Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent

malignancies of the digestive system. According to global cancer

statistics, >1.9 million new CRC cases and ~900,000 mortalities

due to CRC were recorded in 2022, making it the third most commonly

diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related

mortality worldwide (1). The

incidence and progression of CRC are influenced by various factors,

including age, genetic predisposition, lifestyle choices and

environmental exposures. Because early symptoms are subtle, several

patients present with advanced disease or distant spread, leading

to a poor outcome (2). Currently,

the mainstay of CRC treatment is comprehensive therapy centered

around surgical resection, complemented by radiotherapy,

chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Preoperative

neoadjuvant therapies and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or

radiotherapy have improved the chances of curative outcomes.

Standard adjuvant chemotherapy regimens include oxaliplatin based

xeloda and oxaliplatin and folinic acid and fluorouracil and

oxaliplatin regimens (3,4). Additionally, targeted therapies

focusing on EGFR and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

pathways have demonstrated clinical benefit in select patient

populations (5,6). Nevertheless, response rates are modest

and adverse effects substantial (7–9).

Immunotherapy has transformed outcomes in several

malignancies and is now a key focus in CRC. Immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs), in particular, have shown favorable efficacy in

patients with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) CRC.

Nonetheless, ~85% of CRC cases exhibit microsatellite stability

(MSS) or proficient mismatch repair (pMMR) status, and these

patients typically exhibit limited responses to ICIs (10). Thus, elucidating the immune

microenvironment of CRC and developing novel immunotherapeutic

strategies have emerged as key areas of current research.

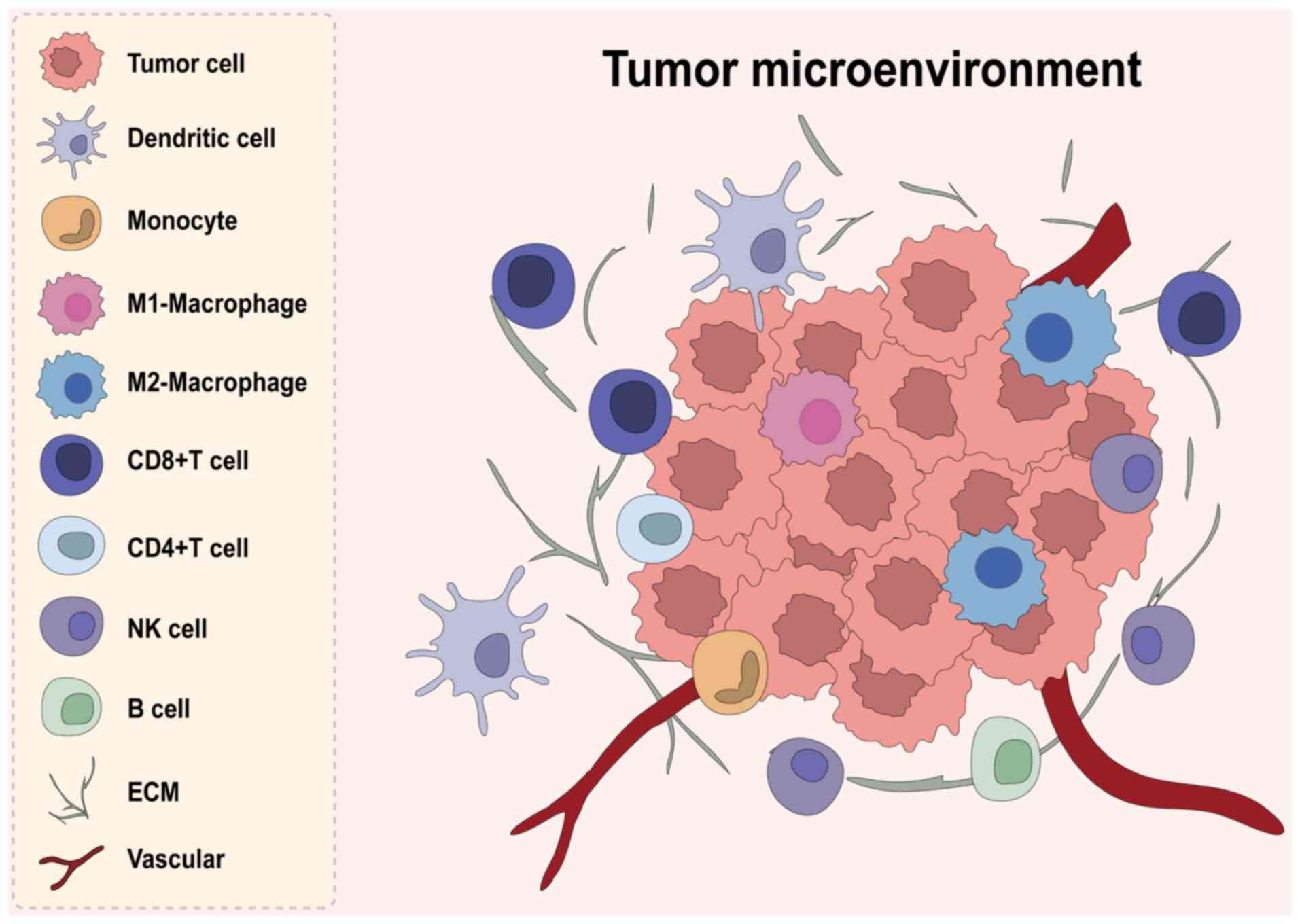

The tumor microenvironment (TME) comprises various

components associated with tumor tissues, carrying out key roles in

tumor initiation and progression. Multiple immune cells, including

but not limited to macrophages, T cells, B cells, natural killer

(NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils, are recruited

into the vicinity of tumor cells, interacting with extracellular

matrix (ECM) components and cytokines to collectively form the

tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) (11) (Fig.

1). These cells can mount potent antitumor responses yet also

enable immune escape. Their relative abundance and functional state

help determine tumor immunogenicity, therapy response and patient

survival. Intensive research has explored the roles and regulatory

mechanisms of various immune cells within the CRC TIME.

