1. Introduction

Periodontology and implantology represent dynamic

and evolving disciplines within clinical dentistry, marked by

continuous innovations in diagnostic methodologies, biomaterials

and surgical techniques (1). The

advent of minimally invasive procedures, regenerative therapies and

computer-guided implantology has revolutionized patient care,

enabling clinicians to achieve functional and aesthetic

rehabilitation with increasing predictability and precision

(2,3).

However, these advances have led to a parallel

increase in clinical complexity and the potential for procedural

errors and biological complications. Treatment-related mishaps may

arise at any stage, from initial diagnosis and treatment planning

to intraoperative execution and long-term maintenance. Factors

contributing to such complications include inadequate case

selection, an incomplete understanding of anatomical intricacies,

surgical inexperience and patient-specific considerations, such as

systemic health, compliance and oral hygiene practices (4,5).

While some complications are minor and

self-limiting, others can be severe, resulting in delayed healing,

graft or implant failure, aesthetic dissatisfaction, or

irreversible damage to surrounding tissues. Notably, a number of

these adverse outcomes are preventable through comprehensive

treatment planning, adherence to evidence-based protocols and

continuous clinical vigilance (6,7).

The literature on periodontal and implant

complications is expanding; however, a large amount of this

research remains fragmented, anecdotal or lacking in standardized

classification (1,3). There remains a pressing need to

consolidate current knowledge and identify recurring patterns of

clinical error to foster improved protocols and training.

The present review aimed to provide a structured and

in-depth exploration of the errors and complications encountered in

both periodontal and implant therapy. By dissecting the

multifactorial causes, highlighting diagnostic pitfalls and

outlining contemporary management strategies, the present review

aimed to equip clinicians with the insights necessary to mitigate

risks and refine their practice. A proactive, prevention-driven

approach is paramount, not only to preserve hard-won clinical

outcomes, but also to uphold the highest standards of patient care

in an increasingly demanding therapeutic landscape (8).

Successful outcomes in periodontal and implant

therapy are highly dependent on appropriate patient and site

selection. Several systemic, local, anatomical and patient-related

factors need to be evaluated before deciding on the treatment plan.

A balanced consideration of these determinants allows clinicians to

distinguish between favorable and unfavorable cases. A summary of

the essential aspects of good vs. poor case selection is provided

in Table I.

| Table ICase selection criteria. |

Table I

Case selection criteria.

| Aspect | Good case

selection | Bad case

selection |

|---|

| Systemic

health | Medically fit

patients or those with well-controlled conditions (e.g., diabetes,

hypertension). | Uncontrolled

systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes, bleeding disorders, recent

cardiac events, patients on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or IV

bisphosphonates). |

| Oral hygiene and

motivation | Consistently low

plaque levels, compliance with oral hygiene instructions, and

willingness to attend maintenance visits. | Poor oral hygiene,

persistent plaque/calculus, and lack of cooperation with

maintenance therapy. |

| Periodontal

defects | Well-contained

infrabony pockets, class I furcations, and moderate gingival

recessions that are surgically manageable. | Non-contained

vertical bone loss, class III furcations, or teeth with hopeless

prognosis and advanced mobility. |

| Gingival/tissue

factors | Thick gingival

biotype, sufficient keratinized gingiva, stable soft tissue

conditions. | Thin biotype,

minimal keratinized tissue, high risk of gingival recession and

poor flap stability. |

| Anatomical

considerations | Manageable anatomy;

no severe fenestrations, minimal mandibular tori or tuberosities,

adequate vestibular depth for flap reflection. | Unfavourable

features: prominent external oblique ridge, high genial tubercle,

thin mucosa over mandibular tori, or pronounced undercuts risking

perforation/bleeding. |

| Bone factors

(implants) | Adequate ridge

dimensions (≥6-7 mm width and ≥8 mm height), favourable bone

density (type II-III). | Severe ridge

atrophy, knife-edge ridges, poor bone density, extreme sinus

pneumatization with <4 mm residual bone. |

| Anatomical

safety | Safe distances from

vital structures; inferior alveolar nerve, mental foramen, incisive

canal, sublingual/submental arteries; sinus anatomy favourable or

correctable. | Unclear nerve

location, large anterior loop/incisive canal, high-risk sinus

anatomy, or proximity to critical structures. |

| Radiographic

planning | CBCT or OPG used to

map out implant site and confirm safety margins. | Inadequate imaging

or proceeding without precise radiographic assessment. |

| Patient

factors | Motivated

individuals with realistic aesthetic and functional expectations,

willing to invest in long-term care. | Heavy smokers,

parafunctional habits (e.g., bruxism) without protective therapy,

non-compliant with maintenance, or unrealistic expectations. |

2. Treatment errors and complications in

non-surgical periodontal therapy

Non-surgical periodontal therapy (NSPT),

particularly scaling and root planing (SRP), is the foundation of

periodontal disease management. Although considered conservative

and minimally invasive, these procedures are not free of

complications, particularly when performed without proper

technique, careful instrument selection or sufficient clinical

awareness (9,10). One of the most frequent

complications is trauma to the soft tissues, which may occur due to

excessive lateral pressure, incorrect instrument angulation, or use

of dull curettes. Similarly, improper handling of ultrasonic

scalers without adequate irrigation can generate excess heat,

jeopardizing pulpal health and adjacent periodontal tissues

(11). Hard tissue complications

also arise from aggressive root planing, which may strip away vital

cementum or dentin, thereby reducing the regenerative potential of

the root surface and even damaging restorative margins. Misuse of

air-polishing devices can additionally cause epithelial abrasions

and, in rare cases, subcutaneous emphysema (10). Common sequelae include dentinal

hypersensitivity due to exposed tubules, temporary increases in

tooth mobility in patients with advanced bone loss, and instrument

fractures within periodontal pockets, which occasionally require

surgical retrieval (1,10).

