Introduction

Globally, thyroid pathologies constitute a major

public health challenge, with prevalence rates reaching ~5% across

populations. Predominant manifestations include autoimmune thyroid

disease (AITD), particularly Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT) and

Graves' disease (GD). These conditions develop through

immune-mediated inflammatory processes involving lymphocyte

invasion and elevated concentrations of thyroid-specific antibodies

(1). The thyroid is exceptionally

susceptible to autoimmune dysfunction (2). Within populations maintaining an

adequate iodine consumption, the aetiology of thyroid malfunction

predominantly involves autoimmune pathways rather than dietary

insufficiencies (3).

Building on this autoimmune framework, HT is a

chronic autoimmune condition typically causing hypothyroidism. It

is characterised by the destruction of thyroid follicles, leading

to low T3/T4 and elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels,

and is often accompanied by anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO)

antibodies (4). Conversely, GD

causes hyperthyroidism with thyrotoxicosis, goitre and orbitopathy

driven by stimulating thyrotropin receptor antibodies (1). Both conditions are markedly more

common among women and can progress through hyper-, eu-, and

hypothyroid phases as thyroid damage evolves (5).

Concurrent with these autoimmune thyroid disorders,

vitamin B12 deficiency represents a clinically significant

nutritional concern, as this water-soluble vitamin serves as a

vital cofactor for DNA biosynthesis and cellular metabolism. Due to

a low dietary intake or malabsorption, B12 deficiency is relatively

common and may produce non-specific, yet severe haematological and

neurological effects (6). The

clinical evaluation of B12 status relies on total serum B12 as the

primary biomarker, supplemented by holotranscobalamin for enhanced

diagnostic precision (7,8).

Moreover, the association between B12 deficiency and

autoimmune conditions warrants particular attention. While

affecting only 3 to 4% of the general population, vitamin B12

deficiency demonstrates a significantly higher prevalence among

patients with autoimmune diseases, including autoimmune thyroiditis

(AIT) (9). Given these patterns,

the B12-thyroid association is particularly relevant in the Iraqi

population, among whom both AITDs and nutritional deficiencies,

such as vitamin B12 deficiency, are prevalent health concerns

(10,11). This association is strengthened by

the frequent coexistence of AITDs with other autoimmune disorders,

including type 1 diabetes, vitiligo and particularly pernicious

anaemia, which directly impairs B12 absorption through autoimmune

gastritis (1). Furthermore, recent

research investigating the roles of B12, folate, vitamin D and

anaemia in HT has suggested that the metabolic status can influence

thyroid autoimmunity, underlining the importance of nutritional

factors in thyroid immunity (12).

Considering such convergences, B12 deficiency

symptoms mimic thyroid dysfunction, requiring diligent evaluation.

Thus, the early identification of B12 deficiency is essential in

patients with thyroid disorders. Symptoms such as fatigue,

cognitive impairment and neuropathy often overlap with thyroid

disorders, potentially delaying diagnosis and leading to suboptimal

treatment outcomes (13). A direct

comparison of the vitamin B12 status between patients with HT and

GD could therefore reveal disease-specific patterns of deficiency,

inform targeted screening strategies, and lead to an improvement in

patient management protocols in clinical practice.

While serum vitamin B12 levels have been examined in

the context of thyroid dysfunction, prior research reveals

contradictory evidence (14).

Direct comparisons of the vitamin B12 status between patients with

HT and GD, particularly in Middle Eastern populations, such as in

Iraq, remain limited, despite their clinical importance. Therefore,

in order to strengthen the evidence-based research in this

understudied area, the present case-control study was designed to

assess and compare vitamin B12 levels across patients with HT, GD

and healthy controls, while investigating correlations with thyroid

function parameters [TSH and free thyroxine (FT4)] and autoimmune

markers [thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) and thyrotropin

receptor antibodies (TRAbs)].

Subjects and methods

Research design and sample size

determination

Designed with a case-control method, the present

study was conducted between December, 2024 and March, 2025 at the

Thyroid Centre, Smart Health Tower, Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. Patient

recruitment involved the random selection of cases among

individuals with confirmed HT or GD. All diagnoses were established

prior to study inclusion by a team of specialised physicians

following standard clinical protocols. Healthy controls were

recruited from among hospital staff and individuals presenting for

routine check-ups, after ensuring they had no history of thyroid or

autoimmune diseases.

In order to establish the required sample size, a

power analysis was performed using G*Power statistical software for

Windows (Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany), setting

included α at 0.05, power at 0.95 and effect size at 0.4 (14,15).

The minimal sample size required was determined as 102

participants, which was increased to 120 to compensate for

potential procedural errors. The three experimental arms consisted

of the HT, GD and control groups, preserving a balanced 1:1:1

proportion across the enrolment process. Each group was composed of

an equal number of 40 participants.

Participant selection criteria

The inclusion criteria comprised of adults aged

25-60 years with a confirmed diagnosis of HT or GD for the case

groups and the absence of autoimmune or major health conditions for

the control group. The exclusion criteria included recent vitamin

B12 supplementation over the past 6 months, the presence of

non-thyroidal autoimmune diseases, a history of thyroidectomy,

gastrointestinal surgery affecting nutrient absorption, a

vegetarian diet and pregnancy or lactation. In order to minimise

the potential for confounding variables, the ages and sex of the

participants were balanced across the case and control groups

(16).

Data collection and laboratory

assessments

In order to capture a comprehensive patient profile

for research, a structured questionnaire was designed to obtain

demographic data, such as age and sex, medical backgrounds

including surgical history, thyroid treatment use, a family history

of autoimmune conditions and disease duration, alongside lifestyle

factors, such as the use of supplements, dietary habits, smoking

status and alcohol consumption, and any relevant health symptoms.

The body mass index (BMI), measured in kg/m2, was

determined by dividing the recorded weight by the height squared.

Based on WHO standards, participants were classified as

underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese according to

their BMI thresholds of <18.5, 18.5 to 24.9, 25.0 to 29.9, and

≥30.0 in kg/m2, respectively (17).

All study participants provided a blood sample

without prior fasting. For patients with thyroid disorders,

sampling coincided with routine clinical visits for thyroid

monitoring, whereas control participants provided samples within

the same time frame. To minimise temporal variability, samples were

collected at comparable times for all participants. A volume of 3

ml venous blood was drawn into VACUETTE® serum separator

tubes (Greiner Bio-One) containing a clot activator and separation

gel. The sample was allowed to clot at room temperature for ~20

min, and then centrifuged at 2,500 x g for 15 min at 20-25˚C using

a Hettich RotoFix 32A centrifuge. The separated serum was

immediately analysed for the quantitative determination of vitamin

B12, TSH, FT4, anti-TPO and TRAb concentrations. Laboratory

analyses were conducted using the cobas® pro e 801

analysers (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), which employ

electrochemiluminescence technology for immunoassay detection with

daily internal quality controls and standard calibration. Reference

ranges were established according to manufacturer specifications as

follows: Serum vitamin B12: Reference range, 197-771 pg/ml;

categorised as deficiency: <197 pg/ml; borderline, 197-300

pg/ml; and normal, 300-771 pg/ml; TSH: Reference range, 0.4-4.2

µIU/ml; FT4: Reference range, 12-22 pmol/l; anti-TPO: Reference

range, <35 IU/ml; and TRAbs: Reference range, <1.75 IU/l

(18,19). While the guidelines exhibit some

inconsistency in terms of the exact threshold values for vitamin

B12 deficiency and no single universal cut-off is recognised, this

scheme is concordant with commonly adopted international

thresholds, which typically define deficiency at <200 pg/ml and

a borderline range of 200-300 pg/ml (20,21).

