Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) ranks as the second most

prevalent solid tumor among men, and its incidence and mortality

rates are on the rise, particularly in developed countries. This

increase can be attributed to several factors, including an aging

population, improved screening practices and heightened awareness

of the disease (1,2). Treatment options are diverse and may

include active surveillance, chemotherapy, radiation therapy,

hormone therapy, surgical procedures and cryotherapy (3). Despite these approaches, the

development of hormone resistance remains a notable challenge

(4). However, the detailed

mechanism underlying the development of PCa, particularly

castration-resistant PCa (CRPC), remains elusive thus far.

Challenges persist in implementing chemotherapy, targeted therapy

and immunotherapy for high-risk PCa and CRPC (5–7).

Consequently, there is an immediate need to discover and validate

robust biomarkers for improved diagnostic applications.

The preservation of genomic integrity depends

largely on the accuracy and precision of DNA replication.

Nevertheless, this crucial process faces several internal and

external stresses that can greatly affect the overall stability of

the genome (8,9). DNA replication stress refers to a

range of challenges that hinder, obstruct or halt the process of

DNA replication (10,11). Tumor cells frequently experience

chronic replication stress as a result of a weakened replication

stress response, reduced activity of repair proteins and persistent

signaling for proliferation (12–15).

This greatly contributes to genomic instability and abnormal cell

growth in tumors (12,14). In addition, reproduction involves an

intricate process where DNA is accurately duplicated (11). DNA replication stress, which

disrupts this tightly controlled process, can lead to genomic

instability and may ultimately promote the onset and advancement of

tumor formation (11). Recent

research reported that DNA replication stress is a notable

characteristic of advanced PCa (16). Therefore, identifying prognostic

genes associated with this stress could enhance risk assessment and

inform treatment strategies for PCa (16).

Cancer cells must reprogram their metabolism to meet

the heightened energy demands and produce the building blocks

necessary for rapid tumor growth (17). In the case of PCa, cells often gain

energy through de novo lipid synthesis to produce fatty

acids. This metabolic shift towards a lipogenic phenotype is a

crucial turning point in the development of PCa (18,19).

The Warburg effect is characterized by a change in the preferred

energy production pathway. Unlike normal cells, which primarily

produce ATP through oxidative phosphorylation, cancer cells,

including PCa cells, preferentially undergo aerobic glycolysis to

generate ATP (20,21). For normal prostate epithelial cells,

utilizing glucose to produce citrate and releasing it as part of

the process is an unusual and inefficient way of energy metabolism.

During the transformation to PCa, cells shift from this inefficient

energy metabolism to a more efficient one (22,23).

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a heterotrimeric protein

complex, serves a vital role in regulating metabolism and energy

homeostasis (24). Under metabolic

stress conditions, AMPK can conserve cellular energy and viability

by modulating metabolism and key biological functions (24). Studies have reported that AMPK

activation provides strong protective effects against the

progression of PCa, both in the early and late stages of the

disease (25). Thus, energy

homeostasis is a critical factor in the progression of PCa.

In the present study, PCa-related datasets obtained

from public databases, as well as DNA replication stress-related

genes (DRGs) and energy homeostasis-related genes (EHRGs) were

utilized to explore the mechanisms of PCa. Differential expression

analysis, enrichment analyses were performed to explore potential

key mechanisms in PCa. In addition, biomarkers were identified by

expression validation. The genes were further transfected into PC-3

cells to regulate the expression of the biomarkers, and cancer cell

proliferation was evaluated using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

assay. Furthermore, cancer cell migration was assessed using cell

scratch and Transwell migration assays to explore the prognostic

impact of the biomarkers. This comprehensive analysis provided new

targets for the diagnosis of PCa.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Transcriptomic data and corresponding clinical

features [including age, tumor (T) and node (N) stage, Gleason

grade and relapse-free survival (RFS)] for The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA)-prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) were downloaded from the UCSC

Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/), with a total of

551 samples. After screening, 532 samples were obtained, with

PCa:Control=481:51. A total of 409 of the PCa samples had survival

information and biochemical recurrence (BCR) information. GSE103512

(GPL13158), GSE21034 (GPL10264), GSE70770 (GPL10558) and GSE54460

(GPL11154) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/),

and each dataset was subjected to independent analysis. GSE103512

comprised 60 PCa samples along with seven control samples.

Similarly, GSE21034 and GSE70770 contained PCa:Control=150:29 and

PCa:Control=219:74, respectively, and GSE54460 contained 106 PCa

samples, of which 96 samples without a recurrence time 0 were

retained. The sample information of the five datasets are presented

in Table SI. In addition, 982 DRGs

were identified from the literature (26) and 78 EHRGs were obtained from the

Gene Ontology (GO) database (GO:0097009; R package org.hs.eg.db;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/org.Hs.eg.db/).

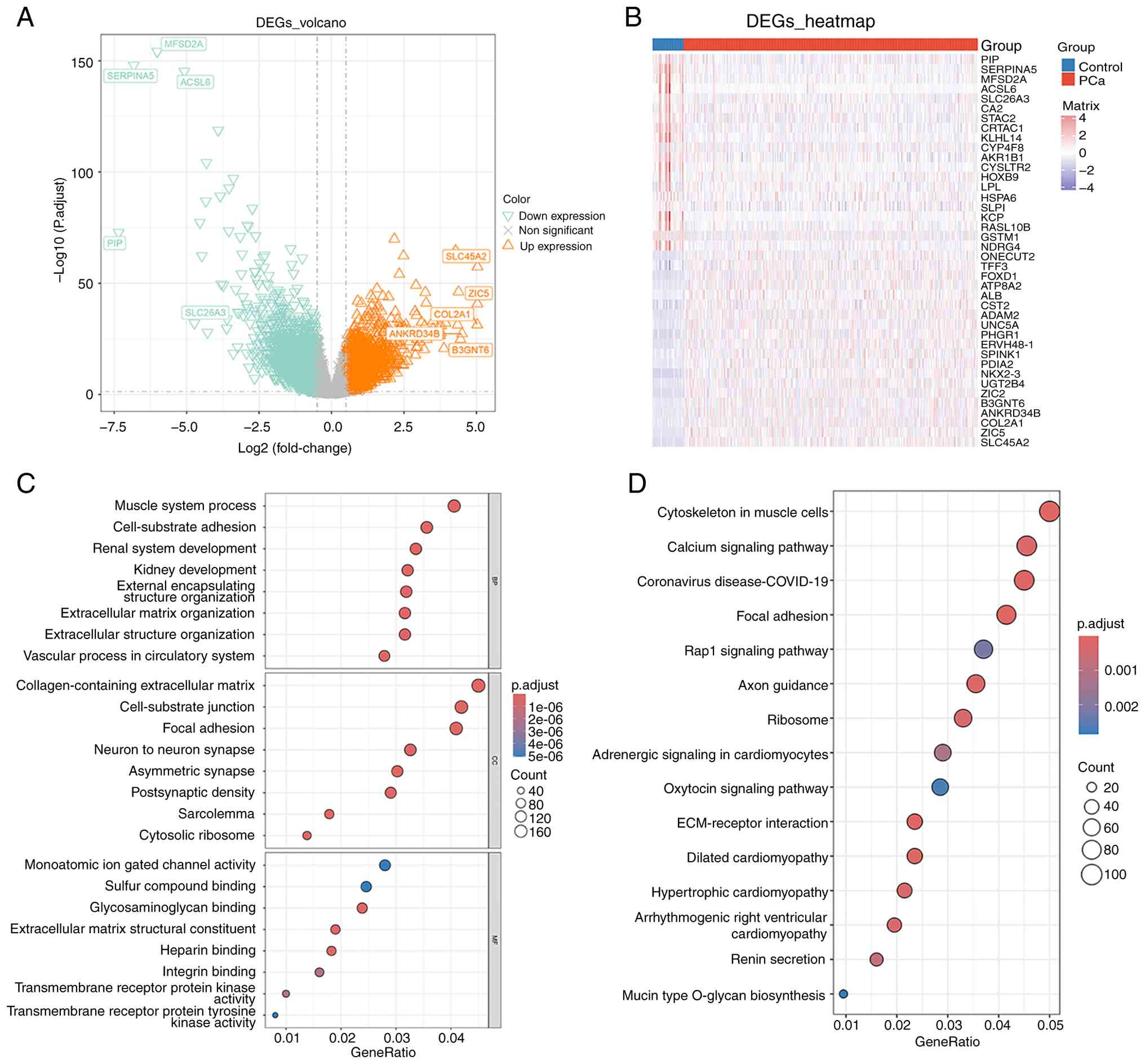

Identification and enrichment analysis

of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in PCa

To identify DEGs between PCa and control samples in

the TCGA-PRAD dataset, the DESeq2 (v 1.36.0) package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/DESeq2/) was

employed (adj.P<0.05 and |Log2 fold change|>0.5).

Subsequently, the ggplot2 (v3.3.6; http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2) and

pheatmap (v1.0.12) packages (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap) were

utilized to plot the volcano map and heatmap, respectively

(27). Finally, the clusterProfiler

(v4.7.1.001) package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler/)

analyzed the biological functions for DEGs for GO and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment (P<0.05).

