Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO),

body mass index (BMI) is the most effective marker for measuring

overweight and obesity in the population; BMI is determined in the

same manner in both sexes and adults of all ages (1). A BMI of 25-29.9 kg/m2 is

classified as overweight, while and a BMI >30 kg/m2

is classified as obese in adults, regardless of sex or age to

predict body fat percentage in the population (2).

Obesity is defined as the abnormal or excessive

accumulation of fat that can affect the health of an individual

(3). It is caused by a disruption

in the homeostatic control of food intake, which results in

increased energy intake in relation to the metabolic demands of the

body and consequently, increased energy intake in relation to

energy expenditure, and hence weight gain (4). Previous epidemiological studies have

demonstrated that body weight is related to a risk of developing

infections and disease (5-7).

However, in children and adolescents, being underweight increases

the chances of developing a variety of infections. It has been

shown that being both obese or underweight is associated with an

increased U-shaped risk of acquiring infections in adults,

suggesting that a normal weight is associated with the lowest risk

of acquiring infections in the majority of participants (7).

In previous research, there are variations in

population and environmental variables, such as diet and lifestyle

conditions (8). A previous study

demonstrated that the underweight population had a 19.7% higher

risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) compared with the

normal weight population, whereas the overweight and obese

populations had a 50% and a 96% elevated risk, respectively

(9).

Concentrations of cholesterol and serum

triglycerides (TGs) are closely related to obesity (10). A higher BMI has been conclusively

linked to higher levels of total cholesterol, low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and TGs, and is inversely associated

with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), according to

epidemiological and clinical research. It has been suggested that

the association between BMI and lipoprotein levels, particularly

LDL, plays a role in the development of CVDs linked to obesity

(11,12).

Human fat cells are a major source of endogenous

TNF-α production. TNF-α is a cytokine released mainly by

macrophages in response to inflammation, endotoxemia and cancer

(13). Research has consistently

demonstrated that serum TNF-α levels are markedly elevated in

overweight and obese individuals compared to those with a normal

BMI. A positive association exists between the TNF-α concentration

and BMI, waist-to-hip ratio and other anthropometric indicators of

obesity (14,15).

The aim of the present study was to determine

whether any change in the normal value of BMI has an effect on

biochemical and immunological parameters in adult males. This was

analyzed by measuring the complete blood count, lipid profiles,

leptin levels and TNF-α levels. In order to evaluate and improve

therapies for obesity-related diseases, the present study

emphasizes that it is crucial to evaluate these markers and their

association with BMI. The present study also provides key insight

that may aid in the development of more focused and efficient

therapeutic approaches.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The present study was carried out on 120 Iraqi male

participants of various BMI categories (16 to >43

kg/m2) with an age range of 30-60 years and a median age

of 42 years, who attended the obesity medical center at Al-Kindy

Teaching Hospital and the Nutrition Research Institute (Baghdad,

Iraq) during the period extended between June, 2024 to May, 2025.

These sites were selected as they are major centers for handling

the target samples. The BMI of the volunteers was calculated by

dividing the weight by square height; the participants were then

divided into six groups according to the BMI value. The study

participants were categorized as ‘apparently healthy’ based on a

comprehensive clinical screening process. This included: i) A

detailed medical questionnaire to exclude individuals with

self-reported chronic diseases; ii) the measurement of vital signs

(Blood Pressure); and iii) routine blood tests (including fasting

blood glucose and a lipid profile) to objectively exclude

individuals with subclinical metabolic abnormalities. Only

individuals with all screening results within normal clinical

ranges were included. The exclusion criteria included individuals

with major metabolic diseases, chronic or acute infections, those

who recently underwent major surgery, and the use of medications

that could alter body composition or metabolic profiles. All

volunteers gave their informed consent for the use of their

clinical data for scientific purposes. The Research Ethics

Committee of Mustansiriyah University (Baghdad, Iraq) reviewed and

approved the present study (approval no. BCSMU/162 4/00070Z).

Ethics approval was obtained from the authors' institution as the

governing document. This approval was presented to the

administrations of Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital and the Nutrition

Research Institute. As these are affiliated teaching hospitals with

established inter-institutional collaboration protocols, they

granted administrative site permission for sample collection based

on the university's central ethics clearance.

Blood samples

A total of 5 ml peripheral venous blood was

collected from each of the 120 male participants with varying BMI

categories using a sterile syringe. A total of 2 ml blood samples

were transferred into anticoagulated tubes containing ethylene

diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) and used immediately to determine

the complete blood count (CBC) using a Sysmex XP-300 automated

hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation). The remaining 3 ml blood

samples were transferred into a Gel Activator tube and left for 15

min, followed by centrifugation at 1,006 x g at 4˚C for 10 min to

separate serum. The serum obtained from each individual was

dispended into several sterilized Eppendorf tubes and stored at

-20˚C until use for the analysis of various parameters using the

Reader automated ELISA system and an automated microplate reader at

450 nm (Human GmbH) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Each sample was designated by a serial number and the name of the

individual.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error

(SE). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for

Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp). The normality of data

distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For normally

distributed data, differences between the six BMI groups were

analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by

the Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test post hoc

test for multiple comparisons to identify significant differences

among group means. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

The distribution of the 120 male participants in the

present study according to BMI categorization is demonstrated in

Table I.

| Table IDistribution of the study

participants according to BMI categories. |

Table I

Distribution of the study

participants according to BMI categories.

