1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and periodontitis are two

prevalent chronic inflammatory conditions with profound systemic

and local consequences. RA, a systemic autoimmune disease,

predominantly affects synovial joints, leading to progressive joint

destruction and systemic comorbidities, including cardiovascular

disease and osteoporosis. Periodontitis, on the other hand, is a

destructive inflammatory disease of periodontal tissues

characterized by bone loss and potential tooth loss if left

untreated (1). While they affect

different anatomical regions, pathophysiological mechanisms

underlying both diseases show considerable overlap, particularly in

the context of immune-mediated inflammation.

Recent systematic reviews and large population

cohorts confirm a bidirectional association between periodontitis

and RA, with periodontitis linked to a higher risk of developing RA

and patients with RA exhibiting a greater periodontal burden

(2-4).

However, current evidence still supports an association rather than

a definitive causal association (5). The present review summarizes the

interconnectedness of oral health conditions, examining

inflammatory mechanisms, the role of oral pathogens and clinical

implications for the management of these conditions.

2. Historical background

RA and periodontitis, although distinct in their

anatomical manifestations, share a rich and evolving medical

history marked by significant advancements in understanding their

pathogenesis and clinical management. RA has been a subject of

medical interest since the 19th century, with Alfred B. Garrod

formally distinguishing it from other forms of arthritis in

1859(6). Early conceptions of RA

were grounded in the notion of chronic synovial inflammation;

however, the discovery of rheumatoid factor (RF) in the early 20th

century and the subsequent identification of autoantibodies, such

as the anti-perinuclear factor in the 1960s, later recognized as a

precursor to the modern anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)

tests, marked a pivotal shift toward recognizing RA as an

autoimmune condition. These immunologic insights lay the groundwork

for the development of biological and targeted therapies, most

notably tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors, which markedly

alter disease outcomes by reducing inflammation, attenuating joint

destruction and improving the quality of life of patients. Despite

these advancements, RA continues to be a progressive systemic

disorder with multifaceted manifestations beyond joint involvement

(7).

In parallel, periodontitis has been recognized as a

significant oral health concern for the millennia, with

archeological evidence of periodontal destruction found in ancient

human remains. However, it was not until the 20th century that its

microbial etiology was firmly established. The identification of

specific periodontal pathogens, such as Porphyromonas

gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema

denticola, revolutionized the understanding of periodontitis as

a biofilm-mediated disease (8).

This paradigm shift was further reinforced in the 1970s with the

emergence of the microbial biofilm concept, which emphasized the

structured and cooperative nature of bacterial communities in

dental plaque. In addition to microbial research, increasing

attention has been paid to the host immune response, particularly

the role of inflammatory cytokines in mediating periodontal tissue

breakdown (9). Together, these

discoveries have shaped the modern view of periodontitis as a

chronic inflammatory disease driven by complex interactions between

dysbiotic microbial communities and a dysregulated host immune

response.

The historical development of knowledge surrounding

RA and periodontitis highlights a shared trajectory wherein

advances in immunology and microbiology have informed both

diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. This convergence has sparked

growing interest in their potential bidirectional association,

particularly in the context of systemic inflammation and immune

modulation (10).

3. Epidemiological data

RA and periodontitis share common epidemiological

features in that both conditions are prevalent worldwide and

exhibit sex-based differences. RA affects ~0.5-1% of the global

population, with women being more frequently affected than men.

Onset typically occurs between the ages of 30 and 50 years. Global

epidemiological studies suggest that periodontitis affects >50%

of adults, with estimates ranging from 45-55% for any form of

disease. Notably, ~10-15% of adults are affected by severe

periodontitis, while the remainder exhibit mild-to-moderate

disease. The prevalence varies substantially depending on

population, socioeconomic status, and risk factors (11).

Numerous studies have highlighted the connection

between RA and periodontitis, with several population-based studies

revealing a greater prevalence of periodontitis in patients with RA

than in healthy controls (12).

The meta-analysis by de Pablo et al demonstrated that

patients with RA are at a 2-fold greater risk of developing

moderate-to-severe periodontitis. Additionally, patients with

periodontitis show a greater prevalence of RA, particularly when

the levels of serological markers, such as anti-cyclic

citrullinated peptide antibodies are elevated. Current evidence

supports an association, but does not confirm causality (13).

