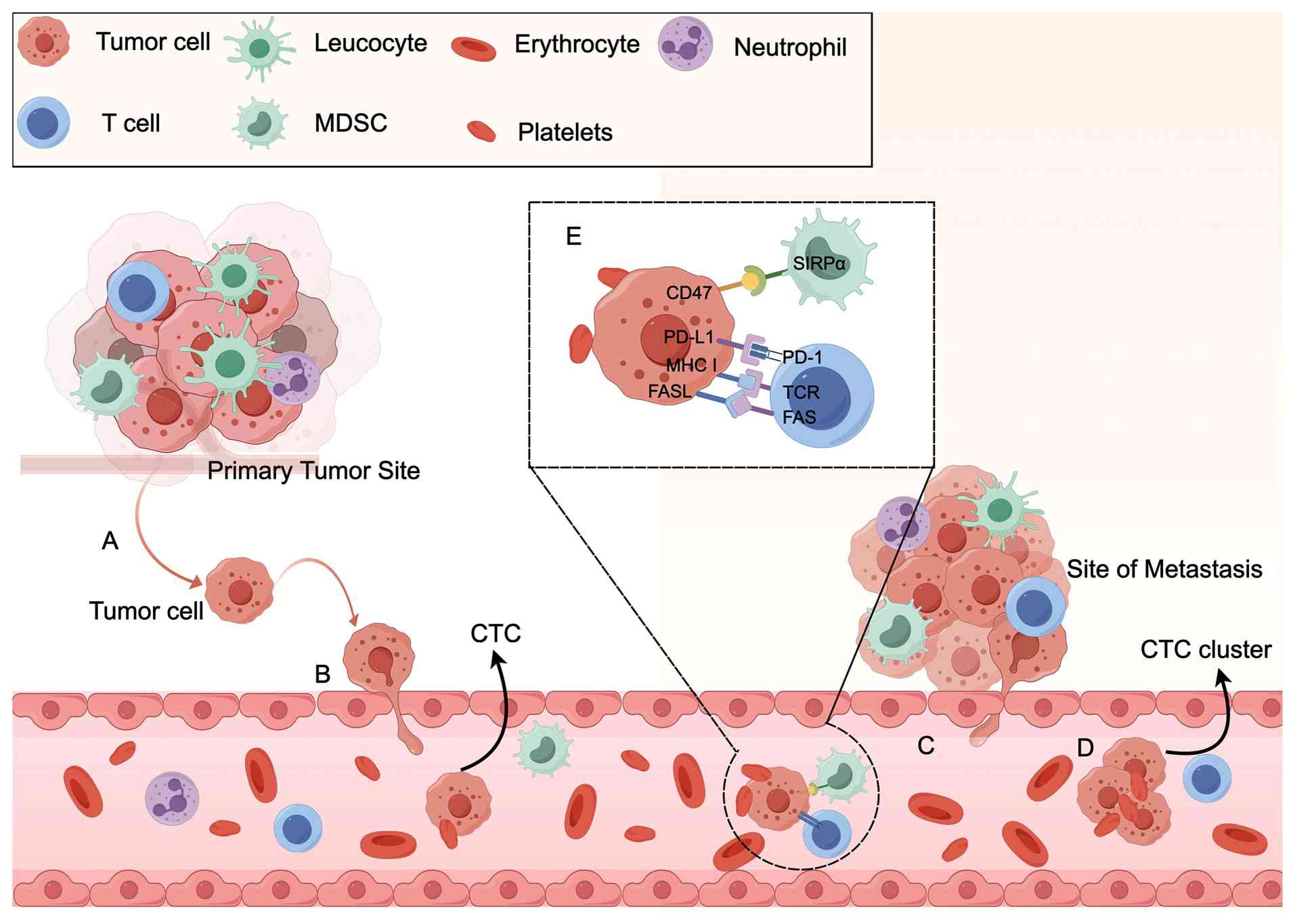

Cancer remains one of the most serious diseases that

threaten human health, with metastasis being the leading cause of

cancer-related deaths worldwide and posing a major challenge in

cancer treatment (1,2). Metastasis is a complex process

involving multiple steps (3),

including intravasation, extravasation, migration and regeneration.

During metastasis, tumor cells from the primary site invade distant

tissues through the bloodstream, where they form metastatic foci

(4). In recent years, the

prevailing view has been that metastatic disease is usually

extensive and incurable. However, the advent of immunotherapy has

led to significant breakthroughs in cancer treatment. When combined

with surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, immunotherapy can

improve patient survival (5).

Tissue biopsy is among the clinical methods used to guide

immunotherapy (6). However,

traditional tissue biopsies are not 100% accurate and have several

limitations: They are invasive (7),

have limited sensitivity and specificity, provide only local tissue

samples, and fail to capture tumor heterogeneity (8). Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are a

cornerstone of liquid biopsy and offer undeniable advantages that

can compensate for some of the limitations of traditional tissue

biopsy. They are non-invasive (9),

easy to administer, and more patient friendly. Additionally, they

address the issue of tumor heterogeneity, which enables more

effective monitoring of tumor progression through serial testing

and provides valuable insights to guide treatment decisions

(10–12).

CTCs are tumor cells that are shed from primary

tumors or metastatic sites and enter the peripheral bloodstream

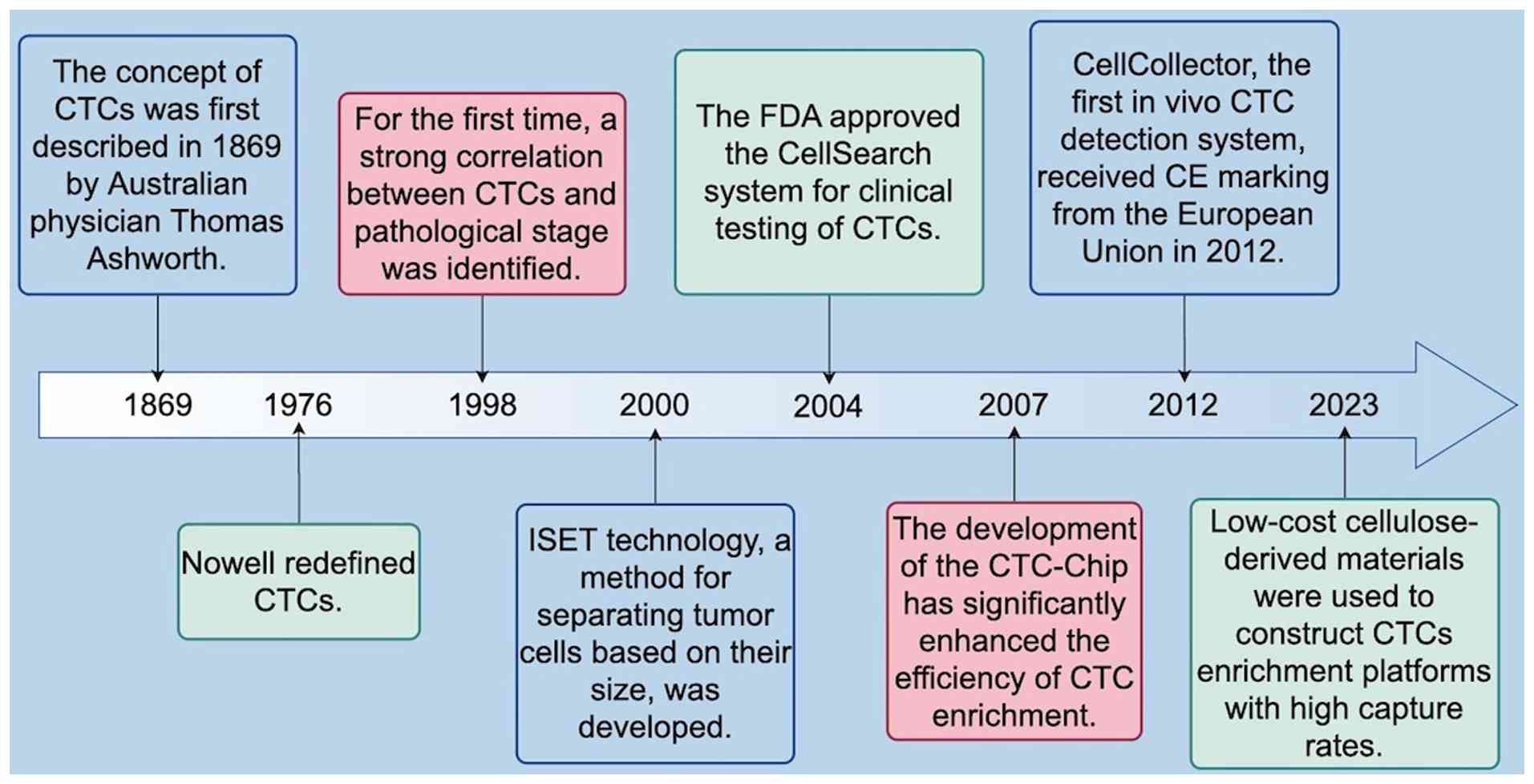

(13,14). The concept of CTCs was first

introduced in 1869 by the Australian physician Thomas Ashworth, who

observed cells in the blood of a patient with metastatic cancer

that were similar to the primary tumor cells (15,16).