Another well-recognized limitation of NSPT is the

incomplete removal of calculus and biofilm, particularly in deep

periodontal pockets (>6 mm), furcations and root concavities.

Despite modern powered instrumentation, residual deposits

frequently persist. This challenge can be reduced by combining hand

and ultrasonic instruments, using slim ultrasonic tips in narrow or

deep sites, prescribing adjunctive antimicrobials such as

amoxicillin with metronidazole in advanced or aggressive cases, and

re-evaluating sites with unresolved inflammation to determine the

need for surgical access. Over-instrumentation should also be

avoided, since endotoxins are weakly bound to root surfaces and

minimal debridement is usually sufficient. Post-treatment

hypersensitivity can be managed with topical desensitizing agents

and patient reassurance (10.11).

Discomfort during SRP may compromise compliance;

therefore, the judicious use of local anaesthesia, quadrant-wise or

full-mouth protocols and personalized oral hygiene instruction can

improve patient cooperation. Adjunctive treatments, such as lasers,

photodynamic therapy, or antiseptic irrigants have exhibited only

limited or short-term benefits and should be considered secondary

to thorough debridement, with patients clearly informed of their

restricted role. Likewise, systemic antimicrobials, though

beneficial in selected advanced cases, carry risks of resistance,

drug interactions and adverse events, and should be prescribed only

with strict clinical justification (8,9,11).

Clinical decision-making must also respect the principle of

‘critical probing depth’: SRP is most effective at sites with

probing depths >2.9 mm, whereas flap surgery provides superior

results in pockets >5.4 mm (11).

Evidence from long-term studies emphasizes that NSPT

in advanced disease may present further risks (12). For instance, almost one-third of

patients treated with SRP experience disease recurrence within 3

years, compared with approximately half that proportion following

surgical access therapy. Residual deep pockets >6 mm function as

high-risk sites for biofilm persistence, facilitating recurrent

breakdown and eventual tooth loss. Both surgical and non-surgical

approaches have also been shown to cause attachment loss in shallow

sites (≤3 mm), underscoring the iatrogenic risks of unnecessary

instrumentation. A further error involves undervaluing supportive

periodontal therapy; although the average annual attachment loss in

well-maintained SRP and surgical patients is only 0.07-0.1 mm,

individuals with poor recall compliance or untreated residual deep

sites are much more likely to experience recurrent disease.

Therefore, inadequate maintenance, incomplete instrumentation in

deep lesions and failure to detect residual ‘loser sites’ represent

key clinical errors (6,12). To prevent these outcomes,

clinicians should recognize that surgical access often yields more

stable long-term results in advanced cases, enforce rigorous

supportive care, and customize treatment strategies according to

probing depth, anatomical complexity and patient susceptibility,

thereby optimizing safety and the predictability of outcomes

(12).

3. Treatment errors and complications in

flap surgeries

Poor case selection, surgical technique flaws and

anatomical difficulties are frequently the causes of errors and

complications in periodontal and implant therapy. An example of how

intraoperative mistakes, such as a poorly designed incision or

overharvesting >7 mm from the greater palatine foramen, can

result in major complications, such as arterial damage, excessive

bleeding, or tissue necrosis, is the palatal donor site, which is

frequently used for harvesting connective tissue and free gingival

grafts. Inadequate flap tension or graft immobilization during

periodontal operations can result in delayed healing or graft

failure. Similarly, flap necrosis, soft tissue abnormalities, or

reduced function and appearance may arise from inadequate flap

reflection, severe tissue damage, or incorrect implant angulation

in implant therapy (13).

In such situations, the risk of infection, graft

shrinkage, or colour mismatch is further increased by subpar

post-operative care. Thorough anatomical evaluation, accurate

surgical planning, cautious execution and attentive post-operative

monitoring are necessary for prevention. To minimize problems and

guarantee positive results, clinician experience and adherence to

best procedures are essential (13).

4. Treatment errors and complications in

regenerative periodontal surgery

Regenerative periodontal procedures involving the

use of membranes and bone grafts are among the most complex and

biologically demanding interventions in periodontology. These

procedures aim to restore lost periodontal structures through the

regeneration of bone and soft tissue. However, the technical and

biological complexity of these surgeries increases the potential

for complications. One of the most frequent errors is poor flap

design, which can result in excessive tension on the surgical site

and prevent optimal passive closure. This failure to achieve proper

closure can lead to premature exposure of the membrane, allowing

bacteria to colonize and compromise the regenerative process

(14).

Membrane exposure is a critical complication in

regenerative surgery, as it greatly hampers the healing process and

reduces the regenerative potential of the surgical site. This

exposure can lead to infection, graft displacement, fibrous

encapsulation and delayed healing, all of which diminish the

effectiveness of the regenerative procedure. Inadequate space

maintenance is another common error, often resulting in graft

collapse or resorption, further complicating healing (3,15).

The selection of biomaterials is crucial to the

success of regenerative procedures. Using materials that are not

biocompatible or clinically proven can result in material allergy,

graft failure and poor clinical outcomes. Additionally, patient

factors, such as smoking, diabetes and poor compliance with

post-operative care can markedly increase the risk of developing

complications. Smokers are at an increased risk of delayed healing

due to a reduced blood supply and compromised immune function.

