Introduction

Epidemiology and unmet clinical

needs

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant

epithelial tumor of the nasopharynx with an uneven global

distribution. East and Southeast Asia account for ~80% of cases,

with the highest incidence concentrated in southern China,

particularly Guangdong, Guangxi and Fujian (1), making NPC both regionally clustered

and globally consequential. The disease primarily affects

individuals aged 40–70 years and shows a pronounced sex disparity,

with men affected 2- to 3-fold more often than women (1). Despite advances in cross-sectional

imaging and conformal radiotherapy, early detection remains elusive

and long-term quality of life is still shaped by late toxicities,

such as xerostomia, dysphagia and otologic injury.

Clinical presentation in the early stages is

frequently silent or non-specific and includes blood-tinged sputum,

unilateral nasal obstruction or painless cervical lymphadenopathy,

so that 70–80% of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages

(III/IV) (2) This late-stage

predominance at diagnosis largely explains the pronounced survival

gradient across stages and highlights the clinical value of

shifting detection toward earlier disease: The 5-year survival rate

is >90% when NPC is detected early, but falls to >40% in

late-stage disease. Distant metastasis and local recurrence remain

the principal modes of treatment failure (3). Collectively, these realities define

three persistent unmet needs: i) Scalable, non-invasive screening

deployable at the population level; ii) risk-stratified care

pathways that minimise overtreatment without compromising oncologic

safety; and iii) implementation models that preserve quality and

outcomes in resource-limited settings (4). Addressing these gaps will require

earlier, more reliable detection and exact therapies capable of

improving durable survival while mitigating treatment-related

morbidity.

Current diagnostic bottlenecks and

emerging precision solutions

Legacy serology and conventional imaging lack the

resolution to capture preclinical or very-early NPC across diverse

populations (5). Epstein-Barr virus

(EBV)-centric assays have advanced non-invasive detection but

remain vulnerable to EBV-negative disease and cross-platform

variability; T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire profiling and

radiomics/radiogenomics add discrimination yet require standardized

pipelines and prospective external validation (6). In practice, the present review

advocates a molecular-imaging co-screening approach that pairs

liquid-biopsy signals with advanced endoscopy to address historical

blind spots in very-early disease (4).

The emergence of molecular and

surgical precision paradigms

Converging advances now support a dual-front

precision strategy for NPC. On the molecular/imaging side,

CRISPR-enabled assays, antibody-augmented platforms and integrated

multi-omics/radiomics enable non-invasive, risk-stratified

co-screening suitable for population deployment (2). On the interventional side, endoscopic

nasopharyngectomy (ENPG) has re-emerged as an organ-preserving

option restricted to carefully selected T1-T2 disease in

experienced centers; it does not constitute a universal substitute

for radiotherapy. Bringing these strands together, a pragmatic

tri-axis framework was adopted: Molecular detection, precision

surgery (indication-bounded ENPG) and immune modulation,

coordinated through analytics spanning screening, diagnosis/triage,

treatment and surveillance (long-term endpoints and PROs have been

synthesised in Table SI) (4).

Looking ahead, the field will hinge on harmonising

precision detection with targeted intervention to shift care

upstream. Artificial intelligence-assisted models that fuse

multi-omics [including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)],

immune-repertoire signatures and radiomic biomarkers can refine

dynamic risk stratification and flag pre-clinical disease. In

parallel, rational sequencing, for example, protocol-guided

programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand 1

(PD-L1) strategies alongside indication-bounded ENPG, may sustain

oncologic control while preserving function in selected patients.

Progress will depend on multi-center prospective programs with

harmonized endpoints [5/10-year OS; late ≥G3 toxicities and PROs

such as M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI)/quality of life

questionnaire-head and neck module (QLQ-H&N35)], and on

equitable implementation via portable diagnostics and tele-enabled

expertise in endemic regions where the burden is greatest.

Early screening for NPC: Current status and

recent advances

EBV and its associated biomarkers

The EBV, a central oncogenic driver of NPC,

establishes its pathogenicity through persistent latent infection

and immune evasion (1,2), making EBV-specific biomarkers

important for early detection. Current serological screening

strategies targeting EBV antigens, such as viral capsid antigen IgA

(VCA-IgA) and early antigen IgA, exhibit limited diagnostic

utility, with single-antibody assays achieving only a sensitivity

of ~25% (6). Dual-antibody

approaches (such as VCA-IgA with EBNA1-IgA) have been shown to

improve sensitivity to ~75%, yet their clinical translation is

hampered by persistently low positive predictive values (<20%)

and high false-positive rates, underscoring the need for

complementary biomarkers (7,8).

Legacy serology and conventional imaging lack the

granularity to consistently detect preclinical or very-early NPC

across heterogeneous populations. EBV-centric assays, including

plasma EBV DNA and methylome (cfDNA), exhibit advanced non-invasive

detection but remain vulnerable to EBV-negative disease,

pre-analytical variability and cross-platform threshold drift

(9–11). TCR repertoire profiling and

radiomics/radiogenomics add discriminatory power, yet require

standardised pipelines and rigorous prospective external validation

(7,12). The net effect is a patchwork

evidence base marked by heterogeneous cut-offs and inconsistent

reporting windows, which impedes guideline adoption and real-world

scale-up (13,14).

Recent advances in NPC screening have revolutionized

EBV biomarker detection through multi-dimensional technological

innovations. Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-enabled composite

models now decode both quantitative and fragmentomic profiles of

plasma EBV DNA via real-time PCR, achieving unprecedented precision

(15). A landmark study by Lam

et al (15) demonstrated

that algorithmic optimization of NGS data elevates screening

specificity from 98.6 to 99.3% and boosts positive predictive value

by 78% (from 11.0 to 19.6%), markedly enhancing early-stage

detection. Parallel breakthroughs in nucleic acid testing include

the CRISPR-Cas12a-based non-amplification digital detection system

developed at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China

(15,16). By targeting EBV genomic repetitive

sequences, this platform outperforms conventional quantitative PCR

(qPCR), achieving superior sensitivity (98.5 vs. 95.2%) and

specificity (99.1 vs. 97.8%), while reducing assay time by 60% and

enabling real-time monitoring of tumor load dynamics. These

innovations not only address historical limitations in EBV-driven

screening but are also aligned with global efforts to reduce

mortality due to NPC in endemic regions, where >80% of the cases

occur (17).

Serological testing for NPC has undergone

transformative innovation, addressing long-standing gaps in early

detection. The VCA-IgA/EBNA1-IgA dual-antibody ELISA platform

increases screening sensitivity threefold (from 25 to 75%) while

maintaining 98.5% specificity, earning endorsement as the National

Health Commission's preferred protocol for high-incidence regions

(15). Complementing this, the P85

antibody (P85-Ab) assay, co-developed by Xiamen University (Xiamen,

China) and Wantai Biotech marks a paradigm shift in serological

screening. As a standalone test, it achieves 97.9% sensitivity and

98.3% specificity, surpassing conventional biomarkers. When

integrated with dual-antibody screening (18), P85-Ab elevated the positive

predictive value from 10 to 44.6%, quadrupling diagnostic

efficiency while reducing per-test costs by 30% in pilot

implementations (19). Approved for

clinical use in late 2024, this combinatorial strategy redefines

cost-effective mass screening, particularly in endemic areas where

NPC accounts for >80% of global cases (6). By harmonizing high-throughput serology

with precision biomarkers, these advances align with World Health

Organization targets to reduce NPC-caused mortality through early

interception, exemplifying how translational innovation can bridge

diagnostic accuracy and scalability in resource-variable settings

(20).

The current landscape of EBV-related biomarker

detection is characterized by three key developments. First, NGS

and CRISPR-based technologies are enhancing diagnostic precision

through multi-indicator nucleic acid testing strategies. Secondly,

the identification of novel biomarkers, such as P85-Ab, has opened

new avenues for early screening. In combination, these advances

provide key technical support for establishing a tiered prevention

and control framework encompassing initial screening, refined

screening and definitive diagnosis. Of note, the advent of high

positive predictive value assays contributes to reducing the risk

of overdiagnosis in clinical settings. Despite these promising

developments, challenges remain. The high costs associated with NGS

and CRISPR limit their accessibility at the primary care level,

while the long-term stability and clinical utility of emerging

biomarkers such as P85-Ab require validation in large-scale

cohorts. Future research directions include the development of

portable, low-cost diagnostic platforms, the integration of

multi-omics data to construct dynamic early warning systems and the

application of artificial intelligence to optimize screening

algorithms. These innovations aim to enable standardized, accurate

and widely accessible early detection of NPC.