| BMI groups | BMI

(kg/m2) | No. of

participants | Range of BMI sample

(kg/m2) |

|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 | 20 | 16-18.2 |

| Normal | 18.5-24.9 | 22 | 18.8-24.5 |

| Overweight | 25-29.9 | 21 | 25.1-29.2 |

| Obese I | 30-34.9 | 19 | 30.2-34.2 |

| Obese II | 35-39.9 | 20 | 35.3-38.5 |

| Obese III | ≥40 | 18 | 40.3-42.9 |

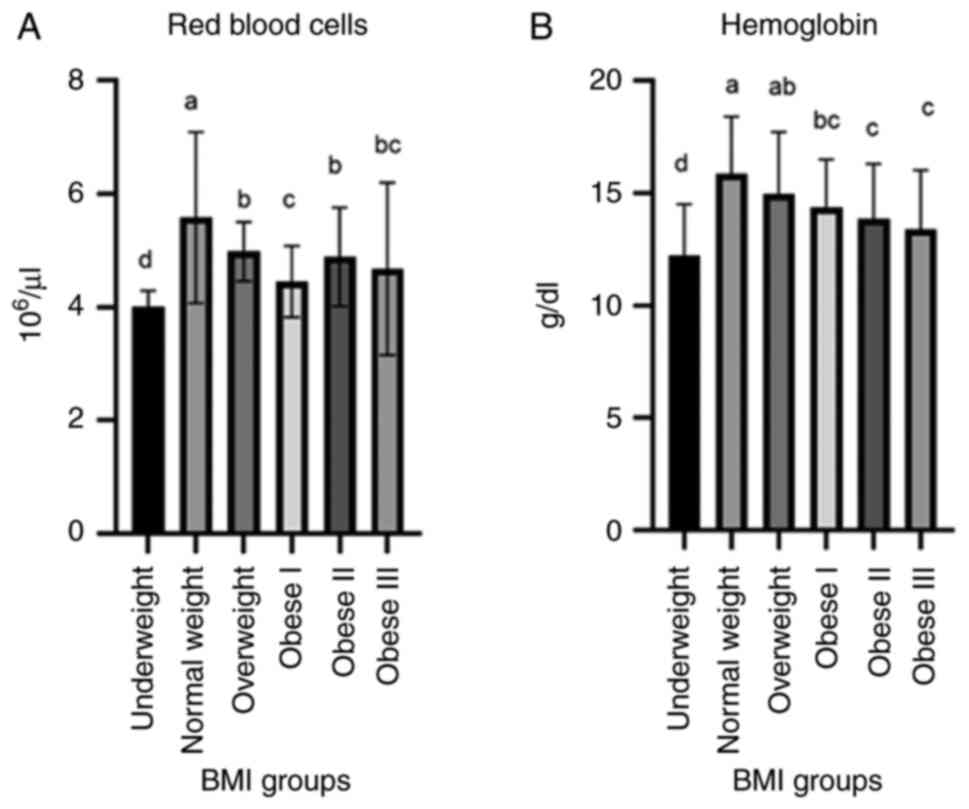

The level of hemoglobin (g/dl) was significantly

increased in the overweight, obese I and obese II groups; however,

the lowest value was observed in the underweight and obese III

group. The values for red blood cells (RBCs, 106/µl)

were decreased in the underweight and obese (class I-III) groups;

these values differed significantly from those of the normal weight

group (Fig. 1).

