Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) imposes a substantial global health burden, with region-specific risk factors exacerbating its impact. In Iraq, Helicobacter pylori infection, particularly cytotoxic CagA-positive strains, has been linked to the increased incidence of CRC (1). The financial burden of cancer care further compounds healthcare disparities, limiting equitable treatment access (2,3).

Oxaliplatin, a platinum-based chemotherapeutic agent, is integral to CRC treatment across disease stages (4,5). Its mechanism involves DNA crosslinking at the N7 position of guanine, inducing structural distortion, replication blockade and apoptosis (6). However, oxaliplatin also elicits dose-limiting neurotoxicity, including acute cold-induced symptoms and chronic cumulative neurotoxicity (CN), which often necessitates dose modifications and markedly impairs the quality of life of patients (7).

CN typically emerges following 8-10 treatment cycles (incidence rate, 40-93%) (8), with symptoms persisting between cycles and worsening at cumulative doses exceeding 700-800 mg/m2 (9). Sensory nerve conduction deficits manifest early (e.g., at 410 mg/m2) and progress with dose escalation (10).

The glutathione S-transferase pi-1 (GSTP1) gene (chromosome 11q13) encodes a detoxification enzyme critical for metabolizing carcinogens and chemotherapeutics (11). Comprising ~4% of hepatic soluble proteins, GSTP1 functions as a dimer with G- and H-sites that bind glutathione to facilitate xenobiotic detoxification. Polymorphisms in GSTP1 may alter substrate affinity, influencing drug efficacy and toxicity (12).

In oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity, GSTP1 plays a dual role: i) By detoxifying oxaliplatin metabolites; and ii) modulating neurotoxic pathways (13,14). It regulates the Nrf2-Keap1 oxidative stress response (11,15) and interacts with DNA repair mechanisms; impaired function may exacerbate neuronal DNA damage and apoptosis (12,16). Additionally, GSTP1 modulates transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily A member 1 expression, an ion channel implicated in neuropathic pain (17).

The present study examined GSTP1 polymorphisms (rs1695 and rs1138272) as predictive biomarkers for CN in Iraqi patients with CRC, aiming to optimize treatment cycles and guide therapeutic alternatives.

Patients and methods

Study design

A prospective observational cohort study was conducted between January, 2024 and January, 2025 at two Iraqi oncology centers (Oncology Teaching Hospital, Medical City, Baghdad and Warith International Cancer Institute, Karbala) in an aim to evaluate the association between GSTP1 polymorphisms (rs1695 and rs1138272) and oxaliplatin-induced CN in patients with advanced-stage CRC. Of the 150 initially screened patients, 120 eligible Iraqi adults (61 males and 59 females) with histologically confirmed colorectal adenocarcinoma were enrolled in the present study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were patients with histologically confirmed CRC and those treated with planned oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy at a cumulative dose ≥500 mg/m2. The exclusion criteria were patients with pre-existing neuropathy or those previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

Clinical data collection

The present study adhered to the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-Colon Cancer v.2024(18) to maintain consistency in patient care and outcome assessment. Clinical assessments were conducted systematically prior to each chemotherapy cycle. Symptoms of CN were assessed at baseline and subsequently monitored through follow-up evaluations conducted 2 weeks post-administration of each chemotherapy cycle. The evaluations comprised physical examinations and complete blood count tests. The cumulative neurotoxicity resulting from oxaliplatin was assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) (19). Although objective tools for assessing chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity were not employed, thorough clinical evaluations provided consistent and reliable monitoring of CN-related symptoms.

Collection of genetic data

Alongside clinical assessments, blood samples were obtained from all participants for the analysis of GSTP1 gene polymorphisms. Patients were classified into two groups according to their cumulative oxaliplatin dosage: Those with a total dose <1,000 mg/m2 and those with a total dose >1,000 mg/m2. The categorization aimed to assess the impact of genetic variations on the initiation timing of CN. The present study aimed to integrate clinical data and genetic analysis to provide evidence on the potential role of GSTP1 polymorphisms in predicting susceptibility to CN.

Ethical considerations and approvals

The research adhered to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) principles; the present study adhered to ethical standards established by the Research Ethics Committee of Mustansiriyah University of Pharmacy (permission no. 37) and was granted authorization from the Ministry of Health (no. 7026) and approvals from the Ministry of Health (no. 7026) and Warith International Cancer Institute (no. 892). The permission form emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary, and individuals could withdraw at any time without incurring any consequences. Anonymity and confidentiality were preserved by using coded identifiers instead of names or medical record numbers. The research upheld rigorous ethical standards in accordance with international ethical norms, including the Declaration of Helsinki. A statement of consent for publication was obtained from the patient according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The genomic DNA was purified from peripheral white blood cells (isolated form collected blood samples from each patient) and extracted according to the protocol of the manufacturer using the ReliaPrep™ Blood gDNA Miniprep kit (cat. no. A5081, Promega Corporation) and stored at -20˚C until the use in PCR. Of note, two pairs of primers were used to amplify gene fragments corresponding to the target polymorphisms. The sequences of these primers were as follows: rs-1695 forward, 5'-ACGCACATCCTCTTCCCCTC-3' and reverse, 5'-TACTTGGCTGGTTGATGTCC-3'; and rs-1138272 forward, 5'-CAAGGATGGACAGGCAGAATGG-3' and reverse, 5'-ATGGCTCACACCTGTGTCCATC-3'. The reference gene used was HLA-DRB1 gene for which the primer sequences were: DRB1 forward, 5'-TGCCAAGTGGAGCACCCAA-3' and reverse, 5'-GCATCTTGCTCTGTGCAGAT-3'.