Diabetic patients may experience impaired wound healing and an

increased risk of infection due to poor metabolic control (3).

To minimize complications and improve success rates,

clinicians need to adhere to strict case selection criteria and be

sure that the materials used are supported by robust clinical

evidence of efficacy and biocompatibility. Moreover, comprehensive

patient education regarding post-operative care, including smoking

cessation and the management of comorbid conditions, is essential

for optimizing surgical outcomes. Regular follow-up visits are also

critical for monitoring healing and addressing any potential issues

promptly (16-19).

5. Treatment errors and complications in

root coverage therapy

Root coverage procedures, such as coronally advanced

flaps and connective tissue grafts, are frequently employed to

manage gingival recession defects for both functional and aesthetic

purposes. While these techniques have high success rates, they

remain inherently technique sensitive and prone to various clinical

errors that may compromise outcomes (5,20-22).

Diagnostic inaccuracies are among the earliest

pitfalls in root coverage therapy. Mistaking altered passive

eruption or gingival overgrowth for true recession can lead to

misguided treatment decisions. Moreover, neglecting to assess key

risk factors, such as tobacco use, traumatic tooth brushing habits,

or an insufficient zone of keratinized mucosa, can markedly reduce

the predictability of root coverage procedures (23).

Intraoperative complications often stem from poor

flap design or execution. Inadvertent flap perforation, inadequate

thickness, or improperly released incisions may jeopardize the

vascular supply to the grafted area. Donor site morbidity,

particularly when harvesting from the palatal region, may present

as immediate or delayed haemorrhage, hematoma, discomfort, or

tissue necrosis if anatomical landmarks are not used (23,24).

Post-operative healing may be complicated by graft

sloughing, partial or complete flap necrosis, infection, or

excessive scarring, particularly in cases of excessive tissue

tension or compromised patient compliance. Inadequate haemostasis,

flawed suturing, or premature mechanical trauma (e.g., from

brushing or mastication) may further disrupt the healing process

and aesthetic integration (25).

Optimal outcomes depend on a combination of factors:

Precise anatomical assessment, atraumatic surgical technique,

stable graft immobilization and meticulous post-operative care.

Patient education, particularly in maintaining hygiene without

disrupting the surgical site, plays an equally critical role in

ensuring long-term success. A delicate balance between surgical

finesse and biological principles underpins the successful

execution of root coverage procedures (26).

6. Treatment errors and complications in

ridge augmentation

Ridge augmentation procedures, such as guided bone

regeneration, are vital for creating sufficient bone volume for

implant placement. These procedures often involve the use of

autogenous or xenograft materials, which are typically covered by

barrier membranes to prevent soft tissue invasion. However, one of

the most common complications associated with ridge augmentations

is membrane exposure, which can occur due to insufficient soft

tissue thickness, improper flap design or premature trauma to the

area (27).

Other complications include wound dehiscence,

infection, graft resorption and failure of the graft to integrate

properly with the host bone. Procedural errors, such as overfilling

the defect with insufficient stabilization of the graft or

inadequate space maintenance, contribute to compromised outcomes

and a greater risk of treatment failure (17).

In order to reduce the risk of such complications,

meticulous planning is paramount. Pre-operative imaging, such as

cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), allows for precise defect

evaluation and optimal graft material selection. Tension-free flap

advancement and patient-specific graft selection tailored to

individual anatomical needs can enhance the success of the

procedure. Post-operative care, including clear instructions on

diet and hygiene and avoiding trauma, is equally crucial in

promoting healing and ensuring favourable outcomes (17).

7. Wound healing dynamics, morbidity and

complications of palatal soft tissue harvesting

Owing to the abundant keratinized tissue and

advantageous regeneration qualities, the palatal donor site is

frequently employed for harvesting connective tissue grafts and

free gingival grafts in mucogingival procedures. However, there are

a number of vascular and anatomical issues at this location that

could cause issues. As the palatal mucosa is extremely sensitive,

post-operative pain and discomfort are typical, particularly when

large or thick grafts are harvested. This can affect patient

comfort and recovery (23,28). Significant bleeding or hematoma

formation can be caused by intraoperative issues, such as

unintentional injury to the larger palatine artery, which calls for

prompt medical attention. Additionally, if the surgical site is not

sufficiently protected during the early healing phase, delayed

bleeding or the formation of a liver clot may occur within 48 h

(23,29).

A thick layer of epithelial tissue at the donor site

may further impede healing, causing prolonged discomfort; improper

incision design can compromise the blood supply, resulting in

tissue necrosis or sloughing, complicating healing and increasing

morbidity; delayed healing, colour mismatch, graft shrinkage and

unsatisfactory aesthetic outcomes; in certain cases, this can also

result in inadequate vascularization or poor graft immobilization,

which can lead to graft failure. To reduce these risks, clinicians

need to carefully plan the dimensions of the graft, avoid

harvesting >7 mm from the greater palatine foramen and ensuring

tension-free suturing; effective post-operative care, including the

use of palatal stents, analgesics, cold packs and close monitoring,

is essential for promoting healing and minimizing discomfort

(3,22,29,30).

