Introduction

Anemia is a global health issue; in 2019, the World

Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 29.9% of all women of

reproductive age, 39.9% of all children and 60.2% of all African

children are anemic (1). Anemia

can lead to several adverse health effects that have a negative

impact on cognitive functioning in children and on work capacity in

adults (1,2). Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) comprises

66.2% of all types of anemia, rendering it a crucial health issue,

particularly for women of reproductive age and children (3,4).

Several factors for anemia have been reported, including dietary

causes, hemoglobinopathies, malaria and other infectious diseases

(3).

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is a hemoglobin fraction

that is used as a diagnostic tool for diabetes mellitus and its

related complications (5).

Previous studies have shown inconsistent results regarding the

association between HbA1c, iron depletion and IDA (6-11).

While some studies have reported a low level of HbA1c in IDA

(12,13), others have found that anemia/IDA is

associated with high HbA1c levels (6-11).

In Sudan, there is a high prevalence of anemia among

various age groups, including children (49.4%) (14), adults (25.2%) (15) and pregnant women (37.0%) (16). There is also a high prevalence of

diabetes mellitus in Sudan; 20% of adults have diabetes mellitus

and 80.0% of these adults have uncontrolled diabetes mellitus

(17). The high prevalence of

anemia may underestimate the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is

crucial to assess whether HbA1c levels are influenced by IDA and

whether this can lead to the revaluation of the cut-off for HbA1c

in diagnosing diabetes mellitus, as well as the level of control of

diabetes mellitus. Such results would prove helpful for clinicians

who provide patient care, health planners and academicians. The

present study was conducted in an aim to compare the HbA1c levels

in adolescents with IDA to those in their peers without IDA.

Patients and methods

Study population

A school-based case-control study was conducted in

Northern Sudan from September to December, 2022. The number of

adolescents from each school was determined by the total number of

adolescents in that school, following a probability proportional to

size. Thus, schools with more students greatly contributed to the

study sample. The assigned sample size was selected from the list

of students in each school through the use of a simple random

technique (lottery method). The present study was carried out in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical

practices. The study obtained ethics approval from the Ethical

Board of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum,

Sudan, under reference no. 9, 2021. All included students and their

guardians agreed to participate and signed a written informed

consent form. The author followed all measures to ensure the

participants' privacy, safety and confidentiality, such as

excluding personal identifiers during data collection.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study population comprised of adolescents (aged

10-19 years) with IDA and no other diseases; the controls were

adolescents with no such anemia (and otherwise healthy, as

described below). On the other hand, students whose guardians or

parents did not provide their consent to participate in the study

and those who were ill, pregnant, or lactating were excluded from

the study.

Study variables and measures

The questionnaire included data on various

sociodemographic characteristics, such as age in years, sex (male

or female), parental educational levels (less than secondary or

greater than or equal to secondary), the occupational status of the

mother (housewife or employed), the occupational status of the

father (laborer or skilled worker), anthropometric measurements,

including weight and height [expressed as body mass index (BMI)

z-score] and hematological parameters, including serum ferritin.

The investigator trained five medical research assistants to

collect the data; all trainings were complete prior to the

commencement of the study. The training emphasized proper

measurement techniques for weight and height, effective utilization

of the study questionnaire, and adherence to the study

protocol.

The medical research assistants (three males and two

females) approached the selected adolescents after the participants

and their guardians had agreed to participate and signed an

informed consent form. The selected adolescents were informed about

the aims of the study and provided with all necessary information,

including their voluntary participation in the study and their

right to withdraw at any time without needing to give a reason. The

study also took preventive measures to ensure the privacy and

confidentiality of the participants, such as excluding personal

identifiers during data collection, further reinforcing the study's

ethical integrity.

Weight, height, anemia and serum ferritin levels

were measured using standard procedures, as detailed below

(sociodemographic data, BMI and hematological parameters).

Weight and height measurements

The weights of the adolescents were measured in kg

using standard procedures (i.e., well-calibrated scales adjusted to

zero prior to each measurement). Weight was measured to the nearest

100 g. Shoes and excess clothing were removed before the

adolescents stood with minimal movement, with their hands by their

sides. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, with the

adolescents standing straight with their backs against the wall and

their feet together. The BMI for the age z-score was determined

based on the WHO standards (18).