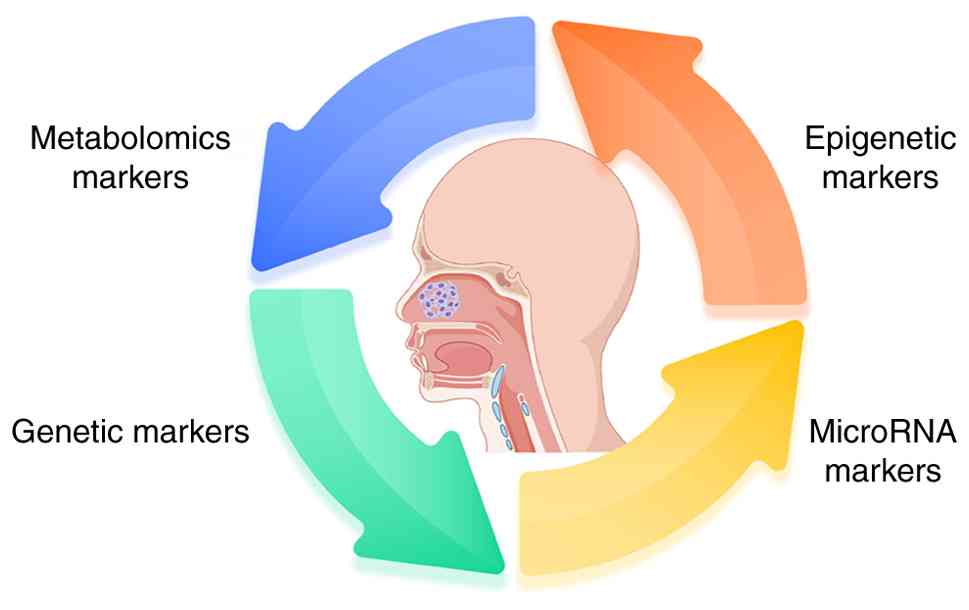

Plasma free DNA cfDNA and ctDNA

Recent advances in circulating biomarkers and

protein-based assays have transformed the non-invasive diagnosis

and prognostic stratification of NPC. cfDNA, comprising short DNA

fragments shed into the bloodstream, includes a tumor-derived

fraction, ctDNA, that harbors somatic alterations such as TP53 and

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α

(PIK3CA) mutations (21,22). Leveraging ultra-sensitive platforms

such as digital PCR and NGS, trace levels of ctDNA can now be

reliably detected, enabling earlier diagnosis and real-time

monitoring of tumor burden in patients with NPC. Complementing

these molecular assays, the immunohistochemical analysis of the p53

tumor suppressor protein provides key prognostic insights:

Loss-of-function TP53 mutations often result in aberrant p53

accumulation and elevated p53 expression within NPC tissues has

been consistently associated with worse overall and disease-free

survival (23). Together, ctDNA

profiling and p53 immunostaining offer a powerful, minimally

invasive toolkit for guiding individualized treatment decisions,

facilitating both the early detection of NPC and the tailoring of

therapeutic intensity based on tumor biology (Fig. 1).

Biomarker detection

Progress in microRNA (miRNAs) research

of related biomarkers

miRNAs, a class of ~22-nucleotide non-coding RNAs,

modulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to the

3′ untranslated regions of target messenger RNAs, thereby playing

key roles in oncogenesis. In NPC, a distinct and consistent pattern

of miRNA dysregulation has been widely observed, underscoring their

potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers (24–26).

This aberrant miRNA expression landscape not only reflects

underlying tumor biology but also offers a promising avenue for

non-invasive molecular diagnostics. However, the clinical

translation of miRNA-based biomarkers in NPC remains contingent on

the development of robust, standardized detection platforms and

optimized analytical strategies that ensure sensitivity,

specificity and reproducibility across diverse patient

populations.

Early studies on miRNAs focused on identifying

miRNAs specific to NPC. Zhang et al (27) found that miR-93 was markedly

upregulated in NPC tissues and Zhou et al (28) further confirmed its serum levels

were positively associated with tumour stage. However, the

sensitivity and specificity of miR-93 alone for diagnosis are

insufficient, suggesting the limited clinical value of a single

miRNA. Zhou et al (28),

Duan et al (29), and Zhang

et al (30) demonstrated

that the combined detection of miR-17-5p and miR-20a can increase

the sensitivity of early NPC to 80% and the specificity to 87%,

notably outperforming traditional serum antibodies (such as

VCA-IgA). Of note, the specificity of miR-17-5p in distinguishing

patients with early-stage NPC from healthy individuals is

relatively low (73%), indicating the need to combine other markers

to improve accuracy.

The inherent limitations of single-miRNA diagnostic

approaches have catalyzed the development of multi-analyte

biomarker integration strategies, with recent advancements

demonstrating marked improvements in clinical detection accuracy.

Of note, Zhu et al (31)

pioneered a serum triplex miRNA panel (miR-140-3p, miR-192-5p and

miR-223-3p) achieving 93.2% sensitivity and 93.5% specificity

through the synergistic regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathways. This paradigm

shift toward biomarker combination was further validated by Jiang

et al (32), who reported

that incorporating circulating EBV microRNA BART2-5p (miR-BART2-5p)

into screening/triage markedly improved diagnostic performance (AUC

~0.96–0.97 in validation cohorts)., outperforming conventional

plasma EBV DNA assays (50% detection rate), while maintaining 94.2%

sensitivity. Considerably advancing the field, Li et al

(24,25) and Allaya et al (22) established a multi-omics diagnostic

framework combining miR-10b with EBV Latent Membrane Protein 1

(LMP1). EBV-related transcripts (for example, LMP1) and host

regulators such as TWIST1 have been associated with NPC

pathobiology, supporting their potential as components of

multi-marker panels (24). These

collective findings underscore the potential of cross-modal

biomarker integration in overcoming biological heterogeneity and

pathway redundancy limitations inherent to single-marker

approaches, establishing a new standard for precision diagnostics

in complex disease states.

Although miRNA biomarkers hold considerable promise

for the clinical management of NPC, their translation into routine

practice is hindered by three principal challenges. First, tumor

heterogeneity poses a notable obstacle: Molecular subtypes of NPC,

such as variations in EBV latency patterns and the degree of

stromal infiltration, result in marked differences in miRNA

expression profiles. For instance, miR-93 is consistently

upregulated in EBV type III latency tumors, yet exhibits variable

expression in type I, limiting its utility as a broadly applicable

biomarker (33). Secondly, the lack

of technical standardization undermines reproducibility and

comparability across studies. While qPCR and microarray platforms

are widely used for miRNA detection, there remains no consensus on

key methodological parameters, including sample preprocessing

protocols (such as exosome isolation) and reference gene selection

(such as U6 small nuclear RNA vs. cel-miR-39). Finally, the

clinical utility of miRNAs has been predominantly explored in the

context of diagnosis, whereas their potential roles in prognosis

and therapy remain underdeveloped. Of note, miR-205 has been

implicated in radiotherapy resistance, highlighting the need to

further investigate miRNAs as prognostic indicators and therapeutic

targets (34). Addressing these

challenges will be essential for harnessing the full clinical

potential of miRNA-based tools in NPC.

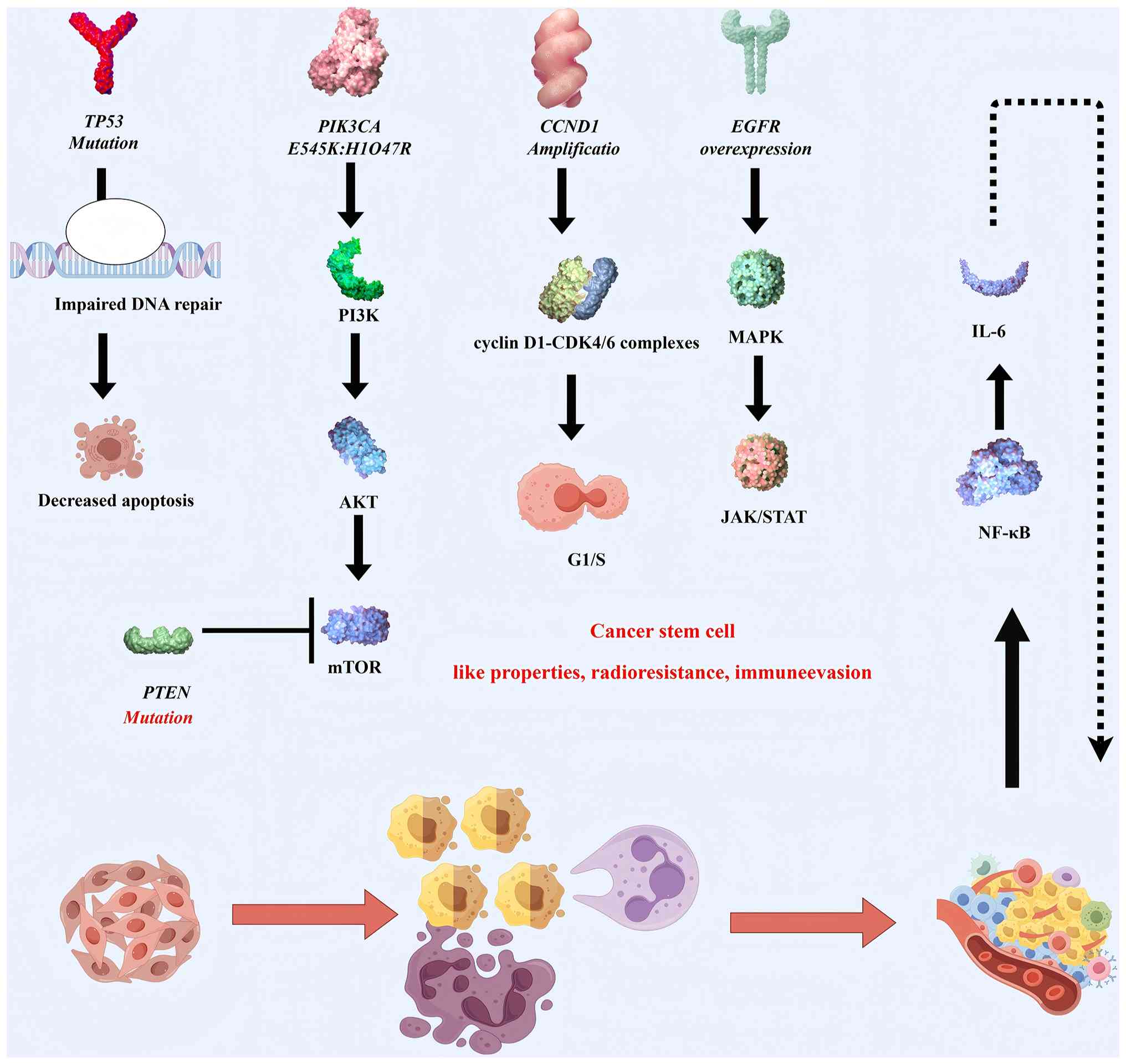

Genetic markers

Recent large-scale genomic sequencing efforts have

substantially advanced understanding of the molecular landscape of

NPC, revealing recurrent alterations in tumor suppressor genes and

oncogenic drivers with marked clinical implications. Among these,

TP53 mutations, one of the most common genetic events across

different types of human cancer, display distinct patterns in NPC,

being predominantly enriched in EBV-negative subtypes and recurrent

tumors. These mutations, which include missense variants, point

mutations and splice site alterations, result in the functional

inactivation of the p53 protein, thereby impairing key pathways

involved in DNA damage response, cell cycle regulation and

apoptosis. The consequence is enhanced tumor resistance to

radiotherapy and chemotherapy, often associated with poor clinical

outcomes (35–38).