The results were then visualized using the GOplot (v1.0.2;

http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=GOplot) and

enrichplot (v1.16.2) (https://bioconductor.org/packages/enrichplot/)

packages.

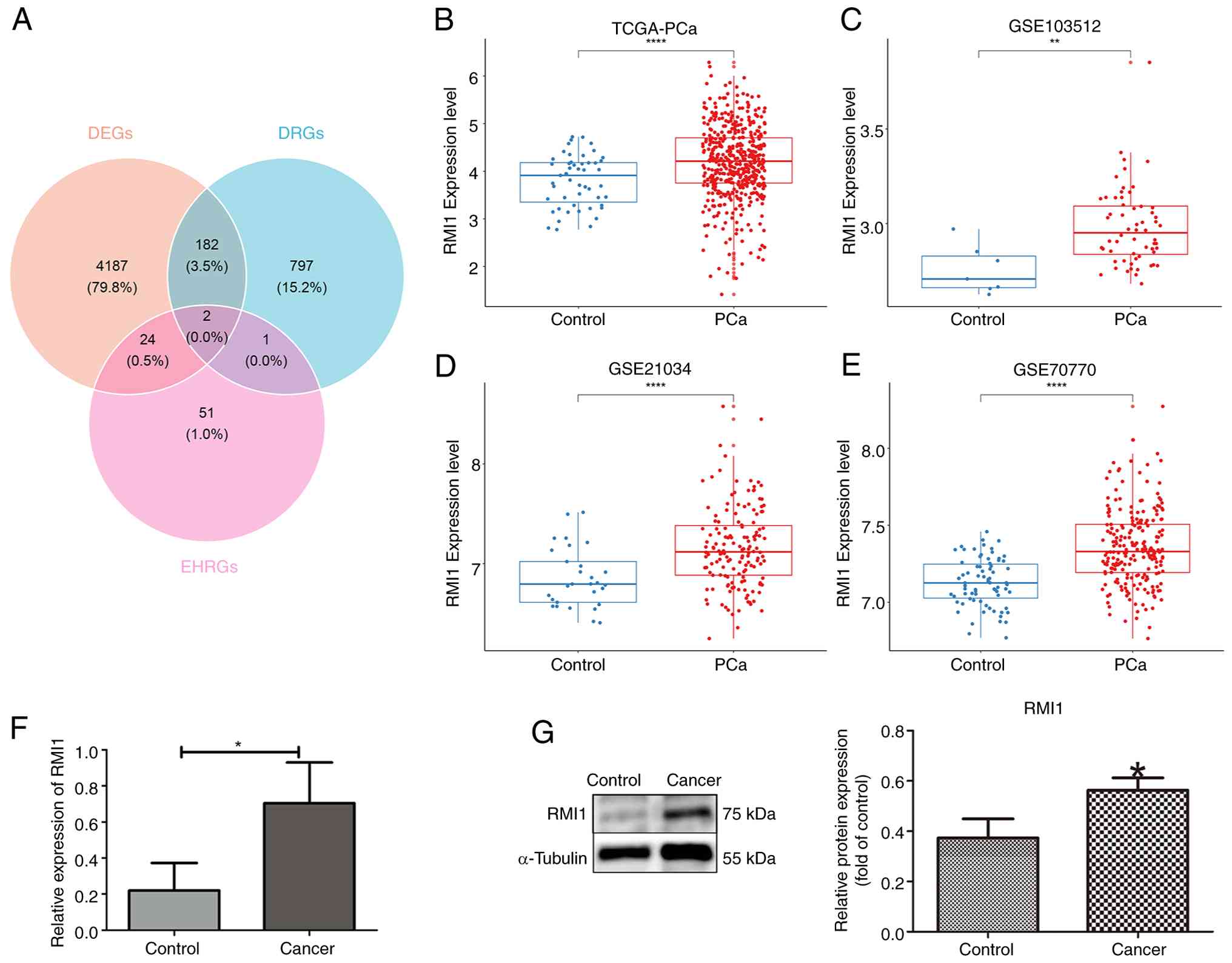

Identification of biomarkers

Candidate biomarkers were identified from the

intersection between DEGs, DRGs and EHRGs using the ggvenn (v0.1.9)

package (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggvenn).

Additionally, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to assess the

expression level of candidate biomarkers between PCa and control

groups in the TCGA-PRAD, GSE103512, GSE21034 and GSE70770 datasets

(P<0.05). The mRNA expression and protein contents of candidate

biomarkers were determined using western blotting and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR, respectively. Finally, genes

with consistent expression and significant difference in both four

datasets and experiments (western blotting and RT-qPCR) were

identified as biomarkers.

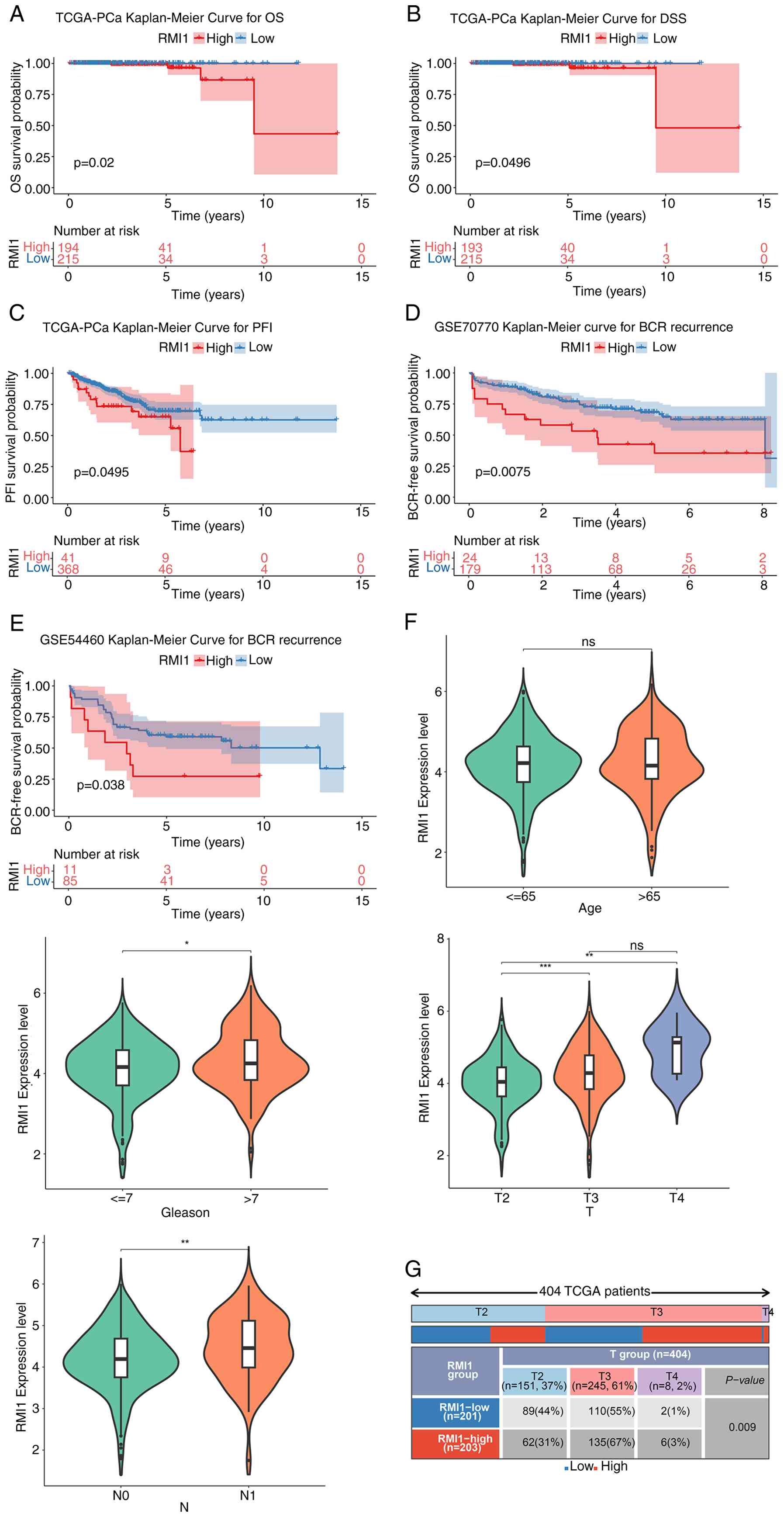

Survival difference and clinical

association analysis

According to the expression levels of biomarkers

among PCa samples in the TCGA-PRAD dataset, they were divided into

high- and low-expression groups, utilizing the optimal cut-off

value for expression as the boundary using the surv_cutpoint

function in the survminer (v0.4.9) package (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer).

Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves for the expression groups were

then plotted using the survminer (v0.4.9) package to determine the

difference in overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival

(DSS), disease-free interval (DFI) progression-free interval (PFI)

and RFS between the two expression groups. Meanwhile, the survival

difference between two expression groups was compared using the

log-rank test. Furthermore, the difference in biomarkers between

different subtypes of clinical characteristics were compared in the

TCGA-PRAD dataset and the results was visualized using a violin

plot using the ggplot2 (v3.3.6) package (P<0.05). Finally, the

χ2 test was used to assess the distribution of several

clinical features between two expression groups.