Blood sample processing

To analyze hemoglobin and serum ferritin levels, 5

ml blood were obtained from each student and transferred into an

EDTA tube under aseptic conditions. These samples were used as part

of a complete blood count. An automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex

KX-21, Sysmex Corporation) was used to measure the hemoglobin

levels (19). Based on the

recommendation of the WHO for adolescents, a hemoglobin

concentration <12 g/dl in females and 13 g/dl in males was

considered a sign of anemia (20).

Furthermore, the hemoglobin values were categorized as mild (>10

g/dl), moderate (7-9.9 g/dl) and severe (<7 g/dl) (21) anemia.

The remaining blood samples (3 ml) were centrifuged

(at 3,000 x g, for 10 min at room temperature) and the serum was

stored at -20˚C in the laboratory. Serum ferritin levels were

subsequently measured using a radioimmunoassay gamma counter

(Riostad, Berthold Technologies GmbH & Co. KG) and kits

provided by Beijing Isotope Nuclear Electronic Co. (22). HbA1c levels were measured in all

participants, including those who were later diagnosed with mild,

moderate, or severe anemia, using enzymatic methods on the

ARCHITECT clinical chemistry analyzer (Abbott Pharmaceutical Co.

Ltd.).

In accordance with previous studies (23,24),

a serum ferritin level ≥15 µg/ was considered normal, while a level

<15 µg/l was considered low (iron deficiency). In the present

study, IDA was defined as the presence of anemia as per the

definition of the WHO (a hemoglobin level <12 g/dl and serum

ferritin level <15 µg/l). To ensure accurate and consistent

results, both the automated hematology analyzer and the

radioimmunoassay gamma counter were calibrated on a monthly basis.

Additionally, quality control measures were taken prior to daily

operation of these instruments.

Sample size calculation

OpenEpi Menu software was used to compute the

desired sample size (25). The

present study required a sample of 47 cases and 94 controls (a

ratio of 1:2). The mean (standard deviation) of HbA1c was set at

5.5% (0.3) for the cases and 5.7% (0.4) for the controls. This

sample size would have a confidence interval (CI) of 95% (1.96) and

a margin of error of 5% (0.05).

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into IBM Statistical Product

and Service Solutions (SPSS) for Windows (Version 22.0; IBM Corp.)

for analysis. Continuous data, such as age, BMI, and hemoglobin and

serum ferritin levels, were evaluated for normality using the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. They were found to be non-normally

distributed; therefore, they were expressed as a median

[interquartile range (IQR)]. Additionally, the Mann-Whitney U test

was used to compare the continuous variables between adolescents

with IDA and adolescents without IDA. The Chi-squared test was sued

to compare proportions between two groups). Univariate analysis was

conducted initially, and all variables were then shifted for

multivariate logistic regression to adjust for covariates. Adjusted

multivariate analysis was performed on anemia and iron deficiency

as categorical variables, as dependent variables, and

independently, as well as on sociodemographic characteristics (age,

sex, BMI z-score as independent variables). Adjusted odds ratios

(AORs) and 95% CIs were calculated as they were applied. A

two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

General characteristics of the study

subjects

A total of 141 adolescents were enrolled in the

present study. Of these, 75 (53.2%) were females, and 66 (46.8%)

were males. The median (IQR) of the adolescents' age was 14.1

(12.3-16.1) years (Table I).

| Table IComparison of the age, body mass

index, HbA1c levels, parents' education and occupation of

adolescents with and without iron deficiency anemia in Sudan in

2022. |

Table I

Comparison of the age, body mass

index, HbA1c levels, parents' education and occupation of

adolescents with and without iron deficiency anemia in Sudan in

2022.

| Variables | Total adolescents

(n=141) | Adolescents with IDA

(n=47) | Adolescents without

IDA (n=94) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years; median

(interquartile range)a | 14.1 (12.3-16.1) | 14.1 (12.4-16.2) | 14.3 (12.2-16.1) | 0.832 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2; median (interquartile range)a | 17.0 (15.3-19.8) | 16.9 (15.0-19.8) | 17.1 (15.4-19.9) | 0.875 |

| Blood glucose,

mg/dl2; median (interquartile range)a | 80.1 (71.5-90.0) | 83.0 (75.0-95.0 | 80.0 (70.0-88.0) | 0.174 |

| HbA1c, %; median

(interquartile range)a | 5.5 (5.2-5.7) | 5.4 (5.3-5.7) | 5.5 (5.1-5.8) | 0.890 |

| Serum ferritin, µg/l;