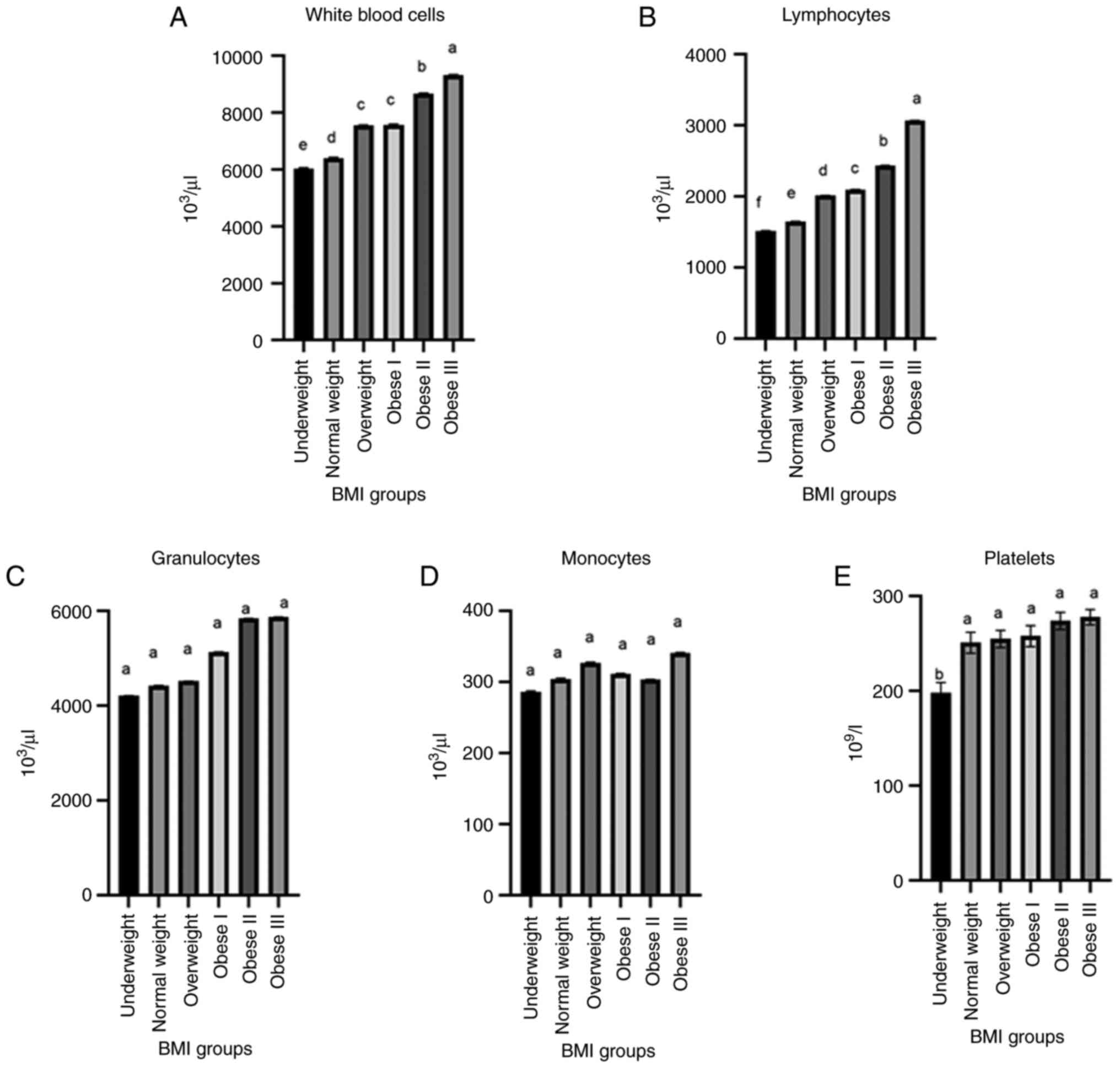

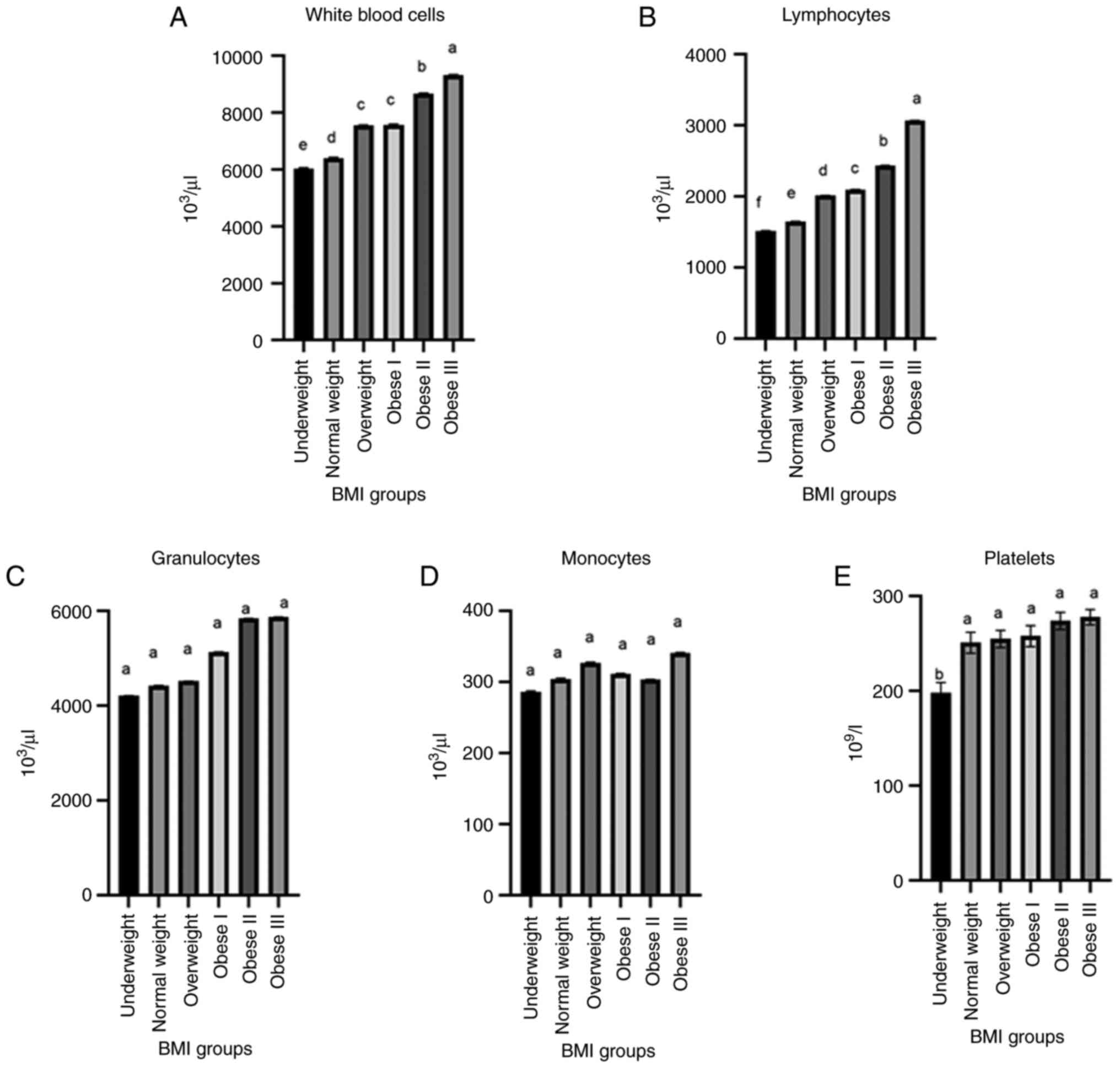

The values for white blood cells (WBCs,

103/µl) were significantly increased (P<0.003) in the

obese II and obese III groups in comparison to the WBC counts in

the underweight and normal weight groups (Fig. 2A). Lymphocyte counts exhibited

highly significant differences across all study groups (P=0.029).

Lymphocyte counts were significantly decreased in the underweight

group (1516.49±4.2) in comparison with the obese II and obese III

groups (2437.11±4.1 and 3068.58±3.3, respectively). In the normal,

overweight and obese I groups, the lymphocyte counts were

1649.80±2.1, 2017.13±2.1 and 2097.31±3.1, respectively (Fig. 2B). However, for the monocyte and

granulocyte levels, the post hoc analysis indicated no significant

differences between any of the study groups (P>0.05) (Fig. 2C and D). Furthermore, the platelet count was

significantly increased (P<0.05) in the obese II and obese III

groups (274±9.15 and 278±8.12, respectively) in comparison with the

underweight group (198±11.13) (Fig.

2E).

| Figure 2Comparison between (A) white blood

cells, (B) lymphocytes, (C) granulocytes, (D) monocyte, and (E)

platelets according to the BMI categories of the study

participants. In the graphs, bars marked by different lowercase

letters (a, b, c, d, e, f) indicate statistically significant

differences (P<0.05). The different BMI categories are explained

in Table I. BMI, body mass

index. |

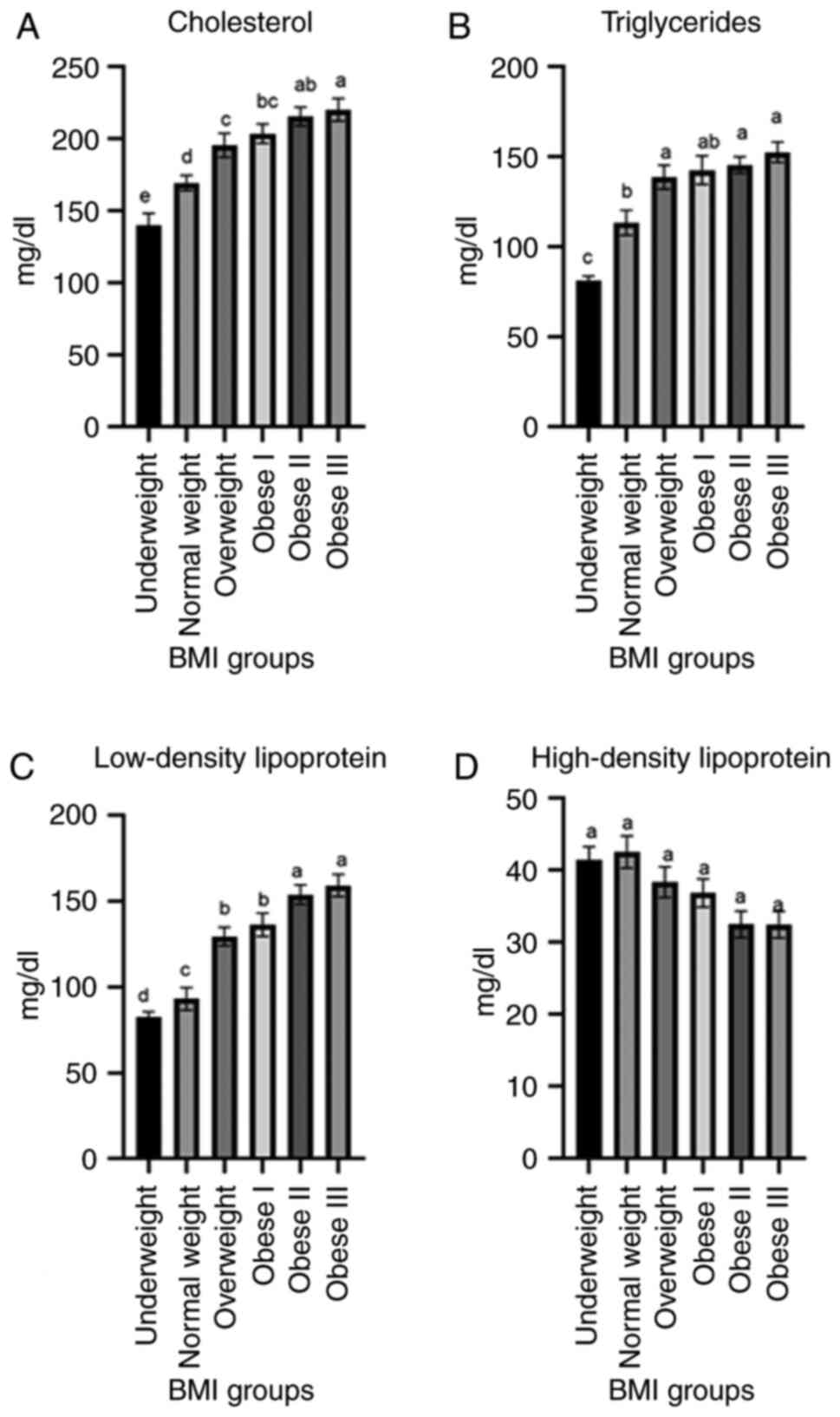

The results of the analyses of lipid profiles are

presented in Fig. 3. The

cholesterol level (mg/dl) was significantly increased (P<0.003)