Anti-TPO was measured specifically in the HT cases, and TRAbs in

the GD cases, while both antibodies were evaluated in the control

group.

Ethical considerations

The present study was executed in strict adherence

to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,

safeguarding the rights and dignity of the participants. Formal

approval was granted by the Ethics Board of the College of Health

and Medical Technology at Sulaimani Polytechnic University

(reference no. 30/245, dated December 1, 2024). After receiving a

thorough explanation of the purpose of the study, processes,

possible risks and advantages, participants provided written

informed consent. Additionally, they were made aware of their

freedom to discontinue participation at any point during the study

without consequence. All data were collected and stored in

accordance with institutional privacy and confidentiality

guidelines (22).

Statistical analysis

The evaluation of data in the present study was

carried out using IBM SPSS statistical software, version 26.0 (IBM

Corp.), to execute a range of statistical computations necessary

for the analysis. The normality of continuous variables was tested

using the Shapiro-Wilk test to ascertain their distribution

patterns. It was observed that the majority of continuous

variables, including TSH, FT4, anti-TPO, TRAbs and vitamin B12

concentrations, did not conform to a normal distribution, leading

to the decision to report the results as the median and quartile

range (QR) for a precise depiction of central tendencies and

variability. For comparisons between two distinct groups, the

Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-parametric data, and the

independent samples t-test was applied for parametric data to

detect significant differences, while the Kruskal-Wallis test was

applied for analyses involving three or more groups to assess

variations across categories. When the Kruskal-Wallis test

indicated statistical significance, post hoc pairwise comparisons

were performed using Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction to

adjust for multiple testing. Categorical data, encompassing

variables such as sex, smoking status, residential location,

familial history, vitamin B12 status, and BMI classifications-were

summarised as frequencies and corresponding percentages, with

differences being evaluated using either the Chi-squared test or

Fisher's exact test, selected based on the expected frequencies in

contingency tables. To explore the potential correlations between

serum vitamin B12 levels and thyroid-related markers, such as TSH,

FT4, anti-TPO, and TRAbs, Spearman's rank correlations were

reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to indicate the

precision of association estimates. Independent associations

between vitamin B12 status and thyroid autoimmunity were initially

evaluated using univariate logistic regression and subsequently

assessed with multivariate logistic regression adjusted for BMI,

residence, and smoking. All statistical tests were conducted as

two-tailed to ensure a thorough evaluation. A value of P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

The baseline demographic and clinical

characteristics of the 120 study participants are presented in

Table I. The median age of all the

participants was 42.5 years, with no significant difference

observed between the patient group (median, 42.0 years) and the

healthy group (median, 43.0 years) (P=0.640). Similarly, there was

no significant difference in sex distribution between the patients

(65.8% males and 67.1% females) and the healthy controls (34.2%

males and 32.9% females) (P=0.890). The mean BMI was comparable

between the patient group (29.50±5.4) and the healthy group

(28.83±4.58), with no statistically significant difference

(P=0.515). Significant differences were found in terms of the

family history of autoimmune thyroiditis (AIT), smoking status and

residence of the participants. A significantly higher proportion of

patients (78.9%) reported a family history of AIT compared to the

healthy individuals (21.1%) (P=0.007). As regards smoking status, a

significantly greater percentage of patients (93.3%) were smokers

compared to the healthy group (6.7%) (P=0.019). Furthermore, a

significantly higher proportion of patients resided in rural areas

(93.2%) compared to the healthy participants (6.8%), while a larger

percentage of healthy individuals resided in urban areas (48.7%)

compared to the patients (51.3%) (P<0.001) (Table I).

| Table IFoundational demographic and clinical

attributes of the study participants. |

Table I

Foundational demographic and clinical

attributes of the study participants.

| Variables | Total | Patients | Healthy | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years), median

(QR) | 42.5

(35.0-47.0) | 42.0

(34.5-47.0) | 43.0

(35.5-46.5) | 0.640 |

| Sex, n (%) | | | | |

|

Male | 38 (100.0) | 25 (65.8) | 13 (34.2) | 0.890 |

|

Female | 82 (100.0) | 55 (67.1) | 27 (32.9) | |

| BMI (mean ±

SD) | 29.3±5.1 | 29.50±5.4 | 28.83±4.58 | 0.515 |

| Family history of

AIT, n (%) | | | | |

|

Yes | 57 (100.0) | 45 (78.9) | 12 (21.1) | 0.007 |

|

No | 63 (100.0) | 35 (55.6) | 28 (44.4) | |

| Smoking status, n

(%) | | | | |

|

Yes | 15 (100.0) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0.019 |

|

No | 105 (100.0) | 66 (62.9) | 39 (37.1) | |

| Place of residence,

n (%) | | | | |

|

Urban | 76 (100.0) | 39 (51.3) | 37 (48.7) | <0.001 |

|

Rural | 44 (100.0) | 41 (93.2) | 3 (6.8) | |

Among the 120 study participants, vitamin B12

deficiency was identified in 13 individuals (10.8%), with the

highest prevalence observed in the healthy control group (n=6,

46.2%), followed by the participants with GD (n=5, 38.5%) and HT

(n=2, 15.4%). Borderline vitamin B12 levels were documented in 38

participants (31.7%), with the majority concentrated in the HT

group (n=18, 47.4%), while the GD and healthy control groups each

contributed 10 participants (26.3% each). A normal vitamin B12

status was found in 69 participants (57.5%), distributed relatively

evenly across the three groups: GD (n=25, 36.2%), healthy controls

(n=24, 34.8%) and HT (n=20, 29.0%). Statistical analysis

demonstrated no significant association between the vitamin B12

status categories and study group classification (P=0.215). In

alignment with the categorical distribution of the vitamin B12

status, the analysis of serum vitamin B12 concentrations revealed

no statistically significant differences among the study groups

(P=0.556). The median vitamin B12 level for the total study

population was 318.0 pg/ml (QR, 255-427.5). When assessed by group,

the HT group demonstrated a median value of 301.5 pg/ml (QR,

250.5-370.5), the GD group had a median of 321.0 pg/ml (QR,

269.0-445.0), and the healthy control group exhibited a median of

347.5 pg/ml (QR, 247.0-438.0) (Table

II).

| Table IIComparison of vitamin B12 status,

thyroid function parameters and thyroid autoantibodies among

participants with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves' disease and

healthy controls. |

Table II

Comparison of vitamin B12 status,

thyroid function parameters and thyroid autoantibodies among

participants with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves' disease and

healthy controls.

| Variables | Total | Hashimoto's

thyroiditis | Graves'

disease | Healthy

controls | HT vs.