In parallel, the dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway carries out a complementary oncogenic role.

Activating mutations in PIK3CA, notably E545K and H1047R, directly

enhance AKT phosphorylation, promoting cell proliferation and

survival (39). Meanwhile, the

tumor-suppressive function of PTEN, a key negative regulator of

this pathway, is frequently compromised by inactivating mutations

or copy number loss, resulting in a sustained activation of the

PI3K/AKT/mechanistic target of rapamycin axis. These molecular

aberrations are further amplified by the dysregulation of EGFR

signaling (39,40). In EBV-positive NPCs, EGFR

amplification or overexpression concurrently activates multiple

downstream pathways, including MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and Janus

kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling

pathway, which collectively contribute to radioresistance and the

acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties. This mechanistic

convergence provides a compelling rationale for the clinical

evaluation of EGFR-targeted therapies, such as erlotinib, in

selected subsets of patients with NPC (41–43).

Given the clinical relevance of EGFR, the use of targeted

therapies, including anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies such as

cetuximab (44,45), are increasing. Detecting EGFR

expression levels allows for the selection of more appropriate

treatment strategies and facilitates the prediction of patient

response and overall prognosis.

The dysregulation of cell cycle checkpoints in NPC

exemplifies a paradigm shift in understanding tumorigenic

mechanisms. The amplification of cyclin D1 (CCND1) drives the

aberrant G1/S transition through the enhanced assembly

of cyclin D1-Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) complexes,

while the concomitant epigenetic silencing of cyclin-dependent

kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) via promoter hypermethylation induces

the functional inactivation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor

2A, isoform p16, thereby relieving its restraint on CDK4/6 kinase

activity. This dual disruption of cell cycle surveillance

constitutes a hallmark of NPC pathogenesis, providing a robust

biological rationale for the clinical evaluation of CDK4/6

inhibitors that have shown a therapeutic promise in other head and

neck malignancies (46–49). Paralleling these proliferation

anomalies, the tumor microenvironment (TME) exhibits constitutive

NF-κB activation, a pathognomonic feature mediated by convergent

genetic lesions including nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide

gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, α truncating mutations

impairing IκBα function and heterozygous deletions affecting TNF

receptor-associated factor 3/cylindromatosis-mediated negative

regulation. These molecular defects sustain NF-κB transcriptional

activity, resulting in the paracrine secretion of immunosuppressive

cytokines (such as IL-6 and TNF-α) that create a pro-tumorigenic

niche while conferring radioresistance through EMT programming

(50–52).

Of note, the immunogenetic predisposition of NPC

reveals an evolutionary arms race between viral persistence and

host immunity: Genome-wide association studies implicate human

leukocyte antigen A/B (HLA-A/B) class I allele variants in

defective EBV antigen presentation, compromising cytotoxic T-cell

surveillance and enabling viral oncogene-mediated transformation

(53–55). The synergistic interplay between

these cell-intrinsic (CCND1/CDKN2A axis) and cell-extrinsic

(NF-κB-inflammatory loop) drivers, superimposed upon

(HLA)-restricted immune evasion mechanisms, defines the landscape

of the molecular heterogeneity of NPC. Such integrative molecular

cartography not only elucidates the biological basis of the

distinct clinical behavior of NPC but also informs precision

therapeutics, exemplified by the combinatorial targeting of

PI3K/AKT and EGFR axes that converge on dysregulated growth factor

signaling. This multi-layered mechanistic dissection positions NPC

as a paradigm for viro-immunogenetic tumor models requiring

context-specific therapeutic interventions (Fig. 2).

Epigenetic markers

The epigenetic and transcriptional dysregulation of

key genetic elements has emerged as a key mechanism in the

pathogenesis of NPC. One notable example is Septin 9 (SEPT9_v2), a

tumor suppressor gene whose promoter hypermethylation leads to

transcriptional silencing and is closely associated with NPC

progression. Functional studies have demonstrated that SEPT9_v2

suppresses tumor cell proliferation, migration and invasion by

inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade through the

miR-92b-3p/frizzled class receptor 10 axis (55,56).

Conversely, the kinesin family member kinesin family member 23

(KIF23), an established oncogene, is notably overexpressed in NPC

tissues and promotes tumor aggressiveness through the activation of

the same Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Of note, KIF23 expression is

transcriptionally regulated by the androgen receptor, providing a

mechanistic association with the observed sex-specific differences

in NPC incidence and outcomes. Collectively, these findings

underscore the dual role of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as both a

downstream effector and an integrative hub for epigenetic and

hormonal regulation in NPC, positioning SEPT9_v2 and KIF23 as

promising biomarkers for prognostic evaluation and as candidate

targets for therapeutic intervention.

Emerging evidence highlights the key role of

non-coding RNA signatures and epigenetic alterations in shaping the

molecular landscape and clinical trajectory of NPC. Specific miRNA

expression profiles, particularly hsa-miR-142-3p, hsa-miR-29c and

hsa-miR-30e, have shown robust associations with overall survival

and when integrated with clinical parameters, substantially improve

the accuracy of prognostic models. In addition to their

intracellular regulatory functions, miRNAs packaged into exosomes,

such as miR-34a-5p, exert paracrine effects that modulate the TME

and intercellular signaling networks (57,58).

Epigenetic dysregulation, especially DNA

methylation, is another hallmark of NPC. The promoter

hypermethylation of protocadherin 17 (PCDH17) leads to its complete

silencing across NPC cell lines and the functional restoration of

PCDH17 inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses vascular endothelial

growth factor secretion (59). In

addition, differentially methylated regions in genes such as

calcitonin-related polypeptide α, ALX homeobox 4 and homeobox D9

are detectable in cfDNA, laying the foundation for non-invasive

liquid biopsy-based diagnostics (60,61).

Of particular note, the methylation status of SEPT9_v2 and

protocadherin 17 not only holds diagnostic potential but may also

serve as predictive biomarkers for treatment responsiveness,

underscoring the multifaceted utility of epigenetic markers in

early detection, prognosis stratification and therapy

optimization.

Metabolomics markers

Metabolic reprogramming represents a hallmark of

NPC, contributing to tumor progression, invasion and metastasis.

One notable feature of NPC is the abnormal accumulation of

metabolites, such as lactic acid and glutamine, within the TME,

reflecting a shift in energy metabolism and biosynthetic demands

(62). By integrating single-cell

Raman spectroscopy with mass spectrometry, recent studies (63–65)

have revealed markedly elevated levels of unsaturated fatty acids

in highly metastatic NPC cell lines (such as 5-8F and CNE2),

implicating dysregulated lipid metabolism as a driver of metastatic

potential. Complementary NMR-based metabolomics analyses have

identified specific lipoprotein subfractions, very low-density

lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein, as closely associated with

NPC onset. A metabolite-derived risk score incorporating these

lipoproteins demonstrated strong discriminative power in

multicentre cohorts (AUC=0.841), supporting their potential as

early diagnostic and stratification biomarkers (66).

Furthermore, disturbances in amino acid metabolism,

particularly elevated levels of 4-aminobutyric acid, have been

shown to facilitate tumor invasion through the activation of the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, specifically through

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C (67). These findings not only enhance

understanding of the metabolic underpinnings of NPC but also

provide a framework for the development of targeted metabolic

interventions. The integration of multi-omics platforms with

artificial intelligence-aided analysis is expected to further

refine metabolic phenotyping and identify actionable

vulnerabilities in NPC (Fig.

3).

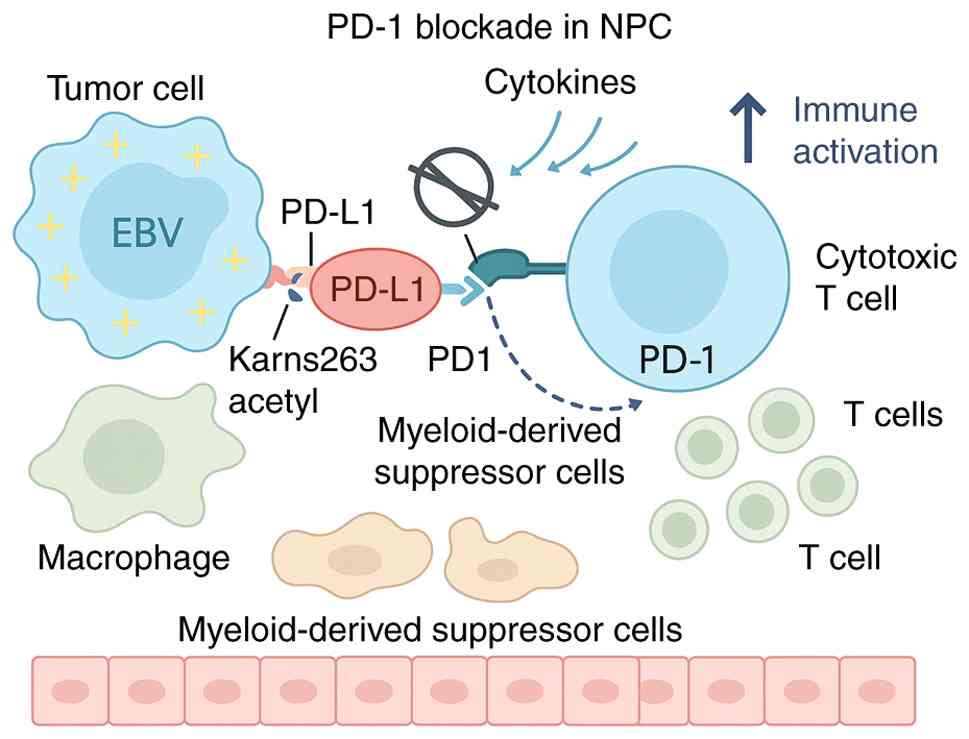

Application and cutting-edge progress of

immunotherapy in NPC

In NPC, an EBV-associated malignancy with pronounced

immune infiltration and viral antigenicity, immune checkpoint

blockade has emerged as a transformative modality. The PD-1/PD-L1

axis plays a central role in immune evasion by impairing cytotoxic

T-cell activation within the TME. High PD-L1 expression, driven in

part by EBV-related inflammation and epigenetic regulation (such as

acetylation-mediated nuclear translocation), suppresses anti-tumor

immunity, enabling tumor persistence (68–70).

