Introduction

Enchondromas are benign tumors composed of mature

hyaline cartilage found within the medullary cavity of bones. They

originate from cartilage cell nests that separate from the central

growth plate during the development process. This leads to the

abnormal accumulation of mature hypertrophic hyaline cartilage that

fails to undergo normal resorption or ossification (1-3).

Enchondromas vary in prevalence depending on their

location within the human body. They constitute ~90% of all bone

tumors in the hand. By contrast, foot enchondromas are much less

frequent and primarily affect the phalanges and metatarsal bones.

While these tumors can occur at any age, they typically manifest

between the first and fourth decades of life, affecting both sexes

equally (1,4,5).

Enchondromas in the small bones of the feet are

typically asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally during

routine X-ray examinations. When they become symptomatic, patients

may present with pain primarily due to increased pressure from the

growth of the lesion, which can deform the cortex of the affected

bone or from fractures within the lesion, including pathological or

stress fractures. Patients may also report a gradual enlargement of

the affected digit (1,2,6).

Enchondromas in different locations of the foot have

been documented in the literature (1-5,7-12).

The presented study reports a case of symptomatic enchondroma in

the proximal phalanx of the left second toe. The case report has

been prepared in accordance with the CaReL guidelines, and

referenced studies were reviewed to ensure the exclusion of

non-peer-reviewed data (13,14).

Case report

Patient information

A 20-year-old male patient presented to Smart Health

Tower (Sulaymaniyah, Iraq) with a painless, slow-growing lump on

his left second toe, which had gradually caused deformity over the

past 6 months. Over the past 2 weeks, he began experiencing pain

while wearing shoes, hindering his daily activities. He reported no

history of foot trauma, chronic medical conditions, or prior

surgical interventions.