GDa | HT vs. healthy

a | GD vs

healthya | P-value |

|---|

| Vitamin B12

status | | | | | | | | |

|

Deficient | 13 (100.0) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (38.5) | 6 (46.2) | - | - | - | 0.215 |

|

Borderline | 38 (100.0) | 18 (47.4) | 10 (26.3) | 10 (26.3) | | | | |

|

Normal | 69 (100.0) | 20 (29.0) | 25 (36.2) | 24 (34.8) | | | | |

| Vitamin B12, median

(QR) | 318.0

(255-427.5) | 301.5

(250.5-370.5) | 321.0

(269.0-445.0) | 347.5

(247.0-438.0) | - | - | - | 0.556 |

| | | | | | - | - | - | |

| TSH level, median

(QR) | 1.875

(0.925-3.990) | 5.045

(2.020-8.505) | 0.626

(0.005-2.935) | 1.565

(1.330-2.075) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| FT4, median

(QR) | 15.85

(13.45-18.50) | 16.25

(12.47-18.75) | 16.0

(12.5-32.20) | 15.50

(14.35-17.55) | - | - | - | 0.876 |

| Anti-TPO, median

(QR) | 26.55

(11.90-280.50) | 280.50

(146.0-511.5) | - | 11.90

(9.72-15.55) | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| TRAb antibody,

median (QR) | 1.37

(0.87-3.55) | - | 3.55

(2.11-9.28) | 0.88

(0.80-1.05) | - | - | - | <0.001 |

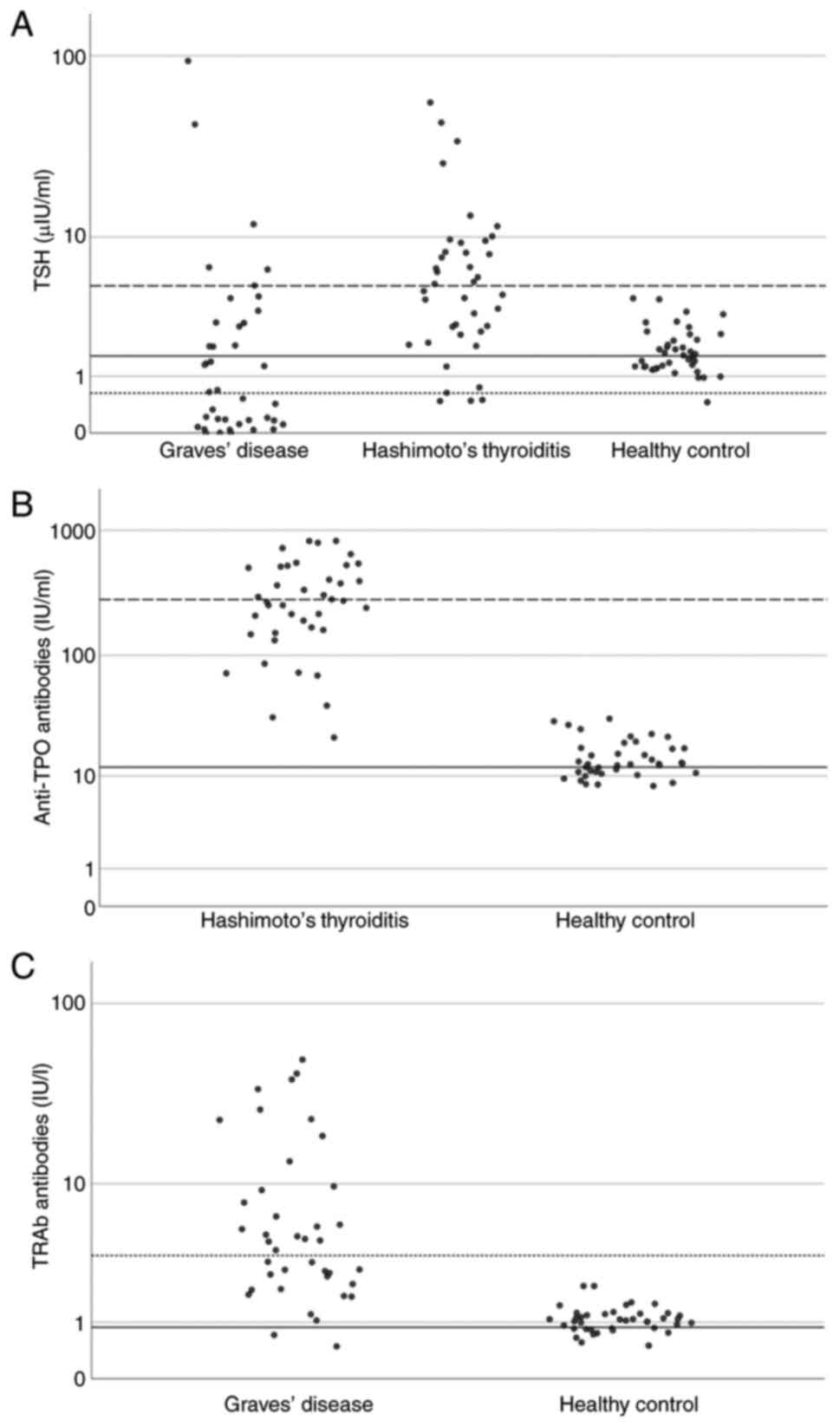

Thyroid function parameters demonstrated distinct

patterns across the study groups. The TSH levels varied

significantly among the participants, with the HT group exhibiting

the highest median concentration at 5.045 µIU/ml (QR, 2.020-8.505),

while the GD group exhibited the lowest at 0.626 µIU/ml (QR,

0.005-2.935) and the healthy controls had intermediate values at

1.565 µIU/ml (QR, 1.330-2.075). Statistical analysis confirmed a

significant difference in the TSH concentrations between the three

groups (P<0.001) (Table II and

Fig. 1A). Conversely, the FT4

levels remained comparable across all groups, with values of 16.25

pmol/l (QR, 12.47-18.75), 16.0 pmol/l (QR, 12.5-32.20) and 15.50

pmol/l (QR, 14.35-17.55) for HT, GD and healthy controls,

respectively (P=0.876) (Table

II).