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors restore T-cell function and have demonstrated

meaningful clinical efficacy in recurrent/metastatic NPC (R/M

NPC).

Multiple early-phase trials have established the

monotherapeutic activity of PD-1 blockade in pretreated R/M NPC.

The KEYNOTE-028 study reported an objective response rate (ORR) of

25.9% and median overall survival (OS) of 16.5 months with

pembrolizumab (71), while the

NCI-9742 trial showed similar outcomes for nivolumab (ORR, 20.5%;

OS 17.1, months) (72).

Camrelizumab also achieved an ORR of 28.2% in the CAPTAIN trial

(73). However, despite encouraging

activity, monotherapy responses were limited by modest durability

and heterogeneous patient benefit, prompting combination

strategies.

The paradigm shifted with the emergence of

immune-chemotherapy combinations. In the landmark JUPITER-02 trial,

toripalimab plus gemcitabine-cisplatin prolonged progression-free

survival (PFS) to 11.7 vs. 8.0 months with chemotherapy alone,

reducing the risk of mortality by 40% (73). Similar benefits were observed in

NCT03707509 with camrelizumab, further confirming the synergy

between chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death and PD-1

blockade (74). Of note, PD-L1

positivity and EBV DNA clearance were predictive of superior

responses (75), underscoring the

importance of biomarker-driven treatment selection.

Yet, immune resistance remains a key challenge.

Mechanisms include loss of PD-L1 expression, T-cell exhaustion,

immune desertification and neoantigen depletion (75–78).

Tumor-intrinsic alterations, such as NF-κB pathway activation and

cytokine-driven immunosuppression, further impair durable response

(79). To overcome these barriers,

neoadjuvant immunotherapy (such as PD-1 inhibitors preceding ENPG),

immune-antiangiogenic combinations and AI-assisted immune landscape

modeling are being investigated.

In conclusion, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have redefined

the therapeutic landscape of NPC, particularly in the metastatic

setting and are increasingly being integrated into frontline

regimens. Future directions focus on optimizing combinatorial

immunotherapy, identifying predictive biomarkers and tailoring

interventions based on EBV load, TME and host immune features.

These efforts aim to achieve durable functional remission in a

historically therapy-resistant malignancy (Fig. 4).

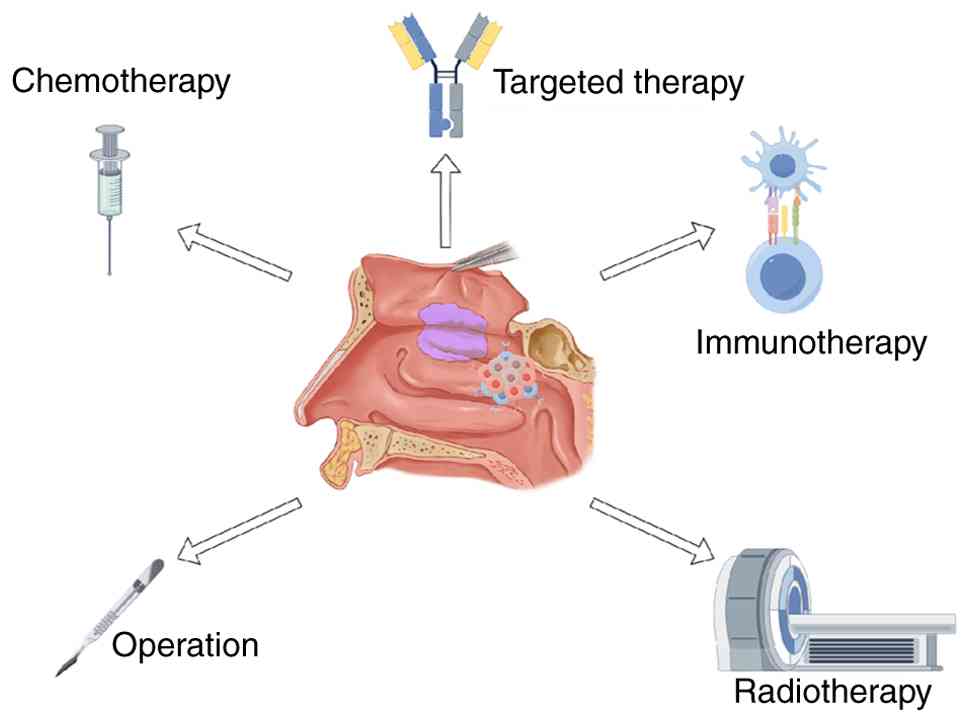

Examination and treatment of NPC

In the early screening system for NPC, endoscopic

technology has progressed from traditional white light observation

to advanced image enhancement stages. Optical enhancement

platforms, represented by narrow band imaging (NBI) and I-scan

virtual chromoendoscopy, have markedly transformed the mucosal

lesion identification system (80–82).

NBI enhances microvascular patterns using narrow-band blue-green

light, excelling in detecting microinvasive lesions with diameters

>5 mm, achieving a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of

93.1%, far surpassing white light endoscopy. I-scan, through

digital image post-processing, enhances vascular morphology and

glandular structure details, identifying potential vascular

abnormalities in white-light negative regions with a detection rate

of 23%, thus making it a powerful secondary screening tool for

high-risk populations. However, challenges in clinical application

remain, such as high false-positive rates, operator dependence and

high equipment costs (83). Future

breakthroughs will likely focus on building a multimodal fusion

intelligent screening system, integrating signals such as EBV DNA

load, TCR subtype typing and AI image recognition, to establish a

new ‘visual + molecular diagnosis’ paradigm for grassroots

applications.

Radiotherapy has long been regarded as the

first-line treatment for early-stage NPC. However, the long-term

survival benefit of re-irradiation is limited (5-year OS <45%),

with a high incidence of complications (such as NP necrosis and

temporal lobe damage), leading to the return of surgery as the core

treatment approach. Traditional open surgical methods, such as

those involving the hard palate or maxillary bone, achieve high

local control rates (10-year OS ≤73.8%) (84–87).

However, their high margin positivity rates (≤29%), postoperative

functional impairment (such as swallowing and facial issues) and

aesthetic damage limit their applicability. The rise of endoscopic

technology (such as ENPG) marks a key turning point in NPC surgical

treatment paradigms. By offering high-definition magnification

views, ENPG allows for precise exposure of the skull base

structures while preserving key anatomy (such as the eustachian

tube and internal carotid artery), achieving a postoperative 5-year

OS improvement to 48–52%, while markedly reducing the incidence of

≥3-grade toxicity events (88,89).

More importantly, the anatomical classification system developed

based on the endoscopic platform, such as the four-segment internal

carotid artery classification for the parapharyngeal segment and

four-level recurring NPC surgical classification, provides key

support for enhancing surgical safety and expanding

indications.

Building on the demonstrated efficacy of ENPG in

treating recurrent NPC, clinical studies have progressively

extended its application to patients with early-stage NPC (90–92).

Several prospective studies indicate that for patients at T1-T2

stage, the combination of ENPG with chemotherapy or low-dose

radiotherapy achieves survival outcomes comparable with those of

standard radiotherapy [3-year OS of 100% and disease-free survival

(DFS) of 95.8–100%]. Of note, ENPG also enhances quality of life

metrics, particularly in preserving salivary gland function,

reducing dry mouth and improving speech function. More importantly,

ENPG successfully meets the dual objectives of precise lesion

resection and functional preservation by shortening the irradiation

path, circumventing the need for repeated radiation and minimizing

the trauma to the adhesion zones (Table

I).

| Table I.Summary of key advances in early

detection technologies for NPC, focusing on innovations in

diagnostic platforms and their clinical applicability. The table

provides an overview of sensitivity, specificity, advantages and

limitations of each method discussed in the manuscript. |

Table I.

Summary of key advances in early

detection technologies for NPC, focusing on innovations in

diagnostic platforms and their clinical applicability. The table

provides an overview of sensitivity, specificity, advantages and

limitations of each method discussed in the manuscript.

| Detection

method | Key technology | Sensitivity

(%) | Specificity

(%) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|

| CRISPR-Cas12a | CRISPR-based | 98.5 | 99.1 | High sensitivity

and | Requires

advanced |

|

(Amplification-free) |

non-amplification |

|

| specificity;

rapid | technology and

trained |

|

| digital

detection |

|

| and

cost-effective | personnel |

| P85 antibody

profiling | Antibody

detection | 97.9 | 98.3 | High positive | Limited

validation |

|

| (P85) |

|

| predictive

value; | across

different |

|

|

|

|

| cost-efficient

for | populations |

|

|

|

|

| mass screening |

|

| T-Cell

receptor | TCR sequencing

of | 98.6 | - | Ultra-early | Not widely

accessible; |

| sequencing | EBV-related

clonal |

|

| prediction of

NPC | requires high- |

|

| expansions |

|

| risk (6–12

months | throughput

sequencing |

|

|

|

|

| prior to

clinical | platforms |

|

|

|

|

| diagnosis) |

|

| Narrow-band

imaging | Optical | 92.3 | 93.1 | Can detect | High false-positive

rate; |

|

| enhancement

with |

|

| micro-invasive |

operator-dependent |

|

| blue-green

light |

|

| lesions <5

mm; |

|

|

|

|

|

| superior to

white |

|

|

|

|

|

| light

endoscopy |

|

| I-Scan virtual | Image

enhancement | 87.5 | - | Enhances

vascular | Limited to

higher-end |

|

chromoendoscopy | for detailed

mucosal | (Stage II) |

| morphology and | equipment;

operator- |

|

| patterns |

|

| glandular

structure | dependent |

|

|

|

|

| detail |

|

Although ENPG is currently used as part of a

multimodal treatment regimen, emerging evidence is gradually

confirming its potential as a standalone therapy for stage INPC. A

10-year retrospective study from the Cancer Center of Sun Yat-sen

University revealed that patients with stage T1N0M0 NPC who

underwent ENPG alone achieved a 100% three-year PFS, markedly

surpassing intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) in terms of

cost-effectiveness and quality of life (93,94).