Clinical findings

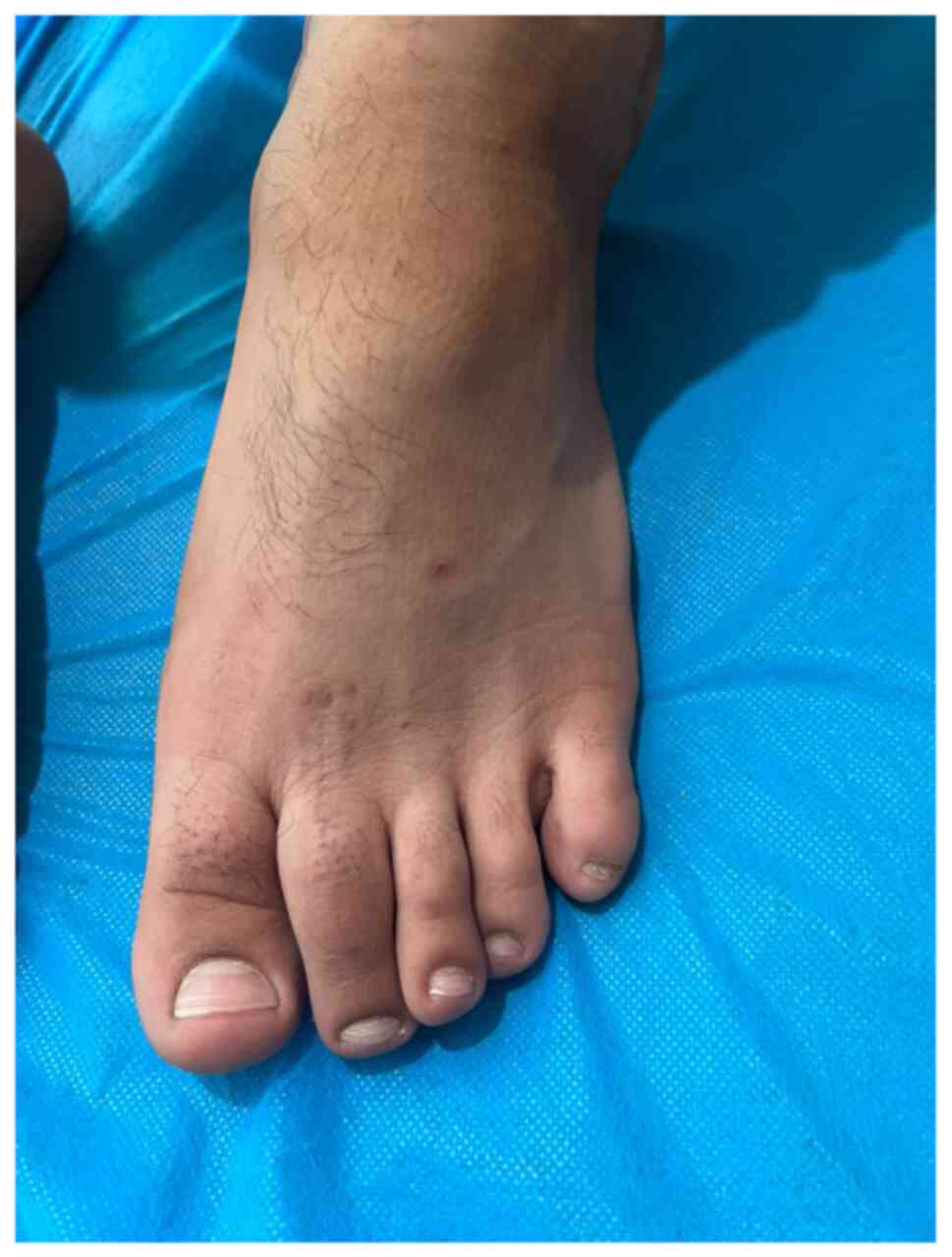

Upon a physical examination, a hard mass on the

medial border of the proximal phalanx of the left second toe was

found, causing a lateral deviation of the toe (Fig. 1). The mass was firmly fixed to the

underlying bone, with no tenderness upon palpation or signs of

local inflammation. The metatarsophalangeal and interphalangeal

joints exhibited a good range of motion and no sensory deficits in

the toe.

Diagnostic approach

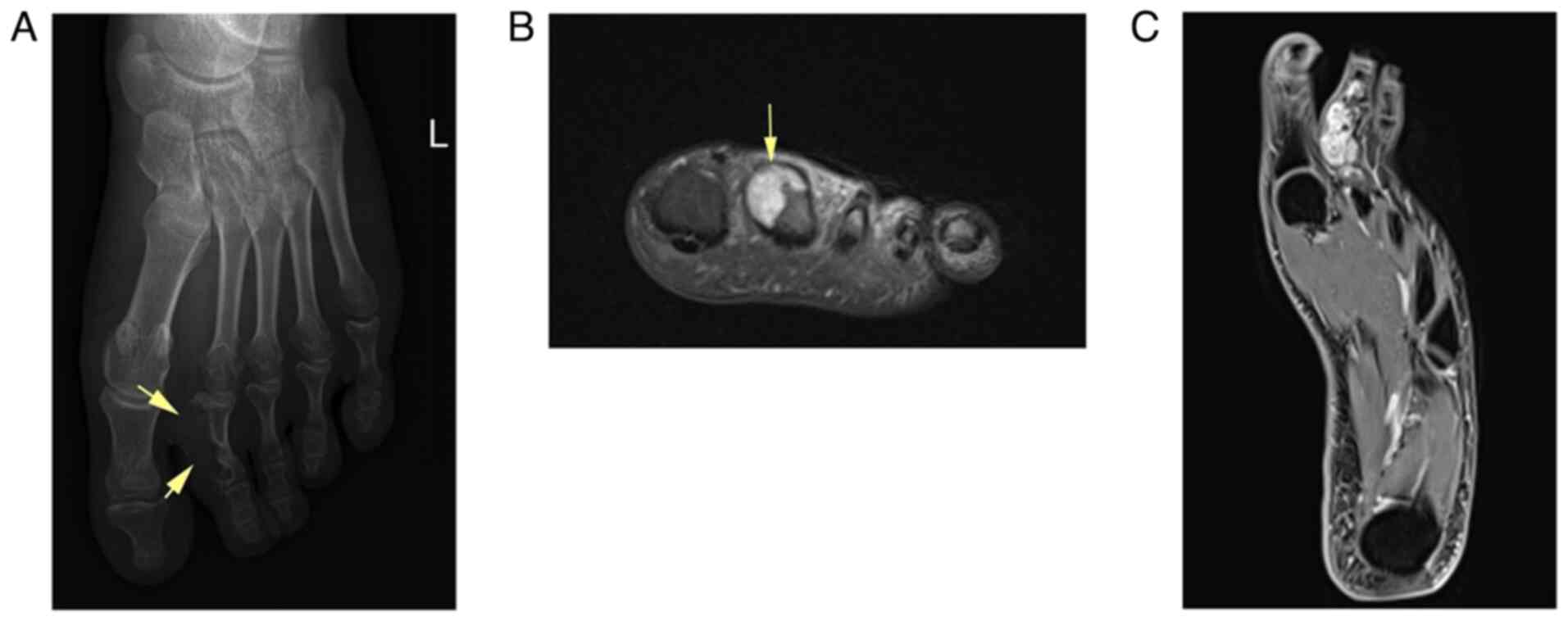

An X-ray revealed a radiolucent, eccentric lesion

within the proximal phalanx of the left second toe, with the loss

of the medial bone cortex. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

revealed an expansile osteolytic lesion breaching three cortices of

the proximal phalanx of the left second toe, with no involvement of

soft tissue, consistent with enchondroma (Fig. 2).