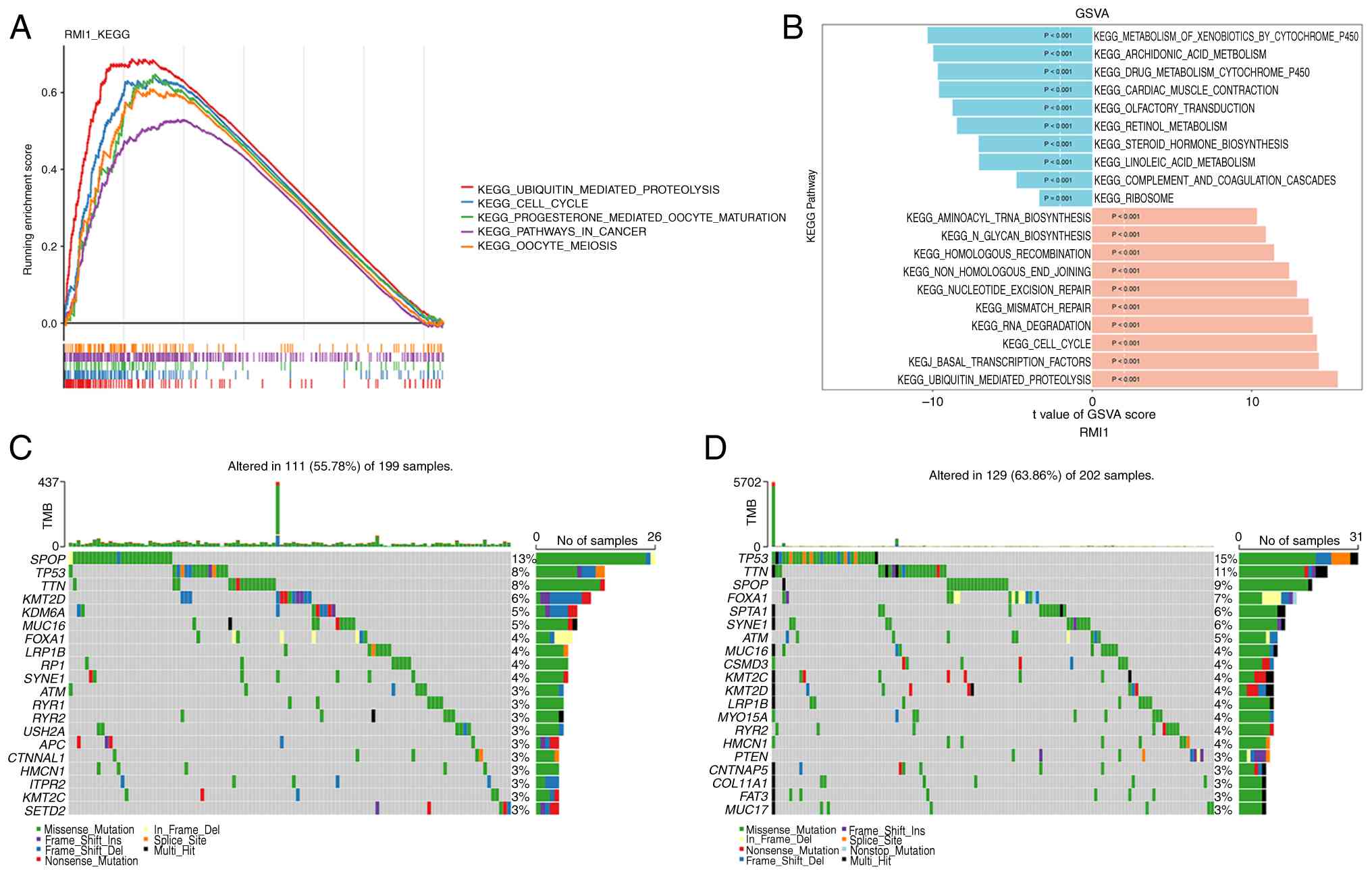

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

and gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

To elucidate the biological processes associated

with the identified biomarkers which were involved in PCa, the

c2.cp.kegg.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set was used as reference

gene set from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB; http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/human/collections.jsp)

using the clusterProfiler (v4.7.1.001) package. Spearman's

correlation analysis of the biomarkers with all genes in the

TCGA-PRAD dataset was performed and they were then ranked according

to the correlation coefficient. The ranked genes were then analyzed

for GSEA enrichment and the results of the top 5 pathways from

largest to smallest were visualized based on their |normalized

enrichment score (NES)| values (|NES|>1; P<0.05). To further

assess pathway changes between two expression groups in the

TCGA-PRAD dataset, and based on the

c2.cp.kegg.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set from the MSigDB, the

GSVA (v1.44.5; http://bioconductor.org/packages/GSVA/) and limma (v

3.52.4) packages (https://bioconductor.org/packages/limma/) were used to

calculate GSVA scores for each pathway and to compare the GSVA

score differences of all KEGG pathways between the two expression

groups (|t|>2; P<0.05).

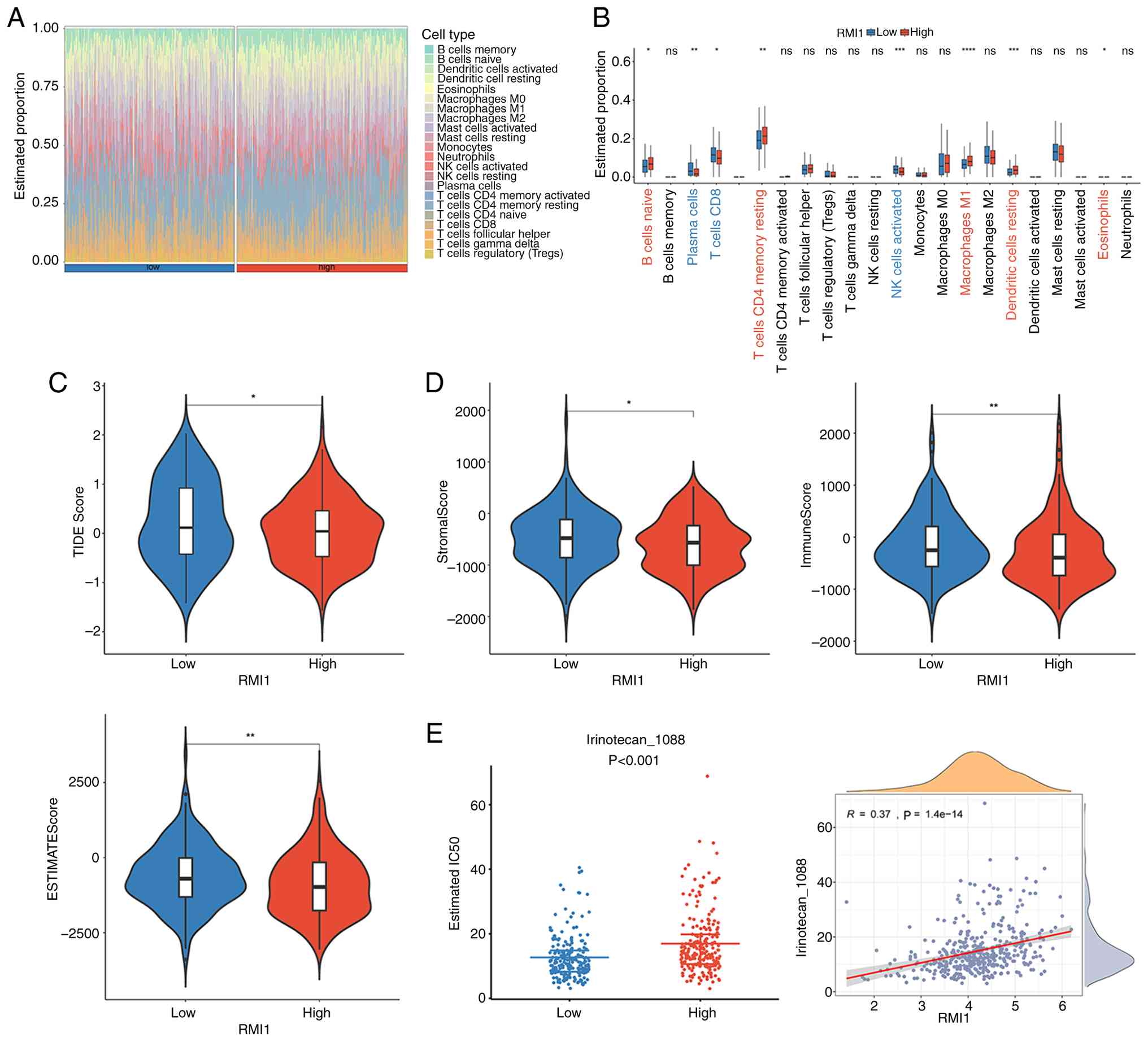

Immune microenvironment analysis

To evaluate the changes in the immune

microenvironment of PCa, the content and relative infiltration

abundance of 22 immune infiltrating cells in the TCGA-PRAD dataset

were calculated utilizing the CIBERSORT (v1.03) algorithm

(https://cibersort.stanford.edu;

P<0.05) and visualized using the ggh4× (v4.2.2) package

(https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggh4×).