One particularly notable finding was derived from

the study of Porphyromonas gingivalis, a key periodontal

pathogen. This bacterium is capable of generating citrullinated

peptides, which are major targets of autoantibodies in RA,

suggesting a microbial trigger for the autoimmune response observed

in RA (14).

4. Pathophysiology

RA and periodontitis are both chronic inflammatory

diseases characterized by dysregulated immune responses and

progressive tissue destruction, albeit occurring in different

anatomical sites. RA primarily affects the synovial joints and is

classified as an autoimmune disease. It arises from a complex

interplay of genetic predispositions, environmental exposures and

immune dysregulation (15). A key

genetic factor linked to RA susceptibility is the presence of

specific HLA-DRB1 alleles, particularly those encoding the ‘shared

epitope’, a conserved amino acid sequence associated with an

increased risk. Environmental triggers, such as cigarette smoking

and exposure to certain microbes, can initiate an aberrant immune

response in genetically susceptible individuals, leading to chronic

synovial inflammation (2,15).

Immunologically, RA is characterized by the

infiltration of immune cells, including CD4+ T-cells,

B-cells, macrophages and neutrophils into the synovial membrane.

These cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α,

interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and IL-17, which sustain the inflammatory

environment and contribute to synovial hyperplasia and pannus

formation (16). The receptor

activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin

(OPG) axis is critically involved in bone remodeling in RA; an

imbalance favoring RANKL promotes osteoclastogenesis and bone

resorption, leading to characteristic joint destruction (15).

Similarly, periodontitis is driven by a chronic

immune-inflammatory response initiated by the accumulation of

pathogenic subgingival bacteria, such as Porphyromonas

gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema

denticola. These organisms form structured biofilms on tooth

surfaces and subvert the host immune response, leading to a

persistent inflammatory state. Immune cell infiltration in gingival

tissues involves neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and T

helper 17 (Th17) cells, with IL-17 playing a pivotal role in

sustaining inflammation. IL-17 enhances neutrophil chemotaxis and

stimulates the release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which

degrade extracellular matrix components and contribute to

connective tissue breakdown (17).

Moreover, the RANKL/OPG axis is also dysregulated in

periodontitis. The increased expression of RANKL by activated

T-cells and osteoblasts enhances osteoclast differentiation and

activity, resulting in alveolar bone resorption and periodontal

attachment loss. The overlapping pathogenic mechanisms,

particularly the roles of proinflammatory cytokines, Th17 cells and

the RANKL/OPG pathway, highlight the shared molecular pathways

between RA and periodontitis, supporting the growing body of

evidence linking these two chronic inflammatory diseases (18).