Therapeutic intervention

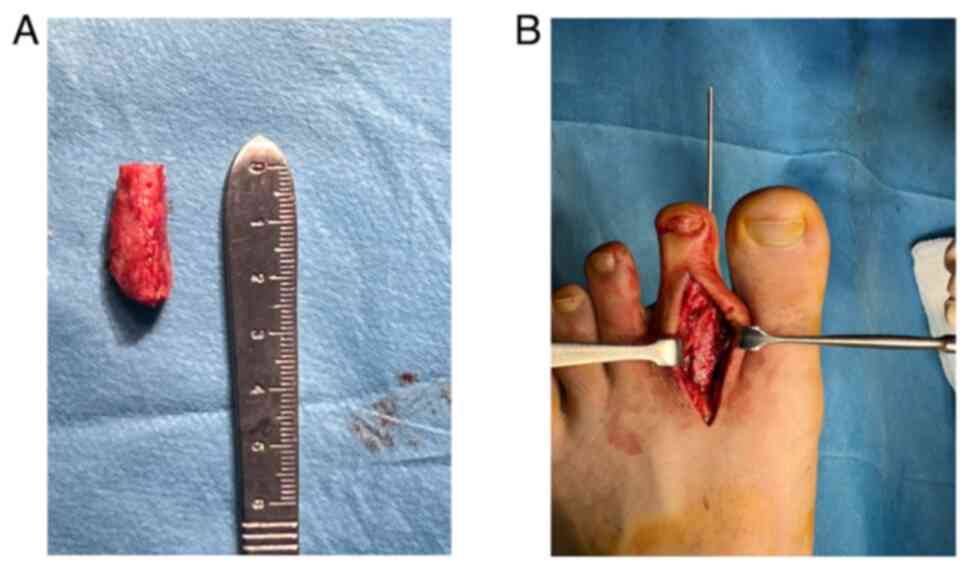

Surgery was decided under spinal anesthesia. The

left limb was prepped and draped, and the ipsilateral iliac crest

was prepared for harvesting a bone graft. Using a thigh tourniquet

following the exsanguination of the leg, a longitudinal dorsal

approach incision was made over the center of the toe, extending

from the metatarsophalangeal joint to the proximal interphalangeal

joint. The extensor digitorum longus tendon was exposed and

retracted laterally, revealing the proximal phalanx with its

lesion. After separating and protecting the neurovascular

structures, the lesion was resected using a no. 15 surgical blade.

The tumor bed was subsequently cleaned using Rongeur forceps and a

bone curette, followed by shaving the tumor bed with a small,

high-speed burr (Fig. 3).