Additionally, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (P<0.05) was used to

analyze the difference in immune cell infiltration between the two

expression groups, and the ggplot2 (v 3.4.1) package was used to

depict the data in a box plot.

Mutation analysis

The maftools (v 2.12.0) package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/maftools/) was used

to analyze two patient cohorts with mutation data to assess the

genetic differences between the two expression groups in the

TCGA-PRAD dataset.

Prediction of immunotherapy response

and drug sensitivity

To predict immunotherapy response in patients with

PCa, the tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion (TIDE) score was

used to evaluate the response to immunotherapy in the Tumor Immune

Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/). Differences between

expression groups was assessed utilizing the Wilcoxon rank-sum test

(P<0.05). A higher TIDE score indicates a greater immune escape

of tumor cells. Subsequently, Spearman's correlation analysis was

utilized to determine the correlation between biomarkers and TIDE

score.

Furthermore, using the TCGA-PRAD dataset, the

estimate (v1.0.13) package (https://R-Forge.R-project.org/projects/estimate/)

was utilized to calculate the StromalScore, ImmuneScore and

EstimateScore of biomarkers in the expression groups, and the

differences in these groups were compared using the Wilcoxon

rank-sum test (P<0.05). Lastly, the immune subtypes of disease

samples were divided according to the gene expression of immune

cells in tumors using the ImmuneSubtypeClassifier (v0.1.0) package

(https://github.com/CRI-iAtlas/ImmuneSubtypeClassifier),

and the differences among immune subtypes were then compared using

the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (P<0.05).

Subsequently, using the oncoPredict (v0.2) package

(28), the 50% inhibitory

concentration (IC50) values of 198 chemotherapeutic

drugs were determined according to the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity

in Cancer (GDSC; http://www.cancerrxgene.org/), and the IC50

values of each chemotherapeutic drug were compared between the

expression groups using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (P<0.05).

RT-qPCR

PCa and adjacent non-cancerous tissues were obtained

from the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (Taiyuan,

China). A total of 6 cancer tissues and 6 adjacent non-cancerous

tissue were collected from the pathological specimens of 6 patients

after radical prostatectomy. All the participants were male, and

the age range of patients was 60–75 years, with an average age of

68±5 years. Ethical approval was granted by the hospital Ethics

Committee (approval no. KYLL-2024-100). All participants provided

written informed consent to participate in the present study.

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol®

method (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc), and cDNA was

synthesized following the instructions of the

PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (cat. no. RR047A; Takara

Bio, Inc.). For RT-qPCR, the reactions were performed using an

Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR machine (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc). The reaction mixture consisted of 10 µl 2X SYBR

Green qPCR MasterMixII (Universal; Saiwen Innovation (Beijing)

Biotechnology Co., Ltd), 2 µl cDNA, 0.4 µl each of upstream and

downstream primers and ddH2O to a final volume of 20 µl.

The specific reaction conditions were the pre-denaturation in the

first stage: 95°C, 3 min. The second stage of denaturation,

annealing and extension: 95°C, 5 sec; 60°C, 30 sec; 60°C, 30 sec,

respectively (40 cycles). Final extension of the third stage: 60°C,

5 min. A total of 12 samples were collected and each sample was

tested three times. GAPDH served as the internal control, and the

data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (29). The primers used are listed in

Table SII.

Western blot analysis

Protein was extracted from PCa tissues using RIPA

lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Biotechnology). The

bicinchoninic acid protein assay was used to determine protein

concentration. The percentage of gel was 10%, 30 µg of the sample

was added to each well and was then subjected to SDS-PAGE and

transferred to a PVDF membrane (cat. no. 0000279048;

MilliporeSigma). To block nonspecific binding, the membranes were

incubated with 5% skimmed milk (cat. no. GC310001-100g; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and 0.1% Tween-20 (cat. no.

GC204002-100 ml; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) in Tris

buffer at room temperature for 30 min. RMI1 primary antibodies

(cat. no. 14630-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) were diluted with

antibody dilution buffer (1:1,000; cat. no. P0023A; Beyotime

Biotechnology) and incubated overnight with the membrane at 4°C,

followed by three washes with TBST. Subsequently, the appropriate

goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibodies (cat. no. 31460;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was diluted with 1X

TBST (1:3,000) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Protein

bands were visualized using an ultra-sensitive ECL

chemiluminescence kit (cat. no. PK10003-100 ml; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), and images were captured using an imaging system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The relative gray values of the protein bands

were measured by ImageJ (v2.16.0; National Institutes of Health),

using tubulin as the internal control. The molecular weights of

RMI1, GAPDH and tubulin are 75, 36 and 55 kDa, respectively.

Cell culture and transfection

Human PCa cells PC-3 were purchased from Immocell

(Xiamen Yimo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. IM-H075; http://www.immocell.com/?ryxbx/1680.html). The PC-3

cell line was verified using short tandem repeat profiling and

passaged in the laboratory for <6 months.

Knockdown in the present study was performed using

RNA silencing. The plasmids used in the experiment were constructed

by our research group independently. The plasmid concentrations of

the short hairpin negative control (shNC) and RMl1-shRNA-1,

RMl1-shRNA-2, and RMl1-shRNA-3 were 524, 465, 369, and 350 ng/µl,

respectively. Transfection was performed at 37°C for 24 h using the

jetPRIME® transfection reagent (cat. no. 101000025;

Polyplus-transfection SA). The medium was replaced, followed by

continuous culture for 48 h. Subsequent functional experiments were

performed when the cells reached confluence. RT-qPCR and western

blotting were used to assess the silencing efficiency of short

hairpin (sh)RNA-transfected cells. The targeted sequences of shRNA

and the shNC sequence were shown in Table SIII.

CCK-8 assay

Transfected cell suspensions were added to 96-well

plates at a volume of 100 µl per well and subsequently incubated

with 10 µl CCK-8 solution (Beyotime Biotechnology) for 4 h at 37°C.

Absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader

(Feyond-A300; Hangzhou Allsheng Instruments Co., Ltd.).

Cell scratch test

In the scratch assay, cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were digested and plated at a designated density into

6-well culture plates. The seeding process aimed to achieve 100%

confluence following overnight incubation, using a final medium

volume of 2 ml per well. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C with 5%

CO2, the cells were scored perpendicular to the bottom

of the wells using a 200 µl pipette tip, with the lid or ruler of

the 6-well plate serving as a reference. Subsequently, the cells

were washed three times with PBS to eliminate debris, and

serum-free medium was added. Images were captured under a ×4

magnification though an inverted fluorescence microscope (cat. no.

MF52-N; Mshot) to ensure that the scratch was centered and

perpendicular with a consistent background. Test samples of

different concentration gradients were added. Samples were taken at

0 and 40 h and images were captured. Results were analyzed using

ImageJ software (v1.4.3.67; National Institutes of Health). In the

scratched area, 6–8 horizontal lines were randomly drawn, and the

average distance between cells was measured to determine the cell

migration rate.

Transwell migration assay

The Transwell migration assay was performed using a

Transwell chamber. After 24 h of cell culture, a serum-free

suspension of 1×105 cells (100 µl) was added to the

upper Transwell chamber, while 600 µl complete medium supplemented

with 30% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added to the

lower chamber. Following 24 h of incubation at 37°C, a wet cotton

swab was used to carefully remove the non-migratory cells from the

upper membrane surface, whilst crystal violet was used to stain the

migrating cells on the bottom surface at room temperature for 10

min. After another 24-h incubation at 37°C, the process was

repeated to ensure thorough staining. The migrating cells were then

observed and images were captured under an inverted fluorescence

microscope (cat. no. MF52-N; Mshot). Cell counts were performed in

three randomly selected fields, and the average number of migrating

cells was calculated to assess cell migration capability.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2

(The R Foundation) and GraphPad Prism 9 (Dotmatics). For

comparisons between groups, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, log-rank

test and unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test were used. For group

comparisons of three or more groups, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for

pairwise comparisons and then adjusted the significance levels

using Bonferroni correction was used. Data values were presented as

mean ± standard deviation (SD) in the experimental analyses.

Statistical analysis of the experimental section employed unpaired

two-tailed Student's t-tests and one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA), followed by the least significant difference test. For the

comparison of the three sets of data involved in the experiment

section, Tukey's test was used for statistical analysis. The

experimental data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26;

IBM Corp.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Functional characteristics of DEGs in

PCa

The gene expression levels of DEGs between PCa and

control samples were assessed. This analysis identified a total of

4,395 DEGs, comprising 2,039 genes that were upregulated and 2,356

genes that were downregulated. The volcano plot and heatmap are

presented in Fig. 1A and B. In

addition, according to the results of GO analysis, 1,075 biological

processes, 102 cellular components and 93 molecular functions were

enriched by DEGs. They were mostly engaged in ‘positive regulation

of DNA-binding transcription factor activity’, ‘ribosomal subunit’

and ‘regulation of stress-activated protein kinase signaling

cascade’ (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, 39

KEGG pathways were enriched by DEGs, such as ‘regulation of actin

cytoskeleton’, ‘ribosome’, ‘adrenergic signaling in

cardiomyocytes’, ‘MAPK signaling pathway’ and ‘cAMP signaling

pathway’ (Fig. 1D). These analyses

suggested that the identified DEGs may be involved in a wide range

of biological mechanisms underlying PCa development.