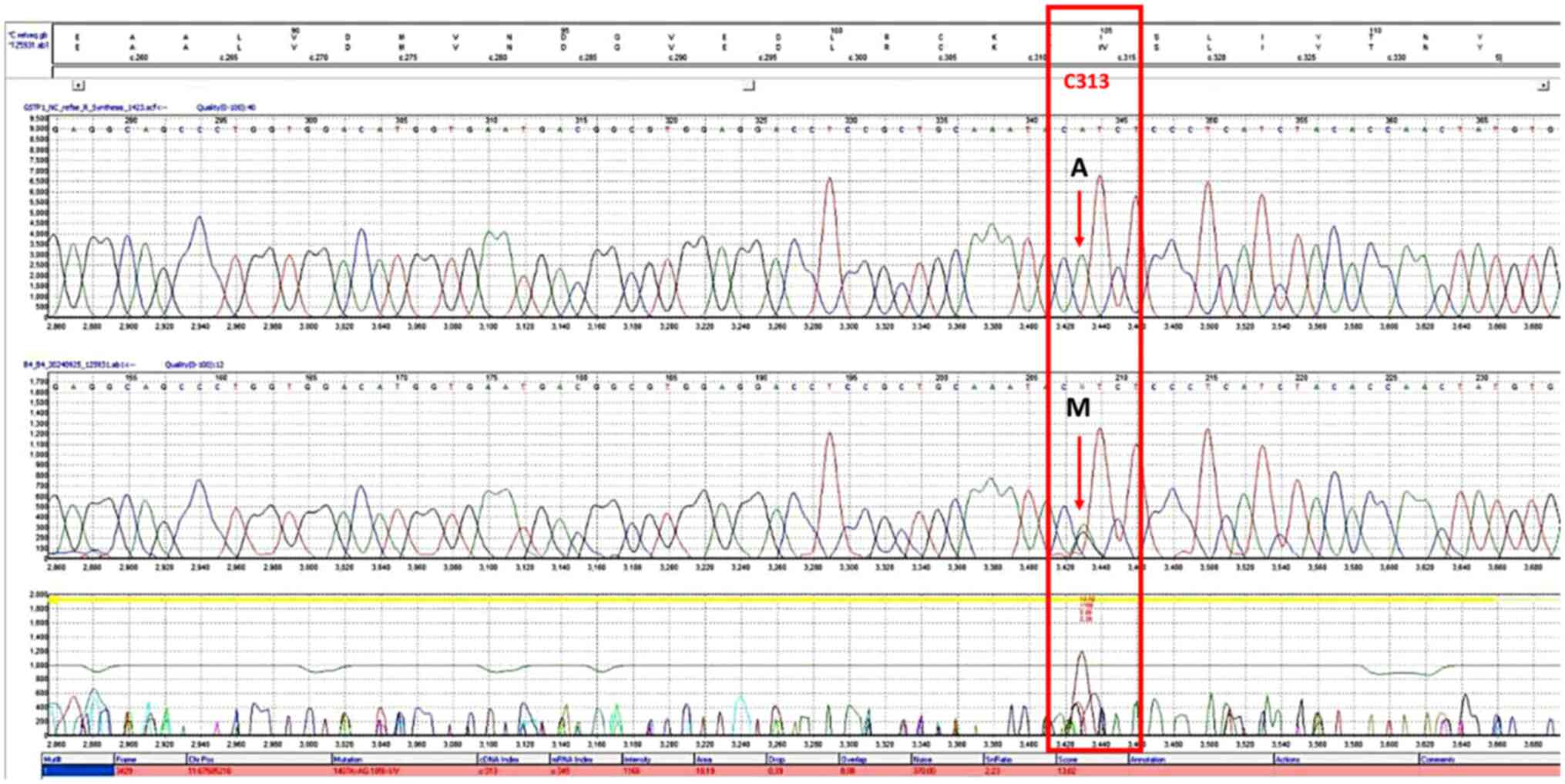

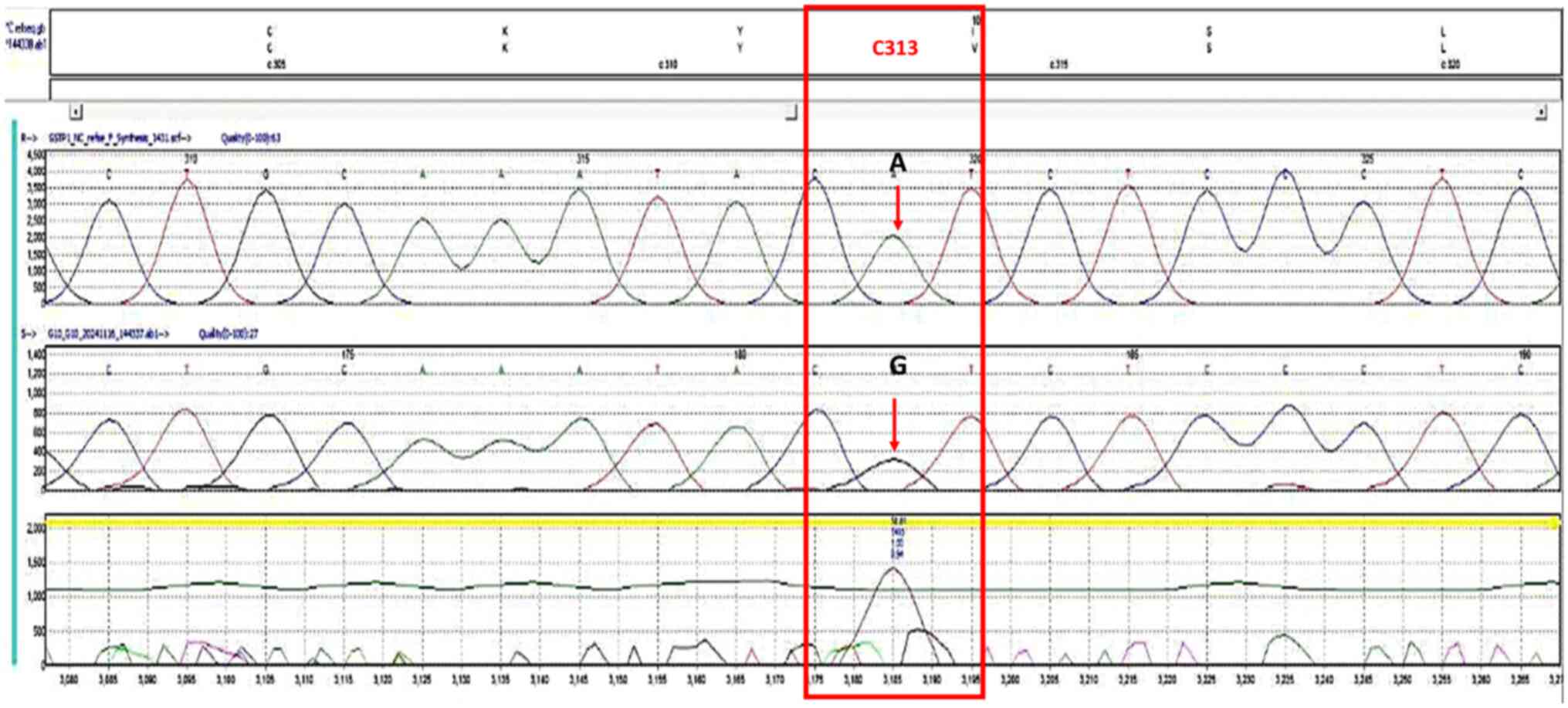

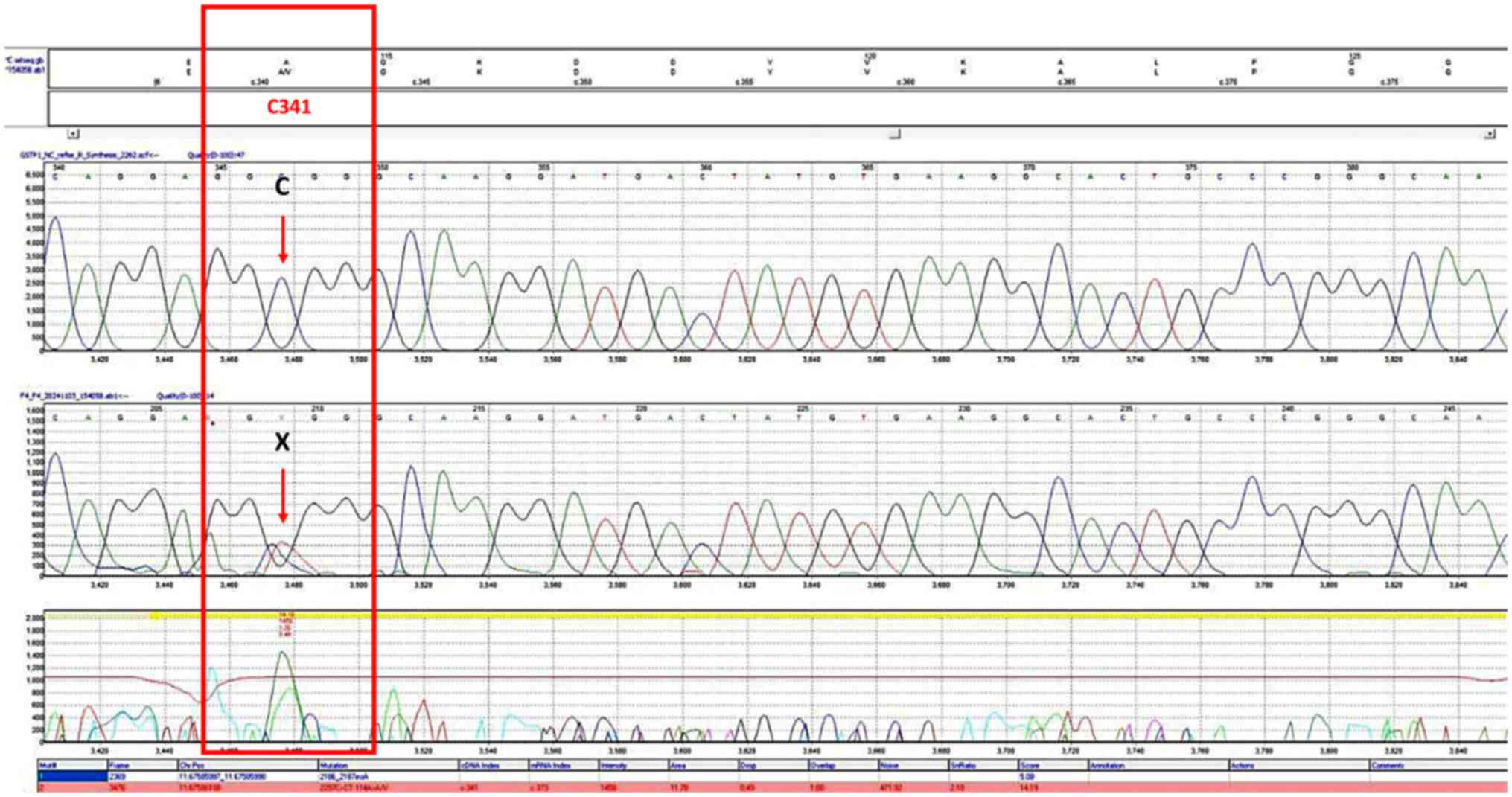

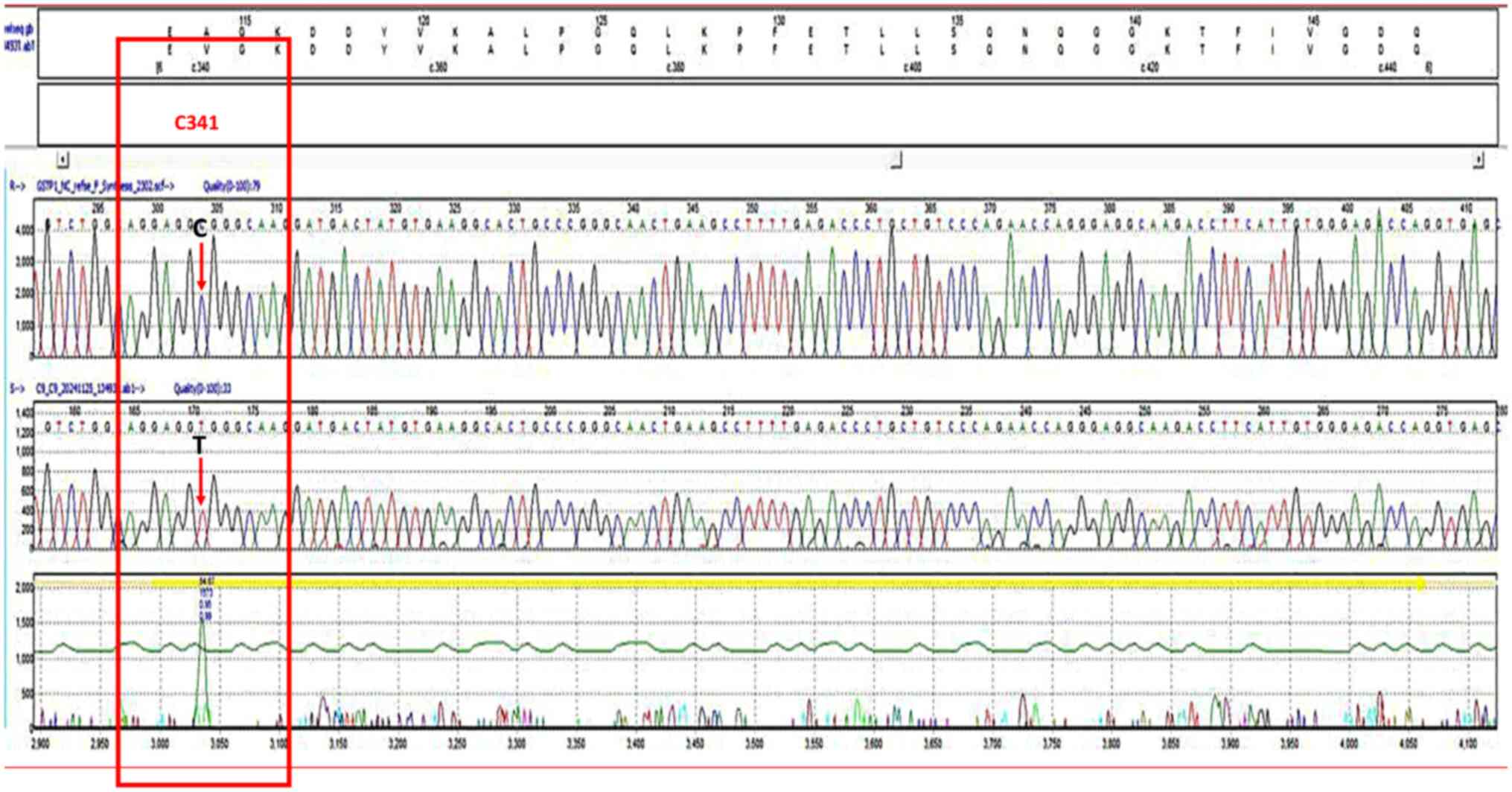

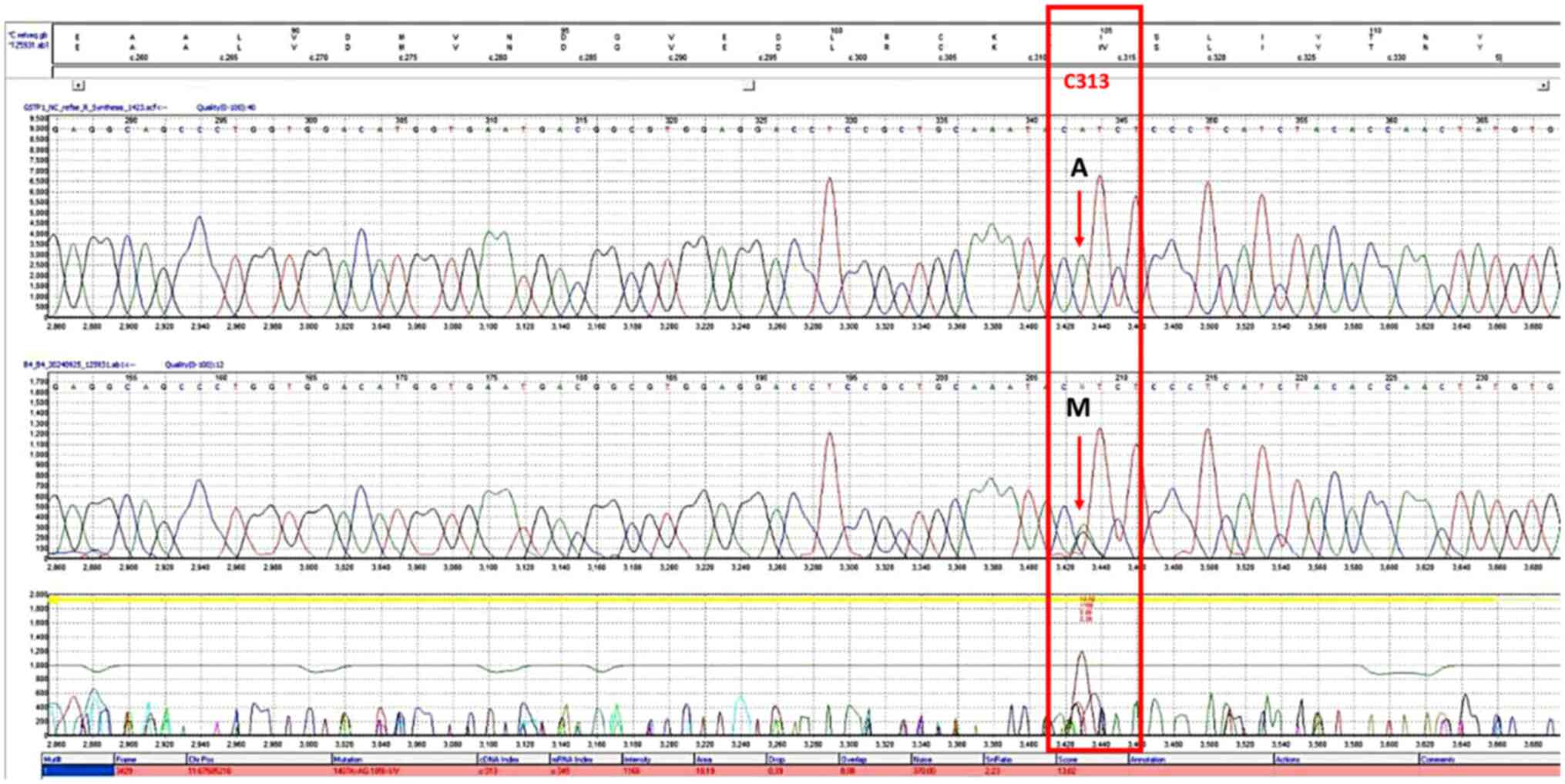

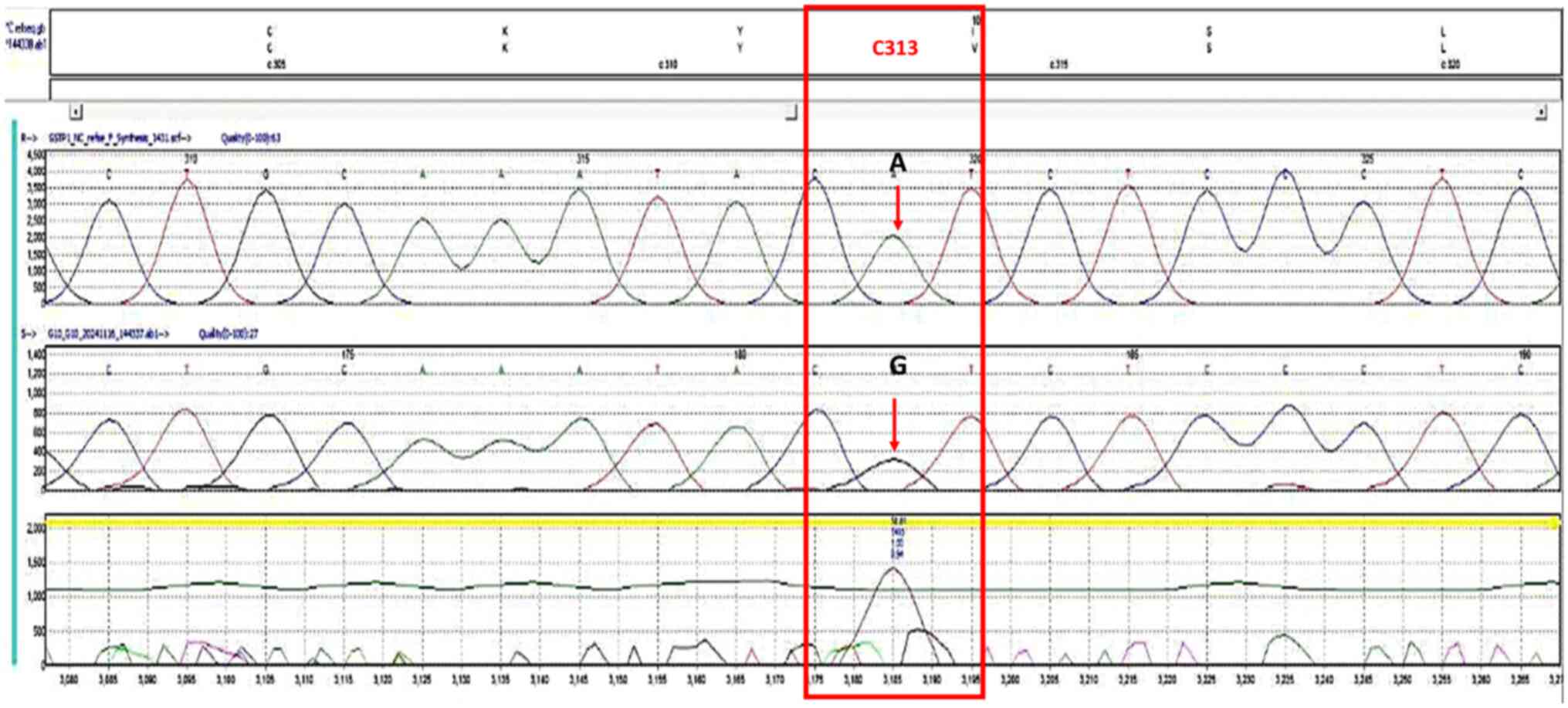

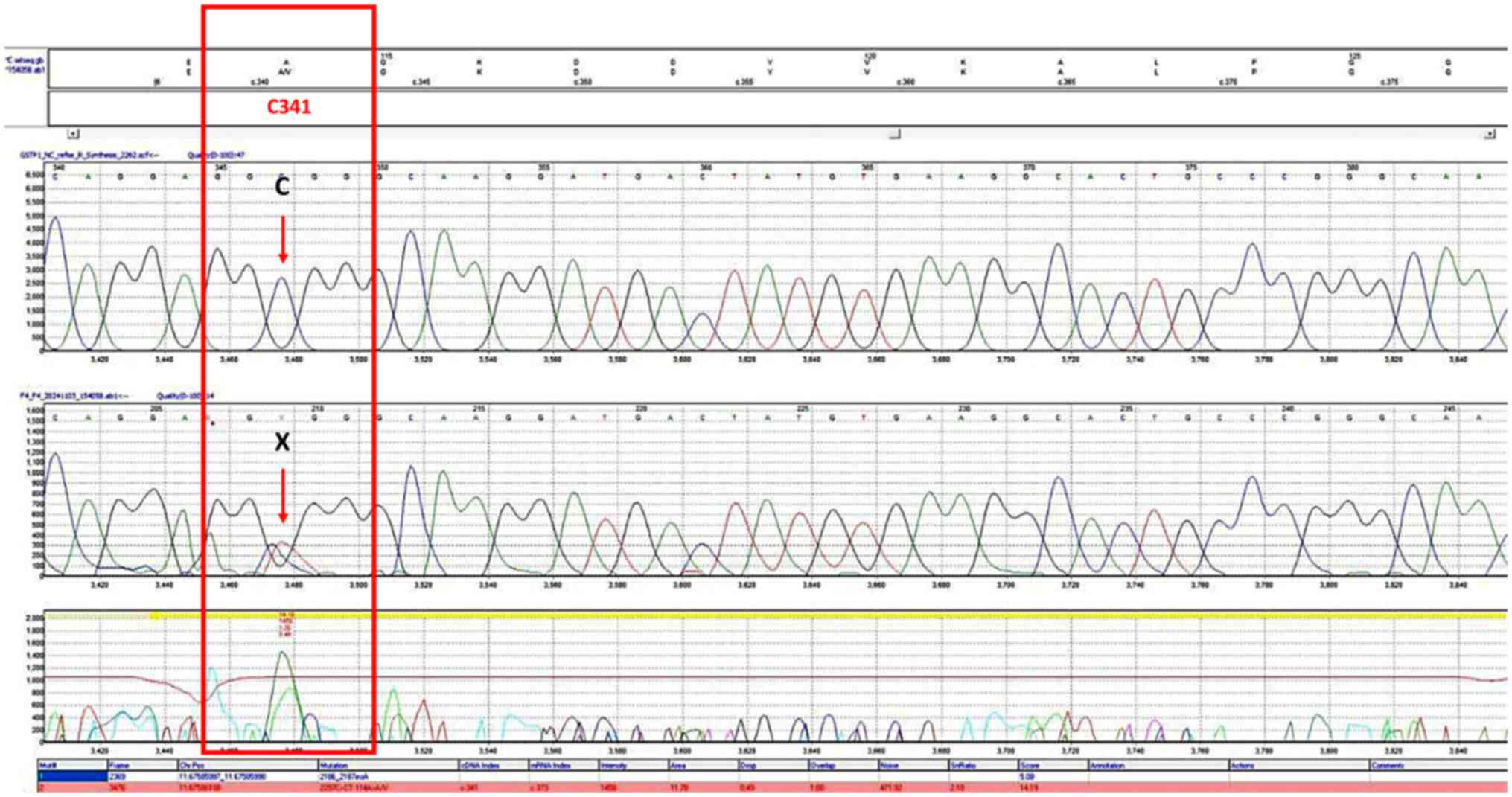

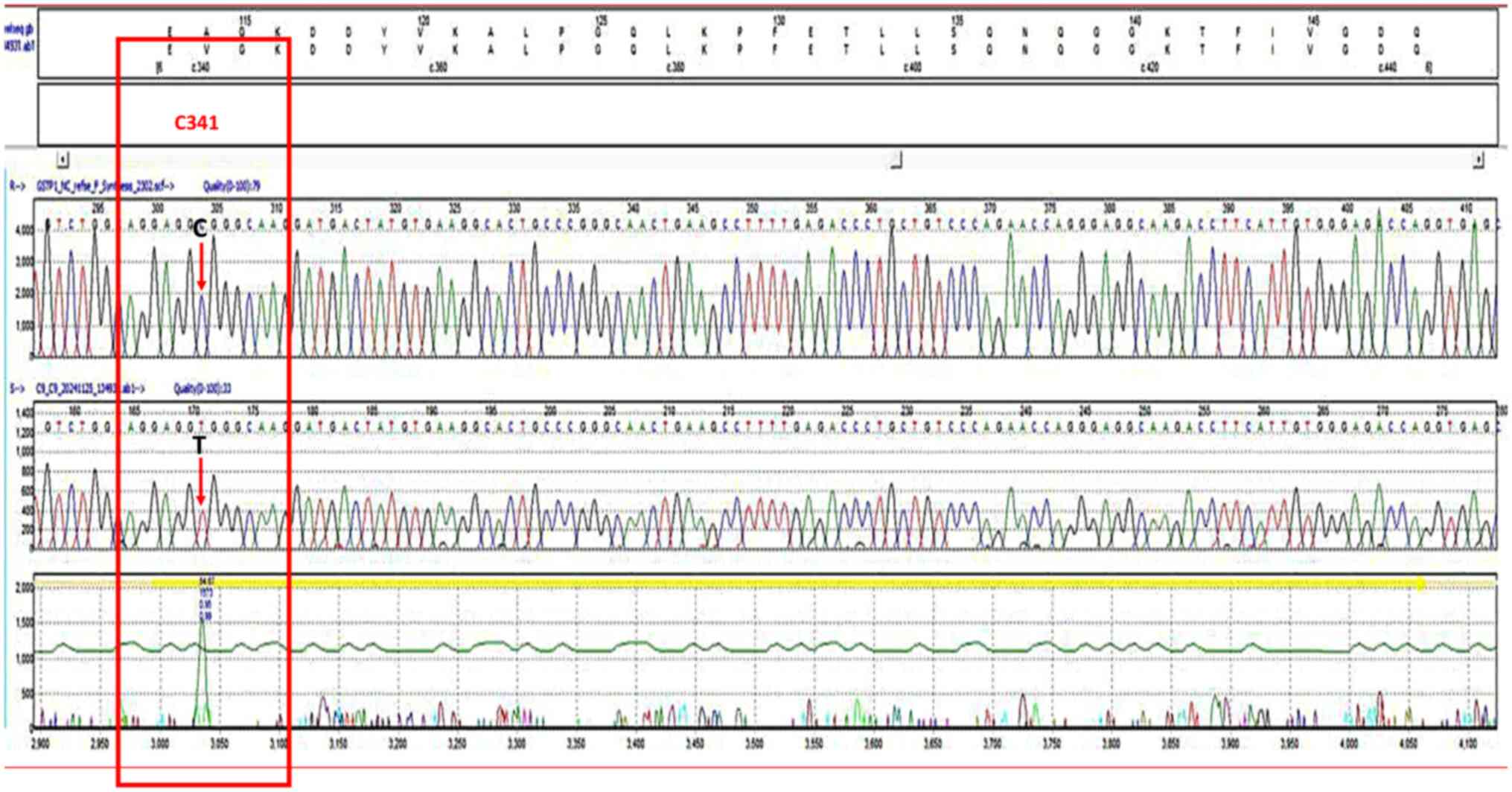

All the PCR analyses were done according to the manufacturing protocol utilizing the GoTaq® Green Master Mix kit (cat. no. M7122, Promega Corporation) and using a reaction volume of 25 µl containing 3 µl DNA, Green Master Mix (12.5 µl), 1 µl of each primer (10 pmol), and 7.5 µl of nuclease-free water (20). PCR was conducted in a Veriti thermal cycler (cat. no. 4375305, Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The PCR conditions included an initial denaturation at 95˚C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 30 sec, annealing at 60˚C for 30 sec, and extension at 72˚C for 30 sec. After cycling, a final extension at 72˚C for 7 min was performed, and the reaction was held at 10˚C for 10 min or as needed. The amplification products (5 µl) underwent electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and using 100 bp DNA Ladder kit (cat. no. 15628019, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The genotyping of exon 5 and 6 of the GSTP1 polymorphism was conducted according to the instructions of the manufacturer using Sangar sequencing by Applied Biosystems™ SeqStudio™ Genetic Analyzer System with SmartStart utilizing Smart Start, System (cat. no. A35644; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), SeqStudio™ Cartridge (cat. no. A33671), SeqStudio™ Cathode Buffer Container (cat. no. A33401), SeqStudio™ Integrated Capillary Protector (cat. no. A31923) and the Sanger Sequencing Kit (cat. no. A38073) (all from Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The sequencing data were interpreted using Mutation Surveyor software (SoftGenetics, LLC). The corresponding chromatograms of rs1695 and rs1138272 in homozygous and heterozygous states are illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4.

|

Figure 1

Chromatogram of the single nucleotide polymorphism, rs1695, on the forward strand. The bases in the frames indicate the polymorphism sites. The letter M in the upper section represents the heterozygous genotype (AG).

|

|

Figure 2

Chromatogram of the single nucleotide polymorphism, rs1695, forward strand. The bases in the frames represent the polymorphism sites. The G letter in the upper part represents the homozygous genotype (GG).

|

|

Figure 3

Chromatogram of the single nucleotide polymorphism, rs1138272, forward strand. The bases in the frames represent the polymorphism sites. The X letter in the upper part represents the heterozygous genotype (CT).

|

|

Figure 4

Chromatogram of the single nucleotide polymorphism, rs1138272, forward strand. The bases in the frames represent the polymorphism sites. The T letter in the upper part represents the homozygous genotype (TT).

|

Statistical analysis

The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Normally distributed data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using the Student's t-test, while non-normally distributed variables are summarized as the median (range) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages, with group differences were evaluated using the Chi-squared test of Fisher's exact test. To examine the association between GSTP1 polymorphisms and CN, binary logistic regression was performed, adjusting for potential confounding factors where appropriate. Additional analyses assessed the association between genetic variants and both the threshold oxaliplatin dose for CN onset and the severity of neurotoxic manifestations. These associations were quantified using odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Genotype frequencies were tested for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using an online calculator (https://scienceprimer.com/hardy-weinberg-equilibrium-calculator). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with P<0.05 considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25; IBM Corp.).

Results

Demographic and clinical data, and association with oxaliplatin-induced CN

The present study analyzed multiple variables among the 120 patients enrolled in the present study, including genetic polymorphisms, tumor characteristics and treatment parameters. Of these participants, 53 (44.2%) developed oxaliplatin-induced CN, while 67 (55.8%) did not exhibit this adverse effect.