This finding suggested that minimally invasive surgery could

challenge the established standards of radiotherapy for specific

NPC subtypes. However, this approach remains in its infancy and

current evidence is constrained by small sample sizes and limited

follow-up durations. Future research should prioritize multicenter

randomized controlled trials that incorporate molecular

characteristics, such as EBV DNA load, PD-L1 expression and TME

features. This would enable the development of a more refined

treatment model, emphasizing surgery complemented by

immunoradiotherapy. The focus should be on targeting low-risk

molecular subgroups, with the aim of expanding the role of ENPG as

a curative therapy. Accordingly, ENPG is not recommended beyond

T1-T2 indications and should not be generalized outside centers

with the requisite skull-base expertise; radiotherapy remains the

reproducible standard elsewhere.

Looking ahead, three key strategies are poised to

establish ENPG as a primary treatment modality: i) Preoperative

neoadjuvant therapy, such as PD-1 inhibitors combined with

gemcitabine-platinum regimens, can markedly reduce tumor volume and

broaden surgical indications; ii) intraoperative integration of

AI-assisted navigation, enhanced vascular imaging and robotic

manipulation will lower technical barriers and iii) the

incorporation of multidisciplinary collaboration (involving ENT,

radiotherapy, oncology and immunology) alongside the dynamic

monitoring of EBV load will enable the development of an

individualized treatment decision-making system, ultimately

targeting ‘functional cure’ rather than mere ‘lesion elimination’

(Table II).

| Table II.A comparative analysis of ENPG and

traditional radiotherapy in treating early-stage NPC. This table

highlights key clinical outcomes, functional preservation and the

challenges associated with each treatment modality. |

Table II.

A comparative analysis of ENPG and

traditional radiotherapy in treating early-stage NPC. This table

highlights key clinical outcomes, functional preservation and the

challenges associated with each treatment modality.

| Parameter | ENPG | Traditional

radiotherapy |

|---|

| 5-Year survival

rate | 92.1% | ~90% |

| Negative resection

margins | ≥90% | N/A |

| Functional

preservation | Swallowing, hearing

and cervical mobility preserved | Notable loss in

swallowing, hearing and neck mobility |

|

Radiotherapy-related morbidity | Reduced incidence

of mucosal necrosis, fibrosis and other side effects | High incidence of

mucosal necrosis, neck fibrosis and functional impairments |

| Eligibility | Early-stage (I/II)

and recurrent NPC; precision-based patient selection | Broader

eligibility, including advanced stages |

| Technical

requirements | High precision

surgery; AI-assisted navigation; specialized equipment | High-dose

radiotherapy; established protocols |

| Patient

recovery | Faster recovery;

fewer long-term side effects | Slower recovery;

long-term functional impairments |

| Cost and

accessibility | Expensive; limited

access in low-resource regions | Widely available;

lower initial treatment cost |

Long-term outcomes and functional

assessment

Across available comparative studies, endoscopic

nasopharyngectomy has been explored as an organ-preserving option

in highly selected early-stage disease, with oncologic outcomes

that appear broadly comparable to radiotherapy in some cohorts,

while potentially offering advantages in selected functional

domains; however, the evidence remains limited by small sample

size, centre expertise, and heterogeneity in endpoints and

follow-up (90,93,94).

Beyond oncologic parity, convergent patient-reported data indicate

functional advantages, with higher MDADI scores for

swallowing-related quality of life and lower European Organisation

for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-H and N35 symptom burdens

in xerostomia-linked domains (such as dry mouth and sticky saliva),

consistent with the organ-preserving intent of ENPG (1,3,95).

Accordingly, radiotherapy remains the reproducible standard,

whereas ENPG should be reserved for carefully selected T1-T2

patients in experienced centres, ideally within registries or

prospective trials (90,93). To provide a transparent evidence map

for clinicians and health systems, 5-/10-year survival and

functional readouts were synthesized and summarized in

Supplementary Table SI, annotated

by assessment windows (baseline, 12–24 months, and last follow-up)

and highlighting the heterogeneity of instruments that currently

limits cross-study pooling (93,96–100).

Conclusion

In recent years, notable advances have been made in

the early screening and treatment strategies for NPC, culminating

in the development of a new paradigm of ‘precise

screening-minimally invasive intervention-functional preservation’

(9). In the realm of screening,

continuous innovations in detection technologies for EBV-related

markers have substantially improved diagnostic performance

(18,101). The introduction of

CRISPR/Cas12a-based non-amplification detection and the novel

P85-Ab has enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of NPC

screening to 97.9 and 98.3%, respectively (18,102).

Furthermore, the integration of mRNA multi-marker combined

detection (such as the miR-140-3p triad model) with imaging

techniques, such as NBI and I-scan, marks a notable shift from a

‘single indicator’ approach to a more robust ‘molecular-imaging’

collaborative model (30,82).

In the treatment domain, ENPG has raised the 5-year

survival rate for patients with early-stage NPC to 92.1% through

precise resection and functional preservation. In addition,

quality-of-life metrics, such as swallowing and hearing functions,

are markedly superior when compared with those achieved with

traditional radiotherapy, signifying a shift in treatment goals

from ‘survival first’ to a balanced emphasis on both ‘survival and

quality of life’ (90,93). However, several key challenges

persist, tumor heterogeneity results in limited universality of

markers (such as fluctuations in miR-93 expression) (103); the low penetration of NBI/I-scan

technologies at the grassroots level and the lack of operational

standards hinder their widespread use, and the indications of ENPG

remain confined to early-stage NPC, with long-term efficacy

requiring further large-scale validation (104). EBV-based detection anchors current

non-invasive screening, yet gaps persist in EBV-negative disease

and cross-population generalizability; ENPG remains

indication-bounded (selected T1-T2; experienced centers), with

radiotherapy as the reproducible standard elsewhere (105,106).

Future research should prioritize multi-omics

integration to build AI-driven risk stratification models combining

EBV-related signals with immune and metabolic features.

Surgery-immunotherapy synergy also warrants exploration, including

neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade with ENPG in trial settings and adjuvant

strategies guided by dynamic EBV monitoring. Meanwhile,

standardization and access should be improved through portable

assays and consensus endoscopic grading systems. Multidisciplinary

collaboration across ENT/head-and-neck surgery, oncology and

radiotherapy is essential to implement stage-appropriate precision

care. Finally, multicenter prospective studies with harmonized

endpoints and standardized PROs are required to validate long-term

efficacy and functional benefit.

The diagnosis and treatment of NPC are rapidly

evolving from empirical approaches to precision medicine. By

fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and embracing

technological innovation, the goal of achieving an ‘early diagnosis

rate of >80% and functional preservation rate >90%’ is within

reach. Ultimately, these advancements will help overcome the

persistent challenges in the prevention and control of NPC.

