1. Introduction

The investigation of the genetic factors influencing

cancer susceptibility has been increasing in recent years. The

International Human Genome Sequencing Project and the International

HapMap Project have both conducted substantial research into the

location, amount, type and frequency of genetic variants in the

human genome (1-4).

Numerous observational studies examining the association among

polymorphisms in genetic variations and the risk of cancer

development have led to ongoing technology advancements that enable

more rapid and more economical genotyping results (5). A recent genome-wide association study

identified several novel susceptibility loci for prostate cancer

risk, providing new insight into the genetic architecture of this

disease across diverse populations (6). A large cohort study involving

>113,000 women emphasized the contribution of both common and

rare genetic variants to breast cancer susceptibility,

demonstrating the complex genetic architecture underlying breast

cancer risk (7).

Knowledge of the genetic propensity to cancer has

generally improved with the increasing amount of research that has

been performed. The lack of replication has been a major critique

of genetic epidemiology. There have been many ‘false positive’

claims, as evidenced by the failure of numerous research that

attempted to reproduce a statistically significant outcome for a

genetic condition that had already been published (8,9).

Meta- and pooled analyses have been employed to incorporate both

statistically meaningful and non-significant data from several

studies and grade these results according to their precision.

Another significant methodological issue is the scale of these

studies of genetic associations (a proportion of sample size)

(10-12).

The programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), encoded by

the CD274 gene located on chromosome 9p24.1, plays a

critical role in immune regulation by mediating immune checkpoint

pathways that allow tumors to evade immune surveillance. PD-L1

expression is detected in various cells, including

antigen-presenting cells, lymphocytes and epithelial cells, where

its regulated activity helps maintain immune homeostasis during

inflammation (13,14). Toll-like receptors (TLRs),

expressed in immune cells, have been shown to modulate PD-L1

expression by responding to pathogen-associated molecular patterns,

thus influencing the immune microenvironment.

Notably, the aberrant expression of PD-L1 has been

implicated in the pathogenesis of several types of cancer. The

overexpression of PD-L1 in tumors, such as non-small cell lung

cancer is associated with oncogenic mutations, such as those in the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), highlighting the interplay

between oncogenic signaling pathways and immune evasion mechanisms.

Genetic and epigenetic alterations, including polymorphisms and

mutations in PD-L1 regulatory regions or associated signaling

genes, such as phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and

anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), may contribute to a

variable PD-L1 expression and consequent differences in tumor

immune escape and patient prognosis (15).

Despite the recognized importance of PD-L1,

comprehensive studies focusing on genetic polymorphisms within the

CD274 gene and their associations with cancer susceptibility

remain limited. Integrating the mechanistic understanding of PD-L1

regulation with genetic variation analyses could provide valuable

insight into individual susceptibility and response to immune

checkpoint therapies.

TLRs, a subtype of non-catalytic receptor that is

widely expressed in APCs and activated by epitope molecular

patterns, have a notable impact on PD-L1 expression (16). The driving oncogenic events in

carcinogenesis may be the cause of PD-L1 overexpression. For

instance, in lung cancer, PD-L1 expression is positively associated

with EGFR mutations in the EGFR (17). Through the unregulated stimulation

of the protein kinase pathway, PD-L1 overexpression is maintained

in enzymatic activity and in PTEN-mutant tumors (18,19).

Through constitutive STAT3 activation, the recombinant genes for

the protein nucleophosmin (NPM) and ALK enhance the expression of

PD-L1 in T-cell lymphoma (20).

Lin et al (21) explored

the genomic and transcriptomic characteristics regulating PD-L1

expression, highlighting the impact of genetic polymorphisms on

PD-L1 and its role across various types of cancer.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes, which include

those from the CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3 families, as well as additional

exogenous and endogenous compounds, metabolize drugs. The key CYP

enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of procarcinogens are

CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, CYP2E1, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5(22).

The majority of CYPP450 enzymes that belong to the

CYP 1, 2, or 3 groups are polymorphic due to gene deletion,

single-nucleotide polymorphisms that occur all alone in

combination, or gene duplications, where mutant alleles result in

discontinued, reduced, modified, or enhanced enzyme activity.

Genetic polymorphisms in CYP enzymes, such as CYP2D6 and CYP2E1

significantly affect enzyme activity and have been linked to

altered cancer susceptibility across diverse populations (23,24).

Phenotyping experiments were utilized to investigate the potential

link between CYP polymorphisms and the risk of developing cancer

before genotyping methods were developed. The delivery of CYP

enzyme substrate and the analysis of the products in plasma and

urine were common procedures used in research. Following the

analysis of the associations among CYP polymorphisms and the risk

of cancer development over the period of a decade in numerous

studies encompassing thousands of patients, the association between

CYP polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility is now understood; the

mechanisms involved include simultaneous genes that code for phase

1 and phase 2 enzymes (25).

Recent studies have shed light on CYP polymorphisms influencing the

risk of cancer development and treatment outcomes. Tan et al

(26) reported on the impact of

CYP2D6 genotypes on breast cancer outcomes and pharmacogenomics,

emphasizing the clinical relevance of CYP2D6 polymorphisms.

Additionally, Jiang et al (27) conducted an updated meta-analysis

linking CYP2E1 polymorphisms with an increased risk of developing

various types of cancer, supporting the role of CYP2E1 genetic

variations in cancer susceptibility.

Numerous biological mechanisms, including bone

metabolism, inborn resistance, proliferation and differentiation

are regulated by the vitamin-D endocrine system (28). Numerous common diseases, such as

cancers, diabetes, cardiac disease, autoimmune disorders, rickets,

as well as other bone diseases, have been firmly related to vitamin

D deficiency by epidemiological and laboratory research (29-32).

The biologically highly active naturally occurring metabolite of

vitamin D, known as 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3,

calcitriol), has been found to control the proliferation and

differentiation of a range of cell types, including cancer cells

(33-35).

Research has also demonstrated that angiogenesis, cancer growth and

cell death are all regulated in cancer (36-38).

Previous research has revealed the existence of intracellular

enzyme 25(OH) D3-1-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) activity in a wide range

of cell types, including macrophages, keratinocytes, prostate and

colon cancer cells (39,40). It has been shown that a number of

tissues locally synthesize 1, 25(OH) 2D3. Recent research has

uncovered that vitamin D can be activated via an alternative

pathway by the steroidogenic enzyme CYP11A1. This pathway

complements the classical activation involving CYP27B1 and expands

the understanding of vitamin D metabolism beyond traditional

mechanisms. The CYP11A1-mediated conversion produces novel

secosteroids with potential biological activities relevant to

cellular proliferation, differentiation, and immune modulation in

cancer and other diseases. This alternative pathway adds complexity

to vitamin D regulation and may have implications for cancer

susceptibility and therapy (41,42).

The nucleotide excision repair (NER) system is one

of the main mechanisms by which cells defend themselves from

genotoxic damage, such as that caused by UV radiation and exposure

to chemical carcinogens. Human syndromes, such as trichotillomania,

Cockayne syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) are caused by NER

system anomalies (43,44). An exceptionally high sensitivity to

UV light and a comparatively high chance of developing skin cancer

are two features of the heritable human condition known as XP. The

UV sensitivity of patients with XP led to the initial connection

between the illness and DNA repair (45). Based on the ability of distinct

cell types to complement UV sensitivity, eight XP-complementation

groups were identified (46,47),

and the genes encoding the various complementation groups have also

been identified (48-50).

UV radiation plays a dual role in human homeostasis, with both

harmful and beneficial effects that extend beyond simple DNA

damage. Beyond its capacity to induce genotoxic lesions repaired by

the nucleotide excision repair system, UV radiation also plays a

central homeostatic role in neuro-immuno-endocrine regulation.

Recent insights highlight how UV exposure modulates systemic

physiology by affecting neural, immune and endocrine pathways, thus

contributing positively to body regulation and immune surveillance.

This dual nature of UV radiation underscores the complexity of its

impact on health and carcinogenesis, balancing its carcinogenic

potential against vital homeostatic functions (51).