However, given the technical limitations of that time period, CTCs

were not further examined (17). It

was not until 1976 that Nowell redefined CTCs as tumor cells

originating from primary or metastatic tumors that have acquired

the ability to detach from the basement membrane and invade the

vasculature through tissue stroma. In 1998, Peck et al

(18) explored the feasibility of

using CTC assays for the rapid assessment of chemotherapeutic

responsiveness. Their study revealed that serial assays of changes

in CTC counts correlated with tumor burden and therapeutic response

in patients. Furthermore, in 2004, a prospective multicenter study

demonstrated that the number of CTCs in peripheral blood prior to

treatment was an independent predictor of progression-free survival

(PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic breast

cancer (19,20). That same year, the U.S. Food and

Drug Administration (FDA) approved the CellSearch System for the

treatment of metastatic colorectal, breast and prostate cancers

(21). With continued technological

advancements, the CTC chip developed by Nagrath et al

(22) in 2007 markedly improved the

efficiency of CTC enrichment. This microfluidic platform enables

the efficient and selective isolation of viable CTCs from

peripheral whole blood under precisely controlled laminar-flow

conditions. Using this system, CTCs were successfully detected in

115 of 116 peripheral blood samples (99%) obtained from patients

with metastatic lung, prostate, pancreatic, breast, and colon

cancers. The detected CTC counts ranged from 5–1,281 cells/ml of

blood, with an approximate purity of 50% (22). However, most CTC enrichment

techniques during that period were performed in vitro.

Hartmann et al (23)

reported that this approach is inherently limited by the minimal

number of CTCs that can be captured from small-volume blood

samples. Moreover, preanalytical handling procedures, including

sample transport, preservation, centrifugation, and subsequent

in vitro enrichment and isolation, frequently introduce

artifactual alterations, such as cellular contamination, loss,

inactivation and morphological distortion (23). To overcome these challenges, the

first in vivo CTC detection system, known as Cell Collector,

received CE certification from the European Union in 2012. The

cells captured by this system require no pretreatment, such as

transfection or fluorescent labeling, and can be directly

identified within the immunomagnetic separation device. This

feature effectively minimizes the detrimental effects associated

with clinical sample collection, preprocessing, and CTC isolation

on cellular integrity and overall quality (24). Compared with the Cell Collector

system, the CTC enrichment platform developed in recent years by

Hazra et al (25), which

employs cellulose derivatives, may reduce costs and thus improve

affordability for a larger patient population; moreover, this

method achieves an overall capture efficiency of ~40%. Despite

these advancements, isolating CTCs from blood with high sensitivity

and specificity remains a significant challenge (26). Most patients with cancer have

extremely low concentrations of CTCs in their peripheral

circulating blood (from 1–100 cells/ml) (27), and factors such as blood shear

stress and immune system activity result in a short half-life for

CTCs, usually from 1–2.5 h (28,29).

Additionally, CTCs exhibit significant heterogeneity across

individuals and tumor types, even within the same patient. With the

rapid advancement of new digital technology, researchers have

established a new interdisciplinary field of medical, industrial

integration by combining biology, chemistry, physics, computer

science and medicine. This integration has led to the development

of innovative technologies for the capture, detection, and analysis

of CTCs. These advances have significantly facilitated the clinical

application of CTCs in cancer screening, treatment response

monitoring and prognosis (28).

A search of the PubMed database through December

2023 using ‘CTCs’ as a keyword retrieved more than 33,000 studies.

The number of publications per year has shown an upward trend,

reaching more than 2,000 by 2020. Although there has been a slight

decline since then, the annual number of relevant publications

still exceeds 1,500, confirming continued interest in advancing the

technology and developing new applications. These findings indicate

that research on CTCs is advancing rapidly, yielding significant

findings (Fig. 1). The present

study provides a systematic comparison of the advantages and

disadvantages of the current methods for collecting and identifying

CTCs and assessing their clinical applicability in

immunotherapy.

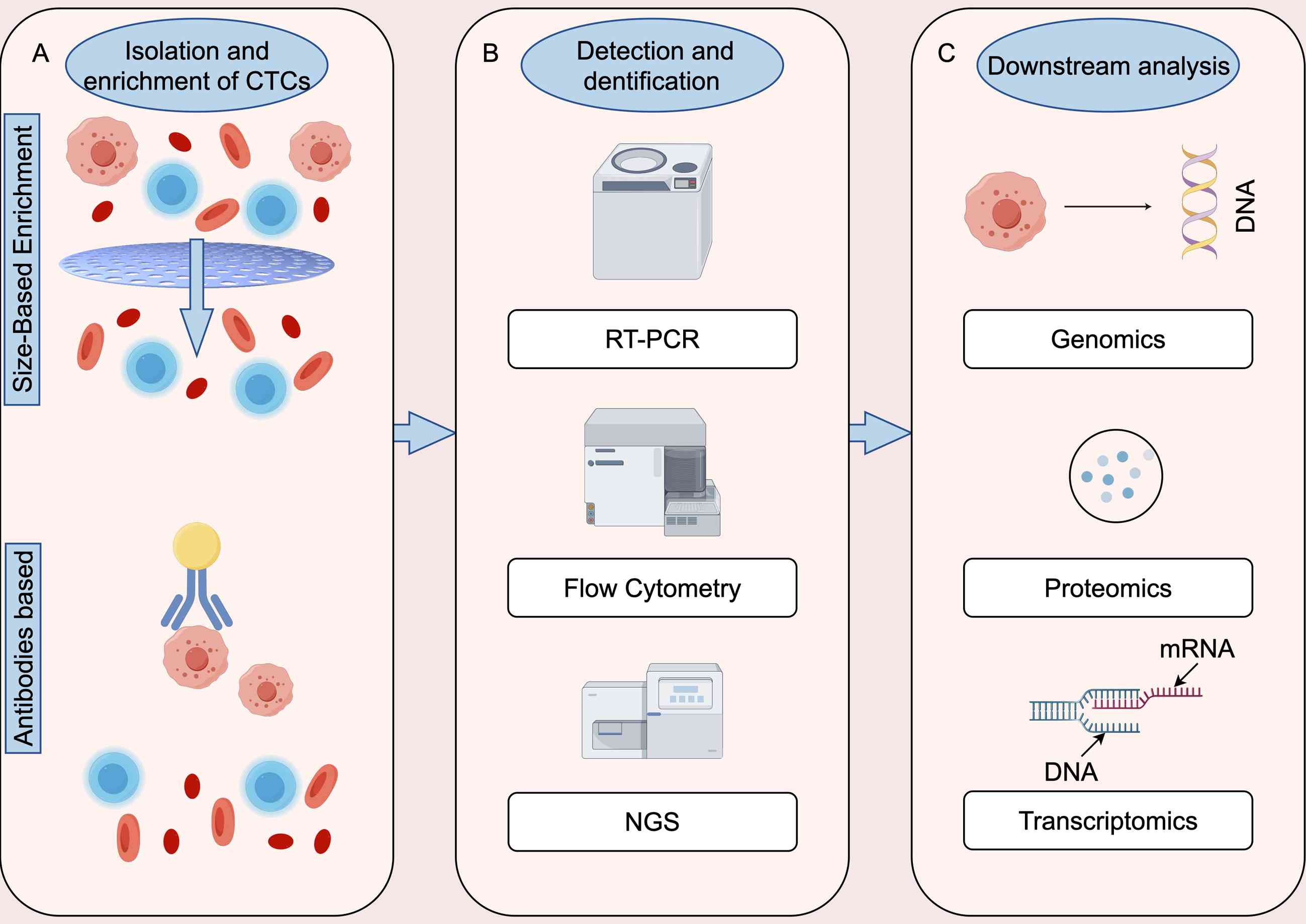

In general, technologies for identifying CTCs

involve three critical steps: Capture and enrichment, detection and

identification, and release for further analysis (30). As noted by Wang et al

(31), capture and enrichment

methods rely primarily on the interaction between specific

materials and certain physical, chemical or biological properties

of CTCs. After collection, various identification methods can be

used, such as flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy and DNA

sequencing. Released CTCs are typically utilized for downstream

analyses, such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and

immunofluorescence assays of cultured cells (31). Enrichment methods for CTCs are based

on certain biological and physical properties (32,33).

Since most tumors originate from epithelial tissues, epithelial

cell adhesion molecules (EpCAMs) are the most commonly used

biomarkers for CTCs. Physically, CTCs can be differentiated by

properties such as size, density, charge, and deformability

(34–37). In recent years, detection techniques

that integrate both the physical and biological properties of CTCs

have emerged, offering enhanced efficiency and sensitivity

(38,39) (Fig.

2).

Studies have shown that CTCs are typically larger

and firmer than hematopoietic cells are, and numerous CTC

enrichment techniques have been developed on the basis of these

physical properties (40). For

example, the epithelial tumor cell size separation (ISET) method

primarily uses a two-dimensional membrane microfilter and is the

first assay to allow the direct filtration of peripheral blood. In

this system, blood samples are diluted 1:10 and passed through a

polycarbonate track-etch-type membrane with 8-µm pores (41,42).