Subsequently, after measuring the osseous defect, a tricortical

iliac bone autograft was harvested from the ipsilateral site and

placed into the defect. A 1.6-mm Kirschner wire was inserted

antegrade through the harvested graft into the middle and distal

phalanges and then retrograded back into the metatarsal head

(Fig. 4). Layered closure was

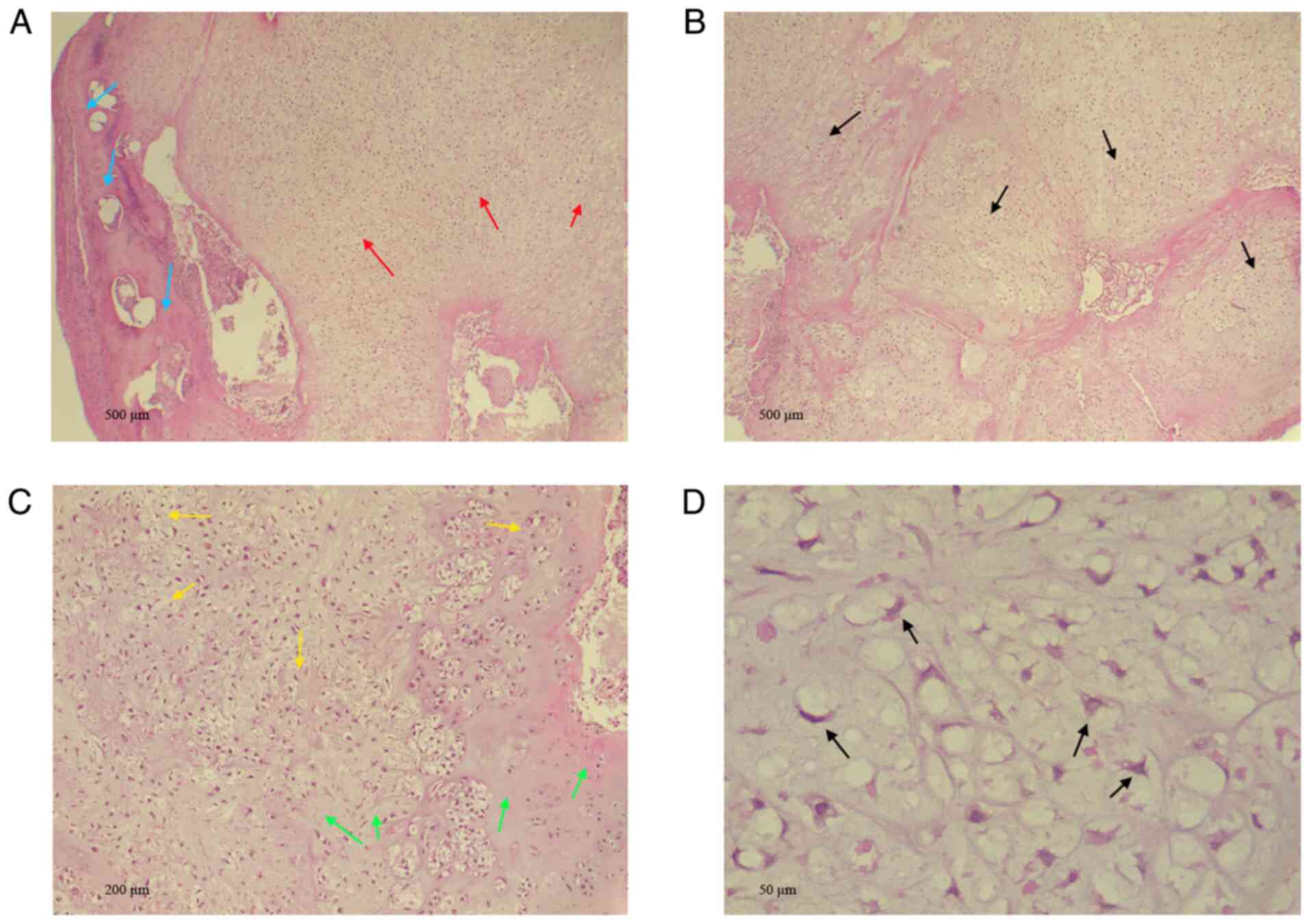

performed for both wounds. A histopathological examination was

performed by the laboratory at Smart Health Tower, as follows: The

analysis was performed on 5-µm-thick, paraffin-embedded sections.

The sections were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at room

temperature for 24 h, and the sections were then stained with

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Bio Optica Co.) for 1-2 min at room

temperature. The sections were then examined under a light

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). The histopathological

analysis of the tumor revealed hypercellular sheets of chondrocytes

encased by mature bone trabeculae without cortical destruction,

pre-existing lamellar bone entrapment, or soft tissue invasion. The

tumor had a partly lobular configuration with varying cellularity.

Chondrocytes within lacunae in a myxoid and hyaline matrix had

elongated and stellate nuclei with fine chromatin. There was no

multinucleation, significant pleomorphism, mitotic activity, or

necrosis (Fig. 5).

Follow-up

Post-operatively, the patient was placed in

heel-touch weight bearing. The Kirschner wire was removed after 6

weeks, and the bone showed good signs of healing. At 6 months

postoperatively, the patient demonstrated excellent toe range of

motion, was pain-free and maintained proper alignment (Fig. 6). An X-ray revealed a complete

union of the bone with the graft.

Discussion

Enchondromas grow gradually without infiltrating

nearby tissues or spreading to distant body parts (3,15).