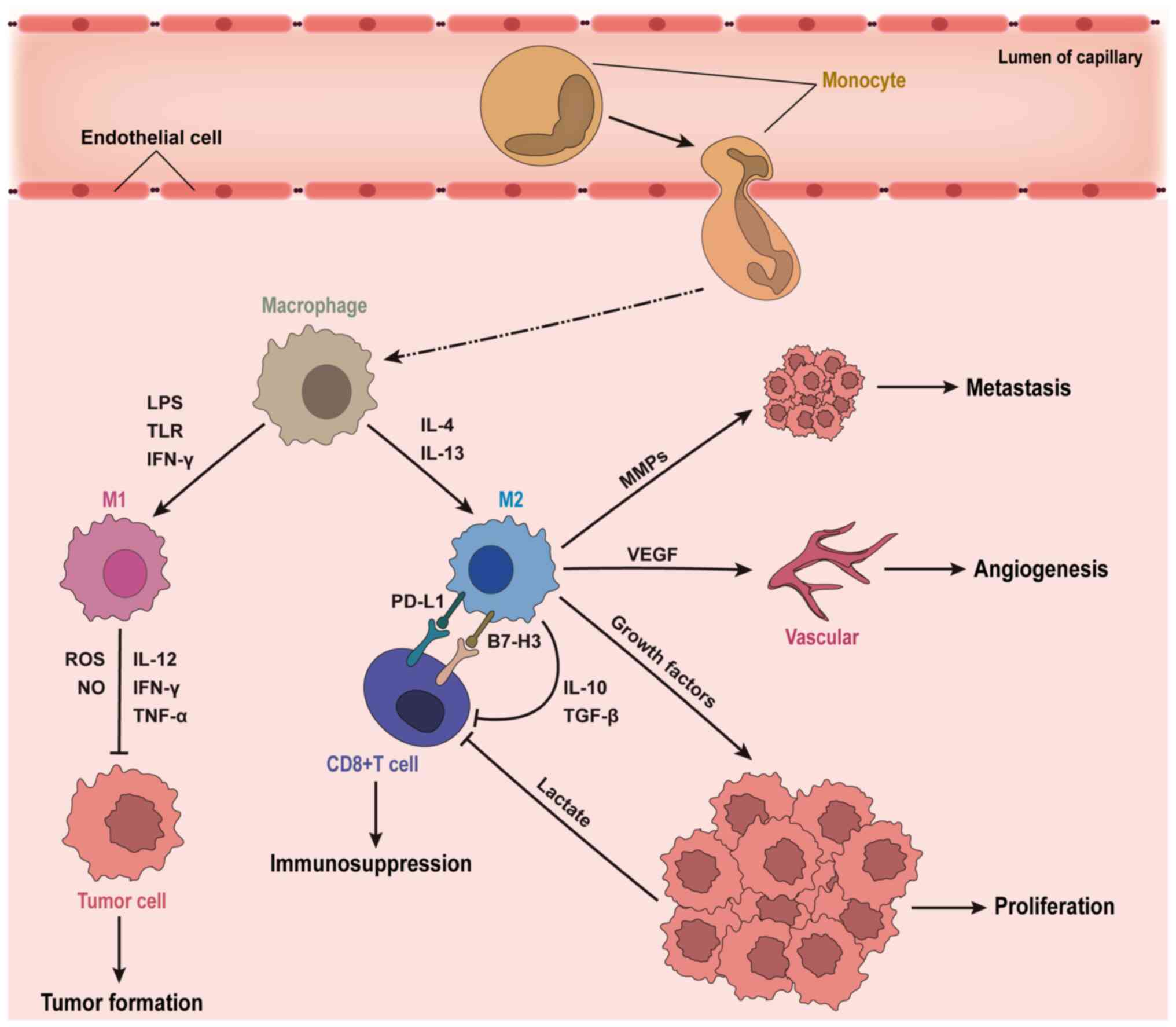

Based on functional characteristics, TAMs are

typically classified into pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory

M2 phenotypes. M1 macrophages, activated by IFN-γ,

lipopolysaccharide or Toll-like receptor ligands, express markers

such as major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II, CD68, CD80 and

CD86. They enhance anti-tumor immune responses through secretion of

cytokines including IL-12, TNF-α and IFN-γ, and directly exert

cytotoxic effects on tumor cells via reactive oxygen species and

nitric oxide (NO) production (15–19).

Conversely, M2 macrophages exhibit immunosuppressive roles,

expressing inhibitory receptors such as programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) and B7-H3 (20–22). Activated by Th2 cytokines IL-4 and

IL-13, M2 macrophages express CD163, CD206 and ARG1, and secrete

cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β and VEGF, suppressing T cell

activity, promoting angiogenesis and facilitating immune escape

(Fig. 2) (23–25).

High infiltration of M1 macrophages associates with

improved prognosis in CRC. Studies have shown an inverse

relationship between the proportion of M1 macrophages and lymph

node and distant metastases (26–28).

Wang et al (29) reported

that ANKRD22 expression in M1 macrophages positively associates

with survival and macrophage infiltration levels in patients with

colon cancer. Nussbaum et al (30)Q analyzing single-cell RNA sequencing

(scRNA-seq) data from 23 patients with CRC, identified high

SPP1-CD44 interactions within inflammatory macrophages. Targeting

SPP1+ macrophages exhibiting an anti-inflammatory phenotype could

disrupt these interactions, potentially reducing tumor progression

and immunosuppression.

Conversely, M2 macrophage infiltration in CRC is

associated with tumor progression and immune evasion. Their

presence associates notably with increased tumor aggressiveness,

metastatic potential and immunosuppressive capabilities (31,32).

Tumor-derived exosomes serve as key mediators of intercellular

communication, facilitating tumor-macrophage interactions. After

internalization by macrophages, these exosomes activate

polarization pathways, driving M2 macrophage polarization, creating

pre-metastatic niches and subsequently promoting CRC metastasis

(33–36). M2 macrophages further enhance tumor

invasion and metastasis by secreting pro-tumor factors such as

VEGF, MMPs, IL-4 and IL-13, contributing to angiogenesis and ECM

degradation (37–39). Additionally, M2 macrophages

facilitate immune escape through expression of PD-L1, engaging with

PD-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4),

impairing T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling and inhibiting cytotoxic

T cell function (40). They also

expand Tregs via TGF-β secretion, further suppressing CD8+ T cell

activities and promoting immune evasion (41).

Studies have demonstrated the dual influence of TAMs

on the effectiveness of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, either

antagonizing therapeutic efficacy by facilitating tissue repair and

immunosuppression or enhancing overall antitumor effects (42,43).

De Palma et al (44) found

that TAMs also drive repair mechanisms following vascular-targeted

therapy. Furthermore, low-dose γ irradiation of macrophages during

neoadjuvant therapy can induce vascular normalization and

counteract immunosuppression, diminishing pro-tumor effects of TAMs

(45). Studies indicate that ICIs,

such as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and agents such as selicrelumab, can

enhance macrophage phagocytosis, reducing tumor burden (46,47).

Current clinical trials targeting TAMs primarily follow three major

strategies, with differential therapeutic efficacy revealing

distinct underlying mechanisms of action. First, strategy targeting

the C-C motif chemokine receptor 2/C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 or

colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) axis represent a

common therapeutic approach. This strategy inhibits TAM

recruitment, effectively reducing their overall density within the

TIME. Published results from clinical studies largely support the

feasibility of this approach (48–51).

However, likely due to limited anti-tumor clinical

activity, the majority of ongoing trials in solid tumors are Phase

I/II studies focusing on safety and preliminary efficacy (50,52,53).

This constrained efficacy may be partly attributed to the

concurrent suppression of potentially anti-tumor M1-type TAM

recruitment, thereby weakening anti-tumor immunity. Furthermore,

the high plasticity of TAMs may trigger compensatory activation of

other pro-tumor signaling pathways upon CSF1R inhibition,

potentially restoring the pro-tumor functions of TAMs and

diminishing therapeutic effectiveness (54). Second, blocking the ‘don't eat me’

signal using anti-CD47/SIRPα antibodies to activate macrophage

phagocytosis constitutes another common strategy. This approach

bypasses the dependency on TAM quantity and directly enhances their

intrinsic tumor-killing capacity (55). Results from the NCT02953782 trial

demonstrated that combined anti-CD47 and anti-EGFR therapy was

tolerable and showed potential anti-tumor activity in heavily

pre-treated patients with CRC, despite no notable changes in immune

cell infiltration levels being observed (56). Additionally, since CD47 is involved

in maintaining erythrocyte homeostasis, off-target toxicity of CD47

antibodies often limits the efficacy of monotherapy (57). Third, Chimeric Antigen Receptor

Macrophage (CAR-M) therapy, which utilizes genetically engineered

macrophages, represents a precision empowerment strategy. This

approach not only enables specific tumor antigen recognition but

may also promote macrophage polarization towards the M1 phenotype

upon activation. The subsequent secretion of pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-12 could potentially convert ‘cold’ tumors

into ‘hot’ tumors. Clinical trial results (NCT04660929) indicated

that CAR-M therapy is safe and feasible in patients with

HER2-overexpressing solid tumors and can induce TME remodeling and

anti-tumor immune responses (58),

offering a novel strategy to address prevalent immunosuppression in

CRC (Table I).

Substantial advancements have been realized in the

field of cancer immunotherapy over recent years (59–61).

Although numerous early-phase clinical trials have explored

targeting TAMs, these studies (62–64)

have revealed several key and unresolved challenges: i) The lack of

predictive biomarkers to prospectively identify patients who are

likely to benefit; ii) difficulties in managing toxicities

associated with combination therapies, as well as uncertainties

regarding the optimal sequencing of treatments and their underlying

mechanistic basis; iii) obstacles in genetically engineering

macrophages, including their poor expansion in vitro and

limited self-renewal capacity following adoptive transfer.

Therefore, future efforts should focus on integrating specific

biomarkers to identify patients most likely to benefit, and

exploring combination regimens with chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

immunotherapy or therapies targeting other immune cells. This

strategy is essential to overcome treatment resistance and maximize

therapeutic efficacy.

T cells are prominent immune cell populations within

the CRC TIME, playing essential roles in tumor defense. They are

categorized primarily as CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and

CD4+ helper T cells based on functional differentiation.

CD8+ T cells serve as key effectors in adaptive

immunity, recognizing tumor antigens presented via MHC class I

molecules and directly killing tumor cells through secretion of

perforin and granzyme B (65). They

also release IFN-γ and TNF-α, strengthening local immune responses

and initiating apoptosis via the Fas/FasL signaling pathway

(66). Increased infiltration of

activated CD8+ T cells is associated with improved

patient prognosis (67).

B cells represent a key component of adaptive

immunity, mediating anti-tumor responses primarily through antibody

production, antigen presentation and the promotion of T cell

activation (101). The antibodies

secreted by B cells can bind to tumor cells, facilitating cytotoxic

activities mediated by NK cells, macrophages and the complement

system. Additionally, B cells function as antigen-presenting cells,

stimulating CD4+ T cells via MHC class II molecules, thereby

enhancing antitumor immune responses (102). However, the role of B cells within

the TME is not exclusively protective.