median (interquartile range)a | 18.3

(10.2-37.4)) | 10.0 (10.0-11.6) | 29.1

(18.1-53.7)) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n

(%)b | | | | |

|

Male | 66 (46.8) | 20 (42.6) | 46 (48.9) | 0.591 |

|

Female | 75 (53.1) | 27 (57.4) | 48 (51.1) | |

| Mother's education, n

(%)b | | | | |

|

>

Secondary level | 97 (68.8) | 32 (68.1) | 65 (69.1) | 0.522 |

|

≤ Secondary

level | 44 (31.2) | 15 (31.9) | 29 (30.9) | |

| Mother's occupation,

n (%)b | | | | |

|

Housewife | 119 (84.8) | 39 (83.0 | 80 (85.1) | 0.460 |

|

Employed | 22 (15.6) | 8 (17.0) | 14 (14.9) | |

| Father's education, n

(%)b | | | | |

|

>

Secondary level | 102 (72.3) | 34 (72.3) | 68 (72.3) | 0.999 |

|

≤ Secondary

level | 39 (27.7) | 13 (27.7) | 26 (27.7 | |

| Father's occupation,

n (%)b | | | | |

|

Skilled | 49 (34.8) | 16 (34.0) | 33 (35.1) | 0.999 |

|

Labourer | 92 (65.2) | 31 (66.0) | 61 (64.9) | |

In total, 47 cases (adolescents with IDA) and 94

controls (adolescents without IDA) were enrolled in the present

study. The two groups exhibited no significant differences in age,

BMI, or blood glucose levels, using Mann-Whitney U test (Table I). Of note, 27 of the cases (57.4%)

and 48 of the controls (51.1%) were females (P=0.591).