In reviewing 19 cases of foot enchondroma (Table I), only two instances were found

where an enchondroma transformed into chondrosarcoma, leading to

amputation (11,12).

| Table IReview of 19 cases of enchondroma of

the foot . |

Table I

Review of 19 cases of enchondroma of

the foot .

| First author, year of

publication | No. of cases | Age (years) | Sex | Site of the

lesion | Tumor size (cm) | Presenting

symptom | Medical history | Physical

examination | U/S | X-ray | CT | MRI | Management | Histopathology | Follow-up

(months) | Recurrence | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Komurcu, 2015 | 1 | 53 | M | Calcaneus | 2.1 | Pain | Negative | Tenderness and

swelling | NA | A lesion with

calcification and peripheral sclerosis | Cortical thinning

adjacent to the lesion | A lesion with

hyperintense signaling on T2-weighted sequences and peripheral

heterogeneous enhancement pattern on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted

sequences | Curettage of the

lesion and grafting | Lobules of different

sizes of hyaline cartilage tissue and chondrocytes without atypia

inside hyaline cartilage | NA | No | (1) |

| Lui, 2014 | 1 | 51 | F | 1st toe PP | NA | Pain | Negative | Swelling | NA | Fracture with an

enchondroma | NA | NA | Endoscopic curettage

and bone grafting | NA | 31 | No | (2) |

| Edwards, 2020 | 1 | 27 | M | 4th toe PP | 1 | Pain | Controlled type I

diabetes mellitus and depression | Moderate edema and

tenderness | Mild soft tissue

edema | Lucent lesion | NA | Expansile lesion

breaching the inferior and lateral cortical bone | Resection and tibial

bone graft | A well circumscribed

tumor composed of lobules of hyaline cartilage encased in bone and

covered by fibrous tissue. | 12 | No | (3) |

| De Yoe, 1999 | 2 | 43 | F | 3rd toe MT | 0.7 | Pain | Controlled

hypertension | Tenderness | NA | A lytic ovoid lesion

with disrupted lateral cortex of the metatarsal | NA | NA | Surgical excision

with autogenous bone grafting | Confirmed enchondroma

(no detail available) | 10 | No | (4) |

| | | 45 | M | Cuneiform | 0.4 | Pain | Negative | Tenderness | NA | Lytic lesion | NA | NA | Curettage with

autogenous bone graft | Confirmed enchondroma

(no detail available) | 12 | No | (4) |

| Goto, 2004 | 8 | 48 | F | 3rd toe PP | 0.8 | Pain | Negative | NA | NA | Eccentrically

located radiolucent area, and pathological fracture | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 13 | No | (5) |

| | | 25 | F | 1st toe DP | 2.1 | Incidental

finding | Negative | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 30 | No | (5) |

| | | 32 | F | 3rd toe PP | 0.6 | Pain | Negative | NA | NA | Pathological

fracture | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 6 | No | (5) |

| | | 39 | M | 1st toe DP | 0.54 | Pain | Negative | NA | NA | Pathological

fracture | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 41 | No | (5) |

| | | 23 | F | 2nd toe PP | 0.33 | Pain | Negative | NA | NA | Pathological

fracture | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 34 | No | (5) |

| | | 50 | M | 3rd toe PP | 0.24 | Incidental

finding | Negative | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 13 | No | (5) |

| | | 31 | M | 2nd toe MP | 2.1 | Pain | Negative | NA | NA | Radiolucent area

with some calcifications and ballooning of the cortex | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 18 | No | (5) |

| | | 31 | M | 1st toe DP | 0.2 | Pain | Negative | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 12 | No | (5) |

| | | | | 1st toe PP | 4.7 | Incidental

finding | Negative | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 12 | No | (5) |

| | | | | 1st toe MT | 4.6 | Incidental

finding | Negative | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Simple curettage

without bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 12 | No | (5) |

| Stess, 1995 | 1 | 36 | M | 2nd toe PP | 2.2 | Pain | NA | Swelling and

tenderness | NA | An osseous

metaphyseal lesion with diminished density | NA | NA | Total phalangectomy

of the proximal phalanx with syndactylization of the second and

third toes. | NA | 12 | No | (7) |

| Remba, 2021 | 1 | 30 | M | 1st toe MT | NA | Inversion of the

foot | Negative | Edema and pain

during mobility and walking | NA | Tumor and soft

tissue edema | NA | Heterogeneous

intramedullary lesion, hypo-intense in T1 and hyper-intense in

T2 | Curettage of the

lesion with bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 6 | No | (8) |

| Patel, 2022 | 1 | 17 | M | 1st toe PP | 2.8 | Pain | Negative | Swelling | NA | Lytic lesions,

scalloping of the cortex, and whorls of calcification | NA | Hyperintense mass

on FS-PD, and soft tissue edema and swelling on T1-weighted

sequences | Surgical excision

with bone grafting | Confirmed

enchondroma (no detail available) | 24 | No | (9) |

| Alhosain, 2020 | 1 | 16 | F | 2nd toe PP | 1.3 | Pain | Negative | Hard, round mass