Certain subsets of B cells, particularly regulatory

B cells (Bregs), may promote tumor progression (103). Bregs secrete immunosuppressive

cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, inhibiting CD8+ T

cell and NK cell functions, thus facilitating tumor immune escape

(104). Moreover, B cells can

exacerbate tumor-associated inflammation by producing

pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, thereby enhancing

cancer cell proliferation and metastasis (105). Clinical studies demonstrate that

increased infiltration of Bregs in CRC tissues associates

positively with tumor progression and predicts poor patient

prognosis (106,107).

Targeting B cells for immunomodulation has emerged

as a novel direction for CRC treatment. On one hand, enhancing

antigen-specific B cell responses, such as developing B-cell-based

vaccines, might potentiate antitumor immunity (108). On the other hand, inhibiting Breg

functions to reduce their immunosuppressive effects could improve

responses to immunotherapy. Monoclonal antibodies targeting

Breg-specific markers, such as CD19 or CD38, have been proposed as

promising therapeutic approaches (109,110). Additionally, interactions between

B cells and T cells are key within the CRC immune microenvironment

(111). Thus, future therapeutic

strategies should comprehensively consider dynamic interactions

among various immune cell subsets to optimize immunotherapy

outcomes.

NK cells constitute essential components of innate

immunity, capable of directly recognizing and killing tumor cells

independently of antigen presentation. NK cells induce apoptosis in

target cells through the secretion of perforin and granzyme B, and

enhance antitumor immune responses via IFN-γ production (112). Additionally, NK cells contribute

markedly to antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, enhancing the

efficacy of antibody-based therapies (113). NK cells are principally stratified

into two distinct functional subsets contingent upon the surface

density of CD56 expression: The CD56dim and CD56bright

subpopulations. The former constitutes the numerically predominant

fraction, characterized by potent cytotoxicity and serving as the

primary effector killer cells; in contradistinction, the latter

subpopulation is specialized chiefly in cytokine secretion and the

orchestration of immune responses (114).

NK cell activity is notably impaired. CRC tissues

often exhibit reduced NK cell infiltration and functionality due to

immunosuppressive factors present within the TME (115). For example, cytokines such as

TGF-β and IL-10, abundant in the CRC microenvironment, directly

inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity, inducing a state of functional

exhaustion (116,117). Furthermore, increased expression

of inhibitory receptors, such as PD-1 on NK cells within CRC

tumors, reduces their capacity to recognize and eliminate tumor

cells, thereby allowing tumor cells to evade immune surveillance

(118). The modalities

underpinning this immune escape are multifaceted. Initially, CRC

neoplastic cells elude immunosurveillance mediated by the NK

activating receptor NKG2D via the specific downregulation of MHC-I

related molecular expression (119). Concomitantly, NK cells exhibit

elevated surface expression patterns of novel immune checkpoint

receptors beyond PD-1, namely NKG2A/CD94, TIGIT and TIM-3. The

cognate ligands for these inhibitory receptors are abundantly

expressed by tumor cells or residing within the TME,

collaboratively engendering a state of profound NK exhaustion

phenotype (120). Moreover, the

deleterious metabolic milieu within the TME constitutes another key

determinant: Overexpressed CD73 enzymatically catabolizes

extracellular ATP into adenosine, which subsequently engages the

A2AR receptor on the NK cell surface, thereby abrogating their

proliferative capacity and cytotoxic effector functions (121).

Strategies to enhance NK cell antitumor activities

include CAR-NK cell therapy, NK cell stimulants, such as IL-15 and

combination treatments involving PD-1/PD-L1 blockade (122). Preclinical studies indicate CAR-NK

cells exhibit potent antitumor activity and possess superior safety

profiles compared with CAR-T cell therapies (123–125). However, due to challenges

associated with NK cell proliferation and survival in vitro,

further optimization of NK cell-based immunotherapies remains

essential to improve their clinical utility in CRC treatment.

DCs, originating from hematopoietic stem cells in

the bone marrow, are the most potent professional

antigen-presenting cells. DCs capture exogenous antigens, process

them into antigenic peptides and present them in complex with MHC

molecules on their surface, initiating naïve T cell activation. DCs

are a highly heterogeneous group, primarily categorized into

conventional DCs (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). Functionally,

cDCs specialize in antigen processing and presentation, while pDCs

are less proficient in antigen presentation but produce substantial

amounts of type I interferons (126).

Within the TME, DCs serve as pivotal

antigen-presenting cells, capturing, processing and presenting

tumor antigens to activate T cell-mediated antitumor immune

responses. DCs stimulate CD4+ T cells via MHC-II

molecules and also facilitate CD8+ T cell activation

through cross-presentation (127).

cDCs constitute the predominant DC population within the TME and

are further delineated into distinct cDC1 and cDC2 subsets.

Notably, the cDC1 subpopulation, whose development is dependent

upon the transcription factor BATF3, assumes an indispensable role

in orchestrating anti-tumor T cell immune responses (128), whereas cDC2s are principally

tasked with initiating Th2-type immunity. However, DC functionality

in the CRC microenvironment is frequently compromised, impairing

effective antitumor immunity. Immunosuppressive factors, such as

prostaglandin E2 and IL-6, inhibit DC maturation, thereby limiting

their capacity to activate T cells effectively. This specific

functional deficit is particularly salient within the context of

CRC. Investigations have elucidated that in MSS CRC phenotypes,

aberrant intrinsic activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling axis

constitutes a pivotal mechanism underpinning immunosuppression

(129). Mechanistically, this

pathway acts to repress the expression of chemokines CCL4 and CCL5,

thereby specifically impeding the efficacious intratumoral

infiltration of the key cDC1 subset; this cascade consequently

renders the TME an immunologically ‘cold’ landscape, ultimately

conferring primary resistance to ICIs (130). Additionally, some DC populations

may acquire tolerogenic properties, failing to effectively present

antigens and instead promoting Treg expansion, further suppressing

antitumor responses (131).

Current strategies aiming to restore DC-mediated

antitumor immunity include DC vaccines, autologous DC infusion and

combination therapies with ICIs (132,133). DC vaccines hold promise for CRC

treatment, with several clinical trials currently evaluating their

efficacy in combination with ICIs. Furthermore, prospective

therapeutic avenues could involve targeted intervention against the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling axis to ameliorate the established

impediments to cDC1 recruitment within the TME, thereby

orchestrating the conversion of immunologically ‘cold’ tumors into

a ‘hot’ phenotype (134–136). This strategy could subsequently be

leveraged in synergistic combinations with ICIs to augment overall

antitumor therapeutic efficacy.

Neutrophils represent a primary barrier of innate

immunity, carrying out key roles in inflammation and immune

responses. Within the TME, neutrophils can be further categorized

into N1 phenotypes, which exert anti-tumor effects and N2

phenotypes, which facilitate tumor progression. Growth factors,

cytokines and chemokines present in the TME recruit neutrophils

into the tumor tissue, where they participate in the regulation of

diverse and complex biological processes (137). Prevailingly, elevated

concentrations of TGF-β function as a cardinal impetus driving the

phenotypic skewing of neutrophils from an N1 state towards the

pro-tumorigenic N2 phenotype (138). N2-polarized neutrophils

predominantly manifest immunosuppressive functionalities, exerting

these effects via the regulated secretion of a complex array of

chemokines, pro-angiogenic factors and immunosuppressive moieties.

Consequently, this bioactive secretome actively recruits and

activates collateral immunosuppressive cell populations,

facilitates neovascularization and concurrently subverts host

immune system recognition and cytotoxic clearance of tumors

(139).

Neutrophils carry out a key role in the metastatic

process of CRC. Under specific signaling stimuli, neutrophils

undergo a unique form of cell death known as neutrophil

extracellular trap (NET) formation. The released NETs not only

physically capture circulating tumor cells (140), but studies have also revealed that

NETs interact via histones on DNA with specific receptors on tumor

cell surfaces, activating downstream signaling pathways that

promote the colonization and survival of tumor cells in distant

organs (141,142). Furthermore, NETs facilitate immune

evasion by degrading anti-tumor molecules within the TME (143). Clinical evidence further confirms

that an elevated peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

serves as an independent predictor of poor prognosis and resistance

to immunotherapy in patients with CRC (144).