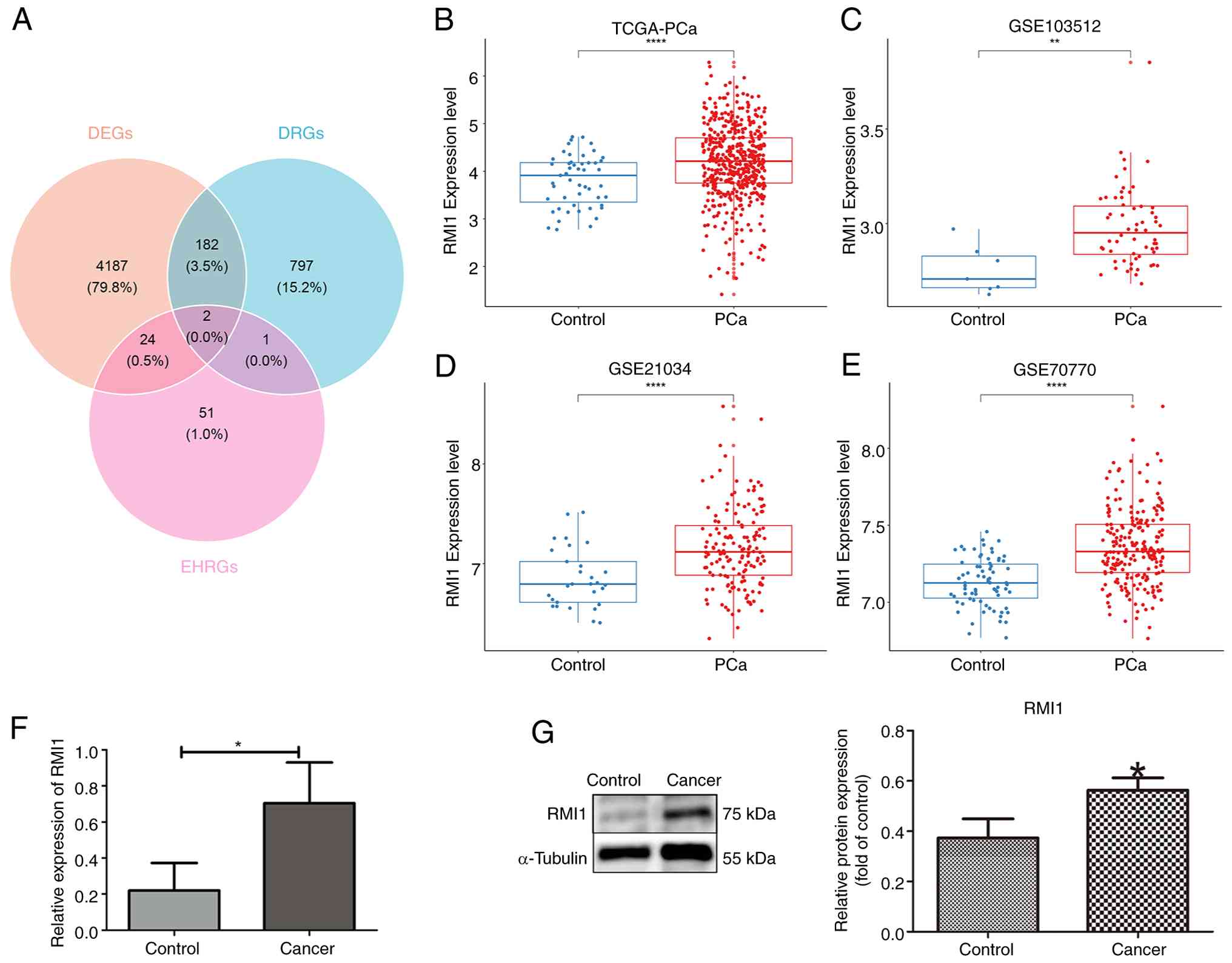

RMI1 identified as a biomarker

Through Venn diagram analysis, it was revealed that

growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) and RMI1 were jointly

screened out at the intersection of DEGs, DRGs and EHRGs (Fig. 2A). The research on the GDF15 gene in

the field of PCa has been relatively in-depth, with a number of

studies exploring its functions and mechanisms of action (30–34).

Therefore, RMI1, whose biological functions in PCa have not yet

been fully elucidated, was chosen as the key research target.

Further analysis demonstrated that the expression trends of RMI1

were consistent and significant across four datasets, and were

revealed to be highly expressed in the PCa group compared to the

control group based on the Wilcoxon test results (Fig. 2B-E). Additionally, RMI1 expression

demonstrated consistent and significant differences (P<0.05) in

both RT-qPCR and western blot analyses, establishing it as a robust

biomarker (Fig. 2F and G). The

consistent and statistically significant expression patterns of

RMI1 observed across multiple datasets and experimental validations

suggest that RMI1 might serve a pivotal role in the progression of

PCa.

| Figure 2.Screening of biomarkers. (A) GDF15

and RMI1 were obtained from the intersection of DEGs, DRGs and

EHRGs. (B-E) A total of four datasets validated the expression of

RMI1, (B) TCGA-PCa, (C) GSE103512 dataset (D) GSE21034 dataset (E)

GSE70770 dataset. (F) RT-qPCR box plot of RMI1. (G) Protein

differential expressions of RMI1. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. GDF15, growth

differentiation factor 15; RMI1, RecQ mediated genome instability

1; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; DRGs, DNA replication

stress-related genes; EHRGs, energy homeostasis-related genes;

TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; PCa, prostate cancer; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. |

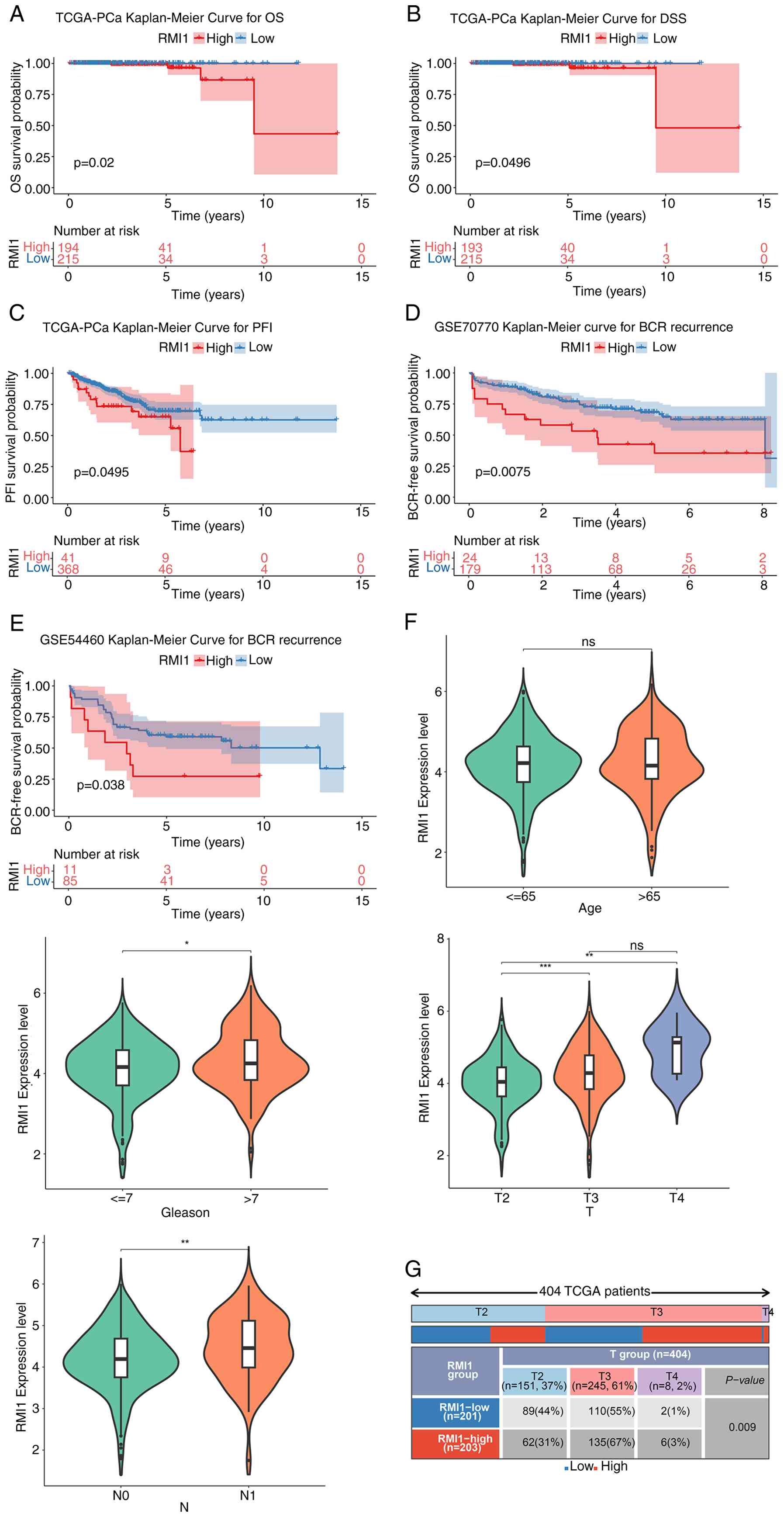

Analysis of survival difference

between the expression groups

To evaluate the effect of RMI1 expression on patient

survival, patients were categorized into high and low expression

groups according to their levels of RMI1 expression. Survival

outcomes were then compared, including OS, DSS, DFI, PFI and RFS,

between these groups. The analysis indicated notable differences in

OS, DSS and PFI between patients with high and low levels of RMI1

expression in the TCGA-PRAD dataset (Fig. 3A-C). However, this dataset did not

show any significant differences in DFI and RFS (Fig. S1A and B). In addition, although the