Factors associated with HbA1c

levels

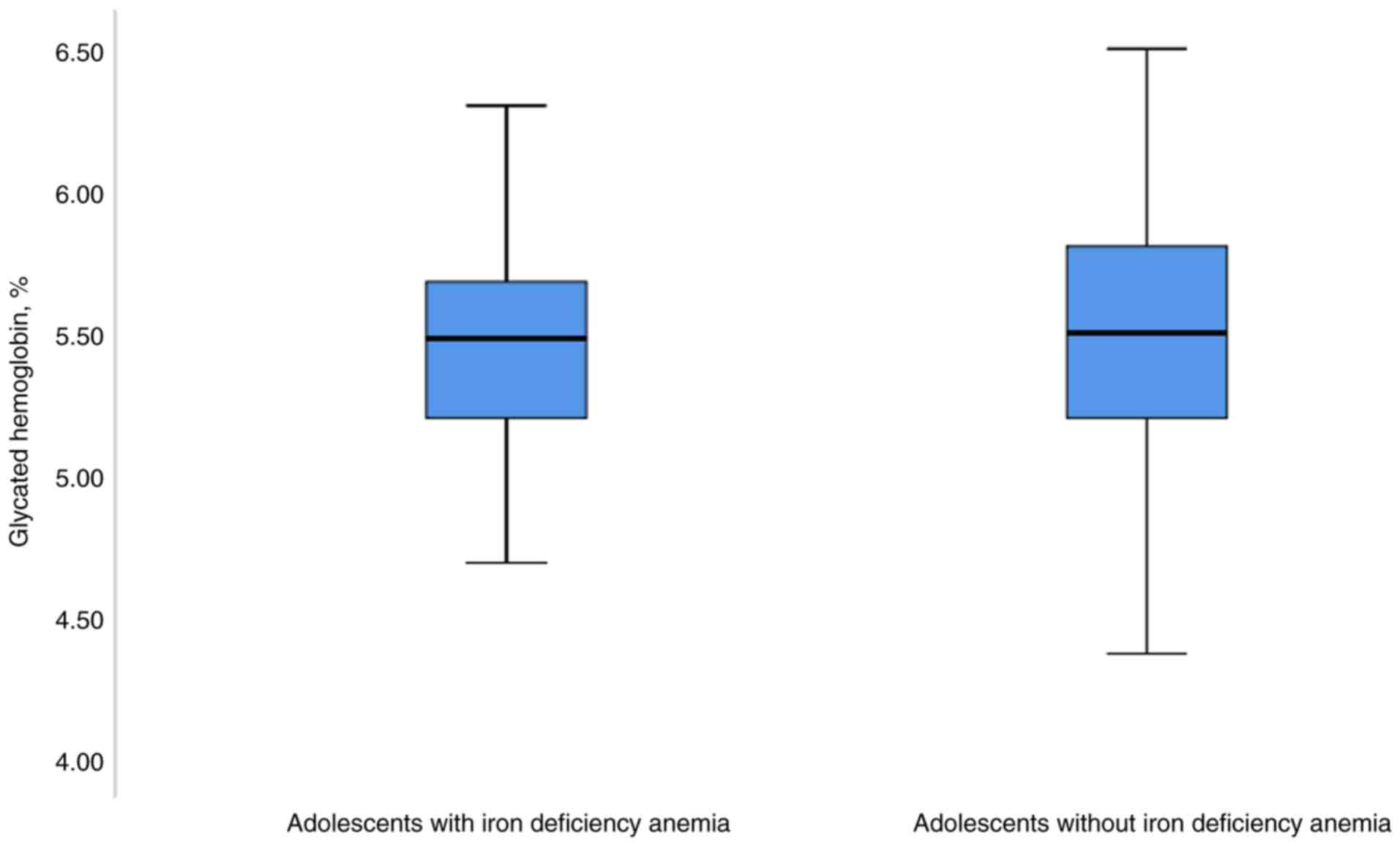

The median (IQR) of HbA1c was 5.4% (5.3-5.7%) in the

cases and 5.5% (5.1-5.8%) in the controls; the Mann-Whitney U test

did not reveal any significant differences between the two groups

(P=0.890; Fig. 1 and Table I). In the univariate linear

analysis, age, sex, BMI and iron deficiency (IDA: coefficient,

0.008; 95% CI, -0.1570-0.174; P=0.921) were not found to be

associated with HbA1c (Table II).

Moreover, in the multivariate linear analysis, age, sex, BMI and

iron deficiency (IDA: coefficient, 0.008; 95% CI, -0.16-0.17;

P=0.929) were also not found to be associated with HbA1c (Table II).

| Table IIUnivariate and multivariate linear

regression analysis of the factors associated with HbA1c in

adolescents in Sudan, 2022. |

Table II

Univariate and multivariate linear

regression analysis of the factors associated with HbA1c in

adolescents in Sudan, 2022.

| | Univariate linear

analysis | Multivariate linear

analysis |

|---|

| Variables | Coefficient | 95% confidence

interval | P-value | Coefficient | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | -0.007 | -0.038-0.024 | 0.658 | -0.007 | -0.04-0.03 | 0.717 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | -0.002 | -0.022-0.017 | 0.826 | 1.11 | -0.023-0.023 | 0.999 |

| Sex | | | | | | |

|

Male | Reference | | | | | |

|

Female | -0.014 | -0.170-0.143 | 0.865 | -0.004 | -0.17-0.16 | 0.958 |

| Iron deficiency

anemia | | | | | | |

|

No | Reference | | | | | |

|

Yes | 0.008 | -0.1570-0.174 | 0.921 | 0.008 | -0.16-0.17 | 0.929 |

Discussion

The main findings of the present study were that no

difference was found in HbA1c between adolescents with and without

IDA, and HbA1c was not associated with IDA. This is consistent with

the findings of a recent meta-analysis that included six studies

and demonstrated that IDA had no effect on HbA1c in patients with

diabetes mellitus (26). However,

the results of the meta-analysis revealed that IDA had an effect on

HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals (26). By contrast, it has been reported

that in 263 patients without diabetes mellitus, HbA1c levels were

significantly lower in patients with IDA than in their peers who

had no such anemia (6). Moreover,

a moderate correlation has been reported between HbA1c and serum

iron levels in children with type 1 diabetes (13).

As aforementioned, the results of previous studies

on HbA1c levels in iron deficiency have been inconsistent. Building

upon earlier results that demonstrated that IDA is associated with

high HbA1c (in diabetic patients), a previous study found that a

high level of glycated hemoglobin was markedly corrected

(decreased) following treatment with iron supplements (6). By contrast, other research has

suggested that a low level of HbA1c is associated with IDA

(12). Furthermore, a recent

systematic review concluded that iron replacement therapy reduced

HbA1c in patients with uncontrolled diabetic mellitus who had an

iron deficiency (27). However, in

another study, the mean HbA1c level was higher in anemic than

non-anemic Indian euglycemic patients (7). In addition, HbA1c was significantly

increased in iron-deficient patients (non-diabetic) compared to the

control group (8).