fixed to the bone | NA | Well circumscribed,

lucent, a central medullary lesion with cortical expansion and

thinning | NA | NA | Curettage and

subsequent bone grafting | Lobules of hyaline

cartilage encased by normal bone and fibrous tissue | 3 | No | (10) |

| Mahajan, 2009 | 1 | 86 | F | 3rd toe PP | NA | Pain | Negative | Movement

restriction of the metatarso-phalangeal joint, swelling | NA | Expansile swelling

contained within the cortex without malignant change | NA | Cystic change,

consistent with benign lesion. Six months later, it turned into

malignancy | Ray amputation due

to malignant change into chondrosarcoma | chondrosarcoma

grade II, mainly and III focally | NA | NA | (11) |

| Koak, 2000 | 1 | 33 | F | 3rd toe DP | NA | Pain and

swelling | Foot trauma | The toe had a

drumstick appearance with enlargement | NA | Expanding lytic

lesion with a fracture | NA | NA | Partial amputation

of the toe | The features

indicated low-grade (Grade 1) chondrosarcoma | NA | NA | (12) |

Enchondroma primarily manifests in the phalanges of

the hand, although it can also occur in the phalanges and

metatarsal bones of the foot (1).

Among the reviewed cases, the most commonly affected toe was the

first toe (38%), followed by the third toe (28.6%), the second toe

(19%), the fourth toe (4.8%), the calcaneus (4.8%) and the

cuneiform bone (4.8%). Among the 17 cases with 19 lesions located

on the toes, the most common sites were the proximal phalanx

(57.9%), followed by the distal phalanx (21%), metatarsal (15.8%)

and middle phalanx (5.3%). In the present case, the lesion was

located on the proximal phalanx of the second toe.

The tumor is typically found as a solitary lesion,

known as a solitary enchondroma (8). However, they can also appear as

multiple lesions, as seen in conditions such as multiple

enchondromatosis (Ollier disease) and multiple enchondromatosis

associated with hemangiomas (Maffucci syndrome) (3). Enchondromatosis is linked to somatic

mutations in the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 and IDH2 genes.

These mutations produce defective IDH, an enzyme in the

tricarboxylic acid cycle that converts isocitrate to

α-ketoglutarate. The mutated enzyme facilitates the reduction of

α-ketoglutarate to the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate

(D-2-HG), and by competitively inhibiting α-ketoglutarate-dependent

enzymes, D-2-HG results in hypermethylation of DNA and modification

of histones. These processes encourage the development of

cartilaginous tumors and disrupt the normal osteogenic

differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (6). All reviewed cases in the present

study involved solitary enchondromas, apart from 1 patient with

multiple lesions in the distal phalanx, proximal phalanx, and

metatarsal bones of the first toe of the same foot (5).

Foot enchondromas can occur at any age, although

they are most commonly observed in patients between the first and

fourth decades of life (9). The

youngest case reported among the cases reviewed herein involved a

16-year-old female, while the oldest was an 86-year-old female

(1,11). In accordance with the study by De

Yoe and Rockett (4), in the

present study, a review of the literature revealed no sex

predilection in the prevalence of foot enchondromas, with 10 males

and 9 females. The case in the present study was a 20-year-old

male.

Generally, enchondromas remain asymptomatic for

extended periods of time. When symptoms do manifest, they may

include pain, swelling, or deformity of the affected bone (6). The primary source of pain often stems

from elevated pressure caused by the cortical expansion of the

lesion, pathological fracture, or malignant conversion of the

lesion (1,3,4). The

lesion in the majority of the reviewed cases caused pain (76.2%)

and food inversion in 1 case (4.8%), while the remaining lesions

were diagnosed incidentally on foot radiographs (19%).

Additionally, 6 out of the 19 cases had pathological fractures.

Various modalities and methods are available to

healthcare professionals for detecting and diagnosing enchondromas.

The primary and most crucial method remains a comprehensive

clinical history (8). After

assessing the clinical presentation, plain radiographs are the

preferred initial diagnostic imaging modality (9). Radiographically, enchondromas appear

as lytic lesions with clearly defined borders and variable degrees

of stippled or punctate calcifications, typically without the

involvement of the surrounding soft tissues (3). In general, computed tomography scans

and MRIs can provide additional detail about the lesion,

particularly when there is rapid growth or suspicion of soft tissue

involvement (4). In the identified

literature, plain radiography was the most commonly employed

diagnostic modality, showing lytic lesions. In the case presented

herein, the radiograph revealed a radiolucent, eccentric lesion

with loss of the medial bone cortex, and the MRI revealed an

expansile osteolytic lesion breaching three cortices of the

affected phalanx.