8. Treatment errors and complications in

implant positioning in the aesthetic zone and posterior region

Aesthetic zone

Successful implant placement in the anterior maxilla

requires precise three-dimensional alignment within the prosthetic

envelope. Even minor deviations in depth or angulation can

compromise the harmony of the gingival margin and papillary

architecture, leading to aesthetic disharmony that patients readily

perceive (31). Errors usually

arise from the inadequate use of prosthetically driven planning

tools or failure to respect the underlying bone anatomy and

soft-tissue biotype. Restorative challenges, such as compromised

emergence profiles may necessitate additional grafting or

prosthetic modifications. Incorporating CBCT-based planning,

surgical templates and coordinated treatment with restorative

specialists helps safeguard against these aesthetic failures

(32-34).

Posterior region

Implant placement in posterior sites is complicated

by reduced visibility and the proximity of vital anatomical

structures. In the maxilla, the insufficient evaluation of residual

bone height or sinus morphology may result in intraoperative

mishaps and long-term sinus complications. In the mandible, the

underestimation of lingual concavity depth or bone thickness can

increase the risk of perforation and vascular injury. Beyond

surgical risks, limited interarch space and dense bone quality can

complicate prosthetic alignment and osseointegration. Reliance on

advanced imaging, meticulous assessment of anatomic landmarks, and

staged augmentation procedures are critical strategies to reduce

errors in these challenging regions (6,35,36).

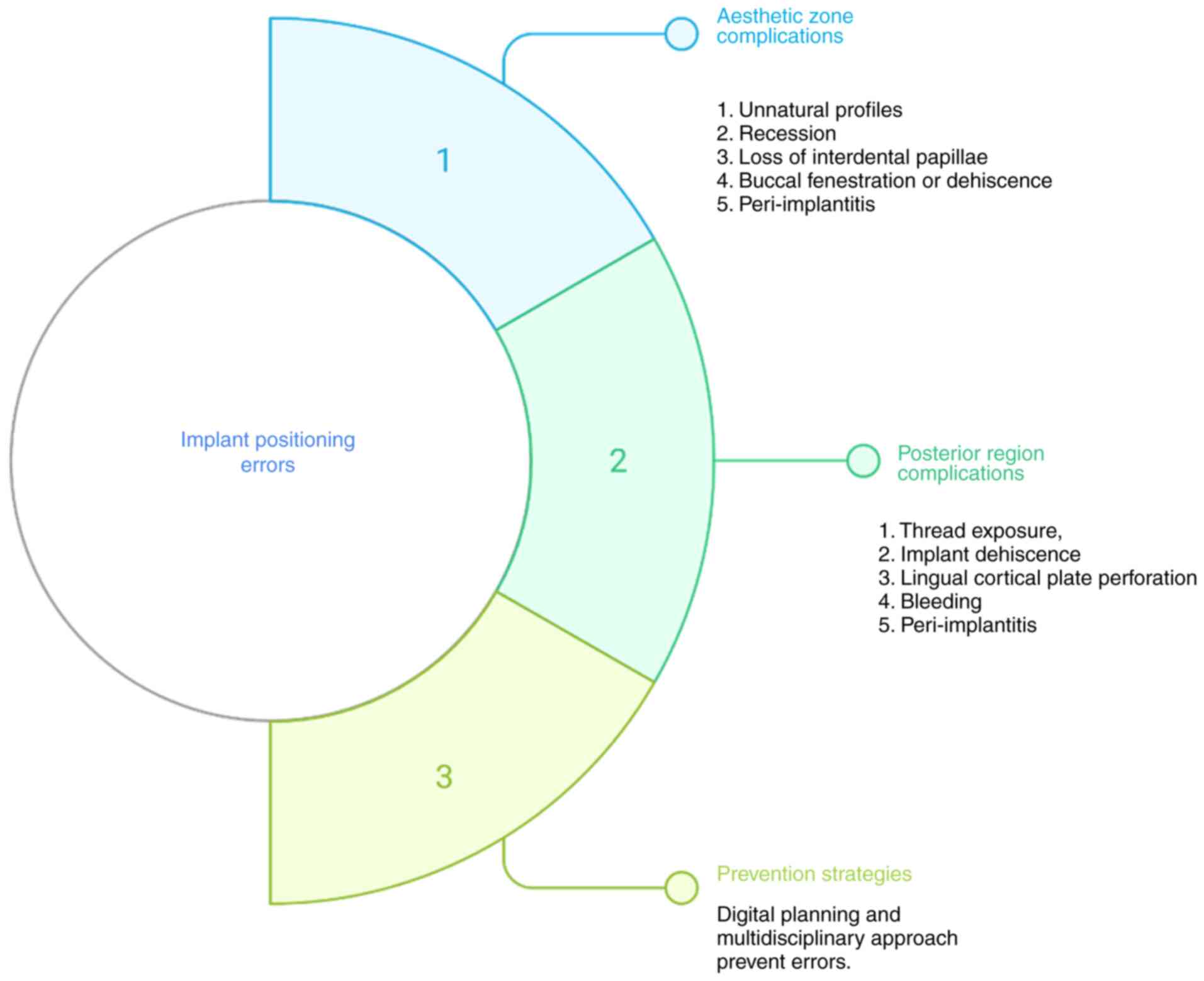

A schematic diagram of the treatment errors and

complications in implant positioning in the anterior and posterior

zone is presented in Fig. 1.