CTCs, which are generally larger than peripheral blood leukocytes,

are retained, while the other cells pass through. However, this

method is not very efficient. A similar system, the ScreenCell,

enriches CTCs by processing blood samples through a microporous

membrane filter with 8 µm pore size. Unlike ISET, ScreenCell system

can consistently process large numbers of blood samples with high

throughput (43). In addition, the

ScreenCell system offers other advantages, including the use of

cellular and molecular technologies for identifying CTCs and

analyzing their underlying genetic abnormalities, which facilitate

the easy analysis of tumor cells extracted onto the filter

(44). Furthermore, the cells

isolated from blood maintain a high level of activity and

integrity, allowing for in vitro tissue culture. To minimize

cell damage and preserve cell viability, a flexible miniature

spring array device ensures the harvesting of CTCs with greater

viability (45). This device uses a

pressure-regulated system to capture CTCs with an efficiency of up

to 90%. However, experiments have shown that the device tends to

yield variable CTC counts across different samples, making it less

reliable (46). There are also 3D

membrane microfilters, such as the Parsortix system (47), Resettable Cell Trap (RCT) (48) and FaCTChecker and Cluster-Chip,

which allow for the separation of individual CTCs and/or CTC

clusters, depending on the size and/or variability of the CTCs

(38). Unlike the FaCTChecker

microfilter, the Parsortix system employs a horizontal

configuration rather than a vertical one. This microdevice features

a stepped architecture with channel widths progressively narrowing

to ≤10 µm. CTCs larger than the channel width become trapped in the

gaps, while smaller cells pass through. After CTC capture, reverse

flow releases the captured CTCs for collection and subsequent

molecular characterization. The RCT employs a strategy similar to

that of Parsortix; however, rather than reducing the channel

height, the device uses pneumatically controlled microvalves to

modulate the channel aperture and capture CTCs within pockets that

are taller than the main channel. When the microvalves are relaxed,

the aperture widens, enabling the release of the captured CTCs

(44). Both 2D and 3D membrane

microfilters have distinct characteristics in the separation and

enrichment of CTCs, with the choice depending primarily on the

enrichment principle of the specific method. With respect to

microfiltration techniques, the cross-sectional area of 2D surfaces

is more critical, whereas volumetric measurements are more relevant

for 3D shapes in flow separation. However, since the size of CTCs

may vary in size during aggregation, apoptosis, and different

stages of the cell cycle and can partially overlap with the size of

leukocytes, false-positive results may occur during the enrichment

process (38). Although size-based

enrichment of CTCs is a simple and label-free technique for

high-throughput assays, the capture rates and specificity are

influenced by the size heterogeneity of CTCs, necessitating

combination with other assays to improve accuracy.

In addition to size-based enrichment methods,

density-based enrichment is a workable strategy with distinct

advantages. One commonly used density gradient centrifugation

technique involves the use of a sucrose polymer with a high

synthetic molecular weight (Ficoll-Paque; GE Healthcare) as the

primary density gradient medium (49). The high centrifugal force applied in

this method creates a density gradient and the size and density of

the cells determines their sedimentation rate. The cell loading and

harvesting procedures must be determined empirically as they are

significantly influenced by the Ficoll-Paque, the rotor, and the

type of centrifuge tube used. Excessive cell loss and low

separation efficiency for CTCs isolated by Ficoll-based density

gradient centrifugation have been attributed to density-related

toxicity (38,50). The OncoQuick gradient system

addresses these problems by minimizing cell loss and contamination,

thereby achieving higher CTC enrichment rates than the traditional

Ficoll-Paque technology does (38,51).

The dielectrophoretic array (DEPArray) system,

developed in 2013, is a semiautomated platform capable of selecting

and isolating individual CTCs and small populations of cells

(52). The primary advantage of the

DEPArray system lies in its ability to identify multiparameter

immunofluorescence staining characteristics of individual cells

before isolation. Additionally, it can be integrated into a

continuous, semiautomated workflow platform, such as with the

CellSearch System. However, the system's advanced capabilities for

imaging and isolating individual CTCs have significant drawbacks,

including high costs and an average cell loss of ~40% during sample

preparation and separation (52).

To address these challenges and achieve higher separation

resolution, researchers developed an integrated dielectrophoretic

(DEP) and magnetophoretic (MAP) microfluidic chip in 2022. This

integrated MAP-DEP approach enables the separation of various types

of CTCs on the basis of their size and dielectric properties

(53).

In 2019, an investigator introduced a novel

multiflow microfluidic (MFM) system designed for the high-purity

separation of CTCs. By utilizing the inherent differences in the

inertial migration of cells flowing within microchannels, the MFM

system demonstrated a sensitivity that achieved over 87% purity in

label-free separations. However, the system has serious

limitations. Its sensitivity and recovery rates are compromised

when CTCs exhibit significant size overlap with other cell types.

Additionally, compared with other label-free separation systems,

the device operates at a relatively low flow rate. To address these

limitations, a new class of collectors based on similar principles,

known as inertial microfluidic labyrinth devices, was developed

(54). These devices incorporate 12

distinct arrays of microfilters and combine inertial focusing with

Dean flow dynamics. This approach achieves size-based cell

separation by continuously focusing all cells while selectively

isolating CTCs from smaller blood cells at the device's outlet.

Current CTC and CTC cluster separation techniques often rely on

biomarker-dependent antibody-based capture. However, compared with

individual CTCs, CTC clusters pose unique challenges: They have a

lower surface-area-to-volume ratio (55) and often exhibit mixed

epithelial-mesenchymal phenotypes, resulting in reduced antibody

binding regions (56).

Consequently, these methods may result in lower enrichment rates

for CTCs and CTC clusters with stem-like or mesenchymal

characteristics. By contrast, physical property-based separation

methods, such as inertial microfluidic labyrinth devices, avoid the

biases inherent in molecular marker-dependent systems. These

advanced devices offer a more effective solution for separating

CTCs and CTC clusters, including those with diverse phenotypes,

because they rely on size-based rather than molecular-based

characteristics (54).

In summary, CTC enrichment methods based on physical

properties are label-free and relatively simple to perform.

However, they often suffer from limited enrichment purity and a

risk of cell loss. As a result, they are best suited for

preliminary enrichment, and their combination with immunoaffinity

methods may offer a more effective strategy to increase detection

sensitivity and specificity.

CTCs are typically enriched through positive

selection using antibodies targeting tumor-associated antigens.

These antigens include epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM),

mesenchymal markers, cytokeratins (CKs), mucin-1, human epidermal

growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and epithelial growth factor

receptor (EGFR), among others (57,58).

Alternatively, CTCs can be enriched through negative selection by

removing unwanted leukocytes using antibodies against markers such

as CD45; however, the EpCAM-dependent positive selection technique

is the most widely used (59,60).

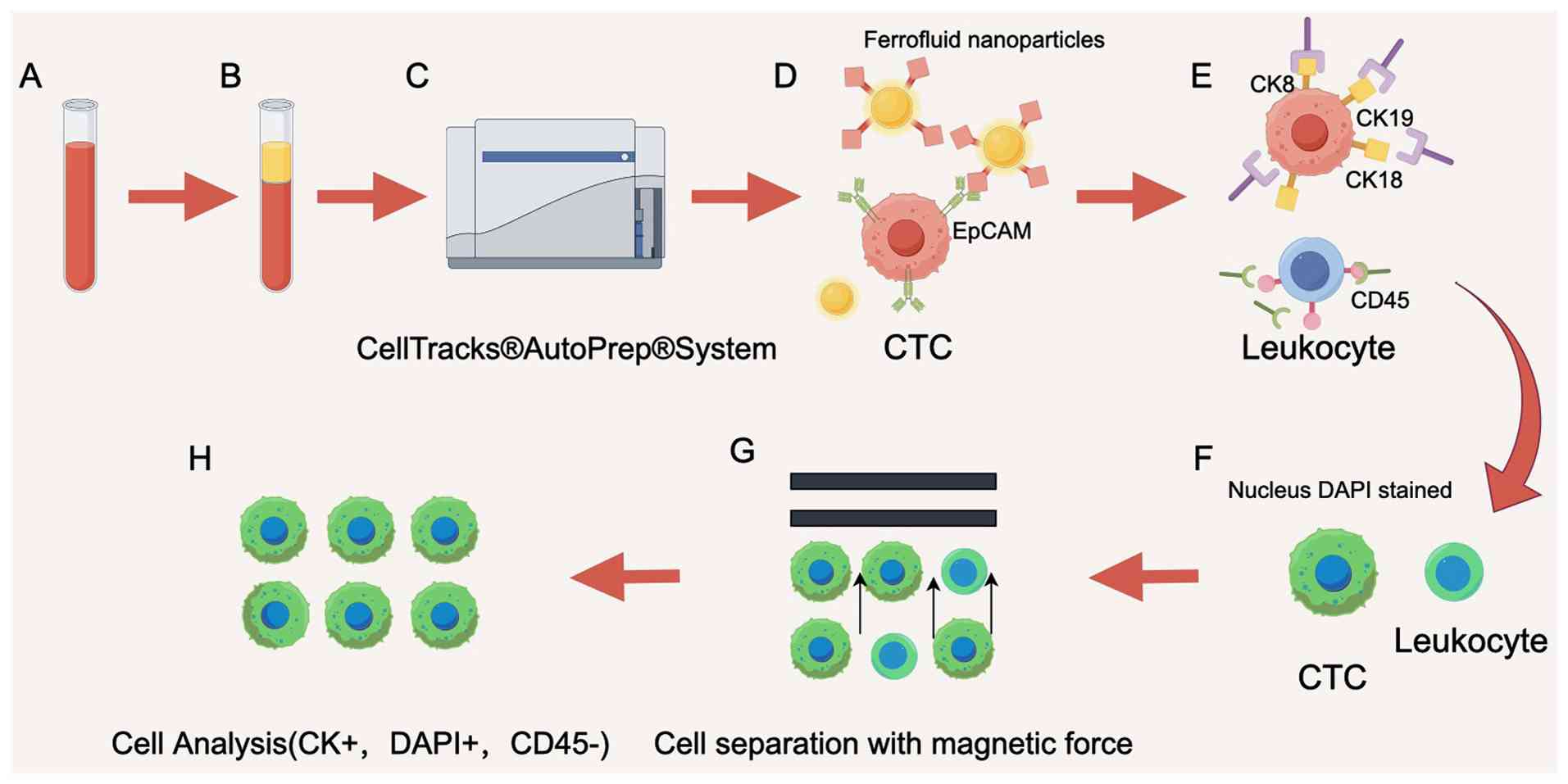

Currently, several methods are popular for the

positive enrichment of CTCs. The CellSearch system, which uses an

EpCAM-based immunoassay, is the first and only FDA-approved CTC

assay (61) for colorectal, breast,

prostate and other tumors (62).