Thyroid autoantibody measurements revealed

characteristic patterns specific to each disease group. The

anti-TPO antibody concentrations were substantially higher in the

HT group, with a median of 280.50 IU/ml (QR, 146.0-511.5). This

contrasted sharply with the healthy controls, who had a median of

11.90 IU/ml (QR, 9.72-15.55). The overall median anti-TPO antibody

level across all participants was 26.55 IU/ml (QR,11.90-280.50),

with statistical analysis confirming a highly significant

difference between groups (P<0.001). TRAb concentrations

exhibited a similar pattern of group-specific elevation, with

participants in the GD group exhibiting markedly increased levels

at 3.55 IU/l (QR, 2.11-9.28) compared to healthy controls at 0.88

IU/l (QR, 0.80-1.05). The overall median TRAb concentration was

1.37 IU/l (QR, 0.87-3.55), with statistical analysis confirming

significant differences between the groups (P<0.001) (Table II, and Fig. 1B and C).

These distinct biochemical and immunological

profiles are clearly illustrated in Fig. 1. TSH values cluster at elevated

levels for HT and are suppressed in GD. The anti-TPO concentrations

exhibited a pronounced increase in the HT group compared to the

controls, and TRAb values were distinctly elevated in the GD group,

but remained low in the controls. This graphical representation

reinforces the specific diagnostic and pathophysiological features

distinguishing each group (Table

II and Fig. 1).

The analysis of the vitamin B12 status concerning

demographic and clinical characteristics revealed that obesity was

the predominant BMI category among the participants with vitamin

B12 deficiency (61.5%), followed by the normal BMI (23.1%) and

overweight (15.4%) categories. A similar pattern was observed in

the borderline group, where obesity also constituted the largest

subgroup (44.7%), with the overweight (39.5%) and normal BMI

(15.8%) categories also represented. Among the individuals with

normal vitamin B12 levels, the overweight category was the most

prevalent (47.8%), while the obesity (31.9%) and normal BMI (20.3%)

categories were also noted (Table

III).

| Table IIIDistribution of demographic and

clinical characteristics by vitamin B12 status. |

Table III

Distribution of demographic and

clinical characteristics by vitamin B12 status.

| | Vitamin B12

status | |

|---|

| Parameters, n

(%) | Deficient

(n=13) | Borderline

(n=38) | Normal (n=69) | P-value |

|---|

| BMI group | | | | |

|

Underweight | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.168 |

|

Healthy

weight | 3 (23.1) | 6 (15.8) | 14 (20.3) | |

|

Overweight | 2 (15.4) | 15 (39.5) | 33 (47.8) | |

|

Obese | 8 (61.5) | 17 (44.7) | 22 (31.9) | |

| Sex | | | | |

|

Male | 2 (15.4) | 11 (28.9) | 25 (36.2) | 0.326 |

|

Female | 11 (84.6) | 27 (71.1) | 44 (63.8) | |

| Age group,

years | | | | 0.533 |

|

25-30 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.5) | 9 (13.0) | |

|

31-35 | 2 (15.4) | 5 (13.2) | 12 (17.4) | |

|

36-40 | 1 (7.7) | 8 (21.1) | 10 (14.5) | |

|

41-45 | 8 (61.5) | 8 (21.1) | 13 (18.8) | |

|

46-50 | 2 (15.4) | 8 (21.1) | 16 (23.2) | |

|

51-55 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (8.7) | |

|

56-60 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (4.3) | |

| Disease

durationa | | | | 0.649 |

|

<1

year | 2 (28.6) | 7 (25.0) | 15 (33.3) | |

|

From 1 to 3

years | 3 (42.9) | 6 (21.4) | 10 (22.2) | |

|

From 3 to 5

years | 2 (28.6) | 7 (25.0) | 8 (17.8) | |

|

>5

years | 0 (0.0) | 8 (28.6) | 12 (26.7) | |

As regards sex distribution, females constituted the

majority across all vitamin B12 classifications, notably among

those exhibiting deficiency (84.6%) and borderline levels (71.1%).

As for age, vitamin B12 deficiency was notably clustered within the

41-45-year cohort (61.5%). By contrast, the participants with a

borderline status demonstrated a more uniform age distribution,

primarily spanning the 36-50-year range. Those with normal vitamin

B12 levels exhibited a wider age spread, with the 46-50-year

category containing the largest proportion (23.2%) (Table III).

The assessment of disease duration within the

patients with AIT indicated that vitamin B12 deficiency was most

prevalent among individuals diagnosed for 1 to 3 years (42.9%); the

remaining deficient cases were equally divided between disease

durations of <1 year and 3 to 5 years (28.6% each). Participants

with borderline vitamin B12 levels displayed a varied distribution

of disease duration: 28.6% had a duration >5 years, 25.0% each

were in the <1 year and 3 to 5 year categories, and 21.4% had a

duration of 1 to 3 years. Among the individuals with normal vitamin

B12 levels, the largest subgroup (33.3%) had a disease duration of

<1 year, followed by those with a duration of >5 years

(26.7%) (Table III).