difference in RFS did not reach statistical significance in the

TCGA-PRAD dataset (despite there being a trend towards a lower

recurrence-free rate noted in the high expression group with

P<0.1), significant differences in RFS were demonstrated in

other datasets, specifically GSE70770 and GSE54460 (Fig. 3D-E). This suggested that RMI1 may

influence BCR in PCa. Furthermore, notable variations in RMI1

expression levels were observed across different subgroups based on

Gleason grading, T-staging and N-staging (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, the χ2

test results indicated a significant difference in T-staging among

patients with varying levels of RMI1 expression (Fig. 3G).

| Figure 3.Analysis of survival difference

between RMI1 high- and low-expression group. KM curves of (A) OS,

(B) DSS and (C) PFI between high and low expression groups. KM

curve for BCR recurrence in (D) GSE70770 and (E) GSE54460. (F)

Violin maps of differential RMI1 expression in subgroups with

different clinical characteristics. (G) Statistical map of the

percentage of subtypes with clinical features in the high and low

expression groups of the RMI1. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. ns, not significant. RMI1, RecQ mediated genome

instability 1; KM, Kaplan-Meier; OS, overall survival; DSS,

disease-specific survival; PFI, progression-free interval; BCR,

biochemical recurrence. |

Enrichment analysis and mutation

analysis

Enrichment analysis was used to delve deeper into

the functions of RMI1. GSEA demonstrated that RMI1 is involved in

71 KEGG pathways, primarily associated with the cell cycle, oocyte

meiosis and cancer-related pathways (Fig. 4A). In addition, GSVA revealed

significant differences in 143 pathways between the groups with

high and low RMI1 expression. Specifically, pathways related to the

metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 were activated in the

low expression group, whilst pathways such as aminoacyl-tRNA

biosynthesis were activated in the high expression group (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the role of somatic

cell mutations on PCa was assessed using the mutated landscapes.

According to the waterfall plot, the low-expression group had the

highest frequency of speckle type POZ protein (SPOP) gene mutations

(13%), whilst the high-expression group had the highest frequency

of TP53 mutations (15%). SPOP and TP53 were both missense mutations

(Fig. 4C and D).

Analysis of RMI1 expression in immune

cell infiltration and drug sensitivity

The results of immune cell infiltration are

presented in Fig. 5A. A total of

eight differential immunity cells were identified, such as naive B

cells, plasma cells and CD8 T cells (P<0.05; Fig. 5B). At the same time, the TIDE score

was markedly greater in the high-expression group (P<0.05;

Fig. 5C). In addition, the

StromalScore, ImmuneScore and EstimateScore of the high-expression

group were all markedly higher than those of the low-expression

group (P<0.05; Fig. 5D). This

suggests that high levels of the RMI1 may be associated with immune

escape and poor prognosis.

Furthermore, based on the 198 chemotherapy/targeted

therapy drugs provided by GDSC, 164 drugs with significant

differences in their IC50 values were identified in

different expression groups. In the boxplot demonstrating

differences in IC50 between the expression groups for

three common chemotherapy drugs for PCa (5-fluorouracil,

oxaliplatin and irinotecan), only irinotecan showed a significant

difference between the two expression groups (P<0.001) and had a

positive correction with RMI1 (cor=0.37) (Fig. 5E).

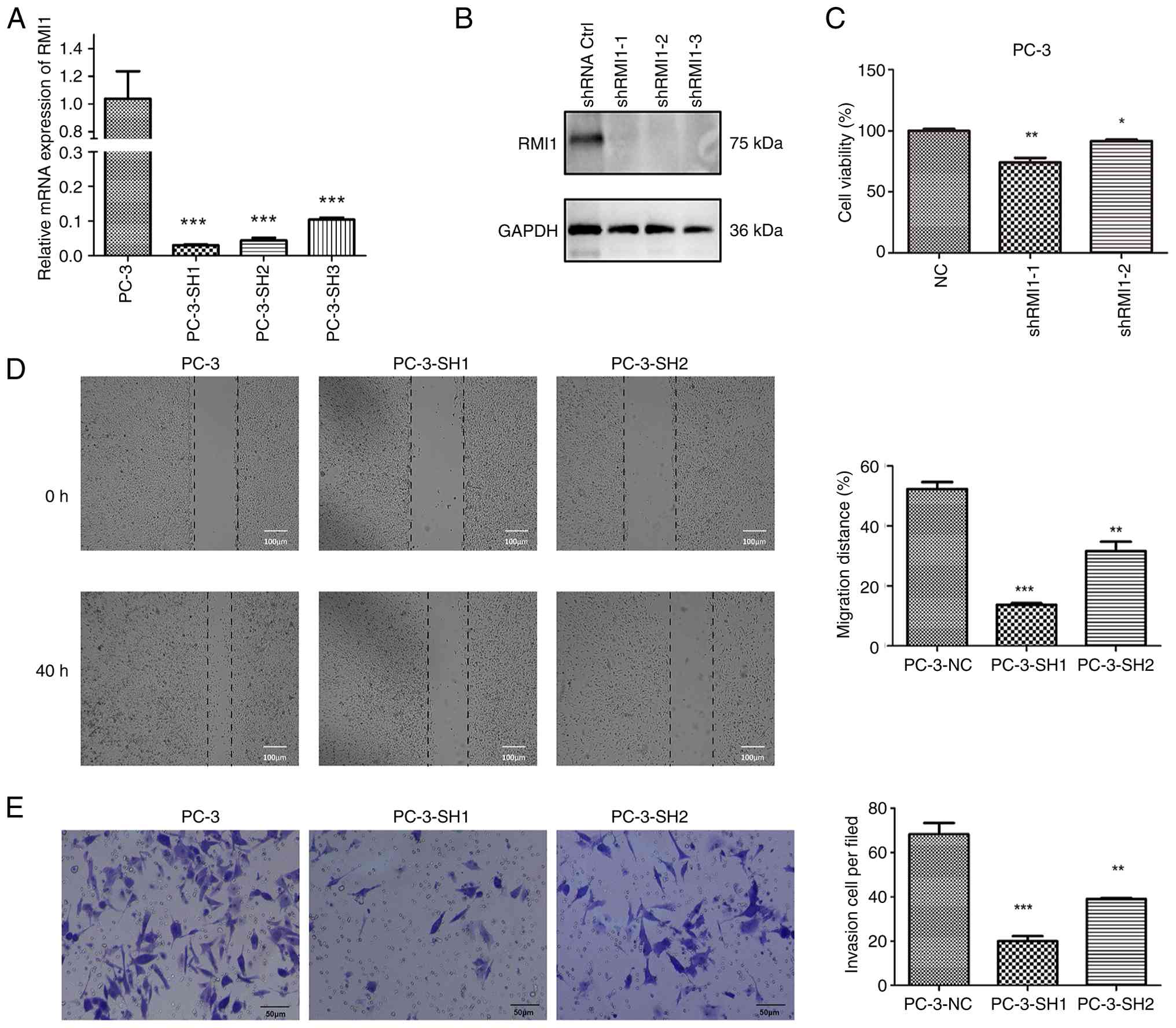

Effect of RMI1 expression on PCa cell

proliferation and migration

KM survival analysis indicated that higher RMI1

expression was associated with a worse prognosis in patients with

PCa. As a result, PC-3 cells with an improved prognosis were

constructed by transfecting sh-RMI1. The mRNA and protein

expression levels of the transfected cells confirmed that the

transfection was successful (Fig. 6A

and B). Furthermore, the CCK-8 assay results indicated a

significant reduction in cell viability for sh-RMI1 cells with

decreased RMI1 expression (P<0.05; Fig. 6C), suggesting that lowering RMI1

levels can inhibit the proliferation of PCa cells. Furthermore, the

findings from the scratch assay (Fig.

6D) and the Transwell migration assay (Fig. 6E) revealed that cells with reduced

RMI1 expression demonstrated markedly decreased migration

(P<0.05). These experiments suggested that RMI1 may serve a role

in enhancing the proliferation and migration of PCa cells. A

reduction in RMI1 expression led to decreased proliferation and

migration in these cells, indicating that RMI1 could be crucial for

the progression and metastasis of PCa.