In addition to genetic polymorphisms, epigenetic

modifications, such as DNA methylation play a crucial role in

regulating gene expression and influencing cancer susceptibility.

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine

residues, typically at CpG dinucleotides, leading to changes in

chromatin structure and gene activity without altering the DNA

sequence itself. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns can result in

gene silencing or activation that contributes to carcinogenesis,

affecting tumor suppressor genes, oncogenes and DNA repair genes.

The interplay between genetic polymorphisms and epigenetic

alterations is increasingly recognized as fundamental to

understanding the risk of cancer development, progression and the

therapeutic response. Therefore, integrating both genetic and

epigenetic perspectives provides more comprehensive insight into

cancer susceptibility and personalized medicine approaches.

Taken together, the diversity of biological systems,

such as immune surveillance (antigen-presenting cells and

checkpoint proteins), metabolic detoxification (cytochrome P450

enzymes), cellular signaling (vitamin D pathways), DNA repair

(nucleotide excision repair system), and epigenetic regulation (DNA

methylation) forms an intricate network maintaining cell

homeostasis and genomic integrity. Genetic polymorphisms within the

genes governing these systems can significantly alter their

functions, leading to variability in how individuals respond to

environmental exposures, carcinogens and intrinsic cellular

stresses. These variations may influence cancer susceptibility by

affecting immune evasion, the activation or detoxification of

carcinogens, DNA damage repair efficiency, and the epigenetic

regulation of oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Thus, understanding

the complex interplay among these elements is essential for

elucidating the multifactorial nature of cancer risk and

identifying genetic and epigenetic markers for cancer prevention,

diagnosis and personalized therapy.

2. Various genes and genetic

polymorphisms

The following chapter provides an overview of genes

involved in key cellular pathways; it is important to emphasize

that the relevance of these genes to the risk of cancer development

is principally determined by the specific genetic polymorphisms

they harbor. A detailed understanding of the normal function of

each gene provides the necessary foundation to appreciate how

alterations in the genetic sequence, such as single nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, deletions and copy number

variations, can influence an individual's susceptibility to cancer.

Throughout this section, gene variants with established or

potential links to cancer risk will be highlighted. It should be

noted, however, that some gene polymorphisms discussed in the

subsequent sections affect human health through mechanisms that may

extend beyond cancer alone; these examples are included to

underscore both the complexity and the far-reaching consequences of

genetic variation in human populations. This integrative approach

aims to provide a nuanced perspective, facilitating a comprehensive

understanding of the multifactorial risk factors contributing to

cancer and related diseases.

Within the broad family of CYP enzymes, several

members such as CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, CYP2E1, CYP2D6, CYP3A4 and

CYP3A5 participate in the metabolism of carcinogens and drugs.

Among these, CYP1A1 and CYP2E1 have emerged as particularly

critical, due to their significant roles in activating

procarcinogens commonly found in tobacco smoke and other

environmental toxins. Genetic polymorphisms in these enzymes

influence enzymatic activity and expression levels, thereby

modulating individual susceptibility to various cancers. While all

CYP enzymes contribute to xenobiotic metabolism, the extent of

evidence linking CYP1A1 and CYP2E1 variations to the risk of cancer

development is more substantial, warranting focused research

attention.

CYP1A1

On human chromosome no. 15, the CYP1A1 gene

is only activated in organs other than the liver, such as the

lungs. The enzyme CYP1A1 converts polycyclic aromatic

compounds, which are present in cigarette smoke, into hazardous

arene oxide that can result in DNA mutation and cancer (47,48).

Since CYP1A1 is not expressed in the human liver, it is

dubious whether human studies on animals have any application

(49). There are several

polymorphic CYP1A1 alleles known. A point mutation causes an

MspI restriction fragment-length polymorphism in the 3'

non-coding region (RFLP). The heme-binding domain of CYP1A1

contains the exon 7 polymorphism, which increases the inducibility

of the enzyme. Recent research suggests that the MspI, as

well as exon 7 mutation may increase the risk of developing lung

cancer, although Asians are more likely to be affected. In the 3'

non-coding region of CYP1A1, a second MspI RFLP is

only present in individuals of African origin. Its connection to

the risk of developing lung cancer remains unclear. According to

recent studies, nicotine can boost pulmonary CYP1A1 activity

(50). This research has important

implications for how sensitive humans are to acquiring cancer, even

if it is currently only applicable to rats. First, nicotine most

definitely contributes to the induction of CYP1A1 by

cigarette smoke. Second, the emergence of smoking cessation aids

raises serious concerns about the possibility for nicotine

replacement medications to increase CYP1A1 activity and

hence trigger the bio-activation of carcinogens (51). Last but not least, it remains

unknown how CYP1A1 functions in the presence of nicotine and

an allele variation.

CYP2D6

CYP2D6 (debrisoquine hydroxylase) is

considered to be involved in the metabolism of 25% of all

prescribed medications (52). At

least 29 allelic variations of CYP2D6 have been identified,

and this has been linked to significant inter-individual

variability in drug metabolism (53).

In ~6% of Caucasians, deletions, abnormal splicing

and gene duplication result in the absence of functional

CYP2D6. It is interesting that CYP2D6 cannot be

induced. It is understood that CYP2D6 activates metabolism

(54).

Smoke from cigarettes contains

4-(methylnitrosamine)-1- (3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, which is

considered to cause cancer and is a factor in the development of

human lung adenomas. Extensive metabolizers may be more susceptible

to lung cancer (54).

E-Cadherin

The CDH1 gene, that is found on chromosome

16q22.1, is responsible for producing the 120 kD single

transmembrane glycoprotein known as E-cadherin. One intracellular

and five external domains are present. It converses with catenins.

The development and maintenance of tissue architecture, cell

polarity, intracellular signaling and intercellular adhesion depend

on this protein. It plays a critical role in the formation of

sticky junctions in epithelial cells. The lack of E-cadherin

directly affects essential cellular processes including motility.

Additionally, it has been demonstrated that its expression

decreases typically happen during tissue metastasis. An association

has been found between an increased aggressive behavior and the

decreased expression of E-cadherin. The frequency of OSCC

E-cadherin gene hypermethylation varies between 7 and 46% (55).

PTEN

The tumor-suppressor gene, PTEN, is located

on chromosome 10q23.3. It is anticipated that essential cellular

functions such as survivability, differentiating, proliferating,

apoptosis and invasion are affected by the lack of expression

Ras/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, which lack control over

the signal transduction that control apoptosis and migration, and

also play a crucial role in the survival, proliferation and

metastasis of tumor cells. Due to mutations or epigenetic

modifications, PTEN is frequently lacking in a variety of

cancer types. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that

endometrial cancer, gastric cancer, non-small cell lung carcinoma

and cervical cancer all exhibit the methylation of the PTEN

promoter CpG islands (56). The

functions, regulation and implications of PTEN polymorphisms in

cancer were comprehensively reviewed by Song et al (57), detailing the role of PTEN as a key

tumor suppressor. Han et al (58) further performed a meta-analysis of

PTEN mutations, associating genetic alterations with prognosis

across multiple cancer types.

p53

Cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation,

DNA repair and apoptosis are some of the key cell activities that

the TP53 gene, also known as p53, is involved in. It

is located on chromosome 17p13.1. p53 levels increase in response

to endogenous or exogenous stress, which stops the cell cycle and

enables DNA repair. Genomic instability results from p53 loss of

function, which affects how cells react to stress or damage. With a

frequency ranging from 25 to 69%, p53 is mutated in the

majority of human malignancies, including oral tumors (59,60).

In addition to this, p53 frequently exhibits a decrease of function

brought on by epigenetic rather than genetic processes.

Comprehensive analyses of TP53 variations across multiple human

cancers were provided by Bouaoun et al (61), utilizing database and genomic data

to reveal new insight into TP53 mutation patterns. A further

mechanistic understanding of mutant p53 roles in cancer

pathogenesis was provided by Mantovani et al (62), elucidating its function as a cancer

cell guardian.