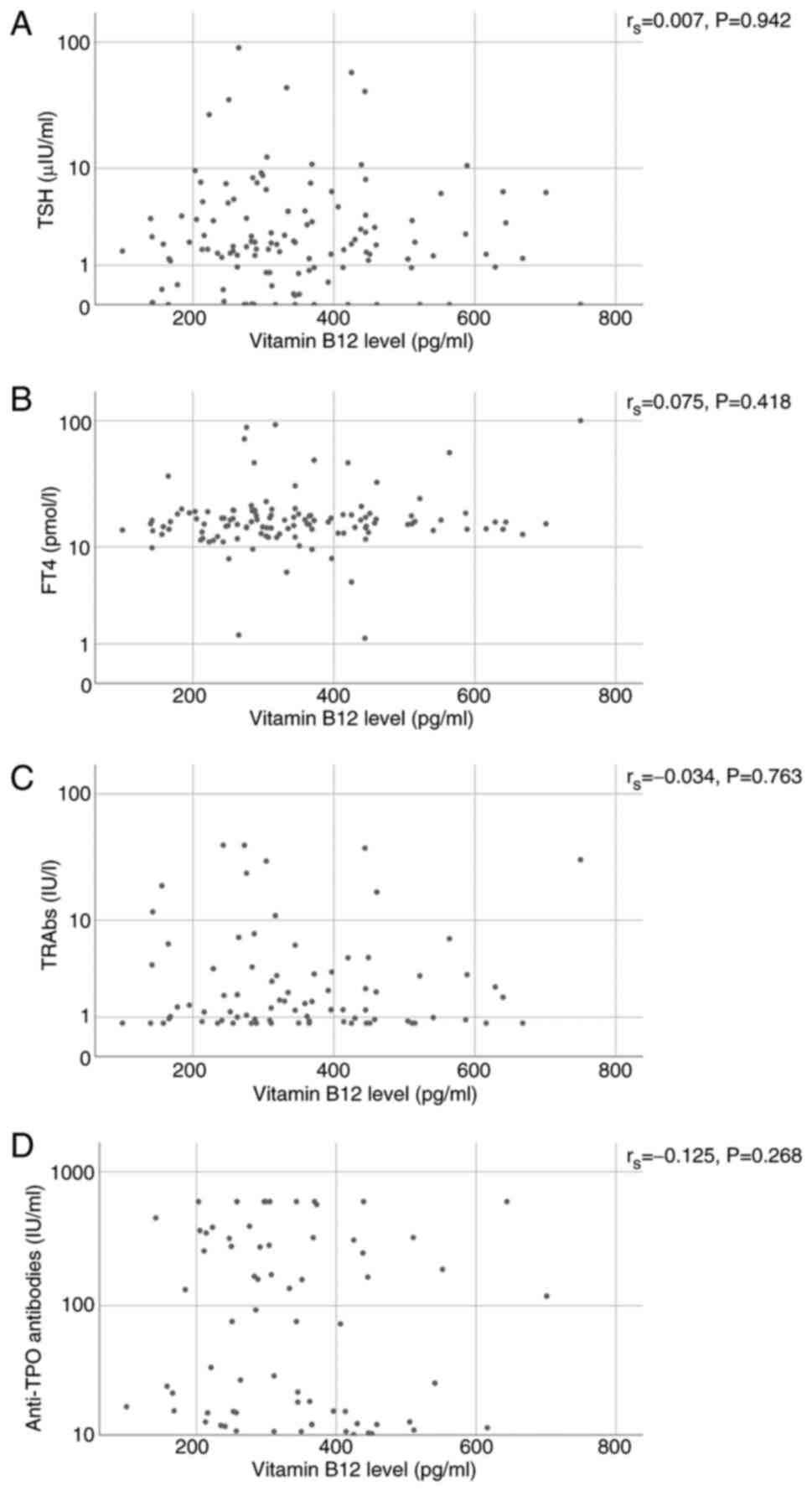

Spearman's correlation analysis was performed to

assess the correlation between serum vitamin B12 concentrations and

various thyroid-related parameters, including TSH, FT4, TRAbs and

anti-TPO antibodies. The choice of Spearman's correlation analysis

was based on the non-normal distribution of the data. The analysis

revealed that the correlation coefficient (rs) between vitamin B12

and TSH was 0.007, with a P-value of 0.942, indicating no

observable correlation between these variables (95% CI, -0.158 to

0.183). Similarly, the correlation between vitamin B12 and FT4 was

weakly positive (rs=0.075; P=0.418), suggesting a negligible

association (95% CI, -0.098 to 0.234). For the thyroid

autoantibodies, TRAbs displayed a slight negative correlation with

vitamin B12 (rs=-0.034; P=0.763; 95% CI, -0.275 to 0.214), while

anti-TPO antibodies exhibited a modest negative correlation

(rs=-0.125, P=0.268; 95% CI, -0.339 to 0.088). However, none of

these associations reached statistical significance, as all

P-values exceeded the conventional threshold (Table IV and Fig. 2).

| Table IVSpearman's rank correlation analysis

between serum vitamin b12 levels and thyroid-related parameters in

study participants. |

Table IV

Spearman's rank correlation analysis

between serum vitamin b12 levels and thyroid-related parameters in

study participants.

| Variables | No. of

participants | rs | P-value | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper |

|---|

| Vitamin B12 level

and TSH | 120 | .007 | .942 | -0.158 | 0.183 |

| Vitamin B12 level

and FT4 | 120 | .075 | .418 | -0.098 | 0.234 |

| Vitamin B12 level

and TRAba | 80 | -.034 | .763 | -0.275 | 0.214 |

| Vitamin B12 l level

and anti-TPOb | 80 | -.125 | .268 | -0.339 | 0.088 |

To further explore the determinants of the vitamin

B12 status among the study participants, a univariate logistic

regression analysis was initially conducted (Table V). BMI exhibited an odds ratio (OR)

of 0.946 (95% CI, 0.846-1.058; P=0.329), rural residence had an OR

of 0.483 (95% CI, 0.125-1.859; P=0.290), and smoking status had an

OR of 1.806 (95% CI, 0.218-14.989; P=0.584); none of these factors

reached statistical significance. A subsequent multivariate

logistic regression model including the same variables confirmed

these finding. Similarly, none of the examined factors emerged as

statistically significant predictors of the vitamin B12 status.

Specifically, BMI [odds ratio (OR), 1.046; 95% CI, 0.933-1.174;

P=0.441], the place of residence (urban vs. rural: OR, 0.507; 95%

CI, 0.131-1.969; P=0.327) and smoking status (OR, 1.506; 95% CI,

0.172-13.157; P=0.711) did not demonstrate independent associations

with vitamin B12 deficiency following adjustment for confounding

factors.

| Table VUnivariate and multivariate logistic

regression of factors associated with vitamin B12 status. |

Table V

Univariate and multivariate logistic

regression of factors associated with vitamin B12 status.

| | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| Variables | B | SE | Exp(B) (OR) | 95% CI for OR | P-value | B | SE | Exp(B) (OR) | 95% CI for OR | P-value |

|---|

| BMI | -0.056 | 0.057 | 0.946 | 0.846-1.058 | 0.329 | -0.045 | 0.059 | 1.046 | 0.933-1.174 | 0.441 |

| District

(residence) | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Urbana | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Rural | -0.728 | 0.688 | 10.483 | 0.125-1.859 | 0.290 | -0.679 | 0.692 | 10.507 | 0.131-1.969 | 0.327 |

| Smoking status | | | | | | | | | | |

|

Yesa | | | | | | | | | | |

|

No | -0.591 | 1.080 | 11.806 | 0.218-14.989 | 0.584 | -0.409 | 1.106 | 11.506 | 0.172-13.157 | 0.711 |

Discussion

The analysis of the demographic data in the present

study revealed patterns that are largely consistent with both

regional and international literature. The pronounced female

predominance in the HT and GD groups is a well-established

epidemiological feature of AITD, consistent with the findings from

the studies by Zoori and Mousa (23) in Nasiriya, Iraq, and by Aon et

al (24) in Kuwait, which

similarly identified a notably higher occurrence of AITD among

females in their respective regions. The median age of the

participants in the present study was 42.5 years, which was also

comparable to the mean age of 42.48 years reported in the Indian

study by Kaur et al (25)

and that of 41.21 years in the Iraqi study by Abed et al

(26) for patients with an

autoimmune hypothyroid and GD, positioning the present study cohort

within a typical age range for AITD diagnosis. The significantly

higher rates of a positive family history of AITD in the patient

groups herein reinforce the strong genetic component of these

diseases. The observed associations with smoking and rural

residence are novel findings that warrant further investigation, as

they may point to specific environmental triggers or lifestyle

factors relevant to our regional population.

The present study validated participant grouping

with distinct thyroid function and autoantibody profiles across HT,

GD and the controls, demonstrating significant differences in TSH,

anti-TPO and TRAb levels (all P<0.001), while FT4 remained

comparable (P=0.876). The hormonal and immunological patterns align

with the synthesis in the study by Vargas-Uricoechea (27), who confirmed TSH and FT4 as the

foundational laboratory tests in the initial assessment of thyroid

dysfunction and noted the defining roles of TRAb and anti-TPO

antibodies in differentiating autoimmune thyroid disease entities.