9. Treatment errors and complications in

peri-implant soft tissue management

In healthy conditions, the peri-implant site is

characterized by the absence of erythema, and the absence of

bleeding on probing, swelling and suppuration. Peri-implantitis is

a plaque-associated pathological condition that occurs in tissues

around dental implants and is characterized by inflammation in the

peri-implant mucosa and subsequent progressive loss of supporting

bone. Histologically, peri-implantitis manifests as apically

extending lesions beyond the junctional epithelium, with dense

infiltrates rich in neutrophils, macrophages and plasma cells,

reflecting a more advanced and destructive state than peri-implant

mucositis does. Clinically, peri-implantitis is characterized by

mucosal recession, increased probing depths, bleeding on probing

and/or suppuration and progressive radiographic bone loss, which is

frequently associated with plaque accumulation and inadequate

maintenance (19,37). The health and stability of

peri-implant soft tissues are critical to the long-term success of

dental implants. Complications, such as mucosal recession,

insufficient attached gingiva and inadequate vestibular depth can

arise from poor flap management, improper soft tissue handling, or

failure to perform soft tissue augmentation procedures when

indicated. Thin biotypes are particularly prone to gingival

fenestrations, whereas inadequate stabilization or improper

suturing during soft tissue grafting can lead to graft exposure,

infection, or loss of the graft (38).

In order to mitigate these risks, the early and

thorough assessment of mucosal thickness and biotype should guide

treatment planning. The use of autogenous grafts or xenogenic

collagen matrices, alongside the careful timing of soft tissue

augmentation, either at the time of implant placement or as a

separate procedure, can significantly reduce the likelihood of

complications. Ensuring proper graft stabilization and a

well-designed flap that accommodates the needs of the graft are

essential for the success of soft tissue management around implants

(20,38).

10 Treatment errors and complications in

peri-implant hard tissue management

Peri-implantitis represents one of the most

formidable challenges in ensuring the long-term success of dental

implants. Characterized by progressive bone loss, chronic

inflammation and pocket formation, peri-implantitis compromises the

structural integrity of the implant and its surrounding tissues. A

multifactorial aetiology underlies this condition, with poor plaque

control, cement remnants, excessive occlusal loading and a history

of periodontitis contributing significantly to its onset and

progression (6,19).

Early diagnosis and intervention are paramount.

Failure to recognize mucositis, often the precursor to

peri-implantitis, can lead to irreversible bone destruction and

implant failure. Once diagnosed, effective management involves a

comprehensive approach, including implant surface decontamination

techniques such as air abrasion, laser therapy, or the use of

chemical decontaminants. In advanced cases, surgical or

regenerative treatments are required to arrest disease progression

and promote tissue healing.

Prevention remains the cornerstone of successful

implant therapy. Ensuring accurate implant placement, avoiding

excessive occlusal stress and educating patients on optimal oral

hygiene practices are essential for reducing the risk of

peri-implant complications. Additionally, regular maintenance

visits and early intervention in the event of tissue changes are

critical for prolonging the lifespan of implants (33,34).

11. Avoiding intra- and post-operative

complications in maxillary sinus elevation

Maxillary sinus elevation procedures are critical

components of implantology when insufficient bone volume in the

posterior maxilla is addressed. The procedure, however, is not

without its complications, particularly intraoperative challenges

(35). One of the most common and

concerning intraoperative complications is perforation of the

Schneiderian membrane. This delicate membrane plays a pivotal role

in maintaining sinus integrity, and its perforation can lead to

severe complications, including infection, graft migration and

oroantral communication (24).

Other intraoperative challenges include the risk of

developing sinusitis, haemorrhage and excessive post-operative

congestion. These issues can be mitigated by adopting minimally

invasive techniques, such as piezosurgery, which enables atraumatic

bone cutting and preserves accurate localization of the sinus

anatomy, reducing the likelihood of membrane perforation and other

complications (39).

Post-operative management is equally critical.

Antibiotics to prevent infection, nasal decongestants to reduce

swelling and patient positioning recommendations to avoid undue

pressure on the graft site are essential components of

post-surgical care. In cases of significant membrane perforation,

adjunctive therapies, such as collagen membranes or platelet-rich

fibrin can promote membrane healing and further safeguard the

success of the procedure.

12. Lack of evidence regarding errors and

complications in periodontal and implant therapy

Despite the well-established nature of complications

in periodontal and implant therapies, there remains a notable

paucity of high-quality evidence documenting their true incidence

classification and long-term outcomes. An ample amount of the

available evidence is derived from small cohort studies, case

series, or anecdotal reports, which limits the ability to

generalize findings or identify consistent patterns across diverse

patient populations and clinical settings (5,36).

The absence of standardized definitions for

complications exacerbates the difficulty in comparing outcomes

across studies and clinical practices. A comprehensive and unified

classification system would allow for more reliable reporting and a

clearer understanding of complication rates. In order to fill these

gaps, there is an urgent need for longitudinal, randomized

controlled trials, as well as the establishment of national and

international registries to track implant-related failures and

complications over extended periods of time.

Furthermore, the development of evidence-based

clinical guidelines would greatly benefit clinicians by providing

clear frameworks for the prevention, early detection and management

of complications. Such evidence will not only improve patient

outcomes, but will also enhance training programs for future

clinicians, equipping them with the tools necessary to mitigate

risk and optimize treatment strategies (5).

13. Treatment errors and complications in

periodontal therapy in medically compromised patients

Periodontal therapy in medically compromised

patients presents unique challenges, as systemic conditions such as

uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, bleeding disorders, cardiovascular

diseases and immunosuppression exacerbate the risk of

complications. For example, poor glycaemic control in diabetic

patients markedly impairs wound healing, elevates infection rates

and increases the risk of periodontal breakdown. Similarly.

