Introduction

The world has faced an unexpected public health

crisis since 2019 due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, known as COVID-19. The

COVID-19 epidemic has caused an astounding number of fatalities and

poses a distinct threat to the global food and public health

systems. The devastating economic and social effects of the

epidemic raise the prospect that many individualscould be pushed

into extreme poverty (1-4).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (https://covid19.who.int) (5), symptoms of COVID-19 can range from

fever and coughing to respiratory illness, bronchitis, renal

disease, and, in extreme cases, death (6,7). WHO

has documented 659,108,952 confirmed COVID-19 cases, including

6,684,756 fatalities. Up to December 21, 2022, 13,073,712,554 doses

of vaccine had been administered (https://covid19.who.int) (5).

Understanding the life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 and its

interactions with host cells is crucial for developing effective

strategies to fight the virus. The ~30-kb genome of SARS-CoV-2

shares significant similarities with other coronaviruses, such as

SAR-CoV and MERS-CoV, and contains two open reading frames (ORF)s1a

and ORF1b, capable of translating numerous structural and

non-structural proteins. The viral genome enters host cell

membranes with the aid of the spike protein, facilitating

attachment and membrane fusion via subunits S1 and S2. The rough

endoplasmic reticulum synthesizes the 1,273-amino acid polyprotein

precursor for the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein, which is subsequently

processed into two subunits, S1 and S2. These subunits play key

roles in viral attachment to host cells and membrane fusion

(8,9).

The predominant type I transmembrane S glycoprotein

of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope incorporates with the cognate receptor

of the host cell through membrane fusion. The S-surface

glycoprotein specifies its target for host immune responses and

serves as a prime target for antibody neutralization. Moreover,

S-glycoprotein can promote the fusion of infected and uninfected

cells to produce multinucleated giant cells by entering the plasma

membrane through the secretory route (10,11).

This could enable direct virus transmission across cells and

possibly change the pathogen city of SARS-CoV-2. Spike proteins

function as antiviral medications and vaccines due to their

essential parts in viral infection and their ability to induce

protective innate immune and cell-mediated adaptive immunity in

susceptible hosts (12).

The four non-structural proteins identified in the

virus are RNA polymerase, helicase, papain-like (PLpro) and

3-chymotrypsin-like (3Clpro) proteases (13). The viral replication and

transcription are performed by proteases, Plpro and 3Clpro. Among

these, the 3Clpro plays a critical role in the ability of the

virusto reproduce (14). The key

protease, also known as Mpro, is 3Clpro, and it is crucial for

viral replication. One of the main targets for developing

anti-SARS-CoVdrugs is the protease 3Clpro, which generates 11 of

the 16 non-structural proteins (NSPs) that are produced when Plpro

and 3Clpro cleave the PP chain into NSPs (15,16).

According to apreviousstudy, the primary protease Mpro of COVID-19

shares 96% of its sequence with SARS-CoV (17). Despite being in development,

effective therapeutic and preventive methods, such as medications

and vaccines, are still lacking. Herein, it is necessary to

identify novel therapeutic candidates that specifically target

certain SARS-CoV-2 proteins to treat COVID-19. A computational

method for identifying possible therapeutic candidates counter to

the treatment of emerging infectious diseases such as COVID-19 is

to create drugs based on protein structures (18,19).

The majority of anti-infective drugs are derived

from secondary metabolites found in nature, sourced from microbial,

oceanic, or plant origins (20,21).

The pharmacological qualities of ~20% of all known plant species

have been investigated; phytochemicalanalyseshave improved

healthcare by aiding in the treatment of diseases such as cancer.

Plants are able to generate a wide range of bioactive substances;

fruits and vegetables, in particular, are able to store large

amounts of phytochemicals that guard against harm from free

radicals (22). The bioactive

compounds have been classified as alkaloids, saponins, diterpenes

and flavonoids. These bioactive compounds play a vital role in the

discovery of new drugs from natural plants.

1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane

(SL-MHDC) is an important secondary metabolite and is isolated from

Spinifex littoreus (S. littoreus) which belongs to

the family Poaceae (23). This

coastal grass thrives on dunes, characterized by extremely hard,

in-rolled and curved leaves, with rough margins and spiky tips. The

inflorescence of this plant is a raceme with an imbricate spikelet.

This species forms substantial colonies and stabilizes dunes making

it an effective sand binder (24).

The ethnomedical history of S. littoreus indicates that the

root extract of S. littoreus has been traditionally

administered orally for the treatment of digestive disorders in the

Purba Medinipur District of West Bengal, India (25). Root decoction is also used to treat

joint and muscle pain (26).

Furthermore, the therapeutic potential of this plant has been

studied in order to elucidate its antimicrobial, antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties (27). This plant is also used

traditionally as a diuretic medicine. The methanol and aquatic

extract of this herb have been demonstrated in numerous

pharmacological tests to have analgesic, anti-inflammatory and

antibacterial effects (28).

However, no therapeutic evidence is available for the antiviral

property of the plant S. littoreus, as well as for the

phytocompound MHDC. Dampalla et al (29) conducted a structure-guided design

of conformationally constrained cyclohexane inhibitors of

SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease. Considering this, the present study

performed molecular docking analysis of the phytocompound MHDC

identified from the plant S. littoreus against the 3CL main

protease and spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2(30).

The present study aimed to investigate the

phytochemical diversity of S. littoreus (Burm.f.) Merr.

through preliminary phytochemical screening techniques and to

validate the findings using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

(GC-MS) analysis. Furthermore, the present study sought to identify

the inhibitory effects of the bioactive compound SL-MHDCon the key

proteins of SARS-CoV-2, i.e., the spike protein. By leveraging the

phytochemical diversity of this coastal grass, the authors aimed to

contribute to the ongoing efforts to mitigate the devastating

impact of COVID-19 on global health.

Materials and methods

Plant collection

S. littoreus was collected from Kunthukal

Beach, Pamban, Tamil Nadu, India (latitude: 9.25323; longitude:

79.21829). The collected plants were authenticated, and the

prepared herbarium sheets of the plantwas submitted to the Rapinat

Herbarium and Centre for Molecular Systematics, St. Joseph's

College, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India. (Voucher nos. J.V 001

and J.V 002).

Plant extraction

The young leaves of S. littoreus were

separated from the plant, cleaned and shade-dried. The dried S.

littoreus leaves were mechanically pulverized. The powdered

sample of S. littoreus was extracted with methanol and

chloroform through the Soxhlet apparatus (Borosil Scientific

Ltd.)for 16 h. To concentrate the collected extract, it was

subjected to a rotary evaporatorand weighed. The extraction process

was repeated until obtaining 5 g of powdered form of the extracts

(31).

Preliminary phytochemical screening.

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative analysis of carbohydrates, proteins,

amino acids, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids,

steroids, phenols, glycosides, quinones, coumarins and

anthraquinones was performed in six different solvent-mediated

(aqueous, acetone, ethanol, methanol, chloroform and ethyl acetate)

extracts of S. littoreus. All the chemicals and glassware

used for the phytochemical screening were sourced from Royal

Scientific Suppliers.

Carbohydrates. A total of two drops of

Molisch reagent were added to 2 ml S. littoreus extract.

Subsequently, 2 ml concentrated H2SO4 were

added on the sides of the tube. The formation of purple colour was

an indicator of the presence of carbohydrates (32).

Proteins. A few drops reagent were combined

with 2 ml S. littoreus extract. The presence of proteinswas

indicated by the production of a white precipitate, which

subsequently turns brick red in colour (33).

Amino acids. In a boiling water bath, 1 ml

S. littoreus extract along with 1 drop of ninhydrin solution

was heated. The development of a purple colour indicated the

presence of amino acids (32).

Tannins. In a test tube, 0.5 g powdered S.

littoreus extract was heated in 20 ml distilled water, filtered

and treated with 0.1% iron III chloride (FeCl3). The

samples were then observed for the development of brownish-green or

blue-black coloration, indicating the presence of tannins (33).

Terpenoids. In a test tube, 5 ml S.

Littoreusextract were used along with 2 ml CHCl3.

Subsequently, 3 ml concentrated H2SO4 were

gently added to the mixture to form a layer. In the case that

terpenoids are present, an interface with a reddish-brown colour

will form (33).

Alkaloids (Mayer's test). A test tube was filled

with 1 ml S. littoreus extract and 1 ml potassium mercuric

iodide solution (Mayer's reagent). When this mixture was shaken

gently, aprecipitate will be formed, confirming the presence of

alkaloids (33).

Quinines. To 10 mg S. littoreus

extract in isopropyl alcohol, one drop of concentrated sulfuric

acid was added. The presence of quinones was indicated by the

formation of a red colour (33).

Steroids. A total of 5 ml S. littoreus

extract was mixed with 2 ml chloroform and concentrated

H2SO4. A red colour appeared in the lower

chloroform layer, indicating the presence of steroids (34).

Coumarin. A total of 2 ml S. littoreus

extract was mixed with 3 ml 10% NaOH. The presence of coumarin was

indicated by a yellow coloration (35).

Saponins. A total of 20 ml distilled water

and 2 g powdered S. littoreus extract were heated together

in a water bath and then filtered. Subsequently, 10 ml of the

filtered sample were mixed with 5 ml distilled water in a test tube

and vigorously shaken to form a stable, long-lasting froth. This

was followed by the addition of three drops of extra virginolive

oil to the froth to create an emulsion, indicating the presence of

saponins (34).

Phenols. A few drops of FeCl3 and

1 ml water were added to a test tube along with ~2 ml of the S.

littoreus extract. The presence of a blue, green, red, or

purple colour indicates the presence of phenols (35).

Anthraquinones (Borntrager's test). A total

of 1 ml S. littoreus extract was added to a mixture of

diluted ammonia, chloroform, or benzene. The presence of

anthraquinone derivatives causes the ammonical layer to change

colour from pink to bright red (35).

Flavonoids. S. littoreus extract was

added to a test tube along with a few drops of a 1% NH3

solution. Yellow colour concludes the presence of flavonoids

(36).