Radiological findings suggesting a lesion are not

always conclusive for diagnosing an enchondroma; therefore, a

histopathological analysis is mandatory (9). Distinguishing between benign and

malignant lesions presents a significant challenge. All available

tissues need to be thoroughly examined. Enchondromas can be

visually identified as bluish, semi-translucent masses of hyaline

cartilage arranged in lobular patterns. Microscopically,

enchondromas display small chondrocytes within lacunar spaces

characterized by round, uniform nuclei resembling those found in

hyaline cartilage. Some enchondromas may also exhibit areas of

ossification within the cartilage matrix (4,6). The

nuclei of these cells are generally regular, showing a few mitotic

activities. Enchondromas located near the bone cortex, including

those in the hands, may exhibit increased cellularity and atypia

while remaining benign (6).

Histologically, enchondroma and low-grade (well-differentiated)

chondrosarcoma can appear deceptively similar, although they can be

distinguished by their tissue architecture and patterns of

invasion: enchondromas typically display multiple discrete nodules

of hyaline cartilage separated by normal marrow elements and are

often surrounded by lamellar host bone conforming to the shape of

the cartilage lobules; by contrast, low-grade chondrosarcomas tend

to form a single confluent mass of cartilage that permeates the

marrow, ‘trapping’ host lamellar bone, infiltrating the Haversian

systems or marrow fat, and often exhibiting fibrous bands between

peripheral cartilage lobules. These features reflect its malignant

nature. Additional supportive indicators include the presence of

lobulation patterns and fibrous tissue formation around the lesion,

which have been shown to correlate with malignant recurrence in

follow-up studies, whereas enchondromas generally remain benign

(16,17). The histopathological analysis of

the specimen in the case in the present study revealed

hypercellular sheets of chondrocytes encased by mature bone

trabeculae at the periphery without cortical destruction,

entrapment of pre-existing lamellar bone, or soft tissue invasion.

There was no multinucleation, significant pleomorphism, mitotic

activity, or necrosis.

The treatment of enchondroma can range from close

monitoring and regular follow-up, particularly for small,

asymptomatic lesions, to complete surgical removal with bone

grafting for larger, symptomatic lesions (2). Surgery is recommended for patients

experiencing ongoing symptoms and lesions >2 cm, as they pose a

significant risk of pathological fractures. It includes complete

tumor removal with or without bone grafting, as well as curettage

followed by bone grafting. Goto et al (5) reported that the radiographic and

functional outcomes of simple curettage without bone grafting are

comparable to those of curettage with autologous bone grafting.

They also highlighted several advantages of performing curettage

without bone grafting for foot enchondromas: i) It eliminates the

pain and discomfort associated with the bone donor site; ii) the

procedure can be performed on an outpatient basis; and iii) the

shorter operation time provides economic benefits and decreases the

risk of infection (5). However,

Edwards and Kingsford (3) reported

that curettage alone is not recommended due to a high rate of

non-union (67%). They found that the surgical option involving bone

grafting is more suitable, as it offers a recovery period similar

to that of curettage alone, despite the additional wound that

requires healing (3). Patel et

al (9) also reported that the

latest management option for foot enchondroma involves using an

autologous bone graft from the iliac crest, which can be either

cortical or cancellous. Chun et al (18) reported a series of 20 cases in

which all patients underwent tumor curettage followed by bone

grafting. No recurrences or post-operative complications were

observed during the 24-month follow-up period (18). In addition, Futani et al

(19) conducted a retrospective

cohort study comparing osteoscopic and conventional open surgery

for foot enchondromas. A total of 17 patients underwent osteoscopic

surgery, and 8 patients underwent open surgery. They reported that

functional recovery was significantly improved in the osteoscopic

group at 1 and 2 weeks post-operatively, though no differences were

noted after 1 month. Additionally, osteoscopic surgery was

associated with fewer complications (12% vs. 50%) and no

recurrences in either group (19).

Among the reviewed cases, 8 (42.1%) cases were managed with

excision or curettage combined with bone grafting, another 8

(42.1%) cases were managed with simple curettage without bone

grafting, 1 (5.3%) case was managed with total phalangectomy, and 2

cases underwent partial and ray amputation (10.5%). All reported

cases had favorable surgical outcomes without any recurrence. In

the case in the present study, the tumor was surgically removed,

and a tricortical iliac bone autograft from the ipsilateral site

was placed into the defect. The surgical outcome was favorable,

with no signs of recurrence or complications. The unretrievable

last follow-up X-ray image, which revealed the complete union of

the bone with the graft, may be a limitation of the present case

report.