Patients receiving anticoagulant therapy are at an increased risk

of perioperative bleeding, which can complicate surgical

procedures.

Failure to adequately modify treatment protocols for

these patients can lead to severe outcomes, such as delayed wound

healing, wound dehiscence, osteonecrosis, or even systemic

infections. A thorough pre-operative evaluation, including a

comprehensive medical history, interprofessional communications

with the healthcare team of the patient, and relevant laboratory

investigations (such as international normalized ratio, HbA1c

levels and platelet count), is essential for mitigating these

risks.

Treatment strategies to reduce complications include

the use of local haemostatic agents, the use of therapeutic

interventions to limit stress on the patient, antibiotic

prophylaxis to prevent infection, and patient-specific oral hygiene

instructions. Clinicians need to balance the therapeutic benefits

of periodontal intervention with the potential systemic risks,

proceed with caution and adjust the treatment approach as necessary

to safeguard patient health (40).

A summary of preventive and corrective measures is

outlined in Table II. This table

provides practical strategies to minimize errors and manage

complications across different phases of periodontal and implant

therapy.

| Table IIStrategies for the prevention and

management of errors and complications in periodontal and implant

therapy. |

Table II

Strategies for the prevention and

management of errors and complications in periodontal and implant

therapy.

|

Section/procedure | Common errors and

complications | Preventive and

management strategies |

|---|

| 1. Non-surgical

periodontal therapy (SRP/NSPT) | Soft tissue trauma,

root surface over-instrumentation, dentinal hypersensitivity,

incomplete calculus removal in deep pockets, instrument fracture,

subcutaneous emphysema, discomfort, poor compliance. | Use proper

instrument angulation and sharp curettes; ensure adequate

irrigation with ultrasonics; combine hand and powered instruments

in deep/narrow pockets; avoid aggressive root planing; prescribe

adjunctive antimicrobials (e.g., amoxicillin + metronidazole) only

in advanced cases; use local anaesthesia for comfort; re-evaluate

unresolved pockets for surgical access; manage hypersensitivity

with desensitizing agents; emphasize supportive periodontal therapy

(SPT) with strict recall. |

| 2. Flap

surgeries | Poor incision

design, overharvesting palatal tissue, flap necrosis, excessive

bleeding, graft mobility, tissue shrinkage, infection, compromised

aesthetics. | Careful case

selection; respect anatomical landmarks (avoid >7 mm from

greater palatine foramen); achieve tension-free flap closure;

ensure graft immobilization; atraumatic reflection; meticulous

suturing; good post-operative instructions; clinician training and

surgical experience. |

| 3. Regenerative

periodontal surgery | Flap tension,

membrane exposure, infection, graft collapse/resorption, allergic

reactions, poor healing in smokers/diabetics. | Design tension-free

flaps with primary closure; ensure space maintenance; use

biocompatible, evidence-based biomaterials; control systemic

conditions (diabetes); enforce smoking cessation; provide rigorous

post-operative care and frequent monitoring. |

| 4. Root coverage

procedures | Misdiagnosis of

recession, poor flap thickness/design, flap perforation, donor site

morbidity, graft necrosis, scarring, colour mismatch. | Correct diagnosis

(differentiate from altered passive eruption); evaluate risk

factors (smoking, trauma, thin biotype); use atraumatic harvesting

with respect to palatal landmarks; ensure adequate flap thickness

and vascularity; stabilize grafts; maintain haemostasis; instruct

patients on careful hygiene; ensure tension-free sutures. |

| 5. Ridge

augmentation (GBR) | Membrane exposure,

wound dehiscence, infection, graft resorption, graft

instability. | Perform CBCT-based

pre-operative planning; select graft materials appropriately; avoid

overfilling; achieve set al fixation and space maintenance;

tension-free flap advancement; prescribe proper post-operative

instructions to avoid trauma. |

| 6. Palatal soft

tissue harvesting | Post-operative

pain, bleeding, hematoma, tissue necrosis, delayed healing, graft

shrinkage, poor aesthetics. | Limit graft size

and thickness; avoid harvesting too close to greater palatine

foramen; design incisions preserving blood supply; use palatal

stents and cold packs post-operatively; ensure meticulous

haemostasis; prescribe analgesics; close monitoring for delayed

bleeding or necrosis. |

| 7. Implant

placement-aesthetic zone | Incorrect 3D

positioning, poor emergence profile, gingival recession, papilla

loss, aesthetic failure. | Prosthetically

driven planning; CBCT-based site analysis; use surgical

guides/templates; coordinate with restorative specialists; assess

gingival biotype and bone morphology pre-operatively. |

| 8. Implant

placement-posterior region | Limited visibility,

sinus perforation, vascular injury, poor interarch space, dense

bone complications. | Detailed CBCT

assessment; identify sinus anatomy and mandibular landmarks; staged

augmentation if inadequate bone; use careful drilling protocols;

manage occlusion precisely. |

| 9. Peri-implant

soft tissue management | Mucosal recession,

thin biotype complications, graft exposure, inadequate vestibular

depth. | Assess soft tissue

biotype early; plan augmentation when indicated; use autografts or

collagen matrices; design tension-free flaps; ensure graft

stabilization; educate patients on post-operative hygiene. |

| 10. Peri-implant

hard tissue management (peri-implantitis) | Bone loss,

pocketing, implant failure, progression from mucositis to

peri-implantitis. | Early detection and

treatment of mucositis; regular maintenance visits; avoid excess

cement/occlusal overload; decontaminate implant surfaces (air

abrasion, laser, chemicals); use regenerative surgery in advanced

cases; reinforce patient hygiene. |

| 11. Maxillary sinus

elevation | Schneiderian

membrane perforation, sinusitis, graft migration, bleeding,

oroantral communication. | Use minimally

invasive techniques (e.g., piezosurgery); precise anatomical

localization via CBCT; manage membrane perforation with

collagen/PRF; prescribe antibiotics and decongestants; patient

positioning instructions post-op. |

| 12.