In a large-scale retrospective study, patients with

IDA had higher HbA1c levels than those without anemia (10). A later study confirmed these

results and found that patients with nutritional anemia (such as

IDA) exhibited a higher mean level of HbA1c, which was then reduced

in response to the treatment of anemia (9). Intra et al (10) demonstrated that the mean HbA1c was

higher in anemic patients than in non-anemic patients.

In Dutch children with diabetes, the mean HbA1c did

not differ in patients with an iron deficiency (28). However, an inverse finding was

reported among Egyptian children with type 1 diabetes, who had

significantly higher levels of HbA1c than non-anemic diabetic

children (11). In addition, serum

iron has been negatively correlated with glycated hemoglobin in

children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (13). The diverse sociodemographic

characteristics of the enrolled participants and the varied

prevalence of anemia and severe anemia in different areas may

explain these variable results. Moreover, some of these studies

assessed HbA1c and iron deficiency in diabetic patients, while

others investigated these variables among healthy cohorts.

Although the exact mechanism by which HbA1c

increases in association with IDA remains unclear; it is considered

that the reduction in iron and ferritin levels affects the rate of

red blood cell turnover. This leads to a prolonged half-life of the

red blood cells eligible for destruction, thereby increasing the

rate of hemoglobin glycation (29). Additionally, hemoglobin with a

lower iron content is more vulnerable to oxidative stress,

resulting in elevated malondialdehyde levels, which further

accelerate hemoglobin glycation (30).

From a clinical perspective, in cases of IDA, it is

essential to correct hemoglobin and iron levels before interpreting

HbA1c, as falsely elevated results are likely. Furthermore, it is

advisable to measure hemoglobin levels whenever elevated HbA1c is

detected to rule out potential false-positive results.

The present study has certain limitations that

warrant consideration. Potential confounding factors that could

influence HbA1c levels, such as recent dietary habits, physical

activity and a family history of diabetes, were not examined. As a

result, further research is needed to address these variables and

provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship

between IDA and HbA1c levels. In conclusion, the present study did

not find any notable differences in HbA1c levels between

adolescents with IDA and those without IDA.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Author's contributions

The author AM was involved in the conceptualization

of the study, in the design of the study methodology, in data

curation and formal analysis, as well as in the investigation and

procedural aspects of the study. The author AM was also drafted and

reviewed the manuscript. AM confirms the authenticity of all the

raw data. The author has read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was carried out in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practices. The study

obtained ethics approval from the ethical board of the Faculty of

Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan, under reference

no. 9, 2021. All included students and their guardians agreed to

participate and signed a written informed consent form. The author

followed all measures to ensure the participants' privacy, safety,

and confidentiality, such as excluding personal identifiers during

data collection.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

World Health Organization (WHO): WHO

Global Anaemia estimates, 2021 edition. WHO, Geneva, 2022.

|

|

2

|

Gardner WM, Razo C, McHugh TA, Hagins H,

Vilchis-Tella VM, Hennessy C, Taylor H, Jean P, Nandita F, Kia C,

et al: Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in

anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990-2021: Findings from the

global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 10:e713–e734.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

The Institute for Health Metrics and

Evaluation (IHME): The Lancet: New study reveals global anemia

cases remain persistently high among women and children. Anemia

rates decline for men. IHME, Seattle, WA, 2023.

|

|

4

|

Hamdan SZ, Hamdan HZ, Nimieri M and Adam

I: The association between Helicobacter Pylori infection and iron

deficiency anemia in children: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Pediatr Infect Dis. 17:59–70. 2022.

|

|

5

|

International Expert Committee.

International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay

in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 32:1327–1334.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Aydın B, Özçelik S, Kilit TP, Eraslan S,

Çelik M and Onbaşı K: Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin

and iron deficiency anemia: A common but overlooked problem. Prim

Care Diabetes. 16:312–317. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sharda M, Gandhi N, Bansal D and Gadhwal

M: Correlation of anemia with glycated hemoglobin among euglycemic

type 2 diabetic patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 71:11–12.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Alzahrani BA, Salamatullah HK, Alsharm FS,

Baljoon JM, Abukhodair AO, Ahmed ME, Malaikah H and Radi S: The

effect of different types of anemia on HbA1c levels in

non-diabetics. BMC Endocr Disord. 23(24)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pilla R, Palleti SK, Rayala R, SKSS SR,

Abdul Razzack A and Kalla S: Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)

variations in nondiabetics with nutritional anemia. Cureus.