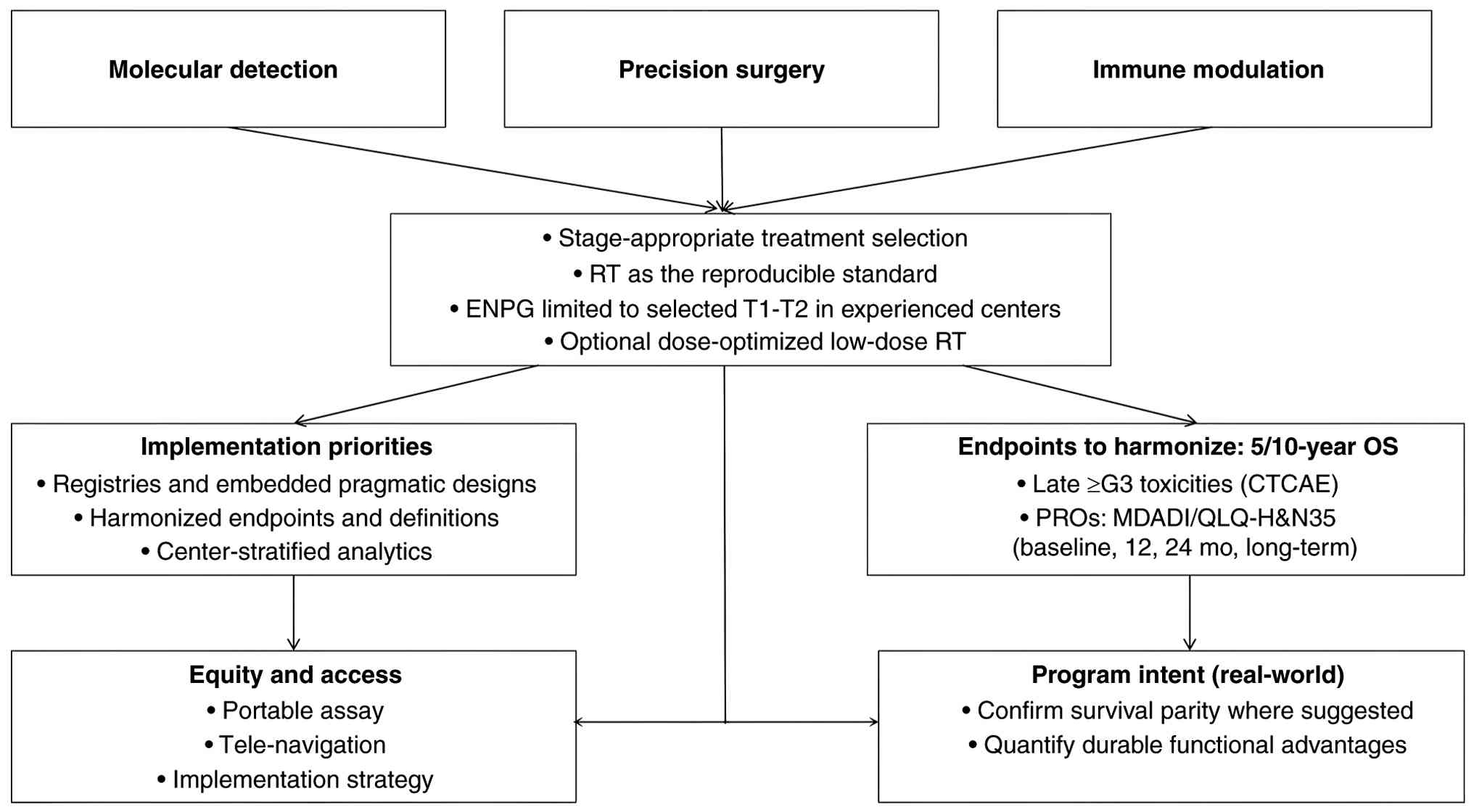

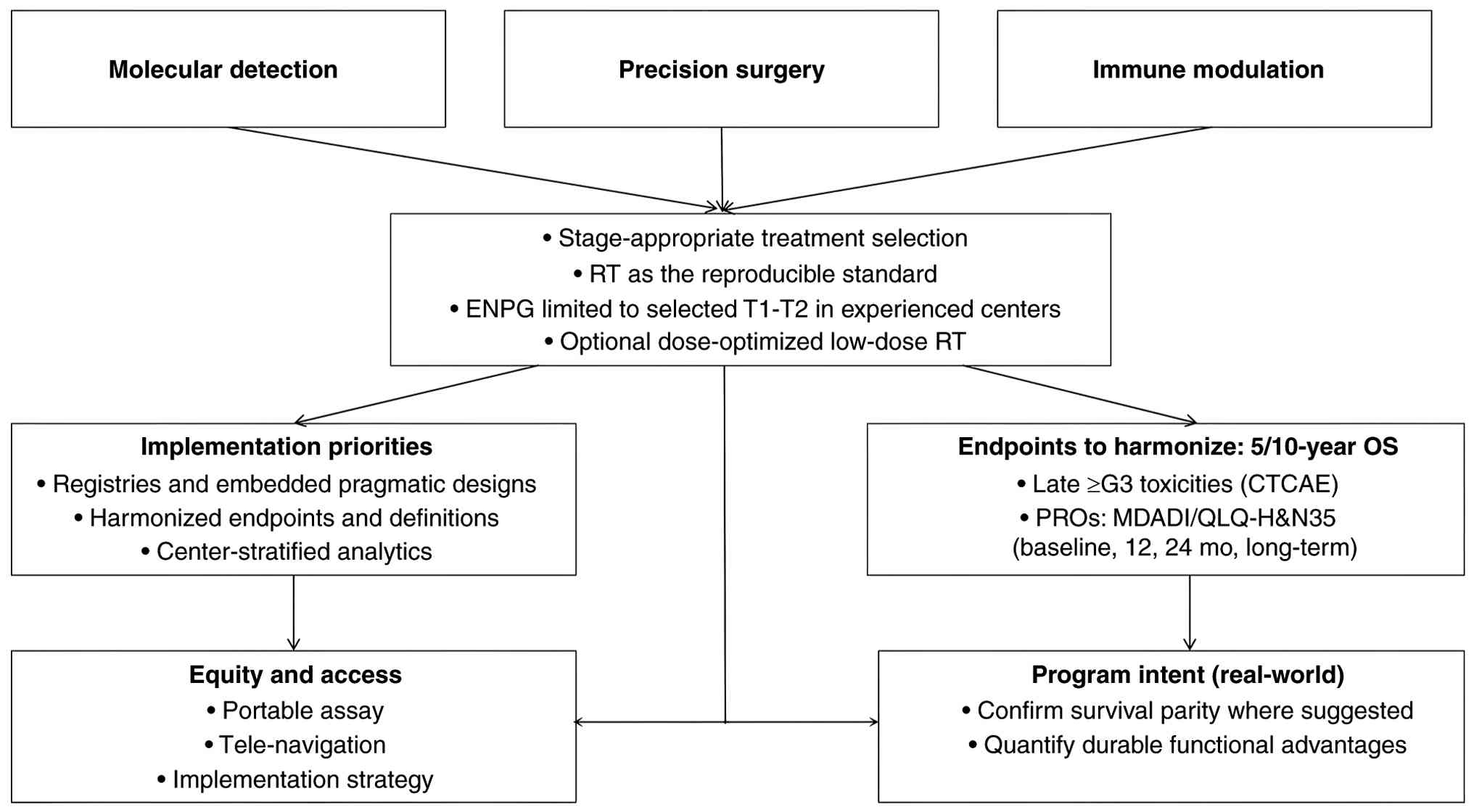

Going forward, the present review will adopt an

indication-bounded pathway anchored by three coordinated axes.

Molecular detection (EBV DNA/methylome cfDNA, TCR and selected

multi-omics) will be deployed as co-screening with predefined

cut-offs and external controls (107,108). Treatment selection remains

stage-appropriate: Radiotherapy as the reproducible standard, and

ENPG reserved for carefully selected T1-T2 in experienced centers

(with optional dose-optimized low-dose RT). Immune modulation

(PD-1/PD-L1) is integrated for high-risk biology and in trial

settings. Implementation will prioritize registries and embedded

pragmatic designs with harmonized endpoints, 5/10-year OS, late ≥G3

toxicities and standardized PROs (MDADI/QLQ-H&N35 at baseline,

12 months, 24 months and long-term), and will explicitly address

equity and access (such as, portable assays, tele-navigation and

center-stratified analytics) (109,110). This program is intended to confirm

survival parity where suggested and to quantify any durable

functional advantages under real-world constraints (Fig. 5).

| Figure 5.Practice-facing outlook for NPC

precision care. NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma. RT, radiotherapy;

ENPG, endoscopic nasopharyngectomy; OS, overall survival; CTCAE,

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; PROs,

patient-reported outcomes; MDADI, MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory;

QLQ-H&N35, EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck

35; mo, months; T1-T2, tumor stage T1-T2; G3, grade 3. |

Limitations

Several constraints temper inference from the

present synthesis. i) Biology and case-mix: EBV-centric algorithms

underperform in EBV-negative NPC and may vary across ethnicities

and prevalence settings; current evidence lacks adequately powered,

externally validated cohorts for these subgroups. ii) Assay and

pipeline heterogeneity: Platforms (qPCR/ddPCR/NGS/CRISPR),

thresholds and pre-analytics (plasma handling, batching) differ

across studies, introducing spectrum and incorporation biases that

limit cross-study pooling. iii) Functional outcomes and toxicity:

PROs (MDADI, QLQ-H&N35) are inconsistently timed and analyzed

(directionality, responder thresholds) and acute vs. late (≥G3)

toxicities are not uniformly separated. iv) Surgical

generalizability: ENPG results largely reflect stringent selection

(T1-T2) and center experience/learning curves; requirements for

navigation, imaging and rescuability restrict applicability in

low-resource settings. v) Long-term endpoints: 10-year OS/DFS and

durable functional stability remain sparse and heterogeneous, with

non-randomized designs susceptible to residual confounding

(adjuvant and salvage policies). vi) Implementation and equity: Few

studies report cost-effectiveness, access or workforce

implications, impeding translation at scale.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

EJ contributed to the study design, literature

search and selection and analysis of the literature/information. WL

and XZ were involved in the writing process, including manuscript

drafting, editing and reviewing, as well as the creation of figures

and tables. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Tang LL, Chen YP, Chen CB, Chen MY, Chen

NY, Chen XZ, Du XJ, Fang WF, Feng M, Gao J, et al: The Chinese

society of clinical oncology (CSCO) clinical guidelines for the

diagnosis and treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 41:1195–1227. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bossi P, Chan AT, Licitra L, Trama A,

Orlandi E, Hui EP, Halámková J, Mattheis S, Baujat B, Hardillo J,

et al: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice

guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

32:452–465. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen YP, Ismaila N, Chua ML, Colevas AD,

Haddad R, Huang SH, Wee JT, Whitley AC, Yi JL, Yom SS, et al:

Chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy for definitive-intent

treatment of stage II–IVA nasopharyngeal carcinoma: CSCO and ASCO

guideline. J Clin Oncol. 39:840–859. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lam WJ, King AD, Miller JA, Liu Z, Yu KJ,

Chua ML, Ma BB, Chen MY, Pinsky BA, Lou PJ, et al: Recommendations

for Epstein-Barr virus-based screening for nasopharyngeal cancer in

high-and intermediate-risk regions. J Natl Cancer Inst.

115:355–364. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cao SM, Liu Z, Jia WH, Huang QH, Liu Q,

Guo X, Huang TB, Ye W and Hong MH: Fluctuations of epstein-barr

virus serological antibodies and risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma:

A prospective screening study with a 20-year follow-up. PLoS One.