The comparable FT4 levels across groups suggest that a number of

participants were in subclinical stages or under effective therapy.

This biochemical distinction confirms the precision of the disease

classification and underpins the reliability of the analyses in the

present study.

The principal finding of the present study was the

lack of a statistically significant association between the serum

B12 level and the presence of either HT or GD in the Iraqi cohort

(P=0.215). The analysis demonstrated no significant variations in

themedian B12 concentrations or the prevalence of B12 deficiency

among the HT, GD and healthy control groups (P=0.556). Moreover,

vitamin B12 levels did not significantly correlate with any of the

measured thyroid function or autoimmune markers. This outcome

contributes a crucial, albeit null, finding to a field

characterised by markedly conflicting evidence and highlights the

complexity of the relationship between vitamin B12 and autoimmune

thyroid disorder.

The absence of significant group differences may be

explained by several physiological and genetic factors. For

example, pernicious anaemia, a manifestation of autoimmune

gastritis, leads to vitamin B12 malabsorption. Notably, intrinsic

factor antibodies and anti-parietal cell antibodies, which play a

decisive role in B12 absorption (28), were not screened in the present

study cohort. Their absence may partially explain the lack of B12

deficiency detected, although they are recognised mediators in the

link between gastric and thyroid autoimmunity. Moreover, pernicious

anaemia is observed only in a subset of patients with thyroid

disorders. According to Vaqar and Shackelford (28), up to one-quarter of individuals

with autoimmune gastritis develop pernicious anaemia, and these

patients often present with coexisting autoimmune conditions,

including thyroiditis. However, such an overlap may vary across

populations, potentially reflecting a low prevalence of gastric

autoantibody positivity in some regions or differing genetic

backgrounds compared with populations in which thyroid-gastric

associations are more common. A recent genome-wide association

study identified susceptibility loci for pernicious anaemia, such

as PTPN22, HLA-DQB1, IL2RA and AIRE, that overlap with loci

implicated in autoimmune thyroid disease (29). In other words, only patients with

thyroid disorders carrying these susceptibility variants are prone

to B12 malabsorption, while those without such predispositions are

likely to maintain normal B12 levels. Consequently, the combined

effects of the incomplete expression of gastric autoimmunity and

genetic heterogeneity may explain the null association observed in

our study.

The results of the present study are strongly

corroborated by a notable subset of studies that also failed to

find a clear association. Notably, the study by Al-Mousawi et

al (9) performed in Duhok,

Iraq, aligns with the findings of the present study, as it reported

no significant difference in total vitamin B12 levels between

patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and healthy controls. This

regional alignment suggests that in some Iraqi populations, a

strong link may not be present. Similarly, the large meta-analysis

performed by Benites-Zapata et al (14), which included >28,000

participants, provides nuanced support for the findings of the

present study. Whereas it did find lower B12 levels in patients

with overt hypothyroidism, it notably found no significant

difference in B12 levels for patients with hyperthyroidism, AITD or

subclinical hypothyroidism when compared to healthy controls

(14), which perfectly mirrors the

results from our well-defined AITD cohorts. Further support comes

from the study by Aon et al (24), who found no statistically

significant variation in the occurrence of vitamin B12 deficiency

among the hypothyroid groups compared to the control group.

Additionally, the literature reviews performed by Collins and

Pawlak (13), and Kacharava et

al (30) also emphasise the

highly variable and inconsistent findings across the field,

highlighting that the link is far from established and validating

the importance of null findings such as those of the present study.

Conversely, the findings of the present study are in contrast to

certain other scientific studies that have reported a significant

association between thyroid dysfunction and B12 deficiency. For

instance, both Chatterjee et al (31) and Kaur et al (25) reported a high prevalence of B12

deficiency (68 and 70%, respectively) in their hypothyroid cohorts

within their studies conducted in India.

Furthermore, another notable result of the present

study was the non-existence of a statistically significant

correlation with the 95% CI values for these correlations all

including zero, reinforcing the absence of any meaningful

association between vitamin B12 levels and the main thyroid

function parameters (TSH) or autoimmunity (anti-TPO and TRAb).

Similarly, this result is supported by the findings reported in the

studies by Bhuta et al (32), Sinha et al (33) and Chatterjee et al (31), who all reported no significant

correlations between TSH levels and vitamin B12 in their

hypothyroid cohorts (31-33).

In addition to this, the observation in the present study of a

non-significant association with thyroid autoantibodies is

consistent with several key investigations, including the studies

by Aon et al (24) and

Kumari et al (34), who

also failed to establish a significant associative link between B12

status and anti-TPO levels. Similarly, the regional Iraqi study by

Al-Mousawi et al (9) failed

to establish a significant link between B12 status and hypothyroid

autoantibodies However, this body of evidence stands in stark

contrast to other published research. For instance, Chatterjee

et al (31) demonstrated a

strong negative correlation between vitamin B12 levels and the

level of anti-TPO, a finding echoed in the studies by Aktaş

(35) and Kacharava et al

(36), who also reported weak, yet

significant negative correlations between B12 and anti-TPO levels.

This clear dichotomy in the literature, in which the present study

aligns firmly with one perspective, underlines the ongoing

scientific debate. This suggests that the association between

vitamin B12 and thyroid autoimmunity is not necessarily direct or

universal, and may instead be influenced by other unmeasured

confounding factors, such as co-occurring autoimmune conditions or

specific population genetics, which vary between study cohorts.

A granular examination of the present study cohort

revealed several descriptive trends that, while not reaching

statistical significance, provide valuable context. The apparent

preponderance of females in the B12-deficient group, which

comprised 84.6% of diagnosed cases, is most plausibly interpreted

as a reflection of the underlying demographics of autoimmune

thyroid disorder, a pattern well-documented by studies, such as

those by Zoori and Mousa (23),

and Aon et al (24), rather

than an independent sex-based risk for deficiency. Furthermore, the

descriptive clustering of deficiency within the 41-45-year age

bracket and its prevalence among patients with a 1-3-year disease

duration suggests a potential temporal window of vulnerability

post-diagnosis. However, the lack of statistical significance in

the present study is in agreement with the previous study by Kumari

et al (34), who also

reported no significant correlation between B12 levels and either

patient age or disease duration. This convergence suggests that

while these patterns may be observable, they do not represent

robust, independent predictors of B12 status in AITD

populations.

Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed no

independent predictive role for BMI, residential location, or

smoking status in determining vitamin B12 deficiency. This finding

contributes to a complex and inconsistent body of literature on the

B12-obesity association. For example, while the study on adults by

Sun et al (37) in the USA

reported a significant inverse association, other research such as

a large randomised trial in a European cohort by de Araghi et

al (38) found no significant

link. The results of the present study, however, align more closely

with evidence from the Middle East, such as the study by Abu-Shanab

et al (39) on Jordanian

adults, in which similar demographic variables showed poor

predictive value. Furthermore, although a national Iraqi survey

identified rural-urban disparities in B12 level (10), the adjusted model used herein did

not detect a significant residence effect. Collectively, these

results suggest that BMI, residential location and smoking status

are not robust predictors of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients

with AIT.

The discordant findings within the literature and

the contrast between the results of the present study and studies

reporting a positive association may likely be attributed to marked

methodological heterogeneity. Firstly, a number of studies

aggregate all hypothyroid patients, regardless of aetiology,

whereas the present study differentiated between HT and GD.

Secondly, the lack of a standardised diagnostic threshold for

vitamin B12 deficiency, with cut-offs varying across different

studies, greatly affects reported prevalence rates. As demonstrated

by Kumari et al (34),

raising the cut-off value from <145 to <200 pg/ml increased

the observed prevalence from 45.5 to 55%. Of note, beyond such

methodological heterogeneity, deeper population-based factors play

a critical role in generating divergent results across studies.

Genetic predisposition, such as varying frequencies of HLA types

and immunoregulatory gene variants, differs substantially among

ethnicities and may influence both thyroid disease risk and

comorbid gastrointestinal autoimmunity such as pernicious anaemia

(29). Nutritional habits,

particularly with respect to animal product intake, impact baseline

B12 status; this was demonstrated in a study from northern India,

in which 86% of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency were pure

vegetarians (40). It was found

that, among those with both B12 deficiency and hypothyroidism, 17

of 19 were strict vegetarians (40). Collectively, these considerations

underline that results from one study population may not be

directly translatable to another, thereby highlighting the

necessity of region-specific research and interpretation.

The present study possesses several methodological

strengths that enhance the validity of its findings. A key strength

is the inclusion of two distinct, well-defined AITD cohorts (HT and

GD) alongside a healthy control group. This design allows for a

more granular analysis than studies that aggregate all hypothyroid

patients or focus on only one AITD type. The groups were

well-matched for age and sex, and we utilised robust statistical

power analysis to ensure an adequate sample size. The carefully

crafted inclusion and exclusion criteria minimised the potential

for confounding variables to influence the results. Additionally,

the present study addressed a key research gap, as there is

insufficient evidence to establish a direct correlation between

vitamin B12 levels and TRAb titres in GD. Finally, the use of a

single, high-precision ECLIA platform for all hormonal and vitamin

assays reduced inter-assay variability and increased the

reliability and consistency of our measurements.

Notwithstanding the merits of the present

case-control study, certain constraints need to be recognised.

Initially, although age and sex were matched between cases and

controls, the omission of matching for additional demographic and

lifestyle variables may have affected the findings. Moreover, the

significant overrepresentation of female participants, in line with

the epidemiology of AITD, limits the ability to thoroughly examine

sex-specific associations and impedes direct comparisons between

males and females. Additionally, despite drawing participants from

varied regions within the province, the single-centre framework may

constrain the applicability of the findings to other populations

with distinct healthcare environments or demographic

characteristics. Finally, the focus of the present study precludes

any determination of causality concerning B12 deficiency. Future

longitudinal or multi-centre studies, which should include thorough

matching for these demographic and dietary factors, as well as

relevant biomarkers and factors, such as gastric autoantibodies,

are essential for advancing comprehension of this intricate

association.

The findings of the present study suggest that

routine screening for vitamin B12 deficiency in all patients with

autoimmune thyroid disease may not be justified in low-prevalence

populations. Instead, testing should be considered for those with

clinical symptoms, risk factors, such as vegetarian diets, or

concomitant gastric autoimmunity. This targeted approach can

improve resource allocation and reduce unnecessary interventions.

When B12 deficiency is detected, timely supplementation remains

critical to prevent neurological and haematological complications.

Ultimately, the present study supports adopting individualised

screening strategies in clinical practice rather than blanket

testing for all thyroid autoimmunity cases.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates no

significant association between serum vitamin B12 levels and

autoimmune thyroid diseases, including HT and GD, with similar

findings for thyroid function markers and disease-specific

autoantibodies. These null results contribute to the existing

literature by highlighting the variability in B12-AITD associations

across populations, potentially influenced by genetic, nutritional,

or methodological factors. While routine B12 screening may not be

warranted for all patients with AITDs in similar settings, targeted

assessment is advisable for those with relevant risk factors. In

order to better elucidate potential influences and long-term

patterns, future multicentre longitudinal studies are

recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the

medical team of Dr Abdul Wahid at the Thyroid Centre, Smart Health

Tower, Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, for their collaboration during the data

collection process.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

Both authors (BHA and KRK) contributed equally to

the writing, revising and finalisation of the manuscript, as well

as to data analysis and table creation. BHA and KRK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study received official approval from

the Ethics Board of the College of Health and Medical Technology at

Sulaimani Polytechnic University (reference no. 30/245, dated

December 1, 2024). All participants gave written informed consent

after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study's

objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. They were

also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any

time.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ben Salah R, Hadj Kacem F, Soomauro S,

Chouaib S, Frikha F, Charfi N, Abid M and Bahloul Z: Autoimmune

thyroiditis associated with autoimmune diseases. Electron J Gen

Med. 19(em409)2022.

|

|

2

|

Lichtiger A, Fadaei G and Tagoe CE:

Autoimmune thyroid disease and rheumatoid arthritis: Where the

twain meet. Clin Rheumatol. 43:895–905. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Soetedjo NN, Agustini D and Permana H: The

impact of thyroid disorder on cardiovascular disease: Unraveling

the connection and implications for patient care. Int J Cardiol

Heart Vasc. 55(101536)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Verma MK, Tripathi P, Saxena N and Singh

AN: Association of vitamin B12, folate and ferritin with thyroid

hormones in hypothyroidism. Ann Int Med Dent Res. 5:2395–2814.

2019.

|

|

5

|

Dyrka K, Obara-Moszyńska M and Niedziela

M: Autoimmune thyroiditis: An update on treatment possibilities.

Endokrynol Pol. 75:461–472. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mucha P, Kus F, Cysewski D, Smolenski RT

and Tomczyk M: Vitamin B12 metabolism: A network of multi-protein

mediated processes. Int J Mol Sci. 25(8021)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Harrington DJ, Stevenson E and

Sobczyńska-Malefora A: The application and interpretation of

laboratory biomarkers for the evaluation of vitamin B12 status. Ann

Clin Biochem. 62:22–33. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nexo E and Parkner T: Vitamin B12-related

biomarkers. Food Nutr Bull. 45 (Suppl 1):S28–S33. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Al-Mousawi M, Salih S, Ahmed A and

Abdullah B: Serum vitamin B12 and holotranscobalamin levels in

subclinical hypothyroid patients in relation to thyroid-stimulating

hormone (TSH) levels and the positivity of anti-thyroid peroxidase

antibodies: A case-control study. Cureus. 16(e61513)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sabeeh HK, Ali SH and Al-Jawaldeh A: Iraq

is moving forward to achieve global targets in nutrition. Children.