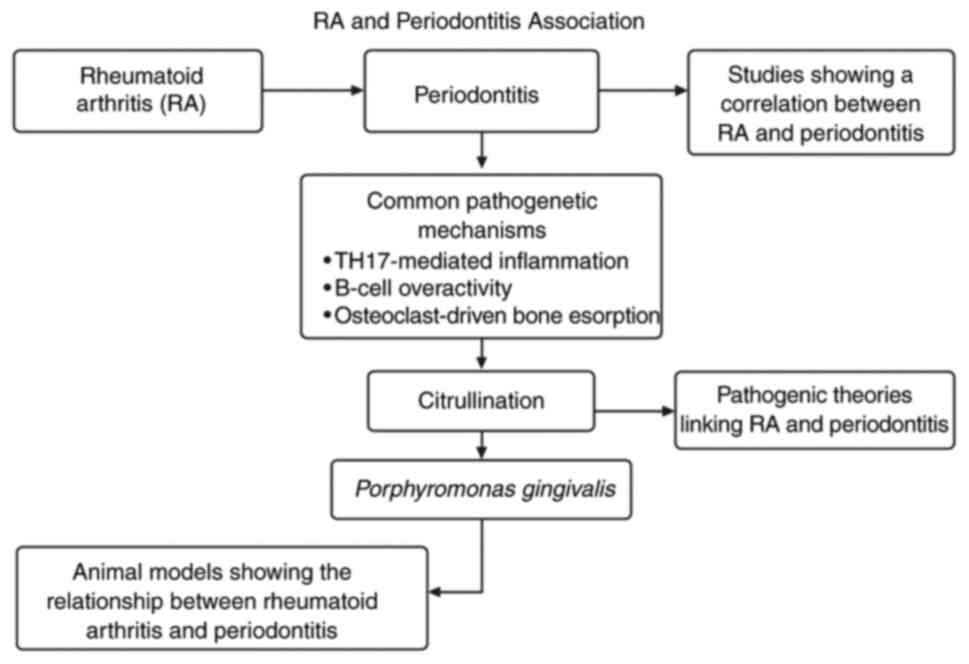

5. Common pathogenetic mechanisms

The overlapping immunopathological mechanisms

between RA and periodontitis suggest a bidirectional association

(Fig. 1). Both diseases are

characterized by excessive inflammation mediated by Th17 cells and

increased levels of IL-17. This cytokine promotes the activation of

osteoclasts via the RANKL/OPG axis, leading to bone resorption in

both the joints in RA and the alveolar bone in periodontitis

(19).

Another key intersection is the presence of

citrullinated proteins. Among periodontal pathogens,

Porphyromonas gingivalis produces peptidyl arginine

deiminase, which catalyzes the citrullination of host proteins,

thereby providing a possible link to ACPA formation. In addition,

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans can induce neutrophil

hypercitrullination, representing another microbial mechanism

potentially associated with RA. These findings highlight that

multiple periodontal pathogens may contribute to autoimmune

responses, although a definitive causal role has not yet been

established. These citrullinated peptides can initiate an

autoimmune response in genetically susceptible individuals,

contributing to the development of RA (16,20).

Systemic inflammation is another common feature of

both diseases, with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines,

such as TNF-α, IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP). These markers not

only reflect disease activity, but may also contribute to the

pathogenesis of both RA and periodontitis (1).

6. Correlative studies and animal

models

Several observational studies have confirmed the

association between RA and periodontitis. The Epidemiological

Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) study, for example,

revealed that individuals with severe periodontitis are at an

increased risk of developing RA (21). Other studies have shown that

patients with RA with periodontitis exhibit increased levels of

systemic inflammation and worse disease outcomes (5,7).

Clinical intervention studies have also demonstrated

the benefits of periodontal therapy in the management of RA. For

example, Kaushal et al (22) reported that non-surgical

periodontal treatment improved the disease activity score in 28

joints (DAS-28) in patients with RA, suggesting that managing

periodontal health can have a positive impact on systemic

inflammation in patients with RA.

Animal models have also been instrumental in

elucidating the bidirectional association between RA and

periodontitis. In a previous study, in a mouse model of

collagen-induced arthritis, it was shown that when combined with

Porphyromonas gingivalis infection, animals developed more

severe joint damage (23).

Similarly, the ligature-induced periodontitis model in rats has

been used to determine how periodontal disease exacerbates systemic

inflammation and joint pathology (24).

Double-hit models, in which both RA and

periodontitis are induced simultaneously, provide further evidence

for the synergistic association between these two diseases. These

models reveal elevated levels of IL-17, RANKL and MMPs, mimicking

the clinical scenario observed in human patients (25,26).

7. Pathogenic theories

There are two primary theories that explain the

connection between RA and periodontitis, as follows:

i) Autoimmune hypothesis

Periodontal inflammation leads to the systemic

dissemination of citrullinated peptides, which prime the immune

system to produce ACPAs. These autoantibodies target citrullinated

proteins, leading to the development of RA (27).

ii) Microbial hypothesis

Periodontal pathogens, including Porphyromonas

gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans,

may translocate to joints or initiate immune responses that

cross-react with joint tissues. DNA from oral bacteria has been

detected in synovial fluid, supporting their potential association

with the pathogenesis of RA, although direct causality remains

unproven (28).

8. Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of RA and periodontitis

involve inflammation and progressive tissue destruction, with

overlapping inflammatory pathways that complicate diagnosis and

management when both conditions are present.

RA typically presents with symmetrical

polyarthritis, affecting both large and small joints, often

beginning in the hands and feet. Symptoms include joint pain,

stiffness, swelling and warmth of the affected joints (15,20).

Morning stiffness that persists for at least 1 h tends to improve

with movement. Over time, joint damage may cause deformities, such

as ulnar deviation and swan-neck deformities. Systemic symptoms

include fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss and anemia.

Extra-articular manifestations, such as rheumatoid nodules,

cardiovascular complications, such as atherosclerosis, pulmonary

fibrosis and severe rheumatoid vasculitis can also occur, affecting

small blood vessels and causing skin lesions and ulcers (1,29).