Glycosides. S. littoreus extract was

used along with 2 ml acetic acid and 2 ml chloroform. Once the

mixture was cooledat room temperature, concentrated

H2SO4 was added. The steroidal glycosides can

be identified by their green colour appearance (37).

Quantitative screening of

phytochemicals

The presence of alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics,

flavonoids and tannins was quantitatively estimated with their

respective standard using the following methods:

Quantitative estimation of alkaloids. To

estimate the quantity of alkaloids in S. littoreus, the

extracts were treated with 5 ml bromocresol green and PBS. Atropine

was used as a standard solution. Alkaloids were measured in

milligrams of atropine equivalents per gram (mg AE/g) of chloroform

extract of sample (38).

Quantification of terpenoids. A total of 500

g S. littoreus leaf powder was soaked in ice-cold 95%

methanol and then centrifuged at 4,000 x g for 15 min at room

temperature. The supernatant was mixed with 1.5 ml chloroform and

100 ml concentrated sulfuric acid. Following incubation at room

temperature for 1.5-2 h in the dark, a brown precipitate appeared

at the bottom, which was dissolved in 1.5 ml 95% methanol, and its

absorbance was measured in the colorimeterat 538 nm (39).

Quantification of flavonoids. A colorimetric

test was used to determine the quantity of flavonoids in the S.

littoreus extract. To 1 ml of the extract, 0.3 ml of 10%

aluminum chloride, 5% sodium nitrite and 2 ml of NaOH were added.

The absorption spectrum of this mixture was measured using

UV-visible instrumentat 510 nm. Similarly, a set of quercetin

solutions was prepared and measured as standards. Flavonoid

concentration was expressed as mg of quercetin equivalents per gram

of extract (mg QE/g) (40).

Quantification of tannins. A total of 1 ml

S. littoreus extract was mixed with 0.5 ml Folin-Ciocalteu

reagent and 1 ml of 35% Na2CO3, followed by

the addition of 7.5 ml distilled water. This mixture was then

incubated at 30˚C for 30 min. Similarly, a set of tannic acid

solutions was prepared, and the optical density was measured at 700

nm with an UV/visible spectrophotometer. The amount of tannins in

the S. littoreus extract was expressed in milligrams of

tannic acid equivalent per gram (mg TAE/g) (41).

Determination of total phenolics. A total of

1 ml S. littoreus extract was dispersed in 9 ml of distilled

water along with 1 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu and 10 ml of 7%

Na2CO3 solution. This was incubated at 30˚C

for 2 h at room temperature. Gallic acid was used as standard.

Gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE/g) were used to represent mg of

total phenolic component per gram of extract (42).

GC-MS analysis

The phytoconstituents present in the methanolic

ethanol, ethyl acetate and chloroform extracts were screened using

GC-MS analysis. The experimental condition of the instrument was a

fused silica column filled with Elite-5MS (5% biphenyl, 95%

dimethylpolysiloxane, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID, 250 m df) utilized in the

analysis by the Clarus 680 GC, and the Helium carrier gas was used

to separate the components at a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. The

injector temperature was set to 260˚C. The operating parameters of

the mass detector were 240˚C for the transfer line, 240˚C for the

ion source, 70 eV for the electron impact in the ionization mode,

0.2 sec for each scan, and 0.1 sec between scans. The component

spectra were compared to a database of component spectrums

maintained in the GC-MS NIST (2008) library (43,44).

No standard compounds were used for the spectral comparison.

Drug suitability and pharmacokinetic

profile

The physicochemical, pharmacokinetic and

drug-likeliness properties of the compound SL-MHDC were predicted

using the SwissADME server (http://www.swissadme.ch/) to optimize the compound

based on its bioavailability, safety and efficacy (45,46).

Molecular docking. Ligand

preparation

Based on the GC-MS results of S. littoreus,

the chemical structure of the phytocompound SL-MHDCwas retrieved

from the PubChem database (PubChem CID: 550196) as an optimized 3D

ligand molecule. The downloaded ligand was prepared using the

Autodock MGL application (https://autodock.scripps.edu/) by detecting its

torsion root and saved in pdbqt format. This was then used for

docking with AutodockVina (47,48).

Target protein preparation. The target

protein selected for the study was the structure of SARS-CoV-2

XBB.1. The structure was downloaded from the protein data bank (PDB

ID: 8IOV) in PDB format. The chain B spike glycoprotein (RBD) of

XBB.1 was used as a target receptor for the docking analyses. The

protein preparation was performed by removing the water molecules

and the heteroatom within the structure. The structure was then

examined for the missing residues and it was saved in pdbqt format.

Both the optimized protein and ligand were then subjected to

docking analysis using Autodock 4.2.6 software (49) to identify the affinity of the

GC-MS-derived compound towards the SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1. The optimal

pose with the least energy of binding was used for further

analyses.

Molecular dynamics simulations (MDS). MDS is

a computational paradigm that enables atomistic interrogation of

biomolecular systems, which serves as a cornerstone in

pharmaco-reconnaissance. Thus, MDS were executed using Desmond

module (Schrödinger Suite) (50)

(https://www.schrodinger.com/platform/products/desmond/).

The SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1 spike glycoprotein complexed with SL-MHDC was

solvated via system builder by employing TIP4P aqueous solvation

within an orthorhombic solvent box. Moreover, the cell size was

49.6x68.1x51.7 Å, as well as the solvent buffer extending 10 Å,

which is beyond the protein in all Cartesian directions. As a

corollary, OPLS_2005 force field was deployed to parameterize

molecular energetics. Judiciously, electrostatic neutrality was

achieved by the incorporation of counter ions (Na+ and

Cl-) that was followed by constrained energy

minimization with the exorbitant of 2,500 iterations, as well as

the convergence thresholds of 1 kcal/mol/Å. Furthermore, the

present study exploited NPT ensemble with the Nose-Hoover

thermostat algorithm which is lauded for thermal fluctuations set

at a reference temperature of 300 K. A >30 nsec trajectory was

generated and the post-simulation analyses encompassed with

Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and the interrogation of

SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1 integrated with SL-MHDC complex persistent was

designated against the binding locus.

Results

Screening of phytoconstituents

The preliminary phytochemical screening of S.

littoreus was carried out to identify the presence of secondary

metabolites, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins,

glycosides, quinones, coumarins, steroids, phenols, terpenoids and

anthraquinones using six different solvents (aqueous, acetone,

ethanol, methanol, chloroform and ethyl acetate). Among these, the

chloroform extract revealed sevensecondary metabolites and one

primary metabolitein S. littoreus followed by the acetone,

methanol and ethanol extracts, which revealed sixsecondary

metabolites and one primary metabolite. The ethyl acetate extract

only revealed four compounds (Table

I).

| Table IQualitative assessment of

phytochemicals. |

Table I

Qualitative assessment of

phytochemicals.

| | Solvents |

|---|

| Metabolites | Aqueous | Acetone | Ethanol | Methanol | Chloroform | Ethyl acetate |