XPD

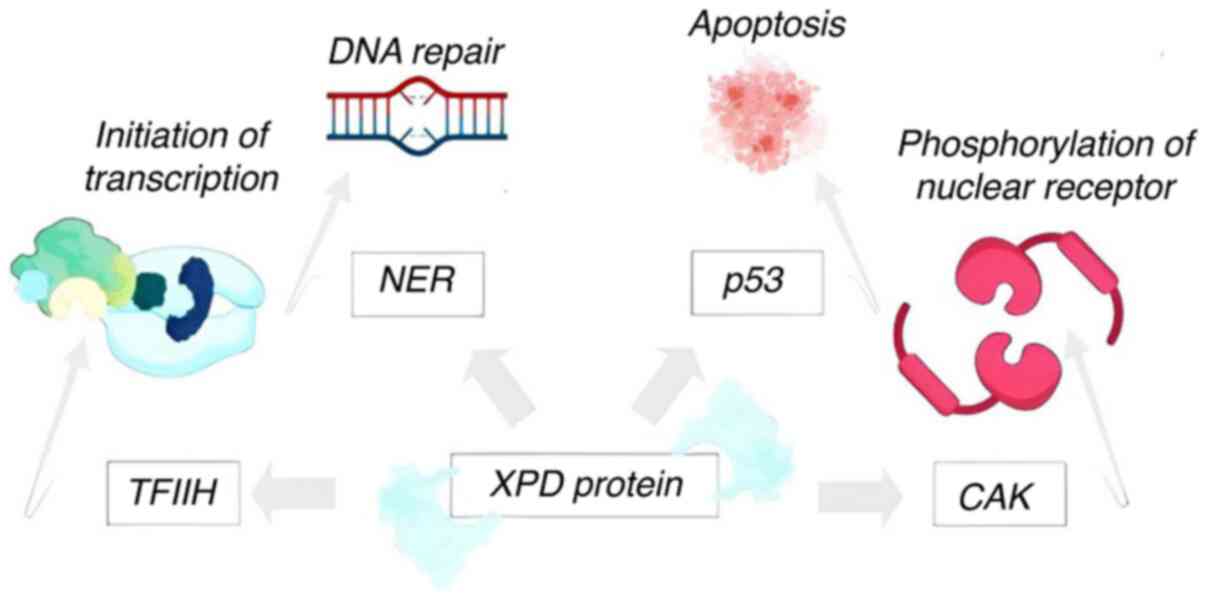

TFIIH phosphorylates a wide range of substrates,

including nuclear hormone receptors such as RAR or ER,

transcription activators and RNA polymerase II (63). Additionally, TFIIH is

present as a nine-subunit complex, a transcriptionally active core

TFIIH, and a CDK-activating kinase (CAK) complex (Fig. 1). The XPD protein is a component of

all three of these complexes (64). The activity of these complexes can

be decreased by mutations in the XPD gene, which can cause issues

with transcription, the apoptotic response, repair, or, most

likely, hormonal function. All of these deficiencies result in

syndromes that are associated with immature sexual development,

skeletal abnormalities, mental impairment, and, in the case of the

majority of patients with XPD mutations, a high propensity for

cancer. Only a limited amount of research has been performed into

the connection between XPD mutations and DNA repair capacity, as

determined by the biological tests mentioned in the literature. The

Lys/Lys codon 751 XPD genotype was previously linked to a decreased

repair of X-ray-induced DNA damage in a brief study on 31 women at

risk of developing breast cancer (65). More chromatid aberrations are

present in individuals with the wildtype Lys allele than in those

carrying one or more Gln alleles (65).

3. Methods for analyzing genetic

polymorphisms

Association studies are most frequently used to

determine whether polymorphisms contribute to genetic

susceptibility or progression. As a result, the focus is on

variables that determine the effectiveness of associations. If a

specific allele exhibits a greater frequency in cases compared to

controls, that polymorphism is then considered to be linked to the

disease (66). Researchers compare

individuals with extreme phenotypes when analyzing polymorphisms as

contributing factors to the course of disease, rather than diseased

individuals with unaffected controls. There are three possibilities

if a substantial association is found: Either the polymorphism is

at the locus of interest, it is in genetic linkage [namely linkage

disequilibrium (LD)] with the locus, or confounding factors are

involved.

When alleles from two different genetic loci

co-occur more frequently than would be predicted according to their

respective allelic frequencies, a population is considered to

exhibit LD. Possible sources of LD include early mutation, founder

effects and selection. Population admixture, which occurs when

groups that have been separated for a long time unite to form a

hybrid population, is another possible source of LD (67). The resulting LD can be prolonged

beyond distances typically observed in populations with greater

stability, depending on the sort of mixing. The most precise

estimates of LD in an outbred population indicate that LD is

unlikely to span distances >1-2 centimorgans (cM), or ~1-2

million base pairs, whereas LD may occur across 10-fold that

distance in an inbred group, such as the Hutterites (68).

Confounding variables need to be taken into account,

particularly when polymorphisms reported in one study are absent in

another ethnic group. One perplexing aspect is population

stratification. This could be brought on by unequal ethnic

admixture, such as the presence of Caucasians in the gene pool of

an African-American community. Fortunately, this issue can be

resolved by taking great precautions during the analysis or

research plan phases. Association studies based on families are

specifically created to take into account the genetic background

that may add confounding variables, and they include genotyping of

affected people, their parents, and/or their unaffected siblings

(69). These types of

investigations frequently employ the transmissions disparity test

(TDT), as well as the haplo-type relative risk test statistics

(HRR). The TDT compares how frequently each allele is transferred

from a heterozygous parent to a child who has the disease. Similar

to the TDT, the HRR analyses genetic transmission (haplotype) as

compared to allele transmission (70).

The decision of which phenotype to explore is

crucial in genetic polymorphism investigations. In fact, the

presence of numerous phenotypes in the case sample has hampered

much research that analyzing genetic polymorphisms. For instance,

research on asthma has used patient samples from patients with

mild, severe, adult-onset, intrinsic and extrinsic asthma (71). Studying a more precisely defined

intermediate phenotype can significantly enhance studies that aim

to ascertain whether there is a link between a polymorphism and

disease. Total IgE and bronchial hyper responsiveness are examples

of intermediate phenotypes in the case of asthma. Another factor to

take into account is the possibility that the genes involved in

illness progression may not be the same genes responsible for

disease susceptibility. It may be helpful to restrict the sample to

those with a particular stage or severity of disease. In a previous

study, to evaluate potential genes for the disease, the researchers

focused on patients with severe early-onset chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (71).

The evaluation of DNA polymorphisms close to or

within putative genes is the only application of association

studies. Linkage analysis employing families or affected siblings

is necessary to carry out a genome screen to look for candidate

genes. Although linkage analysis is rigorous and uncovers genes

that significantly affect disease susceptibility, it has very

limited power and will miss genes that merely increase the risk of

mild to moderate disease. For instance, hundreds to thousands of

families would need to be typed if a disease susceptibility allele

increased disease risk by 2-fold relative to the wild-type allele,

which may not be a realistic sample size (72). Although linkage analysis detects

connections over considerably larger genomic regions (thousands of

base pairs), association studies have a stronger power (millions of

base pairs). Including current technology, a genome scan with

association studies would need tens of thousands of markers. The

majority of lung diseases need some type of environmental trigger

before they may become visible. Given that genetic susceptibility

only accounts for a small part of illness variation, failure to

consider environmental factors can drastically degrade gene-finding

research for the majority of complex disorders. Furthermore, genome

screening or association studies carried out on populations that

were neither chosen nor stratified according to their environmental

exposure could only be able to find genes whose environmental

exposure is common in that group. For instance, investigating a

randomly chosen sample of asthmatics from the Midwest region of the

USA would be able to discover genes crucial for regulating the

response to house dust mites, although possibly not with absolute

certainty (73).