Periodontitis, an inflammatory disease affecting the

supporting structures of the teeth, is characterized by gingival

inflammation, pocket formation, alveolar bone loss and tooth

mobility. Clinical signs include bleeding gums, swelling and

redness, which worsen with brushing or probing. As the disease

progresses, deep periodontal pockets form, leading to tooth

mobility and visible bone loss on radiographs. Gingival recession

exposes tooth roots, causing sensitivity and aesthetic concerns.

Severe periodontitis may result in abscesses, swelling, pain and

pus formation. Halitosis often accompanies the disease due to

bacterial activity in the pockets (30,31).

The bidirectional association between RA and

periodontitis complicates clinical management. Patients with RA are

often more susceptible to developing periodontal disease due to

factors, such as immunosuppressive therapy, reduced manual

dexterity and medication side-effects such as xerostomia. In turn,

periodontitis in patients with RA can exacerbate systemic

inflammation, worsen joint symptoms, and create a vicious cycle

that accelerates joint damage and decreases treatment

effectiveness. Chronic periodontal inflammation can significantly

affect RA disease activity, rendering both conditions more

difficult to manage (32).

9. Diagnostic considerations

The diagnosis of both RA and periodontitis involves

a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory testing and

imaging studies. For patients with overlapping RA and

periodontitis, early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for

implementing effective treatment strategies.

Diagnosis of RA

The diagnosis of RA begins with a thorough clinical

history and examination. Symmetrical joint involvement and morning

stiffness lasting for >1 h are key symptoms of RA. Specific

serological markers, including RF, which is positive in 60-80% of

patients with RA, and ACPAs, which have high specificity for RA,

help confirm the diagnosis. Additionally, elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rates and CRP levels are indicative of systemic

inflammation and provide evidence of active disease (1).

Imaging analyses play a crucial role in assessing

joint damage. Radiographs reveal joint space narrowing, erosions

and periarticular osteopenia, which are characteristic of RA.

Ultrasound and MRI are valuable tools for detecting early

inflammatory changes and assessing synovial thickening and fluid

accumulation, often before radiographic damage is evident (33,34).

Diagnosis of periodontitis

The diagnosis of periodontitis is based on clinical

and radiographic criteria. A clinical evaluation includes measuring

the probing depth and clinical attachment level, which assess the

extent of pocket formation and tissue destruction. Indicators, such

as bleeding on probing and tooth mobility are suggestive of active

disease. Radiographs provide essential information regarding the

extent of alveolar bone loss and the severity of periodontal

involvement (30).

Periodontitis is classified on the basis of its

severity and extent, ranging from mild gingivitis to severe

periodontitis, which is characterized by significant bone loss and

deep periodontal pockets (5). This

classification is vital for determining the appropriate treatment

approach.

10. Screening for overlap and prognosis

Given the potential for increased disease severity

when both RA and periodontitis co-occur, screening for periodontal

disease in patients with RA and vice versa is strongly recommended.

Routine oral assessments for patients with RA can aid in the early

detection and management of periodontal disease, which may, in

turn, aid in controlling the disease activity of RA. Conversely,

screening patients with RA for periodontal involvement can improve

the management of both conditions through a coordinated care

approach (29,31).

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with RA and periodontitis

is complex due to the interaction between systemic inflammation and

oral health. Both diseases contribute to the other's progression,

with periodontal inflammation exacerbating RA symptoms and vice

versa. In patients with RA, periodontitis increases systemic

inflammation, leading to elevated CRP and pro-inflammatory cytokine

levels, which may exacerbate joint symptoms. Some research suggests

that this could reduce responsiveness to disease-modifying

anti-rheumatic drugs and biologics, although evidence remains

limited and further studies are required to confirm this

association (11). Evidence

suggests that periodontal treatment can improve RA symptoms by

reducing systemic inflammation and potentially slowing joint

destruction (12). In patients

with periodontitis, RA can contribute to the rapid progression of

periodontal disease, and immunosuppressive therapies can impair the

ability of the body to manage periodontal pathogens, leading to

more severe disease. Integrated care for improved prognosis is

crucial, and collaboration between rheumatologists and

periodontists can help manage both conditions more effectively

(6,35).