Therapeutic approaches targeting neutrophils include

inhibition of NET formation and blockade of the CXCR2 signaling

pathway (145,146), with the objective of diminishing

neutrophil recruitment within the TME and augmenting the efficacy

of immunotherapeutic interventions. Consequently, the strategic

modulation of neutrophil polarization states, the suppression of

NET generation and the targeted disruption of their recruitment

signals represent viable avenues for enhancing therapeutic outcomes

in CRC management.

Multi-omics approaches integrate multiple molecular

analyses to elucidate interactions among various biological

components. Recently, notable advancements in scRNA-seq and spatial

transcriptomics have profoundly enhanced the understanding of the

CRC TIME (77,147,148), illuminating immune cell

heterogeneity, functional states and interactions with tumor cells,

thereby offering novel insights into CRC pathophysiology.

ScRNA-seq provides comprehensive information at the

transcriptomic, genomic and epigenomic levels for individual cells,

enabling researchers to identify distinct immune cell subsets

within the TME, characterize their functional states and reveal

potential intercellular communication pathways. Zhang et al

(149) conducted a detailed

scRNA-seq analysis of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells in patients

with CRC, elucidating the characteristics and lineage trajectories

of TAM and DC subpopulations, as well as their interactions with T

cells and other cell types. Their study revealed a specific

enrichment of secreted phosphoprotein 1+ (SPP1+) TAMs in CRC

tissues and demonstrated the similarity between CSF1R

inhibitor-resistant TAM subsets and SPP1+ TAM populations,

providing a mechanistic explanation for the limited efficacy of

anti-CSF1R monotherapy and highlighting the role of SPP1+

macrophages in promoting tumor metastasis (149,150). Importantly, the identification of

this SPP1+ TAM subset provides the molecular evidence for the

therapeutic resistance mentioned in the TAM section, validating

that the compensatory activation limiting CSF1R inhibitor efficacy

is driven by distinct, intrinsically resistant macrophage

subpopulations. The investigation by Zhang et al (149) had elucidated, at single-cell

resolution, a landscape of TAM heterogeneity that was markedly more

intricate when compared with the canonical M1/M2 stratification

paradigm. This had substantially augmented the comprehension of

intratumoral TAM diversity by precisely pinpointing an SPP1+ TAM

subset exhibiting inherent resistance to CSF1R inhibitors. This key

discovery not only offers a mechanistic rationale for the

aforementioned therapeutic predicaments but further delineated that

prospective targeting avenues must focus on the precise therapeutic

interrogation of such distinct pro-tumorigenic subpopulations.

Additionally, Wu et al (151) applied combined scRNA-seq and

spatial transcriptomics to CRC liver metastasis samples,

systematically illustrating spatial expression patterns of SPP1+

macrophages and mannose receptor C-type 1+, CCL18+ M2-like

macrophages, suggesting a key immunosuppressive role of the TAM in

CRC liver metastasis (151).

The advancement and integrated application of

multi-omics technologies have shown considerable potential in

dissecting immune cell composition, functional dynamics and

tumor-immune cell interactions within the CRC microenvironment.

Such comprehensive insights provide key foundations for developing

novel therapeutic strategies and advancing personalized

medicine.

Notwithstanding the remarkable preclinical strides

in TIME-targeted immunotherapies, translating these findings into

tangible clinical benefits for patients with CRC is thwarted by

multifaceted impediments, principally stemming from the profound

heterogeneity of the CRC microenvironment (77). While ICIs demonstrate efficacy in

MSI-H subsets, the vast majority of patients with MSS exhibit an

‘immune desert’ or ‘immune exclusion’ phenotype. This intrinsic

immunological dormancy renders single-agent TIME-directed

strategies insufficient to revert their immune-silent status.

Moreover, the dynamic adaptability of the TIME is another key

determinant of therapeutic failure. The TME possesses a high degree

of compensatory capacity. This mechanism of compensatory immune

evasion severely curtails the durable efficacy achievable with

monotherapies.

The safety profile and the predictive value of

preclinical models also urgently warrant resolution. Several TIME

targets, such as CD47 and TGF-β, are ubiquitously expressed in

healthy tissues, meaning that off-target systemic toxicity severely

constrains the therapeutic window for these agents (154,155). While combinatorial regimens are

deemed the principal strategy to circumvent resistance, this

approach invariably precipitates compounding toxicities and an

escalated risk of immune-related adverse events. Concomitantly,

clear clinical guidance remains lacking for the precise

determination of the optimal sequencing for distinct therapeutic

agents. Furthermore, the widely employed subcutaneous xenograft

models exhibit rapid growth dynamics and lack the complex human CRC

stromal architecture and the long-term co-evolutionary interplay

between the immune system and the tumor (156). The disparity between these models

and clinical pathological features often results in a failure to

recapitulate efficacy in human trials, despite promising results

observed in mice. Therefore, future research should focus on

developing more clinically relevant models and exploring

combination therapy strategies to overcome the limitations of

targeting single pathways.

Accumulating evidence indicates that tumor

progression involves not only the intrinsic characteristics of

tumor cells but also key interactions within the TIME (157,158). Immune cells within the TIME carry

out pivotal roles in CRC initiation, progression and immune evasion

processes. Specifically, these immune cells shape the host immune

responses, considerably influencing tumor development, thereby

positioning the TIME as a promising therapeutic target for cancer

treatment. Immunotherapy has evolved from simply enhancing immune

effector functions to specifically targeting immunosuppressive

factors within the TIME. Consequently, strategies aimed at

effectively modulating the TIME to amplify the therapeutic effects

of immunotherapy are emerging as a key area of ongoing and future

research.

To advance the transition from targeting single

cells toward systematically reshaping the TIME through combination

therapies, future research should focus on multidisciplinary

integration and overcoming challenges such as drug resistance and

the limitations of immunotherapy, thereby enabling the development

of personalized treatment regimens. Although patients with

dMMR/MSI-H CRC benefit from ICIs, the majority of CRC cases are

pMMR/MSS and remain unresponsive to ICI-based immunotherapy

(10). Therefore, a primary

objective is to overcome the immunosuppressive state in pMMR/MSS

CRC by enhancing immunogenicity to render these tumors susceptible

to immunotherapy. For instance, immunosuppressive M2-type TAMs

express inhibitory ligands such as PD-L1 and B7H3, which contribute

to immune suppression and diminish the efficacy of T cell-directed

ICIs. Combining therapies that target these immunosuppressive TAMs

with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is thus a rational strategy. Clinical

evidence supports this approach: The combination of the CSF1R

inhibitor emactuzumab with the anti-PD-L1 agent atezolizumab has

demonstrated a notable objective response rate in ICI-naïve

patients (159). This provides a

promising avenue for improving outcomes in pMMR/MSS patients with

CRC. Furthermore, breakthroughs in drug development technologies

and insights from spatial transcriptomics into TIME-mediated

immunosuppression and resistance mechanisms will be instrumental in

achieving precision medicine and addressing treatment insensitivity

in a subset of patients with CRC. For example, a previous study

showed that deep learning can predict MSI status directly from

routine histology slides with high concordance with standard

molecular testing (160),

underscoring the potential of multidisciplinary integration to

inform individualized precision therapy.

Comprehensive understanding of the composition and

functional dynamics of the TIME, along with its interplay in CRC

development and immune escape mechanisms, can provide key insights

into the underlying pathogenesis of CRC. Such knowledge offers a

robust theoretical framework for developing novel immunotherapeutic

approaches. Future research dedicated to unraveling the regulatory

mechanisms and interactive networks within the TIME will facilitate

individualized, precision-based therapeutic strategies, ultimately

improving both survival outcomes and quality of life for patients

with CRC.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by grants from the Guangxi Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. 2025GXNSFAA069131) and First-class

discipline innovation-driven talent program of Guangxi Medical

University.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sargent D, Sobrero A, Grothey A, O'Connell

MJ, Buyse M, Andre T, Zheng Y, Green E, Labianca R, O'Callaghan C,

et al: Evidence for cure by adjuvant therapy in colon cancer:

Observations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients

on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 27:872–877. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Maughan TS, Adams RA, Smith CG, Meade AM,

Seymour MT, Wilson RH, Idziaszczyk S, Harris R, Fisher D, Kenny SL,

et al: Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line

combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal

cancer: Results of the randomised phase 3 mrc coin trial. Lancet.

377:2103–2114. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A,

Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S, Ludwig H, Schuch G,

Stroh C, et al: Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and

without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:663–671. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Larsen AK, Poindessous V, Ouaret D, El

Ouadrani K, Megalophonos VF, Batistella A, Petitprez A, Escargueil

AE, Tournigand C and De Gramont A: Feasibility of combining EGFR-

and VEGF(R)-targeted agents in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 29

(4_suppl):S4432011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Chibaudel B, Henriques J, Rakez M, Brenner

B, Kim TW, Martinez-Villacampa M, Gallego-Plazas J, Cervantes A,

Shim K, Jonker D, et al: Association of bevacizumab plus

oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy with disease-free survival and

overall survival in patients with stage II colon cancer: A

secondary analysis of the avant trial. JAMA Netw Open.