Periodontal/implant therapy in medically compromised patients | Delayed healing,

excessive bleeding, infection, osteonecrosis, systemic

complications. | Pre-operative

medical consultation and investigations (HbA1c, INR, platelet

count); modify treatment protocols; use local haemostatic agents;

prescribe antibiotics when indicated; minimize surgical trauma;

schedule close follow-up; customize oral hygiene instructions. |

14. Conclusion and future perspectives

Limitations of current evidence

Current knowledge on errors and complications in

periodontal and implant therapy is constrained by weak evidence.

The majority of studies are observational, with small cohorts and

inconsistent outcome measures, limiting comparability and clinical

translation (13,15). In implant research, variations in

operator skill, surgical protocols, and patient selection further

complicate interpretation. Data on long-term outcomes and rare

complications remain limited. These shortcomings highlight the need

for standardized definitions, uniform reporting, and well-designed

prospective multi-centre trials to provide stronger guidance for

prevention and management strategies.

In conclusion, although not uncommon, complications

in periodontal and implant therapy can significantly affect

treatment success and long-term patient outcomes. These

complications often arise from a combination of anatomical

limitations, operator error and systemic health factors,

underscoring the need for a comprehensive and proactive approach to

prevention and management. As summarized in the present review, a

thorough understanding of the potential challenges, combined with

careful planning and adherence to evidence protocols, is critical

for minimizing complications. Emphasizing patient-specific care,

precise surgical techniques and continuous professional development

will allow clinicians to anticipate risks and optimize treatment

strategies. Furthermore, embracing a multidisciplinary,

patient-centred approach will not only enhance clinical outcomes,

but will also ensure the delivery of safe, effective and

personalized care. By refining these practices, clinicians can

markedly improve the success rate of periodontal and implant

therapies, ultimately advancing the standard of care and improving

the quality of life of patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

VR was involved in the conception and design of the

study, the compilation of data from the literature, the analysis

and interpretation of data from the literature and manuscript

preparation. AU was involved in the design of the study, and in the

reviewing and editing of the manuscript. AS was involved in

manuscript preparation, and in the reviewing and editing of the

manuscript. SUN was involved in the conception and design of the

study, the compilation of data from the literature, the analysis

and interpretation of data from the literature, and in manuscript

preparation. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zucchelli G, Wang HL and Chambrone L:

Complications and treatment errors in periodontal and implant

therapy. Periodontol 2000. 92:9–12. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cairo F, Pagliaro U and Nieri M: Treatment

of gingival recession with coronally advanced flap procedures: A

systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 35 (8 Suppl):S136–S162.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sculean A, Stavropoulos A, Windisch P,

Keglevich T, Karring T and Gera I: Healing of human intrabony

defects following regenerative periodontal therapy with a

bovine-derived xenograft and guided tissue regeneration. Clin Oral

Investig. 8:70–74. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Marzadori M, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C, Ganz

S, Sharma P and Zucchelli G: Soft-tissue augmentation procedures in

edentulous esthetic areas. Periodontol 2000. 77:111–122.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Stefanini M, Marzadori M, Aroca S, Felice

P, Sangiorgi M and Zucchelli G: Decision making in root-coverage

procedures for the esthetic outcome. Periodontol 2000. 77:54–64.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Seyssens L, Eghbali A and Cosyn J: A

10-year prospective study on single immediate implants. J Clin

Periodontol. 47:1248–1258. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Buser D, Sennerby L and De Bruyn H: Modern

implant dentistry based on osseointegration: 50 years of progress,

current trends and open questions. Periodontol 2000. 73:7–21.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Coluzzi DJ, Mizutani K, Yukna R, Al-Falaki

R, Lin T and Aoki A: Surgical laser therapy for periodontal and

Peri-implant disease. Clin Dentistry Rev. 6(7)2022.

|

|

9

|

Mizutani K, Aoki A, Coluzzi D, Yukna R,

Wang CY, Pavlic V and Izumi Y: Lasers in minimally invasive

periodontal and Peri-implant therapy. Periodontol 2000. 71:185–212.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Graziani F, Tinto M, Orsolini C, Izzetti R

and Tomasi C: Complications and treatment errors in nonsurgical

periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 92:21–61. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Thennukonda RA and Natarajan BR: Adverse

events associated with ultrasonic scalers: A manufacturer and user

facility device experience database analysis. Indian J Dent Res.

26:598–602. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Heitz-Mayfield LJA and Lang NP: Surgical

and nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Learned and unlearned

concepts. Periodontol 2000. 62:218–231. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Rinieshah Nair R, Baskran and

Ganesh BS: Analysis of localized periodontal flap surgical

techniques: An institutional based retrospective study. Ann Med

Health Sci Res. 11:319–324. 2021.

|

|

14

|

Kripal K, Chandrashekar BM, Anuroopa P,

Rajan S, Sirajuddin S, Prabhu S, Kumuda MN and Apine A: Practical

periodontal surgery: An overview. J Evol Med Dent Sci.