The comprehensive analysis of demographic and clinical characteristics revealed no significant associations between baseline factors and the development of CN. As detailed in Tables I and II, no statistically significant differences were observed between the demographics of the patients with and without CN.

|

Table I

Association of the demographic data of the patients with cumulative neurotoxicity.

|

Table I

Association of the demographic data of the patients with cumulative neurotoxicity.

| Variables |

Without CN (n=67) |

With CN (n=53) |

P-value |

| Age, years |

|

|

|

| Mean ± SD |

54.16±12.11 |

50.49±11.96 |

0.1a |

| Range |

24.40-76.70 |

18.90-69.50 |

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

| Male |

35 |

26 |

0.729b |

| Female |

32 |

27 |

|

| Body mass index, kg/m2 |

|

|

|

| Mean ± SD |

28.09±6.81 |

28.16±5.90 |

0.951b |

| Range |

15.40-49.61 |

17.57-43.66 |

|

| Educational level |

|

|

|

| Primary |

29 (43.3%) |

46 (86.8%) |

0.220b |

| Secondary |

11 (16.4%) |

12 (22.6%) |

|

| Higher |

13 (19.4%) |

9 (17.0%) |

|

| Residence |

|

|

|

| Baghdad |

42 (62.7%) |

35 (66.0%) |

0.492b |

| North governorates |

8 (11.9%) |

3 (5.7%) |

|

| South governorates |

17 (25.4%) |

15 (28.30%) |

|

| Family history |

|

|

|

| No |

53 (79.1%) |

44 (83.0%) |

0.589b |

| Yes |

14 (20.9%) |

9 (17.0%) |

|

| Smoking status |

|

|

|

| Never |

56 (83.6%) |

38 (71.7%) |

0.117b |

| Ex/current |

11 (16.4%) |

15 (28.3%) |

|

| ECOG |

|

|

|

| 0 |

54 (80.6%) |

41 (77.4%) |

0.64c |

| 1 |

13 (19.4%) |

11 (20.8%) |

|

| 2 |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (1.9%) |

|

|

Table II

Disease data associated with oxaliplatin-induced cumulative neurotoxicity.

|

Table II

Disease data associated with oxaliplatin-induced cumulative neurotoxicity.

| Variables |

Without CN (n=67) |

With CN (n=53) |

P-value |

| Past medical history |

|

|

|

| None |

39 (58.2%) |

40 (75.5%) |

0.0758a |

| HT |

16 (23.9%) |

6 (11.3%) |

|

| DM |

5 (7.5%) |

5 (9.4%) |

|

| HT + DM |

5 (7.5%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

| Hypothyroidism |

2 (3.0%) |

2 (3.8%) |

|

| Primary tumor site |

|

|

|

| Colon |

37 (55.2%) |

25 (47.2%) |

0.602b |

| Recto-sigmoid |

12 (17.9%) |

13 (24.5%) |

|

| Rectum |

18 (26.9%) |

15 (28.3%) |

|

| Organ metastasis |

|

|

|

| No metastasis |

29 (43.3%) |

22 (37.29%) |

0.685b |

| Liver metastasis |

32 (47.8%) |

23 (43.4%) |

|

| Other metastasis |

7 (10.4%) |

8 (15.1%) |

|

| Tumor stage |

|

|

|

| II |

3 (4.5%) |

4 (7.5%) |

0.752b |

| III |

25 (37.3%) |

18 (34.0%) |

|

| IV |

39 (58.2%) |

31 (58.5%) |

|

| CEA |

|

|

|

| Median |

6.0 |

17.3 |

0.713c |

| Range |

0.00-2000 |

0.20-1900 |

|

Association of treatment data with oxaliplatin-induced CN

Although the analysis revealed a non-significant association between cumulative oxaliplatin exposure and neurotoxicity development. As demonstrated in Table III, patients receiving higher cumulative doses (>1,000 mg/m2) exhibited a substantially greater incidence of CN compared to those receiving lower doses. Although not statistically significant, this dose-dependent association persisted following the adjustment for potential confounding variables (concomitant medications such as statins and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors), supporting cumulative dose as a key determinant of the risk of developing neurotoxicity.

|

Table III

Association between the treatment data of patients and oxaliplatin-induced CN.

|

Table III

Association between the treatment data of patients and oxaliplatin-induced CN.

| Variables |

Without CN (n=67) |

With CN (n=53) |

P-value |

| Standard dose of OHP (mg/m2) |

|

|

|

| 85 |

27 (40.3%) |

17 (32.1%) |

0.353b |

| 130 |

40 (59.7%) |

36 (67.9%) |

|

| Given dose of OHP, mg/m2 |

|

|

|

| Mean ± SD |

178.70±45.56 |

191.09±45.95 |

0.143c |

| Range |

100-260 |

100-270 |

|

| Cumulative dose of OHP (mg) |

|

|

|

| Median |

2,100 |

2,410 |

0.116d |

| Range |

1,080-3,120 |

750-3,360 |

|

| Concomitant medications n (%) |

|

|

|

| No |

28 (41.8%) |

31 (58.5%) |

0.0884a |

| Statin + RAS-I |

18 (26.9%) |

7 (13.2%) |

|

| Statin + metformin |

6 (9.0%) |

3 (5.7%) |

|

| Statin + metformin + RAS-I |

4 (6.0%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

| Pregabalin |

10 (14.9%) |

9 (17.0%) |

|

| Thyroxin |

1 (1.5%) |

3 (5.7%) |

|

| Chemotherapy settings |

|

|

|

| Neoadjuvant |

24 (35.8%) |

19 (35.8%) |

0.384b |

| Palliative |

38 (56.7%) |

28 (52.8%) |

|

| Adjuvant |

5 (7.5%) |

8 (15.1%) |

|

| Company |

|

|

|

| X |

26 (38.8%) |

21 (39.6%) |

0.927b |

| Y |

41 (61.2%) |

32 (60.4%) |

|

| Protocol |

|

|

|

| XELOX |

25 (37.3%) |

21 (39.6%) |

0.102b |

| XELOX + bevacizumab |

18 (26.9%) |

16 (30.2%) |

|

| FOLFOX |

12 (17.9%) |

2 (3.8%) |

|

| FOLFOX + bevacizumab |

12 (17.9%) |

14 (26.4%) |

|

Genetic predisposition to oxaliplatin induces CN: HWE validation and high-risk genotypes (rs1695 and rs1138272)

Genotype distributions for rs1695 and rs1138272 were tested for HWE using a Chi-squared test calculated via an online calculator (https://scienceprimer.com/hardy-weinberg-equilibrium-calculator). Both polymorphisms were in equilibrium (rs1695: χ2=1.77, df=1, P=0.412; rs1138272: χ2=0.002, df=1, P=0.999), indicating no significant deviation from HWE. Since both P-values were >0.05, the genotype distributions do not significantly deviate from HWE, as shown in Table IV.

|

Table IV

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test results for GSTP1 polymorphisms.

|

Table IV

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test results for GSTP1 polymorphisms.

| SNP ID |

Chi-square (χ²) |

df |

P-value |

HWE Status |

| rs1695 |

1.77 |

1 |

0.412 |

In equilibrium (NS) |

| rs1138272 |

0.002 |

1 |

0.999 |

In equilibrium (NS) |

The sequencing PCR products of rs1695 revealed three genotypes (AA, AG and GG). The sequencing of PCR products of rs1138272 also revealed three genotypes (CC, CT and TT). The results of the association between genotypes of both polymorphisms linked to CN in patients receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy are presented in Tables V and VI. The GG and CT genotypes posed the highest risk (OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 1.08-14.74) and (OR, 5.27; 95% CI, 2.0-13.79) for rs1695 and rs1138272, respectively. These genotypes were found to significantly increase the risk of developing CN, suggesting a strong genetic predisposition.

|

Table V

rs1695 polymorphism as a risk factor for oxaliplatin-induced CN (genotype and allele analysis).

|

Table V

rs1695 polymorphism as a risk factor for oxaliplatin-induced CN (genotype and allele analysis).

| rs1695 |

Without CN (n=67) (%) |

With CN (n=53) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Codominant model |

|

|

|

|

| AA |

44 (65.67) |

22 (41.51) |

0.026 |

1.0 |

| AG |

19 (28.36) |

23 (43.4) |

0.029 |

2.42 (1.09-5.36) |

| GG |

4 (5.97) |

8 (15.09) |

0.037 |

4.0 (1.08-14.74) |

| Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

| AA + AG |

63 (94.03) |

45 (84.91) |

0.109 |

1.0 |

| GG |

4 (5.97) |

8 (15.09) |

|

2.8(0.79-9.87) |

| Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

| AA |

44 (65.67) |

22 (41.51) |

0.009 |

1.0 |

| AG + GG |

23 (34.33) |

31 (58.49) |

|

2.88 (1.36-6.08) |

| Alleles |

|

|

|

|

| A |

107 (79.85) |

67 (63.21) |

0.005 |

1.0 |

| G |

27 (20.15) |

39 (36.79) |

|

2.31 (1.29-4.11) |

|

Table VI

rs1138272 polymorphism as a risk factor for oxaliplatin-induced CN (genotype and allele analysis).

|

Table VI

rs1138272 polymorphism as a risk factor for oxaliplatin-induced CN (genotype and allele analysis).

| rs1138272 |

Without CN (n=67) (%) |

With CN (n=53) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Codominant model |

|

|

|

|

| CC |

59 (88.06) |

32 (60.78) |

0.003 |

1.0 |

| CT |

7 (10.45) |

20 (37.74) |

0.001 |

5.27 (2.0-13.79) |

| TT |

1 (1.49) |

1 (1.89) |

0.669 |

1.84 (0.11-30.47) |

| Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

| CC+CT |

66 (98.51) |

52 (98.11) |

0.867 |

1.0 |

| TT |

1 (1.49) |

1 (1.89) |

|

1.27 (0.08-20.78) |

| Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

| CC |

59 (88.06) |

32 (60.78) |

0.001 |

1.0 |

| CT + TT |

8 (11.49) |

21 (39.62) |

|

4.84 (1.93-12.16) |

| Alleles |

|

|

|

|

| C |

125 (93.28) |

84 (79.25) |

0.002 |

1.0 |

| T |

9 (6.72) |

22 (20.75) |

|

3.64 (1.6-8.29) |

Dose-dependent genetic associations between rs1695/rs1138272 and oxaliplatin-induced CN