3:e20204252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cutroneo PM, Giardina C, Ientile V,

Potenza S, Sottosanti L, Ferrajolo C, Trombetta CJ and Trifirò G:

Overview of the safety of anti-VEGF drugs: Analysis of the Italian

spontaneous reporting system. Drug Saf. 40:1131–1140. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Passaro A, Jänne PA, Mok T and Peters S:

Overcoming therapy resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Nat

Cancer. 2:377–391. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Oxnard GR, Yang JC, Yu H, Kim SW, Saka H,

Horn L, Goto K, Ohe Y, Mann H, Thress KS, et al: TATTON: A

multi-arm, phase Ib trial of osimertinib combined with selumetinib,

savolitinib, or durvalumab in egfr-mutant lung cancer. Ann Oncol.

31:507–516. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A, Mendelsohn

RB, Shia J, Segal NH and Diaz LA Jr: Immunotherapy in colorectal

cancer: Rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:361–375. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tang T, Huang X, Zhang G, Hong Z, Bai X

and Liang T: Advantages of targeting the tumor immune

microenvironment over blocking immune checkpoint in cancer

immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Coussens LM and Werb Z: Inflammation and

cancer. Nature. 420:860–867. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sedighzadeh SS, Khoshbin AP, Razi S,

Keshavarz-Fathi M and Rezaei N: A narrative review of

tumor-associated macrophages in lung cancer: Regulation of

macrophage polarization and therapeutic implications. Transl Lung

Cancer Res. 10:1889–1916. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena

P and Sica A: Macrophage polarization: Tumor-associated macrophages

as a paradigm for polarized m2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends

Immunol. 23:549–555. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Müller E, Christopoulos PF, Halder S,

Lunde A, Beraki K, Speth M, Øynebråten I and Corthay A: Toll-like

receptor ligands and interferon-γ synergize for induction of

antitumor m1 macrophages. Front Immunol. 8:13832017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Jing M, Ma M, Zhang M, Mei Y, Wang L,

Jiang Y, Li J, Song R, Yang Z, Pu Y, et al: The photothermal effect

induces m1 macrophage-derived tnf-α-type exosomes to inhibit

bladder tumor growth. Chem Eng J. 498:1550232024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Aslam M, Ashfaq-Khan M, Qureshi A, Celik

S, Werle J-T, Senkowski M, Kim YO, KAPS L and Schuppan D:

Fri-453-rapamycin promotes tumoricidal immunity in murine HCC by

inducing M1-type macrophages and dentritic cells polarization and

enhancement of cytotoxic T-cells. J Hepatol. 70:e5952019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Han Y, Sun J, Yang Y, Liu Y, Lou J, Pan H,

Yao J and Han W: TMP195 exerts antitumor effects on colorectal

cancer by promoting M1 macrophages polarization. Int J Biol Sci.

18:5653–5666. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Griess B, Mir S, Datta K and

Teoh-Fitzgerald M: Scavenging reactive oxygen species selectively

inhibits M2 macrophage polarization and their pro-tumorigenic

function in part, via Stat3 suppression. Free Radic Biol Med.

147:48–60. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cassetta L and Pollard JW:

Tumor-associated macrophages. Curr Biol. 30:R246–R248. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zheng Y, Ren S, Zhang Y, Liu S, Meng L,

Liu F, Gu L, Ai N and Sang M: Circular RNA circWWC3 augments breast

cancer progression through promoting M2 macrophage polarization and

tumor immune escape via regulating the expression and secretion of

IL-4. Cancer Cell Int. 22:2642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee YH, Martin-Orozco N, Zheng P, Li J,

Zhang P, Tan H, Park HJ, Jeong M, Chang SH, Kim BS, et al:

Inhibition of the B7-H3 immune checkpoint limits tumor growth by

enhancing cytotoxic lymphocyte function. Cell Res. 27:1034–1045.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kee JY, Ito A, Hojo S, Hashimoto I,

Igarashi Y, Tsuneyama K, Tsukada K, Irimura T, Shibahara N,

Takasaki I, et al: CXCL16 suppresses liver metastasis of colorectal

cancer by promoting TNF-α-induced apoptosis by tumor-associated

macrophages. BMC Cancer. 14:9492014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Brigati C, Noonan DM, Albini A and Benelli

R: Tumors and inflammatory infiltrates: Friends or foes? Clin Exp

Metastasis. 19:247–258. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Locati M, Curtale G and Mantovani A:

Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity.

Annu Rev Pathol. 15:123–147. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Inagaki K, Kunisho S, Takigawa H, Yuge R,

Oka S, Tanaka S, Shimamoto F, Chayama K and Kitadai Y: Role of

tumor-associated macrophages at the invasive front in human

colorectal cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 112:2692–2704. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ma J, Liu L, Che G, Yu N, Dai F and You Z:

The M1 form of tumor-associated macrophages in non-small cell lung

cancer is positively associated with survival time. BMC Cancer.

10:1122010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegård J,

Öberg Å, Oldenborg PA and Palmqvist R: The distribution of

macrophages with a M1 or M2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and

the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS One.

7:e470452012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang X, Yang K, Yang B, Wang R, Zhu Y and

Pan T: ANKRD22 participates in the proinflammatory activities of

macrophages in the colon cancer tumor microenvironment. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 74:862025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nussbaum YI, Manjunath Y, Kaifi JT, Warren

W and Mitchem J: Analysis of tumor-associated macrophages'

heterogeneity in colorectal cancer patients using single-cell

RNA-seq data. J Clin Oncol. 40 (4_suppl):S1462025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Liang Y, Li J, Yuan Y, Ju H, Liao H, Li M,

Liu Y, Yao Y, Yang L, Li T and Lei X: Exosomal miR-106a-5p from

highly metastatic colorectal cancer cells drives liver metastasis

by inducing macrophage M2 polarization in the tumor

microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:2812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu Q, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Wei C, Song

J, Lin X, Dou R, Bai J, Xiang Z, et al: Wnt5a-induced M2

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages via IL-10 promotes

colorectal cancer progression. Cell Commun Signal. 18:512020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhao S, Mi Y, Guan B, Zheng B, Wei P, Gu

Y, Zhang Z, Cai S, Xu Y, Li X, et al: Tumor-derived exosomal

miR-934 induces macrophage M2 polarization to promote liver

metastasis of colorectal cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 13:1562020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sun Z, Xu Y, Shao B, Dang P, Hu S, Sun H,

Chen C, Wang C, Liu J, Liu Y and Hu J: Exosomal circPOLQ promotes

macrophage M2 polarization via activating Il-10/STAT3 axis in a

colorectal cancer model. J Immunother Cancer. 12:e0084912024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yang C, Dou R, Wei C, Liu K, Shi D, Zhang

C, Liu Q, Wang S and Xiong B: Tumor-derived exosomal

microRNA-106b-5p activates EMT-cancer cell and M2-subtype tam

interaction to facilitate CRC metastasis. Mol Ther. 29:2088–2107.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wu Y, Xiao Y, Ding Y, Ran R, Wei K, Tao S,

Mao H, Wang J, Pang S, Shi J, et al: Colorectal cancer cell-derived

exosomal miRNA-372-5p induces immune escape from colorectal cancer

via PTEN/AKT/NF-κB/PD-L1 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 143((Pt 1)):

1132612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhu X, Liang R, Lan T, Ding D, Huang S,

Shao J, Zheng Z, Chen T, Huang Y, Liu J, et al: Tumor-associated

macrophage-specific CD155 contributes to M2-phenotype transition,

immunosuppression, and tumor progression in colorectal cancer. J

Immunother Cancer. 10:e0042192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang D, Wang X, Si M, Yang J, Sun S, Wu H,

Cui S, Qu X and Yu X: Exosome-encapsulated miRNAS contribute to

CXCL12/CXCR4-induced liver metastasis of colorectal cancer by

enhancing M2 polarization of macrophages. Cancer Lett. 474:36–52.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hardbower DM, Coburn LA, Asim M, Singh K,

Sierra JC, Barry DP, Gobert AP, Piazuelo MB, Washington MK and

Wilson KT: EGFR-mediated macrophage activation promotes

colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 36:3807–3819. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kuang DM, Zhao Q, Peng C, Xu J, Zhang JP,

Wu C and Zheng L: Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of

hepatocellular carcinoma foster immune privilege and disease

progression through PD-L1. J Exp Med. 206:1327–1337. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yu X, Qian J, Ding L, Pan C, Liu X, Wu Q,

Wang S, Liu J, Shang M, Su R, et al: Galectin-1-induced tumor

associated macrophages repress antitumor immunity in hepatocellular

carcinoma through recruitment of tregs. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24087882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Mantovani A and Allavena P: The

interaction of anticancer therapies with tumor-associated

macrophages. J Exp Med. 212:435–445. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi

L and Allavena P: Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment

targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:399–416. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

De Palma M and Lewis CE: Macrophage

regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell.