Gene-environment interactions can take on many

different shapes, such as distinct exposure risk implications based

on the genotype of an individual or diverse gene risk implications

based on the exposure of an individual. Biological and statistical

interactions are the two main interactions. The coefficient of the

product term of the genetic and environmental risk variables

represents a statistical risk factor interaction, and the

interaction is quantified as a divergence from a multiplicative

model (gene and environment). This approach is arbitrary, relies on

models, and may overlook biological synergy or interaction. The

biologic interaction paradigm states that when two factors cause a

disease to start, they interact. Occasionally, this

co-participation could stand out as a divergence from an additive

model (74).

4. SNPs in the human population

SNPs are single nucleotide variations in the genomic

DNA that occur at different positions in different individuals in a

community (75). Genome-wide

datasets are more frequently used in the drug development process,

as well as to identify molecular pathways and networks underlying

complex disorders (Table I)

(76-79).

In particular, functional pathway analysis of genomic data provides

the possibility of greater capability for discovery and organic

links to biological phenomena. SNPs are the consequence of single

base-pair variations (substitutions or deletions) caused by point

mutations in chromosome sequences, and account for a large portion

of the genetic variation found in the human genome. Finding SNPs in

a genome can be achieved in a variety of laboratories and via

computational mechanisms; however, they all involve comparing the

same DNA segment from various individuals or haplotypes.

| Table IMethods of selecting SNPs. |

Table I

Methods of selecting SNPs.

| Methods | Advantages | Limitations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pathway gene

method | It is simple to

study a subset of SNP based on a description of the pathways

relating to the drug's pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action.

Clinically, general vulnerability is observed in complex genetic

disorders. | The pathway gene

approach will result in fewer false-positive findings than the

genome wide approach because of the disadvantage of multiple

testing. | (76,77) |

| Candidate gene

method | Functional SNPs are

those whose genetic variant affects how a protein functions. This

technique has resulted in the identification of a sizable number of

pertinent SNPs in pharmacogenetics. | As the majority of

complex traits are not considered to be monogenetic, selecting SNPs

using this strategy will frequently result in a limited explanation

of variation in medication response. | (78,79) |

| Genome-wide

method | This strategy may

identify unexpected SNPs linked to drug response. New associations

between SNPs and medication response have been found in genome-wide

association investigations, and complicated features can be

studied, while taking into account polygenetic variation. | In identifying a

related SNP, the discrepancy between type I errors (false positive

findings) and eventually type II faults (false negative results)

may create some issues. | (78,79) |

SNPs can be located using expressive sequence tags,

which are created by single-run sequencing of cDNAs obtained from

various individuals and the assembly of overlapping sequences for

the same region. This allows for the discovery of novel SNPs.

Depending on whether they are located in regions of the genome that

regulate genes, non-coding SNPs can be categorized. A number of

complex disorders may be caused by quantitative discrepancies in

gene products rather than qualitative differences. Based on whether

they alter the amino acid sequences of the protein that the altered

gene encodes, coding SNPs can be categorized. By their impact on

protein structure, modifications that change protein sequences can

be categorized (80).

Genome-wide association studies have emerged as a

crucial method for identifying genes that predispose to complicated

disorders. With the aid of population-based information like as

allele frequency, LD and recombination rates, researchers may

perform genome-wide association analysis on millions of SNP

markers. Some of the discrepancies in association results between

populations for particular traits of interest can be explained by

HapMap data, such as population-specific common variants and LD

blocks (81).

5. VNTR polymorphisms in the human

population

CYP2E1 is a key enzyme found in the microsomal

ethanol oxidation system. It belongs to the CYP superfamily and is

primarily located in the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum.

CYP2E1 plays a crucial role in the metabolism of various

hydrophobic toxic compounds (82-84).

Additionally, it contributes to the conversion of certain

pro-carcinogens and drugs into highly reactive metabolites.

The activation of N-nitrosamines, which are present

in tobacco smoke, foodstuffs, and certain industrial and endogenous

carcinogens, is facilitated by CYP2E1. Furthermore, this enzyme can

generate highly reactive compounds, such as superoxide anion

radical (O2-), singlet oxygen (O2), hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (OH·) by

reducing molecular oxygen. These reactive species are capable of

causing DNA damage and promoting carcinogenesis (85-87).

The human CYP2E1 gene is situated on chromosome 10q26.3 and

consists of 9 exons and 8 introns. The expression of the

CYP2E1 gene can be regulated at multiple levels, including

transcription, translation, mRNA stability and protein degradation.

As with other CYP genes, CYP2E1 exhibits various polymorphic sites

in its 5'-flanking region, introns, and transcribed gene regions.

One notable polymorphism is a variable number tandem repeat (VNTR)

sequence located ~2.0 kilo base pairs upstream of the transcription

start site (88-90).

The activity of the CYP2E1 enzyme exhibits

significant variability among different ethnic groups, influenced

by both environmental and genetic factors, such as polymorphisms.

Polymorphic CYP genes can lead to differences in the ability to

metabolize, detoxify, or activate various substances. Several

studies have indicated that certain polymorphic genes, in

conjunction with alcohol consumption, play a role in the

development of specific types of cancer. Although alcohol itself is

not a carcinogen, it can function as a co-carcinogen by amplifying

the effects of other chemicals that are activated by enzymes, such

as CYP2E1. Research has demonstrated that CYP2E1 is highly

expressed in the liver and pancreas following ethanol ingestion.

The production of acetaldehyde during ethanol oxidation may

directly cause cell damage through the generation of reactive

oxygen species (91-95).

Furthermore, it is widely known that certain tumors

have a hereditary component, and environmental factors associated

with specific habits can increase the risk of tumor occurrence.

6. Using a different approach to identify

human gene polymorphisms

The function of biotransformation enzymes with

reference to occupational health exposure is to provide effective

purification of endogenous or exogenous substances by particular

biochemical pathways. These turn harmful molecules into inactive

compounds, which are then eliminated in urine, preventing the

buildup of metabolites and injury to the human body (96). Although the scanning of specific

gene polymorphisms by molecular biology laboratories is the optimal

approach to determine each the susceptibility of each study

participant, the willingness of study participants to provide the

biosample is essential to move forward with the genetic analysis.

There are some issues, such as the unwillingness of study

participants to consent to venipuncture or, more generally, to the

collection of biopsies, either as they are simply unaccustomed to

the procedure as they consider it to be an invasive and painful

technique, or because they are afraid of the possible outcomes of

the analysis (97). However, the

evaluation of gene polymorphisms does not provide any diagnostic

information regarding the propensity of an individual to develop a

specific disease. In comparison to collecting urine samples,

collecting blood samples may be more difficult. The lack of

language proficiency, the difficulties in communicating, and the

study participants varied cultures, customs, dietary preferences,

and religious beliefs could all play a role in this. To combat this

critical issue and obtain ethnic-specific genotype information

without using laboratory analysis, a publicly available online

library (http://grch37.ensembl.org/Homosapiens/Variation)

appears to contain a tentative catalogue of the majority of

genotype and allele frequencies of several ethnic groups. It is

possible to collect the genetic profiles of many ethnic groups

using this resource, which aids in the prediction and

identification of population-specific susceptibilities in

silico study. This model was created to assess the risk level

of the homozygous variation and heterozygous genotype in relation

to the world population in four macro-groups that includes

Africans, Eastern Asians, South Asians and Europeans. The principal

component analysis statistical technique serves as the foundation

of the model (98). It is intended

to identify the crucial vulnerabilities in the polymorphisms of

genes linked to three main functional biochemical processes,

including detoxification, oxidative stress and DNA repair,

following exposure to the harmful compounds. The SNPs were selected

based on their exposure to harmful and cancer-causing chemicals

that are frequently present in manufacturing plants and shipyards

(99).