Discussion

The therapeutic landscape for PCa is varied,

encompassing active monitoring, chemotherapy, radiation therapy,

hormone therapy, surgery and cryotherapy (35). Despite these options, the

near-universal development of hormone resistance among initially

responsive patients with PCa presents a formidable challenge, which

poses great difficulties for the treatment of PCa (36). Chemotherapy and immunotherapy may

become to be the efficiency treatments to extend survival of

PCa.

DNA replication stress is the main driving factor

for genomic instability and is considered a specific vulnerability

of cancer cells, which can be therapeutically exploitable in PCa

(14,37). Due to the notable heterogeneity

among patients with PCa, there is an urgent need for a dependable

approach to assess replication stress in this population.

Furthermore, to maintain homeostasis, each cell must constantly

monitor its energy levels and appropriately adjust the rate of

energy production in the form of ATP according to metabolic

demands. The continuous fulfillment of this energy demand relies on

the ability of the cell to sense, metabolize nutrients and convert

them into chemical energy (38).

The activation of AMPK enhances ATP production activity to restore

energy homeostasis, which may have beneficial effects on the

treatment of PCa (39). Therefore,

integrating DNA replication stress and energy homeostasis to

investigate their roles in PCa may lead to the identification of

new diagnostic biomarkers.

In the present study, two candidate biomarkers were

identified: GDF15 and RMI1. RMI1 became the focus of research due

to the lack of existing studies on it in PCa. Using four datasets

and performing RT-qPCR and western blotting, it was demonstrated

that the expression levels of RMI1 was notably higher in PCa

tissues than in the control tissues, thus indicating a potential

new biomarker for the diagnosis of PCa.

RMI1 has been reported to be markedly associated

with prognosis across several diseases (40,41).

Research indicates that the expression level of RMI1 remains

unchanged during the G1, S and G2 phases of

the cell cycle, yet it notably increases in the M phase. In

addition, RMI1 undergoes phosphorylation during mitosis.

Particularly under the influence of mitotic microtubule interfering

agents, RMI1 is mainly phosphorylated at serine residues 284 and

292 (42). RMI1 is essential for

DNA repair and is closely associated with several human diseases,

including cancer and obesity (43,44).

Research indicates that RMI1 is markedly involved in the

progression of gliomas (45). In

addition, RMI1 has been identified as a novel regulator of energy

homeostasis, suggesting that RMI1 modulators could improve the

prognosis of several diseases associated with energy homeostasis,

such as obesity (46). However,

there is a lack of data on the role of the RMI1 in PCa, and further

research is needed. The present study silenced RMI1 expression to

further explore its role in PCa progression, focusing on cell

proliferation, migration and invasion. The findings indicated that

knocking down RMI1 markedly decreased cell proliferation and

hindered both migration and invasion. Additionally, clinical data

revealed that elevated RMI1 expression was associated with poor

patient outcomes, including advanced tumor stages and lower

survival rates. These results implied that RMI1 is a key factor in

the progression of PCa, as it promotes tumor growth and metastasis.

Given its dual role in enhancing aggressive tumor behavior and its

association with negative clinical outcomes, RMI1 may be a valuable

biomarker for risk assessment and a potential therapeutic target

for preventing the advancement and spread of PCa.

PCa is generally considered a ‘cold’ tumor,

characterized by relatively few immune cell infiltrations in its

tumor microenvironment (TME) (35,47).

In the present study, immunoinfiltration analysis was performed on

several RMI1 expression groups to elucidate the role of RMI1 in

PCa. The results revealed significant differences in eight types of

immune cells between the groups, including CD8+ T cells

and M1 macrophages. The antitumor immune response in PCa primarily

relies on CD8+ T cells (48). However, the presence of

CD8+ T cells in the PCa microenvironment is limited, and

a large proportion of these cells are exhausted (49). In addition, macrophages are a

crucial component of the TME. Macrophages generated from bone

marrow are essential for preserving tissue homeostasis, regulating

inflammatory responses, encouraging tissue repair and thwarting

infections (50). M1-type

macrophages serve an essential part in the PCa TME by generating

several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (51). In summary, the immune

microenvironment of PCa is complex and has unique characteristics,

and RMI1 may serve a vital role in regulating immune cell

infiltration and function. However, its specific mechanisms and

role in the progression of PCa require further research.

To further explore the underlying biological

mechanisms of RMI1, the present study performed GSEA. The results

revealed that the top five pathways were

‘KEGG_UBIQUITIN_MEDIATED_PROTEOLYSIS’, ‘KEGG_CELL_CYCLE’,

‘KEGG_PROGESTERONE_MEDIATED_OOCYTE_MATURATION’,

‘KEGG_PATHWAYS_IN_CANCER’ and ‘KEGG_OOCYTE_MEIOSIS’: The

‘KEGG_UBIQUITIN_MEDIATED_PROTEOLYSIS’ pathway is crucial for

protein degradation and may regulate the stability and abundance of

RMI1; the ‘KEGG_CELL_CYCLE’ pathway controls the orderly

progression of the cell cycle, and RMI1 likely participates in it,

especially during mitosis; the

‘KEGG_PROGESTERONE_MEDIATED_OOCYTE_MATURATION'pathway is associated

with reproductive processes, yet might have potential intersections

with the functions of RMI1; the ‘KEGG_PATHWAYS_IN_CANCER’ pathway

reflects several aspects of cancer development, and RMI1 may serve

a notable role in it to promote PCa progression; and the

‘KEGG_OOCYTE_MEIOSIS’ pathway is vital for genetic material

distribution in reproductive cells and could also be associated

with the function of RMI1 in maintaining genomic stability.

However, its connection with PCa requires further exploration.

Overall, these pathways may all have different degrees of

association with RMI1 and are worthy of further in-depth study to

improve the understanding of the role of RMI1 in PCa

development.

The present study utilized a diverse range of

bioinformatics techniques, such as enrichment analysis, survival

analysis, immune infiltration assessment and predictions for

chemotherapeutic drugs, to uncover biomarkers associated with DNA

replication stress and energy homeostasis in PCa. Additionally,

functional and molecular mechanism analyses were performed,

revealing that RMI1 may facilitate the progression of PCa. However,

the present study has certain limitations: Although the findings

demonstrated the key role of RMI1 in the proliferation and

migration of PCa cells, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain

incompletely understood. Although bioinformatics analyses such as

GSEA and GSVA indicated the possible molecular pathways involved

(such as cell cycle and oocyte meiosis), these predictive results

lacked direct experimental evidence to support them. Future

research should perform transient transfection of the RMI1 plasmid

in PC-3 cells transfected with sh-RMI1 to detect whether the cell

proliferation and migration abilities are restored. Furthermore,

future studies should investigate whether the expression and

activity of direct downstream effector molecules change in key

pathways such as the cell cycle, to further elucidate the mechanism

of action of RMI1. Finally, due to the limited sample size from a

single center, additional validation studies are necessary to

evaluate the impact of this gene on PCa cell biology.

In conclusion, the present study identified RMI1, a

biomarker associated with DNA replication stress and energy

homeostasis in PCa, and revealed that it has a marked effect in the

development of PCa. These findings may have profound implications

for PCa risk stratification and therapeutic guidance, and provide a

foundation for future research.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study received support from the Shanxi Provincial

Higher Education Institutions Scientific and Technological

Innovation Program (grant number: 2024-83), the Health Commission

of Shanxi Province Fund (grant number: 2020087) and the Academy

Youth Foundation of First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University

(grant number: YQ1504).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization was by XC and BW. Methodology was

by PS. Software was by XW. Validation was by PS, XW and XY. Formal

analysis was by HD. Investigation was by XC. Resources was by BW.

Data curation was by PS. Writing and original draft preparation was

by PS. Writing-review and editing was by XW and HD. Visualization

was by XY. Supervision was by B.W. Project administration was by

XC. Funding acquisition was by PS and XC. PS and XC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee

of First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (ethics approval no.

KYLL-2024-100). The participants provided their written informed

consent to participate in this study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rawla P: Epidemiology of prostate cancer.

World J Oncol. 10:63–89. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Graham LS, Lin JK, Lage DE, Kessler ER,

Parikh RB and Morgans AK: Management of prostate cancer in older

adults. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 43:e3903962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sekhoacha M, Riet K, Motloung P, Gumenku

L, Adegoke A and Mashele S: Prostate cancer review: Genetics,

diagnosis, treatment options, and alternative approaches.

Molecules. 27:57302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shen P, Sun J, Xu G, Zhang L, Yang Z, Xia

S, Wang Y, Liu Y and Shi G: KLF9, a transcription factor induced in

flutamide-caused cell apoptosis, inhibits AKT activation and

suppresses tumor growth of prostate cancer cells: KLF9 inhibits

tumor growth of prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 74:946–958. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yao K, Zhang R, Li L, Liu M, Feng S, Yan

H, Zhang Z and Xie D: The signature of cuproptosis-related immune

genes predicts the tumor microenvironment and prognosis of prostate

adenocarcinoma. Front Immunol. 14:11813702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Altwaijry N, Somani S and Dufès C:

Targeted nonviral gene therapy in prostate cancer. Int J

Nanomedicine. 13:5753–5767. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ziaran S, Varchulova Novakova Z, Bohmer D

and Danisovic L: Biomarkers for determination prostate cancer:

Implication for diagnosis and prognosis. Neoplasma. 62:683–691.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Saxena S and Zou L: Hallmarks of DNA

replication stress. Mol Cell. 82:2298–2314. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bowry A, Kelly RDW and Petermann E:

Hypertranscription and replication stress in cancer. Trends Cancer.