The CellSearch system's principle involves the use of ferromagnetic

fluid nanoparticle-labeled antibodies that specifically bind to

EpCAM, which is highly expressed on the surface of a wide range of

tumor cells. CTCs are then separated from other blood cells by

means of a magnet. The detailed collection process is illustrated

in Fig. 3. However, EpCAM-antibody

interactions can cause CTCs to adhere to the device's surface,

making their release difficult. To address the shortcomings of the

CellSearch system, researchers developed MagSweeper, an

immunomagnetic cell separator that enriches CTCs while eliminating

nonmagnetic particle-bound cells (63).

Advances in microfluidic chip technology and

nanomaterials have further improved the sensitivity, specificity,

and cost efficiency of CTC detection (32). A key feature of microfluidic chips

is their flexible combination and large-scale integration of

multiple functional units on a miniature platform. These chips

represent an interdisciplinary achievement combining physics,

chemistry, material science, medical science, mechanics, optics,

mechanical engineering and bioengineering. Microfluidic devices

utilizing antigen-antibody interactions can be categorized into two

types: Microcolumns (requiring chemical modification of the

monoclonal antibody coating) and devices using antibody-coated

surfaces (38). The CTC microarray

isolates target cells by enabling the interaction of CTCs with an

array of 78,000 microcolumns coated with EpCAM antibodies under

precisely controlled laminar flow conditions. This method does not

require pretreatment of the samples and preserves cellular activity

(22).

The size-determined immunocapture chip, a

deterministic lateral displacement (DLD) microarray, captures CTCs

with high sensitivity, efficiency and purity. This chip features

microcolumns that are surface modified with EpCAM antibodies.

Relatively large CTCs are deflected laterally as they collide with

microposts, prolonging their flow time, while smaller blood cells

advance with the laminar flow (64)

and selectively increase the probability of interaction with the

microposts. This method achieves capture efficiencies exceeding

92%, with a purity of 82% (65,66).

Another approach employs microfluidic encapsulated microarrays with

a staggered herringbone design on channel ceilings, increasing

cell-surface contact points. This design significantly enhances

capture efficiency while preserving cellular activity, enabling

downstream analyses such as cell culture and genomic studies.

However, CTCs undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

exhibit increased invasive and metastatic potential (67). During the EMT, the expression of

tumor markers on the cell surface is downregulated (68,69),

posing significant challenges for devices that rely exclusively on

anti-EpCAM antibodies for CTC capture (70). A synergistic, dual-antibody chip

based on the DLD principle partially addresses this challenge. In

this approach, anti-ASGPR and anti-EpCAM antibodies are

simultaneously modified in parallel on a microfluidic synergistic

chip, with a capture efficiency of more than 87% per channel

(71).

Over time, advancements in research have

transitioned CTC capture technology from first-generation chips,

such as the CTC-Chip, to second-generation chips, such as the

HB-Chip, GO-Chip and GEM-Chip. Currently, a third-generation

microfluidic chip, called the CTC-iChip, has emerged as a

recognized innovation in the field (72–74).

Compared with first-generation CTC microarrays, second-generation

microarray technology, specifically surface capture devices, is

simpler to fabricate and more efficient at capturing CTCs. However,

these devices have serious limitations, as the captured CTCs are

immobilized on the device surface, making their recovery for

downstream genomic analyses challenging. While trypsin digestion

can be used to release the captured cells, this process may remove

some receptor proteins from the surface of the CTCs and interfere

with subsequent analyses.

Third-generation microfluidic chip technology, such

as the inertial focusing-enhanced microfluidic system (CTC-iChip),

enables the efficient negative depletion of anuclear RBCs and

platelets. This is achieved through the hydrodynamic separation of

nucleated leukocytes and CTCs in plasma, followed by inertial

focusing into a single stream. Magnetic bead-labeled leukocytes are

then efficiently removed by magnetophoresis, resulting in a

solution enriched with CTCs with both epithelial and mesenchymal

features (78). However, this

system has notable drawbacks, including high initial cost a long

setup time, limited ability to analyze single-cell molecules,

reliance on multiple manually attached chips, and challenges in

clinical implementation (32).

To reduce the cost of capturing CTCs, a recent study

proposed the use of EpCAM-resistant nanofiber cellulose scaffolds

with immobilized Fe3O4 NPs for harvesting

CTCs (25). Cellulose

nanostructures can be categorized into two main types: Cellulose

nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibers (CNFs). These nanomaterials

offer several advantages, including relatively high aspect ratios,

large specific surface areas, biodegradability, environmental

sustainability, biocompatibility and non-toxicity (25). Compared with fibrous scaffolds,

rigid nanocrystal scaffolds interact more efficiently with CTCs

(25); however, CNFs have a higher

aspect ratio, which increases the probability of intermolecular

interactions. Kumar et al (79) developed a CNF-based microfluidic

chip with a capture efficiency of 79–98%. However, its average flow

rate of 5 µl/min poses a significant limitation for processing

large volumes of blood, as it reduces the point of contact

necessary for effective CTC capture (79). By contrast, a microchip developed by

Cui et al (80) and

integrated with ZnO nanowires achieved a high CTC capture

efficiency of 91.1±5.5% while maintaining excellent cell viability

(96%). Notably, the platform also enabled damage-free release of

captured cells. This advancement in microarray technology

facilitates single-cell analysis and holds considerable potential

for advancing personalized medicine, particularly in the

development of therapeutics targeting cancer stem cells (80). Researchers have also recently

developed a nanoplatform called NICHE for determining the

relationships between host genes and the microenvironment in living

cells (81). This innovative

platform combines microfluidics and nanofluidics to efficiently

capture CTCs from blood samples. The platform then integrates

stable multichannel fluorescent probes into live CTCs, enabling

rapid in situ quantification of target gene expression. The

NICHE microfluidic device is unique in that it allows simultaneous

gene expression and phenotypic analyses on individual cells in

situ. It also has the potential to generate predictive indices

for screening patients who are likely to benefit from ICIs.

The decreased expression of EpCAM on the surface of

cells undergoing EMT results in a reduced capture rate when an

EpCAM-dependent positive enrichment method is used (38). To overcome these shortcomings,

label-free and negative enrichment methods have been developed.

Similar to the previously mentioned CTC-iChip, a 3D microfluidic

device has been developed and fabricated for the negative

enrichment of CTCs from whole blood samples (82). The device captures unlabeled

leukocytes on its inner surface using antibodies targeting

leukocyte-specific membrane antigens and separates red blood cells

and platelets from CTCs according to their small size. This method

is compatible with subsequent molecular, immunocytochemical and

functional analyses.

In conclusion, positive enrichment methods offer

superior specificity and purity, making them effective for

enriching CTCs with known markers. However, their reliance on

specific markers may cause them to miss certain CTC subtypes.

Conversely, negative enrichment methods can capture a more diverse

range of CTCs but generally result in lower enrichment purity and a

risk of cell loss. In simple terms, positive enrichment methods are

best suited for applications requiring high sensitivity and

specificity, whereas negative enrichment methods are more

appropriate for capturing a heterogeneous CTC population,

particularly when markers are unknown or inconsistently expressed.

A combined approach may provide a more thorough CTC detection

strategy, despite being more complex to implement. In addition to

the above-described platforms, numerous potential CTC enrichment

methods have been developed in recent years (Table SI).

Although there are numerous complex methods for

enriching CTCs, the detection procedure is still relatively

straightforward. The current identification methods include

immunofluorescence, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

(RT-PCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS).

This technique involves labeling enriched cells

after fixation using fluorescent markers such as anti-human

pancytokeratin (CK), anti-mouse CD45, DAPI, and a cocktail of

antibodies targeting cell surface proteins such as EpCAM, EGFR and

HER2. CTCs are identified as

DAPI+/CK+/CD45− cells (83). The primary advantage of this method

is its convenience in observing the phenotype and morphology of

cells under a fluorescence microscope (84). However, the expression of protein

markers often lacks stability and cannot be used to distinguish

between viable and non-viable cells (83,85).

RT-PCR can be used to detect target cells by reverse

transcription, in which the enzyme reverse transcriptase converts

RNA into complementary DNA using a specific primer (86). While this method allows for the

genetic identification of target cells, it cannot distinguish

non-viable cells from viable cells, limiting its application in

analyses requiring live cells, such as assessments of cellular

deformability and drug responses.

This method enables the detection of specific

proteins secreted by CTCs. It involves culturing enriched CTCs and

tagging secreted proteins with fluorescently labeled antibodies.

Each immunofluorescent spot represents a living cell, offering high

specificity and stability (87).