7. Benefits of including polymorphisms in

studies on health-related effects

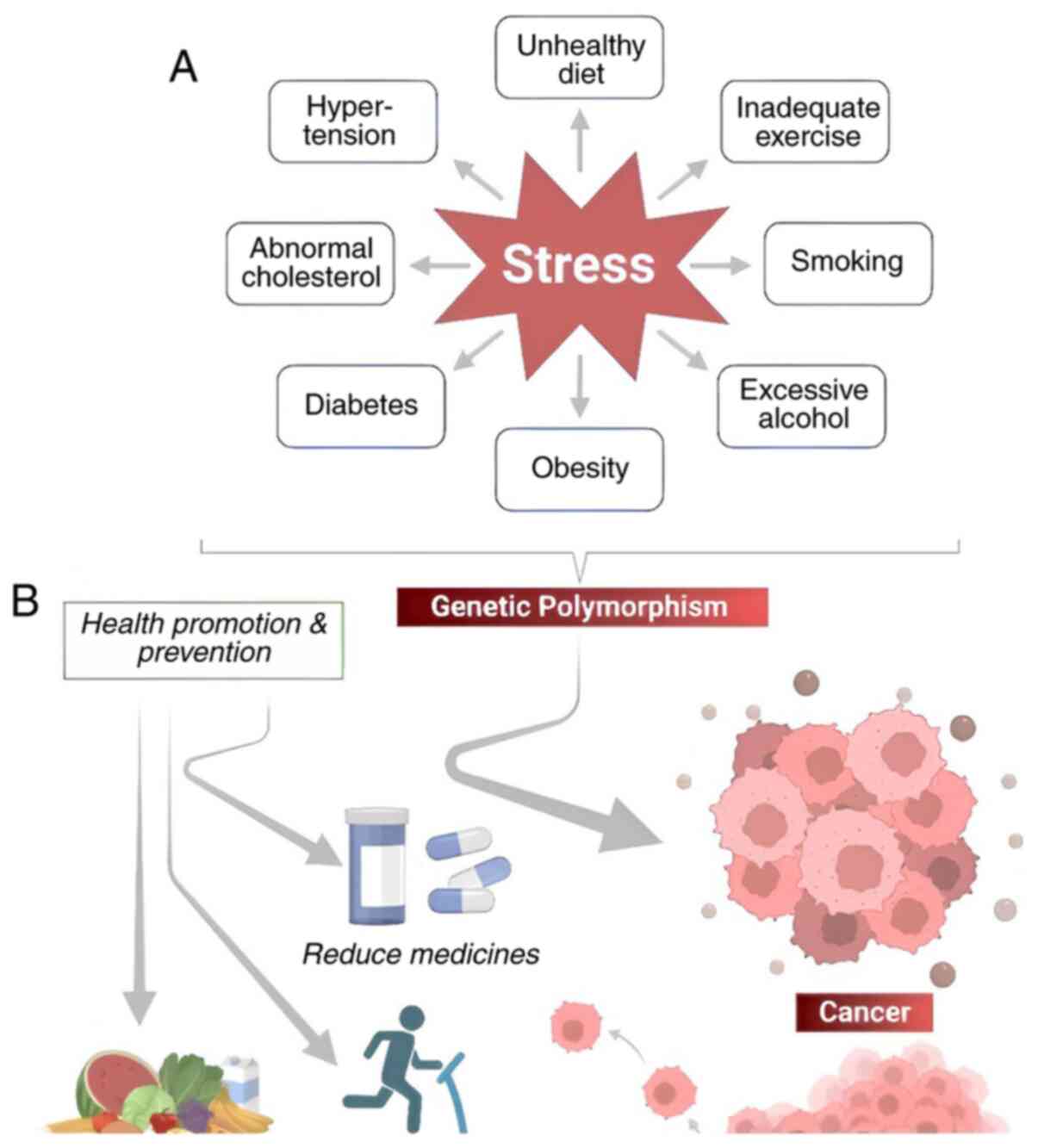

Incorporating polymorphisms opens up a wide range of

intriguing options for investigating the health effects of exposure

to toxins and toxicants in the environment. It is possible to

identify various risk ranges in subgroups of individuals who were

exposed by stratifying a health result or biomarker in accordance

with the relevant genotype (or phenotype) (100), as illustrated in Fig. 2. An implication that corresponds to

the average risk for both fast and slow acetylators is shown by

research evaluating the probability of bladder cancer linked to

exposure to aromatic amines (100). This estimate does not imply that

aromatic amines are as significant etiological factors for

sub-populations or as powerful carcinogens as a stratified study

might. For routine exposures, to food ingredients or carbon

emission, for example, whose relation to a disease consequence is

normally small, effect dilution may be especially crucial. Second,

proof of impact change by genotype provides insight into the

fundamental biologic mechanism of cytotoxicity or carcinogenicity

when substrates or targets of possible genetic variants are

identified as likely causal agents (101). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a

constituent of particulates in rural regions and sometimes known as

an endotoxin, may have a negative impact on lung function metrics.

Kelada et al (101)

demonstrated that the response to LPS varied by TLR4 genotype. The

TLR4, which is encoded by TLR4, binds LPS and begins a signaling

pathway that causes lung inflammation. According to their findings,

although individuals with the mutated TLR4 genotype may be more

susceptible to an inflammatory process, they may not be as

susceptible to an inflammation of the lungs brought on by LPS.

These results may contribute to answering the difficult question of

whether particulates matter component(s) is/are accountable for the

multitude of documented health consequences, particularly in rural

areas where LPS levels are substantial. The development of drugs or

dietary interventions that postpone the start or progression of

disease may be made possible by the increased understanding of

pathologic pathways gained via combined epidemiological and

toxicological investigations. Oltipraz [OPZ;

5-(2-pyrazinyl)-4-methyl-1, 2-dithiole-3-thione] is an example of a

medication that activates phase II XMEs, specifically the GSTs

(102). Aflatoxin B1 can cause

liver cancer in rats, according to early research. Research has

also revealed that administering OPZ to patients significantly

improved the clearance of a phase II substance known as

aflatoxin-mercapturic acids (103). Research suggests that OPZ may

function by competitively inhibiting CYP1A2, preventing the

activation of aflatoxin. Ultimately, hypothesis-based

epidemiological research and the knowledge of aflatoxin

biotransformation routes from investigations on human tissue grown

in vitro and animal models has helped to establish a

chemoprevention method for aflatoxin-induced hepatocellular

carcinoma. Studies on the consequences of exposure to controlled

environmental pollutants that take genetic sensitivities into

consideration will increase our understanding of the range of human

genetic variation in response to these pollutants. Genes that may

be associated with susceptibility should be included in studies

designed to examine the effects of these substances. By replacing

the standard default assumptions (i.e., uncertainty factor of 10)

with more accurate estimates of human variability, the risk

assessment may be improved. As a result, acceptable exposure levels

may be redefined, improving overall public health protection and

industry regulation. Although this benefit has been promoted for

some time, there is still no concrete illustration of how it may be

achieved, particularly in light of the myriad social, legal, or

ethical issues that surround use of genetic data (104). Preventive efforts on those who

are genetically sensitive to disease has started in the

environmental health field, with a focus on the intrinsically

complicated ethical, legal and social issues (105).

8. Synopsis

Polymorphisms and DNA methylation both play critical

roles in the development of cancer. Polymorphisms are DNA sequence

variations that occur when a single nucleotide in the DNA sequence

is altered. These variations can lead to changes in the function of

the gene or the expression of the gene product, which can result in

cancerous changes to cells. Epigenetic changes, such as DNA

methylation are biochemical processes wherein enzymes add a methyl

group to the DNA strand at 5th position of the cytosine to be

precise. These methylation sites can control gene expression by

either silencing a gene or increasing its activity depending upon

the number of methylation sites present. DNA methylation can also

alter splicing patterns, downregulate or ‘turn off’ gene

expression, which can lead to cancerous changes in cells. Overall,

both polymorphisms and DNA methylation function as key regulators

of gene expression and can therefore exert significant effects on

the development of cancer (106).

However, they do differ in their mechanisms of action.

The role of genetic polymorphisms within different

genes in the development and risk of cancer development is a

complex and multifactorial process. While genetic polymorphisms can

contribute to the susceptibility of an individual to cancer, they

are not the sole determinant. Environmental factors, lifestyle

choices and other non-genetic factors also play a crucial role.