9(215)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zaman BA, Rasool SO, Sabri SM, Raouf GAM,

Balatay AA, Abdulhamid MA, Hussein DS, Odisho SK, George ST, Hassan

SM, et al: Prevalence of thyroid dysfunctions in a large,

unselected population in Duhok city, Iraqi Kurdistan: A

cross-sectional study. J Biol Res (Italy). 94(10067)2021.

|

|

12

|

Aslan ES and Gür S: Evaluation and

epigenetic impact of B12, vitamin D, folic acid and anemia in

Hashimoto's thyroiditis: A clinical and molecular docking study. J

Health Sci Med. 6:705–712. 2023.

|

|

13

|

Collins AB and Pawlak R: Prevalence of

vitamin B-12 deficiency among patients with thyroid dysfunction.

Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 25:221–226. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Benites-Zapata VA, Ignacio-Cconchoy FL,

Ulloque-Badaracco JR, Hernandez-Bustamante EA, Alarcón-Braga EA,

Al-kassab-Córdova A and Herrera-Añazco P: Vitamin B12 levels in

thyroid disorders: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14(1070592)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kang H: Sample size determination and

power analysis using the G*Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof.

18(17)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lutsey PL: Case-control studies:

Increasing scientific rigor in control selection. Res Pract Thromb

Haemost. 7(100090)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Purnell JQ: Definitions, classification,

and epidemiology of obesity. Endotext. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279167/.

|

|

18

|

Roche Diagnostics: Elecsys Vitamin B12 II.

Version 3.0. Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, 2024. https://elabdoc-prod.roche.com/eLD/api/downloads/21d33a84-4470-e911-0b9a-00215a9b3428?countryIsoCode=us.

|

|

19

|

Roche Diagnostics: Reference Intervals for

Children and Adults-Elecsys® Thyroid Tests. Roche

Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, 2020. https://www.labgids.be/files/bijlages/12960/Elecsys_Thyroid_Test_Reference_Brochure_2020.pdf.

|

|

20

|

Obeid R, Andrès E, Češka R, Hooshmand B,

Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Prada GI, Sławek J, Traykov L, Ta Van B,

Várkonyi T, et al: Diagnosis, treatment and Long-term management of

vitamin B12 deficiency in adults: A Delphi expert consensus. J Clin

Med. 13(2176)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Aroda VR, Edelstein SL, Goldberg RB,

Knowler WC, Marcovina SM, Orchard TJ, Bray GA, Schade DS, Temprosa

MG, White NH, et al: Long-term metformin use and vitamin B12

deficiency in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab. 101:1754–1761. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

The Innovation Editorial Team: Advancing

human dignity: The latest updates to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Innovation, 2025.

|

|

23

|

Zoori A and Mousa H: Prevalence of thyroid

disorders in Nasiriya City, Iraq. Univ Thi Qar J Sci. 10:122–127.

2023.

|

|

24

|

Aon M, Taha S, Mahfouz K, Ibrahim MM and

Aoun AH: Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in overt and

subclinical primary hypothyroidism. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol

Diabetes. 15(11795514221086634)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kaur R, Singh H and Yadav RS: Prevalence

of vitamin B deficiency in patients with thyroid disorders: A study

from Himalayan region. Int J Clin Biochem Res. 9:123–126. 2022.

|

|

26

|

Abed RM, Abdulmalek HW, Yaaqoob LA, Altaee

MF and Kamona ZK: Serum level and genetic polymorphism of IL-38 and

IL-40 in autoimmune thyroid disease. Iraqi J Sci. 64:2786–2797.

2023.

|

|

27

|

Vargas-Uricoechea H, Nogueira JP,

Pinzón-Fernández MV and Schwarzstein D: The usefulness of thyroid

antibodies in the diagnostic approach to autoimmune thyroid

disease. Antibodies (Basel). 12(48)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vaqar S and Shackelford KB: Pernicious

anemia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure

Island, FL, 2023.

|

|

29

|

Laisk T, Lepamets M, Koel M and Abner E:

Estonian Biobank Research Team. Mägi R: Genome-wide association

study identifies five risk loci for pernicious anemia. Nat Commun.

12(3761)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kacharava T, Giorgadze E, Janjgava S and

Lomtadze N: Correlation between vitamin B12 deficiency and

autoimmune thyroid diseases (literature review). Exp Clin Med

Georgia: doi: 10.52340/jecm.2022.06.009.

|

|

31

|

Chatterjee T, Gupta R and Choudhary S: A

study on vitamin B12 levels in hypothyroid patients presenting to a

tertiary care teaching hospital. J Assoc Physicians India.

71(1)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Bhuta P, Shah A and Muley A: A study of

anemia in hypothyroidism with reference to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Int J Adv Med. 6:1667–1671. 2019.

|

|

33

|

Sinha MK, Sinha M and Usmani F: Study of

the correlation between vitamin B12, folic acid and ferritin with

thyroid hormones in hypothyroidism. Int J Health Sci (Qassim).

16:6877–6884. 2022.

|

|

34

|

Kumari SJ, Bantwal G, Devanath A, Aiyyar V

and Patil M: Evaluation of serum vitamin B12 levels and its

correlation with anti-thyroperoxidase antibody in patients with

autoimmune thyroid disorders. Indian J Clin Biochem. 30:217–220.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Aktaş HŞ: Vitamin B12 and vitamin D levels

in patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism and their correlation

with Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Med Princ Pract.

29:364–370. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kacharava T, Giorgadze E, Janjgava S,

Lomtadze N and Taboridze I: Correlation between vitamin B12

deficiency and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Endocr Metab Immune

Disord Drug Targets. 23:86–94. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sun Y, Sun M, Liu B, Du Y, Rong S, Xu G,

Snetselaar LG and Bao W: Inverse association between serum vitamin

B12 concentration and obesity among adults in the United States.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 10(414)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Araghi SO, Braun KVE, van der Velde N, van

Dijk SC, van Schoor NM, Zillikens MC, de Groot LCPGM, Uitterlinden

AG, Stricker BH, Voortman T, et al: B-vitamins and body

composition: Integrating observational and experimental evidence

from the B-PROOF study. Eur J Nutr. 59:1253–1262. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Abu-Shanab A, Zihlif M, Rbeihat MN,

Shkoukani ZW, Khamis A, Isleem U and Dardas LA: Vitamin B12

deficiency among the healthy Jordanian adult population: Diagnostic

levels, symptomology and risk factors. Endocr Metab Immune Disord

Drug Targets. 21:1107–1114. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Singh J, Dinkar A, Gupta P and Atam V:

Vitamin B12 deficiency in northern India tertiary care: Prevalence,

risk factors and clinical characteristics. J Family Med Prim Care.

11:2381–2388. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|