in the obese (classes I-III) groups in comparison to the

underweight and normal weight groups. The levels of TGs (mg/dl)

exhibited a highly significant (P<0.0031) increase in the obese

III group (152.55±5.65) and obese II group (145.50±4.65) in

comparison to the underweight group (81.20±2.48) and normal group

(113.30±6.87). The LDL levels (mg/dl) also exhibited a significant

(P<0.04) increase in the obese III group (159.24±6.55) and obese

II group (153.90±5.70) in comparison to the underweight group

(82.54±3.24), normal weight group (93.18±6.62) and overweight group

(129.45±5.45). The levels of HDL (mg/dl) were decreased in the

obese III (30.45±1.85), obese II (32.50±1.85) and obese I

(36.85±1.95) groups in comparison to the underweight (41.42±1.85)

and normal weight (53.56±2.23) groups.

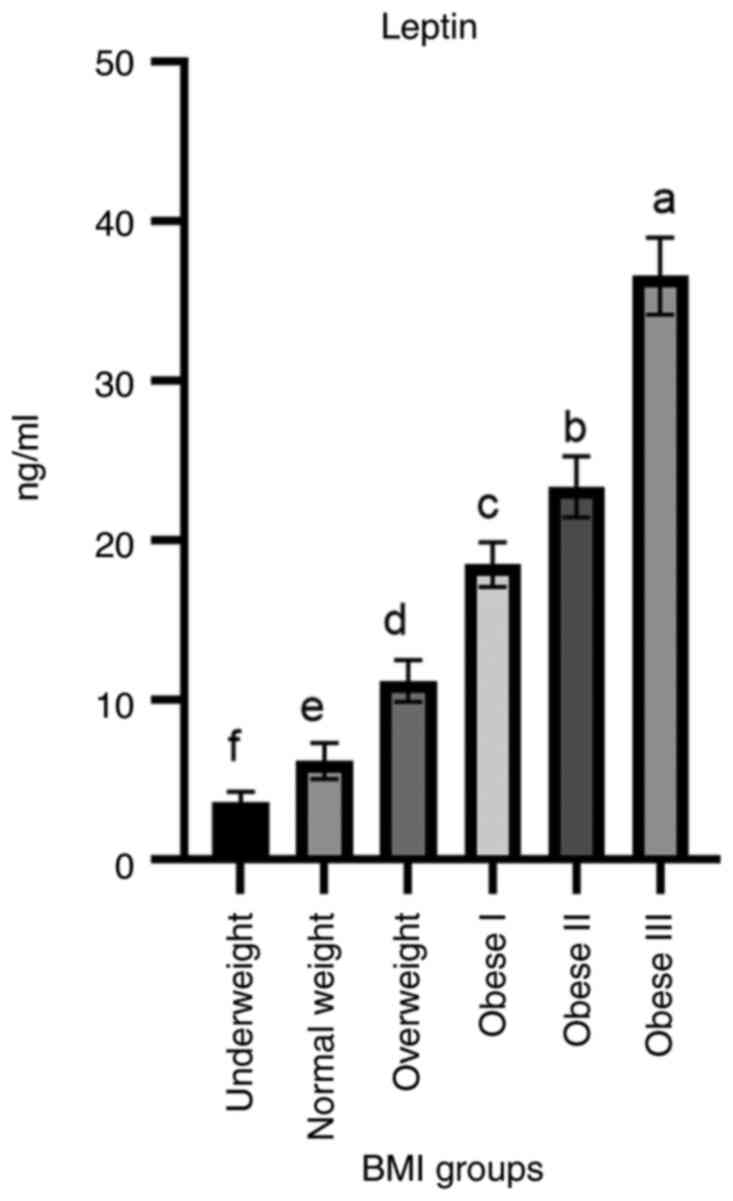

Leptin hormone levels (ng/ml) exhibited a highly

significant (P<0.003) increase in the obese III group

(36.6±2.41) in comparison to the underweight and normal BMI groups

(3.6±0.67, 6.2±1.12 respectively). In addition, the obese II

(23.4±1.92) group exhibited a high level of leptin followed by the

obese I (18.5±1.41) and overweight groups (Fig. 4).

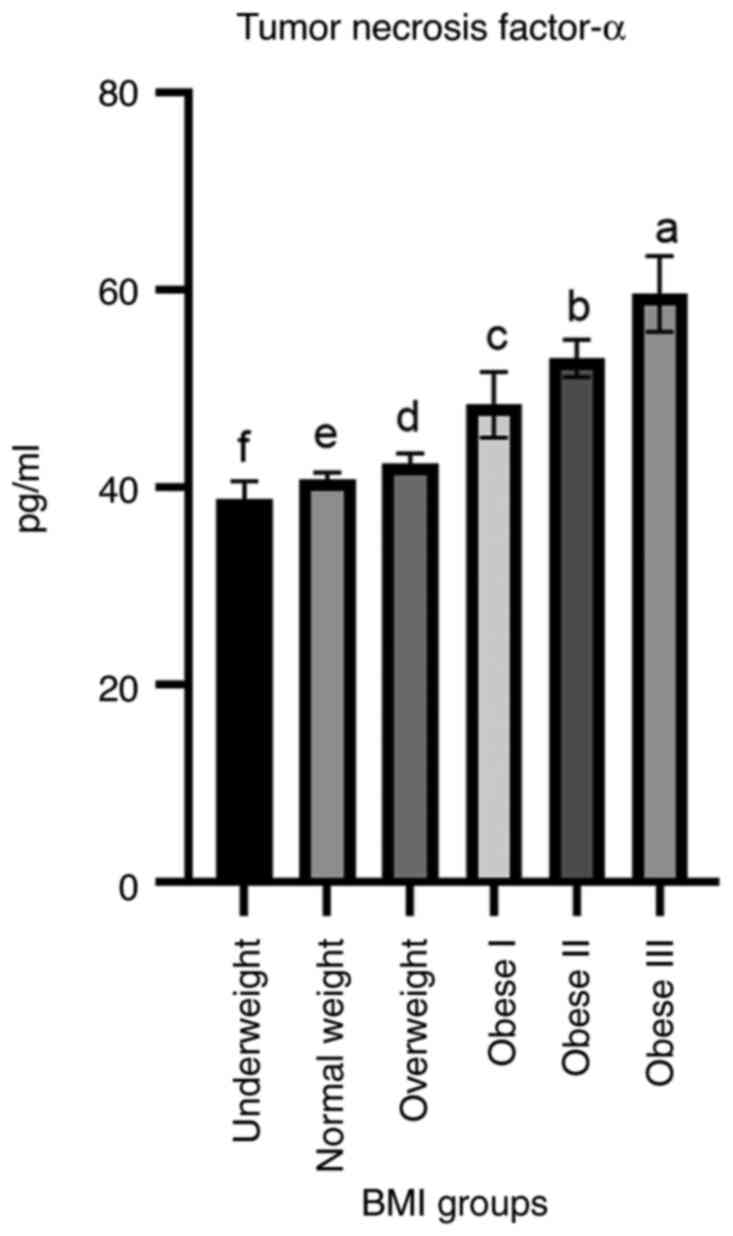

As demonstrated in Fig.