Numerous studies have identified specific genetic polymorphisms

that are associated with an increased risk of developing cancer.

For example, variations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes

have been linked to an increased risk of developing breast and

ovarian cancer, while variations in the TP53 gene have been

linked to an increased risk of developing several types of cancer,

including breast, ovarian and colorectal cancer (107,108). However, it is important to note

that the presence of a genetic polymorphism does not necessarily

mean that an individual will develop cancer. A number of

individuals with these genetic variations never develop cancer, and

numerous individuals without these genetic variations do develop

cancer.

Emerging evidence demonstrates that tumors possess

the capacity not only to modulate their local microenvironment, but

also to dysregulate systemic body homeostasis through

neuroendocrine pathways. This tumor-driven autoregulation

interferes with normal physiological processes, such as metabolism,

immune function and stress response, effectively hijacking the

neuroendocrine system of the body to support cancer progression and

evade host defenses. Understanding this intricate interplay reveals

cancer as a systemic disease with extensive body-wide impacts,

highlighting potential therapeutic targets to restore homeostatic

balance and counter tumor-driven systemic disruption (109).

The study of genetic polymorphisms and cancer risk

is an active area of research, and new discoveries are continuously

being made. As the understanding of the genetic basis of cancer

increases, it is likely that the identification of novel genetic

variations that are associated with an increased risk of cancer

development will be achieved, and the development of novel

strategies for the prevention and treatment of cancer may be

possible.

9. Limitations and future challenges

While the present review comprehensively covers the

role of genetic polymorphisms across various genes associated with

susceptibility to cancer, several limitations should be

acknowledged. First, the heterogeneity of study designs, sample

sizes and populations in the original research contributes to

variability and potential inconsistency in reported associations. A

number of genetic association studies face challenges, such as

population stratification, limited replication and publication

bias, which affect the strength and generalizability of

conclusions. Second, the complex interplay between genetic

polymorphisms, epigenetic modifications and environmental factors

remains incompletely understood, limiting the ability to fully

elucidate causal mechanisms. Third, the functional characterization

of numerous polymorphisms is still lacking, impeding translation to

clinical applications. Finally, rapidly evolving genomic

technologies and the emergence of multi-omics approaches

necessitate continuous updates to maintain a current and holistic

perspective on genetic risks in cancer. Future studies

incorporating large, well-characterized cohorts with integrated

genomic, epigenetic, and environmental data are essential to

overcome these limitations and advance personalized cancer

prevention and therapy.

10 Conclusion

In conclusion, DNA methylation and genetic

polymorphisms both have a major impact on the occurrence and risk

of developing cancer. Genetic polymorphisms are differences in DNA

sequence that may have an impact on gene expression and function,

possibly causing malignant cell alterations. Contrarily, DNA

methylation is an epigenetic change that can influence gene

expression by activating or silencing genes, having an effect on

the onset of cancer. New findings are continuously being made as a

result of ongoing research into genetic variants and the risk of

developing cancer. Additional genetic variants linked to the risk

of developing cancer will probably be discovered as the knowledge

of the genetic basis of cancer increases. This knowledge could

potentially lead to the development of personalized strategies for

cancer prevention and treatment based on the unique genetic makeup

of an individual.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Galgotias

University (Greater Noida, India) for providing the academic

resources and valuable technical assistance during the preparation

of the present review.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author's contributions

RM and NK conducted a significant portion of the

literature search and drafted the manuscript. GS contributed to

editing specific sections of the manuscript. SPS edited and

proofread the manuscript. AKJ contributed to the initial conception

and scope of the review, provided critical review and feedback on

the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C,

Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al:

Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature.

409:860–921. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW,

Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, et al:

The sequence of the human genome. Science. 291:1304–1351.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

International Human Genome Sequencing

Consortium: Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome.

Nature. 431:931–945. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

International HapMap Consortium: The

international HapMap project. Nature. 426:789–796. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Lin BK, Clyne M, Walsh M, Gomez O, Yu W,

Gwinn M and Khoury MJ: Tracking the epidemiology of human genes in

the literature: The HuGE published literature database. Am J

Epidemiol. 164:1–4. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Schumacher FR, Al Olama AA, Berndt SI,

Benlloch S, Ahmed M, Saunders EJ, Dadaev T, Leongamornlert D,

Anokian E, Cieza-Borrella C, et al: Association analyses of more

than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate cancer susceptibility

loci. Nat Genet. 50:928–936. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Breast Cancer Association Consortium.

Dorling L, Carvalho S, Allen J, González-Neira A, Luccarini C,

Wahlström C, Pooley KA, Parsons MT, Fortuno C, et al: Breast cancer

risk genes-association analysis in more than 113,000 women. N Engl

J Med. 384:428–439. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA and

Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG: Replication validity of genetic

association studies. Nat Genet. 29:306–309. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Morgan TM, Krumholz HM, Lifton RP and

Spertus JA: Nonvalidation of reported genetic risk factors for

acute coronary syndrome in a large-scale replication study. JAMA.

297:1551–1561. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dickersin K and Berlin JA: Meta-analysis:

State-of-the-science. Epidemiol Rev. 14:154–176. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mosteller F and Colditz GA: Understanding

research synthesis (meta-analysis). Annu Rev Public Health.

17:1–23. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Morris RD: Meta-analysis in cancer

epidemiology. Environ Health Perspect. 102 (Suppl 8):S61–S66.

1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Chen J, Jiang CC, Jin L and Zhang XD:

Regulation of PD-L1: A novel role of pro-survival signalling in

cancer Ann. Oncol. 27:409–416. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bardhan K, Anagnostou T and Boussiotis VA:

The PD1:PD-L1/2 pathway from discovery to clinical implementation.

Front Immunol. 7(550)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang Q, Lin W, Tang X, Li S, Guo L, Lin Y

and Kwok HF: The roles of microRNAs in regulating the expression of

PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint. Int J Mol Sci.

18(2540)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ and Sharpe

AH: PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev

Immunol. 26:677–704. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Tang Y, Fang W, Zhang Y, Hong S, Kang S,

Yan Y, Chen N, Zhan J, He X, Qin T, et al: The association between

PD-L1 and EGFR status and the prognostic value of PD-L1 in advanced

non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with EGFR-TKIs.

Oncotarget. 6:14209–14219. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cretella D, Digiacomo G, Giovannetti E and

Cavazzoni A: PTEN Alterations as a Potential Mechanism for Tumor

Cell Escape from PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibition. Cancers (Basel).

11(1318)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Suzuki A, Nakano T, Mak TW and Sasaki T:

Portrait of PTEN: Messages from mutant mice. Cancer Sci.

99:209–213. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Marzec M, Zhang Q, Goradia A, Raghunath

PN, Liu X, Paessler M, Wang HY, Wysocka M, Cheng M, Ruggeri BA and

Wasik MA: Oncogenic kinase NPM/ALK induces through STAT3 expression

of immunosuppressive protein CD274 (PD-L1, B7-H1). Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 105:20852–20857. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lin H, Wei S, Hurt EM, Green MD, Zhao L,

Vatan L, Szeliga W, Herbst R, Harms PW, Fecher LA, et al: Host

expression of PD-L1 determines efficacy of PD-L1 pathway

blockade-mediated tumor regression. J Clin Invest. 128:805–815.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : Erratum in: J Clin

Invest 128: 1708, 2018.

|

|

22

|

McDonnell AM and Dang CH: . Basic review

of the cytochrome p450 system. J Adv Pract Oncol. 4:263–268.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chan CWH, Li C, Xiao EJ, Li M, Phiri PGM,

Yan T and Chan JYW: Association between genetic polymorphisms in

cytochrome P450 enzymes and survivals in women with breast cancer

receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 24(e1)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Datkhile KD, Durgawale PP, Gudur RA, Gudur

AK and Patil SR: CYP2D6 and CYP2E1 gene polymorphisms and their

association with cervical cancer susceptibility: A hospital based

case-control study from South-Western Maharashtra. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 23:2591–2597. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Agundez JAG: Cytochrome P450 gene

polymorphism and cancer. Curr Drug Metab. 5:211–224.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Tan EY, Bharwani L, Chia YH, Soong RCT,