23:277–286. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, Seibel T,

Bender N, Halama N, Pfirschke C, Voss RH, Timke C, Umansky L, et

al: Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an

iNOS+/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell

immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 24:589–602. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, Hutter G,

George BM, McCracken MN, Gupta R, Tsai JM, Sinha R, Corey D, et al:

PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits

phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 545:495–499. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Byrne KT, Betts CB, Mick R, Sivagnanam S,

Bajor DL, Laheru DA, Chiorean EG, O'Hara MH, Liudahl SM, Newcomb C,

et al: Neoadjuvant selicrelumab, an agonist CD40 antibody, induces

changes in the tumor microenvironment in patients with resectable

pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 27:4574–4586. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Dowlati A, Harvey RD, Carvajal RD, Hamid

O, Klempner SJ, Kauh JSW, Peterson DA, Yu D, Chapman SC, Szpurka

AM, et al: LY3022855, an anti-colony stimulating factor-1 receptor

(CSF-1R) monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid

tumors refractory to standard therapy: Phase 1 dose-escalation

trial. Invest New Drugs. 39:1057–1071. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Voissière A, Gomez-Roca C, Chabaud S,

Rodriguez C, Nkodia A, Berthet J, Montane L, Bidaux AS, Treilleux

I, Eberst L, et al: The CSF-1R inhibitor pexidartinib affects

FLT3-dependent DC differentiation and may antagonize durvalumab

effect in patients with advanced cancers. Sci Transl Med.

16:eadd18342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Brana I, Calles A, LoRusso PM, Yee LK,

Puchalski TA, Seetharam S, Zhong B, de Boer CJ, Tabernero J and

Calvo E: Carlumab, an anti-C-C chemokine ligand 2 monoclonal

antibody, in combination with four chemotherapy regimens for the

treatment of patients with solid tumors: An open-label, multicenter

phase 1b study. Target Oncol. 10:111–123. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gomez-Roca CA, Italiano A, Le Tourneau C,

Cassier PA, Toulmonde M, D'Angelo SP, Campone M, Weber KL, Loirat

D, Cannarile MA, et al: Phase I study of emactuzumab single agent

or in combination with paclitaxel in patients with

advanced/metastatic solid tumors reveals depletion of

immunosuppressive M2-like macrophages. Ann Oncol. 30:1381–1392.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Falchook GS, Peeters M, Rottey S, Dirix

LY, Obermannova R, Cohen JE, Perets R, Frommer RS, Bauer TM, Wang

JS, et al: A phase 1a/1b trial of CSF-1R inhibitor ly3022855 in

combination with durvalumab or tremelimumab in patients with

advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 39:1284–1297. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Nywening TM, Wang-Gillam A, Sanford DE,

Belt BA, Panni RZ, Cusworth BM, Toriola AT, Nieman RK, Worley LA,

Yano M, et al: Targeting tumour-associated macrophages with CCR2

inhibition in combination with FOLFIRINOX in patients with

borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A

single-centre, open-label, dose-finding, non-randomised, phase 1b

trial. Lancet Oncol. 17:651–662. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Cannarile MA, Weisser M, Jacob W, Jegg AM,

Ries CH and Rüttinger D: Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor

(CSF1R) inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Immunother Cancer.

5:532017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Qu T, Li B and Wang Y: Targeting

CD47/SIRPα as a therapeutic strategy, where we are and where we are

headed. Biomark Res. 10:202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Eng C, Lakhani NJ, Philip PA, Schneider C,

Johnson B, Kardosh A, Chao MP, Patnaik A, Shihadeh F, Lee Y, et al:

A phase 1b/2 study of the anti-CD47 antibody magrolimab with

cetuximab in patients with colorectal cancer and other solid

tumors. Target Oncol. 20:519–530. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yamada-Hunter SA, Theruvath J, McIntosh

BJ, Freitas KA, Lin F, Radosevich MT, Leruste A, Dhingra S,

Martinez-Velez N, Xu P, et al: Engineered CD47 protects T cells for

enhanced antitumour immunity. Nature. 630:457–465. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Reiss KA, Angelos MG, Dees EC, Yuan Y,

Ueno NT, Pohlmann PR, Johnson ML, Chao J, Shestova O, Serody JS, et

al: Car-macrophage therapy for HER2-overexpressing advanced solid

tumors: A phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 31:1171–1182. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Tan PB, Verschoor YL, van den Berg JG,

Balduzzi S, Kok NFM, Ijsselsteijn ME, Moore K, Jurdi A, Tin A,

Kaptein P, et al: Neoadjuvant immunotherapy in

mismatch-repair-proficient colon cancers. Nature. 648:726–735.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wang F, Chen G, Qiu M, Ma J, Mo X, Liu H,

Li Y, Ding P, Wan X, Hu Y, et al: Neoadjuvant treatment of IBI310

plus sintilimab in locally advanced MSI-H/DMMR colon cancer: A

randomized phase 1b study. Cancer Cell. 43:1958–1967.e2. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang X, Wang J, Wang G, Zhang Y, Fan Q,

Lu C, Hu C, Sun M, Wan Y, Sun S, et al: First-line sugemalimab plus

chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: The gemstone-303

randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 333:1305–1314. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ohtani Y, Ross K, Dandekar A, Gabbasov R

and Klichinsky M: 128 development of an M1-polarized, non-viral

chimeric antigen receptor macrophage (car-m) platform for cancer

immunotherapy. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 8 (Suppl

3):doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-SITC2020.0128. 2020.

|

|

63

|

Razak AR, Cleary JM, Moreno V, Boyer M,

Aller EC, Edenfield W, Tie J, Harvey RD, Rutten A, Shah MA, et al:

Safety and efficacy of AMG 820, an anti-colony-stimulating factor 1

receptor antibody, in combination with pembrolizumab in adults with

advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 8:e0010062020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Spierenburg G, van der Heijden L, van

Langevelde K, Szuhai K, Bovée JVGM, van de Sande MAJ and Gelderblom

H: Tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TGCT): Molecular biology, drug

targets and non-surgical pharmacological approaches. Expert Opin

Ther Targets. 26:333–345. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Golstein P and Griffiths GM: An early

history of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat Rev Immunol.

18:527–535. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Pei S, Pollyea DA, Gustafson A,

Minhajuddin M, Stevens BM, Ye HY, Inguva A, Amaya ML, Krug A, Jones

CL, et al: Developmental plasticity of acute myeloid leukemia

mediates resistance to venetoclax-based therapy. Blood. 134

(Suppl_1):S1852019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Li X, Gruosso T, Zuo D, Omeroglu A,

Meterissian S, Guiot MC, Salazar A, Park M and Levine H:

Infiltration of CD8(+) T cells into tumor cell clusters in

triple-negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

116:3678–3687. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gajewski TF, Schreiber H and Fu YX: Innate

and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat

Immunol. 14:1014–1022. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhang L, Shi YC, Yang YX, Wang ZG, Wang SS

and Zhang H: Association of T lymphocyte subset counts with the

clinical features of colorectal cancer. J Nutr Oncol. 8:178–185.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Doering TA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM,

Paley MA, Ziegler CG and Wherry EJ: Network analysis reveals

centrally connected genes and pathways involved in CD8+ T cell

exhaustion versus memory. Immunity. 37:1130–1144. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wherry EJ and Kurachi M: Molecular and

cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol.

15:486–499. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Angelosanto JM, Blackburn SD, Crawford A

and Wherry EJ: Progressive loss of memory T cell potential and

commitment to exhaustion during chronic viral infection. J Virol.

