007 04). Eur J Cancer. 49:3856–3862. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Chassot A, Canale S, Varlet P, Puget S,

Roujeau T, Negretti L, Dhermain F, Rialland X, Raquin MA, Grill J,

et al: Radiotherapy with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide in

children with newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J

Neurooncol. 106:399–407. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Abe H, Natsumeda M, Kanemaru Y, Watanabe

J, Tsukamoto Y, Okada M, Yoshimura J, Oishi M and Fujii Y: MGMT

expression contributes to temozolomide resistance in H3K27M-mutant

diffuse midline gliomas and MGMT silencing to temozolomide

sensitivity in IDH-mutant gliomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo).

58:290–295. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Cavallo G, Reni M,

Franceschi E, Bonaldi L, Bertorelle R, Gardiman M, Ghimenton C,

Iuzzolino P, et al: Correlations between 06-methylguanine DNA

methyltransferase promoter methylation status, 1p and 19q

deletions, and response to temozolomide in anaplastic and recurrent

oligodendroglioma: A prospective GICNO study. J Clin Oncol.

24:4746–4753. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Warren KE, Aikin AA, Libucha M, Widemann

BC, Fox E, Packer RJ and Balis FM: Phase I study of

O6-benzylguanine and temozolomide administered daily for 5 days to

pediatric patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 23:7646–7653.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhang Y, Dong W, Zhu J, Wang L, Wu X and

Shan H: Combination of EZH2 inhibitor and BET inhibitor for

treatment of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Cell Biosci.

7:562017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Sasaki T, Katagi H, Goldman S, Becher OJ

and Hashizume R: Convection-enhanced delivery of enhancer of zeste

homolog-2 (EZH2) inhibitor for the treatment of diffuse intrinsic

pontine glioma. Neurosurgery. 87:E680–E688. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Singleton WGB, Bienemann AS, Woolley M,

Johnson D, Lewis O, Wyatt MJ, Damment SJP, Boulter LJ, Killick-Cole

CL, Asby DJ and Gill SS: The distribution, clearance, and brainstem

toxicity of panobinostat administered by convection-enhanced

delivery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 22:288–296. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Massimino M, Spreafico F, Biassoni V,

Simonetti F, Riva D, Trecate G, Giombini S, Poggi G, Pecori E,

Pignoli E, et al: Diffuse pontine gliomas in children: Changing

strategies, changing results? A mono-institutional 20-year

experience. J Neurooncol. 87:355–361. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Tsoli M, Ung C, Upton DH, Venkat P,

Salerno A, Pandher R, Mayoh C, Vittorio O and Ziegler DS: Dipg-35.

Overcoming the blood-brain barrier challenge in diffuse midline

glioma. Neuro Oncol. 26 (Suppl 4):02024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Ono T, Kuwashige H, Adachi JI, Takahashi

M, Oda M, Kumabe T and Shimizu H: Long-term survival of a patient

with diffuse midline glioma in the pineal region: A case report and

literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 12:6122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Veldhuijzen van Zanten SEM, El-Khouly FE,

Jansen MHA, Bakker DP, Sanchez Aliaga E, Haasbeek CJA, Wolf NI,

Zwaan CM, Vandertop WP, van Vuurden DG and Kaspers GJL: A phase

I/II study of gemcitabine during radiotherapy in children with

newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neurooncol.

135:307–315. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Kilburn LB, Kocak M, Baxter P, Poussaint

TY, Paulino AC, McIntyre C, Lemenuel-Diot A, Lopez-Diaz C, Kun L,

Chintagumpala M, et al: A pediatric brain tumor consortium phase II

trial of capecitabine rapidly disintegrating tablets with

concomitant radiation therapy in children with newly diagnosed

diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

65:10.1002/pbc.26832. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Zhang S, Yang X, Tan Q, Sun H, Chen D,

Chen Y, Zhang H, Yang Y, Gong Q and Yue Q: Cortical myelin and

thickness mapping provide insights into whole-brain tumor burden in

diffuse midline glioma. Cereb Cortex. 34:bhad4912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Krystal J, Hanson D, Donnelly D and Atlas