|---|

| Primary

metabolites | | | | | | |

|

Carbohydrates | + | - | + | + | + | - |

|

Proteins | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Amino

acids | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Secondary

metabolites | | | | | | |

|

Alkaloids | - | - | + | + | + | - |

|

Flavonoids | - | + | + | + | + | + |

|

Tannins | + | + | - | + | - | - |

|

Saponins | + | - | + | - | + | - |

|

Glycosides | + | + | - | - | - | - |

|

Quinones | - | + | + | + | + | + |

|

Coumarins | + | + | + | + | + | + |

|

Steroids | - | - | + | + | + | + |

|

Phenols | + | + | - | - | - | - |

|

Terpenoids | - | - | - | - | + | - |

|

Anthraquinones | - | - | - | - | - | - |

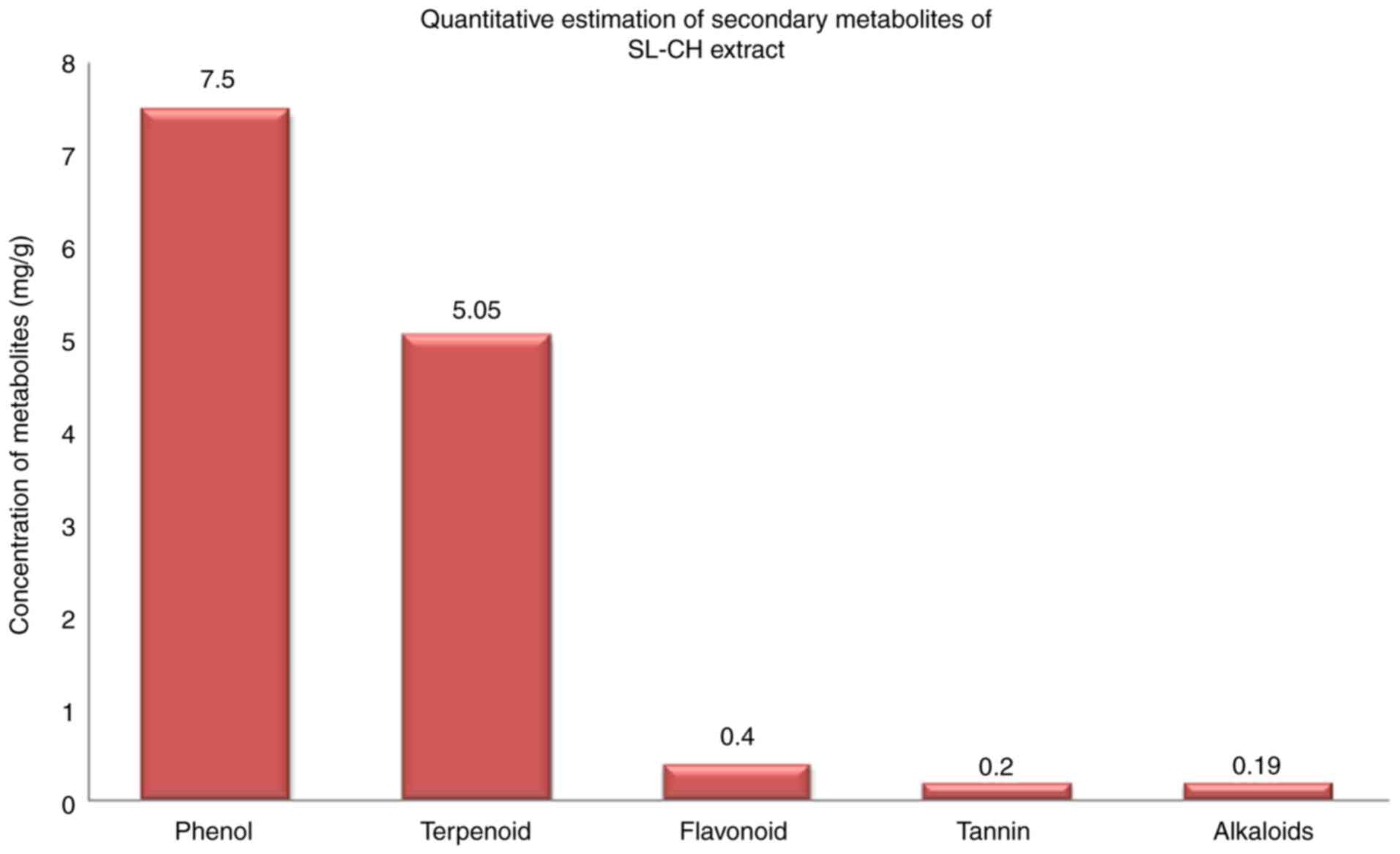

The total amount of terpenoids, phenols, tannins,

alkaloids and flavonoids present in the S. littoreus extract

was estimated using quantitative analysis with their respective

standards. The findings indicated the presence of all five examined

compounds in the S. littoreus plant, albeit in varying

concentrations: Phenol (7.5 mg/g), terpenoids (5.05 mg/g),

flavonoids (0.4 mg/g), tannin (0.2 mg/g) and alkaloids (0.19 mg/g).

The concentrations of phenol, terpenoids, flavonoids, tannin and

alkaloids in the S. Littoreus leaflet extract are

illustrated in Fig. 1. Among these

compounds, phenol and terpenoids accumulated at higher levels in

the S. Littoreus leaflet. Additionally, the leaflet extract

of S. Littoreus also contained trace levels of alkaloids,

tannins and flavonoids.