86:8161–8170. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Im SJ, Hashimoto M, Gerner MY, Lee J,

Kissick HT, Burger MC, Shan Q, Hale JS, Lee J, Nasti TH, et al:

Defining CD8+ T cells that provide the proliferative burst after

PD-1 therapy. Nature. 537:417–421. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Alfei F and Zehn D: T cell exhaustion: An

epigenetically imprinted phenotypic and functional makeover. Trends

Mol Med. 23:769–771. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Baitsch L, Baumgaertner P, Devêvre E,

Raghav SK, Legat A, Barba L, Wieckowski S, Bouzourene H, Deplancke

B, Romero P, et al: Exhaustion of tumor-specific CD8+ T

cells in metastases from melanoma patients. J Clin Invest.

121:2350–2360. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Paley MA, Sharpe A

and Wherry EJ: Genetic absence of PD-1 promotes accumulation of

terminally differentiated exhausted Cd8+ T cells. J Exp Med.

212:1125–1137. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Chen Y, Wang D, Li Y, Qi L, Si W, Bo Y,

Chen X, Ye Z, Fan H, Liu B, et al: Spatiotemporal single-cell

analysis decodes cellular dynamics underlying different responses

to immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell.

42:1268–1285.e7. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Liu Z, Zhang Y, Ma N, Yang Y, Ma Y, Wang

F, Wang Y, Wei J, Chen H, Tartarone A, et al: Progenitor-like

exhausted SPRY1(+)CD8(+) t cells potentiate responsiveness to

neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Cell. 41:1852–1870.e9. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Liu Z, Yang Z, Wu J, Zhang W, Sun Y, Zhang

C, Bai G, Yang L, Fan H, Chen Y, et al: A single-cell atlas reveals

immune heterogeneity in anti-PD-1-treated non-small cell lung

cancer. Cell. 188:3081–3096.e19. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kim YJ, Park SJ and Broxmeyer HE:

Phagocytosis, a potential mechanism for myeloid-derived suppressor

cell regulation of CD8+ T cell function mediated through programmed

cell death-1 and programmed cell death-1 ligand interaction. J

Immunol. 187:2291–2301. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Tanaka A and Sakaguchi S: Regulatory T

cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 27:109–118. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Ma S, Dahabieh MS, Mann TH, Zhao S,

McDonald B, Song WS, Chung HK, Farsakoglu Y, Garcia-Rivera L,

Hoffmann FA, et al: Nutrient-driven histone code determines

exhausted CD8(+) T cell fates. Science. 387:eadj30202025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Li J, Wu C, Hu H, Qin G, Wu X, Bai F,

Zhang J, Cai Y, Huang Y, Wang C, et al: Remodeling of the immune

and stromal cell compartment by pd-1 blockade in mismatch

repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 41:1152–1169.e7.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Borràs DM, Verbandt S, Ausserhofer M,

Sturm G, Lim J, Verge GA, Vanmeerbeek I, Laureano RS, Govaerts J,

Sprooten J, et al: Single cell dynamics of tumor specificity vs

bystander activity in CD8(+) T cells define the diverse immune

landscapes in colorectal cancer. Cell Discov. 9:1142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Donia M, Andersen R, Kjeldsen JW, Fagone

P, Munir S, Nicoletti F, Andersen MH, Straten PT and Svane IM:

Aberrant expression of MHC class II in melanoma attracts

inflammatory tumor-specific CD4+ T- cells, which dampen CD8+ T-cell

antitumor reactivity. Cancer Res. 75:3747–3759. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Borst J, Ahrends T, Bąbała N, Melief CJM

and Kastenmüller W: CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 18:635–647. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Ahrends T, Spanjaard A, Pilzecker B,

Bąbała N, Bovens A, Xiao Y, Jacobs H and Borst J: CD4(+) T cell

help confers a cytotoxic T cell effector program including

coinhibitory receptor downregulation and increased tissue

invasiveness. Immunity. 47:848–861.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Shamoun L, Skarstedt M, Andersson RE,

Wågsäter D and Dimberg J: Association study on IL-4, IL-4Rα and

Il-13 genetic polymorphisms in swedish patients with colorectal

cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 487:101–106. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Li W, Chen F, Gao H, Xu Z, Zhou Y, Wang S,

Lv Z, Zhang Y, Xu Z, Huo J, et al: Cytokine concentration in

peripheral blood of patients with colorectal cancer. Front Immunol.

14:11755132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro

CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ and Littman DR: The orphan

nuclear receptor rorgammat directs the differentiation program of

proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 126:1121–1133. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Huber S, Gagliani N, Zenewicz LA, Huber

FJ, Bosurgi L, Hu B, Hedl M, Zhang W, O'Connor W Jr, Murphy AJ, et

al: IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates

tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature. 491:259–263. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Kryczek I, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L and

Zou W: Endogenous IL-17 contributes to reduced tumor growth and

metastasis. Blood. 114:357–359. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Bai Y, Li T, Wang Q, You W, Yang H, Xu X,

Li Z, Zhang Y, Yan C, Yang L, et al: Shaping immune landscape of

colorectal cancer by cholesterol metabolites. EMBO Mol Med.

16:334–360. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

De Simone V, Pallone F, Monteleone G and

Stolfi C: Role of TH17 cytokines in the control of

colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2:e266172013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X,

Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L,

Burow M, et al: Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in

ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced

survival. Nat Med. 10:942–949. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Sayour EJ, McLendon P, McLendon R, De Leon

G, Reynolds R, Kresak J, Sampson JH and Mitchell DA: Increased

proportion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in tumor infiltrating

lymphocytes is associated with tumor recurrence and reduced

survival in patients with glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

64:419–427. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Merlo A, Casalini P, Carcangiu ML,

Malventano C, Triulzi T, Mènard S, Tagliabue E and Balsari A: Foxp3

expression and overall survival in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol.

27:1746–1752. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Zi R, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang Y, Zhang R, Bian

Z, Jiang H, Liu T, Sun Y, Peng H, et al: Metabolic-immune

suppression mediated by the SIRT1-CX3CL1 axis induces functional

enhancement of regulatory T cells in colorectal carcinoma. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24047342025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Gu J, Zhou J, Chen Q, Xu X, Gao J, Li X,

Shao Q, Zhou B, Zhou H, Wei S, et al: Tumor metabolite lactate

promotes tumorigenesis by modulating MOESIN lactylation and

enhancing TGF-beta signaling in regulatory T cells. Cell Rep.

39:1109862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Adamczyk A, Pastille E, Kehrmann J, Vu VP,

Geffers R, Wasmer MH, Kasper S, Schuler M, Lange CM, Muggli B, et

al: GPR15 facilitates recruitment of regulatory T cells to promote

colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 81:2970–2982. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Akkaya M, Kwak K and Pierce SK: B cell

memory: Building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat Rev

Immunol. 20:229–238. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Choi IK, Wang Z, Ke Q, Hong M, Paul DW Jr,

Fernandes SM, Hu Z, Stevens J, Guleria I, Kim HJ, et al: Mechanism

of EBV inducing anti-tumour immunity and its therapeutic use.

Nature. 590:157–162. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Manfroi B and Fillatreau S: Regulatory B

cells gain muscles with a leucine-rich diet. Immunity. 55:970–972.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Murakami Y, Saito H, Shimizu S, Kono Y,

Shishido Y, Miyatani K, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, Ashida K, Sakabe

T, et al: Increased regulatory B cells are involved in immune

evasion in patients with gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 9:130832019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Griss J, Bauer W, Wagner C, Simon M, Chen

M, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Maurer-Granofszky M, Roka F, Penz T,

Bock C, et al: B cells sustain inflammation and predict response to

immune checkpoint blockade in human melanoma. Nat Commun.

10:41862019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Mao H, Pan F, Wu Z, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zhang

P, Gou M and Dai G: Colorectal tumors are enriched with regulatory

plasmablasts with capacity in suppressing T cell inflammation. Int

Immunopharmacol. 49:95–101. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Liao Y, Zhuo X, Huang Y, Xu H, Hao Z,

Huang L, Zheng H and Zhou J: A SENP7-SIRT1-IL-10 axis driven by

DeSUMOylation promotes breg differentiation and immune evasion in

colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 22:111–125. 2026. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Hou D, Castro B, Dapash M, Rashidi A,

Zhang P, Han Y, Lopez-Rosas A, Lesniak M, Miska J and Chang C:

Immu-36. B cell-vaccine elicits long term immunity against

glioblastoma via activation and differentiation of tumor-specific

CD8+ memory T cells. Neuro Oncol. 23 (Suppl_6):vi100.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Irimia RM, Gerke MB, Thakar M, Ren Z,

Helmenstine E, Imus PH, Ghiaur G, Leone R and Gocke GB: CD38 is a

key regulator of tumor growth by modulating the metabolic signature

of malignant plasma cells. Blood. 138 (Suppl 1):S26522021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Malik H, Buelow B, Rangaswamy U,

Balasubramani A, Boudreau A, Dang K, Davison L, Aldred SF, Harris

KM, Iyer S, Jorgensen B, Pham D, Prabhakar K, Schellenberger U,

Ugamraj H, Trinklein N and Van Schooten W: Tnb-486, a novel fully

human bispecific CD19 × CD3 antibody that kills CD19-positive tumor

cells with minimal cytokine secretion. Blood. 134 (Suppl_1):S4070.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Wang W, Zhong Y, Zhuang Z, Xie J, Lu Y,

Huang C, Sun Y, Wu L, Yin J, Yu H, et al: Multiregion single-cell

sequencing reveals the transcriptional landscape of the immune

microenvironment of colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med.