The association between the polymorphisms and two different ranges of doses (<1,000 mg/m2 and >1,000 mg/m2) was then examined (Tables VII, VIII, IX, and X). The key findings revealed that the rs1695 polymorphism was strongly associated with CN at oxaliplatin doses (<1,000 mg/m2; the GG genotype increased the risk of developing CN by ~7.7-fold compared to the AA genotype (OR, 7.7; P=0.012) (Table VII). At oxaliplatin doses >1,000 mg/m2, the risk remained elevated, with the AG genotype increasing the odds by 5.5-fold compared to the AA genotype (OR, 5.5; P<0.001), as shown in Table VIII.

|

Table VII

Association between the rs1695 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN at doses <1,000 mg/m2.

|

Table VII

Association between the rs1695 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN at doses <1,000 mg/m2.

| Rs1695 |

Without CN (n=100) (%) |

With CN (n=20) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Codominant model |

|

|

|

|

| AA |

58(58) |

8(40) |

0.043 |

1.0 |

| AG |

35(35) |

7(35) |

0.721 |

1.15 (0.52-2.53) |

| GG |

7(7) |

5(25) |

0.012 |

7.7 (1.56-37.96) |

| Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

| AA + AG |

93(93) |

15(75) |

0.022 |

1.0 |

| GG |

7(7) |

5(25) |

|

4.43 (1.24-15.78) |

| Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

| AA |

58(58) |

8(40) |

0.145 |

1.0 |

| AG + GG |

42(42) |

12(60) |

|

2.07 (0.78-5.51) |

| Alleles |

|

|

|

|

| A |

151 (75.5) |

23 (57.5) |

0.022 |

1.0 |

| G |

49 (24.5) |

17 (42.5) |

|

2.29 (1.27-4.61 |

|

Table VIII

Association between the rs1695 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN at doses >1,000 mg/m2.

|

Table VIII

Association between the rs1695 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN at doses >1,000 mg/m2.

| rs1695 |

Without CN (n=87) (%) |

With CN (n=33) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Codominant model |

|

|

|

|

| AA |

58 (66.67) |

8 (24.24) |

0.001 |

1.0 |

| AG |

20 (22.99) |

22 (66.67) |

<0.001 |

5.5 (2.26-13.34) |

| GG |

9 (10.34) |

3 (9.09) |

0.492 |

1.67 (0.39-7.16) |

| Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

| AA + AG |

78 (89.66) |

30 (90.91) |

0.691 |

1.0 |

| GG |

9 (10.71) |

3 (8.33) |

|

0.76 (0.19-2.98) |

| Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

| AA |

58 (66.67) |

8 (24.24) |

0.001 |

1.0 |

| AG + GG |

29 (34.52) |

25 (69.44) |

|

4.31 (1.86-9.98) |

| Alleles |

|

|

|

|

| A |

136 (78.16) |

38 (57.58) |

0.011 |

1.0 |

| G |

38 (21.84) |

28 (42.42) |

|

2.18 (1.2-3.95) |

|

Table IX

Association between the rs1138272 polymorphism with oxaliplatin-induced cumulative neurotoxicity at doses <1,000 mg/m2.

|

Table IX

Association between the rs1138272 polymorphism with oxaliplatin-induced cumulative neurotoxicity at doses <1,000 mg/m2.

| rs1138272 |

Without CN (n=100) (%) |

With CN (n=20) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95%CI) |

| Codominant model |

|

|

|

|

| CC |

81(81) |

10(50) |

0.017 |

1.0 |

| CT |

18(18) |

9(45) |

0.004 |

4.05 (1.44-11.4) |

| TT |

1(1) |

1(5) |

0.150 |

8.1 (0.47-139.8) |

| Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

| CC + CT |

99(9) |

19(19) |

0.250 |

1.0 |

| TT |

1(1) |

1(5) |

|

5.21 (0.31-86.97) |

| Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

| CC |

81(81) |

10(50) |

0.005 |

1.0 |

| CT + TT |

19(95) |

10(50) |

|

4.05 (1.55-11.69) |

| Alleles |

|

|

|

|

| C |

180(9) |

29 (72.5) |

0.004 |

1.0 |

| T |

20 10) |

11 (27.5) |

|

3.41 1.48-7.86) |

|

Table X

Association between the rs1138272 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN at doses >1,000 mg/m2.

|

Table X

Association between the rs1138272 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN at doses >1,000 mg/m2.

| rs1138272 |

Without CN (n=84) (%) |

With CN (n=36) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Codominant model |

|

|

|

|

| CC |

60 (71.43) |

31 (86.11) |

|

1.0 |

| CT |

23 (27.38) |

4 (11.11) |

0.063 |

0.33 (0.11-1.06) |

| TT |

1 (1.19) |

1 (2.78) |

0.645 |

1.93 (0.12-32.0) |

| Dominant model |

|

|

|

|

| CC + CT |

83 (98.81) |

35 (97.22) |

0.546 |

1.0 |

| TT |

1 (1.19) |

1 (2.78) |

|

2.37 (0.14-39.0) |

| Recessive model |

|

|

|

|

| CC |

60 (71.43) |

31 (86.11) |

0.092 |

1.0 |

| CT + TT |

24 (28.57) |

5 (13.89) |

|

0.40 (0.14-1.16) |

| Alleles |

|

|

|

|

| C |

143 (85.12) |

66 (91.67) |

0.172 |

1.0 |

| T |

25 (14.88) |

6 (8.33) |

|

0.52 (0.21-1.33) |

As regards rs1138272, at doses (<1,000 mg/m2, the CT genotype was significantly associated with CN (P=0.004), with a recessive model OR of 4.05. This indicates that individuals carrying at least one T allele (CT or TT) are at a >4-fold increased risk of developing CN compared to those without this allele, as shown in Table IX. The rs 1138272 polymorphism did not exhibit a significant correlation with CN at doses >1,000 mg/m2 oxaliplatin, as shown in Table X.

Dose-independent genetic associations: rs1695 GG/AG and rs1138272 CT genotypes are associated with grade-progressive risk of developing oxaliplatin-induced CN

The present study then examined the association between different genotypes and alleles of the rs1695 polymorphism with varying grades of cumulative neurotoxicity. The findings indicated that both the G allele and the GG genotype of the GSTP1 rs1695 polymorphism were significantly associated with increased severity of cumulative neurotoxicity, particularly at grades 2 and 3 (Table XI) between the GG genotype and the increased the severity of CN.

|

Table XI

Dose-independent genetic risk: rs1695 AG/GG genotypes exhibit a progressive association with higher-grade oxaliplatin-induced CN.

|

Table XI

Dose-independent genetic risk: rs1695 AG/GG genotypes exhibit a progressive association with higher-grade oxaliplatin-induced CN.

| A, Grade 1 CN |

| Genotypes/alleles |

Without grade 1 CN (n=96) |

With grade 1 CN (n=24) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| AA |

59 (61.46) |

7 (29.17) |

0.033 |

1.0 |

| AG |

28 (29.17) |

14 (58.33) |

0.010 |

3.62 (1.36-9.65) |

| GG |

9 (9.38) |

3 (12.50) |

0.666 |

1.45 (0.27-7.84) |

| A |

146 (76.04) |

28 (58.33) |

0.015 |

1.0 |

| G |

46 (23.96) |

20 (41.67) |

|

2.27 (1.17-4.4) |

| B, Grade 2 CN |

| Genotypes/alleles |

Without grade 2 CN (n=105) (%) |

With grade 2 CN (n=15) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| AA |

60 (57.14) |

6(40) |

0.091 |

1.0 |

| AG |

37 (35.24) |

5 (33.33) |

0.638 |

1.35 (0.38-3.74) |

| GG |

8 (7.62) |

4 (26.67) |

0.031 |

5.0 (1.56–21.63) |

| A |

157 (74.76) |

17 (56.67) |

0.042 |

1.0 |

| G |

53 (25.24) |

13 (43.33) |

|

2.65 1.03-5.0) |

| C, Grade 3 CN |

| Genotypes/alleles |

Without grade 3 CN (n=106) (%) |

With grade 3 CN (n=14) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| AA |

63 (59.43) |

3 (21.43) |

0.042 |

1.0 |

| AG |

34 (32.07) |

8 (57.14) |

0.024 |

4.94 (01.23-19.85) |

| GG |

9 (8.49) |

3 (21.43) |

0.029 |

6.2 1.22-40.12) |

| A |

140 (66.04) |

14(50) |

0.001 |

1.0 |

| G |

72 (33.96) |

14(50) |

|

3.65 (1.7-8.01) |

Individuals carrying the AG genotype had a significantly increased risk of developing grade 1 CN compared to the AA genotype (OR, 3.62; 95% CI, 1.36-9.65; P=0.010). The GG genotype did not exhibit a statistically significant association with grade 1 CN (OR, 1.45; P=0.666). The G allele was significantly associated with grade 1 CN (OR, 2.27; P=0.015), suggesting that carriers of the G allele may be predisposed to early-stage CN.

A strong association was observed between the GG genotype and grade 2 CN (OR, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.56-21.63; P=0.031), indicating that homozygous carriers of the G allele have a 5-fold increased risk of developing grade 2 CN compared to the AA genotype. The AG genotype does not exhibit a significant association with grade 2 CN (P=0.638). The G allele again exhibited a significant association with grade 2 CN (OR, 2.65; P=0.042), reinforcing its potential role in the increased susceptibility to CN.

Both the AG and GG genotypes exhibited significant associations with grade 3 CN. The AG genotype was associated with an almost 5-fold increased risk of grade 3 CN (OR, 4.94; P=0.024). The GG genotype exhibited the highest association (OR, 6.2; P=0.029), suggesting a dose-dependent association between the number of G alleles and the severity of CN. The G allele remained significantly associated with grade 3 CN (OR, 3.65; P=0.001) (Table XI).