11. Management and treatment

The management of RA and periodontitis requires a

comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach that addresses both local

and systemic factors. Treatment for both conditions aims to control

inflammation, prevent further damage and improve the overall

quality of life of affected individuals.

Management of RA

The primary goal of RA treatment is to control joint

inflammation and prevent further damage (Table I) (36,37).

| Table IManagement of rheumatoid

arthritis. |

Table I

Management of rheumatoid

arthritis.

| Treatment

Modality | Description | Considerations in

periodontal context |

|---|

| NSAIDs | Alleviate pain and

control inflammation; provide symptomatic relief. | Useful for managing

inflammation but do not alter disease progression. |

| DMARDs (e.g.,

methotrexate) | Slow disease

progression and prevent joint destruction. | May improve

systemic inflammation; immune modulation can affect periodontal

healing. |

| Biological agents

(e.g., TNF inhibitors) | Target

proinflammatory cytokines for severe RA treatment. | Enhanced control of

inflammation may benefit periodontal outcomes. |

|

Corticosteroids | Used during

flare-ups to control inflammation; long-term use limited due to

side-effects. | Long-term use may

cause osteoporosis, complicating periodontal therapy and bone

health. |

| Nonpharmacological

interventions | Physical therapy,

exercise, occupational therapy to maintain joint function and.

mobility | Improved physical

health and reduced disability can enhance oral hygiene

practices. |

| Surgical

interventions | Repair or

replacement of severely damaged joints. | Restoration of

function may indirectly improve oral hygiene ability and overall

health. |

Management of periodontitis

The management of periodontitis primarily focuses on

eliminating the source of infection, reducing inflammation and

regenerating lost tissue (Table

II) (38-40).

| Table IIManagement of periodontitis. |

Table II

Management of periodontitis.

| Treatment

Modality | Description | Purpose/impact |

|---|

| Scaling and root

planing (SRP) | Mechanical removal

of plaque and calculus from root surfaces; smoothing of roots. | Reduces bacterial

load, promotes healing, and establishes a healthier oral

environment. |

| Antibiotic

therapy | Use of topical or

systemic antibiotics targeting specific pathogens (e.g.,

Porphyromonas gingivalis). | Enhances bacterial

control, particularly in aggressive or refractory cases. |

| Surgical

therapy | Procedures to

regenerate lost periodontal tissue or reduce deep pockets (e.g.,

flap surgery, bone grafts). | Improves access for

debridement, restores periodontal architecture, and reduces pocket

depth. |

| Host modulation

therapy | Use of agents such

as low-dose doxycycline to modify the inflammatory response of the

host. | Reduces tissue

destruction, preserves periodontal support, and enhances treatment

outcomes. |

Although some clinical research has reported

improvements in periodontal parameters with anti-TNF-α and

anti-IL-6 therapy, findings are not consistent across populations

(7). Thus, any potential

periodontal benefit of RA biologics should be interpreted with

caution, as current evidence does not establish a definitive

therapeutic effect.

Impact of periodontal treatment on

RA

Effective periodontal treatment has been shown to

have a significant positive effect on RA by reducing systemic

inflammation, a key contributor to disease pathogenesis. It has

been demonstrated that periodontal therapy can lead to lower levels

of CRP, a marker of systemic infection, and improve the DAS-28,

reflecting better control over RA symptoms (41). The bidirectional association

between RA and periodontitis suggests that managing one condition

can help improve the outcomes of the other, reinforcing the need

for a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to patient care

(20,42). Recent randomized trials and

systematic reviews have reported that non-surgical periodontal

therapy (scaling and root planning ± local/systemic adjuncts) can

reduce systemic inflammatory markers and modestly reduce RA disease

activity (mean DAS-28 reductions reported in meta-analyses ~0.3-0.5

points), although the results are heterogeneous and

patient-selection dependent. These data support routine periodontal

screening in RA clinics and collaborative management pathways where

periodontitis is present (43).

These findings underscore the importance of an integrated approach

to treatment, where addressing periodontal disease can directly

enhance the management of RA.