5, the TNF-α levels were significantly increased in the obese

I, obese II and obese III groups compared to other groups of study

participants. The mean level of this cytokine was 48.43±3.34,

53.14±1.91 and 59.69±3.83 pg/ml in the obese I, obese II and obese

III groups, respectively, compared to the other groups.

Discussion

The present study revealed significant associations

between BMI and the examined immunological and biochemical

variables of the study participants, highlighting the importance of

monitoring these markers in high-risk BMI groups to prevent

potential metabolic and immune-related complications. From these

results, it was noted that the underweight group had the lowest

mean hemoglobin concentration; however, this was increased in the

overweight, obese I and obese II groups, with low values also

observed in the obese III group. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein

in the blood that imparts a red hue. It constitutes 95% of an RBC,

fulfilling the average adults requirement of 250 oxygen each minute

(16). In the condition of anemia,

there is a lack of hemoglobin, and this deficiency reduces the

number of RBCs carrying oxygen, which prevents the fat burning

process in an obese state (17).

Therefore, an increased in the amount of body fat may be

interpreted as a sign of a decreased hemoglobin level (18). Moreover, compared to individuals

with a normal weight, those who are overweight or obese are at a

higher risk of developing anemia (19). In the present study, the lowest

values of hemoglobin were found in the obese II and obese III

groups (Fig. 1). This result is in

accordance with the findings reported in the study by Alshwaiyat

et al (20), who

demonstrated that an increased in BMI had an adverse effect on the

iron status. The etiology of iron deficiency anemia in obese

individuals may stem from an inadequate iron intake due to an

unbalanced diet. Additionally, other hypothesized factors

contributing to iron deficiency in individuals with an elevated BMI

include diminished iron absorption in the small intestine,

heightened iron demands resulting from an increased blood volume,

and the association of obesity with a chronic low-grade

inflammatory state. Moreover, Alshwaiyat et al (21) further supported the hypothesis that

hemoglobin levels and a high BMI are negatively associated. As

obese individuals may consume a higher amount of fats or

carbohydrates in their diet rather than nutrient-dense foods high

in vitamins and minerals, their hemoglobin levels decrease (i.e.,

more macronutrients and less micronutrients) (22). In addition, the association of

obesity with a chronic low inflammatory condition may therefore be

one of the proposed causes of iron deficiency in the obesity state

through inflammatory-mediated mechanisms (23). Furthermore, Nasif et al

(24) demonstrated that obesity is

an excessive accumulation of energy as adipose tissue, which

adversely affects health.

The decrease in the level of hemoglobin in the

present study observed in both the underweight and obese III groups

may be related to the low level of RBCs, as the RBCs are comprised

of hemoglobin, which is a metal protein that contains heme groups

whose atoms are temporarily bounds to oxygen molecules in the

lungs. A reduction in the hemoglobin content in RBBs results in a

diminished oxygen-carrying ability of the blood, leading to

insufficient cardiac output. Consequently, individuals with anemia

experience dyspnea, palpitations and angina-like symptoms following

intensive activity (25).

Moreover, iron deficiency anemia is prevalent among urban

populations due to inadequate dietary habits and diminished

physical activity. Conversely, nutritional anemia is observed in

medical students who possess superior nutritional understanding and

reside in healthier environments (26).

Furthermore, in present study, it was found that the

levels of WBCs were increased in the obese groups compared to the

normal group (Fig. 2). These

results are in accordance with those reported by Li et al

(27) who found strong evidence of

an association between obesity and WBCs counts. Obesity is a

chronic inflammatory condition, and an elevated WBC count has

widely recognized associations with inflammatory conditions

(27). There is mounting evidence

to indicate that obesity is a chronic inflammatory disease, and

that the inflammatory features of the condition may be connected to

certain comorbidities and risks associated with being overweight

(28). There is also evidence to

indicate that weight loss may cause the WBC count to decrease

(29).

Indeed, a study conducted on an Indian population

indicated an association among body fat mass, leptin and WBC

counts; however, the association between total WBC counts and

leptin levels was more pronounced than that with fat mass (30). Naturally, there is a substantial

association between elevated levels of pro-inflammatory substances

and obesity, particularly central obesity. Numerous bioactive

proteins, or adipokines, including cytokines that encourage

inflammation such as TNF-α, are secreted by adipocytes (31). Furthermore, baseline WBC,

neutrophils and lymphocyte counts increase with an increasing BMI

and decrease with age (32). In

addition, as granulocytes and monocytes may release substances into

the bloodstream, including free radicals and proteolytic enzymes

that can be detrimental to the health of an individual, the

increase in leukocyte counts associated with obesity is clinically

significant (33).

In the present study, lymphocyte counts were

significantly lower in the underweight group (Fig. 2B). Lymphocyte counts are used as

indicators of nutritional status or potential malnutrition

(34). When BMI decreases, the

lymphocyte counts also decrease; as demonstrated in a previous

study among young Japanese women, the mean lymphocyte count was

higher in the obese group and lower in the underweight group than

in the normal weight group (35).

Another study by Rumińska et al (36), demonstrated that compared to

individuals whose body fat was distributed naturally, obese

individuals had a higher levels of inflammatory markers, including

a 17% higher WBC count.

The results of the present study demonstrated that

although the number of platelets was increased in the obese II and

obese III groups, there were no significant differences between the

obese II and obese III groups as regards the number of platelets

compared to the normal, overweight and obese I group. However, the

lowest value of platelets was observed in the -underweight group

(Fig. 2E). A previous study by

Anık et al (37),

demonstrated an association between obesity and higher platelet

counts in patients used as an inflammatory factor. However, the

majority of diseases may be prevented by resolving behavioral risk

factors by national campaigns, such as tobacco use, an unhealthy

diet, obesity, the lack of physical exercise and alcohol intake. In

fact, the continuous exposure of obese individuals to a

pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic condition, in which platelets

play a crucial role, has been linked to CVDs on numerous occasions

(38). Nevertheless, the exact

mechanisms via which obesity results in platelet dysfunction are

not yet fully understood (39).