Subsequently, the present study examined the impact of the rs1138272 polymorphism on oxaliplatin-induced CN (Table XII). The data indicated that the CT genotype was associated with an increased risk of developing CN, particularly at higher grades. The CT and TT genotypes do not exhibit a significant association with grade 1 CN (P>0.05 for both). The T allele did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with grade 1 CN (OR, 1.47; P=0.389), suggesting that rs1138272 may not strongly contribute to early-stage CN.

|

Table XII

Dose-independent genetic risk: Association between the rs1138272 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN.

|

Table XII

Dose-independent genetic risk: Association between the rs1138272 polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced CN.

| A, Grade 1 CN |

| Genotypes/alleles |

Without grade 1 CN (n=96) (%) |

With grade 1 CN (n=24) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| CC |

74 (77.08) |

17 (70.83) |

0.565 |

1.0 |

| CT |

21 (21.88) |

6(25) |

0.684 |

1.24 (0.43-3.55) |

| TT |

1 (1.04) |

1 (4.17) |

0.307 |

4.35 (0.26-73.14) |

| C |

169 (88.02) |

40 (83.33) |

0.389 |

1.0 |

| T |

23 (11.98) |

8 (16.67) |

|

1.47 (0.61-3.53) |

| B, Grade 2 CN |

| Genotypes/alleles |

Without grade 2 CN (n=105) (%) |

With grade 2 CN (n=15) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| CC |

82 (78.10) |

9(60) |

0.258 |

1.0 |

| CT |

21(20) |

6(40) |

0.100 |

2.60 (0.83-8.13) |

| TT |

2 (1.90) |

0 (0) |

0.202 |

0.41 (0.41-7.23) |

| C |

185 (88.10) |

24(80) |

0.090 |

1.0 |

| T |

25 (13.16) |

6(20) |

|

2.26 (0.88-5.82) |

| C, Grade 3 CN |

| Genotypes/alleles |

Without grade 3 CN (n=106) (%) |

With grade 3 CN (n=14) (%) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| CC |

84 (79.25) |

7(50) |

0.052 |

1.0 |

| CT |

21 (19.81) |

6 (42.86) |

0.043 |

3.43 (1.04-11.28) |

| TT |

1 (0.94) |

1 (7.14) |

0.090 |

3.43 (1.04-11.28) |

| C |

189 (89.15) |

20 (71.23) |

0.052 |

1.0 |

| T |

23 (10.85) |

8 (28.57) |

|

3.29 (1.3-8.31) |

The CT genotype exhibited a trend towards an increased risk of grade 2 CN (OR, 2.60; P=0.100), although the association was not statistically significant. The TT genotype is absent in patients with grade 2, preventing any conclusive interpretation. The CT genotype was significantly associated with grade 3 CN (OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 1.04-11.28; P=0.043). The T allele exhibited a potential association with grade 3 CN (OR, 3.29; P=0.052), although this was not statistically significant (Table XII), indicating a high variability and a need for further validation in larger cohort studies.

Discussion

The present study provides compelling evidence of the role of genetic polymorphisms in modifying susceptibility to oxaliplatin-induced CN, while simultaneously confirming the established dose-dependent nature of this adverse effect. These findings highlight the clinical utility of genetic screening in risk stratification, facilitating the personalization of chemotherapy regimens to effectively minimize oxaliplatin-related CN.

Notably, both polymorphisms-maintained the HWE, strengthening confidence in the genetic findings obtained herein and suggesting that these variants represent true population characteristics rather than genotyping artifacts or selection biases. The findings of the present study suggest that individuals with the G allele (homozygous GG) and T allele contribute to an increased risk of developing oxaliplatin-related CN, particularly at doses <1,000 mg/m2. Of note, the higher chance of requiring a dose reduction for both the GG and CT genotypes may be due to the fact that they had their treatment adjusted or had longer breaks between treatment cycles to manage the risk of oxaliplatin-related CN. That could cause an apparent fall in OR due to increased cumulative dosing. In addition, it could mean both genotypes are associated with early-onset CN. These results are consistent with the theory that both polymorphisms rs1695 and rs1138272 in the GSTP1 gene involve amino acid substitutions that appear to be within the GSTP1 active site and lead to the alteration of substrate affinity. The substitution of adenine by guanine in exon 5 at nucleotide 313 results in valine [Val] replacing isoleucine [Ile] in location 105 of the amino acid sequence (21,22). Replacing cysteine with thiamin in exon 6 at nucleotide 341 causes valine [Val] to take the place of alanine [Ala] at position 114 in the amino acid sequence. This substitution may disrupt the ability of the enzyme to interact critically with glutathione, potentially reducing its detoxification capacity. The structural integrity and flexibility provided by cysteine residues are essential for maintaining the active site's conformation, which is vital for effective substrate binding (23).

In a previous study involving Caucasian patients (24), the prevalence of CN was found to be 52.1%, with 36.8% experiencing grade II neurotoxicity. These numbers differ from those observed in the present study (44.2 and 12.5%, respectively). This disparity may be attributed to differences in genetic backgrounds and allele frequencies, as previously discussed (25).

In a previous study involving Caucasian patients, the prevalence of CN was found to be 52.1%, with 36.8% experiencing grade II neurotoxicity (24). The findings demonstrate that 44% developed chronic neurotoxicity, with 12.5% experiencing grade II CN. This disparity may be due to the difference in genetic background and allele frequency (25).

The findings of the present study are consistent with those of previous research indicating that Japanese individuals with at least one GSTP1 105Val allele are more likely to develop early-onset grade 2/3 neuropathy from oxaliplatin (26,27). Additionally, another study involving 122 patients in Japan found that those with the AG allele experienced more severe neuropathy compared to those with the AA genotype (12). Furthermore, having the homozygous GSTP1 variant (GG) was shown to be associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing grade ≥3 peripheral neuropathy when compared to the wild-type (AA) (12).

The results presented herein are in accordance with the hypothesis that the GSTP1 105Ile variant can lead to increased oxidative stress and neuronal damage (1), exacerbating oxaliplatin-induced CN (28). Research have shown that patients with the Ile105 variant may experience more severe neuropathy, highlighting the clinical relevance of this polymorphism in oxaliplatin treatment (25). Another retrospective study demonstrated that European patients with the Val/Val or Ile/Val genotypes were more likely to have a decreased risk of severe oxaliplatin-related CN (28). A previous meta-analysis of heterogeneity for GSTP1 Ile105Val and oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy demonstrated no significant association between GSTP1 polymorphism and neurotoxicity (13). This indicates that the frequencies of the alleles in Asian populations differ significantly from those in Caucasian populations (25). Based on previous research, the conjugation of oxaliplatin with glutathione is not the only pathway for biotransformation and does not play a substantial role in its effectiveness and side-effects (29). Protein-protein interaction between JNK with wild-type GSTP1 exhibit a higher affinity than mutant GSTP1 (30). The JNK protein interacts with the mitochondrial protein SAB, and the interaction forms a JNK-SAB-ROS activation loop that impairs electron transport and promotes the release of reactive oxygen species, contributing to apoptosis (31).

Ultimately, the modulation of apoptosis depends on the redox status of cells (32). Phosphorylation can enhance GSTP1 activity and can potentially affect signaling pathways, including the signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway involved in the inflammatory response (33). Recent research has illustrated the involvement of immune reactions and inflammation in the body, each of which is diagnosed to contribute to the development of neuropathy (8). It was hypothesized that mutant GSTP1 is essential for sustaining JNK activation and that mutant GSTP1 is activated by phosphorylation with various kinases more than the wild-type on the above bases. However, the mechanisms of oxaliplatin-induced CN rely on the unique structure and function of the neurons, and the complex communication between neurons, the immune system and cancer cells must be considered. The overall impact of this polymorphism on oxaliplatin-induced CN remains complex and may involve other genetic and environmental factors. The results should be interpreted cautiously as some studies used different designs and genotyping methods. To the best of our knowledge, the present study appears to be the first to report that genotypes of the rs1695 and rs1138272 polymorphisms are associated with the severity and onset of cumulative neurotoxicity in West Asia. According to these findings, it can be hypothesized that the variation between West and East Asia is closer than that in Caucasians.

The findings of the present study carry important clinical implications. First, the findings suggest that pharmacogenetic testing may be most valuable for patients anticipated to receive moderate cumulative doses, where genotype could meaningfully influence risk-benefit calculations. Second, these findings indicate that while high-dose regimens universally increase the risk of developing CN, genetic factors still contribute meaningfully even in these scenarios. Several practical applications emerge from these findings: i) Preemptive risk assessment: Incorporating rs1695 and rs1138272 genotyping into pre-treatment workups could identify high-risk patients prior to the development of CN. This may be particularly valuable when considering extended adjuvant regimens where cumulative doses approach risk thresholds. ii) Personalized dosing strategies: For high-genetic-risk patients, clinicians might consider the following: Lower cumulative dose ceilings (e.g., <850 mg/m2 for GG/CT carriers), enhanced monitoring protocols and alternative dosing schedules (e.g., stop-and-go approaches). iii) Regimen selection: In clinical scenarios with equivalent therapeutic options (e.g., FOLFOX vs. XELOX in colorectal cancer), genetic risk profiles can guide regimen selection. In addition, population specificity should be considered: The generalizability of the findings to diverse ethnic populations requires verification, as allele frequencies and linkage patterns may vary across groups.

The present study has certain limitations, which should be mentioned. First, a limited cohort of patients were assessed. The data presented herein should thus be regarded as preliminary. Further studies utilizing the same oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy are necessary to validate the potential of the GSTP1 genotype as a key indicator of CN associated with this treatment. Secondly, the time line of the present study was limited, which did not allow for follow-up on chronic CN to assess whether genetic risk profiles predict long-term neuropathy persistence or recovery patterns.