3:14398–14409. 2014.

|

|

15

|

Tietmann C, Jepsen S, Heibrok H, Wenzel S

and Jepsen K: Long-term stability of regenerative periodontal

surgery and orthodontic tooth movement in stage IV periodontitis:

10-year data of a retrospective study. J Periodontol. 94:1176–1186.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Cortellini P and Tonetti MS: Focus on

intrabony defects: Guided tissue regeneration. Periodontol 2000.

22:104–132. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jepsen S, Schwarz F, Cordaro L, Derks J,

Hämmerle CHF, Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Hernández-Alfaro F, Meijer HJA,

Naenni N, Ortiz-Vigón A, et al: Regeneration of alveolar ridge

defects. Consensus report of group 4 of the 15th European Workshop

on Periodontology on Bone Regeneration. J Clin Periodontol.

46:277–286. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cortellini P and Tonetti MS: Clinical

concepts for regenerative therapy in intrabony defects. Periodontol

2000. 68:282–307. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chiapasco M and Casentini P: Horizontal

bone-augmentation procedures in implant dentistry: Prosthetically

guided regeneration. Periodontology 2000. 77:213–240.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mounssif I, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C,

Marzadori M, Sangiorgi M and Zucchelli G: Esthetic evaluation and

Patient-centered outcomes in Root-coverage procedures.

Periodontology 2000. 77:19–53. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Huang L, Neiva REF and Wang H: Factors

affecting the outcomes of coronally advanced flap root coverage

procedure. J Periodontol. 76:1729–1734. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Rebele SF, Zuhr O, Schneider D, Jung RE

and Hürzeler MB: Tunnel technique with connective tissue graft

versus coronally advanced flap with enamel matrix derivative for

root coverage: A RCT using 3D digital measuring methods. Part II.

Volumetric studies on healing dynamics and gingival dimensions. J

Clin Periodontol. 41:593–603. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Blyleven GM, Johnson TM, Inouye KA,

Stancoven BW and Lincicum AR: Factors influencing intraoperative

and postoperative complication occurrence: A series of 1135

periodontal and implant-related surgeries. Clin Exp Dent Res.

10(e849)2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Testori T, Tavelli L, Scaini R, Saibene

AM, Felisati G, Barootchi S, Decker AM, Deflorian MA, Rosano G,

Wallace SS, et al: How to avoid intraoperative and postoperative

complications in maxillary sinus elevation. Periodontology 2000.

92:299–328. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Griffin TJ, Cheung WS, Zavras AI and

Damoulis PD: Postoperative complications following gingival

augmentation procedures. J Periodontol. 77:2070–2079.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Morzycki AD, Hudson AS, Samargandi OA,

Bezuhly M and Williams JG: Reporting adverse events in plastic

surgery: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 143:199e–208e. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jung RE, Ioannidis A, Hämmerle CHF and

Thoma DS: Alveolar ridge preservation in the esthetic zone.

Periodontology 2000. 77:165–175. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Stefanini M,

Zucchelli G, Giannobile WV and Wang HL: Wound healing dynamics,

morbidity, and complications of palatal soft-tissue harvesting.

Periodontology 2000. 92:90–119. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kumar Sharma V, Kirmani M, Trivedi H, Bey

A and Sharma VK: Post-operative complications of periodontal

surgery. Int J Contemporary Med Res, 2016. www.ijcmr.com.

|

|

30

|

Ripoll S, de Velasco-Tarilonte AF, Bullón

B, Ríos-Carrasco B and Fernández-Palacín A: Complications in the

use of deepithelialized free gingival graft vs. Connective tissue

graft: A one-year randomized clinical trial. Int J Environ Res

Public Health. 18(4504)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Testori T, Weinstein T, Scutellà F, Wang

HL and Zucchelli G: Implant placement in the esthetic area:

Criteria for positioning single and multiple implants. Periodontol

2000. 77:176–196. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sachin PG, Uppoor AS and Nayak SU:

Nanoscale surface modification of dental implants-An emerging boon

for osseointegration and biofilm control. Acta Marisiensis Seria

Med Sci. 68:154–158. 2022.

|

|

33

|

Zucchelli G, Sharma P and Mounssif I:

Esthetics in periodontics and implantology. Periodontology 2000.

77:7–18. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kamakshi L, Uppoor A, Nayak D and Pralhad

S: Evaluation of papilla levels following three different

techniques for the second stage of implants-A clinical and

radiographic study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 25:120–127.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jensen OT: Article in the International

journal of oral & maxillofacial implants [Internet], 1996.

Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13568970.

|

|

36

|

Chambrone L and Zucchelli G: Why is there

a lack of evidence regarding errors and complications in

periodontal and implant therapy? Periodontology 2000. 92:13–20.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Pjetursson BE, Tan WC, Zwahlen M and Lang

NP: A systematic review of the success of sinus floor elevation and

survival of implants inserted in combination with sinus floor

elevation. J Clin Periodontol. 35 (8 Suppl):S216–S240.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Mazzotti C, Stefanini M, Felice P,

Bentivogli V, Mounssif I and Zucchelli G: Soft-tissue dehiscence

coverage at peri-implant sites. Periodontology 2000. 77:256–272.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hegde R, Prasad K and Shroff KK: Maxillary

sinus augmentation using sinus membrane elevation without grafts-A

systematic review. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 16:317–322.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Samara W, Moztarzadeh O, Hauer L and

Babuska V: Dental implant placement in medically compromised

patients: A literature review. Cureus. 16(e54199)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|