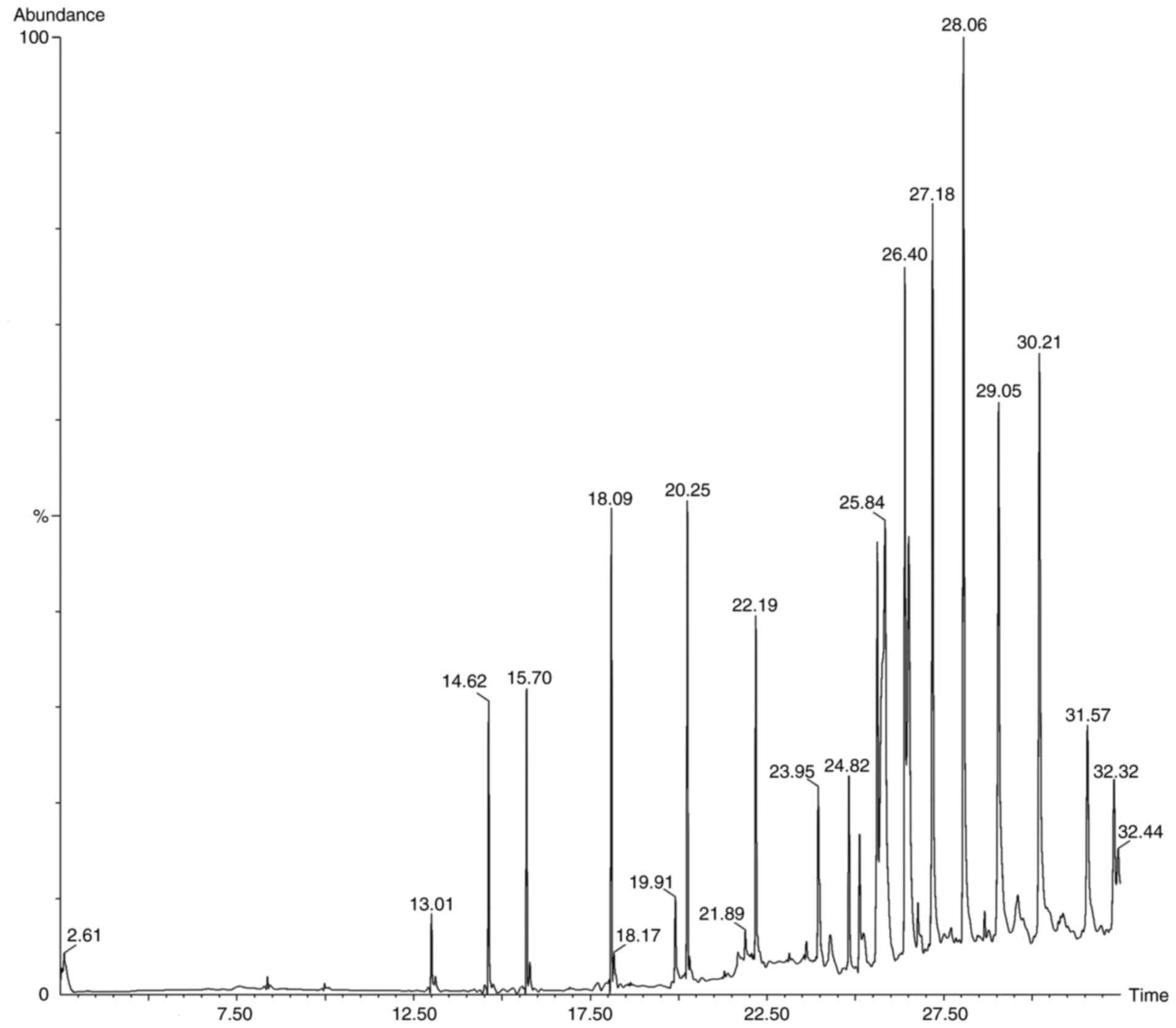

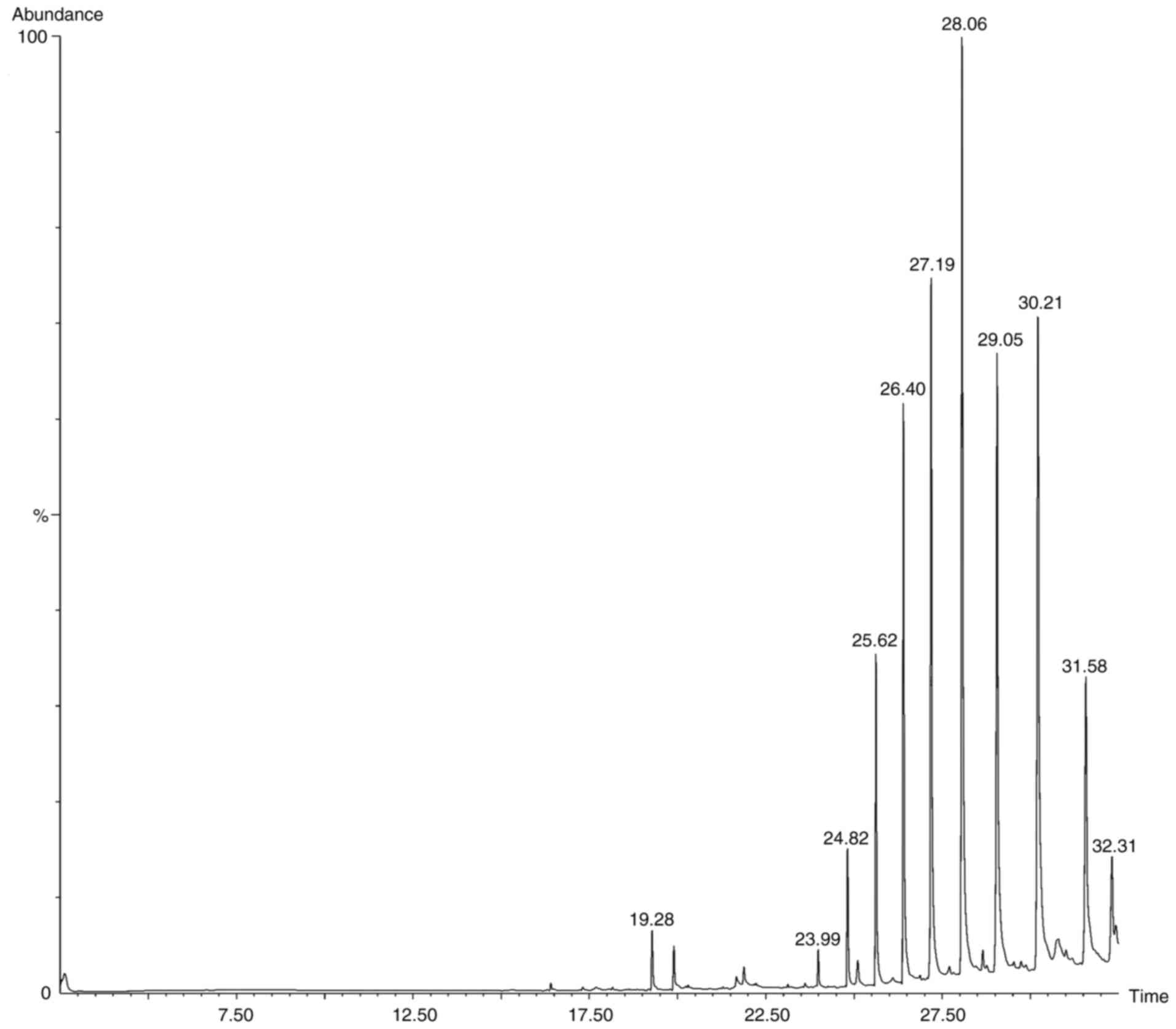

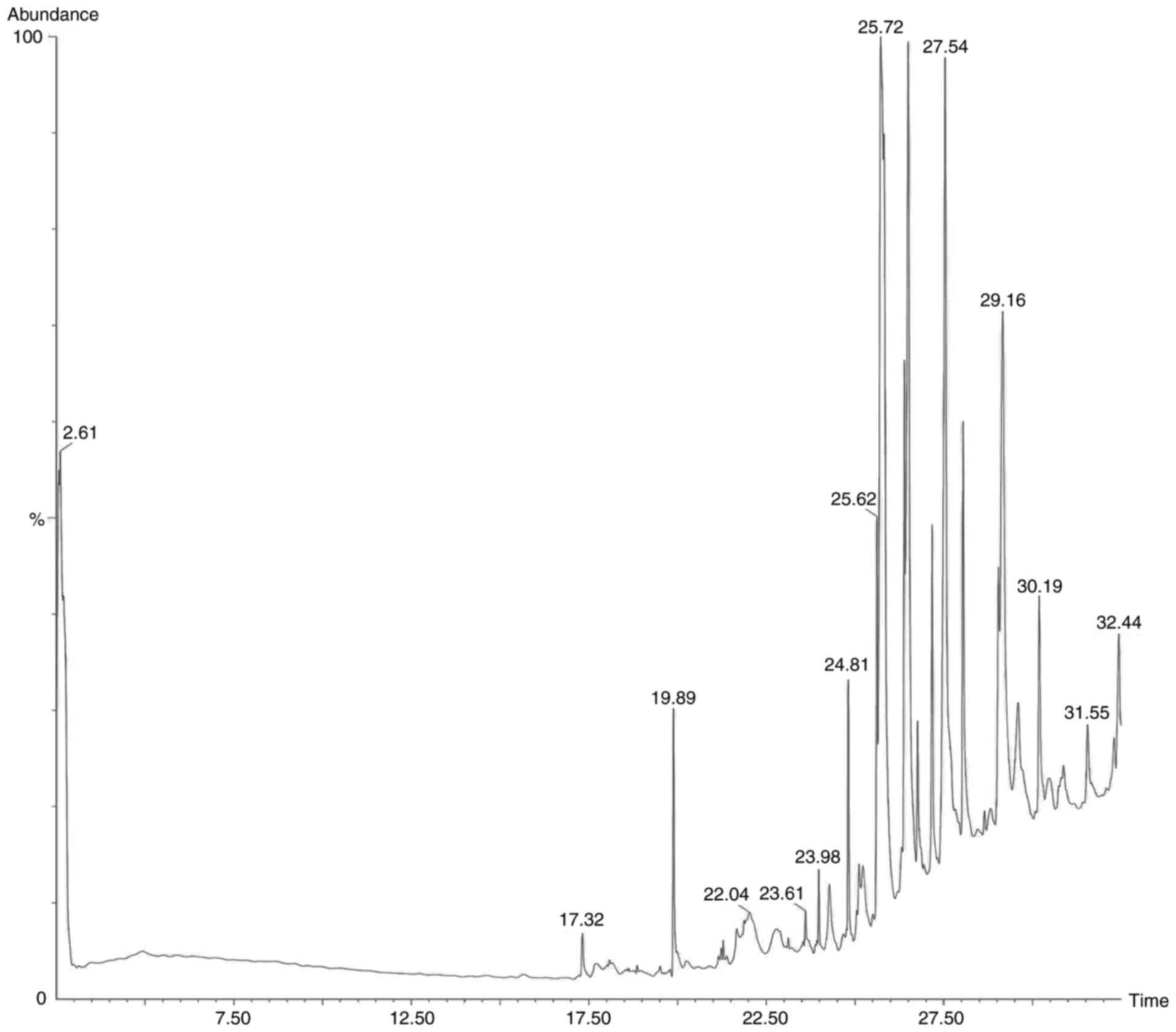

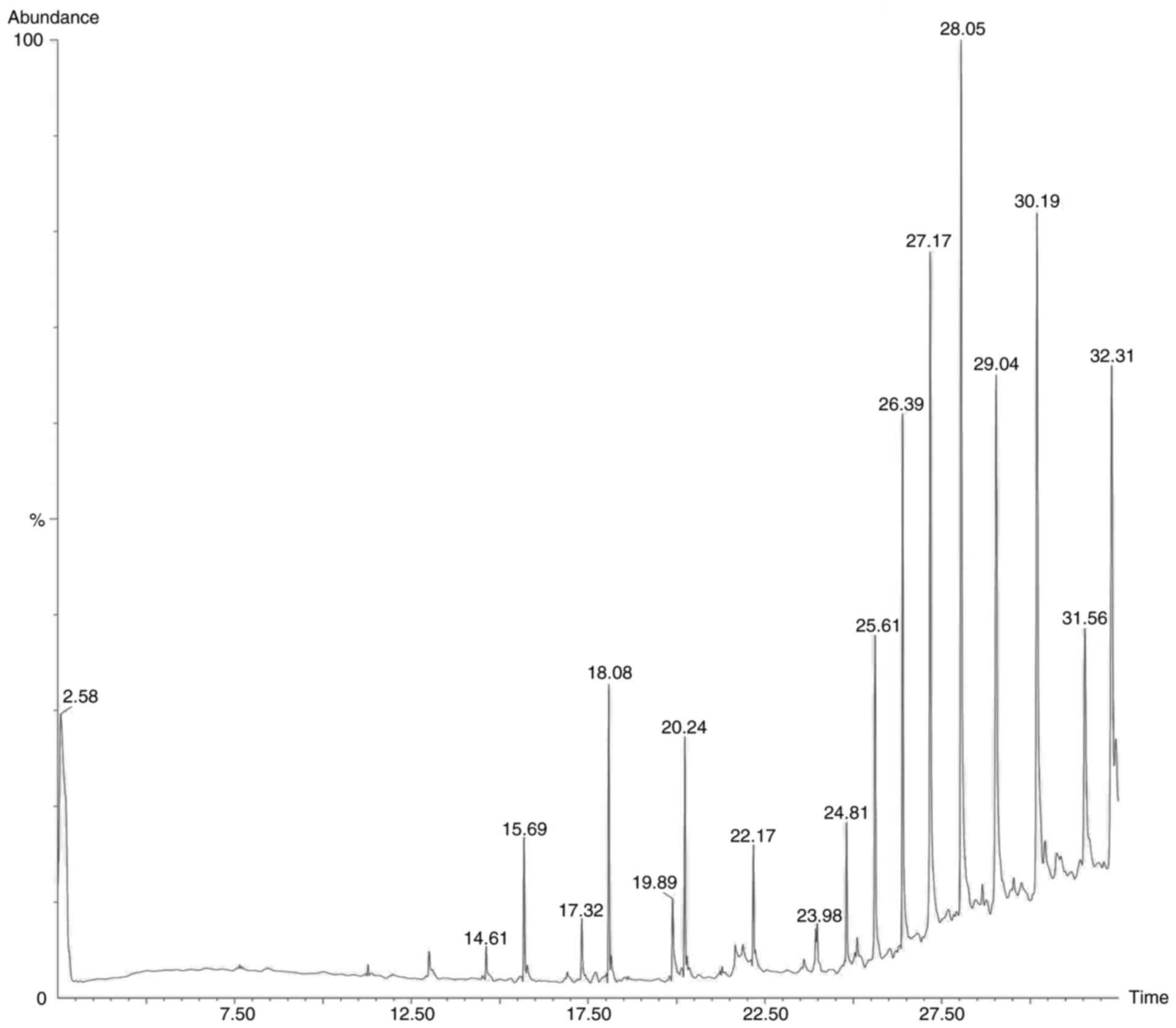

Following the preliminary screening, GC-MS analysis

of the ethanol, methanol, chloroform and ethyl acetate extracts of

S. Littoreus leaves was performed; this revealed the

presence of various active phytocompounds. A total of 33 different

compounds were eluted from this plant. Among these 33 compounds,

1-methylene-2β-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4β-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane

(28.834%), hexadecane (19.962%), tetratetracontane (18.416%),

octacosane (16.136%), octadecanal (15.833%), heptacosane (14.574%),

2-methyl-3-(3-methyl-but-2-enyl)-2-(4-methyl-pent-3-enyl)-oxetane

(14.434%) had the high percentage area. The names, molecular

formulas and area percentages of the screened phytoconstituents are

presented in Table II, and the

biological activities with the 2D structures of the compounds are

presented in Table SI. The

chromatogram images of the tested samples are illustrated in

Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig.

4 and Fig. 5.

| Table IIPhytoconstituents present in the

extract of Spinifex littoreus (Burm.f.) Merr. |

Table II

Phytoconstituents present in the

extract of Spinifex littoreus (Burm.f.) Merr.

| Chloroform | Methanol | Ethanol | Ethyl acetate |

|---|

| Name of the

compound | Molecular

formula | RT | Area % | Name of the

compound | Molecular

formula | RT | Area % | Name of the

compound | Molecular

formula | RT | Area % | Name of the

compound | Molecular

formula | RT | Area % |

|---|

| Phenol, 2,4-bis

(1,1-dimethyl) |

C14H22O | 14.618 | 2.537 |

1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, butyl octyl

ester |

C20H30O4 | 19.885 | 2.118 | Methanediamine,

n,n,n',n'-tetraethyl |

C9H22N2 | 19.275 | 1.090 | 3-tetradecane,

(z) |

C14H28 | 15.689 | 1.921 |

| 3-tetradecene,

(Z) |

C14H28 | 15.699 | 2.498 |

Alpha-bisabolol |

C15H26O | 24.287 | 1.229 | N-hexadecanoic

acid |

C16H32O | 19.896 | 0.918 |

1,6;3,4-dianhydro-2-deoxybeta-d-lyxo-hexopyranose |

C6H8O3 | 17.324 | 1.094 |

| 3-octadecene,

(E) |

C18H36 | 18.095 | 3.790 |

Hexatriacontane |

C36H74 | 24.813 | 2.076 |

1-iodo-2-methylundecane |

C12H25I | 23.987 | 0.683 | 3-tetradecane,

(z) |

C14H28 | 18.085 | 3.427 |

| N-Hexadecanoic

acid |

C16H32O2 | 19.911 | 0.939 |

1-iodo-2-methylundecane |

C12H25I | 25.618 | 2.854 | Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 24.818 | 2.361 | N-hexadecanoic

acid |

C16H32O | 19.891 | 1.593 |

| N-tetracosanol |

C24H50O | 20.246 | 3.852 |

1-methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane |

C15H26O | 25.728 | 28.834 | Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 25.623 | 5.859 |