In conclusion, in the present study, the analysis of polymorphisms rs1695 and rs1138272 revealed meaningful links between certain genotypes and the severity and onset of CN. Genetic analysis revealed significant associations between rs1695 and rs1138272 polymorphisms and oxaliplatin-related CN. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first study to demonstrate a link between rs1695 and rs1138272 polymorphisms and the onset and severity of CN in West Asian populations. These findings support the integration of genetic screening into personalized treatment strategies and highlight the need for further research to validate these associations and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Further research is warranted to fully elucidate the association between GSTP1 polymorphisms, apoptosis pathways in the neurons and neurotoxicity in the context of chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Dr Fawaz S. Al-Alloosh, Head of the Medical Oncology Department at Warith International Cancer Institute, Karbala, and Dr Mohammed Ghanim Mehdi, Head of the Laboratory at Warith International Cancer Institute, Karbala, for their invaluable guidance and support throughout this research. Additionally, the authors would like to extent their appreciation to Mustansiriyah University, Baghdad, Iraq (www.uomustansiriyah.edu.iq), for providing academic and administrative assistance.

Funding

Funding: The genotyping component of the present study was financially supported by the Holy Shrine of Imam Husayn.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RAMJ made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study/ RAMJ also collected blood samples from the patients and performed the laboratory analyses, and also participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, generated the datasets, and drafted and revised the manuscript. BAM played a role in the conceptualization, designing methodology of study, data curation and writing the original draft. QSAM contributed to performing the data analysis and revising the manuscript. All authors (RAMJ, BAM and QSAM) confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study complied with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), ethical standards set by the Research Ethics Committee of Mustansiriyah University of Pharmacy (ref. no. 105). Approval was obtained from the Ministry of Health (no. 7026) and Warith International Cancer Institute (no.892). The consent form emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary, and the participants could withdraw at any time without facing any repercussions. Anonymity and confidentiality were safeguarded by assigning coded identifiers rather than names or medical record numbers. In adherence to international ethical guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki, the study maintained strict ethical standards. A statement of consent for publication was obtained from the patient according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Bakir WA, Ismail NH, Latif AH, Abd DW and Saied ZZ: Cytotoxicity-associated gene (CagA) producing Helicobacter pylori increased risk of developing colorectal carcinoma in Iraqi patients. Al Mustansiriyah J Pharm Sci. 14:143–149. 2014.

|

|

2

|

Liu Y, Zhang C, Wang Q, Wu K, Sun Z, Tang Z and Zhang B: Temporal trends in the disease burden of colorectal cancer with its risk factors at the global and national level from 1990 to. 2019, and projections until 2044. Clin Epidemiol. 15:55–71. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Kobritz M, Nofi CP, Egunsola A and Zimmern AS: Financial toxicity in early-onset colorectal cancer: A national health interview survey study. Surgery. 175:1278–1284. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Al-Saigh THT, Abdulmawjood SA and Ahmed FA: Prognostic factor of serum carcinoembryonic antigen in colorectal cancer patients: A follow up study. Al Mustansiriyah J Pharm Sci. 21:1–6. 2022.

|

|

5

|

Jawad RAM, Mshimesh BAR, Al-Mayah QS and Al-Alloosh F: A case study on complete pathological response in advanced rectal cancer patient with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy without cumulative neurotoxicity. J Gastrointest Cancer. 56(99)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Calls A, Torres-Espin A, Tormo M, Martínez-Escardó L, Bonet N, Casals F, Navarro X, Yuste VJ, Udina E and Bruna J: A transient inflammatory response contributes to oxaliplatin neurotoxicity in mice. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 9:1985–1998. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Cavaletti G, Alberti P and Marmiroli P: Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity in the era of pharmacogenomics. Lancet Oncol. 12:1151–1161. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yang Y, Zhao B, Gao X, Sun J, Ye J, Li J and Cao P: Targeting strategies for oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: Clinical syndrome, molecular basis, and drug development. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40(331)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Stefansson M and Nygren P: Oxaliplatin added to fluoropyrimidine for adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer is associated with long-term impairment of peripheral nerve sensory function and quality of life. Acta Oncol. 55:1227–1235. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Grothey A: Clinical management of oxaliplatin-associated neurotoxicity. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 5 (Suppl 1):S38–S46. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Sun X, Guo C, Huang C, Lv N, Chen H, Huang H, Zhao Y, Sun S, Zhao D, Tian J, et al: GSTP alleviates acute lung injury by S-glutathionylation of KEAP1 and subsequent activation of NRF2 pathway. Redox Biol. 71(103116)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Katayanagi S, Katsumata K, Mori Y, Narahara K, Shigoka M, Matsudo T, Enomoto M, Suda T, Ishizaki T, Hisada M, et al: GSTP1 as a potential predictive factor for adverse events associated with platinum-based antitumor agent-induced peripheral neuropathy. Oncol Lett. 17:2897–2904. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Peng Z, Wang Q, Gao J, Ji Z, Yuan J, Tian Y and Shen L: Association between GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphism and oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 72:305–314. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Cheng F, Zhang R, Sun C, Ran Q, Zhang C, Shen C, Yao Z, Wang M, Song L and Peng C: Oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neurotoxicity in colorectal cancer patients: Mechanisms, pharmacokinetics and strategies. Front Pharmacol. 14(1231401)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Attarbashee RK, Hamodat HF, Mammdoh JK and Ridha-Salman H: The possible effect of Bosentan on the methotrexate-induced salivary gland changes in male rats: Histological and Immunohistochemical study. Toxicol Res (Camb). 14(tfaf007)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Bartolini D, Stabile AM, Migni A, Gurrado F, Lioci G, De Franco F, Mandarano M, Svegliati-Baroni G, Di Cristina M, Bellezza G, et al: Subcellular distribution and Nrf2/Keap1-interacting properties of Glutathione S-transferase P in hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 757(110043)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Rapp E, Lu Z, Sun L, Serna SN, Almestica-Roberts M, Burrell KL, Nguyen ND, Deering-Rice CE and Reilly CA: Mechanisms and consequences of variable TRPA1 expression by airway epithelial cells: Effects of TRPV1 genotype and environmental agonists on cellular responses to pollutants in vitro and asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 131(27009)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Benson AB, Venook AP, Adam M, Chang G, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen SA, Cooper HS, Deming D, Garrido-Laguna I, et al: Colon cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 22(e240029)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

National Cancer Institute (NCI): Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), 2025. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_60.

|

|

20

|

Ijam AH, Mshimesh BAR, Abdulamir AS and Alsaad SF: Analysis of cytochrome P450 2C9 gene polymorphism in a sample of iraqi hypertensive patients. Med J Babylon. 21:653–658. 2024.

|

|

21

|

Cowell IG, Dixon KH, Pemble SE, Ketterer B and Taylor JB: The structure of the human glutathione S-transferase pi gene. Biochem J. 255:79–83. 1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Malempati S, Agrawal N, Ravisankar D, Kothapalli VSRT, Cheemanapalli S, Tamanam RR, Govatati S and Rao PS: Role of GSTP1 functional polymorphisms in molecular pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Hum Gene. 42(201335)2024.

|

|

23

|

Marensi V, Yap MC, Ji Y, Lin C, Berthiaume LG and Leslie EM: Glutathione transferase P1 is modified by palmitate. PLoS One. 19(e0308500)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ben Kridis W, Toumi N and Khanfir A: Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: Single-centre prospective study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 13:e881–e884. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen YC, Tzeng CH, Chen PM, Lin JK, Lin TC, Chen WS, Jiang JK, Wang HS and Wang WS: Influence of GSTP1 I105V polymorphism on cumulative neuropathy and outcome of FOLFOX-4 treatment in Asian patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 101:530–535. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Inada M, Sato M, Morita S, Kitagawa K, Kawada K, Mitsuma A, Sawaki M, Fujita K and Ando Y: Associations between oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy and polymorphisms of the ERCC1 and GSTP1 genes. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 48:729–734. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kanai M, Yoshioka A, Tanaka S, Nagayama S, Matsumoto S, Nishimura T, Niimi M, Teramukai S, Takahashi R, Mori Y, et al: Associations between glutathione S-transferase pi Ile105Val and glyoxylate aminotransferase Pro11Leu and Ile340Met polymorphisms and early-onset oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy. Cancer Epidemiol. 34:189–193. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lecomte T, Landi B, Beaune P, Laurent-Puig P and Loriot MA: Glutathione S-transferase P1 polymorphism (Ile105Val) predicts cumulative neuropathy in patients receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 12:3050–3056. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Nagai N, Okuda R, Kinoshita M and Ogata H: Decomposition kinetics of cisplatin in human biological fluids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 48:918–924. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Asakura T, Sasagawa A, Takeuchi H, Shibata SI, Marushima H, Mamori S and Ohkawa K: Conformational change in the active center region of GST P1-1, due to binding of a synthetic conjugate of DXR with GSH, enhanced JNK-mediated apoptosis. Apoptosis. 12:1269–1280. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Win S, Than TA and Kaplowitz N: Mitochondrial P-JNK target, SAB (SH3BP5), in regulation of cell death. Front Cell Dev Biol. 12(1359152)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Shirmanova MV, Gavrina AI, Kovaleva TF, Dudenkova VV, Zelenova EE, Shcheslavskiy VI, Mozherov AM, Snopova LB, Lukyanov KA and Zagaynova EV: Insight into redox regulation of apoptosis in cancer cells with multiparametric live-cell microscopy. Sci Rep. 12(4476)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Imbaby S, Elkholy SE, Faisal S, Abdelmaogood AKK, Mehana AE, Mansour BSA, Abd El-Moneam SM and Elaidy SM: The GSTP1/MAPKs/BIM/SMAC modulatory actions of nitazoxanide: Bioinformatics and experimental evidence in subcutaneous solid Ehrlich carcinoma-inoculated mice. Life Sci. 319(121496)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|