However, this technique requires sufficient accumulation of

secreted proteins to form immune spots, which can be

time-consuming.

FISH can be used to detect CTCs by labeling abnormal

chromosomal numbers or structures specific to tumor cells. This

genetic method offers high sensitivity and specificity for

identifying CTCs but it can suffer interference from abnormal

chromosomes in the patient's blood and the limited scope of

chromosomal probes, which can detect only a limited number of

specific markers (54,88).

NGS provides insights into genetic structures and

expression states at the single-cell level, allowing for the

genotyping of CTCs and the detection of tumor-specific mutations

(89). While this method offers

unparalleled precision, highly effective upstream enrichment

techniques and stringent QC are needed to ensure the purity and

abundance of CTCs (90) (Table SII).

Immunotherapy involves activating immune cells for

the recognition and destruction of cancer cells (91). Common immune checkpoints include

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, programmed cell death

protein 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1),

lymphocyte activation gene 3, B7-H3 and T-cell immunoglobulin and

mucin-domain containing-3. Among these, PD-1 and PD-L1 are key

molecules in the immune system, and play crucial roles in the

immune escape of tumor cells (92).

PD-1 is an immunosuppressive molecule that is primarily expressed

on activated T and B cells, whereas PD-L1 is predominantly

upregulated in various tumor cells (93). When PD-L1 binds to PD-1 on T cells,

it promotes tumor immune escape. PD-1 inhibitors work by blocking

the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 (94), thereby restoring the antitumor

activity of immune cells, enhancing the immune response, reducing

tumor cell proliferation and metastasis, and increasing patient

survival rates (95,96). Numerous studies have demonstrated

the important clinical value of CTCs in immunotherapy.

Numerous studies have shown the usefulness of CTCs

in clinical prognosis; however, their role in predicting the

response to tumor immunotherapy has been relatively unexplored.

Research has demonstrated that the presence of CTCs serves as an

independent prognostic indicator of shorter overall survival (OS)

in patients with various cancers, including non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC) (97). Lin et

al (98) reported a significant

reduction in the number of CTCs in the peripheral blood of patients

with stage IV NSCLC who were treated with NK cell immunotherapy on

Days 7 and 30 of treatment. These findings suggest that CTCs may

serve as valuable biomarkers for evaluating treatment efficacy

(98). A different study revealed

that the presence of CTCs was a predictor of poor durable response

rates following immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy. A

durable response is defined as stable disease or a partial or

complete response without disease progression at six months

(99). The prognostic and

predictive value of CTCs was further demonstrated in a phase 1b

study using lysosomal virus immunotherapy, where a reduction in CTC

counts was observed in baseline-positive patients who responded

effectively to treatment. Moreover, a study by Castello et

al (100) revealed that the

mean CTC count was significantly lower in patients with NSCLC

treated with ICIs than in untreated patients. The results of the

aforementioned study also revealed that combining the mean CTC

count with the median metabolic tumor volume was associated with

PFS and OS after 8 weeks of ICI treatment (100). Importantly, CTC counts were

identified as independent predictors of both PFS and OS (101,102). Gu et al (103) developed a risk model to predict

prognosis on the basis of aberrantly methylated DNA in CTCs from

patients with lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). In the aforementioned

study, patients were categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups

on the basis of their median risk score. High-risk patients were

associated with poor prognosis, whereas low-risk patients

demonstrated hyperimmunocompetence, which correlated with favorable

prognosis. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

confirmed that the risk score was an independent prognostic factor

for survival in patients with LUAD (103).

Antitumor immunotherapeutic strategies have emerged

as promising approaches for the treatment of various cancers. The

expression level of PD-L1 is a crucial indicator of the immune

status of patients with cancer and a key marker for predicting the

efficacy of immunotherapy (104).

Studies have suggested that PD-L1 expression serves as a predictive

biomarker for immunotherapy response in certain solid tumors,

including NSCLC, melanoma and renal cell carcinoma (95,105,106). For example, in a study of

immunotherapy for NSCLC, patients with PD-L1-negative CTCs at

baseline, as well as at 3 and 6 months of nivolumab treatment,

achieved favorable clinical benefits at the 6-month mark. By

contrast, tumor progression occurred in patients with

PD-L1-positive CTCs. These findings suggest that PD-L1 expression

on CTCs could serve as a predictive marker for the immunotherapy

response (107). Dall' Olio et

al (108) reported that

pretreatment with PD-L1-positive CTCs was associated with improved

survival, whereas posttreatment with PD-L1-positive CTCs was

correlated with worse survival in patients with advanced NSCLC

receiving PD-L1/PD-1 inhibitors as second- or third-line therapy

(108). In a phase 1 trial of the

PD-1 inhibitor IBI308 for the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors,

the presence of CTCs with high PD-L1 expression was associated with

significantly better disease control rates. The abundance of

PD-L1-positive CTCs at baseline was also found to predict PFS,

suggesting that monitoring CTC dynamics could provide an early

indication of therapeutic response.

The authors' hypothesis that CTCs can serve as

predictive biomarkers of tumor immunotherapy efficacy was also

supported by a study on metastatic genitourinary tumors.

PD-L1-positive CTCs, elevated CTC counts, and specific CTC

morphological subtypes were associated with shorter OS from

immunotherapy for metastatic genitourinary cancers (109). Combining an assessment of CTC

cluster abundance with single CTC counts significantly improved

prognostic accuracy (110). Thus,

CTCs not only are useful for assessing the prognosis of patients

with cancer, but they also serve as important predictive biomarkers

for monitoring the efficacy of immunotherapy and developing robust

personalized treatment strategies. Most studies have focused on

NSCLC, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer and

melanoma; the predictive value of CTCs in other cancer types

requires further exploration.

Tumor metastasis and recurrence remain the primary

causes of cancer-related death and present difficult treatment

challenges. The development and successful application of ICIs

represent major breakthroughs in tumor therapy in recent years.

While it is not yet clear whether CTCs are more susceptible to

interventions targeting PD-L1 than cells in solid tumors are,

activating the immune system by blocking PD-L1 expression on CTCs

and reducing their numbers in peripheral circulation could decrease

the likelihood of malignant tumor recurrence and metastasis,

representing a promising new therapeutic approach (8,111).

In addition to PD-L1, CD47 is recognized as a crucial immune

checkpoint that is highly expressed on tumor cells. CD47 interacts

with signal-regulated protein alpha on macrophages, transmitting

inhibitory signals that suppress phagocytosis (112). Thus, PD-L1 acts as the key ‘don't

find me’ signal for the adaptive immune system, whereas CD47

functions as the ‘don't eat me’ signal for the innate immune system

and regulates the adaptive immune response (113,114). Targeting both PD-L1 and CD47

simultaneously with specific antibodies has been shown to be more

effective at suppressing lung metastases than targeting PD-L1 or

CD47 alone (114) (Fig. 4).

CTCs were first discovered more than a century ago,

and extensive studies have since demonstrated their importance in

clinical applications. CTCs offer the potential to detect relevant

target lesions at an early stage, even before imaging can reveal a

tumor. They can also be used in combination with other tumor

markers to guide therapy, monitor patients' postoperative

treatment, and predict prognosis. Despite the promising results

from studies of these novel applications, significant challenges

remain before CTCs can be fully integrated into clinical

practice.

The rarity and heterogeneity of CTCs present major

obstacles. While recent advances in CTC enrichment and detection

technology have been achieved, differences in equipment and

detection methods can lead to differences in the interpretation of

results. Currently, standardized, robust CTC detection procedures

are lacking. Moreover, most existing CTC enrichment and detection

methods are expensive, limiting their widespread use in clinical

settings. To address this issue, numerous researchers are now

focusing on utilizing nanoscale materials to develop more

cost-effective platforms for CTC separation and enrichment. While

laboratory testing of these approaches has shown excellent results,

large-scale experiments are needed to validate their feasibility

for clinical applications.

In summary, CTCs not only are useful for assessing

the prognosis of patients with cancer in clinical applications, but

they also serve as important predictive biomarkers for monitoring

the effectiveness of immunotherapy and personalized treatment

strategies. However, current research on CTCs has focused primarily

on a limited number of cancer types, and their predictive value in

other cancers requires further investigation. Immunotherapy is a

prominent research focus for the treatment of malignant tumors, but

no large studies have been conducted that definitively show the

efficacy of using CTCs as targets for tumor immunotherapy. Using

immunotherapy to target CTCs has the potential to reduce the risk

of metastasis and recurrence in malignant tumors, particularly in

postoperative patients, offering a greater hope for permanent

remission.

In conclusion, advancements in CTC isolation and

detection technologies, along with their gradual integration into

clinical applications, hold great potential as key components of

precision individualized medicine in the future.

Not applicable.

The present study was sponsored by the Technological Innovation

R & D Project of Chengdu Science and Technology Program (grant

no. 2022-YF05-01950-SN) and the CSCO-Merck Oncology Research Fund -

Key Project (grant no. Y-MSD2020-0354).

Not applicable.