In the present study, an analysis was carried out to

compare lipid profiles, including cholesterol, TGs, HDL and LDL

levels among the participants belonging to the different BMI

categories. The results revealed the existence of significant

variations between the different groups of BMI categories (Fig. 3). The term dyslipidemia refers to

altered lipid profiles. The increase in the cholesterol, TC and LDL

levels in the overweight and obese groups in the present study was

in agreement with the findings of a previous study (40), in which obesity was linked to

numerous detrimental alterations in lipid metabolism, characterized

by elevated serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL and TGs,

alongside a decrease in the serum HDL concentration.

The elevation of TGs in lipid particles alters their

metabolism; TG-rich HDL particles are hydrolyzed more swiftly,

resulting in a decrease in HDL levels (41). Moreover, Turki et al

(42) revealed that individuals

who were obese had lower serum levels of HDL than subjects who were

not, while subjects who were overweight had greater levels of total

cholesterol and LDL. In addition, Shamai et al (43) demonstrated that an elevated BMI

exhibited an inverse correlation with HDL and a direct correlation

with TGs. In the previous study by Kawamoto et al (44), it was suggested that a high BMI

status attenuated the associations of alcohol intake with lower

LDL, cholesterol, a higher HDL cholesterol and a lower LDL/HDL

ratio in Japanese males. Moreover, Raja et al (45) found an association of BMI with

cholesterol and TGs in obese and non-obese subjects; they found a

significant association between cholesterol and TGs with BMI.

Cholesterol and TGs levels were strongly associated with obesity;

therefore, obesity may be considered a risk for the development of

hypertension, CVDs (45). Weight

gain is caused by the consumption of junk food, poor nutrition, a

sedentary lifestyle and the lack of physical activity. Hundreds of

individuals suffer from coronary heart disease, hypertension and

diabetes as a result of elevated lipid and blood sugar levels,

which are caused by obesity. Insulin resistance may be the cause of

the association between BMI, and both HDL and TGs; however, in the

present study, the lack of a significant association between BMI

and LDL is an unexpected finding that warrants for further

research.

The present study demonstrated a higher level of

leptin in the obese II and obese III groups (Fig. 4); this finding was in agreement

with that observed in the study by Obradovic et al (10), who demonstrated that the serum

leptin levels significantly increased with BMI, particularly with a

BMI ≥30 kg/m2, which aligns with obesity categories II

and III. Obese patients have excessive levels of leptin; while

leptin is known as the satiety hormone, and its levels are

supposedly low in obese patients, leptin stimulates the release of

gonadotropin releasing hormone; in obesity, excess levels of leptin

cause a resistance later in on life (46). Moreover, Alaamri et al

(47) examined the serum leptin

levels of young Saudi students and demonstrated a substantial and

independent association between elevated serum leptin levels and

BMI. The higher prevalence of infertility in obese males would

undoubtedly be caused by the large amounts of leptin released by

the adipose tissue and its higher circulating levels (48).

Serum leptin concentrations are significantly

associated with body fat percentage and weight. Obesity is linked

to various lifestyle-related diseases and is frequently regarded as

a contributing factor to male infertility. While adipocytes produce

numerous other adipokines, previous research has indicated that

leptin may serve as a crucial connection between obesity and

obesity-related diseases (49).

The finding of the present study are in agreement with those of the

study by Kazmi et al (50),

who demonstrated a positive association between BMI and leptin

levels in obese subjects. Additionally, the structural and

functional resemblance between leptin and its receptor with

inflammatory cytokines suggests that leptin can be classified as a

cytokine. Despite its significance in the normal immune response,

leptin deficiency heightens vulnerability to infectious and

inflammatory stimuli, potentially resulting in the dysregulation of

cytokine production (51). Leptin

also has immunological effects; its signaling can control innate

inflammatory responses, adaptive immunity and even suppress

regulatory T-cell differentiation (52). In addition to its metabolic and

endocrine functions, leptin controls energy consumption and food

intake by a direct effect on the hypothalamus (53). It may also modulate hematopoiesis,

innate and adaptive immunological responses and inflammation,

particularly in the presence of pro-inflammatory activities

(54). Hyperleptinemia,

characterized by an excess amount of leptin, is frequently

associated with obesity and may greatly contribute to the

development of severe health issues, including CVDs and rheumatoid

arthritis (55).

The present study demonstrated that the serum levels

of TNF-α were significantly increased in parallel with the increase

in the BMI value (Fig. 5).

Previous research has confirmed a positive association between the

serum TNF-α concentration and BMI, particularly in overweight and

obese patients. A previous study on an obese population revealed

that increased BMI values were associated with increased serum

TNF-α concentrations (56).

Another clinical study (14),

demonstrated an association between the amount of fat tissue and

obesity and the increase in the TNF-α concentration in blood. TNF-α

leads to brown adipocyte regression and insulin resistance in

adipocytes, which results in an aberrant energy consumption

(57).

Furthermore, in a large comparative study on obese

adults, the serum TNF-α levels were found to be considerably higher

in overweight and obese individuals, and strongly correlated with

BMI (r=0.65, P<0.001), alongside other metabolic parameters such

as glucose and lipids (14). In

addition, the plasma concentrations of TNF-α have been positively

associated with elevated TG levels, which may be explained by its

ability to induce the overproduction of very-low-density

lipoprotein particles (58). The

mechanistic basis lies in TNF-α being a proinflammatory cytokine

secreted predominantly by macrophages in adipose tissue. It

contributes to metabolic disturbances by promoting insulin

resistance and altering lipid metabolism, which is reflected by

high serum TNF-α levels in parallel with an increased BMI (59). Nonetheless, it is undeniable that

optimal immune functions are inextricably related to nutritional

status; this may be as a dietary fatty acid can affect cytokine

formation (60). This has given

rise to the alternative, but not exclusive notion that, at least in

diet-induced obesity, dietary components, particularly fats, may be

crucial in controlling the inflammatory profile of adipose tissue

(61).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

deviations from normal BMI significantly affect hematological,

metabolic and inflammatory pathways in men, underscoring the

critical role of BMI assessment in developing targeted therapeutic

strategies for obesity-related comorbidities. The present study

performed a power analysis test which confirmed that the sample

size (n=120/group) provided adequate statistical power (99.9%) to

detect clinically meaningful effects for the primary endpoints,

based on an effect size of 0.5 and α=0.05. It is important to

emphasize that the present study wa exploratory in nature and did

not intend to establish a diagnostic tool. The findings presented

herein, should be regarded as a preliminary foundation for future,

more comprehensive research. However, the present study has several

limitations that should be mentioned. Firstly, as the present study

was cross-sectional, it was impossible to establish a causal

association between the variables that were observed. Second, the

results are limited in their capacity to be applied to women as

they are based solely on a cohort of adult men. Additionally, even

when key variables were taken into account, the results may still

have been affected by confounding variables that were not taken

into account, such as dietary habits, specific amounts of physical

activity and genetic predispositions. Despite these limitations,

however, the present study provides new information about the

association between adult male obesity, and indicators of immune

function and systemic physiology. In order to validate these

associations and clarify their underlying causative mechanisms,

further longitudinal studies that involve a variety of populations

and include more accurate assessments of adiposity and potential

confounders are warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Ali A. Mahdi, at

the College of Health and Medical Technology, Middle Technical

University in Baghdad, Iraq, for providing academic assistance and

guidance.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TJT and MMB contributed to the conception and design

of the study, and wrote and edited the manuscript. HQM and YFF

collected and analyzed data. MQM reviewed and edited the

manuscript, and was also involved in data curation, and supervised

the study All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

TJT and MMB confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the

Research Ethics Committee of Mustansiriyah University (approval no.