N-tetracosanol-1 |

C24H50O | 20.236 | 2.714 |

| 1-hexacosanol |

C26H54O | 22.187 | 3.300 |

1-iodo-2-methylundecane |

C12H25I | 26.388 | 3.628 | Sulfurus acid,

butyl decyl ester |

C14H30O3S | 26.398 | 10.570 | Oleic acid |

C18H34O2 | 21.661 | 1.135 |

| 1-hexacosanol |

C26H54O | 23.947 | 1.541 |

2-methyl-3-(3-methyl-but-2-enyl)-2-(4-methyl-pent-3-enyl)-oxetane |

C15H26O | 26.503 | 14.434 | Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 27.189 | 13.820 | 1-docosene |

C22H44 | 22.171 | 1.852 |

|

1-octonal,2-butyl |

C12H26O | 23.987 | 0.807 |

5-ethyl-1-nonane |

C11H22 | 26.768 | 1.199 | Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 28.064 | 19.962 |

1-iodo-2-methylundecane |

C12H25I | 24.813 | 2.223 |

| Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 24.818 | 2.139 |

1-iodo-2-methylundecane |

C12H25I | 27.173 | 3.313 | Octacosane |

C28H58 | 29.054 | 14.993 | Nonadecane |

C19H40 | 25.613 | 5.161 |

| DI-N-Octyl

phthalate |

C24H38O4 | 25.118 | 1.250 | Octadecanal |

C18H36O | 27.539 | 15.833 |

Tetratetracontane |

C44H90 | 30.220 | 18.416 | Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 26.393 | 7.837 |

| Nonadecane |

C19H40 | 25.623 | 3.660 |

Hexatriacontane |

C36H74 | 28.049 | 4.191 | Nonadecane |

C19H40 | 31.575 | 8.984 | Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 27.173 | 11.655 |

|

1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane |

C15H26O | 25.838 | 12.558 | Octadecylpentaflu

oropropionate |

C21H37F5O | 29.039 | 2.659 | Octadecanol |

C18H36O | 32.316 | 2.345 | Heptacosane |

C27H56 | 28.049 | 14.574 |

| Nonadecane |

C19H40 | 26.403 | 7.461 | 1-hexacosanol |

C26H54O | 29.169 | 11.664 | | | | |

Tetratetracontane |

C44H90 | 29.039 | 11.422 |

|

2-methyl-3-(3-methyl-but-2-enyl)-2-(4-methyl-pent-3-enyl)-oxetane |

C15H26O | 26.513 | 9.114 | Hexadecanal |

C16H32O | 29.594 | 2.114 | | | | | Octacosane |

C28H58 | 30.200 | 16.136 |

| Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 27.184 | 9.437 | 1-decanol,

2-ethyl |

C12H26O | 30.195 | 2.677 | - | - | - | - |

Cis-9,10-epoxyoctadecane-1-ol |

C18H36O2 | 30.425 | 1.004 |

| Hexadecane |

C16H34 | 28.064 | 11.368 | Undecanal |

C11H22O | 31.545 | 1.176 | - | | - | - |

Hexatriacontane |

C36H74 | 31.555 | 6.475 |

| Tetracontane, 3,5,

24-trimethyl |

C43H88 | 29.059 | 9.041 | - | - | - | | - | - | - | - | Pentadecanal |

C15H30O | 32.306 | 9.777 |

| Nonadecane |

C19H40 | 30.210 | 8.803 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

1-octanol,2-butyl |

C12H26O | 31.571 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pentadecanal |

C15H30O | 32.316 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Assessment of drug-likeliness and

pharmacokinetic profiles

The compound selected from the GC-MS analysis was

subjected to in silico drug-likeliness and pharmacokinetic

prediction to investigate its absorption, distribution, metabolism

and toxicity profiles, and to evaluate whether there are any

violations in Lipinski's rule of 5. According to Lipinski's rule of

5, the molecular weight should be <500 g/mol, not >10 g/mol,

with >5 hydrogen bond acceptors and donors, and a log P-value

>5. It is important to consider any bioactive compounds as a

lead molecule in the process of drug discovery. From the results of

ADME analysis, it was identified that there were 0 violations in

Lipinski's' rule of 5, the molecular weight of the compound was

observed to be 222.37 g/mol, there was 1 hydrogen bond donor and

acceptor, the MLogP of the compound was 3.56 (Table III). Additionally, the

pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds were evaluated,

including the calculation of inhibition, which includes the

subfamilies of cytochrome P450, such as CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2,

CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, and BBB permeant. All these results, including

the drug likeliness of the compounds are presented in Tables IV and V. This suggests that the compound has

drug-like properties, as it meets the Lipinski's and Ghose's rules,

which evaluate the properties for drug-likeliness, indicating that

it falls within the range of properties commonly found in known

drugs. The compound meets Veber's criteria suggesting its good oral

availability potential. In addition, the compound meets the Egan

rule, indicating it is less likely to be a P-glycoprotein

substrate.

| Table IIIPhysicochemical properties of the

compound selected through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

analysis. |

Table III

Physicochemical properties of the

compound selected through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

analysis.

| Compound name | Molecular weight

g/mol (<500) | H-bond acceptors

(<10) | H-bond donors

(<5) | MlogP

(<4.15) | Lipinski

violations |

|---|

|

1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methyl

but-2-enyl)-cyclohexane | 222.37 | 1 | 1 | 3.56 | 0 |

| Table IVPharmacokinetic properties of the

compound selected from chromatography-mass spectrometry

analysis. |

Table IV

Pharmacokinetic properties of the

compound selected from chromatography-mass spectrometry

analysis.

| Compound name | Gi absorption | BbbPermeant | P-Gp substrate | Cyp1a2

inhibitor | Cyp2c19

inhibitor | Cyp2c9

inhibitor | Cyp2d6

inhibitor | Cyp3a4

inhibitor |

|---|

|

1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane | High | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Table VDrug-likeness of the compound

selected through chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis computed

using SWISS-ADME. |

Table V

Drug-likeness of the compound

selected through chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis computed

using SWISS-ADME.

| Compound name | Lipinski | Ghose | Veber | Egan | Muegge | Bioavailability

score |

|---|

|

1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane | Yes; 0

violation | Yes | Yes | Yes | No, 1 violation:

heteroatoms <2 | 0.55 |

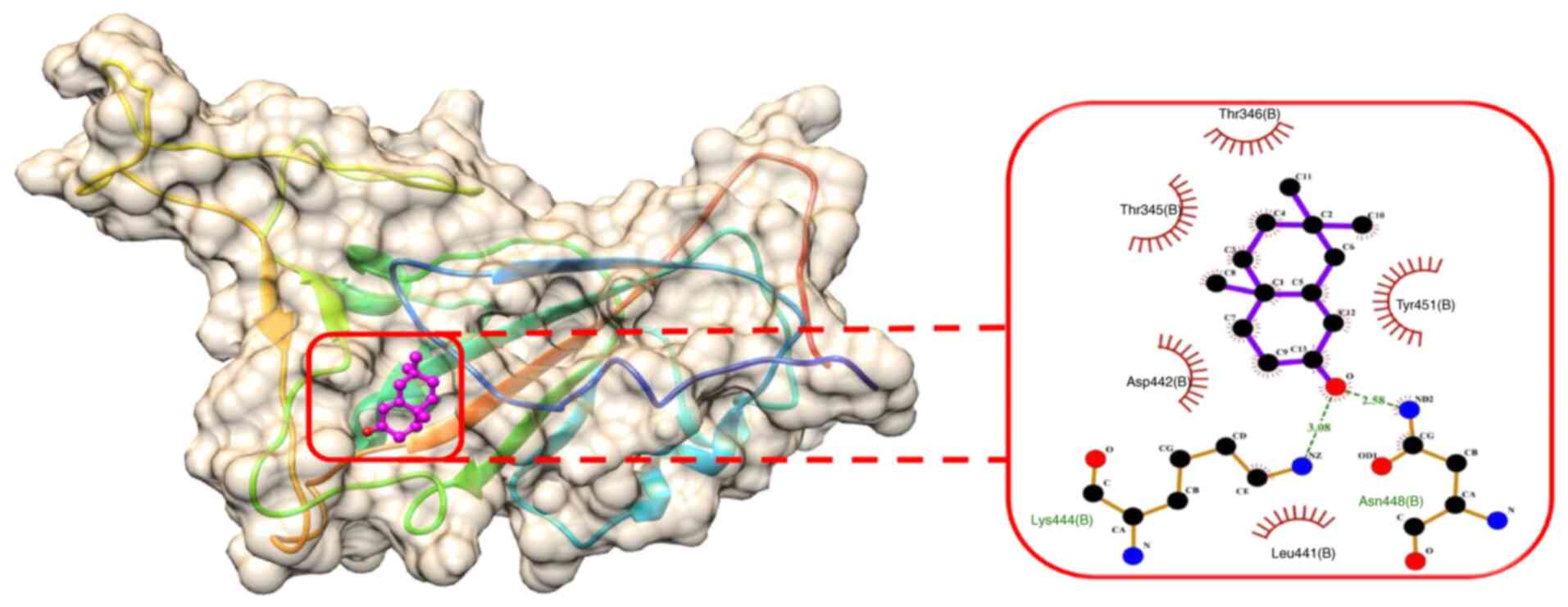

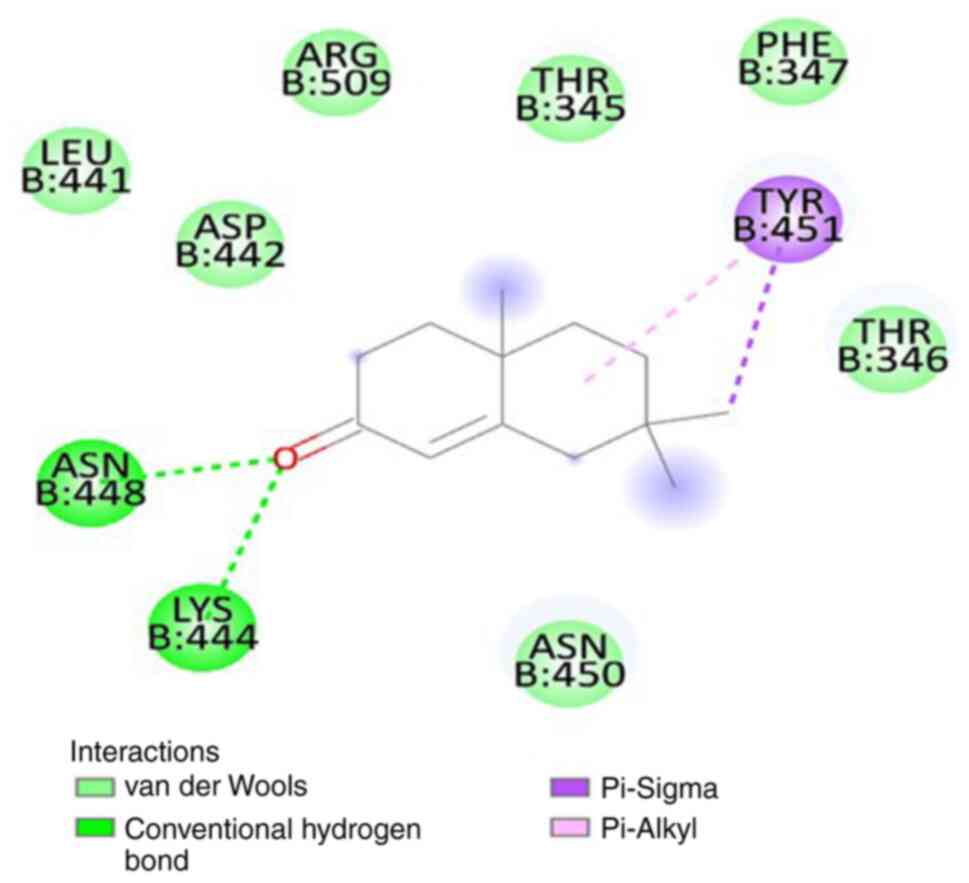

Docking analyses results

To evaluate the activity of the compound SL-MHDC

against the SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1 spike RBD (PDB ID: 8IOV), both the

target protein and the selected ligand were subjected to docking

analyses. The computational docking was performed using the

AutoDock tool, which generated binding modes in the lowest energy

state. The binding energy of SL-MHDC with the XBB.1 was observed to

be -4.86 kcal/mol. This interaction formed two conventional

hydrogen bonds with the amino acid residues LYS444 (B) and ASN 448

(B) (Fig. 6) in the spike

glycoprotein. The bond lengths were measured as 3.08 and 2.58 Å,

respectively (Table VI). The

other non-bonded interactions include the Vander der Waals

interaction formed by the residues, such as LEU 441 (B), ASP 442

(B), ARG 509 (B), THR 345 (B), PHE 347 (B), THR 346 (B), ASN 450

(B), the Pi-sigma and Pi-Alkyl interaction was formed by TYR 451

(B) (Fig. 7). Hence, from the

molecular docking it could be inferred that the compound SL-MHDC

S. littoreus can be used as a putative inhibitor potent drug

against the spike glycoprotein of XBB.1.

| Table VIDocking results of

1-methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane

with SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1. |

Table VI

Docking results of

1-methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane

with SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.

| Compound name | Protein ID | Binding energy

(kcal/mol) | No. of H-bonds | H-Bond forming

residues | Bond length

(Å) |

|---|

|

1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl- | 8IOV | -4.86 | 2 | LYS444 | 3.08 2.58 |

|

3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane | | | | ASN448 | |

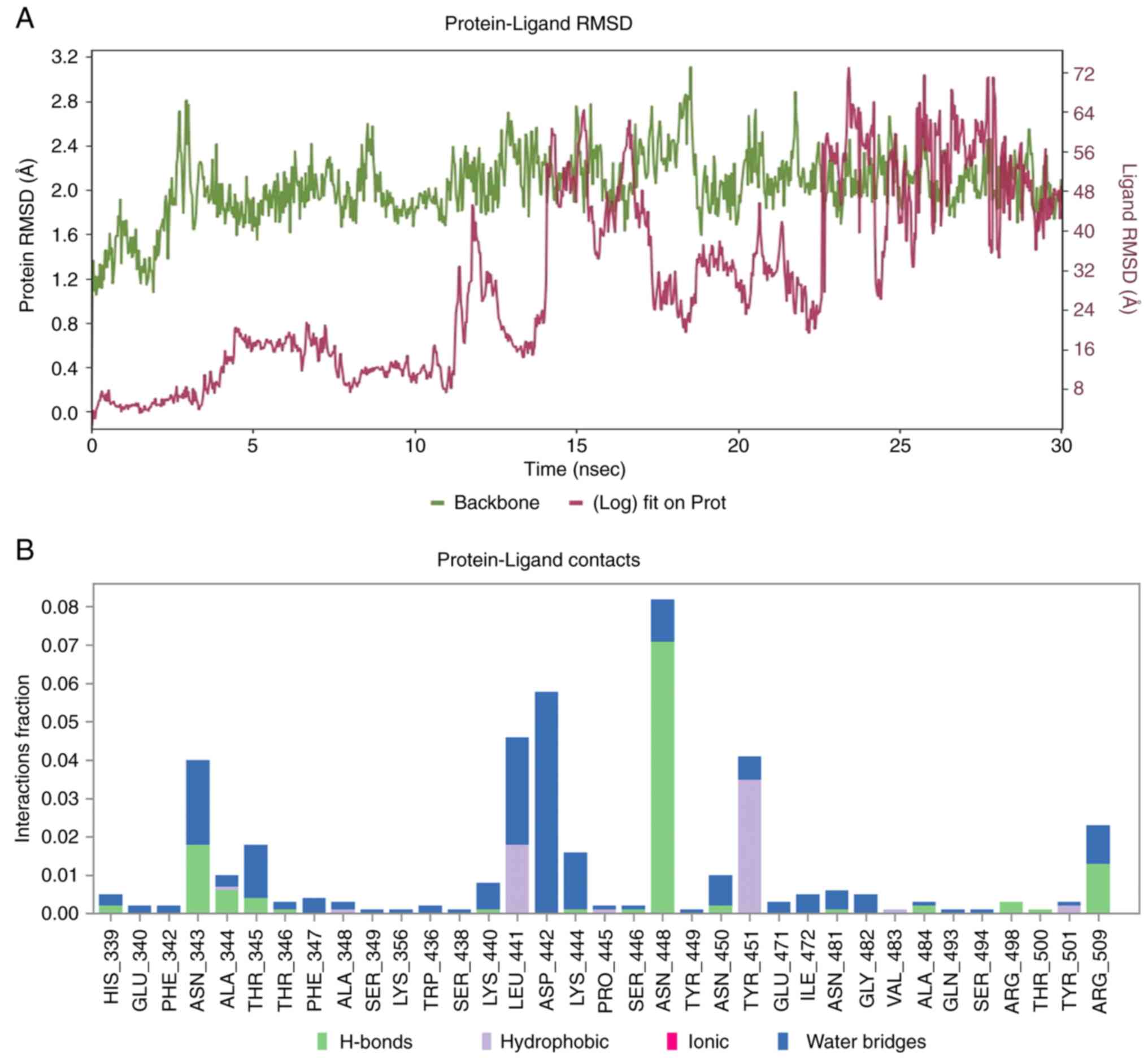

Molecular dynamics evaluation of the

XBB.1 - SL-MHDC complex

In order to assess conformational stability and

interaction fidelity of the SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1 spike glycoprotein

complexed with the phyto-ligand SL-MHDC, explicit MDS were

effectuated for a 30 nsec. The simulation encompassed with the

canonical analyses including RMSD profiling and protein-ligand

contact mapping (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Phytochemicals are non-nutritive plant compounds

considered to be beneficial for human health due to their potential

therapeutic properties (51).

Worldwide, due to their perceived effectiveness, scientists are

investigating the potential use of pharmacologically active

compounds derived from therapeutic plants. Of note, 80% of

individuals globally utilise herbal medications due to their

effectiveness, affordability, non-narcotic nature and lack of

adverse effects (52). The present

study aimed to identify a potent anti-coronaviral compound from a

coastal grass S. Littoreus by screening its

phytoconstituents. The preliminary phytochemical screening

of S. Littoreus leaflet revealed the presence of major

constituents, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins,

glycosides, quinones, coumarins, steroids, phenols and terpenoids.

Chandran et al (53) in

2014 also supported the presence of phytocompounds of alkaloids,

flavonoids, saponins and phenol in S. littoreus. These

compounds are considered therapeutically significant metabolites

due to their pharmacological activities, such as anti-malarial,

anticancer, anti-microbial, anti-ulcer, anti-inflammatory and

diuretic actions (54-58).

Quantitative analysis revealed the marked abundance of phenolic

compounds and terpenoids. Phenolic compounds play a vital role in

the plant by protecting them from UV radiations, pathogenic

microorganisms and parasites (59). Additionally, they can serve as

sources of anti-carcinogenic and anti-mutagenic agents (60). Terpenoids play a crucial role in

plant defence against biotic and abiotic stresses and as signal

molecules for pollination insects (61). Along with this, they are also

effective in preventing and treating various diseases, including

cancer. They do have pharmacological importance as antimicrobial,

antifungal, antiparasitic, antiviral, anti-allergenic,

antispasmodic, antihyperglycemic, anti-inflammatory and

immunomodulatory agents (62). A

trace amount of flavonoids, tannin and alkaloids was also recorded,

which in plants serve as a defence system and possesses

antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties (63). While quantitative determination is

a key technique used to set the standard of a crude medication,

solvent efficiency in phytochemical extraction provides an early

indicator of medicinal grade (64).