11:e2532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Nicolai CJ and Raulet DH: Killer cells add

fire to fuel immunotherapy. Science. 368:943–944. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Dixon K, Hullsiek R, Snyder K, Davis Z,

Khaw M, Lee T, Chu HY, Abujarour R, Dinella J, Rogers P, et al:

Engineered iPSC-derived NK cells expressing recombinant CD64 for

enhanced ADCC. Blood. 136 (Suppl 1):S10–S11. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG and

Bryceson YT: Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine

production by target cell recognition. Blood. 115:2167–2176. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Liu YJ, Han M, Li JP, Zeng SH, Ye QW, Yin

ZH, Liu SL and Zou X: An analysis regarding the association between

connexins and colorectal cancer (CRC) tumor microenvironment. J

Inflamm Res. 15:2461–2476. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Yang L, Yi J, He W, Kong P, Xie Q, Jin Y,

Xiong Z and Xia L: Death receptors 4/5 mediate tumour sensitivity

to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity in mismatch repair

deficient colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 131:334–346. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Otegbeye F, Ojo E, Moreton S, Mackowski N,

Lee DA, de Lima M and Wald DN: Inhibiting TGF-beta signaling

preserves the function of highly activated, in vitro expanded

natural killer cells in AML and colon cancer models. PLoS One.

13:e01913582018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Vuletić A, Martinović KM, Miletić NT,

Zoidakis J, Castellvi-Bel S and Čavić M: Cross-talk between tumor

cells undergoing epithelial to mesenchymal transition and natural

killer cells in tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9:7500222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Tang S, Fu H, Xu Q and Zhou Y: Mir-20a

regulates sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells to NK cells by

targeting mica. Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201806952019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Lin A, Ye P, Li Z, Jiang A, Liu Z, Cheng

Q, Zhang J and Luo P: Natural killer cell immune checkpoints and

their therapeutic targeting in cancer treatment. Research (Wash

DC). 8:07232025.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Lupo K and Matosevic S: 123 natural killer

cells engineered with an inducible, responsive genetic construct

targeting tigit and CD73 to relieve immunosuppression within the

gbm microenvironment. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 8 (Suppl

3):doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-SITC2020.0123. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Strassheimer F, Strecker MI, Alekseeva T,

Macas J, Demes MC, Mildenberger IC, Tonn T, Wild PJ, Sevenich L,

Reiss Y, et al: Os12.6.A combination therapy of CAR-NK-cells and

anti-pd-1 results in high efficacy against advanced-stage

glioblastoma in a syngeneic mouse model and induces protective

anti-tumor immunity in vivo. Neuro Oncol. 23 (Suppl_2):ii152021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Kong R, Liu B, Wang H, Lu T and Zhou X:

CAR-NK cell therapy: Latest updates from the 2024 ASH annual

meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 18:222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Duan J, Zhao S, Duan Y, Sun D, Zhang G, Yu

D, Lou Y, Liu H, Yang S, Liang X, et al: Mnox nanoenzyme

armed CAR-NK cells enhance solid tumor immunotherapy by alleviating

the immunosuppressive microenvironment. Adv Healthc Mater.

13:e23039632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Wang W, Liu Y, He Z, Li L, Liu S, Jiang M,

Zhao B, Deng M, Wang W, Mi X, et al: Breakthrough of solid tumor

treatment: CAR-NK immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 10:402024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Reizis B: Plasmacytoid dendritic cells:

Development, regulation, and function. Immunity. 50:37–50. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Wculek SK, Cueto FJ, Mujal AM, Melero I,

Krummel MF and Sancho D: Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 20:7–24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Jhunjhunwala S, Hammer C and Delamarre L:

Antigen presentation in cancer: Insights into tumour immunogenicity

and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 21:298–312. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Klempner SJ, Cecchini M, Khushman M,

Kummar S, Pelster M, Rodon J, Sharma S, Yaeger R, Rojo J, Wells AL,

et al: Abstract B031: A phase 1/2 trial of fog-001, a

first-in-class direct β-catenin:Tcf4 inhibitor, preliminary safety

and efficacy in patients with solid tumors bearing wnt

pathway-activating mutations (WPAM+). Mol Cancer Ther. 24

(10_Suppl):B0312025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Suryawanshi A, Hussein MS, Prasad PD and

Manicassamy S: Wnt signaling cascade in dendritic cells and

regulation of anti-tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 11:1222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Dhodapkar MV, Dhodapkar KM and Palucka AK:

Interactions of tumor cells with dendritic cells: Balancing

immunity and tolerance. Cell Death Differ. 15:39–50. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Itai YS, Barboy O, Salomon R, Bercovich A,

Xie K, Winter E, Shami T, Porat Z, Erez N, Tanay A, et al:

Bispecific dendritic-T cell engager potentiates anti-tumor

immunity. Cell. 187:375–389.e18. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Aznar MA, Planelles L, Perez-Olivares M,

Molina C, Garasa S, Etxeberría I, Perez G, Rodriguez I, Bolaños E,

Lopez-Casas P, et al: Immunotherapeutic effects of intratumoral

nanoplexed poly I:C. J Immunother Cancer. 7:1162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

He F, Wu Z, Liu C, Zhu Y, Zhou Y, Tian E,

Rosin-Arbesfeld R, Yang D, Wang MW and Zhu D: Targeting BCL9/BCL9L

enhances antigen presentation by promoting conventional type 1

dendritic cell (cDC1) activation and tumor infiltration. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:1392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Singer M, Valerin J, Zhang Z, Zhang Z,

Dayyani F, Yaghmai V, Choi A, Imagawa D and Abi-Jaoudeh N:

Promising cellular immunotherapy for colorectal cancer using

classical dendritic cells and natural killer T cells. Cells.

14:1662025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Passardi A, Sullo FG, Bittoni A, Matteucci

L, De Rosa F, Bulgarelli J, Tazzari M, Petrini M, Scarpi E, Testoni

S, et al: CombiCoR-Vax trial: Study protocol for a phase II,

single-arm, multicenter trial of sequential pembrolizumab plus

dendritic cell vaccine followed by trifluridine/tipiracil and

bevacizumab in refractory microsatellite-stable metastatic

colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 25:19212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Guo FF and Cui JW: The role of neutrophils

in cancer development. Journal of Nutritional Oncology. 4:85–90.

2019.https://journals.lww.com/jno/Fulltext/2019/05150/The_Role_of_Neutrophils_in_Cancer_Development.5.aspx

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Peng H, Shen J, Long X, Zhou X, Zhang J,

Xu X, Huang T, Xu H, Sun S, Li C, et al: Local release of TGF-β

inhibitor modulates tumor-associated neutrophils and enhances

pancreatic cancer response to combined irreversible electroporation

and immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 9:e21052402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Giese MA, Hind LE and Huttenlocher A:

Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood.

133:2159–2167. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Yang L, Liu L, Zhang R, Hong J, Wang Y,

Wang J, Zuo J, Zhang J, Chen J and Hao H: IL-8 mediates a positive

loop connecting increased neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and

colorectal cancer liver metastasis. J Cancer. 11:4384–4396. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Yang L, Liu Q, Zhang X, Liu X, Zhou B,

Chen J, Huang D, Li J, Li H, Chen F, et al: DNA of neutrophil

extracellular traps promotes cancer metastasis via CCDC25. Nature.

583:133–138. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Tohme S, Yazdani HO, Al-Khafaji AB, Chidi

AP, Loughran P, Mowen K, Wang Y, Simmons RL, Huang H and Tsung A:

Neutrophil extracellular traps promote the development and

progression of liver metastases after surgical stress. Cancer Res.

76:1367–1380. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Wang X, He S, Gong X, Lei S, Zhang Q,

Xiong J and Liu Y: Neutrophils in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms,

prognostic value, and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol.

16:15386352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144