BCSMU/162 4/00070Z), and subsequently authorized by Obesity Medical

Center at al-Kindy Teaching Hospital, and Nutrition Research

Institute administration per standard institutional collaboration

procedures. These sites were selected as they are major centers for

handling the target samples. All patients who participated in the

present study provided written informed consent for the publication

of their data. The consent form emphasized that participation was

entirely voluntary, and the participants could withdraw at any time

without facing any repercussions. Anonymity and confidentiality

were safeguarded by assigning coded identifiers rather than names

or medical record numbers. In adherence to international ethical

guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki, the study

maintained strict ethical standards.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ahmed SK and Mohammed RA: Obesity:

Prevalence, causes, consequences, management, preventive strategies

and future research directions. Metab Open.

27(100375)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Khanna D, Peltzer C, Kahar P and Parmar

MS: Body mass index (BMI): A screening tool analysis. Cureus.

14(e22119)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lin X and Li H: Obesity: Epidemiology,

Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12(706978)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mohajan D and Mohajan HK: Body mass index

(BMI) is a popular anthropometric tool to measure obesity among

adults. J Innov Med Res. 2:25–33. 2023.

|

|

5

|

Yang WS, Chang YC, Chang CH, Wu LC, Wang

JL and Lin HH: The association between body mass index and the risk

of hospitalization and Mortality due to infection: A prospective

cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 8(ofaa545)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ghilotti F, Bellocco R, Ye W, Adami HO and

Trolle Lagerros Y: Obesity and risk of infections: results from men

and women in the Swedish National March Cohort. Int J Epidemiol.

48:1783–1794. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pugliese G, Liccardi A, Graziadio C,

Barrea L, Muscogiuri G and Colao A: Obesity and infectious

diseases: Pathophysiology and epidemiology of a double pandemic

condition. Int J Obes. 46:449–465. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Carey IM, Harris T, Chaudhry UAR, DeWilde

S, Limb ES, Bowen L, Audi S, Cook DG, Whincup PH, Sattar N, et al:

Body mass index and infection risks in people with and without type

2 diabetes: A cohort study using electronic health records:

Epidemiology and Population Health. Int J Obes (Lond).

49:1800–1809. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pozorska K, Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Raducha

D, Kupnicka P, Bosiacki M, Bosiacka B, Szmit-Domagalska J,

Ratajczak J, Horodnicka-Józwa A, Walczak M, et al: The assessment

of anthropometric measures and changes in selected biochemical

parameters in obese children in relation to blood lead level.

Metabolites. 14(540)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Obradovic M, Sudar-Milovanovic E, Soskic

S, Essack M, Arya S, Stewart AJ, Gojobori T and Isenovic ER: Leptin

and obesity: Role and clinical implication. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 12(585887)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hu H, Han Y, Cao C and He Y: The

triglyceride glucose-body mass index: A non-invasive index that

identifies non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the general

Japanese population. J Transl Med. 20(398)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Veghari G, Sedaghat M, Maghsodlo S,

Banihashem S, Moharloei P, Angizeh A, Tazik E, Moghaddami A and

Joshaghani H: The association between abdominal obesity and serum

cholesterol level. Int J Appl basic Med Res. 5:83–86.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Aladhami AK, Unger CA, Ennis SL, Altomare

D, Ji H, Hope MC III, Velázquez KT and Enos RT: Macrophage tumor

necrosis factor-alpha deletion does not protect against

obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction. FASEB J.

35(e21665)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Eswar S, Rajagopalan B, Ete K and

Nageswara Rao Gattem S: Serum tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)

levels in obese and overweight adults: Correlations with metabolic

syndrome and inflammatory markers. Cureus.

16(e64619)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ameen EM and Mohammed HY: Correlation

between tumor necrosis factor-alfa and anti-tyrosine phosphatase

with obesity and diabetes type 2. Iraqi J Sci. 3322–3331. 2022.

|

|

16

|

Al-Shura AN: Advanced Hematology in

Integrated Cardiovascular Chinese Medicine: Volume 3. Academic

Press, 2019.

|

|

17

|

Salman MS, Shwaish H, Jassim MN and Hasan

W: The relationship between hemoglobin and BMI. Acta Sci Microbiol.

3:20–22. 2020.

|

|

18

|

Acharya S, Patnaik M, Mishra SP and

Panigrahi AK: Correlation of hemoglobin versus body mass index and

body fat in young adult female medical students. Natl J Physiol

Pharm Pharmacol. 8(1371)2018.

|

|

19

|

Hamed M, Zaghloul A, Halawani SH, Fatani

BA, Alshareef B, Almalki A, Alsharif E, ALhothaly QA, Alhadhrami S

and Abd Elmoneim HM: Prevalence of Overweight/obesity associated

with anemia among female medical students at Umm Al-Qura University

in Makkah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus.

16(e57081)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Alshwaiyat NM, Ahmad A, Wan Hassan WMR and

Al-Jamal HAN: Association between obesity and iron deficiency. Exp

Ther Med. 22(1268)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Alshwaiyat NM, Ahmad A and Al-Jamal HAN:

Effect of diet-induced weight loss on iron status and its markers

among young women with overweight/obesity and iron deficiency

anemia: A randomized controlled trial. Front Nutr.

10(1155947)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ahire ED, Pathan AS, Pandagale PM,

Khairnar SJ, Surana KR, Kshirsagar SJ, et al: Role of Dietary in

the Prevention and Management of Obesity. In: The Metabolic

Syndrome. Apple Academic, pp139-161, 2023.

|

|

23

|

Clark P: Iron deficiency related to

obesity. J Infus Nurs. 47:163–174. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Nasif ZN, Eltayef EM, Al-Janabi NM and

Niseaf AN: Relationship of obesity to serum ferritin, lipid

profile, uric acid and urea at obesity medical center in Iraq.

Al-Mustansiriyah J Sci. (29)2018.

|

|

25

|

Turner J, Parsi M and Badireddy M: Anemia.

[Updated 2023 Aug 8]. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Isl StatPearls

Publ, 2024.

|

|

26

|

Vibhute NA, Shah U, Belgaumi U, Kadashetti

V, Bommanavar S and Kamate W: Prevalence and awareness of

nutritional anemia among female medical students in Karad,

Maharashtra, India: A cross-sectional study. J Fam Med Prim care.