One of the most effective methods for determining

the components of volatile matter, including alcohols, esters,

acids and long-chain hydrocarbons, is GC-MS. Considering the

molecular formula, peak area and retention time, it was established

that the phytochemical substances were what they claimed to be

(65). The GC-MS results in the

present study revealed the presence of pharmaceutically important

phytoconstituents. GC-MS in conjunction with methanolic and aqueous

extraction has been extensively utilized to discover phytochemicals

of clinical significance (66,67).

Tetradecanoic acid can be used as a lubricant,

hypercholesterolemic, anticancer, antioxidant and cosmetic.

Hexadecanoic acid functions as a pesticide, flavouring agent,

5-alpha-reductase inhibitor, lubricant, haemolytic,

antifibrinolytic, nematicide and anti-alopecic. Octadecanoic acid,

or stearic acid, is used in the cosmetics, flavour and perfumery

industries (68). Heptacosane,

heptadecane, octacosane and pentacosane have all been shown to have

antioxidant activity (69-71).

Undecanal and N-tetracosanol have potential antiviral properties

(72). The compound

1-methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane

wasthe first hit in the methanolic and chloroform extract of S.

littoreus.

As there were no violations in Lipinski's rule of 5,

the compound was taken as a lead compound for further analysis.

Additionally, the binding affinity between the selected target and

the compound indicated the lowest energy binding of -4.86 kcal/mol,

with two hydrogen bonds formed between residues LYS444 and ASN448,

respectively. Furthermore, the stability of the complex was

evaluated by the RMSD (Fig. 8A);

it was inferred that complex became equilibrated around 13 nsec and

it fluctuates around its average value. According to the

protein-ligand contact analysis (Fig.

8B), residues interactions with the SL-MHDC were meticulously

monitored throughout the simulation. Protein-ligand contacts are

stratified into hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, ionic

linkages and water-mediated bridges. A total of 35 residues were

engaged with SL-MHDC among which His339, Asn343, Ala344, Thr345,

Asn448, Asn450, Ala484, Arg498, and Arg509 were identified as

critical constituents of the XBB.1 variant. Notably, Ala348,

Leu441, Tyr451 and Tyr501 manifested with hydrophobic contacts,

while His339, Asn343, Ala344, Thr345, Thr346, Lys440, Lys444,

Ser446, Asn448, Asn450, Ala484, Arg498, Thr500 and Arg509 exhibited

hydrogen bonding. Particularly, Asn448 demonstrated persistent

hydrogen bonding throughout the simulation which also corroborating

interactional role during molecular docking (Figs. 6 and 7). Furthermore, Asn343, Ala344, Thr345,

Asn448, Arg498 and Arg509 were implicated in hydrogen bonding with

water bridge formation, which underscores the multifaceted

capabilities of ligand anchorage. This suggests that the compound

could effectively inhibit the Spike glycoprotein. Furthermore, the

presence of all these essential components in S. Littoreus

enhances their potential therapeutic value in combating

life-threatening diseases such as COVID-19.

In conclusion, in the present study, an innovative

in silico molecular docking approach was utilized to

pinpoint a putative compound for combating severe acute respiratory

syndrome caused by coronavirus. The analysis identified the

bioactive

compound1-methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane,

from the leaf extracts of coastal grass as a potential inhibitor

against the SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1 spike glycoprotein (PDB ID: 8IOV).

Furthermore, in order to validate the docking results and to shed

light on to the stability of protein-ligand interaction, MDS were

conducted. Through this process, the binding potential of the

complex under dynamic physiological conditions and its structural

stability were demonstrated. These findings indicate a possible

interaction that necessitates further analysis to determine the

therapeutic potential of the compound. Additionally, the present

study focused on the test compounds rather than known inhibitors,

such as remdesivir and nirmatrelvir; thus, such comparisons need to

be included in future studies. Moreover, further investigations of

the influence of the compound on the spike-angiotensin-converting

enzyme 2 interface could provide a more detailed understanding of

its antiviral potential. Nevertheless, further research on its

in vitro and in vivo efficacy against SARS.CoV-2 is

imperative for possible clinical translation and patient

well-being.

Supplementary Material

2D structure and biological

applications of phytocompounds of Spinifex littoreus.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very much grateful to the Rapinat

Herbarium and Centre for Molecular Systematics, St. Joseph's

College (Autonomous), Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India for their

support in authenticating the experimental plant.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JV, INPA and SS conceived and designed the study.

JV, INPA, JSM, SKRN, VCS and SS surveyed the scientific literature.

JV, INPA, JSM and SS analysed data and wrote the draft manuscript.

JV, INPA, SKRN, VCS and SS interpreted the data and reviewed the

manuscript. INPA and SS revised the manuscript. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript. INPA and SS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Morens DM and Fauci AS: Emerging pandemic

diseases: How we got to COVID-19. Cell. 182:1077–1092.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G and

Tan W: Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical

specimens. JAMA. 323:1843–1844. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM,

Osterhaus AD and Fouchier RA: Isolation of a novel coronavirus from

a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 367:1814–1820.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song

J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, et al: A novel coronavirus from

patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 382:727–733.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Pilia E, Belletti A, Fresilli S, Lee TC,

Zangrillo A, Finco G and Landoni G: full anticoagulation. The

effect of heparin full-dose anticoagulation on survival of

hospitalized, non-critically Ill COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis

of high quality studies. Lung. 201:135–147. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mehta OP, Bhandari P, Raut A, Kacimi SEO

and Huy NT: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Comprehensive review of

clinical presentation. Front Public Health.

8(582932)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mustafa M, Abbas K, Ahmad R, Ahmad W,

Tantry IQ, Islam S, Moinuddin Alam M, Hassan M, Usmani N and Habib

S: Unmasking vulnerabilities in the age of COVID-19 (Review). World

Acad Sci J. 7(2)2025.

|

|

8

|

Cheng F, Li W, Zhou Y, Shen J, Wu Z, Liu

G, Lee PW and Tang Y: admet SAR: A comprehensive source and free

tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J Chem Inf Model.

52:3099–3105. 2012.

|

|

9

|

Low KO, Md Iqbal N, Ahmad A and Johari N:

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Delta, Omicron and XBB variant using

colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal

amplification and specific primers. World Acad Sci J.

7(50)2025.

|

|

10

|

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S,

Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH,

Nitsche A, et al: SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2

and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell.

181:271–280.e8. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Selvavinayagam ST, Karishma SJ, Hemashree

K, Yong YK, Suvaithenamudhan S, Rajeshkumar M, Aswathy B, Kalaivani

V, Priyanka J, Kumaresan A, et al: Clinical characteristics and

novel mutations of omicron subvariant XBB in Tamil Nadu, India - a

cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia.

19(100272)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Malik YS, Sircar S, Bhat S, Sharun K,

Dhama K, Dadar M, Tiwari R and Chaicumpa W: Emerging novel

coronavirus (2019-nCoV)-current scenario, evolutionary perspective

based on genome analysis and recent developments. Vet Q. 40:68–76.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zumla A, Chan JF, Azhar EI, Hui DS and

Yuen KY: Coronaviruses-drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat

Rev Drug Discov. 15:327–347. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

De Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D and

Munster VJ: SARS and MERS: Recent insights into emerging

coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 14:523–534. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Anand K, Ziebuhr J, Wadhwani P, Mesters JR

and Hilgenfeld R: Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure:

Basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 300:1763–1767.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Needle D, Lountos GT and Waugh DS:

Structures of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

3C-like protease reveal insights into substrate specificity. Acta

Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 71:1102–1111. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xu J, Zhao S, Teng T, Abdalla AE, Zhu W,

Xie L, Wang Y and Guo X: Systematic comparison of two

animal-to-human transmitted human coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-2 and

SARS-CoV. Viruses. 12(244)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Talluri S: Computational protein design of

bacteriocins based on structural scaffold of aureocin A53. Int J.

Bioinformatics Research and Applications. 15:129–143. 2019.

|

|

19

|

Talluri S: Molecular docking and virtual

screening based prediction of drugs for COVID-19. Comb Chem High

Throughput Screen. 24:716–728. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Jalota K, Sharma V, Agarwal C and Jindal

S: Eco-friendly approaches to phytochemical production: Elicitation

and beyond. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 14(5)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang YM, Ran XK, Riaz M, Yu M, Cai Q, Dou

DQ, Metwaly AM, Kang TG and Cai DC: Chemical constituents of stems

and leaves of Tagetespatula L. and its fingerprint. Molecules.

24(3911)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Altemimi A, Lakhssassi N, Baharlouei A,

Watson DG and Lightfoot DA: Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation,

and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts.

Plants (Basel). 6(42)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Vedhamani J, Ajithkumar IP and Jemima EA:

Exploring the in vitro antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer

potentials of Spinifex littoreus Burm f. Merr. against human

cervical cancer. Plant Sci Today. 11:242–251. 2024.

|

|

24

|

Connor HE: Breeding systems in

Indomalesian Spinifex (Paniceae: Gramineae). BLUMEA. 41:445–454.

1996.

|

|

25

|

Sen UK and Bhakat RK: Ethnobotanical study

on sand-dune based medicinal plants and traditional therapies in

coastal Purba Medinipur District, West Bengal, India. Eur J Med

Plants. 26:1–19. 2019.

|

|

26

|

Neamsuvan O, Singdam P, Yingcharoen K and

Sengnon N: A survey of medicinal plants in mangrove and beach

forests from sating Phra Peninsula, Songkhla Province, Thailand. J

Med Plants Res. 6:2421–2437. 2012.

|

|

27

|

Shakila K: Bioactive Flavonids of Spinifex

littoreus (Burm. f.) merr-investigation by elisa method. J Stress

Physiol Biochem. 16:107–112. 2020.

|

|

28

|

Thirunavukkarasu P, Ramanathan T, Ramkumar

L and Balasubramanian T: Anti microbial effect of a coastal sand

dune plant of Spinifex littoreus (Burm. f.) Merr. Curr Res J Biol

Sci. 2:283–285. 2010.

|

|

29

|

Dampalla CS, Kim Y, Bickmeier N,

Rathnayake AD, Nguyen HN, Zheng J, Kashipathy MM, Baird MA,

Battaile KP, Lovell S, et al: Structure-guided design of

conformationally constrained cyclohexane inhibitors of severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 3CL protease. J Med Chem.