12. Conclusions and future directions

Research gaps and future

directions

Despite progress being made in the understanding of

the association between RA and periodontitis, there gaps remain in

research. Longitudinal studies are required to determine whether

treating one disease can prevent the onset or progression of the

other, with a focus on biomarkers of disease progression and the

effect of periodontal treatment on RA progression. Specific

biomarker candidates include: Citrullinated vimentin (anti-MCV),

implicated in osteoclast activation and bone resorption;

citrullinated α-enolase/CEP-1 and related ACPA specificities that

cross-react with bacterial enolases; neutrophil-derived proteases

(e.g., elastase, proteinase-3) detectable in saliva and gingival

crevicular fluid reflecting neutrophil hyperactivation; and oral

microbiome signatures (16S/shotgun panels) that may distinguish

early RA or predict periodontal disease progression. Evidence of

the role of citrullinated vimentin in bone resorption has been

demonstrated in animal models, and clinical studies have revealed

increased levels of antibodies against citrullinated bacterial

epitopes in early-stage RA (32,44,45).

Incorporating these markers into prospective, standardized cohort

studies will clarify temporal relations and may enable precision

screening in high-risk patients. Potential candidates under current

investigation include citrullinated vimentin and α-enolase as

autoantigens, salivary protease markers reflective of periodontal

tissue destruction, and microbiome signatures specific to

periodontitis. Incorporating these markers into longitudinal

studies may clarify the temporal association between RA and

periodontitis and guide precision medicine approaches.

Understanding the role of specific microbes and their interactions

with the host immune system could provide new insights into the

pathogenesis of both diseases and the genetic basis for the overlap

in susceptibility to RA and periodontitis. Future clinical trials

are required to evaluate the efficacy of co-management strategies

for RA and periodontitis, assessing whether integrated care

improves patient outcomes in both oral and systemic health.

Limitations of current evidence

While numerous studies support an association

between RA and periodontitis, the current body of evidence has

several limitations. A number of investigations are cross-sectional

in nature, rendering it difficult to establish temporal

associations or causality. Potential confounding factors, such as

smoking, socioeconomic status, diabetes and other systemic

comorbidities may influence both diseases, and complicate the

interpretation of the associations. Furthermore, heterogeneity in

diagnostic criteria for both RA and periodontitis across studies

reduces comparability. Sample sizes in interventional trials are

often small, limiting generalizability. Longitudinal and

multicenter studies with standardized definitions are thus

warranted to strengthen the evidence base.

In conclusion, the association between RA and

periodontitis is complex, with inflammation being a common factor

accelerating their progression. This highlights the need for

integrated care approaches that address both systemic and oral

health. Early diagnosis and effective management of periodontitis

in patients with RA can improve patient outcomes, reduce joint

damage and enhance treatment response. Collaborative efforts

between rheumatologists and periodontists are essential to unravel

the underlying mechanisms linking these diseases. Future research

into biomarkers, genetic predispositions and microbial interactions

will lead to personalized therapies and to an improved quality of

life for affected patients. Bridging the gap between oral and

systemic health care is now necessary for holistic,

patient-centered treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

The current review represents an original synthesis

by the authors, integrating immunopathological, clinical and

therapeutic perspectives on the RA-periodontitis relationship. AS

was responsible for the conceptualization of the study, conducted

the literature search, curation of data from the literature and

drafted the manuscript. DGK and NS supervised the study, critically

reviewed the content, and provided expert input on periodontology

and systemic disease interactions. All authors contributed to

refining the manuscript, ensuring accuracy, and reading and

approving the final version. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Batool H, Afzal N, Shahzad F and Kashif M:

Relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and chronic

periodontitis. J Med Radiol Pathol Surg. 2:11–14. 2016.

|

|

2

|

Dolcezza S, Flores-Fraile J, Lobo-Galindo

AB, Montiel-Company JM and Zubizarreta-Macho Á: Relationship

between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease-systematic

review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 14(10)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chang Y, Chung MK, Park JH and Song TJ:

Association of oral health with risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A

nationwide cohort study. J Pers Med. 13(340)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bolstad AI, Fevang BTS and Lie SA:

Increased risk of periodontitis in patients with rheumatoid

arthritis: A nationwide register study in Norway. J Clin

Periodontol. 50:1022–1032. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zielińska A and Tabarkiewicz J:

Correlation between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. Eur J

Clin Exp Med. 20:451–458. 2022.

|

|

6

|

Bartold PM and Lopez-Oliva I:

Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: An update 2012-2017.