Lee SSY, Chen JJC and Chan PMY: . Impact of cytochrome P450 2D6

polymorphisms on decision-making and clinical outcomes in adjuvant

hormonal therapy for breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 13:712–724.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jiang O, Zhou R, Wu D, Liu Y, Wu W and

Cheng N: CYP2E1 polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a HuGE

systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 34:1215–1224.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Holick MF: Sunlight and vitamin D for bone

health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and

cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 80 (6 Suppl):1678S–1688S.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mathieu C and Badenhoop K: Vitamin D and

type 1 diabetes mellitus: State of the art. Trends Endocrinol

Metab. 16:261–266. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A,

Collett-Solberg PF and Kappy M: Drug and Therapeutics Committee of

the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society. Vitamin D

deficiency in children and its management: Review of current

knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 122:398–417.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Handono K, Sidarta YO, Pradana BA, Nugroho

RA, Hartono IA, Kalim H and Endharti AT: Vitamin D prevents

endothelial damage induced by increased neutrophil extracellular

traps formation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta

Med Indones. 46:189–198. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Van Belle TL, Vanherwegen AS, Feyaerts D,

De Clercq P, Verstuyf A, Korf H, Gysemans C and Mathieu C:

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analog TX527 promote a stable

regulatory T cell phenotype in T cells from type 1 diabetes

patients. PLoS One. 9(e109194)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Reddy KK: Reply to Glossmann: Vitamin D

compounds and oral supplementation methods. J Invest Dermatol.

133(2649)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Takahashi H, Hatta Y, Iriyama N, Hasegawa

Y, Uchida H, Nakagawa M, Makishima M, Takeuchi J and Takei M:

Induced differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells into M2

macrophages by combined treatment with retinoic acid and

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. PLoS One. 9(e113722)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang Z, Zhang H, Hu Z, Wang P, Wan J and

Li B: Synergy of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and carboplatin in growth

suppression of SKOV-3 cells. Oncol Lett. 8:1348–1354.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Henry HL: Regulation of vitamin D

metabolism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 25:531–541.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Hossein-nezhad A and Holick MF: Vitamin D

for health: A global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 88:720–755.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Cantorna MT, Zhu Y, Froicu M and Wittke A:

Vitamin D status, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune system.

Am J Clin Nutr. 80 (6 Suppl):1717S–1720S. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Weinstein SJ, Purdue MP, Smith-Warner SA,

Mondul AM, Black A, Ahn J, Huang WY, Horst RL, Kopp W, Rager H, et

al: Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D binding protein and risk

of colorectal cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian

cancer screening trial. Int J Cancer. 136:E654–E664.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Slominski AT, Kim TK, Janjetovic Z,

Slominski RM, Li W, Jetten AM, Indra AK, Mason RS and Tuckey RC:

Biological effects of CYP11A1-derived vitamin D and lumisterol

metabolites in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 144:2145–2161.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Slominski AT, Tuckey RC, Jenkinson C, Li W

and Jetten AM: Alternative pathways for vitamin D metabolism. In:

Hewison M, Bouillon R, Giovanucci E, Goltzman D, Meyer M and Welsh

J (eds.), Feldman and Pike's Vitamin D: Volume One: Biochemistry,

Physiology and Diagnostics. 5th edition. Academic Press, pp85-109,

2024.

|

|

42

|

Hoeijmakers JH: Genome maintenance

mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 411:366–374.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Stary A and Sarasin A: The genetics of the

hereditary xeroderma pigmentosum syndrome. Biochimie. 84:49–60.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Cleaver JE: Defective repair replication

of DNA in xeroderma pigmentosum. Nature. 218:652–656.

1968.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kraemer KH, Levy DD, Parris CN, Gozukara

EM, Moriwaki S, Adelberg S and Seidman MM: Xeroderma pigmentosum

and related disorders: Examining the linkage between defective DNA

repair and cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 103 (5 Suppl):96S–101S.

1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wood RD: DNA damage recognition during

nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells. Biochimie. 81:39–44.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

de Boer J and Hoeijmakers JH: Nucleotide

excision repair and human syndromes. Carcinogenesis. 21:453–460.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Friedberg EC, Feaver WJ and Gerlach VL:

The many faces of DNA polymerases: Strategies for mutagenesis and

for mutational avoidance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:5681–5683.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Whitlock JP Jr: Induction of cytochrome

P4501A1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 39:103–125. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Iba MM, Scholl H, Fung J, Thomas PE and

Alam J: Induction of pulmonary CYP1A1 by nicotine. Xenobiotica.

28:827–843. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

San Jose C, Cabanillas A, Benitez J,

Carrillo JA, Jimenez M and Gervasini G: CYP1A1 gene polymorphisms

increase lung cancer risk in a high-incidence region of Spain: A

case control study. BMC Cancer. 10(463)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Johansson I, Xanthopoulou EM, Zhou Y,

Sanchez-Spitman A, van der Lee M, Wollmann BM, Størset E, Swen JJ,

Guchelaar HJ, Molden E, et al: Improved prediction of CYP2D6

catalyzed drug metabolism by taking variant substrate specificities

and novel polymorphic haplotypes into account. Clin Pharmacol Ther.

118:218–231. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wolf CR and Smith G: Cytochrome P450

CYP2D6. In: Metabolic Polymorphisms and Susceptibility to Cancer.

Vol 148. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon,

pp209-229, 1999.

|

|

54

|

Crespi CL, Penman BW, Gelboin HV and

Gonzalez FJ: A tobacco smoke-derived nitrosamine,

4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3- pyridyl)-1-butanone, is activated by

multiple human cytochrome P450s including the polymorphic human

cytochrome P4502D6,. Carcinogenesis. 12:1197–1201. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Lorenzo-Pouso AI, Silva FFE, Pérez-Jardón

A, Chamorro-Petronacci CM, Oliveira-Alves MG,

Álvarez-Calderón-Iglesias Ó, Caponio VCA, Pinti M, Perrotti V and

Pérez-Sayáns M: Overexpression of E-cadherin is a favorable

prognostic biomarker in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Biology (Basel). 12(239)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Chen CY, Chen J, He L and Stiles BL: PTEN:

Tumor Suppressor and Metabolic Regulator. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 9(338)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Song MS, Salmena L and Pandolfi PP: The

functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 13:283–296. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Han F, Hu R, Yang H, Liu J, Sui J, Xiang

X, Wang F, Chu L and Song S: PTEN gene mutations correlate

to poor prognosis in glioma patients: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets

Ther. 9:3485–3492. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Aubrey BJ, Kelly GL, Janic A, Herold MJ

and Strasser A: How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this

relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ.

25:104–113. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Vaddavalli P and Schumacher B: The p53

network: Cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in cancer and

aging. Trends Genet. 38:598–612. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Bouaoun L, Sonkin D, Ardin M, Hollstein M,

Byrnes G, Zavadil J and Olivier M: TP53 variations in human

cancers: New lessons from the IARC TP53 database and genomics data.

Hum Mutat. 37:865–876. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Mantovani F, Collavin L and Del Sal G:

Mutant p53 as a guardian of the cancer cell. Cell Death Differ.