6:e191002011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu Y, Huang Q, Liu W, Liu Q, Jia W, Chang

E, Chen F, Liu Z, Guo X, Mo H, et al: Establishment of VCA and

EBNA1 IgA-based combination by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as

preferred screening method for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A

two-stage design with a preliminary performance study and a mass

screening in southern China. Int J Cancer. 131:406–416. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li Y, Wang K, Yin SK, Zheng HL and Min DL:

Expression of Epstein-Barr virus antibodies EA-IgG, Rta-IgG, and

VCA-IgA in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and their use in a combined

diagnostic assay. Genet Mol Res. Mar 18–2016.(Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

8

|

Ai P, Wang T, Zhang H, Wang Y, Song C,

Zhang L, Li Z and Hu H: Determination of antibodies directed at EBV

proteins expressed in both latent and lytic cycles in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 49:326–331. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jiang W, Zheng B and Wei H: Recent

advances in early detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Discov

Oncol. 15:3652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lo KW, To KF and Huang DP: Focus on

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 5:423–428. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wong KC, Hui EP, Lo KW, Lam WKJ, Johnson

D, Li L, Tao Q, Chan KCA, To KF, King AD, et al: Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: An evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:679–695.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang S, Zhou Y, Liu Z, Wang Y, Zhou X,

Chen H, Zhang X, Chen Y, Feng Q, Ye X, et al: Immunosequencing

identifies signatures of T cell responses for early detection of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 43:1423–1441. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ni XG and Wang GQ: The role of narrow band

imaging in head and neck cancers. Curr Oncol Rep. 18:102016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chan JL, Lin L, Feiler M, Wolf AI, Cardona

DM and Gellad ZF: Comparative effectiveness of i-SCAN™ and

high-definition white light characterizing small colonic polyps.

World J Gastroenterol. 18:5905–5911. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lam WKJ, Jiang P, Chan KCA, Cheng SH,

Zhang H, Peng W, Tse OYO, Tong YK, Gai W, Zee BCY, et al:

Sequencing-based counting and size profiling of plasma Epstein-Barr

virus DNA enhance population screening of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:E5115–E5124. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu X, Tay JK, Goh CK, Chan C, Lee YH,

Springs SL, Wang Y, Loh KS, Lu TK and Yu H: Digital CRISPR-based

method for the rapid detection and absolute quantification of

nucleic acids. Biomaterials. 274:1208762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jiang C, Zheng X, Lin L, Li X, Li X, Liao

Y, Jia W and Shu B: CRISPR Cas12a-mediated amplification-free

digital DNA assay improves the diagnosis and surveillance of

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Biosens Bioelectron. 237:1155462023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li T, Li F, Guo X, Hong C, Yu X, Wu B,

Lian S, Song L, Tang J, Wen S, et al: Anti-Epstein-Barr virus

BNLF2b for mass screening for nasopharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med.

389:808–819. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pan YX, Huang Q, Xing S and Zhu QY: A

novel serum protein biomarker for the late-stage diagnosis of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 25:5852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ji MF, He YQ, Tang MZ, Xue WQ, Yu X, Diao

H, Yang DW, Mai ZM, Cheong IH and Zhao ZY: Epstein Barr virus

antibody and cancer risk in two prospective cohorts in Southern

China. Nat Commun. 16:59402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu Y, Zhao W, Mo Y, Ma N, Midorikawa K,

Kobayashi H, Hiraku Y, Oikawa S, Zhang Z and Huang G: Combination

of RERG and ZNF671 methylation rates in circulating cell-free DNA:

A novel biomarker for screening of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer

Sci. 111:2536–2545. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hsu CL, Chang YS and Li HP: Molecular

diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Past and future. Biomed J.

48:1007482025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Islam KA, Chow LKY, Kam NW, Wang Y, Chiang

CL, Choi HCW, Xia YF, Lee AWM, Ng WT and Dai W: Prognostic

biomarkers for survival in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A systematic

review of the literature. Cancers. 14:20222122.

|

|

24

|

Li G, Wu Z, Peng Y, Liu X, Lu J, Wang L,

Pan Q, He ML and Li XP: MicroRNA-10b induced by Epstein-Barr

virus-encoded latent membrane protein-1 promotes the metastasis of

human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 299:29–36. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Allaya N, Khabir A, Sallemi-Boudawara T,

Sellami N, Daoud J, Ghorbel A, Frikha M, Gargouri A,

Mokdad-Gargouri R and Ayadi W: Over-expression of miR-10b in NPC

patients: Correlation with LMP1 and Twist1. Tumor Biol.

36:3807–3814. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen Y, Lin T, Tang L, He L and He Y:

MiRNA signatures in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Molecular mechanisms

and therapeutic perspectives. Am J Cancer Res. 13:5805–5824.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang Y and Xu Z: miR-93 enhances cell

proliferation by directly targeting CDKN1A in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 15:1723–1727. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhou W, Chang A, Zhao H, Ye H, Li D and

Zhuo X: Identification of a novel microRNA profile including

miR-106b, miR-17, miR-20b, miR-18a and miR-93 in the metastasis of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 27:533–539. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Duan B, Shi S, Yue H, You B, Shan Y, Zhu

Z, Bao L and You Y: Exosomal miR-17-5p promotes angiogenesis in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma via targeting BAMBI. J Cancer.

10:6681–6692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang H, Zou X, Wu L, Zhang S, Wang T, Liu

P, Zhu W and Zhu J: Identification of a 7-microRNA signature in

plasma as promising biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma

detection. Cancer Med. 9:1230–1241. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zou X, Zhu D, Zhang H, Zhang S, Zhou X, He

X, Zhu J and Zhu W: MicroRNA expression profiling analysis in serum

for nasopharyngeal carcinoma diagnosis. Gene. 727:1442432020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Jiang C, Chen J, Xie S, Zhang L, Xiang Y,

Lung M, Kam NW, Kwong DL, Cao S and Guan XY: Evaluation of

circulating EBV microRNA BART2-5p in facilitating early detection

and screening of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer.

143:3209–3217. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lyu X, Fang W, Cai L, Zheng H, Ye Y, Zhang

L, Li J, Peng H, Cho WC, Wang E, et al: TGFβR2 is a major target of

miR-93 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma aggressiveness. Mol Cancer.

13:512014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yang W, Tan S, Yang L, Chen X, Yang R,

Oyang L, Lin J, Xia L, Wu N, Han Y, et al: Exosomal miR-205-5p

enhances angiogenesis and nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis by

targeting desmocollin-2. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 24:612–623. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hsia B, Sure A, Dongre R, Jo N, Kuzniar J,

Bitar G, Alshaka SA, Kim JD, Valencia-Sanchez BA, Brandel MG, et

al: Molecular profiling of nasopharyngeal carcinoma using the AACR

project GENIE repository. Cancers (Basel). 17:15442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wan X, Liu Y, Peng Y, Wang J, Yan SM,

Zhang L, Wu W, Zhao L, Chen X, Ren K, et al: Primary and orthotopic

murine models of nasopharyngeal carcinoma reveal molecular

mechanisms underlying its malignant progression. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e24031612024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen W, Yang KB, Zhang YZ, Lin ZS, Chen

JW, Qi SF, Wu CF, Feng GK, Yang DJ, Chen M, et al: Synthetic

lethality of combined ULK1 defection and p53 restoration induce

pyroptosis by directly upregulating GSDME transcription and

cleavage activation through ROS/NLRP3 signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 43:2482024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Agaoglu FY, Dizdar Y, Dogan O, Alatli C,

Ayan I, Savci N, Tas S, Dalay N and Altun M: P53 overexpression in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In Vivo. 18:555–560. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li YY, Chung GT, Lui VW, To KF, Ma BB,

Chow C, Woo JKS, Yip KY, Seo J, Hui EP, et al: Exome and genome

sequencing of nasopharynx cancer identifies NF-κB pathway

activating mutations. Nat Commun. 8:141212017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Papa A and Pandolfi PP: The PTEN-PI3K axis

in cancer. Biomolecules. 9:1532019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang S, Hong HI, Mak VCY, Zhou Y, Lu Y,

Zhuang G and Cheung LWT: Vertical inhibition of p110α/AKT and

N-cadherin enhances treatment efficacy in PIK3CA-aberrated ovarian

cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 19:1132–1154. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Shamsuri AS and Sim EU: In silico

prediction of the action of bromelain on PI3K/Akt signalling

pathway to arrest nasopharyngeal cancer oncogenesis by targeting

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit

alpha protein. BMC Res Notes. 17:3462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhou Z, Li P, Zhang X, Xu J, Xu J, Yu S,

Wang D, Dong W, Cao X, Yan H, et al: Mutational landscape of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on targeted next-generation

sequencing: Implications for predicting clinical outcomes. Mol Med.