8:2369–2372. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Li Z, Yao Z and Liu Q: The association

between white blood cell counts and metabolic health obesity among

US adults. Front Nutr. 12(1458764)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza'ai H, Rahmat A

and Abed Y: Obesity and inflammation: The linking mechanism and the

complications. Arch Med Sci. 13:851–863. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Purdy JC and Shatzel JJ: The hematologic

consequences of obesity. Eur J Haematol. 106:306–319.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wilson CA, Bekele G, Nicolson M, Ravussin

E and Pratley RE: Relationship of the white blood cell count to

body fat: Role of leptin. Br J Haematol. 99:447–451.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wen X, Zhang B, Wu B, Xiao H, Li Z, Li R,

Xu X and Li T: Signaling pathways in obesity: Mechanisms and

therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

7(298)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hsieh CY, Lee WH, Liu YH, Lu CC, Chen SC

and Su HM: Significant impact of body mass index on the

relationship between increased white blood cell count and new-onset

diabetes. Int J Med Sci. 20(359)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Caiati C, Stanca A and Lepera ME: Free

radicals and Obesity-related chronic inflammation contrasted by

antioxidants: A new perspective in coronary artery disease.

Metabolites. 13(712)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Takele Y, Adem E, Getahun M, Tajebe F,

Kiflie A, Hailu A, Raynes J, Mengesha B, Ayele TA, Shkedy Z, et al:

Malnutrition in healthy individuals results in increased mixed

cytokine profiles, altered neutrophil subsets and function. PLoS

One. 11(e0157919)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Alrubaie A, Majid S, Alrubaie R and Kadhim

FAZB: Effects of body mass index (BMI) on complete blood count

parameters. Inflammation. (8)2019.

|

|

36

|

Rumińska M, Witkowska-Sędek E,

Artemniak-Wojtowicz D, Krajewska M, Majcher A, Sobol M and Pyrżak

B: Changes in leukocyte profile and C-reactive protein

concentration in overweight and obese adolescents after reduction

of body weight. Cent Eur J Immunol. 44:307–315. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Anık A, Çelik E and Anık A: The relation

of complete blood count parameters with metabolic and clinical

parameters in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr Res.

8:161–170. 2021.

|

|

38

|

Jamshidi L and Seif A: Association between

obesity, white blood cell and platelet count. Zahedan J Res Med

Sci. 19(e4955)2017.

|

|

39

|

Vilahur G, Ben-Aicha S and Badimon L: New

insights into the role of adipose tissue in thrombosis. Cardiovasc

Res. 113:1046–1054. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hussain A, Ali I, Kaleem WA and Yasmeen F:

Correlation between body mass index and lipid profile in patients

with type 2 Diabetes attending a tertiary care hospital in

Peshawar. Pakistan J Med Sci. 35:591–597. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Akcan T and Kraemer FB: HDL meets

triglyceride. J Lipid Res. 66(100796)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Turki KM, Hadi Alosami M and Hasan

Abdul-Qahar Z: The effect of obesity on serum leptin and lipid

profile. Iraqi Postgrad Med J. 1:27–32. 2009.

|

|

43

|

Shamai L, Lurix E, Shen M, Novaro GM,

Szomstein S, Rosenthal R, Hernandez AV and Asher CR: Association of

body mass index and lipid profiles: Evaluation of a broad spectrum

of body mass index patients including the morbidly obese. Obes

Surg. 21:42–47. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kawamoto R, Tabara Y, Kohara K, Miki T,

Kusunoki T, Takayama S, Abe M, Katoh T and Ohtsuka N: Low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol to High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

ratio is the best surrogate marker for insulin resistance in

non-obese Japanese adults. Lipids Health Dis. 9(138)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Raja AWK, Liaquat HK, Abdul RK, Kamran A

and Khawaja AY: An Association of Blood Sugar. Cholest

Triglycerides with Obes Hum Subj from Muzaffarabad Azad Kashmir,

Pakistan. Curr Res Diabetes Obesity J. 13(555861)2020.

|

|

46

|

Cabler S, Agarwal A, Flint M and Du

Plessis SS: Obesity: Modern man's fertility nemesis. Asian J

Androl. 12(480)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Alaamri S, Serafi AS, Hussain Z, Alrooqi

MM, Bafail MA and Sohail S: Blood pressure correlates with serum

leptin and body mass index in overweight male Saudi students. J

Pers Med. 13(828)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Almabhouh FA, Md Mokhtar AH, Malik IA,

Aziz NAAA, Durairajanayagam D and Singh HJ: Leptin and reproductive

dysfunction in obese men. Andrologia. 52(e13433)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Malik IA, Durairajanayagam D and Singh HJ:

Leptin and its actions on reproduction in males. Asian J Androl.

21:296–299. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kazmi A, Sattar A, Hashim R, Khan SP,

Younus M and Khan FA: Serum leptin values in the healthy obese and

non-obese subjects of Rawalpindi. J Pak Med Assoc. 63:245–248.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bernotiene E, Palmer G and Gabay C: The

role of leptin in innate and adaptive immune responses. Arthritis

Res Ther. 8(217)2006.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Naylor C and Petri WA: Leptin regulation

of immune responses. Trends Mol Med. 22:88–98. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Erusan RR, Nalini D, Manohar G and Malathi

R: Correlation between obesity and inflammation in cardiovascular

diseases-evaluation of leptin and inflammatory cytokines. Open J

Endocr Metab Dis. 2:7–15. 2012.

|

|

54

|

Paz-Filho G, Mastronardi C, Franco CB,

Wang KB, Wong ML and Licinio J: Leptin: Molecular mechanisms,

systemic pro-inflammatory effects, and clinical implications. Arq

Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 56:597–607. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Docanto MM, Ham S, Corbould A and Brown

KA: Obesity-associated inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E2

stimulate glucose transporter mRNA expression and glucose uptake in

primary human adipose stromal cells. J Interf Cytokine Res.

35:600–665. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Ateia YA, Saleh EM, Abdullah TN and Al

Musawee Z: Levels of some proinflammatory cytokines in obese women

with polycystic ovary syndrome after metformin therapy. Al-Kindy

Coll Med J. 9:45–48. 2013.

|

|

57

|

Enayati S, Seifirad S, Amiri P, Abolhalaj

M and Mohammad-Amoli M: Interleukin-1 beta, interferon-gamma, and

tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene expression in peripheral blood

mononuclear cells of patients with coronary artery disease. ARYA

Atheroscler. 11(267)2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Lim J, Yang EJ and Chang JH: Upregulation

of TNF-α by triglycerides is mediated by MEK1 activation in jurkat

T cells. Biomed Sci Lett. 24:213–220. 2018.

|

|

59

|

Ullah MI, Alzahrani B, Alsrhani A, Atif M,

Alameen AAM and Ejaz H: Determination of serum tumor necrosis

factor-alpha (TNF-α) levels in metabolic syndrome patients from

Saudi population. Pakistan J Med Sci. 37(700)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Hotamisligil GS: Inflammation and

metabolic disorders. Nature. 444:860–867. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Mallick R, Basak S, Das RK, Banerjee A,

Paul S, Pathak S and Duttaroy AK: Fatty acids and their proteins in

adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Biochem Biophys. 82:35–51.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|