PZ and QY conducted data mining, writing, draft, and

figure preparation. YH and YF conceptualized, designed and

supervised the study, and revised the manuscript. LZ and KX

reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Feng Z, Wu J, Lu Y, Chan YT, Zhang C, Wang

D, Luo D, Huang Y, Feng Y and Wang N: Circulating tumor cells in

the early detection of human cancers. Int J Biol Sci. 18:3251–3265.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang W, Xu F, Yao J, Mao C, Zhu M, Qian

M, Hu J, Zhong H, Zhou J, Shi X and Chen Y: Single-cell metabolic

fingerprints discover a cluster of circulating tumor cells with

distinct metastatic potential. Nat Commun. 14:24852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

El-Kenawi A, Hänggi K and Ruffell B: The

immune microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Med. 10:a0374242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pereira-Veiga T, Schneegans S, Pantel K

and Wikman H: Circulating tumor cell-blood cell crosstalk: Biology

and clinical relevance. Cell Rep. 40:1112982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Schmidt C: The benefits of immunotherapy

combinations. Nature. 552:S67–S69. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Brozos-Vázquez EM, Díaz-Peña R,

García-González J, León-Mateos L, Mondelo-Macía P, Peña-Chilet M

and López-López R: Immunotherapy in nonsmall-cell lung cancer:

current status and future prospects for liquid biopsy. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 70:1177–1188. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xu H, Zuo Y, Gao S, Liu Y, Liu T, He S,

Wang M, Hu L, Li C and Yu Y: Circulating tumor cell phenotype

detection and epithelial-mesenchymal transition tracking based on

dual biomarker co-recognition in an integrated PDMS chip. Small.

20:e23103602024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhong X, Zhang H, Zhu Y, Liang Y, Yuan Z,

Li J, Li J, Li X, Jia Y, He T, et al: Circulating tumor cells in

cancer patients: Developments and clinical applications for

immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 19:152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Singh B, Arora S, D'Souza A, Kale N, Aland

G, Bharde A, Quadir M, Calderón M, Chaturvedi P and Khandare J:

Chemo-specific designs for the enumeration of circulating tumor

cells: Advances in liquid biopsy. J Mater Chem B. 9:2946–2978.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ye Q, Ling S, Zheng S and Xu X: Liquid

biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Circulating tumor cells and

circulating tumor DNA. Mol Cancer. 18:1142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li M, Li L, Zheng J, Li Z, Li S, Wang K

and Chen X: Liquid biopsy at the frontier in renal cell carcinoma:

recent analysis of techniques and clinical application. Mol Cancer.

22:372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shuai Y, Ma Z, Ju J, Wei T, Gao S, Kang Y,

Yang Z, Wang X, Yue J and Yuan P: Liquid-based biomarkers in breast

cancer: Looking beyond the blood. J Transl Med. 21:8092023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jou HJ, Ho HC, Huang KY, Chen CY, Chen SW,

Lo PH, Huang PW, Huang CE and Chen M: Isolation of TTF-1 positive

circulating tumor cells for single-cell sequencing by using an

automatic platform based on microfluidic devices. Int J Mol Sci.

23:151392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xu CM, Tang M, Feng J, Xia HF, Wu LL, Pang

DW, Chen G and Zhang ZL: A liquid biopsy-guided drug release system

for cancer theranostics: Integrating rapid circulating tumor cell

detection and precision tumor therapy. Lab Chip. 20:1418–1425.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ashworth T: A case of cancer in which

cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after

death. Aust Med J. 14:146–147. 1869.

|

|

16

|

Nasr MM and Lynch CC: How circulating

tumor cluster biology contributes to the metastatic cascade: From

invasion to dissemination and dormancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

42:1133–1146. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Smit DJ, Pantel K and Jücker M:

Circulating tumor cells as a promising target for individualized

drug susceptibility tests in cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol.

188:1145892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Peck K, Sher YP, Shih JY, Roffler SR, Wu

CW and Yang PC: Detection and quantitation of circulating cancer

cells in the peripheral blood of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res.

58:2761–2765. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ,

Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ,

Terstappen LW and Hayes DF: Circulating tumor cells, disease

progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J

Med. 351:781–791. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Magri V, Marino L, Nicolazzo C, Gradilone

A, De Renzi G, De Meo M, Gandini O, Sabatini A, Santini D, Cortesi

E and Gazzaniga P: Prognostic role of circulating tumor cell

trajectories in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cells. 12:11722023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet

M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AG, Uhr JW and Terstappen LW: Tumor

cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but

not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases.

Clin Cancer Res. 10:6897–6904. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell

DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky

A, et al: Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer

patients by microchip technology. Nature. 450:1235–1239. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hartmann C, Patil R, Lin CP and Niedre M:

Fluorescence detection, enumeration and characterization of single

circulating cells in vivo: Technology, applications and future

prospects. Phys Med Biol. 63:01TR012017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tang M, Xia HF, Xu CM, Feng J, Ren JG,

Miao F, Wu M, Wu LL, Pang DW, Chen G and Zhang ZL: Magnetic chip

based extracorporeal circulation: A new tool for circulating tumor

cell in vivo detection. Anal Chem. 91:15260–15266. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hazra RS, Kale N, Boyle C, Molina KB,

D'Souza A, Aland G, Jiang L, Chaturvedi P, Ghosh S, Mallik S, et

al: Magnetically-activated, nanostructured cellulose for efficient

capture of circulating tumor cells from the blood sample of head

and neck cancer patients. Carbohydr Polym. 323:1214182024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang Q, Zhang X, Xie P and Zhang W:

Liquid biopsy: An arsenal for tumour screening and early diagnosis.

Cancer Treat Rev. 129:1027742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ghassemi P, Ren X, Foster BM, Kerr BA and

Agah M: Post-enrichment circulating tumor cell detection and

enumeration via deformability impedance cytometry. Biosens

Bioelectron. 150:1118682020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nikanjam M, Kato S and Kurzrock R: Liquid

biopsy: Current technology and clinical applications. J Hematol

Oncol. 15:1312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kowalik A, Kowalewska M and Góźdź S:

Current approaches for avoiding the limitations of circulating

tumor cells detection methods-implications for diagnosis and

treatment of patients with solid tumors. Transl Res. 185:58–84.e15.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

You Q, Peng J, Chang Z, Ge M, Mei Q and

Dong WF: Specific recognition and photothermal release of

circulating tumor cells using near-infrared light-responsive 2D

MXene simplenanosheets@hydrogel

membranes. Talanta. 235:1227702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang K, Wang X, Pan Q and Zhao B: Liquid

biopsy techniques and pancreatic cancer: diagnosis, monitoring, and

evaluation. Mol Cancer. 22:1672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin D, Shen L, Luo M, Zhang K, Li J, Yang

Q, Zhu F, Zhou D, Zheng S, Chen Y and Zhou J: Circulating tumor

cells: Biology and clinical significance. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 6:4042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu Y, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang X, Kang K, Zhu

N, Wu Y and Yi Q: Floating immunomagnetic microspheres for highly

efficient circulating tumor cell isolation under facile magnetic

manipulation. ACS Sens. 8:1858–1866. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yeo D, Kao S, Gupta R, Wahlroos S, Bastian

A, Strauss H, Klemm V, Shrestha P, Ramirez AB, Costandy L, et al:

Accurate isolation and detection of circulating tumor cells using

enrichment-free multiparametric high resolution imaging. Front

Oncol. 13:11412282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Labib M and Kelley SO: Circulating tumor

cell profiling for precision oncology. Mol Oncol. 15:1622–1646.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen J, Li D, Zhou C, Zhu Y, Lin C, Guo L,

Le W, Gu Z and Chen B: Principle superiority and clinical

extensibility of 2D and 3D charged nanoprobe detection platform

based on electrophysiological characteristics of circulating tumor

cells. Cells. 12:3052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Khan T, Becker TM, Po JW, Chua W and Ma Y:

Single-circulating tumor cell whole genome amplification to unravel

cancer heterogeneity and actionable biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci.

23:83862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dianat-Moghadam H, Azizi M, Eslami S Z,

Cortés-Hernández LE, Heidarifard M, Nouri M and Alix-Panabières C:

The role of circulating tumor cells in the metastatic cascade:

Biology, technical challenges, and clinical relevance. Cancers

(Basel). 12:8672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hyun KA and Jung HI: Advances and critical

concerns with the microfluidic enrichments of circulating tumor

cells. Lab Chip. 14:45–56. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Shimmyo N, Furuhata M, Yamada M, Utoh R

and Seki M: Process simplification and structure design of

parallelized microslit isolator for physical property-based capture

of tumor cells. Analyst. 147:1622–1630. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Huang Q, Wang FB, Yuan CH, He Z, Rao L,

Cai B, Chen B, Jiang S, Li Z, Chen J, et al: Gelatin

nanoparticle-coated silicon beads for density-selective capture and

release of heterogeneous circulating tumor cells with high purity.