Periodontol 2000. 83:189–212. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Hamed MN and Ali BG: Serum level of TNF-α

and IL-17 in patient have chronic periodontitis associated

rheumatoid arthritis. J Bagh Coll Dent. 29:104–110. 2017.

|

|

8

|

Hussain SB, Botelho J, Machado V, Zehra

SA, Mendes JJ, Ciurtin C, Orlandi M and D'Aiuto F: Is there a

bidirectional association between rheumatoid arthritis and

periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin

Arthritis Rheum. 50:414–422. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Agnihotri R and Gaur S: Rheumatoid

arthritis in the elderly and its relationship with periodontitis: A

review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 14:8–22. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

de Pablo P, Chapple ILC, Buckley CD and

Dietrich T: Periodontitis in systemic rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev

Rheumatol. 5:218–224. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mercado FB, Marshall RI, Klestov AC and

Bartold PM: Relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and

periodontitis. J Periodontol. 72:779–787. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Leech MT and Bartold PM: The association

between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. Best Pract Res Clin

Rheumatol. 29:189–201. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

De Pablo P, Dietrich T and Karlson EW:

Antioxidants and other novel cardiovascular risk factors in

subjects with rheumatoid arthritis in a large population sample.

Arthritis Rheum. 57:953–962. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ceccarelli F, Orrù G, Pilloni A,

Bartosiewicz I, Perricone C, Martino E, Lucchetti R, Fais S, Vomero

M, Olivieri M, et al: Porphyromonas gingivalis in the tongue

biofilm is associated with clinical outcome in rheumatoid arthritis

patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 194:244–252. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chatterjee A, Jayaprakasan M, Chakrabarty

AK, Lakkaniga NR, Bhatt BN, Banerjee D, Narwaria A, Katiyar CK and

Dubey SK: Comprehensive insights into rheumatoid arthritis:

Pathophysiology, current therapies and herbal alternatives for

effective disease management. Phytother Res. 39:2764–2799.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Poryadin GV, Zakhvatov AN and Parshina AY:

Pathogenetic relationship of immunological disorders in chronic

generalized periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Russ Arch

Intern Med. 12:203–211. 2022.

|

|

17

|

Syniachenko OV, Yermolaieva MV, Havilei

DO, Liventsova KV, Verzilov SM and Pylypenko VV: Clinical and

pathogenetic features of the joint syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis

with comorbid periodontitis. Travma. 21:10–15. 2020.

|

|

18

|

Na HS, Kim SY, Han H, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Lee

JH and Chung J: Identification of potential oral microbial

biomarkers for the diagnosis of periodontitis. J Clin Med.

9(1549)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Arkema EV, Karlson EW and Costenbader KH:

A prospective study of periodontal disease and risk of rheumatoid

arthritis. J Rheumatol. 37:1800–1804. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Acharya A, Li S, Liu X, Pelekos G, Ziebolz

D and Mattheos N: Biological links in periodontitis and rheumatoid

arthritis: Discovery via text-mining PubMed abstracts. J

Periodontal Res. 54:318–328. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Eriksson K, Nise L, Kats A, Luttropp E,

Catrina AI, Askling J, Jansson L, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L,

Lundberg K and Yucel-Lindberg T: Prevalence of periodontitis in

patients with established rheumatoid arthritis: A Swedish

population based case-control study. PLoS One.

11(e0155956)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kaushal S, Singh AK, Lal N, Das SK and

Mahdi AA: Effect of periodontal therapy on disease activity in

patients of rheumatoid arthritis with chronic periodontitis. J Oral

Biol Craniofac Res. 9:128–132. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shimizu M, Kondo Y, Tanimura R, Furuyama

K, Yokosawa M, Asashima H, Tsuboi H, Matsumoto I and Sumida T:

T-bet represses collagen-induced arthritis by suppressing Th17

lineage commitment through inhibition of RORγt expression and

function. Sci Rep. 11(17357)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Srivastava M, Neupane YR, Kumar P and

Kohli K: Nanoemulgel (NEG) of Ketoprofen with eugenol as oil phase

for the treatment of ligature-induced experimental periodontitis in

Wistar rats. Drug Deliv. 23:2228–2234. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shimizu S, Hayashi K, Takeuchi Y, Tanabe

G, Churei H, Kobayashi H, Ueno T and Fueki K: Effect of

Porphyromonas gingivalis infection on healing of skeletal

muscle injury: An in vivo study. Dent J (Basel).