12(e11479)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Intra J, Limonta G, Cappellini F, Bertona

M and Brambilla P: Glycosylated hemoglobin in subjects affected by

iron-deficiency anemia. Diabetes Metab J. 43:539–544.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mahgoob MH and Moussa MM: Glycated albumin

versus HbA1c as indicators of glycemic control in type I diabetic

children with iron deficiency anemia. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol.

29:151–157. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Solomon A, Hussein M, Negash M, Ahmed A,

Bekele F and Kahase D: Effect of iron deficiency anemia on HbA1c in

diabetic patients at Tikur Anbessa specialized teaching hospital,

Addis Ababa Ethiopia. BMC Hematol. 19(2)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Satriawibawa IWE, Arimbawa IM, Ariawati K,

Suparyatha IBG, Putra IGNS and Hartawan INB: Serum iron is

negatively correlated with the HbA1c level in children and

adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol.

31:242–249. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Elmardi KA, Adam I, Malik EM, Ibrahim AA,

Elhassan AH, Kafy HT, Nawai LM, Abdin MS and Kremers S: Anaemia

prevalence and determinants in under 5 years children: Findings of

a cross-sectional population-based study in Sudan. BMC Pediatr.

20(538)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Musa IR, Hassan AA and Adam I:

Multimorbidity and its associated risk factors among adults in

northern Sudan: A community-based cross-sectional study. J Health

Popul Nutr. 43(13)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Abbas W, Elmugabil A, Hamdan HZ, Rayis DA

and Adam I: Iron deficiency and thyroid dysfunction among sudanese

women in first trimester of pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. BMC

Endocr Disord. 23(223)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Omar SM, Musa IR, ElSouli A and Adam I:

Prevalence, risk factors, and glycaemic control of type 2 diabetes

mellitus in eastern Sudan: A community-based study. Ther Adv

Endocrinol Metab. 27(2042018819860071)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

World Health Organization (WHO):

BMI-for-age (5-19 years). https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age.

|

|

19

|

Ali SA, Hassan AA and Adam I: History of

pica, obesity, and their associations with anemia in pregnancy: A

community-based cross-sectional study. Life (Basel).

13(2220)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

World Health Organization (WHO):

Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and

assessment of severity. WHO, Geneva, 2011.

|

|

21

|

Thomas D, Chandra J, Sharma S, Jain A and

Pemde HK: Determinants of nutritional anemia in adolescents. Indian

Pediatr. 52:867–869. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Abbas W, Adam I, Rayis DA, Hassan NG and

Lutfi MF: Higher rate of iron deficiency in obese pregnant sudanese

women. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 5:285–289. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shaban L, Al-Taiar A, Rahman A, Al-Sabah R

and Mojiminiyi O: Anemia and its associated factors among

Adolescents in Kuwait. Sci Rep. 10(5857)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Scott S, Lahiri A, Sethi V, de Wagt A,

Menon P, Yadav K, Varghese M, Joe W, Vir SC and Nguyen PH: Anaemia

in Indians aged 10-19 years: Prevalence, burden and associated

factors at national and regional levels. Matern Child Nutr.

18(e13391)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Dean AG, Sullivan KM and Soe MM: OpenEpi:

Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, version

2.3.1. http://www.OpenEpi.com.

|

|

26

|

Kuang L, Li W, Xu G, You M, You M, Wu W

and Li C: Systematic review and meta-analysis: Influence of iron

deficiency anemia on blood glycosylated hemoglobin in diabetic

patients. Ann Palliat Med. 10:11705–11713. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

AlQarni AM, Alghamdi AA, Aljubran HJ,

Bamalan OA, Abuzaid AH and AlYahya MA: The effect of iron

replacement therapy on HbA1c levels in diabetic and nondiabetic

patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med.

12(7287)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Akkermans MD, Mieke Houdijk ECA, Bakker B,

Boers AC, van der Kaay DCM, de Vries MC, Claire Woltering M, Mul D,

van Goudoever JB and Brus F: Iron status and its association with

HbA1c levels in Dutch children with diabetes mellitus type 1. Eur J

Pediatr. 177:603–610. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Guo W, Zhou Q, Jia Y and Xu J: Increased

levels of glycated hemoglobin A1c and iron deficiency anemia: A

review. Med Sci Monit. 25:8371–8378. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hellman R: When are HBA1C values

misleading? AACE Clin Case Rep. 2:e377–e379. 2016.

|