Theranostics. 8:1624–1635. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Tamminga M, Andree KC, Hiltermann TJN,

Jayat M, Schuuring E, van den Bos H, Spierings DCJ, Lansdorp PM,

Timens W, Terstappen LWMM and Groen HJM: Detection of circulating

tumor cells in the diagnostic leukapheresis product of

non-small-cell lung cancer patients comparing

cellsearch® and ISET. Cancers (Basel). 12:8962020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Barr J, Chudasama D, Rice A, Karteris E

and Anikin V: Lack of association between Screencell-detected

circulating tumour cells and long-term survival of patients

undergoing surgery for non-small cell lung cancer: A pilot clinical

study. Mol Clin Oncol. 12:191–195. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ferreira MM, Ramani VC and Jeffrey SS:

Circulating tumor cell technologies. Mol Oncol. 10:374–394. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang Y, Wang B, Cai J, Yang Y, Tang C,

Zheng X, Li H and Xu F: Enrichment and separation technology for

evaluation of circulating tumor cells. Talanta. 282:1270252025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Harouaka RA, Zhou MD, Yeh YT, Khan WJ, Das

A, Liu X, Christ CC, Dicker DT, Baney TS, Kaifi JT, et al: Flexible

micro spring array device for high-throughput enrichment of viable

circulating tumor cells. Clin Chem. 60:323–333. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Gkountela S, Castro-Giner F, Szczerba BM,

Vetter M, Landin J, Scherrer R, Krol I, Scheidmann MC, Beisel C,

Stirnimann CU, et al: Circulating tumor cell clustering shapes DNA

methylation to enable metastasis seeding. Cell. 176:98–112.e14.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kurma K, Eslami-S Z, Alix-Panabières C and

Cayrefourcq L: Liquid biopsy: Paving a new avenue for cancer

research. Cell Adh Migr. 18:1–26. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jia Y, Xu H, Li Y, Wei C, Guo R, Wang F,

Wu Y, Liu J, Jia J, Yan J, et al: A Modified ficoll-paque gradient

method for isolating mononuclear cells from the peripheral and

umbilical cord blood of humans for biobanks and clinical

laboratories. Biopreserv Biobank. 16:82–91. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

He S, Wei J, Ding L, Yang X and Wu Y:

State-of-the-arts techniques and current evolving approaches in the

separation and detection of circulating tumor cell. Talanta.

239:1230242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang Y, Li Y and Tan Z: A review of

enrichment methods for circulating tumor cells: From single

modality to hybrid modality. Analyst. 146:7048–7069. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Peeters DJ, De Laere B, Van den Eynden GG,

Van Laere SJ, Rothé F, Ignatiadis M, Sieuwerts AM, Lambrechts D,

Rutten A, van Dam PA, et al: Semiautomated isolation and molecular

characterisation of single or highly purified tumour cells from

CellSearch enriched blood samples using dielectrophoretic cell

sorting. Br J Cancer. 108:1358–1367. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zhao K, Zhao P, Dong J, Wei Y, Chen B,

Wang Y, Pan X and Wang J: Implementation of an integrated

dielectrophoretic and magnetophoretic microfluidic chip for CTC

isolation. Biosensors (Basel). 12:7572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zeinali M, Lee M, Nadhan A, Mathur A,

Hedman C, Lin E, Harouaka R, Wicha MS, Zhao L, Palanisamy N, et al:

High-throughput label-free isolation of heterogeneous circulating

tumor cells and CTC clusters from non-small-cell lung cancer

patients. Cancers (Basel). 12:1272020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Boya M, Ozkaya-Ahmadov T, Swain BE, Chu

CH, Asmare N, Civelekoglu O, Liu R, Lee D, Tobia S, Biliya S, et

al: High throughput, label-free isolation of circulating tumor cell

clusters in meshed microwells. Nat Commun. 13:33852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Fabisiewicz A and Grzybowska E: CTC

clusters in cancer progression and metastasis. Med Oncol.

34:122017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Niu Z, Kozminsky M, Day KC, Broses LJ,

Henderson ML, Patsalis C, Tagett R, Qin Z, Blumberg S, Reichert ZR,

et al: Characterization of circulating tumor cells in patients with

metastatic bladder cancer utilizing functionalized microfluidics.

Neoplasia. 57:1010362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Vidlarova M, Rehulkova A, Stejskal P,

Prokopova A, Slavik H, Hajduch M and Srovnal J: Recent advances in

methods for circulating tumor cell detection. Int J Mol Sci.

24:39022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sajay BN, Chang CP, Ahmad H, Khuntontong

P, Wong CC, Wang Z, Puiu PD, Soo R and Rahman AR: Microfluidic

platform for negative enrichment of circulating tumor cells. Biomed

Microdevices. 16:537–548. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ma S, Zhou M, Xu Y, Gu X, Zou M,

Abudushalamu G, Yao Y, Fan X and Wu G: Clinical application and

detection techniques of liquid biopsy in gastric cancer. Mol

Cancer. 22:72023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Lopes C, Piairo P, Chícharo A, Abalde-Cela

S, Pires LR, Corredeira P, Alves P, Muinelo-Romay L, Costa L and

Diéguez L: HER2 expression in circulating tumour cells isolated

from metastatic breast cancer patients using a size-based

microfluidic device. Cancers (Basel). 13:44462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chowdhury T, Cressiot B, Parisi C,

Smolyakov G, Thiébot B, Trichet L, Fernandes FM, Pelta J and

Manivet P: Circulating tumor cells in cancer diagnostics and

prognostics by single-molecule and single-cell characterization.

ACS Sens. 8:406–426. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Talasaz AH, Powell AA, Huber DE, Berbee

JG, Roh KH, Yu W, Xiao W, Davis MM, Pease RF, Mindrinos MN, et al:

Isolating highly enriched populations of circulating epithelial

cells and other rare cells from blood using a magnetic sweeper

device. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:3970–3975. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Shi J, Zhao C, Shen M, Chen Z, Liu J,

Zhang S and Zhang Z: Combination of microfluidic chips and

biosensing for the enrichment of circulating tumor cells. Biosens

Bioelectron. 202:1140252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Ahmed MG, Abate MF, Song Y, Zhu Z, Yan F,

Xu Y, Wang X, Li Q and Yang C: Isolation, detection, and

antigen-based profiling of circulating tumor cells using a

size-dictated immunocapture chip. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl.

56:10681–10685. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Liu HY, Koch C, Haller A, Joosse SA, Kumar

R, Vellekoop MJ, Horst LJ, Keller L, Babayan A, Failla AV, et al:

Evaluation of microfluidic ceiling designs for the capture of

circulating tumor cells on a microarray platform. Adv Biosyst.

4:e19001622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Kulus M, Farzaneh M, Bryja A, Zehtabi M,

Azizidoost S, Abouali Gale Dari M, Golcar-Narenji A, Ziemak H,

Chwarzyński M, Piotrowska-Kempisty H, et al: Phenotypic transitions

the processes involved in regulation of growth and proangiogenic

properties of stem cells, cancer stem cells and circulating tumor

cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 20:967–979. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gwak H, Park S, Kim J, Lee JD, Kim IS, Kim

SI, Hyun KA and Jung HI: Microfluidic chip for rapid and selective

isolation of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles for early

diagnosis and metastatic risk evaluation of breast cancer. Biosens

Bioelectron. 192:1134952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Cortés-Hernández LE, Eslami-S Z,

Costa-Silva B and Alix-Panabières C: Current applications and

discoveries related to the membrane components of circulating tumor

cells and extracellular vesicles. Cells. 10:22212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Shahhosseini R, Pakmehr S, Elhami A,

Shakir MN, Alzahrani AA, Al-Hamdani MM, Abosoda M, Alsalamy A,

Mohammadi-Dehcheshmeh M, Maleki TE, et al: Current biological

implications and clinical relevance of metastatic circulating tumor

cells. Clin Exp Med. 25:72024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhu L, Lin H, Wan S, Chen X, Wu L, Zhu Z,

Song Y, Hu B and Yang C: Efficient isolation and phenotypic

profiling of circulating hepatocellular carcinoma cells via a

combinatorial-antibody-functionalized microfluidic synergetic-chip.

Anal Chem. 92:15229–15235. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Stott SL, Hsu CH, Tsukrov DI, Yu M,

Miyamoto DT, Waltman BA, Rothenberg SM, Shah AM, Smas ME, Korir GK,

et al: Isolation of circulating tumor cells using a

microvortex-generating herringbone-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:18392–18397. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yoon HJ, Kim TH, Zhang Z, Azizi E, Pham

TM, Paoletti C, Lin J, Ramnath N, Wicha MS, Hayes DF, et al:

Sensitive capture of circulating tumour cells by functionalized

graphene oxide nanosheets. Nat Nanotechnol. 8:735–741. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Sheng W, Ogunwobi OO, Chen T, Zhang J,

George TJ, Liu C and Fan ZH: Capture, release and culture of

circulating tumor cells from pancreatic cancer patients using an

enhanced mixing chip. Lab Chip. 14:89–98. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Rostami P, Kashaninejad N, Moshksayan K,

Saidi MS, Firoozabadi B and Nguyen NT: Novel approaches in cancer

management with circulating tumor cell clusters. Journal of

Science: Advanced Materials and Devices. 4:1–18. 2019.

|

|

76

|

Sun N, Zhang C, Wang J, Yue X, Kim HY,

Zhang RY, Liu H, Widjaja J, Tang H, Zhang TX, et al: Hierarchical

integration of DNA nanostructures and NanoGold onto a microchip

facilitates covalent chemistry-mediated purification of circulating

tumor cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nano Today.

49:1017862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Kolb HC, Finn MG and Sharpless KB: Click

chemistry: Diverse chemical function from a few good reactions.

Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 40:2004–2021. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Fachin F, Spuhler P, Martel-Foley JM, Edd

JF, Barber TA, Walsh J, Karabacak M, Pai V, Yu M, Smith K, et al:

Monolithic chip for high-throughput blood cell depletion to sort

rare circulating tumor cells. Sci Rep. 7:109362017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Kumar T, Soares RRG, Ali Dholey L,

Ramachandraiah H, Aval NA, Aljadi Z, Pettersson T and Russom A:

Multi-layer assembly of cellulose nanofibrils in a microfluidic

device for the selective capture and release of viable tumor cells

from whole blood. Nanoscale. 12:21788–21797. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Cui H, Liu Q, Li R, Wei X, Sun Y, Wang Z,

Zhang L, Zhao XZ, Hua B and Guo SS: ZnO nanowire-integrated

bio-microchips for specific capture and non-destructive release of

circulating tumor cells. Nanoscale. 12:1455–1463. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Dong Z, Wang Y, Xu G, Liu B, Wang Y,

Reboud J, Jajesniak P, Yan S, Ma P, Liu F, et al: Genetic and

phenotypic profiling of single living circulating tumor cells from

patients with microfluidics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

121:e23151681212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Chu CH, Liu R, Ozkaya-Ahmadov T, Swain BE,

Boya M, El-Rayes B, Akce M, Bilen MA, Kucuk O and Sarioglu AF:

Negative enrichment of circulating tumor cells from unmanipulated

whole blood with a 3D printed device. Sci Rep. 11:205832021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ramirez AB, Bhat R, Sahay D, De Angelis C,

Thangavel H, Hedayatpour S, Dobrolecki LE, Nardone A, Giuliano M,

Nagi C, et al: Circulating tumor cell investigation in breast

cancer patient-derived xenograft models by automated

immunofluorescence staining, image acquisition, and single cell

retrieval and analysis. BMC Cancer. 19:2202019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Ren F, Fei Q, Qiu K, Zhang Y, Zhang H and

Sun L: Liquid biopsy techniques and lung cancer: diagnosis,

monitoring and evaluation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 43:962024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Koinis F, Zafeiriou Z, Messaritakis I,

Katsaounis P, Koumarianou A, Kontopodis E, Chantzara E, Aidarinis

C, Lazarou A, Christodoulopoulos G, et al: Prognostic role of

circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving cabazitaxel: A

prospective biomarker study. Cancers (Basel). 15:45112023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Eftekhari A, Alipour M, Chodari L, Maleki

Dizaj S, Ardalan M, Samiei M, Sharifi S, Zununi Vahed S, Huseynova

I, Khalilov R, et al: A comprehensive review of detection methods

for SARS-CoV-2. Microorganisms. 9:2322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Cieślikowski WA, Budna-Tukan J,

Świerczewska M, Ida A, Hrab M, Jankowiak A, Mazel M, Nowicki M,

Milecki P, Pantel K, et al: Circulating tumor cells as a marker of

disseminated disease in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk

prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12:1602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Yang D, Yang X, Li Y, Zhao P, Fu R, Ren T,

Hu P, Wu Y, Yang H and Guo N: Clinical significance of circulating

tumor cells and metabolic signatures in lung cancer after surgical

removal. J Transl Med. 18:2432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Lei Y, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu

J, Yu X and Shi S: Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer

research: progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 14:912021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Kojima M, Harada T, Fukazawa T, Kurihara

S, Touge R, Saeki I, Takahashi S and Hiyama E: Single-cell

next-generation sequencing of circulating tumor cells in patients

with neuroblastoma. Cancer Sci. 114:1616–1624. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Rzhevskiy A, Kapitannikova A, Malinina P,

Volovetsky A, Aboulkheyr Es H, Kulasinghe A, Thiery JP,

Maslennikova A, Zvyagin AV and Ebrahimi Warkiani M: Emerging role

of circulating tumor cells in immunotherapy. Theranostics.

11:8057–8075. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zhang Y and Zheng J: Functions of immune

checkpoint molecules beyond immune evasion. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1248:201–226. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Kloten V, Lampignano R, Krahn T and

Schlange T: Circulating Tumor Cell PD-L1 expression as biomarker

for therapeutic efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition in NSCLC.

Cells. 8:8092019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kennedy LC, Lu J, Kuehn S, Ramirez AB, Lo

E, Sun Y, U'Ren L, Chow LQM, Chen Z, Grivas P, et al: Liquid biopsy

assessment of circulating tumor Cell PD-L1 and IRF-1 expression in

patients with advanced solid tumors receiving immune checkpoint

inhibitor. Target Oncol. 17:329–341. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Hou W, Zhou X, Yi C and Zhu H: Immune

check point inhibitors and immune-related adverse events in small

cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 11:6042272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Ouyang Y, Liu W, Zhang N, Yang X, Li J and

Long S: Prognostic significance of programmed cell death-ligand 1

expression on circulating tumor cells in various cancers: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 10:7021–7039.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Papadaki MA, Messaritakis I, Fiste O,

Souglakos J, Politaki E, Kotsakis A, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D and

Agelaki S: Assessment of the efficacy and clinical utility of

different circulating tumor cell (CTC) detection assays in patients

with chemotherapy-naïve advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC). Int J Mol Sci. 22:9252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Lin M, Liang SZ, Shi J, Niu LZ, Chen JB,

Zhang MJ and Xu KC: Circulating tumor cell as a biomarker for

evaluating allogenic NK cell immunotherapy on stage IV non-small

cell lung cancer. Immunol Lett. 191:10–15. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Tamminga M, de Wit S, Hiltermann TJN,

Timens W, Schuuring E, Terstappen LWMM and Groen HJM: Circulating

tumor cells in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients are

associated with worse tumor response to checkpoint inhibitors. J

Immunother Cancer. 7:1732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Castello A, Carbone FG, Rossi S, Monterisi

S, Federico D, Toschi L and Lopci E: Circulating tumor cells and

metabolic parameters in NSCLC patients treated with checkpoint

inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 12:4872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Banys-Paluchowski M, Fehm TN, Grimm-Glang

D, Rody A and Krawczyk N: Liquid biopsy in metastatic breast

cancer: Current role of circulating tumor cells and circulating

tumor DNA. Oncol Res Treat. 45:4–11. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Heidrich I, Ačkar L, Mossahebi Mohammadi P

and Pantel K: Liquid biopsies: Potential and challenges. Int J

Cancer. 148:528–545. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Gu X, Huang X, Zhang X and Wang C:

Development and validation of a DNA methylation-related classifier

of circulating tumour cells to predict prognosis and to provide a

therapeutic strategy in lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Biol Sci.

18:4984–5000. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Peng QH, Wang CH, Chen HM, Zhang RX, Pan

ZZ, Lu ZH, Wang GY, Yue X, Huang W and Liu RY: CMTM6 and PD-L1

coexpression is associated with an active immune microenvironment

and a favorable prognosis in colorectal cancer. J Immunother

Cancer. 9:e0016382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Wang X, Teng F, Kong L and Yu J: PD-L1

expression in human cancers and its association with clinical

outcomes. Onco Targets Ther. 9:5023–5039. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Yao S, Han Y, Yang M, Jin K and Lan H:

Integration of liquid biopsy and immunotherapy: Opening a new era

in colorectal cancer treatment. Front Immunol. 14:12928612023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Ju S, Chen C, Zhang J, Xu L, Zhang X, Li

Z, Chen Y, Zhou J, Ji F and Wang L: Detection of circulating tumor

cells: Opportunities and challenges. Biomark Res. 10:582022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Dall'Olio FG, Gelsomino F, Conci N,

Marcolin L, De Giglio A, Grilli G, Sperandi F, Fontana F,

Terracciano M, Fragomeno B, et al: PD-L1 Expression in circulating

tumor cells as a promising prognostic biomarker in advanced

non-small-cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint

inhibitors. Clin Lung Cancer. 22:423–431. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Chalfin HJ, Pramparo T, Mortazavi A,

Niglio SA, Schonhoft JD, Jendrisak A, Chu YL, Richardson R, Krupa

R, Anderson AKL, et al: Circulating tumor cell subtypes and T-cell

populations as prognostic biomarkers to combination immunotherapy

in patients with metastatic genitourinary cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

27:1391–1398. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Gu X, Wei S and Lv X: Circulating tumor

cells: From new biological insights to clinical practice. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:2262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Pantel K and Alix-Panabières C: Crucial

roles of circulating tumor cells in the metastatic cascade and

tumor immune escape: Biology and clinical translation. J Immunother

Cancer. 10:e0056152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, Park CY,

Chao MP, Majeti R, Traver D, van Rooijen N and Weissman IL: CD47 is

upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia

cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 138:271–285. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Topalian SL, Drake CG and Pardoll DM:

Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor

immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 24:207–212. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Lian S, Xie X, Lu Y and Jia L: Checkpoint

CD47 function on tumor metastasis and immune therapy. Onco Targets

Ther. 12:9105–9114. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Lian S, Xie R, Ye Y, Lu Y, Cheng Y, Xie X,

Li S and Jia L: Dual blockage of both PD-L1 and CD47 enhances

immunotherapy against circulating tumor cells. Sci Rep. 9:45322019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Yu Y, Cheng Q, Ji X, Chen H, Zeng W, Zeng

X, Zhao Y and Mei L: Engineered drug-loaded cellular membrane

nanovesicles for efficient treatment of postsurgical cancer

recurrence and metastasis. Sci Adv. 8:eadd35992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Terme M, Ullrich E, Aymeric L, Meinhardt

K, Desbois M, Delahaye N, Viaud S, Ryffel B, Yagita H, Kaplanski G,

et al: IL-18 induces PD-1-dependent immunosuppression in cancer.

Cancer Res. 71:5393–5399. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Jacot W, Mazel M, Mollevi C, Pouderoux S,

D'Hondt V, Cayrefourcq L, Bourgier C, Boissiere-Michot F, Berrabah

F, Lopez-Crapez E, et al: Clinical correlations of programmed cell