28:552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhu Q, Duan XB, Hu H, You R, Xia TL, Yu T,

Xiang T and Chen MY: EBV-induced upregulation of CD55 reduces the

efficacy of cetuximab treatment in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J

Transl Med. 22:11112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Piao Y, Yang Y, Wu S and Han L:

Toripalimab plus cetuximab combined with radiotherapy in a locally

advanced platinum-based chemotherapy-insensitive nasopharyngeal

carcinoma patient: A case report. Front Oncol. 14:13832502024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Fang Y, Lv X, Li G, Wang P, Zhang L, Wang

R, Jia L and Liang S: Schisandrin B targets CDK4/6 to suppress

proliferation and enhance radiosensitivity in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma by inducing cell cycle arrest. Sci Rep. 15:84522025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Li HP, Huang CY, Lui KW, Chao YK, Yeh CN,

Lee LY, Huang Y, Lin TL, Kuo YC, Huang MY, et al: Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma patient-derived xenograft mouse models reveal potential

drugs targeting cell cycle, mTOR, and autophagy pathways. Transl

Oncol. 38:1017852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Li HP, Huang CY, Lui KW, Chao YK, Yeh CN,

Lee LY, Huang Y, Lin TL, Kuo YC, Huang MY, et al: Combination of

epithelial growth factor receptor blockers and CDK4/6 inhibitor for

nasopharyngeal carcinoma treatment. Cancers (Basel). 13:29542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liao LJ, Hsu WL, Chen CJ and Chiu YL:

Feature reviews of the molecular mechanisms of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. Biomedicines. 11:15282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Tao W, Jiang C, Velu P, Lv C and Niu Y:

Rosmanol suppresses nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation and

enhances apoptosis, the regulation of MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 72:e27502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liang Y, Xiong XY, Lin GW, Bai X, Li F, Ko

JM, Zhou YH, Xu AY, Liu SQ, He S, et al: Integrative

transcriptome-wide association study with expression quantitative

trait loci colocalization identifies a causal VAMP8 variant for

nasopharyngeal carcinoma susceptibility. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24125802025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wang Y, Chen Y, Liu Y, Zhao J, Wang G,

Chen H, Tang Y, Ouyang D, Xie S, You J, et al: Tumor vascular

endothelial cells promote immune escape by upregulating PD-L1

expression via crosstalk between NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways

in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 16:1292025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang R, Hu Y, Yindom LM, Huang L, Wu R,

Wang D, Chang C, Rostron T, Dong T and Wang X: Association analysis

between HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 with nasopharyngeal

carcinoma among a Han population in Northwestern China. Hum

Immunol. 75:197–202. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Barber LD, Percival L, Valiante NM, Chen

L, Lee C, Gumperz JE, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Bigge JC, Parekh RB

and Parham P: The inter-locus recombinant HLA-B*4601 has high

selectivity in peptide binding and functions characteristic of

HLA-C. J Exp Med. 184:735–740. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Su WH, Chiu CC and Shugart YY:

Heterogeneity revealed through meta-analysis might link

geographical differences with nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence in

Han Chinese populations. BMC Cancer. 15:5982015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Xu H, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Zhang L,

Kang J, Ning C, He Z and Song S: KIF23, under regulation by

androgen receptor, contributes to nasopharyngeal carcinoma

deterioration by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Funct Integr Genomics. 23:1162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ji Y, Wang M, Li X and Cui F: The long

noncoding RNA NEAT1 targets miR-34a-5p and drives nasopharyngeal

carcinoma progression via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Yonsei Med J.

60:336–345. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Song P, Ye LF, Zhang C, Peng T and Zhou

XH: Long non-coding RNA XIST exerts oncogenic functions in human

nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting miR-34a-5p. Gene. 592:8–14.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yang S, Dai Z, Li W, Wang R and Huang D:

Aberrant promoter methylation reduced the expression of

protocadherin 17 in nasopharyngeal cancer. Biochem Cell Biol.

97:364–368. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Loyo M, Brait M, Kim MS, Ostrow KL, Jie

CC, Chuang AY, Califano JA, Liégeois NJ, Begum S, Westra WH, et al:

A survey of methylated candidate tumor suppressor genes in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 128:1393–1403. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Li T, Patel KB, Yu X, Yao S, Wang L, Chung

CH and Wang X: Unveiling targeted cell-free DNA methylation regions

through paired methylome analysis of tumor and normal tissues.

bioRxiv. 29:10.1101/2023.06.27.546654. 2023.

|

|

62

|

Xu J, Chen D, Wu W, Ji X, Dou X, Gao X, Li

J, Zhang X, Huang WE and Xiong D: A metabolic map and artificial

intelligence-aided identification of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via a

single-cell Raman platform. Br J Cancer. 130:1635–1646. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Yi L, Dong N, Shi S, Deng B, Yun Y, Yi Z

and Zhang Y: Metabolomic identification of novel biomarkers of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. RSC Advances. 4:59094–59101. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Liao Z, Zhao L, Zhong F, Zhou Y, Lu T, Liu

L, Gong X, Li J and Rao J: Serum and urine metabolomics analyses

reveal metabolic pathways and biomarkers in relation to

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 37:e94692023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhou J, Deng Y, Huang Y, Wang Z, Zhan Z,

Cao X, Cai Z, Deng Y, Zhang L, Huang H, et al: An individualized

prognostic model in patients with locoregionally advanced

nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on serum metabolomic profiling. Life

(Basel). 13:11672023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Zhou Z, Tang T, Li N, Zheng Q, Xiao T,

Tian Y, Sun J, Zhang L, Wang X, Wang Y, et al: VLDL and LDL

subfractions enhance the risk stratification of individuals who

underwent epstein-barr virus-based screening for nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: A multicenter cohort study. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e23087652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu H, Wang J, Wang L, Tang W, Hou X, Zhu

YZ and Chen X: Multi-omics exploration of the mechanism of curcumol

to reduce invasion and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by

inhibiting NCL/EBNA1-mediated UBE2C upregulation. Biomolecules.

14:11422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Nie RC, Zhao CB, Xia XW, Luo YS, Wu T,

Zhou ZW, Yuan SQ, Wang Y and Li YF: The efficacy and safety of

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in combination with conventional therapies

for advanced solid tumors: A meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int.

2020:50590792020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhou S, Zhu J, Xu J, Gu B, Zhao Q, Luo C,

Gao Z, Chin YE and Cheng X: Anti-tumour potential of PD-L1/PD-1

post-translational modifications. Immunology. 167:471–481. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Lu MM and Yang Y: Exosomal PD-L1 in cancer

and other fields: Recent advances and perspectives. Front Immunol.

15:13953322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Hsu C, Lee SH, Ejadi S, Even C, Cohen RB,

Le Tourneau C, Mehnert JM, Algazi A, van Brummelen EMJ, Saraf S, et

al: Safety and antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in patients with

programmed death-ligand 1-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma:

Results of the KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 35:4050–4056. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ma BBY, Lim WT, Goh BC, Hui EP, Lo KW,

Pettinger A, Foster NR, Riess JW, Agulnik M, Chang AYC, et al:

Antitumor activity of nivolumab in recurrent and metastatic

nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An international, multicenter study of

the mayo clinic phase 2 consortium (NCI-9742). J Clin Oncol.

36:1412–1418. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yang Y, Zhou T, Chen X, Li J, Pan J, He X,

Lin L, Shi YR, Feng W, Xiong J, et al: Efficacy, safety, and

biomarker analysis of camrelizumab in previously treated recurrent

or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (CAPTAIN study). J

Immunother Cancer. 9:e0037902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Yang Y, Qu S, Li J, Hu C, Xu M, Li W, Zhou

T, Shen L, Wu H, Lang J, et al: Camrelizumab versus placebo in

combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin as first-line treatment

for recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (CAPTAIN-1st):

A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 22:1162–1174. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Shi Y, Han G, Zhou J, Shi X, Jia W, Cheng

Y, Jin Y, Hua X, Wen T, Wu J, et al: Toripalimab plus bevacizumab

versus sorafenib as first-line treatment for advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma (HEPATORCH): A randomised, open-label,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10:658–670. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Xue J, Ma T and Zhang X: TRA2: The

dominant power of alternative splicing in tumors. Heliyon.

9:e155162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Xiao M, Xue J and Jin E: SPOCK: Master

regulator of malignant tumors (Review). Mol Med Rep. 30:2312024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Briante R, Zhai Q, Mohanty S, Zhang P,

O'Connor A, Misker H, Wang W, Tan C, Abuhay M, Morgan J, et al:

Successful targeting of multidrug-resistant tumors with bispecific

antibodies. Mabs. 17:24922382025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Li D, Wang J, Li X, Wang Z, Yu Q, Koh SB,

Wu R, Ye L, Guo Y, Okoli U, et al: Interactions between

radiotherapy resistance mechanisms and the tumor microenvironment.

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 210:1047052025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kumazawa Y, Ikenoyama Y, Takamatsu M, Kido

K, Namikawa K, Tokai Y, Yoshimizu S, Horiuchi Y, Ishiyama A, Yoshio

T, et al: ]Differences in clinical characteristics between missed

and detected laryngopharyngeal cancers. J Gastroenterol Hepatol.

40:2037–2045. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

He R, Jie P, Hou W, Long Y, Zhou G, Wu S,

Liu W, Lei W, Wen W and Wen Y: Real-time artificial

intelligence-assisted detection and segmentation of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma using multimodal endoscopic data: A multi-center,

prospective study. EClinicalMedicine. 81:1031202025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Si YF, Deng ZX, Weng JJ, Si JY, Lan GP,

Zhang BJ, Yang Y, Huang B, Han X, Qin Y, et al: A study on the

value of narrow-band imaging (NBI) for the general investigation of

a high-risk population of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). World J

Surg Oncol. 16:1262018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Filauro M, Vallin A, Fragale M, Sampieri

C, Guastini L, Mora F and Peretti G: Office-based procedures in

laryngology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 41:243–247. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Wu KP, Li QQ, Luo XQ, Wang XX, Lai YZ,

Tian D, Yang HC, Wei XL, Wang LY, Li QM, et al: Chemoimmunotherapy

as induction treatment in concurrent chemoradiotherapy for patients

with nasopharyngeal carcinoma stage IVa. Ann Med. 57:24530912025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lan K, Liu S, Li S, Sun X, Xie S, Jia G,

Sun R and Mai H: Comparing outcomes and toxicities among patients

with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with daytime versus evening

radiotherapy: A retrospective analysis with propensity score

matching. Int J Cancer. 157:345–354. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Liang YJ, Luo MJ, Wen DX, Wang P, Tang LQ,

Mai HQ and Liu LT: Optimal induction chemotherapy courses in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the IMRT era: A recursive partitioning

risk stratification analysis based on EBV DNA and AJCC staging.

Oral Oncol. 167:1074042025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Lin SJ, Guo QJ, Liu Q, Ng WT, Ahn YC,

AlHussain H, Chan AW, Chow J, Chua M, Corry J, et al: International

consensus guideline on delineation of the clinical target volumes

(CTV) at different dose levels for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (2024

Version). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 123:415–421. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Qiu QH, Li N, Zhang QH, Chen Z, Huang Y,

Jiang Y and Yang XT: Clinical efficacy of endoscopic

nasopharyngectomy for initially diagnosed advanced nasopharyngeal