In conclusion, enchondroma is a benign tumor rarely

found in the foot. For symptomatic cases, the surgical removal of

the lesion combined with autologous iliac bone grafting may result

in favorable outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FHK and AKG were major contributors to the

conception of the study, as well as to the literature search for

related studies. HOA, MGH and SOK were involved in the literature

review, in the conception and design of the study and in the

writing of the manuscript. RJR, AMA and HAS were involved in the

literature review, in the design and conception of the study, the

critical revision of the manuscript, and the processing of the

figures and table. AAM was the radiologist who performed the

assessment of the case. RMA and AMA were the pathologists who

performed the diagnosis of the case. FHK and AKG confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for his participation in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Komurcu E, Kaymaz B, Golge UH, Goksel F,

Resorlu M and Kılınç N: Atypical localization of enchondroma in the

calcaneus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 105:260–263. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Lui TH: Endoscopic curettage and bone

grafting of the enchondroma of the proximal phalanx of the great

toe. Foot Ankle Surg. 21:137–141. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Edwards SR and Kingsford AC: Surgical

management of an enchondroma of the proximal phalanx of the foot:

An illustrative case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep.

8(2050313X20945894)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

De Yoe BE and Rockett MS: Enchondroma as a

cause of midfoot pain. J Foot Ankle Surg. 38:139–142.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Goto T, Kawano H, Yamamoto A, Yokokura S,

Iijima T, Motoi T and Nakamura K: Simple curettage without bone

grafting for enchondromas of the foot. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg.

124:301–305. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Biondi NL, Tiwari V and Varacallo M:

Enchondroma. In: StatPearls (Internet). StatPearls Publishing,

Treasure Island, FL, 2025. Accessed on August 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536938/.

|

|

7

|

Stess RM and Tang RE: Enchondroma of the

proximal phalanx. J Foot Ankle Surg. 34:79–81. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Remba SJ, San Martín RÁ, Amiga IB and

Santos DP: Solitary enchondroma in a metatarsal bone, an incidental

discovery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 78:254–258. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Patel S, Yadav S, Gurnani S, Yadav P and

Selvin B: A solitary enchondroma of the great toe in an adolescent

male: A case report. Cureus. 14(e21772)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Alhosain D, Kouba L, Dandashy A and Jejan

W: A painful lump on a teenager's toe is a benign enchondroma.

Lancet. 396(1663)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mahajan RH, Dalal RB, Sahu A, Dalal N,

Banzal R and Anand S: Secondary chondrosarcoma in an enchondroma in

a proximal phalanx of toe. A diagnostic problem. A case report.

Foot (Edinb). 19:62–64. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Koak Y, Patil P and Mackenny R:

Chondrosarcoma of the distal phalanx of a toe: A case report. Acta

Orthop Belg. 66:286–288. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA, Kakamad FH, Ahmed

JO, Baba HO, Hassan MN, Bapir R, Rahim HM, Omar DA, Kakamad SH, et

al: Predatory publishing lists: A review on the ongoing battle

against fraudulent actions. Barw Med J. 2:26–30. 2024.

|

|

14

|

Prasad S, Nassar M, Azzam AY, José FGM,

Jamee M, Sliman RK, Evola G, Mustafa AM, Abdullah HO, Abdalla BA,

et al: CaReL guidelines: A consensus-based guideline on case

reports and literature review (CaReL). Barw Med J. 2:13–19.

2024.

|

|

15

|

Abdullah AS, Ahmed AG, Mohammed SN, Qadir

AA, Bapir NM and Fatah GM: Benign tumor publication in one year

(2022): A cross-sectional study. Barw Med J. 1:20–25. 2023.

|

|

16

|

Torbaghan SS, Ashouri M, Naderi NJ and

Baherini N: Histopathologic differentiation between enchondroma and

well-differentiated chondrosarcoma: Evaluating the efficacy of

diagnostic histologic structures. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent

Prospects. 5:98–101. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ferrer-Santacreu EM, Ortiz-Cruz EJ,

Díaz-Almirón M and Kreilinger JJ: Enchondroma versus chondrosarcoma

in long bones of appendicular skeleton: Clinical and radiological

criteria-a follow-up. J Oncol. 2016(8262079)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Chun KA, Stephanie S, Choi JY, Nam JH and

Suh JS: Enchondroma of the Foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 54:836–839.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Futani H, Kawaguchi T, Sawai T and

Tachibana T: Osteoscopic versus open surgery for the treatment of

enchondroma in the foot. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 143:4899–4905.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|