7:863–877. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gaillard H, García-Muse T and Aguilera A:

Replication stress and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:276–89. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Maiorano D, El Etri J, Franchet C and

Hoffmann JS: Translesion synthesis or repair by specialized DNA

polymerases limits excessive genomic instability upon replication

stress. Int J Mol Sci. 22:39242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ubhi T and Brown GW: Exploiting DNA

replication stress for cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 79:1730–1739.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bai G, Smolka MB and Schimenti JC: Chronic

DNA Replication stress reduces replicative lifespan of cells by

TRP53-Dependent, microRNA-Assisted MCM2-7 downregulation. PLoS

Genet. 12:e10057872016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Macheret M and Halazonetis TD: DNA

replication stress as a hallmark of cancer. Annu Rev Pathol.

10:425–448. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang Y, Gao Y, Mutter-Rottmayer L,

Zlatanou A, Durando M, Ding W, Wyatt D, Ramsden D, Tanoue Y,

Tateishi S and Vaziri C: DNA repair factor RAD18 and DNA polymerase

Polκ confer tolerance of oncogenic DNA replication stress. J Cell

Biol. 216:3097–3115. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang RH, Hong YK, Du H, Ke WQ, Lin BB and

Li YL: A machine learning framework develops a DNA replication

stress model for predicting clinical outcomes and therapeutic

vulnerability in primary prostate cancer. J Transl Med. 21:202023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lin C, Salzillo TC, Bader DA, Wilkenfeld

SR, Awad D, Pulliam TL, Dutta P, Pudakalakatti S, Titus M, McGuire

SE, et al: Prostate cancer energetics and biosynthesis. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1210:185–237. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Eidelman E, Twum-Ampofo J, Ansari J and

Siddiqui MM: The metabolic phenotype of prostate cancer. Front

Oncol. 7:1312017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Griffin JE: Androgen resistance-the

clinical and molecular spectrum. N Engl J Med. 326:611–618. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lima AR, Pinto J, Amaro F, Bastos ML,

Carvalho M and Guedes de Pinho P: Advances and perspectives in

prostate cancer biomarker discovery in the last 5 years through

tissue and urine metabolomics. Metabolites. 11:1812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kwon H, Oh S, Jin X, An YJ and Park S:

Cancer metabolomics in basic science perspective. Arch Pharm Res.

38:372–380. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Green SM, Mostaghel EA and Nelson PS:

Androgen action and metabolism in prostate cancer. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 360:3–13. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cardoso HJ, Carvalho TMA, Fonseca LRS,

Figueira MI, Vaz CV and Socorro S: Revisiting prostate cancer

metabolism: From metabolites to disease and therapy. Med Res Rev.

41:1499–1538. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hardie DG: AMP-activated protein kinase:

An energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes

Dev. 25:1895–1908. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Penfold L, Woods A, Pollard AE, Arizanova

J, Pascual-Navarro E, Muckett PJ, Dore MH, Montoya A, Whilding C,

Fets L, et al: AMPK activation protects against prostate cancer by

inducing a catabolic cellular state. Cell Rep. 42:1123962023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shi S, Wen G, Lei C, Chang J, Yin X, Liu X

and Huang S: A DNA replication Stress-based prognostic model for

lung adenocarcinoma. Acta Naturae. 15:100–110. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

R: The R Project for Statistical

Computing.

|

|

28

|

Xu Q, Ma L, Streuer A, Altrock E, Schmitt

N, Rapp F, Klär A, Nowak V, Obländer J, Weimer N, et al: Machine

learning-based in-silico analysis identifies signatures of lysyl

oxidases for prognostic and therapeutic response prediction in

cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 23:1692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Siddiqui JA, Seshacharyulu P, Muniyan S,

Pothuraju R, Khan P, Vengoji R, Chaudhary S, Maurya SK, Lele SM,

Jain M, et al: GDF15 promotes prostate cancer bone metastasis and

colonization through osteoblastic CCL2 and RANKL activation. Bone

Res. 10:62022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mahon KL, Sutherland SI, Lin HM, Stockler

MR, Gurney H, Mallesara G, Briscoe K, Marx G, Higano CS, de Bono

JS, et al: Clinical validation of circulating GDF15/MIC-1 as a

marker of response to docetaxel and survival in men with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate. 84:747–755. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yamamichi G, Kato T, Arakawa N, Ino Y,

Ujike T, Nakano K, Koh Y, Motoyama Y, Outani H, Myoba S, et al:

GDF15 propeptide promotes bone metastasis of castration-resistant

prostate cancer by augmenting the bone microenvironment. Biomark

Res. 12:1472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang W, Hu C, Wang X, Bai S, Cao S,

Kobelski M, Lambert JR, Gu J and Zhan Y: Role of GDF15 in

methylseleninic acid-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation and

induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One.

14:e02228122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang W, Yang X, Dai J, Lu Y, Zhang J and

Keller ET: Prostate cancer promotes a vicious cycle of bone

metastasis progression through inducing osteocytes to secrete GDF15

that stimulates prostate cancer growth and invasion. Oncogene.

38:4540–4559. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Teo MY, Rathkopf DE and Kantoff P:

Treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Annu Rev Med. 70:479–499.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Linxweiler J, Hajili T, Saar M, Maßmann C,

Junker K and Stöckle M: Influence of local treatment on the biology

of advanced prostate cancer : Treatment of the primary tumor may

delay hormone resistance of metastases. Urologe A. 61:518–525.

2022.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Dreyer SB, Upstill-Goddard R, Paulus-Hock

V, Paris C, Lampraki EM, Dray E, Serrels B, Caligiuri G, Rebus S,

Plenker D, et al: Targeting DNA damage response and replication

stress in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 160:362–377.e13.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yu SB and Pekkurnaz G: Mechanisms

orchestrating mitochondrial dynamics for energy homeostasis. J Mol

Biol. 430:3922–3941. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zadra G, Priolo C, Patnaik A and Loda M:

New strategies in prostate cancer: Targeting lipogenic pathways and

the energy sensor AMPK. Clin Cancer Res. 16:3322–3328. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li Y, He X, Zhang X, Xu Y, Chen W, Liu X

and Xu X: RMI2 is a prognostic biomarker and promotes tumor growth

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Med. 22:229–243. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen S, Liu W and Huang Y: Identification

and external validation of a prognostic signature associated with

DNA repair genes in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 11:71412021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Xu C, Wang Y, Wang L, Wang Q, Du LQ, Fan

S, Liu Q and Li L: Accumulation and phosphorylation of

RecQ-mediated genome instability protein 1 (RMI1) at Serine 284 and

Serine 292 during Mitosis. Int J Mol Sci. 16:26395–405. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen H, You MJ, Jiang Y, Wang W and Li L:

RMI1 attenuates tumor development and is essential for early

embryonic survival: RMI1 and Tumor Development. Mol Carcinog.

50:80–88. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Suwa A, Kurama T and Shimokawa T:

Adipocyte hyperplasia and RMI1 in the treatment of obesity:

Adipocyte hyperplasia and RMI1. FEBS J. 278:565–569. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Qian J, Xu Y, Xu X, Tao Z, Luo Y, Xu Y,

Zhang Y and Qian C: Hsa_circ_0091581 promotes glioma progression by

regulating RMI1 via sponging miR-1243-5p. J Cancer. 12:3249–3256.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Suwa A, Yoshino M, Yamazaki C, Naitou M,

Fujikawa R, Matsumoto S, Kurama T, Shimokawa T and Aramori I: RMI1

deficiency in mice protects from diet and Genetic-induced obesity.

FEBS J. 277:677–686. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Isaacsson Velho P and Antonarakis ES:

PD-1/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors in advanced prostate cancer. Expert

Rev Clin Pharmacol. 11:475–486. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang Q, Helfand BT, Carneiro BA, Qin W,

Yang XJ, Lee C, Zhang W, Giles FJ, Cristofanilli M and Kuzel TM:

Efficacy against human prostate cancer by prostate-specific

membrane antigen-specific, transforming growth Factor-β insensitive

genetically targeted CD8+ T-cells derived from patients with

metastatic Castrate-resistant disease. Eur Urol. 73:648–652. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bian X, Wang W, Abudurexiti M, Zhang X, Ma

W, Shi G, Du L, Xu M, Wang X, Tan C, et al: Integration analysis of

single-cell multi-omics reveals prostate cancer heterogeneity. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 11:e23057242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wang N, Wang S, Wang X, Zheng Y, Yang B,

Zhang J, Pan B, Gao J and Wang Z: Research trends in

pharmacological modulation of tumor-associated macrophages. Clin

Transl Med. 11:e2882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gu Q, Qi A, Wang N, Zhou Z and Zhou X:

Macrophage dynamics in prostate cancer: Molecular to therapeutic

insights. Biomed Pharmacother. 177:1170022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|