64:10047–10058. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Nallaiyah VJ and Newton PAI: Antimicrobial

and larvicidal efficacy of the methanolic extract of Spinifex

littoreus (Burm F.) Merr. Biotech Res Asia. 21:1575–1582. 2024.

|

|

31

|

Redfern J, Kinninmonth M, Burdass D and

Verran J: Using soxhlet ethanol extraction to produce and test

plant material (essential oils) for their antimicrobial properties.

J Microbiol Biol Educ. 15:45–46. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Geetha TS and Geetha N: Phytochemical

screening, quantitative analysis of primary and secondary

metabolites of Cymbopogancitratus (DC) Stapf. leaves from

Kodaikanal hills, Tamilnadu. Int J Pharm Tech Res. 6:521–529.

2014.

|

|

33

|

Arya V, Thakur N and Kashyap CP:

Preliminary phytochemical analysis of the extracts of Psidium

leaves. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 1:1–5.

2012.

|

|

34

|

Mohammed J, Oba OA and Aydinlik NP:

Preliminary phytochemical screening, gc-ms, FT-IR analysis of

ethanolic extracts of Rosmarinus Officinalis, Coriandrum Sativum L.

and Mentha Spicata. Hacettepe J Biol Chem. 51:93–102. 2023.

|

|

35

|

Jose JK, Sudhakaran S, Sony J and Variyar

E: A comparative evaluation of anticancer activities of flavonoids

isolated from Mimosa pudica, Aloe vera and Phyllanthus niruri

against human breast carcinoma cell line (MCF-7) using MTT assay.

Int J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 6:319–322. 2014.

|

|

36

|

Ayoola GA, Coker HAB, Adesegun SA,

Adepoju-Bello AA, Obaweya K, Ezennia EC and Atangbayila TO:

Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activities of some selected

-3medicinal plants used for malaria therapy in Southwestern

Nigeria. Trop J Pharm Res. 7:1019–1024. 2008.

|

|

37

|

Yusuf AZ, Zakir A, Shemau Z, Abdullahi M

and Halima SA: Phytochemical analysis of the methanol leaves

extract of Paullinia pinnata linn. J. Pharmacognosy Phytother.

6:10–16. 2014.

|

|

38

|

Krishnaiah D, Sarbatly R and Bono A:

Phytochemical antioxidants for health and medicine: A move towards

nature. Biotechnol Mol Biol Rev. 1:097–104. 2007.

|

|

39

|

Sandosh TA, Peter MPJ and Raj JY:

Phytochemical analysis of Stylosanthesfruticosa using UV-VIS, FTIR

and GC-MS. Res J Chem Sci. 3:14–23. 2013.

|

|

40

|

Shamsa F, Monsef H, Ghamooshi R and

Verdian-Rizi M: Spectrophotometric determination of total alkaloids

in some Iranian medicinal plants. Thai J Pharm Sci. 32:17–20.

2008.

|

|

41

|

Ghorai N, Chakraborty S, Gucchait S, Saha

SK and Biswas S: Estimation of total Terpenoids concentration in

plant tissues using a monoterpene, Linalool as standard reagent.

Protocol Exchange. 1–6. 2012.

|

|

42

|

Marinova D, Ribarova F and Atanassova M:

Total phenolics and flavonoids in Bulgarian fruits and vegetables.

JU Chem Metal. 40:255–260. 2005.

|

|

43

|

Van Buren JP and Robinson WB: Formation of

complexes between protein and tannic acid. J Agric Food Chem.

17:772–777. 1969.

|

|

44

|

Taylor B: The International System of

Units (SI), 2008 Edition, Special Publication (NIST SP). National

Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, 2008.

Accessed on July 8, 2025. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.330e2008.

|

|

45

|

Iordache A, Culea M, Gherman C and Cozar

O: Characterization of some plant extracts by GC-MS. Nucl Instrum

Methods Phys Res B. 267:338–342. 2009.

|

|

46

|

Daina A, Michielin O and Zoete V:

SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics,

drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small

molecules. Sci Rep. 7(42717)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF

and Forli S: AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New docking methods, expanded

force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 61:3891–3898.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Trott O and Olson AJ: AutoDock Vina:

Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring

function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput

Chem. 31:455–461. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF,

Belew RK, Goodsell DS and Olson AJ: AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4:

Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput

Chem. 30:2785–2791. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Bowers KJ, Chow E, Xu H, Dror RO, Eastwood

MP, Gregersen BA, Klepeis JL, Kolossvary I, Moraes MA, Sacerdoti

FD, et al: Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations

on commodity clusters'. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE SC2006

Conference on High Performance Networking and Computing, New York,

NY, 11-17, 2006.

|

|

51

|

Ajuru MG, Williams LF and Ajuru G:

Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening of some plants

used in ethnomedicine in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. J Food

Nutr Sci. 5:198–205. 2017.

|

|

52

|

Rechab SO, Ngugi CM, Maina EG, Madivoli

ES, Kareru PG, Mutembei JK, Kairigo PK, Cheruiyot K and Ruto MC:

Antioxidant activity and antimicrobial properties of

Entadaleptostachya and Prosopisjuliflora extracts. J

Med Plants Econ Dev. 2:1–8. 2018.

|

|

53

|

Chandran M, Vivek P and Kesavan D:

Phytochemical screening and anti-bacterial studies in salt marsh

plant extracts (Spinifex Littoreus (Burm. f) Merr. and

Heliotropium Curassavicum L.). Recent Trends Biotechnol Chem

Eng. 6:4307–11. 2014.

|

|

54

|

Koche D, Shirsat R and Kawale MA: An

overview of major classes of phytochemicals: their types and role

in disease prevention. Hislopia J. 9:1–11. 2016.

|

|

55

|

Shirsat R, Suradkar S and Koche D: Some

phenolic compounds from Salvia plebeia. Biosci Discov.

3:61–63. 2012.

|

|

56

|

Wink M, Schmeller T and Latz-Brüning B:

Modes of action of allelochemical alkaloids: Interaction with

neuroreceptors, DNA, and other molecular targets. J Chem Ecol.

24:1881–1937. 1998.

|

|

57

|

Langenheim JH: Higher plant terpenoids: A

phytocentric overview of their ecological roles. J Chem Ecol.

20:1223–1280. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Dudareva N, Pichersky E and Gershenzon J:

Biochemistry of plant volatiles. Plant Physiol. 135:1893–1902.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Dai J and Mumper RJ: Plant phenolics:

Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer

properties. Molecules. 15:7313–7352. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Khatri S, Paramanya A and Ali A: Phenolic

acids and their health-promoting activity. Plant Human Health.

2:661–680. 2019.

|

|

61

|

Singh B and Sharma RA: Plant terpenes:

defense responses, phylogenetic analysis, regulation and clinical

applications. 3 Biotech. 5:129–151. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Thoppil RJ and Bishayee A: Terpenoids as

potential chemopreventive and therapeutic agents in liver cancer.

World J Hepatol. 3:228–249. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Subiono T, Sadarudin and Tavip MA:

Qualitative and quantitative phytochemicals of leaves, bark and

roots of Antiaris toxicaria Lesch, a promising natural

medicinal plant and source of pesticides. Plant Sci Today. 10:5–10.

2023.

|

|

64

|

Ouandaogo HS, Diallo S, Odari E and Kinyua

J: Phytochemical Screening and GC-MS Analysis of Methanolic and

Aqueous Extracts of Ocimum kilimandscharicum Leaves. ACS Omega.

8:47560–47572. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Konappa N, Udayashankar AC, Krishnamurthy

S, Pradeep CK, Chowdappa S and Jogaiah S: GC-MS analysis of

phytoconstituents from Amomum nilgiricum and molecular docking

interactions of bioactive serverogenin acetate with target

proteins. Sci Rep. 10(16438)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Iikasha AMN, Bock R and Mumbengegwi DR:

Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of selected

medicinal plants against laboratory diarrheal bacteria strains. J

Pharmacogn Phytochem. 6:2337–2342. 2017.

|

|

67

|

Tiwari P, Kumar B, Kaur M, Kaur G and Kaur

H: Phytochemical screening and extraction: A review. Int Pharm Sci.

1:98–106. 2011.

|

|

68

|

Ponnamma SU and Manjunath K: GC-MS

Analysis of phytocomponents in the methanolic extract of

Justiciawynaadensis (nees) T. anders. Int J Pharm Bio Sci.

3:570–576. 2012.

|

|

69

|

Kim DH, Park MH, Choi YJ, Chung KW, Park

CH, Jang EJ, An HJ, Yu BP and Chung HY: Molecular study of dietary

heptadecane for the anti-inflammatory modulation of NF-kB in the

aged kidney. PLoS One. 8(e59316)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Marrufo T, Nazzaro F, Mancini E, Fratianni

F, Coppola R, De Martino L, Agostinho AB and De Feo V: Chemical

composition and biological activity of the essential oil from

leaves of Moringa oleifera Lam. cultivated in Mozambique.

Molecules. 18:10989–11000. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Ma J, Xu RR, Lu Y, Ren DF and Lu J:

Composition, antiproliferative, and antioxidant activity of

cold-pressed seed oils from Paeonialactiflora and Paeoniaostii. J

Food Sci. 80:2465–2474. 2015.

|

|

72

|

Katz DH, Marcelletti JF, Khalil MH, Pope

LE and Katz LR: Antiviral activity of 1-docosanol, an inhibitor of

lipid-enveloped viruses including herpes simplex. Proc Natl Acad

Sci. 88:10825–10829. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|