12(346)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Sakuraba K, Oyamada A, Fujimura K, Spolski

R, Iwamoto Y, Leonard WJ, Yoshikai Y and Yamada H: Interleukin-21

signaling in B cells, but not in T cells, is indispensable for the

development of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Arthritis Res

Ther. 18(188)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kharlamova N, Jiang X, Sherina N, Potempa

B, Israelsson L, Quirke AM, Eriksson K, Yucel-Lindberg T, Venables

PJ, Potempa J, et al: Antibodies to Porphyromonas gingivalis

indicate interaction between oral infection, smoking, and risk

genes in rheumatoid arthritis etiology. Arthritis Rheumatol.

68:604–613. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yilmaz D, Niskanen K, Gonullu E,

Tervahartiala T, Gürsoy UK and Sorsa T: Salivary and serum levels

of neutrophil proteases in periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Oral Dis. 30:1660–1668. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kaczyński T, Wroński J, Głuszko P and

Górska R: Link between rheumatoid arthritis and chronic

periodontitis. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 72:69–80. 2018.

|

|

30

|

Research, Science and Therapy Committee.

Position paper: Diagnosis of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol.

74:1237–1247. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ranade SB and Doiphode S: Is there a

relationship between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis? J

Indian Soc Periodontol. 16:22–27. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Rajkarnikar J, Thomas BS and Rao SK:

Inter-relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis.

Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 11:22–26. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Tan YK and Conaghan PG: Imaging in

rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 25:569–584.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Østergaard M and Boesen M: Imaging in

rheumatoid arthritis: The role of magnetic resonance imaging and

computed tomography. Radiol Med. 124:1128–1141. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Varshney S, Sharma M, Kapoor S and

Siddharth M: Association between rheumatoid arthritis and

periodontitis in an adult population-a cross sectional study. J

Clin Exp Dent. 13:e980–e986. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Krutyhołowa A, Strzelec K, Dziedzic A,

Bereta GP, Łazarz-Bartyzel K, Potempa J and Gawron K: Host and

bacterial factors linking periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Front Immunol. 13(980805)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Monsarrat P, Fernandez de Grado G,

Constantin A, Willmann C, Nabet C, Sixou M, Cantagrel A, Barnetche

T, Mehsen-Cetre N, Schaeverbeke T, et al: The effect of periodontal

treatment on patients with rheumatoid arthritis: The ESPERA

randomised controlled trial. Joint Bone Spine. 86:600–609.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Jajoo NS, Shelke AU and Bajaj RS:

Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: The common thread. Clin Rev

Bone Miner Metab. 18:18–30. 2020.

|

|

39

|

Bingham CO III and Moni M: Periodontal

disease and rheumatoid arthritis: The evidence accumulates for

complex pathobiologic interactions. Curr Opin Rheumatol.

25:345–353. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Koziel J and Potempa J: Pros and cons of

causative association between periodontitis and rheumatoid

arthritis. Periodontol 2000. 89:83–98. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Amos RS, Constable TJ, Crockson RA,

Crockson AP and McConkey B: Rheumatoid arthritis: Relation of serum

C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rates to

radiographic changes. Br Med J. 1:195–197. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Wolf DL and Lamster IB: Contemporary

concepts in the diagnosis of periodontal disease. Dent Clin North

Am. 55:47–61. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AM, Avantario P,

Settanni V, Fatone MC, Piras F, Di Venere D, Inchingolo AD, Palermo

A and Dipalma G: The effects of periodontal treatment on rheumatoid

arthritis and of anti-rheumatic drugs on periodontitis: A

systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 24(17228)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Shindo S, Pierrelus R, Ikeda A, Nakamura

S, Heidari A, Pastore MR, Leon E, Ruiz S, Chheda H, Khatiwala R, et

al: Extracellular release of citrullinated vimentin directly acts

on osteoclasts to promote bone resorption in a mouse model of

periodontitis. Cells. 12(1109)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Sherina N, de Vries C, Kharlamova N, Sippl

N, Jiang X, Brynedal B, Kindstedt E, Hansson M, Mathsson-Alm L,

Israelsson L, et al: Antibodies to a citrullinated Porphyromonas

gingivalis epitope are increased in early rheumatoid arthritis,

and can be produced by gingival tissue B cells: Implications for a

bacterial origin in RA etiology. Front Immunol.

13(804822)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|