26:199–212. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Keriel A, Stary A, Sarasin A,

Rochette-Egly C and Egly JM: XPD mutations prevent TFIIH-dependent

transactivation by nuclear receptors and phosphorylation of

RARalpha. Cell. 109:125–135. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Coin F, Marinoni JC, Rodolfo C, Fribourg

S, Pedrini AM and Egly JM: Mutations in the XPD helicase gene

result in XP and TTD phenotypes, preventing interaction between XPD

and the p44 subunit of TFIIH. Nat Genet. 20:184–188.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Lunn RM, Helzlsouer KJ, Parshad R, Umbach

DM, Harris EL, Sanford KK and Bell DA: XPD polymorphisms: Effects

on DNA repair proficiency. Carcinogenesis. 21:551–555.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Mohamed NS, Ali Albsheer MM, Abdelbagi H,

Siddig EE, Mohamed MA, Ahmed AE, Omer RA, Muneer MS, Ahmed A, Osman

HA, et al: Genetic polymorphism of the N-terminal region in

circumsporozoite surface protein of Plasmodium falciparum field

isolates from Sudan. Malar J. 18(333)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Ju HL, Kang JM, Moon SU, Kim JY, Lee HW,

Lin K, Sohn WM, Lee JS, Kim TS and Na BK: Genetic polymorphism and

natural selection of Duffy binding protein of Plasmodium vivax

Myanmar isolates. Malar J. 11:1–110. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Thompson EE, Sun Y, Nicolae D and Ober C:

Shades of gray: A comparison of linkage disequilibrium between

Hutterites and Europeans. Genet Epidemiol. 34:133–139.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Tibayrenc M: Human genetic diversity and

the epidemiology of parasitic and other transmissible diseases. Adv

Parasitol. 64:377–422. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Guo CY, DeStefano AL, Lunetta KL, Dupuis J

and Cupples LA: Expectation maximization algorithm based haplotype

relative risk (EM-HRR): Test of linkage disequilibrium using

incomplete case-parents trios. Hum Hered. 59:125–135.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Silverman EK, Chapman HA, Drazen JM, Weiss

ST, Rosner B, Campbell EJ, O'Donnell WJ, Reilly JJ, Ginns L,

Mentzer S, et al: Genetic epidemiology of severe, early-onset

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Risk to relatives for

airflow obstruction and chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med. 157:1770–1778. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Karahalil B, Bohr VA and Wilson DM III:

Impact of DNA polymorphisms in key DNA base excision repair

proteins on cancer risk. Hum Exp Toxicol. 31:981–1005.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Bookman EB, McAllister K, Gillanders E,

Wanke K, Balshaw D, Rutter J, Reedy J, Shaughnessy D, Agurs-Collins

T, Paltoo D, et al: Gene-environment interplay in common complex

diseases: Forging an integrative model-recommendations from an NIH

workshop. Genet Epidemiol. 35:217–225. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Daly AK: Pharmacogenetics and human

genetic polymorphisms. Biochem J. 429:435–449. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Mathur R, Rana BS and Jha AK: Single

nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). In: Vonk J, Shackelford T (eds).

Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Springer, Cham,

pp1-4, 2018.

|

|

76

|

Ando Y, Saka H, Ando M, Sawa T, Muro K,

Ueoka H, Yokoyama A, Saitoh S, Shimokata K and Hasegawa Y:

Polymorphisms of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase gene and irinotecan

toxicity: A pharmacogenetic analysis. Cancer Res. 60:6921–6926.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, Molina JM,

Workman C, Tomazic J, Jägel-Guedes E, Rugina S, Kozyrev O, Cid JF,

et al: HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N

Engl J Med. 358:568–579. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Halder I and Shriver MD: Measuring and

using admixture to study the genetics of complex diseases. Hum

Genomics. 1:52–62. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Hu D and Ziv E: Confounding in genetic

association studies and its solutions. Methods Mol Biol. 448:31–39.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Hettiarachchi G and Komar AA: GWAS to

identify SNPs associated with common diseases and individual risk:

Genome wide association studies (GWAS) to identify SNPs associated

with common diseases and individual risk. In: Sauna ZE,

Kimchi-Sarfaty C (eds). Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Springer,

Cham, pp51-76, 2022.

|

|

81

|

Uffelmann E, Huang QQ, Munung NS, De Vries

J, Okada Y, Martin AR, Martin HC, Lappalainen T and Posthuma D:

Genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Methods Primers.

1(59)2021.

|

|

82

|

Umeno M, McBride OW, Yang CS, Gelboin HV

and Gonzalez FJ: Human ethanol-inducible P450IIE1: Complete gene

sequence, promoter characterization, chromosome mapping, and

cDNA-directed expression. Biochemistry. 27:9006–9013.

1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Guengerich FP, Kim DH and Iwasaki M: Role

of human cytochrome P-450 IIE1 in the oxidation of many low

molecular weight cancer suspects. Chem Res Toxicol. 4:168–179.

1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Nakajima T and Aoyama T: Polymorphism of

drug-metabolizing enzymes in relation to individual susceptibility

to industrial chemicals. Ind Health. 38:143–152. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Wang AH, Sun CS, Li LS, Huang JY and Chen

QS: Relationship of tobacco smoking CYP1A1 GSTM1 gene polymorphism

and esophageal cancer in Xi'an. World J Gastroenterol. 8:49–53.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Bartsch H, Nair U, Risch A, Rojas M,

Wikman H and Alexandrov K: Genetic polymorphism of CYP genes, alone

or in combination, as a risk modifier of tobacco-related cancers.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 9:3–28. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Itoga S, Nomura F, Makino Y, Tomonaga T,

Shimada H, Ochiai T, Iizasa T, Baba M, Fujisawa T and Harada S:

Tandem repeat polymorphism of the CYP2E1 gene: An association study

with esophageal cancer and lung cancer. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 26 (8

Suppl):15S–19S. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Danko IM and Chaschin NA: Association of

CYP2E1 gene polymorphism with predisposition to cancer development.

Exp Oncol. 27:248–256. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Hayashi S, Watanabe J and Kawajiri K:

Genetic polymorphisms in the 5'-flanking region change

transcriptional regulation of the human cytochrome P450IIE1 gene. J

Biochem. 110:559–565. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Watanabe M: Polymorphic CYP genes and

disease predisposition-what have the studies shown so far? Toxicol

Lett. 102-103:167–171. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Yang B, O'Reilly DA, Demaine AG and

Kingsnorth AN: Study of polymorphisms in the CYP2E1 gene in

patients with alcoholic pancreatitis. Alcohol. 23:91–97.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Yu SZ, Huang XE, Koide T, Cheng G, Chen

GC, Harada K, Ueno Y, Sueoka E, Oda H, Tashiro F, et al: Hepatitis

B and C viruses infection, lifestyle and genetic polymorphisms as

risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Haimen, China. Jpn J

Cancer Res. 93:1287–1292. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Munaka M, Kohshi K, Kawamoto T, Takasawa

S, Nagata N, Itoh H, Oda S and Katoh T: Genetic polymorphisms of

tobacco- and alcohol-related metabolizing enzymes and the risk of

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 129:355–360.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Norton ID, Apte MV, Haber PS, McCaughan

GW, Pirola RC and Wilson JS: Cytochrome P4502E1 is present in rat

pancreas and is induced by chronic ethanol administration. Gut.

42:426–430. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Catanzaro I, Naselli F, Saverini M,

Giacalone A, Montalto G and Caradonna F: Cytochrome P450 2E1

variable number tandem repeat polymorphisms and health risks: A

genotype-phenotype study in cancers associated with drinking and/or

smoking. Mol Med Rep. 6:416–420. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Christiani DC, Mehta AJ and Yu CL: Genetic

susceptibility to occupational exposures. Occup Environ Med.

65:430–436, 436, 397. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Pizzino G, Bitto A, Interdonato M, Galfo

F, Irrera N, Mecchio A, Pallio G, Ramistella V, De Luca F, Minutoli

L, et al: Oxidative stress and DNA repair and detoxification gene

expression in adolescents exposed to heavy metals living in the

Milazzo-Valle del Mela area (Sicily, Italy). Redox Biol. 2:686–693.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Kringel D, Lippmann C, Parnham MJ, Kalso

E, Ultsch A and Lötsch J: A machine-learned analysis of human gene

polymorphisms modulating persisting pain points to major roles of

neuroimmune processes. Eur J Pain. 22:1735–1756. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Pandiyan A, Lari S, Vanka J, Kumar BS,

Ghosh S, Jee B and Jonnalagadda PR: Genetic polymorphism in

xenobiotic metabolising genes and increased oxidative stress among

pesticides exposed agricultural workers diagnosed with cancers.

Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 24:3795–3804. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100